Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR135470. The contractual start date was in July 2019. The final report began editorial review in July 2021 and was accepted for publication in November 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Grande et al. This work was produced by Grande et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Grande et al.

Background and introduction

Family and friends (hereafter ‘carers’) provide vital unpaid support for people at end of life (EOL). They provide on average 70 hours of care per week in the patient’s final months of life. 1 They are a main factor in sustaining care at home at the EOL,2,3 which both meets patients’ preferences4 and helps reduce acute inpatient care costs and pressures on care home beds. Carers’ contributions therefore are likely to be of considerable benefit both to patient care and to health and social care services.

Our dependency on carers is only likely to increase, given the projected future demographic increases in people aged > 85 years and those with a life-limiting illness,5 as well as increased numbers of deaths. 6 Health and social care services are likely to struggle to meet future demands without carers’ efforts. The COVID-19 pandemic saw increases in deaths at home in England and Wales and decreases in deaths from leading causes in inpatient health care, indicating increased reliance on carers to provide home care when health-care systems are under strain. 7

However, caregiving for patients at the EOL has negative impacts on carers’ own health, with the greatest and most consistent impacts being on carers’ psychological health. 8 Reported prevalence of carer anxiety and depression during palliative care has been estimated at 34–47%9–12 and 39–57%, respectively. 13,14 Furthermore, carer prevalence of clinically significant psychological morbidity during the patients’ final 3 months was 83% in a national census study of cancer deaths in England. 8 This raises concerns about carer health both during caregiving and longer term. Carers’ pre-bereavement psychological health is a main predictor of post-bereavement psychological health. 15–17 Furthermore, if carers become unable to cope, this is likely to have negative impacts on the quality of patient care and increase likelihood of inpatient hospital admissions.

Research shows that there is large individual variation in the level of psychological morbidity from EOL caregiving. 8–14 Understanding what predicts this variation may provide important pointers for action in two ways. First, there are factors that cannot realistically be changed (e.g. age and gender), but whose effects can be mitigated through monitoring those at higher risk and providing early, tailored support when required. Second, there are factors that can be changed (e.g. self-efficacy), which can be subjected to more direct intervention to reduce likelihood of later psychological morbidity. What information is most relevant for supporting carers will depend on the type of stakeholder; for instance, policy-makers may help to modify any work and financial factors affecting carers through legislation, and health-care practitioners may identify and support carers at higher risk or improve carers’ self-efficacy through information and education.

To identify potential factors affecting carers’ mental health when providing EOL care, we conducted reviews of qualitative research18 and observational quantitative research. 19 Each review brought valuable information. The qualitative synthesis identified the factors that carers themselves felt had an impact on their mental health. The observational synthesis subsequently showed us whether or not significant quantifiable associations between these factors and mental health outcomes had been tested for and found (Box 1). However, these bodies of literature can only help us establish whether there is a relationship between factors and mental health, not the direction of causality. It may be that mental health affects the investigated factors, rather than the reverse. For instance, although findings so far indicate that a greater sense of self-efficacy improves mental health, it may equally be that better mental health improves carers’ sense of self-efficacy.

Patient condition, e.g. quality of life, symptom burden, functional impairment

Impact of caring responsibilities, e.g. caregiving demands, life changes

Relationships, e.g. quality of relationships with patient and family

Finances, e.g. financial strain

Internal processes, e.g. self-efficacy, preparedness

Support, e.g. formal support, informal support

Contextual factors, e.g. age, sex, socioeconomic status

Therefore, for the first part of this report we turn to the literature on trials of carer interventions, to ascertain whether or not studies incorporating trial design can further illuminate direction of causality. We review trials of interventions that led to a change in one of our identified factors (see Box 1), and for which the intended outcome was improvement in carers’ mental health, to assess what evidence intervention studies may provide that these factors have an impact on carer mental health.

This synthesis of the trials literature is different from a conventional systematic review of interventions. It is not focusing on whether or not an intervention in itself improves carers’ mental health, but on what it may tell us about the causal nature of the factors identified in our earlier reviews. For instance, an educational intervention may aim to increase carer preparedness to improve carer mental health, but our focus here is whether or not a change in preparedness (an identified factor) is associated with an improvement in mental health, rather than the effect of the educational intervention in itself on mental health. We therefore want to establish whether or not an intervention changed an identified factor, and whether or not any change in the factor was then associated with a change in the carer’s mental health. Thus we are interested in the potential mechanisms by which interventions improve mental health outcomes. An inclusion criterion for this review therefore was that the intervention led to a significant change in one of our identified factors. If a study then reported parallel changes in the factor and mental health outcomes, and moderation/mediation analyses indicated that the factor was the mechanism through which the intervention affected carer mental health, we can be more certain that it is a causal factor.

This report seeks to further validate, synthesise and evaluate the literature on potential factors affecting carers’ mental health during EOL caregiving in two ways: (1) by reporting the findings from our review of trials of carer interventions to illuminate this topic, and (2) by bringing together the findings from the qualitative, observational quantitative and intervention reviews, highlighting the strengths and contributions of each and their combined gaps and implications.

Project patient and public involvement

Core to the project was ensuring that findings would make sense to key stakeholders and could be utilised by them. Our main stakeholders were carers themselves. A carer was a project co-applicant and helped to shape the project. A carer Review Advisory Panel (RAP) consisting of six carers, including the chairperson, was involved at all project stages, including reviewing materials, helping with qualitative analysis and advising on dissemination, to make sure that findings were meaningful, relevant and understandable to carers. In a second stage of the project we worked with a wider range of stakeholders, including additional carers, a patient, practitioners, commissioners and policy-makers, through online workshops and focus groups, to gain feedback on the relevance of findings to their respective spheres of influence and how relevant findings could best be communicated (this work will be reported elsewhere).

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of the project was to help reduce psychological morbidity among carers during EOL care using the following methods:

-

conducting evidence syntheses of qualitative studies, observational quantitative studies and intervention studies

-

integrating syntheses into a coherent framework of factors

-

translating findings into accessible, bespoke information for key stakeholders to help them better target efforts to reduce carer psychological morbidity.

The aim of the current paper is as follows:

-

present the synthesis of the intervention studies and what these tell us about modifiable factors influencing carers’ psychological morbidity, in which morbidity encompasses anxiety, depression, distress and quality of life

-

combine findings from the observational, qualitative and intervention syntheses together in a single framework of factors and assess the main points, strengths and limitations, and implications of this literature overall.

Synthesis of intervention studies

The synthesis of intervention studies was conducted to inform and, if relevant, validate the findings from our earlier qualitative and observational literature reviews of factors related to carers’ mental health during EOL caregiving.

The Method section for the intervention synthesis provides a full account of the search and selection process for the whole project, of which the intervention review was part, as well as the final selection criteria specifically associated with the intervention review.

Method

Search and selection strategy

Studies for the project were identified through an electronic search of the literature from 1 January 2009 to 24 November 2019 in the following databases:

-

MEDLINE (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus (EBSCO Information Services, Ipswich, MA, USA)

-

PsycINFO® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA)

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (Clarivate Plc, London, UK)

-

Excerpta Medica (EMBASE) (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, York, UK).

Dissertations and other grey literature were not searched owing to time constraints and the large number of research papers that the original search strategy returned. Policy literature and professional literature were also excluded as the focus was on peer-reviewed, empirical research published in academic journals. See Appendix 1 for the full search strategy.

Box 2 describes the shared inclusion and exclusion criteria for all qualitative, observational and intervention studies in the project.

Studies had to consider the following:

-

Population. Lay adults who were supporting and caring for an adult patient who was at the EOL. EOL was conceptualised as a palliative, terminal or otherwise ‘advanced’ or ‘end stage’ phase of care in which the patient was likely to die within 1 year. Articles that did not give enough information to ascertain disease stage/palliative phase were excluded.

