Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/190/42. The contractual start date was in June 2017. The final report began editorial review in September 2021 and was accepted for publication in May 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research, or similar, and contains language which may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Clemes et al. This work was produced by Clemes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Clemes et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Truck driving is essential to the economy. Approximately 75% of all goods delivered in the UK are transported via road freight, with the road freight transport sector contributing over £13B to the UK economy. 1 The UK logistics sector currently employs just under 300,000 heavy goods vehicle (HGV) drivers, with a HGV being defined as having a gross vehicle weight between 3.5 and 44 tonnes. 1 Owing to the nature of their occupation, long-distance HGV drivers are exposed to a multitude of health-related risk factors and have been identified as working within one of the most hazardous professions. 2,3 The working environment of long-distance HGV drivers and their job demands (i.e. long irregular hours, enforced sedentarism, poor dietary options, high stress) constrain the enactment of healthy behaviours, leaving drivers vulnerable to a myriad of physical and mental health conditions. 4

Our own systematic review-level evidence has shown that HGV drivers globally exhibit high levels of physical inactivity and accumulate large amounts of sedentary (sitting) behaviour. HGV drivers also tend to make poor dietary choices, have high alcohol intakes and have a high prevalence of smoking. 4 Furthermore, long and variable working hours, including shift work, contributes to sleep deprivation,5,6 and this can lead to metabolic disturbances and further promote the uptake of unhealthy behavioural choices. 3,5–8 The isolated nature of driving a HGV can result in a lack of peer social support and poor mental health. 9,10 Within this occupational group, adverse mental health conditions can be exacerbated by intense job demands and low levels of perceived job control, as a result of chronic time pressures, compounded by tight delivery schedules and traffic conditions. 11 Indeed, our systematic review identified high levels of mental ill-health within HGV drivers. 4

As a result of HGV drivers’ working environment and poor health behaviours, review-level evidence has demonstrated that they nationally and internationally exhibit high rates of obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors. 4,12–14 In addition to elevating their risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes, the incidence of obesity-related comorbidities in HGV drivers is increasing, suggesting that the trajectory of HGV driver health is declining. 2,3,15–18 These factors likely culminate in HGV drivers having an increased risk of accidents, higher rates of chronic diseases and reduced life expectancies in comparison with other occupational groups. 2,19–24 Despite this, HGV drivers are currently underserved in terms of health promotion efforts. 25

To compound the high-risk health profile observed in HGV drivers nationally and internationally,4,12–14 within the UK’s logistics sector, HGV drivers are an ageing workforce, with an average age of 48 years. 26 A report prepared by an All Party Parliamentary Group for Freight Transport has highlighted the challenges that the industry is facing with an ageing workforce, and the health impact of this ageing, at-risk workforce driving such large and potentially dangerous vehicles. 27

The UK’s logistics sector is also experiencing a serious shortfall in HGV drivers, which has recently been described as reaching a ‘crisis point’, with this shortage rising from 60,000 drivers in 201528 to an estimated 100,000 drivers in 2021. 29 Factors responsible for the sharp decrease in driver numbers include the uncertainties around Brexit, with a number of European drivers returning home; the COVID-19 pandemic, with the resulting national lockdowns further encouraging international drivers to return to their home countries and seeing HGV licence testing suspended; and a large number of drivers retiring. 29 Barriers to driver recruitment have been reported to include a lack of roadside facilities, medical concerns and long working hours. 27 Recommendations on how to address this shortfall and attract younger employees to the sector made by the All Party Parliamentary Group for Freight Transport include increasing awareness within the industry of the need to address driver health risks and health behaviours. 27 Indeed, now more than ever, the government and sector urgently need to address working conditions and the poor health profile of this ageing workforce to attract employees to the role. Driver recruitment and a prioritisation of driver health is essential to combat the current challenges seen in maintaining critical supply chains.

A systematic review25 of health promotion interventions in HGV drivers, including only eight studies, observed that the interventions generally led to improvements in health and health-related behaviours. However, the review25 concluded that the strength of the evidence was limited because of poor study designs, no control groups, small samples and no or limited follow-up periods. 25 Since the publication of the systematic review,25 studies have examined the impact of a weight loss intervention in US HGV drivers30 and a smartphone application (app) on physical activity and diet in Australian HGV drivers. 31 Although positive findings were observed, the studies were limited by having relatively small samples and no comparison groups. It has been suggested that health and well-being programmes that focus on health education and improvements in health literacy should be implemented and prioritised across the logistics industry. 4 For example, international research has shown that HGV drivers with higher educational levels are more likely to have higher levels of physical activity32 and lower body mass index (BMI)33 than HGV drivers with lower levels of education. Where they exist, health and well-being programmes within the logistics industry have been considered to have the potential to have a positive impact on employee health4,25 and, in turn, potentially benefit employers through increased employee retention and reductions in health-care costs. 4 Furthermore, health promotion initiatives targeting HGV drivers will likely have a broader public health impact through improving road safety for all users. 25 Research in the USA, for example, has shown that HGV drivers with obesity were 55% more likely to have an accident than normal-weight drivers. 34 In the UK, although only accounting for 12% of all vehicle traffic on motorways, 41% of accident-related fatalities involved HGVs in 2017,35 highlighting the wider public safety impact of health improvement programmes in this at-risk occupational group.

Development of the SHIFT programme

We developed the Structured Health Intervention For Truckers (SHIFT) programme, which is a multicomponent theory-driven health behaviour intervention designed to promote positive lifestyle changes in relation to physical activity, diet and sitting in HGV drivers. This SHIFT intervention has been informed by extensive public and patient involvement (PPI), which has included drivers and relevant stakeholders, a qualitative study exploring the perceived barriers to healthy lifestyle behaviours in drivers,7 an observational study (n = 157) exploring lifestyle health-related behaviours in HGV drivers and markers of health,36 and a pre–post pilot intervention (n = 57)37 with a full process evaluation. 38 Initial pilot testing of our intervention delivery, over a 3-month period, revealed potentially favourable increases in physical activity, with 81% of the sample increasing their daily step counts by an average of 1646 [standard deviation (SD) 2156] steps per day. Significant increases in fruit and vegetable intake were also observed (4.5 vs. 5.4 portions/day), along with favourable changes in markers of cardiometabolic health. 37

The current study extends this work by evaluating the multicomponent SHIFT programme within a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT), with the inclusion of full process and cost-effectiveness evaluations. As the intervention was administered within the worksite setting, a cluster RCT design was employed with delivery sites/depots (i.e. individual worksites) as the unit of allocation to minimise any potential contamination occurring between intervention and control participants.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the multicomponent SHIFT programme, compared with usual care, in a sample of long-distance HGV drivers at both 6 months and 16–18 months.

Primary objective

-

To investigate the impact of the 6-month SHIFT programme, compared with usual care, on device-measured physical activity (expressed as steps/day) at 6 months’ follow-up.

Secondary objectives

-

To investigate the impact of the SHIFT programme, compared with usual care, at 6 months’ follow-up on:

-

time spent in light physical activity and moderate or vigorous physical activity (MVPA)

-

sitting time

-

measures of adiposity (i.e. BMI, per cent body fat, waist–hip ratio, neck circumference)

-

cardiometabolic risk markers [i.e. glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)]

-

fruit and vegetable intake and dietary quality

-

blood pressure

-

psychophysiological reactivity

-

sleep duration and quality

-

functional fitness (i.e. grip strength)

-

cognitive function

-

mental well-being (i.e. anxiety and depression symptoms, and social isolation)

-

work-related psychosocial variables (i.e. work engagement, job performance and satisfaction, occupational fatigue, presenteeism, sickness absence and driving-related safety behaviour)

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

-

health-related resource use [i.e. general practitioner (GP) visits].

-

-

To investigate the longer-term impact of the SHIFT programme, compared with usual care, at 16–18 months’ follow-up on:

-

steps per day

-

time spent in light physical activity and in MVPA

-

sitting time

-

fruit and vegetable intake and dietary quality

-

sleep

-

mental well-being (i.e. anxiety and depression symptoms, and social isolation)

-

work-related psychosocial variables (i.e. work engagement, job performance and satisfaction, occupational fatigue, presenteeism, sickness absence and driving-related safety behaviour)

-

HRQoL.

-

-

To conduct a mixed-methods process evaluation throughout the implementation of the intervention (using qualitative and quantitative measures) with participating drivers and site managers.

-

To undertake a full economic analysis of the SHIFT programme.

