Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/183/08. The contractual start date was in March 2016. The final report began editorial review in May 2019 and was accepted for publication in October 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Eileen Kaner sat on the Public Health Research Research Funding Board (2010–16) and reports National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research grants during the conduct of this study. Denise Howel was a member of NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioning Board (2012–15) and is a member of NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research Subpanel (2017–20). Elaine McColl was a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group; she was an editor for the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (2013–16) and was a member of the NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee until 2016. She reports grants from NIHR Public Health Research programme during the conduct of this study and other NIHR Journals Library-funded grants outside the submitted work.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Alderson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Structure of the report

The report is structured as a series of eight chapters, detailing the design, management and outcomes of both the formative research and the pilot feasibility study. The report begins by providing the background to the research, outlining the rationale informing the design and conduct of the study.

Chapter 1 ends with an overview of the project aims and objectives. Following this, a chapter is dedicated to each of the core components of the study.

Chapter 2 details the patient and public involvement (PPI) work that has taken place throughout the study.

Chapter 3 explores the formative phase of the study and the development of the intervention materials, as well as the training and supervision provided to drug and alcohol staff during the delivery of the interventions.

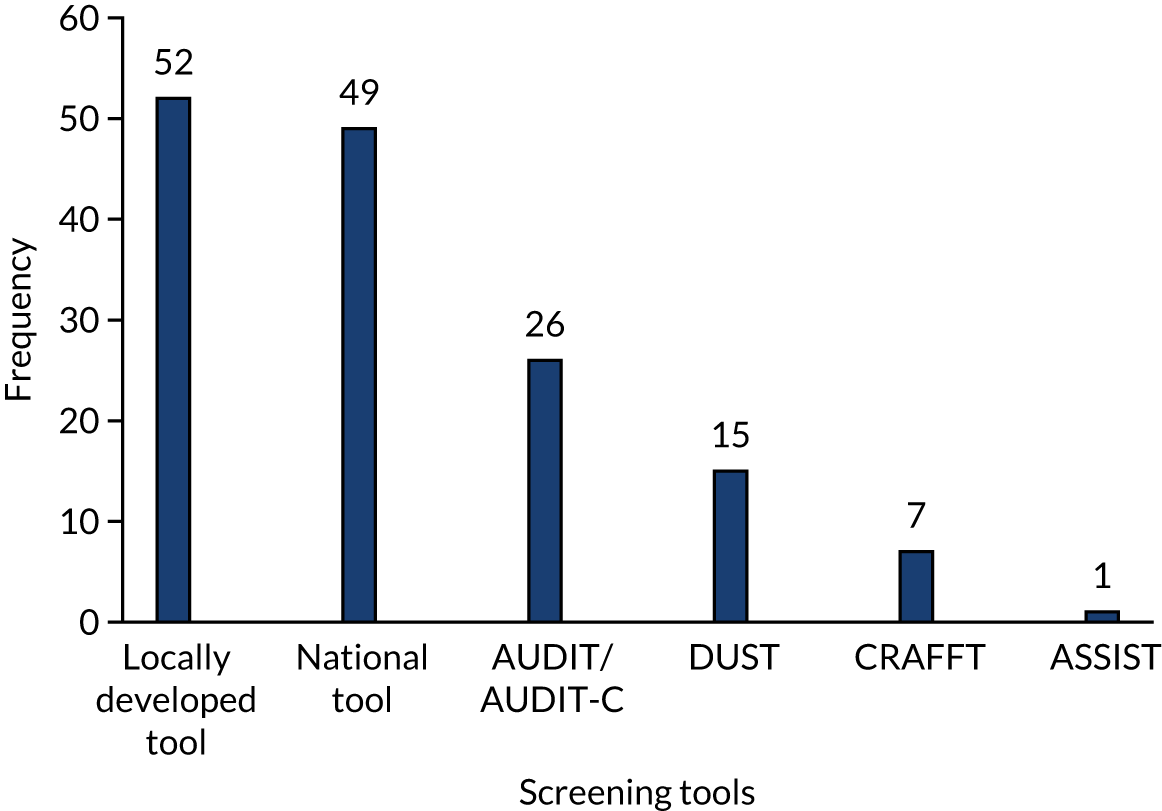

Chapter 4 reports the design, methods and results of the drug and alcohol treatment provider survey.

Chapter 5 provides the design, methods and results of the pilot feasibility trial.

Chapter 6 provides the design, methods and results of the parallel qualitative process evaluation.

Chapter 7 details the design, methods and results of the health economic evaluation of the study.

Finally, Chapter 8 draws together the main findings from the pilot feasibility study, alongside an assessment of whether or not the study met its aims and objectives, before detailing lessons learnt and recommendations for a future definitive trial.

Ethics approval

This study was granted a favourable ethics opinion by Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 National Research Ethics Service Committee (16/NE/0123). Newcastle University acted as trial sponsor.

Research management

The Supporting Looked After Children and Care Leavers In Decreasing Drugs, and alcohol (SOLID) Trial Management Group (TMG) was responsible for ensuring the appropriate and timely implementation of the trial. The TMG met bi-monthly and comprised the chief investigator, project co-ordinator, co-applicants and researchers working on the project. Professor Raghu Lingam, succeeded by Professor Eileen Kaner, chaired this group.

A Trial Oversight Committee (TOC) was appointed to provide an independent assessment of the progress the trial was making and to help determine if a future definitive trial was merited. This group met annually to oversee trial progress, with particular attention paid to recruitment, retention, adherence to trial protocol, participant safety and any new information deemed relevant to the research question. Professor Monica Lakhanpaul chaired this group. The agreed terms of reference can be seen in the Report Supplementary Material 1.

Research governance

This trial was conducted in compliance with the approved protocol and adhered to the UK policy framework for health and social care, good clinical practice guidelines, the relevant standard operating procedures and other regulatory requirements as applicable.

All researchers complied with the requirements of the General Data Protection Regulation, 2018,1 with regard to the collection, storage, processing and disclosure of personal information, and have upheld the Act’s core principles.

Researcher-administered questionnaires completed by participants online were identified by a unique study identification code. Only members of the research team are able to associate this unique study identification code with participant identifiable data needed for record linkage and participant contact.

All study records and investigator site files were stored in the Institute of Health and Society at Newcastle University in a locked filing cabinet with restricted access.

Amendments to study protocol

It was the responsibility of the research sponsor to determine if an amendment was substantial or not. A number of amendments have been made with the mutual agreement of the chief investigator, sponsor and the TOC.

Substantial amendments were submitted to the Research Ethics Committee by the chief investigator, on behalf of the sponsor, and changes to protocol were not implemented until approval was in place. The details of the substantial amendments made throughout the trial are shown in Report Supplementary Material 2.

Background to the research

Introduction

Drug and alcohol use is a major public health problem that places a significant economic strain on the NHS and society. 2 Substance use accounts for 11% of the total burden of disease, calculated as disability-adjusted life-years lost, in high-income countries. 3 It was estimated in 2013 that alcohol-related harm costs the UK £21B annually,4 with an additional £15.4B estimated to result from drug addiction. 5 The Modern Crime Prevention Strategy 2016 states that alcohol is a key driver of crime. 6 The north-east has the record highest rate of alcohol-related deaths in England. 7

Risky substance use in adolescence predicts adult alcohol and drug use and significantly increases the risk of adult mental health disorders, crime and poverty. 8–10 There have been some positive trends over recent years with regard to young people’s substance use and related risky behaviours. For example, fewer young people (aged 16–24 years) in England report drinking alcohol regularly,11,12 and more abstain from using alcohol than in previous years. 4,13 Although there has been an overall fall in drug use in teenagers over the last decade, the UK is still in the top five for lifetime use of cannabis and other illicit drugs in 15- to 16-year-olds and the top 10 for binge drinking (heavy sessional or risky single-occasion drinking) in the last 30 days across 36 European countries. 14 In a 2016 longitudinal survey of English secondary school pupils aged 11–15 years, 19% had tried smoking and 44% had tried alcohol. 15 In addition, 24% had tried drugs, compared with 15% in 2014, which the authors believe is accounted for by new questions on novel psychoactive substances (NPSs) and nitrous oxide. 15 The most recent figures from the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) on young people accessing specialist services show that the number of adolescents accessing such services continues to decline year on year. 16 However, the number of younger people (those aged < 14 years) accessing services has increased by 10% since 2014–15. The most common drug used problematically by those in treatment was cannabis (88% of services users reported a problem with this drug), followed by alcohol at 49%. Eleven per cent of those in treatment reported problematic ecstasy use, 9% used cocaine, 3% used amphetamines and 4% displayed NPS use. 16 Encouragingly, the most recent NDTMS statistics on young people’s substance use suggest a decrease of 45% in problematic NPS use since 2016,16 perhaps because these ‘legal highs’ became illegal in May 2016.

The following sections highlight the specific health, substance use, education, employment and offending status of children in care, henceforth used to make reference to looked-after children and care leavers.

Children in care and health

In the UK context, looked-after children are children up to the age of 18 years who are under the legal guardianship of local authorities. 17 Such young people are described as being in ‘out-of-home’ care in both the USA and Australia. 18,19 Care leavers are young adults who were previously under the legal care of local authorities and are still entitled to support, depending on their circumstances. Care leavers are typically aged 18 to 21 years, but can range in age from 16 to 25 years depending on their circumstances, such as being in education. 17

On 31 March 2018 there were 75,420 children in care in England, which represents 64 children per 10,000 of those aged < 18 years. 20 The number of children ‘looked after’ in England has risen steadily over the past 9 years. The main reasons for children and young people entering the care system are abuse or neglect (61%), family dysfunction (15%), family acute stress (8%) and absent parenting (7%). 20

Children in care may live in a range of placement types, such as children’s residential homes or secure units with foster carers or relatives, or be adopted or unaccompanied asylum seekers, or can remain with birth parents while under supervision from social workers. 21 Recent evidence suggests that levels of placement stability for children in care are low. In 2016–17, the mean placement duration was 314 days (10.5 months) and the median was 140 days (just under 5 months). 20 Twenty-four per cent of placements lasted < 1 month and only 22% of placements lasted > 1 year. 20 The impact of this, as Unrau and Seita explore with care-experienced adults, can have a lasting emotional impact and affect an individual’s ability to trust and build relationships. 22

Children in care have multiple risk factors for substance use, poor mental health, school failure and early parenthood. 23 These factors include parental poverty, absence of support networks, parental substance misuse, poor maternal mental health, early family disruption and, in the majority of cases, abuse and/or neglect. 24,25

