Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1008/30. The contractual start date was in May 2011. The final report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in October 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Pryjmachuk et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Self-care, self-care support and the mental health of children and young people

The mental health of children and young people (CYP) is a major public health concern in the UK. Around one in five CYP will have mild to moderate mental health problems;1 around 1 in 10, a diagnosable mental disorder. 2,3 Given that these statistics are far from insignificant, it is entirely reasonable for clinicians, researchers and policy-makers to examine and question the delivery and organisation of mental health services for CYP, or ‘CAMHS’ (an acronym for child and adolescent mental health services) as they are colloquially known in the UK and Australia.

Regarding the delivery and organisation of such services, evidence from the 2008 CAMHS Review in England4 suggests that mental health service provision for CYP is not always as comprehensive, consistent or effective as it could be, nor is it especially responsive, accessible or child centred. Moreover, the CAMHS Review adds that, when accessing these services, CYP and their parents are often faced with unhelpful legal and administrative processes, unacceptable regional and local variations and busy professionals who have little time to understand the evidence base for effective interventions. In Wales, similar concerns were reported by a Wales Audit Office review in 2009. 5

There is, therefore, clear scope for improvement in the delivery and organisation of CAMHS in England and Wales. Indeed, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has already funded delivery and organisational research into alternatives to CAMHS inpatient care6 and the risks associated with such care. 7 Additionally, over the last decade or so, there has been a growing consensus in British health care – reflected most recently in policy documents such as the NHS Constitution8 and, in mental health, No Health Without Mental Health 9 – that health care must be patient centred and underpinned by a partnership between those receiving and those delivering care.

The most explicit form of patient-centred care is, perhaps, self-care. The utility of self-care in the delivery and organisation of health and social care is limited, however, in that, in its truest sense, self-care excludes anyone other than the individual – including health and social care professionals – from the caring equation. Although there are obviously situations in which true self-care is appropriate (taking aspirin for a mild headache or doing some exercise to maintain a healthy weight, for example), many health concerns, especially the more severe, enduring and complex ones, necessitate the intervention of a professional of one kind or another – whether that intervention is merely guidance and support, or something more like ‘treatment’ in the traditional sense of the word. In these circumstances, there is ample scope for health and other care professionals to work with individuals in order to facilitate self-care as an immediate, short-term or long-term goal, especially when a spirit of partnership and patient centredness permeates the practices of those professionals. 10–12 With this in mind, the ways and means by which self-care might be supported and facilitated by others becomes important. The focus of our inquiry is thus not self-care per se but self-care support (or ‘support for self-care’ as it sometimes known).

There is a notable amount of research and literature on self-care support in long-term physical health conditions, both in adult and (to a lesser extent) children’s services. 13–15 There have also been some inroads in adult mental health, where self-care is often referred to as ‘self-help’. For example, the recent growth in self-help for common mental health problems16 has been captured by England’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative,17 an initiative which has led to the formation of stand-alone primary care mental health services largely operating independently of routine secondary care mental health services. There has also been NIHR-commissioned research work on self-care in adult mental health,12 and the emphasis on ‘recovery’ – which maps well onto a framework of self-care18 – has been promoted by both the previous Labour and current coalition administrations as a key philosophy of adult mental health care.

Regarding services for CYP in general, self-care and self-care support also dovetail well with recent government policy for CYP. The relationship with policy was perhaps more explicit in the previous Labour administration, which wove themes such as supporting parents in their parenting role, early intervention, integrated working and the active participation of CYP into flagship policies such as Every Child Matters19 and the Children’s Plan,20 than in the current coalition administration. Although the coalition has a less specific focus on measurable outcomes,21 there is nothing in current policy that is necessarily at odds with a philosophy of self-care; indeed, the rebadging of ‘every child matters’ as ‘help children achieve more’ implies that support is necessary for CYP to achieve (though there have been some concerns that ‘achieve more’ refers primarily to educational achievement22), and elements of self-care and self-care support are implicit in aspects of the CYP’s IAPT initiative (see below), which was introduced during the lifetime of this study.

Nevertheless, the role that self-care support can play in the mental health of CYP is a largely unexplored area. It is not known, for example, whether or not self-care support interventions and services are being commissioned and provided in England and Wales – the geographical remit of the NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme at the time the study was commissioned – nor whether there exists a substantive body of literature in this area. There is no Cochrane Library entry for this area of work, and the only work we know of that is explicitly embedded in a self-care support framework is the work related to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) that some of us (Kirk; Pryjmachuk) carried out as part of a previous NIHR study,15 and a few examples (eating disorders, bed-wetting and behavioural disorders) cited in a Department of Health effectiveness report on self-care. 23 We are aware of some peripheral work where self-care support might be implied, such as a Canadian (non-systematic) review of self-help therapies for childhood disorders24 and a systematic review of self-help technologies for emotional problems in young people25 (undertaken in part by a member of our team, Bower), as well as British research into psychological well-being in CYP in schools,26–28 resilience29 and the generic Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (‘SEAL’) initiative in schools. 30 However this research has not been systematically explored or co-ordinated within the wider context of self-care support.

The position on self-care support in the mental health of CYP remains opaque despite the launch, shortly after this project commenced, of a CYP’s IAPT initiative in England. 31 Unlike IAPT in adult mental health care, the CYP’s IAPT initiative is not explicitly tied to the notion of self-care (self-help) nor does it operate as a stand-alone service. Instead, the initiative is designed to transform CAMHS through staff (re)training, the use of evidence-based therapies and routine outcome measurements. 31 This is not to say that CYP’s IAPT has no relevance to a project on self-care support in CYP’s mental health (indeed, as we will discuss later, some of our findings have a significant overlap with some of the operating principles of the CYP’s IAPT), just that self-care and self-care support are not explicit in its principles.

Defining self-care and self-care support

Definitions of self-care vary according to who engages in the self-care behaviour (individual, family or community); what the context is (health promotion, illness prevention, limiting the impact of illness or restoration of health); and the degree to which health professionals are involved. 15

A consistent aspect to the various definitions is the conceptualisation of patients/service users as active, knowledgeable individuals rather than passive recipients of health care. The Department of Health32 sees self-care as:

The actions people take for themselves . . . to stay fit and maintain good physical and mental health; meet social and psychological needs; prevent illness or accidents; care for minor ailments and long-term conditions; and maintain health and wellbeing after an acute illness or discharge from hospital[.]

Reproduced from Department of Health. Self-Care – A Real Choice, Self-Care – A Practical Option. Document reference 266332. London: Department of Health; 2005. p. 1. The National Archives is acknowledged as custodian of this document

Self-care has currency in contemporary health-care provision for a number of reasons: a changing pattern of illness from one of acute to one of chronic (long-term) illnesses, together with a change in philosophy from cure to care; dissatisfaction with depersonalised (and, in mental health, often stigmatising) medical care, recently and bleakly crystallised in the Francis Inquiry report into care at Mid-Staffordshire Hospitals;33 consumerism and the desire for personal control in health matters and in interactions with health-care professionals, which is underpinned by the easy availability of health-related information on the internet; an increased awareness of the role lifestyle plays in relation to longevity and quality of life; and, finally, the need to increase access to care while controlling escalating health-care costs. 32,34 Research evidence into the effectiveness of self-care suggests it has many benefits: the development of more effective working relationships with professionals; increases in patient/service user satisfaction; improvements in self-confidence; improved quality of life; increased concordance with interventions; more appropriate use of services; and increased patient knowledge and sense of control. 23,35,36 Moreover, self-care often couples better outcomes with cost savings. 37

As noted earlier, our study focuses on self-care support rather than self-care per se. As the Department of Health notes,14 support for self-care can come in a variety of guises (e.g. information provision, skills training, professional education) and can be delivered through a variety of platforms (e.g. devices and technologies, real and virtual networks). The NHS has a particular role to play in self-care support: through its organisational structures and networks and the appropriate provision of information, interventions and technologies, it can (indeed, it has a responsibility to) create environments that support self-care – though self-care support may, of course, be delivered by other providers in the public, private and third sectors or even spontaneously by service users, as can be the case in real (physical) or virtual (online) support groups and networks.

Within this study, we have defined self-care as:

Any action a child or young person (or their parents) takes to promote their mental health, to prevent mental ill health, or to maintain or enhance their mental health and well-being following recovery from mental ill health.

Self-care support is thus:

Any service, intervention or technology directly or indirectly provided by the public, private or third sectors that aims to enhance the ability of children and young people (or their parents) to self-care in relation to their mental health and well-being.

Our study, therefore, focuses not only on self-care support for specific mental health conditions in CYP, but additionally on self-care support that might promote mental health, prevent mental ill health or help maintain mental health following recovery.

The organisation of child and adolescent mental health services

Throughout this report, we will make reference to two organisational hierarchies that have permeated the organisation of, and the literature on, child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) service provision. The first is very much a British approach; the second is used more internationally, though it is far from irrelevant to UK service provision and there is a degree of overlap between the two.

British child and adolescent mental health services and the ‘tier’ system

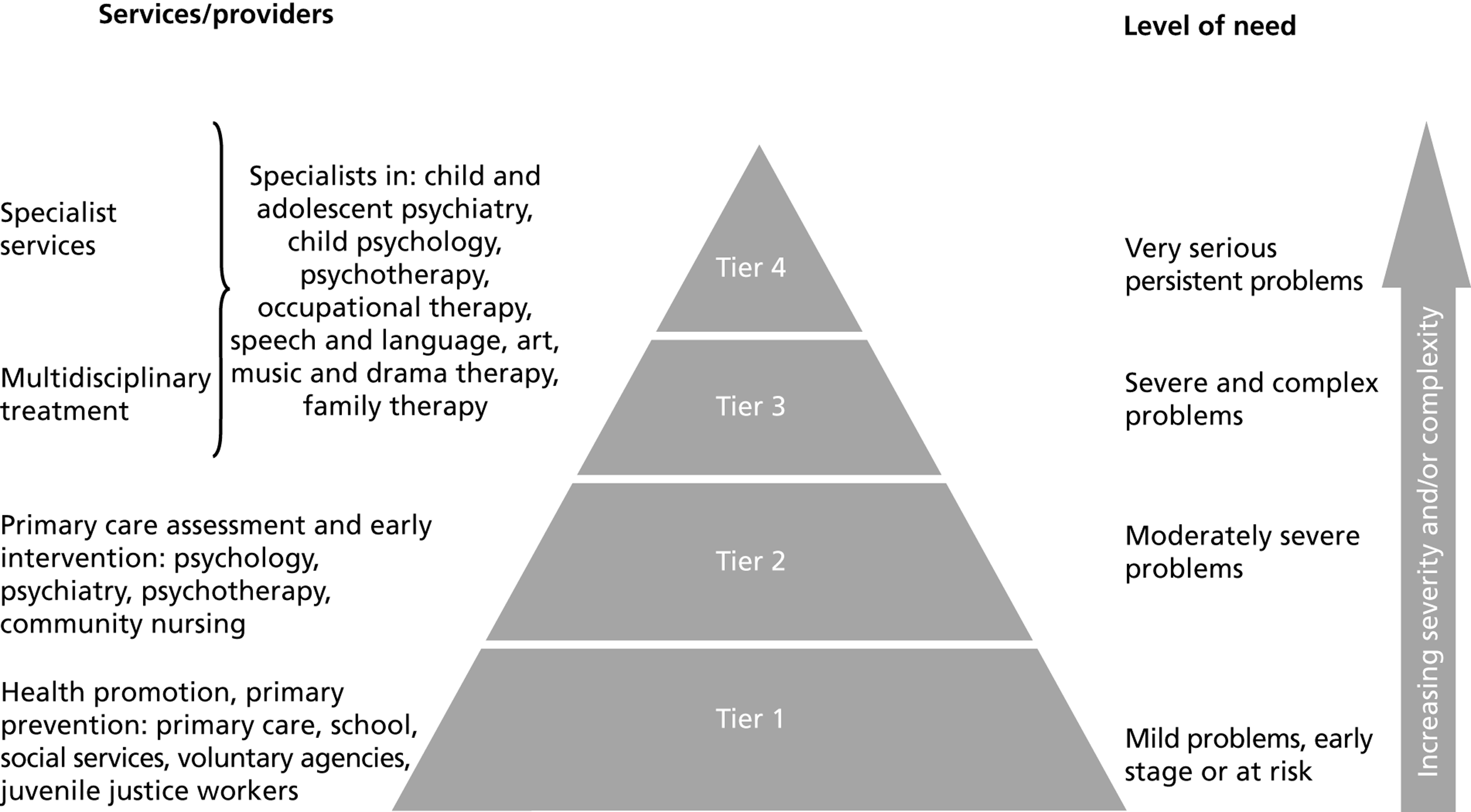

Given that we are interested in self-care support across primary, secondary and even tertiary care, it is worth briefly discussing the organisation of CAMHS in the UK. Since the publication of the seminal NHS Health Advisory Service report Together We Stand in 1995,38 CAMHS have been organised within a hierarchy of four tiers ( Figure 1 ). Tier 4 equates to very specialised, normally inpatient services, including generic as well as specialised inpatient services such as eating disorders units. Tiers 2 and 3 roughly equate to specialised, but less intense, services. Day patient services tend to be Tier 3 services, for example, whereas outpatient and early intervention services would correlate with Tier 2 services. Tiers 2 to 4 are also associated with increasing levels of complexity in the CYP’s mental health experiences and personal circumstances. Tier 1 is the tier embedded within non-specialist, universal children’s services (e.g. in education, child care and primary care) and is concerned with the provision of mental health education and advice, mental health promotion, and prevention and screening in mental health.

