Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PGfAR programme as project number RP-PG-0611-20010 from route sheet. The contractual start date was in October 2013. The draft report began editorial review in May 2019 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Forster et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

SYNOPSIS

Background, aims and objectives of the Improving Longer Term Stroke Care (LoTS2Care) programme

Research into, and the care of, patients after stroke has been transformed in recent years. Rapid clinical change has been underpinned by a dynamic research culture, and the recommended stroke care pathway in the first weeks after stroke is becoming established. Despite this, however, longer-term outcomes remain poor for many. 1–3 Post-hospital services, such as early supported discharge (ESD), are not universally available and are usually time limited, and stroke survivors and their families can feel abandoned without the knowledge or information to access services or support. 4

Almost two-thirds of stroke survivors leave hospital with a disability,1 the prevalence of depression is 31%,5 inactivity is common6 and health-related quality of life (QoL) deteriorates post stroke. 7 Data from the South London Stroke Register indicate that 20–30% of stroke survivors have a poor outcome over a range of physical, social and psychological domains up to 10 years after the event,8 underlining the requirement for a longer-term care strategy.

Many stroke survivors require assistance from informal carers, often family members, for activities of daily living (ADL), including bathing, dressing and toileting. 9 This burden of care has an important effect on carers’ physical and psychosocial well-being,10,11 with up to 48% of carers reporting health problems and two-thirds reporting a decline in social life, and with high self-reported levels of strain. 12

Any strategy for longer-term care needs to be feasible and centred on identified needs, and the outcomes of importance to stroke survivors and their carers. These needs are multifaceted, and influenced by a range of social and environmental factors. Our previous survey (n = 1251 participants) investigated the prevalence of unmet needs in community-dwelling stroke survivors 1–5 years after stroke, reporting that nearly half of respondents had one or more unmet long-term needs. 13 These related to information provision (54%), mobility problems (25%), falls (21%), incontinence (21%), pain (15%) and fatigue (43%). Over half reported a reduction in leisure activities.

Few detailed data are available on the specific needs (and barriers to and facilitators of addressing them) and service requirements for stroke survivors and their carers in the longer term after stroke. Our programme was configured to address this evidence gap. Our Consumer Research Advisory Group (CRAG) was instrumental in prioritising and shaping this research question and has been central to the delivery of this research. We were mindful of the ever-changing NHS and social care environment and wished to work with stakeholders to generate data that would inform the feasible provision of care to enhance the lives of people after stroke.

We sought to develop and test a longer-term integrated stroke care strategy focused on improving the QoL of stroke survivors and their carers by addressing unmet needs and maintenance and enhancement of participation (i.e. involvement in life situations).

Participation is defined in the International Classification of Functioning and Disability (ICF)14 as ‘an individual’s involvement in life situations in relation to health conditions, body functions and structures, activities and contextual factors’ (environmental and personal factors).

It was planned to address the following research questions:

-

What do stroke survivors and their carers identify as the key barriers and enablers that influence unmet needs and participation after stroke?

-

How can services and personnel (health, social care and voluntary sector) be informed and configured to deliver a replicable system of stroke service?

-

Using the framework of intervention mapping, can evidence- and theory-based practical care strategies and associated materials be developed to address unmet need, and maintain and enhance participation for all those affected by stroke?

-

Can key study design considerations for a future large-scale randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the proposed longer-term care strategy be addressed by undertaking a feasibility cluster RCT?

The objectives were to:

-

develop the content of the care strategy through qualitative exploration with stroke survivors and their carers and review of the evidence relating to content and delivery

-

inform feasible means of delivery through a national survey and more detailed examination of four services

-

use the framework of intervention mapping to develop a care strategy, supporting materials and training programmes (for stroke survivors and staff)

-

refine content and test implementation of the care strategy through case studies in three stroke services

-

undertake a feasibility cluster RCT to refine procedures for a future large-scale trial.