Young people who have experience of the care system are more likely than their peers to have experienced adverse childhood experiences. 26,27 A Social Care Institute for Excellence report, Improving Mental Health Support for our Children and Young People, highlights the combined effects of young people’s experiences prior to care and those during care as having an impact on their mental health. 28 Such experiences are associated with a number of poor long- and short-term health outcomes,29 including problematic substance use, mental health problems,30 obesity and cancer. 31 For example, more than 50% of children in care rate their well-being as low, compared with only 10% of their same-age peers. 32 Similarly, 50% of those in care meet the diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric disorder, compared with 10% of non-care children who have mental health issues. 32 All children in care in England aged 4–16 years are required to complete an annual Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) with their foster carer or main residential care worker. In 2017, 49% had a score within the normal range (score of 0–13), 12% had a borderline score (score of 14–16) and 38% had a score giving cause for concern (score of 17–40). 20 Those in foster care placements had the lowest scores, 51% scored within the normal range, 13% were borderline and 36% gave cause for concern. 33 By contrast, within the rest of the population of children in care, 39% were in the normal range, 13% were borderline and 47% gave cause for concern. 34 The mental health needs of children in care are evident in the Children’s Commissioner 2015 report. 35 Children in care significantly over-represented peers in relation to accessing specialist Community Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). Although < 0.1% of children in England are in care, they represented 4% of children referred to CAMHS. 35

Longitudinal data suggest that young people who have been in care have higher levels of depression in adulthood. In the British Cohort Study (BSC70), at age 30 years, 24.2% of care leavers reported depression, compared with 12.4% of those who had not been in care. 36,37 In addition, care leavers were four times more likely than their peers to self-harm in later life. 38 Children in care had a nearly fivefold increased odds of at least one mental health diagnosis, including anxiety, depression or behavioural disorders [odds ratio 4.92, 95% confidence interval (CI) 4.13 to 5.85], than their non-looked-after peers, further increasing their risk of substance misuse and poor life chances. 39

Evidence suggests that children in care have a higher rate of teenage pregnancy than their peers. 40 Over a 14-month period in 2012–13 in Wales, children in care aged 14–17 years had a conception rate of 5.8% compared with 0.8% among peers not in the care system.

Substance use

As outlined in Introduction, risky substance use in adolescence is a predictor of adult-related alcohol and drug use, mental health disorders, crime and poverty. 8–10 Children in care aged 11–19 years have a fourfold increased risk of drug and alcohol use compared with children not in care. 41 Twenty-five per cent of children in care aged 11–19 years drink alcohol at least once a month, compared with 9% of young people not looked after. A national survey of care leavers showed that 32% smoked cannabis41 daily and data from 2012 showed that 11.3% of children in care aged 16–19 years had a diagnosed substance use problem. 42,43

In the year to end of March 2017, 4.1% of children in care were identified as having a substance misuse problem (not including tobacco), with older teenagers being more likely to be identified as such (11% of 16- to 17-year-olds vs. 5% of 13- to 15-year-olds). 20 Those in foster care appear to be the least at risk: 2.1% were identified as having a substance misuse issue, of whom 46% received an intervention and 42% refused an intervention. However, within the rest of the population of children in care (non-foster care placements), 10% were identified as having a substance misuse problem, 62% of whom received an intervention and 39% refused an intervention. 33 In March 2018, there were 15,583 young people accessing specialist substance misuse services, of whom 7% (1093 young people) stated that they were living ‘in care’. In addition, of the 11,052 new presentations in 2017–18, in self-reports via the NDTMS, 1204 (11%) young people identified themselves as a looked-after child, 957 (9%) identified themselves as a child in need and 829 (8%) reported that they had a child protection plan in place. 44 International evidence suggests that those living in institutional or residential care homes are at particular risk of legal and illegal substance misuse, compared with non-care peers and those living in other placement types. 19,45–47

Children in care are over-represented among drug users in later life and tend to start using substances earlier, more regularly and at higher levels than their peers. 48 Relatedly, 12% of young people accessing substance misuse services are children in care,49 and this group are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system.

Recent policies stress that children in care are a high-risk group who are vulnerable to substance misuse and linked mental health problems, as identified in Ethics approval. The 2017 Drug Strategy,49 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2017) guidelines Drug Misuse Prevention: Target Interventions50 and the NICE (2010) guidelines Alcohol Use Disorders: Prevention51 identify children in care as a ‘high-priority group’ who are at increased risk from substance-related harm. Despite this, there is limited research and an absence of cost-effectiveness data, and, at the time of writing (2019), no national guidelines on the most effective interventions to decrease risky drug and alcohol use in this group. This lack of data was highlighted by the Chief Medical Officer’s annual report for 2012,23 which stated that one of the key research areas was to assess the most effective interventions to reduce multiple risk-taking behaviour, including drug and alcohol use, in this group. 23

Literature shows that risk-taking behaviour clusters in adolescence and behaviours, such as smoking, alcohol consumption and unprotected sexual intercourse, co-occur. 52,53 In addition, young people who engage in any one risk-taking behaviour are likely to engage in others. 54,55 The involvement in multiple risk-taking behaviours can be linked to contextual factors. The majority of young people presenting to specialist drug services have multiple and overlapping vulnerabilities in addition to substance use, such as being looked after, mental health problems, not in education, employment or training (NEET), experience of child sexual abuse, offending or domestic abuse. 16 Forty per cent of 19- to 21-year-old care leavers in England are NEET compared with 13% of all 19- to 21-year-olds more broadly. 34

Education

Fifty-seven per cent of children in care aged 11 years have a special educational need, a rate 40% higher than among their peers who are not in care. 20 A child will be defined as having special educational needs if they have a learning problems or disability that mean that they need special education support. 56 The disparity in educational achievement between young people in care and those who are not continues as they progress through the education system. At age 16 years, the average attainment score for children in care is 19.3, compared with a score of 44.5 for children not in care. 20 Children in care have lower educational attainment and participation post secondary level,57 and those who enter care later (i.e. between age 10 and 15 years) do less well in secondary education than those who enter care at a younger age. 58

A study of 181 children in care aged 7–15 years in an English local authority found that they performed less well than the general child population in regard to assessed mental health, emotional literacy, cognitive ability and literacy attainment. 59 However, there were some positive exceptions of children performing well (16%, n = 30) and this was positively correlated with having face-to-face parental contact at least once per month and being in mainstream education. However, there was no significant relationship with the age on entering care, the primary reason for entering care, the length of time in care, or placement type.

A study of longitudinal data of Danish children born in 1995 shows that those in ‘out of home’ care settings change school more often than other young people, and that such change is associated with adverse educational outcomes. 60 Longitudinal data from the UK, Finland and Germany show that, in all three countries, care leavers are more likely to have no qualifications and less likely to have a higher-level qualification than their same-age peers who have never been in care. Males, in particular, are more likely to have no qualifications. 36

Literature shows that young people who truant or are excluded from school have an increased risk of alcohol and/or drug use. 61 It is also reported that young people who have truanted from school are 1.85 times as likely to have consumed drugs within the past 12 months and are over twice as likely to have consumed alcohol within the past week. 62

Employment

Care leavers have a higher risk of unemployment than those who have not been in care. 63 Forty per cent of 19- to 21-year-olds are NEET, compared with 13% of all 19- to 21-year-olds. 20 Such disadvantage and poorer outcomes last into adulthood, showing ‘a continuing legacy of adversity’ for those who have been in care, particularly in relation to education and employment. 36 Across the UK, Finland and Germany, care leavers are over-represented in economically inactive categories. In the 1970 British Cohort Study, of those born in 1970, at age 30 years, 65.8% of those who had been in care had attended full- or part-time education compared with 82.1% of those who had never been in care. By age 30 years, 7.1% of care leavers were unemployed, compared with 3.1% of those who had never been in care. A total of 16.3% of care leavers were not working to take care of family/home, compared with 9.9% of those who had not been in care. In the UK, at age 30 years, care leavers were more likely to have claimed Jobseekers Allowance (4.3% vs. 1.6%), claimed income support (7.7% vs. 1.7%) and were much more likely to have been homeless or of no fixed address before the age of 25 (22.5% vs. 6.5%). 36 Care leavers have three times the risk of being homeless than those who have never been in care. According to the more recent Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (now referred to as Next Steps), a birth cohort study of those born in 1989–90, care leavers at age 20 years are showing similar trends to those in the 1970 cohort at age 30 years. Those who have been in care are over-represented among the unemployed (17.9% vs. 6.2% of 20-year-olds who have not been in care). 64

In line with the disrupted school attendance reported above, young people with poor attendance are more likely to leave school at 16 years of age, with few or no qualifications, and therefore are seven times more likely to be recorded as NEET. 62

Offending

In the year up to 31 March 2017, 4% of children in care aged between 14 and 17 years had received a conviction, final warning or reprimand. Children in care are five times more likely to offend than all children. 20 Of those in foster care and aged between 10 and 17 years, 1.2% received a conviction, final warning or reprimand, compared with 15% of children in all other placements. 33 Research from the criminal justice system in Scotland showed that 34% of youth offenders had been in care. Of these offenders, 75% reported drug use (vs. 57% of those not previously in care). 65

Summary of the needs of children in care and potential solutions

As highlighted in sections Children in care and health to Offending, children in care are at risk of experiencing a myriad of negative outcomes, which will affect their emotional, physical and economic prospects into adult life, resulting in a significant cost to society and increased risk of intergenerational poverty. Effective interventions for children in care could have a beneficial effect on the long-term mental and physical health of these vulnerable young people, importantly reduce health inequality and, due to their increased risk of early parenthood, potentially impact intergenerational health. In response to the needs of children in care, the SOLID trial was developed to test the feasibility and acceptability of two behaviour change interventions in an attempt to address the substantial gap in evidence relating to effective interventions for children in care residing in varying forms of placement.

Overview of the study

The study had two linked phases:

-

A formative phase consisting of adaptation and manualisation of two behaviour change interventions for children in care to help reduce risky substance use: (1) motivational enhancement therapy (MET); and (2) social behaviour and network therapy (SBNT). Phase 1 also incorporated a national survey of drug and alcohol treatment service leads to help characterise usual care across England and identify potential collaborative centres for a definitive trial.

-

A pilot feasibility randomised controlled trial (RCT). This second phase of the project also had a detailed process evaluation (see Chapter 5) and economic component outlined in Chapter 6.

Research aim

The SOLID pilot feasibility trial aimed to assess the feasibility and acceptability of a definitive three-arm multicentre RCT (two behaviour change interventions and care as usual) to reduce risky substance use (illicit drugs and alcohol), and improve mental health in looked-after children and care leavers (children in care aged 12–20 years).

