Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR129491. The contractual start date was in September 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in March 2023 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Ryan et al. This work was produced by Ryan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Ryan et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Plain language summary

-

We present information about what we know about older people with learning disabilities and family carers.

-

We talk about the language we use in the report.

-

We talk about what the research is about and what it is aiming to do.

-

We describe how this report is organised.

Introduction

Although there are an estimated 1 million people with learning disabilities (PWLD) in England,1 there are few accessible published data about the number of older PWLD. C Hatton (22 March 2019, personal communication) estimates that there are around 81,000 PWLD aged > 50 years, many of whom are not in contact with services. 2–4 The life expectancy of PWLD has been increasing, and it is estimated that the number of people requiring social care will have increased by 68% by 2030. 5 The number of PWLD using adult social services is estimated to double by 2030. 6 We know little about the lives of PWLD as they age, such as how they are affected by health issues or the illness or death of family carers. We also know little about the experiences of family carers as they grow older.

There is an even more pronounced absence in the academic and grey literature regarding the lives and experiences of older PWLD without family support. The World Health Organization7 has underlined the importance of PWLD ageing successfully and productively, and this has been operationalised into the concept of ‘active’ ageing,8 which involves living an active and meaningful life in the local community. A recent systematic review of research from England, the Netherlands, Belgium and France9 found that not all PWLD actively age and, instead, many lead sedentary lives, often overmedicalised and at risk of falling, developing depression and other long-term health conditions, and dying prematurely. The authors found a range of issues, such as unfit housing, poor staffing and attitudes, underpinned by a lack of psychological support and planning.

While little is known about the needs and experiences of older PWLD,10 there are clear destabilising factors for this group that make people vulnerable to distress. These include reductions in services in part due to austerity measures,11 the reliance on family carers who eventually grow too old to provide care, changing health needs through ageing, a risk of early-onset dementia,12 and deteriorating physical health. 13,14 A lack of future planning15,16 increases the risk of people moving at crisis point to more intensive and sometimes out-of-area supported care; it also causes distress and can lead to people being labelled with ‘behaviours that challenge others’ (‘BTCO’). There is a further gap in research around people who have attracted the label of ‘BTCO’ as younger adults and who are growing older, and a lack of effective end-of-life care (EOLC), that is care and support in the last year of life for older carers and PWLD. 17 Our research project was designed in response to the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Commissioning Brief 19/14 and addresses remit 2ii:

How can families and professional caregivers be supported to provide care and support for people with learning disabilities and behaviour that challenges?

Learning disabilities and ‘behaviours that challenge others’

We start this report with a note about terminology. Language and definitions of ‘learning disability’ have remained ‘remarkably unstable’ over time, and who is defined as belonging to this group changes ‘due to cultural and social ideas around what constitutes mental faculty’. 18 A static, medicalised model focusing on deficit remains dominant:

A significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn and apply new skills (impaired intelligence). This results in a reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning), and begins before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development.

World Health Organization19

The impact of being labelled as having a learning disability can be considerable, as the term remains associated with stigma and shame,20 demonstrated by the speed at which medical terminology translates into lay terms of abuse. 21 While the term ‘intellectual disabilities’ is widely used internationally, evidence suggests that in the UK it generates scepticism and a sense of stepping back in time. 22 Here we use the term learning disabilities and PWLD as a shortened version for pragmatic reasons.

The term ‘challenging behaviours’ is also contested, and we use ‘BTCO’ to acknowledge the inherently relational and socially constructed nature of this concept. 23,24 ‘BTCO’ are a product of environmental factors including responses of support workers and family members, the quality of the material environment and commissioning processes, how well a service is organised and led, and earlier events in someone’s life which may have been traumatic. 23,25 Mansell23 acknowledges that behaviours may be a way to self-soothe or communicate that may remain even with excellent support. The question then becomes in what contexts and by whom are these behaviours considered to be ‘challenging’, and how can support staff, services, families and wider society adapt to this while keeping the person (and others) safe?

While policy and guidance across the UK over 30 years have stressed the socially constructed nature of ‘BTCO’, the term continues to be used to label people,23 enhance the legitimacy of a service, justify service practices or empower management decisions. 26 It can further disrupt the health care that people receive, as symptoms of pain or serious illness can be attributed to ‘BTCO’, leading to misdiagnosis and premature death. 27,28 In this report, we engage with this concept critically to ensure that we do not legitimise or justify certain practices of labelling people in ways that take attention away from the distress they might be experiencing and shift it onto procedures of managing this distress, as opposed to addressing its causes. A large-scale longitudinal Irish study with a nationally representative sample of PWLD aged > 40 years found that > 50% of older PWLD display what the authors describe as ‘problem behaviours’, and these are associated with a psychiatric diagnosis and high rates of psychotropic medication. 29 Concerns have been raised about potentially inappropriate prescribing in older PWLD that can be related to the label of ‘BTCO’. 29

Finally, our research focuses on PWLD aged ≥ 40 years in line with the above evidence that people may experience early onset of long-term conditions such as neurological, cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders.

Background

Resistance to future planning

We know that parents of PWLD are dissatisfied with statutory and private services and have concerns about the future caring responsibilities of their non-disabled adult children and their own ageing,30,31 although primary research on older family carers of PWLD is sparse in the UK. A body of policies and programmes in the UK, including Valuing People, Valuing People Now and Transforming Care, aimed to enable PWLD to lead independent supported lives. However, family carers remain committed to maintaining long-term care in the family home without support or confidence in existing services. In England in 2021–2, 36% of adults with learning disabilities aged 18–64 years getting long-term social care (47,835 people) were living with their families. 32 There is no equivalent information for PWLD aged ≥ 65 years. The government’s recent Building the Right Support Action Plan33 says very little about supporting people as they grow older.

Six studies were identified in one review34 that found themes of fear for the future, lack of trust in services, lack of proactive support to manage crises and transitions, and declining personal support networks in a period when they are most needed. A systematic review of qualitative studies focusing on the future planning of older family carers found three key themes; reservations about available services, mutual dependency and a sense of helplessness, and that parents were making plans or at least had some idea about what they would like to happen in the future. 35 The authors argue for clarity around who is responsible for starting conversations around the future and what the provider or local authority (LA) are doing, given that parents take responsibility for initiating and facilitating plans. The planning, if it is happening, is not being done early enough or with sufficient clarity. The review also found that the responsibilities of caring for and supporting PWLD do not necessarily end when the person moves from the family home. Gorfin and McGlaughlin36 talked with PWLD and found that participants were aware of the need to think about the future; however, the difficult prospect of leaving behind mutually caring relationships obstructed this.

Comprehensive National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for supporting PWLD as they grow older exist, without consideration of ‘BTCO’, which has its own NICE guidance. 37,38 Recommendations include a multiagency plan to be in place and reviewed annually or as need arises and for health planning. The NICE review for the ‘BTCO’ guideline (to March 2017) includes seven studies that do not include older people. A qualitative synthesis of carer experience with services for this group found concerns about times of crisis and availability of suitable services in later life39 and asking for help from the local community can be particularly difficult for carers from ethnic minorities. 40

The little research that exists focuses on points of contact with health services as people get older, not about how health and social care services could work to support decisions about living arrangements and health services towards end of life (EOL). Studies of carer experience of palliative care, cancer and dementia41 found concerns about how to access palliative care services and how to communicate the prognosis and treatments required to families and to older PWLD with deteriorating health. Social care staff in palliative care settings with people with Down syndrome and dementia experienced dissonance between their enabling role supporting autonomy and their subsequent role of monitoring deteriorating health and diminishing skills. 42 Discrepant views can further exist between PWLD, their families and practitioners on EOLC. 43 In summary, the evidence base points to little focus on PWLD growing older.

