Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 08/1813/256. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The final report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in May 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John E Ellershaw reports grants from Marie Curie Cancer Care and the Department of Health End of Life Care Programme outside the submitted work. In addition, Professor Ellershaw has a patent Liverpool Care Pathway logo which is a registered trademark within the UK and European Community issued to Marie Curie Cancer Care and the Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust (joint holders). All Liverpool Care Pathway documentation is copyrighted as Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, a department of the University of Liverpool, Marie Curie Cancer Care and the Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust, using standard Berne Convention. Professor Ellershaw is employed by the Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust and has an honorary contract at the University of Liverpool.

Disclaimer

This report contains quotations from interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Perkins et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The median age of the population is projected to rise across Europe from 75.1 years to an estimated 81.2 years by 2050, with the proportion of the population over the age of 65 years rising to 27.8%. 1 Such projections threaten to place health-care systems across Europe under considerable strain as older age (i.e. ≥ 85 years) brings with it an increased risk of chronic disease. 2 In England and Wales each year around half a million people die, the majority of whom are aged over 65 years. Death occurs mainly after a period of chronic illness such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic respiratory disease, neurological disease or dementia. In those aged ≥ 65 years, the two most likely places of death are hospitals (52%) and nursing homes (22%), with 20% of deaths occurring at home, 5% in hospices and 1% elsewhere. 3

End-of-life care

End-of-life care in the UK has undergone significant development in the last two decades. End-of-life care has been defined by the National Council for Palliative Care as ‘care that helps all those with advanced, progressive, incurable illness to live as well as possible until they die’. 4 The National Council go on to state that end-of-life care ‘enables the supportive and palliative care needs of both the individual and their family to be identified and met throughout the last phase of life and into bereavement. It includes the management of pain and other symptoms and provision of psychological, social, spiritual and practical support’. 4

Historically, underinvestment in both time and financial resource has rendered the quality of end-of-life care as frequently suboptimal, particularly in the acute setting. 5 The Department of Health published its National End-of-Life Care Strategy in July 2008,6 after a 2-year consultation. Its primary aim was to improve the provision of care for all adults approaching the end of their lives, and the support for their families and informal carers. 7 An allied aim was to reduce inappropriate admissions to hospital and enable more people approaching the end of their life to live and die in the place of their choice. It highlighted both the need for ongoing training for all generalist staff who deliver end-of-life care, and the importance of integrated, interprofessional and cross-sector working. 6 The National End of Life Care Programme was established and a number of documents, including the End of Life Care Strategy: Quality Markers and Measures for End of Life Care8 and the Quality Standard for End of Life Care for Adults,9 were published to support the national delivery of high-quality end-of-life care.

The goals of end-of-life care provision are the promotion of the quality of life for ‘dying’ patients (i.e. those with acknowledged life-limiting illness) and a ‘good death’ when the time comes. The evolution of the ‘good death’ concept over time from the prehistoric era to postmodern times10 suggests that general attributes of a good death include effective pain and symptom management, awareness of death, patient’s dignity, family presence, family support and communication among patient, family and health-care providers. Scarre, however, warns against such a narrowly focused definition and questions the very notion of attaining a ‘good death’. 11 He suggests that current definitions reflect its aetiology in the ‘medical model’ with an emphasis merely on providing the right conditions, which he feels omits the importance of the patient’s own self-preparation for death through the development of ‘qualities of character’.

This project sets out to examine the impact of the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient (or Liverpool Care Pathway; LCP) on the current practices and experiences of dying in two care settings, nursing homes and intensive care units (ICUs), in England.

Death and dying in the context of nursing homes

Care homes (including nursing homes) are currently second only to hospitals as the most likely place of death for people over the age of 65 years in the UK. In 2011, over 90,000 people aged over 65 years died in care homes. 3 This trend is set to increase owing to the predicted increasing median age of the population1 and the drive to decrease the number of inappropriate admissions to hospital from nursing homes at the very end of life. 6 Age- and sex-adjusted mortality has been shown to be approximately four times higher in nursing homes than in the community12 and, for these reasons, nursing homes are likely to play a significant role in end-of-life care provision now and into the future.

Percival and Johnson explored the factors that influenced good-quality end-of-life care in care homes from the point of view of residents, relatives and staff. 13 While these perspectives are inherently likely to be divergent, the authors identify six key priorities for care:

-

personalised care – maintaining informal relationships; having personal items to hand

-

dignity and respect – attention to cleanliness; explaining while carrying out personal tasks; thoughtfulness on the part of staff; culturally relevant care

-

making time – sitting with residents; listening; touch; patience; reorganising the workload

-

talking about end-of-life issues (and death) – staff personal and professional difficulties; can feel they are protecting residents by not talking about it; most residents wanted to talk about it (especially the practical aspects)

-

relatives’ roles and collaboration – relatives willing to work with staff; their collaboration with staff reassured residents; staying overnight; helping with care; the benefits to staff of having a ‘bond’ with relatives

-

staff support and training – readily admit the need for emotional support for themselves; more likely to be informal; attending funerals; recognition of the importance of ongoing education and training.

However, nursing homes are traditionally staffed by a low-paid workforce with limited access to appropriate sources of expertise and support (e.g. palliative care) and relevant education and training opportunities. Inadequate staffing levels threaten the delivery of complex and emotionally laden care for dying residents14 and staffing levels and training have been the subject of recommendations. 6,15,16 Goddard et al. ’s study17 on the views of a range of care home staff and community nurses illustrated that staff thought that managing the complex needs of residents at the very end of life with a largely unskilled workforce was the greatest threat to the delivery of high-quality end-of-life care in this setting.

Support from external health-care professionals, although vital, is often limited in the care home setting. General practitioners (GPs) usually provide support to individual residents within the nursing homes, but this means that often nursing homes are attempting to co-ordinate a large number of individual practices and doctors. For example, in their survey, Froggatt and Payne18 found that individual care homes in their sample were working with up to 17 practices and 27 GPs, with two-thirds of GPs visiting only when asked. District nurses were generally the most regular visitors to care homes, but, in recognition of the presence of on-site nursing, this was not the case for nursing homes. Links to specialist palliative care, including 24-hour advice, was available for around two-thirds of the sample, but the nature and level of input was not assessed. 18

Death and dying in the context of intensive care units

NHS Choices defines ICUs as ‘specialist hospital wards . . . provid(e)ing intensive care (treatment and monitoring) for people in a critically ill or unstable condition . . . A person in an ICU needs constant medical [and nursing] attention and support to keep their body functioning. They may be unable to breathe on their own and have multiple organ failure. Medical equipment will take the place of these functions while the person recovers’. 19 This definition illustrates the nature of interventions that are generally involved in such care, and the expected and desired outcome of the patient’s recovery. Nevertheless, a significant minority of patients admitted to ICU in England die each year. For example, in 2011–12, 19,567 of the 125,760 total ICU admissions (15.5%) resulted in the death of the patient prior to discharge from the unit. 20 This means that ICU doctors and nurses are exposed to dying and death in their day-to-day work, with the associated potential burdens and opportunities that this may entail.

Death and dying in the ICU, however, can be said to be qualitatively different from death and dying in other settings in that it most often occurs after decisions to withhold and/or withdraw active therapy. 21 Although nurses are not responsible for the decision to withhold/withdraw therapy and, it has been reported, are often not represented in the discussions preceding such decisions,22,23 they are usually most closely involved in providing care at the bedside, interacting with relatives and carers and undertaking the actual withdrawal of those interventions,23,24 requiring considerable ‘emotional labour’. 23,25

Recently, there has been a research focus on understanding the differing perspectives on end-of-life care in the ICU. 24 There is recognition that different professional groups may view the decision about the ‘futility’ of life-sustaining treatment from very different perspectives. 23 For example, it is reported that ICU nurses tend to perceive a direct link between ‘futility’ and dying which ICU doctors often do not. 26 This could lead to friction between professionals about the appropriate timing of end-of-life care. Decisions regarding the transition from active, life-sustaining intervention to care designed to ensure comfort involves complex negotiation within staff groups and between staff, patients and families over a relatively short period of time. 26

The concept of a ‘good death’ is multifaceted and complex in the ICU setting. Thompson et al. 27 illustrate a four-stage process (from the perspective of ICU nurses) to secure a ‘haven for safe passage’:

-

facilitating and maintaining the changing of care goals from curative to palliative

-

getting what is needed: plan of care with focus on comfort care

-

being there: providing support to the patient’s family

-

manipulating the care environment: creating a peaceful environment.

Ryan and Seymour28 reviewed the literature and suggest that a ‘good death’ in this environment has been associated with the some or all of the following:

-

consensual decision regarding the withdrawal of therapy – within staff and between staff and relatives

-

expected (not sudden) and prepared for (by both staff and relatives)

-

under the control of the health-care team – timely – not too fast, not too slow

-

patient comfort maintained (pain and symptom management)

-

natural – free from technological intervention

-

according to the wishes of the patient/family

-

loved ones present at the time of death

-

clear, non-conflicting communication.