-

Factor. Any factor that may have affected psychological morbidity in carers.

-

Outcome. Psychological morbidity, defined as anxiety, depression, distress, quality of life and outcomes that carer advisers considered to be important.

-

Setting. Care had to be predominantly provided in a home-care setting.

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria:

-

Factors or outcomes related to bereavement only.

-

Papers that reported most care occurring while the patient was in a facility (i.e. care home, hospital), given that the focus was on factors associated with carer mental health during home care.

-

Studies outside Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, to ensure that health-care structures were comparable with those in the UK.

-

Languages other than English or Scandinavian, which would require further translation.

-

Systematic reviews.

In addition, studies included for the intervention synthesis had to (1) have carer mental health as an intervention outcome; (2) report that the intervention led to a significant change in a factor identified in the observational or qualitative syntheses as associated with carer mental health (see Box 118,19); (3) be a randomised controlled trial (RCT), non-randomised trial, controlled before–after study or interrupted time series; and (4) have a clear comparator in the form of usual care, enhanced usual care, ‘no intervention’ or waiting list controls.

For further information on project searches and inclusion/exclusion criteria see Bayliss et al. 18 and Shield et al. 19

Ten per cent of both titles/abstracts and full texts were screened independently by two reviewers. Over 90% agreement was established in each case, indicating that no further modifications to the inclusion and exclusion criteria were required. Subsequent papers were screened by one reviewer both at title/abstract and full-text screening stages.

Data extraction and quality appraisal process

Data extraction

A data extraction template to extract information on both factors and mental health outcomes was developed jointly by two reviewers and tested independently by the two reviewers on a 30% sample of included studies. Differences were resolved by discussion, and the data extraction template was subsequently refined to militate against any further inconsistencies between reviewers. Remaining data extraction was carried out by one reviewer and reviewed by the second.

When a study reported findings for the overall domain of a factor as well as the individual subdomains of the factor (e.g. carer burden), findings were reported for the overall scale only to avoid ‘over-representing’ factors as much as possible (i.e. providing ‘multiple counts’ of the same factor). However, when only subdomain findings were reported by the study, these were extracted.

The outcomes considered were anxiety, depression, distress and quality of life. When a study reported findings for both the overall outcome measure of quality of life and the mental health/emotional subdomain of quality of life (psychological well-being), only findings related to the mental health/emotional subdomain of quality of life were extracted, to reflect the focus on mental health. If there were repeated outcome measurements, then information relating to the time point at the end of the intervention period was extracted.

Quality appraisal

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for RCTs20 was used to assess the overall quality of the studies reviewed. If a trial reported information relevant for quality appraisal (QA) for patients rather than carers (e.g. assignment to treatment), then the patient information was used for appraisal of the quality of the study. QA was carried out by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. No discrepancies between reviewers were identified in the checking process.

Analysis

Individual factors were synthesised thematically into subthemes using Box scores21 (see Appendices 2 and 3). The association with mental health in each study for each subtheme was categorised as better/worse/no change in mental health. Here, direct statistical assumptions for the direction of effect on mental health were not assessed, thereby indicating only the general direction of the association. Subthemes were then mapped onto the overarching themes identified from our reviews of qualitative research and observational quantitative research (see Box 1 and Table 2). The themes had been developed with input from the carer RAP. The format of table presentation (in Appendices 2 and 3) was also informed by the carer RAP and was seen by them as a useful way of presenting the evidence.

A meta-analysis was not feasible for this review for the following reasons. First, the review aimed to assess whether or not a factor affected by the intervention had an impact on carer mental health, rather than assessing if the intervention per se had an impact on mental health, and there was limited information available from studies regarding relationships between factors and outcomes for such a meta-analysis. Second, there were very few instances in which two studies considered both the same factor and the same mental health outcome, such as depression (see Appendix 3). Finally, there was a large variation in the way factors were measured, making a meta-analysis less meaningful.

Results

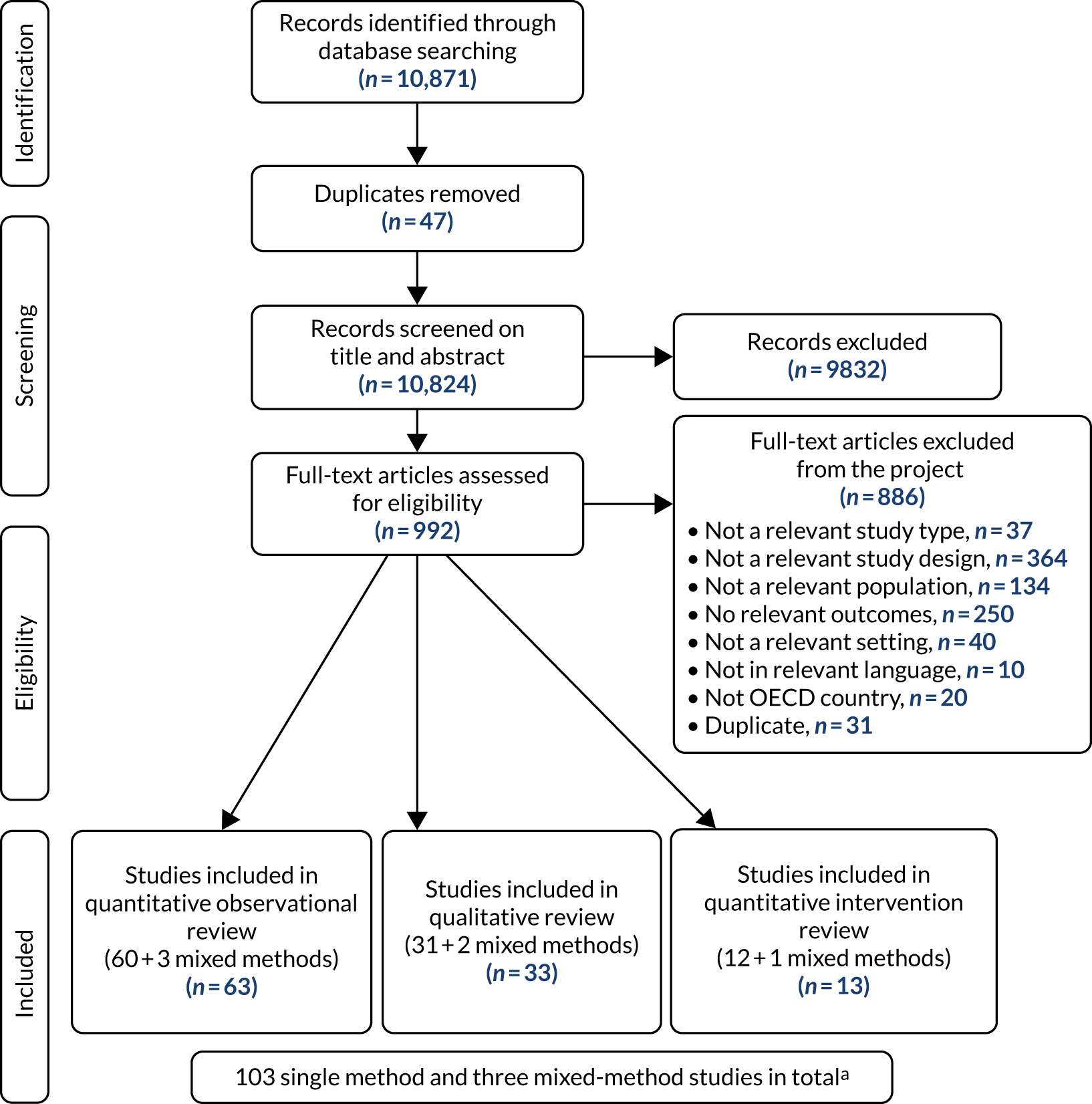

Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram for the project as a whole, including the intervention review. Table 1 provides an overview of the 14 identified intervention papers covering 13 studies (including one mixed-methods study). Only five studies showed a significant impact of the intervention on carer mental health. 22,23,31,33–35 Of these only one showed large treatment effects [standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.8],22 one showed medium effects (SMD 0.5)34,35 and the remaining three showed only small effects (SMD 0.2). 23,31,33

