Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/55/44. The contractual start date was in September 2016. The final report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in April 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Hunt et al. This work was produced by Hunt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Hunt et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and aims

Context

This report describes a study evaluating the process and outcomes of developing and implementing a smoke-free policy in 2018 throughout Scotland’s prison estate. We first outline the legislative and policy context for the study when it was originally designed (see Legislative and policy context prior to commencement of the Tobacco in Prisons study), and then indicate changes to our study protocol that were necessitated by the announcement, in July 2017, of a date (November 2018) to implement a smoke-free prison policy across Scotland’s prisons (see The announcement of new prison rules on smoking, July 2017), in part precipitated by early findings from the study. We then provide a brief overview of relevant literature.

Legislative and policy context prior to commencement of the Tobacco in Prisons study

When we first applied to the National Institute for Health Research’s (NIHR’s) Public Health Research (PHR) board for funding for the Tobacco in Prisons (TIPs) study in 2015, discussions were under way within the Scottish Prison Service (SPS), NHS Health Scotland and Scottish Government about whether or not (and, if so, when and how) changes in prison smoking rules should be formulated and implemented in Scotland. One outcome from these discussions was the publication of a specification for national smoking cessation services in prisons in Scotland,1 because provision across prisons and health boards was known to vary. The specification reinforced the need for ‘equitable’ and ‘consistent’ support for all people in custody who wish to stop smoking,1 which is reportedly up to three in five people in custody (PiC). 2 These discussions, including through a multidisciplinary National Tobacco Strategy Workstream convened by SPS, also informed a document entitled Continuing Scotland’s Journey Towards Smoke-free Prisons,3 which was published on SPS’s website on 13 September 2016 and laid out potential future policy options. This document’s purpose was to obtain agreement to strengthen smoking rules in Scottish prisons. 4 It presented the case for reconsidering current prison rules on smoking in Scotland’s prisons and three potential options for policy-makers to consider. Two members of the TIPs research team (KH and HS) took an active part in regular meetings convened by SPS’s Tobacco Strategy Group at SPS headquarters during the period 2014/15. Their review of existing literature5 informed the policy options paper, and the proposed TIPs study design (a three-phase multimethods study following a natural experimental methodology, as submitted to NIHR in 2015) to evaluate any policy change was included in section 4.7 of the document. 3

The need to reconsider smoking rules in Scotland’s prisons in 2014/15 was informed by many factors. First, legislation [Smoking, Health and Social Care Act (Scotland) 2005]6 enacted in March 2006 banned smoking in indoor public places; however, prisons did not ‘fall within the scope of a “no smoking” place as defined by the Act,’3 although ministers pledged that prisons would operate within the ‘principles’ of the legislation. 3 Second, in 2013, the Scottish Government announced its aspirations to make Scotland ‘tobacco free’ by 2034;7 high rates of smoking among PiC (SPS’s biennial Prisoner Survey suggested that 74% were smokers in 2013,2 and 72% were smokers in 20158 – around three times the national average) presented a challenge to this vision. Indeed, the Scottish Government’s Tobacco Strategy Group noted that ‘[C]reating a smoke-free prison service should be seen as a key step on our journey to creating a smoke-free Scotland’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.). 7 Third, the need to find ways to support a reduction in smoking among PiC was consistent with the Scottish Government’s public health and inequalities strategy. 9 A joint action plan concerning smoking in prisons was submitted to ministers in early 2016. Although the nature and exact timing of any policy change in Scotland was yet to be decided when the TIPs study began, some people who were concerned about second-hand smoke (SHS) exposures were pressing for a short timescale. However, others thought that progress should first be made in reducing levels of smoking among PiC to make any changes towards greater restrictions on smoking in prison achievable, supported and enforceable, or thought that smoke-free prisons were unachievable.

In view of growing concern that high levels of smoking among PiC may damage both their health and that of prison staff and non-smoking PiC through exposure to SHS, alongside the lack of clarity about if, when and how Scotland may change its rules on smoking in prisons,3 we proposed a three-phase multimethods study to evaluate any changes in policy, designed in consultation with key stakeholders in the prison and health services in Scotland and in the Scottish Government. At that time (2015), PiC in Scotland’s prisons were permitted to smoke in their own cells and during outdoor recreation only; staff were not permitted to smoke anywhere on prison grounds3 and e-cigarettes were not available in prisons.

Phase 1 (which commenced in September 2016) proposed multiple components to understand SHS and smoking levels across all of Scotland’s 15 prisons, and the attitudes and experiences of staff and PiC in relation to smoking among PiC, smoking restrictions in prisons and a potential smoking ban. 10 Phase 2 was designed to examine the process of preparing for any change in prison smoking rules (assuming a decision to change the rules was announced) and phase 3 was designed to evaluate the impacts of any such changes. Funding for the later phases of the study was contingent on any substantial change in policy being announced within 2 years. 10 Phase 1 of TIPs included a more comprehensive baseline measurement of levels of SHS across a prison system than had been undertaken in any country to date (see Chapter 2, Interviews with representatives of other jurisdictions, and Chapter 4). 11

The announcement of new prison rules on smoking, July 2017

Phase 1 assessments of SHS exposures in 2016 demonstrated high, although variable, levels of SHS in Scottish prisons, particularly in residential halls11 (see Chapter 4), and partially influenced the decision to introduce a comprehensive smoke-free policy across Scotland’s prison estate. 4 At a press conference, on the day of publication (17 July 2017) of the phase 1 SHS results, Colin McConnell, then SPS Chief Executive, described the findings as ‘a call to action’. He said ‘[I]t is not acceptable that those in our care and those who work in our prisons should be exposed to second hand smoke’ and announced that all of Scotland’s prisons (including the open prison, Castle Huntly) would become smoke free in November 2018. 4 This necessitated revisions to the protocol for the TIPs study12 to take account of the newly announced policy and implementation date (30 November 2018); changes to the protocol also took account of our experience of conducting phase 1 data collection. The timings for the three-phase multimethods TIPs study were thus set as: phase 1 (September 2016–July 2017, baseline assessment before the policy was formulated; ‘pre-announcement phase’), phase 2 (August 2017–November 2018 in anticipation of policy implementation; ‘preparatory phase’) and phase 3 (December 2018–May 2020; ‘post-implementation phase’). 12

Overview of the existing literature (see also Hunt et al.5,12)

Smoking bans in public places decrease exposure to SHS,13 with direct health benefits. 14 Smoking rates have fallen in the general population, except among those in the most deprived areas,7,15 but a review16 in 2008 found that, across Europe, 64–88% of PiC smoked, and another17 in 2018 reported similarly high rates among PiC in low- and middle-income countries in Europe, but substantially lower rates in Africa. An international review18 based on 85 articles published from 2012 to 2016 showed that, in all but one of 36 countries, smoking rates for those incarcerated exceeded rates in the community and concluded that ‘because smoking prevalence is heightened in prisons, offering evidence-based interventions to nearly 15 million smokers passing through [prisons] yearly would improve global health’. 18

High levels of smoking among PiC have resulted in high SHS levels in prisons, even with some restrictions on smoking in these settings. Smoking among PiC thus poses a health risk not just to those who smoke but also to non-smoking PiC and staff, particularly staff opening up or entering cells. Internationally, smoking among prison staff is thought to be high, but evidence is sparse (only one study19 was identified in a recent review).

As the TIPs study was being designed, some countries (e.g. New Zealand, Canada, USA, Australia) had implemented total (i.e. all indoor and outdoor areas) or partial smoke-free policies within their prison estate (see Chapter 3, Interviews with representatives of other jurisdictions) and comprehensive smoke-free policies had been adopted by Broadmoor Secure Hospital in 2007 and Scotland’s State (high-secure psychiatric) Hospital in 2011. Introducing smoke-free legislation in the prison setting presents considerable challenges, underpinned by the social and cultural meanings of tobacco products and smoking in day-to-day prison life, the complexities of managing addiction (including nicotine addiction and associated problems, e.g. poor mental health), and the regulation and delivery of nicotine replacement, and other medications, within the prison environment. 5,20–22 Smoking has been described as ‘integral’ to prison life, serving as ‘a surrogate currency, a means of social control, as a symbol of freedom in a group with few rights and privileges, a stress reliever and social lubricant,’20 and a means of dealing with boredom and the need to ‘kill time’. Use of tobacco by PiC for ‘self-protection, insulating against physical attacks or acts of violence’ and ‘to alleviate immediate danger’ has been described. 23 Given this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that much of the discourse around removing tobacco from prisons has focused on the risk of unrest, at the expense of discussion of potential public health gains. 24

Relatively little research has been published on the process or outcomes of prison smoking ‘bans’. The best evidence available in 2015/16, following New Zealand’s experience of implementing a comprehensive ban,25,26 suggested that at least 1 year is needed to prepare for a smoke-free policy in prisons. Measures of SHS in 32 residential locations in the first four prisons in England to go smoke-free in 2016 showed a reduction of SHS by around two-thirds 3 months after implementation. 27 An analysis of smoking bans in prisons in the US suggested that they can reduce the risk of death among PiC (particularly where more comprehensive indoor and outdoor bans are in place), reduce initiation of smoking in prison, improve health of staff and reduce costs. 28 However, research in Australia suggests very high levels of relapse to smoking after release from smoke-free prisons. 29,30

The introduction of smoke-free prisons therefore has the potential to protect and improve the health of prison staff and PiC,12 but many questions remain about the process and outcomes of introducing a smoke-free policy in prisons. If PiC can be supported to become lifelong non-smokers, these benefits may extend into the community after their release, potentially magnifying their impact on reducing health inequalities and on families of those who are, or have been, in custody in smoke-free prisons. However, there could be risks to the safety and well-being of staff and PiC (as well as potentially costly risks of damage to the fabric of prison buildings and facilities) if prison smoking ‘bans’ do not attract sufficient acceptance from staff and PiC to be enforceable, or if increased tobacco control measures threaten safety and security at the institutional or individual level.

Research objectives

Overall aims

-

To evaluate the process of implementing a smoke-free policy in Scottish prisons to (1) strengthen the evidence base on what is likely to facilitate successful implementation of smoke-free prison policies for other jurisdictions, and (2) inform planning and communication strategies in Scotland and elsewhere.

-

To evaluate the impact of implementing a smoke-free policy in Scottish prisons on (1) changes in smoking status and exposure to SHS, (2) changes in related health indicators among PiC and staff and (3) organisational/cultural impacts.

Objectives

-

To understand barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of smoke-free policies in prisons through a scoping of evidence and experiences internationally within other jurisdictions [work package (WP) 1 (WP1)].

-

To evaluate changes in smoking and exposures to SHS following the implementation of a smoke-free policy in Scotland’s prisons, associated health-related indicators and costs, and other intended and unintended consequences (WP2).

-

To understand staff attitudes to and experiences of smoking-related issues in the prison context, including access to/restriction on tobacco and tobacco-related products (including e-cigarettes) in the prison environment, if/how these vary between prisons and how these changed leading up to and following the implementation of the smoke-free policy (WP3).

-

To understand PiC’s attitudes and experiences of smoking-related issues in the prison context, including access to/restrictions on tobacco/tobacco-related products (including e-cigarettes) in the prison environment, if/how these vary between prisons and how these changed leading up to and following the implementation of the smoke-free policy (WP4).

-

To evaluate the provision and impact of smoking cessation services across Scottish prisons; experiences of providers, users and potential users of these services in the lead-up to implementation of smoke-free prisons; and efforts to harmonise smoking cessation services from 2016 (WP5).

-

To share emerging findings in a timely and ongoing way so that they can inform the development of services, strategies and decision-making in the health and prison services about how best to implement the smoke-free policy, taking account of the views and experiences of PiC and prison staff (WP6).

Patient and public involvement

From the earliest design stages and throughout the conduct of the study, the TIPs study was designed to ensure that the voices of PiC and prison staff were heard and fed back in anonymised form to those within the SPS and NHS overseeing the processes and procedures involved in considering, preparing for and implementing the smoke-free prison policy in Scotland.

We participated in nine SPS Tobacco Strategy Group meetings in 2015 and in further discussions with policy-makers within the Scottish Government, the SPS, NHS Health Scotland and staff trade unions. A research advisory group (RAG) was constituted by the SPS in 2016 (membership included the head of SPS Health and Wellbeing and representatives of staff health and safety, trade unions and people leading tobacco control in NHS Health Scotland and the Scottish Government). RAG members gave extensive feedback on all aspects of the design, including study materials and approaches, and commented on all early findings from phase 1 through face-to-face meetings at SPS headquarters (Edinburgh, UK). Chapter 9 describes our partnership working from phase 2 onwards in more detail.

