Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/114/37. The contractual start date was in May 2015. The final report began editorial review in March 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Morrissey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

People with intellectual and other types of developmental disabilities (IDD), such as autistic spectrum conditions, can face challenges with both adaptive behaviour and general intellectual functioning. As long-stay hospitals for those with IDD were closed from the 1980s onwards, forensic mental health services specifically for those with IDD have increased. These hospital services cater either for people with IDD who have committed criminal acts and are detained under Part III of the Mental Health Act,1 or for those under civil sections whose violent or other challenging behaviour cannot be safely managed in the community. Typically, such patients present with a high level of clinical complexity.

A mapping exercise in 20122 indicated that in the combined NHS and independent sector there were 2393 high, medium and low secure funded beds in 10 strategic health authorities in England, with further access to locked and unlocked forensic rehabilitation beds. In addition, a number of specialised community IDD services provide for those with a forensic history. Inpatient secure beds in particular are high cost, and this is therefore a sector that involves high levels of health expenditure (estimated in 2012 to be £350–430M a year).

Within what we shall henceforth label as the forensic intellectual and developmental disabilities (FIDD) sector, it is notable that there is limited cross-service collation of empirical information on treatment and service outcomes, which in turn limits the ability to measure service effectiveness. 2 This area of service delivery is particularly pertinent in the context of the Department of Health’s Transforming Care programme,3 which aims to move care for people with IDD – including those who have offended – from hospitals to the community with the ultimate aim of closing many hospital beds (indeed, occupied secure beds have already reduced compared with 2012 figures). 3 There is a need to be able to accurately describe the outcomes nationally both for people treated within FIDD services and, in the longer term, those who are discharged from FIDD services, but this is not currently undertaken in a systematic way.

The Clinical Research Group in FIDD funded by the then Mental Health Research Network branch of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), which included the authors, considered the research needs in this area in 2013. As a starting point, we know that there are no agreed areas of outcome domains or routine measures employed in this sector. No systematic review has been published in relation to outcomes or outcome measures from such services and, therefore, little is known about the commonality of outcome measures across services. Neither outcome measures developed for mainstream mental health services (explored in a systematic review by Gilbody et al. )4 nor those developed for mainstream forensic services (identified in a systematic review by Fitzpatrick et al. ,5 are necessarily appropriate for FIDD services. The current project therefore aimed to begin to address this existing gap in knowledge by conducting a preliminary study suitable for informing a future primary research project on FIDD service outcomes.

Research group

The research steering group comprised academic and clinical experts in the FIDD field, a systematic review expert, a methodology expert and an ‘expert by experience’ (see Acknowledgements). The group met for two full-day meetings during the project.

Aims of the research

The aims of the research were:

-

To systematically review empirical studies that relate to short- and long-term outcomes from FIDD services including secure, forensic rehabilitation and community forensic services. The review aimed specifically to synthesise the range of outcome domains studied and to identify specific measures that have been employed.

-

To consult a group of FIDD patients/carers regarding the outcome domains of most relevance to these groups of stakeholders.

-

To obtain consensus on appropriate outcome domains and measures for FIDD services based on the expert opinions of professionals and providers.

-

To synthesise the findings and develop a framework of outcomes in order to inform a large-scale primary research project.

Overview of design

The preliminary study needed to examine the evidence from a range of perspectives and, therefore, three stages were planned. The first study was a systematic review and evidence synthesis of outcome domains and measures as found within the FIDD literature. The second was a consultation exercise with FIDD patients and carers and the third was a clinician and expert modified Delphi consensus exercise. The planned timescale of the research was short: May 2015 to February 2016.

This report

This report is divided into four further substantive chapters. Chapter 2 summarises the systematic review and evidence synthesis, which addresses aim 1. Chapter 3 describes the patient and carer consultation, which addresses aim 2. Chapter 4 describes the Delphi study of clinicians, which addresses aim 3. Chapter 5 synthesises the studies and describes the direction for further research and evaluation of services.

Note on terminology

In this report ‘outcome domains’ or ‘subdomains’ refer to specific areas of outcome. These are distinct from outcome ‘measurements/indices’, which refer to how these domains are indexed or measured. Thus, for example, within the patient experience superordinate domain, patient satisfaction would be an outcome subdomain and a patient satisfaction rating scale assessment would be an outcome measure for that domain, whereas the percentage of patients ‘very satisfied’ might be a specific indicator.

Chapter 2 Stage 1: systematic literature review of outcome domains researched in forensic intellectual/developmental disabilities services

Research questions/objectives of the review

The objective of the current review was to identify quantitative studies that examined either short- or long-term outcomes from FIDD service-level treatment. The review sought specifically to identify and categorise the range and type of outcome domains examined in the literature as well as the outcome measures and indicators used to measure these domains. The findings from the studies themselves were therefore not of direct relevance to this review.

Review methods

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to identify studies from a range of sources. Reports were included regardless of publication status. Searches were conducted on 1 June 2015. The electronic databases searched were MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Allied and Complementary Medicine, Health Management Information Consortium, the British Nursing Index and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature from inception to May 2015. A broad search strategy was employed, with intellectual disability terms being combined with forensic terms. For terms specific to intellectual and developmental disabilities, search terms employed were based on those used for a previous Cochrane review. 6 Forensic and offender terms search terms were adapted from a large review for the Department of Health by Duggan et al. 7 The full search terms including ‘explode’ terms, keywords and text words are in Appendix 1.

In addition, the grey literature (opengrey.eu) was searched online on the same date using the same keywords. References of suitable studies were examined to identify additional relevant articles. Finally, expert members of the project steering group were consulted in order to identify any key references not retrieved by the search strategy or in press or unpublished articles and service evaluation reports.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Scope

The search related to studies worldwide written in any language. When studies were written in languages other than English, translations were obtained. The search was limited to studies from 1980 onwards, as provision for FIDD patients was either sparse or non-existent prior to this date.

Types of studies

We included any study design, including those at the lower levels of the hierarchy of evidence. Owing to the likely paucity of randomised or controlled studies, the search strategy was designed to capture two primary types of quantitative study:

-

Cohort studies with follow-up. These are studies that report outcomes of intervention at the whole service level from one point in treatment to another (e.g. from admission to present; from admission to discharge) or post discharge, with any length of follow-up.

-

Cross-sectional studies. We also aimed to include cross-sectional studies that reported outcomes either at a single point or for a defined period of time during FIDD service intervention. While the primary goal of such studies is not necessarily to evaluate outcomes from services, studies were included provided they presented data on potential measures or indicators of outcomes. For example, the purpose of the study might be prediction of risk, but outcome data pertaining to ‘incidents of aggression’ in the service may be presented: this was considered to be a potential outcome domain/indicator. This type of study was included within the review for two reasons. First, the aim of the review was to identify outcome domains and outcome indicators appropriate for measuring the effectiveness of FIDD services; the cross-sectional studies provided important information in this regard. Second, FIDD services often provide long-term treatment and, therefore, what happens to patients during treatment and prior to discharge can also be considered an indicator of effectiveness.

Participants and settings

The search strategy sought to capture studies that included data on adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities who had current or previous access to specialist FIDD services. Both male and female samples, with a range of offending histories, were included. High-, medium- and low secure inpatient forensic health services, forensic rehabilitation services (service categories 1 and 4 as defined by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, 20132) and community FIDD services were all included. Studies of prison and youth offending services were not considered for this review, as services specifically for people with IDD tend not to exist in these settings. Studies of mixed FIDD and non-FIDD populations were included provided the FIDD data were identifiable.

Intervention

The intervention of interest was at the whole service level, that is, the effect that being treated in the service as a whole has on patients’ outcomes and how that is measured. Studies that evaluated the effects of specific interventions (e.g. sex offender treatment) were excluded. The outcome domains and indicators/measures of such domains were of primary interest, as opposed to the findings of the studies.

Outcomes

There are as yet no agreed outcome measures for use in FIDD services, which was a primary driver for the review. Therefore, inclusive criteria regarding the types of outcomes of interest were adopted. Outcomes were nevertheless broadly conceptualised as falling into the following three overarching domains, reflecting the three key quality areas outlined by the Department of Health in the first NHS Outcomes Framework. 8

Effectiveness

This domain was conceptualised to include any factors that related to the impact of FIDD service-level treatment on the patient, in both the long and short term.

Patient safety

In the current context, the patient safety domain was conceptualised to include outcomes related to avoidable harm such as the extent of restrictive practices in services, and patient injury or death.

