Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/45/22. The contractual start date was in September 2018. The final report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in November 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Law et al. This work was produced by Law et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Law et al.

Chapter 1 Context

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Law et al. 1,2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

In the 2011 census of England and Wales, nearly one in five people (17.9%) in England and Wales reported having a disability that limited their daily activities. 3 Furthermore, approximately 25% of people with one long-term condition reported having ‘problems walking about’ and ‘problems performing usual activities’; this figure rises to > 60% among people with three or more long-term conditions. 4 In 2016, 24% of men and 31% of women in England aged ≥ 65 years needed help with at least one ‘activity of daily living’ (ADL). 5 The global estimate of disability is approximately 15% of the world’s population, and this figure is rising due to population ageing and the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases. 6

Long-term conditions (also called chronic diseases) are the most common cause of disability in the UK. 4 A long-term condition has been defined as one that cannot currently be cured but can be controlled using medication and other therapies. 7 Examples of long-term conditions are hypertension, coronary heart disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, depression, chronic kidney disease and osteoarthritis. In 2019 in the UK, > 18 million adults (i.e. aged ≥ 18 years) had a long-term condition (i.e. 38% of the total adult population). 8 Long-term conditions constitute the biggest burden on the NHS, being the reason for more than half of all general practitioner (GP) consultations, 65% of outpatient visits and 70% of inpatient bed-days. 4 The prevalence of long-term conditions rises with age, affecting 50% of people aged > 50 years and 80% aged > 65 years. 8 In particular, older populations often have more than one condition (multimorbidity) and, as the population ages, the number of people with two or more conditions is projected to increase. 9 As older people accumulate more long-term conditions, they can also become increasingly frail. This is a consequence of accumulated age-related defects in different physiological systems,10 with frail older adults at the highest risk of adverse outcomes such as falls, disability, admission to hospital and the need for long-term care. 11,12 Treatment and care for people with long-term conditions is estimated to account for around £7 in every £10 of total health and social care expenditure. 4 This increasing prevalence of long-term conditions is one of the biggest challenges facing our health and social care systems. 4

Physical functioning

Physical capability, a concept also referred to as ‘physical functioning’, is a term used to describe an individual’s capacity to undertake the physical tasks of everyday living. 13 Poor physical functioning is associated with negative outcomes, including higher risk of 30-day hospital re-admission,14 increased morbidity and mortality15,16 and long-term disability. 12,17 Multimorbidity predicts future functional decline, which is more marked with increasing numbers of conditions and with condition severity. 18 Worsening physical function also affects older adults with long-term conditions in terms of health and independence, and may have an impact on how they perceive their overall health and symptom management. 19 Thus, physical function is one of the most important factors in quality of life among older adults,19,20 and optimising and preserving physical functioning should be a central goal for all people with long-term conditions. Increasing awareness about the important relationship between physical function and overall health status is likely to lead to improvement in care for people with long-term conditions. 21,22

Physical activity

A different, but related, concept is physical activity, defined as ‘any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure’. 23 ‘Physical activity’ refers to what one actually does (i.e. a behaviour), rather than just the capacity to do something. Habitual performance of at least minimal levels of recommended physical activity is important for preventing and managing long-term conditions, with positive effects comparable to those from optimal medication. 24 Previous studies of middle-aged and older adults show that more physically active people have better levels of physical functioning. 13,25–28 Indeed, physical inactivity, or sedentarism, is one of the strongest predictors of physical disability in older people. 29,30 The proposed process behind this association is that physical activity helps to maintain muscle and cardiac function, improves gait, balance and mood, and subsequently prevents functional decline. 31–34 Moreover, regular physical activity prevents or improves conditions that underlie disability in older adults, including falls,35 hip fracture,36 cardiovascular disease,37 diabetes,38 obesity39 and frailty,40 with longitudinal studies suggesting that regular physical activity is associated with reduced mortality. 41 Several studies have also demonstrated the benefits of physical activity for psychosocial functional outcomes in older adults. 42–44

There are known benefits of physical activity for the management of long-term conditions and particularly for improving physical function. 40,45–50 Despite this evidence, the proportion of the adult population in England and Wales reporting moderate levels of physical activity (i.e. participating in moderate physical activity for at least 30 minutes, five times per week) was 66% in 2017/18,51 22% were classified as inactive (i.e. participating in < 30 minutes of physical activity per week), and increasing age associated with less physical activity. However, individuals overestimate the amount of physical activity they do in self-reported surveys and so the true situation is likely to be worse. For example, objective measurements of physical activity collected using accelerometery have demonstrated that only 6% of men and 4% of women meet the recommended activity guidelines, suggesting considerably lower levels of participation. 52

Levels of physical activity in people with long-term conditions are even lower, and an inverse association has been found between physical activity and multimorbidity. 53,54 The worldwide economic burden of physical inactivity has been estimated to be at least £51.5B per year55 and the estimated annual direct cost of physical inactivity to the NHS across the UK is £1.06B. 56 This is not just a UK issue, as the World Health Organization has the target of achieving a 10% reduction in physical inactivity by 2025. 57

Public Health England launched ‘One You’, the first nationwide campaign to address preventable disease in adults. This aimed to encourage people, particularly adults in middle age, to take control of their health by ‘moving more’ to enjoy significant benefits now and in later life. 58 In addition, the importance of physical activity and physical function was emphasised in the ‘Start Active, Stay Active’ report from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers on physical activity for health. 59 The variation in physical function that exists among people as they age was acknowledged and the report gave recommendations for groups of older adults with different functional status and activity needs, including the following:

-

People who are already active, through daily walking, an active job or engaging in regular recreational or sporting activity. This group may benefit from sustaining their current activity levels and potentially by increasing their general activity or introducing an additional activity to improve specific aspects of fitness or function.

-

People whose function is declining owing to low levels of activity and excessive sedentary time, who may have lost muscle strength, or are overweight but otherwise remain reasonably healthy. This is the largest group with a great deal to gain from changing behaviour, restoring function and preventing disease.

-

People who are frail or have very low physical or cognitive function, perhaps as a result of old age or long-term conditions such as arthritis and dementia. This group requires a therapeutic approach (e.g. falls prevention programmes) and many will be in residential care.

In Wales, the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 201560 put in place seven well-being goals, including ‘a heathier Wales’. A strategic aim of this policy is ‘to encourage more adults to be more active, more often, throughout life’.

The important role of primary care

In total, 90% of patient interaction with the NHS occurs in primary care and people with long-term conditions are in regular contact with primary care services. 7 The management of these conditions has been strongly influenced by the Quality and Outcomes Framework,61 which emphasises disease-centred outcomes and the recording of risk factors, such as blood pressure and body weight, rather than the assessment of physical activity and physical function. Although managing disease remains important, placing more emphasis on functional limitations, such as whether or not people can perform ADLs, has the potential to improve care for people with long-term conditions. Organisational interventions targeted on patient-specific difficulties (e.g. functional ability) appear to be more effective than generic interventions,62 especially when the intervention is more comprehensive and integrated into routine care. 63

Physical activity could be promoted in primary care by making physical activity an explicit element of regular behavioural risk factor screening, patient education and referral, as well as developing and maintaining strong links between primary care settings and local community-based opportunities. Patients can be referred from primary care to exercise referral schemes. 64 However, the effectiveness of these schemes is limited by low rates of recruitment and retention. 65 There are several possible reasons for this. First, the benefits of physical activity and fitness are poorly taught in medical education. 66 Second, referral to these schemes is not routine in primary care management of long-term conditions. Third, these gym-based schemes may appear irrelevant to people’s day-to-day lives. A different approach is warranted. Interventions could also be widened to include community care, as primary and community care are increasingly integrated. Further examples of areas for integration include social care, leisure services and the third sector.

International examples of importance include the ‘Exercise is Medicine’67 movement in the USA and the Canadian Chronic Care model, which takes the perspective that function is the ‘sixth vital sign’. 22 A multicomponent rehabilitation intervention including function-based individual assessment and action planning, rehabilitation self-management workshops, online self-assessment of function, and organisational capacity-building has been explored in a Canadian primary health-care setting. 21 This functional approach is different from the medical model of illness that focuses on the diagnosis, categorisation and medication of disease. 68 Rather, it concentrates on functional limitations, such as whether or not people can perform ADLs. 69 In addition, to improve care for people with long-term conditions, it has been suggested that there is a need to shift away from a reactive, disease-focused, fragmented model of care towards one that is proactive, holistic and preventative. 63 Similarly, the chronic care model, which has influenced health policy around the world, also stresses the need to transform health care for people with long-term conditions from a system that is largely reactive in responding mainly when a person is sick to one that is much more proactive and focuses on supporting patients to self-manage. 70

Systematic reviews and guidelines

Previous systematic reviews and guidelines have explored the effects of physical activity interventions in sedentary adults and people with multimorbidity, osteoarthritis, obesity and chronic pain in the primary care setting. 45,71,72 They have also explored barriers to and facilitators of physical activity and the effectiveness of different intervention ‘deliverers’. 73,74 However, although the links between physical activity and physical function are evident and the benefits of physical activity are clear, the best way for primary care to help people with long-term conditions increase physical activity is unclear.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the clinical assessment and management of multimorbidity recommend that functional assessments, such as objective measurement of gait speed and grip strength and subjective patient self-reported health status, should be used in primary care to assess frailty. 71 NICE has also issued guidelines for the prevention of frailty, disability and dementia in mid-life by increasing habitual physical activity. 75 NICE recommends that campaigns should promote the message that it is not inevitable for older people to experience sustained ill health, it is possible to reduce the risk and severity of dementia, disability and frailty, and, although it is better to make changes earlier in life, even changing behaviours in mid-life can bring about health gains. Moreover, NICE recommends that future research should focus on determining the most effective and cost-effective mid-life services and interventions, including how these can be delivered in a consistent and sustainable manner.

In summary, insufficient habitual physical activity levels are most apparent in those with long-term conditions. However, despite the benefits of physical activity for physical (and psychosocial) functioning and the regular contact with primary care for long-term condition management, primary care interventions to increase physical activity for people with long-term conditions are used in only a limited way in the UK NHS. Therefore, a better way for primary care to help reduce functional decline and promote physical activity is needed. 76 This includes a consideration of changes in the culture of primary care and an understanding that physical activity promotion is an important health promotion activity and long-term condition management, as well as having the tools available to assist the workforce and change behaviour.

Rationale for a realist approach

Optimising physical function and physical activity is likely to involve a complex intervention, drawing on a range of resources that activate different participant responses. 77 Therefore, a methodology that focuses on this complexity is required. A realist approach recognises how ‘patterning of social activities are brought about by the underlying mechanisms constituted by people’s reasoning, and the resources they are able to summon in a particular context’ (p. 220). 78

Realist methods examine the interplay between different contexts and mechanisms that underpin interventions in primary care to improve physical activity and physical function for people with long-term conditions, and how these different contexts and mechanisms lead to different outcomes.

The rationale for using realist synthesis, as opposed to a systematic non-realist review, is that through the identification of context, mechanism and outcome (CMO) configurations it provides a contextualised explanation of ‘what works, for whom, in what circumstances, in what respects and why’. 79 It has also been recommended that the research community should shift from designing and testing small-scale interventions to change individual behaviour towards expanding the evidence on strategies for translating, disseminating, implementing and scaling up effective policy and practice for physical activity promotion worldwide. 80 As increasing habitual physical activity plays an important role in maintaining and improving physical function, this synthesis considers these issues. It also explores the potential for a ‘culture shift’ in the focus of NHS general practice from a disease-centred approach, emphasising diagnosis, categorisation and medication, to one that promotes overall function and well-being.