Prior to starting any fieldwork, Kate Hunt (or, on occasion, HS) visited every prison with Sarah Corbett (SPS Health and Wellbeing team and, from 2016, Smoke Free Prisons Project Policy Manager) or Ruth Parker (then SPS Head, Health and Wellbeing team). During these visits, we met the Governor-in-Charge or their appointed deputy and any members of staff with whom they wanted us to discuss the proposed research design and procedures. Opportunities to meet with those residing in prisons prior to commencement of the study were limited, but allowing them a voice as PiC or as users of smoking cessation services in prisons was fundamental to all phases of the study.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Project overview

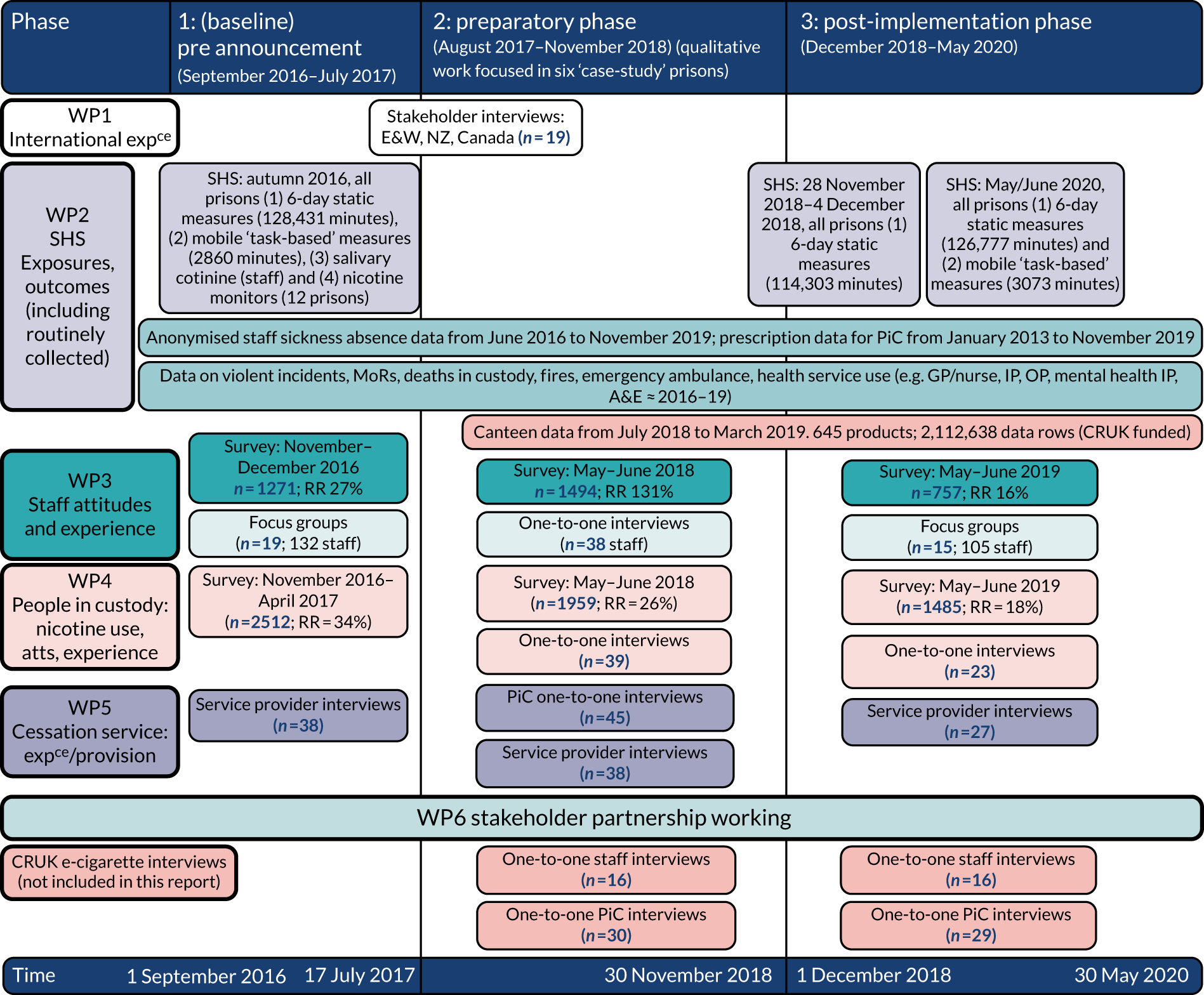

The TIPs study was a three-phase, multimethods study using a natural experimental methodology to assess the development and impact of the implementation of the smoke-free prison policy across Scotland’s prison estate on 30 November 2018. As indicated in Chapter 1, Context, the SPS announced in July 2017 that its prisons would become smoke free from November 2018, informed by the measurement of SHS exposures conducted as part of phase 1 of TIPs;11 the study protocol (V2.5)12 describes the revised timeline. Figure 1 depicts the study’s six integrated WPs, conducted across three phases;12 in summarising information about sample sizes and timings of different elements of TIPs, it gives an indication of the breadth and depth of the data collected and analysed. It also notes additional primary data collected for a complementary study, funded by Cancer Research UK (CRUK; London, UK), of the introduction of rechargeable e-cigarettes (hereafter ‘e-cigarettes’, unless otherwise stated) for information; these data do not contribute to this report. As detailed below, most of the research involved the collection and analysis of data relating to all 15 of Scotland’s prisons; some more detailed data collection was conducted in six of the (closed) prisons. We refer to these as ‘case study’ prisons in this report and they were selected in consultation with the SPS to represent a range of prisons and of PiC. However, although they were the sites for our more intensive qualitative research, they are not traditional case studies (e.g. we did not conduct observation research within these prisons). Furthermore, to respect assurances about anonymity and confidentiality given to participating prisons, staff and PiC, we do not provide extensive detail about the sites or local policies.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the TIPs study methods and data by study phase. A&E, accident and emergency; atts, attitudes; E&W, England and Wales; expce, experience; GP, general practitioner; IP, inpatient; MoR, management of offenders at risk owing to any substance; NZ, New Zealand; OP, outpatient; RR, return rate.

All aspects of the study obtained ethics approval from both the SPS Research Access and Ethics Committee and from the University of Glasgow College of Social Sciences Ethics Committee.

Interviews with representatives of other jurisdictions (work package 1)

To understand the barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of smoke-free prison policies within other jurisdictions, we conducted telephone interviews with personnel (including health staff) in prisons that had introduced smoking bans to elicit views and advice on key challenges, successes and pitfalls. Originally, we aimed to include personnel from New Zealand, the Isle of Man, Canada, the USA and Australia. 12 However, consultation with SPS staff and focus group data from phase 1 of TIPs [see Focus groups and interviews with prison staff (work package 3) and people in custody (work package 4)] indicated their greater interest in recent experience in prisons that had become smoke free in England and Wales (E&W) from 2016 onwards. Hence, we weighted sampling to include more prisons in E&W than elsewhere. Additional ethics permission for interviews in E&W was obtained from the HM Prison and Probation Service National Research Committee (REF 2017–140).

In-depth interviews were conducted with 19 people (17 one-to-one interviews and one paired interview, at the request of the participants) (see Appendix 1 for topic guide). In-depth interviews were selected as the most appropriate method, balancing pragmatic considerations in conducting the interviews in recognition of both distance and pressures on participants’ time and the utility of in-depth interviews in allowing people to discuss their views and experiences in confidence. The sample included 13 participants in prison-based roles and six non-operational staff. Almost all had been directly involved in the implementation of a smoke-free prison policy at a national, regional or local level. Participants were encouraged to speak freely and raise any relevant issues. After obtaining informed consent, interviews lasting 28–58 minutes (mean 43 minutes) were audio-recorded with participants’ permission. All data were transcribed by an external transcribing agency which, as for all transcription for the TIPs study, had signed a confidentiality agreement. To preserve participants’ anonymity, data were de-identified prior to analysis. Analysis followed the principles described in Approach to qualitative analysis for focus groups and interviews with staff, people in custody and representatives from other jurisdictions and Appendix 2.

Measuring exposures to second-hand smoke (work package 2)

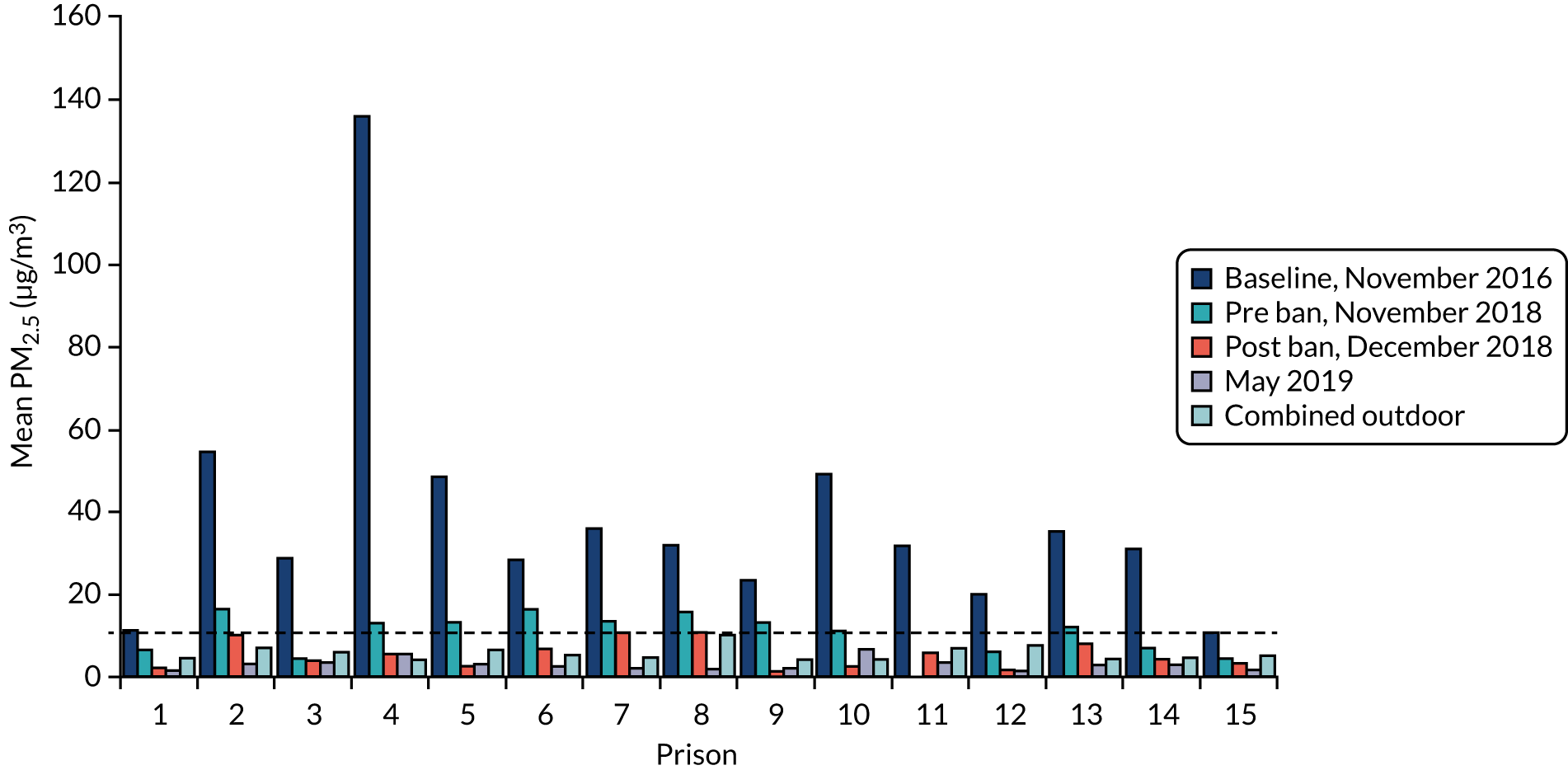

When the TIPs study was originally funded, we had planned to be the first study internationally to undertake comprehensive measures of SHS across a whole national prison estate prior to any decision about when and how to change prison smoking rules, and after implementation of any changes, measuring markers of SHS in all Scotland’s prisons in phases 1 and 3. 10 As described in the updated TIPs protocol,12 we extended these plans to include additional measurements in the week of implementation. Here we describe the methods used at each time point, that is 2016 (pre announcement), November/December 2018 (in the week that the ban was introduced) and May 2019 (6 months post implementation).

Over the course of the TIPs study, we used four methods of assessment: fixed-site monitoring of airborne concentrations of fine particular matter (PM2.5; particulate matter ≤ 2.5 μm in diameter), mobile-task monitoring of PM2.5; fixed-site air nicotine concentrations and cross-shift changes in cotinine concentrations in saliva of non-smoking staff. Data on outdoor ambient air PM2.5 concentrations were also obtained to provide reference levels. These measures are described below, in TIPs publications11,31,32 and a report provided to the SPS in July 2017. 33

Staff training and engagement

In preparation for the phase 1 assessments of air quality, representatives from Scotland’s 15 prisons were invited to a half-day training session (29 September 2016) at the SPS College. This provided the opportunity to train attendees as ‘citizen scientists’ through an overview of the TIPS study, training in the air quality measurement and the specific measuring devices used in the study (see Fixed-site monitoring and Alternative Scottish Prison Service exposure measures – fixed-site nicotine concentrations and cotinine concentrations in saliva of non-smoking staff), and the rationale for taking saliva samples from non-smoking staff in phase 1. A half-day training session was also provided for prison staff on 8 November 2018 in preparation for air quality measurements in the week of policy implementation and in phase 3. On completion of these sessions, at least one designated trained staff member from each prison took responsibility for a box containing the instrumentation and associated forms.