Patient experience

This domain was conceptualised to include any factors that related to the patient experience of care, such as patient quality of life, patient satisfaction, etc.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Appendix 2.

Study selection

After removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts of articles were screened against the inclusion criteria. In order to avoid false negatives, all studies that could not be shown to be outside the inclusion criteria were initially included. The full texts of the remaining articles were screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria in order to identify appropriate articles for the review. Two reviewers (CM and NG) independently rated each article using a screening tool developed for the purposes of the study (see Appendix 3). Any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (MF).

Data extraction

The articles were subjected to data extraction using a structured form (see Appendix 3). Details regarding the sample, design, service type, methods, outcome domains and related measures were obtained, coded and reported. The information is presented in the form of data summary tables (see Tables 1–6).

Hierarchy of evidence

On the advice of the systematic review consultant on the project, it was decided a priori that no structured quality assessment was to be undertaken. This decision was taken for a number of reasons. First, as noted above, the aim of the current review was to identify the range and type of outcome domains and related measures that have been used in FIDD services research. Its purpose was not to critique the methodology of the studies or to draw robust conclusions about the findings. Furthermore, it was recognised the studies were likely to be heterogeneous and there would be no single quality assessment tool that would be appropriate for included studies. Quality or risk-of-bias ratings would not have influenced the inclusion of studies as, arguably, a poor-quality study could nevertheless have presented outcome domains of interest for the review. We therefore decided simply to code study design using a hierarchy of evidence. The York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination hierarchy of evidence was considered, but it was found that included studies were difficult to classify using that hierarchy. Instead, study designs were coded with reference to the simpler hierarchy of evidence employed by Greenhalgh9 as follows:

-

systematic reviews and meta-analyses

-

randomised controlled trials with definitive results

-

randomised controlled trials with non-definitive results

-

cohort studies (follow participants over time)

-

case–control studies (matched control group)

-

cross-sectional surveys

-

case reports or case series.

Analysis

The broad inclusion criteria applied for the review meant that the included studies represented a wide variety of services, study designs, outcome domains and measures. A method of content analysis10 was used to synthesise the outcome domain types and related measures and indicators. This approach involved an iterative process of identifying categories to capture the outcome measures reported in the studies. Using the aforementioned three core outcome domains (effectiveness, patient safety and patient experience) as an a priori superordinate framework, the outcome measures from all included studies were listed. A process of refining and grouping similar subdomains together was then undertaken. This led to the construction of a ‘framework’ to describe the outcome domains that have been studied in the literature. The number of studies falling into each final outcome domain was also quantified.

Results of the review

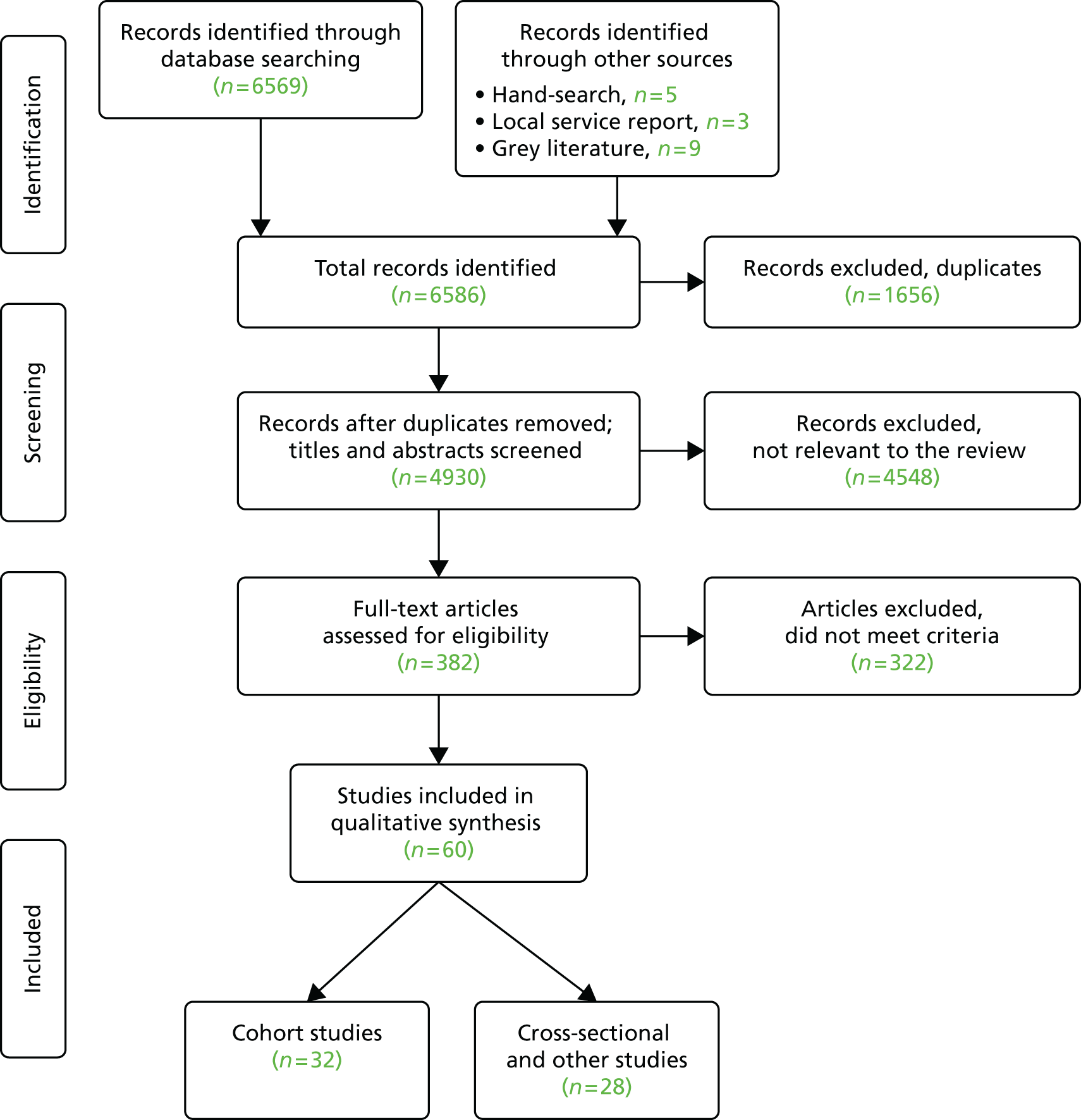

Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the study selection process and details number of studies identified at each stage. A list of the 322 excluded studies is available on request from the authors.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of study selection process.

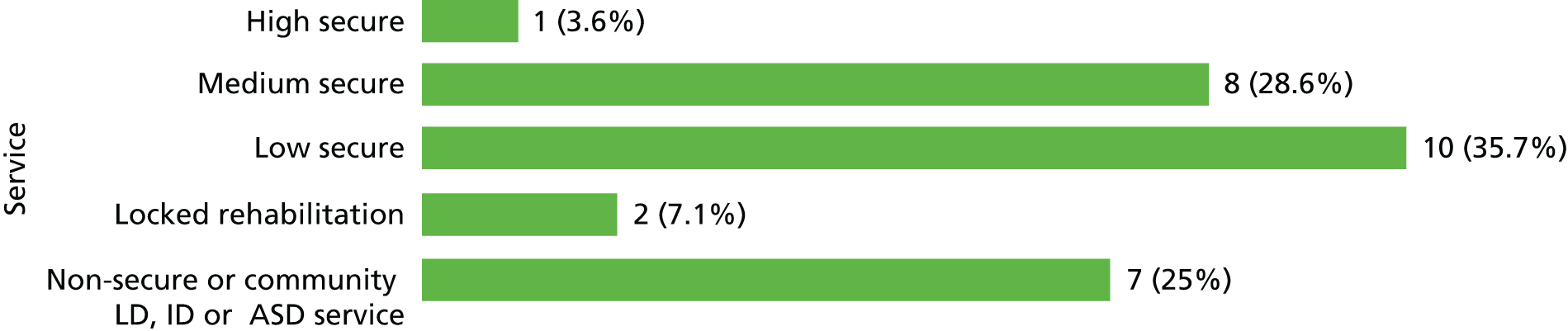

Sixty studies met the inclusion criteria; of these, 28 were cohort outcome studies (type 4) as described (with follow-up from 1 to 20 years) and a further 32 were other study designs. These were primarily cross-sectional studies (type 6) which reported service-level outcome data at one time point, with a small number of case–control and case series designs. Some of these included studies reported overlapping samples. Only two studies were from outside the UK. Most studies were of predominantly male or male-only samples; only two studies reported exclusively on female FIDD samples. Of the 60 included studies, 83% were conducted in a variety of secure inpatient settings, and 17% in community settings. The numbers of participants ranged from 10 to 1891.

