Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/156/10. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The final report began editorial review in February 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Cornes et al. This work was produced by Cornes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Cornes et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

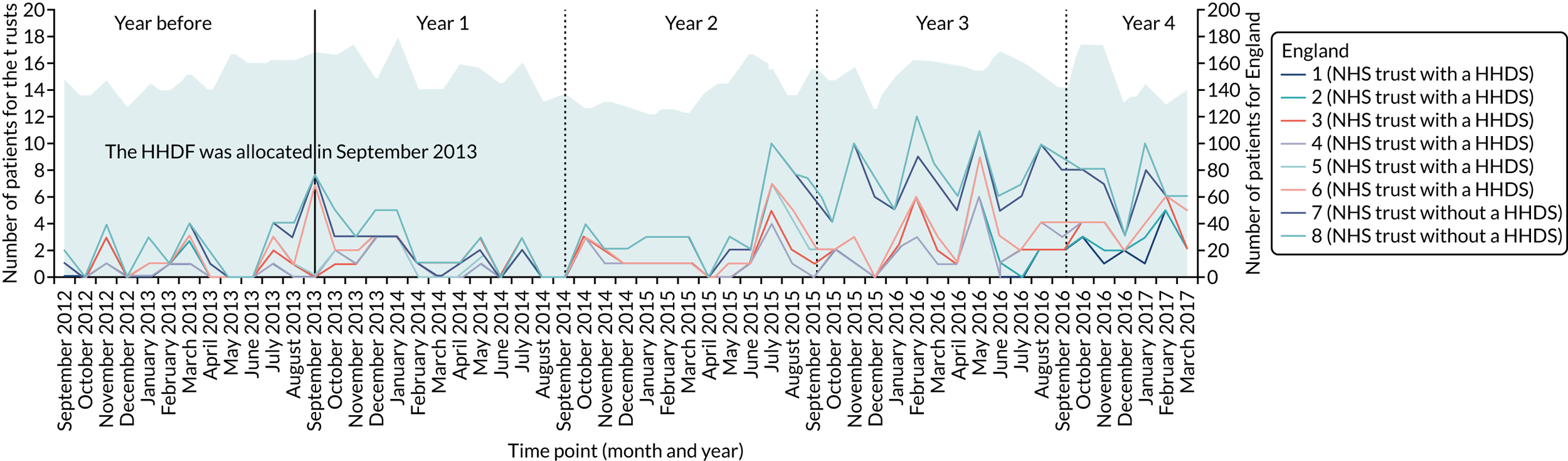

This realist evaluation was commissioned in response to a call from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme (reference 13/156/10). The call sought to provide evidence for commissioners and service leaders on ‘what works best’ with regard to the appropriateness, quality and cost-effectiveness of specialist integrated homeless health and care (SIHHC). Two studies were commissioned: one study,1 which explored specialist primary care services, and this present study, which explores hospital discharge. The call was made in response to an announcement in September 2013 that £10M funding was to be made available by the Department of Health [now the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC)] to develop specialist homeless hospital discharge schemes (HHDSs), including ‘step-down’ intermediate care. Fifty-two schemes were funded across England as part of the Homeless Hospital Discharge Fund (HHDF). This evaluation of these and other specialist homeless hospital discharge arrangements commenced in September 2015 and was completed in December 2019. It was carried out by a consortium of researchers from different universities, led by King’s College London (London, UK). The reporting of this research adheres to the Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards II (RAMESES II) for realist evaluation. 2,3 Ethics approval was obtained from the London and South East Research Ethics Committee in April 2016 (reference 16/EE/0018)

Research objectives

The overall aim of the study was to explore how SIHHC works, for whom, in what circumstances and why to deliver consistently safe, timely transfers of care. The study objectives were to:

-

situate what is already known about delayed transfers of care (DToCs) among people who are homeless in terms of the broader literature on hospital discharge and intermediate care

-

explore how different models of SIHHC are being developed and implemented across England to facilitate effective hospital discharge

-

explore the views and experiences of people who are homeless and if and, if so, how SIHHC works to improve experiences of hospital discharge and deliver improved health and well-being outcomes

-

explore how SIHHC has an impact on outcomes and different patterns of service use across the whole system (e.g. the use of unplanned care) and the associated cost implications of this

-

produce a ‘toolkit’ for commissioners on developing SIHHC if the findings support this.

Report structure

In the remainder of this chapter, we outline the broader policy context in which the HHDF was operationalised. This includes background information about homelessness in England, the impact of austerity on public services, including the NHS, and the development of intermediate care services as a means of maintaining ‘patient flow’ in the face of rising demand for acute care.

In Chapter 2, we outline why we used a realist evaluation approach and how we applied realist principles of generative causation to the evaluation of specialist homeless hospital discharge arrangements. First, we describe the findings of a realist synthesis of the literature that situates what is already known about DToCs among people who are homeless in terms of the broader literature on hospital discharge and intermediate care (objective 1). We then show how this evidence was used to inform the development of our initial (tentative) programme theories about what works to deliver consistently safe, timely transfers of care.

The results section comprises three chapters, each of which outline the findings of a separate work package (WP) designed to interogate programme theory. We consider the data collection methods used in each WP at the beginning of each chapter.

Chapter 3 reports the findings of WP1. This WP comprised qualitative observational case studies of seven study sites in England. This involved (non-participant) observation of discharge practices in sites with ‘specialist care’ (n = 5) and comparing these with sites with ‘standard care’ (n = 2), interviews with service users (n = 70) at baseline and the 3-month follow-up, and interviews with a wide range of stakeholders (n = 77). The overall purpose of this chapter is to explore how specialist care is being implemented and perceptions of the barriers to and facilitators of successful implementation from the perspective of a range of stakeholders, including service users (objectives 2 and 3).