Although the scope for improving service delivery and organisation cuts across both specialist (Tiers 2 to 4) and non-specialist (Tier 1) CAMHS provision, the scope for improvement is perhaps more marked in Tier 1 provision because mental health promotion and mental ill health prevention are central to provision at this tier. Moreover, and as a consequence, services at this tier can also help reduce referrals to the potentially stigmatising higher tiers. However, because there seemed to be little knowledge about self-care support at any level of CAMHS provision, we did not limit our investigation to any particular tier(s).

Intervention levels

The British tiers approach offers a service- and needs-focused perspective on the organisation of CAMHS; it is not the only approach, however. An alternative approach – also hierarchical and popular in both the USA and Australia – is to organise by intervention, whereby interventions are categorised according to the specific populations of CYP for whom they are suitable. These populations are determined by the presence or absence of symptoms and the degree to which symptoms, if present, are mild or severe ( Table 1 ). In taking this approach, the lower intervention levels (universal and selective) can be seen broadly as preventative interventions, whereas the higher levels (indicated and treatment) can be seen broadly as interventions designed to manage specific symptoms.

| Group | Level | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Preventative | Universal | Includes all CYP Enhances resilience in all children regardless of risk Screening not required Avoids stigmatisation |

| Selective | Selects CYP at risk Involves screening |

|

| Management | Indicated | Selects CYP displaying mild symptoms Involves screening |

| Treatment | Targets CYP with a diagnosed condition |

Study overview

The need for this study was based on three principal factors: the relative paucity of research on mental health self-care support for CYP; the potential to change and enhance service provision in this area, to the benefit of both the NHS and the service user; and its capacity to build upon and complement existing work on CYP’s mental health, including work carried out by members of the study team. This last point is pertinent as the study was commissioned to follow on from a previous NIHR-funded study that several of us were involved in,15 and it is complemented by a variety of relevant research from all of the study team members, including work with school nurses,40 work on emotional well-being in schools27,28 and work on self-help technologies in CYP’s mental health. 25

In carrying out the study, we were guided, advised and supported by a stakeholder advisory group (SAG), made up of representatives from the health, education and social care professions as well as CYP and parent representatives (for details, see Appendix 1 ).

Aims and objectives

The aims of the study were:

-

to identify and evaluate the types of mental health self-care support used by, and available to, CYP and their parents

-

to establish how such support interfaces with statutory and non-statutory service provision.

These aims were operationalised via a series of specific objectives, namely:

-

the provision of a descriptive overview of mental health self-care support services for CYP in England and Wales, including a categorisation of these services according to a self-care support typology developed in a previous study

-

an examination of the effectiveness of such services

-

an examination of the factors influencing the acceptability of such services to CYP and their parents

-

an exploration of the barriers to the implementation of mental health self-care support services for CYP

-

an exploration of the interface between such self-care support services and the NHS and other statutory and non-statutory service providers, in order to guide future planning in health and social care

-

the identification of future research priorities for the NHS in this area.

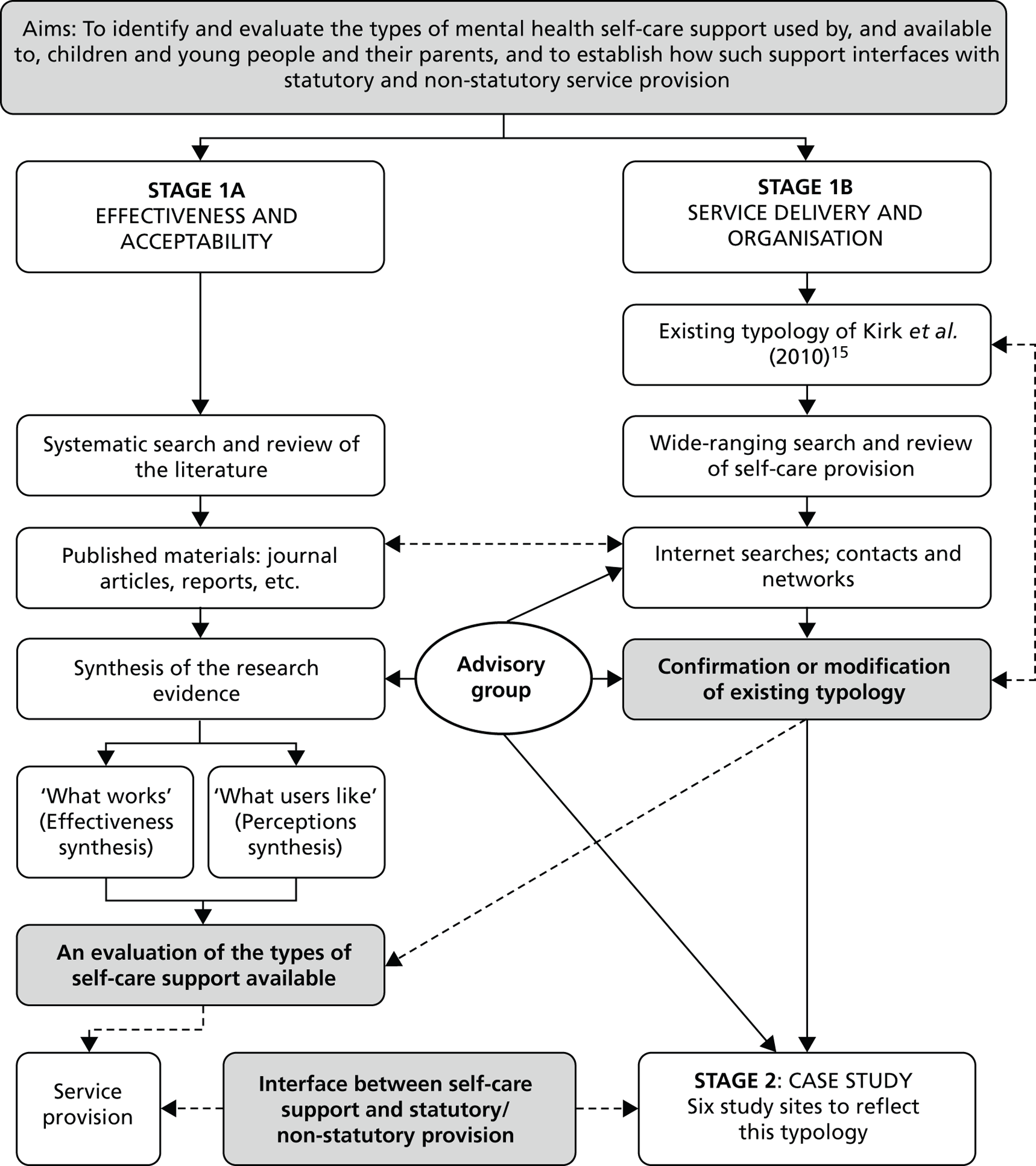

The study comprises an evidence synthesis combined with primary research, conducted as two overlapping stages over a 2-year period. Stage 1 consisted of two inter-related elements that ran concurrently, both of which were designed to help us identify the types of mental health self-care support available to CYP. Stage 1a was designed to address questions about the effectiveness and acceptability of such self-care support, and consisted of a systematic search and two inter-related reviews of the international literature, together with a meta-analysis. Stage 1b was designed to identify service provision relating to mental health self-care support for CYP in England and Wales, and consisted of a wide-ranging and systematic search of relevant resources (the internet, physical and virtual networks, policy documents, etc.) in order to elicit a ‘typology’ of service provision similar to the one we produced for a previous NIHR project. 15

Stage 2 involved a case study of service provision and was undertaken once Stage 1b’s systematic search was complete. In Stage 2, qualitative data were collected from key stakeholders in six sites, chosen to represent the typology emerging from Stage 1b, and in order to further explore issues such as acceptability, barriers to implementation, and the interface between self-care support services and statutory/non-statutory sector provision.

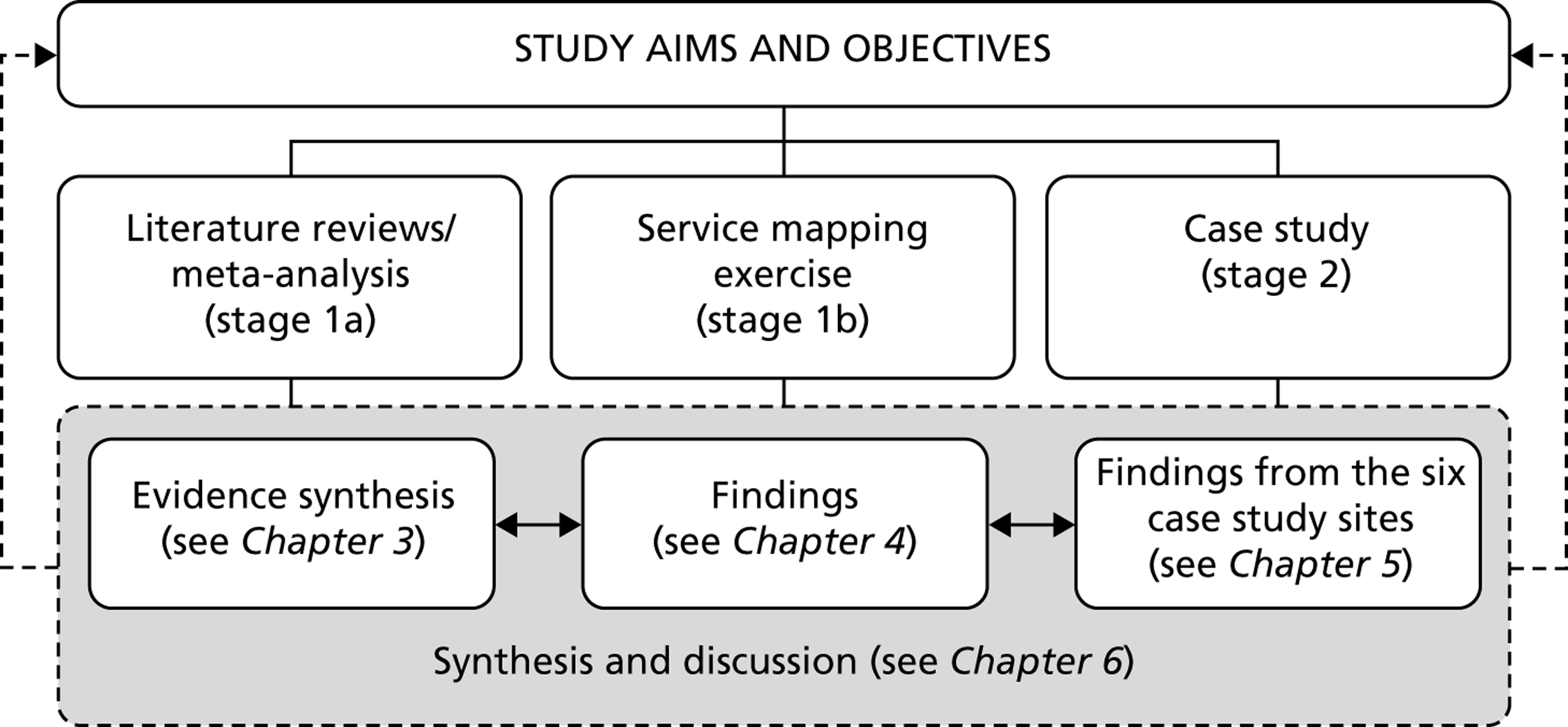

Stage 1a addressed research objectives 1, 2 and 3; Stage 1b, research objectives 1 and 5. Stage 2 addressed research objectives 3, 4 and 5. All of the stages of the study contributed to research objective 6. A schematic overview of the study can be found in Figure 2 .

FIGURE 2.

Schematic overview of the study.

The report

This report is organised such that Chapter 2 outlines the methods underpinning Stage 1a – the systematic literature reviews and meta-analysis – while the findings from these reviews and the meta-analysis are reported in Chapter 3 . Chapter 4 provides an overview of the methods and findings from the mapping exercise (Stage 1b), and Chapter 5 an overview of the methods and findings from the case study research (Stage 2). Chapter 6 , the discussion chapter, synthesises the data from the various strands of the study, concluding with some comments on the implications of the study for commissioners and managers of services, as well as for the practice and research communities.

A note on terminology

Throughout this report, we use ‘parent’ in preference to other terms such as ‘guardian’ or the more widespread ‘carer’ merely to avoid inelegant terms such as ‘parent/carer’ or ‘parent/guardian’. We have done this purely because our experience of working with parents is that they prefer this term. In opting for this preference, however, we fully acknowledge that some of those successfully parenting children are not necessarily biological parents.

Chapter 2 Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: methods

This chapter focuses on Stage 1a of the study, presenting the methods for the two inter-related systematic literature reviews that we carried out. We conducted these reviews in order to address research objectives 2 and 3, which were concerned with the effectiveness and the acceptability of mental health self-care support interventions and services for CYP, respectively. The findings from the two systematic reviews are reported in the next chapter.

The effectiveness review was undertaken as a systematic review with meta-analysis, whereas the acceptability review was premised on service user and service provider views of the interventions and services provided. We have termed the former our ‘effectiveness’ review and the latter our ‘perceptions’ review. The protocol for the effectiveness review is registered with the PROSPERO database, number CRD42012001981.

The literature reviews: methods

Review question

The systematic reviews were driven by two related questions:

-

What empirical studies have been undertaken on mental health self-care support for CYP?

-

What is the evidence for the effectiveness and acceptability of such support?

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for both the effectiveness and perceptions reviews were determined through an appropriate Population, Interventions, Comparators, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) designs formulation. 41

Population

Our population was ‘children and young people’, defined as those under the age of 18 years. This reflects the definition of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child,42 of which the UK is a signatory. Because of differing international views of the age range for a ‘young person’, there is often ambiguity at the top of the childhood range (17+ years), thus we also considered studies with populations that included young people up to 25 years of age, so long as we had evidence that the mean age of participants was, or the majority of participants were, under the age of 18 years.