End-of-life care tools to support the delivery of high-quality end-of-life care

The end-of-life care strategy6 highlighted and promoted the use of three key end-of-life care tools, which can be used together or separately at different time points in the dying trajectory. The first two of these tools are designed to support appropriate co-ordination and planning of care for people with life-limiting conditions based in the primary care sector. Preferred Priorities for Care promotes timely discussions, documentation and communication about patient’s wishes and choice around their priorities and preferred place of care and death. 29 It is particularly important to offer people with cognitive degenerative illnesses, such as dementia, the opportunity to think, document and share their wishes before they lose the capacity to make complex decisions about their future care as the disease progresses. This document is a patient-held record of such discussions and decisions. The Gold Standards Framework (GSF)30 aims to optimise the quality of care for patients in the last year of life, including enabling choice in place of care and death, through improving the organisation and co-ordination of local services. 31 The GSF began in primary care in the early 2000s (GP surgeries, district nursing services) and has expanded more recently to include nursing and care homes. 32

The LCP33 specifically focuses on the last hours or days of life and can be used to support care wherever people die. The responsibility for use of the LCP document as part of a continuous quality improvement programme sits within the governance of the organisation and the authors stipulate that it must be underpinned by a robust education and training programme. The LCP guides and enables health-care professionals to focus on care in the last hours or days of life, when a death is expected. It is a framework for good practice, and aims to support but not replace clinical judgement. 34 The LCP has been disseminated widely in a variety of settings, including the two settings of interest for this project, ICUs and nursing homes. As the impact of the LCP is a focus of interest in this study, a more comprehensive overview of the LCP is provided below.

An overview of the Liverpool Care Pathway

The care of people who are imminently dying takes place in a number of settings, not all of them specialist in nature, and there is wide variation in understanding of the needs and necessary care required to support patients at the very end of life. 35 The LCP originated in Liverpool and was developed as an end-of-life care tool in the mid-1990s through collaboration between specialist palliative care services at the Royal Liverpool University Hospitals Trust and the Marie Curie Hospice in Liverpool. It aimed to transfer best practice from hospice institutions to the wider context of organisations which provided end-of-life care, for example hospitals, care homes and nursing homes, and was intended to be adapted by organisations to suit their specific organisational contexts. 6 Latterly, its development and dissemination has been overseen by the Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute Liverpool (MCPCIL). 36

The LCP was designed to support clinical decision-making when the multidisciplinary team (MDT) considers that the patient is in the last hours or days of life, and where there is no appropriate reversible treatment available. The challenge in accurately diagnosing the imminently dying phase is identified as a major concern. In this report, the term ‘dying phase’ pertains specifically to the last hours or days of life. Some health-care practitioners and members of the public have articulated concerns that the identification of a person as ‘dying’ could become a self-fulfilling prophecy. A crucial component of the LCP, however, is the continual review of the patient, involving the MDT, which should prompt a reassessment of the patient’s condition. A patient who is no longer thought to be imminently dying should no longer have their care supported by the LCP.

The LCP document is an integrated care pathway with a goal-orientated approach and is organised into three sections: initial assessment, ongoing assessment and care after death (see Appendix 6). One of the most important aims of the LCP is to facilitate the comprehensive documentation of care delivery and outcomes during the last hours or days of a patient’s life in an efficient yet effective manner. Hence the LCP documentation, as with other integrated care pathways, is designed to replace all other documentation in this specific phase of care. 33

The LCP has been reviewed and revised over time. Version 12, published in 2009, was subject to a 2-year international consultation exercise. This version maintained the focus of earlier documents on communication, information and comfort care in the last hours or days of life, and included an algorithm to support staff in reviewing their recognition of the dying phase. It also contained explicit goals to support care with regard to hydration, nutrition and skin integrity. The use of the LCP in hospitals has been the focus of four national audits in England; the latest results are published on the website of the Royal College of Physicians. 37

The LCP has been cited as an example of good practice specifically for care in the last hours or days of life in several national publications38,39 and was disseminated nationally as part of the End of Life Care Initiative to improve care for imminently dying patients in the UK. 6 At the time of writing, in the UK over 2000 organisations were ‘registered’ with the MCPCIL, including hospitals, hospices, care homes and home teams. Additionally, at the time of writing, over 20 countries outside the UK used the LCP to some degree. 34 An International Reference Group, including representation from 12 countries, met annually to oversee the development of the international LCP programme.

A recent independent review of the LCP40 was undertaken in response to growing concerns represented in the media about the use of the LCP to support care for imminently dying people. Reports included stories focused in particular on the challenge of accurately ‘diagnosing dying’, the provision of food and fluids in the last hours or days of life and the use of sedation. The review of the LCP considered written evidence from members of the public and health professionals who had experience of the LCP. They also took evidence from a variety of professional bodies and other relevant organisations and held four public sessions to hear people’s experiences first hand. The review concluded that the LCP represented the right ethical principles for the care of the dying patient and, when the LCP was implemented properly, it could support a peaceful and dignified death. However, the examples of poor care led them to recommend that the LCP be phased out over a 6- to 12-month period to be replaced by individual care plans.

A review of academic literature and hospital complaints was also undertaken as part of the review process. The review focused on the effectiveness of the LCP and other care pathways in end-of-life care. 41 The authors concluded that the evidence base for accurately predicting the imminence of death did not exist. In addition, the authors highlighted a paucity of high-quality, robust empirical studies into how the LCP is used in practice and the impact it has on the care of people who are imminently dying. The authors concluded that independent research focusing on the outcomes and experience of care – as reported by relatives and carers – as well as the quality of dying was urgently required.

Aims of this study

This study sought to develop a comprehensive picture of care in the last hours or days of life in two very different health-care settings, ICUs and nursing homes, in England, half of which used the LCP to support the care of their patients in the last hours or days of life, and half of which did not. It attempted to do so from a variety of perspectives, including undertaking direct observation at the bedside of dying patients, examining the views of bereaved relatives regarding their experience of the last hours or days of their loved one’s life and the views of those directly engaged in the delivery of care. In so doing, it aimed to assess the impact of the LCP in nursing homes and ICUs on the nature and quality of care delivery and outcomes for patients and their relatives and carers. The study was also designed to provide evidence on costs and outcomes. The project aimed to generate evidence to support the commissioning, development, implementation and management of generalist end-of-life care services in the NHS and wider health and social care system.

Section 1

Chapter 2 Methods

Introduction

The LCP is cited as good practice in national health-care documents. 6,38 However, there is limited research evidence on exactly how the LCP is used in practice and the impact it has on the care of people who are dying. This study was designed to produce evidence by examining the impact of the LCP on care in two different settings, ICUs and nursing homes, in England. In so doing, this study met the criteria set out by the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme (since renamed Health Services and Delivery Research) in their programme on patient- and carer-centred services. This research also builds on the scoping review of generalist end-of-life care undertaken by Higginson et al. 35 and incorporates an economic component, which aims to compare the costs and outcomes associated with the implementation of the LCP in the two different settings.

Study aim

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of the LCP on care in two different settings: nursing homes and ICUs. The study was designed to examine the impact on patients, carers, bereaved relatives and clinicians including nurses, doctors and other members of the MDT involved in the care of patients in the last hours or days of their lives. The impacts studied include the physical care of the patient; the psychological needs of the patient; the social, spiritual and religious needs of the patient; the information/communication needs of carers; and the economic costs of care.