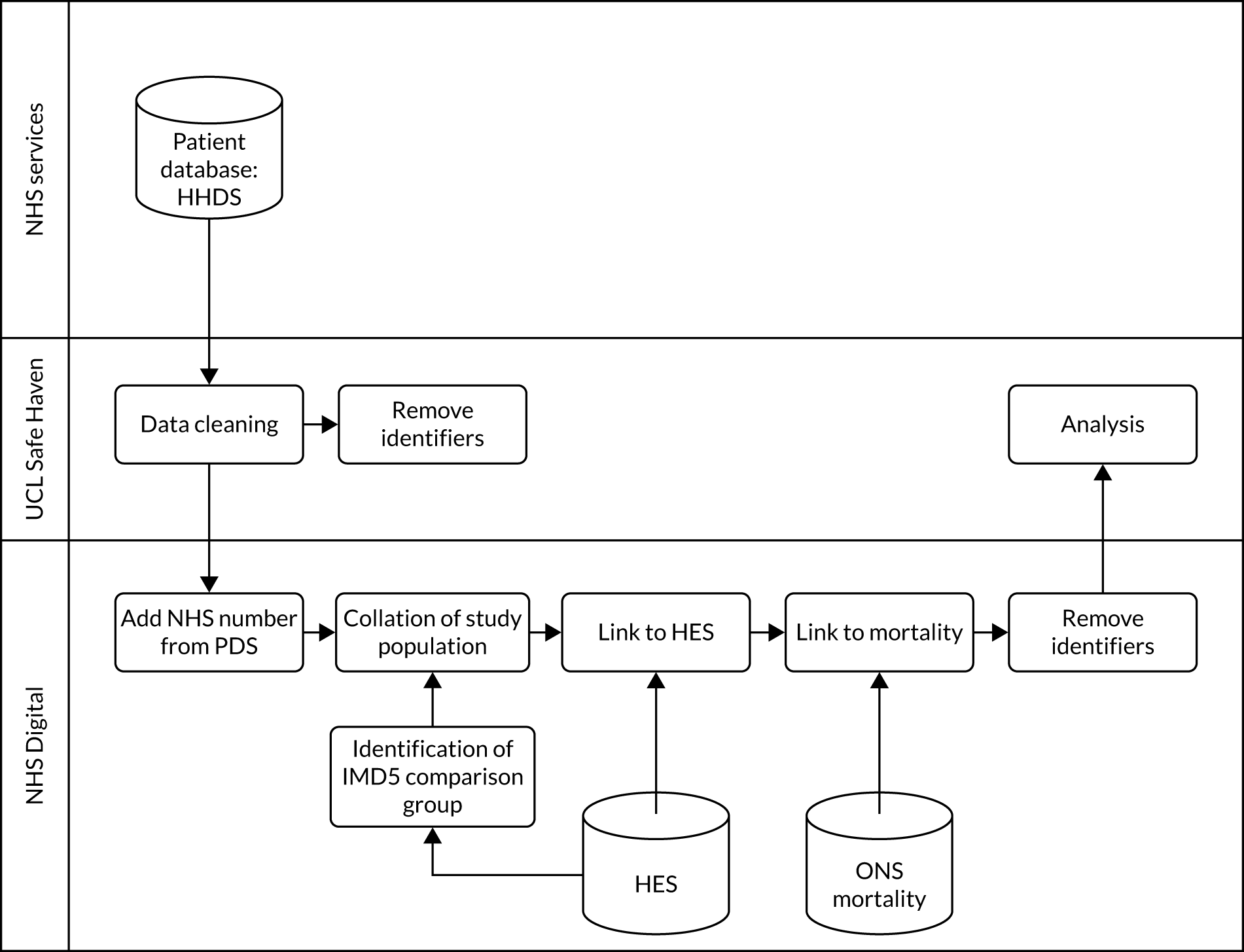

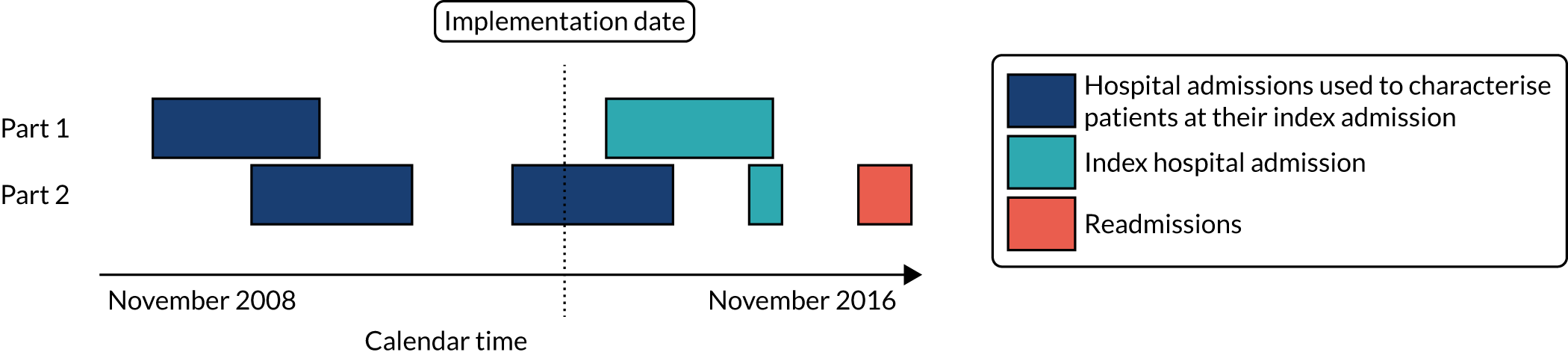

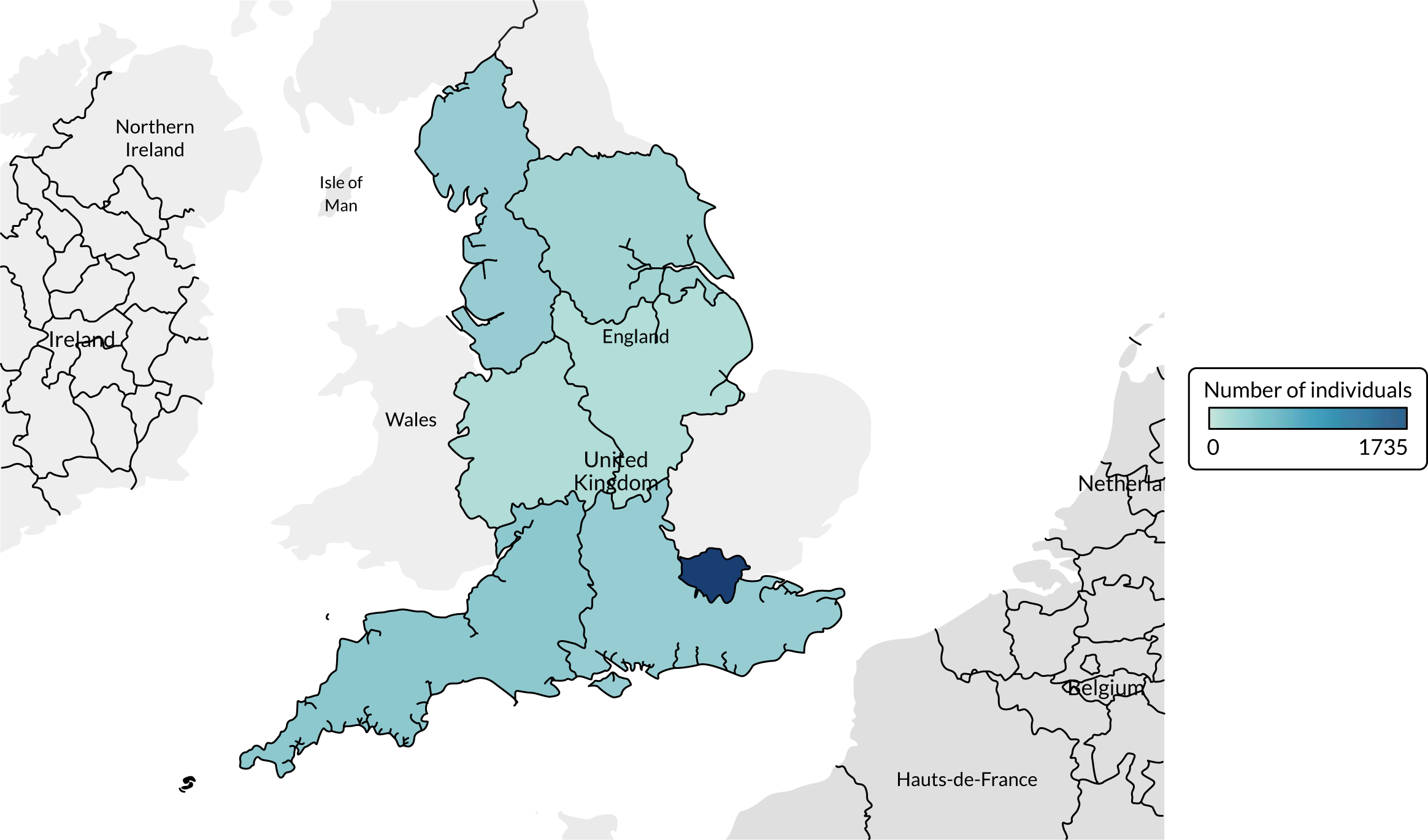

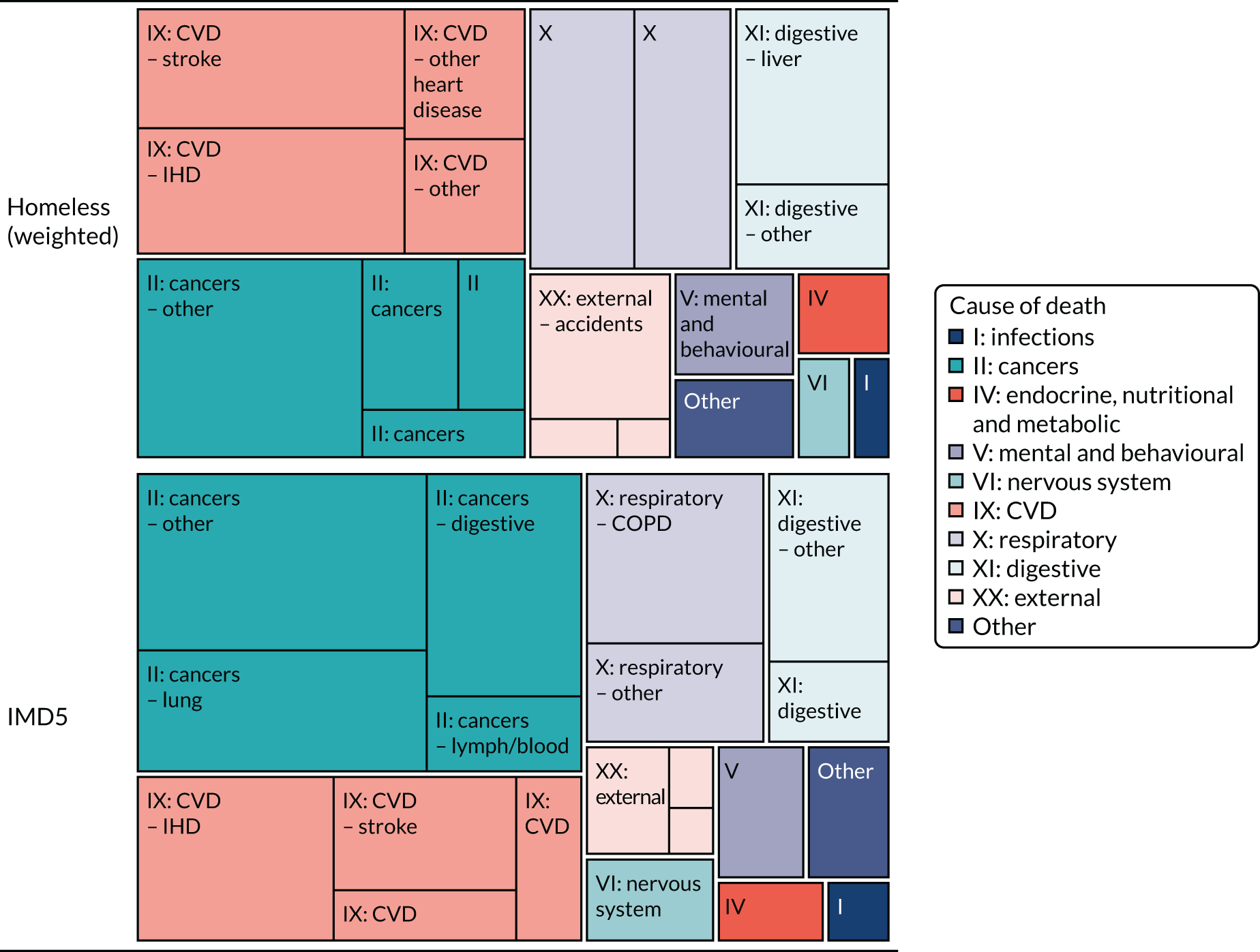

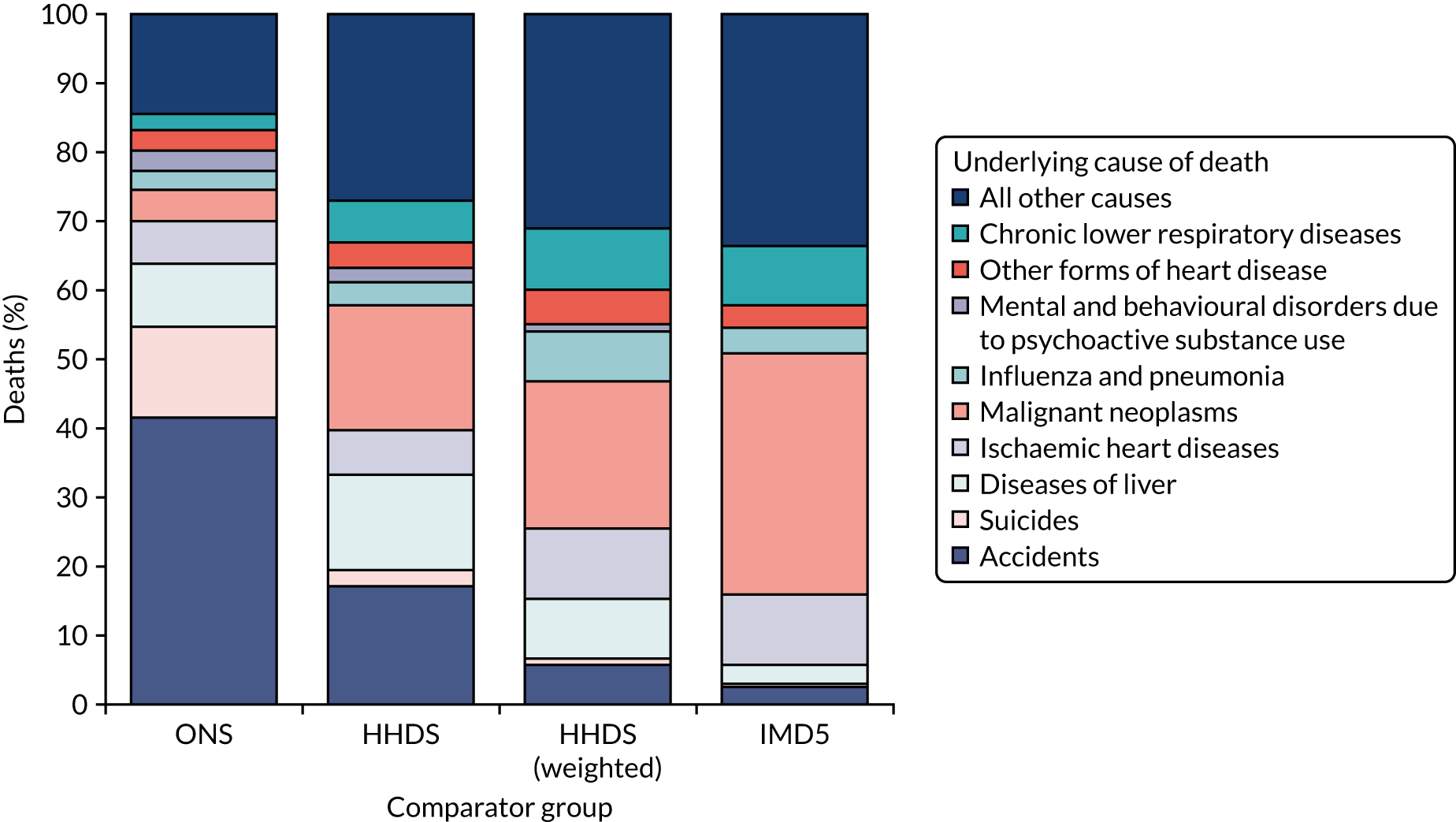

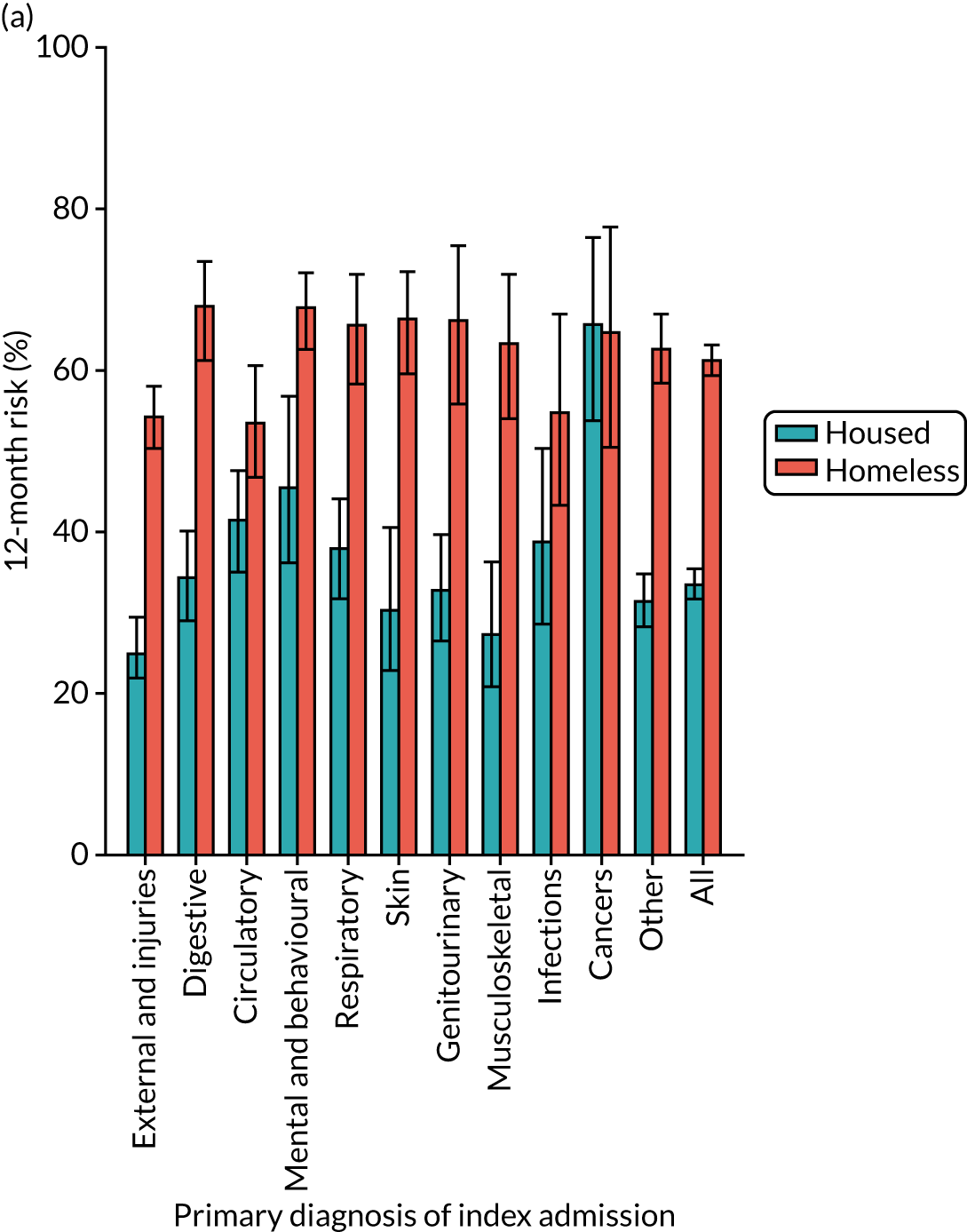

Chapter 4 reports the findings of WP2. This comprised a ‘data linkage’, tracking outcomes for 3882 homeless patients by means of Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and civil registration death data. WP3 provides quantitative evidence to enable the interrogation of our programme theories (e.g. that schemes with ‘step down’ will be more effective) by reporting a range of outcomes, such as hospital readmission rates and time from discharge to next accident and emergency (A&E) attendance. Chapters 4 and 5 address research objective 4.

Chapter 5 reports the findings of WP3. This is an economic evaluation that explores the effectiveness and cost-effectives of specialist compared with standard hospital discharge arrangements, and also the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different typologies of HHDS. WP3 also generates evidence that can be used to interrogate our programme theories (e.g. that schemes offering ‘step down’ will be more cost-effective than schemes that do not offer this).

In Chapter 6 we triangulate the evidence generated across the three individual WPs to further interrogate and refine our programme theories. We present the overall findings of this realist evaluation as an evidence-informed ‘checklist’ of the complex set of factors that decision-makers will need to consider to ensure consistently safe, timely transfers of care for people who are homeless (objective 5).

Definition of homelessness

Homelessness is a complex phenomenon that covers a wide range of circumstances. According to the Homeless Monitor,4 it encompasses people sleeping rough; single homeless people living in hostels, shelters and temporary supported accommodation; statutorily homeless households that are seeking housing assistance from local authorities on grounds of being currently or imminently without accommodation; and the hidden homeless (e.g. ‘sofa surfing’ in the homes of friends and relatives).

The primary focus of this study is on ‘multiple exclusion homelessness’ (MEH). This term is used to capture the overlap between homelessness and other domains of deep social exclusion, such as ‘institutional care’ (e.g. prison, local authority care, stays in mental health hospitals or wards), ‘substance misuse’ (e.g. drug problems, alcohol problems, abuse of solvents, glue or gas) and participation in street culture activities (e.g. begging, street drinking, ‘survival’ shoplifting or sex work). 5

We decided to focus on MEH because it was anticipated that people falling within this group may be more likely to be admitted to hospital and to have more complex discharge experiences. The excess morbidity and mortality associated with MEH and other forms of deep social exclusion are extreme. Aldridge et al. 6 studied four inclusion health populations (homeless populations, individuals with substance use disorders, sex workers and imprisoned individuals) and found all-cause mortality standard mortality ratios (SMRs) of 7.9 in male individuals and 11.9 in female individuals compared with those living in the least deprived areas of England and Wales.

National policy context

This study took place against the backdrop of the Coalition and Conservative governments’ policies of austerity that were implemented following the global financial crises of 2007/8, leading to heavy cuts to welfare services and benefits, an NHS funding freeze and extensive cuts to local government budgets. 7 From 2010, there were significant rises in the levels of homelessness in England, particularly rough sleeping. By the time this study was reporting in 2020, the situation has been characterised as a ‘national crisis’8 and a ‘public health disaster’. 9

In October 2018, the Homeless Reduction Act 2017 (HRA)10 came into force in England and widened access to assistance from housing authorities to all households at risk of homelessness (not just those in priority need). The Act also introduced a ‘duty to refer’, in which specified public services (including NHS trusts) now have a legal duty to refer patients they consider may be homeless or threatened with homelessness to a local housing authority. In August 2018, the HRA was complemented by a new rough sleeping strategy. 11 This strategy aims to end rough sleeping by 2027, focusing on three ‘core pillars’ of prevention, intervention and recovery. Both of these measures were implemented outside the data collection time frame of the study; however, we will return to discuss them later in the light of the study findings.

Poor hospital discharge arrangements

The research literature on hospital discharge goes back at least 50 years and there is remarkable consistency in its findings, which continue to report the frequent breakdown of routine discharge arrangements. 12 In a comprehensive review of the policy and research landscape, highlighting the often-neglected housing dimensions of hospital discharge, Glasby13 describes feeling left with an overwhelming sense of the intractable and persistent nature of many of the problems.

Older people and people with multiple and complex needs (e.g. long-term conditions), including people who are homeless, are particularly affected by poor discharge. 14 In 2012, the DHSC commissioned a report on how homeless patients were being treated in hospital. 15 This identified ‘countless examples’ of the mention of homelessness on admission, triggering prejudice among hospital staff. The report highlighted that premature and unsafe discharge tended to be more of a problem for homeless patients than delayed discharge. The review reported that > 70% of homeless patients were being discharged back onto the streets without having their care and support need assessed, further damaging their health and all but guaranteeing their readmission. According to the then Secretary of State, Paul Burstow, ‘We commissioned the report to expose poor practice . . . What it reveals is too many hospitals simply discharging homeless people back to the streets. Patching a person up and sending them out without a plan makes no sense’16 (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0).

