Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0608-10073. The contractual start date was in April 2010. The final report began editorial review in March 2018 and was accepted for publication in December 2019. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Fitzmaurice et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

This programme of work comprises three interconnecting work packages:

-

a RCT of extended anticoagulation treatment versus standard treatment for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) and post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) [the ExACT (Extended Anticoagulation) trial]

-

a qualitative study to explore existing knowledge and barriers, across the spectrum of health care from patients to health-care professionals (HCPs) [the ExPeKT (Exploration of Patient knowledge and expectation) study]

-

a health economic modelling study to evaluate the most cost-effective methods of treating and preventing recurrence of VTE.

Protocols for the ExACT trial [work package (WP) 1]1 and the ExPeKT study (WP2)2 have been published. These WPs are summarised in Table 1 and detailed in subsequent pages of the report.

| Work package | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| WP1: the ExACT RCT | First patient recruited July 2011 | Last patient recruited February 2015 | Last patient follow-up February 2017 | |||||

| WP2: the ExPeKT studies | HCP interviews | |||||||

| Patient interviews | ||||||||

| WP3: health economic analysis | Data collection | |||||||

| Modelling June 2017 to February 2018 | ||||||||

Background

Venous thromboembolism, defined as deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is the third most common cardiovascular disorder, after myocardial infarction and stroke. DVT is common (i.e. an incidence of approximately 1 per 1000 people per annum) and is associated with mortality and serious morbidity, particularly PE and PTS.

The largest attributable risk for acquiring VTE is hospital admission for either medical or surgical conditions. Most hospitalised patients have one or more risk factors for VTE,3 with mortality from hospital-acquired thrombosis (HAT) greater than the combined total number of deaths from breast cancer, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and road traffic accidents each year in the UK. There is evidence to show that around 60% of people undergoing hip or knee replacement will suffer a DVT if they receive no preventative intervention, and that the mortality rate is around 30% if this is left untreated. 4

Venous thromboembolism is therefore a substantial health-care problem that is associated with significant mortality, morbidity and economic cost. In 2005, there was an estimated cost to the NHS of £640M for the management of VTE. 5

Some people suffer an unprovoked DVT, where no identifiable reason for the DVT can be found. These unprovoked DVTs are treated with oral anticoagulation therapy (OAT), which generally continues for between 6 weeks and 6 months. However, the optimal duration of treatment is still uncertain. 6 When OAT is discontinued, there is an annual recurrence rate of approximately 10% in the first year and around 5% thereafter, irrespective of the duration of treatment.

Prevention of venous thromboembolism

Hospital-acquired thrombosis

The largest risk for acquiring VTEs is hospital admission. 4 Current UK guidelines for preventing HAT recommend using the Department of Health and Social Care’s risk assessment tool to assess appropriate thromboprophylaxis for individuals. 7 Thromboprophylaxis has been shown to reduce the risk of VTE by 75% in surgical patients and 50% in medical patients.

In 2010, Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) agreements were introduced that required all UK acute trusts to assess risk for VTEs for at least 90% of patients, or risk financial penalties. 8 However, an All-Party Parliamentary Thrombosis Group (APPTG) survey found that implementation of risk assessment was poor,9 and only 58% of trusts carry out a regular clinical audit of thromboprophylaxis. Furthermore, HAT can occur up to 90 days post discharge, but there is little or no understanding of the role that primary care can play in the process; there is also no evidence of the use of care plans for community VTE prophylaxis.

Unprovoked deep-vein thrombosis

The risk of recurrence among patients with unprovoked thrombosis is higher than for those with identifiable risk factors, such as surgery or long-haul travel. The cumulative rate of recurrence for those with unprovoked VTE is about 25% at 5 years and 30% at 10 years.

The risk varies with time, with the highest risk evident during the first 6–12 months; the risk never reaches zero. Furthermore, these recurrent events are fatal in about 5–9% of people. Most recurrences can be prevented by appropriate antithrombotic therapy, but there is a concern in terms of the duration of treatment owing to the increased risk of bleeding from prolonged OAT.

Several studies have investigated the optimal duration of OAT, with the British Committee for Standards in Haematology recommending between 6 weeks and 6 months, depending on the aetiology. 6 However, the optimal duration of OAT for patients with a first unprovoked DVT remains uncertain, with randomised controlled trials (RCTs) suggesting that the duration has little effect on the rate of recurrence. 10 Research to address the most appropriate approach to preventing recurrences is still required.

Identification of patients at the highest risk of recurrence

Given the balance of risks and benefits of anticoagulation therapy (AT) described above, it may be beneficial to identify those at the highest risk of recurrence. It may be possible to stratify individual risk based on a variety of clinical factors, including sex or comorbidities, or to measure laboratory markers such as coagulation factors. Alternatively, risk prediction models can be used, such as the Vienna Prediction Model, although this is most accurate in people already at low risk of recurrence. 11 There is evidence that normal D-dimer levels, measured around 4 weeks after cessation of OAT, are associated with lower risk of recurrence. 12

D-dimer is a fibrin degradation product present in the blood after a blood clot is degraded by fibrinolysis; levels of D-dimer can be tested using laboratory and point-of-care testing devices. The primary clinical use of levels of D-dimer has been in conjunction with probability scores to determine whether or not further investigation is required for the diagnosis of VTE.

More recently, interest has been shown in studies that have investigated whether or not the levels of D-dimer can be utilised as a guide for determining who is at risk of recurrent VTE following treatment of the initial acute episode. Some small studies have suggested that the levels of D-dimer could act as a useful predictor of recurrent VTE in patients whose OAT is discontinued. 13 There are limited data on the utility of levels of D-dimer as a predictor in patients still on therapy, but Rodgers et al. 14 have shown that the levels of D-dimer can be used to predict recurrence in low-risk female patients. Two systematic reviews of D-dimer testing after cessation of treatment for VTE (seven studies with total of 1888 patients) concluded that ‘additional research is needed to establish the optimal interval between stopping anticoagulation and performing D-dimer testing, (and) to identify the optimum cut-off point that predicts recurrence’. 14

No studies to date have investigated the utility of D-dimer testing while a patient is still undergoing therapy, and there are no studies that have investigated the utility of D-dimer testing in conjunction with clinical algorithms to prevent recurrence of DVT.

Post-thrombotic syndrome

Post-thrombotic syndrome is a frequent and costly complication of DVT that can lead to chronic venous insufficiency and ulceration, and reduced quality of life for patients. Prevalence of PTS in one study was found to be 37% after 2.2 years, with 4% of people having severe PTS. 15 PTS has a cumulative incidence after 2 years of around 25%, and it has been postulated that prolonged treatment with OAT could prevent the development of PTS. 16 However, the only randomised data available suggested no association between long-term low-dose warfarin treatment and the development of PTS,15 and there are no data available for patients treated with long-term therapeutic warfarin.

Barriers to implementation of thromboprophylaxis

For the reasons discussed above, the prevention of VTE and appropriate management of the risk of recurrence is important. However, despite the introduction of guidelines8 and CQUIN agreements, it seems that the guidelines and recommendations are not universally implemented.

It is known that there is little knowledge about VTE in the public arena,4 which is perhaps unsurprising, as it is apparent that HCPs also underestimate the extent and impact of the problem. The APPTG report highlighted the role that primary care could play in improving the management of VTE. 17 General practitioners (GPs) are in a good position to deliver education to patients, and to improve the management of patients post hospital discharge. However, there is little evidence to date of the use of care plans for community VTE prophylaxis.

When considering patient barriers, diabetes studies have shown the desire to avoid injectable drugs, so low-molecular-weight heparin therapy may, therefore, introduce concordance issues. 18 Patients were educated about the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, a life-threatening, immune-mediated prothrombotic adverse drug effect. Patients appreciated the information about the potential adverse reactions to the drug; the information given did not lead to a treatment refusal, with all patients choosing treatment. 19

The lack of public awareness could be addressed through public education programmes, as improving understanding will empower patients with the knowledge to request a risk assessment on admission to hospital. 20 However, we do not know patients’ attitudes to education and information in this area. Furthermore, we do not know how best to deliver this information; no educational measures have been developed.

The HCP barriers to initiating VTE prophylaxis may be manifold. There is some evidence that non-adherence to guidelines is an issue for clinicians but barriers to implementation are unclear. Knowledge to practice translational issues are extremely important for the successful integration of thromboprophylaxis into the community and clarity around processes is necessary.

The guidelines stipulate a supporting role for GPs, based on notification that a patient has been discharged from hospital and the treatment prescribed. However, communication between care settings is known to be problematic, leading to the role performed by primary care being unclear. If primary care is to contribute more effectively to the prevention of HAT, then a better understanding of its role and of the factors that influence the role is required.

Summary

The VTE prevention and treatment programme was designed to provide an evidence base to improve the prevention and treatment of VTE in the NHS, through addressing some of the existing gaps in the evidence, as discussed above. The programme consists of a series of studies including a RCT; a survey of stakeholders; qualitative interviews with patients, doctors, nurses and other stakeholders; cost-effectiveness analyses; patient preference survey; and a number of economic modelling studies. Each work package is detailed below.

Patient and public involvement

Mrs Eve Knight, Director of Anticoagulation Europe, a patient-based charitable organisation, was involved in this programme from its conception and continued to provide input throughout the lifetime of the programme as a member of the Programme Board. She approved all patient-facing material and also contributed to the develoment of the interview schedule for WP2. The charity was not involved in the identification of patients for the programme. The programme of work was reviewed and edited by the two public representatives on the Primary Care Research Network, Central England (PCRN-CE) Management Group.

Work package 1: randomised controlled trial of extended anticoagulation treatment versus standard treatment for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism and post-thrombotic syndrome in patients being treated for a first episode of unprovoked venous thromboembolism (the ExACT trial)

Overview

The background section described the existing evidence around the most appropriate treatment to prevent recurrent clots in people who have had a first unprovoked VTE, and the identification of people likely to be at the highest risk of recurrence. Uncertainty remains about the optimum duration of anticoagulation treatment following a first unprovoked VTE, and there is no clear guidance to help clinicians identify those at a high risk of recurrence. There is also a lack of data available around the use of anticoagulation treatment to prevent the development of PTS. This work package aimed to address these gaps in the knowledge.

This section reports on the ExACT trial. The cost analysis and patient preference study are presented in subsequent sections.

The ExACT trial was approved by Trent Research Ethics Committee on 21 October 2010.

Methods

The ExACT trial was a non-blinded, prospective, multicentre RCT. The full methods of the ExACT trial have been published. 1,21 The methods are further described in Appendix 1.

Aim

The aim of the ExACT trial was to investigate the effect of extending treatment with oral anticoagulation for those patients with first unprovoked proximal DVT or PE prior to discontinuing treatment, in terms of reduction in incidence of VTE and PTS.

Objectives

-

To determine the protective effect of prolonged AT on recurrent events of DVT or PE.

-

To determine the protective effect of prolonged AT on the severity of PTS.

-

To establish the performance characteristics of D-dimer testing while still on treatment as a prediction tool for recurrence of VTE in patients with first unprovoked proximal DVT or PE.

-

To establish factors that contribute to the recurrence of VTE in patients with a first unprovoked proximal DVT or PE.

-

To determine the cost-effectiveness of extended treatment with anticoagulation (described in WP3).

-

To determine patient preferences and utilities with regard to extended anticoagulation treatment (described in WP3).

