Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/07/68. The contractual start date was in July 2014. The final report began editorial review in January 2017 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Keen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

A number of developments at the turn of the millennium highlighted problems with the quality and safety of acute hospital services. The Institute of Medicine’s landmark 1999 report, To Err Is Human, highlighted high adverse event rates in hospitals in the USA. 1 The likelihood that NHS hospitals also had high adverse event rates was raised in An Organisation With A Memory, published the following year. 2 The 2001 Kennedy report on high mortality rates in cardiac surgery at Bristol Royal Infirmary humanised the problem. 3 Put starkly, many adults and children who were operated on died when they could and should have lived.

In the intervening years it has become clear that it is difficult to make substantial and sustained improvements in the quality and safety of hospital services. As a result, and real improvements in some localities notwithstanding, it is generally agreed that acute hospitals still need to provide higher-quality and safer services. This point was brought home in the two reports by Sir Robert Francis on the failings in some wards and departments at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust,4,5 published in 2010 and 2013 respectively, and subsequently by the Kirkup report on maternal and infant deaths at University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust, published in 2015. 6 This research study was commissioned following the ‘After Francis’ call for proposals issued in 2013 by the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme.

The problems have generated a range of policy responses over the last 15 years. A recurring theme concerns the need for cultural change in NHS trusts, moving away from a ‘blame culture’ and towards a culture in which staff have the confidence to report mistakes and are able to learn from them. 7 National bodies, including the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and NHS Improvement, have been created and given responsibility for the oversight of quality and safety of services across the NHS. Our interest in this study is in another long-standing policy prescription: the generation and use of data on the quality and safety of services, and investment in the information technology (IT) needed to manage the data.

High-quality data

There are different views, in the NHS and in academic circles, on the data that are needed to monitor and manage the quality and safety of health services. One is that doctors, nurses and other clinicians are always concerned with quality and safety. Patients’ records, updated in the course of clinicians’ work, reflect the quality and safety of services provided. Thus, albeit at the risk of oversimplification, we might take the following scenario as an example: if a patient’s temperature and blood pressure are normal, the most recent pathology tests are normal and the patient says that she is happy with the care she has received, then the treatment and care were of reasonable or good quality. There is no distinct category of data that reflect quality and safety; rather, the data are part and parcel of everyday service delivery.

A second view is held by practitioners and academics with interests in service improvement. They argue that data play a vital role in improvement projects, perhaps most obviously in the ‘study’ phase of ‘plan-do-study-act’ cycles. That said, few authors talk in any detail about data or information systems. 8,9 The 2013 report by Donald Berwick, the respected US physician, is one of the exceptions to the general rule. He identified a range of routine data that ward staff – and wider clinical teams – needed to investigate unwarranted variations in services and to support service improvement (Table 1). 10 Berwick argued that these data were not routinely available to ward or directorate staff in NHS trusts, and that neither did they have appropriately trained staff to analyse and present the data – the staff lacked expertise in data analytics. His arguments are based on quality management principles, and, as such, stress the importance of learning from adverse events through root cause analyses or ‘deep dive’ reviews. Accounts of adverse events are, therefore, an important source of evidence to inform service improvements.

| The perspectives of patients and their families | Measures of harm | Measures of the reliability of critical safety processes |

| Information on practices that encourage the monitoring of patient safety | Information on the capacity to anticipate safety problems | Information on the capacity to respond to and learn from safety information |

| Data on staff attitudes, awareness and feedback | Mortality rate indicators | Staffing levels |

| Data on fundamental standards | Incident reports | Incident reporting levels |

The second Francis report provides an example of a third view, which is that the quality and safety of services should be monitored by trust managers and external agencies,3 who therefore need appropriate performance data. In recent years, the NHS has required all hospital trusts to provide an increasing number of indicators. Current submissions from trusts include the number of complaints and of incidents (where a patient has been harmed in the course of treatment and care), and data for the NHS Safety Thermometer. The Thermometer includes the number of patients who have developed severe pressure ulcers, experienced a fall, experienced a venous thromboembolism (VTE) and developed a urinary tract infection following the use of a catheter.

There have been a number of studies on the use of data to manage hospital performance, including the recent HSDR study by Mannion et al. 11 There have also been reports that draw attention to the large number of routine data that are captured, and the limited use of these made by the trusts or organisations that have access to them. 12 There are also many studies of individual indicators, notably those on mortality. 13 We have not, however, found any published studies of the processes involved in producing data sets for NHS performance management purposes. Indeed, given the marked differences in the views about the types of data that reveal the quality and safety of services, and the people who are in a position to review and act on those data, it was not at all clear what data trusts were actually capturing and using, or whether or not their uses of data were changing over time.

Information technologies in acute hospitals

Investments in IT systems were recommended by the Bristol Inquiry in 2001,14 which argued that they were a prerequisite for providing the data that clinical teams needed to manage services, and for managers to monitor those services and ensure that they were safe. The Wanless review15 on the future of the NHS, published in 2002, also recommended substantial increases in IT investments. This led to the creation of the NHS National Programme for IT, which had an initial budget of around £7B, eventually increasing to > £10B. The programme had a vision of making patients’ records available anywhere in England: if a Manchester resident fell ill in Norfolk, NHS staff in Norfolk would be able to access that person’s clinical records. However, a succession of National Audit Office reports between 2006 and 2011 reported that billions of pounds were largely wasted. 16 In particular, new, integrated IT systems for acute hospitals were not delivered on time, and even today only a minority of trusts have implemented them. The vision of an integrated, England-wide IT service has never been realised.

The result was that, at the beginning of this decade, most hospitals found themselves with ageing systems and a pressing need to upgrade and replace them. 17 Many trusts made rapid progress once the National Programme was officially abandoned in 2011, and implemented systems across most wards and departments. Even so, having been held back for so long, most trusts needed to make further substantial investments at the time this study started in 2014.

The literature: evidence and theory

Our interest in this study is in the data and IT systems that are used to monitor and manage the quality and safety of services. There are a number of literatures that could be drawn on. Taking our cue from the ‘views’ outlined above, one focus of current investments is on acute hospital wards. There is a rich literature on human–computer interaction in health care. 18 However, most studies focus on accident and emergency departments and intensive care units rather than on acute wards. 19,20 There is also a growing literature on the use of mobile devices, including laptops and tablets, on wards. 21 This study contributes to the literatures on whiteboards and mobile devices on acute wards. It is worth noting that wall-mounted systems are typically referred to as ‘dashboards’, or ‘clinical’ or ‘quality dashboards’, in the literature. There is a risk of confusion in this report, because the term ‘dashboard’ is also used to refer to the graphical displays used in board reports in the NHS. Following the use of terms in the NHS, we refer to whiteboards on wards, and dashboards in board reports, from Chapter 2 onwards.

We are also interested in hospital-wide systems: in the kinds of systems that NHS trusts need in order to provide data to managers. Most trusts have eschewed the single hospital-wide – or ‘big bang’ – solutions favoured under the NHS National Programme. They have instead opted to develop communication networks and integration engines – in effect, software that supports access to several systems via a single screen – that allow clinicians to access data from several departmental systems via a single screen. They build on what is there, rather than replacing existing systems in a single hospital-wide implementation.

There are a number of traditions of studies on these systems. 22 For example, some writers have drawn on structuration theory to understand the deployment of IT systems in organisations. Barrett et al. 23 and Beane and Orlikowski24 built on this work, and critiques of it, and used practice theory to explore the ways in which health-care organisations and IT systems shape one another. Other writers work in a very different tradition, whereby organisations are viewed as complex systems, and IT systems are technologies that can be used to address complexity. 25 Additionally, other writers have taken a more instrumental view of organisations, arguing that it is possible – and useful – to identify barriers to, and facilitators of, organisational change. In this study, our approach has more in common with the tradition represented by practice theory than with the view that uses complexity or barriers and facilitators. On the latter, we note that our fourth study objective refers to barriers and facilitators. For reasons we discuss in Chapter 11, we did not find thinking in terms of barriers and facilitators helpful in this study.