Fixed-site monitoring

Following earlier validation studies,34 Dylos DC1700 air quality monitors (Dylos Corporation, Riverside, CA, USA) were used to measure concentrations of PM2.5 to estimate SHS levels via fixed-site and mobile-task monitoring methods. These devices measure particle concentrations every second and log an average measurement result for each minute of use. Details of the method of converting particle number concentration to PM2.5 mass concentration, together with calibration of the Dylos monitors against AM510 SidePak Personal Aerosol Monitors (TSI Incorporated, Shoreview, MN, USA) are provided elsewhere. 31 Fixed-site monitoring over a 6-day period was undertaken within the same location, in one residential hall, at the three time points, overseen by the trained designated staff member(s), in each prison: in phase 1 (during 1 week in the period 30 September–22 November 2016),11,33 in the week of implementation (09.00 on 28 November 2018 to 09.00 on 4 December 2018),32 and in phase 3, 6 months after the smoke-free policy was implemented (09.00 on 22 May 2019 to 09.00 on 28 May 2019). 31 During phase-1 training, the designated prison staff had discussed their choice of location for the 6-day fixed-site continuous monitoring in a residential area within their prison with members of the TIPs study WP2 team. On occasion, the TIPs study researchers (KH, HS, ED) also went to the prison site to discuss the exact location of the instruments in more detail with the designated prison staff. The location needed to be secure (e.g. at the staff desk) to prevent accidental or malicious interference, within reach of an electrical plug and within the atrium/landing of one residential hall. The designated prison staff were responsible for ensuring that the location and daily equipment checks were recorded on the forms provided, together with relevant contextual information.

After each 6-day period, the designated prison staff securely packed the device and forms, and returned them either directly to a research team member for immediate download or by secure courier. Data were downloaded using Dylos Logger software (v3.1.0.0) (Dylos Corporation), and typical daily PM2.5 exposure profiles were constructed for each prison, as described in detail elsewhere. 11,31–33

Mobile-task monitoring

Mobile-task monitoring was undertaken in phases 1 and 3 only; it was not feasible to conduct these measures in the week of implementation because of operational considerations. After the 6-day fixed-site monitoring data were downloaded, the Dylos DC1700 monitors were returned to the designated staff. In 2016, staff were asked to choose four to eight tasks to assess SHS concentrations in various locations (e.g. gyms, workshops) and during specific activities (e.g. cell searches, maintenance, meal service), based on their knowledge and perceptions of areas with potential SHS exposures;11 in 2019, they were asked to include the same monitoring locations/activities assessed in 2016. 31 The monitoring period for each ‘task-based’ measurement lasted ≈ 30 minutes, and staff recorded time, location and associated activity for each measurement. Data from the mobile-task monitoring were downloaded after the instruments had been returned to research staff in person or by secure courier. Time-weighted average exposure concentrations were estimated for the typical shift patterns of residential staff pre and post smoke-free policy implementation (see Demou et al. 31 for full details).

Alternative second-hand smoke exposure measures: fixed-site nicotine concentrations and cotinine concentrations in saliva of non-smoking staff

In phase 1 only, estimates of SHS exposure calculated using the Dylos DC1700 monitors were compared with (1) measures of nicotine concentration from a sodium bisulfate-treated filter in passive diffuse monitors (‘nicotine monitors’) placed next to each Dylos monitor during the fixed-site 6-day measurements; and (2) salivary cotinine measures (a biomarker of recent SHS exposure) obtained from samples collected during fieldwork across all 15 prisons, between 7 November 2016 and 16 January 2017, to enable an estimation of the amount of nicotine inhaled over a work shift. As the main measure of change in SHS exposures over time in this report (see Chapter 4), and in the models reported in Chapter 8, are derived from the fixed- and mobile-task Dylos measurements, here the methods and findings of the nicotine monitor and salivary cotinine measures are summarised only. Full details are published elsewhere,11 but we note that measures from the nicotine monitors demonstrated a high association with the Dylos-derived estimate (R2 = 0.91). 11

For the salivary cotinine measures, non-smoking prison staff were invited to provide pre- and post-shift samples of saliva on entry to and exit from the secure area of the prison. Eligible staff were non-smokers not using any nicotine product (e.g. gums, patches, e-cigarettes) who neither lived with a smoker nor travelled to work in a vehicle in which anyone had smoked. Written consent was obtained from all volunteers (n = 422). Saliva samples were collected by TIPs research staff, who had been trained using similar methods developed for other occupational groups. 13 They recorded the exact time of sample collection pre and post shift so that exposure time over the shift could be calculated. The storage, shipping and analysis of samples are described elsewhere. 11 Our revised study protocol12 details the rationale for not repeating saliva measures in phase 3; the principal reasons were high correlations between measures of SHS exposures,11 the burden imposed by the measurement procedures on staff as they entered/left the prison and on the prison regime, and minimising costs to maximise value for money of funding.

Outside air pollution

Fine particulate matter is not specific to SHS and also occurs in outdoor and indoor air from traffic and industrial pollution sources. Most previous studies measuring PM2.5 in prisons have not accounted for concentrations of PM2.5 in outdoor air. To identify whether or not ambient/outside air pollution was likely to have contributed significantly to the PM2.5 concentrations measured in prisons, we acquired data from the nearest local authority PM2.5 static environmental measuring device. Hourly outdoor PM2.5 concentration data were downloaded from www.scottishairquality.scot (accessed 30 September 2021) for each monitoring period. 11,31,32 Data for the appropriate measurement periods from the outdoor monitor closest to each prison were used. 11,31,32 The median distance between each prison and the nearest PM2.5 measuring station was 16 km (range 3–133 km), with all but one within 50 km.

Statistical analysis: second-hand smoke data

Statistical analysis was conducted in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), R version 3.6.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and IBM SPSS Statistics v23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Analysis of objective measures of SHS followed previously published methods. 34 To test the significance of change between different measurement periods, mean PM2.5 concentrations were log-transformed and a paired t-test conducted across mean concentrations from all prisons for each comparison (see Demou et al. 31).

Our PM2.5 data provided time-resolved information on SHS concentrations over the course of each day, with lower levels at night-time and peaks evident during the day and evening periods. These unique data, gathered for 6-day periods from all prisons, enabled the reconstruction of exposures of residential staff during different shift patterns. 35–37 Using information on shifts provided by the SPS, time-weighted average shift exposures were estimated for a ‘typical’ residential officer in a Scottish prison, taking into account the average levels of exposure in an area and the time spent in each area. The four (overlapping) shifts were an ‘early shift’ (modelled as a 6-hour shift; staff on this shift have the responsibility of unlocking cells first thing in the morning), a ‘day shift’ (modelled as 8 hours), a ‘back shift’ (modelled as a 9-hour shift) and the ‘night shift’ (modelled as 10 hours).

Surveys of prison staff and people in custody (work packages 3 and 4)

Online surveys of prison staff and paper-based surveys of PiC were conducted in each phase. Participation was entirely voluntary for both groups and we offered no incentives to either group for completion. Methods of data collection are summarised below; further details are provided elsewhere. 38–40 As noted in our protocol, we consulted widely within the prison service on whether staff should be asked to enter their unique SPS employee identifier (ID), so that we could send reminders to those who had not returned a questionnaire and remove duplicate responses, with assurances that staff IDs would be immediately removed, or whether the survey should be completely anonymous. The most widely expressed view was that staff would not wish to divulge their staff ID or other potentially identifying information; hence, all staff questionnaires were entirely anonymous and could not be traced back to individual staff members. Union representatives of prison staff indicated that we should anticipate a high response rate from both smoking and non-smoking staff, at least in phase 1, given the concern expressed by some prison staff about exposure to SHS during the course of their work. Similarly, for PiC, we have no data that enable us to link responses to individuals. Hence, we are unable to link survey responses over the three different time points; for both groups they were repeat cross-sectional surveys.

Survey circulation/distribution

In each phase, an invitation with information on the TIPs study and a link to the staff survey were circulated to an appointed contact (‘staff contact’) in each prison, with a request to forward these to all prison (but not NHS/visiting) staff. The online survey was housed by information technology (IT) staff at the University of Glasgow, to ensure the highest standards of security. As the TIPs research team, SPS management and union representatives believed that it was very important that the research was clearly seen to be independent of SPS management, the questionnaire link was forwarded directly by the research team to the nominated staff contact in each prison for them to forward to all staff in their prison. 12 Staff were informed that the survey would take 10–15 minutes to complete. Staff surveys were open November–December 2016 (phase 1), May–July 2018 (phase 2) and May–July 2019 (phase 3). One reminder was sent (via the staff contacts) in phase 1, two in phase 2 and three in phase 3. The staff contacts were provided with current response rates when reminders were sent, and this information was sometimes included in the e-mail to staff.

Surveys with PiC were undertaken from November 2016 to April 2017 (phase 1), June to July 2018 (phase 2) and June to July 2019 (phase 3). We wanted to ensure that PiC were provided with information about the questionnaire to enable them to make an informed decision about whether or not they wished to take part. In our original planning,12 we thus wanted to offer the opportunity for PiC to discuss any questions they might have about the study directly with a member of the research team, before deciding whether or not to participate. We also wanted to ensure that people were able to complete their questionnaires without disturbance from other prisoners, given the role of smoking and tobacco products in prison life, including in relation to bullying and intimidation.

We discussed ways to maximise inclusion of any potential participants with literacy or other learning difficulties, including carefully considering the content, wording and layout of the questionnaire. When the SPS conducts its biannual prisoner survey, PiC with literacy/learning difficulties are offered help with questionnaire completion by other PiC. We wanted to avoid this for our surveys (to allow PiC to express their views without concerns about reprisals from any other PiC), and so planned for provision of impartial (research team) assistance if required. This involved offering to make trained fieldworkers available to any PiC who required help.

We anticipated that the administration of questionnaires to PiC would be completed over a short time period in each prison (≈ 1–3 days, depending on operational considerations and prison size), with sufficient fieldworkers available to support administration of the survey. We agreed to liaise closely with the prison governor/their appointed representative(s) about the best way to achieve our aims in respect of prisoner questionnaire administration in their prison (e.g. numbers of fieldworkers required), recognising that operational considerations would determine the preferred means of administration of the survey with PiC in each prison. 12 In our original planning for the phase 1 survey of PiC and our funding application, we anticipated that questionnaires would be distributed to a proportion of PiC by TIPs fieldwork/research staff (who would be available to help with confidential completion), aiming for returns from around 20% of PiC.

In phase 1, in two prisons, TIPs staff were escorted around residential areas and distributed questionnaires to all PiC who said they were willing to complete one, answered queries and helped with completion if necessary. In a third prison, TIPs staff were asked to distribute the questionnaires during an evening meal. 12 However, in the remaining 12 prisons, the staff contacts expressed a strong preference for us to use similar methods to those used in the SPS’s own biennial Prisoner Survey,2,8,41 because the escorting of several research staff in prison residential facilities can prove very onerous to the prison regime. Sufficient questionnaires were therefore supplied to each prison so that prison staff could distribute one to every PiC. To allow PiC the opportunity to complete their questionnaire in private, questionnaires were generally distributed immediately prior to an overnight lock-up. To reassure PiC that no-one in the prison (staff or other PiC) would be able to see their responses, PiC were asked to return the completed questionnaire in a sealed envelope (provided with the questionnaire). Although the method that we were required to use for most prisons in phase 1 (and all prisons subsequently) inhibited confidential support in questionnaire completion for those with literacy or learning difficulties, return rates from the three prisons where TIPs staff distributed questionnaires were below the overall 34% return rate. Because prison staff distribution was preferred by prisons and resulted in higher return rates, this method was used in all prisons in phases 2 and 3.