Sample size calculation

The study was designed to compare 2-year VTE recurrence rates between participants in the extended versus discontinued AT arms, and also to compare these rates for a group of participants with a baseline raised levels of D-dimer. A sample size of 352 (176 per arm) would be sufficient to detect a clinically important difference between the arms with minimum 86% power, two-sided alpha = 0.05, assuming recurrence rates between 1.4% and 4.3% for the extended AT arm and 14.2% in the discontinued AT arm. Recruitment was lower than expected and, at the request of the Trial Steering Committee, the power calculation was re-estimated, as a result of which it was determined that a sample of 270 participants (allowing for 10% loss to follow-up) would provide at least 80% power to detect the planned effect sizes.

Summary of changes to the protocol (version 2.11)

-

We listed an additional objective (to determine the protective effect of prolonged AT on the severity of PTS) that was included as a planned secondary outcome in the protocol but was not detailed in the objectives.

-

We clarified that VTE and bleeding events are time-to-event outcomes.

-

We excluded the second analysis outlined in section 4.1 of protocol version 2.11 (number of recurrent thrombotic events between those with a raised level of D-dimer who were randomly allocated to the no-treatment arm and those with normal levels of D-dimer who were randomly allocated to the no-treatment arm), as the first analysis listed in this section is the only subgroup analysis required to investigate the cut-off point analysis.

Results

Participant recruitment

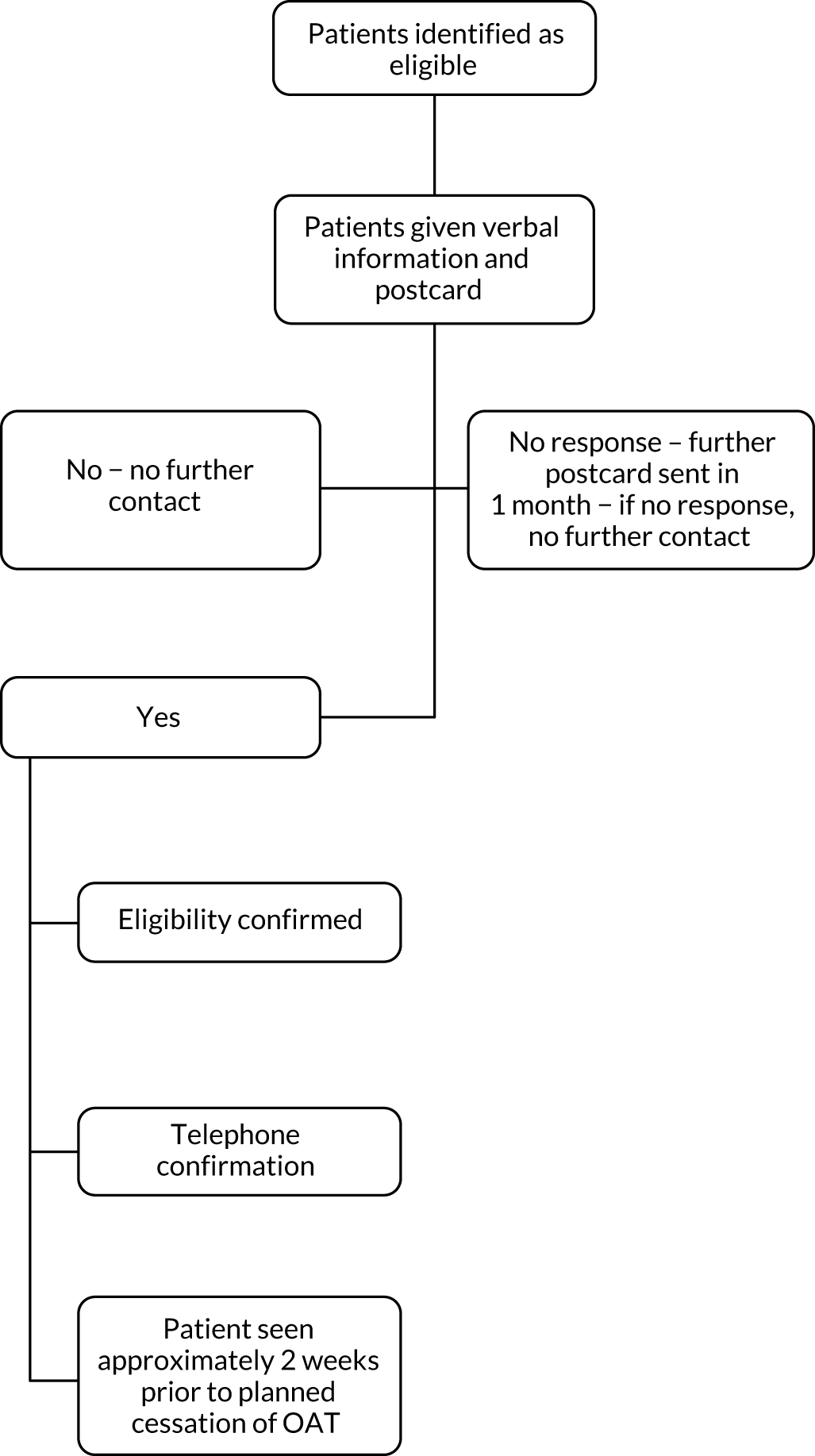

The first patient was randomised in July 2011 and the last patient was randomised in February 2015. The records of 8422 patients presenting to the recruiting sites with a suspected DVT/PE were screened to identify potentially eligible patients who met the inclusion criteria. Following application of the criteria, 5034 patients were identified as ineligible for invitation to participate. Invitations to participate in the trial in the form of postcards and participant information sheets were provided to 3388 potentially eligible patients. Responses were received from 1361 out of 3388 (40%) potentially eligible patients, with 993 out of 1361 (73%) notifying the research team that they were interested in participating in the study and providing their permission for the research team to contact their GP to confirm their eligibility to participate. Overall, 368 out of 3388 (11%) patients responded stating that they did not wish to participate. Responses to the invitation were not returned by 2027 out of 3388 (60%) patients (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Patient flow diagram. a, Data for suspected DVT or PE are taken from site screening logs and are therefore only estimates of the total number with DVT or PE.

The GPs of the 993 potentially eligible patients were contacted to confirm patient eligibility to take part. GPs confirmed eligibility for 393 out of 993 (40%) patients, and 499 out of 993 (50%) were ineligible. GPs did not complete the eligibility checks for 101 out of 993 (10%) patients. The main reasons for exclusion were that the patient had recently stopped oral anticoagulation (20%), they had an indication for long-term OAT (15%) and they had a provoked DVT or PE (14%). The reasons for ineligibility were not reported for 112 out of 499 (22%) patients.

A total of 281 patients provided written informed consent to participate and were randomised: 141 were randomly allocated to the intervention arm of the study (group E) and 140 to the control arm (group D) of the study. All 281 trial participants attended visit 1, 273 (97%) attended visit 2, 263 (94%) attended visit 3 and 260 attended (93%) visit 4 (Figure 2). Post oral anticoagulation cessation visits were completed by 182 out of 281 (65%) participants.

FIGURE 2.

Patient flow diagram following randomisation. a, Includes four participants who withdrew consent to use their data; b, includes one participant who withdrew consent to use their data; and c, includes two patients receiving rivaroxaban (Xarelto; Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany) therapy.

Baseline characteristics

No differences were found in baseline characteristics between the intervention and control groups (Table 2). The mean age of participants was around 63 years, with a roughly even split between DVT and PE, and approximately two-thirds of participants were male.

| Characteristic | Trial group | Total (N = 273) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (group D) (N = 134) | Intervention (group E) (N = 139) | ||

| Age at time of randomisation (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 63.3 (12.7) | 62.2 (13.0) | 62.7 (12.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 64.5 (55.6–74.0) | 64.4 (53.3–72.4) | 64.4 (54.4–72.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 44 (32.8) | 45 (32.4) | 89 (32.6) |

| Male | 90 (67.2) | 94 (67.6) | 184 (67.4) |

| Diagnosis (DVT/PE),a n (%) | |||

| Unprovoked DVT | 69 (51.5) | 70 (50.4) | 139 (50.9) |

| Unprovoked PE | 65 (48.5) | 69 (49.6) | 134 (49.1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 131 (97.8) | 131 (94.2) | 262 (96.0) |

| Mixed | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Asian or Asian British | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.2) | 3 (1.1) |

| Black or black British | 2 (1.5) | 5 (3.6) | 7 (2.6) |

| Other ethnic groups | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Non-smoker | 63 (47.0) | 60 (43.2) | 123 (45.1) |

| Ex-smoker | 48 (35.8) | 60 (43.2) | 108 (39.6) |

| Current smoker | 19 (14.2) | 18 (13.0) | 37 (13.6) |

| Smokes occasionally | 4 (3.0) | 1 (0.7) | 5 (1.8) |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | |||

| No | 44 (32.8) | 51 (36.7) | 95 (34.8) |

| Yes | 90 (67.2) | 88 (63.3) | 178 (65.2) |

| BMI classification (kg/m2), n (%) | |||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| Normal range (18.5–24.99) | 47 (35.1) | 47 (33.8) | 94 (34.4) |

| Overweight (25–29.99) | 51 (38.1) | 53 (38.1) | 104 (38.1) |

| Obese (≥ 30) | 33 (24.6) | 37 (26.6) | 70 (25.6) |

| Missing | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| Family history of VTE, n (%) | |||

| No | 102 (76.1) | 102 (73.4) | 204 (74.7) |

| Yes | 32 (23.9) | 37 (26.6) | 69 (25.3) |

| Medical history | |||

| Stroke, n (%) | |||

| No | 130 (97.0) | 136 (97.8) | 266 (97.4) |

| Yes | 4 (3.0) | 3 (2.2) | 7 (2.6) |

| Transient ischaemic attack, n (%) | |||

| No | 129 (96.3) | 138 (99.3) | 267 (97.8) |

| Yes | 5 (3.7) | 1 (0.7) | 6 (2.2) |

| Angina, n (%) | |||

| No | 129 (96.3) | 136 (97.8) | 265 (97.1) |

| Yes | 5 (3.7) | 3 (2.2) | 8 (2.9) |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | |||

| No | 133 (99.3) | 134 (96.4) | 267 (97.8) |

| Yes | 1 (0.8) | 5 (3.6) | 6 (2.2) |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | |||

| No | 130 (97.0) | 136 (97.8) | 266 (97.4) |

| Yes | 4 (3.0) | 3 (2.2) | 7 (2.6) |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | |||

| No | 134 (100.0) | 134 (96.4) | 268 (98.2) |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.6) | 5 (1.8) |

| PTS score (categorical), n (%) | |||

| No PTS | 70 (52.2) | 66 (47.5) | 136 (49.8) |

| Mild PTS | 42 (31.3) | 51 (36.7) | 93 (34.1) |

| Moderate PTS | 15 (11.2) | 18 (13.0) | 33 (12.1) |

| Severe PTS | 5 (3.7) | 2 (1.4) | 7 (2.6) |

| Missing | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (1.5) |

| PTS score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.2 (4.2) | 5.1 (3.8) | 5.2 (4.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0–7.5) | 5.0 (2.0–8.0) | 4.0 (2.0–8.0) |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| EQ-5D-3L | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) |

| Missing | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| VEINES-QOL score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 48.2 (10.7) | 49.6 (9.9) | 48.9 (10.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 51.1 (41.1–57.6) | 53.0 (44.6–56.7) | 52.1 (43.3–57.5) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Health-care utilisation because of PTS | |||

| Patient receiving primary care treatment, n (%) | |||

| No | 124 (92.5) | 128 (92.1) | 252 (92.3) |

| Yes | 9 (6.7) | 11 (7.9) | 20 (7.3) |

| Missing | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Type of nurse patients were seen by, n (%) | |||

| Practice | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (1.1) |

| District | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| HCA | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| None | 59 (44.0) | 70 (50.4) | 129 (47.3) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing | 73 (54.5) | 68 (48.9) | 141 (51.7) |

