Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3002/09. The contractual start date was in November 2011. The final report began editorial review in April 2016 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Harry Sumnall reports that his department has previously received funding from the alcohol industry (indirectly via the industry-funded Drinkaware) for unrelated primary research. David Foxcroft reports that his department has previously received funding from the alcohol industry for unrelated prevention programme training work. The sponsor university (Liverpool John Moores University) received and administered a payment from the alcohol industry for the printing of pupil workbooks in the Glasgow trial site.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Sumnall et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background and explanation of rationale

Adolescence is a period in which young people experiment with alcohol and establish use behaviours, and, as they age, the amount and frequency of use increases. 1 There is some evidence to suggest that earlier initiation of drinking is associated with later problematic misuse of alcohol (e.g. Bonomo et al. 2 and DeWit et al. 3), although systematic review has highlighted weaknesses in the evidence base for this. 4 The complexity of the relationship between earlier use and later problems is confounded by factors such as parental drinking and problem behaviours and/or behavioural disinhibition (e.g. Donovan et al. 5) and, accordingly, some authors have concluded that earlier initiation is better characterised as a marker of general risk proneness than as a causal influence. 6 However, there is stronger evidence to suggest that earlier age of self-reported drunkenness and the establishment of regular alcohol drinking is associated with a greater risk of adult alcohol-related problems. 4 Other acute and long-term consequences of heavy alcohol use in young people are evident, and these adversely impact on health, educational achievement, societal cohesion, criminality, welfare and well-being. 7,8 There are also clear geographic differences in the burden that alcohol places on the population, and these are closely associated with other major indicators of ill health and health inequalities (e.g. Public Health England9). Indeed, differences in alcohol use and the consequences of alcohol use are thought to be one of the major determinants of health and social inequalities. 10,11

Prevalence of alcohol use in the UK

The consumption of alcohol by those under the age of 18 years remains a public health concern in the UK. Evidence continues to suggest that, although the proportion of adolescents drinking alcohol across the UK has declined in recent years, those who do drink appear to be consuming more on each occasion. 12–18 Although this may be true at a national level, regional variations in drinking patterns also exist. 14,16,19 In comparison with the rest of the UK, drinking prevalence and excessive weekly drinking among adolescents has increased in Northern Ireland (NI) in recent years. 15 The results of the most recent Young Persons’ Behaviour and Attitudes Survey20 show that, of those who had ever drunk a full alcoholic drink (not just had a sip or taste), 56% had done so by the age of 13 years and 84% had done so by the age of 15 years. This is in comparison with 32% of 13-year-olds and 70% of 15-year-olds in Scotland reporting lifetime consumption of a full drink. 21 This does suggest a greater degree of alcohol use overall in NI than in Scotland (period prevalence). However, when comparing lifetime drunkenness in Scotland and NI, figures show that 39.3% of 11- to 16-year-olds in NI report lifetime drunkenness20 compared with 44% of 13-year-olds and 70% of 15-year-olds in Scotland. 21

Consequences of drinking

Adolescents are much more vulnerable than adults to the adverse effects of alcohol because of a range of physical and psychosocial factors that often interact (e.g. Newbury-Birch et al. 7). These adverse effects include (1) neurological factors due to changes that occur in the developing adolescent brain after alcohol exposure (e.g. Windle et al. ,22 Zeigler et al. 23 and Witt24); (2) cognitive factors due to the psychoactive effects of alcohol, which impair judgement and increase the likelihood of accidents and trauma (e.g. Rodham et al. 25); (3) social factors that arise from a typically high-intensity drinking pattern that leads to intoxication and risk-taking behaviour (e.g. Ellickson et al. 8 and MacArthur et al. 26); and (4) physiological factors resulting from a typically lower body mass and less efficient metabolism of alcohol (e.g. Windle et al. 22 and Zucker et al. 27). Physiological factors are compounded by the fact that young people have less experience of dealing with the effects of alcohol than adults, and that have fewer financial resources to help buffer the social and environmental risks that result from drinking alcohol. 28

Parental influence on young people’s drinking

Family factors are important in determining the nature and extent of adolescent alcohol use. These relate not only to the structure of families but also to family cohesion, family communication about issues such as substance use, parental modelling of behaviour (e.g. parental use of substances or rules on substance use), family management, parental monitoring/supervision, parent/peer influences and availability of alcohol in the family home. 16 For example, it has been argued that a trusting relationship between adolescents and their parents with open expression of ideas and feelings is an important factor in the reduction of health risk behaviours (e.g. Bahr et al. 29 and Riesch et al. 30). Moreover, parent–child communication processes have been proposed to mediate the effects of risk factors on problematic behaviour30 and better family communication processes have been shown to be protective against negative alcohol-related outcomes in young people. 31–35

The rapid escalation in the numbers of lifetime users and levels of use throughout adolescence is mirrored by the progressive detachment of adolescents from their parents and an increase in parental tolerance of adolescent drinking behaviour. 36 Although there are significant shifts in attachments of adolescents from parents to peers, there is still evidence that the influence of parents is considerable up to later adolescence and into early adulthood. 37 In a review of current evidence, Gilligan et al. 38 classified the environmental factors that determine adolescents’ propensity to engage in risky drinking as (1) social and (2) peer or family/parental. In the case of the latter, children are exposed to and learn about alcohol from an early age. 38 There has been much debate regarding the extent (if at all) to which parental tolerance of adolescent supervised drinking in the home, and by extension parental supply of alcohol to their children, can reduce heavier drinking and result in greater responsibility in terms of alcohol use. Young people’s drinking behaviours are said to be affected by their parents’ attitudes towards this behaviour and by parental supervision of their drinking (e.g. van der Vorst et al. 36), and parents often supply alcohol to their children, believing that it teaches them responsible drinking. 39 However, the risk arising from parental supply of alcohol is not well understood, and there is little evidence to support this as a harm-reducing practice. 38 In fact, although there is evidence suggesting that parental disapproval of drinking and limiting the supply of alcohol reduce adolescent drinking behaviour,36,40 some have suggested that parental supply of alcohol may reduce barriers to drinking, encouraging more frequent drinking and consumption of greater amounts of alcohol and even promoting a progression to unsupervised drinking. 41

Perceived parental approval of drinking has been linked to heavy drinking among high school and college students (e.g. Abar et al. 42). In support of the argument that permitting drinking at home promotes drinking in other contexts, van der Vorst et al. 43 reported that adolescents who were permitted to drink at home were also more likely to drink outside the home and to report more alcohol-related problems over a 2-year period than those who were not permitted to drink at all. In a survey of around 12,000 15- to 16-year-olds in the UK, Bellis et al. 44 reported that among those identifying any measure of unsupervised consumption, or heavy or frequent drinking, there was a significantly greater likelihood of alcohol-related violence, regretted sex or forgetting things after drinking. Furthermore, those reporting any measure of unsupervised consumption were also more likely to drink frequently and to drink heavily. 44 Livingston et al. ,45 in a 1-year follow-up of young women making the transition from high school to college, reported that those who were allowed to drink at home, either at meals or with friends, reported more frequent heavy episodic drinking (HED) at college, but those allowed to drink with friends reported the heaviest drinking episodes at both time points. However, in one Dutch longitudinal study, van der Vorst et al. 43 reported no differences in progression to problem drinking among young people whose parents provided high or low levels of supervision of alcohol use.

Universal interventions for preventing alcohol-related problems

Reviews of effective school-based universal alcohol prevention programmes for adolescents have failed to consistently identify interventions that are well designed, well implemented and properly evaluated (e.g. Jones et al. ,46 Foxcroft and Tsertsvadze,47–49 Nation et al. ,50 Faggiano et al. 51 and Spoth et al. 52). Foxcroft and Tsertsvadze,47–49 in their reviews of school-based universal interventions, were unable to recommend any single prevention initiative. However, one conclusion, which is consistent in all reviews, is that prevention interventions that effectively develop social skills appear to be superior in their impact to those that seek to enhance only knowledge (e.g. Foxcroft and Tsertsvadze,48,49 Nation et al. 50 and Faggiano et al. 51). In the absence of substantial evidence on particular programmes, guidance issued by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)53 in 2007 called for partnership working between schools and other stakeholders in efforts to prevent misuse. NICE also suggested that school-based interventions should aim to increase knowledge about alcohol, to explore perceptions about alcohol use and to help develop decision-making skills, self-efficacy and self-esteem. In family settings, universal prevention typically takes the form of supporting the development of parenting skills including parental support, nurturing behaviours, establishing clear boundaries or rules and parental monitoring. 47 Social and peer resistance skills, the development of behavioural norms and positive peer affiliations can also be addressed with these types of approaches. Most of the studies included in Foxcroft and Tsertsvadze’s 2011 Cochrane review47 of family-based alcohol prevention activities reported positive effects on behaviour and, although these tended to be small, they were generally consistent and persisted into the medium to longer term.

School-based alcohol education programmes in the UK for those aged < 18 years have predominantly been classified as universal, as they have been typically targeted at all pupils regardless of screened or perceived level of alcohol-related risk. 54 Outcomes assessed in universal prevention programmes have included those related to quantity and frequency of alcohol use (e.g. period prevalence, frequency of drunkenness, HED), as well as harms associated with consumption. 48 With respect to this last set of outcomes, harms can arise both from the actions of the drinker (e.g. accidents, health problems) and from the drinking of others (e.g. drunk driving, violence). Universally targeted alcohol prevention programmes (e.g. McBride et al. ,55 Newton et al. 56 and Vogl et al. 57) that aim to reduce harms associated with alcohol may, therefore, provide messages of harm reduction rather than focus on abstinence. In addition to aiming to reduce alcohol-related harm through reducing consumption, these types of programmes aim to reduce those direct and indirect harms reported by those recipients who continue to drink.

Introduction to the intervention components of STAMPP

The Steps Towards Alcohol Misuse Prevention Programme (STAMPP) combined a school-based alcohol harm reduction curriculum and a brief parental intervention that is designed to support parents in setting family rules around drinking. Chapter 2 (see Intervention) provides further information on the development, delivery and content of the intervention.

The classroom component of STAMPP is the School Health and Alcohol Harm Reduction Project (SHAHRP), which is an example of a universally targeted classroom intervention. It combines a harm reduction philosophy with skills training, education and activities designed to encourage positive behavioural change. 55,58 It is a curriculum-based programme delivered in two phases over a 2-year period, and is described by its developers as having an explicit harm reduction goal. The development of the SHAHRP is described by Farringdon et al. 59 It was originally developed in the 1990s in Western Australia, and the core components of the intervention were based on a systematic literature review of effective substance use education. The curriculum was written by practising teachers (with experience of developing student-centred learning approaches), with the assistance of research academics, and underwent piloting, evaluation and further development processes. Key evidence-based features of the programme include (according to the formative evaluation of the SHAHRP):59

-

social inoculation (phase 1 of the intervention, delivered prior to alcohol initiation)

-

relevance to drinking trajectories of recipients (i.e. phase 2 of the intervention, introducing harm reduction, is implemented after pupils are most likely to have initiated alcohol use)

-

core intervention (phase 1) with booster sessions (phase 2)

-

experientially focused and based on the drinking experiences of young people

-

skills based with normative components

-

incorporation of utility knowledge about alcohol use.

Includes specialist training of programme deliverers (e.g. teachers)

In the original Australian programme evaluation,55 which compared the intervention group with the control group receiving education as normal (EAN), the intervention group reported significantly less alcohol use: a difference in quantity of 31.4%, 31.7% and 9.2% at 8, 17 and 32 months after baseline, respectively; and significant differences in reports of hazardous drinking, defined as consuming more than two (female)/four (male) standard drinks (10 g of alcohol) per occasion, once per month or more often at 8 months (25.7%) and 17 months (33.8%) after baseline but not at the 32-month follow-up (4.2%). Intervention students also reported significantly greater knowledge at the 8-month follow-up, and this was maintained at the 20-month follow-up but not at 32 months. In addition, there was a significant difference between the study groups in the number of self-reported harms they experienced from their own use of alcohol after both phases of the intervention. This was maintained 17 months after the intervention but not at the final follow-up at 32 months. Finally, the intervention group developed significantly better alcohol-related attitudes (attitudes that supported less harmful alcohol-related behaviours) from first follow-up at 8 months, and this was maintained to the 32-month follow-up point.

A previous investigation of the SHAHRP utilising a non-experimental design was conducted in NI by some of the current STAMPP investigators,60 and found that, after appropriate adaptation (e.g. normative epidemiological facts updated, timings of lessons altered), participation in the SHAHRP was associated (across 32 months of follow-up) with benefits for pupils. Between-group comparison showed that intervention pupils reported significantly fewer alcohol-related harms over time, and, when drinking behaviour trajectories were modelled using latent class growth modelling, intervention pupils were significantly more likely than pupils receiving EAN to be members of those latent classes that reported less increase in drinking over time, that had a larger increase in alcohol knowledge and healthy attitudes, and that were more likely to report a smaller increase or no increase at all in alcohol-related harms.

The parental component of STAMPP was developed by the trial team and was based on earlier work by Koutakis et al. ,61 who found that giving advice to parents about setting strict rules around alcohol consumption reduced drunkenness and delinquency in 13- to 16-year-olds in Sweden (the Örebro Prevention Programme). The original Swedish intervention was based on empirical evidence that suggested that lower levels of youth alcohol drinking were associated with stricter parental attitudes against youth alcohol use and involvement in structured, adult-led activities. Similarly, permissive parental attitudes towards children’s alcohol use have been shown to be better predictors of offspring alcohol use than parents’ own use. 62 However, the original Swedish programme was relatively intensive (six 20-minute standardised presentations and discussion given to parents of 13- to 16-year-olds during regular school-based parent–teacher meetings) and so Koning et al. 63,64 adapted this intervention further (a single parents evening) and combined it with a school-based alcohol curriculum (the Dutch Healthy School and Drugs programme). They found that this combined intervention was associated with a significantly reduced rate of frequency of drinking or weekly drinking, and this was partly mediated by changes in parental rules and attitudes towards alcohol (i.e. stricter rules and attitudes were developed).