A key part of realist synthesis is the interrogation of relevant theory-rich literature. However, realist evidence syntheses are also participatory in nature, drawing on the lived experiences of service users and professionals providing services to identify ‘nascent’ theories based on individual experiences. 78 To enable this, creative methods from the field of co-design were used to ensure that the views of all stakeholders were included and embedded in the review process. The co-produced theory and ideas from these stakeholders were fed back into the literature searches, refining the search criteria, adding an interpretative frame to interrogate the literature, and corroborating and refuting the evidence. The resulting theories then informed a co-design stage, during which they were refined and prioritised before being used to generate implications for service innovation and implementation. 1

Aims and objectives

-

To identify and produce a taxonomy of physical activity interventions that aim to reduce functional decline in people with long-term conditions managed in primary care.

-

To work with patients, health professionals and researchers to uncover the complexity associated with the range of physical activity interventions in primary care, and how they directly or indirectly affect the physical functioning of people with long-term conditions.

-

To identify the mechanisms through which interventions bring about functional improvements in people with long-term conditions, and the circumstances associated with the organisation and operation of the interventions in different primary care contexts.

-

To understand the potential impacts of these interventions across primary care and other settings, such as secondary health care and social care, paying attention to the conditions that influence how they operate.

-

To co-produce an evidence-based, theory-driven explanatory account in the form of refined programme theory to underpin and develop a new intervention through a co-design process with patients, health professionals and researchers. 1

Chapter 2 Methodology and theory-building stakeholder workshops

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Law et al. 1,2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

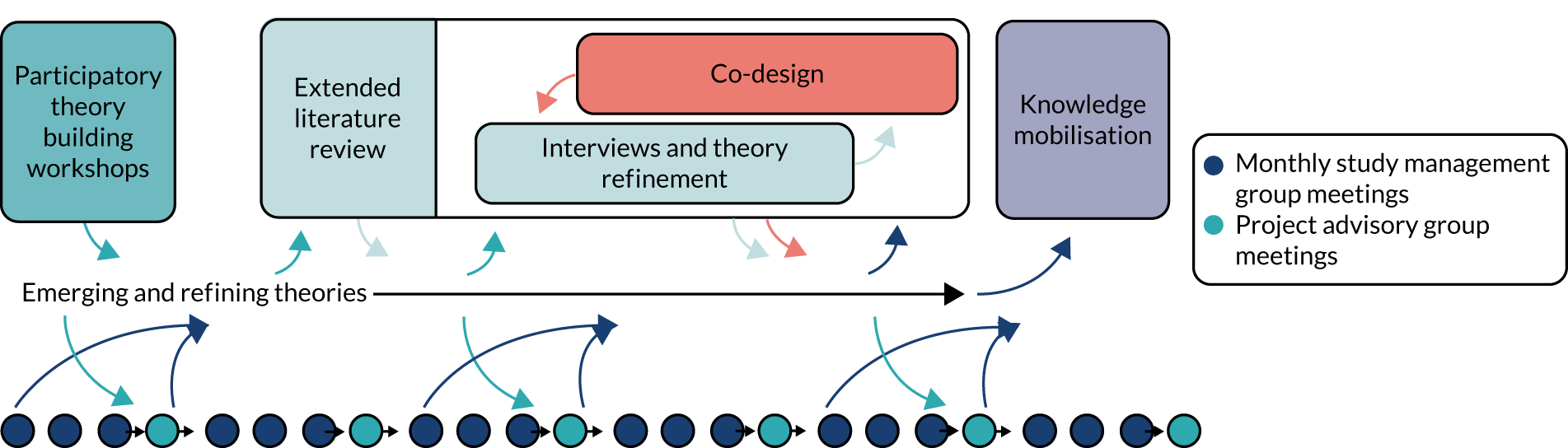

This project involved a realist synthesis of literature, with input from key stakeholders, public contributors and study management and advisory groups. Co-production was embedded throughout and included a co-design process where intervention ideas were developed. The process was iterative, with data sources informing each other as the synthesis progressed (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic showing the iterative, integrated flow of information throughout the synthesis. Arrows indicate how each element informed another. The Study Management Group and Project Advisory Group meetings continuously informed the synthesis throughout the life of the project, and both groups involved input from public members.

Co-production of the short title and acronym

Members of the study management group, including public research partners, worked together to develop the short title of the study ‘Function First’ and the strapline ‘Be Active, Stay Independent’. We first discussed project keywords and gathered suggestions to develop 11 options. The final version was chosen following a vote and subsequent discussion.

Summary of the overall methods

We used Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) methodological guidance and standards to inform our application of realist methods. 81

The first stage of the synthesis developed initial theories about how and why primary care interventions aiming to improve physical function and physical activity among patients with long-term conditions work (or may not work), for whom, and in which circumstances. These theories were developed through two theory-building stakeholder workshops and an early scoping search of published and grey literature. This phase informed theory development and literature searches by helping to develop a shared understanding of the key topic areas and stimulate initial ideas.

Following the theory-building workshops, a list of ‘if . . . then’ statements were created, and the search strategy and inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed and refined. The ‘if . . . then’ statements also formed part of the activities included in the first co-design workshop, where stakeholders took part in activities and games to familiarise themselves with the emerging ideas and match different statements.

After an initial sift of titles and abstracts, we refined our inclusion and exclusion criteria a second time and identified relevant systematic reviews. We created an evidence table to capture relevant realist critique from the systematic reviews. This evidence table and the ‘if . . . then’ statements were then used to develop eight emerging ‘theory areas’. To explore these theory areas, we then conducted 10 individual ‘theory-refining’ interviews with stakeholders. These theory areas were explored during the second co-design workshop, with stakeholders considering how particular intervention assets related to the theory areas.

Data were extracted from papers that were identified as rich and relevant to the eight theory areas, including individual qualitative and quantitative studies, guidelines and the grey literature. Through this process, and iterative discussion, we developed initial ‘candidate’ CMO statements. These were further refined and tested through the organisation of extracted information into evidence tables representing the different sources of evidence, including the individual stakeholder interviews. This enabled exploration of confirming or refuting evidence. We also developed a taxonomy of primary care physical activity interventions for people with long-term conditions.

The CMOs formed part of the final co-design and knowledge mobilisation workshops, where participants considered the emerging CMOs and how they were embodied within the co-designed resources. The ‘final’ five CMO statements were then defined, alongside the co-designed ‘Function First’ product.

As this was an iterative process, there were some changes to the original protocol, and these changes are outlined in more detail below.

Changes to the original proposal

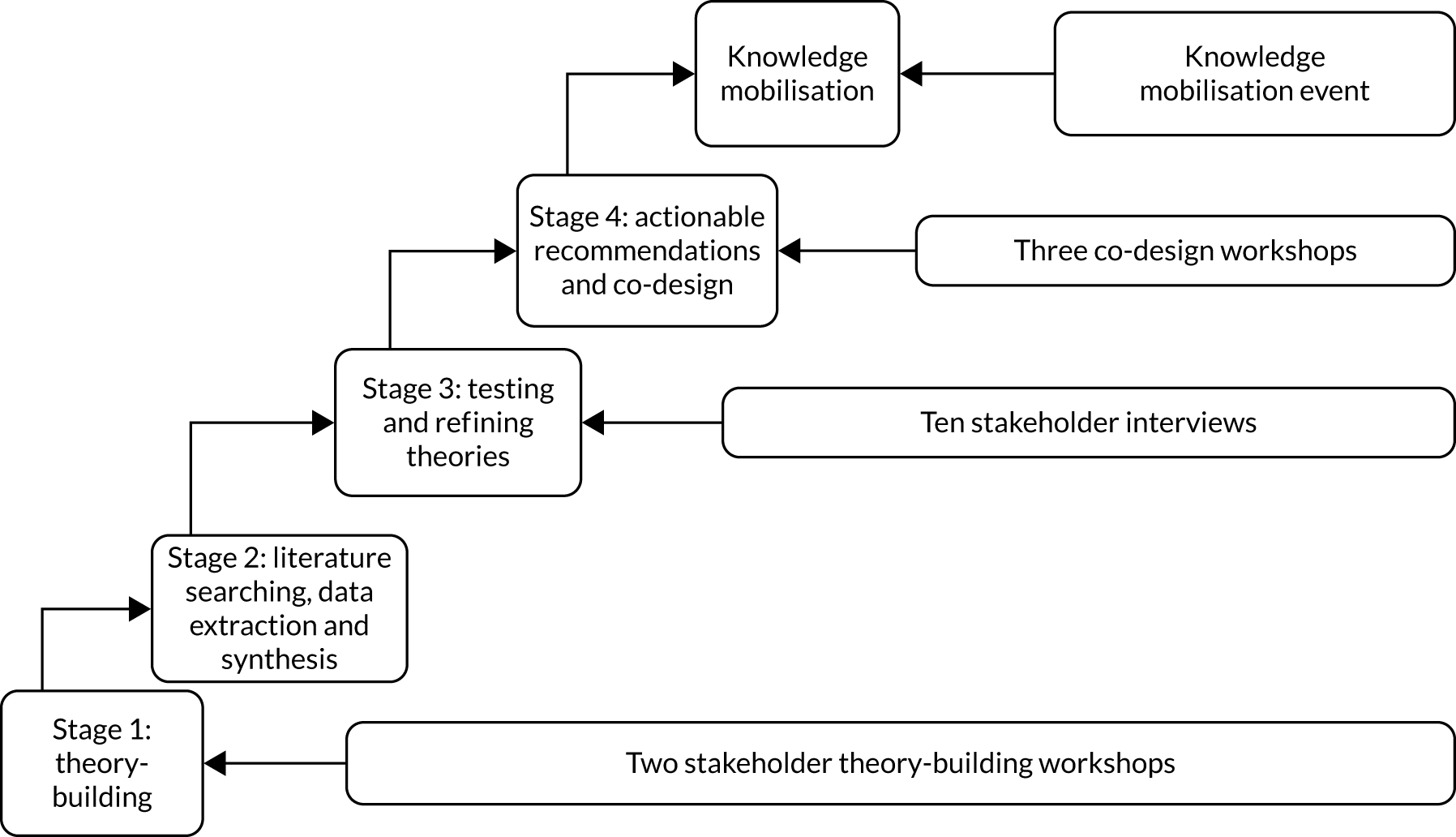

Figure 2 shows the original schematic of project progression.

FIGURE 2.

The original schematic of project stages. See Figure 1 for the actual process of project progression.

All elements of the protocol were completed as planned. However, there was more overlap in the stages than originally anticipated because of the large evidence base in the areas of physical activity, physical function and primary care for people with long-term conditions. This meant that:

-

We discussed emerging ‘theory areas’ with stakeholders in the theory-refining interviews, rather than conjectured CMO statements.

This was necessary to enable refinement of the key emerging theories and to avoid artificially ‘jumping ahead’ to CMO development. It allowed for a deeper understanding of the areas involved, strengthening the eventual theories developed.

-

The CMOs were not finalised before the first co-design workshops began and developed further as we progressed through the workshops.

The integration of CMO development with the co-design workshops was an unanticipated strength of the research process and meant that the refinement of the final CMOs benefited greatly from further stakeholder input, including suggestions for additional literature searches. In addition, the co-design process was not limited by a final set of CMO statements and was more authentic as a result. Chapter 6 discusses this further.

Data sources, analysis and synthesis

The data sources and how they were analysed and synthesised are described in the following sections. The realist synthesis of literature including stakeholder interviews, co-design workshops and knowledge mobilisation event are described in the Chapters 3 and 4.

Early scoping exercise of published and grey literature

To gain familiarity with the literature and aid with the identification of keywords, we carried out a preliminary scoping of the literature to retrieve reports, theses, key articles, systematic reviews and any relevant websites to help inform our formal search strategy. This scoping exercise was informed by previous work in this area,82–84 proposal work-up, early study management, and Project Advisory Group meetings and discussions with patient and public representatives.