| Patient receiving treatment for a leg ulcer, n (%) | |||

| No | 66 (49.3) | 71 (51.1) | 137 (50.2) |

| Yes | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| Missing | 67 (50.0) | 66 (47.5) | 133 (48.7) |

| Patient receiving secondary care treatment, n (%) | |||

| No | 131 (97.8) | 135 (97.1) | 266 (97.4) |

| Yes | 1 (0.8) | 4 (2.9) | 5 (1.8) |

| Missing | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) |

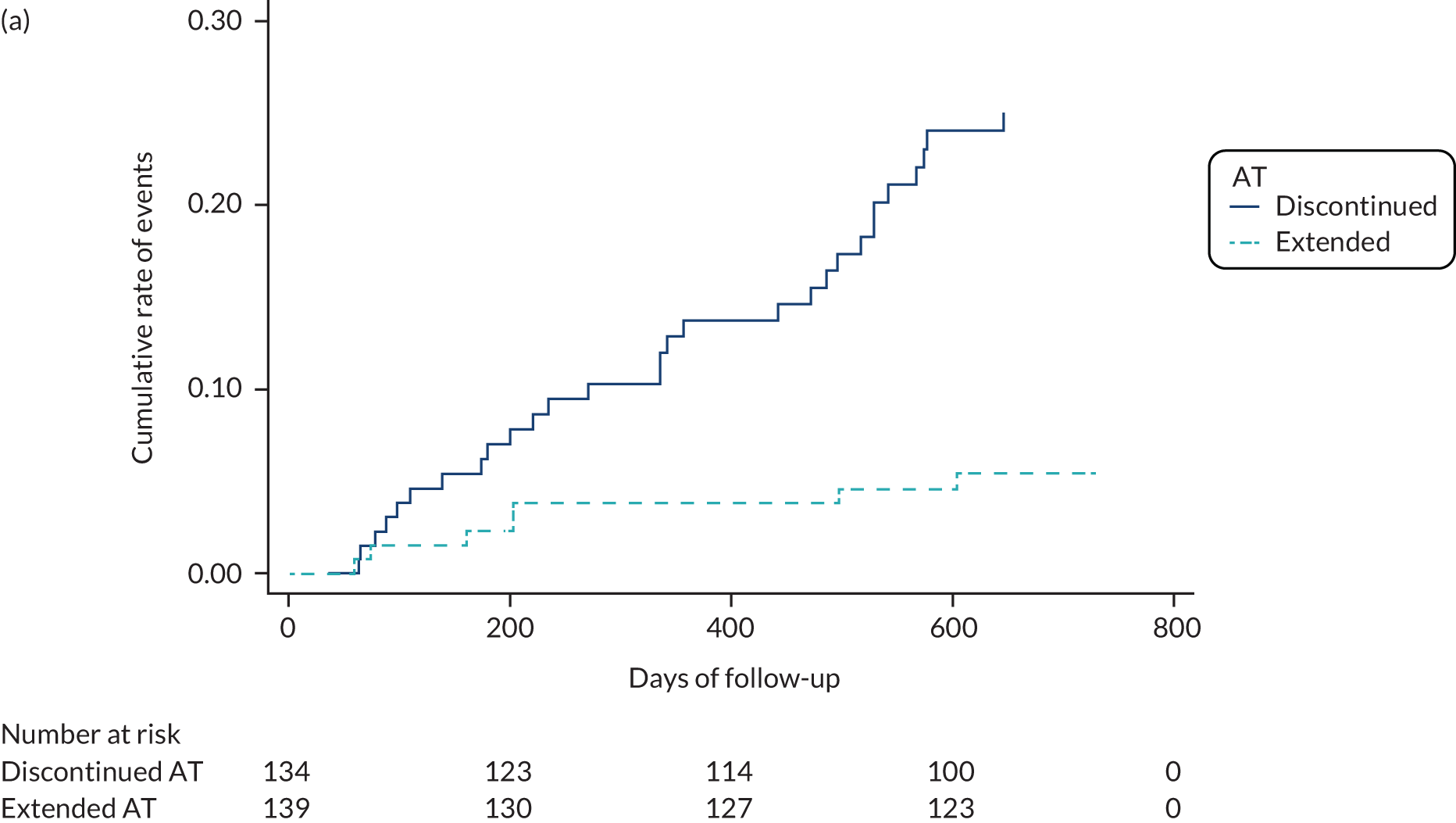

Primary outcome

In terms of the primary outcome, there were 32 recurrent VTEs in 31 patients (13.54 events per 100 person-years) within the control group (group D) compared with seven events in seven patients (2.75 events per 100 person-years) in the intervention group (group E). This gave an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.2 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.09 to 0.46; p < 0.001], meaning that patients receiving extended AT were 80% less likely to suffer a recurrent event than those patients who discontinued AT (Table 3 and Figure 3). Age did not affect the rate of recurrence in either group, but males had numerically more recurrences off treatment than females. The intervention effect does not differ significantly between the two age groups (p = 0.267), but the intervention group (group E) had significantly reduced VTE recurrences than the control group (group D) in males (adjusted hazard ratio 0.11, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.38) but not in females (adjusted hazard ratio 0.48, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.59), even though the associated interaction effect is not significant at the 5% level (p = 0.099) (see Table 4).

| Outcome | Trial group | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (group D) (N = 134) | Intervention (group E) (N = 139) | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Recurrent VTE | ||||

| Number of participants with one or more events, n (%) | 31 (23.1) | 7 (5.0) | 0.20 (0.09 to 0.46) | < 0.001 |

| Number of eventsb | 32 | 7 | ||

| Number of events per 100 person-yearsc | 13.54 | 2.75 | ||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Major bleeding events | ||||

| Number of participants with one or more events, n (%) | 3 (2.2) | 9 (6.5) | 2.99 (0.81 to 11.05) | 0.100 |

| Number of events | 3 | 9 | ||

| Number of events per 100 person-yearsc | 1.18 | 3.54 | ||

| Clinically relevant non-major bleeding events | ||||

| Number of participants with one or more events and non-missing event dates,d n (%) | 19 (14.2) | 28 (20.1) | 1.51 (0.84 to 2.71) | 0.165 |

| Number of participants with one or more events,d n (%) | 21 (15.7) | 32 (23.0) | ||

| Number of eventsd | 25 | 43 | ||

| Number of events per 100 person-yearsc | 8.13 | 12.50 | ||

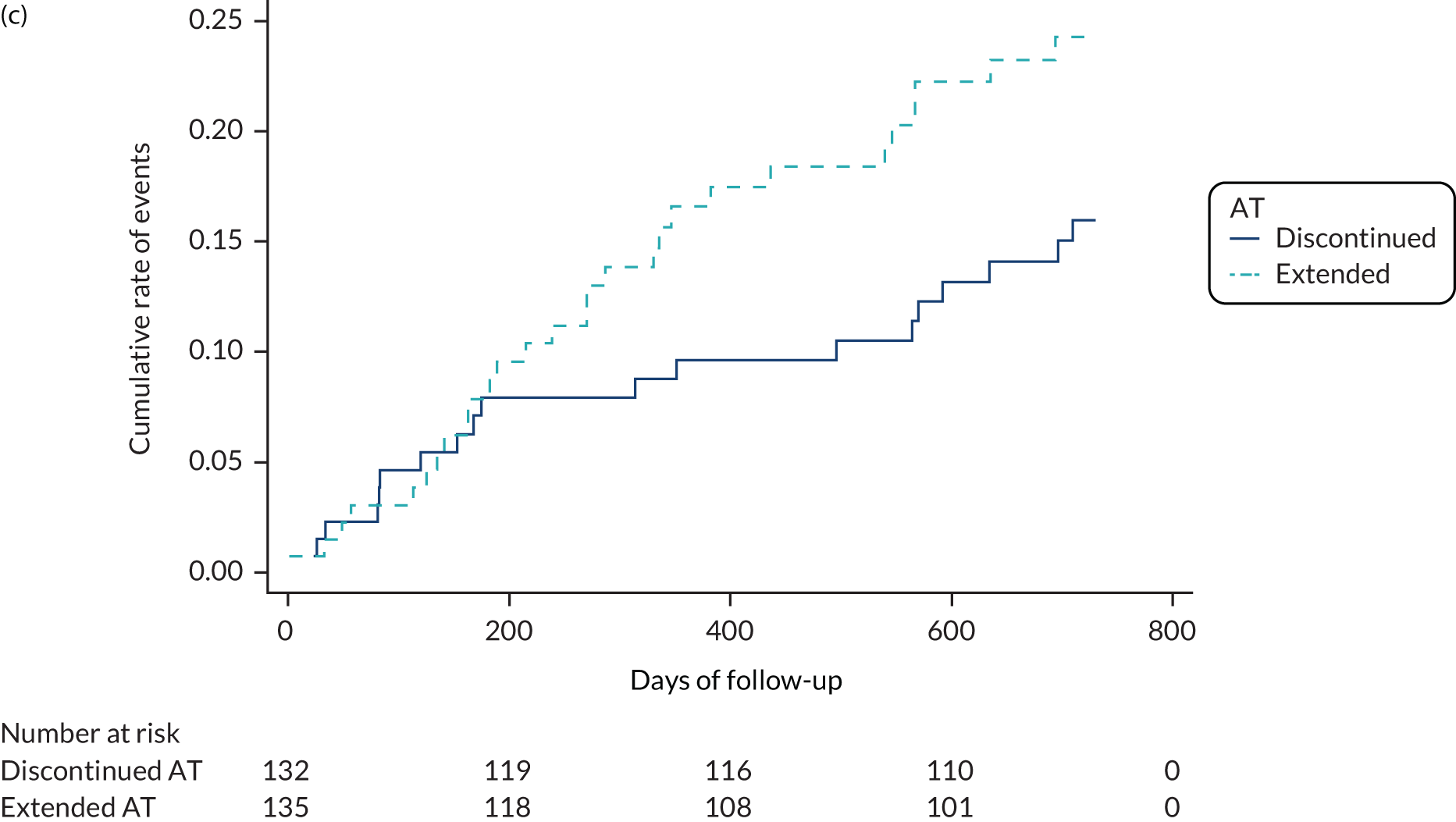

FIGURE 3.

Cumulative risk of the primary outcome of time to first recurrent VTE (a) and of the secondary outcomes of time to first major bleeding (b), and time to first clinically relevant non-major bleeding event (c) between discontinued AT and extended AT.

