Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3002/07. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The final report began editorial review in September 2013 and was accepted for publication in June 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor Eileen Kaner is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research funding board panel member. Professor Elaine McColl is a member of the NIHR Journal Editorial Group. Denise Howel is a NIHR Health Services and Delivery Programme board panel member.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Newbury-Birch et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Structure of the report

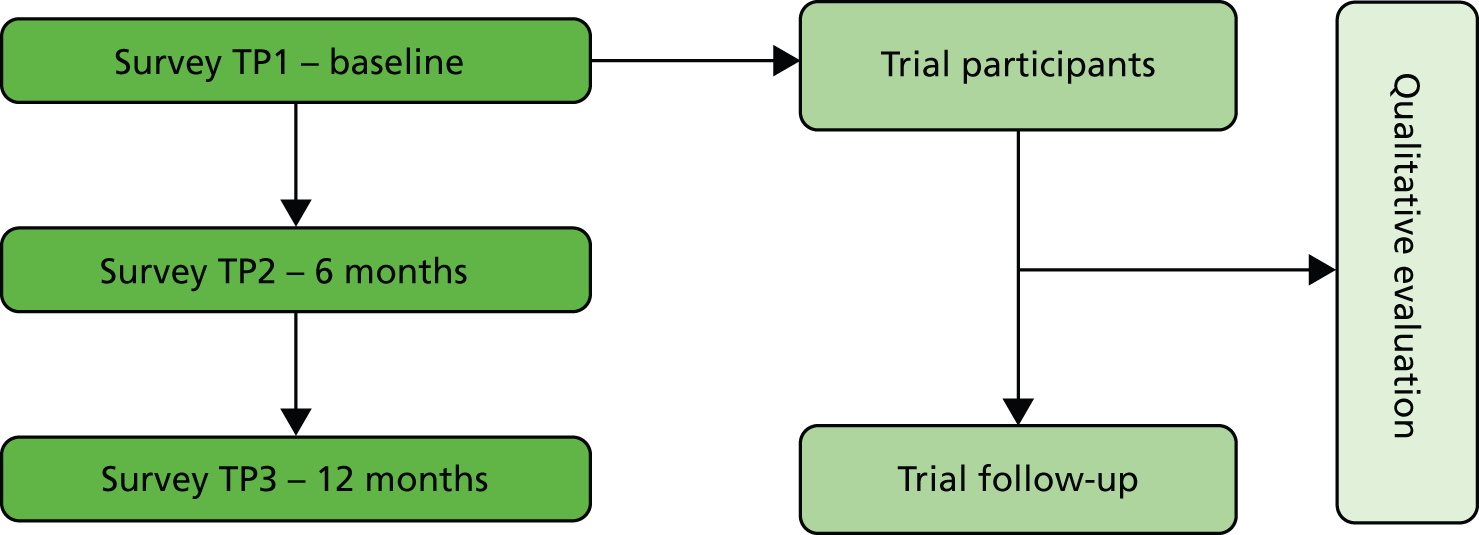

This study assessed the feasibility of a cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT) of Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention (ASBI) (in a school setting) to reduce hazardous drinking in adolescents. This was achieved by way of a three-arm parallel group cluster randomised (with randomisation at the level of school) external (rehearsal) pilot feasibility trial in young people aged 14–15 years in Year 10 at seven secondary/high schools across one small local authority area of North East England. The trial ran in parallel with a repeat cross-sectional survey, three times in the same year group and at the same schools, which facilitated screening (case identification for the trial at the first time point). The study included an integrated qualitative process evaluation (Figure 1) with key stakeholders. The three arms were control, intervention 1 and intervention 2. Young people allocated to the control arm received feedback and an alcohol information leaflet only. Young people allocated to intervention 1 took part in a 30-minute one-to-one structured intervention session based on motivational interviewing (MI) principles with a member of trained school staff. Young people allocated to intervention 2 received the same input as intervention 1 plus a subsequent session, facilitated by trained school staff, with parental/family involvement.

FIGURE 1.

Data time points for the study. TP, time point.

Research questions

The Medical Research Council (MRC) has presented a framework for the evaluation of complex interventions. 1 This work represents the development and piloting phases of the framework. Conducting a full-scale cRCT and economic evaluation of ASBI compared with ‘standard care’ in this population is likely to need many schools and to be resource intensive. As there are uncertainties regarding rates of eligibility, consent, participation in the intervention and retention for follow-up and regarding the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention for a range of stakeholders (teachers, learning mentors, young people and parents) this feasibility study was essential to inform the design and conduct of a larger scale definitive study.

The study sought to answer the following research questions: ‘Is it feasible to deliver ASBI in schools in England?’ and ‘What are the likely eligibility, consent, participation and retention rates of young people in a UK-relevant trial of ASBI compared with standard practice?’. Answers to these research questions will inform the development of a definitive multicentre cRCT to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ASBI in reducing hazardous drinking in adolescents. Our hypothesis for the definitive cRCT will be that ASBI is more effective and cost-effective at reducing hazardous drinking in adolescents than a control condition of usual advice in high/comprehensive schools, as well as feedback on their drinking and an information leaflet.

Research objectives

-

To conduct a three-arm pilot feasibility cRCT (with randomisation at the level of school) to assess the feasibility of a future definitive cRCT of ASBI in a school setting.

-

To explore the feasibility and acceptability of ASBI and trial processes to staff, young people and parents.

-

To explore the fidelity of the interventions as delivered by school-based learning mentors.

-

To estimate the parameters for the design of a definitive cRCT of ASBI, including rates of eligibility, consent, participation and retention at 12 months.

-

To pilot the collection of cost and resource-use data to inform the cost-effectiveness/utility analysis in a definitive trial.

-

To develop the protocol for a definitive cRCT and economic evaluation of the impact of ASBI compared with standard advice to reduce alcohol consumption.

Chapters of the report

The report is structured as a series of eight chapters detailing the design, management and outcomes of the pilot feasibility study. The report begins by providing the background to the research and outlines key literature informing the design and conduct of the study (see Chapter 2). Following this, a chapter is dedicated to each core component of the study. Chapter 3 explores the design of intervention materials as well as the training and support provided to school staff in the delivery of the project. Chapter 4 reports the design, methods and results of the repeated cross-sectional survey. Chapter 5 provides the design, methods and results of the external pilot trial. Chapter 6 details the design, methods and results of the integrated qualitative process evaluation. Chapter 7 details the design, methods and results of the health-economic evaluation of the study. Finally, Chapter 8 provides a synthesis of the main findings from the pilot feasibility study, together with an assessment of whether the study met its aims and objectives, before detailing any recommendations for a future definitive cRCT.

Research ethics

The research study was granted ethical approval in November 2011 by Newcastle University, which acted as a sponsor for the research (reference 0508), and the trial is registered with the ISRCTN register as ISRCTN07073105. Approval was also granted by the local education authority in the study catchment area. Ethical approval was extended to accommodate a change in study protocol in October 2012, which related to measures completed at the 12-month follow-up of trial participants.

Changes to the original study protocol

The study protocol was published in 2012. 2

-

The published protocol indicates 6- and 12-month follow-ups for the trial group; however, it is not clear on the protocol that the full year group was followed up at 6 months and 12 months, as no identifiable data were taken at the year group level or the trial participant level at 6 months, therefore we have identifiable data for only the trial group at baseline and 12-month follow-up. The reason for this was that having a one-on-one interaction with the learning mentor could have acted as a ‘top-up’ to the intervention. We do not intend to include a 6-month follow-up in the proposed definitive study.

-

Objective 5 of the study – ‘to pilot the collection of cost and resource-use data to inform the cost-effectiveness/utility analysis in a definitive trial’ – was not included in the original study protocol.

-

The original protocol reported the control group as Personal, Social, Health and Economic Education (PSHE) only; however, the control condition was PSHE and also included the young person receiving feedback that he/she was drinking in a way that may be harmful and being provided with an advice leaflet. The reason that we added feedback and the leaflet (and therefore a change to the protocol) was that the research team and the University Ethics Committee believed that this was the minimally acceptable thing we could ethically do should a young person be identified as a risky drinker.

Research management

The Programme Management Group (PMG) was responsible for ensuring the appropriate, effective and timely implementation of the project. The PMG met once per month (more or less frequently dependent on the needs of the project) and comprised the Chief Investigator, Project Manager, co-applicants, named collaborators and researchers working on the project. Professor Eilish Gilvarry chaired this group. A Trial Steering Group (TSG) was also appointed to provide an independent assessment of the data analysis and to help determine if a future definitive trial is merited. This group met biannually and their remit was the progress of the study against projected rates of recruitment and retention, adherence to the protocol, participant safety and the consideration of new information of relevance to the research question. Professor Mark Bellis chaired this group. Written terms of reference were agreed and used by the PMG and TSG (see Appendix 1).

Research governance

The project complied with the requirements of the Data Protection Act 1998 and the Freedom of Information Act 2000, and other UK and European legislation relevant to the conduct of clinical research. The project was managed and conducted in accordance with the MRC’s guidelines on good clinical practice in clinical trials (www.mrc.ac.uk), which includes compliance with national and international regulations on the ethical involvement of patients in clinical research (including the Declaration of Helsinki, sixth revision 2008). All data were held in a secure environment with participants’ information identified by a unique participant identification number. Master registers containing the link between participant identifiable information and participant identification numbers were stored in a secure area that was separate from the majority of data. All staff working on the project were employed by academic organisations and subject to the terms and conditions of service and contracts of employment of the employing organisations. Where relevant, staff were trained in good clinical practice and all staff worked to written codes of confidentiality. The project used standardised research and clinical protocols, and adherence to the protocols was monitored by the PMG and TSC.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was sought at different time points and at multiple levels, and is reflected upon throughout this report.

Patient and public involvement representatives included local authority employees, parents, young people and members of staff at participating school sites. Their contribution to the development, management and delivery of this research included input into the design and conduct of the feasibility study (the local authority lead for education was a co-applicant for this research) and piloting of study documentation and intervention materials (parents and young people) to ensure readability and understanding (see Chapter 3). Participating schools were also heavily involved in the conduct of the feasibility study (trial and survey) and were regarded as key stakeholders (see Chapters 4 and 6). Finally, Chapter 8 includes modifications recommended for a definitive trial, which include input from PPI representatives.

Chapter 2 Background to the research

Key points for Chapter 2

-

Adolescents in England are among the heaviest drinkers in Europe, with consumption highest in the north-east.

-

Young people are more vulnerable than adults to the adverse effects of alcohol owing to a range of physical and psychosocial factors that often interact.

-

Literature shows that the ASBI for young people has been successful for selected individuals in certain settings.

-

There is currently insufficient evidence to be confident about the use of ASBI to reduce risky drinking and alcohol-related harm in younger adolescents in a school setting.

-

Despite well-documented parental influences over adolescent alcohol use, the evidence for interventions to reduce young people’s drinking that include family members is equivocal.

Prevalence

Adolescents in England are among the heaviest drinkers in Europe. 3 The percentage of young people who have ever had an alcoholic drink in England increases with age from 12% of those aged 11 years to 74% of those aged 15 years,4 and the prevalence of drinking in the last week rises from 1% of those aged 11 years to 25% of those aged 15 years. 4 Although the proportion of young people in England aged between 11 and 15 years who report that they have ever drunk alcohol decreased from 54% to 43% between 2007 and 2012, the mean amount of alcohol consumed by this age group has fluctuated between 10.4 units per week in 2011 and 14.6 units per week in 2008, with an increase to 12.5 units per week in 2012. There are, however, age-related differences in patterns of consumption. The amount consumed among those aged 14 years has increased from 13.2 units per week in 2007 to 16.15 units in 2012, whereas for 15-year-olds the mean amount has decreased slightly from 14.2 units per week in 2007 to 12.3 units in 2012. 4 This clearly shows that drinking increases throughout adolescence, but recent data show that this is not immutable with changes in trends between years and age.

In particular, the north-east has been shown to have the highest rates of alcohol misuse by young people in England, with 51% of 11- to 15-year-olds reporting having ever drunk alcohol. 4 This compares with 48% in the south-east, 46% in the north-west and 31% in London. 4 Further, the mean alcohol consumption in the previous week for young people in England in 2011 was highest in the north-east and north-west (15.7 units per week) compared with the south-east (11.0 units) and London (9.4 units). 4 Therefore, the north-east is a key place to study the issue of alcohol risk reduction in young people.

Consequences of drinking

The impact of alcohol on the development and behaviour of young people has been well researched in early,5 middle6 and late adolescence. 7 It is now well known that young people are much more vulnerable than adults to the adverse effects of alcohol due to a range of physical and psychosocial factors that often interact. 8 These adverse effects include physiological factors resulting from a typically lower body mass and less efficient metabolism of alcohol;5,6 neurological factors due to changes that occur in the developing adolescent brain after alcohol exposure;6,9–11 cognitive factors due to psychoactive effects of alcohol that impair judgement and increase the likelihood of accidents and trauma;12 and social factors that arise from a typically high-intensity drinking pattern that leads to intoxication and risk-taking behaviour. 13,14 The social factors are compounded by the fact that young people have less experience of dealing with the effects of alcohol than adults15 and they have fewer financial resources to help buffer the social and environmental risks that result from drinking alcohol. 7

Evidence suggests that hazardous drinking among young people occurs commonly in the context of other forms of ‘disinhibitory behaviour’, such as aggression and risk-taking. 16 Although these behaviours are well known to be linked,16 it is not clear if drinking leads to these behavioural problems or if they all arise due to a common linked trait. 17 A significant positive association between alcohol dose and aggression for both genders has been found. 18 As a result of the above risk factors, the list of negative consequences that result from drinking in young people is extensive and includes physical, psychological and social problems in both the shorter and the longer term. Immediate problems result from accidents and trauma, physical and sexual assault (including rape in young people), criminal behaviour (including driving while intoxicated and riding as a passenger with an intoxicated driver) and early onset of sexual intercourse and sexual risk-taking. 8,14,19 In relation to education, alcohol use can have a negative effect on school performance20 and those who have drunk are also more likely to have truanted from school. 4 Longer-term problems include the development or exacerbation of mental health problems,21 self-harm and/or suicidal behaviour. 22 Moreover, individuals who begin drinking in early life have a significantly increased risk of developing alcohol use disorders, including dependence, later in life. 23,24 Owing to this extensive array of damage, the prevention of excessive drinking in young people is a global public health priority. 25 In 2009, the Chief Medical Officer for England provided recommendations on alcohol consumption in young people,26 based on an evidence review of the risks and harms of alcohol to young people. 8 The recommendations state that children should abstain from alcohol before the age of 15 years and those aged 15–17 years are advised not to drink, but if they do drink it should be no more three to four units and two to three units per week in males and females, respectively, on no more than 1 day per week. 26

Young people’s views on their own health

It is important to note that young people often feel that they want to be empowered to be part of any decision-making in relation to their own health and feel that they have choices (C Sands, Newcastle University, 2013, unpublished data). For young people, confidentiality is a key issue, particularly within the school setting. However, to young people it is really important that they are familiar with the staff working with them, and therefore these issues should be taken into consideration when undertaking research with young people.

Primary and secondary prevention interventions for risky drinking

There is a large volume of evidence on primary prevention in the school setting,27–32 which is directed at all young people, whether they drink alcohol or not, with the aim of delaying the age at which drinking begins, and which uses general health education to prevent underage drinking. This body of work has shown mixed results and been reported to be methodologically weak,33 with only a relatively small number of programmes reporting positive outcomes. 30 One programme that has shown effectiveness is the School Health and Alcohol Harm Reduction Project (SHAHRP) project, a curriculum programme delivered across two consecutive school years in Ireland with 2349 pupils (mean age of 13.84 years at baseline and 16.48 years at final follow-up at 32 months). The programme had an explicit harm-reduction goal that explores knowledge, attitudes, alcohol consumption, and context of use and harms associated with a person’s own, or other people’s, use of alcohol. This showed significant improvements among young people in the intervention group in relation to alcohol knowledge and significant reductions in alcohol consumption. 34 Furthermore, research from the USA found that targeting young people and parents simultaneously but separately was effective in postponing the onset of heavy drinking among adolescents. 35,36 However, the results are equivocal, with some studies showing effectiveness and others not, and questions remain about the applicability to the UK setting. 27 As has been shown, there is limited evidence to support primary prevention programmes to reduce alcohol consumption in young people. Thus secondary prevention, i.e. targeting interventions at young people who are already drinking alcohol, is likely to be a more effective strategy, as the interventions will have more salience for the individuals receiving them.

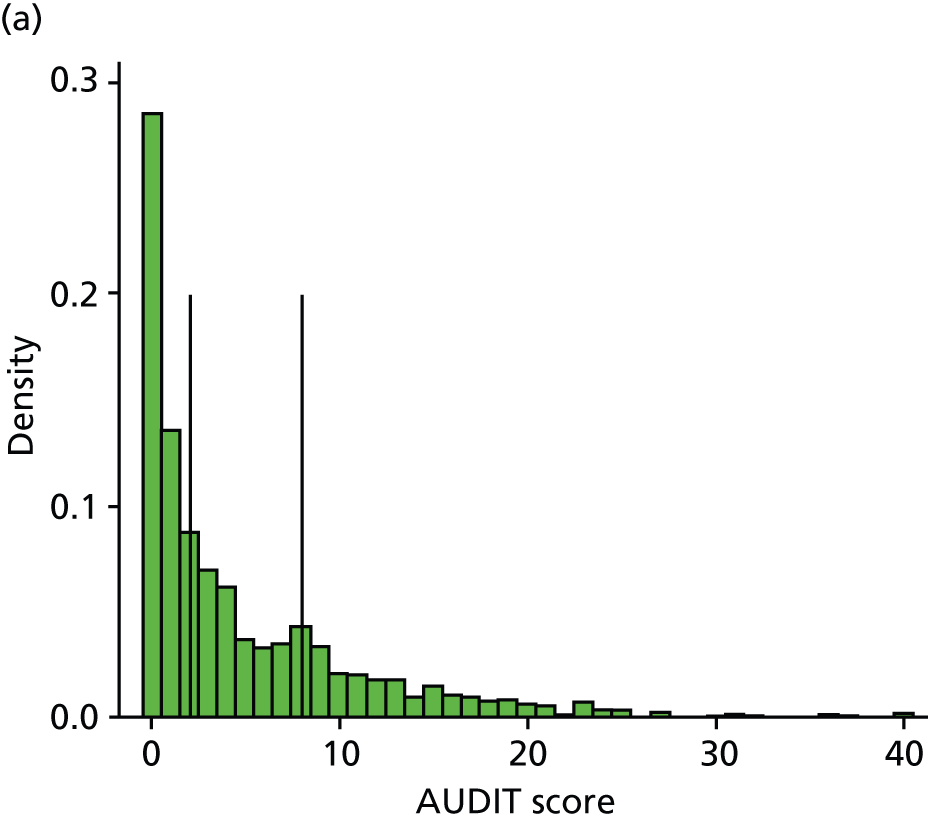

Various screening measures have been used with young people to identify those who are at risk from their drinking including using measures of total alcohol consumption, levels of binge drinking and alcohol-related injury levels. 37 Research suggests standardised alcohol screening tools, such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)38 are a highly sensitive and specific means of identifying current hazardous use of alcohol in adult populations, including college students. 39–41 Among adult drinkers, the AUDIT detects approximately 92% of genuinely excessive drinkers (sensitivity) and excludes approximately 94% of false cases (specificity),42,43 for which a cut-off score of ≥ 8 (out of a possible score of 40) is used to detect hazardous use of alcohol and alcohol-related problems. Broken down further, respondents can be categorised as ‘abstainers’ (0); ‘lower risk’ drinkers (1–7); at ‘increasing risk’ (8–15); at ‘higher risk’ (16–19); or ‘probably dependent’ (≥ 20).

There is some evidence from emergency department settings in the USA to suggest that the AUDIT is an appropriate means of detecting hazardous use of alcohol and alcohol-related problems among adolescents. 44–46 However, evidence remains equivocal whether it is either practical or appropriate for use with adolescents in other settings, including primary care and education. At 10 items, the length and wording of the full AUDIT may make it impractical for use with adolescents. 42,47 Evidence is especially equivocal as to the AUDIT tool’s ability to detect hazardous level drinking (the AUDIT positive score) among this age group or whether the concepts of hazardous or harmful drinking in adults are similarly meaningful in adolescents. Several studies have used AUDIT positive cut-off scores of ‘8’, designed for use with adults, to screen for alcohol use disorders among adolescents. 47,48 In comparison, other evidence supports using lower cut-off points, which generally fall between ‘2’ and ‘4’,43,49,50 when using the AUDIT in adolescent populations. For example, Chung et al. 44 recommend using a cut-off score of ‘4’ with young people aged 13–19 years (sensitivity 0.94; specificity 0.80) and Knight et al. 50 suggest that a score of ‘2’ is optimum for the identification of alcohol problems and disorders among those aged 14–18 years (sensitivity 0.88; specificity 0.81). Santis et al. 49 suggest different scores according to the level of alcohol consumption, with cut-off points of ‘3’ for hazardous, harmful and dependent alcohol use (sensitivity: 96%; specificity: 63.3%), ‘5’ (sensitivity: 75%; specificity: 64.5%) and ‘7’ (sensitivity 64%; specificity 75%), respectively.

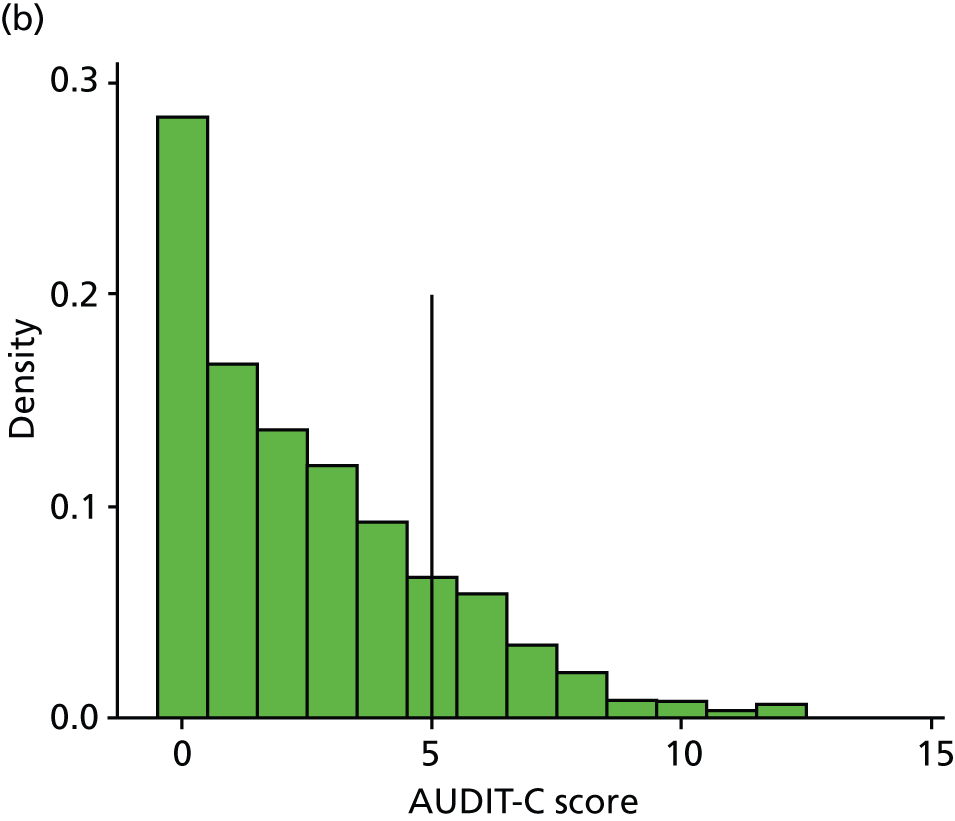

Others suggest using a shortened version of the AUDIT tool, such as AUDIT-C (AUDIT-Consumption), which is scaled 0–12, and for which a score of ≥ 5 (among adults) is used to indicate increasing or higher risk drinking. 40,51 No specific score for young people has yet been recommended. It has also been shown that a single question screen based on drinking frequency can adequately identify youths with alcohol-related problems. 52,53 Bailey et al. 53 used the frequency of binge drinking (question three of the AUDIT tool – six or more drinks in one drinking session) to identify risky drinking in young people. 53 Thus, there is no clear consensus on which screening tool should be used, the validity of lower AUDIT or AUDIT-C cut-off points for use with adolescent populations or as to what this score should be, and whether the AUDIT or AUDIT-C or another measure should be the screening measure of choice. It could therefore be argued that in a school setting a shorter screening tool could be useful, and quick, to administer.

In terms of interventions for dealing with people who are drinking at harmful or hazardous levels, ASBI is a secondary preventative activity, aimed at individuals whose consumption level or pattern is likely to be harmful to their health or well-being. 54 They generally consist of screening (to identify relevant recipients) followed by structured advice or counselling of short duration, which is aimed at reducing alcohol consumption or decreasing the number or severity of problems associated with drinking. 55 They are based on social cognitive theory (from health psychology), which is drawn from the concept of social learning. 56 Here, behaviour is regarded to be the result of an interaction between individual, behavioural and environmental factors. It is assumed that each individual has cognitive (thinking) and affective (feeling) attributes that affect not only how they behave, but also how their behaviour is influenced and/or reinforced by aspects of the external world. Thus ASBIs generally focus on individuals’ beliefs and attitudes about a behaviour, their sense of personal confidence (self-efficacy) about changing it and how an individual’s behaviour sits in relation to other people’s actions (normative comparison).

A key feature of ASBI is that it is designed to be delivered by generalist practitioners (not addiction specialists) and targeted at individuals who are generally not experiencing severe problems (such as alcohol dependence) and who may not even be aware that they are experiencing alcohol-related risk or harm. Thus the goal is usually reduced alcohol consumption or a decrease in alcohol-related problems. 57 There is variation in the duration and frequency of ASBI58 but there are two broad types: simple structured advice – based on the FRAMES (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy and Self-efficacy)59 – and behaviour change counselling – based on MI. This is a person-centred approach that aims to resolve conflicts regarding the pros and cons of behaviour change and thus enhance motivation. MI is characterised by empathy and an avoidance of direct confrontation. Elicited statements associated with positive behaviour change are encouraged so as to support self-efficacy and a commitment to take action. Since the time available for delivering BI may not allow for MI in its full form,58 its ethos and techniques have been59 distilled into a more directive format called Behaviour Change Counselling. 60

There is a large amount of high-quality evidence to support the effectiveness of ASBI with adults who have an alcohol use disorder. 58 Most of the evidence for ASBI demonstrates effectiveness for non-treatment-seeking adults in primary health care. 58,61–68 Furthermore, meta-analyses have consistently reported that students aged ≥ 18 years who received ASBI subsequently reduced their drinking behaviour compared with control group participants who typically received assessment only. 69,70 The key elements of the ASBI were personalised feedback on alcohol consumption, typically with a normative component70 and/or MI approaches. Such interventions typically achieved small to medium effect sizes71 across multiple measures of alcohol consumption, including quantity, frequency and intensity of drinking. The effects of BIs on drinking behaviour often peaked in the shorter term (generally 6 months) then diminished over time. 69 However, reductions in alcohol-related problems often took longer to emerge but were found in longer-term follow-up (12–18 months). Hence it is important to have BI outcomes measuring both consumption and alcohol-related problems and to follow-up participants at shorter- and longer-term time points.

Numerous systematic reviews have been published on ASBI in younger adolescents in recent years37,72–79 (details given in Appendix 2). Jackson et al. ’s review37 of ASBI for young people in health settings identified eight controlled trials53,80–85 for young people. The work was part of a larger review of ASBI in adults and young people. The trials were published between 1999 and 2009 and the majority (seven)80–86 were carried out in the USA. Study population sizes ranged from 34 to 655 young people and included young people aged between 12 and 24 years with two of the included studies being for those aged ≥ 18 years only. Five of the trials tested a brief MI, which lasted between 20–45 minutes,81,83–86 whereas one tested an audio programme;80 another involved a more intense programme of MI which included four sessions53 and one comprised an interactive laptop computer-based intervention. 82 The length of follow-up varied between 2 and 12 months. Four of the studies53,83–85 found statistically significant benefits as a result of the intervention. However, one80 of the studies found negative consequences following intervention, with an increase in heavy alcohol use among the intervention group. The authors offer two possible explanations for this. First, adolescents in the control group, unlike adolescents in the intervention groups, reported less bingeing after baseline, suggesting self-report bias in the direction anticipated if the control adolescents were trying to please the researchers. Second, the authors argue that the apparent increase in self-reported alcohol use in the intervention groups relative to the control groups was the result of an educational intervention influence leading adolescents to be more forthright. 80 Wachtel and Staniford77 also reviewed the literature in relation to alcohol misuse and binge drinking in adolescents in the clinical setting (hospital-based emergency departments, college health centres and adolescent healthcare clinics). 77 The review included 14 studies,53,80,82–85,87–94 12 of which were from the USA. 53,80,82–85,87–91,93 Nine of the included studies83,84,87–93 related to young people aged ≥ 18 years and included a heterogeneous range of interventions from very brief MI to four group sessions of 30–40 minutes, which meant that generalisability could not be ascertained. A review of the literature by Yuma-Guerrero et al. 78 around BI in emergency departments in the USA for young people identified seven randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 82–85,95–97 The primary studies included young people aged 12–20 years. Four82–84,98 of the included studies demonstrated a significant intervention effect; however, none reduced both alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences.

Mitchell et al. ’s systematic review75 identified 15 studies81,82,85,86,95–105 of alcohol and drug interventions delivered to adolescents in primary care (one study81), emergency departments (seven studies82,85,95–98,103), schools (five studies99,101,104–106) and other settings (one study with homeless young people86 and one in the community100) with young people aged 12–21 years. The authors identify the need for screening instruments to be brief to administer and quick and easy to score and interpret. 75 Because of the heterogeneous populations (ages 12–22 years), inclusion criteria (adolescents who use alcohol and drugs as well as those who reported being in a car with an intoxicated driver but who themselves had not used alcohol or drugs) and differences in outcome measures, the data did not allow for meta-analysis, although some individual studies did show reductions in alcohol consumption at follow-up. The review identified two studies101,102,106 (three articles) carried out in further education colleges in the UK, with older young people aged between 16 and 20 years, in which no differences were found between groups at 12-month follow-up.

Three systematic reviews included meta-analyses of ASBI for young people. 73,74,76 Tripodi et al. 76 carried out a meta-analytic review on interventions for alcohol abuse in a range of settings. Sixteen primary studies were included with young people aged 12–19 years. 81,105,107–120 The studies included various interventions including BI, cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and multidimensional family therapy. The main outcome measures included abstinence and quantity of alcohol use measured between 1 and 12 months post intervention. Pooled effects of standardised mean differences indicate that interventions significantly reduce alcohol consumption [Hedges’ g = −0.61; 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.83 to −0.40]. Stratified analyses revealed larger effects for individual treatment (Hedges’ g = −0.75; 95% CI −1.05 to −0.40) compared with family-based treatments (Hedges’ g = −0.46; 95% CI −0.66 to −0.26). 76

Jensen et al. ’s review74 of the effectiveness of MI for substance-use interventions for adolescents included 21 primary studies, of which 12 had alcohol-related outcomes. 53,81,85,86,99–102,108,121–123 These studies were from a variety of different settings: educational,99,101,102,123 community53,86,100,108 and health. 81,85,121,122 No information was given on the nature of the interventions; however, the number of sessions ranged from one to four. The age range included in the studies was 12–23 years. Included studies that addressed alcohol and other drug use yielded a small, but significant, post-treatment effect size in reduction of substance use [mean d (standard mean difference) = 0.146 (95% CI 0.059 to 0.233), n = 16)].

Carney et al. ’s meta-analysis73 aimed to identify and evaluate early interventions that target adolescent substance use (alcohol and illicit drugs) as a primary outcome, and criminal or delinquent behaviours as a secondary outcome. They identified nine studies53,81,85,86,97,99,109,124,125 in emergency departments, juvenile correctional facilities, alternative high schools and a homeless drop-in centre – eight from the USA81,85,86,97,99,109,124,125 and one from Australia. 53 Study sizes ranged from 18 to 472. The age range was 15–17 years. Results showed that single sessions of BIs significantly reduced the frequency of alcohol use among young people (I2 = 0%; z = 2.13; overall effect, p = 0.03). 73

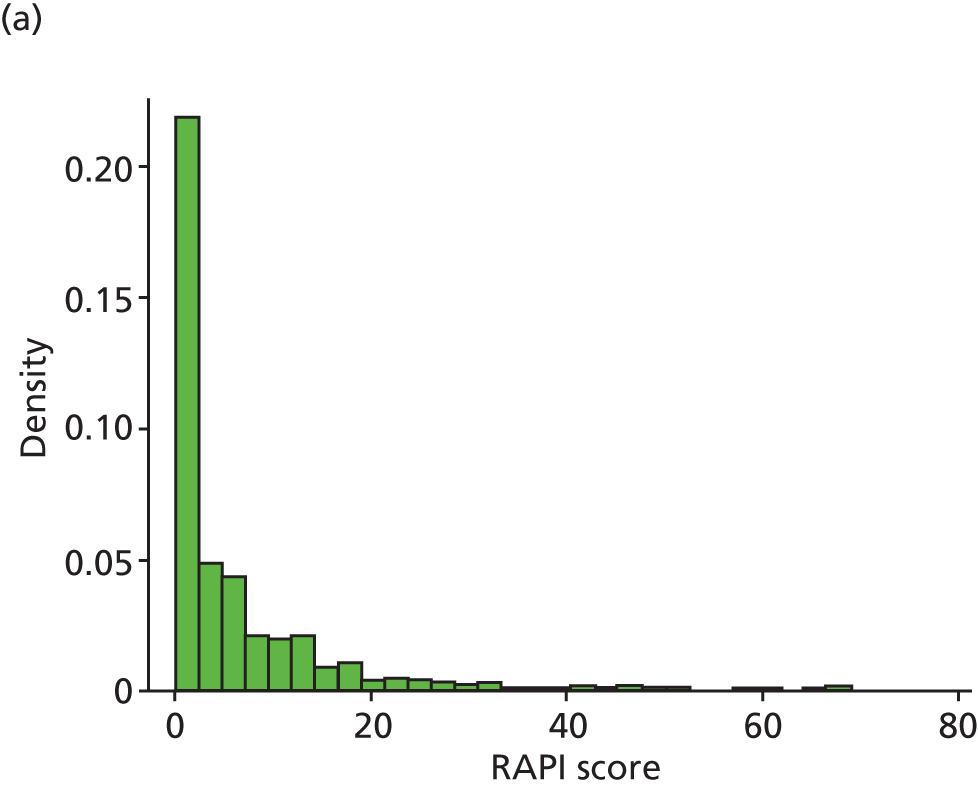

Conrod et al. 126–128 have carried out a number of trials in London of group-based personality-targeted prevention for young people aged 13–14 years who are risky drinkers or drug users. The interventions consisted of two 90-minute group sessions that incorporated components of motivational enhancement therapy and CBT. The intervention was unique in that it targeted personality traits rather than problems. In fact, alcohol and drug use were a minor focus of the intervention. Young people have been followed up every 6 months for 2 years and long-term effects (at 2 years) have been found for problem drinking (measured using the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI) tool) (p = 0.02) and binge-drinking rates (p = 0.03). Finally, a study of US accident and emergency attendees97,129 who received ASBI showed reductions in aggression, as well as reductions in alcohol misuse following a brief alcohol intervention.

It has been shown that the family is a source of both risk and protective factors for adolescent alcohol use. 8 Parents in particular have been found to have a significant effect upon alcohol initiation and patterns of use. 130 Such parental factors include parental modelling,131–133 supervision and discipline,8 quality of parent–child relationship and communication among others. 134 It is therefore important to identify whether parents can play a role in helping to reduce their children’s drinking.

Parents

The majority of parents are aware that their children are drinking. 135 Parenting ‘style’ and ‘good’ family relationships have been demonstrated to have a positive effect on young people’s drinking behaviour regardless of family structure or whether parents consume alcohol. 8,134,136 Excessively authoritarian and permissive parenting styles are both associated with earlier onset of alcohol use or higher levels of drinking behaviour,137,138 and Foxcroft and Lowe139 identify a possible curvilinear relationship between control and adolescent drinking, where significantly stricter or lax parenting styles appear to increase the frequency of alcohol misuse.

Parents can also be a primary source of the supply of alcohol to young people. 140,141 This may be through the provision of money, by having alcohol available or by purchasing alcohol for young people directly. Easy availability of alcohol is associated with increased adolescent alcohol consumption142 and Elliott et al. 141 found that 65% of drinkers (aged 11–17 years) accessed alcohol via their parents. Further, it is implicitly assumed that if parents purchase alcohol for their children directly, the amount of alcohol consumed can be strictly monitored. In other words, that providing young people with alcohol will stop them from accessing it elsewhere, thus reducing the risk of alcohol-related harm. Again, the evidence for this is equivocal. On the one hand, Bellis et al. 143 found that (in contrast with other ways of obtaining alcohol) young people (aged 15–16 years) whose parents bought alcohol for them were less likely to drink in a public setting, ‘binge’ drink, drink heavily or drink frequently. On the other hand, receiving alcohol from a parent or getting it from home has been demonstrated to be the strongest predictor of increased alcohol use over time. 144 However, Gilligan et al. 145 found that negative outcomes from parental provision of alcohol are dependent on the context of supply. In other words, if parents supplied young people with alcohol, this did not increase the odds of risky drinking (although it also did not have the protective effect that motivated the behaviour). However, if alcohol was supplied for consumption without parental supervision then the odds of risky drinking were four times higher.

Given the well-documented parental influences over adolescent alcohol use, interventions that aim to involve parents who enhance parents’ awareness of the variables and strategies that can delay onset and reduce consumption levels in their child offer an opportunity for limiting the harms of adolescent drinking. 134

Alcohol Screening and Brief Interventions that include parents

Mixed effects have been found for ASBI for reducing young people’s drinking that include family members. 33,54,146,147

A RCT examining the effectiveness of 45–60 minutes of individual motivational interviewing (IMI) compared with IMI and a family check-up session found that both interventions resulted in significant reduction of drinking outcomes at 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups. The family check-up consisted of a 1-hour meeting, at which the parent(s) and the young person discussed family beliefs regarding alcohol and other drug use. Results show there was only one significant between-group difference on the number of high-volume drinking days at 3- and 6-month follow-up, with family check-up reporting lower alcohol prevalence compared with IMI. This effect had diminished at 12-month follow-up. 103

A RCT with three arms: (1) two 60-minute individual sessions of BI (young person and interventionist only); (2) two 60-minute individual sessions of BI (young person and interventionist only) and a BI session with the parent(s) [parent(s) and interventionist only]; and (3) control arm of assessment only found that both intervention groups showed significantly better drinking outcomes than the control arm for number of alcohol days and number of binge days with a small sample (n = 78). The intervention arm that included parental involvement reported significantly fewer alcohol days at 6-month follow-up than the intervention group without parental involvement but no difference in number of binge days. 105 This study was repeated with a large sample (n = 315) and, again, both intervention arms were found to be superior to the control condition. Significant between-group differences were reported by this trial in favour of the arm with parental involvement for drug outcomes but not alcohol. Indeed, the intervention arm without parental involvement reported significantly greater alcohol abstinence in the previous 90 days than the arm with parental involvement. 125

Mixed results have been found for intensive BIs for drug and alcohol using adolescents, with parental involvement (see Appendix 2). 112,115,117,148,149 However, significant variation exists between experimental conditions examined with regards to both the intensity and the frequency of the intervention (ranging from a single 1-hour family check-up to 64 hours of family and individual CBT), as well as the theoretical basis of the therapeutic approach. Moreover, the heterogeneity of the adolescent samples, which included dually diagnosed adolescents, risky drinkers, drug and alcohol users, runaways and gang-affiliated young people, made it difficult to compare the findings of the trials. Therefore, the evidence is equivocal.

Rationale for the present research

The literature shows that ASBI for young people has been successful for selected individuals, in certain settings. In particular, the current available evidence relates primarily to white, USA-based subjects, most often in educational settings and at the older end of the youth spectrum (see Appendix 2). However, there is currently insufficient evidence to be confident about the use of ASBI to reduce excessive drinking and/or alcohol-related harm in younger adolescents and in a school setting. Nevertheless, the current evidence base suggests that the most effective forms of BI are those containing personalised feedback about a young person’s drinking behaviour and MI approaches to help reduce levels of alcohol-related risk. Furthermore, there is some evidence to show that involving parents in ASBI may be beneficial. This present work builds on the evidence base by focusing on ASBI to reduce hazardous drinking in younger adolescents (aged 14–15 years). It is highly likely that if a BI was effective at reducing hazardous drinking, it might also result in a range of other positive behavioural outcomes, as has been found in the adult literature as well as work with older adolescents.

Chapter 3 Development of intervention materials and training

Key points for Chapter 3

-

Learning mentors were identified to be best placed within a school setting to deliver an intervention about alcohol. They were trained in study procedures and intervention delivery.

-

The study incorporated control, intervention 1 and intervention 2 conditions, all manualised and designed to be delivered on a one-to-one basis to young people who screened positive for risky drinking and left their name on the questionnaire.

-

Young people who were in control group schools met with the learning mentor who explained the study to them, and provided feedback that they may be drinking at a risky level, along with an alcohol information leaflet to take away and read.

-

In addition to feedback and an alcohol information leaflet, young people allocated to intervention 1 took part in a 30-minute, six-step, interactive intervention led by the learning mentor.

-

In addition to receiving intervention 1, young people who received intervention 2 were invited to attend a subsequent session with parental/family involvement, designed to last approximately 30–60 minutes, led by the learning mentor.

-

Learning mentors were asked to record time spent with participants using open-ended case diaries.

Introduction

The present study incorporated control, intervention 1 and intervention 2 conditions. All three interventions were manualised to ensure consistency of delivery across schools allocated to that arm of the trial and reproducibility by other deliverers (see Appendix 3). Owing to availability of resources, all tools and manuals were provided in the English language only. All young people recruited into the trial, regardless of arm, continued to receive ‘standard alcohol advice’, delivered as part of the school curriculum. The first section of this chapter is concerned with defining what this consisted of in the study catchment area. In addition, young people in schools allocated to the control arm received feedback that they may be drinking at a risky level and an alcohol information leaflet. Young people in schools allocated to the intervention 1 arm took part in a 30-minute one-to-one structured intervention session with a trained learning mentor. In addition to receiving intervention 1, young people in schools allocated to the intervention 2 arm were invited to attend a subsequent session, facilitated by trained school staff, with parental/family involvement, designed to last approximately 30–60 minutes. Young people from schools allocated to intervention 1 and intervention 2 received the same alcohol advice leaflet as those allocated to control. All young people recruited into the trial were followed up 12 months post intervention.

The rest of the chapter describes the design of intervention materials, as well as the training and support provided to learning mentors in the delivery of interventions. The rationale behind, and development of, each intervention condition (control, intervention 1, intervention 2) is detailed, and the outcomes of piloting of materials and consultation with key groups (parents and young people) are outlined with any resultant modifications to intervention materials reported.

Defining ‘standard alcohol advice’

In order to fully understand the control context, it was first important to determine the scope of ‘standard alcohol advice’ received by all young people aged 14–15 years at secondary school (Years 10 and 11). Provision of classroom-based drug and alcohol education continues to be recognised as an important aspect of the secondary school curriculum (for those aged 11–16 years) for England, Scotland and Wales, and is generally tackled within PSHE classes. PSHE is non-statutory yet the provision of high-quality PSHE forms a significant part of the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (OFSTED) inspections and contributes to the statutory responsibility of schools to ‘promote children and young people’s personal and economic well-being; offer sex and relationships education; prepare pupils for adult life and provide a broad and balanced curriculum’,150 delivered as part of a wider ‘well-being’ remit through the National Healthy Schools Programme151 and the Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) strategy. 151

However, there are no prescriptive guidelines on what PSHE should actually entail, as long as it encompasses these wider statutory responsibilities. As a result, schools have developed their own versions of PSHE, and different ways to deliver it, rather than following standardised frameworks of study. 150 Our observations mirror this and the research team recorded different PSHE arrangements in each of the participating schools. For example, several schools timetabled weekly lessons dedicated to PSHE topics, sometimes described as ‘citizenship’ or ‘extended tutorial’. One participating school had no PSHE provision and instead timetabled a ‘health day’ once per academic year. Schools were also able to elect a key ‘well-being’ focus for the coming academic year. Thus, if they chose to elect alcohol rather than another area (such as self-harm or sexual health) then this could feasibly have an impact on educational provision. Thus, the control context was a highly variable condition, with ‘standard alcohol advice’ defined in this study as the regular provision of classroom-based alcohol education to Year 10 pupils as delivered at each particular school site.

School staff identified to deliver interventions

Learning mentors are specifically trained to provide a service complementary to that of teachers and other school staff, addressing the needs of children who require assistance in overcoming barriers to learning in order to achieve their full potential. All secondary schools have learning mentors working in them. They work with a range of pupils, but give priority to those who need the most help, especially those experiencing multiple disadvantages. Mentoring covers a wide range of issues, from punctuality, absence, bullying, challenging behaviour and abuse to working with able and gifted pupils who are experiencing difficulties. Learning mentors support, motivate and challenge pupils who are underachieving. They help pupils overcome barriers to learning caused by social, emotional and behavioural problems. Learning mentors need good listening skills and an understanding of health and social issues that affect children and young people’s development. The mentors mainly work with children who experience ‘barriers to learning’, including poor literacy/numeracy skills, underperformance against potential, poor attendance, disaffection, danger of exclusion, difficult family circumstances and low self-esteem. Thus, learning mentors were thought to be most well-placed within a school setting to deliver an intervention to young people about alcohol use.

Local areas vary in their essential qualifications for appointment for learning mentors. However, as a minimum, they need to have a good standard of general education, especially literacy and numeracy, as well as experience of working with young people. Within the present study, learning mentors were defined as the members of school staff trained in the delivery of the control condition/interventions to participating students. However, in practice, within each school, titles, roles and responsibilities varied, and this did not constitute a homogeneous professional group. Thus, for consistency, school staff responsible for the delivery of interventions are referred to only as learning mentors throughout the rest of this report.

Patient and public involvement: selecting an alcohol information leaflet (control)

All young people recruited into the trial were provided with an alcohol advice leaflet. It was important that this leaflet was age appropriate (for 14- to 15-year-olds) and suitable for use in a school setting, yet with a presentation style favoured by young people. Owing to time and resource constraints, it was not feasible for the study team to design a new alcohol information leaflet. Instead, we reviewed a large amount of national and regional resources (including materials from the Department of Health, NHS Choices, Home Office, Talk to FRANK, Change4Life, ‘Know Your Limits’ and resources from local youth drug and alcohol services) and liaised with experts in the field. Two appropriate packs or leaflets were sourced, both designed by the Comic Company (www.comiccompany.co.uk/: the ‘Cheers! Your Health’ alcohol leaflet, and ‘snapper’, a quiz question folding game). Both leaflets were discussed with colleagues at Newcastle University, who are experts in working with young people in the school setting and who supported their use. Following this, they were piloted during five focus groups held with young people from years 9–11 (aged 13–16 years) at participating schools.

Young people across all focus groups agreed that the ‘Cheers! Your Health’ alcohol leaflet and ‘snapper’ resources were suitable for young people aged 14–15 years, and these materials were selected as alcohol advice leaflets and provided to young people in all arms of the pilot trial (see Appendix 3). In particular, young people indicated that encouraging them to engage with anything in a non-pictorial way would be challenging. Young people wanted the information presented to them in a fun or humorous way, without too much text, and liked leaflets to include games or puzzles. In particular, positive comments about the ‘Cheers! Your Health’ leaflet included that it was ‘detailed’, ‘interesting’ and ‘interactive’.

Young people who were in the control group schools met with the learning mentor who explained the study to them. The young people were told that they may be drinking alcohol in a way which may be harmful to them. Once consented to the study the young people were given the alcohol leaflets mentioned above to take away and read.

Development of intervention 1

The intervention 1 session was a manualised intervention, which combined simple structured advice and behaviour change counselling techniques commonly used within the extended BI. The tool was a colourful, six-step intervention, intended to be an interactive discussion between the young person and the learning mentor (see Appendix 3). It sought to increase awareness of risks and enable the young person to consider their motivations for changing their alcohol use. The intervention was designed to last approximately 30 minutes and take place in the learning mentor’s office or alternative suitable space. It was expected that young people would be taken out of class to attend appointments with learning mentors. The rest of this section details each step of the intervention tool in turn. Intervention 1 consists of six sections.

Intervention 1

Section one: how many units are in my drink?

This section sought to raise the young person’s awareness of the units of alcohol contained in drinks that are commonly consumed by young people. It was similar to the information commonly provided in simple structured advice. 152 Young people were encouraged to calculate the number of units that they drank during a typical drinking day. This calculation was then used as a basis for discussing the recommended levels for adults and the Chief Medical Officer’s (CMO’s) recommendation that young people aged < 15 years do not drink alcohol at all and to enable personalised feedback about the risks associated with the young person’s drinking. The young person was also asked to consider how common alcohol use is by young people aged 14–15 years. Learning mentors then advised the young people of the actual numbers before asking young people to reflect upon their thoughts about this. This component was informed by social learning theory. 56 This information was delivered in accordance with the elicit–provide–elicit approach to informing within MI.

Section two: typical drinking day

Young people were asked to discuss their typical drinking day in more detail within this section of the intervention. This background description was intended to provide a useful context for the ensuing discussion about the young person’s drinking, associated risk and change. The typical drinking day was informed by the SIPS Brief Lifestyle Counselling (BLC) structure (www.sips.iop.kcl.ac.uk/blc.php). It was developed to provide greater structure and useful prompts about drinking behaviour (with, where, because) for both the young person and the learning mentor. In particular, the additional prompts were intended to provide information that might have been useful in the identification of risk (e.g. when a young person consumes alcohol this may increase or decrease risk), as well as reinforce positive drinking behaviours (e.g. times when young people drink in ways that are not risky) and the behaviours that may become the focus of change.

Section three: are there any risks with my drinking?

Section three of intervention 1 built upon section two and encouraged the young person to consider the risks associated with their alcohol use. The intention was that, by asking the young person to identify risks relevant to him/her, the young person would begin to identify motivation for change. It was expected that this would lead naturally on to how important it is for the young person to change their drinking. Young people were then advised of the common risks associated with drinking above CMO recommendations before being asked to reflect upon this in relation to their own drinking. As well as acting as a further prompt to identifying risks relating to their drinking, the delivery of this information was again in accordance with the elicit–provide–elicit approach to informing within MI.

Section four: importance/confidence

Section four encouraged the young person to rate the importance of changing his/her drinking and confidence in ability to change using a scaling question. Importance scales are used within behaviour change counselling in order to elicit change talk and assess readiness to change. 153 By prompting the young person to consider what would need to happen in order for this number to increase, ratings may also be positively affected and motivation developed. Confidence scales are useful in identifying barriers to change. Exploration around this can enable the young person to find ways to overcome these barriers and assist in the development of a coping plan in section six.

Section five: what do I think about reducing my drinking?

Section five asked the young person to consider the ‘bad’ and the ‘good’ things about reducing their drinking. This is comparable to the ‘pros and cons of changing your drinking’, which is included in the extended BI tool (www.sips.iop.kcl.ac.uk/blc.php) and discussed by Rollnick et al. 153 The terminology ‘pros and cons’ was changed to ‘bad and good’ to make the language more age appropriate.

Section six: what could I do about my drinking?

The final section of intervention 1 was concerned with developing an action plan and coping plan for change. It was acknowledged that not all young people will want to agree to making such a plan. For those who did, it was expected that the young person would set his/her own goals, facilitated by the learning mentor, based upon the content of the MI. The purpose of this section of the intervention was to elicit commitment talk from the young person,154 as well as identifying existing life skills and developing coping strategies to enable young people to achieve and maintain change. Learning mentors employed a strengths-based approach wherein self-efficacy is promoted.

Development of intervention 2

Although BIs are mostly delivered on a one-to-one basis, intervention 2 sought to build upon the rationale for intervention 1 by involving parents. Young people from schools allocated to intervention 2 received an individual BI (intervention 1), followed by a group family intervention based on MI principles held approximately 1 month after. 155 By involving parents within a family intervention, the approach focused upon the dynamic between the individual, attitudes and the environment. 56 Indeed, the addition of a family intervention has elsewhere been found to improve drinking outcomes in adolescents at follow-up. 103

Intervention 2 was a manualised intervention based upon the principles of MI. It was intended to be a discussion that built upon intervention 1 described above, wherein the young person and the learning mentor explored the young person’s drinking and their motivation for change. Intervention 2 sought to build upon the young person’s motivation by encouraging the parents/family members to share their thoughts about the young person’s drinking. The young person and the parents/family member were then encouraged to consider an action plan for change. The intervention was designed to last approximately 30–60 minutes (see Appendix 3). At the end of the session parents were provided with a parenting information leaflet about young people and alcohol use. It was expected that this session would take place either during or after school hours, either within the school or in a community centre nearby, and would take place only if the young person consented to parental involvement and parents subsequently agreed to take part. Intervention 2 consisted of four sections.

Intervention 2

Section one: review of first session

Similar to techniques used within motivational enhancement therapy, section one provided a review of the first session. It was preferable if this review was led and delivered by the young person in order to promote an empowering child-centred approach to the family intervention. However, if the young person felt unable to do this, the learning mentor would summarise the content of intervention 1. Using the intervention 1 sheet, it was expected that the review of the first session would reinforce the young person’s motivation, by emphasising change talk. 154 It also provided background information for the parents/family members to inform the ensuing discussion about the young person’s drinking, associated risk and change, and the parents’/family members’ concerns about this.

Section two: what concerns you about your child’s drinking?

Section two of intervention 2 built upon section one and encouraged the parents/family members to share any concerns they have about their child’s drinking. It was intended that by asking the parent to share their feelings, the young person would begin to consider their drinking from another person’s perspective, which would build upon their current motivation for change. It was expected that this would lead naturally on to a discussion about how important it was for the young person to change their drinking.

Section three: importance/confidence

Section three encouraged the parents/family members to rate (using a scaling question) the importance of their child changing their drinking and their confidence in their ability to help them to change. Although the importance scale was used in intervention 1 to assess the young person’s readiness to change, within intervention 2 the aim is to develop further the young person’s motivation. By prompting the parents/family members to share why they have rated the importance in a particular way, as well as what would need to happen in order for this number to increase, it was expected that both the parents/family members and the child’s motivation to support and achieve change may be positively affected and motivation developed. Confidence scales are useful in identifying barriers to change. Specifically asking how confident the parents/family members feel in their ability to help the young person encourages a ‘family approach’ to change while also finding ways to overcome barriers and assist in the development of a coping plan in section four.

After identifying barriers and how confident parents/family members may feel about their ability to help the young person overcome these barriers, the learning mentor provided information detailed on the tool regarding the potential influence of parents/family members upon young people and their drinking, as well as the benefit of a supportive relationship. The learning mentors then asked parents/family members and the young person to reflect upon this and share their views. The delivery of this information was in accordance with the elicit–provide–elicit approach to informing within MI. It was also informed by the approach used within the Spirito et al. 103 study on family MI with alcohol-positive teenagers.

Section four: what could I do about my drinking?

The final section of intervention 2 was concerned with developing a family action plan and family coping plan for change. This was informed by the extended BI and the intervention manual for the family intervention used by Spirito. 103 It was acknowledged that not all families would want to agree tomake such a plan. If they did, it was expected that the young person and parents/family members would negotiate these goals, facilitated by the learning mentor and based upon the combined content of interventions 1 and 2. The purpose of this section of the intervention was to elicit commitment talk154 from the young person and parents/family members, enabling them to work together to agree an action plan and develop coping strategies to enable young people to achieve and maintain change.

The young person and parents/family members were encouraged to think of two or three good reasons for change. This was to reinforce motivation. They were then encouraged to set goals for change and, in doing so, evoke ‘commitment talk’. It was expected that the learning mentor would explore the feasibility of these goals with all parties. The later part of the action plan was concerned with developing a coping plan. This was largely informed by the discussion, which developed from the confidence scale. Here the young person was asked about times or situations when change might have been difficult to achieve or maintain before then considering how they might deal with such times or situations. Planning for change in this way is assumed to be the most effective way to achieve and succeed. Through identifying by whom and how the young person may be supported in their efforts, the parents/family members were afforded an opportunity to support and encourage the young person. This also allows families to plan for and celebrate success. 103

Patient and public involvement: piloting of interventions

Interventions 1 and 2 were piloted with one young person and their mother by the research interventionist who had experience in MI techniques (December 2011 and February 2012, respectively). The intervention 1 session lasted approximately 25 minutes, whereas the intervention 2 session lasted approximately 45 minutes. The young person suggested adding information about calories to the intervention 1 tool as a way of making information about alcohol use more memorable and pertinent to young people. In particular, they suggested that they would have found this to be an effective motivator to changing drinking behaviour. A focus group was also held, in February 2012, with a convenience sample of four female parents, to discuss the intervention 2 tool, as well as anticipated methods for contacting parents to take part in the intervention. In particular, this group highlighted that the initial approach of school staff would be very important when introducing the project to parents for the first time over the telephone.

Modifications to the intervention materials as a result of piloting and consultation

As a result of piloting and consultation, the following modifications were made to intervention tools and materials:

-

Provision of information about calories on the intervention 1 tool. The number of calories in popular food items (depicted using pictures) was mapped against alcohol brands and quantities that were popular with young people.

-

A slight change to the guidance that was provided to school staff in relation to contacting parents for the first time about taking part in intervention 2. Specifically, the importance of non-judgemental language was reinforced with the learning mentors.

Training and support

All learning mentors received training prior to commencing the study. The training was split into four sessions, with each session lasting a minimum of 1 hour and a maximum of 3 hours. PowerPoint 2010 slides (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) were used to guide each training session. An intervention manual relevant to each arm of the trial was provided to supplement the training (see Appendix 3).

Training was conducted in a community venue or school, as outreach training has been found to be the most cost-effective implementation strategy for ASBI delivery in other settings. 156 The training was jointly delivered by an experienced interventions trainer and researcher, using training materials that were customised for the school setting. A total of 27 learning mentors across the seven schools were trained by the research team. The biggest individual school team of learning mentors comprised nine members of staff, whereas the smallest had two members of staff.

The first training session was delivered to learning mentors from all seven schools as a group to raise awareness of the risks associated with young people drinking and to introduce the study. The training included a PowerPoint presentation, group discussion and simulated young-person scenarios. Learning mentors were also trained to issue the participant information leaflet, gather informed consent from the young person, and deliver the alcohol information leaflet (control intervention). This concluded the training for learning mentors from schools allocated to the control intervention arm of the trial who, in order to prevent contamination, received no training on interventions 1 or 2.

Learning mentors at schools randomised to intervention 1 and 2 were then trained to deliver intervention 1. Again, learning mentors were trained together as a group. In addition to a PowerPoint presentation, training consisted of a demonstration of how to deliver the intervention and simulated young-person scenarios. Learning mentors randomised to intervention 2 were asked to return for a further half-day training session. For intervention 2, training sessions were delivered per school site, as a training date could not be identified which accommodated all learning mentors. This session trained learning mentors in how to gather informed consent from parents for the intervention and organise and facilitate intervention 2, as well as how to respond to difficult disclosures.

The final training session focused on delivery of the 12-month follow-up appointment. Training consisted of a PowerPoint presentation and a demonstration of how to deliver each of the measures included in the follow-up assessment. All learning mentors received the same training; however, training sessions were delivered per school site, as a training date could not be identified which accommodated learning mentors from all participating schools. A manual relevant to the 12-month follow-up appointment was provided to supplement the training (see Appendix 3).

Learning mentors were supported in the delivery of interventions and follow-up appointments by the research team, who organised weekly visits throughout the study period to answer questions or concerns, collect materials from completed interventions (such as consent forms and hard copies of intervention tools) and encourage learning mentors to complete outstanding interventions. The research team also provided telephone and e-mail support. Finally, learning mentors were provided with a case diary sheet, on which they were asked to record any interactions with the individual young people in the trial (see Appendix 3). A main resource-use component of the economic evaluation (for the larger definitive trial) will be the cost of learning mentor time required to prepare for and conduct interventions and follow up with the young people during the trial. Thus, time spent for the present study was calculated by observing the average minutes per case, as documented in self-completed case diaries. The appropriateness of the case diary tool for collecting these data was assessed according to rates of missing data (incomplete or wholly unused diaries) and of diaries missing relevant information (see Chapter 7).

Chapter 4 Survey

Key points for Chapter 4

-

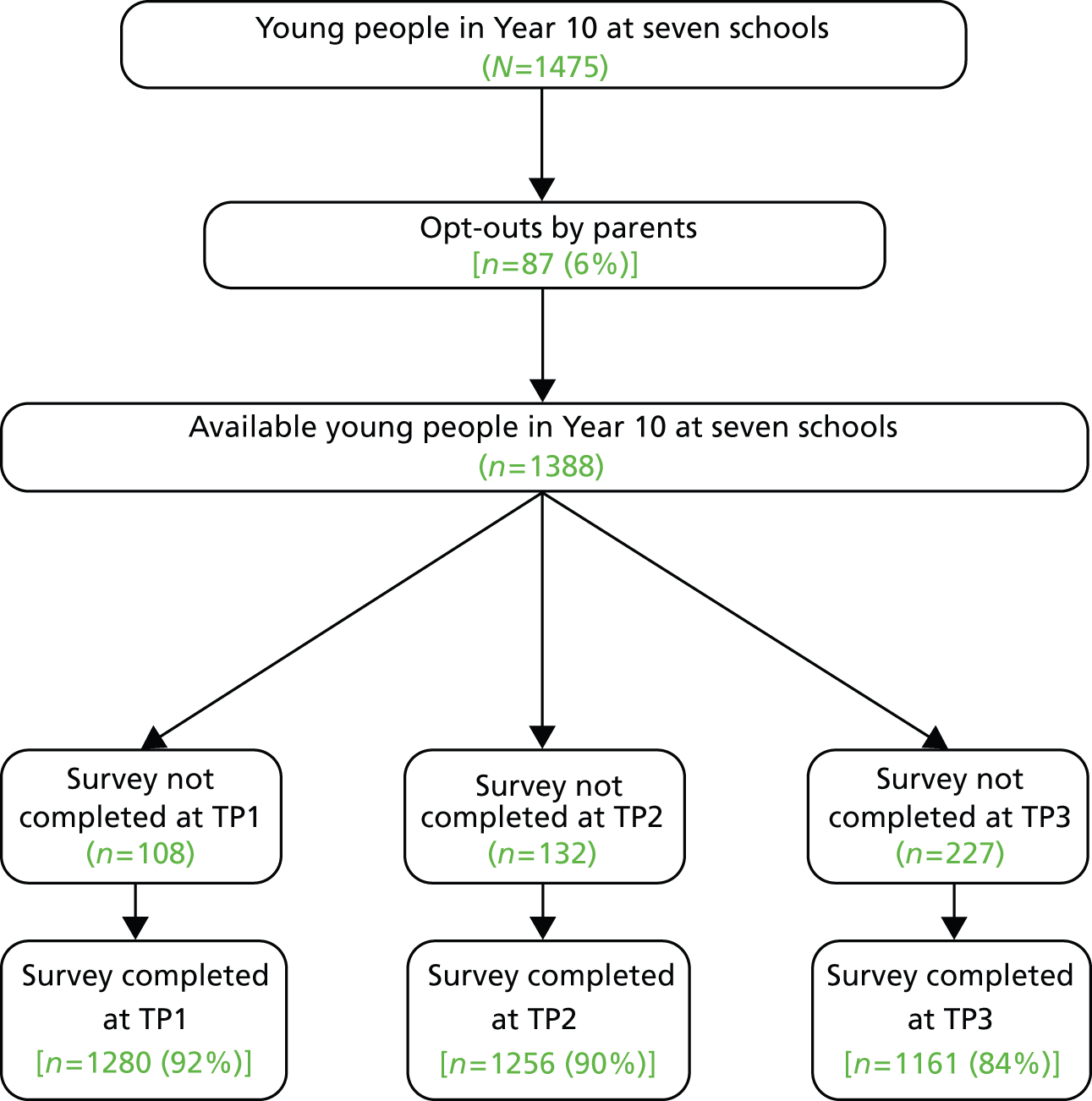

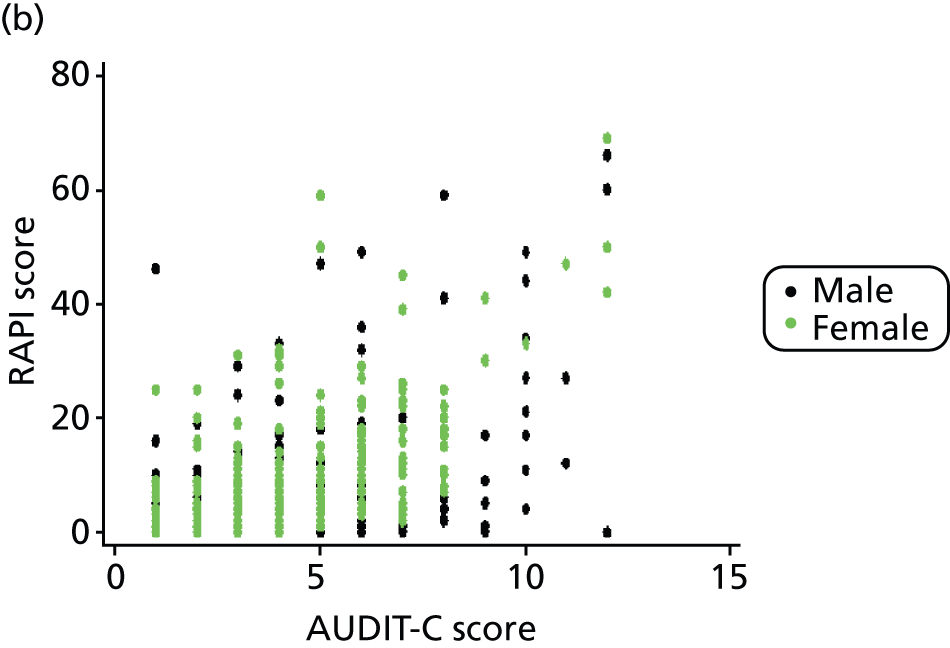

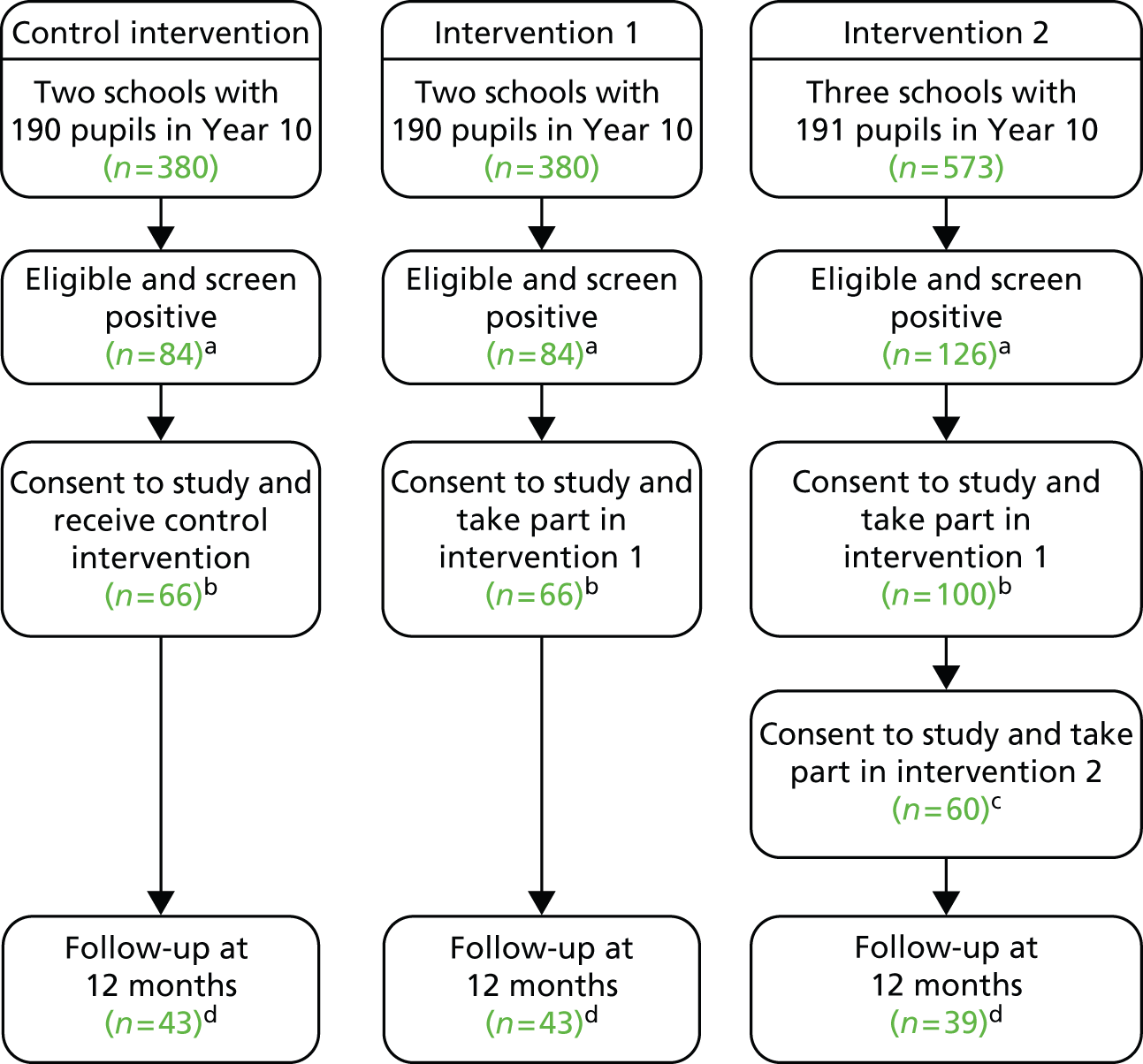

Seven schools took part in a set of three cross-sectional surveys administered at baseline (TP1), 6 months (TP2) and 12 months (TP3). Surveys administered at TP1 facilitated screening for the pilot trial.

-

Six per cent (n = 87) of parents indicated that they did not wish their child to take part in the study by completing and returning a tick-box opt-out form.

-

Survey response rates among pupils whose parents allowed them to take part were 92% at baseline (TP1), 90% at 6 months (TP2) and 84% at 12 months (TP3).

-

Levels of missing data were low for all variables.

-

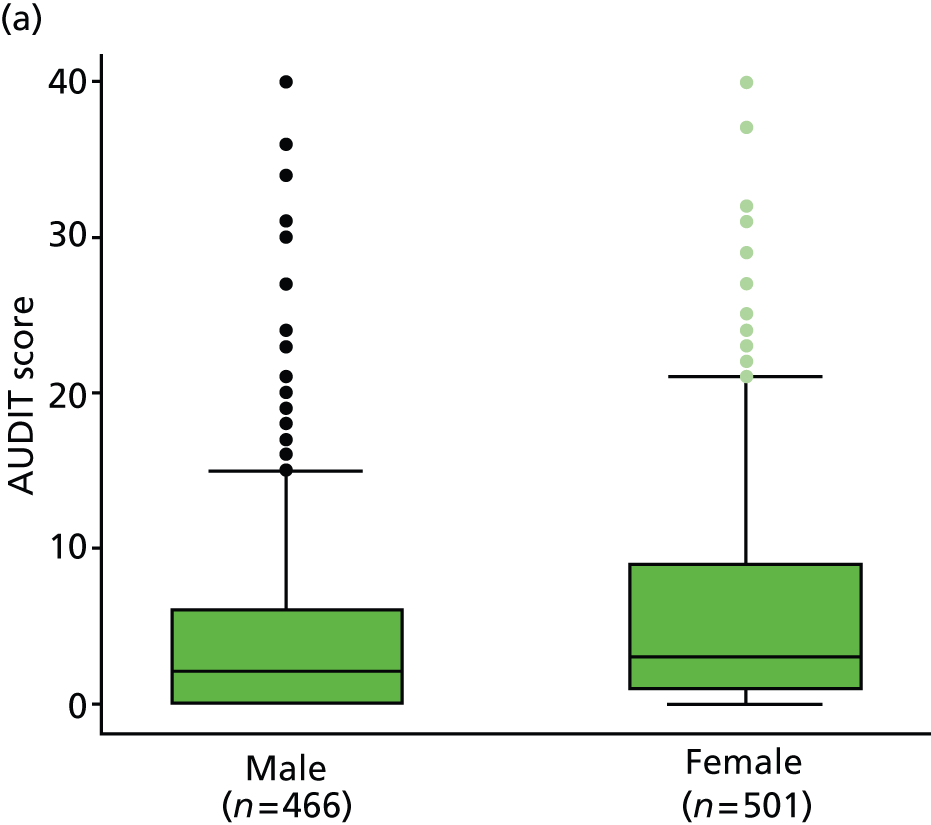

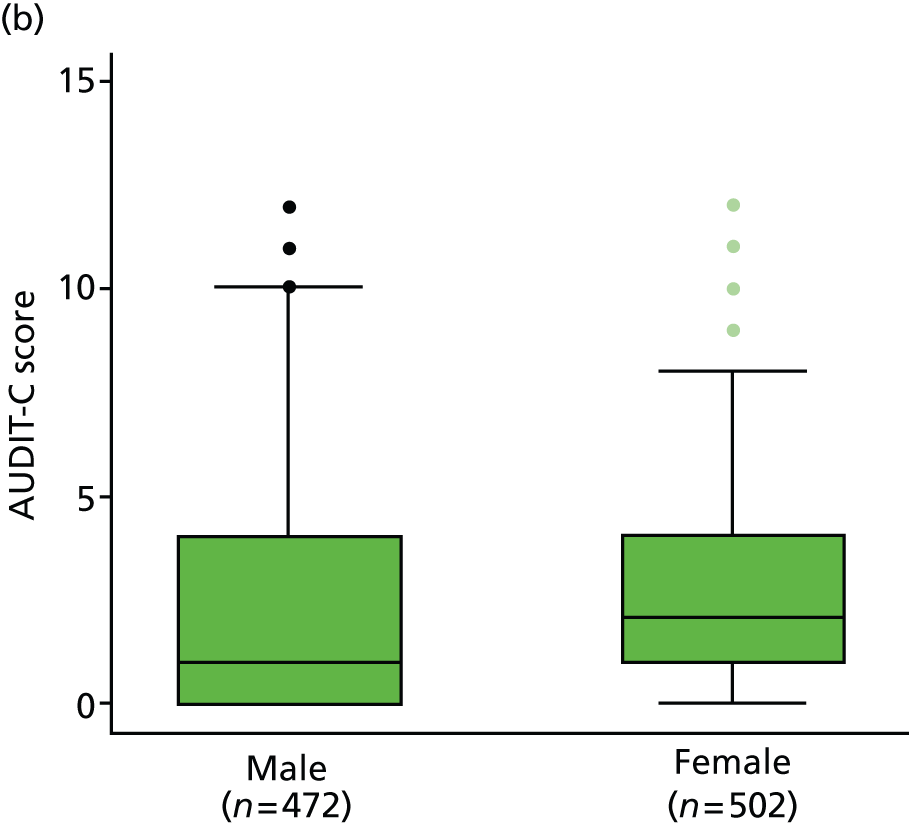

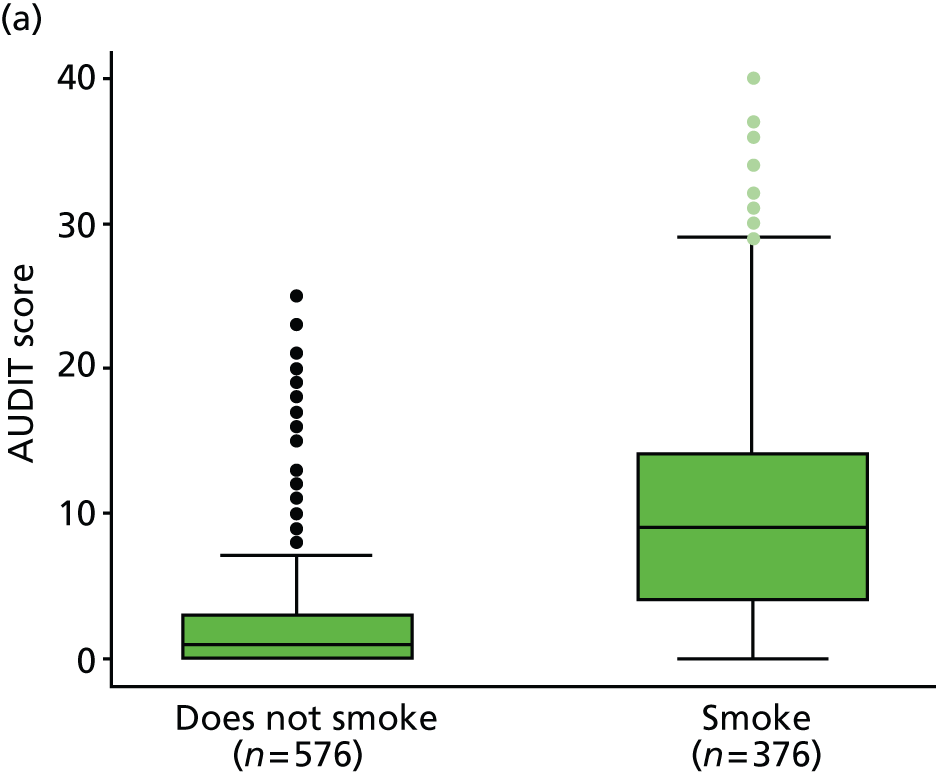

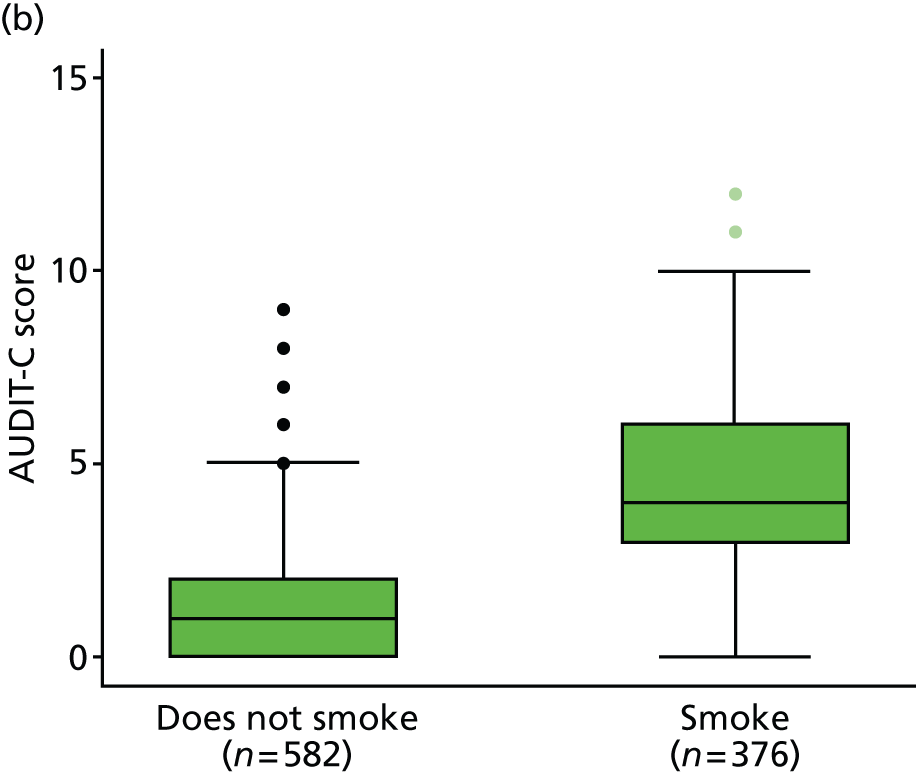

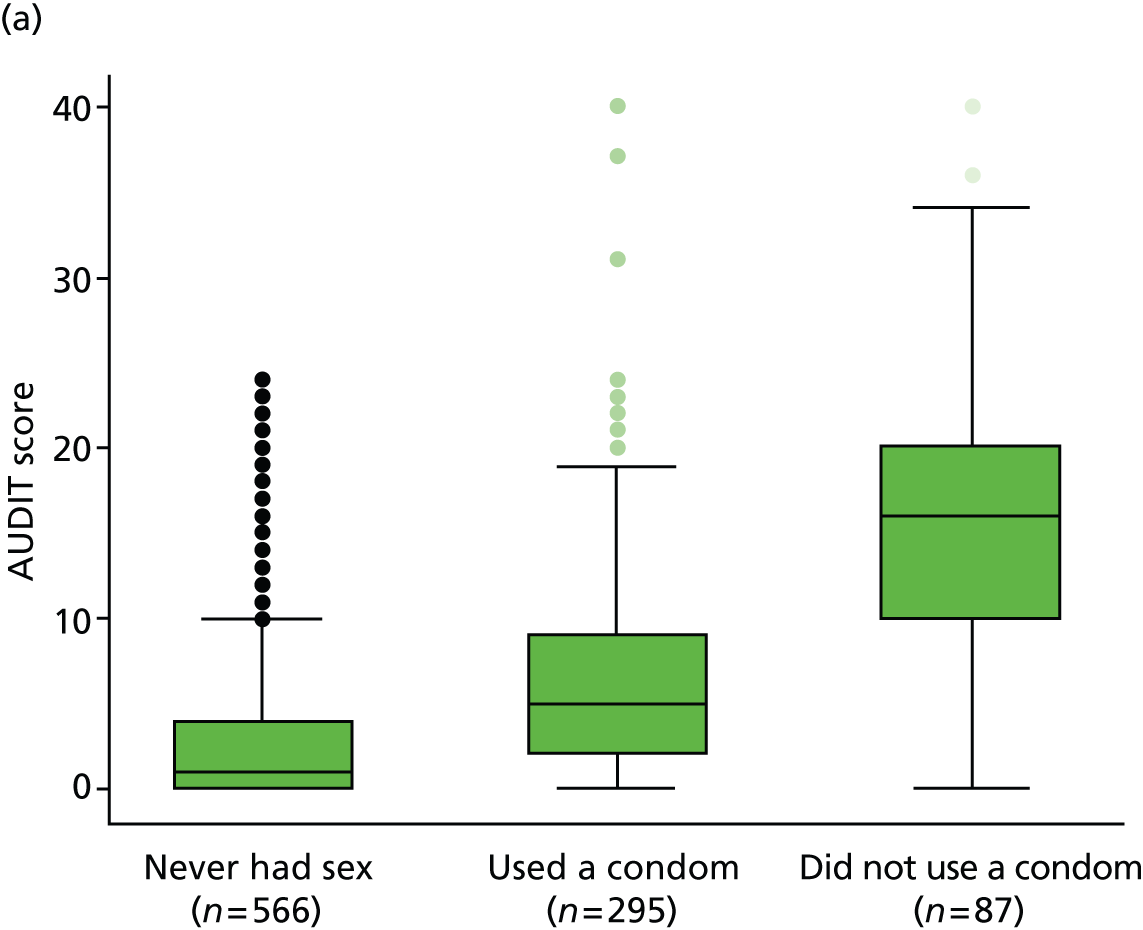

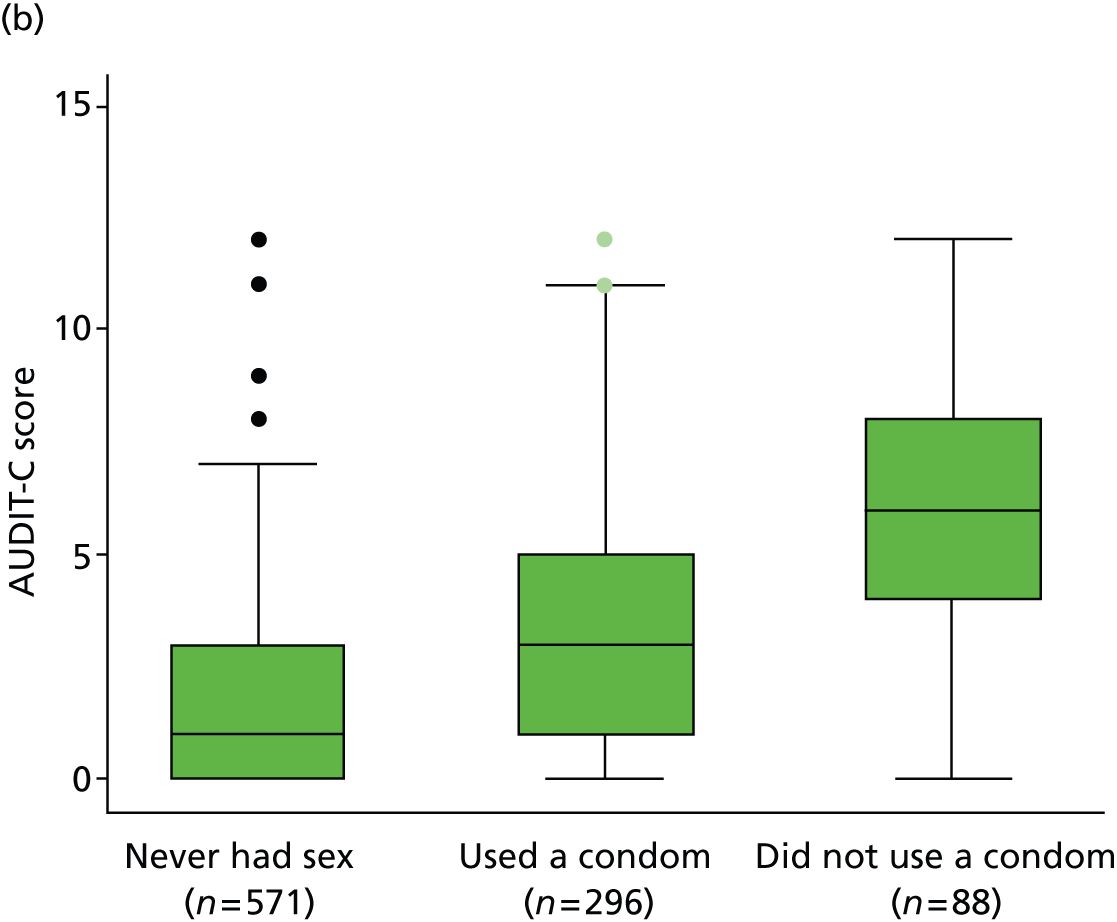

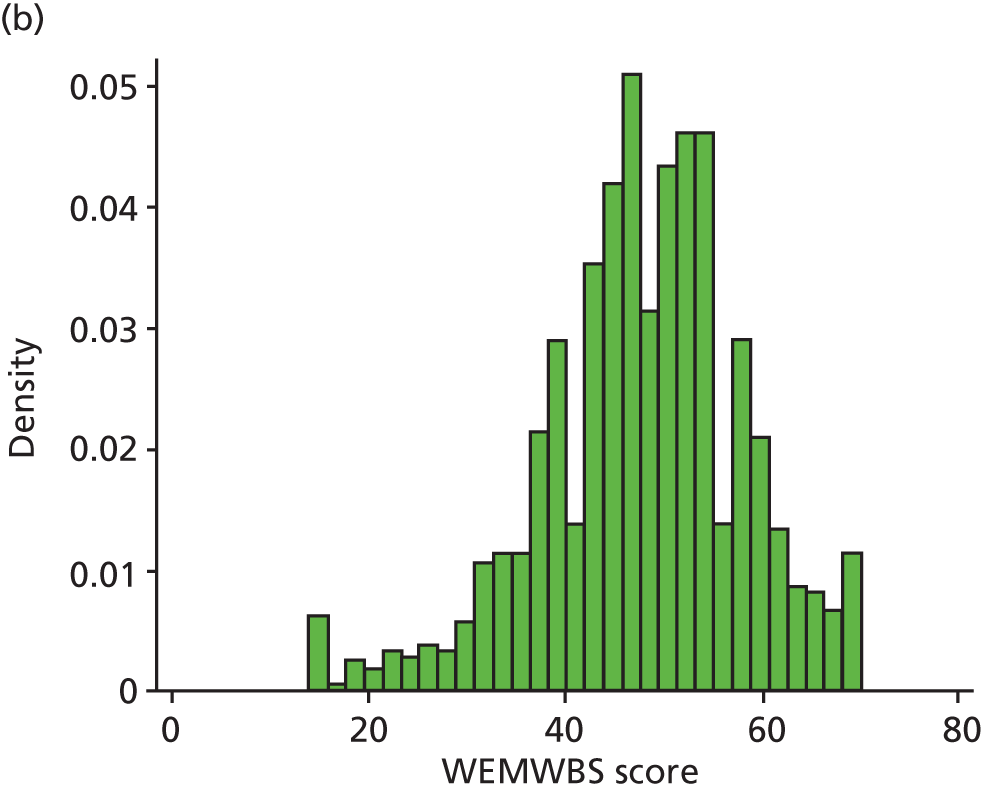

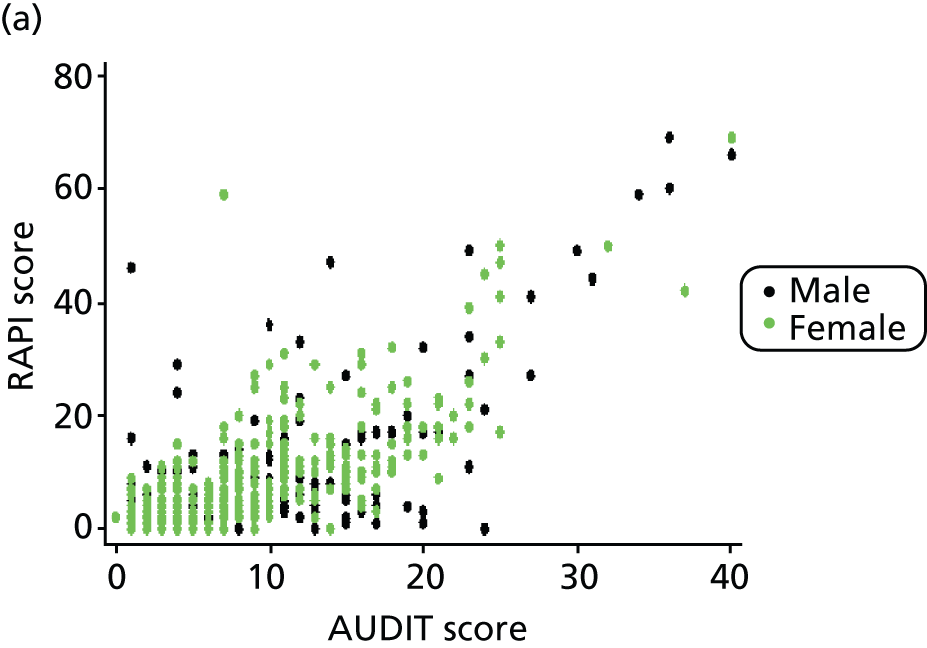

A comparison of the distributions of AUDIT and AUDIT-C scores between subgroups at TP1 demonstrated that gender, smoking and sexual behaviour were significantly associated with young people’s current drinking behaviour.

-

Mean AUDIT scores were higher for young people who did not leave their names on the questionnaire than for those who did.

-

Comparison of scores over three time points suggests there was little or no change in measures of alcohol use, alcohol-related problems and well-being within this age group over the course of a year, except for small but statistically significant shifts upwards in the distributions of AUDIT, AUDIT-C and A-SAQ scores between the first and second surveys.

This chapter reports the methods and results of a set of three cross-sectional school surveys, administered at baseline (TP1), at 6 months (TP2) and at 12 months (TP3).

Methods

Recruitment of school sites

Written approval was obtained from the relevant local education authority, stating that it was willing for the project to go ahead in the study catchment area. All secondary/high schools in the study catchment area governed by the relevant local authority were eligible to take part in the study. Contact details for each school were provided by the local education authority. Contact from the research team with each school site was initially made by telephoning and e-mailing the school office and securing appropriate points of contact, such as the Head or Deputy Head (of Year 10 or the whole school) and pastoral leads. These individuals are described here and throughout this report as ‘lead liaisons’ and are defined as the key member of staff at each school site who made or brokered the decision about participation in the study on behalf of their school.

During an initial meeting between the research team and lead liaisons, the study protocol was explained and lead liaisons were provided with a short written outline of the study in an attempt to secure school participation. A written outline was provided, as it was anticipated that lead liaisons would need to share details of the study with other members of the school management team, such as head teachers (if not already the point of contact) or the board of governors. Final approval to participate in the study was then obtained from the head teacher on behalf of the school and board of governors at each school, and communicated by the school lead liaison to the research team verbally or by e-mail. A second visit was arranged by the research team to all participating schools in order to organise screening of Year 10 pupils and training for school staff who had responsibility for the delivery of interventions. Each school site received a £1000 payment to cover costs associated with the research.

Recruitment of pupils

In advance of the study, all parents/legal guardians of young people in Year 10 at participating schools were informed by letter that the study would be taking place in their child’s school (see Appendix 3). Letters were addressed on site at each participating school and posted directly to parents. Letters included a prepaid return envelope, addressed to the research team at the Newcastle University. Parents were given the option to indicate that they did not wish their child to take part in the study by completing and returning a tick-box opt-out form. Parents were asked to return this form within 2 weeks of the date shown on the letter. Returning this form to the research team resulted in their child not being included in both the survey and the pilot trial. No further parental consent for young people’s participation was sought. An opt-out process, rather than opt-in, was chosen, as sending letters home in order to obtain permission from parents for all young people to fill in a screening survey (and potentially take part in the trial) ran the risk of bias in recruitment and the potential loss of a large number of participants. An opt-out process was supported by the local education authority in the study catchment area, who advised that collection of health and lifestyle data without parental opt-in was a routine approach in school settings. Further, collection of questionnaire data in schools without parental opt-in is a method widely used in various national youth surveys of alcohol consumption and other health behaviours, such as those conducted by the NHS Information Centre annually exploring drinking and drug use by young people aged 11–15 years in England and Wales. 4

All Year 10 pupils at participating schools, except those whose parents had opted out of the research, were asked to complete a health and lifestyle questionnaire administered during a predefined school lesson falling in the week that the survey was due to take place. Pupils were asked to complete the questionnaire at three separate time points: TP1 (between November 2011 and January 2012), TP2 (6 months later: June and July 2012) and TP3 (12 months later: November and December 2012), by which time they were in Year 11. The research team provided support to school staff in implementing the survey tailored to the needs of the school setting. In advance of the survey, packs containing the correct number of survey materials were delivered to each school. The lead liaison in each school was actively involved in setting the survey date. All surveys took place during tutorial or PSHE lessons. However, tutorials or PSHE lessons did not follow exactly the same format at each school and their duration ranged from 30 minutes to 1 hour or an entire day. A minimum of one researcher was present at each school site when surveys took place. At each time point, data collection predominantly took place across one day at each school. However, young people absent on the date of the survey were followed up by school staff to minimise missing data. If young people were opted out by their parents, class teachers provided them with an alternative task while their peers completed questionnaires (e.g. outstanding homework or computer-based research). Young people were informed at every survey that their involvement was voluntary and the survey could be completed anonymously. At TP1 young people were asked to indicate willingness to participate in the pilot trial by including their contact details on the questionnaire. All young people who completed the questionnaire at TP1 were provided with a healthy living leaflet and £5.00 retail gift voucher.

Questionnaire measures

Young people were asked to complete a series of questionnaires including the A-SAQ, a modified version of the M-SASQ (Modified-Single Alcohol Screening Question),157 which aims to identify whether an individual’s drinking is above low risk, with the quantity/frequency measures adjusted to reflect guidelines for an adolescent population of half the adult daily limits (three units). 26 Young people were asked ‘In the last 6 months how often have you drunk more than three units of alcohol?’ with the response options of ‘Never’, ‘Less than four times’, ‘Four or more times but not every month’, ‘At least once a month but not every week’, ‘Every week but not every day’ and ‘Every day’. The A-SAQ contained pictorial references of what constitutes a unit of alcohol. A score of ‘four or more times’, or more frequently, indicated a positive screen and was indicative of being potentially eligible for inclusion in the trial.