Other concerns highlighted in the report included hospital staff not asking people about their housing situation on admission; failure to manage drug and alcohol withdrawal, leading to early self-discharge; hospital staff not alerting accommodation providers to the fact that a person is in hospital, leading to tenancies being terminated; hospital staff having a poor understanding of the services available to homeless people, including overestimating the level of care that can be provided in hostel settings, leading to unsafe discharges; a lack of practical support, such as no replacement of soiled clothing; uncertainty regarding where the involvement of one sector should start and end, including little agreement about how far hospital staff should be expected to proactively seek accommodation; and a lack of appropriate accommodation options, raising the question of whether of not ‘signposting’ is an adequate response if this potentially leads to discharge back onto the streets.

The Homeless Hospital Discharge Fund

In 2013, the DHSC announced that £10M funding would be made available to the voluntary and community sector to work with the NHS and local councils to develop specialist hospital discharge arrangements and intermediate care services for people who are homeless:

All too often, the homeless end up in a hostel that is an inappropriate environment for treatment plans and for their recovery. For those who are TB [tuberculosis] patients, homelessness is a major barrier to completing their treatment and recovery from infection. [The HHDF funding] will ensure adequate provision of intermediate care facilities to be available upon discharge from hospital.

DHSC. 17

What is intermediate care?

In the literature on hospital discharge, it has long been recognised that there is tension between two competing notions of ‘good practice’. On the one hand, a perspective that is narrowly concerned with the most cost-effective use of hospital resources (and hence rapid throughput). On the other hand, a perspective that emphasises the importance of needs-led assessments and choice for individuals. 13 Increasingly, intermediate care and discharge to assess (D2A) are being promoted as ways of addressing the need to ensure both ‘patient flow’ and safe discharge practice.

Intermediate or ‘step-up’ and ‘step-down’ care is an umbrella term for a wide range of admission avoidance and out-of-hospital care services, including Rapid Response, Crises Response, D2A, Home First, Reablement and Safely Home. It usually comprises:

Networks of local health, housing and social care services, which deliver targeted, short-term support to individual patients, in order to: prevent inappropriate admission to NHS acute inpatient or continuing care, or long-term residential care; facilitate timely discharge from hospital; and, most importantly, maximise people’s ability to live independently.

Cowpe18

Bolton19 summarises the thinking behind out-of-hospital care services as follows. First, there should be less focus on assessment for longer-term care and support at the point of discharge and more emphasis on recovery. Second, there is a specifically commissioned set of services to help people recover post hospital. He suggests that intermediate care will not work at its best if services are solely commissioned from existing services where they were not established for that purpose (e.g. using standard home care agencies that are not geared up to take a regular flow of new people).

Guidance is clear that ‘step-down’ care should not be used to warehouse people. That is, creating an additional transfer in a person’s care pathway to free up a hospital bed without adding value to their experience of care or meeting good outcomes for the person. 20

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)21 guideline for intermediate care recommends that commissioners should consider making home-based intermediate care, reablement, bed-based intermediate care and crises response all available locally. These services need to be delivered in an integrated way so that people can move seamlessly between them, depending on their changing needs.

Eligibility for intermediate care

Intermediate care entered the mainstream of health and care services delivery in England through the National Service Framework for Older People. 22 Here, it was recognised that although intermediate care services are likely to be of particular importance for older people, service planning and investment need to take account of the needs of all potential services users. Updated guidance23 defined intermediate care as support for anyone with a health-related need through periods of transition and made the point that no-one should be excluded on the basis of age or ethnic or cultural group. Specific reference was made in this guidance to the eligibility of homeless people and prisoners. 23 However, later guidance has tended to move away from this broader, more inclusive definition. One reason for this may be that investment in intermediate care services (particularly reablement) has not kept pace with rising demand. 24

Housing-led intermediate care

The £10M investment that underpinned the HHDF was restricted to voluntary and community sector providers. This targeting led to the development of a new tier of specialist ‘housing-led’ intermediate care services (i.e. services that are designed and delivered mainly by housing associations and homeless charities/voluntary sector organisations). Until this point, intermediate care had been delivered mainly as a health and social care service. 25 In total, 52 schemes were funded through the HHDF. Two principal models emerged:

-

a housing-led [Home First (floating support)] ‘step-down’ model (n = 37)

-

a housing-led (residential/bed-based) ‘step-down’ model (n = 7).