Secondary outcomes

There were three major bleeding events (1.18 events per 100 person-years) in the control group (group D) and nine major bleeding events (3.54 events per 100 person-years) in the intervention group (group E), giving an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.99 (95% CI 0.81 to 11.05; p = 0.10). There were 19 clinically relevant non-major bleeding events (8.13 events per 100 person-years) in the control group (group D) and 28 clinically relevant non-major bleeding events (12.50 events per 100 person-years) in the intervention group (group E), giving an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.51 (95% CI 0.84 to 2.71; p = 0.165). These differences were not statistically significant (see Table 3 and Figure 3). In both groups, more people aged > 65 years experienced bleeding (Table 4).

| Characteristic | Trial group | Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | p-value for interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (group D) (n = 134) | Intervention (group E) (n = 139) | |||||

| Number of events (%) | Number of events per 100 person-years | Number of events (%) | Number of events per 100 person-years | |||

| Recurrent VTE | ||||||

| Sex | 0.099 | |||||

| Male | 23 (25.6) | 15.26 | 3 (3.2) | 1.75 | 0.11 (0.03 to 0.38) | |

| Female | 8 (18.2) | 10.23 | 4 (8.9) | 4.83 | 0.48 (0.14 to 1.59) | |

| Age (years) | 0.267 | |||||

| ≤ 65 | 17 (23.3) | 13.77 | 2 (2.8) | 1.52 | 0.11 (0.03 to 0.48) | |

| > 65 | 14 (23.0) | 13.28 | 5 (7.5) | 4.07 | 0.31 (0.11 to 0.85) | |

| Major bleeding events | ||||||

| Sex | 0.961 | |||||

| Male | 2 (2.2) | 1.18 | 6 (6.4) | 3.57 | 2.92 (0.59 to 14.48) | |

| Female | 1 (2.3) | 1.18 | 3 (6.7) | 3.49 | 3.13 (0.33 to 30.12) | |

| Age (years) | 0.190 | |||||

| ≤ 65 | 2 (2.7) | 1.45 | 2 (2.8) | 1.50 | 1.01 (0.14 to 7.17) | |

| > 65 | 1 (1.6) | 0.86 | 7 (10.5) | 5.79 | 6.89 (0.85 to 56.03) | |

The D-dimer levels pre-randomisation showed no difference in terms of risk of recurrence. Although a higher percentage of those patients with VTE recurrence had a baseline D-dimer level > 0.5 µg/l, this was not statistically significant (Table 5). Further work is being done as part of an ongoing Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) project to investigate whether or not there is an alternative cut-off point for D-dimer levels while still on therapy, which might be predictive of further events.

| D-dimer level at baseline | Recurrence, n (%) | Total (n = 273), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No recurrence (n = 235) | Recurrent VTE (n = 38) | ||

| < 0.5 µg/l (%) | 216 (91.91) | 33 (86.84) | 249 (91.21) |

| ≥ 0.5 µg/l (%) | 9 (3.83) | 3 (7.89) | 12 (4.40) |

| Missing | 10 (4.26) | 2 (5.26) | 12 (4.40) |

Similarly, there was no significant difference in time in therapeutic range for patients on extended treatment between those with or without recurrence, but the number of participants was small (Table 6).

| Therapeutic range | Recurrence | Total (n = 121) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No recurrence (n = 116) | Recurrent VTE (n = 5)a | ||

| Mean (SD) | 76.27 (15.27) | 83.93 (13.86) | 76.59 (15.24) |

| Median (IQR) | 77.03 (67.81–86.53) | 76.95 (75.22–97.63) | 77.02 (68.21–86.66) |

In terms of the quality of life and PTS outcomes, there were no differences between the groups (Table 7).

| Outcome | AT | p-value for time–treatment interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinued (n = 134) | Extended (n = 139) | ||||

| n | Adjusted meana (95% CI) | n | Adjusted meana (95% CI) | ||

| VEINES-QOL | 0.766 | ||||

| 6 months | 118 | 50.13 (48.98 to 51.29) | 126 | 49.87 (48.74 to 51.00) | |

| 12 months | 116 | 50.13 (48.97 to 51.29) | 124 | 50.34 (49.20 to 51.48) | |

| 18 months | 112 | 50.74 (49.57 to 51.91) | 117 | 50.20 (49.04 to 51.35) | |

| 24 months | 108 | 50.33 (49.14 to 51.51) | 120 | 50.30 (49.16 to 51.45) | |

| EQ-5D-3L | 0.908 | ||||

| 6 months | 118 | 0.80 (0.76 to 0.83) | 126 | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.84) | |

| 12 months | 117 | 0.81 (0.77 to 0.84) | 124 | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.85) | |

| 18 months | 113 | 0.82 (0.79 to 0.86) | 117 | 0.82 (0.79 to 0.86) | |

| 24 months | 108 | 0.82 (0.79 to 0.85) | 120 | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.85) | |

| Severity of PTSb | 0.907 | ||||

| 6 months | 117 | 4.77 (4.24 to 5.30) | 126 | 4.73 (4.22 to 5.25) | |

| 12 months | 116 | 4.68 (4.14 to 5.21) | 123 | 4.88 (4.36 to 5.40) | |

| 18 months | 111 | 4.73 (4.19 to 5.28) | 115 | 4.96 (4.43 to 5.49) | |

| 24 months | 110 | 5.00 (4.45 to 5.54) | 120 | 5.09 (4.57 to 5.62) | |

| Outcome | AT | p-value for time–treatment interaction | |||

| Discontinued (n = 134) | Extended (n = 139) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Category of PTSb | |||||

| 6 months | |||||

| None (0–4) | 66 | 49.25 | 71 | 51.08 | |

| Mild (5–9) | 42 | 31.34 | 36 | 25.90 | |

| Moderate (10–14) | 7 | 5.22 | 15 | 10.79 | |

| Severe (≥ 15) | 2 | 1.49 | 4 | 2.88 | |

| 12 months | |||||

| None (0–4) | 67 | 50.00 | 71 | 51.08 | |

| Mild (5–9) | 38 | 28.36 | 38 | 27.34 | |

| Moderate (10–14) | 10 | 7.46 | 10 | 7.19 | |

| Severe (≥ 15) | 1 | 0.75 | 4 | 2.88 | |

| 18 months | |||||

| None (0–4) | 63 | 47.01 | 63 | 45.32 | |

| Mild (5–9) | 39 | 29.10 | 37 | 26.62 | |

| Moderate (10–14) | 8 | 5.97 | 11 | 7.91 | |

| Severe (≥ 15) | 1 | 0.75 | 4 | 2.88 | |

| 24 months | |||||

| None (0–4) | 66 | 49.25 | 65 | 46.76 | |

| Mild (5–9) | 29 | 21.64 | 37 | 26.62 | |

| Moderate (10–14) | 11 | 8.21 | 12 | 8.63 | |

| Severe (≥ 15) | 4 | 2.99 | 6 | 4.32 | |

Discussion

Work package 1 adds to the accumulating evidence base that patients with a first unprovoked VTE, either DVT or PE, can benefit from prolonged anticoagulation in terms of reducing recurrence of VTE with no statistical increased risk of bleeding. Data that have been published subsequent to the start of WP1 have also demonstrated reduction in recurrence of VTE with no increase in bleeding using lower doses of alternative agents in RCTs. 21 The previously published study used apixaban at two doses or placebo in a population who had already been treated for 6 or 12 months and in whom there remained clinical equipoise in terms of continuing or stopping the AT, with follow-up for 12 months. The event rates for recurrence were somewhat higher in the current study, at 8.8% for the placebo group in the apixaban study compared with 23.1% for the control group (group D) in the current study. In terms of the treated populations, the event rates in the apixaban study were 1.7% for both the 2.5-mg and the 5-mg group compared with 5% in the intervention group (group E) from WP1. Patients were, of course, followed up for 2 years in WP1.

There were no differences found in the current study with regard to any of the other secondary outcomes, quality of life (including both disease-specific and generic measures) or the incidence or severity of PTS.

The results of D-dimer levels at baseline, prior to cessation of AT, were not discriminatory in terms of predicting VTE recurrence.

Limitations

Work package 1 did not achieve its recruitment target, which made it difficult to draw strong conclusions on the generalisability of these data. Two similar studies are currently being undertaken in Canada [DODS (D-dimer Optimal Duration Study)22] and the Netherlands [the Venous thrombolISm: Tailoring Anticoagulant therapy duration (VISTA) study], and we have an agreement with those triallists to combine data.

Another weakness of this study was that there was no blinding for some of the end-point adjudication, particularly the evaluation of PTS. However, in terms of thrombosis and bleeding, an independent end-point adjudication committee was established.

The cost-effectiveness of the approach followed in WP1 will be explored in the subsequent sections.

Summary

Work package 1 has demonstrated that extended treatment with anticoagulation for up to 2 years following initial treatment of a first unprovoked VTE provides protection in terms of recurrent VTE with a non-significant increase in the risk of major and non-major clinically relevant bleeding. No protection was seen in terms of PTS and there was no difference on either of the quality-of-life measures. Finally, no evidence was seen in this study to support the use of measuring levels of D-dimers while the patient is still taking anticoagulant treatment in terms of predicting who will have a recurrent VTE event.

Work package 2: Exploring Prevention and Knowledge of venous Thromboembolism (ExPeKT) – surveys

In previous sections, the findings from WP1 were described and summarised. This section reports on WP2, the qualitative element of the programme. The aim of this WP was to explore existing knowledge and barriers to implementing thromboprophylaxis pre and post hospital admission.

We would like to acknowledge both the British Medical Journal23,24 and the British Journal of General Practice25 for their permission in reproducing text and data from previous publications. Some parts of this report have been reproduced with permission from McFarland et al. 23 [This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/] and Apenteng et al. 24 [This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/]. Some parts have also been reproduced with permission from Litchfield et al. 25

Overview

Venous thromboembolism is a recognised risk following hospital admission. Most hospitalised patients have one or more risk factors for VTE. Around 60% of people undergoing hip or knee replacement will suffer a DVT without preventative intervention. Appropriate thromboprophylaxis reduces the risk of VTE by up to 70% for medical and surgical conditions. The introduction of the VTE Quality Standard [National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)26] and the CQUIN27 goal has led to improved VTE risk management in the hospitals.

Objectives

The objective of this series of studies was to explore the views of primary HCPs, patients and other relevant organisations on the potential role of primary care in hospital-acquired VTE risk management. Other objectives were to assess the level of existing knowledge of VTE risk among a range of primary HCPs and patients, to assess current practice and the perceived role of primary care in thromboprophylaxis among primary HCPs and patients; and to explore the interface between primary and secondary care in terms of thromboprophylaxis.

Methods and analysis

The studies were carried out using a two-stage, mixed-methods approach using surveys with primary HCPs and patients followed by interviews with primary HCPs, patients, acute trusts and other relevant organisations. Survey and qualitative interview data were used to examine the current practice of thromboprophylaxis, and the knowledge and experience of VTE prevention.

Survey data were analysed using SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Open-ended responses were analysed using qualitative thematic methods. The recorded and transcribed semistructured interview data were analysed using constant comparative methods.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was provided by the National Research Ethics Committee (reference: 11/H0605/5), and site-specific research and development approval was granted by the relevant research and development departments in each NHS trust.

Setting

Two acute trusts in the UK, and Oxfordshire and South Birmingham PCTs.

Participants

-

Patients were recruited from medical, surgical and orthopaedic wards from acute trusts in Oxfordshire and Birmingham.

-

All of the GPs and practice nurses in Oxfordshire and South Birmingham PCTs took part.

-

HCPs and personnel based in other organisations involved in supporting patients with thromboembolic disease contributed to the other elements of this WP.