Interventions

Using our definition of self-care (see Chapter 1 ), we included any health, social care or educational intervention or service designed to support or facilitate CYP (or their parents) to take action to promote their mental health, prevent mental ill health, or maintain or enhance their mental health and well-being following recovery from mental ill health. We therefore included self-care support interventions and services which targeted CYP with specific mental health problems as well as those designed to improve the general mental health of CYP. As we were interested in self-care support rather than self-care per se, a support ‘agent’ (e.g. a health, social care or education professional, peer or lay person) who worked with the CYP and/or their parents needed to be present for the intervention or service to qualify.

Comparators

For the effectiveness review, we were unsure whether or not we would find sufficient trials with a control or other such comparison group (see Study design below), and so did not specify a comparator at the outset. As the perceptions review was concerned with absolute, rather than relative, service user views of specific self-care support interventions and services, this aspect of the PICOS framework was disregarded for the perceptions review.

Outcomes

For the effectiveness review, we were interested in whether or not self-care support interventions brought about a demonstrable positive change in mental health. Included studies, therefore, needed to contain a valid standardised mental health measure. We also considered, where available, a range of relevant secondary outcomes (measures of general functioning, general well-being and self-esteem, for example). For the perceptions review, we were not interested in outcomes per se, but in qualitative and quantitative data that captured service user or service provider views.

Study design

For the effectiveness review, we were initially interested in studies containing trials, with ‘trial’ being defined as any study in which there was, at minimum, a relevant pre- and postintervention outcome measure. This meant that, initially, uncontrolled pre/post designs, non-randomised controlled trials and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were all included. We did, however, add a caveat that should there be sufficient RCTs, we would restrict the effectiveness review solely to RCTs. For the perceptions review, we included any empirical study (qualitative or quantitative) in which service user and/or service provider views about any element of the self-care support intervention or service were available.

Search strategy

To estimate the size and scope of the literature, we first conducted a brief scoping review. 43 Our experience with literature searching in a previous NIHR project exploring self-care support in CYP’s physical health15 led us to believe that using ‘child/young person’, ‘mental health’, ‘self-care’ and associated medical subject heading (MeSH) synonyms in combination might be an appropriate baseline strategy for a scoping search. We consequently searched the MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and PsycINFO databases using this strategy, only to find that the search produced very few relevant returns.

Although we had little idea of the size of the literature on mental health self-care support for CYP, there was sufficient expertise in the team to know that there was more material in the literature than our scoping search suggested. Thus, to prepare for a more comprehensive search, the team subsequently identified additional synonyms for our three search categories (child/young person, mental health and self-care). We gave particular emphasis to synonyms for ‘self-care’ as, unlike in CYP’s physical health, it seemed that self-care was not generally a part of the professional language of CYP’s mental health and was unlikely to be indexed as such. Members of the SAG were also particularly helpful in helping us understand how self-care might be conceptualised in this context and in developing a wider range of search terms.

As our review question demanded that we focus on empirical studies, we included a fourth category – empirical research – in our search strategy. The final search terms used in the review are presented in Box 1 .

-

Child/young person = child* OR p#ediatric OR teen* OR adolesc* OR young person OR young people OR youth OR school

-

Mental health = a OR b OR c

-

[mental health synonyms] mental health OR emotional health OR psychological health OR psychological well*being OR emotional health OR emotional* litera* OR emotional well*being OR emotional* competen* OR aspects of learning OR self esteem OR self efficacy OR CAMHS OR resilien* OR feelings

-

[mental disorder synonyms] mental disorder OR psychiatr* OR mental illness OR mentally ill OR mental* distress* OR emotional problem* OR emotional difficult* OR emotional* distress*

-

[conditions] ADHD OR attention deficit OR conduct disorder OR behavio*r problem* OR anger OR angry OR aggress* OR affective disorder OR anxi* OR worr* OR depress* OR obsessive compulsive OR OCD OR traumatic stress OR PTSD OR suicid* OR self harm* or self injur* OR psychos*s OR schizophren* OR eating disorder OR anorexi* OR bulimi* OR mood disorder OR phobi* OR school refusal OR panic OR enuresis OR bedwetting OR encopresis OR soiling

-

-

Self-care = a OR b OR C OR d OR e OR f

-

[self-care synonyms] self manag* OR self car* OR self help* OR self report* OR self monitor* OR self medicat* OR self administer* OR self treat* OR self control* OR collaborat* OR expert patient OR patient involve* OR patient participat*

-

[models] parenting OR parent training OR cognitive therapy OR CBT OR behavio#r* therapy OR behavio#r* modification OR solution focus#ed OR mindfulness OR promot* OR exercise OR mutual support OR peer support OR buddy OR buddies OR friend OR partnership OR mentor* OR empower*

-

[generic intervention synonyms] intervention OR prevention OR training OR program* OR coach* OR behavio#r* management OR toolkit

-

[psychoeducation synonyms] psychoeducation OR group education OR patient education OR patient information OR information giving OR educational material* OR bibliotherapy OR manual *OR leaflet OR booklet OR pamphlet

-

[skills synonyms] communication skills OR decision making OR goal setting OR action plan* OR problem solving OR coping skills OR assertiveness OR conflict resolution

-

[telemedicine synonyms] tele* OR virtual communit* OR ehealth OR messaging OR multimedia OR Internet OR computer* OR online OR web based OR web site OR world wide web OR technolog* OR email OR social networking OR interactive OR cyber* OR chat room OR forum OR electronic OR web 2

-

-

Empirical research = study OR design OR review OR synthes* OR pilot OR case OR mixed method OR quantitative OR experiment* OR trial OR RCT OR questionnaire OR survey OR follow up OR qualitative OR interview* OR focus group OR experience OR observation* OR descripti* OR evaluat* OR ethnograph* OR view OR perception

Aggregate search = 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4

* = truncation; # = wildcard.

Searches were conducted in the following databases: MEDLINE (medicine); CINAHL (nursing and allied health); PsycINFO (psychology); Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (applied social care); Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) (education); and All Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) Reviews. All EBM Reviews is a multifile database, accessible via the OvidSP interface, that incorporates the seven EBM Reviews databases, namely ACP Journal Club, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCRCT), Health Technology Assessment (HTA), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and Cochrane Methodology Register (CMR).

We limited our search to studies published from 1 January 1995 onwards as 1995 can be considered a watershed in British CAMH practice, being the year in which the seminal report Together We Stand 38 was published (see Chapter 1 ). No other limiters were applied. The searches were conducted in July 2011.

Search results and study selection

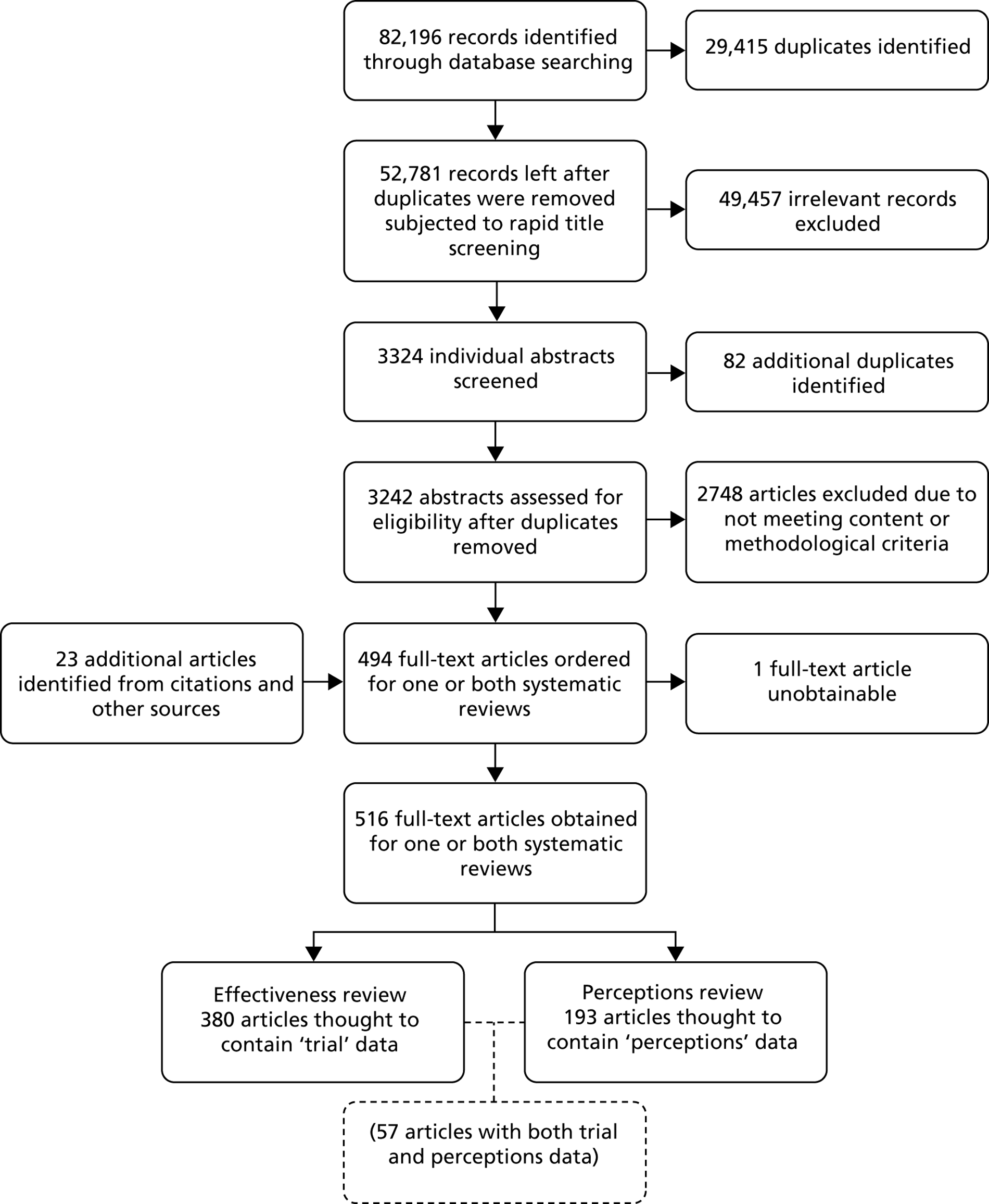

The aggregate search results from each of the six databases searched were exported into Reference Manager Version 11 (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA). The titles were screened by one team member (Elvey) and duplicates were removed. The remaining records were then screened for relevance by reading titles and abstracts; owing to a high number of extraneous records about physical conditions (including psychological well-being in these conditions), relevant terms (e.g. cancer, asthma) were entered into the Reference Manager search function and the results were removed. Non-empirical books, general review articles, letters, commentaries, etc. were screened out in a similar manner. As Figure 3 illustrates, these processes reduced the number of records to 3324.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram for the initial pool of articles.

The data on the remaining 3324 articles were exported from Reference Manager to a Microsoft Access 2010 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Using Access enabled us to enhance our records management by the creation of additional fields (see Appendix 2 ). A further 82 duplicates were identified within the Access database, leaving a pool of 3242 abstracts for consideration. This was a substantial number of abstracts to deal with in the time available, so one team member (Elvey) used the search function in Access to speed the process of finding terms which would allow us to remove articles on the basis of irrelevance to the study. These included articles that focused primarily on issues that we considered peripheral to mental health and mental disorder – articles focusing, in particular, on resilience, bullying, aggression and general, rather than serious or ‘diagnosed’, behaviour problems – unless there was explicit reference to CYP’s mental health symptomatology, for example anxiety, depression or externalising symptoms.

The abstracts of the remaining 494 articles were independently screened by two team members (Elvey and Pryjmachuk), who categorised the source according to its study design [using an adaptation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) algorithm44 for classifying study designs] and also assessed whether or not it met our inclusion criteria and, if so, for which review – effectiveness, perceptions or both. Where there was agreement on inclusion, a full copy of the source was obtained. Where there was insufficient information in the abstract to enable a judgement to be made on its inclusion, or where there was disagreement between the two team members, the abstract was put into abeyance while a full copy of the source was obtained. If, after a full copy of the source had been obtained, there was still disagreement on inclusion, a third member of the team (Kirk or Kendal) was asked to arbitrate.

In all, 494 full-text articles were initially identified as potentially relevant for one or both of the reviews. One article (a paper from China) proved impossible to obtain via the University of Manchester interlibrary loans and document supply service, despite making international requests, and a further 23 articles were identified through the reference lists and bibliographies of retrieved articles, making a grand total of 516 full-text articles in our initial pool.

Most of the full-text articles were obtained in portable document format (PDF). Consequently, where there was insufficient information in an abstract to determine an article’s eligibility for one or both reviews, rather than read the entire article, we were able to rapidly search the respective PDF, using the ‘full search’ function in Adobe Reader X (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA, USA). This arose when the abstract was vague about whether a RCT was being reported or not (in which case the PDF was searched using the term ‘random’) or, most often, to determine eligibility for the perceptions review, in which case the PDF was searched using the full search outlined in Box 2 .

Acceptability: accepta (acceptable, acceptability); uptake; adher (adhere, adhered, adherence); engage (engage(s), engaged, engagement); evalua (evaluate(s), evaluation).

Perceptions: perce (perception(s), perceived); perspect (perspective(s)); view (view(s)); feedback; experience (experience(s)).

Satisfaction: satisf (satisfied, satisfaction); prefer (prefer(s), preferred, preference).

Access: access (access, accessible); choice; barrier (barrier(s)).

Adobe Reader full search: match any of “accepta uptake adher engage evalua perce perspect view feedback experience satisf prefer access choice barrier”.

