Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PGfAR programme as project number RP-PG-0612-20010. The contractual start date was in March 2015. The draft report began editorial review in August 2019 and was accepted for publication in July 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Downs et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

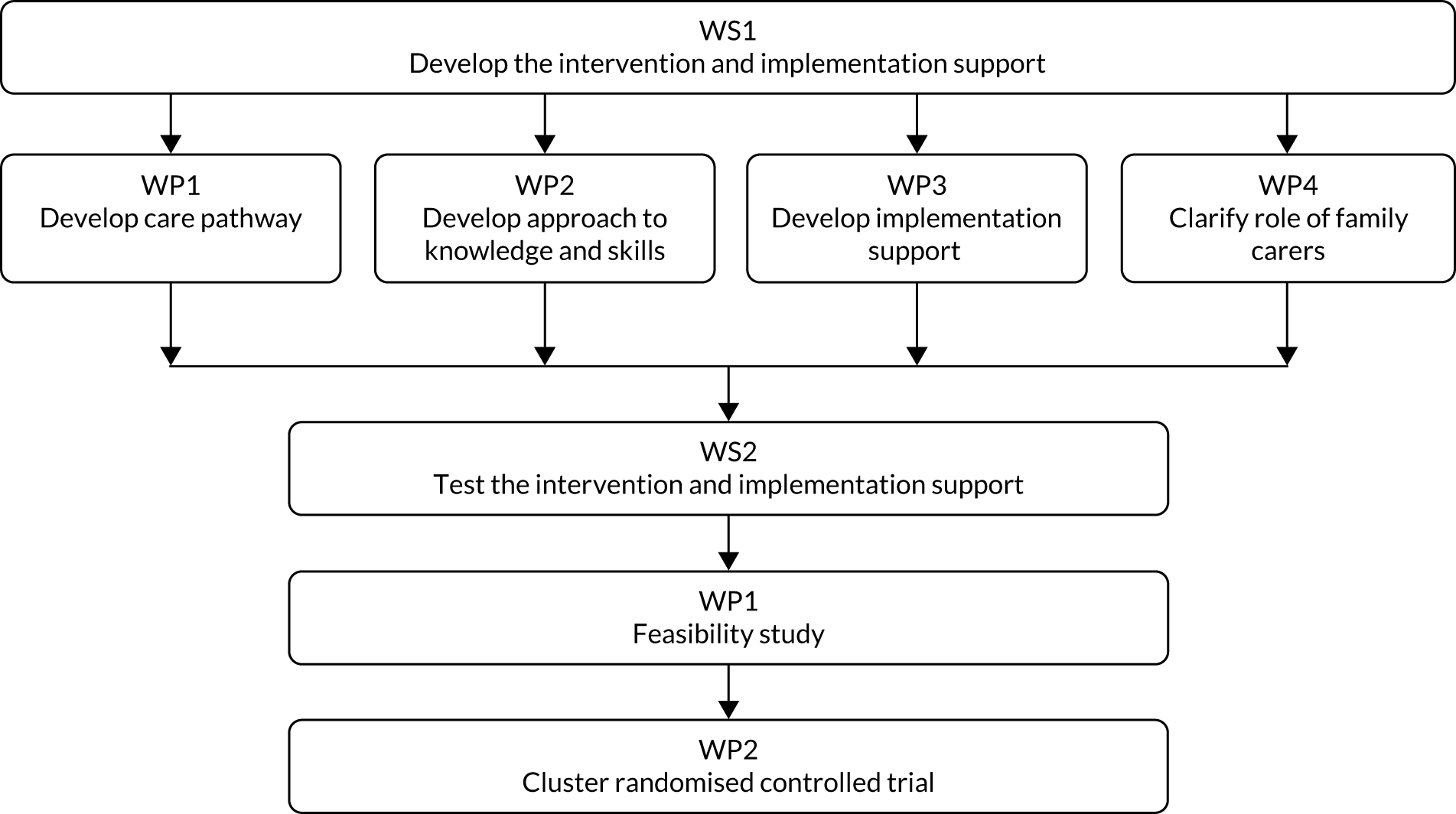

Research pathway diagram

Figure 1 depicts the research pathway.

FIGURE 1.

Research pathway diagram. WP, work package; WS, workstream.

Alterations to programme aims or design

The main alterations to the programme include:

-

aim

-

use of interviews and informal conversations rather than focus groups to gather feedback during the feasibility study

-

location of Yorkshire pilot homes

-

duration of post-intervention pilot study period

-

number of, and approach to, clinical record reviews

-

use of laptops for data collection and entry

-

use of additional human resources.

Aim

In the original proposal, the aim was to reduce rates of hospital admissions from nursing homes for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions (ACSCs), conditions whose early detection and active management in nursing homes could have prevented the exacerbation that led to the unplanned admission. We aimed to optimise and pilot test a pragmatic, acceptable, evidence-based intervention for ensuring active management of ACSCs in nursing homes, thus reducing avoidable hospital admissions.

The overall aim was revised to the following: to develop and pilot test an intervention to improve rates of early detection and treatment for four conditions. This allowed us to have an explicit focus on the active management needed for early detection and treatment in order to reduce hospitalisations. This change in emphasis meant that the project was more closely aligned with policy on improving health care for residents as a route to decreasing hospitalisations. Therefore, we called it the Better Health in Residents in Care Homes with Nursing (BHiRCH-NH) study.

Use of interviews and informal conversations rather than focus groups to gather feedback during the feasibility study

We had intended to conduct two focus groups with staff in the two feasibility homes to further refine the intervention and implementation support. These proved difficult to arrange as the staff in both homes were under significant time pressure and unable to take time out to join a group. Indeed, even seeking one-to-one time with them proved difficult, because of pressure of work. Instead, we conducted one semistructured interview (during which there were frequent interruptions), which we transcribed, and otherwise made notes during impromptu conversations with staff. We took a pragmatic approach to analysis, noting key points to share with the team.

Location of Yorkshire pilot homes

In Yorkshire, we had to recruit nursing homes outside Bradford for the pilot study. Following a presentation we made to the Bradford and District Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) in autumn 2017, tools similar to the project intervention tools were sent to all nursing and care homes in the district, meaning that these homes were essentially pre-exposed to the intervention. We therefore had to move the intervention to areas that had not had this exposure.

Duration of post-intervention pilot study period

In the original proposal, we expected to have a 12-month post-intervention study period. Owing to delays of approximately 10 months in obtaining ethics approval, the post-intervention study period was reduced to 6 months. This meant that we had a shorter period in which to embed the intervention and were unable to look at the seasonal effects on the primary and secondary outcome measures.

Number of, and approach to, clinical record reviews

We reviewed 11, as opposed to 30, nursing home residents’ records because of the shortened post-intervention period and the lower than anticipated numbers of hospital admissions. We had planned to review a random sample of residents’ records, using a structured audit template comparing the care pathways developed for the intervention with a pathway analysis of the events leading to hospitalisation or treatment for an ACSC, and noting if changes were made to the care pathway documentation.

This approach depended on the intervention being adopted as planned. However, in the event, only 16 Stop and Watch Early Warning Tool (S&W) forms were completed in the study period, with 11 of them coming from a single home. Furthermore, we were able to locate only three of the eight completed care pathway forms. During interviews, some nursing home staff stated ‘we do this anyway’, and some were able to point to local practices that formalised and supported those claims.

We therefore changed the approach to focus on any reference to the observations or actions in the care pathway. We hoped that this would allow us to confirm (or refute) the claim that the principles of the intervention were already in use as normal practice. We also hoped that it would give us insights into which aspects of the intervention were seen as most useful. We thought that this would be the most helpful approach in deciding whether or not to pursue a definitive trial.

Use of laptops for data collection and entry

We had intended that we would enter data while in the field using laptops. We instead relied on completing paper-based case report forms, which were then manually entered into the database prepared by University College London’s Clinical Trials Unit, Priment.

Use of additional human resources

Research facilitator

To facilitate access to residents’ records, we identified a research facilitator in each home who could assist. Fieldworkers reported positive experiences in working with such staff.

Clinical Research Network colleagues

We had intended to recruit nursing homes from the Bradford area. However, having presented an overview of the project to the Bradford and District CCG, the project details were distributed to care homes, meaning that they were essentially pre-exposed to the intervention. This meant that we had to recruit nursing homes from outside the Bradford area. Colleagues from the Yorkshire and Humber Clinical Research Network (CRN) helped with recruiting nursing homes and with data collection from these homes.

Background to the research programme

Introduction

Too many residents living in nursing homes go to hospital for conditions that, if detected and treated earlier, could have been managed in the nursing homes. In the UK, significant attention has been paid to the lack of consistent, equitable and adequate NHS support to nursing homes to ensure enhanced health care in nursing homes. 1 NHS England has had a programme of vanguard sites modelling innovative practice to enhance health care in nursing homes. Few robust studies of hospital admission reduction programmes in the UK were available when we started this study. Our work addressed the NHS policy focus on reducing avoidable hospital admissions and the lack of proactive and timely health care for frail older people living in nursing homes.

Number of frail older people with comorbidities in care homes

In England, approximately 450,000 adults aged > 65 years live in care homes; of these, slightly more than 220,000 live in nursing homes. Older people living in nursing homes have significant levels of comorbidity, frailty and complex physical and mental health needs. 2–9 Residential care home residents also have significant health-care needs. 6 Victor et al. 10 found that most of their residential care home study participants had three to four diagnosed conditions.

Health-care needs poorly met in care homes

A consistent and concerning picture of care home residents’ varied and inequitable access to primary and specialist NHS services has been documented for > 15 years,3,5,11–15 with efforts continuing to address this concern. 8 Iliffe et al. 14 demonstrated persistent variable and inadequate NHS service provision to these settings. It is equally well established that unmet health-care needs can result in unplanned, unnecessary and avoidable hospital admission. 8,11

Ambulatory care-sensitive conditions and hospitalisation

Ambulatory care-sensitive conditions are conditions that can lead to unplanned hospital admissions that may have been avoidable or manageable by timely access to medical care in the community. 16 The conditions include angina, asthma, cellulitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure (CHF), dehydration, diabetes mellitus, gastroenteritis, epilepsy, hypertension, hypoglycaemia, urinary tract infections (UTIs), pneumonia, and severe ear, nose and throat infections. 15

In the UK, ACSCs account for one-sixth of hospital admissions in all age groups. 17 The ageing population has led to a 40% increase in admissions between 2001 and 2011,18 and all-cause hospital admissions from nursing homes rose by 63% between 2011 and 2015. 19 Four ACSCs contribute to a large proportion of hospitalisations from nursing homes (i.e. respiratory infections,16,20–22 acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure,23,24 UTIs16,25 and dehydration16) and may underlie other problems such as falls and delirium.