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA diagram of study identification and selection. a Several mixed-methods studies provided input to more than one review. OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

| Author (year), country | Study aims | Study design | Carer participants (number, demographics, carer–patient relationships) | Patient condition | Intervention and factors targeted | Carer outcomes (anxiety, depression, distress and quality of life) | CASP score (range 3–11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Badr et al.22 (2015), USA | To test the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of a dyadic psychosocial telephone intervention for advanced lung cancer patients and their caregivers | Randomised pilot trial |

N: 39 Mean age, years (SD): 51.1 (10.24) Female: 69% Spouse/partner: 51% Child:a 31% |

Lung cancer: Non-small cell – 84% Small cell – 16% |

Dyadic psychosocial intervention vs. usual care Self-efficacy: 38-item scale Autonomy: five-item scale Quality of patient–caregiver relationship: four-item scale Caregiver burden: 12-item short-form Zarit Burden interview Patient depression: PROMIS-D |

Anxiety: PROMIS-A Depression: PROMIS-D |

9 |

| Boele et al.23 (2013), The Netherlands |

Determine whether or not HRQoL and neurological symptoms of the patient as perceived by caregivers are related to the informal caregiver’s HRQoL and feelings of mastery Investigate whether or not a structured intervention consisting of psychoeducation and CBT leads to improvements in the mental component of HRQoL and mastery of caregivers |

RCT |

N: 56 n = 31, intervention; n = 25, control Mean age, years (SD): 50.77 (11.47), intervention; 50.56 (10.36), control Female: 74%, intervention; 52%, control Carer–patient relationship not reported |

High grade glioma: Grade 3 glioma, 30.4% Grade 4 glioma, 69.6% |

Psychoeducation and CBT vs. usual care Mastery: Seven-item Caregiver Mastery Scale |

Quality of life: SF-36–MCS | 3 |

| Farquhar et al.24 (2014), UK | Determine whether or not Breathlessness Intervention Service is more effective than standard care for patients with intractable breathlessness from advanced malignant disease | Mixed-methods RCT |

N: 67 n = 35, intervention; n = 32, control Mean age, years (SD): 64.6 (12.7), total; 65.6 (13.4), intervention; 63.5 (12.2), control Female: 68%, total; 70%, intervention; 67%, control Carer–patient relationship not reported |

Mixed cancer: Lung, 45% Breast, 25% Rectal/bowel, 6% Prostate, 6% |

Breathlessness Intervention Service vs. usual care Patient distress due to breathlessness: 0–10 NRS Patient mastery: CRQ Mastery Scale Patient disease-specific HRQoL: CRQ Patient anxiety: HADS-A Patient depression: HADS-D |

Depression: HADS-D Anxiety: HADS-A Distress: NRS distress due to patient breathlessness |

6 |

| Henriksson et al.25 (2013), Sweden | Investigate the effects of a support group programme for family members of patients with life-threatening illness during ongoing palliative care | Prospective quasi-experimental |

N: 125 n = 78, intervention; n = 47, control Mean age, years (SD): 54.8 (15.8), intervention; 63.2 (14.0), control Female: 62.8%, intervention; 57.4%, control Spouse: 46.2%, intervention; 78.7%, control Child: 26.9%, intervention; 14.9%, control |

Mixed: Cancer, 95% |

Support group programme vs. standard care Preparedness for caregiving: eight-item Preparedness of Caregiving Scale Caregiver competence: four-item Caregiver Competence Scale Rewards of caregiving: 10-item Rewards of Caregiving Scale |

Depression: HADS-D Anxiety: HADS-A |

7 |

| Holm et al.26 (2016), Sweden | Evaluate short-term and long-term effects of a psychoeducational group intervention for family carers in specialist palliative home care | RCT |

N: 194 n = 98, intervention; n = 96 control Mean age, years (SD): 63 (13.4), intervention; 60 (14.3), control Female: 69.4%, intervention; 63.5%, control Spouse: 55.1%, intervention; 41.7%, control Child: 32.7%, intervention; 36.5%, control |

Mixed: Cancer, 90% |

Psychoeducational group vs. standard care support Preparedness for caregiving: eight-item Preparedness of Caregiving Scale Caregiver competence: four-item Caregiver Competence Scale Rewards of caregiving: 10-item Rewards of Caregiving Scale |

Depression: HADS-D Anxiety: HADS-A |

8 |

| Hudson et al.27 (2013), Australia | To conduct a larger trial based on an earlier pilot study to test hypotheses that family carers who receive a psychoeducational intervention alongside usual care will have decreased distress and increased perceived preparedness, competence and positive emotions compared with those receiving usual care | RCT |

N: 298 n = 150, intervention; n = 148, control Mean age, years (SD): 59 (13.9) Female: 71.3%; Carer–patient relationship not reported |

Mixed cancer |

Psychoeducational intervention vs. standard care Preparedness for caregiving: eight-item Preparedness of Caregiving Scale Caregiver competence: four-item Caregiver Competence Scale Rewards of caregiving: 10-item Rewards of Caregiving Scale Level of need: Family Inventory of Need part B |

Distress: GHQ-12 | 5 |

| McDonald et al.28 (2017), Canada | To test the hypothesis that carers of patients who received early palliative care would have improved quality of life and satisfaction with care compared with carers of those receiving standard oncology care | Cluster RCT |

N: 182 n = 94, intervention; n = 88, control Median age, years (range): 58.0 (25–83), intervention; 57.0 (22–81), control Female: 61.7%, intervention; 69.3%, control Spouse: 78.7%, intervention; 88.6%, control Child: 14.9%, intervention; 9.1%, control |

Mixed cancer: Lung, 16.0% Gastrointestinal, 41.5% Genitourinary, 13.8% Breast, 17.0% Gynaecological, 11.7% |

Early referral to palliative care vs. standard oncology care Satisfaction with care: 19-item FAMCARE caregiver satisfaction with care scale |

Quality of life: SF-36 – MCS | 8 |

| Mosher et al.29 (2016), USA | To examine the preliminary efficacy of telephone-based symptom management for symptomatic lung cancer patients and their family caregivers | Randomised pilot trial |

N: 106 n = 51, intervention; n = 55, control Mean age, years (SD): 56.33 (14.09) intervention; 56.75 (13.81), control Female: 72.55%, intervention; 72.73%, control Spouse/partner: 62.75%, intervention; 61.82%, control Child: 17.65%, intervention; 21.82%, control |

Lung cancer |

Telephone symptom management vs. education/support condition (controlled for time and attention provided to participant) Self-efficacy for managing patient’s symptoms: 16-item standard self-efficacy scale Self-efficacy for managing carer’s own emotions: eight-item scale Perceived constraint in discussing patient’s illness with them: five-item social constraints scale Caregiver burden: Caregiver Reaction Assessment |

Depression: PHQ-8 Anxiety: GAD-7 |

8 |

| Nguyen et al.30 (2018), USA |

Describe the effects of a palliative care intervention on patients with lung cancer (on quality of life, distress and health-care utilisation) and family caregiver (on quality of life, preparedness, burden and distress) outcomes over 3 months compared with usual care Describe strategies to address several modifiable implementation barriers identified in an earlier report to further strengthen, sustain and spread components of the intervention within the health-care system |

Prospective quasi-experimental |

N: 122 n = 60, intervention; n = 62, control Mean age, years (SD): 63.0 (12.4), intervention; 63.8 (11.5), control Female: 58.3%, intervention; 61.3%, control White: 83.9%, intervention; 85.5%, control Spouse/partner: 75%, intervention; 67.7%, control Daughter: 13.3%, intervention; 14.5%, control |