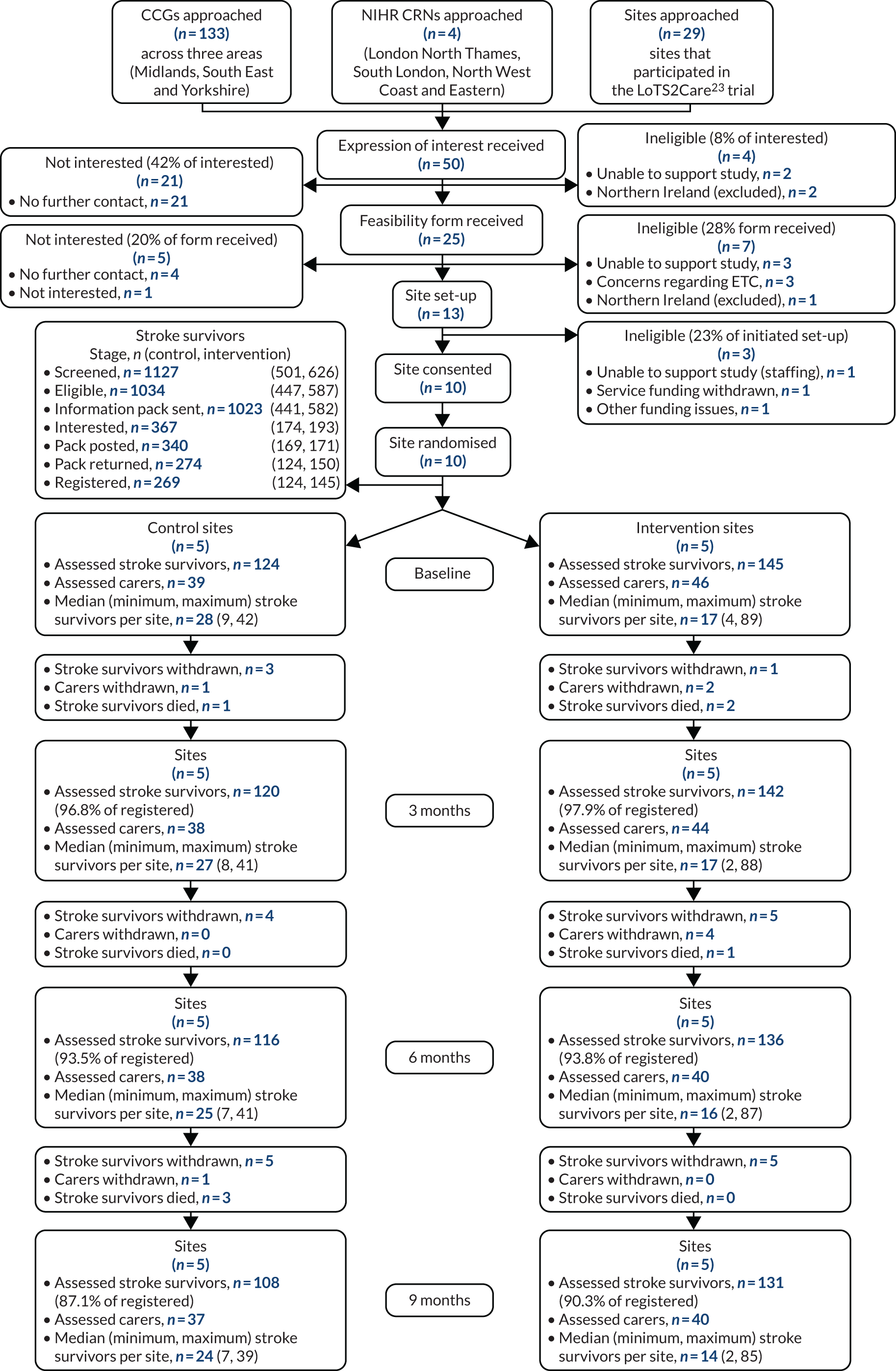

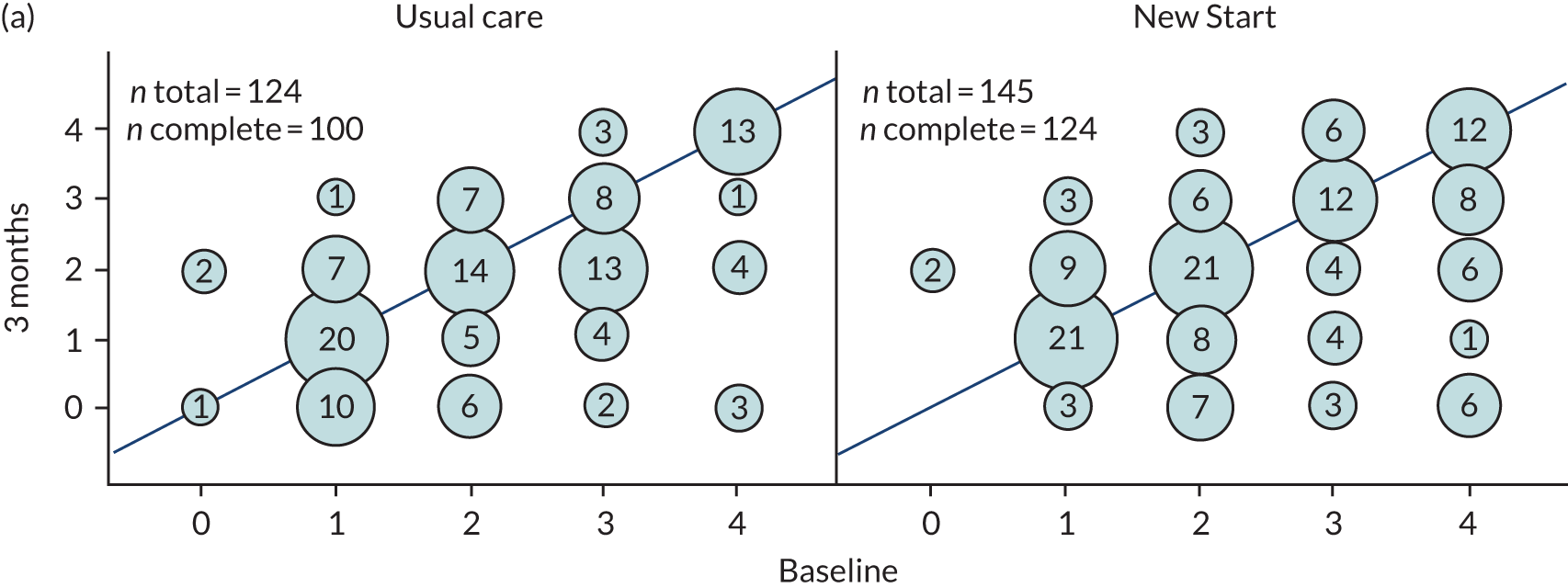

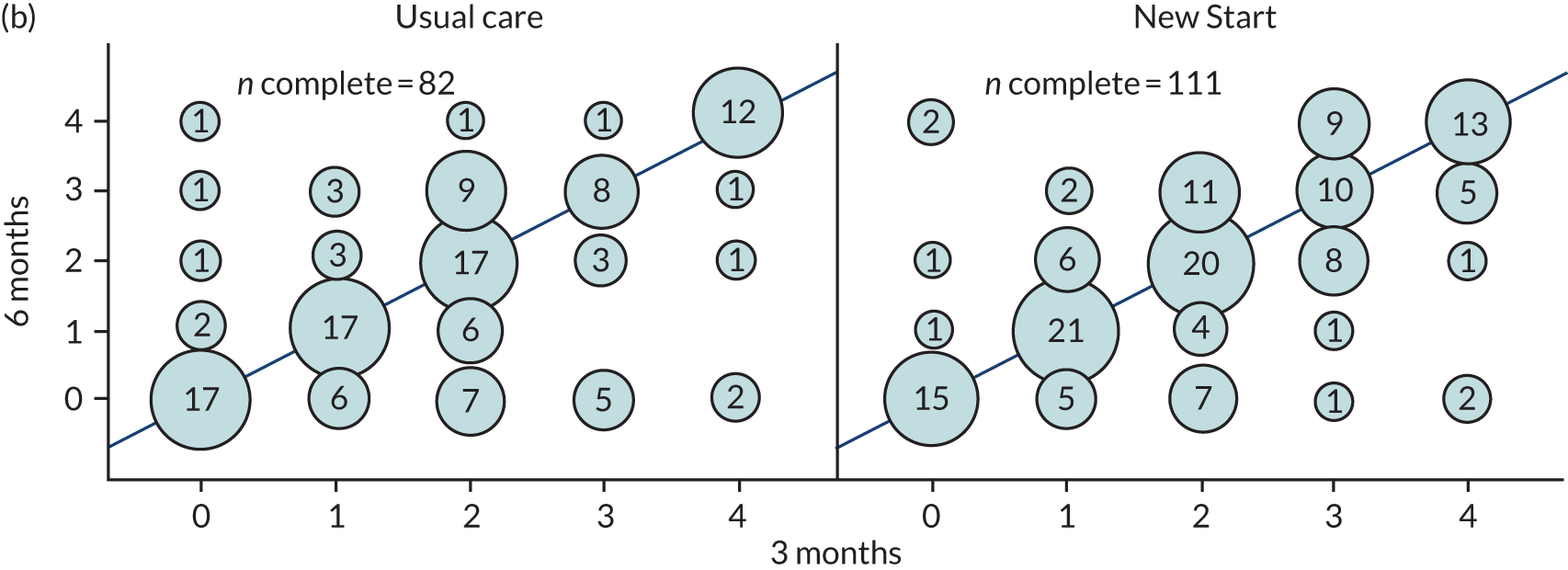

The programme was delivered through five overlapping workstreams (WSs) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Inter-relationship between the different WSs of the LoTS2Care programme. LoTS2Care, Improving Longer Term Stroke Care.

Workstream 1a: an exploration of the predictors of longer-term unmet needs and participation post stroke

Semistructured interviews with stroke survivors and their carers

Introduction

To develop patient-centred services for stroke survivors in the longer-term, a comprehensive understanding of the needs, experiences and priorities of those living with stroke was required. 15

Although the existing literature provided an understanding of the level of unmet needs,13 how stroke is experienced, some of the challenges faced by stroke survivors16,17 and the way these challenges are managed by stroke survivors are not fully understood. Evidence suggested that stroke survivors do play an active role in their recovery;18 however, little is known about the processes that influence whether or not stroke management strategies are carried out successfully, particularly in the longer term.

Therefore, the first study in the programme aimed to address these gaps by exploring the specific longer-term needs of stroke survivors (e.g. type of information) from their own perspectives. The barriers to and facilitators of behaviours which impact on these longer-term needs and participation14 were also explored. The findings informed the intervention development process for the longer-term care strategy.

Aims and objectives

The objectives of this study were to:

-

gain further insight into specific longer-term needs (e.g. type of information required) of stroke survivors and their carers

-

explore the barriers to and enablers of the behaviours that affect longer-term needs and participation

-

explore how stroke survivors and carers develop strategies for managing problems/resolving the issues that they face post stroke.

Methods

Full details of methods are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1 (the research protocol).

Study design

This was a qualitative study involving semistructured interviews and a thematic approach to data analysis.

Participants

Participants were community-dwelling stroke survivors and their carers at two different time points: 9–12 months post stroke and between 2 and 4 years post stroke. This allowed for the identification of ongoing needs and provided an opportunity to reflect on what information and support had been useful and how this could be improved.

Potential participants were identified from an established research database held at Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. In brief, stroke survivors were eligible for the study if they had a confirmed primary diagnosis of new stroke, were > 9 months post stroke, resided in the community and were able to provide informed consent (or consultee assent). Carers were eligible if they were identified by the stroke survivor as the main informal carer who provides support a minimum of once per week.

A maximum variation purposive sampling strategy was used to select a heterogeneous population with a range of disability levels (assessed by the Barthel Index19), high and low levels of unmet need,20 differing socioeconomic status (assessed by postcode), living circumstances (alone/with carer) and age range at the two time points.

Semistructured interviews

Unmet needs and the barriers and facilitators experienced in trying to overcome these were explored across all of the interviews (topic guides are provided in Report Supplementary Material 2).

Efforts were made by the researchers to tailor the interviews for stroke survivors with communication difficulties (by using pictures/adapting topic guides/use of keywords). The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A thematic approach21 to data analysis was taken, with the transcripts analysed in two categories (those who were 9–12 months post stroke and those who were > 24 months post stroke), to establish any differences in the experiences at different time periods post stroke.

For the purpose of this analysis, needs were defined as those that stroke survivors perceived as challenges to overcome or address. Standard approaches to demonstrating trustworthiness and quality in qualitative research were used. 22 Throughout data collection and analysis, data, codes and emerging categories and theories were presented to and discussed with the research team and Programme Management Group (PMG) at regular intervals.

Results

A full report is provided in Appendix 1.

Twenty-eight stroke survivors and 11 carers (eight wives and three husbands) were recruited to the study from November 2013 to April 2014. Thirteen of the stroke survivors were between 9 and 12 months post stroke, and 15 were between 32 and 47 months post stroke. They represented a range of ages, disability levels and reported unmet needs (see Appendix 1, Table 8). All of the stroke survivors and their carers decided to be interviewed together.

Identified needs, barriers and facilitators

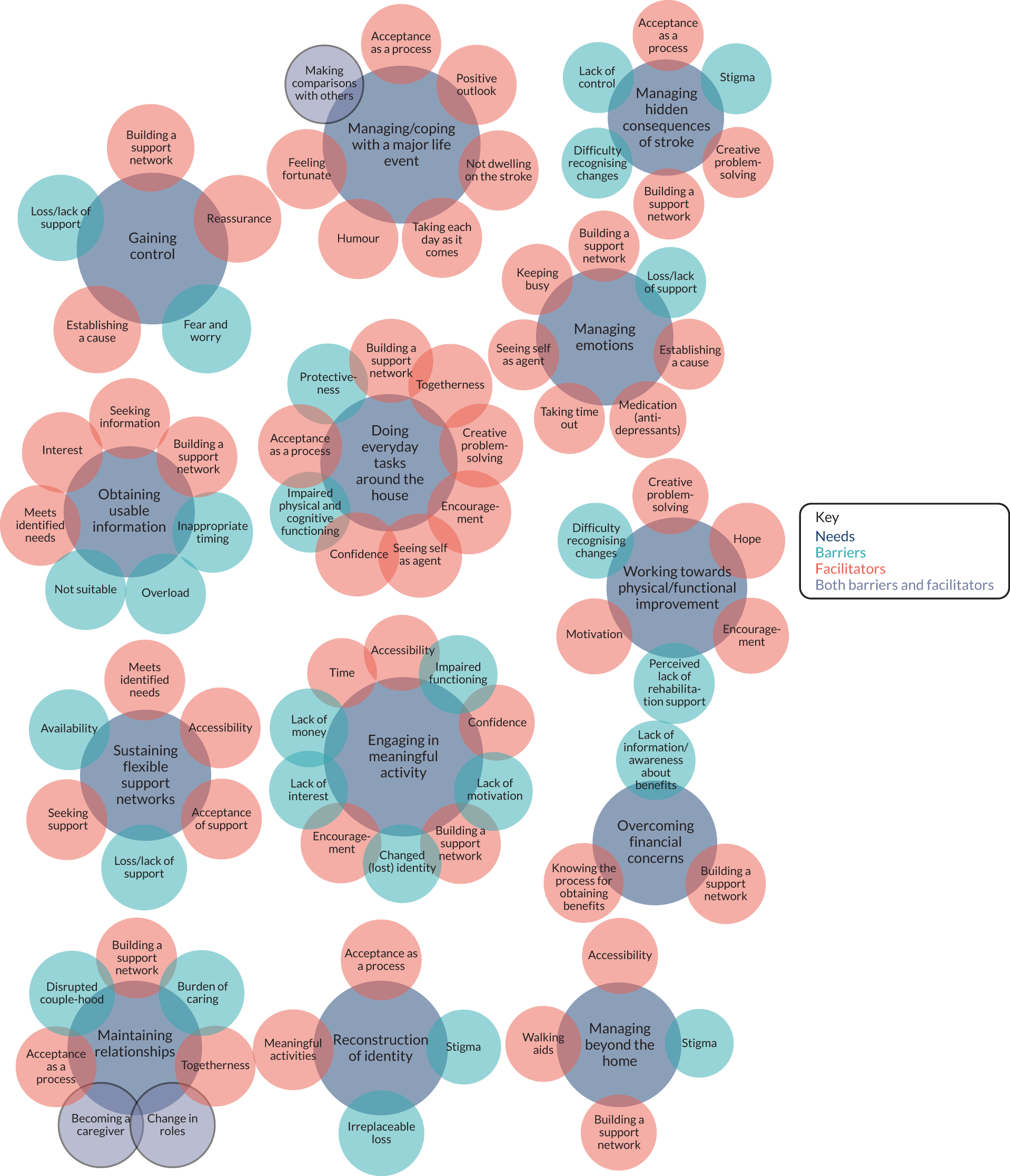

The needs identified and the barriers and facilitators that the stroke survivors and their carers experienced are summarised in Figure 2. This figure highlights where barriers and facilitators relate to more than one need. For example, ‘building a support network’ is a facilitator across nine of the 13 needs. Other common barriers and facilitators include lack/loss of support, stigma, acceptance as a process and creative problem-solving.

FIGURE 2.

Stroke survivor needs, barriers and facilitators.

Thirteen key needs were identified:

-

managing and coping with a major life event

-

gaining control

-

managing emotions

-

reconstruction of identity

-

doing everyday tasks around the house

-

working towards physical and functional improvement

-

managing hidden consequences of stroke (e.g. difficulties with concentration and processing of information, memory impairments and mood swings)

-

obtaining usable information

-

sustaining flexible support networks

-

engaging in meaningful activity

-

overcoming financial concerns

-

maintaining relationships

-

managing beyond the home.

Some differences were recognised in the two time frames. Feelings of hope in terms of the need to work towards physical functioning were more common amongst those who were 9–12 months post stroke. These stroke survivors also talked more often about establishing a cause for their stroke as part of understanding and making sense of their situation (linked to the need to gain control and facilitate this process). More of the participants who were at least 24 months post stroke talked about the process of reaching acceptance. This was important for addressing many of their needs, including doing everyday tasks around the house, managing and coping with the major life event, managing the hidden consequences of stroke, reconstruction of their identity and maintaining relationships. Aside from these slight differences at each time point post stroke, the identification and management of needs remained similar across the two time points.

Four of the unmet needs related to emotional needs: gaining control; managing and coping with a major life event; managing daily stressors and strains; and reconstruction of identity.

Key findings

This qualitative study examined the needs of 28 stroke survivors at two time points [9–12 months (n = 13) and > 24 months (n = 15)]. Thirteen needs were identified from the perspectives of the stroke survivors and their carers. Participants’ accounts of their lives comprised complex and interacting factors that shaped how they managed their needs post stroke. The existing literature has previously indicated the areas where stroke survivors and their carers commonly experience unmet needs. 13,23 Although insightful, such research has not provided a comprehensive understanding of how needs can be addressed, or acknowledged the factors that may facilitate or hinder this process. It also neglects the notion that needs may change over time. A unique approach to understanding the stroke experience was taken through exploring specific needs across all areas of the stroke survivors’ lives and investigating the factors that influence whether or not these needs are addressed. This study contributes to the wider body of literature by gaining an in-depth understanding of the broad scope of needs experienced by stroke survivors in the longer term, from their own perspectives, and explored the barriers and facilitators that stroke survivors and their carers faced as they worked to manage and overcome these needs.

The participating stroke survivors still had needs that were unaddressed, even up to 3 years post stroke. Across both time points, emotional needs were emphasised, supporting findings from a previous qualitative review. 24 In the current study, stroke survivors felt that there was a lack of emotional support, which often led to feelings of neglect, particularly when they initially returned home. Some stroke survivors and their carers also experienced a sense of abandonment following withdrawal of support from health professionals (e.g. physiotherapists). Stroke survivors expressed a range of emotional difficulties, which included, for some, frustration and anger as they tried to manage the impacts of the stroke, indicating the need for services and interventions to encompass longer-term emotional support.

This work highlighted the importance of understanding needs in different contexts. Perceived and actual stigma was a barrier to going out in public areas, for example with regards to walking aids, for which a distinction was made between perceived stigma (because they felt that people would make negative judgements) and their own lived experiences of being stigmatised. Interestingly, some stroke survivors who actively managed their impairments in their own homes were reluctant to spend much time out of their home because of some of the difficulties they faced in interactions with others. Such findings suggest that efforts must be made to increase public awareness around stroke in order to increase social participation amongst stroke survivors. Alternatively, techniques for stroke survivors and their carers could be encouraged to reduce feelings of perceived stigma.

Although stroke survivors and their carers faced barriers to addressing their needs, the findings indicated that stroke survivors and carers do play an active role in managing their circumstances/situation, using both practical and mental coping strategies, supporting findings from previous research. 18,25,26 Although previous literature has provided examples of such strategies (e.g. mobilising support networks26), this study identified how these are used to address specific needs. This study confirmed the importance of support networks and identified this (‘sustaining flexible support networks’) as an unmet need after stroke. This was identified as one of the needs of stroke survivors and also one of the key mechanisms for addressing other identified needs, for example engaging in meaningful activities, overcoming financial concerns, doing everyday tasks around the house and managing beyond the home.

A more nuanced understanding of the role of the stroke survivor in seeking and maintaining support was gained, particularly in circumstances in which this could be vulnerable to change. Interestingly, many of the stroke survivors were reluctant to join support groups, often because they did not feel that they were a ‘group person’ or because they did not feel that their stroke was ‘bad’ enough.

The need to ‘obtain usable information’ supported findings from prevalence studies in which information is commonly reported as an unmet need. 13,23 From the stroke survivors’ accounts, it was clear that they were given some information following their discharge from hospital; however, there was a general sense of negativity attached to this, as concerns were raised about both the timing and the amount of information provided. This may explain this being regarded as an unmet need, despite information being available. The findings indicated that stroke survivors and their carers continue to need information in the longer term following the stroke as they draw on this information to resolve a specific problem, as and when it arises.

Many of the needs experienced by stroke survivors who were 9–12 months post stroke were similar to those of stroke survivors at 3 or 4 years post stroke, suggesting that some needs are persistent. However, there were some subtle differences apparent across the two time points, an example being around reaching acceptance. This emerged as a key facilitator for managing life after stroke, supporting research that highlighted acceptance as a critical factor in being able to cope. 18 Those who were at least 24 months post stroke talked about this more than those who were 9–12 months post stroke, suggesting that those who have more recently had their stroke may have had less time to reach the point of acceptance.

Some stroke survivors spoke about acceptance in broad terms, of accepting the stroke and moving forward, whereas others talked about this more specifically in terms of accepting that tasks take longer around the house and accepting their new identity. Some stroke survivors struggled to accept the changes to their lives and themselves following the stroke. One stroke survivor made an interesting distinction between realisation and acceptance. She realised that things were different, yet she failed to accept this. This suggested that acceptance has both an emotional and a cognitive/intellectual meaning. The process of achieving it is one aspect of adjustment to long-term illness, a process that must be worked towards over time, which was reflected in other accounts from the stroke survivors. Amongst those who had managed to accept their stroke, there was a sense that they felt that they had little choice but to do this to move forward.

Evidently, acceptance is complex and a number of factors shape whether or not this is possible. Supporting stroke survivors in reaching acceptance is important, as it affects a number of needs, for example maintaining relationships, managing and coping with a major life event and reconstruction of identity.

Relationship with other parts of the programme

Consistent with the aims of this workstream (WS), longer-term needs have been identified. These findings suggested that stroke survivor needs should be routinely monitored during the recommended routine reviews. The needs were captured in behavioural terms and the barriers to and facilitators of addressing needs have been identified, providing a useful insight into how stroke survivors develop strategies for managing difficulties that they face post stroke. However, it is important to note that stroke survivors did not always talk in terms of specific behaviours as part of their narratives. This had implications for how the next steps of intervention mapping were managed.

To obtain a comprehensive picture of unmet needs after stroke, the programme team undertook two additional pieces of work, as outlined in the following section.

Exploration of the literature in which stroke survivors identify unmet needs

With the assistance of an experienced information scientist, a detailed search of the literature was undertaken in August 2014. No language or date limitations were applied. See Report Supplementary Material 3 for the search strategy. The strategy was appropriately modified and applied to MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, and Web of Science; 897 papers were identified. Following review, 34 papers were taken forward to full-text scrutiny and seven were identified as describing unmet needs of stroke survivors and/or their carers2,8,13,15,23,27,28 (see Report Supplementary Material 3). The research team recorded the unmet needs reported in these papers. The unmet needs identified are summarised elsewhere (see Figure 5 and Report Supplementary Material 3).

In addition, to inform our work on unmet needs, all of the enquiries received by the UK Stroke Association helpline between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2014 were collated. 29

Workstream 1b: review of literature to inform content and delivery of the care strategy

The aim of this WS was to complete literature reviews to inform content and delivery of the care strategy. The objectives comprised:

-

identifying community-based interventions that enhance mood, QoL or participation of stroke survivors, their carers or both at least 6 months after incident stroke, and any adverse events

-

scoping the literature on mechanisms of delivery in stroke and other long-term conditions, including identification of:

-

models of care

-

success factors for supported self-management

-

mediators and assessment tools

-

methods for engaging with participants with communication and cognitive problems

-

-

identifying other appropriate candidate primary outcome measures

-

updating the Cochrane review of information provision after stroke. 30

Because of the diverse nature of community-based post-stroke interventions, an overview of Cochrane reviews was conducted to identify effective interventions that may be relevant to longer-term stroke survivors or their carers, and to provide an initial framework for such interventions, followed by a systematic review of community-based interventions for survivors or their carers at least 6 months after stroke.

See Report Supplementary Material 4 for protocols of both reviews.

Systematic overview of Cochrane reviews to identify effective interventions that may be relevant to long-term stroke survivors or their carers

Methods

All reviews produced under the remit of the Cochrane Stroke Group (May 2014) were screened to identify systematic reviews of community interventions for stroke survivors or carers.

Reviews were included if any of the participants in the included studies were at least 6 months post stroke at the start of intervention delivery. ‘Community interventions’ were defined pragmatically as follows: not delivered to inpatients (i.e. outpatient and wider community), and not pharmaceutical, surgical, radiological, radiotherapy or ‘medical devices’ [including acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, robotics].

In keeping with our long-term focus, main outcomes were participation, QoL, health status, mood and, additionally for carers, burden. We also incorporated the primary outcomes of the included reviews as secondary outcomes in our overview, using the ICF as a framework. We grouped interventions by the post-stroke problems that they were intended to address. One reviewer extracted data, which another checked. Quality was assessed by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) criteria. 31 Effectiveness was summarised per intervention based on our main and secondary outcomes. We assessed the evidence as good or limited based on the precision and consistency of effects, or very limited in the case of evidence from single studies.

Key findings

Through our search strategy, 329 reviews were retrieved, and 28 (see Appendix 2) were included in the review, encompassing 352 studies. Seventeen reviews met all quality criteria; 11 met five of the six criteria.

The main findings of this review are diagrammatically presented in Table 1. There was very little evidence of effect on mood, participation, health status, QoL or carer burden. This was primarily because few studies measured these outcomes.

| Intervention | Survivors | Carers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived health status | Mood | Participation | QoL | Perceived health status | Mood | Participation | QoL | |

| CIMT | ||||||||

| Circuit class therapy | ||||||||

| Hands-on therapy | ||||||||

| Home-based therapy | ||||||||

| Information provision | ○ | ○ | – | ○ | ○ | ○ | – | |

| Inspiratory muscle training | ○ | |||||||

| Interventions for visual-field defects | – | |||||||

| Mental practice | ||||||||

| Mirror therapy | ||||||||

| Music therapy | ||||||||

| Non-pharmaceutical interventions for attention deficits | – | – | ||||||

| Non-pharmaceutical interventions for fatigue | ||||||||

| Non-pharmaceutical interventions for problems faced by caregivers | ○ | ○ | ||||||

| OT for ADL | – | – | – | |||||

| OT in care homes | ||||||||

| Overground gait training | ||||||||

| Physical fitness training | ○ | ○ | ||||||

| Physical rehabilitation | ||||||||

| Psychotherapy | – | |||||||

| Rehabilitation at home < 1 year after stroke | – | – | – | |||||

| Rehabilitation at home > 1 year after stroke | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Repetitive task training | – | |||||||

| Speech and language therapy | – | |||||||

| Stroke liaison workers | – | – | – | |||||

| Telerehabilitation | ○ | |||||||

| Treadmill training | ||||||||

| Virtual reality | ||||||||

| Water-based exercises | ||||||||

For stroke survivors:

-

Ten reviews30,32–40 reported perceived health status – information provision,30 inspiratory muscle training,34 fitness training33 and telerehabilitation40 reported limited evidence of improvements.

-

Nine reviews30,32,33,35–37,39,41,42 reported mood, with limited evidence of improvements found for information provision30 and fitness training. 33

-

Two reviews30,43 reported measures of QoL: information provision had very limited evidence of improvement. 30

-

One review30 reported no evidence of effect of information provision on participation.

For carers, very limited evidence from one study reported in two reviews30,44 suggested that teaching procedural knowledge could improve perceived health status and reduce strain and depressive symptoms. However, our own work45 has superseded those reviews; we found that the intervention was not effective when evaluated in a large pragmatic trial.

Looking at our secondary outcomes, there was evidence that interventions targeting ICF mobility (e.g. walking, handling objects), self-care (ADL) and domestic and interpersonal life (extended ADL) could improve these outcomes.

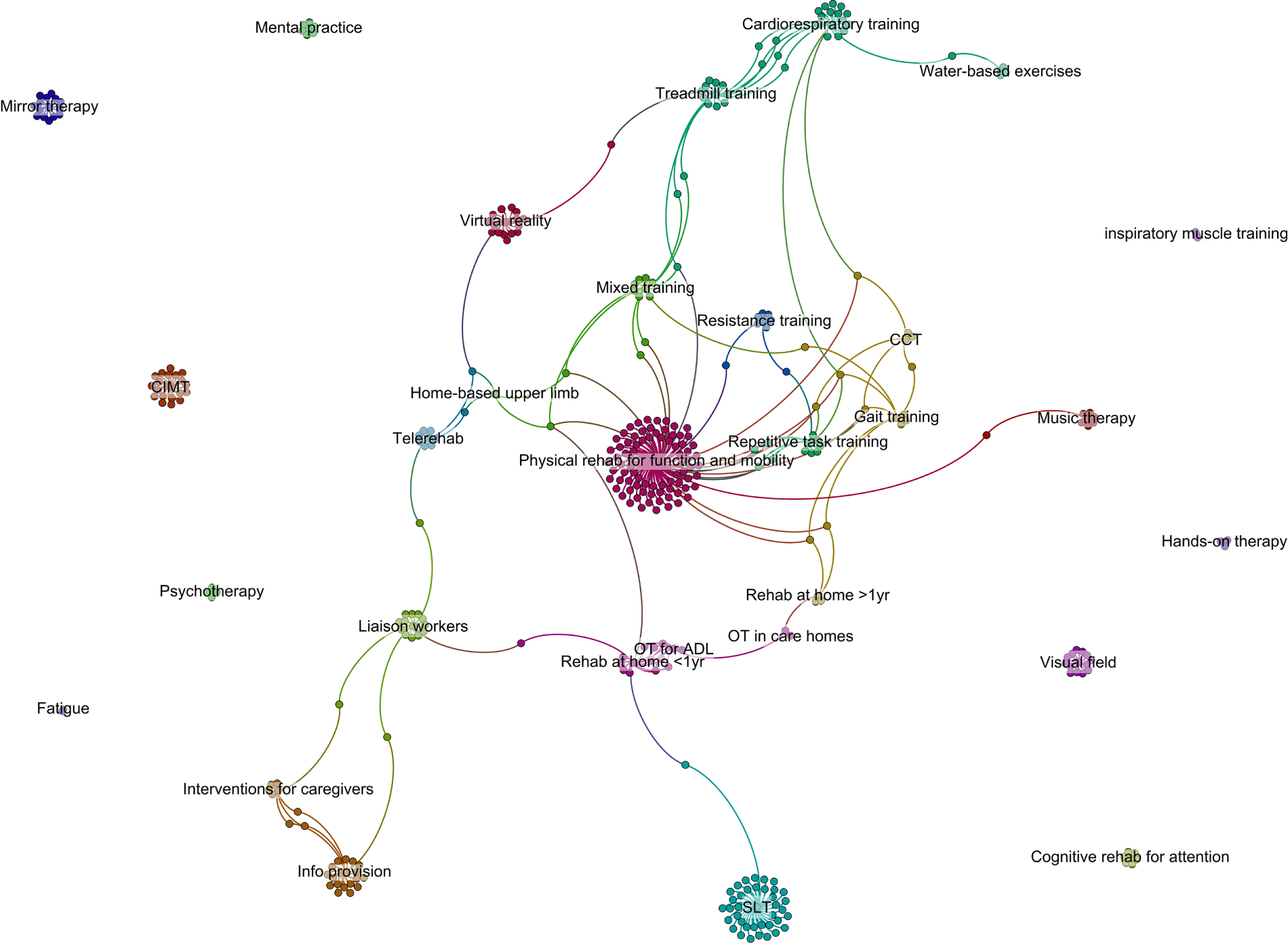

The schematic in Figure 3 provides a graphical illustration of the distribution of research activity, which is not necessarily in the areas of most importance to stroke survivors and their carers. The lines link reviews to the studies they include, indicating when studies are included in more than one review (e.g. a study included in the liaison workers’ review and the support for caregivers review).

FIGURE 3.

Schematic demonstrating linkage between Cochrane reviews.

Thus, despite considerable efforts, we were unable to identify any pre-existing community-based interventions with good evidence for improving the QoL, participation, mood or health status of stroke survivors or their carers.

This overview has now been registered as a Cochrane review. 46

Review of studies

Methods

In this review, all stroke studies identified by the Cochrane Stroke Group [via AskDORIS (Database Of Research Into Stroke)], except those examining medicine, surgery, radiology and radiography, were screened. Studies were excluded when they were not a RCT or cluster RCT; patients were, on average, < 6 months post stroke at the start of the intervention; the intervention was not community based; and < 20 participants were included. The review of studies considered the risk of bias, the type of intervention and adherence to the intervention (when this was reported). Effectiveness of the studies was assessed based on the outcomes of interest to our research programme: stroke survivor QoL, health status, mood, participation, ADL, extended ADL, communication, other measures of behaviour and, additionally for carers, burden. We thematically grouped the components of each intervention to enable access to relevant details during intervention development. We also catalogued all measures used in the studies to identify possible alternative primary outcomes and indicators of behaviour change.

Key findings

Through our search strategy, 8054 studies were identified, reduced to 3501 when medicine, surgery, radiology and radiography interventions were excluded. Of 3501 studies screened on title/abstract, 630 were identified as being potentially eligible; 2871 were excluded. Following full-text retrieval, 105 studies were included in the review. Sixty-four studies were primarily of impairment-focused physical training, which we grouped into 15 intervention types. Other kinds of intervention included speech and language therapy (n = 11), combinations of educational, social and recreational activities (n = 8), tailored occupational rehabilitation (n = 4), social work or social network therapy (n = 3), provision of aids and devices (n = 2), ADL practice (n = 2), vision training (n = 2), combined exercise and education (n = 2), care co-ordination and interdisciplinary management (n = 2), a multifaceted long-term rehabilitation programme (n = 1) and carer-focused interventions (n = 4).

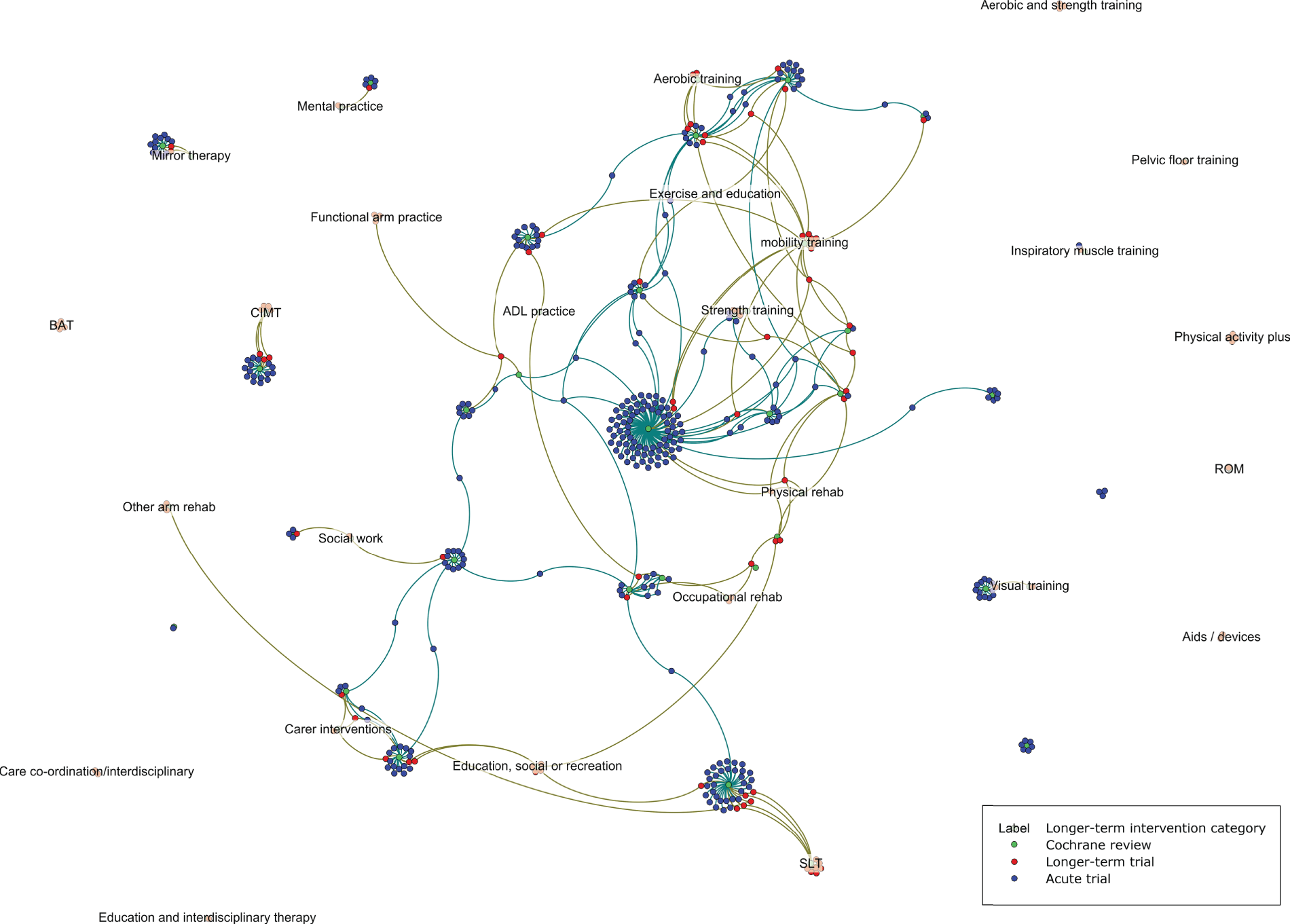

Figure 4 builds on Figure 3 and shows the studies that were included in both the overview and review of studies, indicating the overlap between these two reviews and the comparative lack of longer-term studies. Approximately half (52/105) of the trials included in the review of studies also featured in the overview. Among those not included in Cochrane reviews were specific physical rehabilitation interventions, such as pelvic floor training and bilateral arm therapy, as well as combinations of interventions, such as aerobic and strength training, or physical activity and education. The evidence for other intervention types (e.g. mobility training; combinations of educational, social and recreational activities) is split between several Cochrane reviews and excludes multiple longer-term studies.

FIGURE 4.

Schematic demonstrating linkage between the overview and review of studies.

Sixty-two studies reported at least one outcome of interest, 24 of which reported a significant difference between groups in one of these outcomes in favour of the intervention:

-

Two carer interventions47,48 and one care co-ordination and interdisciplinary management intervention49 reported an effect on carer mood and burden.

-

Of the eight interventions in the category of education, social engagement and recreational activity, four50–53 reported effects on outcomes including mood, participation and communication.

-

Of 33 physical training trials reporting an outcome of interest, 1354–66 reported effects on outcomes including health status, mood, participation, ADL and extended ADL.

-

One67 of two interventions combining exercise and education reported improved health status.

-

One study68 of long-term rehabilitation and counselling with social, educational and recreational courses reported effects on mood and extended ADL.

-

Two69,70 of four tailored occupational rehabilitation interventions were reported to improve extended ADL and participation.

-

No studies reported an effect on QoL, although only six relatively small studies68,71–75 measured this.

No association between risk of bias and ‘successful’ interventions was identified.

Although measures of ability were routinely reported, measures of specific, everyday behaviours were rarely reported. Only two studies70,76 reported an effect: reduced incontinence following pelvic floor muscle training and76 increased number of outdoor journeys for people receiving an outdoor mobility intervention. 70

The majority of trials related to physical exercise, and there was a noticeable lack of trials evaluating other interventions for longer-term stroke survivors and their carers. Although many studies reported significant effects, trials were small and there were no consistent patterns to indicate effective types of intervention. Some trials of promising interventions have recently been replicated and demonstrated no effect. 45,77,78 However, trials incorporating aspects of education, social engagement and recreational activity and those incorporating functional training appeared more promising than others.

These comprehensive literature reviews demonstrated that relatively little research has been undertaken to try to enhance longer-term outcome after stroke, focusing on the outcomes of importance to stroke survivors and their families. There was no strong evidence on the most effective components of an intervention.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures were extracted from the reported studies and reviewed by the PMG and research team. A shortlist of measures was reviewed by the CRAG. These discussions and consultation with the Programme Steering Committee (PSC) informed the outcomes selected for our evaluation work.

Delivery mechanisms

A scoping review of reviews addressing delivery mechanisms of health care in chronic illness was undertaken. Seven eligible review studies, including two additional papers from the references, were identified. 79–85 Details are provided in Appendix 3. Relevant policy documents were also identified. 86–92

Looking across the identified reviews, the majority of the primary evidence being synthesised was focused on diabetes, and the most convincing evidence was of supported self-management.

Following the completion of the overview and review of studies, the Cochrane review Self management programmes for quality of life in people with stroke was published. 93 This reported possible small effects on QoL and self-efficacy, with further research likely to have an important impact on these results.

Materials development for people with communication problems

This was recognised as an ongoing challenge, not only for our programme, but across the spectrum of stroke research. To address this issue, our colleague Faye Wray undertook a linked Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) focused on assessing the appropriateness of self-management for stroke survivors with impaired communication. 94 Insights into amendment of materials for people with communication impairment were provided. This included detailed guidelines previously developed by the Stroke Association, which can be summarised as making sets of messages that are short, with clear sentences, using easy words and having a good layout. 95 We also sought guidance from an aphasia group in Grimsby on their specific needs and means of addressing those needs. In addition, we formed a collaboration with colleagues at the Greater Manchester Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) who have extensive experience in this area and provided expert guidance.

Update on Cochrane review of information provision

The Cochrane review was updated while the grant was under consideration; the results were published in 2012. 30

The review30 indicated that there is evidence that information improves patient and carer knowledge of stroke and aspects of patient satisfaction, and that it reduces patient depression scores. However, the reduction in depression scores was small and may not be clinically significant.

At the time of publication of this report, an update has been submitted to the editors and is being revised accordingly.

Workstream 2: national survey of post-discharge stroke services, and focus groups and interviews to identify service needs, barriers and enablers

An exploration of care models for longer-term stroke care in England

The objectives of this WS were to gather information on:

-

mechanisms (if any) in place for identifying and/or maintaining contact with stroke survivors, up to and after the recommended 6-month review

-

current arrangements for the 6-month and annual reviews

-

the configuration of local stroke services in the light of the development of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), including identification of stroke lead and governance arrangements

-

services available, for example Stroke Association provision, fitness classes.

This information was gathered to inform the development of the longer-term care strategy by ensuring that any proposed strategy was feasible in current service models by determining methods of case ascertainment, the optimal timing of delivery and who might be best placed to undertake the review process and deliver the care strategy.

Methods

Development of the survey

Using the information collated in the LoTSCare programme of work, a detailed six-page survey tool was formulated that collected data on the community stroke team (CST): where they received referrals from, what services they offered and for how long, and what other services were available in their area. This survey was sent to two community teams for feedback, and then e-mailed to the 29 Community Stroke Services that participated in the LoTSCare trial. The survey was sent out in August 2013 and a reminder was sent at the beginning of October 2013; however, only eight (28%) of the surveys were returned. The research team and PMG concluded that this pilot survey was too long and too difficult to complete in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and that the method of contact was not effective.

At the same time that the survey was being prepared, the Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP) started to plan collection of national data on the 6-month stroke reviews and the Stroke Association offered the research team data on its service provision across England as commissioned from April 2014. Consequently, it was agreed that the SSNAP data would be utilised to inform our understanding of objectives 1 and 2, and a simple one-page survey would be sent out to all CCGs to achieve objectives 3 and 4. The Stroke Association data would be used to complement the survey findings.

The survey asked how long stroke services were commissioned for, whether or not any other providers commissioned services in the longer term and whether or not an annual review was commissioned (see Appendix 4).

Survey participants

Clinical Commissioning Groups

A directory of contacts for all CCGs (n = 203) listed on the NHS England website in November 2013 (www.england.nhs.uk/ccg-details/; accessed 18 August 2020) was compiled.

Community stroke teams

A directory of CSTs, as listed in the Stroke Association website UK Stroke Contacts Map (www.stroke.org.uk/professionals/uk-stroke-contacts-map; accessed November 2013) in November 2013, was compiled.

The e-mail addresses of all National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Stroke Research Network (SRN) managers were also gathered from the NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) website in November 2013.

Survey administration

The survey (see Appendix 4, Figure 10) and a cover letter, signed by Anne Forster (lead investigator) and co-investigator Matthew Fay, were sent via e-mail on 18 December 2013. The e-mail to the CCGs was addressed to the lead for longer-term conditions/stroke. Completion of the survey could be via an electronic Word document or a SurveyMonkey® (Palo Alto, CA, USA) link. A written reminder was sent to all CCGs, and an e-mail reminder was sent to all community teams 1 month later on 20 January 2014.

The same e-mail and copy of the survey was also sent to the NIHR SRN managers who were asked to forward the survey to local CSTs. The survey was also promoted at the UK Stroke Forum Exhibition Stand (December 2013), and completed then by a number of community teams.

Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme data

The first round of data collection on 6-month reviews, collected between October 2013 and March 2014, was reported in August 2014. 96 SSNAP data are collected on every stroke survivor admitted to hospitals across England and Wales, and are not summarised at the level of service provision (CCGs). Data on the 6-month reviews were collected and reported for each patient. These data were reviewed to explore objectives 1 and 2.

Stroke Association data

These data were provided to the research team by the Stroke Association director for the North of England Life After Stroke Services (co-investigator Elaine Roberts) and detailed all Stroke Association services commissioned across CCGs in England from April 2014 to March 2015, including the number of CCGs that commissioned the Stroke Association or other services to complete 6-month reviews. These data were reviewed to explore objectives 2 and 4.

Data synthesis

Survey data were entered into a database and the length of service provision was categorised as (1) up to 6 months post stroke, (2) up to 12 months post stroke or (3) > 12 months post stroke. This service consisted of stroke or neuro-specific community rehabilitation teams. Commissioning of general community rehabilitation teams was not accepted as provision of support to stroke survivors.

Provision of other services was taken from the free text in the survey and grouped according to the type of service: (1) Stroke Association or (2) other support, including exercise classes, stroke clubs, etc. Provision of Stroke Association services was verified by the Stroke Association data; when there were discrepancies, the Stroke Association data were taken as being correct.

Information on the provision of 6-month reviews was taken from the SSNAP data report, and also from information on the commissioning of 6-month reviews in the Stroke Association data.

Provision of annual reviews was collated from the survey. The survey did not distinguish between 12-month general practitioner (GP) health checks and annual health and social care reviews.

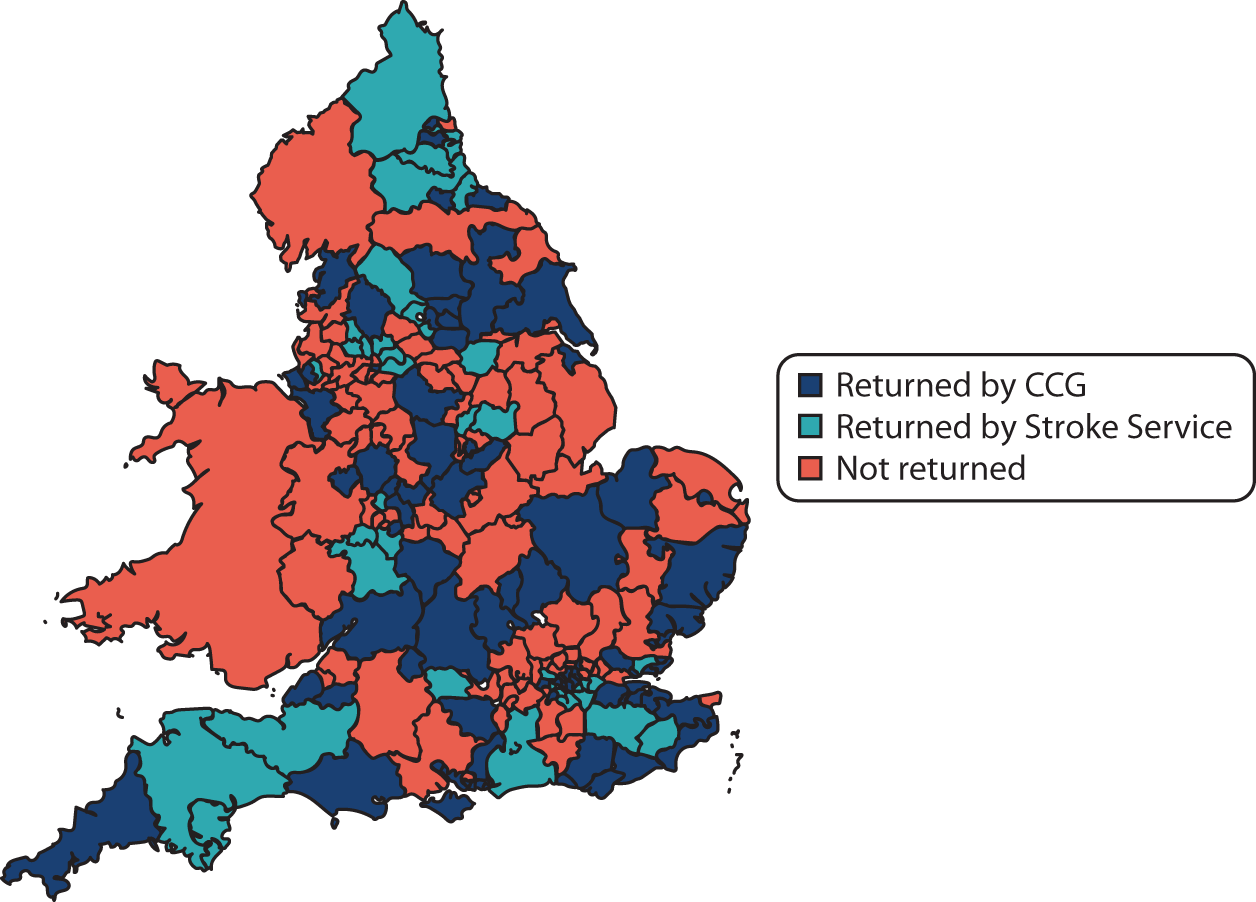

Results

Service provision

Of 203 identified CCG areas, 116 (57%) responded to the survey (see Appendix 4, Figure 11, and Report Supplementary Material 5). Of these, 30% (35/116) provided a stroke or neuro-specific community rehabilitation team service up to 6 months post stroke, 40% (46/116) provided a service up to 12 months post stroke and 29% (34/116) reported a service beyond 12 months post stroke.

Stroke Association Life after Stroke services were commissioned in 74% of CCGs, providing support to stroke survivors up to 12 months post stroke. In the survey, other support, such as exercise groups and stroke clubs, was reported by 57% (66/116) of CCGs.

Six-month and annual reviews

The return rate for the SSNAP 6-month review data was low (only 22.8% of patient records had an answer in this section). Overall, only 15% (3360/22,273) of survivors received a 6-month review.

In the Stroke Association data, 12% of CCGs commissioned the Stroke Association to complete 6-month reviews, and a further 16% of CCGs commissioned NHS community services to complete the 6-month reviews.

In the survey, 39% (45/116) of CCGs commissioned an annual review for stroke survivors (including 12-month health checks completed by GPs and annual health and social care reviews).

Key findings

The national survey identified three types of service provision – up to 6 months post stroke, up to 12 months post stroke and beyond 12 months post stroke – with the most common model being provision up to 12 months. The Stroke Association Life After Stroke services were commissioned by 74% of services and other support, such as groups and clubs, by 57% of CCGs.

The provision of longer-term support for stroke survivors was highly variable across the country, with a substantial number of survivors potentially receiving no support after hospital discharge. Our survey results suggested that, 12 months post stroke, approximately 70% of services provide no formal support to stroke survivors. This is in stark contrast to research indicating a high number of stroke survivors with unmet need beyond the first year post stroke. 13

Despite current policy recommendations of a 6-month and annual health and social care reviews,97,98 the SSNAP data revealed that only 15% of survivors had received a 6-month review. The Stroke Association data indicated that 6-month reviews were commissioned in fewer than one-third of CCGs in 2014, and our survey demonstrated a similarly low number of annual reviews being commissioned.

Strengths and weaknesses

Our survey was completed by 57% of CCGs across England. CCGs completing the survey may have differed from those that did not; for example, responses may have included a larger proportion of exemplar CCGs keen to demonstrate commissioning of services beyond 12 months, because CCGs that commissioned no service and/or one up to 6 months may have been less motivated to respond.

It is important to note that reporting the proportion of CCGs that commissioned a particular service did not necessarily equate to the number of stroke survivors actually receiving this service. Many community rehabilitation teams and 6-month review procedures had eligibility criteria, meaning that the service was not available to all.

The completion of the 6-month review data from the SSNAP was very low in 2014. This was the first round of 6-month review data collection for the SSNAP, and it demonstrates how challenging the collection of community survey data can be.

Relationship with other parts of the programme

This survey demonstrated that the provision of longer-term support for stroke survivors was highly variable across the country, with a substantial number of survivors potentially receiving no support after hospital discharge, and with fewer than one-third of services completing 6-month reviews with stroke survivors. Findings from this research indicate that strategies for longer-term stroke care need to be developed and implemented across the country. It was concluded that attempting to establish a longer-term service beyond 12 months post stroke, when many services were struggling to commission anything beyond 6 months, was unlikely to be feasible in the current climate. This programme of work subsequently focused on the 6-month review, to provide support to stroke survivors based on the needs identified at this time point.

An exploration of care models for longer-term stroke care in England and the barriers to and enablers of longer-term service provision

Aim

This study aimed to gain further insights and understanding from service deliverers about barriers to and enablers of the development and implementation of our care strategy by conducting focus groups with a purposive sample of different models of service identified in the national survey.

Methods

Full details of the methods are provided in the protocol (see Report Supplementary Material 6).

Study design

Having identified different models of post-discharge support, we originally intended to gain insights, through focus groups, from CSTs that exemplified the three models. However, given the diversity of stroke service provision and the professional make-up of CSTs, additional focus groups were required to gain a fuller, more informed understanding of the barriers to and enablers of delivering longer-term support.

On review of the survey data, eight CSTs were purposively selected to be invited to participate in focus groups on the basis of their location and the pattern of post-discharge support they provided. CSTs were selected from different English regions, including both urban and rural districts. Initial contact and invitations were extended to a lead member of the CSTs identified from the survey data (i.e. stroke service co-ordinator, team leader, head of service, service manager or therapy consultant), who subsequently discussed the invitation with team members and invited fellow team members to participate. There were no set inclusion criteria for participation other than to include secondary care clinicians as well as community-based professionals who undertook clinical, organisational or managerial roles in supporting stroke survivors.

Research governance

Approval was obtained from the relevant NHS trusts’ research and development departments.

Focus groups

Focus group methodology was used to explore the views of CST members as to their understanding of stroke survivors’ longer-term (i.e. ≥ 6 months post stroke) unmet needs, barriers that inhibit CSTs from addressing them and enablers that support them to do so. Written informed consent was taken from all participants, who were assured that all data would be treated confidentially, and that all reporting would be anonymised.

The focus groups were facilitated by a researcher, with a fellow researcher taking notes. An identical topic guide was used for each focus group (see Report Supplementary Material 7). The staff mix supported an exploration of different perspectives and produced insights into the service group dynamic. All focus group discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed, and data were thematically analysed. 21

Data analysis

The researcher (AP) began by familiarising himself with the transcripts, and the contextual nature of the materials contained in them. Subsequently, the researcher engaged in an interrogative process of sifting carefully through the data and identifying initial codes, later grouped into themes, relating to barriers to longer-term support for stroke survivors, and enablers of longer-term support for stroke survivors. Ongoing analysis then refined the specifics of each theme. Further analysis of these themes uncovered distinct categories in the overarching contextual framework of each theme. Hence, the complexity of service providers’ perceptions of their needs, and the factors that presented barriers to their being met, could be captured and explored. Finally, a selection of compelling extracts was used to exemplify identified themes.

Similarly, practical examples of how identified service provider needs were being met in the context of current organisational practice were classified as ‘actual enablers’. In addition, practices that potentially enabled service providers’ needs being met were classified as ‘potential enablers’.

Results

All eight sites that were approached agreed to participate and hosted focus group discussions. Five of the CSTs provided post-stroke support for up to 12 months (in accordance with the common model), two provided support for up to 6 months (model 2) and one for up to 3 years (model 3) (Table 2). Sixty-five participants occupying a multidisciplinary range of predominantly clinical roles took part in focus groups between April and June 2014, with eight participants per group on average (Table 3).

| Site | Model type | Geographical region |

|---|---|---|

| B | Up to 12 months | North-west (urban) |

| N | Up to 6 months (no Stroke Association) | North-east (rural) |

| S | Up to 12 months | North Lincoln (rural) |

| C | Up to 12 months | South London (urban) |

| W | > 12 months | Midlands (urban) |

| A | Up to 12 months | Yorkshire (rural) |

| P | Up to 12 months | Peninsula (urban/rural) |

| NA | Up to 12 months | Peninsula (rural) |

| Service | Physiotherapist | Occupational therapist | Speech and language therapist | Therapy assistant | Nurse | Senior manager | Stroke co-ordinator | Rehabilitation/therapy consultant | Stroke Association IAS | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (n = 8) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Social worker | |||

| N (n = 8) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Psychologist | ||||

| S (n = 9) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | GP, dietitian | |||

| C (n = 8) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| W (n = 7) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| A (n = 7) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| P (n = 9) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | CCG commissioner | ||||

| NA (n = 9) | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Social familiarity within CSTs meant that opinions were generally expressed in a frank and open manner. Although each discussion was intended to continue for approximately 1 hour, they often over-ran considerably.

Subsequent to the group discussions, it was intended to conduct semistructured interviews with purposively sampled individuals identified through the focus groups as having a key role in community-based service delivery. The aim of such interviews would have been to cover topics in greater depth and to explore nuances of opinion, in a manner that the constraints of the focus group format would not allow. However, initial analysis of the focus groups indicated that the key issues had been explored in considerable detail, that differences of opinion had been identified and that there would be little substantive benefit in undertaking supplementary interviews. Hence these proposed interviews were not undertaken.

Key findings

This qualitative study used a focus group approach to explore the perspectives of eight English CSTs regarding unmet needs of stroke survivors and their carers and the barriers to and enablers of delivering longer-term support to stroke survivors. The research uncovered a complex and interwoven range of barriers and enablers.

Perceived needs of stroke survivors

The key longer-term needs of stroke survivors were identified by focus group members, and are presented as a summary here and in Appendix 5:

-

a meaningful role and sense of identity

-

psychological support

-

ongoing information and advice

-

non-stroke-specific wider community engagement opportunities

-

stroke-specific group engagement

-

appropriate health and social care at home

-

longer-term supported self-management

-

support with personal relationships

-

support with physical health needs

-

employment and financial support

-

effective transportation to facilitate access to services and activities

-

social acceptance by society at large.

Barriers and enablers

The barriers generally fell into the following broad categories:

-

deficits of skills and resources

-

availability of training

-

prevailing cultural systems and organisational processes in the NHS

-

failure of multiagency partnership-working.

Enablers were often antithetical to the barriers and could be grouped into the following categories:

-

creative in-house approaches to training and educational enhancement

-

flexible operational, managerial and cultural approaches

-

effective multiagency partnerships

-

strong training and educational links with other agencies.

Barriers relating to resources and skills deficits were beyond the control of CSTs. These included the absence of sufficient funded psychologist posts in their teams, inadequate public transport systems that meant survivors found it difficult to access community facilities and unwillingness on the part of employers to support survivors in undertaking retraining in order for them to return to work. Similarly, a lack of nationally funded opportunities to support survivors and employers in maintaining employment, bureaucratic procedures concerning state benefits and the way in which mainstream community facilities, such as gyms, are not mindful of the needs of survivors were additional barriers that CSTs were unable to influence.

Cultural and organisational processes in the NHS created additional barriers. A target-driven, largely inflexible approach that placed adherence to the requirements of the SSNAP database over a clinically driven, person-centred approach created considerable barriers. The organisational shift from a traditional community rehabilitative approach to a short-term ESD-style intervention approach reduced the potential for longer-term support. Additional barriers rooted in NHS organisational systems included bureaucratic telephony processes that inhibited survivors from contacting CSTs. The orientation of NHS commissioning, with a perceived relatively low emphasis on funding rehabilitative support in the community, and the absence of evidence-based guidance on the components of a good longer-term support structure, represented further barriers.

The absence of effective multiagency partnerships lay at the heart of key barriers inhibiting longer-term support. Poor strategic relationships between the NHS and social services manifested itself in the lack of a shared vision for longer-term support, with social services seen to be pursuing a narrower, more limited goal centred on social care packages in the home. High staff turnover, insufficient time spent in survivors’ homes and, on occasion, delivery of incorrect advice to survivors characterised the perceived social care agency approaches. Largely piecemeal joint budgetary arrangements, and a reluctance to engage with voluntary-sector bodies, provided further evidence of ineffective multiagency partnership-working.

Shortfalls in training involved both in-house training and training issues pertaining to other agencies. A lack of in-house training in CSTs meant that the capacity to support survivors affected by psychological difficulties was diminished. Staffing pressures and organisational patterns of work made it very difficult to deliver training to private care agency staff. GPs were felt to have inadequate training in spasticity management, and were poor at signposting survivors to other services. These training issues collectively reduced longer-term support for survivors.

Creative in-house promotion of education and training was delivered in various formats, and helped to enable longer-term support. In-house psychology training programmes to promote basic understanding of techniques to support survivors affected by low mood, and multidisciplinary team (MDT) clinics to promote a culture of interdisciplinary learning across professional boundaries were examples of enablers of longer-term support. Similarly, a culture that supports work-based learning and self-study, and the development of educational programmes for survivors that involve the participation of different agencies (e.g. therapists, benefit advisers, pharmacists), can also advance longer-term support in creating greater awareness among survivors on how to cope more successfully. Self-management programmes, such as Bridges,99 and the delivery of the Expert Patient Programme100 in a group environment were also cited as helping to achieve this goal. The delivery of peer support by survivors, who had undergone rigorous training, to offer guidance to survivors was also highlighted, in addition to the potential value of a keyworker approach in acting as a mentor/guide to more recent survivors.

Flexible operational and managerial approaches to delivering health care to survivors also seemed to enable longer-term support. Hence, an open-door referral policy that facilitated ease of access to therapists, collective working patterns within CSTs that ensured that the geographical region was adequately covered and the use of MDT clinics were indicative of flexible operational systems. Interdisciplinary methods that enabled more timely fitting of necessary equipment aids in survivors’ homes and a more clinically driven approach for delivering short bursts of therapy according to survivors’ needs further illustrated a flexible managerial approach that advanced longer-term support.

Although reported relatively infrequently, there were examples of multiagency partnerships that facilitated longer-term support. A post-stroke physiotherapy group, managed by leisure services and the local NHS, was an example of this. Furthermore, some services reported positive links with local employment services, and positive engagement with national programmes supporting disabled people into work. Community-based stroke groups, often run by the Stroke Association or other voluntary groups, sometimes involved different agencies coming together to support aphasic and younger survivors. A day centre that involved the participation of different voluntary groups, as well as a gym, and that hosted a cafe that promoted social interaction among survivors, was also cited.

Some support built around training and educational activities could also be effective. The positive impact of training of re-enablement workers by therapists to promote independent living at home could be considerable. Training survivors to utilise information technology (IT) methods to promote independence, particularly through using Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and e-mail to enhance communication, was considered a positive approach to enhancing longer-term support.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A key strength of the study was the involvement of therapeutic and non-therapeutic staff with direct experience of interacting with stroke survivors, who were able to deliver informed perspectives regarding barriers and enablers, based on a wealth of collective experience. The content of the discussions drew on a broad range of cross-cutting issues that enabled participants to reflect on operational, managerial and cultural factors that influenced outcomes for longer-term stroke survivors. This produced rich and varied material that, in reflecting on different issues confronting survivors, appeared more insightful than might have been revealed by other qualitative methods, given the cross-cutting themes that emerged from the thematic analysis.

A weakness of the study concerns the non-participation of some key members of the stroke teams, in particular consultant stroke physicians and local commissioners of services. Their participation may have highlighted additional issues that this study has not considered.

Relationship with other parts of the programme

The study highlighted the value of 6-month and annual reviews for maintaining contact with stroke survivors so that changing circumstances can be monitored and managed accordingly. The potential benefits of interdisciplinary team learning and practice across professional boundaries in clinical and non-clinical settings, innovative in-house training programmes for CSTs (combined with an open-door self-referral policy), survivor-to-survivor peer support schemes to help overcome practical and emotional challenges and the delivery of self-management programmes focused on a goal-setting approach to problem-solving informed our subsequent thinking.

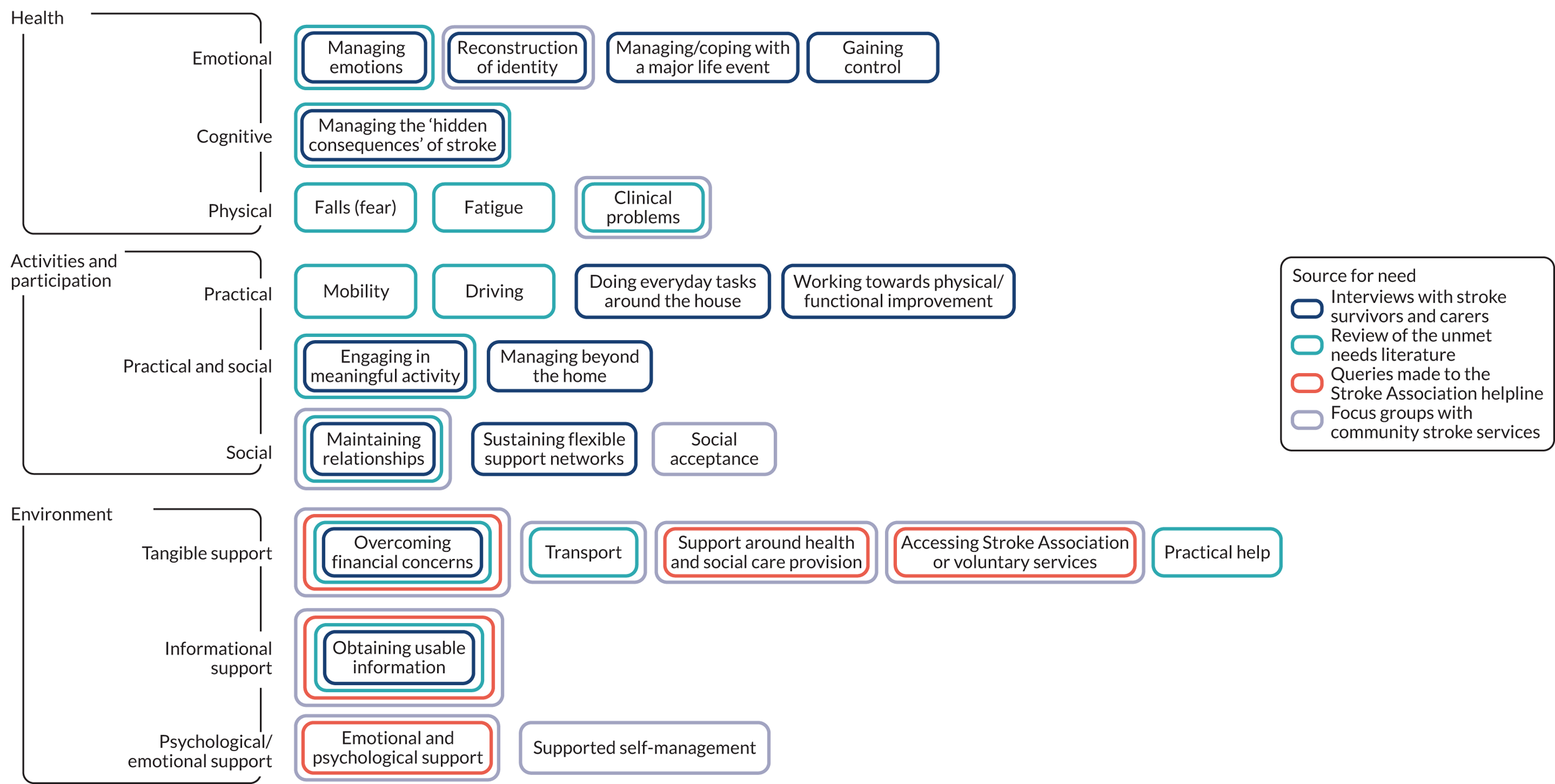

Synthesis of unmet needs after stroke

At the completion of this WS, we reviewed all data gathered in WS1 and WS2 to synthesise the unmet needs of people after stroke (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Unmet needs after stroke.

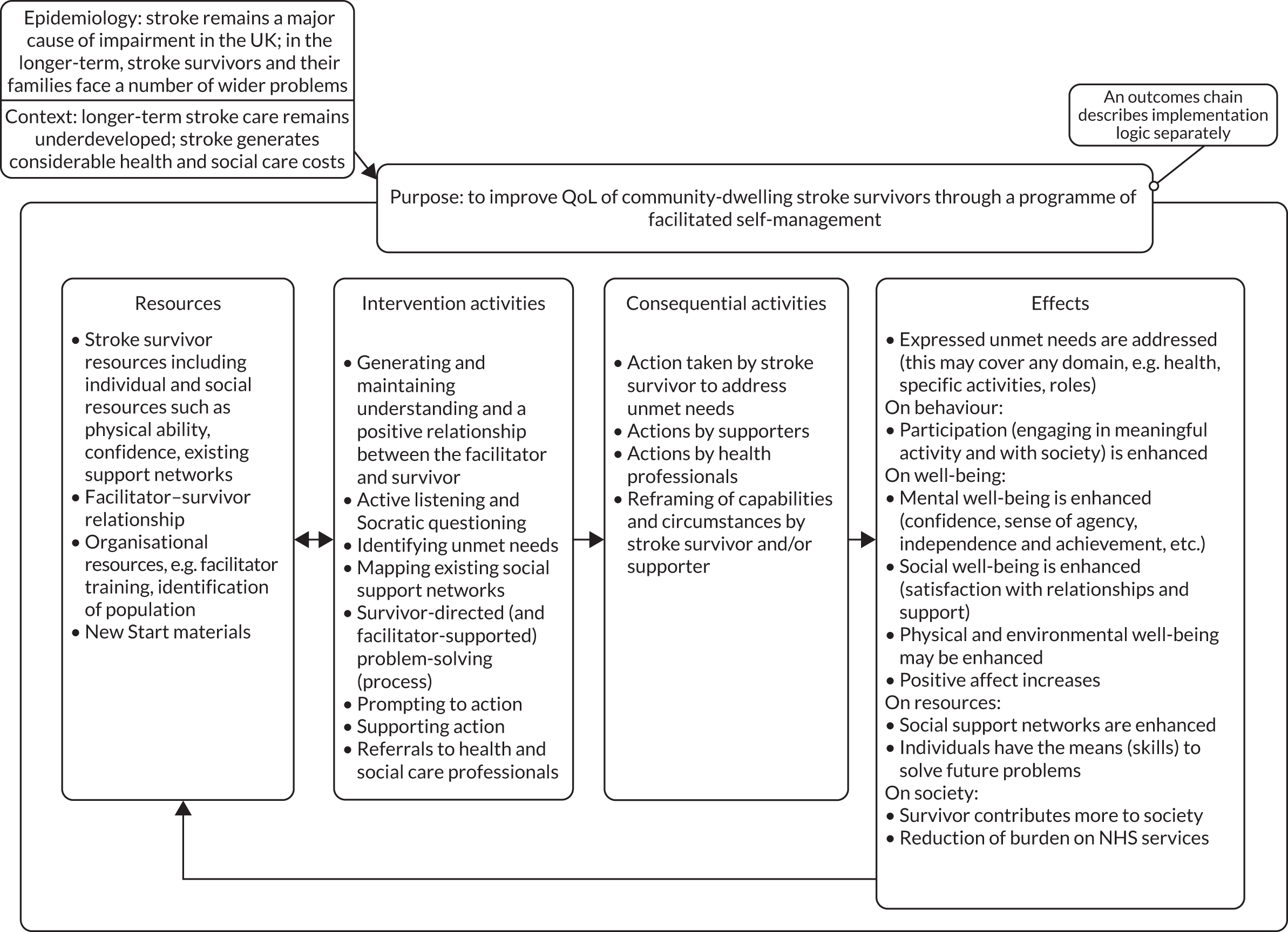

Workstream 3: development of a theory-based supported self-management intervention based on targeted behaviours

Aim

The aim was to develop an intervention with appropriate supporting materials and plans for implementation that was grounded in existing research and practice, and focused on improving QoL by addressing unmet needs and maintenance and enhancement of participation of stroke survivors, while not increasing the burden on their carers (as outlined in the grant application).

Methods

Although, for ease of comprehension, the research is described as a linear process, in reality, the work was completed iteratively using a participatory approach involving the PMG, the CRAG and the following groups, established for this WS:

-

The project working group comprised Anne Forster, Rosemary McEachan, Josie Dickerson, Thomas F Crocker, Jessica Hall and Arvin Prashar, with additional input sought from Allan House, Jenny Hewison, Robbie Foy, David Clarke, Rebecca J Hawkins, Mary Godfrey, Katie Grenfell, Christopher McKevitt and members of the PMG. The working group and associated academics gave us insight from a range of disciplines, including stroke rehabilitation, psychology, psychiatry, social anthropology, health services research and implementation science, as well as previous experience of the intervention mapping approach.

-

A reference group (RG) comprised the project working group; representatives from commissioning (GR), local authority social care (JW and AW), a community integration service run by the Stroke Association and Momentum Skills (AM), Carers’ Resource (AJ), the Stroke Association (LH) and community neurophysiotherapy (SM); and a stroke survivor (SF). This RG gave us access to tremendous experience and a range of insights on how longer-term stroke services should be shaped with particular respect to what was wanted and needed and what would be practicable and fit with existing services. The RG met monthly for 5 months and was instrumental in framing the intervention.

Clarifying general features and needs to be met by the intervention

Methods

With input from the RG and PMG, the principles for the intervention were developed based on those outlined in the grant proposal.

The total list of 23 needs, identified in WS1a from the qualitative work, literature reviews and helpline data and from the focus groups in WS2 (see Figure 5), was prioritised by members of our RG and our established CRAG. Members sorted cards of the needs into piles of ‘most important’ and ‘less important’ and provided explanations for their choices. The selection of needs were iteratively reviewed and refined in discussion with these groups.

Results

Principles for the intervention were developed, and included the overall aims of improving QoL and participation for stroke survivors; that the intervention be relevant and accessible to all stroke survivors and their carers; that it be responsive to context, be feasible and sustainable; and that it can be developed in a context of existing health and social care resources.

The RG and CRAG emphasised that the importance of specific needs would vary widely between individuals. However, they provided guidance as to the needs that our intervention should concentrate on, emphasising psychosocial needs and arguing that these were less likely to be addressed by current services, and, moreover, were most likely to influence QoL and participation.

The prioritised needs to address were gaining control, managing emotions, maintaining relationships, managing or coping with a major life event, reconstruction of identity, managing hidden consequences of stroke, communication, mobility, clinical problems, support around health and social care provision, obtaining usable information, sustaining flexible support networks and engaging in meaningful activity (see Appendix 6).

Of the 10 remaining needs from the list of 23, six were needs with existing service responses, and therefore remained as needs to be addressed by referral and not directly by the intervention (e.g. falls, driving, financial). Four needs had barriers and enablers similar to those already included, and were therefore likely to be encompassed in the intervention (e.g. ‘managing beyond the home’ has barriers and enablers that are similar to those of ‘engaging in meaningful activity’).

The RG discussed the following challenges:

-

Complex psychological and relationship issues – it was agreed that these were beyond the scope of the intervention and should be managed through referral to existing psychological services and organisations (e.g. Relate).

-

Carer-specific needs – although acknowledging the importance of recognising carers’ needs (and implementation of the Carer Act 2014101) it was agreed that the intervention would focus on survivors’ needs. Those delivering the intervention should be equipped to recognise problems and to help carers find alternative appropriate services. Detailed exploration of carer needs was not undertaken to inform an intervention. Carers’ Resource were an active participant in our research programme and ensured that we were aware of the needs and perspectives of carers and other family members at all times. Our research team had undertaken considerable previous work addressing carer needs. 45 A colleague in our unit undertook a linked PhD specifically continuing that work, focused on developing an intervention to reduce carers’ burden. 102

Developing specific objectives for the intervention

Methods

In accordance with the intervention mapping framework,103,104 behavioural outcomes for the 13 prioritised needs of survivors and their families were identified. For each of these behavioural outcomes, performance objectives were developed (what participants and agents in the environment need to do to achieve the behavioural outcome). Matrices of change objectives were developed, identifying specific determinants from the theoretical domains framework (TDF)105 that were likely to influence achievement of these performance (e.g. self-efficacy, skills) objectives in a range of domains. Fourteen domains of the refined TDF were used, along with two further domains particularly relevant to a stroke population: physical function and communication.

Results

A catalogue of 263 performance objectives and hundreds of change objectives designed to address the identified needs was developed (an example is provided in Appendix 7). As a result, the intervention mapping approach became too overwhelming in the face of the complexity, the interindividual variation and the lack of several specific behaviours that longer-term stroke survivors’ outcomes of QoL and participation could be focused on. The hundreds of change objectives that were generated highlighted the limited applicability of intervention mapping for an intervention designed to meet such a wide range of needs, each with a large variety of possible barriers and enablers. The working group agreed that there were too many performance and change objectives to take through the proposed steps of intervention mapping. In addition, the relevance of these objectives to overcoming the needs of survivors or carers would be very dependent on the particular needs and circumstances of the survivors and carers. There appeared to be some similarity between many of the performance objectives organised under different behavioural outcomes.

Instead of identifying methods and applications for each change objective in accordance with intervention mapping, the intervention plan was developed using:

-

the similarities identified in the performance objectives above

-

problem-structuring and shared knowledge creation, shaped by discussion with the PMG and RG

-

information gained from all WSs and from the expertise of stroke survivors and carers

-

consultation with health, social and academic professionals

-

the research evidence review (see Appendix 8).

These sources converged to produce three intervention components: problem solving, building and sustaining a flexible support network, and obtaining usable information. When compared with the interim outputs from the intervention mapping work that had attempted to merge performance objectives across multiple needs, the approaches were compatible in cases for which it was feasible to check.

Recognised approaches to each component of the intervention were selected, consulting the relevant literature, the RG and the PMG. Practical applications to enact the components of the intervention were then considered and identified.

Problem-solving

To clarify, problem-solving was intended to address prioritisation of needs, and developing and enacting solutions that were specific and feasible for each survivor’s lived experience and circumstances. This would be allied with opportunities to access existing therapies when this was desired, deemed necessary and available. Existing approaches were adapted, because social problem-solving is a well-developed method with underpinning models, established components and approaches to application (e.g. problem-solving therapy106).

Building and sustaining a flexible support network

Building and sustaining a flexible support network enabled current problem-solving, but was also intended to provide a protective effect against the negative consequences of future challenges. Relevant methods and applications to incorporate into the intervention were identified.

Obtaining usable information

Access to usable information would also enable problem-solving, as well as satisfy the need to understand the personal and mutual ramifications of stroke and future prospects for recovery. In specifying this component, the RG and CRAG recognised what the evidence base suggested: that provision of large swathes of material would tend to overwhelm, rather than support, survivors, and that assistance in identifying and interpreting relevant information would better fit the principles of self-management.

Delivery format

Because the intervention was being designed to cater for all stroke survivors beyond 6 months after stroke, and given that the preceding work had demonstrated that some survivors are averse to attending groups, it was concluded that individual person-centred delivery must be the starting point. In addition, owing to the incorporation of facilitated problem-solving and the importance of tailoring the delivery to a survivor’s needs, it seemed likely that the intervention would include face-to-face delivery. Individual delivery was also deemed helpful in catering for ‘hard-to-reach’ groups, such as people affected by aphasia or cognitive impairment. The benefit that many survivors and service providers report from peer support was recognised. However, given that peer support was already available across the UK (for example, through the Stroke Association), raising awareness and encouraging engagement with it was incorporated in the intervention rather than incorporated as a component in itself.

Timing

Although the original grant suggested that this intervention would probably incorporate the annual review, the exploration of current services suggested that relatively few survivors were receiving a 6-month review; therefore, it was concluded that the 6-month review was an appropriate anchor point.

Producing materials

Methods

The literature was searched for existing self-management interventions in stroke and other chronic conditions (details of the search strategy can be found in Report Supplementary Material 8). Existing materials were reviewed to determine whether or not they fitted with the selected approaches. When this was the case, these were adapted to the target group. When this was not the case, new materials were developed in accordance with the selected approach. The RG, PMG and CRAG contributed to this process.

Results

The comprehensive search of the literature relating to self-management in stroke produced 2492 titles. From these, 171 papers were scrutinised in detail. The form and content of numerous intervention materials were considered, in particular the Chronic Disease Self-Management Programme; the West Lothian Stroke Workbook; a problem-solving approach previously developed by Professor Allan House for stroke/diabetes; the Greater Manchester CLAHRC Patient-Led Assessment for Network Support (PLANS) website; Professor Lewin’s The Heart Manual; and The Pain Management Plan, a stroke recovery video guide developed in New Zealand.