Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number HSDR 17/49/42. The contractual start date was in January 2019. The final report began editorial review in August 2022 and was accepted for publication in April 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Long-Sutehall et al. This work was produced by Long-Sutehall et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Long-Sutehall et al.

Structure of the report

This report has 3 sections and 10 chapters. For this report, the WP (illustrated in Figure 1) and data arising from each stage (S) will not be presented in the order they are laid out in Figure 1. The layout in Figure 1 was established at the start of the study in order to facilitate project planning. Instead, the report will follow a narrative as follows:

-

Section 1 comprises three chapters. Chapter 1 provides the background and introduction to the study and the research questions and objectives guiding the study; Chapter 2 outlines the study methodology and study design, including details of partner research sites, participants, data management and analysis. Chapter 3 delivers a review of the extant literature specific to the context of the study.

-

Section 2 comprises four chapters which combine all findings from service providers and service users and includes the methods, findings and commentary of findings related to associated WP and stages (S). Each chapter is supported by tables, figures and quotes from participants. Chapter 4 presents the findings of the retrospective note review (WP1S1). Chapter 5 presents the findings from interviews with service providers, participant observation in research sites and investigation of existing clinical and policy information regarding ED (WP1S2). Chapter 6 reports findings from the national survey with service providers (WP1 and 2), and Chapter 7 presents findings from service users and recommendations for improving ED-related support for these groups. Recommendation for practice related to all service providers is outlined in the conclusion of Chapter 6, and service users’ findings (see Chapter 7).

-

Section 3 comprises three chapters. Chapter 8 presents the development and evaluation process for identifying priorities for intervention development through a TEC. Chapter 9 provides a description of the resulting complex service development intervention, the STEPS. Chapter 10 presents a detailed discussion of key findings, and their implications for future service development research, concluding with a review and reflection on PPI involvement, Equality and Diversity, study limitations, acknowledgements and statement of ethical approval.

Because of the mixed-methods nature of this project, involving multiple participant groups and addressing different aspects of health service development, we have structured each chapter so that it includes a discussion of findings and implications for practice. This is to ensure that specific points are summarised and made explicit prior to the overarching discussion in Chapter 10, which focuses on bringing together the broad scope of the project. Chapter 10 therefore draws on points introduced in preceding chapters, with a focus on more general themes that cut across different areas of the project.

Chapter 1 Background and introduction

The need for corneal tissue – global and UK national contexts

Globally, the estimated number of people who are visually impaired is reported [by World Health Organization (WHO) databases] to be 285 million, with 39 million individuals recorded as blind, and 246 million recorded as having low vision. 1 According to Pascolini and Mariotti,1 over 10 million of those people reported as blind have bilateral corneal blindness, which could be restored with a corneal transplant. However, these individuals do not have access to the benefits of sight-saving and sight-restoring transplantation surgery, due to a shortfall in the supply of tissue (cornea and sclera) that is only available via eye donation.

According to the Royal National Institute of Blind (RNIB), over 2 million people in the UK are living with sight loss2 caused by conditions such as keratoconus and Fuchs’ corneal dystrophy, which can be treated if eye tissue is available (e.g. by corneal transplantation and reconstructive surgery). Eye tissue is also needed for research into a wide variety of eye diseases, for example endothelial failure post cataract surgery. 1,3 The RNIB reports that approximately 5000 corneal transplants are required annually in the UK to address disease and injury resulting in sight loss, with annual costs to the UK economy (unpaid carer burden and reduced employment rates) reported as £4.34 billion. 2 Critically, the organisation predicts that by 2050, the number of people with sight loss will double to nearly 4 million, mainly due to the ageing population. 2 If the burden of disease is to be minimised, it is imperative that the tissue needed to intervene in these conditions via corneal transplantation, reconstructive surgery, glaucoma surgery and research into the causes and treatment of eye disease is available.

The unique and specific case of eye donation

Addressing barriers to eye donation (ED) requires attention to the unique and specific challenges that are associated with this form of donation; for example, why do family members of organ donors frequently reject ED despite agreeing to other organs (and tissues)? Data from UK-based studies indicate that personal views of potential donors and family decision-makers are influential in triggering a decline to donate when ED is proposed. 4 Prominent concerns include potential for disfigurement,5 beliefs compatible with eyes being needed in the afterlife and/or that eyes as ‘windows to the soul’ are an essential aspect of a person even after death. 5,6 ED is also known to elicit specific disgust-type responses in some patients and family members, characterised as an ‘ick factor’ attended by feelings of squeamishness in respondents7 that is not observed in other forms of donation.

Compounding the problem of low supply is the historic lack of attention that this form of donation has received from key policy-generating organisations. For example, eye and tissue donation was not mentioned in the 2008 UK Department of Health Organ Donation Taskforce Organs for Transplants national report,8 and therefore has not featured in ongoing planning initiatives and research agendas. This lack of attention to factors acting as barriers and facilitators to ED may contribute to explaining the continuing low levels of eye tissue supply via donation.

Optimising the supply of eye tissue for use in sight-saving and sight-restoring surgery and medical research

The National Health Services Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) Tissue and Eye Services (TES) Bank (based in Speke, Liverpool) supplies most eyes for surgical purposes in the UK and aims to achieve a weekly stock of 350 so that they can provide 70 eyes every working day for use in surgery or research. From April 2021 to March 2022, donation of eyes from all sources (solid organ donation, tissue donation) generated 4555 from 2286 donors, equating to only 88 eyes per week (13 eyes per day). These levels are not supplying sufficient tissue necessary for the roughly 5000 corneal transplants required each year for conditions such as keratoconus, Fuchs’ corneal dystrophy and endothelial failure post cataract surgery. 9 The actual number of people waiting for a corneal transplant is difficult to confirm as there is no centralised waiting list for patients who need a corneal transplant (unlike in solid organ donation where there is a centralised waiting list, and the actual need may therefore be greater). The Keratoconus Society, writing in support of the current project, has reported contact with patients who often face extended waiting periods for corneal tissue to become available for transplant. A further pressure on the nationally reported donation rate of 4555 eyes (NHSBT statistics and clinical studies, November 2022, personal communication) is that approximately 30% will be discarded due to infection/viruses, with supply further compromised by a 28-day limit to storage requiring disposal of tissue thereafter.

Current UK routes of eye tissue supply

There are currently two potential routes of supply for eye tissue in the UK:

-

Route 1: Eye donation from solid organ donors – Eye donation from solid organ donors (EPSOD) continues to prove problematic, with slow progress in increasing supply from this specific cohort of donors. For example, EPSOD generated 446 eyes between 1 April 2019 and 31 March 2020. 10

-

Route 2: Eye donation from deaths outside of ICU/ED environments – Unlike tissues such as heart valves, bone, tendons and skin, eye tissue can be considered for donation even if the donor has a diagnosis of cancer, because of the avascular status of the cornea and sclera. Current data indicate that approximately 258,900 deaths in hospital11 and 25,498 annual deaths in hospices12 could potentially result in donation of eye tissue. However, from April 2021 to March 2022, NHSBT-TES only received 443 referrals from 63 hospice locations with 293 of those referrals resulting in the donation of eyes. Therefore, on average, these 63 hospices referred 7 donors each to NHSBT-TES in that year. As there are 208 hospices across the UK, there appears to be significant potential for donation within these settings that is currently unrealised.

Increasing supply is a key strategic aim for the NHSBT-TES division13 with other professional bodies including the Royal College of Ophthalmology (RCO),14 and NHSBT-TES OtAG (Ocular tissue Advisory Group)15 expressing the need for research into the barriers to eye donation and new supply routes. Therefore, in view of the low referral rates generated by palliative care services in the UK and with the aim of identifying current barriers and facilitators to ED in palliative care settings, the ED from palliative and hospice care contexts: investigating potential, practice, preference and perceptions (EDiPPPP) study was designed with specific objectives aimed at answering key questions (Table 1).

| Research questions | Study objectives |

|---|---|

| RQ1a: Potential – What is the potential for ED in HPC and HC? RQ1b: What consequences will any increase in ED from these settings have for NHSBT tissue and eye services in relation to resources/infrastructure/logistics? |

Objective 1: To scope the size and clinical characteristics of the potential ED population from research sites. Objective 2: To map the donation climate of each research site via a systematic assessment tool RAPiD. |

| RQ2: Practice, Preference and Perceptions – What system-based/attitudinal and educational barriers/facilitators to ED influence the identification and referral of potential eye donors in clinical settings and the embedding of ED in EoLC planning? | Objective 3: To identify factors (attitudinal, behavioural) that enable or challenge service providers to consider and propose the option of ED as part of EoLC planning from a local and national perspective. Objective 4: To identify service users’ views regarding the option of ED and the propriety of discussing ED as part of admission procedures or as part of EoLC planning conversations. |

| RQ3: What behaviour change strategies will be effective in increasing ED across the community of service providers and service users within HPC and HC? | Objective 5: To develop an empirically based theoretically informed intervention designed to change behaviours in relation to the identification, approach/request and referral of patients from HPC and HC for ED. |

Chapter 2 Methodology and study design

Changes to protocol – summary

Changes to the study protocol and related procedures were made in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (2020 onwards). All data collection was paused at sites on 18 March 2020 owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. Data collection resumed on 2 July 2020 following approval of a non-substantial amendment from the University of Southampton institutional ethics committee (ERGO REF – 59185).

Prior to this, amendment data collection, as per the study protocol, had been completed at two sites (S01 and S02) using in-person methods (researcher embedded at the site undertaking observation, interviews and facilitating focus groups). Following the ethics amendment, data collection recommenced using remote data collection methods. Therefore, data collection methods were adapted at four sites (S03–S06) to comply with social-distancing guidelines provided by the government, NIHR and the sponsor (University of Southampton).

Post COVID-19 ethical amendment key changes were: Data collection: WP1 and 2: all interviews with service providers and service users were conducted via telephone as the first-line option, with Microsoft Teams added as a second-line option if preferred by the participant [this was the case in several instances in hospital-based palliative care (HPC) settings where mobile telephone reception was poor, but Wi-Fi was available]. Where Microsoft Teams was used, only audio was recorded (in line with existing procedures for data collection). In-person, on-site observations ceased with the observation of multidisciplinary team meetings moving online via Microsoft Teams.

On 6 May 2021, the University of Southampton ethics committee (ERGO) approved a non-substantial amendment (ERGO ID 59185.A1) to allow the transparent expert committee (TEC) process to be conducted online using the Microsoft Teams platform, as opposed to in-person as originally stated in the protocol.

All other TEC processes were unaffected, with recruitment and consent documents being updated to reflect the new format. See Report Supplementary Material 1 for a summary of documents changed in response to both amendments.

Study design – overview

This section describes the overall study design and methods used for data collection and analysis across EDiPPPP. The project is structured in line with the six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID) framework. 16 Study design incorporates applying qualitative17–20 and quantitative methodologies,21–23 theoretical perspectives24,25 and intervention mapping methodologies26–30 to deliver three interlinked and developmental WPs that answer the research questions and meet the study objectives (Table 2).

| Steps (6sQuID) | Research questions and objectives |

|---|---|

| Step 1: Define and understand the problem and its causes (WP1) | RQ1a: Potential – What is the potential for ED in HPC and HC? Objective 1: To scope the size and clinical characteristics of the potential ED population from research sites. Objective 2: To map the donation climate of each research site via a systematic assessment tool: the RAPiD. |

| Step 2: Clarify causes/contextual factors that are malleable (WP1 and 2) | RQ2: Practice, Preference and Perceptions – What system-based/attitudinal and educational barriers/facilitators to ED influence the identification and referral of potential eye donors in clinical settings and the embedding of ED in EoLC planning? Objective 3: Identify factors (attitudinal, behavioural) that enable or challenge service providers to consider and propose the option of ED as part of EoLC planning from a local and national perspective. Objective 4: Identify service users’ views regarding the option of ED and the propriety of discussing ED as part of admission procedures or as part of EoLC planning conversations. |

|

Step 3: Identify how to bring about change: the change mechanism

Step 4: Identify how to deliver the change mechanism (WP2 and 3) |

RQ3: What behaviour change strategies will be effective in increasing ED across the community of service providers and service users within HPC and HCS? Objective 5: Develop an empirically based theoretically informed intervention designed to change behaviours in relation to the identification, approach/request and referral of patients from HPC and HC for ED. |

| Steps 5: Test and refine on a small scale conduct a small proof of concept study (WP3) | RQ1b: What consequences will any increase in ED from these settings have for TS in relation to resources/infrastructure/logistics? |

| Step 6: Establish the evidence that the intervention would warrant a large-scale test | Objective 6: Pilot and evaluate the empirically based theoretically informed intervention described in step 4. |

Changes to theoretical perspectives

Our intention had been to apply two theoretical perspectives to the analyses of data (interviews with service providers and service users): the Theory of Paradoxical Death (ToPD)31 and Burden of Treatment (BoT) Theory. 32 It became apparent as interviews were reviewed that the ToPD was not relevant to these data, as service providers and service users did not articulate cognitive dissonance regarding the topic of ED. In addition, no carers were interviewed post death and the ToPD is specific to that situation. Similarly, BoT was not supported in patient/carer interviews as they did not perceive ED as adding to their burden of action and work as they were not aware of the option of ED and so it was not on their radar as ‘another thing to do’.