Chapter 2 Study design and methods

This chapter summarises the study protocol for this RCT as originally funded. Some of the material, including tables and figures, has already appeared in Clemes et al. 39 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Study design and setting

The SHIFT trial was a two-armed cluster RCT, which incorporated an internal pilot phase and included a mixed-methods process and economic evaluations. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry before participant recruitment commenced (URL: www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN10483894; accessed 13 July 2021). The trial protocol paper was published in November 2019,39 and protocol revisions can be accessed via the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Journals Library (URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/1519042/; accessed 13 July 2021). A summary of the amendments to the original protocol are listed in Table 1.

| Amendment number | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 November 2018 | Owing to one pilot site [a BP (London, UK) site] not allowing participants to wear the accelerometers during working hours for health and safety reasons and, therefore, limiting the collection of the primary outcome measure [i.e. activPAL™ (PAL Technologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK)-determined steps/day] to non-working hours only, the TSC approved the recruitment of an additional site in the main trial phase. The total site recruitment target changed from 24 to 25 |

| 2 | 5 April 2019 | Owing to the time needed to undertake baseline measurements in the main trial phase, sites (i.e. clusters) were randomised into the study arms in blocks of three following completion of baseline measures, as opposed to randomising all sites after all baseline measures were completed |

| 3 | 13 July 2020 |

Owing to COVID-19, face-to-face 12-month follow-up measures were no longer viable in the majority of sites. The primary outcome was assessed following completion of the 6-month intervention, with the sustainability of the intervention assessed by the self-report questionnaire-based measures at approximately 10–12 months following intervention completion The process evaluation conducted with sites within the main trial phase involved telephone interviews as opposed to face-to-face interviews and/or focus groups An additional ‘COVID-19’ online questionnaire was distributed to participants in May–June 2020 The trial was extended by 15 months because of delays due to COVID-19 |

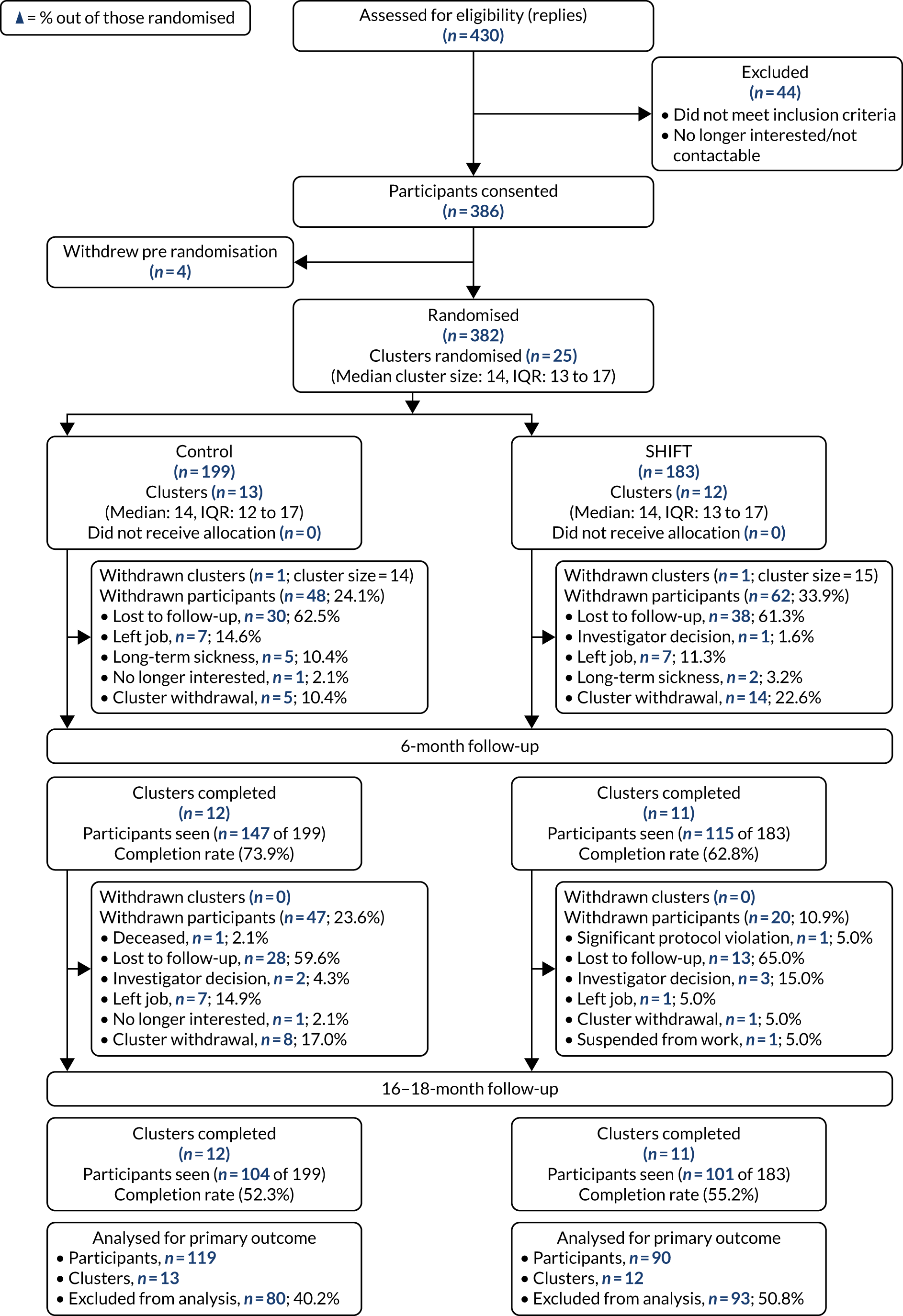

The trial took place within the worksite setting of a major international logistics and transport company, DHL Supply Chain (Milton Keynes, UK). DHL Supply Chain agreed to provide the setting and gave access to their drivers and sites for our research. Transport sites/depots formed individual clusters. Following the completion of baseline measurements, clusters were randomised 1 : 1 to receive either the SHIFT programme or to continue with usual practice (i.e. the control condition). Outcome measurements were undertaken at baseline and at 6 months’ follow-up. A third set of outcome measures were originally planned to take place 6 months following completion of the intervention (i.e. 12 months’ follow-up); however, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, these measurements were unable to be completed within this time frame for the majority of sites. As a result, the primary outcome was assessed following completion of the 6-month intervention (at 6 months’ follow-up) to mitigate potential confounding factors associated with the pandemic, along with a threat of increased rates of loss to follow-up caused by drivers on furlough/isolating or drivers being re-deployed. The easing of government COVID-19 restrictions enabled a range of secondary outcome measures to be collected approximately 10–12 months following completion of the intervention (i.e. 16–18 months’ follow-up), informing an assessment of the potential longer-term impact of the intervention. The study methods are reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension statement for cluster RCTs. 40

Ethics approval

The trial was approved by the Loughborough University Ethics Approvals (Human Participants) Sub-Committee (reference R17-P063). Loughborough University (Loughborough, UK) sponsored the study.

Cluster recruitment and eligibility

The health and safety director of DHL Supply Chain, UK and Ireland, nominated individual DHL Supply Chain transport sites/depots for participation in this study. Sites were eligible for participation if they contained at least 20 long-distance HGV drivers and were located within a 2-hour drive of Loughborough University. Depots containing HGV drivers who made many delivery stops, for example drivers who delivered consumer goods to domestic customers throughout the day, were excluded. During enrolment into the study, transport managers were informed that their site would have a 50% chance of being randomised to the current practice control condition.

Participant recruitment

Within the nominated sites, transport managers were provided with recruitment material to promote the study. Posters advertising the study were displayed in participating sites for up to 4 weeks prior to the scheduling of baseline measurements. In addition, all drivers within participating sites received a letter and a participant information sheet informing them of the study. Following the distribution of the marketing material (e.g. posters and participant information sheets), members of the research team visited each site for at least 1 day. During these visits, the research team had stands in the lobby area with posters showcasing the study, along with example materials used in the SHIFT education session (see The SHIFT programme) and example devices used as part of the outcome measures (e.g. a grip strength dynamometer). Interested drivers could ask the research team any questions about the study before providing a member of the research team their name, if they were interested in taking part. On completion of these visits, the researchers provided a list of the drivers’ names who had signed up to the trial to their transport manager, who then scheduled a time for participating drivers within their sites to attend the baseline (and follow-up) measurements. The baseline measurements were scheduled for at least 1 week after the site recruitment visits to enable drivers to have sufficient time to fully decide on their willingness to participate. All outcome measurements were undertaken in a private room at each participating DHL Supply Chain site. In the UK logistics industry, 1% of HGV drivers are women. 41 At the time of participant recruitment, the proportion of female HGV drivers employed by DHL Supply Chain reflected this national average. All drivers (male and female) at participating sites were invited to participate in this study.

Participant eligibility

All HGV drivers within participating sites were eligible to participate, unless they met any of our exclusion criteria. Drivers were excluded from the trial if they were suffering from clinically diagnosed CVD, had mobility limitations that prevented them from increasing their daily activity levels, were suffering from haemophilia or any blood-borne virus, or were unable to provide written informed consent.

Informed consent

During the baseline measurement session, the study details were verbally reiterated to potential participants, including full details of the study procedures. The expectations of participating in the trial were explained, along with participants’ right to withdraw. This information was provided by a member of the research team who was suitably qualified and who was authorised to do so by the principal investigator. Written informed consent was obtained prior to any measurements being taken at baseline, and at each follow-up assessment.