Tables 1–6 display the included studies. As the cohort studies are the more ‘prototypical’ studies of outcome, these are tabled separately. Thus, Tables 1–3 show the cohort studies and Tables 4–6 show cross-sectional and other studies in each of the three superordinate domains of effectiveness, safety and patient experience, respectively. Tables 1 and 2 cover the effectiveness studies, Tables 3 and 4 cover safety studies and Tables 5 and 6 cover patient experience studies. Studies can therefore appear in more than one table. The tables present data for each study: study setting; design and the hierarchy of evidence code (1–7; see p. 16); subdomains of outcomes examined in the study, and the indicators or measures used to measure these subdomains.

| Study and setting | Design (hierarchy of evidence code, p. 18) | n | Outcome subdomain | Measure/indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander et al. (2006) 11 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 64 | Treatment response | Level of CPA support, MHA status and CGIS |

| Medium secure | Follow-up: up to 13 years | Discharge outcome/pathway | Level security/type of placement at discharge | |

| Readmissions | % of patients readmitted to the same unit | |||

| Relapse in MH | % of patients who experienced a relapse in MH symptoms | |||

| Reoffending | Number of patients formally reconvicted, cautioned or who had police contact | |||

| Offender-like behaviour | Behaviour that could be classed as an offence but did not lead to police contact | |||

| Alexander et al. (2010) 12 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 138 | Length of stay | Mean and median number of days |

| Medium secure | Discharged patients Follow-up: 6 years |

Discharge outcome | % of positive (move to a lower level of security) or negative (move to higher level of security) discharges | |

| Discharge pathway | Level security/type of placement at discharge | |||

| Alexander et al. (2011) 13 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 138 | Length of stay | Mean and median number of days |

| Medium secure | Follow-up: 6 years | Discharge outcome | % discharged successfully (to a lower level of security) or not (to same/higher level of security) | |

| Alexander et al. (2015) 14 | Retrospective cohort study (4) (arson vs. no arson) |

30 | Length of stay | Discharged patients only; mean and median days |

| Medium secure | Follow-up: 6 years | Discharge pathway | % of discharged patients who moved to either a lower or same/higher level of security | |

| Alexander et al. (2012) 15 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 145 | Length of stay | Median number of days and age on discharge |

| Medium secure | Discharged patient (personality disorder vs. intellectual disabilities) | Clinical symptoms | PCL-SV pre-treatment scores (clinician rated) | |

| Risk assessment | HCR-20 pre-treatment scores (clinician rated) | |||

| Follow-up: up to 9 years | Reoffending | Reconvictions at 1-, 2- and 5-year follow-up. Categorised as serious/violent offending (as defined by Home Office) | ||

| Time to reoffend | The difference between discharge date and reconviction date for subsequent offence (median) | |||

|

Ayres and Roy (2009)

16

Community |

Case series (7) Follow-up: up to 3 years |

26 | Cost | Average cost saving per patient (based on hourly rate of support) and for the service over 3 years |

| Level of support | Hours per annum providing both direct/indirect support | |||

| Barron et al. (2004) 17 | Cohort study (4) | 61 | Clinical symptoms | ABC and Mini PAS-ADD (clinician rated) |

| Community | Follow-up: 9.5 months average | Treatment response | Categorised treatment use and % with history of service use | |

| Reoffending | Number of patients who reoffended; mean number of offences per patient | |||

| Offender-like behaviour | Telephone call with carers regarding police contact | |||

| Benton and Roy (2008) 18 | Cohort study (4) | 113 | Reoffending | Number of patients arrested and reconvicted and cases dropped |

| Community | Follow-up: up to 3 years | Discharge pathway | Level security/type of placement at discharge | |

| Discharge outcome | % of referrals discharged | |||

| Prevention of inpatient admissions | Number of patients whose inpatient admission was prevented by community treatment | |||

| Butwell et al. (2000) 19 | Cohort study (4) | Up to 278 | Length of stay | Median and mean years, calculated per episode |

| High secure | Follow-up: 10 years | Discharge pathway | Level security/type of placement at discharge | |

| Day (1988) 20 | Cohort study (4) | 20 | Length of stay | Mean number of months |

| Medium secure | Follow-up: 3 years | Treatment response | Categorised as either good (settled and co-operative), fair (continuing lesser problems) or poor (severe problems) | |

| Discharge pathway | % of patients discharged to rehabilitation villa, community or hostel | |||

| Discharge outcome | Level of adjustment at follow-up, based on personal knowledge, hospital notes and liaison with involved agencies | |||

| Readmission | % of patients readmitted to the same unit | |||

| Reoffending | Number who reoffended or returned to prison | |||

| Dickens et al. (2010) 21 | Cohort study (4) | 48 | Length of stay | Mean number of days |

| Medium and low secure | Follow-up: 15 months | Clinical symptoms | HoNOS: change between baseline and final rating. Quartile points used to allow for different lengths of stay (clinician rated) | |

| Fitzgerald et al. (2011) 22 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 145 | Reoffending | Home Office records; % of patients with general and violent offences |

| Medium secure | Follow-up: 2 years | Risk assessment | OGRS | |

| Gray et al. (2007) 23 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 145 | Reoffending | Home Office records; % of patients with both general and violent offences |

| Medium secure | Follow-up: 2 years | Risk assessment | HCR-20/VRAG/PCL-SV scores (rated once) | |

| Halstead et al. (2001) 24 | Cohort study (4) | 35 | Length of stay | Mean and median months |

| Medium secure | Discharged patients Follow-up: up to 13 years |

Treatment outcome | Rated as either good (risks reduced, safe for discharge), some (progress made in some areas, risk remains), none (no change) or poor (worse than admission) | |

| Discharge outcome | % of patients discharged | |||

| Discharge pathway | Level security/type of placement at discharge and follow-up | |||

| Relapse in MH | Recurrence of symptoms of illness or challenging behaviour | |||

| Readmissions | % of patients readmitted to hospital | |||

| Offender-like behaviour | Behaviour that could be interpreted as an offence | |||

| Reoffending | Number of patients reconvicted | |||

| Lindsay et al. (2002) 25 | Cohort study (4) | 62 | Offender-like behaviour | % of patients suspected of reoffending |

| Community | Follow-up: 13 years | Reoffending | % of patients with clear evidence of reoffending | |

| Lindsay et al. (2004) 26 | Cohort study (4) | 184 | Reoffending | Number of patients with clear evidence of reoffending |

| Community | Follow-up: 7 years | Harm reduction | Decrease in the number of incidents 2 years before referral vs. incident data at follow-up | |

| Lindsay et al. (2004) 27 | Case series (7) | 18 | Reoffending | Number of patients with clear evidence of reoffending |

| Community | Follow-up: 3 years | |||

| Females only | ||||

| Lindsay et al. (2006) 28 | Cohort study (4) | 247 | Reoffending | Number of patients with clear evidence of reoffending |

| Community | Follow-up: 12 years | Harm reduction | Decrease in the number of incidents 2 years before referral vs. incident data at follow-up | |

| Lindsay et al. (2013) 29 | Cohort study (4) | 309 | Reoffending | Number of patients with clear evidence of reoffending |

| Community | Follow-up: up to 20 years | Harm reduction | Standardised service incident report data; number of offences committed in the 2 years before referral vs. follow-up reoffending data | |

| Lindsay et al. (2010) 30 | Cohort study (4) | 197 | Discharge pathway | Number of patients discharged and level security/type of placement at discharge at the 1-year and 2-year follow-ups |

| Mixed services | Follow-up: 2 years | |||

| Linhorst et al. (2003) 31 | Cohort study (4) | 252 | Reoffending | Local law agency data and arrests frequencies used |

| USA community service | Follow-up: 6 months | Treatment response/engagement | Number of patients who completed treatment | |

| Marks (E Marks, University of Birmingham, 2011, personal communication) | Retrospective cohort study (4) Follow-up: 4 years |

28 | Reoffending | % of patients who reoffended (even if this did not lead to police contact), determined by interview with current care team |

| Length of stay | Mean and median number of years | |||

| Discharge pathway | % of patients in high, medium, low and community services | |||

| Morrissey and Taylor (2014) 32 | Prospective cohort study (4) | 13 | Clinical symptoms | YSQ (patient rated), IPDE Screen and PCL-SV (clinician rated): change in mean scores |

| High secure | Follow-up: 2 years | Discharge outcome | Number of patients remaining in treatment, discharged to a medium secure ward or transferred to another high secure ward | |

| Morrissey et al. (2014) 33 | Cohort study (4) | 70 | Risk assessment | HCR-20: change in mean scores over 5 years |

| High secure | Follow-up: 5 years | |||

|

Morrissey

et al.

