Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0707-10059. The contractual start date was in October 2008. The final report began editorial review in September 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Elaine McColl is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research subpanel and also a member of the NIHR Journals Editorial Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Thomas et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Urinary incontinence (UI) following stroke is common, with prevalence estimates suggesting around half of stroke survivors are affected in the acute phase. Findings are similar across countries (e.g. UK 48%,1 Denmark 47%,2 Germany 53%3). As many as 43.5% and 38% stroke survivors remain incontinent at 3 months and 1 year respectively. 4 In longer-term stroke survivors (on average 9 years post stroke), prevalence has been reported as 17%. 5

Problems with continence have been shown to be amenable to early intervention, particularly in the 3 months following stroke. 6 Stroke outcome may be better in those stroke survivors who remain continent or regain continence. 7 Although there are problems with attributing better stroke outcome to improvements in continence, it is possible early intervention aimed at promoting recovery from incontinence may improve morale and self-esteem and therefore speed overall stroke recovery. 7,8 It is also possible that the recovery of continence reduces barriers to participation in rehabilitation activity.

Despite the availability of clinical guidelines for the management of UI in women9 and after stroke,10 national audit data11 suggest incontinence is often poorly managed. In the latest Sentinel audit,11 63% of patients had a plan for continence management, an increase of only 5% since 2004. Improvements in continence have not kept pace with those in other aspects of stroke care, for example establishing a safe swallow, where the proportion assessed has increased from 63% to 83% over the same period. Although continence is already recognised as a component of organised stroke care, it is known that nurses find managing continence in the context of stroke challenging,12 with over-reliance on urinary catheterisation as a management strategy especially in the acute phase of illness. 13 There are medical therapies which can be appropriately used to assist continence but these need to be based on appropriate first-line assessment and behavioural management in line with national guidelines. 10

The more severe the stroke, the greater the likelihood of UI;14,15 other factors linked to UI include older age or cognitive impairment. 16 Problems experienced include urinary retention or complete incontinence. The most likely pattern of incontinence is urinary frequency, urgency (a sudden compelling desire to pass urine which is difficult to defer) and urge incontinence (involuntary leakage immediately following, or concurrent with, an urgent sensation of needing to void). 6 Urge incontinence is the most common type after stroke,17 but the cerebral lesion may also lead to practical difficulties with bladder control caused by, for example, motor impairment, depression and aphasia18 (termed functional incontinence).

The symptoms of UI are reported to be more severe and have more of an effect on the lives of stroke survivors, when compared with other groups of people. 19 Incontinence is not just a physical problem, but impacts on what people can do, for example participate in rehabilitation activities, and how they feel. Depression is twice as common in stroke survivors who are incontinent20 and there may be a link between depression associated with urinary symptoms and suicide. 21 Continuing incontinence is associated with poor outcome in both stroke survivor and carer. 2 Furthermore, the negative social consequences of dealing with incontinence for both survivor and carer cannot be ignored, as both may become isolated and marginalised. 22 If post-stroke incontinence is targeted early, not only is there the potential to reduce the poor outcome of stroke associated with incontinence, but also the negative social consequences associated with it post-hospital discharge.

Evidence to guide the management of UI after stroke is poor; our systematic review23 found no rigorously conducted studies evaluating interventions in secondary care. No published trials of behavioural interventions for UI after stroke were found other than a single trial of pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT). 24

Available conservative interventions for UI include bladder training (BT),25 timed voiding (TV),26 prompted voiding (PV),27 habit retraining (HT)28 and PFMT. 29 BT is generally used for urge incontinence and aims to increase the time interval between voids so continence is regained. It involves patient education, scheduled voiding and positive reinforcement, but can also include self-monitoring and urge suppression techniques. PV and TV have mainly been used with people who have cognitive deficits. They are based on a system of scheduled voids, with PV including reminders and reinforcement for self-initiation of toileting. To date, trials of PV have mainly taken place in US nursing homes; however, there was no a priori reason why this approach should not be introduced into the care of stroke patients in secondary care in the UK.

The effectiveness of conservative interventions has been systematically reviewed in adults. The review of TV26 included only two trials of poor methodological quality and concluded there was no empirical evidence for or against the intervention. Similarly, the review of HT28 found insufficient evidence of an effect on continence outcomes to recommend this approach. In the review of BT,25 trials tended to favour BT and there was no evidence of adverse effects. The review of PV27 found evidence of increased self-initiated voiding and decreased incontinent episodes in the short term.

Pelvic floor muscle training may also be effective in assisting the individual to manage urge, stress or mixed incontinence29 and has been shown to be effective as a combined intervention with BT. 30,31

As urge strategies have been shown to be effective in stress incontinence32 and stress strategies in urge incontinence,33 a number of trials have tested combined behavioural interventions (CBIs) for both stress and urge incontinence, on the premise that combining techniques may be more effective than single techniques. Existing reviews have considered mixed types of interventions (e.g. physical + behavioural) for UI. 34–36 There are also two reviews that have included pooled results for CBIs,37,38 but these reviews are specific to women and include studies relating to the prevention of incontinence, i.e. including continent people. There is no current review of CBIs for UI.

Despite a growing evidence base, existing evidence for continence management has not been widely implemented in clinical practice, even by stroke specialist teams working on recognised stroke units. 12 This lack of implementation in stroke clinical practice is in keeping with a recent and growing recognition that the implementation of research in practice is influenced not only by individual clinicians, but also by the organisational context in which they operate. 39–44 Organisational context has been defined as ‘the environment or setting in which the proposed change is to be implemented’. 45 At its simplest level, context may refer to the physical environment where health care takes place. However, Rycroft-Malone et al. 45 concluded from their concept analysis that contexts conducive to research implementation included a range of less tangible process elements: ‘clearly defined boundaries; clarity about decision-making processes; clarity about patterns of power and authority; resources; information and feedback systems; active management of competing “force fields”. . . and systems in place that enable dynamic processes of change and continuous development’. 45

Theories underpinning organisational influence include those of learning organisations (with characteristics encompassing hierarchical structure, information systems, human resource practices, organisational culture and leadership46) and knowledge management (how organisational mechanisms affect knowledge uptake and use47–49). Successful implementation of an intervention to improve the management of post-stroke UI is likely to be mediated not only by individual members of staff and availability of evidence-based guidance, but also by the complexity of the intervention as well as the interplay of patient, social and organisational factors. 49,50 Careful attention needs to be paid to the specific barriers to change in any given setting, identified through ‘diagnostic analysis’ at levels that may include the individual, groups or teams, organisations and the wider health-care system. 51 Strategies then need to be ‘tailored’ to overcome barriers identified. 52

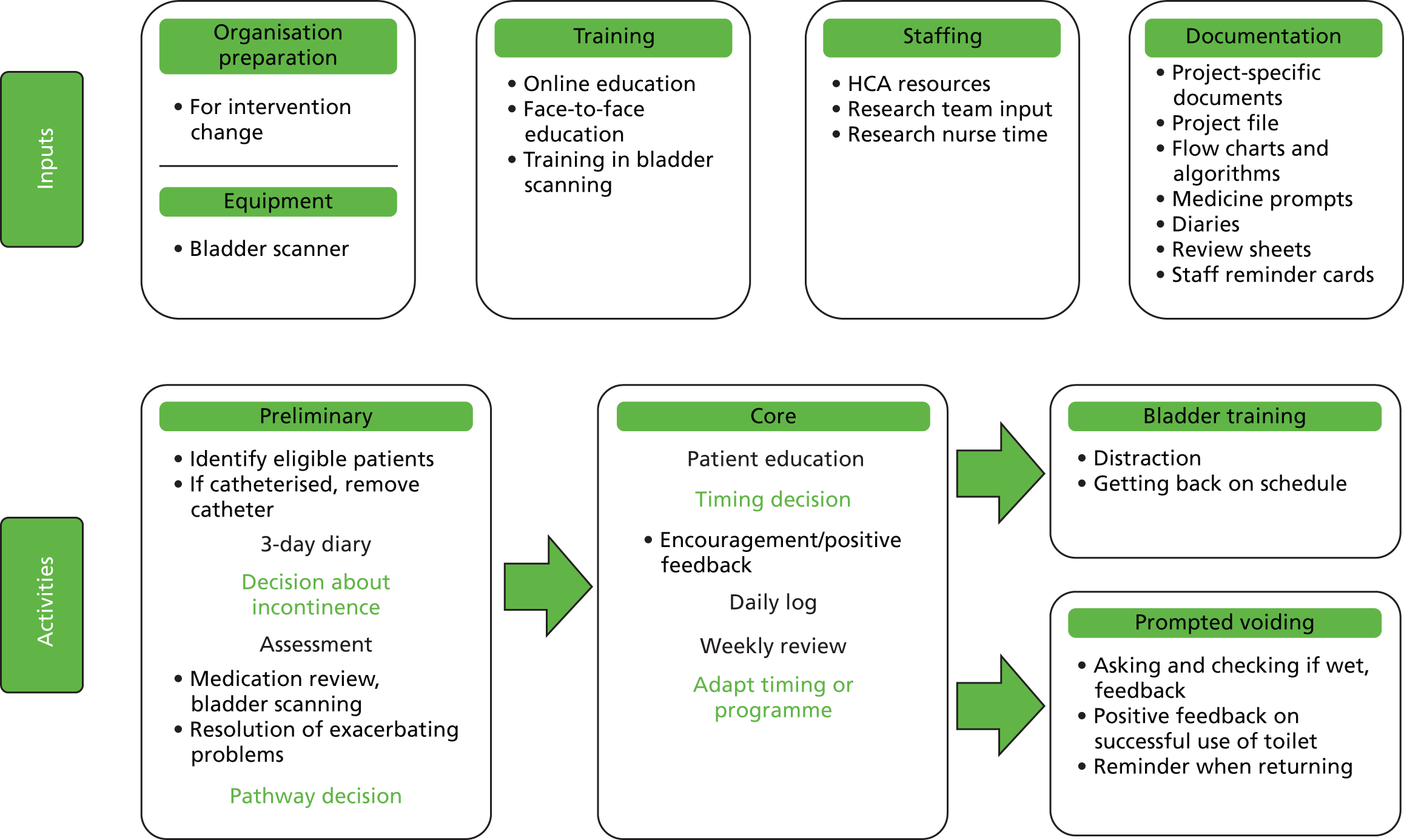

The intervention in our programme focused on conservative strategies shown to have some effect with participants in studies included in Cochrane systematic reviews,25,27,29,53,54 but which had not had their effectiveness demonstrated with stroke patients. These strategies included a combined package of BT and (where possible) PFMT and PV.

We also evaluated whether or not supported implementation, through targeted organisational development aimed at ‘normalising’ the intervention,55–58 showed more preliminary evidence of effectiveness than introduction of the intervention alone, as well as evaluating both in comparison to usual care.

Programme aims

The programme aimed to develop, implement and evaluate the preliminary clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a systematic voiding programme (SVP), with or without supported implementation, for the management of UI after stroke in secondary care. The programme was structured in line with the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for the evaluation of complex interventions59,60 and comprised two phases:

Phase I (MRC development phase):

-

evidence synthesis of quantitative and qualitative literature on combined approaches to manage UI post stroke

-

case study of the introduction of the SVP in one stroke service.

Phase II (MRC feasibility and piloting phase):

-

cluster randomised controlled exploratory trial, incorporating a process and health economic evaluation.

Structure of the monograph

Chapter 2 summarises the aims, methods and findings of the evidence synthesis. Development of the interventions (SVP and supported implementation) is described in Chapter 3. The case study of the introduction of the SVP in one stroke service is reported in Chapter 4. Phase II comprised the exploratory cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) and is reported in Chapters 5 and 7 (methods and findings, respectively); evaluation of process in Chapters 6 and 8 (methods and findings, respectively) and health economic evaluation in Chapter 9. Finally, we report the methods and evaluation of patient, public and carer (PPC) involvement (see Chapter 10). Chapter 11 discusses implications of the programme for the Phase III trial.

Chapter 2 Combined behavioural interventions for urinary incontinence: systematic review of effectiveness, acceptability, feasibility and predictors of treatment outcome

Introduction

Overview

Our systematic review of interventions to promote urinary continence after stroke showed a lack of evidence to inform practice. 23 Current guidelines recommend behavioural strategies targeted to the type of incontinence as a first-line therapy in UI for both men and women, and also suggest that combining behavioural interventions may be useful. 9 This chapter presents the evidence for combined interventions from three linked reviews: a descriptive review of intervention content, an effectiveness review including meta-analysis of randomised and quasi-RCTs specific to voiding function and a narrative review of barriers and enablers to successful behavioural interventions.

Description of the intervention

Behavioural interventions aim to improve bladder control by altering the behaviour of the recipient. This may include changing attitudes, knowledge or skills in order to encourage or enable the implementation of alternative strategies to manage voiding activity (e.g. using distraction, muscle clamping). Behavioural components specifically targeting voiding activity can include PFMT, bladder inhibition training, PV, urge suppression techniques (urge strategies), urethral occlusion techniques (stress strategies), urethral emptying techniques, or lifestyle management such as altering dietary or fluid intake. Additional behavioural components may be directed at enhancing adherence to therapy by increasing sensory or cognitive awareness [e.g. biofeedback (BIO), or by motivational techniques such as coaching]. A meta-study of systematic reviews of behavioural interventions has called for clarity in the theory underpinning the use of behavioural interventions for UI. 53,54

Systematic reviews of the effectiveness of single behavioural interventions already exist for BT;25 TV;26 PV;27 HT28 and PFMT. 29 As urge strategies have been shown to be effective in stress urinary incontinence (SUI)32 and stress strategies in urge urinary incontinence (UUI),33 a number of trials have tested CBIs for both SUI and UUI, on the premise that combining techniques may be more effective than single techniques. Existing reviews have considered mixed types of interventions (e.g. physical + behavioural) for UI. 34–36 There are also two reviews that have included pooled results for CBIs,37,38 but these reviews are specific to women and include studies relating to the prevention of incontinence, i.e. including continent people. There is therefore no current review of CBIs for UI.

Our review found no published trials of behavioural interventions for UI after stroke other than a single trial of PFMT,24 so a systematic review limited to stroke is not an option. In addition, the conditions and contexts for successful implementation of behavioural interventions for UI have not been reviewed. This review therefore aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of CBIs in the general population together with the evidence for factors influencing adherence and outcome, to inform the design of an intervention specific to post-stroke UI.

An effective intervention could be more easily replicated if it were explicitly described. The focus of this review is a complex intervention, combining multiple behavioural intervention components targeting UI with additional cognitive and/or behavioural components to improve uptake or adherence. Maximising the potential for the success of the intervention will depend on clear specification of, and fidelity to, distinctive techniques. A secondary purpose of this review is therefore to construct a standard intervention, by clear description and categorisation of intervention content from existing research.

To maximise the potential for success, staff implementing the intervention will need to tailor it to the characteristics of their client group and setting. The third purpose of the review is to identify moderators of successful outcome of behavioural interventions for UI.

Objectives

To identify best practice in the delivery of an optimal behavioural intervention for UI, the objectives of the review were to:

-

Determine whether or not combined/complex behavioural interventions improve urinary continence in adults, compared with usual care or another/single intervention.

-

A secondary objective was to determine the effect of CBIs on:

-

– subjective or objective improvement in severity or symptoms

-

– quality of life (QoL)

-

– treatment satisfaction

-

– adverse effects; and

-

– socioeconomic outcomes (e.g. cost).

-

-

-

Describe and define the potential components/mechanisms of action of the intervention.

-

Identify the barriers to and enablers of the successful implementation of a behavioural intervention for UI in adults.

Scope of the review

First, a descriptive review delineates intervention content using a standardised model. The effectiveness review includes a meta-analysis of randomised and quasi-RCTs of CBIs that are specific to urinary voiding function. The narrative review considers three separate types of information relating to barriers and enablers of successful behavioural interventions for UI:

-

studies reporting client or staff views of barriers and enablers

-

data relating to rates of uptake and adherence; and

-

studies identifying independent predictors of adherence or outcome.

Structure of the review

The following section outlines the review methods. The results of the review are presented in four sections:

-

Description of the included studies and the content of the behavioural interventions

-

Findings: studies of effectiveness

-

Findings: narrative review of acceptability and feasibility, comprising three subsections:

-

Client views

-

Staff views

-

Studies of feasibility.

-

-

Findings: predictors of adherence and treatment outcome.

The report’s conclusions will draw together the findings from the different sources of information and evaluate the implications for the design of an intervention for post-stroke UI.