Explanation of rationale

Given the prevalence of underage drinking in the UK, the reported problems, costs and harms associated with this behaviour and the lack of a robust UK evidence base for universal alcohol prevention interventions, this work aimed to investigate an adapted form of the evidence-based SHAHRP55,60 in a culturally appropriate and curriculum consistent manner in the NI and Glasgow/Inverclyde post-primary school settings. Furthermore, considering the strong links between family behaviours and young people’s substance use, the effect of introducing a parental component to the core SHAHRP curriculum was examined.

Specific objectives

Primary objectives

-

To ascertain the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a combined classroom and parental intervention (STAMPP) in reducing alcohol consumption (HED, defined as self-reported consumption of ≥ 6 units for males and ≥ 4.5 units for females in a single episode in the previous 30 days) in school pupils (in school year 9 in NI or in S2 in Scotland in the academic year 2012–13 and aged 12–13 years) at 33 months after the baseline time point (T3).

-

To ascertain the effectiveness of STAMPP in reducing alcohol-related harms, as measured by the number of self-reported harms (harms caused by own drinking) in school pupils (school year 9 or S2 in the academic year 2012–13 and aged 12–13 years) at T3.

Secondary objectives

-

To ascertain the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of STAMPP in reducing alcohol consumption (HED, defined as self-reported consumption of ≥ 6 units for male students and ≥ 4.5 units for female students in a single episode in the previous 30 days) in school pupils (school year 9 or S2 in the academic year 2012–13) at 12 months after the baseline time point (T1), and 24 months after the baseline time point (T2).

-

To ascertain the effectiveness of STAMPP in reducing alcohol consumption (self-reported alcohol use in lifetime, previous year and previous month; number of drinks in ‘typical’ and last-use episodes; age of alcohol initiation, unsupervised drinking) in school pupils (school year 9 or S2 in the academic year 2012–13), at T1, T2 and T3.

-

To ascertain the effectiveness of STAMPP in reducing alcohol-related harms, as measured by self-reported harms caused by own drinking at T1 and T2 and self-reported harms caused by the drinking of others at T1, T2 and T3, in school pupils (school year 9 or S2 in the academic year 2012–13).

Chapter summary: introduction to the research

Although alcohol use in the general population of young people is falling in the UK, there are regional differences, and those who initiate use early, are regular drinkers or report early drunkenness are more likely to experience adverse outcomes or a greater number of years of ill health. The responses to young people’s alcohol use have traditionally focused on school-based educational approaches, although general population policies, such as restrictions on marketing and pricing increases, are also likely to affect consumption. However, the evidence base for school-based universal alcohol interventions (i.e. those that target a whole population, regardless of level of risk) is weak and, although some skills-based approaches have been shown to produce changes in different indicators of alcohol use, effect sizes are often small and the longevity of the intervention effect is limited. Other research has shown that family factors are an important determinant of young people’s alcohol use. For example, in those families in which there is good communication and authoritative rules on alcohol are in place, young people are less likely to drink. In keeping with the literature on school-based interventions, however, there are few family-based programmes that have found significant reductions in indicators of alcohol use and alcohol harm.

This research sought to determine the effectiveness of a programme, STAMPP, that is a school-based alcohol harm reduction curriculum with a brief parental intervention designed to support parents/carers in setting family rules around drinking. We examined whether or not STAMPP was effective in reducing HED and self-reported harms related to recipients’ own use of alcohol. The programme rationale was that stricter parental/carer rules and attitudes towards alcohol would reinforce learning and skills development in the classroom. The classroom component, SHAHRP, was a universally targeted curriculum that combines a harm reduction philosophy with skills training, education and activities designed to encourage positive behavioural change. It was delivered in two phases over a 2-year period and was adapted from an original Australian programme in an early study,55 with the assistance of education and prevention specialists. The brief intervention delivered to intervention pupils’ parent(s)/carer(s) comprised a short, standardised presentation delivered at specially arranged evenings on school premises. The presentation included an overview of the Chief Medical Officer (CMO)’s guidelines for drinking in childhood,65 information on alcohol prevalence in young people, corrected (under)estimates of youth drinking rates and highlighted the importance of setting strict family rules around alcohol. The presentation was followed by a brief discussion on setting and implementing authoritative family rules on alcohol. All intervention pupils’ parents/carers were followed up by a mailed leaflet, whether or not they attended the parents’ evening, which provided a summary of the key information delivered in the evening and coincided with phase 2 of the classroom intervention.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design and setting

A cluster randomised controlled trial (CRCT) in NI and Glasgow/Inverclyde Education Authority areas in the UK, with schools as the unit of randomisation.

Sample and participants

The sampling frame comprised all mainstream post-primary schools in NI (n = 208) and Glasgow/Inverclyde (n = 36). All schools in the sampling frame were initially assessed for satisfaction of the inclusion criteria and willingness to participate in the trial. Schools in the Eastern Health Board of NI, which included the capital city Belfast, were excluded, as the classroom component, SHAHRP, was already being delivered to some schools in that area by a non-governmental organisation independently of the trial.

Male and female students attending mainstream secondary schools in NI and Glasgow/Inverclyde were included. Schools were randomised into the trial and baseline data were collected when pupils were in school year 8 or S1, and the intervention was delivered when pupils were in school year 9 or S2 in the academic year 2012–13 and aged 12–13 years.

Pupils not in the specified school year and age group, and pupils in non-mainstream and vocational education (e.g. pupil referral units, further education colleges) were excluded. Pupils with special educational needs in mainstream classrooms were excluded at the discretion of teachers, as the intervention materials had not been developed for use with this population.

In each participating school, all students in attendance at the time of data collection were asked to complete the project questionnaires. Questionnaires were administered to participants at the baseline time point (T0) in June 2012 and at three follow-up points: T1, T2 and T3.

Intervention

Students in the intervention condition received the SHAHRP,55 as previously adapted and tested for use in NI. 60 The parent(s) or carer(s) of intervention condition students were also invited to receive a brief intervention. All intervention pupil parents/carers, regardless of attendance at the parents’ evenings, were mailed a follow-up information leaflet.

Phase 1 of the NI SHAHRP classroom curriculum consisted of six lessons (with 16 activities) delivered to students in school year 9 or S2 (aged at least 12 years) by trained teachers. Phase 2 consisted of four lessons (with 10 activities) delivered in school year 10 or S3 (aged 13–14 years) by trained teachers.

Training sessions for teachers took place annually in a neutral location and included an introduction to the concepts involved in alcohol harm reduction, rehearsal of delivery of each of the sessions in that phase of delivery and raising of awareness of potentially difficult issues/areas. Teachers were trained by the STAMPP trial manager prior to phase 1, and by the STAMPP trial manager, STAMPP research assistant and an alcohol worker from a local third-sector organisation before phase 2. Phase 1 was delivered between September and December 2012 and phase 2 was delivered between September and December 2013. Curriculum activities incorporated various strategies for interactive dissemination including delivery of utility information, skill rehearsal, individual and small group decision-making, and discussions based on scenarios suggested by students. There was a particular emphasis on identifying alcohol-related harms in specific scenario-based exercises (e.g. a night out) and specific discussions on strategies that might be employed to reduce harms.

Phase 1 lessons broadly examined myths about alcohol, reasons why people drink or do not drink alcohol, alcohol and the body, the relationship between amount consumed and behavioural consequences, alcohol and the media, and real-life situations. Phase 2 lessons focused on more specific adolescent drinking behaviours, real-life scenarios or potential experiences while in an environment in which alcohol is consumed. These lessons specifically examined peer pressure, similarities and differences between males and females in a drinking context, drink spiking, responsibilities towards friends, grading of risk environments or situations and peer advice around alcohol.

Interactive involvement was a key feature of the lessons, and a workbook and compact disc (CD) accompanied both phases of the project, allowing for more active learning. Further details of the SHAHRP curriculum used in this study can be found elsewhere. 60 However, an important difference between the present study and that of McKay et al. 60 is that the pupils in the present study were 1 year younger at both intervention stages. The targeting of younger pupils in the current trial (i.e. ages 12–13 years) was justified on the basis of survey data suggesting that the median age of initiation of alcohol use was < 13 years. 20,21 In addition, the intervention was only delivered by teachers in the current study, whereas in the earlier work, both teachers and external facilitators (youth workers) were used. Pupils in Scotland received the SHAHRP curriculum but, when necessary, the materials were further refined for the cultural context. For example, information that was provided about emergency services related to the Scottish Ambulance Service rather than the Police Service of Northern Ireland.

The classroom component of STAMPP differed from the original Australian SHAHRP curriculum in a number of ways. The Australian programme was targeted at pupils aged ≥ 13 years in phase 1 (as was the original NI adaptation of the SHAHRP described in Chapter 1, Introduction to the intervention components of Steps Towards Alcohol Misuse Prevention Programme), the curriculum was longer (17 activities delivered in 8–10 lessons in phase 1, and 12 activities delivered over 5–7 weeks in phase 2) and Australian reference data were used in the lessons.

The brief intervention delivered to the parent(s)/carer(s) of children in the intervention comprised a short, standardised presentation delivered by a team of trained facilitators (independent of the trial team) at specially arranged parent evenings on school premises. The presentation included an overview of the CMO’s 2009 guidelines for drinking in childhood,65 information on alcohol prevalence in young people and corrected (under)estimates of youth drinking rates, and it highlighted the importance of setting strict family rules around alcohol, with the recognition that children often model their own alcohol use behaviour on that of their parent(s)/carer(s). The presentation was followed by a brief discussion on setting and implementing authoritative family rules on alcohol. All intervention pupils’ parent(s)/carer(s) were followed up by a mailed leaflet (March 2014) that provided a summary of the key information delivered over the course of the evening. The delivery of the parental intervention coincided with phase 2 of the SHAHRP between September and December 2013.

The parental/carer activity was developed by the research team for this trial, and was partly based on the Dutch adaptation of the Swedish Örebro Prevention Programme undertaken by Koning et al. 64 These researchers delivered a brief intervention to parents on setting strict rules around alcohol in combination with a school-based alcohol curriculum (the Dutch Healthy School and Drugs programme). The parental component in STAMPP differed from the Dutch intervention in a number of ways. First, the Dutch activity was delivered at two annual parent evenings as part of general school discussions; second, the intervention was delivered by a member of the Dutch research team; third, the content of the presentations used Dutch data and was orientated towards challenging societal alcohol norms; and, fourth, attendees set their own family alcohol rules through discussion with a classroom learning mentor, whereas in STAMPP rules were based on the CMO’s guidance. 65 Both approaches utilised a follow-up mailed information leaflet.

The control group participants continued with EAN within their school, which would include standard personal, social and health education but would not be uniform across all such schools. Parents/carers of control students received no intervention. Provision of alcohol use education as part of statutory education or usual school activities (and, therefore, not able to be experimentally manipulated) was monitored through information collected as part of an online teacher questionnaire (see Chapter 4, Online survey with teachers).

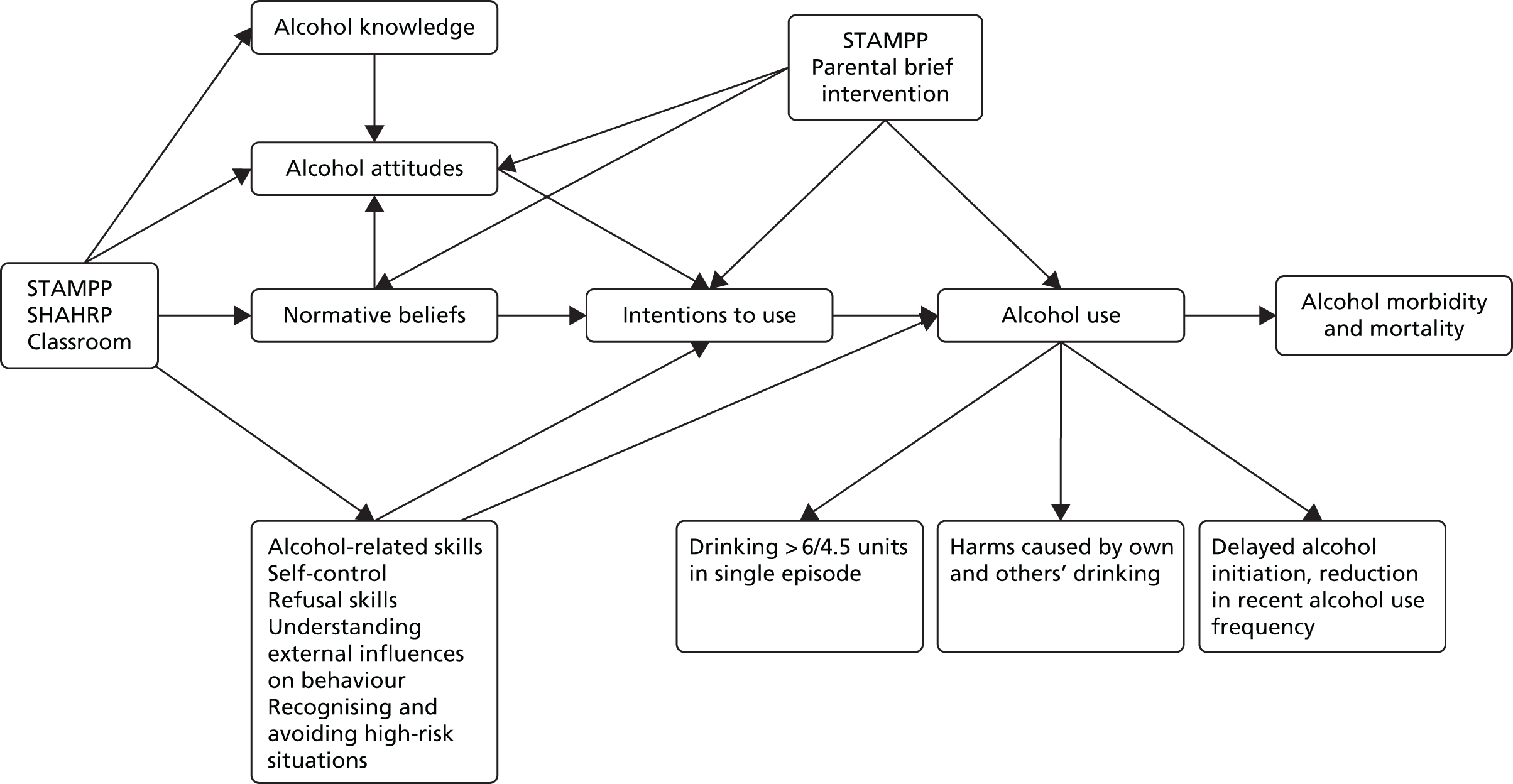

Please refer to Appendix 1 for the logic models underpinning the intervention.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Self-reported alcohol use (HED, defined as self-reported consumption of ≥ 6 units for male students and ≥ 4.5 units for female student in a single episode in the previous 30 days) assessed at T3. This was dichotomised at never/one or more occasions.

