Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in July 2019. This article began editorial review in September 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Shield et al. This work was produced by Shield et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Shield et al.

Background and introduction

Family and friends (hereafter ‘carers’) provide vital unpaid support for people at end of life (EOL), including physical and psychological support, co-ordinating care and monitoring. A national survey of carers of people with cancer in England found that they provided a median of 70 hours of care per week in the patient’s final months of life. 1 Reviews have consistently shown carers to be a main factor in sustaining care at home at EOL,2,3 which is likely to reduce acute inpatient care costs and pressures on care home beds, and to be in accord with patient preferences. 4 Carers’ contributions therefore are likely to be of considerable benefit both to patient care and to health and social care services.

Our dependency on carers is likely to increase, given projected future demographic increases in people over 85 and those with life-limiting illness,5 dependency in the final years of life6 and number of deaths. 7 Health and social care services are likely struggle to meet increasing future demands. The COVID-19 pandemic saw increases in deaths at home in England and Wales, between waves of the pandemic, while deaths from leading causes in inpatient health care decreased, indicating an increased reliance on carers to provide home care when healthcare systems are under strain. 8

However, caregiving for patients at EOL has substantial negative impacts on carers’ own health. The greatest and most consistent impacts are on carers’ psychological health,9 where the greatest gains may be made. The prevalence of carer anxiety and depression during palliative care have been reported as 34–72%10–15 and 39–69%,14–17 respectively. Moreover, during the patient’s final 3 months of life, the prevalence of clinically significant carer psychological morbidity was found to be 83% in a national census study of cancer deaths in England. 9 An estimated 500,000 carers provide EOL care per annum in England. 18 Given the numbers affected, these high levels of psychological morbidity arguably represent a sizeable public health problem with likely long-term effects. Carers’ pre-bereavement psychological health is a main predictor of post-bereavement psychological health. 19,20 If carers become unable to cope, this is likely to have negative impacts on the quality of patient care and increase the likelihood of inpatient hospital admissions.

Research shows that there is large individual variation in level of psychological morbidity from EOL caregiving. Understanding what predicts this variation provides important opportunities for identifying those at risk and pointers for intervention. An earlier, comprehensive review of the quantitative carer literature from 1998–2008 by Stajduhar et al. 20 identified potential predictors as: patient characteristics (including disease type and severity); carer sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity, socio economic status); carers’ internal appraisals (e.g. of self-efficacy, preparation) and coping strategies; characteristics of the caregiving context and disruptions and restrictions to activities. The review also noted a lack of research into relational variables and available support, and of features of interaction with the healthcare system and providers. While valuable, this earlier review considered potential predictors only as one part of a wider review and only provided a narrative summary of findings.

A more systematic, detailed synthesis of the potential predictors is needed to give clearer pointers for action and illuminate two broad approaches to reduction in carer psychological morbidity. First, there are factors that cannot realistically be changed (e.g. age and gender), but whose effects can be mitigated through early, targeted support for those at higher risk. Second, there are factors that can be changed, for example self-efficacy, that can be subjected to more direct intervention to reduce likelihood of later psychological morbidity. What is non-modifiable or modifiable will partly depend on the stakeholder using the information – for instance, policy-makers may through legislation help modify work and financial factors that may put carers at risk, while practitioners may improve carers’ self-efficacy through information tailored to their individual caregiving situation.

Two points can be made from the above. First, there are likely to be a range of potential predictors that require different strategies; therefore, we need a comprehensive rather than piecemeal understanding of what may predict carer psychological morbidity, to enable a co-ordinated and integrated approach to maximise impact. Second, any findings need to be communicated to different stakeholders in ways that are meaningful and relevant to them, so that they can use this information to help enact change within their own remits.

The review of quantitative, observational studies reported here is part of a larger project to synthesise the qualitative and quantitative literature on potential predictors of carer psychological morbidity and to communicate these to stakeholders with capacity to act on this information through formats and media that they find most useful. The project is novel in its comprehensiveness and detail, and in its focus on engaging with stakeholders.

The present review will help establish whether research indicates that there is a measurable, significant relationship between a potential predictor and carer psychological morbidity. However, it cannot directly establish likelihood of causality, nor can it give insight into carer experiences, or the reasons why a factor may cause distress. This will be covered in further papers on our reviews of the intervention and qualitative literature, respectively. The way the findings are presented here is informed by our patient and public involvement (PPI) work with a carer Review Advisory Panel (RAP), whose role was to assess the validity, relevance and accessibility of findings to carers. The collaboration with the carer RAP and a wider end-of-project stakeholder consultation will be reported in detail elsewhere.

This project focuses on factors associated with carer mental health during home care, as this is the setting where most care takes place, where the carer is most involved in a breadth and depth of care tasks, and where most patients want care to take place.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of the project is to help reduce psychological morbidity among carers during EOL by

-

conducting quantitative and qualitative evidence synthesis of factors that increase or decrease carer psychological morbidity during EOL caregiving

-

integrating these syntheses into a coherent framework of factors

-

translating the findings into accessible, bespoke information for key stakeholders to help them better target efforts to reduce carer psychological morbidity.

The objective of the current review is to conduct a comprehensive evidence synthesis of observational quantitative studies to identify factors associated with carer psychological morbidity during caregiving at home for adults at EOL, where morbidity is defined as anxiety, depression, distress or reduced quality of life (QoL).

Two additonal project reports have been published, one on the qualitative synthesis and one on the intervention synthesis and metasynthesis, respectively:

Bayliss K, Shield T, Wearden A, Flynn J, Rowland C, Bee P, et al. Understanding what affects psychological morbidity in informal carers when providing care at home for patients at the end of life: a systematic qualitative evidence synthesis [published online ahead of print September 12 2023]. Health Soc Care Deliv Res 2023. https://doi.org/10.3310/PYTR4127

Grande G, Shield T, Bayliss K, Rowland C, Flynn J, Bee P, et al. Understanding the potential factors affecting carers’ mental health during end-of-life home care: a meta synthesis of the research literature [published online ahead of print December 21 2022]. Health Soc Care Deliv Res 2022. https://doi.org/10.3310/EKVL3541

Remaining reports on stakeholder involvement and a synopsis of the project as a whole will be published in Health and Social Care Delivery Research and will also be available at https://arc-gm.nihr.ac.uk/carer-project-.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search and evidence synthesis of the literature. To accommodate the wide-ranging literature, findings were synthesised thematically using box scores, supported by meta-analysis where data permitted. The review was registered with PROSPERO (PROSPERO 2019 CRD42019130279) and was carried out in accordance with the reporting guidelines: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE).

Search and selection strategy

Studies were identified through an electronic search of the literature from 2009 to 2019 in the following databases:

-

MEDLINE (Ovid online)

-

CINAHL Plus (EBSCO)

-

PsycINFO (Ovid online)

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (Institute for Scientific Information; Clarivate Analytics platform)

-

EMBASE (Ovid)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination).

Following piloting, searches were completed in December 2019, using medical subject headings (MESH) terms relevant to caregivers supplemented with string carer terms, including variations on ‘family care giver’ and ‘informal carer’. These were combined with MESH terms for ‘palliative care’ supplemented by string terms ‘end-of-life’ and ‘end of life’. The search strategy can be viewed in full in Appendix 1.

Study inclusion was based on the following inclusion criteria:

Population: adult informal/family carers caring for adult patients at EOL (EOL was defined as the likelihood that the patient would die within a year). Focus was on home, community and outpatient settings. Only Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries were included, to ensure healthcare structures were comparable with the UK.

Intervention: factors associated with psychological morbidity in EOL carers; studies which reported on the relationship between factors and outcomes.

Outcome: mental health outcomes in carers focused on anxiety, depression, distress and QoL (whether self-reported or clinically defined) in home, community and outpatient settings. Psychological well-being was defined as the primary outcome for QoL, with general QoL used as a proxy measure where a psychological well-being QoL score was not available.

Study: observational studies.

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria:

-

factors or outcomes related to bereavement only

-

inpatient settings, given the focus on factors associated with carer mental health during home care

-

in languages other than English or Scandinavian, which would require further translation

-

systematic reviews.

Finally, the review was limited to published peer-reviewed empirical studies.

Ten per cent of both titles/abstracts and full texts were screened independently by two reviewers. Over 90% agreement was established in each case, indicating that no further modifications to the inclusion and exclusion criteria were required. Subsequent studies on title/abstract and full texts were screened by one reviewer.

The above represents some tightening and simplification of the search and selection process due to time pressures, and on advice from the project’s external Study Steering Committee (and notification to NIHR HSDR), including limitation to most recent decade, fewer databases, OECD country and English or Scandinavian publications, omission of dissertations and grey literature and single screening once consistency was established. Similar simplification was applied to the data extraction below.

Data extraction and quality assessment process

Data extraction

A data extraction template to extract information on both factors and mental health outcomes was developed jointly by two reviewers and subsequently tested independently by the two reviewers on a 10% sample of included studies. Differences were resolved by discussion and the data extraction template subsequently clarified to mitigate for any further inconsistencies between reviewers. Data extraction was then carried out by one reviewer and a random sample of 10% of remaining studies checked by another. No discrepancies between reviewers were identified in the checking process.

Where a study reported findings for both the overall outcome measure of QoL and the mental health/emotional subdomain of QoL (psychological well-being), only findings related to the mental health/emotional subdomain of QoL were extracted, to reflect the focus on psychological morbidity.

Where a study reported findings for the overall domain of a factor as well as the individual subdomains of the factor (e.g. caregiver burden), findings were reported for the overall scale only to avoid ‘over-representing’ factors as much as possible (i.e. providing ‘multiple counts’ of the same factor). However, where only subdomain findings were reported by the study, these were extracted.

Findings relating to the relationship between individual mental health outcomes were not extracted, in keeping with the project aims to identify factors associated with carers’ mental health.

Statistical information was only extracted for bivariate relationships to avoid potential collinearity. Where studies reported multivariate analysis only, a narrative summary of the findings was documented.