Review methods

Search strategy for the identification of studies

A composite search was used to underpin all of the review components, drawing on the search developed by the Cochrane Incontinence Review Group for terms related to UI. Specific terms related to behavioural interventions or terms for relevant research aims/designs (e.g. behaviour therapy, predictor, behavioural research, etc.) were collated from the Cochrane Effective Professional and Organisational Care Review Group search strategy, and from previous Cochrane reviews on behaviour change. The searches above were combined, and then limited for exclusions related to age (child), condition (pregnancy, prostatectomy) and language (non-English). The search was designed for MEDLINE (see Appendix 1) and then adapted for other databases.

The following sources were searched:

-

Databases of published material, including Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (latest issue), MEDLINE (1966 to October 2008), EMBASE (1980 to October 2008), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (1982 to October 2008), PsycINFO (1966 to October 2008), Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (1985 to October 2008).

-

Databases of unpublished trials and theses, including metaRegister of Controlled Trials, CRISP, CentreWatch, National Institutes for Health Research (including back searches on National Research Register/Research Findings Register), Index to Theses and Dissertation Abstracts International.

-

Conference proceedings of the International Continence Society (ICS) (2006–8).

-

Forward and lateral citation searching, via ISI Web of Knowledge for all included studies, and on references for included studies from existing systematic reviews of behavioural interventions for UI (traced via Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, and International Health Technology Assessment).

Searches on smaller databases used the free-text terms ‘incontinence’ or ‘urinary incontinence’ depending on suitability.

After removal of duplicate records and records obviously not relevant to the review by one reviewer (BF), two reviewers (BF, LT) independently screened the remaining records on title and abstract (see Appendix 2 for screening criteria). Full-text papers were obtained for screened records identified by either reviewer. Two reviewers (BF, LT) also independently filtered all full-text papers for inclusion, using the filtration pro-forma (see Appendix 3).

Data extraction templates for different types of study were designed with suitable outcome formats and criteria for critical appraisal (see Appendix 4), together with coding frames and guidance (see Appendix 5). After training and inter-rater reliability checks for coding and quality assessment, critical appraisal and data extraction were undertaken independently by two reviewers (BF, LT).

Inter-rater reliability for such complex data extraction was difficult to maintain at a consistently high level. In particular, despite a detailed coding frame, difficulties were experienced with reliabilities in the classification of the behavioural strategies used in interventions and the predictor variables tested in multivariate analyses, mainly because of inadequate detail in the original studies. Therefore all differences in data extraction and classification between the two reviewers were discussed and agreed throughout the process of data extraction, with one of two additional reviewers (ML/CS) checking outcome data extraction and predictor classification.

We contacted triallists to obtain data collected but not reported, or where data were reported in a form that could not be used. Only further details of study design were obtained, with no additional outcome data gained via this route.

Narrative review search additions

The search undertaken for the full review was also used to identify studies for the narrative review. The identification of studies relating to predictors was not found to be reliable during filtering because it did not include studies testing predictors of adherence for single behavioural interventions, or trials including subgroup analysis. Therefore, all trials included in existing systematic reviews of single behavioural interventions identified by the original search were checked. The review of predictor variables by Goode61 was also used to trace further studies, with forward and lateral citation searching for all included studies.

Criteria for considering studies for inclusion

Criteria for included study types (i.e. trials, observational/qualitative studies) were different for each component of the review, but other aspects could also be slightly different. For example, the effectiveness review was limited to a tight definition of CBIs to ensure homogeneity of included studies, whereas the narrative review of barriers and enablers included any study collating people’s views of any behavioural intervention for UI. The definitions used for the effectiveness review will be given first, followed by any differences in inclusion criteria for other review components.

Review of effectiveness

Participants

Adults aged ≥ 18 years, diagnosed either by symptom classification or urodynamic study as having any type of UI, excluding people with short-term incontinence for physiological reasons (e.g. within 1 year of urological surgery or childbirth). UI was defined in its widest sense to include people with signs, symptoms or urodynamic evaluation of overactive bladder or urine leakage, as defined by the study authors. People with or without cognitive impairment were included, on condition that the person had an active role in the behavioural intervention (e.g. behaviour modification).

Interventions

Interventions with more than one behavioural technique directly targeted at improving the management of different types of incontinence were included (e.g. PFMT + BT, PFMT + urge strategies, BT + stress strategies).

Pelvic floor muscle training was included as a behavioural intervention, because it could be argued that it targets behaviour change to develop muscle training as an established habit. Although the mechanism of action of PFMT on UI is possibly physical, this is unlikely to be effective without sustained practice over a period of time. Encouraging and sustaining behavioural practice is therefore a focus of the intervention in many PFMT trials, as much as ensuring correct physical technique.

Prompted voiding was included because the behavioural component is primarily targeted to influencing the behaviour of the person with UI.

Trials using BIO could be included if BIO was used as an intermittent assessment or aid to teaching the correct use of pelvic muscles.

Trials using BIO as a continuous component of the intervention were excluded, as this could be categorised as a physiological treatment rather than a behavioural intervention. Trials using physical mechanisms to augment or enhance muscle training, such as the use of vaginal cones or electrical stimulation, were excluded for the same reason.

Habit retraining or TV were excluded as behavioural techniques because the behavioural component targets the behaviour of staff or carers as much as the person with UI.

Interventions where an additional behavioural mechanism was targeted towards improving adherence to a single behavioural intervention for UI (e.g. reminders for PFMT) were excluded, as their primary outcome for comparison was adherence, with secondary impact on incontinence. Interventions composed of mixed behavioural interventions (e.g. BT + exercise, PFMT + lifestyle adaptations) were also excluded, because they include components not designed to target different types of incontinence.

The specific comparisons to be made in the effectiveness review included:

-

multicomponent behavioural intervention compared with no treatment, attention control or usual care

-

multicomponent behavioural intervention compared with another intervention.

If enough comparisons were available, the second group would be split into:

-

CBI compared with single behavioural intervention

-

CBI compared with another treatment (e.g. drug therapy).

Randomised or quasi-RCTs where one arm includes a CBI, compared with no treatment control, or another treatment/single behavioural intervention.

The primary outcome for the meta-analysis of the impact of CBIs on UI was the number of people who reported continuing UI. This was defined by subjective measures (e.g. the number of incontinent episodes as measured in a urinary diary, mean per week) or objective measures (e.g. pad test of quantified leakage).

Secondary outcomes included:

-

patient/carer perceptions of improvement

-

objective measures of severity (e.g. grams of urine lost per 24 hours on pad test)

-

patient/carer perceptions of severity of incontinence

-

urinary symptoms

-

QoL or symptom distress

-

satisfaction with treatment

-

adverse effects; and

-

costs for the client or service.

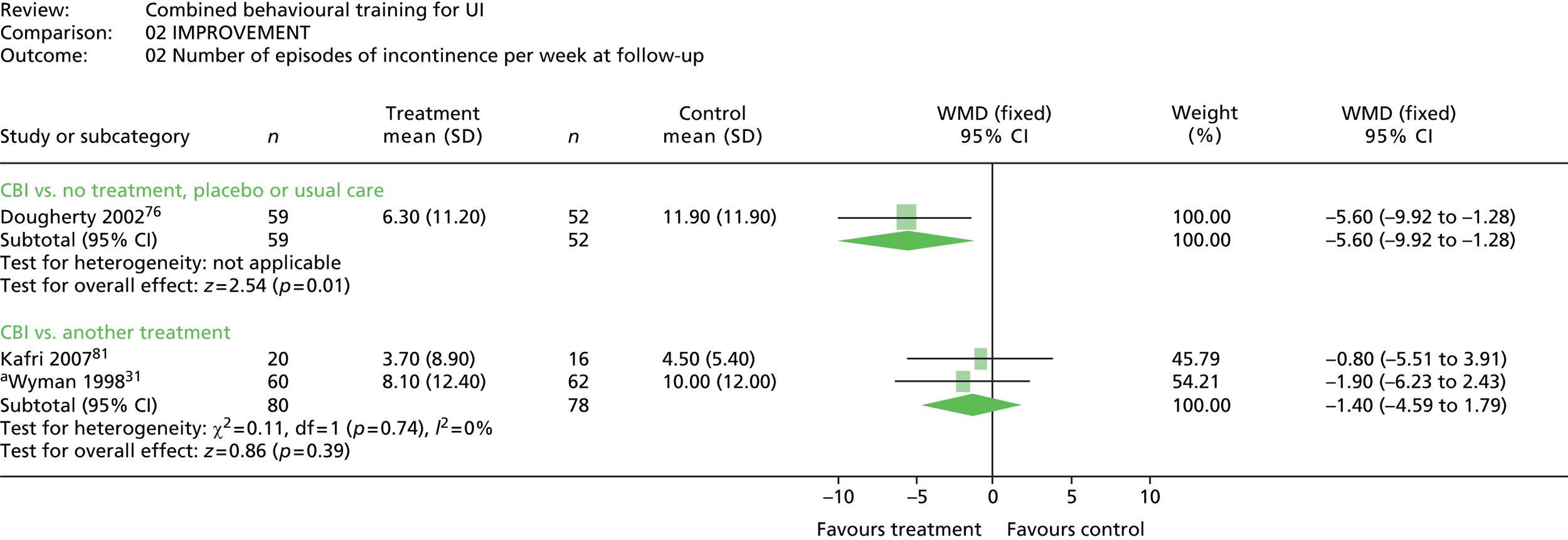

Short-term (up to 12 months post treatment) follow-up measures were collated for primary and secondary outcomes. If data from multiple follow-up time points were available from a single study, the time point nearest to 6 months post treatment was used because this was judged to be a reasonable length of time to assess whether or not behavioural change has been embedded.

Review of acceptability and feasibility

Acceptability

Study designs included were qualitative or quantitative, where data were collected from service users or from staff about their perceptions or experiences of behavioural interventions, including information on factors influencing:

-

choice or uptake of behavioural interventions for UI

-

adherence to/maintenance of a behavioural programme

-

withdrawal/dropout from a behavioural programme.

Studies exploring client experience of self-management strategies for UI in general were excluded if behavioural interventions (i.e. BT, PFMT, PV) were not referred to specifically.

Feasibility and implementation data

We had planned to review information about implementation of behavioural interventions from studies reporting the process of development or implementation of a behavioural intervention for UI. These studies were screened and filtered, but owing to the high number of studies found (n = 33), detailed information on implementation was not extracted and processed. However, data on rates of uptake, treatment adherence and withdrawal were extracted from any study implementing a behavioural intervention for UI.

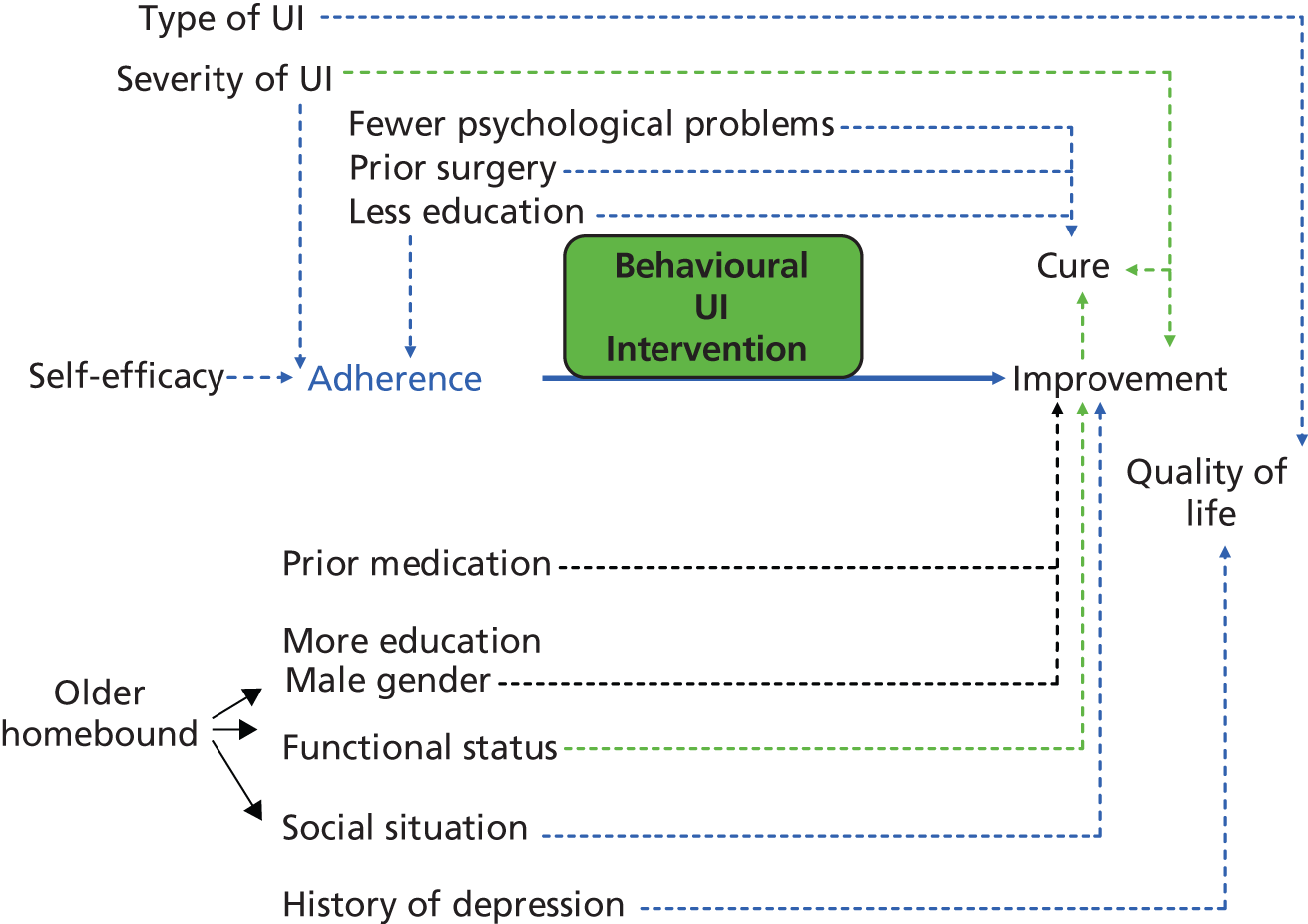

Review of predictors of treatment adherence or outcome

Studies of predictors of adherence or treatment outcome of CBIs, or studies of predictors of adherence to single behavioural interventions were included. Predictors of adherence for single interventions were included because they were thought to be generalisable to behavioural adherence to combined interventions. Predictors of treatment outcome of single interventions were not included because they were not judged to be reliably predictive of treatment outcome for combined interventions, due to the potential for differences in physiological mechanisms of action.

Study designs included were:

-

prospective longitudinal cohort studies or clinical trials

-

RCTs that include subgroup analysis of factor(s) influencing adherence/outcome

-

retrospective cohort or cross-sectional studies.

To be included, studies had to include a description of the method of data analysis, and provide data on the relationship between the predictor and outcome based on individual study participants (other than the baseline value of that variable). For full data extraction of results for predictor variables, studies had to identify independent predictors using multivariate analysis. Studies using univariate analysis were only partially data extracted, for the identification and listing of potential predictor variables.

The dependent variables included were any of the following:

-

intention to adhere/short- or long-term adherence

-

treatment failure/non-response

-

cure

-

improvement

-

psychological status/QoL.

Any time points for outcome measurement were considered.

Methods of the review

Review of effectiveness

Data relevant to the pre-stated outcome measures, characteristics of the study, interventions and participants were extracted. The elements of the voiding intervention were categorised based on a previous meta-study. 53,54 The categorisation of the client behaviour change intervention was based on a taxonomy of behaviour change techniques. 62

Assessment of methodological quality was undertaken using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tables to include assessment of adequate sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of outcome assessors; incomplete data addressed; freedom from selective reporting; and freedom from other bias (see Appendix 4).

Where appropriate, data were quantitatively combined using meta-analysis to determine the typical effect of the intervention. Intention-to-treat analysis was used, where participants are analysed in the group to which they are randomised. Trial data were processed as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook63 using the Cochrane Collaboration statistical package RevMan 4.2.8 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark).

For individual clinical indicators, a fixed-effects model was used to calculate pooled estimates of treatment effects with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using:

-

relative risk (RR) for binary data

-

weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous data using similar measurement

-

standardised mean difference (SMD) for continuous data from different measurement sources

-

standardised effect (SE) when generic inverse variance (GIV) was used to pool binary and continuous outcomes.

For trials with missing data, primary analysis was based on observed data, without imputation. Assessment of heterogeneity of intervention effects was made using the I2 statistic. If substantial heterogeneity of treatment effects was evident (I2 ≥ 50%), a random-effects model was used.

