Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/10/75. The contractual start date was in July 2014. The final report began editorial review in August 2016 and was accepted for publication in May 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Alison Faulkner received consultancy fees for her role in the project.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Simpson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction, background and aims

Improving the treatment and care of people with mental illness is among the key priorities for health and social care in both England and Wales. 1 However, despite the shift towards community-based models of care, considerable resources are still spent on acute inpatient beds: as much as £585M in 2009–10. 2

In 2014–15, in England, 103,840 people in contact with mental health and learning disability services spent time in hospital. For every 100 female inpatients, 41.9 were detained using the Mental Health Act (MHA) 1983;3 for every 100 male inpatients, 38.5 were detained. 4 In Wales, 9466 admissions to hospital for mental illness took place in 2014–15,5 with 1662 of these taking place using sections of the MHA 1983. 3 Such high numbers of admissions mean that considerable planning and co-ordination is required to ensure that effective care is delivered consistently.

The context and delivery of mental health care is diverging between the countries of England and Wales while retaining points of common interest, thereby providing a rich geographical comparison for research. Across England, the key vehicle for the provision of recovery-focused, personalised, collaborative mental health care is the Care Programme Approach (CPA). The CPA is a form of case management that was introduced in England in 1991 and then revised and refocused. 6 In Wales, the CPA was introduced in 2003,7 but it has been superseded by The Mental Health (Care Co-ordination and Care and Treatment Planning) (CTP) Regulations (Mental Health Measure), a new statutory framework. 8 Data for England show that 403,615 people were on the CPA in 2011–12. 9 Centrally held CPA numbers supplied by the corporate analysis team at the Welsh Government indicate that there were 22,776 people in receipt of services as of December 2011, just 6 months before the introduction of CTP under the Mental Health Measure (James Verrinder, Welsh Government, 2012, personal communication).

In both countries, the CPA or CTP obliges providers to comprehensively assess health/social care needs and risks; develop a written care plan (which may incorporate risk assessments, crisis and contingency plans, advanced directives, relapse prevention plans, etc.) in collaboration with the service user and carer(s); allocate a care co-ordinator; and regularly review care (Table 1). In Wales, as evidence of further divergence, statutory advocacy has been extended to all inpatients. CPA/CTP processes are now also expected to reflect a philosophy of recovery and to promote personalised care. 6,10

| CPA | CTP |

|---|---|

| Was first introduced in England in 1990 via a joint health service/local authority circular | Was introduced on a legislative basis in Wales as part of the Mental Health (Wales) Measure 2010 |

| Identifies the role of the care co-ordinator (initially referred to as key worker) | Confirms the role of the care co-ordinator, who must be a member of one of the specified health or social care professions |

| Requires the development of an individual written care plan | Requires the development of a CTP, to be produced using an all-Wales template |

| Identifies the role of the care co-ordinator in managing plans of care and in ensuring timely review | Identifies the role of the care co-ordinator in managing plans of care and ensuring timely review |

The concept of recovery in mental health was initially developed by service users. It refers to ‘a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations caused by illness’11 while developing new purpose or meaning. The importance of addressing service users’ personal recovery, alongside more conventional ideas of clinical recovery,12 is now supported in guidance for all key professions. 13–16 To this has been added the more recent idea of personalisation. Underpinned by recovery concepts, the aim of personalisation is for people and their families to take much more control over their own support and treatment options, alongside new levels of partnership and collaboration between service users (or citizens) and professionals. 17 Recovery and personalisation in combination mean practitioners tailoring support and services to fit the specific needs of the individual and enabling social integration through the increased involvement of local communities. 18

The CPA and CTP are central to modern mental health care, and yet there are few studies that explicitly explore the practices of care planning and co-ordination in community services and even fewer that focus on inpatient care planning. A relatively rare example of the former is the recently completed COCAPP (Collaborative Care Planning Project) study,19,20 with this current sister project extending the field of research to the hospital setting. National quality statements include the requirement that service users in adult mental health services jointly develop a care plan with mental health professionals, are given a copy with an agreed review date, and are routinely involved in shared decision-making. 21 National policies1,10 outline the expectations that people will recover from mental ill health and be involved in decisions about their treatment. This holds true for both informal and detained inpatients, with reasonable adjustments made when necessary to ensure that people are supported to live lives that are as full and socially participative as possible. 22 In the light of this, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) recommended that:

Care planning should have clear statements about how a person is to be helped to recover, and follow guidance set out in the national Care Programme Approach. Care plans should focus on individual needs and aspirations, involving patients at all stages so as to reflect their views and individual circumstances.

Reproduced with permission from the CQC © CQC, Monitoring the Mental Health Act in 2011/12, p. 622

However, in care plans checked by the CQC, 37% showed no evidence of patients’ views being included; 21% showed that patients were not informed of their legal right to an independent mental health advocate; and almost half (45%) showed no evidence that patients consented to treatment discussions before medication was administered. The CQC was also concerned that cultures may persist in which control and containment are prioritised over the treatment and support of individuals, and in 20% of visits the CQC expressed concerns about the de facto detention of patients who were voluntary rather than compulsory patients. However, in other settings, excellent practice was found to lead to care and treatment that were in line with policy expectations.

Earlier national reviews across both nations found that service users remained largely mystified by the care planning and review process itself, with significant proportions not understanding their care plans, not receiving written copies of their plan and, often, not feeling involved in writing plans and setting goals. 23,24 Clearly, there are significant problems with inpatient care planning, with the CQC noting a:

significant gap between the realities observed in practice and the ambitions of the national mental health policy.

Reproduced with permission from the CQC © CQC, Monitoring the Mental Health Act in 2011/12, p. 622

The House of Commons Health Committee25 subsequently reported widespread concerns about delays and imbalance in care planning, with a focus on risk rather than recovery. In Wales, the National Assembly’s Health and Social Care Committee reported a low uptake of advocacy services by people admitted to hospital care. 26

Further evidence is clearly needed to develop care planning interventions that embed dignity, recovery and participation for all of those who use inpatient mental health care.

In 2008, the Healthcare Commission27 measured performance on 554 wards across 69 NHS trusts that provided mental health acute inpatient services. The commission found that almost two-fifths of trusts (39%) scored weakly on involving service users and carers; 50% of care plans sampled did not include a record of the service user’s views; and nearly one-third of care records (30%) did not include a record of whether or not the service user had a carer. One-third of all care records sampled (33%) showed that community care co-ordinators provided input into the service user’s care review meetings only ‘some or none of the time’. The commission27 called for more to be done to address the divisions between hospital and community services and to:

ensure that acute inpatient services are more personalised as a basis for promoting recovery.

Reproduced with permission from the Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection © Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection 2008, The Pathway to Recovery, p. 327

An even earlier study of inpatient stays in England reported that large numbers of patients are admitted for a week or less, which had implications for inpatient and community services, and the authors suggested that the CPA was ‘cumbersome’, ‘rigid’ and ‘impractical’ in relation to short admissions. 28

Although the evidence base for community care planning and co-ordination is sparse,20 research studies exploring care planning and co-ordination in acute inpatient mental health settings are almost non-existent, as will be shown in Chapter 3. This may reflect the reported historical neglect of inpatient care by policy-makers and researchers,29 or some of the ethical and practical challenges faced when conducting research in settings in which a significant proportion of patients are detained under legislation or may lack the capacity to consent. These challenges are addressed directly in this study.

To summarise: the CQC22 identified serious concerns in relation to care planning, patient involvement and consent to treatment for patients detained under the MHA3 and the de facto detention of patients who were voluntary rather than compulsory patients. Earlier reports by the Healthcare Commission27 had identified serious concerns about care planning and called for measures to ensure that acute inpatient services are more personalised as a basis for promoting recovery. To date, there has been almost no research exploring the realities and challenges of planning and providing care and treatment in inpatient settings that includes people detained under the MHA. 3

The design of our initial COCAPP study of care planning and co-ordination in community mental health care settings (Health Services and Delivery Research programme project 11/2004/12), published in Health Services and Delivery Research in February 2016,20,30 has informed the design and procedures of this COCAPP-A (Collaborative Care Planning Project-Acute) inpatient study. Owing to the similarities in the study design and methods, some material in this report has been adapted from that publication, but all data and analysis are new and the results from both studies are compared in Chapter 6 of this report.

Aims

The aim of this study is to identify factors that facilitate or hinder recovery-focused personalised care planning and co-ordination in acute inpatient mental health settings.

We intend the results of this study to complement and build on our study of care planning and co-ordination in community settings20 (Health Services and Delivery Research project 11/2004/12) to provide a whole-systems response to the challenges faced in providing collaborative, recovery-focused care planning. We also aim to respond to the CQC’s22 question of how to embed dignity, recovery and participation in inpatient practice when people are subject to compulsory care and treatment.

As an exploratory study guided by the Medical Research Council31 Complex Interventions Framework, the study will generate empirical data, new theoretical knowledge and greater understanding of the complex relationships between collaborative care planning, recovery and personalisation. It will help identify the key components required and provide an informed rationale for a future evidence-based intervention and evaluation aimed at improving care planning and patient outcomes within and across care settings, likely to be acceptable to service users, families/carers, practitioners and service managers. It will also provide lessons for similar, equally problematic, care planning processes in a range of other health/social care settings. 32

Research question

The main research question for this study is ‘what facilitates or hinders recovery-focused personalised care planning and co-ordination in acute inpatient mental health settings?’. To answer this, the following questions are explored:

-

What impact do national and local policies and procedures have on care planning and co-ordination?

-

What are the key drivers that have an impact on care planning and co-ordination?

-

What are the views of staff, service users and carers on care planning, therapeutic relationships, recovery-orientation and empowerment in acute care settings?

-

How is care planning and co-ordination currently organised and delivered in local services?

-

How, and in what ways, is care planning and co-ordination undertaken in collaboration with service users and, when appropriate, carers?

-

To what extent is care planning and co-ordination focused on recovery?

-

To what extent is care planning and co-ordination personalised?

-

What specific features of care planning and co-ordination are associated with the legal status of service users?

-

Is care planning and co-ordination affected by the different stages of stay on a ward (i.e. at admission, during stay, pre discharge)?

-

What suggestions are there for improving care planning and co-ordination in line with recovery and personalisation principles?

Objectives

This study investigated care planning and co-ordination for inpatients in acute mental health settings. The objectives were to:

-

conduct a literature review on inpatient mental health care planning and co-ordination and review English and Welsh policies on care planning in inpatient settings

-

conduct a series of case studies to examine how the care of people with severe mental illness using inpatient services is planned and co-ordinated

-

investigate service users’, carers’ and practitioners’ views of these processes and how to improve them in line with a personalised, recovery-oriented focus

-

measure service users’, carers’ and staff’s perceptions of recovery-oriented practices

-

measure service users’ perceptions of inpatient care, and their views on the quality of therapeutic relationships and empowerment

-

measure staff’s views on the quality of therapeutic relationships

-

review written care plan documentation and care review meetings

-

conduct a multiple comparisons analysis within and between sites to examine the relationships and differences in relation to perceptions of inpatient care, recovery, therapeutic relationships and empowerment.

Structure of report

This report presents the key findings of our empirical research building on a metanarrative policy and literature review within the context of continuing developments in the organisation, structure and delivery of inpatient mental health care in England and Wales.

In Chapter 2 we outline the methodology and design of the study, including public and patient involvement and ethics issues. In Chapter 3 we outline the methods and findings of the comparative policy analysis and metanarrative literature review. In Chapter 4 we present the results from the within-case analysis, with findings from quantitative and qualitative analyses for both meso- and micro-level data presented for each case study site. Then, in Chapter 5 we draw out comparisons and contrasts across sites set within the cross-national policy contexts and provide summary charts of the factors identified from this cross-case analysis that appear to act as facilitators of and barriers to the provision of recovery-focused, personalised care planning and delivery. Finally, in Chapter 6, we compare the results from this study with those from our earlier community study, consider the limitations of the study and explore the findings in relation to our aims and objectives and recent and ongoing research in relevant and overlapping areas. We end by outlining some tentative implications for mental health care commissioning; service organisation and delivery; clinical practice and health-care professional education and training; and recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

We conducted a cross-national comparative study of recovery-focused care planning and co-ordination in inpatient mental health-care settings, employing a concurrent transformative mixed-methods approach with embedded case studies. 33 Concurrent procedures required that we collect quantitative and qualitative data at the same time during the study and then integrate those data to provide a comprehensive analysis of the research problem. One form of data is nested within another larger data collection procedure to allow the analysis of different questions or levels of units in an organisation.

In this study, we nest in-depth micro-level case studies of everyday ‘frontline’ practice and experience with detailed qualitative data from interviews and reviews of individual care plans within larger meso-level survey data sets and policy reviews in order to provide potential explanations and understanding.

At the macro level is the national context. Cross-national comparative research involves ‘comparisons of political and economic systems . . . and social structures’ (p. 93)34 where ‘one or more units in two or more societies, cultures or countries are compared in respect of the same concepts and concerning the systematic analysis of phenomena, usually with the intention of explaining them and generalising from them’ (pp. 1–2). 35 In this study, devolved government and the emergence of similar but distinct health policy, legislation and service development in England and Wales provided the backdrop for the investigation of inpatient mental health care.