Avoidable hospital admissions are not unique to the UK. For example, Jeon et al. 26 examined insurance claims for long-term care residents in Japan and found that > 70% of potentially avoidable hospital admissions were related to respiratory infections, UTIs or CHF. 26

Negative effects of hospitalisation

As well as causing distress to residents, their families and staff, hospitalisation is expensive for the health and social care system. Hospital admission increases the risk of decline in functional ability, delirium, adverse events and prolonged stays. 27,28 Areas with many nursing homes tend to have higher rates of unplanned hospital admission among those aged > 75 years. 29 The King’s Fund17 and the British Geriatrics Society5 have raised concerns about the quality of health care to nursing homes. In economic terms, avoidable hospital admissions are costly to the NHS. The Care Quality Commission (CQC)30 described suboptimal experiences for residents moving between care homes and hospitals. The NHS has made reducing avoidable hospital admission from nursing homes a policy imperative. 8

Reducing avoidable hospital admissions

Interventions have been developed to address avoidable hospital admissions. These fall into two categories: multicomponent interventions (implementation of a range of tools) and single-component interventions (predominantly advance care planning or single-disease care pathways, e.g. pneumonia). Multicomponent interventions show significant reductions in avoidable admissions. 31–35 Key characteristics of these include enhancing the knowledge and skills of nursing home staff,36 clinical guidance and decision-support tools (care pathways), engaging with families,37 and specialist input from geriatricians or nurse practitioners. 31,38 In addition, research highlights the importance of collaborative development of interventions with nursing home staff,39 residents and families,37 consider implementation support,24,40 including using local champions.

In the USA, financial incentives and penalties have prompted co-ordinated care across care settings to reduce hospital admissions. 41 One quality improvement project to reduce avoidable hospitalisations in the USA is the Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) programme. 42 This focuses on improving well-being and quality of care through (1) (training in) prompt recognition, identification (diagnosis) and management (treatment) of acute conditions; (2) communication, documentation and decision support tools; and (3) advance care planning. Although a pilot study of INTERACT in 25 homes demonstrated reduced rates of hospitalisations,24 a more robust design [cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT)] failed to find such effects. 40 Rantz et al. 38,43 studied the effects on hospitalisation rates of embedding an advanced practice registered nurse in nursing homes. Such an approach was not pursued in this programme as its sustainability in times of austerity may have proven difficult.

In England, the NHS Five Year Forward View44 made a commitment to improve health-care services to residents to reduce avoidable hospital admissions from care homes. The new care models included a commitment that general practitioners (GPs) be assigned to care homes and be required to make at least weekly visits. In 2016, NHS England established vanguards, demonstration sites for the new care models, the Enhanced Health in Care Homes7 initiative. The aim was to redress the inadequacy of current health care in care homes and to ensure that residents received adequate health care, in order to reduce the resulting avoidable hospitalisations. The care home vanguards have had a positive effect, with reports of lower growth in emergency admissions than the rest of England.

Baylis and Perks-Baker7 conducted interviews with care providers about progress on closer working between health and social care. They found positive results, although most benefits were measured with respect to reduced NHS costs, rather than improved quality of care and quality of life for residents. They noted that successful projects had worked in partnership with care providers and were not just about quality improvement in the home, but were engaged in changing practice at the interface between care homes and the NHS. In this project, we were keen to measure quality of life, as well as rates of hospital admission. This project focused on quality improvement in the nursing home, including improving nurse communication with primary care. We focused on nursing homes, as nursing expertise on site allowed for local ownership and relevant clinical expertise to drive change.

Enhancing health care to care homes

Concerns were raised by Baylis and Perks-Baker,7 the British Geriatrics Society,3,5,45 and a joint working party from the Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Nursing and the British Geriatrics Society45 about health-care provision to the care home sector.

Six of the vanguard projects focused on enhanced health in care homes, proactively monitoring residents’ health, improving multidisciplinary support to care homes and improving workforce skills. In 2014, a project in Rushcliffe, Nottinghamshire, which implemented an enhanced health-care model (aligning care homes with general practices, regular visits from a named GP, improved support from community nurses, independent advocacy and support from the third sector, and a programme of work to engage and support care home managers), demonstrated a reduction in emergency hospital admissions and accident and emergency (A&E) attendances. 46 A programme implemented between 2013 and 2017, in east London, which provided residents of nursing homes with increased GP access and continuity of primary care, with support to nursing home staff, also reduced the rate of emergency hospital admissions and A&E attendances. 47 It is noteworthy that there have been several system-based changes to the provision of health care in nursing homes during the BHiRCH-NH programme.

It is only relatively recently that empirical research has been conducted to ensure proactive health care in UK care homes (e.g. Devi et al. 48 and Goodman et al. 49). Furthermore, the quality of intervention studies is highly variable. Insufficient attention has been paid to key methodological issues, particularly issues of implementation, adherence to the intervention or the clustering effect within nursing homes. There is a lack of robustly conducted RCTs.

Research on enhancing health for residents in UK care homes, published since we started this project, has focused on identifying service delivery models that optimise the integration between the care home, the NHS and social care services. For example, the Optimal study49,50 explored how nursing homes worked with the NHS and how different delivery models affected residents’ and staff access to health care. They concluded that NHS professionals and care home staff need dedicated time and resource to work together to discuss, plan and review health care for individuals and all residents. Staff from both sectors need to be trained to provide collaborative care.

An ongoing quality improvement collaborative in the UK, Proactive HEAlthcare of Older People in Care Homes (PEACH),48 focuses on implementing and delivering comprehensive geriatric assessment to care homes. This collaborative project includes health-care and social care professionals, care home staff and specialists in clinical aspects, quality improvement methodology and research. Chadborn et al. ’s51 realist review identified three elements required to ensure effective health care for older people in UK care homes: comprehensive geriatric assessment, care planning and working towards a patient’s goals. Health care in care homes will be improved by ongoing contact between health care and care home staff and opportunities for care home staff to liaise with a wider system of health care, including access to dementia-specific expertise. 52

When we developed and conducted this study (2010–13), there was a policy imperative to reduce avoidable hospital admissions. This project focused on developing an intervention that would enhance the quality of health care in care homes to reduce resident hospital admissions.

Implementing change in care homes

A range of implementation strategies that optimise engagement with the intervention have been identified. These include establishing local implementation teams in the form of quality collaboratives and identifying local intervention champions and ensuring resident and family involvement. These approaches are consistent with the literature on practice development in nursing homes in the UK and international frameworks for knowledge translation [e.g. Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS)]. 53 In this programme, we used PARiHS as the overarching framework to ensure local ownership of the change process and to introduce the intervention. 53–56

The PARiHS framework proposes that implementation is a function of a dynamic relationship between:

-

Evidence57 – in this study, the evidence implemented was the synthesis of findings from the systematic literature review, additional research, and clinical and family experience.

-

Context56 – in this study, issues such as organisational commitment and leadership, role alignment, and decision-making were dimensions of the context to be addressed.

-

Facilitation54 – in this study, we used the implementation method of continuous quality improvement; within that approach, we elected to use the intervention champion role and quality collaboratives as the facilitation processes.

Studies into why evidence is not used in practice consistently raise the challenge of ‘the black box of context’. 58,59 Despite robust studies demonstrating efficacy, translation into practice is not straightforward. The most successful implementation occurs when evidence is robust, the context is receptive to change and when the change process is facilitated. 53,60 However, finding a method that pays attention to context and that is facilitated is a challenge in nursing homes, because of limited resources. 61 Studies of nursing home organisational culture change conducted in the USA concluded that interventions need to be aligned with the administrative, operational and management structure of nursing homes. Furthermore, nurses needed to work with and mentor care assistants, helping them to apply new knowledge and supporting them in decision-making. 62

We used intervention champions and quality collaboratives to drive forward practice change from within the home. 63,64 These reflected the evidence identified in the programme about the role of local champions and local implementation teams. Quality collaboratives had been applied internationally and in many sectors, including health care. A quality collaborative involves diverse stakeholders working together to close the gap between actual and potential practice, in this case the proactive detection and management of ACSCs in frail nursing home residents. Quality collaboratives provide a framework for quality improvement that is not dependent on external facilitators. Instead, the method draws on the existing expertise of stakeholders who are familiar with the context and culture of the setting, and thus have greater insight into the factors that can enable or hinder improvements. In a recent study, Harvey et al. 62 identified the importance of recruiting and retaining staff who have facilitation skills and support from managerial leaders as key criteria for achieving practice change in nursing homes. 61

In this programme, we promoted local ownership of the change process, including how to introduce and embed the intervention. We collaborated with stakeholders to design and evaluate the intervention and the implementation guidance.

We identified the likely elements of a multicomponent intervention:

-

observation, communication and decision-making tools and documentation for care of ACSCs in UK nursing homes

-

knowledge and skills development of nurses and care assistants

-

involvement of family members

-

nurse confidence, empowerment and leadership

-

robust implementation guidance.

Workstream 1: develop the complex intervention

Aim

The aim of workstream (WS) 1 was to develop and manualise a pragmatic and acceptable multicomponent intervention to ensure proactive health care in nursing homes for four ACSCs associated with avoidable hospital admissions for care home residents: respiratory infection, exacerbation of CHF, UTI and dehydration.

There were four work packages (WPs):

-

WP1 – develop care pathways for ACSCs (respiratory infection, exacerbation of CHF, UTI and dehydration) in UK nursing homes

-

WP2 – develop optimal approaches to enhancing the knowledge and skills of nursing home staff

-

WP3 – develop optimal approaches to implementation support and an implementation support package

-

WP4 – clarify the role of family in early detection.

Work package 1: develop care pathways for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions in UK nursing homes

Led by health-care specialists in primary care (LR) and geriatrics (JY), we sought to develop a care pathway to ensure early detection and treatment of four index conditions: respiratory infection, exacerbation of CHF, UTI and dehydration.

Methods of data collection and analysis

We worked with stakeholders, including nursing home staff and our Carer Reference Panel (CRP), to develop and adapt the INTERACT tools for use in the UK.

The following were conducted:

-

Co-applicant specialists in geriatric medicine (JY) and primary care (LR) reviewed care pathways identified in a search for care pathways (see Appendices 1 and 2). This led to version 1 of the care pathway.

-

We obtained expert panel input via e-mail on this version of the care pathway (see Appendix 3). Experts included three international advisory group members, two members of the British Geriatrics Society and three members of the Royal College of General Practitioners. This input was reviewed by John Young and Louise Robinson, and led to version 2.

-

We held a consensus workshop with 17 stakeholders with diverse areas of expertise, including eight nurses (four community/district nurses, three nursing home nurses and one nurse consultant), two nursing home managers, three care assistants, one geriatrician and three family members (see Appendix 4). This led to the final draft of the care pathway.