Survey content

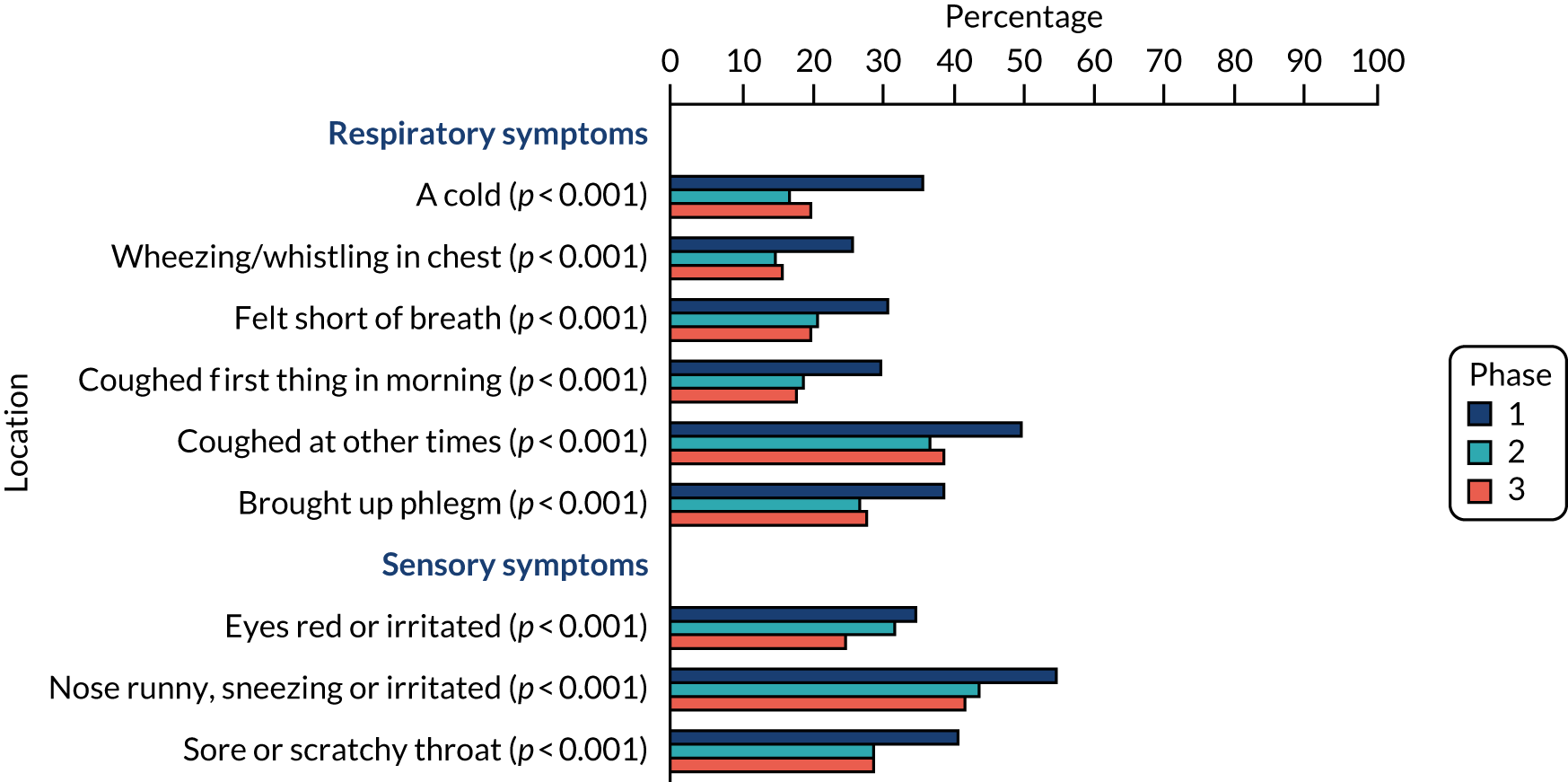

The surveys were designed to take approximately 10–15 minutes to complete (although time to complete was longer for some PiC) and to cover relevant predictors, effect modifiers and mediators, and outcomes. Wherever possible, the questionnaires included identical items for the two participant groups (staff/PiC) and across all phases to maximise opportunities for comparison and to use validated/existing measures. Report Supplementary Materials 1 and 2 detail the survey questions and basic frequencies for surveys for all phases and both groups. Items were based on previous surveys of health;42–44 smoking;42,45–47 experiences of PiC;41 and smoking bans in public places, prisons or secure hospitals,19,43,48–51 and comprised the following:

-

basic sociodemographic items (sex, age, education; for staff – work role, band, number of prison-based working hours per week, number of years worked in prisons in total and in their current prison; and for PiC – whether convicted or on remand, with length of sentence and time until release if convicted, and length of time in current prison)

-

current smoking, smoking history, e-cigarette use and vaping history, past year smoking cessation attempts and support

-

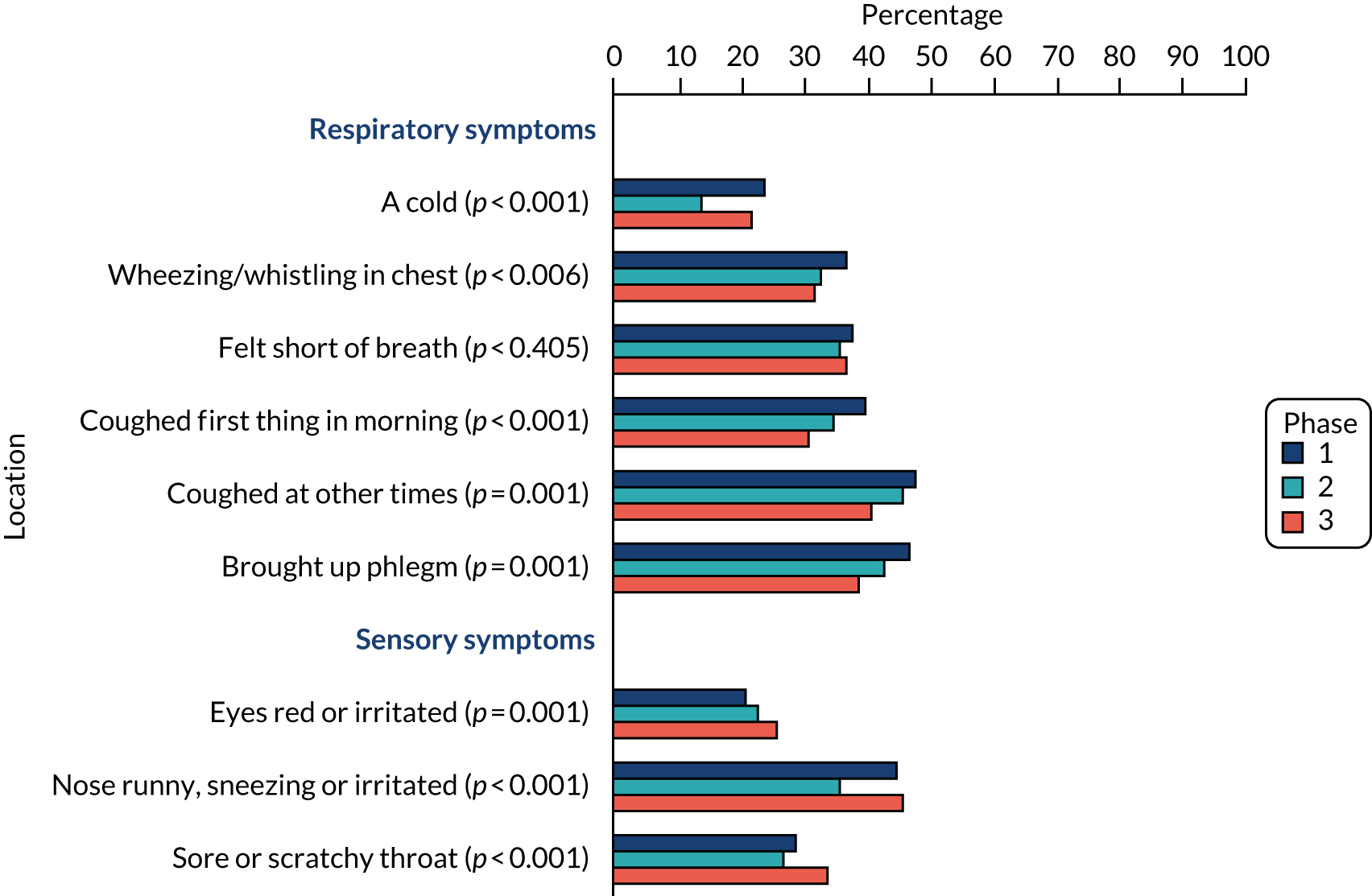

health, including general health, sickness absence (staff), medication use and asthma diagnosis; International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease self-reported past month respiratory (wheezing/whistling, shortness of breath, morning cough, other cough, phlegm) and sensory symptoms (red/irritated eyes, runny nose/sneezing, sore/scratchy throat);52 and a standardised measure of health status,53 for which we received permission to amend the ‘usual activity’ examples for the survey of PiC

-

estimated exposure to SHS and e-cigarette vapour within the prison

-

opinions on smoking among PiC, prison smoking bans (adapted from surveys of US prison staff19 and Scottish bar workers’ attitudes to smoke-free places51), e-cigarettes and, in phase 3, the introduction of the Scottish prison smoking ban.

Survey feedback to prisons and participants

In addition to feeding back results to the study’s SPS RAG and at regular meetings of the SPS stakeholder advisory group (SAG) for the implementation of smoke-free prisons, phase 1 and phase 2 survey results (basic frequency distributions) were formatted into easy-to-read documents that were posted on the SPS SharePoint (SPS intranet system, accessible to all staff) and e-mailed to the staff contacts in each prison (phase 1 reports were tailored to include overall and each prison’s individual results). Phase 1 main results were also compiled into summary infographics that were distributed as hard copies (and so were available to PiC) and electronically.

Focus groups and interviews with prison staff (work package 3) and people in custody (work package 4)

Recruitment and data collection

Staff

To investigate the opinions and experiences of staff in more depth, we aimed to conduct focus groups with staff in all 15 Scottish prisons in phases 1 and 3, and interviews with staff in six ‘case-study’ prisons in phase 2 (see Figure 1).

Focus groups in phases 1 and 3 were chosen to ensure a wide range of staff across the prison service (i.e. in every prison) to express their views on smoking in prisons, smoking regulations and management of nicotine addiction (including e-cigarettes) and smoking bans,54 with minimal disruption to the prison regime. Focus groups can also be used to explore areas of agreement and disagreement within the group. Furthermore, prison staff were judged to be able to respect the confidentiality of views expressed by their colleagues in the context of the focus group.

A point of contact within each prison was asked to arrange a group in their prison, ideally inviting up to eight staff, including smokers and non-smokers and staff in residential and other roles. In phase 1, a total of 132 staff from 14 prisons took part in 17 focus groups (range of participants 5–12) and two paired interviews (conducted from November 2016 to April 2017) (see also Brown et al. 54,55).

In phase 2, our strategy was to elicit more detailed data from the six ‘case study’ prisons, rather than collecting some data from all prisons. This made it practical to conduct one-to-one interviews with staff and 38 staff (32 men and 6 women) across the six prisons were interviewed [range 10–62 minutes (mean 36 minutes)]. Again, the point of contact within the prison was asked to approach a mixture of smoking and non-smoking staff in a range of roles who might be interested. Most (n = 24) were non-smokers and often worked in residential areas within the prison (n = 18) (data on smoking status and/or work role were missing for five participants).

In our original protocol10 we did not plan to include further qualitative work with prison staff in phase 3. However, when the protocol was amended following the announcement of a specific timetable for the implementation of smoke-free prisons,12 we sought permission from NIHR to include focus groups in phase 3 to explore in depth the views of staff on the success (or otherwise) of the (process of) implementation (see also Brown et al. 56). These groups included a total of 105 staff from across all prisons, in 15 focus groups (range of participants 3–14), conducted from May to August 2019. Four SPS staff members who had taken a leading role in the implementation of the smoke-free policy at the local (prison) level were also interviewed to capture their perspectives on the transition. Most of the staff participating were male (n = 83), prison officers (n = 71) and never- or ex-smokers (n = 91); around one-quarter (n = 28) reported ever using e-cigarettes.

Topic guides for the focus groups (summary versions provided in Appendix 1, together with those for one-to-one staff interviews) covered such issues as participant background, opinions of smoke-free policy, perspectives on working in a smoke-free prison (including successes/challenges and positive/negative consequences), compliance and enforcement of the smoking ban, and lessons learned.

People in custody

Interviews with PiC were conducted in phases 2 and 3 in the six ‘case-study’ prisons (see also Brown et al. 56), selected in consultation with the SPS to represent a range in terms of size and population as noted earlier (see Project overview). Data collection took place between October 2017 and February 2018 in phase 2, and between May and August 2019 in phase 3, 6–8 months after implementation. Abbreviated topic guides are provided in Appendix 1. The point of contact in each prison was asked to approach participants [aiming to interest a range of people with respect to their smoking (vaping in phase 3) status, length of sentence, and (if appropriate for their prison) gender] (Table 1). We chose to conduct one-to-one interviews with PiC, rather than focus groups, to ensure that each person could express their views in confidence, without fear of reprisals for voicing opinions that they perceived not to be shared or popular with other people in the group, or within the prison community more broadly, and concerns that other people in a group context may not fully respect the need for confidentiality after a group had concluded. Designated points of contact (nominated staff who liaised with the research team in each of these prisons) provided information to potential participants; these staff contacts were well briefed in our aim to recruit people with a wide range of views, whether supportive of or opposed to the smoke-free prison policy, and to include smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers.

| Characteristic | Phase 2 (n) | Phase 3 (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (n) | ||

| Male | 32 | 18 |

| Female | 6 | 5 |

| Remanded/convicted status (n) | ||

| Convicted | 35 | 23 |

| Remanded | 3 | 0 |

| Sentence length (n) | ||

| Short term | 15 | 13 |

| Long term | 20 | 10 |

| Smoking status (n) | ||

| Smoker | 26 | – |

| Ex-smoker | 7 | – |

| Never smoker | 5 | – |

| Vaping status (n) | ||

| Vaper | – | 17 |

| Ex-vaper | – | 6 |

| Never vaper | – | 0 |

| Interview length (minutes) | ||

| Minimum | 21 | 22 |

| Maximum | 59 | 68 |

| Average | 33 | 38 |

Topic guides for the phase 3 interviews with 23 PiC in the six ‘case study’ prisons largely covered similar topics to those covered in the phase 3 focus groups with staff (see Appendix 1): participant background, opinions of the smoke-free prison policy, perspectives on living/working in a smoke-free prison (including successes/challenges and positive/negative consequences), compliance and enforcement of smoke-free prison policy, and lessons learnt.

Approach to qualitative analysis for focus group and interviews with staff, people in custody and representatives from other jurisdictions

All focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded, with permission from all participants involved, and transcribed by an external transcribing service that had signed a confidentiality agreement. To preserve participants’ anonymity, data were de-identified prior to analysis.

De-identified transcripts were thematically analysed, supported by the framework approach, following a process described in Appendix 2 and in publications based on the qualitative data. 38,54,55 In brief, data were organised under themes and summarised and displayed in a grid format (row = focus group/interview; column = theme) in NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). For pragmatic reasons, for two of the data sets, transcripts were summarised against themes in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) [WP1 interviews with representatives from other jurisdictions and WP3 (phase 2) interviews with prison staff]. Detailed thematic analysis entailed comprehensively and systematically searching framework grids and reviewing data excerpts to identify and compare perspectives and experiences. Using an iterative process, different dimensions of the data were organised into themes and subthemes. Extracts from interviews have been selected to evidence and illustrate key findings. In the staff and PiC interviews/focus groups, quotations are attributed to participants (staff/PiC) using a serial number (a letter randomly allocated to each prison specifically for this report and a participant number) and an indication of smoking/vaping status [smoker (S), ex-smoker (ExS), never-smoker (NS), vaper (V), ex-vaper (ExV) and never-vaper (NV)].

Interviews with users and providers of smoking cessation support in prison (work package 5)

Interviews with health-care and prison staff providing smoking cessation support

Qualitative interviews were conducted with staff responsible for managing and delivering cessation support across Scotland’s prison estate. Participants were from three main areas: topic specialists working in health board Stop Smoking Services (SSSs), practitioners working in prison health-care and addiction services who were trained to provide cessation support, and SPS officers who had volunteered or been nominated by prison management to support cessation delivery in the lead-up to implementation (see Appendix 3, Table 27). To maximise efficiency, and particularly to reduce burden on participants, the majority of interviews were conducted as one-to-one interviews either face-to-face or by telephone using a semistructured topic guide (see Appendix 1) at participants’ convenience. Interviews lasted 40–60 minutes and were audio-recorded with participants’ consent, fully transcribed and analysed using NVivo software to aid data management.

Phase 1 fieldwork was conducted from February to June 2017, phase 2 from May to August 2018, and phase 3 from May to September 2019. Interviews in phases 1 and 3 were conducted with participants from across the entire Scottish prison estate and the health board cessation services where the prisons were located. Interviews in phase 2 were conducted with participants from the six ‘case study’ prisons and the local health board cessation services supporting these prisons. To preserve anonymity, quotations are attributed to speakers using designation and study phase.

Interviews with about smoking cessation support

During phase 2, one-to-one qualitative interviews were conducted face-to-face with 45 PiC in five of the six ‘case study’ prisons in May and June 2018 using a semistructured topic guide (see Appendix 1). Participants all had recent experiences of using local prison cessation support and were at various stages in their journey to becoming smoke free (see Appendix 3, Table 28). They included PiC who were currently attending a 12-week cessation programme, had relapsed and had successfully completed the programme. All interviews (duration 30–60 minutes) were conducted face-to-face and audio-recorded, with participants’ consent, then fully transcribed, anonymised and analysed using NVivo software to aid data management. Analysis followed similar principles to those outlined above.

Analyses of routine data (work package 2)