A science and technology study

We made our decisions about the nature of the study in the context of these literatures, and in the light of the comments we have made about data and IT systems. Specifically, our task was to investigate and understand developments at the levels of both the hospital ward and the board. This ruled out a narrow focus on individual technologies such as electronic whiteboards. More positively, we were able to draw on the conceptual and methodological developments in institutional approaches, such as practice theory, and on the critiques of those theories that have developed over the years. We opted for the Biography of Artefacts approach, which is located in the tradition of science and technology studies. 26,27 This approach appears to have developed in parallel with structuration, practice and other institutional theories, with which it shares a number of features. It starts from the observation that IT systems in organisations are implemented over many years. New functions are added periodically, and existing systems are linked to one another and to new systems. Systems thus develop in piecemeal fashion, producing digital infrastructures that are deeply embedded in the day-to-day work of an organisation.

We use the term ‘infrastructure’ throughout this report. An infrastructure is an amalgam of a number of previously separate components. Siskin provides a useful description:

. . . infrastructures are never built from the centre with a single design philosophy. Rather they are built from the ground up in modular units, their development an oscillation between the desire for smooth, system-like behaviour and the need to combine capabilities no single system can provide.

Siskin, p. 628

As the quotation implies, the ways in which infrastructures are used can change over time. As a result, if we want to understand any IT system in an organisation – understand why it looks the way it does today – we need to understand its history. This led us to design a study that adheres closely to the technologies of interest and to the working practices associated with them. It is, in part, a ‘hidden history’ of the people who capture and validate data, who prepare dashboards for board papers and who upload data sets to NHS Digital. It is also a story of what happens when the data arrive in different places: hospital directorates, board meetings and national and local agencies. We are not aware of any previous studies of the NHS trust infrastructures that produce the data used to monitor and manage the quality and safety of services.

Aims and objectives

In our proposal, we described our research aims and objectives as follows:

The research has two aims. The first and principal aim is to establish whether or not ward teams in acute NHS trusts have the information systems they need to manage their own work, and to report on that work to trust boards and other stakeholders, in the post-Francis environment. The research will focus on the design and implementation of a key technology, ward-level dashboards. Dashboards are already the preferred NHS vehicle for integrating information from diverse sources, are being actively promoted by NHS England and NHS Digital (formerly the Health and Social Care Information Centre). As earlier sections show, dashboards will need to be redesigned in the light of the Francis, Keogh and Berwick recommendations. The second aim is to establish the extent to which ward-level dashboards provide a basis for achieving the openness, transparency and candour envisaged by Francis, and supported by Keogh and Berwick. As the reports emphasise, although there are examples of excellent practice, the NHS as a whole needs to undergo a culture change, moving from low to high trust working practices. The extent of sharing of detailed information about performance will be an important source of evidence about that culture change.

Keen et al. 29

There are four research objectives:

-

Design. We will assess the extent to which trusts are able to integrate activity, quality, outcome and cost information in dashboards, to enable ward teams to manage their services effectively and to improve services over time.

-

Implementation and use. We will evaluate the impact of the use of dashboards on clinical and management practices at ward level.

-

Governance. We will assess the extent to which dashboards provide data that are valuable to other local stakeholders, including trust boards, Healthwatch and commissioners.

-

Barriers and facilitators. We will identify the barriers to, and facilitators of, the effective redesign and use of dashboards.

We referred to dashboards in the text reproduced here, and throughout the proposal, but, as we noted above, we make a distinction in this report between whiteboards used at ward level and dashboards used at board level. It should also be noted that we address both aims and the first three objectives in the report, but we do not discuss barriers and facilitators. We explain our technical concerns with these terms in Chapter 11.

The structure of this report

In Chapter 2, we set out the study design and methods used in the study. In Chapter 3, we outline the development of national arrangements for data collection and IT over the last 30 years. In Chapter 4, we present the methods and findings of the first phase of the study, a 2014 telephone survey of senior trust nursing managers about their use of whiteboards and dashboards, and of trust board papers in January 2015. In Chapters 5–10, we set out the main findings of the study, starting with a brief overview of the four study sites and following with mini-biographies of developments on wards, in data and technology infrastructures, of board quality committees, of directorates (also termed clinical service or business units in NHS trusts) and of external bodies including commissioners and regulators. In Chapter 11, we discuss our findings and identify implications for practitioners and recommendations for researchers.

Chapter 2 Study design and methods

Key points

-

A telephone survey of 15 acute hospital trusts and a survey of board papers of all acute hospital trusts in England were undertaken in 2014 and early 2015 respectively.

-

We then observed the use of information systems in four acute hospital trusts over an 18-month period in 2015 and 2016.

-

We used a number of methods, including the direct observation of the use of whiteboards and other technologies on wards, an observation of board quality committees, semistructured interviews and an analysis of board papers.

-

Normalisation process theory was used to direct our fieldwork.

-

The Biography of Artefacts approach was used to analyse our findings.

Introduction

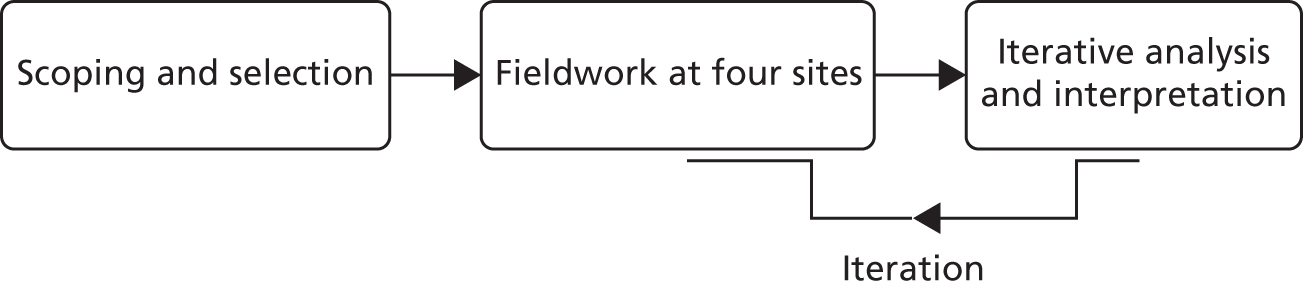

This chapter describes the study design and methods. It has three main sections, reflecting the three phases of the study: scoping and selection, field research at four sites, and analysis and interpretation. As Figure 1 emphasises, the fieldwork and analysis were undertaken iteratively: they are presented separately here for clarity.

FIGURE 1.

Sequence of research activities.

Scoping and site selection

The study was approved by the University of Leeds Faculty of Medicine and Health Research Ethics Committee (see Appendix 1). We identified 18 acute trusts that were within a reasonable travelling time – 75 minutes each way – of our university base, and thus were potential sites for the in-depth phase of our study. Research governance approval was successfully obtained from 15 of the 18 trusts. We were unable to obtain research governance approval in the other three trusts. We undertook one interview in each trust, 11 with chief nurses and four with senior colleagues whom chief nurses nominated.

Data collection

All interviews were semistructured and undertaken by telephone. Each interviewee was asked to describe the ways in which dashboards and whiteboards were currently used in their trusts, how they were used and future plans for design, deployment and use. The consent form and information sheet are in Appendix 2, and the interview topic guide is in Appendix 3. Two members of the research team (CG and JK) conducted 15 interviews between September and November 2014. The interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed.

Analysis

The transcripts were analysed using framework analysis. 30–32 The framework approach allowed us to investigate transcripts in two ways, namely by identifying themes that emerged from the data and by exploring themes derived from our research questions. The researchers first listened to the audio files and read the transcripts to familiarise themselves with the data. Two members of the research team (CG and EF) undertook the initial coding of a sample of transcripts and identified emerging themes. These were then shared and discussed with the research team, and an initial set of themes was agreed. The full set of transcripts was then coded using NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). The coded text was organised into a matrix with rows representing interviewees and columns representing key themes. The matrix was reviewed by members of the research team; column headings were refined and text was moved within the matrix to develop consistent themes.