In the Home First ‘step-down’ model, HHDSs provide access to a ‘link worker’. Link workers aim to support the patient to find accommodation (i.e. somewhere safe to stay). They will also assist with other aspects of discharge planning using their knowledge of local homeless services and resources. Once the patient has been discharged from hospital, the link worker will stay in touch, providing (floating) ‘step-down’ support in the community for a time-limited period until longer-term care and support are in place.

In addition to Home First (floating support) schemes, HHDF capital funding was used to develop a number of residential (bed-based) intermediate care facilities. Two of the largest HHDF capital grants (totalling in excess of £1M) were allocated to charities to establish medical respite centres with 24-hour clinical staffing. The first HHDS failed to become operational because of difficulties finding a building. The second HHDS failed to secure revenue funding for clinical staffing once the refurbishments were complete and hence did not became operational. Five smaller residential ‘step-down’ (without 24-hour clinical staffing) schemes did become operational, but only one of these (a housing association-led scheme) is currently operational.

Clinically led teams

In addition to the ‘housing-led’ schemes, we consider, as part of this evaluation, a number of ‘clinically led’ schemes (some of which predate/or were not funded by the HHDF). These are often called Pathway Homeless Teams by virtue of their affiliation with the Pathway Charity [URL: www.pathway.org.uk (accessed 3 June 2021)]. The Pathway model is a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach that employs general practitioners (GPs), nurses, housing workers, social workers, occupational therapists and peers (i.e. people with lived experience of homelessness). The Pathway homeless teams are usually led by the GP or senior nurse and focus on individual care co-ordination (including discharge planning). As the primary aim of the clinically led team is to maximise the window of opportunity afforded through a hospital stay, these schemes usually close cases at the point at which the patient leaves hospital (i.e. they do not routinely integrate ‘step-down’ care as part of the service model).

Summary

In this section, we have introduced the background to HHDF programme and some of the problems that it set out to address, namely ‘discharge to the street’ and a lack of appropriate ‘step-down’ intermediate care facilities for recuperation and recovery. We have also introduced the wider policy context in which the HHDF was implemented, charting the impact of austerity, including increased rates of homelessness; severe shortages of housing, care and support; and a consequent rising demand for acute hospital services and intermediate care. We now turn our attention to the evaluation of specialist HHDSs and their role in delivering consistently safe, timely transfers of care.

Chapter 2 Realist evaluation and literature synthesis: constructing an initial tentative programme theory

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted from Cornes et al. 26

Overview of realist evaluation approach

Realist evaluation is a theory-driven approach based on a realist philosophy of science that addresses the question ‘what works, for whom, under what circumstances and how’. 27 Central to the realist method is the identification and refinement of propositions about how a programme is supposed to achieve its intended outcomes, known as ‘programme theories’. Programme theory is operationalised as ideas about (1) what works and why, (2) how to remedy any identified deficiency and (3) how the remedy itself may be undermined. 25

According to the RAMESES II quality standards for realist evaluation,2 the main ideas that go into the making of an intervention should be surfaced and made explicit at an early stage. An initial tentative programme theory should be constructed, setting out how and why an intervention is thought to ‘work’ to generate the outcome(s) of interest. This initial tentative theory (or theories) are then progressively refined (recast) over the course of the evaluation.

In this chapter we describe how we applied realist principles of generative causation to the evaluation of specialist HHDSs and show how we used the literature to arrive at an initial tentative programme theory about what works to deliver consistently safe, timely transfers of care. We start with an overview of the generic hospital discharge literature and then present a more a detailed synthesis of the specialist (homeless) intermediate care literature. First, we explain why we considered a realist approach to be the most appropriate methodology for this evaluation and how we anticipated the findings would be used.

Selecting the most appropriate research methodology

The HHDF is a complex service development initiative. This is because of the diversity of the projects funded (level of professional input, intensity and duration, etc.) and the wide range of geographical contexts in which they are situated. In designing the research, we drew on the methodological learning from earlier evaluations of similar policy developments that sought to pilot a range of intermediate care or ‘step-up’ and ‘step-down’ projects for older people. 22 In England, considerable variation in the design, definition and configuration of intermediate care services has been permitted at local levels. Consequently, the range of possible combinations/schemes made it difficult to establish any strong link between scheme features and effectiveness. 28 As a result, it has not been possible to arrive at definitive conclusions about particular service models being more effective than others (e.g. ‘nurse led’ vs. ‘therapy led’). This inconclusiveness led the DHSC to observe that ‘A thousand flowers have bloomed’. 18 This captured not only the diversity of intermediate care development in England, but also an unintended outcome, namely the benefits arising from the enthusiasm that had been unleashed through opportunities of piloting many new and innovative ways of working.

It has also been suggested that working towards a ‘standardised model’ of intermediate care is undesirable because different areas will have different levels of need and different resources. 29 As the DHSC23 pointed out, intermediate care should provide the function of linking and filling the gaps in the local network, leading to what Medcalf and Russell30 term ‘independent local pathways of care’. According to the DHSC, Association of Directors of Adult Social Services and NHS England,20 no one model can meet all the needs of all patients leaving hospital. The aim should be to develop a ‘complex adaptive system’ that involves simple rules to function rather than rigid, inflexible criteria.

We opted for a realist evaluation approach because we considered this research lens to be most suited to overcoming the challenges outlined above, namely the need to move beyond questions of effectiveness. Realist evaluation starts from the premise that ‘Nothing will work everywhere all of the time’. 31 The fundamental question that researchers working with a realist perspective ask is how do certain causal mechanisms (e.g. GP-led advocacy) operating in particular circumstances (e.g. a HHDS) create certain changes or outcomes (e.g. improved experiences of hospital discharge). In many respects, the purpose of a realist evaluation is to support decision-makers to implement successful schemes in contexts that may differ markedly from those in the original effectiveness studies. Pearson et al. 25 argue that using a realist synthesis to build a conceptual ‘road map’ that can guide future intervention development about ‘what works for whom and in what circumstances’ may be an important step in complementing more traditional evidenced-based approaches, which often leave these questions unaddressed.

Realist principles of generative causation

In a realist evaluation, ‘context + mechanism = outcome’ configurations are used as a heuristic device by the researcher to develop programme theories about how an intervention is supposed to function. The theories are then tested using empirical data. To illustrate the correct utilisation of these concepts, Dalkin et al. 32 use the example that programme evaluators do not suppose that closed circuit television (the intervention) simply causes a fall in crime rates (the outcome). It does so by persuading potential perpetrators of increased risks of detection where there is a camera (this is the mechanism). Within this view, it is acknowledged that programmes and interventions do not change people, rather it is how people interpret and use what the programme provides that changes things. 31 Within a realist evaluation a context describes the conditions in which programmes and interventions are introduced, acknowledging that mechanisms will be active only in particular circumstances. Context includes cultural norms, economic conditions, public policy, etc. Mechanism describes what it is about programmes and interventions that bring about any effects (i.e. changes in reasoning). The focus is on the ‘intervention resources’ and new practice approaches that programmes offer to enable them to work. The process of how subjects interpret and act on these ‘intervention resources’ is known as the mechanism. Here, impact is understood as the process through which these ‘intervention resources’ facilitate or ‘fires’ a change in reasoning and behaviour, leading to different outcomes and costs. Outcomes are the intended and unintended consequences of programmes resulting from the changes in reason.

It should be noted that in this study we adopt Dalkin et al. ’s32 slightly modified formula for realist evaluation. In the original framework proposed by Pawson and Tilley,27 the change process is conceptualised as ‘context + mechanism = outcome’. In Dalkin et al. ’s32 formula ‘intervention resources’ and ‘reasoning’ are seen as mutually constitutive of a mechanism, but are explicitly disaggregated to allow for the interplay of context. The revised formula is:

Applying realist principles to the research design

In this section, we describe how we incorporated realist principles in the overall design of the study. The specialist HHDS is the intervention or ‘black box’. The main outcome of interest is securing safe, timely transfers of care for people who are homeless or in housing need.

Step 1: literature synthesis

The first step in this realist evaluation (literature synthesis) sought to identify the many different ‘intervention resources’ [including ‘simple rules’ and key practice principles (KPPs)] that might be deployed in a HHDS to facilitate the outcome of interest. The literature was then used to develop programme theories by exploring the existing evidence for each of these ‘intervention resources’.

Step 2: mapping typological configurations

Once the research team was familiar with the full range of (possible) intervention resources, the next step was to explore HHDS documentation (project leaflets, evaluation reports, etc.) and to undertake a series of preliminary site visits and discussions with key HHDS stakeholders. The objective here was to map the ‘intervention resources’ that are actually being deployed across the 52 HHDSs and, importantly, to tease out the underpinning logic for their use (i.e. why the scheme has opted to utilise these resources and practices). This preliminary mapping also informed site selection, enabling subsequent testing of the initial tentative programme theories.

Step 3: testing and refining programme theories through empirical data collection

The third step was to test and refine programme theories through empirical data collection. This study employed a mixed-methods approach comprising three WPs, allowing for both qualitative and quantitative interrogation. We will return to discuss the design of each WP later in the report once we have specified the theories being tested. In the remainder of this chapter, we focus on how our initial tentative programme theories were generated through a realist synthesis of the intermediate care literature.

Towards an initial tentative programme theory

According to the RAMESES II quality standards for realist evaluation, initial ‘hunches’ about what works should be clearly described at the outset. 2 The starting point for this evaluation was to ascertain a broad overview of the generic literature on hospital discharge in terms of what is known to work for all patient groups. This evidence base is summarised for commissioners and service planners in High Impact Change Model. Managing Transfers of Care between Hospital and Home. 33 This guidance outlines eight key high-impact changes.

Change 1: early discharge planning

Underpinning logic

In emergency/unscheduled care, robust systems need to be in place to develop plans for management and discharge and to allow an expected date of discharge to be set within 48 hours.

Change 2: systems to monitor patient flow

Underpinning logic

Protocols enable teams to identify and manage problems (e.g. if capacity is not available to meet demand) and to plan services around the individual.

Change 3: discharge co-ordination underpinned by multidisciplinary team working, including the voluntary and community sector

Underpinning logic

Co-ordinated discharge planning based on joint assessment processes and protocols, and on shared and agreed responsibilities, promotes effective discharge and good outcomes for patients.

Change 4: Home First (intermediate care) and discharge to assess

Underpinning logic

Providing short-term care and reablement in people’s homes or using ‘step-down’ beds to bridge the gap between hospital and home means that people no longer need to wait unnecessarily for assessments in hospital. In turn, this reduces delayed discharges and improves patient flow.

Change 5: flexible working patterns

Underpinning logic

Successful, joint 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (24/7) working improves the flow of people through the system and across the interface between health and social care, and means that services are more responsive to people’s needs.

Change 6: trusted assessment

Underpinning logic

Using trusted assessors to carry out a holistic assessment of need avoids duplication and speeds up response times so that people can be discharged in a safe and timely way.

Change 7: focus on choice

Underpinning logic

Early engagement with patients, families and carers is vital. A robust protocol, underpinned by a fair and transparent escalation process, is essential so that people can consider their options and the voluntary sector can help patients consider their choices and reach decisions about their future care.

Change 8: improved discharge to care homes

Underpinning logic

Offering people joined-up, co-ordinated health and care services, for example aligning community nurse teams and general practices with care homes, can help reduce unnecessary admissions to hospital, as well as improve hospital discharge.

Initial hunch

Our initial hunch was that these eight high-impact changes [or mechanism intervention resources (MIRs)] might prove to be equally important in delivering consistently safe, timely transfers of care patients who are homeless. More specifically, we hypothesised that specialist HHDSs encompassing all of most of these changes would deliver better outcomes for service users than those schemes employing fewer or none.

Testing this programme theory empirically through new research was important because much of the evidence underpinning the high-impact change model (HICM) (version 2015) was based on research with older people. At the outset of the research, very little was known about if and how the HICM might work for patients who were homeless.

How we anticipated the research might be used

In terms of the potential to lever change and improve outcomes for patients who are homeless, the HICM is an important tool. Developing pathways out of hospital is a key objective of the government’s programme for ‘integration and better care funding’. 34 The Better Care Fund (BCF) is the main source of funding for intermediate care in England and places clear expectations on health and well-being boards to oversee health and social care, including (1) pooling budgets, (2) integrating services to ensure more people can leave hospital when they are ready and (3) following guidelines laid down by the HICM. Local progress to implement the HICM is actively monitored by NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSE&I), meaning that any research that is embedded as part of this is potentially more likely to be implemented than other research that is not linked to government priorities.

In terms of how we envisaged the research would be used, we anticipated that the evaluation findings would either confirm the relevance of the HICM in its current format or make recommendations as to how it could be sensitised to better meet the needs of homeless patients.

Realist synthesis of the intermediate care literature

In testing and further refining our initial programme theory (prior to empirical data collection), the next step was to interrogate the literature more fully with regard to how each of the HICM changes might work for homeless patients and also to identify any other intervention resources that might support timely discharge. However, undertaking a literature synthesis for all eight changes was beyond the scope of the present study. As intermediate care is the key change recommended in the HHDF, we decided to concentrate the searches around change 4. We also thought it probable that the evidence for intermediate care would surface information on many of the other HICM changes, such as benefits of MDT working and promoting patient choice. Furthermore, of the different changes outlined in the HICM, intermediate care arguably has the greatest impact (transformational), especially with regard to outcomes linked to reducing the number of DToCs. 35 We also had the added advantage of being able to build on an already completed realist synthesis of the ‘generic’ intermediate care literature, as we discuss in the next section.

A conceptual platform for intermediate care

In 2013, a realist synthesis of the (generic) intermediate care literature was published. 25,27–36 This identified over 10,314 sources for potential inclusion and generated an extensive list of ‘programme theories’ for testing and refinement. An iterative Delphi-style technique was then used to arrive at a conceptual framework for intermediate care. This identified three programme theories as having the most ‘explanatory power’ when seeking understanding of how intermediate care works to improve outcomes for service users in a wide range of contexts. According to this conceptual framework, improved service user outcomes are achieved when:

-

the place of care and timing of transition to it are decided in consultation with service users based on the pre-arranged objectives of care and the location that is most likely to enable the service user to reach these objectives (programme theory 1)

-

health and social care professionals foster the self-care skills of service users and shape the environment so as to re-enable service users (programme theory 2)

-

health and social care professionals work in an integrated fashion with each other and carers (programme theory 3). 25

However, a limitation of this review was that it did not include literature on (specialist) intermediate care services for patients who are homeless.

To fill this knowledge gap and further develop our own initial programme theory, we applied the same methods and search strategy as outlined by Pearson et al. ,25 but extended the scope of the search to include ‘homelessness’. Although Pearson et al. ’s25 search strategy used, what they believed to be, a comprehensive list of phrases relating to intermediate care, we extended the scope of this search to encompass [‘medical respite’] and [‘homelessness AND ‘hospital discharge’ (schemes)] and [‘homelessness AND ‘delayed discharge’.] This is because the term intermediate care is not widely or consistently used in the homelessness sector. The search terms used are shown in Box 1.

Homelessness AND

‘hospital discharge’ (scheme)

‘delayed discharge’

‘Intermediate care’

‘Hospital at home’

‘Admission avoidance’ (scheme)

‘Early discharge’ (scheme)

‘Step-down’ (care)

‘Step-up’ (facilities)

‘Geriatric day hospital’ (day care)

‘Rapid response’ (team)

‘Intensive rehabilitation’ (service)

‘Recuperation facilities’ (residential or nursing home)

‘Integrated home care team’

‘One-stop primary care centre’

‘Nurse-led’/‘Consultant-led’/‘GP-led’/‘Physician-led’ (schemes/inpatient units)

‘Residential (care) rehabilitation’

‘Supported discharge’

‘Day (centre) rehabilitation’

(Acute care) ‘at home’

Hospital in the home

‘Rehabilitation at home’

‘Community Assessment and Rehabilitation Teams’ (CARTs)

‘Re-ablement’

‘Restorative care’

To this list we added the term ‘medical respite’, as it is often applied to residential-based intermediate care schemes for homeless people.

In terms of analysis, the overall aim of this exercise was to map how this additional evidence on specialist (homeless) intermediate care ‘speaks’ to the conceptual ‘road map’ already proposed for generic intermediate care by Pearson et al. 25 The literature synthesis is reported in accordance with the RAMESES II publication standards for realist reviews. 3

Methods used in literature synthesis

Searching processes

Electronic searches were carried out for peer-reviewed articles published in English from 2000 to June 2019 in the MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed, EMBASE, Social Policy & Practice, Health Management Information Consortium, British Nursing Index, The Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts. We searched the ‘grey’ literature through relevant websites [e.g. DHSC and Homeless Link (London, UK)], as well as through the internet using the Google search engine (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). We also contacted the 52 HHDF schemes seeking copies of any local evaluations and project reports.

It should be noted that an earlier version of this literature synthesis was published by the research team in 2018. 26 In preparing this present report, the original searches were updated to cover the period June 2017 to June 2019.

Selection and appraisal of documents

Intermediate care is a complex term that can encompass a wide range of different service configurations and functions. In selecting material for inclusion in the review, Pearson et al. 25 helpfully distinguish between conventional ‘hand-overs’ of care between providers and interventions that have been specifically designed to support service users’ transitions. The inclusion criteria for this present review was that articles and reports should describe specific interventions to support homeless service users in transition and that the intervention should encompass most of the key characteristics of intermediate care (Box 2). We included a small number of additional articles that considered homeless health or hospital discharge more generally, but only where they raised questions about the need for intermediate care. 26,30–37

Supports transition (e.g. hospital to home).

Occurs at a critical point (i.e. on the cusp of the shift from independence to dependence, at the point of acquisition of a chronic illness or disability, or at the intersection of illness and frailty).

FunctionsA bridge between (1) locations, (2) health or social care sectors (or within these sectors) and (3) health states. Views people holistically as individuals in a social setting.

Time limited (e.g. 72 hours, 2 weeks, 6 weeks).

StructureDesigns and embeds new routes through services (which enhance sensitivity to needs and wishes of service users).

ContentTreatment or therapy (to increase strength, confidence and/or functional abilities).

Psychological, practical and social support.

Support/training to develop skills and strategies.

Each source was read by at least two members of the research team. Papers were assessed based on the same realist ‘quality’ criteria utilised by Pearson et al. 25 This makes distinctions between those that are ‘conceptually rich’ (with well-grounded and clearly elucidated theories, ideas and concepts), ‘thick’ (a rich description of a programme, but without explicit reference to theory underpinning it) and ‘thin’ (weaker description of a programme, where discerning a programme theory would be problematic).

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis process

The literature was synthesised to discern how it addressed Pearson’s et al. ’s25 conceptual framework. When reviewing the literature, we sought to identify programme theories that were both explicitly argued and those that were tacit or implied, making it clear which was the case. A data extraction pro forma was designed to allow the evidence to be carefully mapped against each of the three programme theories. This included space for identification of any new programme theories. The final stage of the synthesis was to take the evidence as a whole and to reflect on the overall utility of Pearson et al. ’s25 conceptual framework, highlighting where any changes or refinements could be made.

Limitations

The limitations of a synthesis approach are that, although we have outlined our search strategy, we made judgments about the interpretations of the findings. Identifying programme theories and mechanisms from sources that are not explicitly theory driven, or do not provide adequate descriptions of the services, is also problematic and risks bias arising from the perspectives of the reviewers. Using multiple reviewers for each literature source helped address any uncertainty in the utility of the findings, challenging any bias.

Results of literature synthesis

The searches yielded 87 references, of which 48 met the inclusion criteria. Additional hand-searching revealed eight further articles. Internet-searching and direct contacts with intermediate care projects yielded 13 reports. These were mostly project reports and/or small-scale external evaluations. In total, 69 reports and articles were included in the synthesis.

Document characteristics

Appendix 1 summarises the articles and reports (n = 69) that were included in the review, the methods they used, their ‘richness rating’ and to which programme theories they aligned. Most of the literature fell into the ‘thick’ category, with few papers including a theoretical perspective. Most of the empirical evidence was from the USA and focused on medical respite. The UK evidence comprised mainly local grey literature reports and was focused mainly on the hospital discharge schemes that had been set-up with the HHDF funding.

Programme theory 1: the place of care and timing of transition to it are decided in consultation with the service user

The literature on homeless intermediate care confirms the central importance of consulting with service users about all aspects of their care and support. 38,39 In an early feasibility study, Lane40 noted that a particular advantage of intermediate care was its focus on person-centred care, rather than disease management, and that this could benefit people experiencing homelessness who are often familiar with and respond well to individually tailored care, as in supported housing. Poor outcomes, such as ‘self-discharge’ or a return to ‘rough sleeping’, are a significant problem where there is a failure to tailor care and support to the specific needs of people experiencing homelessness. 26,30–45

Tackling stigma and discrimination

Many people experiencing homelessness encounter stigma and discrimination in hospital. 37 Backer et al. 46 and Canham et al. 47 advise that this requires attention as part of good discharge planning. Indeed, although many of the HHDF schemes focus on ‘delayed discharge’ to meet their funders’ objectives,48 the more immediate concern of front-line practitioners is often preventing premature discharge. 49 Dorney-Smith et al. 50 describe how premature discharges can be linked to low thresholds being employed by ward staff for ‘bad’ behaviour (with no management techniques being tried or employed) and inexperienced staff affecting the overall quality of discharges.

Pearson et al. ’s25 review highlights the training of staff in the specific skills needed to deliver person-centred care as an important mechanism in the delivery of successful intermediate care. However, in homeless intermediate care, ‘cultural distance’ emerges as a complicating factor. Drury,51 for example, describes how the daily lives of health-care practitioners and homeless people are so different that they may become cultural strangers, fearfully avoiding contact with each other. Cultural distance often creates the ‘gaps’ that specialist intermediate care is then expected to fill. In their study of continuity post hospital discharge, Whiteford and Simpson52 found that some community nurses will not provide care inside hostels because they are perceived as ‘dangerous places’.

Many of the HHDSs funded as part of the HHDF perceived it as part of their role to offer mentorship and training to educate (mainstream) hospital staff about working with people experiencing homelessness. However, the grey literature suggests that this learning quickly evaporates without a ‘continuous and consistent presence’. 53,54

Engagement (patient in-reach) as a distinct mechanism

Compassionate kindness, dignity and respect are values that are seen to sit at the heart of psychological- or trauma-informed care and are aspired to by many specialist HHDSs. Halligan and Hewett55 observe how a visit from an empathetic team that is dedicated to the care of homeless patients in the hospital can improve patient experience and also prevent problems such as premature discharge.

Indeed, what also emerges from this literature is the importance of professionals first ‘engaging’ or building rapport with service users and how this may act as a distinct mechanism for underpinning more formal consultative or collaborative care planning processes. As Halligan and Hewett55 observe, it is only once a relationship is established that the hard work of planning community support and negotiating with housing, social care and health-care providers and the voluntary sector can begin.

Discussing a ‘nurse-led’ residential intermediate care scheme, Dorney-Smith56 describes how up to 1 month of engagement work may be needed to counter the suspicion and distrust patients may have of professional support. In the hospital setting, this work is often conceptualised as primary care or ‘patient in-reach’. This brings highly specialist clinical knowledge and understanding of homelessness onto the hospital ward, whereby specialist GPs and nurses are employed to work side by side with hospital consultants and ward staff to raise awareness about homelessness and tackle stigma and problems, such as the prevention of early self-discharge.

One of the key mechanisms for achieving patient in-reach is the ‘homeless ward round’, in which clinicians from the homeless team will identify and support homeless patients located across the hospital site. Identification of homeless patients at an early stage of admission is key to early discharge planning. Teams will use ‘concerned curiosity’ to understand a patient’s housing circumstances, mindful of the stigma of homelessness and that some patients will not want to reveal that they are homeless. They will then work with patients in psychologically informed ways to build relationships and support them to remain in hospital, have their voices heard and complete treatment.

As noted above, when working with patients who are homeless, the main challenge is not delayed discharge but more usually preventing ‘early self-discharge’. Often this can be a result of substance misuse and the patient wanting to discharge themselves against medical advice because of the onset of unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal can also be at the root of much challenging behaviour on the wards, for example where the patient feels that his or her withdrawal is not being appropriately managed and leaves the ward to use street drugs. Ward staff will then often address such absenteeism from the hospital bed, issuing behavioural contracts that can lead to conflict. In such circumstances, homeless team nurses and GPs can intervene to de-escalate the situation through more appropriate skilled clinical management (e.g. correct titration of opiate substitution medication such as methadone). The homeless team will also raise awareness among ward staff about many other forms of ‘silent stigma’ that lead people who are homeless to feel uncomfortable in hospital, such as being mindful that they may have no visitors to take home their washing and provide access to clean clothes and toiletries. Ultimately, the main goal of GP- or primary care-led ‘patient in-reach’ is to maximise the benefits of a hospital admission. However, Canham et al. 47 make the point that, in the absence of adequate aftercare resources, the benefits of trauma-informed care and patient in-reach can quickly evaporate.

Tomita and Herman57 undertook a randomised controlled trial (RCT) that evidenced reduced hospital readmission rates and other positive outcomes for 150 homeless psychiatric (mental health) patients receiving a care co-ordination intervention (vs. usual care). This suggested that the relationship with the social services’ worker may be as equally an important mechanism in delivering these positive results as securing housing tenure and stability.

Place of care

The strongest correlate of hospital readmission among homeless people is discharge location. 58 Kertesz et al. 59 showed that discharge to a medical respite facility was associated with significantly lower odds of readmission than discharge to ‘own care’ (including homeless shelters). Discharge to supportive housing has similar benefits. 60

Pearson et al. 25 reported that the characteristics of the local health and social care system could significantly limit care options for service users. This was evidenced in the homelessness literature, with people who are homeless having little opportunity to influence decisions about their place of care because few options might be available. 61

Doran et al. 58,62 reported that many US respite schemes will not admit homeless people who continue to drink and whose behaviour is identified as ‘challenging’. It might be argued that the lack of system capacity in the community, geared to the realities of persons’ needs, equates to acute care being a fall-back option. According to the Housing Learning and Information Network,29 having a specialist homeless hospital discharge worker does not eradicate delayed discharge if appropriate community care is not available. However, it can work to highlight where the gaps exist. The Housing Learning and Information Network caution that finding placements for people who continue to drink and have disabilities is often challenging. 29

The notion that intermediate care might itself fill some of these gaps raises questions about scope and remit and how far this should extend into the territory of longer-term care. According to van Laere et al. ,63 the high mortality rate among users of a Dutch medical respite scheme might be explained by the fact that the homeless population in Amsterdam most commonly comprises people with mental health challenges, long-term opiate users and people misusing alcohol who are not able to live independently and depend on fragmented services. In addition, many intermediate care schemes for people experiencing homelessness currently provide palliative care to compensate for the lack of provision elsewhere. 63–65

Generic or specialist?

Mainstream intermediate care facilities may not currently meet the needs of people who are homeless. 66 The argument for ‘specialist’ provision stems, in large, from the challenges of co-housing people with different challenges and vulnerabilities. 67 For example, Lane40 charts the advantages and disadvantages of admitting people who use substances and are experiencing homelessness to mainstream intermediate care. On the one hand, it is considered that when someone is in recovery they should not be exposed to hostel environments in which drug and alcohol use is commonplace. On the other hand, it is recognised that people who use substances may have ways of being that are problematised by health and care providers and other users of intermediate care services.

Rather than being understood in the context of patient choice and the need for person-centred care planning, debates around ‘place of care’ may be conflated with potentially discriminatory assumptions about the characteristics of different user groups. For example, Lane40 reports that some GPs and hostel managers he interviewed expressed concerns that ‘homeless people’ would not mix well with other users of intermediate care because they may be older and fragile both physically and emotionally. They were, therefore, overlooking the potential for challenging behaviours among older people related to conditions such as dementia.

Safe spaces for women

A study of early exit from medical respite reported that ‘respite structure’ (i.e. rules and regulations) could make some service users feel unsafe and may account for why up to one-third of people leave medical respite earlier than planned. 41 Women in this study were significantly more likely to leave respite before discharge completion than men. According to Bauer et al.,41 gender-specific treatment models or women-only spaces could enhance safety and consequently retention outcomes.

Programme theory 2: professionals foster the self-care skills of service users and shape the environment so as to re-enable them

One of the key objectives of intermediate care is that people should not be admitted straight from hospital to long-term care facilities without the opportunity for ‘reablement’, ‘recuperation’ and ‘rehabilitation’. 23 Importantly, although some local intermediate care services are integrated in England, physical rehabilitation tends to fall within the domain of the NHS, whereas recuperation (in a care home) and reablement fall under the banner of local authorities (councils) with social services responsibilities. Although health care is free in England, social care is means tested and potentially subject to a financial charge, as well as having eligibility thresholds. However, because recuperation and reablement are badged as intermediate care they are usually provided free of charge for a period of up to 6 weeks. The optimum time frame for intermediate care is considered to be between 2 and 8 weeks.

Reablement and physical rehabilitation needs

A feasibility study reviewed the caseload of a specialist homeless primary health-care team in Ireland to assess the need for a specialist homeless intermediate care centre. 68 It found that 15% of homeless people on the caseload had mobility and disability challenges attributable to health conditions, such as stroke, hip replacement, fracture or amputation.

In the literature on homeless intermediate care, ‘re-enablement’ or ‘reablement’ were not mentioned. Many studies reported difficulties collaborating with local authority adult social care, which may indicate that local authority reablement services are not easily accessible to people who are homeless. 42,45,65,69,70

Reports also suggest that the physical rehabilitation needs of people experiencing homelessness are not well catered for. 61–71 Whiteford and Simpson65 observed that many homeless people struggled to access rehabilitation not because they were homeless, but because of their age, with many services excluding people under the age of 55 years. Indeed, there is a recognised need for improved disability access in many UK hostels for homeless people. 45–73

‘Reablement’ environments

Mainstream residential intermediate care facilities in care homes or in hospitals often provide access to specially adapted environments, such as a ‘training kitchen’, in which people can practice the activities of daily living. A complaint arising from service users in one (specialist homeless) hostel-based intermediate care facility was boredom due to the lack of any kind of structured daily activity. 64 More recently, Pathway teams in London have employed occupational therapists to address this risk by promoting meaningful activity. 50

Recovery

There is emerging consensus in the intermediate care literature specific to people experiencing homelessness that to stop the ‘revolving door’ of hospital readmissions, support needs to extend beyond the discharge process itself and into the community, either by means of a residential ‘step-down’ facility or ‘floating support’ arrangement. 45,48,54 However, what is less clear is the ideal time frame for such arrangements, which may be termed intermediate care.

In the literature on specialist homelessness intermediate care, ‘recovery’ from drug and alcohol misuse and/or mental health problems emerges as the primary rehabilitative focus. O’Carroll et al. ’s68 feasibility study, for example, found that 48% of the caseload were experiencing problematic substance misuse, 33% had mental health challenges and 17% were dually diagnosed. However, the setting of goals around ‘recovery’ raises further questions about the accepted time frames for intermediate care. Dorney-Smith,56 for example, charts how service users’ health deteriorated when they were discharged from a nurse-led intermediate scheme that provided between 6 and 8 weeks of support. Dorney-Smith56 observes that recovery is a ‘long game’ for many homeless clients and time frames may be upwards of 24 months.

Resettlement

The 6- to 8-week time frame for intermediate care is further brought into question by the multiple overlapping natures of the transitions facing service users who are homeless (i.e. from ‘hospital to home’ and from ‘homelessness to housed’). Managing the transition from ‘homelessness to housed’ encompasses both the practical aspects of securing accommodation, as well as meeting what are termed ‘resettlement needs.’74 Indeed, there are many parallels to be drawn between ‘reablement’ and ‘resettlement’ work, with the latter being ‘housing’ rather than ‘social care’ led. Both share the aim of ‘doing things with rather than for people’ and have the overall aim of promoting independence. It might even be suggested that ‘resettlement’ work has a broader, more personalised focus than ‘reablement’, as it is often encompassing of both ‘citizenship goals’, such as securing employment, education and volunteering opportunities, as well as those linked to reablement and the promotion of ‘self-care’. Describing a specialist residential intermediate care facility for homeless people in northern England providing up to 3 months of resettlement support, Lowson and Hex75 describe the goal of the service as giving people the opportunity to make real life-changing decisions and to have a ‘real go’ at their lives, improving their life chances and quality of life, as well as improving independence with daily living tasks.

Pearson et al. ’s25 review noted that one drawback with (mainstream) intermediate care is that it has tended to prioritise a desire for service users to attain certain functional goals within a specified time period over service users’ self-knowledge and desire to reach a wider set of goals over longer, less clearly defined time periods.

Programme theory 3: health and social care professionals work together in an integrated fashion with each other and carers

Multidisciplinary team skill mix

Many hospitals in England now employ discharge co-ordinators to manage the most complex discharges. As recommended in the HICM,33 these roles are usually embedded in MDTs comprising senior nurses and social workers. The main focus of their work is usually on managing transfers of care for older people requiring continuing health care and/or moves into care homes. 76 Where there are large numbers of homeless patients (≥ 200 per year), it is recommended that hospital trusts develop specialist clinically led multidisciplinary ‘homeless teams’ to work alongside existing discharge teams. 77 As noted earlier, these are often called Pathway Homeless Teams by virtue of their affiliation with the Pathway charity, and these employ GPs, nurses, housing workers and a range of other staff. A RCT of the costs and benefits of two ‘clinically led’ services (vs. ‘standard care’) indicated that this clinically led approach does not alter length of stay, but improves the quality of life of homeless people (with fewer service users returning to the streets) at a cost deemed cost-effective under current guidelines. 78

An early evaluation of the HHDF similarly concluded that those schemes taking a specialist MDT approach were more effective in delivering improved health and housing outcomes than other models. 70 Without the benefit of a clinician, some of the (uniprofessional) housing link worker projects described difficulties in engaging with what they described as the ‘medical model’. 79 Wood et al. 80 suggest that the combination of nursing and social care is particularly effective for people who have complex problems or who have experienced long-term homelessness, given that the early stages of being housed can be immensely challenging, with poor physical and mental health adding to the concomitant stress of adjusting to a very different way of life. Case study evidence also highlights the important role of the GP in the MDT, particularly in advocating for homeless patients’ needs in a holistic way where there may be pressure from senior clinicians to discharge prematurely. 39–81

In the wider literature, discussions around ‘skill mix’ could reflect different ‘occupational lenses’ or types and levels of comprehensiveness around how homelessness might be addressed. Although the focus of the housing link worker schemes was often on housing and benefits advice, with ‘referrals on’ to primary care and other agencies, Hendry64 describes how staff in one medical respite scheme provided a full assessment under one roof, including a full screen blood test, screening for sexually transmitted diseases, medication compliance work, pre-detox work, smoking cessation, mental health, social services, occupational therapy referrals, benefits advice and chiropody. This comprehensiveness is a key feature of many residential step-down or medical respite schemes. 66

Involving carers and family members

In none of the material reviewed was there explicit reference to family member, carers and friends being involved in discharge and intermediate care support planning. However, there was an account of one discharge scheme that focused specifically on linking people who were experiencing homelessness back to their country of origin or their home town where they may have a ‘local connection’ and, therefore, a better chance of securing housing and social care support. 69

Mechanisms for integrating services

For many of the HHDF projects, integration into the hospital setting was described as challenging. 70 Formal protocols (e.g. developing a homeless hospital discharge protocol) were identified as important in most of the grey literature accounts, especially with regard to making sure ward staff asked about homeless and housing on admission. However, the main problem was sustaining them. 29 Successful ways of doing this and raising awareness about the schemes more generally included having the scheme championed by senior hospital staff and actively promoting the scheme through posters, leaflets and contact cards. 44 Co-location and being ‘a face’ on the ward were thought to help ensure the flow of referrals and ease of communication. 54–61,72 Participating in ward rounds, attendance at weekly hospital staff meetings to discuss patient discharge planning and running reflective practice and training sessions for hospital staff on the subject of homelessness were also considered helpful. Once the referral pathways were established in HHDF schemes, hospital staff seemed to appreciate being able to ‘hand over’ responsibility for the homeless people on their wards. 54 ‘Passing the baton’ could, however, potentially reduce opportunities for collaborative working.

