Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as award number 17/92/39. The contractual start date was in March 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in November 2022 and was accepted for publication in October 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Pallan et al. This work was produced by Pallan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Pallan et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction/background

Nutrition in adolescents

Adolescence is a key period of growth and development, during which young people undergo dramatic physical and psychosocial changes. 1 Good nutrition is essential to support these changes, while poor nutrition can lead to a variety of health consequences, including obesity, which is increasing in prevalence worldwide,2 compromised growth and higher non-communicable disease risk in later life. 3 Adolescence is one of the major risk periods for obesity development. In England, over one-third of children have excess weight, and nearly one-quarter have obesity by the age of 15 years,4 putting them at risk of short- and long-term morbidity. 5,6

Overall, evidence from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) indicates that dietary intake in adolescents in the UK is suboptimal. Consumption of free sugars (defined as all sugars added to foods by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, and natural sugars found in honey, syrups and unsweetened fruit juices7) is high, contributing to 12.5% of the daily energy intake of 11- to 18-year-olds,8 which substantially exceeds the recommended 5% of daily energy intake from free sugars. 9 Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption is one of the key contributors to this high sugar intake, with those aged 11–18 years consuming more than any other age group. 8

In addition to contributing to energy density and the development of obesity,10–12 high intake of free sugars and SSBs are major risk factors for dental caries. 13 Almost half of UK adolescents aged 15 years have some caries experience,14 which, as well as causing pain and distress, can impact on school attendance, academic performance and psychosocial well-being. 15,16

Other aspects of dietary intake are also of concern in the adolescent age-group, including higher than recommended intakes of saturated fatty acids and lower than recommended intakes of fibre and fruit and vegetables (F&V). Only 12% of the 11–18 years age group meet the recommendation of five daily portions of F&V. 8,17 Again, these patterns of dietary intake can lead to higher risk of obesity and later non-communicable diseases such as cancers and cardiovascular disease. 18–20 Poor dietary intake, dental health and obesity in adolescence all demonstrate a socioeconomic gradient, with the most disadvantaged being at greatest risk. 21–24

Adolescence is a key period for establishing dietary patterns, with rapid biological development and increased nutrient needs, greater autonomy over dietary decisions, and more interaction with peers and the wider environment. 25 Dietary patterns established in adolescence often track into adulthood,26,27 and thus adolescence represents an important period in the life course for intervention to influence food and drink choices and encourage the development of healthy dietary patterns.

The role of schools in supporting healthy nutrition

Among the many influences on adolescent dietary intake and eating behaviours, schools play a significant role. 28 Younger adolescents spend a substantial portion of their time at school, and it is widely recognised that supporting health and well-being is an integral part of the overall educational remit of schools. 29,30 Adolescents attending secondary schools in the UK typically consume at least one meal per day at school, so the school setting offers an opportunity for intervention to improve the nutritional intake of their pupils.

The provision of school meals as a public health measure has a long history, predominantly to address undernutrition. 31 School feeding programmes are in place in many countries,32 and there is evidence to suggest that they have educational and health benefits in disadvantaged communities and low income settings. 33 In the UK, some provision of school meals for poorly nourished children was introduced in the late 19th century, and in 1941 a national school meal policy was launched that enabled the provision of school meals to all children who wanted them. 34 Since the late 20th century, when large increases in obesity prevalence among children started to be seen, the focus of school meals in the UK and other high-income countries has shifted from addressing undernutrition to providing high-quality, nutritionally balanced foods and drinks with lower energy density. 31,34 In terms of the influence on dietary intake of interventions to improve the nutritional quality of school meals and other school food provision, some positive effects have been seen. For example, F&V schemes in schools and the introduction of nutritional standards and guidelines for school food have been shown to have a beneficial impact on nutritional intake in the short term. 35,36

The influence of schools on healthy eating and nutritional intake not only involves food provision, but also encompasses the physical, social and cultural environmental aspects of schools and school communities. 28,37 This is reflected in a wide range of school-based approaches to improving healthy eating, which include alterations to the food and dining environment, educational and behavioural approaches, and whole-school approaches involving peers, parents and communities. 38 Overall, the evidence for school-based intervention to improve nutrition, through either school food provision or a wider environmental approach, is mixed. In particular, there is an evidence gap in relation to the effects of these interventions on secondary-school-aged pupils, with few studies of high quality and no clear messages about the most effective approaches for improving dietary intake. 38,39

National school food policy in England

Nutritional standards for school food as a strategy for improving children’s dietary intake were first introduced in the UK in 1941 along with the introduction of the national school meals policy, and various revisions to these standards were introduced over the following three decades. The nutritional standards were removed in the 1980s as part of a wider move to reduce the welfare state. 34 In 1992, in response to the poor quality of school meals, the Caroline Walker Trust convened a working group to develop nutritional guidelines for school lunches, and although these were accepted as the standards that school meals should ideally meet, they were not compulsory for schools. 40 In an attempt to address the increasing levels of obesity and poor nutritional intake in children, some regulation of school food was reintroduced in England in 2001 to ensure that school caterers provided healthy school food options, but there was little evidence of any impact on children’s nutritional intake in school. 34,41 From 2006, following a national review of school meals prompted by a campaign led by Jamie Oliver to improve the quality of school food,41 comprehensive food- and nutrient-based school food standards (SFS) legislation was introduced in England and applied to state-funded schools. 42 Alongside the SFS, the government established the School Food Trust as a non-governmental public body between 2006 and 2011 to work to improve the quality of school food (and ensure that schools met the SFS) and promote the education and health of children. 41

In 2012, the government commissioned a further independent review, undertaken by Henry Dimbleby and John Vincent, and the following year they published the School Food Plan (SFP; see The School Food Plan). 43 Actions for the government that were outlined in the SFP included the introduction of a revised set of SFS, designed to be operationally easier for school food providers to implement, and legislation for these revised standards came into force in January 2015. 44

Exemptions to national school food standards legislation

The way in which the SFS legislation in England has been applied means that a group of state-funded schools are exempt from the statutory requirement to comply with the SFS. Academies and free schools (state-funded schools that are independent of local authorities) that were established between 2010 and 2014 are not required by law to comply with the SFS. 45 However, as part of the SFP, and following the introduction of the revised SFS in 2015, these exempt schools were encouraged to voluntarily sign up to the SFS. 46,47 By March 2016, only around one-third of the exempt schools had done so. 48 Although the legislation has not been changed to address this exemption of schools, in the last 18 months of this study there has been a shift in the expectation of the government, whose position is now that all schools, regardless of their exemption status, should be complying with the SFS. 49

The current national school food standards

The SFS currently in place are food-based (rather than nutrient based) but underpinned by a nutrient framework. Before their introduction, the standards were pilot tested to ensure that they led to the same or improved nutrient content of school meals compared with the 2006 SFS. 50

The SFS specify six groups of foods and drinks: (1) starchy foods; (2) F&V; (3) milk and dairy; (4) meat, fish, eggs, beans and other non-dairy sources of protein; (5) foods high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS); and (6) healthier drinks. There are rules for portion, variety and frequency of provision for each group. The standards are divided into three groups: those applying to school lunch, those applying to foods provided in school other than at lunchtime, and standards that apply across the whole school day. 51 Standardised checklists are available to assist schools and caterers in checking their compliance with the SFS. 51

Despite their legislative status, there are no formal national arrangements for monitoring schools’ compliance with the SFS. 52 Responsibility for ensuring the SFS are met is placed with the governing bodies of schools, but in England there is no requirement for school governors to report on their school’s SFS compliance. 49 As part of their inspection visits to schools, Office for Standards in Education,Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted, the English schools inspection body) observe the school canteen food and environment and the effect of this on pupils’ behaviour, but they do not review SFS compliance. 53

The School Food Plan

The SFP established a set of wide-ranging recommendations for actions by the government, schools and headteachers to promote a ‘whole-school’ approach to a healthy-eating culture and ethos in schools. 43 One of the central aims of the SFP was to increase school meal uptake, both for economic reasons (higher demand drives better-quality food provision at lower cost) and because there is evidence to suggest that packed lunches are of poorer nutritional quality than school meals. 54,55 The other key aim was to provide practical support, advice and information for headteachers and others involved in school leadership in the form of a set of non-statutory recommendations for action to help improve the quality and uptake of school food and incorporate healthy eating into all aspects of school life and the wider school community. 43

Broadly, the recommendations in the SFP for schools include actions relating to leadership, vision and a whole-school approach; school food monitoring and accountability; school food provision and affordability; the physical and social eating environment; food education encompassing healthy-eating knowledge and skills; linking healthy eating to wider health and well-being; and involving school children and the wider school community in school food and healthy eating.

A checklist of actions for headteachers and guidance for school leadership teams and governors were developed to assist schools in implementing the SFP recommendations and a whole-school approach to creating a healthy-eating culture and ethos. 56–58 The Department for Education (DfE) continues to encourage the implementation of SFP recommendations and the use of these checklists and guidance in schools. 59

Evaluation of English national school food policy to date

Evaluation of the impact of the SFS on nutritional intake following the introduction of the 2006 food- and nutrient-based standards has been conducted among younger children in primary and middle schools. Repeated cross-sectional studies were conducted pre and post introduction of the SFS, collecting nutritional intake data from children aged 4–7 years in primary schools (n = 12)60,61 and children aged 11–12 years in middle schools (n = 6)62 to determine the effect of the SFS on lunchtime and total dietary intake. Following the introduction of the SFS, improvements were seen in the overall nutritional intake of children aged 4–7 years, with the greatest improvements seen in those receiving a school-provided lunch (vs. having a packed lunch). 60,61 By contrast, in the 11–12 years age group, there was limited evidence of a positive impact on the nutritional intake of children following introduction of the SFS, and levels of free sugar intake remained well above the recommended guidelines. 62 Another study examined how food provision and food choices had changed following the introduction of the 2006 standards in a sample of 136 primary schools across England, and reported that lunchtime food provision was healthier, with more fruit, vegetable and salad provision, and less starchy foods cooked in oil, desserts, crisps and confectionery. In line with this, improvements were seen in children’s F&V consumption. 63

Evidence of impact of the SFS on the dietary intake of secondary school pupils is more limited. One study in 80 secondary schools compared school food provision and consumption of foods and drinks by pupils aged 11–18 years at lunchtime in 2011 with that in 2004. 64 They reported an improvement in the nutritional content of school food, with the greatest impact on the availability of confectionery. Small improvements were observed in pupils’ lunchtime food consumption, such as decreased consumption of starchy foods cooked in oil and slight increases in F&V intake. Total dietary intake was not examined.