Review of acute NHS trust board papers

The NHS Choices website listed 156 NHS acute trusts in England in November 2014. We reviewed the board papers that we were able to obtain for January 2015 and recorded whether or not they included data on quality and safety, including the NHS Safety Thermometer (data on falls, pressure ulcers and other adverse events), waiting time and other data included in the NHS Constitution, number of incidents, number of complaints and patient experience data (the NHS Friends and Family Test and patient-reported outcome measures). We also recorded whether or not the papers included workforce data, Monitor’s risk assessment framework, a balanced scorecard (a method for presenting data that Monitor had recommended for foundation trusts (FTs) since the mid-2000s) and any data that were presented even though they were not requested or required by national bodies.

Selection of main fieldwork sites

One purpose of the telephone survey was to select four sites for the main field study. Site selection was partly pragmatic and partly purposive. It was pragmatic because we could select only from sites that were within reasonable travelling distance of Leeds – given the volume of proposed fieldwork – and that were willing to participate. In the proposal, our purposive sampling strategy was based on the assumption that trusts would be designing and deploying new information systems, with ward whiteboards as their visible manifestations. We would therefore select trusts on the basis that they had formally agreed on implementation plans. We also undertook to select a mix of FTs and non-FTs on the basis that they had different governance arrangements and might, therefore, be expected to use different data in different ways. The telephone survey, reported in Chapter 4, revealed that two trusts had already implemented real-time (electronic) ward management systems. We therefore decided to amend our sampling criteria to include sites with these systems.

Monitoring of publications

We did not undertake a formal literature review as part of this study. We did, however, monitor and collect relevant publications throughout our study. We used publication alerts (see Appendix 4) and we also used a Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) account to follow a number of feeds, including Digital Health Intelligence and the Health Foundation, to identify relevant publications – for example by the CQC or NHS Improvement – that might not be identified by publication alerts.

Field study in four acute hospital trusts

We designed this phase of the study as a prospective, iterative case study design, focusing on two wards – one surgical and one medical – in each of the four acute NHS trusts. Given the focus of the ‘After Francis’ HSDR call, and of Sir Robert’s second report, we excluded intensive care units from the study. More positively, the fact that this was an ‘After Francis’ study focused our attention on the management of the quality and safety of services on wards, and upwards ‘from ward to board’. We named the four trusts Solo, Duo, Trio and Quartet to protect their identities.

There are many types of case study approaches, ranging from Yin’s scientific to more naturalistic ones. 33 Our approach was towards the naturalistic end of the spectrum, on the basis that the best way to understand implementation is to spend time observing the people doing the implementing. 34 As a result, we were principally interested in the working practices of nurses and nurse managers, although we did also observe and interview other clinicians on wards, and we observed and interviewed a range of staff elsewhere in the four trusts. We judged that focusing on wards alone would be outside the scope of the call. Accordingly, we did not propose to observe clinician–patient interactions or detailed data capture in medical and nursing records; that would be an interesting study, but one undertaken in response to a different call for proposals.

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Leeds Faculty of Medicine and Health Ethics Committee in July 2014 (see Appendix 5). The observations and interviews undertaken at the four sites are set out in Tables 2 and 3. We were able to interview almost everyone we approached. We were not, however, able to interview one trust informatics director, one medical director, one member of an information team, two junior doctors, two nurse managers (both towards the end of the fieldwork) and representatives of one Healthwatch and three clinical commissioning groups (CCGs). We do not think that the omission of most of these interviews had a significant impact on the conduct of the study or on our analysis. We do, however, note that reliance on one CCG interview limits what we can say about the role of CCGs. Two CCGs refused to talk to us – one instructed us to ‘remove us from your records’ – and we were not able to get a response from a third. We do not know why some CCG staff responded in the way that they did; their reactions to our approaches stand in marked contrast to the positive responses from the great majority of people whom we approached.

| Intervention or procedure (as described in study proposal) | Site | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solo | Duo | Trio | Quartet | ||

| Observation of meetings where dashboards are used in divisional and trust board meetings | 18 | 12 | 8 | 13 | 50 |

| Semistructured interviews with trust managers, CCG staff and Healthwatch representatives | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 29 |

| Semistructured interviews with staff involved in the design of dashboards | 2 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 23 |

| Observation of meetings about the design of dashboards | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Semistructured interviews with ward staff using dashboards | 8 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 37 |

| Observation of the implementation and use of dashboards on wards | 13 | 22 | 17.5 | 19.5 | 79 |

| Fieldwork activity | Breakdown of fieldwork numbers | Total fieldwork |

|---|---|---|

| Observation of quality management meetings (number of meetings) | 35 | 50 |

| Observation of directorate meetings (number of meetings) | 15 | |

| Interviews with NEDs/medical directors (number of interviews) | 10 | 29 |

| Interviews with chief nurses (or equivalent) (number of interviews) | 10 | |

| Interviews with CCG/Healthwatch (number of interviews) | 3 | |

| Interviews with directorate lead nurses/matrons (number of interviews) | 6 | |

| Interviews with IT/informatics (design) (number of interviews) | 23 | 23 |

| Observation of informatics meetings (number of meetings) | 5 | 5 |

| Interviews with ward managers (number of interviews) | 15 | 37 |

| Interviews with ward staff (number of interviews) | 22 | |

| Observation of handovers/whiteboards/MDT meetings/ward meetings (number of observation hours) | 79 | 79 |

| Interviews with regulators (number of interviews) | 7 | 7 |

Normalisation process theory

A number of established theoretical frameworks have been used to guide the design of studies of technologies in organisations, including health-care organisations. Our interest was in the implementation of new ways of working associated with IT. In our proposal, we argued that normalisation process theory provided the appropriate focus and had a track record of successful use in case studies in the NHS. 35,36

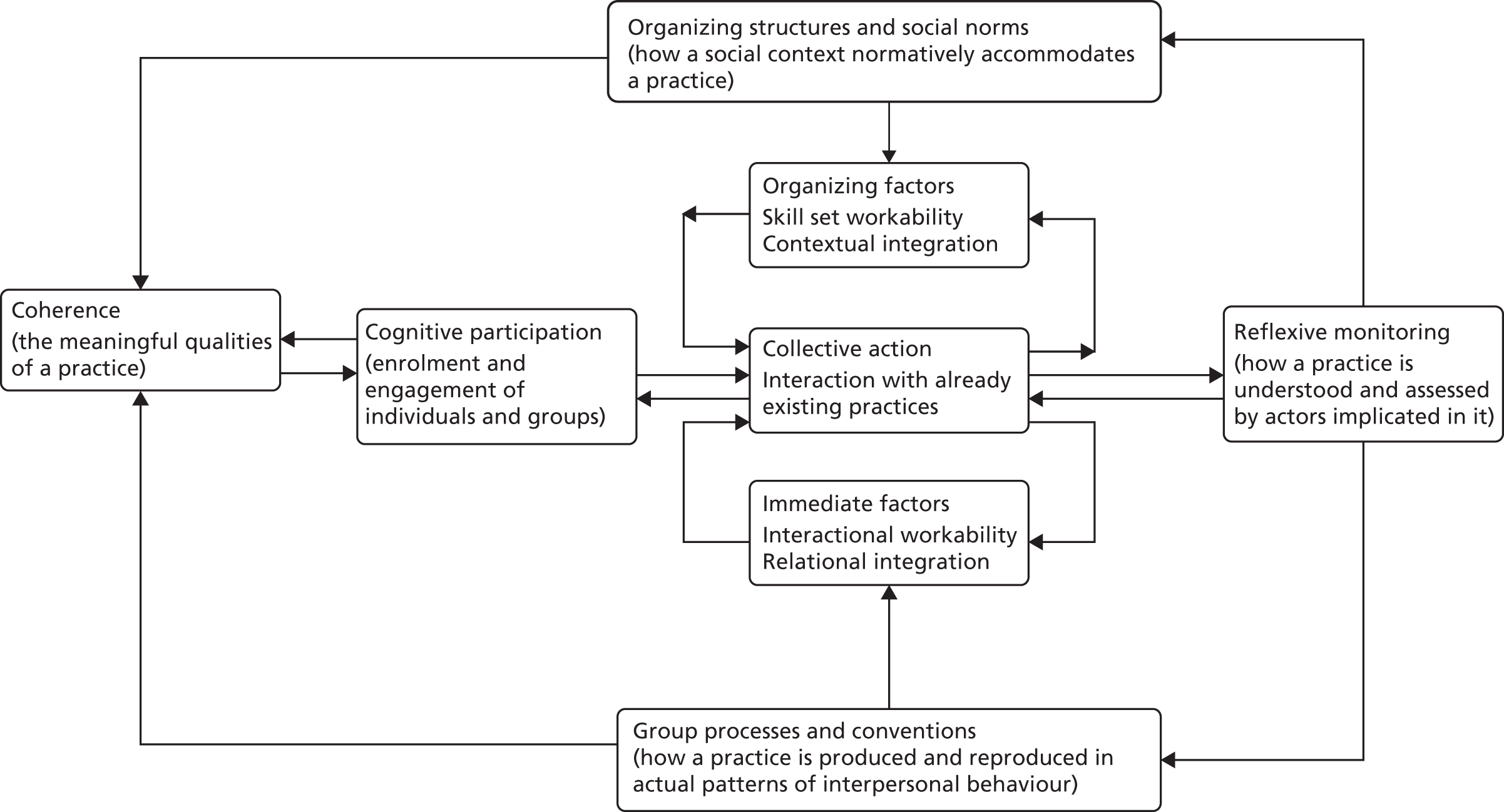

We used the theory to guide us towards phenomena of interest and, thus, to design our data collection methods. The theory rests on three main arguments. First, it proposes that practices become embedded in social contexts as a result of people working, individually and collectively, to implement them. Second, implementation is operationalised through four generative mechanisms – coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring. 35,36 If those involved in the implementation of dashboards can identify coherent arguments for adopting them, are engaged in the process of implementation, are able to adapt their work processes to use dashboards (or dashboards to fit in with practices) and judge them to be valuable once they are in use, then the dashboards are more likely to become embedded in routine practice. Third, embedding new ways of working is not a ‘one-off’ process, but requires continuous investment by the parties involved in implementation.

Figure 2 shows how the components of the theory are related. The lower half of the figure emphasises the importance of understanding working practices in local contexts. The upper half draws attention to institutional arrangements: the ways in which prevailing values and norms influence the behaviour of trust staff. The theory, and in particular the four generative mechanisms, provided a framework for designing the fieldwork. For example, it focused our attention on the value of observing ward working practices and, thus, evaluating the extent to which whiteboards were integrated into them (collective action). Similarly, it encouraged us to ask interviewees about their experiences of implementation and of using new technologies (cognitive participation and reflexive monitoring).

FIGURE 2.

Model of the components of normalisation process theory. From May C, Finch T. Implementation, embedding, and integration: an outline of Normalization Process Theory. Sociology, vol. 43, iss. 3, pp. 535–54,37 copyright © 2009 by SAGE Publications. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications, Ltd.

The theory also encouraged us to consider what it would mean to move from left to right across the diagram. The main point here, we felt, was that new technologies would become progressively embedded in people’s working practices. For example, as we describe in Chapter 7, when electronic whiteboards were introduced at Solo, some staff were initially sceptical about them. On one ward, technological problems led to the whiteboards being withdrawn and later reintroduced, with mixed results. Viewed in the light of normalisation process theory, the initial experience involved limited movement from left to right, and the later experience was one in which different members of staff moved different distances to the right. One would not say that the whiteboards had been fully embedded in local working practices by the end of the observation period. In Trio, in contrast, the whiteboards were fully embedded throughout the observation period; staff frequently used them and had found ways to integrate them into routines.

Data collection

Using a combination of methods, we collected data at the four sites over an 18-month period between April 2015 and September 2016. One focus was on direct observation of working practices; that is, we were interested in the use of information systems ‘as performed’ rather than ‘as imagined’ (i.e. how they were reported in interviews). We also used semistructured interviews and an analysis of site documentation to capture information about practices that we could not observe directly, for example key decisions made in meetings that we were not able to attend. The combination of methods draws on the work of Crabtree et al. ,38 Crosson et al. 39 and Ventres et al. 40 The consent form and a representative information sheet are in Appendix 6. The guides were developed iteratively in the course of the fieldwork.

Observation of handovers and the routine use of whiteboards

We discussed with ward managers where and when we should observe the use of whiteboards and then undertook an initial phase of ethnographic observation to establish that we could observe practices effectively and do so without getting in the way of staff going about their work. The chosen locations were in, or near, nursing stations. During this period we got to know staff and made sure that they were comfortable with our presence. Team members recorded their observations in field notes, which were written up in detail as soon as possible after data collection. The conversations with ward managers informed a decision to observe each of the eight wards approximately once per month, and to do so during a morning handover meeting and for up to 1 hour after handover, as staff began their shifts.

Given our aims and objectives, we were interested in when and how whiteboards – the outward manifestations of the information systems – were used. We were also interested in the sources of, and use of, information more generally. This included the data used in handovers, including ‘soft intelligence’, where staff passed on information from one shift to the next, and messages from senior managers. In addition, the observers occasionally asked staff to explain their actions ‘on the spot’ when it seemed important for the study, for example why those involved in a handover meeting had spent so long discussing a particular topic.

Observation of meetings

A range of meetings was observed, including board-level quality meetings, directorate meetings and IT design and development meetings. At all meetings, team members took contemporaneous notes, focusing both on the substance of discussions and on the deep assumptions informing them, for example whether boards were acting as performance managers, assurance managers or in some other mode. These notes were written up as soon as practicable after meetings.

Site documents

Local staff were asked to provide relevant documents. Most of these were meeting papers and minutes. The principal documents used in the analysis were the papers for the board-level quality meetings, discussed in the board mini-biography, and for directorate meetings, discussed in the directorate mini-biography. We also collected a number of other documents, including IT project plans and Quality Accounts.

Semistructured interviews

Semistructured face-to-face interviews were conducted for each of the mini-biographies. An initial series of interviews was conducted at ward, directorate and board levels in the spring and summer of 2015, using topic guides. The guides were developed during the course of 2015, partly to reflect our own improving understanding of the work of the trusts, and partly to reflect the extension of our interview programme to include trust information teams (interviews conducted in late 2015 and early 2016) and then external bodies – regulators, CCGs and Healthwatches. The number of interviews are set out in Tables 2 and 3. The interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed.

Quantitative data

We collected hospital- and ward-level quality and safety data, drawing on internal trust papers, Quality Accounts and other trust publications and NHS Digital. The main hospital-level data were mortality indices, reported incidents and complaints, the NHS Safety Thermometer, the NHS Staff Survey and the NHS Friends and Family test.

Roles of the patient and public involvement group and steering group

We had a patient and public involvement (PPI) group and a steering group for the project. Both met during the course of the project, commenting on our research plans in 2014 and 2015 and on our emerging findings in 2016. Both had a substantive influence on the conduct of the main fieldwork phase of the study. At the first meeting of the steering group, in late 2014, members gave us a clear steer about the focus of our work: we should focus on data on the quality and safety of services. Moreover, it would make sense to focus on a number of specific measures. This may appear to be a trite point: a study undertaken on acute wards, in the wake of the Francis report, would naturally focus on quality and safety. We had, however, initially assumed that we would also cover cost and outcome data. The point being made was that we should be less concerned with cost and outcomes than with quality and safety measures.

Our PPI group reinforced this point. The members of the group were recruited from the University of Leeds School of Healthcare’s own PPI group. A member of the study team (RR) sent an explanatory note to one of their meetings, and explained the study at the meetings, inviting expressions of interest. Our PPI group members were those who expressed interest following the School of Healthcare meeting. We held four meetings with the group and, throughout the study, members made detailed comments on our research plans and emerging findings. Our relationship with the group was mediated by Claire Ginn – the patient representative on the study team – and Elizabeth McGinnis. We asked the group, at the second meeting in the spring of 2015, what data we should focus on. We told them the measures that we were considering: incidents, complaints, mortality, NHS Safety Thermometer and vital signs (reflected in the National Early Warning Score (NEWS)). The PPI group took the view that these measures were appropriate, but also recommended the addition of two topics, namely nutrition and pain management. Their argument was that if a ward manager or a more senior manager had access to all of these data, they would be able to make overall judgements about the quality and safety of services on a given ward. In practice, this had a significant effect on the ward mini-biography (see Chapter 6) and the board mini-biography (see Chapter 8). In both, we noted when nutrition and pain management were mentioned, along with the other measures. The PPI group also commented on drafts of the ward and board mini-biographies at our fourth meeting in October 2016.

Biography of Artefacts and practices

We assumed at the start of the study that we would be observing the design, implementation and use of discrete technologies over time. We further assumed that ward whiteboards and board-level dashboards would be part of the same IT systems, with data captured on wards being available to trust managers. However, the findings of the telephone survey and the early observations at the four sites indicated that the situation on the ground was more complicated than we had anticipated. In our early fieldwork, we found that:

-

There was a separation, technologically, between real-time ward management systems – systems that make data immediately available to all users of a system once they have been entered – and the systems used to manage data for management meetings. The ward systems did not, as we had assumed, provide the primary ‘feeds’ for management reports.

-

There was also a distinction between data used on wards and elsewhere, and the IT used to capture, store, manage and present them. The same data were available on different technologies – magnetic whiteboards, digital whiteboards and tablets – across the four trusts.

-

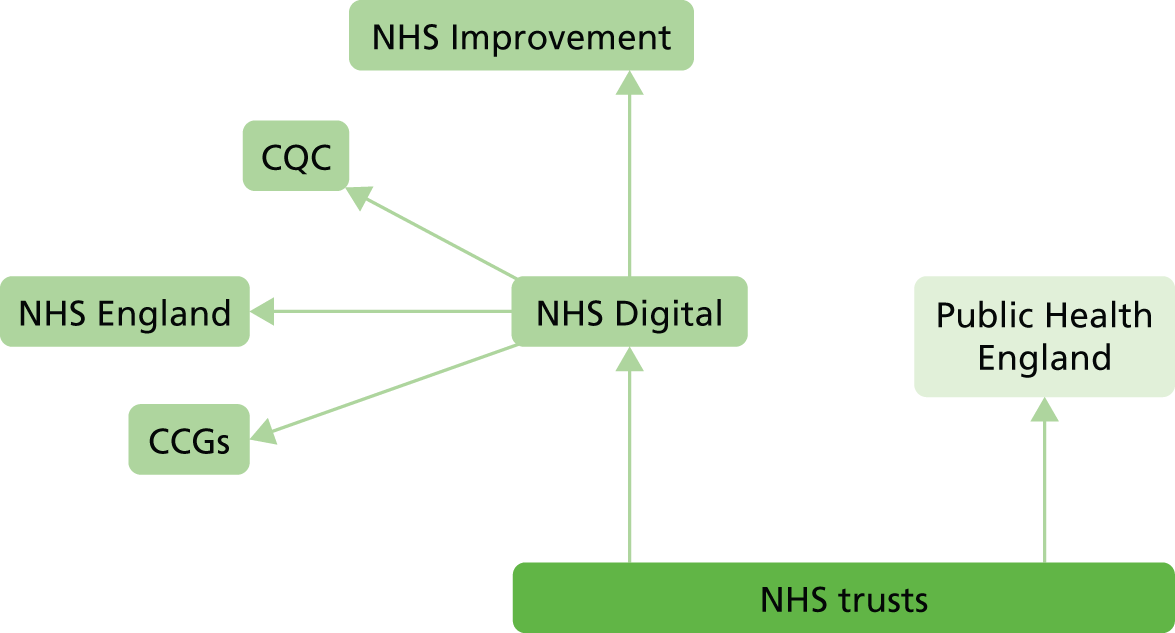

National bodies – including NHS England, the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC; now known as NHS Digital) and regulators – play an important role in determining what data are captured by trusts and how they are structured and submitted to NHS Digital. That is, it did not make sense to assume that trust informatics teams – and suppliers – had a free hand to develop discrete systems; they had to take account of existing data and IT infrastructures.

Normalisation process theory had proved to be valuable in the design of our fieldwork. We realised, however, that it assumes that a single, discrete technology is being implemented. As the points above imply, this was not the case in this study: there were a number of technologies being implemented. The theory is not suited to the complicated mix of technologies that we found. Moreover, we were dealing with a large-scale technology, and thus groups of people who were engaging with it in very different ways – at ward and board levels – in different parts of an organisation. We therefore needed to identify an analytical framework that allowed us to address our aims and objectives, and that retained the key features of the approach set out in our protocol – but that was suited to the nature of the technologies that we found at the sites.

We considered a range of alternatives, but the Biography of Artefacts approach, developed by Pollock and Williams26 at Edinburgh, was the only one that we felt dealt with the development of large-scale systems over time. The approach stems from the observation that many IT systems in organisations have been implemented over many years. New functions are added periodically, and existing systems are linked both to one another and to new systems. Systems thus develop in piecemeal fashion, producing digital infrastructures that are deeply embedded in the day-to-day work of an organisation.

Pollock and Williams argue that it is simply not possible to study any large-scale organisational technology in its entirety. The pragmatic solution is to observe developments at a number of ‘key points’ where significant things happen, for example meetings in which system developers meet users to discuss the design of a system, or in which ward nurses use systems in the course of their work. The usual field methods are ethnographic, with researchers effectively undertaking ‘mini-ethnographies’ at each of the key points. In this study, we drew particularly on a narrative approach, whereby informants’ stories provide insights into how they are achieving or getting to achieve their aims, and how the narrative unfolds over time. 41 The authors further argue that if we want to understand any IT system in an organisation, and understand why it looks the way it does today, we need to understand its history. The method therefore involves the development of a number of ‘mini-biographies’ based on observations made, over time, at each of the key points. A Biography of Artefacts is, then, made up of a number of mini-biographies. The result is an account of developments from an unusual perspective. For example, there are a number of studies on the use of performance management data by trust board. However, we are not aware of any that, as in the current study, ask how the data get there and why those arrangements have developed, as well as how they are used.

We decided to use the Biography of Artefacts approach in the autumn of 2015. We were committed in our original protocol to understanding developments over time, and the decision to produce mini-biographies did not have a substantial effect on our fieldwork. That said, our realisation that the technologies were more complicated than we had expected led us to expand the scope of our fieldwork in two directions. The first was to ‘go behind the scenes’ to understand how trusts transformed data from a range of systems into consolidated reports for boards and other audiences. The second was to explore what happened to data sets when they were submitted to NHS Digital and sent onwards to other organisations, including the CQC and CCGs.

Chapter 3 National infrastructures

Key points

-

Technologies for handling national data submissions have developed over the last 30 years.

-

They were initially developed to manage routine activity data but, more recently, have been used to manage the increasing number of quality and safety data.

-

Developments have been piecemeal, resulting in hybrid infrastructures: amalgams of different technologies.

-

Current IT arrangements support the submission of data sets to national bodies, rather than supporting trusts to manage their own affairs effectively or share data with one another.

-

Some recent policies advocate ‘real-time management’: these, too, envisage national monitoring of the quality and safety of services.

-

Nurses’ data and IT needs have been barely visible during the whole period.

Introduction

This chapter discusses the government policies, and the national data and IT infrastructures, that have shaped the development of information systems in the study sites. It became apparent early in the study that national policies had had a very significant influence on the technologies and practices that we were observing. There were, for example, many data sets on the quality and safety of services that trusts were required to submit routinely to NHS Digital and other national bodies.

We present developments in national infrastructures, unfolding over a period of 30 years, albeit with the major changes occurring since the early 2000s. This is consistent with the Biography of Artefacts approach, which we outlined in Chapter 2. Developments are presented in three ‘clusters’, which have emerged at different points in time and are characterised by different ways of thinking about the nature and purposes of data and technology infrastructures. The three clusters are, performance management from the late 1970s onwards; a hybrid of New Public Management-style inspection and advocacy of local governance of quality and safety from 1997 onwards; and ‘real-time management’ since 2012.

First cluster: managerialism, 1979–97

The Conservative administration that came to power in 1979 argued that traditional bureaucracies, including the NHS, were inefficient. They believed that efficiency could be improved by the introduction of a range of measures, some of which were borrowed from private firms, including the use of performance management, the devolution of authority to local managers and the use of market-like mechanisms to commission public services. 42,43 These policies led to the introduction of institutional arrangements that are familiar today, including the separation of commissioning and provision of services. In the context of this study, a key development concerned national data collections. Hospitals submitted a Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data set and a set of performance indicators (the latter on paper) from 1987 onwards (Professor Paul Aylin, based on evidence paper submitted to Bristol Inquiry, personal communication, Imperial College London, 2015). 44 HES included mortality data, as hospitals had to record all discharges, and death was one category of discharge. HES data sets were initially extracted monthly from hospitals’ Patient Administration Systems (PAS) onto tapes or compact discs (CDs), which were sent (by post or courier) to Regional Health Authorities. 45

There was one other policy that led to the routine collection of data on quality in this period: the Patient’s Charter of 1991. This introduced a maximum waiting time target of 18 months from GP referral to hospital admission. Hospitals were required to report the number of patients who were waiting more than 18 months.

The first significant national IT infrastructure investments were made in the 1990s, prompted in part by the perceived need to move large data sets between locations for contract monitoring in the then-new NHS internal market. 46 Contracts for a national internal network, NHSnet, were signed in 1994. From 1996, hospitals submitted data sets to Regional Health Authorities electronically via a national service, the NHS-wide Clearing Service, called ClearNET.

Second cluster: centralising performance management, 1999 onwards

A Labour government was elected in 1997. From 1999 onwards it decided to pursue managerial policies, continuing in the broad direction set by the previous Conservative administration. At the same time, policy-makers became concerned about the quality and safety of NHS services, prompted by official reports that highlighted far higher hospital mortality rates than anyone had realised, as well as a scandal in cardiac surgery services at Bristol Royal Infirmary. 1,2,47,48

There were a number of policy responses, notably in the creation of national bodies, that would need data on trusts to do their work. Two new bodies were announced in The New NHS:49 the National Institute for Clinical Excellence and the Commission for Healthcare Inspection (later renamed the Healthcare Commission and then the CQC). The latter was to be responsible for governance of the quality of services in NHS organisations. These organisations were subsequently joined by Monitor, which started its work in 2004, as the regulator of the (then) new foundation hospitals. 50

The National Patient Safety Agency was created in 2001; NHS organisations were required to report clinical incidents to it. There was a substantial overhaul of professional regulation, which, among other things, led to a revised system for the licensing of doctors and a National Clinical Assessment Authority for investigating poor performance. The net effect of policies in this period was twofold: a step change in the number of centrally mandated data ‘returns’ in the years after 1997, and the creation of new agencies that would use them (Table 4).

| Year | Policies/reports | New agencies | New indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | The New NHS: Modern, Dependable 49 | Announced creation of NICE and CHI | |

| 1999 | Modernising Government (all public services)51 | ||

| 2000 | The NHS Plan 52 | Staged reduction of maximum waiting time from 18 to 6 months | |

| 2000 | NHS Cancer Plan 53 | A set of referral/diagnosis-to-treatment targets | |

| 2001 | Reforming Emergency Care 54 | Thrombolysis within 20 minutes in accident and emergency; maximum of 4 hours from arrival to admission | |

| 2001 | National Patient Safety Agency established | Reporting of incidents/development of NRLS | |

| 2001–2 | CHI star ratings (0–3 for hospitals) published | ||

| 2002 | Payment by Results (tariffs) announced55 | ||

| 2004 |

CHI now Healthcare Commission Monitor starts work |

||

| 2004 | NHS Improvement Plan 56 | RTT |

Expansion and consolidation

In the period from 2004 onwards there were countervailing tendencies. One was a centralising tendency, as the new regulators got down to work. The CQC from the beginning undertook inspections of individual trusts and collected a range of data directly from them, using them to publish ratings (0–3 stars) based on a basket of indicators. 57,58 It also used routine data sets to ‘scan’ NHS trusts, for example looking for outliers on key variables such as waiting times, and, in so doing, built up data sets of indicators. In 2009, it introduced Quality and Risk Profiles, which amalgamated the indicators and information gathered in inspections to create ‘risk scores’ for each trust. These were provided to inspectors as a series of dials (dashboards) in advance of an inspection.

The National Patient Safety Agency also developed its reporting arrangements – the National Reporting and Learning System – during this period. 59 Additionally, Monitor started its work in 2004. Initially, it focused on financial measures, but later it included a limited set of quality measures. Overall, then, there was a substantial increase in the number of data on quality and safety that NHS organisations were required to submit to national bodies.

The other tendency was to develop local management arrangements, drawing on Total Quality60 and Lean61 approaches, among others. For example, the Productive Ward initiative,62 a rare nursing-focused initiative in this account, drew on Lean thinking and was thus intended to improve quality and reduce costs simultaneously. Interest in the use of nurse staffing data, including ratios of nurses to patients, increased in this period. However, staffing data aside, it appears that limited attention was paid to the data that were needed to drive local initiatives or to the IT systems needed to support them. There was no local equivalent of the national data submission requirements.

There was a clear focus on data in High Quality Care For All,63 widely known as the Darzi report, published in 2008. It recommended a move away from centrally driven performance management towards more local ownership of the quality of services. The report argued that quality had three components: clinical effectiveness, patient experience and patient safety. These were used to develop the NHS Outcomes Framework, which was first published in 2010. There were five ‘domains’, each linked to one of the three components. 64 Public Health England now commissions the Framework, which currently has over 60 indicators. The Darzi report also recommended the publication of Quality Accounts:

to help make quality information available, we will require, in legislation, health-care providers working for or on behalf of the NHS to publish their ‘Quality Accounts’ from April 2010 – just as they publish financial accounts. These will be reports to the public on the quality of services they provide in every service line – looking at safety, experience and outcomes.

p. 51,63

The first Quality Accounts were published in 2010. 65

2010 onwards: policy turbulence

A Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government was formed in 2010. In the following 3 years it abolished a number of bodies created in the previous decade, including the National Patient Safety Agency. The National Patient Safety Agency’s functions were transferred to NHS England.

The coalition introduced major structural changes in the NHS, set out in the Health and Social Care Act 2012. 66 From 2013 onwards, five organisations were formally responsible for the governance of the NHS: NHS England, the CQC (responsible for quality), Monitor (responsible for market regulation), the Trust Development Authority (TDA) (responsible for oversight of the preparation of trusts for foundation status, particularly in relation to their governance) and Public Health England. Later, in 2015, the patient safety function of NHS England, Monitor, TDA and other smaller bodies was brought together in a single new organisation, NHS Improvement. This was the patient safety function’s third ‘home’ in 5 years. In 2016, a new Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch was created, which started work in 2017.

The HSCIC was also created by the new act, merging the NHS Information Centre – which managed HES and other data sets in the 2000s – and Connecting for Health, the agency that had been responsible for the NHS National Programme for IT. HSCIC was legally responsible for acquiring data from all NHS organisations (i.e. it was to manage data collection on behalf of other national organisations and CCGs). The net effect of these structural changes was, again, to reinforce centralisation of data submissions.

At the same time, concerns about the safety of services intensified, prompted in part by clear evidence of poor treatment and care at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust from 2006 onwards. Robert Francis (now Sir Robert) chaired an inquiry and published a report in 2010, setting out many harrowing experiences of patients and their carers. A second report was commissioned on the management and regulation of services at the trust, which was published in 2013. It emphasised three points that are relevant to this account. First, it criticised the board, Strategic Health Authority and regulators (including CQC and Monitor), but recommended that the arrangements needed to be strengthened rather than changed. Second, the report noted that NHS trusts published very limited information about their performance, and argued that problems would be less likely to occur if trusts were required to publish more. This echoed wider developments, notably in cross-government open data policies. 67 Third, and echoing the Bristol Inquiry from 12 years earlier, Francis argued that better use could and should be made of data and IT systems:

The recording of routine observations on the ward should, where possible, be done automatically as they are taken, with results being immediately accessible to all staff electronically in a form enabling progress to be monitored and interpreted. If this cannot be done, there needs to be a system whereby ward leaders and named nurses are responsible for ensuring that the observations are carried out and recorded.

Recommendation 243, p. 111,5

These recommendations were accepted by the government in its formal response to the report in November 2013. Yet again, the overall arguments were in favour of centralising data submissions and, by implication, the capability to monitor and manage quality and patient safety from the centre.

There were some voices in favour of localism. In the wake of the Mid Staffordshire report, the government commissioned a report from the respected US clinician and analyst Donald Berwick. His 2013 report identified a role for local data and IT services:

Patient safety cannot be improved without active interrogation of information that is generated primarily for learning, not punishment, and is for use primarily at the front line. Information should include: the perspective of patients and their families; measures of harm; measures of the reliability of critical safety processes; information on practices that encourage the monitoring of safety on a day to day basis; on the capacity to anticipate safety problems; and on the capacity to respond and learn from safety information . . . Most health care organisations at present have very little capacity to analyse, monitor, or learn from safety and quality information. This gap is costly, and should be closed.

p. 27,10

This report was, however, the one exception to the general trend towards centralisation of authority.

Information technology policies 1997–2012

There was little overlap between data and IT policies in this period. Earlier policies prevailed in the first few years: the one significant change involved explicit support for integrated electronic patient records, presented as part of a move to more patient-centred care. 68,69 There was, however, a marked shift in the nature of IT policy-making in 2001 and 2002. A series of reports paved the way for a decision to provide funding for an ambitious IT infrastructure for the whole of the NHS. 70–72

The implementation of the NHS National Programme for IT – as it was termed – did not go well. The biggest problem concerned the flagship of the programme, namely the five contracts for electronic health records (EHRs), which were worth > £5B. 73 Five years into the programme, in 2008, systems had been implemented in a handful of hospitals in the south of England and in single departments in two hospitals in the north. There were calls for a fundamental review, and even abandonment of the programme. 74 Initially, NHS organisations waited for these systems – they had been told forcibly that they had to – but many eventually decided to pursue their own plans. A new policy was published in 2008, which tacitly endorsed these decisions, encouraging trusts to focus on implementing the ‘clinical five’: five key systems that all acute hospitals were deemed to need. 75

The main bright spot for policy-makers was the N3 network, the successor to NHSnet. N3 worked, in the straightforward sense that GP and hospital (including pathology department) systems could link to it and send messages over it. The success of N3 is significant in this report, because it extended the technology infrastructure in a way that reinforced the ‘pathways’ from trusts to national bodies but did not provide infrastructure for other data flows, for example between trusts.

A new policy, The Power of Information, was published in 2012. 76 There was continuity with the arguments that had underpinned the NHS National Programme for IT, notably in its focus on IT and on maintaining a clear separation from data and other policies. However, the policy also had novel features, notably its aim to promote:

a culture of transparency, where access to high-quality, evidence-based information about services and the quality of care held by government and health and care services is openly and easily available to us all.

p. 5, Department of Health and Social Care,76

This echoed the arguments in the Francis report and in open data policies, noted earlier.

Third cluster: real-time governance

At the same time as later ‘second cluster’ policies were published, the government published policies with two distinctive characteristics. The most important of these is the Five Year Forward View,77 published in 2014. Rather than emphasising competition, performance management and other managerial policies, the Five Year Forward View talks of the NHS as a ‘social movement’, and of the importance of engaging with local communities, with organisations in a locality working closely together. It talks, too, of the devolution of authority to groups of organisations working together, with the freedom to develop new working practices appropriate to the populations they serve. This implied distinctive data flows between organisations rather than upwards from trusts to national bodies. Subsequently, in early 2016, the Secretary of State for Health announced IT investments totalling £4.2B, with a significant proportion of this to be used to ensure that systems could share data with one another. 78,79

A second new theme concerned the use of clinical data in ‘real time’: using data on services while memories of those services are still fresh, as opposed to using them for retrospective reviews weeks or months after the activities described. Thus, the second Francis report,5 introduced earlier, stated that:

All healthcare provider organisations, in conjunction with their healthcare professionals, should develop and maintain systems which give them:

Effective real-time information on the performance of each of their services against patient safety and minimum quality standards;

Effective real-time information of the performance of each of their consultants and specialist teams in relation to mortality, morbidity, outcome and patient satisfaction.

Recommendation 262, p. 113,5

Similarly, a new IT policy, Personalised Health and Care 2020,80 proposed that all patient records would be real-time and interoperable by 2020.

Finally, the government published a clinical utilisation review in 2015. 81 This argued that NHS trusts should implement IT infrastructure for collecting and analysing real-time vital signs data. These data would, it was envisaged, be made available to NHS England in real time (i.e. presumably within a few hours). Few details were given about the ways in which data would be used, but the text implied that managers at NHS England would be able to monitor the work of nurses and doctors in the course of a shift.

Discussion

This brief account emphasises the long period over which the current infrastructures have developed. In the main, the infrastructures that have been implemented support centralisation: the flow of data sets from trusts to NHS Digital and other bodies. This has happened in spite of the fact that policy-making for data and policy-making for IT have been largely separate throughout the last 30 years. In later chapters we will explore the nature and extent of the overlap between the two, in practice, in trusts.

The nature of the third cluster, with its emphasis on the use of real-time data, is not yet clear: there is not enough policy or experience to date. It appears, however, to have some of the characteristics of Digital Era Governance, wherein IT systems are integrated and used to enable staff in different services – and different trusts – to co-ordinate their work. 82 This contrasts with the centralising tendencies of developments in earlier periods. We will also explore the extent of the moves towards the use of real-time data in trusts.

Chapter 4 Telephone survey and board paper review

Key points

-

This phase of the study comprised a telephone survey of 15 acute NHS trusts and a survey of the content of board papers of all trusts in England in 2014.

-

The telephone survey revealed that two sites in our region were already using electronic ward whiteboards.

-

The board paper survey showed that all acute NHS trusts used dashboards to present data on the quality and safety of services.

-

The surveys, taken together, indicated that national bodies had a substantial influence on the data used by boards: the boards submitted the data collected to national bodies.

Introduction

This chapter presents the findings of a telephone survey of senior nurses, undertaken between September and November 2014, in 15 NHS acute hospital trusts in northern England. We also surveyed the routine quality and safety data presented in papers tabled for board meetings in all 156 acute trusts across England in January 2015.

Telephone survey

Dashboards were used by all 15 of the trusts interviewed and were described as a graphical means of displaying data on the performance of wards and departments, and, more broadly, as key components of trust management information systems. Most participants told us that dashboard information was collated manually from a number of operational systems, including PAS and Datix, the NHS system for reporting patient safety incidents. Reports were typically assembled manually by central performance management teams, and retrospective reports were circulated monthly to wards, directorates and trust boards. The assembly of board reports was easier in two trusts that had real-time data capture and reporting systems.

Regulators

The focus of our questions was on ‘ward to board’ information systems, but many of our interviewees stressed the importance of regulators in determining the information that their trusts collected and used. All trusts in the sample were required to report to national bodies including Monitor, CQC and NHS England.

Several participants pointed out that compiling data for national reporting was onerous:

The information colleagues are so busy doing the national reports and making sure things are validated that there’s very little time for development.

Site A

We were told how regulators scrutinised trusts’ data collection and reporting:

We had an external review of our governance arrangements earlier in the year as part of Monitor’s commitment to 3 yearly reviews of governance, and part of the review of the governance was, is the information that we provide to people fit for purpose and does it help, you know, with planning and you know improving services? So that review took place and made some recommendations about some of the dashboards, particularly the dashboards that go to the board of directors.

Site A

Some interviewees noted that reports to regulators were aggregated, and that this could mask significant variations within and between trusts.

Participants noted that, historically, reports were sent to commissioners, whereas now they were available to other trusts and to the general public. Participants shared a concern that data might be misinterpreted:

. . . it’s all in public now . . . the devil’s in the detail sometimes and actually sometimes a dashboard can almost be too simplistic.

Site B

For example, local circumstances, such as a trust having a prison in its catchment area, which made some targets difficult to achieve, might not be apparent in nationally published data. On the other hand, participants said that the availability of key national targets allowed trusts to compare their performance with that of others and to benchmark themselves. Indeed, one trust indicated that it reviewed other trusts’ information to see where improvements had been made and how they, in turn, could improve.

Trust boards

All participants told us that dashboards were important tools for trust boards. Board members used a number of dashboards covering a wide range of services and topics, including mortality, infection control and the nursing workforce. Dashboard data presented at board level tended to be for activity 4–6 weeks in arrears; for example, data for the month of May would be reviewed at a July meeting.

Most interviewees told us that dashboards provided warning signs, highlighting specific wards or topics that needed monitoring or action. Trusts used colour-coded dashboards – red, amber and green – to highlight areas that needed attention. Many of the trusts reported that dashboards were used to identify poorly performing services, which could be ‘escalated’ for senior management review if necessary. One interviewee described dashboard review as a ‘trigger or a proxy for escalation’.

Interviewees were aware that dashboards could be viewed as opportunities for learning:

[Dashboards are] not something that they see as a way of kind of something to beat them up with but actually something to celebrate that’s good and something to say you’re doing a really good job.

Site C

Less positively, there were concerns that summaries could provide false-positive information:

Ward 1 might be doing really badly and ward 99 might be doing exceptionally well and you end up with an average that’s good or worse than that in terms of post Francis, results that look like the organisation is doing very well, so then the board is reassured but if you get in to the detail you might find you’ve got two or three areas that you should be concerned about.

Site C

Furthermore, some participants said that, at board level, problems may be masked by the lack of detail in reports:

It is very easy to fall down the trap of just looking at the crude numbers without understanding the clinical area, so for example an area will come out with a high number of falls but it’s going to have because it’s an area that has got a high risk of falls . . . so it’s very easy to say Ward A is brilliant, look they’ve had no falls, when it’s a paediatric ward . . . I think in the wrong hands the information can be quite dangerous.

Site B

Other participants were also wary of dashboards containing too much information for the board to understand or use:

There’s always an appetite at the board for more and more information, and if I was a vindictive person or wanted to hide something the one way to deal with that is to give the board more and more information.

Site D

Finally, trusts with real-time data capture and reporting told us about the ways in which they used their systems:

Every Friday, myself, the medical director, the director of governance, director of risk and quality, we meet to go through harm, to understand the root cause and how it’s reported, and then the learning, and the actions that are taken, and then follow that through with what we call . . . it’s like a recipe card . . . it’s a very high-level visual message board which goes out to the whole trust.

Site E

Board paper survey

These comments, and the comments about regulators, prompted us to review the papers for board meetings at all 156 acute trusts in England for January 2015, in the week beginning 16 March 2015. One hundred and fifty-two trusts published full sets of board papers, consistent with post-Francis reporting requirements. We requested papers from the other four trusts, two of which sent them by return and two of which did not send them within 4 weeks of our request. Almost all trusts (152 out of 154 published sets of papers) had papers on waiting times, the NHS Safety Thermometer, serious incidents, complaints and patient experience measures. Almost all (153 out of 154) had dashboard-based workforce reports. A total of 115 out of 154 trusts reported risk assessment framework data, and 58 out of 154 presented balanced scorecards. Eight out of 156 trusts reported data items that were not requested or required by any national body.

Wards

Our interviewees reported considerable variation between trusts in the availability of management information to ward staff. A majority reported that management reports were prepared by a central team, were limited in scope and reported 4–6 weeks in arrears. A minority told us that dashboards were actively used by ward staff. One participant considered this active use to be because the content was nurse driven and nurses had had a big influence on how their information systems were designed and used:

What you have to do is make them intelligent and useful to the user, something that they feel they understand their business better, and also be prepared to invest where it’s needed if it tells you something you need to invest in that you do it in a responsive way so staff feel listened to and you engage them in what’s important to them as well as what’s important to the organisation.

Site E

The engagement of ward staff with management issues was an ongoing issue across all trusts. For example:

What we’re looking at is how we absolutely get that down in to ward level and them actually using it and being able to interpret the data and what it’s telling them.

Site F

Interviewees offered a number of reasons why information was not being used on wards, including clinical staff struggling with the perceived low value of retrospective information, problems with local IT systems, lack of staff education and training to use information, and earlier versions of dashboards having been poorly received, colouring renewed attempts to engage staff. A number of interviewees told us that their ward staff viewed dashboards as management tools, and as tools for control rather than as a means to support their work.

As noted above, there were differences between trusts with real-time systems and those without them. Where real-time systems were available, interviewees told us that emerging risks could be addressed as they arose. These trusts had implemented risk-based management systems, for example by ensuring that all admitted patients had NEWS and other risk metrics. These could be viewed on screen and risks could be proactively managed:

When you go on to our wards you’ll see a single computer screen that’s got a patient’s bed number and then there’s a tick or a cross against all the bits and pieces that need to be done, like have they had VTE assessment . . . and it’s very obvious where the gaps are . . . I need to know very quickly where they’re not doing stuff so I can ask questions.

Site D

Discussion

We found that board-level dashboards are integral parts of acute NHS trusts’ management information systems. All acute NHS trusts used dashboards to summarise information for board-level meetings. The evidence suggests that trusts are working within a centralised NHS reporting system, using data for retrospective review.

In most of the 15 trusts, in contrast, the overall picture was of ward managers receiving limited, retrospective management reports. They were not in a position to manage risks in real time in the manner envisaged by Berwick and others. That said, two trusts told us that they had deployed real-time ward management systems and were able to manage quality and safety risks proactively in this way. Four further trusts told us that they had plans to implement such systems. The fact that ward systems had already been implemented influenced our thinking that it would be most valuable to observe, in the main, fieldwork at four acute hospital trusts. We described the effect of this decision on our sampling strategy in Chapter 2.

The surveys provided initial indications of the developing governance arrangements and shed some light on our aims and objectives. They suggested that authority was exercised in two ways. First, there was authority to determine what data were collected and reported, and the findings indicate that national bodies determine the majority of data items reported at trust board level. Viewed in historical context, this is not surprising. Ever since they were introduced in the late 1980s, performance indicators have been designed and managed by national bodies. The authority to define the performance framework still resides with national bodies. This point is consistent with the account of national data and technology infrastructures in Chapter 3.

Second, we found that board members receive a great deal of detailed data on wards and departments, presented in a wide range of graphical formats. There was general agreement that dashboards were valuable, both for trust boards in monitoring performance and for non-executives and governors holding boards to account. Some weaknesses of dashboard-based reporting were also noted, including the risk that aggregation of data masked important information about outliers.

Finally, the importance of IT infrastructure in capturing and making quality and safety data available to managers and ward teams, is not stressed by either Francis or Berwick, but is highlighted by these findings. This point also influenced our thinking about the fieldwork that we were to undertake in four trusts in phase 2; we felt that we should investigate the nature and role of IT infrastructures for handling quality and safety data in trusts.

Chapter 5 The four trusts: infrastructures and performance

Key points

-

We identify five distinct technology ‘development paths’, concerning data used on wards, national data submissions, data processing systems, real-time ward management systems and infrastructures.