Medications

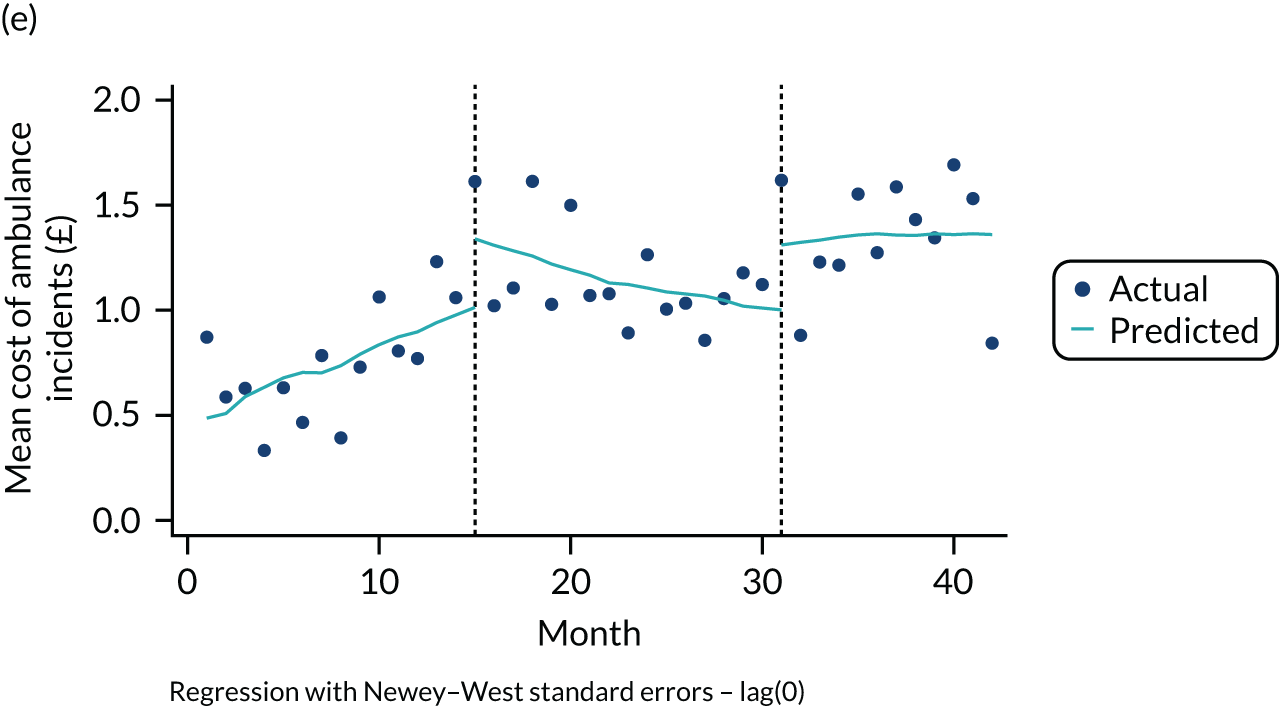

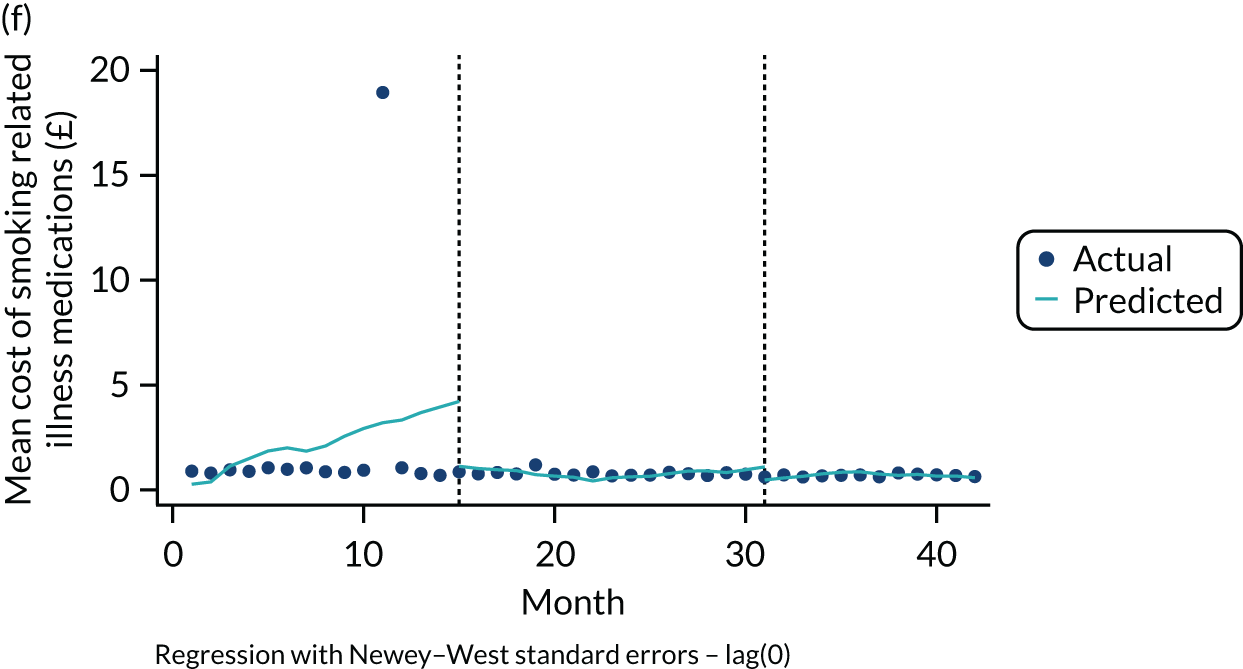

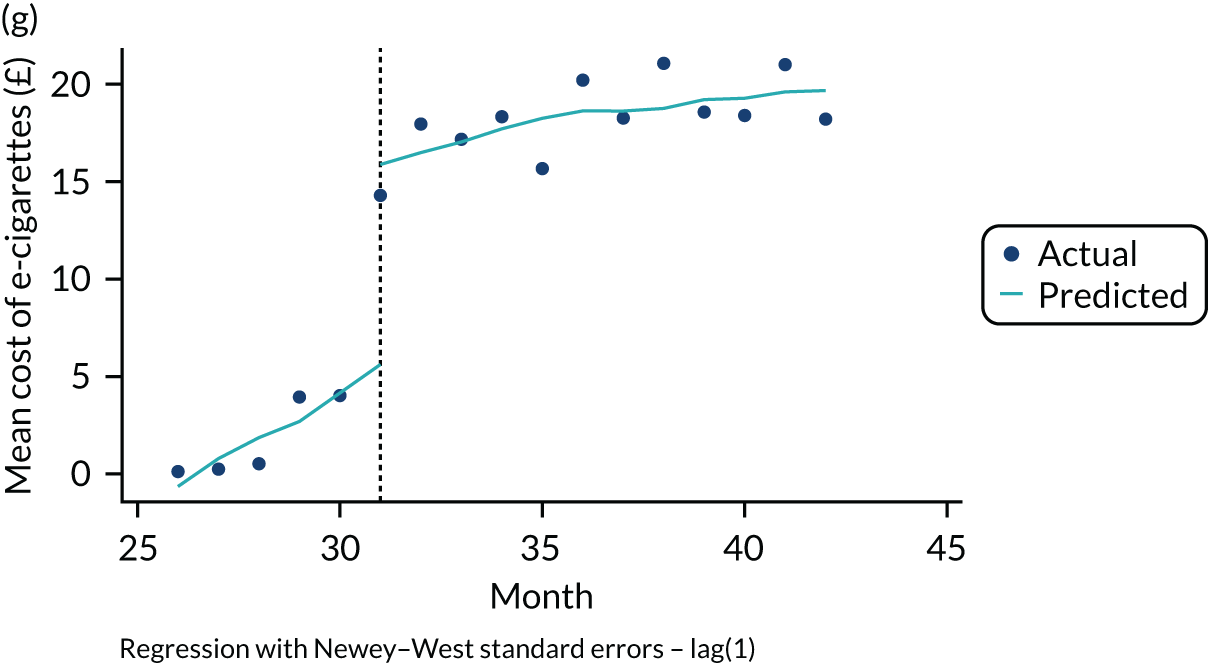

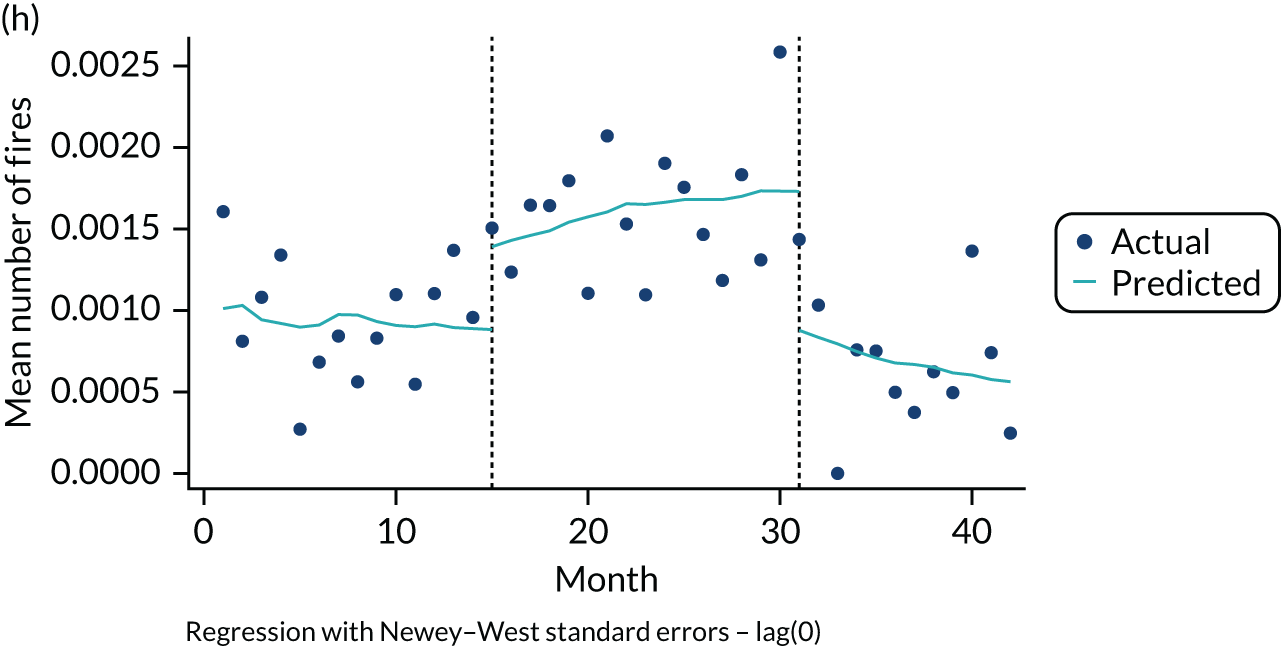

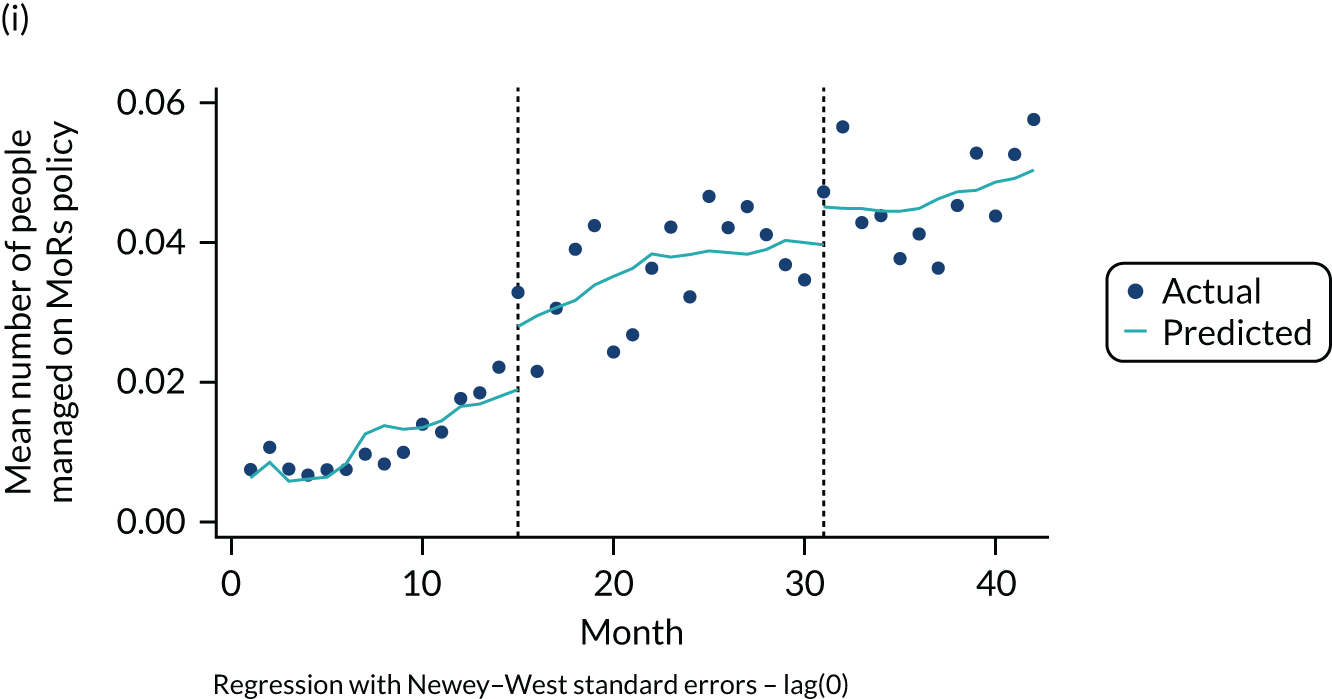

Analyses of medications prescribed for PiC were designed to investigate any associations between the smoke-free prison policy and the dispensing of medications for smoking cessation, nicotine replacement and specific smoking-related health conditions, and potential unintended consequences among people in prisons in Scotland. Data (number of items dispensed in prison) were provided by National Procurement, NHS National Services Scotland (NSS) from January 2014 (3.5 years prior to the announcement of the smoke-free policy in July 2017) to the end of November 2019 (1 year post implementation). The data series’ were analysed using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) time series methods, incorporating two prespecified breakpoints (date of announcement to 17 July 2017, and date of implementation to 30 November 2018). Two analytical approaches were tested for the presence of structural breaks and outliers using (1) a Wald test applied to the white noise residuals of the seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (SARIMA) errors model, and (2) an indicator saturation applied to the white noise residuals of the SARIMA errors model. In each approach, the estimated breakpoints were then incorporated into the final intervention model ensuring efficient effect estimates and standard errors. Measures of overcrowding were included in all models as potential confounding factors. Interpretation was informed by the TIPs qualitative workstreams. The primary analysis included the 14 closed prisons only, as the nature, implementation and effectiveness of the smoke-free policy is likely to differ substantially in open versus closed establishments. Secondary analyses included all Scottish prisons. Analyses were delayed by reallocation of staff who were leading the analyses to service public health roles during the COVID-19 outbreak and are reported in detail in a paper published57 after the reporting period for this grant; see Acknowledgements, Publications.

Staff sickness absence

Analyses of staff sickness absence data were designed to explore any changes in staff sickness absence rates before and after the introduction of the smoke-free policy across the SPS. Weekly days lost were provided in anonymised form by the SPS for the 13 publicly managed prisons. Data were requested from June 2016 (1 year prior to the announcement of the smoke-free policy) to the end of November 2019 (1 year post implementation). The data series were analysed using the Box–Jenkins ARIMA time series methodology. For the SPS sickness absence time series, we adopted an input series to allow the change in policy on smoking (intervention) to be modelled. Specifically, the intervention was modelled as a 0 up to 30 November 2018 (date of prisons going smoke free) and then coded as a 1 after that date. The announcement of the date for a change of the smoking policy in Scottish prisons (July 2017) was also taken into account in the model, as this involved designing and implementing the changes necessary for the smoke-free policy to come into effect and, although there was no intervention per se at this point (i.e. policy change), other changes may have occurred (e.g. raised awareness of SHS levels leading to decreased smoking among PiC outwith permitted areas, information on SHS levels affecting strictness in enforcing current rules). We used a dummy variable to account for the announcement (value of 0 from June 2016 to July 2017, value of 1 from July 2017 to November 2018, and value of 0 from November 2018 onwards). As all prisons implemented smoke-free rules on the same date and the policy was the same across Scotland, there was no ‘control/comparator’ population. However, we examined differences by sickness absence causes (self-reported in the data), by job (operational vs. non-operational) and across ‘baseline SHS exposure prison types’. Other sensitivity analyses (SAs) (e.g. placebo intervention dates) were explored. Final analyses were delayed (because the COVID-19 outbreak led to a delay in obtaining all data from the SPS) and will be reported separately.

Health economic evaluation (work package 2)

Overview and overall aims

The aim of the health economic evaluation was to estimate the change in health-related costs and outcomes following the implementation of Scotland’s smoke-free prison policy. The cost-effectiveness of the policy was evaluated over two time periods: first, within the time period of the study (within-study analysis) and, second, over a lifetime (long-term analysis), for both operational staff and PiC, from the perspective of the NHS and including nicotine-related products. The within-study and long-term analyses are reported in line with current best practice. 58 Further detail is provided in Report Supplementary Material 3.

Within-study analysis

Cohort and time frame

The time period of the within-study analysis was 1 June 2016 (1 year prior to policy announcement) to 30 November 2019 (1 year after implementation). Costs and outcomes are compared over the three phases of the TIPs study (‘pre announcement’, ‘preparatory’ and ‘post implementation’; see Figure 1).

Data from Scotland’s 14 closed prisons were included in all analyses. Data from PiC in Scotland’s only open prison were excluded from base-case analyses where possible, as the PiC spend some time in the wider community (e.g. at work, with family) and have access to tobacco while away from the prison, but were included in SAs. Report Supplementary Material 3, Table 4, illustrates, for each category of cost and outcome, whether or not open prison data could be identified and excluded. Staff at the open prison were included in all analyses for prison staff.

Non-operational staff were excluded from the analyses given that they are less likely to be exposed to SHS at work and so less likely to be affected by the smoke-free policy.

