Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/21/52. The contractual start date was in November 2015. The final report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Janssens et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Context

Introduction

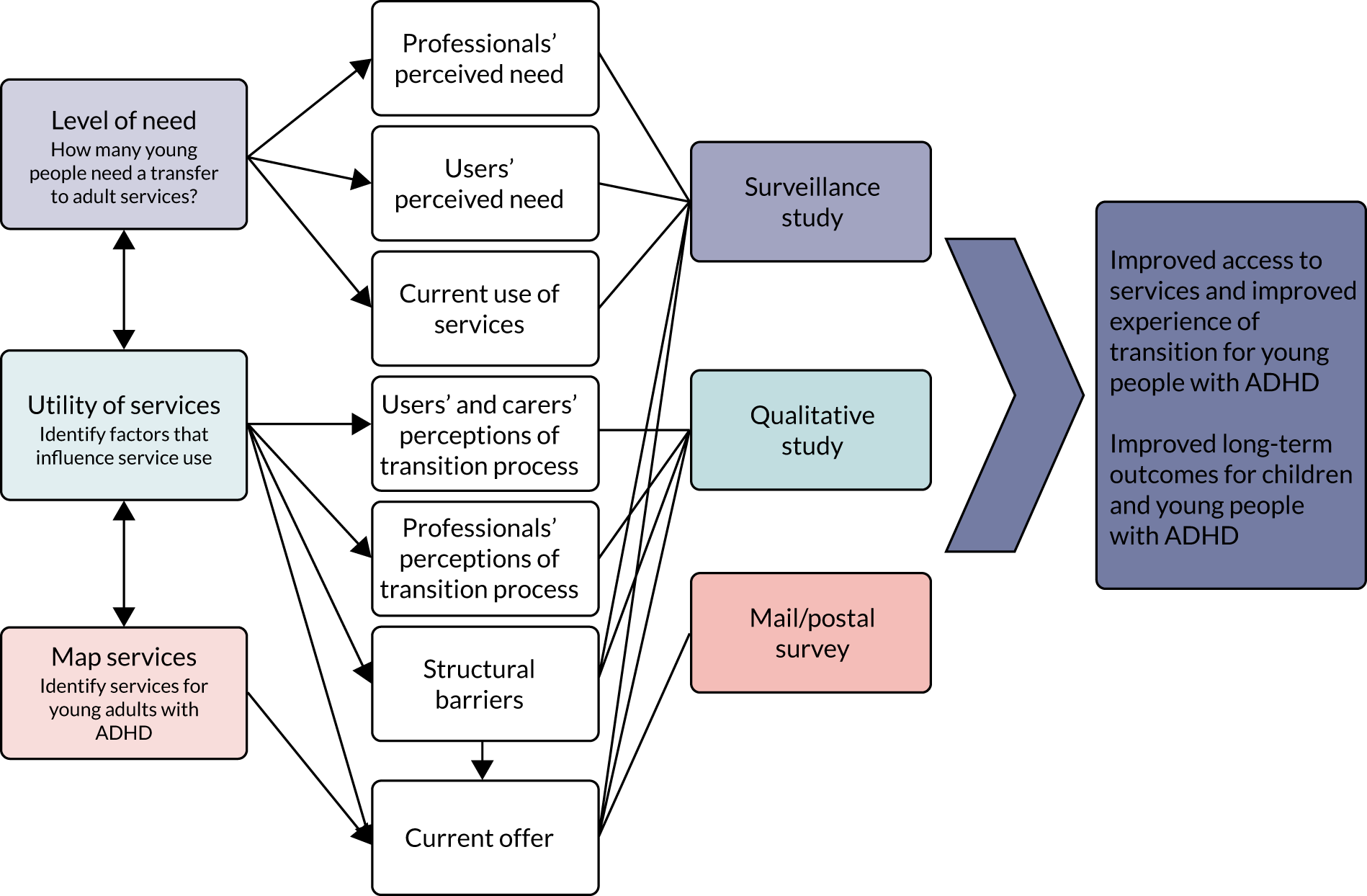

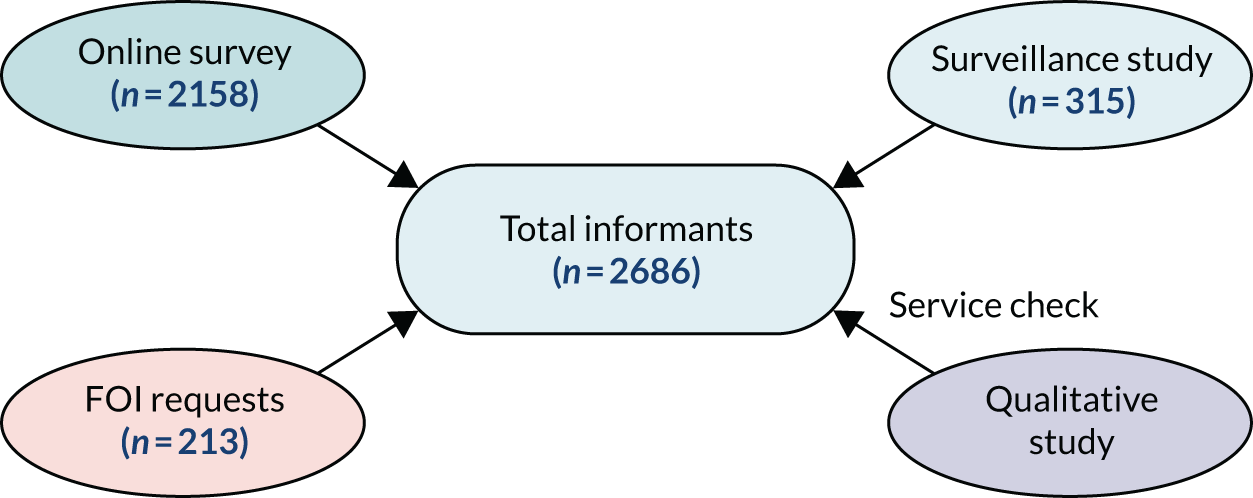

This report presents the results of a mixed-methods study conducted between 2015 and 2019 exploring the transition of young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) from child to adult health services. First, we provide a brief overview of the arrangement of health services for ADHD in the UK and the existing literature, before describing study objectives. Chapter 2 describes the methodology of this three-strand mixed-methods study (Figure 1). The following three chapters then focus on each of these strands. In Chapter 3, surveillance methods suited to the study of rare conditions/difficulties are used to estimate the national incidence of young people who are in need of a transition, and the incidence rate of successful transition. Chapter 4 maps service availability for adults with ADHD. In Chapter 5 we present the patient, carer and clinician perspectives and experiences of the transition process. The final chapter integrates the results of each of the strands before presenting our conclusions, recommendations for future research and examples of the impact of our work to date.

FIGURE 1.

Three strands of the CATCh-uS mixed-method study.

The relationship between a provider and a receiver of health care depends on how they address each other; it is one of the most important and sensitive relationships. The receiver has been historically referred to as a ‘patient’. In recent times, the use of terms such as ‘service user’ and ‘client’ has become commonplace. Some of these terms have their origins outside health care and may not encompass the sacred and sensitive relationship that is found between a patient and a clinician. We do not generally check with our patients how they would like to be referred to. Interestingly, research carried out in this area supports the long-held practice, as a large majority of patients (73–77%) prefer to be referred to as such, in a clinical setting. 1,2 The Royal College of Psychiatrists also explored this issue and concluded that ‘the term patient would be used in all College documents’. 1 For this reason, we will use the term ‘patient’ in this report.

Some of the results and study methodology have been discussed further in separate scientific papers. Where appropriate, these are referenced within the report and a list is provided in the Impact section of the report. Further papers based on this study will be added to the list on the project web page as and when they are published. For a list of further project documentation available, see Report Supplementary Material 1–28. For any further information, please contact catchus@exeter.ac.uk.

The Chief Medical Officer (CMO)’s 2012 report entitled Our Children Deserve Better: Prevention Pays3 acknowledged that we need to improve access for patients with ADHD in transition from child to adult services. The most recent UK data on transition revealed that one in two young people with ADHD and an ongoing clinical need do not transfer to or engage with adult mental health services (AMHS). 4 The CMO’s report identified that the annual short-term costs of emotional, conduct and hyperkinetic disorders among children aged 5–15 years in the UK are estimated to be £1.58B and the long-term costs £2.35B. Key themes emerged around the importance of data sharing, service provision and prevention, with the report concluding with a call for a programme of evaluative research that increases the knowledge base as the burden of disease continues to shift towards long-term conditions.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as a long-term condition

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is classified as a childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder defined by the presence of a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development. 5 People with ADHD often find organisation and time management challenging, with associated negative outcomes in education, employment and relationships. 6 They are at an increased risk of mortality, driving accidents and divorce, and have higher rates of criminal justice contact, particularly if left untreated. 6–9 ADHD is also commonly associated with comorbid anxiety, mood difficulties and substance abuse. 10–12 There are effective interventions,13–17 and there is a risk of potential and preventable adverse health outcomes if individuals disengage from treatment. 18–21 There is evidence that treatment with medication is associated with a significant reduction in drug and alcohol disorders,22 a reduction in the likelihood of road traffic accidents in males23 and a reduction in criminality rates of > 30% compared with periods of no treatment. 24

Originally conceptualised as a disorder of childhood, ADHD is now recognised as a long-term condition, with many experiencing ongoing difficulties into adulthood. Cross-sectional epidemiological surveys found that 5–6% of children and 3–4% of adults meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), criteria for ADHD. 25–28 Meta-analysis of follow-up studies of children with ADHD found that 15% retain the full diagnostic criteria by the age of 25 years, and a further 50% struggle with subthreshold symptoms and continued impairments. 29 Other studies report similar persistence of impairment into adulthood. 30–32 Since 2008, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) treatment guidelines have recognised and formalised ADHD’s status as a long-term condition, recommending lifelong, age-appropriate service provision. 33–36 NICE guidelines recommend that there should be continuity of care for people with ADHD, and that they should be treated by health-care professionals with training and expertise in diagnosing and managing ADHD. 36 The guidelines officially apply to England only, but are widely accepted as indicators of best practice across the UK.

Transition in health-care services

In the context of health care, transition extends beyond the simple transfer of clinical responsibility to supporting a young person towards and onto a new life stage. 37 Existing evidence indicates optimum transition is characterised by planning, information transfer across teams, joint working between teams and continuity of care during and following the transfer. 38 The importance of getting health-care transitions right for young people with long-term health conditions is increasingly recognised. 39,40 NICE has published a guideline for transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health or social care services;41 however, these are not condition specific and do not address barriers to the transition process. Rigorous evaluation of different models of transitional care is needed. 42

A recent longitudinal study of young people in the UK with a range of long-term conditions [i.e. diabetes, cerebral palsy and autism spectrum condition (ASC)] found three features of transitional health care that were strongly associated with better outcomes: appropriate parent involvement, promotion of health self-efficacy and meeting the adult team before transfer. 43 This observational study also found differences in transitional experiences between health conditions, indicating gaps that need to be addressed through service development. 43 A systematic review of barriers to transition from paediatric to adult care across chronic illness groups in the USA found that each chronic illness presented specific challenges. Certain barriers were universal, including difficulties with changing relationships, difficulties accessing or funding adult services, negative beliefs about adult care, lack of knowledge about the transition process and lack of self-management skills. 44

Several studies45–47 on transition for both physical and mental health conditions have found that young people, families and clinicians experience transition and the provision of support by health services differently. This underlines the importance of consulting with patients, their families and providers, to better understand key aspects of transition. Existing research suggests that a seamless transition process between child and adult services happens much less often than can be expected based on adult prevalence rates. 4 Poor transition may result in young people with ongoing needs disengaging from services48,49 and experiencing poorer health as a result. Transitions, even successful ones, are often stressful. Adolescence is a life stage that is characterised by major developmental changes and challenges. There is considerable development at the level of behaviour, cognition and the brain,50 and the timing of transition can coincide with other important changes in young people’s lives, such as leaving school, starting further education or employment, and leaving care. 51

The transition from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) to AMHS poses particular challenges, as the peak onset for severe and enduring mental illness falls in the late teens around the age boundary between services focused on children and those focused on adults. 52 This is further compounded by differences in thresholds and focus between CAMHS and AMHS, leaving a proportion of children without a clear pathway into adult services. 53,54 Several studies, government documents and policy guidelines highlight the difficulty faced by young people who require a transition from child to adult services. 39,53 Young people with neurodevelopmental disorders, such as ADHD, may be less likely to make the transfer from child to adult health care. 39,53 Studies of long-term conditions, such as ADHD, rarely follow participants across developmental transitions,55,56 and national empirical data on the number of young people who wish to access ongoing care for ADHD in adulthood or the number that successfully access follow-up care in early adulthood are sparse. To our knowledge, there has yet to be an in-depth study of this issue in the UK.

Two multimethod studies of transition and a case note review in mental health have demonstrated that transition is often poorly planned, lacks co-ordination and frequently results in discontinuity of care, particularly for children with neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD. 53,56,57 The limited qualitative research available also indicates that unsupported or non-existent transition for young people with ADHD, combined with inadequate adult service provision, leads to cessation of treatment and emotional distress for young people with ADHD and their families. 58,59 The lack of a national estimate of service leavers hampers commissioning and provision of services for this group. The latter is made even more difficult by a lack of national-level data on existing services for young adults with ADHD.

UK and Ireland mental health services configuration

Health service organisation varies widely across the world, as well as within countries over time. The focus on the UK and Ireland in this chapter provides the context for the programme of research that we will describe. The study had a UK focus, but the surveillance study was carried out in the UK and Ireland because Ireland reports to the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Surveillance System (CAPSS) so its exclusion from the CATCh-uS study was logistically impossible; therefore, a brief discussion of Irish health-care models is included. Different models and the international context will be discussed in Chapter 6.

In the UK, taxation provides a health-care service via the NHS that is free to access at the point of delivery. Health care for children with ADHD may be provided by CAMHS teams or community paediatricians, often depending on whether or not there are other mental health or physical illnesses, or developmental delay. Children’s services are commissioned to provide care until a patient is 16–18 years old, sometimes with stipulations about remaining in education for older teenagers. Adult services for individuals with ADHD may be provided by community-based AMHS, shared care agreements between psychiatrists and general practitioners (GPs), the private sector or voluntary organisations.