Such an approach fits well with a case study method36 that allows the exploration of a particular phenomenon within dynamic contexts whereby multiple influencing variables are difficult to isolate. 37 It allows the consideration of historical and social contexts38 and is especially useful in explaining real-life causal links that are maybe too complex for survey or experimental approaches. 39 So, in this study, we conducted a detailed comparative analysis of ostensibly similar approaches to recovery-focused care planning and co-ordination within different historical, governmental, legislative, policy and provider contexts in England and Wales.

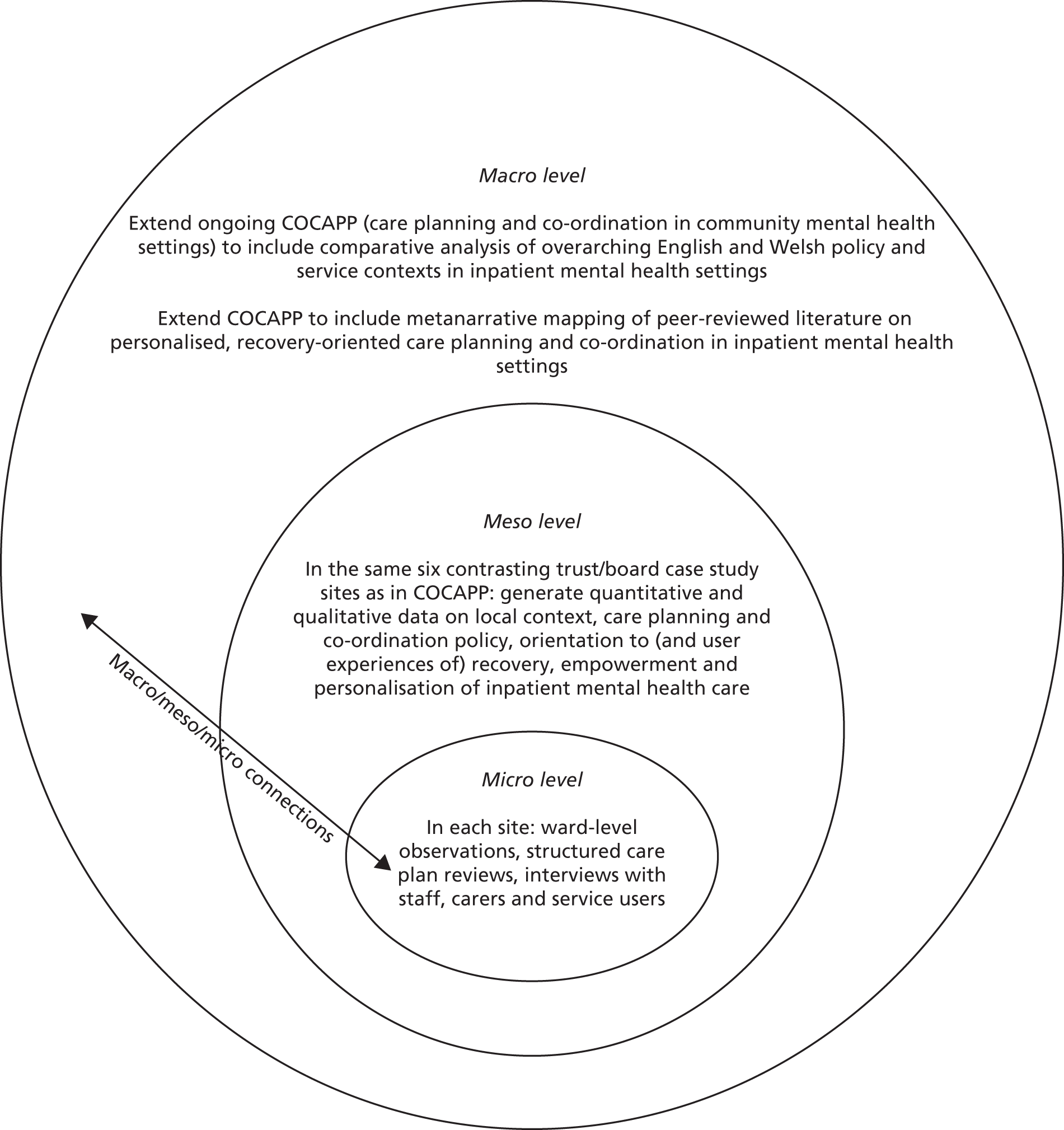

The definitions of the case studies were predetermined40 and focused on six selected NHS trust/health boards. Data collection at this level involved identifying local policy and service developments alongside empirical investigations of care planning and inpatient care, recovery, personalisation, therapeutic relationships and empowerment, employing mixed quantitative and qualitative methods. This design is represented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram illustrating embedded case study design and integration with (and extension of) initial COCAPP study of care planning and co-ordination in community mental health settings. Adapted with permission from Simpson et al. 20

Theoretical/conceptual framework

Transformative research seeks to include an explicit ‘intent to advocate for an improvement in human interests and society through addressing issues of power and social relationships’. 41 In line with this, transformative procedures require the researcher to employ a transformative theoretical lens as an overarching perspective. 42 This lens provides a framework for topics of interest, methods of collecting data, and outcomes or changes anticipated by the study.

This study is guided by a theoretical framework emphasising the connections between different ‘levels’ of organisation43 (macro/meso/micro) and concepts of recovery and personalisation that foreground the service user perspective and, arguably, may challenge more traditional service/professional perspectives. Furthermore, our research team and processes involve mental health service users throughout. We employed mixed methods across two phases.

Methodology

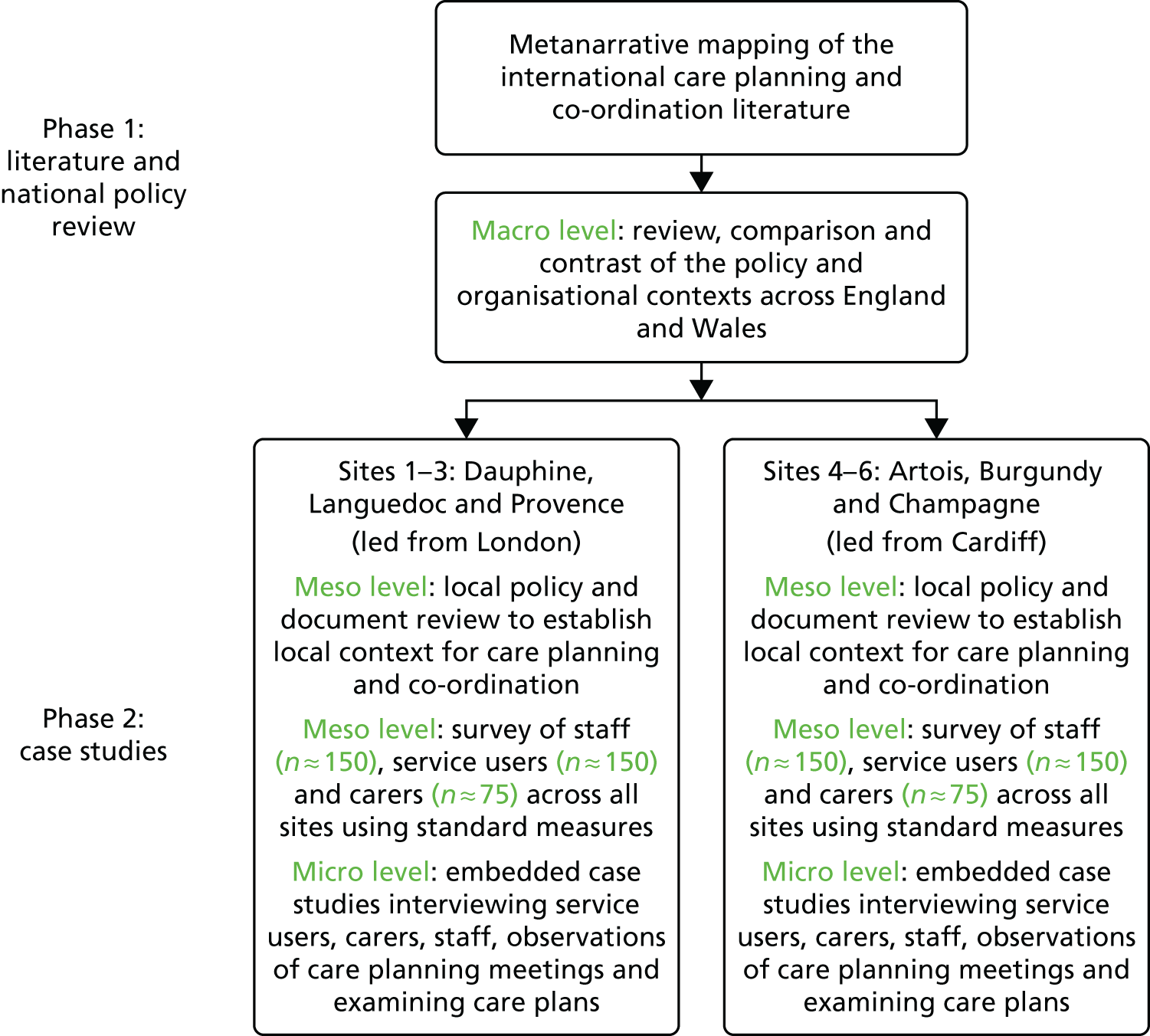

Phase 1: literature and policy review and synthesis

Literature review on inpatient mental health care planning and co-ordination

We extended our previous review of international peer-reviewed literature, and English and Welsh policies,20 to include recovery-oriented care planning in inpatient settings (macro level). We employed Greenhalgh et al. ’s44 metanarrative mapping method, which focuses on providing a review of evidence that is most useful, rigorous and relevant for service providers and decision-makers and that integrates a wide range of evidence. 45 Our metanarrative mapping method review provides a preliminary map of current mental health care planning and co-ordination by addressing four points: (1) how the topic is conceptualised in different research traditions, (2) what the key theories are, (3) what the preferred study designs and approaches are and (4) what the main empirical findings are. We describe the methods employed in Chapter 3, where we also bring together our broad narrative synthesis.

Comparative analysis of policy and service frameworks

By searching English and Welsh government websites we also identified all key, current, national-level policy and guidance documents directly relating to inpatient mental health care planning and co-ordination across the two countries, along with those which relate directly to the promotion of recovery and the delivery of personalised care. Drawing on these, we produced a narrative synthesis identifying the major themes and areas of policy convergence and divergence (see Chapter 3), and used these materials to lay out the large-scale (or ‘macro-level’) national policy contexts to inform our case study research interviews (see Chapter 4).

Phase 2: case studies

In phase 2, we conducted six in-depth case study investigations36 in six contrasting NHS trust/health board case study sites in England (n = 4) and Wales (n = 2) (meso level), employing mixed quantitative and qualitative methods. Then, in each site, we secured access to a single acute inpatient ward from which up to six service users, six multidisciplinary staff and four informal carers were sampled as embedded micro-level case studies. 33 Qualitative data were generated related to care planning and co-ordination processes in each inpatient ward (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Sample size and data collection targets for COCAPP-A. Adapted with permission from Simpson et al. 20

Inclusion criteria

Ward inclusion criteria

-

The ward provided an acute mental health care admissions facility to the local adult population.

-

The ward had an established ward manager/team leader in post.

-

The ward was not subject to any plans for closure or merger during the study.

-

The ward was not currently experiencing excessive pressures or responding to elevated levels of untoward incidents (so that we did not add to participant burden).

-

There was multidisciplinary team (MDT) support to participate in the study.

Service user/patient inclusion criteria

-

Was admitted to inpatient unit.

-

Had been on the ward for a minimum of 7 days.

-

Was aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Had a history of severe mental illness.

-

Was able to provide informed consent.

-

Had sufficient command of English/Welsh.

These criteria were deliberately broad to allow the inclusion of patients with organic brain disorders, people with substance abuse and people who were not fluent in English or Welsh, which is very often the case in NHS routine care.

Staff inclusion criterion

-

Any qualified or unqualified staff working on inpatient wards who were involved in care planning or review.

Sampling

We selected the same six case study sites that had participated in the initial COCAPP study to enable us to draw comparisons and connections between community and inpatient services. These sites consisted of four NHS trusts in England and two local health boards (LHBs) in Wales that were commissioned to provide inpatient mental health services. These sites were identified to reflect variety in geography and population and to include a mix of rural, urban and inner-city settings in which routine inpatient care is provided to people with complex and enduring mental health problems from across the spectrum of need. The selection of six sites in the original COCAPP study followed advice from reviewers and was decided pragmatically, balancing variety of settings and populations with logistical and data management pressures in the time available.

In each meso-level trust/health board site, we aimed to survey a large sample of service users, carers and ward staff (see Figure 2). Survey questionnaires focused on recovery-oriented practices (all groups), the quality of therapeutic relationships (service users and staff), feelings of empowerment (service users only) and perceptions of acute mental health care, including involvement in care planning and ward round discussions (service users only).