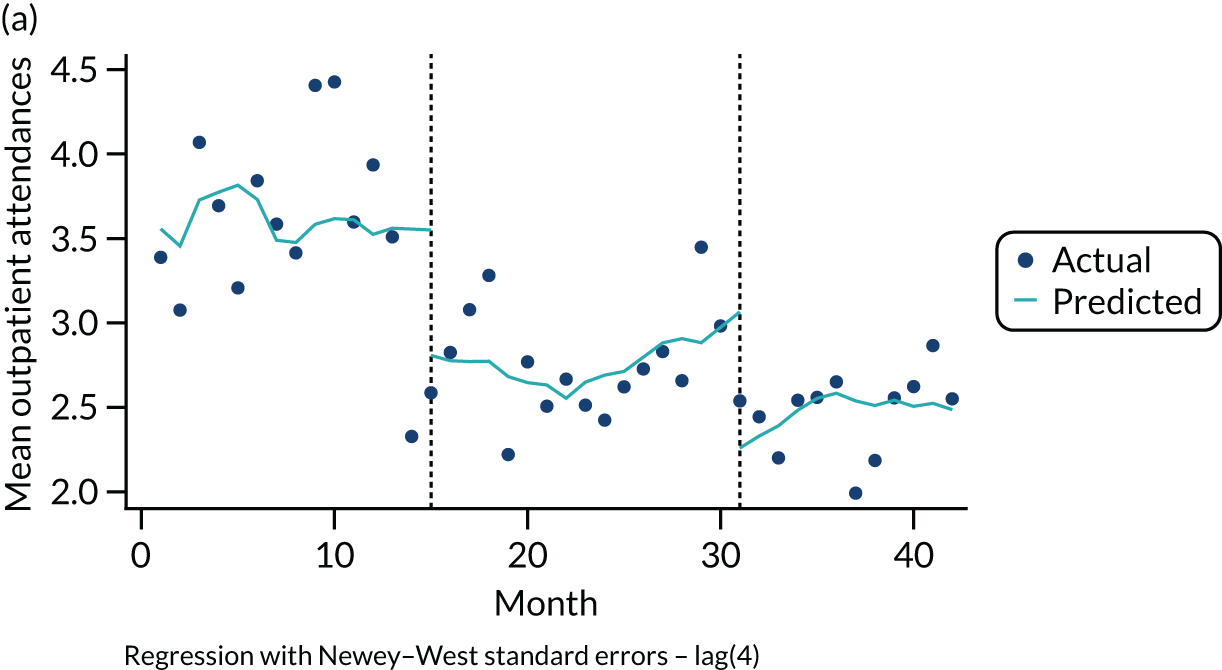

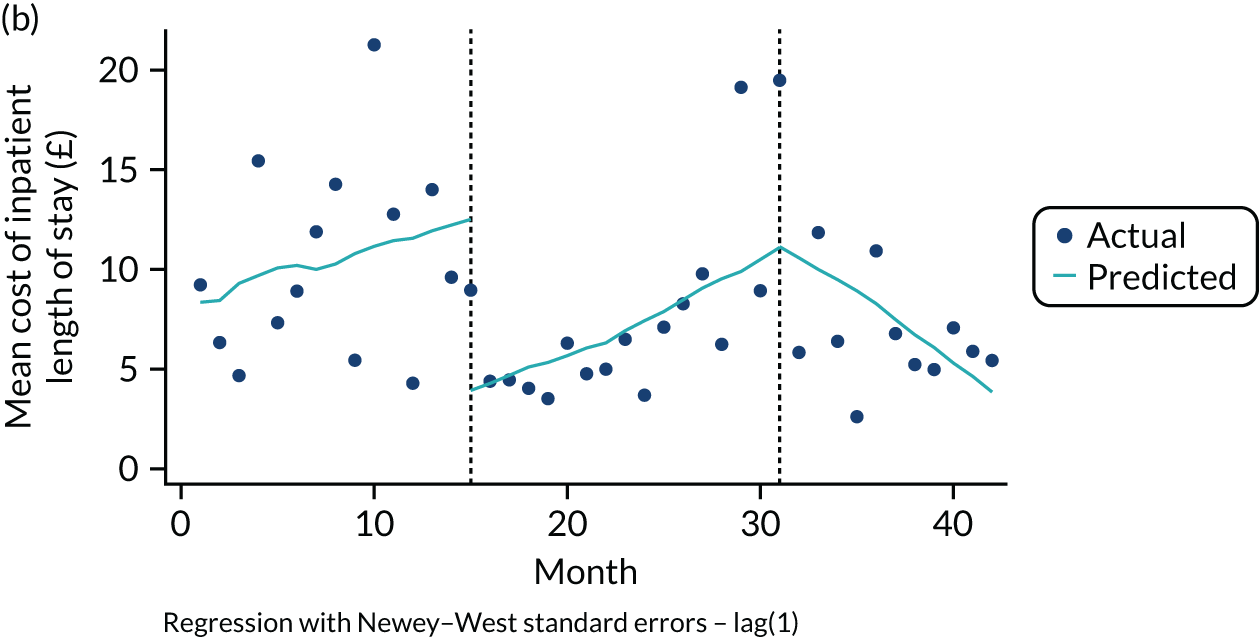

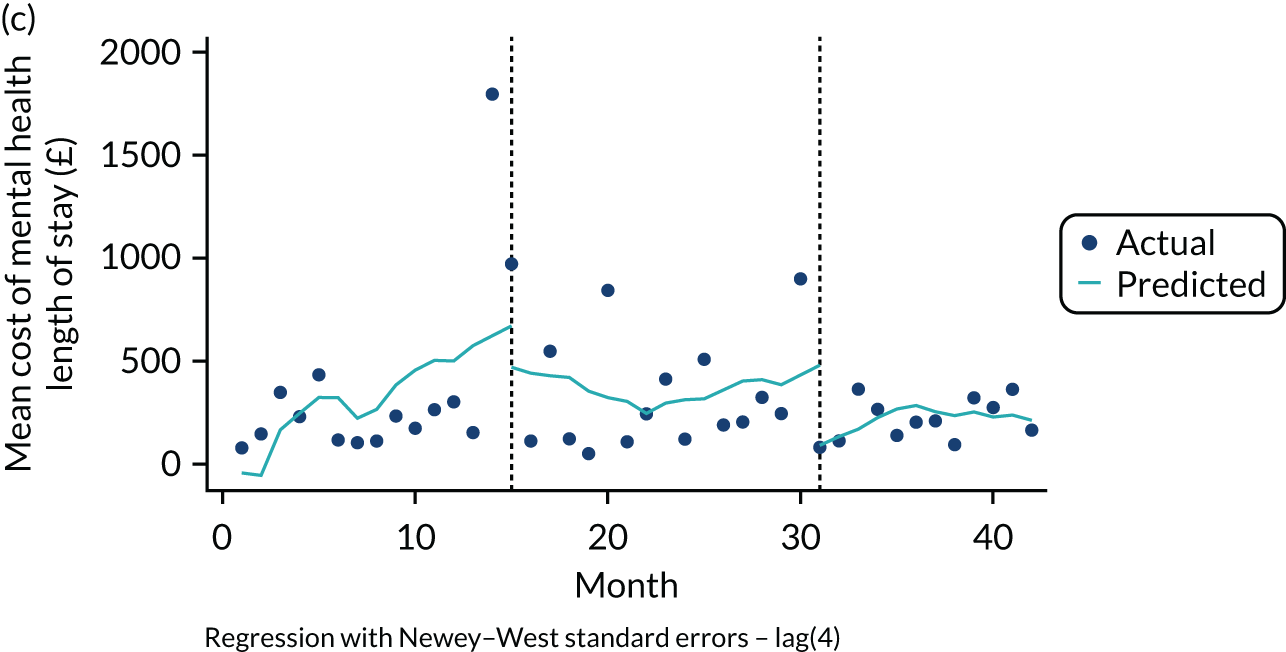

Data measurement and valuation

Resource use included two categories: health service use (staff and PiC), and tobacco and e-cigarettes spend (staff and PiC). Resource use data were obtained from several sources: TIPs staff and PiC surveys (Surveys of staff and people in custody); summary data on spend by PiC in the prison shop (‘canteen’), sourced from the SPS for an allied complementary study funded by Cancer Research UK (see Figure 1) (Cath Best, University of Stirling, 2021, personal communication); and NHS NSS data. Different resource categories were available for different time periods, collected at different frequencies and in different formats; details of resource use data are provided in full in Report Supplementary Material 3, Table 1. In brief, health service resource use categories comprised general practitioner (GP) and nurse visits for staff and PiC, and for PiC only; outpatient attendances; inpatient and mental health stays; accident and emergency (A&E) visits; ambulance incidents; and summary measures of medication dispensing. Nicotine product resources comprised tobacco for staff and PiC, and e-cigarettes for PiC only.

Unit costs: valuing resource use

Unit costs were for the year 2017/18 in Great British pounds (GBPs) and are presented in Report Supplementary Material 3, Table 2.

The GP and nurse costs were taken from the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2017 report published by the Personal Social Services Research Unit. 59 For PiC, the mean cost of a GP or nurse visit was calculated, as there was no way of ascertaining which visits were made by a GP and which were made by a nurse. Outpatient attendance, inpatient and mental health stays, ambulance incident and A&E attendance unit costs were taken from the Information Services Division Scotland cost book. 60

The cost of medications was included in the National Procurement data set as ‘gross value’. The average cost of a cigarette for staff was obtained from the Office for National Statistics. 61 PiC’s canteen spend was included in the SPS canteen data set (Best et al. , personal communication).

We applied unit costs to the relevant resource use to calculate total costs for each resource use.

Outcomes

Several health and organisational outcomes were included in the analyses, sourced from TIPs study data and the SPS. Outcomes comprised: SHS levels, health related quality-of-life, violence-related incidents, deaths in custody, fires and the management of offenders at risk owing to any substances (MoR).

Analysis

Base-case analysis

Three analyses were conducted for the within-study base-case analysis and are described in the following sections. For each of these analyses, where possible, data on PiC incarcerated in the open prison were excluded. To account for an increased number of PiC within the Scottish prison system, the effects of overcrowding were adjusted for using a ratio of prison population to contracted available places; this was feasible in the cost–consequences interrupted time series analysis only.

The cost–consequences analysis (CCA) analysis presented disaggregated costs and outcomes of interest to stakeholders in a balance sheet format, with no attempt to aggregate costs and outcomes into a single measure. 62 Disaggregated costs and outcomes were presented for all three phases of the within-study time period as a monthly mean per person per phase. The change in costs and outcomes between phases was estimated using two techniques, depending on the format of the data: (1) where data were available monthly at an aggregate level, interrupted time series methods were used to estimate the changes and predict the monthly means; and (2) where data were available at an individual level in each phase (but with no linkage between phases), a regression framework was used.

The cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) analysis result is presented as an incremental cost per additional 10 µg/m3 change in SHS, comparing pre-announcement and post-implementation costs and SHS outcome (Measuring exposures to second-hand smoke and Chapter 4, Changes in indicators of second-hand smoke concentration between phases 1 and 3). We compared costs for 12-month periods in the pre-announcement (June 2016–May 2017) and post-implementation (December 2018–November 2019) phases of the smoke-free policy, and SHS measures from November 2016 (pre announcement) and May 2019 (post implementation). The change in costs and SHS were estimated using a simple decision tree model with two arms.

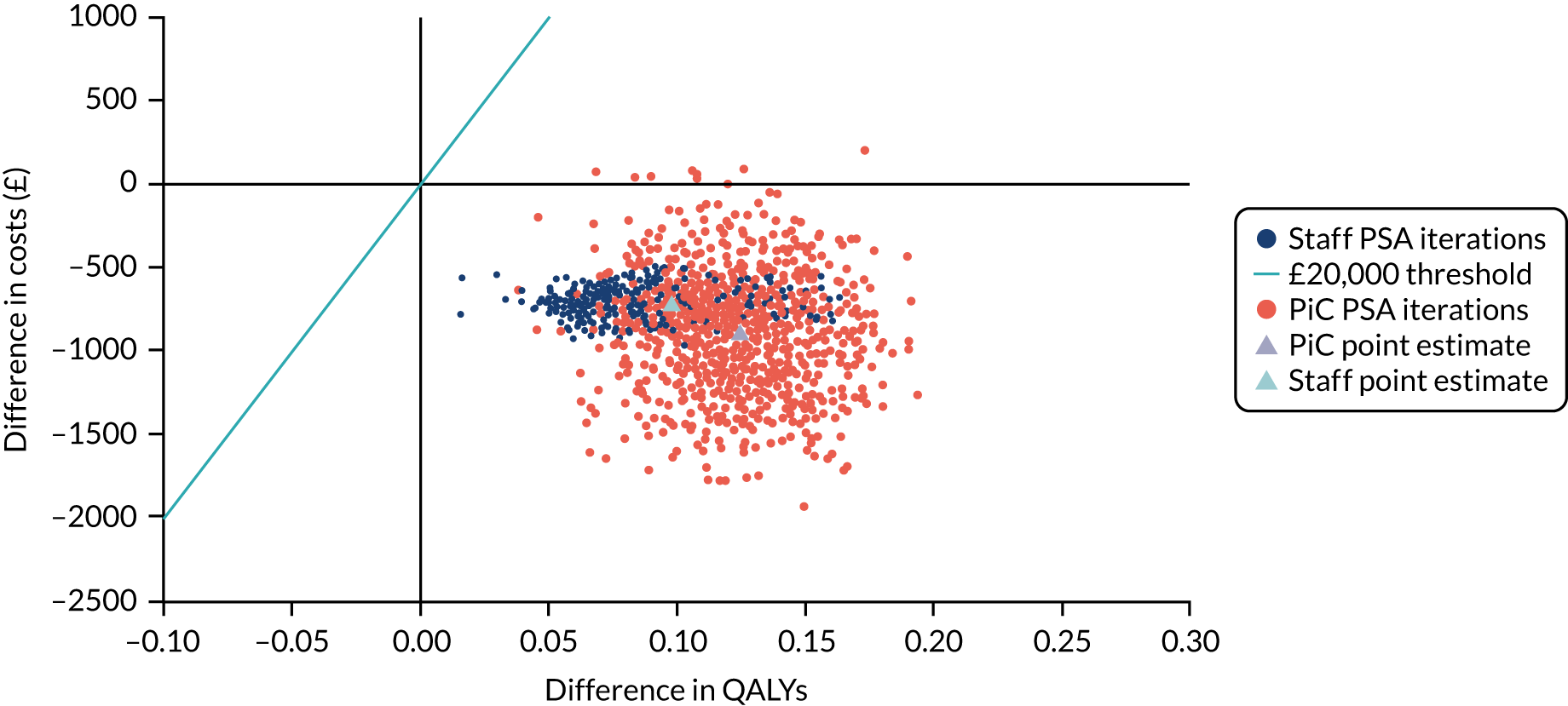

The cost–utility analysis (CUA) analysis result is presented as an incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), comparing pre-announcement and post-implementation costs and QALYs. QALYs were a combination of quality of life and length of life; the quality of life was the utility extracted from the staff and PiC surveys and the length of life was 1 year. Costs covered the same time period as in the CEA. The CUA result is presented as an incremental cost per QALY. The change in costs and SHS was estimated using a simple decision tree model with two arms.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty was explored in two SAs:

-

Sensitivity analysis 1 (SA1). The base-case analysis excluded PiC’s costs and outcomes for the open prison, where possible; a SA was conducted where these data were included. A summary of where it was possible to include and exclude the open prison for resource use and outcomes is presented in Report Supplementary Material 3, Table 4.

-

Sensitivity analysis 2 (SA2). In the base-case analysis, medications that were indicators of treatment for nicotine dependence and for smoking-related illnesses or associated symptoms were included only; a SA was conducted where all medications were included.

Long-term analysis

Overview

The aim of the long-term analysis was to conduct a CUA to estimate the incremental lifetime costs and QALYs for operational staff and PiC, with and without the smoke-free prison policy in place. Sources informing model parameters included literature, TIPs study outcomes, SPS reports and information, and expert opinion. Unit costs were for the year 2017/18 in GBP and the model perspective took a broader approach than NHS only, including personal spend on tobacco and e-cigarette products and NHS health-care costs. The outcome measure was the QALY. Costs and outcomes incurred beyond the first cycle were discounted at 3.5%, as recommended by NICE. 63,64 Cycle length was 1 year and the model was run for a total of 70 cycles.

The model populations were operational staff and PiC. Comparators were ‘with smoke-free policy’ and ‘without smoke-free policy’ and results were compared to estimate a lifetime incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of mean cost per QALY. Uncertainty was measured using a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) to estimate confidence intervals around the ICER; the effect on the ICER of different scenarios was explored in SAs.

Model structure

A Markov model was used, in which a notional cohort of people travelled through model states accumulating costs, quality of life and life expectancy, depending on their smoking status and SHS exposure.