Project rationale

We know little about the ageing of PWLD and ‘BTCO’, or how family carers manage their caring role as they themselves age. How can forward planning be introduced in an acceptable and reassuring way to older PWLD and family carers? How can health, social care and EOLC services effectively support carers and older PWLD including where active family involvement is absent? How can commissioners be innovative in developing a service infrastructure that better meets the needs of this group? This study explored the support and health needs of older PWLD and family carers to identify ways of easing the move to different homes and support services through planning ahead and reducing the distress and so-called ‘BTCO’.

Aims and objectives

Research questions

What are the information, health and social care support needs of family carers and older PWLD with ‘BTCO’ that enable effective forward planning around supported living and EOLC for older carers?

What are the characteristics of exemplars of good practice in services and support interventions in the UK for older PWLD (and their carers) towards EOL and how are they delivered?

Aim

The aim is to improve support for family carers and older PWLD (aged ≥ 40 years) with ‘BTCO’ by producing effective and workable recommendations and resources including EOLC planning for carers.

Objectives

-

To develop an understanding of existing evidence about the health (physical, mental and social) needs, service interventions and resources for family carers and older PWLD with a focus on those labelled with ‘BTCO’ who are moving to greater supported care, including EOLC [work package (WP) 1].

-

To identify exemplars of good practice in services and support interventions in the UK for older PWLD, and their family and professional carers, towards the EOL (WP2).

-

To explore how older PWLD and their carers can be better supported in later life by researching the commissioning and delivery of exemplar services using ethnographic case studies (WP3).

-

To co-produce decision aid tools to support future planning and EOLC discussions for carers and future planning for older PWLD and evaluate their initial use (WP4).

-

To co-produce actionable recommendations for commissioners and providers, resources and decision aids for carers and PWLD, and online training materials about care in later life for social workers and professional carers (WP5).

Additional funding

In early 2022 we were awarded additional funding to add a new study site based in the north of England to the ethnographic work, to conduct a new rapid scoping review on the co-ordination of health and social care for older PWLD and ‘BTCO’, and to update one of the existing rapid scoping reviews on the experiences of older PWLD to incorporate searches about access to EOLC provision. We have incorporated the findings of this additional funding into the main body of the report.

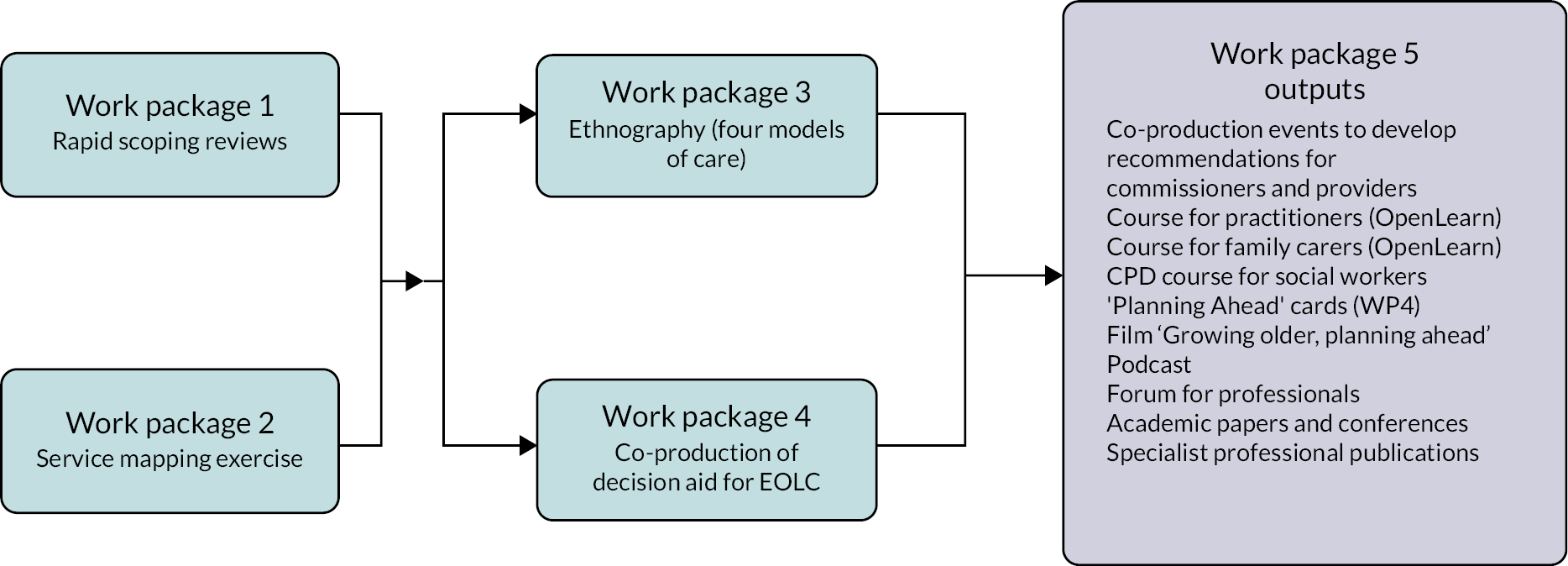

Research plan

This qualitative study comprised five WPs (Figure 1). WP1 and WP2 are scene-setting. WP1 involved three rapid reviews (RRs) focusing on the needs and support of older PWLD and family carers, practice guidance, interventions, resources and the co-ordination of support. WP2 involved a scoping study to identify exemplars of community living services and support interventions across England for older PWLD, including those with so-called ‘BTCO’. In WP3, research teams, including family carers and PWLD, used ethnographic methods of observation, interviewing and documentary analysis to study exemplary provider sites. Case studies were mainly selected from the findings of the scoping exercise in WP2, with one site identified during the proposal development stage (see Chapter 4). WP4 focused on planning ahead and the EOLC planning experiences of older carers and the use of decision aid interventions in forward planning for PWLD. The two central strands of facilitating and enabling forward planning for older PWLD, and EOLC for carers, came together in WP5 when we co-produced the final project outputs.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram.

Outline of this report

This report is structured to follow the WPs sequentially, with the methods and findings covered in the same chapter, or in the subsequent chapter in the case of WP3. Chapters 2–6 present the findings from WPs 1–4, and each chapter begins with a plain language summary. The co-production work from WP5 is discussed in Chapter 7 and Chapter 8 discusses public involvement. Chapter 9 draws the project findings together with a discussion of the implications of our findings, recommendations and conclusion.

Chapter 2 Work package 1: reviewing the literature on older people with learning disabilities and ‘behaviours that challenge others’ and their family carers – needs, experiences and care co-ordination

Plain language summary

-

We did three reviews of the literature. This means we read lots of articles and reports and found out what other people said about our topic.

-

Review 1 looked at what is written about the lives of older people with learning disabilities and ‘behaviours that challenge others’.

-

Review 2 looked at what is written about the lives of family carers of older people with learning disabilities and ‘behaviours that challenge others’.

-

Review 3 looked at what is written about how care is co-ordinated for older people with learning disabilities and ‘behaviours that challenge others’.

-

We found there is not enough good support or information available for people and their family carers as they get older. We learnt that more research is needed to understand how things can be improved.

Introduction

Despite the challenges and stresses that can be faced by older PWLD, and their family carers, we know little about their experiences of moving out of the family home or between homes or providers. Two previous systematic reviews that addressed the experiences of PWLD and ‘BTCO’ were focused on younger adults. 44,45 A previous systematic review on support for older PWLD did not include a focus on ‘BTCO’. 46 Previous systematic reviews on ageing carers of older PWLD have not dealt specifically with the experiences and needs of older carers of PWLD and ‘BTCO’. 34,35,47,48

To address this evidence gap, we undertook three rapid scoping reviews. The first (RR1) addressed older PWLD and ‘BTCO’, with a specific focus on ageing, including issues relating to moving home. Additional project funding awarded in 2022 was used to extend RR1 to include a detailed search on EOLC. The second review (RR2) addressed family carers, with a focus on ageing and issues relating to supporting their family member to move home. The third review (RR3), also undertaken with the additional project funding in 2022, explored the effective co-ordination of health and social care for older PWLD and ‘BTCO’ who live in the community.

Objective

Our key objective in WP1 was to develop an understanding of what is known about the health (physical, mental and social) needs, support and resources for older PWLD and ‘BTCO’ and their family carers, with a focus on experiences, interventions and resources related to moving home and care co-ordination.

Methods

Review research questions

What are the health and social care needs, experiences, service interventions and resources of and for older PWLD and ‘BTCO’ as they move to different care contexts in the UK? (RR1)

What are the health and social care needs, experiences, service interventions and resources of and for family carers of older PWLD and ‘BTCO’ as they move to different care contexts in the UK? (RR2)

What enables the best co-ordination of care for older PWLD with ‘BTCO’ living in the community? (RR3)

Rapid scoping reviews: rationale

Systematic rapid scoping reviews were used because our review questions were inclusive and exploratory in nature, designed to capture evidence pertaining to multiple aspects of the health and social care needs and experiences of and service interventions and resources for older PWLD and family carers. Scoping reviews allow evidence drawn from diverse sources, which is typically heterogeneous in nature, to be systematically synthesised. 49 RRs are a streamlined and/or accelerated version of systematic reviews50 and are an increasingly accepted approach to evidence generation. 51,52

The reviews were reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist53 (see Report Supplementary Materials 1–4). We drew on relevant expert guidance. We used the SelecTing Approaches for Rapid Reviews (STARR)54 decision tool to help make broad decisions concerning the overall review process. Regarding specific methods, we drew on guidance from the Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine52 and the World Health Organization. 55

Throughout the review process we consulted with the wider project team, the Professional Advisory Group and Public Advisory Group to ensure that the review remained relevant and useful. 51,52 The groups contributed ideas, discussed ongoing findings, and helped to ensure that the analysis was clear and relevant.

Eligibility criteria

We were interested in the nature and findings of evidence that could be used to draw conclusions about our topics of interest. Published and unpublished (grey) literature, including research articles, reports and policy and practice guidance, were included; discussion papers, position papers, expert opinion pieces, editorials and study protocols were excluded. Within the published research we included primary (using quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods) and secondary (e.g. review) level evidence. For pragmatic reasons, for RR1 and RR2 we included only literature written in English and related to the UK context. This was extended for RR3 to cover international literature written in English to increase the likelihood of retrieving relevant material. RR1 and RR2 included evidence from 2001 onwards, to coincide with the publication of the Valuing People White Paper,56 which included an explicit focus on the needs of older PWLD and people with ‘BTCO’. For RR3, we removed the date restrictions to increase the likelihood of returning relevant hits.

Table 1 sets out the focus of RR1, RR2 and RR3, using the Population, Concepts and Context framework. 57

| Population | Concepts | Context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR1 | Older (aged ≥ 40 years) PWLD and ‘BTCO’ | Health and social care needs, experiences, service interventions and resources of and for these older adults | Older (aged ≥ 40 years) PWLD and ‘BTCO’ moving to different contexts of care |

| RR2 | Family carers of older (aged ≥ 40 years) PWLD and ‘BTCO’ | Health and social care needs, experiences, service interventions and resources of and for these family carers | Family carers of older (aged ≥ 40 years) PWLD and ‘BTCO’ moving to different contexts of care |

| RR3 | Older (aged ≥ 40 years) PWLD and ‘BTCO’ | Co-ordination of health and social care; multidisciplinary working for these older adults; age-related care | Older (aged ≥ 40 years) PWLD and behaviours requiring specialist health and social support related to ageing |

Definitions

We defined older PWLD as aged ≥ 40 years, as described in Chapter 1. We adopted a broad and inclusive approach to ‘family carers’ but were particularly interested in the experiences of parents and siblings in alignment with the empirical WPs.

A wide-ranging definition of ‘care contexts’ was used, encompassing service model [independent supported living (ISL), nursing home or family home]; provider type (NHS/LA, private provider, third-sector organisation, family); relationships (family members, paid carers, personal assistants); place (the geographical location of care); and commissioning and funding arrangements such as personal budgets. We focused our search strategy on ‘challenging behaviour’, ‘ageing’ and ‘learning disability’ rather than specific conditions (e.g. dementia) and/or specific forms of behaviour (e.g. self-injury, violence) after an initial trial returned a vast number of returns unmanageable for a rapid scoping review (an initial scan also indicated that many returned items had no relevance to our research question). While we refer to ‘BTCO in our reporting for WP1 in line with the wider report (see discussion in Chapter 1), our search strategy included terms commonly used in the academic and grey literature, for example, ‘challenging behaviour’ and ‘behaviours of concern’. These are nebulous terms and definitions vary according to context, but they are broadly understood to be a form of communication and may refer to aggression, self-injury, stereotypic behaviour, withdrawal, and disruptive or destructive behaviour. 58

Information sources and search strategy

Database selection, search strategies and searches were undertaken with the support of a subject specialist librarian. Given the short timescale and consequent need to achieve a balance between sensitivity and specificity, we focused on priority information sources such as CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PsycInfo, SICEN and Scopus. For RR1 (conducted in 2020–1) we used CINAHL, Healthcare Management Information Consortium (HMIC), NHS Evidence, Scopus, Turning Evidence Into Practice (TRIP), Web of Science (WoS), Google (first five pages) and Google Scholar (first five pages); and then MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, SCIE (Social Care Institute for Excellence), and Social Policy and Practice for the additional searches for EOLC in 2022. For RR2 (conducted in 2020–1), we used CINAHL, HMIC, NHS Evidence, TRIP, WoS, Google (first five pages), Google Scholar (first five pages), the Carer Research Knowledge Exchange Network (CAREN) and SCIE. For RR3 (conducted in 2022) we used MEDLINE, PsycInfo, CINAHL, SCIE and Social Policy and Practice.

In addition, we used the expertise of the project research team and advisory groups and hand-searched the reference lists of included documents.

For electronic databases, we generated search terms (words and phrases, including synonyms and terminology variations). These terms were combined using the Boolean operators ‘and/or’ and appropriate truncation and phrase symbols to form initial search strategies, which we piloted against selected key databases. Based on this exercise, we confirmed our final search strategies to be used for each of the databases. The same keywords as for the main search were used to search grey literature (see Report Supplementary Material 7).

Selection of sources of evidence

Electronic search data sets were imported into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and duplicate records were removed prior to screening. For RR1 and RR2, two reviewers independently screened all returned titles and abstracts (where available) against the inclusion criteria. Three reviewers independently screened all returned titles and abstracts for the extended RR1 search on EOLC. For RR3, three reviewers independently screened a selection of 50 returned titles and abstracts and met to discuss decisions and agree criteria for inclusion. All three researchers screened the remaining articles and titles.

Any discrepancies or queries were discussed between the reviewers and, if necessary, with the wider review team.

Full-text copies of potentially relevant articles and reports were obtained. For each review, one researcher independently reviewed full texts, with other members of the team reading a selection. Articles or other sources of evidence excluded based on full-text review were recorded, alongside the reasons for exclusion. Where evidence was not immediately available, we attempted to source it using various means, such as contacting authors. If the evidence did not become available within a 1-month period, it was recorded as missing.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed and piloted on three sources of evidence selected to ensure variation in focus and content, and a final version was used to extract data from included evidence. One reviewer led data extraction for each review, and completed forms were shared among the review team to be checked for gaps and inconsistencies.

Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence

The conduct of critical (quality) appraisal in scoping and RRs is considered optional. 50,55,57 For scoping reviews, the central issue is inclusion of many types of evidence,57 some of which are not amenable to quality appraisal. For RRs the central issues are lack of or limited availability of information on which to base quality assessment decisions55 and time available to complete the review, including in respect of chasing up missing information. 51 Given the variety of included evidence and the project management plan, we took a pragmatic decision not to undertake critical appraisal. However, we considered how included papers framed the concept ‘BTCO’ and the extent to which the research took a critical stance towards this concept. We were alert to papers that presented a medicalised perspective on ‘BTCO’ and considered how this may have impacted on the findings presented.

Synthesis of findings

Alongside primary and secondary empirical research findings, evidence included non-research case studies, and resources providing information and guidance relevant to older (aged ≥ 40 years) PWLD and ‘BTCO’, and family carers. Such diversity necessitated a flexible approach to bringing together the evidence in its entirety. Key characteristics of included evidence were summarised in a table of characteristics for each review (see Appendix 1). Using these tables, we identified patterns and trends in the volume, focus and content of included evidence as the basis of our discussion.

The findings were integrated using a narrative approach. 59,60 An iterative process of reviewing the entirety of the research evidence allowed us to identify patterns in what the evidence was suggesting, however derived and expressed, which we captured in a series of themes and subthemes. The process was led by two researchers per review, with the sustained involvement of review team members from an early stage, and from advisory groups once an initial thematic draft had been developed.

Our aim was to interpret, rather than describe, the original (author-generated) findings to generate new conceptual understandings, set out as analytical themes. Deductively, we took the focus of the review as our point of entry into the data. Inductively, we followed the three-stage process outlined in Table 2.

| Stage | Analysis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: development of coding framework | Article-by-article development of codes, which reflected the meaning and content of the author-generated findings | Equivalence of coding/categorisation of data across the collective body of findings |

| Stage 2: development of descriptive themes/subthemes | Iterative review of codes to identify those that clustered together in terms of their meaning to produce ‘descriptive themes’ | Equivalence of ‘descriptive themes’ across the collective body of findings |

| Stage 3: development of analytical themes/subthemes | Iterative review of descriptive themes, including their individual codes and associated segments of data, in terms of their meaning/relevance to the focus of the review. To develop analytical themes Shared research team/ project advisory input to enhance the robustness of the final analytical framework |

Set of conceptually relevant analytical themes/subthemes |

Results

Rapid review 1: health and social care needs of older (aged ≥ 40 years) people with learning disabilities and ‘behaviours that challenge others’ moving to different contexts of care

This review was based on collaborative working with key stakeholders, using systematic methods of data searching, extraction and analysis. It explored what is known about the health and social care needs, experiences, service interventions and resources of and for this population as they transition to different care contexts in the UK.

In the original search in 2020–1, database searches yielded 261 returns, of which 223 were excluded based on initial screening using titles/abstracts. The remaining 38 were read in full, 32 were excluded and 6 were identified for inclusion. A total of 37 returns were identified from the reference lists of database-included articles, all of which were read in full. Of these, one article was included. A total of 40 additional items of evidence were identified by the research team, Professional Advisory Group and Public Advisory Group. Of these, two were included. Therefore, a total of nine items of evidence were included in our review conducted in 2021–2. The extended RR1 search conducted in 2022 on EOLC yielded 355 database returns, of which 346 were excluded based on initial title/abstract screening. The remaining nine papers were excluded after full reading. There was no additional evidence for RR1. Our analysis generated four main themes – transition over the long term: laying the necessary foundations; avoiding the need for unwanted/inappropriate transition; at the point of transition: making it work; and an absence of target resources – which we briefly summarise here:

-

‘Transition over the long term: laying the necessary foundations’ addresses factors that work for and against moving home successfully over the long term, captured in three subthemes: ‘opening up choice’, ‘promoting independence’ and ‘making choice a reality’. Future planning involves proactive planning for circumstances in which PWLD are no longer able to remain in their home, which is typically the family home. 61 Evidence showed limited planning by ageing family carers and PWLD, albeit for various reasons. Professional involvement in supporting a ‘whole family’ approach to future planning is advocated by Forrester-Jones62 and Slevin et al.,61 with the latter stressing the need for planning to start before problems associated with ageing manifest. Commissioners have a responsibility to proactively plan for the delivery of appropriate housing and support. This requires detailed knowledge of the needs of the people involved locally, and how these are likely to change over time, premised on robust databases of ageing family carers and older PWLD. 61

-

‘Avoiding the need for unwanted/inappropriate transition’ addressed factors to help maintain residence and prevent crisis moves in three subthemes: ‘optimising health and social care’, ‘the importance of staff training’ and ‘specialist community teams for people with “BTCO”’. The need to avoid delays in the completion of needs assessment went far beyond the 4–6 weeks specified in the Care Act 2014. Given the relationship between mental and physical health issues and ‘BTCO’, a proactive approach to the effective health care of older PWLD and ‘BTCO’ is particularly needed. Slevin et al. 61 highlight the evidence for annual health checks as a useful preventative strategy, as they can reveal ongoing or changing health needs. That older PWLD have been shown to underuse health services further underscores the need for proactive engagement. 61 Linked to this is the criticality of bespoke staff training, focused on what people need as they age63 and the benefits of community specialist teams who have the breadth of skills and professional knowledge to meet the complex health and care needs of this group. 61

-

‘At the point of transition: making it work’ deals with factors that promote the potential for successful transition in two subthemes: ‘specialist support in making transition happen’ and ‘front-line staff skills and attitudes’. Leaning and Adderly64 identify the benefits of specialist involvement at the point of transition, including community nurses, social services colleagues, psychiatrists and ‘challenging needs specialists’. They also emphasise the need for professionals and family to resist and challenge ‘problem-saturated narratives’ that focus excessively on behavioural concerns, and instead promote alternative narratives that are informed by the person’s capabilities and what makes them happy. The role of creative, compassionate and consistent staff and senior managers is also critical. 65

-

‘An absence of targeted resources’ deals with the limited information and guidance currently available to PWLD as they grow older.

Rapid review 2: health and social care needs and interventions for family carers of older (aged ≥ 40 years) people with learning disabilities and ‘behaviours that challenge others’ moving to different contexts of care

This rapid scoping review of published and unpublished literature explored what is known about the health and social care needs, experiences, service interventions and resources of and for these carers in the context of the transition of their adult family member to different care contexts in the UK.

Database searches yielded 157 returns, of which 110 were excluded based on initial titles/abstract screening. Of the remaining 47 read in full, 45 were excluded and 2 were included. A total of 35 returns were identified from the reference lists of included articles, all of which were read in full. Of these, one article was included. A total of 40 additional items of evidence were identified by the research team alongside our Professional and Public Advisory Groups, all of which were read in full. Of these, four were included. Therefore, a total of seven items of evidence were included in our review. Details of the seven included items are in Appendix 1. RR2 identified four key themes: support for ageing family carers of PWLD and ‘BTCO’; challenges facing carers when considering planning ahead; availability of suitable housing and support; and limited availability of information and guidance:

-

Support for ageing family carers of PWLD and ‘BTCO’. The review highlighted a lack of accessible advice, information and support. Black and McKendrick66 found that 29 out of 36 participants in Northern Ireland reported not knowing what help was available from services. Significantly, 28 out of 36 reported a lack of regular contact with their social worker, meaning that they did not have consistent access to an important source of information. Slevin et al. 61 discuss a range of interventions that can act ‘as a form of prevention, maintenance and also crisis management’, including planning, support groups, support co-ordination, direct services and sibling support, which can provide information, emotional and practical support.

-

Challenges facing carers when considering planning ahead. Forrester-Jones,62 Slevin et al. 61 and Black and McKendrick66 note a tendency for carers to avoid thinking about the future. Forrester-Jones62 found that family carers can be reluctant to relinquish their caring role, which can be a source of profound satisfaction and purpose, within a context of mutual caring and interdependence that develops over time. Using a ‘whole family’ approach to address issues around future planning that are acceptable to carers is strongly advocated. 61,62,66 The potential role of siblings as future main caregivers needs consideration and sensitivity;61,62,66 for example, siblings may not want to or be able to assume a caregiving role. 62,66 The revisiting of plans is recommended so changes in family circumstances and needs can be considered, and plans amended accordingly. 61,62

-

Availability of suitable housing and support. RR2 highlighted the burden on carers of struggling to find appropriate accommodation for their relative. Even when families are ready and prepared for the move the process can be protracted, complex, debilitating and frequently futile. 67 On average, PWLD had been on a housing waiting list for 2–3 years, with two families (out of nine) waiting over 5 years. A key obstacle to progress was communication with social services and housing staff, and meetings were held with no follow-up action. This lack of action was often associated with constant changes in personnel, and the fact that no one professional appeared to take responsibility. Participants described growing distrust of social services and housing department staff, and disillusionment with the system in general.

-

As with RR1, our final theme addressed the limited information and guidance available to aid PWLD to navigate moving from the family home. We found no targeted resources to guide PWLD, family carers or professionals (either front-line or planners/commissioners) in planning ahead.

Rapid review 3: the co-ordination of care for older people with learning disabilities with ‘behaviours that challenge others’ living in the community

Database searches yielded 1449 returns, of which 1391 were excluded based on initial screening using titles/abstracts. The remaining 58 were read in full; 49 were excluded and nine were identified for inclusion. Manual reference list and forward citation searching were undertaken for these 9 papers. Based on initial screening, 6 papers from the reference lists and 108 from the forward citation searching were excluded. The remaining 12 papers were read in full. However, none met the inclusion criteria and all were excluded. Therefore, nine items of evidence were included in our review. See Appendix 1 for details about the nine included items.

Rapid review 3: findings are presented at individual, service and commissioner levels

-

At an individual level, the review emphasises the importance of professionals, PWLD and family members developing positive relationships. This involves effective communication and a sharing of knowledge. 68–73 It also requires the co-ordination of specialised, bespoke and person-centred planning and a focus on pre-empting and responding to ‘health-related loss’, such as a deterioration in mobility. 70 This may involve the recruitment and training of specialist staff teams, with relevant input from both clinical and social care staff. 69,71 The benefits of a family-centred approach to the delivery of primary care to older PWLD was also identified, with the caveat that professionals should ensure that the views of family members are balanced against the wishes and preferences of PWLD. 73

-

At a service level, proactive collaboration between different agencies is critical. 68–70,72–75 This involves bringing together professional expertise within learning disability (e.g. via community learning disability teams), mental health and gerontology services as needed, alongside housing agencies. However, when professionals work with other agencies, there may be knowledge gaps around learning disabilities, particularly for those who do not frequently work with PWLD. 72,74 Training and resources are suggested for professionals who do not regularly work with older PWLD, including experiential training alongside PWLD.

-

At a commissioning level, the review identified that provision for older PWLD was frequently fragmented, leading to critical opportunities for diagnosis and referrals (e.g. for mental health support) being missed. The importance of local strategic frameworks to support planning and resourcing for this group of people as they age was highlighted. This was described as a needs-led service system that ‘has capacity to take account of current and future age-related needs’. 70 There was some consensus that the system should be developed from the bottom up in response to the needs of local people. 68,70–72,76 How well funded and well planned service provision is locally or regionally impacts the potential for success at the individual and service levels. This includes the provision of multidisciplinary outpatient healthcare practices that provide co-ordinated physical and mental healthcare services for PWLD. 76

Discussion

The absence of a critical understanding of ‘BTCO’ as a socially constructed phenomenon, predicated on the understanding of all involved within interpersonal, organisational and systems contexts of interaction, is a limitation in existing research. These social dynamics are critical to promoting and impeding the effective move of PWLD from their family home or from one provider to another. Within the limited evidence available detailing examples of successful moves for older PWLD, the role of suitably trained, consistent and compassionate staff, supported by effective senior service managers, was notable. 65

Our reviews highlight gaps in the promotion of proactive planning, the provision of appropriate housing, effective needs-based assessments, inconsistent or absent approaches to collaborative working across different professionals and agencies, and the availability of timely and consistent professional support, most notably from social workers. The criticality of local strategic frameworks to facilitate effective planning and bespoke service development for PWLD and their families was clearly identified in RR3. RR1 and RR2 also draw attention to the dearth of resources and guidance available to support PWLD and their family members to plan ahead.

We identified several systems issues that need to be addressed in order to build capacity to support people as they age. The importance of proactive preparation and planning across multiple areas of activity is clear. This includes building PWLD’s confidence over time to live outside the family home (thus avoiding an unanticipated move in the context of a crisis), more robust support for family carers from health and social care professionals (particularly social workers) and the strategic commissioning of suitable housing and support services. This means people planning to move out of the family home before services deem that they ‘need’ to. Commissioners across learning disability, older people’s services and mental health need to work collaboratively in such strategic planning. Forrester-Jones62 also highlighted the critical role played by social workers in supporting the transitions of older PWLD as they age (and their families), acknowledging the importance of consistency and relationship building over time. In addition, Forrester-Jones62 identified a widespread lack of a ‘whole family’ approach to needs assessment, with significant implications for planning and the mitigation of crises for people.

Timely and effective engagement with health services is also needed to help identify the onset of conditions that may be labelled as ‘BTCO’ as a result of people becoming unwell or experiencing pain/discomfort. Our reviews show that education and training should be provided to family and front-line professional staff in relation to both the recognition of the early symptoms of dementia and the care of PWLD who develop dementia. 61

Ageing can impact the ability of family carers to care for their adult family member with a learning disability. 61,62,67 The relationship between ageing and diminishing capacity to care in the family home, as well as the profound anxieties engendered, is highlighted in the broader literature. 2,77,78 Evidence also demonstrates the additional distress when this happens in the context of a lack of future planning,35,47,48 exacerbated by (often severe) limitations in the availability of appropriate housing. 13,37,79

Our reviews have confirmed an inadequate evidence base concerning the experiences, needs and support of older carers. That which does exist demonstrates major deficits in how the carers of older adults who may display ‘BTCO’ are being supported when their family member’s preference is to remain at home and/or to consider and achieve a move outside the family home. Although premised on a limited evidence base, our reviews provide important insights into what is required to effectively support PWLD and their family members as they grow older.

Limitations

We note that all three reviews had a low rate of inclusion despite initially promising returns. The key reasons for exclusion were that the evidence was not sufficiently focused on our target population and/or that the substantive content was not relevant to our research questions. Focusing our search strategy on ‘challenging behaviour’ rather than associated conditions (e.g. dementia; profound mental ill health) and/or specific forms of behaviour (e.g. self-injury; aggression) risked missing relevant material. However, a trial of alternative approaches generated an immense number of returns, unmanageable for the purposes of a rapid scoping review. Moreover, on scanning these returns, they showed no relevance to our research question. The possibility that we missed relevant evidence was reduced by strenuous efforts to read a wide body of evidence, and, in addition, the search strategy for RR3 was widened to include international literature and work published before 2001. We also adopted an enhanced RR process, including the use of multiple reviewers alongside consultation with the wider project team and advisory groups to mitigate the risks of missing relevant evidence.

Having undertaken three rapid scoping reviews, the possibility remains that we have missed some relevant evidence. This is reduced by strenuous efforts to read a wide body of evidence that was eventually excluded. In addition, the search strategy for RR3 was widened to include international literature and work published before 2001. We also adopted an enhanced RR process, including the use of multiple reviewers alongside consultation with the wider project team and advisory groups to mitigate the risks of missing relevant evidence.

We found little evidence specifically focused on older PWLD labelled with ‘BTCO’ in the context of moving home. We were therefore largely dependent on evidence that addressed our review questions as part of a broader focus, typically either older PWLD or PWLD labelled with ‘BTCO’ (and their carers). From this evidence, we extracted relevant content. This required close reading of many items that did not contain relevant content. Most of the evidence included in our reviews was over 10 years old, pre-dating significant developments in the UK context, notably the impact of austerity,11 the roll-out of annual health checks by general medical practice from 2009,1 and guidance for strategic commissioning to develop capacity for suitable community provision across the life course, such as Building the Right Support,80 Building the Right Home81 and the Transforming Care programme. 82 Although we have been able to identify some key learning concerning current planning and implementation of transition-related care and support for older PWLD labelled with ‘BTCO’ (and their family carers), gaps in research remain.

Conclusion and recommendations

The reviews show that the needs of older PWLD, and of their family carers, must be afforded greater priority within health and social care policy and commissioning practices. Wider research exploring learning disability and ageing highlights the need for social care staff training to facilitate more nuanced and proactive approaches to support people as they age. 83,84 The promotion of healthy ageing among PWLD relies on services and front-line staff understanding the specific health needs of this population, clearly evidenced through large-scale longitudinal research. 85,86 The policy challenge lies in disseminating this knowledge effectively to practitioners, family carers and PWLD, while developing approaches to healthy ageing in services that are person-centred and responsive. Involving PWLD and their families/advocates (where possible) is also critical to ensuring that well-planned decisions are made – decisions that take account of people’s whole lives, including their relationships, homes, activities and hobbies, as well as health needs.

Research has shown that, despite policy commitments to ageing ‘in place’ (i.e. within their chosen home), progress in developing or adapting existing accommodation for PWLD as they age has been slow across a range of international contexts. 87 Our reviews demonstrate that macro-level strategic commissioning for PWLD and ‘BTCO’ as they age is urgently needed. Fundamentally, contemporary policy for PWLD has not been developed to take account of people growing older. This means that systems are not designed to support comprehensive commissioning for this population, and, in many cases, they prohibit effective, timely and inclusive discussions of future care,47 with consequent distressing, avoidable and costly crisis management.

Chapter 3 Work package 2: scoping and mapping exemplars of good practice in living arrangements for older people with learning disabilities and ‘behaviours that challenge others’ living in the community

Plain language summary

-

We wanted to find out how people describe excellent support for older people with learning disabilities who may be labelled as having ‘behaviours that challenge others’.

-

We read what is written by organisations for people with learning disabilities and those who decide what services should be provided in England.

-

We contacted around 260 people and about 80 organisations and found four key types of support.

-

We talked with professionals and people with lived experience to come up with a shortlist of excellent providers.

-

We made a shortlist of excellent providers for the next stage of our research.

Introduction

Work package 2 aimed to scope out models of service provision and identify exemplars of good practice in services and support interventions in England for older PWLD and ‘BTCO’, and their family and professional carers, towards the end of their life.

Service models focus

Services are defined in this research as those that support people to live in the community. This includes services that support people to live in their family home, housing with a tenancy and with types of paid support, Shared Lives (also known in Northern Ireland as adult placement) where the PWLD lives in a registered care provider’s own home as a family member,37 and residential care homes (with or without nursing care).

Service support includes domiciliary care, personal assistance funded by personal budgets, respite care, support with activities including employment, day-centre-based activities, supported living personal and social care, and a range of health, personal and social care provided in care homes. Individualised care provision can be shared via a team across a group of people living together or provided to one person. Health services are generally provided by generic primary care, specialist learning disability community health teams, and generic secondary and tertiary care services, supported by specialist learning disability liaison nurses. EOLC services provided to the general adult population are also accessed by PWLD. Support services that enable people to be discharged from assessment and treatment units and other inpatient settings are in scope where they are provided in the community and commissioned and/or provided by mainstream health and social care services.

Objective

Our objective in WP2 was to identify exemplars of good practice in services and support interventions in England for older PWLD, and their family and professional carers towards their EOL.

Methods

Criteria of exemplar services

The Professional Advisory Group considered and suggested standards in use by commissioners and providers. Some recommendations of standards related specifically to services for older PWLD and ‘BTCO’, but none were felt to be sufficient in themselves to be criteria of excellence for the purposes of this research, particularly as they addressed different needs, such as EOLC, dementia care and the needs of people leaving inpatient care. Therefore, the approach to defining excellence was developed through the data collection activity with a range of stakeholders.

Selected published standards and guidance, including the grey literature of WP1, with input from the Professional Advisory Group and views of key stakeholders, were analysed. We used a combination of predetermined and emerging categories to extract data supporting one or more of the criteria of excellence (see Criteria of excellence). The first step was a desk-based exercise of examining standards and descriptions of services derived from the literature and consultation. The second step involved using data from mapping interviews and a survey about participants’ relationships to services or those they had experienced, managed or were involved with commissioning.

Rapid analysis was used as described by Taylor et al. 88 for use with interviews and the survey comments using a combination of predetermined and exploratory themes. This was relevant for a subset of 30 participants in the mapping exercise interviews or who completed a survey equivalent (see Report Supplementary Material 5). Comments from interviewees and survey participants related to the general criteria of excellence that emerged from the desktop review were recorded into predetermined categories, and new themes were generated. Quality assurance of the coding was undertaken by a research associate, and differences were resolved by discussion. There were several new criteria describing participants’ relationships to services.

The third step involved both advisory groups commenting on the drafts and suggesting ways to refine the criteria.

Mapping

A mapping approach was adapted from three NIHR service mapping studies. 89–91 The aim was to identify services and whether they met the criteria of excellence while operating in the service models described by participants and the characteristics of older PWLD and ‘BTCO’ for whom these services were provided.

Recruitment of participants to identify services and/or for interview

The mapping approach used multiple routes to identify commissioning and provision of exemplar services and then to find out key information about the service from interviews, an online survey, websites and other documentary sources. Recruitment involved two parallel approaches:

-

NHS and social care commissioners: The initial plan was to use the approach adopted in the evaluation of Building the Right Support. 80 This evaluation used a survey of Transforming Care Partnership (TCP) members to identify case studies at TCP level and a snowballing approach to generate evaluation responses. 92,93 In this scoping exercise, we anticipated identifying, using a cascade approach, one or two key strategic-level participants who could identify relevant exemplar services if these existed in their area. We also anticipated that as the NHS was undergoing significant structural changes there was likely to be geographic variation in the strategic oversight of services over the period of study of 2020–1. Furthermore, TCPs are concerned with a small subset of PWLD with specialised service needs. We approached NHS England (NHSE) Learning Disability and Autism programme leads at regional and integrated care system levels via the Clinical Director for Learning Disability at NHSE. At this level, we sought exemplars and contacts with the Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), LAs and NHS Mental Health partnership trusts. The NHSE Head of Nursing for End-of-Life Care also shared the invitation with her networks and senior clinical leads.

-

Third-sector providers and bodies representing the public: These organisations were contacted via commissioners and NHS providers, contacts from an article in Care Management Matters,94 a press release, the project website (http://wels.open.ac.uk/research/growing-older-planning-ahead) and social media presence (@OlderAhead and #OlderAhead), a subsample of the 386 ‘outstanding rated’ services that included adults or the elderly and PWLD on the Care Quality Commission (CQC) database, an online survey promoted via social media, a web chat with the ‘Our partners — Learning Disability Nurses’ forum, a clinical senate meeting in NHSE Southern region, and a webinar of Shared Lives providers.

Data generation

Data were generated by e-mail or telephone contact with social care professionals who gave information about services and information about others who could inform the study by identifying services and commenting on the criteria of excellence. Those willing to give information directly were offered either a semistructured interview conducted by telephone or online call or an online survey (see Report Supplementary Material 5).

Data analysis

A template was produced (see Report Supplementary Material 8) for summarising data collected from interview transcriptions and the open text survey. Notes were taken when the conversations were primarily referring the researcher to a primary source. This included data on the characteristics of people who use services, and the services themselves as well as the scope of commissioner responsibilities. Further sections were used to record key documents, web content, quotations and reflections relating to both the criteria of excellence (i.e. how they would apply across services) and specific exemplary practices or case examples of personal experiences of the services. These data were used to develop criteria of excellence described above. The interview and survey data were coded to identify descriptions of specific services. Interviews were conducted with up to four managers and commissioners per service to complete the template.

The final templates and supporting summaries of interviews together with a shortlist of exemplars were presented for consideration by both advisory groups and research team. Preparatory work with the research team and advisory groups was conducted virtually (due to pandemic restrictions) to gain views on the emerging criteria of excellence and how these should be applied to derive the shortlist of services from the mapping exercise. Quality assurance of the mapping exercise results was undertaken by the WP3 team considering the service models by reviewing all the data compiled on each service. The Professional Advisory Group considered the finalised criteria of excellence and consideration of the outcome of the mapping work. The Public Advisory Group and Study Steering Committee (SSC) considered the final shortlist of case sites.

Findings

Criteria of excellence

The criteria of excellence in services were derived from four sources: NICE, CQC standards, NHSE and related third-sector body standards. Sources of the standards are summarised in Appendix 2 and the initial criteria are described in this section, with emerging themes summarised in Table 3. The research literature included in the initial scope of WP1 was examined to draw out sources of published evidence for the emergent criteria. Additional evidence from the mapping interviews in support of the criteria is presented in Appendix 3.

| Criteria | Rationale | Selected evidence and references |

|---|---|---|

| Personalisation, assessment, goals, daily plans/activities | Personalisation is a key standard for all learning disability services, as evidenced in NHSE standards. It is a driver of the NHS Long Term Plan:

|

NICE guidance NG96:96

|

| Research evidence: Bissel et al.,97 Forrester-Jones,62 Slevin et al.,61 Bigby and Beadle-Brown98 | ||

| Matching staff to people being supported | Enabling people and families to choose who provides support, or work with the provider to match the values and interests of support staff to the person | NICE guidance NG93 1.9.6:

|

| Personalised living space/and choices of whom this is shared with | For PWLD and ‘BTCO’, the NICE guidance recommends people should have the option to ‘live alone with appropriate support if they prefer this and it is suitable for them’. Alternatively, ‘offer them the option of living with a small number of other people in shared housing that has a small-scale domestic feel. Involve people in choosing how many people, and who, they live with’37 | NICE guidance NG93, section 1.5, housing and related support, including 1.5.4:

|

| CQC standards on campus and congregate living: www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/autistic-people-learning-disability/right-support-right-care-right-culture | ||

| Health; proactive, preventive, primary care, and involvement of NHS MDT | Assessment and planning to meet health needs, prevent lifestyle related disorders and manage comorbidities (such as epilepsy) requires proactive access to generic services such as primary care, and specialist services such as hospital Learning Disability Liaison nurse services, NHS learning disability multidisciplinary health team | NICE NG96 1.5 identifying and managing health needs, (1.2) physical health care96 NHS Long Term Plan commitment annual health checks99 Selected research evidence: Watchman100 |

| Staff recruitment underpinned with the right values and skills | This enables support staff to engage with people’s values, choices and activities they can relate to and share | Core Capabilities Framework for Supporting People with a Learning Disability101 NICE guidance NG93, staff skills and values (1.9), for example, involvement staff recruitment (1.9.6)37 Selected research: Bigby and Beadle-Brown,98 Leaning and Adderley64 |

| High staff retention to provide continuity of care | This was suggested by the Professional Advisory Group as it enables staff to better understand people’s needs and choices and how these might be changing. High turnover and use of agencies can be commented on in CQC inspections | NICE guidance NG96 (1.7 staff skills and expertise) has some relevance but does not cover continuity of care directly96 NICE guidance NG93 – principles – continuity of relationships37 Selected research: Hubert and Hollins65 |

Care Quality Commission standards

The CQC’s key lines of enquiry (KLOEs) focus on safety, effectiveness, caring, responsiveness and organisational leadership. The inspection process centres around five key questions that inspectors use to determine whether a service is fulfilling their duties for care: is the service safe, effective, caring, responsive and well led?

The Professional Advisory Group suggested that we look at ‘outstanding’ reports of services. This rating may involve a service being at the second level of ‘good’ for a minority of KLOEs, and if the next level rating of ‘good’ was used overall, then it was important that the ratings were ‘outstanding’ in the caring and safe domains, as these are most relevant to people labelled with ‘BTCO’. It was also advised that ratings will apply across a whole service, where the unit or service of interest may be a small unit in a larger service or have few if any service users eligible for the study at the time of the rating, or not recently had a new rating [particularly the case during the coronavirus-19 (COVID-19) pandemic]. Not all services (including, in some instances, the accommodation element of supported living services) are registered with the CQC, so some would not have ratings. Where available, we used CQC ratings to identify possible providers and provide additional information on possible candidate services suggested via other routes. CQC ratings were not regarded as sufficient evidence of exemplar services alone because they lack specificity to older PWLD and the rating may be from some years ago.

Service standards

Standards of services commissioned in England have been issued by NHSE, often in collaboration with social care and third-sector providers, disability rights and advocacy organisations, and carer organisations. These were gathered through the research team’s networks, the Professional Advisory Group, the communications activities of the project (website, social media), the WP2 survey (see Report Supplementary Material 5) discussion with senior NHS commissioners and interviews. These relate to EOLC, to standards for learning disability services applied to all adults, and to specialised learning disability services. Various tools have also been developed for providers and commissioners, families and advocates about what to look for in excellent services (see Appendix 3).

From the above sources, the initial criteria were developed (see Table 3). These were triangulated with selected empirical studies, including those reviewed for WP1, and NICE guidance.

Additional themes for criteria of excellence arising from work package 2 data

Our analysis generated additional themes (Table 4); see Appendix 4 for a thematic analysis of interviews and survey data.

| Criteria | Rationale and data from thematic analysis | Selected evidence references |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusive communication methods | Suggested by the Professional Advisory Group as part of personalisation | NICE guidance NG96 (1.1.7), review of changing communication needs as people grow older96 Selected research: Leaning and Adderley64 |

| Good practices such as EOLC planning, dementia assessment and management embedded as routine | Anticipation of the development of early dementia requires systems to risk assess and detect early signs and seek referral for assessment | NICE guidance NG96, consider training of carers/family members in early signs of dementia (1.5.6, 1.5.37), information about dementia (1.5.36). NICE guidance NG96 (1.6), EOLC for PWLD96 |

| Family involvement | Involvement of families in decision-making about provision and daily life. This involvement is in the context of service provision respecting the rights of the PWLD to autonomy and to a family life if they wish it, along with the caring and advocacy roles often assumed to be the concern of family members | This is integral to NICE guidance (e.g. NG96) (1.1.9–1.1.13)96 and the CQC102 and NHSE standards80 above Selected research: Leaning and Adderley64 |

| Community engagement and inclusion | Enabling people to be part of communities: the engagement of local communities includes in-reach by communities with providers and engagement with community activities in the local area in mainstream venues (or services regularly frequented by local people) as part of the daily activity of individuals | NICE guidance NG96 (1.2.5), access to community (1.2.11), social opportunities (1.2.12), community-based physical activity (1.2.13), education, employment and volunteering, accessible travel (1.2.14)96 Selected research: McConkey and Collins,103 Perry et al.,104 Slevin et al.,61 Bigby et al.105 |

| Trauma-informed services including PBS where appropriate | The use of ‘positive behaviour support’ approaches in the design and delivery of services is relevant to PWLD and ‘BTCO’. This approach may be achieved by regular training across staff groups, an in-house expert team and/or access to such expertise in NHS community learning disability services. Trauma-informed practices can be employed to prevent and to manage distress-related behaviours associated with past traumas |

NICE guidance NG93 describes the service requirements for adult37 and NG11 describes the interventions and their context, for example, including staff training (1.1.6), organisation of intraorganisational leadership (1.1.9–1.1.14)38 Selected research: Harvey106 |

| Commissioner endorsement of provider quality and resilience (low placement breakdown) | Health and social care commissioners are key to forecasting and planning for services, the assessment and monitoring of services and individual placements, and stimulating capacity in providers where high-quality capacity is in short supply | NICE guidance NG93 (1.1.10), stability of placements, contingency fund (1.1.5)37 |

| Commissioners are working with providers, PWLD and families building capacity for future services | The strategic role of commissioners has emerged as important in planning for future provision, with knowledge of the local PWLD and those returning from out-of-area placements, building capacity to enable more local provision, and working with providers to enable them to adapt services and facilities to enable older people to stay in their homes rather than in generic older people’s nursing homes | NICE guidance NG96 (1.2), planning and commissioning local services (1.2.1 and 1.2.3), local needs assessment, housing options (1.2.4), family and support options (1.2.5)96 NICE guidance NG93 (1.5), housing, choice of types and who they live with, tenancy, etc.37 Evaluation of TCPs found skilled commissioners able to work strategically (predicting need, at population level, stimulating provider capacity) was the top success factor92 |

A summary of the key criteria of excellence

The final criteria we used are:

-

personalisation, with goals, daily plans and activities shared and updated

-

matching staff to people being supported

-

personalised living space and choice around who this is shared with

-

proactive, preventative healthcare involving primary care, and involvement of NHS multidisciplinary learning disability teams

-

staff recruitment underpinned by the right values and skills

-

high staff retention to provide continuity of care

-

inclusive communication methods

-

family involvement

-

community engagement and inclusion

-

trauma-informed services where appropriate

-

good practices such as EOLC planning, dementia assessment and management, embedded as routine

-

commissioner endorsement of provider quality and resilience (low placement breakdown)

-

commissioners working with providers, PWLD and families building capacity for future services.

Findings of the mapping exercise

The CQC’s database of registered services was searched with the assistance of a CQC analyst in August 2020. This involved the following steps:

-

Categories were selected to focus on the types of services relevant to PWLD and ‘BCTO’ living in the community, aged ≥ 40 years, as no categories are specific to services for this group. These were (1) inspection category – residential social care, community-based adult services; (2) directorate inspection category (adult social) and (3) primary inspection category – residential social care or community-based adult social care services.

-

To narrow the search, it was necessary to specify categories of ‘adult’ (18–64 and ‘65 and over’) and include learning disability in its regulated categories. As services are registered for multiple groups, such as learning disability and physical disability and dementia, the search was expected to show services that did not necessarily currently support PWLD. Some 386 provider locations in England were rated ‘outstanding’ using these selection criteria.

-

Initial sifting of services with potentially relevant registration (B – regulated activity; C – service type; and D – service use user band), resulted in 330 registered locations with outstanding ratings. See Report Supplementary Material 6 for codes.

-

Services were removed that were clearly outside the remit, such as diagnostic screening and community healthcare services (n = 19).

-

Hand-searching the websites and/or title of the provider was carried out to remove ineligible services, such as those specialising in autism alone (n = 6), and one that had recently lost its outstanding rating (n = 1).

-

Providers were contacted that appeared most often (such as franchises) to verify that they included eligible service users and read their CQC report. If the identified provider was not contactable, contact was attempted with head office. This process removed many services that were not contactable or did not currently have eligible service users. The result was a list of four providers involving 74 registered services, and several Shared Lives schemes.

-

Finally, this data set was used to discuss how the criteria of excellence were met according to the views of providers and commissioners of these services.

Data from interviews, surveys and webinars: response rates and coverage of England

The methods described above (see Methods) involved contacting around 260 individuals. Exact numbers are not known as group online meetings are included for which numbers were not available. Many responses were helpful in providing further contacts and suggestions, and, among these, 89 contacts gave information in formal interviews and informal discussions and in e-mails about at least one specific service, with around 3–6 provider and commissioner perspectives collected on the same services.

Some 81 organisations contacted either passed on information to others or responded directly to a request for a conversation about exemplar services: NHSE regions (n = 7), integrated care system learning disability leads, learning disability and autism partnership boards (n = 10), CCGs (n = 13), LA commissioners (n = 3), mental health partnership provider NHS trusts (n = 4), LA provider managers of Shared Lives services (n = 6) and third-sector providers (n = 38). Geographic coverage was greatest in the south-west, south-east, north-west and north-east, with fewer responses about services in East Anglia, London and the Midlands.

From these contacts, informal conversations were conducted and 30 formal interviews, and notes were recorded about further key contacts and service model descriptions about services with 80 people: Expert researchers (n = 6), NHSE national leads (n = 2), NHS regional leads (n = 3), CCG leads (n = 11), LA leads (n = 7) and provider members (n = 51), and a further nine people completed a qualitative survey instead of the interview (see Report Supplementary Material 5), giving a total of 89 responses. Where there was sufficient input from both providers and commissioners, and they met the eligibility criteria described in the three steps above (see Methods, Criteria of excellence), 15 templates were completed. This included residential and supported living services with identified sites provided by six providers and several locally based Shared Lives franchises.

Interpretation and recommendations for work package 3

Who should be included?

Learning disability services are not organised around age criteria. Services specifically commissioned for PWLD and ‘BTCO’ include autistic people and younger people. Two groups emerged whose services are commissioned differently. Group A are older people who may have greater physical and mental health needs than their peers. This is a large group, with several hundred people in each CCG or LA area, and many may not be known to services.