Box 1 provides an overview of provider organisations across the UK and Ireland, with subtle differences between countries. The King’s Fund (London, UK) has produced a helpful summary of commissioning of government-funded health services in England, which it defines as ‘the process by which health and care services are planned, purchased and monitored’ (Reproduced with permission from The King’s Fund. 60 This is distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 licence. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). 60 As they indicate, service configurations and commissioning processes change over time. During data collection for the CATCh-uS study there were geographical variations in provision depending on the local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), NHS England, local authorities or collaborative commissioning groups for specialised services. Other bodies, such as sustainability and transformation partnerships and devolved cities and local authorities, may also influence what is provided. 61 Commissioning in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland differs from that in England and between the three nations according to which health-related issues are devolved from the UK Parliament to the Scottish or Welsh Parliaments or Northern Ireland Assembly, as well as the constituent agencies and ‘arm’s length’ partner organisations involved. 62–64 In general, the devolved nations have largely avoided the market-based reforms that are increasingly adopted by the English health system.

In England, government-funded services may be delivered by:

-

NHS organisations (e.g. NHS trusts)

-

national or specialist services (directly commissioned by NHS England)

-

single private sector or third-sector organisations (i.e. non-governmental and non-profit-making organisations or associations, including charities)

-

conglomerates of NHS and/or private sector and/or third-sector organisations.

In Scotland [see Scotland’s Health; URL: www.scot.nhs.uk/organisations/ (accessed 19 September 2020)], such services are delivered by:

-

fourteen regional NHS boards

-

seven special NHS boards that provide a range of specialist and national services.

In Wales [see Health in Wales; URL: www.wales.nhs.uk/ourservices (accessed 19 September 2020)], such services are delivered through a variety of providers, including:

-

local health boards

-

NHS trusts.

In Northern Ireland [see Health and Social Care ONLiNE; URL: http://online.hscni.net/ (accessed 19 September 2020)], services are provided by:

-

six health trusts

-

the Health and Social Care (HSC) board

-

other HSC agencies.

In the Republic of Ireland, the Health Services Executive delivers mental health services [URL: www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/mental-health-services/services/ (accessed 19 September 2020)].

In Ireland, government-funded health care is managed by the Heath Service Executive (HSE). A person living in Ireland for at least 1 year is considered by the HSE to be ‘ordinarily resident’ and is entitled to either full eligibility (category 1) or limited eligibility (category 2) for health services. If an ordinary resident attends an outpatient department of a public hospital without being referred by a GP, he or she may be charged a standard fee. 65 All five nations have private health-care provision.

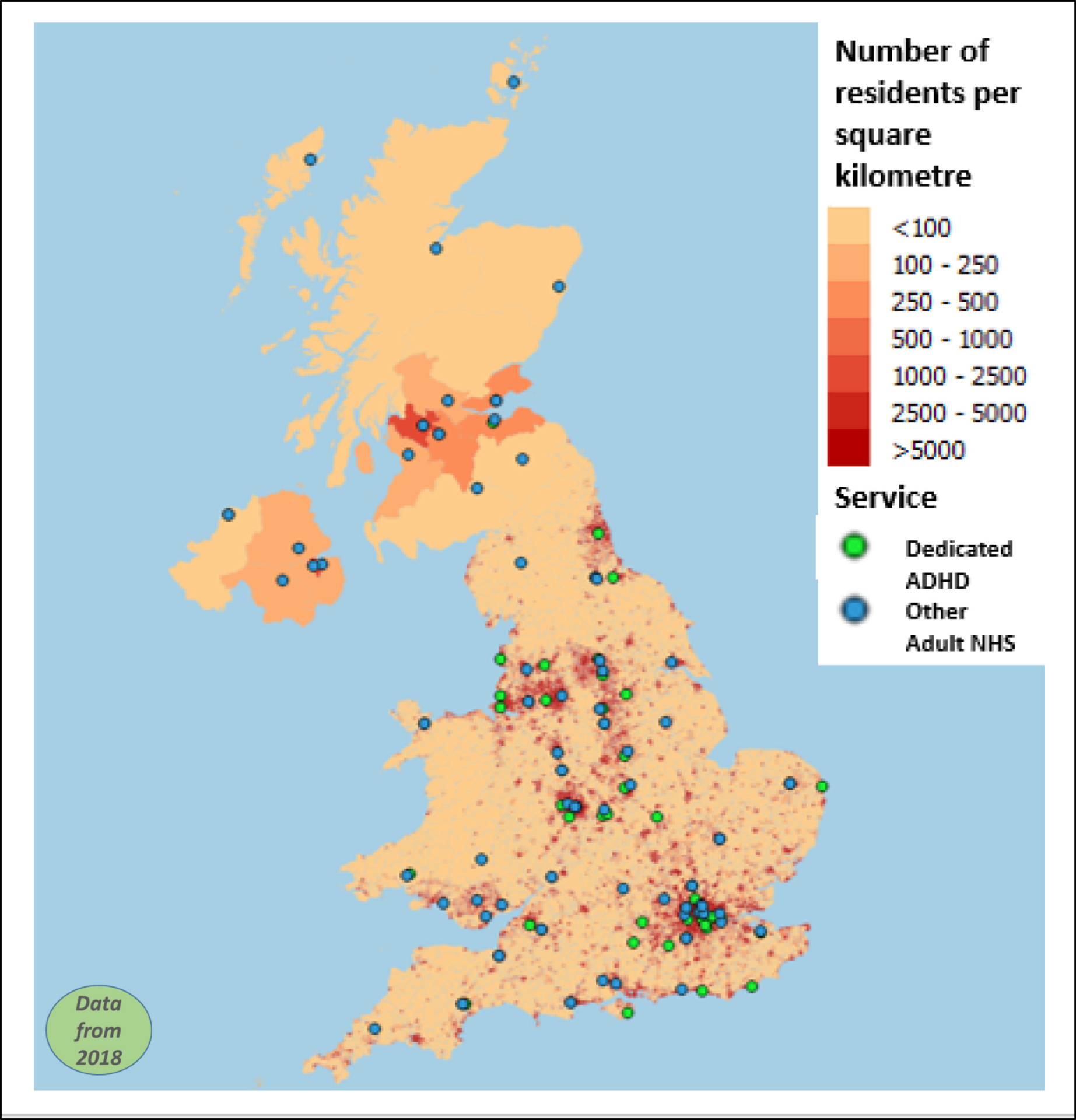

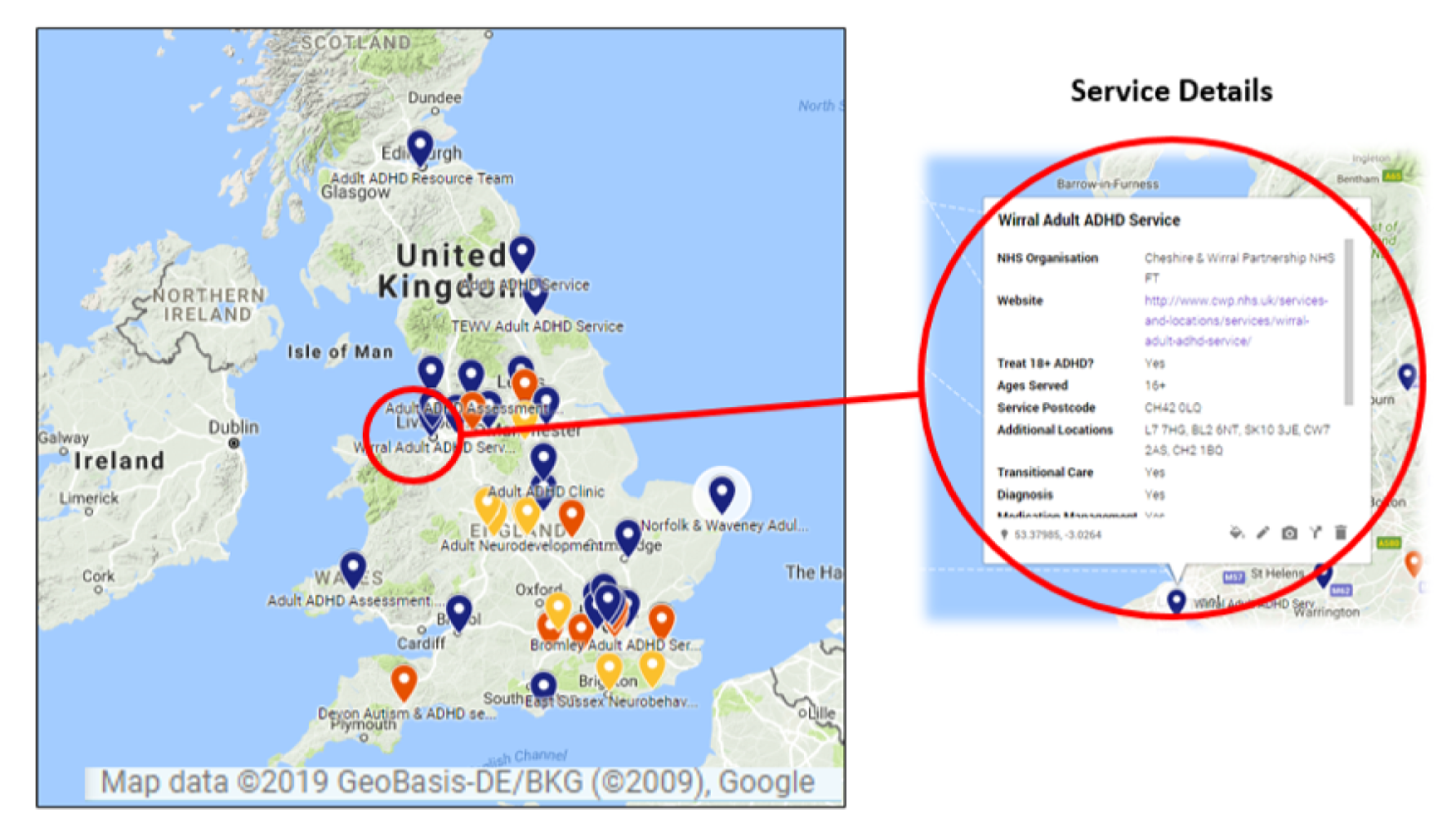

Health services change over time,60 and there is no ‘definitive’ way to ensure that health service workers, patients, carers and commissioners identify the same ‘unit of service’. For example, in England, a patient might report a locality base that they attend, which organisationally falls under a community mental health team (CMHT), which in turn might be one of a number of CMHTs forming an adult community mental health service, which in turn may be a directorate within an NHS trust that also provides learning disability (LD) liaison and inpatient mental health care. A clinician might report to the CMHT within which they work or to the directorate or the trust that employs them. A commissioner could report to NHS trusts or tender-winning conglomerates within their purview. To further complicate matters, some highly specialist services may be set up and commissioned as national or regional services. Clarity of definitions as well as the time and location at which data were collected are, therefore, key to thinking about health service provision. We defined services as ‘dedicated’ services where the service name indicated that it had dedicated staff to see adult patients with ADHD, and defined other AMHS where the name of the service did not communicate ADHD-specific dedicated time or resource as ‘generic’ services.

Need for the current study

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is one of the most common long-term conditions managed by child mental health and paediatric services,66 and an increasingly large cohort of young adults who have been diagnosed and managed within children’s services are growing out of the remit of these. Previous studies have reported the proportion of young people with ADHD who reach adulthood with an ongoing need for services for residual difficulties from general population surveys. 25–28 However, we have no national figure for young people in services who reach the end of child service’s provision and have an ongoing need for service input, nor do we have a national figure for successful transition.

As ADHD has been only recently recognised as a life-long condition, service configuration and workforce development have yet to respond to the growing ongoing treatment needs of adults with ADHD. 67,68 Adult community mental health services are often not configured to work with young adults with ADHD, who struggle with rather different issues to those of individuals with chronic psychosis, or personality, eating and affective disorders, who constitute the majority of AMHS attenders. Many adult mental health practitioners lack experience and/or training in the management of ADHD as training pathways diverge into specialisation early, and for many practitioners who have been in generic roles, such as nursing, occupational therapy and social work, it may be largely absent prior to qualification;69 some have negative or sceptical attitudes towards ADHD as a condition that warrants intervention. 70–73 Similarly, very few GPs have direct experience of child psychiatry and are unfamiliar with ADHD management without support from specialist services. 74 In the UK, at least, patchy service provision leaves young people with ADHD particularly vulnerable to poor transition or loss of service. Recent research reported that half of health trusts have prematurely discharged young people with ADHD from CAMHS because there were no suitable adult services. 75

In summary, there is perception of significant problems in the health-care transitions of young people with ADHD. However, we lack evidence to inform change in policy and practice: we do not know how many young people in the UK need to transition to adult services for ongoing management of their treatment, we do not know which services support young people with ADHD, and there is no evidence on the experiences of young people at all stages of the transition process (pre, post and no transition). This research aimed to address these gaps by exploring what happens to young adults with an ongoing need for management of their ADHD when they are too old for children’s services.

Research objectives

-

To assess the current need for adult services for young people with ADHD and describe young people with ADHD in need of a transfer to adult services.

-

To identify the range and type of services that are currently available for young people with ADHD in transition from childhood to adulthood.

-

To explore the quality of service delivery during transition and identify factors that (1) influence the experience of transition and could improve continuity of care and (2) contribute to disengagement and subsequent (dis)continuation of treatment.