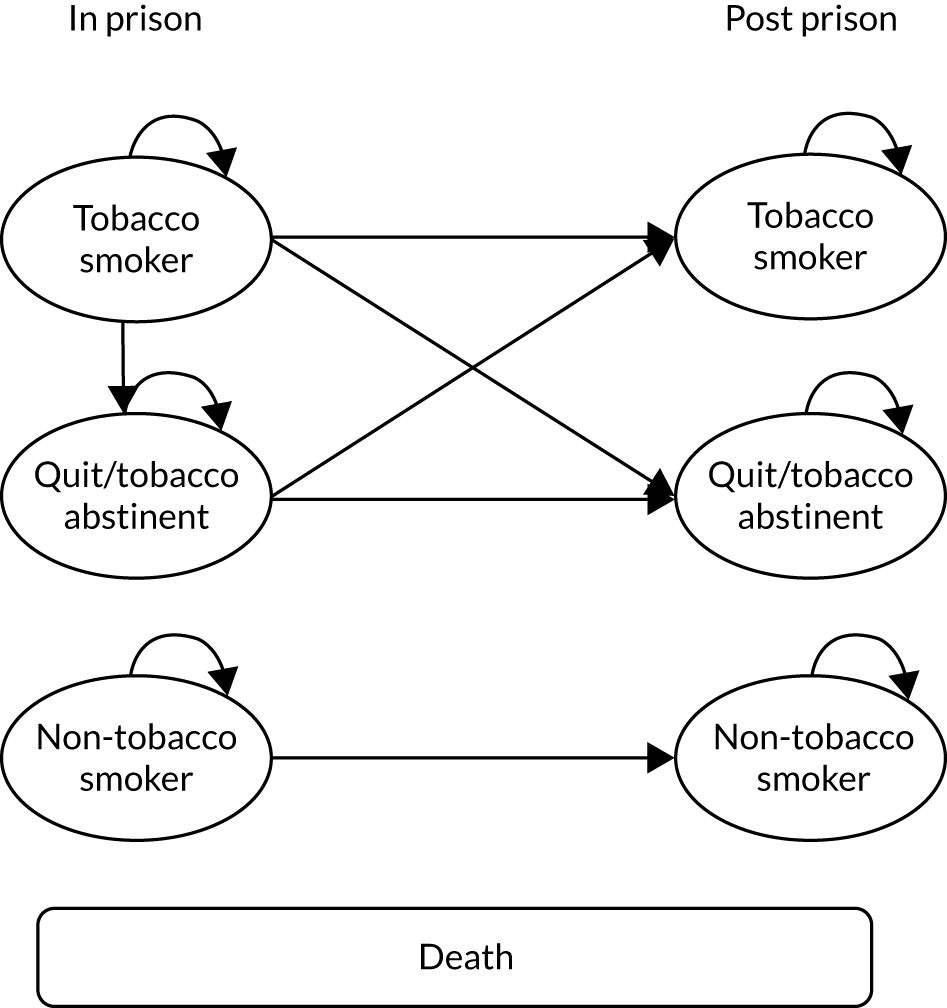

The model structure diagram is presented in Figure 2. Cohorts of staff and PiC entered the model at the start of their SPS employment (staff) or first incarceration (PiC), and both cohorts were closed, that is no additional staff or PiC were added during the time period of the model. The states in the model were not health states, but mainly related to smoking statuses, which were assigned different morbidity and mortality transitions; this is typical of other cost-effectiveness smoking cessation models. Four states were included: ‘tobacco smoker’, ‘quit/tobacco abstinent’, ‘non-tobacco smoker’ and ‘death’. A ‘tobacco smoker’ was defined as someone who smokes tobacco and did not include e-cigarette users. A person who had/was ‘quit/tobacco abstinent’ was someone who was a smoker on entry to the model and who had stopped smoking (voluntarily or otherwise) during their prison work/custodial sentence or after leaving the prison environment. A ‘non-tobacco smoker’ was someone who did not smoke tobacco prior to working/having a custodial sentence in prison and did not take up tobacco smoking while in prison or post prison.

FIGURE 2.

Long-term model diagram.

The structure was split into two time periods: ‘in prison’ and ‘post prison’. For staff, ‘in prison’ represented the time employed by the SPS and ‘post prison’ represented the time after working for the SPS (assumed to be retirement). For PiC, ‘in prison’ represented the time in custody and ‘post prison’ represented the time after release.

The cohorts entered the model in the ‘in-prison’ section as ‘tobacco smoker’, ‘quit/tobacco abstinent’ or ‘non-tobacco smoker’. After the implementation of the smoke-free policy, all ‘tobacco smokers’ in the PiC cohort immediately become ‘quit/tobacco abstinent’ on entering the ‘in-prison’ section of the model.

In the ‘post-prison’ section, ‘tobacco smokers’ from the ‘in-prison’ section remained ‘tobacco smokers’ (except PiC who were ‘quit/tobacco abstinent’ ‘in prison’ as a result of the smoke-free policy; 100% of these reverted to ‘tobacco smokers’ ‘post prison’). Those in the ‘quit/tobacco abstinent’ state in the ‘in-prison’ section could remain ‘quit/tobacco abstinent’ or resume tobacco smoking on entering the ‘post-prison’ section.

‘Non-tobacco smokers’ in the ‘in-prison’ period remained non-smokers in the ‘post-prison’ period. We assumed that ‘non-tobacco smokers’ ‘in prison’ were exposed to SHS in the ‘without smoke-free policy’ comparator and were not exposed to SHS ‘with smoke-free policy’.

Anyone in the model could transition to the ‘death’ state at any time and from any state.

Assumptions

Several structural assumptions were made for the Markov model:

-

A ‘non-tobacco smoker’ in the ‘post-prison’ period was not exposed to SHS because of the lack of evidence to support alternative assumptions.

-

People who did not smoke on entering the model (non-smokers reported in the SPS’s 16th Prisoner Survey 201741) were assumed to be never smokers, as there was no information on whether they were never or former smokers (recent or otherwise); they were thus assigned ‘never-smoker’ utilities mortality and morbidity.

-

‘Tobacco smokers’ immediately became ‘quit/tobacco abstinent’ on entry to the model in the ‘with smoke-free policy’ comparator, and were allocated former smoker utilities, risk of morbidity and mortality, in line with other economic smoking cessation models. 65

-

‘Non-tobacco smokers’ did not take up smoking in the model; this assumption was mitigated by applying the prevalence of PiC smoking in prisons41 to model seeding.

Model transitions and parameters

Full details of the model transitions and parameters are described in Report Supplementary Material 3; parameters are provided in Report Supplementary Material 3, Table 5.

In summary, model transitions comprised smoking status and prevalence; smoking status and sex-specific morbidity; and smoking status, age and sex-specific mortality. Model parameters comprised intervention costs; smoking-related, disease-related health-care costs; nicotine product costs; QALY outcome; age of the cohorts entering the model; length of time both cohorts spend in the ‘in-prison’ time period of the model and the total population numbers in each cohort.

Analysis

The Markov model was constructed in Microsoft Excel for Office 365 (Microsoft Corporation). Male and female staff and PiC were modelled using different parameters; the results were combined by applying a ratio of male to female. For the operational staff male/female split, 73% were male and 27% were female (based on the position on 31 March 2020); this information was provided by the SPS (Emma Christie, Scottish Prison Service, 2020, personal communication). For PiC, the male/female split reported in the Scottish Prison Service Prisoner Survey 201741 (95% male, 5% female) was used. Results were presented for mean costs and QALYs per staff and PiC, and an ICER was calculated for each cohort. The cost-effectiveness of these results was assessed using the £20,000 willingness-to-pay threshold. 64

Uncertainty

To reflect the uncertainty of input parameter estimates, we carried out a PSA using established methods66 to estimate the confidence intervals (CIs) around the difference in costs and QALYs and the ICER. Appropriate distributions were fitted to means as follows: relative risks characterised by log-normal distribution, costs characterised by gamma distribution, and utility values characterised by beta distribution. Random picks were taken from these distributions. Guidance67 on model convergence was followed and 1000 iterations were undertaken. Results were displayed as estimates on a cost-effectiveness plane.

Scenario analyses

Ten scenarios were explored to assess uncertainty in the model assumptions; full descriptions are available in Report Supplementary Material 3, Table 6. The scenarios explored included varying the levels of resuming tobacco smoking for PiC on release from prison, varying the length of sentence for PiC, using health utilities from the TIPs surveys for PiC, an alternative to PiC mortality-standardised mortality ratios, varying nicotine product spend for PiC, and using a different discount rate.

Overall impact of policy

The overall impact of implementing the smoke-free policy was assessed by estimating the prison population total costs and QALYs for all PiC and operational staff over a lifetime. The overall implementation cost to the SPS included in this analysis was the total amount that the SPS expected to spend on the vaping kits (£150,000). 68

Chapter 3 International landscape

Interviews with representatives from other jurisdictions

We analysed data from our interviews with staff representatives from three other jurisdictions that had already implemented smoke-free policies in prisons (New Zealand,25 parts of Australia69 and E&W) to identify factors that may aid implementation of a smoke-free prison policy elsewhere. Most of the representatives interviewed (15/19) were from E&W.

In 2011, New Zealand was the first of these jurisdictions to go smoke free in prisons, and its comprehensive approach to implementation appears to have guided other jurisdictions. The themes identified through analyses of our participant interviews in relation to implementation strategies were substantively similar across jurisdictions, although there were some notable variations in practice. One important difference was in relation to e-cigarettes. We note that New Zealand prisons (2011) and those in parts of Australia (2013) went smoke free before e-cigarettes became more widely available internationally; in contrast, e-cigarettes were made available in prisons in E&W when smoke-free policies were rolled out across the estate in 2016–18, and participants from these jurisdictions reflected on their place in implementing a smoke-free policy in prisons (see Smoking cessation support).

Managing policy implementation

Several dimensions of project management in relation to removing tobacco from prisons were discussed by participants. First, allowing good time – as far as possible – was regarded as helpful, as it gave prisons the opportunity to prepare for the implementation of smoke-free policies and for PiC (and staff) to adjust to changes and prepare to abstain or quit tobacco (‘You can’t start too early I don’t think,’ interview 11). There were some suggestions that it is helpful to set a ‘clear date’ for implementation to generate the impetus to drive forward preparatory work:

. . . we started to prep for going smoke-free [several years] before we actually did. Because we kept getting told it’s going to be introduced, it’s going to be introduced. But it never did. But rather than stand down our preparation . . . we just ran the meeting quarterly to keep it . . . everybody’s agenda . . . as soon as we had a clear date we just cranked things up.

WP1, interview 16

Second, participants articulated the importance of appropriate governance arrangements. This included an adequately resourced implementation team to guide and support prisons, and local implementation groups within prisons, involving local personnel with sufficient capacity and credibility/seniority, to take forward the smoke-free policy. Other examples that participants discussed related to the use of a ‘readiness assessment’ tool to drive and monitor progress (ensuring that associated documents were not too onerous to complete), and processes for foreseeing and responding promptly to potential risks associated with removing tobacco from prisons. Regular and open communication at all levels about progress, successes and challenges in preparing to go smoke free was described as important, as were opportunities for peer-to-peer support and sharing of good practice across the prison estate and from other jurisdictions that had implemented a smoke-free prison policy:

. . . rather than . . . [saying] ‘Right, governors! This is what you’ve got to do, crack on!’, we really did try to go in and support them . . . We would do our reports and we would have a look at their report that they’d submit each month and . . . we would go in and say, ‘Well, we were concerned about this’ or actually, ‘Yes, we’re really happy with your progress’ . . . It was . . . colleagues trying to help other colleagues . . .

WP1, interview 13

Third, participants highlighted that good partnership working, including with external partners, was likely to be beneficial, including prison and health services having shared responsibility for implementation, supporting one another in their respective roles and communicating regularly to monitor progress and identify issues. Support from all functions in prisons (a ‘whole-prison approach’) in preparing for smoke-free rules was also considered beneficial:

I think it can feel for the health providers that this is kind of their project and they’re on their own and it’s just about delivering smoking cessation with as many [PiC] as you can as quickly as you can, but that really isn’t actually the biggest issue. The biggest issue is the whole-prison approach to this and what everybody’s doing to chip in.

WP1, interview 6

Finally, our interview data highlighted the need for ongoing management of smoke-free policies post implementation to support continued success (e.g. strategies for effective management of nicotine dependence among new arrivals) and to support efforts to reduce any unintended adverse consequences of smoke-free policies (e.g. addressing contraband tobacco black markets and supporting PiC who find smoking abstinence challenging).

Communication and engagement

Participants also described how extensive communication and engagement with PiC, staff and other stakeholders about the forthcoming changes to smoking rules could aid successful implementation:

Communication was absolutely crucial and vital in everything that we did . . . we just made sure that it was always communicated where we were at with the project, what the next steps were.

WP1, interview 19

Ideas about ways to build awareness, support and acceptance for smoke-free prison policies included using multiple communication channels to publicise the policy (e.g. posters, leaflets, prison television screens, prisoner radio, announcements over a loudspeaker system, displays in the prison library, publicising smoke-free rules in the visitor centre); cascading information via peer mentors/PiC representatives to enhance message credibility and reduce misinformation and rumours; repeating communications over time to maintain visibility, dispel beliefs that smoke-free rules would not be implemented as intended and ensure that new arrivals were well informed of the impending changes: