Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as award number RP-PG-0514-20002. The contractual start date was in March 2016. The draft manuscript began editorial review in December 2022 and was accepted for publication in May 2024. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 MacArthur et al. This work was produced by MacArthur et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 MacArthur et al.

Synopsis

Summary of alterations to the programme’s original aims/design

Cluster randomised controlled trial changed to pilot and feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial

The major change within this programme was a change from a full cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) to a pilot and feasibility RCT – details of this change and the reasons for it are described below.

The original Antenatal Preventative Pelvic floor Exercises and Localisation (APPEAL) programme was of 5 years’ duration and included four work packages (WPs) with the ultimate aim of developing and testing an intervention to train midwives to advise and support women during antenatal care in undertaking pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFME) to reduce post-partum urinary incontinence (UI). There is high-quality Cochrane evidence1 that antenatal interventions to increase PFME substantially reduce the proportion of women who experience post-partum UI. However, many midwives do not offer advice and support to women, and many pregnant women do not undertake these exercises. Thus, it was considered important to develop an intervention to integrate this advice and support into routine midwifery antenatal care and investigate its effectiveness.

The programme was planned to develop an intervention in the earlier WPs and to undertake a definitive cluster RCT within WP4. The aim was to assess whether women in community midwife teams (clusters) allocated to receive intervention care reported less UI at 10–12 weeks post partum than women in clusters allocated to receive standard care. Approximately 40 community midwife teams were to be recruited and randomised in 8–10 NHS Trusts across England.

Piloting the trial data collection instruments was the first phase of WP4 (4.1) but it was in the first stage of the programme (stage 1 being assessed to progress to stage 2) and a low rate of return of women’s questionnaires was found, at 31%. Shortly after commencing the programme, the team examined recent surveys in similar populations and realised that the proposed estimate in the grant application of 60% of women returning a postal questionnaire in the pilot study and 80% in the full trial (after developing additional online methods) was substantially over-estimated: recent return rates were around 30–35%. 2,3 The team considered what might maximise return rate. A Cochrane Review (‘Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires’) showed that giving incentives, and ones not dependent on returning the questionnaire, both increased response rates. 4 As a consequence, it was decided to send women a £10 voucher with the first questionnaire rather than on questionnaire receipt. The Cochrane Review also found a higher response from shorter questionnaires. The questionnaire developed for the pilot study was only four pages, but given that women who have recently given birth are busy, it was decided to pilot whether an even shorter questionnaire just including main outcomes might elicit a higher return rate. Thus, the WP4.1 pilot study was designed as a RCT to test a longer versus a shorter questionnaire. Women who had antenatal care from 15 community midwife teams in two NHS Trusts were randomly allocated to either long or short questionnaires. Those who returned the short questionnaire were then sent the remainder of the questions in another questionnaire. No difference in return rate was found between those randomised to the long or short questionnaire.

Possibly it was this pilot trial, of a long versus a short questionnaire, that led to a misunderstanding by National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) stage 1 assessors that the pilot study had been a pilot trial assessing the proposed intervention, and that there was no difference across trial arms in the proportion of women doing PFME often enough (a few times a week or more) to possibly reduce post-partum UI. There had been no PFME intervention, but the misunderstanding was that there had been but with a lack of difference in PFME adherence. This, together with the low return rate, meant that the assessors considered that there was too much of a risk for a full trial to go ahead in WP4.2. Following the pilot trial of a long versus a short questionnaire, it was decided, in consultation with NIHR stage 1 assessors, that a full trial was a risk because, in addition to the low return rate, it may be burdensome to staff. The midwifery staffing levels and workload difficulties occurring subsequent to the programme being funded may have meant that additional midwifery tasks may be more problematic.

The APPEAL team therefore proposed a pilot and feasibility trial to collect additional process outcomes to determine whether a full trial could be feasible. A variation to contract (VTC) was submitted and NIHR agreed to this proposed change. This reduced second stage also included dropping the health economic analysis.

Work package 2 was discontinued following funding review

COVID-19 pandemic

The intervention developed in the early WPs of the programme was a training package for community midwife teams to enable them to advise and support pregnant women in undertaking PFME. The first face-to-face training session was delivered to six midwives in the week before lockdown (March 2020).

The APPEAL trial was then paused, along with all non-COVID trials, until January 2021. Following restart, it was likely that routine maternity care would continue to be affected by the pandemic, so during the trial pause it was necessary to take steps to ensure that the training intervention was ‘COVID-proof’. This meant amending the intervention so it could be delivered to midwives online and organising for women to be provided with resources in ways that reflected some routine maternity care contacts not being face to face. This was approved in a VTC, and some additional funding was given, which together with use of underspend, allowed the programme to be completed.

Implications for full trial

Members of the APPEAL team had been liaising with the Maternity and Women’s Health Policy Team at NHS England (NHSE) since 2018. As part of the NHSE Ten-Year Long Term Plan there was an intention to set up new perinatal pelvic health services across England, and NHSE were aware of our work and its relevance to the planned roll-out of this service. A significant component of the new pelvic health service is to ensure that midwives are trained in how to advise and support women to achieve better pelvic health, a central part of which includes women undertaking PFME in pregnancy and post partum. Had it not been for the pandemic, this service would not have been set up until the results from the APPEAL programme had been available. The APPEAL team are pleased that this new service is going ahead, members having previously undertaken research providing findings to show its need. It does mean, however, that a full RCT is no longer possible since many elements of the intervention will become part of standard maternity care.

The APPEAL team have continued to work with the NHSE Maternity and Women’s Health Policy Team in the early phases of the new NHS services being introduced. In July 2021 14 ‘early adopter’ local maternity and neonatal systems (LMNSs) were funded to develop a service, and 9 more ‘fast follower’ LMNSs were funded in July 2022. The aim is that by March 2024 all LMNSs will be required to set up a new perinatal pelvic health service. The APPEAL team are already working with numerous of these LMNSs, and more details are given later in the report.

Work package 1 particular context awareness: identifying barriers and enablers of change

Work package 1.1: critical interpretive synthesis

See also protocol Salmon et al. 5 (https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-017-0420-z) and full paper Salmon et al. 6 (https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.24256).

Aims

The aim of WP1.1 was to undertake a systematic review using critical interpretive synthesis of what is known about the complex individual, professional, and organisational issues that enable or hinder the implementation of PFME training during women’s childbearing years.

Methods

Sources for inclusion were identified through structured database searches supplemented by purposive searches. Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility and critically appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool7 by two independent reviewers. Following data extraction using a structured template, the findings of included studies were coded using a framework based on the initial research questions. Patterns and themes were identified. New (synthetic) constructs were generated and linked to broader theory to explain the overall findings.

Key findings

Fifty quantitative and qualitative sources were included. The concept of agency (people’s ability to effect change through their interaction with other people, processes and systems) provided an overarching explanation of how PFME can be implemented during childbearing years. Women and healthcare professionals (HCPs) (individually or in groups), maternity services and organisations, funders, and policy-makers all have agency, although their capacity to implement PFME is enhanced or diminished by the professional, organisational, and policy environment.

Numerous factors constrained women’s and HCPs’ capacity to implement PFME. It is unrealistic to expect women and HCPs to implement PFME without reforming policy and service delivery to genuinely support women and HCPs in this endeavour. The implementation of evidence-based PFME requires policy-makers, organisations, HCPs, and women to value the prevention of incontinence by using low-risk, low-cost and proven strategies as part of women’s reproductive health care across the lifespan.

Limitations

For the reviewed quantitative studies, limitations included small sample size and lack of reporting of any sample size calculation; too few details regarding reasons for declining participation; lack of details regarding calibre of survey tools/outcome measures; and variable response rates. For the reviewed qualitative studies, many did not consider impact or relevance of contextual factors or did not demonstrate reflexivity.

Work package 1.2: focused ethnographic observation of clinical practice

See also Terry et al. 8 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2020.102647).

Aims

The main aim of WP1.2 was to explore individual, HCP and organisational barriers and enablers to implementation of PFME and assessment in current UK practice. Further aims related to understanding how individual, professional and organisational factors interact to enhance or reduce effective PFME implementation in the UK context with a view to informing subsequent WPs in the APPEAL programme.

Methods

Designed with input from patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) activities, a variety of methods were planned: interviews from three differing sites with antenatal women and, for a subset of women, postnatal follow-up interviews; interviews with midwives and other HCPs; and observations in antenatal clinics. Additional data sources included field notes, photographs, websites, leaflets, clinic documents and antenatal service policies, all obtained from visits to the study sites.

Analysis used reflexivity and reflexive accounting (key aspects of ethnographic research9,10), with initial coding to develop a coding framework and then identify emerging themes (following principles of thematic analysis11) and adopted a process similar to the ‘constant comparative method’12 to guide theme development. Analysis was inductive (data driven) but also deductive in terms of addressing the specific objectives of the APPEAL research programme.

Extensive discussions about emerging findings took place among the research team, including with Jean-Hay Smith and Helena Frawley (our international specialist academic physiotherapy collaborators from New Zealand and Australia, respectively). These were ongoing remote and in-person meetings during June 2018.

Key findings

Data were collected at three sites (large city, small city, coastal town). A total of 23 midwives and 15 pregnant women were interviewed, with 12 also interviewed postnatally. Interviews were carried out with physiotherapists (n = 4), a link worker/translator (n = 1) and obstetricians (n = 2). Seventeen antenatal clinic observations took place.

Key findings based on all data, including clinic observation notes and interviews, were that women and midwives know that PFME training is important, but that midwives may not communicate fully to women the relatively large ‘gains’ available from engaging with PFME. There was widespread lack of confidence among women and midwives to initiate a discourse about PFME and UI. This was exacerbated by both misunderstandings and assumptions and by a lack of clear guidelines and policy, further impacting on communication between women and midwives.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained for the ethnography {HRA approval 15 December 2016 [Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) project ID 215180]}.