Limitations

The main limitation was the limited amount of previous research to guide our approach. Only 22 papers were identified in the literature review. Overall, the quality of intervention studies was rated as being highly variable. There was a lack of robustly conducted RCTs (only two trials were rated as being of ‘strong’ quality). Insufficient attention was paid to key methodological issues, particularly the clustering effect within nursing homes. Furthermore, there were few studies conducted in the UK, thereby having questionable relevance to the UK context.

Key finding

We identified care pathways for ACSCs in nursing homes for our four conditions (respiratory infection, exacerbation of CHF, UTI and dehydration) and adapted them in consensus co-design workshops with staff and family carers. We developed a care pathway to facilitate assessment and diagnosis of the four index conditions from existing care pathways used to facilitate diagnosis and treatment of health conditions in care home residents. The final version of the care pathway is presented in Appendix 5.

Inter-relationship with other parts of the programme

The care pathway was one of three intervention tools that were included in the feasibility study.

Work package 2: develop approaches to enhancing staff knowledge and skills

We sought to identify:

-

the knowledge and skills required to ensure early detection and treatment of the four index conditions

-

effective approaches to enhancing the knowledge and skills of nursing home staff

-

knowledge and skills enhancement programmes for active management of ACSCs in nursing homes.

Methods for data collection and analysis

We used three methods of data collection: semistructured interviews, rapid research review and consensus-building.

Semistructured interviews

We conducted semistructured interviews with 18 key informants to identify their perspectives on the knowledge and skills required and best practice in enhancing care staff knowledge and skills, nationally and internationally. Key informants included 10 nursing home staff, three members of the National Dementia Strategy Workforce Advisory Group and five members of the international advisory group. Interview schedules were developed with feedback from our CRP (see Appendix 6).

Interviews were carried out via telephone or face to face and were audio-recorded and transcribed. Notes were also taken.

We used thematic analysis, which involved becoming familiar with the verbatim transcripts and assigning preliminary codes to each transcript. 65 We then identified patterns or themes across the transcripts.

Rapid research review

We conducted a rapid research review of the knowledge and skills required and approaches to knowledge and skills enhancement. The following databases were searched from 1990 to 2015: the Cochrane Library, EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), PubMed, Social Care Online (Social Care Institute for Excellence, London, UK), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE, PsycInfo® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA), Applied Social Science Index (ASSIA) and Web of Science™ (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) (see Appendix 7).

The review focused on the following three areas for both nurses and care assistants:

-

knowledge and skills required for staff managing complex health conditions

-

training to develop these knowledge and skills

-

evaluations of training in care homes and other settings.

Abstracts were considered for relevance and duplicates were discarded. From the rapid review, we identified knowledge and skills for staff managing complex conditions, including:

-

subject specific –

-

palliative care

-

psychological/psychosocial assessment

-

dementia care/awareness

-

pain management.

-

-

generic –

-

communication skills

-

dealing with challenging behaviour

-

patient-centred approach

-

awareness of the principles of ethical health care

-

involving patients and carers

-

use of evidence-based knowledge

-

leadership

-

teaching skills

-

use of restraints/sedation and associated risks

-

professional self-care

-

nutritional assessment.

-

Combining findings from our rapid research review with findings from the interviews, we developed a set of knowledge and skills for nursing home staff for early detection of health conditions (see Appendix 8).

Consensus workshop

We provided a user-friendly overview of these findings to participants 2 weeks before the consensus workshop. The 10 participants comprised three community/district nurses, three family carers, two care assistants, one care home manager and one GP. We sought consensus on participants’ views in relation to the knowledge and skills required for, and evidence-based approaches to, knowledge and skills enhancement. In addition to nursing home staff, we considered whether or not family carers could become involved in timely detection, and what skills this would require.

We audio-recorded and made notes during the workshop. Using the verbatim transcripts, we conducted a thematic analysis. 66 This involved familiarisation during which initial codes were applied. We then categorised these codes into themes.

We identified ways to enhance knowledge and skills of nursing home staff, including:

-

shadowing for hands-on experience

-

college courses

-

training to reinforce learning on an ongoing basis.

Any limitations

There was a limited literature to inform us about the knowledge and skills required for nursing home care assistants and nurses to achieve early detection, assessment and reporting of acute changes in residents’ health.

Key findings

We derived a set of key knowledge and skills for nurses (see Appendix 8) and for care home staff and family members that are required for early detection of the four ACSCs. These included:

-

knowledge of how ACSCs may manifest

-

ability to detect these changes during daily care

-

knowledge of residents’ medical conditions, care plans and their baseline behaviour and symptoms

-

continuing assessment skills

-

leadership skills

-

communication skills.

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

We examined the use of the knowledge and skills matrix in our feasibility study. We expected Practice Development Champions (PDCs) would use it to conduct a gap analysis and to direct care staff and family members to learning resources that could help to address these gaps.

Work package 3: develop implementation support

We sought to:

-

Agree criteria for recruiting PDCs who would act as internal facilitators of the intervention in each implementation site. We sought to agree the purpose, role and person specification for PDCs.

-

Agree the purpose and composition of the practice development support groups (PDSGs) and guidelines for establishing and supporting them (in each of the sites, to support PDCs with implementation).

-

Develop implementation support resources for care home owners, managers, PDCs and PDSGs including the purpose and key contents of the project handbooks for staff and stakeholders.

Three weeks prior to the third consensus workshop, we sent the 12 participants a draft of our approach to identifying the PDCs and setting up the PDSG, and a draft of the implementation guidance workbooks. 64 The participants comprised one community/district nurse, three family carers, two nursing home managers, one nursing home nurse, two care assistants, one acute care nurse and three GPs. The workshop was facilitated by our co-applicant experts in practice development in nursing homes (KF and BM).

Methods for data collection

We made detailed notes of the consensus workshop discussions and participants generated written notes.

Method for data analysis

We analysed the notes, along with written materials generated by the participants, looking for key themes.

Key findings

The criteria for PDCs were thought to be appropriate. Participants identified situations in which there could be gaps in coverage of staff implementing the intervention. In particular, staff from evening and weekend shifts would need to be recruited to the PDSGs to ensure coverage across the week. Further issues with the language and structure of the staff handbooks were noted, in particular with respect to readability for care assistants and family members.

Participants reported that the purpose of the PDCs and the training methods needed to be clearer. The staff handbooks, which had been designed to provide information about the intervention, and about introducing and embedding change, were felt to be in need of improvement, including the following: be more visually attractive, use simpler language and provide less information.

Based on these findings, we developed the final version of the purpose, role and person specification of PDCs (see Appendix 9). We agreed the key topics to cover in the preparation workshop, using both presentations and interactive exercises. Box 1 presents the topics for the PDC preparation workshop.

-

Considering evidence, context and facilitation in developing practice: the PARiHS framework.

-

What are we putting into practice?

-

Strategies for engaging people.

-

Collective learning, evaluation and critique.

-

Teamwork and leadership in developing practice.

-

Giving and receiving feedback.

-

Working with families and family carers.

-

Process review.

-

Planning and developing individual action plans for moving forward.

Limitations

We intended to provide a 2-day preparation workshop for PDCs. Owing to a diary mix-up with one of the PDCs, we reduced the workshop to 1 day.

Inter-relationship with other parts of the programme

We finalised our approach to recruiting and supporting PDCs and identified the personal characteristics and professional skills required of them. The support to be provided included a preparation workshop, monthly telephone support (with AB, the programme manager) and a website with additional resources for nursing home staff. We tested this implementation support in our feasibility study in WS2, WP1.

Work package 4: clarify the role of family members

Aim

The aim was to explore family members’ perspectives on their involvement in the timely detection of their family members’ changes in health in UK nursing homes. Specifically, we sought to address:

-

How are family carers involved in timely detection of changes in their relatives’ health in nursing homes?

-

How can family carers be supported to engage in timely detection of their family members’ changes in health?

Methods for data collection

We conducted 14 semistructured interviews with family carers of residents living in 13 different nursing homes (see Appendix 10). This allowed us to obtain in-depth information on their perceived and preferred role. All interviewees were adult children and lived near the nursing home. We recruited family members who were regularly involved with their relative. We used telephone interviews to gather data from family members who were unable to attend a face-to-face interview.

In addition, we finalised drafts of the following:

-

a handbook on the intervention and its implementation for the PDCs

-

a handbook about the intervention and its implementation for care home owners and managers

-

a workbook on implementation for the PDSGs.

Method for data analysis

Interview data were transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis. 67

Any limitations

We were unable to identify family members who lived further away from the care home, despite advertising nationally. We had hoped to include these, as they provide an additional perspective on family involvement.

Key findings

Families were involved in the timely detection of changes in health in three key ways:

-

noticing signs of changes in health

-

informing care staff about what they noticed

-

educating care staff about their family members’ changes in health and how they manifest.

Families suggested that they could be supported to detect early changes in health by developing effective working practices with care staff. 66

Inter-relation with other parts of the programme

Family involvement was examined in the feasibility study in WS2, WP1. The intention was for care staff to establish how best to work with family members who would like to be involved in the intervention, recording preferences in each resident’s care record, as well as explaining the purpose and application of the S&W.

Draft 1 of the complex intervention

In summary, the complex intervention we developed comprised five components, plus its implementation, facilitated by identifying and supporting PDCs.

Five components of the complex intervention

1. Stop and Watch Early Warning Tool

The intervention will use an adapted version of Atlantic Florida University’s S&W (version 4.0). 68 This tool is used widely in the USA. It highlights simple signs and behaviours to identify common, but non-specific, changes in a resident’s condition that seem out of the ordinary for the resident. The tool is intended to be used as an alert to determine if further assessment of a resident by a registered nurse (with the care pathway) is necessary. It helps nurses and care assistants to check for potential warning signs of deterioration in health. It can be used whenever anyone in the care home has a concern about a resident.

2. Care pathway

The care pathway is to be used by nurses whenever a change has been noted with the S&W. It is a clinical guidance and decision-support system that includes primary and secondary assessment of respiratory infection, acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure, UTI and dehydration. Primary assessment comprises screening questions and secondary assessment requires more detailed investigation.

3. Modified situation, background, assessment, recommendation technique

The situation, background, assessment, recommendation (SBAR) technique is to be used by nurses to help structure communication with primary care services. We adapted this for use in care homes.

4. Knowledge and skills

We have identified training resources that addresses potential gaps in the knowledge and skills necessary for implementation of the intervention tools. These resources are available using a web link to care home staff and family carers. We have developed a knowledge and skills matrix identifying the key knowledge and skills required of nurses, care assistants and family carers.

5. Involvement of (and support for) family carers

Care staff are expected to ascertain the level of involvement family carers of residents wish to have in the early detection of changes in the health of their relatives.

Implementation support

Implementation support included asking nursing home managers to engage in a change management programme, which included:

-

identifying two PDCs

-

establishing a PDSG to support the work of the PDCs in introducing and embedding the intervention tools.

The study team provided training for the PDCs’ role. We provided two implementation support handbooks:

-

for care home staff (for managers and PDCs)

-

for staff and PDSG members.