Theoretical landscape

As part of the above scoping exercise and to stimulate early thinking about important areas, we identified the overarching theories and frameworks that we determined as likely to inform the realist synthesis. We drew from theories that address a wide social context including theories and models relating to physical function (e.g. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health69); environmental factors and individual compensation strategies;85 psychological theories of motivation, behaviour and behaviour change relevant to patients and health professionals (e.g. self-efficacy and self-determination theory,86,87 intention and behaviour,88 health beliefs, planned behaviour);89,90 interventions based around Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behaviour (COM-B) principles;91,92 and the self-regulation of illness,93,94 sociological theory (e.g. governmentality,95 habitus,96 social and peer support97,98); implementation theories (e.g. diffusion,99 knowledge to action100); and organisational theories relevant to how interventions fit into different ways of delivering services and pathways. 1,101,102

Stakeholder analysis

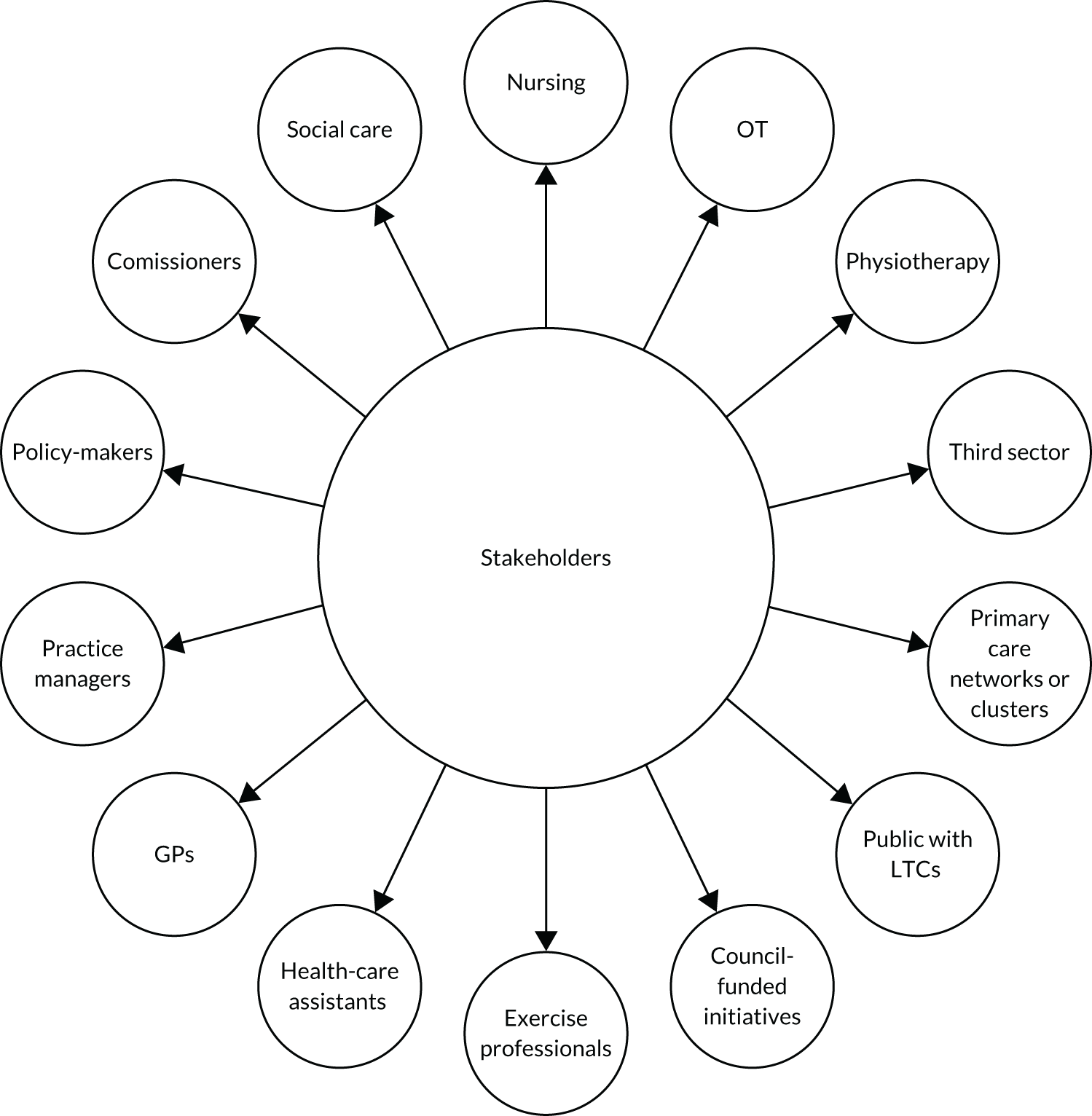

An initial stakeholder analysis helped us to identify and target the most relevant groups for the different stages of the synthesis. 103 It included representation from people with long-term conditions, primary care professionals working in general medical practices, allied health professionals, third-sector organisations, council-funded initiatives, social care, policy-makers and commissioners of services (Figure 3). The stakeholder analysis was used to ensure that no particularly important groups were missed. The stakeholder analysis took place across two or three study management meetings and one external Project Advisory Group meeting, and involved a process of feedback and iteration. This was consistently monitored, and care was taken to incorporate any missing perspectives. Researchers with knowledge and experience relevant to the syntheses were also identified as stakeholders as the project progressed.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of the stakeholder analysis. LTC, long-term condition; OT, occupational therapy.

Theory-building workshops

Data collection using LEGO® Serious Play®

Creative methods, borrowed from the field of co-design, were employed to structure the two theory-building workshops and elicit the views and experiences of all stakeholder representatives, including a facilitated session using LEGO® Serious Play® (LEGO, Billund, Denmark). This method has been used previously in service improvement work, training of health professionals, and research. 104–108 The specific choice to use LEGO Serious Play as opposed to other participatory approaches was because of the tangibility of working with LEGO. LEGO Serious Play enabled a move from ‘research’ activity into ‘co-design’ activity through making tangible outputs. By using these tangible forms, it set some expectations early on in the programme of work about the transition from intangible to tangible (i.e. from evidence to actionable tools). Participants who attended these two workshops are detailed in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Following a series of skills-building activities, each individual created and described LEGO models (physical metaphors) in response to the following questions: ‘What does physical function mean to you?’ and ‘What are your experiences of maintaining physical function?’.

Participants were encouraged to play with the LEGO as they considered the questions, connecting bricks while they thought. This gave the participants’ hands, and part of their mind, an occupation while they pondered the topic in question. What is built by the end of the reflective period then becomes a physical ‘tool’ that can be used to enhance the expression of those thoughts back to the wider group. We also asked participants to summarise their thoughts in three words written on a Post-it Note (Post-it® Brand; 3M, Cynthiana, KY, USA). As shown in Figure 4a, some participants chose to augment this communication further by using illustrations as well as their LEGO model. This demonstrates one of the core values behind the LEGO Serious Play methods; these media give people a greater opportunity for self-expression (using LEGO model plus verbal description) than the sole use of speech or writing.

FIGURE 4.

Example models built by participants in the theory-building workshops to reflect on and describe their interpretation of (a) what physical function meant to them; (b) how they maintained physical function; and (c) an example of a ‘shared landscape’.

This process helped to develop a shared understanding of the key topic areas and stimulate initial ideas and thoughts for theory development. It exposed researchers involved in the workshop to first-hand lived experiences of people with long-term conditions and professionals working in primary care. These LEGO models were then incorporated into a shared ‘landscape’ to explore which aspects of these experiences helped or hindered the maintenance of physical function (see Figure 4b).

As shown in Figure 4, photographics of the models were captured. Participant descriptions were audio-recorded and then transcribed for analysis and interpretation, and were used to shape emerging theories.

Data analysis workshop

The project team members convened for a face-to-face data analysis workshop to interpret the data gathered from the two LEGO Serious Play workshops. The data from the two workshops comprised anonymised transcripts from the audio-recordings of the workshop dialogue, images of the models, three-word text descriptors and images of the landscapes with annotations. The photograph of the LEGO model and the associated transcribed description were linked so that during the group analysis session it was possible to view the LEGO model and the description from each anonymised participant at the same time. This helped to bring the description in the transcript ‘to life’.

The models themselves served three functions:

-

Building these models aided reflection as people considered the question about their experiences.

-

The models were a tangible visual aid to assist people in their explanation of their reflections, or personal theories in their heads. Once their initial explanation was ‘out’, the explanation became refined through careful probing and ‘cross-examination’ by the facilitator until the explanation stood alone without the need of the model to ‘support’ it.

-

The models acted as a tangible representation for all participants in the workshop of each person’s theories.

The models were built in response to two specific questions; thus, the transcripts and images were divided into the relevant sections for each participant. This enabled consideration of the responses of each individual holistically and in depth. Researchers also returned to the transcription to understand the ‘full picture’ of the dialogue between participants, as it was the ‘connecting’ dialogue between participants’ responses that often illustrated how the threads of explanatory narratives were formed.

The transcripts and image models were divided between the project team members who identified any explanatory statements coming from the participants (see Report Supplementary Material 2). For example, statements that explained why they (or others they knew) had (or had not) done certain things, why some things had or had not happened, why health-care professionals had (or had not) done specific things. To gain familiarity with the process, the copies of the first two examples were shared among project team members who reviewed them together as ‘worked examples’. We discussed the statements that identified and moved towards a shared understanding of what we were all looking for.

In some instances, it was helpful to refer to the images of the individual models, the landscapes and annotations. However, there was common agreement that the annotations had often been stated ‘out loud’ and captured on the audio-recording, and the images of the models were limited in their usefulness. The images occasionally prompted a memory but were considered to be more useful in the moment of creation and immediate explanation (in the participatory theory-building workshops) rather than as a longitudinal record of the event for later analysis. We were seeking the theory in the heads of the stakeholders, and so we were reliant on their explanations. Therefore, the models could be defined as a data extraction tool (i.e. something to elicit the personal theories from stakeholders’ heads into forms that others could engage with). Once this was complete, the model no longer served a purpose as the recorded explanation formed the data. Moreover, the models themselves were not interpreted by the research team; it was the transcripts of participants’ explanations that were used to inform theory-building.

All explanatory statements were highlighted, discussed and compiled into a list of 28 ‘If . . . then . . .’ explanatory statements (see Report Supplementary Material 3). These nascent theories were used to identify early clues to possible ‘contexts’, ‘mechanisms’ and ‘outcomes’. The information from these workshops was then used to refine the literature searches and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For example, these workshops raised our awareness of the importance of studies detailing the wide range of barriers to and facilitators of physical activity and the implementation of interventions, as well as the range of community-based physical activity opportunities.

Chapter 3 Methods for realist synthesis of the literature

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Law et al. 1,2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Literature searching

We reviewed the existing literature to look for evidence that suggested how and for whom physical activity interventions work to optimise physical function in the primary care setting. As interventions or services based in other areas of literature (e.g. secondary care, social services, the voluntary sector, exercise science) also hold relevant insight for the development of the initial programme theories, searches were not restricted. A systematic search strategy was developed and amended for use with the following databases: Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycInfo® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA), Sociological Abstracts, Web of Science™ (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA; ProQuest®, ProQuest LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), Social Care Online and Social Care Institute for Excellence (see Report Supplementary Material 4). 1 Keywords were developed from the early scoping exercise and the key themes underpinning the initial programme theories were adapted for each information source as necessary. The searches were run in March 2019 and updated in 2020.

Our searches included adults of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds. We translated non-English-language papers where relevant and practical. We did not limit our searches by publication date and there was no restriction on the type of publication or study type. We examined published and unpublished literature including research articles, systematic reviews and documents detailing policy and local and national initiatives. We did not search for, or include, studies that had limited transferability to NHS primary care, such as interventions involving pharmacological agents or very technical, high-cost equipment.

Literature initially was screened for relevance to the initial programme theories and cross-checked by two members of the research team. To assist with this, articles were uploaded to Covidence (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) to complete the initial sift. This software enabled multiple members of the team to participate in the sifting out of irrelevant articles.