(2007)

34

High secure |

Prospective cohort study (4) Follow-up: 2 years |

73 | Discharge outcome | % of patients who made positive (move to a lower level of security) or negative (the same level of security) progress |

| Risk assessment | HCR-20 | |||

| Clinical symptoms | PCL-R (clinician rated) | |||

| Morrissey et al. (2015) 35 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 68 | Length of stay | Median number of years |

| High secure |

|

24 | Incidents | Frequency per year in the first 4 years of treatment using hospital incident records. Mean number of violent incidents per patient/year |

| Follow-up: up to 6 years | Clinical symptoms | EPS-BRS (clinician rated) and EPS-SRS (patient rated) | ||

| Discharge pathway | Level security/type of placement at discharge | |||

| Discharge outcome | % of patients who moved to a lower level of security | |||

| Readmission | Number of returns from trial leave | |||

| Palucka et al. (2012) 36 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 20 | Length of stay | Median number of days |

| Canadian inpatient unit | Follow-up: up to 9 years | Discharge outcome | Number of patients discharged | |

| Discharge pathway | Level security/type of placement at discharge | |||

| Reoffending | Any criminal justice involvement (even if charges were not pressed) | |||

| Reed et al. (2004) 37 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 45 | Length of stay | Mean number of weeks |

| Low secure | Follow-up: up to 14 years | Discharge pathway | Level security/type of placement at discharge | |

| Discharge outcome | Positive (discharged to a level of lower security) or negative (discharged to a level of higher security) outcome | |||

| Incidents | Collected from hospital incident records. The number of incidents at baseline (weeks 6–10 of stay) was compared with the number at the end of stay (last 4 weeks of treatment). Frequency (total number of incidents per month) was adjusted for length of stay. Change in incidents calculated per person per week | |||

| Xenitidis et al. (1999) 38 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 64 | Length of stay | Mean months of hospital stay |

| Low secure | Follow-up: up to 11 years | Discharge pathway | Level security/type of placement at discharge | |

| Discharge outcome | Good (discharged to community) or bad (not placed in a community setting) outcome | |||

| Incidents | Collected from hospital incident records. The number of incidents at baseline (weeks 6–10 of stay) was compared with the number at the end of stay (last 4 weeks of treatment). Frequency (total number of incidents per month) was adjusted for length of stay |

| Study and setting | Design | n | Outcome subdomain | Measure/indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajmal (2008) 40 | Cross-sectional (6) | 79 | Clinical symptoms | GSI and RSES (patient rated) |

| High secure | ||||

| Beer et al. (2005) 41 | Cross-sectional (6) | 59 | Placement appropriateness | % of patients requiring a less secure placement |

| Low secure | Clinical symptoms | SBS (clinician rated) | ||

| Beer et al. (2005) 42 | Cross-sectional (6) | 68 | Length of stay | Mean number of months |

| Low secure | Placement appropriateness | % of patients requiring less secure care | ||

| Clinical symptoms | Main reason for delayed discharge | |||

| HoNOS-secure (clinician rated) | ||||

| Chaplin et al. (2015) 43 | Cross-sectional (6) | 22 | Risk assessment | HCR-20 median scores |

| Low secure | Incidents | Average per patient at 3-monthly intervals. Coded for severity using the MOAS | ||

| Median number of incidents | ||||

| Length of stay | Median number of days | |||

| Chilvers and Thomas (2011) 44 | Cross-sectional (6) (Males vs. females) |

77 | Clinical symptoms | NAS-PI scores (patient rated) |

| Medium secure | ||||

| Crossland et al. (2005) 45 | Cross-sectional (6) | 60 | Length of stay | Median number of months |

| High, medium and low secure | ||||

| Dickens et al. (2013) 46 | Cross-sectional (6) | 68 | Incidents | Severity rated: near miss, minor, moderate, high or very high |

| Medium and low secure | 16-month period | Incidents/total bed-days × 100. Average number of incidents per 100 occupied bed-days; violent/aggressive incidents and total incidents | ||

|

Esan

et al.

(2015)

39

Medium and low secure |

Cross-sectional (6) (Autism vs. non autism) |

114 | Length of stay | Mean and median months for both discharged and in-treatment patients |

| Discharge outcome | Number of patients with a good (move to a lower level of security) or poor (move to a higher level of security) outcome | |||

| Level of supervision/discharge pathway | Number of patients who were informal, under a MHA Section/guardianship or supervised discharge | |||

| Fitzgerald et al. (2013) 47 | Cross-sectional (6) | 25 | Risk assessment | HCR-20 and VRAG |

| Medium and low secure | Incidents | Number of patients involved in an incident in 6 months | ||

| Hall et al. (2014) 48 | Cross-sectional (6) | 136 | Treatment needs | Clinician ratings |

| Medium and low secure | Security need | Reference group ratings of appropriate security level | ||

| Delayed discharge | Number of patients no longer requiring current security level, main obstacle to progress | |||

| Length of stay | Maximum and average years per level of security | |||

| Incidents | Number of patients with incident in the past 6 months | |||

| Hogue et al. (2007) 49 | Cross-sectional (6) | 228 | Clinical symptoms | EPS-BRS (clinician rated) |

| High, medium, low and community | ||||

| Johnson (2012) 50 | Cross-sectional (6) | 44 | Clinical symptoms | RSES and EBS (patient rated) |

| Medium and low secure | Length of stay | Mean number of months | ||

| Kellet et al. (2003) 51 | Cross-sectional (6) | 45 | Clinical symptoms | BSI (clinical cases) (patient rated) |

| High secure | ||||

| Lindsay et al. (2004) 52 | Cross-sectional (6) | 52 | Offender-like behaviour | % of patients suspected of reoffending |

| Community | Reoffending | % of patients with ‘clear evidence’ of reoffending | ||

| Lindsay et al. (2008) 53 | Cross-sectional (6) | 212 | Risk assessment | HCR-20, VRAG, Static-99, SDRS, RM-2000 |

| High, medium and low secure | Clinical symptoms | EPS-BRS (clinician rated) | ||

| Lindsay et al. (2010) 54 | Cross-sectional (6) | 197 | Risk assessment | VRAG and Static-99 |

| High, medium, low and community | ||||

| Lofthouse et al. (2014) 55 | Cross-sectional (6) | 64 | Length of stay | Mean number of years |

| Rehabilitation, acute admission and residential home | 5 months of data | Risk assessment | CuRV | |

| Incidents | Aggression defined as acts of physical violence, aggression, force to hurt or damage staff, peers or environment. Included verbal abuse. Two researchers rated each incident as aggression present or aggression absent. Number of patients who were aggressive in month 1 vs. month 5 | |||

|

Mansell

et al.

(2010)

56

Medium and low secure |

Cross-sectional (6) NHS vs. private provider units |

1891 | Delayed discharge | % of patients who had completed treatment but did not have any plans to leave the service in the next month |

| Incidents | Average frequency with which another patient was hurt by a patient or staff member (per patient over a 6-month period) | |||

|

McMillan

et al.

(2004)

57

Medium secure |

Cross-sectional (6) 6-month period |

124 | Risk assessment | MDT ratings per patient on risk of physical violence (scale of 0–8) and number of times patient had been violent in 6 months prior to risk assessment |

| Incidents | Author coded each description of incident from computerised record, based on explicit criteria and guidelines | |||

|

Morrissey

et al.

(2007)

58

High secure |

Cross-sectional (6) 12-month period |

60 | Incidents | Coded as either interpersonal physical aggression or verbal aggression/aggression to property. Rated as low, medium or high risk of harm |

| Risk assessment | Number of patients involved in an aggressive incident | |||

| HCR-20 | ||||

| Clinical symptoms | PCL-R and EPS-BRS (clinician rated) | |||

| O’Shea et al. (2015) 59 | Cross-sectional (6) | 109 | Risk assessment | HCR-20 |

| Medium, low and rehabilitation | Incidents | Hospital records in 3-month period following risk assessment for aggression and self-harm. Coded using Overt Aggression Scale. Rated on severity (1–4) | ||

| Number of patients involved in any incident | ||||

| Perera et al. (2009) 60 | Cross-sectional (6) | 388 | Length of stay | Median number of years and % of patients who had stayed longer than 5 years |

| Medium and low secure | Delayed discharge | % of patients assessed as requiring a less secure placement | ||

| Thomas et al. (2004) 61 | Cross-sectional (6) | 102 | Length of stay | Mean and median years |

| High secure | Delayed discharge | Percentage of patients assessed as requiring a less secure placement and main reason for this | ||

| Treatment needs | SDTN scale completed by key worker and RC | |||

| CANFOR-Short and CANDID-Short. Average number of needs and unmet needs | ||||

| Uppal and McMurran (2009) 62 | Cross-sectional (6) | Up to 396 | Incidents | Hospital computerised reporting system. Coded as per the Department of Health:

|

| High secure | 15-month period of incidents (IDD sample included) | |||

| Most frequent location and time of incident. Percentage of incidents which were violent and which were self-harm. Average monthly figure generated |

| Study and setting | Design | n | Outcome subdomain | Measure/indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander et al. (2015) 14 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 30 | Seclusion, restraint and intensive observations | Mean number of episodes per patient/month |

| Medium and low secure | Follow-up: 6 years | |||

| Alexander et al. (2010) 12 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 138 | Seclusion, restraint and intensive observations | Mean number of episodes per patient/month (adjusted for length of stay) |

| Medium secure | Follow-up: 6 years | |||

| Alexander et al. (2011) 13 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 138 | Seclusion, restraint and intensive observations | Mean and median episodes per patient/month |

| Medium secure | Follow-up: 4 years | |||

| Ayres and Roy (2009) 16 | Case series (7) | 26 | Medication | Case study: reduction in frequency of use of PRN medication |

| Community | Follow-up: up to 3 years | |||

| Butwell et al. (2000) 19 | Cohort study (4) | Up to 278 | Death | Frequency of episodes (number and % of all patients) |

| High secure | Follow-up: 10 years | |||

| (IDD subsample) | ||||

| Morrissey and Taylor (2014) 32 | Cohort study (4) | 13 | Seclusion | Hours per patient for every 6 months of treatment over 2 years |

| High secure | Follow-up: 2 years | |||

| Reed et al. (2004) 37 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 45 | Seclusion, restraint and relocation | Episodes at baseline (weeks 6–10 of treatment) were compared with end of stay (last 4 weeks of treatment) |

| Low secure | Follow-up: up to 14 years | Mean monthly rates calculated to control for length of stay | ||

| Xenitidis et al. (1999) 38 | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 64 | Seclusion | Episodes at baseline (week 6–10 of treatment) compared with end of stay (last 4 weeks of treatment) |

| Low secure | Follow-up: up to 11 years |

| Study and setting | Design | n | Outcome subdomain | Measure/indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esan et al. (2015) 39 | Cross-sectional (6) | 114 | Medication | PRN usage: mean number of episodes (total frequency divided by total number of months of stay to provide an average monthly figure) |

| Medium and low secure | (ASD vs. non-ASD) | Restraint, seclusion and intensive observations | ||

| Mansell et al. (2010) 56 | Cross-sectional (6) | 1891 | Medication | PRN usage: average number of episodes |

| Medium and low secure | 6-month period | Seclusion, restraint, locked areas | Average number of episodes | |

| Access to health care | % of units who reported a delay in patients accessing primary (nurse/dentist) health care | |||

| Mason (1996) 63 | Cross-sectional (6) | 36 | Seclusion | Number of patients secluded; average number of seclusion episodes per patient/year; reason for seclusion and distress-related behaviours after seclusion |

| High secure | 12-month period |

| Study and setting | Design | n | Outcome subdomain | Measure/indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish and Lobley (2001) 64 | Cohort study (4) | 20 | Quality of life | QoLS: change from pre to post move |

| Community | Follow-up: 1 year | |||

| Long et al. (2014) 65 | Cohort study (4) | 10 | Milieu | EssenCes change from pre to post move |

| Low secure | Follow-up: 3 months | Satisfaction | Inpatient satisfaction questionnaire: change from pre to post move | |

| Female only | ||||

| Marks (E Marks personal communication) | Retrospective cohort study (4) | 28 | Quality of life | QoLS scores during treatment |

| Medium secure | Follow-up: 4 years | |||

| Trout (S Trout, National High Secure Learning Disability Service, Rampton Hospital, 2011, personal communication) | Cohort study (4) | 44 | Quality of life | PWI scores: change from pre to post move |

| High secure | Follow-up: up to 2 years | Satisfaction | Service specific evaluation questionnaire using a visual Likert scale via interview |

| Study and setting | Design | n | Outcome subdomain | Measure/indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langdon et al. (2006) 66 | Cross-sectional (6) | 18 | Milieu | CIES read aloud to patients, scores during treatment |

| Medium and low secure | ||||

| Mansell et al. (2010) 56 | Cross-sectional (6) | 1189 | Service satisfaction/complaints | Number of patient generated complaints per unit over 6-month period, recorded via standardised survey |

| Medium and low secure | 6-month period | Involvement | Number of patients with an up-to-date and accessible copy of their own care plan and number of visitors for each patient per unit | |

| Steptoe et al. (2006) 67 | Cross-sectional (6) | 28 | Quality of life | SOS and LEC scores during treatment |

| Community | ||||

| Willetts et al. (2014) 68 | Cross-sectional (6) | 45 | Milieu | EssenCES scores during treatment |

| Medium and low secure |

The content analysis of outcomes identified a number of subdomains within each superordinate outcome domain. The final framework of outcome domains is described in Table 7 along with the number of studies that reported outcomes in these domains.

| Effectiveness | Number of studies |

|---|---|

| Discharge outcome/direction of care pathway | 16 |

| Delayed discharge/current placement appropriateness | 6 |

| Length of hospital stay | 22 |

| Readmission (i.e. readmitted to the same setting) | 4 |

| Clinical symptom severity/treatment needs (clinician rated) | 16 |

| Clinical symptom severity/treatment needs (patient rated) | 6 |

| Treatment response | 5 |

| Reoffending (i.e. charges/reconvictions) | 18 |

| ‘Offending-like’ behaviour (which did not result in charges) | 5 |

| Risk assessment measures | 12 |

| Incidents (violence/self-harm) | 14 |

| Security need | 3 |

| Other | 3 |

| Total | 130 |

| Patient safety | |

| Restrictive practices (restraint/relocation//intensive observations) | 12 |

| Restrictive practices (seclusion/segregation) | 9 |

| Medication (i.e. PRN usage/exceeding BNF prescribing limits) | 3 |

| Physical health | 1 |

| Premature death/suicide | 1 |

| Total | 26 |

| Patient experience | |

| Quality of life | 4 |

| Therapeutic milieu | 3 |

| Patient experience: involvement | 1 |

| Patient experience: satisfaction/complaints | 3 |

| Total | 11 |

Discussion: analysis of outcome domains and measures

Domain 1: effectiveness

A total of 53 studies (29 of which were cohort studies) presented data on at least one outcome that measured the effectiveness of FIDD services. Twelve outcome subdomains were identified as a result of content analysis.

Length of stay

An indirect measure of effectiveness, length of hospital or service stay was one of the most commonly reported outcome domains (22 studies; see Tables 1 and 2). Length of stay was usually reported for discharged patients, although it is well known that this is not a comprehensive measure because of the failure to reflect those patients who have never been discharged. Length of stay can therefore also be described at a fixed point in time for a current hospital population, and this was reported in many of the cross-sectional studies (e.g. Beer et al. ,42 Crossland et al. ,45 Esan et al. ,39 Hall et al. ,48 Johnson et al. ,50 Lofthouse et al. ,55 Perera et al. 60 and Thomas et al. 61). Inevitably, these data are less easy to interpret unless an admission cohort is used (as in Morrissey et al. 35) and the numbers in that cohort who are still in treatment and who have exceeded the mean length of stay of discharged patients are reported. Length of stay was variously reported in days,12,13 weeks, 37 months45 or years. 19,35 This was calculated as either a mean or a median measure. Reported average lengths of hospital stay ranged from 9 years in high secure conditions35 to 55 weeks in low secure conditions. 38

Readmission to the same or another hospital setting was clearly recorded in only four cohort studies11,20,24,35 in which there was follow-up. Only one study11 provided more detail, with the mean number of bed-days for those readmissions being supplied. Studies usually described length of stay in the hospital under study rather than total hospital stay (including in other settings) since first admission.

Discharge outcome/direction of care pathway/delayed discharge

A total of 16 cohort studies (see Tables 1 and 2) examined discharge outcome or direction of care pathway in terms of the level of security of the receiving service or type of community placement (e.g. independent living, supported living, residential accommodation). This was frequently coded as either a ‘successful’ (move to a lower level of security) or ‘unsuccessful’ (move within the same or to a higher level of security) discharge outcome. 12,13,24,34,37,38 Follow-up periods for post-discharge pathway outcome ranged from 2 years23 to 13 years11 for former inpatients and 20 years for a forensic community service. 29

A further six studies reported on current placement appropriateness or delayed discharge. For example, this was reported in terms of the percentage of patients assessed as requiring a less secure placement. 38,42,48,60,61 Similarly, Mansell et al. ,56 in their large cross-sectional study of 1891 patients in medium and low secure units, reported more specifically on the percentage of patients who had ‘completed treatment but did not have any plans to leave the service in the next month’. Reasons for delayed discharge were recorded in around half of these studies.

In summary, discharge outcome was generally reported in relation to a fixed point in time at either discharge from hospital or later follow-up. It is not unusual, however, for some patients to demonstrate initial progress on discharge followed by subsequent regression, placement moves and potential readmission. It was notable that few of the studies described these more complex pathways, which can be common in this population, although there was some attempt by Lindsay et al. ,30 in their study of pathways to secure care, to take this into account.

Clinical symptom or severity ratings/treatment needs

Sixteen studies (see Tables 1 and 2) reported on potential outcome domains relating to clinical symptoms or treatment needs using clinician ratings [often known as clinician-rated outcome measures (CROMs)] and six studies used patient ratings of their symptoms/needs [often reported as patient-rated outcome measures (PROMs)] (see Tables 1 and 2). However, of these, only two cohort studies actually reported change over time in such symptoms during treatment in a service, through repeated measurement on the same patients (i.e. treated clinical symptom ‘change’ as an outcome measure). Thus, Dickens et al. 21 reported on change in 48 patients on the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS-secure) (security scales and clinical scales) during 15 months of treatment in medium- and low secure units, finding significant reduction in severity of symptoms over time. Morrissey et al. 35 reported on change over 2–3 years on the Emotional Problem Scales (EPS)69 as a result of treatment of 68 men in a high secure setting. Both the EPS Behaviour Rating Scale (a CROM) and the EPS Self-Report Inventory, a patient-rated outcome measure (a PROM) designed for an intellectual disabilities population, were employed. It is notable that Morrissey et al. is the only included cohort study that has reported on patient-rated symptom change over time as a result of intervention at the service level.

Relatively few additional included studies reported on patient-rated clinical outcome measures at a fixed time point. Those studies that did so used a range of measures, which included the Young Schema Questionnaire,32 Brief Symptoms Inventory,51 Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale,40 Novaco Anger Scale44 and the Evaluative Beliefs Scale. 50 Of these, only the Novaco Anger Scale was reported to be appropriately adapted for IDD respondents.

Most studies reported CROMs at a fixed point in time. These measures included HoNOS-secure,21,42 EPS,49,53,58 Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R) and Psychopathy Checklist Screening Version (PCL-SV),23,32,34,53,58 International Personality Disorder Evaluation Screen,32 Clinical Global Impressions Scale,11 Aberrant Behaviour Checklist,17 Mini Psychiatric Assessment Schedules for Adults with Developmental Disabilities17 and the Social Behavioural Schedule. 41 Treatment needs were assessed in one study using the Camberwell Assessment of Needs-Forensic Short Version or the equivalent intellectual disability version, Camberwell Assessment of Needs for Adults with Developmental and Intellectual Disabilities, and a measure called the Security, Dependency and Treatment Needs Scale. 61

Treatment response

Only five studies (see Tables 1 and 2) reported on outcomes that were categorised as global ‘treatment response’. Most of these used qualitative ratings. For example, Day20 coded responses as ‘good’ (settled and co-operative), ‘fair’ (no serious difficulties but continuing lesser problems) or ‘poor’ (severe behaviour problems). Similarly, Halstead et al. 24 coded responses as ‘good’ (risks reduced, safe for discharge), ‘some’ (progress made in some areas, risk remains), ‘none’ (no change) or ‘poor’ (worse than admission). Only one study11 used a psychometric measure to measure this outcome: the Clinical Global Impressions Scale. Finally, Barron et al. 17 recorded whether patients had ‘current’, ‘previous’ or ‘no’ access to particular treatments, such as psychological therapies using standardised definitions, although they did not report the extent to which patients had engaged in these interventions.

Reoffending/‘offending-like’ behaviour/incidents

In total, 18 studies (see Tables 1 and 2) examined formal reoffending (i.e. formal charges and convictions) on follow-up; most commonly these were retrospective discharge cohort studies utilising official records such as police or Ministry of Justice conviction data. The most comprehensive of these reported the percentage of individuals with serious/violent convictions at 1-, 2- and 5-year follow-up and also examined time to reoffend. 15 Barron et al. 17 reported the number of offences committed as opposed to a dichotomy. Gray et al. 23 and Fitzgerald et al. 22 (using the same data set) reported on whether a conviction occurred within 2 years of discharge and was violent or non-violent. A community forensic service study provided more detailed data on the number of participants arrested or reconvicted or cases dropped. 18 One of the few non-UK studies reported ‘any criminal justice involvement’, which included arrest without charge following discharge from an Australian hospital unit, arrest data being likely to be a better reflection of offending behaviour than conviction. 36 Only one linked series of studies attempted to address change in offending behaviour as a result of treatment, comparing the number of formal incidents in the 2 years before referral to a community FIDDs service with those in a follow-up period. 26,28,29

Five studies examined and attempted to measure ‘offending-like’ behaviour in the community that had not been officially recorded. 11,13,24,25,31 This is arguably an important outcome given the frequency with which people with IDD are not progressed through the criminal justice system. 70 These outcome data were generally based on carer report and were described with various definitions, including ‘behaviour which could be interpreted as an offence’ or ‘suspected offending.’ Alexander et al. 11 differentiated between quasi-offending behaviour that led to police contact (but may not have ended with charges) and that which did not. This study also attempted to identify seriousness and persistency of relapse, differentiating between ‘regular, ongoing offending-like behaviour’ and ‘phasic’ or ‘occasional’ relapse. Because of some reliance on carer report in this domain and the retrospective nature of follow-up, the information reported is likely to have poor reliability.

A proxy measure of maintenance of problem behaviour is the occurrence of violent incidents during inpatient treatment, reported in 14 studies. In general, this was recorded from electronic hospital records, and standardised for length of stay (e.g. reported as average incidents per 100 bed-days). Some studies coded severity or used a rating scale such as the Overt Aggression Scale. 43,46 Other reports differentiated between physical violence and verbal aggression/threats. 58 However, measures of change in incident frequency over the course of treatment in FIDD services were reported in only a small number of studies. Xenitidis et al. 38 and Reed et al. 37 calculated change between a 4-week period at baseline and a 4-week period at the end of stay. Morrissey et al. 35 calculated the number of violent incidents in the first year of high secure intervention for each patient and compared that with the number in each subsequent year in treatment. A series of community studies26,28,29 compared the number of incidents 2 years before referral to the service with the number of incidents during intervention and follow-up. No studies reported change in the level of seriousness of incidents over time as an outcome measure.

Although not a type of offending, self-harm is a form of challenging behaviour that can lead to detention and, therefore, may be a target for behaviour change. Self-harm incidents as a service-level outcome indicator were reported in only two studies. 59,62 Neither of these studies reported change over time in self-harm as a result of intervention at the service level.

Risk assessment

A further potential proxy measure of behaviour change as a result of service intervention is the reduction in scores on dynamic structured risk assessment ratings over time. Twelve included studies reported data from such measures gathered in FIDD services. Most commonly, services used the structured clinical judgement tool the Historical, Clinical Risk 20 (HCR-20). 23,33,34,43,53,54,58,59 Other studies reported on static risk assessment measures such as the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG),23,53,54 Risk Matrix 2000,53 Offender Group Reconviction Scale22 and Static-99,53 although these would not have utility as outcome measures as they would not be expected to change. The vast majority of these studies reported only cross-sectional data and not within-patient change in such measures over time. Indeed, only one study reported change in scores over 5 years on the clinical risk items of the HCR-20 as an outcome indicator in a FIDD service,33 despite the large number of services that are required to collect routine data on this measure.

In addition to risk assessment tools, patients were assessed for their specific security needs in three studies. This was examined as part of the security items in the HoNOS-secure ratings (e.g. Morrissey et al. 32 and Dickens et al. 21) Thomas et al. 61 used the informant-rated Security, Dependency and Treatment Needs Scale which indicated the type of environment required in terms of level of security.

Domain 2: patient safety

A total of 11 studies (see Tables 3 and 4) reported on some aspect of patient safety, which were classified into five subdomains. Two of these subdomains related to interventions that could be perceived as ‘restrictive practices’71: the first included physical restraint or periods of increased intensive nursing observations, and the second included seclusion/segregation in response to risky or ‘challenging’ behaviour. These were reported either in hours or in terms of the number of episodes. In parallel with recording numbers of violent incidents, mean rates per patient/month or year of treatment were typically reported, in order to control for length of stay. These outcomes could arguably also be construed as an effectiveness indicator if change in rates over time in treatment is measured. Only two studies37,38 reported on such change in seclusion rates in a cohort with follow-up. Only one study reported on the reason for seclusion, and on distress-related behaviours after seclusion, that is, the outcome measured had a specific emphasis on patient safety. 63

Premature death was reported in only one study, which differentiated between natural causes and suicide. 19 Physical health outcomes or access to services was reported by one study only. 56 This is surprising given the higher incidence of premature death and physical health-care problems in forensic psychiatric populations. 72 Use of pro re nata (PRN) medication, which could also be perceived as a restrictive practice, was monitored as an outcome in three studies. The number of episodes of PRN use was recorded in two secure service studies39,56 and via a case study demonstrating a reduction in use in a community patient. 16

Domain 3: patient experience

A total of 11 of the included studies reported on four patient experience-related subdomains (see Tables 5 and 6). Four studies addressed quality of life using a number of rating scales. These included the 10-item Personal Wellbeing Index,73 the only measure specifically designed for people with intellectual disabilities (S Trout, personal communication). Other measures employed were the Quality of Life Questionnaire,74 used among both a medium secure (E Marks, personal communication) and female community sample,64 and the Life Experience Checklist67 in a community sample. When change over time in reported quality of life was examined, this was in relation to a change of environment, that is, a service development. There were no community studies of quality-of-life maintenance over time in discharged FIDD patients.

Three studies addressed satisfaction with services. These related to a specific service development or move, in a community setting,64 a low secure unit65 and a high secure unit (S Trout, personal communication). A range of satisfaction instruments that were service specific and tailored for use with people with IDD were used. Only one study evaluated the number of patient complaints as a service outcome measure. 56

A fourth subdomain of patient experience identified from the literature was the therapeutic environment, reported in three studies using either the Essen Climate Evaluation Scale75 (EssenCES), which was rated by both patients and staff, or the Correctional Institutions Environment Scale. 76 There was no indication that these measures had been specifically adapted for IDD patients in any of the studies. These were typically cross-sectional studies66,68 or evaluated a specific change in environment after 3 months. 65 No identified studies reported long-term change over time in milieu quality, although it is feasible that such measures could be used as a repeated cross-sectional service outcome indicator. Only one community study reported on the level of support that patients received. 16

Finally, patient involvement as an outcome indicator was reported in only one study: Mansell et al. ,56 in their large study, reported the number of patients with an up-to-date and accessible copy of their care plan. This is one of the outcomes addressed by the current Transforming Care programme care and treatment reviews. 3

Conclusions

This systematic review identified 60 studies that either examined substantive outcomes or reported on potential outcome measures from generic treatment in forensic services for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Predictably there were no case–control studies that compared FIDD services with some other type of intervention. Around half of the included studies were cohort outcome studies that followed up patients either during or after a period of treatment in such services. The remainder were primarily cross-sectional studies that reported on potential outcome domains at a fixed point in time (although these studies did not necessarily have the explicit aim of evaluating outcomes). Few studies acknowledged the complex outcome pathways common in this clinical population and, interestingly, none mentioned prison as an outcome destination, although this is likely to have been the outcome for some patients.

A broad range of effectiveness outcome domains and measures was identified from the literature, although it is evident that such domains are measured in different ways, with few consistently applied measures other than in the realm of risk assessment. Even apparently categorical data relating to violent incidents or offending were measured differently across studies. Significantly, very few studies examined ‘change’ in patients over their time in treatment using repeated measures of effectiveness, for example change in incident frequency or rated risk, clinical symptoms or progression in achievement of treatment goals. This no doubt reflects the challenges in collecting and analysing longitudinal patient linked data, although it could also relate to the explicit exclusion of studies that evaluated specific treatment interventions as opposed to interventions at the service level. It was notable that that very few of the included service-level outcome studies describe details of the different components of the treatment that patients have received, an issue which needs to be addressed in future research. Finally, there was a relative paucity of reports on patient-rated outcome measures, particularly those relating to treatment progress, recovery and patient experience, and to the quality of community life following discharge from FIDD services.

It is acknowledged that the published research evidence is driven by a range of factors, including the availability of data in services, and does not necessarily reflect the outcomes domains of importance to clinicians, patients and carers. This is addressed in stages 2 and 3 of the project.

Chapter 3 Stage 2: patient and carer consultation groups

Aim

The purpose of consulting patients and carers was to incorporate their views into the framework of outcome domains appropriate for future research on outcomes from FIDD services. It was considered important to obtain perspectives from these different groups, as their views may differ to those of experts in relation to which outcomes are important and relevant.

Consultation methodology

As the consultation related to future research it was construed as patient and carer involvement by the Nottinghamshire Healthcare Foundation Trust Research Governance Group and was therefore deemed not to require a further ethical opinion.

Three patient consultation groups were conducted in May 2015 in the context of routine patient meetings. Patients were provided with information sheets (see Appendix 4), gave written consent to participate and had the opportunity to withdraw at any point. Two groups were conducted in a high-security institution (a NHS service) and one in medium-/low-security institution (an independent sector service). These groups included three female patients, one transgender patient and 11 male patients. Seven were from low- and medium-security institutions and eight were from high-security institutions.

Carer consultation took place in June 2015. Four carers were recruited from one hospital’s carer group and consulted as a group, and two carers were separately recruited and interviewed as a pair. The relatives of those consulted were in three different units at the time of consultation. Of these six carers, one was male and five were female. Carers were provided with an information sheet, and gave written consent to participate, and were provided with travel expenses and costs. Relatives of all carers were in low- or medium secure FIDD care, and one was in a bespoke service within a hospital (these carers expressed a willingness to be identifiable).

All consultation meetings were led by two members of the research team, including in all but one patient group the project lead. An independent advocate was included in the high secure meetings.

A semistructured topic guide was employed to facilitate discussion. This focused on the outcomes that patients and carers would consider important from a period in hospital in the short, medium and longer term (see Appendix 5). The discussion groups ranged in duration from 1 to 1.5 hours, and relative focus on each area depended on the response of the group. Detailed notes or full transcription of consultation meetings was undertaken depending on security restrictions. Interview data were broadly content analysed by the lead researcher according to the three main domains (effectiveness, safety and patient and carer experience), with the initial framework from the stage 1 systematic review used as a starting point (see Table 7). Although a formal qualitative data analysis approach was not undertaken, comments and discussion points were listed under the domain and subdomains already identified. Where appropriate, new subthemes were identified from the consultation data.

Findings

This section of the report summarises the content from the consultation groups, under the three superordinate domain headings. Not all of the original subdomains were commented on in detail in the interviews, and subdomains are therefore combined in the discussion. However, a number of additional outcome subdomains which had not included in the initial framework were identified. Box 1 therefore represents the framework from stage 1 amended to incorporate additional themes generated from patients and carers.

Discharge outcome/direction of care pathway.

Delayed discharge/current placement appropriateness.

Length of hospital stay.

Readmission (i.e. readmitted to the same setting within a specified period).