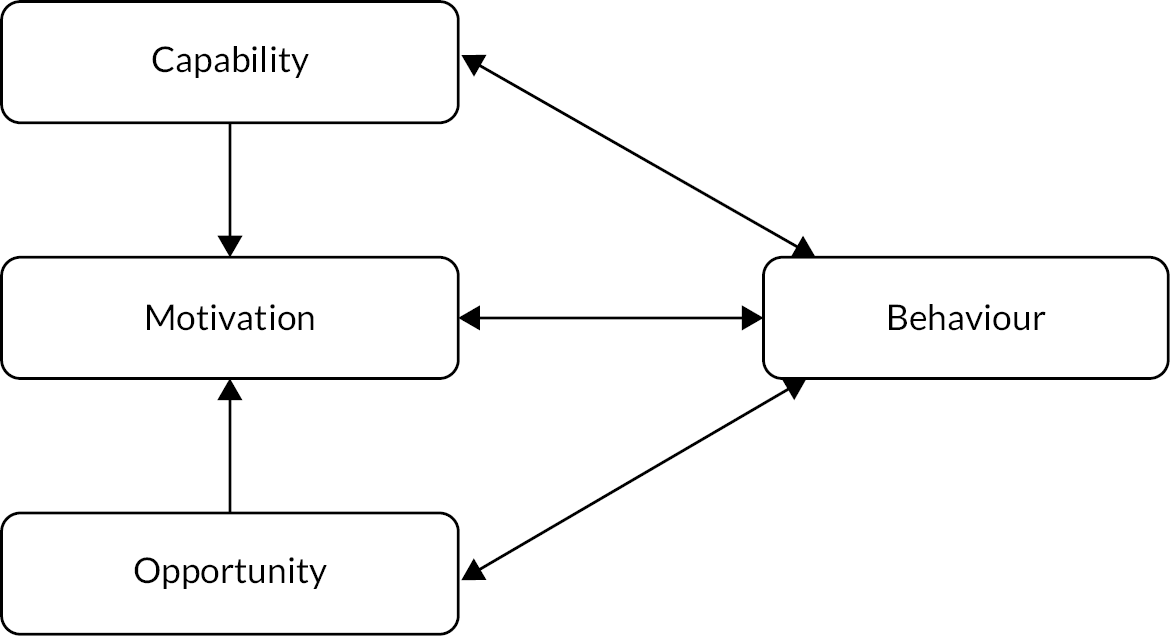

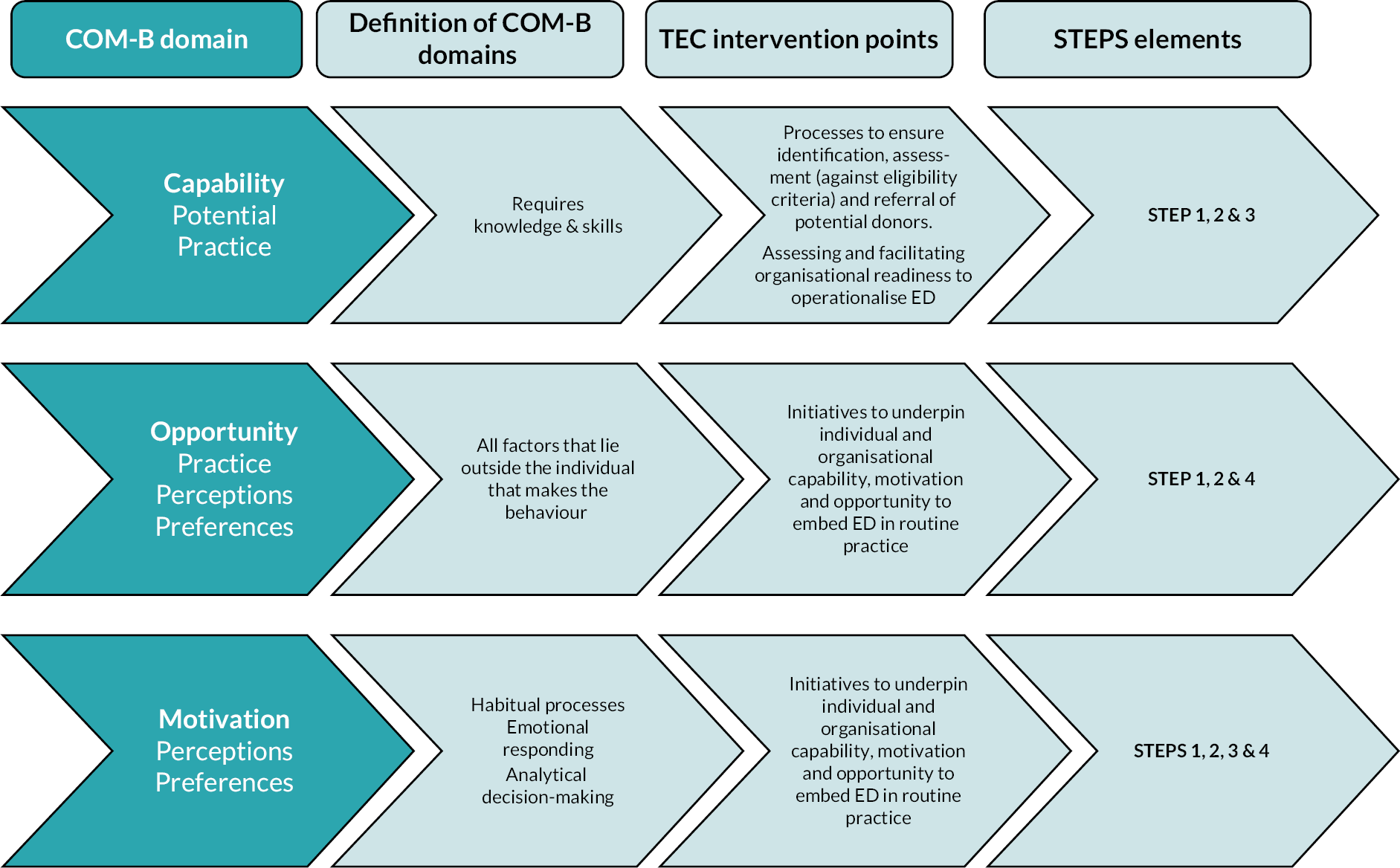

However, our hypothesis that service providers may perceive raising the issue of ED with patients as a burden was supported by our data, and for some service providers, this resulted in a decision not to raise the topic. We, therefore, drew on UK Medical Research Council guidance on the development of complex intervention studies, and sought to ‘refine [the] programme theory’ underpinning EDiPPPP in light of these and other observations encountered as the research progressed. 33 These included observations indicating: that service providers align their behaviour; and their lack of action (to raise the issue of ED with patients or family members) to knowledge gaps, missing skills, absent processes and guidance. These factors acted as barriers to ED. We, therefore, looked towards the behaviour change literature (individual and organisational) to identify relevant theory to frame intervention development. As early findings indicated that context-specific behaviour change initiatives would be a key factor in increasing the ED rates, and as the capability, opportunity, motivation – behaviour change model (COM-B) behaviours change model24 is proposed to articulate what needs to change in order for a behaviour change intervention to be effective, this theoretical framework was applied specifically in intervention design (see Chapter 9).

Project structure

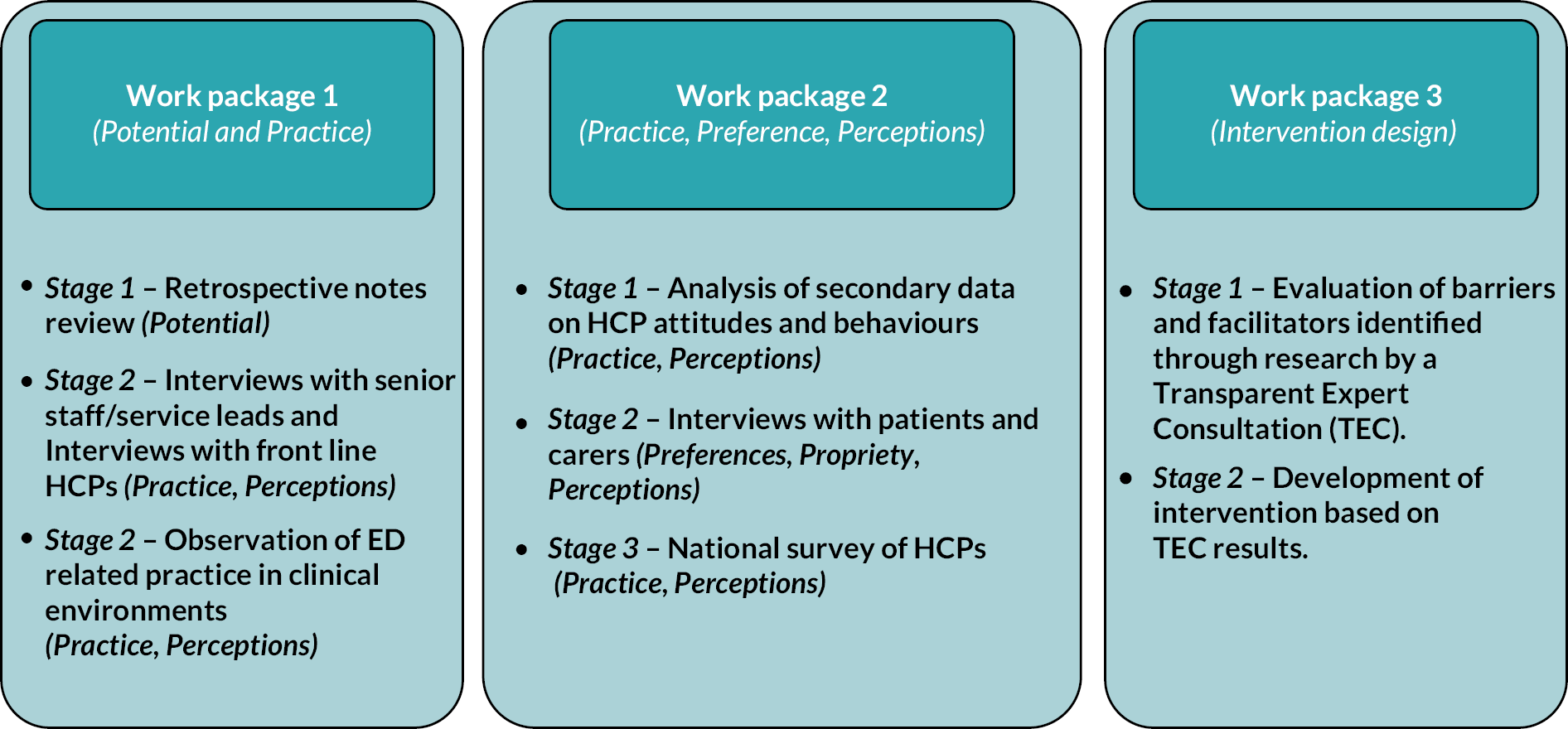

The objectives and research questions specified in Table 1 were addressed through three related WPs. Figure 1 provides an overview of these WPs and their constituent stages; henceforth, WP indicates a work package, and S indicates a stage within the WP – for example, WP1S1 indicates WP1, stage 1.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of work packages and stages for the EDiPPPP project.

Work package 1 explored the potential for, and current clinical practice relating to, ED within participating sites across England. WP1S1 involved a retrospective review of case notes from patients deceased at these sites to establish current referral rates, and clinical characteristics of patient populations. WP1S2 explored the current clinical practice and preferences of HCPs related to ED (e.g. if, when and how a conversation about ED should be initiated with patients and/or their families/carers). This stage involved interviews with HCPs in strategic and/or managerial roles (HCP-Str/Man, i.e. those actually or potentially in positions to affect organisational behaviour relating to ED) and focus groups or interviews with HCPs in front-line roles (HCP-FL, i.e. those actually or potentially involved in processes relating to ED, such as: participating in conversations with patients or providing information relating to ED, but who typically would not be involved in strategic decision-making processes affecting ED). It also involved observations of ED-related practice in clinical environments.