The review team then followed predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to remove irrelevant articles (see Report Supplementary Material 5). Thirty per cent of articles were reviewed by two members of the review team, with conflicts resolved through discussion between the two main reviewers and other members of the review team as necessary. As part of these discussions, study team meetings and following the initial theory-building workshops, we iteratively refined the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After this initial phase of double reviewing, the criteria were deemed sufficiently robust, and the remaining articles were reviewed by a single member of the review team. This resulted in a library of 2083 relevant papers. From that library, a purposive sample of 170 papers were selected for data extraction, chosen on the basis that they were the most relevant to the developing theory areas and gave the clearest and richest examples of evidence of interventions aimed at functional improvements in people with long-term conditions, and evidence of how these interventions are organised and operate with different primary care contexts. We supplemented the systematic search with forwards and backwards citation tracking of key articles. We also drew on the expertise of the project team, external Project Advisory Group, patient and public representatives, and other key researchers (nationally and internationally) and organisations to ensure that we did not miss any relevant evidence that may not have been retrieved by our traditional systematic searching methods.

We also carried out a grey literature search by targeting relevant organisations and programmes:

-

organisational websites of professional bodies (i.e. Royal College of General Practitioners, Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Nursing, Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, Royal College of Occupational Therapists, Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, Royal College of Surgeons, British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences and Royal College of Psychiatrists)

-

government departments and national centres (i.e. Public Health Wales, Public Health England, National Centre for Sport and Exercise Medicine, UK Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine, Sport England, Sport Wales and The King’s Fund)

-

specific organisations and charities for people with long-term conditions

-

Natural Resources Wales and National Parks England.

We also searched the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, NHS Evidence, Social Care Online and OpenGrey. In addition, we conducted an open web search for any grey literature (including from commercial leisure services). We used the grey literature sources to ensure that we had captured information about specific campaigns around physical activity for people with long-term conditions.

As previously described,109 unlike a traditional systematic review, a realist synthesis requires an iterative process for identifying literature. In addition to the systematic review of the literature, we also performed additional purposive searches enabling the initial programme theories developed in stage 1 to be expanded. The purposive searches were as follows:

-

Guidelines: MEDLINE was searched using specific physical function keywords (physical function* OR physical activity OR physical fitness or exercise) with guideline keywords (exp guideline/ OR Guideline$.ti OR (guideline or practice guideline).pt. We also manually checked the websites of major guideline producers: NICE, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, professional organisations, World Health Organization, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network and the National Guideline Clearinghouse.

-

Social prescribing: we carried out a MEDLINE search using the phrase ‘social prescribing’ and filtered for recent reviews. We followed up with forwards and backwards citation searching on those reviews and consulted with the project team for additional references.

-

Physical literacy: we carried out a MEDLINE search using the phrase ‘physical literacy’ and filtering for adults only. We also followed up with forwards and backwards citation searching on the papers identified and consulted with the project team.

Data extraction

Consistent with the realist synthesis approach,110 the test for inclusion was whether or not the evidence was ‘good and relevant enough’ to be included. 79 Relevance was defined as the ability of the data to contribute to the programme theory. 81 Assessment of relevance involved seeking any ‘trustworthy nuggets of information to contribute to the overall synthesis’ (p. 90). 111 For example, evidence-rich papers included detailed and reflective descriptions of what it was about interventions that worked (or not) (e.g. papers including qualitative or service evaluation elements), whereas less-rich papers provided limited in-depth description of the intervention and the factors influencing whether or not it worked (e.g. randomised controlled trials with mainly objective outcomes). Rigour or whether or not the quality of the evidence is ‘good enough’ was the research team’s judgement of the credibility of the data, including fidelity, trustworthiness and value. 82

Owing to the large data set, we adopted the following approach to data extraction:

-

We identified all of the systematic reviews and conducted a ‘realist critique’ of all those which were relevant to gather an overview of the evidence available. The realist critique consisted of brief notes describing what information the paper provided about what was working or what was not working to improve physical activity or physical function and why, for whom and in what settings. It enabled us to identify the rich systematic reviews and also increased our awareness of broader patterns in the emerging contexts, mechanisms and outcomes.

-

Using the information from this process and from the stakeholder work, we then developed eight theory areas.

-

To facilitate data extraction, we designed a bespoke data extraction form to ensure that we captured data informing the developing theory areas, including intervention details and any differences in implementation.

-

We then identified literature that was specific to primary care and used the bespoke data extraction form to capture relevant data (see Report Supplementary Material 6).

When discrepancies were encountered, the project team discussed whether or not the evidence provided met the criteria to be included.

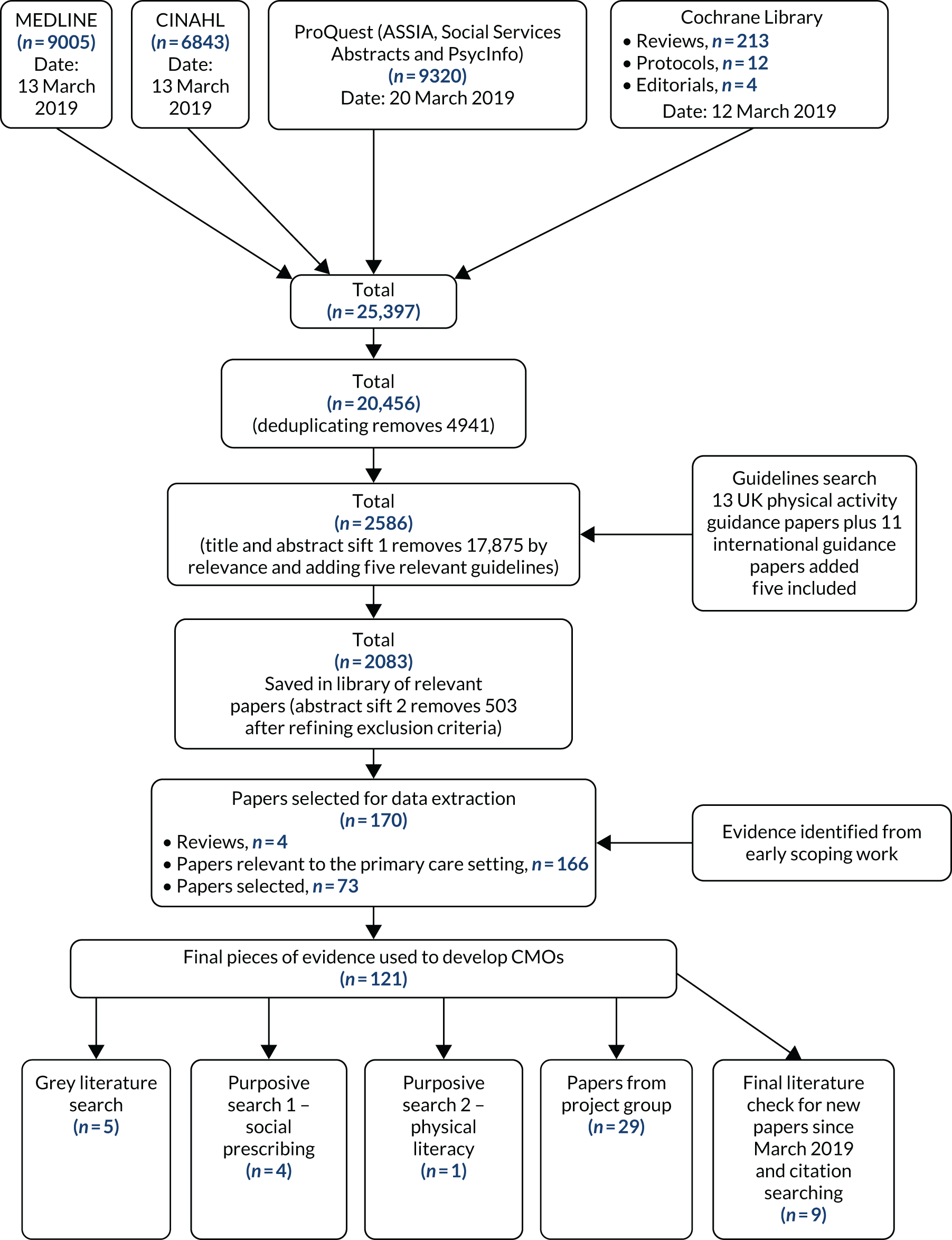

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of the synthesis, and details the number and type of papers identified, included and excluded (Figure 5). The list of final included papers is included in Report Supplementary Material 7.

FIGURE 5.

The PRISMA flow diagram detailing the flow of information through the different phases of the review and the purposive searches.

Theory-refining interviews

As part of the iterative process of refining final programme theories, we explored the developing theory areas with stakeholders through 10 qualitative telephone interviews. Purposive sampling of the stakeholders was informed by the stakeholder analysis to provide a range of perspectives, which included three people with long-term conditions, three GPs, two practice nurses, one health-care assistant and one researcher with a background in pedagogy. One of the people with a long-term condition and one of the GPs were also participants in a theory-building workshop. The researcher with a background in pedagogy also participated in a later co-design and knowledge mobilisation workshop.

A semistructured interview topic guide was used to elicit the views of stakeholders on their resonance with the developing theory areas. The approach used in the interviews was a ‘teacher–learner cycle’ whereby the researcher presented the developing theory areas to the stakeholder (‘teaching’) and then verified with the stakeholder where they needed adjusting (‘learning’) to create an improved, refined version and a ‘mutual understanding’ of the developing theories. 1,112

With permission, the telephone interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for descriptive analysis of the key themes, which contributed to refinement of the theories. 1 NVivo version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to organise the data. Coding linked the themes with the developing theories.

Synthesis of evidence from literature and interviews

This analytical stage involved synthesising the evidence to elicit relationships between the contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. Through the research team’s experience of conducting realist syntheses,82,108,113 suggestions from Pawson and Tilley,78 and underpinned by the principles of realist enquiry, we used the following approach:

-

organisation of extracted information into evidence tables representing the different bodies of evidence

-

developing themes across evidence tables in relation to emerging patterns among the developing programme theories to seek confirming or refuting evidence

-

linking patterns to develop hypotheses that support or refute the developing programme theories. 1