In total, 323 of the initial pool of 516 articles were allocated to the effectiveness review, 136 to the perceptions review and 57 to both reviews, giving a pool of 380 full-text articles for the effectiveness review and a pool of 193 for the perceptions review.

Effectiveness review

Study selection

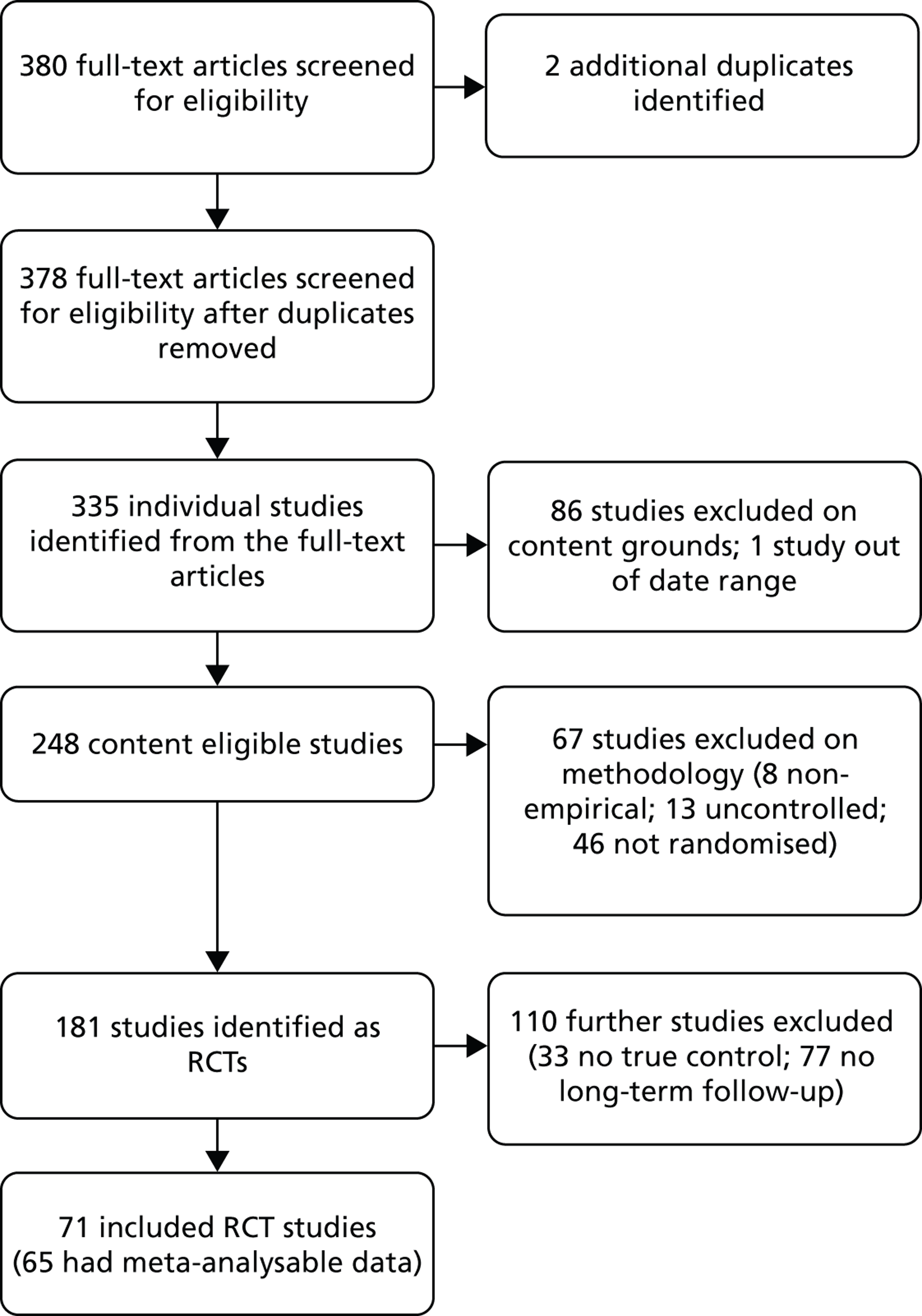

Of the 380 full-text articles in the initial pool for the effectiveness review, a further two were identified as duplicates, leaving 378 articles for consideration. These 378 articles represented 335 separate studies (some studies generated more than one paper) and two members of the study team (Elvey and Pryjmachuk) independently considered each study against the inclusion criteria. Eighty-six studies were excluded on content grounds – including a few studies concerned with enuresis and encopresis, which the study team and stakeholder group felt did not really fit in with our conceptualisation of mental health problems in CYP – and one on the grounds that it was published before 1995, leaving some 248 content-eligible studies ( Figure 4 ).

FIGURE 4.

Flow diagram of eligible studies for the effectiveness review.

Eight of the content-eligible studies had no empirical data, leaving us with 240 trials (‘trial’ meaning, at minimum, an uncontrolled pre/post design). Given the small proportion of uncontrolled (5.4%) and non-randomised trials (19.2%), we made a post hoc decision to restrict to formal RCTs, leaving us with 181 studies. The very large number of trials meant that it was not possible to extract and analyse data from all of the studies, and we made a second post hoc decision to include only those studies that met the following criteria:

-

RCTs with a ‘control’ comparator (defined as a waiting list, usual care or attention/placebo control, for example), as these provided the best evidence concerning the primary research question (evidence for the effectiveness of mental health self-care support for CYP)

-

RCTs with long-term follow-up (defined as follow-ups longer in duration than the immediate postintervention follow-up, as these provided the best evidence for the effectiveness of mental health self-care support for CYP in providing enduring gains).

This left us with 71 RCT studies focusing on the longer-term effectiveness of mental health self-care support interventions for CYP and their families. A list of these studies can be found in Table 2 .

| Included in the meta-analysis (n = 63, or n = 71 including substudies) | Excluded from the meta-analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| Not meta-analysable (n = 6) | Outliers (n = 2, or n = 3 including substudies) | |

|

||

Data extraction

Non-English-language papers were translated prior to data extraction. For the effectiveness review, descriptive data for all 71 RCTs were extracted onto a study-specific data extraction sheet (see Appendix 3 ) by one team member (Pryjmachuk), with other team members (Elvey, Kendal and Kirk) providing a second, independent extraction. The two independent extractions were subsequently combined into a separate document (see Appendix 4 for an example) with any discrepancies being resolved through discussion, with referral to a third member of the team for arbitration where a consensus could not be reached.

Quality assessment

In reviews published by The Cochrane Library, quality is assessed by the application of the Cochrane Collection risk of bias tool, a tool that explores several factors known to introduce biases into trials, including the way in which participants are allocated (randomised) into groups; the extent to which this allocation is concealed; the blinding of all those involved, including participants and researchers; the way in which incomplete outcome data are dealt with; and the use of selective outcome reporting. 140

For the current analysis, as well as describing the overall quality of the trials in the review, we sought to assess the impact of study quality through formal quantitative assessment of the relationship between quality and outcomes. To conduct these analyses, we chose a dichotomous measure based on allocation concealment, as this is the aspect of quality most consistently associated with outcomes in trials141,142 and is particularly relevant when outcomes are subjective, as is the case with the bulk of mental health assessments in the current review. 143 Other measures in conventional risk of bias assessments, such as blinding, are less relevant in the current context, as the nature of self-care support means that the conditions for blinding are rarely achievable. Allocation concealment was judged as adequate or inadequate according to the relevant section from the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Two members of the team (Pryjmachuk and Bower) independently assessed all of the included studies on this criterion so that each study could be categorised as either a high-quality (adequate) or a low-quality (inadequate or unclear) study. As with other elements of data extraction, any discrepancies here were resolved by discussion between the data extractors.

As sufficient RCTs were available, our primary data synthesis for the effectiveness review was meta-analysis, although it is augmented by a brief descriptive synthesis of the original 71 included RCTs.

Effectiveness data synthesis: the meta-analysis

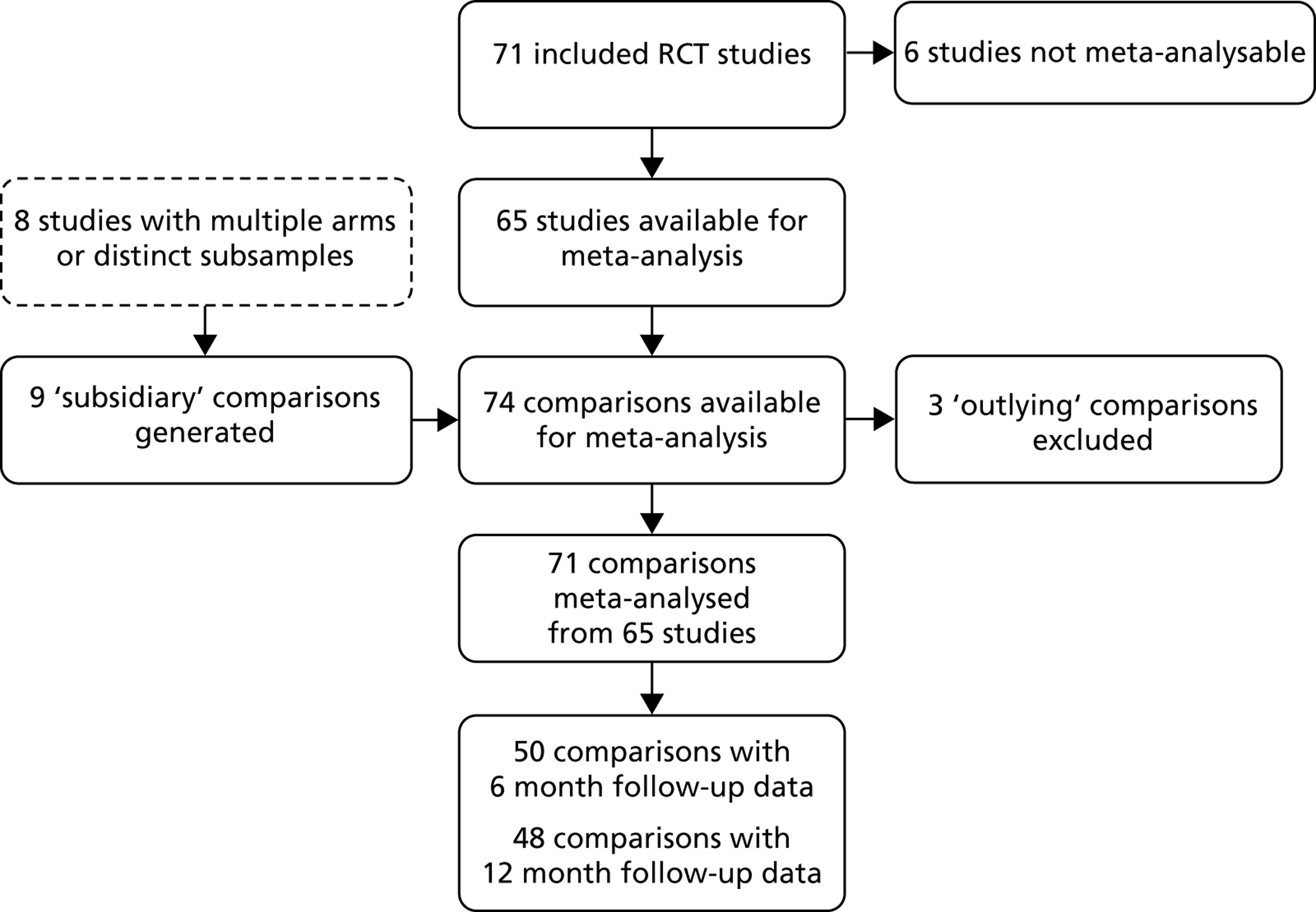

Figure 5 outlines the flow of studies, from the original 71 included studies to those that were ultimately meta-analysed. During the data extraction process (see below), we found that we were unable to obtain useable data from six studies, and eight of the studies had multiple arms or distinct subsamples, which generated nine subsidiary or ‘substudy’ RCTs.

FIGURE 5.

Flow diagram of eligible studies for the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Outcome data for the meta-analysis were independently extracted into a Microsoft Excel 2010 spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) by two team members (Pryjmachuk and Bower). Data were extracted only for those outcome measures identified as ‘direct mental health’ measures ( Table 3 ; see also Appendix 6 ).

| Meta-analysed | Outliers | Not meta-analysable |

|---|---|---|

|

The data extracted for each outcome measure included, where available:

-

the sample sizes for the intervention and control groups at randomisation

-

whether or not a clustered RCT design had been employed and, if so, the number of ‘units’ (schools, clinics, etc.) in each cluster

-

the numerical data necessary to calculate a standardised effect size at each declared follow-up time point, such as the sample sizes, means and standard deviations for the intervention and control groups, or the sample sizes and an event count (e.g. numbers ‘diagnosed anxious’) for each group.

In two studies (Barrett 200547 and Cowell 2009;57 see Table 2 ), discrete subsamples had been used which necessitated splitting each study into several comparisons. Similarly, in six multi-intervention studies (Kendall 2008,83,84 King 2000,86 Pfiffner 1997,101 Simon 2011,112 Stice 2008118,119 and Sánchez-García 2009b;139 again, see Table 2 ), more than one intervention was identified as a self-care support intervention and so these interventions were separated out into individual comparisons. Where a single study included multiple comparisons, the control group sample was split proportionately between each comparison to avoid double counting.

Some notes need to be made about the data extraction for a few other studies. Bernstein 200549,50 was a multi-intervention study [with both cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and ‘parent training’ as self-care support interventions], but the study combined the data for the two interventions at the longer-term follow-up point, meaning that only the combined CBT/parent training data were useable in our meta-analysis. In Hahlweg 2010,73 only the data from mothers were useable. Both Lowry-Webster 200139,90 and Spence 2003113,114 had ‘high anxiety’ subsamples within their overall samples, so a decision was made in each case to use only the total sample. In the multi-intervention Multimodal Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) 1999 study,95–98 only the ‘intensive behavioural treatment’ arm qualified as a discrete self-care support intervention. Similarly, in Rosa Alcázar 2009,106 only ‘IAFS’ (Intervention for Adolescents with Social Phobia) qualified as such. Sheffield 2006110 was a complex four-arm trial which merged universal and high-risk samples across both a targeted and a universal intervention, so a decision was made to use only data from the full sample (universal intervention).

On completion of the outcome data extraction, the two independently extracted Excel spreadsheets were compared and any discrepancies and errors in the extraction were discussed and resolved by the two data extractors.

Primary outcome measure selection

Table 4 outlines the distribution of the various outcome measures used in the 71 included RCT studies. The distribution of outcome measures will be discussed further in the next chapter, but for now it is worth noting that the most frequent direct measure of mental health symptomatology in CYP was one which was obtained from the CYP rather than any other source.

| Source | Direct MH measure, n (%) | Indirect MH measure, n (%) | General functioning, n (%) | Resilience, n (%) | General well-being, n (%) | Self-esteem, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | 56 (79) | 29 (41) | 11 (15) | 7 (10) | 3 (4) | 10 (14) |

| Parent | 27 (38) | 19 (27) | 10 (14) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Teacher | 8 (11) | 5 (7) | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Clinician | 36 (51) | 10 (14) | 11 (15) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Any source a | 71 (100) | 41 (58) | 28 (39) | 8 (11) | 3 (4) | 10 (14) |

In principle, meta-analysis requires the selection of a single measure from each comparison. As almost 79% of the included studies included CYP self-report data (see Table 4 ), preference was given to a validated CYP self-report measure based on a continuous score directly related to the condition on which the intervention was focused (e.g. a depression outcome measure for an intervention designed to help CYP with depression, an externalising outcome measure for an intervention designed to help CYP with behaviour problems, and so on). If more than one measure qualified on this basis, a global or total symptoms measure was chosen in preference to a specific (subscale) measure, and if more than one global measure was available, we made a judgement about which was the most established.

If no CYP self-report, continuous measures were available, parent-reported measures were selected; for the few studies that had neither child- nor parent-reported measures, clinician-reported measures (usually measures eliciting a diagnosis) were employed. Where a choice needed to be made between intensity/severity scales and frequency/number of problems scales, intensity scales took precedence. The primary outcome measures selected from each study are listed in Table 3 .

Once the primary outcome measures for each study had been determined, a combined Excel spreadsheet was prepared ready for transfer to Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) (Biostat, Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA), the meta-analysis software we employed. In preparing this spreadsheet, studies were also grouped according to the follow-up time points for which data were available. We were able to categorise the studies into three broad follow-up periods relatively easily: approximately 6 months, approximately 12 months and approximately 24 months post intervention.

Data preparation: missing data, cluster adjustments and effect direction

Where sample sizes were missing at follow-up, they were estimated by assuming an arbitrary 70% follow-up from baseline (such imputation will only influence the weight associated with the comparison in the meta-analysis, not the estimate of effect of that study). Where there were missing standard deviations, these were estimated using included studies that had the same outcome measure. Missing standard deviations for the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) at 6-month and 12-month follow-ups in Compas 200956 were estimated from other studies with 6-month CES-D data (two studies: Clarke 199553 and Garber 200967) and 12-month CES-D data (four studies: Clarke 1995,53 Clarke 2001,54 Clarke 200255 and Sawyer 2010108,109).

Three studies (Evans 2007,65 Compas 200956 and Tol 2008128) reported only a raw effect size which needed to be converted to a standard error in order to be compatible with CMA.

Cluster trials are frequently used in trials of psychological and mental health interventions as a way of avoiding bias associated with contamination. In line with guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,140 the sample sizes of approximately one-third of studies using cluster randomisation were adjusted by dividing the original sample by the ‘design effect’, which was calculated using the formula 1 + (M – 1) × ICC, where M is the mean cluster size (total sample size divided by total number of clusters) and ICC is the intracluster correlation coefficient, which we assumed to be 0.02.

The effect direction for each primary outcome was coded in CMA such that effects in favour of the intervention (self-care support) were coded negative. All coded effect directions were compared for consistency with what was reported narratively in the papers describing each study.

Primary and secondary analyses

Analyses were conducted in CMA using a random-effects model in each case. Our primary analysis focused on the long-term effectiveness of self-care support interventions in mental health symptomatology in CYP. We also explored subgroup analyses using a variety of prespecified ‘moderators’ (i.e. variables that were associated with the benefit of self-care support) that were chosen on the basis of theory and practical considerations. These moderators were the intervention level (see Chapter 1 , Table 1 ); the mental health condition and the age group the intervention was designed for; the theoretical model underpinning the intervention; the recipients (child/young person, parent or family); whether the intervention was school-based or not; group versus individual interventions; whether the agent was mental health trained or not; and the length of the intervention. Concealment of allocation was also included as a moderator.

There were relatively limited follow-up data at 24 months, so for all analyses we restricted the data to two follow-up points: around 6 months and around 12 months. In all cases, the meta-analysis results are presented in terms of a standardised mean difference (effect size) with 95% confidence limits, together with the relevant I 2 statistic which is a measure of consistency (heterogeneity) across the included studies. I 2 scores above 75%, 50% and 25% are said to have high, moderate and low heterogeneity (inconsistency) respectively. 144 Interpretation of the pooled outcome in meta-analyses with high I 2 scores should be treated with caution. For the primary analyses only, we have additionally provided forest plots, produced via Stata Version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Perceptions review

The perceptions review centred on the views that the various stakeholders – CYP, their families and staff – had about mental health self-care support interventions and services for CYP. It was concerned with aspects of these interventions and services such as acceptability, satisfaction and accessibility.

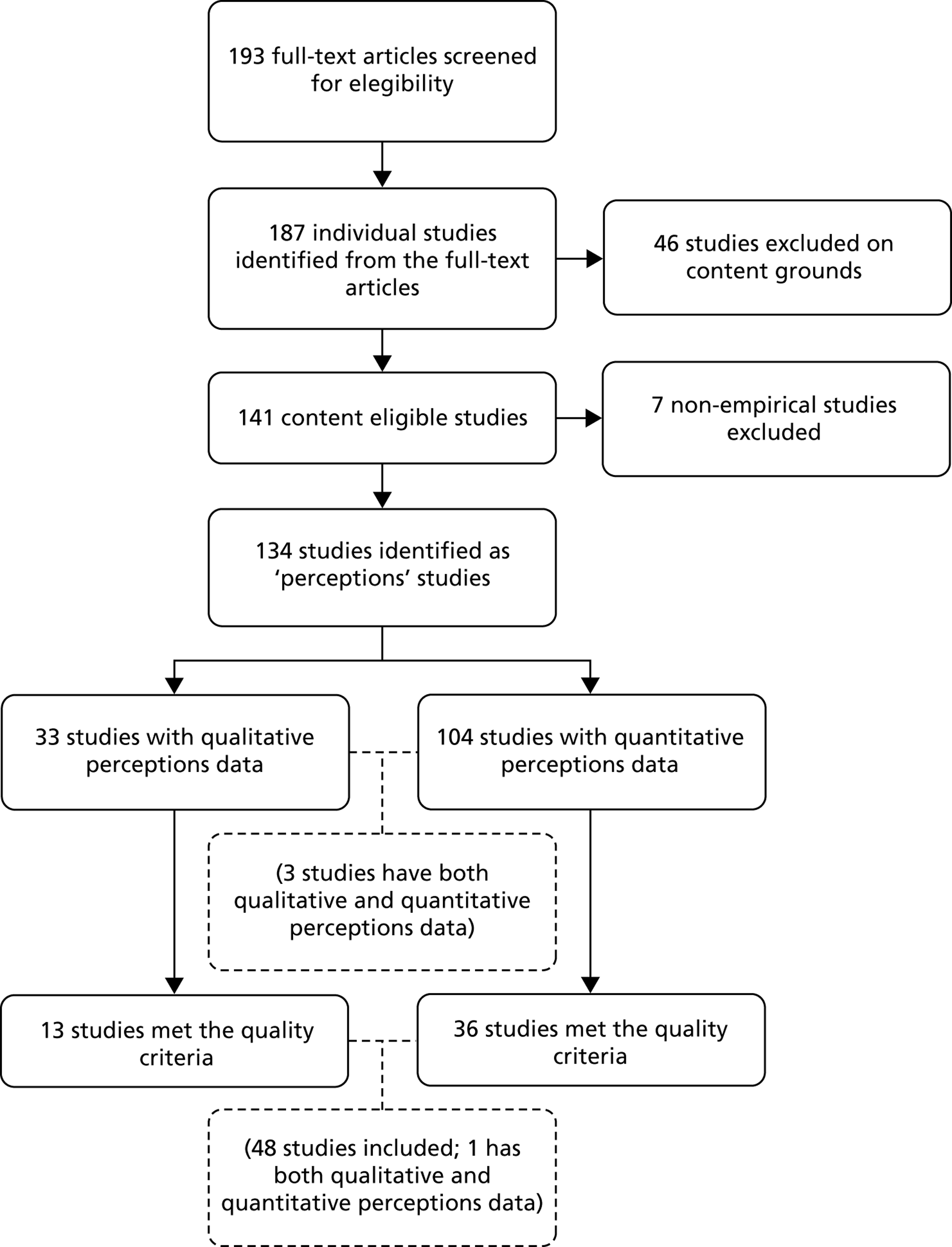

Study selection

For the perceptions review, 187 individual studies were identified from the pool of 193 full-text articles. Forty-six of these studies were excluded on content grounds and seven were identified as non-empirical. This left 134 studies with perceptions data for consideration and quality appraisal: 30 studies with qualitative perceptions data, 101 studies with quantitative perceptions data and 3 studies with both ( Figure 6 ). The application of quality criteria (discussed shortly) ultimately reduced the number of studies to 12 with qualitative perceptions data, 35 with quantitative perceptions data and one with both, making a total of 48 included studies.

FIGURE 6.

Flow diagram of eligible studies for the perceptions review.

Data extraction

As with the effectiveness review, non-English-language papers were translated prior to data extraction. Descriptive data for the 33 qualitative perceptions studies (of which 30 were solely qualitative studies and three were mixed methods studies) were extracted onto a study-specific data extraction sheet (see Appendix 5 ) by one team member (Pryjmachuk), with other team members (Elvey, Kendal and Kirk) providing a second, independent extraction. As with the effectiveness review, the two independent extractions were subsequently combined into a separate document, with any discrepancies being resolved through extractor discussion with referral to a third member of the team for arbitration where a consensus could not be reached. For pragmatic reasons, the 104 quantitative studies (101 solely quantitative and three mixed-methods studies) were filtered for quality prior to data extraction (see below), with data from the 36 quantitative perceptions studies eligible at this point being extracted directly into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet by one team member (Pryjmachuk) and subsequently verified by a second (Elvey).

Quality assessment

For the qualitative perceptions studies, study quality for all 33 studies was assessed during the overall data extraction by one team member (Pryjmachuk) and independently by the second person extracting (Elvey, Kirk or Kendal). Quality was assessed using a modified version of the quality assessment tool used in our previous NIHR study on self-care support,15 which in turn was adapted from tools developed by Dixon-Woods et al. 145 and the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre). 146 A copy of the quality assessment tool can be found in Appendix 5 , embedded into the perceptions review data extraction sheet. Again, any quality assessment discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the extractors and, where necessary, through arbitration by a third member of the team. The tool comprised seven criteria, and for the purpose of this review we decided that a paper had to meet four criteria for inclusion.

We identified 104 studies as containing quantitative perceptions data. This was a substantial number of studies to consider for data extraction so, in contrast to the qualitative studies, we made a pragmatic decision to apply quality criteria prior to, rather than during or after, data extraction. During the process of scanning papers for perceptions data (see Search results and study selection and Box 2 earlier in this chapter), it became evident that trials were the sole source of quantitative perceptions data, i.e. all of the 104 studies containing quantitative perceptions data were controlled or uncontrolled trials. In the main, the quantitative perceptions data came from satisfaction surveys nested within these trials or from statistics concerning intervention uptake or adherence, though we did not consider the latter to be perceptions data. Thus, to manage the number of quantitative perceptions studies, we applied our PICOS criteria (see Inclusion criteria earlier in this chapter), selecting only randomised trials with a true control. Accordingly, only 36 trials with quantitative perceptions data (one of which was a mixed-methods study that also contained qualitative data) were eligible for the perceptions review.

Details of the included studies for the perceptions review can be found in Table 5 .

| Qualitative studies (n = 12) | Quantitative studies (n = 35) | Mixed-methods studies (n = 1) |

|---|---|---|

|

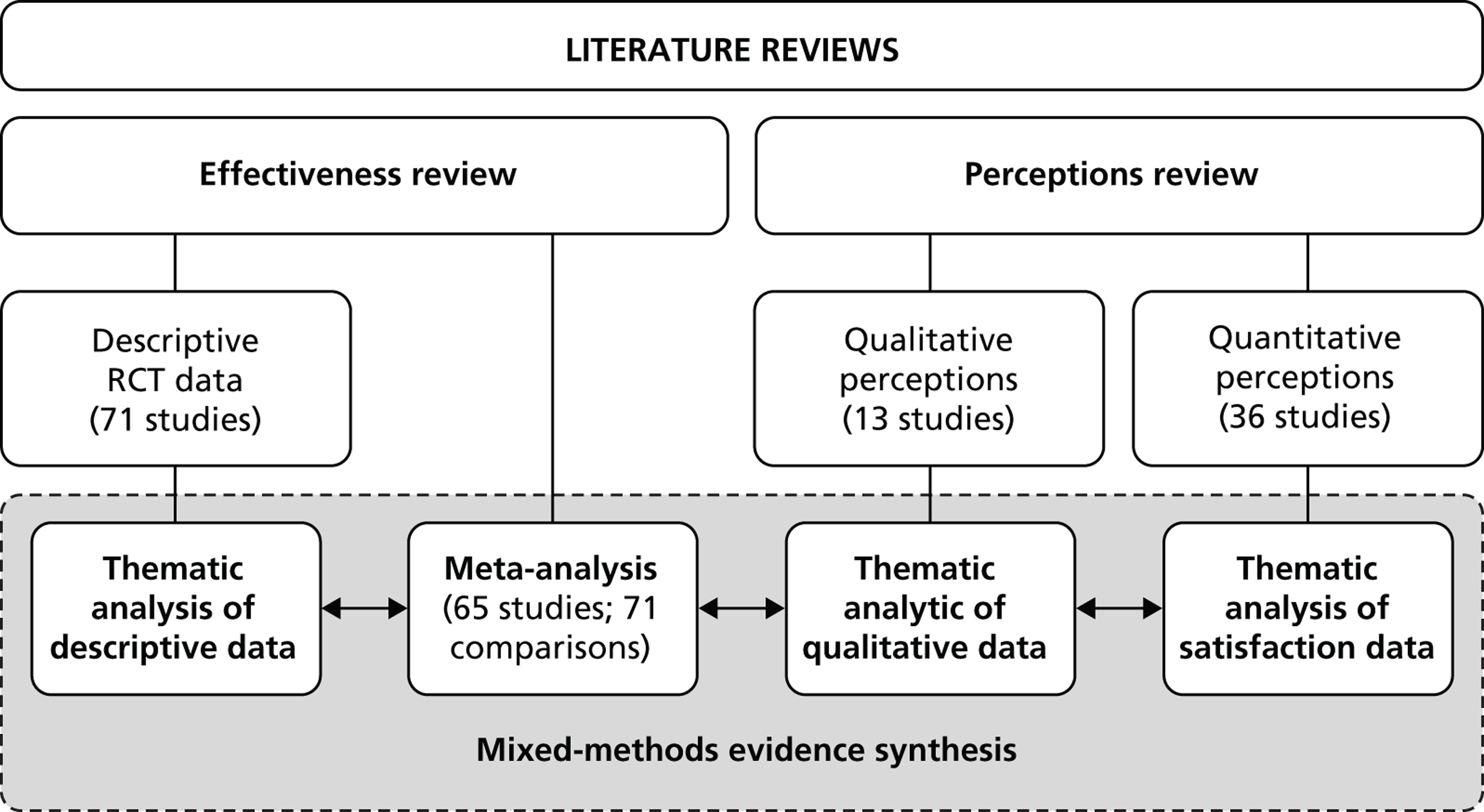

Synthesis of the literature reviews data

The synthesis for the literature reviews data is based on the ‘mixed-methods synthesis’ of the EPPI-Centre,178 an approach to synthesis whereby different data sources (effectiveness, qualitative views and quantitative satisfaction data, for example) are analysed separately but subsequently compared and contrasted. Figure 7 outlines this process schematically.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic diagram of the literature review evidence synthesis.

The methods we used for the literature reviews elicited four sets of data: two for the effectiveness review and two for the perceptions review. A meta-analysis can stand on its own as an evidence synthesis as it essentially distils effectiveness data from many studies into a single meaningful statistic. It is, however, useful to triangulate the meta-analysis results with results from other sources in order to gain a more complete understanding of the evidence for self-care support in CYP’s mental health. In order to do this, summary data from the three remaining data sets – the descriptive RCT data, the qualitative perceptions data and the quantitative perceptions data – were individually tabulated and the three summary tables (see Appendices 7–9 ) were distributed around the study team for independent review. For these summary tables, we organised the descriptive data around the specific dimensions of self-care support ‘typology’ derived from our previous NIHR study on self-care support. 15 Further details of the typology are provided in the service mapping chapter (see Chapter 4 ) but, for now, it is sufficient to report that the typology dimensions included the health conditions for which the self-care support intervention or service is designed; the theoretical basis of the intervention or service; its aims (i.e. what makes it a self-care intervention or service); the recipient (child/young person, parent or family); the delivery medium and the degree to which it is individualised; where it is delivered; and who leads it (i.e. the self-care support agent). Key findings from each study, in narrative form, were also included.

Following an independent review of the three summary tables, any patterns that individual team members identified in each data set were compared and contrasted with those of other team members so that there was a consensus on any key themes emerging from the data. These thematic analyses were compared with each other and with the effectiveness data from the meta-analysis in order to elicit an overall synthesis of the evidence on self-care support in CYP’s mental health.

Chapter 3 Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: results

This chapter presents the results from the systematic reviews. The effectiveness reviews and perceptions reviews are considered separately before being synthesised according to the principles outlined in the previous chapter. For the effectiveness review, we present first a brief, descriptive overview of the included studies, after which we present the results of a meta-analysis of the effectiveness data. Similarly, for the perceptions review, the two data sets (qualitative perceptions data and quantitative perceptions data) are initially described and then analysed. Finally, the four data sources – the descriptive effectiveness data, the meta-analysis data, the qualitative perceptions data and the quantitative perceptions data – are triangulated to elicit a synthesis of the literature on mental health self-care support for CYP.

Effectiveness review

Description of the included effectiveness studies

Descriptive data for the 71 included RCTs39,45–131 are summarised in Appendix 7 . Most (36/71) of the studies were conducted in North America (primarily the USA),49–51,53–57,62–69,77,83–85,87,91,92,95–98,101–104,111,115–126,132–135,137 around a quarter (17/71) in Australia39,47,48,58,59,75,76,78–82,86,88–90,94,105,108–110,113,114,136 and around 20% in Europe (16/7145,46,52,60,61,70–74,99,100,106,107,112,127,129–131,138,139 including seven in the UK52,70–72,74,99,100,127,129–131). The UK accounted for < 10% of the studies.

Around 60% (42/71) of the studies focused on mood disorders,39,45–50,52–59,61–64,66–69,77,81–85,88–91,93,94,103–106,108–114,118,119,121–126,129–131,138,139 mainly anxiety and depression (there was one on bipolar disorder135), with 12 (17%) focusing on serious behaviour problems65,73,75,76,79,80,87,95–102,104,127,132 such as ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD), and eight (11%) on eating disorders. 60,70,71,92,115–117,120,134,136 There were relatively few studies focusing on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (n = 2),86,128 self-harm (n = 4)72,74,78,137 and generic mental health problems (i.e. interventions designed for any mental health problem; n = 3). 51,107,133 There were no studies on psychosis. Most (31/71) of the studies concerned interventions that could be classified as treatments (see Chapter 1 , Intervention levels),48–52,55,65,66,70,71,74,77,78,81,83–86,91,94–98,101–104,106,111,112,121–127,129–131,133,135,139 with the remainder focusing equally on indicated (n = 11),53,58,59,61–64,67,68,72,87,116,117,128 selective (n = 15)45,46,54,56,57,69,82,99,100,105,110,115,118–120,132,137,138 and universal (n = 15)39,47,60,73,75,76,79,80,88–90,92,93,107–110,113,114,134,136 interventions. If, along with treatment interventions, indicated interventions are broadly considered to be ‘management’ interventions and selective and universal interventions are broadly considered as ‘prevention’ interventions, then most of the interventions considered were designed to manage rather than prevent mental health conditions in CYP.

Most (47/71) of the interventions operated within a cognitive–behavioural framework,39,47–50,52–56,58–64,66–71,77,81–91,93,94,102–107,110–114,118,119,121–126,128–131,133,138,139 although few were labelled explicitly as CBT. Instead, the interventions tended to be described with vague reference to CBT, or to cognitive and/or cognitive–behavioural principles, or they listed elements commonly assumed to be associated with CBT such as cognitive restructuring (e.g. Dobson 2010;64 Garber 200967), problem-solving (e.g. de Cuyper 2004;61 Gillham 2006;68 Hunt 2009;82 Merry 2004;93 Spence 2003113) and exposure (e.g. Barrington 2005;48 Hayward 2000;77 Hudson 200981). Many of the interventions were what might be called ‘branded’ cognitive–behavioural approaches, often with idiosyncratic names, such as FRIENDS (Barrett 2005;47 Bernstein 2005;49 Hunt 2009;82 Lock 2003;88 Lowry-Webster 200139), Cool Kids (Hudson 2009;81 Mifsud 200594), Timid to Tiger (Cartwright-Hatton 201152) and Problem Solving for Life (Spence 2003113).

Parent training interventions were the second most popular group of interventions with around one-fifth of studies (16/71) employing such an approach. 49,50,52,56,73,75,76,79,80,86,87,94–102,112,127,132 In most cases, the parent training was shaped by a behavioural model, often social learning theory (e.g. Hiscock 2008;79 Thompson 2009;127 Patterson 200299,100). The remainder of the interventions were premised on approaches such as dissonance theory (Stice 2003;115 Stice 2006;116 Stice 2009120), mindfulness (e.g. Biegel 2009;51 Havighurst 200975) or general psychotherapeutic approaches (e.g. Stice 2008118), or they were eclectic (e.g. Arnarson 2009;45 Green 2011;72 Hazell 200978).

All of the interventions were ‘manualised’ in that there was a written manual giving instructions to those providing the intervention on how the intervention should be delivered. This is relatively unsurprising given that cognitive–behavioural and parenting interventions – interventions where manualisation is normally inherent – were in the majority. The degree of instruction in the manuals varied from intervention to intervention, with some having a degree of flexibility, but many were rigid, expecting full fidelity from those delivering the intervention.

The self-care elements of the interventions related predominantly to the acquisition of relevant skills, usually involving a method whereby the CYP or the parents are required to undertake some sort of practical exercise, either as part of the formal aspects of the intervention itself (such as a workbook or classroom exercise) or as a homework task. Despite the almost universal focus on ‘activities’ and the nature of the client group (children), surprisingly few activities seemed to centre on creativity and play. Many could be – indeed some were – described as tasks, a word that can have negative connotations. There were a few exceptions – the explicit use of games in Rooney 2006105 and the use of drama, dance and music in Tol 2008,128 for example – though it is worth noting that a lack of reference to creativity and fun in the descriptions of the interventions may be more to do with the sober writing style demanded of academic journals than with design faults in the interventions.

More than 80% of the studies related to interventions focusing on school-age children (5–16 years), with only four studies (Green 2011;72 Rohde 2004;104 Stice 2003;115 Stice 2006116) including 17-year-olds and only three (Hahlweg 2010;73 Patterson 2002;99,100 Thompson 2009127) targeting the under-fives. More than half (40/71) were targeted solely at the CYP,45,46,51,53–55,60–68,72,77,78,85,88,89,91–93,103–110,113–120,128,130,131,134,136–139 26 at the family (which usually meant parents and a child; rarely were siblings included),39,47–50,56–59,69–71,74,81–84,86,87,90,94–98,101,102,111,112,121–127,132,133,135 and only five focused on parents only. 52,73,75,76,79,80,99,100

All of the interventions were delivered face to face; none made use of technology, even technology as simple and ubiquitous as the telephone. Sixteen of the interventions were individual child/young person or individual family interventions;48,65,69–71,74,83–87,95–98,111,121–127,129–131,133,135 the remainder were group interventions or group interventions with occasional individual sessions. Of those studies where a delivery location was given, most of the interventions (33/71) took place in a school setting,39,45–47,49,50,53,57–60,62,63,65,73,82,90–98,102,103,105–110,113,114,116,117,120,128–132,134,136,137 14 at hospital sites or clinics,48,51,52,54,55,61,68,72,78,81,86,99,100,121–126,135 and only five took place in the home environment. 57,74,87,127,133

Where the professional background of the agent providing the support for self-care was known, psychologists tended to dominate, being the agent in over one-third (26/71) of the studies,45–48,52,53,56,58–60,64,69,73,81,83,84,86,91,101,102,105–107,111,112,115,118,119,138,139 though other professionals (teachers, n = 11;39,65,82,88–90,93,108–110,113,114,132,136,137 nurses, n = 8;57,79,80,87,99,100,103,120,127,137 counsellors, n = 753,62,63,82,94,110,120,137) were involved. The agent was a medical doctor (child psychiatrist) in only one study (Vostanis130,131). The agent’s principal responsibility was to deliver and facilitate the self-care support intervention, usually by running groups and individual sessions, though more extensive responsibilities were expected in some interventions, e.g. running summer camps and liaising with teachers (MTA 199995), or facilitating the child in the home-school environment (Pfiffner 2007102). In three-quarters (53/71) of the studies, the agents were trained specifically for the intervention,39,45–51,53–59,62–68,72–74,77–79,82–90,93,94,99,100,103–106,108–114,116–120,127,128,132,133,135,137–139 and in just over half (38/71) of the studies, the agents received formal supervision as part of the intervention protocol. 39,45–50,52,53,56–59,62,63,65,67–69,72–74,78,83–87,90,95–100,103,105,110–114,116–120,127,132,133,137

Outcome measures

A wide variety of outcome measures were employed in the 71 studies (see Chapter 2 , Table 4 ). As it was a necessary inclusion requirement, all 71 studies included a direct measure of CYP’s mental health symptomatology. There was, however, no specific pattern to the number, range or source of additional (secondary) outcome measures employed. Some studies employed only a single outcome measure [e.g. Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (CPPRG) 2007132 had a single diagnostic measure of serious behaviour problems and Gillham 200668 a single measure of depression] whereas others (e.g. Biegel 200951 and Kolko 201087) had more than 10 different outcome measures. The range of secondary measures included, in 41 of the 71 studies,39,47,51,52,54–56,58,59,61–63,66,70–74,78–84,86–91,95–100,105,107,110,111,113–126,128–131,133,136,137 indirect measures of mental health symptomology (e.g. Clarke 200154 had a measure of externalising symptoms in an intervention designed for depression), as well as measures of general functioning (in 28 studies),51,53–55,65,66,70–72,74,78,85–87,91,95–102,104,106,108–111,113,114,116–119,128–131 resilience (nine studies),51,83,84,86,87,103,106,108,109,128,137 general well-being (three studies)51,87,107 and self-esteem (10 studies). 51,60–64,106,129–131,134,136 The direct mental health measures were mostly obtained from the CYP (in 56 studies),39,45–64,66–72,74,77,78,81–85,88–94,103–126,129–131,134,136–139 followed by clinicians (36 studies)45,46,48–55,58,59,66,67,69–72,77,78,81,83,84,86,87,91,102,104,106,110,112,118–132,135,138,139 and parents (27 studies). 39,48–50,52,54–56,65,69,73,75,76,79–81,86,87,90–101,104,106,111,127,129–133 Teachers only provided a direct mental health measure in eight studies. 48,65,73,75,76,94–98,101,106 The pattern was similar for the indirect mental health measures, although parents were a more frequent source: there were CYP self-report measures in 29 studies,47,51,56,61–63,66,70–72,78,81–84,86–89,91,95–98,105,107,110,111,113–117,120–126,129–131,136,137 parent report measures in 19 studies,39,52,54–56,58,59,61,66,73,79–81,83,84,86,87,90,95–100,111,129–131,133 clinician report measures in 10 studies54,55,70–72,74,78,87,113,114,118,119,128 and teacher reports in five studies. 73,83,84,87,95–98,111 General functioning data were collected equally by child self-report (11 studies),70,71,74,99,100,104,106,108–110,113,114,116–119,128 parent report (10 studies)65,66,74,87,95–102,111,128 and clinician report (11 studies). 51,53–55,72,78,85,86,91,104,129–131 Teachers only provided data on general functioning in four studies. 65,95–98,101,102 Resilience data were collected from CYP in seven studies,83,84,86,87,103,106,108,109,137 from a parent in one study83,84 and from a clinician in one study. 128 General well-being data were obtained solely from child self-report and in only three studies. 51,87,107 Self-esteem data were collected by child self-report in 10 studies51,57,60–64,106,129–131,134,136 and from a parent in one study. 129–131 Full details of the outcome measures extracted for each study can be found in Appendix 6 ; for a summary of the number of outcome measures of each type, see Table 4 .

As indicated in Table 4 , the majority of outcome measures focused on mental health symptomatology in the CYP, whether directly or indirectly related to the condition of interest. General functioning was measured in a sizeable number (n = 28; 39%) of the papers51,53–55,65,66,70–72,74,78,85–87,91,95–102,104,106,108–111,113,114,116–119,128–131 but few focused on CYP’s resilience, general well-being or self-esteem. Most of the outcome measures were obtained directly from the CYP with clinicians or parents being the most frequent secondary source. Few studies collected outcome data from teachers.

Meta-analysis results

The results of the primary and secondary analyses from the meta-analysis are presented here. Our primary analysis was concerned with the long-term effectiveness of self-care support interventions for CYP’s mental health. Secondary analyses explored a range of comparisons determined a priori through our previous typology, the expertise of the project team and in consultation with the SAG. Analyses were conducted at two follow-up time points: 6 months and 12 months. In interpreting our results, we have adopted standard conventions on effect size179 and study heterogeneity. 144 Regarding effect size, standardised mean differences (SMDs) of 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 reflect small, medium and large intervention effects, respectively. I 2 measures exceeding 75%, 50% and 25% are taken to reflect high, moderate and low heterogeneity, respectively, across the contributing studies.

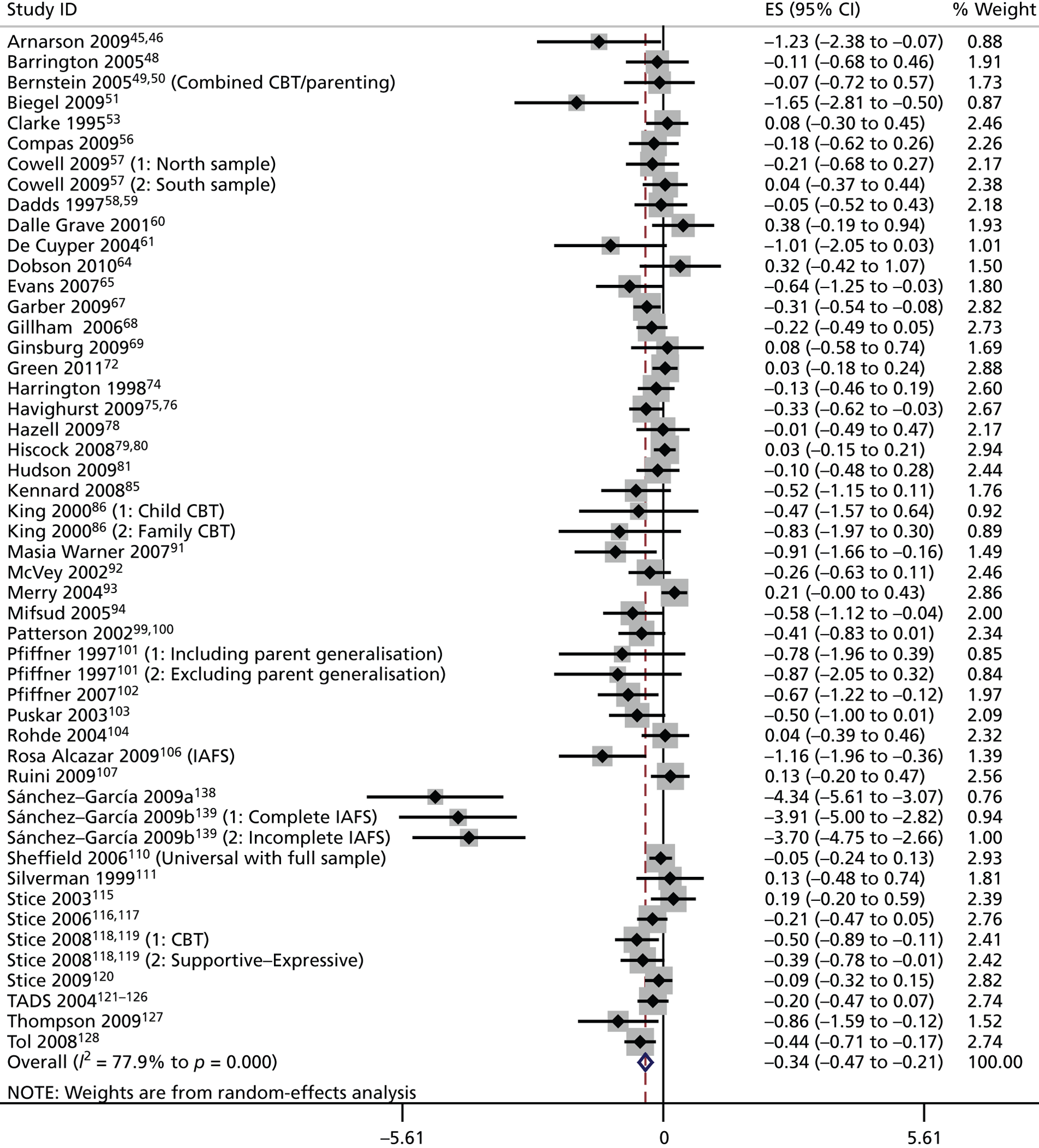

Primary analysis

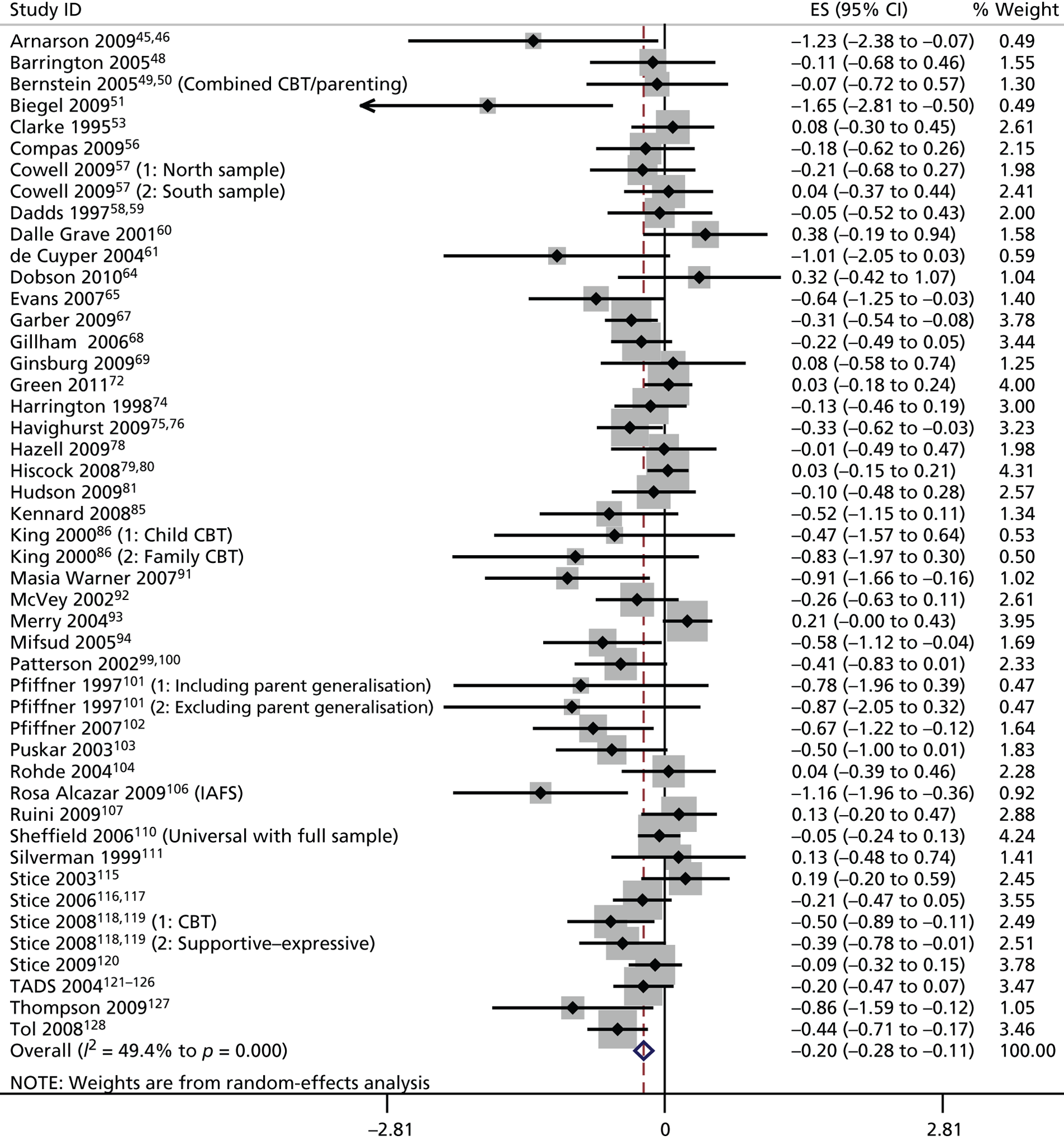

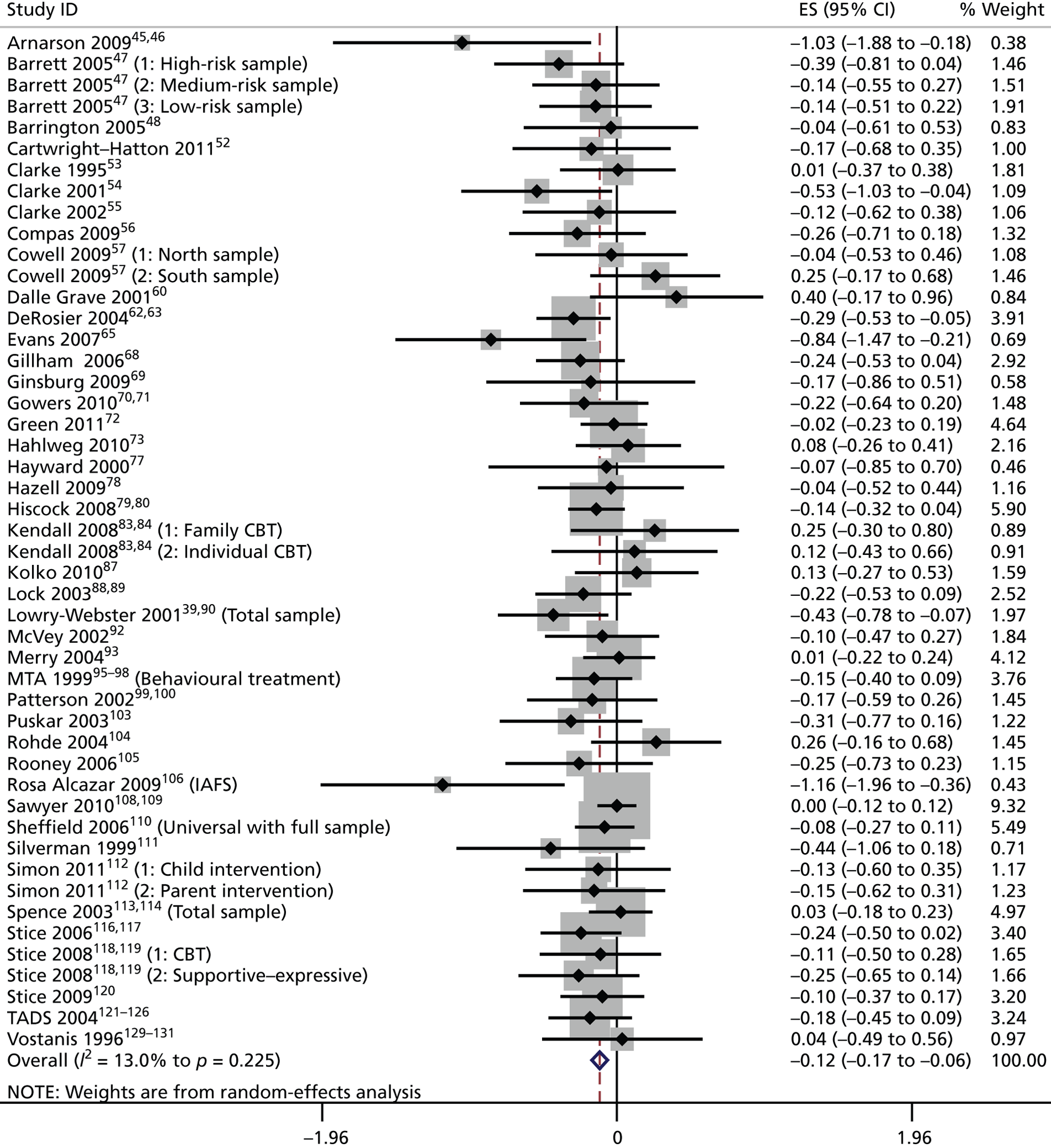

The results of the primary analysis are contained in Table 6 ; forest plots for 6-month (with and without outliers) and 12-month follow-up can be found in Figures 8 , 9 and 10 , respectively.