Work package 2: surveys and interviews with patients and health-care professionals regarding prevention of venous thromboembolism

Background

In 2012, the APPTG (established in 2006 to promote awareness of VTE among parliamentarians) recommended that primary care should take an increasing role in the VTE prevention pathway including pre-assessments of VTE risk for elective hospital admissions. It also recommended that there should be an increasing role for informing patients about the risks of VTE and preventative treatment, and that a robust system be developed to ensure that primary care clinicians are informed when patients are discharged on extended VTE prophylaxis so that patients can be managed and supported effectively. 3

Subsequent to these initiatives, NICE published guidance in 2018, but this was after this WP was undertaken. 7

Venous thromboembolism is a major public health problem, with VTE-related deaths per annum estimated to be almost 550,000, more than double the 209,926 combined deaths due to AIDS, breast cancer, prostate cancer and road traffic accidents. 28 Many of these events are hospital acquired and could be prevented, given the availability of effective VTE prophylaxis. 5

One in every 100 patients undergoing total knee replacement and 1 in every 200 patients undergoing total hip replacement will experience a VTE event before hospital discharge. 4 Without thromboprophylaxis, approximately 60% of patients undergoing major orthopaedic surgery, which includes total knee or hip replacement, will experience a confirmed DVT. 29 Similarly, acute medical illness patients have a moderate (10–20%) risk of developing a DVT. 30 The association between VTE and cancer is well established,31–33 and one in seven inpatients with cancer dies of PE. 34 With appropriate thromboprophylaxis, the risk of VTE can be reduced by up to 70% for medical and surgical conditions,35 and clinical trials have shown that the use of anticoagulants reduces the risk of VTE in hospitalised acutely ill medical patients. 5,6

However, VTE is highly relevant to the primary care context as a large proportion of postoperative VTEs happen in the community. 35 One study showed that 36.8% of patients developed VTE within 3 months of hospital discharge. 36 A further study of 3039 patients admitted to post-acute care after a medical condition or surgery showed that 2.4% of patients developed VTE within an average of 13 days. 37 The average length of hospital stay for medical, surgical and critical care patients is 5.3 days. 16 After discharge from hospital, these patients may discontinue thromboprophylaxis and will remain at risk of VTE for some time. Research suggests that the risk remains for up to 90 days after hospital discharge10 Extended thromboprophylaxis for at-risk medical and surgical patients that is easily administered in a community setting is essential for a reduction in VTE rates and could be cost-effective. 8,9

Many patients do not receive appropriate VTE prophylaxis both as inpatients and post discharge,35,38–40 despite government guidelines (which recommend that all patients admitted to hospital be assessed for risk of developing DVT and be given preventative treatment) and the availability of effective thromboprophylaxis. 41 Recent studies have shown that around 37% of all at-risk patients did not receive thromboprophylaxis in hospital,40 25% of medical or surgery patients at risk of VTE did not receive thromboprophylaxis in post-acute care settings, and only 54% of orthopaedic surgery patients had a prescription for thromboprophylaxis dispensed 30 days after discharge. 40,42 The need for daily injections of low-molecular-weight heparin may create problems with compliance in the outpatient setting. 37

Objectives

The aim of the research was to explore the potential role for primary care in hospital-acquired VTE risk management.

The specific objectives were to:

-

assess the level of existing knowledge of VTE risk among a wide range of primary HCPs and patients

-

assess current practice and the perceived role of primary care in thromboprophylaxis among primary HCPs and patients

-

explore the interface between primary and secondary care in terms of thromboprophylaxis

-

identify local organisations’ perceived and actual clinical barriers to the implementation of thromboprophylaxis for high-risk patients

-

explore potential care pathways for high-risk patients prior to hospital admission in terms of assessment for thromboprophylaxis.

Methods

A mixed-methods approach was employed, which involved a postal survey of patients, GPs and practice nurses followed by interviews with a subset of survey respondents and other stakeholders. This approach was selected to obtain the views of a broad range of GPs, hospital clinicians, practice nurses and other stakeholders but also to further explore specific issues identified in the survey.

Surveys

Patient survey

A postal survey of hospitalised patients who were assessed to be at a high risk of VTE was conducted. Patients were recruited from three hospital trusts in Oxfordshire and the West Midlands.

A range of wards was recruited to ensure that orthopaedic, surgical and medical patients were represented in the sample. The specific wards included orthopaedic surgery, general surgery, cancer, upper gastrointestinal, lower gastrointestinal, cardiothoracic, renal and urology, and trauma.

Patients were eligible for the study if they were admitted to the participating wards during the recruitment period and were assessed to be at a high risk of VTE (identified by screening VTE risk assessments in hospital records). Patients requiring prophylaxis during their admission only and those requiring extended prophylaxis post discharge were eligible to participate. Research nurses approached eligible patients on the wards and those agreeing to participate were asked to provide informed consent. Recruited patients were subsequently sent a study pack immediately after discharge or 1 month following discharge, if they required extended prophylaxis. The study pack contained a questionnaire, cover letter and freepost return envelope. A reminder pack was sent to non-responders after 1 month.

The patient questionnaire was designed to explore patients’ experiences of VTE risk management prior to, during and post hospital admission. The main areas covered were knowledge and understanding of VTE risk and prevention, VTE information received and the format, and VTE prophylaxis received. The questionnaire employed multiple choice and open-response question formats and could be completed in 15 minutes.

Primary care survey

A postal survey of all GPs (n = 817) and practice nurses (n = 583) within Oxfordshire and South Birmingham was conducted simultaneously. GPs were identified from the NHS choices register43 and practice nurses were identified from practice websites or by contacting practices directly. A copy of the questionnaire with enclosed consent form, participant information sheet, cover letter and freepost return envelope was included in the study packs. Respondents were asked to indicate on the survey whether or not they would be willing to participate in an individual interview.

The GP and practice nurse questionnaires were developed using the NICE guidelines8 and the Department of Health and Social Care’s risk assessment tool. 9 The main areas covered by the GP and practice nurse survey were knowledge of hospital-acquired VTE risk and appropriate management; training and current practice of VTE risk management; views of the potential role of primary care in VTE risk management; and the barriers that exist to its implementation. The survey employed multiple choice, Likert scale and open-response question formats and could be completed in 5–10 minutes. Data were double entered into SPSS software and analysed descriptively.

Patient characteristics

A total of 878 patients were recruited and sent the study pack and 564 of these returned completed questionnaires (64.2%). The mean age of respondents was 64.3 years [standard deviation (SD) 11.8 years], 38.8% (219/564) were male and the large majority were from a white background (97.5%, 550/564). A total of 50.5% (285/564) had either a university/college degree or a professional/commercial qualification, over half (53.4%, 301/564) were retired and 33.1% (187/564) were in either full- or part-time employment.

Most admissions were planned (91.7%, 517/564) as opposed to emergencies (7.3%, 41/564). Over two-thirds of admissions were for orthopaedic surgery (69.3%, 391/564) and all other admissions were general medical or surgical cases. The mean length of stay was 8 days (SD 14 days) and the mean time since discharge from hospital to the interview was 39 days (SD 21 days).

Primary care characteristics

Of the 817 GPs and 583 practice nurses who were sent study packs, 92 GPs (11.3%, 92/817) and 19 practice nurses (3.3%, 19/583) returned the surveys. The level of seniority and experience varied within the sample. The sizes of practices ranged from 472 to 52,000 patients (mean = 10,162 patients, SD = 6425 patients). Over one-third of the respondents indicated that they had an anticoagulation clinic at their practice (36.7%, 40/111).

Interviews

General practitioner interviews

One-third of respondents (37/111) indicated on the survey that they would be willing to participate in an interview. All 37 professionals were contacted by telephone. Of these, three had retired and a further 20 were unable to find a convenient time to take part or requested an online or telephone interview, which they failed to complete. Fourteen participants were subsequently interviewed for the study. This comprised 12 GPs and two advanced nurse practitioners who were commissioned by primary care trusts to provide a 24-hour rapid-response service for suspected DVTs. Interviewees were e-mailed an additional information pack comprising a covering letter and a further participant information sheet. Additional informed consent was obtained prior to the completion of the interview or provided verbal consent for telephone interviews. Interviews lasted between 10 and 50 minutes; all interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The interview schedule was developed to further explore the areas covered in the survey and explored the following: GPs’ existing knowledge of the problem of hospital-acquired VTE and whether or not they have a role in reducing this problem; GPs’ current practice in VTE prevention; and GPs’ awareness of patients’ ability to recognise the symptoms of a DVT. We examined potential care pathways for high-risk patients prior to hospital admission and the interface between primary and secondary care with regard to the responsibility for a discharged patient on extended prophylaxis. The interviews sought to identify any barriers to GPs having a role in VTE prevention and management.

Transcripts were identified by code number only. Participants were not identified in any written material resulting from the interviews. The recorded and transcribed semistructured interview data were analysed using constant comparative methods. 44 Data were managed using NVivo 9 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Lorraine McFarland independently reviewed all the transcripts and developed codes in an iterative process to identify emerging patterns in the data and an initial coding framework. Using constant comparison, similarity and differences were identified within and across the transcripts. By comparing each part of the data, analytical categories were established and key concepts selected. Final themes were reviewed and agreed between four of the authors to enhance reliability.

Participants

Fourteen participants from two primary care trusts in the UK were interviewed for the study: 12 GPs and two advanced nurse practitioners who were commissioned by primary care trusts to provide a 24-hour rapid-response service for suspected DVTs.

Interviews with other health-care professionals and relevant organisations

Methods and analysis

A qualitative research design was used with data collected via face-to-face or telephone interviews. Interviews took place with personnel from acute trusts and other relevant organisations and examined the current practice of thromboprophylaxis, and the knowledge and experience of VTE prevention. The interviews explored the interface between primary and secondary care in terms of VTE prevention and the perceived role of primary care, and examined interdisciplinary communication, perceived barriers to VTE management, training provision and future requirements for VTE management. Key informants were identified, followed by snowball sampling. The recorded and transcribed semistructured interview data were analysed using constant comparative methods.

Interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of staff in four acute trusts and a sample of people from relevant organisations such as the Lifeblood Charity (www.thrombosis-charity.org.uk) and Anticoagulation Europe (www.anticoagulationeurope.org).

Participants

Seventeen participants were interviewed for the study. This group comprised a primary care trust commissioner, charity personnel, clinicians and VTE nurses and trainers.

Participants were provided with an information pack comprising a covering letter and a participant information sheet. Participants were asked to complete a consent form at the time of contact or provided verbal consent for telephone interviews. All interviews were digitally recorded with the permission of each participant. Content of the recordings were transcribed verbatim.

Patient interviews

Face-to-face semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of 31 high-risk patients who responded to the survey were undertaken. Interviews explored the topics elicited from the initial survey and were carried out in patients’ homes. The interview schedule topics included patient awareness of VTE; satisfaction with VTE information and understanding of the information received; adherence to treatment; the need for primary care intervention; and issues to increase awareness of VTE.

Methods

Participants were provided with an information pack comprising a covering letter and a participant information sheet and were asked to complete a consent form at the time of contact. All interviews were digitally recorded with the permission of each participant. Voice recordings were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were identified by code number only. Participants were not identified in any written material resulting from the interviews. The recorded and transcribed semistructured interview data were analysed using constant comparative methods. Data were managed using NVivo 9 software. All transcripts were independently reviewed and codes developed in an iterative process to identify emerging patterns in the data and an initial coding framework. Using constant comparison,21 similarity and differences were identified within and across the transcripts. By comparing each part of the data, analytical categories were established and key concepts selected. Final themes were agreed between four of the authors to enhance reliability. Representative quotations that illustrate both typical responses and a range of views have been selected to illustrate the study findings.

Ethics

Ethics approval was provided by the National Research Ethics Committee (reference 11/H0605/5). The trial grant number was NIHR RP-PG-0608-10073.

Participants

A total of 31 surgical, medical, cancer and trauma patients from five separate hospitals in two NHS trusts were interviewed.

Results

Representative quotations that illustrate both typical responses and a range of views have been selected to reflect these themes.

Summary of findings

Although the findings from the individual studies have been published23–25 for the purposes of this report an overview of the findings will be presented.

The following common themes were identified:

-

communication

-

knowledge

-

role of primary care

-

education and training

-

barriers to patient adherence.

Communication

Data from all parts of this work package highlighted the issue of communication, be it between HCPs and patients or between the HCPs themselves.

From the patient survey, 138 out of 878 (16%) patients received information regarding VTE prevention from primary care, whereas 702 out of 878 (79%) reported receiving information on hospital admission, and 471 out of 713 (66%) of those discharged on extended prophylaxis reported receiving information about this.