Trial allocation arms

The SHIFT programme

The SHIFT programme is a multicomponent lifestyle–behaviour intervention that is designed to target behaviour changes in physical activity, diet and sitting in HGV drivers. The 6-month intervention, grounded within social cognitive theory (SCT) for behaviour change,42 consists of a group-based (4–6 participants) 6-hour structured education session, tailored for HGV drivers and delivered by two trained educators. The education session includes information about physical activity, diet and sitting, and details risk factors for type 2 diabetes and CVD. The educational component is founded on the approach used in the award-winning suite of DESMOND (Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed) programmes, including the PREPARE (Prediabetes Risk Education and Physical Activity Recommendation and Encouragement)43 and Let’s Prevent Diabetes programmes,44 created by researchers at the Leicester Diabetes Centre (Leicester, UK) and used throughout the NHS,45 while being tailored to meet the needs of HGV drivers. 7 During the education session, participants are not ‘taught’ in a formal way but are supported to work out knowledge through group discussions. Participants are also encouraged to develop individual goals and plans based on detailed individual feedback received during their health assessments (see Outcome measurements) to achieve over the 6-month intervention period. The education session is supported by specially developed resources and participant support materials for HGV drivers. The education session includes the discussion of feasible strategies for participants to increase their physical activity, improve their diet and reduce their sitting time (when not driving) during working and non-working hours. The content of the educational session is summarised in Table 2.

| Section name | Theoretical underpinning | Main aims and educator activities | Duration (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Welcome and introduction | Participants are introduced to the SHIFT programme and are made aware of both the content and style of the session | 10 | |

| Driver story | Dual process theory46 and common sense model47 | Participants are asked about their beliefs about how being a HGV driver can affect health, the causes of these health problems and controllability of these problems | 30 |

| Risks and health problems | Dual process theory,46 common sense model47 and social learning theory48 | The facilitator uses participant stories to help participants work out why they may be at risk of future health problems, and what to do to reduce/manage risk | 55 |

| Physical activity | Dual process theory46 and social learning theory48 |

The facilitator supports participants to develop knowledge and skills to support confidence, to increase personal activity levels and to set personal goals, which can be self-monitored through the use of a Fitbit® (Fitbit Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) Introduction and practical demonstration of the ‘cab workout’ |

80 |

| Depression, sleeping, smoking | Dual process theory46 and social learning theory48 | The facilitator supports participants to develop strategies to manage depression, poor sleep and smoking | 30 |

| Food choices | Dual process theory46 and social learning theory48 | The facilitator supports participants to develop knowledge and skills for food choices to reduce cardiovascular risk factors and to improve overall health | 90 |

| Self-management plan | Dual process theory46 and social learning theory48 | Participants are supported in developing personal self-management plans | 15 |

| Questions | Common sense model47 and social learning theory48 | The facilitator checks that all questions raised by participants throughout the programme have been answered and understood | 5 |

| What happens next | Social learning theory48 | Follow-up care is outlined | 5 |

During the education session, participants were provided with a Fitbit Charge 2 (Fitbit, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) activity tracker. Participants were encouraged to use the Fitbit activity tracker to set goals (agreed at the session) and gradually increase their physical activity, predominantly through walking-based activity. The Fitbit activity tracker and associated smartphone app provided participants with information on their daily step counts and was used as a tool for self-monitoring and self-regulation. Physical activity tracking using step counters (traditionally pedometers) has been associated with significant reductions in BMI and blood pressure, with interventions incorporating goal-setting being the most effective. 49 Participants were provided with instructions on how to link their Fitbit account to an online monitoring system (Fitabase, Small Steps Labs LLC, San Diego, CA, USA). Participants were encouraged to link their account to Fitabase and to regularly upload their Fitbit data from their device to their mobile phone via Bluetooth. When participants sync their Fitbit through the Fitbit app, their step count data are automatically updated on the Fitabase website. Participants’ data on the Fitabase website were accessible to only two members of the research team, who used the step count data to provide participants with individually tailored step count challenges throughout the 6-month intervention period.

The education session adopted the promotion of the ‘small changes’ philosophy, using the specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time bound (SMART) principle50 to encourage participants to gradually build-up their daily activity levels, within the confines of their occupation, to meet the UK physical activity guidelines. 51 For example, participants were encouraged to establish their own personalised action plan, which may have included making dietary improvements in addition to increases in physical activity, with SMART goals throughout the 6-month intervention. ‘Step count challenges’ were run every 6 weeks throughout the 6-month intervention and were facilitated by members of the research team via a text messaging service (TextMagic™, TextMagic Ltd, Cambridge, UK).

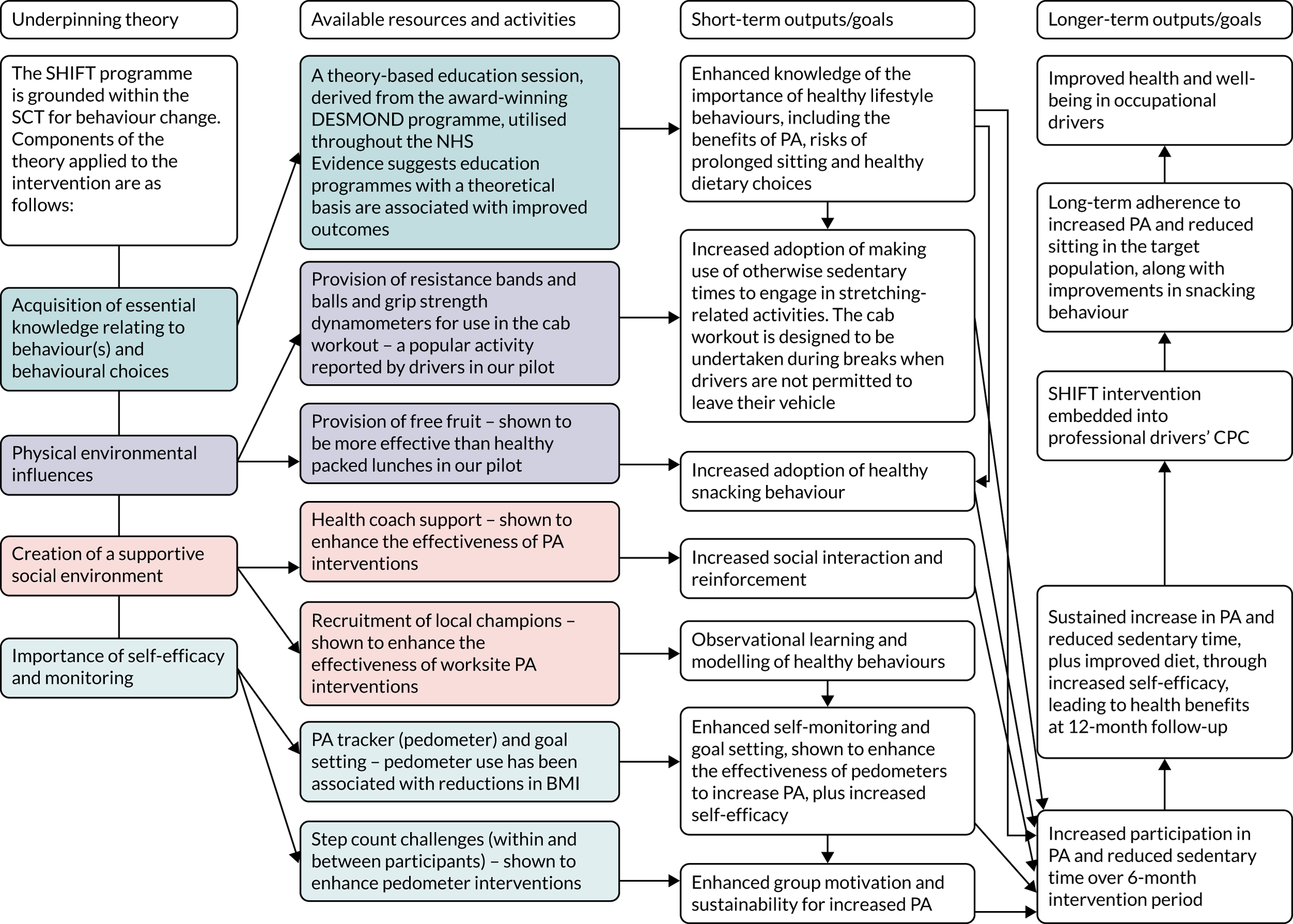

A ‘cab workout’ was introduced and practised at the education session, and participants were provided with resistance bands and balls, and grip strength dynamometers to take away. Participants were encouraged to undertake the cab workout during breaks when they were not permitted to leave their vehicle. Participants were able to keep the intervention tools beyond the 6-month intervention period; however, the step count challenges, as well as the supportive text messages sent by members of the research team, ended after the 6-month intervention period. A logic model detailing the underlying theory behind the intervention components is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

A logic model for the SHIFT programme. CPC, Certificate of Professional Competence; PA, physical activity.

The structured education session was delivered by trained members of the research team in collaboration with trained personnel from DHL Supply Chain. Individuals from DHL Supply Chain co-delivering the education session were predominantly HGV drivers who also acted as driver trainers in each site as part of their role. The ‘driver trainers’ were trained by specialist educators from the Leicester Diabetes Centre and mentored by trained members of the research team. The education sessions took place within appropriate training rooms within the intervention depots. Personnel co-delivering the education sessions in each intervention depot were also trained to act as local champions, which has been shown to enhance the effectiveness of worksite physical activity interventions. 52 They provided ongoing health coach support, along with members of the research team (who provided support via the text messaging service), to intervention participants (during the 6-month intervention period).

The control arm

Sites assigned to the control arm (i.e. usual practice) were asked to continue with their usual-practice conditions. Participants in the control sites received an educational leaflet at the outset, detailing the importance of healthy lifestyle behaviours (i.e. undertaking regular physical activity, breaking up periods of prolonged sitting and consuming a healthy diet) for the promotion of health and well-being. Control participants completed the same study measurements as participants in the intervention worksites, at the same time points, and received the same health feedback immediately following their health assessments (i.e. outcome measurements).

Outcome measurements

This section describes the outcome measurements, as explained in the original trial protocol. 39 The outcome measurements were undertaken as intended at baseline and following the completion of the 6-month intervention for all sites bar one intervention site, where these measurements had been due to take place the same week as the first national lockdown commenced. A change in protocol was required for the final set of measurements, originally intended to take place 6 months following completion of the intervention (i.e. 12 months’ follow-up). The protocol for these measurements is described below.

Protocol for the outcome measurements assessed at baseline and at 6 months’ follow-up

Baseline measurements took place prior to randomisation of the sites into the two study arms. A second set of identical measurements occurred at 6 months’ follow-up. The two sets of measurements were undertaken in suitable rooms within participating DHL Supply Chain sites by trained researchers and lasted approximately 2 hours per participant. Participants were scheduled to attend these measurements, during their working time by their transport manager either before or following their driving shift.

Participants completed a range of self-report questionnaires and had a series of physiological health assessments taken (described below) at baseline and immediately following the completion of the 6-month intervention. Participants were also issued with two devices [an activPAL and a GENEActiv (Activinsights, Kimbolton, UK) accelerometer] to wear over a period of 8 days following the measurement sessions. Participants received detailed feedback on their physiological health assessment measures during these two measurement sessions. If a potential health issue was evident during the measurements, such as undiagnosed hypertension or high cholesterol levels, then participants were advised to visit their GP for further checks. A standard referral letter was provided for participants to give to their GP, which summarised the findings from our point-of-care (i.e. blood markers) and automated (i.e. blood pressure) measures.

Protocol for the 16- to 18-month follow-up assessments (undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic)

A third set of outcome measures were originally planned to take place 6 months following completion of the intervention (i.e. a 12-month follow-up); however, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, these measurements were unable to be completed within this time frame. The easing of government COVID-19 restrictions enabled a range of secondary outcome measures to be collected at 16–18 months (approximately 10–12 months following completion of the intervention). Owing to restrictions on external visitors to DHL Supply Chain sites throughout the pandemic, face-to-face physiological measurements were not able to be conducted at the final follow-up phase. Instead, the case report form (CRF), which contained a series of self-report questionnaires and recording sheets for the physiological measures used during data collection at baseline and immediately following the intervention (see Report Supplementary Material 1), was modified into a self-administered questionnaire booklet (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

Individual participant packs were prepared, which contained an instruction leaflet, a questionnaire booklet, a consent form, an activPAL and logbook, and a return envelope. On prior arrangement with transport managers, a member of the research team delivered the participant packs to each site. The transport managers distributed the packs to participating drivers, who completed the relevant paperwork in their own time and, on request, wore the activPAL for a period of 8 continuous days. After this 8-day period, participants returned their activPAL and their completed logbook, questionnaire booklet and consent form in a sealed envelope to a collection point within their site. Once all packs were returned, the packs were collected from the site by a member of the research team. This protocol was also followed for the one remaining intervention site for its 6-month follow-up (which had initially been due to take place at the beginning of the first national lockdown and, therefore, was unable to be completed as intended). Table 3 summarises all measurements collected at the three time points during the trial. All measurements are described in detail in the following sections.

| Information collected | Time point | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6-month follow-up | 16- to 18-month follow-up | |

| Informed consent | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Physiological measures (i.e. blood pressure, height, weight, body composition, grip strength, finger-prick blood samples, waist, hip and neck circumferences) | ✗ | ✗ | Self-reported weight only |

| Cognitive function and psychophysiological reactivity | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Health Screen Questionnaire and medication use | ✗ | ✗ | Medication use only |

| Demographic information | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| QRISK3 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Short-form FFQ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Smoking and alcohol use | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| HADS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Social Isolation Short Form | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Utrecht Work Engagement Scale | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| OFER scale | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Job satisfaction | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Job performance | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Self-reported sickness absence | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Self-reported presenteeism | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Work ability scale | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Work Demands Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Karolinska Sleepiness Scale | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| MEQ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Driver Safety Behaviour Questionnaire (self-reported) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Health-related resource use questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| activPAL | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| GENEActiv | ✗ | ✗ | |

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was device-measured physical activity, expressed as average steps per day, at the 6-month follow-up (originally intended to be measured at 6 months following completion of the intervention, i.e. at 12 months). Physical activity was measured using the activPAL micro accelerometer, which provides a valid measure of walking and posture (i.e. sitting and standing) in adults. 53–55 As the physical activity component of the intervention predominantly included the promotion of walking-based activity, and as participants were provided with a Fitbit, which provided information on daily step counts and promoted goal-setting to increase daily steps, steps per day was chosen as the primary physical activity-related outcome.

We have previously observed56 that the activPAL provides a more accurate measure of physical activity and sitting in occupational drivers than waist-worn accelerometers. As a further validity check within the current trial, we attached two activPAL devices to the underneath and lateral side of a driver’s seat within a HGV cab for a 24-hour period. Vehicle movement times were extracted from the vehicle’s tachograph data, and the activPAL outputs were assessed during these time periods. No accelerations were detected by the activPAL, confirming that the device is not affected by vehicle accelerations, the suspension system or movement of the driver’s seat during driving time.

During each measurement session, participants were provided with an activPAL and requested to wear the device continuously (i.e. 24 hours/day) for the following 8 days. The activPALs were initialised using the default manufacturer settings and recorded data at a sampling frequency of 20 Hz. The device was waterproofed using a nitrile sleeve and attached (by the participant) to the midline anterior aspect of their non-dominant thigh using Hypafix® transparent dressing (BSN medical, Hull, UK). Participants were provided with a daily logbook in which they were requested to record the times that they got into bed, went to sleep, woke up and got out of bed. Participants were also requested to indicate on the logbook whether each day was a workday or a non-workday, and whether or not the activPAL had been removed for any periods (and, if so, the duration), throughout the 8-day period. Following the completion of the wear period, the activPALs and logbooks were returned to the site, where they were collated by a transport manager and, subsequently, collected by a member of the research team. activPALs were downloaded and visually checked for adequate wear, if a sufficient number of valid days of data were not obtained, then participants were contacted and asked if they would be willing to re-wear the device.

Secondary outcomes

A number of secondary outcomes were assessed during each measurement time point (see below).

Secondary activPAL variables

Sitting, standing, time in light intensity physical activity and time in MVPA were assessed using the activPAL micro accelerometer. The activPAL is regarded as the most accurate method of assessing sitting behaviour in free-living settings,55,57,58 and is recommended for use in interventions when sitting is an outcome measure. 54 From the data provided by the device, the following variables were derived by calculating the average across the number of valid days provided during each measurement period:

-

average total daily sitting time (minutes/day)

-

average total daily sitting time (minutes/day) accumulated in prolonged bouts lasting ≥ 30 minutes

-

average total daily standing time (minutes/day)

-

average total daily stepping time (minutes/day)

-

average number of transitions from sitting to an upright posture

-

average total daily time in MVPA (minutes/day), calculated as total stepping time at a step cadence threshold of 100 steps per minute (in bouts lasting ≥ 1 minute)

-

average total daily time in light physical activity (minutes/day)

-

number of valid days

-

average waking wear time (minutes/day)

-

average percentage of the day spent sitting

-

average percentage of the day spent standing

-

average percentage of the day spent stepping

-

average percentage of total sitting time spent in prolonged sitting bouts (lasting ≥ 30 minutes).

The variables below were calculated and summarised for three different time periods within each measurement period: (1) daily (i.e. across all waking hours on all valid days), (2) during workdays only and (3) during non-workdays only.

Anthropometry and markers of adiposity

Height was measured at baseline only, without shoes and to the nearest millimetre, using a portable stadiometer (seca 206, seca Ltd, Birmingham, UK). Weight (kg) and body fat percentage were assessed via bio-impedance analysis using Tanita DC-360S body composition scales (Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). A clothing allowance of 1.5 kg was entered into the scales, along with participants’ age, sex and height. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Waist, hip and neck circumferences (cm) were measured using standard anthropometric measuring tape (seca Ltd, Birmingham, UK), and waist-to-hip ratio was calculated.