Chapter 2 Study design

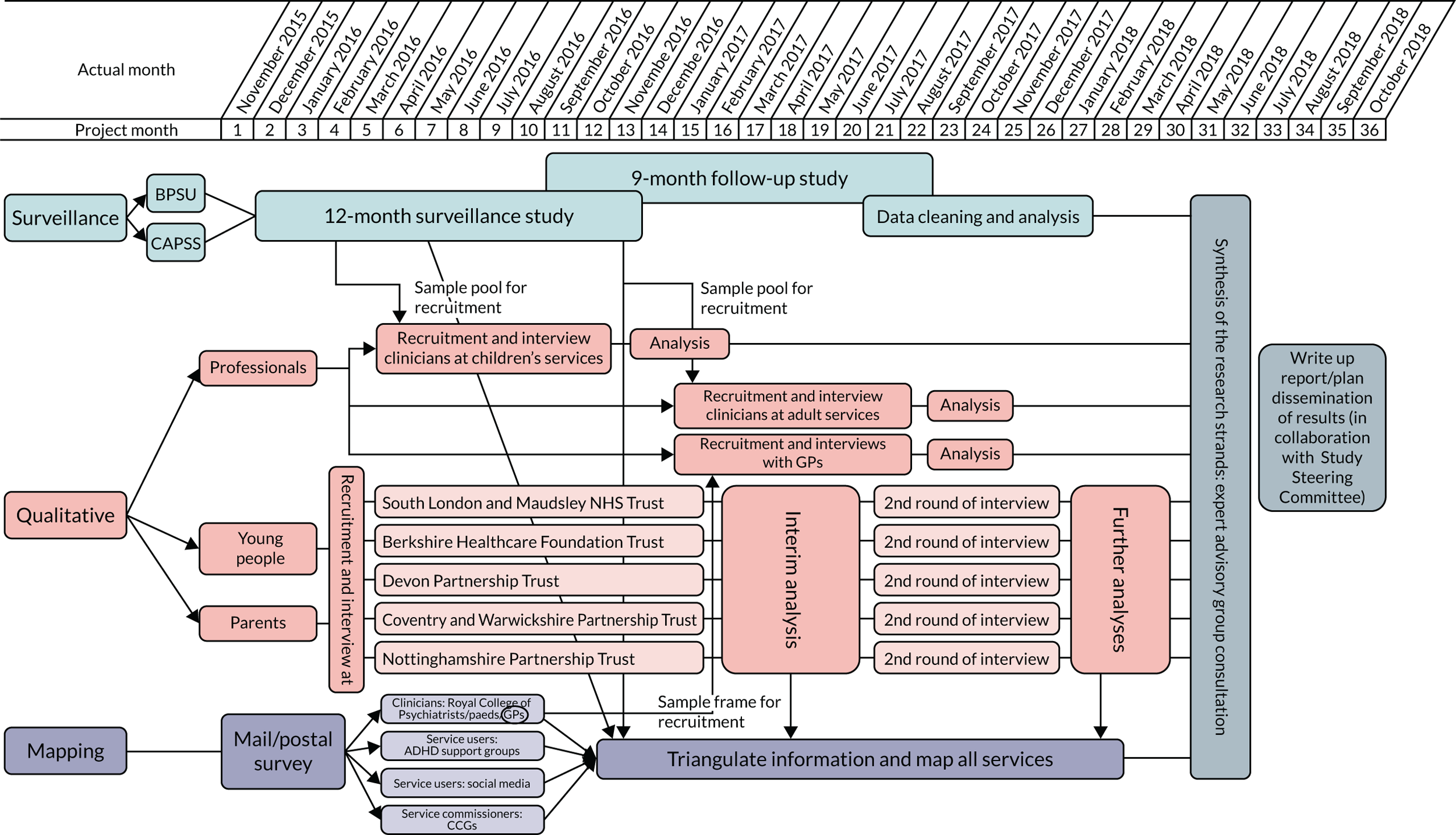

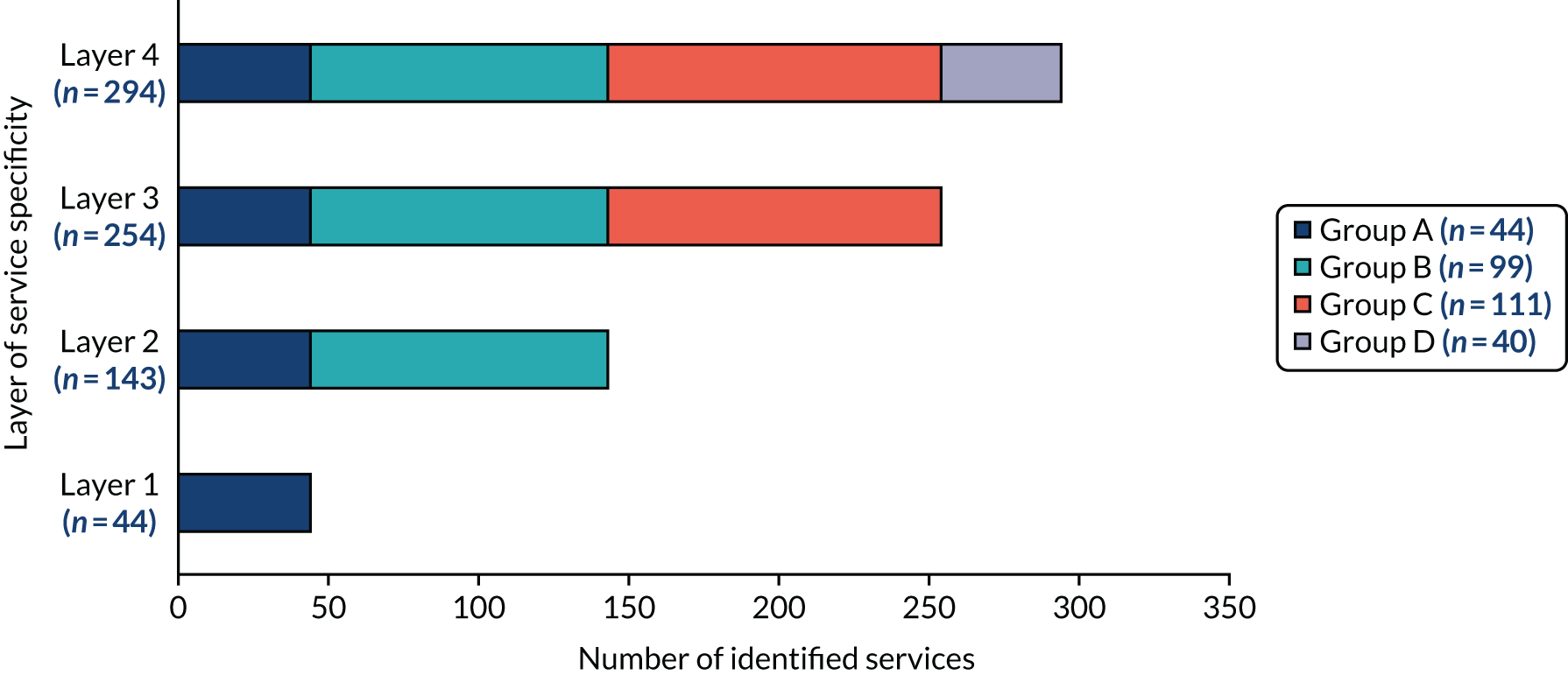

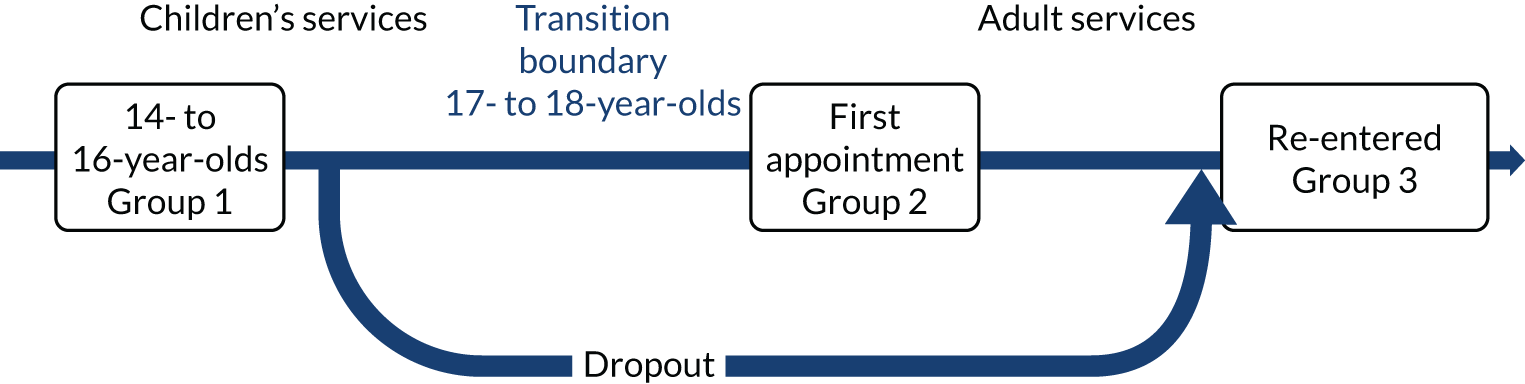

The study adopts a mixed-methods design incorporating three inter-related research strands to answer each of the study objectives: (1) a surveillance of young people diagnosed with ADHD who have ongoing service needs as they cross the upper age boundary of their service, (2) a mapping study to identify and describe services for adults with ADHD and (3) a qualitative study to explore the views and experiences of patients, parents and service providers of the transition process from children’s to adults’ health care. The study protocol is depicted in Figure 2. In this chapter, the reasoning for the mixed-methods approach is explained, followed by a description of the surveillance, mapping and qualitative methods and any changes to the protocol for each strand. Further details about each strand’s method can be found in later chapters. The governance and ethics approval for this project is also described in this chapter. Members of the public actively advised on each stage of this study and a description of this public involvement is also presented below.

FIGURE 2.

Study protocol.

Mixed-methods approach

We took an interactive, systems-based approach to design the study76 to address our three research questions, as illustrated in Figure 1. The multistrand design allowed us to consider and integrate multiple components of research design to reflect the inter-related nature of the questions and choose methods to provide the best available data. Some strands were designed to be conducted sequentially, as the results of one strand fed into the design of another; other strands were designed to be completed concurrently (see Figure 2). The three strands were strongly interlinked and designed to complement each other; for example, the surveillance and qualitative strands both studied various elements of the transition process as well as its success. The data collected via the surveillance provided a national insight into the transition to adult services and how this was organised. The qualitative strand delivered context to the national data and contextual understanding; with in-depth interviews, we explored the reasons behind successful or failed transitions from participating trusts. The surveillance and mapping studies interacted in a similar way with the qualitative study: a database with services accessed by young people and young adults with ADHD served as a sample pool for interviews with clinicians and was checked against the services reported in the mapping study. We required mixed methods for several reasons; we needed the best methods to address the different research questions but, overall, the study was designed to facilitate data triangulation and provide greater validity for the findings. 77,78 Together, the three strands allowed us to provide detailed understanding of the transition of young adults with ADHD in the UK.

Strand 1: the surveillance study

This strand aimed to determine how many young people with ADHD need to transfer to adult services because of ongoing treatment needs. We used two existing methods to assess ongoing service need for young people with ADHD when they are too old for children’s services: a surveillance methodology triangulated with an electronic clinical case note search. The surveillance study ran from November 2015 to August 2017 in parallel through the CAPSS and the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit (BPSU). 79,80 These systems collect prospective reports of cases seen from all consultants registered with the Royal Colleges. Over a period of 13 months (November 2015 to December 2016), consultant paediatricians and child psychiatrists in the UK and Ireland were asked to report patients who were within 6 months of the age boundary of their service who had been diagnosed with ADHD, were on medication and required ongoing services for their medication management. After 9 months (between August 2016 and August 2017), a follow-up questionnaire was sent to the reporting clinician to establish if the young person had been successfully referred to adult services, and data were collected on aspects of optimal transition and the adult services to which they had been referred. This strand was restricted to transition for young people with ADHD who required medication because of the requirement for an unambiguous definition of service need that would be understood similarly by paediatricians and psychiatrists. This means that the estimates produced will necessarily reflect only a minimum level of the need for transition, as young people may change their minds about the role of medication. The qualitative and mapping strands covered transition to adult services for any reason, including medication.

Changes to the study protocol for strand 1

Our application to CAPSS and BPSU required estimates of the number of expected cases, which we based on the best available evidence to be three transition cases per provider trust over 12 months. These units are designed for rare conditions, or fewer than 300 notifications per year, although our estimates suggested a total of 573 cases. 4,56 To protect the participating clinicians from respondent fatigue, BPSU and CAPSS agreed to run the surveillance for 6 months, with the possibility to extend to the more usual period of 12 months should the number of reported cases be fewer than anticipated. We received 138 notifications from BPSU during the first 6 months, 58 of which were eligible for the study. Case notifications for CAPSS were very similar with 118 notifications, of which 38 were eligible for the study. These numbers presented a case for extension to both BPSU and CAPSS, which was approved.

The BPSU and CAPSS encourage the use of additional reporting sources to check for any cases that might have been missed by the original data source. South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) has created an anonymised, regulated database of clinical records for research purposes: the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS). SLaM was one of five trusts associated with this project and, after the submission of the initial protocol, we were granted access to the database to complete a complementary piece of research that provided data that supported the calculation of a national estimate for transition incidence. This allowed us to compare transition from CAMHS to AMHS in SLaM with reports from CAPSS. Unfortunately, there were no comparable data sets for transition from paediatric services to AMHS. Additionally, SLaM is a national centre of excellence for mental health, with national and specialist services for children and for adults with ADHD, as well as local teams for both age groups in each borough of London served. This level of provision is not representative of the UK.

There was also a minor change to the terminology used in the definition in the first month of the 13-month surveillance period as there was some misunderstanding among clinicians (see Chapter 3, Data validation).