Work package 2 involved analysis of secondary qualitative data17 from three sources34–36 reporting hospice care (HC) and HPC stakeholders’ views of ED, findings from HCP interviews/focus groups and interviews with service users. These were used as a foundation to develop the questionnaire applied in the national survey undertaken in WP2S3, aimed at exploring the current practice, preferences and perceptions relating to ED across the wider population of HCPs in the UK.

Work package 2 also included interviews with patients and carers to explore their attitudes, knowledge and preferences concerning conversations about ED within EoLC.

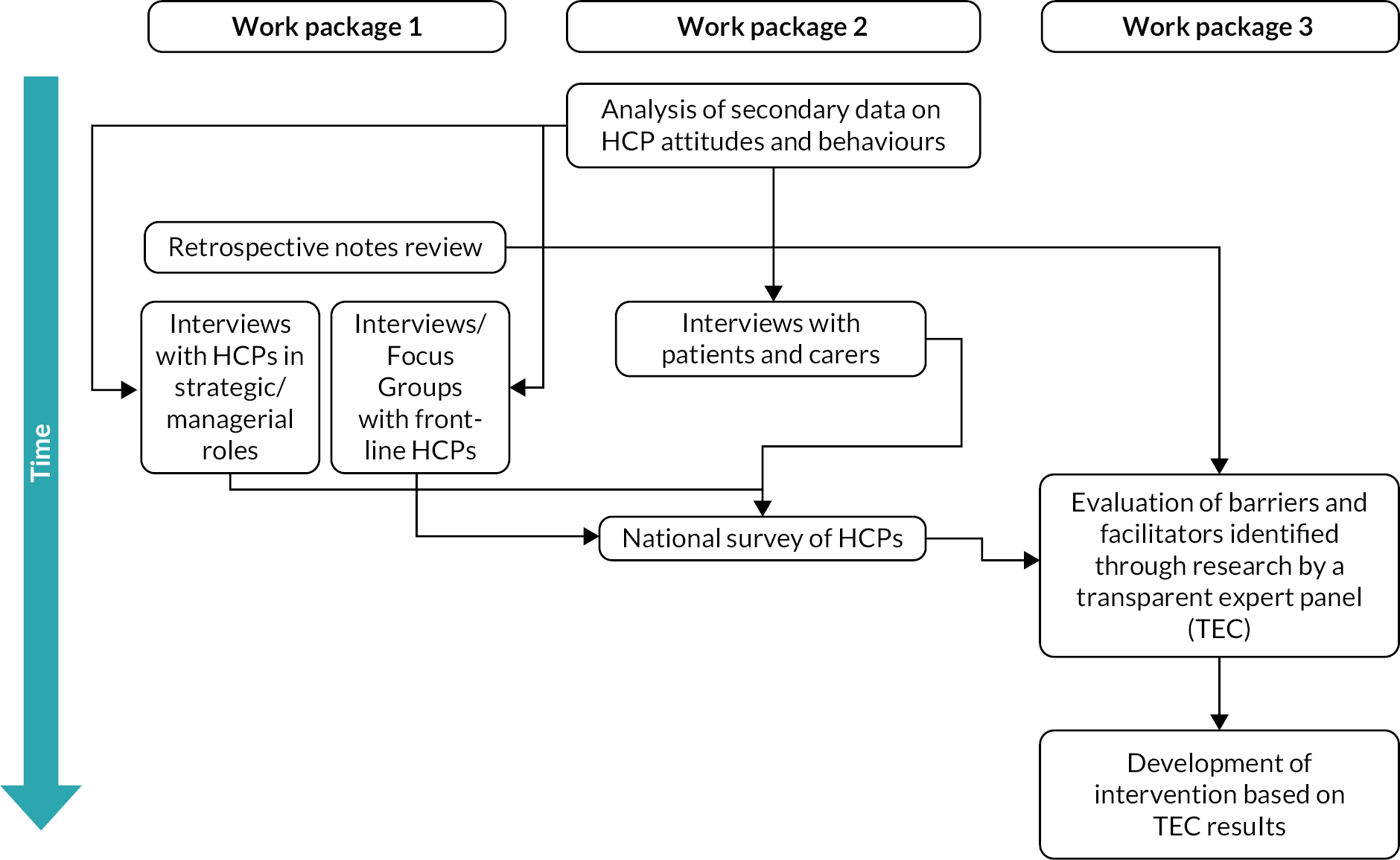

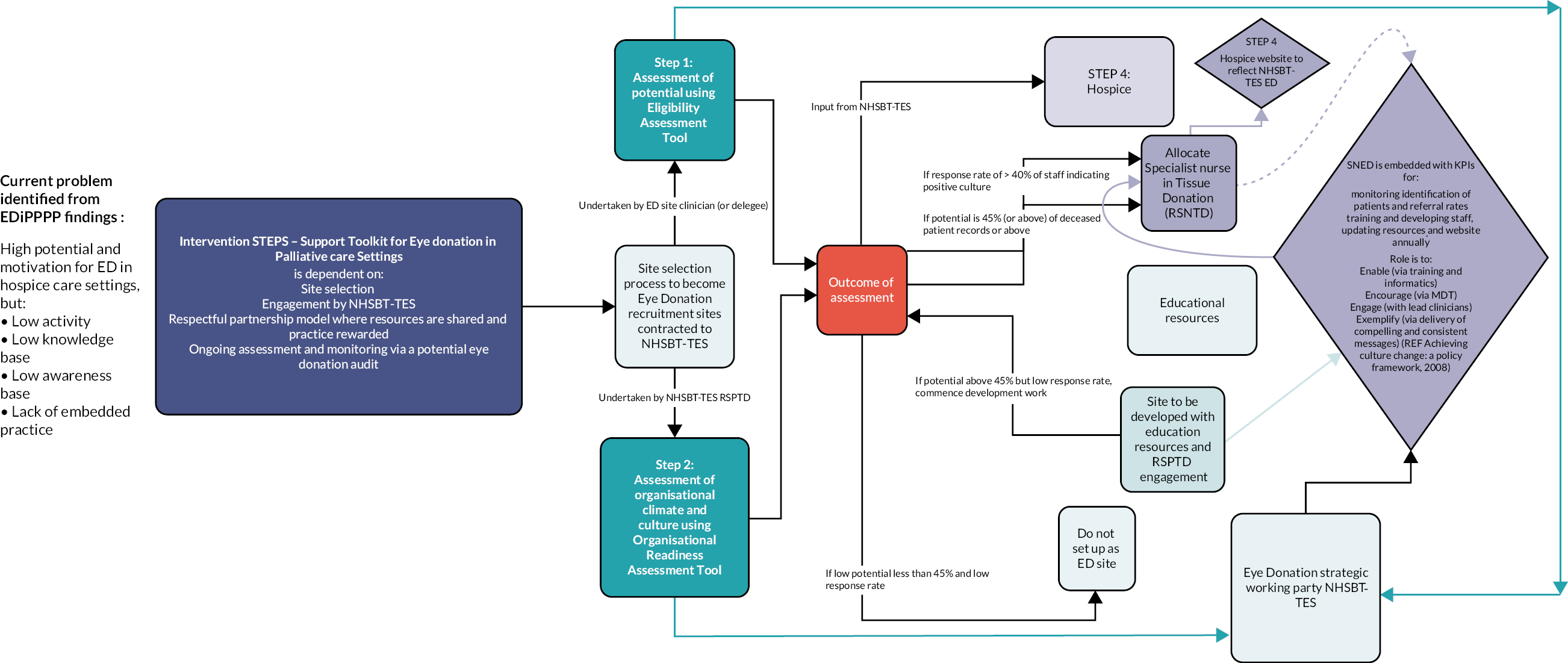

Work package 3 aimed to develop an intervention package aimed at improving ED rates, which could inform practice development and national strategy at NHSBT with respect to engagement with HC and HPC partners. WP3 involved evaluation of evidence presented in the form of reports from WP1 and 2 by a TEC37 comprised of EDiPPPP study co-applicants, patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives, researchers and EDiPPPP Project Steering Committee (PSC) members. A scalable intervention to support development of capacity for ED and embedding ED within routine EoLC practice entitled Support Toolkit for Eye donation in Palliative care Settings (STEPS) was agreed with follow-up pilot testing of two components of the operational aspects of the intervention. Figure 2 summarises the relationships between different WPs and stages across the progress of the project.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram summarising relationship between WP activities across the project (arrows indicate information flows between activities, i.e. how they inform each other across the project).

Partner sites and participants

Hospice care service and HPC sites in the North, Midlands and South of England were selected as study sites, informed by data indicating a difference in donation rates in these regions. 38 Donation sites were paired by region (one HC and one HPC site per region; see Table 3).

| Site1 ID | Region (England) | Site type |

|---|---|---|

| S01 | South | HC |

| S02 | South | HPC |

| S03 | Midlands | HC |

| S04 | North | HPC |

| S05 | North | HC |

| S06 | Midlands | HPC |

In describing participants from each site and activity, henceforth we use the system of anonymisation combining a participant descriptor (e.g. ‘P’ for patient interview participants) with unique ID numbers assigned in order of participation, and the associated site ID. For healthcare professionals in front-line roles, there are two descriptors (HCPF or HCPL) depending on whether the participant is involved in a focus group (‘F’ suffix) or remote interview (‘L’ suffix; Table 4).

| Participant group | Participant descriptor | Example full ID |

|---|---|---|

| Patient | P | First patient to participate at S04 = P00104 |

| Carer | C | First carer to participate at S04 = C00104 |

| Healthcare professional in strategic or managerial role | HCPI | First HCP to participate at S04 = HCPI00104 |

| Healthcare professional in front-line role | HCPF (if focus group) or HCPL (if remote interview) | First healthcare professional to participate (if focus group) at S04 = HCPF00104 First healthcare professional to participate at S04 (if interview) = HCPL00104 |

Data collection

As each WP involved differing data collection methods, including note review, participant observations, interviews, focus groups, survey and consensus methodologies (TEC), data collection methods aligned with each WP are outlined in subsequent chapters.

Data analysis

Analytic approaches for the retrospective note review, survey and TEC are presented in associated chapters. Analysis of data gained in observations, interviews and focus groups followed the five-level qualitative data analysis (QDA) method.

Data management and analysis (interview, focus group and observational data)

Following data collection, audio data from interviews and focus groups were passed to two university-approved (and contracted) transcribers who generated transcripts from an audio source. Anonymised transcription data from interviews and focus groups, and material gathered through observations, were managed and analysed using ATLAS.ti software39 following a study-specific process guided by the five-level QDA method. 40

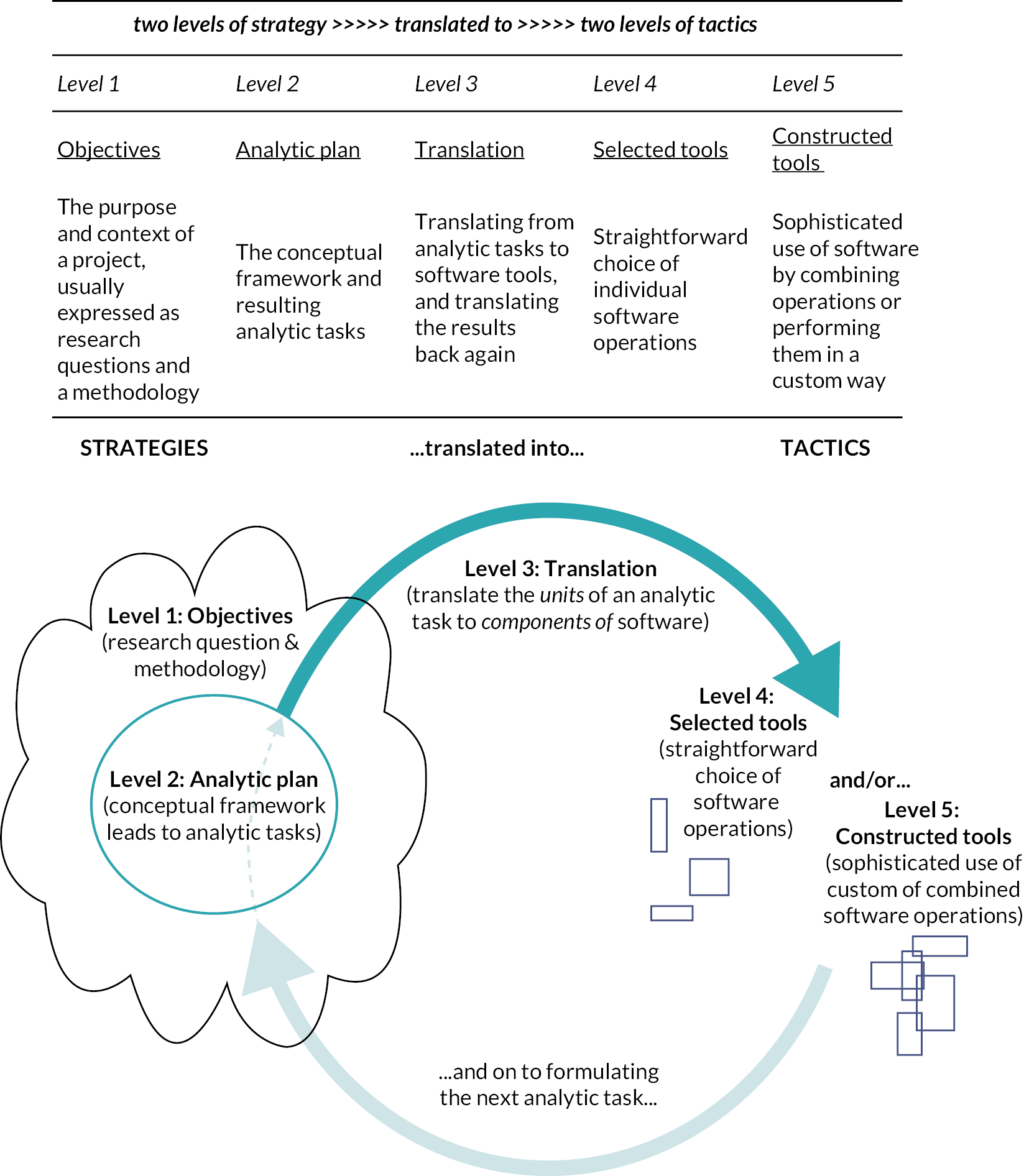

The five-level QDA method applied to all interview, focus group and observational data of HCPs, patients, and carers

The five-level method provides a framework for planning and conduct of data management, analysis and audit trail maintenance for qualitative and mixed-methods projects (Figure 3). This approach proposes two initial stages (levels) of planning (strategy) in which project objectives are defined (level 1), and specific analytic tasks relating to these objectives are identified (level 2). This is followed by an intermediary stage (level 3) in which analytic tasks are then translated into specific software operations. Following the strategic and intermediary stages, two further levels are specified with respect to use of software tools: level four involves use of single or straightforward software operations for given analytic tasks, while level five involves generating more complex (constructed) operations which may involve multiple software operations (the fifth level may not be necessary in all projects). Though the process follows a broad progression, as indicated in Figure 3, this is not strictly linear but can involve several repeated cycles across a project, in which activities at stages four and five amend study objectives (level 1) and/or analytic tasks (level 2). This framework was used in iterative development of the data management and analysis processes used in the EDiPPPP project, as discussed in the following sections.

FIGURE 3.

Components of the five-level method (images reproduced from Silver and Woolf, 201641 p. 101. n.b. permission for replication of image gained from Routledge books 1 August 2020).

Data management and analysis within the EDiPPPP project

At level 1, study objectives included in analysis are: Objective 2: to map the donation climate of each research; Objective 3: identify factors (attitudinal, behavioural) that enable or challenge service providers to consider and propose the option of ED as part of EoLC planning from a local and national perspective, and Objective 4: identify service users’ views regarding the option of ED and the propriety of discussing ED as part of admission procedures or as part of EoLC planning conversations.

At level 2, specific analytic tasks (T) were defined in relation to the objectives and data collection activities defined at stage 1, and then translated into specific software tools (either simple or complex).

T1 – Initial familiarisation and verification of data prior to loading into ATLAS.ti (software) involved reading and checking of transcripts received from transcribers against the recorded audio. The aims of this task were to verify the integrity of transcripts relative to the source audio, ensure anonymisation throughout the document and allow researchers to familiarise themselves with the data prior to beginning content analysis in ATLAS.ti (T3). These tasks were completed using Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) (transcriptions) and Windows Media player (audio) software.

T2 – Load and organise data into ATLAS.ti. Data were loaded into ATLAS.ti software and stored using a combination of document group (categories into which sources can be loaded for organisation) and code functions (codes are identifiers that can be applied to sources, or parts of sources, within ATLAS.ti providing an index to facilitate data management and analysis). 40 Document groups were used to organise data according to relevant attributes (e.g. site ID, participant group, work package/stage and demographic characteristics). Codes (and code groups) were used to identify parts of documents relating to specific areas of interest (e.g. specific domains and questions from interview schedules, study objectives). This process created a data structure and index for navigation, which facilitated content analysis conducted at T3.

T3 – Content analysis of organised data to address study Objectives 2–4. Content analysis of qualitative data involves identification of analytically relevant content, and organisation of these observations into categories of interest through the application of codes. 42 Both inductive codes (as derived from observations of the data) and deductive codes (applied from a pre-determined framework such as a theory, or observation schedule)42 were applied in EDiPPPP analysis. For example, T3 step 1 (Table 5) codes were aligned with components of the objective and organised into a code group covering the whole objective (see Column 3: Code group). These codes were then applied to transcription data across the data set that related to study Objective 2.

| Objective 2 | Component codes | Code group |

|---|---|---|

| To map system-based barriers to operationalising eye donation, including how potential donors are currently identified and referred to NHSBT-TES, and what services, resources, documentation are in place to: raise awareness and embed eye and tissue donation in EoLC planning. | Obj2 – Identification of eligibility | Obj2 |

| Obj2 – Referral to NHSBT | ||

| Obj2 – Services, resources, documentation for EoLC Planning |

T3, step 2 involved using the coded data from step 1 in combination with demographic codes applied at T2, to subset observations of interest by objective component and participant type. This was performed using Smart Codes, a feature of ATLAS.ti that allows data to be automatically assigned to codes based on a set of specific criteria. For example, where data had been assigned both an objective code and demographic code [e.g. the smart code (SmC) SmC1a-Obj2-Identification of Eligibility + HCP (FL) will return data coded at the code Obj2 – Identification of Eligibility and any codes within the code group HCP (FL) Focus Group/Interview Questions (HCPF)].

T3, step 3 involved inductive coding of data to provide more detailed description of content. This process proceeded sequentially through collections of data created by smart codes created at step 2. The researcher responsible for data collection within each site type took primary responsibility for analysis of resulting data (BMS for HC settings, MJB for HPC). The research team held regular meetings to discuss development of codes (i.e. new codes, revisions to codes, grouping, combinations/consolidation, etc.) and recorded relevant analytic decisions affecting interpretation in written notes attached to codes within ATLAS.ti. Subsamples of coded data were also shared with the project chief investigator (TLS), who provided further feedback on development of the descriptive coding framework.

This inductive descriptive process resulted in a set of codes derived from, and applied across, the entire data set (i.e. across objectives and participant groups). In combination with those created through deductive processes at steps one and two of T3, descriptive codes supported the of findings of this report, as described in step five below.

T3, step 4 involved the addition of further codes to allow findings to be mapped to general stages of the ED pathway: for example, Pre-referral (to NHSBT); Referral; Retrieval (of eye tissue); Post-donation; and All (for observations affecting the entire pathway). This additional deductive coding allowed for greater flexibility in exploration of and reporting from the coded data set at step five.

T3, step 5 involved reporting of descriptive analysis. This involved establishing a reporting structure in Microsoft Word in relation to each of the study objectives, their constituent components and findings relating to specific site and participant types within each of these areas (reflecting the data index created by the combination of deductive and inductive coding processes).

Chapter 3 Review of the literature

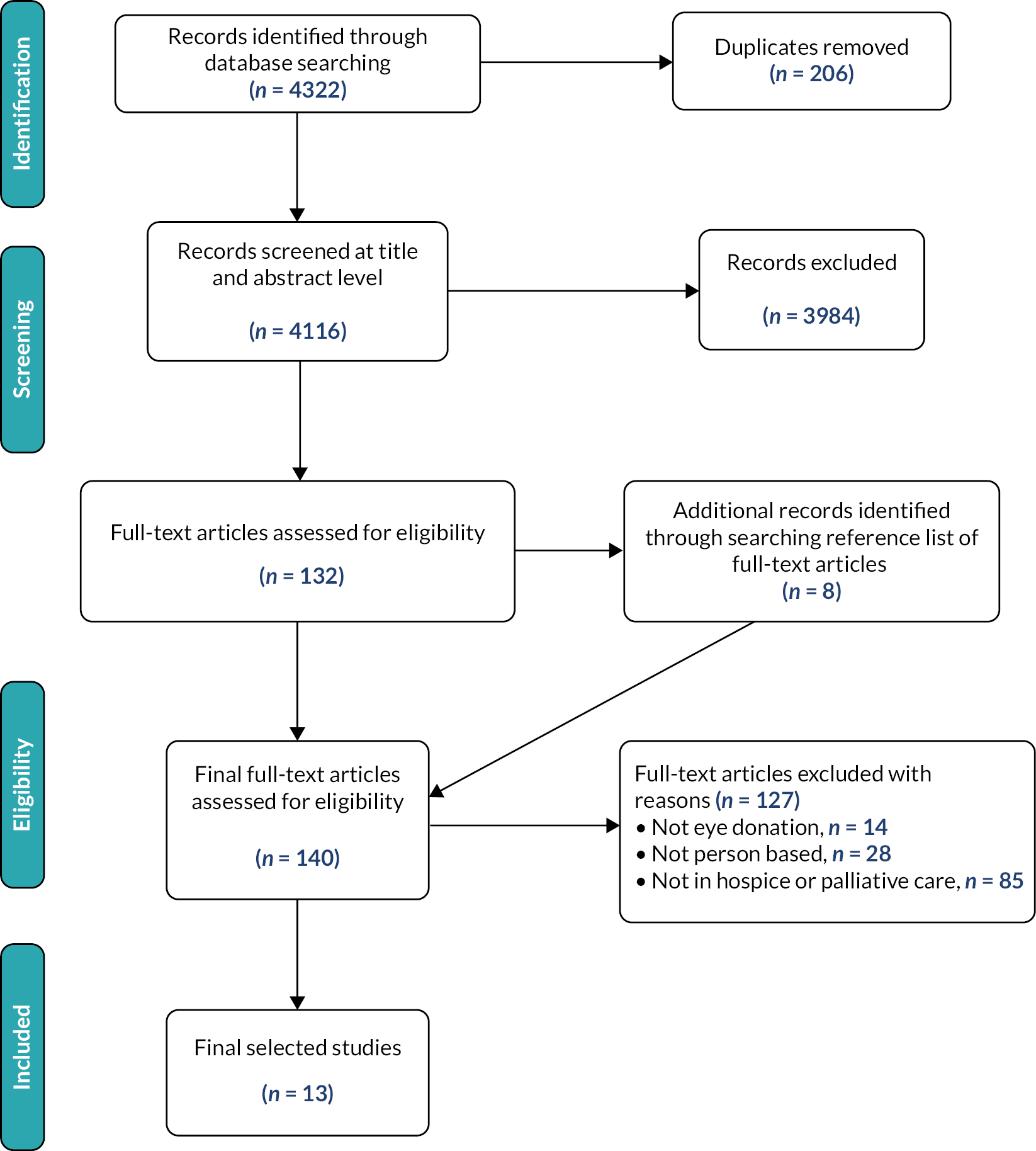

Chapter 3 provides an overview of what has been learnt from searches of the literature undertaken at specific time points in the time frame of the study, including development of the proposal (2017–18), EDiPPPP scoping review (January 2020) and a further check of the literature carried out in January 2022.