A total of 843 out of 878 (96%) patients reported receiving treatment for VTE prevention and 713 out of 878 (81%) reported continued treatment after they were discharged. The majority of patients received pharmacological prophylaxis alone, antiembolism stockings alone, or both pharmacological prophylaxis and stockings during their hospitalisation.

In terms of communication between HCPs, it was clear that there was dissatisfaction from both primary and secondary care.

From the primary care perspective, there was concern about both the quality and timeliness of information received on hospital discharge with delays of up to 6 weeks mentioned:

No not really, we don’t really have that much contact really. A lot of the time the correspondence that we get from hospital is quite delayed. So when a consultant’s decided that there’s going to be a planned surgery, it can sometimes be delayed by up to 4/5/6 weeks before we get told about it. And also, after the procedure, and I guess this probably makes it more difficult, after they’ve had the procedure done, again it can take up to 5 or 6 weeks before we even find out that they’ve had a surgical procedure done . . . So I guess that would be one hindrance to us actually, getting people started on things when we don’t find out sometimes 5 or 6 weeks later. And that’s probably the most critical period, when they’re going to get a DVT or a PE.

GP1

I think it’s one of these areas, it’s like a lot of areas in medicine, where there is no connection between secondary care and primary care. The secondary care somehow thinks that we’ll pick it up. Well we may not because we never get the discharge summary for 2 weeks. We don’t necessarily receive the discharge summary for a couple of weeks after the patient’s been discharged . . . Well now, because the number of appointments has risen and the number of patients on their books has risen an extra bit, it rises by the month, some patients say, well we’ve got this letter and the receptionist just takes it off the patient and so we don’t actually get to see them. It’s all to do with the amount of appointments we have is just limited.

GP6

The content and quality of patient discharge notes received by the GP vary widely and are a concern for many participants. They suggest that discharge notes are often brief and lack basic information:

Completely pot luck it just depends on the quality of the discharge summary. Some discharge summaries are very good, they tell you what the dose of Clexane that they want you to give and for how many weeks and what they’re treating it for. And then on other hand, you just don’t really get any feedback at all. And it’s only sometimes when patients ring you up and say, I’m on a Clexane injection and I’ve been told to get some more from my GP. So it varies largely.

GP1

One participant acknowledged that there is a gap in the care pathway where no one has responsibility for a discharged patient on extended prophylaxis. One GP questioned if the responsibility to make sure that a patient has been discharged with prophylaxis lies with the consultant having done the operation or with primary care:

A lot of the time . . . we get a phone call saying, oh can you come and do a home visit, leg swelling or pain in the chest. And a lot of the time, when you diagnose it, you then look back and think, actually somebody should have been responsible for looking after this patient. I think once they’ve had their operation done, I think it’s a grey area, in terms of where the responsibility lies. Does it lie with the consultants who’ve done the operation to make sure that they’ve sent patients home with prophylaxis, or whether it’s our job then to just make sure that they are on prophylaxis when they’ve come out?

GP1

It was suggested that a solution to this grey area in patient care would be an official handover where acute trusts request that primary care takes over:

Some consultants will probably say responsibility lies with them, they’ve done the operation, they should decide on prophylaxis and how long for. Whereas some consultants would say it should fall upon the GP because it is an extended course and it’s the GP’s responsibility to follow it up. But yes, I think up until we probably get good communication or some kind of pro forma where there’s an official handover occurring saying, right, I’ve done this operation, this is what I’ve started them on, please would you carry on either prescribing this or looking after the patient. So I think that probably needs to be improved.

GP1

Secondary care should be responsible until they have effectively communicated the patient’s needs to primary care and their GP has agreed to take over responsibility.

GP9

However, participants confirmed that they do not make contact with a discharged patient on the assumption that the hospital had made the necessary arrangements. Shortfalls in the procedure are put down to hospitals not doing their job properly:

We wouldn’t make active contact, no, if somebody was discharged, I would assume that the hospital had sorted it all out really. We don’t really have time to phone people up just in case the hospital hasn’t done their job properly.

GP5

Generally, if I think they’re a fit young person or they haven’t got any physical or mental issues, then I would tend to leave the patient alone, unless they contact me with any issues, but otherwise, no.

GP1

The GPs in rural practices are more likely to contact a patient discharged from hospital on low-molecular-weight heparin:

In our practice, when we see they’re on low-molecular-weight-heparin, sometimes I’ll give them a ring and say, are you alright giving yourself a jab or do you want to come up to the surgery to have it done? But that’s because we’re a rural practice. But if you’re in a big city or a big town practice, no you don’t have the time to even breathe let alone ring them.

GP6

Delays in receiving discharge notification could make prescribing difficult for primary care and one participant felt that commissioning should not be split between providers:

Sometimes you don’t hear until the patient has been discharged for a couple of weeks and if you can provide a week’s anticoagulation I really can’t see why you can’t provide a month’s anticoagulation because it would be a much neater package commissioning it this way rather than splitting it between various providers.

GP7

Similar issues were raised by secondary care clinicians with regard to communication both to and from primary care. It was pointed out that VTE occurs and is usually diagnosed in the community and, thus, the GPs have a role to play:

I think we’ve missed a trick here – there’s this belief that thrombosis is an issue that is seen and dealt with within the hospital. Most people who will have a hospital-acquired thrombosis will have it in the community because you don’t tend to get a DVT or a PE until you are discharged. So before you even look at prevention of VTE – the majority of thrombosis will be diagnosed in the community. Prevention even more so . . . So primary care has a large role to do here. Now maybe it’s unfair on them that it’s all being dumped into the community but actually that is the price you pay for having less beds and it’s the price you pay for having to free up beds to admit the acutely ill patients.

Consultant and VTE lead

Hospital staff expressed concerns regarding whether or not patients complete the course of extended prophylaxis when they have been discharged from the hospital as ‘a bit of a grey area’:

We send patients home on Clexane, they’ve been shown how to do it, but they [midwives] feel they are not actually administering it at home. Some will be visited by community midwives more regularly and they can check up on that but you might have a lady that isn’t seen and no one seems to check up that they are actually taking their thromboprophylaxis or not. It could be the same in other patients.

VTE prevention lead

From our root cause analysis we’ve done on patients most of them have gone home with the necessary prophylaxis and certainly now we’ve developed a standard pro forma root cause analysis form. One of the questions on it is now, ‘did you complete the course?’ or ‘did the patient complete the course?’ and we’ve started asking them that if we can, if we are able to contact them. So yes that is a bit of a grey area. You can’t know for certain if they are self-administering. I suppose that is something we could ask when they come back to clinic but then it’s after the horse has bolted then, isn’t it?

Clinical nurse tutor

There also remains a problem of used sharps disposal for the patient:

Used sharps disposal is also a challenge and often the patients are asked to bring them back to hospital.

Consultant nurse for anticoagulation

It was suggested that ‘patients need to know what to expect’. When this participant was asked who could do this, they responded with: ‘The GP’ (consultant nurse for anticoagulation).

There were few positive comments regarding communication between secondary and primary care, with the one notable example being in maternity services:

It seems to work very well for maternity-related thromboprophylaxis with very few problems between secondary and primary care.

Community pharmacist

The need for effective communication between every level of the NHS for the safe management of extended thromboprophylaxis has been recognised at the commissioning level:

Extended thromboprophylaxis can be needed for quite a long time. The whole system needs to manage that safely and that’s about communication . . . Whilst the individual provider or the individual surgery thinks that everything is fine – it’s only when you look at the overall picture you realise, actually patients came out of this clinic and information wasn’t sent to the GP and, therefore, the GP doesn’t know what’s going on, and so we try and monitor that system from an overall point of view . . . the incentives are much more focused on the business of a hospital to deliver a business bottom line in terms of funding than working across a whole system to actually ensure that all the safety and all the protocols are properly joined up with other providers outside their business. There is something there about actually the market system around secondary and primary care it’s not joined up, and that’s a problem.

Commissioner

In areas of high risk such as anticoagulation and that type of management that the commissioner needs to be really understanding, looking at what’s going on and looking at where the risks are and really trawling, quite actively, trawling to try and see where they can identify risks . . . given that things like anticoagulation and the top 10 risks and the top 10 examples of avoidable admission we should be focusing, as commissioners, much more upon those clinical areas we’re being encouraged to do than to focus on other things that commissioners get involved in, which might be less outcome based.

Commissioner

Knowledge

Health-care professionals

As part of the primary care survey, respondents were asked to estimate the annual number of deaths from hospital-acquired VTE. According to the House of Commons 2005 Health Committee Report, the figure is approximately 25,000. 45 Answers ranged from 100 to 90,000 within our sample (mean = 29,619). Respondents were also asked to correctly identify the risk factors for hospital-acquired VTE and the patient groups requiring extended thromboprophylaxis according to the Department of Health and Social Care’s risk assessment tool. The majority correctly identified all risk factors.

From the interviews, one GP suggested that there is very little awareness of VTE in primary care. The results demonstrated that health-care professionals’ experience of DVT ranges from many cases (the advanced nurse practitioner, specifically responsible for attending suspected DVTs, saw one case per day) to the GPs who have seen only a few, or one or two per year (the more common experience). Participants who see many cases of DVT suggested they are related to hospitalisation and orthopaedic surgery. GPs seeing one or two cases every month tended to be those working with patients with drug addiction and compromised veins. Seeing few patients with DVT in primary care was attributed to the protocols being followed in hospitals:

There is very little awareness; there is little awareness amongst primary care staff.

GP7

I see many cases of DVT in the community and the majority are related to previous hospitalisation.

GP10

I see probably one a day . . . connected to orthopaedic surgery mainly.

Advanced nurse practitioner 11

So I mean I don’t see many cases personally of patients coming out of hospital suffering a VTE, and I guess that’s because protocols are being followed in hospital . . . we see very few cases.

GP3

Patients

Patient understanding and awareness of hospital-acquired VTE appeared vague and incomplete. Many patients had an elusive idea about their VTE preventative treatment but they generally deferred to the health professional ‘knowing what they were doing’:

All I had was morphine and my usual tablets. That’s all I had.

Did you say you had stockings, surgical stockings?

Yep, yeah, those nice white ones.

Did you understand why you needed to use those?

Well, it’s obviously to stop the blood clots forming. I don’t understand why, it’s just there and not anywhere else on the body. But there we go, they must know. Yeah.

When I went to see the surgeon, in the follow-up interview, I asked him why I’d been given these anticoagulants, and he said that that was something that everybody was given who had an operation.

P1 Orthopaedic patient

Recollection of information was unspecific. P11 suggested the required information would have been given among all the other information received but the amusing anecdote evokes the best recall:

When you saw the surgeon, he mentioned all of the risks, he went from, you’re going to have this, you’re going to have this but this is what could happen, you could get an infection, you could get this, and he listed so much stuff and by the time he’d finished I went ‘Oh my God I’m gonna die.’. And in there somewhere would’ve been blood clots. But I don’t remember specifically talking to the nurse about, at the hospital.

P11 Orthopaedic patient NOC53

Many patients said that they knew about blood clots but did not link them to their own situation. Recall of the information provided in hospital was vague, even suggesting that they were told about blood clots when flying:

I’m quite ignorant about blood clots. I mean you always think when you’re flying, people say you can get blood clots.

P19 Orthopaedic patient ORH31

Can you tell me about the stockings? Did they explain to you why you were wearing them? Not really, it was to do with the aircraft.

P22 Medical patient ORH60

A patient was aware of the connection between immobility and blood clots:

Nowadays you’re not kept in bed for any longer than absolutely necessary to avoid blood clots. ’Cause years ago they used to keep people in bed and then they had thrombosis and things as a result which wasn’t very good but they know more now.