Biochemical assessments

Capillary blood samples were collected via finger-prick blood sampling. Participants were requested to place their hand in a bowl of warm water (provided) for 5 minutes prior to the sample being collected. Participants were also requested to fast for at least 4 hours prior to attending their health assessment. HbA1c (mmol/mol) was measured using an A1CNow®+ point-of-care analyser (PTS Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Triglycerides (mmol/l), HDL-C (mmol/l) and total cholesterol (mmol/l) levels were assessed using a Cardiocheck® point-of-care analyser (PTS Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). LDL-C (mmol/l) was calculated using Friedewald’s formula. 59

Dietary quality and fruit and vegetable intake

Dietary quality and fruit and vegetable intake (g/day) were assessed using a short-form Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). 60 Using this measure, a dietary quality score was derived from reported fruit, vegetable, oily fish, non-milk extrinsic sugar and fat intakes. The dietary quality score calculated using this short-form FFQ has been shown to demonstrate a significant agreement (κ = 0.38) with dietary quality determined using a 217-item FFQ. 60

Sleep duration and quality, subjective sleepiness and chronotype

Sleep duration and quality were assessed using a GENEActiv tri-axial accelerometer (ActivInsights Ltd., Huntingdon, UK), which was worn (concurrently with the activPAL) on the non-dominant wrist continuously for 8 days. The GENEActiv has been shown to provide an accurate measure of sleep and activity behaviour patterns over a 24-hour period. 61 The device collected data at 100 Hz with a ± 8 g dynamic range. Participants were asked to note any time they removed this device on the same logbook used for the activPAL.

Situational sleepiness was assessed using the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale, which has been shown to be a valid measure of sleepiness when validated against electroencephalography and performance outcomes. 62,63 Participants’ chronotype was determined using the short version of the Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ). 64

Blood pressure

Blood pressure and heart rate were measured from the left arm of the driver after a 20-minute period of quiet sitting using an automated monitor (Omron HEM-907, Omron Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), in accordance with recommendations from the European Society of Hypertension. 65 Three separate measurements of blood pressure and heart rate were taken at 5-minute intervals. The mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and heart rate, recorded from the second and third assessments, were calculated and used in the analyses.

Cognitive function and psychophysiological reactivity

The Stroop test was administered over a 5-minute period using a validated software package (SuperLab 5, Cedrus Corporation, San Pedro, CA, USA) to provide a measure of reaction time, sensitivity to interference and the ability to suppress an automated response (i.e. reading colour names in favour of naming the font colour). 66 The Stroop test was utilised to provide a measure of cognitive function and as part of a battery of measures to induce acute stress to support the assessment of psychophysiological reactivity.

The mirror tracing task (Campden Instruments Auto Scoring Mirror Tracer 58024E, Campden Instruments LTD, Loughborough, UK) was used as the second stress task, which has been routinely used to induce stress in field- and laboratory-based studies. 67 The mirror tracing task immediately followed the Stroop test. The mirror tracing task involved tracing an adonised star pattern using a metal-tipped stylus with the right hand continuously for 5 minutes. Participants were, however, permitted to use only the reflection of the star in an adjacent mirror for reference. The machine beeped if the metal-tipped stylus left the star pattern, and each mistake was recorded on the machine. Participants were told to aim for at least five complete stars in the time frame. 68 Measurements of blood pressure and heart rate were repeated during the mirror tracing task at 2 minutes 15 seconds, and again at 4 minutes 35 seconds, into the task to measure psychophysiological reactivity to acute stress. The mean stress-induced blood pressure and heart rate readings were calculated from these two measurements. Blood pressure and heart rate psychophysiological reactivity were calculated by subtracting the average resting systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and resting heart rate, from the average systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and heart rate, taken during the stress task.

Functional fitness

Grip strength (kg) was assessed from both hands using the Takei Hand-Grip dynamometer (Takei Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd, Niigata, Japan).

Mental well-being

Depression and anxiety symptoms were self-reported using the validated Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 69 The HADS consists of two subscales containing seven questions for anxiety symptoms and seven questions for depressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha for HADS anxiety and HADS depression has been reported as 0.83 and 0.82, respectively. 70 Each answer is scored on a scale from 0 to 3. Therefore, total scores for each construct range from 0 to 21. For each construct, a score of ≤ 7 would be classified as ‘no symptoms’, whereas scores of 8–10, 11–14 and 15–21 are classified as the presence of mild, moderate and severe symptoms, respectively. 70 Social isolation was assessed using the 8-item Social Isolation Short Form from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System. 71,72

Musculoskeletal symptoms

Musculoskeletal symptoms were assessed using the standardised Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire, which is a self-reported measure of musculoskeletal pain covering nine body regions. 73

Work-related psychosocial variables

A series of self-reported questionnaires assessed a range of work-related psychosocial variables. Work engagement (characterised by vigour, dedication and absorption) was measured using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. 74 Occupational fatigue was measured using the Occupational Fatigue Exhaustion Recovery (OFER) scale. 75 Perceived job performance76 and job satisfaction77 were measured using single-item 7-point Likert scales. Perceived work ability was assessed using the single-item Work Ability Index. 78 Sickness presenteeism and absenteeism were assessed using a single-item questionnaires. Participant’s perceptions of their work demands and support was assessed using four subscales from the Health and Safety Executive Management Standards Indicator Tool. 79 Reported driving-related safety behaviour was assessed using a six-item measure. 80

Health-related quality of life and resource use

Health-related quality of life was measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). 81,82 The EQ-5D-5L measure comprises a short descriptive questionnaire and a visual analogue scale. On the descriptive questionnaire, participants rate their current health state across five dimensions (i.e. mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) and across five levels of severity (ranging from ‘no problem’ to ‘unable to/extreme problems’). The visual analogue scale (which ranges from 0 to 100) records the participant’s overall current health, where the end points are labelled ‘the best health you can imagine’ (100) and ‘the worst health you can imagine’ (0).

Information on health-related resource use was collected using a questionnaire designed for this study. Using this tool, participants were asked to report information on the quantity and duration of GP and nurse practitioner visits, inpatient and outpatient appointments, and visits with other relevant health professionals. The information obtained from the EQ-5D-5L and health-related resource use questionnaire was used to inform the within-trial cost-effectiveness analysis (see Chapter 4).

Demographics and additional lifestyle health-related behaviour and risk measures

At baseline, participants completed a brief questionnaire collecting basic demographic information, including date of birth, sex, ethnicity, highest level of education, marital status, postcode (to determine Index of Multiple Deprivation as an indicator of neighbourhood socioeconomic status), working hours, years worked as a HGV driver, shift pattern and years worked at DHL Supply Chain. At each follow-up assessment, participants were asked if there have been any changes in these variables. During each assessment, information on smoking status and typical alcohol intake [using questions 1 and 2 from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)83] was gathered. Using information collected from the self-report questionnaires, and data collected within the health assessments (i.e. systolic blood pressure, cholesterol/HDL-C ratio, height and weight), participants’ 10-year risk of having a cardiovascular event was calculated using the Cardiovascular Risk Score (QRISK3) calculator [URL: https://qrisk.org/2017/ (accessed 16 July 2021)].

Accelerometer data processing

activPAL

activPALs were initialised and downloaded using manufacturer proprietary software (activPAL Professional v.7.2.38, PAL Technologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK). Event files were generated and processed using the freely available Processing PAL software [URL: https://github.com/UOL-COLS/ProcessingPAL (accessed 24 August 2022), version 1.3, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK]. The software provides information on valid waking wear time, sleep time, extended non-wear time and invalid data, according to a validated algorithm. 84 Once data were processed, heat maps were created, showing valid waking wear data and invalid data. The heat maps were visually checked independently by two researchers for any occasions where the algorithm had misclassified waking wear data, and vice versa. On any occasion where suspected misclassifications had occurred, the participant’s self-reported logbook wake and sleep times were compared with the processed data. If a misclassification was confirmed, then the data were corrected. The logbooks were also checked for scenarios where data should be removed, for example if participants reported removing the device for any reason. Once this process was completed, summary variables were calculated (see Secondary activPAL variables). A valid activPAL wear-day was defined as having ≥ 10 hours wear time per day, ≥ 1000 steps per day and < 95% of the day spent in any one behaviour (e.g. sitting, standing or stepping). Participants were included in the primary outcome analysis if they provided at least 1 valid wear-day at both baseline and 6 months’ follow-up (i.e. immediately following completion of the 6-month intervention). One valid day was chosen to maximise our sample and is in line with previous studies. 85,86

GENEActiv

GENEActiv devices were initialised and downloaded using manufacturer proprietary software (GENEActiv v.3.1, Activinsights Ltd, Huntingdon, UK). Accelerometer files were processed in the R package GGIR version 1.11-0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)87 to generate sleep outcome variables, with sleep duration (i.e. minutes/24-hour period) and sleep efficiency [i.e. sleep duration/sleep window duration × 100 (%)] the variables of interest for this report. ‘Sleep windows’ (i.e. the time between ‘lights out’ and out of bed time) were detected from the accelerometer data using a validated algorithm. 88 Sleep duration within the sleep window period was calculated using a validated sleep detection algorithm, which has been shown to demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity in detecting sleep periods. 89 A device wear time of ≥ 16 hours per 24-hour period was required to determine a valid night of sleep data. 89 Individual nights of data with a sleep window > 13 hours or < 2 hours or sleep duration > 12 hours or < 1 hour were identified as erroneous and removed. As with the activPAL data, participants were required to have provided at least 1 valid wear-day at both baseline and follow-up (i.e. immediately following completion of the 6-month intervention) to be included in the analyses within this report.

From the data provided by the GENEActiv, the following variables were derived by calculating the average across the number of valid days provided during each measurement period:

-

sleep window duration [i.e. average duration between ‘lights out’ and ‘out of bed’ time (minutes)]

-

sleep duration [i.e. average time spent asleep during the sleep window (minutes)]

-

sleep efficiency [i.e. sleep duration/sleep window duration × 100 (%)]

-

average number of valid days (days).

The variables below were calculated and summarised for three different time periods within each measurement period: (1) daily (i.e. across all 24-hour periods on all valid days), (2) on workdays only and (3) on non-workdays only.

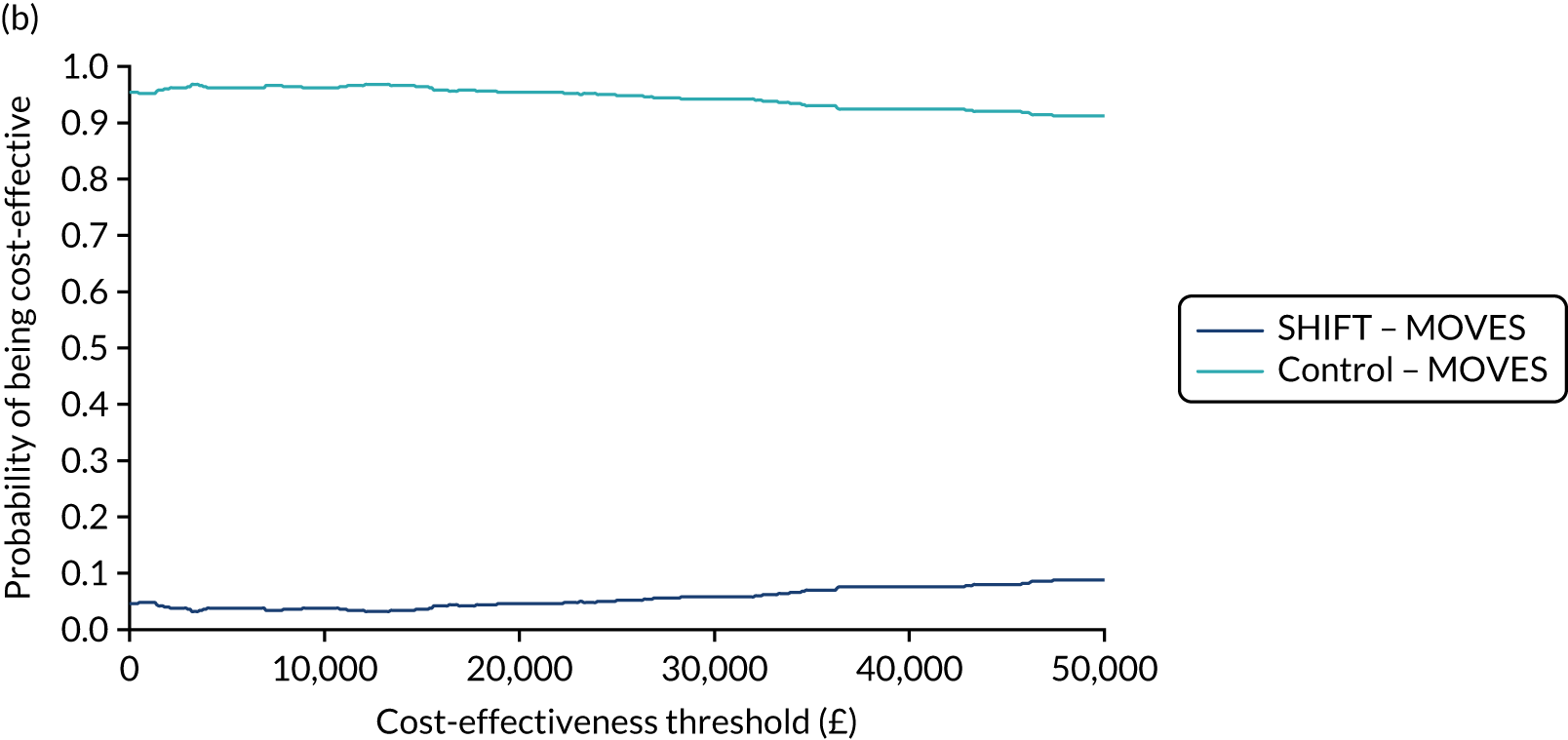

Cost-effectiveness evaluation

Full details of the methods for the cost-effectiveness analysis are in Chapter 4. In brief, the economic evaluation assessed whether or not the SHIFT programme, compared with a control arm, was likely to be cost-effective at commonly used threshold values. The economic analysis consisted of a cost–consequences analysis based on the observed results within the trial period and a cost-effectiveness analysis in which differences between groups in the trial were extrapolated to the longer term.

Within-trial analysis

Within the trial, resource use estimates were collected during each assessment point using the health-related resource use questionnaire. This questionnaire was based on a variant of the Client Service Receipt Inventory and included services that this population are likely to utilise, such as GPs and practise nurse appointments, occupational health visitors and counsellors. Costs of resources were calculated by applying published national unit cost estimates (e.g. NHS reference costs or Personal Social Services Research Unit unit costs of health and social care90,91), where available, to estimates of relevant resource use. A range of trial outcomes were assessed as part of this economic evaluation, including HRQoL, measured using the EQ-5D-5L. 81,82 The within-trial analysis evaluated incremental results for the primary and secondary outcomes [including EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)] in both intervention and control arms and compared the incremental costs mentioned above.