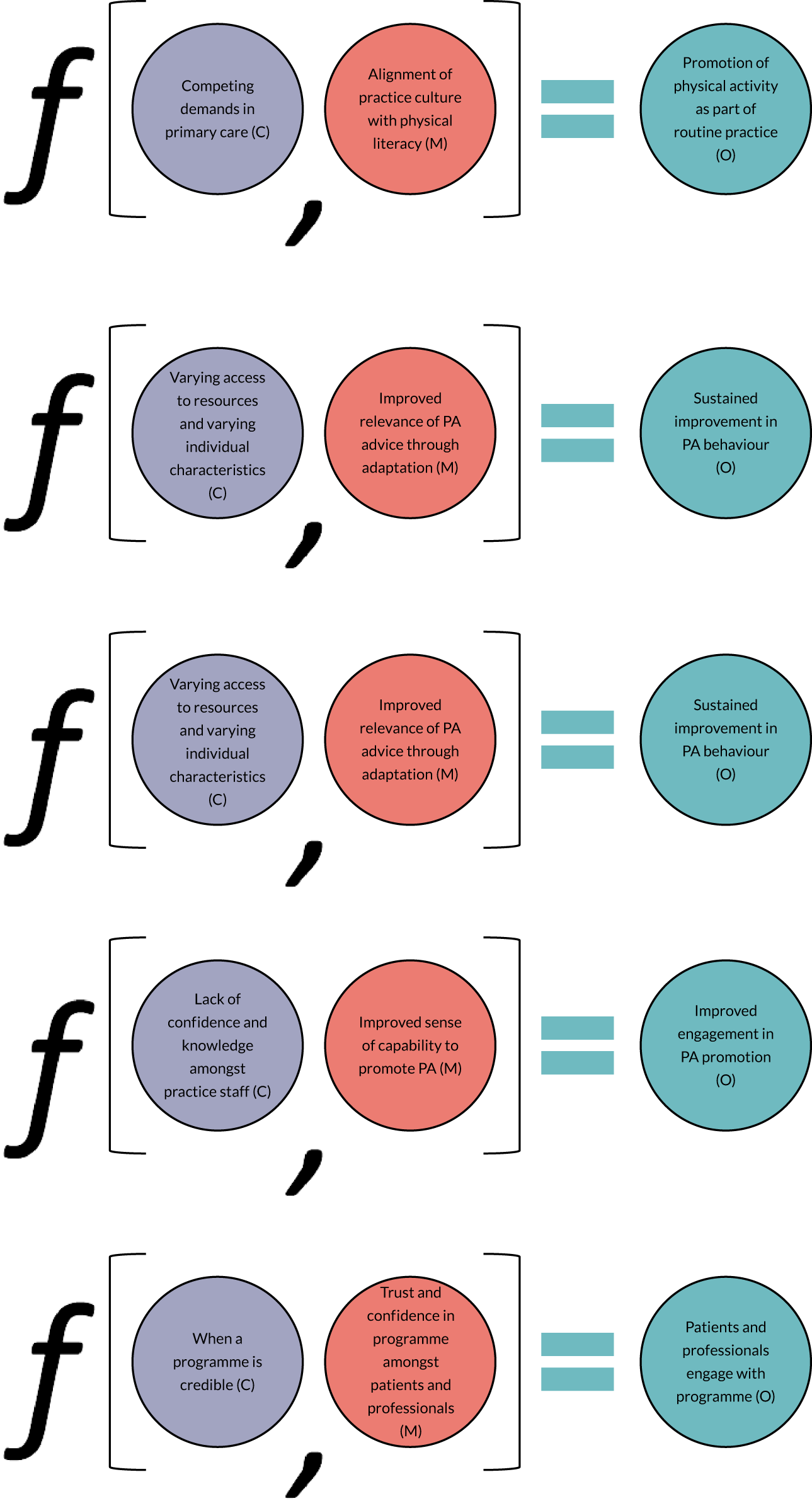

Three very early ‘conjectured’ CMO configurations focused primarily on early themes of primary care culture, providing advice adapted to individual circumstances, and the confidence and behaviour of primary care health professionals. We then developed two overarching CMOs with further explanatory subthemes based on the theory areas, covering organisational and system-wide influences, as well as influences affecting people with long-term conditions at an individual level. However, to clearly acknowledge the interactions between systemic and individual factors, and after incorporating additional evidence and discussion, we settled on five ‘final’ CMOs. These provided further nuance and depth to the initial CMOs and expanded on the area around credibility.

Following this process, a set of synthesised statements were written together with a narrative summarising the nature of the links between context, mechanism and outcome (i.e. what works, for whom and in what circumstances). This also summarised the evidence underpinning the statements (see Chapter 5). This process involved ongoing, iterative discussion among the project team members and the Project Advisory Group, which included public contributors.

Taxonomy

Alongside the evidence synthesis process, we developed a taxonomy of primary care physical activity interventions for people with long-term conditions, which categorised and provided examples of interventions in the following categories:

-

brief interventions

-

telephone interventions

-

online/‘eHealth’ interventions

-

exercise referral schemes

-

community navigators

-

referral to exercise specialists

-

intervention delivery by existing primary care staff

-

physical activity pathways

-

practice-wide initiatives

-

community initiatives

-

whole-system approaches to embed physical activity promotion in clinical practice

-

multifaceted interventions.

Chapter 4 Methods for co-design and knowledge mobilisation workshops

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Law et al. 1,2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

A team of design researchers facilitated three consecutive co-design workshops, involving purposively sampled stakeholders, which included people with long-term conditions; primary care clinicians such as GPs, nurses and therapists; practice managers; service delivery managers; commissioners; and researchers. As much as possible, the three co-design workshops included the same group of participants in each, so that ongoing ideas could be developed and expanded during each workshop. There were key ‘deliverables’ from each workshop and, between workshops, designers worked to develop ideas and provocations for the next workshop, termed ‘design activities’. Although described separately here, the content of these workshops was informed by the developing theory areas, facilitated development of the CMO configurations and eventually helped to refine the ‘final’ programme theories.

Participants

The participants at each workshop were key ‘data sources’ (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Public contributors had a range of long-term conditions including hypertension, previous stroke, cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Some professional contributors also described their own experiences of living with a long-term condition as well as providing care for someone with a long-term condition.

Workshop 1 (immersion)

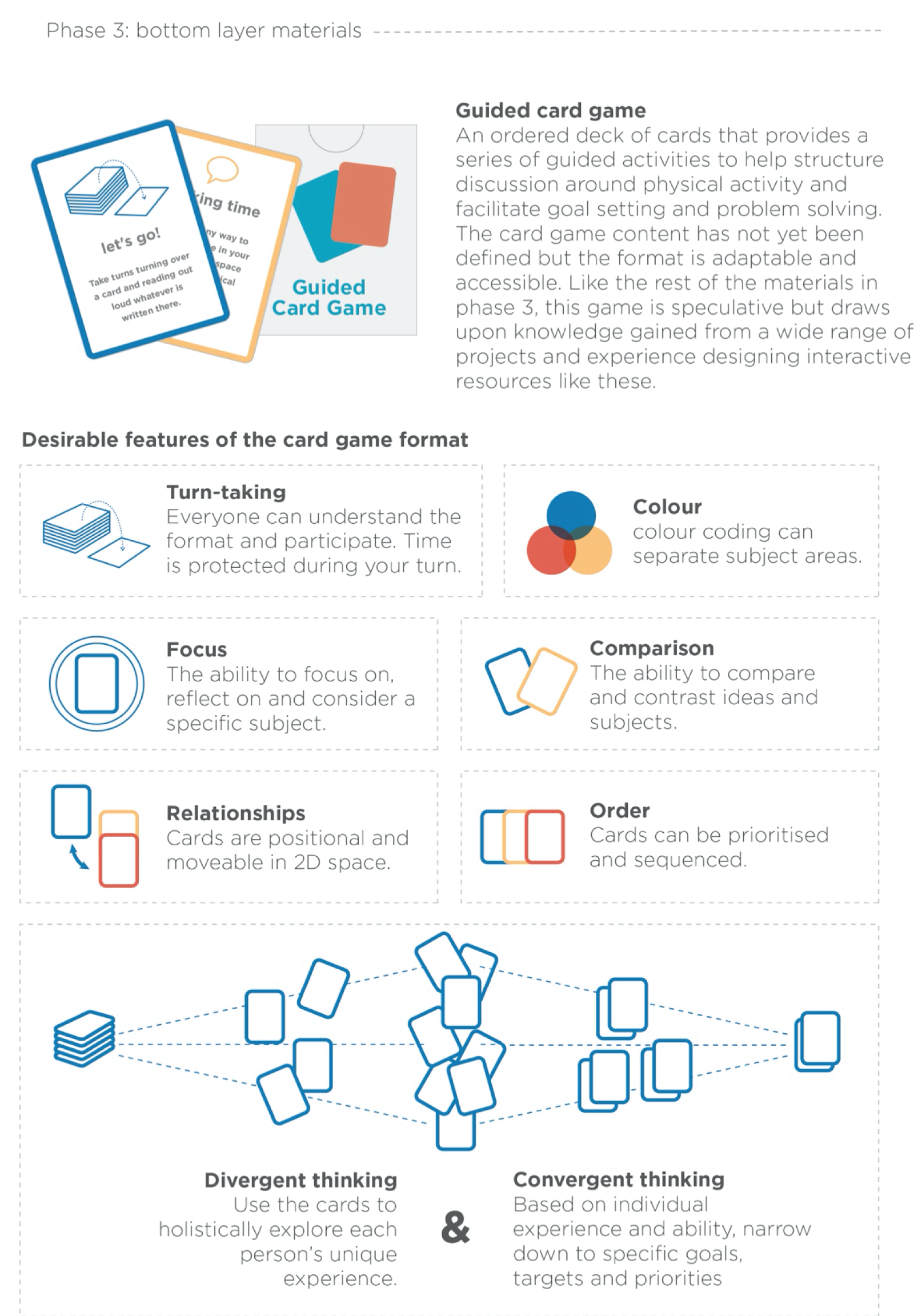

The first activities in this workshop were card games designed to enable participants (in three small mixed groups) to immerse themselves in the evidence and apply it to the context of their own experiences and beliefs, and those of their group peers. This was about developing a nascent, shared understanding based on the evidence available to the whole co-design group both from the literature review and from their own experience.

The two components of the ‘If . . . then’ statements were divided into two decks of cards. The three components of emergent CMOs were also divided into three decks of cards and the eight emergent theory areas were added as a separate deck of cards. The participants were divided into three groups, each containing a mix of project team members, people with long-term conditions, health-care professionals, service providers, managers and other researchers. The cards were shuffled and the participants in each group were challenged to find matching pairs or trios, and to critically reflect on the theory areas in the context of their own experiences. The format of this activity as a card game created an informal and equal environment. People took turns to draw cards, discuss them and then move on to the next ‘player’. This engaged everyone in the group without requiring reference to rules or formal facilitation by a leader. The cards themselves and the notion of this as a card game facilitated this process and supported the agency of all the participants, removing any perceived hierarchy in the group. The groups made their own notes, edited cards if they wished and added cards as they felt necessary (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Illustration of the ‘If . . . then’ card game (a) and sample images of the cards edited by participants (b, c).

The important thing with these card games was that they represented the wider evidence base and playing the game elicited critical discussion among the smaller groups about the evidence, enabling participants to make sense of it in the context of their own experiences and those of the other group members. The groups then shared their discussions with all the participants by selecting one issue arising from the ‘If . . . then’ card game that had created the most discussion in their group, followed by a general point about the discussion emerging from the CMO card game. These discussions were ‘captured’ by the facilitators on paper using flip charts (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Summary notes of the whole-group discussion about the evidence emerging from the literature, following the ‘If . . . then’ and CMO card games.

The next activity in this workshop was designed to get participants thinking about themselves and their individual experiences. They had to identify which CMOs would most support them to engage with physical activities, and which would discourage them. Figures 8a and 8b are examples of some of the personal profiles created by the participants. The ‘data’ from this activity was not essential for developing an intervention but helped the co-design participants to think about the practical application of this evidence to a wider variety of people and the challenges associated with this.

FIGURE 8.

Examples of the personal profiles created by the participants (a, b), an example of one of the personas (c) and suggested relevant CMOs for this ‘case’; and (d) a final group discussion presented the personas and the CMO combinations defined for each case.

To encourage participants to think about the practical application of this evidence to other people, they created archetype personas (two per subgroup). They constructed comprehensive, holistic ‘pictures’ of these people and then considered what might work, and what might not work (in terms of CMOs) for each individual to encourage them to maintain or improve their physical function. To do this, they created personas that were culturally, socially and geographically diverse (in urban and rural settings); built up comprehensive ‘pictures’ of the whole life of each persona; and considered what CMOs would be most relevant in enabling primary care services to support each persona to be active and maintain physical function. Figures 8c and 8d illustrate one persona and the suggested relevant CMOs for this ‘case’.

This was followed by a broad discussion reflecting on everything that had been considered in this first workshop. These discussions were captured on paper on wall and flip charts.

This final discussion opened up some important topics:

-

Ubiquitous or positive pervasive messaging – it is the responsibility of every health-care professional to have an understanding of the importance of physical activity, which should be discussed with patients in a consistent manner.

-

The stages or states of ‘readiness for change’ on the part of the patient. Different strategies or interventions may be required at different stages of readiness, which raised further points –

-

There was a need to think creatively about how to enable people to move from ‘not being ready to engage’ to ‘being ready to engage’.

-

How to identify that ‘key moment’ when someone is ready to change and receptive to help.

-

There was a pragmatic argument to invest more time, effort and resources into that moment.

-

There was a need to think very differently about how to sustain long-term engagement in any activity.

-

The need to personalise or tailor the intervention at a practice level for staff and also for patients.

-

It was acknowledged that the context varied for different workshop participants, so this workshop provided an opportunity for sense-checking as well as further refinement of the emerging theories. Giving everyone the same time and space to do this at the start respected and valued their history and personal narrative, enabling everyone to move towards the main purpose of the co-design process. The activities in these workshops did not contribute directly to the design and development of ‘an intervention’ per se, but were vital building blocks, creating a shared understanding of each other, and of the evidence, as well as raising awareness of potential challenges and opportunities for developing a practical set of resources.