-

The number of self-reported harms (harms caused by own drinking) assessed at T3.

Secondary outcomes

-

Self-reported alcohol use (HED; defined as self-reported consumption of ≥ 6 units for male students and ≥ 4.5 units for female students in a single episode in the previous 30 days) assessed at T1 and T2. This was dichotomised at never/one or more occasions.

-

The number of self-reported harms (harms caused by own drinking) assessed at T1 and T2.

-

Self-reported alcohol use (lifetime, previous year and previous month) assessed at T1, T2 and T3.

-

Support service utilisation assessed at T2 and T3.

-

The number of self-reported harms caused by the drinking of others assessed at T1, T2 and T3. This was assessed in all participants.

-

Age of alcohol initiation (age at which a whole alcoholic drink was first consumed, not just a sip or a shared drink) assessed at T1, T2 and T3.

-

Unsupervised alcohol use (prevalence of drinking with peers without the supervision of parents/guardians) assessed at T1, T2 and T3.

-

The number of units of alcohol consumed in a ‘typical’ episode and the last-use episode assessed at T1, T2 and T3.

Description of primary and secondary outcome measures

Alcohol use behaviours (quantity, frequency and period prevalence measures) and definitions of use were taken from two major surveys on alcohol use in young people: the European Survey Project on Alcohol and other Drugs (ESPAD)13 and Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use in Young People (11–15 years) survey. 12 Frequency and age of first drunkenness were derived from the Growing Up Unequal: Gender and Socioeconomic Differences in Young People’s Health and Well-Being. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study: International Report From The 2013/2014 Survey. 66,67

Harms associated with own use of alcohol were measured using a 16-item scale, developed for the Australian SHAHRP trial (internal consistency 0.9)58 (see Appendix 3). Harms associated with other people’s use of alcohol were measured using a six-item scale (internal consistency 0.7). 55 For both harm scales, participants were asked to indicate on a Likert scale how many times in the past 6 months they had experienced each individual harm. For example, participants were asked to report the frequency of having a hangover after drinking (question 4), and of getting into a physical fight when drinking (question 7).

Data on service use by participants were collected using a bespoke instrument that incorporated items taken from the Client Service Receipt Inventory,68 which was specifically adapted for childhood,69 and items relating to the use of judicial services. The instrument included an information page with definitions of some of the public services in case the students were unfamiliar with them. The instrument was designed with input from relevant professionals (e.g. an educational psychologist, social workers, Scottish and Northern Irish teachers), and was reviewed by a social researcher who was experienced in delivering questionnaires to children, and by other health economists. The instrument asked participants to report their use of services in the previous 6 months, and data were linearly interpolated over the study period to fill in gaps in survey periods and allow for total costs to be estimated. 70 Intervention costs were also measured. These included costs associated with staff training, delivery of the intervention, travel and consumables. In the STAMPP trial, intervention schools delivered the classroom component as part of their usual curriculum time, and so additional delivery costs were not incurred. However, this might not necessarily be true for future delivery, hence the inclusion of estimates of these costs in the economic evaluation.

Other self-reported measures

In addition to the primary and secondary outcomes, study questionnaires also included additional measures and scales. These were included to allow future mediation analysis and other exploratory analyses outside of the data analysis plan (DAP).

-

The period prevalence of alcohol use (self-reported alcohol use in lifetime, previous year, previous 6 months and previous month).

-

The frequency of lifetime (self-defined) drunkenness (Likert scale, ‘never’ to ‘more than 10 times’) and age of first drunkenness.

-

The context of alcohol use [e.g. abstention, unsupervised drinking (prevalence of drinking without the supervision of parents/guardians) or supervised drinking].

-

Support service utilisation, for use in the health economic analysis. 69

-

Parental rules on drinking. 36 This was a 10-item scale developed by van der Vorst et al. 36 to measure the degree to which parents permitted their children to consume alcohol in various situations, such as ‘drinking in the absence of parents at home’ or ‘coming home drunk’. Higher scores indicated stricter rules about alcohol consumption. Response categories ranged from 1 (‘completely applicable’) to 5 (‘not applicable at all’). van der Vorst et al. 36 reported an internal consistency of 0.92.

-

Alcohol knowledge and attitudes. Alcohol-related knowledge was measured using a 19-item knowledge index55 (internal consistency of 0.73). Attitudes were measured using a six-item scale (internal consistency of 0.64). 55

-

Brief Sensation Seeking Scale-4. 71 A four-item scale based on the longer Brief Sensation Seeking Scale (internal consistency of 0.66). 72 Participants indicated responses to all items on five-point scales (strongly disagree to strongly agree).

-

Three domains of self-efficacy (academic, social and emotional) were assessed using the Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for Children73 (internal consistency 0.88). This is a 24-item questionnaire assessing (1) social self-efficacy for the perceived capability for peer relationships and assertiveness; (2) academic self-efficacy for the perceived capability to manage one’s own learning behaviour, to master academic subjects and to fulfil academic expectations; and (3) emotional self-efficacy that pertains to the perceived capability of coping with negative emotions. Items are scored on a five-point Likert scale (‘not at all’ to ‘very well’).

Changes to trial outcomes after commencement

The original primary outcome was self-reported frequency of consumption of more than five ‘drinks’ in a single drinking episode. This was originally chosen on the basis of inclusion in young people’s substance use surveys (e.g. ESPAD), other academic research, World Health Organization guidelines on HED and by the original grant tender document and reviewer feedback. However, concerns arose because it became clear that a ‘drink’ could refer to drinks of different alcohol strength and volume.

The current UK CMO’s guideline65 is that children should not drink alcohol at all, but if they do they should be at least 15 years old, never drink more than once a week, be supervised by a parent or carer and never exceed the recommended adult daily limits (3–4 units of alcohol for men and 2–3 units for women). However, equivalent unit guidelines do not exist for children.

In the UK alcohol literature, it is common to refer to ‘standard drinks’, which are interpreted as containing 1 alcohol unit (8 g of alcohol). It should be noted that internationally there are different definitions with respect to grams of alcohol in such a measure.

As the objective of the intervention was to reduce hazardous and harmful drinking, the STAMPP Trial Management Group (TMG) agreed that primary outcome should be defined as ≥ 6 units for males and ≥ 4.5 units for females; both are 1.5 times the CMO’s maximum daily guideline for adults,65 and this was ratified by the Study Steering Committee (SSC). This change was implemented before the final wave of data collection, unblinding and any analysis of trial outcome measures at any data collection point had been undertaken.

In the survey, participants were presented with pictorial prompts of how much alcohol is represented by ≥ 6/≥ 4.5 UK units (see Appendix 3). Pictures presented the most popular drinks consumed in the two study areas and respondents were asked to report the frequency of consuming this amount of alcohol over the previous month.

Parent/carer completed measures

Parents/carers completed a short postal questionnaire that measured family rules on alcohol and parental self-efficacy in implementing rules and controlling adolescent behaviour. Alcohol Rules was a 10-item scale measuring the degree to which parents permit their children to consume alcohol in various situations, such as ‘in the absence of parents at home’ or ‘at a friend’s party’ (α = 0.86–0.90). 62 Parental self-efficacy was measured using a three-item scale assessing the level of confidence that a parent had in their own ability to prevent their child from drinking (α = 0.67). 74 These data were collected to inform future mediation analysis and were not included in the DAP; therefore, analysis of these data is not included in this report.

Definitions/calculations

The questionnaire outcome scores were calculated in accordance with the original coding system outlined in their corresponding publication (see Outcome measures). A data dictionary was prepared and is available from the authors upon request.

To assess the costs of the intervention for the purposes of economic analysis, overall costs of providing the programme were estimated. This included programme set-up costs and the costs of implementing and delivering the programme. The overall cost per participant and cost per school were also estimated. The costs of implementing and delivering the programme included staff time, venue and equipment costs, provision of support facilities and materials utilised.

Data collection

Students

Data collection took place in schools in a location determined by the co-ordinating teacher. The trial manager co-ordinated the data collection diary in accordance with the preference of schools and, as such, was not blinded to intervention status.

Data were collected through self-completed questionnaires. The primary outcome measure and the service use questionnaire were completed individually. Questions were read out loud by field researchers, in accordance with a preprepared script (see Appendix 4), and participants recorded their answers in an answer book, which also included the written question. The field research team included some members of the trial team (trial manager and research assistant) and temporarily employed researchers who had no other involvement in the trial. When possible, data were collected under examination-like conditions. Participants were identified across waves through a research team-allocated code. The test procedure lasted approximately 40 minutes. At the end of the session, answer books were collected by the field researcher and returned to the field office.

Data were optically scanned (Restore plc, London, UK) and delivered to the Northern Ireland Clinical Trials Unit (NICTU) for processing, cleaning and quality assurance. Data sets were securely transferred to the trial statistician (who was blinded) and health economist (who was also blinded) at the beginning of the data analysis period and to the sponsor institution for secure back-up.

Parents

Questionnaires were posted to parents/carers, self-completed and returned directly to the field office in self-addressed envelopes.

Sample size

It was calculated that a sample size of 90 schools (45 per study arm; 80 pupils per school) would be powerful enough [80%, α = 0.05, intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) = 0.09, based on data from the Belfast Youth Development Study75] to detect a standardised effect size of δ = 0.2 or a 10% absolute reduction in risk (51% vs. 41%) for the primary outcome (HED). Assuming 20% attrition within each cluster (from 100 to 80 pupils), the target sample size was 90 schools and 9000 students at baseline.

Research ethics committee approvals, consent and research governance

The research was approved by Liverpool John Moores University Research Ethics Committee (reference number 11/HEA/097). For data collection from students within schools, the research ethics committee required opt-out consent [i.e. parent(s)/carer(s) were advised about the research requirements and could communicate a refusal for their child to participate]. Students could also refuse to participate at the time of data collection. For data collection from parent(s)/carer(s), consent was provided through the return of a completed questionnaire.

The trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme, sponsored by Liverpool John Moores University, managed by a TMG of study investigators and staff, and overseen by an independent SSC appointed by, and reporting to, the NIHR. The International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number is ISRCTN47028486.

Randomisation

Stratified randomisation of clusters (schools) to intervention or control conditions was performed by a NICTU staff member not involved in the trial and blind to the identity of the schools. Schools were stratified by school type (all-boys’ school/all-girls’ school/coeducation school), socioeconomic status (SES) [percentage of pupils entitled to free school meals (FSMs), categorised as a tertile split: low, moderate or high] and school size.

Randomisation was conducted as an electronic ‘card sort’. Within each stratum, each school had a random number attached. The schools were then sorted by ascending random number and this process was repeated several times by holding down the refresh formula function key. This made it impossible to view intermediate allocations, and the final order was taken as the school allocation.

Two schools in NI that were in very close geographical proximity, and as a result shared staff and facilities, and, therefore, they were treated as one unit to avoid contamination. Two schools in NI that shared pastoral care arrangements were also treated as one unit to avoid contamination. Stratified randomisation was used to balance the arms and was performed separately for Glasgow/Inverclyde and for NI. Schools in Glasgow/Inverclyde were stratified based on FSM provision. As a larger number of schools were recruited in NI, two stratification factors were identified: FSM provision and school type.

The trial manager matched the school codes used in the randomisation to school names, and this matching was then independently verified by the NICTU to ensure allocation concealment. Randomisation took place when children were in school year 8 or S1.

Blinding

Schools and participants were not blinded to study condition. Intervention trainers and delivery staff (teachers) were not blinded to study condition. Data collection was undertaken by a team of researchers that included the trial manager and a dedicated research assistant, neither of whom was blinded to study condition, or by temporarily contracted research staff who were blinded to study condition.

Data analysis of primary and secondary outcomes was undertaken by the project statistician and health economist, with a data set that was blinded for study condition.

Statistical methods

General considerations

Data analysis was prespecified in the DAP and approved by the SSC.