The handbooks were to be used in the nursing home to help staff to understand the intervention and support its implementation. The handbooks offer background information on some of the approaches to change used in this project, promote an understanding of how the intervention can be implemented in the differing contexts of each home, facilitate and improve the learning of others in the nursing home, help teams learn and act alongside the people for whom they care, maximise opportunities for all team members to enhance their leadership capabilities, and offer information for residents and their family carers to help them become active participants in developing practice in their care homes.

Workstream 2, work package 1: test the intervention – feasibility and acceptability study

Aim

The primary aim of the feasibility and acceptability study (conducted from October 2016 to January 2017) was to refine the intervention, the implementation support and the study procedures to inform the pilot cluster RCT. The secondary aim was to identify data to be collected in the pilot study.

Research questions

-

Can the intervention be delivered as intended?

-

What further refinements are required to the implementation guidance?

-

Is the approach to collecting data feasible?

-

What are the resource requirements to collect and analyse the data?

Ethics approval

The feasibility study received ethics approval from London Queen Square Research Ethics Committee (reference number 16/LO/1361). It was registered in the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry (as ISRCTN86811077) (registration date: 12 September 2017).

Results

Can the intervention be delivered as intended?

At the end of the 3 months, we carried out a semistructured interview with one intervention champion to learn about their experience of taking part in the feasibility study, the barriers to and facilitators of using the intervention, the training workshop and the implementation support. In addition, we held informal conversations with six further members of staff from the two nursing homes to explore what had worked well, what had worked less well, and what facilitated and hindered adoption of the intervention. Notes were taken during the conversations. The interview was analysed alongside the notes from impromptu conversations with care staff.

Stop and Watch Early Warning Tool

The S&W was used 25 times across both nursing homes, completed by both care assistants and nurses. The S&W was sometimes used retrospectively rather than at the time the change was observed. One PDC indicated that they valued the S&W as an additional resource in their nursing homes. Another noted that a key benefit of the S&W was that it enabled junior staff members to notice changes in residents’ health conditions. In both nursing homes, its key strength was that it was clear, quick and easy to use. That said, a care assistant reported that there was not enough time to use it as intended. Information about the S&W was not always well communicated. Many staff learned about it through word of mouth, and staff who worked at the weekend stated that the PDC had not sufficiently explained the BHiRCH-NH study and purpose.

Care pathway

The care pathway was used five times across both nursing homes over the 3-month study period. PDCs reported that they had to continually remind their nursing colleagues to use the tool. Nurses sometimes used the care pathway for concerns about deterioration in health for conditions other than the four target conditions. PDCs from both nursing homes reported that staff did not see that it provided any additional benefit to what they were already doing. In some cases, the care pathway was used informally as a prompt to indicate what steps should be taken next, such as when to contact primary care. Some nurses reported that the layout of the care pathway was difficult to follow. Furthermore, PDCs felt that they had not successfully communicated why it was being introduced into their nursing home.

The situation, background, assessment, recommendation technique

Practice Development Champions in both nursing homes reported that they already used a different version of the SBAR technique and were happy to replace this with the modified, nursing home-specific version provided in this study. They reported that it was used as intended by nurses in both nursing homes, suggesting that it is acceptable to nursing home staff. PDCs in both nursing homes indicated that staff members were aware of the key points of the SBAR technique when contacting primary care. The PDCs believed that the SBAR technique gave nurses increased confidence to speak to GPs, for example in ensuring that antibiotics were obtained from a GP. The SBAR technique was viewed as a way of empowering nurses, as it gave them more confidence in speaking with primary care. One of the PDCs mentioned the importance of building rapport and having a good relationship with GPs for the benefit of the residents.

Family involvement

Practice Development Champions in one nursing home did not see the need to collaborate with family to improve detection of changes in residents’ health. PDCs in the other nursing home reported that they made some efforts to include family carers in monitoring the health of residents, but did so inconsistently and without systematically documenting their efforts. Family carers were not informed about how they could be involved in the intervention during the feasibility study. This was because of the lack of a systematic method for communicating with family members regarding the intervention.

Enhancing knowledge and skills

The knowledge and skills matrix was used minimally in one nursing home and not at all in the other.

What further refinements are required to the implementation guidance?

Practice Development Champions

We identified two PDCs, whose role was to train, support and work alongside nurses and care staff to ensure uptake of the intervention. PDCs felt that their role in empowering and motivating staff was key to introducing and embedding this new way of working. PDCs were to establish and co-ordinate the work of the PDSG and maintain momentum for change and development. In the context of the PARiHS framework, the PDSG acts as a collective internal facilitator supporting the PDCs. It was intended that the detail of how PDCs worked with the PDSG would be negotiated at each nursing home site to ensure a mutually supportive relationship, with clear lines of accountability.

Training workshop

Two PDCs from each home attended the 1-day training course to prepare them for their role. The training day was facilitated by our practice development experts (BM and KF). Our geriatrician co-applicant (JY) provided an overview of how to detect changes in health and one of our patient and public involvement (PPI) colleagues (SN or BWC) presented on the role of family in health care for relatives in nursing homes. The presentations were video-recorded to be used as an online resource for the PDCs.

Practice Development Champions in both nursing homes reported that the training workshop was highly informative, in particular the input regarding early detection of changes in residents’ health. In one of the homes, the PDC used the video-recorded session from the training day when cascading information about the intervention to nurses and care assistants. PDCs felt that previous training (e.g. in end-of-life care) had covered similar knowledge and skills, and that no further training was required.

Practice development support group

Three of the four PDCs were managers of the homes and they relied on a top-down approach to implementation. They did not establish a PDSG. Furthermore, PDCs believed that family involvement in PDSGs was unnecessary, as they believed that staff already monitor residents’ health effectively.

Time to embed the intervention

One of the key ways staff members felt that the intervention could be better implemented was through the nursing home having more time and resources. They noted that low levels of staffing in the nursing home had hampered implementation of the intervention. The duration of the feasibility study was also thought to be a hindrance. Three months was considered too short a time frame to implement complex changes to working practices. One of the PDCs stated that an intervention of 1 year would enable changes to be made in a nursing home. They felt that the short time frame was demotivating.

Handbooks

The handbooks were viewed as being overly long and complex. Nevertheless, the PDCs reported that the implementation handbooks contained useful reference material.

Is the approach to collecting data feasible?

Numbers recruited

The managers in both homes assisted with identification of residents, their family carers, staff and PDCs. All residents who were not receiving palliative or end-of-life care were eligible for participation in the study. We recruited 12 residents, 22 staff (six nurses, 13 care assistants and three domestic staff) and eight family carers.

Data collected

We were able to gather individual-level data (for residents, staff and family carers) (Table 1), process-level data (Table 2) and care home-level data for each month over the 3 months. Although we were able to collect data from residents’ care records, this was more time-consuming than anticipated.

| Data collected | Total number of individuals (n) |

|---|---|

| Residents (N = 12) | |

| Demographics | 12 |

| Resident quality of life (DEMQOL-U) | 12 |

| Resident quality of life using the EQ-5D-5L | 12 |

| Medical consumables, such as prescription medication and prosthetics | 12 |

| Use of health and social care services (CSRI) (A&E, GP, etc.) | 12 |

| Serious adverse events | 1 |

| Functional ability of residents assessed by the Barthel Index69 | 6 |

| Staff (N = 22) | |

| Demographics | 22 |

| Degree of perceived organisational support for providing person-centred care (P-CAT; Edvardsson et al.70) | 6 |

| Nurse ratings of communication with primary care (Tjia et al.71) | 6 |

| Context Assessment Index (McCormack et al.72) | 6 |

| Family carers (N = 8) | |

| Demographics | 8 |

| Carer quality of life using the EQ-5D-5L | 8 |

| Carer-perceived quality of life of the resident (EQ-5D-5L Proxy) | 8 |

| Carer-perceived quality of life of the resident (DEMQOL-U Proxy) | 8 |

| Identify preferred role of family carer | 8 |

| Process-level data | Total (n) |

|---|---|

| S&W | |

| Number of completed S&W forms | 25 |

| Most common changes observed | |

| Ate less | 11 |

| Skin change | 8 |

| Talks less | 2 |

| Seems different | 7 |

| Who completed the form | |

| Nurse | 6 |

| Care assistant | 19 |

| Number of S&W forms for which no changes were noted after using the form | 2 |

| Care pathway | |

| Number of S&W forms that resulted in a care pathway being actioned and completed by the nurse | 5 |

| Number of care pathways that were completed by the nurse who was initially informed of a change | 2 |

| Number of primary assessments conducted using the care pathway | 3 |

| Number of secondary assessments conducted using the care pathway | 3 |

| Number of primary and secondary assessments using the care pathway that resulted in an ambiguous outcome | 0 |

| Number of care pathways administered 6 hours after an ambiguous outcome | 0 |

| Outcome of care pathway assessment | |

| Further general monitoring using S&W | 0 |

| Monitoring for specific symptoms | 0 |

| Treatment initiated in care home | 2 |

| Condition communicated with primary care | 1 |

What are the resource requirements to collect and analyse the data?

Although we could collect individual-, process- and care home-level data, it was more time-consuming than expected.

Final draft of complex intervention

In summary, following the feasibility study, the final draft of the complex intervention comprised three intervention tools: the S&W, the care pathway and the SBAR technique.

Stop and Watch Early Warning Tool

We agreed to emphasise the purpose and use of the S&W during the training workshop for PDCs, including our expectation that family carers be offered the opportunity to have a role in alerting staff to any changes they noticed in their relatives’ health.

Care pathway

We clarified the links between sections and changed the form so that data could be entered directly. We expected that PDCs would provide further education to their nursing colleagues about its purpose and aims.

The situation, background, assessment, recommendation technique

We expected that nursing home nurses would use the SBAR technique, when communicating with primary care, as an integral part of their engagement with the intervention.

Involving families

We integrated family involvement into use of the S&W by emphasising the role of family members in early detection of changes in health. Family members were expected to notify staff if they observed any changes in their relative, which, in turn, would prompt the staff member to use the S&W.

We expected nursing home staff to inform family carers about the research at the start of the project and invite them to participate. Nursing home staff were expected to describe to family carers, who had expressed an interest in participating, the potential roles they could play in the project.

Knowledge and skills development

As the PDCs had not engaged in this aspect of the intervention, we decided to use the knowledge and skills matrix as a way of describing nurses’ knowledge and skills at the outset of the study. This would provide us with useful contextual information.

Final draft of the implementation strategy

Components

Practice Development Champions

We revised the content of the training workshop (see Appendix 11). The information provided to PDCs was simplified, was reduced in length and was more focused on directly useable skills and tools.

Practice development support group

We refined the implementation support and training for PDCs to ensure inclusion of all aspects of implementation support. We noted that, in the feasibility study, PDSGs were not established in either nursing home. Greater emphasis was to be placed on supporting PDCs to set up PDSGs.