Design activity 1

Between workshops 1 and 2 the designers created a visual summary of workshop 1 to add to the growing visual narrative of the whole research process (Figure 9). This visual summary was brought back to every workshop as a way of enabling participants to continually position the co-design activity in the context of the process and evidence of the research project to that point.

FIGURE 9.

Visual ‘storyboard’ of the function first co-design process. (See also Report Supplementary Material 8 for a larger version.)

The design researchers reflected on and categorised the data produced by the co-design partners in workshop 1, using this to refine and adapt the plan for the next workshop. They then designed and produced the templates, resources and visual wall displays for the next workshop. Some of these activities included an exploration of previous co-design work strategies for engaging co-design partners and a breadth of existing interventions and analogous practices for presentation at workshop 2 as provocations for new ideas. We also invited participants to bring examples of existing interventions or resources relating to existing interventions that they had experienced or had knowledge of.

Workshop 2 (ideation)

The ultimate goal of this workshop was to generate ideas of tangible things that might help primary care professionals enable people with long-term conditions to sustain and improve their function. Before being able to generate ideas, it was important to enable participants to consider the kinds of ‘assets’ that individuals, communities and primary care services might utilise to support this kind of work (e.g. people, places, services, media, knowledge or technology).

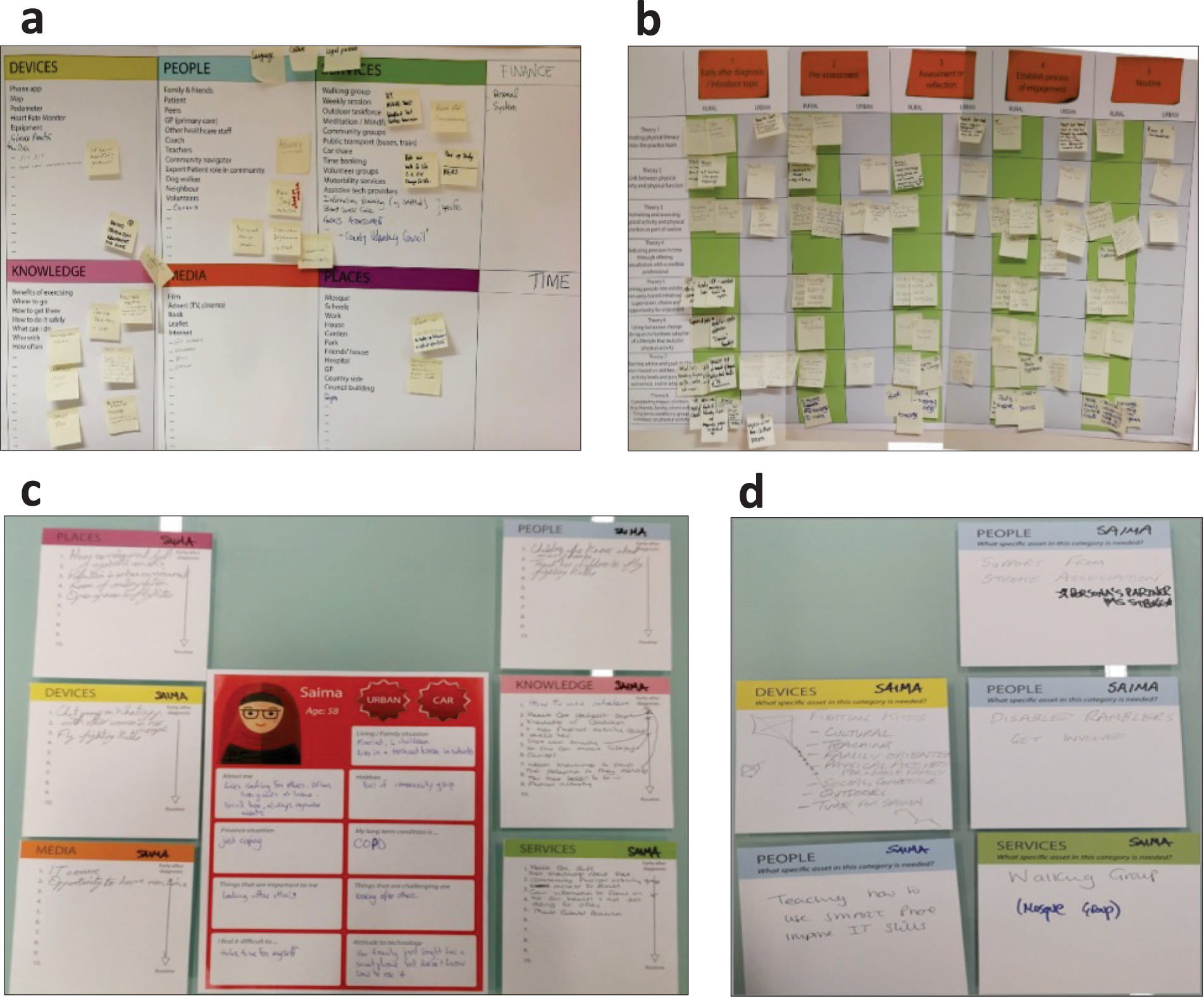

This began by drawing up a working list of potential assets that might be available to people (Figure 10a) and then thinking about how these assets might relate to the eight theory areas. The groups also considered how these assets may have greater (or lesser) utility at different stages of ‘readiness’ to engage in activities related to sustaining physical function (Figure 10b). The participants then returned to the personas that they had created in workshop 1 and listed all of the possible assets that may be relevant to each persona (Figure 10c), before developing a specific ‘package’ of assets that could be used for the persona over a period of time (Figure 10d).

FIGURE 10.

Images showing lists of (a) potential assets; (b) the potential utility of these assets at different stages of ‘readiness’; (c) application to different personas; and (d) development of a specific package of assets.

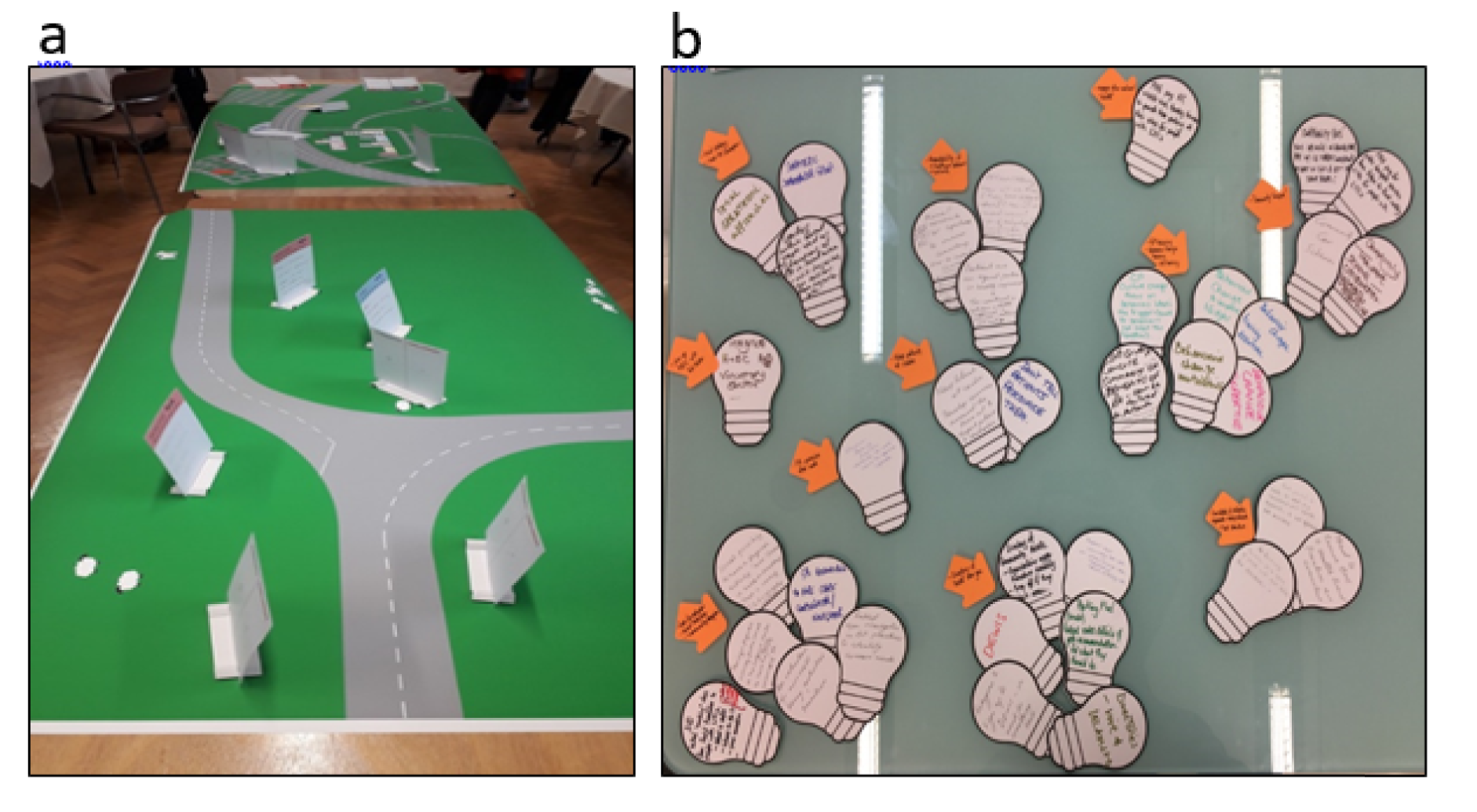

Following this, the participants physically mapped these persona-specific packages of assets onto geographic representations of rural and urban areas (Figure 11a) before considering ‘spanners’ (i.e. disruptions to people’s routines that made it challenging to sustain behaviours). Considering these possible disruptions was an important step to heighten awareness and consider ideas that might overcome these issues. The group also considered what might affect the scaling up of these assets from individual to group, local, regional and then national levels. Finally, the group were challenged to generate novel ideas (new assets, ways of connecting assets or new combinations of assets) that might augment or add value to the existing maps (Figure 11b).

FIGURE 11.

(a) The beginning of the mapping activity; and (b) novel ideas written onto ‘light bulbs’.

Design activity 2

Between workshops 2 and 3, the design researchers visually documented the previous work and updated the storyboard of the research process ready for workshop 3. They grouped the ideas generated by participants into 11 broad categories (see Figure 11b) and made illustrations to represent and challenge these ideas and how they might (or might not) work in practice.

These categories were:

-

credible professional, social prescriber, community navigator

-

directory of ‘assets’ near you

-

community transport

-

consistent and reliable approach

-

primary care staff training, physical literacy, physical activity literacy, behaviour change literacy

-

joining up primary care with health and social care and voluntary sector

-

physical activity provision after work

-

keeping patients at the centre

-

local strategy, local physical activity champions, credible professionals with local knowledge

-

engaging other national assets

-

accountability of health-care professionals and of patients.

Plans for workshop 3 were adapted to reflect these categories and templates and resources for co-design activities in workshop 3 were designed and produced.

Workshop 3 (co-design)

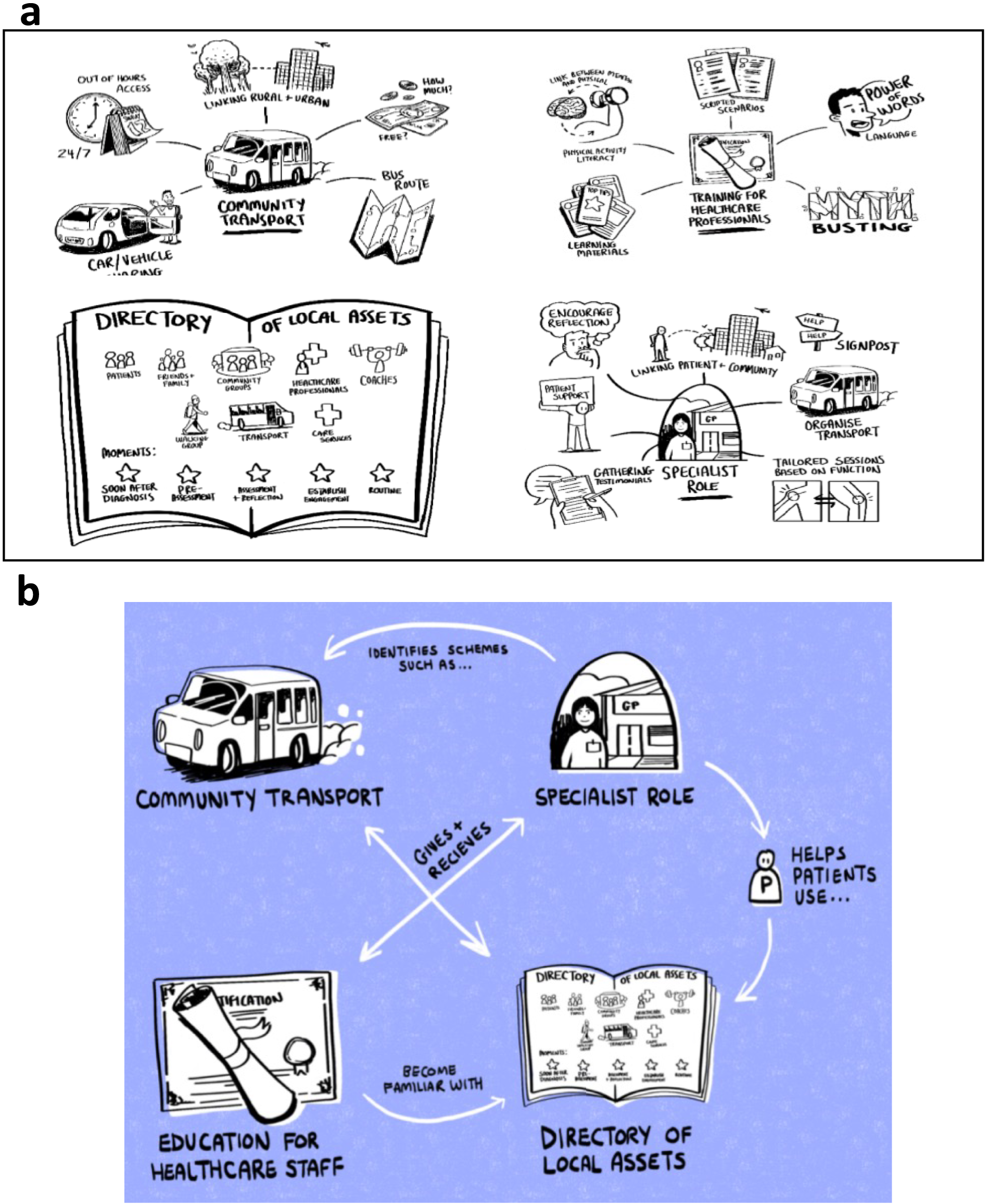

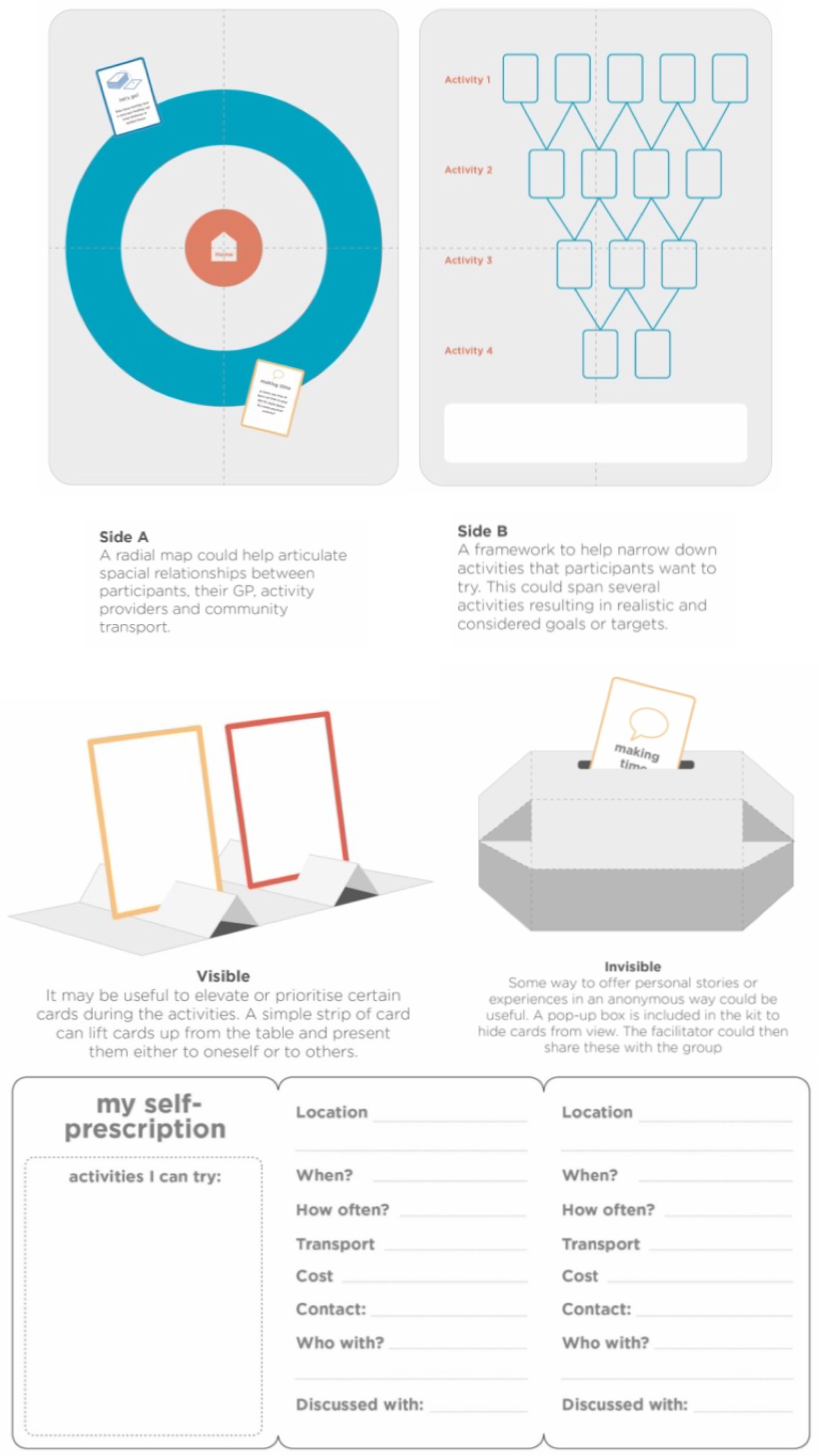

In this workshop, the prototypes were refined and selected. This involved all participants testing and refining the ideas and models further and employing a shared prioritisation process to select the top four ideas. This involved a ‘Dragon’s Den’-style activity, where participants were split into groups. Each group took responsibility for one of the top four concepts (Figure 12a). The participants developed these concepts to a point where they could be shared with a panel of external people; people with expertise and experience in this area who had not been involved in the project to date (see Report Supplementary Material 1). This process provided useful critical feedback that helped the participants develop the four ideas further and begin to make stronger connections between them. The ideas began to coalesce into a cohesive single intervention with four different elements that embodied the evidence and refined CMO statements (Figure 12b).

FIGURE 12.

(a) The four top concepts for the intervention idea; and (b) how they connect together.

Design activity 3

Between workshop 3 and the knowledge mobilisation event the designers extended the visual summary to include workshop 2, adding to the growing visual narrative of the whole research process.

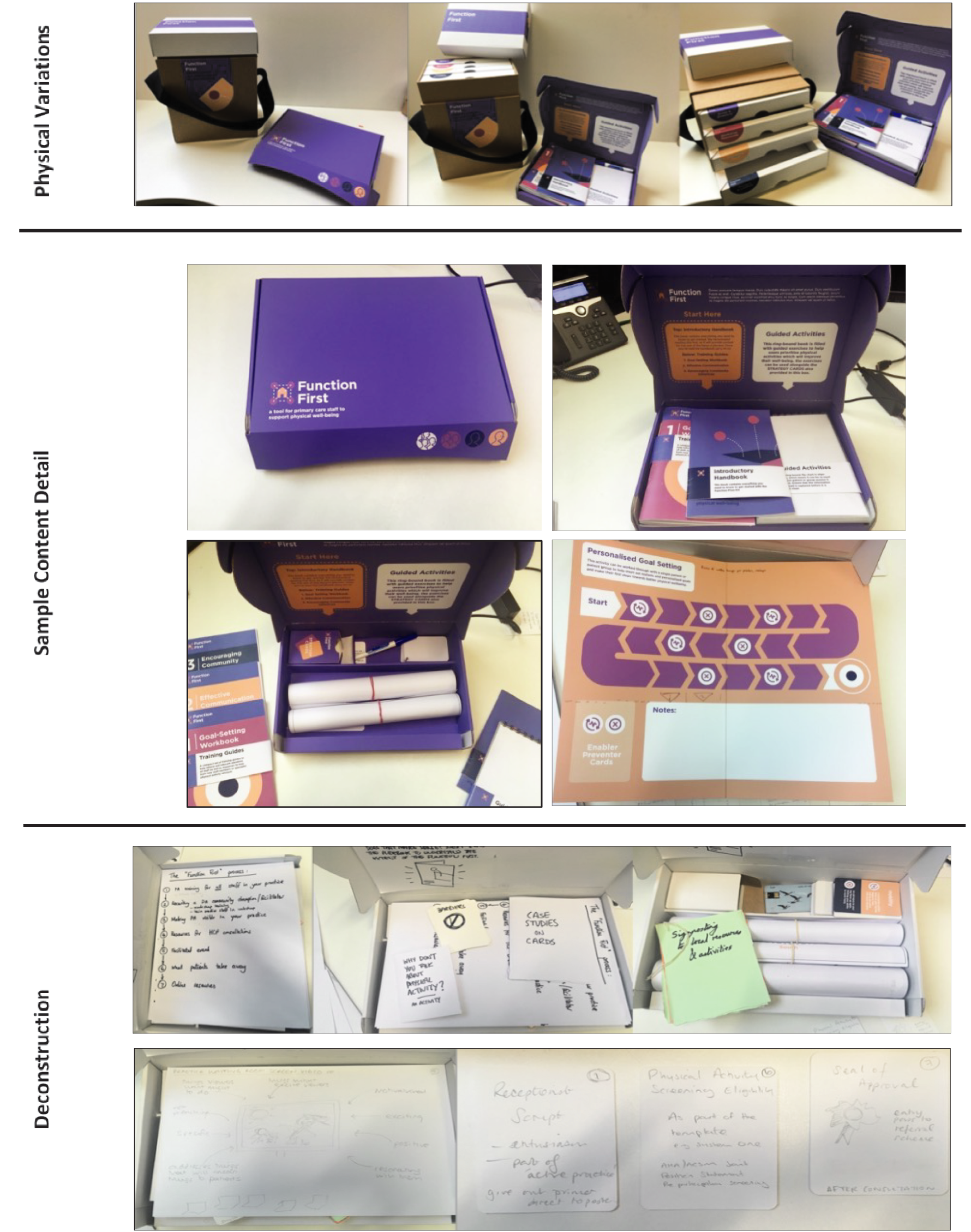

The design researchers reflected on and categorised the data produced by the co-design partners in workshop 3, using this to refine and adapt the plan for the next knowledge mobilisation workshop. They then designed and produced the templates, resources and visual wall displays for the next workshop along with early, rough prototypes based on the ideas and content generated in workshop 2. This conversion of ideas into material form was a key step in setting up workshop 3. These early forms had to be sufficiently vague and roughly finished to encourage participants to critique, change and deconstruct them. Yet they had to have sufficient form to bring the ideas to life and give people a strong sense of what this might or might not be, and how it might or might not work. Part of this process involved presenting a range of possibilities to avoid leading people down a specific route (Figure 13). The design team then made further adjustments based on feedback and developments from the co-design workshop.

FIGURE 13.

Physical variations, sample content detail and an image showing how the content was deconstructed and refined as part of the workshop.

Knowledge mobilisation

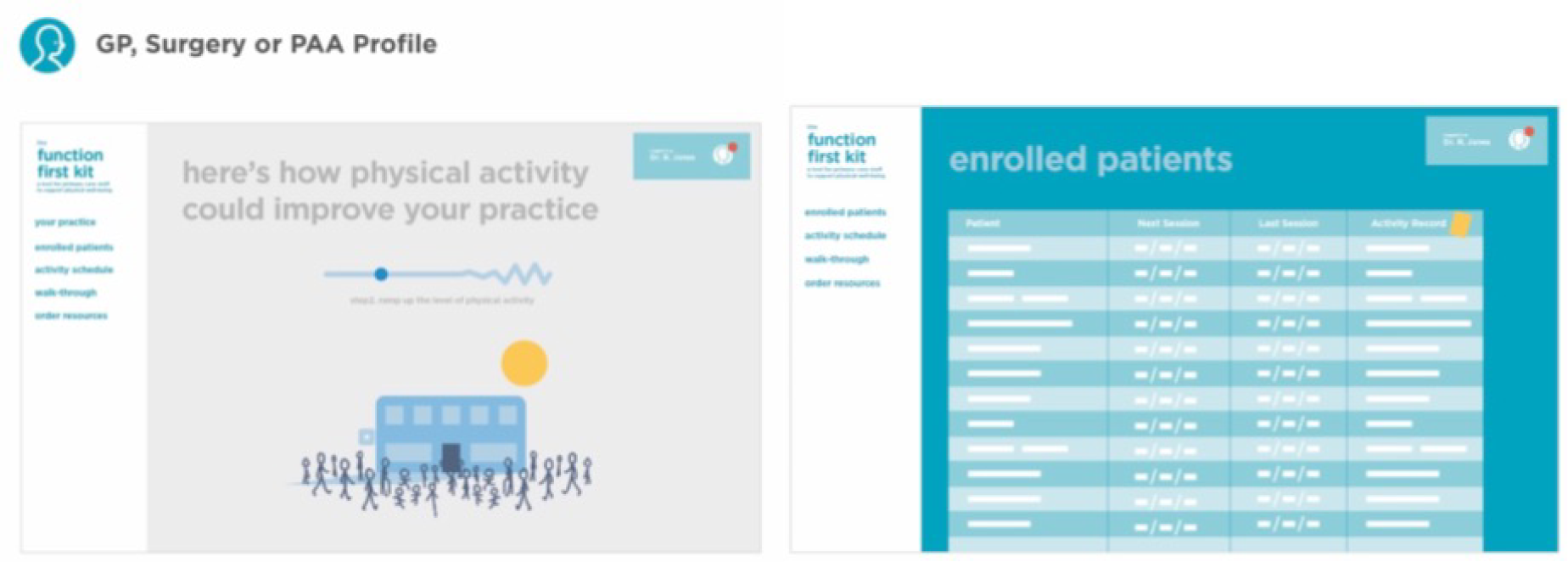

The design researchers presented a physical example and embodiment of the top four concepts generated in the co-design phase. Although detailed content was missing, the demonstration was able to illustrate how each physical element related to the refined CMO statements and theory areas, creating an evidence-informed design solution.

The group were asked to consider these physical elements and add or amend features to ensure that all aspects of the conjectured CMOs were represented in a tangible tool or resource that could be used in primary care settings. The images in Figure 13 show some of the additions that were made to purposefully represent or amplify the representation of elements the evidence indicated were important for this intervention.

The group then presented this to an invited group of representatives from key organisations who were already actively working in this field (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The idea behind this was to gather further feedback, and also to bring the prototype intervention to their attention at an early stage as an invitation to engage in the future use of this set of tools. This raised several useful issues such as ‘branding’ and barriers that might emerge regarding ‘competition’ with other initiatives. The groups worked on possible mechanisms to address these issues.

Summary and storyboard

Evidence from the realist synthesis phases was integrated into the co-design process in an iterative way. Figure 9 shows a storyboard of the overall process (see also Report Supplementary Material 8 for the larger version). This was displayed at each workshop and added to as the process progressed.

The co-designed resources are discussed in full in Chapter 3.

The series of images are a visual representation of the whole research and co-design process. The storyboard was essential in the participatory work, being used as a visual update at each participatory event of the work done to date and as a way of ensuring that participants in the co-design process were continually mindful of the wider evidence and context. This helped to make the co-design work evidence-informed co-design; informed by the wider academic literature as well as personal experiences of those delivering and receiving health-care services or living with a long-term condition.

Patient and public involvement

Use of the UK Standards for Patient and Public Involvement in Research

Understanding what matters to patients is crucial in designing interventions that are acceptable and rooted in the reality of patients’ lives. 114 Our aim was to involve members of the public throughout the project to ensure that our work continued to consider the issues and perspectives that are directly relevant to people who engage with primary care services, and who have long-term conditions. The UK Standards for Patient and Public Involvement in Research115 are based on initial work on the values and principles of public involvement undertaken by NIHR INVOLVE and Health and Care Research Wales. 115 We used the standards and associated audit tool (see Report Supplementary Material 9) to facilitate reflection and learning, and as a framework for what ‘good’ public involvement looks like. In summary, and in response to the six standards, we:

-

Endeavoured to provide ‘inclusive opportunities’ by involving members of the public at the earliest stage; identifying barriers (e.g. we offered remote methods of contributing at times convenient to the individual and offered travel expenses and honoraria); using the Involving People network as a fair, transparent process to identify members of the public; and offering choice and flexibility in involvement. The Involving People network has now been replaced by new infrastructure delivered through Health and Care Research Wales. 116

-

Encouraged ‘working together’ by keeping in regular communication through Study Management Group meetings, discussing roles and responsibilities on a one-to-one basis as needed, and recognising contributions to build and sustain mutually respectful and productive relationships.

-

Promoted ‘support and learning’ through the identification of a named point of contact for public contributors (RL). Public contributors were members of the Involving People network through which training, resources and support was available to them. The study co-chief investigators also attended workshops on public involvement to supplement their own learning.

-

Made our ‘communications’ more relevant with the help of the public contributors, enabling us to decide how we can most effectively share our public involvement activities through local and national dissemination activities.

-

Identified and shared the ‘impact’ of public involvement activities through our use of the national standards. Through our project oversight groups, we considered how well we were using suggestions from public contributors to influence our work, including how to proactively enhance our work by considering possible barriers to public involvement, such as time and work commitments, as well as facilitators.

-

Fully engaged members of the public in the ‘governance’ of this project through inclusion as members of the co-applicant team in regular Study Management Group meetings, participation in Project Advisory Group activities and regular e-mail correspondence about project progress. A named member of the study (RL) was responsible for ensuring that all necessary resources were allocated and monitored to support this.

We have also used the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 (GRIPP2, short form)117 to ensure appropriate reporting of public involvement our final report (see Report Supplementary Material 10).

How members of the public were involved and at what stages

Public involvement in this study began at proposal stage and involved a series of meetings with the project team and two public research partners, both of whom had experience of using primary care services, being involved in research projects and experience relevant to living with a long-term condition. Both became co-applicants, and then members of the Study Management Group once the project was funded. Another public research partner joined the study when one of the two original public research partners stepped down.

As part of the Study Management Group, meetings took place approximately monthly, to which the study public research partners were invited and contributed regularly in person, remotely and via e-mail correspondence. We also involved two members of the public in our external Project Advisory Group, which met four times over the course of the project.

This project also had a strong participatory element and included people with long-term conditions as participant stakeholders throughout the process. For the final co-design workshop, we involved two further members of the public as active partners in the research process. These contributors acted as ‘Dragons’ in the co-design workshop to help provide critical insight and refine the intervention resources that had been co-designed by participants.

The impact of public involvement and how it was useful

At the proposal stage, the two study co-applicants helped to refine the research question, proposed methods, lay summary and public involvement sections, ensuring that they were both relevant and appropriate. This included consideration of ‘who’ the target group would be, the potential for participant burden in workshops, use of language in the lay summary, and consideration of appropriate public involvement activities and reimbursement. They also contributed directly to the co-production of the project short title and tagline: Function First – Stay Active, Be Independent.

Once the project had started, the two public research team members were involved on a regular basis as part of the Study Management Group, and particularly in the following activities, with the following impact:

-

When preparing public-facing materials and responding to comments from the ethics review, changes were made to –

-

the wording of information sheets and consent forms to reduce formality and provide reassurance of processes in place to deal with distress

-

the plans for the workshops by clarifying content and focus of activities, considering time burden and specific issues that may arise for people with long-term conditions (e.g. the use of LEGO bricks by someone with arthritis and the need for rest breaks)

-

the telephone interview topic guides to ensure clarity in explanations of methods, coverage of important issues (e.g. additional prompts to facilitate further information and procedures for if a person discloses information of concern to the interviewer).

-

-

During ‘group analysis’ of the data from the theory-building workshops, the study team public contributors ensured that we considered the patient perspective, including those from varying socioeconomic and ethnic groups.

-

Review of a selection of titles, abstracts and full papers for the literature searching and contributed to ongoing discussions among the project team about our methods (e.g. refinement of inclusion/exclusion criteria).

-

Commenting on abstracts submitted for presentation at conference proceedings, presentations and posters, with changes made to improve clarity of wording and explanations.

-

Writing of ‘Function First’ protocol paper as authors, the study team public contributors reviewed and made comments that helped to improve clarity, particularly for the public involvement section.

-

Participation in co-design and knowledge mobilisation workshops as public members of the research team, enabling influence on intervention development from both a project and public perspective.

-

Help in considering use of resources available to facilitate public involvement. Following discussion, we decided to use the UK Standards for Patient and Public Involvement in Research as a tool to reflect on our ongoing public involvement and keep a record of examples to supplement, and use the GRIPP2 to ensure appropriate reporting in the final report.

-

Help in considering appropriate methods of reimbursement for public contributors and participants. For example, preference for payment to workshop participants using vouchers, consideration of tax and benefit issues, and discussion of updates to guidance from INVOLVE.

-

Writing of this section of the report, ensuring that it was accurate, clear and comprehensive.

As part of the independent Project Advisory Group, two public contributors were actively involved in the following specific activities:

-

providing independent feedback on ‘If . . . then’ statements and emerging theory areas from a public perspective, thus helping to refine and improve their relevance

-

suggesting the inclusion of particular groups as stakeholders

-

discussing options for reporting of public involvement

-

providing independent, reflective feedback during and following meetings on overall project progress, emerging findings and next steps

-

writing this section of the report, ensuring that it was accurate, clear and comprehensive.

Reflections and critical perspective

What went well:

-

continuity in involvement from proposal through to write-up stage

-

regular attendance and contribution to Study Management Group and Project Advisory Group meetings and activities, including the addition of ‘public involvement’ as a regular agenda item

-

ability to enable public contribution using various methods to improve accessibility (e.g. videoconference, telephone, face to face, e-mail correspondence)

-

mutual respect between public contributors and researchers as members of the project team

-

a named point of contact for public contributors

-

implementation of suggestions made by public contributors, including in response to comments from the ethics review panel

-

involvement of public contributors in aspects of the study methods (e.g. literature reviewing, co-design), decision-making (e.g. contribution to project oversight groups) and dissemination (e.g. co-authoring abstracts and papers).

What could have been improved:

-

Better clarity from study outset about arrangements for paying honoraria and reimbursing public contributors for travel and subsistence. Importantly, arrangements and clarity around this have improved as a result.