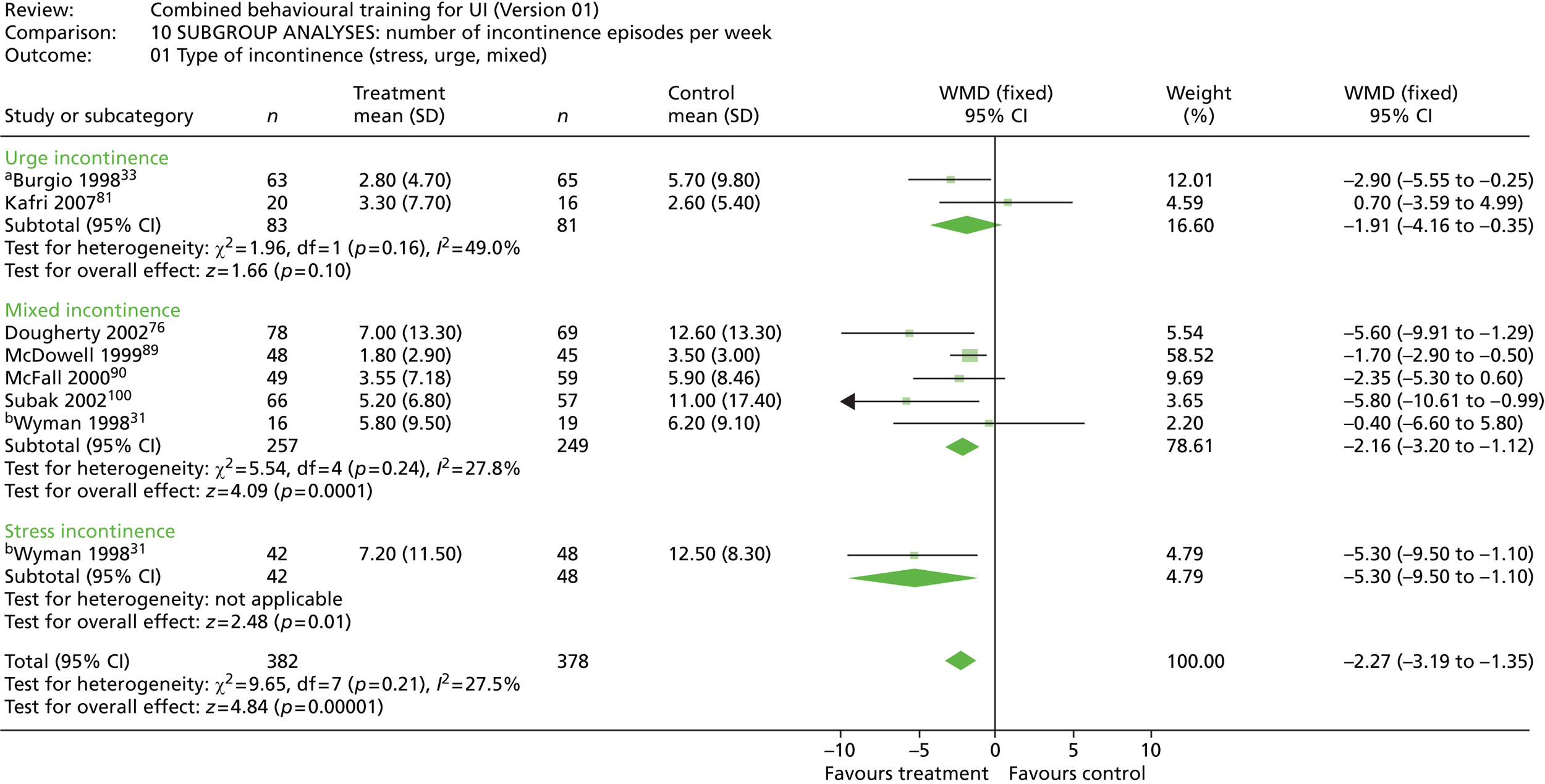

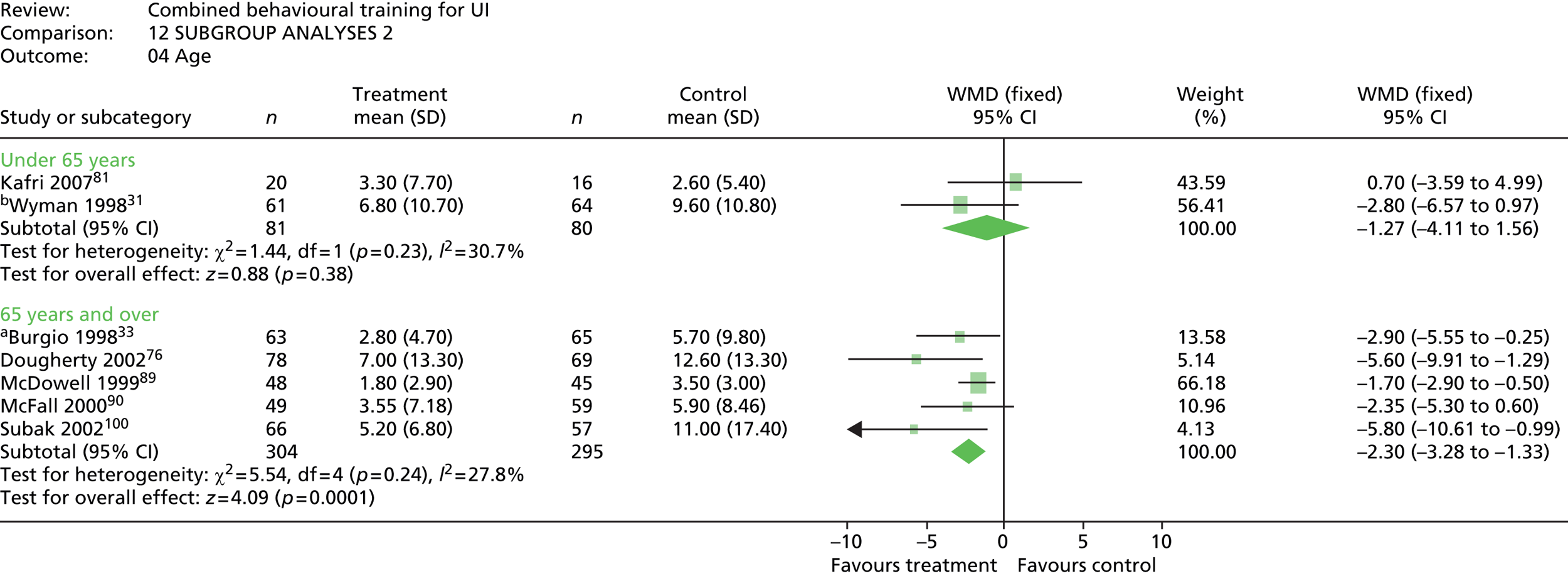

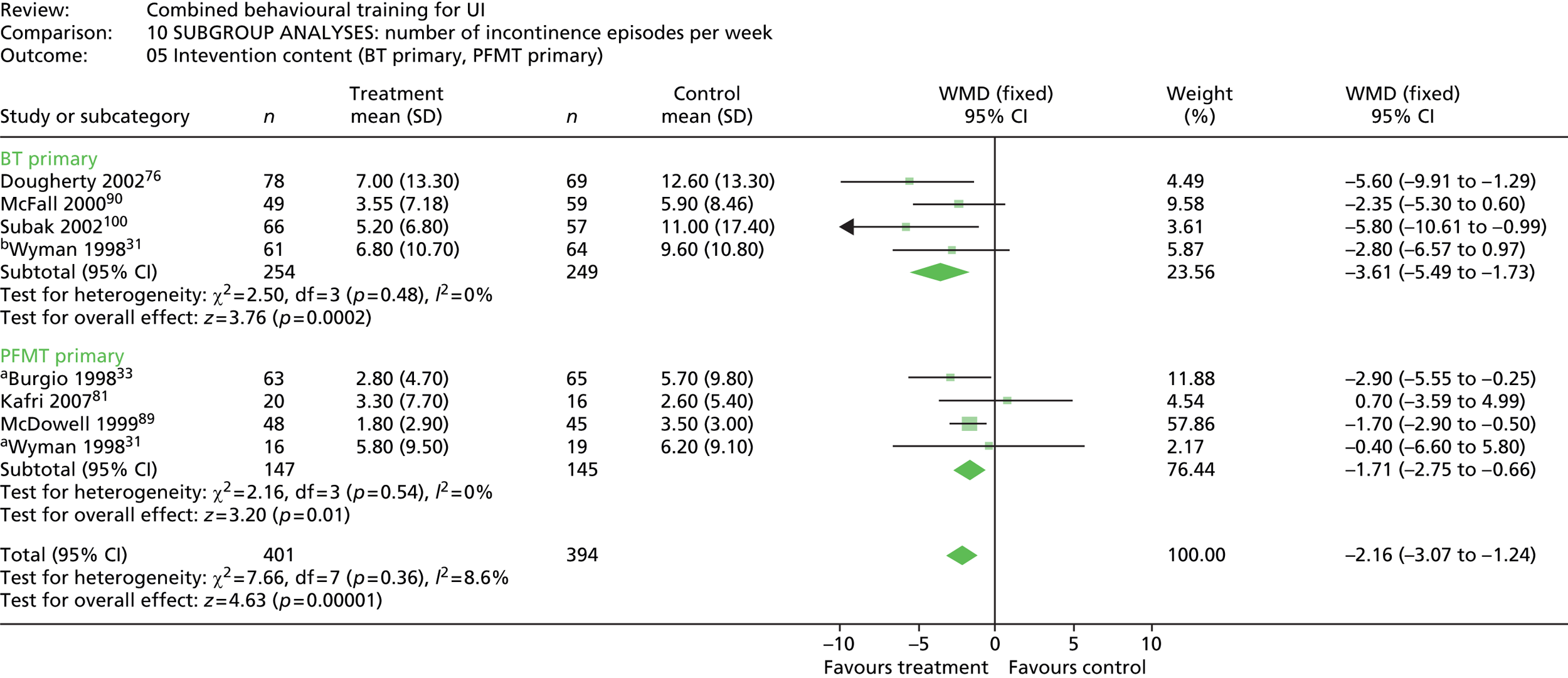

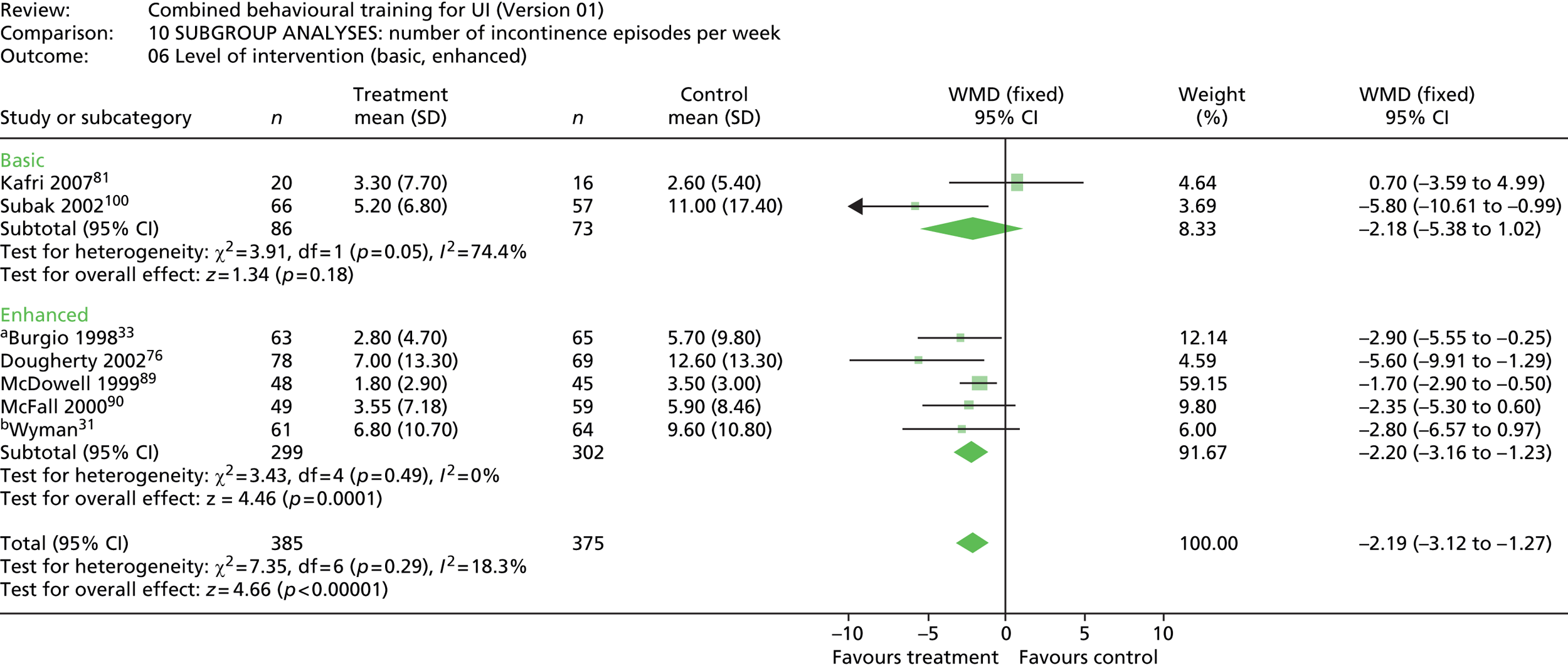

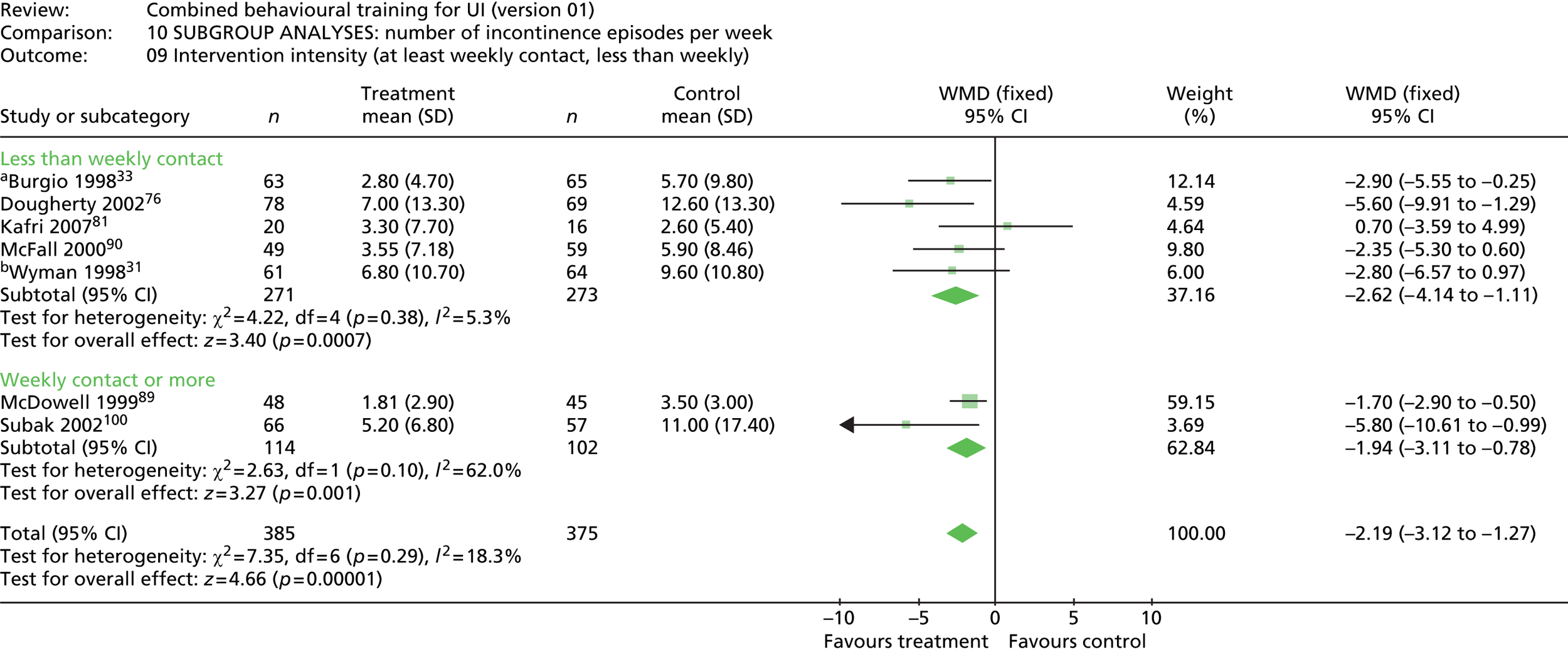

A priori subgroup analyses were planned as follows.