Handbooks

The length and complexity of the implementation handbooks were significantly reduced. Two separate handbooks for PDCs and PDSGs were integrated into a single volume (see Appendix 12). We agreed that the monthly coaching telephone calls would be provided by co-applicants with expertise in practice development (BM and KF) rather than by the programme manager (AB), as he would be involved in data collection.

Data collection

Recruitment

In identifying potential care homes for the pilot trial, we established that the study had the full support of the nursing home manager and that the home was capable of implementing a complex intervention (e.g. noting the level of enthusiasm of the nursing home manager, nursing home involvement in other trials). We refined the recruitment process for residents to facilitate access to personal or professional consultees when necessary. We incorporated a study launch day, detailed set-up procedures (see Appendix 13) and identification of a research facilitator in the nursing home to ensure efficient recruitment and optimal data collection.

We expected a CRP member to input regarding family involvement and the S&W at each launch event, but scheduling proved difficult such that only one person did. We ensured publicity about the study in the nursing home environment. For example, we provided posters (see Appendix 14), leaflets and a newsletter (see Appendix 15).

Resource requirements

We recruited a research facilitator from the nursing home staff to support the research team with recruiting residents and family carers and with accessing residents’ records (see Appendix 16). We also had support from the local CRN with recruitment and consent processes. We reduced the number of questionnaires for use in the pilot trial. For example, we removed the Context Assessment Index as it was too burdensome. Furthermore, we found that some of the questionnaires used in the feasibility study did not provide a great deal of additional information; for example, there was overlap between the Dementia Quality of Life (DEMQOL) scale and the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), as measures of quality of life. We retained the EQ-5D-5L and the EQ-5D-5L proxy (reported by a carer).

Workstream 2, work package 2: pilot cluster randomised controlled trial

Parts of this section appear in Sampson et al. 73. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Aim

The aim of the pilot cluster RCT was to test the intervention and its implementation guidance (developed in WS1 and refined in the feasibility study) to:

-

establish whether or not a future definitive trial is warranted and, if it is, to inform the design, sample size and other key parameters needed

-

further refine the intervention and its implementation guidance.

Methods

For detailed methods, see Appendix 17. Methods are briefly summarised in the following sections.

Trial design

We conducted a pilot cluster RCT of the BHiRCH-NH study intervention in nursing homes and an embedded process evaluation.

Study population

Nursing homes

We recruited 14 nursing homes (eight in West Yorkshire and six in Greater London). Nursing homes were identified via local CRNs and the Enabling Research in Care Homes (ENRICH) network.

Inclusion criteria

Nursing homes that fulfilled the following criteria were recruited: expressed an interest in the project; had adequate staffing for the intervention; and had the capacity to implement the different components and take part in, and support, research activities.

Exclusion criteria

Nursing homes that had been placed in special measures by the CQC, the English body responsible for assuring quality of care, were excluded.

As this was a pilot study to inform the sample size calculation for a definitive trial, no formal sample size calculation was conducted. Nursing homes were purposively selected to include a range of providers (large and small chains, independent providers), locations (urban, suburban and rural) and sizes.