P24 Orthopaedic patient NOC120

A medical patient felt that the hospital was very informative regarding VTE information but was too poorly on the first day to consider the information:

I was aware that they risk assess and also they actually, even though I was having aspirin, I had the injections . . . because I’d been in hospital probably 6 months earlier as well, I’d gone through all that anyway. So I actually, actually I felt too poorly to be bothered the first day, but they were very informative.

P27 Medical patient UHB47

One orthopaedic patient felt that there was too much emphasis placed on blood clot prevention. This patient experienced haemorrhaging after hospital discharge:

If anything I would say probably, over, people are really, really quite frightened of it, the staff are and things like that, there’s no doubt about it. They concentrate very heavily on it . . . What the mistake was, it was the medics in the hospital that were warfarinising me too heavily too quickly, which comes full circle to my analysis of, they’re too paranoid about the blood clots.

P4 Orthopaedic patient NOC99

From the patient survey, it was found that, prior to admission, 15.7% received information from GPs or practice nurses in primary care. Secondary care health professionals provided advice to 79.3% of patients on admission to hospital and to 66.4% of those patients discharged from hospital on extended prophylaxis. Post discharge, 12.8% received information regarding blood clot prevention from GPs or practice nurses in primary care.

Role of primary care

The large majority of the GPs and practice nurses reported that they never or only occasionally conducted VTE risk assessments (94.6%, 105/111), yet 34.2% (38/111) believed that this role should fall within the remit of primary care. Even more respondents (50.5%, 56/111) believed that they should be providing advice to patients prior to elective hospital admissions, but, in practice, 79.3% (88/111) never or only occasionally do this. Involvement in VTE risk management post hospitalisation was higher in those surveyed, with 39.6% (44/111) reporting that they never or only occasionally managed extended thromboprophylaxis and 64.2% reporting that they never or only occasionally provided advice about VTE risk to their patients following discharge from hospital. Three-quarters of respondents (74.8%, 83/111) believed that primary care should manage patients requiring extended prophylaxis and 58.6% (65/111) believed that primary care should provide advice to patients requiring extended prophylaxis following hospital admission.

Despite a substantial proportion of respondents indicating that primary care should take on a greater role, the majority of GPs and practice nurses perceived barriers to conducting VTE risk assessments (84.7%, 94/111), managing extended prophylaxis (73.0%, 81/111) and providing VTE management advice (69.4%, 77/11) in primary care. The main barriers identified were lack of time, resources and expertise; lack of continuity of care and poor communication between primary and secondary care; lack of awareness of planned hospitalisations; lack of knowledge of exact regimes and risk/benefit ratio of prophylaxis; lack of understanding of risk associated with different procedures and the potential complications; lack of consistency over VTE risk management protocols at different hospitals, the cost of prophylaxis and confusion over whether primary or secondary care is responsible; the mobility/wellness of patients to attend surgery for prophylaxis; and the pressure from many other areas in primary care.

One participant who was aware of the NICE guidelines7 for VTE felt that they were hospital focused:

NICE guidance exists but I think current guidance is predominantly hospital focussed.

GP15

Some participants felt that they, as GPs, should have a role in reducing the risk of VTE, but were unaware of any specific guidelines and were vague regarding what that role would entail or how it could be implemented. They suggested that their role should only encompass preventative medicine and that primary care should not be considered as the safety net for VTE prevention. Participants quoted a series of reasons why their involvement would be difficult, in particular the logistical problem of having no contact with patients before hospitalisation and the burden of adding to their already exhaustive workload:

All GPs should have a role in reducing risk of VTE. However cannot recollect any specific guidelines for general practice.

GP8

A good question, we should do [have a role in reducing hospital-acquired VTE]; I don’t think we know what our role is at the moment.

GP4

I don’t think it’s a safe system to rely on primary care alone because there are times when we don’t have anything to do with the patients before they go in. So I think that it’s something that we could be doing, sort of preventative medicine, but I don’t think we could necessarily be the safety net.

GP4

Additional funding and resources to enable primary care to take on a role in VTE prevention was a major factor for several participants. It was felt that primary care was well placed to improve outcomes, particularly as they had access to patient medical details and histories, but their involvement would require clear planning to encompass training, resources and regular audit:

Limited role for primary care due to capacity in general practice to take on additional work which is not funded.

GP8

A small role – but not one that I am prepared to take on without extra time and remuneration.

GP10

Primary care is well placed to improve outcomes in this area but clear planning, training provision and resource, with regular audit, would be needed to ensure this was done effectively and safely.