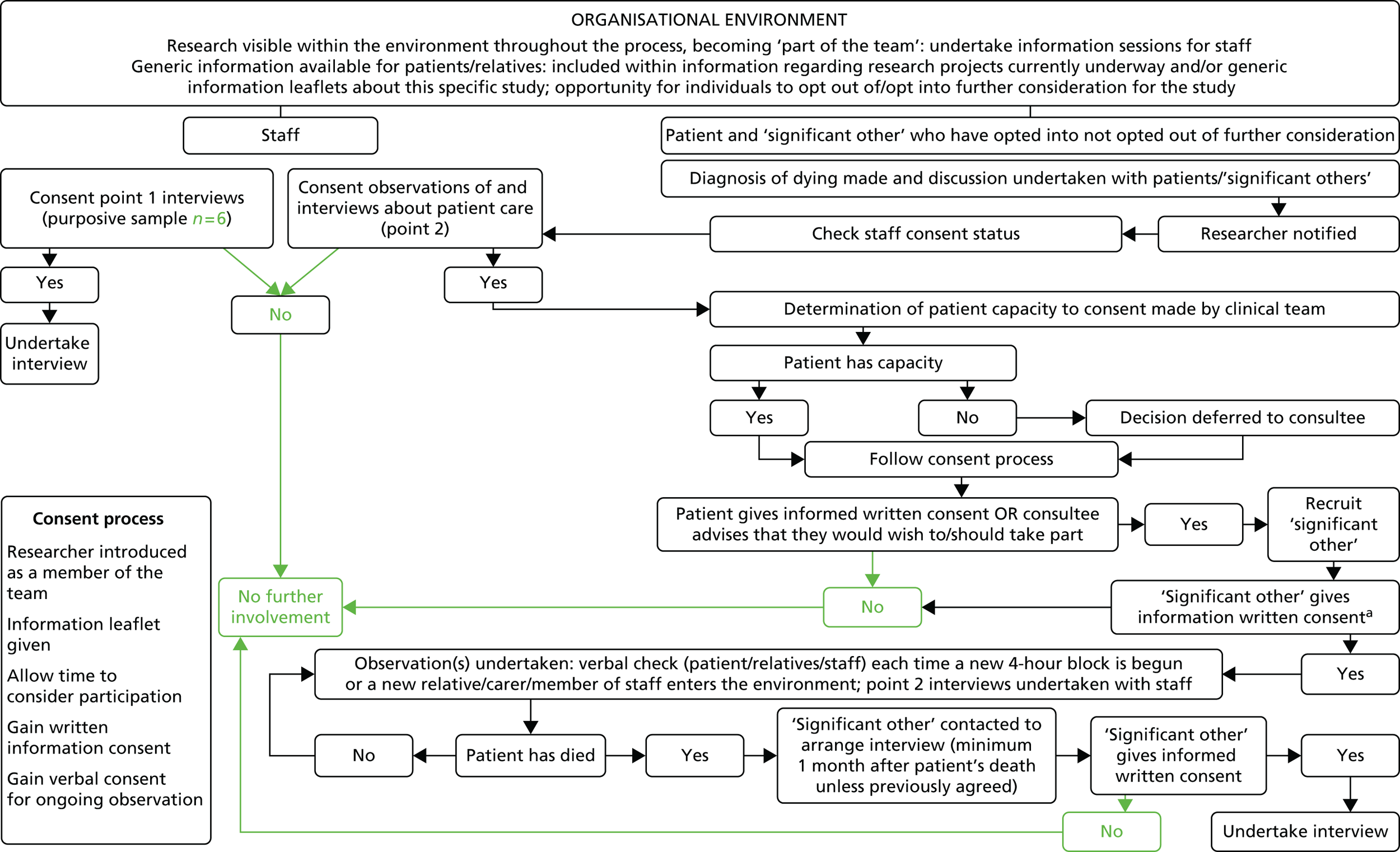

Piloting and ethics committee review

Given the nature of this study, a detailed pilot study (see Appendix 1) was undertaken to establish the most effective and acceptable ways of approaching patients at the end of their life, their family members and the staff caring for them in nursing homes and ICUs to participate in this study. The main implications of the findings informed the procedure for the main study protocol (see Appendix 2) in terms of the process for patient and relative recruitment and, specifically, for gaining informed process consent. Appendix 3 illustrates a brief summary of this protocol, Appendix 4 includes advisory group membership and Appendix 5 shows the terms of reference for this group.

In line with the recommendations resulting from the pilot phase of this study, a flow diagram was developed to map the consent process for the observational phase of the main study (see Appendix 7).

The pilot study and the subsequent main study received ethics committee approval from the North West Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) which was authorised to review studies involving patients who might lack capacity. The pilot study was approved in April 2010 (REC reference 10/WNo01/26) and the main study was approved in September 2010 (REC reference 10/WNO01/51).

Research governance

Research and development (R&D) approval was sought and gained in all 12 hospital trusts, and, for the nursing homes, which were under the governance of the then primary care trusts (PCT), letters of access were sought for the data collection in these sites. The researchers collecting data had enhanced Criminal Records Bureau clearance and current Good Clinical Practice training certificates, and were issued with research passports in order to facilitate these processes. Gaining R&D approvals, however, was a complex and often lengthy process, differing logistically and administratively from site to site and which, on occasion, held back the recruitment of patients in research sites for several weeks.

Study design and sampling

The aim of this qualitative, case study-based approach was to collect a range of data from nursing homes and ICUs that used the LCP to support care and matched sites that did not use the LCP. The following types of data form the basis of this study:

-

documentary analysis of Strategic Health Authority (SHA) plans and collection of local end-of-life policy documents

-

a retrospective analysis of 10 deaths in each location using written case notes

-

interviews with staff about local end-of-life care policies and practice (point 1)

-

observation of interactions with dying patients

-

analysis of the case notes pertaining to the observed patient’s death

-

interview with a member of staff who had provided care up to the period of observation (point 2)

-

an interview with a bereaved relative who had been present during the observation

-

economic analysis focused on the 25 observed cases to provide costings to inform future policy/organisation of care delivery.

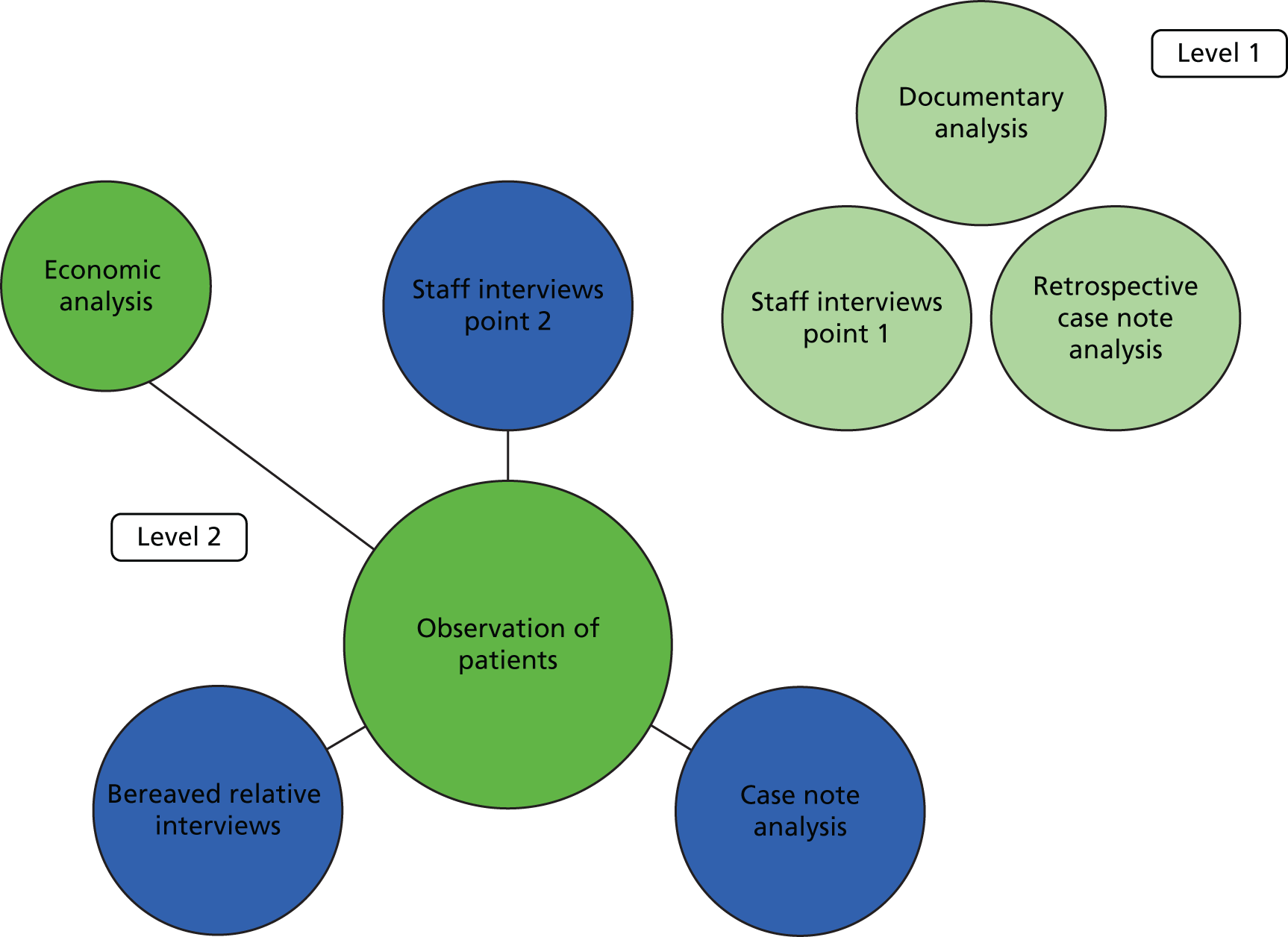

These data work on two levels. Level 1: background, contextual data about views, attitudes and documented practices surrounding end-of-life care in each setting are explored through data types 1–3. This provides a cross-sectional analysis of perspectives in a general sense across all participating sites. Level 2: a case study approach, centred on the observations of patients, allows a detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events from a variety of relevant perspectives. These are explored through data types 4–8. Figure 1 illustrates how these various elements work together to create an in-depth picture at these two levels.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of data collection methods.

A matched case study design was adopted to collect the data in order to assess the impact of the LCP from different perspectives. The original aim had been to recruit 24 sites, 12 in the north-west and 12 in the south-east, half using the LCP and half not using the LCP.