Client group factors:

-

type of incontinence – SUI only, UUI only, mixed urinary incontinence (MUI)

-

sex – female only, male only, mixed

-

age – mean age < 65 years, ≥ 65 years

-

cognitive status – people with cognitive incapacity excluded/not excluded.

Intervention factors:

-

intervention content – BT primary, PFMT primary, PV primary

-

intervention level – basic (i.e. the delivery of multiple strategies aimed at increasing the effectiveness of urinary function activities); enhanced (i.e. the addition of strategies aimed at tailoring an intervention to the specific needs of the individual or enhancing adherence or commitment to practice/activities, e.g. goal-setting, reminder systems, coaching)

-

intervention duration – i.e. length of time in weeks in contact with intervention delivery (≥ 8 weeks, > 8 weeks)

-

intervention intensity – i.e. number of contacts with the person providing the intervention for content delivery or monitoring/feedback (at least weekly, less than weekly).

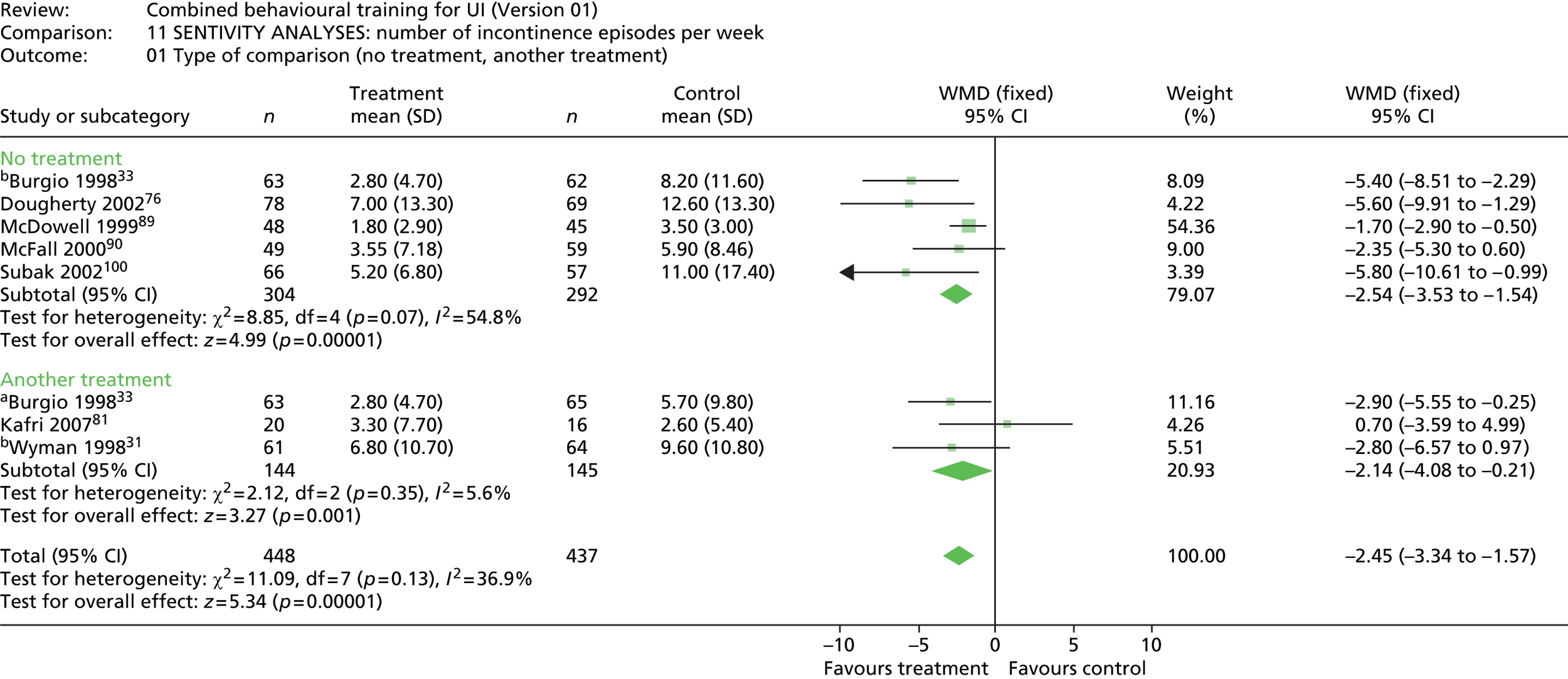

A priori sensitivity analyses were planned for type of comparison group (no treatment vs. another treatment), study quality to include allocation concealment (adequate, unclear/not adequate) and loss to follow-up (≤ 20%, > 20%).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed using a chi-squared test for heterogeneity (via the decomposition of the Q-statistic).

Review of acceptability and feasibility

Acceptability

Data were extracted as follows:

-

client group recruitment and inclusion/exclusion criteria (age, ethnicity, sex, UI type, cognitive status, functional ability)

-

research design classification (qualitative study, survey, process evaluation, action research)

-

intervention classification (combined, PFMT, BT, PV, generic)

-

data collection and analysis methods (framework/model)

-

findings [researcher theme(s), categories and codes].

Findings were identified from secondary data, i.e. the study authors’ aggregate themes, categories or codes relating to potential barriers and enablers to behavioural interventions, and not at the level of the original data (e.g. quotes from respondents). Findings were categorised based on Davidson et al. 64 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on interventions to support behaviour change65 as follows:

-

intervention – combined, PFMT, BT, PV, generic behavioural

-

influencing factor source – client, intervention or context

-

influencing factor direction – enabler or barrier

-

outcome – choice/uptake, participation/adherence, longer-term sustainability, withdrawal/dropout.

Descriptive data extraction was undertaken by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Data extraction and categorisation of findings, and quality appraisal were undertaken by two reviewers independently. Quality assessment was based on quality criteria for qualitative studies or observational designs,66 including criteria related to participant selection and representativeness, data collection and analysis, methods of representation and testing the robustness of findings (see Appendix 4).

Feasibility

Rates of non-participation (i.e. people who were eligible to participate and who did not opt to do so), treatment adherence and withdrawal or dropout (short and long term) were extracted, together with the reasons if given. Data were tabulated, averaged and reported in the context of intervention type, client group and setting.

Review of predictors of treatment adherence or outcome

Data were extracted for (independent) predictor variables relating to characteristics of the client group as follows:

-

sociodemographic variables, i.e. age, ethnicity, sex, education/income

-

physiological variables, i.e. gynaecologic/obstetric status and history, weight/body mass index (BMI), urodynamic variables, prior treatment, type, duration of UI, severity of UI/symptoms

-

health/functional variables, i.e. general health status/comorbidities, self-care ability, functional ability, cognitive status, mental health

-

psychological variables, i.e. health/treatment perceptions; perceived QoL, self-efficacy/esteem, attributions of control, prior adherence, knowledge/skill, motivation/attitude, goal orientation

-

social variables, i.e. social influences and demands.

A coding frame for the definition and classification of predictor variables was used (see Appendix 4). Using a standardised protocol, data extraction for studies using multivariate analysis included:

-

research design classification (prospective cohort/clinical trial, RCT, retrospective cohort/cross-sectional study)

-

client group classification (age range, sex, UI type, cognitive status)

-

intervention classification (combined, PFMT, BT, PV)

-

selection and measurement of independent variables (hypothesis/model for selection, definition, who/how measured, timing, validity and reliability of measurement)

-

measurement of outcome variables (who/how measured, timing, validity and reliability of measurement, definition of outcome categorisation)

-

statistical analysis method

-

variables entered into univariate analysis

-

variables entered into multivariate analysis

-

statistically significant results from univariate analysis not subsequently confirmed as an independent predictor

-

statistically significant results for independent predictor variables for:

-

intention to adhere/adherence behaviour

-

treatment failure

-

cure

-

improvement

-

psychological status

-

QoL.

-

Descriptive data extraction was undertaken by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Data extraction of predictor and outcome variables and quality appraisal was undertaken by two reviewers independently. Quality assessment was based on quality criteria for observational studies67 and for regression studies,68 and included criteria related to participant selection and representativeness, predictor and outcome variable selection, definition and measurement, adequacy of sample size, follow-up and analysis (see Appendix 4).

Stakeholder involvement in the review process

Review Management Group

The Review Management Group was composed of the named authors on the review. They met quarterly during the review process and their input included:

-

discussion of studies referred by reviewers where inclusion was unclear, with subsequent refinement of the criteria for inclusion and exclusion

-

feasibility testing of the classification structures for the review and review of the data extraction proforma

-

checking back to the original study data from the results to comment on robustness of interpretation

-

reading and commenting on all review outputs.

Service User Group

The PPC involvement group were involved at three stages for consultation on the review:

-

to advise on the parameters and scope of the review, and the included interventions, comparisons and outcomes

-

to consider the draft results of the review and comment on their perceptions and priorities for the components of the intervention and mediating factors

-

once the review was completed, to assist in the translation of the findings into practical products for implementation.

Trial Management and Steering Groups

The review findings were presented to the Identifying Continence OptioNs after Stroke (ICONS) Trial Management and Steering Groups, who then made suggestions for:

-

the content of the behavioural intervention for UI to be used with people after stroke

-

optimal conditions of implementation on which to base the tailoring of the intervention to client groups and settings

-

hypotheses about potential mediators and moderators for consideration in the design of the pilot trial.

Their suggestions were then used to adapt the intervention and data collection protocols for use in the case study.

Description of included studies

Results of the search

The main database search identified 8289 records. Duplicate records (n = 1807) and records which were clearly irrelevant on title (n = 4224) were removed, leaving 2258 records for screening. Another 31 records were added from additional searches of trial registers, databases of unpublished studies and conference proceedings, plus 68 records from secondary references. Of the 2357 records screened for inclusion, 538 full-text papers were retrieved. Four records could not be traced.

The 538 papers were filtered independently by two reviewers who discussed any disagreement and were coded as relevant to one or more of the review components. Exclusions were as follows:

-

not English language (n = 1)

-

not research (n = 80)

-

not behavioural (n = 46)

-

not UI (n = 25)

-

excluded client group (e.g. pregnancy, post prostatectomy) (n = 1)

-

not CBI (n = 65)

-

single UI intervention plus adherence intervention (n = 9)

-

compares methods of delivery of behavioural intervention (n = 54)

-

confounded intervention (n = 25)

-

not appropriate research design (n = 75); and

-

review (n = 47); these were combed for secondary references.

Excluded records totalled 428.

Of the remaining 110 papers, 33 related to the implementation of behavioural interventions, either from reports of intervention development, process evaluations or feasibility studies. Owing to the volume of material, these studies were not reviewed in detail, other than to extract data from the feasibility studies on rates of uptake, adherence and withdrawal.

Table 1 details the remaining papers, identifying published, unpublished and ongoing studies exclusive to each component of the review. The number of studies that the published papers refer to are given in brackets.

| Status of paper | Meta-analysis | Narrative review | Predictors | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | Acceptability | Feasibility | |||

| Published | 20 (10) | 12 (11) | 2 (2) | 11 (10) | 45 (33) |

| Unpublished | 0 | 3 (1) | 0 | 4 (3) | 7 (4) |

| Ongoing | 3 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (3) |

| Excluded | 14 (8) | 6 (6) | 2 (2) | 0 | 22 (16) |

| Total papers | 37 (21) | 21 (18) | 4 (4) | 15 (13) | 77 (56) |

In total, 77 papers detailing 56 studies were included at filtration. The table also identifies the number of studies excluded after filtering. The rationale for exclusion is given in a table of excluded studies at Appendix 7. No exclusions are shown for the review of predictors, as filtering was reapplied specifically for predictor studies after the main filtering was completed.

Thirty-three published studies contributed data to different review components (Table 2). Details of the individual studies are given in a table of included studies at Appendix 6.

| Study | Effectiveness | Acceptability | Feasibility | Predictors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alewijnse et al. 2001,69 200370 | ✓ | |||

| Aslan et al. 200871 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Baigis-Smith et al. 198972 | ✓ | |||

| Bear et al. 199773 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Burgio et al. 199833 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Burgio et al. 200374 | ✓ | |||

| Dingwall and McLafferty 200675 | ✓ | |||

| Dougherty et al. 200276 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mather and Bakas 200277 | ✓ | |||

| Gerard 199778 | ✓ | |||

| Hay-Smith et al. 200779 | ✓ | |||

| Johnson et al. 200180 | ✓ | |||

| Kafri et al. 2007,81 200882 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Kincade et al. 199983 | ✓ | |||

| Kincade et al. 200184 | ✓ | |||

| Lee et al. 200585 | ✓ | |||

| Lekan-Rutledge et al. 199886 | ✓ | |||

| Macaulay et al. 198787 | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| McDowell et al. 199288 | ✓ | |||

| McDowell et al. 199989 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| McFall et al. 200090,91 | ✓ | |||

| MacInnes 200892 | ✓ | |||

| Milne and Moore 200693 | ✓ | |||

| O’Dell et al. 200894 | ✓ | |||

| Oldenberg and Millard 198695 | ✓ | |||

| Perrin et al. 200596 | ✓ | |||

| Remsburg et al. 199997 | ✓ | |||

| Resnick et al. 200698 | ✓ | |||

| Rose et al. 199099 | ✓ | |||

| Subak et al. 2002100 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Svengalis et al. 1995101 | ✓ | |||

| Tadic et al. 2007102 | ✓ | |||

| Wyman et al. 199831 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Total per review component | 10 | 11 | 11 | 13 |

Description of studies of effectiveness

Included studies

Of the 21 studies identified for the effectiveness review, eight were excluded (reasons are given in the table of excluded studies in Appendix 7). Three studies are ongoing. 82,103,104 There were no unpublished studies. The remaining 10 studies are detailed in Table 3.

| Study | Study design | Comparison(s) | Client group/setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aslan et al. 200871 (Turkey) | Quasi-RCT (n = 64) | Attention control | F, aged ≥ 65 years, rest home |

| Bear et al. 199773 (USA) | Quasi-RCT (n = 24) | No treatment control | F, aged ≥ 55 years, home |

| Burgio et al. 199833 (USA) | RCT (n = 197) |

|

F, aged ≥ 55 years, UUI, community |

| Dougherty et al. 200276 (USA) | RCT (n = 178) | No treatment control | F, aged ≥ 55 years, rural area, home |

| Kafri et al. 2007,81 200882 (Israel) | Quasi-RCT (n = 44) | Medication | F, UUI, community |

| Macaulay et al. 198787 (UK) | RCT (n = 50) |

|

F, UUI |

| McDowell et al. 199989 (USA) | RCT (n = 105) | Attention control | M/F, aged ≥ 60 years, home bound |

| McFall et al. 200090,91 (USA) | RCT (n = 145) | Waitlist control | F, aged ≥ 65 years, community |

| Subak et al. 2002100 (USA) | RCT (n = 152) | Waitlist control | F, aged ≥ 55 years, community |

| Wyman et al. 199831 (USA) | RCT (n = 204) |

|

F, community |

Study design

The 10 studies included 1163 participants in 13 intervention–comparison pairs. Table 3 details the trial arms compared against CBIs. Of the seven control comparisons, three were attention controls,33,71,89 two were waitlist controls90,91,100 and two were no treatment controls. 73,76 The remaining six treatment comparisons included three medications [propantheline bromide (Pro-Banthine®, Roxane Laboratories Inc.) or oxybutinin (Ditropan, several manufacturers) (× 2)],33,81,82,87 two single behavioural interventions (BT or PFMT)31 and one psychotherapy comparison. 87

Seven of the trials were undertaken in the USA31,33,73,76,89–91,100 one in the UK,87 one in Turkey71 and one in Israel. 81,82 Three were quasi-RCTs. 71,73,81 All of the quasi-RCTs and the oldest trial87 had fewer than 100 participants. The remaining trials all had more than 100 participants. One of the quasi-RCTs73 was an external pilot for a larger RCT. 89 One study did not provide outcome data suitable for pooling. 87

All of the trials except one89 were limited to female participants, and the sample for McDowell et al. 89 was also 90% female. Only three trials included people aged > 55 years, and two of these had samples with a mean age of ≥ 55 years. 31,81

Three trials were undertaken with participants with UUI. 33,81,87 The remaining trials were undertaken with people with all types of incontinence. One trial provides outcome data for intervention subgroups based on urodynamic diagnosis. 31

The definition of incontinence differs slightly: four trials specifying that UI episodes had to occur at least twice a week,33,73,76,89 one trial specifying at least once a week31 and one trial specifying more than two episodes a month. 71 Of the remaining four trials, two confirmed UUI by urodynamic testing,81,87 McFall et al. 90 used self-report of UI for 3 months or more as an inclusion criteria and Subak et al. 100 did not define UI but referred to standard diagnostic criteria sourced from US guidelines.