Research objectives

The primary objectives within the SOLID pilot RCT were as follows.

Phase 1: formative study –

-

To adapt two behaviour change interventions for children in care to help reduce risky substance use (MET and SBNT). This phase was carried out with children in care, their carers (residential key workers and foster carers), drug and alcohol workers, and social workers with responsibility for children in care, to ensure acceptability and feasibility of the intervention packages.

Phase 2: pilot feasibility randomised controlled trial –

-

To conduct a three-arm pilot RCT [comparing MET, SBNT and a control (usual care)] to determine if rates of eligibility, recruitment and retention of children in care, and acceptability of the interventions, are sufficient to recommend a definitive multicentre RCT.

The secondary research objectives were as follows.

Phase 1: formative study –

-

To refine the intervention packages for integration into care pathways for children in care.

-

To conduct a survey of the leads for young people’s drug and alcohol treatment services across England to identify ‘standard practice’ within and across agencies.

Phase 2: pilot feasibility randomised controlled trial –

-

To establish response rates, variability of scores, data quality and acceptability of the proposed outcome measures for the future definitive trial (i.e. self-reported alcohol and drug use, health-related quality of life, mental health and well-being, sexual behaviour and placement stability 12 months post recruitment), to inform a sample size calculation for a definitive multicentre RCT.

-

To assess acceptability, engagement and participation with the MET- and SBNT-based interventions by children in care, their carers and front-line drug and alcohol workers.

-

To carry out a process evaluation to include fidelity of intervention delivery and qualitative assessment of the barriers to successful implementation, and to assess if key components from the MET and SBNT interventions can be combined to develop a new optimised intervention.

-

To develop cost assessment tools, assess intervention delivery costs and carry out a value of information analysis to inform a definitive study.

-

To apply prespecified STOP/GO criteria and determine if a definitive multicentre RCT is feasible, and, if so, to develop a full trial protocol.

-

To consider findings from the study as a whole in order to develop a core intervention delivery package, potentially of a single optimised intervention, linked to a theory of change model to use in the definitive trial.

The study setting

The research took place in six local authorities in the north-east of England (Newcastle, Gateshead, County Durham, Middlesbrough, Stockton and Redcar). The north-east of England is an area of increased health and social care need and has the highest rates of poverty in the country, with 24% of households living below the poverty line. The region is, however, not uniform and encompasses a mixture of urban, periurban and semi-rural areas. The percentage of black and ethnic minority groups across the region varies from 10% in Newcastle to 2% in Durham. 66 The North East region had 95 children in care per 10,000 as of March 2018, far higher than the average rate for England as a whole (64 children per 10,000) (Table 1). Each local authority area provides a range of placement types, such as residential care homes, foster care placement and kinship foster care. 67

| Region/local authority | Total number of children in care to end of March 2018 | Number of children in care per 10,000 children aged < 18 years |

|---|---|---|

| England | 75,420 | 64 |

| North East England | 5020 | 95 |

| Gateshead | 393 | 99 |

| Newcastle | 566 | 98 |

| County Durham | 800 | 80 |

| Stockton | 468 | 108 |

| Middlesbrough | 445 | 137 |

| Cleveland and Redcar | 284 | 103 |

Chapter 2 Participant and public involvement

Introduction

Patient and public involvement was sought at multiple time points and at various levels throughout the SOLID project.

Patient and public involvement representatives included children in care, local authority employees, drug and alcohol practitioners and non-looked-after young people. Their contributions have informed the development and delivery of this research. Input has included influencing the study design (see Patient and public involvement in study design and Patient and public involvement throughout the pilot randomised controlled trial) and the co-design of study documents and the adapted manuals to ensure acceptability and readability to both children in care and practitioners. Participating local authorities and drug and alcohol services were heavily involved in the conduct of the feasibility study through screening, recruitment and delivery of interventions.

Examples of PPI throughout the project are documented below.

Patient and public involvement in study design

Three groups of children in care (n = 11, aged 12–20 years) were consulted at the point of designing the study to develop the study proposal. As a result of our PPI, the target age range of the study changed from 13–17 years to 12–20 years, so that we did not exclude early substance users (at the lower end) or young people as they transition out of care and into adult services (at the upper end). The children in care judged it essential to involve young people in the development of the interventions and felt that this research was important, especially with the rise in use of ‘legal highs’. We also consulted widely with service providers, including drug and alcohol workers, social workers and managers. In response to this work, we amended our strategy for recruiting children in care into the study. Children in care and professionals felt that social workers, rather than ‘looked-after children’s’ nurses, were best placed to screen for substance use.

Patient and public involvement throughout the pilot randomised controlled trial

Patient and public involvement was carried out regularly during the study and fed into the management meetings and TOC. The following forums were used within the study.

The research team attended several young persons’ advisory group meetings. The north-east young persons’ advisory group is one of six groups across England and is made up of young people aged 11–18 years who live in the north of England. The groups meets on a monthly basis to help researchers with their projects and raise research awareness among young people. The research team attended a meeting in March 2016 to discuss study documentation to be used within the formative research phase of the study; this included looking at the initial consent leaflets, the participant information leaflets and consent forms. There were 29 participants at the meeting (13 male/16 female, aged 12–18 years). Following discussion at the meetings, a number of changes were recommended and actioned regarding the participant information leaflets. The changes included a complete reformat of the leaflets that we proposed to use, with a change of graphics, simplified language and it was agreed to devise two slightly different versions of the leaflets for those aged 12–15 years and those aged 16–20 years, to accommodate different literacy levels.

The research team attended a North East Children in Care Council Conference in May 2016. Six participants were present (three male/three female) to discuss the topic guides to be used with young people within the formative research and we explored how to introduce the theory of change models. The outcome of the discussions was that participants liked the idea of using graphics to explore the complex ideas of the models. The young people preferred graphics that included ‘people’ in them, as opposed to just words or pictures. Young people identified some graphics that could be used when conducting interviews with children in care.

We also attended a Regional Looked After Networking Group meeting in July 2016 to discuss the survey to be completed with looked-after children’s leads. There was eight participants present, all were female managers or senior members of local authority public health and social work teams. A number of recommendations were made regarding terminology used within the survey and the flow of questions.

Thirty-six participants across three of the local authority sites took part in developing and revising the initial contact form and the car, relax, alone, forget, friends, trouble(s) (CRAFFT) screening tool to be used within the RCT phase of the trial. A number of recommendations were made and implemented, inclusive of the graphics needing to be enlarged and the text to be presented in different colours. Participants also recommended that the research team developed a ‘crib sheet’ for social workers to guide them when introducing the study to young people and that training sessions be offered prior to screening beginning. All of the recommendations were implemented, ‘crib sheets’ were designed and distributed with the CRAFFT forms and training was delivered by researchers (HA and RB) in each local authority site.

The research team attended a further North East Children in Care Council meeting in July 2017. Eight participants were present, including the personal advisor (PA) facilitating the session (seven female/one male), to discuss the topic guides to be used with children in care as part of the process evaluation phase of the research project. Recommendations included minimising the number of questions asked and making the interviews as informal and ‘conversational’ as possible. The recommendations were taken on board and researchers had hints and probes to use, rather than lots of individual questions.

Research patient and public involvement group

While carrying out the PPI with young people, members of the Children in Care Council suggested that they would like to be involved more extensively in PPI work regarding research. This led to a successful application being written to enable a PPI-specific piece of work to be completed. A research PPI group was established at the request of children in care attending one of the North East Children in Care Councils. Additional funding from the Catherine Cookson Foundation covered expenses, such as vouchers, transcription costs and dissemination of the final product (which was a short, 5-minute video). When children in care participated in this particular piece of PPI work, the research team adhered to the same process of obtaining informed consent from children in care and their corporate parent, as explained fully in Chapter 3, Recruitment and sampling strategy. In addition, participants in the research PPI group also signed an additional release form to allow the video that they developed as part of the PPI work to be shown.

Eighteen qualitative semistructured interviews were conducted with seven children in care, the participation officer within a North East Children in Care Council and the four researchers involved in developing and facilitating the PPI group. PPI sessions (nine sessions), each approximately 1 hour in length, were conducted over an 18-month period. Data gathered within the qualitative methods were used to produce a video of the children in care, describing why it was important to have their voice heard and how they could influence research and ‘10 top tips’ of working with vulnerable young people, such as children in care. The overall findings of this piece of work suggested that it was feasible to develop a PPI group with children in care to be involved in academic research projects. The development process and findings from this PPI project have been published elsewhere. 68

Conclusion

Patient and public involvement has played a central role within this research project. It has ensured that the study design is as inclusive as possible and that the study documentation is acceptable to study participants. The relationships and links made with local Children in Care Council groups have been successful and have opened up dialogues regarding children in care’s involvement in future pieces of academic research.

Chapter 3 Development of intervention materials and training (formative research study)

Introduction

As outlined in Chapter 1, Overview of study, the formative phase of the study aimed to adapt the two intervention approaches (MET and SBNT), to ensure that they were feasible to deliver within the existing health and social care system, and acceptable to children in care and other key stakeholders inclusive of social workers, drug and alcohol workers and ‘carers’. The intervention adaptation process occurred through a series of stages, involving interviews, focus groups and workshops, which were all based on qualitative methodology. The steps taken are documented below (see Methods); qualitative research findings are included to illustrate how participants influenced the adaptation and manual development of our two evidence-based interventions so that they could be delivered through existing alcohol and drug treatment services.