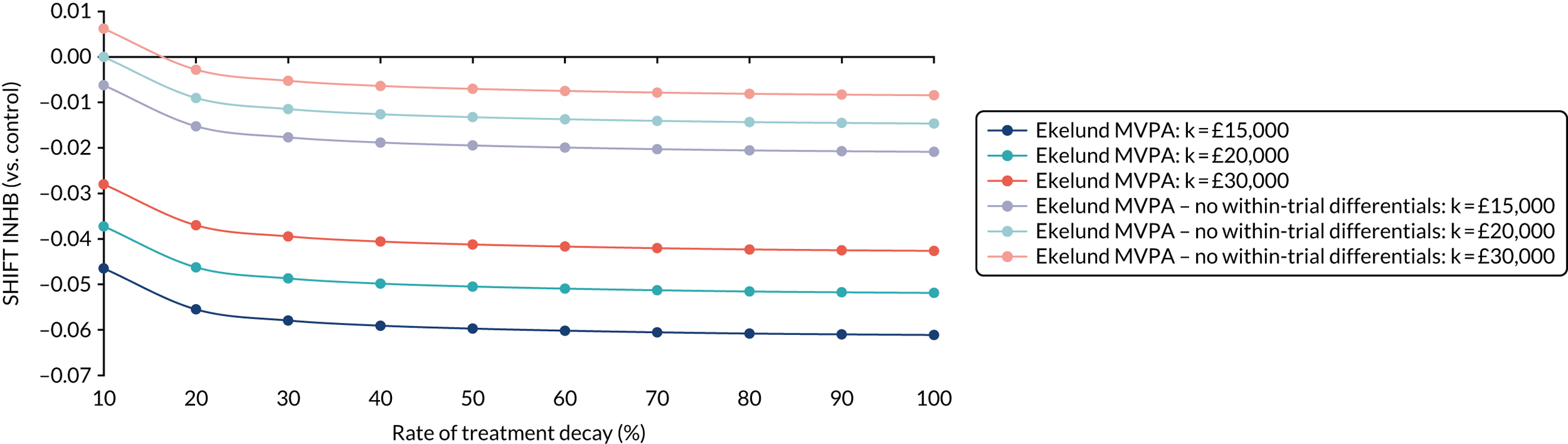

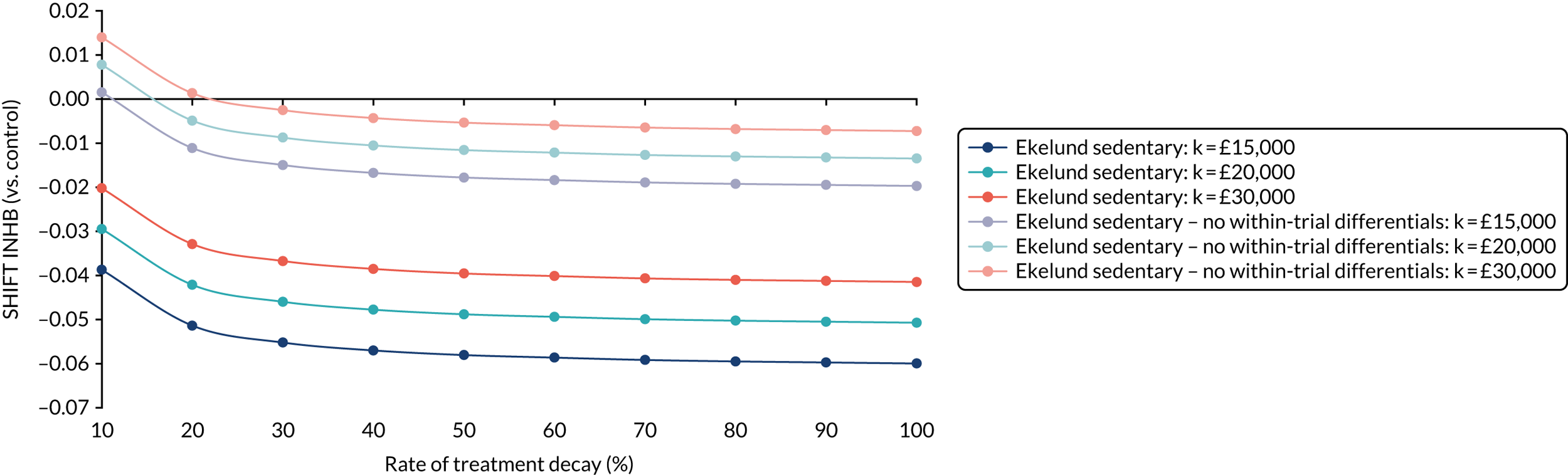

Longer-term analysis

Existing models linking physical activity to quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs)92 were utilised to extrapolate costs and effects of the intervention beyond the trial period to a more appropriate time horizon. An incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for the extrapolated period was reported using the QALY. Costs and effects were discounted at the prevailing recommended rate (currently 1.5% per annum on both costs and effects), and a sensitivity analysis was also conducted to reflect the ongoing uncertainty around appropriate discount rates for public health interventions. Sensitivity analyses were performed to determine the robustness of the results to altering certain assumptions, such as the discount rate or inclusion/exclusion of productivity losses.

Process evaluation

Full details of the methods for the process evaluation are included in Chapter 5. In brief, the process evaluation aimed to examine any discrepancies between expected and observed outcomes, increase our understanding of the influence of each intervention component and context on the observed outcomes, and provide insight for any further intervention development and implementation. 93 Throughout the trial, we monitored the implementation fidelity, dose, attrition, adaptation, contamination, barriers and facilitators, and sustainability, using the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework. 94 The process evaluation adopted a mixed-methods approach. Self-report questionnaires that were provided to study participants were used to evaluate the various intervention components (e.g. structured education session, Fitbit, cab workout). Interviews with participants and transport managers examined further engagement in the various components of the intervention, along with any perceived barriers to and facilitators of participating in these components.

Sample size

Our earlier exploratory pre–post study revealed that, on average, HGV drivers accumulated 8786 steps per day across both workdays and non-workdays, with a SD of 2919 steps. 37 This trial was powered to look for a difference in step counts (i.e. the primary outcome) of 1500 steps per day (equivalent to approximately 15 minutes of moderately paced walking) between the intervention and control groups. Evidence demonstrates a linear association between step counts and a range of morbidity and mortality outcomes, as well as markers of health status, including inflammation and adiposity, insulin sensitivity and HDL-C in adults. 95–97 The linear association between step counts and health outcomes indicates that, regardless of an individual’s baseline value, even modest increases in daily step counts can yield clinically meaningful health benefits. For example, a difference in daily steps of 1500 steps per day has been associated with around a 5–10% lower risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the general population and in those with a high risk of type 2 diabetes, respectively. 98,99 This proposed level of change was chosen based on findings from our exploratory pre–post intervention,37 while also being clinically meaningful.

Based on a cluster size of 10, a conservative intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05 (as there were no previous data to inform this, we were guided by recommendations of Campbell et al. 100), an alpha of 0.05, power of 80% and a coefficient of variation to allow for variation in cluster size of 0.51 (based on information provided by DHL Supply Chain), we required 110 participants from 11 clusters per arm. From experience in conducting such studies, it was originally estimated that retention and compliance rates would be approximately 70% at 12 months’ follow-up, and, therefore, the sample size was inflated by 30% to ensure that we had adequate power in the final analysis. The number of clusters was also inflated by two to allow for whole-cluster drop out. Therefore, we aimed to recruit 24 clusters (i.e. DHL Supply Chain sites), with an average of 14 participants per cluster, providing a total target sample size of 336 drivers.

Owing to one pilot site [i.e. a BP (London, UK) site] not allowing participants to wear the accelerometers during working hours for health and safety reasons and, therefore, limiting the collection of the primary outcome measure (i.e. activPAL-determined steps/day) to non-working hours only, the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) approved the recruitment of an additional site in the main trial phase (in November 2018) (see Internal pilot). The total number of sites recruited increased, therefore, from 24 to 25.

Internal pilot

The trial incorporated an internal pilot, which was conducted using the first six clusters (i.e. sites) recruited. The internal pilot examined issues surrounding worksite and participant recruitment, randomisation, compliance to the primary outcome and retention rates at 6 months’ follow-up. The following progression criteria were reviewed by the TSC on the completion of the measurements collected from these six sites at 6 months, and the trial was considered eligible to progress to the main trial phase if it confirmed the following:

-

All 24 sites required for the full sample size agreed to take part.

-

A minimum of 84 drivers (based on an average of 14 participants per cluster, across the six pilot sites) had provided informed consent to participate in the internal pilot.

-

An average of 75% of drivers opting into the study, randomised into the intervention arm, attended the education session across the three intervention sites in the internal pilot phase. This figure was based on the intervention uptake rate seen in our exploratory pre–post intervention study (i.e. 87%),37 but the figure also recognises that take-up rates tend to be lower when moving from an efficacy study to a larger multicentre effectiveness trial.

-

No more than 20% of participants failed to provide valid data for the primary outcome measure (i.e. activPAL-determined step counts) at baseline and at 6 months’ follow-up (i.e. immediately following completion of the intervention), or had withdrew or were lost to follow-up during the 6-month intervention phase.

If the final two progression criteria were not fully met, then it was agreed that strategies to improve these metrics for the full trial would be discussed with the TSC and the TSC would have the final say on whether or not the trial progressed to the main trial phase.

Allocation to treatment groups

Clusters (i.e. individual DHL Supply Chain sites) were randomised at the worksite level into the two trial arms (i.e. intervention and control), using an allocation ratio of 1 : 1. Randomisation was conducted by a statistician from the Leicester Clinical Trials Unit using a pregenerated list. The statistician was blinded to any identifiable cluster features and all clusters were represented by a unique cluster identifier. Randomisation took place in two phases, initially as part of the internal pilot phase and then as part of the main trial phase. Within both trial phases, the research team were responsible for co-ordinating the deployment of the intervention across sites and were, therefore, unable to be blinded to allocation arm. Similarly, owing to the nature of the intervention, participants were unable to be blinded to their assigned trial arm.

Internal pilot

Within the internal pilot, the six sites were randomised into the two trial arms following the completion of baseline measurements across the sites, using simple randomisation.

Main trial

Within the main trial phase, sites/clusters were randomised in blocks of three on completion of the baseline measures in these sites. Sites were also stratified by cluster size [i.e. small (< 40 drivers) vs. large (≥ 40 drivers)].

COVID-19: impact of a temporary change in driving hour regulations on SHIFT participants

As a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the government temporarily relaxed the driving regulations during the first national lockdown in England, extending the permitted fortnightly driving limit from 90 hours to 99 hours for HGV drivers. 101 To investigate the impact of the changes in driving regulations, along with the impact of the pandemic on SHIFT participants’ mental health and health-related behaviours, participants were invited to complete an additional optional short online survey in May 2020. The online survey also asked if participants had been furloughed and if participating in the study had an impact on their lifestyle behaviours during the initial government lockdown.

Ethics approval for this additional survey was obtained from the Loughborough University Ethics Approvals (Human Participants) Sub-Committee (reference 2020-1444-1221). The online survey was created and distributed via the Jisc Online Surveys platform (Jisc, Bristol, UK), which is a General Data Protection Regulation-compliant online survey tool designed for academic research. Participants were contacted via the study’s text messaging service and were invited to participate in the survey. A link to the online survey was included in the text message. In addition, a participant information sheet and a consent statement were included on the opening page of the survey.

The following measures were included in the online survey:

-

Working situation (whether participants continued to work or had been furloughed).

-

Working hours, driving hours, in-cab waiting hours and between-shift resting hours before and during the pandemic.

-

Sitting, standing and moving time before and during the pandemic.

-

Whether or not participants had commenced any new forms of physical activity during the pandemic.

-

Symptoms of anxiety and depression during the pandemic, assessed using the HADS.

-

Work-related chronic and acute fatigue during the pandemic, assessed using the OFER scale.

-

Whether or not participants habitually spent time in nature before the pandemic, and whether or not they were spending time in nature during the pandemic. Nature was defined as spaces such as gardens, parks, sports fields, allotments, woodland, lakes, rivers, coastline, beaches or mountains. Participants also indicated the frequency with which they spent time in nature, before and during the pandemic, using the following options: no time in nature, once per week, 2–3 times per week, almost every day and every day. 102

-

Whether or not participants had made any changes to their activity levels, diet, smoking status or alcohol intake during the pandemic.

-

Sleep duration over the past 14 days.

-

Whether or not participating in the SHIFT study had provided participants with the right knowledge to maintain a healthy lifestyle during the COVID-19 restrictions.