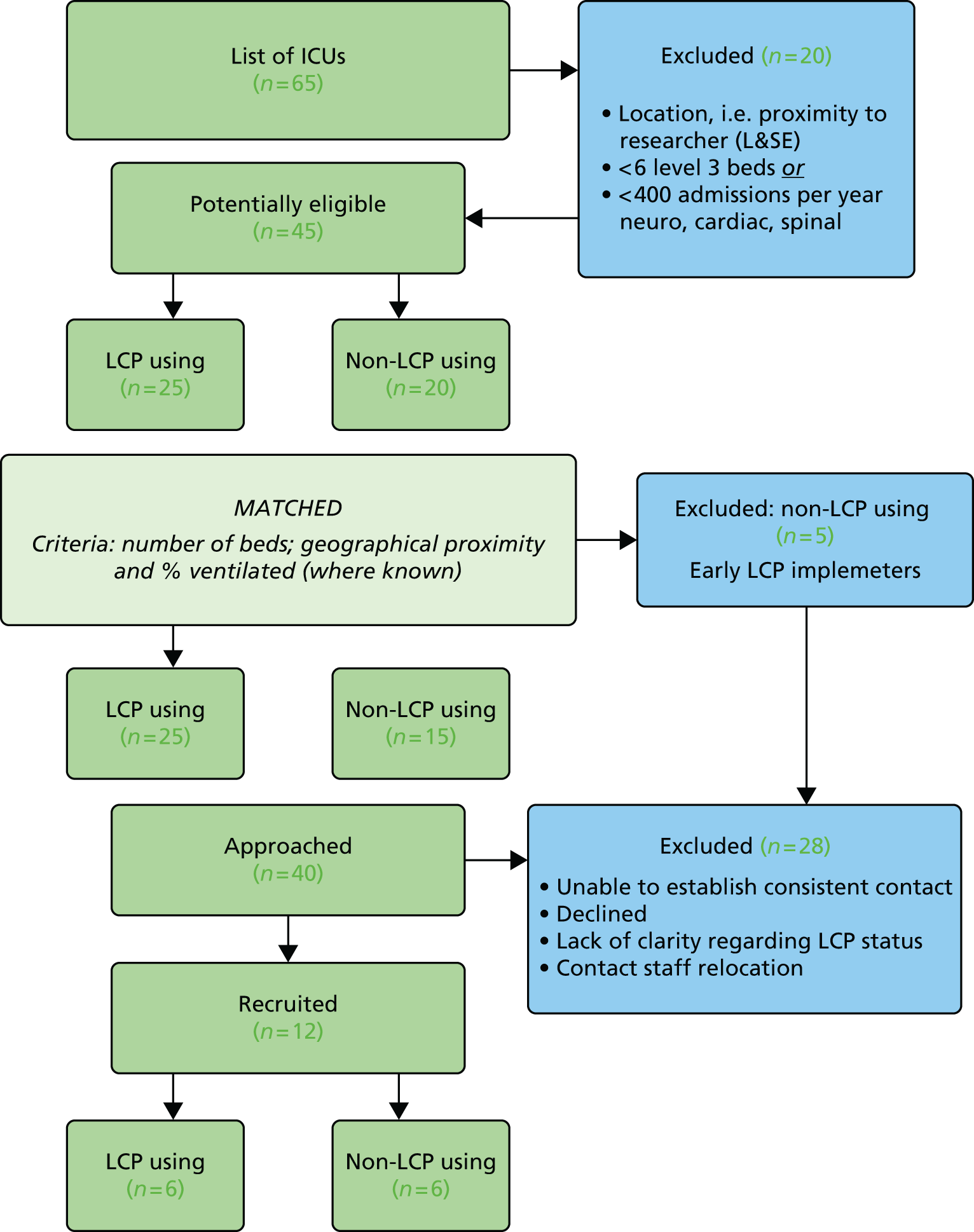

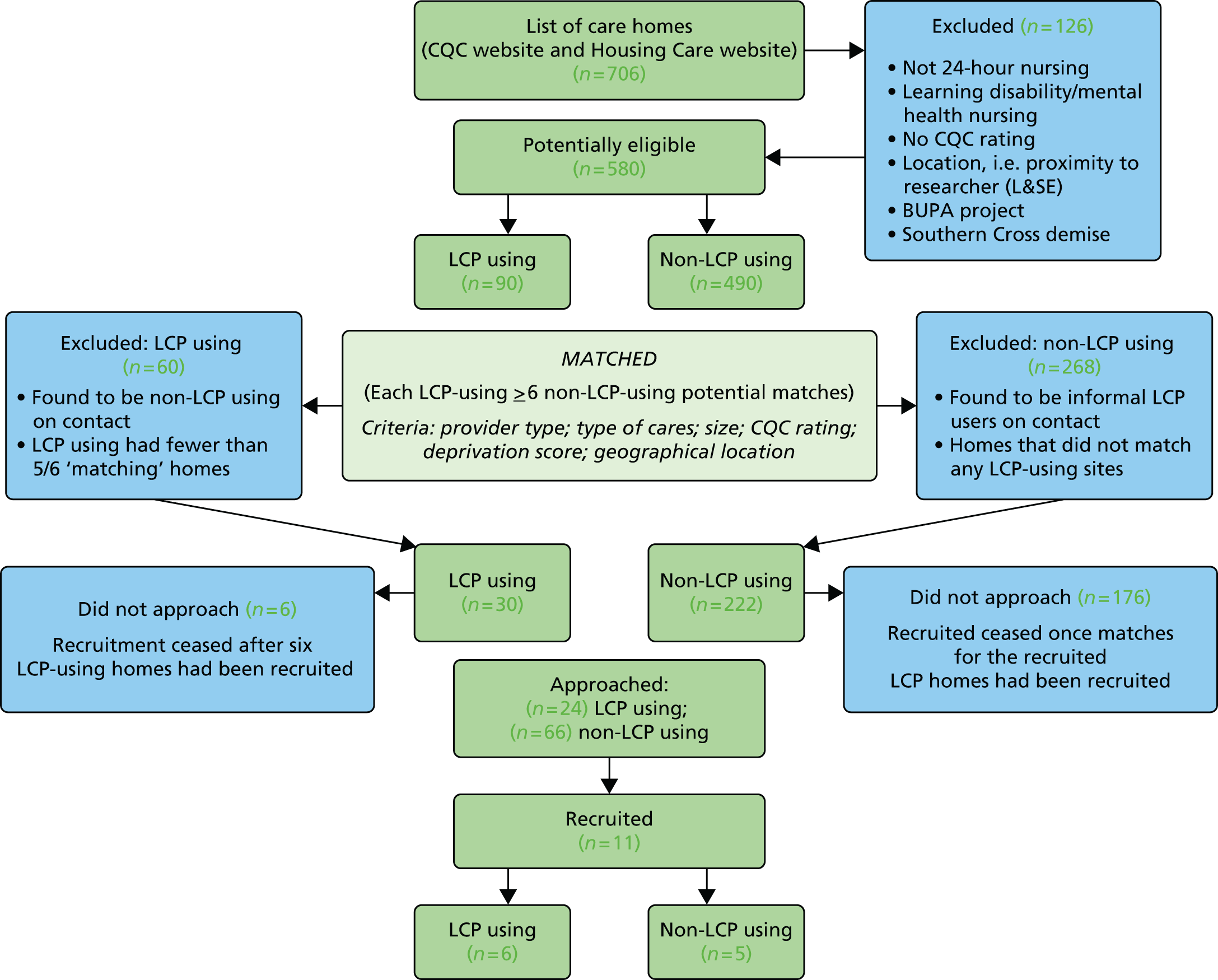

Identifying potential sites

Appendices 8 and 9 contain flow diagrams that indicate the way in which ICUs and nursing homes were considered, approached and recruited to the study. A ‘master’ list of nursing homes and ICUs in each geographical location was developed. The nursing home list was created using information held on two relevant websites at the time (autumn 2010). These were the Care Quality Commission (CQC) website (www.cqc.org.uk) and the Home Care Choices website (www.homecarechoices.co.uk). The ICU ‘master’ list in the north-west was developed from the acute hospital trusts identified on the then North-West SHA website (www.northwest.nhs.uk). In London and the south-east, it was generated from information held at the time on ‘Dr Foster’ (London, UK; www.drfosterhealth.co.uk/).

Site inclusion criteria

The following criteria were applied to all sites on the two master lists:

-

nursing homes

-

24-hour, ‘on-site’ nursing care

-

within travelling distance of the location of the researcher and each other.

-

-

ICUs

-

level 3 care, i.e. patients who required one-to-one nursing care

-

under the clinical direction of an intensivist

-

> 400 admissions per year (this was amended early in the study to > 6 level 3 beds)

-

> 80% of patients mechanically ventilated

-

general ICU (e.g. not heart and lung, burns or neurological specialty)

-

within travelling distance of the location of the researcher and each other.

-

Definition of a Liverpool Care Pathway-using site (for the purposes of this study)

As part of the national dissemination process of the LCP, organisations interested in using the framework were invited to register their interest with the MCPCIL. While registration was not compulsory, it gave organisations the opportunity to review their practice.

At the time of the commencement of the study, organisational details were held on the MCPCIL national database for 503 care homes and 66 ICUs across the UK.

Any relevant organisation represented on the MCPCIL database within the two geographical locations was potentially eligible for consideration as a ‘LCP-using’ site in this study. Sites were deemed to be eligible for inclusion in the study as a LCP-using site if they had registered with the MCPCIL and/or had used at least one LCP in the previous 6 months to support the care of a dying patient. Potential non-LCP-using sites were matched against those LCP-using sites which agreed to participate in the study.

Matching of sites

The main purpose of matching was to ensure that each of the LCP-using sites within the sample in each setting could be compared with a site that was similar in most important respects apart from LCP implementation and use. In all cases LCP sites were recruited first and then matched with a non-LCP-using site. Matching was based on the following set of key variables in each setting:

-

nursing homes

-

provider type

-

type of care offered

-

size of home

-

CQC rating

-

geographical locality (based on the postcode)

-

deprivation rating.

-

-

ICUs

-

number of beds

-

geographical locality.