Methods

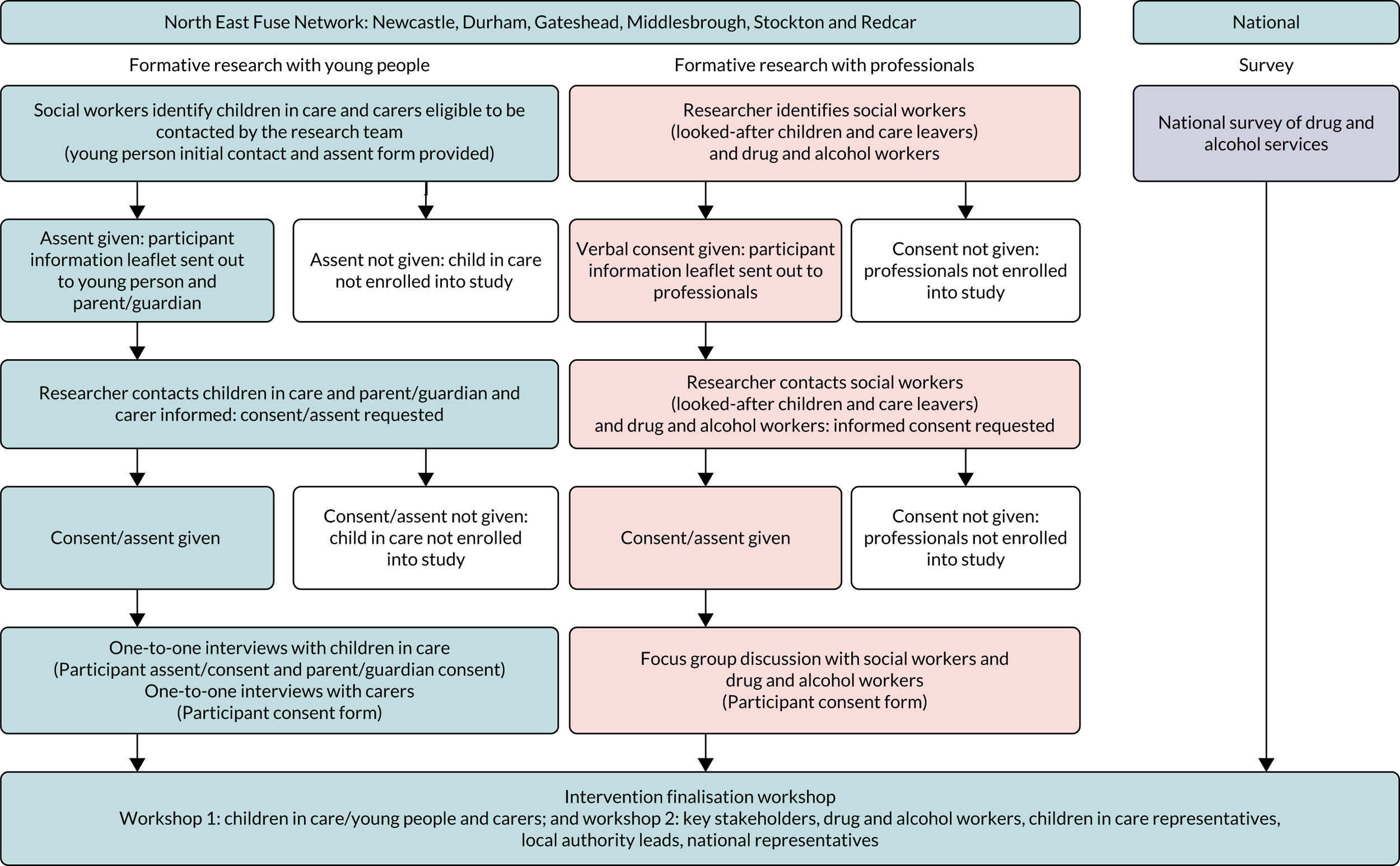

The formative research work consisted of five separate, but interconnected, stages. The first was to select two evidence-based interventions suitable for adaptation to be used with the population of children in care. This was followed by developing a theory of change model, conducting qualitative interviews and focus group discussions with key stakeholders and the analysis of the qualitative data, before co-producing the final interventional manuals within a finalisation workshop. Each stage is discussed in detail in sections Rationale for choosing SBNT and MET interventions to Consent. Figure 1 also visually shows the component parts of the formative phase of the study.

FIGURE 1.

Component parts of phase 1: formative study.

Rationale for choosing SBNT and MET interventions

Two evidence-based interventions, MET69 and SBNT,70 were chosen to be adapted as they have been shown to be effective in decreasing substance use in a range of participants including adolescents. 71

Motivational enhancement therapy is a concentrated version of motivational interviewing. This client-centred, counselling approach adds a problem feedback component to standard treatment. 72 The problem feedback component enables the practitioner to reflect on the material elicited about the impact of drug and alcohol use on the young person’s mental health, physical health, relationships, behaviour and offending, and encourages the young person to discuss this further, for example:

We discussed the fact that your foster carer was worried about your drinking. You told me that you found that you were more irritable the day after you had drunk alcohol. Can you tell me more about this?

Within the MET approach, there is a basic assumption that the motivation and responsibility for change lie within the client, and it is the therapist’s role to create an environment to enable the client to change. A systematic review by Carney and Myers73 concluded that motivational interviewing and MET have shown therapeutic promise for adolescents with problem substance use. 73–75

Social behaviour and network therapy is a counselling approach which utilises a combination of behavioural and cognitive strategies to help clients build social networks that are supportive of positive behaviour change in relation to problem substance use and goal attainment. 76 NICE recommends family interventions when working with young people presenting with complex needs, such as substance misuse and mental ill health. 77 SBNT offers an intervention with the potential to galvanise a support network for children in care that can draw support beyond the immediate family. This is important, as most forms of help focus mainly on the individual with the drug and/or alcohol problem and pay little or no attention to the social context. In addition, given the potential for family fragmentation and broken relationships, it is unlikely that the more traditional family interventions would be feasible for the population of children in care. Therefore, the challenge that Copello76 tried to address when developing the SBNT approach was to find a way of working and helping people that takes the social context into account and uses a whole social or family system to help and support change and reduce problems, while also developing an approach that is simple enough to be used in routine practice. The principle of incorporating a support network into the intervention was believed to be suitable to use within this study, as it was hoped that the six sessions could be used as a platform to create a support network, or at least start a dialogue that could consider potentially supportive individuals, and promote cohesion that could ideally continue to be developed beyond the period when the young person is in contact with services.

Although both MET and SBNT have been shown to be effective at reducing substance use in the general population of children and young people, less is known about their effect with those who are likely to have more fragmented family relationships and are currently looked after by the local authority. For the SBNT approach, the nature of social networks and how they differ for children within the care system was paramount to understanding how to effectively engage and work with this group of young people.

