Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3002/03. The contractual start date was in May 2012. The final report began editorial review in August 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Segrott et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this text are reproduced with permission from Segrott et al. 1

This report describes an exploratory trial of Kids, Adults Together (KAT), a primary school-based, universal programme to promote prosocial family communication about alcohol, with the aim of preventing alcohol misuse in young people. This chapter summarises the literature on early preventative interventions for alcohol misuse, and describes the background and theoretical basis of KAT and the aims and objectives of the trial.

Scientific background and rationale

Public health context

Alcohol misuse has high personal, social and economic costs, and widens inequalities in health. 2 Harmful drinking has risen steeply in the UK during the last 20 years3 and the annual cost of alcohol misuse in the UK has been estimated at £25B, of which £1B was spent in Wales. 4,5 Misuse of alcohol by young people has raised particular concerns about the number who initiate alcohol consumption at a young age, and the high levels of regular and harmful alcohol use. 6,7 For example, 5% of 11-year-old boys in Wales report drinking alcohol at least once a week; the proportion increases to 35% at 15 years, by which age nearly half report having been drunk at least twice. 8 Alcohol misuse in young people has a range of health and social impacts, including disorderly and violent behaviour, risky sexual behaviour,9 accidental injury, and poor school attendance and achievement. 10,11 In the longer term, early initiation of alcohol consumption increases the risk of alcohol-related problems in later life. 12–15 There is also evidence to suggest that alcohol misuse in young people clusters with other risk behaviours. For instance, the 2011 survey of drug use, smoking and drinking among 11- to 15-year-olds in England found strong associations between past-year drug taking and alcohol use, while people who smoked were roughly twice as likely to have consumed alcohol in the previous 7 days. 16

Interventions to prevent alcohol misuse in children and young people

Schools have long been considered an important setting for delivering health behaviour interventions to young people, including those addressing alcohol misuse. In May 2013, four electronic databases [MEDLINE, Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED), EMBASE and PsycINFO] were searched from 2010–13 to identify recent evaluations of school-based alcohol misuse programmes for children and young adolescents (see Appendix 1). Search terms for alcohol misuse (alcohol, alcoholic, binge drinking) were combined with a term for school based (school*) and terms for programme (interven*, prevent*, promot*, program*), with results limited to English-language publications. Evaluations identified by the search, including those that were community rather than school based, are presented in Appendix 1 and illustrate the breadth of approaches being investigated and the scarcity of programmes focused on younger children. Rather than focusing exclusively on individual behaviour, school-based interventions provide an opportunity to draw on the socioecological health promotion framework, thereby acknowledging and exploiting the wider influences on health behaviours, such as friendship groups and organisational (school) system influences. 17,18 Furthermore, schools have near-to-complete coverage of the target population, and so intervention reach is potentially very high, and they also have an expanding function as health-promoting institutions. 19–21 Health-promoting schools work within a framework based on the World Health Organization’s Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion22 and promote health through the whole school environment, not just through health education curricula. 23 Health-promoting schools, therefore, strive to integrate their curriculum teaching with the school’s physical, social and policy environment, and the wider school community including parents.

Teaching about alcohol is a component of the personal and social education (PSE) curriculum from Key Stage 2 (8- to 11-year-olds) onwards in Wales,24 and so classroom-based alcohol misuse interventions do not necessarily place additional strain on the curriculum and can help to fulfil key requirements. Since 2003, the All-Wales School Liaison Core Programme, funded by the Welsh Government,25 has provided lessons on alcohol and other drugs to pupils at Key Stages 1–4, delivered by police school liaison officers. While the programme has been well received by pupils and schools26,27 and is currently delivered in approximately 97% of schools in Wales,28 it has not been subjected to a rigorous outcome evaluation. Many studies of similar classroom-based programmes suggest that preventing alcohol misuse requires an approach which may be more complex than that used to teach subjects in which students are required to demonstrate knowledge, rather than to adopt and observe a behavioural principle. 29–34 Such complex interventions might have multiple interacting components and target different levels of the socioecological framework. 35 Effective alcohol-misuse prevention programmes for young people have been found to share characteristics which generally fall into one or more of three main themes outlined below: (1) use of a clear theoretical basis in programme design; (2) interactive delivery style; and (3) community (including family and parental) involvement. 29–34 We summarise each in turn.

Theory-based programme and design

Health-promotion research and practice have been criticised for being poorly theorised,36,37 but recent and influential guidance on the development and evaluation of complex health interventions has clarified the importance of identifying and developing the theory/theories upon which interventions are based. 35 The explication of programme theory, namely the assumptions of how and why an intervention will produce specified outcomes, is essential for meaningful programme evaluation and intervention development, and can be visually presented in a logic model. 38

Nation et al. 39 distinguish aetiological theory, which focuses on the causes of behaviour, from intervention theory, which focuses on how to address aetiological factors associated with the behaviour, and say that both are required to drive effective programmes. Aetiological theory around problem behaviours in adolescence has centred on risk factors and protective influences. 40 Risk factors, however, are often common to several problem behaviours, and so effective programmes addressing the aetiology of alcohol misuse will share many characteristics of interventions addressing other behaviours arising from the same risk factor(s), for example tobacco and other substance use. This is significant because interventions aimed at addressing one health behaviour may also have effects on other behaviours that share common antecedents. The development of KAT has, therefore, drawn on evidence about the prevention of antisocial behaviour in children and adolescents generally, as well as that specific to alcohol-prevention programmes.

The social influence model has been recommended as the most suitable intervention theory for school-based programmes which address risk and protective factors. 41 The model posits that children can be ‘inoculated’ against social pressure to adopt undesirable behaviours such as drug and alcohol use. 42 Social pressure can be active, for example explicit offers of drugs from peers, or passive, such as overestimating alcohol consumption among peers. The model suggests various programme mechanisms that can help children counter social pressures, for example resistance and refusal training, public pledges, critiques of tobacco and alcohol advertising, learning about real and perceived norms, and the use of peer leaders. 42–44

Interactive delivery style

Most of the mechanisms through which the social influence model is operationalised are highly compatible with an interactive delivery style, and programmes that employ such a style are more effective than those using more didactic, non-interactive methods. 43 According to the social influence model, interactive teaching and learning methods (e.g. role play) might increase programme effectiveness by providing opportunities for communication and social interaction and enhancing young people’s critical awareness of social norms and pressures around substance use. 41,45 Effective interactive learning strategies also enhance children’s negotiation skills and let them rehearse problem-solving strategies. 45 Involvement of peer leaders can make programmes highly interactive and participatory and can increase engagement of young people who feel more comfortable talking to peers than to teachers. Young people may also talk more openly with peers and find it more fun. 44

Community and family involvement

Engaging the wider community beyond the school strengthens the effects of school-based programmes41 and, like interactive delivery, is consistent with the social influence model. Community involvement increases young people’s opportunities for communication and social interaction, including opportunities to develop positive relationships with adults, be they parents, teachers or other community members. 39 Where parents or other community members are actively involved in programmes, they are exposed to the same health-behaviour messages as younger participants and, if they accept those messages, can reinforce them through their own actions, behaviours and attitudes. The consistency of what children learn in school with their experiences outside school may, therefore, increase,46 for example in the rules their parents set around drinking or the vigilance of alcohol vendors. 47

Involvement of pupils’ families in school life is part of schools’ core business48,49 and may be more important than other aspects of community engagement in alcohol misuse programmes. 50 In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that schools involve families in alcohol education initiatives. 34,51 Dimensions of family functioning such as parenting operate as key protective and risk factors for later alcohol misuse by young people. 29,31,32,52–54 The family environment plays an important role in shaping young people’s attitudes and behaviour towards alcohol, including the timing of first use. 29,55,56 Parental norms and examples may encourage children’s early alcohol use through providing models of alcohol consumption56 or easy access to alcoholic drinks. Parental rules relating to alcohol are also an important factor,57 but the sharing of values within a trusting parent–child relationship is more effective in preventing antisocial behaviour than formal rule-setting and surveillance by parents. 58

Despite the importance of parent participation being widely noted, programmes continue to be designed with no parent component (see Appendix 1). Meanwhile, those that do try to involve parents, be they community or school based, have experienced significant challenges in recruiting and retaining parents. Community-based interventions commonly seek to strengthen parenting skills, for example the Chicago Parent Programme for low-income parents of 2- to 4-year-olds. This programme recruited parents through day-care centres, but only 31% of those eligible in intervention centres enrolled; the most frequent reasons for not enrolling were being unaware of the programme, being too busy or the programme conflicting with work/school schedules. 59 Retention often proves equally problematic. When Incredible Years, a parenting programme for parents of 2- to 10-year-olds, was implemented in one English city, 38% of enrolled families never attended a session, and even after efforts to improve retention this only fell to 30%. 60 School-based programmes have experienced similar problems and low levels of engagement are common. 31,61 Even when school-based programmes have been modified to increase levels of parental involvement, poor engagement has persisted. 62–64 In the Blueprint Programme for drug prevention in English secondary schools, for example, attendance of parents at the programme launch in phase 1 schools was only 16% of those invited and, despite revised and more intensive recruitment strategies, attendance fell to < 10% in phase 2 schools. 62

Factors which affect parent participation in community and school-based prevention programmes include practical barriers such as programme timing and travel arrangements;65,66 programme length and location;67 parent beliefs about their child’s susceptibility to problematic behaviours;67 and sociodemographic characteristics such as educational background. 68,69

While reaching families at higher risk of alcohol misuse problems is important, accurate identification of such families is often challenging, and programmes targeted at families on the basis of risk may stigmatise attendance, thus affecting take-up. 70,71 Universal programmes are less likely than targeted interventions to deter parents, and, ideally, will reach families at higher risk from alcohol misuse while avoiding stigmatisation. Because alcohol consumption is a part of everyday life in the UK, a universal programme is relevant to everyone because they either drink alcohol themselves or are exposed to the effects of others’ alcohol consumption. From near-abstinence to alcohol dependence, drinking is associated with a continuum of alcohol-related risk. A universal programme can potentially significantly reduce the overall prevalence of alcohol-related harm by shifting the distribution of risk. 72 Patterning of take-up is a possibility, however, and care is needed to ensure that universal programmes fully cover the spectrum of risk. In terms of implementation in schools, a programme delivered to a whole class or year group is likely to cost no more than identifying and targeting a smaller group.

In addition to being consistent with the social influence model, parent participation in alcohol misuse programmes is also compatible with the social development model (SDM), a theory of antisocial behaviour upon which KAT draws.

The social development model

In terms of aetiological theory, the SDM supports the view that parental involvement should be a key principle of intervention theory. In addition to the general model, the SDM incorporates four key age periods, showing how social influences expand over time beyond the family environment to include school and peer influences and legal sanctions through the preschool period and (US) elementary, middle and high school periods. 73 By high school, peer norms, classroom management, school policies and legal sanctions are influential in addition to the family.

The SDM has predicted alcohol misuse in young people74 and interventions such as the Seattle Social Development Project in the USA and Preparing for the Drug Free Years, which operationalise the model, have achieved reductions in alcohol misuse. 75,76 The SDM proposes that young people learn social behaviour through interactions with others, resulting in the formation of attachments which, if strong, can have a lasting effect on behaviour through supporting the acquisition of skills and influencing norms and values. 77 Attachment to others who offer opportunities for and reward prosocial behaviour is a protective factor against antisocial behaviour. 73,78,79 Thus, involvement of both parents and children in interventions may increase the quality and frequency of parent–child interactions.

Pre-adolescent children who are still highly dependent on their parents will usually have more opportunities for interacting with and forming attachments to their parents than when they enter adolescence and develop a social life outside the home. Social influences expand over time beyond the family environment to include school and peer influences and legal sanctions. 73 Thus, a further implication of the SDM for intervention theory is that programmes involving parents and children will be more likely to succeed if they are based in primary rather than secondary schools. Intervention earlier in the life course is also supported by evidence that programme effectiveness is enhanced by involving young people who have not yet adopted the targeted behaviour(s). 39,53

The SDM also explains why interactive delivery methods and other features of the social influence model have been identified as elements in more effective preventative programmes. According to the SDM, initiation of social interactions depends on people perceiving that there is an opportunity for them to get involved with someone or some activity around them. That is, they see that interactions are relevant to, and intended for, themselves, and that they are competent to take part. Prevention programmes using interactive methods will boost opportunities for prosocial interaction. Perception of opportunities for social interaction is influenced by social structural factors (socioeconomic status, age, sex and race78), suggesting that programmes should include features which are acceptable to all social groups in the target population and which enhance participants’ confidence and skills.

Strength of the evidence base

Gaps remain in the knowledge base for alcohol misuse prevention, particularly in countries outside the USA, where most programme development and evaluation has been conducted. This was borne out in a recent Cochrane Library systematic review of school-based programmes which identified 53 randomised trials, 41 of which were conducted in North America and none in the UK. 50 Promising programmes from the USA may require adaptation and further evaluation when used elsewhere,80,81 to ensure that both aetiological and intervention theories are appropriate for participants with different cultural values and customs. While reviewers are clear that several programme components are needed and that components work together to increase effectiveness, the large number and variety of programmes, the relative rarity of long-term outcome evaluation (e.g. see the range of interventions and follow-up periods in Appendix 1) and systematic adaptation complicate efforts to understand the essence of effective prevention. 50 Lastly, most evidence relates to older age groups because relatively few interventions have been based in primary schools,31,82 despite the SDM indicating that programmes for younger children may be efficacious. Furthermore, most primary school programme evaluations use aggressive behaviour as a precursor to alcohol use as their primary outcome, as their follow-up of participants is not long enough to measure impact on alcohol use in adolescence. 82

An urgent priority in improving the evidence base is to identify and develop effective methods of engaging parents in prevention programmes. As outlined above, while the importance of family-based protective factors for alcohol misuse is widely recognised,29,32,52 knowledge remains limited regarding effective mechanisms for engaging parents in prevention programmes, particularly those that are school based, and differences in programme reach and acceptability between different socioeconomic groups. 83–86

Kids, Adults Together

Anecdotal evidence that some prevention programmes have attracted large numbers of parent participants is not well supported by detailed accounts of percentages or mechanisms of engagement. One such programme was the Parents, Adults, Kids Together (PAKT) programme in Victoria, Australia. 87 PAKT was designed as a family drug education forum prepared by children aged 10–12 years in class and presented to their parents after school. The forum was delivered in addition to existing school drug-education work. A police community safety officer from Wales visited Australia to see PAKT in action and subsequently adapted it for use in south-east Wales, specifically for prevention of alcohol misuse. An advisory group developed a teacher’s pack for the classroom work and Gwent police commissioned a digital versatile disc (DVD) for distribution to participants. The adapted programme was called Kids, Adults Together Family Forum, subsequently shortened to Kids, Adults Together or KAT, and piloted in two primary schools in Gwent, with the police officer presenting the family events.

Kids, Adults Together integrates specially designed classroom activities with a family education evening and a DVD to promote prosocial communication. The programme design addresses key factors affecting parental engagement and is promoted to parents as an opportunity for them to learn about the work their children have been doing in class, rather than as an educational evening about alcohol misuse. To encourage take-up by schools and parents, KAT is of much shorter duration and intensity than other such interventions; the Strengthening Families Programme 10–14 (SFP10–14), for example, requires parents to attend seven weekly 2-hour sessions. 88 A shorter approach is supported by evidence that brief interventions can be as effective as longer interventions in older adolescents. 89

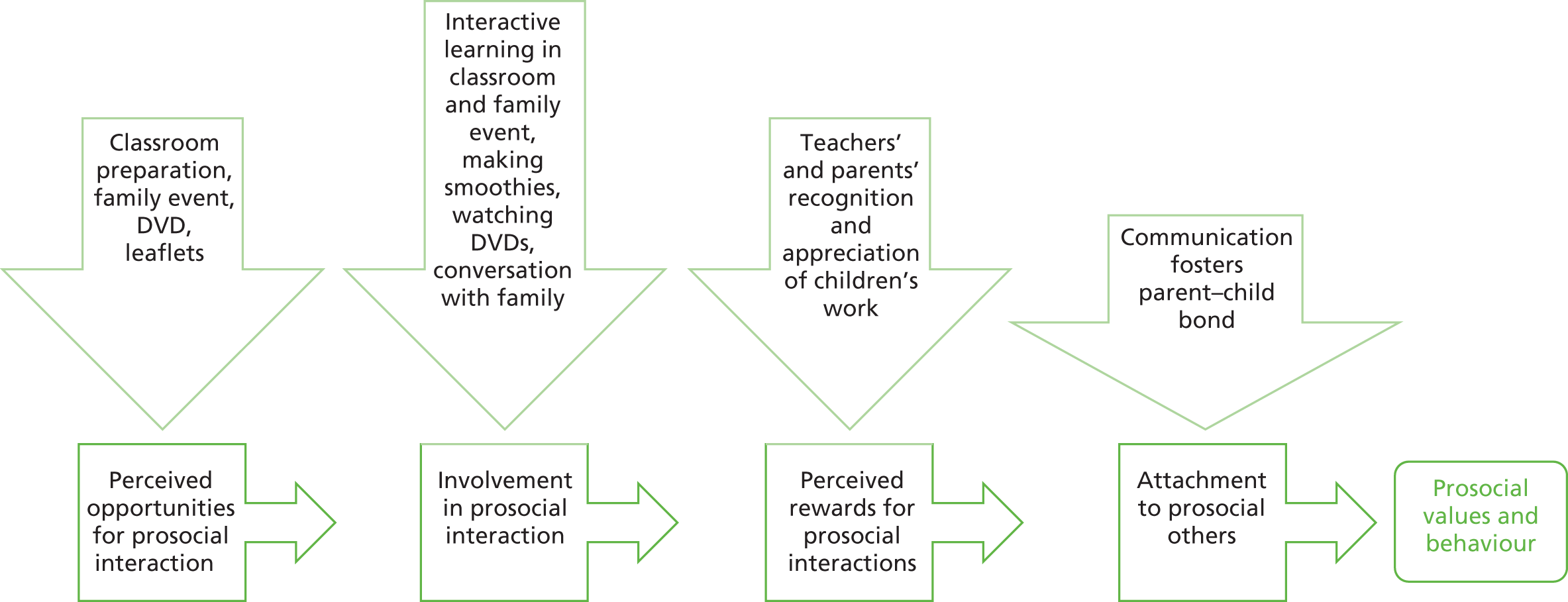

An evaluation at the development stage90 found that KAT had important features previously identified in more effective interventions. Interactive delivery methods are used throughout, and it is based in primary schools, where most children have not yet become regular drinkers. The early timing of programme delivery and the programme content were acceptable to parents, children and school staff. Figure 1 illustrates how KAT incorporates three crucial aspects of the causal pathways to prosocial behaviour contained within the SDM: (1) the creation of opportunities for prosocial interaction between and within families; (2) the strengthening of the necessary skills which parents and young people need to communicate about alcohol-related issues; and (3) the encouraging of parents to reward and reinforce prosocial behaviour and attitudes in relation to alcohol. 91 Crucially, the programme succeeded in involving 40–50 adult family members in the family events at both schools.

Aims and objectives

Findings from the evaluation at the development stage were promising,90 but questions remained about the acceptability and feasibility of KAT across a larger number of schools; its reach across social groups; and its effectiveness in preventing alcohol misuse. In line with the Medical Research Council (MRC) evaluation framework for complex interventions,35 it was, therefore, appropriate to move forward to an exploratory trial, the aim of which was to further develop and evaluate KAT in a larger number of schools in order to determine the value and feasibility of conducting a definitive effectiveness trial.

Specific objectives are listed below and pertained to the level of the individual participant, the family, the cluster or all three:

-

to refine the theoretical model and outcome pathways of the intervention (all)

-

to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention (all)

-

to establish intervention participation rates and reach, including equality of engagement across socioeconomic groups and localities (all)

-

to assess trial recruitment and retention rates (individual and school)

-

to identify potential effect sizes that are likely to be detected as part of a definitive trial and an appropriate sample size (individual and school)

-

to determine the feasibility and cost of the proposed methods for measurement of the primary and secondary outcomes (individual and school)

-

to identify the costs of delivering KAT, and to pilot methods for assessing cost-effectiveness as part of a future definitive trial (school); and

-

to determine whether or not to proceed with a definitive trial (individual and school).

This exploratory trial was, therefore, not assessing the effectiveness of KAT, but testing the feasibility of the intervention and the trial methods. The logic model for the exploratory trial is shown in Table 1.

| Inputs | Outputs | Study outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actions | Participants | Short term | Medium term | Long term | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The objectives are those of a Phase II trial described in the MRC framework for evaluation of complex interventions92 as:

-

acceptability and feasibility, including optimising the intervention and study design

-

defining the control: in this study, examining the acceptability of ‘usual practice’ in control-group schools

-

designing the main trial: in this study, noting the relevance of findings to the design of any future effectiveness trial and estimating sample size

-

outcomes: piloting measures which could be used in the main trial.

The study presented an opportunity to scrutinise two pertinent methodological issues:

-

family communication measures appropriate for 9- to 11-year-olds; and

-

criteria for progressing to an effectiveness trial.

Measures of both general family communication and family communication about alcohol were required for the study. While validated measures for both exist,93–102 they have been developed with adolescents (usually 12 years and/or older) and their acceptability and validity for younger children and their parents is unclear. The lack of communication measures likely reflects the fact that programmes targeting the late primary school years are less common. An opportunity, therefore, arose in KAT to use some of the measures developed for older children in 9- to 11-year-olds, to evaluate their acceptability and, if appropriate, to suggest adaptations.

The MRC guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions recommends a systematic and phased approach which moves through literature review and theory development to pilot studies, exploratory trials and finally definitive (effectiveness) evaluations. 35 While the guidance is a welcome acknowledgement of the role and importance of exploratory trials, it neither provides comprehensive advice on how to conduct such trials nor describes the hallmarks of a ‘good’ exploratory trial. Detailed reports of exploratory trials of complex interventions in public health are beginning to emerge and these provide valuable insights,103–105 but detailed guidance on the design, analysis and reporting of exploratory trials remains absent.

One crucial area yet to be addressed in the literature is the decision that arises at the end of an exploratory trial on whether or not to recommend proceeding to a full effectiveness trial. This is a core purpose of exploratory trials, yet there are no precedents in the literature to guide the development of criteria upon which to make an objective decision. There were three key areas to consider in relation to KAT. First, whether or not structures and capacity were in place in schools and among the practitioners (police) who would support schools (through training and compering the family events) to implement the programme on a wide scale. Second, whether or not a randomised controlled trial (RCT) design using the piloted measures of family communication and pupil alcohol consumption would be an appropriate and acceptable method to evaluate KAT in an effectiveness trial. Finally, whether or not the intervention appeared to work as planned in schools (in a range of socioeconomic settings) (and in line with its logic model), and the extent to which it was acceptable to school staff, pupils and parents/carers. Criteria had to be developed to ensure that an objective and transparent decision was made at the end of this study. Reporting this process addresses an important gap in the literature and will possibly be of value to others conducting exploratory trials of complex interventions. Chapter 2 includes a description of how the criteria were developed and assessed (see Health economics).

Study design

An exploratory cluster RCT was used to evaluate KAT. A RCT is the most robust design available to obtain an unbiased estimate of a potential effect size, even with a complex intervention in a ‘real-world’ setting such as schools. 106 As an intervention delivered in the classroom, randomisation at the level of the individual child was not appropriate, and so schools were chosen as the unit of randomisation.

Because it was originally anticipated that programme delivery as part of the trial would need to take place before the outcome of a funding decision on our grant application, we did not request funding to cover recruitment of schools, parents and pupils, or baseline data collection. Recruitment and baseline data collection, therefore, took place before the start of the funded study. While the main trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), a nested process evaluation was conducted by a PhD student from the Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer). The process evaluation assessed implementation processes, fidelity and acceptability to families and schools. Qualitative methods, described in Chapter 2, were used to capture the experiences and perspectives of those delivering and receiving the intervention. A summary of key findings from an interim analysis is presented in Chapter 3.

Public and stakeholder involvement

The involvement of children, and stakeholders from the police, education, public health and national government has been integral to both KAT and this exploratory trial. Their involvement has included the development and piloting of KAT and development of the pupil questionnaires. Public and stakeholder involvement is fully described in Chapter 2.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this text are reproduced with permission from Segrott et al. 1

Research design

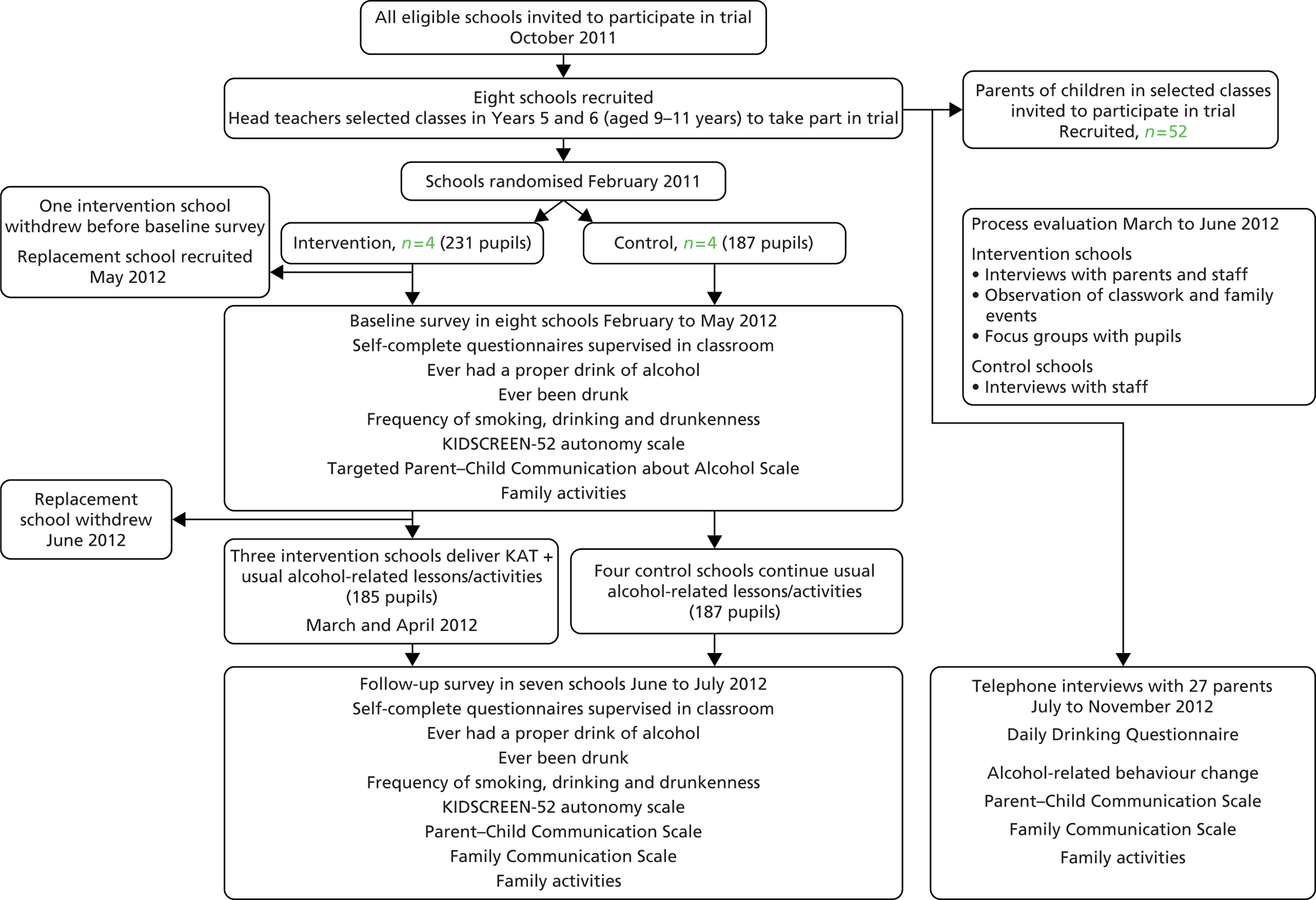

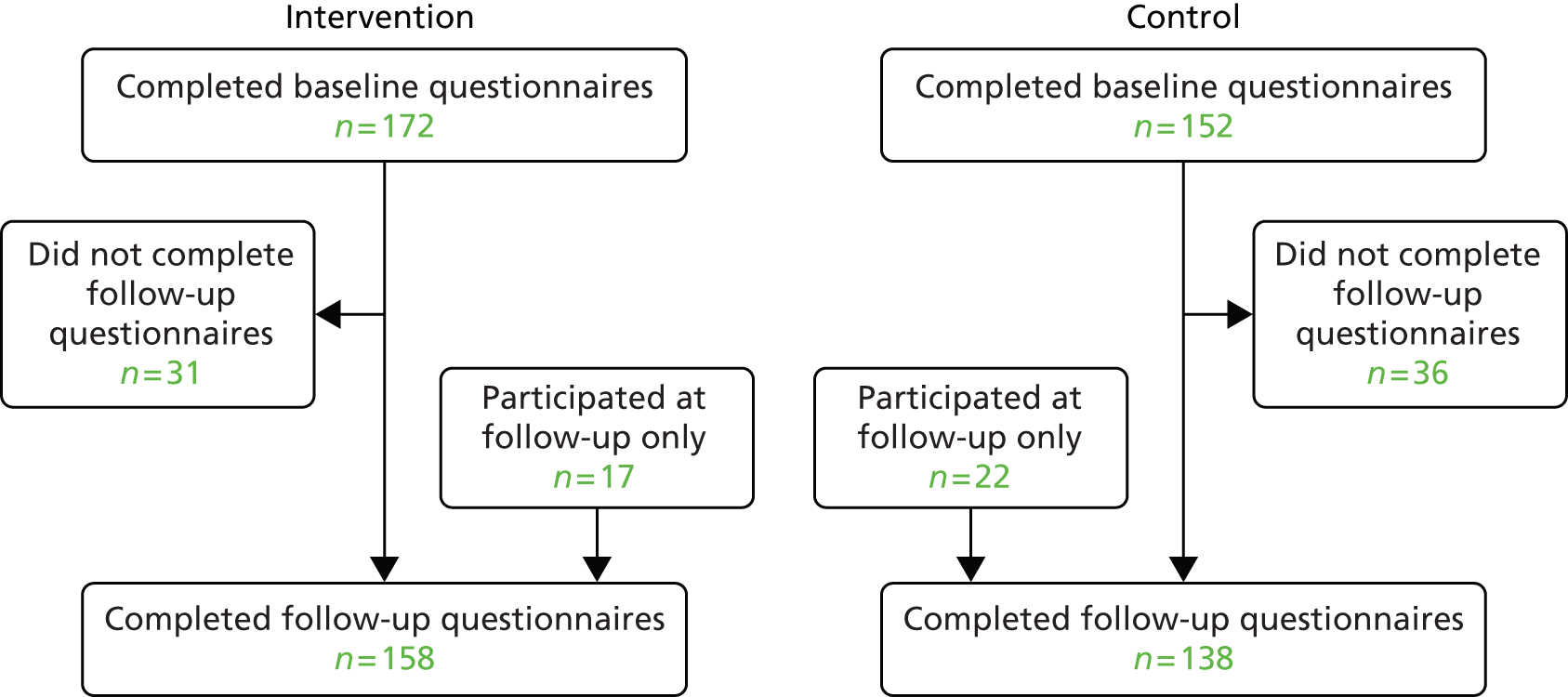

The study is a parallel-group cluster exploratory trial, with an embedded process evaluation. Schools were the unit of randomisation and were randomly assigned to intervention and control in a 1 : 1 ratio. Figure 2 provides a summary of the study.

FIGURE 2.

Research design.

The funded study lasted 14 months. Each child in the study was asked to complete two questionnaires: one at baseline and another approximately 4 months past baseline. Programme delivery in intervention schools took place immediately after baseline data collection. Children in intervention schools were also invited to take part in focus groups following the family events. Parents/carers who took part in the study participated in one telephone interview approximately 6 months post baseline, and parents of children in intervention-group schools also participated in interviews as part of the study’s process evaluation.

Ethical approval was given by the Cardiff School of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (SREC reference SREC/697). Amendments to the protocol were approved by the Trial Management Group; recorded; and communicated to the NIHR programme manager and the chair of the Research Ethics Committee. Because of delays in school recruitment, the interval between baseline and follow-up pupil questionnaires was changed from 6 months (stated in the original protocol) to 4 months, so that follow-up data collection could be carried out before the end of the summer term, when Year 6 pupils would be leaving their primary schools. Although this change was made for pragmatic reasons, it did not present a barrier to assessing the feasibility of measuring outcomes, which was a central aim of the evaluation. Process evaluation gives a detailed account of process evaluation methods.

The intervention

Kids, Adults Together has three main components: (1) classroom work (delivered by teachers) on the effects of alcohol consumption, and preparation for a family event; (2) the family event, delivered in school, and involving children and parents in activities addressing key health messages around alcohol; and (3) a ‘goody bag’ to take home, containing fun items, educational leaflets and an educational DVD for families to watch together.

Development

The first pilot study90 theorised the function of each KAT component using Valente’s framework of exposure, knowledge and attitudes, and practice. 107 There was evidence that each component had set off family communication which could mediate later drinking behaviour through parental regulatory practices (Figure 3). Viewing the DVD at home (and, as originally intended, on national television) had the potential to sustain, over a longer period, the immediate impacts of a short intervention. All of the components were thought to be necessary because of their cumulative effect: the classroom preparation led into the family event; the goody bags with the KAT badging and contents were physical reminders of the programme in children’s homes; and the DVD was particularly important for impact in the longer term.

FIGURE 3.

How KAT is expected to achieve its long-term aim. TV, television.

The first pilot study also established the importance of the classwork component in attracting parents to the family events. Children’s eagerness to show parents their work and parents’ status at the family events as proud supporters of their children were powerful factors in securing parental participation in the programme and were likely to be constant across different school contexts.

A further pilot study in 2011 focused on refining the materials provided to schools. An independent health education consultant employed by the research team modified the teachers’ handbook which had been developed for the earlier pilot study, clarifying the aims, learning outcomes and links to the curriculum for each lesson/activity and providing supporting information such as a timetable for the family event and a list of suggested questions for a quiz. As part of this work, the programme was implemented in two schools outside the trial area (one school which had previously implemented the programme, and one with no prior involvement) and feedback from staff, pupils and parents drawn upon. The number of suggestions for classroom activities in the teachers’ handbook was reduced and teachers were encouraged to choose their own way of achieving programme aims. That is, they had freedom (within limits) to alter the form of the activities, as long these still performed the same function. 108 The handbook included contact details of alcohol support services, and schools were encouraged to request one of them to attend the family event to facilitate contact between agencies and families needing support.

Implementation

The intervention was administered at cluster level (schools) and consisted of the KAT programme in addition to any existing alcohol-related lessons/school activities.

Kids, Adults Together requires approximately 1 week’s total classroom contact time (or around 20 hours). Classroom preparation for children was planned to take place over at least 1 week, with flexibility for schools to take longer according to, for example, the timing of the family event and the needs of the class. The KAT family event lasts about 1 hour and the contents of the ‘goody bag’ may be used by children and their families over an indefinite period.

Following baseline data collection in all schools, the health education consultant asked to visit all intervention schools to train teachers whose classes would be involved and to provide information about the programme to any other relevant members of staff. Staff training covered the key points in the KAT handbook and staff were also given a Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentation for use at the family event; appropriate information from websites, downloaded and photocopied; and Tacade’s Keys to Alcohol for Children Aged 7 to 11 Years Old resource. 109 Teachers were asked to ensure that support would be available for children who might be distressed by the topic (although this should usually have been in place to back up the usual alcohol-related curriculum content).

Evidence gathered during the pilot110 suggested that school staff would modify KAT in order to achieve programme aims and objectives in ways they thought would be more appropriate in the context of their own schools. The process evaluation included observation of classroom work so that analysis of any such adaptations could inform future programme development and evaluation.

The four schools randomised to the control group did not receive KAT, but continued with their usual activities, including any classroom work/school activities on alcohol. Process evaluation interviews with staff in control schools identified normal practice in relation to both substance education and structures for involving parents in school life.

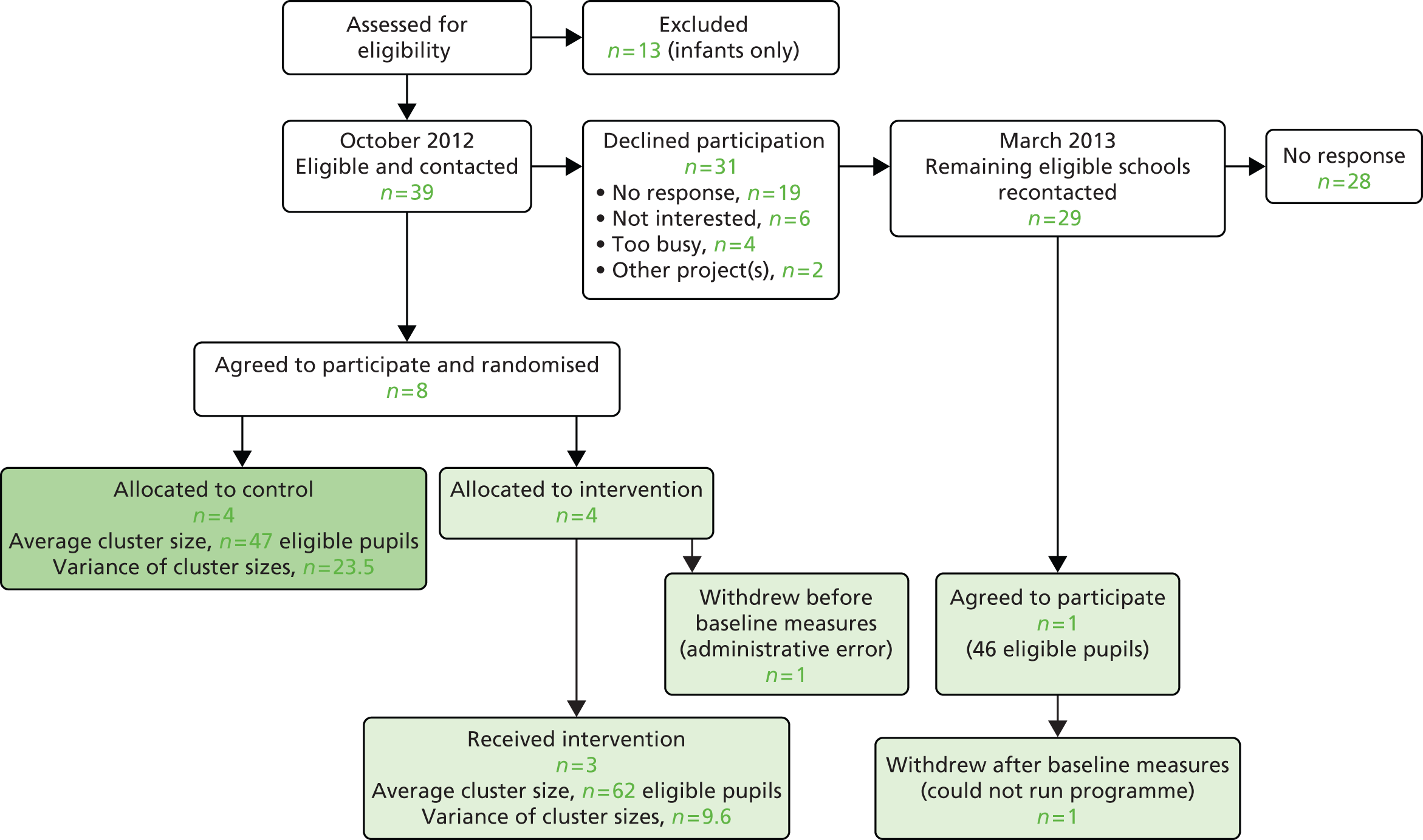

Recruitment of schools

All English-medium primary schools (n = 39) in Newport County with Year 5/6 classes were invited to participate in the trial. Letters were sent to all 39 schools, inviting them to participate in the research, and telephone calls were then made to each school until eight schools had agreed to participate. The letter (see Appendix 2) sent to schools was drafted with input from the education consultant and the Healthy Schools Team in Newport. A member of staff from the Healthy Schools Team also accompanied the research team at some of the initial meetings with interested schools.

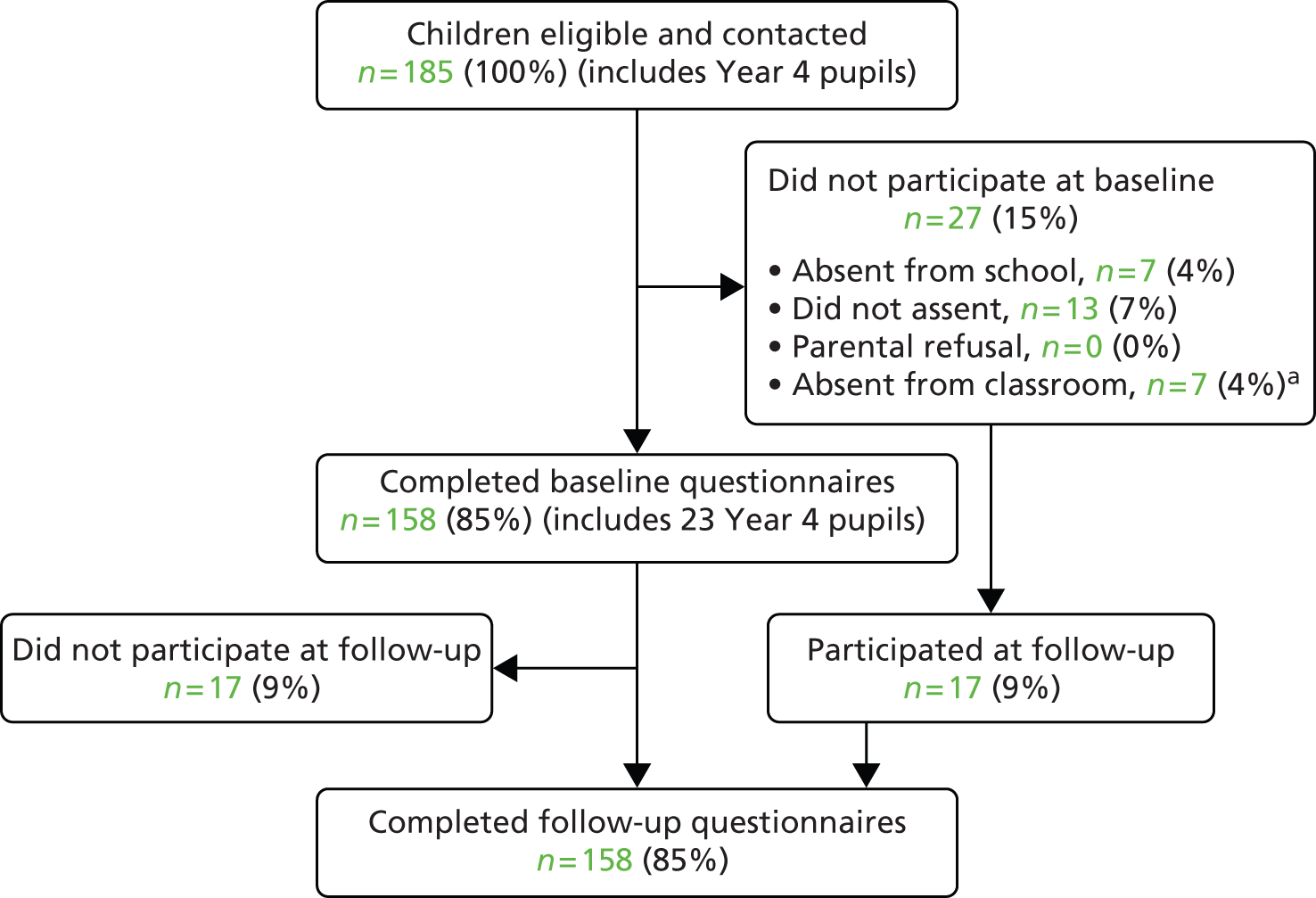

Recruitment of pupils

In each school, a member of the research team visited the classes which it had been agreed would participate in the trial. The researcher explained the study to the pupils, described the proposal to involve them in the study and answered any questions they had. All pupils in the class were provided with age-appropriate participant information sheets (see Appendix 3). Teachers were asked to ensure that pupils who were absent on the day of the visit received a copy of the participant information sheet.

Recruitment of parents/carers

Owing to data protection regulations, it was not possible for the research team to access names or any contact details of parents/carers of pupils who had been invited to participate in the trial. We therefore prepared a letter (which began ‘Dear parent/carer’) which we asked schools to send by Royal Mail to all parents/carers of pupils in those classes which were participating in the trial (see Appendix 4). This letter was accompanied by a participant information sheet (see Appendix 4). The letter asked parents/carers to return a reply slip to the research team if they were interested in participating in the research.

A follow-up letter to parents/carers was sent home via ‘pupil post’ (i.e. pupils were asked to take the letter home and show it to their parent/carer) approximately 1 week after the initial letter.

Parents who returned reply slips indicating that they would like to take part in the research telephone interviews were contacted by a member of the research team to check contact details and ascertain the best time to conduct a telephone interview.

Consent

Consent from head teachers for school participation was obtained before randomisation, and consent from children and parents as individual participants was sought after randomisation, with allocation revealed to both cluster and individual participants. Each head teacher signed a formal commitment form (see Appendix 5) for their school to take part in the study. The commitment form described the roles and responsibilities of the school and the research team, respectively, during the research period at the school.

The study tested the feasibility and acceptability to schools of using ‘opt-out’ parental consent to develop recruitment and data collection systems which would maximise response rates and minimise selection bias. 111,112 The use of ‘opt-out’ consent methods is more effective than ‘opt-in’, which often results in sample sizes which are too small to power a RCT. 112–114 Approval for the use of ‘opt-out’ consent was obtained from the ethics committee which had reviewed our study. At each school, we explained our preference to use ‘opt-out’ parental consent, but head teachers were able to stipulate that ‘opt-in’ consent should be used, and schools could participate in the study regardless of their preferences concerning parental consent. None of the schools raised any objections to us using ‘opt-out’ consent procedures, and this method was, therefore, used in all participating schools.

Approximately 1 week after the second letter was sent to parents, a member of the research team visited the class and asked those pupils who were willing to participate to complete a written questionnaire. An assent form for completion by pupils was attached to the front of each questionnaire.

Each potential parent participant was sent an information sheet, a booklet to assist them during telephone interviews and a consent form (see Appendix 6). They were requested to complete the consent form and return it in a prepaid envelope to the research team.

Individual teachers were asked to give informed consent to take part in the research. School and individual participants could withdraw at any time, without giving a reason, by informing the principal investigator or study manager that they did not wish to continue.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Primary schools which included Years 5 and 6 and taught through the medium of English were eligible to take part in the research. Welsh-medium schools and those with infant classes only were excluded. In each participating school, all children in Year 5 and Year 6 classes were eligible. Head teachers were encouraged to involve as many classes as possible, but were allowed to select which classes should take part, because we were interested in understanding how schools’ preferences would shape the likely cluster sizes as part of a future effectiveness trial. Table 2 gives details of numbers of classes taking part in intervention and control schools. A number of the schools had mixed year-group classes, and we allowed those with Year 4/5 classes to participate in the trial.

| School | Trial arm | Classes selected, n | Total classes selected, n | Total classes eligible, n | Eligible classes taking part, % | Reason for selection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 4/5 | Year 5/6 | Year 5 | Year 6 | ||||||

| 3 | I | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 100 | All eligible classes involved |

| 4 | I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 40 | All Year 6 involved; Year 5 not selected because of impending inspection and demands on staff time |

| 6 | I | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 100 | All eligible classes involved |

| 8 | I | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 50 | All Year 5 involved; Year 6 not selected (reasons unknown) |

| Total (%) in intervention group | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 14 | 64 | ||

| 1 | C | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 50 | All Year 5 involved; Year 6 not participating as have already done SM work this year, and also practical considerations |

| 2 | C | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100 | All eligible classes involved |

| 5 | C | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 100 | All eligible classes involved |

| 7 | C | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 50 | Year 6 not included – reasons unknown |

| Total (%) in control group | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 70 | ||

| Total (%) in both trial arms | 2 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 16 | 24 | 67 | ||

Where parents/carers or children refused consent for children’s participation, these children did not participate in the trial. Children who were absent at both baseline and follow-up data collections and parents who were unable to communicate in English or who did not return their contact details did not participate in the trial. In intervention schools, all children in participating classes received KAT whether or not they participated in the trial. KAT programme activities were integrated into their normal classroom work and their parents/carers were invited to attend the KAT family events. Head teachers in all participating schools, and parents and teachers of children in the relevant classes at intervention schools, were invited to take part in process evaluation interviews. Children in intervention schools also took part in focus groups.

Confidentiality

The chief investigator and the research team protected the confidentiality of participants in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. 115

All focus-group participants were asked to treat the discussion as strictly confidential. In reporting the results of the process evaluation, care has been taken to use quotations which do not reveal the identity of respondents. Individual teachers at participating schools were assured that if they decided not to participate, their decision would be handled confidentially.

All data collected as part of the trial were treated as confidential and accessed only by members of the trial team; anonymised data have been used wherever possible. However, all participants were informed that if they disclosed information about neglect, abuse, serious suicidal thoughts or self-harm, we would pass this information on to an appropriate agency: their assent for this was sought prior to data collection. The study adhered to the Cardiff University policy on safeguarding children and vulnerable adults and to schools’ own child protection policies. In each school, we also asked for guidance on which member of staff we could speak with if any children became upset during questionnaire completion or focus groups, and what procedures we should follow.

Measures

Key outcomes were the quality of programme implementation; recruitment and retention of research participants; and the acceptability and feasibility of research processes, including data collection methods. The study also assessed the feasibility and acceptability to children of providing demographic data and of answering questions measuring potential primary and secondary outcomes of any future effectiveness trial.

Table 3 lists outcome measures used with parents and children, and their function within the exploratory trial.

| Measure (potential primary outcomes in bold) | Children | Parents | Rationale | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | Assess feasibility and acceptability | Assess potential effect sizes | ||

| Ever had a proper drink | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Ever drunk | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Drinking frequency | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Drunkenness frequency | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Smoking frequency | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| KIDSCREEN-52: parent relationship and home-life dimension | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Targeted Parent–Child Communication about Alcohol Scale | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Family Activities Scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Parent–Child Communication Scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Family Communication Scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Change in alcohol-related behaviour | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Daily Drinking Questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | |||

Questionnaire piloting

The MRC guidance on complex interventions encourages researchers to include user involvement in key phases of intervention development and evaluation, so as to maximise the relevance of research and the opportunities to implement findings. 116 Further still, the involvement of the public in research has been advocated to ensure that research is relevant, reliable and understandable. 117,118 Although the previous documents recommend involvement, they do not advise how to conduct public involvement and what issues should be covered.

As part of the trial, it was deemed most important to capture children’s views on the questionnaires, particularly as some of the measures had been taken from studies of older young people (≥ 11 years old) (e.g. an ongoing trial of the SFP10–14).

Prior to baseline data collection, the pupil questionnaire was piloted in a school not involved in the study. A group of pupils from Year 6 (five boys and four girls) were asked to read through the questionnaire and to use a highlighter pen to indicate any questions, response categories or other text which was unclear or difficult to understand, and to mark with an ‘X’ any question that they thought people in their class might feel uncomfortable or unhappy about answering. The pupils were then asked to discuss their thoughts about the questionnaire.

In general, the pupils felt that the questionnaire content was acceptable and accessible. In response to pupils’ comments about the sensitivity of questions concerning family structure and ethnicity, we made a number of changes to the baseline questionnaire. For example, in relation to questions on who participants lived with, we changed the closed questions with tick-box responses to an open question and invited participants to describe, using free text, who they lived with all or most of the time.

Children’s follow-up questionnaires were piloted with 36 children in Year 5 at a school outside the study area. The children were divided into small groups, each of which commented on a different part of the questionnaire. Children were asked about the meaning of questions and answers, and the acceptability and difficulty of the questions. Any questions children did not understand were explained by the researchers, and children were further asked to give examples of how we should word the questions. In this second round of piloting, we specifically asked the pupils to explain to us what they thought individual questions meant so that we could ascertain that participants were likely to derive the correct meaning from them. Amendments were made to the questionnaire; for example, the majority of children did not understand the term ‘peer pressure’, so this was changed to ‘pressure to use alcohol from other children who are about my age’.

The pilot was conducted during the school day, with each group spending about half an hour away from their class. Parents at the same school were invited to pilot the questions for telephone interviews but there were no volunteers.

Feedback to schools

Schools were offered a presentation on the KAT study at the end of the summer term in 2013. Two schools, both from the intervention group, accepted the offer. Presentation topics included information about research generally, the number of schools, children and parents who had taken part and some of the key findings. Parents were invited to both presentations but only two (both in the second school) attended.

Feasibility and acceptability of primary outcomes

The primary outcome for any future effectiveness trial was likely to be drinking initiation (at age 11–13 years). The age at which young people start drinking alcohol is strongly associated with later alcohol-related harm, and greater harm is related to earlier initiation. 119 An intervention which delayed drinking initiation, therefore, could reduce the prevalence of alcohol-related health and social problems in the long term. At the exploratory stage described here, the aim of asking children about alcohol consumption was to understand its acceptability and feasibility for this age group. Drinking initiation was assessed by adapting a question from the Survey of Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use Among Young People in England in 2008. 120

Measures of two other key alcohol initiation behaviours, namely alcohol consumption frequency and drunkenness frequency, were also used. The relevant questions from the 2009 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey were used as measures in this study. 121 The original item incorporates three questions measuring frequency of smoking cigarettes, drinking and drunkenness over the previous 30 days. The item on smoking was retained, in case any effectiveness trial might examine the intervention’s impact on more than one risk behaviour.

These three measures were adapted from an earlier HBSC survey and the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and other Drugs (ESPAD) for the HBSC 2009 survey. The alcohol items had previously been used in the HBSC 2005–6 optional package. The alcohol questions have good consistency with other HBSC measures of alcohol use but the smoking question has not been validated. The wording of the questions was:

On how many occasions (if any) have you done the following things in the last 30 days?

-

smoked cigarettes

-

drunk alcohol

-

been drunk.

(Never/1–2 times/3–5 times/6–9 times/10–12 times/20–39 times/40 or more.)

During baseline data collections, many children did not understand the term ‘occasions’; the concept of ‘30 days’ was troublesome for many; and those with low literacy had difficulty in linking the items in the list to the core question. Therefore, at follow-up the wording and response categories were adapted and a separate question was asked for each behaviour:

On how many days (if any) have you drunk alcohol in the last month?

On how many days (if any) have you been drunk in the last month?

On how many days (if any) have you smoked cigarettes in the last month?

(Never/1–2/3–5/6–9/10–12/13–19/20–29/every day.)

We also asked pupils a single question about whether or not they had ever been drunk, and adapted this question from the HBSC international survey of 11- to 15-year-old schoolchildren. 121 The original question (p. 282) asked, ‘Have you ever had so much alcohol that you were really drunk?’ (no, never/yes, once/yes, 2–3 times/yes, 4–10 times/yes, more than 10 times). It has been used in six HBSC surveys and found to be correlated with other measures of alcohol consumption. In this study, because the prevalence of drunkenness is generally low among 9- to 11-year-olds, it was not considered useful to distinguish between different frequencies of drunkenness; and as the term ‘really drunk’ may not be commonly used by children in this age group, they were thought likely to question the term ‘really’. Therefore, the question and response categories were simplified to read:

Have you ever had so much alcohol that you were drunk? (Yes/no)

Data on past-month frequency of drinking and frequency of drunkenness from 11- to 13-year-old pupils in the 2009 HBSC study in Wales were used to estimate prevalence of drinking in this age group as a basis for estimation of the sample size required for a potential future effectiveness trial. Data on rates of drinking among 11- to 13-year-olds from an ongoing trial of the SFP10–14 were also examined.

Feasibility and acceptability of secondary outcomes for a future effectiveness trial

We have proposed that the SDM73 can explain how KAT is expected to prevent alcohol misuse through improving adult–child communication and, thus, promote the formation of attachments to parents or other influential adults. Adult–child communication appears to be an important secondary outcome and appropriate measures would be needed to test programme theory. Measures of opportunities for communication and the quality and quantity of interaction were therefore used in this study.

The SDM postulates that perception of opportunities for communication is a preliminary to communication taking place. The KIDSCREEN-52 subscale on parent relations and home life was used as a measure of children’s perceptions of such opportunities at home. The Family Activities Scale and questions about the degree of involvement in KAT classwork and attendance at the family event were used to measure involvement in prosocial activity, assuming these also to be measures of the minimum number of participants who perceived such activities as opportunities which were relevant to them. We accept that there may have been some people who perceived KAT as a social opportunity but were prevented by other commitments from taking part.

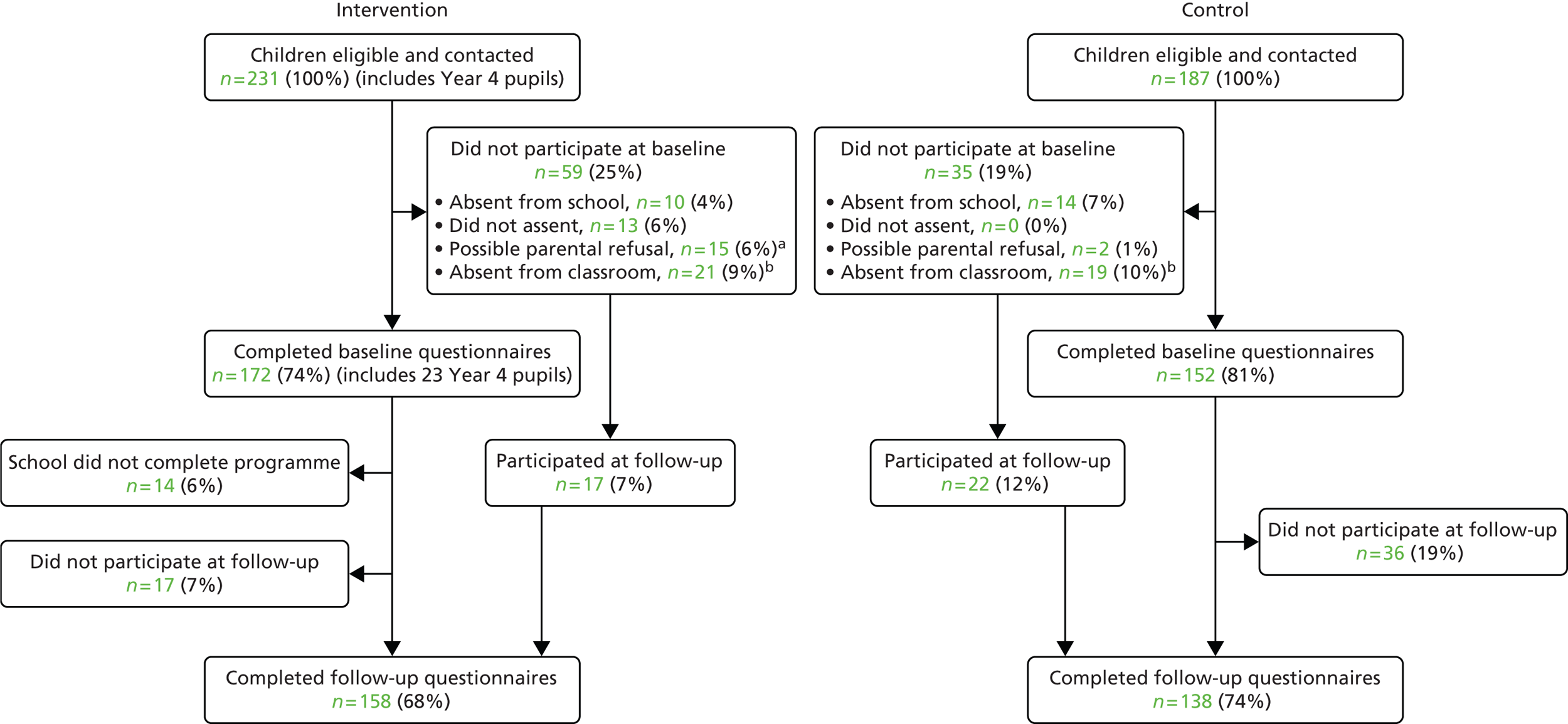

Measures of family communication and of parent–child communication specifically about alcohol which could assess the quantity and quality of interaction taking place were also used. No measure of attachment was used because KAT is not aimed directly at increasing parent–child attachment but focused on earlier stages of the model. We speculate that in any future effectiveness trial, changes in scores for measures used at baseline (opportunities for, quality and quantity of communication in families) might be regarded as indicators of increased or decreased potential for attachment to a parent/caregiver. However, a more direct measure of attachment might be desirable for use in any effectiveness trial in which measures would be used to test the theoretical pathways hypothesised in the model. Figure 4 illustrates the relationship of the measures to the KAT logic model and the SDM.

FIGURE 4.

Kids, Adults Together programme activities and measures and their relationship to the SDM.

The main aim of this trial is to assess the feasibility of the communication measures, and they were expected to provide some indication of short-term differences between the groups which might be detected at follow-up in an effectiveness trial, probably falling short of statistical significance. We describe each of the measures below.

The Family Activity Scale formed part of the HBSC international survey of 11- to 15-year-old schoolchildren. 121 There are eight items in the scale, which was used in baseline and follow-up questionnaires for children and parents. Participants are asked ‘How often do you and your family usually do each of the following things?’ followed by the list of potential activities, for example watching television (TV) or a video together (every day/most days/about once a week/less often/never).

The context for family communication was assessed with the KIDSCREEN-52122 Parent Relation and Home Life dimension, which measures the quality of children’s home life, including parent/child interaction. KIDSCREEN-52 is a generic measure of children’s health-related quality of life across 10 dimensions, each of which has been independently validated with European children aged 8–18 years and their parents. The parent and home life subscale includes items on the home atmosphere and the child’s feelings towards parents/carers, each scored on a five-point scale (never/not very often/quite often/very often/always). In this study, question wording was adapted to facilitate responses from children who lived with adults other than parents, so, for example, ‘Have your parent(s) understood you?’ became ‘Has at least one of the grown-ups at home understood you?’

The Targeted Parent–Child Communication about Alcohol Scale (TPCCAS)123 measures general openness, frequency and, specifically, alcohol-related content of parent–child communication. Development of the measure was based on evidence that parent–child communication which was more protective against substance misuse not only involved open and frequent general communication but also specifically addressed the topic of substance misuse. As with the KIDSCREEN-52 measure, the wording was adapted by us to facilitate responses from children who lived with adults other than parents by substituting ‘the grown-ups at home’ for ‘parents’. The scale was validated with US children aged 11–13 years, and, to facilitate responses from the younger children in this study, a separate question was asked for each item instead of presenting the scale as one question followed by a list. In addition, children were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with each statement instead of being asked to indicate the extent of agreement on a five-point scale, for example ‘At least one of the grown-ups at home has warned me about the dangers of drinking alcohol’ (agree/disagree); ‘At least one of the grown-ups at home has talked to me about how to handle offers of alcoholic drinks’ (agree/disagree), etc. Nevertheless, the questions presented difficulties for a substantial number of children at baseline and the scale was not used at follow-up.

The Parent–Child Communication Scale (PCCS),101 which was used at follow-up in place of the TPCCAS, has been developed for use with parents and children to assess the nature of alcohol-related content in parent–child communication during the previous 6 months. Ten items are parallel in both questionnaires but the parent version has an eleventh question asking whether or not parents check the child’s room or clothes for evidence of alcohol use, and measures frequency of communication. The scale was used in telephone interviews with 537 parent–adolescent pairs in a US longitudinal study across 48 states. Adolescents in the sample were aged from 12 to 15 years. This was not the first choice for the KAT study because of the three types of communication identified by the US researchers – relating to rules, consequences and media examples – rule-related communication appeared to be associated with a small increase in adolescent alcohol misuse and there was no evidence that the other types of communication were predictive of later alcohol-related behaviour. However, Ennett et al. 101 point out that the timing of communication in relation to adolescent drinking initiation is likely to be an important influence on the impact of parent–child communication, and this factor was not accounted for in their study. More generally, imposition of rules by parents in the absence of reciprocity in the parent–child relationship has been found to be ineffective in preventing children’s antisocial behaviour. 58 Thus, the scale was judged likely to be satisfactory when used with younger children, of whom a larger proportion would not have initiated alcohol use, and when combined with measures of the home context and more general qualities of communication, as in this study.

With parents participating in the KAT study, the scale was used in an unmodified form. In the children’s questionnaire, the wording of six items was revised in line with guidance from children who piloted the questionnaire; in addition, the format was changed from a single question followed by a list to a series of discrete statements. References to parents were removed as for other questionnaire scales and the 6-month recall period was not specified. For example, the questions in the original scale were:

During the last 6 months, how many of the (n) other people living in your house

. . . encouraged you not to use alcohol?

. . . talked to you about how they would discipline you if you used alcohol?

These became:

At least one of the grown-ups at home has said I should not use alcohol (true/not true).

At least one of the grown-ups at home has talked to me about what they would do if they found out that I had used alcohol (true/not true).

Response categories ‘true/not true’ were preferred to ‘agree/disagree’ following advice from a teacher present at a baseline data collection who said that some children might feel reluctant to ‘disagree’ because the word held strong oppositional connotations for them.

The Family Communication Scale (FCS)95 evaluates respondents’ satisfaction with communication processes between family members. It was included in parent and pupil follow-up questionnaires to supplement the PCCS (see above), which covered only the alcohol-related content of communication. It is uncertain whether KAT would work through alcohol-specific or more general communication, and so measures of both were piloted.

The FCS was developed from the Parent–Adolescent Communication Scale124 which has previously been used to assess the role of parent–child communication in the pathways to adolescent drinking. 97 The FCS is briefer (10 items) and includes only the more predictive of the two subscales included in the earlier measure. It has been validated for use with both adolescents and their parents. In the parent interviews, the scale was used unchanged, for example ‘Family members are satisfied with how they communicate with each other’ (strongly disagree/generally disagree/undecided/generally agree/strongly agree). Scores are summed. Very high scores indicate that ‘family members feel very positive about the quality and quantity of their family communication’ and very low scores indicate that they ‘have many concerns about the quality of their family communication’.

Children who piloted the follow-up questionnaire suggested some changes to the wording to facilitate responses from 9- to 11-year-olds. ‘Family members’ in the original was changed to ‘the people in my family’ throughout, and the vocabulary was simplified; for example, ‘When angry, family members seldom say negative things about each other’ became ‘Even when they are angry, the people in my family hardly ever say nasty things about each other’. Following guidance from the children who piloted it, responses in the children’s questionnaire were changed from the original five-point scale to ‘true/not true’ except for two items, for which the option ‘sometimes true’ was added.

Effect sizes detected in previous studies

We undertook a search for previous studies which had used these selected outcome measures, to identify what size of effect had been detected in evaluations of interventions comparable with KAT. We present the results of this search in Chapter 3 [see Effect sizes detected in previous studies (secondary outcomes)].

Feasibility and acceptability of measuring changes in alcohol-related behaviour (parent telephone interviews)

Because evidence from our previous research on KAT110 suggested that adults might change their behaviour after participating in KAT, the following two questions were included to assess their feasibility and acceptability:

Thinking now about the last six months, has there been any change in your drinking habits (yes/no/don’t know/rather not say)?

How have your drinking habits changed (drink more than I used to/drink less than I used to/drink a different kind of alcohol/drink in a different place/take measures to ensure drinking does not cause harm)?

We also used the Daily Drinking Questionnaire in our telephone interviews with parents/carers. This measure asks for details of a typical week, rather than exact quantities for the last 7 days, to ensure that it reflects habitual drinking. Although it has been developed for, and used mainly with, student populations125,126 we decided to assess its acceptability to parents because of its proven ability to detect post-intervention changes.

Demographic information

Measures of sex, age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status and (for parents) qualifications and employment were used to assess their acceptability to participants and comparability between intervention and control groups. For children, the Family Affluence Scale127,128 was used as a measure of socioeconomic status.

Holstein et al. 129 point out that the Family Affluence Scale measures family consumption rather than occupation, education and income, which are usually considered to constitute a more accurate measure of socioeconomic status. However, the scale has been developed for use in HBSC surveys because younger children had difficulty in answering questions about parents’ occupations and because it measures more than one dimension of socioeconomic status. It was considered the best available measure for use with the children in our sample, some of whom are younger than the youngest taking part in the HBSC surveys and so may be considered even less likely to provide accurate data on parental occupation. The scale’s validity and the suitability of the items are subject to continual review, and in our study the scoring used in the 2009–10 survey was used. 121 The scale is composed of four items:

-

Does your family own a car, van or truck?

-

[no (0); yes, one (1); yes, two or more (2)]

-

-

Do you have your own bedroom for yourself?

-

[no (0); yes (1)]

-

-

During the past 12 months, how many times did you travel away on holiday with your family?

-

[not at all (0); once (1); twice (2); more than twice (3)]

-

-

How many computers does your family own?

-

[none (0); one (1); two (2); more than two (3)]

-

Participation in Kids, Adults Together

To assess reach, parents and children in the intervention group were asked about their own and other family members’ participation in KAT. The process evaluation also examined this issue in order to provide information about parents’ and children’s motivation to participate and their response to the programme.

Scale scores

Methods for calculating scores for the following scales are described in Appendix 7:

-

Family Activity Scale

-

Quality of parent relations and home life KIDSCREEN-52 subscale

-

PCCS

-

TPCCAS

-

FCS

-

Family Affluence Scale.

Data collection

In addition to piloting the acceptability and feasibility of measures, the study aimed to identify optimal data collection methods and to assess their costs.

At baseline and 4-month follow-up, measures were collected through self-completion questionnaires by children who were present on the day of data collection in all classes participating in KAT, subject to their own assent and parents not refusing permission. Questionnaires were completed in classroom time, supervised by members of the research team. Researchers and school staff assisted children who had difficulties in reading or writing English. Some children who were absent at baseline completed follow-up questionnaires.

The original study protocol stated that the follow-up data collections in schools would be conducted at 6 months after baseline. However, delays in the early stages of the project meant that the interval between baseline and follow-up data collection was reduced to ensure that the latter took place before the school summer holidays, and before Year 6 pupils left their primary school. This change would be significant in a trial which aimed to measure effects. However, in the current exploratory phase it has not been a barrier to achieving the aims of establishing recruitment and retention rates (for intermediate outcomes), and has resulted in some learning about time scales to be considered in the design of any future effectiveness study.

Contact details of parents who volunteered to participate in the research were forwarded to trained telephone interviewers at Cardiff University, who conducted the interviews approximately 6 months post baseline. Personal interviews would not be a practical method to collect data from larger numbers of parents who would participate in any future effectiveness trial, and so the feasibility and acceptability of telephone interviews were assessed by staff at the Participant Resource Centre (PRC) at Cardiff University. Calls were recorded (with the knowledge of interviewees) and responses were recorded on paper schedules during the interviews. Parents who completed interviews were given £15 gift vouchers.

Following baseline data collection, each participant was allocated a numerical identifier stored in an index list of study participant numbers and names held separately from the project data. At follow-up data collection, we gave each pupil a questionnaire which had their unique participant ID pre-printed on it. Pupils who had not completed baseline questionnaires (because either they had been absent from school/class or they did not want to complete the questionnaire) but wished to complete follow-up questionnaires were allowed to do so. All files were stored in secure password-protected folders with restricted access. Data from completed questionnaires and interviews were encrypted at the point of entry and stored in anonymised form, using participant identification numbers. PASW 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software was used to store pupil questionnaire data, and parent data were stored in Excel (Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Corporation. Redmond, WA, USA). Ten per cent of questionnaires were selected at random from the electronic files and checked against the original paper questionnaires. The error rate was < 0.4% and the files were passed to the trial statistician for analysis.

During the study, we followed the Cardiff University Child Protection Guidelines. 130 As our data collection included issues relating to young people’s alcohol consumption, and family relationships, it was important for us to be prepared for responses that indicated that a child (or other person) was at risk of harm or abuse. In such cases, as data were collected in schools, Cardiff University policy dictated that any child protection concerns should be communicated to the head teacher of the school in question. A number of questionnaire responses (as can be seen in Chapter 3) indicated that child participants had consumed alcohol or been drunk – either in the last 30 days or in their lifetime. This presented us with a challenge in terms of how to respond to such information. It was important that we preserved confidentiality wherever possible, but also shared any information that might indicate risk of harm with schools. In the case of alcohol use, it was not appropriate or ethical to simply report all cases of children’s alcohol consumption to school staff. The law permits parents to provide alcohol to children aged ≥ 5 years within the family home, and so the consumption of alcohol by a child aged 9–11 years (as in this study) does not necessarily indicate illegality or parental irresponsibility. The measuring of alcohol consumption also raises challenges, in that, for instance, a child reporting having had a drink of alcohol could be referring to a whole drink or just a sip. The notion of drunkenness is subjective, and we, as adult researchers, and participants, being children, might have had very different understandings of the term. There was also clear evidence in our data (see Chapter 3) of inconsistent responses by pupils to alcohol-related questions. For instance, some participants reported drinking in the last month but also reported that they had never had an alcohol drink, and their responses also contradicted each other across data collection points. The ability to assess these reports was also made more difficult due to the fact that, unlike face-to-face interviews (where participants provide a response to the researcher), our questionnaire data were via written reports from pupils which were entered into the project database some time later. In many cases, children had moved schools, transferring to secondary schools at age 11 years.

Our approach to this issue was that reports of frequent drunkenness during the last month would constitute concern regarding the potential for an individual to experience harm, and would be shared. During data entry, significant concerns were raised regarding the responses of one child who answered ‘yes’ at both baseline and follow-up to the question ‘Have you ever had so much alcohol that you were drunk?’ Although this child answered ‘yes’ at baseline and ‘no’ at follow-up to the question ‘Have you ever had a proper alcoholic drink – a whole drink, not just a sip?’, they also reported in both questionnaires having drunk alcohol during the previous 30 days: on 3–5 occasions (baseline) and 6–9 days (follow-up). We complied with Cardiff University’s Child Protection Guidelines130 by following the policy of the relevant school and informing the teacher responsible for child protection.

Sample size

As this was an exploratory cluster randomised trial, no formal sample size calculation was carried out. However, in order to collect enough data to validate the outcome measures being tested and to calculate intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs), eight schools were anticipated to equate to approximately 640 families, which with an estimated consent rate of 50% at baseline would achieve a sample of 320 families: 160 per group. No interim analyses or stopping guidelines were implemented.

Randomisation

The schools were stratified by size and free school meal (FSM) entitlement and these variables were used to balance the randomisation. The method of optimal allocation was used to determine the randomisation sequence. Here, a balance algorithm was used to provide a predefined sequence, and all schools were randomised jointly. 131,132 The method was implemented in R statistical software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) in the South East Wales Trials Unit (SEWTU) and the allocation was concealed until after recruitment and the start of the intervention. An independent statistician within SEWTU assigned schools to the intervention arm. During recruitment of schools in the autumn term of 2011, a pragmatic decision was made to randomise in advance of baseline data collection so that schools allocated to the intervention group would have time to plan for programme delivery in the spring term of 2012. As explained earlier (see Chapter 1, Study design), recruitment and baseline data collection took place before the start of the funded study and there was no capacity to finalise children’s baseline measures until early 2012, by which time all schools in the study would have embarked upon their scheduled activities for the spring term.