Limitations

A criticism of ethnographic research is that the presence of a researcher will impact the behaviour of those observed, creating an observer effect bias. 13 The midwives were fully informed of the purpose of this study, so it is possible that this bias occurred. It is argued, however, that even if this happens, ethnographies can still expose honest accounts about the topic under investigation. 14 Ethnographies do provide a detailed account and thus findings cannot be generalised to other women or HCPs; furthermore, we were not able to carry out interviews with women who did not speak English.

Inter-relationship of work package 1 with other parts of the programme

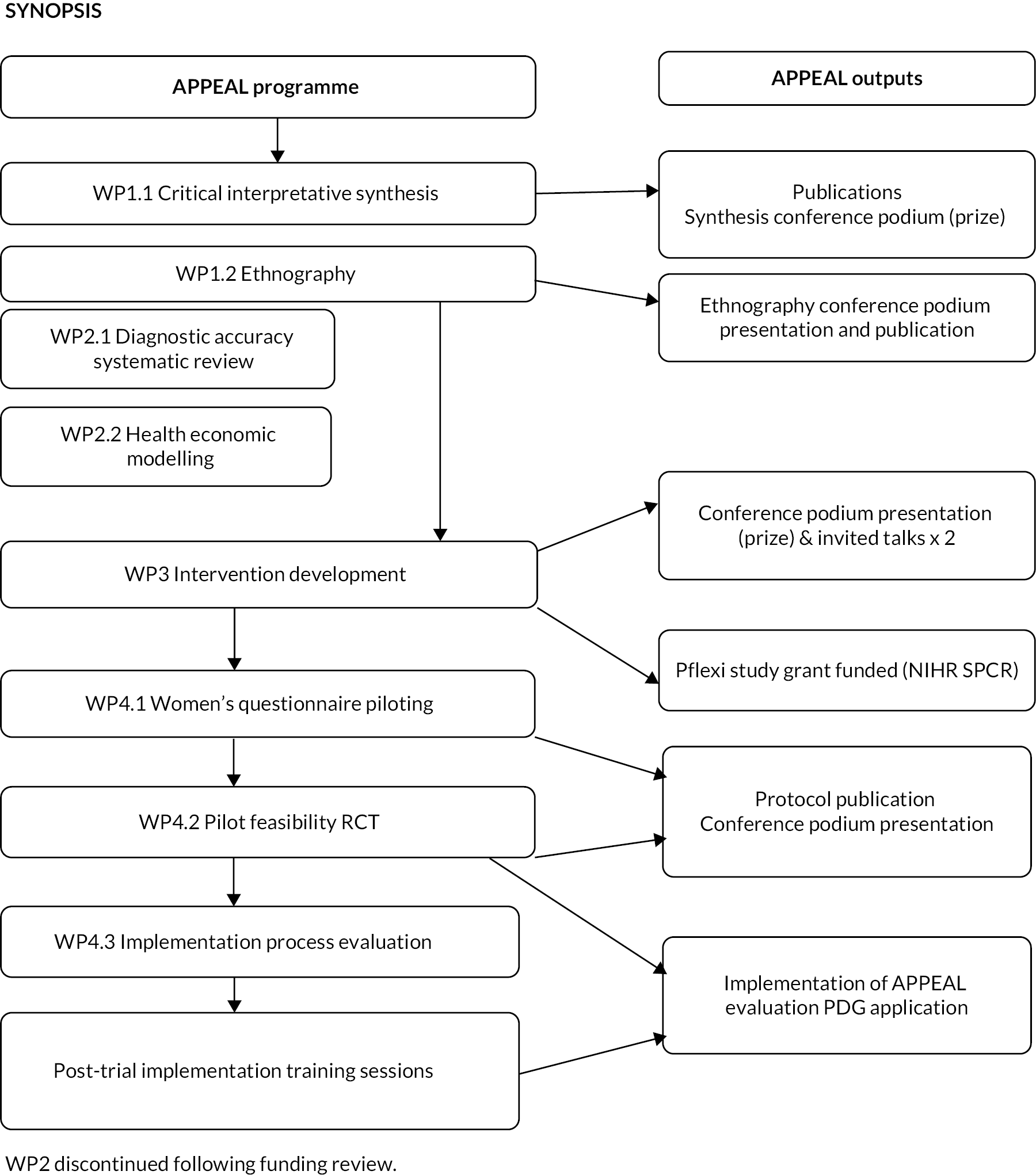

Both studies from WP1, one evidence synthesis and one empirical, were combined to create a platform of research to inform WP3 activities for the development of the APPEAL intervention, which would then be tested in the feasibility and pilot trial in WP4. Figure 1 shows diagrammatically how the whole programme fits together.

FIGURE 1.

Research pathway diagram. PDG, Programme Development Grant.

Work package 2: performance measurement: determining relevant measures of performance

Work package 2.1: diagnostic accuracy systematic review and data synthesis to identify the accuracy of tests for assessment of pelvic floor muscle localisation and contraction in women

Aims

The main aim of this study was to determine whether there were any tests for assessment of pelvic floor muscle (PFM) localisation that might be used to assist in the trial intervention.

Methods

A diagnostic test accuracy systematic review was undertaken to compare the accuracy of tests for assessment of PFM localisation and contraction in women. The population was not restricted to pregnant women to maximise data available; however, pregnancy was considered as a potential source of heterogeneity.

The secondary objectives of the review were to investigate other sources of heterogeneity; that is, factors which may affect test accuracy. Potential sources of heterogeneity included population characteristics (e.g. presence or absence of UI, obesity, menopausal status, parity, current pregnancy); index test characteristics (e.g. index test technology, expertise of test operator); and reference standard characteristics: whether digital vaginal palpation was conducted by a specialist [e.g. physiotherapists, obstetricians, gynaecologists, general practitioners (GPs) with accreditation/specialist interest in women’s health, specialist midwife or health visitor] or a non-specialist HCP. A further objective was to combine findings from WP1 to identify which of the most accurate tests are likely to be most acceptable to pregnant women. A comprehensive search strategy was developed in consultation with an international PFME expert. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (Ovid), MEDLINE In Process (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), Cochrane Library (Wiley) CDSR, DARE, HTA, NHS EED and CENTRAL; CINAHL (EBSCO); SCI Web of Science SSCI. Ongoing trials registers (CT.gov and the World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform register) were searched and abstracts and conference proceedings sought using Conference Proceedings Citation Index (CPCI) – Science and CPCI – Social Science and Humanities (Web of Science). Electronic searches were supplemented by citation searching and searching references of included studies and relevant systematic reviews. Databases were searched from inception to October 2016. No language limits were applied. In anticipation of a paucity of studies with a primary objective of estimating test accuracy, all study design types were considered for inclusion, except for diagnostic case–control studies as these are known to overestimate test accuracy. Test accuracy study design filters were avoided as these have been shown to miss studies. Titles and abstracts and full-text articles were screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers, with disagreements resolved by a third. A data extraction proforma and a quality assessment tool based on the QUAlity of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies tool15 tailored to the topic were prepared a priori.