Developing a theory of change model

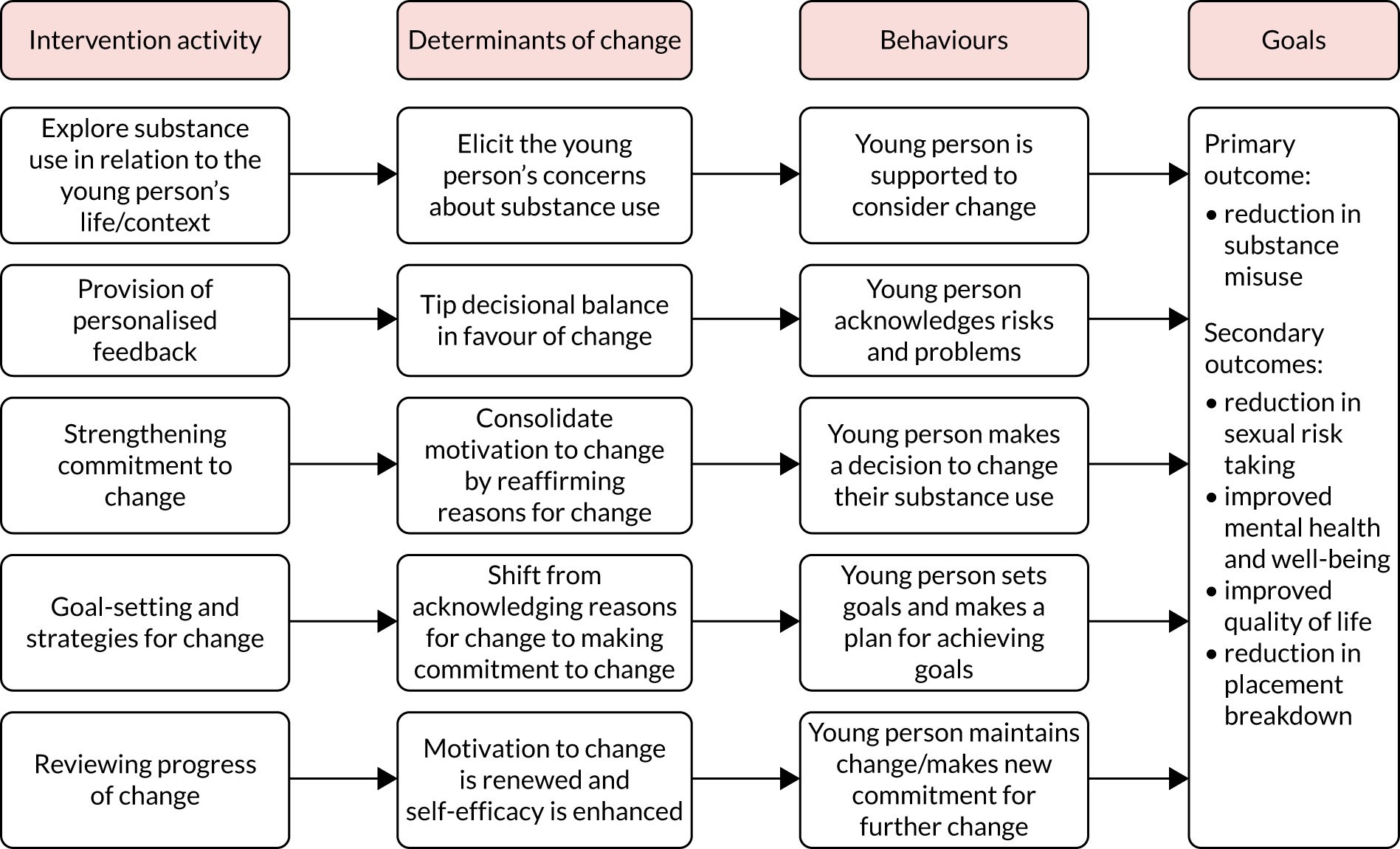

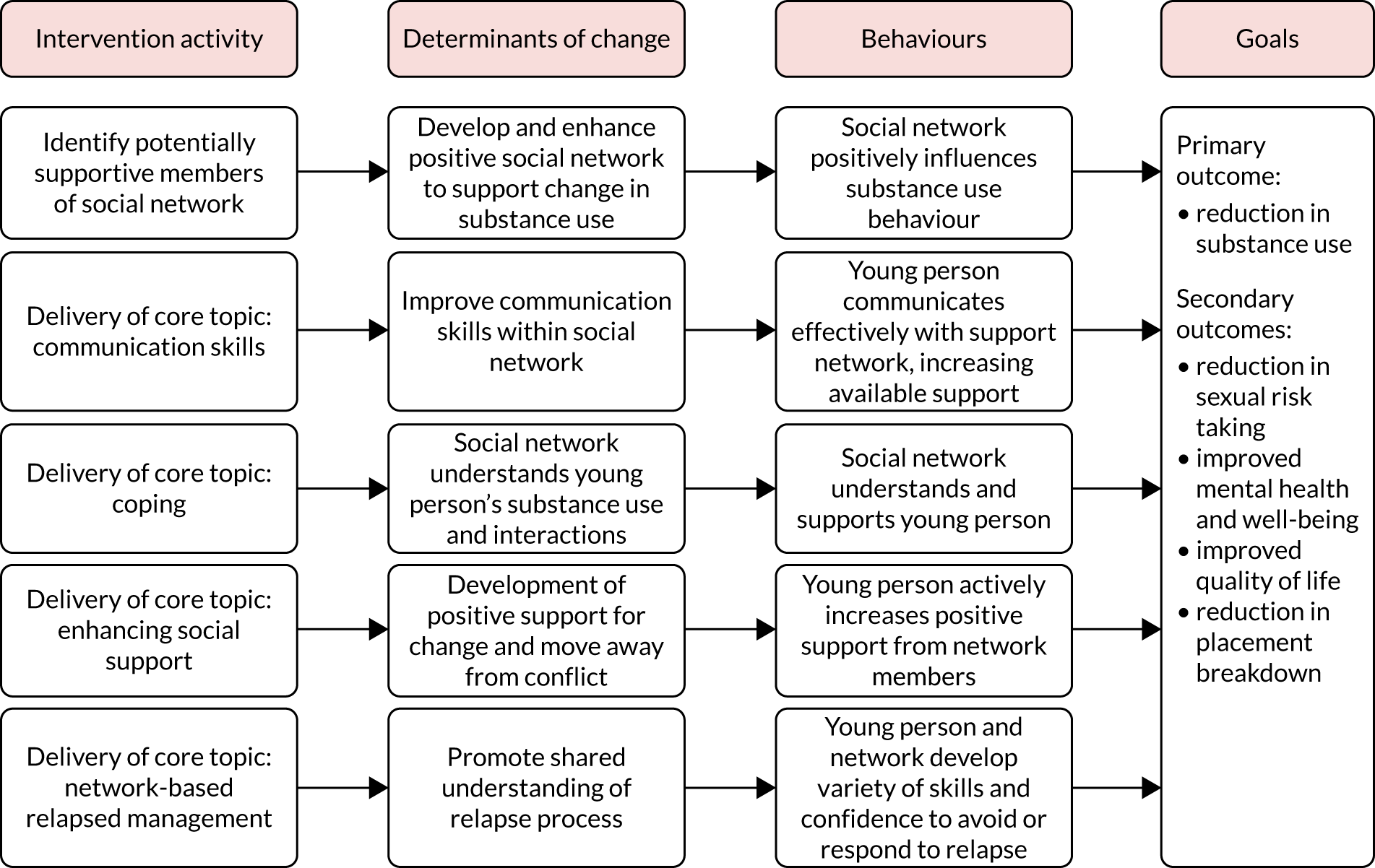

In accordance with guidance from the Medical Research Council (MRC) on developing and evaluating complex interventions,78 we commenced the adaptation of the interventions by building a theory of change model relating to our target population. We developed a behaviour determinants intervention (BDI) model for each intervention (RL, RM, EK and AC). 79 These models highlighted the key behaviours targeted by the interventions, the determinants for change and how the team visualised the proposed change pathways for the interventions. The models are illustrated in Figures 2 and 3. We also considered the absence of appropriate family support and supervisions, and the life experiences which led to an individual’s placement into care, as the central vulnerabilities of children in care. We predicted that an intervention seeking to decrease substance misuse by this group would need to address the behaviour determinants identified in the BDI models (see Figures 2 and 3).

FIGURE 2.

Behaviour determinants intervention theory of change model: MET.

FIGURE 3.

Behaviour determinants intervention theory of change model: SBNT.

When delivering the MET intervention, the therapist can elicit self-motivational statements from children in care by employing strategies to build and strengthen their motivation. By using this technique it was hoped that children in care could resolve the inherent ambivalence about their substance-misusing behaviour. 69 When developing the MET BDI model (see Figure 2), alongside the goal of strengthening motivation, we thought that it would also be helpful to provide personalised feedback to assist the young person to consider risks and tip the decisional balance.

When developing the SBNT BDI model (see Figure 3), we thought that the approach should promote the recognition of an informal network of supports that extended beyond traditional caregivers. We were aware that networks of support available to children in care would differ from those available to children and young people residing within more traditional biological families. However, evidence exists that social network support is key to helping people deal with problem behaviours, including substance misuse. Therefore, within SBNT, the therapist could usefully employ cognitive and behavioural strategies to help children in care to build social networks of positive behaviour change in relation to their goal attainment. 76

Formative qualitative research methods

In-depth one-to-one interviews, dyad interviews and focus groups were used to explore the assumptions inherent within our logic models (see Figures 2 and 3), the principles behind the MET and SBNT approaches and their relevance to children in care, and the broader therapeutic approaches, including the key behavioural and motivational domains that the interventions should address when working with the population of children in care.

All data were collected using semistructured topic guides. Guides were developed and adapted throughout the study in response to early research findings to ensure deeper understanding of emerging themes. Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were collected until data saturation was reached within each participant group and no new themes were emerging. Transcripts were anonymised and identifiable participant details removed. A participant key was developed and stored separately. Pseudonyms were allocated to each transcript and have been used within all reports and publications to maintain participants’ anonymity.

Interviews with children in care and carers (foster and residential) were chosen as the method of data collection. Interviews were chosen, as the semistructured nature of the topic guides meant that sensitive issues could be explored and personal experiences shared. Interviews also recognised individuals as experts in their own experiences, in respect of the topics of drug and alcohol use, any barriers and facilitators experienced when engaging with services (e.g. substance misuse services, mental health and services, such as Barnardo’s) and any potential recommendations for service improvements. The topic guides used for the interviews with children in care were developed with the SOLID PPI group, as discussed previously in Chapter 2. All study documentation relating to the formative research is shown in Report Supplementary Material 3.

Focus groups and dyad interviews were chosen as the primary method of data collection with social workers and drug and alcohol practitioners and participants were interviewed with colleagues within the same profession (i.e. social workers were interviewed together and drug and alcohol practitioners were interviewed together). The group interaction encouraged the exploration of a range of responses in a relatively short space of time. Furthermore, they proved to be an effective way to explore issues and quickly establish a range of experiences, views and knowledge. The professional focus groups and interviews enabled us to discuss the original components and principles behind the MET and SBNT interventions, alongside the proposed adaptations and whether or not they were perceived to be relevant to the context of children in care. They also enabled us to explore the broader therapeutic approaches required to work with children in care, the feasibility of delivering the interventions to this population and to consider potential barriers to delivering the interventions at scale.

Recruitment and sampling strategy

Social workers within the looked-after children and 16+ teams (teams working with children in care aged ≥ 16 years and supporting young people who are transitioning out of the care system) approached eligible children in care from their caseload. Eligible participants were defined as children in care aged 12–20 years, known by a social worker to have experience of substance use (previous or current personal use or exposure to substance use), who were able to provide informed consent and who resided in the study area. Social workers acted as gatekeepers, and shared a brief participant information leaflet with the young person. If the young person in care was willing to take part, the social worker completed a written assent or consent form with the young person and returned it to the study team. Children in care (n = 19) expressed an interest in taking part in the study. Once the form was received the study team was able to formally approach the young person in care. All 19 interested children in care were contacted by the research team to discuss the research and to arrange an appropriate time to visit and conduct an interview. Written informed assent or consent (depending on age of the child in care) was taken by the researcher before starting the interview, as described in Consent.

A purposive sample was recruited to ensure diversity with regard to age, exposure to drug and alcohol use, and placement type. The final sample was representative of the population of children in care, in so far as there was an equal mix of male and female participants and a range of placement types across the different local authority areas, as identified in Table 2.

| Qualitative method | Participant group | Number of participants | Sex | Placement type/job role | Substance use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual interviews | Children in care | 19: aged between 12 and 20 years | 9 female and 10 male |

Foster care, n = 5 Residential care, n = 8 Independent/supported living, n = 5 Living with biological parent, n = 1 |

Current/previous substance use, n = 16 Never used substances, n = 3 |

| Carers | 13 | 8 female and 5 male |

Foster carers, n = 6 Residential workers, n = 4 Supported living workers, n = 2 Biological parent, n = 1 |

||

| Drug and alcohol workers | 3 | 1 female and 2 male |

Service manager, n = 1 Drug and alcohol workers, n = 2 |

||

| Dyad interviews | Social workers | 4 | 4 female |

Local authority managers, n = 2 Social workers, n = 2 |

|

| Focus groups | Drug and alcohol workers | 5 | 3 female and 2 male |

Service manager, n = 1 Drug and alcohol workers, n = 4 |

|

| Social workers | 4 | 3 female and 1 male |

Senior social workers, n = 3 Social worker, n = 1 |

||

| Carers | 4 | 3 female and 1 male | Foster carers, n = 4 | ||

| Total | 52 |

Separate one-to-one interviews (n = 13) were carried out with carers across the research sites to ensure diversity of sample in terms of age, ethnicity and carer type (i.e. foster carer/family member/residential worker). An additional focus group with four carers was also conducted as part of an already established carer support group.

Social workers (n = 8) were purposively approached to take part in a focus group and four took part. This was complemented with two further dyad interviews with four social work staff. Sampling took place to ensure diversity in terms of the local authority site in which they worked, level of experience (i.e. social worker, team manager) and sex. The social workers within the looked-after children and care leavers teams were interviewed because of their key knowledge of the context of children in care, as well as of many of the ethical issues that informed the intervention development.

A focus group also took place with specialist young people’s drug and alcohol practitioners (n = 5). Practitioners were purposively approached to ensure diversity in terms of local authority site they worked in, job title (substance misuse practitioner, service manager) and sex. The drug and alcohol practitioners had key knowledge of interventions that currently work well with young people and they used their professional knowledge and expertise to inform the adaptation of the MET and SBNT interventions.

In addition to the focus group with drug and alcohol practitioners described above, one-to-one interviews were also carried out with three drug and alcohol workers who had delivered youth social behaviour and network therapy as part of a previous trial. 70 These interviews aimed to build on previous knowledge and experience of delivering youth social behaviour and network therapy to young people within a substance misuse setting and contributed towards adapting the treatment manual for the population of children in care.

