Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number NIHR134931. The contractual start date was in April 2021. The final report began editorial review in February 2022 and was accepted for publication in July 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Blank et al. This work was produced by Blank et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Blank et al.

Introduction

Definitions of home, remote and tele working

In its broadest sense, working from home involves the practice of conducting paid occupational work in the home. Various terms have been used to describe working from home, including ‘teleworking’, ‘telecommuting’, ‘e-working’ and, more recently, ‘new ways of working’. Teleworking and telecommuting were terms coined in 1973 by Jack Nilles,68 and refer to the direct substitution of travel to a workplace for telecommunication (e.g. telephone calls, email, videoconferencing), and apply generally to managerial and office work. 68 The emphasis was on reducing travel (and thus traffic, particularly at peak times), and therefore Nilles68 considered that working for home-based businesses would not be considered as telecommuting, since there was no commuting to be substituted. In contemporary times, the focus is on internet connectivity, and the term ‘remote e-working’ is also used to describe this, with some suggestion that this is a preferred term in Europe,12,69 and again relates to traditional office work.

Nowadays, working from home can be positioned as one type of ‘flexible working arrangement’ (alongside part-time work and flexible hours), with the flexibility arising in the location of the work. 70 Messenger and Gschwind70 refer to three generations of telework as mobile technology advanced over time and locate these in a conceptual framework. The first generation (the ‘home office’) located telework in the home, the second generation (the ‘mobile office’) located telework additionally in third spaces (anywhere where work can be done regularly away from the workplace and home aided by information communication technologies, e.g. trains, airports, the client’s premises) and the third generation (the ‘virtual office’), referred to as ‘new ways of working’, located telework additionally in intermediate spaces (those that fall between the workplace, home and third spaces, e.g. car parks, lifts, pavements). Thus, working from home and telework/e-working overlap to a large extent, as telework can be undertaken in the home (but in other places too, under the most recent definition); however, not all work from home (WFH) is telework (e.g. running a small business, such as small-scale manufacture, or childcare). Working from home also includes work that is temporally flexible as well as temporally constrained by the employer.

Originally, telework was conceptualised as a complete substitution for traditional office work,68 mainly due to technological constraints at the time, for instance, the need to use a fixed-location desktop computer and telephone. With advances in technology and reconceptualisation of telework as ‘new ways of working’, it is possible for employees to engage in ‘hybrid working’ (i.e. working from home on some days and working in the workplace on others). Thus, contemporary definitions refer to telework as working away from the employer’s premises ‘for a portion of the work week while keeping in contact via information and communications technology’ (p. 511). 71

Initially, working from home (mainly via telework, among office workers), based mainly on a hybrid working model, was conceptualised as beneficial to both employees, who could benefit from the flexibility it afforded, and employers, who could benefit from more satisfied employees and lower turnover. 71,72 However, the prevalence of teleworking did not rise as rapidly as initially expected, due to resistance from management and a lack of trust, with the most famous example being Yahoo’s decision to abandon its working from home policy in 2013. 70 More recently, the widespread adoption of working from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic has also revealed many disadvantages, which may counteract the advantages that previously drove arguments for its uptake. 72

Prevalence of home working

Various data sources report data on the prevalence of working from home. According to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD),73 in pre-pandemic times 18% of the UK workforce worked from home occasionally, and just over 2% worked mostly from home. The UK Office for National Statistics (ONS)74 reported that, in 2019, 5.2% of people in employment reported working mainly from home, 12.3% reported working from home at some point in the week prior to the interview and 26.7% people reporting ever having worked from home. These rates were highest in the information and communication sector (14.8%, 32.8% and 53.1%, respectively), the professional and scientific sector (12.8%, 26.3% and 46.3%, respectively) and the real estate sector (12.3%, 18.4% and 40.3%, respectively), and lowest in the accommodation and food services sector (2.1%, 4.4% and 10.0%, respectively), the transport and storage sector (1.8%, 3.4% and 11.0%, respectively), and the wholesale, retail and vehicle repair sector (3.2%, 6.2% and 13.4%). The ONS data show a clear social gradient in home working, with the highest rates among managers, directors and senior officials (10.0% mainly worked from home, 24.3% worked from home in the week prior to the interview and 46.7% ever worked from home), followed by professional occupations (5.8%, 20.3% and 45.0%, respectively) and associate professional and technical occupations (8.1%, 19.3% and 36.5%, respectively), intermediate levels in administrative and secretarial occupations (6.9%, 10.5% and 19.9%, respectively), skilled trades occupations (2.4%, 5.5% and 17.9%), and caring, leisure and other service occupations (4.5%, 5.3% and 14.1%), and the lowest rates found among elementary occupations (0.5%, 0.9% and 4.2%, respectively), process plant and machine operatives (1.2%, 2.1% and 6.5%), and sales and customer service occupations (1.6%, 3.1% and 8.7%, respectively). 74

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a rapid increase in working from home across many sectors and occupational types. The CIPD73 report that employers estimated that around 54% of their workforce were working continuously at home (with 35% of employers reporting that up to a quarter were, over 40% reporting that 75–99% were and 21% reporting that all of their workforce were working continuously from home). This was highest in the business and financial services sector (75–80%) and the public administration sector (67%), but lower in education, healthcare and other services (between 40% and 46%) and lowest in distribution (31%) and production (39%).

The ONS reports similar figures. In April 2020 specifically, towards the start of emergency pandemic control measures in the UK, 46.6% of people in employment did some work at home, with 86.0% reporting that they worked at home as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. 75 As with pre-pandemic data there was a social gradient in home working; the highest proportions of those who did some work at home were among managers, directors and senior officials (67.3%), those who worked in professional occupations (69.6%) and associate professional and technical occupations (63.7%), although those working in administrative and secretarial occupations were not far behind (57.2%), perhaps because of the prevalent use of ICTs in those roles, and the lowest proportions of those who did some work at home were process plant and machine operatives (5.4%), those who worked in sales and customer service occupations (15.9%), caring, leisure and other service occupations (14.9%), and skilled trades occupations (18.9%). 75

In 2020, 35.9% of those employed did some work in the home (9.4 percentage points higher than in 2019). 76 Similar to pre-pandemic figures, the highest proportions of people mainly, recently and occasionally working from home in 2020 worked in the information and communication sector (21.9%, 32.3% and 7.8%, respectively), professional and scientific sector (17.4%, 29.2% and 9.6%, respectively), and the financial services and real estate sector (13.3%, 33.3% and 7.5%, respectively), with the lowest proportions in the accommodation and food services sector (2.7%, 3.2% and 6.4%, respectively), transport and storage sector (3.3%, 8.4% and 6.9%, respectively) and wholesale, retail and vehicle repair sector (5.0%, 7.4% and 7.4%, respectively). 76 As with pre-pandemic data, the social gradient in working from home in 2020 is reflected in educational qualifications; the highest proportions of people working from home mainly, recently and occasionally had a higher degree (11.7%, 29.2% and 13.4%, respectively), or a degree or equivalent (10.9%, 25.0% and 11.0%, respectively), with intermediate proportions among those educated to A-level or equivalent (8.0%, 17.0% and 10.1%, respectively) and GCSE or equivalent (6.4%, 12.7% and 9.4%, respectively), and the lowest proportions among those with no qualifications (4.0%, 3.2% and 6.7%, respectively) and entry-level qualifications (5.9%, 9.4% and 6.9%, respectively). 76

Looking to the future, the CIPD73 reports that employers expect 37% and 22% of their workforce to WFH after the COVID-19 pandemic on a regular basis and all the time, respectively, with many companies preparing for hybrid working, where people would either WFH 1–2 days a week or work from the workplace 1–2 days a week. Employees surveyed also preferred a hybrid approach overall. Thus, with a shift towards working from home for at least part of the working week over the medium to long term, evidence on the impact of working from home takes on greater importance than in previous times.

Guidance for the health of home workers

The current review is also timely in the sense that while there is a plethora of guidance on workplace health for other types of workplace, supported by an extensive range of workplace health programmes and specific interventions, there is a dearth of appropriate evidence-based workplace health guidance that specifically relates to the home as the workplace. The transition to wide-scale working from home at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was rapid and unprecedented, and many organisations lacked the infrastructure and systems to support employees with these changes, at least initially. 77 Schall and Chen78 argue that specific challenges to occupational safety and health inherent in working from home can arise from a lack of face-to-face supervision, a lack of information and support relating to ergonomics, increased isolation from colleagues, and blurred boundaries between work and home. Such occupational safety and health risks may include musculoskeletal issues resulting from a sub-optimal workstation (potentially also combined with long work hours) and mental health issues resulting from isolation, blurred boundaries, overwork and work–home conflict. 78

Since the COVID-19 pandemic and associated emergency measures began, a large volume of survey data has been collected, which has raised concerns about the impact of working from home on health, wellbeing and inequalities. 79 Health and wellbeing are undeniably important among workers. As well as being important as outcomes in their own right, the health and wellbeing of workers can play an important role in the functioning of organisations, since those with higher levels of health and wellbeing are likely to have greater job satisfaction and organisational commitment and lower absenteeism and turnover intention. 69,71 Any potential detriment to health and wellbeing due to working from home is likely to have been magnified at a population level during the pandemic, because of the increased prevalence of home working and the crisis situation. Following the crisis, large numbers of people are expected to continue to WFH, at least some of the time, as discussed earlier.

Inequalities

Wide-scale working from home has also highlighted inequalities. Women with children have faced disproportionate challenges in working from home without childcare support during the pandemic. 80 Disproportionate challenges have also been experienced by those with a smaller living space and more people in the home. The Royal Society for Public Health42 reported that 26% of people working from home were working from a sofa or bedroom, and a greater proportion of people (41%) were more likely to think that working from home was worse for their health and wellbeing if they lived with multiple housemates compared with those who lived on their own (29%) or just with a partner (24%). Social gradients in the proportions of people able to WFH documented in pre-pandemic times have persisted during the more widespread use of working from home during the pandemic, as discussed earlier, with higher rates of home working reported among higher-grade professions and those with more advanced educational qualifications. The ONS76 reported that ‘The average gross weekly pay of employees who had recently worked from home was about 20% higher in 2020 than those who never worked from home in their main job, when controlling for other factors; this continues a long running trend’ (p. 3).

Thus, the issue of the impact of working from home on health and wellbeing is highly topical and of great interest to employers and employees alike, with a strong need for up-to-date guidance. There is therefore a need to formally and systematically synthesise evidence from both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic to understand the potential impact of current trends in home working and hybrid working and how negative impacts might be mitigated. Previous reviews examining this issue either predate the pandemic (and therefore did not consider the mass home working of recent times), or were conducted rapidly and/or focused on a specific aspect of working from home (e.g. virtual teams, teleworking), a specific timeframe (e.g. since the start of the pandemic) or a specific outcome (e.g. psychological distress, lived experience). There is currently a dearth of comprehensive systematic reviews on this topic, and the current review aims to fill this gap to provide evidence that can inform recommendations and guidance on working from home. This could inform decision-making by employers and workers about future patterns of home and hybrid working and about how employers can support workplace health, when the workplace is the worker’s home, and aim to mitigate inequalities brought about or exacerbated by working from home.

Methods

Review methodology and approach

We undertook a systematic review synthesising qualitative, quantitative and observational data. As the review was time-constrained, we employed elements of rapid review methodology as outlined by Kelly et al. (2016)81 and described in the methods sections below (for example limiting the number of papers which were formally double extracted, and not routinely contacting included authors for additional references).

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of this review was to identify, appraise and synthesise existing research evidence that explores the impact of home working on health and wellbeing outcomes for working people. We aimed to gain a better understanding of the factors that influence the physical health, mental health and overall wellbeing of home workers (including hybrid working where some time is spent working at home and some in the office or traditional place of work) as well as the potential for the wider impacts of home working on health inequalities.

The objectives in order to achieve this aim were:

-

to conduct a systematic review drawing on relevant, qualitative, quantitative and observational studies on the factors which influence the impact of home working (on the health of people working at home)

-

to describe the evidence for the potential impact of these factors in relation to health inequalities

-

to co-produce with stakeholders, a conceptual model to represent the factors that influence the health and wellbeing of home workers, and including the impact of home working on health inequalities

-

to identify the implications of the findings for developing evidence-based recommendations for policy and practice, including guidance to employers, and for future research priorities.

Search strategy

The searches were informed by a literature mapping exercise which was undertaken to scope out the volume and type of potentially relevant literature available. 3

We began by conducting searches in relevant databases. The search, which comprised subject headings and free-text terms, was initially developed on MEDLINE before being adapted for the other databases (see Supplementary Material: Search strategies). The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science (Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), International Bibliography of Social Sciences (IBSS), PsycINFO and LabourDiscovery.

The search was restricted to papers in English from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)4 published from 2010 to current.

Database searching was accompanied by the following additional search methods:

-

scrutiny of reference lists of included papers and relevant systematic reviews (within search dates)

-

searches for UK grey literature

-

search of relevant key websites

-

citation searching of key included papers.

Authors were not routinely contacted to source additional papers. However, one study author was contacted to clarify a point in their paper.

Due to the rapidly expanding nature of the evidence on this topic, more citation searching was conducted than anticipated in order to identify papers published within the timeframe of the review. Citation searches were continued until no further new factors (not previously included in the analysis) were identified. Previous systematic reviews of relevant studies identified during the searches were not included, but their reference lists were checked to identify potentially relevant primary studies (within our search dates) that had not been identified by other methods.

Inclusion criteria

Population

The population included anyone in the working population who spends all or some of their working time at home. Papers which look at students, and those studying, rather than undertaking paid employment at home, are excluded from this review. Studies which looked at the impact of temporary remote teaching on teachers (where that was not their normal mode of teaching) as a result of COVID-19 lockdown measures were also excluded from the main review (these studies are discussed separately; see Supplementary Material: Full paper excluded studies).

Exposure

This included hybrid models of home working where some time is spent working at home and some in the office or other traditional place of work. Other aspects of flexible and remote working which do not relate directly to home working, for example studies about flexible office hours or specifically about working in remote locations away from the home, along with the impact of work accessibility (e.g. the impact of remote access to emails on home life), were considered to be outside the scope of this review.

Context

The extent to which people have been asked to work at home has escalated dramatically in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and much of the recent evidence relates to the specific circumstances of home working during the pandemic. The review and model take steps to take account of this by considering evidence from both before and during the pandemic and also considering the implications for future research and policy directions.

Outcomes

Any factor that has been shown to be associated with the health of people working at home was included. An association is defined as the link between two variables (often an exposure and an outcome) where no causal relationship between the variables can be defined. This included all measures of physical health (including self-reported outcomes) and mental health (including clinical indicators such as diagnosis and treatment and/or referral for depression and anxiety alongside self-reported measures). All measures associated with wellbeing including but not limited to wellbeing, happiness, mood and stress-related outcomes were included. Work satisfaction, along with all other employment-related outcomes such as job performance and work-life balance, is outside the scope of this review.

Studies

We included quantitative, qualitative, mixed-method and observational studies. Studies with and without a comparator group were included. Books and dissertations were excluded (but references were checked for relevance in specific cases). Case studies were considered on an individual basis in terms of their study design and risk of bias. Studies from OECD4 countries only were included in the review.

Study selection

Title and abstract screening

Search results were downloaded to a reference management system (EndNote). The title and abstract of each reference were screened against the inclusion criteria by one reviewer, and checked for agreement by a second reviewer. Keyword tags were used to identify the reviewer who had screened the record and to determine whether each record should be retained for consideration at the full paper stage. Full papers of potentially included studies were download as the pdf version and linked to the EndNote record for that reference. Where reviewers disagreed on the potential inclusion of a paper (i.e. one tagged the paper to be considered at the next stage and the other did not) the full paper was obtained to clarify the relevance of the work to the inclusion criteria. This was agreed by consensus between the three reviewers.

Full paper screening

The full paper of all potentially relevant papers was read by one reviewer. Where a decision to exclude the paper (due to lack of relevant data) was made the reason for this decision was tabulated and checked by a second reviewer. Uncertainties were resolved by discussion between the three reviewers and among the wider review team as required until a definitive list of included papers was obtained.

Data extraction

A data-extraction form was devised based on forms used successfully in previous reviews of public health topics using similar approaches undertaken by the review team. The extraction form was piloted by each of the three reviewers and any suggested revisions discussed and agreed.

We extracted and tabulate key data from the included papers. This included the study first author and year, country of origin, study design and methods of analysis, study population, outcome measures, study aims, summary of results, key messages and conclusions, and any study limitations.

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer, with a 10% sample formally checked for accuracy and consistency by a second reviewer. The lead reviewer (LB) also re-read all papers and extractions in order to be as familiar as possible with the evidence base. The data-extraction process for this review focused on identifying the links between factors reported in the papers. We included quantitative measures of any associations where these were reported. For qualitative papers we extracted data from both the authors’ findings and from raw data within the published paper. The descriptions of factors was recorded exactly as defined by the study authors; definitions were not manipulated nor was any attempt to classify or group factors attempted at this stage. In practice, the included papers were revisited and the extraction-table data checked on several occasions throughout the data-synthesis and report-writing stages.

Quality appraisal

Quality (risk of bias) assessment was undertaken using appropriate tools for the types of study designs included in the review (see Table 1. Quality appraisal tools). Quality assessment was performed by one reviewer, with a 10% sample checked for accuracy and consistency by a second reviewer. Mixed-methods studies were quality appraised for each type of method and data included in the study. Where there was not enough information contained in the paper to do this, the study was quality appraised with respect to the main focus of the data and approach.

| Study type | QA tool | Accessed via |

|---|---|---|

| Crosssectional studies | CEBMa | Center for Evidence-Based Management (2014). Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cross-Sectional Study. Retrieved (month, day, year) from www.cebma.org |

| Qualitative studies | CASP | CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf (b-cdn.net)https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ |

| Cohort studies | CASP | CASP Cohort Study Checklist 2018_DRAFT.docx (b-cdn.net)udy Checklist 2018_DRAFT.docx (b-cdn.net) |

| Quasi-experimental studies | JBI Systematic Reviews | https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2020-07/Checklist_for_Quasi-Experimental_Appraisal_Tool.pdf |

| Grey literature | AACODS checklist | http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/ |

The overall quality of the evidence base and its impact on the review findings was also considered in order to describe the volume, quality and degree of consistency in the evidence, and where there are gaps requiring primary research.

Data synthesis

The extracted data were synthesised narratively due to the diverse nature of the evidence. 1 The variance in reported outcomes precluded any meta-analytical approaches to the data. We aimed to summarise all of the factors reported in the included papers to develop an overall picture of the how working from home affected health.

Once we had extracted data from the papers a meeting was held with the reviewers to construct mind maps and summary tables of the factors reported in the papers. We did this by tabulating the factors reported by the authors and noting whether the factor had a positive or negative influence (or no influence) on the association between working from home and health. Consensus was obtained within the review team as to where the factors reported could be effectively grouped together (for example different measures of stress or anxiety were grouped together). The grouping of factors was further discussed and validated by our patient and public involvement (PPI) group in order to ensure that they made sense in relation to their experiences.

As well as including qualitative studies in the above analysis, an additional thematic analysis of these studies was also undertaken to establish whether any further insights could be gathered by considering the depth of analysis presented in these types of studies. As our research question was very specific, and the qualitative research identified rarely had the same aim (findings were usually much broader), we chose to focus on data relating to working from home and its impact on health and wellbeing. We synthesised studies from before and during the COVID-19 pandemic separately, due to differences in context and implications for future home and hybrid working. Rather than coding extracted data line-by-line, we coded units of meaning, in the form of text extracts, which could have been a line, or a larger passage of text, to retain contextual information within each code. 82,83 Direct quotations from participants were coded where possible, and where an illustrative quotation was not provided then the interpretations of study authors were coded (i.e. a second-order interpretation84). The codes were then organised into categories, which were organised into themes and subthemes for each set of studies (pre-pandemic and during-pandemic) by looking for similarities and differences between the codes and text extracts,85 using tables in Microsoft Word. This process was undertaken by one author (EH) and checked by another (LB).

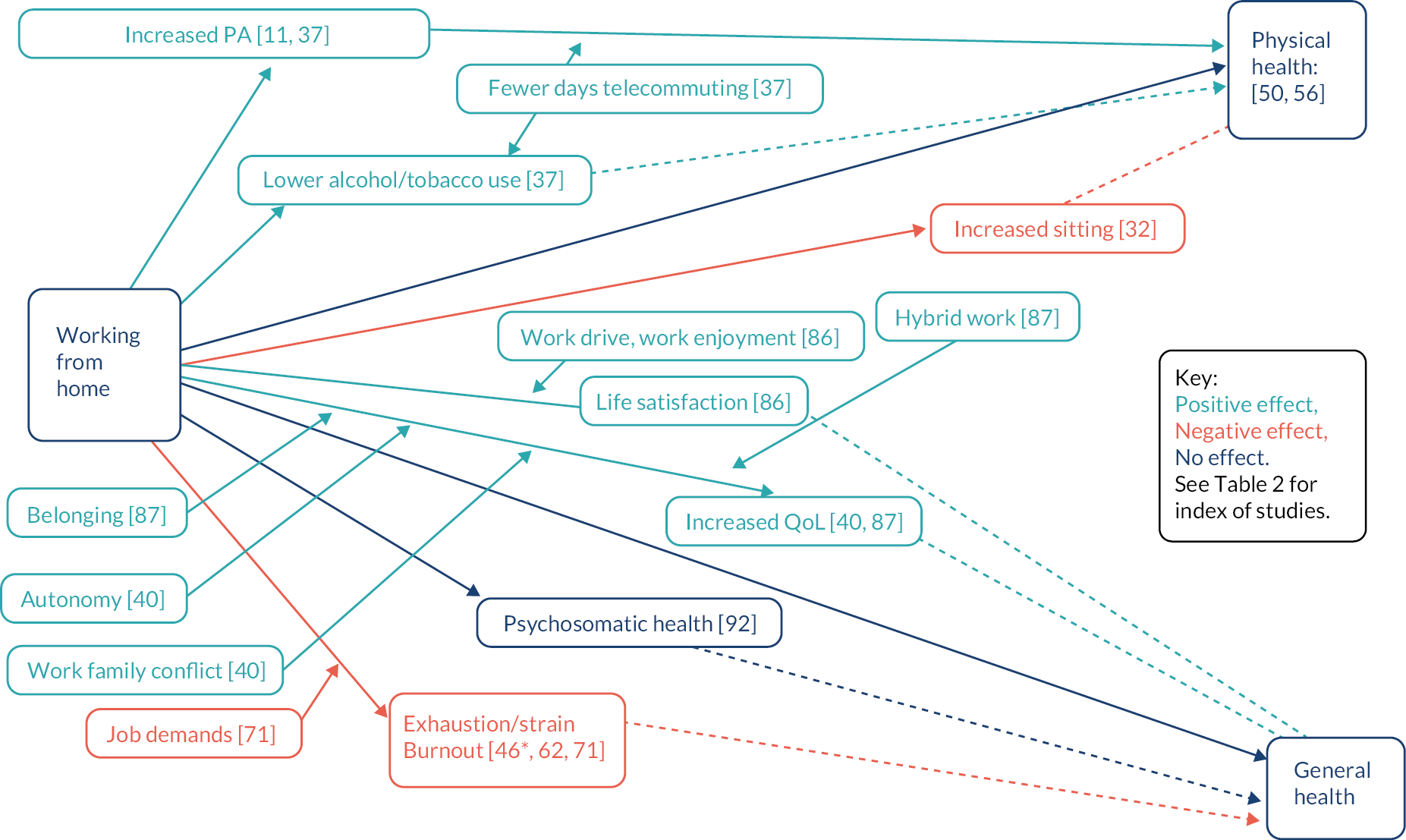

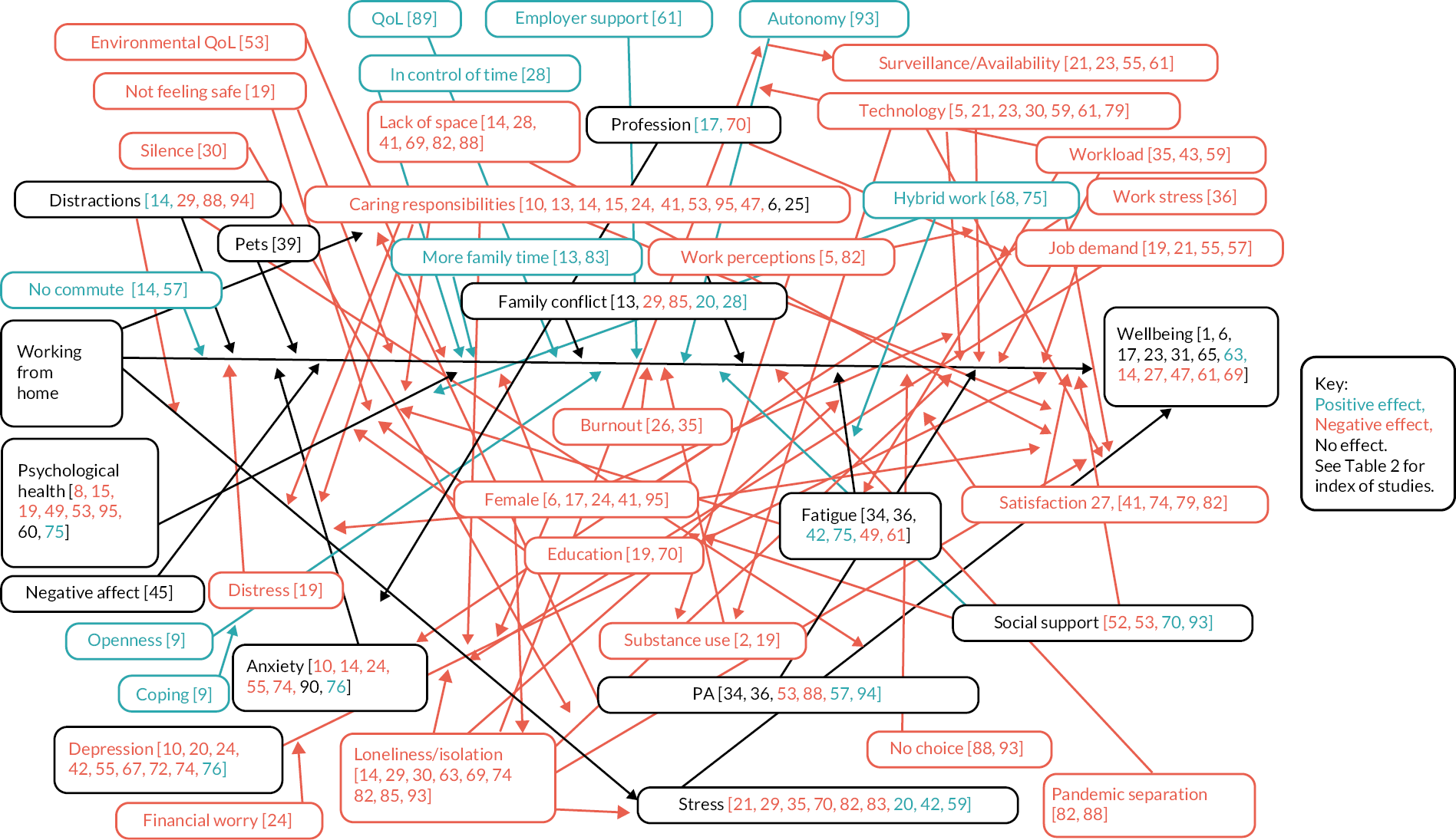

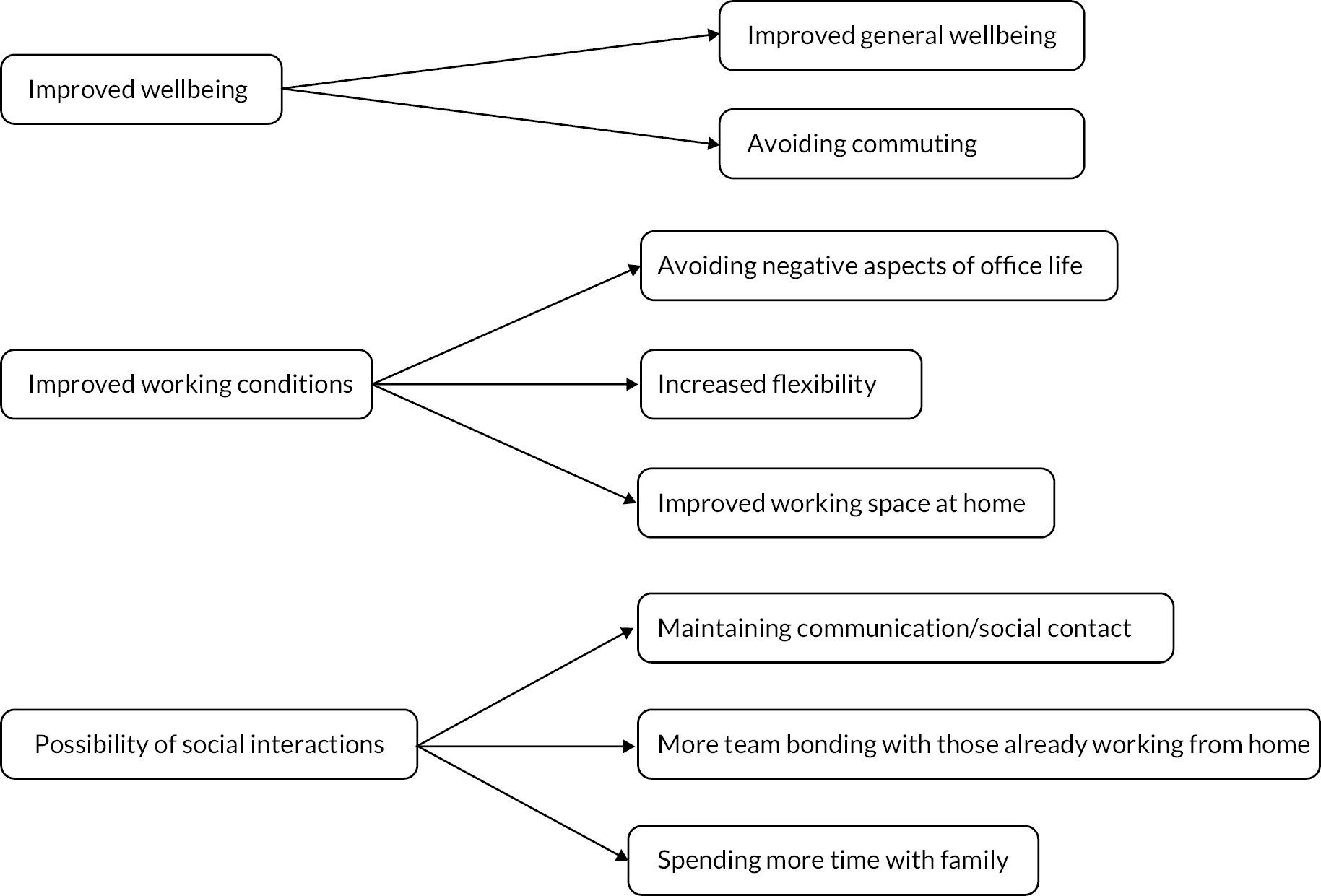

Developing a model to visualise the results

Prior to this work we development an a priori model of potential links between working from home and health-related outcomes. 3 Contextual and background factors for the model were identified through recent reviews and grey literature publications summarising the factors which have contributed to the increases in home working seen both prior to and as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The a priori model also defined the main outcomes as outlined by the research questions for this review. However, this did not provide information about the factors which influence the relationship between working from home and health-related outcomes. This systematic review allowed us to develop a more informed, evidence-based model to detail what is known about these factors and the relationships between them.

The first step to build on the a priori model was to use the factors which influence the associations reported in the literature to construct mind maps to visualise the extent and complexity of the relationships reported. We used our extracted data from the included papers which detailed the reported factors which influence the relationship between home working and the health and wellbeing outcomes as defined in the individual papers. Any interim factors which shape the pathways between variables were noted. We recorded the factors as they were reported by the authors and did not change or interpret any wording used.

Due to the volume of evidence and the complexity of the relationships and factors reported, we divided the evidence into studies published before the COVID-19 pandemic (where no reference to COVID-19 was made) and those published during the pandemic (where specific reference to COVID-19 was made in the paper). We also divided the studies into those reporting physical health, mental health and wellbeing and/or overall health outcomes, again to help with data presentation and understanding. The reported factors were tabulated from the data in the extraction tables, and then transferred to the mind maps (with a box and line to represent each reported factor and the outcome it was linked to) to give a summary of the overall volume, direction and consistency of the reported factors. Where a variety of factors and outcomes were reported, studies were included in more than one mind map to reflect this. The colours we selected for the mind maps were chosen in order to be accessible to those with colour-blindness.

The following colours are used in the mind maps and tables to attempt to give an overall visual statement regarding the influence of working from home on health:

-

blue: factor which positively influences the health of those working at home

-

orange: factor which negatively influences the health of those working at home

-

black: factor which has no influence on the health of those working at home.

Due to the high volume of studies reporting mental health and wellbeing outcomes published during the COVID-19 pandemic we developed a summary mind map for these outcomes as the original mind map was too complex to be clear. Studies reporting similar research findings were grouped together to generate a summary typology of factors which influence the associations between home working and health. This grouping occurred, for example, where studies reported on similar factors, or where the same factor is discussed but in more or less detail. In all cases we were confident that the authors were essentially reporting on the same factor, even if the terminology and wording used was different. This approach to grouping factors was validated by two reviewers independently grouping factors and then comparing grouping and making alterations where necessary to reach consensus. This approach is further described in the results section of this report.

The findings from our review were combined with the a priori model which was validated in consultation with stakeholders.

Patient and public involvement and stakeholder involvement

To ensure that the review was informed by, and useful to, all stakeholders who have an interest in the evidence base for home working, we have taken into account the views and recommendations of diverse stakeholders. Stakeholders have contributed to the review in the following ways:

-

consultation with members of the public prior to and during the review

-

consultation with employer representatives prior to and during the review

-

consultation with union bodies representing employees.

Three online discussion meetings were held with members of the public with experience of working from home. Potential participants were recruited via the People in Research website,86 which advertises opportunities for public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. These discussion meetings were undertaken prior to starting the review (to comment on the scope and focus of the review), in the initial stages of the review (to comment on inclusion criteria and search terms), and at the end of the review process (to comment on the review finding and interpretation). In total eight people contributed to these online sessions. The individuals involved varied by demographic characteristics and their length and amount of experience of working at home. They also represented several different industries and occupations and included people who were self-employed as well as employees. As we had a significant response to our call for participants, we were able to select those we invited to the discussion based on these characteristics to ensure that they were sufficiently diverse in experience and viewpoints.

In each discussion meeting (which took place on line) members of the group were presented with up-to-date information regarding the progress and findings of the research and asked to comment and raise questions in order to ensure that the data presented made sense from their perspective. In the final meeting the participants were presented with the mind maps and final model and discussed their understanding of the data presented and whether anything did not reflect their experience. Minor changes to wording within the final model were made as a result.

Emails were sent to employer and union representatives in the initial stages of the review to ask for comments on the scope of the review and suggestions of evidence which should be considered for inclusion in the review. Towards the end of the review process respondents were re-contacted to ask for their comments on the main findings of the review (see Appendix 1: PPI and stakeholder participants for a full list of participants).

Results

Study selection

After de-duplication, the initial database searches generated 2514 records, of which 135 were retrieved as full papers and 23 found to meet the inclusion criteria for the review. A further 635 papers were identified via citation searching; of these, 42 were found to meet the inclusion criteria. An additional 20 papers were identified from checking the reference lists of the included studies and previous systematic reviews. Therefore, 85 peer-reviewed articles were included in the review. Grey literature searches identified a further 50 sources of which 11 were found to meet the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Although 12 pieces of research were suggested by stakeholders, these were all found to have been already identified through the searches process, or to be beyond the scope of the review.

In total, 96 pieces of relevant evidence were identified and included. These have been summarised (see Figure 1. Study selection; and Table 2. Summary table of included studies) and are also presented as full extractions for each included study (see Supplementary Material: Full extraction tables).

| ID no. |

Study | Covid yes/no | Country Population |

Study design | Primary outcomes | Factors Work from home |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Allen 202147 | Y | UK Workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Psychological wellbeing, Anxiety, depression Loneliness, insomnia |

No factors associated with working from home/wellbeing. Self-isolation (β = −0.162, p = 0.004) and loneliness scores (β = −0.596, p < 0.001) were the only significant predictors of wellbeing. |

| 2. | Alpers 202187 | Y | Norway Adults |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Health worries Alcohol consumption |

Increased alcohol consumption more common in those working from home. Self-assessed increased alcohol consumption during the lockdown period was more frequently reported by people working or studying from home (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.3 to 16). |

| 3. | Anderson 201413 |

N | USA Workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Job-related affective wellbeing scale | The relationship between telework and positive affect is moderated by one’s social connectedness outside of the workplace such that the relationship becomes more positive as social connectedness increases (γ = 0.75, p < 0.001), also individuals experience less negative affect while teleworking as social connectedness increases; γ = −0.73, p < 0.01). |

| 4. | Argus 202140 | Y | Estonia Office workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Musculoskeletal pain (MSP)PA: BPAQ | Self-reported PA was significantly lower during than before the (mean change in BPAI −0.41, SD 1.37, 95% CI −0.62 to −0.19, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.26 (small effect)), but not leisure-time PA (mean change in BPAQ −0.07, SD 0.59, 95% CI −0.16 to 0.02, p = 0.15, Cohen’s d = 0.11), and work-related PA significantly increased (mean change in BPAQ0.18, SD 0.54, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.26, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.50 (medium effect)). Negative correlation between change in self-reported sports-related PA and change in the numbers of body regions with MSP during the lockdown (r = −0.206, p < 0.01). The number of body regions with MSP onset during the lockdown was also negatively correlated with change in workplace comfort score (r = −0.262, p < 0.001) and change in workplace ergonomics score (r = −0.231, p < 0.01). |

| 5. | Bennett 202188 | Y | USA Workers (range of industries) |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Video conference fatigue (Profile of Mood States scale) | Muting the microphone (γ = −0.09,p = 0.02) and perceptions of group belongingness (γ = −0.21, p = 0.003) were negatively related to fatigue (i.e. were associated with lower fatigue, whereas turning the webcam off, attention during the meeting, and videoconference meeting duration were not significantly related to post-meeting fatigue. Muting and perceptions of belongingness were significantly negatively correlated with each other (−0.45, p < 0.05). |

| 6. | Bentham 202148 | Y | UK CAMHS Services staff |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing: Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) | Proportion of hours working from home not related to wellbeing: An independent samples Kruskal-Wallis H-test showed no statistically significant differences in wellbeing score based on the proportion of hours worked remotely during the pandemic (χ2 (4) = 4.45; p = 0.349). No difference with and without dependents. |

| 7. | Bentley 201614 | N | New Zealand Teleworkers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Psychological strain | Organisational social and teleworker support resulted in increased job satisfaction (t = 10.02, 7.81; p < 0.001) and reduced psychological strain (t = 6.09, p < 0.001; t=2.06, p < 0.05). Social isolation mediated the relationship between organisational social support and the two outcome variables. Some differences in the structural relationships for hybrid and low-intensity teleworker sub-samples. |

| 8. | Bevan 202089 | Y | UK Home workers |

Survey Cross sectional |

Mental health Wellbeing Physical health |

Mental health is poorer for: younger workers, looking after elderly relatives (but parents are no different to non-parents), living with parents or renting, new home workers, working more than contracted hours, reduced contact with boss. Significant decline in musculoskeletal health. Poor sleep and increased fatigue a concern. Alcohol, diet & exercise declining for many. Emotional concerns over finance, isolation, energy, work-life balance and family health. |

| 9. | Boncor 202090 |

Y | UK Lone researcher |

Qualitative Ethnography |

‘Living and working during the COVID-19 pandemic’ | Openness to new ways of living linked to coping with COVID (and working at home wellbeing). Assumed link to wellbeing. |

| 10. | Burstyn 202191 | Y | USA General population |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Anxiety Depression |

Anxiety and depression negative link to concerns about return to work, childcare, lack of sick leave, and loss/reduction in work. Patterns differed by sex. Men (but not women) who identified as essential workers (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.96, 1.40), had one-on-one contact with people at work (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.34), including known or suspected cases of COVID-19 (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.74), who were hourly employees (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.60), and did not have access to disability/sick leave through work (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.60) were more anxious. |

| 11. | Chakrabarti 201892 | N | USA Telecommuters |

Survey Cross-sectional |

PA | Working from home increased walking, cycling; PA decreased driving. Both frequent and occasional telecommuters engaged in 8–9 minutes more per day of PA than non-telecommuters, on average; 31% frequent, 27% occasional and 21% non-telecommuters met or exceeded the 30 minutes per day activity target. |

| 12. | Charalampous 202112 | N | UK Male workers |

Qualitative. Interviews | Wellbeing | Working from home had better work life balance and were happier. But were lonely and bored due to lack of social interaction. No impact on psychosomatic health, but increased sedentary behaviours. Stress linked to issues with technology. |

| 13. | Chung 202093 | Y | UK UK employees |

Survey Cross sectional |

Wellbeing (some assumed links) | Positive effects were the ability to: take care of children, do housework and spend more time with their partners. Negative aspects included: blurred boundaries between work/home, missing interactions with colleagues. Increased workload and conflict between work and family negatively impacted parents’ mental wellbeing, especially for mothers. Almost half of all mothers felt rushed and pressed for time, more than half of the time during the lockdown. In addition, 46% of mothers felt nervous and stressed more than half of the time. |

| 14. | CIPD 202149 | Y | UK Working population |

Online survey Interviews |

Wellbeing | Increased wellbeing through avoiding the commute, greater flexibility of hours, reduce distractions, normalising use of technology (helped disabled). The most frequently mentioned benefit of working at home was increased wellbeing through avoiding the commute (46% of survey participants), followed by enhanced wellbeing because of greater flexibility of hours (39%). Reduced wellbeing: isolation, unsuitable home circumstances, increased health anxiety, home-schooling. |

| 15. | Clark 202160 | Y | Ireland Working mothers |

Qualitative interviews | Psychological wellbeing | Increased levels of psychological distress as a result of the pandemic and working from home. Mediated by increased childcare and domestic duties. |

| 16. | Collins 201615 | N | UK Local authority workers |

Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews | Wellbeing Social support relationships with colleagues. |

Social relationships only with workers known face to face. Personal phones used for social support. Pressure (from self) to achieve expectations in order to maintain tele working. |

| 17. | Cotterill 202050 | Y | UK Water sector |

Survey Cross-sectional |

General wellbeing since lockdown. | More women saw a decrease in wellbeing (39%) than men (32%), although this was not statistically significant, and there were no significant difference between the median wellbeing values for men and women (U = 27 030, z = −1.472, p = 0.141). Essential workers had largest improvement in wellbeing. |

| 18. | Daniel 201816 | N | England Online home businesses |

Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews | Mobility, isolation and paradox. | Positive: feeling more fulfilled by having more time and mental space, and the inherent autonomy of scheduling from working from home. Negative: loneliness, isolation (professional and social). Fear of equipment/internet failure. |

| 19. | De Sio 202151 | Y | Italy Teleworkers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Psychological distress and perceived wellbeing | Poor wellbeing was associated with having a higher job demand during pandemic (OR 2.61; 95% CI 1.10 to 6.19), with feeling not ‘sheltered at home’ (OR 8.80; 95%CI 2.60 to 29.75), with smoking more cigarettes during pandemic (OR 2.47; 95%CI 1.13 to 5.59), and with experiencing psychological distress (OR 8.01; 95% CI 2.57 to 24.97). |

| 20. | Delanoeije 202094 | Y | Belgium Employees |

Quasi-experimental | Stress | Working from home associated with lower stress, lower work-to-home conflict, higher work engagement and higher job performance. Univariate F tests showed there was a significant interaction effect between time and group for stress (F(1,62) = 4.21, p = 0.04, ηp2 = .06)’; however, the decrease in stress among the teleworking group could be accounted for by pre-existing differences in commuting time. For daily stress, ‘the standardized estimate of teleworking day on daily stress (γ = −0.20, p < 0.001) was negative and significant’. |

| 21. | Delfino 202152 | Y | Italy Professional services |

Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews |

Wellbeing, and factors affecting wellbeing | Employees experienced stress in relation to increased demands from working from home. Increased monitoring and expectation to all always be available (and increased video calling) reduced wellbeing. |

| 22. | Deloitte 202195 | Y | UK National population sample |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing | Lockdown negative impact on wellbeing. After lockdown most office workers would prefer to work at home more often. |

| 23. | Di Tecco 202135 | Y | Italy Public admin workers |

Prospective cohort study | General health Wellbeing Job satisfaction, work-life balance, psychosocial factors |

Working from home (smart working) one day per week had no effect on wellbeing. Predictors of wellbeing were work demands, management of change. Demands and higher education significantly predicted general health. There was no significant change in general health (p = 1.00) and wellbeing (p = 0.247) as evaluated by t-tests. In the regression models, significant predictors of wellbeing were demands (−0.703, p = 0.027) and effective management of change (1.461, p = 0.003), and demands (−1.00, SE 0.048, p = 0.037) and higher education (0.238, SE 0.100, p = 0.018) significantly predicted general health. |

| 24. | Docka‐Filipek 202161 | Y | USA University workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Self-reported mental health (depression and state anxiety) | Gender accounted for unique variance in both depression (β = 0.17, p ≤ 0.01) and anxiety (β = 0.17, ss ≤ 0.01) risk. Higher financial concern accounted for unique risk for both depression (β = 0.30, p < 0.001) and anxiety (β = 0.26, p < 0.001), and having more dependents accounted for unique risk for anxiety (β = 0.13, p < 0.05). |

| 25. | Dunatchik 202153 | Y | USA Adults |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Altered responsibilities for domestic labour | The rise of remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic has not appreciably altered the domestic division of labour. 66% mothers and 65% fathers reported feeling ‘some’ or ‘a lot’ of pressure regarding children’s home learning. |

| 26. | Evans 202196 | Y | UK Remote workers |

Longitudinal survey | Wellbeing | Burnout, no effect overall. Extroversion and conscientiousness became a risk during the pandemic. |

| 27. | Felsted 202017 | Y | UK Workers |

Survey Cross sectional |

Wellbeing | Those who worked mainly at home reported greater difficulties in enjoying normal day-to-day activities compared to those not working at home, (48.2/49.3% vs. 38.5%) and more often felt constantly being under strain and unhappy with life (36.0/33.9 vs. 31.2). |

| 28. | Fukumura 202197 | Y | USA General population |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing | Wellbeing: time use, working in home space, work-life balance, temporality. |

| 29. | Galanti 202198 | Y | Italy Public and private employees |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Stress due to working from home | Stress was positively correlated with family-work conflict (r = 0.50, p < 0.01), social isolation (r = 0.62, p < 0.01), distracting working environment (r = 0.36, p < 0.01), and negatively correlated with productivity (r = −0.39, p < 0.01) and work engagement (r = −0.47, p < 0.01). |

| 30. | Gao 202061 | Y | UK Female academics |

Qualitative Ethnography |

‘Living and working during the COVID-19 pandemic’ | Both women experienced social isolation as a result of being physically distanced from their workplace and colleagues, even if working alone was previously sought/preferred. Technology and silence were challenges. |

| 31. | Gijzen 202054 | Y | Netherlands Workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Mental health and wellbeing | Working from home was reported as a positive outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic for 17% (n = 142) participants. Others negative – so no effect overall. |

| 32. | Grant 201318 | N | UK e-workers |

Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews | Wellbeing | Communication and support from colleagues critical success factors for successful remote working and to balance the psychological aspects of wellbeing. Wellbeing enhancing: Fewer days lost through absenteeism, relieve stress from travel and child-care issues. Wellbeing detracting: Social interaction limited to family and local friends, Office grapevine and important information missed. Sitting behaviours may increase. |

| 33. | Hall 201917 | N | UK Employees |

Survey Cross-sectional |

How home working makes people feel | Home working can increase employee engagement, job satisfaction and wellbeing (no data presented). |

| 34. | Hallman 202197 | Y | Sweden Office workers |

Mixed: Survey Diary and accelerometer data |

PA (proxy to physical health), standing, sedentariness and sleep | Sedentariness, standing and movement did not differ significantly between working from home and working at the office. Time spent sleeping (relative to time spent awake) was significantly greater on working from home days than for days working at the office. Days working from home were associated with more time spent sleeping relative to awake, and the effect size was large (F = 7.4; p = 0.01; ηp2 = 0.22). The increase (34 min) in sleep time during WFH occurred at the expense of a reduction in work and leisure time by 26 min and 7 min, respectively. |

| 35. | Hayes 202199 | Y | USA (and global) Home workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Stress and work-related burnout | There was a significantly greater increase in perceived stress score from pre-COVID (retrospectively rated) to the current time among those whose job typically did not provide opportunities to WFH (mean increase 3.9, SD 6.4) than those whose did (mean increase 2.4, SD 5.3) (t(290) = 2.23, p = 0.03). Conversely, those who previously had flexibility to WFH before the pandemic had higher work-related burnout scores at data collection (mean 57.9, SD 21.5) than those without the flexibility to WFH (mean 41.0, SD 21.6) (t(284) = −16.84, p < 0.0001). Although women had lower pre-COVID and during-COVID perceived stress scores than men, the mean increase in stress scores was higher for females (4.2, SD 6.0) than males (2.4, SD 5.8) (t(294) = 2.59, p = 0.01). Women had significantly lower mean work-related burnout scores (43.3, SD 20.8) than men (53.0, SD 24.6) (t(299) = −3.82, p < 0.0002). |

| 36. | Heiden 2021100 | Y | Sweden University staff |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Perceived health, stress, recuperation, work-life balance and intrinsic work motivation | Those who teleworked several times per week or more reported more stress relating to indistinct organisation than those who teleworked less than once a month. There were no significant pairwise differences for fatigue. None of the outcomes were significantly predicted by the amount of telework per week in regression analyses but did show significant differences on fatigue (F = 3.47; p = 0.032) and work stress relating to indistinct organisation and conflicts (F = 4.80; p = 0.009). |

| 37. | Henke 201620 | N | USA Finance employees |

Retrospective cohort study | Telecommuting intensity and selected health indicators | Telecommuters were less likely to be at risk for most health risks studied (alcohol abuse, physical inactivity, tobacco use, depression, Edington risk scores) or stress risk; the predicted probability of being at risk appeared to increase with increasing telecommuting intensity. |

| 38. | Hislop 201521 | N | UK Self-employed home workers |

Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews | Experiences of work and isolation | Positive: spacio-temporal flexibility Negative: isolation, sense of perpetual contact |

| 39. | Hoffman 202119 | Y | USA Workers (hybrid) |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing (positive and negative affect) Companion animals |

Neither the presence of dogs or cats nor the presence of other humans in the household predicted where participants preferred to work. For participants who worked from home, neither PAWB scores nor NAWB scores were associated with the presence of dogs or cats in the home. Paired samples t-tests indicated that neither positive or negative wellbeing scores differed significantly by workplace location (PAWB: t = 1.17, df = 453, p = 0.24; NAWB: t = −1.74, df = 453, p = 0.08). |

| 40. | Hornung 20095 | N | Germany Public admin workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

QoL | There were small but statistically significant positive effects of telecommuting intensity on QoL mediated via both autonomy (βindirect = 0.02, z = 2.56, p < 0.01) and work-family conflict (βindirect = 0.11, z = 5.96, p < 0.01). |

| 41. | Hubbard 202163 | Y | UK Adults of working age |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Satisfaction with working from home | Women reported less satisfaction than men (chi-square 7.011, df = 3, p = 0.071), as did people with children (chi-square 7.299, df = 3, p = 0.063) – especially young children aged 0–4 years (chi-square 8.01, df = 3, p = 0.046). A significant predictor of dissatisfaction with home working was caring for a responsible adult (chi-square = 7.837, df = 3, p = 0.049). |

| 42. | Ignacio Gimenez-Nadal 202064 | Y | USA Employees |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing (happiness, sadness, fatigue and stress) | Among males, teleworkers reported lower levels of sadness, stress and tiredness compared with commuters. Among females, teleworkers had significantly higher happiness levels than commuters. |

| 43. | Ingusci 202156 | Y | Italy Remote workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Behavioural stress | Behavioural stress was found to be positively related to work overload (β1 = 0.48, p = 0.015) and negatively related to job crafting (β3 = −0.38, p < 0.000), with a significant and negative indirect effect of work overload on behavioural stress through the intervention of job crafting (βa×b = −0.07, p = 0.029). |

| 44. | Jacukowicz 202022 | N | Poland Office and online workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Satisfaction with work-life balance | Working online significantly predicted lower satisfaction with work-life balance (β = –0.17, p < 0.01) but greater quality of social life (β = 0.13, p < 0.05). |

| 45. | Janssen 202065 | Y | Netherlands Adolescents and caregivers |

Ecological study | Positive and negative affect | Working from home was not related to the increase in parents’ negative affect during the COVID-19 pandemic, as compared with pre-pandemic data. |

| 46. | Kaduk 20196 | N | USA IT workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing: work family conflict, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived stress, psychological distress | Involuntary WFH associated with greater work-to-family conflict, stress, burnout, turnover intentions, and lower job satisfaction (p < 0.10) Voluntary WFH is protective, and associated with greater job satisfaction, lower turnover intentions, and less stress (p < 0.10). |

| 47. | KCL 2021101 | Y | UK Large employers |

Survey Cross sectional |

Wellbeing | Increased anxiety and stress due to lockdown. Wellbeing poorer in organisations not supporting alternative ways of working. Disproportionally negative impact on parents/carers. |

| 48. | Koehne 201223 | N | USA,UK, Estonia, Spain, Mexico Workers |

Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews | Personal experiences of working from home, and coping strategies. Wellbeing | A lack of possibility for person-to-person social interaction could negatively impact on remote workers’ wellbeing. |

| 49. | Kotera 2020102 | Y | UK Working population |

Ecological | Wellbeing | Working from home: increase blurred work-home boundaries, fatigue and mental demands. |

| 50. | Kroll 2019103 | N | Germany Employees |

Longitudinal Survey |

Perceived health | Working from home did not have a significant effect on health when controlling for individual heterogeneity (b = 0.02, SE = 0.05, ns). There was also no statistically significant effect of working from home on leisure satisfaction, however (b = −0.01, SE = 0.10, ns). |

| 51. | Kubo 202136 | Y | Japan Workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Diet | Working from home had a negative effect on diet. The odds ratios (95% CI) for those who telecommuted at least 4 days per week relative to those who rarely telecommuted were: Skipping breakfast: 1.15 (1.03 to 1.29); Solitary eating: 1.44 (1.28 to 1.63); Lower meal frequency: 2.39 (1.66 to 3.44); and Meal substitution: 1.26 (1.04 to 1.51). |

| 52. | Lal 2021104 | Y | UK Working from home |

Qualitative interviews | Social interactions | Working from home had a negative effect on social interactions. The findings highlight the difficulty in maintaining social interactions via technology such as the absence of cues and emotional intelligence. |

| 53. | Limbers 202066 | Y | USA WFH mothers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

QoL, parenting stress, PA | Moderate intensity PA may attenuate the negative impact of parenting stress on social relationships and satisfaction with one’s environment in home working mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Greater levels of parenting stress were associated with lower physical health QoL (r = −0.42, p < 0.001), lower psychological QoL (r = −0.28, p < 0.001), lower social relationships QoL (r = −0.21, p < 0.01) and lower environment QoL (r = −0.19, p < 0.01). |

| 54. | Lundberg 200224 | N | Sweden White-collar government workers. |

Observational field study | Psychophysiological reactivity (blood pressure plus urine and saliva samples) Self-rated health/wellbeing |

No significant difference in self-ratings of stress between telework and office work. Blood pressure was significantly higher during work at the office than when teleworking at home, and men had significantly elevated epinephrine levels in the evening after telework at home (p < 0.01). |

| 55. | Magnavita 2021105 | Y | Italy Workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Happiness Anxiety Depression |

Intrusive leadership and overtime work were associated with reduced happiness, anxiety and depression in teleworkers (hybrid workers) (p < 0.001 for all the parameters). |

| 56. | Mann 200325 | N | USA Journalists |

Mixed: Survey cross-sectional Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews |

Physical health Mental health |

Higher levels of emotional ill health for the teleworkers. No significant difference for physical health. But, reduced stress at home due to: no office politics and transport and no travel to work perception of having control over their work (environment and work schedules). Negative effects of working from home: irritability, loneliness, lack of social support, insecurity/lack of confidence. Intrinsic rewards of working from home motivate to overcome negative emotions. |

| 57. | Mari 2021106 | Y | Italy Practitioners, managers, executives, teachers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Stress Coping |

There were no significant differences between professional groups on the PSS (perceived stress), nor on the perceived self-efficacy subscale. For the perceived helplessness subscale, teachers had a higher mean score (11.07, SD 3.90) than managers (9.79, SD 3.81). |

| 58. | Mellner 201726 | N | Sweden Professional workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Psychological detachment | Working at several different places (hybrid) was inversely associated with weekly work hours and had no association with psychological detachment. |

| 59. | Molino 2020107 | Y | Italy Workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Technostress | Remote working reduces stress. Significant positive correlations were found between behavioural stress and work-family conflict (r = 0.23), the three techno-stress creators (techno-overload, techno-invasion and techno-complexity; r = 0.22, r = 0.24 and r = 0.23, respectively), and workload (r = 0.19) (all p < 0.01). Work-family conflict was also positively correlated with the three techno-stress creators (r = 0.35, r = 0.48 and r = 0.19, respectively) and workload (r = 0.47) (all p < 0.01). Remote working was positively correlated with techno-overload (r = 0.29), techno-invasion (r = 0.25), and workload (r = 0.13) (all p < 0.01), but not behavioural stress (r = −0.07), work–family conflict (r = 0.03) or techo-complexity (r = 0.01). |

| 60. | Moretti 202041 | Y | Italy Admin officers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Work-related stress and musculoskeletal issues | Working from home increased risk of mental health and musculoskeletal problems, particularly affecting the spine. Neck pain worsened in 50%, improved in 8.3% and was the same in 41.7% of participants, whereas lower back pain worsened in 38.1%, improved in 14.3% and was the same in 47.6% of participants. |

| 61. | Parry 202157 | Y | UK Newly working from home |

Mixed: Survey Cross-sectional Interviews |

Wellbeing Physical health |

Working from home: experiencing worse symptoms of musculoskeletal pain, higher levels of fatigue, poor sleep, and higher levels of eye strain. Wellbeing score low compared to previous rounds of survey. Wellbeing scores lower for introverts – maybe due to video conferencing |

| 62. | Perry 20187 | N | USA Full time workers |

Longitudinal survey Additional cross sectional survey |

Emotional stability Strain Autonomy |

[Study 1]: Remote work was only correlated with ‘disengagement aspect of strain’. Moderated by emotional stability. [Study 2]: Remote work was not significantly correlated with strain outcomes or forms of need satisfaction. Positive ‘remote work-exhaustion slope’ among employees reporting low autonomy. Those with high autonomy and high emotional stability exhibited the lowest overall level of strain. There was a significant remote work × autonomy interaction for exhaustion, such that there was ‘a positive remote work–exhaustion slope among employees reporting low autonomy (0.82; t = 2.12, p < 0.05) but no significant relationship among those reporting high autonomy (slope = −1.20; t = − .68, p = 0.10).’ |

| 63. | PWC 202058 | Y | Malta Workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing | Mostly positive experience on wellbeing. Negatively affected by loneliness (lack of social interactions and feeling detached from the office). |

| 64. | Ray 202127 | N | USA National sample |

Retrospective cohort | Wellbeing Work flexibility |

Working from home was associated with an increase in job stress and an increase in job satisfaction. In regression analyses, working from home was associated with a 22% increase in job stress and a 65% increase in job satisfaction (p < 0.01). Stress and non-healthy days increased in women, non-whites, lower income, lower health status, living with spouse, family interfering with work, and more hours worked. |

| 65. | Restrepo 2020108 | Y | USA Working age |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Sleeping Food prep Eating |

Those working from home the previous day had significantly more minutes of sleep than those who worked away from home the previous day. Assumed link to wellbeing. |

| 66. | Reuschke 201928 | N | UK Working age |

Retrospective cohort | Life satisfaction | Home working did not have an impact on overall life satisfaction overall, not among men or women, not by type of employment. Home working was found to be significantly positively related to leisure time satisfaction (men and women). |

| 67. | Ripoll 202137 | Y | Spain Adults |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Mental health and psychological wellbeing | Working from home associated with increased depression symptoms during early COVID-19 pandemic. Working from home (compared with other working arrangements) was not associated with increased consumption of psychotropic drugs between weeks 1 and 4 (consumed by 6.5% and 7.1%, respectively, p = 0.306) or weeks 1 and 8 (consumed by 8.4% and 8.9%, respectively, p = 0.952), nor consultations to improve mood/anxiety between weeks 1 and 4 (undertaken by 27.3% and 26.9%, respectively, p = 0.918) and weeks 1 and 8 (undertaken by 28.0% and 31.5%, respectively, p = 0.388). |

| 68. | Rodriguez 2020109 | Y | Spain General population |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Stress: Perceived Stress Scale | Lowest stress response those who combined teleworking and commuting (in-person working). Highest stress response (and lowest stress control) those who were dismissed during lockdown. Teleworking reported the highest stress control (a very slight increase), followed by those who were both teleworking and commuting. Working situation (during COVID-19 lockdown confinement) was related to stress response (F(4,918) = 4.914; p < 0.01; ηp2 = 0.020) and control of stress (F(4,928) = 4.017; p < 0.01; ηp2 = 0.016). |

| 69. | RSPH 202142 | Y | UK Newly working from home |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing Physical health |

Working from home: less connected to colleagues (67%), taking less exercise (46%), developing musculoskeletal problems (39%) and disturbed sleep (37%). Feeling isolated. Working from sofa or bedroom increased musculoskeletal problems. Women more likely to feel isolated and to develop musculoskeletal problems. Poorer mental health if shared with many housemates. |

| 70. | Russo 2021110 | Y | Denmark Software professionals |

Longitudinal survey | Wellbeing Stress: Perceived Stress Scale. |

Quality of social contacts predicted positively, and stress predicted negatively an individual’s wellbeing. At Wave 1, stress negatively affected social contacts and daily routines predicted stress at α = 0.05. At Wave 2, need for competence and autonomy, stress, quality of social contacts, and quality of sleep uniquely predicted wellbeing at a = 0.05. No evidence that any predictor variable causal explained variance in wellbeing. |

| 71. | Sardeshmukh 20128 | N | USA Telecommuters (large company) |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Exhaustion Hours of telework |

Telework is negatively related to both exhaustion and job engagement, and job demands ((time pressure, role ambiguity, role conflict) and resources mediate these relationships. |

| 72. | Sato 2021a111 | Y | Japan General population |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Depressive symptoms | Working from home was negatively associated with depressive symptoms. In the logistic regression model, shifting to WFH was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.99). |

| 73. | Sato 2021b38 | Y | Japan General population |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Diet | Working from home was more clearly associated with increased intake of vegetables, fruits and dairy products and decreased alcohol intake among women than men. Working from home was associated with increased intake of vegetables (1.02, 1.004- 1.03), fruits (1.06, 1.03–1.09), dairy products (1.03, 1.01–1.06) and snacks (1.04, 1.02–1.06) but decreased intake of seaweeds (0.94, 0.91–0.97), meats (0.98, 0.96–0.999) and alcohol (0.93, 0.86–0.997). |

| 74. | Schifano 202159 | Y | France, Italy, Germany, Spain and Sweden General population |

Prospective cohort Survey |

Wellbeing Life satisfaction |

Working from home was associated with lower wellbeing on all five variables – life satisfaction (coefficient = −0.09, p < 0.01), worthwhile (coefficient = −0.07, p < 0.05), not lonely (coefficient = −0.08, p < 0.05), not depressed coefficient = (−0.09, p < 0.01) and not anxious (coefficient = −0.09, p < 0.01), although not working had a greater negative impact. Switching to working from home reduced anxiety (coefficient = 0.05, p < 0.10) but also reduced the sense of a worthwhile life (coefficient = −0.07, p < 0.05), with no significant impact on other wellbeing variables. |

| 75. | Shockley 202129 | Y | USA Married couples with children |

Prospective cohort Survey |

Psychological distress Sleep quality |

In the latent class analysis, for health outcomes (psychological distress and sleep quality), those adapting the strategy of ‘alternating days’ fared the best (mean PD score 1.54 and 1.58 for wives and husbands, respectively). |

| 76. | Smith 2021112 | Y | Canada | Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing Anxiety and depression: Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-2); Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) |

Anxiety and depression scores significantly lower than onsite workers. Among those working remotely, the adjusted proportion of respondents with GAD-2 scores of ≥3 was 35.3% (95% CI 27.1 to 43.5) and the adjusted proportion of respondents with PHQ-2 scores ≥3 was 27.4% (95% CI 20.1 to 34.8), both of which were significantly lower than among site-based workers or those no longer employed. |

| 77. | Song 202030 | N | USA General population |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Subjective wellbeing | Telework on weekdays or weekends/holidays is associated with more stress. Parents, especially fathers, report a lower level of subjective wellbeing when working at home on weekdays but not weekends. Childless females feel more stressed teleworking instead of working in the workplace. |

| 78. | Stitou 201831 | N | Canada Homebased childcare workers |

Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews | Wellbeing proxy measures | Factors affecting health and wellbeing were reported as the absence of contact with other adults during working hours, a lack of external help during working hours (i.e. working alone, without breaks), difficulty filling spots, noise, interference with personal and family life, low and precarious remuneration, and incomplete or no benefits. |

| 79. | Taser 2022113 | Y | Turkey Financial services employees |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Mental experiences (flow) | Working from home positive effect on the flow (mental experiences related to concentration and satisfaction at work). Technostress and loneliness mediated the relationship between WFH and flow. Those who had a good remote e-working experience tended to have lower levels of technostress (b = - 0.17, SD = 0.06, p < 0.01). Those experiencing technostress were likely to feel lonely (b = 0.23, SD = 0.06, p < 0.001). |

| 80. | Thulin 201932 | N | Sweden Workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

QoL and social sustainability | Advantages of teleworking included being able to work more undisturbed, work more efficiently, avoid commuting, and facilitate everyday life. In the logistic regression model for time pressure, never teleworking (β = −0.644, p < 0.05), only teleworking within regular hours (β = −0.866, p < 0.01), age (being older; β = −0.032, p < 0.01), working full time (β = −0.806, p < 0.05) and using a smartphone for private purposes often (β = −1.115, p < 0.05) or all the time (β = −1.089, p < 0.05) were associated with experiencing less time pressure, whereas having children at home (β = 0.406, p < 0.01) was associated with experiencing more time pressure. |

| 81. | Tietze 201129 | N | UK Home workers |

Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups | Wellbeing | Home workers felt less stressed and more relaxed. Participants also reported being better able to combine their work and domestic responsibilities and be better parents. New working procedures were a source of stress. |

| 82. | Toscano 2020114 | Y | Italy Employees |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Social isolation Stress |

Social isolation was significantly correlated with stress (0.50, p < 0.01), perceived remote work productivity (−0.43, p < 0.01), remote work satisfaction (−0.50, p < 0.01) and COVID-19 concern (0.32, p < 0.01). Stress was significantly correlated with perceived remote work productivity (−0.35, p < 0.01), remote work satisfaction (−0.54, p < 0.01) and COVID-19 concern (0.16, p < 0.05). |

| 83. | Travers 2020115 | Y | UK/Worldwide General population |

Qualitative Ethnography | Demands of home working | Working from home new and excessive demands creating worry, stress and pressure, but also opportunities afforded by a lack of commute and spending more time with the family, also the opportunity to exercise. |

| 84. | Trent 199434 | N | USA Private-sector companies |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Stress Perceived social support |

No differences in perceived stress score between telecommuters, those who worked from home, those who worked from the office. Isolation scores were highest among the work-at-home group (mean 3.1, SD 1.1), higher than the office group (mean 2.4, SD 0.9), and lowest in the telecommuting group (mean 1.7, SD 1.0), and the ANOVA showed a significant difference of group (F = 5.82, p = 0.007). |

| 85. | University of Exeter 2020116 | Y | UK Working from home |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing | Working from home: loneliness, increased demands to juggle work and domestic responsibilities (incl. child care) – negative effect on wellbeing. More anxious, less enthusiastic about job due to pandemic. Also lower wellbeing due to increased job insecurity, the unpredictability of future workloads, new ways of working and a lack of support from employers. |

| 86. | Virick 20109 | N | USA Employees |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Life satisfaction | Relation between extent of telecommuting and life satisfaction, with worker type (work drive and work enjoyment) moderating that relation. |

| 87. | Vitterso 200310 | N | Europe (UK, Norway, Iceland, Portugal) Workers |

Mixed: Survey Cross-sectional Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

QoL | Employees’ sense of belonging increased with a greater number of days working from home (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). There were no significant impacts of WFH on control, flexibility or concentration in this model. |

| 88. | Waizenegger 202043 | Y | Worldwide | Qualitative. Semi-structured interviews | Experiences of home workers | Impact of working from home during COVID: no choice, health concerns, spaces shared with others. Participants’ mental and physical wellbeing was (equally) affected by a lack of PA, due to sports facilities being closed and minimal contact with others being allowed. |

| 89. | Weitzer 202139 | Y | Austria General population |

Survey Cross-sectional |

QoL | Working from home: positive effect on QoL, negative effect on perceived productivity. Older participants, men, university educated and persons not working from home were most likely to report no changes in QoL. Those who worked from home all the time were more likely to report an increased QoL compared with those who were not working from home (OR 3.69, 95% CI 1.86 to 7.29). Working part of the time from home was also associated with an increased QoL compared with not working from home (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.09 to 3.91). |

| 90. | Wickens 2021117 | Y | Canada Adults |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Depressive symptoms | Working from home depressive symptoms lower than laid off / not working. After adjusting, from home was not a significant predictor of depressive symptoms (adjusted OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.77). |

| 91. | Wilke 202144 | Y | Worldwide Adults |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Mental wellbeing | Working outside the home vs. working remotely was associated with clinically relevant reductions in mental wellbeing (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.44), as was working both outside the home and remotely vs. working remotely (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.47). No factors associated with physical wellbeing (bodily pain) were found for work mode (p = 0.76). |

| 92. | Wöhrmann 202111 | N | Germany White-collar workers |

Survey Cross-sectional |

Wellbeing Psychosomatic health complaints |

No significant correlations were found between telework and psychosomatic health complaints. |

| 93. | Wood 202110 | Y | UK University staff |