Two related studies73,89 were undertaken with people who were housebound and a further study was undertaken using home visits to women from rural areas of the USA. 76 One study was undertaken with people in rest homes. 71 Five studies involved community samples with interventions delivered in clinic visits. 31,33,81,90,100 The setting for one study was unclear. 87

Three trials did not exclude people with cognitive impairment. Two of these required that a person with cognitive impairment had a caregiver present who was willing to undertake PV. 73,76 One other trial did not exclude people with cognitive impairment,89 but outcome data are only reported for people without cognitive impairment.

Description of urinary incontinence interventions

Table 4 summarises details of the interventions used in the 10 trials, including the components of the intervention, method of delivery, and the duration and intensity of contact with professionals. Some of these details were provided by contact with study authors.

| Study | UI intervention components | Method of delivery | Duration/intensity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | BT | PFMT | Urge strategies | Stress strategies | Other | I or G | H or C | N or O | Number of weeks | Number of contacts | Intensity of contact (weekly = 1) | |

| Aslan et al. 200871 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | I | H | N | 8 | 8 | 1 | |||

| Bear et al. 199773 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | I | H | N | 6–24 | 2–40 | – | ||

| Burgio et al. 199833 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | I | C | N | 8 | 4 | 0.5 | |||

| Dougherty et al. 200276 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | I | H | N | 6–24 | NS | – | |||

| Kafri et al. 200781 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ?G | C | O | 12 | 5 | 0.4 | |||

| Macaulay et al. 198787 | ✓ | ✓ | NS | C | N | 12 | 7 | 0.6 | ||||

| McDowell et al. 199989 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | I | H | N | 8 | 8 | 1 | ||

| McFall et al. 200090 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | G | C | N/O | 9 | 5 | 0.6 | ||

| Subak et al. 2002100 | ✓ | ✓ | G | C | N | 6 | 6 | 1 | ||||

| Wyman et al. 199831 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | I | C | N | 12 | 9 | 0.8 | ||

All of the trials included PFMT, albeit to various degrees. All of the trials except one33 included BT, with one trial73 including BT or PV, depending on the cognitive status of the individual. Six trials included the teaching of either urge strategies (e.g. distraction) or stress strategies (e.g. muscle clamping), with three trials teaching both31,33,89 and three trials teaching one or the other. 71,81,90 However, description and labelling of the techniques used tended to be inconsistent. Three trials included other strategies, such as advice about alterations to diet and/or fluid intake. 73,76,90

Interventions in two trials were delivered to groups. 90,100 The delivery format was unclear in two trials81,87 and the remainder were delivered to individuals. Eight out of 10 interventions were delivered by nurses, with another intervention predominantly delivered by nurses but including other professions. 90 One intervention was delivered by physical therapists. 81

Most of the interventions ran over 6–12 weeks, with interventions in two related trials running over a minimum of 6 weeks and a maximum of 24 weeks. 73,76

Three trials had weekly contacts with a health-care professional for the duration of the intervention,71,89,100 with four trials having at least bi-weekly contact. 31,33,87,90 The number of contacts was stated as being in the range of 2 to 40 contacts in an intervention lasting a minimum of 6 weeks and a maximum of 24 weeks in one pilot trial. 73 This is unstated, but likely to be similar in the related trial. 76 Most of the trials stated a requirement for practice of the techniques between contacts.

Intensity of intervention was defined as the ratio of the number of contacts with a person delivering the intervention to the length of the intervention period. An intensity of 1 is weekly contact. Intensity could not be derived for the two trials that did not specify the exact number of contacts. 73,76 Three trials had at least weekly contact71,89,100 and four trials had at least bi-weekly contact. 31,33,87,90 Only one trial had less than bi-weekly contact. 81

Features of urinary incontinence intervention components

Table 5 details the features of the BT and PFMT interventions in the included trials. A dash in the table means that the feature was not stated in the paper. The level of description of the interventions was variable and lack of description cannot be interpreted as absence of the feature in practice.

| Study | BT | PFMT | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient education | Scheduled voiding | Positive reinforcement | Self-monitoring | Urge suppression | Confirm correct technique | Individual instruction | Adherence check | Monitoring progress | Longer training | |

| Aslan et al. 200871 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ |

| Bear et al. 199773 | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Burgio et al. 199833 | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | |||||

| Dougherty et al. 200276 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kafri et al. 200781 | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ |

| Macaulay et al. 198787 | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ✓ |

| McDowell et al. 199989 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| McFall et al. 200090 | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – |

| Subak et al. 2002100 | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Wyman et al. 199831 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Bladder training

Core features of BT were identified from the Cochrane systematic review of BT,25 to include patient education, scheduled voiding, positive reinforcement, self-monitoring and urge suppression.

-

Patient education about basic urinary physiology and function was stated as included in six out of nine trials. 31,71,76,89,90,100 Eight out of nine trials described a system of scheduled voiding, where voiding intervals were specified. 31,71,73,76,81,87,89,100

-

Six trials31,71,73,76,89,100 described the use of a system of gradually increasing void intervals tailored to the baseline and progress of the individual, as described by Wyman and Fantl. 105 Two trials described gradual increases in voiding interval81,87 without describing tailoring to the individual. The remaining trial just described the intervention as bladder retraining without further detail. 90

-

Four out of nine trials specifically described positive reinforcement for progress. 31,71,76,89 One other trial73 is likely to have included positive reinforcement because they were using the same protocol, but it is not specifically mentioned in the trial report.

-

All of the trials except one87 described using bladder diaries for self-monitoring of voiding patterns. Two trials73,76 used 3-day diaries and the remainder used daily diaries.

-

Four out of nine trials specifically detail instruction in urge suppression techniques such as distraction. 31,76,89,90

Pelvic floor muscle training

Core features of PFMT were identified from the review by Bo,106 including details of the exercises (e.g. type of exercise, frequency, intensity and duration). In terms of PFMT, this relates to whether contractions are maximal or submaximal, the duration of exercise and relaxation periods, the speed and duration of muscle contraction, and the amount of exercise in the form of repetitions and duration. Additional data were extracted about whether or not exercise was generalised to different body positions and activities/situations, whether or not practice was progressive in terms of intensity or amount, and the method of teaching. Table 6 gives details of PFMT teaching regimes included in the trials.

| Study | Exercise detail | Positions | Activities | Increased pressures | PFMT teaching method | Number of teaching sessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aslan et al. 200871 | NS | ✓ | – | – | Digital | 1 |

| Bear et al. 199773 | NS | – | – | – | BIO | NS |

| Burgio et al. 199833 | 15, three times a day, aim for a 10-second contraction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | BIO | 2–4 |

| Dougherty et al. 200276 | 45 per day, three times per week | – | – | – | BIO | 1 |

| Kafri et al. 200781 | 12, two times a day, aim for a 10-second submaximal contraction | ✓ | – | ✓ | Digital | 1 |

| Macaulay et al. 198787 | NS | – | – | – | NS | NS |

| McDowell et al. 199989 | 10–15, three times a day, aim for a 10-second contraction | ✓ | ✓ | – | BIO | ≤ 4 |

| McFall et al. 200090 | NS | – | – | – | NS | NS |

| Subak et al. 2002100 | 100 per day, 2–3 second tighten/relax five times, as quickly as possible | – | – | – | Verbal | – |

| Wyman et al. 199831 | 50 per day, 10 fast, 40 sustained | – | – | – | BIO | ≤ 4 |

Four trials did not give details of the exercises. 71,73,87,90 Three of the remaining trials aimed for 30–50 repetitions daily. 31,33,89 Two trials had lower intensities of practice76,81 and one trial had a higher intensity of practice. 100 Most of the trials specified aiming for 10-second maximum sustained contractions, except Subak et al. 100 which used sets of rapid 2–3-second contractions. Wyman et al. 31 used a mix of fast and sustained contractions.

-

Three trials did not describe confirming correct initial pelvic floor muscle contraction technique, either by digital palpation or BIO. 87,90,100 One other trial did use digital palpation, but 30% of older women living in a nursing home refused. 71

-

Three trials did not describe individual instruction for PFMT. 87,90,100 Of these, two used group teaching. 90,100

-

Two out of nine trials report the level of adherence of the individual to the prescribed exercise regime. 31,89

-

Five trials describe repeating sessions (or the opportunity to repeat session dependent on progress) of BIO during the intervention. 31,33,73,76,89

-

Of the 10 trials using PFMT, five had a longer intervention period (i.e. ≥ 12 weeks) where sustained impact on muscle performance is more likely to be achieved. 31,73,76,81,87

Features of behavioural intervention components

Table 7 details and categorises the behavioural component of the interventions, as per the taxonomy of behavioural interventions described by Abrahams and Michie. 62 The categorisation was based only on the published accounts given of the interventions. The level of description of intervention components was variable. Given the restrictions on length of publication, absence of description of a feature may not constitute its absence in practice.

| Study | Behavioural intervention components | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information provision | Self-monitoring | Adherence reminders | Tailoring/goal-setting | External monitoring | External motivation | Counseling | |

| Aslan et al. 200871 | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| Bear et al. 199773 | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| Burgio et al. 199833 | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| Dougherty et al. 200276 | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| Kafri et al. 200781 | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – |

| Macaulay et al. 198787 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| McDowell et al. 199989 | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| McFall et al. 200090 | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Subak et al. 2002100 | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – | – |

| Wyman et al. 199831 | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Information provision

Information provision could include providing general information on health, health behaviour, or the consequences of behaviour; or providing explicit instruction on how to perform a behaviour. All except one of the trials87 described some level of information provision, although the content varied markedly.

Nine of the 10 trials described skills instruction on behavioural techniques. Two trials describe only skills instruction. 33,81 Additional educational content described by other trials included:

-

Structure and function of the urinary tract, normal voiding mechanisms and the causes and symptoms of incontinence. 71,100

-

Two trials31,76 that describe patient education as per the protocol for BT by Fantl et al. 32 This includes discussion of normal bladder control; explanation of the pathophysiology underlying different types of incontinence; and stressing the importance of continence as a learned behaviour and brain control over lower urinary tract function. Three other trials used this protocol71,73,89 but do not refer to the content of their information provision. Two of these trials identify giving lifestyle advice on dietary or fluid intake behaviour, or environmental adaptations. 71,73,89 McFall et al. 90 also taught definitions and types of UI, identified resources which provided educational material on UI and included the aim ‘to learn that the condition is treatable’. No trial reported including information about the consequences of behavioural techniques (e.g. pros and cons), although McFall et al. 90 did include discussion of coping strategies that help control incontinence or its negative consequences.

Self-monitoring and adherence reminders

Self-monitoring involves keeping a record of specified behaviours. Nine trials included a behavioural technique for self-monitoring of urinary function by the inclusion of a bladder diary – only the early trial by Macaulay et al. 87 did not include a regular bladder diary during treatment. Two trials also included self-monitoring of treatment adherence behaviour. 31,89

Adherence reminders include the use of passive or interactive devices or systems to self-prompt practice (e.g. sheets to fill in, computerised counters, display items such as fridge magnets). No trial specifically mentioned a reminder system, or a method of recording that served a dual purpose of data collection and behavioural prompting, although it is likely that the simple presence of the bladder diary did have a reminder function. One trial did use audio cassettes for PFMT practice, which could have a reminder function. 31

Tailoring/goal-setting

A number of techniques are relevant to tailoring and goal-setting, including intention formation, barrier identification, relapse prevention, setting graded tasks, detailed goal-setting, review of behavioural goals and agreeing a behavioural contract.

By their nature, both BT and PFMT involve setting goals and graded tasks based on operant conditioning principles, but these are also based on physiological reasons related to bladder capacity or muscle fibre action. The setting of goals and the incremental nature of the targets are not necessarily behavioural techniques to assist learning and do not tend to meet the definitions given in Abraham and Michie62 as described below.

Intention formation

Intention formation involves encouraging the person to set a general goal or resolution to decide to change. It does not involve planning exactly what will be done, when and how, which would be classified as goal-setting. Two trials included reference to people being asked about their own goals for continence. 73,76

Barrier identification

Barrier identification involves thinking about potential barriers and planning ways to overcome them. One trial included reference to strategies to remove environmental barriers (e.g. installing night lights, assistive mobility devices such as grab bars, etc.). 89

Relapse prevention

Relapse prevention involves identifying situations that increase the likelihood or failing to perform a new health behaviour and planning to manage the situation. One trial referred to reviewing the voiding diary for ‘problem-solving’. 90

Setting graded tasks

Setting graded tasks involves planning a sequence of actions or task components that increase in difficulty over time until the target behaviour is reached. No trials explicitly met this criterion for what appeared to be behavioural reasons, but separating physiological from behavioural rationales was almost impossible to do. Details of intervention components (other than straightforward BT or PFMT schedules where void intervals/exercise intensity increases over time) that could be seen as graded in difficulty for behavioural reasons are described here.

Seven trials sequenced the introduction of components of the intervention,31,33,73,76,81,89,90 but only three of these appear to base sequencing on increasing task difficulty. One trial referred to teaching BT after urge strategies had been taught, so that participants could use the skills learned to suppress urge sensations during BT. 89 Two trials included practising PFMT against increasing bladder pressure, once PFMT had been learned. 33,81 Four trials referred to generalising skills, by practising exercises in different positions, and during different activities. 33,71,81,89 This could be interpreted as practising learned skills in situations of increasing challenge.

Goal-setting and behavioural contracts

This requires detailed planning of what the person will do, where, when and how. Both BT and PFMT include detailed instruction, so all trials could be said to include an element of this. However, using behavioural principles for the learning and application of the techniques by detailed planning of goals for the individual subject is not a strong feature of any of the trials. Two trials included formal review of individual goals at each stage of the programme,73,76 but because this goal-setting did not include detailed planning, it was categorised as intention formation, and reported earlier.

Monitoring, motivation and reinforcement

Adherence interventions included in this section include feedback on performance, provision of general encouragement or contingent reward, teaching to use prompts and cues, prompting practice and use of follow-up prompts.

Six trials described regular external review and feedback on performance by a health professional, via the bladder diary. Three trials included weekly review,71,89,100 and two trials reported bi-weekly review. 33,89 In one other trial,90 the review was weekly, but it is not clear if the bladder diary review was done on an individual basis, as the teaching was done in fairly large groups. Two trials stated a review of progress was done at the end of each phase of the intervention73,76 and one trial did not refer to feedback. 87

Four trials describe providing general encouragement to adhere to the programme. 31,33,71,90 The other six trials do not explicitly describe providing encouragement or reinforcement, but, of these, four were following the BT protocol by Fantl et al. ,32 which includes the requirement for positive reinforcement. 73,76,89,100 No trials included the provision of contingent rewards.

Two trials referred to embedding behavioural practices into daily routines,89,90 but none of the trials included prompts to practice other than regular contact with professionals. Two trials used written recording of adherence to the programme. 31,89

These include prompting self-talk, identification as a role model, planning social support, using social comparison, motivational interviewing and techniques for stress and time management. Wyman et al. 31 used affirmations and self-statements. McFall et al. 90 referred to the opportunities for modelling of behaviour and the social support provided by delivering the intervention in a group setting.

Allocation of interventions

Not all participants received the same interventions in all trials. In two trials73,76 participants received intervention components dependent on need. Participants were allocated to a self-monitoring phase if they had problematic fluid or caffeine intake, excessive daytime void intervals, nocturia or constipation. Participants were then allocated to BT, or to PV if functionally or mentally dependent on a caregiver. Finally, participants progressed to PFMT if insufficient progress had been made in earlier stages. How many participants progressed through each phase of the intervention is not reported for Bear et al. ,73 but Dougherty et al. 76 report that out of 94 people in the intervention group, the number progressing through each phase was as follows: self-monitoring (n = 41), BT (n = 89), PFMT (n = 45).

In the trial by McDowell et al. ,89 urge strategies were taught to participants who reported involuntary urine loss following a strong urge to void (85/105), stress strategies were taught to those who reported leaking urine with sudden increases in abdominal pressure (44/105), and only participants who reported frequent voiding got BT. However, in a related paper Engberg et al. 107 reported that many participants had high urinary frequency.