The full search strategy (see Appendix 1), inclusion criteria (see Appendix 2, Table 25), search outcomes (see Appendix 3, Table 26), study selection (see Appendix 4, Figure 14) and outcomes (see Appendix 5, Table 27) for the scoping review undertaken to seek literature specifically speaking to Perceptions and Practice in HC and HPC settings is presented. Some text in this section has been reproduced from Barriers and Facilitators to Eye Donation in Hospice and Palliative Care Settings: A Scoping Review in the journal Palliative Medicine Reports in 2021). 43 This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CCBY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Supply of eye tissue is a global concern

Low levels of eye tissue are a global issue. 3 Studies from Brazil,44 France,45 the USA,46 Canada,47 Australia48 and the Netherlands49 report barriers such as low levels of referral (to retrieval services) for ED outside of areas where organ donation is carried out; negative attitude towards ED held by HCPs across a variety of care settings;48–52 and lack of knowledge among the general public regarding the needs for and uses of eye tissue for transplant and research. 53,54 There are low levels of support for this option on the Organ Donor Register (ODR) with ED being the most ‘restricted’ option (individuals can restrict which organ and tissue they would donate) on the ODR. 55 There is also evidence of HCP reluctance to raise the issue of tissue donation as part of usual EoLC discussions56–59 despite national guideline recommendations,8,60–62 and a failure to recognise potential donors due to poor knowledge among HCPs of the medical contraindications and donor suitability criteria. 63,64

Perceptions of service providers in palliative and hospice care settings towards eye donation

Healthcare providers are reported to be generally favourable towards ED, perceiving it as worthwhile. 34,47,65 Authors report that although participants felt uncomfortable discussing ED, the majority felt it was their professional responsibility to do so. 64 Authors exploring the attitudes, knowledge, practice and experiences of corneal donation across a sample of 410 HCPs respondents reported that 70% (291/410) perceived corneal donation as a rewarding opportunity for patients and/or their families, with 82% (345/410) indicating that corneal donation was compatible with their personal beliefs. 34 Furthermore, survey findings indicate that 42% (8/14) of doctors who had raised the issue of ED reported that, based on their experience, the option of ED was perceived by patients and family members as a way of giving something back to society. 66

Practice of service providers in HC and HPC in raising the option of eye donation

While HCPs often acknowledge that ED is worthwhile, evidence indicates that discussing ED is not common practice,58,65,67,68 with two surveys, including HCPs, reporting that 92% (92/100) and 93% (399/431) never or rarely raise the subject of corneal donation with patients or relatives. 34,65

Research surveying HCPs within a large UK HC setting reported that 90% of 434 staff hardly ever, or never, initiated discussions regarding corneal donation with their patients or families. 34 Other authors surveying 76 hospice staff, reported that while 49/76 (65.3%) of the staff would discuss donation if the topic was raised by relatives, ‘only one respondent reported routinely discussing the issue’ (p. 100) with family members. 35

Healthcare professionals’ reasons for not initiating conversations about ED with patients include: concerns about the impact on patients and families (i.e. potential for distress),50,58,69 perception that donation is not part of hospice culture, and the personal significance of eyes making such conversations potentially detrimental with respect to maintaining a supportive environment within the hospice,70 and a perception that donation requests could cause patients and their families physical and psychological harm. 64 However, service evaluation data from other HC settings indicate that 86% (12/14) of doctors reported that conversations did not cause additional distress with 57% (8/14) reporting that the conversations about ED were perceived by patients and families as a positive outcome from the death. 68

Service providers knowledge: assets and deficits

Healthcare professionals report knowledge deficits as barriers to raising the option of ED, including not having sufficient knowledge about the process of ED44,46,47,64 and the eligibility criteria for ED,45,48,49 and lacking confidence to initiate ED conversations. 35,50–52 While evidence confirms the facilitative impact of education and training, and that a willingness to discuss donation is positively associated with knowledge about the process of ED (referral and retrieval), and being aware of local policy and guidance,58,71 training is not a guarantee that ED would be discussed. 34

Palliative care service users’ perceptions of eye donation

Evidence about what patients feel towards discussing ED is in short supply. However, one study72 reported that HCP introduction of the topic of ED at admission to an HC setting did not elicit concerns from family members (e.g. distress or concern at the option being raised). HCPs at this site also indicated that both patients and families were not aware that they could donate. These findings are supported by work from co-applicants to the EDiPPPP study, reporting that patients within HC settings were in favour of having discussions about ED,36,73 and that some patients changed their minds regarding ED (from negative to positive) after a conversation. 65,73 Patients are reported to be willing to participate in discussions about the option of ED, but were unaware of the option of ED or assumed that they were ineligible. 65 Furthermore, participating patients were motivated to be eye donors and felt positive about the possibility of helping others. 65,73

A survey of inpatients65 found that the majority of participants, that is 73% (8/11), reported that they did not find it upsetting to discuss ED and that asking about donation enabled them to make an informed decision about donation. A further potentially important finding is that participants reported their preference to talk about ED while they were still well, rather than when deteriorating. 73

Comments from nursing logs after the introduction of an admission script that included questions about ED indicated that the patients (n = 121) and families were not aware of their eligibility to donate their eyes, but they were not concerned about the topic of ED being mentioned during admission. 66 Furthermore, nurses were positive about introducing the option of donation at admission in view of these findings. 66

Publications that reported family/carer attitudes towards donation found a lack of awareness of their dying family member’s eligibility to be a potential eye donor. 58,66 Findings indicated a range of beliefs including that donation was right, that it is a social duty to donate and that it would be ‘wasteful’ not to. 74 Family members’ decision to decline ED was based on the prior stated wishes of the patient not to donate or the family’s uncertainty about the patient’s wishes. 68,74

However, retrieved publications indicate that HC and HPC patients are generally unaware about ED and eligibility criteria. For example, in two studies, patients thought they could transmit their cancer to recipients via donated corneal tissue,73,75 or that their eyes would not be good enough for use in transplantation. 65,73,75 Furthermore, next of kin (NoK) are unaware that their dying family member with cancer could donate their eyes. 74 Retrieved evidence further indicates that not knowing the beliefs/wishes of the deceased regarding ED is a key barrier to increasing ED. 68,74

Commentary on findings – literature review

Little evidence exploring barriers and facilitators to ED from palliative and hospice care settings was available before 2001, with a limited range of study designs/evidence synthesis methodologies being adopted in the reported empirical work (see Appendix 1). The UK has generated most literature, with comparatively little literature from other countries and cultures. The USA and India reportedly supply 55% of all corneas available globally,3 and it is surprising that there is no literature from these countries.

Although the evidence available includes representation from relevant participant groups (i.e. patients, family members and healthcare providers), sample sizes are frequently small; however, the themes generated by the retrieved publications speak to recurring barriers and facilitators. To date, the available literature base is very slim with a lack of high-quality primary research adopting mixed methods of investigation/exploration that would support practice and policy development.

The retrieved evidence indicates that patients and family members are not averse to, nor distressed by, discussions around the option of ED; however, as with all end-of-life discussions, timing is key. Evidence supports the benefits in ‘introducing’ this issue at admission with this discussion being merely to assess donation status. 66

Key findings from the review were that studies that reported retrospective note reviews (n = 3) indicated that the potential for ED from HC settings was: 52/100 (52%),67 67/77 (87%) and 30/85 (35%)65 of deceased patients, while in HPC settings the potential was 229/704 (32%). 56 These figures are of concern as they clearly show that large numbers of potential donors are being cared for in HC settings in particular and that these potential sources of supply are not being realised.

This review highlights a number of key barriers to increasing ED from HC and HPC settings, including:

-

reluctance of HCPs to raise this issue to avoid causing perceived distress to patients and their NoK

-

evidenced knowledge deficits related to the process of ED in these settings

-

lack of awareness on the part of patients and family members about their own or their relative’s eligibility, donation options and wishes in relation to these.

In the next chapter, we begin our exploration of issues raised in our discussion thus far, reporting on the results of our retrospective review of deceased patient case notes from six partner sites, in order to develop a detailed and systematic understanding of the potential for ED from HPC and HC settings in the UK.

Chapter 4 Potential (retrospective note review WP1S1)

Chapter 4 responds to study Objective 1: to scope the size and clinical characteristics of the potential ED population from research sites. This chapter describes data collection, analysis and findings from a retrospective review of case notes from patients deceased within partner organisations (HC and HPC). Aims were to establish current potential, referral rates and clinical characteristics of patient populations.

Methods

Data collection

Eligibility for ED was assessed against criteria specified by NHSBT-TES (see Report Supplementary Material 2) that constitute a list of contraindications (conditions) barring the use of eye tissue in transplant operations. If patient case notes were assessed as indicating that the patient had any of the contraindications listed, then the patient would be assessed ineligible for referral for ED. Assessment of HPC or HC case notes alone can only ever provide evidence sufficient to satisfy the referral threshold, as further checks would be carried out by NHSBT-TES prior to retrieval if a patient were referred to them. Therefore, when referring to eligibility with respect to the outcome of the EDiPPPP notes review, this always refers to the threshold needed to refer to NHSBT-TES for final determination of ED eligibility.

Each clinical principal investigator (JS, CF, CR, SM, AH, JW) (from here on reviewers) was asked to assess 200 of their sites’ deceased patient notes from the previous 2 years against eligibility criteria (with FJ, SG, NS and KG also contributing to clinical review at these sites). Reviewers completed a data collection proforma in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). 76

Proformas incorporated both closed responses and free-text (written) options (see Report Supplementary Material 3). Free-text fields were intended to capture issues not covered by closed measures, with free-text options aiming to identify contraindications that were particularly challenging for reviewers to assess with respect to ED eligibility (and thereby identify areas potential information and/or training needs).

Video guidance on proforma completion was provided to reviewers, providing an on-demand reference (created using OBS Studio screen recording software). 77 Reviewers then returned completed proformas to the study team for missing data checks (MJB). Sharing of proformas was undertaken using the University of Southampton’s secure filesharing service (SafeSend).

Data analysis

Proformas submitted to the study team (MJB) were then circulated for evaluation by specialist colleagues at NHSBT-TES (MB and JJ), using an evaluation proforma developed by the team [also completed using Microsoft Excel (see Report Supplementary Material 4)]. Evaluation was intended to assess agreement between reviewer and evaluator regarding patient eligibility for referral to NHSBT-TS for ED with respect to established criteria.

Numerical data underwent descriptive statistical analysis to identify numbers and proportions of cases deemed eligible/ineligible. Data were also interrogated with respect to differences in the assessment between reviewers and evaluators, with free-text comment boxes offering the option to comment on the decision made. All percentage figures have been rounded up or down to full numbers following the usual convention in reporting.

Results of deceased patient note review

Site characteristics

Clinical reviewers at the six partner sites completed retrospective note reviews of 1199 (missing data on one case) deceased patients’ notes for patients who had died between February 2019 and March 2021. Median deaths per year for all sites for this period was 429 (range = 120–1984 deaths per year). For HC settings, the median number of deaths per year was 250 (range = 120–386), while for HPC, median deaths per year was 513 (range = 250–1984). Notes review was completed between January 2020 and March 2021, with evaluation taking place between March 2020 and August 2021. The mean time required for review was 21.3 minutes per case (SD = 45.4; range = 12.5–27).

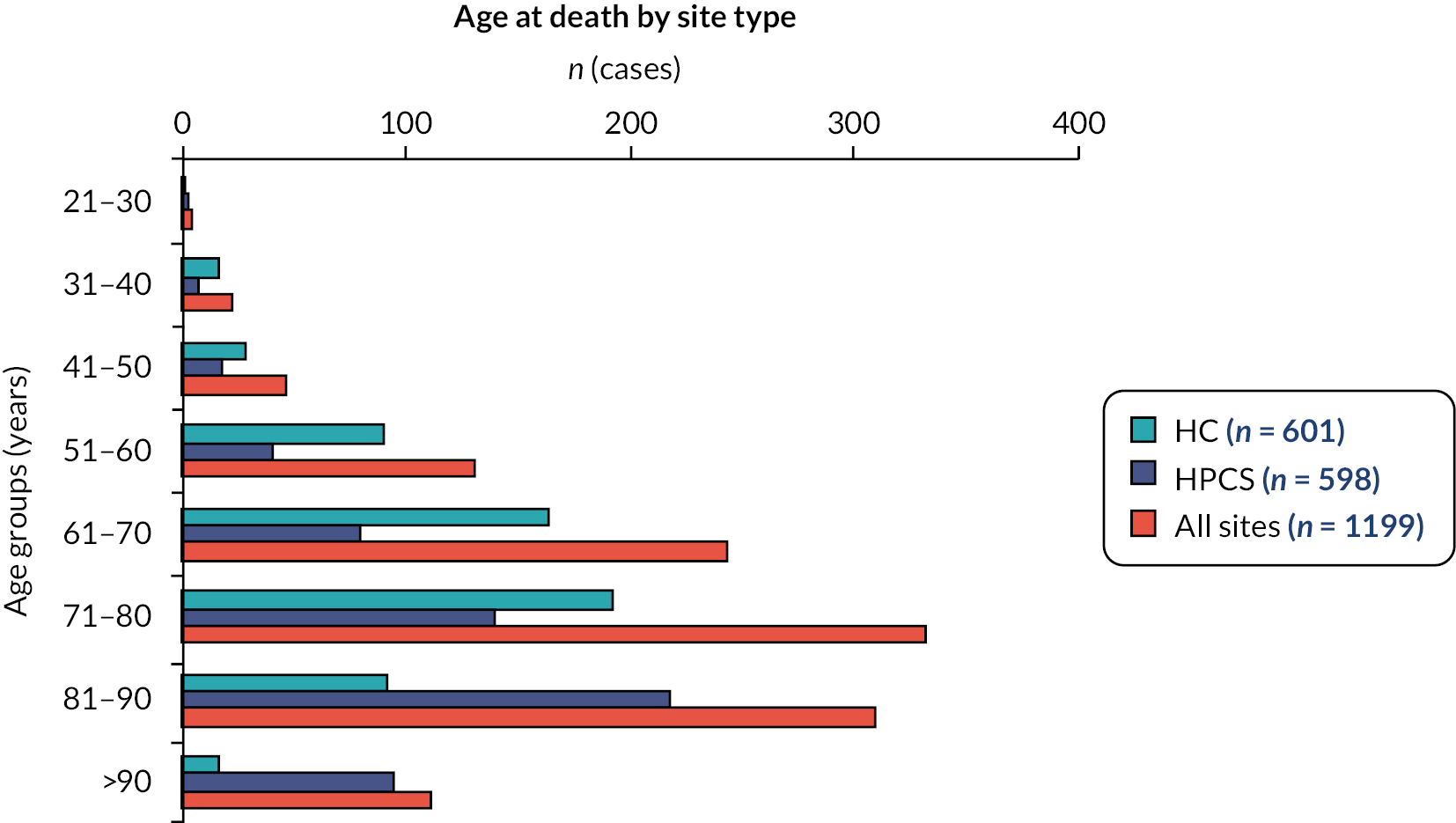

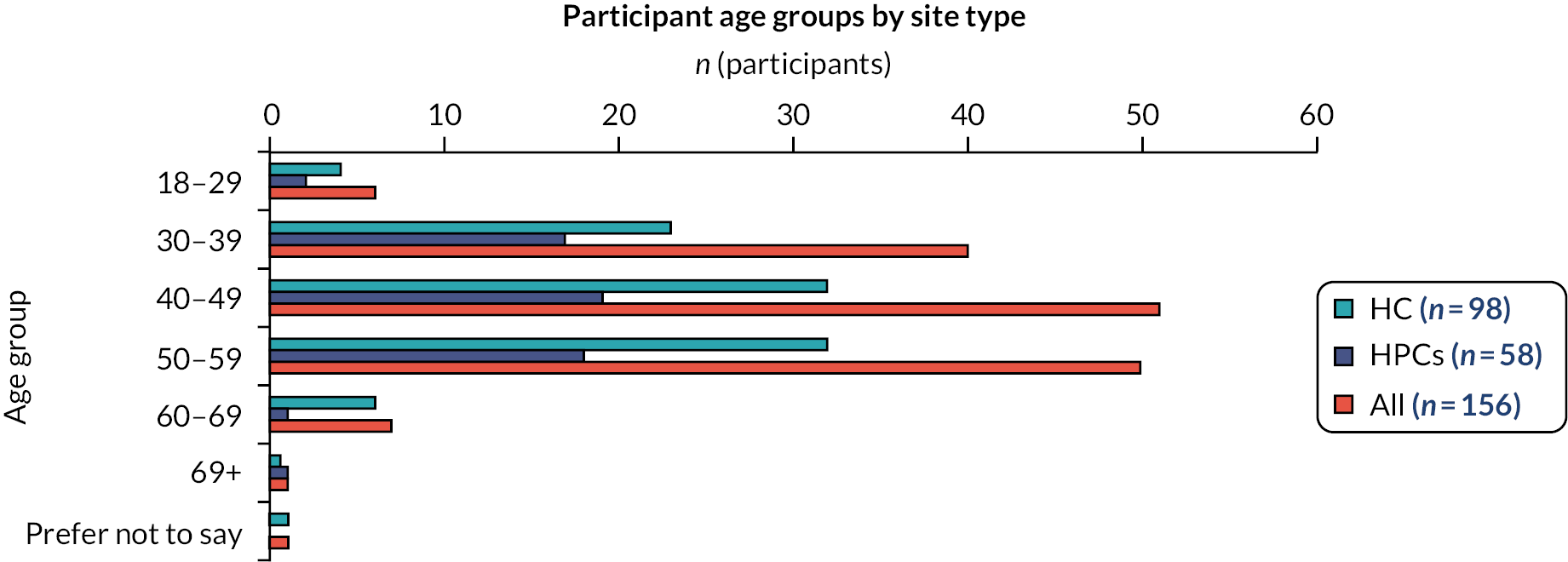

Sample demographics

For all cases (n = 1199), mean age at death was 73.4 years (SD = 13.8; range = 21–105; Figure 4). For HC settings, mean age at death was 68.9 years (SD = 12.6; range = 21–98), while for HPC this was 77.9 years (SD = 13.5; range = 21–150). Female cases represented 47.9% of the total (HC = 48%; HPC = 48%). ‘White British’ was the recorded ethnicity in 82% of total cases. Ethnic diversity was slightly higher in HC settings compared with HPC (HC = 74.0% ‘White British’ vs. HPC = 88% White British) (for full reporting of deceased patient demographics and characteristics see Report Supplementary Material 5).

FIGURE 4.

Age at death by site type.

Agreement rate on eligibility for referral to NHSBT-TES

The total agreement rate (i.e. where reviewer and evaluator agreed the same outcome, whether eligible, ineligible or uncertain re: eligibility) was 81% [n = 972 of 1199 total case (one missing case)]. Differences in outcome of eligibility assessments between reviewers and evaluators occurred in 19% (n = 227 of 1199 total cases).

Agreement rate on eligibility for referral to NHSBT-TES by site

Of the 601 deceased patients’ notes reviewed in HC the agreement rate was 79%, n = 475 cases and of the 598 deceased patients’ notes reviewed in HPC the agreement rate was 83%, n = 497.

Potential for eye donation

Forty-six per cent of (n = 553 of 1199) deceased patients’ notes were agreed by reviewer and evaluator as eligible. Twenty-four per cent (n = 289) of patients’ notes were agreed as ineligible and 11% (n = 130) were logged as uncertain (i.e. the reviewer and evaluator both indicated that further information would be needed to determine eligibility).

Potential for eye donation by site

Of the 601 deceased patients’ notes reviewed from HC settings, 56% (n = 337) were agreed as eligible, 13% (n = 77) ineligible, with 10% (n = 62) requiring further information. Of the 598 deceased patients’ notes reviewed from HPC settings, 36% (n = 216) were agreed as eligible, 35% (n = 212) of cases ineligible and 12% (n = 68) requiring further information.

Record of request for eye donation, family approach and referral to NHSBT from deceased patients’ notes

For all eligible cases (n = 553) the option of ED was recorded as being raised in only 14 cases (3%). In 337 of the eligible cases in HC, the referral rate was 8 cases (2%), and in 216 of the eligible cases in HPC, it was 6 cases (3%). Approaches to family members to discuss ED was recorded in only 13 cases (2%). There were 6 cases recorded for HC (2%) and 7 cases in HPC (3%). Referral to NHSBT-TES for ED was recorded in 14 cases (3% of all cases) with 11 cases recorded for HC (3%) and 3 cases (1%) for HPC. Finally, the ODR status of the patient was recorded in the case notes in only 5 cases (< 1% of total cases – HC = < 1%, 2 cases; HPC = < 1%, 3 cases).

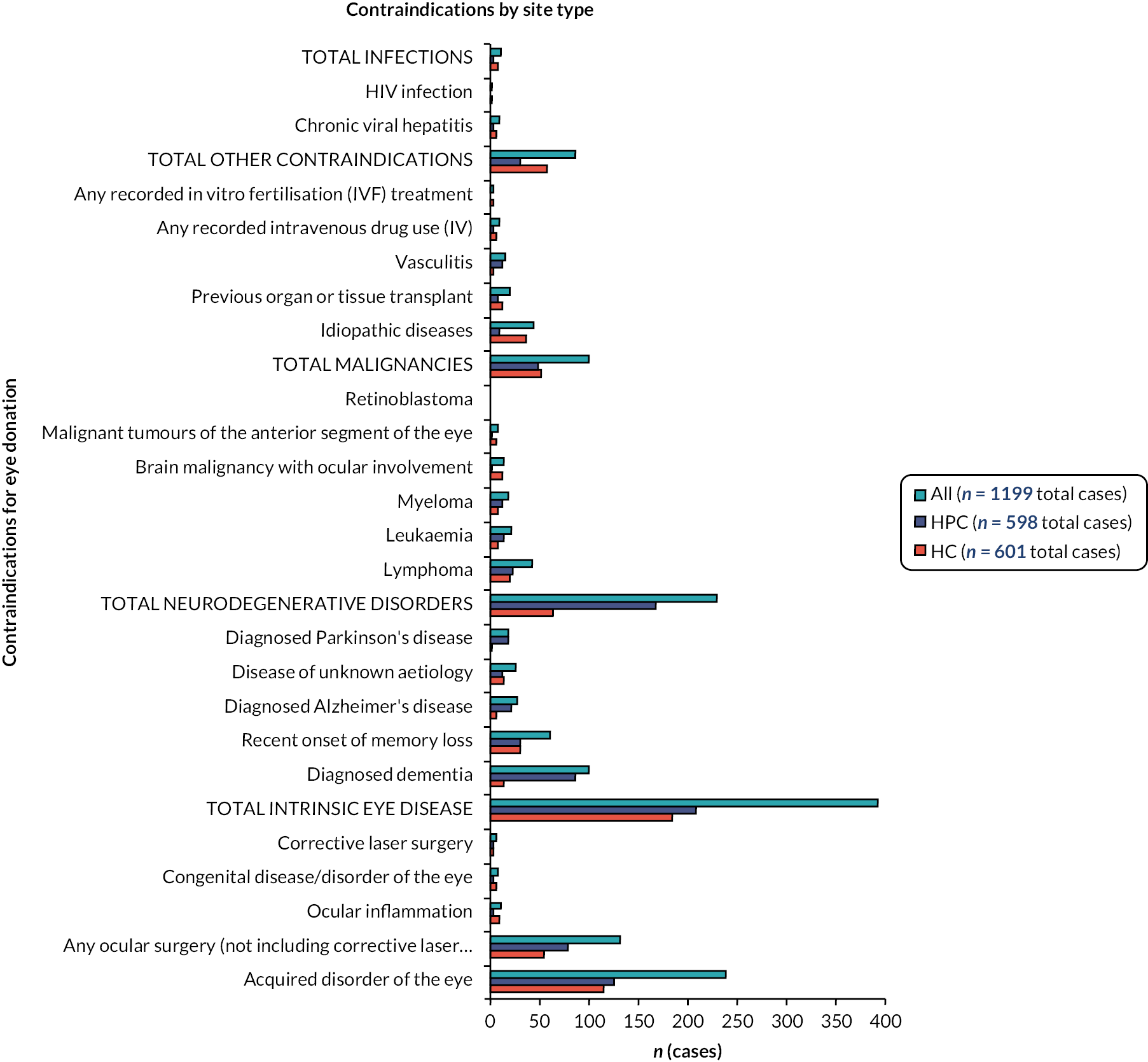

Contraindications for eye donation

For all cases, ‘Intrinsic Eye Disease’ was the most frequent contraindication reported (33%, n = 391 total cases), followed by ‘Neurodegenerative disorders’ (19%, n = 229), ‘Malignancies’ (8%, n = 99), ‘Other’ contraindications (7%, n = 86) and ‘Infections’ (8%, n = 10) (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Contraindications by site type.

Frequencies for occurrence of contraindication types across HC and HPC sites were comparable (i.e. within a < 5% range of the other), except in the case of ‘Neurodegenerative disorders’ where the proportion of excluded cases was 17% higher in HPC settings compared with HC (11%) (see Report Supplementary Material 6 for full reporting of contraindications by site type).

Disagreement rate from retrospective note review

This section describes numbers and types of differing assessments between reviewers and evaluators as a basis for identifying and clarifying the information support needs of HC and HPC staff, in assessing eligibility for ED through clinical records. Differences in outcome of eligibility assessments between reviewers and evaluators occurred in 19% (n = 227/1199) of cases.

Disagreement rate on eligibility for referral to NHSBT-TES by site

Of the 601 notes reviewed and evaluated for HC settings, there was a disagreement rate of 21% (n = 125 cases), and of the 598 notes reviewed and evaluated for HPC a disagreement rate of 17% (n = 102 cases). The following subsections describe types of difference in assessment outcome. Reviewer decisions are reported first, followed by evaluator decisions in response.

Differences in assessment outcome where the reviewer determined eligibility for referral

Of all cases, 34 (15% of total differences in assessment) involved reviewer determination of eligibility, while the evaluator determined ineligibility or uncertainty (i.e. more information needed – HC, n = 26; HPC, n = 8). Of these cases, the majority (n = 28) involved miscellaneous reasons (e.g. ‘active ocular infection’, ‘Raynaud syndrome’) assessed as not being contraindications for ED by the reviewer but assessed as such by the evaluator.

Differences in assessment outcome where the reviewer determined ineligibility for referral

Forty-three per cent (n = 97) of differences in assessment outcome for all cases involved reviewer determination of ineligibility for ED (HC, n = 32; HPC, n = 65). Of these, 67% (n = 65) involved evaluator assessment that there were no contraindications to exclude ED referral (i.e. that the reviewer had identified factors that would not exclude a patient for ED, or that key information on which to base an ineligibility decision was missing; HC, n = 16; HPC, n = 49). For example, in 31% (n = 30) of cases in this category, reviewers had excluded a patient on the basis of ocular- or vision-related factors (i.e. cataracts, retinopathy, ‘vision impairment due to stroke’), none of which were assessed as contraindications by the evaluator.

In 27% of further cases in this category (n = 26), the reviewer had assessed the patient’s age as exceeding the upper age cut-off for ED; however, evaluators indicated that absence of excluding ocular history or other contraindications meant the patient would be eligible for referral to NHSBT. The remaining 10% of cases in this category (n = 10) involved miscellaneous reasons for ineligibility (e.g. ‘renal transplant’, ‘confusion’) assessed by the evaluator as insufficient grounds for determining ineligibility.

Differences in assessment outcome where the reviewer indicated uncertainty regarding eligibility for referral

Additional differences were found in 96 cases (HC = 67; HPC = 29) with differences in assessment where reviewers had indicated uncertainty regarding eligibility for referral (e.g. ‘unsure if myelodysplasia is a contraindication’), while evaluators indicated either eligibility (n = 51 cases all sites; HC = 34; HPC = 17) or ineligibility (n = 45 cases all sites; HC = 33; HPC = 12).

In 16 cases (HC, n = 13; HPC, n = 3) evaluators determined eligibility, while reviewers indicated uncertainty based on potential issues with eye tissue (e.g. ‘cataract surgery’, ‘ocular issues in posterior chamber of the eye’). Thirty-five further cases (HC = 21; HPC = 14) involved evaluator determination of eligibility where reviewers had indicated uncertainty for miscellaneous reasons (e.g. ‘history of asbestos exposure’, ‘Autism’). All cases in which evaluators determined ineligibility (all sites, n = 45; HC, n = 33; HPC, n = 12) involved reviewer uncertainties that were determined to be grounds for ineligibility by evaluators (reasons were miscellaneous).

Cases in which no cause of death was available

In 18 cases, no cause of death was logged on the reviewer proforma, of which 11 resulted in evaluator determination of ineligibility due to a lack of cause of death; 5 were assessed as requiring further information regarding eligibility; and 2 were assessed as eligible for referral with a note that cause of death could be determined after referral through contact with the coroner or pathologist.

Site-specific feedback

The analysis carried out by the research team facilitated generation of site-specific reports, which were fed back to the principal investigators (PIs) to provide an overview of results relating to their site. This feedback included a summary report, together with a full export of data and review/evaluation results for the site. Summary reports included information on (1) agreement rate between reviewer and evaluator; (2) acceptance rate for referral as agreed by reviewer/evaluator against assessment criteria; (3) other outcomes of assessment (e.g. cases, where the reviewer had indicated that the patient was a decline for referral to NHSBT, the evaluator indicated acceptance).

An example feedback sheet for one participating site is provided in Report Supplementary Material 7. Feedback sheets were provided prior to the TEC in WP3S1 and thus informed discussions with respect to current knowledge and processes for evaluation of ED eligibility. This process also informed the development of the Eligibility Eye Donation Assessment Checklist (EEDAC) (see Appendix 6), which is a key component of the intervention (see Chapter 9) and aims to streamline eligibility assessments of potential donors at prospective partner sites for NHSBT.

Commentary on findings

The retrospective note review reported here demonstrates significant potential for ED across HC and HPC settings, which is currently unrealised. Across 1199 cases, 553 (46%) deceased patients’ notes were agreed as being eligible for referral for ED. However, < 4% of all cases agreed as eligible recorded an approach or referral to the relevant organisation (e.g. NHSBT-TES). Potential for donation is evidenced as higher in HC (56%) than HPC (36%), potentially influenced by patients with greater complexity and comorbidities dying in hospital care settings. Our findings regarding potential are supported in the literature where authors undertaking note reviews in the UK65,67,68 and Australia48 have all identified high potential from hospice care settings [ranging from 52% and 87%,67,68 with lower potential in hospital palliative care settings (hospitals) (32%)]. 56

Key findings supporting potential practice change are that site reviewers (applying the screening tool) reached high levels of agreement with evaluators (81% agreement rate outcome for all sites). In those cases where there was disagreement (n = 113), this was due to a need for further information regarding eligibility from NHSBT-TES. For example, in 13% (n = 30) of total disagreements (n = 113), the reviewer assessed the patient as ineligible on the grounds of age as the information available to them was that the age cut-off was > 84 years and 364 days. However, the evaluator (at NHSBT-TES) subsequently determined eligibility based on the fact that the upper age limit for acceptance had changed during the life of the study to > 85 years and 364 days – information that neither reviewer (clinicians) or researchers were aware of.

This change appears to have taken place in response to the shortage of eye tissue for retrieval exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e. raising the age cut-off to increase the number of potential donors for referral). However, NHSBT-TES evaluators also indicated that age was NOT a definite exclusion for ED (unlike other criteria illustrated in Figure 5) but would be a consideration in decision-making influenced by patient comorbidities and physical condition at death. Therefore, it is essential that clinicians’ decision-making regarding eligibility for referral is supported by systems developed and operationalised by NHSBT-TES that provide access to relevant up-to-date information and advice and minimise additional resource burden on clinicians by providing easy and timely access to these resources. As NHSBT-TES does not currently have any information on their website specifically focused on the needs of referring clinicians (e.g. there is currently no online resource on eligibility criteria or referral processes to which clinicians can easily refer), this is a key service development gap.

Recommendations for practice

-

In view of the potential for ED in HC settings in particular, it is essential that the option of ED is routinely raised with patients and family members so that they are facilitated in making decisions that represent what may be a lifelong wish to be a donor.

-

Healthcare professionals need to proactively inform patients and their families about the option of ED because patients and their carers want the opportunity to make a choice. This information would be best provided as part of normal EoLC conversations.

-

NHSBT-TES need to develop accessible (online via their website) clinically relevant information to support service providers in the early identification and assessment of all patients admitted to HC and HPC settings against eligibility criteria, for example the EDiPPPP developed EEDAC. This website should have updates of changes to donor eligibility (e.g. the upper age limit for eye donation, current stock levels). This change will ensure that the work of clinicians is not increased, as they assess every patient who is admitted to their service for ED before making an approach to the patient.

-

NHSBT-TES need to develop easily accessible web content that clinicians can access when they have a query.

-

Clinical sites require access to the ODR so that they can assess patient status (in or out) via that resource.

Chapter 5 Perceptions, practice, preferences of service providers at research sites (WP1S1 and 2)

Chapter 5 addresses study Objective 2 to map the donation climate of each research site via a systematic assessment tool and Objective 3 to identify factors (attitudinal, behavioural) that enable or challenge service providers to consider and propose the option of ED as part of EoLC planning from a local and national perspective. This chapter describes the recruitment process and data collection methods for interviews with HCPs in strategic and/or managerial roles (HCP-Str/Man) and focus groups or interviews with HCPs in front-line roles (HCP-FL). Data collection also involved observations of ED-related practice in clinical environments. As Chapters 5 and 6 report findings from service providers, the commentary of findings for both chapters is placed at the conclusion of Chapter 6.

Methods

Sampling strategy (interviews and focus groups with HCP-Str/Man and HCP-FL participants)

As an aim for data collection was to explore the current clinical practice and preferences of HCPs related to ED (e.g. if, when and how a conversation about ED should be initiated with patients and/or their families/carers), two main participant types were targeted for recruitment: HCP-Str/Man participants were those actually or potentially in positions to affect organisational behaviour relating to ED (e.g. design and implementation of clinical/practice guidelines), while HCP-FL participants were those actually or potentially involved in processes relating to ED (e.g. advance care planning conversations with patients), but who typically would not be involved in strategic or managerial activities relating to ED.

Understanding current practice as it is enacted within organisations is a key aim of the EDiPPPP study, and it is essential to developing evidence-based complex interventions that can be adapted and scaled across different services. 33 Therefore, first steps were to establish who the people were that we needed to talk to so that we gained an understanding of differing organisational cultures and ED climate.

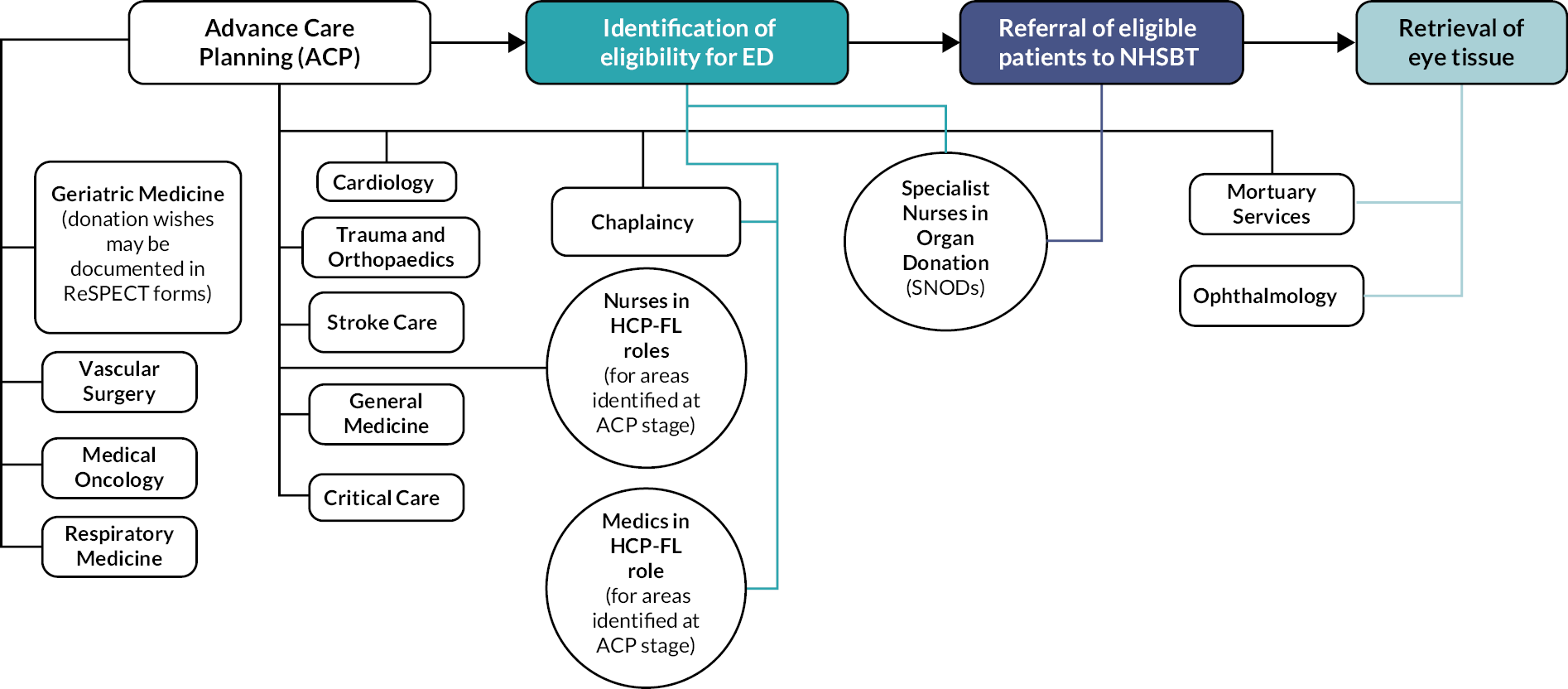

Mapping eye donation pathways at partner sites

Through discussions with NHSBT-TES colleagues, we identified four generic processes forming the core of the ED pathway, which could be expected to exist at all sites in some form and in which HCPs would be involved. This framework provided a foundation for discussions with PIs at partner sites and construction of a purposive sampling frame by which both HCP-Str/Man and HCP-FL participants who were actually or potentially involved in these different processes could be identified. Processes included:

-

Advance care planning (ACP) – processes relating to plans for EoLC, including wishes for donation.

-

Identification of eligibility for ED – processes within the organisation relating to identification of patient eligibility for ED (prior to contact with NHSBT).

-

Referral of eligible patients to NHSBT – processes relating to referral of potentially eligible patients to NHSBT for further assessment and potential retrieval of eye tissue post-mortem.

-

Retrieval of eye tissue – processes relating to facilitation of retrieval from eligible donors.

Discussions with PIs were held via video conference, using a whiteboard to log results of discussion regarding specific areas/services to target within the organisation (for HCP-FL recruitment) and specific individuals within HCP-Str/Man roles. Figure 6 provides an example outcome of these discussions from one HPC site. This example outlines a range of departments and areas within the organisation (indicated by square boxes) that were understood by the PI to be actually or potentially involved in activities relating to the ED pathway (indicated by coloured lines corresponding to each of the four generic stages illustrated in Figure 6). In addition, specific role groups (indicated by circular boxes) were also identified and linked to different domains. These processes and resulting diagrams were then used to identify areas for interview and focus group recruitment for HCP Str/Man and HCP-FL participants.

