Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/186/11. The contractual start date was in January 2017. The final report began editorial review in February 2020 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Littlewood et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Depression and long-term conditions

Depression is the largest cause of disease burden of all mental health problems and is estimated to become the highest among all health problems by 2030. 1 It accounts for 4.3% of the global disease burden and causes 63 million disability-adjusted life-years each year. 1 Approximately 30% of the UK population have a long-term health condition (LTC) (e.g. diabetes mellitus or asthma), and in those who do there is a two- to threefold increase in the prevalence of depression. 2 This combination of depression and LTCs can result in poorer health outcomes, lower quality of life and a reduced ability to self-manage, and contributes substantially to health inequalities. 2–4 Furthermore, people with depression are more likely to have two or more LTCs and this group experience the greatest decrements in quality of life. 5

The importance of comorbid depression and LTCs (mental–physical multimorbidity) is well established from the epidemiological and economic perspectives. The cost of care for people with mental–physical multimorbidity is 45% higher than for those without. 2 The NHS Five Year Forward View6 recognises that 30% of the population live with a LTC, the treatment of which accounts for 70% of total NHS costs; the most common and disabling multimorbidity is physical health alongside common mental disorders. 7 There is a need for an integrated patient-centred approach to support the mental–physical care of this underserved population. 7 The NHS Long Term Plan8 emphasises the need to provide better care for people with LTCs with expanded neighbourhood teams comprising a range of staff, such as general practitioners (GPs), pharmacists, district nurses, community geriatricians, dementia workers and allied health professionals (e.g. physiotherapists and podiatrists/chiropodists), joined by social care and the voluntary sector. 8

Subthreshold depression

Subthreshold depression is highly prevalent and is a major risk factor for progression to major depression. 9 It is defined as between two and four symptoms of depression, at least one of which must be either low mood or loss of interest or pleasure. 10 With comparable rates of excess mortality to those of major depression,11 estimates suggest that the prevalence of subthreshold depression in community samples ranges from 1.4% to 17.9%. 12 Prevalence estimates increase to up to 20% in those with LTCs; for this population, clinical guidelines recommend brief psychological support. 13 Although psychological interventions can reduce symptoms of depression in those with subthreshold depression (thus reducing the incidence of major depression), over 80% of people with ‘below-threshold’ mental health conditions remain untreated in psychological health-care services because they are often unable to meet the demand for treatment of major depression. 14 However, when people with frailty or physical health problems are referred to mental health services, they often do not make use of such services because of access issues and they often find the psychological approaches on offer unacceptable. 15 There is perhaps a need to move beyond traditional reliance on health services delivery; a public health approach to subthreshold depression in at-risk groups, such as those with LTCs, may offer alternative opportunities to provide health-care interventions in innovative and accessible settings.

Community pharmacies

In England, community pharmacies (CPs) are the most accessible and available health-care provider in the community, with 89% of the population able to access a CP from home within a 20-minute walk. 16 Importantly, in areas of the highest deprivation, this figure increases to almost 100%, an observation termed the positive pharmacy care law. 17,18 In terms of delivering health-care services to the people who need the services the most, CPs are uniquely placed in our local communities to achieve this. At present, there are approximately 11,600 CPs in England. Many of these are open in evenings and at weekends, which allows a range of different people, including those who work during the day, access to health care and public health services. 16 They offer people the opportunity to consult with a community pharmacist without a prior appointment, at a convenient time and in an accessible location. Published qualitative research also suggests that people often form trusting relationships with their local community pharmacist, which means that they are more likely to consult with them and ask for health advice than they are to consult with some other health-care professionals. 19 Further work has also shown that people with mental health conditions value CP services, particularly those reflecting patient-centred care, and are happy to engage with such services. 20 Examining experiences of CP users more broadly showed that people do not expect to routinely receive public health services in this setting, but that when they do they are highly satisfied with such services; however, there were mixed views on the ability of the pharmacist to do this effectively. 21

Community pharmacies, therefore, have the potential to deliver services that are aimed at promoting health and preventing disease. Recent examples of these services have focused on health promotion, including smoking cessation and weight management services. 22 These opportunities are also supported by recent policy drivers that allow CPs to deliver more patient-focused services, as outlined in the recently published Summary of the Five-Year Deal on the Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework. 23 The potential of the CP network has also been acknowledged by policy-makers as a way of helping the NHS to deliver on its long-term strategic plan. 24

An example at the national level of the changing role of the CP is the Healthy Living Pharmacy (HLP) programme. This is a tiered and structured commissioning framework that aims to deliver high-quality, patient-focused services from CPs to improve the health and well-being of the local population. 25 Crucially, the framework has provision to involve the wider pharmacy team who are able to train as Healthy Living Champions (HLCs): a formal qualification in understanding health improvement, accredited by the Royal Society of Public Health. Since April 2020, all CPs in England have been required to obtain HLP status as part of the agreement between the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee, NHS England and NHS Improvement, and the Department of Health and Social Care.

These developments support and complement the existing patient-focused services available through CPs, such as the flu vaccination and smoking cessation. A recent review of reviews26 examined the effectiveness of CP-delivered public health services and concluded that there are a number of CP services that have positive intervention effects on health outcomes. These services are predominantly focused on primary disease prevention and include smoking cessation, weight management programmes, syringe exchange programmes and inoculation services. The review also concluded that, although there is evidence of CP-delivered services being able to target people with physical health conditions, there is a dearth of literature exploring if (and how) CPs could deliver public mental health services and, given the reach of CPs in deprived areas, how these services could impact on health inequalities.

Developments such as the HLP programme lend support to the NHS and Public Health England’s Five Year Forward View6 plan, which calls for a radical upgrade in public health, including new partnerships that ‘break down barriers’ to support people with multiple health problems. In support of this, and owing to the socioeconomic disparities and the impact of physical–mental comorbidities, the Marmot27 report on health inequalities recommended a focus on the mental health of people with LTCs. There are many similarities between the behaviour change/management approaches to subthreshold depression (i.e. goal-setting, facilitated self-help and diary-keeping) and the public health interventions already being delivered by HLCs in CPs. CPs may, therefore, be well placed to offer and deliver opportunistic enhanced support to people with a range of health problems, such as comorbid subthreshold depression and LTCs, alongside the health promotion services and behaviour change programmes that they already provide. 28

Evidence for enhanced support interventions

A number of non-pharmacological treatments are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for depression in people with LTCs. 12,13 A recent Cochrane review29 highlighted collaborative care as having particular relevance to people with multimorbidity. Collaborative care ensures delivery of effective forms of treatment30 and uses session-by-session symptom profiling, medication management, patient education and brief evidence-based psychological interventions to optimise outcomes. 31,32 The evidence supporting collaborative care for people with depression33,34 is strong, especially when it includes a structured psychological intervention. 35 Collaborative care for depression is also effective when delivered by non-mental health specialists and for comorbid LTCs. 36

This collaborative care framework has been adapted to include a low-intensity psychosocial intervention for subthreshold depression. 37,38 The Collaborative Care for Screen Positive Elders (CASPER) trial38 developed an effective intervention for people with subthreshold depression (90% of whom also had comorbid LTCs) within primary care. This collaborative care intervention involved facilitated self-help and was based on behavioural activation (BA) supported by non-mental health specialists. This study reported a significant reduction in depression symptoms at 4 and 12 months (with an effect size of 0.30) for those people in the intervention group compared with those in the usual-care group. Importantly, significantly fewer people in the intervention group than in the usual-care group progressed to major depression at 12 months. 38 This finding supports existing depression prevention literature30 and lends support to the use of similar non-mental health specialist-supported interventions to target at-risk populations. 39,40 Further research is now needed to establish the suitability and effectiveness of such a prevention intervention as a public health initiative.

Rationale for CHEMIST

The Community Pharmacies Mood Intervention Study (CHEMIST) aimed to evaluate the potential for delivery of a behavioural change depression prevention intervention (similar to that implemented in the CASPER trial) within the important public health setting of CPs. Reviews of the literature at the time of the design of CHEMIST indicated that the existing evidence was not sufficiently robust, or experience in this area of research sufficiently developed, to support a definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT) at this stage in the evolution of this public health intervention. CHEMIST, therefore, sought to adapt ‘what works’ for people with subthreshold depression in primary care38,41 and evaluate this for use within a CP public mental health setting for people experiencing comorbid subthreshold depression and LTCs.

To the best of our knowledge, CHEMIST is the first to test the feasibility of an intervention (and associated study procedures) developed to utilise the unique opportunity of CPs to offer depression prevention alongside their other health promotion activities. CHEMIST aimed to provide high-quality evidence to inform the design and delivery of such a service and deliver the important preparatory work ahead of a definitive RCT that is needed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of such an intervention. CHEMIST adds to the existing limited evidence base on the use of CPs for the management of people’s mental health-care needs. 42,43

Research objectives

Feasibility study

-

To refine the bespoke enhanced support intervention (ESI) (including patient self-help materials, ESI manual and training) for implementation by CP staff to people with subthreshold depression and LTCs based on evidence-supported interventions in primary care.

-

To develop and refine study procedures (CP set-up and recruitment strategies; participant screening, recruitment and assessment; suitability of outcome measures; and data collection procedures) for testing in the external pilot RCT. 42

External pilot randomised controlled trial

-

To quantify the flow of participants (eligibility, recruitment and follow-up rates).

-

To evaluate proposed recruitment, assessment and outcome measure collection.

-

To examine the delivery of the ESI in a CP setting (ESI uptake, retention and dose) to inform the process evaluation.

-

To conduct a process evaluation, using semistructured interviews with participants, pharmacy staff and GPs across a range of socioeconomic settings, to explore the acceptability of the ESI within the CP setting, elements of the ESI that were considered useful (or not), and the appropriateness of study procedures. 42

Progression criteria

Progression criteria would inform the decision of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the funder in the continuation of the study from the feasibility study to the external pilot RCT, and in the feasibility of conducting a definitive RCT (to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the ESI for people with subthreshold depression and LTCs within a CP setting).

Feasibility study to external pilot randomised controlled trial

-

Recruit five participants at each of four to six CPs by month 6.

-

For 80% of participants to receive two or more ESI sessions within the 4-month post-recruitment period.

-

Collect valid (intended) primary outcome measure on 80% of recruited participants at the 4-month post-recruitment follow-up.

-

A fidelity score of ‘acceptable’ (3) or above to be achieved in at least 90% of assessed audio-recorded ESI sessions.

External pilot randomised controlled trial to a definitive randomised controlled trial

-

Recruit and randomise 100 participants across five or six CPs by month 20.

-

For 80% of participants randomised to the ESI to receive two or more ESI sessions within the 4-month post-randomisation period.

-

Collect valid (intended) primary outcome measure on 80% of participants at the 4-month post-randomisation follow-up.

Chapter 2 Feasibility study: methods

Parts of this chapter have been reported in Littlewood et al. 44 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Some of the information in this chapter is reported in Chew-Graham et al. (paper under review).

Study design

This was a feasibility intervention study with a nested qualitative evaluation. Participants with subthreshold depression and at least one LTC were recruited and offered the intervention. Quantitative data were collected at baseline and at 4 months. Qualitative feedback and data were collected throughout the study.

A number of modifications were made throughout the delivery of the feasibility study; the majority of these were considered minor and did not involve changes to key aspects of the study design (e.g. eligibility criteria). These changes are detailed in Chapter 5. Analysis of the qualitative data was initially intended to involve normalisation process theory (NPT),45 but instead the data were analysed following a framework analysis46 using the theoretical framework of acceptability (TFA). 47 The rationale for this revised analysis plan is detailed in Qualitative Study, Analysis.

Study approvals

Ethics approval was sought and granted on 18 November 2016 by North-East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 2 Research Ethics Committee (16/NE/0327). Approval was also obtained from the North East and North Cumbria Clinical Research Network on behalf of study sites. The study is registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trials Number (ISRCTN) registry (ISRCTN11290592).

Study sites

The study was conducted in eight CPs in the north of England. Five CPs were involved from the commencement of the study and three additional CPs were recruited during the recruitment period.

Participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in the feasibility study, participants needed to meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

had subthreshold depression

-

had at least one LTC

-

were aged ≥ 18 years.

Subthreshold depression was defined as two to four symptoms of depression, at least one of which must be either low mood or loss of interest or pleasure on the major depressive episode module of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). 48

Long-term conditions were defined according to the Department of Health and Social Care definition:

. . . a condition that cannot, at present, be cured; but can be controlled by medication and other therapies.

Department of Health and Social Care. 49 Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0

The LTCs were those that were included in the NHS Quality and Outcomes Framework50 at the time of recruitment and included exemplar conditions, such as arthritis, cancer, cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, respiratory conditions, stroke and progressive conditions.

Exclusion criteria

People were ineligible for the study if they met any of the following exclusion criteria:

-

had alcohol or drug dependence

-

had cognitive impairment

-

had bipolar disorder, psychosis or psychotic symptoms

-

had active suicidal ideation

-

were in receipt of psychological therapy.

Participant recruitment

Potential participants were identified via CPs or general practices using a number of recruitment methods. These recruitment methods were refined and/or implemented as the feasibility study progressed (see Chapter 5).

Potential participants were deemed eligible to receive study information via their CP or general practice if they met the following inclusion criteria (from those described above):

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

had a least one LTC.

An assessment of depression symptoms was conducted by the study team as part of the screening assessment with those potentially eligible participants who returned a consent form to the CHEMIST study team (see Screening for eligibility).

Study information pack

Potentially eligible participants were given the opportunity to receive a study information pack (see Community pharmacy-based recruitment and General practice-based recruitment). This contained an invitation letter (printed on CP- or general practice-headed paper, as appropriate), a patient information sheet (PIS), a consent form, a background information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 1) and a prepaid return envelope. The PIS advised interested CP customers/patients to complete and return the consent form and background information sheet to the study team in the prepaid envelope provided. They would then be contacted by the study team to discuss the study and to assess their suitability to take part.

Community pharmacy-based recruitment

Four methods of CP-based recruitment were employed during the feasibility study. All of the approaches were recorded (including the method of approach) on the customer’s patient medical record (PMR) to avoid duplication of approach via these recruitment methods.

Opportunistic approach by community pharmacy staff

Potentially eligible participants (CP customers) who attended the CP were approached by CP staff (see Study training) and were advised that the CP was taking part in a research study involving people with LTCs and were invited to receive information about the study. Interested CP customers were provided with a brief information sheet (BIS) (one page) to read while they were waiting to collect their prescription or to take away and read at home (see Report Supplementary Material 2). The BIS included the two short Whooley depression case-finding questions51 recommended by NICE. 13,52 A positive response to one or both of these two questions indicated suitability for further assessment of depression symptoms. The BIS advised CP customers that if they responded positively to either/both questions they may be suitable for inclusion in CHEMIST, and to request a study information pack from their CP to take away and read. The BIS included contact details for the CHEMIST study team if the individuals had any questions about the study. CP customers may have been attending the CP for a variety of reasons related to their LTC, for example to access services, such as the medicines use review (MUR) and new medicines service, or to collect their prescription, or for reasons unrelated to their LTC; therefore, the study approach could come from any CP staff member.

Community pharmacy customers who requested and were provided with a study information pack were asked for their ‘verbal consent to contact’. This was a verbal agreement for a member of the CHEMIST study team to contact them to discuss the study. CP customers providing their ‘verbal consent for contact’ gave the CP staff their name and contact details. These were then securely faxed to the CHEMIST study team who would then contact the CP customer a minimum of 2 days following the date of verbal consent to discuss the study and answer any questions.

Home-delivered prescriptions

Potentially eligible CP customers who received their prescriptions via the CP home delivery service were provided with a study information pack with their delivered prescription.

Community pharmacy system search

Community pharmacy staff conducted searches on their systems to identify potentially eligible CP customers. Lists of potentially eligible CP customers were reviewed by appropriately trained CP staff for exclusion of any customers whom it would be inappropriate to invite or any customers who had been previously invited by an alternative method. Following this check, the CP posted a study information pack to potentially eligible CP customers.

Study posters

Study posters were displayed in recruiting CPs (see Report Supplementary Material 3). These encouraged CP customers to contact the CHEMIST study team directly or speak to the CP staff for more information about the study and to request a study information pack.

General practice-based recruitment

General practices that were located nearby participating CPs conducted database searches on their systems to identify potentially eligible patients. Searches were restricted to patient postal codes within 2 miles of the participating CP(s) to ensure patient suitability of access, and included the exclusion criteria (see Participant eligibility). Lists of potentially eligible patients were reviewed by practice staff to exclude patients whom it would be inappropriate to invite. Practice staff then posted a study information pack to eligible patients.

Screening for eligibility

On receipt of a completed consent form, the potential participant was contacted by telephone by a trained CHEMIST researcher. The researcher provided a detailed explanation of the study, emphasising that the person may withdraw their consent to participate at any time without providing a reason, and that this would not affect the care that they received from their CP or GP. Potential participants were provided with an opportunity to ask any questions that they may have about the study. The researcher then confirmed the person’s LTC(s); if the person did not report having a LTC they were ineligible to take part and the screening interview was terminated at that point. The major depressive episode module of the MINI48 was then administered to assess for depression symptoms and disorders (subthreshold depression/major depression). The MINI is a standardised diagnostic interview that determines the presence or absence of depression (and other common mental disorders) in accordance with internationally recognised criteria. 53,54

Potentially eligible participants who met the criteria for subthreshold depression (indicated by two to four depression symptoms on the MINI) were then asked additional screening questions to check exclusion criteria (i.e. alcohol/drug use, bipolar disorder/psychosis/psychotic symptoms and current use of psychological therapy). Those who met any of the study exclusion criteria were not eligible to take part and were advised to speak with their GP, where appropriate. Eligible participants were then informed of their eligibility and arrangements were made to complete the baseline assessment (see Baseline assessment). Participants were reminded that their GP would be informed that they were taking part in the study (participants were required to provide their written consent for this to be included in the study).

Those who did not reach criteria for subthreshold depression (indicated by fewer than two depression symptoms on the MINI) or who met criteria for major depression (indicated by five or more depression symptoms on the MINI) were ineligible to participate, and the additional screening questions were not asked. If major depression was present, the person was informed of the probable presence of depressive symptoms and were advised to speak with their GP. In addition, a letter was sent to the person’s GP (with the person’s consent) informing them of the probable presence of depression and that further assessment/treatment may be required.

A telephone appointment screening letter was sent to those potential participants who could not be reached by telephone following several attempts. If this appointment was not attended, potential participants were sent a second letter that advised them to contact the study team if they would like to take part, otherwise there would be no further contact from the study team.

Baseline assessment

Eligible participants were posted a baseline questionnaire to complete and return to the study team in a prepaid envelope (see Outcome measures; see Appendix 1 for non-validated feasibility baseline questionnaires). The questionnaire included a £5 note where participants had provided their consent for this. If participants indicated that postal completion would be difficult, a telephone appointment was arranged with a researcher. A blank copy of the questionnaire (and £5 note where applicable) was posted to the participant to facilitate the subsequent telephone interview. A copy of the participant’s completed consent form was sent with their baseline questionnaire.

On receipt of a completed baseline questionnaire, a researcher contacted the participant by telephone to advise them that they would shortly be contacted by a ‘Healthy Living Advisor’ (a member of the CP team trained to deliver the CHEMIST intervention) to arrange their first pharmacy support session (see Intervention). They were then posted a copy of the self-help workbook and associated materials. Where applicable during this contact, the researcher also obtained any missing data or clarified any unclear responses on the returned baseline questionnaire (the date and method of any additional data collected/clarified was recorded on the questionnaire).

Participants who did not return a baseline questionnaire were sent a reminder letter (with a further copy of the baseline questionnaire) and/or were contacted by telephone to confirm receipt and check if they required help with completing the questionnaire. Participants who did not return a baseline questionnaire following these reminders were judged to be no longer interested and were not considered as recruited to the study.

Sample size

Given that the feasibility study was designed to refine the intervention and develop the study procedures for testing in the pilot RCT, the sample size required for the feasibility study was small: between 20 and 30 participants.

Intervention

No treatment was withheld from study participants.

The intervention is described in line with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 55

Intervention name

The intervention was an ESI: a brief psychological intervention (BA) delivered within a collaborative care framework.

Rationale

The ESI was based on a collaborative care approach and involved BA as the core psychological component.

The CHEMIST ESI was adapted from existing training and intervention materials. These materials have undergone extensive development exploring the theoretical framework, acceptability and validity in previous multicentre RCTs. 38,56 The existing intervention and training materials were refined for use in CHEMIST to provide a focus on functioning in people with mental–physical multimorbidity. This was achieved through discussions with CHEMIST co-applicants, members of the research team and with a range of stakeholders (see Patient and public involvement).

Central to the ESI were CP staff (referred to as ‘ESI facilitators’ hereafter; referred to as ‘Healthy Living Advisors’ in participant-facing information) who were trained to deliver the ESI with study participants. ESI facilitators were responsible for employing BA techniques to support study participants to work through a self-help workbook and for proactively following up with participants, monitoring depression symptoms and facilitating communication with other members of the participant’s health-care team to ensure synergy with any current care being provided. These key elements of the ESI are described in the following sections. This approach is responsive to individual patient needs and fits the core elements of BA and collaborative care (see the following sections).

Collaborative care

Collaborative care is based on chronic disease management models and may be useful in the management of common mental health problems. 35 It is a way of managing the treatment of an individual that seeks to maximise the integration of their care across all of the health-care professionals who make up their health-care team. This is achieved through the input of a person who forms part of the patient’s care team, often called a case manager (referred to as ‘ESI facilitator’ within CHEMIST), who liaises with all members of the team when necessary. A brief psychological intervention (such as BA) may be delivered by the case manager in addition to their liaison role. They may also help with medication management and treatment adherence.

Behavioural activation

At the core of the ESI is a brief psychological intervention based on utilising BA. 57 BA focuses on addressing the behavioural deficits common among those with depression and long-term health problems by reintroducing positive reinforcement of functional behaviours and reducing avoidance. Supporting people to identify and reintroduce valued activities that they have stopped doing by reason of physical frailty, or activities they would like to take up, is an important component of BA; previous work has demonstrated that this is helpful for people with functional deficits secondary to long-term health problems. 58

Behavioural activation is a simple intervention that has four key elements. The initial step introduces the BA cycle and how life changes, such as a long-term health condition, have resulted in a reduction in positive reinforcement from valued activities. Resultant low mood then leads to increased avoidance to mitigate the moment of distress. The cycle highlights how this avoidance subsequently further distances the person from the valued activity, which results in a downward spiral of mood and functioning. Using the combination of the collaborative care and BA structure, this treatment explanation is individualised to the specific patient and draws on their priorities and values to understand what changes are important for them.

Building from this, the core elements of BA (self-monitoring, activity scheduling and functional analysis) are then used to break the cycle. Self-monitoring identifies the link between mood and activity/functioning. Activity scheduling targets behaviours that are important and useful to the individual patient in the context of their health priorities and plans these in a diary to increase positive reinforcement. This approach introduces the concept of ‘rather than waiting to feel better to do something, do something to feel better’. Functional analysis introduces an ‘Antecedent, Behaviour, Consequence’ breakdown of problem areas identified in the course of the intervention to support the change process. In CHEMIST, the adapted ESI utilised these core BA strategies to address problems of functioning and subthreshold depression associated with long-term health problems. BA strategies were individualised based on individual patient’s needs using a BA patient self-help workbook and contact with and support from the ESI facilitator (or case manager, as described earlier).

The CHEMIST enhanced support intervention

The CHEMIST ESI consisted of four main elements:

-

Self-help support – this focused on BA (as described above) with the provision of a self-help patient workbook, supported by the ESI facilitator.

-

Proactive follow-up – the participant’s use of the self-help patient workbook was supported by the ESI facilitator via ESI sessions (face-to-face and/or telephone delivery) conducted at regular (weekly) intervals. ESI facilitators were encouraged to be proactive in scheduling and following up patient contact/sessions where necessary.

-

Depression symptom monitoring – depression symptoms were monitored at each ESI session by the ESI facilitator, using the depression scale from the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS). 59 The DASS is widely used and validated in a UK community context and is sensitive to change over time. 60 It is brief and simple to score with clear clinical cut-off scores (non/mild/moderate/severe depression symptoms).

-

Decision-supported signposting – scores on the DASS were used to guide decision-making by the ESI facilitator and guided by supervision provided by clinical members of the research team. Where significant clinical/symptom deterioration was observed, the participant was supported to access more formal health-care interventions and was encouraged to contact their GP to discuss this, or the ESI facilitator would talk with their GP directly if the participant so wished. Through discussion with the participant, other areas where functioning deficits may exist could be identified. These might include necessary adaptations within the home, access to transport or financial advice. If it was felt that the involvement of other services, such as social services or voluntary sector organisations, was warranted, the ESI facilitator could help to enable access to these (with support provided where necessary via clinical supervision from the CHEMIST study team).

Materials and procedures

Study participants received a 28-page self-help workbook that was divided into eight stages (‘stages to keeping well’). The stages covered recognising symptoms of low mood/depression, diary-keeping, defining activity types, breaking activities down, identifying benefits of activities, identifying ways to be active, spotting symptoms of depression and setting an action plan. The workbook also included a number of tasks for participants to complete (e.g. making a list of activities that keeps the person well). A notes section was included at the end of the workbook, and participants were provided with additional copies of the diary and task pages. The workbook was used during and between contacts with the ESI facilitator. Participants were also provided with a blank copy of the DASS for use during each session.

The ESI was supported by a detailed ESI facilitator manual that included an outline of the key elements of the ESI, detailed session-by-session content, the DASS and the risk protocol (see Risk management). The ESI facilitator manual was supplemented by participant treatment logs, in which session information (e.g. scores on DASS, outcome of risk assessment and general session notes) was recorded for each participant and used to guide clinical supervision.

The CHEMIST ESI and training materials are not currently available outside the context of the study.

Enhanced support intervention facilitators were provided with information about study participants via the study team (following randomisation in the pilot RCT; see Chapter 6). The assigned ESI facilitator would contact the participant to arrange their first intervention session (to take place face to face in the pharmacy consultation room or over the telephone). Subsequent sessions were arranged during the previous session. Participants were encouraged to contact their ESI facilitator if they were unable to attend sessions so that these could be rearranged. ESI facilitators were advised to proactively contact participants who did not attend prearranged sessions. Contacts were monitored during clinical supervision.

Enhanced support intervention sessions followed a schedule outlined in the ESI facilitator manual. Each session involved a discussion between the participant and the ESI facilitator based on the stages within the self-help workbook. The first session included discussing how the participants were, including how they felt physically and mentally. Information was gathered on how the participant’s activities were being affected by their mood or physical health, as well as their understanding of the self-help workbook. Subsequent sessions began by gathering information related to the participant’s understanding of the previous session, discussion of the work undertaken since the previous session and reflection in relation to the BA approach. Opportunities to collaborate with health-care or social care professionals and voluntary sector organisations were identified and discussed. Support to access such services was provided if the participant wished. The DASS was administered during all sessions to monitor depression symptoms and the outcome was discussed. Potential risk was checked at the beginning of all sessions and the risk protocol was activated if necessary (see Risk management). Finally, the next stage(s) of the self-help workbook was discussed and the ESI facilitator and participant agreed the work to be undertaken before the next session.

Intervention providers

The CP pharmacist and/or pharmacy manager identified and approached suitable CP support staff about the study and the ESI facilitator role. ESI facilitators were CP support staff experienced in the delivery of pharmacy extended roles (such as smoking cessation behavioural–change approaches) and/or training to Royal Society of Public Health standards (Understanding Health Improvement Level 2).

Enhanced support intervention facilitators attended a 2-day training workshop prior to delivering the ESI. The workshop included presentations (copies of presentation slides were provided) that outlined the study and explained the concepts of BA and collaborative care. Clinical scenarios were used to outline the ESI rationale and process. The materials to be used as part of the ESI (patient self-help workbook, ESI facilitator manual and participant treatment logs) were provided and described. Clinical role-play exercises were used to practise skills and ESI session content based around the self-help workbook. Opportunities were provided to discuss the ESI and the role-play exercises. The workshop also included training on risk assessment (with opportunities to practise this via role-play) and other important study procedures [including serious adverse event (SAE) reporting and participant withdrawal]. ESI facilitators were required to undertake and pass a telephone-based competency assessment before they could be assigned an ESI participant.

Enhanced support intervention facilitators received telephone supervision from a clinical member of the research team on a session-by-session basis.

Mode of delivery

The ESI was designed to be delivered on a one-to-one basis by a combination of face-to-face and telephone contact (based on participant preference). Participants were offered the first session as a face-to-face contact within the CP, with telephone delivery encouraged for subsequent sessions.

Location

The ESI was delivered via CPs located in the north of England.

Personalisation

Although all participants received the same self-help workbook, the ESI was designed to be personalised by the ESI facilitator to the participant’s situation and long-term health problems using the self-help workbook as a guide.

Intervention dose

The ESI was designed to be between four and six sessions, delivered where feasible on a weekly basis over a period of up to 4 months. The first session was designed to take up to 60 minutes, with subsequent sessions taking between 20 and 30 minutes.

Modifications

The ESI was adapted from existing intervention and training materials. The ESI was not modified during the course of the feasibility study. Modifications were made following the feasibility study in advance of the pilot RCT; these modifications are reported and described in Chapters 5 and 6.

Competency and intervention fidelity

The competency of ESI facilitators to deliver the ESI in line with training and the ESI facilitator manual was assessed using procedures adapted from previous related studies. 61 Following the ESI training workshop, mock telephone ESI sessions were conducted with ESI facilitators, and behaviours and performance were evaluated against a competency checklist. ESI facilitators were offered additional training, if necessary, to enable them to achieve the required standard to pass the competency assessment.

Fidelity to the ESI was supported by the ESI facilitator manual, which included ESI session guides. Telephone supervision was offered by clinical members of the research team after every ESI session. ESI facilitators also had access to ad hoc telephone supervision if they required further support. Fidelity assessment also involved obtaining audio-recordings of ESI sessions (where participant consent was provided for this). A random selection (10–20%) of audio-recordings across different phases of the ESI (early/late) was to be independently reviewed and assessed against a fidelity checklist. The feasibility of obtaining these audio-recordings was to be explored in the feasibility study, given that the delivery of the ESI to research participants was a new approach for CPs.

Follow-up

Participants were followed up 4 months after completion of their baseline questionnaire (see Outcome measures; see Appendix 2 for non-validated follow-up questionnaires).

Those participants who completed their baseline questionnaire via post were sent a 4-month follow-up questionnaire to complete and return to the study team in a prepaid envelope. Participants who completed a telephone baseline questionnaire were contacted by telephone by a researcher to determine how they wanted to complete the follow-up questionnaire. Telephone follow-ups were arranged where this was requested and a blank copy of the questionnaire was posted in advance of the telephone appointment. A £5 note was included with posted follow-up questionnaires where participant consent for this was provided. Participants who did not return a follow-up questionnaire were sent a reminder letter (with a further copy of the follow-up questionnaire) and/or were contacted by telephone to confirm receipt and check if they required help with completing the questionnaire. Where applicable, participants were contacted by telephone to obtain missing data or to clarify any unclear responses on returned follow-up questionnaires (the date and method of any collection of additional data or clarification were recorded on the questionnaire).

Participants were sent a study completion letter on receipt of a completed follow-up questionnaire.

Outcome measures

Participants completed a number of measures to assess the quality and acceptability of data collection at the various time points during the feasibility study and to inform the pilot RCT phase and any future definitive RCT (see Chapter 1).

Participants completed a background information sheet at the point of consent to the study (see Report Supplementary Material 1). This included the two Whooley depression case-finding questions51 and demographic information. The Whooley questions and a subset of the demographic information were completed again as part of the 4-month follow-up questionnaire. It was also planned for participants to complete the 9-item Behavioural Activation for Depression Scale (BADS)62 during ESI sessions in order to inform the process evaluation in the pilot RCT. The BADS is a measure of activation and is a tool commonly used in studies involving behavioural activation for depression. Additional information (to include depression onset age and number of episodes) obtained via the MINI at baseline would also inform the pilot RCT process evaluation.

Intended primary and secondary outcome measures were collected at baseline and at the 4-month follow-up.

See Appendix 3 for the data collection schedule.

Intended primary outcome measure

The intended primary outcome measure was self-reported depression severity at the 4-month follow-up, as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). 63 The PHQ-9 is widely used in clinical and research settings and has good sensitivity and specificity in a UK population. 64

Intended secondary outcome measures

-

Self-reported binary depression severity (PHQ-9),63 using a score ≥ 10 to indicate moderate depression caseness at the 4-month follow-up (thus providing a measure of the potential preventative aspects of the intervention in their ability to prevent progression of depression).

-

Anxiety [Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale]. 65

-

Physical/somatic health problems (PHQ-15). 66

-

Health-related quality of life [Short Form-12, version 2 (SF-12v2)]. 67

-

Health state utility [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)]. 68

-

Health and social services use collected via a bespoke resource use questionnaire.

Study completion and participant withdrawal

Participants were considered to have exited the study when (1) the participant had completed their 4-month follow-up (and qualitative interview if this was to be conducted following the 4-month follow-up; see Qualitative Study), (2) the participant wished to fully withdraw from the study, (3) the participant’s GP advised full withdrawal from the study or (4) the participant had died.

Where participants expressed a wish to withdraw from the study, they were given the choice of (1) withdrawal from the ESI sessions only (participants were still followed up at 4 months and could participate in a qualitative interview), (2) withdrawal from follow-up (participants could continue to receive the ESI sessions up to the 4-month follow-up time point) or (3) full withdrawal from the study, including the ESI and follow-up. Where withdrawal from the study was because of a SAE, the SAE standard operating procedure (SOP) was followed (see Serious adverse events).

Where possible, data were collected on reasons for withdrawal. Participants were reminded that withdrawal from the study would not affect the care that they received from the CP or their GP. Data collected from participants up to the point of full withdrawal were still included in any data analyses, unless the participant requested that their data were not used in the analysis.

Quantitative data analysis

Owing to the small sample size for the feasibility study, no formal analysis was planned. A single analysis was performed at the end of the feasibility study using Stata® v15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Feasibility baseline data and all standardised measures are summarised descriptively, and the number of missing responses detailed. Continuous data are reported using means, standard deviations, medians, and the minimum and maximum. Categorical data are reported as counts and percentages. The flow of participants through the study will be reported.

Outcomes

In the feasibility study, the outcomes of interest were recruitment and retention rates, the quality of data collected and engagement with the ESI. The number of pharmacy customers/patients approached and the number of participants recruited and who completed the 4-month follow-up are detailed, along with the completeness of the standardised measures used. The number of ESI sessions attended and the number of participants who did and did not start the ESI sessions will be detailed, with reasons provided where possible.

Serious adverse event data were summarised descriptively by treatment arm.

Qualitative study

A qualitative evaluation was nested within the feasibility study with the primary aim of exploring the feasibility and acceptability of the study, ESI training and delivery, and study procedures. Qualitative interviews were conducted with study participants and ESI facilitators, and a focus group was held with CP staff. The qualitative findings would inform adaptations for the pilot RCT (see Chapter 5).

Participants and recruitment

Semistructured interviews

The aim was to conduct in-depth semistructured interviews with (1) up to 10 study participants (purposively sampled, where feasible, across recruiting CPs and with a mix of LTCs and from different areas of deprivation) to explore the acceptability of the ESI and delivery within a CP setting; and (2) approximately 10 ESI facilitators following ESI training and/or delivery of the ESI, to explore the acceptability and feasibility of the ESI training and delivery, and the study procedures.

Study participants provided their consent to participate at the same time as consenting to the feasibility study (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for a copy of the participant consent form). Participants who declined to consent to an interview were still eligible to participate in the feasibility study.

Study participants who had provided their consent for an interview were contacted by telephone by a member of the research team once they had finished their ESI sessions. Study participants who did not commence ESI sessions or who started ESI sessions but then dropped out were also approached to take part in an interview (where they had provided consent for this) to explore their reasons for disengagement. Study participants were advised that interviews would last around 45 minutes and could be conducted at a time and location convenient to them (e.g. at home, in the pharmacy or by telephone).

All ESI facilitators were invited to participate in an interview. Following completion of the ESI training, ESI facilitators were sent a study invitation pack (containing an invitation letter, PIS, consent form and prepaid return envelope; see Report Supplementary Material 4) in the post (individually addressed to them at the pharmacy). Interested ESI facilitators were required to send their completed consent form directly to the study team. This process was carried out independently from the pharmacy (including pharmacy managers and co-workers) to ensure that ESI facilitators felt comfortable to talk about their experiences.

Enhanced support intervention facilitators who returned a consent form following the ESI training were contacted by telephone by a member of the research team to arrange an interview to explore their experiences and views of the ESI training. Once delivery of the ESI had commenced, those ESI facilitators who had participated in an initial (training) interview and who had supported at least one participant through the ESI were invited to participate in a brief second interview to explore their experiences of delivering the ESI. A second reminder invitation pack was posted to those ESI facilitators who did not respond to the initial invite. Those ESI facilitators who returned a consent form following this second invite participated in a single interview to explore their experiences of the ESI training and ESI delivery. ESI facilitators could indicate whether they wanted to be interviewed in person, in a private room at the pharmacy or over the telephone, and a time convenient to them.

To ensure confidentiality and to encourage interviewees to speak freely, interviews with ESI facilitators were not conducted with those study researchers who had been involved in their training (either ESI training or general study/recruitment training). Only anonymised interview transcripts could be accessed by those researchers involved in their training.

Focus group

The aim was to hold a focus group consisting of 8–10 CP staff, to include a range of CP roles from across the recruiting CPs. All CP staff (including ESI facilitators) within each recruiting CP were invited to take part in a focus group to explore their experiences of the study, including recruitment, delivery of the ESI, study procedures and impact on pharmacy routine practice. CP staff were invited to participate following the procedure described above (see Report Supplementary Material 5). Interested CP staff returned a completed consent form directly to the study team indicating their availability for a focus group. The focus group was held at a community facility away from their place of work.

Topic guides

Individual topic guides were used for each participant type (study participants, ESI facilitators, focus group with CP staff) (see Report Supplementary Material 6). Interview topic guides were developed based on existing literature and were amended iteratively throughout the data collection process.

Analysis

The interviews and focus group were recorded using an encrypted digital audio-recorder and were professionally transcribed verbatim. All data were analysed thematically initially using constant comparison69 followed by a framework analysis46 using the TFA to sensitise the analysis. 47 Although it was initially intended that a secondary analysis using NPT45 would be undertaken, as the analysis progressed the TFA was felt to be more appropriate as this framework offers the opportunity to focus on acceptability of the ESI and ESI training, and what modifications are needed for the pilot RCT. The analyses were undertaken by a team of researchers with varying professional backgrounds to increase the reliability of the analysis. 70 Regular coding and analysis meetings were held to ensure that the emerging themes remained grounded in the data, and that the TFA appropriately represented the data.

Health economic analysis

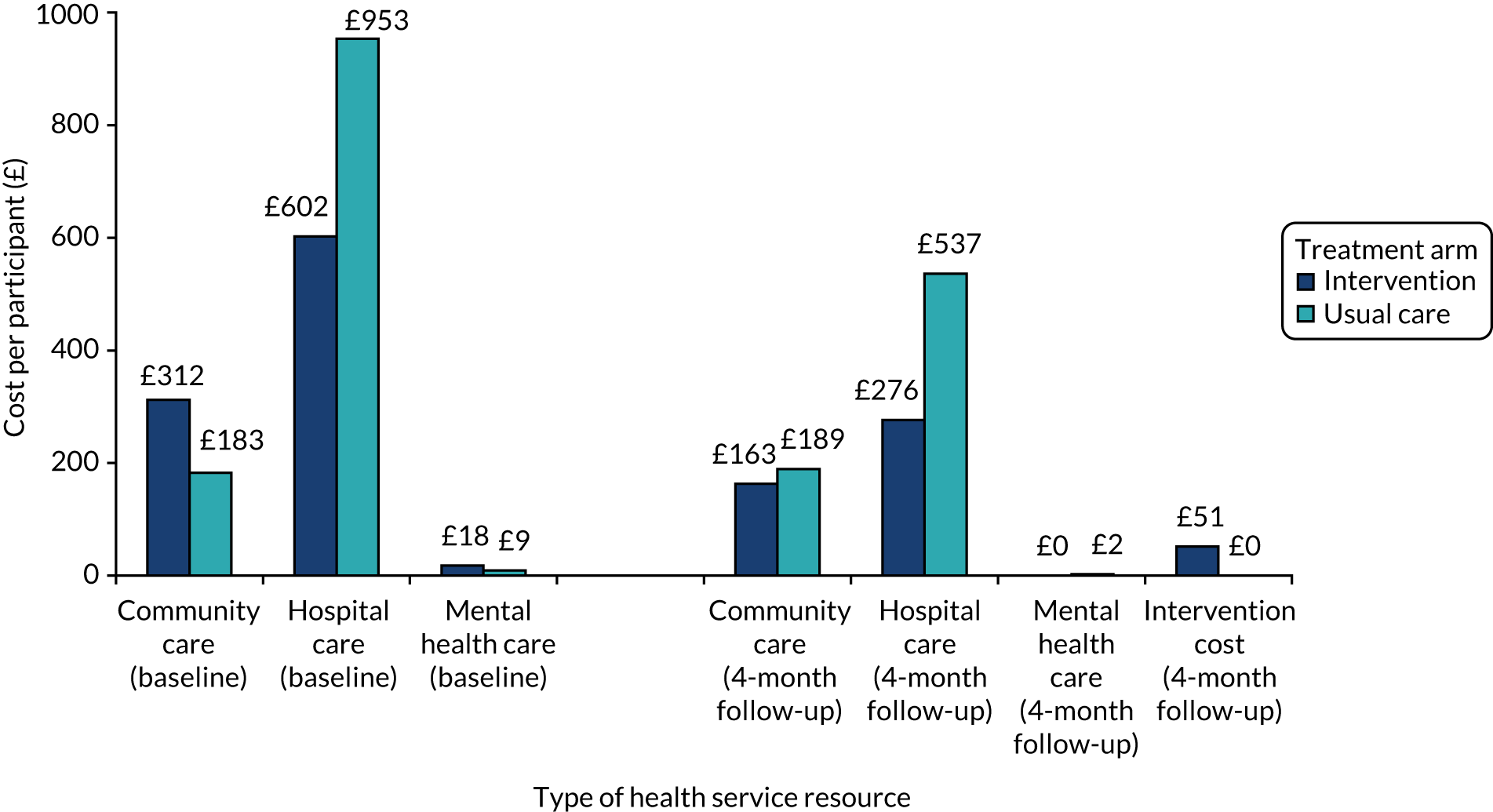

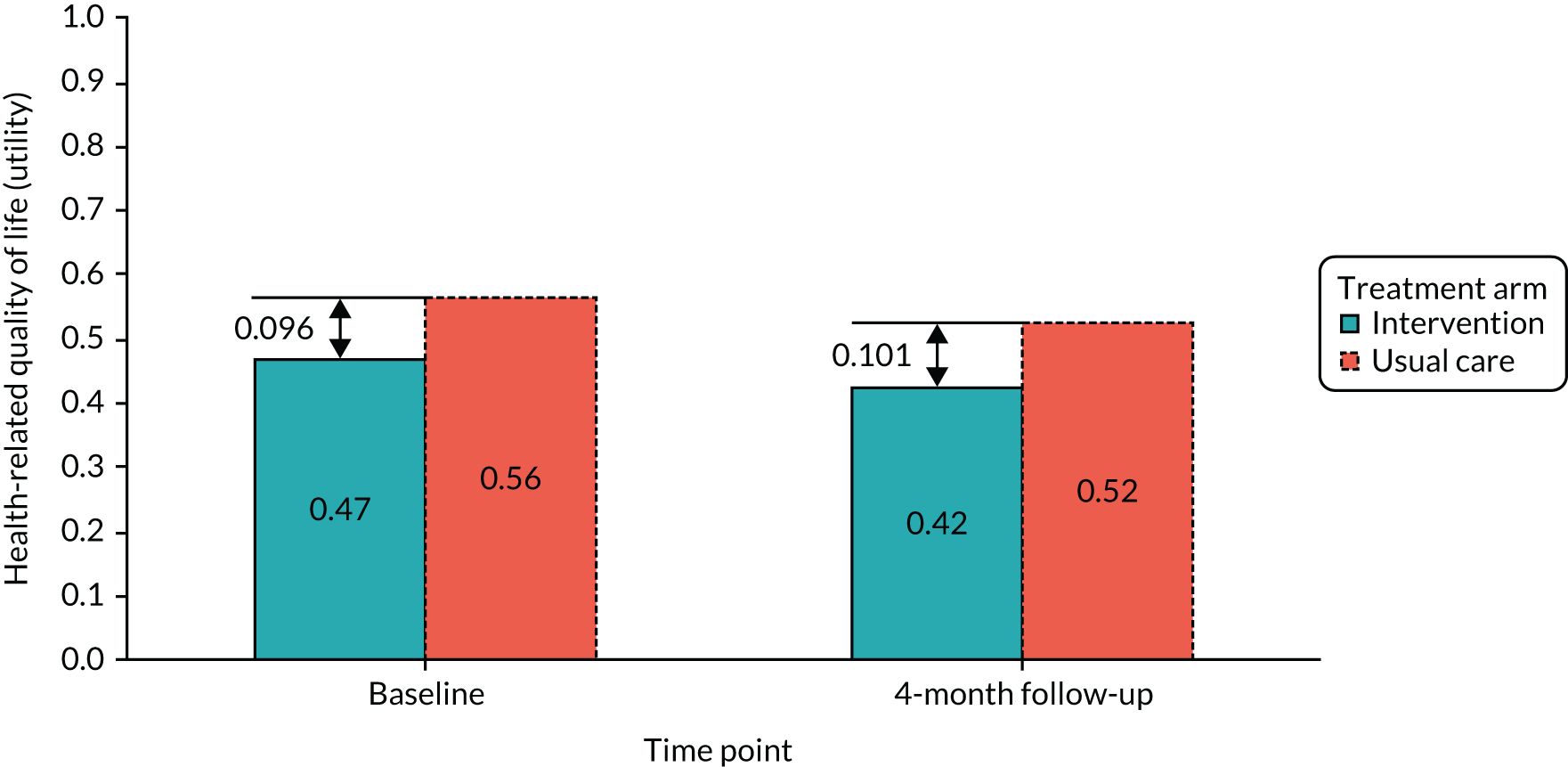

Economic analysis was conducted with the aim to evaluate the feasibility of collecting data on costs and health-related quality-of-life outcomes to inform the pilot RCT. Data were collected at baseline and at 4 months post recruitment. The economic analysis evaluated the overall response rates, item completion rates and the range of values provided in response to the bespoke resource use questionnaire and health-related quality-of-life questionnaire, EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) (described below). 71

Health service resource use data were collected using a bespoke self-reported resource utilisation questionnaire (adapted from the Adult Service Use Schedule72) (see Chapter 2 and Appendix 1). The questionnaire collected data on the following service use categories in the previous 4 months:

-

General health and community service use (i.e. appointments with GP, nurse, NHS direct and walk-in centre, occupational health services, social worker or community support worker or drug and alcohol support worker). Participants were also asked how many of each of these visits were because of low mood.

-

Mental health services (i.e. appointments with psychotherapist or counsellor, clinical psychologist, community mental health team or community psychiatric nurse or consultant psychiatrist).

-

Hospital-based services [i.e. outpatient appointments, accident and emergency department visits, urgent care centre or minor injuries unit, or inpatient admission(s) with or without overnight stays].

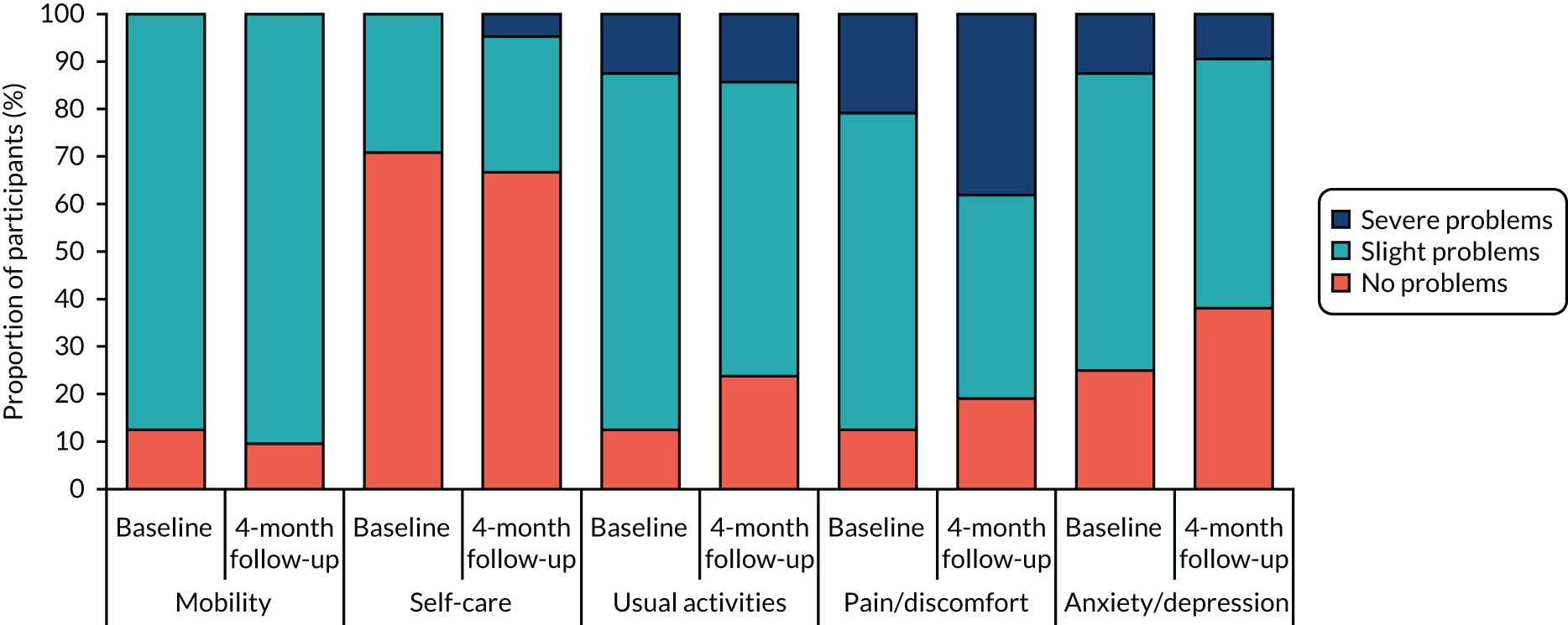

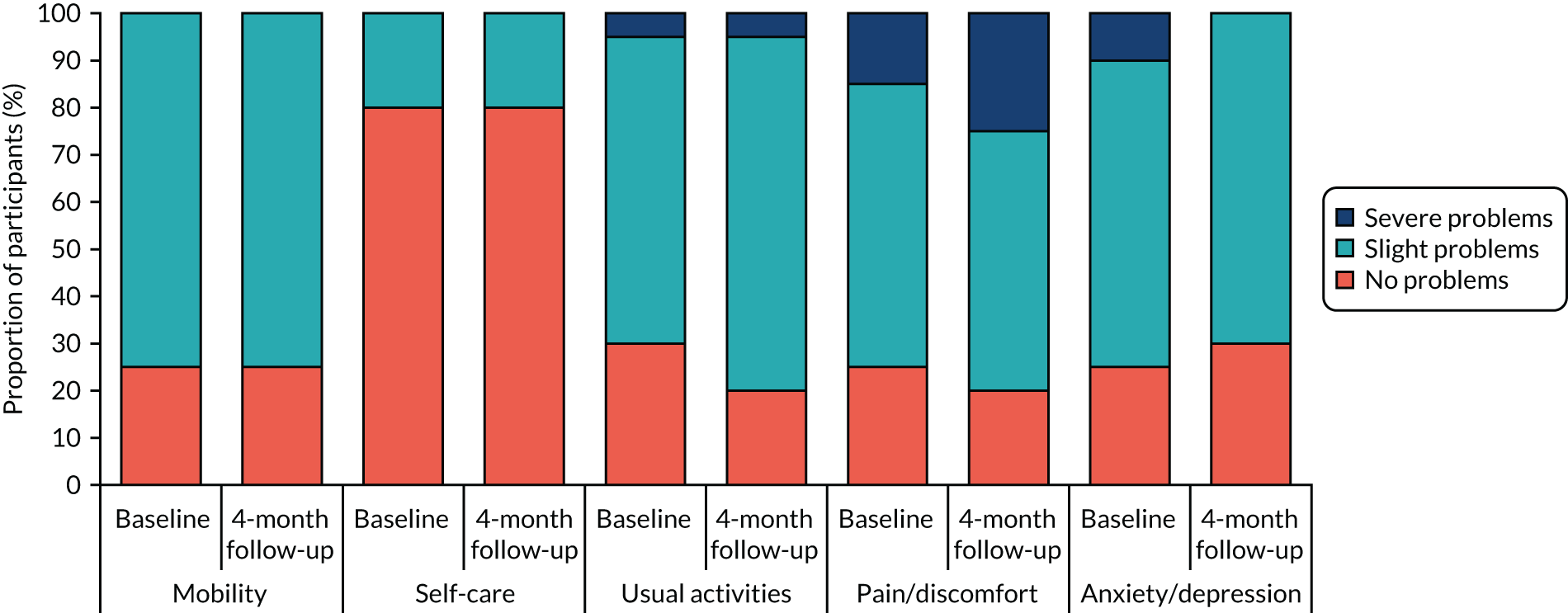

Health-related quality of life was measured using the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire. 73 Individual-level responses on the EQ-5D were used to estimate health-related quality of life based on a UK population valuation set. The EQ-5D, originally developed by the EuroQol group, is a widely used measure of health-related quality of life. Using this measure, respondents are able to classify their own health on a three-point scale: 1 = no problems, 2 = some problems and 3 = severe problems. Health-related quality of life is measured over five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and/or discomfort, and anxiety and/or depression. All questions refer to the participant’s health state ‘today’.

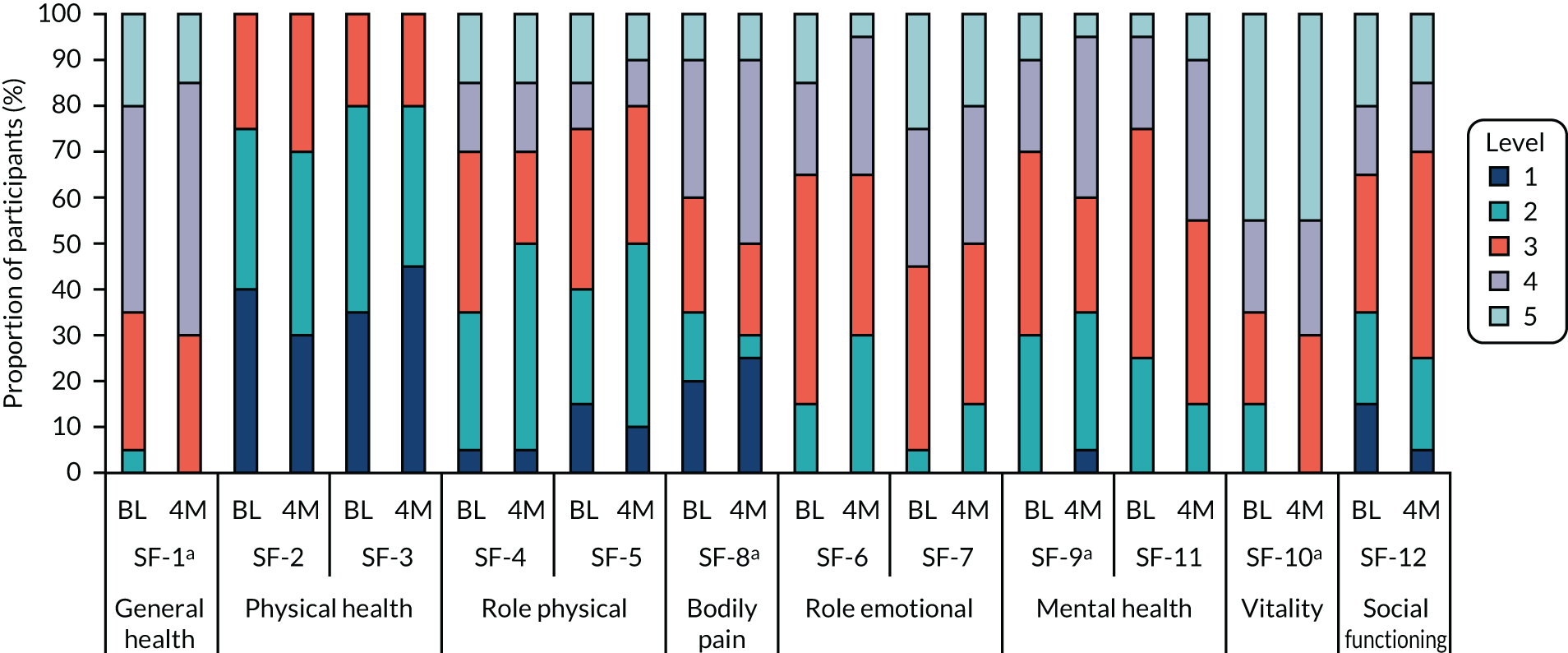

Quality of life was also measured using the SF-12v2 health questionnaire. 74 The SF-12v2 measures health by asking participants about eight domains of physical and mental health. These include the following:

-

general health – one item (SF-1) provides a rating of general health (levels 1–5: 1 = excellent, 5 = poor)

-

physical health – two items measure health limitations on moderate (SF-2) physical activities (e.g. moving a table) and more demanding (SF-3) physical activities (e.g. climbing several flights of stairs) (levels 1–3: 1 = limited a lot, 3 = not limited at all)

-

role physical (SF-4 and SF-5) – two items measure lower accomplishment (SF-4) and limited activity (SF-5) at work owing to physical problems (levels 1–5: 1 = all of the time, 5 = none of the time)

-

role emotional (SF-6 and SF-7) – two items assess limitations in work or daily activities owing to emotional problems (levels 1–5: 1 = all of the time, 5 = none of the time)

-

bodily pain (SF-8) – one item related to the presence of and limitations as a result of pain (levels 1–5: 1 = not at all, 5 = extremely)

-

mental health (SF-9 and SF-11) – two items assess feeling calm (SF-9) and feeling downhearted/low (SF-11) (levels 1–5: 1 = all of the time, 5 = none of the time)

-

vitality (SF-10) – one item assesses abundance of energy level and fatigue (levels 1–5: 1 = all of the time, 5 = none of the time)

-

social functioning (SF-12) – one item assesses limitations owing to physical or emotional problems (levels 1–5: 1 = all of the time, 5 = none of the time).

The SF-12v2 items refer to the participant’s health in the past 4 weeks (except general health and physical health that do not specify a time period).

Finally, the results of the cost and health-related quality-of-life data were reported in terms of the overall response rate for each questionnaire, rate of missing items within each questionnaire and level of health service resource use and health-related quality of life (by item/domain) at baseline and follow-up.

Serious adverse events

A study-specific SOP was implemented for the identification and reporting of suspected SAEs. Standard criteria for the definition of a SAE were used. Study researchers and ESI facilitators were instructed to report any suspected SAEs to the trial manager and chief investigator via a standard SAE reporting form.

All suspected SAEs were reviewed by a clinician independent to the study team. Any SAEs judged to be related to study treatment or procedures, or that were unexpected, were referred to the Research Ethics Committee. SAEs were reviewed by the TSC and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee.

Risk management

Study-specific risk protocols were implemented for the identification, assessment and reporting of any risk relating to suicide or self-harm during all designated participant contacts (screening assessment, baseline and follow-up questionnaires, ESI sessions and qualitative interviews). Participants were asked specific questions about risk as part of the MINI (screening assessment) and PHQ-9 (baseline and follow-up questionnaires), and during each intervention session. A risk assessment was conducted immediately following a positive response to any of the specific risk questions asked, or in instances where participants voluntarily expressed thoughts of suicide or self-harm during any participant contact. The researcher asked the participant a set of questions to determine the level of risk and where necessary this was then discussed (within the same day) with a clinical member of the study team. Where any risk was identified, regardless of level of risk, the participant was advised to speak with their GP. Risk was reported to the participant’s GP (with the participant’s consent) where deemed necessary by a clinical member of the study team. Where risk was identified on a returned postal questionnaire, the participant was contacted within 24 hours of knowledge of the potential risk to conduct the risk assessment. Where contact could not be made within this time frame, the potential risk was discussed with a clinical member of the study team and relevant actions taken (this may include continuing to make contact with the participant after the 24-hour time frame or contacting the participant’s GP). At least one clinical member of the study team was on call to respond to risk during working hours (unless otherwise arranged) while participants were involved in the study. All instances in which a risk protocol was implemented were recorded and signed by the researcher conducting the risk assessment and the clinician who provided the risk advice.

Study training

All study researchers and ESI facilitators completed study-specific training on all those activities relevant to their role (to include assessment of risk) before commencing contact with participants. ESI facilitators completed a 2-day training workshop on the ESI (see Intervention). Study researchers and ESI facilitators were provided with support following risk assessments or any participant contact, if required, from relevant members of the study team. Study researchers completed good clinical practice training.

Study researchers delivered face-to-face study training with CP staff (including pharmacists/pharmacy managers and ESI facilitators where possible) from all recruiting CPs. The training provided an overview of the study, a detailed explanation of recruitment methods and processes, and associated study paperwork requiring regular completion. Training emphasised that all CP staff could be involved in the recruitment process. Study training was supported by a training document that CPs stored in their investigator site files. Recruiting CPs received regular telephone calls and/or visits from study researchers to discuss recruitment progress and to gather feedback on the study processes (including recruitment methods).

Patient and public involvement

CHEMIST benefited throughout its duration from the involvement from people who disclosed lived experience of mental health problems (including depression) and/or long-term health conditions. The study was developed in partnership with people (including service users and those accessing CP services) from the University of Durham Pharmacy patient and public involvement (PPI) Group and the Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust Service User Research Consultation Group. Members of these two groups provided feedback on the study research topic/question and the study and intervention design in advance of submission of the funding application via face-to-face group discussions and through follow-up e-mail communication.

A CHEMIST PPI advisory group (AG) was established from those members involved in the initial consultation and feedback process. Members were involved in the development of various recruitment materials (such as the PIS) and the patient self-help workbook, and were consulted on various study procedures. For example, the patient self-help workbook was amended to include less age-specific activity examples in the light of feedback from this group, and members suggested useful ways in which participant recruitment might be improved. Members were also consulted on various planned changes ahead of the pilot RCT phase. This lead to the restructuring of the PIS and a clearer explanation of instructions for completion of study questionnaires.

Expressions of interest were sought from PPI AG members for membership of the Trial Management Group (TMG) and the independent TSC. Two PPI AG members sat on the TMG and two (different) PPI AG members sat on the TSC. These four members contributed to TMG/TSC meetings where possible, either in person or via teleconference, and provided input into the running of CHEMIST (although two of these PPI AG members, one from each of the TMG and TSC, resigned from their roles on these committees and the PPI AG before the study finished).

In addition to the above PPI input, a CHEMIST special interest group consisting of public health specialists and CP staff (including pharmacists and counter staff) convened on three occasions throughout the development of the study and funding application to advise on aspects including local pharmacy recruitment procedures and materials. Throughout the duration of the study, meetings were held with Local Pharmacy Committees, Local Pharmacy Networks and those CP staff and public health specialists involved with the study (including those from recruiting CPs). This provided an opportunity to discuss issues relating to study delivery and progress (with a particular focus on recruitment processes and strategies) and study promotion within local CP community/networks.

The final study findings were discussed at a results and interpretation meeting before submission of this report; representation from the PPI AG was sought for this meeting, although, unfortunately, attendance was not possible. Two PPI AG members were invited to help with drafting the Plain English summary for this report and one member provided useful comments. Members of the PPI AG will be provided with a summary of the study findings and will be invited to provide input on the development and implementation of an appropriate dissemination strategy (to include the development of an accessible summary of the study findings to distribute to study participants). A summary of the findings will also be made available to all recruiting CPs and general practices, those involved in the special interest group, and local CP community/networks.

Chapter 3 Feasibility study: quantitative and health economic findings

Some of the information in this chapter is reported in Chew-Graham et al. (paper under review).

Quantitative results

Recruitment

The target sample size for the feasibility study was 20–30 participants, who were to be recruited over 5 months (February to June 2017) from four to six CPs (see Chapter 1, Progression criteria).

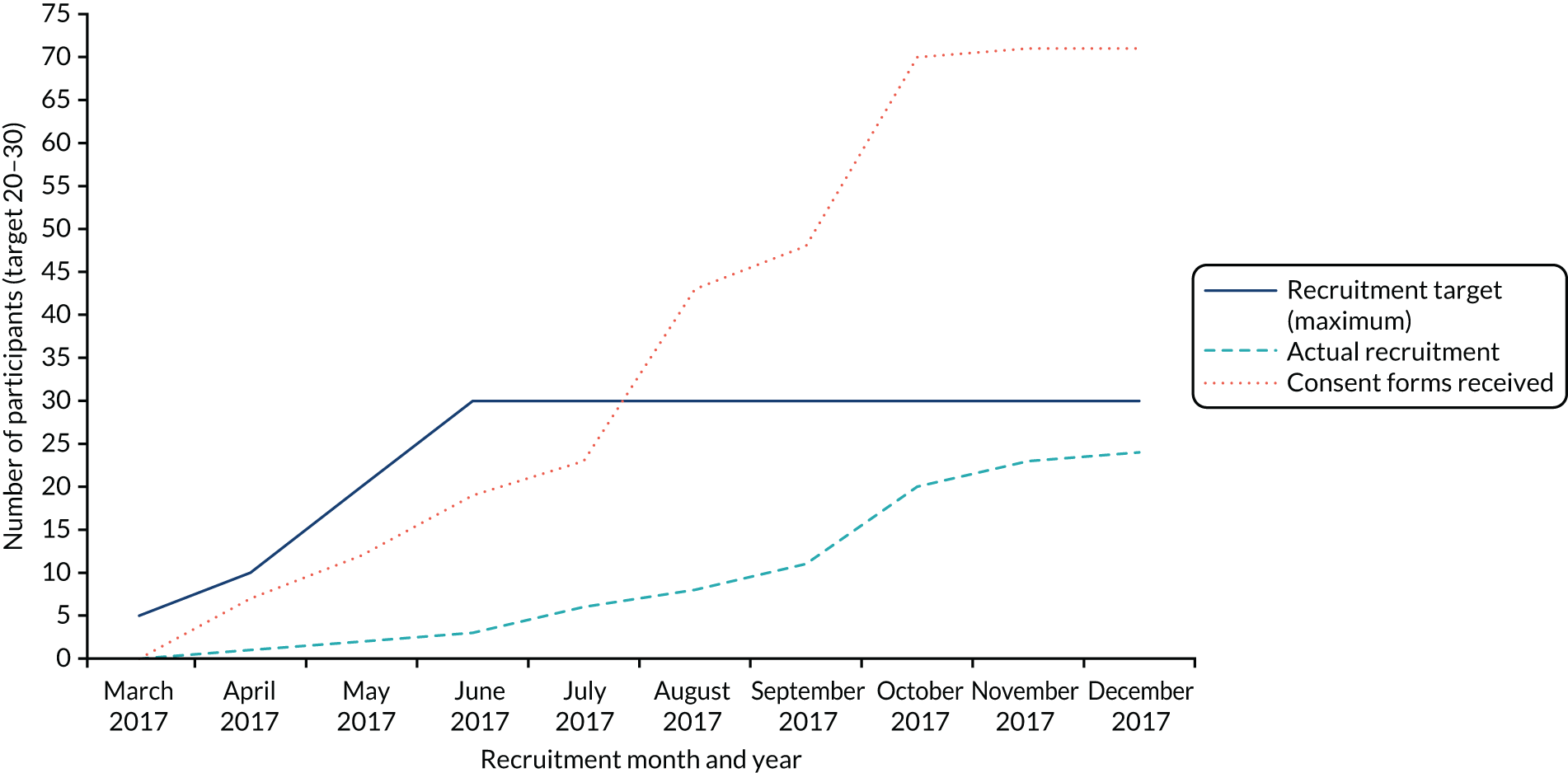

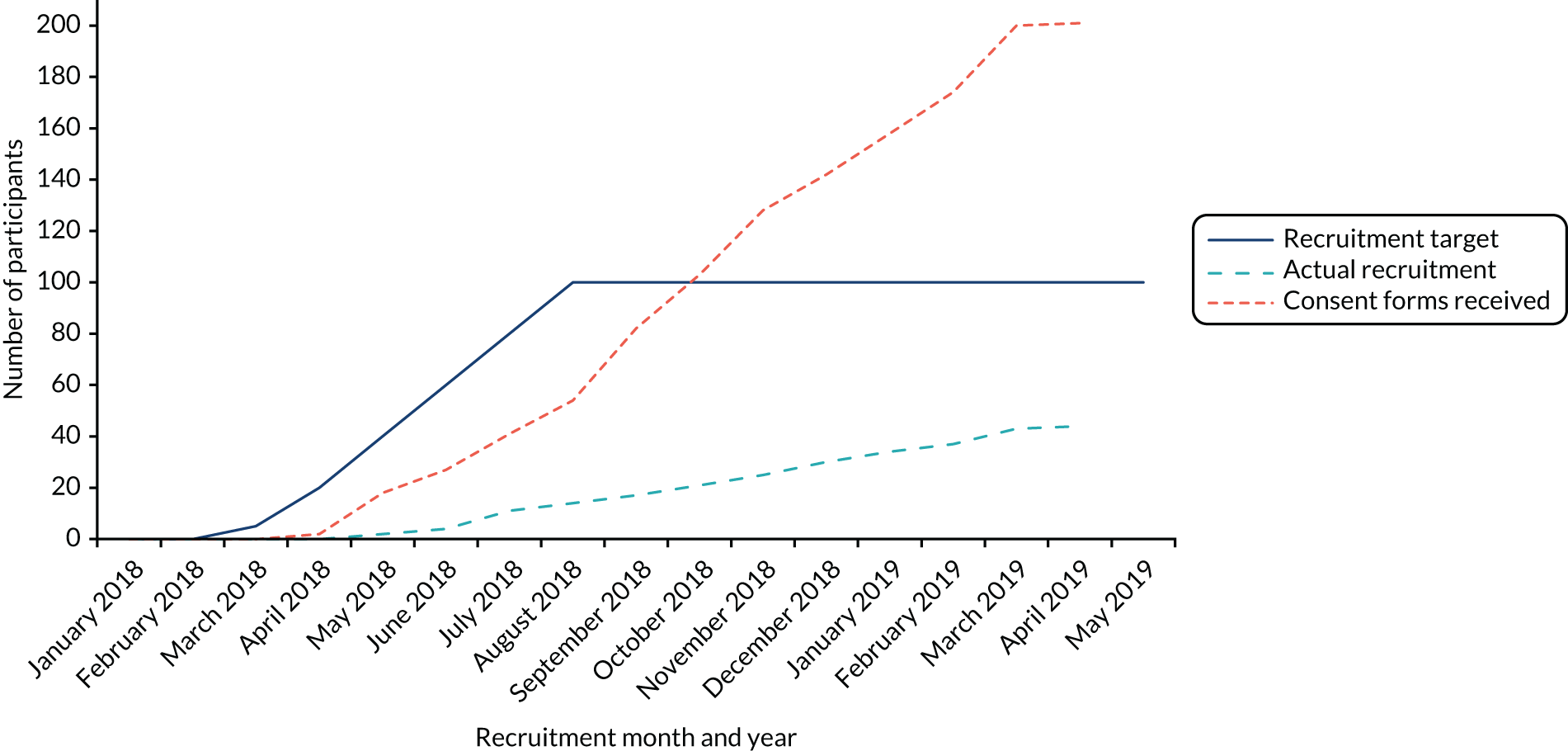

A total of 24 participants were recruited to the study over a period of 9 months (April to December 2017) and from across a total of eight CPs, indicating that recruitment was slower than anticipated. Five CPs commenced recruitment in April 2017; however, owing to the observed slow recruitment, the recruitment period was extended (by 4 months) and three additional CPs were recruited to the study (from August 2017). One general practice conducted a database search and mailed out study information packs to eligible patients (eligible and recruited participants were associated with a single recruiting CP). Figure 1 shows a breakdown of recruitment over the 9-month recruitment period.

FIGURE 1.

Feasibility study: target and actual recruitment rates. Reproduced with permission from Chew-Graham et al. 75 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

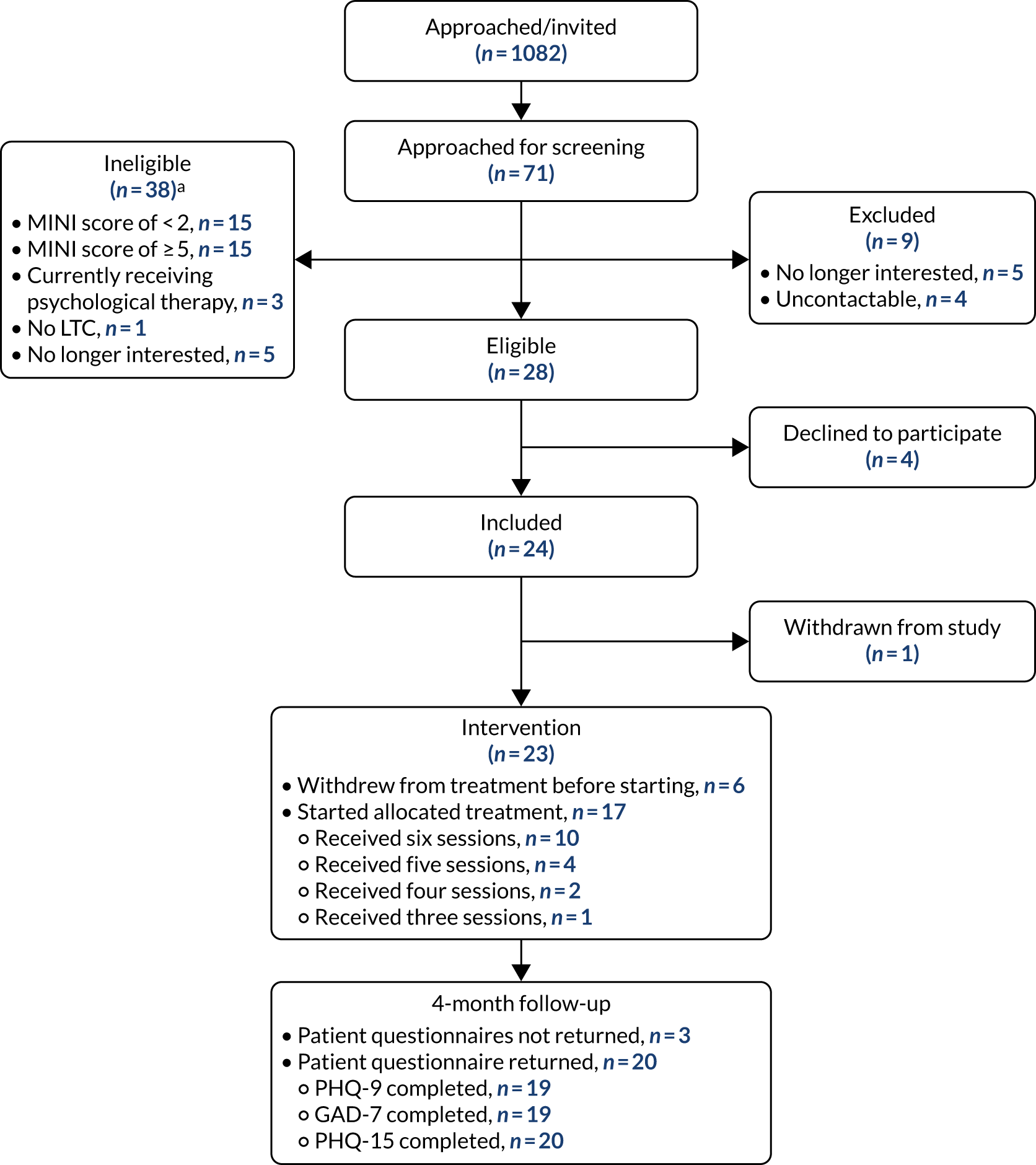

Overall, 1082 study information packs were distributed: 882 packs via pharmacy-based recruitment methods (opportunistic approach within the CP, via home-delivered prescriptions and via pharmacy system searches) and 200 packs via GP-based recruitment methods. From this, 71 pharmacy customers/patients returned a consent form to the study team to indicate their interest in the study (6.6%), of whom 28 were eligible to participate in the study following eligibility screening (39.4% of the 71 screened) and 24 (85.7%) decided to take part in the study. Reasons for ineligibility can be found in Table 1, with the most common reason being either non-depressed (34.9%) or currently experiencing an episode of major depression (34.9%). Table 2 details the distribution of study information packs, returned consent forms and resultant screened and recruited participants. Recruitment activity by pharmacy is shown in Table 3.

| Reason for ineligibility | Number of people ineligible, n (%) (N = 43) |

|---|---|

| Non-depressed (MINI score < 2) | 15 (34.9) |

| Major depressive episode (MINI score ≥ 5) | 15 (34.9) |

| Currently receiving any form of psychological therapy | 3 (7.0) |

| Does not have a CHEMIST LTC | 1 (2.3) |

| No longer interested when contacted for eligibility screening | 5 (11.6) |

| Uncontactable | 4 (9.3) |

| Recruitment method | Study information packs given out (n) | Returned consent forms, n (%)a | Recruited, n (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| In the CP | 168 | 32 (19.0) | 14 (8.3) |

| Via home-delivered prescriptions | 414 | 23 (5.6) | 6 (1.4) |

| CP system searches (one conducted) | 300 | 9 (3.0) | 2 (0.7) |

| General practice searches (one conducted) | 200 | 7 (3.5) | 2 (1.0) |

| Total | 1082 | 71 (6.6) | 24 (2.3) |

| Pharmacy | Study information packs given out (n) | Returned consent forms, n (%) | Participants recruited, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacy | GP | Pharmacya | GPa | Pharmacya | GPa | |

| 1 | 347 | 0 | 11 (3.2) | – | 2 (0.6) | – |

| 2 | 17 | 200 | 4 (23.5) | 7 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| 3 | 28 | 0 | 12 (42.9) | – | 5 (17.9) | – |

| 4 | 147 | 0 | 15 (10.2) | – | 7 (4.8) | – |

| 5 | 39 | 0 | 4 (10.3) | – | 2 (5.1) | – |

| 6 | 34 | 0 | 1 (2.9) | – | 0 (0.0) | – |

| 7 | 129 | 0 | 9 (7.0) | – | 5 (3.9) | – |

| 8 | 141 | 0 | 8 (5.7) | – | 1 (0.7) | – |

| Total | 882 | 200 | 64 (7.3) | 7 (3.5) | 22 (2.5) [34.4]b | 2 (0.2) [28.6]b |

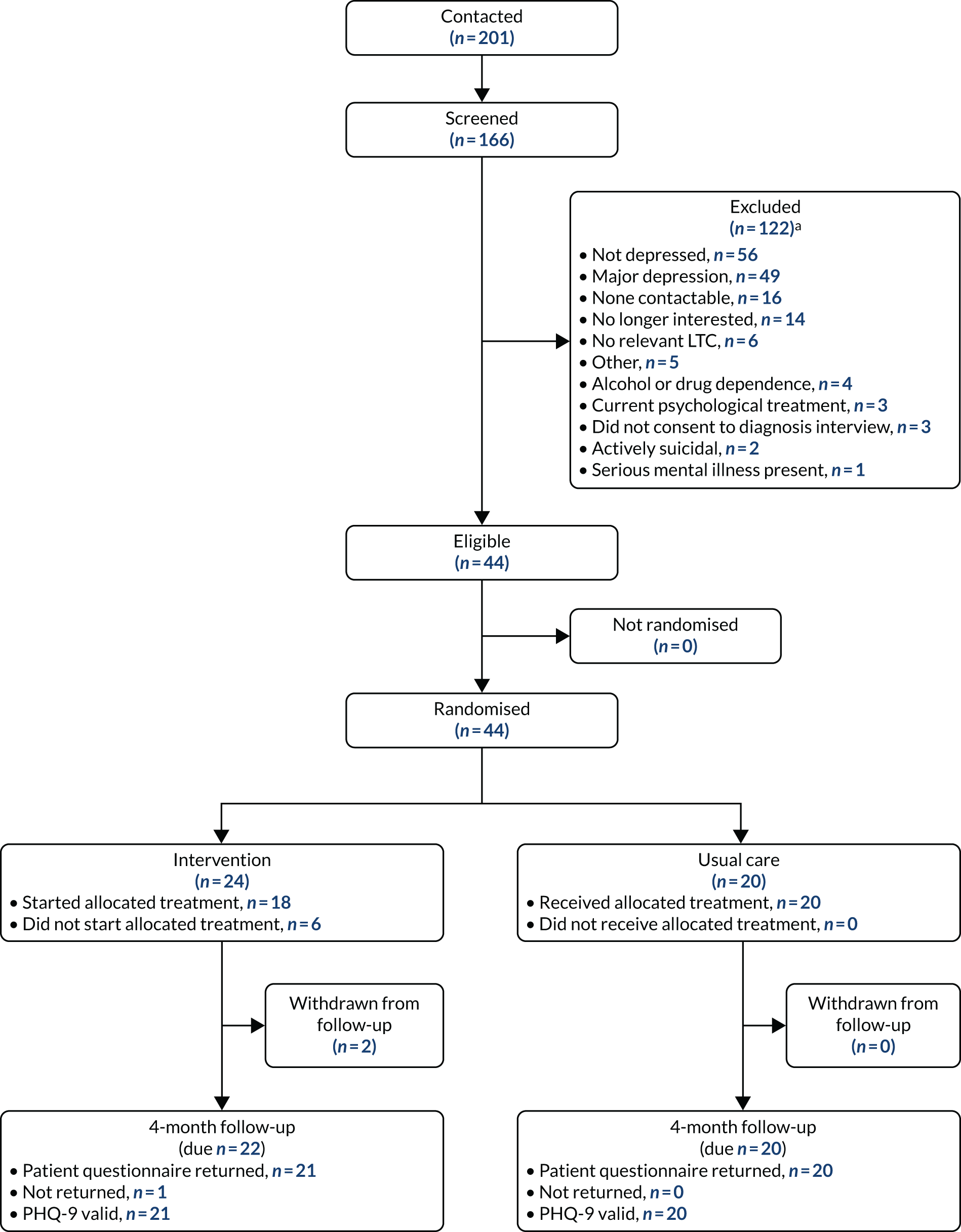

The active recruitment period across CPs varied from 2.7 months to 7.2 months, with an average period of 5.5 months; however, it should be noted that the three pharmacies that were recruited part-way through the 9-month recruitment period were open to recruitment for a maximum period of 5 months. This gives an average recruitment rate of 0.55 participants per pharmacy per month. Rates of recruitment varied across the pharmacies, with the proportion of those participants screened who were subsequently recruited to the study ranging from 0 to 0.55 and with, on average, 30.3% of those screened participating in the study; Figure 2 details the screening and recruitment for each pharmacy. The flow of participants through the study is shown in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2.

Feasibility study: overall screening and recruitment per pharmacy. Reproduced with permission from Chew-Graham et al. 75 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

FIGURE 3.

Feasibility study: CONSORT flow diagram. a, Multiple reasons for exclusion may be given. Reproduced with permission from Chew-Graham et al. 75 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Participant characteristics

Baseline data for the 24 recruited participants are detailed fully in Table 4. There were no missing data with respect to participant characteristics. The average age of the participants was 66.8 years, ranging from 51.3 years to 83.6 years. One-quarter of the participants were male and most (87.5%) responded positively to Whooley question 1 (‘During the last month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?’) and to Whooley question 2 (‘During the past month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?’) (95.8%). There was a wide variety of health problems, with the most common being high blood pressure (n = 16). All of the participants classified themselves as being of white ethnicity; it is noted that all of the recruiting CPs were located in the north-east of England, which has a largely white population. The majority of participants (n = 14) did not continue with education after the minimum school leaving age; however, six participants indicated that they had a degree or equivalent-level qualifications. See Table 6 for the baseline standardised measures alongside those at the 4-month follow-up.

| Baseline characteristic | Participants (N = 24) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 66.8 (9.8) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 65.9 (51.3, 83.6) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 6 (25.0) |

| Female | 18 (75.0) |

| During the last month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless, n (%) | |

| Yes | 21 (87.5) |

| No | 3 (12.5) |

| During the past month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things? n (%) | |

| Yes | 23 (95.8) |

| No | 1 (4.2) |

| On average, do you drink 3 or more units of alcohol each day? n (%) | |

| Yes | 1 (4.2) |

| No | 23 (95.8) |

| Do not know | 0 (0.0) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Non-smoker | 12 (50.0) |

| Current smoker | 4 (16.7) |

| Ex-smoker | 8 (33.3) |

| Health problems,a n (%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (29.2) |

| Osteoporosis | 2 (8.3) |

| High blood pressure | 16 (66.7) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 (12.5) |

| Osteoarthritis | 9 (37.5) |

| Stroke | 5 (20.8) |

| Cancer | 2 (8.3) |

| Respiratory conditions | 7 (29.2) |

| Eye conditions | 3 (12.5) |

| Heart disease | 8 (33.3) |

| Other | 14 (58.3) |

| Did your education continue after the minimum school leaving age? n (%) | |

| Yes | 10 (41.7) |

| No | 14 (58.3) |

| Do you have a degree or equivalent professional qualification? n (%) | |

| Yes | 6 (25.0) |

| No | 18 (75.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 24 (100.0) |

| Asian or Asian British | 0 (0.0) |

| Black or black British | 0 (0.0) |

| Other ethnic group | 0 (0.0) |

| Number of children, n (%) | |

| 0 | 4 (16.7) |

| 1 | 7 (29.2) |

| 2 | 8 (33.3) |

| 3 | 5 (20.8) |

| ≥ 4 | 0 (0.0) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 1 (4.2) |

| Divorced/separated | 1 (4.2) |

| Widowed | 5 (20.8) |

| Cohabiting | 2 (8.3) |

| Civil partnership | 3 (12.5) |

| Married | 12 (50.0) |

Intervention delivery

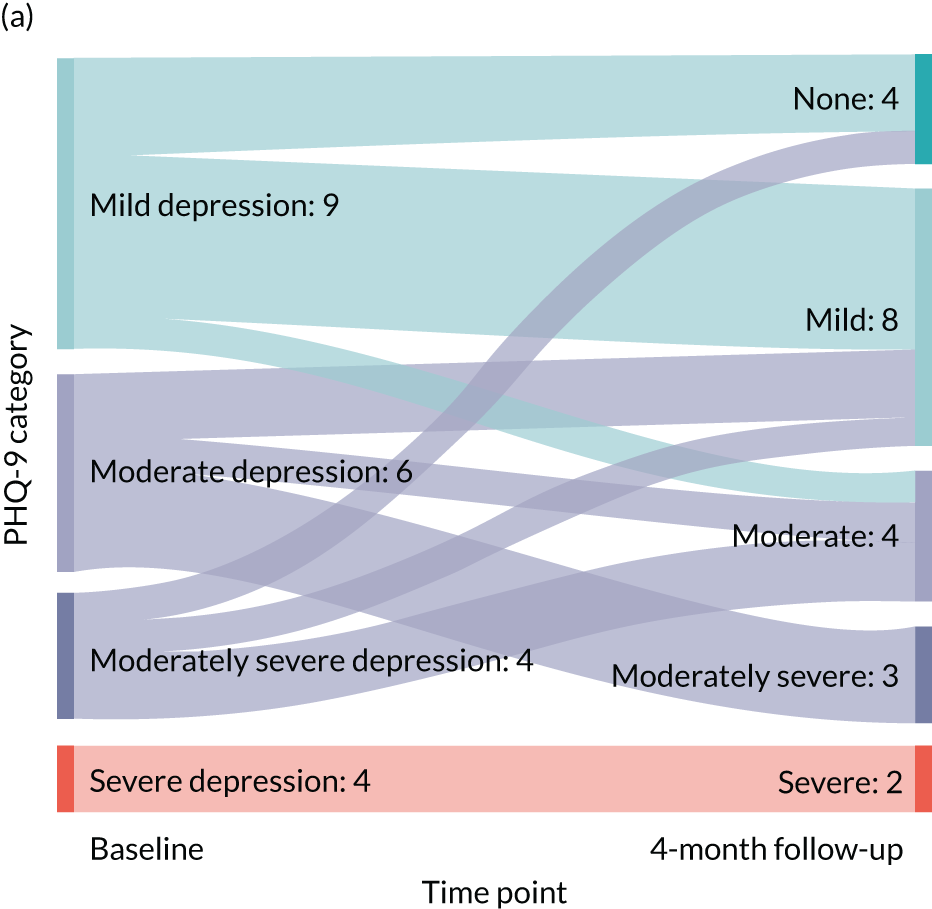

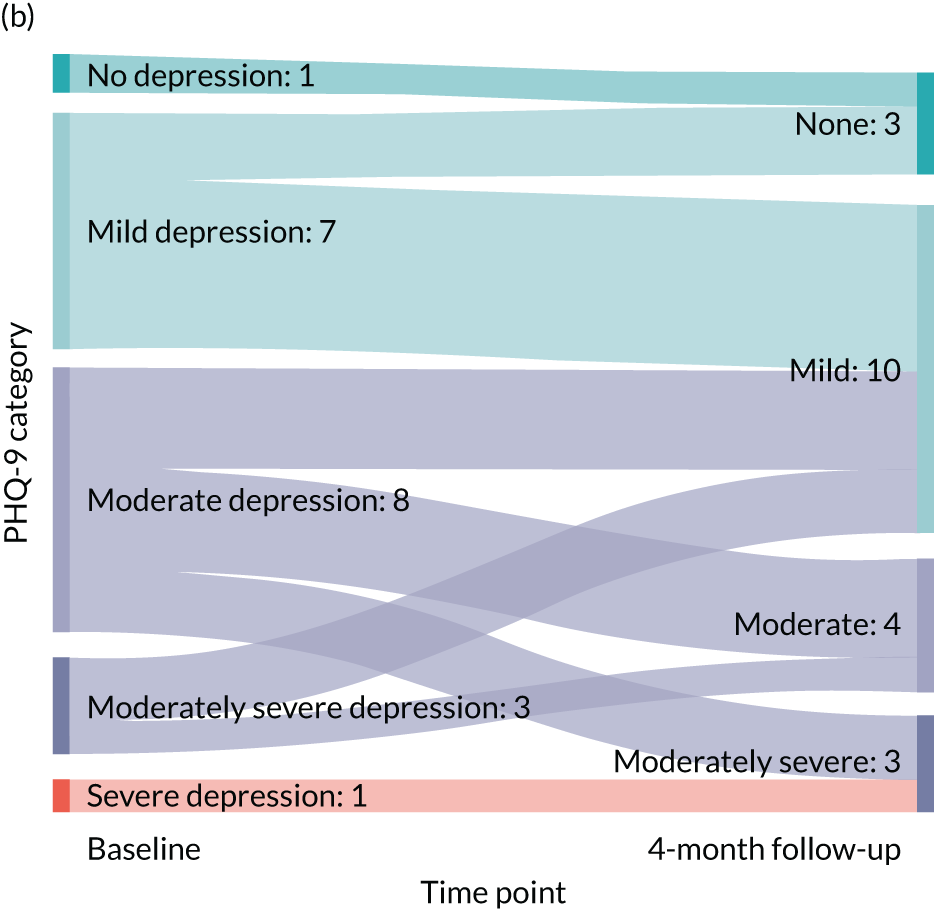

All of the 24 participants were offered the ESI, of whom 17 (70.8%) commenced the ESI. Engagement with the ESI sessions is detailed in Table 5. In total, 10 out of the 17 participants completed all six sessions of the ESI (58.8%), with all those participants who commenced the ESI receiving at least three of the ESI sessions. A total of 91 ESI sessions were conducted, of a possible 102, giving an average completion of 86.1% for those who commenced the ESI.