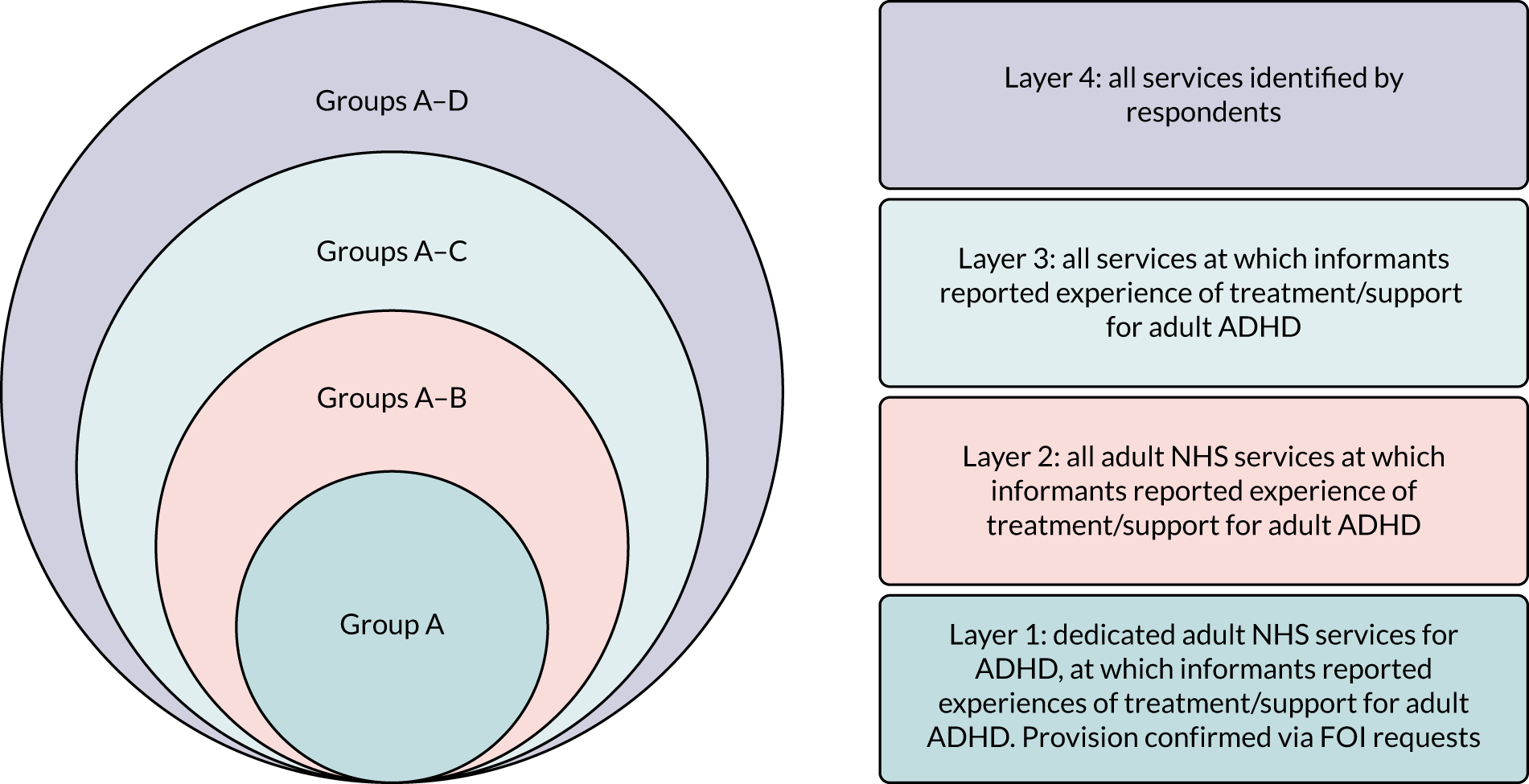

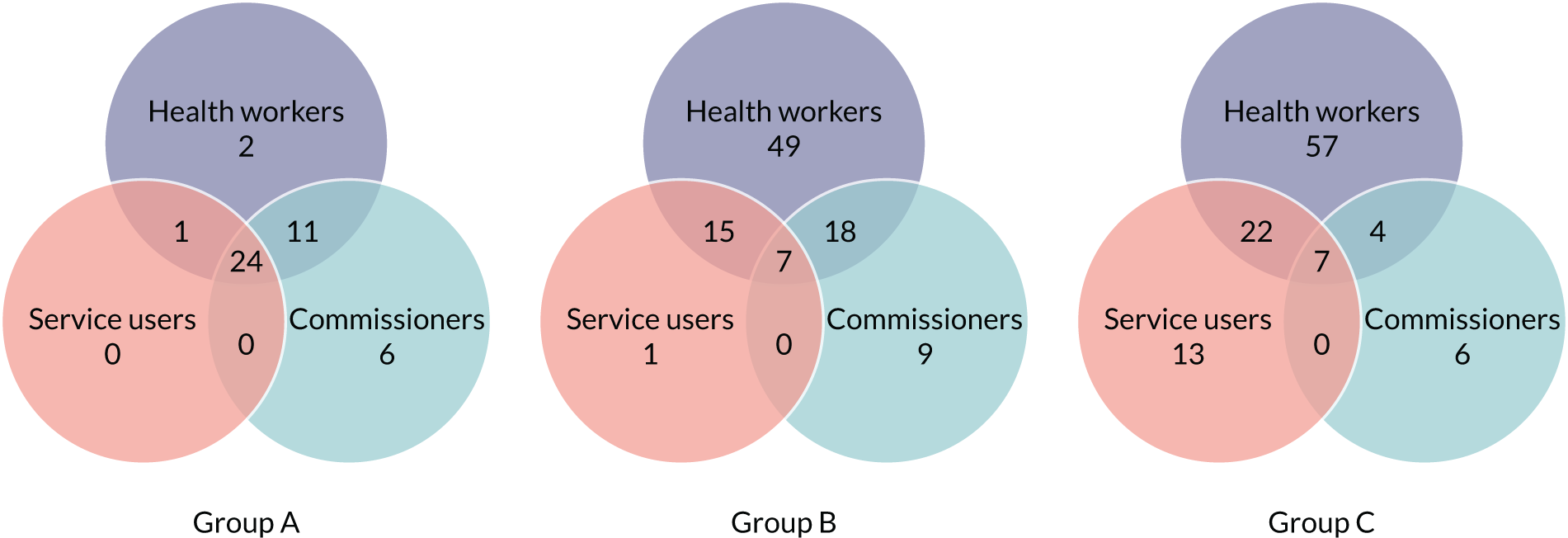

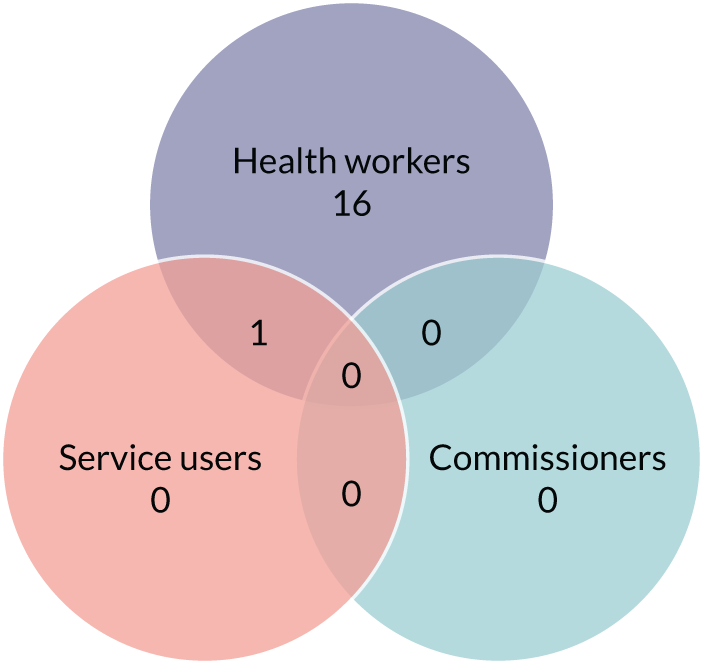

Strand 2: the mapping study

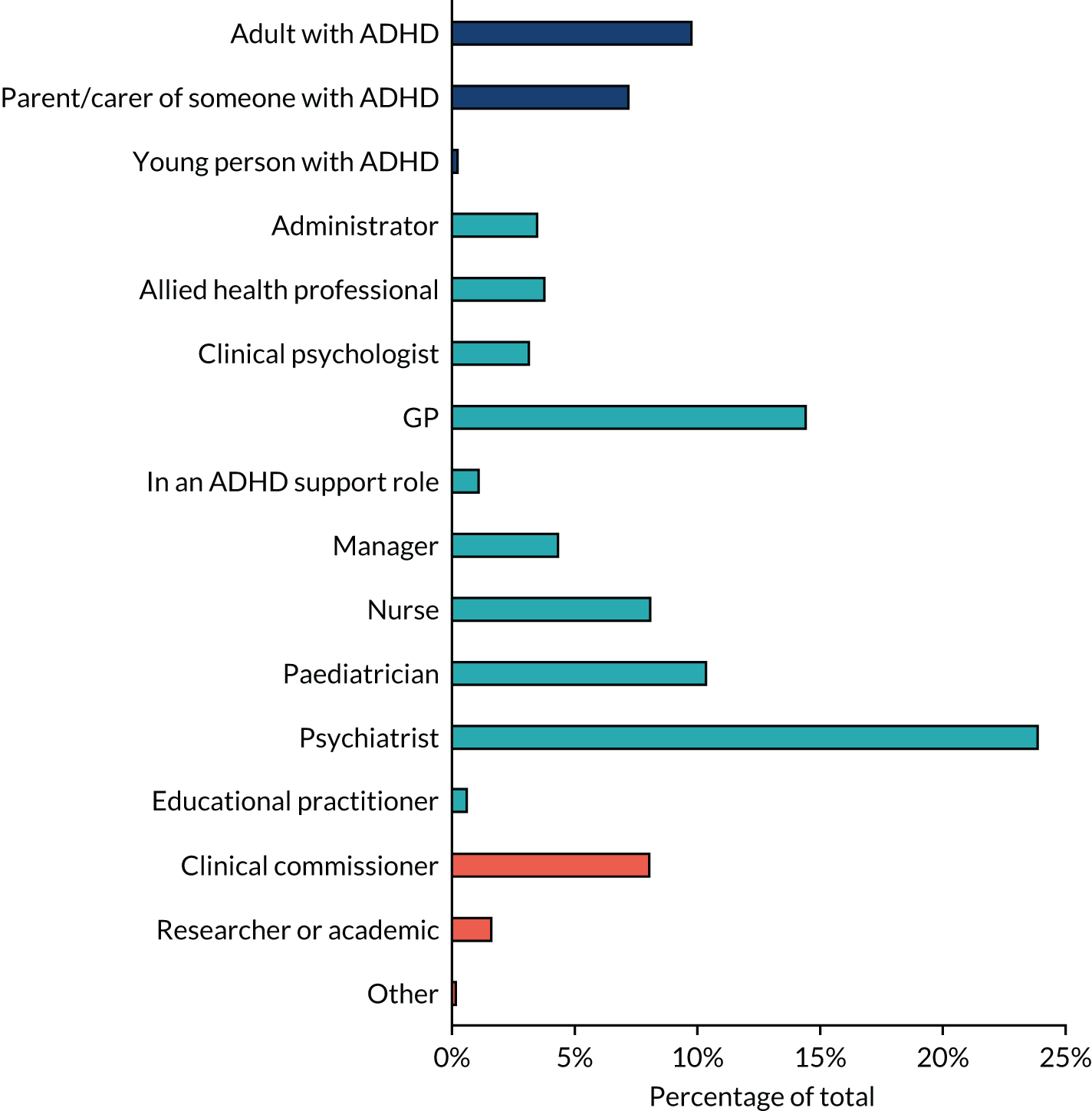

Previous studies have investigated services for young people with ADHD; however, their findings could not be linked to a geographical location. The aim of this part of the study was to map the variation in NHS AMHS for young people with ADHD in the UK. To maximise the completeness of our map, we collected data using an online survey from different sources:

-

those receiving treatment/support (patients)

-

those providing services (clinicians, health-care professionals)

-

those funding services (commissioners).

The technique was piloted in 2016. After an iterative process of trialling and refining the methodology, the mapping survey was repeated in 2017. Service provision information collected via the surveillance and qualitative strands were included in the mapping study.

Changes to the study protocol for strand 2

At the project start-up meeting [with co-applicants and members of the Study Steering Committee (SSC) present] it became evident that seeking one informant per area to inform the national service provision map would fail to deliver a complete map. The clinicians and researchers who were present had conflicting information on service provision for some areas because of the idiosyncratic knowledge of individuals. The mapping study developed into a multistakeholder, multi-informant study that included a pilot phase to test the new methodology. We had not planned a pilot for this work, yet it proved essential to work out which stakeholders to include and the most efficient method of mapping services to produce a useful and accurate map.

Strand 3: the qualitative study

Qualitative research with individuals representing four key stakeholder groups was carried out. Semistructured interviews were used to gather data relevant to generating a detailed understanding of heath-care transitions in the UK for patients with ADHD. The four stakeholder groups were:

-

young people with ADHD at different stages in the transition (pre transition, post transition and those who disengage and do not transition but return to adult services later)

-

parents of young people with ADHD who identify themselves as a primary carer, again representing different stages in transition

-

clinicians in children’s services

-

clinicians in adult services.

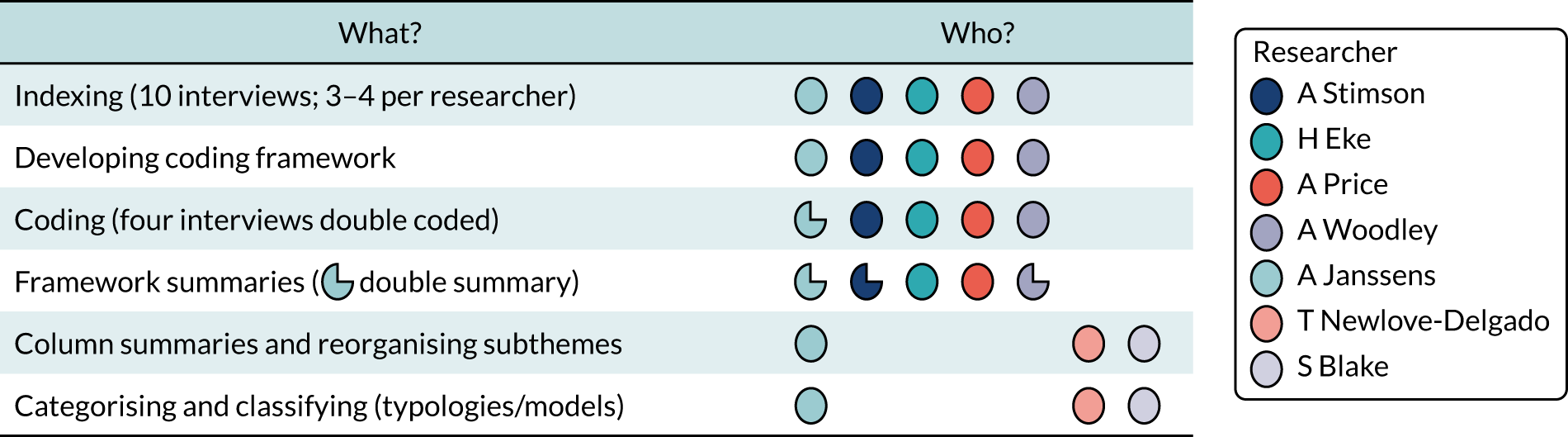

Paediatricians and child psychiatrists who reported cases to the surveillance study were invited to take part in an in-depth interview on transition. Information collected regarding the reported cases included details of the ongoing referral; this information was used to identify and approach clinicians working in adult services. The initial design involved recruitment of patients and parents from five different NHS trusts purposefully chosen to represent different service provision models and geographical spread. Individual interviews were conducted face to face or by telephone. Data were analysed thematically using a framework analysis approach. NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) version 10 software was used to facilitate systematic and transparent analysis.

Changes to the study protocol for strand 3

The adoption of the CATCh-uS study by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) portfolio created a lot of interest among health trusts, which then contributed to the study and requested to be added as recruitment sites. This offered an opportunity to diversify our sample geographically and increase the diversity of service models accessed by the recruited patients (with or without follow-up services within or outside the trusts).

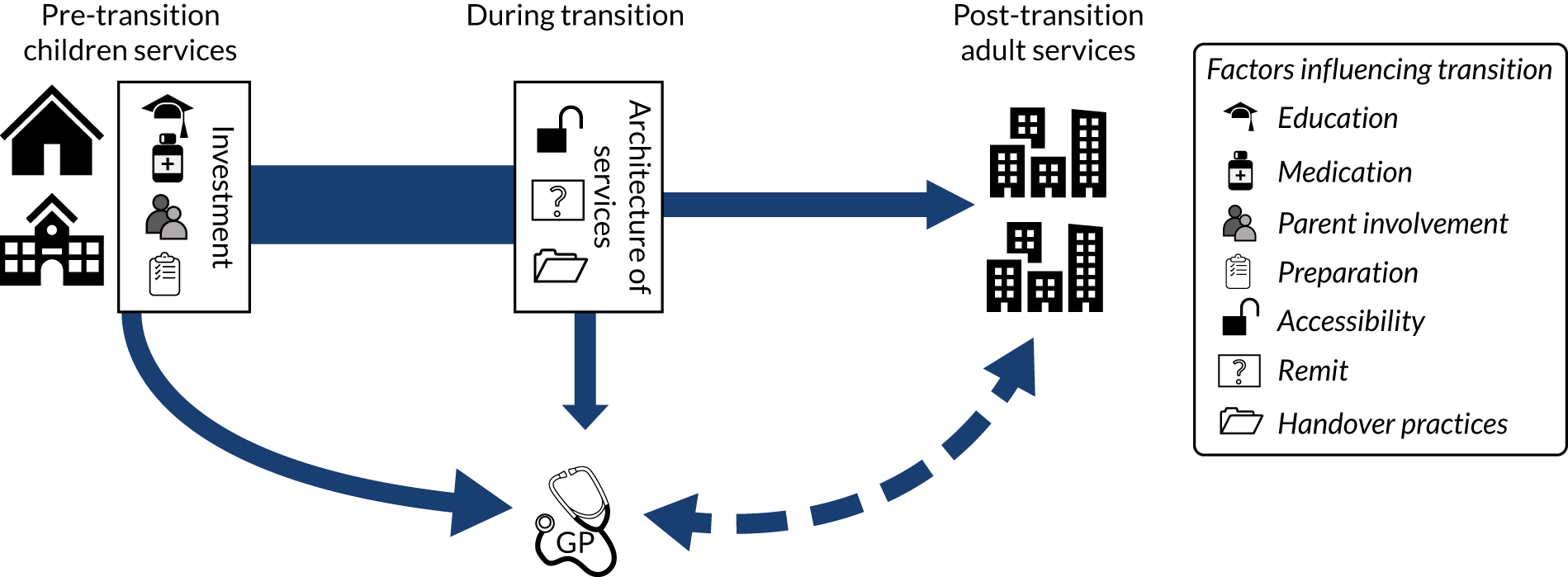

In addition, preliminary analysis of our interviews with clinicians highlighted primary care as a potential ‘destination’ for patients with ADHD leaving children’s health care, particularly for young people dropping out of services or for whom no ongoing services were available. Representation of GPs was not originally included in the design of the qualitative study; however, given no existing studies could be identified that included this stakeholder group, the decision was taken, in consultation with the SCC and with approval from our programme manager at NIHR, to recruit a sample of GPs. It was possible to resource this work from the existing funding envelope.

Research governance and ethics

We started informal discussions with the University of Exeter Medical School (UEMS) Research Ethics Committee (REC) and the NHS REC/Health Research Authority (HRA) regarding which of these bodies we should apply for ethics approval shortly after the study was accepted for a stage 2 application of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme funding call for long-term conditions. As a result of a change in the ethics approval system (HRA replacing NHS REC for multisite studies), we had to go through all systems: HRA (17 June 2016) and NHS REC and research and development (R&D) governance processes for each individual trust participating in the study (the last trust was approved by the HRA on 20 January 2017). Ethics approval from the UEMS REC was sought to assure that some elements of the study, which did not require NHS REC approval, were approved to ensure a timely start.

The CATCh-uS study and subsequent amendments received ethics committee approval from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee Yorkshire and the Humber – South Yorkshire; the original protocol was approved in October 2015 (REC reference 15/YH/0426). Both surveillance units, CAPSS and BPSU, by virtue of their rigorous two-stage application processes, have HRA approval for access to case note information without patient/parent consent, provided that the study has Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) approval. CAG approval is a fast-track process occurring as a result of the established rigour of the application process to the surveillance units that prospective studies go through. This type of surveillance required HRA approval as cases may be reported from any NHS trust that works with children. In addition, a section 251 approval was required from and granted by the CAG to permit clinicians to report anonymous case note information without patient/parent consent provided there is no requirement or expectation for additional patient contact as a result of the study (CAG reference number 15/CAG/0184). The CRIS was approved as an anonymised data resource for secondary analysis by Oxfordshire REC (08/H0606/71+5). The searches that were run as part of this project were reviewed and approved by the CRIS patient-led oversight committee (CRIS reference: 961).

Research and development approval was sought and gained in all 12 hospital trusts that contributed to the qualitative strand of the study; letters of access were sought for the data collection in these sites. The researchers collecting data had enhanced Criminal Records Bureau clearance and current Good Clinical Practice training certificates and were issued with research passports to access the premises and conduct interviews with NHS patients on site. Gaining R&D approvals, however, was a complex and often lengthy process, differing logistically and administratively from site to site, and in some sites delayed patient recruitment for several weeks. The full CATCh-uS study and subsequent amendments obtained ethics approval from the UEMS Ethics Committee. The original protocol was approved in December 2015 (reference: PF/CB/15/07/070).

Obstacles in obtaining ethics approval

The need to approach several different local R&D committees in addition to a central REC (and despite central ethics approval already having been given) led to very significant delays in recruitment. Opinions vary across R&D committees about how to conduct research with children or adults with mental health problems, for example the appropriateness of seeking assent from minors. The absence of systematic patient databases often hindered case finding. The surveillance study was CAG approved; yet some trusts were reluctant for their clinicians to contribute to the BPSU and CAPSS surveillance study unless we also had R&D approval from their trust, despite HRA approval. They did not allow their clinicians to spend time completing the paperwork related to the study although participating in research is a central tenet of the NHS.

Patient and public involvement

The Peninsula Childhood Disability Research Unit (PenCRU) at UEMS involves families of children and young people with a disability in all their activities through a family faculty. We presented our idea of a research project on transition for young people with ADHD to a group of parents with children who had ADHD identified through PenCRU’s family faculty. We discussed the project proposal and explored further involvement by designing a patient and public involvement (PPI) plan. As a result, one parent with lived experience of ADHD in adults and young people was named as a co-applicant, which helped keep our focus on issues of importance to those in need of services during the study planning and communication with the parent advisory group. The proposed research was strongly endorsed by our parent advisors, who acknowledged that transition to adult services is a big challenge and a source of worry for them and their children. In response to parents’ concerns, interviews with young people who dropped out of services to understand why they chose not to continue mediation or treatment were added to the study design. Parents who were interested in the project became our parent advisory group (n = 21), which we consulted with throughout.

Over the years, our research group has developed good relationships with local secondary schools (including a special needs school), and pupils attending these schools demonstrated great interest in participating in new research projects. The project was introduced to year 9 students, who advised the team on how to conduct interviews with young people and helped design patient interview consent forms for the qualitative study. In addition, we were supported by Cerebra (Carmarthen, Wales), UK Adult ADHD Network (UKAAN) and Adult Attention Deficit Disorder-UK (AADD-UK), three third-sector organisations that work extensively with young people with ADHD and their families, or clinicians working with young adults with ADHD. These organisations supported communication throughout the project, notably sharing the map of services and helping to obtain feedback from patients with ADHD, which they now plan to host and update in perpetuity. PPI in this project contributed to the:

-

definition of case study for the surveillance strand

-

design of topic guides and information leaflets for the qualitative study

-

development of the recruitment strategy for the qualitative study

-

development of an online survey asking patients about service availability (mapping study)

-

analytical process, through preliminary discussions of the findings

-

dissemination of findings.

Chapter 3 Strand 1: the surveillance study

To plan services, commissioners and service providers need data about how many people may require that service. Although previous studies have reported on the proportion of young people still meeting diagnostic criteria in adulthood,29 few studies provide empirical data on the number of patients who wish to access ongoing care, or the number who successfully do so. Studies for common developmental disorders, such as ADHD, also rarely follow participants across developmental transitions. 55 Two previous studies have reviewed case notes to identify transition cases between CAMHS and AMHS for all children with all types of mental health conditions over a 12-month period. 53,56 The first study identified an average of 12 neurodevelopmental cases per CAMHS team who were eligible for transition in 1 year, of whom 40% were never referred to any adult service; in addition, only 67% of those referred actually made the transition. 39,53 This study was limited to health trusts in two geographical areas of England. The second study focused on ADHD cases in Ireland and identified 20 patients from four CAMHS teams who required transition. None of these patients were directly transitioned to AMHS; they were retained by CAMHS, referred to a private service or discharged to their GP. 56 The CATCh-uS surveillance study was the first national study that aimed to determine how many young people with ADHD, with an ongoing need for medication, need to transfer to an adult service, and to describe this population across the UK and Ireland.

Surveillance is the collection of reliable and timely information about health conditions in the population to improve health. 81 It is defined as the systematic ongoing collection of data, including analysis and interpretation, and, by its continuous nature, is more than just routine outcome monitoring. It is also separate from screening, because of the broader focus on factors that influence prevalence and management; screening, in contrast, is intended to detect individuals who need care. 82 Surveillance of a condition over time has the potential to provide national estimates of incidence and highlight needs or gaps in service provision that should be addressed at policy level to inform commissioning.

Monthly surveillance with reporting via questionnaires in paediatric services was developed in the 1980s to measure and monitor important infectious and rare diseases by the BPSU, which has been a prominent influence on child health policy and practice. 83 It studies the national incidence of rare conditions across the UK via monthly reports from consultant paediatricians. Much mental health surveillance has involved collection of data via morbidity surveys, such as the surveys of psychiatric morbidity,84 or enquiries, and data collection at mental health services, which still continues; however, since the 1990s, recognition of the impact of mental illness on the health of the population has led to more continuous surveillance being conducted. CAPSS was developed as a pilot in 2005 for a study of early onset eating disorders to maximise the identification of cases, and was fully established in 2009. 85 It applies the same methods as the BPSU, but obtains reports from consultant child and adolescent psychiatrists. The current study focused on surveying the incidence of a service need: the need for transition between child and adult services for young people with ADHD.

The objectives of the surveillance study were to:

-

estimate the range and mean age for transition to adult services and variation within this across the UK and Ireland for CAMHS and paediatric services

-

estimate the incidence rate of young people with ADHD requiring ongoing medication for ADHD after they pass the age boundary for the service that they attend, and variation within this across the UK and Ireland

-

describe the services offered to young people going through this age boundary

-

estimate the proportion of young people with ADHD judged in need of transition who successfully transfer to a specialist adult health service, defined as an accepted referral to a specialist adult service within the time frame of the current study.

Methods

This study used the BPSU and CAPSS to collect surveillance data on transition in health services that support young people with ADHD. As young people with ADHD (especially those who require medication) are most commonly seen by CAMHS or paediatric clinicians, the CAPSS and BPSU system offered access to the most appropriate clinicians and care pathways. This was one of only five studies to use the CAPSS and BPSU system simultaneously and was unique in that it focused on the incidence of transition as a process in ADHD as opposed to the incidence of ADHD as a condition. Additional work compared the relative strengths and weaknesses of surveillance and electronic case note review methods in quantifying the need for transition, which is summarised below and described in more detail in a separate paper. 86

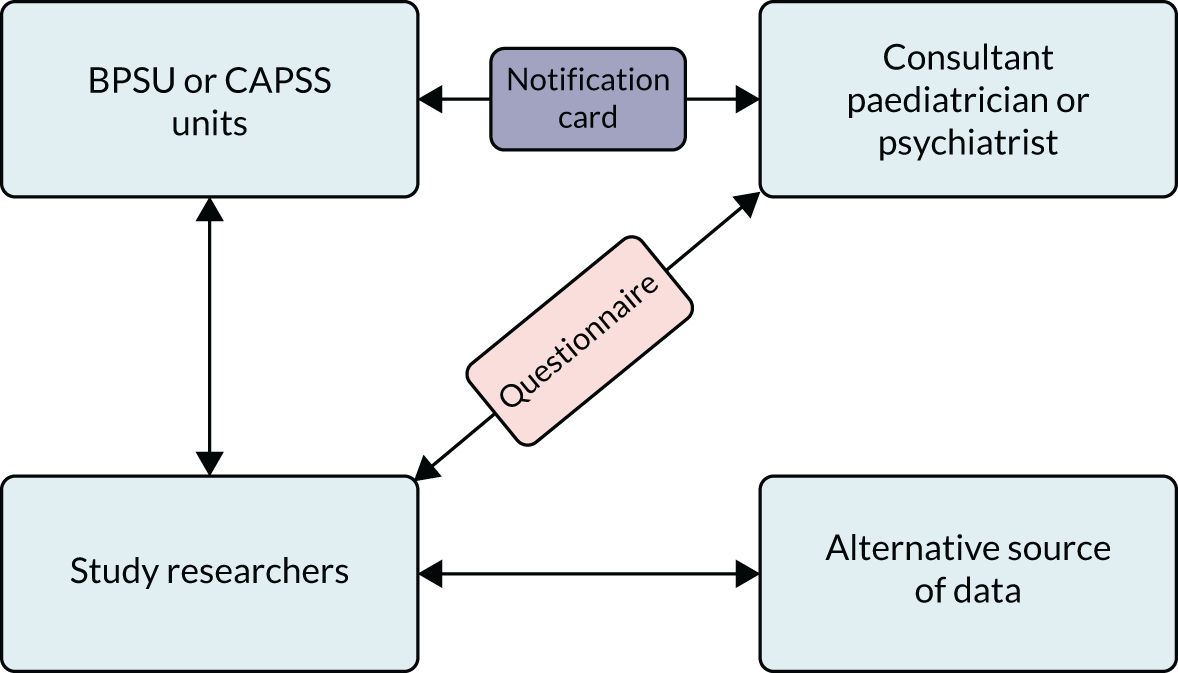

Surveillance methodology design

The BPSU and CAPSS methodology is well established and replicated in 14 countries; the study results influence management, planning and policy internationally. 87 Figure 3 illustrates how the system works. Over 3800 registered paediatricians from BPSU88 and 1000 psychiatrists from CAPSS89 are sent a surveillance orange/yellow ‘reporting card’ (now by e-mail) each month that lists the rare disorders or events currently under study. A limited number of research studies can be featured on the card at any one point in time, and the clinician returns the notification card indicating how many patients they have seen that meet the relevant study criteria. The research team then sends a questionnaire directly to the clinician. Usually BPSU and CAPSS studies run for 13 months; the first month is considered a pilot to identify any potential difficulties raised by clinicians, with the remaining 12 months’ data included as the full study.

FIGURE 3.

BPSU and CAPSS surveillance methodology. Reproduced with permission from Richard Lynn, British Paediatric Surveillance Unit, 2019, personal communication.

Governance and ethics

Both BPSU and CAPSS have a two-phase application process before granting approval to run a study. Phase I assesses the suitability of the research question to this type of surveillance methodology, whereas Phase II ensures that the surveillance definition and questionnaires cover only what clinicians would be expected to know or be able to access from clinical notes. Respondent burden is a prime consideration.

The approval granted by BPSU and CAPSS for this surveillance study was initially for 6 months with review thereafter. Both units were concerned that a large number of notifications would be received that would be beyond the capacity of each organisation and, thus, swamp the system. The plan was to review at 6 months and extend to 12 months, if warranted. At 6 months, 138 notification reports from BPSU and 118 from CAPSS had been received, which allayed the fears that both the clinicians and the surveillance organisations would be overburdened. The surveillance period was duly extended and, in total, ran from November 2015 to November 2016 with a 9-month follow-up post notification from August 2016 to August 2017. Responses were followed up for 3 months after the end of the surveillance and follow-up periods. Relevant ethics approval was sought and granted for this part of the study. Both BPSU and CAPSS have HRA approval for access to case note information without patient/parent consent, provided the study has CAG approval (Integrated Research Approval System registration number 159209, REC reference 15/YH/0426 and CAG reference 15/CAG/0184).

Case definition criteria

The surveillance unit asked consultants to report if they had seen any of the following in the previous month:

-

young people with a clinical diagnosis of ADHD under the care of CAMHS or paediatric services who were reviewed within 6 months of the service age boundary

-

young people considered to require continued drug treatment for their symptoms of ADHD after crossing the age boundary of the child service

-

young people with ADHD and comorbid diagnoses, including learning/developmental disabilities, but only if it was their ADHD that required ongoing drug treatment.

Young people were excluded if they:

-

had a diagnosis of ADHD but did not require medication or were unwilling to take it

-

required transition to an adult service only for a psychiatric comorbid condition

-

had already been notified to the study.

The definition was designed in close collaboration with members of both BPSU and CAPSS and had to be appropriate for both paediatricians and psychiatrists, to ensure that both sets of clinicians would identify young people to be reported in the study in as similar a manner as possible. The development of the definition required an iterative process of discussions and revisions. The final definition that was used unequivocally specified the need for ongoing support from specialist AMHS, as outlined in the NICE guidelines. 36 The aim of the definition was to provide a minimum estimate of the number of young people requiring a transfer from CAMHS and paediatric services to adult services during the surveillance period. Because not all children’s services extend to the age of 18 years, and some extend beyond this age, the age boundary was left unspecified to prevent the loss of cases in measuring when transition was occurring. The requirement for ongoing medication was chosen as a criterion to rule out subjectivity in the application of definitions of ‘ongoing care’. It would not capture those who did not need or want medication but did need ongoing psychological support.

Questionnaires

Baseline notification and follow-up questionnaires were developed using the corresponding systems templates, which comprised structured questions (30 at baseline and 19 at follow-up) with two open-text responses. All four surveillance study questionnaires are available (see Report Supplementary Materials 1–4). The baseline notification questionnaire was sent to all clinicians who reported a case to the study; questions confirmed eligibility and gathered semi-identifiable data on the patient (NHS number, gender, age in months and truncated postcode) to allow duplicate reports of patients seen by both general and specialist services, or by both CAMHS and paediatric services, to be identified. It also collected details of patient treatment and details of the planned transition to an adult service. Any professional with access to the patient notes could complete the baseline notification questionnaire on behalf of the lead clinician if necessary, although the reporting card was sent only to consultant paediatricians and child and adolescent psychiatrists.

Only cases confirmed as eligible in the baseline questionnaire were sent a follow-up questionnaire 9 months later. The follow-up questionnaire was sent to the same clinician who reported the case at baseline, with questions to confirm the outcome and details of the transition. There were nine elements of transition listed at follow-up and only five at baseline. This was to reflect what was stated in the NICE guidelines,33–36 and it was anticipated that at follow-up the transition would have occurred and clinicians would therefore be able to report on factors such as continuity and consistency that would not have been possible at baseline.

E-mail and postal reminders for non-returned questionnaires were sent after 4 weeks and again after 6 weeks, and finally a follow-up telephone call was made if the questionnaire was still outstanding. Clinicians were offered certificates to represent time committed to research to acknowledge their participation.

Data validation

Most BPSU studies choose to triangulate their data with other sources to help improve completeness and accuracy. 90 To check the reliability and validity of the data collected in this surveillance study, additional data were collected using clinical case notes from the Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre CRIS at SLaM. These additional data had several limitations. First, SLaM provides only CAMHS and not paediatric services; only the total numbers of cases and descriptive data captured by both systems could be compared because neither CRIS nor CAPSS allows individuals to be identified. Second, the geographical boundary of SLaM could not directly map with CAPSS data as researchers are blind to patient data and the information provided on each case related to the reporting consultant and not the service or clinic; therefore, the comparison with CAPSS reports could not get closer than the wider boundary of ‘London’. This method enabled a real-time data comparison and provided an indication of the completeness of the CAPSS reporting systems at collecting data on the incidence of rare events and processes in mental health services. We expected that CRIS would reveal fewer cases, as SLaM encompasses four London boroughs and the CAPSS data encompassed the whole of London.

The case definition criteria were the same as those applied to the surveillance study; criteria were operationalised into a structured query language, which was used to identify eligible cases in CRIS. Manual review of the electronic records by two researchers extracted the individual, clinical and service-related characteristics of the case, including details of transition (Table 1). The aim, given the previously mentioned limitations, was to replicate the data collected by the surveillance study.

| CRIS identifier | Reason for appointment | Other medication 3 |

| Gender | Current CAMHS or AMHS | Other medication 4 |

| Ethnicity | Seen by clinician | CGAS score (1–100) |

| Date of birth (specified) | Comorbidity 1 | SDQ assessment date |

| Truncated postcode | Comorbidity 2 | SDQ total score |

| Indices of social deprivation (LSOA) | Comorbidity 3 | SDQ hyperactivity score |

| Date of diagnosis of ADHD | Comorbidity other | SDQ impact score |

| CAMHS directorate | ADHD medication 1 | Contact frequency |

| Last date seen | ADHD medication 2 | DNA rate |

The CRIS was approved as an anonymised data resource for secondary analysis by Oxfordshire REC (08/H0606/71+5). This project was reviewed and approved by the CRIS patient-led oversight committee (CRIS project reference: 961).

Challenges from case definition and questionnaires: British Paediatric Surveillance Unit and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Surveillance System responses combined

It became clear from queries to the researchers and the surveillance units during the pilot month that some consultants misunderstood the term ‘first time’ used in the original surveillance definition. They were unclear if this meant the first time they had ever met the patient or the first time the patient was reviewed in the surveillance period. This was resolved by changing the terminology to ‘the first time the case is reported’ (Table 2).

| Original | Final |

|---|---|

|

|

Other detected errors from clinicians included reporting a whole caseload of ADHD patients rather than reporting only the patients who required a transition (n = 2), duplicate reports of the same case if seen more than once (n = 13), reporting a case but not remembering the patient details (n = 31), reporting a case that did not meet one or more of the case definition criteria (n = 90) and ‘reporting in error’ (e.g. ticking the wrong box on the card, misreading the card, no recollection of reporting) (n = 43). Queries were resolved by direct contact with the reporting clinician.

Analysis of surveillance data

Response rates at each stage of the study are described, as are sociodemographic details of the reported cases by each reporting surveillance unit, and overall. The response rate was generated from the number of notification cards returned to BPSU or CAPSS divided by the total sent. Incidence is defined as the number of new health-related events, in a defined population, in a set period of time. 91 Using the data collected in this surveillance study, the incidence rate was calculated by determining the number of confirmed cases of transition in patients with ADHD identified over the course of the study’s 12-month surveillance period. The population at risk (n = 116,651) was derived by applying the estimated prevalence of ADHD (approximately 5% in the child and adolescent population)92 to the total number of young people aged 17–19 years in the UK, as reported in 2016 (n = 2,333,035). 93 Our incidence rates were calculated by dividing the estimate obtained from the surveillance of cases aged 17–19 years by the population at risk and multiplied by 100,000 to provide the incidence rate of transition per 100,000 young people.

Two incidence rates were calculated: the incidence of young people who were eligible for transition and the incidence rate of successful transition in the obtained sample. The incidence rate was adjusted to take into account the non-returned or missing data from the surveillance study (via monthly reporting cards and surveillance questionnaires). The following corrections were made:

-

Correction for unreturned BPSU/CAPSS notification cards. To account for incidence among unreturned cards, a correction to the observed incidence rate was applied, using two assumptions as suggested by Petkova et al. 94 in a previous study:

-

Assumption 1 considers that the incidence observed in the study applies to half of the unreturned cards, assuming no incidence of transition among the remaining half of unobserved cases. The rationale for the assumption is that a larger proportion of missing notification cards are negative (i.e. those reporting no cases that month) given that it is more likely that people will fail to submit a nil return than a positive return. This assumption translates to a correction coefficient derived from the calculation (half of unreturned cards + percentage returned cards)/percentage of returned cards.

-

Assumption 2 considers that the incidence observed in the study applies to all unreturned cards, assuming that all unreturned notification cards follow the same pattern of yes/no responses as those notification cards already received. This assumption translates to a correction coefficient (100/percentage unreturned cards).

-

-

Correction for unreturned baseline questionnaires. To account for incidence among the unreturned baseline questionnaires, a correction coefficient calculated from the return rate for baseline questionnaires (100/percentage returned baseline questionnaires) was applied. The two correction coefficients described above were combined in the following adjusted rates:

-

Adjusted incidence rate 1 –

-

= observed incidence rate × correction for unreturned notification cards (assumption 1) × correction for unreturned baseline questionnaires

-

this estimate applied the study observed incidence rate to half of all missing cases owing to unreturned notification cards and to all unobserved data owing to unreturned baseline questionnaires.

-

-

Adjusted incidence rate 2 –

-

= observed incidence rate × correction for unreturned notification cards (assumption 2) × correction for unreturned baseline questionnaires

-

this estimate applied the study observed incidence rate to all missing cases due to unreturned notification cards and to all unobserved data due to unreturned baseline questionnaires.

-

The observed incidence rate and adjusted incidence rate 2 will provide a likely minimum to maximum range within which the actual rate is likely to fall.

Results

The results below are further described in a separate paper. 95 The mean response rate to the monthly cards was 94% in BPSU and 53% in CAPSS. In total, there were 614 notifications reported by clinicians, all of whom were sent a baseline questionnaire. Table 3 illustrates the data responses for each stage of the surveillance study.

| Data obtained | BPSU (%) | CAPSS (%) | Combined (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | n = 314 | n = 300 | n = 614 |

| Not returned (error/reason) | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Not returned (no reason) | 13 | 42 | 27 |

| Returned baseline questionnaire | 76 | 46 | 61 |

| Duplicate cases | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ineligible cases | 11 | 9 | 10 |

| Eligible cases | 64 | 38 | 51 |

| Follow-up | n = 202 | n = 113 | n = 315 |

| Returned questionnaire | 80 | 76 | 78 |

| Not returned (error/reason) | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| Not returned (no reason) | 14 | 17 | 15 |

These response rates take into account any contact with clinicians resulting in an explanation for not returning the questionnaire, which included not remembering the patient, reporting the case in error or the clinician realising that the case did not meet the definition criteria. Some contact details provided by both surveillance organisations were out of date (n = 26), which prevented the research team being able to provide the clinician with the questionnaire. Questionnaires were returned blank (n = 7) or with missing data (n = 86), and anecdotally some clinicians reported that they struggled to find the time to complete the questionnaires (n = 17). Of the reported cases who were defined as ineligible for the study, 35% (BPSU) and 19% (CAPSS) became ineligible as they no longer took medication.

There was no overlap in cases reported through BPSU and CAPSS. The 13 duplicate cases identified were from clinicians who reported the same case more than once in the surveillance period. There were 17 questionnaires that could not be completed at follow-up, as the clinician either no longer had access to the medical records or no longer worked at the service. Some questionnaires at baseline and follow-up were returned blank or not completed in full (n = 86). The sections most frequently left blank at baseline were one or more of the plans regarding transition and, at follow-up, one or more of the elements of optimal transition (see questions 7.2, 7.3 and 7.1 of the questionnaires; see Report Supplementary Material 1–4).

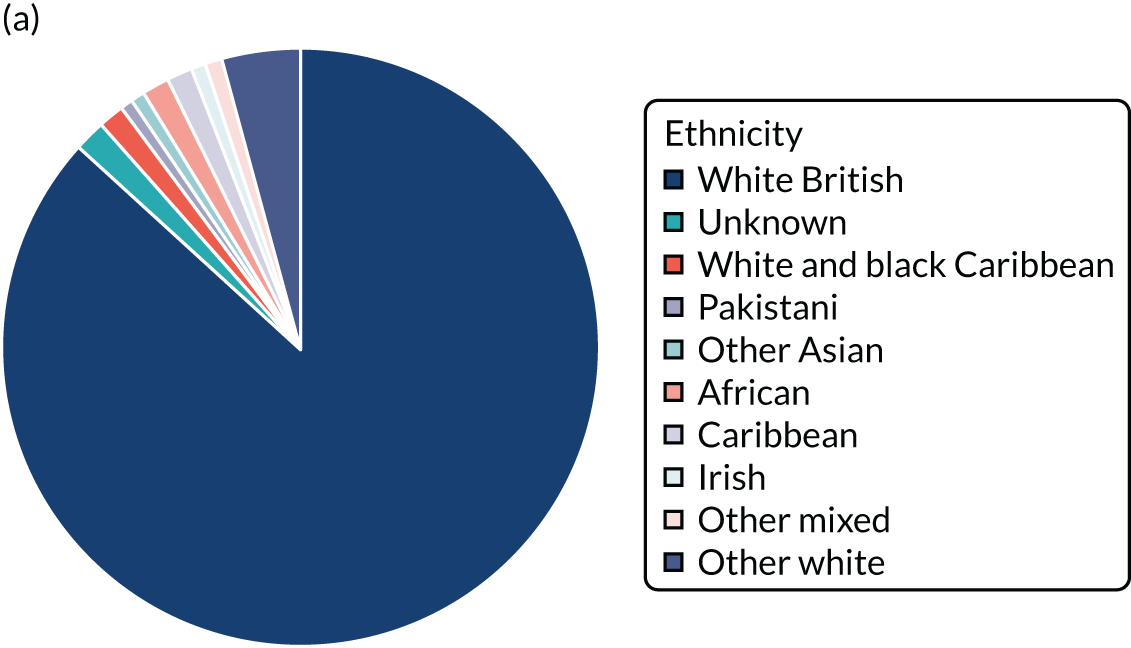

Characteristics of eligible young people reported

The population of young people reported via surveillance was largely male (80% of BPSU cases and 74% of CAPSS cases) and white British (91%), which would be expected from what is known about the epidemiology of ADHD in children and young people96 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Ethnicity of the population. (a) CAPSS; and (b) BPSU.

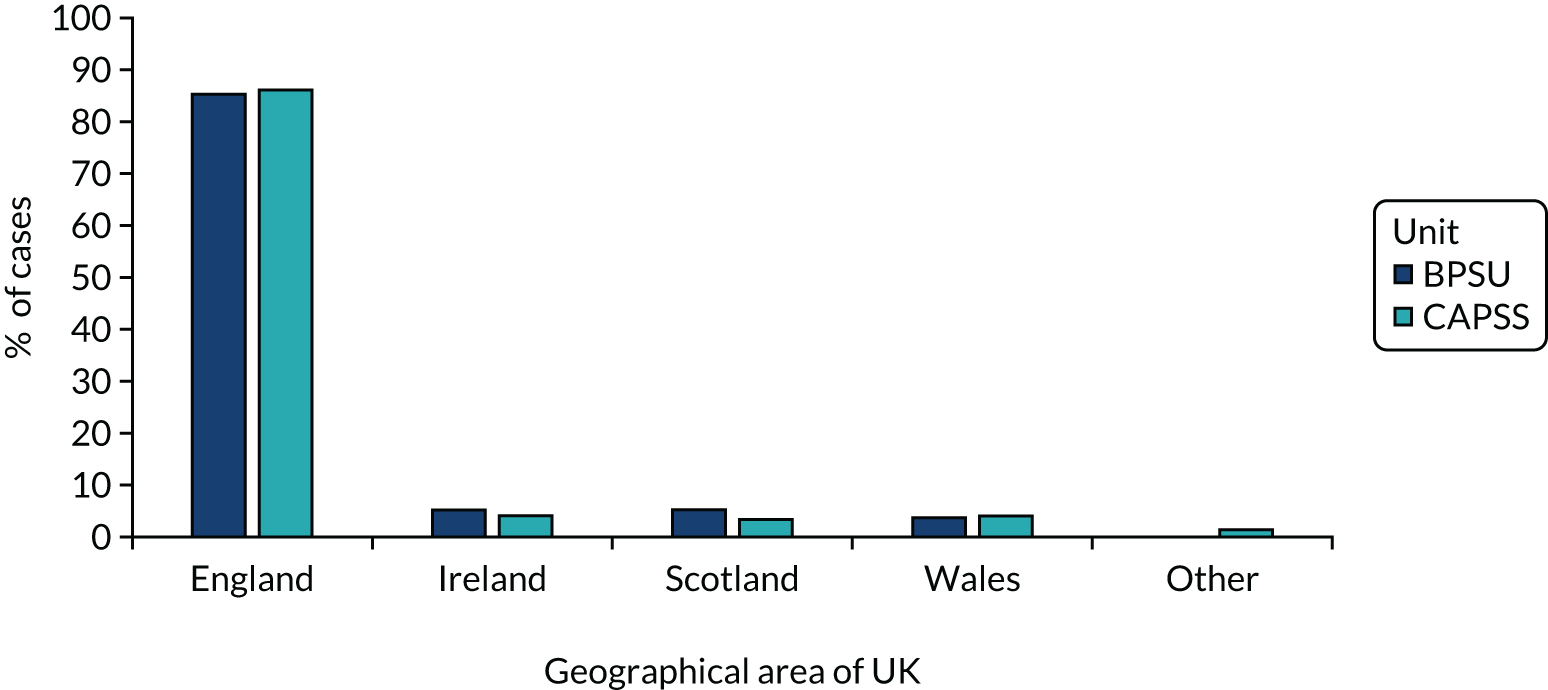

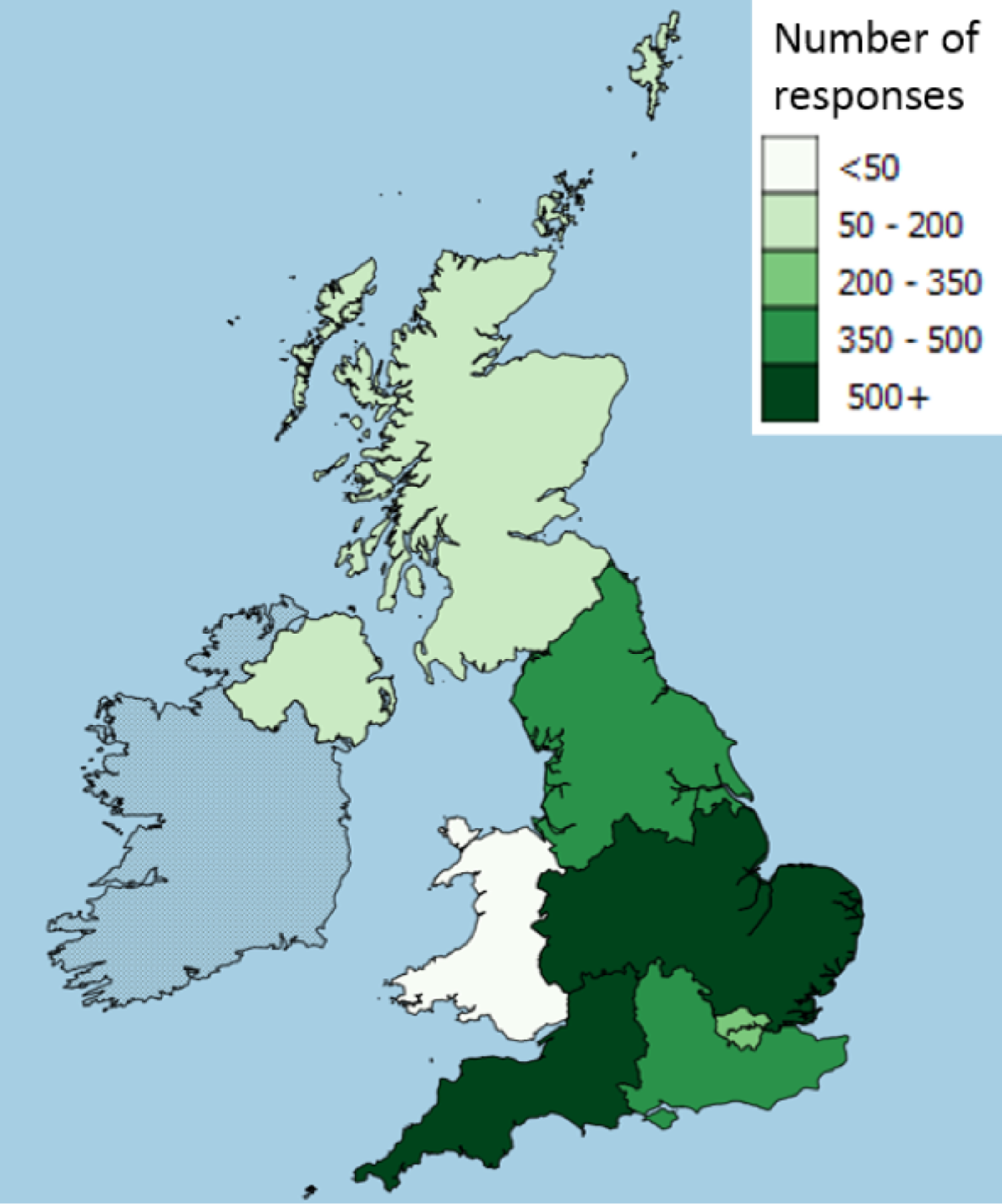

Cases were reported from across the UK, but, as would be expected, the majority (> 85%) were from England (Figure 5). All cases reported from Wales, Scotland or Ireland were identified as white British or white Irish.

FIGURE 5.

Geographical spread of cases in the UK. Owing to low numbers of reports, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland cases are reported together.

Table 4 shows the proportion of clinicians who reported the age boundary that their service works within, and Table 5 shows the range of the age boundary by country. Two cases originated from the USA, but were registered students who were seen in private practice in England. Over 80% of reported patients were aged 17 or 18 years at the point of referral for transition (mean age 17.4 years for BPSU, mean age 17.7 years for CAPSS), although the reported range extended from 14 to 20 years. A small percentage of clinicians (3%) stated that the age boundary for transition was variable. Paediatricians reported a more variable age boundary than child psychiatrists. Services in Wales, Scotland and Ireland appear to have more consistent age boundaries than services in England, perhaps as a result of the smaller administrative area covered.

| Age boundary | BPSU (%) | CAPSS (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 14 to 14 years 11 months | 0 | 1 |

| 15 to 15 years 11 months | 0.5 | 0 |

| 16 to 16 years 11 months | 12 | 0 |

| 17 to 17 years 11 months | 17 | 12 |

| 18 to 18 years 11 months | 63 | 83 |

| 19 to 19 years 11 months | 3 | 1 |

| Variable | 3 | 0 |

| Unknown | 2 | 3 |

| Country | BPSU | CAPSS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service age boundary 18 years (%) | Age range (years) | Service age boundary 18 years (%) | Age range (years) | |

| England | 62 | 15–19 | 82 | 14–19 |

| Ireland | 75 | 17–18 | 100 | – |

| Wales | 75 | 16–18 | 67 | 17–18 |

| Scotland | 80 | 16–19 | 100 | – |

A large proportion of patients (56% of those reported by paediatricians, 68% of those reported by psychiatrists) had a comorbid condition, which in 25% of cases was ASC. Nearly one-quarter (23%) of patients reported by paediatricians and over one-third (41%) reported by psychiatrists were prescribed more than one medication.

Transition details reported

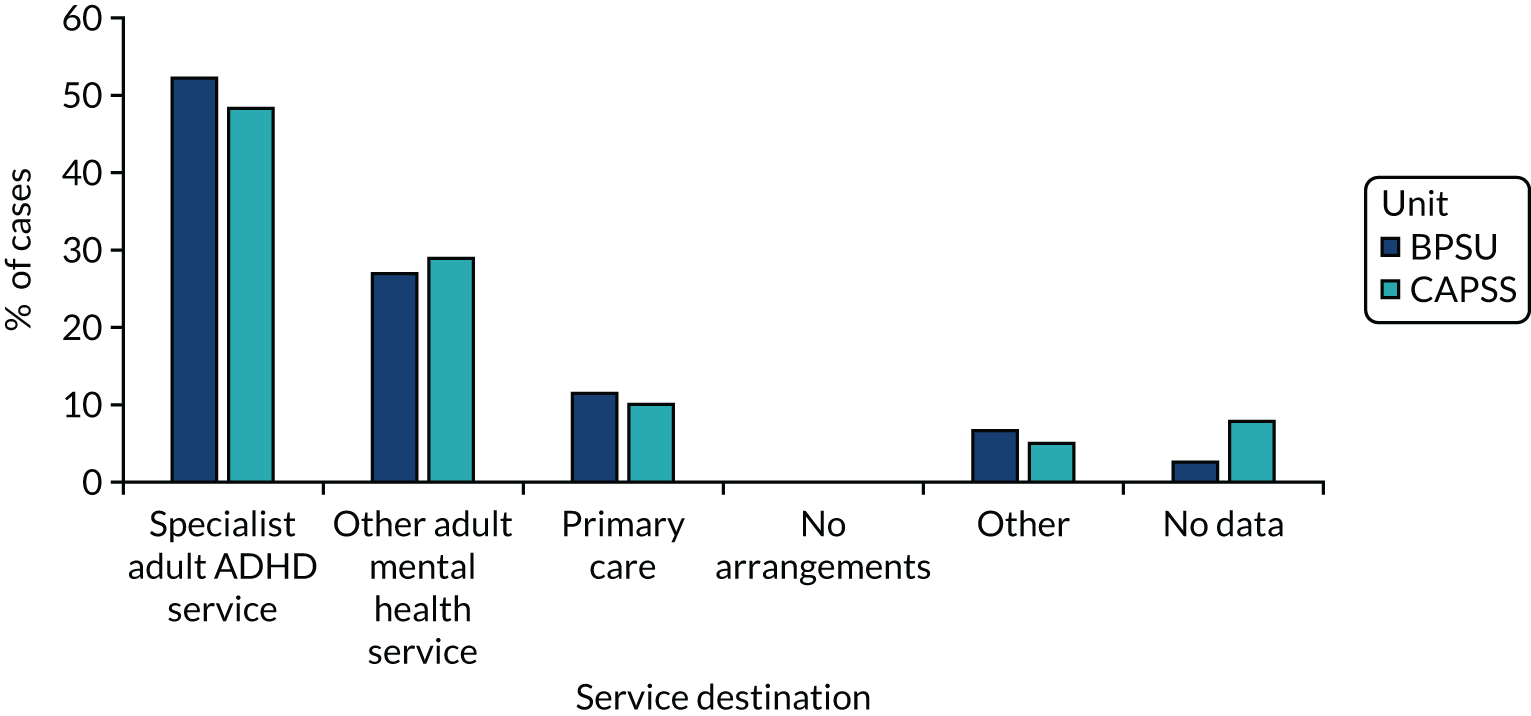

Figure 6 illustrates the range of services to which patients were referred half were referred to a specialist adult ADHD service, just over one-quarter were referred to general AMHS and 10% were referred to primary care. Referral destinations were similar regardless of whether the young person was reported by a paediatrician or a psychiatrist. In total, 64% of patients who were referred to an adult service were accepted (BPSU 52%, CAPSS 86%), but only 22% of those accepted were reported to have attended an appointment at AMHS (14% BPSU, 38% CAPSS). A number of clinicians provided extra free-text details about why transition failed, which included that the patient disengaged or did not want medication or referral, the patient did not meet service criteria, there was no funding available, and the adult service was closed to new referrals because of a lack of resources or long waiting lists.

FIGURE 6.

Transition referral destinations.

Nearly all clinicians reported that the patient had been involved in the planning of the transition process (93%), and > 80% reported that the parent or carer was also involved in the process. Access to and use of a transition protocol was reported more frequently by psychiatrists than paediatricians; psychiatrists reporting having access to a protocol in 81% of cases and using it in 66% of cases; the corresponding figures for paediatricians were 39% and 36%. There were nine elements of transition listed at follow-up, compared with five at baseline. At baseline notification, only 6% of paediatricians and 10% of psychiatrists indicated that all five listed criteria for optimal transition (as illustrated in Table 6) were apparent in the transition planning.

| Transition factor | BPSU (n = 202) | CAPSS (n = 113) | Combined (n = 315) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total ‘Yes’ response | % | Total ‘Yes’ response | % | Total ‘Yes’ response | % | |

| Information sharing | 176 | 87.1 | 93 | 82.3 | 269 | 84.6 |

| Young person involvement | 162 | 80.2 | 97 | 85.8 | 259 | 81.4 |

| Planning meeting | 23 | 11.4 | 29 | 25.7 | 52 | 16.3 |

| Plan and agree care plan | 49 | 24.3 | 46 | 40.7 | 95 | 29.9 |

| Handover period | 56 | 27.7 | 25 | 22.1 | 81 | 25.5 |

At follow-up, only 2% of paediatricians and 6% of psychiatrists considered all nine criteria of optimal transition to have been adhered to (Table 7). At follow-up, some elements of optimal transition were reported to occur significantly less frequently than they were at baseline. This suggests that the element had not actually been adhered to, or that the clinician could not recall whether it had been in place. These included information sharing (84.6% at baseline vs. 68.8% at follow-up), young person involvement (81.4% vs. 69.6%) and joint working/handover (25.5% vs. 10.5%).

| Transition factor | BPSU (n = 161) | CAPSS (n = 86) | Combined (n = 247) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total ‘Yes’ response | % | Total ‘Yes’ response | % | Total ‘Yes’ response | % | |

| User/carer involvement | 116 | 72 | 56 | 65.1 | 172 | 69.6 |

| Information sharing | 105 | 65.2 | 65 | 75.6 | 170 | 68.8 |

| Care plan agreed | 35 | 21.7 | 44 | 51.2 | 79 | 32.0 |

| Joint working before transfer | 12 | 7.5 | 14 | 16.3 | 26 | 10.5 |

| Alignment of assessment procedures | 9 | 5.6 | 12 | 14.1 | 21 | 8.5 |

| Continuity of care | 35 | 21.7 | 41 | 47.7 | 76 | 30.8 |

| Consistency of care | 13 | 8.1 | 36 | 41.9 | 49 | 19.8 |

| Consideration of appropriate service | 78 | 48.4 | 50 | 58.1 | 128 | 51.8 |

| Clarity of funding and eligibility | 66 | 41.1 | 51 | 59.3 | 117 | 47.4 |

Incidence of transition

A total of 315 reported patients were confirmed to be eligible for transition (202 BPSU, 113 CAPSS) during the surveillance period. A total of 55 transitions (22 BPSU, 33 CAPSS) were confirmed to be successful defined as a referral made, accepted and young person attended their first appointment in the adult service. The observed incidence rate and adjusted incidence rate 2 provide a likely minimum to maximum range within which the actual rate is likely to fall. Table 8 demonstrates the incidence calculations for all cases, and an adjusted version for those aged 17–19 years only [there were 46 eligible cases (32 BPSU, 14 CAPSS) who were not aged 17–19 years and, therefore, were not included in the adjusted incidence calculations].

| Description of incidence rate to be calculated | CAPSS | BPSU | Combined |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence: eligible for transition (all eligible patients identified in 12 months) per 100,000 per year | (113/116,651) × 100,000 = 96.9 | (202/116,651) × 100,000 = 173.2 | (315/116,651) × 100,000 = 270.0 |

| Incidence: successful transition (referral made, accepted and first appointment attended) per 100,000 per year | (33/116,651) × 100,000 = 28.3 | (22/116,651) × 100,000 = 18.9 | (55/116,651) × 100,000 = 47.1 |

| Observed incidence for people aged 17–19 years only | |||

| Incidence: eligible for transition aged 17–19 (all eligible patients aged 17–19 years identified in 12 months) per 100,000 per year | (99/116,651) × 100,000 = 84.9 | (170/116,651) × 100,000 = 145.7 | (269/116,651) × 100,000 = 230.6 |

| Incidence: successful transition aged 17–19 years (referral made, accepted and first appointment attended) per 100,000 per year | (31/116,651) × 100,000 = 26.6 | (20/116,651) × 100,000 = 17.1 | (51/116,651) × 100,000 = 43.7 |

| Correction for non-returned notification cards | |||

| Returned | 53.2% | 94.2% | 73.7% |

| No response | 46.8% | 5.8% | 26.3% |

| Assumption 1 (the same incidence applies to half non-returned) | (23.4 + 46.8)/53.2 = coefficient 1.32 | (2.9 + 5.8)/94.2 = coefficient 0.09 | (13.2 + 26.3)/73.7 = coefficient 0.54 |

| Assumption 2 (the same incidence applies to all non-returned) | 100/53.2 = coefficient 1.88 | 100/94.2 = coefficient 1.06 | 100/73.7 = 1.36 |

| Correction for non-returned baseline questionnaires | |||

| Returned | 139/300 = 46.3% 100/46.3 = coefficient 2.15 | 238/314 = 75.7% 100/75.7 = coefficient 1.32 | 377/614 = 61.4% 100/61.4 = coefficient 1.63 |

| Combined coefficients | |||

| Adjusted incidence rate 1 = incidence rate × correction for unreturned notification cards (assumption 1) × correction for unreturned baseline questionnaires |

Eligible for transition: 96.9 × 1.32 × 2.15 = 275.0 Successful transition: 28.3 × 1.32 × 2.15 = 80.3 |

Eligible for transition: 173.2 × 0.09 × 1.32 = 20.6 Successful transition: 18.9 × 0.09 × 1.32 = 2.2 |

Eligible for transition: 270.0 × 0.54 × 1.63 = 243.8 Successful transition: 47.1 × 0.54 × 1.63 = 41.5 |

| Adjusted incidence rate 2 = incidence rate × correction for unreturned notification cards (assumption 2) × correction for unreturned baseline questionnaires |

Eligible for transition: 96.9 × 1.88 × 2.15 = 391.7 Successful transition: 28.3 × 1.88 × 2.15 = 114.4 |

Eligible for transition: 173.2 × 1.06 × 1.32 = 242.3 Successful transition: 18.9 × 1.06 × 1.32 = 21.3 |

Eligible for transition: 270.0 × 1.36 × 1.63 = 598.5 Successful transition: 47.1 × 1.36 × 1.63 = 104.4 |

| Combined coefficients for people aged 17–19 years only | |||

| Adjusted incidence rate 1 = incidence rate × correction for unreturned notification cards (assumption 1) × correction for unreturned baseline questionnaires |

Eligible for transition: 84.9 × 1.32 × 2.15 = 240.9 Successful transition: 26.6 × 1.32 × 2.15 = 75.5 |

Eligible for transition: 145.7 × 0.09 × 1.32 = 17.3 Successful transition: 17.1 × 0.09 × 1.32 = 2.0 |

Eligible for transition: 230.6 × 0.54 × 1.63 = 202.9 Successful transition: 43.7 × 0.54 × 1.63 = 38.5 |

| Adjusted incidence rate 2 = incidence rate × correction for unreturned notification cards (assumption 2) × correction for unreturned baseline questionnaires |

Eligible for transition: 84.9 × 1.88 × 2.15 = 343.2 Successful transition: 26.6 × 1.88 × 2.15 = 107.5 |

Eligible for transition: 145.7 × 1.06 × 1.32 = 203.9 Successful transition: 17.1 × 1.06 × 1.32 = 23.9 |

Eligible for transition: 230.6 × 1.36 × 1.63 = 511.2 Successful transition: 43.7 × 1.36 × 1.63 = 96.9 |

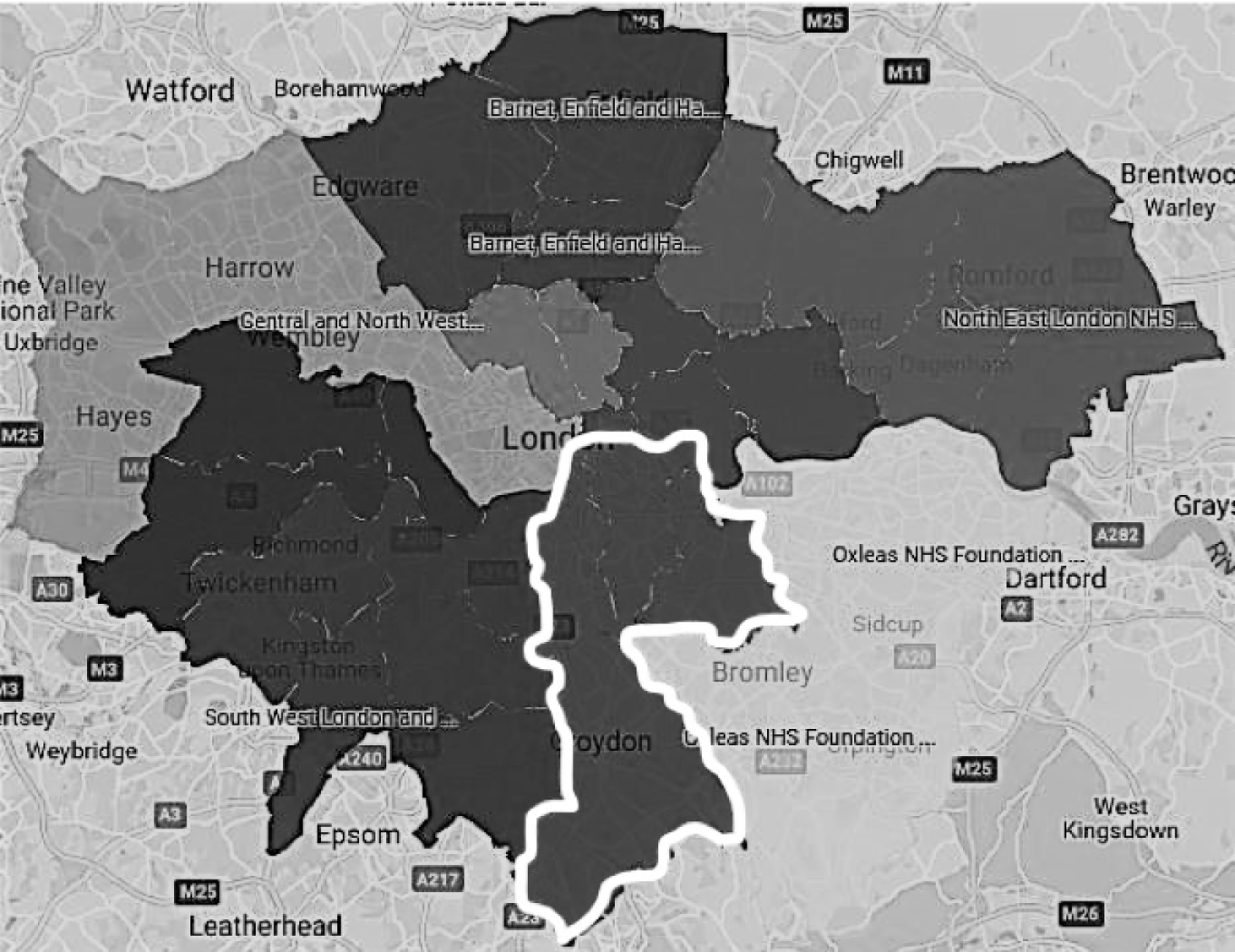

Data validation results

In total, 91 people with a clinical diagnosis of ADHD who were within 6 months of the service age boundary and, therefore, potentially eligible for transition were identified in the search of SLaM case notes. However, 15 people were discharged prior to transition or were no longer taking medication or requiring treatment, leaving 76 people eligible for transition according to our definition. The London CAPSS identified 45 notified cases, 18 of which were confirmed eligible cases. However SLaM, and thus CRIS, is only one of nine mental health trusts in London, which covers 7 out of 32 London boroughs. 97 CAPSS encompasses all of the London boroughs in this example. Figure 7 demonstrates the SLaM boundary in the rest of London. Table 9 shows a comparison between the CAPSS and CRIS data.

FIGURE 7.

London Mental Health NHS Trust boundaries (SLaM highlighted). Reproduced with permission from https://myhealth.london.nhs.uk98

The ratio of male to female was similar in both sets of data (83%: 17% surveillance; 84%: 16% CRIS); however, ethnic diversity was much greater in the CRIS sample (46% white British compared with 72% white British in CAPSS), which more closely reflects the ethnicity seen in the London boroughs served by SLaM. 99 Approximately half (54%) of the 76 eligible CRIS cases were seen by a consultant psychiatrist, which probably explains much of the disparity in reports of transition cases. The remaining young people were seen by a range of clinicians that included specialist ADHD nurses, junior doctors or clinical psychology trainees. Evidence in the case notes of a completed transition (referral made, accepted and first appointment attended in AMHS) could be found for only 37% (28) of cases in CRIS compared with 22% (4) of cases in CAPSS.

| Factor | CAPSS | CRIS |

|---|---|---|

| Notifications/identified cases (n) | 45 | 91 |

| Did not meet eligibility criteria (n) | 27 | 15 |

| Met all eligibility criteria (n) | 18 | 76 |

| Eligible cases only | ||

| Gender ratio (male % : female %) | 83 : 17 | 84 : 16 |

| Ethnicity (% white British) | 72 | 46 |

| Reported/reviewed by consultant (n) | 18 | 41 |

| Reported/reviewed by other health professional (n) | 0 | 35 |

| Transition referral made, accepted and first appointment offered in adult service (n) | 10 | 37 |

| First appointment confirmed attended (n) | 4 | 28 |

In total, 76 patients reported by CRIS were potentially eligible for transition, 28 of whom were confirmed to have been referred, accepted and attended the first appointment in the adult service. When compared with CAPSS (see Table 9), this validation exercise suggests that the surveillance study figures are likely to have been significantly under-reported; four times as many more eligible cases and seven times more successful transitions were identified via CRIS than CAPSS in the London area.

The same method of calculating incidence rate as used for the surveillance study data was applied to the CRIS data. The population at risk was calculated from the total number of young people aged 17–19 years in the area served by SLaM, as reported in 2016 (n = 40,382). 93 The same ADHD prevalence estimate of 5%29 was applied, resulting in a population at risk of 2019 young people. This results in an incidence rate for eligibility for transition of 3764.3 per 100,000 young people with ADHD; approximately one-third [36% or 1386.8 per 100,000; (28/2019) × 100,000] of transitions were successful. In contrast, the ratio of successful to eligible transitions from the surveillance data was only 17%.

Discussion

Our data suggest that the minimum annual need for young adults with ADHD to transition to adult services for ongoing medication would lie between 270.0 and 598.5 per 100,000 people aged 17–19 years. This amounts to 96.9–391.7 per 100,000 people aged 17–19 years among CAMHS attenders and 173.2–242.3 per 100,000 people aged 17–19 years from paediatric services. These data provide the current best estimate into early adulthood for commissioners and service providers to consider. It is important to note that even the upper estimate is likely to significantly underestimate the level of need according to our triangulation with the CRIS data, which suggested that the upper limit could be as many as 3764.3 per 100,000 young people. As a centre of excellence, SLaM have much more highly developed national and local ADHD services for both children and adults than most areas. We, therefore, consider the surveillance data to provide more reliable national estimates of current service-driven levels of need, but suspect that many more children and adults may remain undetected in the wider community. Moreover, these figures relate only to those who require and are willing to take medication for their ADHD, and thus excludes those who do not want or cannot tolerate medication but require ongoing care.