Statistical analysis

A detailed statistical analysis plan (SAP) (see Report Supplementary Material 3) was created and signed off before the independent statistician had access to the data. Cluster- and participant-level baseline characteristics were summarised by trial arm and for the sample as a whole. In addition, we carried out a descriptive comparison of baseline data (specifically cluster size, age, BMI, number of years as a HGV driver, number of steps/day) between completers (i.e. participants who provided valid activPAL data at baseline and at 6 months) and non-completers, within randomisation groups and overall.

Primary outcome analysis

The primary analysis was performed using a mixed-effect linear regression model, with each participant’s daily average number of steps (measured using the activPAL) at 6 months’ follow-up as the outcome, adjusting for the participant’s daily average number of steps at baseline and for the average waking wear time at baseline and at 6 months. The model also included a categorical variable for randomisation group (control as reference) and a term for the stratification factor [i.e. cluster size: small (< 40 drivers) vs. large (≥ 40 drivers)]. Depot was included as a random effect to model driver heterogeneity within participating sites. The structure of the variance–covariance matrix for the random effect was assumed to be identity and the models were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood. The primary analysis examined the effect of the intervention using a complete-case population. All clusters randomised, and the recruited participants in these clusters, excluding participants with missing outcome data (i.e. without at least 1 valid day of activPAL data at baseline and follow-up), were included in the primary analysis, which followed the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle (i.e. participants were analysed in the arm to which they were randomised). The estimate of the difference between the SHIFT arm and the control arm for daily average number of steps at 6 months and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values are presented. Statistical tests were two sided. Furthermore, the ICC was estimated to assess the strength of the clustering effect.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted (see Full intention-to-treat analysis and Effects on the number of valid activPAL days), using similar methodology as the primary outcome analysis. There was no formal adjustment for multiple significance testing. The sensitivity analyses were conducted for the primary outcome (i.e. average daily step counts at 6 months’ follow-up). All tests and reported p-values were two sided. Estimates are presented with 95% CIs.

Per-protocol analysis

The effect size was also estimated using a per-protocol analysis. The per-protocol population were participants who did not exhibit any protocol deviations, and excluded participants who:

-

did not provide valid activPAL data at baseline or at the 6 months’ follow-up (as applied in the primary outcome analysis)

-

had time window deviations for their follow-up (> ± 2 months) assessment.

Full intention-to-treat analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the impact of missing data on the primary results and to account for uncertainty associated with imputing data (full ITT analysis). To allow for analysis of the full data set, missing data from variables included in the primary analysis model (i.e. average daily steps at baseline and immediately following the intervention) were imputed using a multiple imputation procedure, which substituted predicted values from a regression equation. The following variables were used as predictors of the primary outcome in the regression equation: baseline BMI, sex, ethnicity, age, cluster size category, years worked as HGV driver and average waking wear time across baseline and 6 months. Missing values for these predictor variables were also imputed if needed. The imputation was carried out by the MI command in Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). MI replaced missing values with multiple sets of simulated values to complete the data, performed standard analysis on each completed data set and adjusted the obtained parameter estimates for missing data uncertainty using Rubin’s rules to combine estimates. 103 Twenty imputations were estimated and a seed was set to allow reproducibility.

Additional worst- and best-case scenario ITT analyses using basic imputation methods were also carried out. A simple worst-case scenario ITT analysis was carried out, where missing covariate data in the final analysis model were replaced using cluster means. Where it was not possible to impute using the cluster mean, the mean for the respective arm was used instead. Missing outcome data in the final analysis model (i.e. at baseline and 6 months) were replaced using the mean for the standard care arm. Furthermore, a simple best-case scenario ITT analysis was also carried out using the same approach as above, but outcome data were replaced using the mean for the respective arm.

Effects on the number of valid activPAL days

We carried out further sensitivity analyses by assessing the effect of the number of valid activPAL days on the primary outcome analysis. This analysis was performed by including participants who provided valid activPAL data (including weekdays and weekend days) on:

-

≥ 2 valid days at both baseline and 6 months

-

≥ 3 valid days at both baseline and 6 months

-

≥ 4 valid days at both baseline and 6 months.

Secondary outcome analysis

Secondary outcomes, including those measured at 6 months and at 16–18 months, were analysed using similar methodology to the primary outcome. Owing to the volume of secondary outcomes assessed, statistical analysis of secondary outcome variables was restricted to the following key secondary outcomes: steps per day (16–18 months’ follow-up), activPAL-determined time spent sitting, standing and stepping, and time in light intensity physical activity and MVPA daily, during workdays and during non-workdays (at both 6 months’ follow-up and 16–18 months’ follow-up). The models for each of these secondary outcomes were adjusted for their respective variable at baseline and for the respective average wear time period (i.e. daily, workdays or non-workdays) at baseline and follow-up.

Fruit and vegetable intake (g/day) and dietary quality score were also analysed at 6 months and at 16–18 months. The models for each of these outcomes were adjusted for their respective baseline levels. Furthermore, the following markers of cardiometabolic health were also compared statistically at 6 months’ follow-up: weight, BMI, per cent body fat, waist circumference, HbA1c (mmol/mol), triglycerides (mmol/l), HDL-C (mmol/l), LDL-C (mmol/l) and total cholesterol (mmol/l). The models for each of these outcomes were adjusted for their respective baseline levels.

The models above included a categorical variable for intervention group (control as reference) and the stratification factor (cluster size). No corrections for multiple testing were made. In all models, estimates of the difference between the SHIFT arm and the control arm for the variables examined are presented, along with corresponding 95% CIs and p-values. Statistical tests were two sided.

For the other secondary outcomes (see Secondary outcomes), continuous data that were approximately normally distributed were summarised in terms of the mean and SD. Skewed data are presented in terms of the medians and interquartile range (IQR). Ordinal and categorical data are summarised in terms of frequency counts and percentages. All variables are summarised by trial arm.

Statistical analysis plan deviations

Mixed-effect linear regression models were fitted, instead of analysis of covariance models, because the analysis of covariance set-up in Stata did not allow all of the options specified in the SAP. The MEQ data were added together to create a total MEQ score, which was analysed as a continuous variable. Where BMI at 6 months was missing but weight data were available, baseline height was used to calculate BMI at 6 months, and likewise for BMI at 16–18 months. Medians (IQR) were calculated for AUDIT scores and job satisfaction and performance in addition to the planned descriptive statistics in the SAP.

Analysis of the COVID-19 questionnaire

The data were downloaded from the Jisc platform and imported into Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), where all data cleaning and reduction took place. Data were then imported into SPSS v25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for analysis. Continuous data that were approximately normally distributed were summarised in terms of the mean and SD, whereas skewed data are presented in terms of the medians and IQR. Comparisons between questionnaire responses from control and SHIFT arm participants, and between participants who had been furloughed and participants who were working at the time of questionnaire completion, were conducted using between-samples tests. Baseline characteristics in terms of age, duration working as a HGV driver, duration working for DHL Supply Chain, hours worked per week, BMI, per cent body fat, waist circumference, self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression, musculoskeletal complaints, physical activity levels, and sleep duration and efficiency were compared between participants completing the additional COVID-19 questionnaire and participants not using between-samples tests. For participants completing the online questionnaire, comparisons were made, using repeated measures tests, between participants’ working, driving, in-cab waiting or rest hours reported before and during the pandemic. Similarly, comparisons were made between participants’ reported time spent sitting, standing and walking/moving around on a workday before and during the pandemic, along with reported symptoms of anxiety and depression and fatigue. The impact of spending time in nature before and during the pandemic on symptoms of anxiety, depression and fatigue were explored. The impact of participating in the study on maintaining a healthy lifestyle during the pandemic, along with any lifestyle- or work-related changes experienced by participants, were explored descriptively.

Public and patient involvement

The initial development and refinement of the SHIFT intervention, and the implementation and running of this trial, have been informed by extensive PPI. The preparatory work,7,36–38 which informed the original grant application, was the result of a 3-year partnership between the research team and a large transport and logistics company (not DHL Supply Chain) located in the East Midlands, UK. This preparatory work was instigated by the company. The company requested help in improving the lifestyle behaviours and health of their long-distance drivers, who were proving difficult to engage. As part of the preparatory work, the SHIFT programme was developed in collaboration with long-distance HGV drivers and health and safety personnel working within the logistics sector. Following pilot testing,37 and input from drivers and associated stakeholders,38 the intervention and outcome measures were refined. Specifically, the duration of the intervention increased from 3 months to 6 months, as it was felt that a longer intervention duration would lead to more sustainable changes in health behaviours. The provision of free fruit at the participating DHL Supply Chain sites was removed as an intervention component, as senior health and safety personnel at DHL Supply Chain felt that this would not be feasible to implement across the wide range of sites across their business. Assessments of lung function were removed from the collection of outcome measures, as the relevance of this particular measure was questioned.

As part of the implementation planning for the trial, an initial meeting was held with transport managers from a range of DHL Supply Chain sites. The feedback obtained during this meeting informed our driver recruitment plans and highlighted effective strategies for informing and engaging office staff and drivers about the study across the individual sites. Extensive input and feedback were obtained from DHL Supply Chain health and safety personnel and human resources staff on our study marketing materials and on our health assessment feedback booklet produced for drivers.