We initially proposed to carry out individual one-to-one interviews with children in care and carers, and focus groups with professional participants. For pragmatic reasons we conducted a combination of individual interviews, dyad interviews and focus groups, depending on participants’ availability and preferred method of involvement. On reflection, the research team felt that the combination of interview and focus group data collection had a positive impact on the quality of the data generated. As planned, the interviews enabled us to collect an individual’s thoughts, attitudes and personal beliefs about being involved in and interacting with the child welfare system, and the focus groups provided an opportunity to consider how the interactional data between participants resulted in similarities and differences in experiences being highlighted.

Table 2 shows the qualitative methods that participants engaged in and the demographics of the participants recruited in the first round of qualitative work.

Consent

The children in care aged < 16 years were seen with an accompanying adult (parent, carer, social worker, children’s home lead) prior to the interview taking place and they were asked to provide informed assent. If the accompanying adult did not have parental responsibility (PR), the research team contacted the adult with PR to obtain informed consent. If the parent was not contactable or, in the view of the designated social worker, it was a risk to the young person for the parent to be contacted, the social worker or local authority guardian with PR was contacted to sign the consent form. Informed young person assent and consent, dependent on age and carer consent, were obtained prior to the young person taking part in any element of the study. Information on the study was shared with parents and carers as appropriate.

For those children in care aged ≥ 16 years and for all other participants within the formative phase of the research, informed consent was taken directly from the individual concerned by the researcher. Prior to informed consent being taken, a participant information leaflet was shared with each participant, and the research team talked through the leaflet and provided an opportunity for any questions to be asked. The research team also explained that participants could withdraw at any point.

After informed consent had been given to the research team, interviews and focus groups were carried out by qualitative researchers with experience of working with young people. The data collection took place at a location convenient for the participant. For young people this was in their home or at an alternative convenient private location, which ensured the safety of both the young person and researcher. For professionals, data collection took place in a private location within their usual working environment. When interviewed the young person was given a choice of whether or not they wanted to be accompanied by a trusted adult who would act as an observer; however, only two young people requested this.

Children in care participants were remunerated for their time with a £10 ‘love2shop’ voucher.

Qualitative analysis

Transcripts were analysed thematically;80 it was an iterative process, using the constant comparative method,81 in order to identify key themes and concepts. In practice, this entailed a line-by-line coding process and then analysis within a given transcript and across the data set as a whole. Analysis with qualitative software (NVivo) aided the organisation of thematic codes. The data were compared across the participant groups (i.e. children in care, professionals and carers), with similarities and differences being highlighted. In the first instance, data were analysed by two researchers in order to ensure intercoder consistency and agreement. The main themes and findings were presented to the wider multidisciplinary team that included expertise in a variety of backgrounds, including community child health, public health, social care, social science, drug and alcohol use, and clinical psychology. These qualitative data were used to refine the SBNT and MET approaches to ensure that they were responsive to the needs and views of substance-using children in care.

Data analysis focused on understanding internal and external drivers of behaviour and also on views about interventions promoting well-being and self-care in early life. Components of the logic models (behaviours, determinants and intervention components) were explored with participants to further refine the theory of change pathway and clarify intervention delivery issues.

Finalisation workshops: modification of interventions

A series of intervention finalisation workshops took place, during which findings from the preliminary thematic analysis of the qualitative interviews and focus groups were presented. The purpose of the workshops was to co-produce the final intervention manuals. Within the initial phase of the workshop, the research team presented the main themes that had emerged from the interview and focus group data, and participants were asked to consider the MET and SBNT interventions and discuss what the final manual should ‘look like’.

Five workshops were conducted: one with professionals (n = 14), all of whom had been interviewed earlier; and four with young people (n = 13), none of whom had been previously interviewed. All participants involved in the young people’s workshops either were currently in or historically had experience of receiving specialist drug and alcohol treatment. The workshops were inclusive of both children in care (n = 5) and non-looked-after children (n = 8). We took the decision to include young people not involved with the care system, as this element of the study needed to understand current treatment provision. Owing to social workers not systematically recording this information and gatekeeping to ‘protect’ young people, we found it difficult to identify young people in care currently on their case load with experience (current or previous) of accessing treatment. We decided to approach the drug and alcohol services involved in the study to recruit young people into the workshops. We wanted to ensure that we had maximum variation of young people, regarding age, sex and location of participants, who had experience of accessing drug treatment agencies, to discuss the developed interventions. We held a workshop in each active study site to enable participants to be involved in the study without having to travel long distances to take part. The workshops were all held within the well-established young people’s drug and alcohol services involved in the study, so participants were in a familiar environment.

The workshops provided an opportunity for the research team to present the preliminary findings to key participants. Verbatim anonymised quotes were used to identify areas of potential importance and to facilitate discussion between researchers and participants. Four researchers and participants then worked collaboratively to co-produce the final manuals. Co-production occurred through group discussions and using flip charts and paper to design worksheets and complimentary materials to be used within sessions.

The themes discussed within the workshops are shown in Table 3.

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| Therapeutic relationships |

Time and reciprocal self-disclosure Genuine care Non-judgemental approach |

| Engagement and challenges |

The need to use creative methods to enhance engagement Young person’s inability to recognise support Treatment goals wider than substance use |

Areas of potential intervention adaptation were discussed within and across interviews, focus groups and workshops, and the findings from the qualitative data collection have resulted in a number of adaptations being made to the manualised interventions.

Following the workshops, the final adaptation of both manuals took place. Ongoing communication took place between the on-the-ground researchers involved in developing the manuals and the original intervention authors [Professor Alex Copello (SBNT) and Dr Gillian Tober (who has adapted both MET and SBNT for other clinical trials)], to ensure that the core components of each approach were retained throughout the adaptation process.

Formative qualitative research findings

The formative phase highlighted generic principles of working with children in care, rather than changes to the core components of the interventions. These are outlined in Theme 1: therapeutic relationships and Theme 2: engagement and challenges of working with children in care. The main themes that arose were relevant regardless of which intervention (SBNT/MET) was being discussed and adapted. The influential themes and subthemes are discussed as follows.

Theme 1: therapeutic relationships

A successful therapeutic relationship was highlighted as important by both professionals and children in care when working towards reducing substance use. The qualities of trust and genuine care were identified as the two main constructs that underpin a successful therapeutic relationship. The ability of children in care (and often inability) to trust and confide in professionals was a recurrent theme. Professionals acknowledged that children in care often experience disorganised and difficult attachment and recognised that their experiences leading up to their placement in care may have had an impact on their ability to trust other people. Therefore, although trust is one of the necessary conditions for any therapeutic relationship to be successful, it is particularly important for children in care, who may have experienced relationship breakdown and abandonment, being let down and having their essential needs unmet.

Professionals displayed a clear understanding of these complex attachment issues and discussed the need to ‘earn’ trust when engaging with children in care:

You need to put in the groundwork initially. I think with teenagers you need to gain their trust, you need to work for it. Because if they have been hurt, which they will have been, they will try to push you away. They won’t want to trust you.

Carly, social worker, focus group

Owing to the often inherent ‘lack of trust’ in professionals, practitioners recognised that they were expected to demonstrate their trustworthiness when engaging with children in care. Typically this involved practitioners being consistent and reliable. Equally, children in care described seeking qualities such as empathy, reliability and partiality, all of which are qualities that may have been missing in their early attachments. One foster carer described displaying his reliability in terms of being available ‘24/7’, stating that he is permanently ‘on call’ if a young person needs him:

. . . it is not a job because there is no job that makes you work 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and 365 days of the year, but this one does.

James, foster carer, focus group

From the perspective of children in care, the relationship between themselves and their allocated key worker within an organisation was a pivotal factor that determined whether or not they engaged with services. When establishing and facilitating a trustworthy relationship, young people explained the importance that they placed on professionals allowing them to ‘work gradually’, only sharing ‘personal information’ and making disclosures when they felt ready. Furthermore, the idea of professionals making self-disclosures was repeatedly reported: children in care felt it was important for professionals to ‘trade’ personal information, such as a hobby they enjoyed, details of a pet they owned, or an example of how they had resolved a problem successfully in their own lives. This process of sharing information was perceived to be beneficial to developing a trusting relationship, as sharing information was not completely one-sided. Children in care reported that such disclosure enhanced their sense of connection to the practitioner, as well as their own safety to disclose information:

When you work with someone you have to build a bond up first, before you can open up to them . . . It’s, well the way I’ve done [it] is just ask questions about them, and then if they tell you, then you know well if they’ve told me this then I can tell them that.

Sophie, 17, young person interview

Children in care described having multiple professionals involved in their ‘care package’ and a quality that young people desired was ‘genuine care’, inclusive of professionals going ‘above and beyond’ what is expected and providing unconditional care, although they did not always feel that they received this. Professionals, especially those within the social services teams, take on the corporate parenting role. This role dictates that safeguarding and risk management take precedence over the provision of emotional support. Therefore, much of the care a child usually receives from family members within a personal environment is provided by a professional who is employed to provide such care. To demonstrate that they care, many social workers describe being available outside their contracted working hours and going ‘above and beyond’ their role:

Myself and his YOT [youth offending team] worker had agreed between us that we would have our phones on 24/7. So that if he wanted to get in touch and check in we knew he was OK. So we did, we took turns and he did check in and he did arrange to meet up which was really good.

Steph, social worker, focus group

Children in care showed an acute awareness that social workers had a corporate parenting role to fulfil and that carers provided a role that they were ‘paid’ to do. This led to children in care emphasising the importance of practitioners who made them feel like they ‘genuinely cared about their welfare’. Interestingly, foster carers reinforced that they attempted to provide the same level of care and support to both their biological children and the children placed in their care, despite the paid position they were in:

Any child that comes to live with me, I know they are not mine, however I will work with them, I will play with them, I will live with them and I will do everything to my best ability in every area, in every arena because I want what is best for them.

Liz, foster carer, interview

Genuine care also involved professionals showing empathy to the young person and being available to provide ‘unconditional’ support. There was a belief, sometimes verbalised explicitly, at other times more implicitly, that genuine care stemmed from personal investment rather than a contractual obligation:

Like Josie talks to me, not like I’m just someone she has to work with, she talks to me like she cares.

Carla, 17, young person interview

Children in care felt that they were cared for if they were shown unconditional positive regard, regardless of their behaviour. This was a recurrent theme for professionals, who reported children in care regularly disclosing information to them regarding historical experiences that they had been witness to or subjected to. Foster carers described having to respond in a sensitive and non-judgemental way:

We had a young man who had been abused by a family member. He was feeling guilty himself about it and thought that we would feel disgusted that things like that had been done. It is letting him see that we are not disgusted. Straight away, ‘I have heard all of this before, you are not the only one. It is not your fault’.