Staff and residents

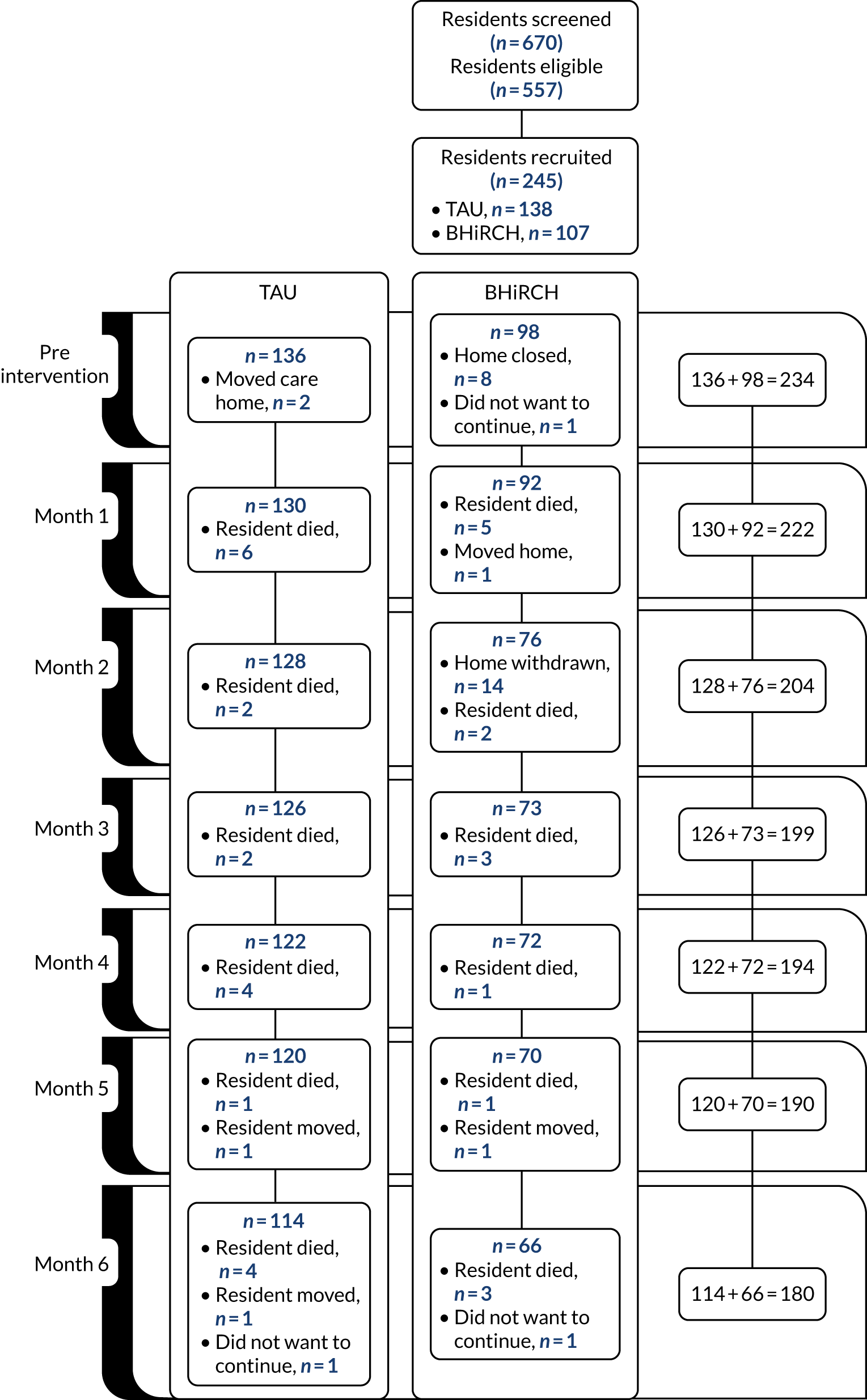

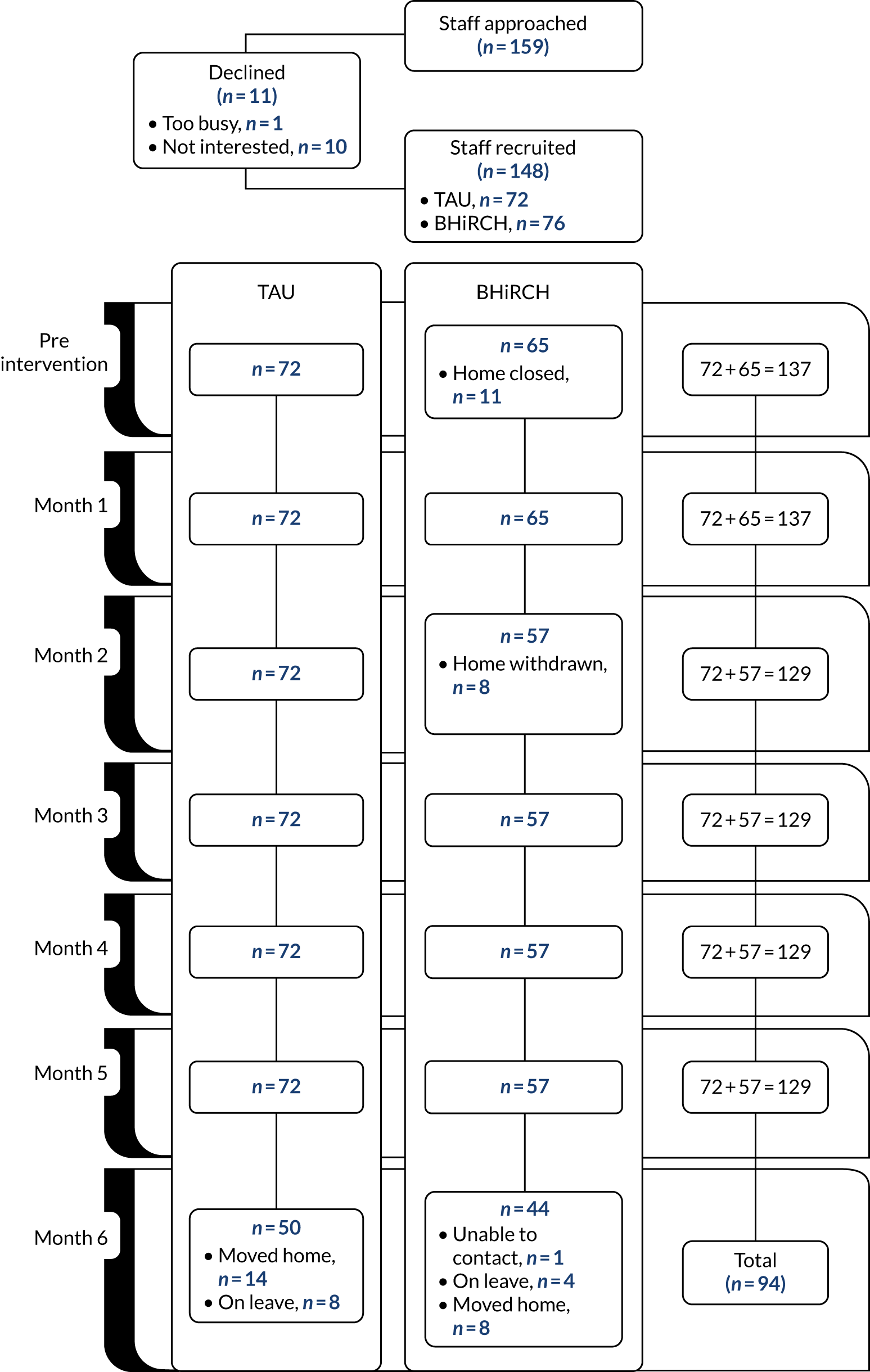

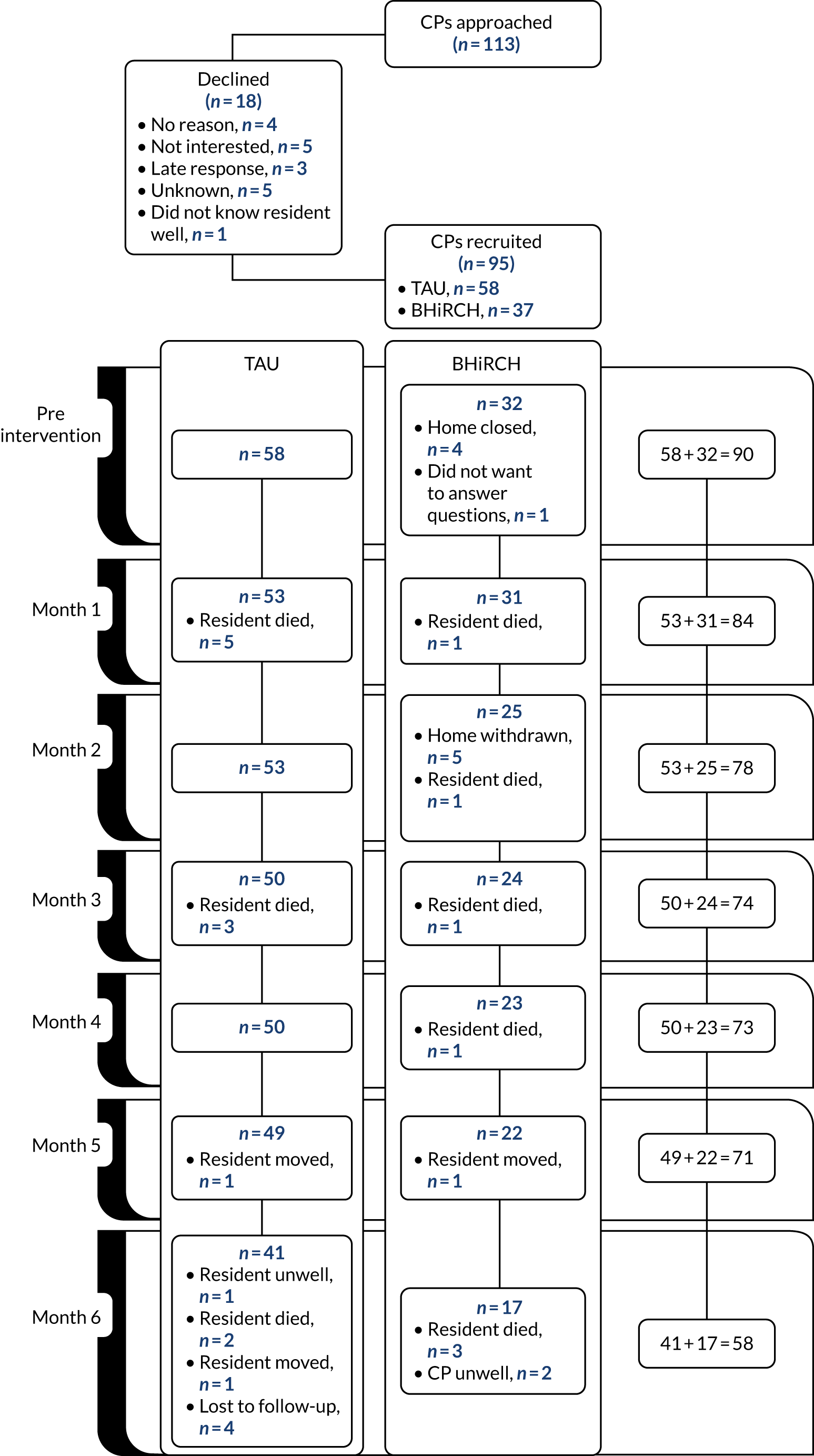

All English-speaking staff and residents aged > 65 years and their family carers were invited to participate in the collection of individual-level data until we recruited approximately 20 residents and staff from each nursing home (for recruitment figures and reasons for exclusion, see Appendices 18–21).

Randomisation and masking

Nursing homes were randomised prior to the intervention starting (considered to be the day after the training workshop); four in West Yorkshire and three in Greater London (seven in total) were randomised to the intervention arm and four in Yorkshire and three in Greater London (seven in total) were randomised to the treatment-as-usual (TAU) arm, stratified by location, by an independent statistician from the Priment Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). The statistician and health economists analysed the data while remaining blind to randomised allocation. Data were not collected by people who were blind to allocation because of resource issues and the visibility of the intervention in nursing homes.

Ethics and consent

Ethics approval was obtained from the Queen Square London Research Ethics Committee (reference number 17/LO/1542). We gained written permission from the manager, regional manager or owner for the intervention to be implemented at nursing home level. We obtained individual consent for the collection of individual-level outcome data from residents. If they lacked capacity, we consulted a personal or professional consultee, as per the Mental Capacity Act 2005,74 for their agreement for the person to participate. A member of the nursing home staff identified potentially eligible residents. Adhering to the Mental Capacity Act 2005,74 the research team conducted a capacity assessment with respect to participation. Consent was sought from family carers associated with residents recruited to the study and from nursing home staff to answer questionnaires and/or take part in qualitative interviews.

Care record reviews

To explore fidelity to the intervention, two nurse researchers (SG, HP) reviewed a convenience sample of five records for residents who had been admitted to hospital, or received treatment in the nursing home, for an ACSC. The nurse researchers used free text to record reference to the observations and actions in the care pathway.

To ascertain whether or not hospital admissions were avoidable, one of the co-applicants (JY) and two nurse researchers (SG, HP) extracted data from the care home records of 11 residents who had been hospitalised, and completed the first section of the structured implicit record review (SIRR) tool. 75

Trial procedures

The trial ran for 10 months between November 2017 and August 2018. Each nursing home appointed a research facilitator to support the research team with recruitment activities and to ensure that nursing home-level data collected without consent from resident files were pseudoanonymised prior to being given to the research team. The intervention was delivered as described in Workstream 2, work package 1: test the intervention – feasibility and acceptability study. Nursing homes in the control arm received TAU according to existing local policy and practice. Data were collected for 3 months prior to the intervention phase starting and for 6 months after. All medications and treatments were permitted.

Trial measures

We collected data across three domains (Table 3):

-

Individual-level data on nursing home residents, their family carers and staff – these were collected from staff, family carers or residents who had given informed consent or from residents from whom we obtained agreement from a consultee.

-

System-level data – collected from each nursing home as a whole using existing record systems, pseudoanonymised and provided by the nursing home manager or research facilitator.

-

Process-level data – we examined how the intervention was implemented in practice, including fidelity. To understand the effectiveness of the trial procedures, we collected data on recruitment rates and consent and the numbers of family carers who wished to be involved in the residents’ care, and assessed the completeness of outcome measures, data collection and the return rate of questionnaires.

| Data collected and tool used | Collected by, at time point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre intervention | Monthly | At 6 months only | Post intervention | |

| Resident | ||||

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, highest level of education | Researcher | – | – | – |

| Service use in the previous month | ||||

| CSRI. Estimates health-care service use and helps to calculate the total health-care costs | Researcher | Researcher | Researcher | Researcher |

| Functional status | ||||

| The Barthel Index69 | Researcher | – | Researcher | Researcher |

| Resident quality of life – self-rated | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L self-rated health index and visual analogue scale of current health state | Participant | – | Participant | Participant |

| Resident quality of life – proxy rated | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L Proxy family carer or staff member view of the resident’s quality of life | Family carer/care home staff | – | Family carer/care home staff | Family carer/care home staff |

| Family carer | ||||

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, years of schooling, highest level of education | Family carer | – | Family carer | Family carer |

| Quality of life | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L | Family carer | – | Family carer | Family carer |

| Preferred role | ||||

| How much and how they like to be involved in the residents care | Family carer | – | – | – |

| Staff | ||||

| Staff sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, gender, ethnicity, number of years of education | Researcher | – | – | – |

| Staff work characteristics | ||||

| Highest qualification, role in care home, duration of service, shift pattern, first language | Researcher | – | – | – |

| Organisational support for person-centred care | ||||

| P-CAT | Care home staff | – | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| Communication with primary care | ||||

| Nurse–physician communication in the long-term care setting | Care home staff | – | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| Perceived knowledge and skills for early detection of changes in health | ||||

| Developed from feasibility study. Assesses key knowledge and skills needed to implement the intervention. Rated on a 5-point Likert scale | Care home staff | – | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| System-level data | ||||

| Number of hospital admissions | ||||

| Respiratory infection, exacerbation of CHF, UTI and dehydration | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| ‘Avoidability’ of admissions | ||||

| SIRR76 | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| Use of primary assessment tool | ||||

| Respiratory infection, exacerbation of CHF, UTI and dehydration | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| Use of secondary assessment | ||||

| Respiratory infection, exacerbation of CHF, UTI and dehydration | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| Out-of-hours GP contacts | ||||

| GP visits or telephone contact | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| Ambulances and hospital use | ||||

| Number and length of hospital stays (days), A&E attendances and re-admissions | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| Deaths in the previous calendar month | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| Staff turnover | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff |

| Care home occupancy level | ||||

| Number of available beds to potential new residents | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff | Care home staff |

We conducted semistructured interviews with five nursing home managers, six PDCs, three nurses, seven care assistants and five family carers from across the five homes that were able to deliver the intervention. We explored participants’ views on their knowledge of, engagement with, and views on effectiveness of, the intervention. Family carers were purposively sampled to ensure a range of genders, ages and types of family carer. The interviews lasted ≈ 40 minutes, and were conducted either face to face or by telephone.

Serious adverse events

Participants were monitored each month for potential adverse events. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were defined, using the standard operating procedures of the Priment CTU, as any untoward occurrence that resulted in death, was considered life-threatening at the time of the event, required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity or was any other important medical condition. Each untoward event was then considered and designated as ‘related’, that is it resulted from administration of any of the research procedures, or ‘unexpected’, that is the type of event is not listed in the protocol as an expected occurrence.

Statistical analysis

We followed Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for reporting randomised trials. Given that this was a pilot trial, analyses were mainly descriptive, focusing on recruitment, participant characteristics, other baseline and outcome variables, loss to follow-up and tabulation of SAEs. We summarised completeness of data collection on all outcome measures. Analyses were carried out in Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). We aimed to consider the rates of hospital admission for ACSCs to inform the sample size calculation for a full trial.