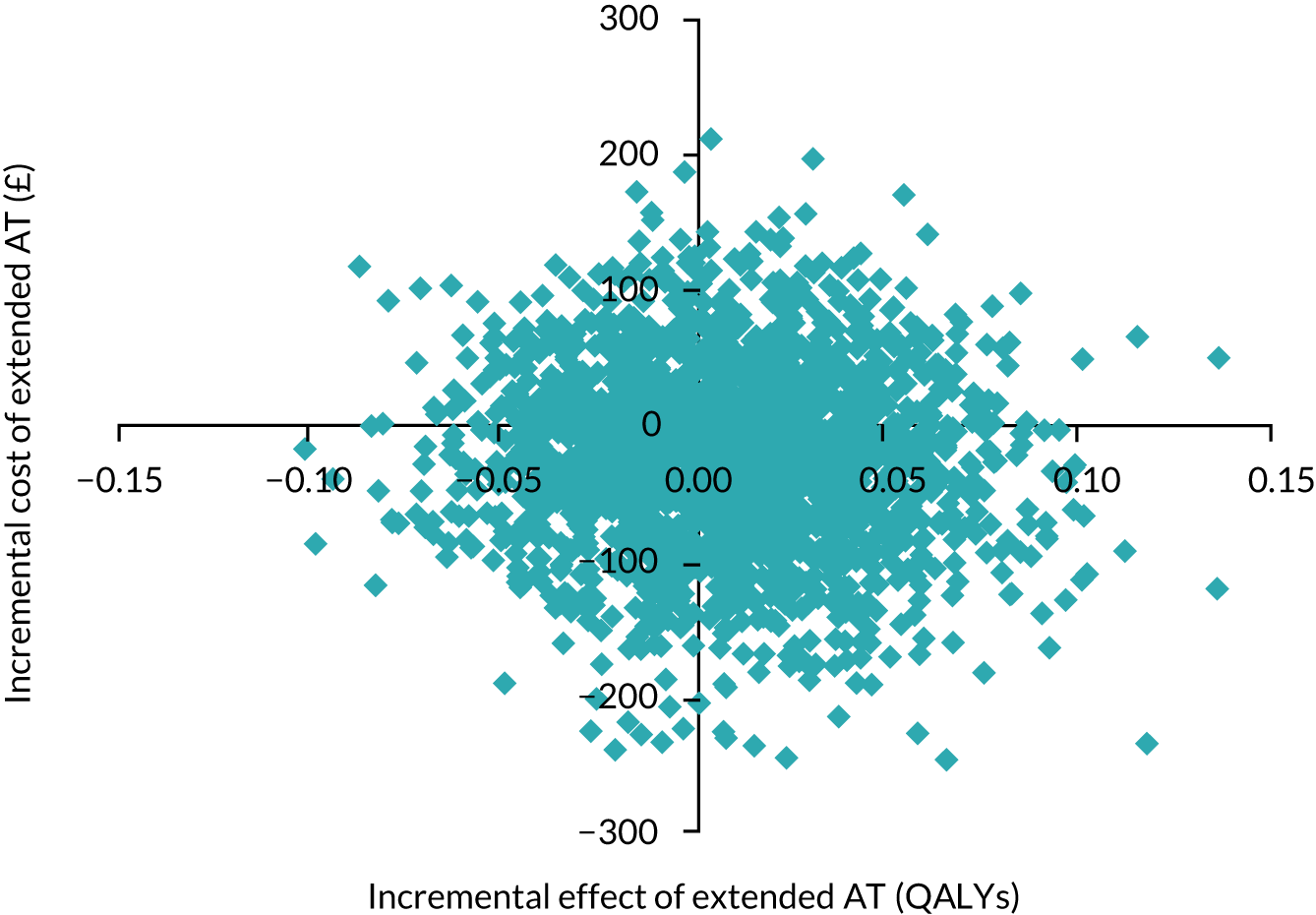

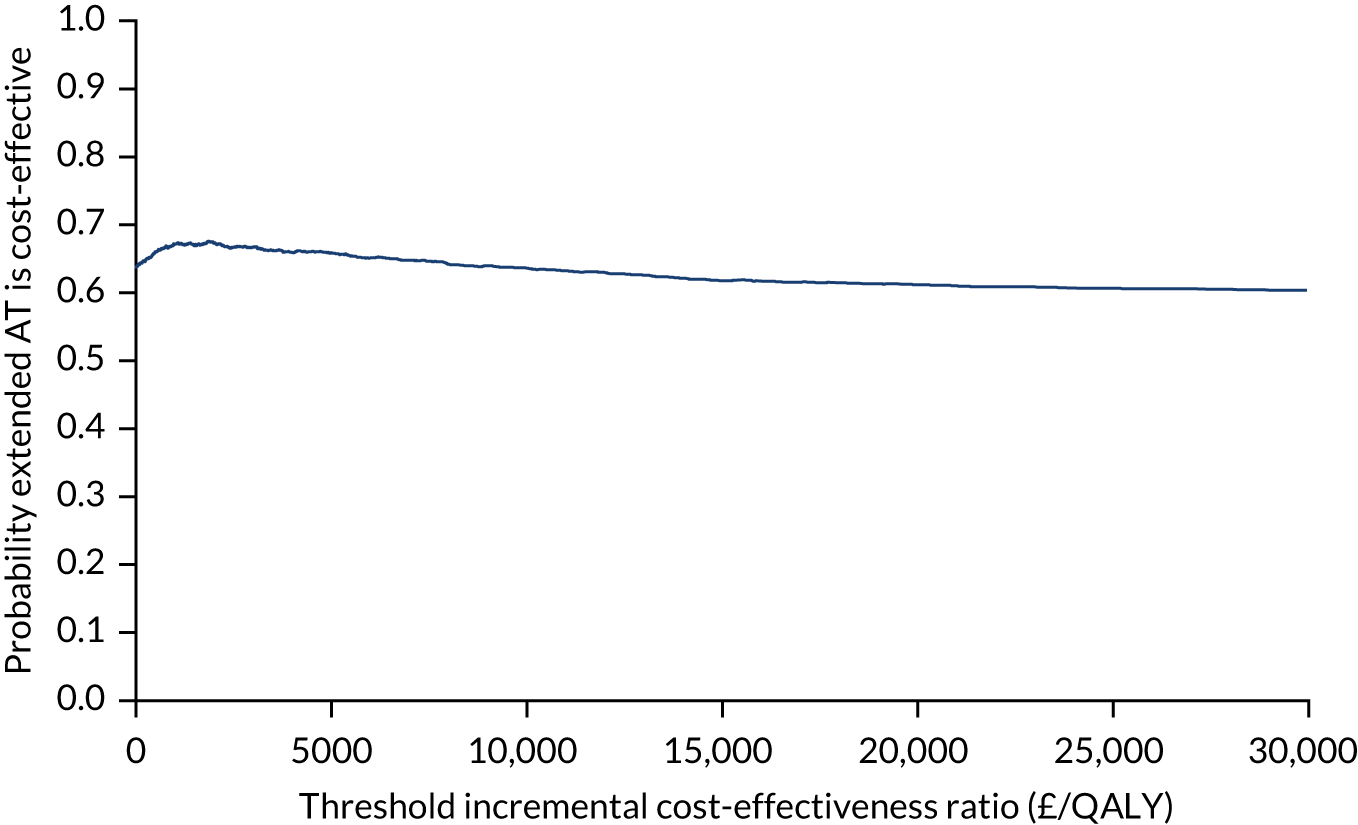

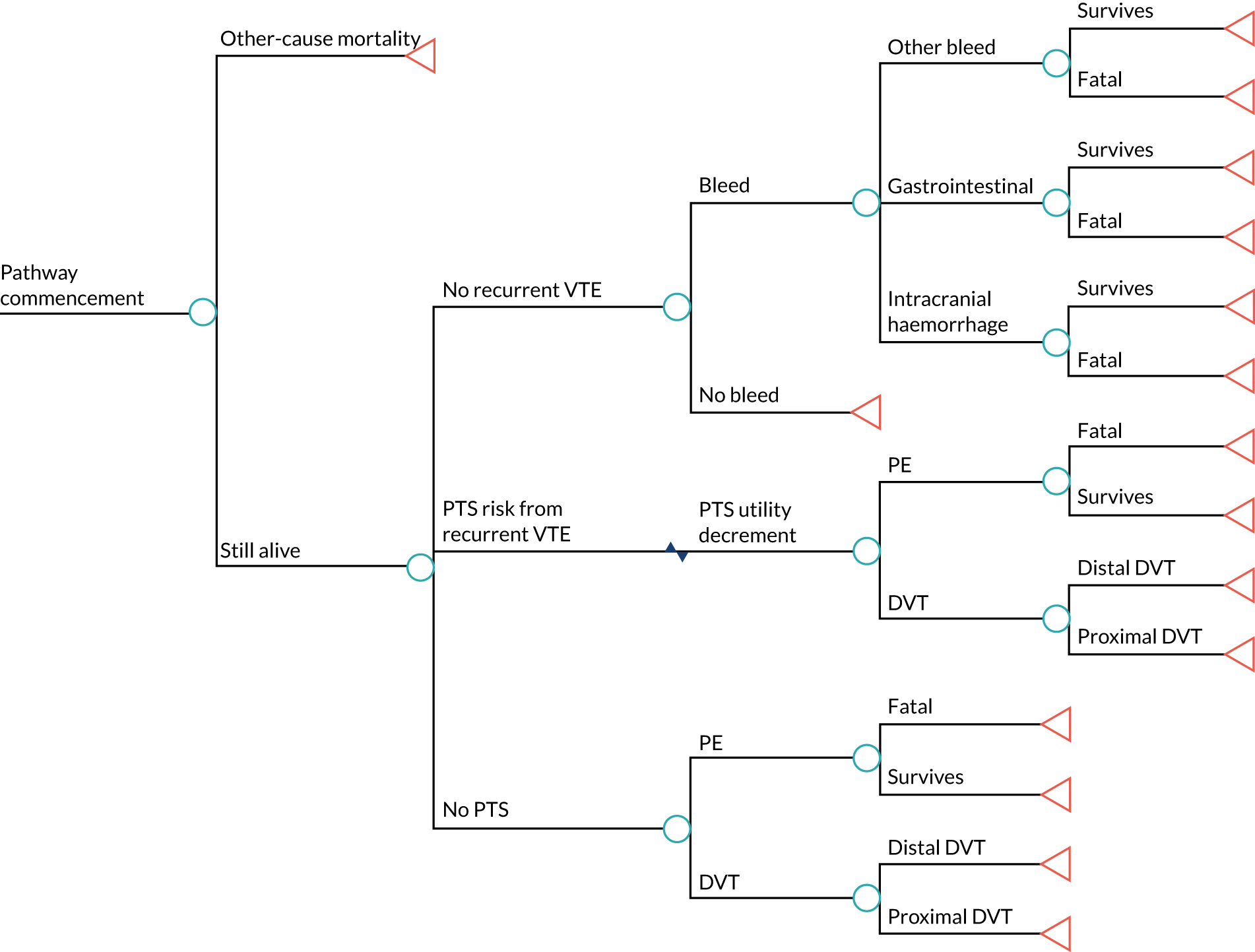

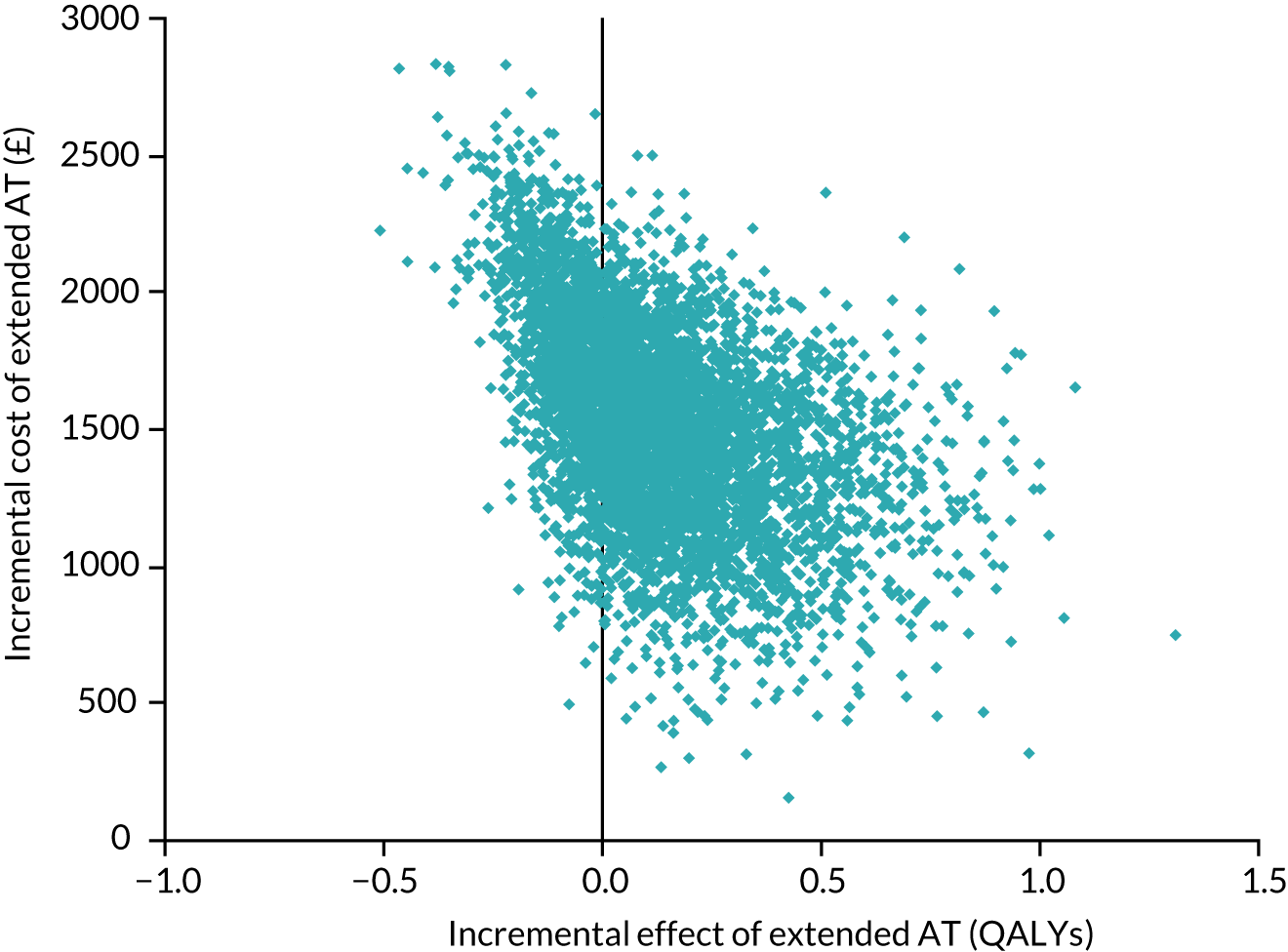

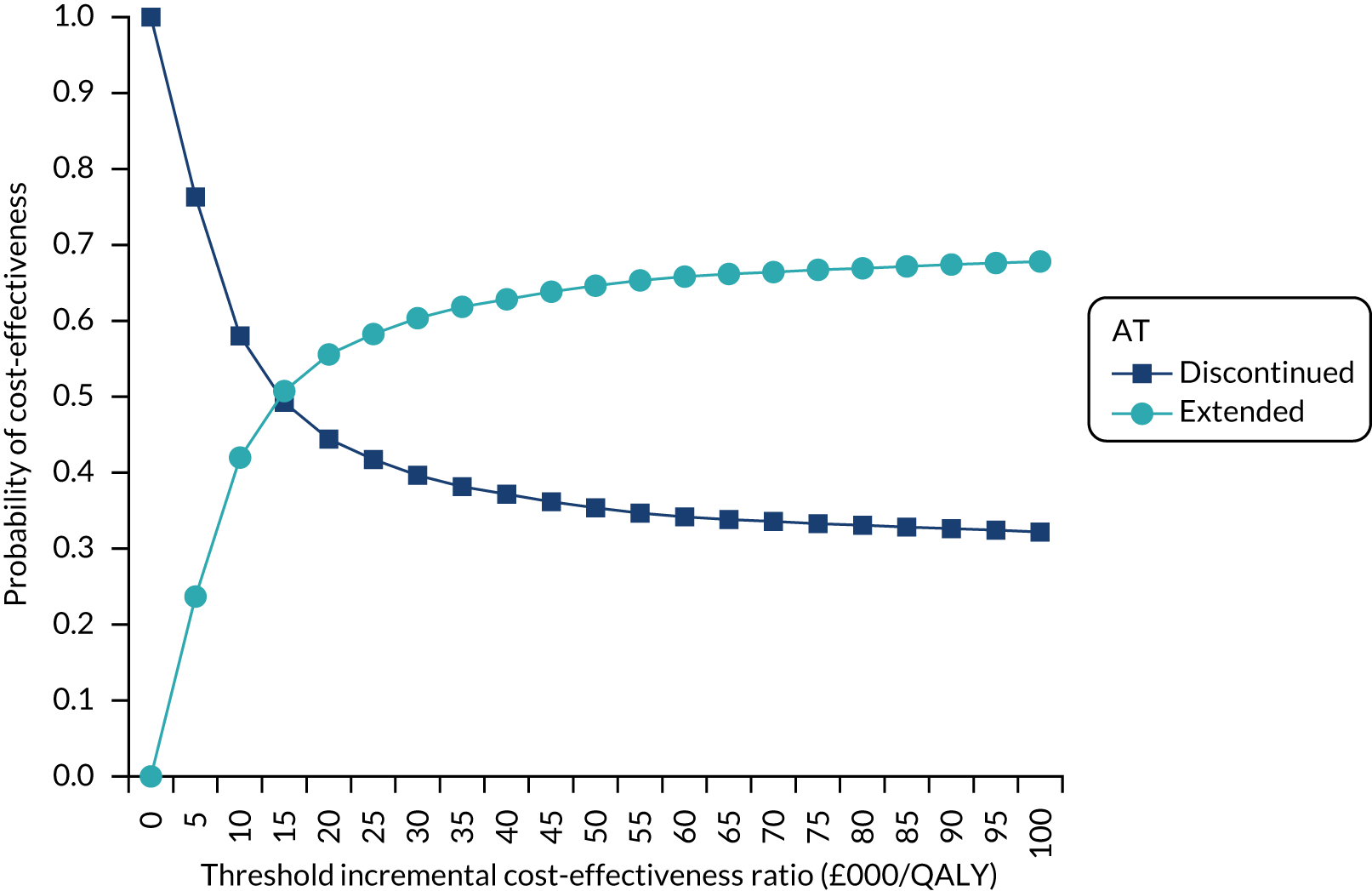

GP9