Lung cancer |

Lung Cancer Palliative Care Intervention for Community Practice vs. usual care Preparedness for caregiving: Archbold Caregiving Preparedness Scale Caregiver burden: Montgomery Caregiver Burden Scale Patient QoL: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Lung |

QoL: City of Hope-QOL-Family instrument – MH Distress: Distress Thermometer |

3 |

| Northouse et al.31 (2013), USA |

To determine whether or not patient–caregiver dyads, assigned to either a brief or extensive dyadic intervention (the FOCUS Program), had better intermediary outcomes (fewer negative appraisals and increased resources) and better primary outcomes (improved QoL) than control dyads receiving usual care only Determine whether risk for distress and other antecedent factors (e.g. gender, type of dyadic relationship, cancer type) moderated the effect of the brief or extensive programme on intermediary and primary outcomes |

RCT |

N: 484 Mean age, years (SD): 56.7 (12.6) Female: 55.8% White: 82.5% Spouse: 74% |

Mixed cancer: Breast, 32.4% Colorectal, 25.4% Lung, 29.1% Prostate, 13.0% |

FOCUS – brief and extensive dyadic intervention providing information and support for advanced cancer patients and their families vs. usual care Appraisal of caregiving: Appraisal of Caregiving Scale Uncertainty in Illness: Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale Hopelessness: Beck Hopelessness Scale Caregiver coping patterns: Brief Cope Healthy behaviours/lifestyle: researcher-developed scale assessing exercise, nutrition, adequate sleep etc. Dyadic support: modified version of Family Support Subscale of Social Support Questionnaire Communication: Lewis Mutuality & Sensitivity Scale Self-efficacy: Lewis Cancer Self-Efficacy Scale |

QoL: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (version 4) – emotional | 9 |

| Parker Oliver et al.32 (2017), USA | Examine the effect of ACTIVE on caregivers’ perceptions of pain management, caregivers’ QoL, caregivers’ anxiety and patients’ pain | RCT paired with a parallel mixed-methods analysis |

N: 446 n = 223, intervention; n = 223 control Mean age, years (SD): 60.1 (12.5), intervention; 59.2 (13.3), control Female: 48%, intervention; 52%, control White: 49.9%, intervention; 50.1%, control Child: 48.1%, intervention; 51.9%, control |

Mixed |

ACTIVE involvement in care plan meetings to ensure co-ordination of care and an interdisciplinary approach to symptom management vs. usual care Carer perception of pain management: Caregiver Pain Medicine Questionnaire |

QoL: CQLI-R – emotional Anxiety: GAD-7 |

7 |

| Sulmasy et al.33 (2017), USA | Conduct a trial (TAILORED) to test the impact of a nurse-facilitated discussion between surrogates and patients with incurable GI malignancies or ALS about the role patients would prefer that their surrogates play in making decisions for them should they lose decision-making capacity | RCT |

N: 163 n = 78, intervention; n = 85, control Mean age, years (SD): 56.1 (12.1), total; 56.2 (11.8), intervention; 55.9 (12.4), control Female: 73%, total; 69.2%, intervention; 76.5%, control Spouse/partner: 69.33%, total; 74.36%, intervention; 64.71%, control Child: 7.98%, total; 3.85%, intervention; 11.76%, control |

Mixed: Gastrointestinal cancer, 59% Pancreatic cancer, 30.77% ALS, 39.74% Other GI cancer, 29.49% |

Nurse-directed discussion of the EOL decision control preferences of the patient vs. usual care + discussion about nutrition Caregiver burden: Zarit Scale Self-efficacy: Family Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale Support for mutual decision-making: Decision Control Preferences Scale Satisfaction with involvement in decision-making: Single item question – ‘Regarding the extent to which you are involved in helping your family member to make decisions about his/her health care: How satisfied are you with your level of involvement?’ |

Distress: IES | 6 |

| Von Heymann-Horan et al.34,35 (2019, 2018), Denmark |

To examine the effect of the Domus trial on caregivers’ symptoms of anxiety and depression35 To investigate whether or not Domus increased stress communication and common coping and whether or not effects differed according to dyad characteristics34 |

Parallel group RCT |

N: 249 n = 134, intervention; n = 115, control Female: 63%, intervention; 65%, control Spouse/partner: 77%, intervention; 80%, control Child: 18%, intervention; 9%, control |

Mixed cancer: Lung, 21% Prostate, 13% Female genitalia, 13% CNS, 12% Lower gastrointestinal, 11% |

Domus-specialised palliative care and dyadic psychosocial intervention (an accelerated transition from hospital-based oncological treatment to specialised palliative care at home with patient–caregiver psychological support) vs. usual care Stress communication and caregiver coping: Dyadic Coping Inventory |

Depression: SCL-92 – depression subscale Anxiety: SCL-92 – anxiety subscale |

11 |

Only one study34,35 conducted path analysis to investigate whether or not factors may be mediators of carer mental health outcome. For the remainder we could therefore at best assess only whether or not there was an association between a factor and carer mental health. Table 2, which summarises findings, can therefore show only whether a significant change in a factor (subtheme) was associated with a parallel significant change in mental health, together with the related studies and their QA score. The main attention in intervention studies was on carers’ internal processes (included within 11 interventions), with little research into how changes in patient condition (five interventions), impact of caring responsibilities (three interventions), relationships (one intervention) or support (one intervention) may have an impact on carers’ mental health. Appendices 2 and 3 provide Box score tables with more detail on variables investigated for each factor, the findings and their references [please see the project webpage for the original appendix designs; URL: https://arc-gm.nihr.ac.uk/the-carer-project-evidence-synthesis (accessed 5 December 2022)].

| Subthemes | Studies underpinning overarching theme with QA scores, overall QA score (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| Patient condition (five studies) | 6.8 ± 2.5 |

| Patient social QoL (+) | Northouse et al.31 (9) |

| Patient overall QoL (0) | Nguyen et al.30 (3) |

| Patient depression (–) | Badr et al.22 (9) |

| Patient distress from breathlessness (0) | Farquhar et al.24 (6) |

| Patient pain control (0) | Parker Oliver et al.32 (7) |

| Impact of caring responsibilities (three studies) | 6 ± 3 |

| Carer burden (–/+) | Badr et al.22 (9); Sulmasy et al.33 (6) |

| Carer perceived caregiving demands (0) | Nguyen et al.30 (3) |

| Relationships (one study) | 9 ± 0 |

| Relatedness in patient–carer relationship (+) | Badr et al.22 (9) |

| Finances (no studies) | N/A |

| – | – |

| Carer internal processes (11 studies) | 6.9 ± 2.5 |

| Belief that patient pain is inevitable (0) | Parker Oliver et al.32 (7) |

| Avoidant coping strategies (–) | Northouse et al.31 (9) |

| Healthy behaviours (+) | Northouse et al.31 (9) |

| Dyadic coping (+)a | Von Heymann-Horan et al.34,35 (11) |

| Communication of stress (+)a | Von Heymann-Horan et al.34,35 (11) |

| Constraint in discussing patient’s illness (0) | Mosher et al.29 (8) |

| Control through mutual decision-making and satisfaction with decision-making (+) | Sulmasy et al.33 (6) |

| Autonomy (+) | Badr et al.22 (9) |

| Self efficacy in managing caregiving (+) | Northouse et al.31 (9), Badr et al.22 (9) |

| Confidence in managing own emotions (0) | Mosher et al.29 (8) |

| Mastery (+) | Boele et al.23 (3) |

| Feelings of adequacy or competence (0) | Henriksson et al.25 (7); Holm et al.26 (8); Hudson et al.27 (5) |

| Preparedness (0) | Henriksson et al.25 (7); Holm et al.26 (8); Hudson et al.27 (5); Nguyen et al.30(3) |

| Support (one study) | 8 ± 0 |

| Satisfaction with support (0) | McDonald et al.28 (8) |

| Contextual factors (no studies) | NA |

| – | – |

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Quality Appraisal

When there was more than one study for a theme, the mean CASP QA scores for each theme was quite similar: patient condition had a mean score of 6.8 [standard deviation (SD) 2.5] out of 11, impact of caring responsibilities had a mean score of 6.0 (SD 3.0) and carer internal processes had a mean score of 6.9 (SD 2.5). The relationships and support themes had only one study each, but with relatively high mean scores of 9 and 8, respectively. These numbers hide considerable variety in the quality of studies, ranging from 3 to 11.

If we consider where studies did not meet CASP20 criteria or where there was insufficient information given to assess this, blinding was the main area in which criteria were not met. It would be difficult to blind recipients to the fact that they received the intervention, given the types of intervention tested. However, only 4 of the 13 studies reported any form of single blinding of assessors. Regarding the criterion of size of treatment effect, only Badr et al. 22 showed large effects [standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.8], one study showed medium effects (SMD 0.5)34,35 and three showed small effects (SMD 0.2),23,31,33 with the remaining studies showing no significant effects. Only six studies had the requisite precision of estimate of the treatment effect, in terms of providing both p-values and confidence intervals, or enough information for these to be reliably calculated. Criteria met by a majority of studies (eight each) were as follows: it was clear that all participants who entered the trial were accounted for at its conclusion; that groups entering the trial were similar at baseline; all important outcomes were considered, for example in terms of completeness of outcome data; and that participants had been randomly allocated to trial arms. For randomisation, three further studies indicated that this had taken place, but that there was insufficient reporting on how this was done to satisfy the CASP criteria. For eight studies it was clear that the benefits outweighed harms and costs, whereas for the remainder it was simply difficult to tell based on the information available, rather than any indication of harm. All studies but one were able to treat groups equally apart from delivering the intervention.

The lack of blinding of participants, and to some extent the researchers, was therefore a main weakness of this literature. As all the outcomes and many of the factors were based on self-report measures, participants may have been biased towards giving responses that they thought met with study expectations, and whatever effects were observed could have been due to this. However, it would be difficult to blind participants to the fact that they are receiving an intervention and to obtain measures through other means than self-report in these cases. Therefore, we could not fully remove this bias, but had to take it into account in the interpretation of results. However, few studies showed significant impact on mental health in any case, and only two showed medium to large effects. Just over half of studies reported p-values and confidence intervals. This may raise some concerns about the quality of interventions and the reporting in some of this literature, and therefore this literature’s ability to form a robust basis for progress in the field. We were probably less likely to see bias due to systematic differences in characteristics of the intervention and control groups (given randomisation, similarity at baseline and data completeness) or in the way they were treated, apart from the intervention itself. Regardless, the main issue for our synthesis remained the lack of investigation of factors as mediators or moderators.

Patient condition

A dyadic intervention (i.e. involving both patient and carer) that improved the patients’ and carers’ social quality of life (QoL) (relating to support from family and friends) also improved the carer’s emotional QoL (but not the patient’s). 31 However, it is difficult to ascertain if carers’ improved mental QoL here is due to patient improvement or their own improved sense of social support. The improvement in the patients’ overall QoL in another study was not associated with changes in carers’ distress or their QoL. 30

An intervention that reduced patient depression also improved two aspects of carers’ mental health (depression and anxiety). 22 In contrast, a study that reduced patients’ distress due to breathlessness had no impact on carer depression, anxiety or distress,24 and carers’ perception that the patients’ pain was better controlled was not associated with changes in carer anxiety and QoL. 32

Impact of caring responsibilities

One study found that reduction in carer burden was related to two aspects of carers’ mental health (depression and anxiety). 22 In contrast, Sulmasy et al. 33 found that carers with increased carer burden also had lower carer distress. The focus of the latter intervention was, however, to support carers as ‘surrogate’ decision-makers, and it may be that this places greater burden on carers, although such involvement may leave them less distressed. Ngyen et al. 30 found that reducing carers’ perceptions that care responsibilities were overly demanding was not related to carer mental health (as shown through QoL and distress levels).

Relationships

An intervention that increased levels of relatedness (i.e. quality of the carer–patient relationship) also improved two aspects of carers’ mental health (depression and anxiety). 22

Carer internal processes

Changing carers’ belief that pain is inevitable (fatalism) was not related to any change in carer mental health (QoL or anxiety). 32

An intervention that decreased the use of avoidant coping strategies (e.g. denial) and increased healthy behaviours (e.g. exercise) improved carer QoL. 31 Increased dyadic coping and stress communication by carers within the patient–carer relationship seemed to be associated with improved mental health (depression and anxiety). 34,35 However, the intervention only increased dyadic coping and stress communication for partner carers, and it in fact decreased stress communication in parents cared for by an adult child. Furthermore, path analyses did not show that common coping and stress communication mediated the effects on carers’ anxiety or depression. Finally, Mosher et al. 29 found that reducing carers’ perceived constraint in discussing patients’ illness with them was not related to changes in carers’ depression or anxiety levels.

Improving carers’ control over the care situation (through improved support for mutual decision-making or satisfaction with involvement in decision-making) was associated with lower carer distress. 33 A greater sense of autonomy (internal motivation/willingness to provide care) among carers was also associated with both lower depression and lower anxiety levels. 22

Regarding self-efficacy, an intervention that improved carers’ and patients’ confidence in their ability to manage the illness and its related caregiving also improved carer QoL. 31 Furthermore, an improved confidence in ability to manage a range of caregiving components was related to lower depression and anxiety. 22 However, improving carers’ confidence in managing their own emotions showed no relationship with either depression or anxiety. 29

Improving carers’ sense of mastery (both perceived and actual ability to perform caregiving) was associated with maintaining QoL over time. 23 In contrast, several studies found that improving carers’ perceived adequacy of performance or feelings of competence for caregiving was unrelated to changes in their mental health (depression and anxiety25,26 and distress27). Similarly, improving carers’ preparedness for caregiving showed no association with their mental health (QoL,30 depression and anxiety,25,26 and distress27,30).

Support

Improving carers’ satisfaction with care received (for both patient and family) was not associated with changes in their QoL. 28 Otherwise, no intervention studies investigated whether improving carers’ support or perceived support improved their mental health.

Discussion of the intervention research

Summary

This intervention literature can at best indicate associations between modifiable identified factors and carer mental health, as only one study directly investigated whether or not factors may be mediators of carer mental health. 34,35 Overall, this literature may show some support for a link between identified factors (see Box 1) and mental health, but studies were few and the findings were mixed. Potential biases in this literature are likely to stem from a lack of blinding, rather than systematic differences between intervention and control groups.

Carers’ internal processes received most attention. There was an indication that improvement in carers’ sense of control, autonomy, self-efficacy and mastery in their management of caregiving were associated with better mental health. However, in contrast, several studies found no indication that improved sense of competence or preparedness for caregiving were related to carer mental health. These apparently contradictory results indicate a need for a better understanding of the underlying concepts that interventions aimed to target, to help resolve contradictions and develop more effective interventions. Regarding coping, there was some evidence that reduction in (dyadic) avoidance coping and increased healthy behaviours were related to improved mental health. 31 In contrast, Heymann-Horan et al. 34,35 found no evidence from path analysis that dyadic coping and stress communication were mediators in improvement of carer mental health. However, they noted that their intervention may only indirectly target coping, and highlighted the need to assess more directly targeted mechanisms (factors) and the range of coping strategies employed, which again indicates the importance of gaining a better understanding of underlying concepts.

Otherwise, intervention studies provided some evidence that improvement in patients’ condition (through improved QoL and reduced depression) may relate to improved carer mental health. However, improvement in patients’ physical symptoms showed no relationship. Interventions to reduce the impact of caring responsibilities through the reduction in carer burden or demands showed mixed results. Only one study considered relationships, indicating that improving patient–carer relationships may be associated with better carer mental health. Further, only one study considered support, in terms of carers’ satisfaction with care, and found no effect.

The correspondence between findings from the intervention studies and the wider literature will be considered in Synthesis of combined findings from qualitative, observational and intervention reviews.

Challenges for drawing firm conclusions from the data

Several issues affected our ability to draw firm conclusions from the intervention review given the remit of our synthesis. With the exception of Heymann-Horan et al. ,34,35 interventions were not focused on investigating factors per se and their impact on mental health. First, although all sought to improve mental health, for some this was not the primary outcome or aim. For instance, the main outcome for Sulmasy et al. 33 was improved decision-making, and for Parker Oliver et al. 32 it was carers’ perception of pain. For other studies mental health was often a part of a range of outcome measures, such as for Nguyen et al. 30 Second, the focus was on testing the impact of the intervention, not the mechanisms through which it worked or relationships between mediating factors and mental health. Our factors of interest may not be what the intervention sought to change (its target) to improve mental health, and may simply be included as another outcome to be measured alongside mental health outcomes (e.g. Parker Oliver et al. 32 and Sulmasy et al. 33). Furthermore, even when the intervention did seek to change a factor of interest, the factor and outcome may have been measured only once at the same time after baseline (e.g. Badr et al. ,22 Henriksson et al. 25 and Sulmasy et al. 33) or, if repeated measurements were available, these were normally not analysed to consider how an early change in a factor may lead to a later change in outcome. Therefore, we could only establish that the putative ‘factor’ and ‘outcome’ both changed together; we could not establish the sequence of change. The information gained from intervention studies was therefore in fact often similar to that gained from cross-sectional studies, and in some ways less informative to our investigation because the correlation between factor and outcome may not have been directly tested.

Interventions may furthermore be unsuccessful in changing a putative ‘factor’ sufficiently to have an effect, but it might still be an actual factor affecting carer mental health. Although we only included interventions that had a significant impact on a factor, the change in the factor may not have been large enough for it to influence mental health (statistically significant differences may not have made a clinically meaningful difference). Changes in the factors mainly appeared small even if significant (e.g. Mosher et al. 29 and Nguyen et al. 30), and effect sizes, when reported, were often small or at best moderate (e.g. Henriksson et al. ,25 Holm et al. 26 and Hudson et al. 27).

The delivery of dyadic interventions (involving both patient and carer) is fairly common in carer intervention research,22,29,31,33–35 but further complicates our understanding of mediating factors. These interventions may maximise effect by influencing patients, carers and their interactions. However, they may also dilute the effect on the carer if the patient takes precedence. Plausibly, whether or not dyadic interventions maximise or detract from the impact on carers may depend on their target factor, e.g. they may maximise for communication and shared decision-making, but detract for factors relating more to carers’ own needs as opposed to patients’.

A strength of this review was its novel approach in reviewing the trials literature to uncover further information about factors that potentially affect carers’ mental health, guided by comprehensive reviews from the qualitative and observational carer literature. Although this review provided little added information, an important contribution of the review was to highlight how the current interventions literature fails to reach its potential in improving our understanding of the factors and underlying mechanisms affecting carers’ mental health.

Conclusion

The intervention review on the whole showed modest support for the influence of factors identified in the qualitative and observational reviews; self-efficacy, sense of control, autonomy and some coping strategies were associated with improved carer mental health. In addition, mastery was identified as a potential factor. However, these concepts may need to be better understood and defined for us to resolve apparent contradictions and make progress. Furthermore, the patients’ psychological symptoms, QoL and improvement of patient–carer relationships may matter, but findings are otherwise less clear. Although the intervention studies may be good studies in their own right, their design and analysis make it difficult to ascertain whether a factor affects carer mental health, is affected by mental health or the intervention itself just changes both at the same time. Therefore, the current intervention research did not add much to our understanding of factors affecting carer mental health compared with observational studies.

One may ask if it matters if interventions are not linked to discernible factors and designed to understand their effect on carers’ mental health, and whether the main point should simply be whether the intervention improves carer mental health? However, to ensure that an intervention is as effective as possible and its effects are replicable, we do need to understand the mechanisms through which it works. 36 Furthermore, interventions generally have had limited success in improving carer mental health, as evidenced by this review and earlier reviews. 37 This again indicates a need to understand mechanisms and active components better, to ensure both that we target the right factors and that interventions are designed and then carried out (with fidelity) to actually have an impact on these factors.

An important part of understanding underlying factors better is more preparatory conceptual work; several reviewed studies drew on theoretical frameworks,22,26,27,29,31 but these could be utilised more. It is also crucial to utilise study design better, for instance by taking multiple trial measurements of putative mediators and outcomes to assess if and how potential factors may influence mental health outcomes. Such longitudinal measurement can be resource intensive and may require more complex statistical modelling methodologies. However, many of the reviewed intervention studies did take repeated measures,23,26,28–32 but only Heymann-Horan et al. 34,35 conducted an analysis to investigate whether or not a factor may have a mediating effect on carers’ mental health. It is important that future intervention research should create and utilise more opportunities to investigate potential causal mechanisms. Trials of interventions should be a powerful tool to identify durable solutions to improving carer mental health by uncovering core mechanisms that then can be reliably translated to other interventions and settings.

Synthesis of combined findings from qualitative, observational and intervention reviews

It is important to bring together the different parts of the carer literature and draw on the strengths of each to gain a full picture of the potential factors that affect carer mental health, and assess the implications for research and practice. The qualitative literature provided carers’ own perspective, and the observational literature allowed us to test relationships and with larger carer groups. Trials, if designed for the task, provide a powerful tool for investigating the impact of factors, but can only tell us about factors that are modifiable by interventions, not contextual factors that may put carers at risk or that may require societal changes. In this section we synthesise the combined findings from the qualitative, observational and intervention reviews to assess our current knowledge and its strengths and weaknesses, and the implications for future research and practice.

Method

Search, selection and data extraction

Synthesis of intervention studies, Method, Box 2 and Appendix 1 provide the search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria for the project as a whole, and for the intervention review. Added inclusion criteria for the qualitative review were that studies had to have as their aim to investigate carers’ mental health from the perspectives of EOL carers themselves, and for the observational review that studies had to report on the relationship between a factor and carer mental health outcome. For full details of the search, selection, data extraction and QA for the whole project, see Bayliss et al. 18 for the qualitative review, Shield et al. 19 for the observational review and Synthesis of intervention studies, Method, in this report for the intervention review. A summary is provided below.

For all studies, 10% of both titles/abstracts and full texts were screened independently for inclusion by two reviewers. Over 90% agreement was established in each case, and subsequent studies were screened on title/abstract and full texts by one reviewer. Owing to project time pressures, and on advice of the project’s external Study Steering Committee [and notification to the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) programme], this process represents some tightening of the search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria (i.e. most recent decade, fewer databases, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country and English or Scandinavian publications, and peer reviewed publications only), and simplification of the screening process.

See Synthesis of intervention studies, Method, for data extraction and QA information for the intervention studies. For qualitative studies, first order themes were extracted for 10% of studies by two researchers and carer RAP members, and the remaining data extraction was carried out by one reviewer. Second order themes were created by one researcher and reviewed by a second researcher, and presented to the carer RAP for any comments. For the observational review, the data extraction template was tested independently by two reviewers on 10% of included studies, any differences were discussed and the data extraction template was clarified, and the remaining data extraction was carried out by one reviewer with a random sample of 10% checked by another.

Quality appraisal of qualitative studies used the CASP Qualitative Studies checklist. 38 The QA of observational studies used an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort and case-control studies,39 modified to encompass cross-sectional studies based on an adjusted NOS scale. 40 QA was carried out independently by two reviewers on 10% of the studies. Over 90% agreement was achieved, and subsequent studies were quality assessed by one reviewer.

Synthesis of findings from the qualitative, observational and intervention reviews

The starting point for the synthesis was the thematic framework template developed from the qualitative review in collaboration with carer RAP members (see Box 1 for overarching themes and Bayliss et al. 18 for the full thematic framework). Findings from the observational review were synthesised thematically into subthemes using Box scores21 and mapped onto the relevant overarching themes within the qualitative framework template. Materials were sent to RAP members, discussed between researchers and RAP members in an online meeting, and amended to improve the clarity and meaningfulness of presentation to carers (see Shield et al. 19 for the observational results). The same process was then repeated for the intervention review (see Analysis and Appendices 2 and 3).

Next, findings within subthemes from all three reviews were combined into one document, which indicated (1) which findings were from the quantitative reviews and which were from the qualitative review, (2) where there was a direct match between the qualitative subthemes and quantitative subthemes and (3) where there was no evidence of a relationship from the quantitative findings (see Appendix 4). This draft document was sent to the RAP and discussed in a further meeting for feedback. Members were asked to consider the following:

-

How clear is the information presented?

-

Do these themes/subthemes make sense? Are they logical? Do they reflect reality?

-

Do the themes/subthemes need to be changed in any way?

The document was considered a useful way of summarising all the findings, but again there were some suggested changes to make it clearer and more meaningful to carers. See Appendix 4 for the final presentation.

Finally, findings from the individual reviews and combined syntheses were presented to additional carers and practitioners, commissioners and policy-makers for their assessment of the validity, importance and relevance of findings to their respective stakeholder groups.

Results

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA diagram for the whole project. Three studies were mixed methods and appear in more than one review. Appendix 4 presents the combined evidence from the qualitative (n = 33 studies), observational (n = 63 studies) and intervention reviews (n = 13 studies) under the main themes of patient condition, impact of caring responsibilities, relationships, finances, carer internal processes, support and contextual factors. Statistically significant observation and intervention review findings were grouped together as ‘quantitative’ findings in the subthemes under each main theme. However, unique contributions of intervention findings can be identified in the ‘Strategies to support mental health’ column in Appendix 4 (specifically, the items in blue text). See Shield et al. 19 and Bayliss et al. 18 for further details on findings from the observational and qualitative reviews, respectively. The order of themes does not imply order of importance; themes are presented in the same order across all syntheses for consistency.

Patient condition

Patient condition was the theme investigated by the largest number of observational studies: 31 studies reporting on 95 bivariate investigations into relationships between patient condition factors and mental health. A further six studies reported multivariate analyses only, which confirmed findings from bivariate investigations. Five intervention studies also considered factors within this theme, the second most investigated within intervention research. Within qualitative research, carers mentioned issues related to this theme as important to their mental health in 19 out of 33 studies.

Within the theme, the quantitative research appeared mainly to focus on factors relating to patient information recorded in clinical records (e.g. diagnosis, treatment) or measured and monitored in clinical practice (e.g. QoL, functional status, symptoms). The quantitative evidence was most consistent in linking severity of patients’ psychological symptoms to worse carer health, and patient QoL to better carer health, whereas evidence for physical and functional decline was more mixed. The qualitative carer narratives confirmed the importance of patient condition to carer mental health, but seemed to reflect more the emotional connotations of the physical and cognitive decline or expected decline in the person cared for.

Impact of caring responsibilities

This theme received modest consideration by observational research: 14 studies and 34 bivariate investigations. A further three studies reported multivariate analyses only, confirming themes from the bivariate analyses. Only three intervention studies considered this theme. Within qualitative research, carers mentioned issues related to this theme as important to their mental health in 18 studies.

A considerable amount of qualitative evidence contributed to this theme. Carers considered how their mental health was affected by caregiving workload, conflicting or added responsibilities; the exhaustion, physical impact felt and crises experienced; the lack of rest, time for self-care and respite, and the impact of employment. Carers also highlighted the effects of isolation, loneliness and the inability to socialise. The observational evidence complemented the qualitative findings, showing consistent relationships between carers’ mental health and lifestyle adjustments (e.g. negative life changes) or demands of caregiving (e.g. difficulty of tasks, time spent on caregiving). Similarly, standard measures of carer burden were consistently related to mental health (covered under the heading relating to ‘Workload/physical burden/carer workload’ and that relating to the impact of ‘Caring for patient’ in Appendix 4). Intervention findings were few and mixed, showing negative, positive or no impact of carer burden.

Relationships

Relationships received little consideration in observational research: eight studies and 16 bivariate investigations. A further two studies reported only multivariate analyses, which confirmed themes from the bivariate analyses. Only one intervention study considered relationships. Within qualitative research, carers mentioned issues related to this theme as important to their mental health in 13 studies.

In qualitative studies carers highlighted the impacts of relationship changes, strains or conflicts caused by the patient’s illness or by caregiving. This included the patient sometimes not going along with treatment (‘non-compliance’), which could cause distress if the carer feels the patient is not doing as well as they possibly could do and they feel unable to influence this. Quantitative research, both observational and intervention, seemed to be more focused on the general quality of the patient–carer relationship and communication. What little evidence there is suggests that higher quality was related to better carer mental health. Wider family relationships were not highlighted in the qualitative research and considered only in observational studies. These indicate that families’ ability to cope with stressors, cohesion, supportiveness or levels of conflict were related to mental health.

Finances

This received the least consideration in quantitative research: only six observational studies through eight bivariate investigations, and no intervention studies. Within qualitative research, carers mentioned issues related to this theme as important to their mental health in 14 studies.

Overall, finances have received less consideration than other themes. However, the impact of costs, concerns about finances, access to benefits and impact on work appear to have been emphasised more in the qualitative literature by carers themselves than in the quantitative research. Still, observational study findings indicate a relationship between finances and carer mental health when sufficiency or insufficiency of resources are considered, as opposed to the level of income per se, and also highlight impact on work as a factor.

Carer internal processes

This received modest investigation by observational research: 13 studies and 36 bivariate investigations. Furthermore, four multivariate analysis-only studies found associations for preparedness, but mixed results for coping, which corresponds with bivariate analysis findings. This theme, however, received the largest focus by intervention research, with 11 out of 13 studies including a factor within this theme. Carers mentioned issues related to this theme as important to their mental health in 22 qualitative studies (15 studies noted factors detrimental to mental health and 13 noted strategies to improve it).

In the qualitative literature, carers highlighted how a loss of self-determination and autonomy and a lack of control affected their mental health, as well as a lack of experience of acting as a carer. Lack of control included uncertainty about future events and progression. The impact of transitions, and coming to terms with these, also featured strongly in carers’ narratives. The above seems to highlight the dynamic and uncertain nature of caregiving from carers’ perspectives.

Carers also stressed ways of coping as important, which moves us on to potential strategies to support mental health. Having time for respite, and using strategies to enable such time, was seen as positive for mental health. Carers also mentioned the use of positive self-talk for coming to terms with the situation and retaining positivity, and of spirituality for acceptance and lessening of isolation. They also highlighted the suppression of their own emotions and needs, which may be detrimental longer term but can be seen as a rational strategy for managing day-to-day caregiving from a carer’s perspective.

Observational study findings on coping strategies were very mixed. There were some indications in this literature that lack of acceptance, avoidance or substance abuse are related to worse carer mental health, whereas being optimistic and having time for oneself are positive. Intervention research indicated that a decrease in avoidant coping and an increase of healthy behaviours were associated with improved mental health. However, overall there was little clarity within this literature, and, to make progress, quantitative research may need more conceptual clarity in terms of how coping strategies are defined and are expected to work, and better methods for studying them (e.g. moving from generic coping measures of hypothetical scenarios to more investigation into real-life situations).

Quantitative research, in particular interventions, focused considerably on self-efficacy, mastery and preparedness. Carers themselves appeared generally to emphasise this less, although they mentioned a lack of carer experience, autonomy and control as factors. Observational studies indicated that self-efficacy and preparedness overall were associated with better mental health. Intervention studies also indicated that improved self-efficacy, confidence, mastery, autonomy, control and communication related to improved carer mental health, but showed no such relationships for preparedness or sense of competence.

Support

This was the second largest category for observational research, considered by 18 studies, with 42 bivariate investigations and one multivariate study confirming that good support was related to better mental health. Support was considered in only one intervention study. However, carers were most likely to mention issues related to this theme as important to their mental health: it was mentioned in 29 out of 33 qualitative studies (22 studies noted factors detrimental to mental health and 23 noted strategies to improve it).

Carers highlighted features of the formal care system as having a negative impact on their mental health, such as shortfalls in the availability and quality of care; disjointed care; and a lack of information, practitioner skill and adequate pain management. They also noted features of interaction with practitioners, such as a lack of empathy, poor communication, not listening to wishes of patients and carers, not recognising carers’ expertise and lack of collaboration. Some also experienced cultural barriers related to language. In terms of strategies to support mental health, carers highlighted the importance of formal support and access to information. Observational study findings within this theme showed little consistency of focus and clarity. However, unmet needs in general were associated with worse mental health, and carer satisfaction with available support was associated with better health (conversely, the one intervention study found no relationship regarding satisfaction). Observational studies of communication showed little relationship with mental health, but focused on components within the communication (e.g. dialogue pace), not its perceived quality, accessibility or adequacy. Accessible information was positively related to good mental health in one study. Findings regarding receipt of services per se were mixed and difficult to interpret without further information on what was provided, its perceived usefulness and how well it matched with carers’ needs.

Regarding informal support, qualitative studies found a lack of informal support to be detrimental. Conversely, strategies to support mental health included support from friends and family and a sense of community and shared responsibility. Support and information from others in the same situation was also important. Some observational studies found informal support to be positively related to mental health whereas others showed no relationship, but again it would be important to ascertain what support was provided, its usefulness and how well it matched with the carer’s needs.

Contextual factors

Contextual factors were considered in observational research only, in which they represented the third largest body of evidence: 16 studies with 104 bivariate investigations, and a further seven studies with multivariate analysis only that mainly confirmed bivariate results.

Older carer age generally seemed to be associated with better carer mental health, and being female with worse mental health. The remaining findings consisted of the occasional significant relationship set against a much larger set of non-significant relationships for the same factors. Therefore, it is difficult to draw further conclusions from this research at present. A notable gap in the literature is the limited research on caregiving experiences and outcomes relating to differences in ethnicity, race or culture.

Discussion

Summary

In general, the findings of the qualitative, observational and intervention literature fell within the same themes and arrived at similar or complementary results, adding validity to the findings overall.

Patient condition was the most researched theme, possibly owing to the availability of clinical data, but also indicating how important patients’ well-being is to carers’ mental health, in particular patients’ psychological symptoms and QoL. However, we must not assume that by simply focusing on improving patient well-being, carers’ mental health will also be fully addressed. Rather, it is important to ensure that the patients’ basic well-being is covered, so that carers do not have to expend added energy and frustration on getting adequate formal support to meet patients’ clinical needs. We need to be aware that patients’ psychological symptoms may be particularly distressing to carers and may require particular focus to address both these symptoms and carers coming to terms with these symptoms. Finally, within EOL care elements of patients’ decline is natural and inevitable, but carers may need emotional support to cope with distress related to this.

The impact of caring responsibilities emerged as an important theme for carers themselves and was the focus of a fair amount of observational research. The evidence seems quite consistent that the life changes and increased workload associated with caregiving were related to worse carer mental health. General measures of carer burden also showed consistent relationships with mental health. However, to help identify where to focus interventions, it is important to consider further what is measured within different carer burden measures to clarify which factors here are the likely predictors of carers’ mental health (and whether they are likely precursors to mental health, rather than being influenced by mental health themselves). Potential interventions or remedies within this theme are wide ranging, including changes to employment law, help with negotiating change, support with care tasks, and respite to prevent exhaustion and to promote self-care.

Relationship with the patient seems to be important to carer mental health but is under-researched and merits further study. In terms of implications for supporting carers, it is important to be aware of the role relationships may play and potentially of how to facilitate open and constructive communication during adjustment to terminal illness. This includes situations in which the patient does not understand the impacts of the carer’s responsibilities for caring, and, for example, may resist carers bringing in added help. Dyadic interventions may be of particularly high value in addressing factors that can be exacerbated or eased by relationship dynamics, compared with interventions focused on carers only. Particularly ‘dysfunctional’ relationships or families may still require more specialist help.

Finances was the least researched theme, but appears important to carer mental health and clearly warrants further research. However, the potential sensitivity of this topic to families and its likely political implications may be elements limiting research so far, and would need to be considered and tackled for future studies. In terms of current implications for practice, findings highlight the importance of ensuring that carers are able to access the benefits that they are entitled to and are aware of any entitlements for flexible working and carer leave under their terms and conditions of employment. This often requires that carers recognise themselves as ‘carers’, and they may sometimes also require support to come to terms with this label. Future initiatives at policy level to support carers should consider employment law and benefits provision.

Internal carer processes formed the main focus for intervention research, but also received substantial attention within qualitative and observational research. Quantitative findings relating to coping strategies were very mixed, which may reflect several issues: a failure to meaningfully measure strategies, the fluidity and changeability of such strategies, difficulty of establishing direction of causality between strategies and health, and that a ‘maladaptive’ strategy may ‘do the job’ of getting the carer through the situation at a given time. Quantitative research here needs more conceptual clarity and better methods to progress our understanding of coping strategies. In addition, quantitative research, in particular interventions, focused considerably on self-efficacy, mastery and preparedness. Both observational and intervention studies indicate that improved self-efficacy is beneficial, whereas results for preparedness and related concepts, such as mastery or competence, were mixed. Although promising, contradictions in findings again highlight that we need a better understanding of these constructs, and how best to improve and measure them, to progress further.

There appeared to be a discrepancy in emphasis placed on self-efficacy, mastery and preparedness between observational/intervention research and carers themselves. Carers mentioned lack of caregiving experience, but seemed more likely to emphasise loss of self-determination, autonomy and control, which may instead reflect the impact of the caregiving situation on them. Researchers may focus on self-efficacy, mastery and preparedness because they see them as more amenable to intervention than other factors. However, this focus may also reflect a general ‘self-management’ perspective in health and social care delivery. Interventions to boost self-management-related factors may indeed improve carer mental health if sensitively designed and delivered. However, such initiatives could also add burden by placing added responsibility and onus on carers and detracting from factors that carers themselves see as important in preserving their mental health. In strategies to support mental health, carers themselves focused more on allowing for respite and emotional acceptance, which are compatible with a ‘self-management’ perspective but give more emphasis to respite and interventions to enable acceptance than the more ‘active’ self-management often championed. Although interventions to foster self-efficacy show considerable promise in improving carer mental health, it is therefore important to ascertain carers’ own perspective on such interventions and incorporate elements that work for them.

Support, and the quality of support provided, appeared to be important to carer health. Aspects of formal support formed a large part of carers’ narratives in qualitative studies. The relationship between formal support and carer mental health was also considered by a substantial number of observational studies, but notably was nearly absent from intervention research, although interventions to improve aspects of formal support should be possible. However, for all its investigations, observational research appeared to fail to measure the features of formal support that were important to carers (e.g. co-ordination of care, sufficiency of information, empathy), and there should be greater future research emphasis on features of service provision likely to affect carer mental health. Informal support received less attention from both carers and quantitative research, but still appears important for carer mental health. The findings from the qualitative research can provide good pointers for improvements in service delivery that matter to carers and, similarly, important elements to foster within social networks. When carers have limited networks of family and friends, it would be important to consider alternative social network options, such as bringing in peer support.