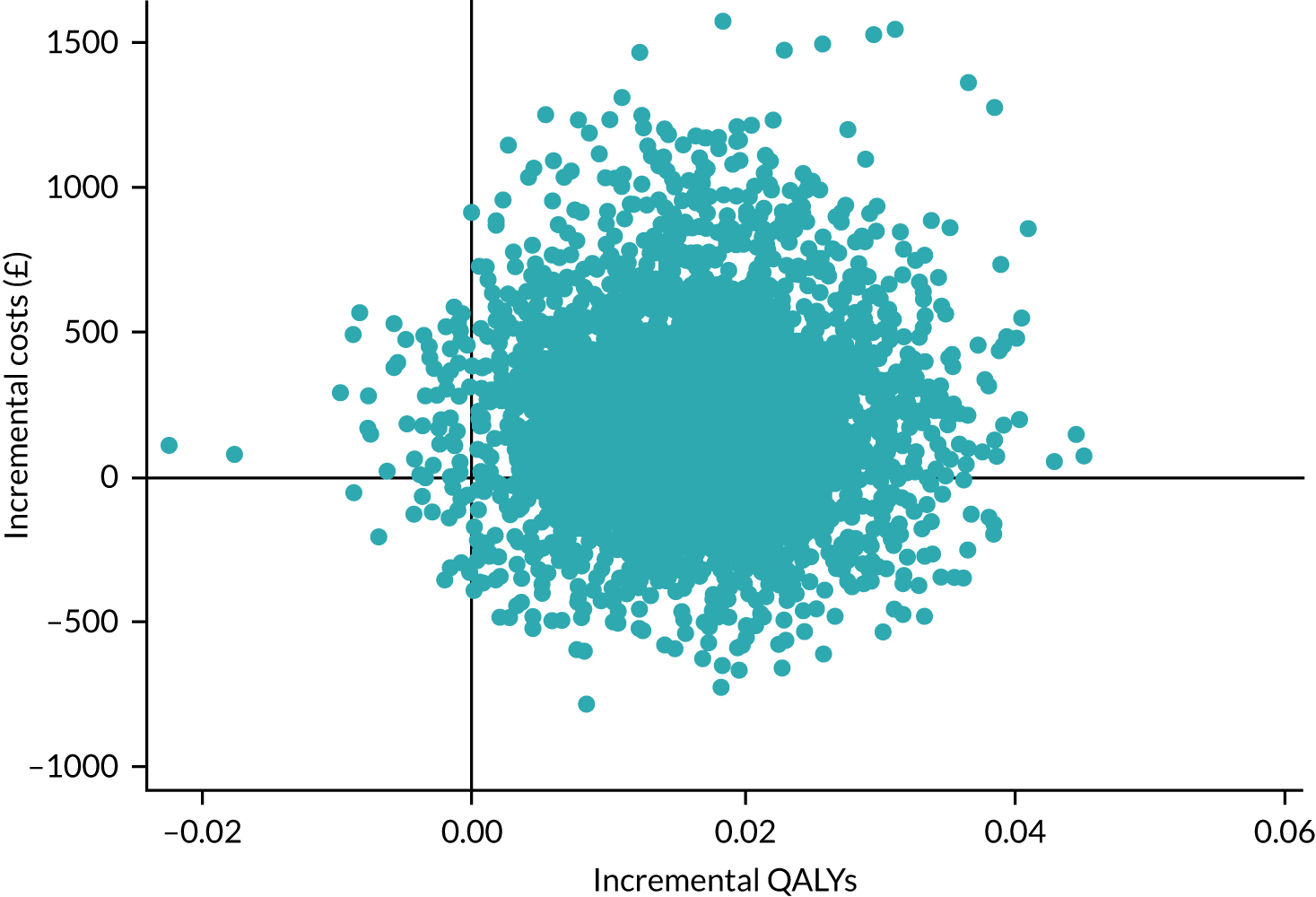

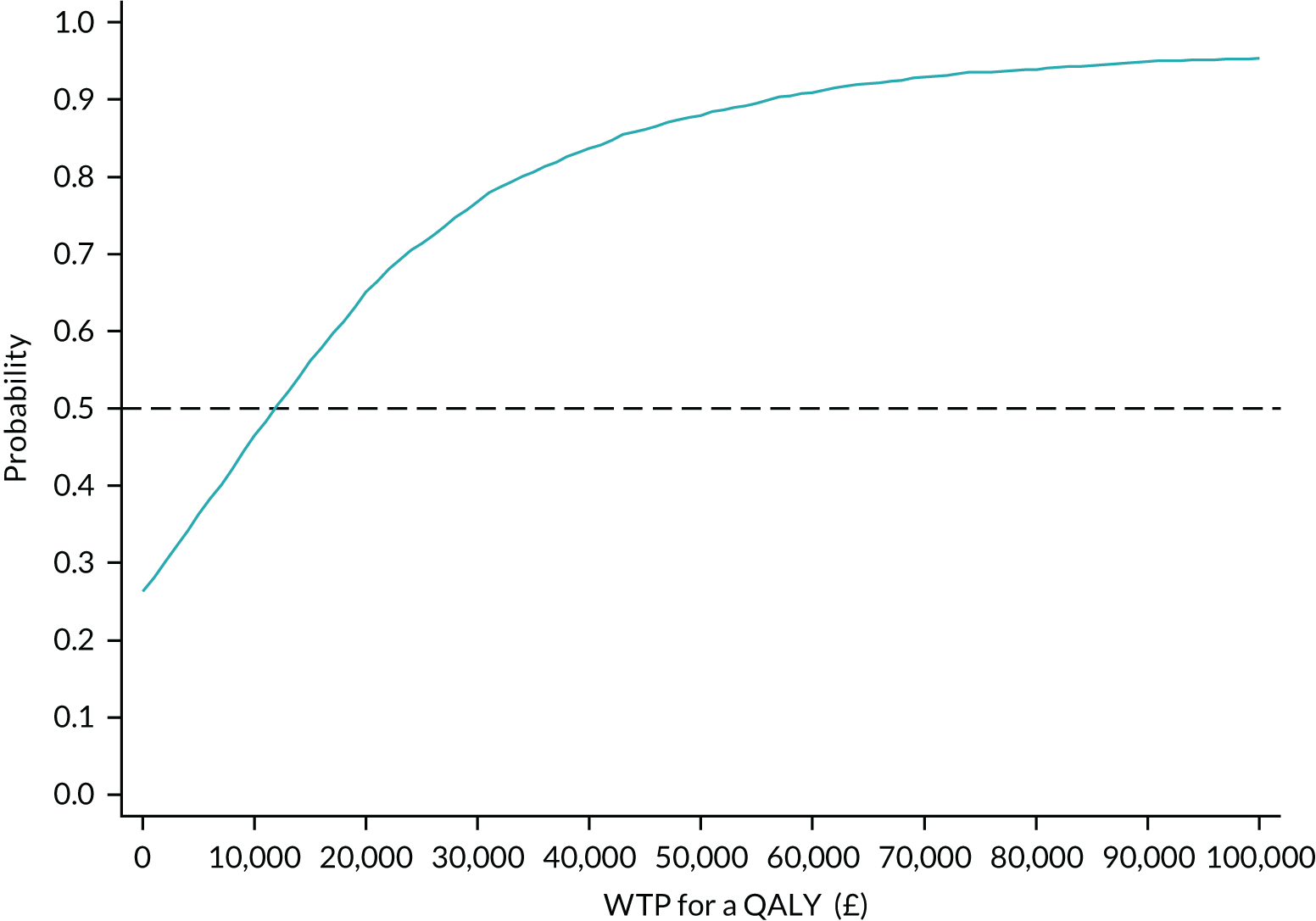

We calculated costs associated with the intervention. Resource use associated with NHS and social care provision was collected and costs were calculated from the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective. We assessed the feasibility of calculating quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for residents and family carers. The health economic analysis was conducted using utility values (to calculate QALYs) from resident self-reported EQ-5D-5L questionnaires.

