Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 11/3008/11. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The final report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in January 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Stanley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

A range of interventions that aim to prevent domestic abuse have been developed for children and young people in the general population. While these have been widely implemented in the UK, the USA and Australia, few have been rigorously evaluated and so little is known about which interventions work, what settings they do and do not work in, and which specific populations and groups they work for. Most large-scale evidence of effectiveness of such programmes is from North America and there are questions about the transferability of these programmes to other countries. Moreover, we understand little about the mechanisms of change that make programmes effective and which theories can be harnessed to explain how change occurs.

This mixed knowledge scoping review was undertaken to address these questions in the UK context. It aimed to capture the complexity of these interventions by drawing information from a variety of sources and by involving a wide range of stakeholders from practice, policy and research. To this end, the study was developed in partnership with representatives from two organisations that have been closely involved in the development of preventative initiatives in the UK: Women’s Aid and the Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE) Association. They have played a valuable role in assisting with the development of the proposal and the recruitment and co-ordination of the expert consultation groups and they have also commented on drafts of this report. Some aspects of this study have been developed in line with their interest in obtaining ‘a broad map of what’s going on and . . . to recommend what we need in terms of future research’ (education consultation group 1). They also emphasised from an early stage in the research that it would be ‘unfair on the intervention to judge its effectiveness without taking the incredibly complex context on board’ (education consultation group 1).

Policy background

The prevention of domestic abuse in the four UK nations is integrated into policies to tackle violence against women and girls. In England, prevention work emerged firmly on the national policy agenda in 2009 with the publication of Together We Can End Violence Against Women and Girls,1 and this has remained an important aspect of current strategy. 2,3 Latterly, there has been a shift in emphasis from children experiencing domestic abuse in their parents’ relationships to young people’s experiences of abuse in their own intimate relationships, largely in response to Barter et al. ’s4 prevalence study, which exposed the extent of interpersonal abuse among young people in the UK. The Northern Irish government set out its strategy on domestic violence in 2005 in Tackling Violence at Home: A Strategy for Addressing Domestic Violence and Abuse in Northern Ireland;5 this was refreshed in 20116 and has been merged with the sexual violence strategy. 7 In Scotland, the prevention of domestic abuse is framed within a joint strategy articulated by the Scottish government and Convention of Scottish Local Authorities in Safer Lives: Changed Lives – A Shared Approach to Tackling Violence Against Women in Scotland,8 which was due to be updated in 2014. Policy devoted to preventing domestic abuse has a longer history in Scotland; the recent strategy was preceded in 2000 by The National Strategy to Address Domestic Abuse in Scotland9 and, more specifically, Preventing Domestic Abuse: A National Strategy in 2003. 10 Welsh Assembly government policy on domestic abuse was laid out in The Right to be Safe,11 a 6-year strategy to tackle all forms of violence against women. More recently, a mandate for all schools in Wales to incorporate domestic abuse prevention into the curriculum was included in the 2012 White Paper;12 this was due to come into law in 2014.

Background to the review

There have been four systematic reviews published in this general area to date. Two included only randomised or quasi-randomised trials, and reported only on the incidence of victimisation and/or perpetration. 13,14 This study extends beyond that approach to consider a range of other data that can take us much closer to the issue of what works for who in what circumstances, what theoretical models of effect are held by stakeholders and programme designers (conscious and unconscious), what outcomes matter to stakeholders, and what mechanisms might (need to) be fired to ensure that different programmes effect change in different contexts. A further systematic review encompassed a wider range of studies and outcomes, but included only data published up to 2003. 15 The recent review undertaken for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) covered a broad range of populations, including children who were exposed to domestic abuse, but did not include educational interventions, thus missing most initiatives aimed at prevention in a general population of children and young people. 16 Both of the reviews that focused on incidence outcomes found some evidence of effect, but the authors caution that the included studies were generally of low or moderate quality only, and that the generalisability of the findings beyond the study populations is not yet established. 13,14 The generalisability from the USA to the UK is even less clear. While some of the non-randomised studies included in Whitaker et al. ’s 2006 review15 provide insights into other aspects of the included programmes beyond effectiveness, a review published in 2003 is likely to include data generated somewhat earlier, meaning that there is no current systematic review of non-randomised evaluations that includes data from any studies undertaken over the past 12 years or so.

Aims and objectives

The following aims and objectives were identified for this study at the outset.

Aims

-

To identify and synthesise the evidence on effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of preventative interventions addressing domestic abuse for children and young people under 18 years of age in the general population.

-

To produce advice on what form future research might take in the context of England and Wales.

Objectives

-

To locate and describe the existing body of evidence relating to preventative interventions addressing domestic abuse for children and young people under 18 years of age in the general population.

-

To identify the range of short-, medium- and long-term outcomes achieved by preventative interventions for children and young people under 18 years of age to date.

-

To distinguish between different preventative interventions including educational programmes, media and community campaigns and other initiatives in terms of effectiveness, cost and cost-effectiveness.

These aims and objectives were used to generate a series of specific research questions.

Research questions

-

What is the nature of preventative interventions in domestic abuse for unselected children and young people under 18 years of age, and what theories underpin the chosen intervention strategies?

-

What outcomes are assessed in studies of preventative interventions in domestic abuse for unselected children and young people?

-

Which elements of the described programmes or interventions have proved to be effective, for which groups of children and young people, and in which contexts?

-

What is the cost of preventative interventions in domestic abuse for unselected children and young people under 18 years of age, and which elements of programmes or interventions have been the principal cost drivers?

-

What are the experiences and views of children and young people about interventions aimed at preventing domestic abuse, and are these influenced by gender?

-

Which of the successful intervention programmes are most likely to be acceptable to stakeholders, and cost-effective in the context of services and developments to date in the UK?

Some of these questions have proved more likely to yield answers than others and this is primarily due to the uneven nature of the evidence. For instance, the systematic review provided few data in relation to cost-effectiveness. These gaps are identified throughout the report.

Definition of terms

One of the features of the interventions addressed by this study is that they involve practitioners and researchers from a wide range of disciplines and professions, including education, health, social care, community development and the domestic violence sector. It is, therefore, particularly important to define the terms used for this study.

The following definitions were adopted for the purposes of the review.

Children and young people

This term includes all school-age children, that is those aged between 5 years and 18 years.

Preventative interventions

While the original research brief for the study called for a focus on interventions to prevent children and young people becoming victims/perpetrators of domestic abuse in later life, it was evident from an early stage, both from the UK mapping survey and from the literature retrieved, that much activity in this field was aimed at assisting children and young people to manage domestic abuse as they might currently or soon experience it in their own intimate relationships as well as in their parents’ relationships. Prevention in this review is, therefore, not confined to the prevention of domestic abuse in adulthood.

Preventative programmes are delivered in schools and other settings (such as young people’s centres) to children and young people under 18 years of age in the general population. They aim to prevent domestic abuse through raising awareness and changing attitudes and behaviour. They address domestic abuse in young people’s own interpersonal relationships and often also address any experience of domestic abuse in their parents’ relationships.

Preventative interventions also include media and community campaigns and initiatives aimed at preventing domestic abuse that address children and young people in the general population.

We have tried to distinguish clearly between different forms of initiatives throughout this report. However, in places, particularly in Chapter 3 where we report the findings of the mapping study, the term ‘programme’ is used as a shorthand to indicate a range of initiatives that includes both manualised programmes and one-off lessons or events such as a school assembly.

Domestic abuse

In line with the government definition, this study has adopted a broad definition that includes coercive and controlling behaviour in addition to physical, sexual, threatening, emotional/psychological or financial abuse of those who are or have been an intimate partner, regardless of gender or sexuality. 17 The definition adopted includes ‘honour-based’ violence and forced marriage but not female genital mutilation (FGM) (in line with definition adopted by NICE’s Public Health Guidance18 on domestic abuse).

Structure of the report

This report begins with an account of the mixed-methods approach underpinned by the principles of realist review19 employed for the study (see Chapter 2). The methods used for the four main elements of the study – the mapping survey, the systematic literature review, the review of the grey literature and the consultation groups and interviews – are described in detail here. The next four chapters report the findings from these key phases of the review (see Chapters 3–6), with a fifth chapter reporting the analysis of costs and benefits which drew on data from all four elements of the review (see Chapter 7). Chapter 8 synthesises these findings under the principal themes, while the final chapter details the study’s conclusions and recommendations. A number of additional tables and other types of information, as well as research tools, are included as appendices in order to make the body of the report more accessible for the reader.

Chapter 2 Study methods

The study was originally designed as a realist review. In the event, for pragmatic reasons, the primary methodological approach taken was that of a mixed knowledge review. 20 This allowed for different sources of evidence to be included and enabled a synthesis of current practice in the UK and of stakeholder views with a systematic review of the published literature. Realist principles informed the study throughout, specifically in terms of the inclusion of stakeholder priorities at three critical time points, identification of the theories that underpinned the programmes under examination, and exploration of the trigger mechanisms that might explain both the intended and the unintended consequences of these programmes for specific groups of young people in particular contexts. 19,21 The methods described here are an amalgamation of those set out in the initial proposal, and of changes introduced as the project evolved, based on interactions with the consultation groups over time, and emerging data from the four main phases of the study. This emergent approach is a feature of realist synthesis, in which data from each iteration of a review inform the focus and processes of the next one. However, in this time-limited scoping study, each element took place in parallel rather than sequentially, and so feedback to and from consultation groups and the review team was iterative rather than linear.

The study had four main phases, which were undertaken in parallel: a mapping survey; a systematic mixed-methods literature review; a review of the UK grey literature; and consultation with key stakeholders. The analysis of costs and benefits drew on data produced by these four phases. The methods used for each of these are described below.

Mapping survey

The mapping survey aimed to build a picture of current and recent practice across 18 selected local authority areas in the UK. Following discussion with the expert consultation groups, the sample of local authorities was selected using two criteria: police data on rates of domestic violence incidents and the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). The relevant police data were more readily available for some parts of the UK than others. While these data could be accessed from the relevant websites for Scotland, Northern Ireland and London,22–25 there were difficulties encountered in accessing these data for local authorities in England and Wales. The Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) provided the required information for all police force areas in England and Wales. Local authority deprivation scores for 201026 (the most recent year available) were obtained from the relevant government website. These two data sets were used to construct a sample planned to include 12 English local authorities, with another six selected from Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (two from each country). For Scotland and Northern Ireland, local authorities were ranked according to their domestic abuse incidence rates. We selected one with high rates of domestic abuse and one with low rates in each country. For England and Wales, the police force area data provided by ACPO were used to identify local authorities with high, medium and low rates of domestic abuse incidents, and within each of these three bands we selected local authorities with high, medium and low IMD ratings. The same approach was adopted to select three London boroughs. The full list of local authorities included in the sample is shown in Chapter 3 (see Table 6).

The online survey used the Survey Monkey software package (www.surveymonkey.com) and was designed with input from the two expert consultation groups. It was piloted with a group of practitioners from outside the sample local authorities and was refined in response to their feedback; the final version is included in Appendix 1.

The internet, together with the professional networks of consultation group members and our study partners, Women’s Aid and the PSHE Association, was used to compile distribution lists of relevant professionals and community organisations, such as safeguarding leads, police and crime commissioners, community safety and domestic abuse co-ordinators, and domestic abuse organisations in the 18 local authorities. The researchers distributed the survey by e-mail to 230 professionals in non-school organisations and to the administrator in all primary and secondary schools in the sample of 18 local authorities. Additionally, Women’s Aid and the PSHE Association e-mailed the survey link to their members in the sample local authorities. A snowballing approach27 was adopted, with those receiving the e-mail link to the survey asked to forward it to relevant practitioners involved in prevention work in their own or other organisations in the sample areas. Therefore, the total number of those invited to participate in the survey is not available. This means that we are unable to report a response rate for the survey and its generalisability is limited. The initial survey and three subsequent reminders were distributed by e-mail between October 2013 and December 2013. The survey was closed in January 2014. The Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS: IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) software package was used to analyse the survey findings, and answers to open questions were listed and analysed thematically.

Systematic literature review

Primary research question for the literature review

The research questions (see Chapter 1) were reframed into a single overarching question for the purpose of the systematic review of published literature. This was:

What is the nature of, underlying theory for, and evidence of effect of interventions designed to help children and young people avoid and/or deal with domestic abuse, and what interventions work to trigger effective mechanisms for change in specific groups and individuals in which specific contexts?

Search strategy

The search strategy was designed to be broad and to ensure that a wide range of relevant literature was included. Included studies were those published in any language between 1990 and 2012 (updated in February 2014). The year 1990 was chosen as the start date for inclusion of material for review, as prevention programmes emerged in North America in the mid-1980s28 and evaluations and research into such programmes did not appear until the 1990s.

Study types

Each of the detailed research questions in the protocol was mapped against the knowledge matrix of Petticrew and Roberts29 (modified for this specific research topic) to establish the kinds of data that were most likely to answer the question posed (Table 1). This indicated that the search strategy should not be limited to studies with randomised designs. The strategy therefore allowed for inclusion of studies using a wide range of methods. Because we were aware that the existing reviews in this area either were narrowly focused on randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-RCTs,13,14 or included data that were at least 12 years old,15 we did not include systematic reviews, although we did ensure that our search strategy located all of the relevant studies included in these prior reviews.

| Research question | Type of question | Study type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Survey | Case–control | Cohort | RCT | Quasi-experimental | Non-experimental evaluation | ||

| 1. What is the nature of preventative interventions in domestic abuse for unselected children and young people under 18 years old, and what theories underpin the chosen intervention strategies? | Process of service delivery: How might this work? | ++ | + | + | ||||

| 2. What outcomes are assessed in studies of preventative interventions in domestic abuse for unselected children and young people? | Salience: Does it matter? | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3. Which elements of the described programmes or interventions have proved to be effective, for which groups of children and young people, and in which contexts? | Effectiveness: Does this work? | + | + | ++ | + | |||

| 4. What is the cost of preventative interventions in domestic abuse for unselected children and young people under 18 years old, and which elements of programmes or interventions have been the principal cost-drivers? | Cost-effectiveness: Are the benefits worth the costs/resource use required? | + | + | ++ | + | |||

| 5. What are the experiences and views of children and young people about interventions aimed at preventing domestic abuse, and are these influenced by gender? | Acceptability/satisfaction: Will children/young people be willing to take part in the programme? | ++ | ++ | + | ||||

Databases searched and other means of locating literature

A wide range of databases were searched, as follows: Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED); Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); EMBASE; Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC); MEDLINE; PsycARTICLES; PsycINFO; Social Policy and Practice; Social Work Abstracts; Sociological Abstracts; Studies on Women and Gender Abstracts; Australian Education Index; British Education Index; and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED). Searches were undertaken for the period 1990 to February 2014. The initial date of searching was 3 July 2013 and the searches were updated in February 2014.

The protocol planned for the establishment of a Zetoc Alert list, but in the event two members of the team (Jane Ellis and Nicky Stanley) were in receipt of a wide range of relevant journals regularly. They are also experts in the field, with extensive networks in this area. Along with a search of the Controlled Trials Register, the National Institute for Health Research portfolio of ongoing studies, and formal contact with leading authors in the field, this was deemed to be adequate to scope the ongoing and new studies in the field. The following journals were, therefore, reviewed regularly across the period of the study: Journal of School Health; Children and Society; Journal of Adolescent Health; Violence Against Women; Violence and Victims; Prevention Science; Journal of Interpersonal Violence; Journal of Primary Prevention; Scandinavian Journal of Public Health; and Child Abuse Review.

Search terms

The search terms were chosen to generate a wide range of hits in the first instance. The example terms described in the protocol were amended as the study progressed in the light of the data and insights emerging from the consultation groups and from the initial testing of the search for parsimony and comprehensive inclusiveness. They were structured using a version of the PICO framework (population, intervention, context and outcome, which was divided into general and intermediate outcomes, such as attitudes and knowledge, and specific types of violence and/or perpetration outcomes) relevant for a realist review of studies employing a range of headings. Table 2 sets out a summary version of the search terms that were used. Appendix 2 gives an example of the full search in EBSCOhost.

| Population | Intervention | Context | Outcome (general) | Outcome (specific) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child* OR | Prevent* OR | Media OR | Outcome OR | Domestic AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR |

| Young person OR | Educat* OR | Communit* OR | Cost OR | home AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR |

| Young adult OR | Train*OR | Public* OR | Cost analysis OR | family AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR |

| Young people OR | Teach* OR | School* | Cost effectiveness OR | families AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR |

| Adolescen* OR | Promot*OR | College | Acceptabl* OR | gender AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR |

| Teenager* OR | Instruct*OR | School-based | Effective* OR | spous* AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR |

| Youth* | Campaign* OR | Experience* OR | partner* AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR | |

| Social Marketing OR | View* OR | fiancé AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR | ||

| Attitude* OR | cohabitant*AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR | |||

| Help seeking OR | intimate AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR | |||

| Protective Behaviour*OR | interpersonal AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*))OR | |||

| Harm reduction OR | dat*AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR | |||

| Healthy rel*OR | relationship AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR | |||

| Respectful rel*OR | marital AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) OR | |||

| Resources | conjugal AND ((abuse OR violen* OR batter*)) | |||

| Perpat* | ||||

| Victim* |

The reference lists of all included studies were searched to check for any frequently cited studies not identified by the primary search (‘back-chaining’).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 3 details the inclusion and exclusion criteria for included studies.

| Include | Exclude |

|---|---|

| Papers and reports published/dated between 1990 and 2012, updated to February 2014 | Papers and reports published/dated before 1990 |

| Published in any language | No language restrictions |

| Peer-reviewed research papers: all countries | Research papers that are not subject to peer review |

| Meta-analyses, research reviews, controlled studies, before-and-after studies, independent case evaluations, qualitative and ethnographic studies | In-house evaluations, internal audits |

| Qualitative studies that do not include the views of children and young people participating in interventions using their direct quotes | |

| Children and young people at or below the age of 18 years | Studies with minimal or no data relevant to children/young adults below 18 years |

| Studies focused on prevention programmes for adults who perpetrate abuse | |

| Studies including interventions to prevent domestic abuse | Studies focused only on child abuse and neglect or on bullying |

| Studies including children/young people in the general population | Studies only including children and young people who have experienced domestic abuse |

| Studies only including children and young people who have perpetrated domestic abuse | |

| Studies of interventions aiming to prevent children and young people becoming either/both victims or perpetrators of domestic abuse | Studies focused only on prevalence or outcomes of domestic abuse |

Quality appraisal

In realist review methods, the quality assessment of the included literature is less important than the information it generates about programme theory and design, the contexts it has been used in and the mechanisms (both intended and unintended) that might have been triggered as a consequence: criteria that have been labelled relevance and rigour. 19 In the case of the current review, however, we wanted to focus particularly on programmatic and mechanism effects for studies where the programme under review seemed to have had an effect either on the hypothesised mediating variables, or on any component of relationship/dating violence. To establish if any such effect was real and likely to be generalisable beyond the original setting for the study, we needed to undertake a basic assessment of quality.

In the original protocol, it was planned that all studies meeting the inclusion criteria would be subject to quality assessment using a specific tool relevant to the methods used, such as Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT; for any RCTs that are identified)30, Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE; cohort, case–control or cross-sectional designs)31 or Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA; systematic reviews). 32 As it had been agreed that all identified studies regardless of quality would be included in the literature review, the initial quality screening was undertaken using relevant Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools,33 as an overall guide to the quality of the included studies. In the event, this process provided a fair guide to the quality of the included studies, and, indeed, the CASP tools include the key elements of all of the specific assessment tools we originally planned to use. We therefore did not undertake more detailed quality assessments of the quantitative studies, especially as there were no plans to meta-analyse the findings from the included data set. For the qualitative data, the search produced so few papers that the decision was made not to exclude studies on quality grounds, and that, in these circumstances, the CASP tool provided an adequate assessment of general quality. 34 The interpretation of the quality scores for quantitative studies is given in Table 4.

Analysis

Six intersecting narrative analyses were planned: a description of study characteristics; an examination of the theoretical basis of the programmes; a summary of the kinds of interventions used; a description of the outcomes assessed; an overview of the effectiveness of the included interventions and programmes, both overall and for specific groups (including analysis by gender, ethnicity and prior risk status) and contexts; and a synthesis of the views and experiences of participants and staff involved in interventions in this area. Costs and cost-effectiveness data derived from the review data are reported separately in Chapter 7.

Quantitative findings were reported by study and summarised narratively across the data set. Qualitative data were synthesised using a meta-synthesis approach that included reciprocal and refutational narrative analysis, and the production of a line-of-argument synthesis. The summary of the findings entailed an interpretation of the findings of the review against prior theoretical constructs for what might work, for whom and in what contexts.

Detailed analytic process

The studies were grouped and described in a range of different ways to allow for insights to emerge. The structure of these descriptive processes varied somewhat from those proposed in the protocol in order to reflect the concerns arising from the consultation groups, and the nature of the emerging data from each phase of the study:

-

The characteristics of each study were logged on a pre-designed data extraction form by study type (controlled trials; cohort/caseload studies; qualitative data). This included a description of the intervention components of, participants in, context of and outcomes assessed in each study.

-

The outcomes measured used across the studies were then described to assess the commonality and differences between them and the number of studies that included each specific outcome. Outcomes were summarised under four headings: measures of knowledge, attitudes, behaviours (such as help-seeking), and incidences of victimisation or abuse related to relationships.

-

Studies assessing similar intervention components and/or which described elements of the same programme were then grouped together (regardless of methodology or outcomes examined at this stage) to establish the type of interventions tested in the included studies, how these fitted with the theoretical principles identified and what the range of resource requirements might be for each programme.

-

Following the first set of consultation meetings, the researchers developed a matrix of theories that might have been used to frame programmes. A wide range of potential theories was identified, ranging from those addressing causation (such as various feminist and social norms theories) to learning and education theories and theories of change and adoption of innovation. The team then assessed the underlying programme theory in each paper included in the search (where this was evident or could be deduced) to determine whether or not any of the theories identified in the initial theory matrix were present in the reviewed programmes and interventions.

-

The findings of each study were assessed. Outcomes noted to be significant at the p = 0.05 level (or p = 0.01 where it was evident that more than 100 separate analyses were carried out without correction for multiple testing) were logged, by time point (within 1 month of the end of the intervention; between 2 and 5 months; 6 months to under 4 years; and 4 years or more). The same organisational structure was used for the outcomes as in point 2, above.

-

For each included study/programme, data showing post-intervention changes that were statistically significant (using the criteria in point 5 above), and that were identifiably linked to gender, grade, age and history of perpetration/victimisation at baseline, were separately analysed by subgrouping by the relevant data and then summarising them narratively.

-

Where authors provided logic models for their programmes, these were examined for similarities and differences.

-

Given the lack of strong evidence of effect in the included studies, formal context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) models were not constructed.

Review of the grey literature

As this was a scoping review, the included studies were not limited to formal published research papers. Much of the literature on UK interventions is available only as ‘grey literature’, and so this aspect of the review was fundamental to building a fuller picture of the nature and impact achieved by prevention work in the UK context. This element of the review addressed UK-based grey literature, including local independent evaluations, national reports, technical reports and theses; in-house evaluations were excluded. The time parameters used were the same as those for the systematic review.

The systematic review search yielded three grey literature publications and an online search of relevant websites (listed in Appendix 3) yielded a further nine. Back-chaining produced an additional five items and the remainder consisted of publications identified through requests to consultation group members and in response to a request circulated by Women’s Aid as well as through the research team’s own knowledge of the field.

Forty-six documents were identified by these means and data were extracted and recorded on a pre-designed form using the same categories as were employed for the peer-reviewed papers. A narrative approach was utilised for this aspect of the review, with analysis identifying the main findings and themes in independent programme evaluations undertaken in the UK.

Consultation with stakeholders and experts

The consultation element of the study was designed to capture the views of relevant stakeholders including young people themselves as well as experts from the various sectors involved in designing and delivering preventative interventions in domestic abuse. It offered a means of adding rigour to the study36 both by generating new data describing current policy and practice in the UK and by offering expert reflection on early findings from the review. Three consultation groups were established with each meeting on three occasions in the course of the study. The two expert groups were convened by the two organisations partnering and supporting the work of the research team. Women’s Aid recruited and managed the media consultation group and the PSHE Association recruited and managed the education consultation group. Membership of these groups was determined by discussions which drew on the expert knowledge of both the research team and the partner organisations, with the aim of achieving a mix of policy, practitioner and researcher representation in each group as well as ensuring representation from all four countries of the UK. Research commissioners were also invited to join these groups and some of those invited nominated additional group members. Membership of these groups is shown in Appendix 4.

The third group was a young people’s group. This group was recruited from an established youth participation group that had experience of being consulted on similar issues. The membership of the group fluctuated between meetings: 18 young people aged 15–19 years attended the first meeting of this group, with seven or eight young people attending subsequent meetings.

The three consultation groups were similarly structured, with participants being provided with feedback from the study that included progress reports and early findings, as well as being asked to discuss key questions chosen to reflect the research questions.

International perspectives were fed into the study through 16 interviews with international experts, all of whom were involved in the design, delivery or commissioning of preventative interventions for children and young people. These experts were selected by drawing on the knowledge and networks of the research team, and of the study’s two partner organisations and the expert consultation groups. While most of those interviewed were based in North America, Australia or New Zealand, some UK experts who were unable to attend the expert consultation groups also took part in these interviews. Only one expert approached by the researchers declined to be interviewed; a further four did not respond to e-mail requests. Most interviews were conducted by telephone; one interview was conducted face to face. A topic guide (see Appendix 5) which allowed interviewees to reflect on essential themes in depth was employed.

All consultation group members and interviewees were provided with appropriately formatted information about the study, and informed consent procedures were adopted which allowed for all discussions and interviews to be audio-recorded and transcribed. The involvement of the young people’s consultation group was approved by the University of Central Lancashire’s Psychology and Social Work Ethics Committee (PSYSOC).

Both interview and consultation group transcriptions were analysed thematically using a framework structured using the main headings used for data extraction in the systematic literature review: context, programme theory, mechanism including delivery and content, audience and outcomes. Subthemes and new themes arising from the data were added as appropriate. The software package NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to assist with the sorting and storing of data.

Economic analysis

This element of the study was conceived in the original proposal as an aspect of the systematic review of the literature. However, the paucity of information on costs and cost-effectiveness available in the published literature led to a broadening of the evidence base on which this element of the study drew. Therefore, four main sources were used to obtain information on resources and/or costs required to run different types of preventative programmes in domestic abuse and to identify the stated outcomes of the various programmes. These four sources were mined from the data collected in the four main phases of this study, namely (1) the mapping survey of prevention activity across a sample of 18 local authorities; (2) the systematic review of published literature; (3) the review of grey literature, which was reinforced by personal contact with the programme designers; and (4) the consultation groups with young people and media and education experts.

We describe below how relevant data from the four sources were identified, extracted and analysed to draw conclusions about the costs and benefits of programmes aimed at preventing domestic abuse for children and young people.

Mining the mapping survey data

The mapping survey administered in 18 local authorities (see Table 6 for the local authorities surveyed) consisted of 46 questions about each programme reported. A subset of the 23 questions listed in Table 5 was identified as being relevant to assessing the costs and benefits of the programme; responses to questions marked with an asterisk in Table 5 were deemed necessary to be able to draw useful conclusions. Therefore, those programmes reported in response to the survey, which provided complete data in these 13 areas, were included in this aspect of the study.

| Question number | Question wording |

|---|---|

| 4 | Please list below the title of all the preventative programmes in your locality that you know of |

| 5 | Please describe the programme if it does not have a formal name and you have not listed it above |

| 6a | Where is the programme delivered? (14 options including ‘other’) |

| 7 | What does the programme address? (Eight options including ‘other’) |

| 8a | Who is involved in delivering the programme? (16 options including ‘other’) |

| 9 | Please specify agency |

| 10a | When did the programme begin? (Month/year) |

| 11a | Is the programme still running? (Yes/no/don’t know) |

| 12a | When did the programme end? (Month/year) |

| 13 | Why did it stop running? (Six options including ‘don’t know’) |

| 14 | Was it built on a programme obtained from elsewhere? |

| 16a | Were children and young people involved in designing the programme? (Yes/no/don’t know) |

| 22a | Who is/was the main funder of the programme? (14 options including ‘other’) |

| 23a | What is the approximate total length of the programme in hours? (Free text) |

| 24a | What pattern of delivery does the programme take? e.g. one block of 3 hours, a daily advert, 1 hour a week for a school term (Free text) |

| 32a | Which methods of delivery are used? (14 options including ‘other’) |

| 33a | Is the programme delivered in conjunction with a programme for parents and carers/other adults in the local community/professionals working with the local community/service managers/don’t know/other |

| 34a | Did the facilitators of face-to-face programmes undertake specific training to deliver it? (Yes/no/some but not all/don’t know) |

| 35a | Please estimate how many CYP have participated in the programme in the previous 12 months (free text) |

| 40 | Has the programme been evaluated? |

| 41 | Was the evaluation undertaken: in house/independently/don’t know |

| 42 | Is there a report available? |

| 44 | In your view, what has the programme achieved? |

For the included programmes, responses to the questions listed in Table 5 were extracted and tabulated. These data were described narratively and common features were identified. Resource inputs were identified as far as possible using the information reported, with particular attention given to who delivered the programmes, the pattern of delivery and who funded the programmes. Outcomes were identified from the responses provided to the question about achievements (question 44) and evidence of any relationship between resources and outcomes was noted.

Extracting economic data from the literature review

All papers included in the literature review were scrutinised to identify any data on resources required to run a programme and/or the cost of a programme as described in the paper.

The following data, relevant to cost and cost-effectiveness analysis, were extracted, where present, from all papers included in the literature review:

-

resources required to set up the programme, for example training

-

resources required to run the programme

-

pattern of delivery, for example number and frequency of sessions

-

cost information

-

funder of programme development and implementation or, if appropriate, the research

-

outcomes.

Information about resource use was reviewed and each programme assigned a broad category of high, medium or low resource use. This classification was judged on the information provided in the literature, and was carried out by two members of the team (Soo Downe and Sandra Hollinghurst). The criteria used to assign the categories were the intensity and scale of resources reported.

The resource requirements were described narratively and common features identified. Resource inputs were identified using the information reported, and particular attention was paid to who delivers the programme, the pattern of delivery and the source of funding. Outcomes, as reported in the papers, were noted, as was the reporting of any relationship between resources and outcomes. The general pattern of resources and outcomes was reviewed, and conclusions about any relationship between them were described narratively.

Extracting economic data from the grey literature and personal contact with experts

The UK grey literature identified in the main study was examined for any evidence about resource use and/or cost. In cases where some information was available, we contacted authors of papers and reports directly for clarification or more detail.

During the process of identifying important unpublished reports and conducting the consultation groups with experts, the researchers followed up any mention of resource use and/or cost that was judged to be potentially useful. The research team contacted all experts whose work was brought to our attention with the aim of obtaining precise details of the cost of programmes and understanding how decisions about cost-effectiveness were handled. The information collected was recorded narratively by programme. In respect of analysis, the individual and diverse nature of these data prevented any systematic synthesis and analysis was, therefore, restricted to a descriptive framework.

Extracting economic data from the expert consultation groups

Identification of evidence

During the consultation meetings with young people, educational experts and professionals with expertise in using the media for preventative interventions, contributors were asked about resources, cost, value for money, and budgets and funding. In particular, in the second and third meetings of these groups, members of the education and media groups were specifically asked to consider the following questions.

Second expert consultation meetings

-

Thinking of your last campaign, what resources went into designing, delivering and evaluating it?

-

– What resources were involved in developing it: who was involved?

-

– Was development carried out in-house or contracted out?

-

– How was it delivered and what was involved in that: was it constrained to one medium or several?

-

-

What criteria of success were established for the campaign? How are these judged: does cost come into it?

-

Would you do something similar again, and if not why not (e.g. budget constraints, evidence of effectiveness)?

-

What represents value for money in designing, delivering and evaluating a campaign?

Third expert consultation meetings

-

To what extent are programmes budget-driven or content-driven?

-

Who sets the budget?

-

How is success measured? . . . What ‘deliverables’ are expected?

The transcriptions were reviewed for any mention of funding sources, resource use, cost and cost-effectiveness and relevant data were extracted, tabulated and examined for common threads and overlapping views. Of particular interest were responses to the questions posed specifically about resources, cost and the relationship between cost and outcome.

Chapter 3 The mapping survey

The mapping survey undertaken in 2013–14 in 18 local authorities aimed to develop a snapshot picture of preventative initiatives currently being delivered to children and young people in the UK, collecting information on content, audiences, funding and sustainability. A full account of the construction of the survey sample and the approach to data analysis is provided in Chapter 2 of this report. The survey content and design were influenced by Ellis’s 200437 survey and were developed in collaboration with the three consultation groups. Questions included addressed a range of topics, which asked about programme content, context, facilitators, audience and impact of current or recent work (see Appendix 1 for a copy of the survey tool).

Survey response

A total of 232 responses were received from schools and other organisations in the 18 sample local authorities, and four responses were received from three ‘other’ local authority areas not included in the sample, probably as a consequence of respondents being invited to cascade the survey to other relevant practitioners or organisations. These additional responses were excluded from analysis. Table 6 shows the variation in responses in the sample local authorities; a large number of respondents (n = 136) did not report their location, possibly because this question was asked at the end of the survey.

| Local authority area | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| England | |

| Bournemouth | 3 |

| Brent | 6 |

| Buckinghamshire | 3 |

| Kent | 16 |

| Lancashire | 13 |

| Liverpool | 13 |

| Newcastle | 6 |

| Newham | 1 |

| North Yorkshire | 8 |

| Nottinghamshire | 8 |

| Richmond | 3 |

| Slough | 5 |

| Northern Ireland | |

| Derry | 1 |

| Down | 1 |

| Scotland | |

| Aberdeen | 2 |

| Glasgow | 5 |

| Wales | |

| Ceredigion | 1 |

| Merthyr Tydfil | 1 |

| Area not specified | 136 |

| Total | 232 |

Respondents were asked to specify their job title and the organisation they worked for. A significant number (n = 135) of respondents did not answer these questions, but where this information was given, responses were classified as provided by schools or other organisations. The latter group included, for example, domestic violence co-ordinators, police, staff from community safety partnerships, education service staff, youth services and voluntary sector domestic violence services. Table 7 shows responses by organisational type.

| Type of organisation | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| Schools | 46 (19%) |

| Other organisations | 51 (22%) |

| Not known | 135 (59%) |

| Total | 232 |

It is not possible to calculate a survey response rate as respondents were asked to cascade the survey to the appropriate person in their organisation. We are not, therefore, able to treat the survey findings as representative or to generalise from them. The number of responses received was likely to have been affected by the fact that in schools, the survey could be addressed only to school administrators, who might have failed to forward the survey to the appropriate person; recent reductions in posts of local authority specialist PSHE advisors and domestic violence co-ordinators, who constituted key groups of respondents to Ellis’s37 survey, also reduced the potential pool of respondents. However, the survey responses included a reasonable mix of respondents from schools and from a range of other community organisations with an interest in preventing domestic abuse.

Distribution of preventative interventions

The survey collected information on current or recent interventions for children and young people in the respondents’ localities that aimed to prevent domestic abuse. Of the 186 respondents answering this question, 109 (59%) answered ‘yes’, they were aware of such programmes, while 77 (41%) did not know of any in their locality. Of the 109 respondents who knew of relevant programmes, only 64 also told us their locality. Where the locality of respondents was known there was considerable variation in the proportion of respondents who knew of programmes in their area. In some local authority areas such as Newcastle and Bournemouth, where a number of responses were received, all of the respondents knew of such programmes. However, no respondents identified in Aberdeen or Newham knew of any relevant programmes. The variations by local authority area are presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Number of respondents reporting current or recent programmes by local authority area.

Those who reported interventions were able to name or describe up to five interventions and answer questions on each. Some programmes reported were discovered not to be primary prevention interventions and these responses were omitted from analysis. Each identified intervention was classified as a ‘school’, ‘media’ or ‘community’ intervention. Of the total number of interventions reported across the 18 local authorities, 98 were considered to be primary prevention programmes for children and young people in the general population. In what follows in this chapter, the findings reported are based on these 98 reported programmes rather than on numbers of respondents (see Appendix 6 for details of all of the reported programmes included).

As Table 8 shows, the vast majority of these interventions (89%) were school-based programmes; only five interventions (four community-based and one media) did not have a school component. Very little information was reported on these five initiatives beyond their locations. One consisted of informal education in the Liverpool Youth and Play Service; the others were in North Yorkshire (Respect Young People’s Service), Lancashire and Nottinghamshire. The media campaign was delivered in Newcastle and led by Northumbria Police.

| Type of intervention | Number of relevant programmes reported | Per cent of relevant programmes reported |

|---|---|---|

| School | 88 | 89 |

| Media | 1 | 1 |

| Community | 4 | 5 |

| School and community | 1 | 15 |

| School/media/community | 4 | 45 |

| Total | 98 | 100 |

Of the 98 programmes reported, 65 were known to be currently or recently delivered in the sample local authority areas and 33 were delivered in areas that could not be identified by respondents but which were assumed to be within the sample local authorities. Preventative programmes were reported to be currently or recently delivered in 14 of the 18 local authorities but no relevant programmes were identified as being delivered in four areas, although this may not reflect an absence of programmes as not all respondents identified their local authority area.

Some programmes were reported more than once, both within the same local authorities and across different authorities. Of the 98 reported programmes, we were able to identify approximately 74 individual programme models, some of which were the same programme being delivered under different names.

The programme most frequently reported (n = 10) was the ‘Great Project’ (also named ‘Great’) by five respondents in Nottinghamshire and five respondents who did not state their locality. ‘Miss Dorothy’ (also identified as ‘Miss Dorothy Watch Over Me’ and ‘Miss Dot’) was the second most commonly cited programme, reported by four respondents: two in North Yorkshire and two respondents who did not state their locality. ‘16 Days of Action’ was reported by three of the four respondents from Richmond. ‘Beat Abuse’ (also identified as ‘Beat Abuse Before It Beats You’) was reported by two respondents from two different local authorities. ‘Equation’ was reported by three respondents, none of whom identified their locality. ‘Project Salus’ was reported by two respondents from Kent and one from an unidentified local authority. ‘Healthy Relationships’ workshops were reported by individuals in three different local authorities (Lancashire, North Yorkshire and an unidentified local authority). All other programmes were reported just once or twice, indicating considerable diversity in the programmes currently delivered, although, as discussed below, many have common elements. Respondents were asked to state whether or not they were personally involved in setting up the programme. The majority of those who responded said ‘yes’ (35%) and 23% said ‘no’ (see Appendix 6 for details of all programmes reported).

Programme content

Forms of violence addressed in programmes

Respondents were asked to select from a list of seven options what forms of violence or abuse the 98 programmes reported addressed (here, programme is used to mean any initiative, project, one-off event, media campaign, school assembly, lesson plan, scheme of work or external resource). The majority of programmes (62%) focused on domestic abuse/violence in young people’s intimate relationships, with a substantial number of programmes (46%) addressing the broader issues of peer violence/bullying and domestic abuse/violence in adult relationships (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Forms of violence and abuse addressed in reported programmes (n = 98).

Respondents were asked to indicate any ‘other’ forms of violence or abuse addressed by programmes in an open-text box. Other examples given included raising awareness, healthy relationships, conflict management, FGM and honour-based violence, staying safe, feelings, gender inequality and positive role models. Every programme reported addressed more than one form of violence; the most common combination was domestic abuse in adult relationships with domestic abuse in young people’s relationships (n = 42), with the latter combined with child abuse being the second most frequently reported combination (n = 22) along with child abuse and peer violence (bullying).

Topics covered

The survey collected information on all the topics covered by programmes. Participants were given a list of 23 options and were asked to tick all those that were addressed; they were also given the opportunity to add information on other topics covered in an open-text box. Figure 3 shows that most common topics included in the 98 programmes reported were types of abuse (51%), recognising domestic abuse when it is happening (49%), personal safety (48%) and definitions of domestic violence (46%). The least common topics covered were domestic violence and issues for children with disabilities and/or learning difficulties (12%) and FGM (10%). Other topics indicated by respondents included aspirations, positive male role models, self-esteem, gender inequality and emotions. While there appeared to be an emphasis on awareness and recognition of violence/abuse, a significant number of programmes, over one-third in all cases, also addressed issues related to keeping safe and help-seeking, including topics on safety strategies (44%), information on support services (40%), disclosure and safeguarding (37%) and help-seeking (37%). Content that aimed to address the needs of minority groups was less frequently reported.

FIGURE 3.

Topics covered in reported programmes (n = 98). BAMER, black, Asian, minority ethnic and refugee; LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender.

Programme aims

An open question asked respondents to describe the aims of programmes; information was received for 51 programmes. The most frequently mentioned aims were to raise awareness (n = 21); to increase knowledge and understanding (n = 14); and to increase knowledge and understanding of healthy/unhealthy relationships (n = 19). Thirteen sought either to provide support directly to children and young people living with domestic abuse or to provide information on support services. In 10 cases, safety for children was an identified aim; this was mostly in relation to programmes delivered in primary schools. The focus in almost all programmes was the reduction or prevention of victimisation rather than perpetration, and only three reported a specific focus on promoting gender equality. A comprehensive long-term strategic aim was reported in one case:

Develop consistent preventative work on domestic violence and abuse accessed by all young people across their childhood, with recognisable themes from nursery to college. Each element has a different approach and set of aims depending on age and setting of delivery.

Programme delivery

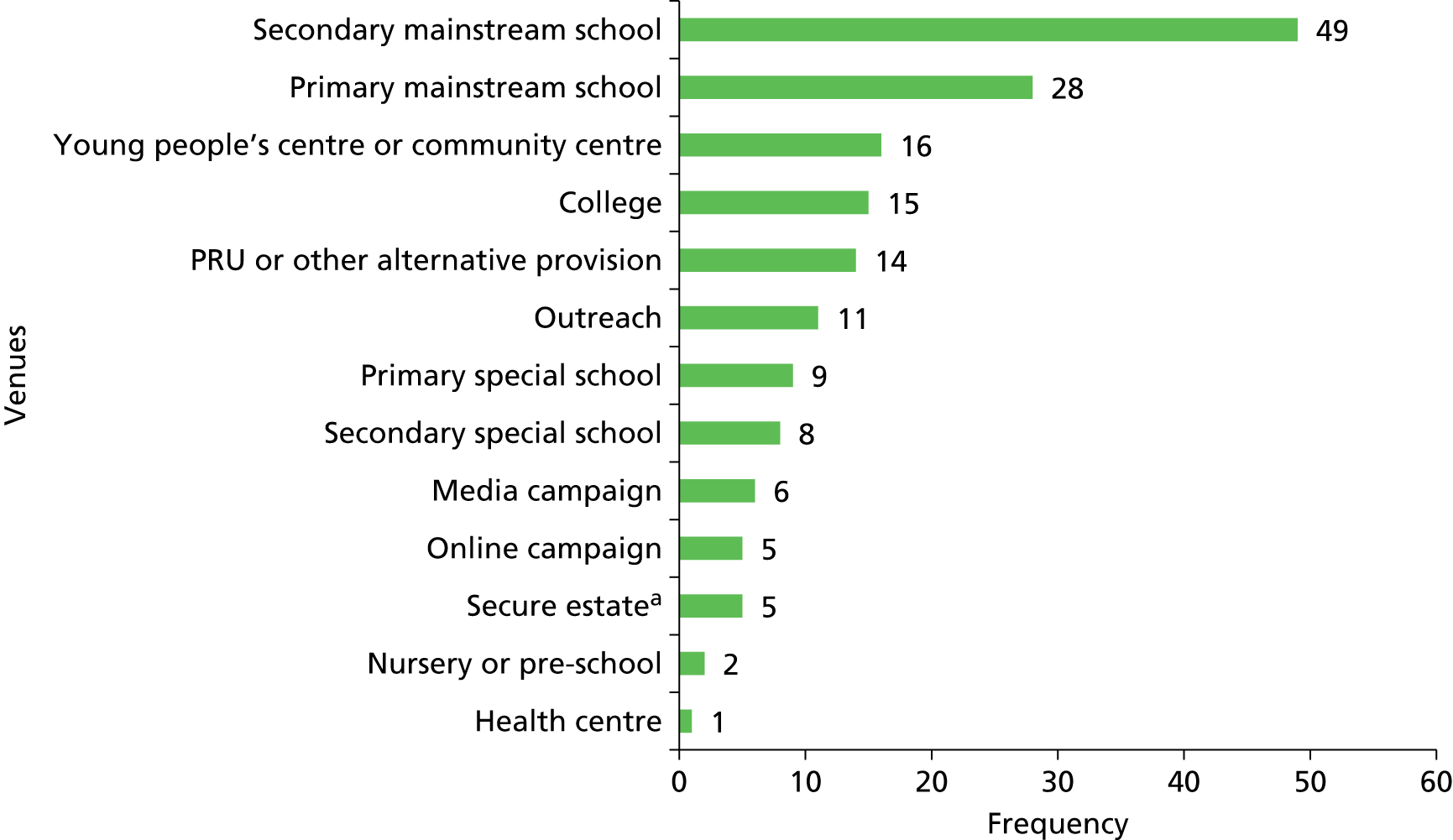

Venues

Respondents were asked to indicate all venues where a programme was delivered; these are shown in Figure 4. Programmes were mostly delivered in mainstream secondary schools (n = 49), with mainstream primary schools (n = 28) being the second most frequent setting. Twenty-three programmes were delivered in one venue only; of these, 10 were in secondary mainstream schools only and 11 in primary mainstream schools. Nine school-based programmes were delivered in a range of types of schools. Five programmes were delivered in more than six venues and all included work with young people in colleges, the secure estate and/or young people’s centres. Programmes involving a media and/or online aspect (n = 6) were delivered alongside work in schools. Of the community-based programmes, one programme was delivered in a health centre; other community venues included domestic violence advice centres and a local conference centre. A peer education project had undertaken street-based work with young people as well as using other venues. Eleven programmes, two schools and four other organisations (five were unknown) reported that they used outreach as an approach to delivering the programme. (Outreach is the delivery of services to people where they spend time or in their homes; it is common practice in youth work.)

FIGURE 4.

Venues where programmes were delivered. a, Secure estate refers to a young offender institution, a secure children’s home or a training centre. PRU, pupil referral unit.

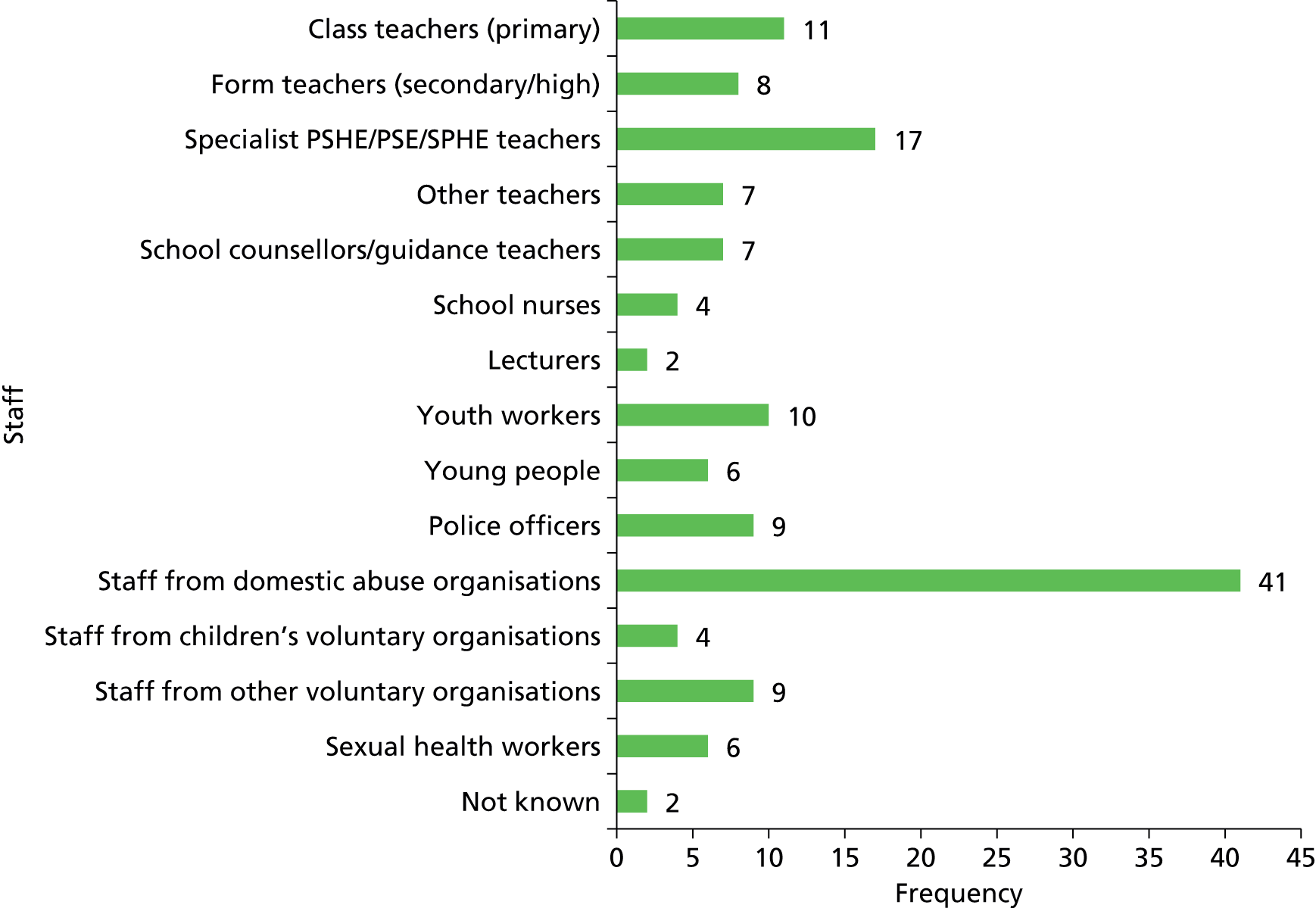

Facilitators

There are ongoing debates in the literature regarding which groups of professionals are best equipped and placed to deliver these interventions (e.g. Hale et al. 38). The survey asked for information on who delivered the programmes. Of those who responded to this question (n = 65), the vast majority (89%) reported that external staff were involved in some way in delivering programmes, with only 11% of programmes being delivered solely by teachers. However, teachers were involved in a further 31% of programmes working jointly with one or more other staff, meaning that, overall, teachers were involved in 42% of programmes (Figure 5). How co-working between teachers and external staff was organised varied and its adoption could be linked to a number of factors. One domestic abuse organisation reported that teachers were merely present in the classroom while specialist staff from the domestic abuse organisation delivered the programme.

FIGURE 5.

Staffing arrangements for programmes.

A range of teachers was involved in programme delivery, including class teachers in primary schools, form teachers in secondary/high schools, specialist PSHE teachers and ‘other’ teachers. As Figure 6 shows, school counsellors/guidance teachers and school nurses were involved in a small number of programmes (n = 7 and n = 4, respectively).

FIGURE 6.

Practitioner groups involved in delivering programmes. PSE, personal and social education; SPHE, social, personal and health education.

The practitioners most widely involved in programme delivery were those from specialist domestic abuse organisations who were involved in 63% (n = 41) of the programmes for which staffing data was provided; in almost half of these cases (31%) they were the only practitioners involved. A further 14% of programmes were delivered by other professionals from outside schools; these included sexual health workers, youth workers and staff from voluntary organisations (other than domestic abuse or children’s voluntary organisations).

In addition to the staff listed in Figure 6, 12 programmes involved ‘other’ people delivering the intervention; these included a community safety officer, a safeguarding team, a trainee social worker, theatre company staff, nurses (not school nurses), a domestic violence co-ordinator (local authority) and youth offending service practitioners.

Facilitator training

The survey asked respondents to indicate whether or not those delivering the programme had received specific training to enable them to do so. The question was unanswered for 45% of the programmes reported. Figure 7 shows that, for those programmes where information was available, almost two-thirds (61%) reported that all of the staff had undertaken specific training to deliver the programme, with only 9% reporting that staff had not had any such training. A small number (15%) reported that ‘some but not all’ of the staff had undertaken training.

FIGURE 7.

Staff who had undertaken specific training to deliver the programme.

Location of programmes in the curriculum

Where programmes were delivered in schools, respondents were asked to indicate in which lessons programmes were delivered. As expected, school programmes were most likely to be delivered in PSHE classes, with a few programmes being delivered in citizenship or drama lessons. None of the reported programmes were taught in science lessons. Two respondents reported that programmes were delivered in English lessons; one respondent who described ‘Equate: A Whole School Approach’ programme reported that one aspect of the programme – ‘personal space’ – was delivered in physical education lessons and another element – ‘global gender inequalities’ – was taught in geography classes. Five respondents reported that programmes were delivered in separate sessions outside mainstream lessons either to individuals or in small groups; this was likely to occur in cases where young people had disclosed abuse.

Methods of delivery

All respondents who answered a question on methods used to deliver programmes (n = 56) reported using multiple methods. Figure 8 shows that the most commonly used method of delivering programmes/interventions was small-group discussion (71% of those programmes reported), with heavy use also made of whole-group discussions (64%) and digital versatile discs (DVDs) (52%). The DVD material was likely to have been drawn from national and regional campaigns and one respondent explicitly identified the media campaigns as an influence on the genesis and content of their local programme. Theatre in education (7%), community events (7%) and adverts (13%) were less frequently mentioned, and this is likely to reflect the costs attached to such approaches.

FIGURE 8.

Methods of programme delivery.

The survey also asked respondents whether or not reported programmes were delivered in conjunction with programmes for other non-school groups, for example parents or carers. The majority of respondents answering this question did not know whether or not this was the case. Where this question was answered, 11 programmes were described as delivered in conjunction with programmes for professionals working in the local community, six were described as delivered in conjunction with programmes for parents/carers (n = 6) and two were delivered alongside programmes for other adults in the community (n = 2). One programme was also delivered in conjunction with a programme for teachers as part of in-service training.

Target audiences

Target audiences by age

The survey classified children and young people receiving programmes into four age ranges: 0–4 years (early years), 5–10 years (primary), 11–15 years (secondary) and 16–18 years (further education). As the focus of the study was interventions for children in the general population, programmes targeted at those over 18 years of age or at specific groups, for example pregnant women, were excluded. Where programmes were reported as aimed at a wide range of age groups, for example at children aged 5–16 years, these were described as targeting combined audiences. Table 9 shows that one-third of the programmes for which this information was received (n = 49) were targeted at secondary school-aged children, nearly one-fifth were delivered to primary school age and 14% were aimed at both primary and secondary school ages. Only a small number of programmes were targeted at young people in secondary and further education but the survey was not sent to further education colleges. None of the programmes reported were targeted at children under 5 years of age.

| School ages | Number of programmes | Per cent of programmes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | 9 | 19 |

| Secondary | 32 | 65 |

| Primary and secondary | 7 | 14 |

| Secondary and further education | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 49 | 100 |

The survey asked respondents whether or not different components of the programme were delivered to more than one age group. Where this information was available (n = 56), 54% (n = 30) said that programme content was adjusted for different age groups, 29% (n = 16) answered ‘no’ and 18% (n = 10) did not know. Respondents described delivering differing content to different age groups in respect of material addressing their children’s or young people’s own intimate relationships. Topics such as violent crime or drugs were delivered to older children, while younger children were more likely to be offered material addressing friendship or internet safety. Different materials such as books and DVDs were selected for primary- and secondary-aged children, and the depth of the discussion varied according to age, with games and role-play seen as more appropriate for younger children. While most of this adaptation and selection was described as being undertaken in-house by the programme facilitators, one programme, ‘Equate: A Whole School Approach’, was described as designed to include age-appropriate components, with a built-in ‘shift from general domestic abuse awareness to more specific issues such as sexual consent or teenage romantic relationships as children move up through the school’. Three programmes designed specifically for primary school-age children were cited: the ‘Helping Hands’ programme (this programme is discussed in detail in Chapter 7); ‘Miss Dorothy’ (also known as ‘Miss Dot’ and ‘Miss Dorothy Watch Over Me’) and ‘Themwifies’.

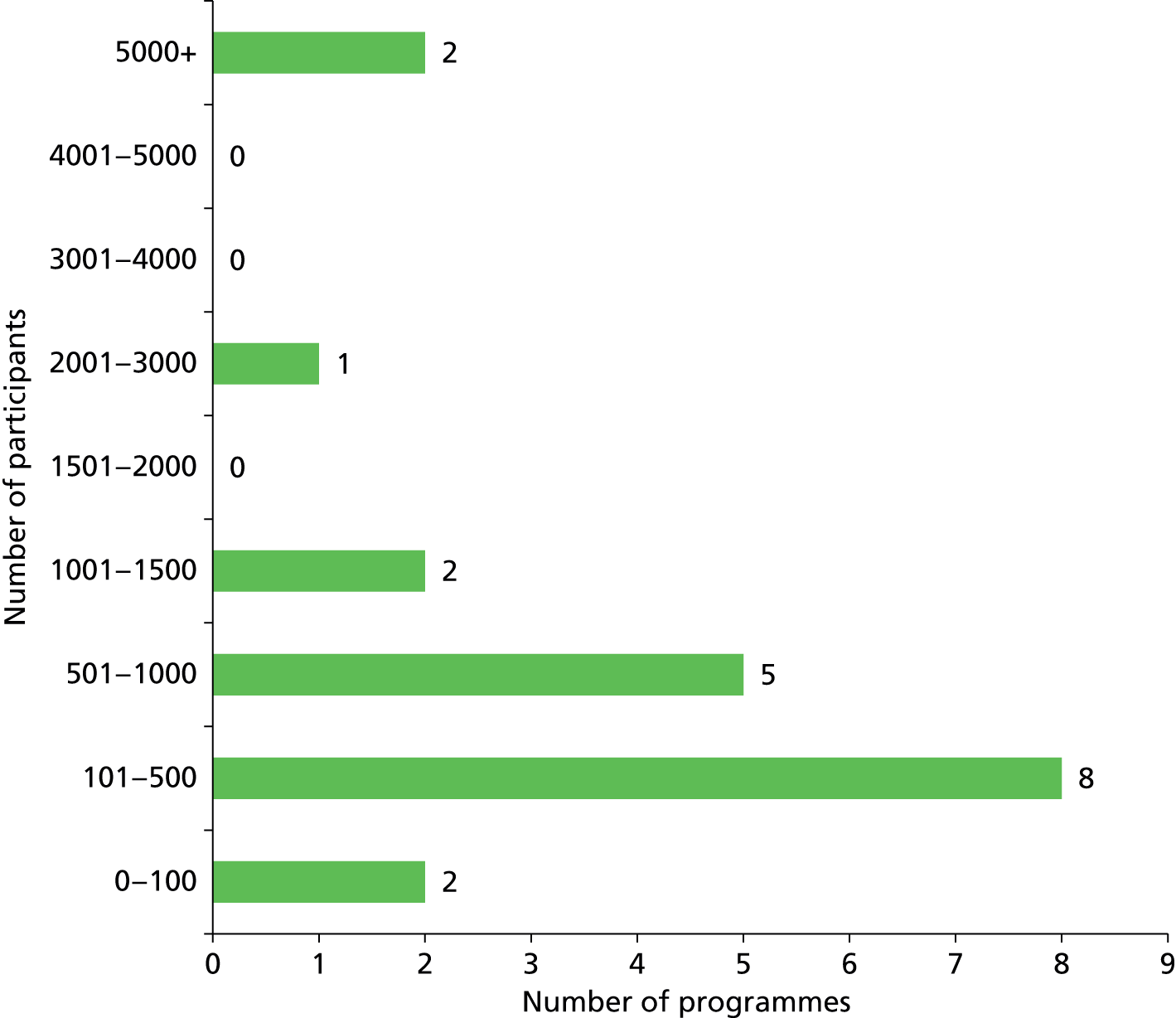

Programme participants

Thirty-six respondents provided information on the number of children and young people participating in programmes in the previous 12 months (Figure 9). Half of the programmes for which this information was provided had between 30 and 499 participants; the largest number reported was 2300 participants. Four newly established programmes had no participants to report as yet.

FIGURE 9.

Number of children and young people participating in programmes in the previous 12 months.

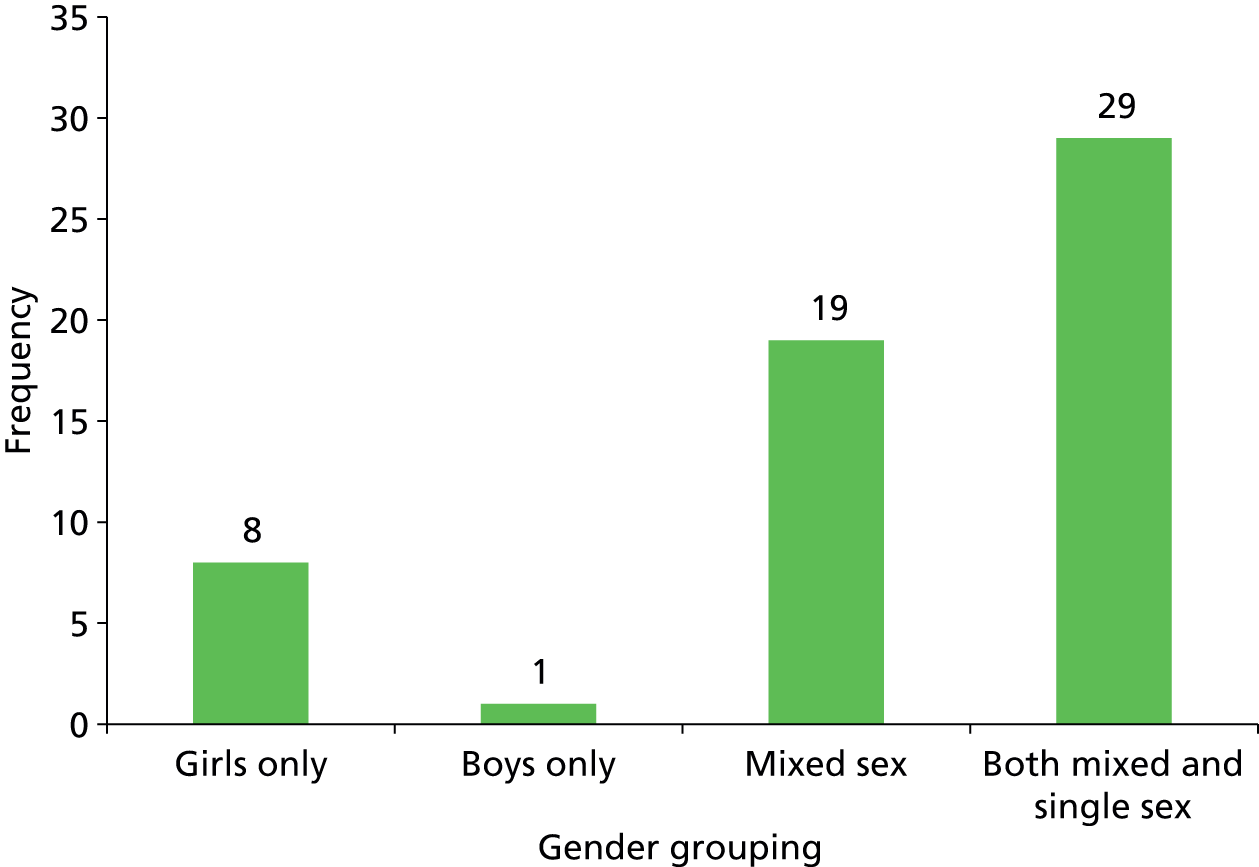

Programmes delivered by gender

Figure 10 shows that most respondents reported that programmes/interventions were delivered to both mixed-sex groups and single-sex groupings. Only a small proportion of those answering this question described programmes that were targeted specifically at girls only and only one reported a programme targeted at boys only. Three of the girls-only programmes were delivered in single-sex schools.

FIGURE 10.

Target audiences by gender grouping.

Among the reasons given for programmes being delivered in mixed-sex groups were that it was relevant, suitable and important for both boys and girls; that it ‘mirrors society’; that it was ‘in line with the agency ethos’; and to ‘get balance’ and a range of views. Other responses focused on practical arrangements such as ‘it reflected class composition’ and to ‘achieve maximum coverage’. The most commonly stated reasons given by those advocating single-sex groups were that young people talked more freely in this context; it enabled discussion on gender-specific experiences; and that girls could talk ‘without offending anyone, i.e. potentially boyfriends can be in the group’. Those employing both mixed- and single-sex groupings reported that flexibility enabled the programmes to be more responsive to the needs of particular groups and brought the advantages of both approaches to learning by affording opportunities to discuss issues in different settings. One respondent described such an approach in more detail:

Most [name of organisation] elements are delivered in class groups that are mixed sex, but certain elements such as Personal Space include issues around sexual consent, rights and responsibilities. This part is delivered to single sex groups as it needs to be targeted specifically to meet the needs of either young men or women.

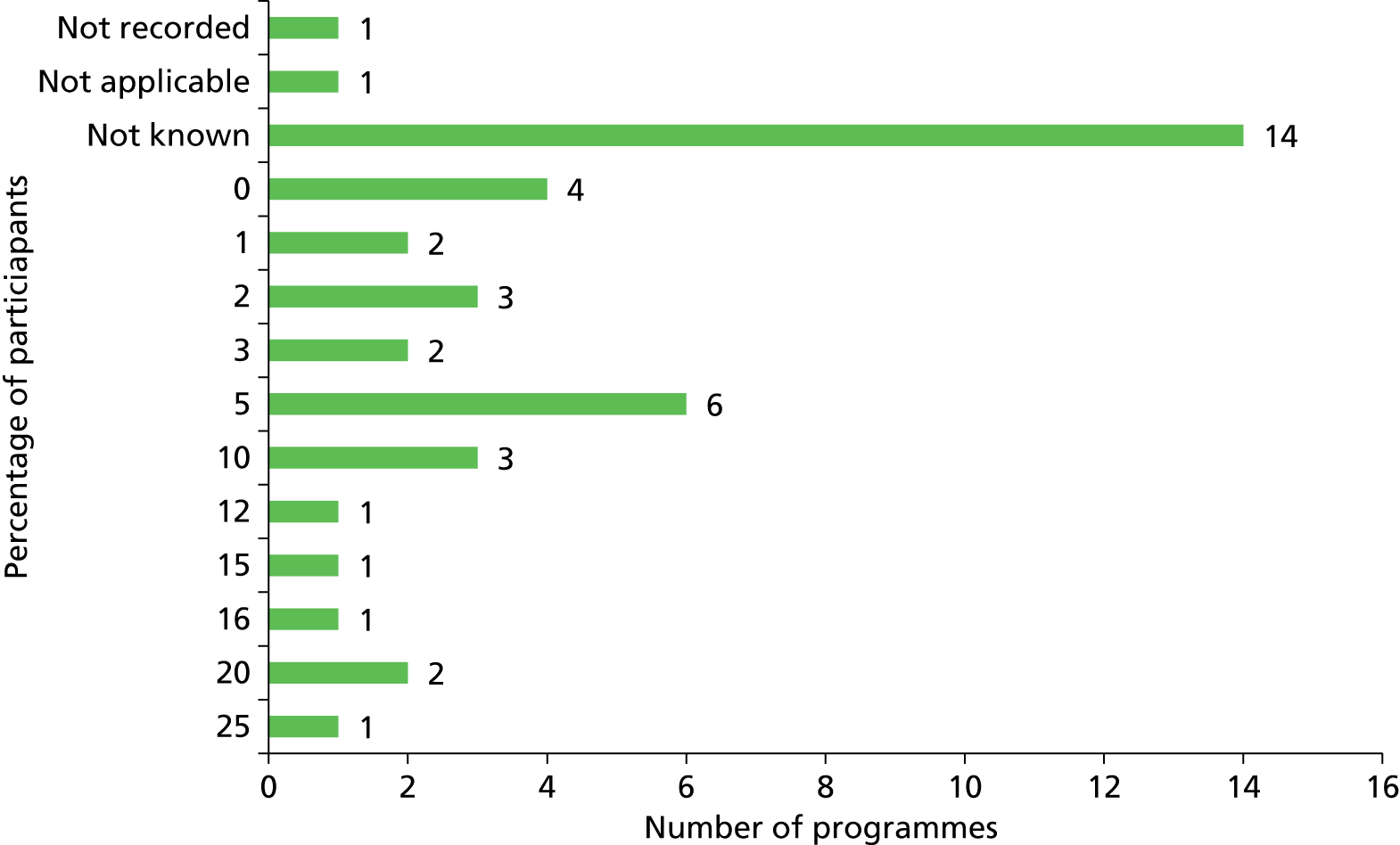

Programme participants by race and disability

Respondents were asked to identify the proportion of black, Asian, minority ethnic and refugee (BAMER) programme participants and those who had a disability or special needs. Forty-two per cent of respondents (n = 41) provided information relating to ethnicity and a similar number did so in relation to disability and special needs.

Respondents’ reports of numbers of BAMER participants on programmes ranged from none (n = 4) to 90% (n = 1), and in 15 cases (37%) this information was not known. As we lack the information required to identify respondents’ locations in a number of cases, we are unable to report on the extent to which this represents the make-up of the local population in these areas. However, although the number of respondents answering this question was low, Figure 11 shows that the majority of those responding described programmes that were delivered to audiences of which 10% or more were made up of BAMER children and young people. This can be contrasted with the finding from the analysis of programme content, reported above, that only 17% of programmes were explicitly addressing the issue of domestic abuse in BAMER families.

FIGURE 11.

Proportions of BAMER participants on programmes in last 12 months.

Thirty-eight per cent of respondents (n = 42) did not know the proportion of participants with disabilities or special needs on programmes. Where this information was provided, the numbers of children and young people with disabilities or special needs on programmes in the last year ranged from none to 25% (Figure 12). For comparison purposes, the number of pupils with special educational needs in England, recorded by the Department for Education, in 2012–13 was 18.7%,39 while in Wales it was 22.3%40 and in Northern Ireland it was 21.1%. 41 In Scotland, the term ‘additional support needs’ is used to encompass a wider range of children with support needs (e.g. bereavement is included). The recorded figure in 2013 was 19.5%. 42

FIGURE 12.

Proportions of programme participants with disabilities or special needs in the previous year.

Programme funding and development

Funding

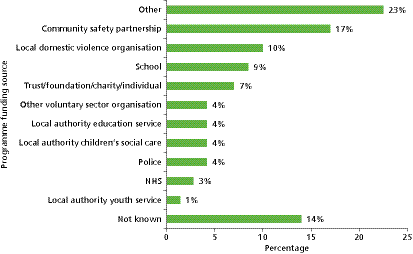

The survey asked respondents to specify the main funders of programmes. Twenty-seven respondents did not answer this question (28%), and of those who did, 10 respondents (14%) did not know who funded programmes. The most common source of funding identified for the 71 reported programmes was community safety partnerships (17%) followed by local domestic violence organisations (10%), with schools being the main funder in 9% of cases. Other funders included trust/foundations, the police, local authority children’s education services or social care. The NHS (3%) and local authority youth services (1%) were the least frequently cited sources of funding for these programmes (Figure 13). These patterns were consistent across high and low responding low authorities. Additional information provided in respect of other funding sources identified a wide range of national and local funders such as the Big Lottery, Lancashire Children’s Trust, a local solicitor’s office, Preston Children’s Trust, Comic Relief, Coalfields Regeneration Fund, Scottish Government and Public Health.

FIGURE 13.

Main sources of programme funding.

Influence on programme design

The survey collected information on whether or not programmes/interventions were built on an existing programme. Sixty-four programme accounts provided information on this issue; the most frequent response (42%) was ‘no’, that the programme was designed locally, while 39% reported that the programme was modelled on another intervention and in 19% of cases the original was not known. Those who answered ‘yes’ were asked to describe what influenced or informed the design and content of the programme. Various influences were described including feedback from young people themselves, personal knowledge and research as well as replication of other established programmes. The range of responses is outlined below:

Feedback from the young people

Inventor’s own personal involvement with subject and also media campaign

Successful outcomes from similar work in the US. MVP [Mentors in Violence Prevention] Scotland is based on the MVP model developed by Dr. Jackson Katz in the mid1990s. Content driven by current issues within society around abuse and exploitation.

Respondents were also asked whether or not children and young people had been involved in designing the programme. Where this question was answered, there was a fairly even spread between responses; 37% (n = 23) answered ‘yes’, 27% (n = 17) answered ‘no’ and in 36% (n = 22) of cases this was not known.

Programme adjustments