Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/178/17. The contractual start date was in November 2014. The final report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in August 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Allen et al. This work was produced by Allen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Allen et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Paediatric mortality rates in the UK are among the highest in Europe. 1 Although perinatal events account for a major part, there continues to be evidence to suggest that missed deterioration and difference in hospital performance contribute. 2–4 More than a decade ago, the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health highlighted identifiable failures in a child’s direct care in just over 25% of deaths; for an additional 43% of deaths, potentially avoidable factors were highlighted. 2 More than 700,000 children are admitted to hospital overnight in the UK annually, with 8000 of these admitted to paediatric intensive care units (PICUs) as an emergency. 5 Half of these are from wards in the same hospital, suggesting that patients deteriorated acutely or had a cardiopulmonary arrest. These missed opportunities to detect and intervene in hospital are instances of failures in care, with physiological, psychological and social costs to the child and family. 6,7 There is significant short-term added cost to the NHS from the rising cost of litigation (£1.1B). 8,9 For a society that values its NHS, this is widely recognised to be a situation that needs to be reversed. It is estimated that 1951 child deaths would need to be prevented to compare with the best performers in Europe. 10

Track-and-trigger tools (TTTs), otherwise known as early warning scores, have been a popular response to address missed deterioration in both adults and children. 11 A TTT consists of sequential recording and monitoring of physiological, clinical and observational data. 12 When a certain score or trigger is reached, this directs a clinical action, including, but not limited to, altered frequency of observation, a senior clinical review or more appropriate treatment or management. Tools may be paper based or electronic, and monitoring can be automated or undertaken manually by staff. 13 Research in the adult care context has shown that acute in-hospital deterioration is often preceded by a period of physiological instability, which, when recognised, provides an opportunity for earlier intervention, and improved outcome. 14,15 As a result, the Royal College of Physicians endorsed the implementation of a national early warning TTT for adults to standardise the assessment of acute illness severity, predicting that 6000 lives would be saved. 16

Standardising the use of TTTs to detect deterioration in children has been more challenging. Variation in accepted physiological normal parameters for respiratory rate, heart rate and blood pressure across the age range makes it challenging to develop a standardised tool suitable for generic application for all hospitalised children. Some single-site studies have reviewed the performance of individual TTTs, with preliminary data on the sensitivity of different cut-off points for physiological measurements. 17–19 However, it was difficult to prove an ‘effect’ based on the outcome measures described, because the event rate of in-hospital cardiac arrest or death is low. Subsequent systematic reviews demonstrated potential benefits but no clear improvement in patient outcomes. 20,21 Furthermore, a 2014 review of paediatric track-and-trigger tools (PTTTs) throughout Great Britain found that 85% of units were using a tool; however, there was huge variability in the tools used, and most were unpublished and unvalidated. 22 The ad hoc use of unvalidated TTTs and variance in organisational capacity to respond to a deteriorating child has been felt to represent a serious clinical risk.

The Paediatric early warning system Utilisation and Morbidity Avoidance (PUMA) study was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under a call for studies that generated interventions to reduce in-hospital mortality. The original aims of the study were to:

-

identify, through a systematic review of the literature, the evidence for the core components of a PTTT

-

identify, through a systematic review of the literature, the evidence for the core components of an effective paediatric early warning system.

-

identify, through a systematic review of the literature, the contextual factors that are consequential for PTTT and paediatric early warning system effectiveness

-

develop a PTTT implementation package

-

evaluate the ability of the PTTT to identify serious illness and reduce clinical events by examining core outcomes

-

identify the contextual factors that influence PTTT effectiveness

-

identify the key ingredients of successful implementation and normalisation.

The findings of the systematic reviews, which are presented in detail in Chapter 3, did not support an exclusive focus on PTTTs. The quality of studies evaluating PTTTs was generally low and there was limited evidence of the effectiveness of PTTTs in reducing adverse events in hospitalised children. Most of the studies reviewing the effectiveness of PTTTs also simultaneously implemented changes to the system, making it difficult to disentangle effects of the tool from system changes. However, the systematic reviews provided evidence of multiple failure points in systems for detecting and responding to deterioration, particularly around detection, preparation and action. There was also emerging evidence on common issues in traditional approaches to implementation and improvement, which often are solution driven, fail to engage the expertise of those responsible for implementing in practice, and focus on the use of a tool or intervention, rather than considering how an issue might be addressed in context.

As a result of the systematic reviews, the focus of the PUMA study shifted from PTTTs to a system-wide approach. The revised aims were to:

-

identify, through a systematic review of the literature, the evidence for the core components of an effective PTTT and paediatric early warning systems

-

identify, through a systematic review of the literature, the contextual factors that are consequential for PTTT and paediatric early warning system effectiveness

-

develop and implement an evidence-based paediatric early warning system improvement programme (i.e. the PUMA programme)

-

evaluate the effectiveness of the PUMA programme by examining changes in clinical practice and core outcomes trends

-

identify the key ingredients of successful implementation and normalisation of the PUMA programme.

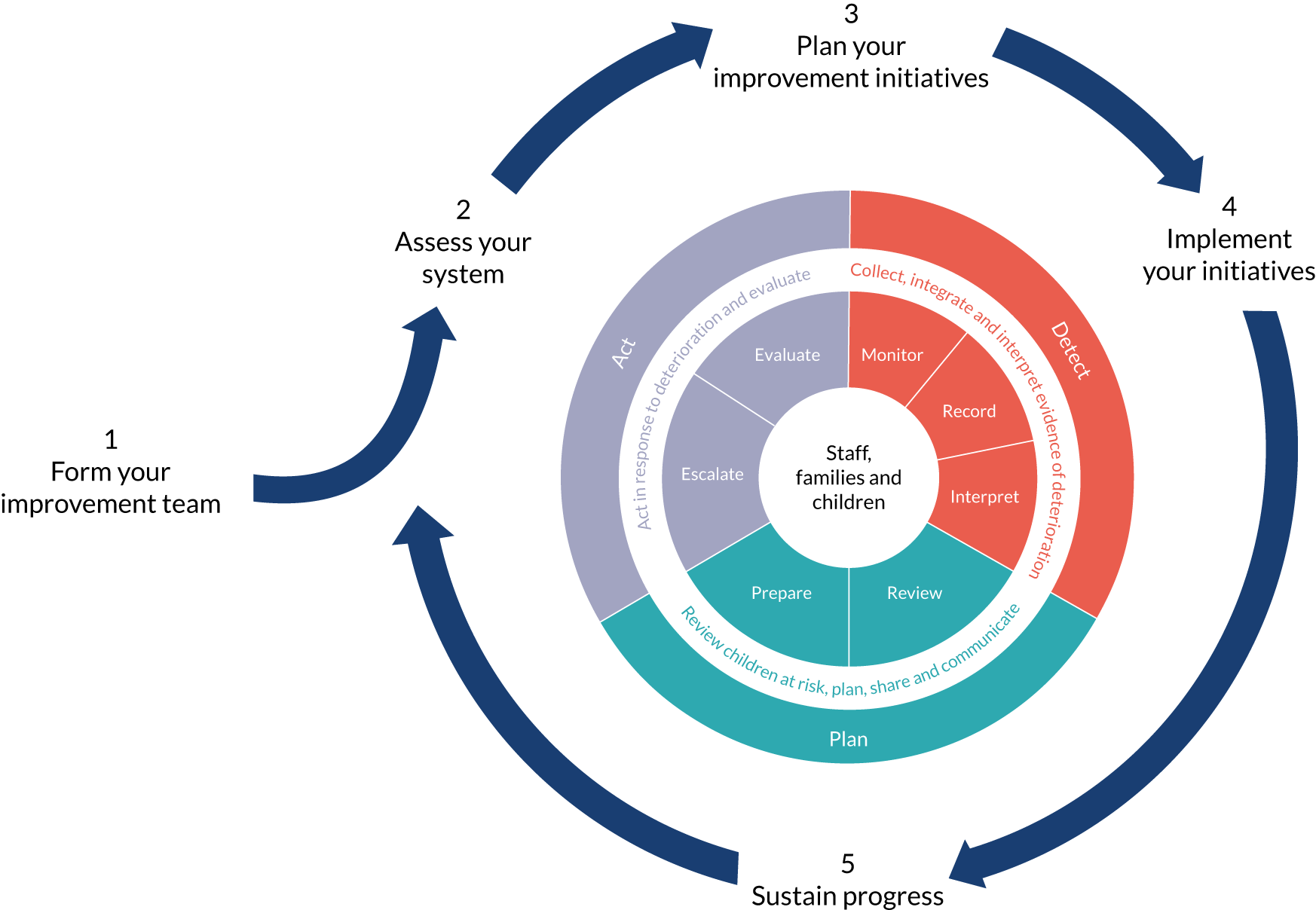

Drawing on evidence from improvement and implementation literature, the PUMA programme was underpinned by a novel approach, developed as part of the study, that aimed to create a better understanding of system strengths and weaknesses in each setting, to capitalise on the expertise of those with knowledge of how the system worked, and to focus on the goals (improving detection and response to paediatric deterioration), rather than prescribing specific interventions.

Chapter 2 describes the study methods. Chapter 3 presents the key findings from the systematic reviews. Chapter 4 describes the development and implementation of the PUMA programme. Chapters 5–8 describe the four case studies, drawing on both quantitative and qualitative data. Chapter 9 provides a cross-comparative analysis of the effects of the PUMA programme across the four sites. Chapter 10 presents the findings of the parallel process evaluation of the delivery of and response to the PUMA programme and key areas of learning. Chapter 11 summarises the findings of the PUMA study, considers their implications for policy, practice and research, and signposts next steps.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter outlines the study methods. Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Thomas-Jones et al. 23 © The Authors. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Jacob et al. 13 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Trubey et al. 24 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Ethics approval was granted on 13 April 2015 by the National Research Ethics Service Committee South West, registration number 15/SW/0084 (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Study design

The research was a prospective, mixed-methods, before-and-after study, divided into two workstreams:

-

Workstream 1 involved the development of an evidence-based paediatric early warning system improvement programme (the PUMA programme), drawing on three systematic reviews of the literature. 13,24

-

Workstream 2 involved the implementation and prospective evaluation of the PUMA programme in four UK hospitals, with an embedded process evaluation. Evaluation was conducted both quantitatively (comparing trends in rates of adverse outcomes on inpatient wards before, during and after implementation) and qualitatively (through ethnographic observations and interviews, and evaluating the implementation process and clinical practice before and after implementation).

Theoretical framework

Translational mobilisation theory

Translational mobilisation theory (TMT) was deployed in order to think systematically about paediatric early warning systems and the sociotechnical contexts into which an improvement programme would be introduced. 25,26 TMT is a practice theory that describes projects of goal-oriented collective action in conditions of emergence and complexity. The ‘project’ is the basic unit of analysis in TMT and refers to an institutionally sanctioned sociomaterial network of time-bounded co-operative action and actors that follows a trajectory in time and space: in this case the detection of physiological deterioration and timely intervention in the care of sick children. TMT directs attention to the institutional contexts in which projects are progressed and that provide the sociomaterial resources that condition collective action and the mechanisms through which projects are mobilised. TMT was deployed to identify the core components and mechanisms of action central to achieving the goal of detecting and acting on deterioration in hospitalised children, the elements of context that are most salient to enacting the goal and the processes by which that may be achieved.

Normalisation process theory

Normalisation process theory (NPT), which has a high degree of conceptual affinity with TMT, provided an additional theoretical lens to inform the evaluation of implementation processes. 27 NPT is concerned with ‘how and why things become, or don’t become, routine and normal components of everyday work’28 and it defines four mechanisms that shape the social processes of implementation, embedding and integrating ensembles of social practices. These are inter-related and dynamic domains, and include:

-

coherence (the extent to which an intervention is understood as meaningful, achievable and desirable)

-

cognitive participation (the enrolment of those actors necessary to deliver the intervention, which, for our purposes, can be human and non-human)

-

collective action (the work that brings the intervention into use)

-

reflexive monitoring (the ongoing process of adjusting the intervention to keep it in place).

Settings

A convenience sample of four UK hospitals was selected to represent inpatient units of varying size: two tertiary centres with integrated PICUs (Alder Hey Children’s Hospital and Noah’s Ark Children’s Hospital for Wales) and two large district general hospitals (DGHs) without a PICU (Arrowe Park Hospital and Morriston Hospital) (Table 1). Two hospitals had a PTTT in place for the duration of the PUMA study and two did not.

| Site | Number of beds (excluding PICU) | Annual inpatients (excluding day cases) (n) | PTTT in use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alder Hey Hospital, Liverpool | 337 inpatient, 15 HDU | > 200,000 | Yes |

| Arrowe Park Hospital, Wirral | 32 inpatient, 2 HDU | 2500 | Yes |

| Noah’s Ark Children Hospital for Wales, Cardiff | 61 inpatient, 4 HDU | 23,000 | No |

| Morriston Hospital, Swansea | 38 inpatient, 7 HDU | 7500 | No |

Patient and public involvement

The project’s patient and public involvement (PPI) liaison officer, Jenny Preston, convened a PPI group, consisting of four parents with direct experience of a child deteriorating in hospital.

The group met at several stages of the project. Table 2 summarises those meetings, their objectives and outputs, and the way in which the group’s feedback was incorporated into the project. More detailed outputs of those meetings and reflections on the challenges of integrating PPI into the project are considered in Appendix 1, Table 19.

| Meeting date | Objectives | Summary of feedback | Summary of changes made |

|---|---|---|---|

| November 2014 |

|

|

|

| December 2015 |

|

As a result of the systematic review, the group was informed that the PUMA study team had revised the original aims of the study away from developing a single PTTT to the development of a paediatric early warning system improvement programme |

|

| March 2016 |

|

Suggested changes to SHINE |

|

| June 2018 |

|

Suggested changes to language, structure and content of FFT |

|

| March 2019 |

|

Suggested changes to funding proposal for project focusing on family involvement in detection of deterioration |

|

Workstream 1: evidence reviews

Quantitative systematic reviews

Two systematic reviews aimed to assess in depth the evidence base for the validity of PTTTs for predicting inpatient deterioration and the effectiveness of broader early warning systems at reducing instances of mortality and morbidity in paediatric settings. The review questions were as follows:

-

Review 1: how well validated are existing PTTTs and their component parts for predicting inpatient deterioration?

-

Review 2: how effective are paediatric early warning systems (with or without a PTTT) at reducing mortality and critical events?

Search strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted across a range of databases to identify relevant studies in the English language. Published and unpublished literature was considered if publicly available, as were studies in press. The following databases were searched from inception to May 2018: British Nursing Index, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process, Scopus and Web of Knowledge (Science Citation Index). To identify additional papers, either published or unpublished, or research reported in the grey literature, a range of relevant websites and trial registers were searched, including ClinicalTrials.gov. To identify published papers that had not yet been catalogued in the electronic databases, recent editions of key journals were hand-searched. The search terms included ‘early warning scores’, ‘alert criteria’, ‘rapid response’, ‘track and trigger’ and ‘early medical intervention’. See Appendix 2, Tables 20 and 21, for the search strategies and results.

Eligibility screening and study selection

Population, intervention, control/comparison, outcomes (PICO) parameters guided inclusion criteria for the validation and effectiveness studies (see Appendix 3, Tables 22 and 23). Papers reporting development of validation of a PTTT were included for review 1, whereas papers reporting the implementation of any broader ‘paediatric early warning system’ (with or without a PTTT) were eligible for review 2. Both reviews were limited to studies that involved inpatients aged 0–18 years. Outcome measures considered were mortality and critical events, including: unplanned admission to a higher level of care, cardiac arrest, respiratory arrest, medical emergencies requiring immediate assistance, children reviewed by PICU staff on the ward (in specialist centres) or reviewed by external PICU staff (for non-specialist centres), acuity at PICU admission and PICU outcomes. A range of study designs was considered for both reviews.

Two of the review authors independently screened the titles and abstracts yielded in the search. Full texts were reviewed independently by six reviewers against the above eligibility criteria and were assigned to the relevant review question if included. Reasons for exclusion were recorded. Separate data extraction forms were developed for validation and effectiveness studies. The forms had common elements (study design, country, setting, study population, description of the PTTT or early warning system, statistical techniques used, outcomes assessed). Additional data items for validation studies included the items in the PTTT, modifications to the PTTT from previous versions, predictive ability of individual items and the overall tool, sensitivity and specificity and inter-rater and intrarater reliability. Effectiveness studies included an assessment of outcomes in terms of mortality and various morbidity variables. Two reviewers carried out data extraction; discrepancies were resolved by discussion. For effectiveness studies, effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated or reported as risk ratios (RRs) or odds ratios (ORs) as appropriate, with p-values reported to assess statistical significance. Data analysis was conducted using an online medical statistics tool.

Quality appraisal

The methodological quality and risk of bias were assessed for each included study using a modified version of the Downs and Black rating scale29 (see Appendix 4, Tables 24 and 25).

Qualitative systematic review

A third, qualitative, systematic review addressed the following question:

-

What sociomaterial and contextual factors are associated with successful or unsuccessful paediatric early warning systems (with or without PTTTs)?13

Study design

We performed a hermeneutic systematic review of the relevant literature. A hermeneutic systematic review is an iterative process, integrating analysis and interpretation of evidence with literature searching and is designed to develop a better understanding of the field. 30 The popularity of the method is growing in health services research, for which it has value in generating insights from heterogeneous literatures that cannot be synthesised through standard review methodology, and which would otherwise produce inconclusive findings. 21,31 The purpose of the review was not exhaustive aggregation of evidence, but to develop an understanding of the social, material and contextual factors associated with successful or unsuccessful paediatric early warning systems.

Theoretical framework

Translational mobilisation theory and NPT informed the data extraction strategy, interpretation of the evidence and the development of a propositional model of the minimal conceptual requirements of a paediatric early warning system. 25,27,28,32

Focus of the review

The literature in this field identifies four integrated components that work together to provide a safety system for at-risk patients: (1) the afferent component, which detects deterioration and triggers a response; (2) the efferent component, which consists of the people and resources providing a response; (3) a process improvement component, which includes system auditing and monitoring; and (4) an administrative component focusing on organisational leadership and education required to implement and sustain the system. 33 Our focus was limited to the afferent components of the system.

Stages of the review

Stage 1: scoping the literature

Literature was identified through a recent scoping review,34 team members’ knowledge of the field, hand-searches and snowball sampling techniques. The purpose was to (1) inform our review question and eligibility criteria and (2) identify emerging themes and issues. Although we drew on several reviews of the literature, we always consulted original papers. 20,34,35 Data were extracted using data extraction template 1 (see Appendix 5) and analysed to produce a provisional conceptual model of the core components of paediatric early warning systems. Additional themes of relevance were identified: family involvement, situational awareness, structured handover, observations and monitoring, and the impact of electronic systems and new technologies.

Stage 2: searching for the evidence

We undertook systematic searches of the paediatric and adult early warning system literature (the goals and mechanisms of collective action in detecting and acting on deterioration are the same) (searches 1 and 2). For the adult literature, we used the same search strategies but added a qualitative filter to limit the scope to studies most likely to yield the level of sociomaterial and contextual detail of value to the review. Literature informing additional areas of interest was located through a combination of systematic searches and hand-searches. Systematic searches (searches 3 and 4) were undertaken in areas for which we anticipated locating evidence of the effectiveness of specific interventions to strengthen early warning systems. Theory-driven searches reflected the conceptual requirements of the developing analysis.

Four systematic searches were conducted across a range of databases from 1995 to September 2016 to identify relevant studies in English-language papers reporting on:

-

paediatric early warning systems

-

adult early warning systems

-

interventions to improve situational awareness

-

structured communication tools for handover and handoff.

Detailed information on the search methodology can be found in Appendix 6.

Theory-driven searches were conducted in the following areas:

-

family involvement

-

observations and monitoring

-

the impact of electronic systems.

These were a combination of exploratory, computerised, snowball and hand-searches. As the analysis progressed, we continued to review new literature on early warning systems as it was published.

After removing duplicates, 5256 references were identified for screening. Papers were screened by title to assess eligibility and then by full text to assess relevance for data extraction. Searches 1 and 2 were screened by two researchers; searches 3 and 4 were screened by the lead reviewer. Grey literature was excluded to keep the scale of the review manageable.

Stage 3: data extraction and appraisal

Data extraction template 2 (see Appendix 7) was applied to all papers included in the review. Evidential fragments and partial lines of inquiry formed the unit of analysis, rather than whole papers. Fragments were drawn from papers that were assessed for quality according to study type and the contribution made to the developing analysis. Data extraction and quality appraisal were undertaken concurrently and checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements and areas of uncertainty were resolved by discussion.

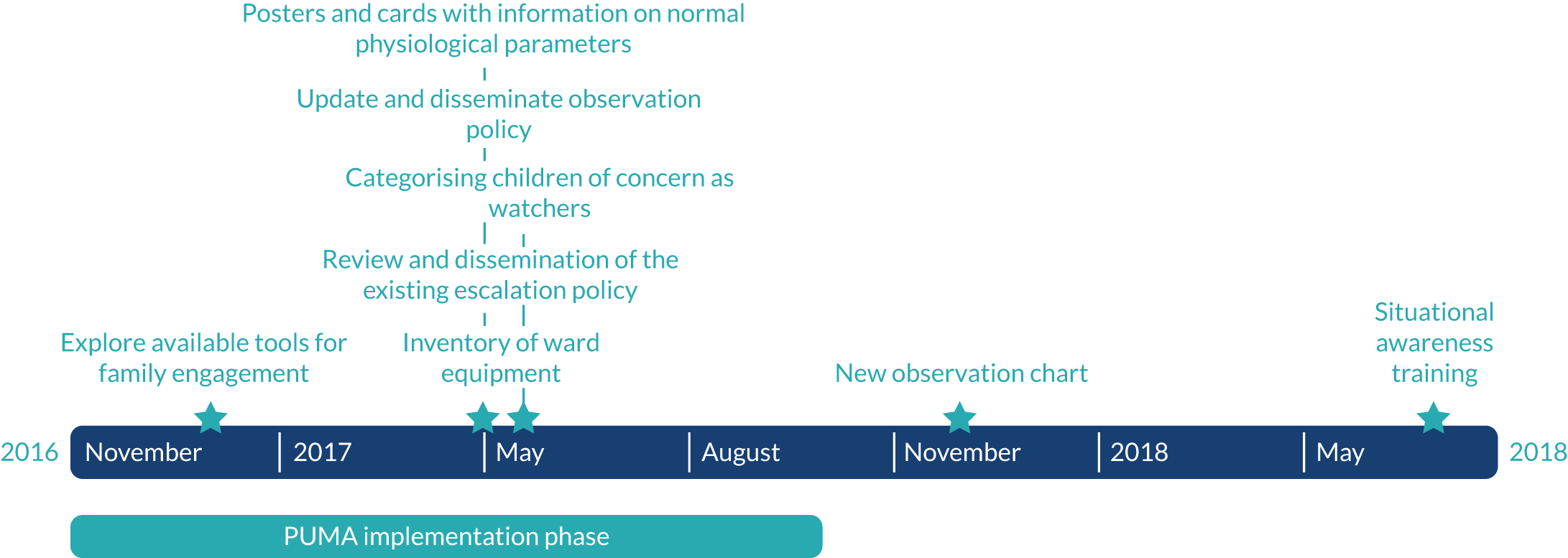

Intervention development

Building on the findings of the qualitative systematic review, the intervention (the PUMA programme) was developed iteratively and modified in the light of experience in use. Chapter 4 describes the intervention and its development in detail.