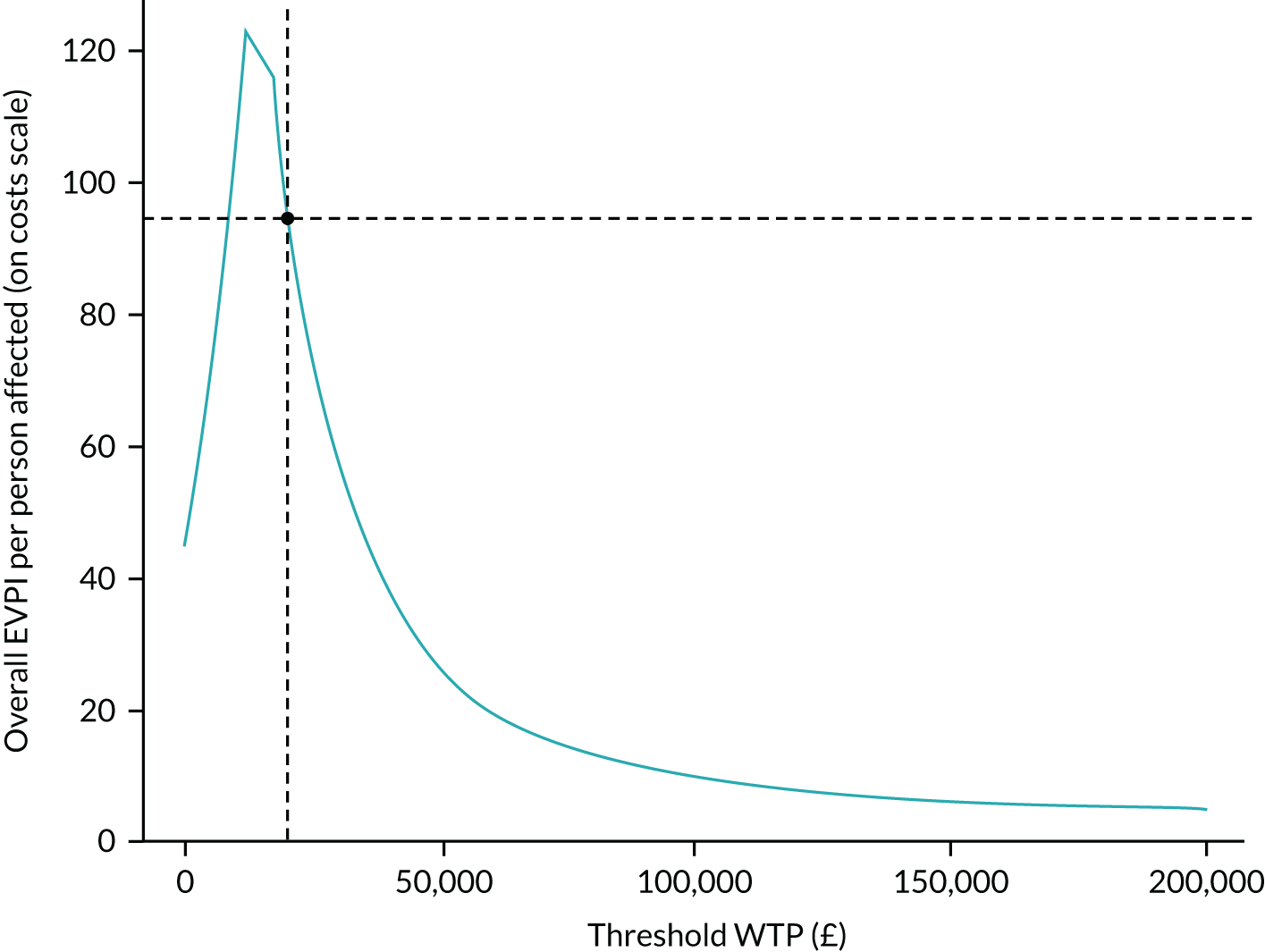

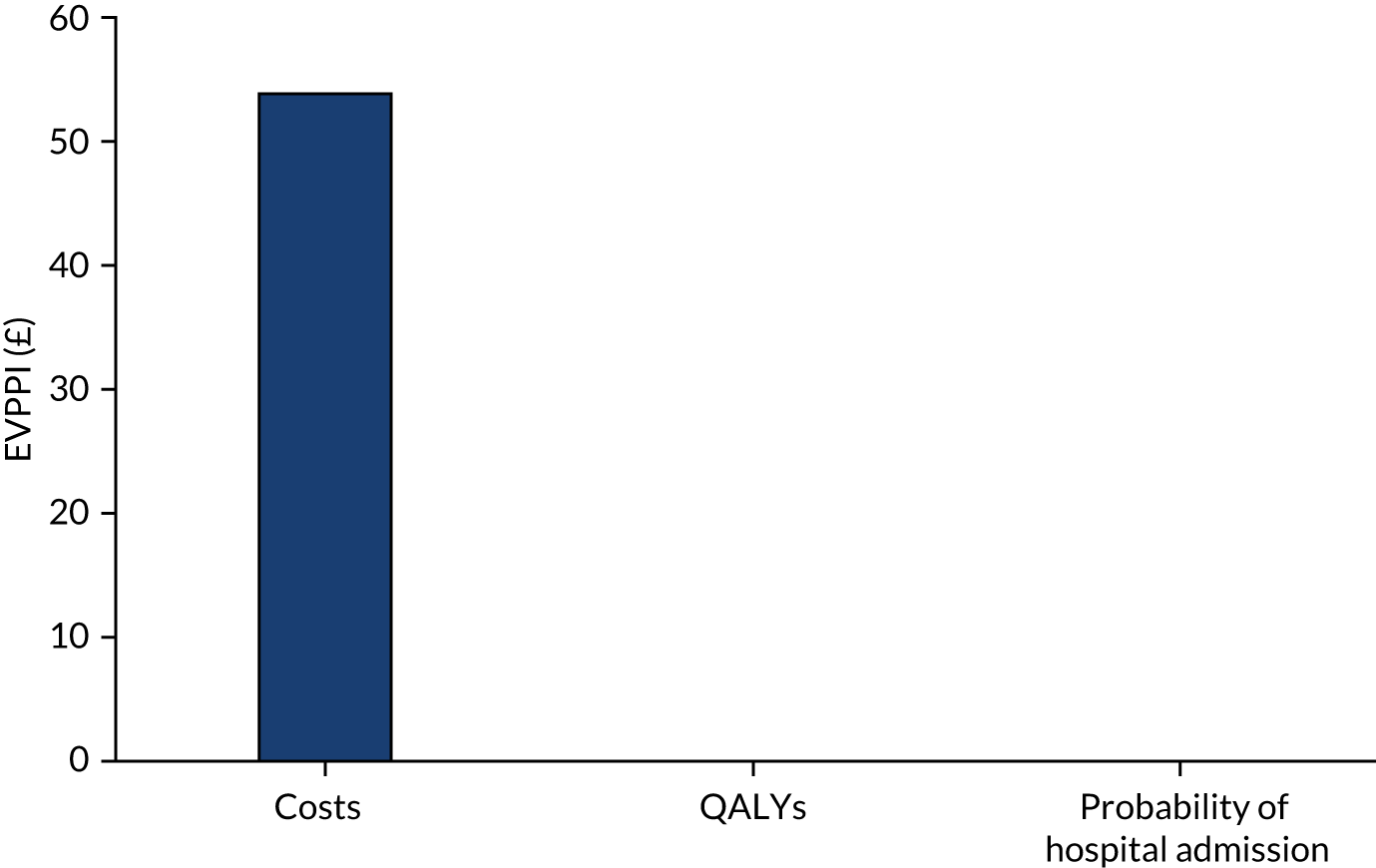

We provided an initial estimate of the incremental mean cost per QALY gained in the intervention arm, compared with the TAU arm, and reported the probability that the intervention is cost-effective for a range of willingness-to-pay (WTP) values for a QALY gained. We then estimated the price that a health-care decision-maker would be willing to pay to have perfect information regarding all factors that influence which treatment choice is preferred as the results of a cost-effectiveness analysis in the form of expected value of perfect information (EVPI) and expected value of partial perfect information (EVPPI). 76,77

Qualitative analysis

Verbatim transcripts of the interviews were made. Key themes were coded using framework analysis. 66 This involved the following stages:

-

Familiarisation – reading through each transcript and making notes.

-

Identifying a thematic framework – identifying key themes, issues or discussion points. We used the topic guide as a starting point.

-

Indexing – annotating transcripts to identify patterns.

-

Charting – rearranging the data and framework to create order.

-

Mapping and interpretation – understanding how themes relate to one another.

The process was assisted by the use of NVivo qualitative data analysis software, version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). For the family carer transcripts, stages 1 and 2 were conducted by the CRPs in collaboration with the research team. A workshop on framework data analysis was held with the CRP and members were also offered the opportunity to send input by post (see Box 2).

Context: management and care home practice.

Knowledge: knowledge about the study and the intervention tools.

Engagement: use of the intervention tools. Note that this aspect of the framework applied only to nursing home staff.

Impact: impact of the intervention tools on staff, nursing home practice and family carers.

Stages 3–5 were conducted by members of the research team. A sample of the interviews was independently coded by an additional member of the team to check levels of agreement. For interview transcripts from nursing home staff, the research team conducted stages 1–5. The thematic framework developed at stage 2 for the family carers was adapted for these staff transcripts. We explored the extent of engagement with the intervention in terms of knowledge about, and use of, its three elements: the S&W, the care pathway and the SBAR technique. We explored the effectiveness of the key elements of the implementation strategy: PDCs, the training workshop, monthly coaching telephone calls, the handbook and the web-based resources. We presented the qualitative data under these headings as they directly address the questions posed in the pilot study about the knowledge of, and engagement with, the intervention and its implementation strategy. We have added commentary to the discussion about how these findings link to the PARiHS framework, with an emphasis on context and facilitation.

Findings

We describe the trial settings and participants: residents, staff and family carers at baseline and after randomisation. We then highlight the key findings according to each of the objectives for this WP.

Trial settings

Fourteen (which was the target number) nursing homes were recruited and randomised as planned: seven to the intervention (three in London and four in West Yorkshire) and seven to the control (three in London and four in West Yorkshire). One Yorkshire intervention nursing home dropped out during pre intervention as it was closed by its owners. A further intervention group nursing home in London dropped out following PDC training as it was unable to implement any aspects of the intervention.

Nursing homes were predominantly privately managed; one was a local authority nursing home. They had a median of 50 residents [interquartile range (IQR) 34–68 residents]. The majority (73%) were ‘Dementia Registered’ and were rated overall as ‘good’ by the CQC. Table 4 allows comparison with the national average overall CQC rating for care homes: 3% are rated ‘inadequate’, 31% are rated as ‘requires improvement’, 65% are rated as ‘good’ and 1% as ‘outstanding’. Therefore, overall CQC ratings for nursing homes in this trial were above average, when compared with UK care homes.

| Nursing Home ID | Rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safe | Effective | Caring | Responsive | Well led | Overall | |

| 1 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| 2 | Requires improvement | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| 3 | Requires improvement | Good | Requires improvement | Good | Requires improvement | Requires improvement |

| 4 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| 5 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| 6 | Requires improvement | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| 7 | Good | Requires improvement | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| 8 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| 9 | Good | Outstanding | Outstanding | Outstanding | Outstanding | Outstanding |

| 10 | Requires improvement | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| 11 | Requires improvement | Good | Good | Good | Requires improvement | Requires improvement |

| 12 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| 13 | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| 14 | Requires improvement | Good | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| Trial average |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 5 shows nursing home characteristics at baseline. There were 13 nursing homes, with a median of 60 resident places (IQR 36–71 resident places). A median of 20 residents had dementia (IQR 15–33 residents) in each nursing home. There were relatively few hospital admissions, ambulances called and A&E attendances at the nursing home level in the month before baseline. There was a median of three hospital admissions per participating home (IQR 2–5), three ambulances called (IQR 2–6) and three resident A&E attendances (IQR 2–5).

| Characteristic | Median | IQR |

|---|---|---|

| Residents and beds | ||

| Beds available to new residents (N = 12a) | 1 | 1–3 |

| Resident places (N = 12a) | 60 | 36–71 |

| Number of residents present in home (N = 13) | 50 | 34–68 |

| Number of residents with dementia present in home (N = 13) | 20 | 15–33 |

| Number of residents currently in hospital (N = 13) | 0 | 0–1 |

| Medical attendances | ||

| Number hospital admissions (N = 12a) | 3 | 2–5 |

| Number of ambulances called (N = 12a) | 3 | 2–6 |

| Unscheduled (out-of-hours) GP visits or telephone contacts (N = 12a) | 1 | 1–3 |

| A&E attendances (N = 12a) | 3 | 2–5 |

| Staffing | ||

| Number of qualified nursing staff who were rostered on during the day (N = 13) | 3 | 2–5 |

| Number of care staff who were rostered on during the day (N = 13) | 11 | 9–13 |

| Number of qualified nursing staff who were rostered on during the night (N = 13) | 2 | 1–3 |

| Number of care staff who were rostered on during the night (N = 13) | 3 | 3–7 |

| Number of staff in 24-hour period who were agency/bank staff (N = 13) | 1 | 0–3 |

| Number of permanent registered nursing staff (including those on sick/carer/compassionate leave) (N = 13) | 10 | 8–13 |

| Number of permanent other care staff (including those on sick/carer/compassionate leave) (N = 13) | 26 | 24–57 |

| Number of registered nursing staff from those above on sick/carer/compassionate leave (N = 13) | 0 | 0–1 |

| Number of other care staff from those above on sick/carer/compassionate leave (N = 13) | 0 | 0–2 |

| Nursing home | n/N | % |

| Privately managed | 12/13 | 92 |

| Local authority managed | 1/13 | 8 |

| Nursing | 6/13 | 46 |

| Nursing and personal care | 7/13 | 54 |

| Dementia registered | 8/11 | 73 |

| Dementia specialist | 2/12 | 17 |