Since the introduction of the revised SFS in 2015, there have been no large-scale evaluations of their impact on nutritional intake52 and no comprehensive evaluations of the implementation of the SFP actions in secondary schools. In 2017, the Jamie Oliver Food Foundation published A Report on the Food Education Learning Landscape. 65 This reported findings from surveys, interviews and focus groups with school leaders, governors, teachers, children and parents, and focused on food education and the food culture in schools. Key findings relating to secondary schools were cheap and unhealthy (SFS non-compliant) foods on offer throughout the school day; noisy dining environments, often with long queues; inconsistent messaging with unhealthy foods used for fundraising and as rewards; and patchy provision of food education. More recently, in 2020, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity (Impact on Urban Health) published a report66 that outlined the findings of a study of primary and secondary schools across London, in which the food on offer, pupils’ food choices and the wider dining and food environments were observed. Only a small number of secondary schools participated, but the key findings in these schools were poor awareness and implementation of school food policies, food offers that were non-compliant with the SFS (particularly at breakfast and breaktimes), and pupils often choosing less healthy options, such as ‘grab and go’ food, even when a more nutritionally balanced meal was on offer. Both reports highlighted the lack of monitoring and enforcement of the SFS in secondary schools. In addition, similar issues were highlighted in the 2019 State of the Nation: Children’s Food in England report by Food for Life, Soil Association. Through consultation with 30 caterers, they estimated that around 60% of secondary schools may not be compliant with the SFS and recommended better monitoring of SFS compliance. 67 The need for robust and independent monitoring of food standards compliance in schools was also identified by Dame Sally Davies in the report she published as outgoing Chief Medical Officer for England in 2019, Time to Solve Childhood Obesity. 68

Two papers, one published in 201369 and one published in 2022,52 provide a comprehensive summary of the introduction and changes to the SFS over the last 20 years across all UK nations, including England. The first reported that in England, since the introduction of compulsory SFS in 2006, school lunch uptake had increased, and there was some evidence to suggest nutritional benefit from the standards, particularly in younger children. 69 However, the 2022 paper identified that no studies had examined the impact of the updated food-based SFS on children’s nutritional intakes, and highlighted that this lack of studies, together with the lack of monitoring of compliance of the SFS, made it difficult to determine the impact of the SFS policy on children’s nutritional intake. 52

School food policy in the context of wider government strategy

The SFS legislation remains an important national strategy for tackling childhood obesity and is a key component of the government’s report Childhood Obesity: A Plan for Action. 70,71 In this, the government states plans to update the SFS, with a particular focus on reducing the sugar content of foods. 71 However, this was put on hold during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the focus has moved to ensuring compliance with the current SFS. 72 Also as part of the their childhood obesity action plan, the government’s DfE introduced the healthy schools rating scheme in 2019. 73 This is a school self-assessment scheme to achieve bronze, silver or gold awards based on a number of factors related to healthy eating and physical activity, which include compliance with the national SFS and food education provision.

More recently, in 2021, Henry Dimbleby led the development of an independent national food strategy report74 in which he makes broad-ranging recommendations for the food system in England. In this are a suite of recommendations relating to food education and a recommendation to extend free school meal (FSM) eligibility. Following this independent report, the government launched two White Papers in 2022: Levelling Up the United Kingdom and the Government Food Strategy. 75,76 While not all of Dimbleby’s recommendations were taken up, in these White Papers the government set out plans to provide training to school governors on a whole-school approach to food, and to invest up to £5M in the food curriculum with the aim of children leaving secondary school with the knowledge of how to cook six basic recipes to support healthy eating. It also set out the intention to test approaches to ensuring transparency of school food arrangements and compliance with the SFS.

Rationale for evaluation of school food standards and School Food Plan in secondary schools

There is a clear gap in the research relating to the implementation of the most recent iteration of the SFS in secondary schools and their impact on school pupils’ nutritional intake, and no studies evaluating the SFS have explored their impact on dental health, even though sugar consumption is high in adolescents and is targeted within the SFS. Similarly, although there have been some attempts to characterise the secondary school food environment and culture, there have been no full evaluations of the implementation of SFP recommendations since it was launched in 2013. Furthermore, there has been no economic evaluation of the SFS or the SFP.

All previous studies evaluating the impact of the national SFS on pupils’ nutritional intake have reported pre- and post-implementation data, with no contemporaneous comparator group. The exemption from the SFS of academies and free schools established between 2010 and 2014 provided us with an opportunity to compare the implementation of the SFS and SFP and to compare pupil nutritional intake in schools mandated and schools not mandated to comply with the SFS during the same time period, albeit this latter group have been encouraged to voluntarily comply with the standards. As we have outlined in Exemptions to national school food standards legislation, since the start of this study, the national landscape has changed and there has been a shift in the government’s approach to the national SFS, the current expectation being that all schools should comply with the standards. 49 In this report we present and interpret our findings considering these changing expectations.

Chapter 2 Study aims and objectives

We conducted the Food provision, cUlture and Environment in secondary schooLs (FUEL) study,77 in which we aimed to compare the implementation (including economic considerations) of the SFS and the SFP, and the nutritional intake and dental health of pupils in two groups of secondary school academies and free schools: those mandated and those not mandated to comply with the SFS. We also set out to explore the variation in implementation of the SFS and SFP and the food culture and environment across both school groups, and whether this variation is associated with nutritional intake and dental health. In relation to nutritional intake, we were interested in a range of key nutrients and food groups, but we focused on free sugar intake as our main outcome of interest, given the high consumption of free sugars in the adolescent age group8 and the focus of several of the school standards on reducing the intake of foods and drinks high in free sugars. 51

Research objectives

-

In secondary schools either mandated or not mandated to comply with the national SFS legislation, compare:

-

school food provision and compliance with the SFS

-

the school food environment/culture and the food curriculum, and implementation of the SFP actions

-

the nutritional intake and dental health of school pupils, focusing on free sugar intake as the primary outcome

-

the costs of food provision, food curriculum delivery, and other measures to influence the school food culture and environment.

-

-

Explore the variation in compliance with the SFS and implementation of SFP actions in secondary schools and use this to develop a typology of schools.

-

Use the developed school typology to explore associations between the school types and pupil dietary and dental outcomes.

Research questions

-

In secondary schools mandated or not mandated to comply with the national SFS, are there differences in:

-

provision of school food?

-

sales of different food types?

-

uptake of school-provided food?

-

the school food environment, culture and curriculum?

-

-

How does implementation of the SFS and SFP vary across secondary schools, and how does the school context influence this?

-

What are the different school types in relation to SFS and SFP implementation?

-

What is the economic impact of the SFS and SFP?

-

In pupils attending secondary schools mandated or not mandated to comply with the national SFS, are there differences in:

-

nutritional intake (including free sugar intake) at school lunchtime, in school time and overall?

-

dental caries experience?

-

-

Do any differences in pupil dietary and dental outcomes across the SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated schools vary by:

-

year group?

-

lunch source (school-provided vs. brought from elsewhere)?

-

socioeconomic status?

-

-

Is there an association between the identified school types and dietary and dental outcomes in school pupils?

Chapter 3 Methods

Study design

The study design was an observational, multiple-methods study comprising two phases. The first phase involved collecting a variety of data on SFS/SFP implementation, and school and pupil outcomes in the SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated schools. These data were used to compare outcomes across the two groups and develop a typology of schools based on SFS and SFP implementation. The second phase was a qualitative case study in which a small number of schools were identified to understand the experiences of schools in implementing and embedding the SFS and SFP, and the influence of the wider school context on this implementation. In addition, we undertook an economic evaluation to assess how the costs and outcomes compare across SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated schools.

Setting and population

The sampling frame for the study comprised secondary-phase academies and free schools located in 14 local authority areas in the West Midlands (Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Herefordshire, Sandwell, Shropshire, Solihull, Staffordshire, Stoke-on-Trent, Telford and Wrekin, Walsall, Warwickshire, Wolverhampton and Worcestershire) and 8 local authority areas in the East Midlands (Derby, Derbyshire, Leicester, Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Nottingham City, Nottinghamshire and Rutland). The West and East Midlands include urban and rural areas and have populations of around 6 million and 5 million, respectively. Compared with other regions in England, the West Midlands has a young age structure, with 18% of the population under 15 years of age. 78 Both regions have relatively high ethnic diversity, with 24% of the West Midlands and 18% of the East Midlands populations of ethnicities other than White British,79 and contain a number of local authority areas with high deprivation (e.g. Birmingham, Walsall, Wolverhampton, Nottingham). 80

Sampling and sample size calculation

Schools

To generate our sampling frame, we identified all state-funded secondary school academies and free schools in the 22 local authority areas outlined above using DfE routine data. As we were comparing two groups of schools, those mandated and those not mandated to comply with the SFS, we restricted the sampling frame to include only academies and free schools. The reason for this was that these are the only types of state-funded secondary schools that can potentially have exemption from the SFS (i.e. if they were established between 2010 and 2014). We excluded other secondary school types as they are all legally required to comply with the SFS and so could only be recruited to the SFS-mandated group, and we wanted to enable comparability in terms of other school characteristics across the two school groups. The excluded school types significantly differ from academies and free schools in their governance structures (local authority-maintained schools) or because they are specialist/alternative educational providers, and therefore their inclusion in the SFS-mandated group would reduce comparability across the two school groups. In 2019, at the start of this study, academies and free schools were providing education to 72% of secondary school pupils in England,81 and by the end of the study this figure had risen to 80%. 82

We used stratified sampling, based on propensity score methods,83 to increase the comparability of schools and reduce the influence of confounding. Propensity scores were generated using the following school characteristics:

-

local authority area

-

establishment type (academy sponsor-led, academy convertor or free school)

-

rural or urban categorisation

-

number of pupils

-

percentage of female pupils

-

proportion of pupils from ethnic minorities groups

-

proportion of pupils with English as an additional language (EAL)

-

proportion of pupils with special educational needs (SEN)

-

proportion of pupils eligible for FSM

-

Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index [IDACI, a component of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) representing the proportion of children aged 0–15 years living in income-deprived families, measured for the lower-layer super output area in which the school is situated]

-

presence or absence of a sixth form (education provision for 16- to 18-year-olds)

-

selective or non-selective admission policy

-

religious status: faith school or secular.

The propensity score was derived from a logistic regression model, fitted using these variables to predict whether SFS compliance was mandated. The schools were split into four strata using the propensity score quartile cut-offs, and within each strata schools were divided into SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated schools, generating eight sampling groups within the sampling frame. Schools in each group were randomly ordered and invited sequentially, the intention being to recruit schools from across all eight groups and achieve an even split of SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated schools.

Pupils

We sampled pupils attending participating schools. We identified form groups or other class groupings [such as personal, social, health and economic education (PSHE) classes], attempting to select class groupings that were representative of the general year group and avoiding groupings that were streamed according to academic ability or related to a non-core, selected subject. From these class groupings, one class from each of years 7 (age 11–12 years), 9 (age 13–14 years) and 10 (age 14–15 years) were selected to ensure that a range of ages was included in the sample. Pupils in these three selected classes were invited to take part in data collection.

School staff and governors

We invited a selection of staff and governors from participating schools to take part in the study, aiming for at least four representatives from each school (see School-level data capture for details of the staff groups recruited).

Sample size

We conducted a power analysis to estimate the required sample size, based on the comparison of free sugar intake in pupils attending SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated schools. We used data on free sugar intake pre and post implementation of the 2006 legislation from a study conducted in English middle schools84 to inform the analysis. The study reported a reduction in free sugar intake at school lunch of 6 g [standard deviation (SD) 11 g] in pupils consuming school-provided food, and 2 g (SD 13 g) in those consuming packed lunches; therefore, for this study we based our power analysis on the ability to detect a 4-g difference between groups. Assuming a SD of 11 g, an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.1 (a conservative estimate85) and balanced cluster sizes, we estimated that to detect this difference with at least 90% power and at 5% significance, we would require 990 evaluable participants and 22 clusters (schools) in each group (total schools, n = 44; total participants, n = 1980). Within each year group cluster, we anticipated that there would be a minimum of 15 students, with a total of at least 45 students for each school (average cluster size, n = 45).

An additional power analysis was conducted in November 2021, as it became apparent that we were unlikely to achieve the original target school sample size (n = 44) due to ongoing interruptions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. At this point, based on data collected until that time, we calculated that the average number of students participating from each school was 68, and we took note that it was unlikely that we would be able to recruit equal numbers of schools to the SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated groups (due to a lower number of SFS-mandated schools in the sampling frame). We therefore used a cluster size of 68 and accounted for a likely imbalance across the school groups in this additional power analysis. With all the other parameters kept the same, we estimated that 14 schools in the SFS-mandated and 20 schools in the SFS-non-mandated groups would give 87% power, and 17 schools in the SFS-mandated and 23 schools in the SFS-non-mandated groups would give 92% power.

Recruitment and consent

Recruitment materials, including school, school staff and participant invitation letters, and school staff, pupil and parent information sheets and consent forms, were reviewed by the study public advisory groups (see Public involvement methods) and revised according to their feedback.

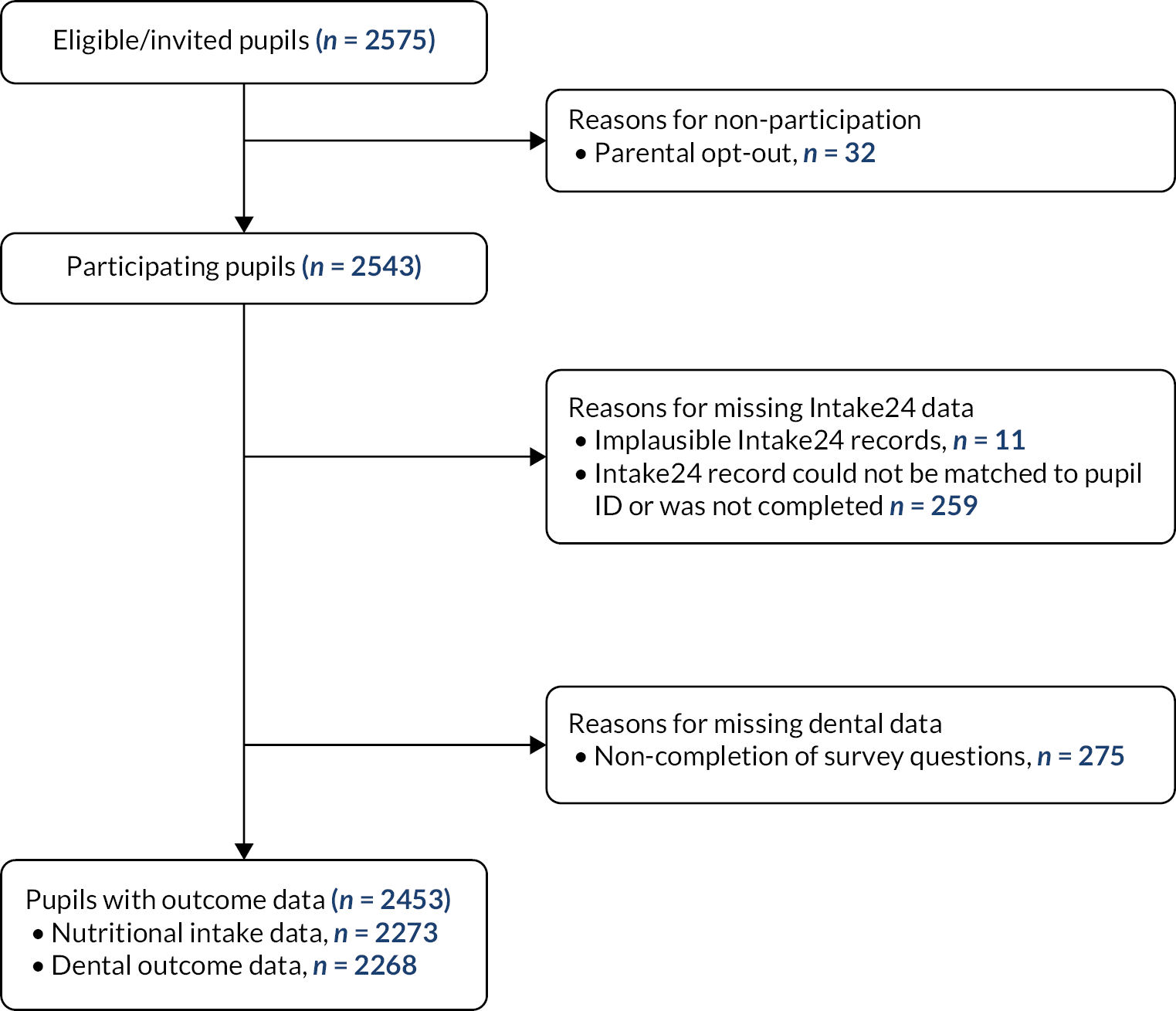

School and pupil recruitment commenced in October and November 2019, respectively, and was due to be completed in the 2019–20 academic year. However, because of restrictions in place in England during the COVID-19 pandemic, recruitment and data collection were suspended in March 2020 but recommenced in May 2021 and ran until April 2022.

Schools

Postal and e-mail invitations, including a study information leaflet, were sent to the headteachers of schools in a staggered manner, inviting several schools from each of the eight sampling groups at a time. Invitations were followed by telephone calls to schools, with additional e-mails sent as required. For schools expressing an interest, we arranged face-to-face or remote (telephone call or video) meetings to discuss the study and explain what taking part would involve, and to provide an opportunity for the school to ask questions. Once a school agreed to participate, they were asked to complete and sign a school agreement outlining the expectations of the school and the research team. Schools received a £300 payment for participating in phase I and a tailored report detailing the school’s compliance with the SFS and implementation of SFP actions. Schools were asked to provide the study team with a specific study liaison member of staff.

Staff/governors

Relevant staff and governors were identified by the liaison person and invited to take part by e-mail, which included a participant information leaflet. Written consent was obtained. Invited staff were those identified within the school to have roles relating to food provision, the eating environment, the food curriculum or SFS/SFP implementation (including headteachers, catering staff, PSHE leads, teachers with responsibility for the food/cooking curriculum and relevant representatives from the governing body).

Pupils

All pupils in selected classes were invited to participate. Parents were given written detailed information about the study at least 1 week prior to the first data collection session. Schools assisted in the distribution of this information to parents in different formats (e.g. e-mail, post, website). Parents were not asked for active consent but were given the opportunity to complete and return a form to opt their child out of participating in the study. This approach to parental consent was used to ensure that there was no socioeconomic bias in our sample, as previous research has shown that active consent letters distributed by schools are less likely to be returned by more socioeconomically disadvantaged parents. 86 Participant information leaflets were distributed to pupils at least 1 week prior to data collection. Researchers also gave a verbal overview of the study on the day of the first data collection session and pupils were invited to ask questions. Written assent was be obtained from pupils whose parents had not opted them out of participating. Based on the advice we received from our youth public advisory group (see Public involvement methods), pupils were given a £5 shopping voucher as a thank-you for taking part.

Data collection

Theoretical considerations guiding data collection

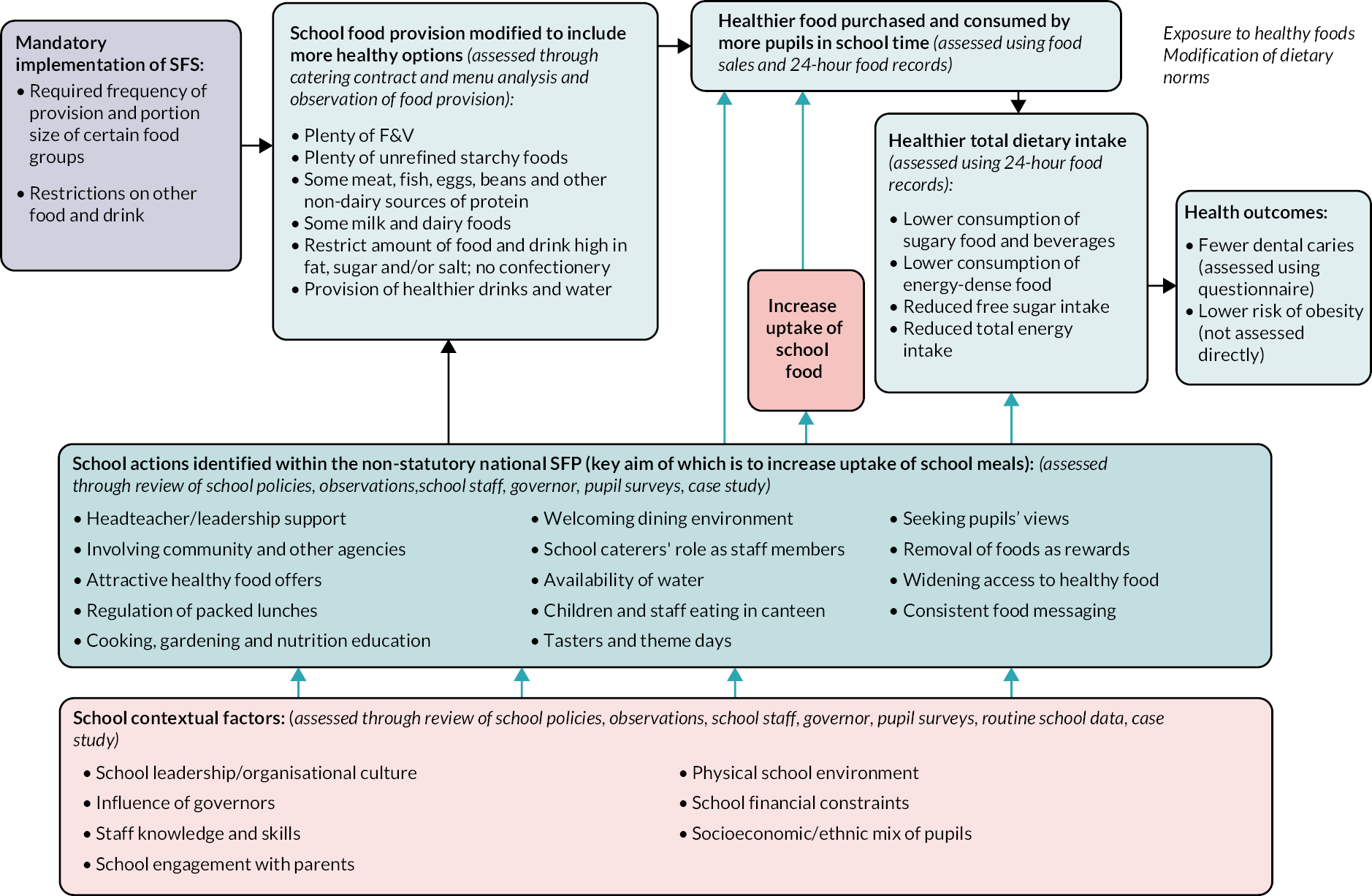

We developed a logic model to outline the processes by which the SFS and SFP are assumed to produce health gains (Figure 1). Through this model we articulated that health gain is generated:

FIGURE 1.

Logic model for the influence of SFS and SFP actions on children’s dietary intake and health outcomes.

-

directly via a change in school food consumption

-

indirectly through healthy food environments, and curricular and other activities that are designed to change pupils’ dietary knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, which impact on their food and drink consumption in and out of school.

The logic model also outlines that the extent to which the SFS and SFP positively impact on dietary intake and health depends on their implementation within a school, which is influenced by contextual factors (e.g. school leadership, the wider school culture, the physical environment).

The logic model, along with the principles outlined in the UK Medical Research Council framework for process evaluation,87 guided our data collection strategy. We planned to capture data aligned with each of the boxes in the logic model, enabling us to assess schools’ compliance with the SFS and implementation of the SFP actions. We also planned to assess the wider school context and the extent to which the two national school food policies (SFS and SFP) were adopted by and embedded within schools. Broadly, we structured our data collection to encompass:

-

food provision

-

the school food culture and environment

-

costs relating to school food provision, culture and environment

-

school contextual data

-

embedding of school food policy within schools

-

school meal uptake

-

school food sales

-

pupil outcomes (nutritional intake and dental caries experience; see Pupil outcomes).

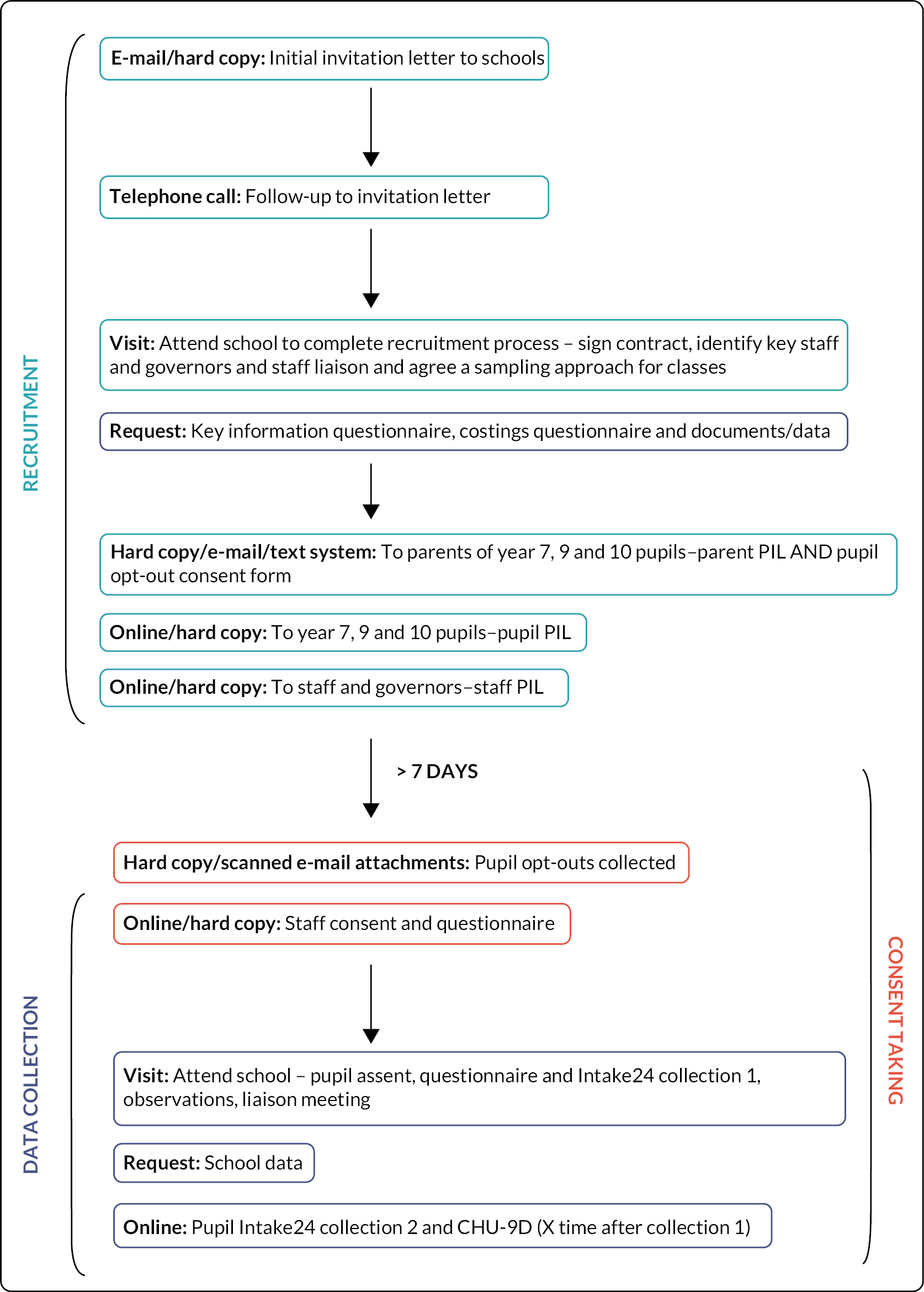

Data collection was undertaken at the school and the individual pupil levels and is outlined below. Recruitment and data collection processes are presented in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment and data collection flow chart. CHU-9D, Child Health Utility 9-Dimensions; PIL, participant information leaflet.

School-level data capture

School surveys and document collection

Schools were asked to complete two paper-based surveys (available on the study web page at www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/92/39). The first was a survey to collect information on catering and dining arrangements, school meal uptake and features in place to support healthy eating (key information survey). In this survey, schools were also asked to nominate relevant staff/governors to be invited to complete the staff/governor survey. The second was a survey to collect information on costs relating to food provision, food/healthy-eating education and other support for healthy eating (costing survey). The two school surveys were reviewed by our public advisors (senior school leaders) and were edited based on feedback on the wording and ease of completion. Because of the initially low response rates for the costing survey, it was shortened and converted to an online format in November 2021, which was again reviewed by a public advisor.

We also collected key documents relating to food provision and food/healthy-eating education, including catering contracts (where external catering providers were in place), school food and other relevant policies (e.g. behaviour policy), information on the school curriculum relating to food and diet, minutes of meetings relating to school food (e.g. Board of Governors meetings, School Council/Student Voice meetings), school development plans or school self-evaluation forms, and other documents identified by the school relating to food provision or food/healthy-eating education, for example school-administered pupil surveys and school food reviews.

Current school menus were obtained for each food outlet and mealtime, where available, to enable assessment of menus against the SFS.

Staff and governor surveys

Questionnaires were sent to key staff and governors who had been identified within the school to have roles relating to the school food provision, environment, curriculum and/or SFS/SFP implementation. These were available in online or paper formats (including a stamped addressed return envelope). Four separate questionnaires (available on the study web page at www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/92/39) were developed for the key staff/governor groups: (1) catering survey, (2) senior leadership survey, (3) teaching survey and (4) governor survey. The purpose of these surveys was to:

-

assess implementation of SFP recommendations

-

gather their views on the school food culture and environment

-

assess the extent to which the two national policies were embedded within their school.

Questions relating to SFP implementation were informed by the SFP headteacher, governor and school checklists. 56–58 Questions relating to the embedding of the SFS and SFP were adapted from the Normalisation Measure Development (NoMAD) survey [underpinned by normalization process theory (NPT) and designed to assess how a way of working becomes embedded as normal practice88,89]. Staff/governor surveys were reviewed by relevant public advisors and were edited based on feedback on the wording and ease of completion.

Observation of school canteens and food outlets

Researchers visited all participating schools to undertake a 1-day observation of the school food provision and eating areas (including dining and communal facilities), the food on offer and the wider environment in the school. An observation tool (available on the study web page at www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/92/39) was developed to enable assessment of the food provision against the SFS and assessment of implementation of SFP actions and to gather data on the eating and wider school environment, including where food and drink is available and where pupils go to consume foods. The observation tool captured all foods and drinks available in food outlets, including main meals, snacks, drinks and condiments. Items in the observation tool relating to the implementation of SFP actions were informed by the headteachers, school governors and school healthy-eating culture and ethos checklists. 56–58 The observation tool was piloted by two researchers in one secondary school (not within the sampling frame) prior to data collection and edited for ease of completion.

All school food provision occasions over the course of a single day were observed, which typically included breakfast, mid-morning break and lunch provision, and occasionally afternoon-break/after-school provision. For each occasion researchers completed an observation tool for each food outlet and dining area in the school.

Members of the core research team and sessional researchers were employed to undertake school observations. Sessional researchers received a half-day training session prior to data collection visits and were supported during their first observation by a member of the core research team. Observation tools were checked by a member of the research team following data collection visits so that any queries could be resolved.

School food sales data

To assess sales of food in schools, we requested aggregated itemised data on food sales from participating schools’ online payment management systems for two designated months in the current/previous academic year (June and November). For schools recruited in 2021–2, we also requested food sales data from June to November 2019 to enable a comparison of pre-pandemic sales with current sales. Sales data were converted to Microsoft Excel files where required, with the conversion checked for accuracy.

Pupil outcomes

We aimed to compare dietary intake and indicators of dental caries in pupils in the SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated secondary school groups. As one of the main outcomes of interest was free sugar intake, and for the purposes of our sample size calculation, we defined our primary outcome as intake of free sugars (in grams). We assessed free sugar intake during school day lunch, while present at school, and during the full 24-hour period of the same school day.

Secondary nutritional outcomes were:

-

percentage of dietary energy intake from free sugars

-

total energy intake (TEI; kcal)

-

total fat intake (g)

-

fibre intake (g)

-

fruit and vegetable portions consumed

-

number of SSBs consumed

-

number of sugar and chocolate confectionery items consumed

-

number of HFSS foods consumed (defined according to the Nutrient Profiling model90)

-

free sugar intake providing ˃ 5% of 24-hour TEI

-

consumption of five or more portions of F&V during a 24-hour period

-

number of eating/drinking occasions (excluding plain water) during a 24-hour period.

As with the primary outcome, the secondary nutritional outcomes numbered 1–8 above were assessed during school day lunch, while present at school, and during the full 24-hour period of the same school day.

Dental outcomes were:

-

the presence of any symptoms indicating dental caries in the past 3 months

-

the number of dental caries symptoms in the past 3 months

-

past dental caries treatment.

Pupil data capture

Pupils were invited to two computer-based sessions, completed during timetabled lessons, and asked to complete (1) an online survey (using REDCap software;91 available on the study web page at www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/92/39) hosted at the University of Birmingham and (2) an online 24-hour dietary recall. For the first session, at least one researcher was present to facilitate the session. This included providing a verbal overview of the participant information leaflet, answering any questions related to participation and providing assistance throughout the session to pupils who required it. The second session was facilitated by the class teacher approximately 2–4 weeks later. Paper copies of the surveys were available if there were any issues with computer/internet access. In some situations, pupils were asked to complete the survey or 24-hour dietary recall at home, for example if a pupil was late to the session, if a pupil had issues with computer/internet access or if the school could not find a timetabled session to complete the second data collection session.

Dietary intake

Dietary intake data were collected using Intake24, an online self-completion 24-hour recall tool that is based on the multiple pass method (shown to be the most accurate for assessing dietary intake in older children and adolescents92) and has been used successfully to collect data from secondary-school-aged children. 93 A comparison of Intake24 with interviewer-led recall in participants aged 11–24 years reported that Intake24 underestimated energy intake by just 1% and differences in mean macronutrient/micronutrient intakes between the two methods were within 4%. 93 Photographs are used for portion size estimation, a method that has shown good agreement with 4-day weighed intakes in adolescents. 94,95 Intake24 matches foods and drinks to the NDNS food database containing over 2300 foods, and links to nutrient composition data from the UK Nutrient Databank codes. 96

While Intake24 contains several culturally diverse food items, it does not include some traditional foods that would be commonly consumed by some cultural groups in the Midlands population (particularly South Asian traditional foods). To improve the applicability of the tool to the study population, the research team adapted Intake24 for a more culturally diverse population. Adaptation methods included piloting Intake24 with members of minority ethnic communities, community nutritionist consultation and literature review to identify food/drinks commonly consumed by minority ethnic groups but not included in the Intake24 database. Identified foods (n = 63) were added to Intake24. Nutrient composition data for these items were obtained by matching to existing items in Intake24 or from other existing food composition sources. 97,98

We collected dietary intake data from pupils for a minimum of one complete 24-hour school day period and a maximum of two complete, non-consecutive school days. In Intake24, pupils entered all foods and drinks consumed at named mealtimes and outside mealtimes as appropriate. Pupils were asked to provide information of the source of the food/drink consumed (school café/canteen/shop; school vending machine; shop café/restaurant/fast food place/take away/vending machine outside school; from home) and location of consumption (in school; at home; on the journey to/from school; another location) for each eating occasion. Source of foods/drinks consumed was used to generate the explanatory variable ‘lunch source’. This variable was further coded into two categories: 100% school-provided (school café/canteen/shop or school vending machine) or other (shop café/restaurant/fast food place/take away/vending machine outside school, home, or multiple sources including school and elsewhere).

Dental health

Data on dental health were gathered in the session 1 survey. We used validated self-report measures from the national Child Dental Health Survey14,99 to assess dental symptoms in the previous 3 months (toothache, a sensitive tooth, bleeding or swollen gums, a broken tooth, mouth ulcers, bad breath, a filling or a decayed tooth taken out) and treatment received in the past (filling of a permanent or milk tooth, permanent or milk tooth taken out due to decay, a general anaesthetic before dental treatment or sedation before dental treatment) to indicate caries experience. The survey also included questions on frequency of tooth-brushing and self-rated dental health.

Sociodemographic and other data

The online surveys included questions relating to sociodemographic characteristics of pupils, including age, gender, ethnicity (using the 2011 Census classification) and postcode data. Postcodes were mapped to IMD 2019 scores100 and used to obtain water fluoridation levels at participants’ homes (obtained from the websites of local water companies). Participants were also asked if they were receiving FSM.

In the first survey, we also asked questions relating to SFP recommendations, for example availability of water and awareness of school food policies, and gathered participants’ views on the school food culture and environment, for example the eating experience, facilities and school support for healthy eating. In the second survey, we asked questions relating to pupil expenditure on food and included the Child Health Utility 9-Dimensions (CHU-9D),101–103 a preference-based paediatric health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measure.

Data matching and cleaning

Data from the online (REDCap) surveys were matched to dietary data (Intake24) using a one-time unique username for each pupil, which pupils entered into their online survey and Intake24 record. Where different usernames were required (e.g. the username failed on one of the systems), an alternative username was provided and a note was made so that the records could be matched. Some REDCap survey records could not be matched with Intake24 records due to errors in pupil data entry (e.g. wrong username entered), in which case the dietary data for these pupils could not be included. Some pupils completed the online survey but did not finish their 24-dietary recall within the allocated time slot.

Session 1 and session 2 data were matched on personally identifiable characteristics recorded in the online surveys, that is name, date of birth, postcode and school. Some participants completed only session 1 or session 2 of the data collection due to absence from school, or pupil non-assent for one of the two sessions. As a result, some participants had only one Intake24 record and had missing survey data collected at only one of the two time points; for example, dental outcome data were collected in session 1 only and CHU-9D data were collected in session 2 only. Data on receipt of a FSM were originally collected in the session 2 survey only. This question was subsequently added to the session 1 survey to reduce the number of missing data due to non-completion of session 2. In some schools (n = 5), we were unable to complete the second session of data collection with pupils due to prolonged school closures put in place as part of the COVID-19 pandemic response.

Other cleaning steps applied to the sociodemographic data were as follows: adjusting year of birth when respondents had entered implausible values; reassigning school year group where appropriate (based on date/time stamp of survey completion and age); converting addresses to postcodes; and assigning free-text descriptions of ethnicity to existing defined categories where appropriate (only when these matched defined categories, e.g. White British).

A series of steps were required for cleaning nutritional intake data generated from Intake24 records. These are provided in Appendix 1, Table 31.

Nutritional outcomes were generated from the cleaned data, and the distribution of values for each outcome was checked in Stata version 17 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to identify outliers, defined as values above or below 3 SDs from the mean. The Intake24 data underlying identified outliers were visually inspected for potential errors (e.g. portion sizes, duplication of items), and a judgement was made about whether these records were plausible, taking an inclusive approach. Where records were deemed to be implausible due to excessive portion sizes, these were edited by taking the Wrieden average portion values,104 where available, or alternatively the most common portion size for that item from the Intake24 data set. If more detail was provided by the participant regarding portion size, for example three packets of crisps, we used this information to calculate the revised portion size. Items deemed to be duplications of foods/drinks already entered by a participant were removed. Full records considered to be implausible were removed (these are detailed in the results below).

Public involvement methods

Aim

Through our public involvement activities, we aimed to consult with young people, parents and school staff/governors on the design and conduct of the study, including recruitment, data collection, data presentation and dissemination.

Recruitment and membership

Throughout the study, we had a teacher in a school senior leadership role as part of our research team (SW; see Acknowledgements), who provided advice on a range of aspects of the study, including engaging schools and pupils, access to school-owned food sales data, considerations around school management and governance systems, and planning data collection as part of timetabled school sessions.

We convened three public advisory groups: (1) young people, (2) parents and (3) school staff and governors. Members of the young people’s group were originally recruited through two schools with whom we had established relationships. In each school we met face to face with two groups of six pupils (year 7, age 11–12 years; and year 10, age 14–15 years), with a total of 24 pupils involved. As the study progressed, we linked with the established Young People’s Advisory Group for the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) West Midlands Clinical Research Network. We met with this group via video call on two occasions, with 7–9 young people in attendance.

We initially recruited a group of four parents of secondary school pupils via personal contacts and networks within the University of Birmingham. This group met face to face on one occasion, with further interaction over e-mail due to the national lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020). A new parent group was established towards the end of the study (July 2022) using social media and participating school contacts. This group comprised eight members and met remotely on one occasion to advise on study dissemination.

The school staff/governor group members were recruited through personal contacts and networks within the University of Birmingham. This group met on four occasions, both face to face and remotely, with additional interaction over e-mail during the national lockdown. Membership of this group fluctuated between three and six members and included teachers, senior leadership team (SLT) representatives and governors. Members of all public advisory groups received reimbursement for time and expenses.

We also had three public representatives on our Study Steering Committee (SSC): SB (teacher with a senior leadership role in a multi-academy trust; SSC member March 2019–January 2020), AH (SSC member January 2020–September 2022) and CM (retired headteacher and chief executive officer of multi-academy trust; SSC member March–September 2022). These public representatives provided advice and oversight throughout the study.

Methods of engagement

We developed terms of reference for the parent and staff advisory groups. In the initial meetings with all the public advisory groups, we presented a summary of the study and outlined the role of the group. During group meetings, we used an interactive approach to engaging with our public advisors. This involved working in small groups to review study materials with questions to prompt discussion, and using voting buttons, emoticons, the chat function (if online) and audio–visual materials to engage group members. We took structured notes and presented the thoughts and views expressed in the meetings to the Study Management Team and the SSC for consideration.

Data analyses

Assessment of school food standards adherence

We assessed compliance with the SFS based on (1) observation of mealtimes across a full school day and (2) review of weekly menus. The purpose of completing an assessment of SFS compliance on the 1-day observational data was to capture the off-menu foods on offer in secondary schools such as breakfast and breaktime offers, drinks, condiments, snacks and sandwiches. The observational data also enabled us to gain further information on menu items, as menus often lacked detail such as the types of fruit/vegetables or cakes/biscuits offered. The menu review was required in addition to the 1-day observational data to enable assessment of standards that apply to schools on a weekly (e.g. starchy foods cooked in fat or oil) or 3-weekly (e.g. oily fish) basis.

School food standards compliance criteria were guided by the UK statutory instrument The Requirements for School Food Regulations 201444 and School Food Standards Practical Guidance. 51 A SFS question-and-answer document was also used to check the interpretation and definitions of food categories. 105

Some additional definitions of food categories beyond those given in the SFS documentation were required to categorise all foods and drinks offered, for example desserts, confectionery and snacks (available on the study web page at www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/92/39). We did not collect recipes, so we developed and applied rules for some of the food types described in the SFS; for example, for ‘fruit-based desserts’ (with a content of at least 50% fruit measured by volume of raw ingredients), we included desserts such as fruit pie, fruit crumble, fruit cobbler and jelly made with fruit. For other dessert items, the research team searched the internet and reviewed a standard recipe (e.g. British Broadcasting Corporation Good Food) for the dessert or a similar item to make a judgement on whether it met the criteria for a fruit-based dessert. Drinks and prepackaged snacks, biscuits and cakes were reviewed for compliance using the ingredients lists detailed on brand or shopping websites.

All foods and drinks recorded in the observation tool and menus were extracted into Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheets and coded based on the food/drink type. One researcher carried out data extraction, and two researchers familiar with the SFS independently coded foods and drinks and judged SFS compliance for the two sets of data (observation and menu), entering their judgements into a data entry form. The judgements of the two researchers were compared, and, where discrepancies arose, the research team met to agree on a final judgement. The 1-day observation data judgements and menu judgements were combined into an overall SFS compliance judgement for each standard. Details on the standards assessed and how judgements were combined across 1-day and menu assessments are available on the study web page (www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/92/39).

As a final quality check, the coded food/drink data were back-checked against menus and observations for any missing foods/drinks or errors in data entry, and final SFS judgements for all schools were checked for consistency in application (MM). Any judgements that were deemed inaccurate were reviewed and corrected by two researchers (MM and AD). Final judgement options were yes (meets standard), no (does not meet standard), can’t tell (it was not possible to assess compliance due to lack of information) or not applicable (standard did not apply). Not applicable (N/A) was used for standards relating to drinks, condiments, dried fruit and crackers/breadsticks when these items were not sold/not available in the school. We calculated the proportion of standards met for each school using the number of assessable standards as the denominator (i.e. excluding ‘can’t tell’ judgements).

Assessment of School Food Plan actions

Actions included in the SFP were identified following a comprehensive review of relevant SFP resources: the checklist for headteachers, the creating a culture and ethos of healthy-eating guidance, and the guidance for school governors. 56–58 Some actions were unique to each document, whereas others were repeated or similar across documents. Those that were repeated or similar were merged to form single actions, retaining as much of the original wording as possible. We identified a total of 69 actions, which we grouped into 9 ‘themes’ based on the headings used in the SFP resources. More detail about the specific actions within each theme is provided in Appendix 2, Table 32.

We assessed the implementation of SFP actions using a variety of data sources, including researcher observation, survey responses from schools, staff and pupils, and the review of school documents, for example curriculum documents, catering contract and meeting minutes. Further detail on the source of data for specific actions and data points/questions used for assessment is provided in Appendix 2, Tables 32 and 33.

A judgement of red, amber or green (RAG) was made on each action for each data source, with red indicating that the action had not been implemented, amber indicating that it had been partially implemented and green indicating full implementation. If data were missing (e.g. incomplete survey responses or documents not provided by schools), a judgement could not be made, indicated by a ‘no judgement’ rating. A final judgement of high, medium or low implementation was made for each action point based on RAG ratings across all data sources, with rules for combining these judgements agreed in advance by the research team (available in Appendix 2, Table 34). The assessment was conducted by one researcher. Uncertainties were discussed with the research team, who then agreed on a final judgement.

The proportion of actions judged as ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’ was calculated using the number of assessable standards as the denominator (i.e. excluding those actions for which a judgement could not be made).

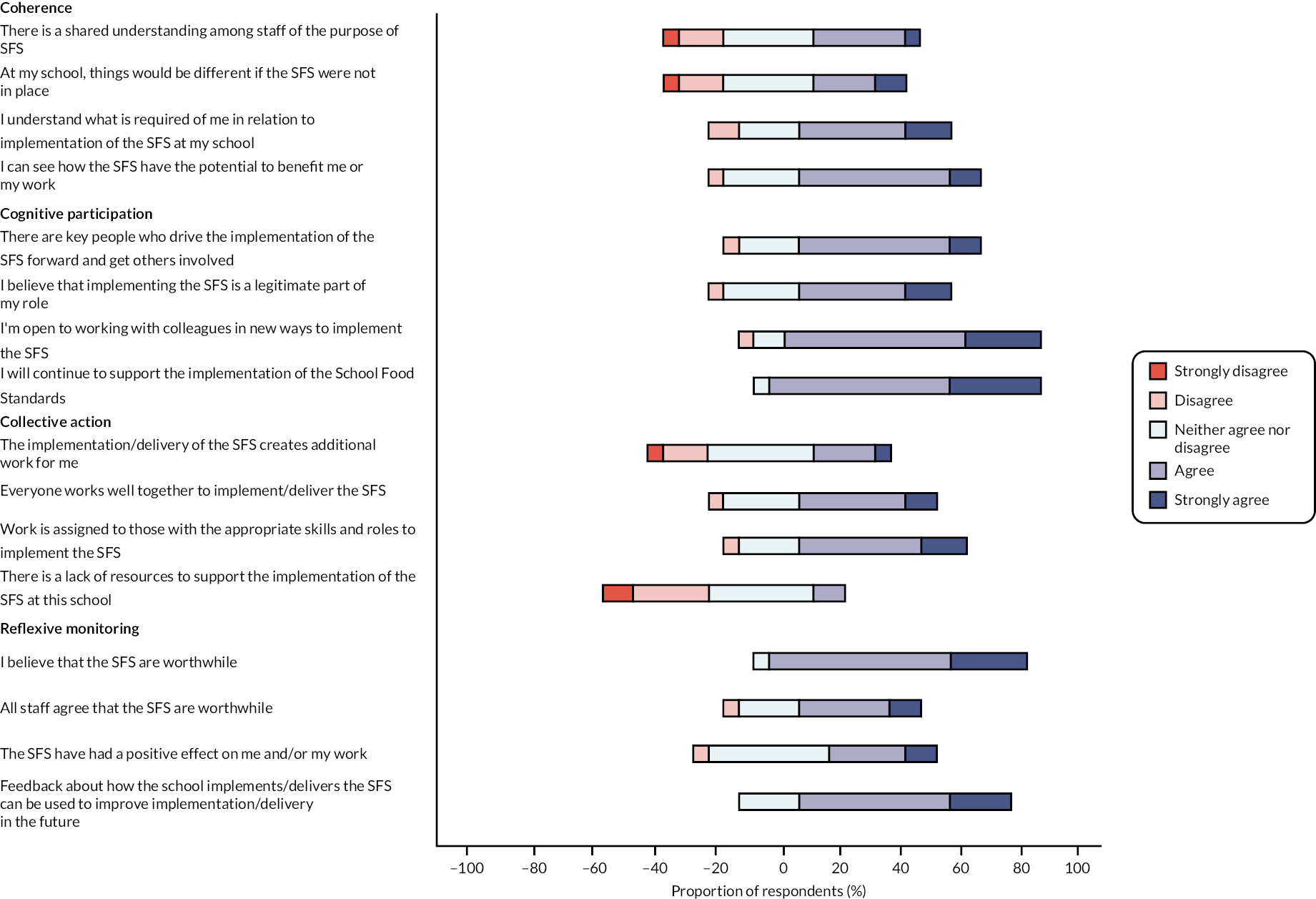

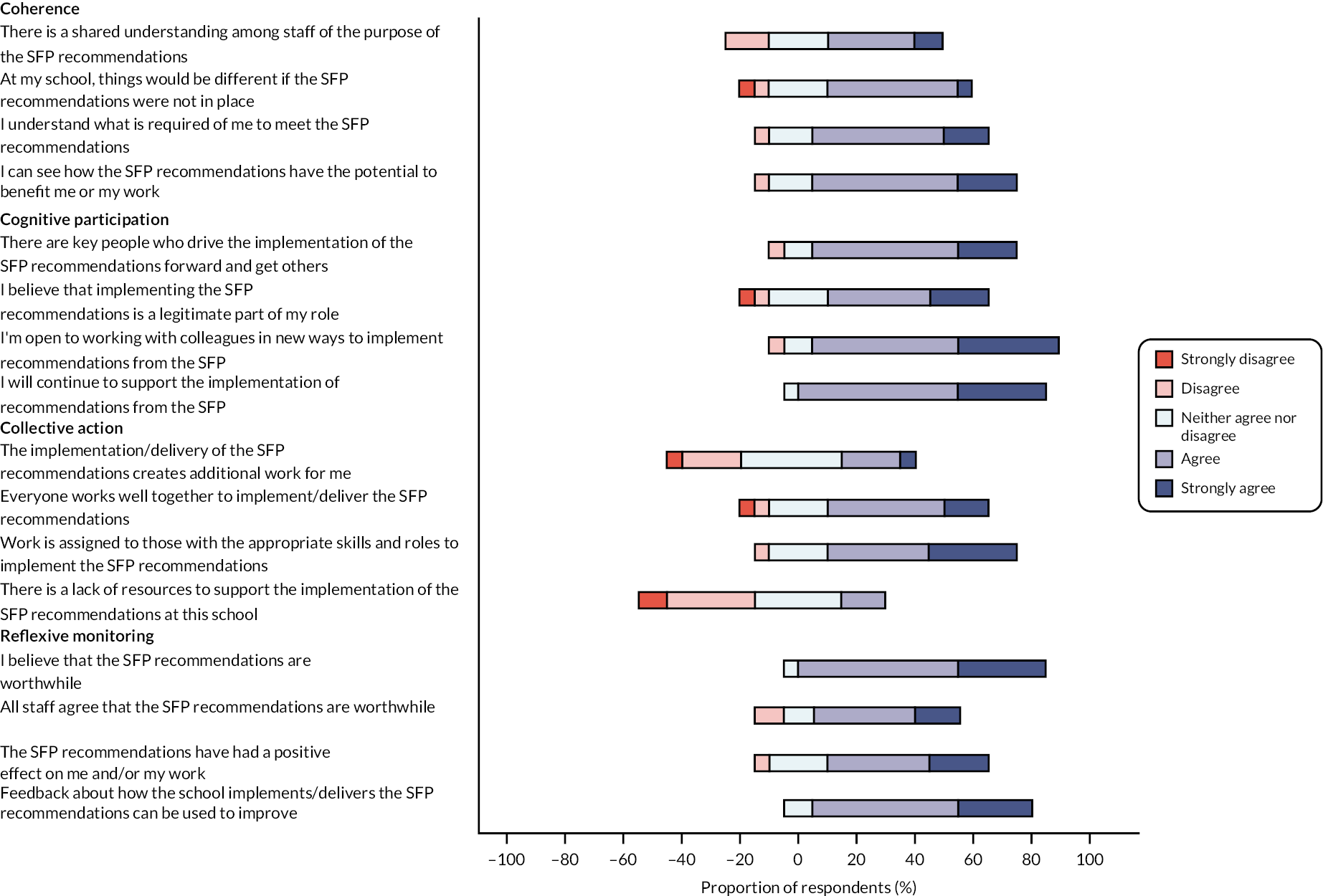

Assessment of the embedding of national school food policy within schools

Questions were developed to assess the embedding of the SFS and SFP within schools. These were adapted from the NoMAD instrument88,89 (based on NPT106) with statements mapping onto the relevant NoMAD constructs and their constituent components in relation to coherence (individual and collective sense-making), cognitive participation (relational work, building a community of practice), collective action (operational work, enacting a new set of practices) and reflexive monitoring (appraisal, understanding how a new set of practices affects individuals and others). Details of relevant questions and their relation to NPT constructs are available on the study web page (www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/92/39). Data from these questions were extracted from the staff and governor survey data sets and responses presented in tables and graphs to explore variation in responses across the SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated school groups and across staff/governor groupings [see Embedding of the school food standards and School Food Plan national school food policies within schools (research objectives 1a and 1b)].

Development of typology schools in relation to school food provision and support for healthy eating

School-level data were used to identify different school ‘types’ in a two-stage process. In the first stage, we used SFS compliance data to generate school types. In the second stage, we inspected SFP implementation data to identify subtypes within the types generated in stage 1.

Stage 1

Among the 32 SFS, we focused on two subsets of standards. These were selected based on their relation to obesity or dental health (i.e. food/drinks that are energy-dense and/or high in fat or sugar; n = 12 standards) or their relation to achieving a wide range of foods across the week (variety; n = 15 standards). The rationale for selecting these standards were as follows: (1) reducing obesity and improving dental health are public health priorities in this age group, and the pupil outcomes explored in this study relate to these priorities; and (2) one of the aims of the SFS is to ensure that children have access to a healthy, balanced diet with a wide range/variety of foods. The selected standards and those which were excluded are detailed in Appendix 3, Table 35.

The extent of compliance with the two sets of standards was rated as ‘low’, ‘medium’ or ‘high’ based on the proportion of standards met, with ≤ 33% indicating low compliance, 34–66% indicating medium compliance and ≥ 67% indicating high compliance. Any actions that could not be assessed were removed from the denominator. The schools were then grouped into types according to the two ratings that they received for the two sets of SFS (those relating to obesity and dental health and those relating to dietary variety).

Stage 2

We selected ‘indicator’ SFP actions (n = 17 out of 69) and classified schools as having ‘low’, ‘medium’ or ‘high’ levels of implementation for each of these actions based on the overall judgements described in Assessment of School Food Plan actions. We selected actions where there was a wide variation in implementation across schools and we excluded actions were there was a low response rate (i.e. where there were a large number of schools where no judgement could be made) to enable better comparison of implementation across schools. The selected actions are detailed in Appendix 3, Table 36.

The selected actions represent eight of the nine themes that we identified within the SFP actions. No indicator actions were selected within the theme of ‘School Food Policy’ because there was little variation in implementation of actions across schools and a high proportion of schools where no judgement could be made.

The school types identified in stage 1 (based on compliance with two sets of SFS standards) were divided into SFP subtypes A and B based on the proportion of selected SFP actions receiving a ‘high’ rating, with type A indicting a lower level of SFP implementation (≤ 50% SFP actions implemented to a high level) and type B indicating a higher level of SFP implementation (> 50% SFP actions implemented to a high level).

We presented school contextual data for the identified school types to explore any differences in the wider school context between the types.

School food uptake and sales data analysis

School food uptake

Data on uptake of school lunches at the school level were self-reported through the school key information survey. As these data were missing for some schools, we also used individual pupil participant data on the source of their lunch consumed during the school day from Intake24 records to give an estimate of the proportion of uptake of school lunches in each school. For each of these data sources we calculated the mean percentage uptake across all schools and across SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated schools.

School food sales

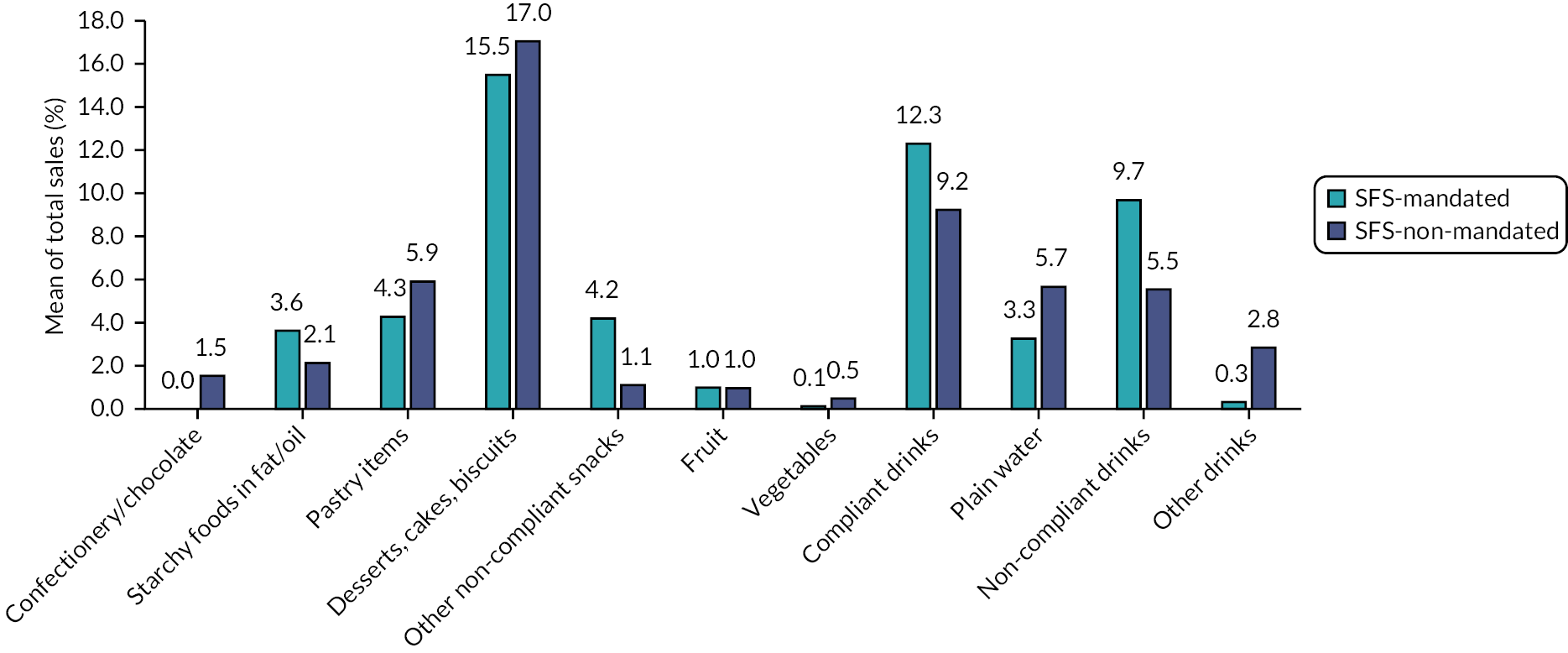

Owing to differences in how schools label foods within their payment systems and variation in the level of detail captured in food sales records, we were unable to explore all food/drink items sold in the schools. Instead, we focused on ‘indicator items’ from within the broader categories of foods detailed in the SFS (i.e. those prohibited, such as confectionery; restricted, such as pastry items; or encouraged, such as fruit), which appeared to be consistently recorded in the sales data across different schools. The indicator items included in our analyses are:

-

starchy foods cooked in fat/oil

-

pastry items

-

desserts, cakes, biscuits, puddings

-

confectionery, chocolate or chocolate-coated products

-

non-compliant snacks

-

fruit

-

vegetable sides and salads

-

non-compliant drinks

-

compliant drinks

-

plain water

-

other drinks.

Further details on the rationale for their inclusion, examples and exclusions are available on the study web page (www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/92/39).

We calculated the number of each indicator item sold over the month as a proportion of total sales for the month. Some items were removed from the ‘total sales’ calculation, for example condiments, non-food/non-drink items and staff sales (where indicated). All schools had some items coded as miscellaneous, but the extent to which this code was used by schools varied. We calculated the proportion of the total sales that were coded as miscellaneous for each school to explore this variation (details are available on the study web page at www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/92/39), as this presents a potential limitation when comparing sales of indicator items across schools (i.e. indicator items may be coded as miscellaneous in some schools but not in others).

We compared total sales across SFS-mandated schools and SFS-non-mandated schools for pre-COVID-19 pandemic time periods (June 2019, November 2019) and mid-/post-pandemic time periods (June 2020, November 2020, November 2021). We also estimated sales per pupil using the number of pupils on roll for the period of overall data collection to account for variation in school sizes.

We compared mean sales of indicator items as a proportion of the total sales for the month of data provided to give an overall summary of sales of indicator items for all schools. We also compared the monthly mean sales for indicator items as a proportion of the total sales in SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated schools.

Analyses of pupil nutritional intake and dental health data

The study statistical analysis plan is available on the study web page (www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/92/39).

Generation of pupil nutritional intake outcomes

Nutritional outcomes were generated from raw Intake24 data in Microsoft Excel using pivot tables for the three time points, as follows:

-

During school day lunch, which incorporated all foods and drinks participants indicated as ‘lunch’ using the Intake24 predefined meal names.

-

While present at school (school day), which incorporated any foods and drinks eaten between 9.00 a.m. and 2.00 p.m. inclusive, representing a typical school day but accounting for later start times and earlier finish times in some schools (based on information from participating schools about their school hours); and any foods or drinks consumed outside this period but on school premises, based on meal location provided by the participant (to account for earlier/later start/finish times in some schools, and the availability of breakfast, afternoon break or after-school food provision in some schools).

-

During the full 24-hour period of the same school day.

The process of generating the nutritional outcomes is presented in Appendix 4, Table 37.

Generation of pupil dental outcomes

Three dental outcomes were generated from the survey data relating to dental health:

-

Presence of dental caries (binary outcome) was indicated by self-report of the presence of at least one of the following conditions in the previous 3 months: toothache, sensitive tooth, bleeding or swollen gums, a broken tooth, mouth ulcers, bad breath, a filling, or a decayed tooth taken out.

-

Number of dental caries symptoms (count variable), indicated by the number of conditions listed above that were self-reported as present.

-

Treatment for dental caries (binary variable) was indicated by self-report of at least one of the following: a filling of a permanent or milk tooth or a permanent or milk tooth taken out due to decay.

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the primary and secondary outcomes for the study sample overall and by SFS group (SFS-mandated and SFS-non-mandated). Where participants had two 24-hour dietary intake (Intake24) records, the mean outcomes were presented.

Primary analysis

The primary outcome of free sugar intake (measured in grams) at lunch, during the school day and during the whole day (24 hours) was compared for pupils who attended SFS-mandated schools and pupils who attended SFS-non-mandated schools. The primary outcome was recorded in Intake24 for a minimum of 1 day and a maximum of 2 days for each participant. Each available observation was used in our analyses. For the comparisons of free sugar intake and other secondary nutritional outcomes at lunch and across the school day, participants with zero TEI at these time points were excluded. Linear multilevel models were used, with random effects allowing for repeated 24-hour dietary recall information for students, and clustering of students within classes and schools. However, we looked to simplify the models where appropriate when analysing the data. Following assessment of the random effects, we retained allowance for repeated assessment for individuals and clustering within schools but included year group as a fixed effect, rather than a random effect. The model was used to evaluate differences in outcomes between SFS status (mandated/non-mandated) adjusted for school-level and pupil-level variables (see adjustment variables: Adjustment).

Secondary analyses

There were 11 additional nutritional outcomes, 8 of which were explored at each of the 3 time points: school lunch, school day and over 24 hours. The analyses of these outcomes used multilevel linear models or multilevel Poisson models depending on the variable type (continuous or integer counts) and were constructed in the same way as described for the primary outcomes.

There were three dental outcomes, collected at one time point. Models for these outcomes used multilevel logistic or Poisson models (depending on binary or integer count outcome data) to evaluate differences between SFS status with adjustment for confounders, again with random effects allowing for the clustering of students within schools.

Adjustment

School- and pupil-level covariates were included as adjustment variables. School-level variables initially included those used for generating propensity scores (listed in Schools) as well as model of catering provision (in-house or external catering) and academic year of data collection (2019–20, 2020–1, 2021–2) to account for the potential influence of COVID-19 restrictions on school food provision and uptake and pupil dietary behaviours. Pupil-level variables included year group, age (generated from date of birth), gender (male, female, other/not stated), ethnicity (using 2011 Census high-level categories: Asian/Asian British, Black/African/Caribbean/Black British, White, and other/mixed/multiple/not stated), IMD (2019) quintiles (based on home postcode) and lunch source (100% school-provided or not; obtained from Intake24 records). Home and school water fluoridation levels (based on postcodes) and tooth-brushing frequency (from the pupil survey) were added as adjustment variables to the dental outcome models.

We simplified the models by reducing the number of school-level variables included as covariates. We conducted a backwards elimination process on the model with the outcome of free sugar intake at lunch. The school-level variables of in-house/external school food provision, percentage of pupils eligible for FSM and time of data collection were included as model covariates because of their relevance to the research question, and a backwards elimination process was conducted on all other school-level variables using an alpha value of 0.1. Following this process, establishment type, urban/rural location, number of pupils, percentage of male pupils, percentage of ethnic minorities pupils, percentage of pupils with EAL and selective/non-selective admissions policy variables were excluded from this and all other models with nutritional intake outcomes.