FIGURE 6.

Reconstructed example outcome of planning discussion for HCP-FL recruitment at a HPC site (n.b. square boxes denote candidate departments or areas for recruitment; circles indicate specific role groups; coloured lines indicate potential involvement).

Resulting diagrams also functioned as starting points for investigation of relations between current understanding of service structure as perceived by the PI (i.e. PI understandings of who does what within their organisation in relation to the four generic stages of the ED pathway), and findings from interviews and researcher observation (i.e. do findings support and/or challenge the model of organisational structure agreed in recruitment discussions with PIs?). The significance of this to observations of clinical practice is discussed in the findings section.

Approach and recruitment process (interviews and focus groups with HCP-Str/Man and HCP-FL participants)

Approaches to HCP-Str/Man participants or to gatekeepers within areas of interest (e.g. Heads of Services) were made by the PI responsible for the specific partner site, who provided the participant information sheet (PIS). Contact details of potential participants were shared with the study team (MJB, BMS) via secure systems. Responsible researchers contacted interested participants to discuss the study and confirm participation. All study materials (e.g. letters of invitation, PIS, reply slips) were (where possible) shared with potential participants via electronic means (e.g. e-mail). In instances where this was not possible, information was mailed to the participant following a telephone conversation with the study team. All recruitment data, including demographic information and completed consent documents, were held securely on University of Southampton servers.

Once agreement was in place for the interview to commence, the responsible researcher (MJB or BMS) explained the consent process (i.e. that consent to participate would be audio recorded before the interview commenced). The researcher then read out the consent form over the telephone asking the participant to respond by stating ‘Yes/No’ or ‘I agree/disagree’ to the relevant questions. The researcher recorded (electronically) the responses of the participants on the consent form, adding a countersignature and date of consent.

Electronically returned consent forms were stored in a secure location within the EDiPPPP project drive on the University of Southampton systems, to which only the study team had access. Hard copies of returned consent forms were scanned and saved to the same folder, then shredded and disposed of securely.

Data collection: interviews and focus groups with HCP-Str/Man and HCP-FL participants

Interview schedules (see Report Supplementary Material 8: HCP-Str/man interview schedule, v2, 20 March 2019) and focus group guides (see Report Supplementary Material 9: HCP-FL Focus Group and interview guide, v2, 2 March 2019) were informed by the Rapid Assessment of hospital Procurement barriers in Donation (RAPiD),78 and the available literature.

Direct in-person observation of eye donation-related clinical practice (sites S01 and S02, pre-COVID-19)

Prior to the change in protocol (18 March 2020), observations were carried out at S01 and S02 over a 5-day period (Monday–Friday) by responsible researchers assigned to respective site types: HC (BMS) and HPC (MJB). Information gained from interviews, focus groups and naturally occurring talk informed observation of practice. For example, an interview response indicating uncertainty as to the availability of patient information leaflets for ED in publicly accessible areas of the clinical site led to further investigations by the researcher as to whether this material was in fact available. Data collection also involved identification, observation and (where appropriate) collection of materials relating to ED practice (e.g. images of publicly available information, copies of blank example process documents relating to ED).

The observation schedule (see Report Supplementary Material 10: Direct observation of ED-related practice topic guide, v1, 4 April 2019) was informed by areas of inquiry identified in the RAPiD assessment tool aimed at identifying institutional policies, procedures and other documents that facilitated evaluation of the informational climate (e.g. whether or not clear policies and procedures exist regarding ED; what information is available for patients, carers and HCPs regarding ED; what formal institutional support existed to support ED) of the site.

Observations (both in-person and remote following change to protocol) were thus informed by ongoing interviews and provided a forum to explore congruence between beliefs and knowledge about ED practice, and observable practice. Both data streams also informed a web-based audit of information on ED currently available on public-facing sites. Results and implications for service development (commentary) for each of these activities are presented below.

Findings

Outcome of recruitment

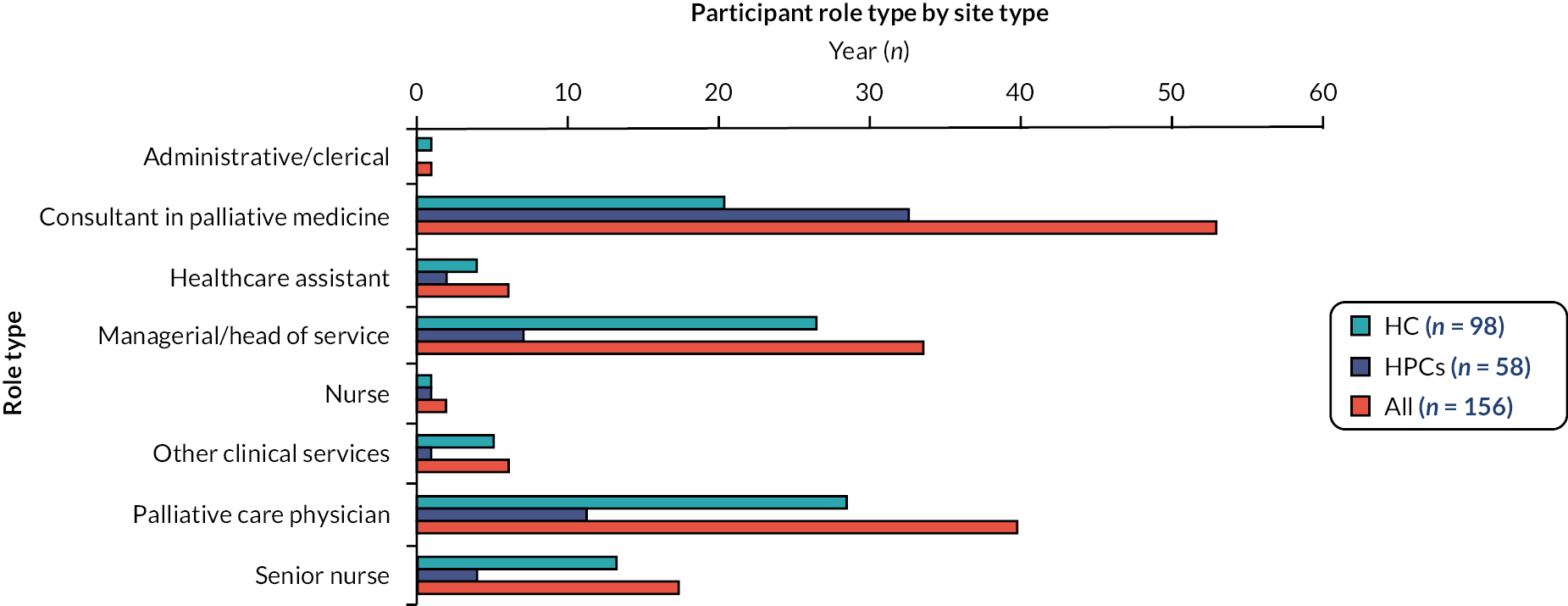

Planned targets for recruitment to interviews at each site were: 36 completed interviews total (6 per site) with HCP-Str/Man participants; and 2 focus groups per site (involving a maximum of 12 participants across both groups) with HCP-FL participants. Following the change to protocol and non-substantial ethics amendment (ERGO ID 59185) in March 2020, targets for HCP-FL participants were revised to a maximum of 10 interviews per site. In total, 105 HCPs participated: 38 HCPs in strategic/managerial roles took part (20 in HC settings, 18 in HPC settings), 67 HCP-FL participants were involved in either focus groups (28 participants) or interviews (39 participants), with 30 participants in HC settings and a further 37 in HPC settings (Table 6). For full participant demographics (see Report Supplementary Material 11).

| Participant group | Recruitment maximum target (pre-ethical amendment due to COVID-19 pandemic) | Recruitment target (post amendment) (n = 105) | Actual participants HC | Actual participants HPC setting | Total participants all sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCP strategic/managerial | 36 (6 per site) | Unchanged | 20 | 18 | 38 |

| HCP frontline | Two focus groups (FGs) per site (maximum 6 participants per FG) Nil interviews |

Maximum 10 interviews per site | 11 FG participants 19 interview participants |

17 FG participants 20 interview participants |

67 |

| Total | 108 | 105 | 50 | 55 | 105 |

Findings – interviews and focus groups

Findings from WP1S2 interviews and focus groups are reported under the EDiPPPP study domains Perceptions, Practice and Preferences. The purpose of this section is to focus discussion of each domain towards implications for service development and intervention design.

Findings for HCPs are combined (i.e. both Str/Man and FL participants are reported together) unless stated, in cases where relevant differences in responses were observed. Exemplar quotes have been selected to illustrate specific points and the diversity of responses that relate to a specific observation. For example, when reporting on HCP perceptions of ED, quotes are selected in this case to illustrate the range of professional, ethical and spiritual perspectives observed. Furthermore, a range of quotes are provided as they reflect both general characterisations of patterns of thinking and also thinking that may be pathway or setting specific (e.g. HCP or HPC). Context-specific data of this type illustrate the variety of HCP motivations and orientations of HCPs towards ED across EoLC settings, thereby providing information relevant to intervention design.

Quotes for HCPs in HC and HPC settings are specified by context. This is necessary because while all roles in HC settings will in some way be focused on EoLC, that is not true of all HPC participants, whose role may be only one part of a larger role within the hospital. The quote below illustrates the relevance of this presentation:

ʻSo, I don’t … I don’t think I’ve ever talked to patients about it [ED] because … because I’m in an emergency physician so, it’s usually … in my experience, unplanned death. If you see what I mean. But family members, as I say, I … in my experience, I usually … well, it’s usually them that raise it with me and therefore they usually respond well to … to knowing it’s a possibility.ʼ

(HCPI00502, HPC, Senior Emergency Medic with additional trust executive role)

We can see that this participant describes a role in which involvement in EoLC planning is limited, in a way that would not be reflected in the typical organisation of HC services. This affects interpretation of the quote because it provides a rationale as to why conversations of this type would not be typical for someone in that role. In this quote, the participant makes this context clear; however, this is not the case for all quoted material and therefore all such examples from HPC area associated with their area of service.

Perceptions

The perceptions domain of EDiPPPP relates to individual attitudes, views, opinions and experiences about donation generally and ED specifically, from a personal or professional perspective.

HCPs’ personal feelings about donating their own organs and/or tissues and organ and tissue donation were generally positive in both HPC and HC settings, reflecting a variety of professional, ethical and spiritual concerns.

ʻSo, I’m for it, I think my, my view is that once, once we die, then our spirit, if you like, separates from our body so our bodies are kind of a, what’s the word, like a vessel if you like, so I think once we die our spirit separates and it doesn’t necessarily matter what happens to our body and I think the value on what could happen for other people from using parts of my body far outweighs the concern I would have over what would happen to my body. So, for example, any part of an eye donation if that could help somebody to see or, you know, to have a better quality of life, that would be more important to me than thinking about what would happen to my body after I’ve died.’

(HCPL00303, HC)1

ʻYeah. I mean, personally, very strong and positive about organ and tissue donation. It’s clearly very important. It’s always a difficult subject to broach but one that we probably should broach more often in advance care planning. But personally, my … my views are that we should be … we need to be talking it more and also there’s been a lot of … of push from, you know, blood and transplant and things to talk about those things more. But, yeah, certainly my feelings about it are quite … you know, that it’s very important. Important to be talking about with our patients.’

(HCPL00204, HPC, Palliative Medicine)

However, while most HCPs said they were in favour of donating eyes, some reported ‘squeamish[ness]’ or reticence on the part of themselves or family members in relation to this option:

ʻOK. Personally, I’m a little bit squeamish. I’m a bit squeamish about eyes. I’m a bit squeamish about eyes because I just don’t really like eyes. The sort of … touching eyes but can see the huge advantages of donating organs for the recipients of those organs.’

(HCPI00204, HPC, Palliative Care)

ʻAnd whilst I have no issue personally donating I do still think about my eyes being tampered with because I believe when I die it doesn’t matter to me, it matters to those who are left behind and that, so my personal beliefs about funerals or my body is, it doesn’t matter to me, what does it matter to my family? My family, I then had a conversation with my family and they are very pro donation, but they also weren’t sure that they liked my eyes being tampered with, so what, what I suppose I came to the conclusion it’s important to talk about it to recognise that in lots of ways, they needn’t know very much about that and what they need to know is that I’m happy with It.’

(HCPI00201, HC)

While a majority expressed generally supportive views of ED, most HCP respondents indicated that they did not discuss the option of ED with patients. One key reason indicated by participants was the perception that they do not have the capability to handle requests for information if they raise the option of ED as part of end-of-life discussions with patients: