Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/19/26. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The final report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in October 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Simon de Lusignan is a Professor of Primary Care and Clinical Informatics and reports that the University of Surrey runs a physician associate course. Jim Parle chairs the UK and Ireland Board for Physician Associate Education and is director of the physician associate programme at the University of Birmingham. Phil Begg is an honorary faculty member at the University of Birmingham and has taught on the physician associate programme since 2008. James Ennis teaches part time on the University of Birmingham physician associate course. Vari M Drennan was a Health Services and Delivery Research Board Member in 2015.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Drennan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

This study addresses questions about the introduction of a new role, the physician associate (PA), within the hospital medical workforce. It is focused, in the first instance, on providing information that addresses the questions of clinicians, managers and those involved in commissioning services and education programmes in the UK. This chapter provides the background and rationale of the study by presenting contextual information and the evidence at the time the study was commissioned (September 2015). The aims and objectives of the study are presented, followed by brief detail of the advisory process and the public’s role in advising the study team. The chapter concludes with an outline of the rest of the report.

Rationale

Physician associates, previously known in the UK and elsewhere as physician assistants, are a new and rapidly growing occupational group in the UK NHS, with the first significant number of UK-trained PAs graduating in 2009. 1 From 2012, the employment of PAs in medical teams in secondary care was advocated by bodies such as the Royal College of Physicians (RCP),2,3 the College of Emergency Medicine4 and the Department of Health-commissioned Centre for Workforce Intelligence. 5 The increase in the employment of PAs was supported by the doubling of training places to > 200 per annum, as announced by Jeremy Hunt, the Secretary of State for Health, in August 2014, and the increasing number of universities offering PA courses. 6

Although the response from The Patients Association and the British Medical Association to the announcement by Jeremy Hunt was mixed, expressing caution and concern,7 the increase of PAs in the UK was supported by NHS workforce policy and medical royal colleges. Health Education England (HEE), the body responsible for the planning and education of the NHS workforce in England, included PAs in its workforce plans for the first time in 2013 and created a national PA development group. 8 The medical director (MD) of HEE publicly spoke of the need for 5000 PAs in the NHS and the expectation that there will be 500 PAs graduating each year in England by 2018. 9 In Scotland, the inclusion of PAs in NHS workforce planning was agreed in 2012 and PA training was subsequently commissioned from Aberdeen University by the NHS. 10 The Council of the Royal College of Physicians (London) agreed, in March 2014, to establish a Faculty of Physician Associates (FPA) in collaboration with the UK Association of Physician Associates (UKAPA), HEE and other royal colleges to support and develop the role. 11 At least 30 NHS hospital trusts were early adopters of PAs in their medical staffing1,12 and demand was reported to outstrip the supply of UK-trained PAs by 2014. 9 Key drivers of the policy and employer initiatives have been the pressures on the medical workforce, particularly in emergency medicine,4 but more widely linked to the implementation of the EU’s Working Time Directive,13 which currently controls junior doctors’ working hours. 2,3,5,14 PAs were seen as one type of mid-level practitioner (i.e. non-physician clinicians trained to undertake some of the diagnostic and clinical activities of doctors15) that could help address these problems in the immediate and long term without recruiting from another, already-pressured workforce, such as nursing. 5,9,16

Despite this growth of interest and policy support, there was very little published evidence regarding PAs’ contribution to patient care and effectiveness in the secondary care setting. There was, however, published evidence of their contribution in primary care. 17 The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded study,17 led by the same principal investigator as this report, reported that ‘physician assistants were found to be acceptable, safe, effective and efficient in complementing the work of general practitioners (GPs). Further research is required as to the contribution PAs could make in other services’.

Hospitals are very different from general practice in organisation as well as in type of treatment and care provided to patients. The evidence established in the general practice setting could not automatically be applied to a hospital setting. The primary care study demonstrated that NHS managers, senior clinicians and commissioners were seeking hard evidence to inform their decision-making as to the benefits or otherwise of including PAs in medical teams. 17,18 Patients and representatives from patient organisations also wanted evidence that this professional group was safe and did not result in some patients receiving an inferior service or unnecessary double-handling (i.e. being seen by one professional prior to repeating the consultation with a doctor). 17,19 This study was funded by NIHR as a follow-on study to the primary care research,17 recognising the need for evidence in the hospital setting, where there was increasing employment of PAs in England. 1,8,12

We turn now to provide more detailed information on PAs, PAs in the UK setting and the evidence of their contribution in hospital settings in 2015 (the starting point of this study).

Physician associates

Physician associates are trained at postgraduate level in a medical model to work in all settings and undertake medical history taking, physical examinations, investigations, diagnoses and treatments and to prescribe within their scope of practice as agreed with their supervising doctor. 20,21 PAs have a 50-year history in the USA. 22 By 2014, about 94,000 PAs were employed in US health services;23 of these, an estimated 30% worked in hospitals. 24 A growing number of high-, middle- and low-income countries have developed or are developing PA roles within their health-care workforce to varying degrees, including Ghana, Liberia, South Africa,25 the Netherlands26 and Canada. 27

Reviews of mainly pre-2013 US studies found patients to be very satisfied with PA care and that PAs can provide equivalent and safe care for the case mix of patients they attend. 28–31 The two systematic reviews (one general30 and one specific to primary care31) noted that the quality of most studies was weak to moderate and there was limited evidence on resource utilisation, costs and cost-effectiveness. Three small US studies of PAs in hospital settings published in 2013 and 2014 provided new positive evidence as to the contribution that PAs made to patient outcomes and resource use in a trauma–orthopaedic setting32 and in low- and high-acuity emergency department (ED) settings. 33,34 One study35 had reported that the indirect impact of employing PAs in a general surgical residency programme was to reduce the resident doctor workload, increase the doctors’ ability to attend their training activities and improve results in their American Board of Surgery in Training Examination. In 2014, a study protocol was published for research investigating the substitution of medical doctors with PAs in hospitals in the Netherlands. 36

Physician associates in secondary care in the UK

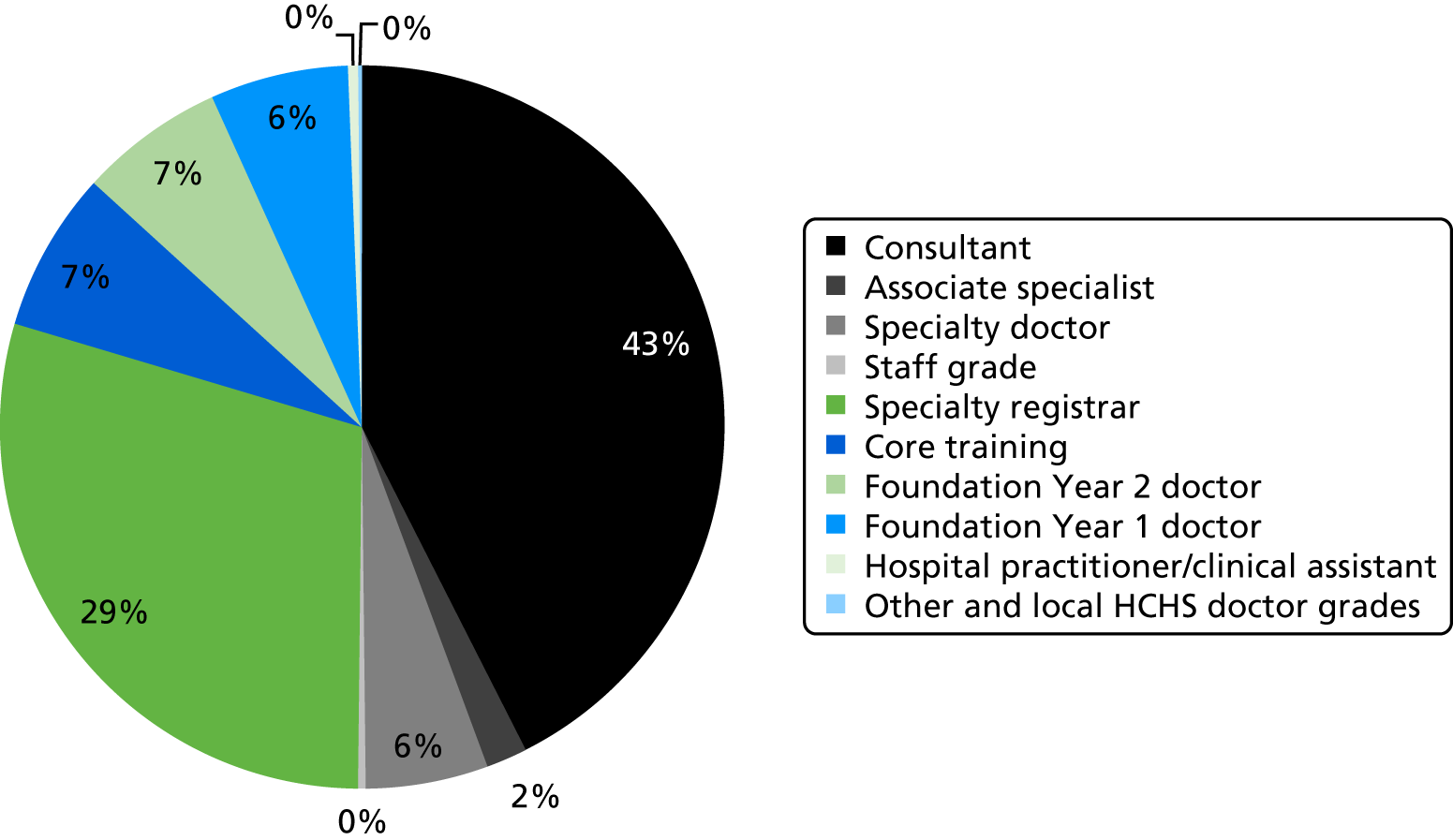

Health policy, NHS funding and concomitant organisational arrangements are devolved to the respective country administrations within the UK. 37 In England, where this study was undertaken, there were 163 NHS trusts (organisations providing NHS services) providing acute secondary care in 2017. 38 The medical workforce in these NHS organisations was formed of doctors of different grades, including training grades. Of the 94,045 full-time equivalents (FTEs) in the medical workforce in these acute secondary care trusts in 2017, 39,993 FTEs (43%) were consultants and 11,871 FTEs (11%) were Foundation Year doctors39 (Figure 1). The NHS workforce descriptor ‘hospital practitioner/clinical assistant’ may include, but is not exclusive to, PA staff; 425 FTEs were recorded in this occupational group. 40

FIGURE 1.

The medical workforce by grade in NHS trusts (excluding psychiatry and community staff). Data were sourced from NHS Digital. 39 HCHS, Hospital and Community Health Service.

In 2015, there was very limited published evidence about the contribution of PAs to hospital care in the UK. A Department of Health-supported pilot project of PAs in England included two PAs in hospitals,41 who worked in EDs. The evaluation concluded that they could make a range of contributions working at the clinical assistant level. 42 A similarly supported pilot project in Scotland included 11 USA-trained PAs working in emergency medicine, intermediate care and orthopaedics. 43 It reported that the PAs were well received by patients, were working safely and at the level of a trainee doctor (in some instances, almost at the level of a specialist trainee). The advantages of their employment were noted to be increased consultant productivity, increased continuity in the consultant team and positive impact on patient throughput. There were, however, issues with PAs’ lack of authority to prescribe medicines and order radiographs (both consequences of a lack of a statutory regulation) and also assuring appropriate medical supervision when there were shortages of medical staff. 43 A commentary in 2013 on the introduction of PAs in one English paediatric intensive care unit described a positive impact on patient care and continuity in the running of the unit and that initial, predictable, implementation problems were soon resolved. 44 A survey,45 conducted in England in 2012, of doctors supervising PAs in primary and secondary care reported that they considered the PA as a flexible member of their team, who was well received by patients and made a positive contribution to patient outcomes and efficiency. The issue of a lack of regulation was seen as the major problem, which also resulted in increased requirement for time from the supervising doctor.

In the UK, there were positive evaluations of US-trained PAs in pilot projects in primary and secondary settings in 2005 (England42) and 2009 (Scotland43). These reports, combined with the first validated PA programme at the University of Wolverhampton in 2004, led to a nationally agreed competency and curriculum statement20 (which was subsequently updated21) and postgraduate programmes in a growing number of universities. PAs were not (and continue to not be) regulated by the state, although application has been made for regulation, supported by HEE and the RCP. 11 The lack of state regulation means that, among other issues, PAs cannot prescribe or order ionising radiation. At present, PAs maintain a voluntary register and undertake revalidation every 6 years. 46 In October 2017, the Department of Health and Social Care announced a public consultation on the inclusion of PAs in UK state regulation processes. 47

There has been an increase in PA employment in UK hospital settings. In 2012, Ross et al. 1 reported that > 200 PAs were employed in 20 hospitals and within 15 medical and surgical specialties. Two years later, in spring 2014, evidence on the UKAPA website (the UKAPA has since disbanded to create the FPA at the RCP and the website has been closed down) showed that PA employment in hospitals had increased by ≥ 50 PAs and in > 30 hospitals. 48 PAs were reported to be in 20 adult and paediatric specialties, including psychiatry, geriatrics, paediatric intensive care, infectious diseases, cardiology, neurosurgery and genitourinary medicine. 48 In 2012, the greatest numbers of PAs were employed in emergency medicine and the medical specialties of respiratory medicine and cardiovascular medicine. 1

Although the rapid spread and growth of PAs in different hospital settings suggested that the role was seen as advantageous by early adopters, there was little evidence available for the public, patients or health service leaders as to the deployment, acceptability, effectiveness and costs of PAs in different types of hospital medical teams. This study aimed to address the evidence gap.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the contribution of PAs to the delivery of patient care in hospital services in England.

The research questions that have been addressed are:

-

What is the extent of the adoption and deployment of PAs employed in acute hospital medical services?

-

What factors support or inhibit the inclusion of PAs as part of hospital medical teams at the macro, meso and micro levels of the English health-care system?

-

What is the impact of including PAs in hospital medical teams on patients’ experiences and outcomes?

-

What is the impact of including PAs in hospital medical teams on the organisation of services, working practices and training of other professionals, relationships between professionals and service costs?

The full study protocol was published on the NIHR Journals Library website (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/141926/#/; accessed 5 February 2019). The study team had the benefit of both an advisory group and patient and public involvement throughout (see Appendix 1). The patient and public voice was important to this study and is detailed in Chapter 2.

The following chapters provide details of the study methods and findings. The report concludes with the discussion and recommendations.

Chapter 2 Methods

This investigation was a follow-on study and used the same theoretical framing and methods as those used by the research team in the original study of PAs in primary care. 17 As an applied health service research study, we used an evaluative framework described by Donabedian49 and applied it to the UK setting by Maxwell. 50 The contribution of PAs, as new types of personnel, was investigated through the dimensions of effectiveness, appropriateness, equity (fairness), efficiency, acceptability and cost in secondary health care. 49,50 The interactions within and between the macro, meso and micro levels of the health-care system in supporting or inhibiting the adoption of PAs as an innovation were also investigated. 51 Furthermore, the study was framed by an awareness of theories concerning substitution and supplementation to task shift from one group of professionals to another30,52 and the potential for contest between professional groups. 53 Overall, the study employed a mixed-methods approach54 in four interlinked workstreams:

-

Investigation of the extent of the adoption, deployment and role of PAs in hospital medical teams through two national electronic surveys: one to MDs of acute trusts and one to PAs (addressed research questions 1 and 2 at the macro and meso levels of the health-care system).

-

Investigation of the evidence of the impact of PAs and factors supporting or inhibiting the adoption of PAs at the macro and meso levels of the system through a review of published evidence for the specialties that most commonly reported employing PAs in the national surveys (workstream 1) and updating the published policy review from the prior study17 (addressed research questions 1, 3 and 4).

-

Investigation, through case study methodology in six hospitals employing PAs, of the impact, contribution and consequences of PAs in the medical teams. This included interviews with patients, managers and team and service members as well as requests for routine management data and observation of PAs at work. It also included a comparison of patient outcomes and service costs in EDs by PAs and Foundation Year 2 (FY2) junior doctors, where these two professional groups are deployed interchangeably (addressed research questions 1–4).

-

A synthesis of evidence from the three workstreams. This was presented and tested at an emerging-findings workshop with invitees from the research participants, the patient and public forum members and other advisors to the study (addressed the overarching study aim).

The following section describes the process of patient and public involvement. The methods of the study itself are then detailed.

Patient and public involvement

The patient and public voice was important to this study. The public and patient representative forum for the previous primary care study17 stressed that the innovation of bringing in a new group of professionals was of concern to the public. Key issues that the forum emphasised in discussion concerned (1) patient choice of the professional to consult or be attended by, (2) whether or not some groups of patients will receive a ‘second-class ‘or inferior service, (3) how patients will judge if this new professional is competent and (4) the ways in which the public and patients are informed of and understand this new role in different settings. Those issues were incorporated in the design of this study.

Within the study itself, the patient and public voice was interwoven in the following ways. First, Sally Brearley, as a public voice representative, was a co-applicant and member of the research team and the study paid for her time. Second, the study advisory group had two public voice members who were reimbursed for their time, following NIHR INVOLVE guidance. 55 Third, two patient and public voice groups were formed: one in London and the other in the West Midlands. Invitations to join were sent to the members of the patient and public group forum involved in the previous primary care study, through the public and patients network of the Centre for Public Engagement (at the Joint Faculty, Kingston University London and St George’s, University of London). Invitations were also circulated through an established patient involvement group of the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham. Members of these groups who attended research meetings were reimbursed for their time, again following NIHR INVOLVE guidance. 55 The patient and public voice groups met first of all to hear about the study and meet a PA, who was able to describe their work and education and answer questions. The early meetings were used to inform the interview topic guides and interview questions. Later meetings brought members together to help inform the analysis and interpretation of interview transcripts. All patient and public representatives were invited to participate in the final emerging-findings workshop (workstream 4).

We now describe the methods in detail.

Workstream 1: investigating the extent of the adoption, deployment and role of physician associates in hospital medical teams

Two electronic, descriptive, self-report surveys56 using Survey Monkey® (San Mateo, CA, USA) were conducted to map and describe the employment and deployment of PAs in secondary care services in England.

The first survey was of NHS MDs. It was designed by the research team and piloted by a MD. The survey addressed questions of employment and factors supporting or inhibiting that (see Appendix 2). The sample was of MDs in all acute and mental health NHS trusts in England as listed by NHS Choices (the NHS information portal) in December 2015. Contact details were obtained from Binley’s database. 57 The invitation was sent by e-mail in December 2015, and two reminder e-mails were sent.

The second survey was sent to the UK voluntary register and/or UK-trained PAs. It was adapted from the primary care study58 by the research team and piloted by a PA board member of the FPA (see Appendix 3). The questions addressed the PAs’ work settings, activities and supervision. E-mail invitations were sent in February 2016 by the FPA to its members and by university course directors to their alumni. Two reminder emails were sent.

Anonymous responses to both surveys were imported into IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Data from closed questions were used to produce frequency counts and open responses were analysed for thematic groupings.

This workstream was approved by the Faculty of Health, Social Care and Education Research Ethics Committee at Kingston University London and St George’s, University of London.

All respondents were invited to complete a separate Survey Monkey page (following a link from the completed survey) to provide contact details if they wished to be kept informed of the study progress and outputs.

The findings from this workstream informed workstreams 2 and 3.

Workstream 2: investigating evidence of the impact and factors supporting or inhibiting the adoption of physician associates in the literature and policy

We undertook a systematic review and a policy review.

The systematic review

A systematic review investigated the impact of PAs on patients’ experiences and outcomes, service organisation, working practices, costs and other professional groups for the secondary care specialties of acute medicine, care of the elderly, emergency medicine, trauma and orthopaedics and mental health. These were the specialties that PAs were most frequently reported to work in by the FPA59 and this was confirmed in workstream 1.

The review was conducted as per the international Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 60 The protocol was published on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) as CRD42016032895. 61 In summary, nine electronic databases were systematically searched from 1 January 1995 to the second week of December 2015. The research team undertook periodic update searches, with the last search undertaken on 5 January 2018.

The databases were MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature Plus (via EBSCOhost), Scopus version 4 (via Elsevier), PsycINFO, Social Policy and Practice (via Ovid), EconLit (via EBSCOhost) and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. A search strategy is presented in Appendix 4. Lateral searches were also undertaken. 62 Relevant studies were identified first through abstract screening and then through full-text reading by two researchers, with any disagreements resolved by a third researcher. The inclusion criteria were:

-

Articles had to have been peer reviewed.

-

Population – PAs in accordance with the UK definition. 20

-

Intervention – the implementation of PAs in the following secondary health-care specialties: acute medicine, care of the elderly, emergency medicine, mental health and trauma and orthopaedics.

-

Comparison – the comparison group was any health-care professional with whom PAs were compared.

-

Outcome – any measure of impact, informed by recognised dimensions of quality (effectiveness, efficiency, acceptability, access, equity and relevance). 50

-

Study design – any study design that allowed the measurement of the impact of PAs in a primary study.

Articles were excluded if they were not published in English; were from countries not defined by the International Monetary Fund as advanced economies;63 did not provide empirical data; did not provide data for PAs separately from other advanced clinical practitioners, such as nurse practitioners; did not focus on the PAs as the intervention; only provided data before and after a service redesign or educational programme; or only presented literature reviews or commentary.

A data extraction spreadsheet was populated by two researchers independently, with differences resolved by a third researcher. Quality assessment was undertaken with Qualsyst checklists for quantitative and qualitative studies,64 with additional questions from the mixed-methods appraisal tool. 65 No study was excluded on the basis of its quality score, but the limitations of lower-quality evidence were considered in the final synthesis. 66

Owing to the heterogeneity of the included studies, a meta-analysis was not possible, and the results are presented as a narrative synthesis. 67

The policy review

The previous study reported on a review of policy (up to 2013) to identify supporting or hindering factors in the development of the PA profession in the English health-care workforce. 17,18 This policy review68 was therefore updated with a particular focus on secondary care using documentary review methods. 69 Internet searches of relevant English government, NHS and associated agencies’ websites were conducted periodically throughout the study period to identify relevant policy documents and reports on health-care workforce planning, education, regulation and development. The time period was September 2013 to October 2017. These electronic documents were then searched using the ‘find’ function for any references to PAs. A data extraction framework, as used in the previous primary care study, was used to classify the document, note the presence or absence of PAs and record text relevant to the problem analysis that PAs were the policy solution,68 as well implementation concerning the education, employment and deployment of PAs. A narrative synthesis was then undertaken.

Workstream 3: investigating the deployment and contribution of physician associates at the micro level of the health system

A mixed-methods case study design70 addressed all of the research questions at the micro level of the health-care system through investigation in six NHS trusts that employed PAs in their acute care hospitals. Similar methods have been used in other studies investigating new staff groups in NHS hospitals. 71,72 The mixed-methods approach within a multiple case study design70 was designed to both describe and, as far as possible, quantify the impact of PAs in the context of secondary care. The aim was to achieve diversity in the hospitals by geographical location, size and type. At the time of the application for funding, the research team had agreement in principle to participate from trusts in the West Midlands and London that employed PAs. The intention was also to have diversity in the medical and surgical specialties within which PAs were employed. The final decisions regarding the inclusion of hospital trusts in the study was informed by the surveys in workstream 1, as well as the willingness of the trust senior managers and PAs and their consultants to participate. In addition, as PAs are a relatively small staff group and, therefore, potentially identifiable, the design ensured that volunteer PAs came from a specialty in which more than one PA and more than one trust participated. The aim was also to include more than two hospitals employing PAs in emergency medicine (being the acute specialty reported to employ the largest number of PAs). 1 The intention was to report the evidence from the multiple case studies in the manner described by Yin70 as the ‘fourth way’, that is to only present cross-case analysis of the issues of interest rather than from each individual case study site. With this understanding of the reporting intentions, the research team approached hospital executive staff to explain the research and gain formal permission to undertake the study; this was gained from a NHS trust board-level executive (chief executive or MD). Initial meetings were then held with PAs and their consultants to explain the study and ask for volunteers to participate. The sites were recruited sequentially but with data collection being undertaken in two or three sites at a time over a period of between 4 and 6 months. Permission to start data collection was in the control of each hospital research governance team and, in some instances, it took 6 months from the point of overall permission being given to agree. Characteristics of the six hospital trusts are provided in Table 1. At the time of the study, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) rated the overall quality of one of the trusts as ‘outstanding’, one as ‘good’ and the other four as ‘requires improvement’.

| Case study site | Rural/urban locationa | Number of | Annual incomeb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital sites | Inpatient beds | Staffb | |||

| 1 | Urban with major conurbation | 2 | ≥ 1000 | 9001–11,000 | > £500M |

| 2 | Urban with city and town | 1 | 601–800 | 3001–5000 | < £200M |

| 3 | Urban with city and town | 3 | 601–800 | 3001–5000 | £201–500M |

| 4 | Urban with significant rural (rural including hub towns 26–49%) | 2 | ≥ 1000 | 9001–11,000 | > £500M |

| 5 | Urban with major conurbation | 3 | 601–800 | 3001–5000 | £201–500M |

| 6 | Urban with major conurbation | 2 | 201–400 | < 3000 | £201–500M |

The characteristics of some aspects of the medical staffing and training in each of the hospital trusts are given in Table 2.

| Case study site | Number of FTEs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All doctors | Consultants | FY2 doctors | FY1 doctors | |

| 1 | > 1000 | 401–500 | 41–50 | 41–50 |

| 2 | < 300 | < 100 | 11–20 | 21–30 |

| 3 | 501–700 | 101–200 | 31–40 | 21–30 |

| 4 | > 1000 | 401–500 | 61–70 | 71–80 |

| 5 | 301–500 | 101–200 | 21–30 | 31–40 |

| 6 | 301–500 | 201–300 | < 20 | < 20 |

In overview, data collection in each hospital trust included:

-

interviews with senior managers (including operations directors and human resources), lead consultants, members of the health-care teams (medical, nursing and support staff), PAs and patients

-

requests for relevant routine management information (data and reports) as well as any internal documents, reports or audits on the work or impact of the PAs

-

work activity diaries and observation of the PAs at work

-

for those with PAs working in the EDs, anonymised patient records to allow comparison of patient outcomes and costs for the treatment of patients by PAs and FY2 doctors in the ED, a setting where individual clinicians are allocated to conduct an assessment and propose a plan for the patient.

An overview of the numbers of PAs volunteering to participate and the data collection in each site is provided in Table 3.

| Case study site | Number of | Pragmatic comparative investigation in the ED? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA participants (number of specialties) | Interviews (all types of participants) | Observation periods (4–9 hours) | Contextual documents (e.g. trust reports and board minutes) | ||

| 1 | 11 (6) | 51 | 24 | 35 | No |

| 2 | 8 (7) | 34 | 15 | 25 | No |

| 3 | 9 (7) | 32 | 25 | 27 | Yes |

| 4 | 2 (1) | 14 | 6 | 19 | Yes |

| 5 | 9 (5) | 24 | 11 | 21 | Yes |

| 6 | 4 (4) | 18 | 7 | 12 | No |

Semistructured interviews

Semistructured interviews were conducted with trust executive-level managers, lead consultants, members of the health-care teams (medical, nursing and support staff), PAs and patients. Topic guides75 appropriate to each group were developed in consultation with the advisory group and the study patient and public forum (see Appendix 5). The topic guides for patients included questions about the patient experience and perceptions of the role as well as acceptability. For managers and senior clinicians, topic guides included questions on factors inhibiting and supporting the employment of PAs as well as the impact on organisation, patient outcomes and costs. The topic guides for professionals included questions on deployment, acceptability and impact on working practices, role boundaries and patient experience. Each group was invited in different ways: senior staff were invited by e-mail and other staff were invited following introductory meetings or introductions by other members of the clinical team. Patients were approached by the clinical team in the first instance. With permission, the interviews were digitally recorded, or notes were taken if preferred. Recordings were transcribed, and the recordings were destroyed at the completion of the study. Transcripts and notes were anonymised. The transcriptions and notes were coded using NVivo version 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia). Initial coding frameworks were developed by five researchers (CW, MH, LN, JP and VMD). These were developed and agreed with the wider research team as well as the patient and public forum, using a variety of transcripts. Thematic analysis was conducted. 76

Routine data and reports

The managers and clinicians were invited to share any relevant organisational documents or management data for all of the services employing PAs that could assist in answering the research questions concerning deployment, patient outcomes and organisation and cost. Examples were suggested, including patient throughput and outcome data, adverse events/serious untoward incidents, patient feedback, audit reports and expenditure on medical locums. The intention, if data were available, was to compare data before and after PAs were employed in a particular service. These data were to be descriptively analysed and, if appropriate, subjected to tests of significance to explore differences in time periods or between providers. It should be noted that no data of this type were offered from any of the cases study sites, a finding that is discussed in more detail in Chapters 4, 8 and 11.

Work activity diaries and observation of physician associates at work

The PAs were invited to complete work activity diaries, better described as logs. These were adapted from the primary care study17 in discussion with PAs on the research team and also with the advisory group (see Appendix 6). PAs were requested to complete these for 7-day periods up to three times, and for periods likely to demonstrate some differences in their activities (e.g. rotational duties of PAs or rotation times for junior doctors). These work activity diaries were designed to provide detailed information on the deployment, work setting and role of the PA. Data were entered into IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23 and Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and were analysed descriptively for summary characteristics and distribution, central tendency, dispersion and measures of the spread of individual variables.

The PAs were invited to volunteer to be observed by a researcher while they were working. This element of the study drew on the ethnographic tradition used in many health service research studies in the UK. 77 For any PA volunteering, permission was also sought from the lead consultant for that service. The PAs sought assent for the researcher’s presence from patients they were attending, in the same way as permission is sought for students to be present during clinical care and treatment (see Appendix 7). Observations of any intimate activities with patients or in which the patient was, or was likely to be, distressed were excluded. PAs were observed for up to three sessions; this was intended to capture diversity in their work or the work environment. These sessions of observations were for all or part of their shift hours, including shifts not in the 09.00–17.00 period and shifts at weekends. Field notes of observations of the PAs’ activities and interactions were made at the time and written up in full later. The analysis method drew on that used in other, similar studies of health professional work in the UK. 78 Rather than trying to impose a coding structure on what were usually fast-moving, dynamic events, the notes were read and particular ethnographic vignettes were identified from each. These were vignettes judged by the observer and one other researcher as being most relevant to the research questions, the theoretical framing of the study or the themes derived from the interview and documentary data. The reading and judgement of the vignettes was conducted with a lens that looked for both confirmatory and also disconfirming evidence of that obtained through sources such as interviews.

Pragmatic retrospective assessment comparing the outcomes and service costs for patients attended by physician associates and Foundation Year 2 doctors in the emergency department

The ED is a setting where PAs are employed and may work in different physical sections [minors, also known as the minor injuries, and majors (i.e. serious illness or trauma79)] alongside, and substituting for, junior doctors. 1,80 Patients, triaged by a clinical professional to these sections of the ED, are assigned and initially assessed by a clinical professional (a PA, a doctor, or, in the case of the minor injuries section, another professional, for example an emergency care practitioner). Consequently, a pragmatic comparison of the patient outcomes and service costs of consultations by PAs and junior doctors (FY2) was undertaken based on the methods and data from two English studies, which compared minor injuries section consultations by nurse practitioners, as the mid-level professional (in the absence of UK data for PAs), with those of doctors. 81,82

Revisions to the protocol

Following the surveys and preliminary recruitment of case study hospitals in 2015 and 2016, it was found that additional ED sites (from the four initially proposed) were required to undertake this element. Although the initial proposal had only included a comparison in the minor injuries section, it became apparent in trying to recruit the hospitals and PAs in January 2017 that PAs were rarely working in the ED at all as they were more frequently assigned to the acute medical assessment units. When they were assigned to the ED, it was usually to the majors section. In addition, practical constraints within trusts made the proposed prospective data collection impractical. Hence, a decision was taken and agreed with NIHR to change to a retrospective analysis of anonymised patient records from hospital databases. This had a concomitant effect in that the proposed linked patient satisfaction surveys could not be conducted. The study protocol was amended twice in pragmatic responses to changing NHS environments.

The pragmatic retrospective record review

In consultation with lead clinicians in EDs, a time period of 16 weeks (covering a national FY2 doctor rotation) in 2016 was designated for data collection. This period was sufficient to ensure that the required sample size of records for patients seen by PAs could be obtained (see Sample size). Each patient case attended by a PA or FY2 doctor in that time period was identified by information management staff and assigned a pseudonymised code number, with the link to the patient-identifiable record kept by the trust. The sample for the primary outcome was identified from the identification (ID) numbers using random sample numbers generated in Stata® version 14.6 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and stratified to ensure equal numbers of cases by type of professional (PA or FY2 doctor) attending the patient and coverage across the period of the rotation. Data items that were requested for the sample included demographics, triage scores, treatment and investigations, prescriptions, diagnoses and outcomes (destinations), time in the ED and reconsultations within seven days. Postcode, to be used to calculate the Index of Multiple Deprivation score as a proxy for socioeconomic status, was requested but information governance review in trusts declined this request as having the potential to make individuals identifiable. Anonymised records were then passed to the research team in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and entered onto Stata version 14.6.

For a subsample of 10% of the above sample for the primary outcome, the patient’s full (anonymised) electronic or paper clinical record was supplied by the trust. Each record was assessed by four clinicians in emergency medicine [two emergency medicine registrars (in the final year of their specialty training), one PA (with > 20 years’ experience in emergency medicine) and one emergency medicine medical consultant]. Blinded to each other’s assessments and to the type of professional who was undertaking the patient consultation, they made a judgement as to the clinical adequacy of care. A pro forma (see Appendix 8) was used to guide and record the judgement. The pro forma employed the criteria used in the study by Sakr et al. ,81 which compared consultations between junior doctors and nurse practitioners. When disagreement in judgments was found, the decision of the emergency medicine consultant was used.

Outcome measures

This was a pragmatic study designed to provide information for clinicians, the public, service managers and commissioners on a wide range of measures of quality, satisfaction, impact and cost. The primary outcome was specified in order to assist in calculating a sample size and was a proxy for patient safety and clinical effectiveness, but the goal of this element of the study was to synthesise evidence emerging from all the outcomes, along with the other workstreams, and we therefore used the sample calculation as a guide to avoid futility at either end of the scale.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was unplanned re-attendance at the same ED within 7 days for the same condition. Unplanned re-attendance by patients, seen in any section, within 7 days for the same condition at the same department is one of the NHS clinical quality indicators for accident and EDs in England. 83

Secondary outcomes

These secondary outcome measures were derived from two studies investigating the substitution of doctors by nurse practitioners in the minors section of the ED. 81,82

-

Measures of consultation processes (taken from the clinical record), including length of consultation (time stamp), use of diagnostic tests, immediate outcomes of the consultation (including prescriptions, treatments, referrals and follow-ups) and associated costs.

-

The clinical adequacy of care. This was an expert clinical judgement. Criteria included record of medical history, examination of patient, requests for diagnostic tests, diagnosis, treatment decisions, referrals and planned follow-up provided by the PA or FY2 doctor at the initial consultation.

Sample size

Anticipated rate of unplanned re-consultation

In the absence of UK data on PAs in the ED setting, we considered three sources of information, including two randomised controlled trials substituting nurse practitioners for doctors in the minors section of the ED. 81,82 First, NHS ED clinical quality indicator data show that unplanned re-attendance at the same ED in England within 7 days for patients seen in any section and by any professional was 7.4%, with individual EDs ranging from 2.4% to 21.7% in December 2014. 84 Second, Sakr et al. 81 reported unplanned reconsultation rates, for the same condition within 28 days, of 8.6% (nurse practitioners) and 13.1% (doctors). Third, Cooper et al. 82 reported rates of 18.3% and 21.5%, respectively. Clearly, the 7-day data at the same ED site will underestimate a 28-day outcome at any ED, urgent care or general practice site. Both studies were conducted in single ED sites and we did not know whether they were high or low on the spectrum seen in the clinical quality indicator data. Taking this into account, we chose Cooper et al. ’s82 18.3% as an anticipated base rate towards the higher end of the observed range.

Minimum clinically important difference

We took the study by Sakr et al. 81 as having the least risk of bias from the comparison and study design. Their sample size calculation was to detect a difference between groups of 2.5% versus 5%. Although this proved to be an underestimate, we were also interested in finding a relative difference of 50%, although in a non-inferiority hypothesis, so we compared 18.3% with 27.4%. It should be noted that as this is a pragmatic study investigating a wide range of measures of impact and cost, we considered that estimating with confidence intervals (CIs)85 and understanding the differences between professions would be more informative for clinicians, service managers and commissioners than a binary hypothesis test on one of the outcomes. We anticipated that 18.3% of patients would reconsult (unplanned) within 28 days for the same problem in any health service. We aimed to test a non-inferiority hypothesis on this primary outcome measure, which stated that PAs do not exceed 27.4% unplanned reconsultations, with 80% power at a 5% significance level. This required 284 patients in each group (calculation from Stata version 11.1 software). We included an extra 20 patients to allow for adjustment for case mix,86 requiring a total of 304 patients in each group (those seen by PAs vs. those seen by FY2 doctors).

Analysis

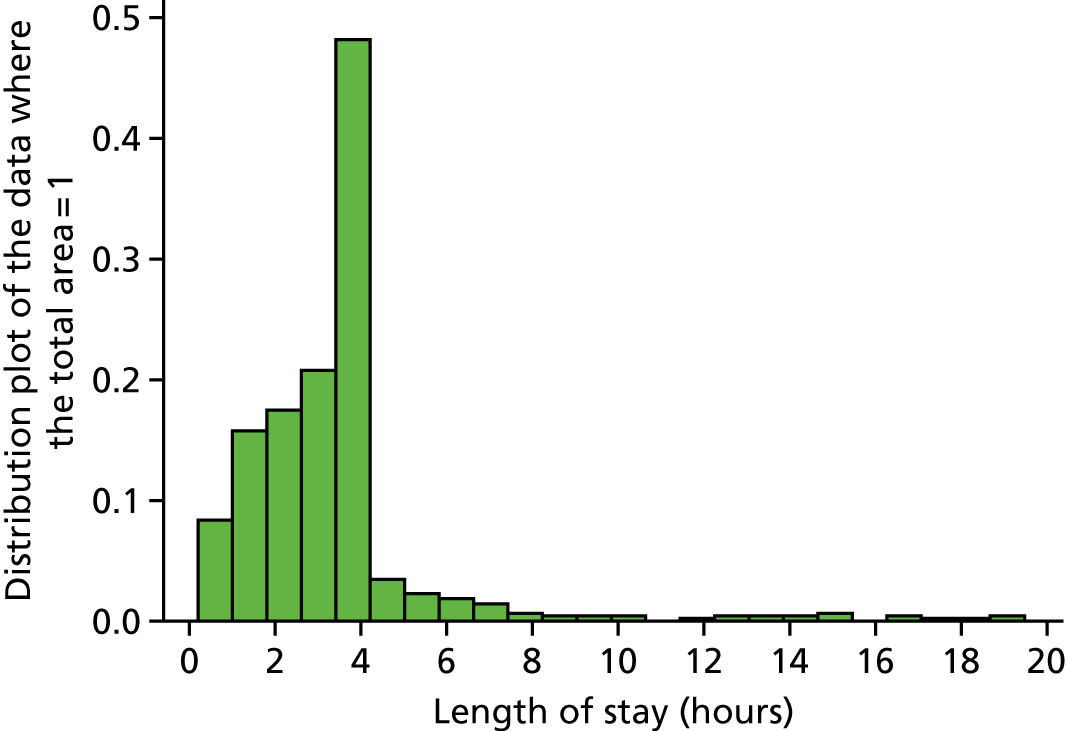

Data were entered into a patient-level Stata version 14.2 file. Analysis and presentation of these data involved summary measures as cross-tabulation (frequency/proportions) for categorical variables, and location (e.g. means/medians) and dispersion (standard deviations/percentiles) appropriate for continuous variables. The distribution of length of stay in the ED was inspected using a histogram plot. Descriptions of difference at the aggregate level were made between those patients seen by PAs and those seen by FY2 doctors for all patient outcomes. A likelihood ratio (LR) χ2 test was used to assess whether or not the primary and secondary outcomes differed between PAs and FY2 doctors. A logistic regression86 was also carried out for the primary outcome (i.e. the patient making an unplanned reconsultation at the ED within 7 days), while adjusting for confounding factors, such as age, sex and Manchester Triage Score (MTS)87 the latter as a proxy measure of patient acuity. Although the advice of the lead clinicians in EDs and the advisory group was that patient acuity, as recorded through an early warning score,88 was the most appropriate method of classifying differences in patient caseload in the ED, one of the trusts did not supply this variable and missing data, therefore, precluded using that as the main adjustment variable. Because the difference between PAs and FY2 doctors may be different at different sites, an interaction term between profession and site was also tested. The odds ratios (ORs) estimated from the logistic regression were reported and their significance levels were assessed using Wald tests. All p-values are two-sided.

Economic analysis

An analysis of the comparative costs of using PAs and FY2 doctors in the ED was planned from a NHS perspective. The a priori analysis plan was for variables of interest to be extracted from the anonymous patient records, including consultation length (time in and time out in minutes); diagnostic tests ordered (blood, X-rays), treatments (e.g. prescriptions), referrals made and follow-on care recommendations; whether the PA or FY2 doctor sought advice from a senior colleague in the ED during the consultation; and unplanned reconsultations (primary outcome). The protocol stated that if statistically significant differences were observed between the two professional groups in any of these variables, after controlling for case complexity, costs would be attributed. The cost of consultation times would be based pro rata on salaries, with oncosts and overheads, obtained from professional bodies and national sources. 89 The costs of tests and treatments would be obtained from NHS sources90 and local financial managers as needed. It was planned to use a cost–consequences framework91 to indicate differences in costs to the hospital of employing PAs and FY2 doctors in the ED, in relation to appropriateness outcomes, obtained from the record review. However, data limitations restricted the analysis to a comparison of a reduced number of variables and the employment costs of the professionals.

Ethics and governance

The research was undertaken using ethical principles derived from the Medical Research Council92 guidance. Professional and patient participants were volunteers and individual consent to participation was sought. Assurance was given to participating trusts and individuals that they would not be identified in any reports or papers that were published. Data storage and disposal complied with the Data Protection Act 1998. 93

Workstream 3 was reviewed and approved (including amendments) by NHS London – Central Research Ethics Committee (reference 15/LO/1339). For the first case study sites, NHS research governance permission was obtained via the central single process application to the NHS trusts (Integrated Research Application System project ID 181193). The replacement of this system and subsequent delays to all research projects in the transfer are well documented. This study was no exception. Each study site had to then give formal written permission to proceed. The shortest time period from application for local research governance permission was 3 months and the longest was 10 months.

Workstream 4: synthesis of evidence

The evidence from workstreams 1, 2 and 3 was developed into an overall synthesis against the research questions by the research team. This was then discussed in an emerging-findings seminar (see Appendix 9). Participants included those who had advised the research team (patients, members of the public, health professionals and non-clinical health service managers) as well as some of those who had participated. The workshop was organised into presentations followed by round-table discussions in small groups. The presentations were then discussed as a whole group, led by the patient and public representative on the research team. A member of the research team took contemporaneous notes, which were then typed up and circulated to participants. The views, questions and issues raised in the seminar were then incorporated into the final report.

Chapter 3 Findings: evidence from the reviews and surveys

This chapter reports on the evidence identified through workstreams 1 and 2, consisting of a survey across English hospitals, a systematic literature review and a policy review. From macro- and meso-level perspectives of health-care systems, it identifies the factors influencing the extent of the adoption and deployment of PAs in English NHS hospitals as well as research evidence of the impact of employing PAs within the medical and surgical workforce. We report first on the systematic review of evidence, then on the national surveys and finally on the policy review.

The systematic review

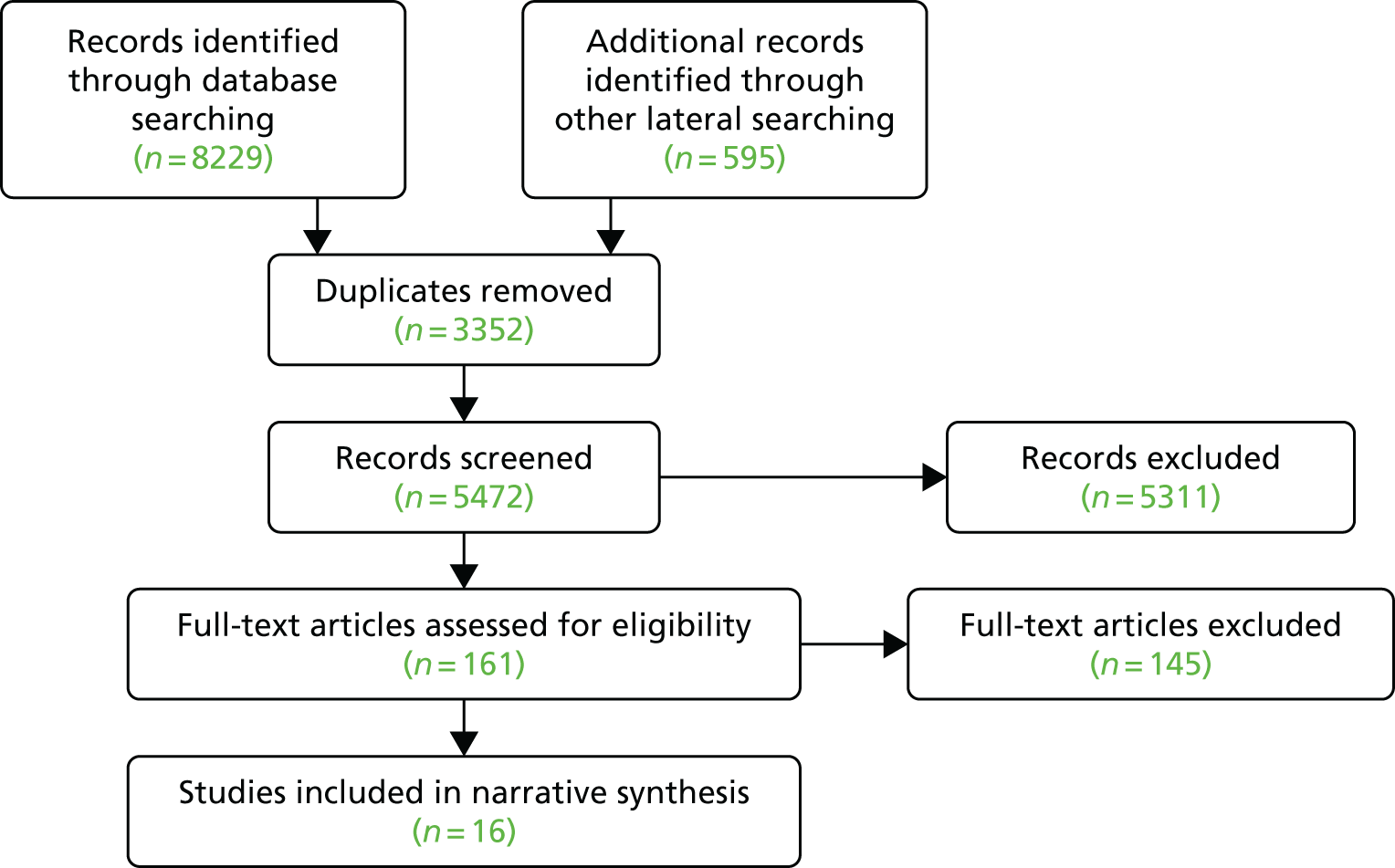

From 5472 references identified through the search strategy, 161 papers were selected for full-text reading, of which 16 papers32,94–108 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 2). Brief characteristics of each of the included studies are presented in Table 4 and in full in Appendix 10. The studies were all from North America (mainly the USA) and addressed different types of questions using a range of methodologies with different outcome measures. Seven studies were in emergency medicine,94–100 six were in trauma and orthopaedics,32,101–105 two were from internal medicine and one was from mental health. 106–108 No studies from acute medicine or care of the elderly were identified.

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA60 flow diagram of the included papers. Adapted with permission from Halter et al. 109 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| First author, year and study design | Study setting | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency medicine | ||

| Arnopolin, 2000,94 comparative retrospective | USA; walk-in urgent care facility | PAs (n = 5) work solo from 08.00–12.00 |

| Ducharme, 2009,95 descriptive retrospective | Canada; EDs in six community hospitals | PAs introduced in EDs under the supervision of a physician |

| Hooker, 2008,96 longitudinal | USA; national sample of ED patient-level data survey | PAs as providers of ED care and prescribers of medication (7.9% of patients were seen by PAs in 2004) |

| Kozlowski, 2002,97 prospective cohort | USA; one suburban ED | PAs were deployed to patients with isolated lower extremity trauma |

| Pavlik, 2017,98 comparative retrospective | USA; one general urban ED | PAs independent of emergency physician |

| Ritsema, 2007,99 retrospective cohort | USA; national sample ED patient-level data survey | PAs attending patients with a long bone fracture |

| Singer, 1995,100 prospective observational | USA; one urban ED | Patients with lacerations assigned to PAs |

| Trauma and orthopaedics | ||

| Althausen, 2013,32 comparative retrospective | USA; trauma care at a level II community hospital | PAs (n = 2) deployed to cover all orthopaedic trauma needs, under the supervision of orthopaedic surgeons |

| Bohm, 2010,101 mixed methods | Canada; one academic hospital arthroplasty programme | Addition of PAs (n = 3) to the operating room team as first assists |

| Hepp, 2017,103 mixed methods | Canada; peripheral hospital | One PA filling provider gaps in preoperative screening, theatre assist, postoperative care and clinic follow-up |

| Mains, 2009,104 prospective cohort | USA; urban, community-based level I trauma centre | Core trauma panel (consisting of full-time, in-house trauma surgeons) plus PAs |

| Oswanski, 2004,105 before and after | USA; level I trauma centre | PAs substituting for doctors in trauma alerts |

| Internal medicine | ||

| Capstack, 2016,106 retrospective comparative | USA; community hospital | Expanded PA group (n = 3) in dyads with physicians (n = 3) for inpatient care |

| Van Rhee, 2002,107 prospective cohort study | USA; two general internal medicine units, teaching hospital | The use of PAs (n = 16) with 64 attending physicians, scheduled to admit to either a PA or a teaching service |

| Mental health | ||

| McCutchen, 2017,108 qualitative | Canada; mental health service | A PA supervised by a psychiatrist |

The studies were of variable methodological quality. The most important methodological flaws in the included studies were the failure to adjust the analysis for confounding variables, the absence of information to evaluate participants’ selection adequacy and the lack of information about baseline and/or demographic information of the investigated patients or PAs. The evidence in the following sections is presented by specialty and framed by the quality dimensions of interest. 50

Emergency medicine

Of the seven studies of emergency medicine,94–100 treatments offered were reported in three studies, a clinical outcome and length of stay were reported in two studies and waiting times were reported in one study. Only two studies reported PAs substituting for doctors. 94,97

Treatments offered

In terms of analgesia prescribing,96,97,99 the studies gave conflicting results. Secondary analysis of national (USA) ED survey data reported a higher proportion of patients receiving prescriptions, and within that for opiate analgesia, when attended by PAs compared to physicians and nurse practitioners. 96,99 This contrasted with a survey study of a similar-quality study, although based on patient self-report, reporting that those attended by an emergency physician had adjusted odds of 3.52 for receiving pain medication compared with those attended by PAs. 97

Clinical outcome of care

A clinical outcome of care was reported in only two studies. 98,100 The older study reported that experienced PAs had no statistically significant difference in wound infection rates compared with other medical staff providers (medical students, residents and attending physicians) in a large sample of patients presenting with lacerations at the ED. 100 The other, newer, large study98 reported a significantly lower 72-hour re-attendance rate to the ED for children aged ≤ 6 years for those patients treated only by a PA (6.8% vs. 8.0% for those treated by an emergency physician; p = 0.03). However, these rates were unadjusted, with PAs seeing the older of the children, who were much less likely to be admitted.

Length of stay

The studies by Arnopolin and Smithline94 and Ducharme et al. 95 showed contradictory results. In the study with PAs as additional staff, patient length of stay was reduced by 30% (mean 80-minute reduction). 94 The study of experienced ED PAs substituting for physicians95 reported a statistically significant longer mean length of visit (8 minutes) for patients of PAs but noted a range of difference (5–32 minutes) by diagnostic group. This study also considered costs through total charge (hospital and physician charge) for the visit and reported a small but statistically significant decrease per patient reported when patients were treated by a PA,95 although, again, this varied by diagnostic group.

Waiting or access outcomes

As an additional staff resource, the PA’s presence significantly reduced the likelihood of a patient leaving without being seen by 44%, and the odds of a patient being seen within their benchmark waiting time was 1.6 times greater; this was further increased to 2.1 if a newly appointed nurse practitioner was present instead. 91

Trauma and orthopaedics

Six papers reported on PAs working in trauma and orthopaedics. 32,101–106 PAs were substituting for doctors (residents105 and GP surgical assistants101,103) in three of these studies.

The impact of PAs on access and service delivery time was ambiguous in three studies. 32,101,105 PAs acting as substitutes for doctors were reported to shorten waiting times in the ED but the authors attributed this in part to other service redesign, such as there being more registered nurses. 32,105 Waiting times for surgical procedures were also reported to be reduced,101 attributed by the authors to the use of two operating theatres by the surgeon, made possible by the PA preparing and finishing the case. However, one study examining in detail the impact of PAs in teams on time to, in and from theatre found no statistically significant difference. 32 In two studies, PAs were found to release the time of doctors for other activities: for supervising physicians for 2 hours a day32,103 and for GPs (not quantified), who had previously acted as surgical assistants. 101

Length of hospital stay was examined in three high-quality studies,32,104,105 with one showing a significant reduction (of 3 to 4 hours) for all patients when PAs were an addition to staffing. 104 The studies in which PAs substituted for doctors found no difference in length of stay. 32,105

Health outcomes were reported as improved in two studies. 32,104 One study reported that the presence of PAs decreased postoperative complications measured by antibiotic and deep-vein thrombosis prophylaxis use. 32 The presence of PAs in the clinical team was found to reduce mortality by 1% for a trauma panel and by 1.5% for general surgery residents’ teams,104 although some of this could be attributed to other contemporaneous service improvements. Two studies found no overall difference between groups in mortality105 and in the likelihood of fracture malunion. 102

Patient satisfaction was surveyed and reported as positive from a small103 and large101 number of respondents, without a comparator, in two studies. 101,103 Responses from staff were more equivocal, with physician team members being positive on the contribution of PAs and nursing staff expressing concern about the overlap of work. 101 A different study found that although staff appreciated the continuity and PA skills in the operating room, they did not consider that the role could offer everything a previous surgical extender did postoperatively, despite being collaborative team members. 103

There was also mixed evidence regarding impact on cost. One study in which PAs were an addition to the team reported specific cost savings in the ED and operating room, although it was noted that only 50% of PA costs were reimbursable. 101 Another study32 suggested that although the costs of employment were similar to those of the GPs assisting in the operating room, there was an opportunity cost for others through released time for supervising physicians.

Internal (acute) medicine

Two studies investigated PAs in internal (acute) medicine and both examined resource use and clinical outcomes. 106,107 Neither study reported any significant differences in length of stay (used as a proxy for severity of illness). Cost in terms of relative value units (based on billing information for physician-ordered items, excluding administrative costs outside the physician’s control) was also mostly similar, although laboratory relative value units were lower for PAs (i.e. they ordered fewer investigations after adjustment for demographics in each diagnostic group). 107 Capstack et al. 106 reported a statistically significantly lower mean patient charge for the expanded PA group with physicians [US$7822 vs. US$7755 for the conventional PA group (3.52% lower, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.66% to 4.39%; p < 0.001]. Inpatient mortality was stated to be higher for the PA group in pneumonia care only,107 although the authors reported neither the percentage nor the statistical values, and the larger study reported no significant differences in mortality or 30-day all-cause readmission. 106 The authors concluded that PAs used resources as effectively as, or more effectively than, residents107 at the same time as providing similar clinical quality. 106

Mental health

One study was included from mental health services. 108 Participants described improved access to primary care for patients; more timely access to psychiatric appointments and longer appointments; equal team cohesion for the PA or the psychiatrist; decreased waiting times and improved access to tertiary care and screening programmes; and implementation challenges of triage hierarchy and patient understanding of the term ‘physician assistant’.

Summary

Sixteen papers were included; four were published in 2017. 98,102,103,108 Most were from emergency medicine and trauma and orthopaedics specialties, with two from acute medicine and one from mental health. All studies were observational, and quality varied widely. The synthesis was further complicated by the difference between studies in which the PA was a substitute for doctors or was an additional staffing resource, or in which the introduction of PAs was only one of a number of contemporaneous service changes.

Although every paper reported the contribution of PAs as positive overall, it is important to contextualise within these issues of method and methodological quality. Summarising across the specialties, we have reported five studies in which PAs were an addition to the team. 32,95,103,104,108 In these studies, more patients are reported to have been treated; waiting times, time in EDs and time in operating rooms are said to have been shorter and mortality to have been lower; however, assessment of the contribution of PAs as opposed to any increase in team capacity is limited. Eight studies that compared outcomes of care by PAs and physicians when either one or the other was providing care or when PAs were substituting overall for physicians94,97,98,100,101,105–107 presented mixed results: either no or a very small difference in length of stay, reduced resource use but at equal or reduced cost, some time savings to senior physicians, lower analgesia prescribing, no difference in wound infection rate, inpatient mortality or re-attendance or acceptability to staff and patients. In three of the studies carrying out secondary data analysis, we do not know if the PAs were additions or substitutions, but two studies reported higher prescribing by PAs96,99 and one reported no difference in negative outcomes from fracture. 102

The strength of this review was its systematic method. Although it may be considered a weakness that only some specialties were included, this strengthens its applicability to the UK in that these are the specialties most frequently employing PAs in the NHS. We excluded any studies including intensive care data as these overlapped with acute medicine in many abstracts and we could not separately draw these out. Similarly, we excluded studies with medical and surgical specialties combined. We note that this literature appeared to include a greater proportion of studies with stronger study designs, including prospective and randomised designs; in particular, we have excluded the recent matched controlled large study from the Netherlands in which several specialties – some within and some not within our inclusion criteria – were studied. 110,111

A meta-analysis was planned but the heterogeneity of papers precluded this. Although narrative review is more limited in its precision, in following a framework for this, we have aimed to provide a clear rationale for the synthesis and conclusions we draw from it.

All of the included papers were from North America, with the majority from the USA, where health service organisation and the PA role may differ from that in other countries developing the PA role. In the USA, PAs can prescribe and order ionising radiation, and are, as a body, more experienced than those in countries more recently embracing this role.

The studies included in this review can be seen as complex interventions in complex systems and yet this has not been considered in the conclusions drawn by the authors. Well-controlled studies are needed to fill in the gaps in our knowledge about the outcomes of PAs’ contribution to secondary care. The review is published in full elsewhere. 109

We now turn to consider the evidence from the macro level of the policy context in England.

The policy review

At the point when the policy review was finalised in the preceding primary care study17 (in August 2013), it was concluded that ‘there was no reference to PAs in English policy documents’. By the end of the year, that had changed. In response to an acute shortage of doctors in emergency services, HEE (the executive non-departmental body responsible for NHS workforce planning as well as funding of training in England) had identified PAs as one of a number of non-medical roles that it would support to address the shortages. 8 Over the subsequent 4 years, we identified 17 published statements of policy intent at the macro level regarding PAs within the NHS workforce in England. 6,112–127 These are listed by type in Table 5.

| Type of document | Number of statements |

|---|---|

| Secretary for State for Health policy statement6,112–114 | 4 |

| House of Commons Health Select Committee report recommendations115 | 1 |

| Department of Health open consultation116 | 1 |

| NHS England policy statement117–119 | 3 |

| HEE policy statement120–126 | 7 |

| NHS England, HEE, British Medical Association and Royal College of General Practitioners joint policy statement127 | 1 |

| Total | 17 |

In all the policy statements, the problem being addressed was a shortage of doctors. Initially, this was in emergency medicine;6,120 later, GP shortages were the identified problem that a state-supported increased supply of PAs was aimed at addressing. 6,112,115,117–127 In all the policy documents, increased supply of other groups were also specified as in this exemplar from the GP workforce plan. 119

NHS England, HEE and others will work together to identify key workforce initiatives that are known to support general practice – including e.g. physician associates, medical assistants, clinical pharmacists, advanced practitioners (including nursing staff), healthcare assistants and care navigators.

The state support for the training of PAs became marked in 2015, with financial support for numbers of PAs in training increasing by 854% from 24 in 2014/15 to 205 in 2015/16. 121 This was quickly followed by a growth in English universities providing PA courses. 128 The only other group with a large increase in financial support for training over the period was paramedics, with numbers increasing from 853 in 2014/15 to 1231 in 2015/16 (44%). 121

The limitation of the PAs not being within the state regulation framework and, thus, being unable to prescribe or order ionising radiation was noted in the 2014 HEE workforce plans. 120 Two years passed before the intention to consult on the state regulation of PAs was announced113 in November 2016, and a further year passed before this actually commenced (in October 2017). The reasons for this gap between problem identification and action is not apparent in the documents.

At the macro level of the health-care system, sustainability and transformation plans (STPs) were developed in the winter of 2016 across 44 areas of England. 129 These were plans for the NHS and beyond, agreed and informed by health and social care partners across defined geographies. Among other issues, the workforce had to be considered in the plans. We analysed the 41 publicly available plans130 for stated policy intent to develop the PA workforce. We identified that under half were planning to increase the employment of PAs and were specified mainly in support of primary care (Table 6).

| STP reference or otherwise to PAs and ACPs | Number of plans (%) (n = 41) |

|---|---|

| STPs that made no reference in their workforce plans to PAs or advanced clinical practitioners specifically | 19 (46) |

| STPs that specified PAs as new roles being or to be developed | 18 (43) |

| Referred to the primary care sector only | 8 |

| Referred to development both in primary care and in secondary care sectors | 3 |

| Did not specify a sector | 7 |

| STPs that specified developing new or more advanced practitioners (this included terms such as advanced clinical practitioners, and sometimes referred to professions such as nurses, pharmacists, paramedics) | 15 (36) |

| Did not specify the sector | 10 |

| Specified primary care and out-of-hospital care | 5 |

In summary, the policy review identified macro-level support for the development of the PA workforce to address the problem of clinical workload and the immediate and predicted shortages of doctors. The support included not only positive statements but also state funding for training places to increase the supply to employers, particularly general practice. At the meso level, using the STPs as the evidence source, not all plans included the detail of planned growth of advanced clinical practitioners, although this may have been an artefact of the way these were written rather than actual intent. Of those specifying growth in advanced clinical practitioners, four plans did not include PAs and 18 plans did. The majority of plans that specified a sector for support of growth of PAs referred to primary care rather than secondary care.

We now turn to examine the employment of PAs in the secondary care sector through views from the meso and micro levels of the health-care system.

Survey of medical directors

At the time of the survey, there were 214 NHS acute and mental health trusts in England; MDs from 33% of trusts (n = 71) replied. Of these, 68% (n = 48) were acute trusts.

Physician associates were employed in 20 of the responding trusts, only one of which was a mental health trust. Most trusts (n = 16) employed fewer than five PAs but three employed more than 10. MDs reported that PAs were employed in a total of 22 specialties, both medical and surgical (adult and paediatric). The most frequently reported specialties for PA employment were acute medicine (n = 7 trusts), trauma and orthopaedic surgery (n = 6 trusts) and emergency medicine (n = 5 trusts). The majority reported that the supervising doctor was a consultant. Eight MDs reported that their trust was expanding its number of PAs owing to a positive experience to date.

Of the remaining respondents, 61% (n = 44) were considering employing PAs at their trusts and 10% (n = 7) were not considering employing PAs.

Respondents were asked to report supporting and inhibiting factors to the employment of PAs. In general, MDs at trusts employing or considering employing PAs reported multiple supporting factors whereas those at the seven non-employing trusts reported only inhibiting factors.

The most frequently reported supporting factor was to address gaps in medical staffing and to support medical specialty trainees. Other common factors were to improve workflow and continuity in medical/consultant teams, to help address the management of junior doctors’ working hours to be compliant with the EU Working Time Directive,13 and to reduce staff costs.

It was also reported that a number of trusts were piloting or testing out PA roles. Some had specific strategies to increase the numbers of PAs they employed through linking with university PA course providers.

The inhibiting factors that were cited most frequently were the lack of statutory regulation for PAs and the consequent lack of authority to prescribe. The relative lack of PAs to recruit was another commonly reported problem, as was resistance to their employment from (some) consultants. Seven of the 20 respondents reporting PA employment also indicated that PAs had left and not been replaced. Most indicated financial reasons or lack of PAs to recruit. One stated that the consultant considered that a doctor was more effective and efficient than a PA in that particular team. The small number of respondents not considering employing PAs offered a slightly different perspective, suggesting that other professionals – either nurses or doctors – were better placed to meet their trust’s employment needs.

This survey provides evidence of the changing employment context for PAs in England at one point in time and, for this reason, offered insights, not available elsewhere, from those in medical leadership positions within NHS trusts. The survey was conducted at the time of the junior doctors’ strike in England,131 which may help explain the low response rate, although other surveys of NHS MDs report similar rates. 132 The supporting and inhibiting factors reflect those previously reported by us from our survey of the GP employers of PAs. 17 Shortages of doctors have also been the most commonly reported reason for employing PAs in the USA. 133 Although this survey suggested that there was an appetite for employment of PAs in secondary care, it also suggested that there were issues that needed addressing, such as state regulation. Eighteen months later, a consultation on regulation116 was launched; however, this survey suggested that there might be other issues that will need attention, such as senior medical staff resistance to employment.

A full account of this survey has been published elsewhere. 134 We now turn to report findings from the survey of PAs in secondary care.

Survey of physician associates

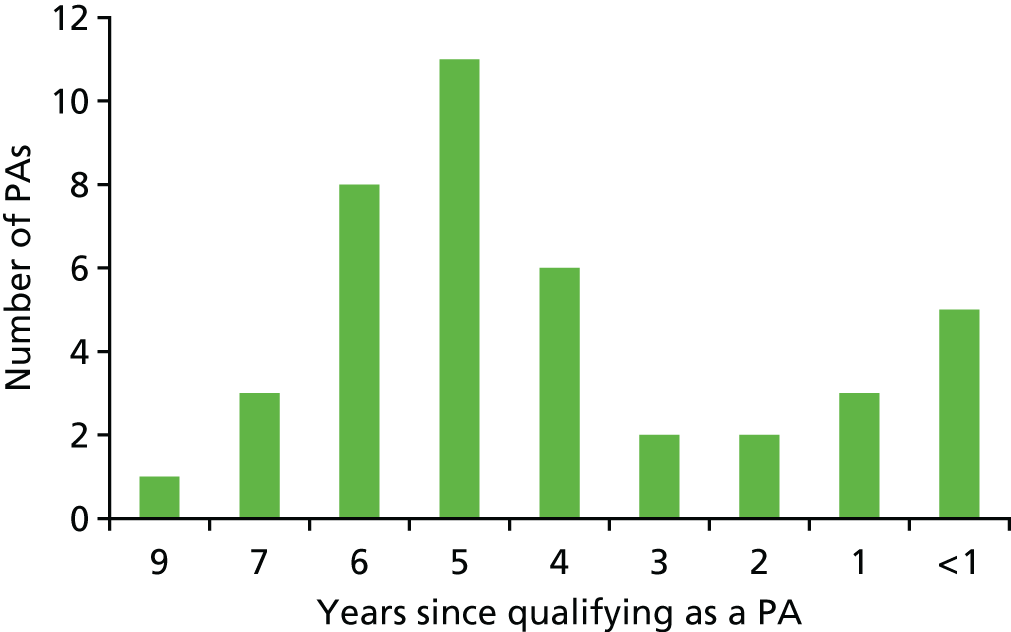

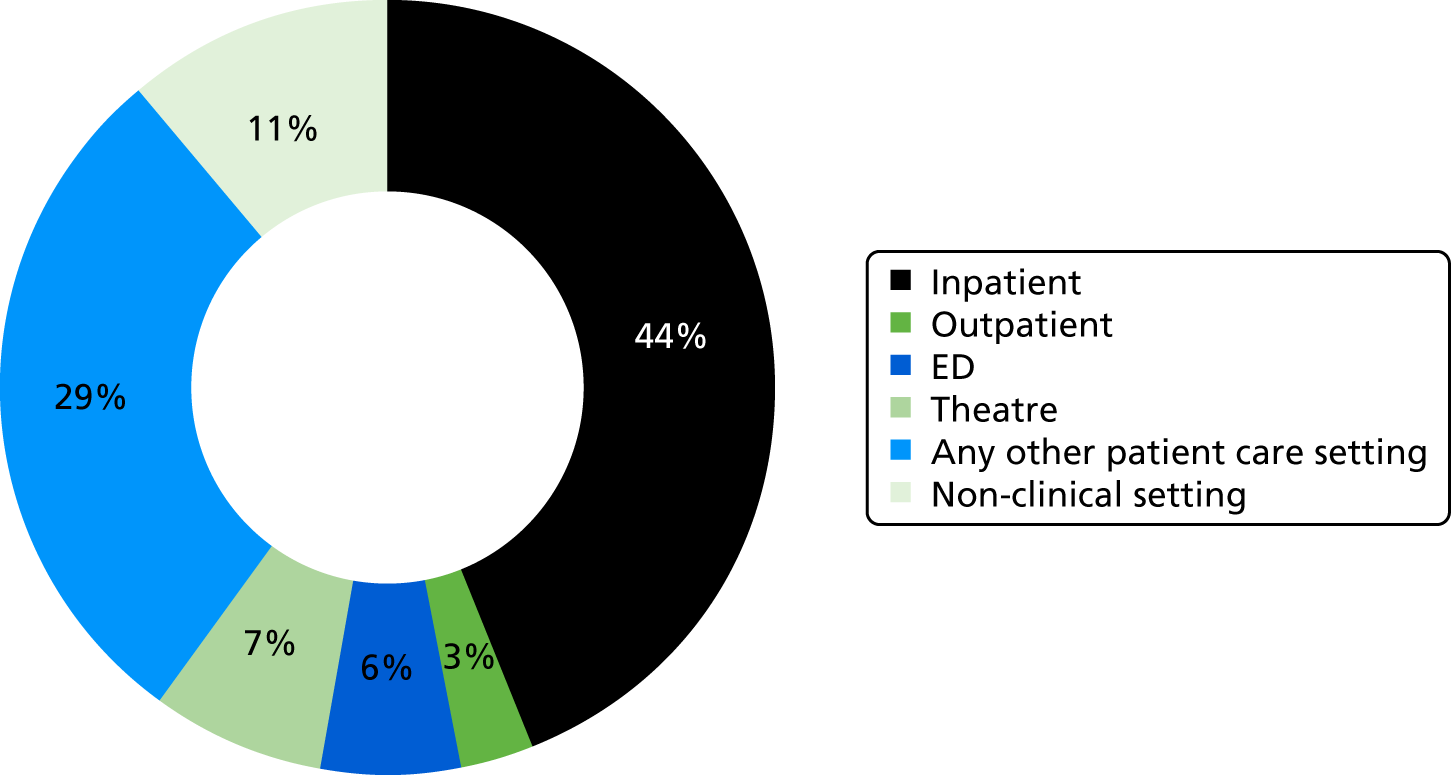

Out of the 223 PAs on the UK voluntary register and practising in primary and secondary care in the UK at the time of the survey, 63 PAs working in secondary care in England completed the online survey. Of these, 49 provided responses to all 18 questions. Three additional participants started the survey but were filtered out as they were practising in a country other than England.

The majority of respondents had trained in the UK (Table 7) and the mean length of time since qualification was 3.1 years [standard deviation (SD) 2.1 years]. Most worked in large acute hospital trusts. The respondents reported working in 33 medical or surgical specialties; the most frequently reported was acute medicine, followed by elderly care medicine and trauma and orthopaedic surgery (see Table 7).

| Training and work setting characteristics | Number of PAs |

|---|---|

| Country that the PA was trained in (missing data, n = 14) | |

| UK | 48 |

| USA | 1 |

| Hospital type that the PA was employed in (missing data, n = 14) | |

| Acute | 48 |

| Mental health | 1 |

| Number of inpatient beds in employing hospital (missing data, n = 14) | |

| ≤ 250 | 7 |

| ≥ 251 | 31 |

| Unsure | 11 |

| Specialty with more than three respondents (missing data, n = 7) | |

| Acute medicine | 10 |

| Elderly care medicine | 8 |

| Trauma and orthopaedic surgery | 8 |

| Accident and emergency | 7 |

| Neurosurgery | 4 |