-

Recruitment of sites

Overall, 23 sites participated in the study, as shown in Table 1.

| Type of organisation | Location | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| North-west | London and south-east | ||

| NH with LCP | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| NH without LCP | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| ICU with LCP | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| ICU without LCP | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Total | 12 | 11 | 23 |

The recruitment strategy for nursing homes and ICUs was underpinned by three principles:

-

Although the management of an organisation might agree to take part in the study, individual employees had the freedom to decide whether or not they wished to take part.

-

Once an organisation had agreed to participate, meetings were held with staff, individually and in groups, in order to air concerns and clarify procedures. A log of attendance at these meetings was maintained to ensure that, where possible, a minimum of 50% of the staff had received information about the study.

-

Individuals could opt out of the study at any stage without the need for explanation.

Given the nature of the study and the findings of the pilot study, we anticipated reluctance on the part of some staff to consent to participate. Meetings were held to establish the level of organisational interest in taking part. High levels of staff choosing not to participate would have made the observational element of the research difficult to conduct. The purpose of these early meetings was to identify what proportion of staff were unwilling to participate in the study. It was decided that only those organisations in which it was known that a majority of staff were not against participating in the study in principle should be included in the sample.

Nursing homes

A hierarchical ‘top-down’ approach was adopted to the recruitment of nursing homes. Nursing home managers and owners were contacted by telephone to establish LCP-using status, and to ascertain whether or not they would be interested in receiving information about the study. A letter (see Appendix 10) was then sent to all who wished to receive it stating the purpose of the study and the nature of their potential participation. This was followed up by a telephone call to arrange an introductory meeting. If site participation was agreed in principle at this meeting, arrangements were made for the researcher to meet with individuals and groups of staff to give further information about the study.

As previously discussed, the researcher aimed to see at least 50% of the workforce, to give the staff an opportunity to ask questions, express concerns and talk about the proposed research. The researcher would meet the staff in small groups or as individuals, and a record was kept of the names and numbers of staff seen in this way. Visits and meetings were held at different times of the day, including through the night, in order to reach as many staff as possible. Any staff who felt strongly that they did not wish to participate in the study were asked to let the researcher know by e-mail or telephone (to ensure confidentiality), and this information was noted so that these individuals would not be approached for interview or for the observational element of the research.

Intensive care units

A similar recruitment process was adopted in the ICUs. Managers and consultants were approached initially by telephone to check their LCP using status and to gauge initial interest. They were then sent an introductory letter and more information (see Appendix 10). A follow-up telephone call was made, and if there was interest in participation at this stage a face-to-face visit was arranged. If agreement in principle was achieved from ICU managers at this stage, meetings were organised for staff, primarily nurses and doctors, which in the ICU setting were often formal and provided staff with an opportunity to ask questions and/or voice concerns. Again, these meetings were held at various times of the day and night in order to reach as many relevant staff as possible. The researcher kept a record of staff attending these meetings. In some of the larger ICU sites employing over 300 clinical staff, it was only possible to see a small proportion of the workforce. The aim in these large sites was to cascade general written information through the system, using notice boards and by word of mouth. Staff were invited to approach or contact the researcher if they had any questions or concerns about the research.

Challenges in site recruitment and retention

A significant amount of time and resources were used to identify, approach, gain access to and eventually recruit sites to this study. As detailed above, the recruitment process was complex and iterative and, therefore, often protracted. There was a tremendous amount of activity involved in making initial contact with potential sites. Appendix 11 illustrates the level of activity for each site.

Almost all of the issues raised by staff were related to concerns about the observation of their care. In the majority of cases, staff were reassured by the fact that they would not be identified or identifiable and that they had a right to withdraw from the research at any time without giving a reason. Only a small minority of staff (n = 5) in all of the participating sites notified the research team in advance that they would not want to take part in the research study. There were, however, a number of issues, specific to each setting, which impinged on the recruitment and retention of sites to this study.

Nursing homes

Staff turnover in nursing homes was a particular challenge for the recruitment and retention of sites in this study. This was predominantly the case for sites in London and the south-east. Six nursing homes were quite quickly recruited to the study and a significant amount of work had already been undertaken to introduce the research to individual staff in each site. However, three of these subsequently withdrew as a result of a change in the home’s management. Several attempts were made to recruit replacements, but it proved possible to replace only two of the three homes in time for meaningful data collection to take place. An additional problem was experienced with another nursing home in the south-east, where a decision was taken by the management team half-way through the study to opt out of the observational stage of the research. Unfortunately, this happened too late in the course of the study for the site to be replaced.

Similar problems were experienced in the north-west sites. In one, home agreement for the observational phase of the research was withdrawn 5 months after their initial agreement to participate and following a significant amount of data collection (documentary analysis and point 1 interviews had been undertaken). A replacement was found for this nursing home. Another home was taken over by a different management company during the course of the study and, although the home did not formally withdraw, no opportunities for observation were made available to the researcher after this point.

Similar challenges to recruitment and retention have been reported in the literature. For example, Tilden et al. 42 reported a higher rate of turnover of key personnel in ‘non-completer’ sites in their study of the relationship between communication, teamwork and palliative/end-of-life care practices on patient outcomes. They concluded that researchers wishing to undertake large-scale studies in nursing homes should ‘anticipate significant challenges and delays in recruitment and retention of the sample, and should budget accordingly’.

Intensive care units

The speed of recruitment in the ICU setting was slowed by uncertainty about whether or not the LCP was being used. Many of the sites in the north-west had implemented the LCP at some point in some shape or form and it was necessary to recruit from a wider geographical area than originally planned.

In addition, at the time of the recruitment, ICUs were experiencing significant organisational change. Some ICUs were in the process of merging and the allocation of level 3 beds across the sample often changed in response to emergent need; the maximum number of level 3 beds that were available in each site are detailed later (see Table 3). Robust statistics on the proportion of ventilated patients in ICUs at any one time was difficult to locate and the proportion of patients required for inclusion in this study (> 80% mechanically ventilated) was not always reached. Together, these factors made the identification and recruitment of appropriate sites challenging and time-consuming.

Liverpool Care Pathway-using/non-Liverpool Care Pathway-using distinction in nursing homes and intensive care units

Six ‘LCP-using’ sites (coded as NNA sites in the north-west and coded as SNA sites in London and the south-east) and five ‘non-LCP-using’ sites (coded as NNB sites in the north-west and coded as SNB sites in London and the south-east) were recruited to the nursing home sample. However, early on in the data collection it became clear that the distinction between LCP-using and non-LCP-using sites was not clear-cut. A more complex continuum of exposure to the principles and experience in the use of the LCP and of other key end-of-life care initiatives such as the GSF and advance care planning (ACP) existed. Seven of the 11 sites had implemented the GSF and one had recently commenced the North West End of Life Care Six Steps to Success programme for care homes. 43 Both initiatives focus primarily on the last 12 months of life and aim to support the development of a coherent system for planned and co-ordinated care. All 11 managers reported having a process of ACP in place to support the patient choice agenda, and the seven sites using the GSF were also using the LCP to support care in the last hours or days of their patients’ lives. In one site (NNB1) managers reported that although the care provided by nursing home staff was not supported by the LCP, the district nurses who attended the nursing home used the LCP, and another (NNB6), although initially recruited as a non-LCP-using home, began to use it during the course of the study.

In ICUs the situation was more complicated. In those sites recruited as LCP-using, the LCP was not always used. In the main this was because the speed of death was viewed as too quick to allow for the monitoring and assessment of the patient using the LCP documentation. In addition, there was evidence in the case note analysis that three of the sites in the north that had been recruited as non-LCP-using sites (NIB3, NIB4 and NIB5) had used the LCP to support care at the end of life.

The issue of recruiting sites was discussed at the advisory board meetings and with the Department of Health. Given the investment of time in recruiting sites and keeping them on board and the late stage at which some of these issues emerged, a decision was taken, supported by the project advisory board, that these sites should remain in the study. Tables 2 and 3 illustrate the matching characteristics of the samples recruited for nursing homes and ICUs, respectively.

| Geographical location | NH | CQCa rating | Number of beds | Care provided | Provider |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North-west | LCP using | 3 | 32 | Old age | Private |

| Non-LCP using | 2 | 38 | Old age | Private | |

| LCP using | 2 | 62 | Old age | Private | |

| Non-LCP using | 2 | 60 | Old age | Private | |

| LCP using | 3 | 32 | Old age | Private | |

| Non-LCP using | 3 | 32 | Old age | Private | |

| London and south-east | LCP using | 2 | 35 | Old age | Private |

| Non-LCP using | 2 | 30 | Old age | Private | |

| LCP using | 3 | 30 | Old age | Private | |

| Non-LCP using | 3 | 25 | Old age | Private | |

| LCP using | 2 | 37 | Old age | Private | |

| Non-LCP using | – | – | – | – |

| Geographical location | ICU | Maximum number of level 3 bedsa | 1 : 1 intensivist | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North-west | LCP using | 13 | Yes | General |

| Non-LCP using | 8b | Yes | General | |

| LCP using | 8 | Yes | General | |

| Non-LCP using | 8b | Yes | General | |

| LCP using | 6 | Yes | General | |

| Non-LCP using | 8b | Yes | General | |

| London and south-east | LCP using | 9 | Yes | General |

| Non-LCP using | 11 | Yes | General | |

| LCP using | 11 | Yes | General | |

| Non-LCP using | 11 | Yes | General | |

| LCP using | 6 | Yes | General | |

| Non-LCP using | 6 | Yes | General |

Recruitment of patients, relatives and staff

The process for the recruitment of individuals within participating sites was based on the principles of ‘informed’ and ‘process’ consent. In accordance with best practice,44 the research team sought consent each time data were collected from study participants. The study employed eight types of data collection, some of which were undertaken concurrently and alongside the recruitment of sites and study participants. The specific consent procedure is described within the relevant sections below.

Data collection

Level 1: background, contextual data about views, attitudes, and documented practices surrounding end-of-life care in each setting are explored through data types 1–3

Type 1: documentary analysis of Strategic Health Authority plans and organisational end-of-life care policies

Shortly after the commencement of this study, the SHAs were disbanded and responsibility for end-of-life care was transferred to PCTs and NHS regional offices. Therefore, the documentary analysis of these SHA plans that was originally planned to contextualise this study was refocused to include the collection of information about specific organisational policies and procedures that were expected to more directly underpin the delivery of care.

Key personnel in each site were asked to provide all available current policies, guidelines and frameworks that underpinned the delivery of care to dying patients in each of the sites recruited to the study. Copies were made, wherever possible, of the documentation made available to the researcher. These were then categorised and details entered into a database for ease of comparison of types of documentation available across sites. We had expected that this process would elicit a combination of standard organisational policies as well as locally derived documents. We had planned to analyse these documents in conjunction with the care that we observed and the interviews that were conducted.

As the collection of documents progressed across the sites, we were struck by the huge variation in the number of policies we were given per site, the nature of the policies and the dates of the policies we were handed.

In one site only one policy was provided; in another, 27 policies were provided. In general, ICU sites provided more policies than nursing homes. We are discounting the possibility that what we received was the sum total of their relevant policies in the majority of cases. The variability in what we were given makes interpretation difficult; however, there are a number of possible explanations. We have grouped these under three headings: irrelevance, ignorance and expediency.

-

Irrelevance: policies were not seen as relevant to care at the end of life. Practice was conveyed orally and its relationship to policy was historical.

-

Ignorance: although senior staff had been asked to identify and provide these policies, it is possible that staff were not aware of their existence.

-

Expediency: staff were reluctant to spend time thinking about the policies that might relate to end-of-life care and just gave us what was to hand.

Some or all of the above might have played a role in the variation. Given that protocols and policies pervade the provision of much of NHS care currently, this was perhaps a surprising finding. It raises a number of questions about the relevance of policies and their relationship to the care provided in the last hours or days of life. A more detailed analysis of these documents will be undertaken for journal publication. For this reason, the policy analysis will not be referred to again in this report.

Type 2: retrospective analysis of deaths in each location

The 23 case study sites were asked to provide a consecutive sample of 10 case notes for the most recent ‘expected’ deaths that had occurred in their site, in the 12 months prior to the site being recruited into the current study, wherever possible.

A data capture form was developed [case note analysis form (CNAF)], piloted and refined for use (see Appendices 12 and 13). Researchers also copied the last 24 hours of medication usage from the medication chart. A total of 110 CNAFs were completed for the 11 nursing homes and 120 CNAFs were completed for the 12 ICU sites. Wherever possible, these forms were completed during the early part of data collection in each of the sites. Their completion was time-consuming, but it meant that the researcher had a visible presence in these sites in order to enhance potential recruitment for the observational element.

Type 3: interviews with staff in each site (point 1)

Initially, semistructured interviews were planned with a maximum of six key clinical and (sometimes) administrative staff in each participating site. These are referred to as point 1 interviews throughout this report. Undertaking interviews with a range of staff within each participating site was an important way in which to both publicise and further embed the research study within the site, as well as to gain an important insight to the perspectives of a range of staff regarding the provision of end-of-life care in their site. This was a purposive sample to include, in ICUs, a senior doctor, a junior doctor, a senior nurse, a junior nurse, a health-care assistant and administrators. In nursing homes, the sample included managers, senior nurses, health care assistants and administrators. Members of staff were given written information about the study and a consent form (see Appendix 14) and were given a minimum of 24 hours to consider participation. In total, 138 interviews were undertaken across the 23 sites.

A topic guide (see Appendix 15) was used to draw out experiences of caring in general for patients/residents in the dying phase (last few days or hours of life).

The interviews were designed to ascertain:

-

how care of the dying was organised and managed in each location, including symptom control, ethical issues, spiritual and psychosocial care and relevant policies and documentation (including the use of documents other than the LCP, such as the GSF)

-

the barriers and levers for LCP implementation in those organisations using the LCP

-

how staff felt about care at the end of life, both in general and with respect to the organisation in which they worked

-

how staff defined and assessed the dying phase

-

how patients’ needs and preferences were assessed

-

how relatives were involved in the care of a dying patient

-

the extent and type of training in end-of-life care that was available/had been received.

It is important to note, however, that this was a topic guide rather than a set of questions and interviewees were encouraged to raise and explore any issues that were pertinent to their own experience. All interviews were recorded (with the permission of the participant) and transcribed verbatim before being analysed.

Level 2: case study approach, centred on the observations of patients to allow a detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events from a variety of relevant perspectives, explored through data types 4–8

The following five ‘types’ of data are all inter-related and driven by the observations of care in the last hours or days of life. The central component of this study was the collection of observational data, alongside the accounts of staff who had delivered care during the observed period, the case notes reporting the care provided and the views of bereaved relatives about the care during the observed period.

Type 4: observations of care in the last hours or days of life

The use of the observational method with ‘vulnerable’ groups, including people who are dying, is not unprecedented. 44–47 Lawton suggests that observational methods enable the researcher to keep the focus on the dying patients, eliciting important data without the need to involve them in long-winded and potentially tiring and distressing interviews. 44 Indeed, many patients who are in the final hours or days of life may be comatose and unable to participate in research that requires their active participation. In this study, ‘overt non-participant observation’ was undertaken of the care provided by staff and relatives to patients in the last hours or days of their lives.

The role of the researcher was designed as the ‘complete observer’ during the observations. 48 Although it was the intention that the research team should have minimal impact on the care being received and provided, there was an agreement that should any suboptimal care be observed the researcher would intervene according to an agreed process (see Appendix 16). This issue is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

The purpose of the observations was to record the nature and content of interactions between patients, relatives and staff, including the administration of nursing care, drugs, fluid and food as well as their withdrawal. The intention was for the researcher to observe for periods of up to 4 hours at a time, which would enable them to take breaks away from the bedside. Observations took place at all times of the day and night. For this reason, a lone worker policy (Fieldwork Code of Practice) was followed to ensure the safety of researchers (see Appendix 17).

Recording observational notes

A range of observational recording techniques were considered initially for use in this study, including the grid technique (noting down whether or not pre-defined tasks/interventions took place); focused observation (noting down not only whether or not something happens but how it happens and the consequences)49,50 and the contemporaneous narrative method (a non-predetermined approach that involves noting all interventions and interactions relating to care as they occur). The third method was chosen, as it offered the most open, flexible and comprehensive approach to data collection.

The times and duration of events such as nurse, doctor, family and friend visits to the bedside were recorded in the observations alongside the handwritten narrative. Researchers adopted similar approaches to the recording of aspects of the environment, for example whether it was quiet or noisy, lighting and smells, as well as their own thoughts and feelings about the events they were observing. Diagrams of the setting proved to be a useful way of creating a visual representation of the context for ‘thick rich description’ (p. 437). 51

Where possible, following Hammersley and Atkinson,52 the researchers noted their impression of what was actually said by participants in the observations as the events were unfolding. All handwritten observational notes were typed up by a clerical member of the research team for the purposes of analysis.

Recruitment of patients/residents to the observational component

It was expected that the physical health of many patients potentially eligible for inclusion in this study (due to their proximity to death) would prevent them from being able to comprehend information sheets or to provide either verbal or written informed consent. Where this was the case, the consenting procedures were designed to conform to the Mental Capacity Act53 guidance on involving people who lack capacity in research.

The Mental Capacity Act53 recognises the importance of undertaking research to gain knowledge of the care of people who lack capacity, as well as the need to protect their interests and safety, and it contains provisions for the authorisation and regulation of research involving people who lack capacity to consent to taking part in a research study. The Mental Capacity Act53 sets out a clear single test for assessing whether or not a person lacks capacity to take a particular decision at a particular time. It is, therefore, a decision-specific test. An individual cannot be labelled as incapable purely on the basis of a particular medical condition or diagnosis. Section 2 of the Act also warns against making unjustified assumptions about capacity on any grounds but makes particular mention of age, appearance and behaviour.

In those circumstances in which a patient lacks capacity, the Act53 identifies the appointment of a consultee. This is defined as a person who knows the potential particpant and who must be consulted about whether or not it is appropriate to involve the person lacking capacity in the research. In these circumstances, the Act suggests that the researcher must take reasonable steps to identify someone who is engaged in caring for the person who lacks capacity (not in a professional capacity nor for remuneration) or who takes an interest in a person’s welfare and who is willing to be the consultee. It is recognised that the consultee is likely to be a family member or an attorney acting under a lasting power of attorney. For instances where the researcher is unable to find a carer willing to be a consultee, the Secretary of State has issued guidance on nominating an individual. In some cases an Independent Mental Health Capacity Advocate (IMCA) may be the most appropriate person.

The expectation was that the majority of patients would be deemed not to have capacity to provide informed consent to participate in this study; however, at an individual level, a lack of capacity was not presumed to exist. Researchers were required to establish, through consultation with staff and relatives, the patient’s level of consciousness and capacity to make a decision about research participation and to identify the most appropriate person to act as a consultee.

Consent process for observations

Appendix 7 provides a flow diagram to explain the complex process for gaining consent for the observational element of this study. Once a site had agreed to participate in the study, a number of strategies were adopted to ‘publicise’ the research to staff, patients and relatives in advance of asking for any individual’s participation. Information sheets based on generic information about the study (see Appendix 18) and adapted for local use were displayed and made available in accordance with local policy and procedure. These information sheets provided contact details of the researcher should anyone require further information about the study. Background information about the research was provided in this way to give relatives time to think about the research, raise issues and discuss it in less pressurised circumstances.

In the majority of cases, recruitment and consent followed a call from staff to say that a patient in an ICU or a resident in a nursing home was identified by the multidisciplinary health-care team as entering the dying phase. Accurately predicting dying is difficult and this is discussed in more detail in the findings, for example in Chapter 5 (see Physical decline and prognostication), Chapter 9 (see Narratives drawing on clinical data to justify a transition from cure to palliation), Chapter 10 (see The meaning of withdrawal) and Chapter 12 (see The Liverpool Care Pathway and withdrawal). For the purposes of this study, in LCP-using sites, a decision to commence an LCP to support the patient’s care was taken as an identification by the clinical team that a person was thought to be imminently dying. In non-LCP-using sites, the clinical team was able to identify deterioration in the person’s condition which suggested that his or her death was imminent. Once a judgement had been reached that a patient was likely to be in the last hours or days of life, and this understanding had been shared with the patient and/or their relative or consultee, a senior member of staff would ask the patient and/or their relative if they would be willing to talk to a researcher about the end-of-life care study. The decision regarding when and how to recruit the patient and/or relative was made by the staff member most closely involved with the patient’s care. If there was agreement to meet the researcher at this time, the member of staff contacted the researcher, who then travelled to the site.

When the researcher arrived at the site, the first task was to establish whether or not the staff on duty had any reservations about the research and if any member of staff currently involved in the care of the patient did not wish to be involved in the study. The next step was to ascertain the patient’s level of capacity to make a decision regarding participation and the arrangements that had been made for decision-making in the absence of patient capacity. Among the 25 patients enrolled in this study, there were only two instances, both in nursing homes, where the patient was conscious and capable of giving informed consent.

The researcher then approached the patient (where applicable) or designated patient consultee (most often a family member) to discuss the study and give written information and consent forms (see Appendices 19 and 20). Relatives were asked to take as much time as they needed before making their decision known to the researcher.

Where a patient was deemed to lack capacity, the consultee was asked to make two decisions. First, they were asked to decide whether or not the patient would have been likely to agree to take part in the study had they had capacity to make this decision. If the consultee decided that this would have been the case, they were asked to sign a consultee consent form to confirm this (see Appendix 20). Second, they were asked to decide whether or not they themselves were happy to participate in the study and, if this was the case, to sign a second consent form (see Appendix 21). Staff were also given information leaflets and asked to provide informed consent for the observation of their care at the bedside and for being approached to undertake an interview about the observation at a later date, if appropriate (see Appendix 22).

Observation in the vicinity of other patients or residents

In nursing homes there were occasions on which residents had been sharing a room with another resident for a period of time prior to the deterioration in their health. Consequently, care at the end of life was often provided in the presence of another resident. A number of strategies were operated by staff to minimise the distress to the co-resident, including the use of screens and curtains and taking the co-resident to the day room for periods of time during the day. When this situation occurred during an observation, the researcher always introduced herself to the co-resident and any relatives present, explained her role as a researcher and summarised the research. On the four occasions when this scenario occurred, verbal consent was obtained.

It was customary in ICUs for curtains to be drawn around the patient’s bedside at the end of life. Relatives and researchers were contained within this bounded world, which gave little or no access to the care provided to other patients in neighbouring beds.

Absence of relatives

The research team had anticipated that there would be instances in which dying patients were not conscious and did not have relatives or family members who were able to act as consultees and give consent for an observation. In fact, this occurred in two cases in this study. In one case an ICU patient received visits only from a neighbour. The staff reported that the patient had no other contactable family or friends. The consultant discussed the withdrawal of the patient’s treatment with the neighbour. The consultant also asked the neighbour if she would be willing to talk to the researcher about the research. The researcher explained the research to the neighbour; the neighbour was then asked if she thought, knowing all she knew about him, that the patient would have been likely to consent to taking part in the research had he been conscious. The neighbour hesitated and asked the consultant’s opinion. As a result of the consultant’s answer the neighbour reported that the patient could be enrolled in the study. However, on reflection, the neighbour later withdrew her consent to the observation. She reported feeling overwhelmed by all the decisions she was being asked to make and reiterated her status as the patient’s neighbour and not a family member or close friend. She reported feeling that ‘agreeing’ to the withdrawal, and then also to the observation, was too much responsibility for her as a neighbour.

In another example, where the patient had no relatives or friends, the staff contacted an IMCA as they wanted to involve an IMCA in their medical decision-making. Unfortunately, the IMCA representative was unable to visit the ICU for at least 48 hours. The IMCA consulted the patient’s GP by telephone and faxed a report through to the ICU regarding the patient’s attitude to life. The consultants agreed that the patient was dying, that it was not in the ‘best interests’ of the patient to continue treatment and that as far as the IMCA, via the GP, was concerned, he would not want to be kept alive with a poor quality of life. The plan was, therefore, to withdraw treatment.

The researcher discussed the patient’s participation in the study with the IMCA over the telephone. The IMCA was supportive of the research and could not see any reason why the patient might not want to take part. The IMCA agreed over the telephone to the enrolment of the patient into the study, and a member of the clinical staff witnessed this telephone call. However, when the researcher asked the IMCA if she would sign a form confirming the enrolment, the IMCA reported that she would have to check with her manager. After a number of e-mails and telephone calls, the agency providing IMCA support to this ICU reported that they had not been commissioned by the PCT to provide IMCA support for anything other than clinical care. They were, therefore, not willing to provide signed confirmation of what had previously been agreed verbally in relation to this patient. As a consequence, the patient was not enrolled in the study.

Process consent during the observations

Process consent44 or ongoing consent was established to ensure that participants (relatives and staff) were content to continue participating in the research study in the last hours or days of the dying person’s life. This required great sensitivity, with a balance needing to be struck between checking and assuming that continued participation was acceptable. As has been noted in the literature,44,45 deciding when and how often to ask respondents directly if they want to continue participating is a judgement call. The most natural point in the observations for researchers to check consent arose when the researcher took a break, roughly every 3 or 4 hours. In addition, when any ‘new’ people (relatives, friends, staff) entered the bed space, the researcher would, wherever possible, find a suitable time to speak to that person to ensure that they were content with the researcher’s presence. The researcher would also check intermittently that those present were happy for her to continue to be at the bedside, particularly when intimate care was being given to the patient. The experience of being observed was explored with relatives and staff in the interviews following the patient’s death.

Rate of patient/relative recruitment

Based on the likely numbers of ‘expected’ deaths in the ICU and nursing home settings each month, and factoring in the possibility that there would be a low uptake by patients and relatives for the research, a ‘notional target’ was set of up to five observations in each ICU (n = 60) and up to two observations in each nursing home (n = 24) for the proposed data collection period.

A total of 25 observations were undertaken in the period between November 2011 and May 2013. Although it is not possible to identify absolutely all of the reasons that the target number of observations was not reached, several contributory factors are offered in explanation.

First, the project suffered a series of delays. The loss of one researcher for personal reasons and the organisation of her replacement created a 4-month gap during which only very limited contact with sites in London and the south-east was maintained. In addition, a substantial amount of work was required within each site before any data collection could begin. Gaining R&D approval within sites, particularly in the ICU settings, was slow, with different sites requiring different documentation and contact with different members of staff. Although it was essential to contact and provide study information to as close to a majority of staff in each site as possible, this was also time-consuming. Delays in achieving organisational consent to take part in the research meant that the first observation did not take place until December 2011. The data collection period was extended until May 2013 in an attempt to maximise the number of observations. Clearly, this then had an impact on the time that was available to undertake analysis and report on the data.

Second, the recruitment of patients and relatives was complex. Appendix 23 provides a log of referrals that were made to the researchers but, for a variety of reasons, did not result in observations. These reasons included patients dying unexpectedly quickly, staff–relative disputes, patients not meeting the strict inclusion criteria and researcher issues such as a researcher being contacted about a possible observation while he or she was undertaking an observation at another site. In only 25 instances, however, did a patient’s family decline to participate in the study.

Third, over the course of the project there was a marked decline in the willingness of staff to identify patients for inclusion in the study, and also in the willingness of consultees to give consent for participation. Interestingly, 14 of the 25 relatives who declined to enter the study (56%) did so between November 2012 and May 2013. This coincided with a period of intense negative media publicity about the LCP, which gained momentum after November 2012 when an independent review was announced. 40 Sites became unwilling to publicise their use of the LCP. In one site the LCP was renamed as ‘palliative care guidelines’ requiring the research documentation to be amended and resubmitted for ethics approval (see Appendix 24).

Strategies to increase the recruitment of patients and relatives

A number of strategies were implemented to attempt to improve recruitment. Two additional researchers were employed to support the collection of data. These researchers undertook point 1 interviews with staff and collected retrospective case note analysis data. Importantly, they also made frequent telephone calls to each site (sometimes daily and sometimes twice weekly, but at least once a week) to ascertain whether or not there were patients who might be eligible for inclusion in the study. In addition, one of the lead researchers visited the sites to promote the importance of the study and to ascertain whether or not there were any specific barriers to the recruitment of patients and relatives. This ‘supplementary’ activity meant that the primary researchers could concentrate their time on carrying out observations, staff point 2 interviews and bereaved relative interviews. However, despite this increased level of activity, only seven new patients were enrolled into the study between November 2012 and May 2013 (a rate of one per month on average, compared with a rate of 1.6 per month in the preceding 11 months of data collection).

Type 5: interviews with staff following a period of observation

Interviews with staff following the patient’s death formed an important aspect of understanding the care that was observed to have taken place during the observation. These interviews, referred to as point 2 interviews in this report, were conducted with one of the nurses who was most involved in the care of the patient during the observation period. The purpose of these interviews was to explore with staff the care that was delivered (see Appendix 25). Potential staff interviewees received information about the data collection methods at several stages: before, during and after the observation (see Appendices 22 and 26). The aim was to conduct the interview as soon after the patient’s death as was possible. In some cases, interviews took place at the end of the nurse’s shift; in other cases, the interview was conducted the following day. In exceptional circumstances where the staff member had days off after the patient’s death, the interview was arranged at the earliest opportunity. Written consent was recorded for all interviews, which were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Twenty-five staff interviews were undertaken. One interviewee subsequently withdrew consent, because on reflection they felt uncomfortable about the interview being recorded, but another staff member who had also been observed providing care to the same patient agreed to undertake an interview.

Type 6: case note analysis

The third element in the collection of data to support the observations involved the analysis of the patient’s case notes recorded during the observed period. The structured pro forma (see Appendix 7) developed for the retrospective case note analysis was used to extract data in a systematic way. The case notes of the 25 patients whose deaths were observed were examined in this way.

Type 7: interviews with bereaved relatives

The final element in the triangulation of data around the patient’s death was the perspective of relatives present during the observation. The importance of the views of bereaved relatives about care that was provided is reported in the literature. 54 These interviews were designed to elicit information from the relatives about the care that was provided in the last days and hours of life (see Appendix 27). They were not designed to provide proxy data about how the patient might have felt about the quality and timing of care received.

The timing of the interviews with bereaved relatives was important. Ethical concerns about intruding on grieving relatives too soon after the patient’s death needed to be balanced with facilitating recall. The literature suggests that interviews should be conducted 5–6 months following the death of a relative. In this study we allowed relatives to identify the time frame with which they were most comfortable. Relatives received information about the proposed interviews as part of the written information given to them when they initially consented to take part in the study (i.e. prior to the period of observation). At this time they were asked merely to confirm that they would be happy to be approached after the death of the patient to consider participation in an interview (see Appendix 21). They were also asked at this time how soon after the death they were willing to be approached or if they would prefer to contact the researcher themselves when they felt ready to do so. If they did not specify a time for approach at this point, it was agreed that the researcher would contact them no sooner than 1 month after the patient had died to seek their consent for interview. One month was chosen as the time point because this would generally have allowed enough time for patient’s funeral to take place, but was still soon enough after the death to optimise the level of recall. When the researcher telephoned or contacted the relative in accordance with their wishes arrangements were made for the interview. Relatives who gave consent to participate in this interview (n = 22) elected to be interviewed at time points ranging from 38 days to 148 days after the patient’s death. The majority of relatives elected to be interviewed between 2 and 3 months after the death.

Type 8: economic analysis

The economic element to this study was based on a comparative study design examining the benefits and costs associated with care using the LCP as opposed to care without the LCP. This element of the study, including the specific methodology used, is presented in Chapter 13.

Approaches to data analysis

A multistage approach was adopted for the analysis of data.

-

A preliminary analysis of data was conducted as the data were collected.

-

Data from the case notes were analysed in nursing homes thematically, and in ICUs a discourse analytic approach was applied.

-

Data from the point 1 interviews with managerial and senior nurses were analysed to achieve an organisational perspective within sites as well as across sites.

-

Data from the observations of care provided at the end of life were analysed and then cross-checked with data from the case notes and the interviews (staff point 2 and bereaved relative).

-

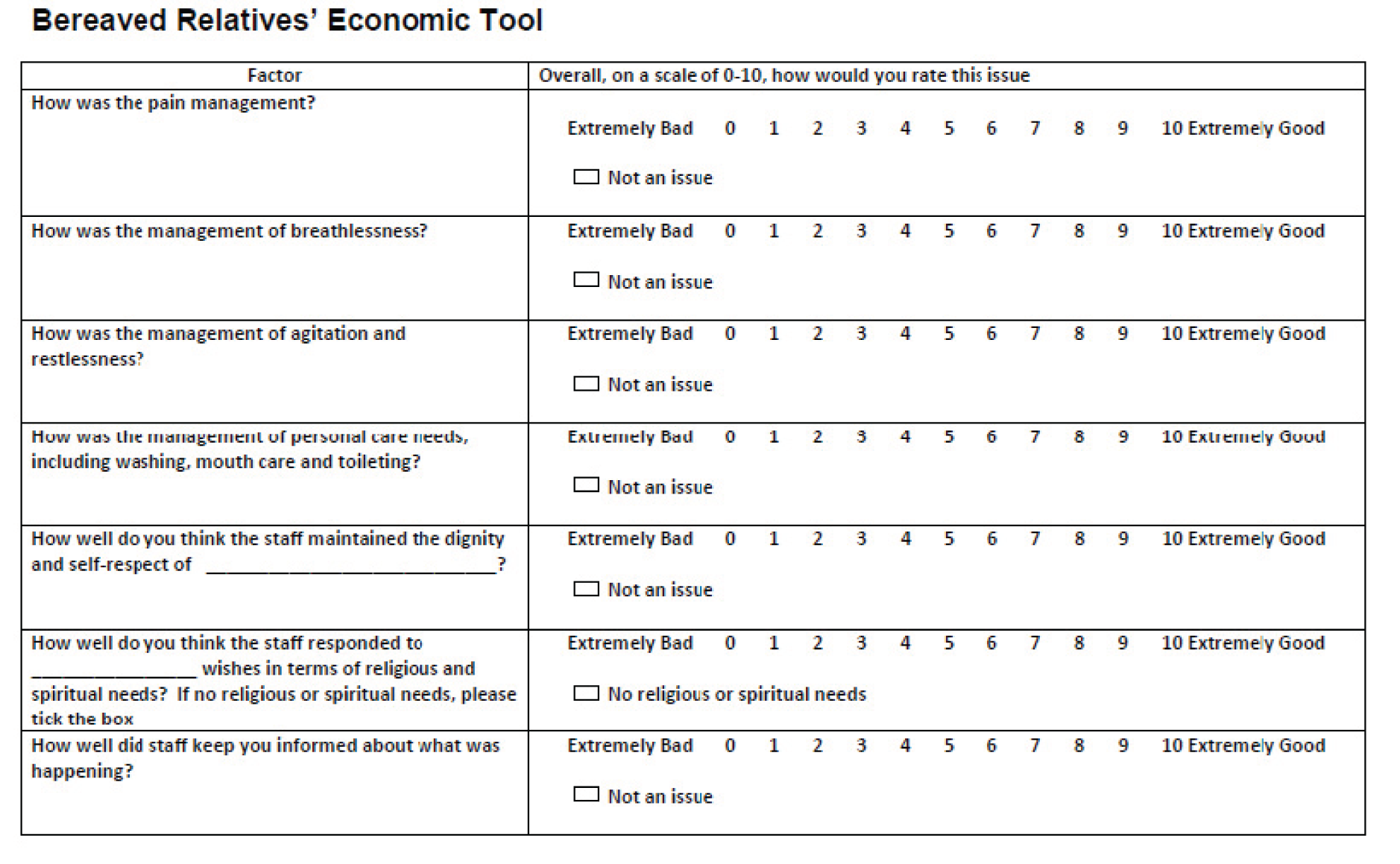

Economic analysis was applied to the observed deaths using the observation notes and the relative’s responses to the Bereaved Relative Economic Tool.

Analysis of case-note data

Initially, for each of the case notes from each site (n = 230) relevant patient demographic data were extracted, including age; gender; religion; ethnicity; diagnosis; time from admission to death; time from recognition of dying phase to death; preferred place of care; do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) recorded; and presence or absence of LCP to support care. This enabled a broad, descriptive overview to be constructed and a comparison of the sample on key variables in terms of whether or not the LCP had been used to support care.

A more in-depth analysis of a proportion of nursing home and ICU case-note data was undertaken by HC, EP and MG. It had originally been planned to undertake a discourse analytical approach to these case-note data in each of the settings. Critical discourse analysis55 considers ‘language as social practice’ and acknowledges the importance of the context of language use. 56 The analysis presented centres specifically on the recorded communication between staff and family members regarding the plan of care for patients in the last days of life. However, as a result of major differences in the nature and depth of data recorded, including that pertaining to communication between staff and relatives, this was not possible in the nursing home sites, and a thematic approach to the analysis was adopted in this setting.

Analysis of observations and interviews