In each trust/health board site, we also selected a single ward that provided routine inpatient mental health care and met our inclusion criteria (outlined in Ward inclusion criteria). Interview data were generated relating to local contexts, policies, practices and experiences from a range of ward staff purposively selected to include ward managers, psychiatrists, senior nurses, psychologists and occupational therapists (OTs) (meso- and micro-level data).

To generate knowledge about how care is planned, co-ordinated and experienced at the ‘micro level’, we then invited a sample of six service users, who were under the care of that ward and approaching discharge, to be interviewed about their experiences of care planning during their admission. They were also invited to jointly review their inpatient care and aftercare plans, as well as their involvement in developing and implementing those plans in line with recovery and personalisation approaches. In addition, we attempted to interview family members/carers about their experiences of inpatient care planning and co-ordination. A structured review of additional care plans and a non-participatory observation of ward activities discussing and reviewing care plans were also conducted.

Sample size calculations

For the questionnaire survey, an a priori sample size calculation was conducted using the software package G*Power (version 3.1; Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). 46 The sample size was based on completing a multivariate analysis (MANCOVA) for comparing the interaction of within (covariates) and between (sites) factors. Assumptions were based on six groups (sites), four outcome measures (questionnaires) and 10 potential predictors (gender, age, ethnicity, time on CPA, etc.). We calculated the sample size using α level of 0.05, power of 0.8047 and a small effect size (Pillai’s Trace V = 0.10). Given the many potential influences on our outcome measures, we expected the magnitude of the observed relationship to be small. A small effect size was therefore chosen to represent the subtleties in relationships of the data. This calculation suggests that a sample size of 276 is required in order to reach power.

Based on this sample size calculation we aimed to obtain complete questionnaire survey responses from 300 service users (n = 50 per trust/health board), 300 inpatient staff (n = 50 per site) and 150 informal carers (n = 25 per trust/health board). By aiming to sample 300 survey responses we were seeking to include more than the sample size suggested for the service users and inpatient staff. We anticipated that with rates of non-response and incompletion of the questionnaires we would need to oversample to meet our sampling targets. In contrast, we anticipated not to achieve this sample size for informal carers. This was because not every service user would have a carer, and therefore analysis for the informal carers was underpowered (estimated power will be 0.44). The data for the informal carers were, therefore, anticipated to be exploratory in preparation for a future, larger-scale study. Further information on our involvement of carers is given in Chapter 4 (see Recruitment and case study sites).

One ward within each trust/health board was selected to participate in micro-level data collection. We planned to undertake semistructured interviews in each ward with staff (target per ward, n = 6; total, n = 36), service users (target per ward, n = 6; total, n = 36; to include joint review of care plan) and carers (target per ward, n = 4; total, n = 24).

Calculations of the sample size for the qualitative interviews were based on previous research with similar populations by the co-investigators and others; an understanding of the practicalities and time commitments involved in recruiting and interviewing participants and analysing in-depth qualitative data; and the numbers required for us to feel confident that the findings would be transferable to other, similar settings.

In addition, we intended to undertake structured case reviews of care plans for service users on each participating ward (target per ward, n = 10; total, n = 60) and non-participant observation of care planning processes on inpatient units (target per ward, n = 3; total, n = 18).

Instrumentation

Table 2 maps data collection methods against the research questions. Permissions were obtained to use all measures.

-

Documentation and officially collected data: local meso-level CPA policy and procedure documents, CQC, national and local audits and reviews were collated when possible.