Clinical symptom severity/treatment needs: patient/carer rated.

Clinical symptom severity/treatment needs: clinician rated.

Treatment response/recovery measures: clinician rated.

Treatment response/recovery measures: patient/care rated.

Reoffending (formal charges/convictions).

‘Offending-like’ behaviour (no formal charges).

Incidents (violence/self-harm) in service.

Risk assessment measures.

Security need (i.e. physical/procedural/escort/leave).

Adaptive functioning.

Engagement in treatment/services.

Patient safetyPremature death/suicide.

Physical health.

Medication (i.e. PRN usage/exceeding BNF limits/side effects/patient experience).

Restrictive practices (restraint).

Restrictive practices (seclusion/segregation).

Victimisation/safeguarding/feeling safe.

Patient and carer experiencePatient experience: involvement.

Patient experience: satisfaction/complaints.

Quality of life: clinician rated.

Quality of life: patient rated.

Therapeutic climate.

Access to work/meaningful activity (when appropriate).

Carer experience: communication.

Carer experience: involvement.

Closeness to ‘home’ area.

Level of support/involvement in community (when appropriate).

BNF, British National Formulary.

Italic = new subdomain following stage 2.

Quotations are included for illustrative purposes. Quotations are referenced only as patient or carer, as linking quotations can lead to potential identification of individuals. In some instances the gender reference in the quotation has been changed in order to preserve anonymity.

Effectiveness domain

Length of hospital stay/readmission/pathways

Length of stay in hospital was identified as an important outcome variable by patients, and a number were frustrated by what they saw as extended time in treatment. However, some of the carers we consulted did not believe a shorter length of stay was necessarily a positive outcome, with fear being expressed by several carer participants regarding premature discharge.

It has to be the right length of stay for that person.

Carer

The fact that the service wasn’t there in the community to start with will make his hospital stay longer. So we can’t just look at the hospital stay – it has to be the overall picture.

Carer

Longer length of stay is not worse – I don’t want him pushed out too soon before he is ready.

Carer

Just because they are out of hospital does not mean they are better.

Carer

Patients in high secure hospital naturally saw a medium secure unit as an appropriate pathway and those in medium and low secure units were looking to community discharge as an indication of progress and positive outcome. Moving up levels of security or readmission to hospital were perceived by patients as negative (albeit sometimes necessary) outcomes. A number of carers noted that frequent changes in hospital or living environment were destabilising and, therefore, constituted a negative outcome.

Placement appropriateness/meeting clinical needs

Placement appropriateness was reported to be very important to carers and patients, with delayed discharge in a progressive direction being a particular concern (e.g. owing to appropriate unit or accommodation availability). Indeed, placement appropriateness in terms of meeting the relative’s specific needs was considered more important to many carers than distance from home:

I would much rather he be further away for 8/9 months [and get the right treatment] than be nearer for 18 months.

Carer

It is very important for people to go to a place where they are happy. Not just because it is closer to family.

Patient

Carers and patients reported that it was important that specific clinical needs were met by appropriate care and treatment in order that progress could be achieved. This included both the model of care (e.g. whether or not it was appropriate for a patient with autism), psychological treatment (e.g. specific treatment programmes) and appropriate levels of meaningful activity being available.

You have to be able to do your offending treatment. I need an arson group and there isn’t one starting.

Patient

[I need] Psychology . . . the Moving On group . . . they make you a pack so you know what to do.

Patient

Other hospitals let patients get real jobs. I want this to happen in this hospital.

Patient

It’s boring here there isn’t enough to do.

Patient

Carers were very clear that their priority for their relatives was an appropriate individualised pathway through hospital care, as opposed to rigid programmes which had to be adhered to regardless of the individual’s needs:

I know from meetings there seemed to be a lot ‘he needed to do this this and this’ – we can’t do this before we do this’ . . . almost setting him up to fail. This is how it works whether you engage or not, whether it’s relevant or not and therefore if it’s not relevant and they’re not going to engage it’s a fail before they’ve started.

Carer

It has got to be individually led.

Carer

He needed an individualised package of support which was right for him.

Carer

Finally, when it came to moving into the community from hospital, carers in particular were concerned that an ‘appropriate’ placement constituted adequate levels of support to keep people safe:

Coming home with me or if he was left in a little flat, he wouldn’t take his medication – he’d go on the drugs and then he would kill somebody or somebody else would kill him.

Carer

I worry about the fact that the service wasn’t there in the community . . . there’s so little support in the community.

Carer

Clinical symptomology/behaviour change

Participants were asked what changes would indicate an improvement in their own or their relatives’ health. Both patients and carers recognised that there would be indicators of clinical improvement which would be reflective of therapeutic change and progress. These included a reduction in the frequency of incidents of violence and self-harm, as well as perhaps less tangible clinical change.

A reduction in incidents. Reduction in restraints, using diversion more frequently, pre-empting incidents.

Carer

[I will know there is change when] he joined in to the real world again because at the moment he is living in . . . his world.

Carer

Clinical progress was typically described by patients as ‘communicating better’ or ‘getting angry less often’:

Before I wouldn’t engage in conversation and now I’ve learnt different strategies so I don’t kick off so often.

Patient

A better attitude towards staff and not taking your bad day out on a staff member.

Patient

Patients also seemed to recognise the difficulty of identifying and measuring progress, often identifying more qualitative changes:

I know what it feels like when I am better . . . I don’t put my head in my hands as much anymore.

Patient

Some people ‘toe the line’ and pretend they’re more agreeable but they aren’t really on the inside.

Patient

There was a feeling expressed by some carers that patients do not really understand what they have to achieve to make progress and that there was too much emphasis on ‘incidents’ in determining progress:

Every time he does something [the goal] gets further ahead. And [name] goes why the hell am I doing this; what’s the point of doing it if I am always going to get failed.

Carer

Furthermore, some carers felt that they were often in a better position than staff to identify nuanced changes in their relative’s functioning, and that this should be included in assessments of change.

[they should get] feedback from families . . . because the families know the person . . . we know our family members best and if the family members flag up a concern or alternatively they say they can see an improvement that should be as critical as the professional.

Carer

A number of patients emphasised that an increase in positive behaviour should be as reflective of change as a decrease in negative behaviour. For example, using low-stimulation areas as opposed to being nursed in seclusion should be seen as positive progress even if incidents were ongoing.

Finally, one carer made the important point that an increase in violent incidents per se need not necessarily be construed as a bad outcome:

It’s important to recognise that even if someone has a bad patch that isn’t a bad outcome – the outcome is how it’s managed. If the staff can see them through the bad patch it’s not necessarily a bad outcome if the service manages it appropriately.

Carer

Similarly, a higher level of observation/staffing was not necessarily seen as negative, if that was necessary for an individual:

I wouldn’t want a reduction [in staffing] because it keeps him happy and safe.

Carer

Finally, a number of participants felt that a concentration on the number of incidents was simplistic and that there should instead be an emphasis on a more nuanced analysis of them:

There is too much focus on incidents and not on understanding them . . . taking it back to the beginning of the process as opposed to just dealing with what the consequences are.

Carer

I get fed up with hearing about the same thing . . . you should just take it off the record and put it somewhere.

Patient

Finally, both patients and carers also spontaneously mentioned engagement with services and therapies as an important positive indicator of clinical progress:

I know when I am doing well. I talk to staff more . . . I’m doing my groups.

Patient

Talking to staff having a good relationship with others. I’m a peer facilitator now.

Patient

. . . at the moment he doesn’t engage in any therapies . . . if it doesn’t meet his criteria he’s not going to bother to engage.

Carer

Reoffending on discharge

Both patients and carers mentioned staying ‘safe’ on discharge as being a positive outcome. Although they talked little about reoffending specifically as an outcome domain which required measurement, a number of the carers considered themselves at potential risk as victims and their own safety was evidently important to them:

If they did say take him home now I’d be too scared.

Carer

Reduction in risk assessment ratings was not mentioned spontaneously, perhaps because patients and carers are less aware of these methodologies than practitioners. Nonetheless, both patients and carers clearly understood the concept of risk reduction and saw it as important.

Adaptive functioning

Patients were very enthusiastic about hospital treatment aimed at improving their life skills such as budgeting and work skills, but some were also fearful that hospital had caused them to lose skills they had previously had:

Since we’ve been locked up here we don’t get a chance to do that sort of thing [budget] so you don’t know what to do when you get it [money].

Patient