Carol, foster carer, focus group

The ability of professionals to be non-judgemental was important to children in care, and some participants voiced concerns that practitioners would not be able to ‘cope’ if they chose to share some of the experiences that led to them being placed into care. One young person in care explained that he elected not to engage with services and open up for fear that professionals would then ‘leave him’:

. . . my family is **** up, really **** up. And if I sat there and told someone they’d probably run a mile, they probably would. So that’s why I’ve never really opened up to anyone, cause if I did they probably would run away, do you know what I mean?

Ewan, 17, young person interview

The above quotations identified the practical issues and challenges that needed to be addressed to facilitate a therapeutic relationship with children in care; therefore, it was important to acknowledge the importance of overcoming insecure attachments and incorporating methods of developing a trusting relationship.

Theme 2: engagement and challenges of working with children in care

Throughout the formative data collection, there was consensus that, if used in isolation, the more traditional one-to-one talking therapies were often unproductive for children in care. From a professional perspective, this approach was thought to be overly formal and could result in children in care disengaging with support services. Children in care also verbalised that they found it harder to engage with overly structured and formalised sessions:

It was like in a room . . . and like there’s a table there and it had like little seats round, and like, he was just on about things. Do you know, he didn’t make it very good, like, he didn’t make it very fun and enjoyable kind of thing. It was just like, boring. He was just writing things down that I was saying basically and it just upset me. He just kept on going over it and over it and over it, he was like ‘so how did that feel? Bla bla bla.’ I didn’t really feel comfortable.

Isabelle, 13, young person interview

There was a clear need for practitioners to be equipped with a number of skills and strategies to engage with young people. Practitioners needed to be responsive to the individual presenting to them and described using techniques such as ‘node-link mapping’, as used in the International Treatment Effectiveness Project,82 and mood cards, while staying true to the intervention they were trying to deliver:

There are not many young people who you’ll get to the point where you’re doing that one to one counselling really. It is few and far between. You’re being creative . . .

Adam, drug and alcohol worker, focus group

Many of the participants in care expressed their desire to attend sessions that enabled them to be actively involved in the work being completed, with practitioners implementing strategies that facilitated young people connecting with the work and the professional themselves, and maintaining concentration:

Writing it down or doing it like arts and crafts way because I don’t like just talking and having conversations cause I just get a bit bored and lose track, then I’ll start fiddling about.

Abbie, 18, young person interview

Alongside the necessity for an interactive approach, was the need for practitioners to be aware of the complexities of living in the care system for the young person. This awareness would help to facilitate a holistic approach to be taken to the work being conducted and could also help to identify goals that are not solely ‘substance use’ related. Children in care stated that they valued discussions that recognised the difficulties occurring in their lives. Professionals also identified the importance of taking a bespoke approach to treatment:

I think what’s coming out here is that with the kids we work with, the drug and alcohol issue is over there, if you like, and a whole raft of other issues are here. As workers we’re dealing with all of these here and that tends to sort the drug and alcohol issues out quite naturally.

Laura, drug and alcohol worker, focus group

Professionals highlighted challenges that arose owing to the transient nature of the population of children in care. It was identified that, when young people experience frequent placement changes, it can result in young people experiencing fragmented support in terms of changes to key workers, carers and professionals supporting them. It can also result in young people being eager to find friends even if these relationships are potentially destructive:

So they might, you know, have contact with their brothers or sisters, you know, it is just they get moved around, and when they are moved around they are vulnerable, they are desperate to have friends or they are desperate to have somebody to call their own . . . people get attracted to them who are, I would say, not the type of kids I would want my kids to knock around with.

Liz, foster carer, interview

Social support was identified as a potential challenge regarding the SBNT approach. Children in care and practitioners recognised that a positive support network was a central part of SBNT and accepted that social interaction is necessary in the resolution of most substance misuse problems; however, it was felt that support was not always available:

It is quite sad sometimes when they haven’t got anybody in the family, not even an uncle or a cousin or somebody who they can put down as a support really.

Steph, social worker, focus group

The challenges of finding appropriate network members was explored. In many interviews, the participant in care struggled to identify someone that they felt they could turn to, and feelings of not having support and the need to be self-sufficient were verbalised:

My boyfriend and his friends, and there’s a few of my friends. Actually they’ve got their own lives as well, they’ve got their own houses and their partners and they’re all settling down as well, so . . . there’s not really many people there. When you think about it though, how many of them can you turn to if you’ve got a problem? Cause there’s not a lot.

Abbie, 18, young person interview

As was expected within the children in care population, when individuals were able to identify individuals who provided positive support, it was often people outside the traditional family support network. This had potential for sources of support to be transient (e.g. teachers who would change with each school year). Professionals were often identified as sources of support, which could be challenging for the delivery of SBNT, as individuals may not be able to provide ongoing or out-of-hours support in the same way as more traditional family members would. Nonetheless, children in care recognised the support that was provided to them:

There’s two main people I’ve got in my life which provides me with support. One’s my boss, he’s a farm manager, I work with him most days. Another person is the manager of [name of school], he owns the company and he helps quite a lot by, when I moved out of here [residential children’s home] the first time, he’s the one that made me come back, and let me get my head back.

Philip, 17, young person interview

Key adaptations made

The MRC framework guided the development and adaptation of the MET and SBNT manuals. 78 In line with the data collected throughout the formative phase of the study, interventions were adapted to reflect the practicalities of working with the population of children in care, often presenting with complex needs. The themes of trust, genuine care, being flexible regarding network members, working creatively and having treatment goals wider than substance misuse were key to the revised training and manuals.