Workstream 2: implementation and prospective evaluation of the PUMA programme

Overview

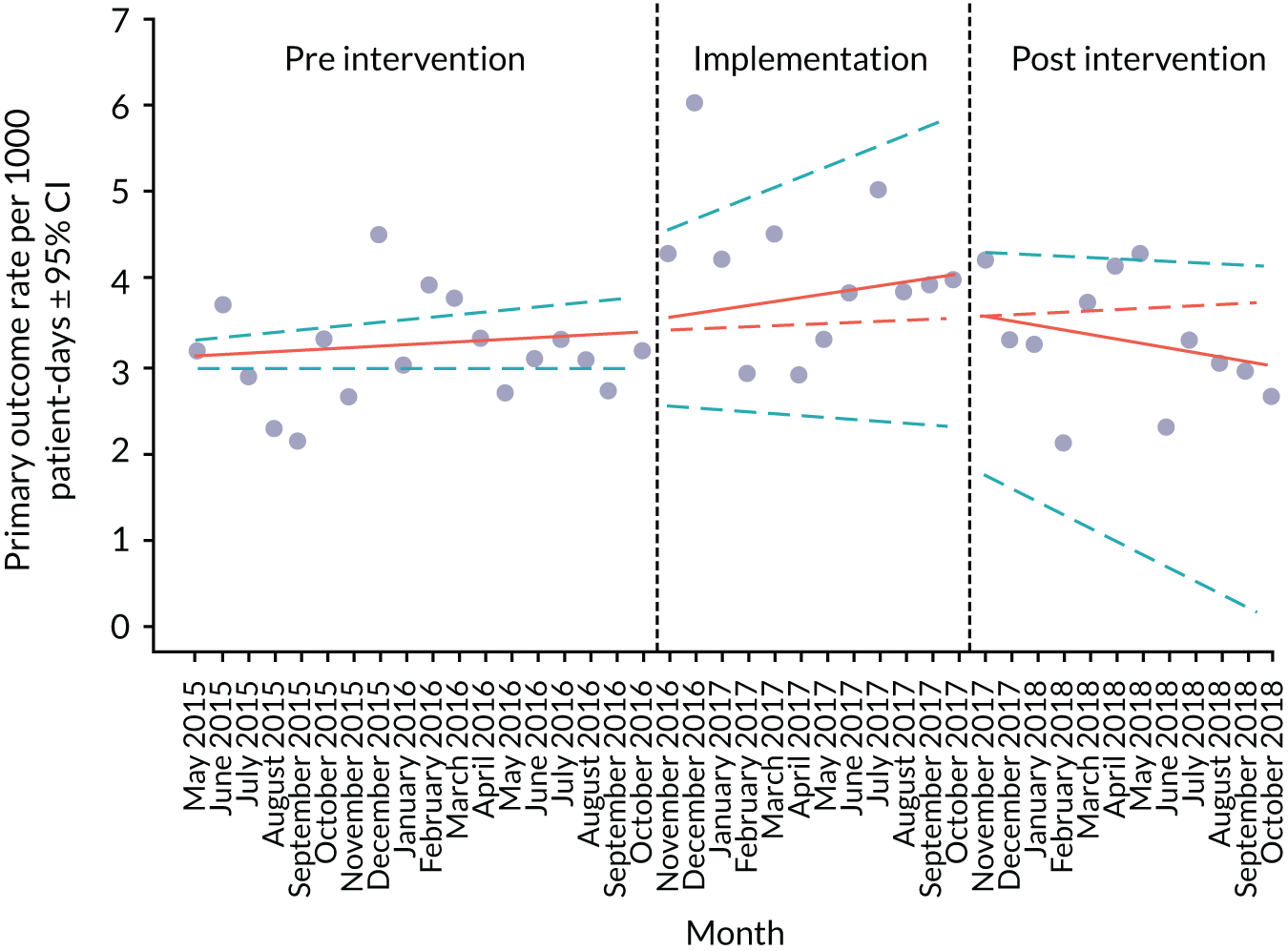

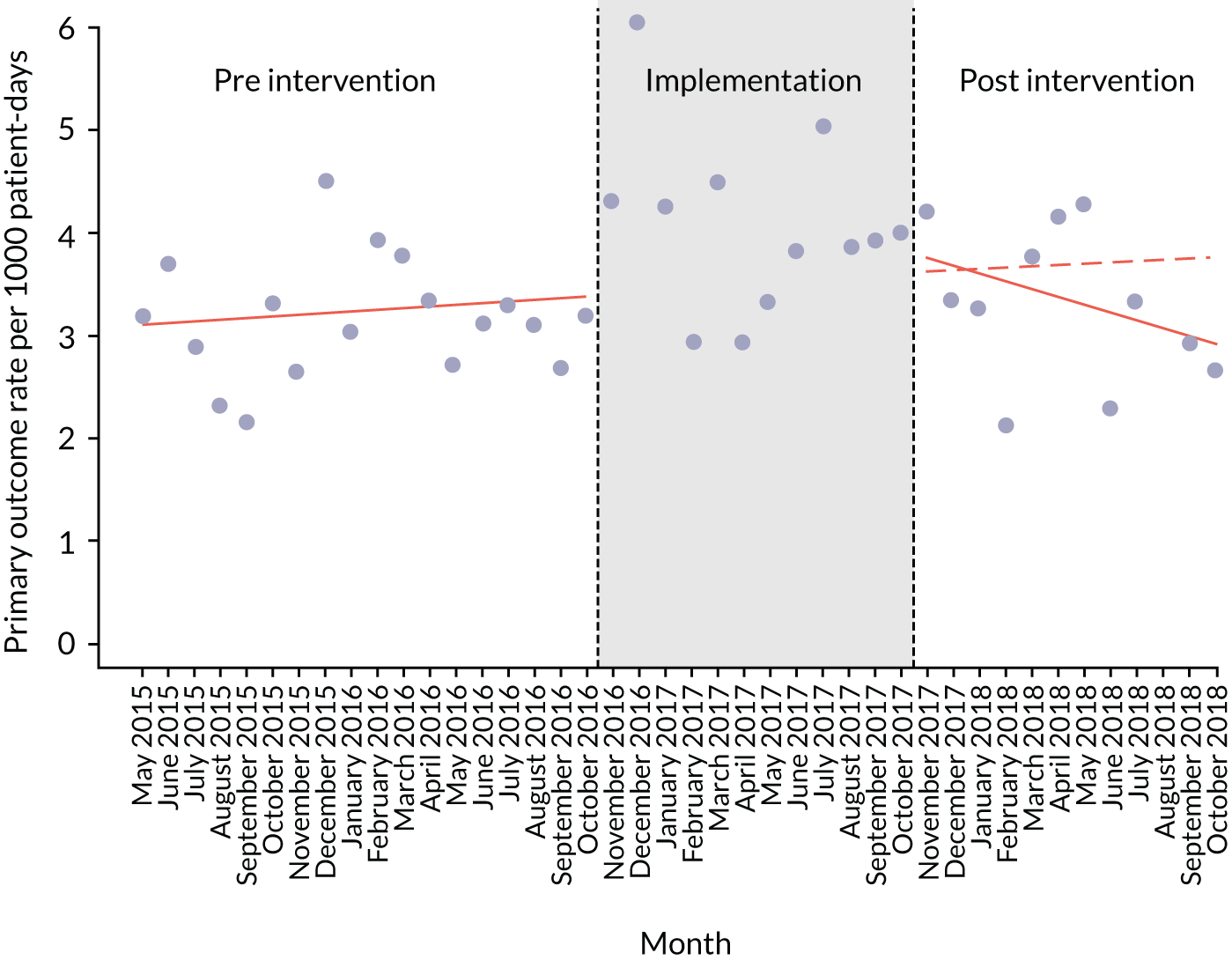

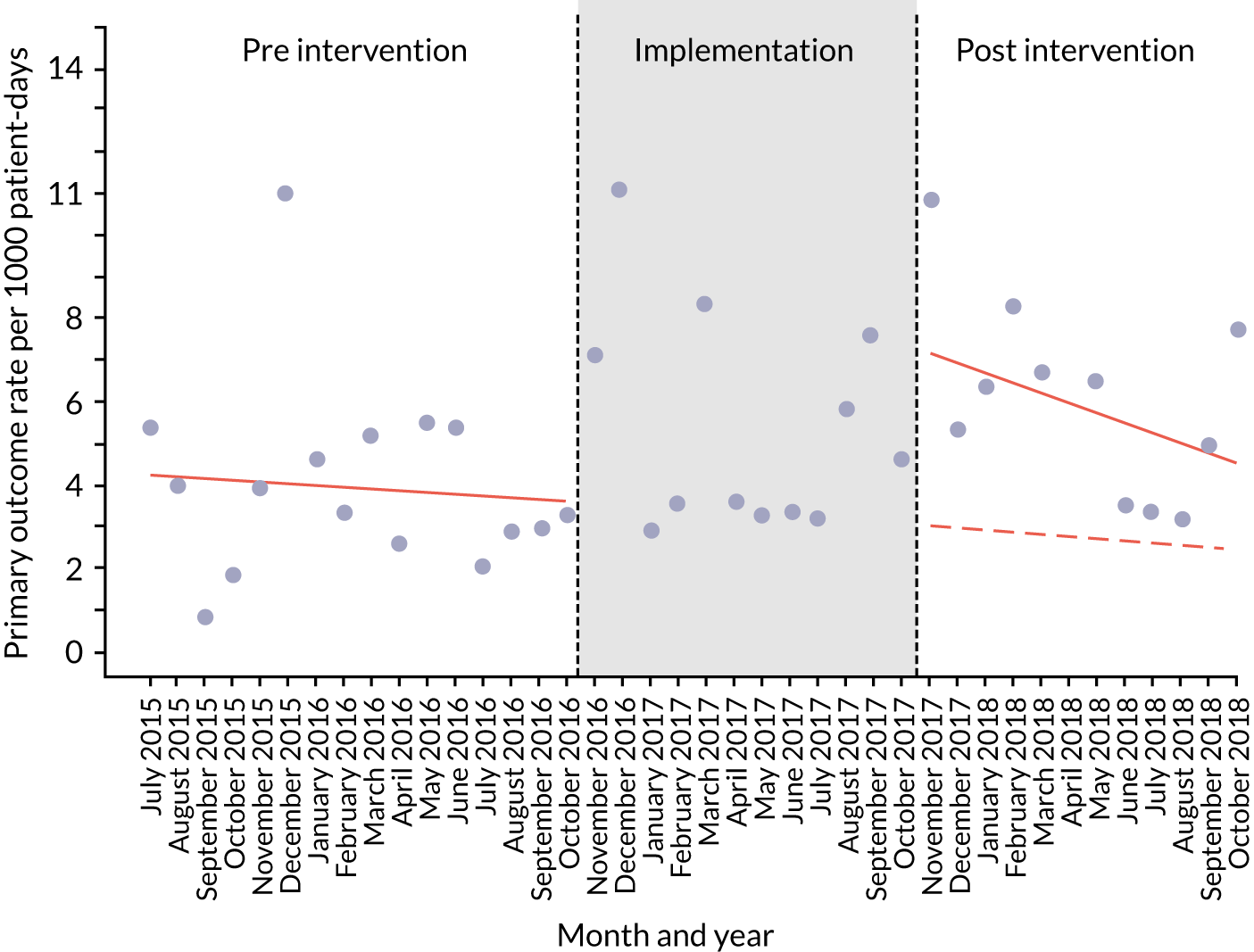

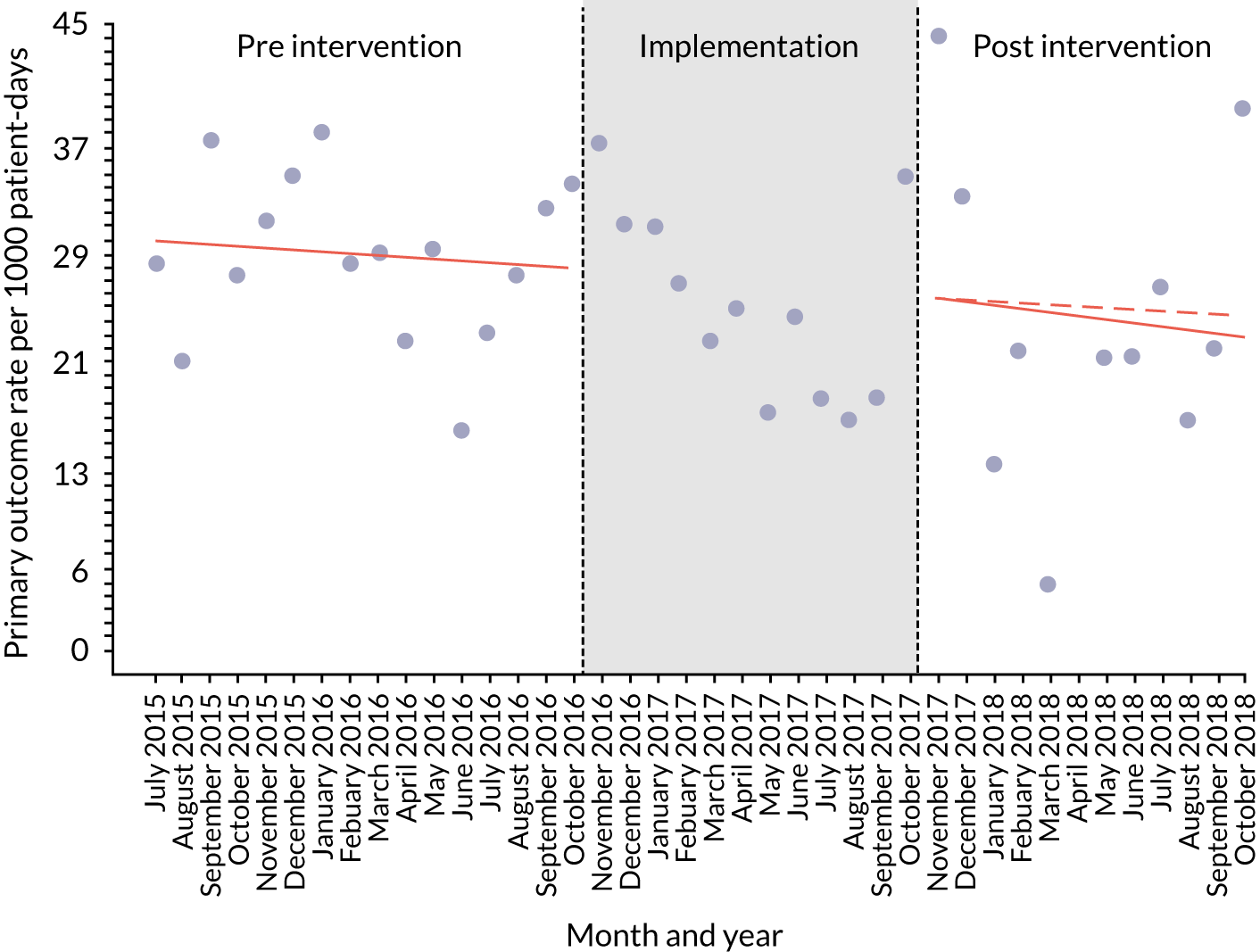

The study deployed an interrupted time series (ITS) design, in conjunction with ethnographic case studies, to evaluate changes in practice and outcomes over time. Ethnographic methods were also deployed to evaluate implementation processes.

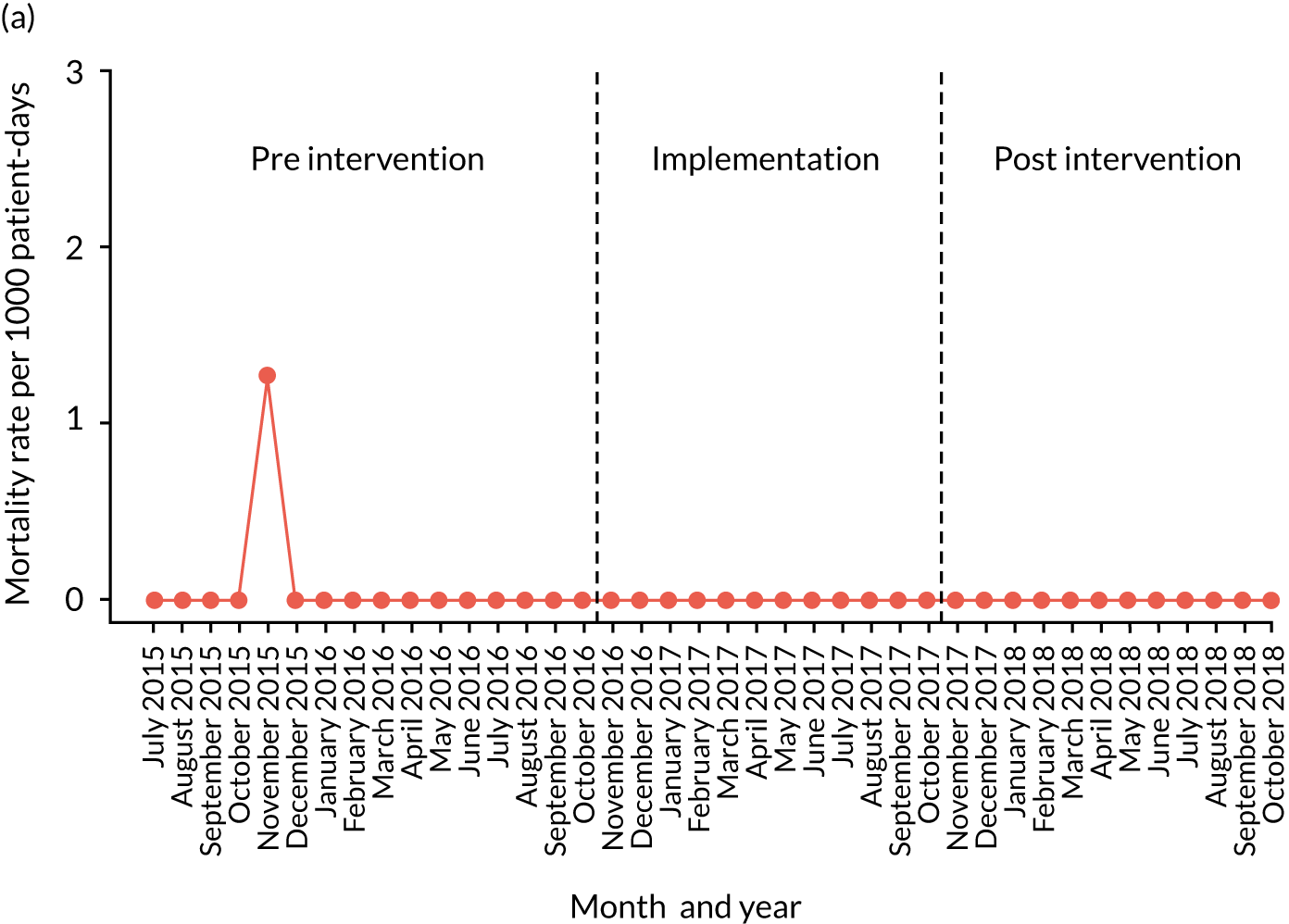

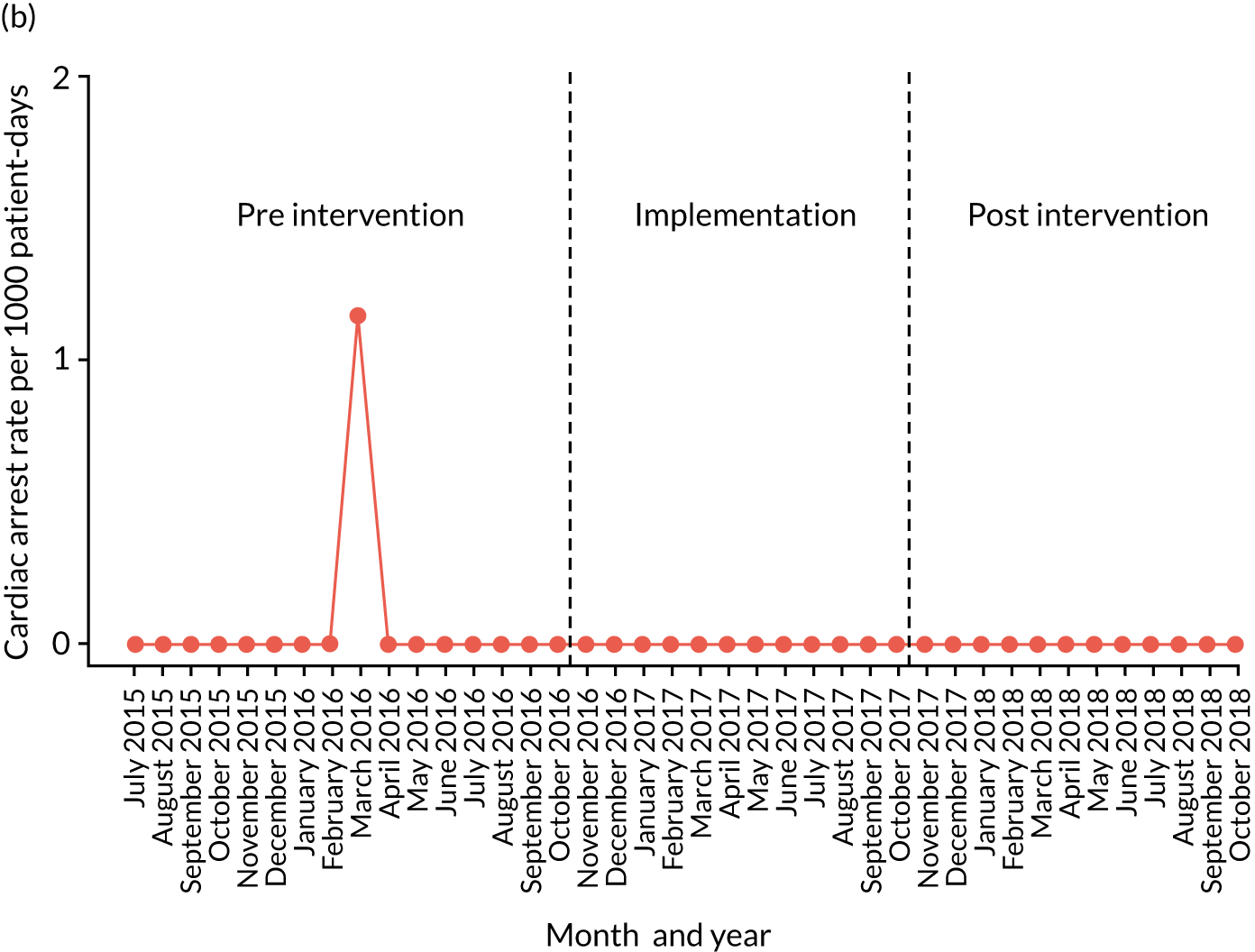

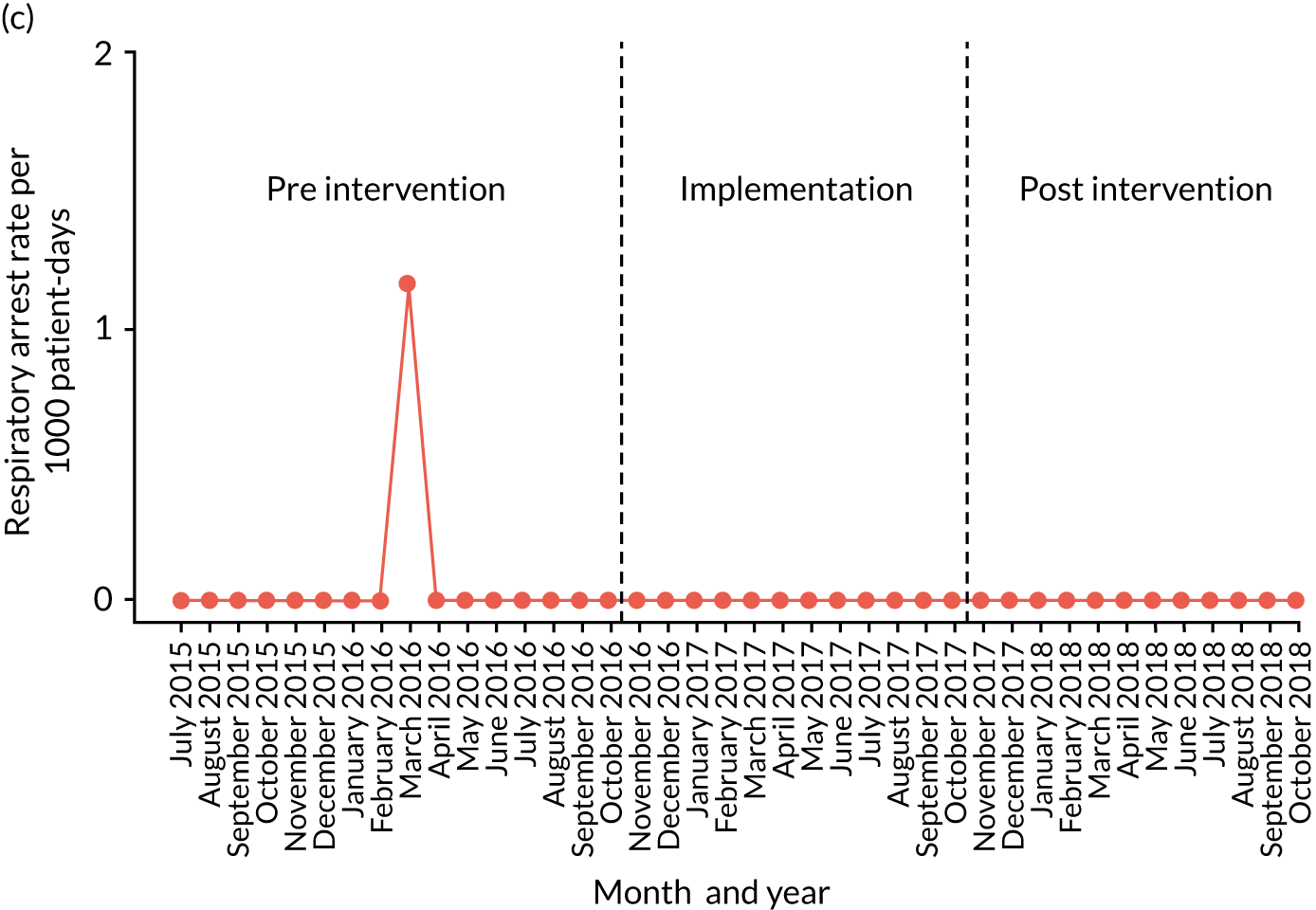

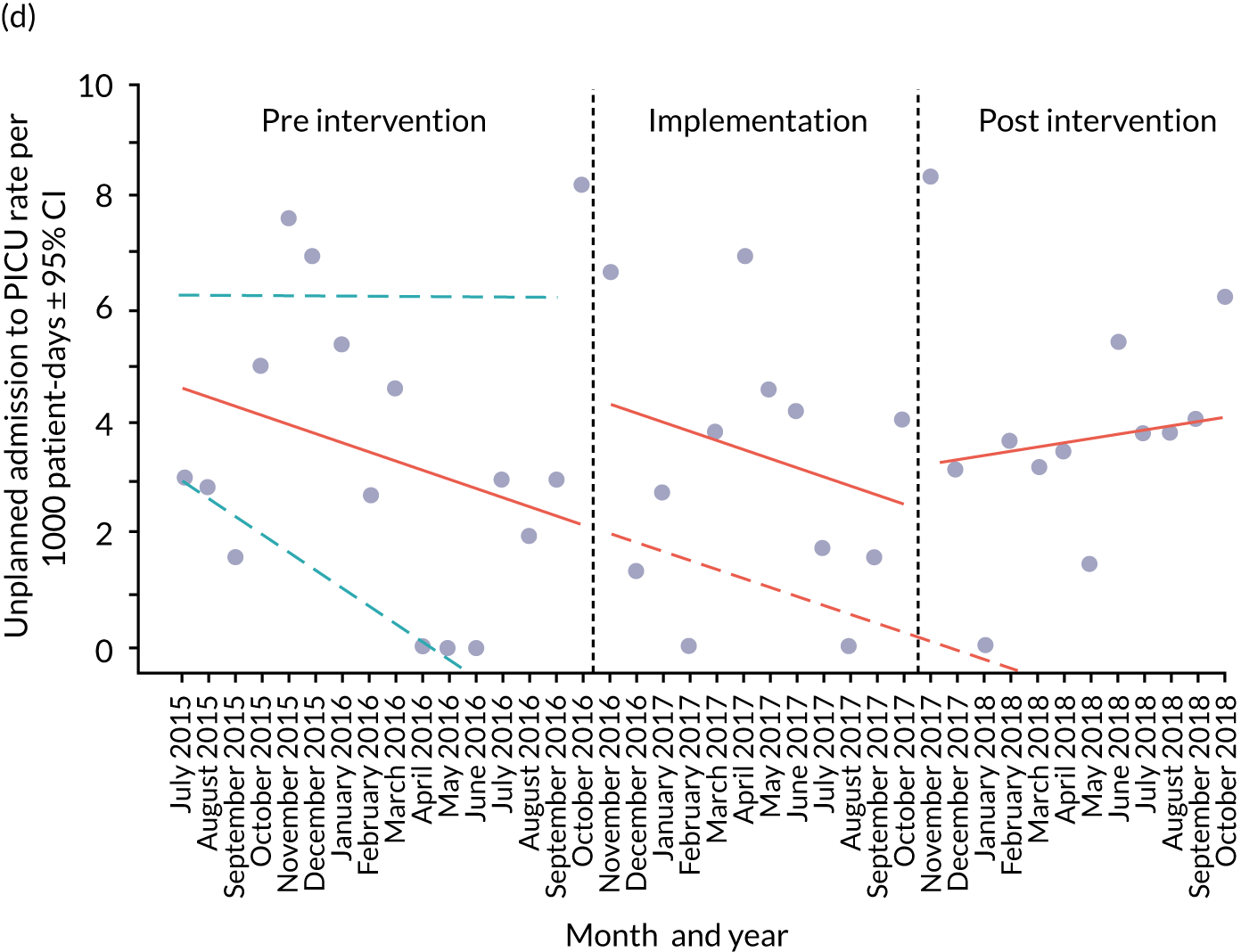

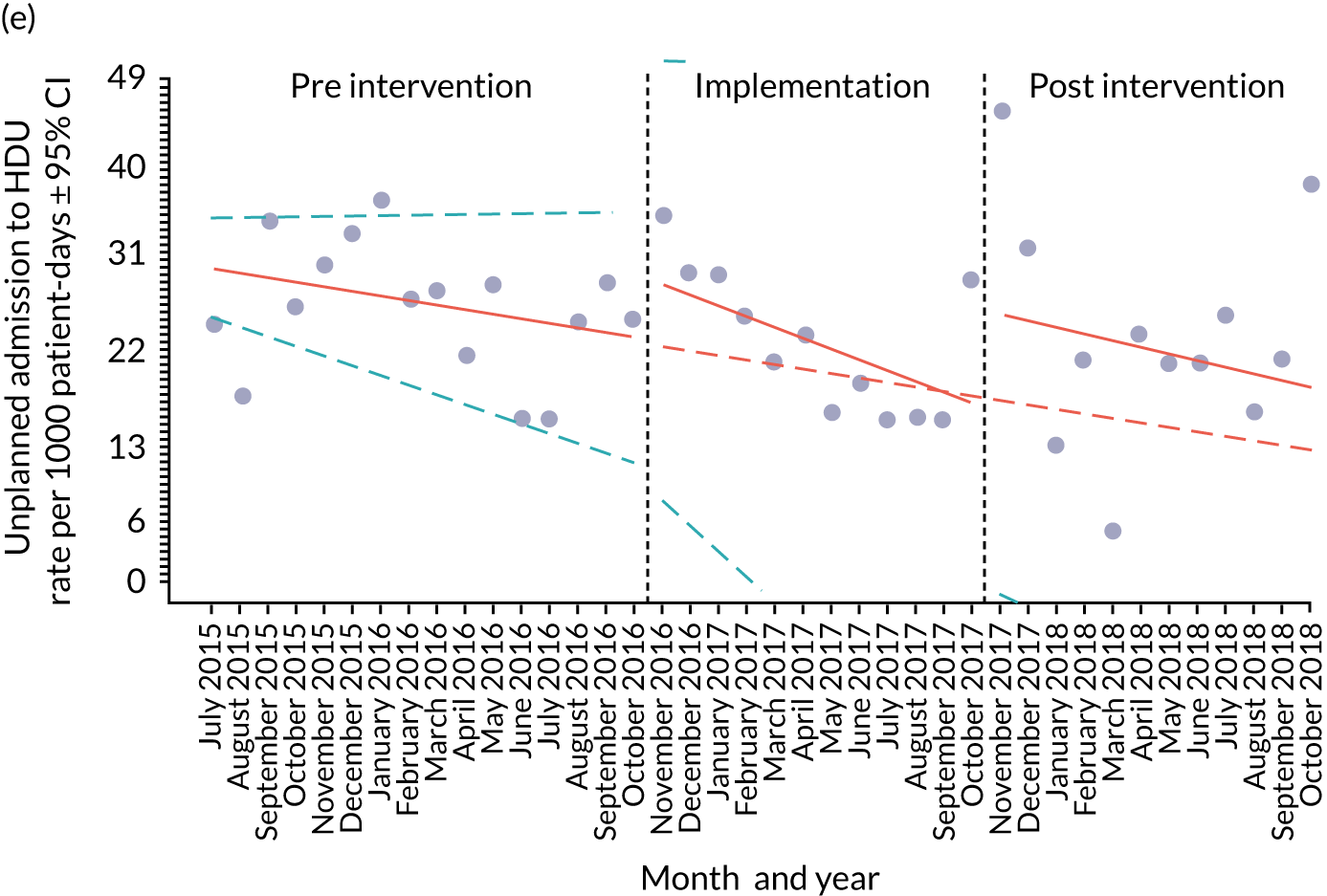

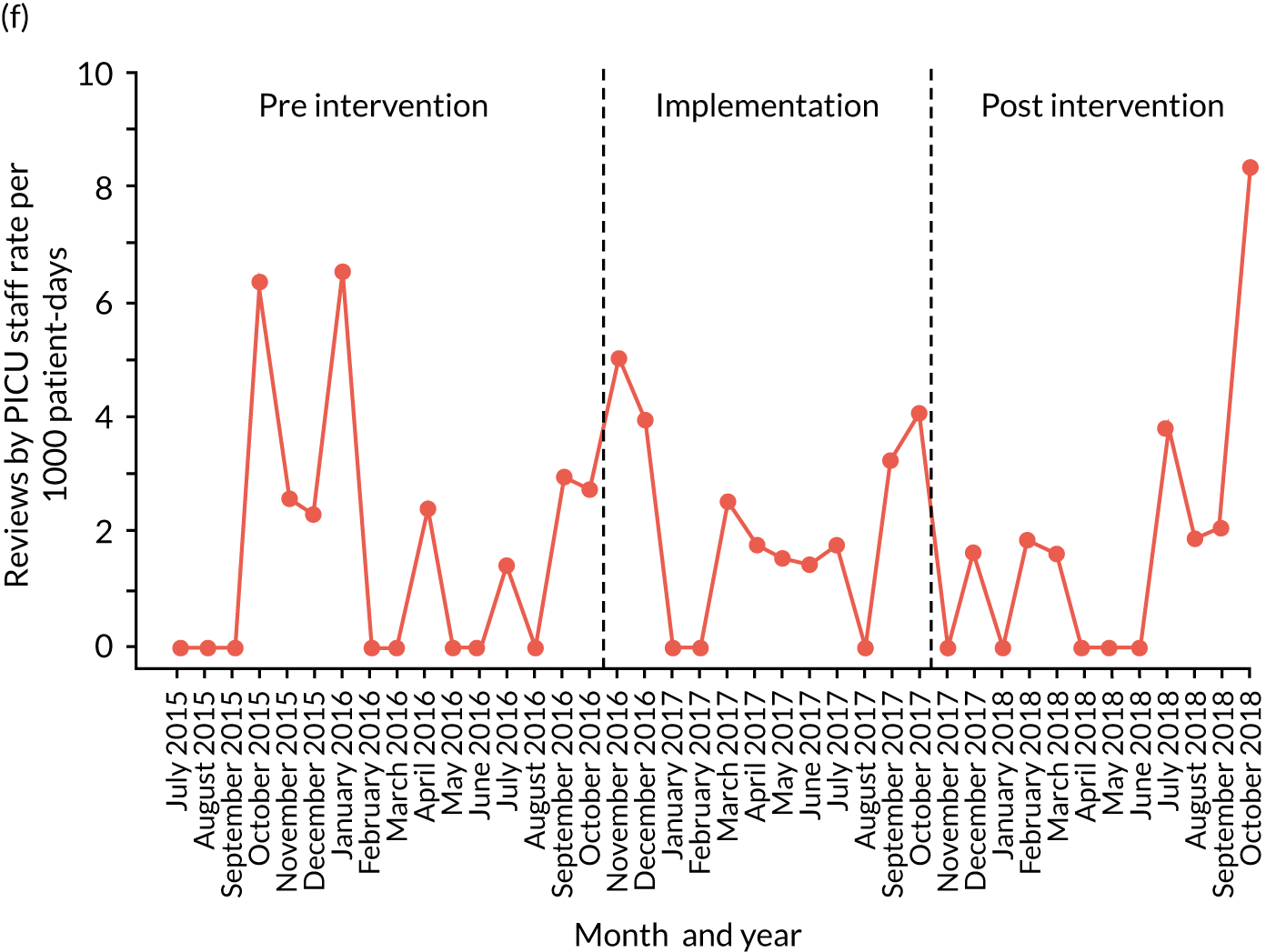

The ITS analysis involved tracking aggregate monthly rates of mortality and morbidity outcomes for up to 18 months before implementation of the PUMA programme, for 12 months during implementation, and for a further 12 months during the post-implementation period.

Embedded ethnographic case studies enabled evaluation of each site’s paediatric early warning system prior to implementation of the PUMA programme and the impact of the PUMA programme on each hospital’s paediatric early warning system post implementation. Ethnographic approaches were also deployed in a parallel process evaluation.

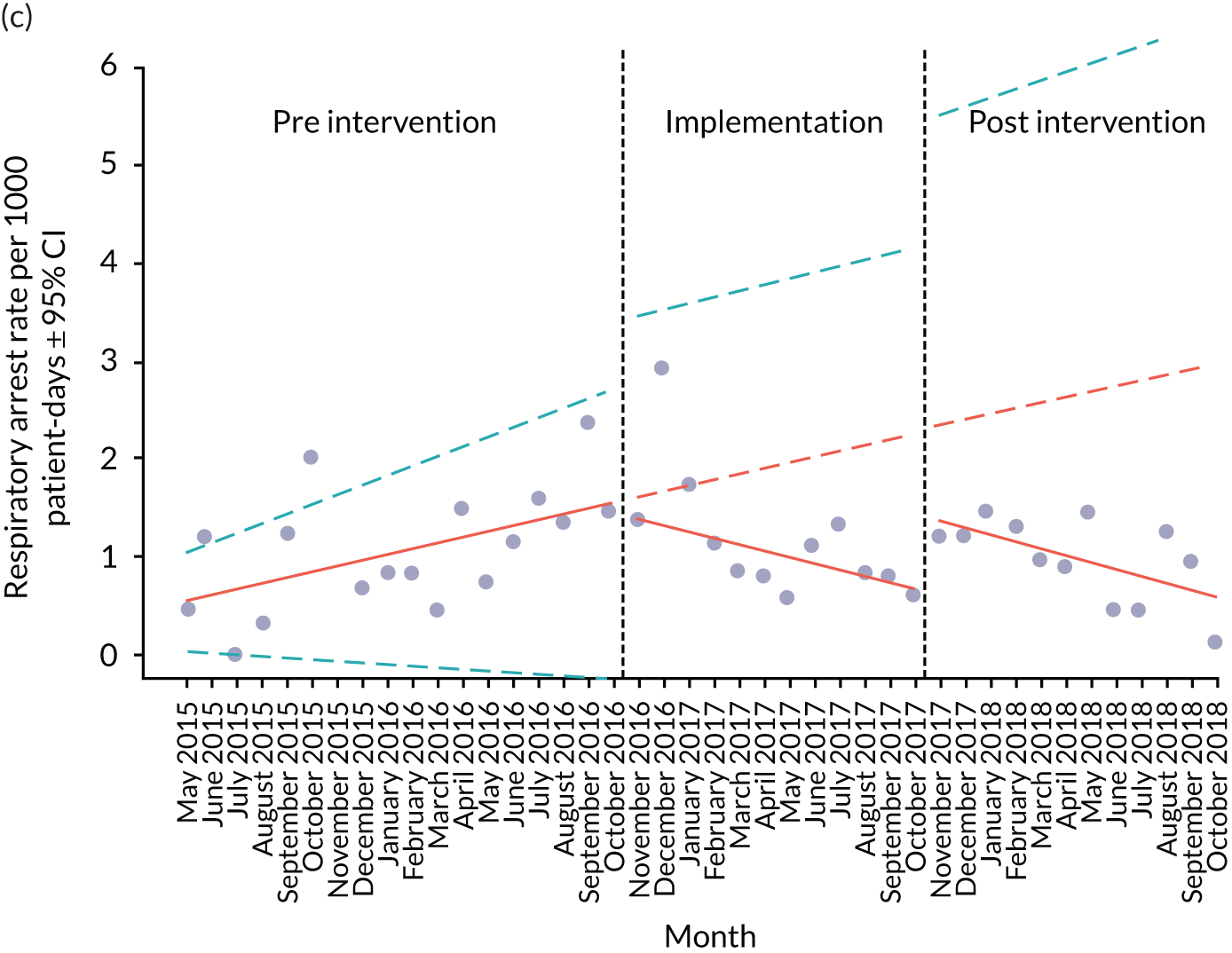

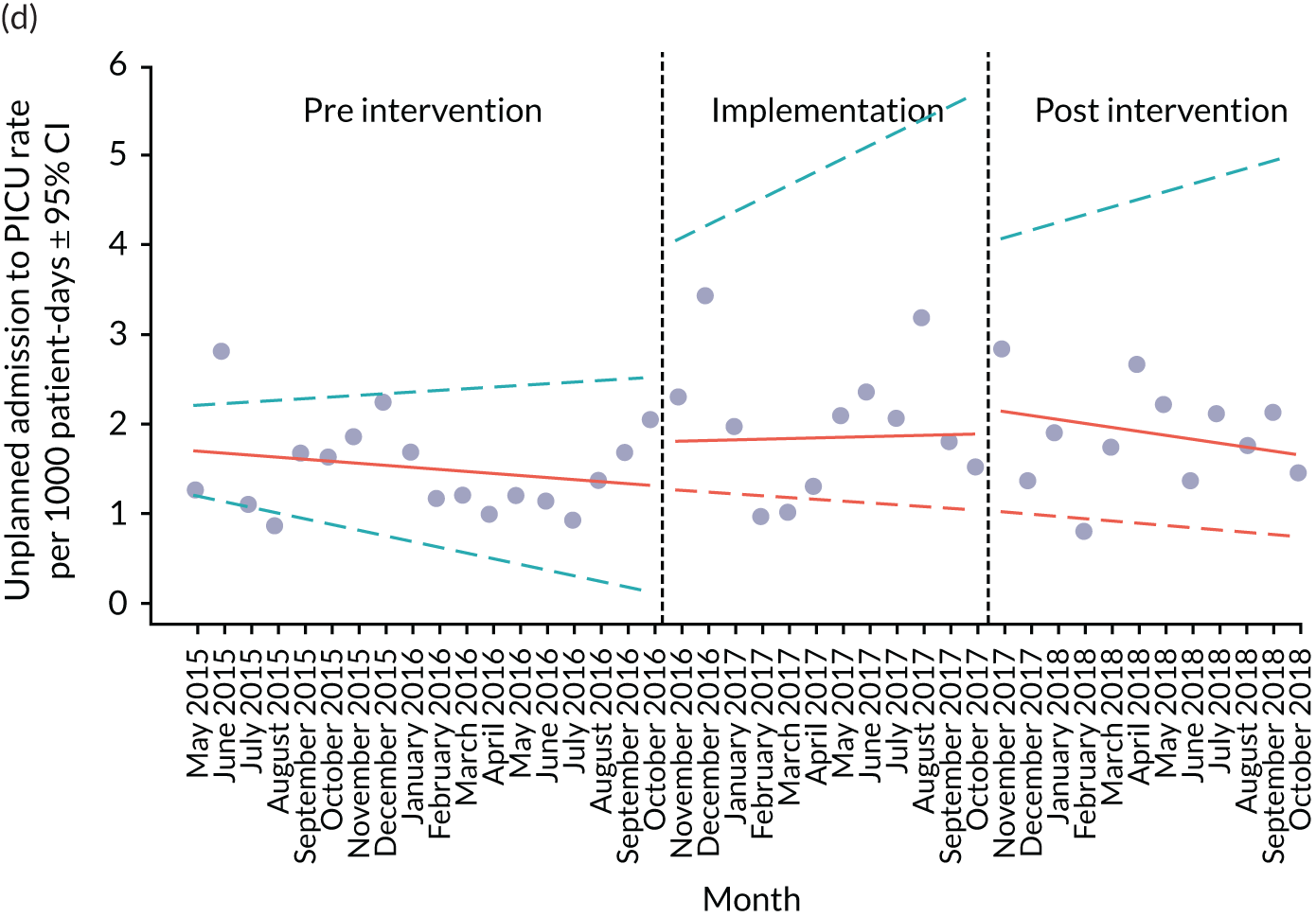

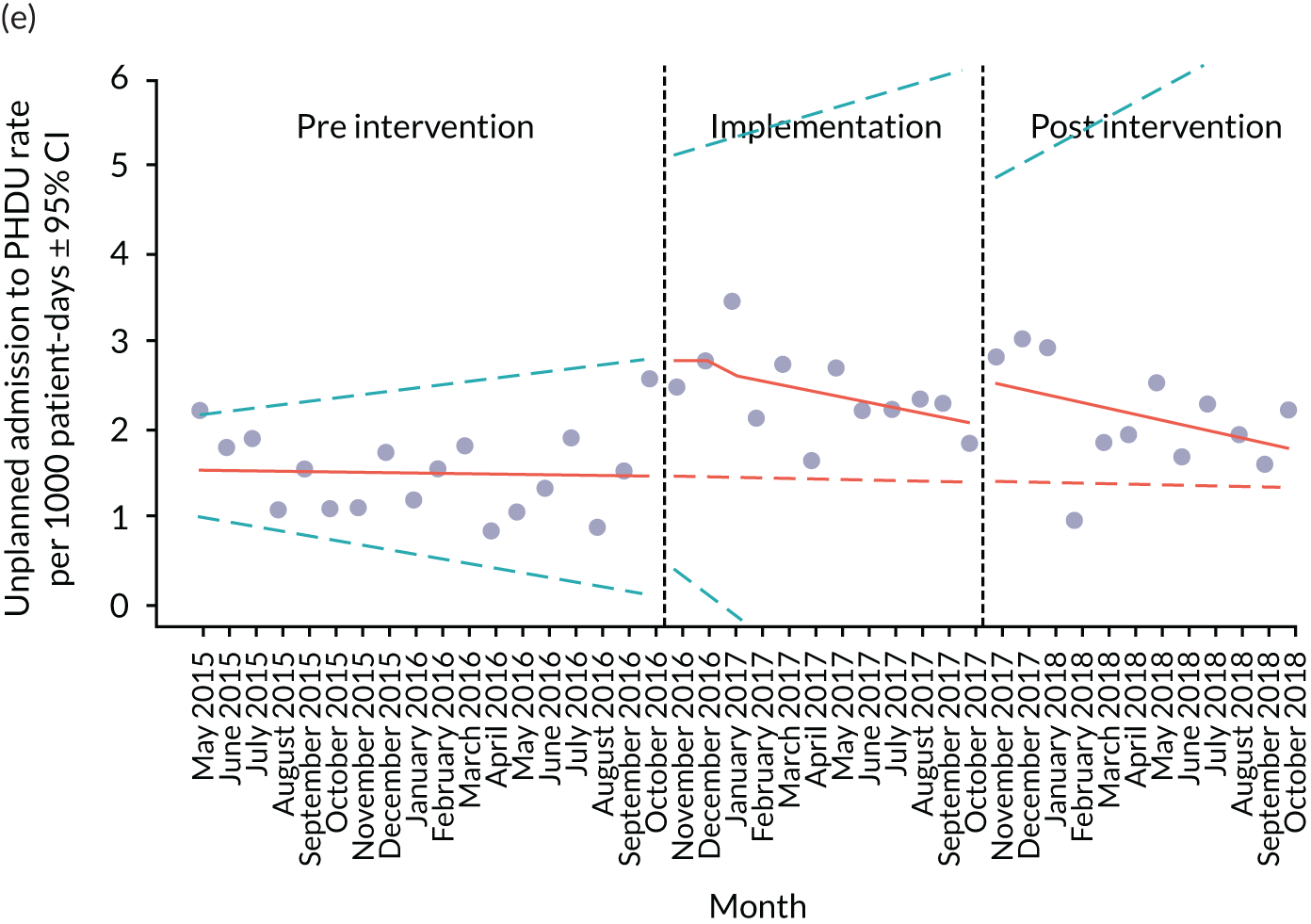

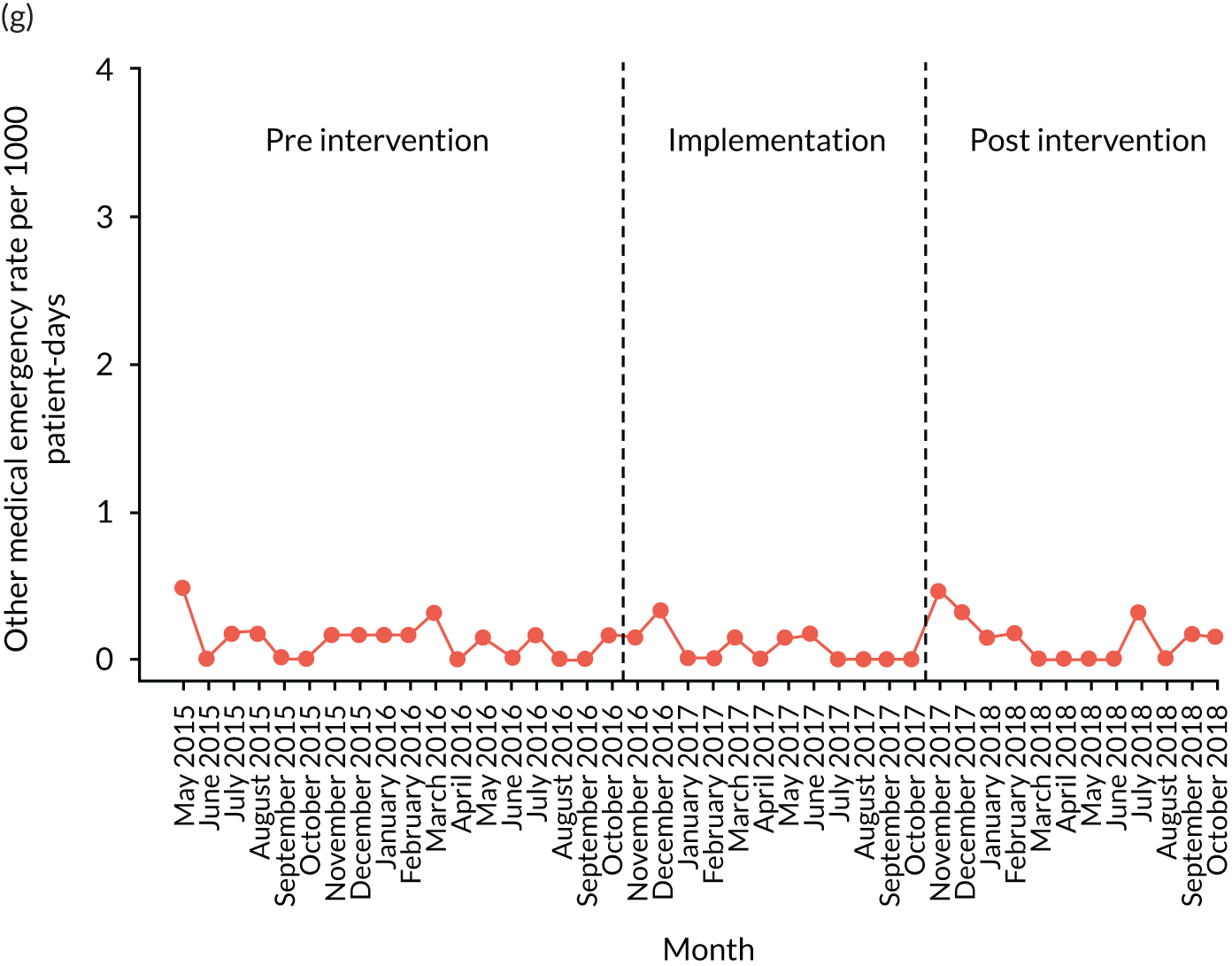

Quantitative evaluation

The quantitative evaluation of the PUMA programme involved tracking monthly aggregate outcomes at each of the four hospitals over a period of up to 42 months (May 2015–October 2018). The purpose was to evaluate the PUMA programme’s effect on measures of inpatient deterioration over time. This section gives details on the way in which data were collected from sites over the study, the outcome measures used to evaluate deterioration and the way in which data were analysed.

Data collection

A customised online PUMA database was created for site staff to upload monthly data forms. Staff were able to log in to the database via a password-protected home screen and were only ever able to access and submit forms for their own site. Data were uploaded by either principal investigators (PIs) or research nurses, and all staff responsible for entering data at each site were trained in using the database prior to entering data. Each monthly submission was quality assessed in real time by a member of the PUMA study team to allow timely resolution of any data queries or missing values.

Outcome measures

A provisional set of outcome measures was drawn up based on preliminary findings from systematic reviews 1 and 2. As part of the systematic reviews, an evaluation was conducted of the most commonly used outcome metrics reported in the literature for assessment of the validity and effectiveness of PTTTs and paediatric early warning systems. The feasibility of collecting these outcomes at each site was explored through preliminary piloting work, prior to commencement of data collection in August 2015.

Appendix 8, Table 26, shows the final outcomes that were selected as the most suitable proxies for inpatient deterioration, and the definition of each outcome that was agreed with the four sites. It is important to note that these cannot be used, in any way, to infer the processes leading to that outcome; for example, it is impossible to determine if the deaths were the result of missed deterioration or an unavoidable consequence of a disease process.

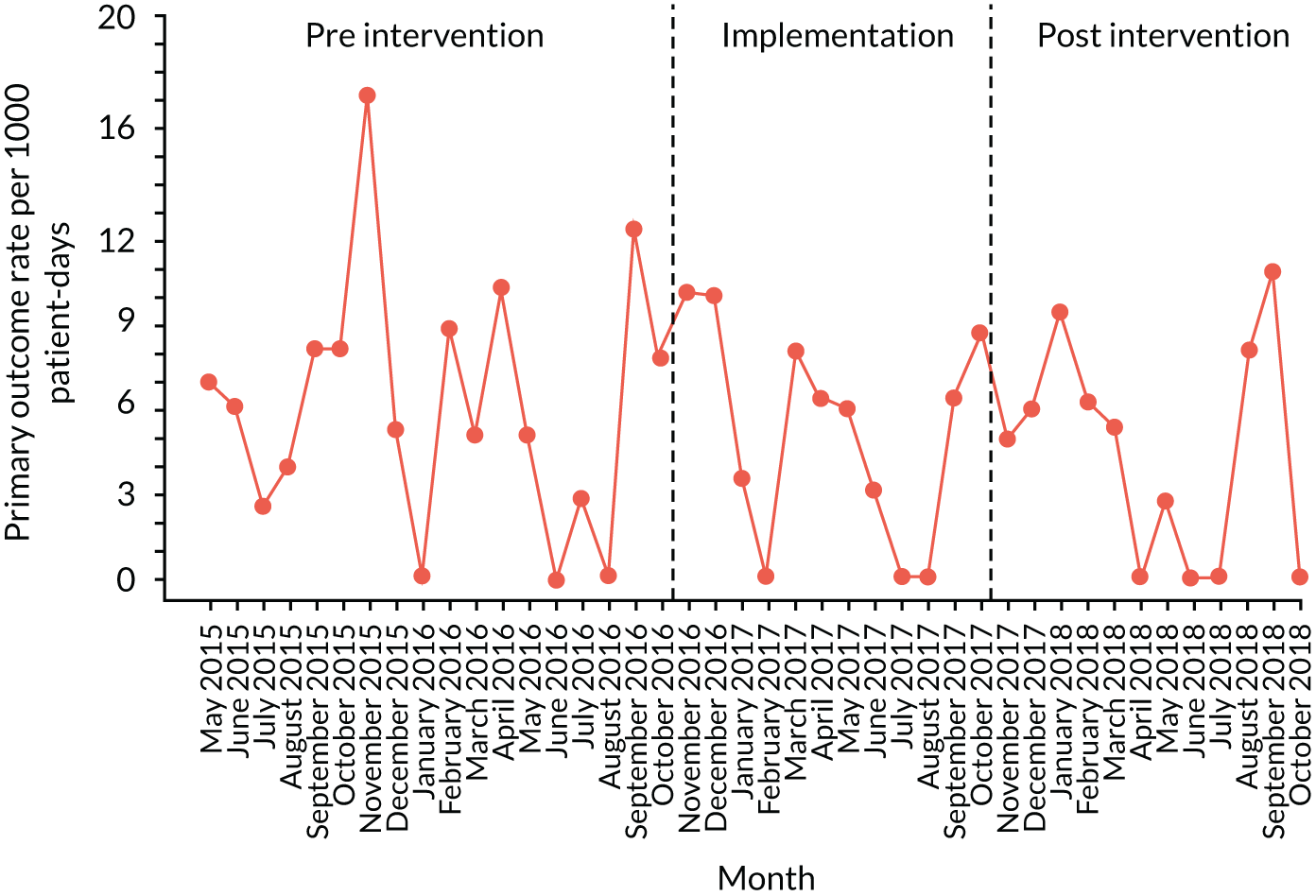

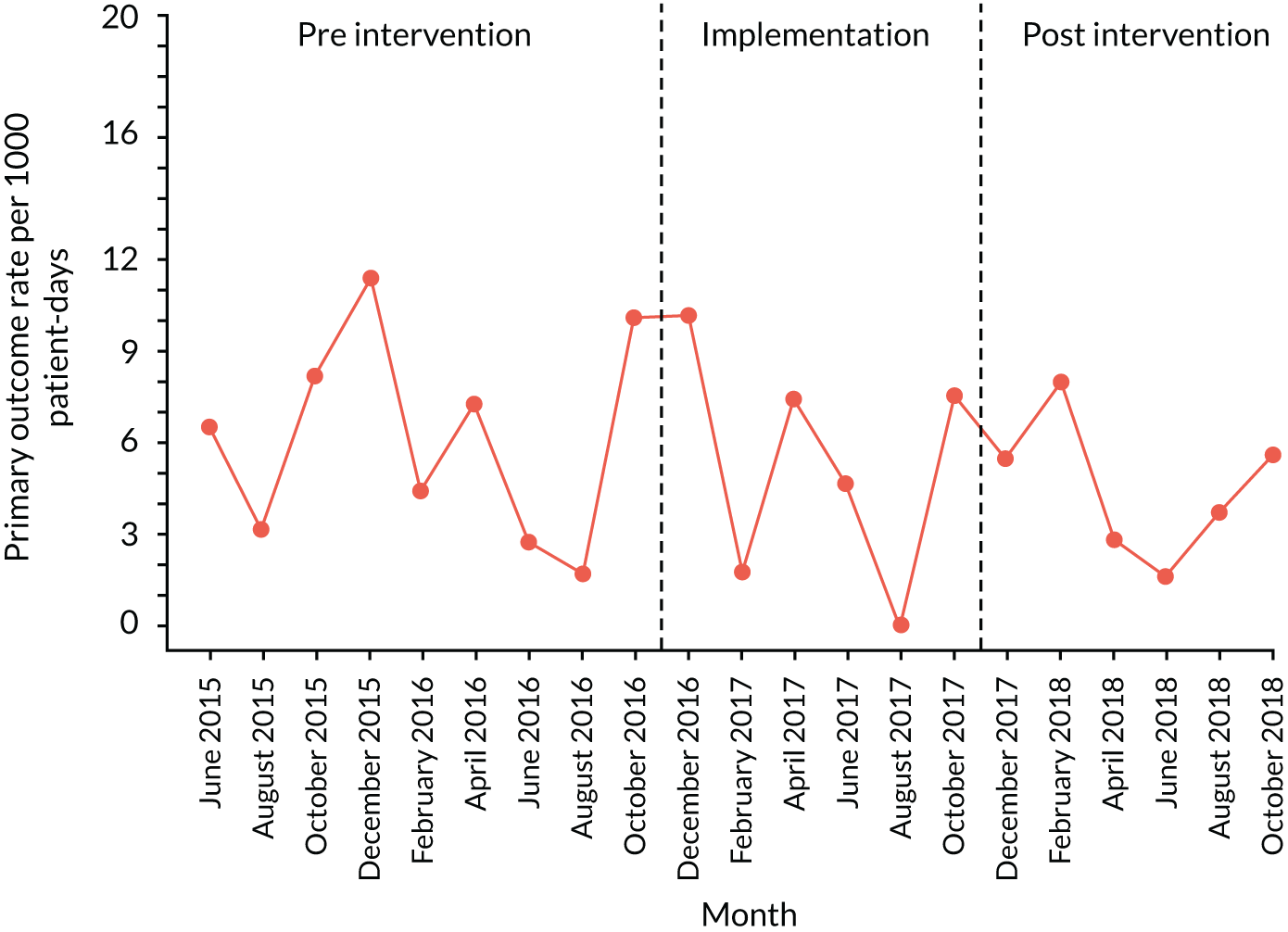

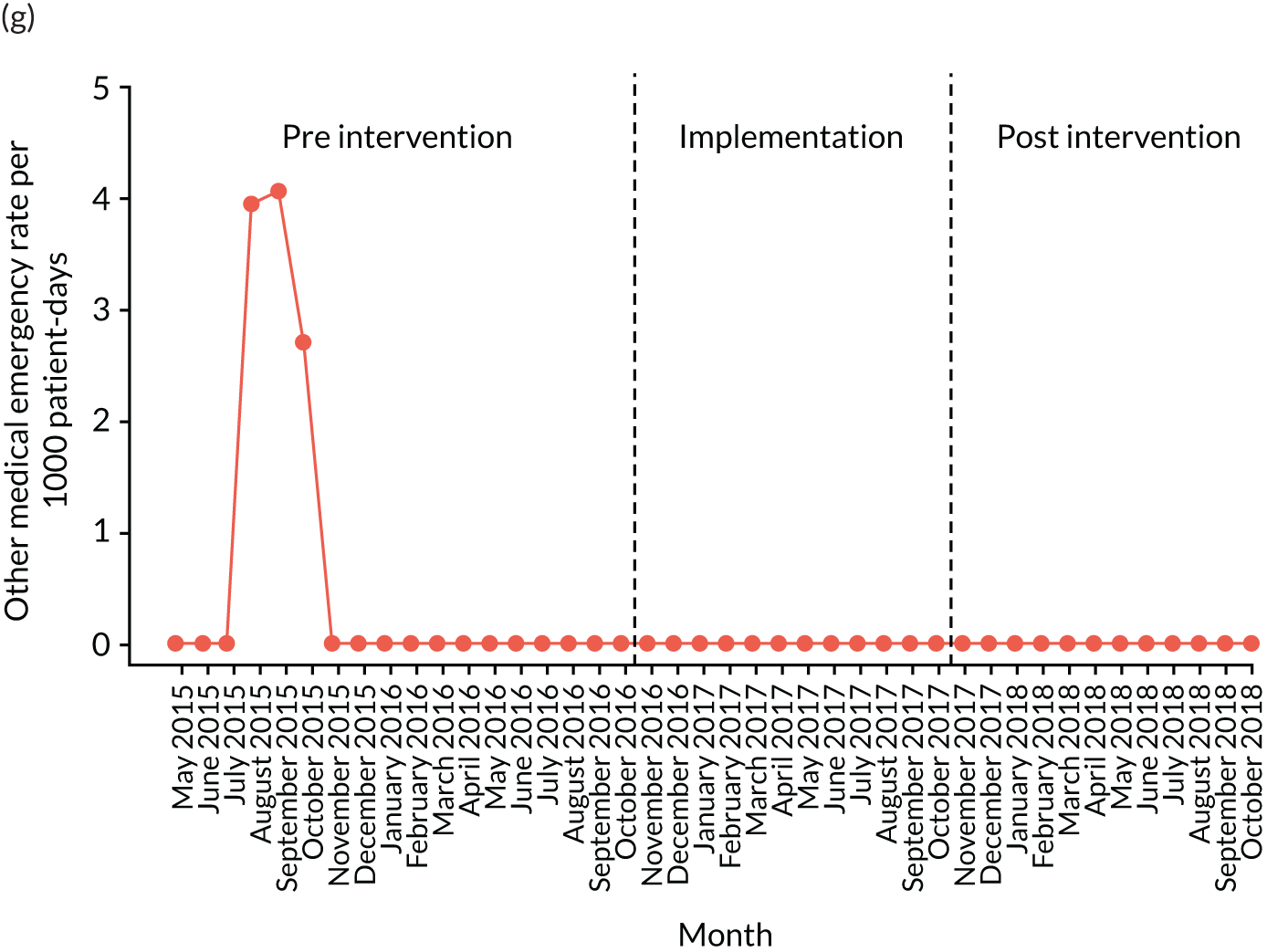

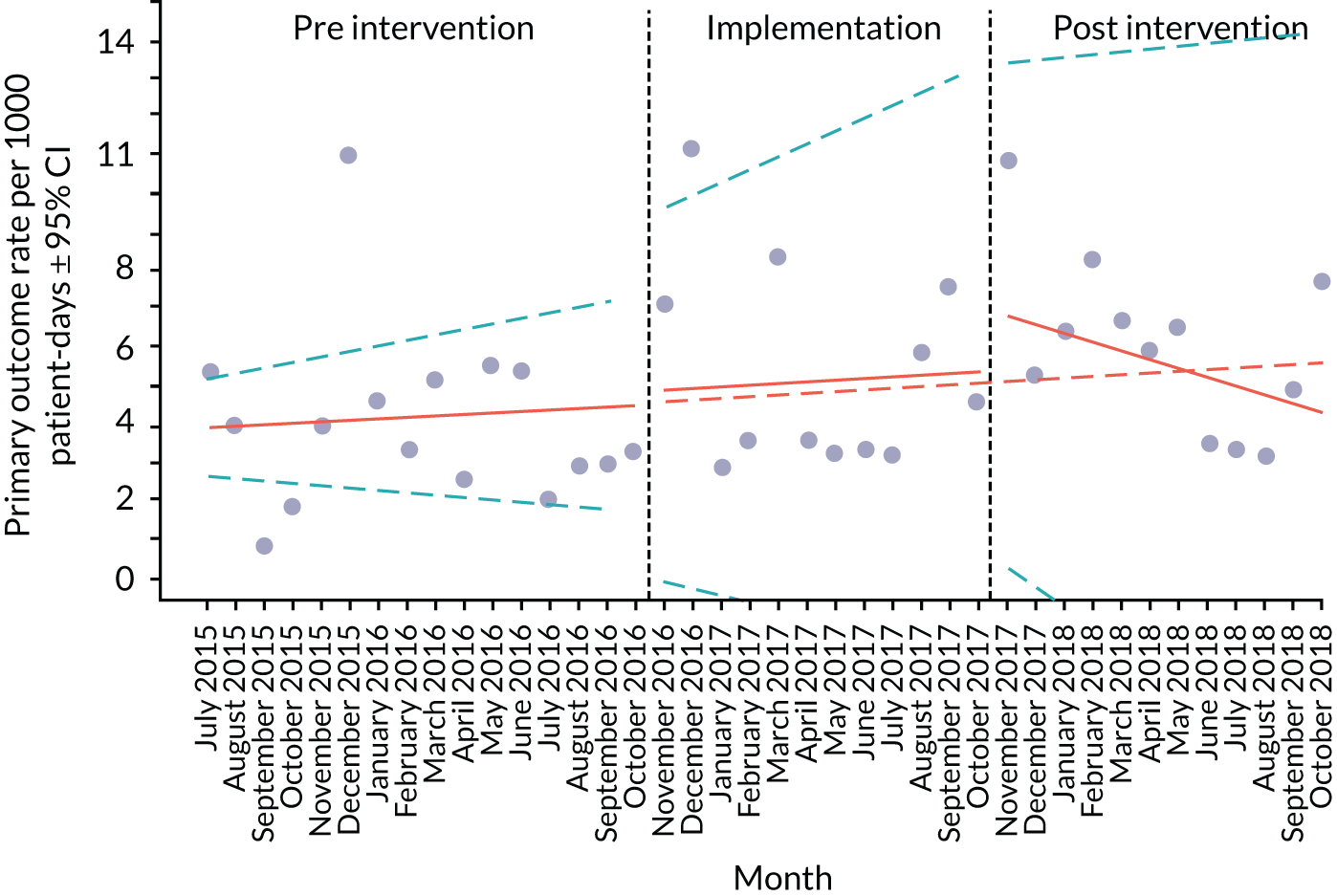

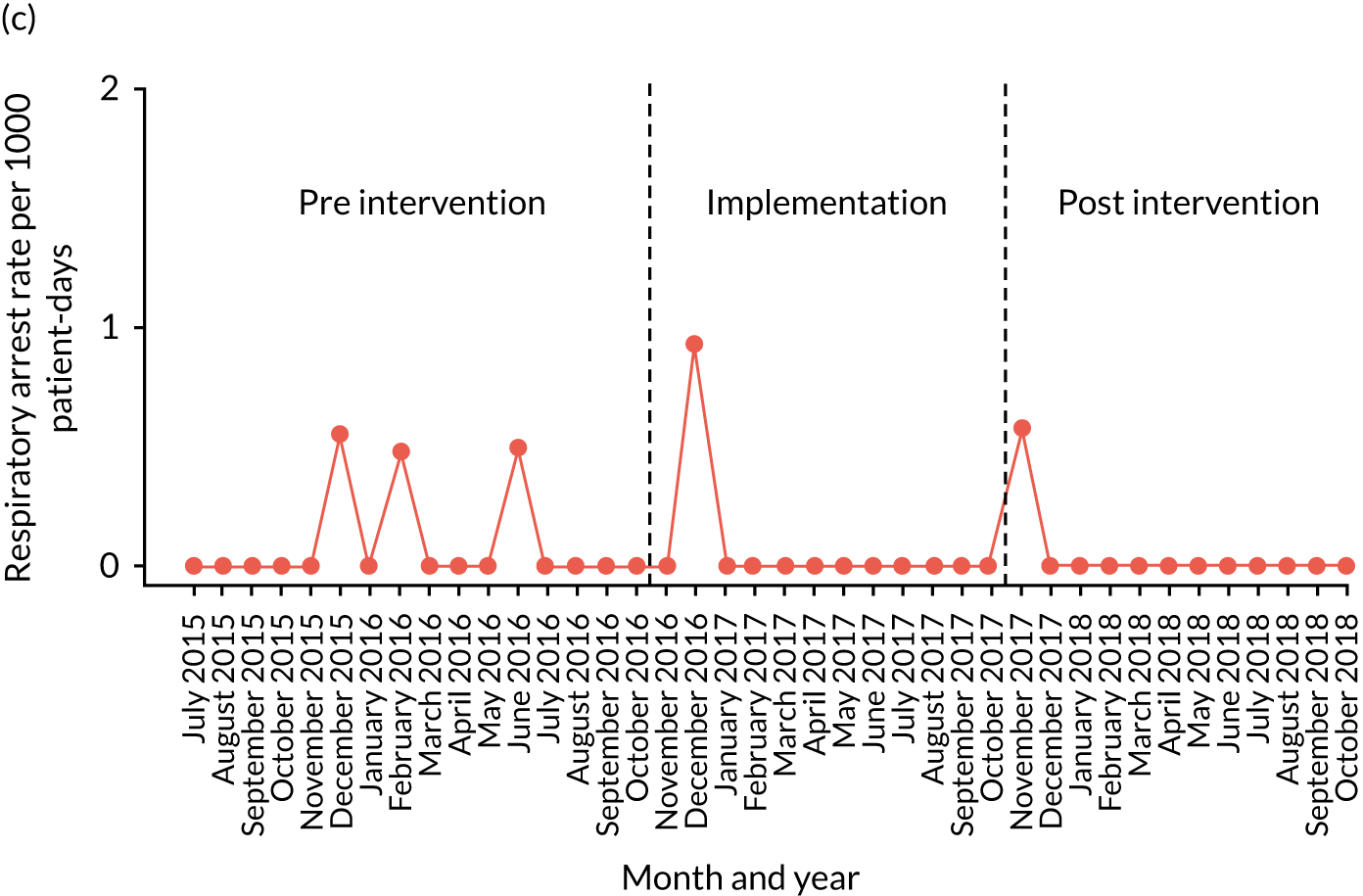

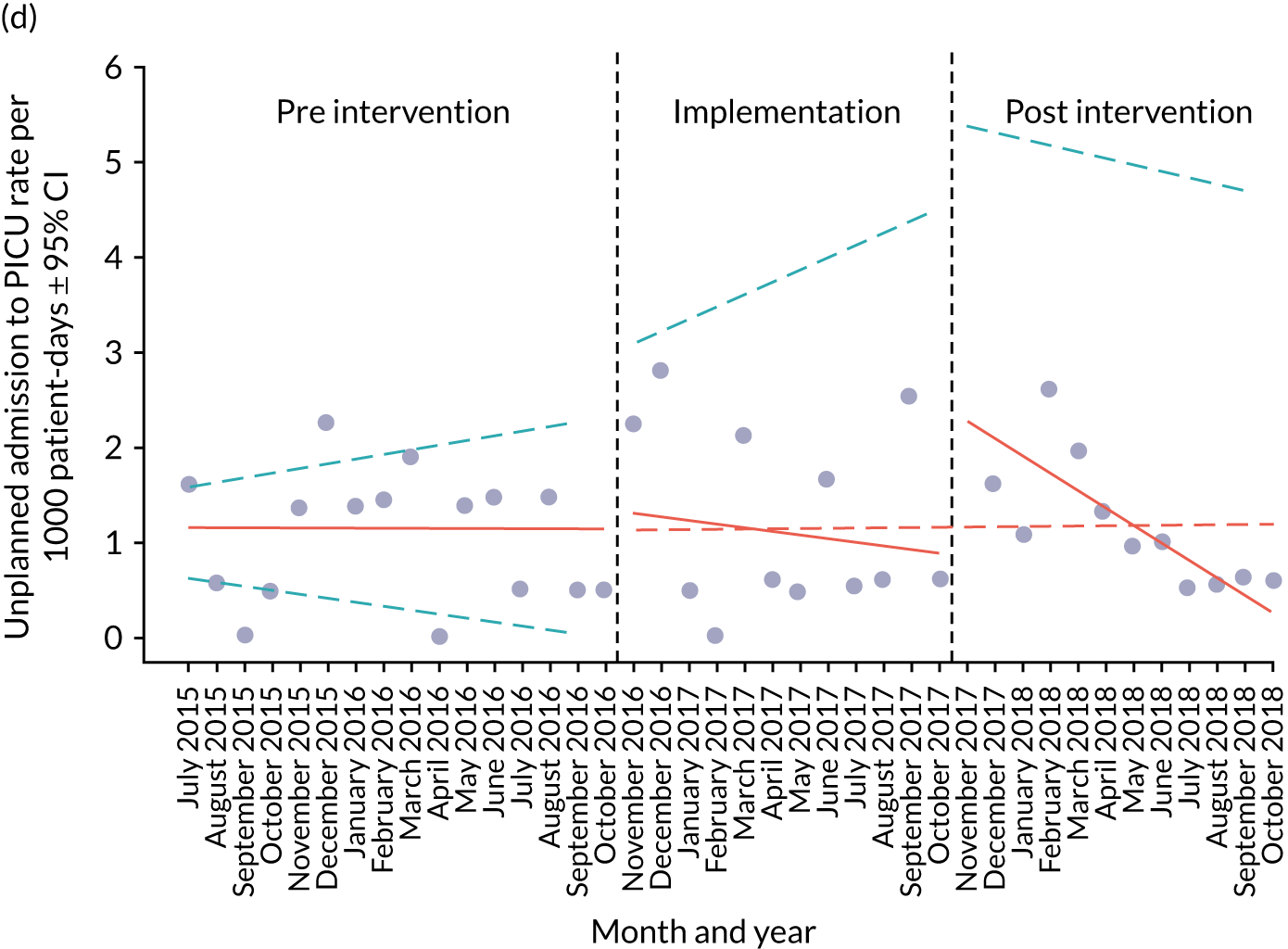

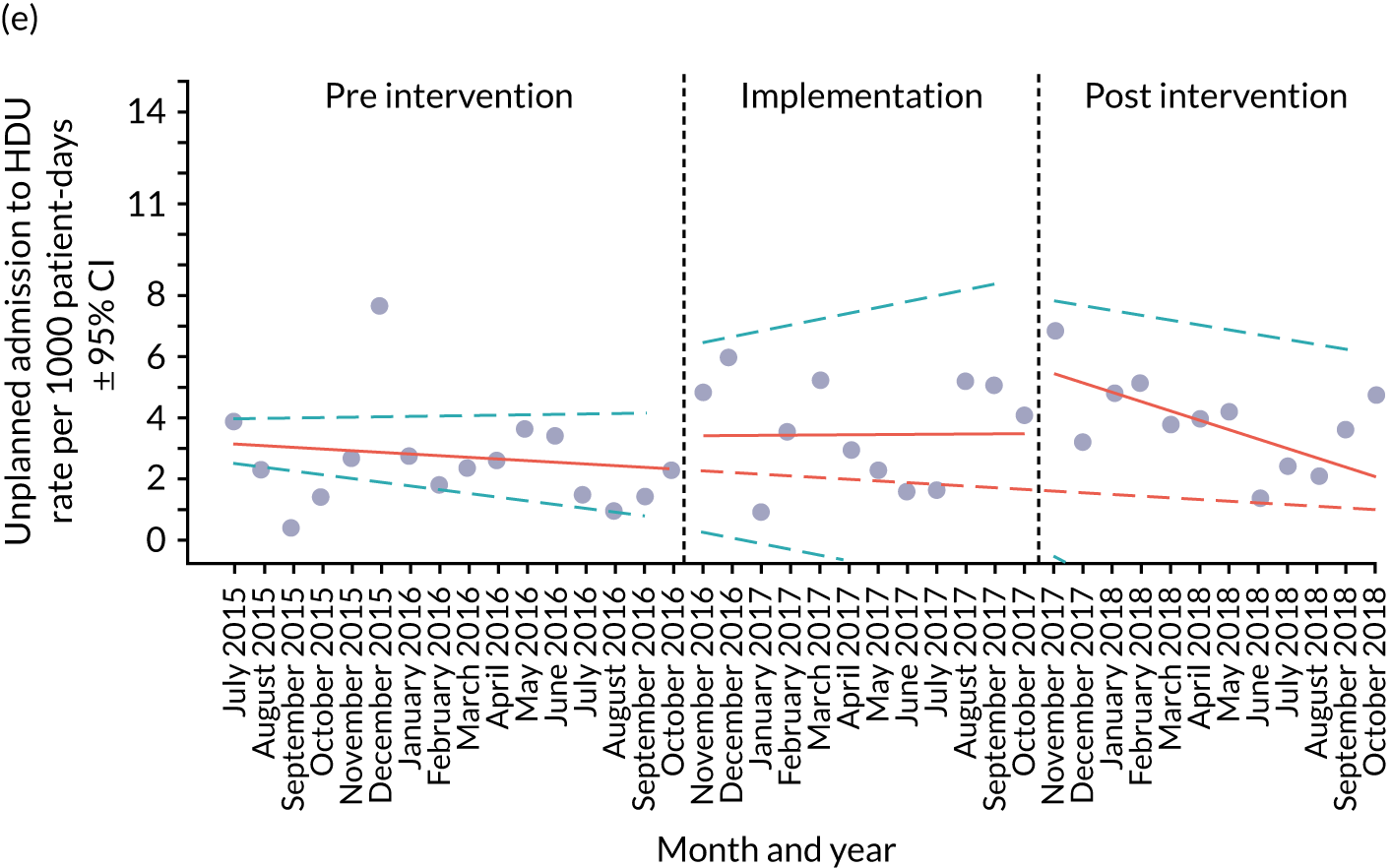

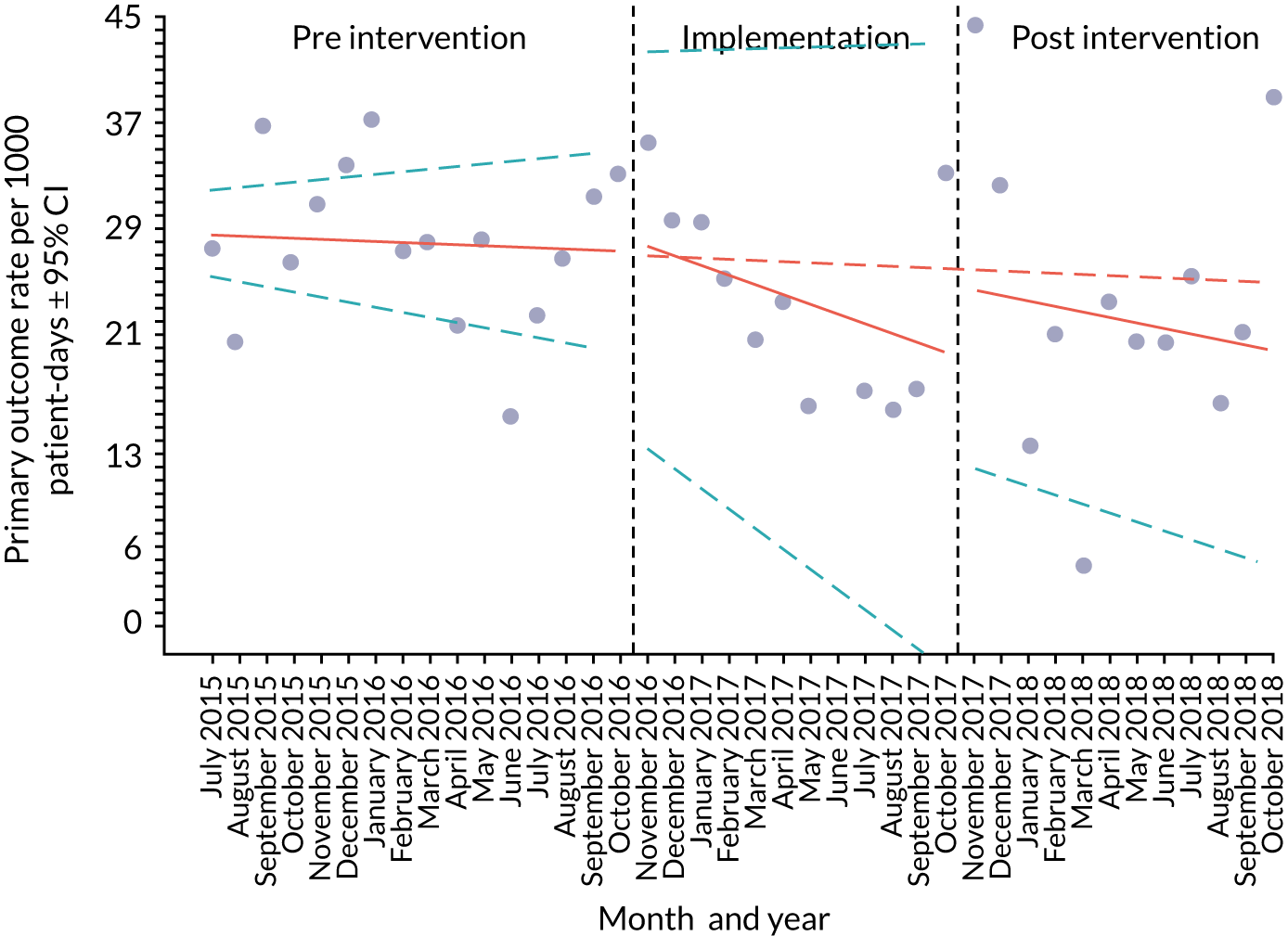

Primary outcome measure

For the primary outcome, we chose a composite outcome metric (‘adverse events’), representing the aggregate number of children in a given month that experienced at least one of the following events:

-

mortality

-

cardiac arrest

-

respiratory arrest

-

unplanned admission to a PICU

-

unplanned admission to a high-dependency unit (HDU).

Children who experienced more than one of these adverse events were counted only once, to avoid double-counting. The primary outcome was expressed per 1000 patient bed-days, using the aggregate number of events and the denominator (total number of patient-days) for each month.

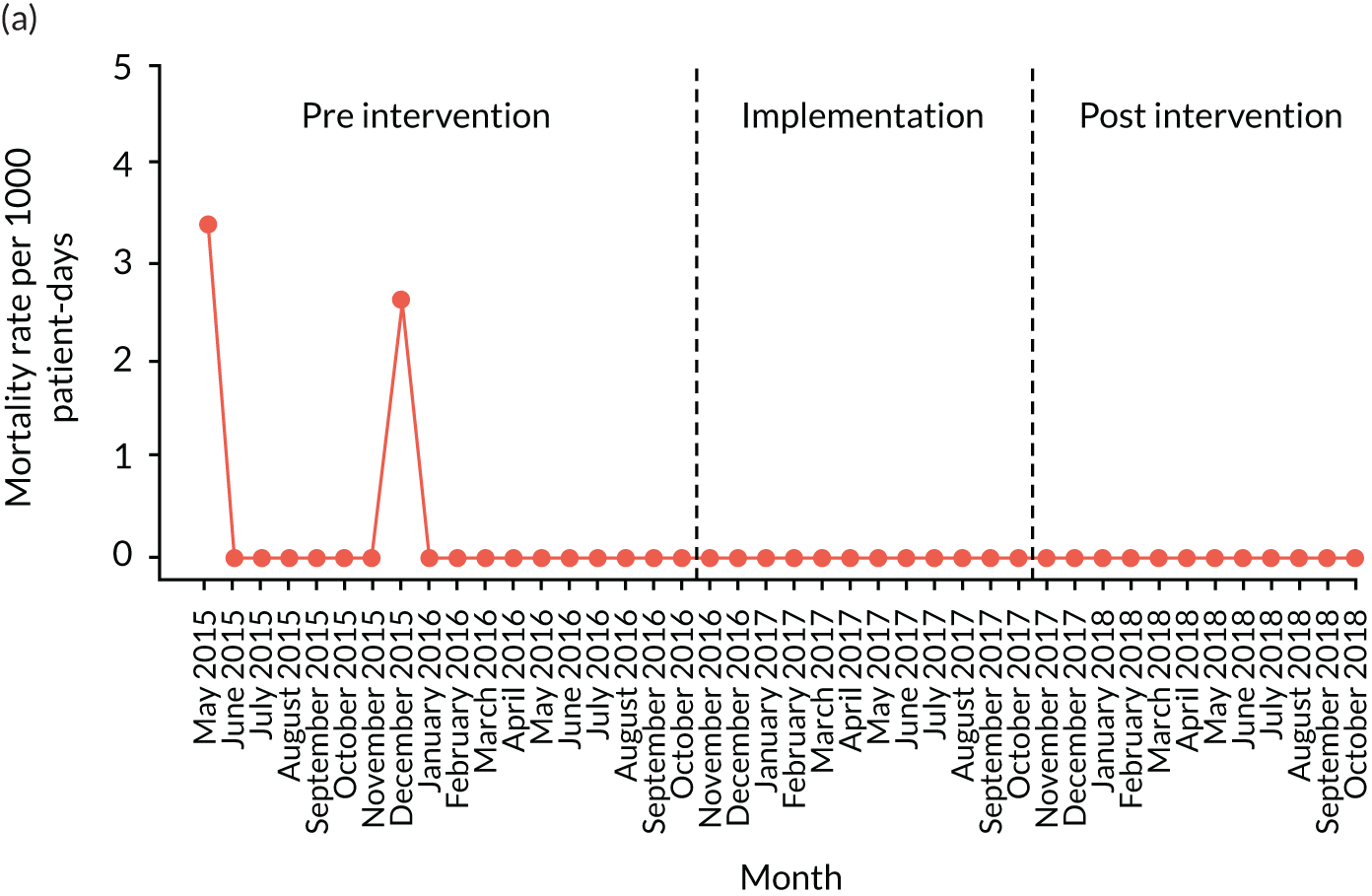

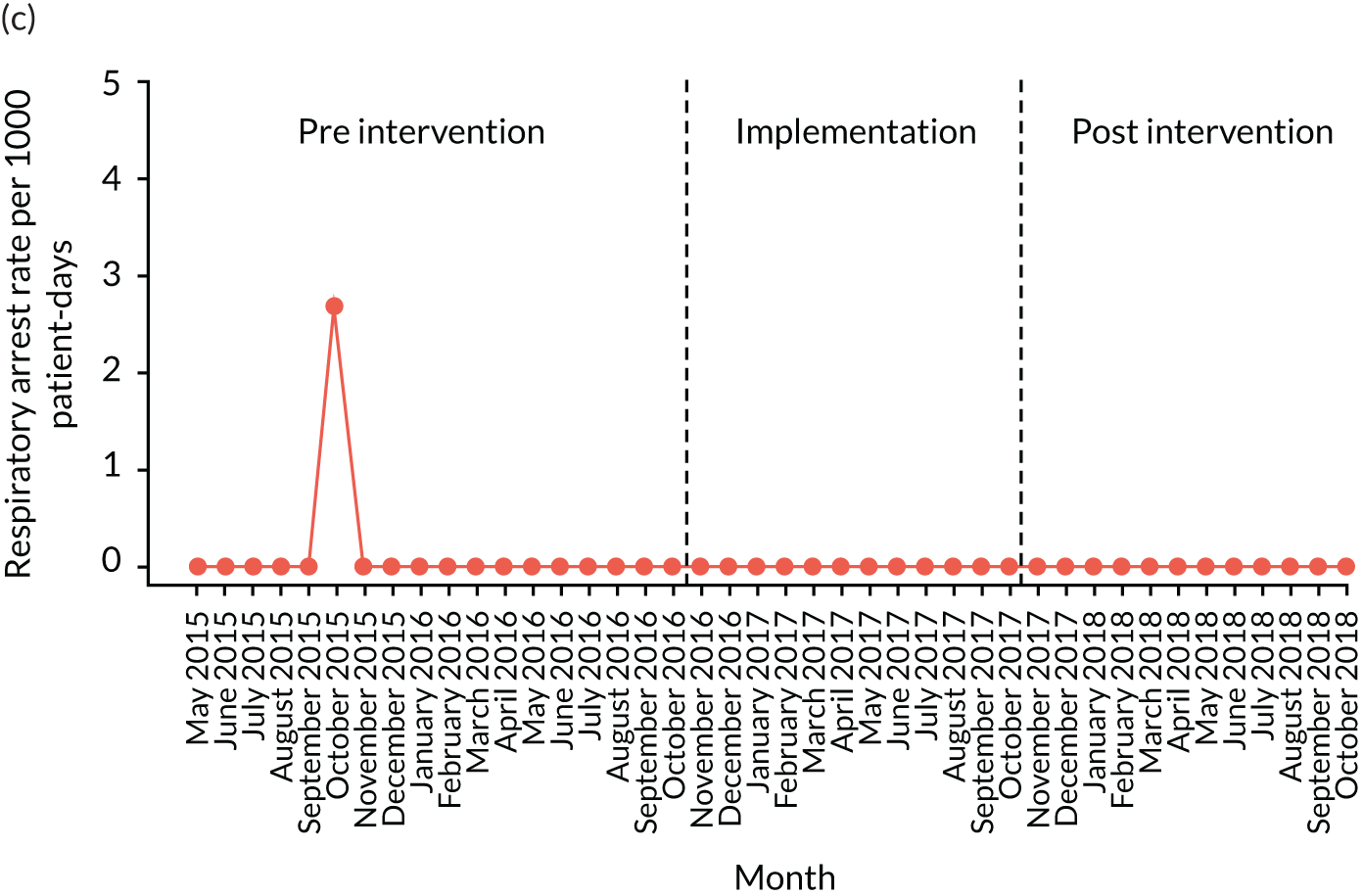

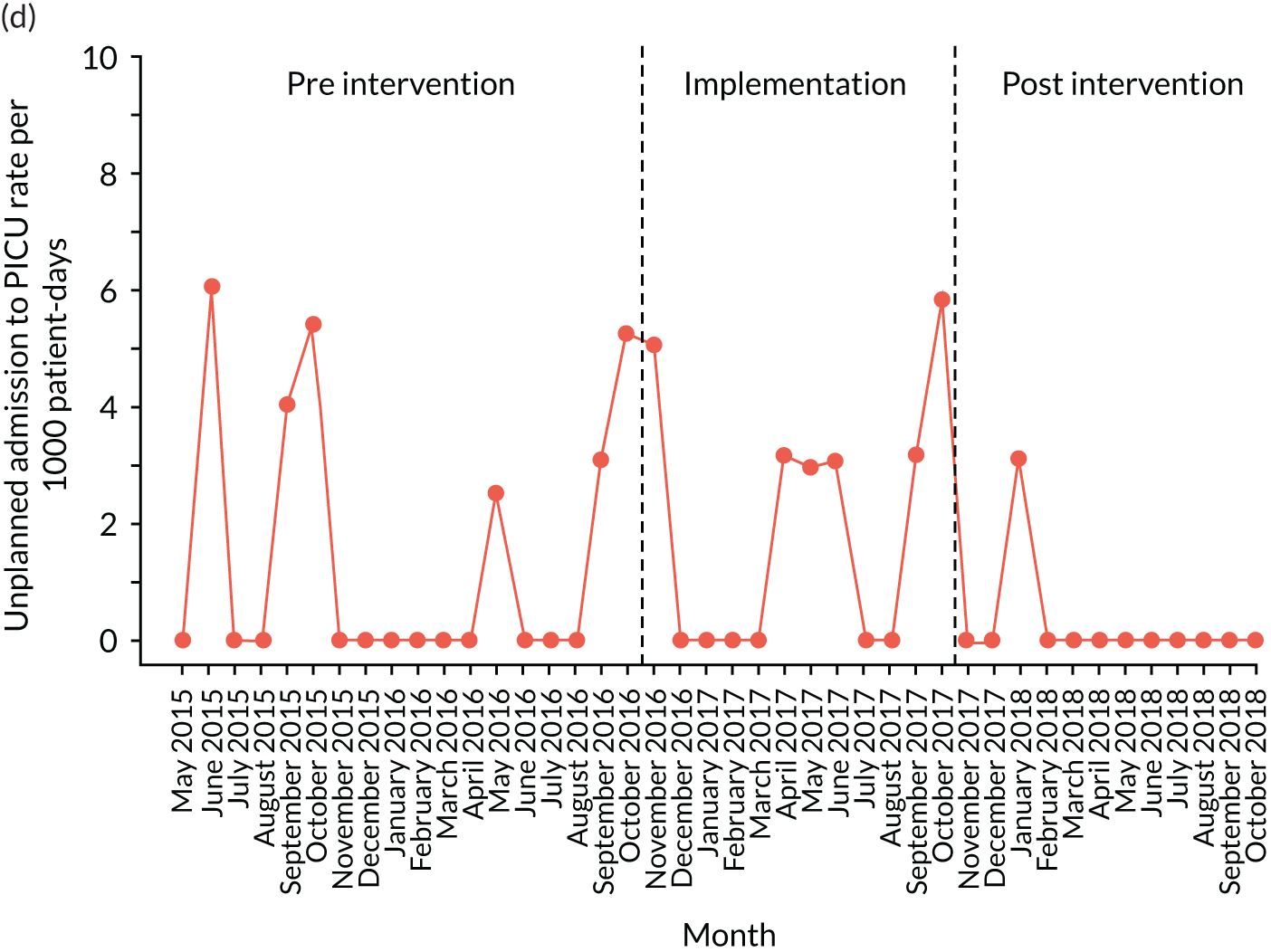

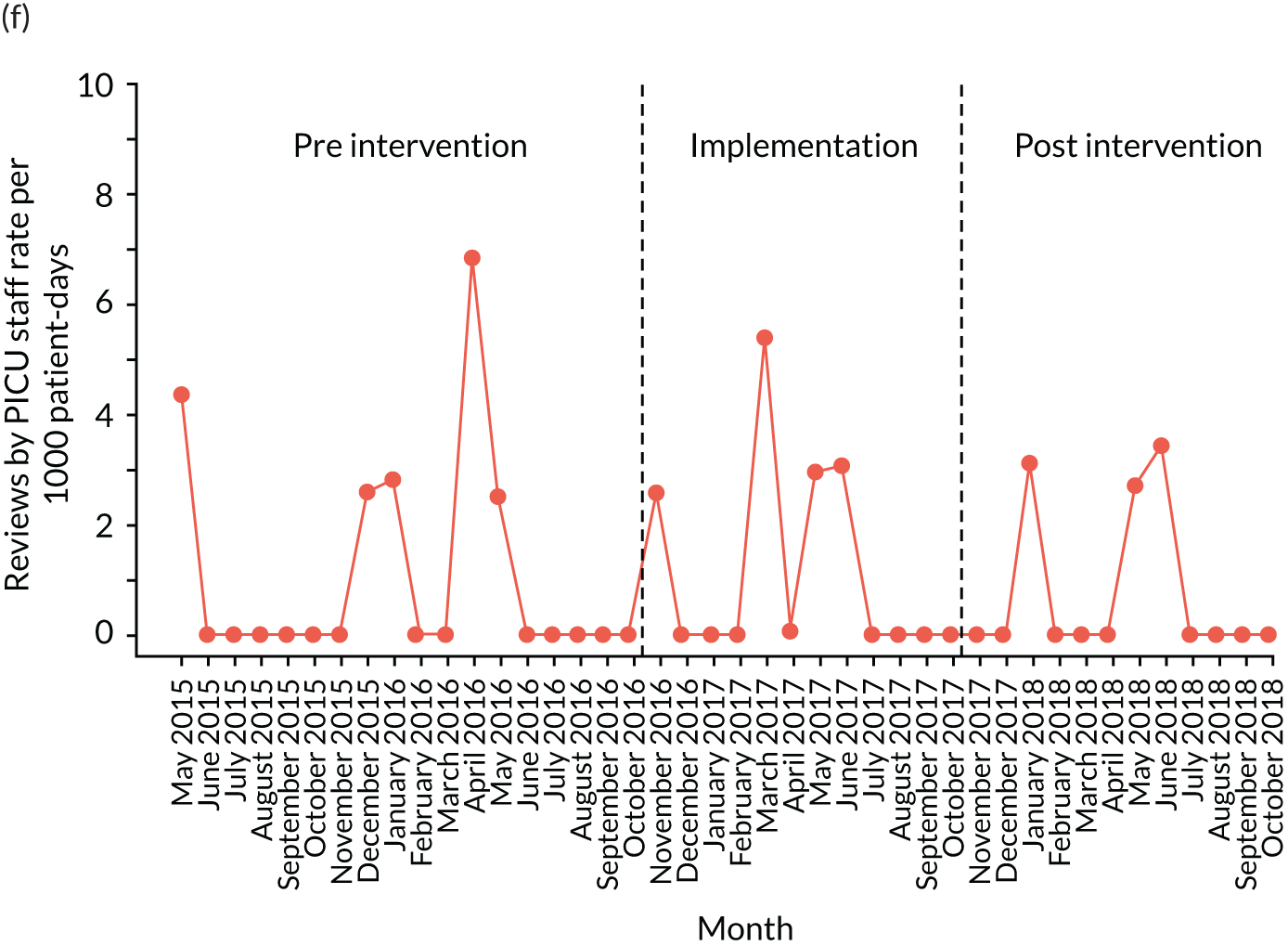

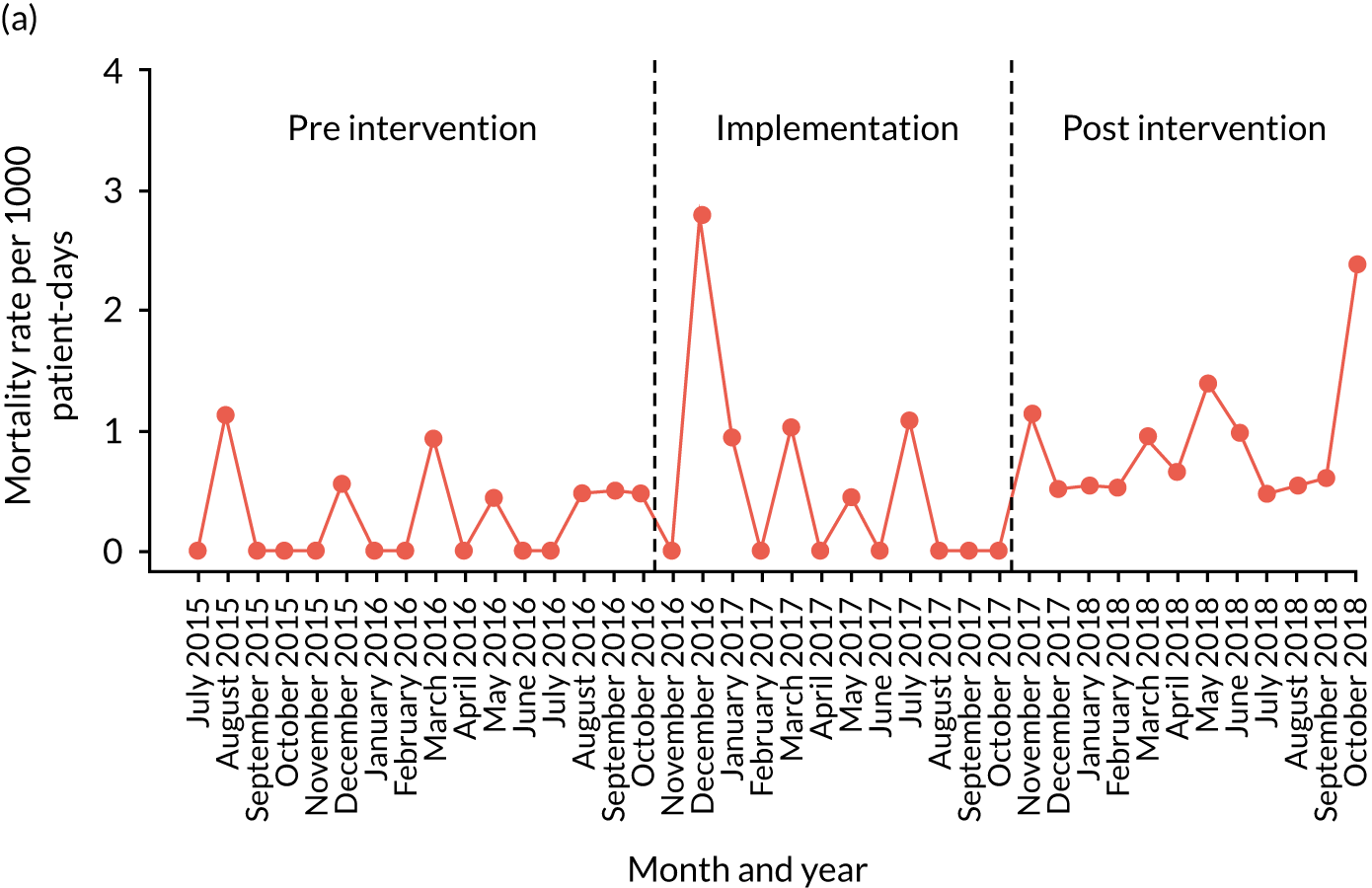

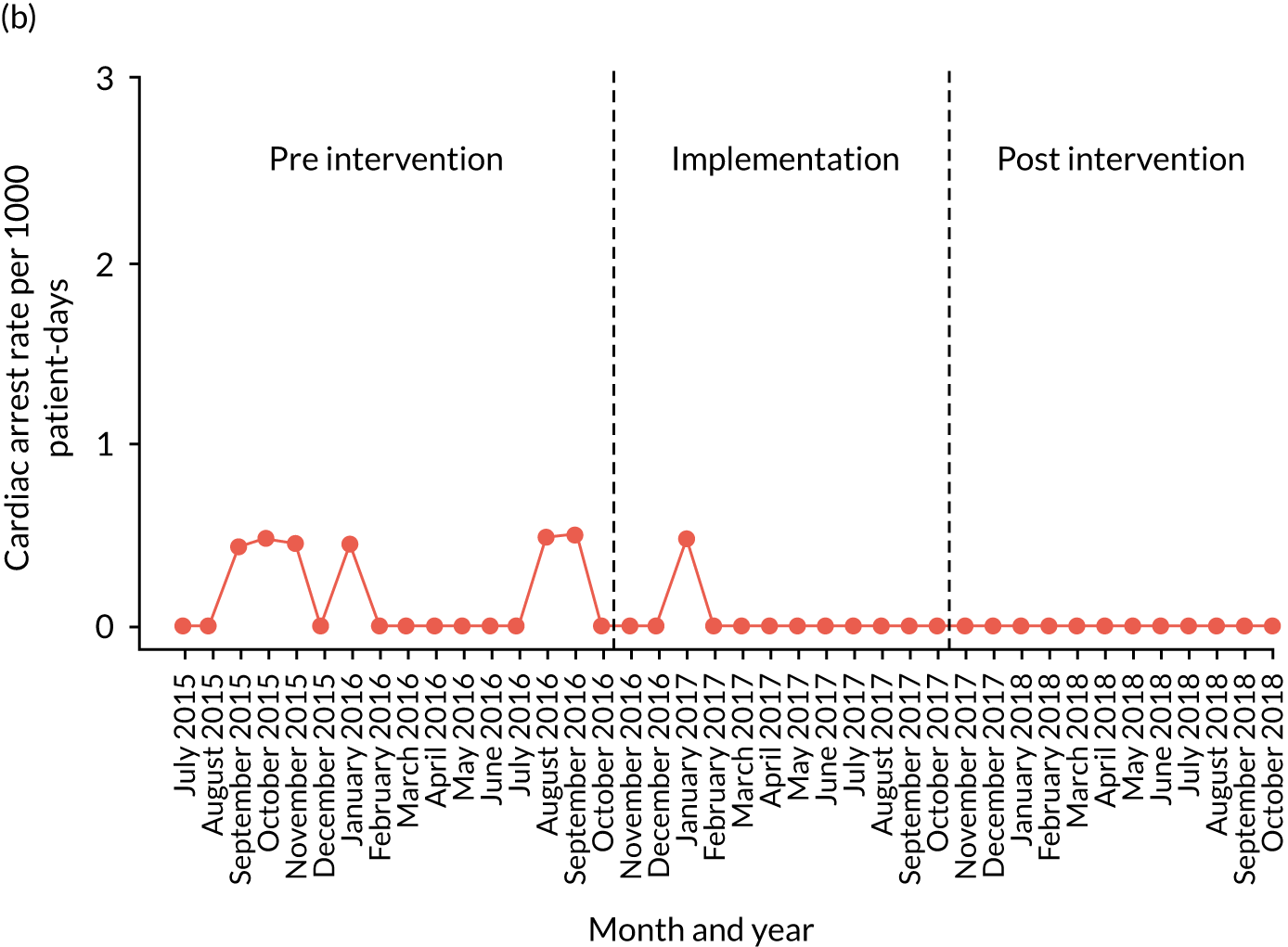

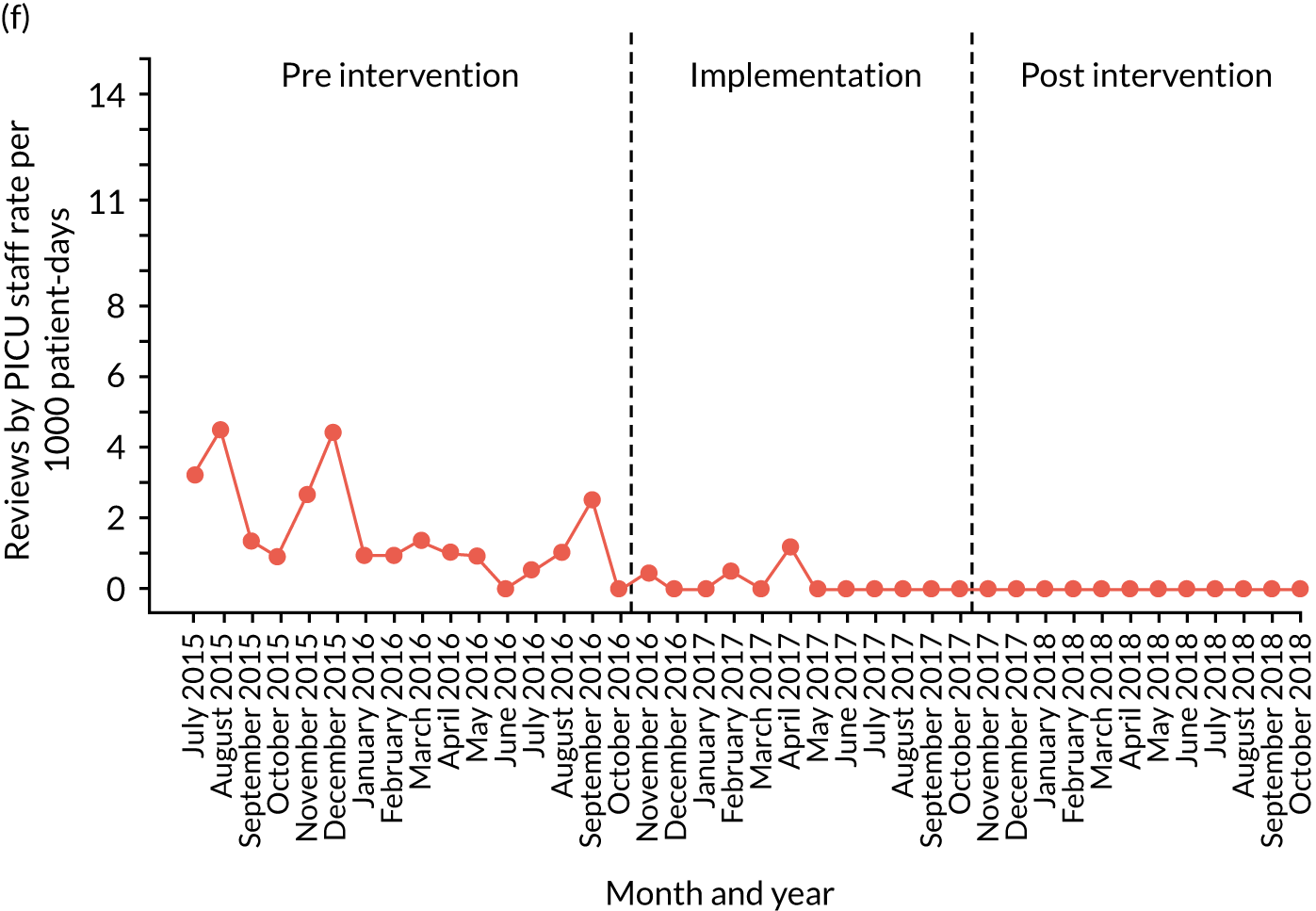

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcome measures were the aggregate number of children experiencing the following adverse events each month, with each event recorded individually as a separate outcome:

-

mortality

-

cardiac arrest

-

respiratory arrest

-

unplanned admission to a PICU

-

unplanned admission to a HDU

-

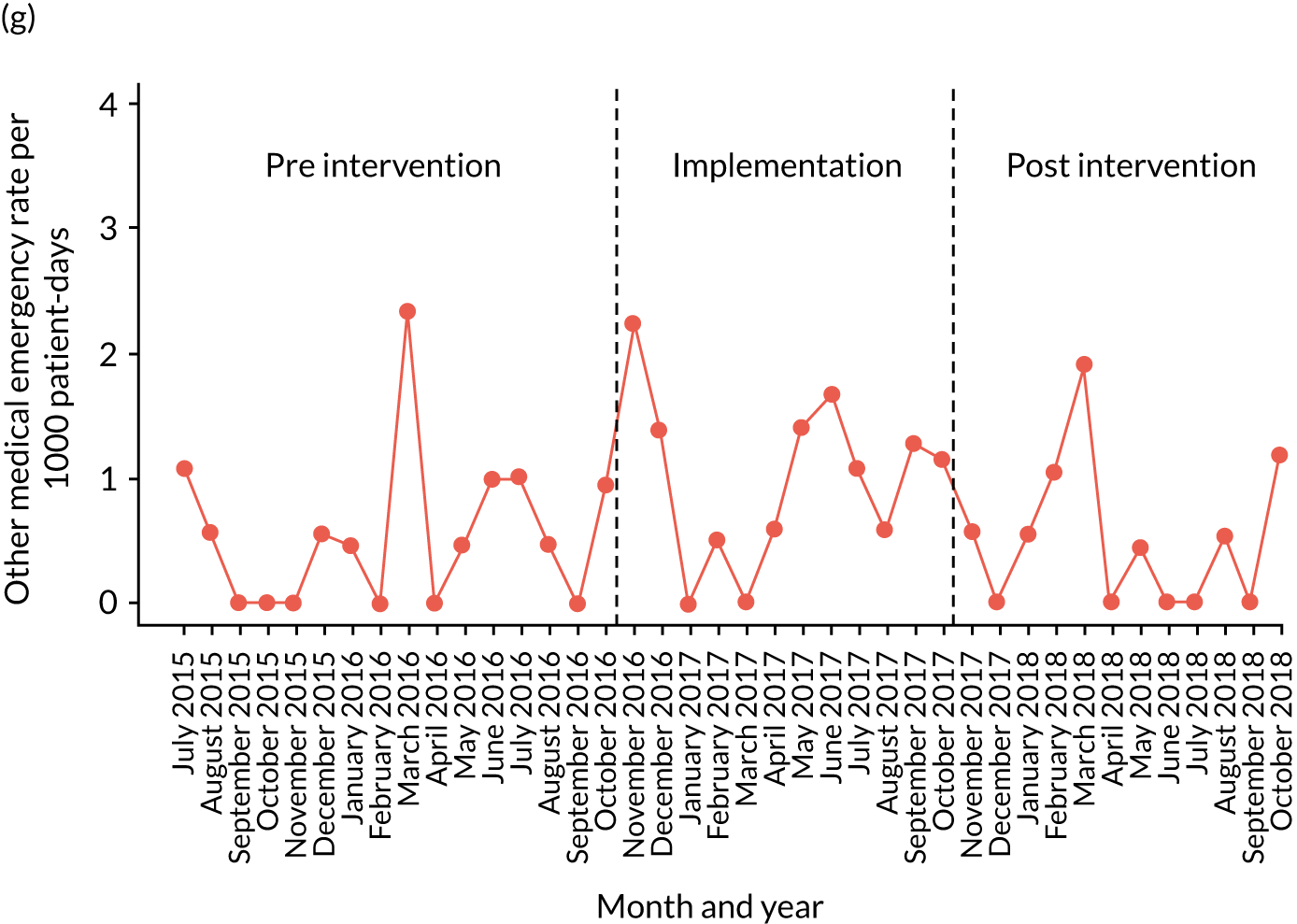

other medical emergencies requiring immediate assistance

-

reviews by PICU staff.

Secondary outcome measures were also expressed as a rate per 1000 patient bed-days.

Timing of outcome assessments

Primary and secondary outcomes, and the patient bed-day denominator, were entered by site staff into the PUMA database on a monthly basis at each of the four sites. Table 3 summarises the various data points for each of the hospitals, for the pre-implementation, implementation and post-implementation stages.

| Outcome | Pre implementation (18 months) | Implementation (12 months) | Post implementation (12 months) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | |

| Primary (composite) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Mortality | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Cardiac arrest | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Respiratory arrest | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Unplanned PICU admission | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Unplanned HDU admission | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Other medical emergency | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| PICU review | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Non-ICU patient bed-days | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

Sample size calculation

We used a simulation-based approach to calculate power, as it was challenging to calculate an accurate sample size. 36,37 Our initial calculation was based on the original aim of the study to implement a PTTT in each site.

We obtained historical data for one tertiary centre (Alder Hey) and one DGH (Morriston Hospital). These data showed a 1% prevalence (i.e. 10 events per 1000 patients) for unplanned transfers to a PICU. Tibballs et al. 38 have previously shown that the implementation of paediatric calling criteria with a rapid response team resulted in a RR of 0.65 in terms of total avoidable hospital mortality. We assumed that the PUMA intervention might result in a similar RR of 0.65. 38 The monthly recorded data for unplanned admission in both hospitals were used to estimate monthly death rate pre and post intervention. From obtained data, the estimated effect size, mean difference and common standard deviation were 2.8, 2.0 and 0.7, respectively. We estimated that we would have 90% power with a total of 24 months of observations (12 pre and 12 post intervention) for an effect size of at least 2. 37

The initial aims of the study were changed from the implementation of PTTT to a complex intervention: the PUMA programme. We retained the focus on collecting data 12 months pre and 12 months post intervention, but allowed 12 months for phase-in of the intervention, to give a total of 36 months. During the lifetime of the project, we were able to collect up to 6 additional months of data retrospectively for the pre-intervention period. This gave us 42 months of data and increased the sample size.

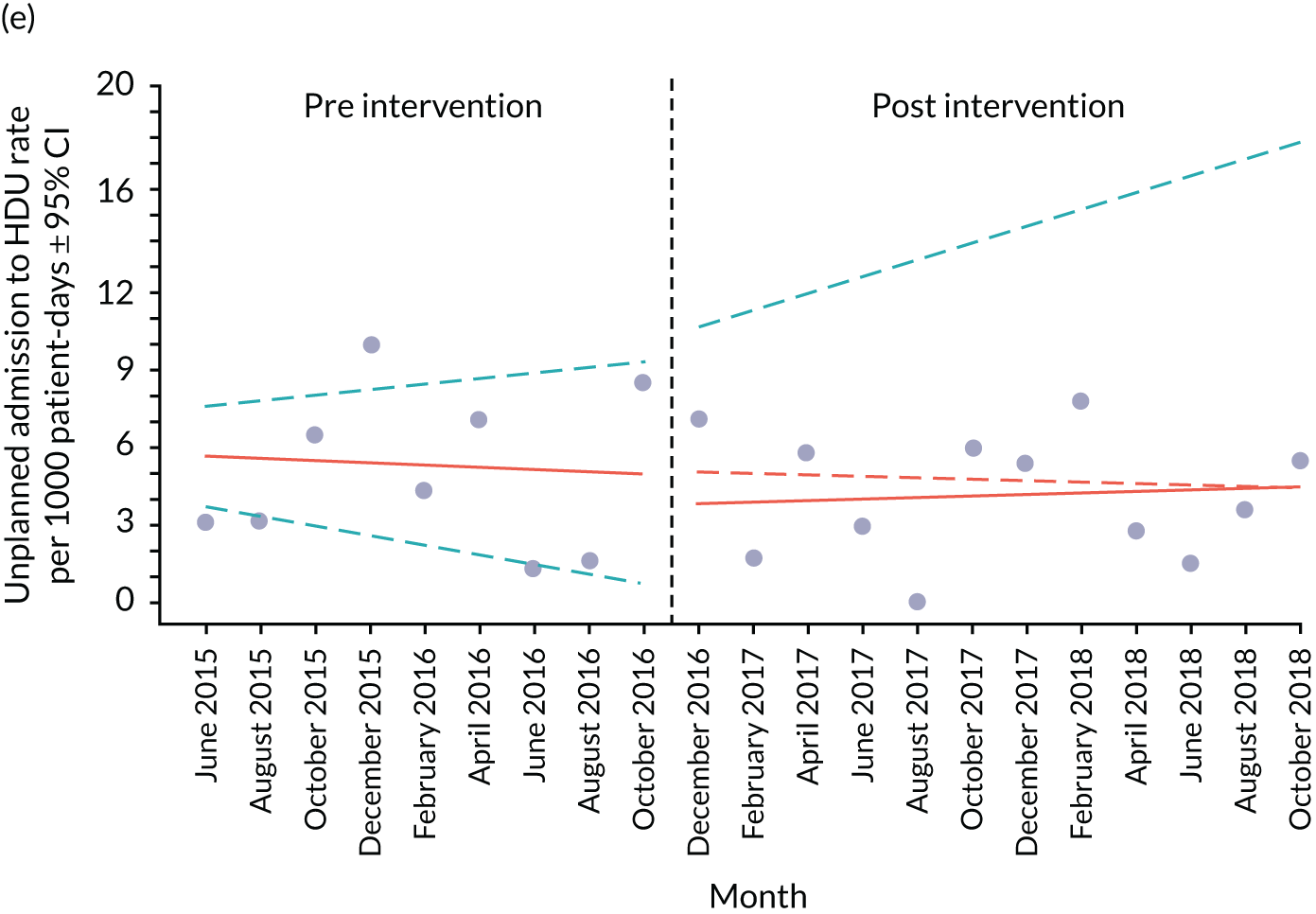

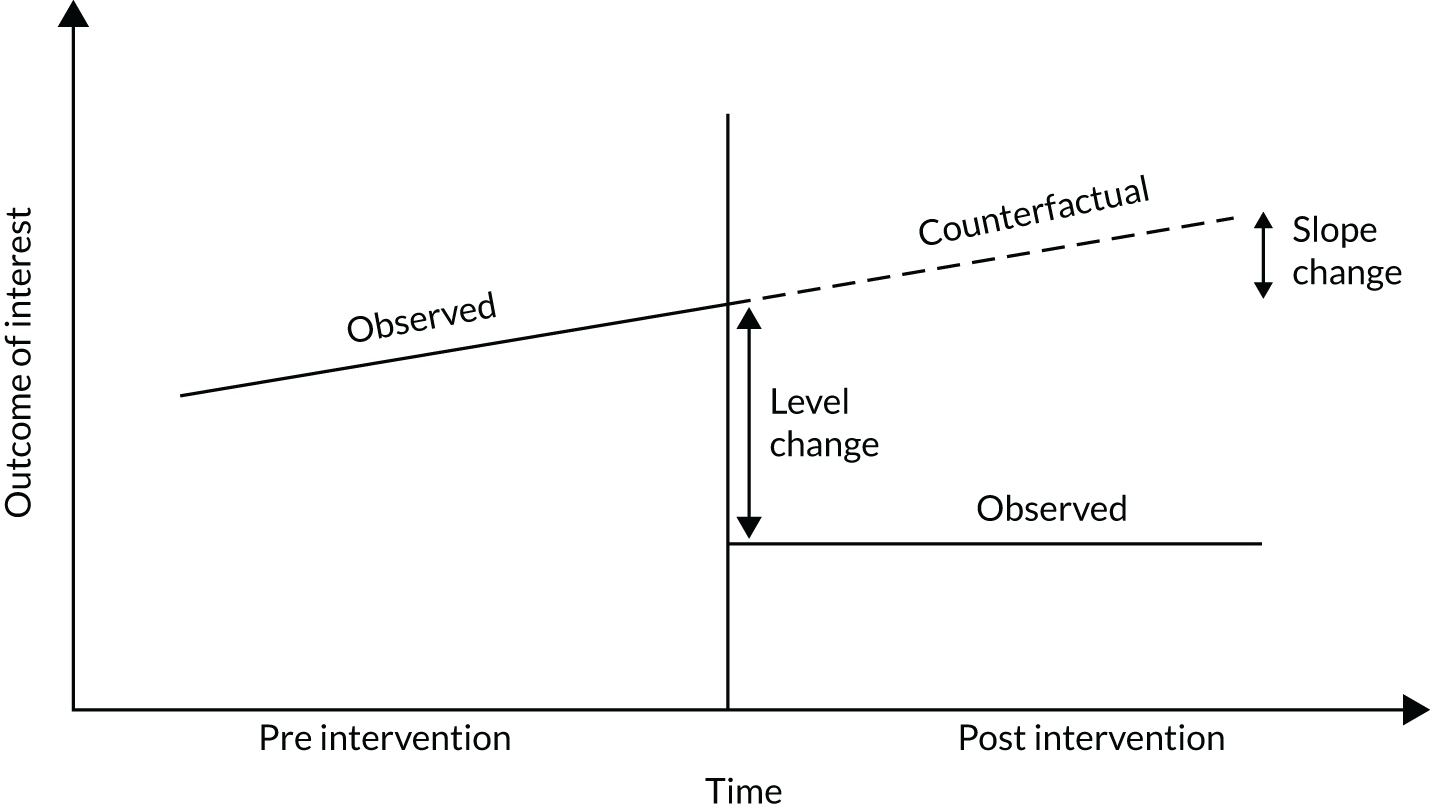

Data analysis

An ITS analysis was used to assess the effectiveness of the PUMA programme at reducing rates of inpatient deterioration over time. An ITS approach allows exploration of the longitudinal effect of the intervention through regression modelling. This approach controls for pre-intervention trends and assesses the extent to which an intervention ‘interrupted’ the trajectory of this trend. 39 See Appendix 9, Figure 27, for further details about an ITS approach.

The most common approach to an ITS analysis is to compare trends across two separate time periods: a pre- and a post-intervention phase. Typically, the intervention being studied is relatively clear-cut, for example a change in national policy, which would be expected to have an immediate effect (i.e. level change) on the outcome being studied. In this study, however, we expected that the complete implementation of the PUMA programme was likely to take longer, but that we might be able to observe gradual changes in measures of inpatient deterioration. Therefore, we decided to investigate both the short-term effect of the PUMA programme (by comparing pre-intervention levels in outcomes with implementation and post-intervention period levels in outcomes) and the longer-term effect (by exploring trends in outcomes during the implementation and after the intervention, in the post-intervention period, when teams would have had some time to embed local initiatives). Data from each hospital were analysed separately as independent case studies.

Primary analysis

There are different approaches to conducting an ITS. 39 We elected to fit a segmented linear regression on data from each hospital using an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) method to analyse the primary and secondary outcomes. 39,40 The residual plot corresponding to each model was investigated to check the assumptions of linear regression. The Durbin–Watson statistic, together with autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation function, was used to identify the order of autocorrelation and moving average.

To model the trajectory for all pre-implementation, implementation and post-implementation periods, two intervention start points were considered:

-

November 2016, the start of the implementation period (when sites began their improvement initiatives)

-

November 2017, the start of the post-implementation period.

Prior to observing the data, we decided to use one of the most commonly used impact models that allows immediate (level) and trend (slope) change after introducing or completing the implementation. 41 Any statistically significant change in either level or trend would imply that the intervention (i.e. the PUMA programme) had had an effect on outcomes.

For some secondary outcomes, we observed several zero monthly counts, particularly for the DGH sites. 42 For these cases, it was easy neither to transform the time series into a stationary series nor to detect a trend. Depending on the number of zero-count months, we adopted different mitigating strategies. If there were not many zero count months (e.g. a maximum of two per time period), an indicator variable was added to the model to account for its effect. Alternatively, if there were more zero counts per time period, we combined data into blocks of 2 months and, when possible, the trajectory was modelled. Otherwise, if there were still too many zero-count months and we were unable to fit a model, trajectory of the outcome only was plotted.

Exploratory and sensitivity analyses

In addition to the main analysis of the primary outcome (conducted using three time periods), we also conducted two sets of additional exploratory analyses to explore the data using different conceptual approaches to designate pre- and post-intervention time periods for analysing changes in trends.

In the first analysis, we simply excluded data collected during the 12-month implementation period (November 2016–October 2017), to create a binary pre- and post-intervention comparison of slopes. In the second analysis, we explored the pattern of changes in level and slope from the start of implementation phase until the end, given the potential for the different local initiatives to exert their effects over different time periods in different sites.

Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome for each site, fitting a segmented Poisson regression model to the data. See Appendix 10, Tables 27–34 and Figure 28, for details.

Qualitative evaluation: ethnographic case studies

Overview

Embedded ethnographic case studies were undertaken on one ward in each of the four hospitals. Qualitative methods (observation, interviews and documentary analysis) were deployed to undertake a pre- and post-implementation review of the local paediatric early warning system in everyday clinical practice.

The aim of the pre-implementation stage was to understand current practice at baseline: evaluating the paediatric early warning system in practice and observing how the system was shaped by local context. The aim of the post-implementation stage was to evaluate any changes to the paediatric early warning system after implementation of the PUMA programme, in order to understand the impact of the intervention.

Case study wards

In contrast to the quantitative analysis, which summarised aggregate outcome measures at a hospital-wide level, the ethnographic case studies were conducted on a single ward. Table 4 summarises the wards selected at each site.

| Site | Number of paediatric inpatient wards | Case study ward selected |

|---|---|---|

| Alder Hey Children’s Hospital | 10 | Cardiac surgical ward |

| Arrowe Park Hospital | 1 | General paediatric ward |

| Noah’s Ark Children’s Hospital | 8 | General medical ward |

| Morriston Hospital | 2 | General medical ward |

Data collection

Table 5 shows the qualitative data collected at each case study site. In both the pre- and post-implementation phase, data were generated through:

-

ethnographic observation of everyday practice (by shadowing individuals – nurses, doctors, support staff – and discussing their practice, and attending key meetings and events)

-

interviews with clinical team members, service managers, PIs and family members or carers

-

analysis of relevant documents and artefacts.

| Site | Pre-implementation data collection (from March 2015 to October 2016) | Post-implementation data collection (from November 2017 to October 2018) |

|---|---|---|

| Alder Hey |

|

|

| Arrowe Park |

|

|

| Noah’s Ark |

|

|

| Morriston |

|

|

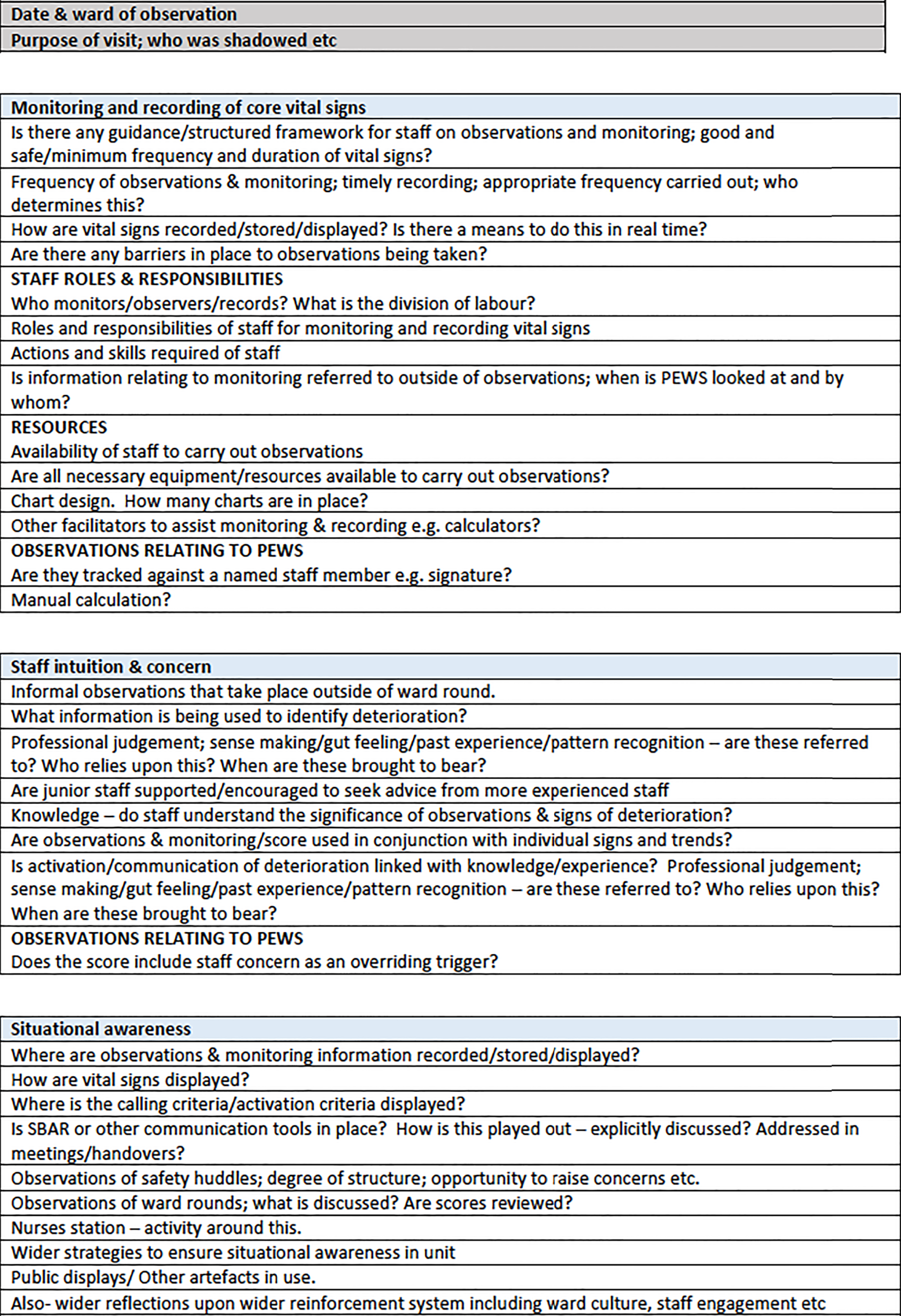

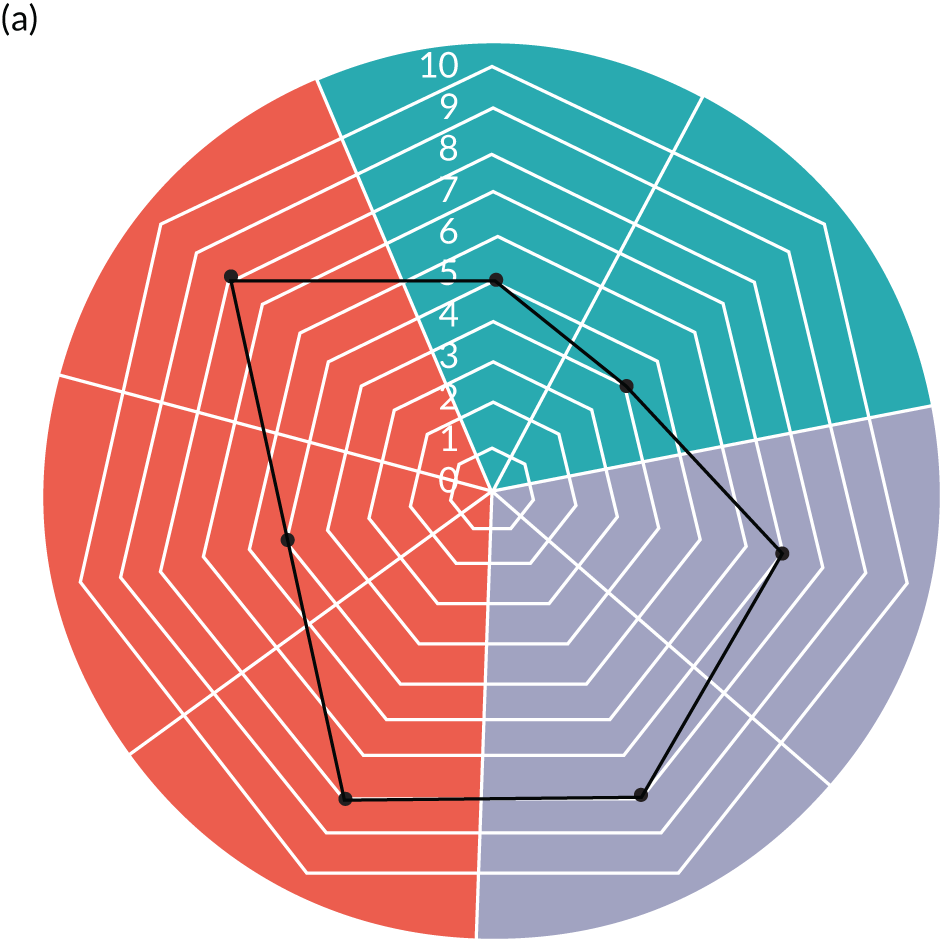

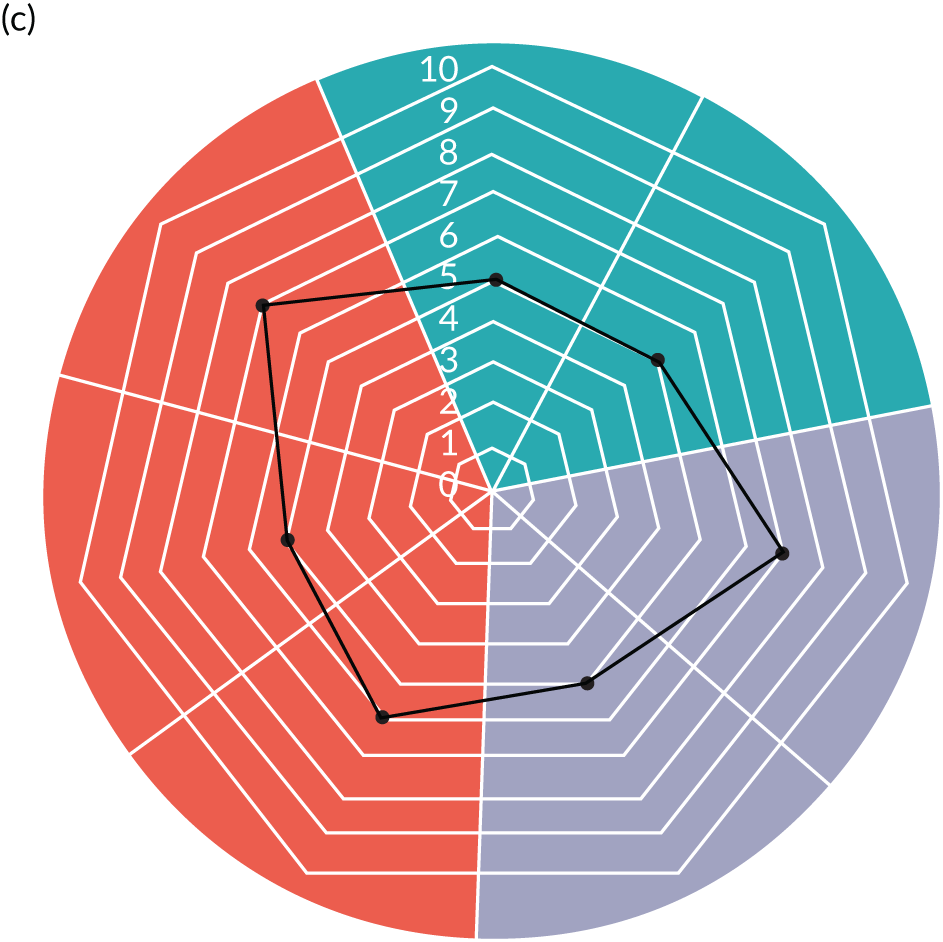

Observations were conducted at different times of day/night and on different days of the week, including weekends, to ensure that a range of time periods were covered. Our concern was with understanding the network of actors (people, processes, technologies and artefacts) and their inter-relationships in each paediatric early warning system. Drawing on the theoretical framework and the systematic review findings, we developed a template to guide the observations and interviews as shown in Figure 1 (see Report Supplementary Material 2). However, data generation was not absolutely constrained by this; rather, in each case, the strategy was to ‘follow the actors’ (human and non-human). This ensured that there was a consistent approach across case studies to facilitate comparative analyses, but flexibility to modify data generation in response to the singular features of each site. We focused on what participants did, the tools they used, the concepts they deployed and the factors that facilitated and constrained action. Adopting a TMT lens directed attention to the sociomaterial relationships within each paediatric early warning system and how the local institutional context conditioned the possibilities for action. 25,26

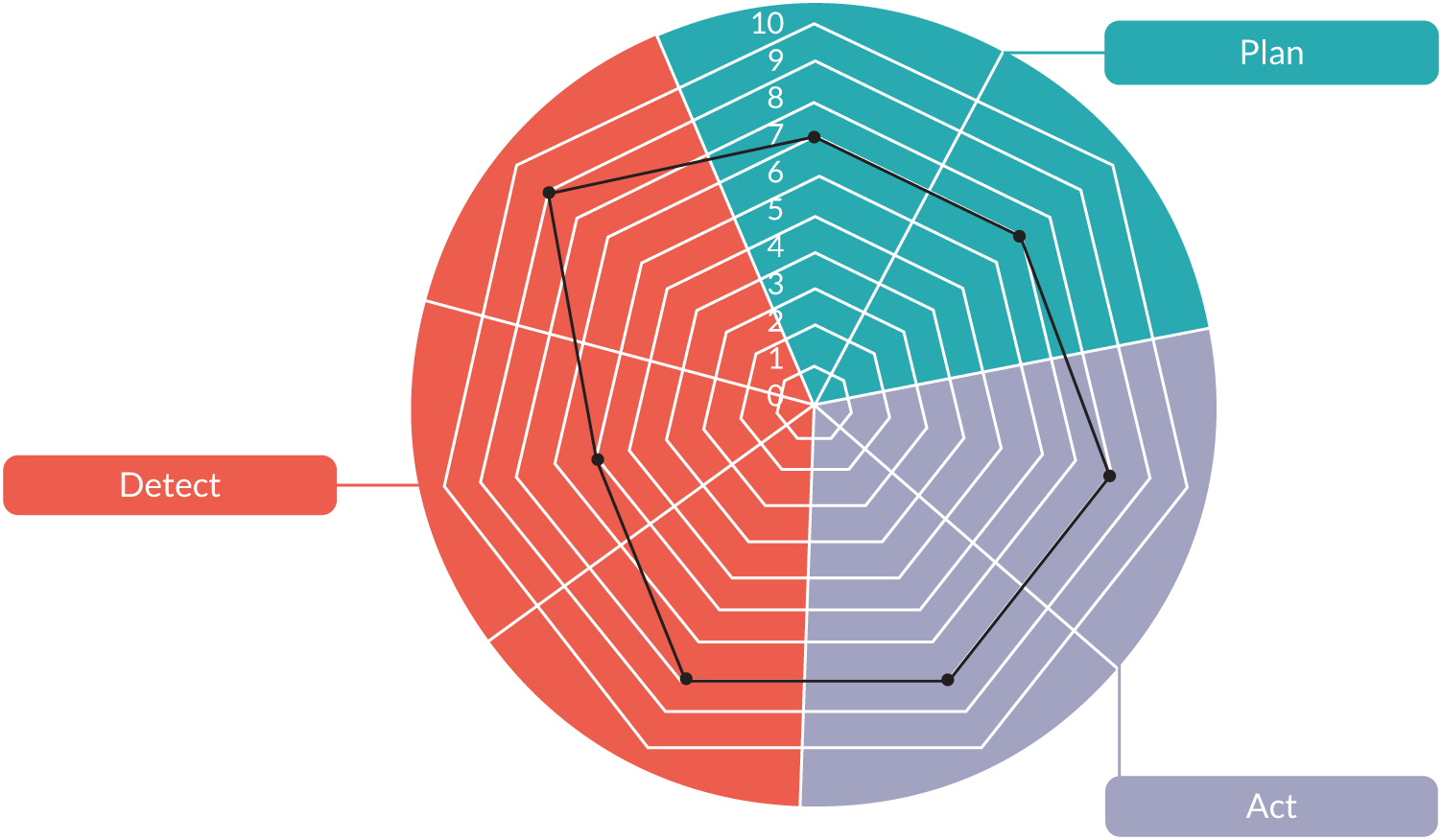

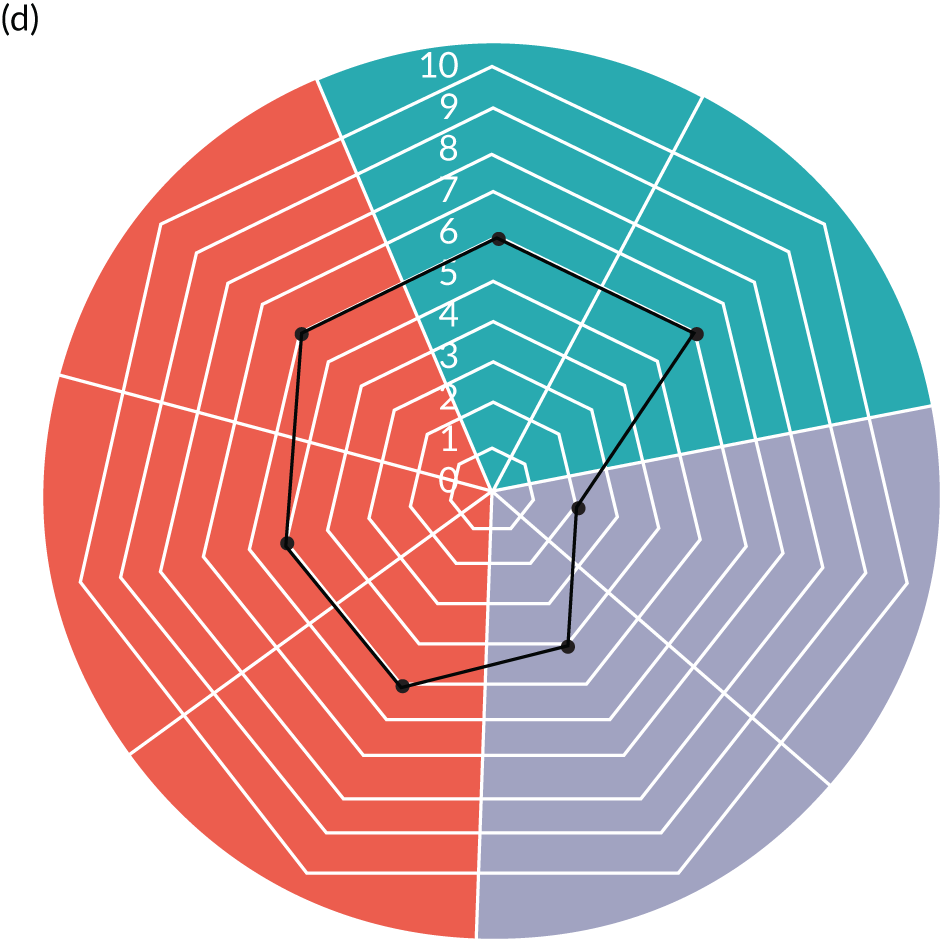

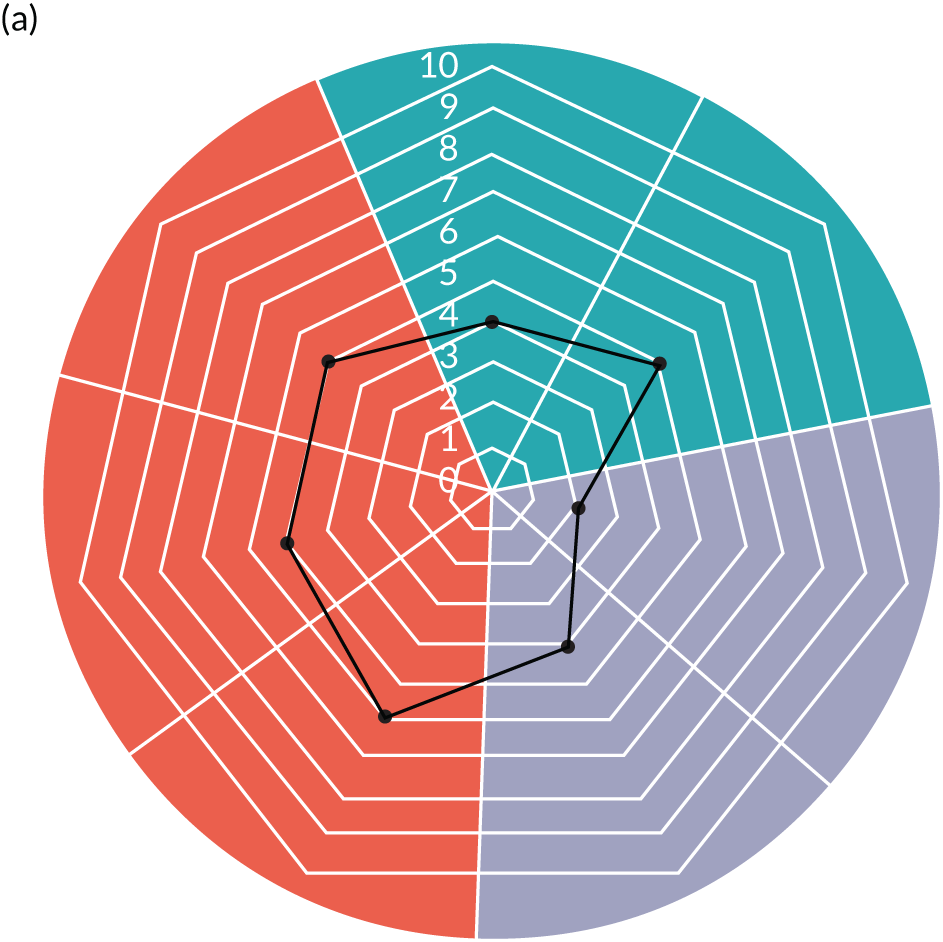

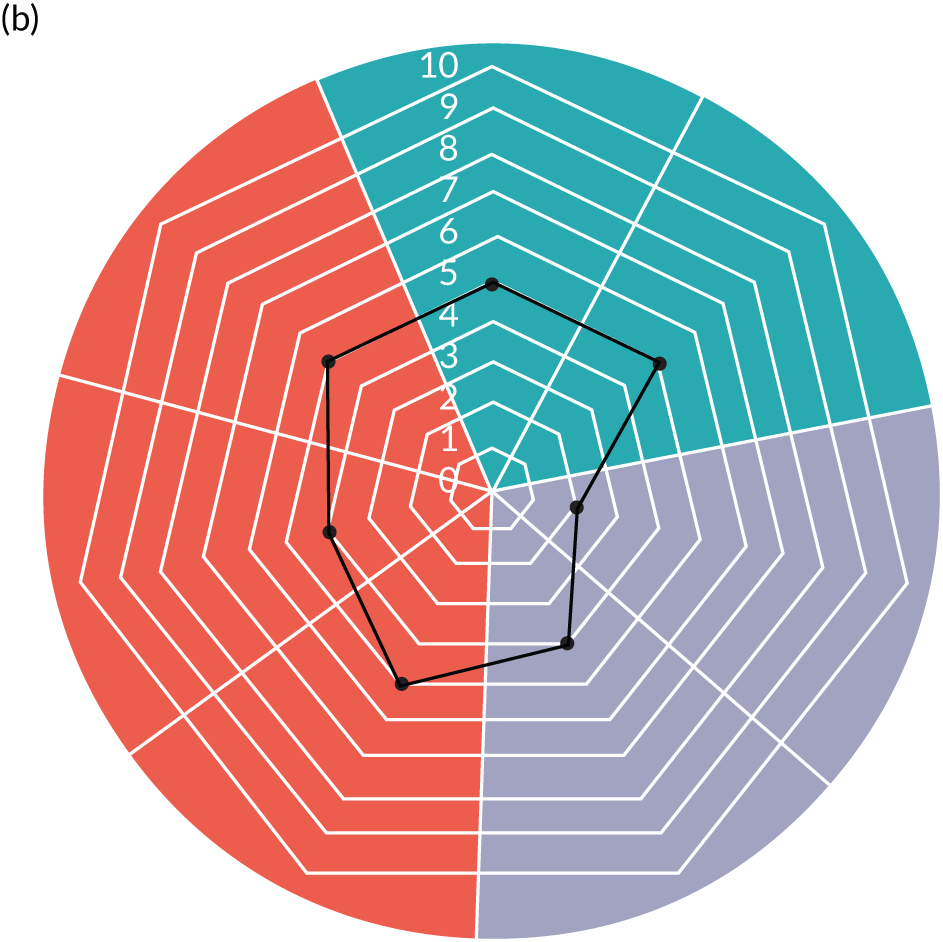

FIGURE 1.

Observations template.

In addition, we also undertook a series of semistructured interviews with parents/carers to explore their views and experiences, and semistructured interviews with a sample of clinical staff and relevant service managers.

Ethnographic observations and embedded interviews were recorded contemporaneously as low inference-style field notes and expanded on as soon as possible after the data were collected. Staff interviews were digitally recorded with consent and organised to take place either in private offices or by telephone. Interviews with an opportunistic sample of parents who had a physiologically unstable child were undertaken when the child was still an inpatient, but at a time when their condition was considered by clinical staff to be stable. For the purposes of this study, we did not include parents whose child had died, but we interviewed parents whose child had (1) been monitored only, (2) received intervention to prevent deterioration or (3) experienced a critical event. Documents/records were treated as both a resource and a topic. Their content was analysed to inform our understanding of organisational processes and practices. Their form was analysed to develop a better understanding of their design, affordances and inter-relationships.

We replicated this ethnographic process (both non-participant observations and interviews) in the post-implementation period, modifying the interview style and content, as well as the primary focus of the observations, to explore, in detail, staff experiences of the PUMA programme, changes to the system, factors consequential for impact and any unintended consequences. We also reassessed the paediatric early warning system using a structured template based on the PUMA Standard as a guide to observation, in order to analyse changes in these relationships brought about by the improvement programme, and the implications this had for normalisation.

Analysis

At all stages, data collection and analysis were undertaken concurrently, facilitating a progressive narrowing of focus designed to develop an in-depth understanding of the paediatric early warning systems and the implications of the improvement programme for practice. The various materials collected (field notes, interview transcripts and documents) were coded using a common framework and used to develop concrete descriptions of relevant aspects of paediatric early warning systems, which were mapped onto the PUMA Standard. Local PIs also contributed to this sense-making process.

Analysis was undertaken in two main stages:

-

Stage 1 involved developing a description and analysis of the pre- and post-implementation paediatric early warning system in each hospital and the implementation process. This entailed the development of richly descriptive accounts, extending to up to 25,000 words, which were then subject to further analysis, refined and condensed into summaries for the purposes of the report.

-

Stage 2 involved cross-case analysis to understand the relationship between the intervention, context, mechanisms and outcomes to inform the extension and development of the PUMA programme.

Qualitative PUMA programme process evaluation

Overview

The process evaluation focused on the implementation of the PUMA programme in order to understand participants’ experiences, but also to identify where and how the programme might be strengthened.

Data

Observations

Observations, recorded as fieldnotes, were made of all facilitated sessions (set-up, action planning) and monthly PUMA study meetings during which PIs provided progress updates on local implementation efforts at their site (some of which were also audio-recorded).

Interviews with principal investigators and staff

Face-to-face digitally recorded interviews were conducted with PIs and clinical staff from each of the four sites at the end of the implementation phase, to gain an understanding of participants’ experiences of, and response to, different elements of the PUMA programme.

Other data sources

Written notes were made on telephone-based facilitation discussions held between one of the PUMA study team members and site PIs.

We also drew on documents shared by sites, including minutes of local improvement team meetings and policies or procedures created as a result of PUMA programme initiatives.

Analysis

Analysis was thematic, focusing on delivery and response to the core components of the PUMA programme, communication of PUMA, understanding of PUMA, barriers to change and implementation, facilitators of change and implementation, and sustainability.

Chapter 3 Evidence reviews

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Jacob et al. 13 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter are reproduced from Trubey et al. 24 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Two linked quantitative reviews were conducted to explore the evidence base for the validity and effectiveness of existing PTTTs and paediatric early warning systems (reviews 1 and 2). A third, qualitative, review was conducted to explore the wider contextual factors associated with successful (or unsuccessful) paediatric early warning systems (review 3).

The results of the reviews are described separately, with the overall findings synthesised in the conclusions. This chapter draws substantially on two published papers. 13,24

The quantitative reviews

Two linked quantitative reviews were undertaken to address the following questions:

-

Review 1: how well validated are existing PTTTs and their component parts for predicting inpatient deterioration?

-

Review 2: how effective are paediatric early warning systems (with or without a tool) at reducing mortality and critical events?

Study characteristics

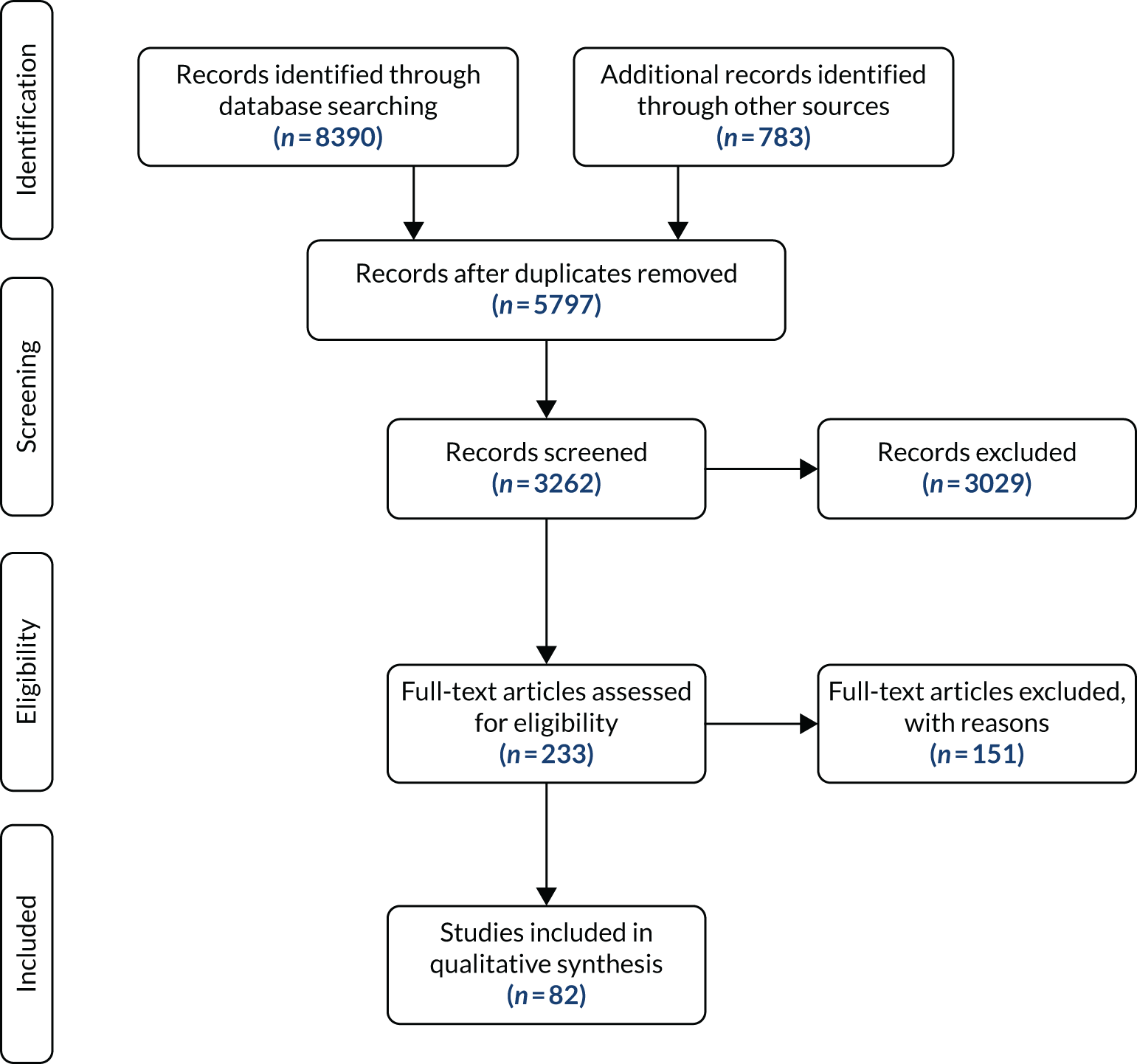

Figure 2 presents a summary of the study characteristics of the 36 validation (question 1) and 30 effectiveness (question 2) papers included in the reviews. Full details are provided in Appendix 11, Table 35.

FIGURE 2.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for study screening and selection: reviews 1 and 2. PEWS, Paediatric Early Warning Score; RQ, review question.

Types of paediatric track-and-trigger tools and components

Across 66 studies, we identified 27 unique PTTTs. Twenty PTTTs were based on one of four different tools: Monaghan’s44 Brighton Paediatric Early Warning Score (PEWS), the Bedside PEWS,19 the Bristol Paediatric Early Warning Tool45 and the Melbourne Activation Criteria (MAC). 38 Other PTTTs described in the literature included the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (NHS III) PEWS, which is the second most frequently used PTTT in UK paediatric settings;22 rapid response team (RRT) and medical emergency team (MET) activation criteria;46–49 and one prediction algorithm developed from a large data set of electronic health data. 50 [Please note that, although the abbreviation PEWS is defined as Paediatric Early Warning Score in the main body of the text, this definition is not necessarily applicable to the wider literature where, for the purposes of the review, the original use is retained.]

The range of physiological and behavioural parameters underpinning PTTTs is illustrated in Appendix 12, Table 36. Common parameters included heart rate (present in 26 out of 27 PTTTs), respiratory rate (in 24 PTTTs), respiratory effort (in 24 PTTTs) and level of consciousness or behavioural state (in 24 PTTTs). All PTTTs required at least six different parameters to be collected.

Review 1: how well validated are paediatric track-and-trigger tools and component parts for predicting inpatient deterioration?

Nine validation papers meeting inclusion criteria were excluded from analysis: eight51–58 did not report any performance characteristics of the PTTT for predicting deterioration, and one study45 calculated incorrect sensitivity/specificity outcomes (see Appendix 13, Table 37).

The remaining 27 validation studies, evaluating the performance of 18 unique PTTTs, are described in Appendix 14, Table 38. Four studies evaluated multiple PTTTs,50,59–61 and one paper described three separate studies of the same PTTT. 62

Five cohort studies were included, three based on the same data set. 17,63–66 All other studies were either case–control studies or chart reviews. Thirteen papers implemented the PTTT in practice,54,62,64,66–75 whereas the remaining studies ‘bench-tested’ the PTTT, that is researchers retrospectively calculated the score based on data abstracted from medical charts and records. All studies were conducted in specialist centres, with only one multicentre study reported. 76

Outcome measures

Paediatric track-and-trigger tools were evaluated for their ability to predict a wide range of clinical outcomes. Composite measures were used in eight studies,17,54,61,63,65,77–79 cardiac/respiratory arrest or a ‘code call’ was used (singularly or as part of a composite outcome) in six studies,18,54,60,61,77,78 and 22 studies used transfer to a PICU or a paediatric HDU as the main outcome. 17,19,50,54,59–62,64–66,68,71,73–77,79–81

Predictive ability of individual paediatric track-and-trigger tool components

Three validation papers reported on the performance characteristics of individual components of the tool for predicting adverse outcomes. 19,65,73 Parshuram et al. ,19 for instance, reported area under receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve values for individual PTTT items of a pilot version of the Bedside PEWS: ranging from 0.54 (bolus fluid) to 0.81 (heart rate), compared with 0.91 for the overall PTTT. 19 All other studies reported outcomes for the PTTT as a whole.

Paediatric early warning system score

The predictive ability of the 16-item PEWS was assessed by one internal (AUROC = 0.90)18 and two external case–control studies (AUROC range 0.82–0.88)60,61 with a range of outcome measures and scoring thresholds. One case–control study18 used an observed prevalence rate to calculate a positive predictive value (PPV) of 4.2% for the tool in predicting code calls (i.e. for every 1000 patients triggering the PTTT, 42 would be expected to deteriorate).

Bedside Paediatric Early Warning Score and derivatives

The Bedside PEWS was evaluated in one internal (AUROC = 0.91)19 and five external case–control studies (AUROC range 0.73–0.90)50,60,61,76,79 for a range of different outcome measures and at different scoring thresholds. One case–control study50 calculated a PPV of 2.1% for identifying children requiring urgent PICU transfer within 24 hours of admission, based on locally observed prevalence rates. A modified version of the Bedside PEWS (with temperature added) demonstrated an AUROC of 0.86 in an external case–control study with a composite outcome of death, arrest or unplanned PICU transfer. 61

Brighton Paediatric Early Warning Score and derivatives

Six different PTTTs based on the original Brighton PEWS were evaluated across 11 studies,50,61,64,69,71–74,77,78,81 The Modified Brighton PEWS (a) was evaluated for its ability to predict PICU transfers in one large prospective cohort study (AUROC = 0.92, PPV = 5.8%),64 and an external case–control study tested the same score for predicting urgent PICU transfers within 24 hours of admission (AUROC = 0.74, PPV = 2.1%). 50

An external case–control study used a composite measure of death, arrest or PICU transfer to evaluate the Modified Brighton PEWS (b) (AUROC = 0.79) and the Modified Brighton PEWS (d) (AUROC = 0.74). 61 The latter tool was evaluated in a further internal case–control study for predicting PICU transfer (AUROC = 0.82). 80

The Children’s Hospital Early Warning Score had a reported AUROC of 0.90 for predicting PICU transfers or arrests in a large internal case–control study. 69 A modification for cardiac patients, the Cardiac Children’s Hospital Early Warning Score (C-CHEWS), was evaluated by one internal study on a cardiac unit (AUROC = 0.90)77 looking at arrests or unplanned PICU transfers, and by two external studies of oncology/haematology units for the same outcome (AUROC = 0.95). 73,74 Finally, the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles PEWS was evaluated in a small internal case–control study for prediction of re-admission to PICU after initial PICU discharge (AUROC = 0.71). 72

Melbourne Activation Criteria and derivatives

The MAC was assessed by one external case–control study with an outcome of death, arrest or unplanned PICU transfer (AUROC = 0.71)61 and by a large external cohort study with an outcome of death or unplanned PICU or HDU transfer (AUROC = 0.79, PPV = 3.6%). 65 A derivative of the MAC, using an aggregate score, the Cardiff & Vale Paediatric Early Warning Score (C&VPEWS), was tested using the same cohort and outcome measures as used in a previously mentioned external study (AUROC = 0.86, PPV = 5.9%)17 and was the best-performing PTTT in an external case–control study evaluating multiple PTTTs (AUROC = 0.89). 61

Bristol Paediatric Early Warning Tool

The Bristol Paediatric Early Warning Tool was evaluated by five external validation studies: two chart review studies (no AUROC);59,67 one small cohort study of PICU transfers (AUROC = 0.91, PPV = 11%);66 and two case–control studies looking at code calls (AUROC = 0.75)60 and a composite of death, arrests and PICU transfers (AUROC = 0.62). 61

Other paediatric track-and-trigger tools

The NHS III PEWS was tested by one external cohort study looking at a composite of death or unplanned transfers to PICU or HDU (AUROC = 0.88, PPV = 4.3%)63 and one external case–control study looking at a composite of death, arrests and PICU transfers (AUROC = 0.82). 61 Zhai et al. 50 developed and retrospectively evaluated a logistic regression algorithm in an internal case–control study looking at urgent PICU transfers in the first 24 hours after admission (AUROC = 0.91, PPV = 4.8%).

Across PTTTs, studies reporting performance characteristics of a tool at a range of different scoring thresholds demonstrate the expected interaction and trade-off between sensitivity and specificity: at lower triggering thresholds, sensitivity is high but specificity is low; at higher thresholds, the opposite is true.

Inter-rater reliability and completeness of data

Accurate assessment of the ability of a PTTT to predict clinical deterioration is contingent on accuracy and reliability of tool scoring (whether by bedside nurses in practice or by researchers abstracting data) and the availability of underpinning observations. Only five papers made reference to accuracy or reliability of scoring,60,64,73,77,78 with mixed results; for example, two nurses separately scoring a subset of patients on the Modified Brighton PEWS (a) achieved an intra-class coefficient of 0.92,64 but a study nurse and bedside nurse achieved only 67% agreement in scoring the C-CHEWS. 77 Completeness of data was reported in 11 studies. 17–19,50,61–63,65,73,76,78 An evaluation of the Modified Bedside PEWS (a) reported that ‘the PEWS was correctly performed and could be used for inclusion in the study’ in 59% of cases,62 a prospective study bench-testing the C&VPEWS found an average completeness rate of 44% for the seven different parameters in daily practice,17 and a multicentre study of the Bedside PEWS reported that ‘only 5.1% [of observation sets] had measurements on all 7 items’. 76

Box 1 presents a summary of the review 1 findings.

Given a growing understanding and emphasis on the importance of local context in health-care interventions, it is perhaps not surprising that such a wide range of PTTTs have been developed and evaluated internationally, and modifications to existing PTTTs are common. The result, however, is that, although numerous versions of PTTTs have been narrowly validated, none has been broadly validated across a variety of different settings and populations. With only one exception,76 all studies evaluating the validity of PTTTs have been single-centre reports from specialist units, greatly limiting the generalisability of the findings.

Paediatric track-and-trigger tools such as the Bedside PEWS, the C&VPEWS, the NHS III PEWS and the C-CHEWS have demonstrated very good (AUROC of ≥ 0.80) or excellent (AUROC of ≥ 0.90) diagnostic accuracy, typically for predicting PICU transfers, in internal and external validation studies. 17,19,50,61,63,73,76,77 However, common methodological issues mean that these results need to be interpreted with caution.

First, each of the studies was conducted in a clinical setting where paediatric inpatients are subject to various forms of routine clinical intervention throughout their stay. There are numerous statistical modelling techniques that can account for co-occurrence of clinical interventions and the longitudinal nature of the predictors,82,83 but none of these was used in the validation studies and so estimates of predictive ability are likely to be distorted. Indeed, most outcomes used in the validation studies are clinical interventions themselves (e.g. PICU transfer). Second, although it is understandable that most studies ‘bench-tested’ the PTTT rather than implemented it into practice before evaluation, the process of abstracting PTTT scores retrospectively from patient charts and medical records introduces potential bias or inaccuracy. For instance, several studies reported either high numbers of missing data (i.e. some of the observations required to populate the PTTT score being evaluated were not routinely collected or recorded, and so were scored as ‘normal’)17,19,50,76,78 or difficulty in abstracting certain descriptive or subjective PTTT components. 50,60,74,80 Assuming missing values are normal or excluding some PTTT items for analysis, are both likely to result in underscoring of the PTTT and skew the results. Finally, studies that evaluated a PTTT that had been implemented in practice are at risk of overestimating the ability of the PTTT to predict proxy outcomes such as PICU transfer, inasmuch as high PTTT scores or triggers automatically direct staff towards escalation of care, or clinical actions that make escalation of care more likely.

The findings reported in several PTTT studies point towards two potential challenges for some centres in implementing and sustaining a PTTT in clinical practice. As noted previously, several studies that retrospectively ‘bench-tested’ a PTTT reported that the observations that were required to score the tool were not always routinely collected or recorded in their centre. It may be that the introduction of a PTTT into practice would help create a framework to ensure that core vital signs and observations were collected more routinely (as demonstrated by Parshuram et al. 84), but this would obviously have resource implications that could be a potential barrier for some centres. Such considerations are important, as evidence from the adult literature points to the potential for tools to inadvertently mask deterioration when core observations are missing. 85

Furthermore, PPVs reported in cohort studies, and case–control studies that adjusted for outcome prevalence were uniformly low (between 2.3% and 5.9%). 17,18,50,63–65 They demonstrate that even PTTTs that demonstrate good predictive performance are likely to generate a large number of ‘false alarms’ because adverse outcomes are so rare. For some centres, these issues may be mitigated, to some extent, by dedicated response teams or other available resources, but other hospitals may not be able to sustain the increased workload of responding to PTTT triggers.

Key messages-

A wide range of PTTTs has been studied in the literature, although the majority are closely derived from a smaller handful of tools.

-

Many of these have demonstrated good predictive value for proxy measures of deterioration; transfers to higher level of care is the most used metric.

-

However, cohort studies suggest very high ‘false alarm’ rates are likely when tools are used in clinical practice.

-

No one PTTT has been broadly validated across different settings. The majority of research studies have been conducted in North America in specialist settings; therefore, generalisability of findings is limited.

Review 2: how effective are early warning systems at reducing the rates of mortality and critical events in hospitalised children?

Eleven papers meeting inclusion criteria were excluded from analysis for providing insufficient statistical information (e.g. denominator data, absolute numbers of events) to calculate effect sizes. 71,86–95 Further details on papers excluded from analysis are provided in Appendix 15, Table 39. Findings from the 19 studies included in the analysis are summarised in Appendix 16, Table 40.

Type of early warning system interventions

Seventeen interventions involved the introduction of a new PTTT,38,46–49,84,96–107 one intervention introduced a mandatory triggering element to an existing PTTT106 and one study reported a large, multicentre analysis of MET introduction with no details on PTTT use. 108 Twelve interventions included the introduction of a new MET or RRT,38,46–49,84,96–100,104 and four further interventions87,89,100,106 introduced a new PTTT in a hospital with an existing MET or RRT. Therefore, only three studies evaluated a PTTT in the absence of a dedicated response team. 102,103,105 A staff education programme was explicitly described in 10 interventions. 38,46,48,84,97,98,102,103,105,107

Of the 18 studies that used a PTTT, only seven used a tool that had been formally evaluated for validity: three used the Bedside PEWS,84,100,105 two used the MAC,38,98 one used the Modified Brighton PEWS (b)107 and one used the C-CHEWS. 102 One study did not report the PTTT used,97 and 10 studies used a variety of calling criteria and local modifications to validated tools that had not been evaluated for validity. 46–49,96,99,101,103,104,106

Mortality (ward or hospital wide)

Two uncontrolled before-and-after studies (both with a MET/RRT) reported significant mortality rate reductions post intervention: one in hospital-wide deaths per 100 discharges (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.95)48 and one in total hospital deaths per 1000 admissions (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.75) and deaths on the ward (‘unexpected deaths’) per 1000 admissions (RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.92). 98 Seven studies found no reductions in mortality, including two high-quality multicentre studies. 38,46,84,96,99,100,108 Parshuram et al. 84 conducted a cluster randomised trial and found no difference in all-cause hospital mortality rates between 10 hospitals randomly selected to receive an intervention centred around use of the Bedside PEWS and 11 usual care hospitals 1 year post intervention (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.69). Kutty et al. 108 assessed the impact of MET implementation in 38 US paediatric hospitals with an ITS study and reported no difference in the slope of hospital mortality rates 5 years post intervention and the expected slope based on pre-implementation trends (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.95).

Paediatric intensive care unit mortality

Two uncontrolled before-and-after studies (both with a MET/RRT) reported a significant post-intervention reduction in rates of PICU mortality among ward transfers (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.72),49 and PICU mortality rates among patients re-admitted within 48 hours (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.99). 99 Six studies (including a high-quality cluster randomised trial and an ITS study) reported no post-intervention change in PICU mortality rates using a variety of metrics. 84,100–104

Cardiac and respiratory arrests

Two uncontrolled before-and-after studies (both with a RRT/MET) reported significant post-intervention rate reductions in subcategories of cardiac arrests: one in ‘near cardiopulmonary arrests’ (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.57),99 but not in ‘actual cardiopulmonary arrests’, and one in ‘preventable cardiac arrests’ (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.97),98 but not ‘unexpected cardiac arrests’. One uncontrolled before-and-after study (with a RRT/MET) reported a significant post-intervention reduction in rates of ward respiratory arrests per 1000 patient-days (RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.95). 47 Seven studies (including one high-quality cluster randomised trial and one high-quality ITS study) found no change in cardiac arrest rates using a variety of metrics,38,46,47,84,97,100 or cardiac and respiratory arrests combined. 96

Calls for urgent review/assistance

Two uncontrolled before-and-after studies (all with RRTs/METs) reported significant post-intervention reductions in the rates of code calls (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.65;48 RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.8399), whereas three studies found no change in the rate of code calls. 46,49,107 One uncontrolled before-and-after study in a community hospital (without a RRT/MET) found significant post-intervention reductions in rates of urgent calls to the in-house paediatrician (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.46) and respiratory therapist (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.95). 105 Two uncontrolled before-and-after studies (with RRTs/METs) found increases in the rates of RRT calls (RR 1.59, 95% CI 1.33 to 1.90)107 and outreach team calls (RR 1.92, 95% CI 1.79 to 2.07). 101 One study found no change in the rate of RRT calls. 106

Paediatric intensive care unit transfers

One uncontrolled before-and-after study (without a RRT/MET) found a significant post-intervention decrease in the rate of unplanned PICU transfers per 1000 patient-days (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.88). 102 Four studies (including one high-quality cluster randomised trial and one high-quality ITS study) found no change in the rates of PICU admissions post intervention. 84,100,101,105

Paediatric intensive care unit outcomes

Two studies, one ITS study and one multicentre cluster randomised trial (both with RRTs/METs), found significant reductions in rates of ‘critical deterioration events’ (life-sustaining interventions administered within 12 hours of PICU admission) relative to pre-implementation trends (incidence rate ratio 0.38, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.75)100 and relative to control hospitals (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.97). 84 One controlled before-and-after study (without a RRT/MET) reported a significant reduction in rates of invasive ventilation given to emergency PICU admissions post intervention (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.97), with no significant change observed in a control group of patients admitted to PICU from outside the hospital. 103 One uncontrolled before-and-after study reported a significant post-intervention decrease in the rate of PICU admissions receiving mechanical ventilation (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.99), but an increase in the rate of early intubation (RR 1.87, 95% CI 1.33 to 2.62). 104

Implementation outcomes

Only three studies reported outcomes relating to the quality of implementation of the intervention. One study reported that 99% of audited observation sets of the Bedside PEWS had at least five vital signs present post intervention, up from 76% pre intervention (no change in control hospitals). 84 A previous study of the same PTTT reported that 3% of audited cases had used the incorrect age chart, but reported an intraclass coefficient of 0.90 for agreement between bedside nurses scoring the PTTT in practice and research nurses retrospectively assigning scores. 105 Finally, error rates in C-CHEWS scoring were reported to have reduced from an initial 47% to < 10% by the end of the study. 102

Box 2 presents a summary of the review 2 findings.

We found limited evidence of early warning system interventions reducing mortality or arrest rates among hospitalised children. Although some effectiveness papers did report significant reductions in the rates of mortality (on the ward or in the PICU) or cardiac arrests after implementation of different early warning system interventions,47–49,98,99 they were all uncontrolled before-and-after studies, which have inherent limitations in terms of establishing causality. They do not preclude the possibility that outcome rates would have improved over time regardless of the intervention,109 or that changes were caused by other factors, and their inclusion is accordingly discouraged by some Cochrane review groups. 110 Three high-quality multicentre studies – two ITS studies and a 2018 cluster randomised trial – found no changes in rates or trends of mortality or arrests post intervention. 84,100,108

There was also limited evidence for early warning systems reducing PICU transfers or calls for urgent review. Again, a small number of uncontrolled before-and-after studies reported significant reductions post intervention,46,48,99 but several other studies reported significant increases in transfers or calls for review,98,107 or no post-intervention changes. We did find moderate evidence across four studies – including a controlled before-and-after study, a multicentre ITS study and a multicentre cluster randomised trial – for early warning system interventions reducing rates of early critical interventions in children transferred to a PICU. 84,100,103,104 Such results are promising, but corresponding reductions in hospital or PICU mortality rates have not yet been reported.

Implementing complex interventions in a health-care setting is challenging and evidence from the adult literature points to challenges and barriers to successfully implementing TTTs in practice. 111–113 However, given that so few effectiveness studies reported on implementation outcomes, it is difficult to know whether negative findings reflect poor effectiveness or poor implementation of early warning systems. Again, effectiveness studies were predominantly carried out in specialist centres, and, in all but three cases,102,103,105 involved the use of a dedicated response team, which greatly limits the generalisability of findings outside these contexts.

Key messages-

Only a handful of studies have reported significant changes in mortality or arrests among hospitalised children as a result of implementing a paediatric early warning system intervention; however, they have typically been uncontrolled before-and-after studies, which limits confidence in their findings.

-

Three high-quality multicentre studies have failed to find any significant reduction in mortality or arrests after paediatric early warning system interventions.

-

There is moderate evidence that paediatric early warning systems may reduce the rates of unplanned transfers to a higher level of care, but corresponding reductions in rates of hospital-wide or PICU mortality have not been reported.

-

Paediatric early warning system interventions are typically multifaceted (often including the use of dedicated response teams) and most studies have been conducted in specialist centres, thereby limiting generalisability of the results.

-

There is very little evidence on how well implemented interventions are in clinical practice, and their corresponding effects on wider system functioning.

The qualitative review

Review 3: what sociomaterial and contextual factors are associated with successful or unsuccessful paediatric early warning systems (with or without track-and-trigger tools)?

A parallel hermeneutic qualitative review was undertaken to address this question. The focus was limited to the afferent components of the system (see Chapter 2).

Search results

Eighty-two papers were included in the review (Figure 3). Forty-six papers focused on TTT implementation and use in paediatric and adult contexts (24 from the paediatric search and the remaining 22 from the adult-focused search); the remaining 36 papers contributed supplementary data on factors related to the wider early warning system. No studies were located that adopted a whole-systems approach to detecting and responding to deterioration. See Appendix 17, Table 41, for a detailed breakdown of the search process.

FIGURE 3.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for study screening and selection: review 3.

Translational mobilisation theory was used to analyse the evidence to identify the sociomaterial and contextual factors associated with successful and unsuccessful paediatric early warning systems. In TMT, the primary unit of analysis is the ‘project’, which defines the social and material actors (people, materials, technologies) and their relationships involved in achieving a goal. The goals of the afferent paediatric warning system are as follows: first, the child is identified as at risk and a vital signs monitoring regime is instigated; second, evidence of deterioration is identified through monitoring and categorised as such; and, third, timely and appropriate action is initiated in response to deterioration.

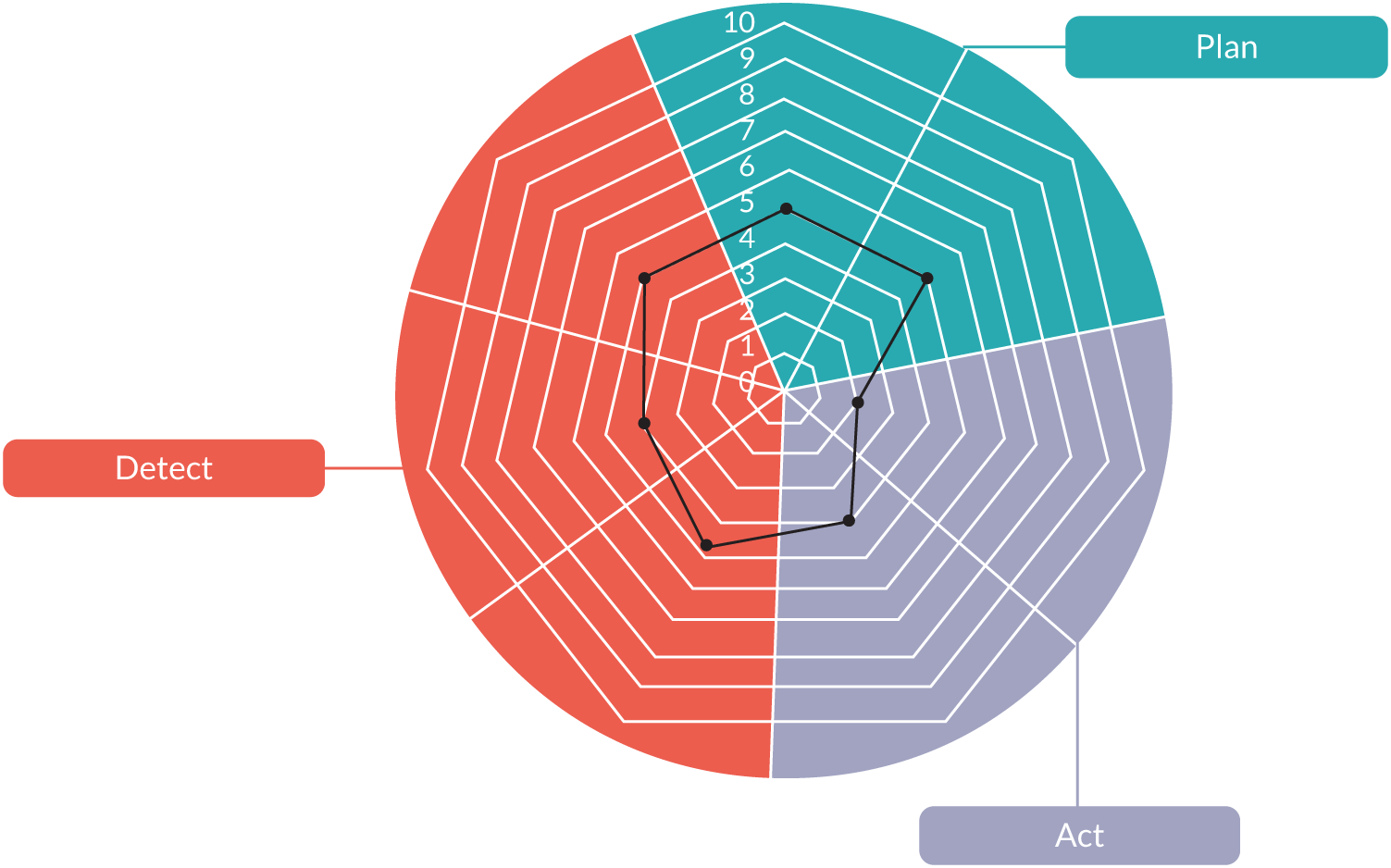

The analysis of the literature suggested that three subsystems within the afferent component of early warning systems support the following:

-

the detection of signs of deterioration

-

the planning needed to ensure that teams are ready to act when deterioration is detected

-

the initiation of timely action.

Detection

The goal of the ‘detection’ subsystem is to recognise early signs of deterioration, so the child becomes the focus of further clinical attention (see Appendix 18, Table 42). This requires, first, that the child is identified as at risk and a vital signs monitoring regime is instigated and, second, that the child is identified as showing signs of deterioration.

Although the evidence on TTT effectiveness in predicting adverse outcomes in hospitalised children is weak,24 the literature does suggest that TTTs have value in supporting process mechanisms in the detection subsystem. Vital signs monitoring is undertaken on all hospital inpatients and, like other high-volume routine activity, is often delegated to junior staff,44,114–132 who may not have the necessary skills to interpret results. 116,117,131 TTTs have value in mitigating these risks: by specifying physiological thresholds that indicate deterioration, they take knowledge to the bedside and act as prompts to action,114,133 which can lead to a more systematic approach to monitoring and improved detection of deterioration. 113,134