Participant population

-

Complete case (CC) population: all randomised pupils with complete follow-up data at T3, including health economic service utilisation data [the intention-to-treat (ITT) population for whom T3 follow-up data were obtainable].

-

ITT population: all subjects who were randomised. Analysis was based on randomisation rather than on receipt of intervention.

Primary and secondary analyses were performed using the CC population. The health economic analysis was also conducted on the CC population. Sensitivity analysis was conducted on the ITT population (employing a range of methods to deal with missing data; see Missing data).

Pupils who joined a trial school after T0 (June 2012) but before phase 1 of the intervention began (September–December 2012) were first captured at T1 (June 2013). These pupils were included in the primary and secondary analyses. Pupils who joined trial schools after the beginning of the intervention were excluded from the primary and secondary analyses, unless they had moved from another participating school.

Missing data

Missing on scale items: when subjects were missing on individual scale items, the coding instruction for the scale was followed. If no guidance was given, those participants with at least 80% of items completed had the remaining 20% pro-rated.

Missing on primary outcome data: a comparison of the baseline characteristics of cases with primary outcome data and cases was undertaken when these were missing.

Depending on the pattern of missingness, one or more of the following sets of analysis were produced as a sensitivity analyses and compared with analysis on the CC population.

Intention-to-treat analysis employing multiple imputation

Information at T1 and T2 was used to impute credible scores for any missing outcome measures at T3, using multiple imputation with 50 imputed data sets.

Intention-to-treat analysis employing a worst-case analysis

All respondents with missing primary outcome data in the intervention arm were assumed to have ‘failed’ (to have consumed ≥ 6/≥ 4.5 units in a single session in the previous month). All respondents with missing primary outcome data in the control arm were assumed to have ‘succeeded’ (not consumed ≥ 6/≥ 4.5 units in a single session in the previous month.

Intention-to-treat analysis employing a ‘missing = success’ analysis

All missing respondents, regardless of trial arm, were assumed not to have consumed ≥ 6/≥ 4.5 units in a single session in the previous month.

Intention-to-treat analysis employing a ‘missing = failure’ analysis

All missing respondents, regardless of trial arm, were assumed to have consumed ≥ 6/≥ 4.5 units in a single session in the previous month.

Missing on baseline covariate data

For time-invariant baseline covariates (sex and SES), missing values at T0 were derived from observed values at follow-up (T1, T2 or T3) when possible. For any remaining missing values in baseline covariates, mean imputation was employed. 76

Outliers

Any unusual measurements were automatically flagged, checked and re-entered when necessary by the trial statistician. Any outlier values that remained after data cleaning and checking were investigated for authenticity. The influence of outlier values on the primary analysis was checked, and any significant influences detected were reported and discussed in Chapter 3.

Analysis time frame

Baseline

The baseline data were collected after randomisation (T0) when pupils were in school year 8 or S1.

Follow-up visits

Adolescent participants were followed up after T1, T2 and T3.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analysis

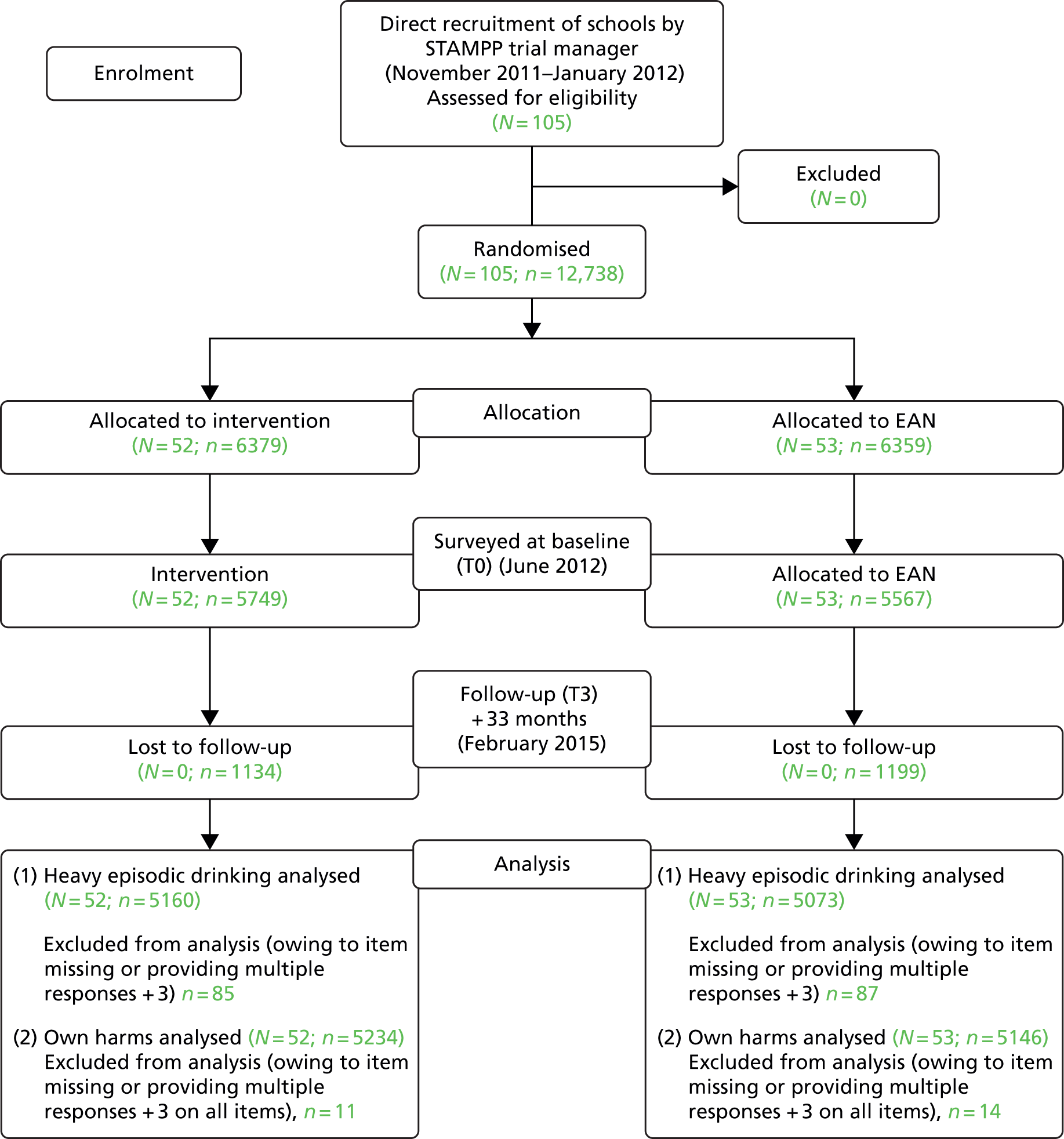

Summary statistics on school and pupil recruitment, withdrawal and dropout were collated for both trial arms and reported as a participant flow diagram for reporting of CRCTs (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

School and participant flow diagram: STAMPP. Analysis was conducted at T3 on pupils who had completed each of the primary outcome measures. N, number of schools; n, number of pupils.

Intraclass correlation coefficient

The ICC for the primary outcomes was calculated and is reported in Chapter 3 [see Heavy episodic drinking T3 (binary outcome)]. This was calculated overall and for each arm separately.

Fidelity test

Appropriate descriptive analysis was used to examine the extent to which the necessary conditions required to permit a valid test of the treatment efficacy were met. This included assessment of achieved statistical power, patterns of attrition, and treatment integrity and discriminability (i.e. that STAMPP was sufficiently distinct from EAN) across the trial sites. This work included analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data.

Randomisation check

Descriptive summaries of baseline participant characteristics from the two trial arms were tabulated to assess between-group equivalence across the trial arms (checked on randomisation). The descriptive data were tabulated to compare attendees at the parental session with those who completed the follow-up questionnaire only. Descriptive summaries were produced for baseline data at the school level. These data were used to check comparability between study arms and generalisability of the study population.

Outcome measure scores from the questionnaires were summarised and tabulated for the trial arms. Descriptive statistics, with confidence intervals (CIs) when appropriate, were used for the tabulation of outcomes in the trial arms. CIs presented were adjusted to allow for clustering effects.

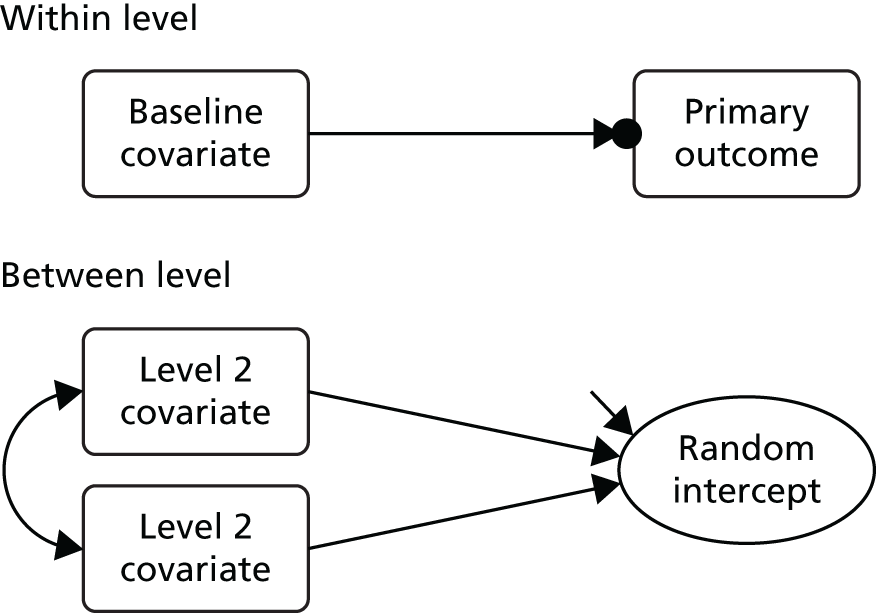

Analysis of primary outcomes

The initial outcome analysis was an ITT using the CC population such that all cases were assessed regardless of intervention and intervention dosage. However, as the study design was clustered (i.e. randomisation occurred at the school level) the lack of independency between individual cluster members was taken into account to avoid underestimated standard errors (SEs) (which would otherwise inflate statistical significance). For each primary outcome, a two-level regression model was fitted, with pupils nested within schools, to assess the impact of STAMPP on the outcome measures. For self-reported consumption of ≥ 6/≥ 4.5 units, the model used was logistic regression. For the number of self-reported harms, a negative binomial model was used.

The primary outcome model was adjusted for the impact of covariates on intervention outcome. Covariates included in the models were those used within the randomisation process (sex and SES), baseline outcome measures (consumption of ≥ 6/≥ 4.5 units and number of self-reported harms depending on outcome) and location (NI or Glasgow/Inverclyde). For each primary outcome, a statistically significant result was concluded if the p-value for the trial arm explanatory variable was < 0.025.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Differences in self-reported alcohol use (HED, defined as self-reported consumption of ≥ 6 units in a single episode in the previous 30 days for males and ≥ 4.5 units for females, which was dichotomised at never/one or more occasions) at T1 and T2 were assessed using two-level logistic regression models with covariates (baseline alcohol use, sex, SES and location). Similar models were constructed for self-reported alcohol use in lifetime, previous year and previous month (all dichotomised) and for unsupervised alcohol use (drinking without the supervision of parents/carers, which was dichotomised) at T1, T2 and T3.

A negative binomial model with covariates (baseline harms, sex, SES and location) was estimated for the number of self-reported harms (harms caused by own drinking) at T1 and T2. Similar models were estimated for the number of self-reported harms caused by the drinking of others and the number of drinks consumed in ‘typical’ and last-use episodes at T1, T2 and T3.

Time to alcohol initiation (age at which a whole alcoholic drink was first consumed, and not just a sip or a shared drink) at T1, T2 and T3 was compared between trial arms by estimating a two-level Cox proportional hazards model in those who had not already initiated alcohol consumption at baseline (T0). The model controlled for sex, SES and location.

Subgroup analyses

To explore differential treatment effects on the primary and secondary outcome measures, prespecified interaction terms were fitted between trial arm and baseline measures thought to predict the effect of treatment.

These were:

-

age, in months, of the pupil at baseline

-

gender

-

SES (using the proportion of FSM provision)

-

alcohol use behaviour at baseline: age of initiation, use of alcohol in the year prior to baseline, context of use (abstainer/supervised/unsupervised)

-

grammar/secondary school analysis (only in NI).

Sensitivity analyses or model testing

Analyses were undertaken to assess the robustness of the outcome analysis. These included the repetition of the analysis on alternative specification of outcomes measures, using the ITT population and with different missing data models.

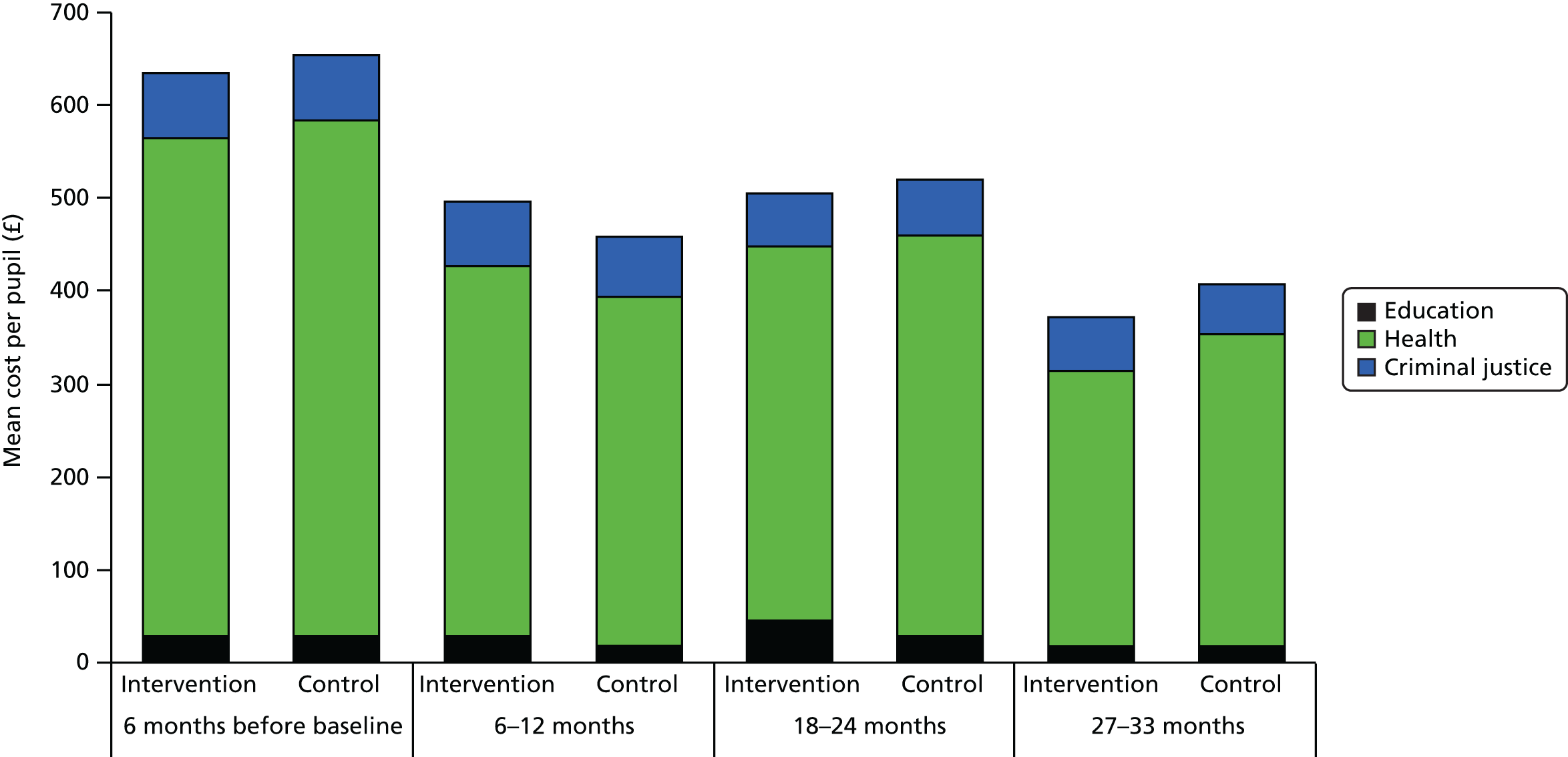

Health economic evaluation

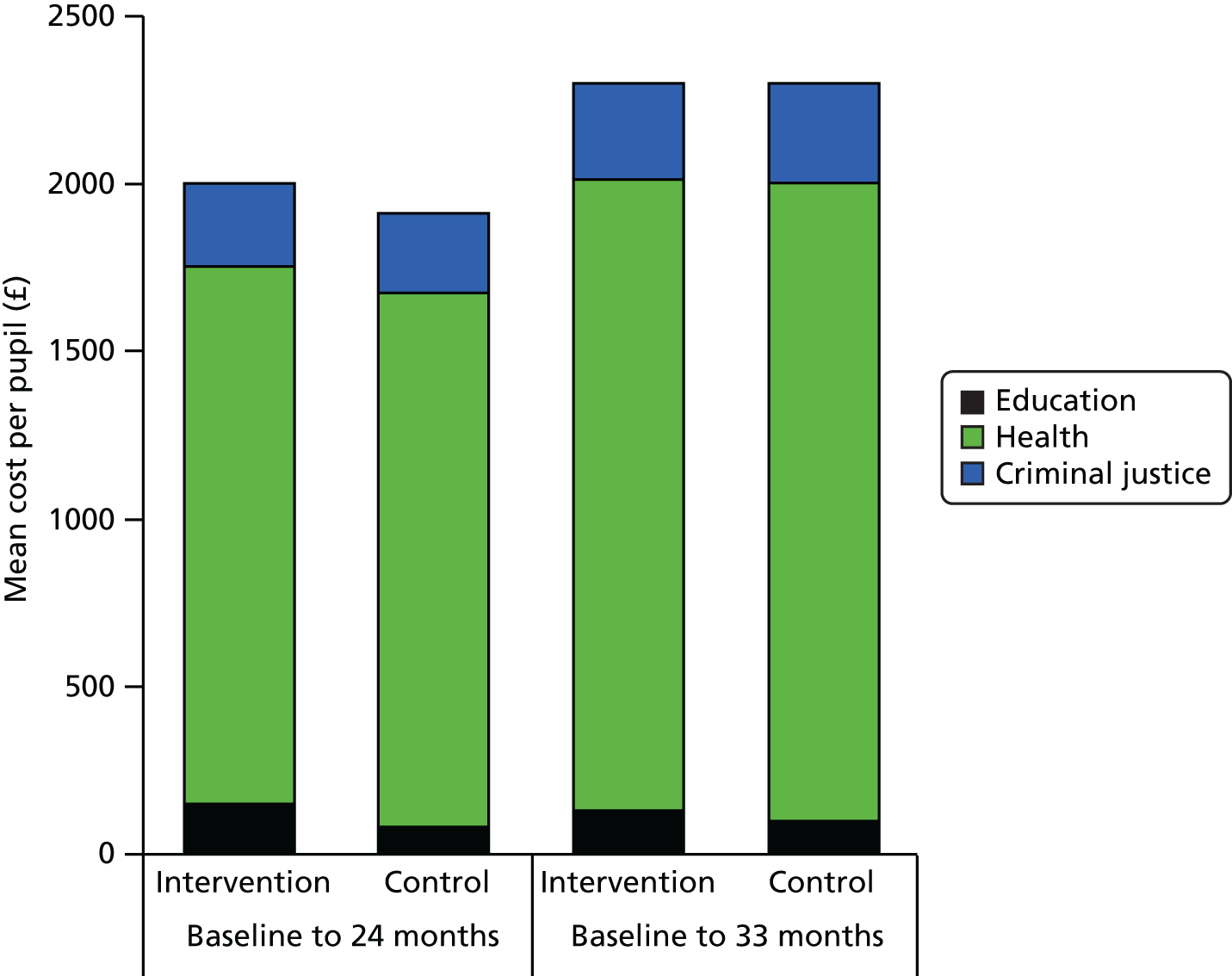

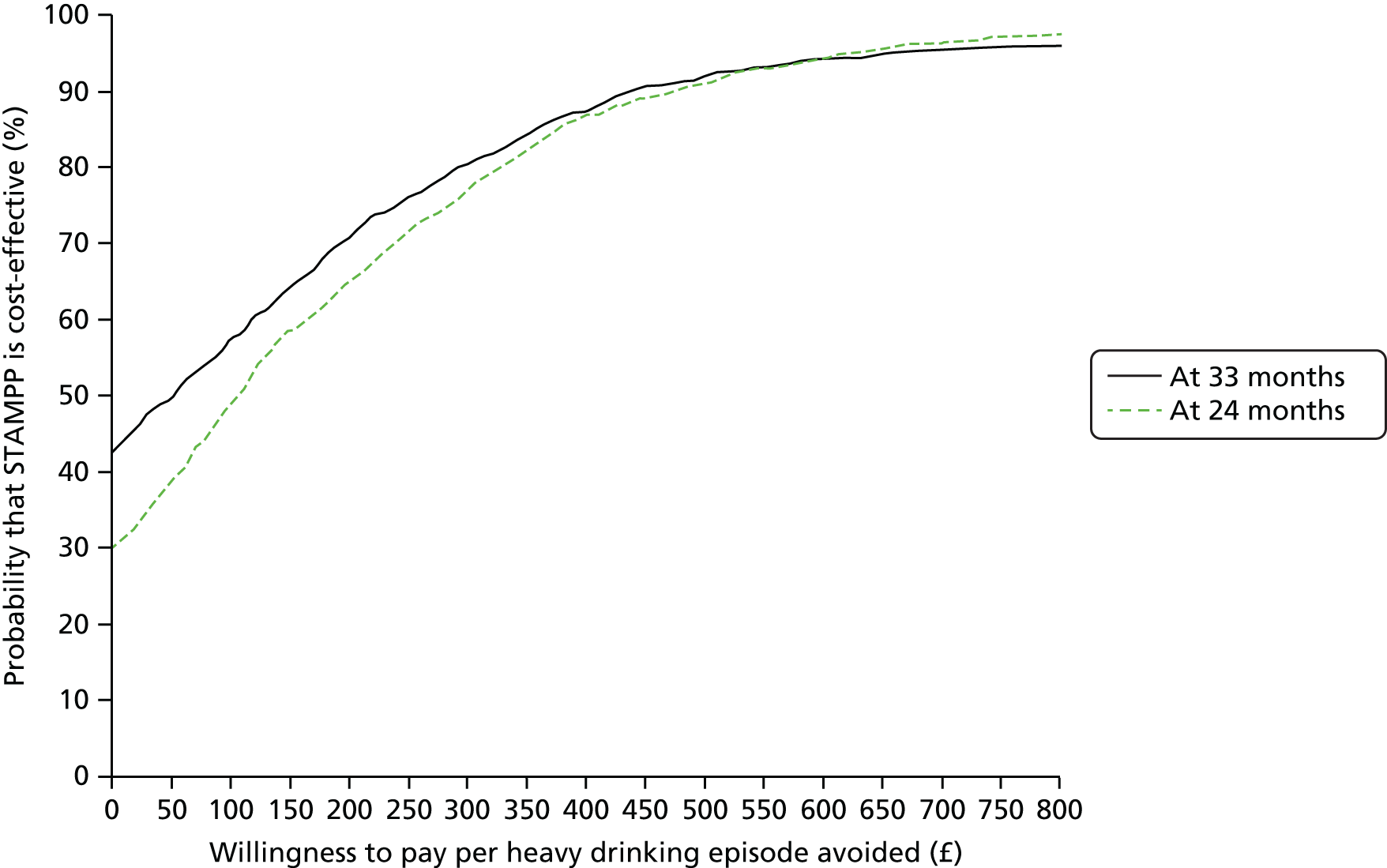

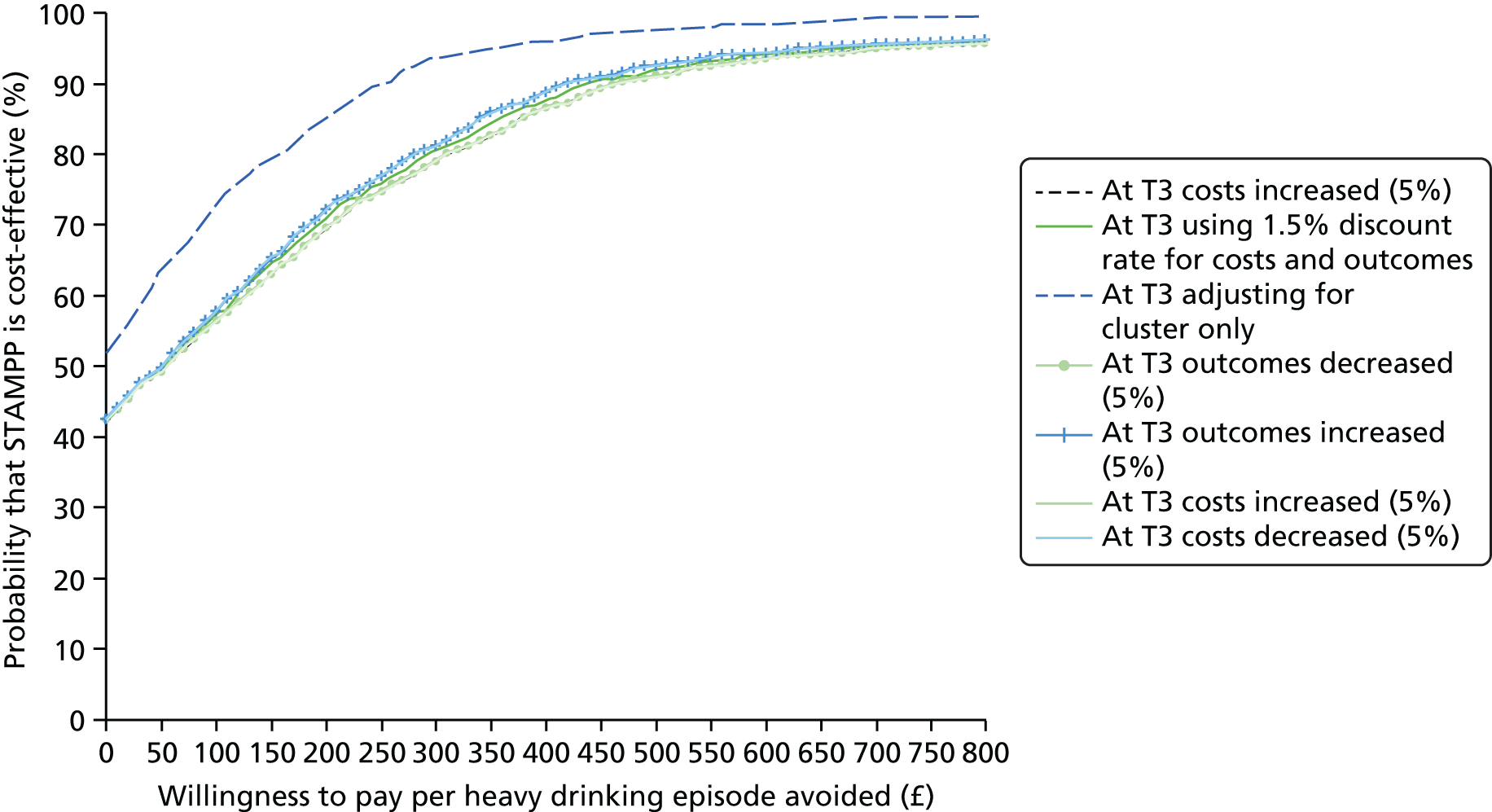

A within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) was undertaken to assess the cost-effectiveness of STAMPP compared with EAN in reducing HED (defined as self-reported consumption of ≥ 6 units for males and ≥ 4.5 units for females in a single episode in the previous 30 days, and which was dichotomised at never/one or more occasions) in year 9 or S2 pupils (aged ≥ 13 years on the 1 September 2012) at T2 and T3. The methodology adhered to the NICE’s Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal. 77

A societal perspective was adopted for the analysis in order to capture resource use related to each child’s contact with the NHS, Personal Social Services and criminal justice services. Data on service use by all participants from T0 to T3 were collected using the tool described in Description of primary and secondary outcome measures.