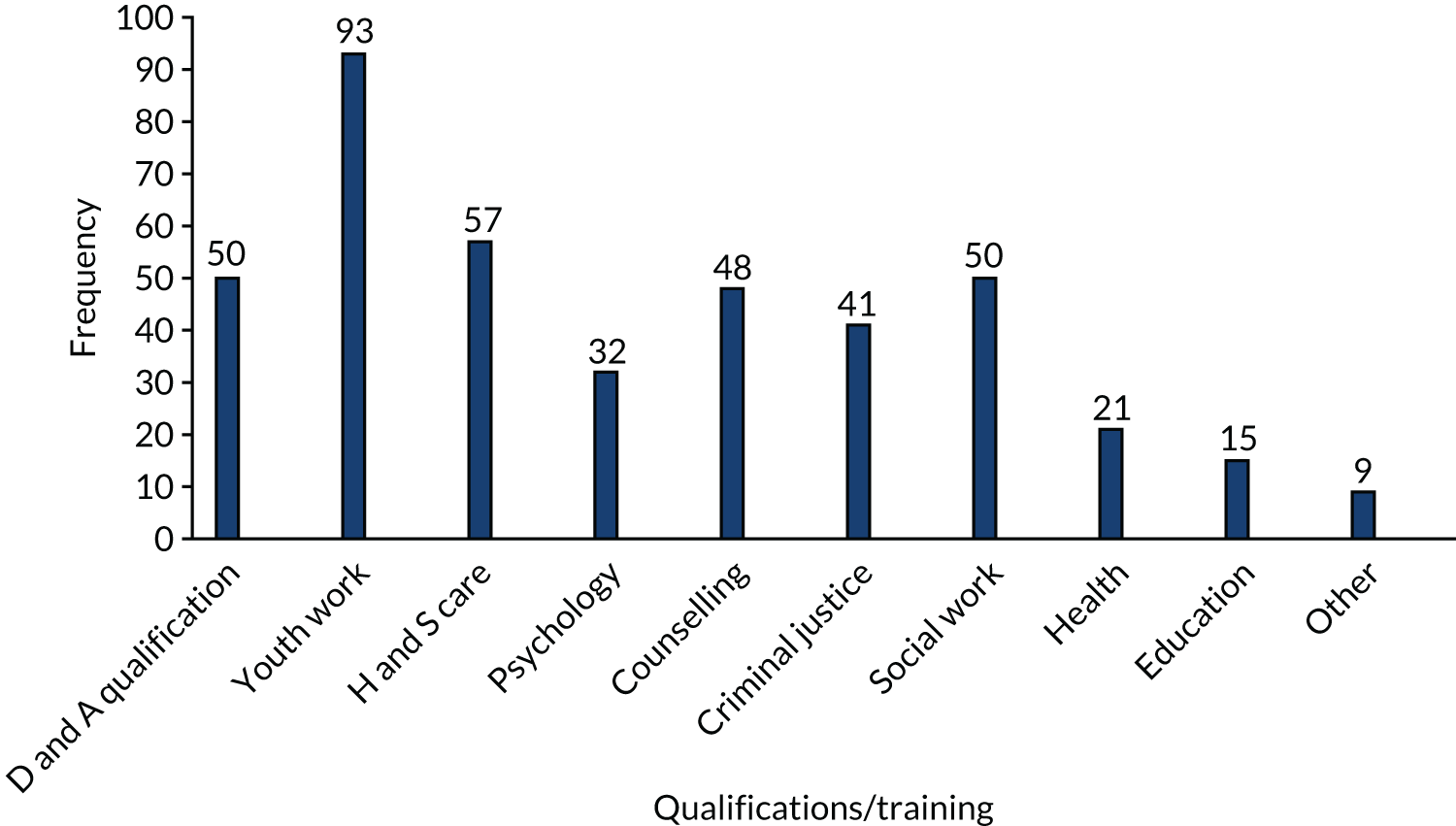

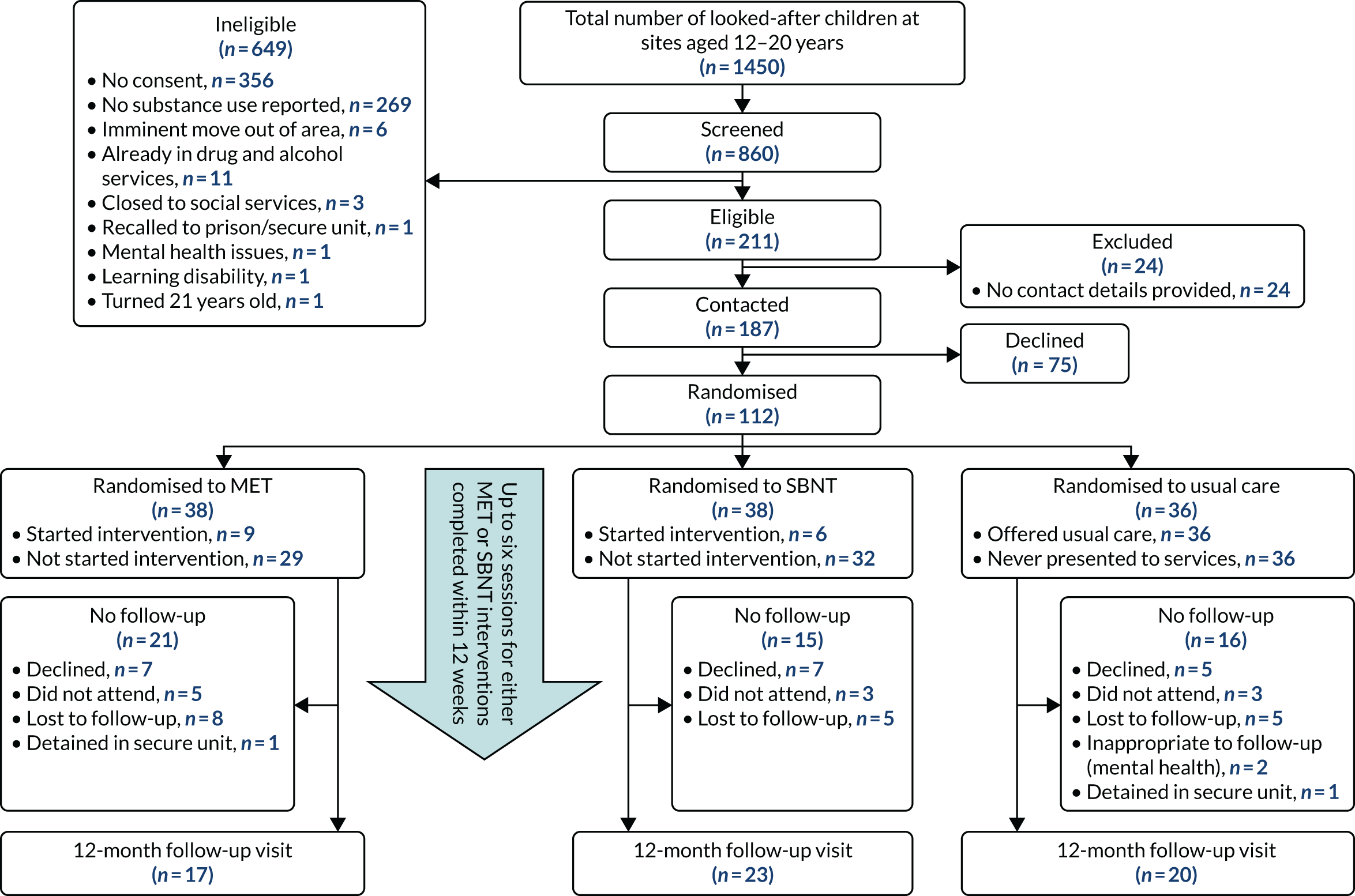

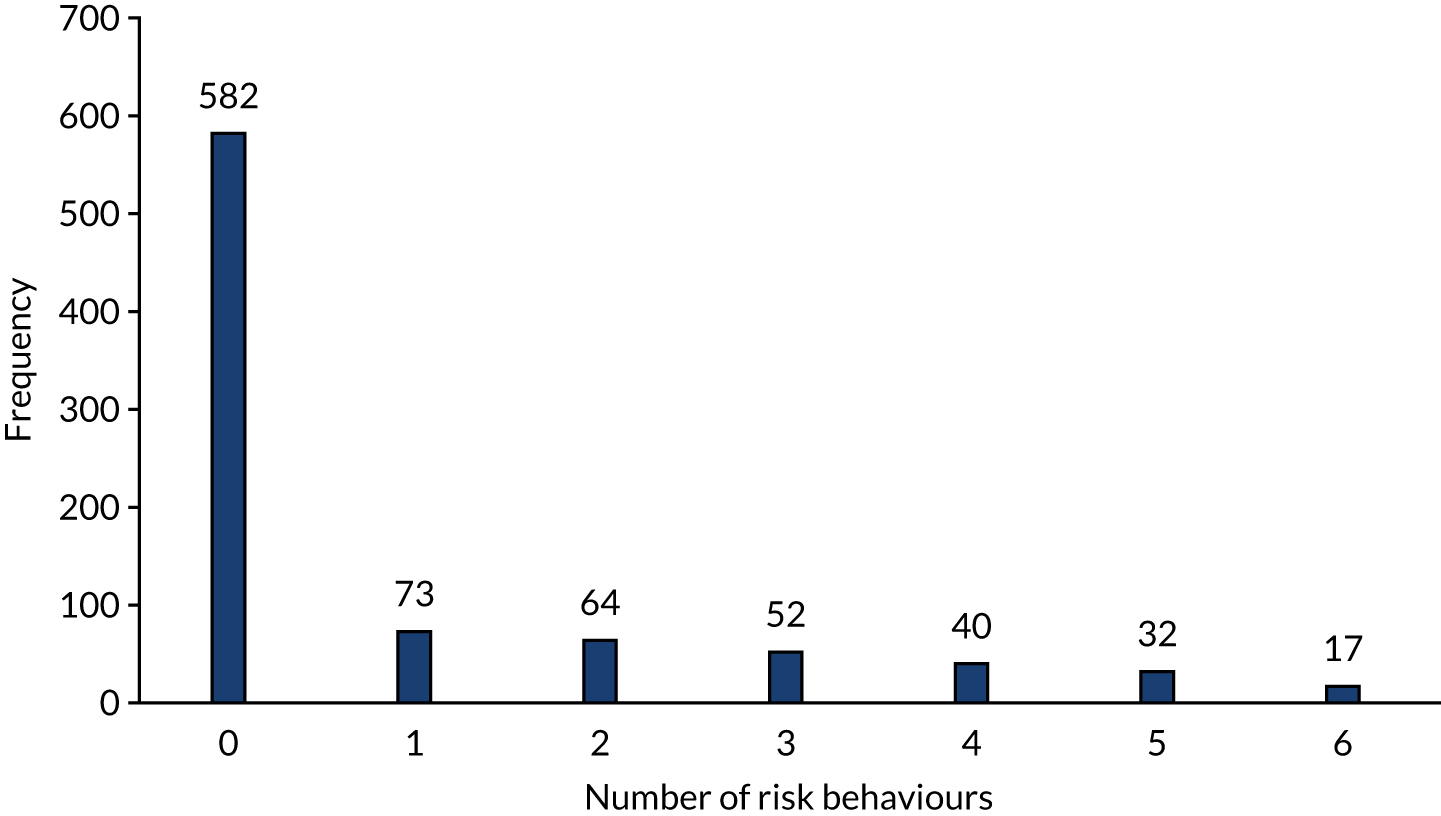

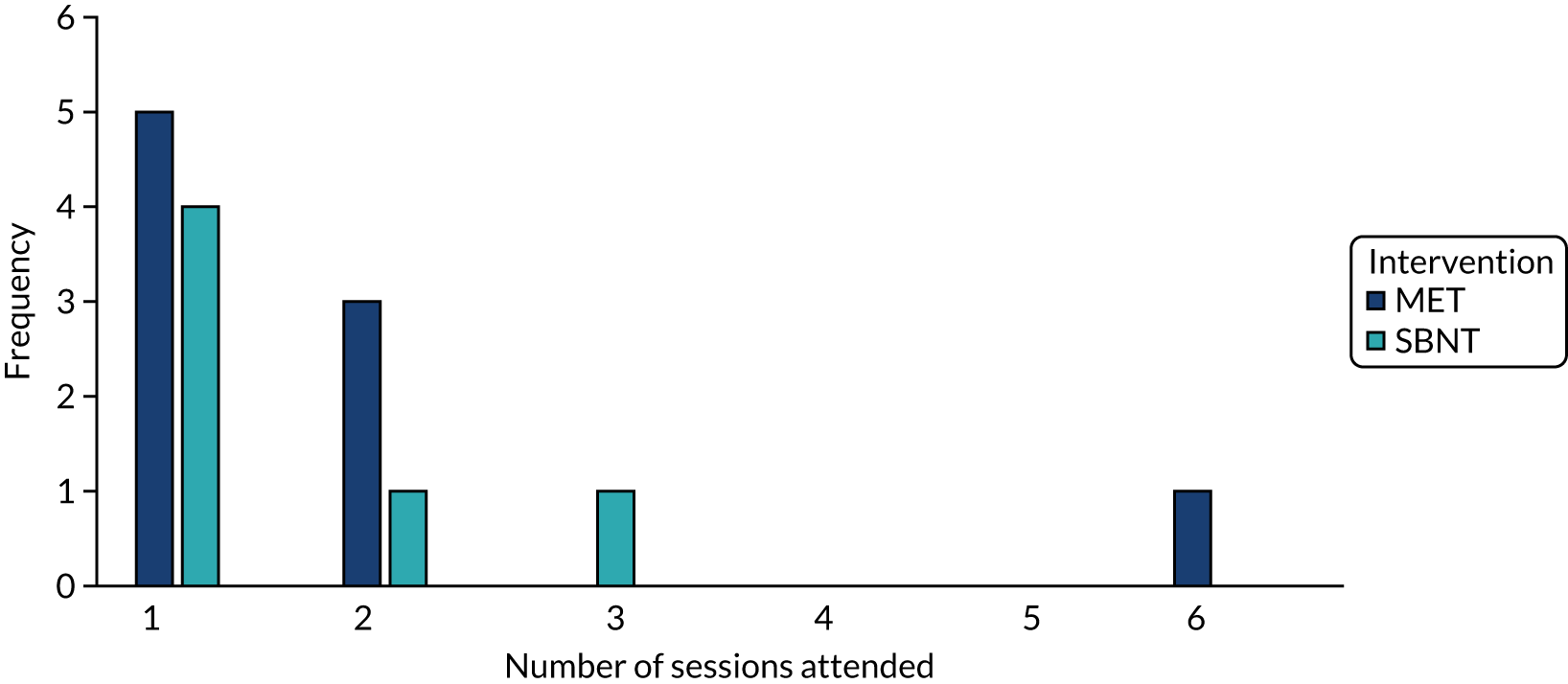

Workshop participants (inclusive of professionals and children in care) recommended that additional resources, such as worksheets and exercises, be developed to support the training of drug and alcohol workers and to complement the adapted manuals. Therefore, additional sources of information were developed to link in with each topic area covered in the manuals; it was not compulsory to use the resources were used, but they were available to support practitioners when delivering the interventions. SOLID trial-specific appointment cards were devised at the request of drug and alcohol practitioners, so that participants could identify that appointments were for the SOLID trial as opposed to the usual treatment services. In addition, a pre-treatment session was written into the manuals as requested, to provide practitioners with an opportunity to contact the young person and encourage a rapport to be established prior to commencing sessions.