Key findings

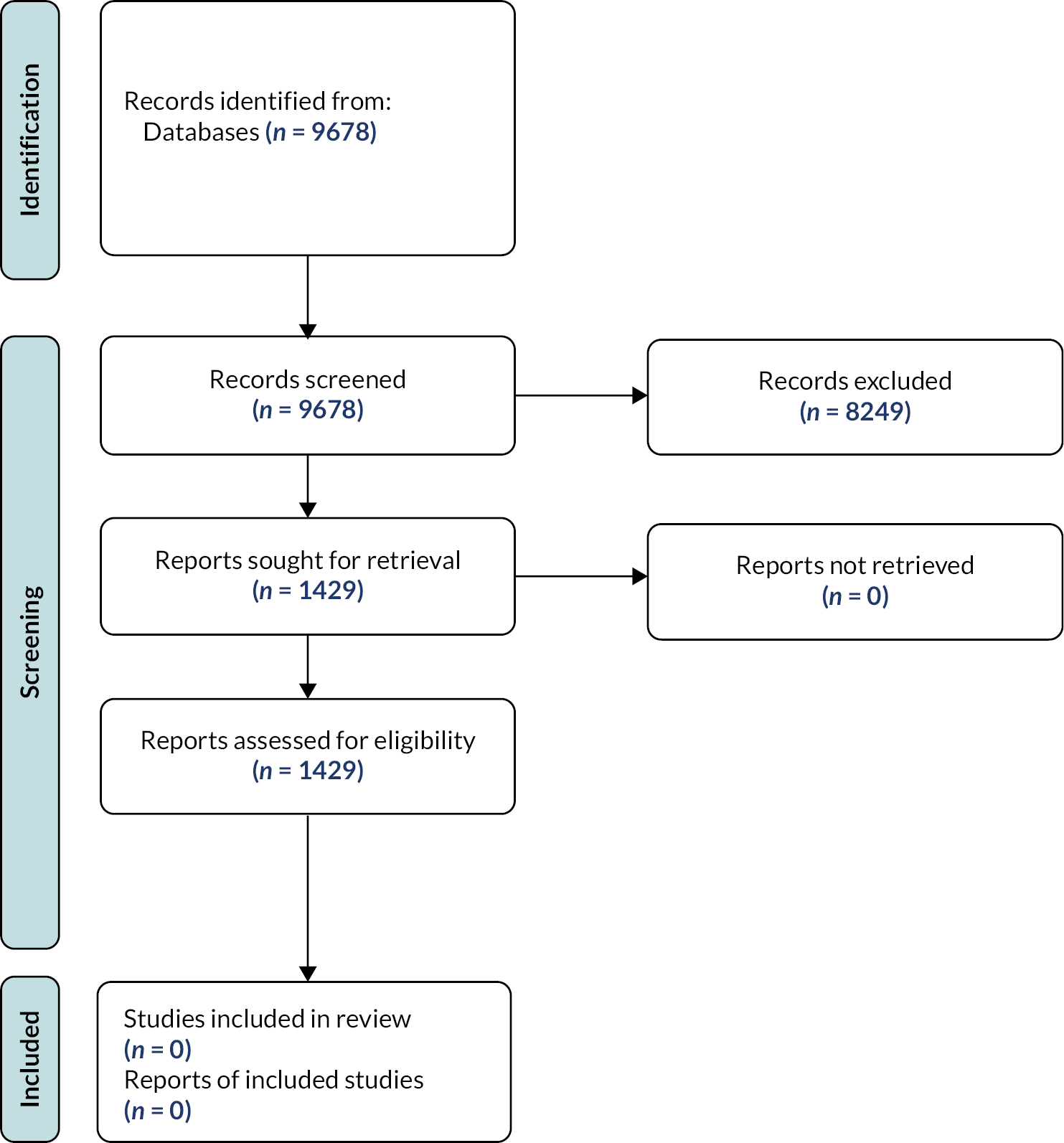

A total of 9678 unique title and abstracts were screened, and 1429 full-text articles subsequently retrieved. No studies met the review inclusion criteria. Most commonly, this was because of the absence of an index test (one or more of: methods for observation, palpation, pressure measurement, measurement of electrical activity by muscles, imaging with ultrasound) in parallel with the reference standard of digital vaginal palpation. In studies where an index test was conducted in parallel with the reference test, the paper did not provide information from which to derive a 2 × 2 diagnostic table and therefore an estimate of accuracy. This was because, except for one test accuracy study (that did not use an acceptable reference standard), all other studies identified used either an index test or the reference standard to measure the outcome of an intervention to improve PFM function. Furthermore, in the majority of these studies women were educated how to contract the pelvic floor musculature correctly so that any improvement in strength and endurance following an intervention could be measured. These studies therefore only had women who were able to contract their pelvic floor; thus, the ability of index tests to identify women unable to localise and contract their PFM could not be estimated (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

PRISMA flow chart of included studies.

Limitations

The lack of any available studies to assist in assessment of PFM localisation that might be used in the trial intervention was a major limitation.

Inter-relationship with other parts of the programme

The intention of this WP was to provide a diagnostic test to use in the intervention for midwives to check whether women were able to locate their PFM.

Work package 2.2: constructing a health economic decision-analytic model

Aims

The aim of this study was to collate relevant evidence to inform and develop a preliminary decision-analytic model (DAM) which would compare a range of alternative tests and treatment pathways for reducing UI among pregnant women. The overall objective of the preliminary model-based evaluation was to identify gaps in the evidence that required specific focus in the full definitive trial.

Methods

Systematic review

A pragmatic search of identified literature from WP2.1 showed insufficient evidence for the proposed model, and a scoping search did not find any economics studies on PFME among pregnant women. Hence a systematic review was conducted with the broader purpose of identifying evidence for economic evaluations of interventions to prevent and treat UI in general, not just in pregnancy, to inform a preliminary model.

The systematic review was conducted according to the guidelines of the UK’s Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 16 A search strategy was developed using the population, intervention, comparison and outcomes framework. 17 Five electronic databases – MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, NHS Economic Evaluation database and CINAHL – were searched.

Formal economic evaluation and cost analysis studies were included if participants were females suffering from UI; the intervention was PFME to prevent or treat UI; the comparison was any alternative test and/or treatment strategy to prevent UI in women; and the main outcome was cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). A two-stage categorisation process was used to screen studies for inclusion using published methods. 18,19 A quality appraisal was not undertaken because the review’s objectives required a description of all economic evidence.

Information on resource use and associated costs were extracted from reviewed studies. In addition, effectiveness data and health-related quality-of-life (QoL) data were sought from the published Cochrane Review1 and pragmatic literature searches. The collated evidence was used to estimate a baseline DAM which explored potential issues and/or gaps relating to either the intervention or QoL.

Preliminary model

We constructed a model in TreeAge (TreeAge Software, Inc., Williamstown, MA, USA) to compare the APPEAL intervention with usual care, based on a series of potential pathways to represent the wide range of viable pathways that women could follow. The pathways included scenarios in the intervention arm where pregnant women were referred to physiotherapists when they had UI or had problems locating their pelvic floor. Group and individual physiotherapy sessions were included in the modelled scenarios.

Effectiveness data were obtained from a Cochrane Review1 identified from a pragmatic literature search and an alternative study20 identified through hand searching. Similarly, utility values were obtained from a pragmatic search. 21,22 Cost and resource-use data used in the model were based on published sources. 23 Assumptions were made about all model parameters to form a complete set of values for the analysis, and these parameters were varied in sensitivity analyses to see the effect on the results.

Key findings

Systematic review

The search identified 10 studies22,24–32 out of a possible 1163. Overall, all the studies evaluated the cost/cost-effectiveness of PFME as treatment rather than as prevention for UI. The delivery of PFME differed between the studies with variations in the number, duration and frequency of physiotherapy sessions.

The studies were mostly formal economic evaluations (n = 8), with only two cost analyses. The majority (n = 6) of the economic evaluations were cost–utility analyses (with outcomes presented in terms of cost per QALY). There were variations, however, in the instruments used to measure QoL. Three of the studies (two cost–utility analyses and one cost-effectiveness analysis) were model-based. All studies included direct medical costs, and six studies included some form of direct non-medical costs (e.g. the cost of incontinence pads). Only three studies included indirect non-medical costs such as time forgone by not working and time for extra laundry loads. All but one study recommended PFME as a cost-effective intervention for treating UI.

Economic analysis

Initial results from the pre-trial economic analysis suggested some potentially helpful information for the trial design and proposed data collection. An example of such information was that the time spent by midwives providing the intervention was not likely to be a key driver in the results; this allowed the trial team to be non-prescriptive about midwives recording the time spent with women, which was initially a cause for concern. However, the preliminary results were extremely sensitive to both the effectiveness of the intervention and the QoL data inputted into the model.

Limitations

The systematic review and additional reviews provided some evidence for the pre-trial model. There were insufficient data, however, to carry out a complete economic evaluation without some fundamental assumptions. Many of the data used were proxy values from other studies of related (but not the same) populations.

Inter-relationships with other parts of the programme

The purpose of the pre-trial model was to identify gaps in the literature and areas worthy of particular focus, such as data collection, in the definitive trial. When the second stage of the programme was changed to be a feasibility and pilot RCT rather than a full definitive trial, however, the health economic analysis was discontinued.

Work package 3: plans for change: developing the constituents and means of delivery of the Antenatal Preventative Pelvic floor Exercises and Localisation intervention

Some text in this section has been reproduced with permission from Dean et al. 33 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

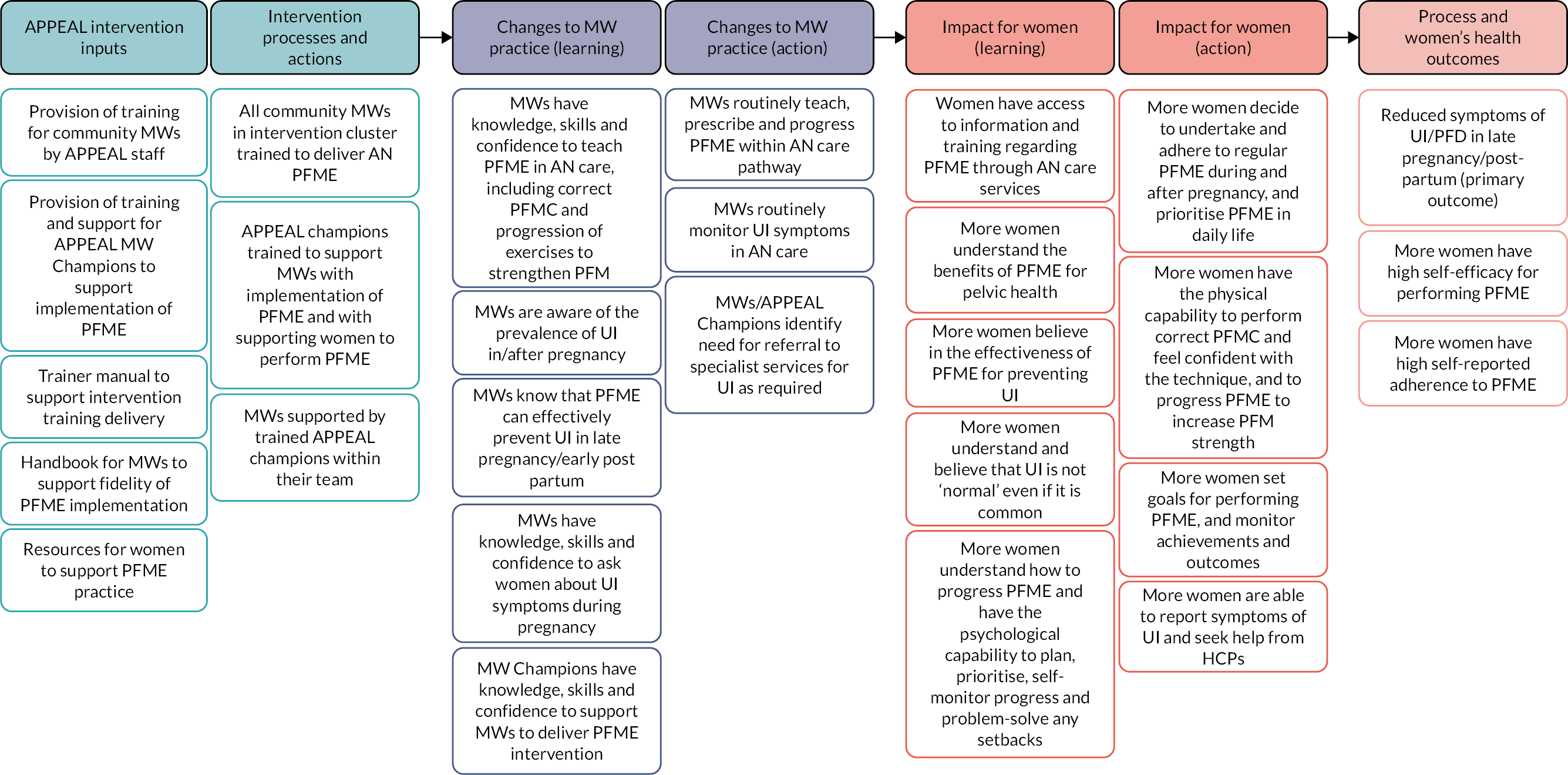

Aims

Work undertaken in WP3 aimed to develop a training package and resources for midwives to give them the confidence to teach and support women to do PFME within routine antenatal care. The aim also included developing resources for midwives to give to women, providing further support for women to do PFME during pregnancy. The developed intervention was planned to operate at two levels: to change midwives’ behaviour (to teach and support women to do PFME) and to change women’s behaviour (to do PFME during pregnancy). The training package and resources would then be evaluated in the pilot and feasibility cluster RCT described in WP4.2 and WP4.3.