Outcomes

The 10 trials used a range of outcome measures, measurement statistics and time intervals for follow-up. Outcomes measured are detailed in Table 8 and summarised below.

| Study | Cure | Improvement: diary | Improvement: subjective | Severity: pad test | Symptoms: frequency | Symptoms: urgency | Symptoms: nocturia | QoL | Satisfaction | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aslan et al. 200871 | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – |

| Bear et al. 199773 | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Burgio et al. 199833 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| Dougherty et al. 200276 | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – | – |

| Kafri et al. 200781 | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Macaulay et al. 198787 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| McDowell et al. 199989 | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| McFall et al. 200090 | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| Subak et al. 2002100 | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – |

| Wyman et al. 199831 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the number of people continent after treatment (i.e. cured). Three trials included a measure of cure,31,33,90 all defined as the number of people reporting 100% improvement in the number of incontinent episodes as measured in a urinary diary (mean per week). One additional trial87 reported the percentage of patients with UI in graphical form, but did not provide numerical results other than p-values for difference between groups.

No trials reported cure using objective measures (e.g. number of people reporting 0% leakage using a pad test of quantified leakage).

Secondary outcomes

The most common method used to express the degree of improvement in UI was reporting the number of incontinent episodes per day or week. This measure of improvement was included in all trials except Macaulay et al. 87 Three trials also included the participants’ perception of improvement; two using a scale of much better, better, no change, or worse;31,33 and one trial reporting whether the intervention had helped a great deal, moderately, slightly, or not at all. 100

Of the four trials that used a pad test, two did not report data. 31,73 One trial reported grams of urine lost in 24 hours. 76 The same trial also reported a subjective assessment of the severity of urine loss, rated from 1 to 7 from ‘the best bladder control you can imagine’ (1), to ‘the worst bladder control you can imagine’ (7). Another trial71 reported binary data on the number of people with improved (vs. no change or worse) results on a pad test.

Six trials reported urinary symptoms. Five trials reported frequency: four trials reporting frequency of voiding per day or week;76,81,90,100 and one trial reporting number of people reporting urinary frequency as better, unchanged or worse. 71 The same trial reported number of people reporting urinary urgency as better, unchanged or worse; and the number of people reporting nocturia as better, unchanged or worse. Four other trials measured frequency of nocturnal micturition. 33,81,90,100

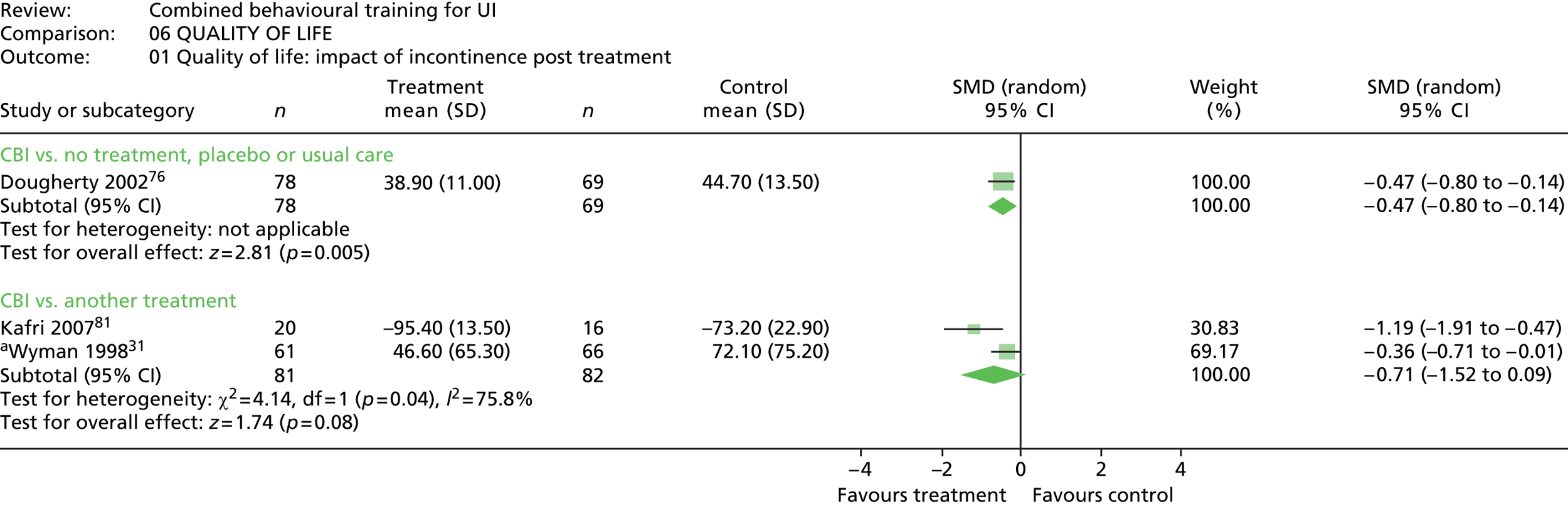

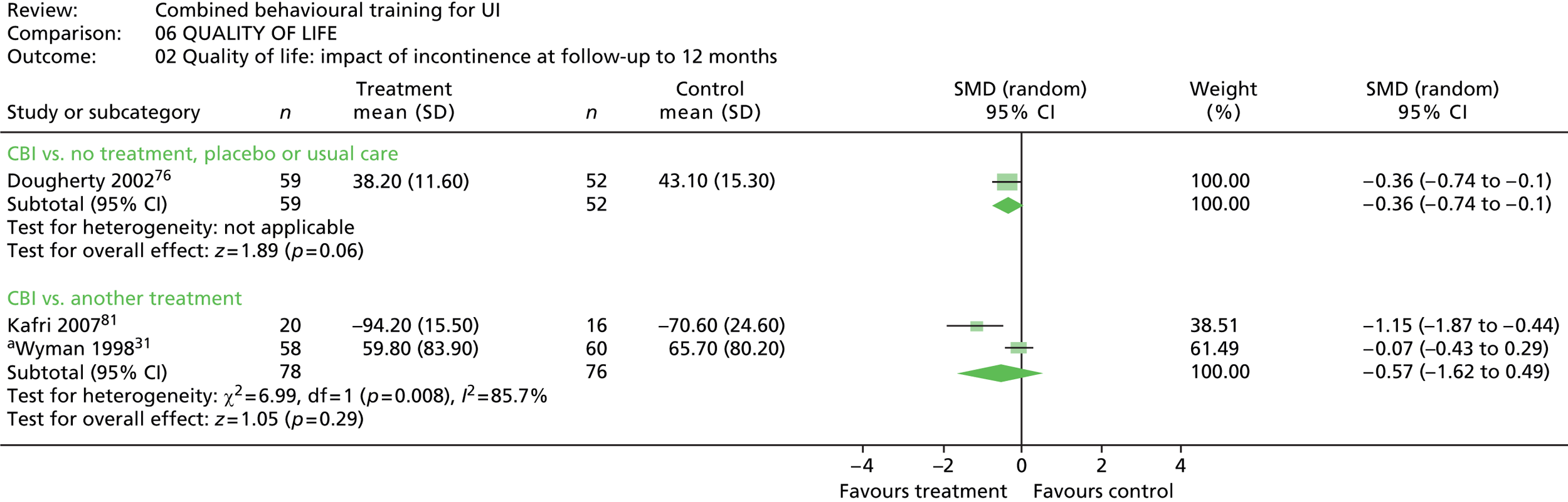

Five trials included a measure of QoL, but data could not be extracted from one trial because the data were not provided separately for intervention and control groups. 90 Of the remaining four trials, two used the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ), which measures symptom distress,31,76 one trial used the Incontinence Quality of Life (Questionnaire) (I-QOL),81 and one trial used the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI). 31

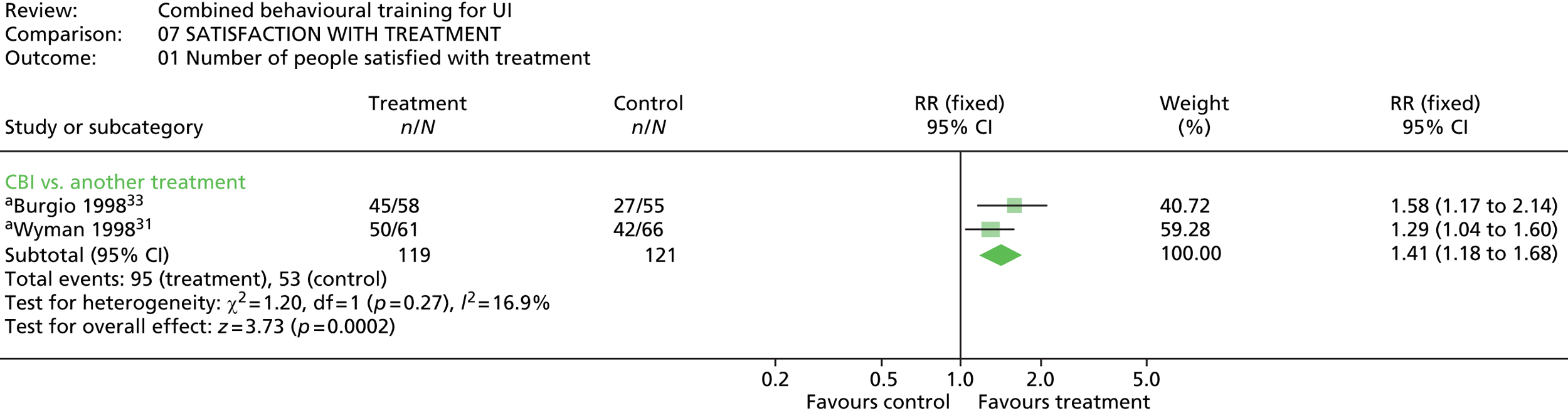

Two trials reported on satisfaction with treatment,31,33 using a four-point scale from not at all satisfied, to very satisfied. One other trial100 asked for participant’s reports on how the behavioural therapy had helped them in dealing with their urine leakage problem (rated not at all, slightly, moderately, or a great deal).

One trial reported total number of adverse events (e.g. discomfort, fatigue, side effects of drugs). 81

Outcome measurement timing

Post-treatment measurement timing was variable (Table 9), with post-treatment measurement at 6 weeks in one trial,100 8–10 weeks in four trials,33,71,89,90 3 months in three trials31,81,87 and 6 months in two trials. 73,76

| Study | < 3 months | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | 15 months | 18 months | 21 months | 24 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aslan et al. 200871 | PT (8 weeks) | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bear et al. 199773 | – | – | PT | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Burgio et al. 199833 | PT (10 weeks) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Dougherty et al. 200276 | – | – | PT | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Kafri et al. 200781 | – | PT | ✓ | – | – | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Macaulay et al. 198787 | – | PT | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| McDowell et al. 199989 | PT (8 weeks) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | – |

| McFall et al. 200090 | PT (9 weeks) | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – | – | – |

| Subak et al. 2002100 | PT (6 weeks) | – | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Wyman et al. 199831 | – | PT | ✓ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Follow-up timing also varied, with the most common being 6 months, which was included in seven trials. 31,71,81,87,89,90,100 Long-term follow-up of ≥ 12 months was included in four trials. 76,81,89,90

Quality of included effectiveness studies

The quality of the included studies was assessed against the Cochrane criteria of adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment; completeness of data reporting and blinding for each main class of outcome measure; selective outcome reporting; and any other sources of bias.

Of the 10 studies, three trials had adequate description of the random sequence generation procedure;33,89,100 five trials stated that sequence allocation was random but did not describe the procedure;31,73,76,87,90 and two trials used non-random sequence generation processes, i.e. alternate allocation. 71,81

Allocation was judged to be adequately concealed in one trial,100 unclear in seven trials31,33,73,76,87,89,90 and not adequately concealed in two trials. 71,81

In the three trials that used objective measures of urine loss, blinding of analysts to the results was judged to be unclear in two trials71,73 and adequate in one trial. 76 Blinding of analysts to the results of the bladder diary was judged adequate in two trials,33,100 unclear in five trials71,73,76,87,89 and not adequate in three trials. 31,81,90 In the seven trials that used subjective outcome measurements, blinding of outcome assessors to the results was deemed unclear in two trials76,87 and not adequate in five trials. 31,33,81,90,100

Objective outcome data were judged to be complete in two trials71,73 and not complete in one trial. 76 Data from bladder diaries were judged to be complete in four trials,33,73,89,90 unclear in two trials31,71 and not complete in three trials. 76,81,100 Data from subjective measurements were judged to be unclear in three trials31,33,87 and not complete in four trials. 76,81,90,100

Outcome reporting was judged to be free of the suggestion of selective outcome reporting in five trials,31,33,76,81,87 unclear in one trial89 and selective in four trials. 71,73,90,100

Generalisability of the included effectiveness studies

All except one of the studies were limited to females, with the remaining study being 10% male. 89 The majority of studies were also limited to older women.