-

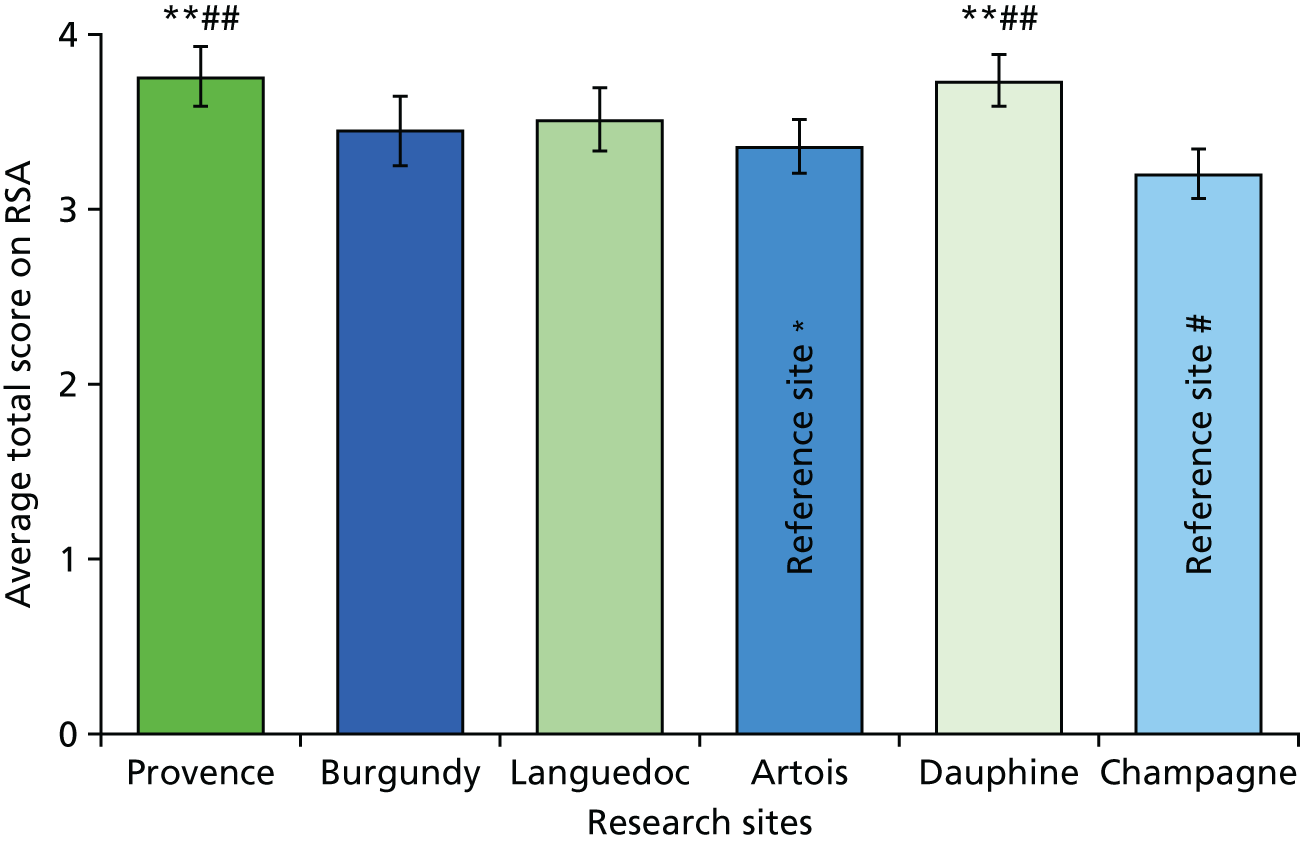

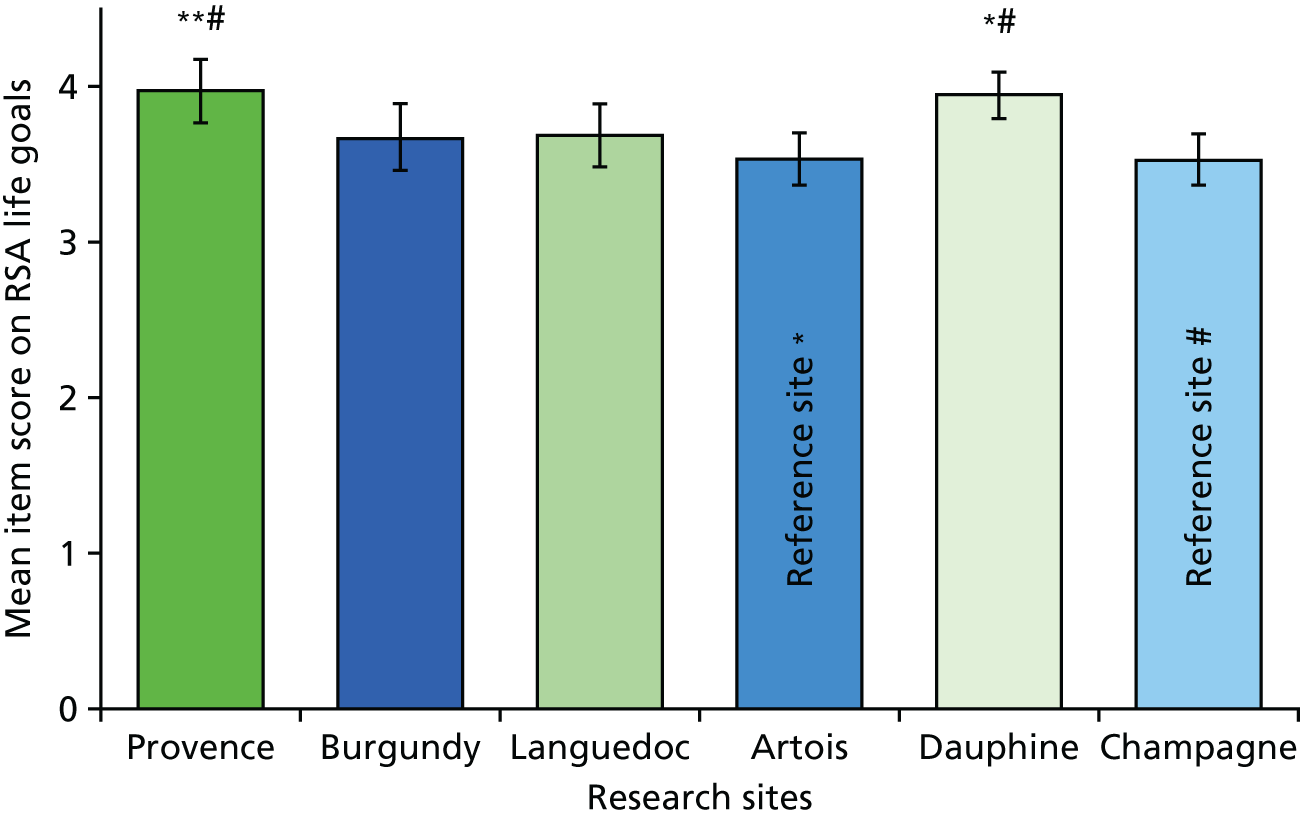

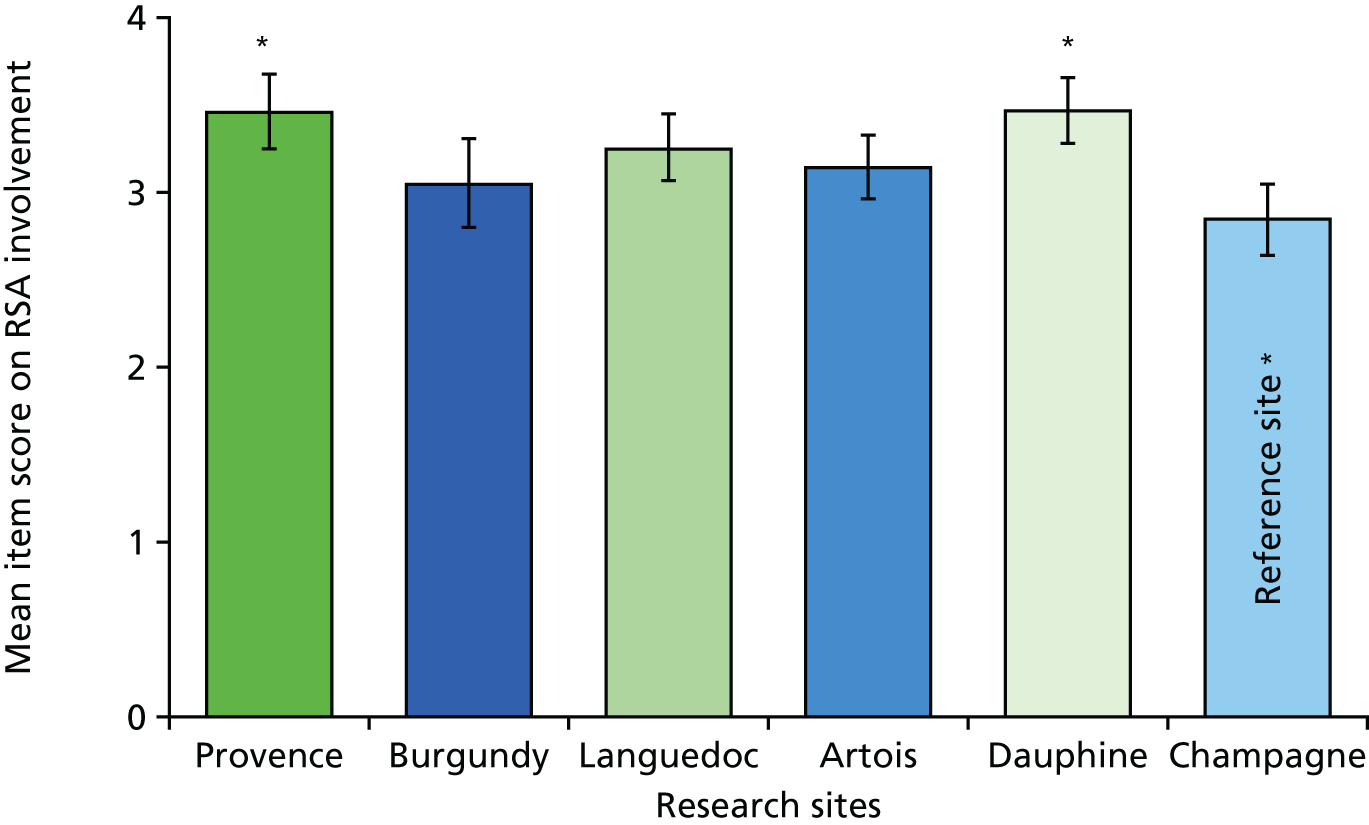

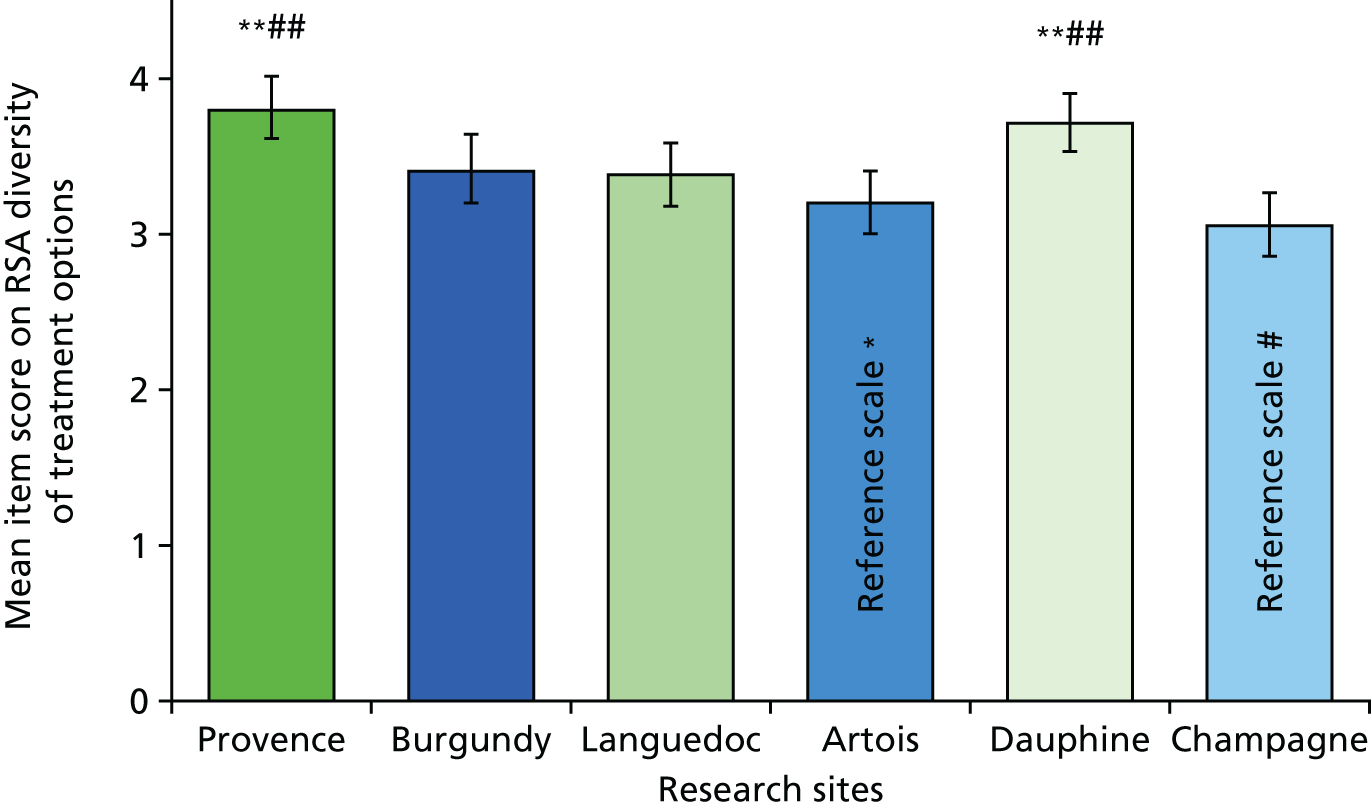

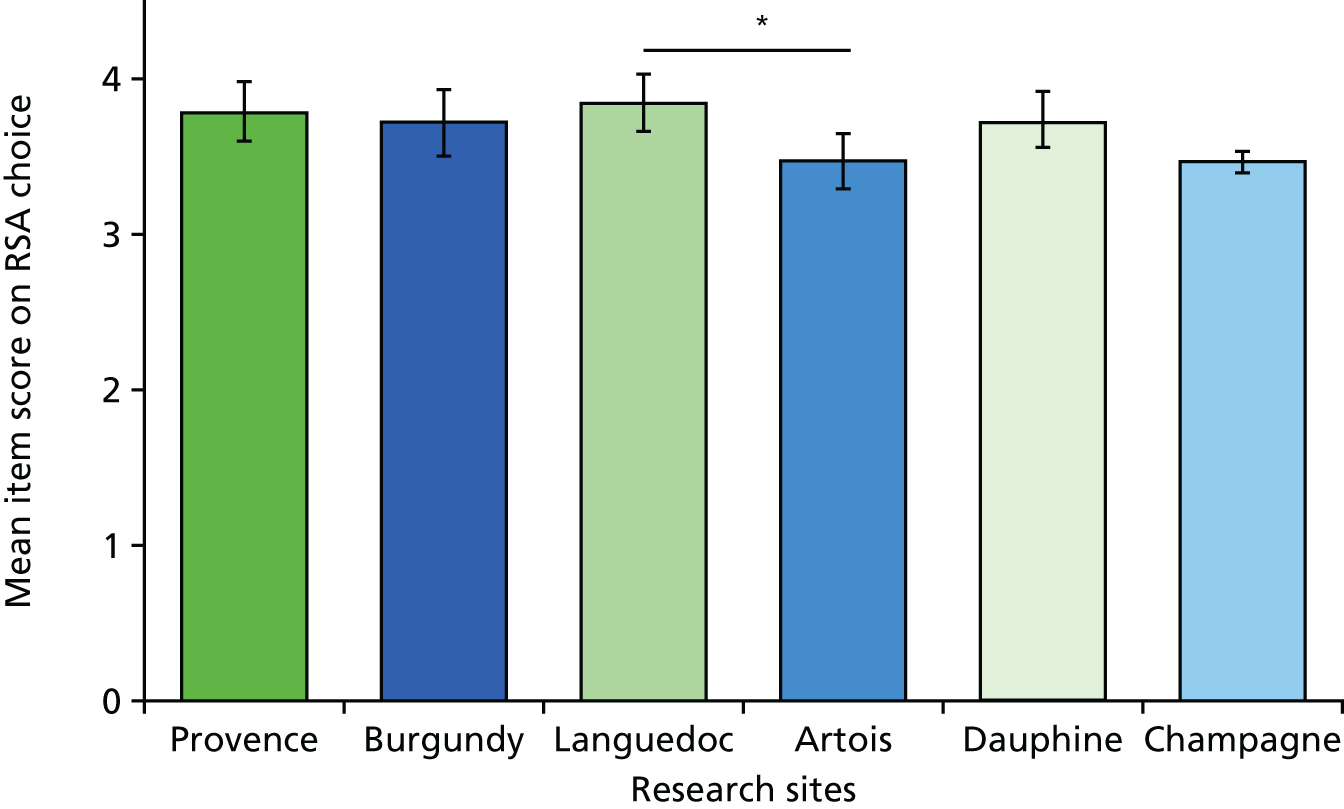

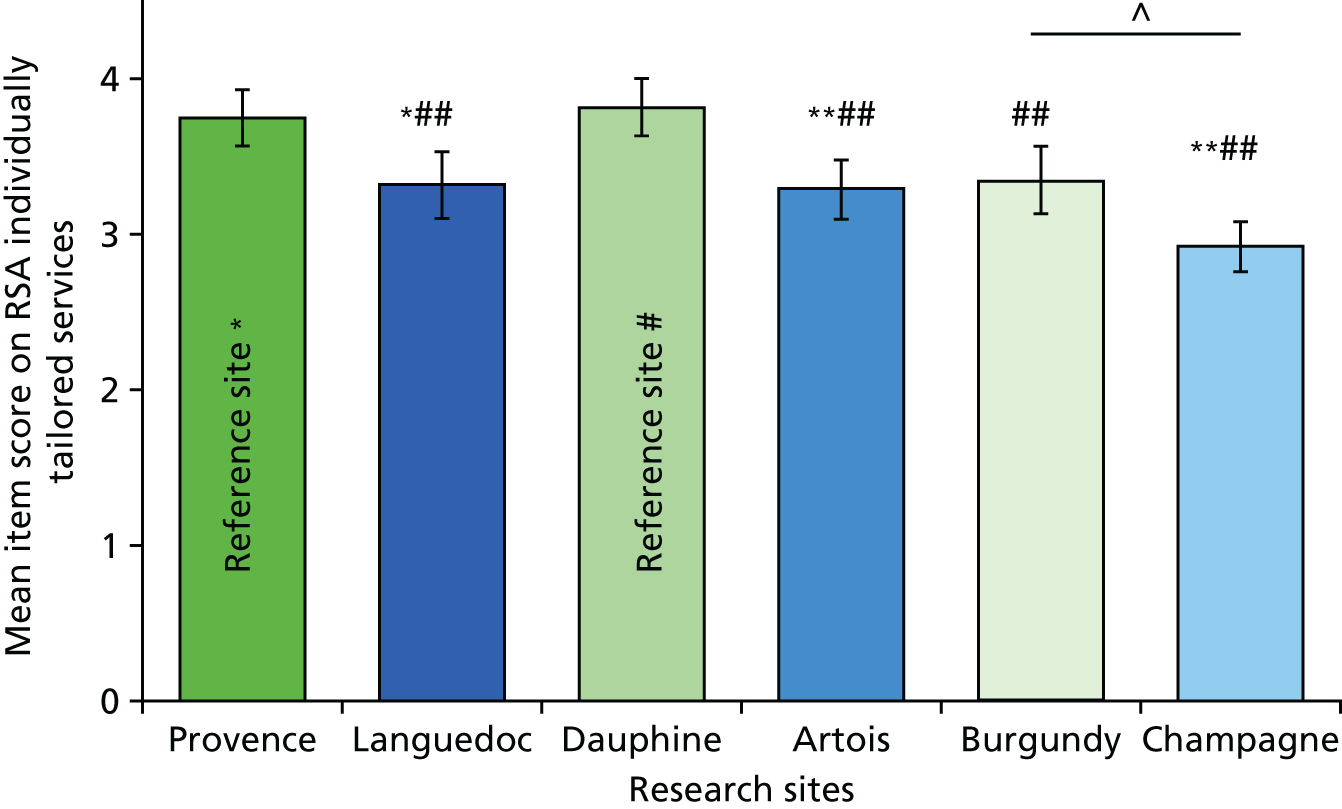

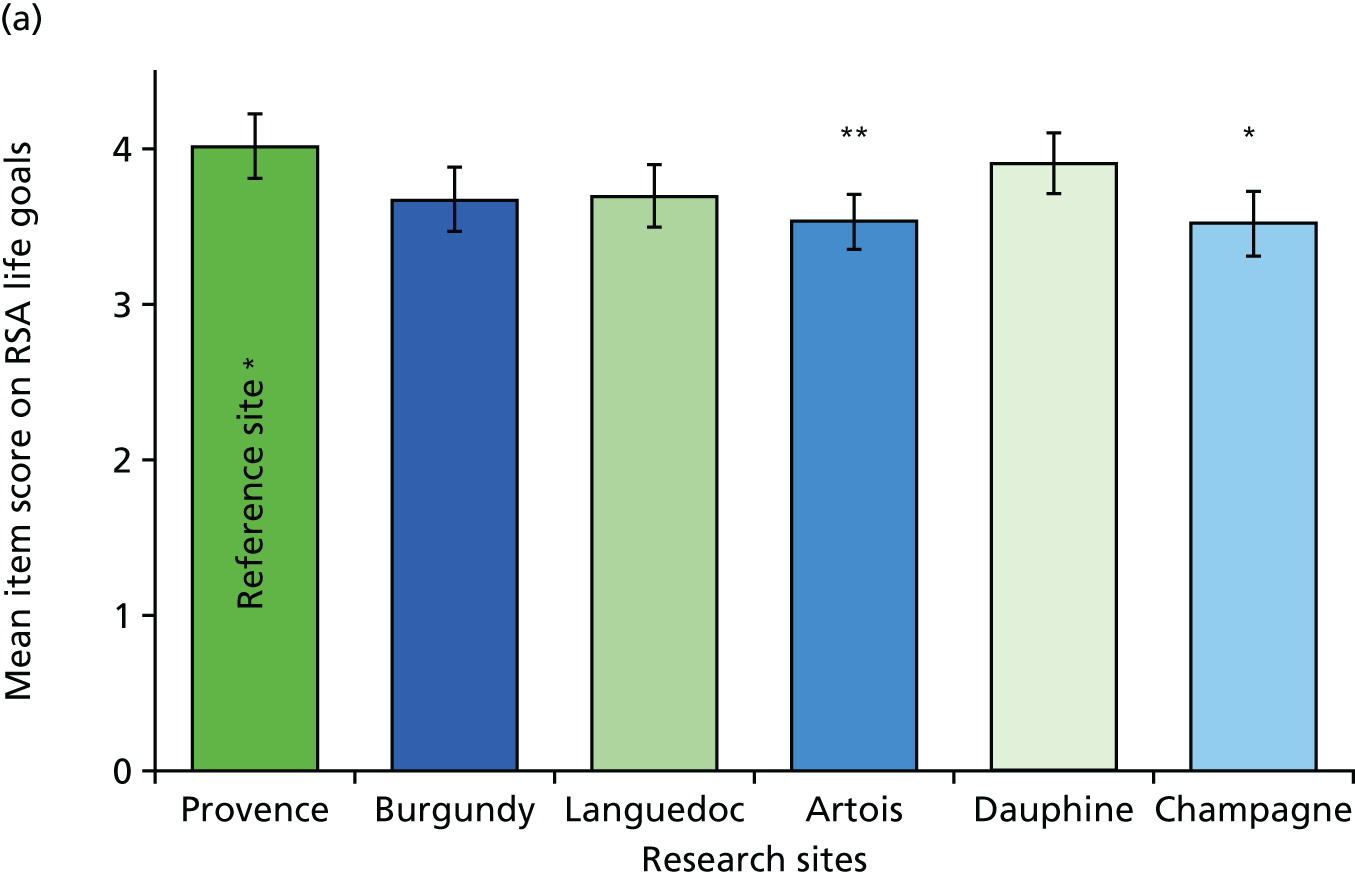

The Recovery Self-Assessment (RSA)48 is a 36-item scale designed to measure the extent to which recovery-oriented practices are evident in services. It was used in the initial COCAPP study. The scale addresses the domains of life goals, involvement, treatment options, choice and individually tailored services. The total RSA score is obtained by summing the individual items and dividing them by the number of items. Individual item scores range from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’). A higher total score refers to a more recovery-focused service. The RSA has been tested for use with people with enduring and complex mental health problems and across a range of ethnic backgrounds. To date, no data are available on construct and external validity for this scale. In our community COCAPP study, we assessed the internal consistency of the RSA with Cronbach’s alpha and demonstrated that alpha levels for the total score and subscales were acceptable. 19 The measure was completed by service users, carers and ward staff.

-

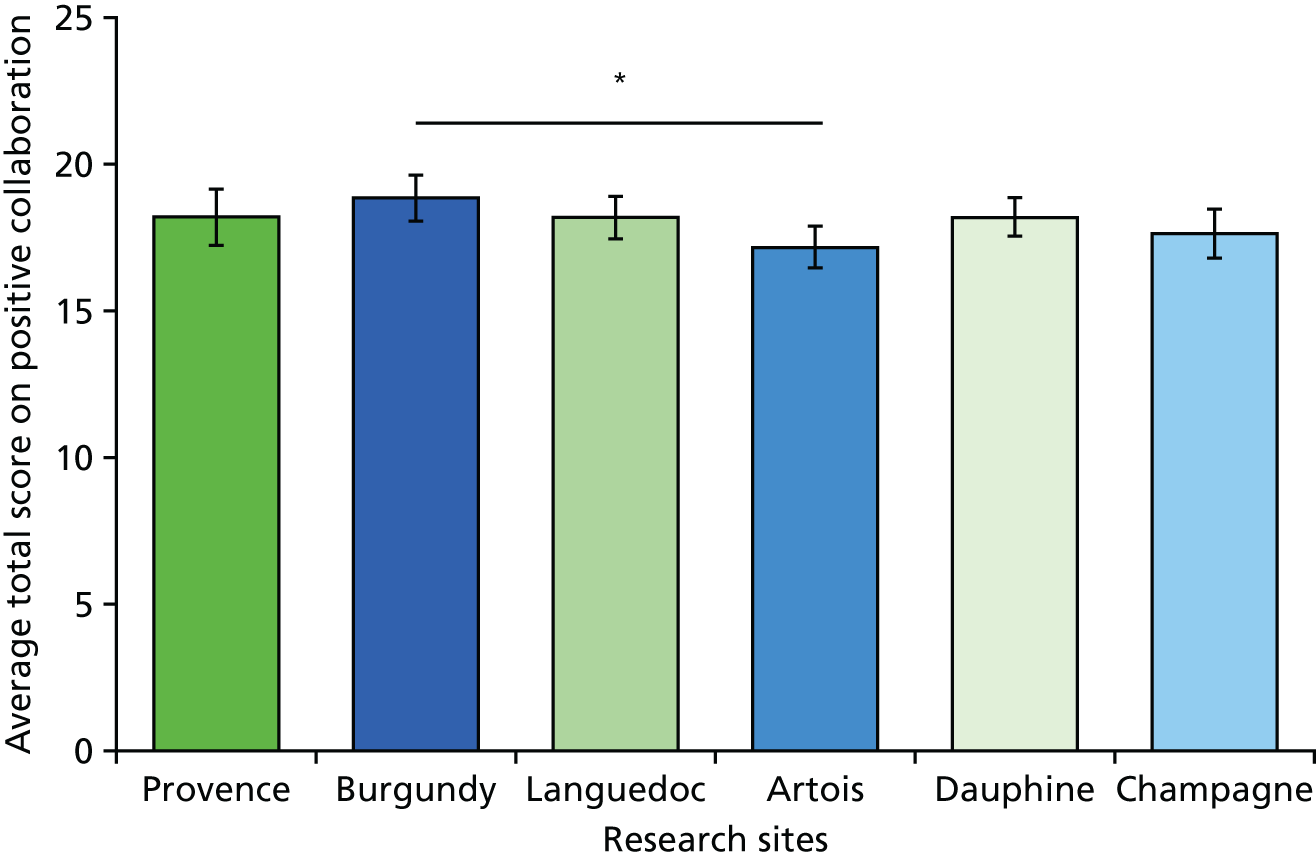

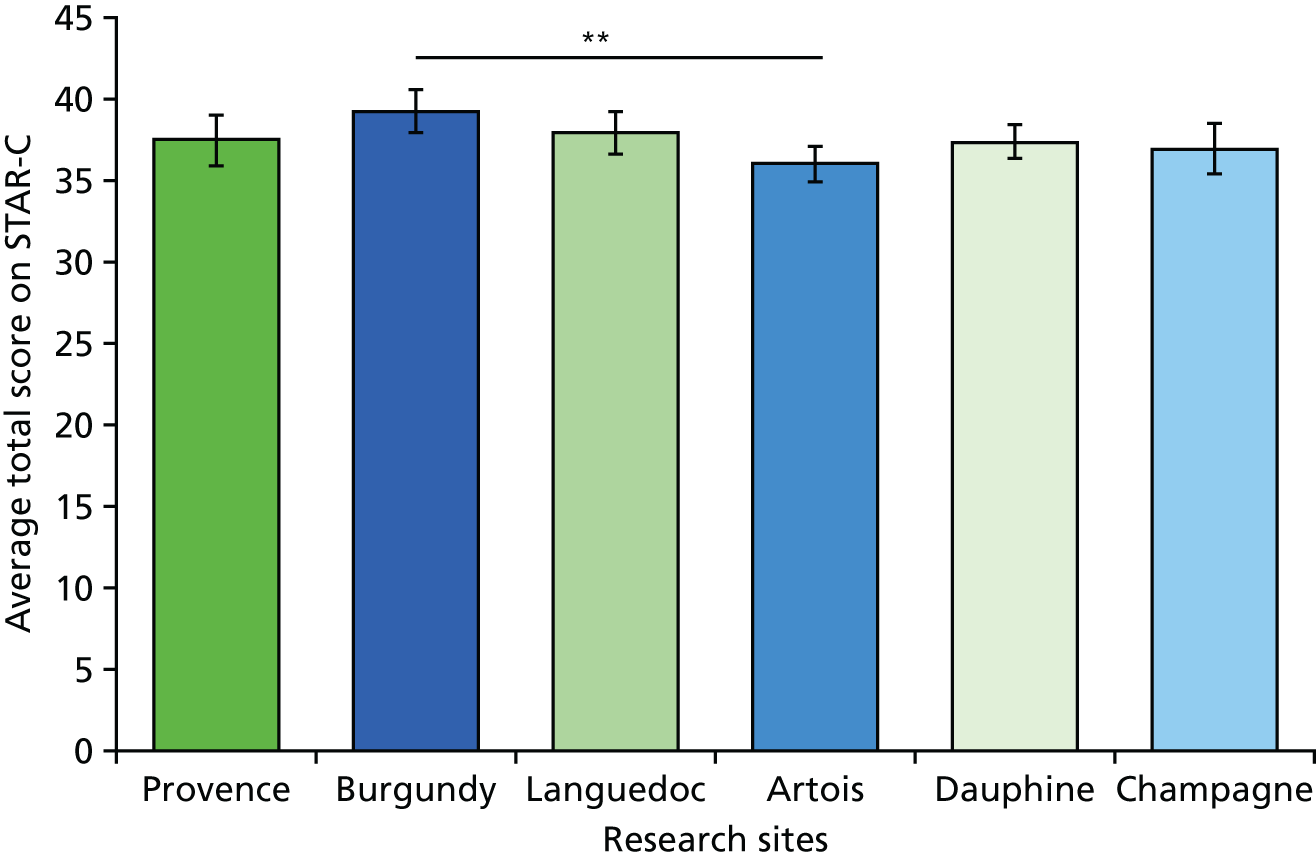

The Scale To Assess the Therapeutic Relationship (STAR)49 is a brief (12-item) scale that assesses therapeutic relationships. The patient version was used in the initial COCAPP community study. It has good psychometric properties, the internal consistency and test-retest reliability are acceptable, and it is suitable for use in research and routine care. A total STAR score is obtained by summing the individual items. Scores for individual items range from ‘0’ (‘never’) to ‘4’ (‘always’) and the total possible score ranges from 0 to 48. A higher score refers to a more positive rating of therapeutic relationships. The subscales measure positive collaborations (possible score 0–24), positive clinician input (possible score 0–12) and non-supportive clinician input in the patient version and emotional difficulties in the staff version (possible score 0–12). The measure was completed by service users and ward staff.

-

The Empowerment Scale (ES)50 is a 28-item questionnaire with five distinct subscales: self-esteem, power, community activism, optimism and righteous anger. Empowerment is strongly associated with recovery and ES is the most widely used scale. The development paper for the scale reported a high degree of internal consistency. A further paper confirmed moderate construct validity. 51 A total empowerment score for each service user respondent is obtained by summing individual items and dividing them by the number of items. At the item level the scores range from ‘1’ (‘strongly agree’) to ‘4’ (‘strongly disagree’). A higher total score indicates a higher perceived level of empowerment. Subscale values can also be provided for ‘self-esteem–self-efficacy’, ‘power–powerlessness’, community activism and autonomy’, ‘optimism and control over the future’ and righteous anger’. This scale was completed by service users and was also used in the COCAPP study.

-

The Views of Inpatient Care Scale (VOICE)52 is a 19-item patient-reported outcome measure of perceptions of acute mental health care that includes questions on involvement in care planning and ward round discussions. An innovative participatory methodology was used to involve service users throughout the development and testing of this measure. The VOICE encompasses the issues that service users consider most important and, therefore, it has high face validity. The original development paper for the scale52 reported that the scale had demonstrated high criterion validity and high internal consistency and that the test–retest reliability was high. It is easy to understand and complete, making it is suitable for use by service users while in hospital; it has also been shown to be sensitive to service users who have been compulsorily admitted and who tend to report significantly worse perceptions of the inpatient environment. An overall VOICE total score was obtained by individual item scores; possible total scores range from 19 to 114. Individual item scores range from 1 ( ‘strongly agree’) to 6 ( ‘strongly disagree’). The higher the total score for the VOICE, the more negative the perception of the quality of care on the ward. The measure was completed by service users (see Appendix 1 for all questionnaires).

-

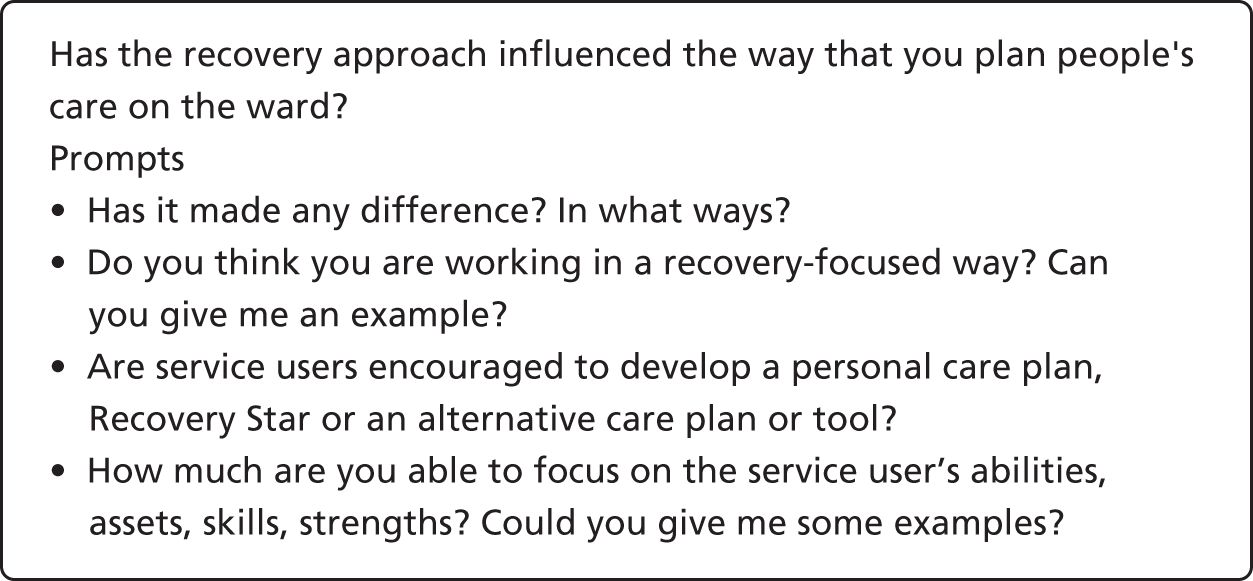

Structured interviews with ward staff, service users and carers: interview schedules were based on those used in the initial COCAPP study and refined by the study team in consultation with our Scientific Steering Committee and Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG) and drawing on relevant literature. The aim of all interviews was to explore participants’ views and experiences of care planning and co-ordination, safety and risk, recovery and personalisation, and the context within which these operated. The interview schedules for each group of respondents comprised 19 lead questions, with numerous prompts suggested for the interviewer (Figure 3; the full schedule is in Appendix 2).

-

CPA care plan review: within each ‘embedded case study’, as part of the interview process, the six purposively selected service users were also asked to look at and provide a narrative review of their care plan with the researcher.

-

Structured review of service user care plans: in addition to the narrative care plan reviews above, anonymised information was obtained from the care plans of a series of consecutively discharged patients (including first admissions and readmissions, with replacements for refusals) at each of the six inpatient wards taking part in the study (target at each trust/health board, n = 10; total, n = 60). When consent was provided, anonymous CPA/CTP care plans were systematically reviewed and appraised against a structured template incorporating identified key concepts of good practice in care planning, user and carer involvement, personalisation and recovery (see Appendix 3). The template was specifically developed and informed by CPA good practice checklists developed by service users and staff;53,54 our community care planning study; and the CPA Brief Audit Tool,55 designed and used to assess the quality of CPA care planning for service users who have had more than one compulsory admission in 3 years.

-

Non-participant observation of care planning processes on inpatient units: this included staff–patient assessment/care planning meetings, ward rounds and discharge planning meetings. Observations were informed by a structured guide, developed to identify good practice in involving service users and carers, and a focus on recovery and personalisation. The guide was developed in consultation with an established Service User and carer Group Advising on Research (SUGAR)56 and the LEAG (see Appendix 4).

| Research questions | Data collected to answer the research question |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 3.

Example question and prompts.

Research ethics

The study received NHS Research Ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee London – Fulham (reference number 14/LO/2062) on 29 December 2014.

Considerable attention was given to ensuring the welfare of service users, carers and other participants, as well as that of the researchers. This included providing opportunities for people to pause or withdraw from interviews, assurances of anonymity and confidentiality and responses to concerns for people’s welfare. Careful arrangements were made for the location and conduct of interviews, and all researchers received training, supervision and opportunities for debriefing.

Procedure

We obtained provisional agreement to participate in the study in writing from senior trust/health board managers (e.g. the chief executive) before submitting the research proposal for funding. Following the commissioning of the study, a formal invitation to take part in the study was communicated to a senior manager, such as the chief executive, in each organisation. All accepted, and identified a principal investigator/link person to facilitate research ethics and governance approvals as well as contact with other staff.

We identified suitable local wards meeting the inclusion criteria with the assistance of local NHS trust/health board principal investigators. Ward managers were approached by a researcher who explained the study, responded to any queries and invited them to participate. Nobody declined to take part. We sought consent to participate in the questionnaire survey from two or three wards, one of which was selected for the more in-depth case study of care planning, including interviews.

Questionnaire survey

With help from the clinical teams, researchers, clinical studies officers57 and research nurses distributed information sheets, consent forms and questionnaires to ward staff, service users and carers, and collated the completed questionnaires. We approached additional wards within the host site to enable us to achieve the sample required for the questionnaire survey.

Researchers attended ward staff meetings to explain the study and respond to any questions. All managers and ward staff involved in care planning or care plan review received written and verbal information about the study and were invited to participate in the questionnaire survey (the target was 50 people per trust/health board). We employed the usual procedures for obtaining informed consent with permission to decline or withdraw, and all participants were anonymised.

Staff from participating wards were asked to identify service users who had been on that ward for a minimum of 7 days, and who in their view had the capacity to participate in the study and complete the questionnaire survey (target n = 50 per trust/health board). Staff made the initial approach to the service user, inviting them to meet with the research assistant to find out more about the study. If the service user expressed an interest, the research assistant provided them with written and verbal information about the study, and invited them to ask any questions. During this process the research assistant appraised the capacity of the service user to understand the information and make an informed decision about whether or not to participate. The service user was encouraged to discuss the study with family, friends, advocates or staff if they wanted to. Once informed consent had been obtained, each service user was given the pack of questionnaires to complete, with assistance available from the research assistant if required.

Ward staff were asked to give carer questionnaire packs to carers (family members and friends) who were visiting service users on the ward (target n = 25 per trust/health board). The packs included an information sheet and a freepost return envelope. Researchers working on the ward also approached carers to invite them to complete the questionnaires, with assistance provided if required.

Semistructured interviews

Key personnel, identified using purposive sampling, were invited to participate in interviews for the in-depth case study and to forward local policies and information (target per case study ward, n = 6; total, n = 36). Staff were given written materials that described the purpose of the study and explained what taking part in an interview would entail; this included the option to decline or withdraw from the study at any time. Informed consent procedures were followed. Interviews took place once informed consent had been obtained and at a time convenient to the staff member.

Staff members identified service users approaching discharge who were deemed to have capacity to give informed consent. Subsequently, the research assistant invited these service users to participate in an interview about their experiences of care planning and jointly review their care plan (target per case study ward, n = 6; total, n = 36) (see Care plan review). Once informed consent had been obtained, arrangements were made to conduct the interview at the service user’s earliest convenience. Appraisal of capacity was continuously assessed during the interview. Service users were also asked for their permission for their care plans to be reviewed.

Service users were asked to identify a carer (if applicable) to take part in an interview (target per case study ward, n = 4; total, n = 24). The research assistant either contacted the carer by telephone or approached them on the ward during a visit, in the presence of the service user if possible. If the carer expressed an interest in participating, the research assistant provided them with written information about the study and gave them the opportunity to ask questions. Carers were encouraged to give some time and thought to whether or not they wanted to participate before they signed the consent form, and to discuss it with a family member, friend or member of staff. Once informed consent had been obtained, the carer was invited to participate in an interview at their earliest convenience. The interview took place in the hospital or at their home, depending on their preference. If they requested to be interviewed at home, lone worker policies and procedures were followed.

Care plan reviews

In addition to the service users who consented to interview and a review of copies of their care plans, a total of 10 further service users’ care plans were reviewed by researchers with consent (target per case study site, n = 10; total, n = 60). Potential participants for this part of the study were identified and consented into the study if they had agreed to complete a questionnaire. When care plans were accessed in this way, efforts were made to ensure that the information extracted for research purposes did not include the real names of service user participants or other details that could have identified them. Care plans were systematically reviewed and appraised against a structured template incorporating the identified key concepts of personalisation and recovery. Anonymised demographic, diagnostic and service use data, for example complexity of case/need, were also collated to describe this sample in relation to the wider population of people using acute inpatient mental health services.

Observations of care planning processes

In addition to this, the research team conducted non-participant observations of care planning processes on inpatient units (target per case study site, n = 3; total, n = 18). On each participating acute ward, and with prior agreement, researchers attended and observed at least three meetings during which patient care was routinely discussed and planned. These included individual care planning meetings, discharge planning meetings and ward rounds. Information about the intention of researchers to attend and observe some of these meetings was included on posters displayed in the ward. Researchers took contemporaneous notes of meetings and, with permission, digitally recorded interactions to check for accuracy when the notes were transcribed and analysed. Observations were informed by a structured guide previously developed to identify good practice in involvement of service users and carers and by a focus on recovery and personalisation.

Staff interviews were conducted by academic researchers (SB, NA, RC and MC) and clinical studies officers. Service user and carer interviews were conducted by service user researchers (KB, BE, AM and AF) with one of the academic researchers in attendance, or occasionally by academic researchers (SB, NA and JM). Clinical studies officers undertook care plan reviews using the template provided. Observations were undertaken by academic researchers (SB and RC) and a service user researcher (AF).

Public and patient involvement

The study was developed and designed with full involvement of co-investigator and independent service user researcher AF and in consultation with SUGAR,56 based at City, University of London and facilitated by the chief investigator (AS). In addition, a LEAG was established, consisting of seven service users and one carer with direct experience of inpatient mental health care planning and co-ordination. This separate advisory group of ‘experts through experience’ ensured that more time could be spent exploring the views of service users and carers and ensuring that their perspectives were able to inform the study. Members were recruited via the previous COCAPP LEAG to provide some continuity and ensure geographic spread.

The group was facilitated by AF and it met with members of the research team three times during the course of the study, contributing in the following ways:

-

suggested relevant literature and terms to inform the literature review

-

suggested things to consider when recruiting people for interviews on the ward

-

informed the structured observation guide and advised the research team based on personal lived experiences of ward rounds and discharge meetings

-

advised on the interview schedules, providing suggestions for additional prompts and ensuring consistency

-

provided suggestions on the recruitment of carers

-

discussed with the service user researchers about their experiences of interviewing service users and using the interview schedules

-

provided suggestions on the challenges in gaining access to observe ward rounds

-

provided suggestions for dissemination of the findings from both studies

-

contributed to a co-produced paper for publication on working in partnership.

The 12-member Scientific Steering Committee consisted of representatives with a clinical or research background from each of the participating NHS trusts/health boards and independent academics. One service user and one carer member also represented the LEAG on the Project Advisory Group (PAG), with input from the LEAG timetabled on the agenda of all meetings, which were chaired by Professor John Baker, Professor of Mental Health Nursing at University of Leeds.

Three service user researcher assistants/service user project assistants were employed to work on the study on a temporary contract basis: one based in London and two based in Swansea. All received training and ongoing support during the study.

Analytical framework

We framed our data analysis by drawing on social scientific ideas and the findings of our phase 1 evidence and policy review, an approach used by co-investigators in previous studies58 and in our previous community study. Our concern to explore commonplace practices in inpatient mental health is congruent with interactionist interests in social processes and human action. 59 This perspective also recognises the importance of social structures, so that in any given setting person-to-person negotiations are shaped by the features of organisational context. 60 The immediate context for frontline practitioners and service users in this study is the inpatient ward, each of which we view as a complex open system. Each participating ward also sits within a larger meso-level NHS trust/health board site, which in turn is located within a national-level system of mental health services. This idea of ‘nested systems’ is a feature of complexity thinking,43 and informed our plan to generate, analyse and connect data at different (but interlocking) macro/meso/micro ‘levels’ of organisation. Analysis and interpretation of the case study data were informed by a conceptual framework that emphasised the connections between different (macro/meso/micro) levels of policy and service organisation, and that drew on the findings of the literature and national policy review in relation to care planning, recovery and personalisation.

Quantitative analysis

Preparation of the data

Data from the questionnaires were entered into SPSS version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and checked and cleaned by a second researcher before statistical analysis. The distribution of the questionnaire data was assessed for normality using descriptive quantitative measures of skewness and kurtosis. Across the sites, normality was assessed for 17 outcomes for service users and 10 outcomes for staff. The outcomes from both groups fell within the range of the normal distribution. There were few deviations from normality (2 out of 27 scale outcomes exceeded the conservative criteria of ± 1) and one was small in the extent of deviation (within ± 2); however, one scale displayed larger deviation of skewness [emotional differences subscale, staff outcome, on the Scale to Assess the Therapeutic Relationship – Clinician Version (STAR-C)]. Parametric tests are robust enough to withstand minor deviations in normality, and therefore the skewness and kurtosis values outlined above do not preclude the use of parametric tests. 61

Comprehensive sensitivity analyses were completed to allow determination of what parameters to use when dealing with missing data. A missing value analysis was completed for the 27 scale outcomes. Moderate to high levels of missing data, not missing at random, were identified on a small number of items (mean level of missing data across the 27 scales/subscales was 20%, range from 6% to 55%). The service user version of the RSA questionnaire in particular had a moderate number of missing data. Mean replacement was used to avoid an unnecessary loss of cases from the analysis. The mean of the available items for the scale and participant was used for replacement of the missing values on the scale. A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine what effect mean replacement would have in the primary analyses at different levels of replacement, ranging from 20% to 50%. A comparison was made between the impact of different levels of mean replacement and a complete case analysis (i.e. participants with no missing values on the scale or subscale). Utilising a 50% mean replacement led to no substantive changes in the key statistical parameters (p-values and associated effect sizes) and the inferences drawn; therefore, it was deemed appropriate to maximise the number of cases included in the analyses.

Exploring the data

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the four questionnaires (VOICE, RSA, STAR and ES). The total scores, subscale means and standard deviations (SDs) were derived to produce a ‘recovery profile’ for each site. When appropriate these scores were compared against reference values (VOICE, STAR and ES) or with the participant groups (RSA). Some further detailed analysis at a descriptive level was completed on the primary outcome scale (RSA) to aid with the triangulation of the qualitative and quantitative data. This was completed at an individual item level on the scale by ranking the mean responses for each question to determine where the most agreement was for the participant groups. The top five items were selected from the questionnaire and presented as a recovery profile for the site. We provide descriptive narratives comparing the results from the community COCAPP study and the COCAPP acute study. We chose to present a comparative analysis descriptively for the within-case analysis and refer the reader to an exploratory inferential analysis in Chapter 5.

Inferential statistics

Several unadjusted one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to compare differences between the six sites on the RSA, STAR, ES and VOICE measures. Subsequent Tukey’s post hoc tests were conducted to ascertain which measures differed between which locations. A series of one-way analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) was completed to adjust the analyses for potential confounders. The demographic variables that were chosen for service users were age, gender, ethnicity and living status. Three care-related variables were chosen for service users: previous admissions, time in mental health services and time on the ward. The demographic variables chosen for staff were age, gender, ethnicity, personal experience of mental illness and family experience of mental illness. Two clinical variables were also chosen: time working in mental health services and time working on the ward. The criteria for adjusted analysis between the ANOVA and the ANCOVA were the p-value from the omnibus test, the adjusted means and the p-value from the post hoc test. If the p-value from the omnibus test for the ANCOVAs was not substantively different from the ANOVAs, then no further post hoc analyses were completed. A series of independent t-tests were completed to determine if there were differences between service users and staff on the outcome measures.

To determine if there were any statistical differences in responses between the two COCAPP studies, a series of exploratory two-way ANOVAs were completed. A comparison was made for the main effects of site (trust/health board) and study type (community COCAPP and COCAPP acute) on all of the outcome measures for service users and staff. Analyses for service users were completed for the RSA total score, Scale to Assess the Therapeutic Relationship – Patient Version (STAR-P)] total score and ES total score. A two-way ANOVA for staff was completed for the RSA Total only. When the acquired assumptions were not met, data are not reported.

Correlations

Correlations of the service user data were carried out to identify if there was a relationship between the outcome measures and to determine if there were relationships among patients in terms of views of the inpatient services (VOICE), recovery-oriented focus (RSA), empowerment (ES) and the quality of therapeutic relationship (STAR). Six Pearson’s correlations were carried out to identify if there were relationships between the mean total scores for the measures RSA and VOICE, RSA and STAR-P, RSA and ES, STAR-P and ES, STAR-P and VOICE, and VOICE and ES for all service user participants and by individual site. Cohen’s47 effect sizes were used to describe the data (small, r = 0.10; medium, r = 0.30; and large, r = 0.50). A Pearson correlation was also completed for staff on the mean total scores for the RSA and STAR-C.

For all of the ANOVAs and ANCOVAs, the statistical significance level was set at a level of 0.05. To account for multiple comparisons for the t-tests the significance threshold was raised to 0.005 to accommodate for the number of tests applied (n = 10).

Qualitative analysis

All of the digital interview recordings were professionally transcribed. The transcripts were then checked against the original recordings for accuracy, and any identifying information redacted, before they were imported into QSR International’s NVivo10 qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Warrington, UK) for analysis using the Framework method. 62,63

In this study, members of the research team read numerous transcripts to familiarise themselves with the data. The Framework matrix used was a slight refinement of that used in the COCAPP study, which was developed a priori from the interview schedules, with sections focusing on organisational background and developments, care planning, recovery, personalisation, safety and risk, and recommendations for improvement. Each matrix section also had an ‘other’ column for the inclusion of data-led emergent categories.

Slight amendments to the matrix were made before each transcript was summarised and charted (by RC, SB, AF, AT, BH, MC and FLG) following an agreed format for notation and linking to text. Researchers read and checked samples of each other’s summarising against transcripts to ensure that the approach was accurate and consistent.

Once all charting was completed, second-level summarising was undertaken (by RC, BH, MC, AS and AF) to further précis data and to identify commonalities and differences within trust/health board sites and groups, e.g. senior managers.

Data recorded in the care plan reviews, such as demographic detail, and examples from the template incorporating identified key concepts of good practice in care planning, user and carer involvement, personalisation and recovery were charted (SB). Brief summaries were produced (MC) with particular attention paid to representing the data according to sample characteristics.

Transcripts of the observations and the contemporaneous notes taken by researchers were read (AS and SB) and compared with the structured guide developed to identify good practice in involving service users and carers and a focus on recovery and personalisation. Brief summaries were produced (SB) that included a reference to the context in which the observations were conducted.

Integration and synthesis of data sets

The Framework method was also employed to bring together charted summaries of qualitative data alongside summary statistics of the quantitative measures for each case study site, noting points of comparison and contrast between what we found in our analysis of each type of data.

Armed with our set of six within-case analyses, we then conducted a cross-case analysis to draw out key findings from across all sites. We then considered the relationships between stated orientations to recovery and personalisation in national and local policy and staff interviews, and what we found by studying the accounts of users, carers and ward staff and by reviewing written care plans and undertaking observations. In this way we were able to investigate the data to identify ‘evidence’ at the intersections between macro, meso and micro levels and CPA/CTP care planning, recovery and personalisation, hence the ‘transformative’ nature of the study design. 33 The results of these within-case and across-case analyses are presented in Chapters 4 and 5.

Chapter 3 Policy analysis and literature review

In our earlier investigation into care planning and co-ordination in community mental health settings, we conducted a narrative overview of the policy context in England and Wales in the areas of care planning and co-ordination, combining this with a metanarrative review of research in this area. 20 Here, we extend this to an analysis of policy as it relates to the organisation and delivery of mental health care in hospitals, combined with an extension of our previous metanarrative review into the inpatient area. Again, we pay particular attention to care planning and co-ordination, and to the relationships between these and the aspiration that services be personalised and oriented to recovery. In the context of this project as a whole, this integrated policy and evidence review serves to frame the new empirical findings reported in Chapters 4 and 5. As per the project protocol, the aim was not to generate a pre-fieldwork synthesis leading to propositions to be tested or otherwise investigated.

Metanarrative reviews are a relatively new type of evidence synthesis. 45 They involve the search for traditions within fields of inquiry, paying attention to the ways in which research questions, assumptions and methods coalesce and diverge across different teams, times and places. 46 They also seek to produce outputs that have obvious value to policy-makers, service managers, practitioners and other decision-makers. Metanarrative reviews are open to the inclusion of evidence from studies that have used the full range of research methods, and many (including this one) reflect, to large degree, the standards embodied in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist. 64 When metanarrative reviews break with some other types of evidence, synthesis is in privileging overarching research traditions and the ‘shape’ of fields of study, rather than paying microscopic attention to the detail (including the formally assessed quality) of individual studies.

Search strategy

Step 1: searching

To retrieve literature in this integrated policy analysis and literature review, we initially searched a number of terms and key words (Box 1) individually and then searched these terms combined in clusters (e.g. ‘mental health’, ‘mental illness’, ‘care planning’, ‘care coordination’ hospital, adult followed by ‘patient care planning’, ‘collaborative care’, ‘person-centred care’, ‘personalis*’, hospital, adult) and then combined all. We took care to search in systematic and reproducible ways, reflecting PRISMA guidelines.

Care plan* OR “care and treatment plan*” OR CTP OR “Care Program* Approach” OR CPA OR “wellness recovery action plan” OR WRAP OR “treatment plan*” OR CTO OR “community treatment order*” OR “care coordination” OR (care N2 coordinat*) OR (care N2 collaborati*) OR (discharge N2 plan*) OR “case management” OR (MH “Patient Care Plans”)

Client-cent#red OR patient-cent#red OR person-cent#red OR Customer-cent#red OR recovery-orient* OR recovery focus* OR individuali?ed OR personali?ed OR patient-participation OR client-participation OR customer-participation OR “shared decision making” OR ((client* OR patient*) N3 involv* N3 (decision* OR plan*) OR patient choice

( MH “Recovery” OR (MH “Patient Centered Care“) OR (MH “Mental Disorders+/RH“) OR (MH “Individualized Medicine“) )

detention OR detained OR involuntary OR sectioned

( (MH “Acute Care” AND (MH “Psychiatric Nursing” OR MH “Psychiatric Care” OR MH “Mental Health Services” OR MH “Mental Disorders+”)) OR (MH “Hospitals, Psychiatric“) OR (MH “Psychiatric Patients“) ) OR ( Psychiatric patients OR psychiatric inpatient* OR psychiatric unit* OR acute psychiatric setting* OR (acute OR psychiatric OR mental*) )OR MH “Involuntary Commitment”)

When appropriate, proximity indicators (such as ADJ or N- as appropriate for each database), truncation ($) and wildcard (*) symbols were also used, as were Boolean commands (AND and OR). Key search terms, such as mental health, care planning, care coordination/co-ordination, were also searched by their subject (PubMed medical subject headings) and by keyword.

Inclusion criteria

Research published in English from 1980 onwards focusing on adult mental health inpatient care.

Exclusion criteria

Non-English-language papers and research undertaken in child and adolescent mental health settings.

Verification

The search strategy was verified by a health and social care librarian. In addition, the search terms and strategy were presented for review to, and approved by, the LEAG/PAG.

The databases searched were Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Scopus and Web of Science (Table 3).

| Database | Results |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE | 371 |

| CINAHL | 135 |

| ASSIA | 185 |

| EMBASE | 6 |

| AMED | 27 |

| Cochrane database: reviews | 4 |

| Cochrane database: ‘other’ reviews | 1 |

| Cochrane database: trials | 26 |

| PsycINFO | 167 |

| Scopus | 147 |

| Web of Science | 289 |

| Less duplicates | 180 |

| Total | 1178 |

Step 2: sifting and sorting

Using the approach tested in our earlier metanarrative review of research into care planning and co-ordination in community mental health settings,20 the titles of all papers were first reviewed by two members of the project team (BH and MC). Papers for inclusion were labelled ‘yes’ (n = 44) and those not meeting the inclusion criteria were labelled ‘no’ (n = 1001). Papers labelled ‘maybe’, for which inclusion was uncertain (n = 33), were discussed with a third member of the team (AJ) and a decision was made about whether or not to include these. Twenty ‘no’ titles were cross-checked by Aled Jones for accuracy of exclusion and found to be consistent. Aled Jones added a further two papers to the ‘yes’ total following back-chaining, hand-searching and expert group LEAG/PAG discussion. As a result, a total of 46 research papers were included in the metanarrative review.

Step 3: data extraction, analysis and synthesis

Again reflecting PRISMA standards, Aled Jones and Jitka Všetečková extracted relevant information from papers into a template designed by the team for collating information during a previous metanarrative review. 20 The information was then used to generate a focused review of the literature, which is reported in the form of a narrative synthesis under the major headings The context of acute inpatient psychiatric care in England and Wales, Service user and carer involvement incare planning and co-ordination, Outcomes of service user involvement in care planning and co-ordination and Interventions to improve service user involvement in care planning and co-ordination. This synthesis interweaves research evidence with an analysis of prevailing policy contexts. Government and other documents used in our policy analysis were not searched for systematically, but were selected by the team drawing on our collective knowledge of the broad history of the UK’s mental health system (and the changing place of hospitals within it) in the period from the 1950s onwards.

Results

The context of acute inpatient psychiatric care in England and Wales

The research evidence makes reference to difficulties experienced by staff in achieving patient-centred care planning and care co-ordination in acute inpatient mental health settings. The root causes most commonly cited were acuity and rapid turnover of patients; the demand for inpatient beds outstripping supply; and insufficient numbers of nursing staff available to undertake meaningful, patient-centred care planning.

In this first section we contextualise these perceptions through a focused review of policies in England and Wales. Viewed over a period of decades, the story of the mental health system is of an historic shift from care provided in hospitals to care provided predominantly in the community. 65 Organised community care emerged in the 1950s, with early policy initiatives including The Hospital Plan of 1962,66 which foresaw the closure of the Victorian asylums, and Better Services for the Mentally Ill in 1975,67 which introduced locality-based community mental health teams (CMHTs). The number of NHS inpatient psychiatric beds in England and Wales reached a peak of approximately 150,000 beds in 1955 and has steadily declined since this point via a process of deinstitutionalisation. 21 In England, the total number of available mental illness beds (for all ages and for all specialties) dropped from its 1955 peak to roughly 22,300 in 2012; in Wales, the number of adult psychiatric beds fell from 2586 in 1989–90 to 771 in 2013–14. 68 This pattern of psychiatric bed reductions has been mirrored internationally.

The original circular that introduced the CPA into England in 1990 was clear that a formalised process for the planning, co-ordination and review of each individual service user’s care was needed precisely because so many were now living outside institutions. 69 Implicit in the circular was the idea that community care has to be purposively co-ordinated because it draws on the efforts of members of multiple professional groups located in dispersed teams spanning both primary and secondary sectors. Without a formalised system of co-ordination, there remained a risk of fragmented services, unmet needs and lack of clarity in roles and responsibilities. This particular attention to community services has largely continued, with the period from the middle of the 1990s being particularly notable for the intensity with which policy-makers set about their work. 70 In England, new types of community team appeared, offering early intervention to people with psychosis, assertive outreach and (significantly for the hospital components of the system) services providing crisis care and home treatment as an alternative to inpatient admission. 71 In Wales, policy first emphasised the value of the locality CMHT model72 before eventually expanding to the introduction of crisis resolution and home treatment teams to sit in the space between CMHTs and hospitals. 73 It was recently stated that acute psychiatric inpatient services exist in a supportive capacity to community services, providing treatment and care in a safe and therapeutic setting for patients in the most acute and vulnerable stage of mental illness, and whose circumstances or acute care needs are such that they cannot, at that time, be treated and supported appropriately at home or in an alternative, less restrictive setting. 74

However, this dominant narrative of a system moving ever further from its origins in psychiatric institutions risks overlooking the continued position of hospitals within it. Hospitals occupy a significant space, and remain an essential part of local networks of services even though inpatient bed numbers have declined sharply over time and efforts have been made to bolster home treatment to avoid admission whenever possible. Evidence of the part hospitals continue to play is shown in official statistics. As has already been noted in the introduction to this report, in England in 2014–15, 103,840 people in contact with mental health and learning disability services spent time in hospital4 and in Wales 9466 admissions to hospital for mental illness took place in 2014–15. 5

Concerns about a perceived shortage of acute inpatient places in England and Wales are also not a recent phenomenon,75 with some arguing that ‘psychiatric bed numbers (in England) are close to the irreducible minimum if they have not already reached it’. 76 More recently, the coalition government’s care services minister admitted that ‘there is clearly, in some parts of the country, a shortage of beds’. 77 The (then) minister’s reference to ‘some parts of the country’ hints at the variation in the provision of inpatient beds reported by the NHS Benchmarking Network mapping exercise in 2014. Provision across England and Wales ranged from 12 beds per 100,000 (weighted) population to 32 beds per 100,000 (weighted) population, with a median position of 21. 74 (The term ‘weighted population’ refers to the process of adjusting figures to reflect the socioeconomic mix of an area, as this will affect the demands made on the health services. For example, people from areas that are socioeconomically deprived typically have worse health than those living in more affluent areas, and use health services more often as a result.)

A related issue to declining numbers of inpatient beds is the question about the efficiency and effectiveness of bed usage, with evidence emerging that some people are being inappropriately admitted. For example, a sixfold variance across providers in admissions to English adult psychiatric inpatient units has been found, suggesting that 15% of inpatient beds could be decommissioned if the median figure of occupied bed-days was achieved by the worst performers. 78 Similarly, a retrospective review of bed usage in one English NHS service found that approximately one-third of patients admitted over a 32-month period could potentially have been cared for in a community setting. 79

Differences in past and present national mental health policies for England and Wales can clearly be detected (e.g. in the degree to which services should reflect national standards or be flexible to local needs and circumstances, in the use of non-NHS providers, and in the extent to which personal budgets might be used). However, a distinctive feature of current (and recent) macro-level frameworks in both countries is how they seek to direct services to become more recovery-focused and centred on the individual, regardless of the setting in which care is provided. Broad ideals of recovery tailored to the person and of meaningful collaboration run through England’s Five Year Forward View for Mental Health,80 as they did in the coalition government’s Closing the Gap81 and, before that, in No Health Without Mental Health. 1 In Wales, the 10-year strategy Together for Mental Health10 claims similar underpinning values, with references to the promotion of recovery and the delivery of services specified to the person.

References to the part played by hospitals, and to the improvement of care therein, are found in all of these policy documents. The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health80 notes that the severity of the needs of people admitted to hospital have been steadily increasing, with the numbers admitted under sections also rising and black men in particular being over-represented. Closing the Gap81 emphasised the importance of avoiding admission whenever possible while also making sure that local beds were available when needed. No Health Without Mental Health1 addressed acute care pathways and the value of avoiding hospital, and when admissions are necessary making these as effective and as short as possible. In Wales, Together for Mental Health10 acknowledges improvements in the fabric of hospitals and places emphasis on developments such as single-sex facilities, welcoming visiting spaces and a focus on dignity, safety and therapy. Distinctively, the Welsh Government passed primary legislation mandating for care and treatment plans (CTPs) and for care co-ordination by suitably qualified professionals. Independent advocacy is also extended to all inpatients (and therefore not only to those detained under sections of the MHA 19833).

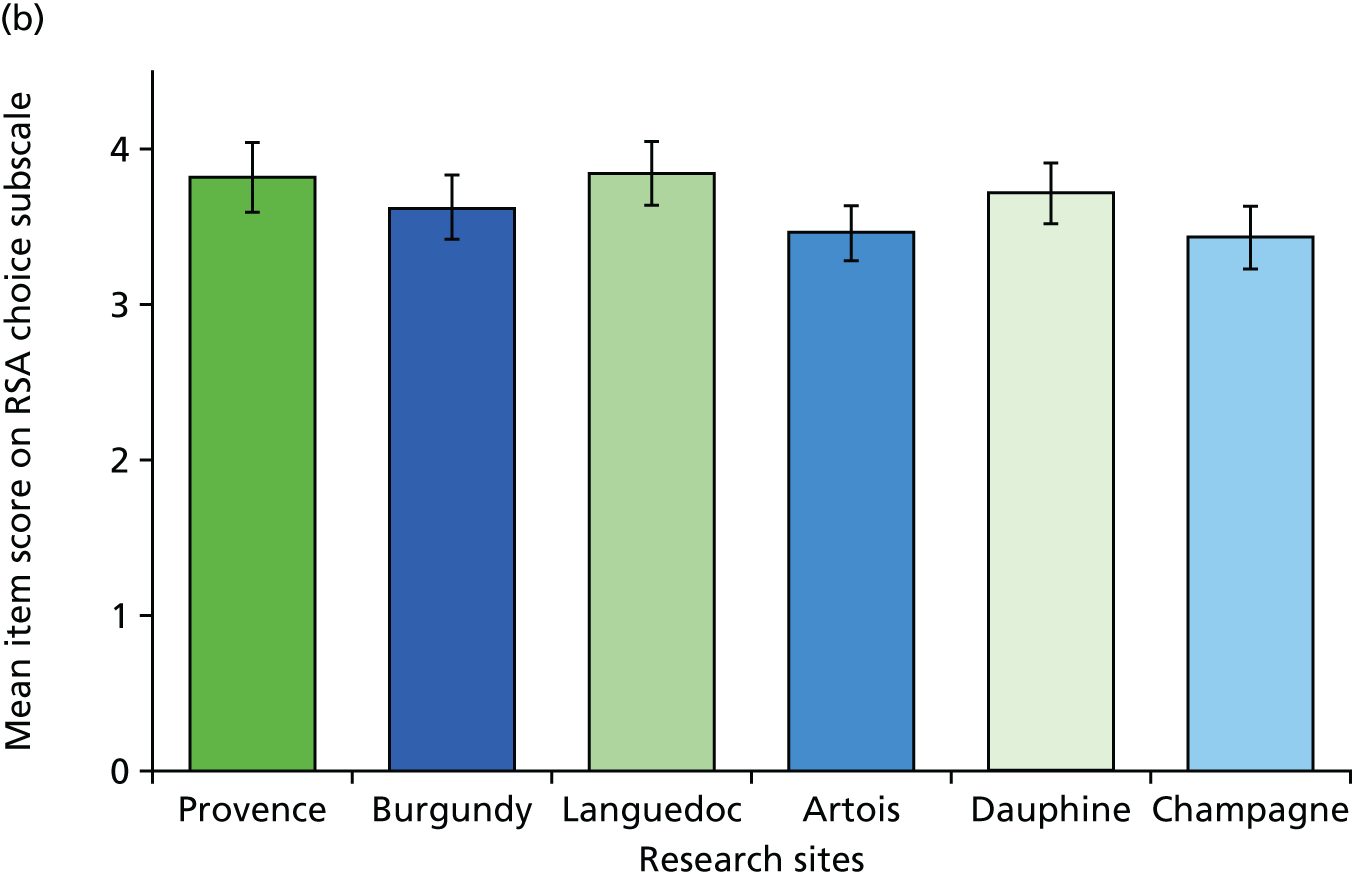

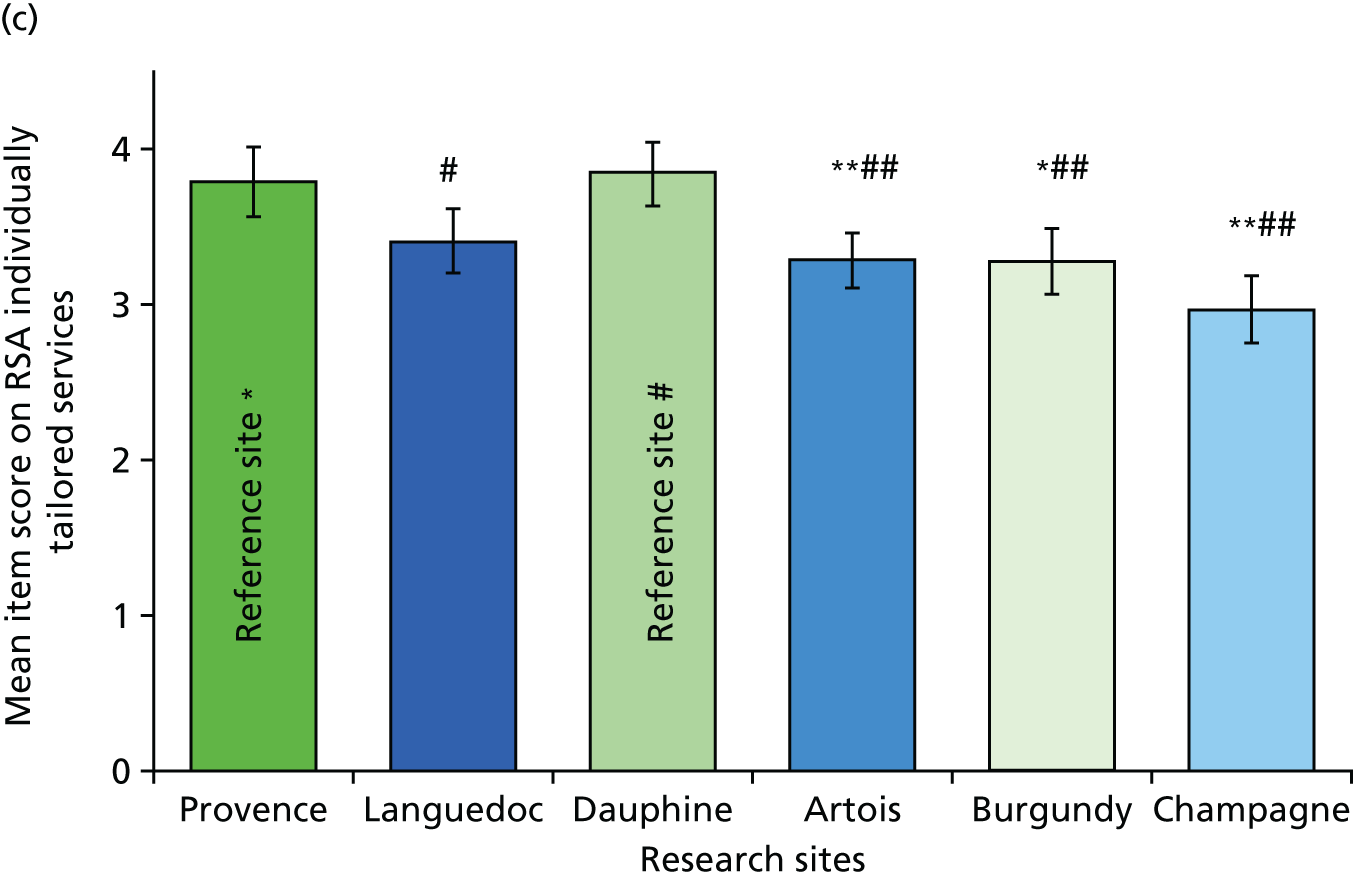

Attention to hospital-based mental health care is also found in guidelines produced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) that are designed to improve the experiences of people using adult NHS mental health services. 82 Expectations are placed on staff to share decisions with inpatients and to be person-centred, to offer service users daily time with someone they know and to clearly plan and co-ordinate care during admission. Managing transitions out of hospital is also addressed, in recognition of the need to collaboratively co-ordinate discharge with the MDT, service users and their families or other carers.