Methods

Development followed the Medical Research Council guidance for complex interventions34 and was guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. 35 Designed over four iterative phases, the intervention development included a stakeholder event and multiple PPIE activities.

Ethics approval was obtained for WP3 phases 1 and 3 (University of Exeter Medical School Research Ethics Committee 18/06/169; HRA approval: IRAS project ID 238874).

Phase 1: focus groups

Two participant groups were planned: pregnant women or those who had given birth within the previous 12 months, and midwives providing antenatal care. They were invited to take part in separate focus groups in a range of sites in England. Data were analysed using thematic analysis. 11

Phase 2: development of a training programme including intervention mapping

The intervention was developed using data from WP3 phase 1 and WP1. A comprehensive mapping exercise was undertaken using the behaviour change wheel (BCW), theoretical domains framework36 and behaviour change technique (BCT) taxonomy (v1). 37 PPIE activity included APPEAL advisory group meetings and a wider group of advisers undertaking a citizens’ jury style assessment of mobile phone apps to determine which might be recommended as part of the women’s resources to support PFME. 38 A national stakeholder event was arranged to consider midwife training needs and antenatal service provision.

Phase 3: practice training event

An in-person practice training event was carried out with a cohort of midwives located in a different region to the future trial. A 5-point (scoring 0–4) Likert scale eight-item questionnaire was designed to assess midwives’ confidence before and after training regarding pelvic floor knowledge and teaching PFME. Focus group style discussions took place after the training session to obtain feedback on intervention format, content, and methods of delivery. An anonymous evaluation questionnaire with options to rate the training and provide free-text comments was also prepared. Researchers facilitated these activities and made field notes to record discussions and recommendations.

Phase 4: intervention refinement

Findings from WP3 phase 3 and further PPIE were used to refine the format and content of the intervention package. Additional refinements were made in response to COVID-19.

Key findings

In WP3 phase 1, 12 women (age 20–44 years; education range: secondary education to postgraduate degree) and 14 midwives (age 25–59 years; midwifery experience: 3–32 years) took part in six focus groups.

The practice training in WP3 phase 3 was attended by a different cohort of 18 midwives (age 25–60 years; midwifery experience: 2–20 years). Of the 32 midwife participants in WP3 phases 1 and 3 of the study, 13 (41%) reported no previous PFME training (formal or informal), 2 (6%) had attended specific pelvic floor rehabilitation courses, 9 (28%) reported varying amounts of training and 8 (25%) did not provide data on this.

The PPIE advisory group included six mothers with young children, with nine meetings held. The citizens’ jury included 10 women who had given birth within the previous 5 years, with two meetings held.

The stakeholders were 20 delegates representing 18 organisations across the UK with an interest in maternity services (see Acknowledgements).

Phase 1

Four themes emerged from the six focus groups. These were: ‘knowing’, ‘doing’, ‘remembering’ and ‘supporting’ antenatal PFME. Illustrative quotes for each theme are available in Appendix 1.

Knowing about pelvic floor muscle exercises and urinary incontinence

Analysis showed a lack of information and promotion of antenatal PFME meaning that women were unaware of the importance of PFME, and a lack of training and guidance for midwives. Midwives needed more knowledge on anatomy and muscle training physiology, and women needed to know why PFME were important and the consequences on UI of not doing them. Both groups agreed that midwives needed the confidence to raise the topic and make sure all women understood about PFME and their relationship to UI. For midwives, knowing the importance of PFME included wider implications, such as economic implications.

Doing pelvic floor muscle exercises

Midwives and women wanted guidance on how and when to teach and perform PFME; analysis made it clear that this should be done early in antenatal care and followed up at every subsequent appointment. Midwives and women were ambivalent about doing vaginal examination for checking the correct muscle contraction was happening. This was not regarded as something universally needed but could be offered if required.

Remembering pelvic floor muscle exercises

Prompts were seen as critical to support women to do PFME and to support midwives to implement PFME teaching. Both wanted consistent and regular reminders to help women put PFME into a daily routine. Women emphasised the need for meaningful dialogue to support them, not just simply asking whether they are doing their exercises. Women suggested signposting to smartphone apps, and midwives suggested a variety of cues, such as key chains, lanyards, and visual prompt cards.

Supporting implementation and delivery of pelvic floor muscle exercises

Women wanted multimedia options for delivery of PFME information, including online and written resources. Although debated by women and midwives, there was overall agreement that a paper leaflet, given at the booking appointment, would be acceptable provided it was accompanied by detailed verbal instruction at a subsequent appointment, hence acting as a reminder.

Midwives wanted PFME training to be delivered face to face, with demonstrations from experts on how to teach effective PFME. E-learning was not regarded as acceptable for initial training but could be an option for refresher training, as it was likely to improve accessibility. Finding time to fit in PFME training was clearly going to be challenging, and many midwives believed it should be mandatory. Implementation of training would require local organisational support to enable midwives to attend.

Further suggestions for maximising implementation included using a ‘train the trainer’ model and having a midwife PFME champion within each midwife team. Midwives also wanted to know more about local referral options and strengthening of referral pathways to physiotherapy services for women they identified as needing further support. Both midwives and women felt the need to raise awareness and strengthen support for antenatal PFME at a wider societal level, and suggested a national campaign.

Midwives were also asked to consider methods for assessing fidelity to the proposed intervention in the future trial; they suggested a PFME tick box on antenatal appointment checklists, audit of antenatal notes, and observations of midwifery practice. They did not consider audio or video recording of appointments acceptable.

Phase 2

In this phase, data from WP3 phase 1 and the earlier APPEAL research6,8 were mapped onto the BCW. This helps identify intervention functions (the broad categories of things that can be done to change behaviour) and intervention content and BCTs and these were all discussed by the research team.

One example relates to the theoretical domain of knowledge (awareness of the existence of something), which is a psychological capability component of the capability–opportunity–motivation–behaviour (COM-B) model. 36 For this to be implemented, women need to develop understanding of PFME and their relationship with pelvic health and UI, and understand the principles of how PFME might reduce UI. Similarly, midwives need to develop knowledge and understanding of the rationale for antenatal PFME for promoting PFM health during pregnancy and childbirth.

The proposed intervention functions (in this example the methods by which these knowledge gains can be achieved) through education, with the policy category (vehicle) being service provision and guidelines, and marketing-style communications. Thus, the ideas for intervention content (application) were designed to follow these principles at the two levels. At the level of women, the intervention needed to ensure that midwives could provide information and facts relating to what the pelvic floor is, its role relating to UI, what happens in pregnancy, what PFME are, why they are important, how to do them, and what the benefits are, including information on their effectiveness for preventing UI as well as other benefits of PFME. At the level of midwives, the intervention needed to cover a review of anatomy, physiology and function of PFMs, presentation, and discussion of evidence for prevalence of UI during/after pregnancy, including effectiveness of antenatal PFME for reducing UI. Furthermore, the intervention needed to impart new knowledge and understanding to midwives about the impact of UI on physical and mental health, giving examples of women’s stories (e.g. social isolation, shame, embarrassment) as well as including information on other benefits of PFME (e.g. sex, reducing time of second-stage labour).

These knowledge elements of the intervention were then coded to the BCT taxonomy, namely: shaping knowledge (instruction on how to perform a behaviour, BCT 4.1) and informing about natural consequences (information about health consequences, BCT 5.1; salience of consequences, BCT 5.2; and information about social and environmental consequences, BCT 5.3).

Finally, comments or issues arising from PPIE advisers and stakeholders were added to the map. In this example they commented that ‘knowledge is power’ for both midwives and women, but also had wider importance within society, as it would help raise the profile, and thus result in a clearer understanding of why PFME is important.

The full mapping exercise is included in Report Supplementary Material 1. Once mapping was completed, the first iteration of the intervention was prepared. Intervention materials included a midwife training programme and resources for midwives to support PFME implementation, and a resource package for women to be given by midwives during the antenatal booking appointment.

The training programme for midwives included five steps for putting PFME into antenatal clinical practice: (1) raise the topic of PFME; (2) screen for UI; (3) teach PFME; (4) prompt/remind women about how to perform PFME; and (5) refresh women’s understanding about PFME and refer to specialist services if required. A manual containing training session slides, summary leaflets and additional resources about PFME and UI was prepared for midwives.

The PPIE advisers helped co-develop the resources for women. In addition, the citizens’ jury work considered smartphone apps from a list provided by the app review undertaken by APPEAL’s collaborators in New Zealand. 38 Jury members tried out various apps and the three most highly rated were added to an app decision card with QR codes supplied to ensure ease of access. Other resources were a leaflet with information about PFME and how to perform a correct PFM contraction, and stickers to use as prompts/reminders for PFME. These, with the app decision card, were placed in a small bag to be given by midwives to women at their antenatal booking appointment.