Pupil service use and intervention-related resource use from T0 to T3 were quantified as outlined in the paragraphs above, and unit costs were applied from national sources such as the NHS reference costs, the Personal Social Services Research Unit’s unit costs of health and social care and the unit costs of criminal justice. When national costs were not available, unit costs were identified in consultation with the appropriate finance departments of the resource provider.

Consistent with the primary outcome of the study, the primary economic effectiveness measure was the number of pupils who reported HED at T3. The secondary economic effectiveness measure was the number of heavy drinking episodes at T3. The latter was calculated using data on the frequency of heavy drinking episodes in the previous 30 days collected at the four survey time points. Data were linearly interpolated over the study period to fill in gaps in survey periods and to obtain an estimate of the number of heavy drinking episodes over the study period.

As the time horizon of STAMPP extended beyond a 12-month period, a 3.5% discounting rate was applied, as recommended by NICE. 77

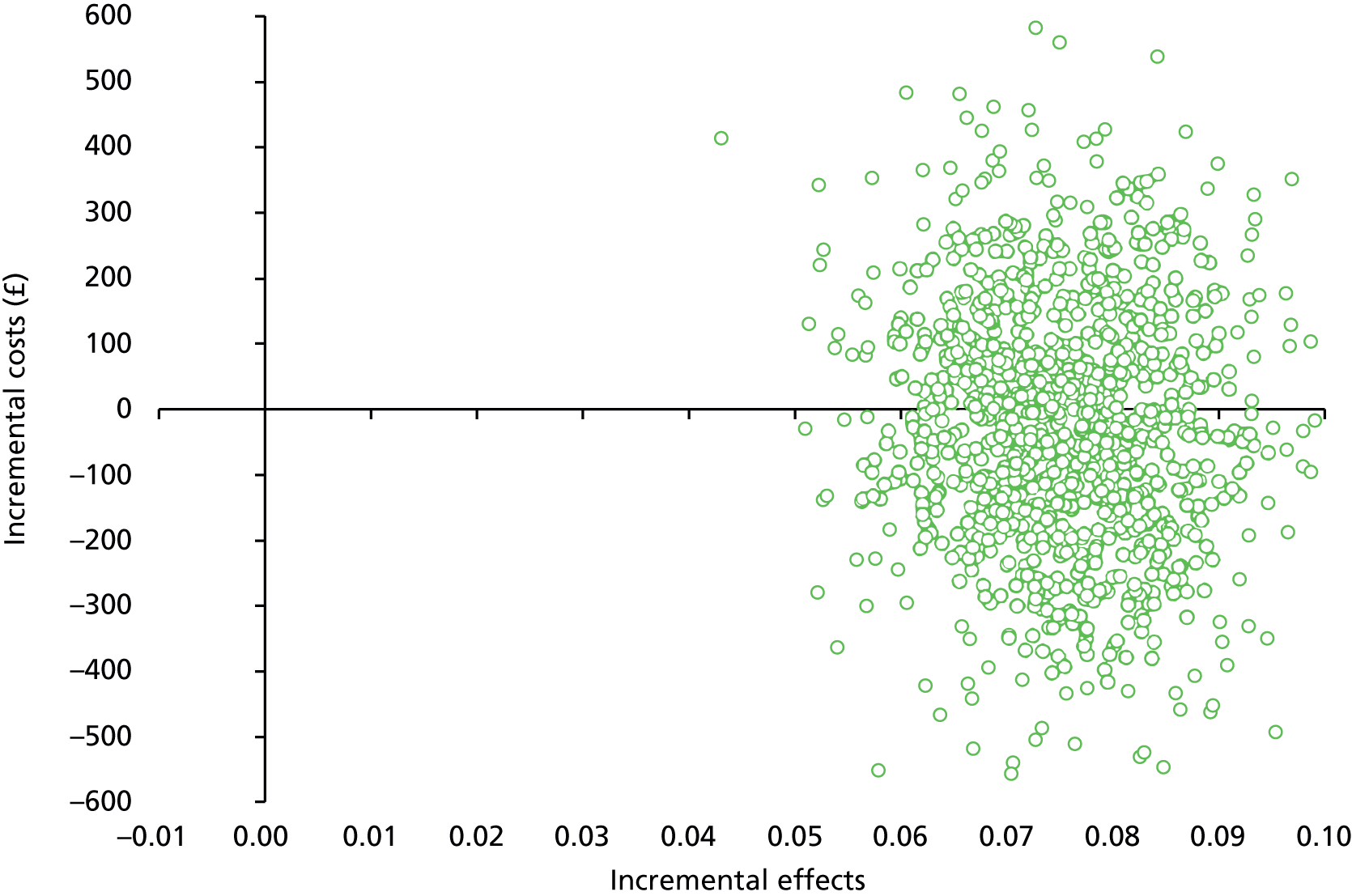

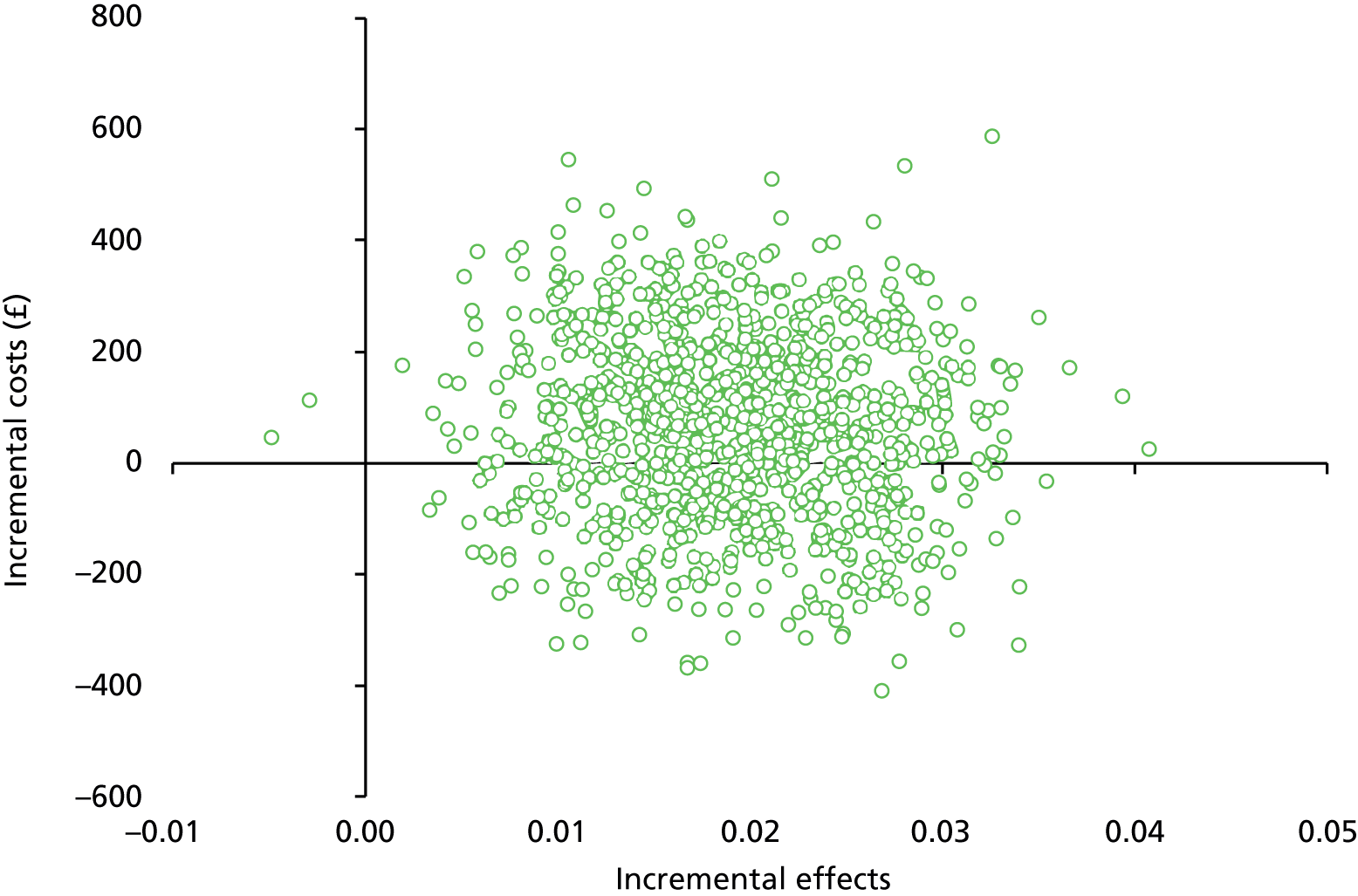

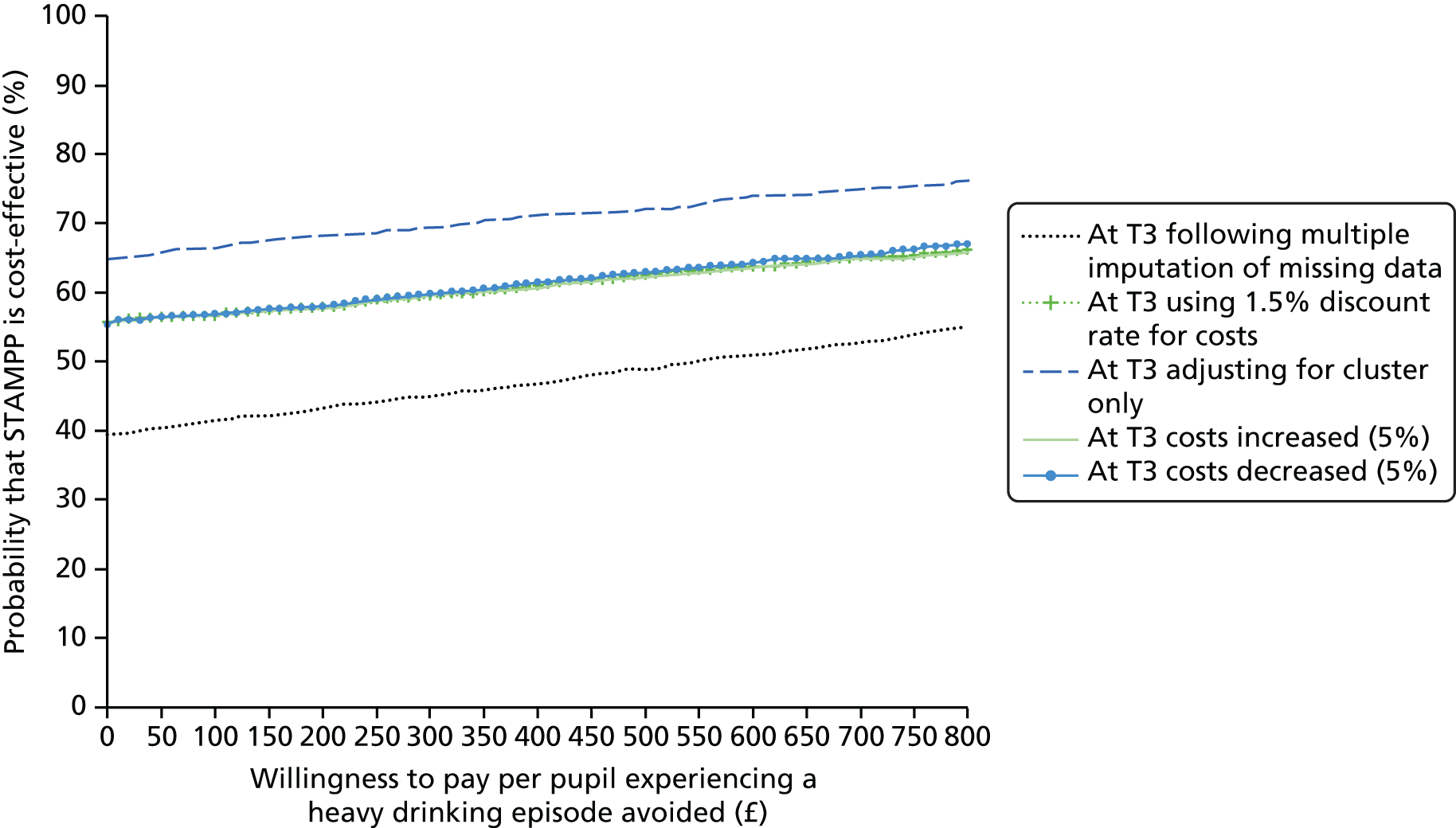

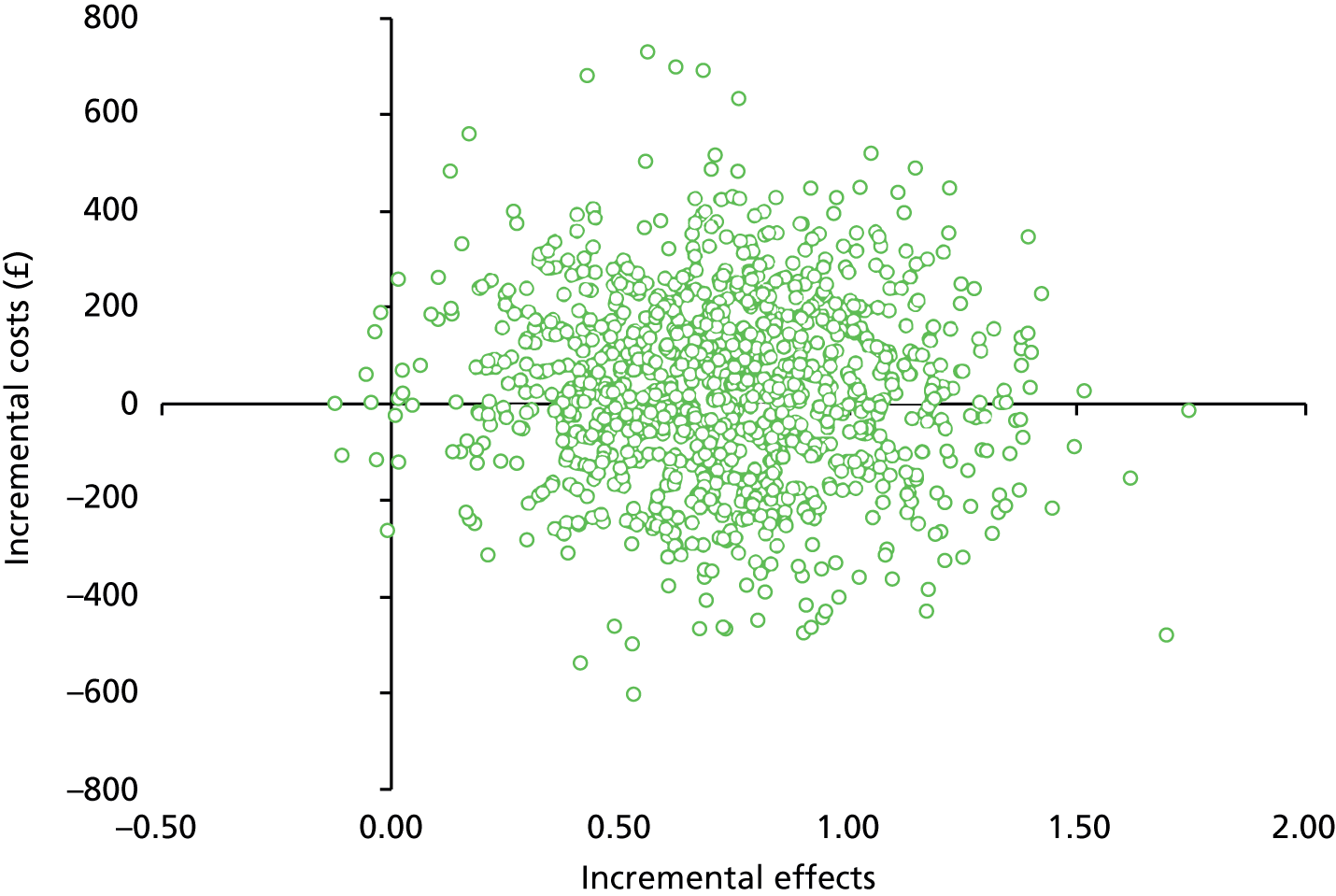

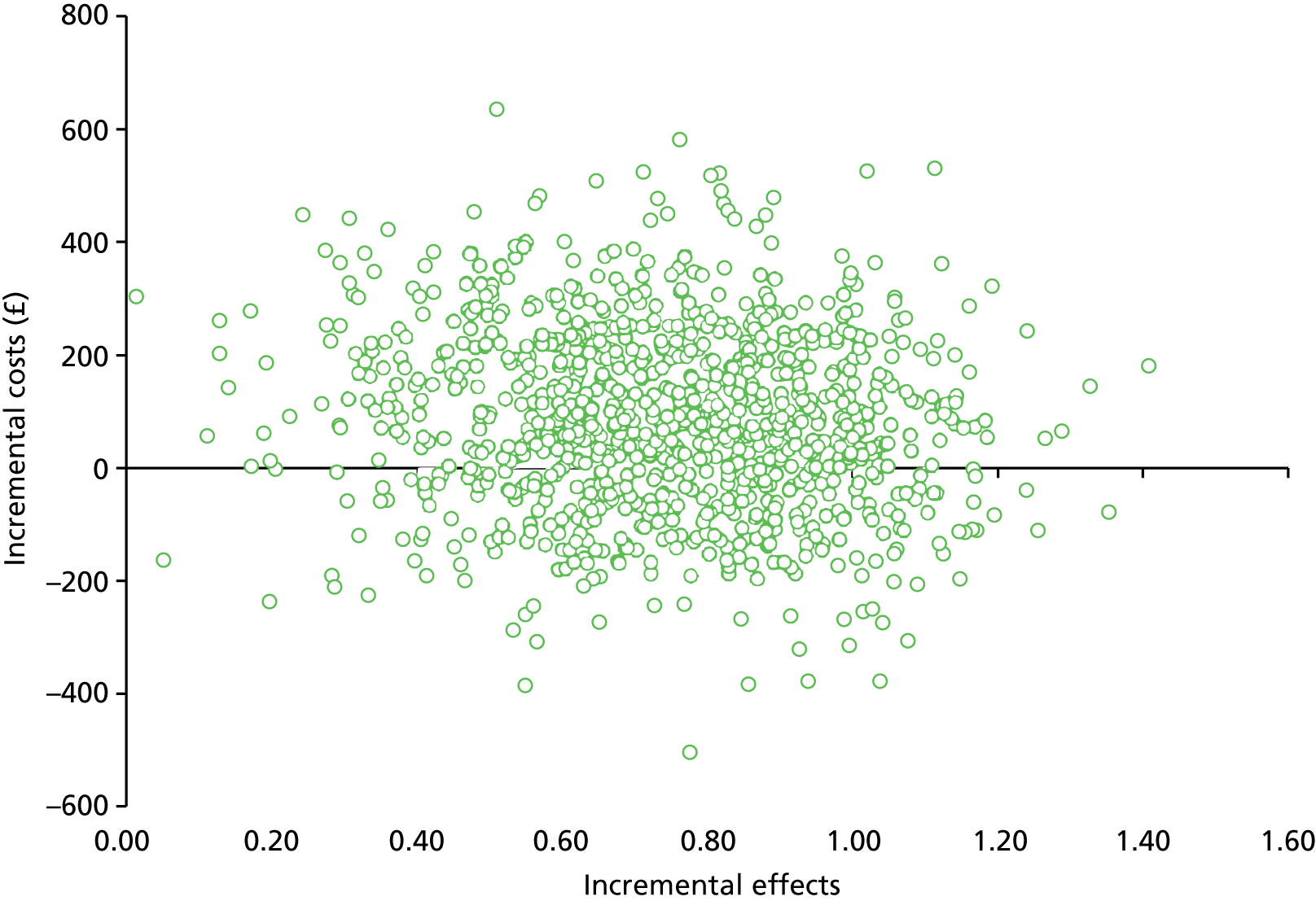

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated. The primary CEA estimated the incremental cost per young person experiencing HED avoided due to STAMPP at T2 and T3. The secondary analysis estimated the incremental cost per episode of heavy drinking avoided due to STAMPP at T2 and T3. Multiple regression models were used to predict costs and effects, adjusted for covariates and taking into account the clustered nature of the data. CRCTs raise analytical issues for CEA; costs in particular may be more similar within, rather than between, clusters. CEA should recognise both that costs and effects are correlated and that individuals are clustered within settings. Thus, appropriate models were used that recognised the clustered nature of the data. 78

Uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness measures was investigated using non-parametric bootstrapping with 1000 replications of the ICERs. The resulting replicates were plotted on the cost-effectiveness plane and used to construct cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs).

Software used

Data cleaning, data management and preliminary analysis were undertaken using IBM SPSS, version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Mplus, version 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA), was used for the multivariate regression models. Stata/IC, version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), was used for the health economic analysis and to verify Mplus models and generate odds ratios (ORs). NVivo, version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), was used for the qualitative analysis.

Public and patient involvement

In addition to participation in the intervention, data collection activities and process evaluation, target group and stakeholder involvement had already been built into the development of the classroom intervention. During the development process, a working group was established, which consulted teachers, local service co-ordinators and voluntary/community sector colleagues on curriculum adaptation. Adapted materials were piloted with pupils in school years 10 and 11 in NI. During the trial, the primary outcome measures were also piloted with a sample of pupils not taking part in the research and their feedback was received. Refinements were made to the questionnaire materials on the basis of this.

A number of public-orientated dissemination activities also took place across the life of the trial, including seminars aimed at academics, school staff and other stakeholders; informational presentations; and the preparation of summary documents for schools describing emerging findings across the trial. Two summary seminars for representatives of schools and stakeholder organisations are also planned for the school year 2016–17 after trial completion.

Changes to protocol

The final version of the protocol was version 7. Significant changes (i.e. those not related to simple language and terminology) to the protocol are detailed below (signed off by the SSC and accepted by the funder):

-

Version 4, 14 June 2013, in accordance with guidance from the SSC:

-

The primary research question was specified: ‘What is the (cost) effectiveness of STAMPP in reducing alcohol consumption (frequency of consuming > 5 drinks in a single episode in the previous 30 days) in year 9 pupils at + 18 months after intervention?’

-

Assessments at other time points were specified as secondary research questions.

-

-

Version 5, 21 November 2013, in accordance with discussions at the TMG held in October 2013:

-

The primary and secondary research questions were restated as objectives to match the DAP and timed as months from baseline and not post intervention.

-

The primary and secondary measures (as defined within the DAP) were added to the protocol, in addition to the general description of the measures used within the study.

-

The immediate post-intervention follow-up was removed to match the DAP.

-

Parent/carer measures were described.

-

-

Version 6, 15 January 2014, in accordance with discussions at the TMG held in December 2013:

-

A second primary outcome was added to reflect the harm reduction basis of the intervention: ‘To ascertain the effectiveness of STAMPP in reducing alcohol-related harms as measured by the number of self-reported harms (harms caused by own drinking) in second-form pupils (school year 9 or S2 in the academic year 2012/2013) at + 33 months (T3) from baseline’.

-

-

Version 7, 8 April 2014, in accordance with discussions at the TMG held in March 2014:

-

Clarified the primary outcome measure: ‘To ascertain the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of STAMPP in reducing alcohol consumption (defined as self-reported consumption of ≥ 6 units in a single episode in the previous 30 days for males and ≥ 4.5 units for females) in school pupils (school year 9 or S2 in the academic year 2012/2013) at + 33 months (T3) from baseline. This will be dichotomised at never/one or more occasions’.

-

Summary of methods

This was a CRCT conducted in NI and Glasgow/Inverclyde Education Authority areas, with schools as the unit of randomisation. The participants were male and female school students (school year 9 or S2 in the academic year 2012–13 and aged 12–13 years) attending mainstream secondary schools in the study areas. In each participating school, all students in attendance at the time of data collection were asked to complete the project questionnaires. Schools were randomised into the trial and baseline data were collected when pupils were in school year 8 or S1.

The study was powered to detect a standardised effect size of δ = 0.2, or a 10% absolute reduction in risk (51% vs. 41%) for the primary outcome of HED (80%, α = 0.05, ICC 0.09) and the target sample size was 90 schools and 9000 students at baseline. Following recruitment, schools (n = 105) were randomised into intervention (schools, n = 52; pupils, n = 6379) or control (schools, n = 53; pupils, n = 6359) groups.

The primary outcomes were (1) self-reported alcohol use (HED, defined as the self-reported number of occasions of consumption of ≥ 6 units for males and ≥ 4.5 units for females in a single episode in the previous 30 days, which was dichotomised at never and one or more occasion); and (2) the number of self-reported harms (harms caused by own drinking). The primary economic effectiveness measures were in line with the primary outcome measures. Primary outcomes were assessed at T3 using a self-completed questionnaire.

A number of secondary outcomes were also assessed and included the primary outcomes assessed at T1 and T2, self-reported alcohol use (lifetime, previous year and previous month), support service utilisation, the number of self-reported harms caused by the drinking of others, age of alcohol initiation, unsupervised alcohol use and the number of units of alcohol consumed in ‘typical’ and last-use episodes.

Primary and secondary analyses and the health economic analysis were performed using the CC population. For each primary outcome, a two-level regression model was fitted, with pupils nested within schools. For self-reported consumption of ≥ 6/≥ 4.5 units, the model used was logistic regression. For the number of self-reported harms, a negative binomial model was used. For each primary outcome, significance was set at p < 0.025.

The cost-effectiveness of STAMPP was estimated using conventional decision rules and reported as ICERs when appropriate. Uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness measures was investigated by bootstrapping multilevel models relating to public service costs and outcomes and using the incremental costs and outcomes to generate 1000 replications of the ICERs. The resulting replicates were plotted on the cost-effectiveness plane and used to construct CEACs.

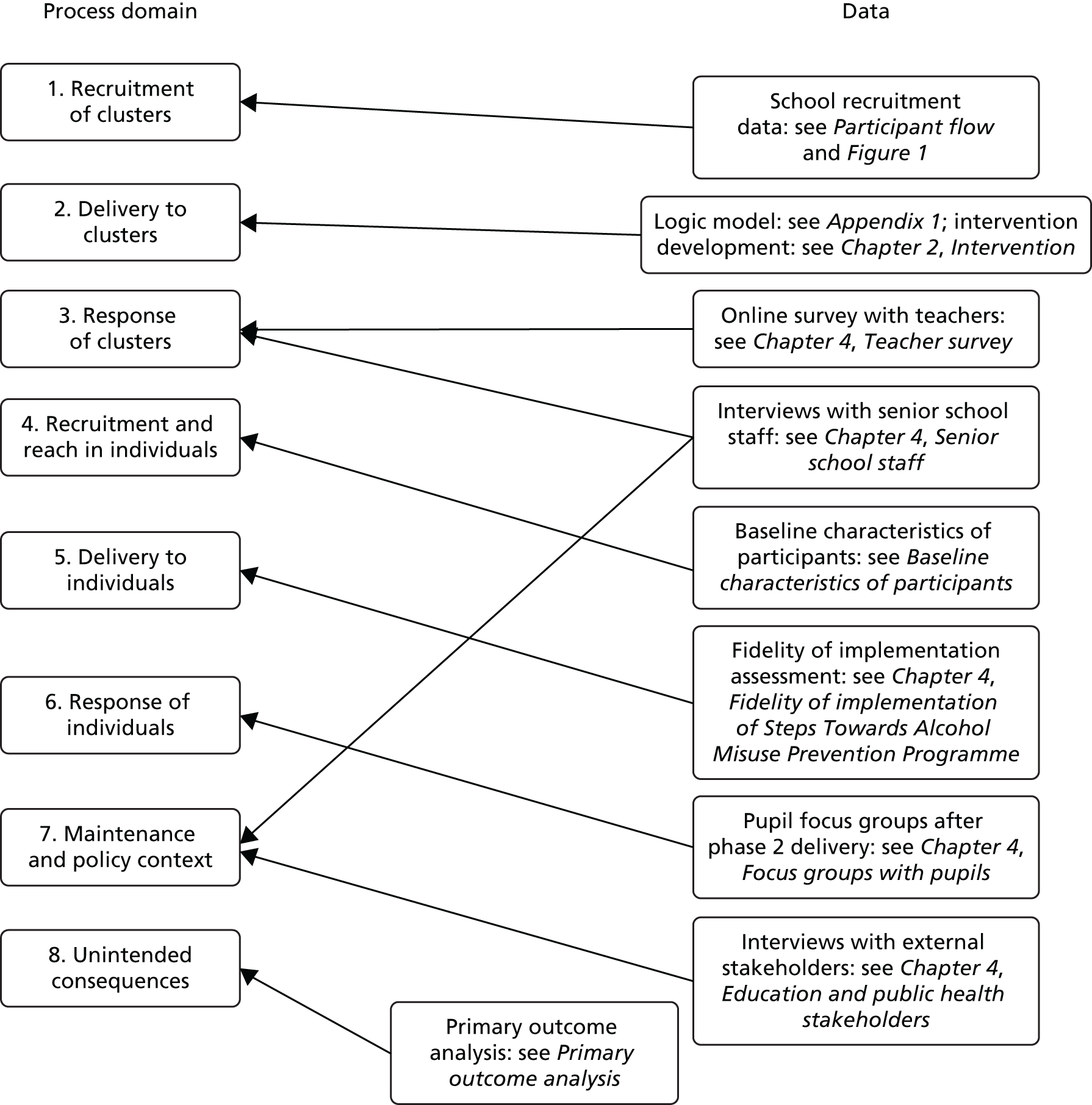

Process outcomes were assessed across eight prespecified domains using nine data sources. Assessments included focus group with pupils, an online survey with teachers, interviews with senior school staff and stakeholders. Fidelity and completeness of delivery were assessed using bespoke tools and calculation of participation rates at the parent/carer evening.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant flow

Figure 1 shows the participant flow through the trial. Recruitment began in November 2011 and ended in January 2012. Our original sample size calculation indicated that a total of 90 schools (with a mean of 80 pupils) were needed to ensure sufficient statistical power. However, we oversampled (105 schools) and, as no schools dropped out over the course of the trial, all schools were retained. As this was a CRCT of an intervention taking place over several weeks, pupil numbers refer to those who completed the questionnaire at each data collection period. No participant or parent/carer requested that data be retrospectively removed from analysis. Multiple data collection ‘mop-up’ visits were undertaken with schools; therefore, attrition represents pupils who were absent on data collection days rather than formal dropout.

Baseline characteristics of participants

A total of 11,316 pupils across 105 school participated in the T0 data sweep. Tables 1 and 2 provide descriptive statistics of the pupils at T0 across the study arms.

| Indicator | Trial arm, n (%) | Total (N = 11,316), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 5567) | Intervention (N = 5749) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 2787 (51.1) | 2834 (50.0) | 5621 (50.5) |

| Female | 2670 (48.9) | 2829 (50.0) | 5499 (49.5) |

| Missing | 110 | 86 | 196 |

| FSM provision | |||

| No | 4289 (77.3) | 4436 (77.5) | 8725 (77.4) |

| Yes | 1258 (22.7) | 1290 (22.5) | 2548 (22.6) |

| Missing | 20 | 23 | 43 |

| Location | |||

| NI | 2196 (38.2) | 3553 (61.8) | 7022 (62.1) |

| Scotland | 2098 (37.7) | 2198 (38.2) | 4294 (37.9) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HED | |||

| No | 5082 (92.2) | 5261 (92.4) | 10,343 (92.3) |

| Yes | 432 (7.8) | 431 (7.6) | 863 (7.7) |

| Missing | 53 | 57 | 110 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 4492 (95.3) | 4495 (94.5) | 8987 (94.9) |

| Non-white | 248 (4.7) | 293 (5.5) | 541 (5.1) |

| Missing | 827 | 961 | 1788 |

| Indicator | Trial arm, n (mean, SD) | Total (N = 11,316), n (mean, SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 5567) | Intervention (N = 5749) | ||

| Harms | 5561 (0.8, 1.9) | 5725 (0.8, 2.1) | 11,286 (0.8, 2.0) |

| Missing | 6 | 24 | 30 |

| Agea | 5432 (12.5 years, 0.4 years) | 5601 (12.5 years, 0.4 years) | 11,033 (12.5 years, 0.4 years) |

| Missing | 135 | 148 | 283 |

Just under two-thirds (62%) of study participants were located in NI, with the remainder sampled from schools in Glasgow/Inverclyde. There was an equal split of girls and boys in the total baseline sample and across the study arms. Around one-quarter (23%) of the participants reported being in receipt of FSMs, and fewer than 1 in 10 (8%) reported any HED (primary outcome measures) at baseline (T0). The sample was predominantly from a white ethnic background.

Table 2 provides a summary of the baseline characteristics for two continuous indicators; respondents’ age and self-reported alcohol-related harms experienced as a result of own drinking (primary outcome measure). The mean age of the sample at baseline (T0) was 12.5 years [standard deviation (SD) 0.4 years] and the mean reported number of harms was 0.8 (SD 2.0).

In addition to the primary alcohol outcomes (HED and alcohol-related harms), the study also assessed a range of basic alcohol consumption indicators at baseline (T0) (Table 3). Although one-quarter of the pupils had consumed at least one full drink at some stage in their lives, 1 in 5 had drunk alcohol in the previous year, over 1 in 10 had drunk alcohol in the previous 6 months and 1 in 20 had consumed alcohol within the previous month.

| Alcohol indicator | Trial arm, n (%) | Total (N = 12,738), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 6359) | Intervention (N = 6379) | ||

| Lifetime use | |||

| Yes | 1359 (24.6) | 1367 (23.9) | 2726 (24.2) |

| No | 4170 (75.4) | 4350 (76.1) | 8520 (75.8) |

| Missing | 830 | 662 | 1492 |

| Previous year’s use | |||

| Yes | 1086 (19.7) | 1119 (19.6) | 2205 (19.7) |

| No | 4424 (80.3) | 4583 (80.4) | 9007 (80.3) |

| Missing | 849 | 677 | 1526 |

| Previous 6 months’ use | |||

| Yes | 673 (12.2) | 711 (12.5) | 1384 (12.3) |

| No | 4835 (87.8) | 4990 (87.5) | 9825 (87.7) |

| Missing | 851 | 678 | 1529 |

| Previous month’s use | |||

| Yes | 254 (4.6) | 261 (4.6) | 515 (4.6) |

| No | 5440 (95.4) | 5433 (95.4) | 10,673 (95.4) |

| Missing | 665 | 685 | 1550 |

In addition to those pupils attending participating schools at T0, pupils who were absent at T0 but present at T1 data collection (i.e. missing on the day of the T0 data collection) and pupils who joined participating schools before the delivery of phase 1 of the intervention in the autumn term of 2012 (between T0 and T1) were included in the study population. Table 4 provides the characteristics of the full combined baseline sample (i.e. pupils present at T0 and/or at T1).

| Baseline characteristic | Trial arm, n (%) | Total (N = 12,738), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 6359) | Intervention (N = 6379) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 3222 (51.4) | 3167 (50.1) | 6389 (50.7) |

| Female | 3052 (48.6) | 3151 (49.9) | 6203 (49.3) |

| Missing | 85 | 61 | 146 |

| FSM provision | |||

| No | 4865 (77.1) | 4874 (77.0) | 9739 (77.1) |

| Yes | 1447 (22.9) | 1452 (23.0) | 2899 (22.9) |

| Missing | 47 | 53 | 100 |

| Location | |||

| NI | 3893 (61.2) | 3849 (60.3) | 7742 (60.8) |

| Scotland | 2466 (38.8) | 2530 (39.7) | 4996 (39.2) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Randomisation check

A formal test of the randomisation process was performed on the baseline assessments of the original primary outcomes and key individual pupils’ characteristics [gender, SES (recipient of FSMs), consuming five or more drinks in the previous month, number of self-reported harms] to assess between-group equivalence across the trial arms (Table 5). Consuming five or more drinks in the previous month was the original primary outcome in the trial, but this was amended after commencement (see Chapter 2, Changes to protocol). The trial arms were equivalent across all of the variables assessed at T0.

| Randomisation variable | Trial arm, n (%) | Estimate | SE | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | ||||

| Gender (female) | 2670 (48.9) | 2829 (50.0) | 0.041 | 0.195 | 0.833 |

| FSM provision | 1258 (22.7) | 1290 (22.5) | –0.009 | 0.149 | 0.954 |

| Five or more drinks | 432 (7.8) | 431 (7.6) | –0.037 | 0.172 | 0.835 |

| Number of self-harms, mean (SE)b | 0.8 (0.039) | 0.8 (0.043) | 0.053 | 0.136 | 0.695 |

Response rates

Of the full sample (those who completed a questionnaire at either T0 or T1, N = 12,738), 10,405 also completed the questionnaire at T3 (81.7%). Table 6 presents the dropout rate by sample characteristic. Dropout rates were higher among male pupils (19%), those who were in receipt of FSMs (25.8%) and those who had used alcohol at baseline (25.4%). There was little difference in dropout between the control and intervention arms of the trial (around 1 percentage point difference). Dropout also varied by location, with a higher rate in Scotland (24%) than in NI (15%), and by school; across schools, dropout rates varied from 1.5% to 32% (see Table 35, Appendix 5).

| Baseline characteristic | Trial arm, n (%) | Total (N = 2333, 18.3%), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 1199, 18.9%) | Intervention (N = 1134, 17.8%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 638 (19.8) | 591 (18.7) | 1229 (19.2) |

| Female | 537 (17.6) | 517 (16.4) | 1054 (17.0) |

| Missingb (gender) | 24 | 26 | 50 |

| FSM provision | |||

| No | 808 (16.6) | 756 (15.3) | 1564 (16.0) |

| Yes | 375 (25.9) | 357 (25.7) | 732 (25.8) |

| Missing (FSM) | 16 | 21 | 37 |

| Location | |||

| NI | 623 (16.0) | 520 (13.5) | 1143 (14.8) |

| Scotland | 576 (23.4) | 614 (24.3) | 1190 (23.8) |

| Missing (location) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lifetime use of alcohol | |||

| No | 755 (16.1) | 730 (15.4) | 1485 (15.8) |

| Yes | 426 (26.3) | 382 (24.3) | 808 (25.4) |

| Missing (lifetime use) | 18 | 22 | 40 |

| Arm | |||

| Control | – | – | 1199 (18.9) |

| Intervention | – | – | 1134 (17.8) |

| Missing (arm) | – | – | 0 |

Description of primary outcomes

The primary outcome analysis employed two primary outcome measures. The first related to self-reported episodes of single-session HED and the second to self-reported experiences of harms related to own drinking.

HED (T3): self-reported alcohol use defined as self-reported consumption of ≥ 6 units for males and ≥ 14.5 units for females in a single episode in the previous 30 days, assessed at T3. This was dichotomised at none/one or more occasions.

Drinking harms (T3): the number of self-reported harms (harms caused by own drinking) assessed at T3. Items included harms such as getting into physical fight or being sick after drinking. The outcome was a count of the number of discrete harms reported (0–16). Therefore, for example, a score of 3 represented a report of three separate harms experienced. The individual harms were not weighted in any way. Pupils who provided a valid response to at least 1 of the 16 items were included in the count. Only pupils who failed to answer any of the 16 items were set to item missing.