Advocacy as an additional key mechanism

Although integration and co-ordination are foregrounded as key mechanisms for the successful delivery of intermediate care,25 the homeless-specific literature suggests that advocacy (‘arguing the case’) may be equally important. 44 Many grey literature accounts of the HHDF schemes alluded to the impact of austerity and depleted budgets, which meant reduced availability of housing and longer-term care and support. It was noted that housing authorities will often defend their budgets by rigidly restricting access to a defined ‘local’ population. This renders care co-ordination particularly challenging for homeless people who often have weak or no ties to any locality and lack documentary proof of any entitlements. 45

Integrating housing as the ‘third pillar’ of intermediate care

UK intermediate care has been delivered primarily as a health and social care service. 25 Canham et al. 47 recognise housing assessment as a key ‘health support’ for persons transitioning from hospital. The HHDF highlights the role of housing services in delivering improved health and well-being outcomes and, consequently, the importance of housing professionals working alongside health and social care professionals. Several grey literature accounts report that hospital staff appreciated this resource, especially in terms of its potential to free up their time. Charles et al. 54 observed that ward staff lacked the knowledge to find accommodation for homeless patients.

One report of a ‘housing link worker’ scheme describes extending its remit beyond ‘homeless people’ so that support could additionally be provided to older people who were being delayed in hospital because of ‘housing issues’. 82 This reflects the importance of integrating housing as the third pillar of health and well-being for all patient groups.

Discussion: framework utility

The additional evidence presented above broadly supports the validity or usefulness of Pearson et al. ’s25 conceptual framework for understanding ‘what works best’ in intermediate care. This is with regard to three key programme theories: (1) the importance of consulting with service users, (2) working in ways that are enabling and (3) ensuring integrated professional working. However, it might be suggested that these three ‘programme theories’ are likely to be implicated in the successful delivery of many other health and social care services. Herein lies a potential limitation of the current framework in that it may not answer some of the more complex or nuanced questions relating specifically to the development of intermediate care services.

The first challenging question to emerge from this review is how to maintain the integrity of intermediate care as a ‘time-limited’ intervention. This question arises where there is a need to encompass multiple and overlapping rehabilitative and resettlement goals, which may require housing solutions underpinned by much longer-term or continued health and social care support. Indeed, decisions around ‘time frame’ and scope are relevant to commissioners of intermediate care for both older people and people who are homeless (some of whom overlap). It is acknowledged that the rehabilitation of older people has sometimes fallen short because it has often prioritised short-term reablement goals linked to ‘physical functioning’ over and above those for inclusion and citizenship. Meanwhile, intermediate care for people who are homeless has reversed the ‘occupational lens’, prioritising longer-term resettlement and recovery outcomes over and above those for reablement. How to encompass these different needs and vulnerabilities under a single service banner is a significant additional challenge, with the danger that ‘specialist’ provision starts to confirm cultural distance (e.g. ‘elderly people’ are quiet and frail and ‘homeless people’ are challenging and disruptive).

These complexities are compounded in times of austerity, when the integrity of intermediate care is further compromised by the need not just to ‘fill the gaps’ in local provision but, on occasions to substitute for the widespread loss of longer-term support services. As Backer et al. 46 suggest, discharge planning and intermediate care will have little impact unless housing and other services are available. Interventions that were shown to work well in areas with well-resourced and efficient community support services were seen to have little or no impact where services are inadequate or lacking. 83

It is recognised that this poses perhaps the most serious threat to the viability of intermediate care as a service organisation and delivery construct. If the boundaries with longer-term care services start to blur, then intermediate care risks quickly becoming ‘blocked’. 66–71,73–84

In terms of a refined ‘conceptual framework’ that might address some of these issues, a US study57–71,73–85 is particularly insightful. It reports the findings of a RCT of a clinically led case management intervention called ‘critical time intervention’ (CTI). 57–71,73–85 CTI was designed to provide emotional and practical support over a 9-month period, with the primary objective of preventing homelessness among people being discharged from a psychiatric (mental health) hospital. In CTI, intermediate care is conceptualised as comprising the following three distinct phases:

-

Transition to the community focuses on engagement and relationship building, providing intensive support and assessing the resources that exist for the transition from in-patient care to community providers.

-

Try out is devoted to testing and adjusting the systems of support and assessing whether or not they are working as planned. By now, community providers are assumed to have adopted primary responsibility for delivering support.

-

Transfer of care focuses on completing the transfer of responsibility to community resources that deliver long-term support. 85

The findings of the RCT, which compared the outcomes of those receiving the CTI intervention with those receiving standard care, suggested that this brief, clearly focused intervention led to a reduction in the risk of homelessness that was evident 9 months after the intervention ended. In accounting for ‘what works and why’, consultation, enabling and ensuring integrated professional working are all implicated in CTI, but the cornerstone of the approach is a potential fourth programme theory. Namely, this is maintaining continuity of care during critical transition periods while responsibility gradually passes to existing community supports that will remain in place after the intervention ends. 85

In CTI, ‘scope’ is clearly defined as being about the management of transitions rather than specific kinds of ‘needs’ or ‘gaps’ in existing provision. It is, therefore, generic in that it can be applied to all client groups and can potentially be operationalised in any given local context, as the aim is to ‘weave together’ the resources and infrastructure that are already in existence. The ‘time frame’ for the intermediate care intervention is also determined not by any rigid ‘service-led’ criteria, but by the adaptive capacity of the local context to meet the person’s needs. It might be added that where CTI becomes ‘blocked’ (i.e. there are no appropriate services to take over responsibility), then this should ring alarm bells for commissioners that there are ‘cracks’ in local provision.

Indeed, CTI also seems to encapsulate the ‘how to’ of what Parker-Radford37 terms a ‘transition of care approach’. This has the additional advantage of shifting the focus of the ‘organisational lens’ from the acute sector to the management of a much wider range of transitions (e.g. ‘prison to community’ and ‘armed forces to civilian’). It is, therefore, potentially key to continuity and seamless care, as seen from the perspective of people who use or reject services.

Summary

Pearson et al. ’s25 conceptual framework proved a useful heuristic device for synthesising the literature on intermediate care for patients who are homeless. It worked as a ‘coat hanger’ on which a wide range of evidence could be hung and critically appraised. As we outline below, it also helped refine our initial programme theory for empirical testing.

First, the findings confirm our initial hunch about the broad utility of the HICM for delivering safe, timely transfers for patients who are homeless. In the specialist homeless literature, there is strong evidence for high-impact change [i.e. change 3 (discharge co-ordination underpinned by MDT working) and change 4 (intermediate care)]. Importantly, an early evaluation of the HHDF suggested that multidisciplinary HHDSs were more effective on some measures than housing-led (uniprofessional) schemes. In addition, there is some evidence that MDT working should encompass ‘clinical input’ (i.e. the inclusion of GPs and nurses) to enable effective advocacy for patients on medical- as well as housing-related matters, preventing problems such as early self-discharge. ‘Patient in-reach’ also emerges as an important additional high-impact change for challenging stigma and underpinning patient engagement and choice (change 7). There is evidence about the importance of specialist homeless hospital discharge protocols to facilitate patient flow (change 2) and specialist ward rounds to facilitate early discharge planning (change 1). Co-locating housing workers on the hospital site is important for keeping protocols live and ensuring that early discharge planning can commence, bringing in housing and homelessness services, home adaptations and equipment. The need to integrate housing (worker/expertise) as the third pillar of health and well-being (i.e. as an integral component of multidisciplinary working) can be conceptualised as an additional high-impact change, such is its importance for early, safe and effective discharge planning. There is less clear evidence for trusted assessment (change 6) and flexible working (change 5). Improving access to care homes was not raised directly (change 8); however, questions were raised about the accessibility (suitability) of residential intermediate care provided in care home settings. This is a potentially important change, which may not feature strongly in the current literature because of the different occupational lenses that may downplay physical frailty and early onset of ageing and cognitive problems in the homeless population. 73 The practice reported of using intermediate care as a palliative care service may be further symptomatic of this.

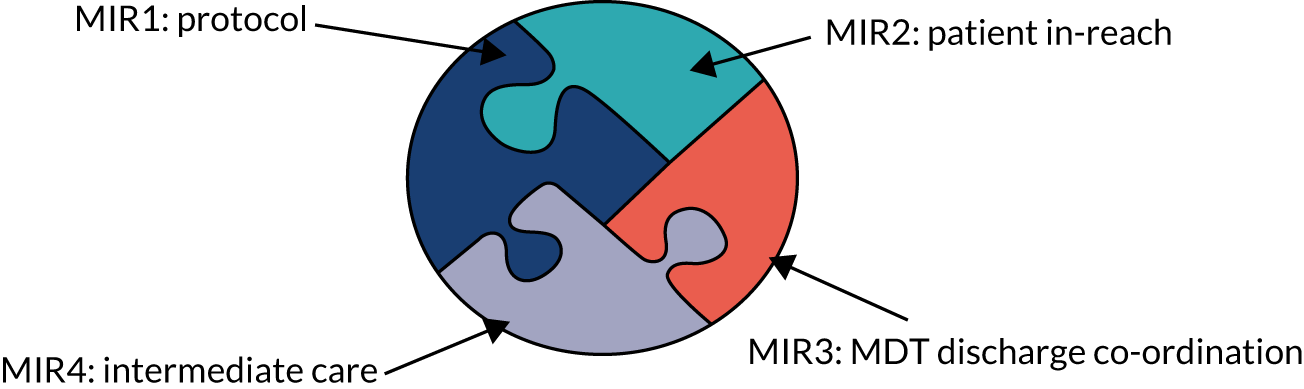

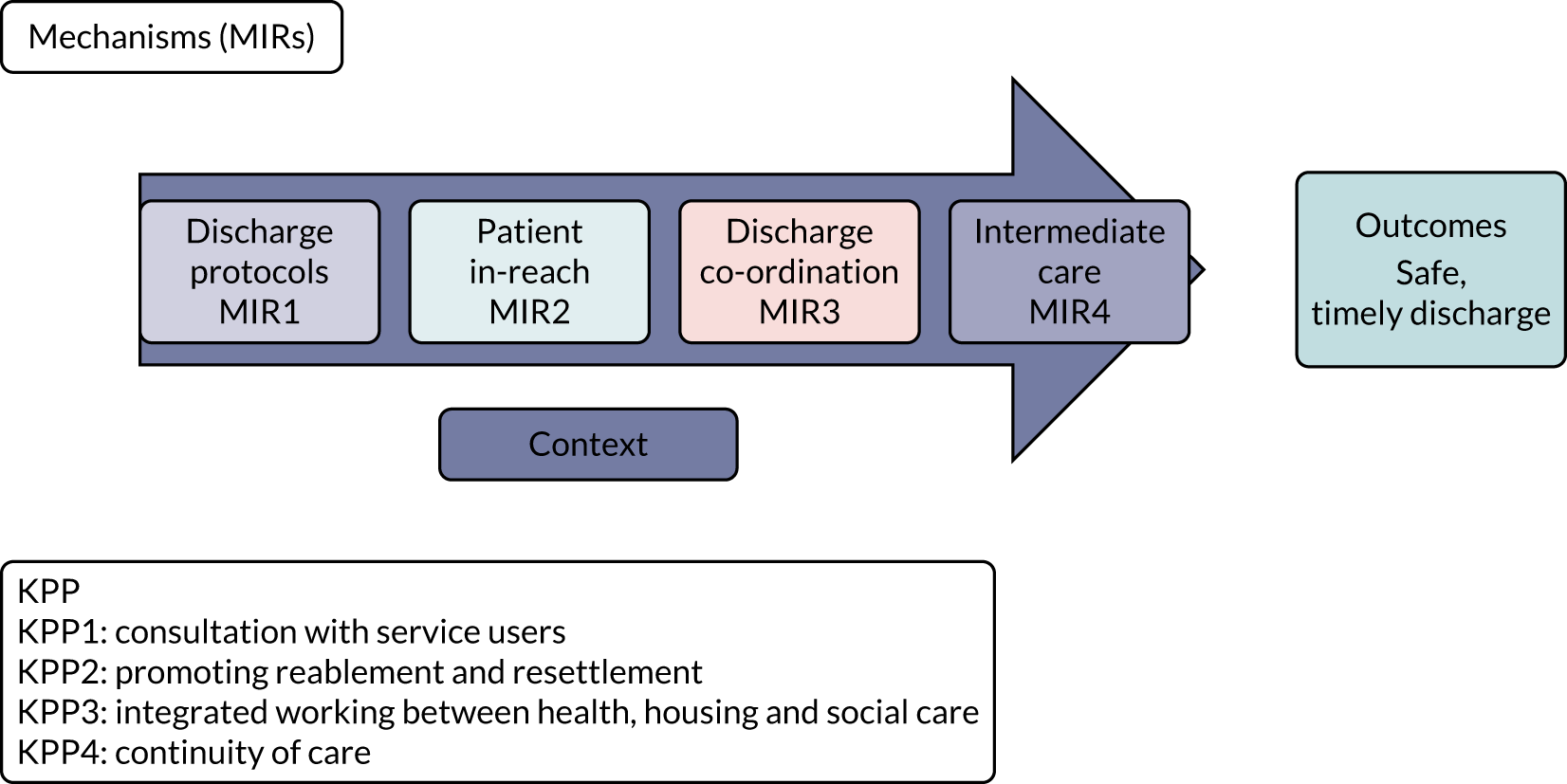

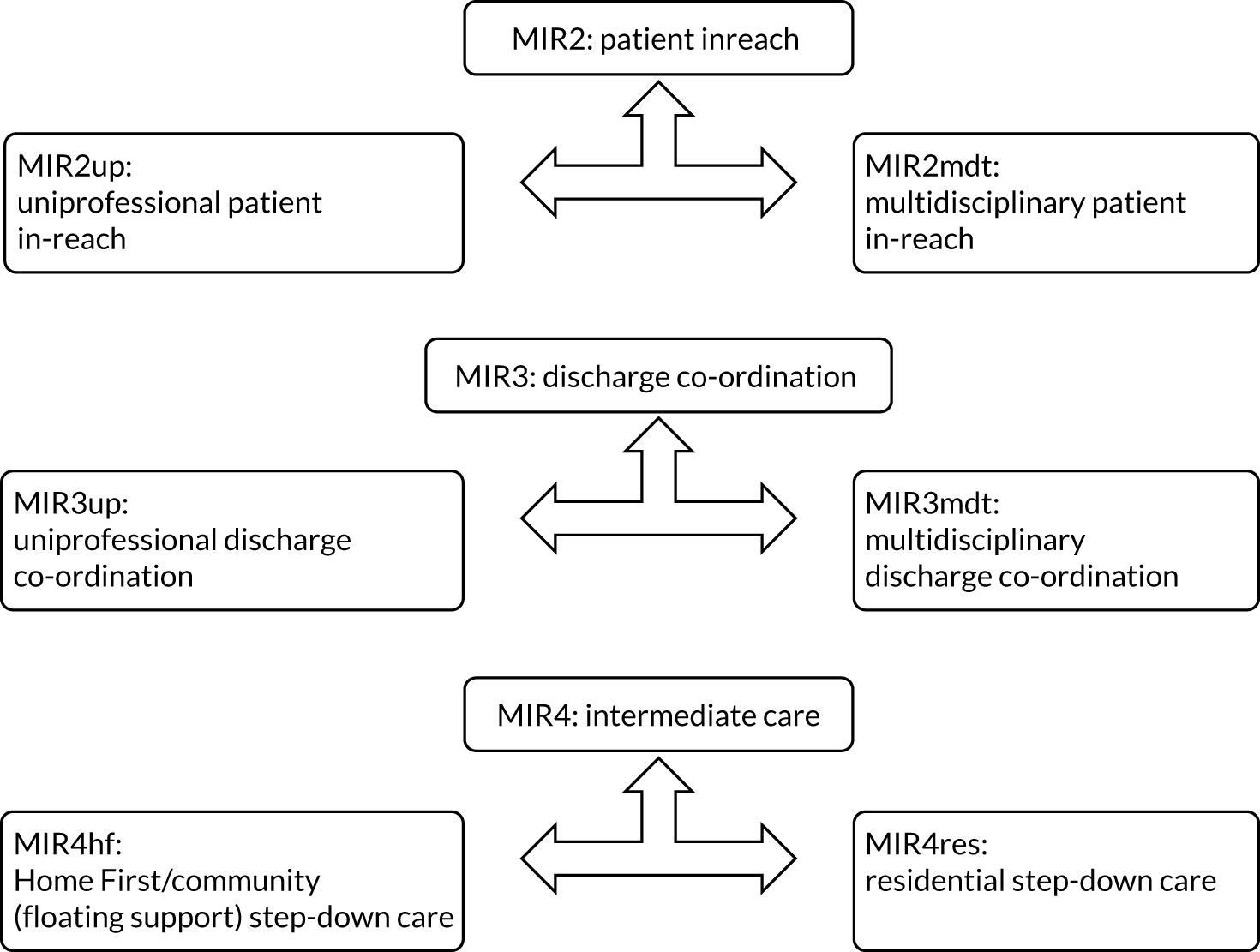

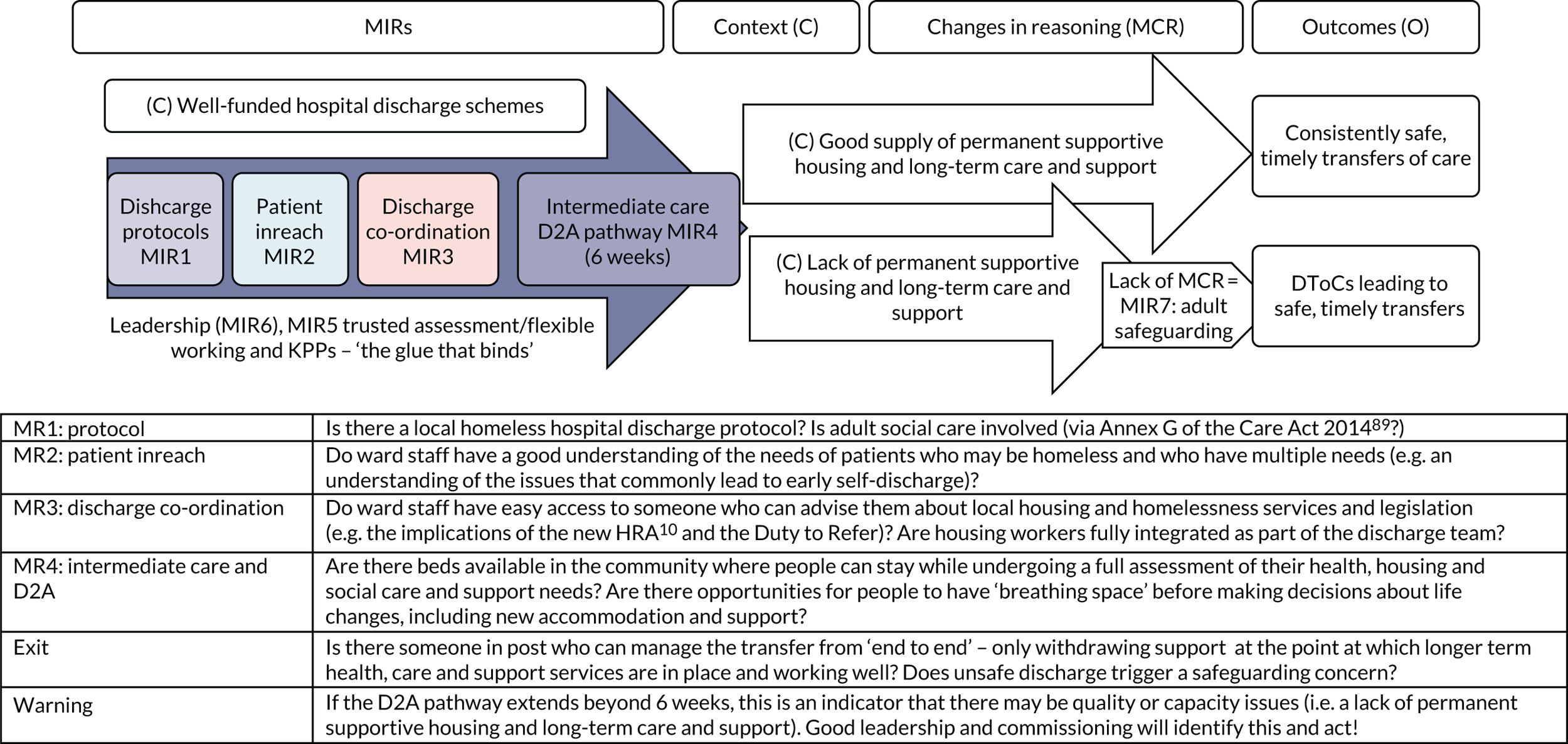

Second, turning our attention to Pearson et al. ’s25 conceptual framework for ‘generic’ intermediate care, it was hypothesised that good outcomes would be secured for patients on the basis of implementing three KPPs (tested as programme theories): (1) consulting with service users, (2) working in ways that are enabling and (3) ensuring integrated professional working. The additional evidence reviewed here suggests the need for some refinement of these generic principles if they are to support the needs of people who are homeless leaving hospital. These refinements are shown in italics in Box 3. Box 3 synthesises all the above evidence to specify the programme theory we took forward into the next stage of the research for empirical testing. It should be noted that Box 3 is also used as the ‘coat hanger’ (coding framework) for our subsequent qualitative data collection and analysis. The coding draws on Dalkin et al. ’s32 formula outlined earlier. The codes are as follows.

-

MIRs:

-

MIR1 [protocols for early discharge planning/patient flow (high-impact change model 1 and 2)]

-

MIR2 (patient in-reach)

-

MIR2mdt [patient in-reach (with clinical and housing advocacy/expertise combined)]

-