Phase 3

Following the practice training event, evaluation scores were positive for content and delivery, and participating midwives (n = 18) found it useful. Free-text responses indicated that midwives acknowledged the importance of taking the lead regarding PFME, but lack of time, confidence, and skills to raise the issue presented challenges for implementing PFME in practice. However, these midwives reported an increase in total confidence relating to PFME from 2.70 (range 1.18–3.50) before training to 3.68 (range 3.37–4.00) after training, suggesting that with additional refinements the training had potential to address some of these challenges. The midwives raised additional considerations for implementation of PFME, time constraints of antenatal appointments, not wanting to overload women with too much information early in maternity care, and whether insufficient continuity of care would impact on their ability to develop rapport with women to teach and support PFME throughout pregnancy. The midwives also highlighted the importance of establishing PFME champions within midwifery teams and the need for buy-in from senior midwives/clinical managers to support implementation.

Phase 4

Intervention materials and content were modified and refined by the research team and PPIE advisory group in response to feedback from the practice training event. Examples were more detail for the anatomy refresher and for the physiology to cover muscle exercise training principles; and to package resources for women in a cloth bag big enough to hold a clean nappy (not a box, which would take too much space for midwives). A second version of the midwives’ manual was prepared as the trainer’s manual, with extensive speaker notes, to facilitate the plan for using a ‘train the trainer’ model in future implementation. The training session was shortened from half a day to 2 hours. Additional training and resources were developed to support a PFME champion midwife role. Further modifications were made at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to enable training delivery via the Zoom online platform (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA), and to support midwives to deliver intervention elements via telephone appointments. The final output of WP3 phase 4 was the development of the logic model for the pilot feasibility trial in WP4 (see Appendix 2, Figure 4).

Limitations

The challenges identified by midwives regarding wider system pressures,6 past difficulty accessing training, and appointment time constraints did limit intervention range and complexity. Despite these constraints, midwives and women believed that implementing PFME in antenatal care would be beneficial for large numbers of women.

At this stage, evaluation of the APPEAL intervention has used observational, before–after or qualitative data; findings from the pilot feasibility RCT in WP4.2 and 4.3 add to this evaluation.

Inter-relationship with other parts of the programme

We benefitted from continuing to work closely with PPIE advisers and drew upon known BCTs throughout the four phases to develop a comprehensive understanding of the needs of midwives, women, and stakeholders within current organisational contexts. Findings from WP1, and behaviour change theory helped us bring WP3 activities together into a training package for midwives and resources for supporting women to address these needs, to be used in WP4.

Work package 3 aimed to ensure that whatever the APPEAL intervention asked of women and midwives for implementing PFME was evidence-based, with sound theoretical underpinnings and consensus acceptance from experts and lay members of the public. Our extensive PPIE, plus national stakeholder involvement, added credibility to intervention development, which has been piloted, refined, and adapted for remote delivery.

Work package 4: piloting the intervention

Some text in this section has been reproduced with permission from Webb et al. 39 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Work package 4.1: what is the response rate for the trial questionnaire and the intraclass correlation coefficient?

See also Appendix 3 for full report of WP4.1 and Tables 5–8.

Aims

The main aim of WP4.1 was to test the data collection instruments in the questionnaire to be sent to women at 10–12 weeks post partum and, in so doing, to test what the return rate might be in a full trial. We also wanted to estimate the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for a full trial. This study was completed in the first stage of the programme before there was a change to a feasibility and pilot trial for the second stage.

Recent studies in similar populations2,3 showed that response rates had been dropping, so it was decided to also assess whether a long or shorter questionnaire might give a higher response.

Methods

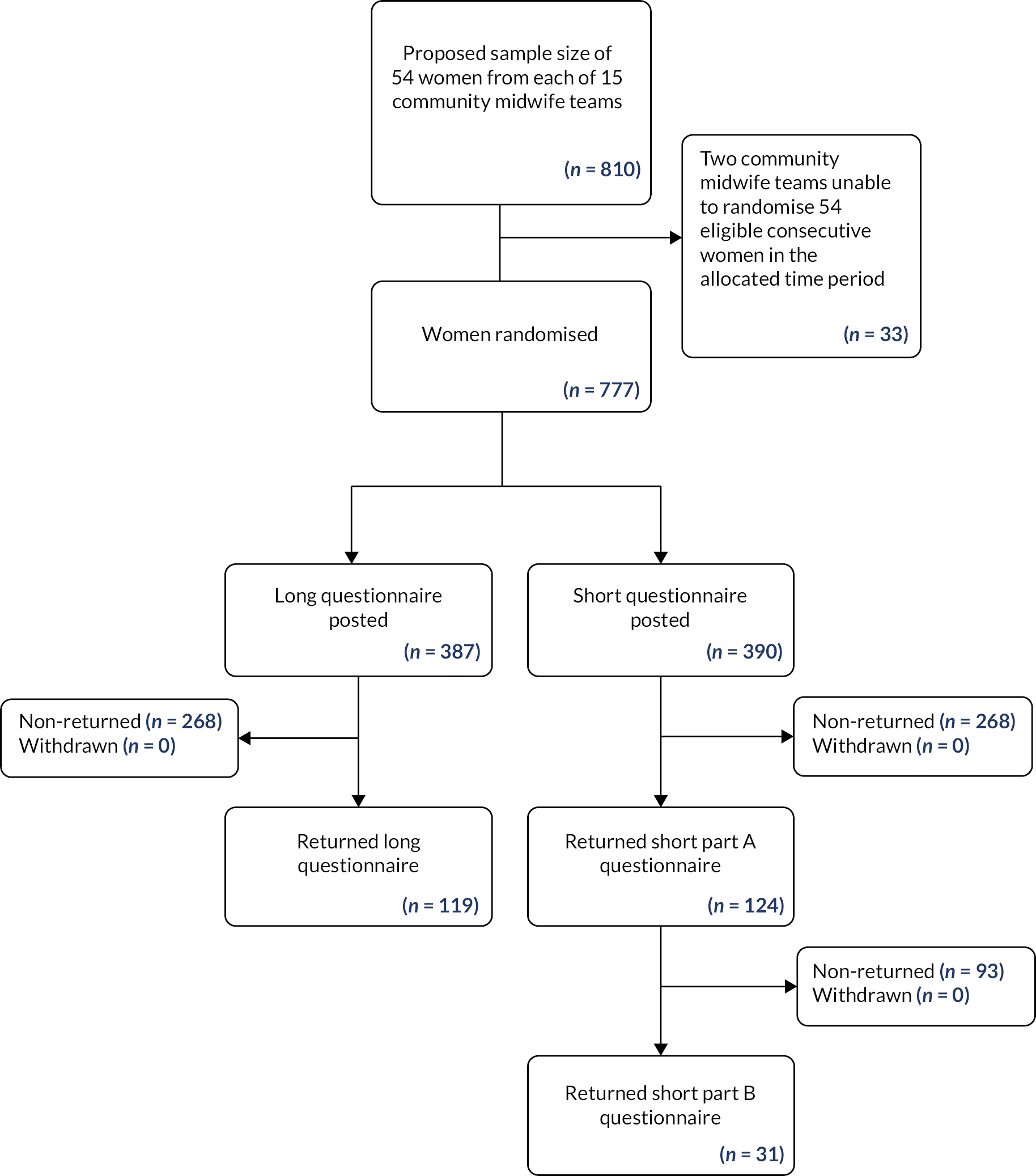

This study was an individually RCT undertaken in the two NHS Trusts which would be part of the subsequent pilot cluster trial. Eligible women (all except those under 16 years or with no live baby on hospital discharge) cared for in 15 community midwife teams who gave birth in two Trusts during the study period were included.

A sample size of 800 women with an anticipated response rate of between 30% and 60% would allow a return of between 240 and 480 questionnaires. With a sample size of 800, with 400 allocated to each trial arm, at 80% power and 5% significance, the study would be able to detect a 10% absolute difference in the percentage response rate between the shorter and longer questionnaires.

The first 54 consecutive women to give birth during July 2018 from each of the 15 midwifery teams were informed by their midwife at their first postnatal home visit that they would receive a postal questionnaire at 10–12 weeks post partum about incontinence and PFME.

The questionnaires comprised several validated measures to assess: UI [International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF40)]; faecal incontinence (FI) [Revised Faecal Incontinence Scale (RFIS41)] (FI was included in APPEAL as PFME are generally considered to be a help but RCT evidence to show that antenatal PFME can reduce post-partum FI is not of high quality, hence not a major focus of APPEAL); confidence in PFME [Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercises Self-Efficacy Scale (PFMESES42) and Exercise Adherence Rating Scale (EARS43)]; and general health [Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-1244)]; as well as questions about advice that women may have received on PFME in pregnancy and their PFME practice. The long questionnaire comprised two double-sided pages with all the above measures. The short questionnaire comprised one double-sided page and did not include PFMESES, EARS or SF-12. For women who returned this questionnaire a second questionnaire, which included PFMESES, EARS and SF-12, was then sent.

Individual randomisation to the long or the short questionnaire was undertaken using a computer programme at the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (BCTU), stratified by community midwifery team to account for potential variation between different sociodemographic areas.

Local Trust research midwives sent the questionnaires with a cover letter, a £10 voucher, and a stamped return envelope, then sent a reminder questionnaire to women who had not responded by 2 weeks.

Permission was obtained from the Proportionate Review Subcommittee of the London – Brighton & Sussex Research Ethics Committee (18/LO/0934).

Key findings

A total of 777 women were randomised to receive a long (n = 387) or short (n = 390) questionnaire. Overall response rate was 31.3% (243/777). Response rate in the long questionnaire arm was 30.8% (119/387) and 31.8% (124/390) in the short questionnaire arm [absolute difference in return rate −1.05%, 95% confidence interval (CI) −7.6% to 5.5%]. While not statistically significant, this finding rules out large differences between response rates. The ICC of response rate was 0.007 (95% CI 0.0005 to 0.094). The baseline characteristics of the women who returned a long questionnaire were similar to those who returned the shorter version.

Of total responders, 49% (119/243) reported some leaking of urine based on responses to the ICIQ-UI SF. 40 A total of 64.2% (156/243) of women reported receiving advice to perform PFME during pregnancy from their midwife. There were 42.4% (103/243) of women who reported doing PFME often enough (a few times a day, once a day, a few times a week) to possibly reduce post-partum UI. All these responses were similar between the long and short trial arms.

The questionnaire in general was well completed by the women, with low rates of missing values, but the response was low, despite having incorporated Cochrane Review4 recommendations to increase responses to postal questionnaires.

The estimated ICC for the return rate was 0.007 (95% CI 0.0005 to 0.094) The upper limit of the 95% CI was taken as a conservative estimate of the ‘true’ return rate ICC and was used to inform the sample size calculation for the pilot trial in WP4.2.

Limitations

The main limitation in this study was the low return rate of questionnaires from the women.

Inter-relationship with other parts of the programme

This WP was planned to test the data collection instruments and procedures ready to undertake a full trial. The low rate of questionnaire return, however, increased the risk of proceeding to a full trial (see Summary of alterations to the programme’s original aims/design). The data obtained from WP4.1 were used to inform the feasibility and pilot trial described in the next section.

Work package 4.2: feasibility and pilot cluster randomised controlled trial of an antenatal preventative pelvic floor muscle exercise intervention led by midwives to reduce postnatal urinary incontinence (Antenatal Preventative Pelvic floor Exercises and Localisation Programme)

Some text in this section has been reproduced with permission from Bick et al. 45 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Aims

The aim of WP4.2 was to assess the feasibility of undertaking a future trial of a midwife-led antenatal intervention to support women to perform PFME in pregnancy to reduce post-partum UI. Other aims were to assess intervention acceptability to midwives and the women they supported. Objectives were:

-

Provide training for community midwife teams randomised to the intervention arm to encourage incorporation of a PFME care package into their usual antenatal care (outcomes related to these objectives reported in WP4.3).

-

Assess whether training, intervention implementation and trial processes were acceptable to midwives (outcomes related to these objectives reported in WP4.3).

-

Assess whether midwife characteristics (e.g. years qualified) were similar across trial arms.

-

Assess questionnaire return rates from women at 10–12 weeks post partum overall and in both trial arms to assess feasibility and allow sample size estimation for a full-scale RCT.

-

Assess characteristics of women overall and within trial arms who returned questionnaires compared with all those who gave birth in the same midwife teams over the same study period but did not respond, using anonymised routine data.

-

Assess whether baseline characteristics collected following birth (self-reported UI at pregnancy commencement, maternal and obstetric characteristics collated from maternity records) were similar across trial arms.

-

Assess midwife support for PFME in both trial groups using women’s questionnaire data and qualitative interviews with midwives and women.

-

Assess women’s practice of PFME during and after pregnancy (outcomes related to qualitative interviews reported in WP4.3) using women’s postnatal questionnaire and interview data.

-

Assess prevalence of UI and FI at 10–12 weeks post partum using women’s questionnaire data to inform the sample size calculation for a full RCT (FI was included in APPEAL as PFME is generally considered to be a help but RCT evidence to show that antenatal PFME can reduce post-partum FI is not of high quality, hence not a major focus of APPEAL).

-

Undertake any necessary revisions to the APPEAL training package and following this, recommend roll-out by midwives to all pregnant women as part of the NHS Long Term Plan (outcomes related to this objective reported in the section on practice implications).

Methods

The study design was a feasibility and pilot cluster RCT, with community midwife teams forming the clusters. This design was chosen as randomisation of individual women would likely lead to contamination because midwives would have to provide two forms of care; and randomisation of individual midwives was not possible because midwives provide care on a team basis.

Midwife teams (clusters) were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to standard care only or standard care plus intervention. A minimisation algorithm ensured approximate balance over the variables:

-

midwife team size, defined by number of monthly births

-

NHS Trust.

Blinding of midwives providing care was not possible. Women receiving antenatal care were not explicitly blinded but the PFME support they experienced was the usual care provided by their midwives. Due to the nature of recorded data, those responsible for conducting trial analysis could not be blind to allocation.

Ethics approval

Protocol version 4.2, dated 21 November 2021, approved by West Midlands – Edgbaston Research Ethics Committee (19/WM/0368, approval date 10 January 2022). Study sponsor is Birmingham Women’s and Children’s Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Intervention

Two research midwives led and facilitated online training sessions developed from earlier WPs which lasted approximately 2 hours. Midwives in intervention teams were asked to introduce the topic of pelvic floor health at antenatal ‘booking’ appointments or as early as possible after this to all women. All women were given an APPEAL resource pack, including an APPEAL leaflet with PFME information, a link to APPEAL developed videos, recommended apps to support PFME, and APPEAL logo stickers to use as reminders. Women were to be asked by the midwife at all subsequent antenatal appointments about PFME progress and any problems with PFME or incontinence symptoms. In teams where a high proportion of women were non-English-speaking, the maternity support workers (MSWs) who provided translation were also trained. Midwives and MSWs had 2–3 months to practise implementing the PFME intervention into their routine care.

Midwife ‘champions’ in each intervention team received additional training on how to support and manage women with more severe UI symptoms, referred to them by team colleagues, and recommend appropriate specialist referral; and provide reminders and advice for their team to implement the intervention.

Feasibility and pilot outcomes

Feasibility of undertaking a definitive future trial was assessed by:

-

questionnaire return rates from women who gave birth over a preselected 1-month period, at 10–12 weeks post partum overall and across trial arms

-

prevalence of UI at 10–12 weeks using the ICIQ-UI SF,40 and FI at 10–12 weeks using the RFIS41

-

women’s practice of PFME, their adherence (predefined as PFME a few times a week or more) and PFME confidence using the PFMESES,42 and EARS43 (as data on QoL were not relevant for a feasibility trial, the SF-1244 scale was not included in the questionnaire used in WP4.2). During data entry, it was noted that responses to four items from the 17-item PFMESES were missing. An error occurred when the questionnaire was downloaded from FORMAP (online tool for designing case report forms for clinical trials), which omitted these four items. However, when viewing the FORMAP version online, all four items were visible. The missing items were raised with the trial statisticians and the Trial Management Group decided to send out a corrected questionnaire containing the full set of questions to women who had not returned the first questionnaire. As this was a feasibility trial, when reporting summary data for the PFMESES questionnaire, no distinction was made between missing responses from women and missing responses due to women being sent incomplete questionnaires. Sites were asked to stop sending reminder copies of the questionnaires until a corrected version was available.

Process outcomes included whether the intervention could be implemented within routine antenatal care; whether midwives provided support for PFME in both trial arms; and women’s and midwives’ experiences in both trial arms of advice and support to perform PFME during pregnancy.

For the original aim of a full trial to go ahead, the following progression criteria had to be met:

-

Questionnaire return rate from women across trial arms did not result in substantial bias, indicated by either a high overall return rate and/or that women who returned questionnaires in both trial arms had similar baseline characteristics.

-

Women’s self-reported adherence to performing PFME was higher among women in intervention clusters than in controls.

-

Midwife support for PFME was reported as greater among women in intervention clusters than in controls.

Sample size

Sample size was based on the number and size of clusters needed to estimate the return rate of questionnaires (across trial arms) to an acceptable level of precision. In WP4.1 the estimated ICC for return rate was 0.007 (95% CI 0.0005 to 0.094). Assuming a conservative ICC of 0.1, the width of the 95% CI for different rates (e.g. return rate of questionnaires) was estimated based on a t-distribution. 46 To set a conservative upper bound on the required sample size, we determined the widest 95% CI for a given sample size which will occur for a rate of 50%.

To reflect changes from WP4.1 in the number of midwife teams and women cared for by the teams, the overall sample size target was around 1400 (17 clusters of average size 82) to estimate the 95% CI for return rate to a maximum width of 17.2%.

Data collection and analysis

Analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle. Data analysis was descriptive, mainly focused on CI estimation, with no hypothesis testing. Analysis methods included:

-

Continuous end points summarised using means and standard deviations (SDs), by arm.

-

Categorical (dichotomous) end points (e.g. return rates of questionnaires, adherence to PFME). The number of participants and percentages experiencing the event were summarised by arm.

For all total scores and dichotomous feasibility outcomes, summary measures and 95% CIs per trial arm were estimated using a cluster-level analysis based on t-distributions with K − 1 degrees of freedom (K denotes the number of clusters in each group) and appropriate transformation where necessary (and weighting if there was variation in cluster sizes). Quantitative data were summarised using descriptive statistics.

Women’s questionnaires

Trust research midwives were asked to exclude women who had a stillbirth or neonatal death, those whose infants were taken into care, and women who had severe mental health problems, providing these data were available in maternity records. All women were to be told by their midwives at their first postnatal home contact that they would receive a questionnaire at 10–12 weeks postnatally enquiring about any incontinence they may have experienced and their PFME performance during and after pregnancy. If more than 2 weeks had elapsed since the initial questionnaire was sent but not returned, another copy was posted to the woman. A £10 voucher was offered to women who returned their questionnaire (questionnaire shown in Report Supplementary Material 2).

Trust research midwives were also asked to identify women who did not speak English as a first language from their maternity record. If the woman’s first language was Urdu, Polish, Romanian or Arabic (main non-English languages in the areas), a shortened version of the questionnaire and a cover letter translated into the relevant language were sent. As only the ICIQ-UI40 SF is translated in these languages, questionnaires sent to women who required a translated version did not include the RFIS,41 the PFMESES,42 or the EARS. 43

Responses from completed questionnaires were entered by a research midwife at the NHS Trust sites, who provided a list of the hospital/NHS numbers of women who consented for their maternity records to be accessed, to obtain information on:

-

woman’s age, ethnicity, parity, onset of labour (spontaneous/induced), mode of birth (spontaneous vaginal, instrumental, caesarean section), anaesthetic/analgesia used, perineal trauma, episiotomy, duration of active second stage

-

baby’s gestation at birth, birthweight and head circumference.

Key findings

As this was a feasibility trial, no statistical tests were used for comparisons between groups for any outcomes with only group-specific point estimates and 95% CIs used.

Women’s questionnaire return rate

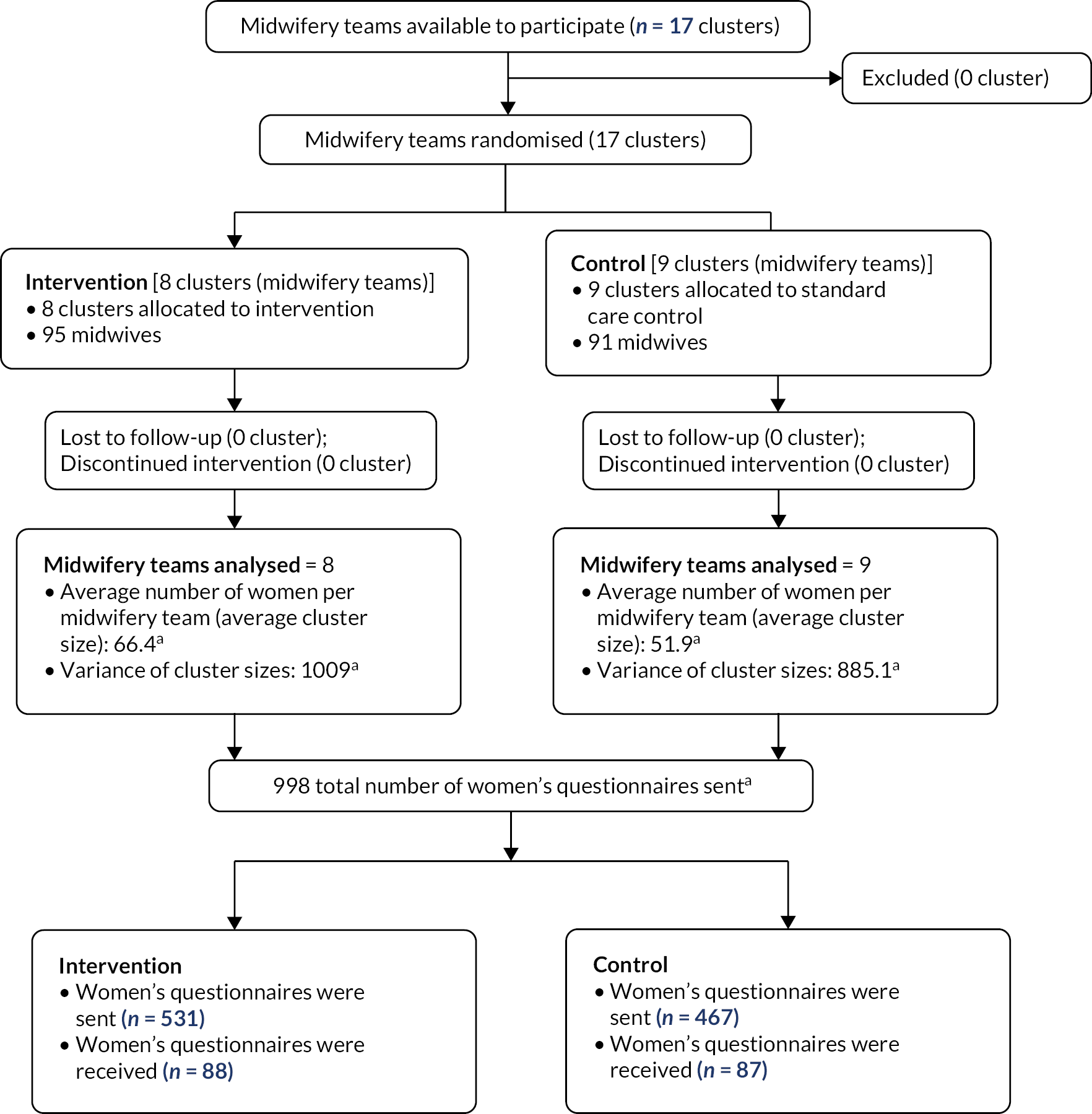

Appendix 4, Tables 9 and 10 present information on sending/receiving women’s questionnaire by group and the total number of women who gave birth at both study sites during the 1-month birth period. Appendix 4, Table 11 presents women excluded from receiving a copy of the questionnaire by study site. After exclusions, a total of 998 women who received antenatal care from 1 of the 17 study clusters randomised to the trial and who met inclusion criteria were sent a questionnaire; 175 (17.5%) women returned a questionnaire. Of 531 questionnaires sent to women in intervention clusters, 88 (16.6%) were returned and of 467 in the control clusters, 87 (18.6%) were returned (Figure 3). Ninety women were sent a translated questionnaire, and eight women (five in intervention clusters and three in control) returned this.

FIGURE 3.

Work package 4.2 CONSORT flow diagram. a, Figures based on the total number of women who received antenatal care and gave birth across both study sites during the 1-month sample birth period.

Table 1 presents the estimation of the return rate of women’s questionnaires pooled across both arms. As the return rate was low, an overall estimation provides more representative information than separate estimates by trial arm.

| Intervention: 8 clusters (n = 531) | Control: 9 clusters (n = 467) | Overall: 17 clusters (N = 998) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % return rate estimationa | % return rate estimationb | % return rate estimation (95% CI)c | |

| Percentage returning women’s questionnaire | 15.8 | 16.4 | 16.0 (11.6 to 21.4) |

A summary of the minimisation variables by treatment arm and those not returning a questionnaire is shown in Appendix 4, Table 12.

Characteristics of women who did not return a questionnaire (see Appendix 4, Table 13)

Characteristics of women who gave birth in the study sample month but did not return a questionnaire were obtained and, using anonymised routine obstetric data, were compared with those who did return a questionnaire. Around one-third of women who did not return a questionnaire were of White British ethnicity (371/34.9%), which is a lower proportion than in the group who did return a questionnaire, and 205 (19.3%) women were of Pakistani origin, which is a higher proportion than among those who did return a questionnaire. Ethnicity data were unavailable for 205 women (19.3%) who did not return a questionnaire. Of the women who did not return a questionnaire, a higher proportion were having a second or higher birth order baby than those who did return a questionnaire. Obstetric and infant characteristics were similar among women who did and did not return a questionnaire.

Women’s baseline characteristics (see Appendix 4, Table 13)

The overall mean age of women who returned a questionnaire was 31.8 years (SD 5.2 years). Of these women, 77 (50%) were recorded as White British, 10 (6.5%) Pakistani, 7 (4.6%) Black African or Black Caribbean, and the remainder as ‘other’ ethnic minority groups. Data on ethnicity were not available for 21 women (12%). Overall, 62 women had given birth for the first time (41%), 61 (40.4%) for the second time, 28 (18.6%) had two or more previous births. Data on parity were missing for 24 (13.7%) women.

Women’s obstetric outcomes were similar across trial arms except for induction of labour: 23 (29.5%) women had induction in control clusters and 12 (15.8%) in intervention clusters. Data on mode of birth were missing for 22 women. Infant outcomes including gestation, birthweight and head circumference were similar across trial arms.

When asked in the questionnaire about their symptoms of UI at pregnancy commencement, 24 women in intervention and 24 women in control clusters reported some degree of UI, although in most cases this was infrequent (Table 2).

| How often did you leak urine at the start of your pregnancy? | Intervention (n = 88) | Control (n = 87) |

|---|---|---|

| Never | 60 (68.1%) | 61 (70.0%) |

| About once a week or less often | 13 (14.7%) | 12 (13.8%) |

| Two or three times a week | 4 (4.6%) | 6 (6.9%) |

| About once a day | 3 (3.4%) | 4 (4.6%) |

| Several times a day | 4 (4.6%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| All of the time | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| Can’t remember | 4 (4.6%) | 2 (2.3%) |

Midwife support for performing pelvic floor muscle exercises in pregnancy

Women were asked in the questionnaire about midwife support for PFME in pregnancy. Overall, 73 (83%) women in the intervention and 54 (62.1%) in the control arms reported that their midwives had advised them to perform PFME. The critical information, however, and the main prespecified assessment of midwife support, was ‘did your midwife explain how to perform PFME when pregnant?’ and 57 (64.8%) of women in the intervention and 33 (37.9%) in the control arms reported that they had (Table 3). Thirteen (14.8%) women in the intervention arms reported that a midwife never talked to them about PFME; this figure was 30 (34.5%) women in the control arms. Other aspects of midwife support are shown in Table 3.

| Outcomes from questionnaire | Response | Intervention (n = 88) | Control (n = 87) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key pilot outcomes | |||

| Did your midwife explain how to perform pelvic floor muscle exercises when you were pregnant? | Yes | 57 (64.8%) | 33 (37.9%) |

| 95% CI | 56.9 to 72.4a | 24.6 to 51.2b | |

| Women’s predefined adherence in performing PFME in pregnancyc | Yes | 43 (50.0%) | 33 (38.4%) |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | |

| 95% CI | 24.1% to 77.1%d | 12.4% to 67.1%e | |

| Prevalence of UIf | Yes | 39 (44.3%) | 47 (54.0%) |

| 95% CI | 32.0% to 56.1%g | 42.2% to 65.8%h | |

| Further outcomes | |||

| Did your midwife advise you to perform pelvic floor muscle exercises when you were pregnant? | Yes | 73 (83.0%) | 54 (62.1%) |

| Did your midwife give you a pack of information on pelvic floor muscle exercises when you were pregnant? | Yes | 49 (57.7%) | 17 (19.8%) |

| Missing | 3 | 1 | |

| When did your midwife give you the pack of information on pelvic floor muscle exercises? | Never given | 35 (42.7%) | 65 (77.4%) |

| At first (booking) appointment | 15 (18.3%) | 10 (11.9%) | |

| At second antenatal appointment | 15 (18.3%) | 3 (3.6%) | |

| At later antenatal appointment | 17 (20.7%) | 6 (7.1%) | |

| Missing | 6 | 3 | |

| How often did your midwife talk to you about pelvic floor muscle exercises when you were pregnant? | Never | 13 (14.8%) | 30 (34.5%) |

| Only at booking appointment | 20 (22.7%) | 15 (17.2%) | |

| Occasionally | 33 (37.5%) | 22 (25.3%) | |

| Every antenatal appointment | 18 (20.5%) | 10 (11.5%) | |

| Can’t remember | 4 (4.5%) | 10 (11.5%) | |

| Did your midwife ever ask you if you had any difficulties with performing pelvic floor muscle exercises? | Yes | 27 (31.0%) | 8 (9.3%) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | |

| Before you were pregnant, have you ever been taught or learned how to perform pelvic floor muscle exercises? | Yes | 36 (41.4%) | 39 (45.4%) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | |

| How often did you perform pelvic floor muscle exercises when you were pregnant? | Never – not advised to | 9 (10.2%) | 18 (20.7%) |

| Never – other reasons | 9 (10.2%) | 4 (4.6%) | |

| Few times a month | 19 (21.7%) | 27 (31.0%) | |

| Once a week | 6 (6.8%) | 4 (4.6%) | |

| Few times a week | 23 (26.1%) | 17 (19.5%) | |

| Once a day | 11 (12.5%) | 5 (5.8%) | |

| Few times a day | 9 (10.2%) | 11 (12.6%) | |

| Can’t remember | 2 (2.3%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Do you currently perform pelvic floor muscle exercises? | Yes | 46 (66.7%) | 45 (64.3%) |

| Missing | 19 | 17 | |

| How often did you do pelvic floor muscle exercises over the last month? | Never – not advised to | 9 (10.2%) | 12 (13.8%) |

| Never – other reasons | 10 (11.4%) | 13 (14.9%) | |

| Few times a month | 25 (28.4%) | 23 (26.4%) | |

| Once a week | 5 (5.7%) | 4 (4.6%) | |

| Few times a week | 24 (27.3%) | 17 (19.5%) | |

| Once a day | 6 (6.8%) | 9 (10.4%) | |

| Few times a day | 9 (10.2%) | 9 (10.4%) | |

Women’s reporting of pelvic floor muscle exercise practice in pregnancy

The main prespecified assessment of undertaking PFME was the women’s responses to the question ‘How often did you perform pelvic floor muscle exercises when you were pregnant?’, with PFME adherence in a manner likely to improve symptoms predefined as a few times a week or more (see Table 3). There were 43 women (50%) in intervention clusters who reported this level of adherence and 33 women (38.4%) in control clusters.

Table 3 also shows whether they currently were performing PFME and how often they had done so in the last month: 39 (44.3%) women in intervention clusters reported performing PFME a few times a week or more during the month prior to completing the questionnaire and 35 (40.2%) in control clusters.

Women’s confidence in performing PFME, assessed using PFMESES42, is shown in Appendix 4, Table 14. Womens excercise adherence was further assessed using EARS43 with adherence score a little higher among women in the intervention arm. As described earlier four items from the PFMESES were omitted rendering the full score invalid.

Prevalence of urinary incontinence and faecal incontinence

Based on women’s completion of the ICIQ-UI SF40 in the 10–12 weeks questionnaire, UI prevalence was categorised into a binary ‘yes’/’no’ outcome, and 39 (44.3%) intervention women and 47 (54%) control women reported they did leak urine (see Table 3). The full ICIQ-UI SF data are shown in Appendix 4, Table 14.

Based on the RFIS,41 completed in the 10–12-week questionnaire, 15 women in intervention (18.1%) and 11 in control clusters (13.3%) reported FI. The full RFIS data are shown in Appendix 4, Table 15.

Midwives’ characteristics

Data relating to midwives’ experience in the intervention and control clusters are shown in Table 4. The number of years working as a midwife and as a community midwife were similar in intervention and control groups, and most midwives in both groups were band 6 level.

| Intervention (n = 73) | Control (n = 31) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Current midwifery band | 5 | 3 (4.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| 6 | 62 (91.2%) | 26 (92.9%) | |

| 7 | 3 (4.4%) | 2 (7.1%) | |

| Missing | 5 | 3 | |

| Number of years working as a midwife | n | 68 | 28 |

| Mean (SD) | 11.3 (9.2) | 13.0 (9.5) | |

| Missing | 5 | 3 | |

| Number of years working as a community midwife | n | 68 | 28 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.2 (6.4) | 8.8 (7.7) | |

| Missing | 5 | 3 |

Limitations

Despite several initiatives, including a short questionnaire, translated versions, £10 voucher on questionnaire return and their midwife telling them that a questionnaire would arrive, the proportion of women who returned a questionnaire was low. This proportion, however, was similarly low in both trial arms, and the characteristics of women in both trial arms were similar. The proportion of women who reported UI was higher than is generally found in studies, so it may be that more women who returned a questionnaire did so because they experienced UI.

Although the intention was, and trial protocol stated, that women may be ‘offered other options of completing the questionnaire, including online or mobile-friendly versions’, when online versions were explored with BCTU, their decision was that this was not possible without women’s prior consent because University of Birmingham would then hold the woman’s internet provider address (potentially identifiable data) and hence would not meet General Data Protection Regulations (GDPRs) requirements.

Not all the midwives completed questionnaires, and fewer did so in the control clusters. This may have been because of the lengthy (six-page) participant information leaflet and consent form that were necessary before coming to the questionnaire because of BCTU’s requirements, which intervention midwives were familiar with. In addition, in both groups some midwives had technical difficulties accessing the questionnaire.

Another limitation was that the BCTU omitted to print four of the questions in the questionnaire from the PFMESES,42 which assessed women’s confidence in their practice of performing PFME, so this scale was invalid.

The pilot and feasibility trial had been set up to assess whether a future definitive trial would be possible. However, as described in Summary of alterations to the programme’s original aims/design, a future definitive trial would not be possible due to changes introduced as part of the NHSE Long Term Plan to improve women’s pelvic health. This meant that we were not able to go on to undertake a study to obtain the best evidence of effectiveness.

Inter-relationship with other parts of the programme

Work package 4.2 piloted the intervention developed in earlier WPs (WP1, 3 and 4.1) and ran in parallel with the trial process evaluation (WP4.3).

Work package 4.3: process evaluation

Aims

This WP explored the feasibility and acceptability of APPEAL training and implementation. Aims included identification of facilitators and concerns or challenges to implementation during the trial, and recommendations for refinement to the training in any subsequent practice implementation (see Implications for practice and Appendix 12). Four objectives listed in WP4.2 relevant to this WP are repeated here with additional details to reflect the theory of change presented in the logic model (see Appendix 2, Figure 4) plus a fifth objective. Objectives were to:

-

Provide training for community midwife teams randomised to the intervention arm to encourage incorporation of a PFME care package into their usual antenatal care.

-

Assess whether training, intervention implementation and trial processes were acceptable to midwives by identifying and investigating factors impacting on:

-

fidelity of training delivery to midwives by trainers

-

uptake of training by midwives

-

effectiveness of the training intervention for improving implementation of PFME by midwives in antenatal care

-

fidelity of PFME intervention delivery to women by midwives.

-

-

Assess women’s practice of PFME during and after pregnancy using women’s postnatal questionnaire and interview data to evaluate potential effectiveness of the PFME intervention for improving women’s practice of, adherence to, and confidence with PFME.

-

Assess midwife support for PFME in both trial groups using qualitative interviews with midwives and women, and women’s questionnaire data, to inform feasibility, including possible acceptability of collecting outcome data from women.

-

Investigate possible intervention contamination between trial arms.

Methods

Multiple methods were used with qualitative and quantitative data sources and analytical methods (see Appendix 5). Research questions, methods used to answer questions, and data source and type are described and were mapped to relevant components of the process evaluation framework for designing and reporting process evaluations in cluster trials. 47 This mapping was tabulated (see Appendix 5, Tables 16 and 17) to show how the multiple methods of data collection fitted together to inform the overall analyses reported here. Reporting followed this sequence: first, the processes involving trial clusters (1a delivery to, and 1b response of, midwifery teams); second, the processes involving the target population of midwives (2a delivery to, and 2b response of, midwives); and third, for the target population of women (3a delivery to, and 3b responses of, women) to meet the first four objectives.

Key findings

Delivery to trial clusters (midwifery teams) (objective 1)

Training was delivered to midwives as intended (mean score 86.4%, SD 9.2%) for training session fidelity observed in the three sessions evaluated during the main training period (January–March 2021), although the first training session observation revealed lower fidelity to the training protocol (75.8%) compared to sessions observed later (92.4%). 48 Only minor refinements were needed: addition of a myth-buster slide, and adjusting the ‘red flag’ screening slide. Throughout the intervention period, 3750 resource packs were provided to intervention midwife teams.

Response of trial clusters (midwifery teams) (objectives 1 and 2)

Uptake of training was successful, with all 95 midwives working in intervention teams during the implementation period receiving training. Those on short-term sick leave were trained when they returned to work. Seven intervention team midwives were on long-term sick leave or maternity leave so did not work during the implementation period. In addition, 11 MSWs were trained because in some teams they provided translation for women who did not speak English. Each team recruited an APPEAL midwife champion.

Delivery to midwives and response of midwives (objectives 2 and 4)

Delivery and content of initial training sessions were evaluated48 among the midwives (n = 65/71, 91.5% of those in the initial training phase). Most midwives reported acceptability for most training aspects, although some expressed preference for in-person training (see Appendix 6, Tables 19 and 20). Positive factors affecting acceptability of training delivery were: flexibility of booking in; offering training at different times of day/days of week; not having to travel to training session. Reasons for six midwives not completing the evaluation were internet connectivity or system login problems; none refused to participate.