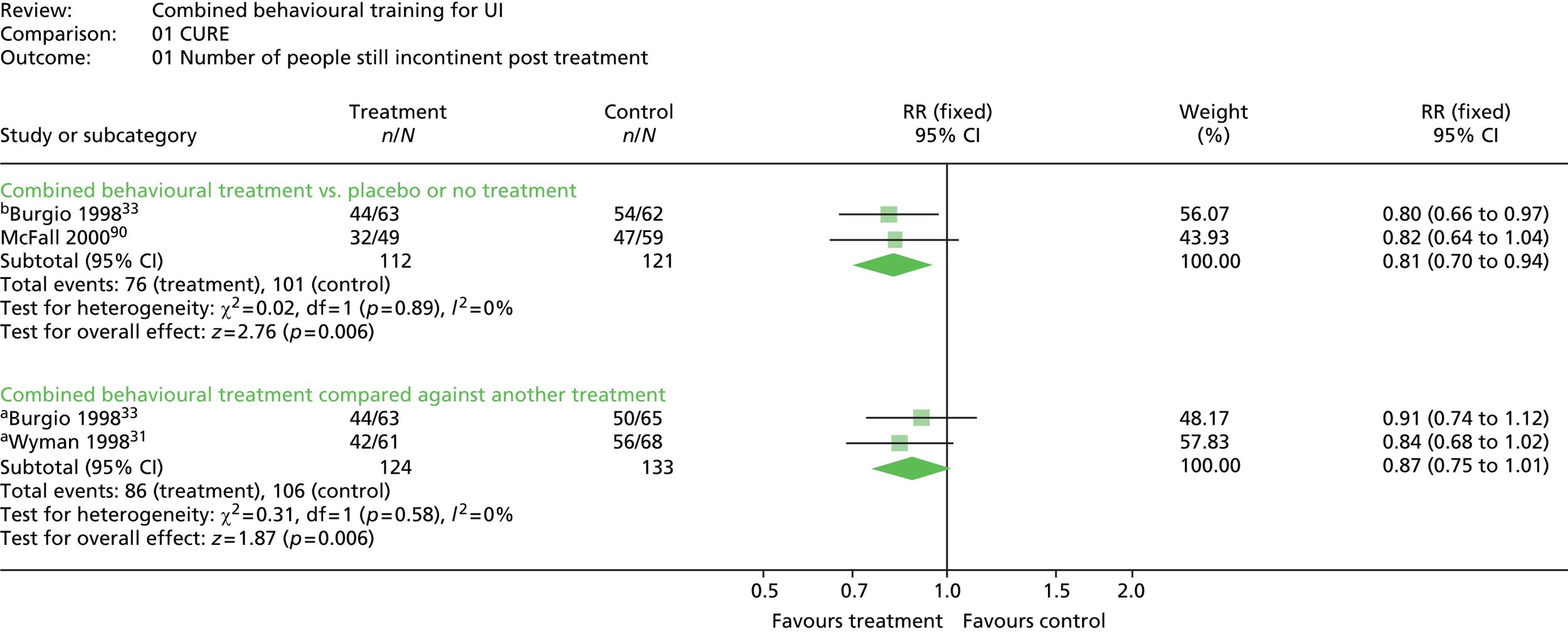

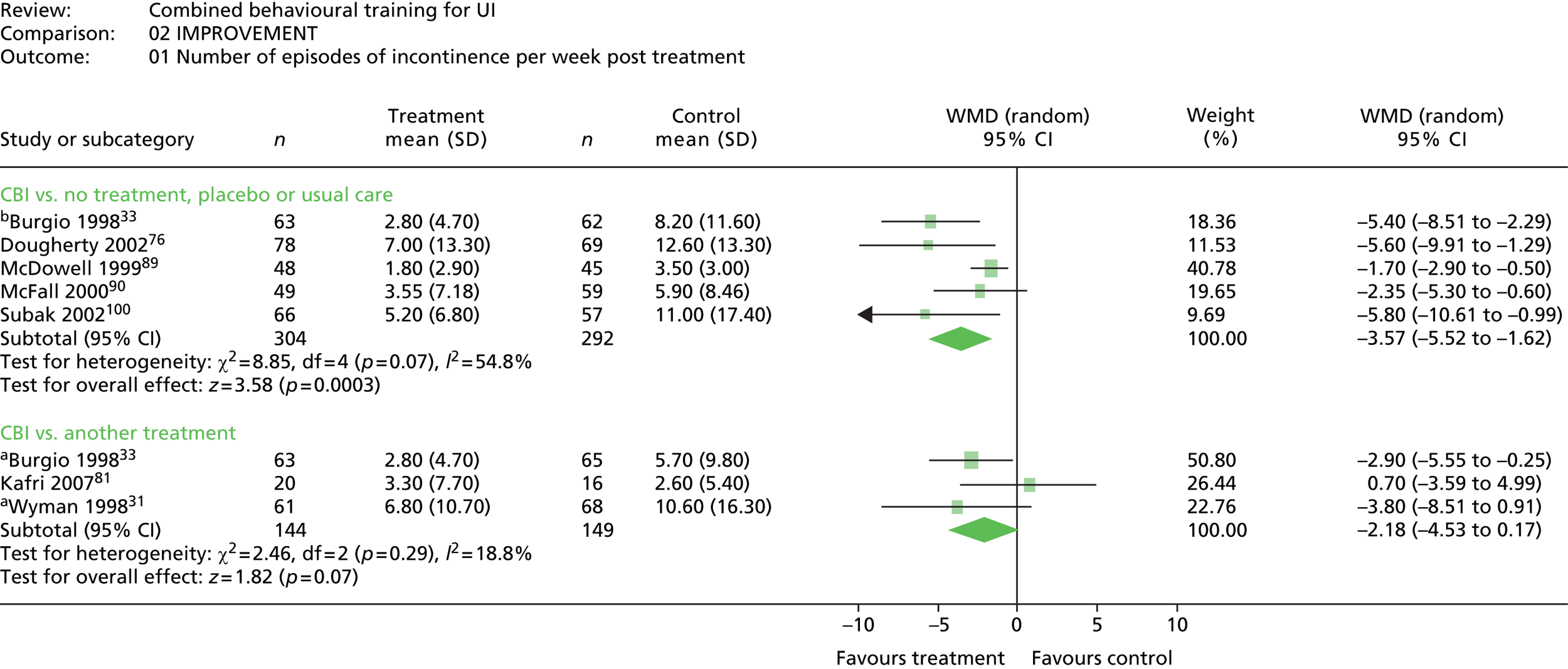

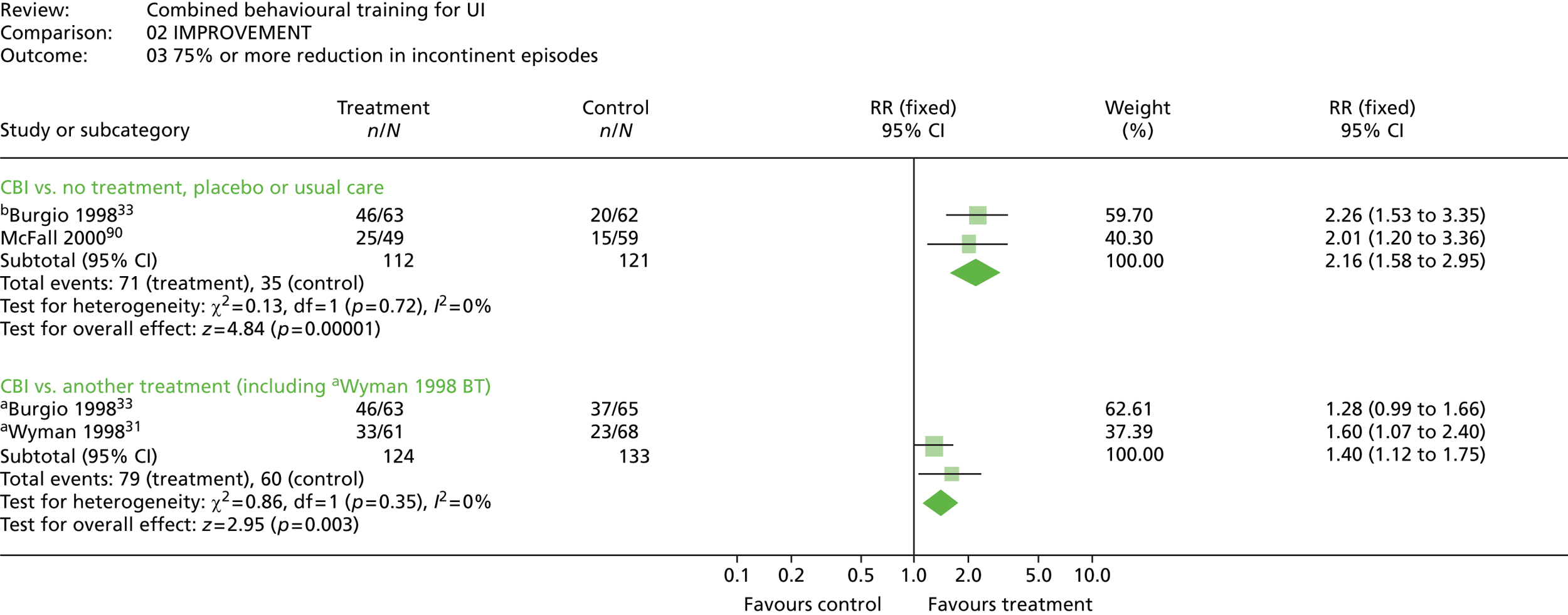

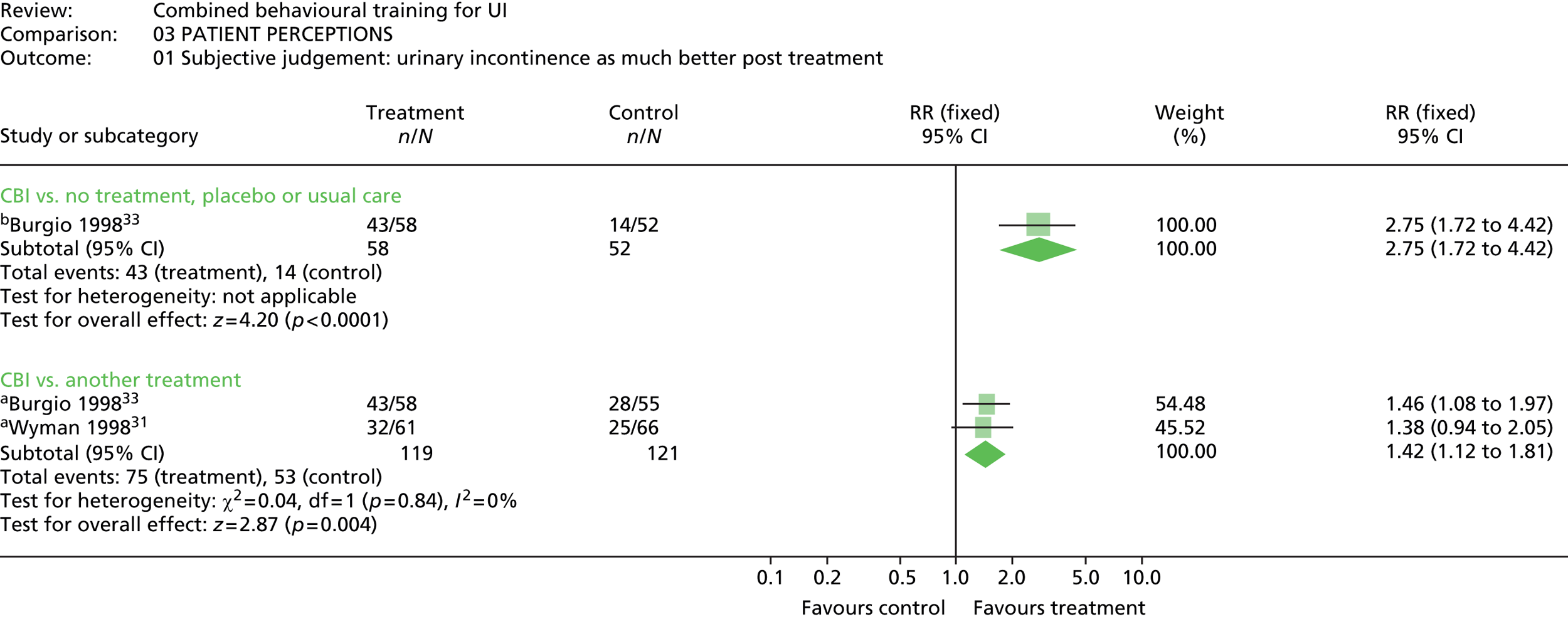

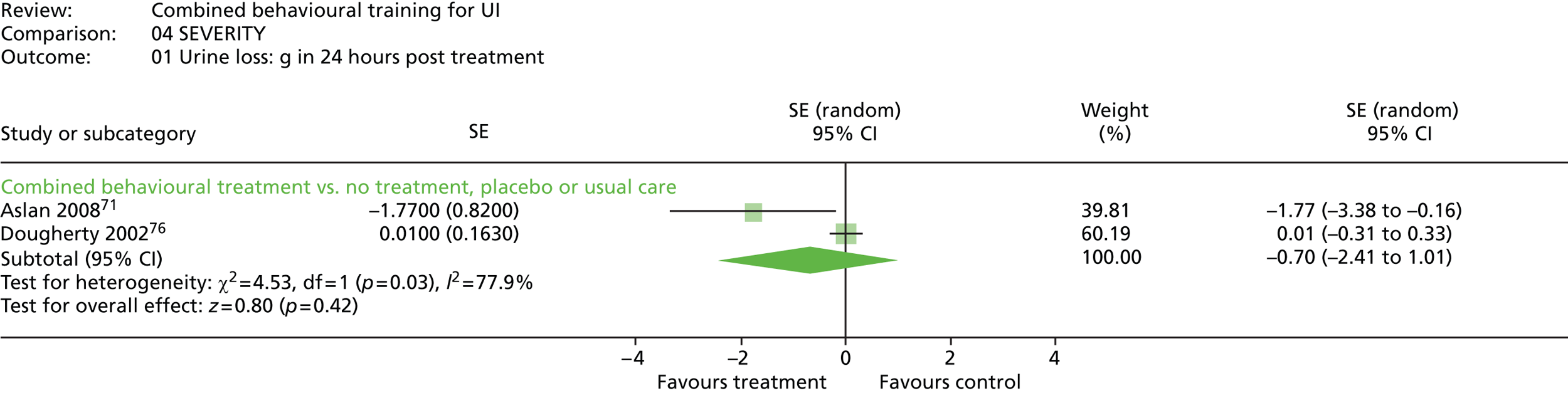

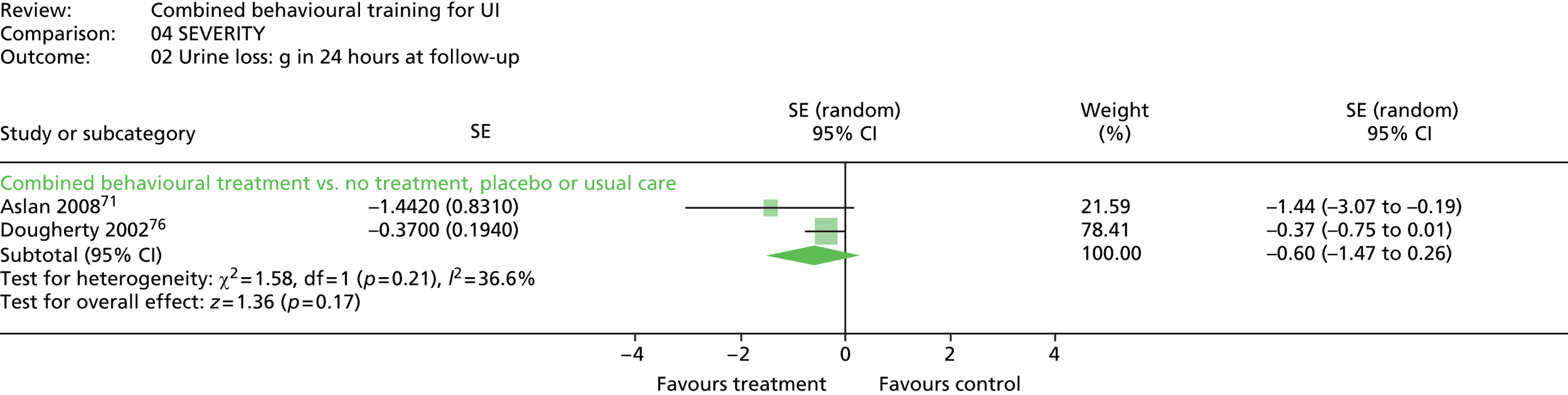

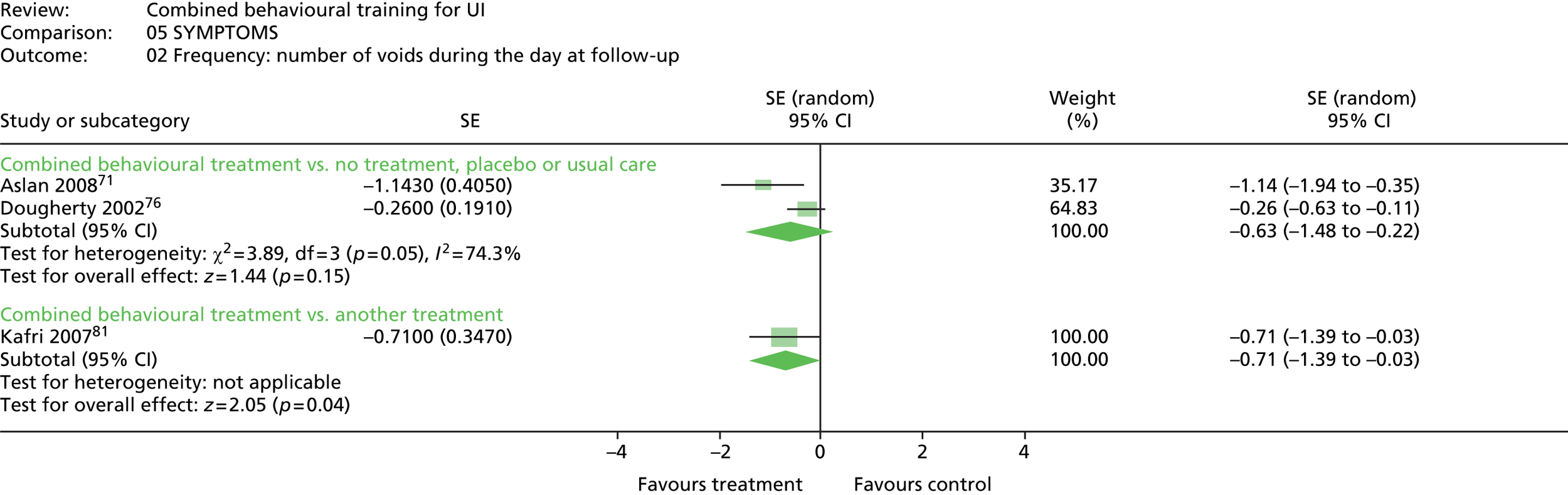

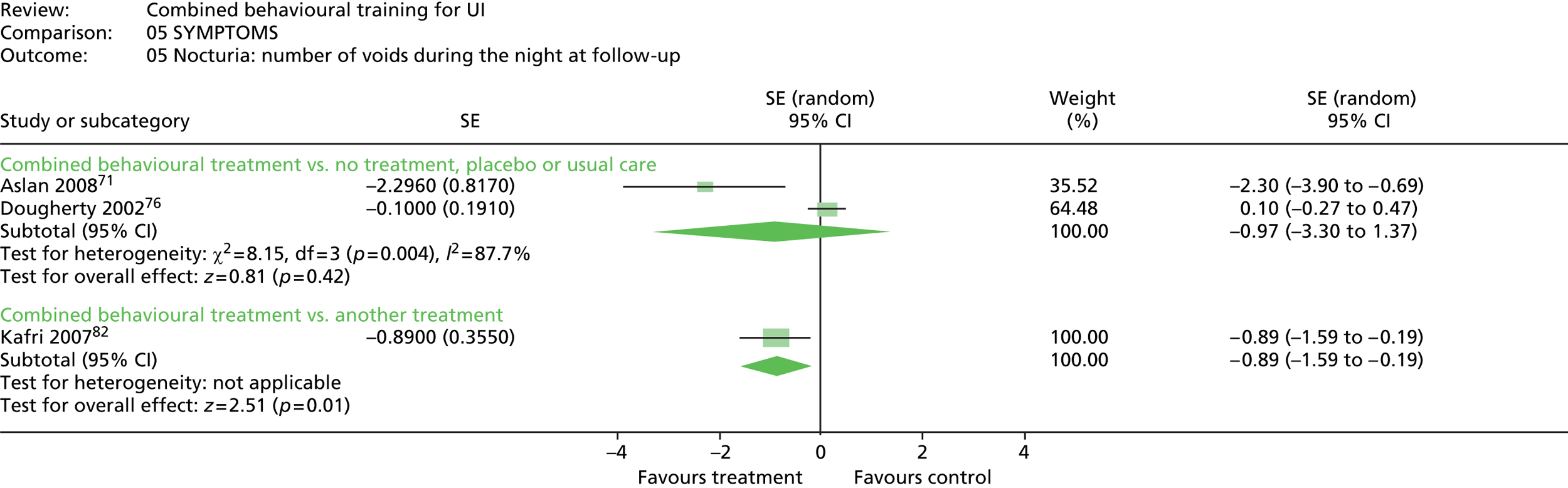

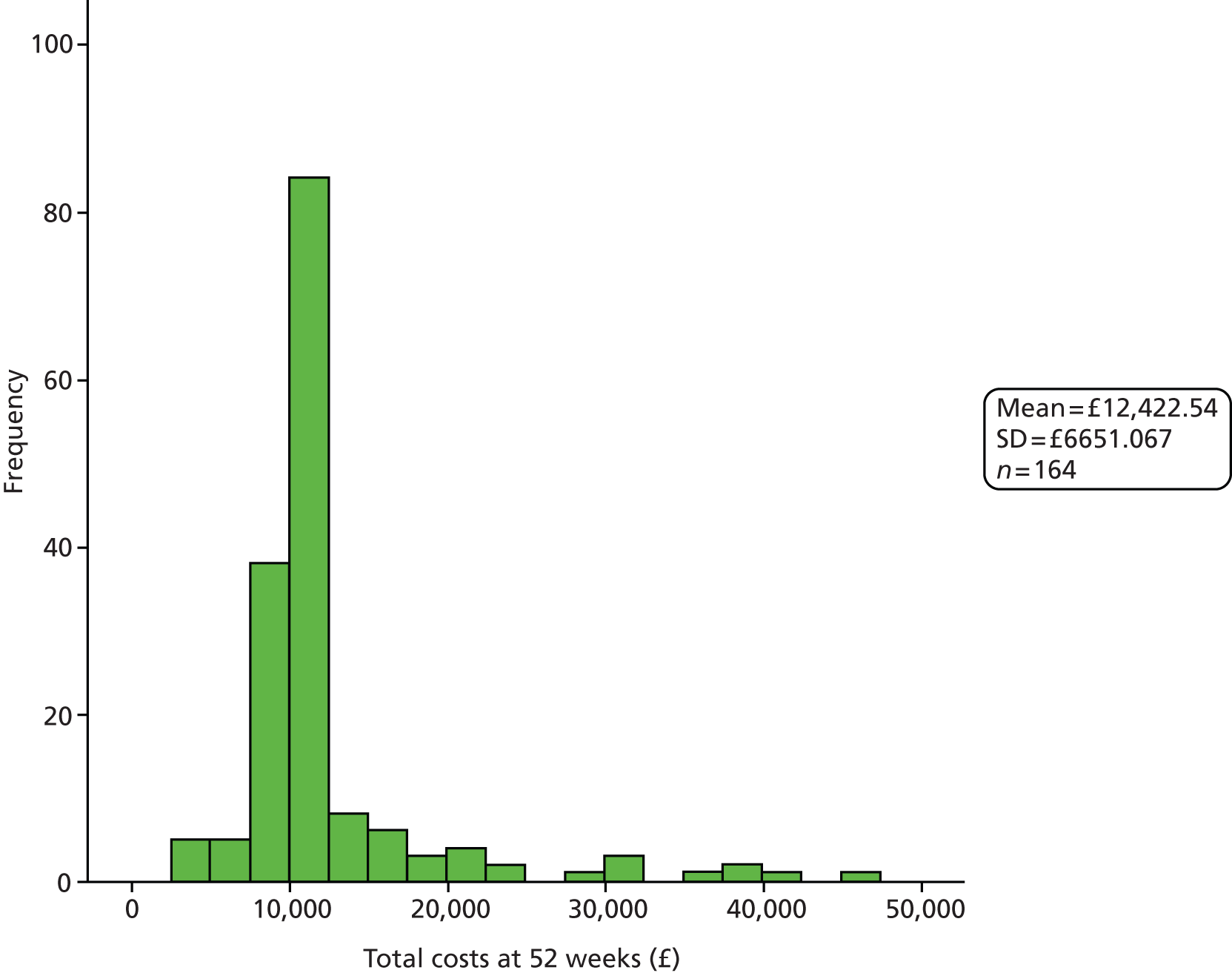

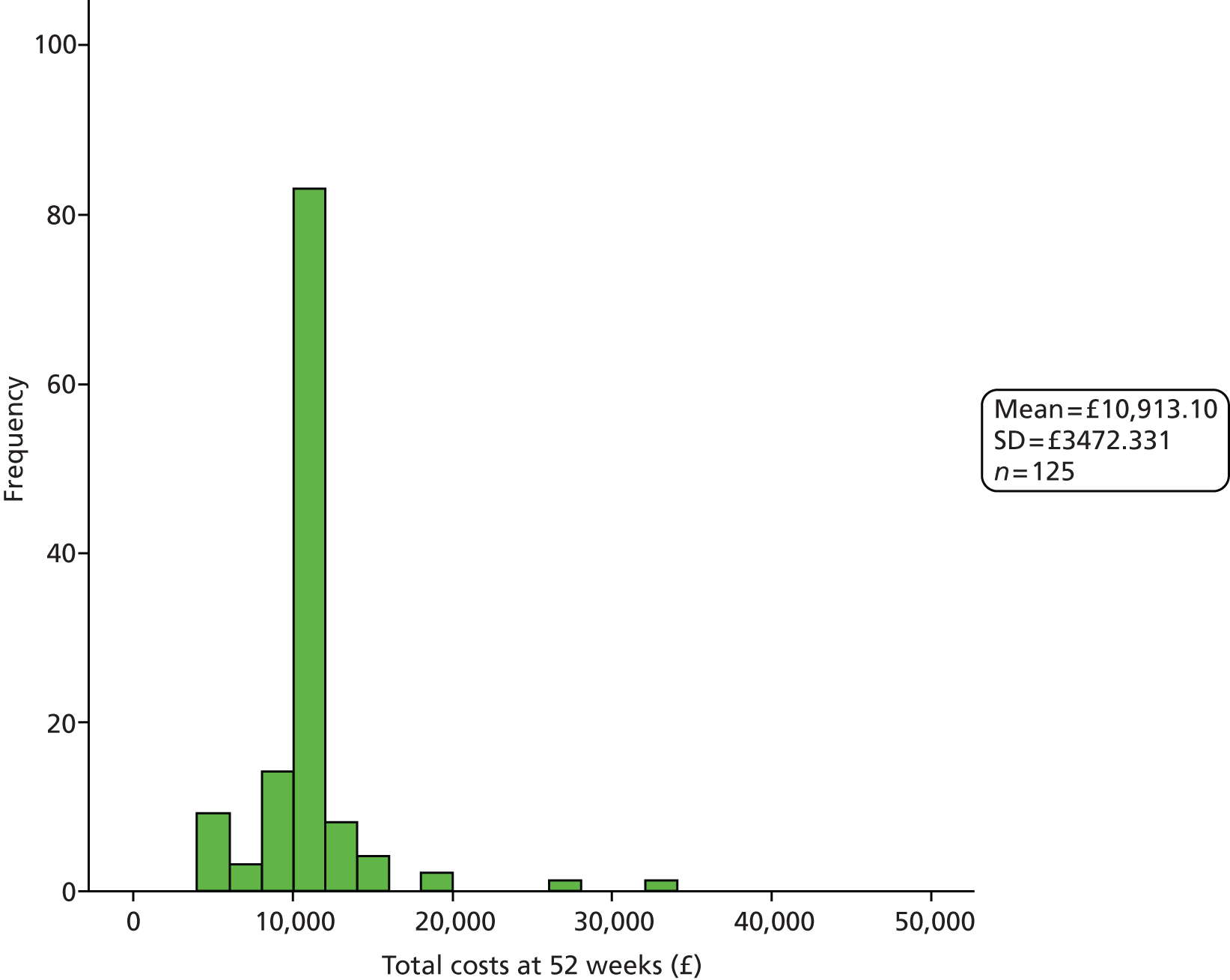

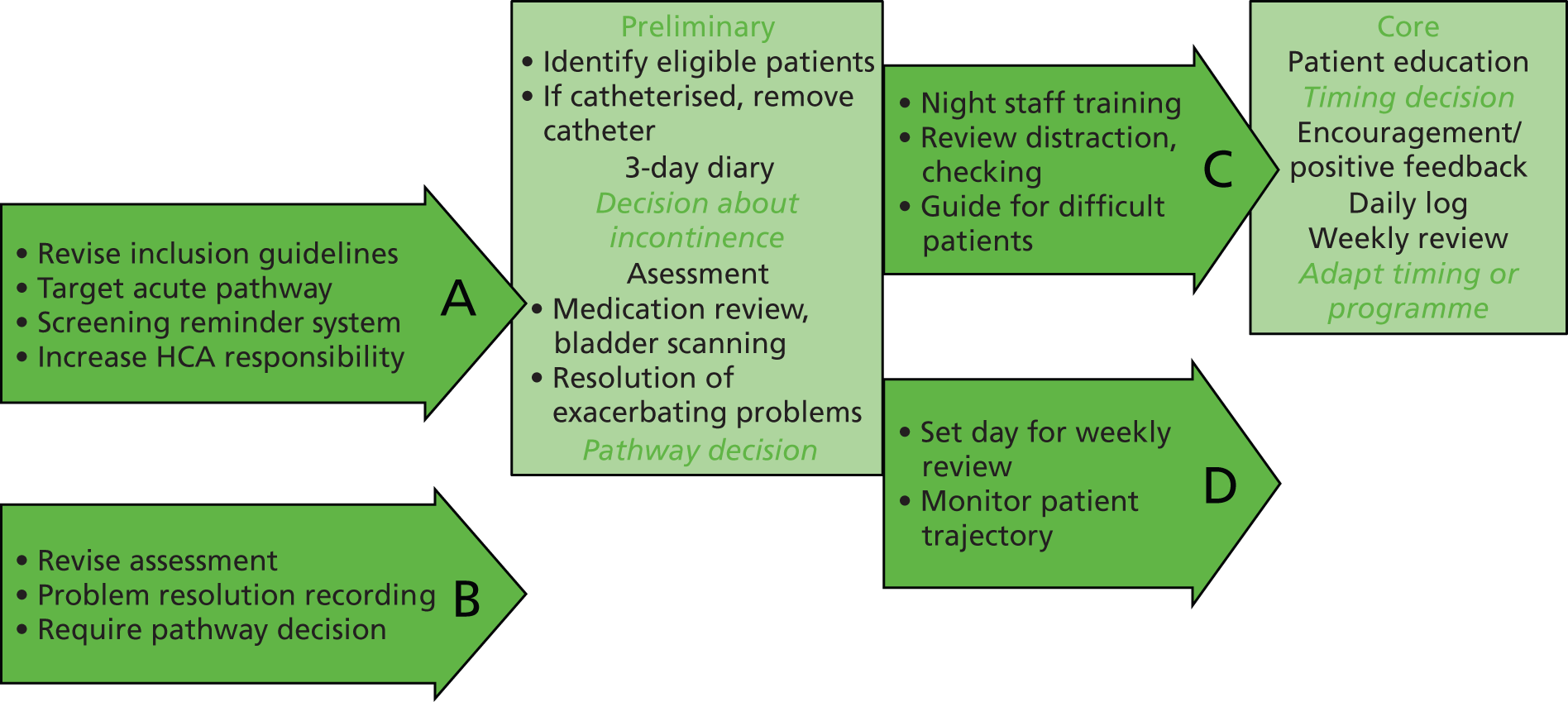

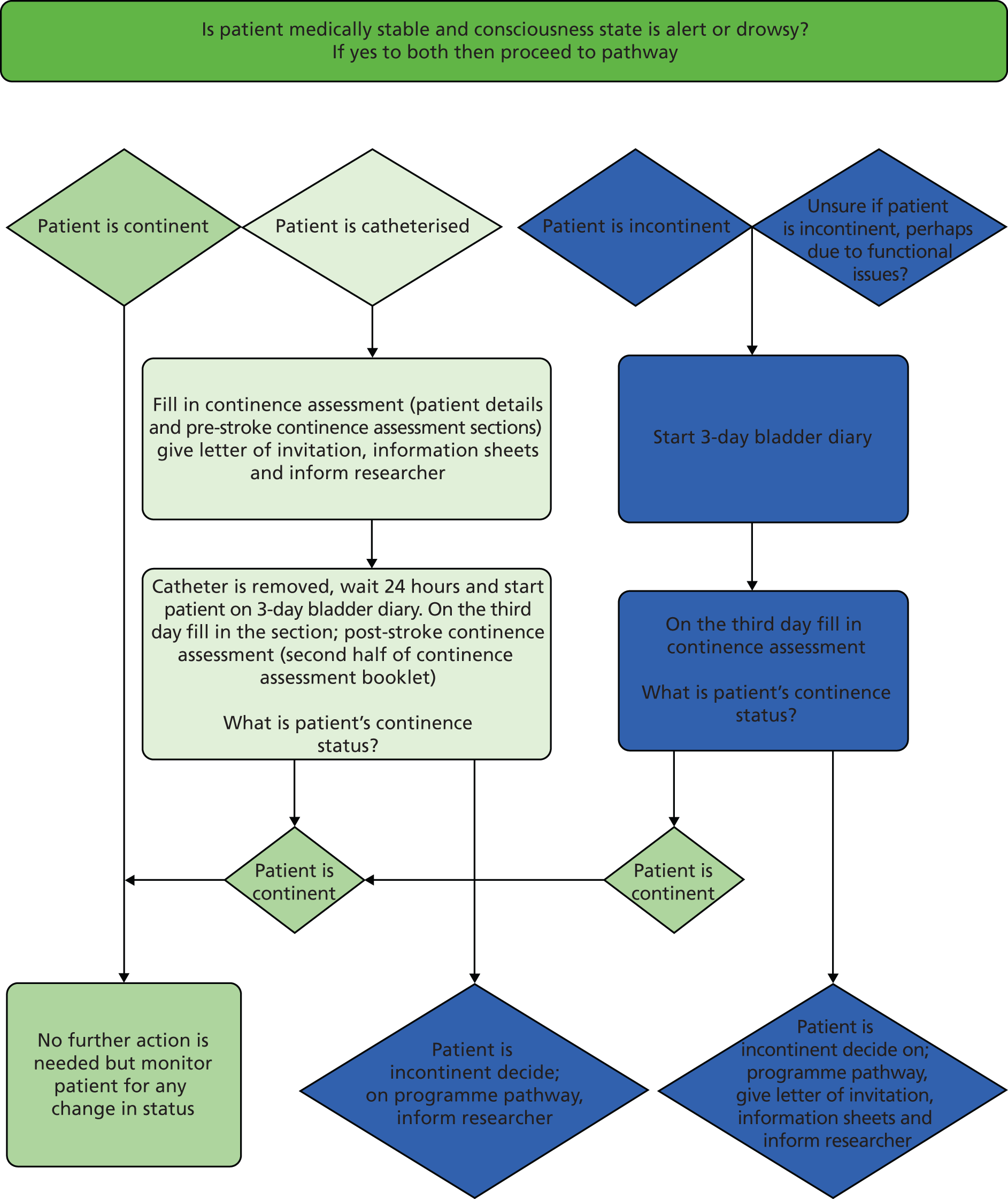

All types of incontinence were included, but there are more data relating to participants with UUI (46%) than with MUI (40%) or SUI (14%). Most of the studies were undertaken with participants who had established and moderate to severe incontinence. Only one study related to people with mild or very mild symptoms. 90 This was the only study to recruit mainly from community populations rather than from clinical settings, although a few other trials did include community advertising as an additional route of recruitment.