| Follow-up | Comparisons | Participants | SMD | L 95% | U 95% | I 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months, outliers included | 50 | 8362 | −0.34 | −0.46 | −0.21 | 78 |

| 6 months, outliers excluded | 47 | 8210 | −0.20 | −0.28 | −0.11 | 49 |

| 12 months | 48 | 4204 | −0.12 | −0.17 | −0.06 | 13 |

FIGURE 8.

Forest plot for the studies with 6-month follow-up data, outliers included. CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; IAFS, Intervención en Adolescentes con Fobia Social (Intervention for Adults with Social Phobia); TADS, Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study.

FIGURE 9.

Forest plot for the studies with 6-month follow-up data, outliers excluded. CI, confidence interval; IAFS, Intervención en Adolescentes con Fobia Social (Intervention for Adolescents with Social Phobia); TADS, Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study.

FIGURE 10.

Forest plot for the studies with 12-month follow-up data. CI, confidence interval; IAFS, Intervención en Adolescentes con Fobia Social (Intervention for Adolescents with Social Phobia); TADS, Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study.

Before discussing the results of the primary analysis, a comment needs to be made about the outliers in the 6-month follow-up data. Three studies from the same research team (Sánchez-García 2009a,138 and the two substudies from Sánchez-García 2009b139) had 6-month data that were included in the primary analysis. However, as is clear from the forest plot in Figure 8 , these studies were outliers. Including these three studies in the meta-analysis meant that inconsistency across the studies, as measured by I 2, increased from moderate to high (see Table 6 ). Accordingly, a decision was made to exclude these outliers, and the analysis with them included is reported here merely for transparency. Furthermore, these outliers were not included in any of our secondary analyses.

The results of our primary analysis imply that self-care support interventions are associated with a ‘medium’ effect on CYP’s mental health in the short to medium term, but the effect declines as time passes (a small intervention effect was sustained at 6-month follow-up, becoming clinically insignificant at 12-month follow-up). I 2 values suggest that there is greater study consistency at the 12-month follow-up than at the 6-month follow-up.

Quality appraisal: sensitivity analysis

As outlined in Chapter 2 , quality appraisal in the meta-analysis was based on a sensitivity analysis using concealment of allocation as a moderator. We deemed ‘high quality’ studies to be those studies where the two assessors agreed that concealment was adequate; ‘low quality’ studies were those where concealment was agreed to be inadequate or reporting was unclear. ‘High quality’ studies were generally in the minority. Table 7 provides details of the sensitivity analysis conducted.

| Follow-up | Quality | Comparisons | SMD | L 95% | U 95% | I 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | High | 7 | −0.04 | −0.21 | 0.13 | 64 |

| Low | 40 | −0.23 | −0.32 | −0.14 | 35 | |

| 12 months | High | 9 | −0.06 | −0.13 | −0.01 | 0 |

| Low | 39 | −0.15 | −0.22 | −0.07 | 19 |

The results of the sensitivity analysis demonstrate a finding similar to the primary analysis when only the ‘low quality’ studies are considered (a ‘medium’ effect that attenuates with time) but a negligible effect across both time points when only the ‘high quality’ studies are considered.

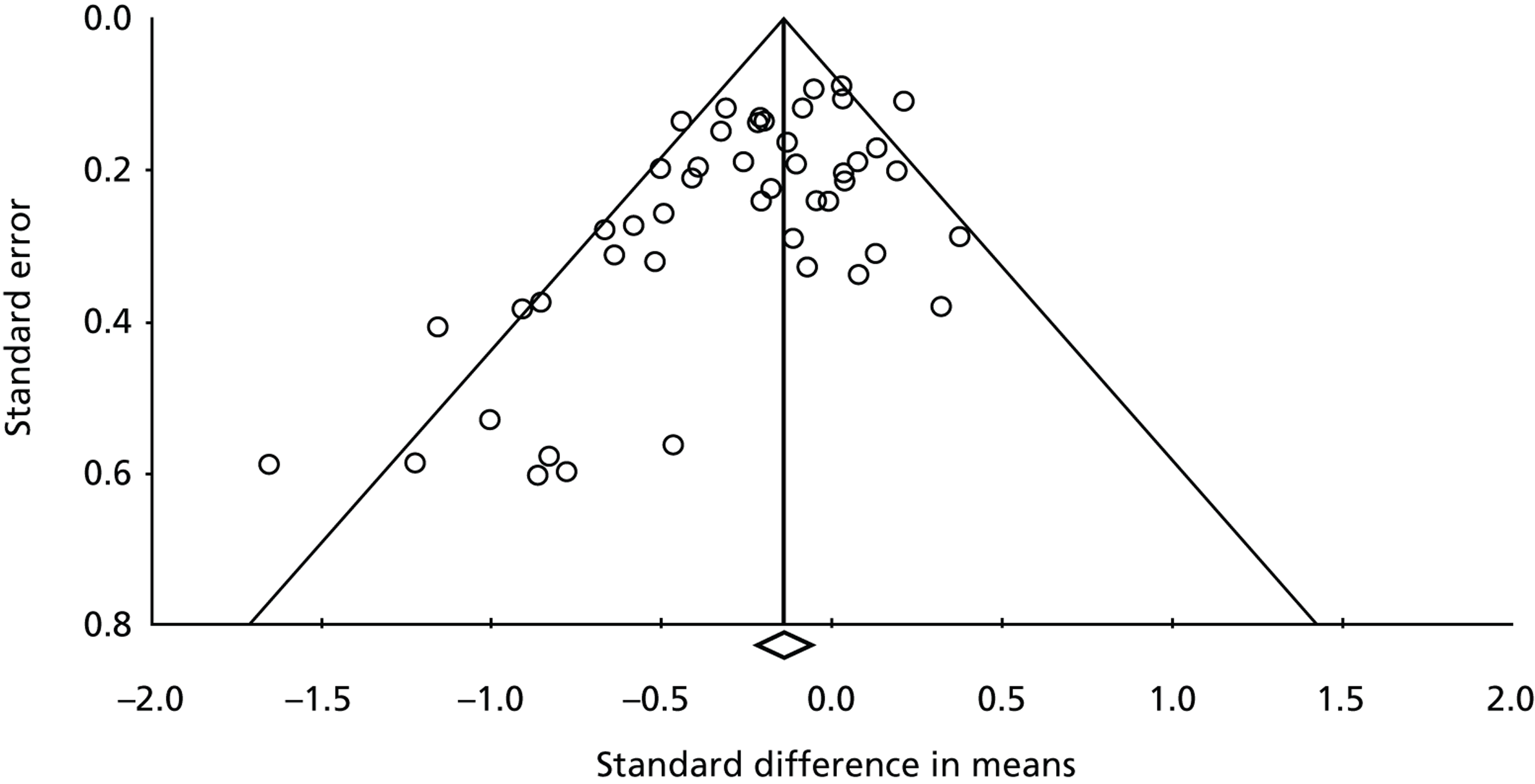

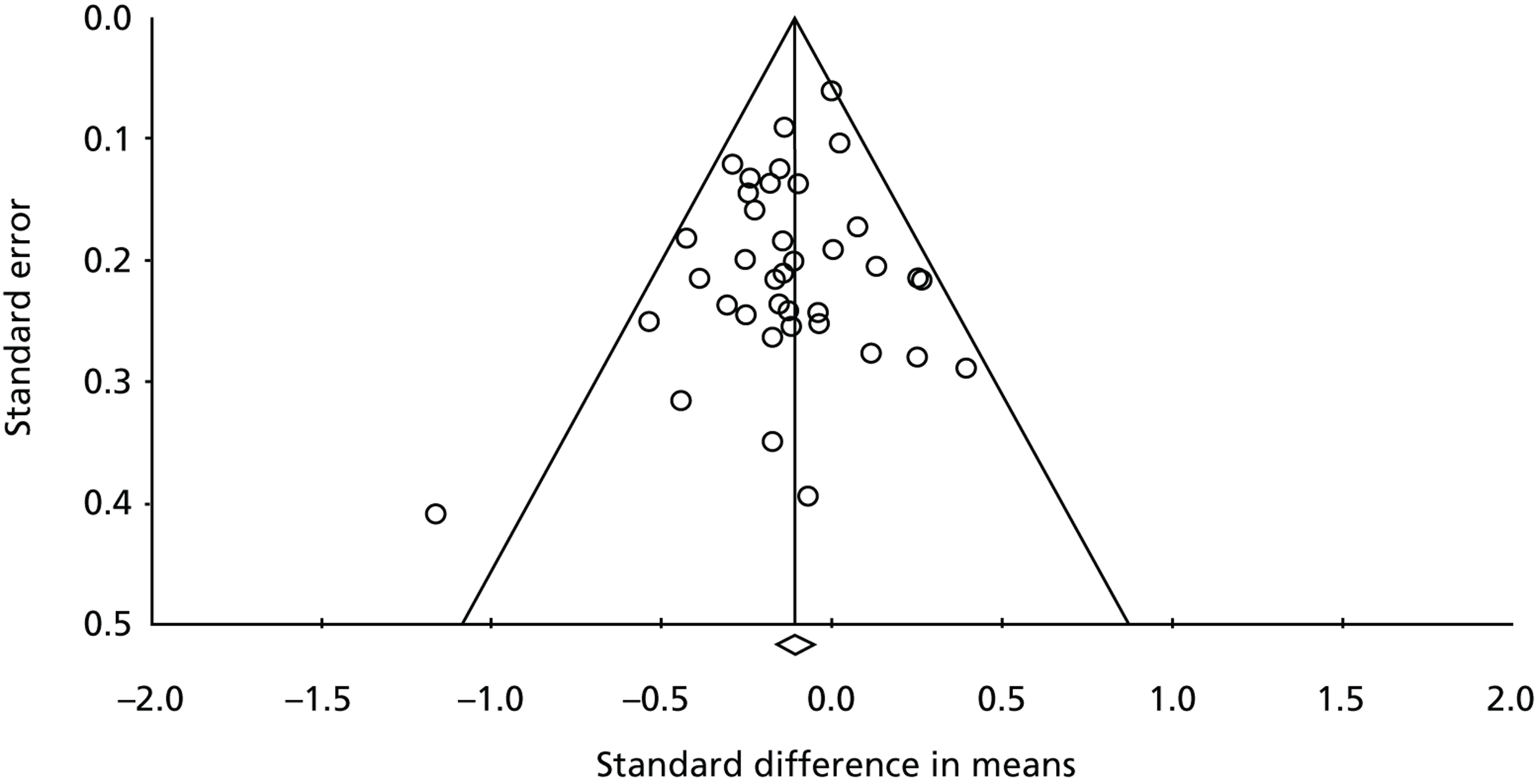

Publication bias

Funnel plots for the two follow-up points are shown in Figures 11 and 12 respectively. The asymmetry in the funnel plots, particularly at 6 months, may reflect some degree of publication bias.

FIGURE 11.

Funnel plot of standard error by standard difference in means for the studies with 6-month follow-up data.

FIGURE 12.

Funnel plot of standard error by standard difference in means for the studies with 12-month follow-up data.

Secondary analyses

The secondary analyses that we carried out related to additional characteristics of the populations and the interventions that might be related to the impact of interventions, namely:

-

intervention level (in terms of whether it was a universal, selective, indicated or treatment intervention)

-

the mental health condition targeted

-

the age of the CYP

-

the theoretical perspective of the intervention

-

the recipient (CYP, parent, family)

-

whether it was school-based or not

-

whether it was group or individual

-

whether the agent was mental health trained or not.

For some dimensions that we had anticipated exploring (e.g. whether the intervention was delivered face to face or via some electronic or telehealth method), we were unable to conduct analyses because there was insufficient variability in the included studies.

Intervention level

This analysis considered whether or not there were differing degrees of effectiveness when the interventions were categorised according to the levels of the intervention hierarchy discussed in Chapter 1 . A summary of the results can be found in Table 8 .