Quality assessment

An adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort and case–control studies21 was used to perform quality assessment of cohort/longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies of included studies (see Appendix 2). This modified version was adapted from the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) used in another study22 to appropriately assess the quality of cross-sectional studies.

Quality assessment was carried out independently by two reviewers on 10% of the studies. Over 90% agreement was achieved, so subsequent studies were quality assessed by one reviewer and a random sample of 10% of studies checked by another. No discrepancies between reviewers were identified in the checking process.

Thematic synthesis with PPI

Individual factors were synthesised thematically into sub-themes using box scores. 23 This was conducted in ways that were meaningful to the carer RAP in order for them to assess the relevance of findings. For example: (1) renaming factors reported in studies in language that made sense to carers; (2) reporting findings from correlation studies so that they referred consistently to improved or worsened mental health to allow easier interpretation; and (3) thematic groupings of factors.

Each sub-theme was then synthesised further by mapping individual sub-themes under one of the overarching thematic groupings identified in the qualitative synthesis (see https://arc-gm.nihr.ac.uk/carer-project-): patient condition, impact of caring responsibilities, relationships, finances, carer internal processes and support. These were informed by the carer RAP as useful ways of presenting the evidence.

Meta-analysis

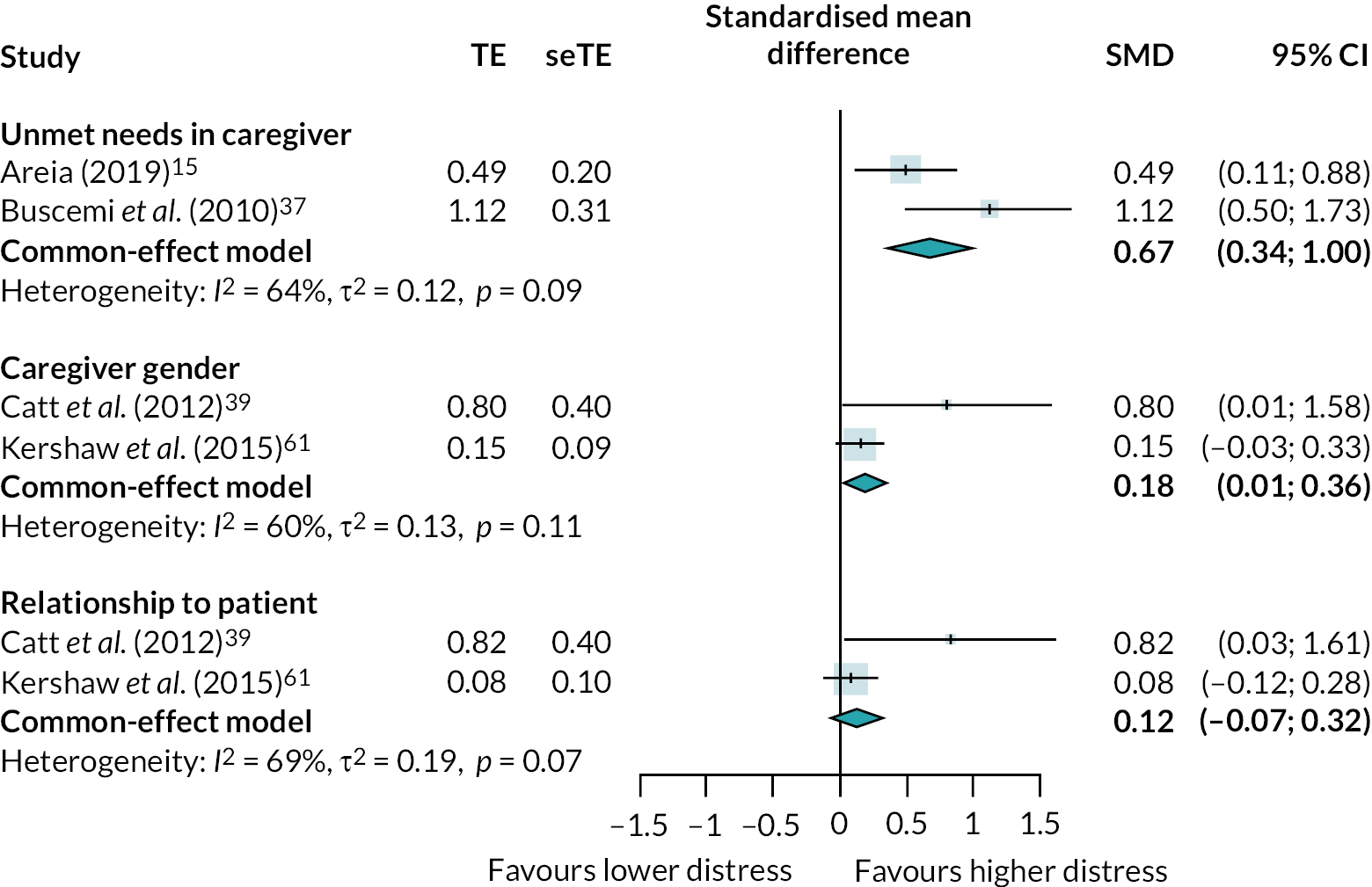

The outcome data were converted to standardised mean difference (SMD) using comprehensive meta-analysis (CMA) software. Effect sizes were then pooled using DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model. 24 Results of each mental health outcome (i.e. anxiety, depression, distress or QoL) were presented in the forest plots with the SMD calculated using Hedges’ g and then interpreted according to Cohen’s criteria. 25 Where data from five or more studies were pooled in a meta-analysis, a random-effects model was performed. For pooled data of fewer than five studies, a fixed-effects model was calculated. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic with values 25%, 50% and 75% indicating low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively. 26 If more than 10 studies were included in a meta-analysis, funnel plots and Begg’s and Egger’s test were used to examine potential for publication bias. 27 All meta-analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) using the ‘meta’ or ‘metafor’ packages. 28,29

The opportunity for meta-analysis was limited due to the wide range of factors and the range of mental health outcomes considered. There were therefore few instances where studies considered sufficiently similar factors and their relation to the same outcome to permit meta-analysis.

Results

Hits and paper selection

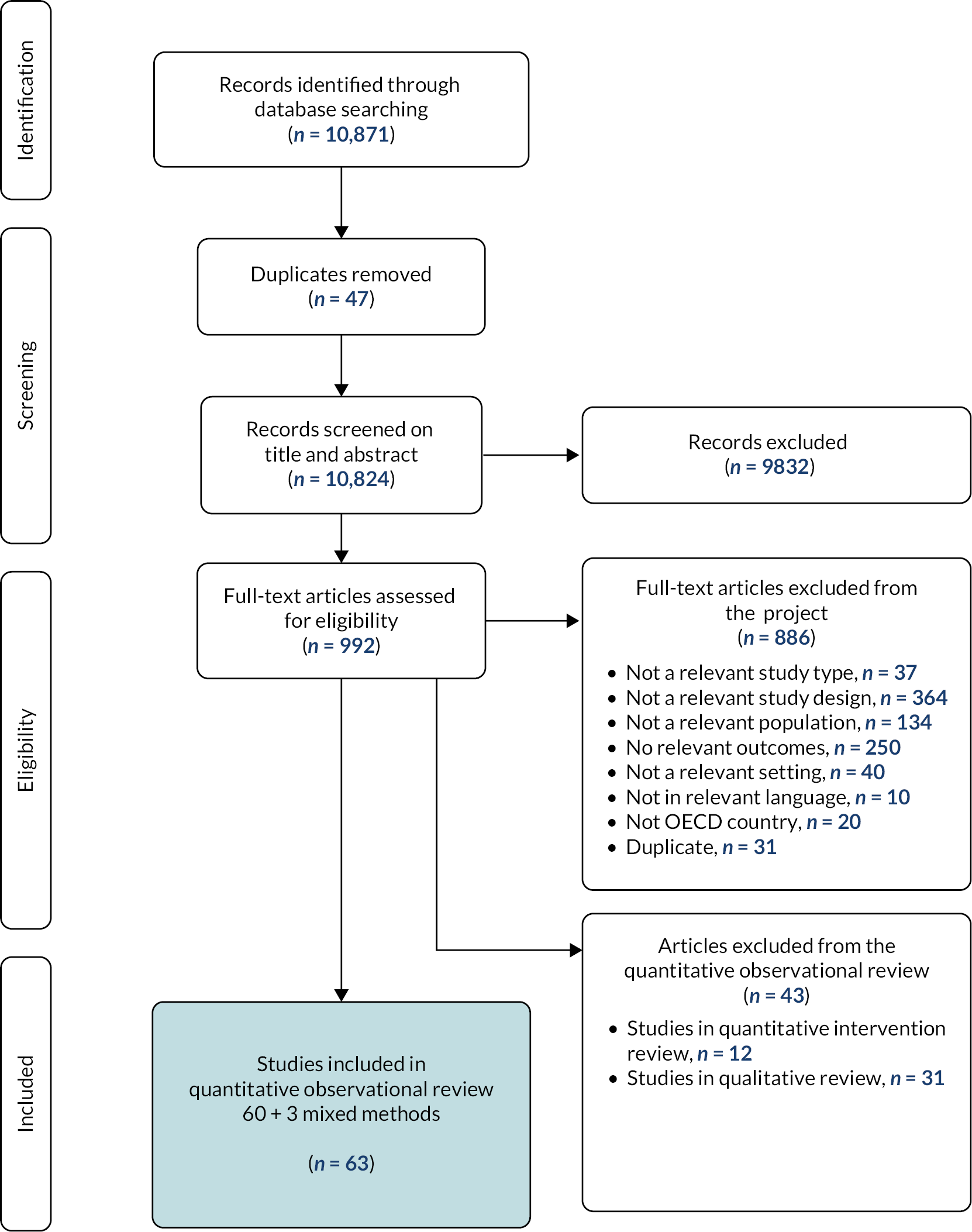

The PRISMA diagram details the study identification and selection process (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA diagram of study identification and selection.

Sixty-three studies met the study inclusion criteria for observational studies. Characteristics of the 63 included studies are specified in Table 1. Studies were excluded where a substantial proportion of the patient population were considered unlikely to be EOL, for example a study which reported metastases in less than 50% of a cancer study population; factors or outcomes related to bereavement only; the outcome measured was anticipatory grief; or the outcome was a composite measure encompassing mental health outcomes included in our review, but where it was impossible to extrapolate findings specifically related to our outcomes, for example a study with the outcome measure Profile of Mood States (POMS), which captures the mood states of anger, depression, fatigue, tension and vigour together; and a substantial proportion of the patient population were unlikely to be cared for at home at the time of the study, for example a study looking at the impact on carers of patient stay in an intensive care unit. Finally, due to the large volume of primary research papers returned, dissertations and conference abstracts were excluded on ‘study type’; systematic reviews were excluded on ‘study design’.

| Reference and country | Study aims | Study design and data collection; QA score | Participants (number; demographics; carer–patient relationships) | Patient condition | Factors investigated in bivariate analysis | Outcomes (anxiety, depression, distress, QoL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aoun et al. (2015)30 Australia |

|

Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 4 |

N = 500; Mean age, years = 60 73% female; 69% spouse/partner, 21% son/daughter |

Mixed cancer: Lung (22.4%) Breast (9.6%) Colorectal (8.8%) Prostate (8%) Pancreas (7.2%) Primary brain cancer (6%) |

Patient condition (primary brain cancer vs. other cancers) | QoL: SF12v2-MH |

| Areia et al. (2019)15 Portugal |

|

Cross-sectional survey; 6 |

N = 112 Mean age, years (SD) = 44.5 (15.3) 82.1% female; 42.9% other (not spouse or child), 37.5% adult child |

Mixed cancer: GI (24.5%) Respiratory (20.9%) Other solid tumours (20.9%) Central nervous system (11.8%) Breast (9.1%) |

Unmet needs in caregiver | Anxiety: BSI anxiety subscale Depression: BSI depression subscale Distress: GSI |

| Bachner and Carmel (2009)31 Israel |

|

Cross-sectional survey; 3 |

N = 236 Mean age, years (SD) = 55.4 (13.7) 77.5% female; 47.9% son/daughter 44.9 % spouse |

Cancer | Quality of patient–caregiver relationship (communication) | Depression: BDI-II (modified) |

| aBachner et al. (2009)32 Israel |

Compare response levels as well as the relative strength of association between mortality communication (candid discussion of the terminal illness and impending death between caregivers and their loved ones) and psychological distress among caregivers of terminal cancer patients within two distinct care contexts (i.e. home hospice vs. inpatient hospital settings). | Cross-sectional survey; 3 |

N = 126 Mean age, years (SD) = 56.61 (14.38) 79.2% female 48.5% spouse, 44.6% son/daughter |

Cancer | Depression: BDI-II (modified) | |

| Bachner et al.(2011)33 Israel |

Compare the relative strength of association between mortality communication (candid discussion of the terminal illness and impending death between caregivers and their loved ones), fear of death, and psychological distress (depressive symptomatology, emotional exhaustion) among secular (non-religious) and religious Israeli Jewish caregivers of terminal cancer patients. | Cross-sectional survey; 2 |

N = 236; Mean age, years (SD) = 55.37 (13.69); 77.5% female; 47.9%, son/daughter 44.9% spouse |

Cancer | Caregiver coping pattern (secular vs. religious) | Depression: BDI-II (modified) |

| Boele et al. (2013)34 The Netherlands |

|

Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 4 |

N = 56; Mean age, years = 50.66; 64.3% female; carer–patient relationship not reported |

Cancer: 30.4% Grade 3 glioma 69.6% Grade 4 glioma |

Patient condition Patient QoL Patient symptoms |

QoL: SF-36 MH |

| Burridge et al.(2009)35 Australia |

Examine how carers’ and patients’ PSOC changes over the patients’ final year in comparison with the perceptions of carer–patient dyads; whether carers’ anxiety and depression scores are correlated with their PSOC, and whether these scores differ by gender. | Cohort Survey; 4 |

N = 57 Mean age, years (SD) = 57 (12.7); 76% female; 76% spouse |

Cancer: Lung (30%) Digestive tract (26%) Other (26%) Breast (18%) |

Patient stage of disease (PSOC) | Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D |

| Burton et al. (2012)36 USA |

Expand understanding of caregiver burden and psychosocial−spiritual outcomes among under-studied groups of caregivers – cancer, congestive HF and COPD caregivers – by including differences in outcomes by disease in a diverse population. | Cross-sectional survey; 7 |

N = 139; Mean age, years (SD) = 57 (14.88) 81.29% female 69.78% white; 56.83% spouse/partner, 43.17% other (child, friend or sibling) |

Mixed: cancer COPD CHF % composition not given |

Patient disease burden Patient disease severity Caregiver coping patterns Caregiver support Caregiver age Caregiver employment status Caregiver gender Caregiver marital status |

Anxiety: POMS-anxiety Depression: CES-D 10 |

| Buscemi et al.(2010)37 Spain |

Analyse the possible relationship between the needs of primary caregivers of patients with terminal cancer and burden, stress and anxiety. | Cross-sectional survey; 2 |

N = 59 Mean age, years (SD) = 53.35 (15.66); 81.4% female; 57.6% spouse, 35.6% son/daughter |

Mixed cancer: Lung (33.9%) Other (33.8%) Colon (13.6%) Breast (11.9%) Liver (6.8%) |

Unmet needs in caregiver Caregiver burden (BCOS) |

Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D |

| Butow et al. (2014)38 Australia |

|

Cohort Survey; 8 |

N = 99; Mean age, years (SD) = 59 (13.2); 20% female; 78% husband/partner, 16% child |

Ovarian cancer (100%) | Patient stage of disease Caregiver gender Relationship to patient Rural location |

QoL: SF12v2 MH Distress: HADS (combined score) |

| Catt et al. (2012)39 UK |

To evaluate and compare oncologist-led follow-up with a multidisciplinary group follow-up method from the perspective of patients and caregivers after patients’ radical treatment for high-grade glioma. | Cohort survey; 6 |

N = 32; Mean age, years = 51; 56.25% female; 87.5% spouse/partner, 62.5% offspring |

Single cancer: High-grade glioma |

Caregiver education Caregiver employment status Caregiver gender Relationship to patient Patient treatment Caregiver lifestyle adjustments Caregiver workload |

Distress: GHQ-12 |

| Duimering et al.(2019)40 Canada |

To assess carers of their patient population, evaluate their expressed caregiving burden and QoL, and determine baseline engagement with support services. | Cross-sectional survey; 6 |

N = 200; Mean age, years (SD) = 58.7 (14.0); 60.8% female; 60.6% spouse, 28.8% child |

Mixed cancer: Lung (25%) Prostate (19.3%) Breast (18.8%) Colorectal (5.7%) Renal (4.5%) Bone (4.5%) |

Caregiver gender Relationship to patient Caregiver employment status Caregiver socio economic status Rural location Caregiver lives with patient Patient disease burden Patient treatment Caregiver workload Caregiver support |

QoL: CQOLC |

| aEllis et al. (2017)41 USA |

To examine the relationship between the number of co-existing health problems (patient comorbidities and caregiver chronic conditions) and QoL among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers, and assess the mediating and moderating role of meaning-based coping on that relationship. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 9 |

N = 484; Mean age, years (SD) = 56.5 (13.4) 56.8% female 79.6% white; 70% spouse, 15.3% son/daughter |

Mixed cancer: Breast (32.4%) Lung (29.1%) Colorectal (25.4%) Prostate (13.0 %) |

QoL: FACT-G (version 4) | |

| Exline et al.(2012)42 USA |

To examine the relevance of forgiveness to carers, and relation to unresolved offences and depression. | Cross-sectional survey; 3 |

N = 142; Mean age, years (SD) = 60.3 (13.8) 74% female 82% white; 44% child, 42% spouse |

Mixed: Cancer (43%) Dementia/Alzheimer’s (32%) Heart disease (23%) Lung disease (18%) |

Quality of patient–caregiver relationship | Depression: CES-D |

| Fasse et al. (2015)43 France |

|

Cross-sectional survey; 9 |

N = 60 (all spouses); Mean age, years (SD) = 62.39 (12.99) 36.7% female |

Mixed cancer: Breast (36.6%) Lung (16.7%) Cervix (10%) Other (36.6%) |

Quality of patient-caregiver relationship Caregiver coping patterns Patient disease severity Caregiver gender |

Depression: BDI-short form |

| Flechl et al. (2013)44 Austria |

To investigate the experiences of 52 caregivers of deceased GBM patients treated in Austria. |

Cross-sectional survey; 1 |

N = 52; Mean age, years = 60 67% female; 88% partner |

Glioblastoma (100%) | Caregiver finances Caregiver age Patient age Duration of care |

QoL: measure from researchers’ own questionnaire |

| aFranchini et al.(2019)45 Italy |

To investigate impact of possible predictors of carers’ QoL. | Cross-sectional survey; 6 |

N = 570; Mean age, years (SD) = 58.8 (13.9) 77.4% female 46.1% partner, 38.4% offspring |

Mixed cancer: GI (33.5%) Thoracic (16.1%) Genitourinary (16.3%) Breast (10.5%) |

QoL: CQOLC | |

| aFrancis et al.(2011)46 USA |

|

Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 7 |

N = 397; Median age, years = 51 78.3% female 68.3% white; 100% family members (no further breakdown) |

Mixed cancer: Stage IV (or stage III lung, pancreatic or liver cancer) % composition not reported |

Anxiety: POMS – Tension/anxiety Depression: POMS – Depression-dejection subscale |

|

| Götze et al. (2014)12 Germany |

|

Cross-sectional survey; 8 |

N = 106; Mean age, years (SD) = 64.1 (11.1) 67.9% female; 75% partner, 16% son/daughter |

Mixed cancer: Prostate cancer (17.0%) Lung cancer (14.2%) Pancreas (13.2%) Colon (11.3%) |

Patient symptoms Quality of patient–caregiver relationship |

Anxiety: HADS –A Depression: HADS –D Distress: HADS (combined score) |

| Govina et al. (2019)47 Greece |

To determine the factors associated with the anxiety and depression of family members caring for patients undergoing palliative radiotherapy. |

Cross-sectional survey; 7 |

N = 100; Mean age, years (SD) = 53.3 (12.6) 76% female; 59% spouse, 27% child |

Mixed cancer: Lung (48%) Breast (22%) Urogenital (20%) |

Patient gender Caregiver gender Patient condition Patient treatment Patient lives with caregiver Previous experience of informal caregiving Caregiver mode of transport Caregiver marital status Patient educational level Caregiver educational level Additional caring responsibilities Relationship to the patient Caregiver employment status Caregiver age Caregiver burden Patient medical history |

Anxiety: HADS-A (Greek) Depression: HADS-D (Greek) |

| Grant et al. (2013)48 USA |

Describe burden, skills preparedness, and QoL for caregivers of patients with NSCLC and describe how the findings informed the development of a caregiver palliative care intervention that aims to reduce caregiver burden, improve caregiving skills and promote self-care. | Cohort survey; 8 |

N = 163; Mean age, years = 57.23 64% female 71% white; 68% spouse/partner, 16% daughter |

NSCLC (100%) | Patient stage of disease | Distress: Psychological distress thermometer QoL: City of Hope QoL Scale-Family version – psychological well-being domain |

| Hampton and Newcomb (2018)49 USA |

To determine the relationship between self-efficacy and perceived stress in adult carers providing EOL care. | Cross-sectional survey; 4 |

N = 78; Mean age, years (SD) = 61.21 (13.91) 74.4% female 74% white; carer–patient relationship not reported |

Mixed: Cancer (37.2%) Heart problems (17.9%) Dementia (11.5%) |

Self-efficacy | Anxiety: PSS |

| Hannon et al. (2013)50 Canada |

|

Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 7 |

N = 191; Mean age, years (SD) = 56.1 (12.1) 66% female; 84.3% spouse/partner, 11.5% son/daughter |

Mixed cancer: GI (37.7%) Genitourinary (17.8%) Breast (17.3%) Lung (16.2%) Gynaecological (11%) |

Quality of care | QoL: CQOLC |

| Henriksson and Arestedt (2013)51 Sweden |

Explore factors associated with preparedness and to further investigate whether preparedness is associated with caregiver outcomes. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 8 |

N = 125; Mean age, years (SD) = 57.7 (15.8) 60.8% female; 58.4% spouse, 22.4% adult children |

Mixed: Cancer (88.8%) Other (11.2%) |

Preparedness for caregiving | Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D |

| Hoefman et al.(2015)52 Australia |

To study construct validation of the CES and the carer QoL and to investigate the effect of caregiving on caregivers in EOL care. | Cross-sectional Survey; 6 |

N = 97; Mean age, years (SD) = 62.3 (11.9) 71% female 98% white; 59% partner, 29% child |

Not reported | Time for respite Caregiver support Positive aspects of caregiving Control over care situation Quality of patient–caregiver relationship Caregiver burden Additional caring responsibilities Caregiver finances |

QoL: CarerQOl-7D dimension-MH question |

| Huang and McMillan (2019)53 USA |

To apply the Actor–Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) to elucidate importance of mutual effects within dyads with advanced cancer examining contribution of depression on their individual (own) QoL and their carers’ QoL. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 6 |

N = 660; Mean age, years (SD) = 65.49 (13.81) 74% female 96% white; 57% spouse, 11% daughter |

Mixed cancer % composition not reported |

Patient symptoms | Depression: CES-D QoL: SF-12 MH |

| Hudson et al.(2011)54 Australia |

To examine the psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of receiving palliative care services. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 6 |

N = 301; Mean age, years (SD) = 56.52 (13.89) 73.1% female; 47.8% spouse, 37.2% adult children |

Mixed cancer: GI tract cancer (20.3%) Lung cancer (13.6%) Head and neck cancer (10.6%) Urogenital cancer (10.6%) |

Impact on caregiver’s schedule Self-esteem Optimism |

Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D |

| Ito and Tadaka (2017)55 Japan |

To identify the associated factors of QoL among family carers of patients with terminal cancer at home in Japan. | Cross-sectional survey; 8 |

N = 74; Mean age, years (SD) = 63.6 (12.2) 79.7% female; 35.1% wife, 28.4% daughter |

Mixed cancer: Lung (29.7%) Colon (18.3%) Liver (14.9%) Brain (12.2%) Prostate (12.2%) Stomach (8.1%) Pancreas (8.1%) |

Patient age Patient gender Patient condition Patient symptoms Patient treatment Patient disease burden Caregiver support Duration of care Caregiver age Caregiver gender Relationship to patient Family dynamics Caregiver finances Caregiver employment status Caregiver health status Caregiver sleeping hours Self-efficacy Caregiver support Quality of care Accessible information |

QoL: CQOLC– Japanese |

| Jacobs et al. (2017)56 USA |

Understand the prevalence of psychological symptoms (depression and anxiety) in patients and carers and to determine whether their distress is interdependent. | Cross-sectional survey; 10 |

N = 275; Mean age, years (SD) = 57.37 (13.61) 69.1% female 93% white; 66.2% spouse/partner, 18.4% son/daughter |

Mixed cancer: Lung (54.6%) Non-colorectal GI (45.4%) |

Patient symptoms | Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D |

| Janda et al. (2017)57 Australia |

To address research gap in quantifying association between patients’ and their immediate carers’ well-being | Cross-sectional survey; 6 |

N = 84 Age: 38% ≤ 60 years 37% 61–70 years 21% 70+ years 73% female; 81% spouse/partner, 12% son/daughter |

Pancreatic cancer (100%) | Patient QoL Relationship to patient Caregiver age Caregiver gender Caregiver education Caregiver support Patient symptoms |

Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D QoL: FACT-GP |

| Janssen et al. (2012)58 The Netherlands |

To assess caregiver burden and positive aspects of caregiving in family caregivers of patients with advanced COPD, CHF or CRF | Cross-sectional survey; 8 |

N = 159; Mean age, years (SD) for each condition group COPD = 62.9 (11.5), CHF = 67.3 (11.5), CRF = 59.1 (15.2) 73% female; 83% spouse, 12% child |

Mixed non-cancer: COPD (45.9%) CHF (28.3%) CRF (25.8%) |

Patient condition (COPD vs. CHF vs. CRF) | Distress: FACQ PC |

| aKapari et al. (2010)59 UK |

To identify the risk factors for poor caregiving and bereavement outcomes by assessing both patients and caregivers on a range of measures | Cohort Survey; 9 |

N = 100; Mean age years = 65.3 75% female 89% white British; 85% spouse/partner |

Mixed: Cancer 96% (lung 22% prostate 12% breast, ovarian and colon 5% bowel 5% bladder 2% other cancer 40%) MND (2%) COPD (1%) Liver failure (1%) |

Distress: CIS-R | |

| aKenny et al. (2010)60 Australia |

To investigate associations between health and a range of caregiving context variables | Cross-sectional survey; 5 |

N = 178; Mean age, years (SD) = 61.7 (13.5) 71% female; 59% spouse, 29% child/grandchild |

Mixed: Cancer 89% (main categories: colorectal 15% lung 14% prostate 13%) Non-cancer 11% (main categories: cardiac failure 2.3% chronic airway limitation 1.7% pulmonary fibrosis 1.7%) |

QoL: SF-36 | |

| Kershaw et al.(2015)61 USA |

To investigate actor and partner effects of advanced cancer patients’ and their family caregivers’ mental health, physical health and self-efficacy over time, and to investigate the effects of patients’ and caregivers’ self-efficacy on their own and the other dyad members’ mental health and physical health over time | Cohort secondary analysis; 11 |

N = 484; Mean age, years (SD) = 56.7 (12.6) 57% female 83% white; 74% spouse, 19% relative |

Mixed cancer: Breast cancer (37%) Lung (24%) Colorectal (23%) Prostate (16%) |

Caregiver age Caregiver gender Relationship to patient Patient disease burden Patient condition |

Distress: FACT-G emotional well-being |

| Kobayakawa et al.(2017)62 Japan |

To determine the prevalence of delirium and suicidal ideation among patients with cancer and determine whether these and other factors influence caregivers’ psychological distress. | Cross-sectional survey; 6 |

N = 532; Mean age, years (SD) = 61.8 (12.1) 74% female; 53% spouse |

Mixed cancer: lung (21%) stomach, oesophagus (17%) colon, rectum (12%) liver, bile duct and pancreas (23%) breast (5%) prostate, kidney and bladder (8%) |

Caregiver gender Relationship to patient Caregiver educational level Caregiver finances Caregiver health status Caregiver support Patient symptoms Health professionals’ understanding of patient needs Control over care situation Patient treatment Acceptance of patient condition |

Depression: Single, self-created question |

| Loggers and Prigerson (2014)63 USA |

Authors interested in whether, and how, the EOL experiences of adult patients with rare cancers differed from that of individuals with common cancers. | Cohort interviews; 7 |

N = 618; Age and gender not reported; Spouse and adult child % composition not reported |

Common cancers N = 423: lung (35.2%) colorectal (18.2%) breast (18.0%) pancreatic (11.6%) Rare cancers N = 195: gastroesophageal (19.0%) ovarian and cervical (15.4%) hepatocellular, biliary and gallbladder (13.3%) head and neck (11.3%) sarcoma and GI stromal tumour (10.8%) leukaemia, multiple myeloma and Hodgkin lymphoma (10.3%) central nervous system (7.7%) Other (12.3%) |

Patient condition | QoL: SF-36 Distress: SCID |

| Malik et al. (2013)64 UK |

|

Cross-sectional survey; 4 |

N = 101; Mean age, years (SD) for each condition group HF = 65.8 (12.7) lung cancer = 59.9 (12.8) 78% female; 72% spouse/partner, 20% child |

HF (50.5%) lung cancer (49.5%) |

Patient condition Caregiver burden |

Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D QoL: SF-36 – MH |

| McIlfatrick et al.(2018)65 UK and Ireland |

To identify modifiable psychosocial factors associated with caregiver burden and to evaluate the support needs of caregivers when caring for people living with advanced HF at the end of life. | Cross-sectional survey and semi-structured interviews; 5 |

N = 84; Mean age, years (SD) = 63.9 (14.3) 80% female; 52% spouse/partner, 22% son/daughter |

HF (100%) | Patient symptoms Patient QoL Preparedness for caregiving Caregiver age |

Anxiety: GAD-7 Depression: PHQ-9 QoL: MLHFQ |

| Mollerberg et al.(2019)66 Sweden |

Determine whether family’s sense of coherence was associated with hope, anxiety and symptoms of depression in persons with cancer in the palliative phase and their family members. [‘Sense of coherence’ consists of comprehensibility (ability to understand the situations clearly), manageability (belief that one has access to sufficient resources to manage challenging situations) and meaningfulness (belief that all challenges are worthy of engagement).] | Cross-sectional survey; 7 |

N = 165; Mean age, years (SD) = 62.1 (13.6) 64.8% female 67.9% spouse/partner |

Mixed cancer: Breast (16.2%) Colon (15.1%) Prostate (10.6%) Kidney (10.6%) Other (47.5%) |

Family dynamics | Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D |

| Nielsen et al. (2017)67 Denmark |

To investigate pre-loss grief symptoms and the associations with situational, intrapersonal and interpersonal factors in family caregivers of EOL cancer patients. | Cross-sectional survey; 7 |

N = 2865; Mean age, years = 60.5 69% female; 63.6% spouse/partner 29% son/daughter |

Mixed cancer: Lung (25.1%) Colorectal (13.1%) Breast (7.0%) Prostate (7.5%) Haematological (3.7%) Other (43.6%) |

Pre-loss grief | Depression: BDI |

| aNipp et al. (2016)68 USA |

To describe rates of depression and anxiety symptoms in family carers of patients with incurable cancer and identify factors associated with family carer psychological distress. | Cross-sectional survey; 8 |

N = 275; Mean age, years (SD) = 57.4 (13.6) 69.1% female 93.1% white; 66.2% spouse, 18.5% son/daughter |

Mixed cancer: Lung (54.2%) Non-colorectal GI (45.8%) |

Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D |

|

| Nissen et al. (2016)69 USA |

To identify family-type clusters in an American sample of carers of terminally ill cancer patients and to examine the relationship between these clusters and carer QoL, social support and carer burden. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 5 |

N = 598; Mean age, years (SD) = 52.89 (14.05) 72% female 82% white; 58% spouse |

Mixed cancer: % composition not reported |

Family dynamics | QoL: SF-36-MH |

| O’Hara et al. (2010)70 USA |

Not directly stated, but paper considers whether patient intervention affected carer outcomes, and whether patient measures affected carer outcomes (univariate correlations for latter). | Cohort survey; 7 |

N = 198; Mean age, years (SD) for each group Intervention = 59.9 (13.0) Control = 58.0 (11.9) 77% female; 96% white; 71% spouse/partner |

Mixed cancer: GI (42.4%) Lung (36.4%) Genitourinary (13.1%) Breast (8.1%) |

Patient QoL Patient symptoms Quality of care |

Distress: MBCBS emotional subscale |

| Ownsworth et al.(2010)71 Australia |

To investigate the association between functional impairments of individuals with cancer and caregiver psychological well-being, and examine the moderating effect of social support. |

Cross-sectional survey; 7 |

N = 29 Mean age, years (SD) = 60.1 (11.7) 71.4% female; 88.8% spouse/partner |

Brain tumour (100%) benign (stage 1 or 2 tumour) (52%) malignant (stage 3 or 4) (48%) |

Patient disease burden | QoL: WHOQOL-BREF-psychological domain |

| aParker Oliver et al. (2017)72 USA |

To explore potential variables affecting depression and anxiety in informal hospice caregivers. |

Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 6 |

N = 395 Mean age, years (SD) = 60.6 (12.6) 81.52% female; 49.1% adult child, 30.4% spouse |

Mixed: Cancer (37.22%) Dementia (30.13%) No additional information on the remainder of the sample given |

Anxiety: GAD-7 Depression: PHQ-9 |

|

| Perez-Ordonez et al. (2016)73 Spain |

To identify the relationship between coping and anxiety in primary family caregivers of palliative cancer patients treated in a pain and palliative care unit. | Cross-sectional interviews; 6 |

N = 50 Mean age, years (SD) = 55 (13.9) 94% female; 52% daughter, 28% spouse |

Mixed cancer: Others (46%) Lung (14%) Prostate (12%) Bladder (12%) |

Caregiving coping patterns Patient disease burden Caregiver burden |

Anxiety: Anxiety subscale of Goldberg Scale |

| aReblin et al. (2016)74 USA |

To describe relationship quality categories among EOL caregivers and to test the effects of relationship quality categories on caregiver burden and distress within a stress process model. | Cross-sectional survey; 7 |

N = 131 Mean age, years (SD) = 65.3 (10.74) 65% female 97% white; 100% spouse |

Cancer % composition not reported |

Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: GDS-SF |

|

| Rivera et al. (2010)75 USA |

To examine predictors of depression symptoms in caregivers of hospice cancer patients. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 7 |

N = 578 Mean age, years (SD) = 64.95 (14.01) 73.7% female 95.8% white; 42.4% wife, 25.2% other |

Mixed cancer: Lung/mesothelioma (36%) Pancreas (8.7%) Colorectal (6.6%) |

Patient psychological symptoms Patient QoL Caregiver gender Relationship to patient Caregiver ethnicity Caregiver support Patient condition Patient disease burden Caregiver age Caregiver health status |

Depression: CES-D 10 |

| Seekatz et al. (2017)76 Germany |

To determine screening-based symptom burden and supportive needs of patients and caregivers with regard to the use of specialised palliative care (SPC). | Cohort survey; 4 |

N = 46 Mean age, years (SD) = 53.3 (14.1) 56.5% female; 57% spouse/partner, 22% child |

Mixed cancer: Glioblastoma (68.4%) Brain metastases (31.6%) |

Patient treatment | Distress: Hornheider Questionnaire (adapted) |

| aShaffer et al.(2017)77 USA |

To examine correlates of mental and physical health among caregivers of patients with newly diagnosed, incurable lung or non-colorectal GI cancer. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 9 |

N = 275 Mean age, years (SD) = 53.37 (13.61) 69.1% female; 66.4% spouse |

Mixed cancer: Lung (54.2%) Non-colorectal GI cancer (45.8%) |

QoL: SF-36 mental health | |

| Siminoff et al.(2010)78 USA |

To investigate depressive symptomatology in stage III or IV lung cancer patients and their identified caregiver. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 7 |

N = 190 Mean age, years (SD) = 55 (13.4) 75% female; 54.7% spouse, 18.9% child |

NSCLC (100%) | Patient psychological symptoms Family dynamics |

Depression: CES-D -20 |

| Stutzki et al. (2014)79 Germany |

To determine the prevalence and stability of wish to hasten death (WTHD) and EOL attitudes in ALS patients, identify predictive factors and explore communication about WTHD. | Cohort survey; 8 |

N = 35 Mean age, years (SD) = 56.4 (12.7) 61% female; 79% partner, 14.5% son/daughter |

ALS (100%) | Patient disease severity | QoL: Numerical Ratings Scale– individual QoL |

| Thielemann and Conner (2009)80 USA |

To examine the role of social support as a mediating factor between caregiver demands and caregiver depression in spousal caregivers of patients with advanced lung cancer. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 8 |

N = 164 Mean age, years (SD) = 61.9 (10.8) 60.4% female 98.2% white; 100% spouse |

Lung cancer (100%) | Caregiver age Caregiver gender Caregiver ethnicity Caregiver educational level Length of patient–caregiver relationship Duration of care Caregiver burden Caregiver support |

Depression: CES-D |

| aTrevino et al.(2019)81 USA |

To conduct secondary exploratory analyses of the relationship between individual and dyadic estimations of the patient’s life expectancy and patient and caregiver QoL. |

Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 8 |

N = 162 Age, years 65+ (42.6%) less than 65 (57.4%) 66% female 89.5% white; 64.2% spouse/partner |

Mixed cancer: Aggressive cancer (50%) – this includes lung, GI cancers (except colon) and GU cancers (except prostate). Less aggressive (50%) – this includes breast, prostate and colon cancers |

Depression: DSM-IV (SCID) QoL: SF12v2 -emotional |

|

| aValeberg et al.(2013)82 Norway |

To examine the level of symptom burden in a sample of cancer patients in a curative and palliative phase. In addition to determine (a) whether the patients’ symptom burden and patients’ demographic variables, and (b) the caregivers’ demographic variables impact on the caregivers’ QoL and mental health. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 6 |

N = 159 Mean age, years (SD) = 57.0 (12.3) 39% female; 89% spouse, 6% friend |

Mixed cancer: Breast (46%) Prostate (18%) Other (18%) Colorectal (13%) Gynaecologic (5%) |

Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D QoL: SF36-MH |

|

| Wadhwa et al.(2013)83 Canada |

To evaluate the QoL and mental health of caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who are receiving ambulatory oncology care and associations with patient, caregiver and care-related characteristics. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 7 |

N = 191 Median age, years (range) = 57 (22–83) 64.9% female 83.2% white; 83.8% spouse/partner, 5.2% son/daughter |

Mixed cancer: GI (37.7%) Genitourinary (17.8%) Breast (17.3%) Lung (16.2%) Gynaecology (11%) |

Caregiver gender Caregiver age Caregiver employment status Relationship to patient Caregiver burden Impact on work Patient treatment Patient symptoms Patient QoL Caregiver health status Patient lives with caregiver Caregiver ethnicity Caregiver education Caregiver finances Caregiver workload Caregiver support Patient age Patient gender Patient disease burden |

QoL: SF36-MH |

| aWashington et al.(2015)84 USA |

To generate an in-depth understanding of the extent to which informal hospice caregivers experience symptoms of anxiety and to identify the characteristics of caregivers who experience clinically significant (i.e. moderate or higher) levels of anxiety. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 7 |

N = 433 Mean age, years (SD) = 60.8 (12) 77.1% female 91.5% white; 50.8% adult child, 30.7% spouse/partner |

Not reported | Anxiety: GAD-7 | |

| Washington et al.(2018)85 USA |

To examine the relationships between sleep problems, anxiety and global self-rated health among hospice family caregivers. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 7 |

N = 395 Mean age, years (SD) = 60.6 (12.6) 81.52% female; 49.10% adult child, 30.40% spouse |

Mixed: Cancer (37.22%) dementia (30.13%) No additional information on the remainder of the sample given. |

Caregiver sleep problems | Anxiety: GAD-7 |

| aWashington et al.(2018)86 USA |

To evaluate mediational relationships among burden experienced by hospice caregivers because of symptom management demands, caregivers’ coping responses and caregivers’ psychological distress. | Cross-sectional survey; 5 |

N = 228 Mean age, years (SD) = 61.35 (12.65) 80.5% female Carer–patient relationship not reported. |

Not reported | Anxiety: GAD-7 Depression: PHQ-9 |

|

| Wasner et al. (2013)87 Germany |

The personal experience-based approaches toward QoL, burden of care and psychological well-being of primary malignant brain tumour (PMBT) patients’ caregivers are examined. | Cross-sectional survey and interviews; 4 |

N = 23 Mean age, years (range) = 51 (34–80) 81.5% female; 70.4% spouse, 29.6% parents or adult child |

Primary malignant brain tumour (100%) | Patient disease burden Patient QoL Caregiver burden Caregiver gender |

Anxiety: HADS-A Depression: HADS-D QoL: SEIQoL-DW |

| Wilkes et al. (2018)88 USA |

To determine the extent to which burden related to patients’ symptom subtypes (emotional/psychological and physical) could predict informal hospice caregiver depression, and to illustrate the differences between caregivers who experience suicidal ideation and those who do not. | Cross-sectional survey; 7 |

N = 229 Mean age, years = 61.4 80.5% female; 43.8% adult child, 33.6% spouse/long term partner |

Mixed: heart disease, lung disease, cancer, dementia included. % composition not reported |

Patient symptoms | Depression: PHQ-9 |

| Wittenberg-Lyles et al. (2013)89 USA |

To investigate the features of oral literacy in recorded care planning sessions between informal caregivers and hospice team members as they related to the caregiving experience. | Cross-sectional secondary analysis; 5 |

N = 18 Mean age, years (range) = 64.5 (49–86) 78% female 94% white; 77% adult child, 11% spouse |

Not reported | Communication with care professionals | Anxiety: CSAI QoL: CQOL-R |

| Wittenberg-Lyles et al. (2014)90 USA |

To compare how caregivers in pairs (informal collective caregivers) experience anxiety and depression compared to solo caregivers and how these outcomes changed over time. Specifically, after controlling for social support and QoL, does being in a caregiver pair affect anxiety or depression? | Cross-sectional survey; 6 |

N = 304 Age 45.07% ≥ 61 years 47.04% 41–60 years 7.89% 21–40 years 76% female 91.4% white; 67.7% adult child, 24% spouse |

Not reported | Caregiver support | Anxiety: GAD-7 Depression: PHQ-10 |

Narrative summary of evidence

The evidence is synthesised under seven themes (Table 2). The order of themes does not imply importance. Rather, themes are presented in the same order across all syntheses in the project for consistency. The first six themes correspond with and provide quantitative evidence for all the themes identified in the qualitative synthesis (see https://arc-gm.nihr.ac.uk/carer-project-). Additionally, the quantitative evidence identified a further, broad theme of contextual factors. This included, for example, age, gender or socioeconomic status, which are factors that carers are perhaps less likely to consider in qualitative reflections on their own carer experience. Table 2 shows a summary of the bivariate evidence synthesised under each of the seven themes, along with the studies underpinning each theme and the corresponding overall quality assessment score per theme.

| Sub-themes | Studies underpinning overarching theme |

|---|---|

| Patient condition | Overall Quality Assessment Score (mean ± SD): 6.65 ± 1.78 |

| Patient condition Patient disease burden Patient disease severity Patient QoL Patient stage of disease Patient symptoms Patient treatment |

Aoun et al.;30 Boele et al.;34 Burridge et al.;35,a Burton et al.;36 Butow et al.;38,a Catt et al.;39,a Duimering et al.;40 Fasse et al.;43 Götze et al.;12 Govina et al.;47 Grant et al.;48,a Huang and McMillan;53 Ito and Tadaka;55 Jacobs et al.;56 Janda et al.;57 Janssen et al.;58 Kershaw et al.;61,a Kobayakawa et al.;62 Loggers and Prigerson;63 Malik et al.;64 McIlfatrick et al.;65 O’Hara et al.;70,a Ownsworth et al.;71 Perez-Ordonez et al.;73 Rivera et al.;75 Seekatz et al.;76 Siminoff et al.;78 Stutzki et al.;79,a Wadhwa et al.;83 Wasner et al.;87 Wilkes et al.88 |

| Impact of caring responsibilities | Overall Quality Assessment Score (mean ± SD): 5.57 ± 2.10 |

| Caregiver workload Caregiver lifestyle adjustments Caregiver sleeping hours Caregiver sleep problems |

Buscemi et al.;37 Catt et al.;39,a Duimering et al.;40 Flechl et al.;44 Govina et al.;47 Hoefman et al.;52 Hudson et al.;54 Ito and Tadaka55 Malik et al.;64 Perez-Ordonez et al.;73 Thielemann and Conner;80 Wadhwa et al.;83 Washington et al.;85 Wasner et al.87 |

| Relationships | Overall Quality Assessment Score (mean ± SD): 6.00 ± 2.20 |

| Family dynamics Quality of patient–caregiver relationship |

Bachner and Carmel;31 Exline et al.;42 Fasse et al.;43 Götze et al.;12 Hoefman et al.;52 Mollerberg et al.;66 Nissen et al.;69 Siminoff et al.78 |

| Finances | Overall Quality Assessment Score (mean ± SD): 5.83 ± 2.48 |

| Caregiver finances Caregiver mode of transport Impact on work |

Flechl et al.;44 Govina et al.;47 Hoefman et al.;52 Ito and Tadaka;55 Kobayakawa et al.;62 Wadhwa et al.83 |

| Carer internal processes | Overall Quality Assessment Score (mean ± SD): 6.23 ± 1.83 |

| Acceptance of patient condition Coping patterns Control over the care situation Self-efficacy or self-esteem Positive aspects of caregiving Pre-loss grief Preparedness for caregiving Previous experience of informal caregiving Time for respite |

Bachner et al.;33 Burton et al.;36 Fasse et al.;43 Govina et al.;47 Hampton et al.;49 Henriksson and Arestedt;51 Hoefman et al.;52 Hudson et al.;54 Ito and Tadaka;55 Kobayakawa et al.;62 McIlfatrick et al.;65 Nielsen et al.;67 Perez-Ordonez et al.73 |

| Support | Overall Quality Assessment Score (mean ± SD): 6.27 ± 1.44 |

| Accessible information Caregiver support Communication with care professionals Health professionals’ understanding of patient needs Quality of care Unmet needs in caregiver |

Areia et al.;15 Burton et al.;36 Buscemi et al.;37 Duimering et al.;40 Hannon et al.;50 Hoefman et al.;52 Ito and Tadaka;55 Janda et al.;57 Kobayakawa et al.;62 O’Hara et al.;70a Rivera et al.;75 Thielemann and Conner;80 Wadhwa et al.;83 Wittenberg-Lyles et al.;89 Wittenberg-Lyles et al.90 |

| Contextual factors | Overall Quality Assessment Score (mean ± SD): 6.63 ± 2.22 |

| Caregiver age, education or gender Caregiver employment, health or marital status Caregiver ethnicity Caregiver socio economic status Composition of household Length of patient–caregiver relationship Patient age, educational level or gender Patient lives with caregiver Relationship to patient Rural location |

Burton et al.;36 Butow et al.;38,a Catt et al.;39,a Duimering et al.;40 Fasse et al.;43 Flechl et al.;44 Govina et al.;47 Ito and Tadaka;55 Janda et al.;57 Kershaw et al.;61,a Kobayakawa et al.;62 McIlfatrick et al.;65 Rivera et al.;75 Thielemann and Conner;80 Wadhwa et al.;83 Wasner et al.87 |

Report Supplementary Material 1 shows the total number of bivariate investigations (tests for relationships both within individual studies and across studies) which found a statistically significant positive, a significant negative or a non-significant relationship between a factor and a carer mental health outcome (anxiety, depression, distress or QoL). A ‘positive’ relationship means that the factor is statistically associated with improved mental health, that is lower anxiety, depression, distress or better QoL. Similarly, a ‘negative’ relationship means a factor is statistically associated with higher anxiety, depression, distress or worse QoL. Results for the outcomes of anxiety, depression, distress or QoL have been grouped in this table to provide a general overview of factors that may have a positive or negative impact on carer mental health. Report Supplementary Material 2 shows bivariate findings reported for each type of outcome separately, along with references to the research studies that looked at each individual factor and identified a positive impact, negative impact or no change on carer mental health for each different type of mental health outcome (anxiety, depression, distress or QoL).

Studies that only reported multivariate analysis results are briefly summarised separately under each theme. Their reporting is more complex because the significance of each factor in this case is highly dependent on the other factors considered in the same analysis (and their collinearity) and with the variable set varying widely from study to study, making comparisons difficult. However, it is important that these results are also reported. For consistency, we report the results for the final model presented. Further, we only report significant results, as the volume of non-significant relationships in this part of the literature was large and their presentation became unwieldy with little gain in information for the reader.

Narrative summary of themes

Patient condition

The largest body of research relates to patient condition: 31 studies (see Table 2) reported on 95 bivariate investigations across all four mental health outcomes. Individual factors that contribute to this theme include the patient’s diagnosis, patient disease burden (i.e. physical and cognitive functioning, QoL, stage or rate of decline, physical and psychological symptoms) and treatment.

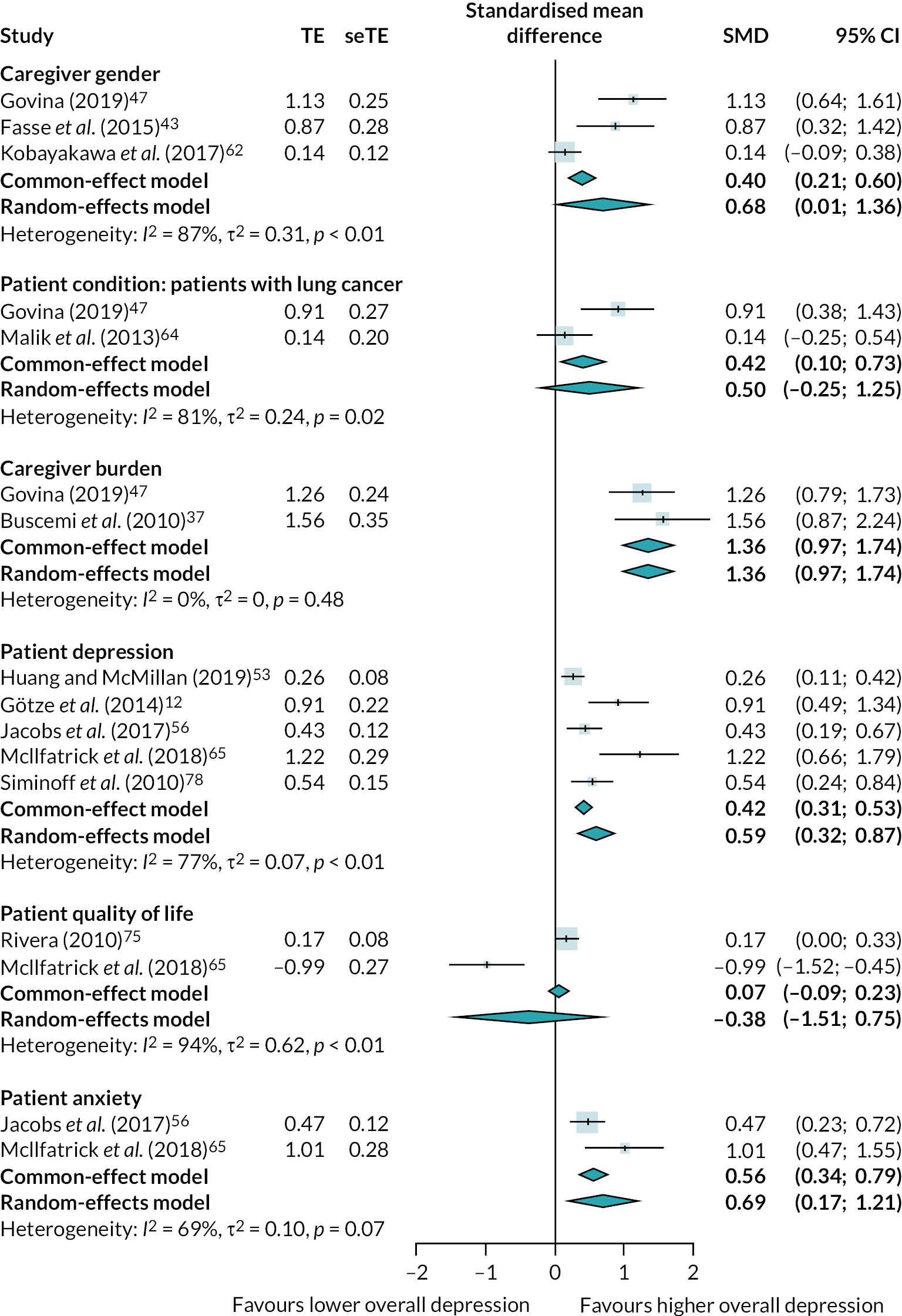

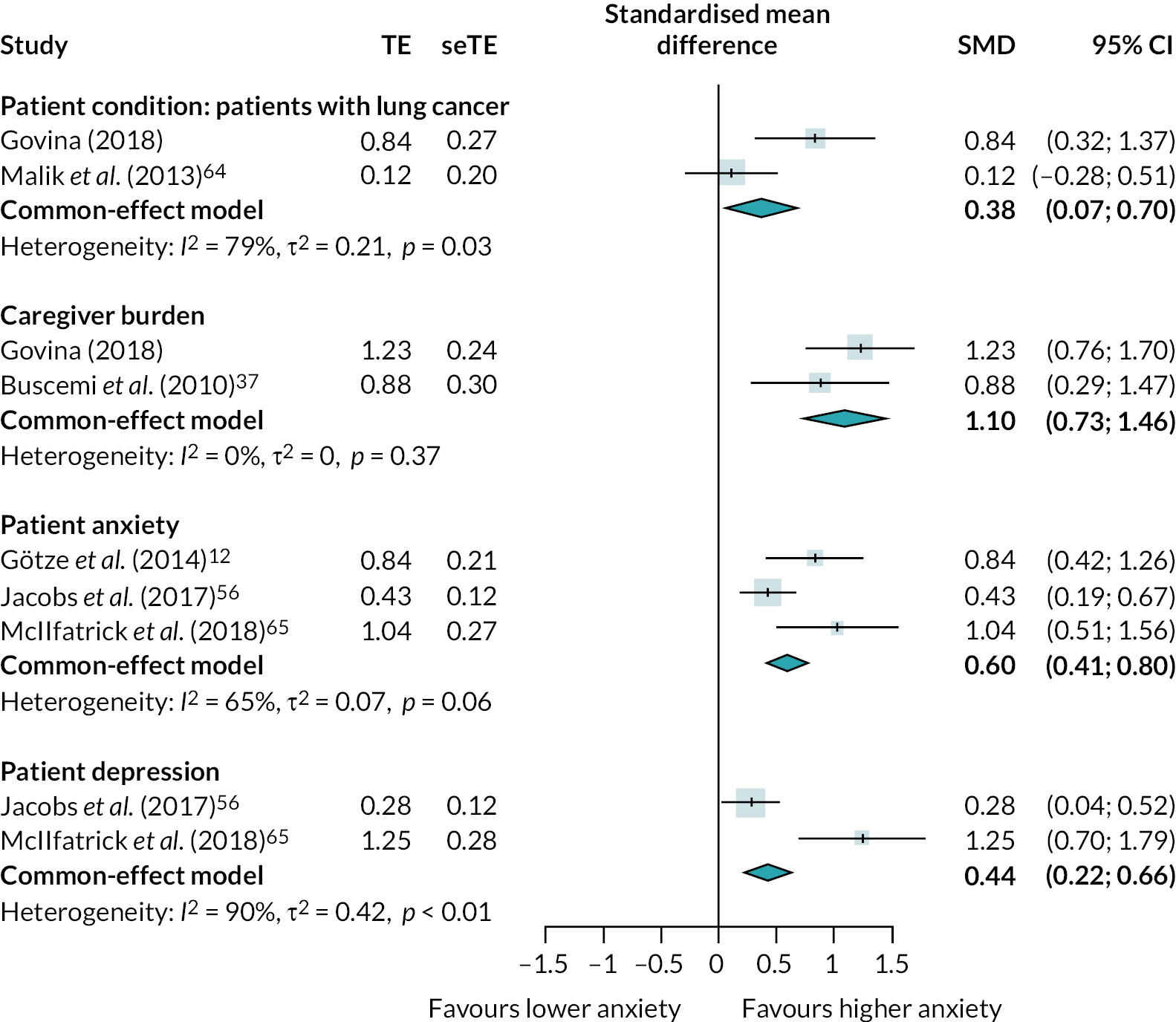

Some studies indicated that a diagnosis of primary brain cancer (one investigation30), rare cancers (one investigation63) or lung cancer (two investigations47) is related to worse carer mental health compared to other cancer diagnoses. However, one investigation comparing rare cancers with other cancers found no difference,63 and three investigations considering a range of cancers, including lung and brain, found no difference between cancer diagnoses. 55,61,75 Further, no differences were reported in three investigations comparing lung cancer with heart failure (HF). 64 One investigation found patient diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to be associated with worse carer mental health when compared with chronic heart failure (CHF) or renal failure. 58 Findings on diagnosis, however, are likely to be highly dependent on what the comparators are, and whether two large comparison groups are considered or a range of smaller size diagnostic groups. Further, diagnosis in itself may mean little without added knowledge of patient stage or disease burden.

Three investigations found a relationship between greater patient functional impairment and worse carer mental health. 40,71,73 However, a further nine investigations of functional impairment showed no association. 36,55,75,83,87 There was no relationship identified between patient cognitive impairment and carer mental health (three investigations87).

Three investigations indicated that a more advanced patient stage of disease is related to worse carer mental health,38,48,79 while a further four investigations found no relationship with carer mental health. 35,38,48 These findings include factors related to patient disease trajectory and patient rate of decline, so may tell us little without considering the impact of these factors on patient stage of disease.

Two investigations into patient disease severity found no relationship with carer mental health. 36

In six investigations, better patient general QoL was related to significantly better carer mental health. 57,65,70,83 In a seventh investigation, general QoL was reported to be associated with carer mental health, although the direction of the relationship was not clarified. 75 One investigation found that better patient psychological QoL was also associated with better carer mental health. 34 Three investigations found no significant relationship, however. 87

Two investigations found patients’ overall symptoms to relate to worse carer mental health,70,88 but one of these incorporated an element of the carer’s stress into the patient symptom measure, thus making an association with mental health outcomes more likely. 88 A third investigation found no relationship. 55 Physical symptoms show a mixed picture: greater drowsiness, fatigue and pain were related to worse carer mental health,83 whereas loss of appetite, breathlessness and nausea showed no relationship (one investigation each per symptom). 83

Patients’ psychological symptoms appear to show a consistent relationship with carer mental health. Higher patient anxiety and depression were related to worse carer mental health in 812,56,57,65,83 and 10 investigations,12,53,56,57,65,78,83 respectively. Only three investigations of patient depression found no relationship. 53,70,75 Worse patient global distress,75 psychological and psychiatric symptoms62 also related to worse carer mental health (one investigation each). In contrast, one investigation of patient sense of well-being showed no association. 83

Regarding patient treatment, carers had worse mental health if the patient had been admitted to hospital or long-term care within the previous 7 days,40 had received no cancer therapy83 and no surgery47 (one investigation each), which could imply, respectively, deterioration or that ‘nothing could be done’. However, other investigations found no association with receiving no surgery47 (one investigation), with receipt of chemotherapy47 (two investigations) or medical care provided55 (one investigation). Other treatment variables showing no relationships were patients awaiting a new line of treatment,83 frequent visits to emergency outpatient clinics,62 type of oncology follow-up39 and patient receipt of specialist palliative care76 (one investigation each).

Some corresponding findings were reported in studies only reporting multivariate analyses. Patient QoL41 and better functioning45 were related to better carer QoL, and patients’ need for help at night60 and problems sleeping82 to worse carer mental health. A perceived lower life expectancy was associated with worse carer emotional QoL81 and worse patient mental health was related to worse carer mental health. 68,77 There was also worse carer depression where patients had worse social well-being, patients used more emotional support seeking, less acceptance coping and perceived that the primary goal of their cancer treatment was ‘to cure my cancer’,68 whereas patients’ use of less emotional support seeking was associated with higher carer anxiety. 68

Impact of caring responsibilities

A smaller body of research, based on 14 studies (see Table 2) and 36 bivariate investigations across all four mental health outcomes, concerns the impact of caregiving in terms of life changes and care demands, a construct similar to objective burden. Where studies investigated impact using carer burden measures, we need to exercise some caution, due to the wide variety of these measures, some of which incorporate emotional impact. In our selection and synthesis, we therefore sought to avoid studies using burden measures that essentially measure subjective burden or psychological impact, as these may in effect be synonymous with the outcomes we were investigating.

Studies consistently indicated that the impact of caring responsibilities is associated with worse mental health. Five investigations found that negative changes to carers’ lives from caregiving were associated with worse mental health (using Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale). 37,47 Two investigations each found that difficulty of caregiving tasks and time spent on tasks were also related to worse health [using Oberst Caregiving Burden Score (OCBS)-D and OCBS-T, respectively]. 47 One investigation found that the impact on carers’ schedules (using the Caregiver Reaction Assessment) had a similar relationship with mental health. 54 In terms of overall burden, three investigations using the Zarit Burden Inventory,64 three using the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers87 and one using the Caregiver Strain Index,73 all found increased burden to be associated with worsening mental health.

Studies have also found that making greater lifestyle adjustments,39 greater demands on the carer,80 assistance with activities of daily living40 and medical tasks,40 number of days spent caregiving,83 physical strain from caregiving52 and sleep problems85 relate to worse mental health (one investigation each), although one investigation found no relationship with carer sleeping hours. 55

Other demands on carer time52 or childcare responsibilities39 may relate to worse mental health, found by one investigation each. However, two further investigations that considered if carers had children of minor age47 and one whether they cared for others83 found no relationship. No relationships with mental health were found in one investigation of the number of caregiving hours per week80 and three considering duration of care. 44,55,80

Studies only reporting multivariate analyses also found that higher carer burden was associated with worse QoL (Caregiver Burden Inventory)45 and mental health (Caregiving Burden Interview – Zarit59; Caregiver Reaction Assessment74), and similarly that more impairment to daily life was associated with worse mental health. 59

Relationships

There is evidence that the family dynamics and the quality of the carer-patient relationship are related to carer mental health, although this is based on a relatively small number of studies (eight) (see Table 2) reporting only 16 bivariate investigations across all four mental health outcomes.

Two investigations within the same study found better carer mental health where carers felt that the family had high ability to cope with stressors (measured by Family Sense of Coherence Scale). 66 Investigations in another study using the Family Environment Scale found carer mental health to be worse both when the patient and when the carer perceived there to be low family cohesion (i.e. low commitment, help and support that family members give to one another);78 low family expressiveness (i.e. low encouragement of direct expression feelings);78 and high family conflict (i.e. openly expressed anger and conflict). 78 Correspondingly, one further study also reported worse carer mental health both when the patient and when the carer perceived there to be unresolved family conflicts,42 whereas another found better mental health when supportiveness of family relationships was high. 69

Looking specifically at the patient-carer relationship, one study found that carer dissatisfaction with the relationship was associated with worse carer mental health,12 whereas a second found no relationship in terms of the carer getting on with the patient. 52 Good carer communication with the patient about their illness and approaching death was related to better carer mental health. 31

Finally, one study found worse carer mental health where the carer had an insecure-anxious attachment style,43 whereas no relationship was found if they had an insecure-avoidant attachment style. 43

Studies only reporting multivariate analyses have also found that carers with good family relationships had better mental health,46 and one study considering mediators concluded that carers with supportive relationships had better mental health through decreased carer burden. 74

Finances

Although there were relatively few studies considering the role of financial factors (six) and only eight bivariate investigations relating to three of the four mental health outcomes (QoL, anxiety and depression), the majority of studies indicate a relationship between finances and carer mental health.

Having a sufficient family budget was related to better carer mental health (one study),55 whereas having financial difficulties due to the patient’s disease44 or to providing informal care52 were related to worse carer mental health (one study each). Changes to work situations in terms of reduction, change or ending of work (one study)55 were also associated with worse mental health.

However, level of income in itself (two studies)62,83 showed no relationship. Having a private car as a means of transport was, perhaps surprisingly, related to worse mental health in one investigation, but showed no relationship with another mental health measure within the same study. 47 Level of income or possessions may in themselves be less informative; what matters may be whether they provide sufficient or insufficient resources during caregiving. Findings may also depend on the populations studied. For example, a study population in which everyone is generally affluent may show different patterns of association with carer mental health compared with study populations with a range of incomes.

Carer internal processes

Thirteen studies (see Table 2) reporting 36 bivariate investigations relating to QoL, anxiety and depression have considered how carers’ internal, psychological processes and coping strategies are related to their mental health, and they have investigated a wide range of variables.

In terms of coping strategies, the picture is quite mixed and mostly showing little association with mental health, which may reflect the challenge of using questionnaires to ask carers about dispositions to cope with hypothetical situations. Difficulty accepting the patient’s condition62 or ‘dysfunctional’ coping strategies73 (including lack of acceptance and avoidance) were associated with worse mental health in one study each. Worse mental health was also found in relation to disengagement through substance misuse in one investigation. 43 However, other investigations considering denial (one investigation),43 cognitive avoidance (two investigations)36 or mental disengagement (one investigation)43 found no relationship.

Being optimistic was associated with better mental health (one study),54 whereas using humour,43 having a ‘fighting spirit’ coping style36 or using emotion-focused strategies73 (e.g. seeking a positive outlook and acceptance) showed no relationship (one study each). Having a secular outlook was related to better mental health in one study,33 while religious coping showed no significant association in a second. 43

Suppression of competing activities (staying focused on the problem) has been found to relate to worse mental health (one study). 43 Conversely, problem-focused coping strategies73 or active coping to solve a problem43 was found to be unrelated to mental health (one study each).

Finally, in terms of coping strategies, seeking emotional social support43 or venting of emotions43 was associated with worse mental health in one study, although it may be important to consider here which is cause and which is effect. Seeking information support was unrelated to mental health in the same study. 43

Three investigations found that carer self-efficacy (confidence in one’s ability to carry out a task) was related to better carer mental health. 49,55 Conversely, if carers felt helpless or guilty because they could do nothing for the patient, they had worse mental health (one investigation). 62 However, carers’ sense of control over the care situation was not found to relate to mental health (one investigation). 52

Two investigations found that preparedness for caregiving was also associated with better health,51,65 although one investigation found no relationship. 51 Further, if carers had provided care to a loved one in the past, they reported worse health (two investigations),47 indicating that the experience gained from past caregiving may not be protective.

Pre-loss grief67 and, perhaps surprisingly, higher carer self-esteem54 were related to worse mental health (one study each), whereas fulfilment from caring and being happy to care (both investigated in the same study)52 showed no relationship.

Having enough time for oneself was associated with better mental health in one study,52 but activities outside caring measured within the same study showed no association. 52

Studies that reported only multivariate analyses have also found higher carer preparedness to relate to better QoL45 and also report mixed results for coping. Carer meaning-based coping was associated with better QoL,41 and carers’ use of escape/avoidance coping with worse mental health. 86 Active coping was in fact associated with worse mental health, and substance abuse with better mental health in a further study. 59 Carers with stronger religious/spiritual beliefs had better mental health. 59 Among studies considering coping strategies as mediators, Washington et al. 86 concluded that the relationship between patients’ psychological symptoms (reported above) and carers’ mental health was partially explained by carers’ increased use of escape/avoidance coping, whereas Ellis et al. 41 reported that the number of carers’ chronic conditions had an indirect negative effect on their QoL mediated by meaning-based coping.

Support

The third largest body of research has been conducted on support, based on 15 studies (see Table 2) reporting on 42 bivariate investigations across all four mental health outcomes.

Accessible information for patients and for carers are both related to better carer mental health (one study). 55

In terms of support for carers themselves, there is some evidence that the presence of informal support is positive. Carers who have social support from family and friends (two studies),52,80 who have a sub-caregiver (one study)55 and who are satisfied with physical, emotional and informational support (one study)75 have better mental health. However, no relationship with mental health was found for carers who were in receipt of informal help (one investigation),83 availability of someone to stay with the patient (one investigation),62 who worked in pairs (two investigations)90 or where support was perceived (two investigations). 36

In terms of formal support for carers, one study found better mental health for carers who received support services55 or requested home care for the patient. 55 However, other studies have found no relationship for formal40,83 or institutional help. 52 One investigation within one study found that carers who had professional psychological help, in fact, had worse health, while two further investigations found no relationship. 57 We need to consider what may be cause or effect here, as carers with higher distress may be more likely to seek psychological help. Carers interested in accessing future support services,40 and those who received no help from home-visit practitioners in managing symptoms,62 had worse mental health (one study each). Type and frequency of formal support services showed no association in one study. 55

Unmet needs in the carer appears to be important. Three investigations relating to carers’ unmet psychological, social and physical needs in one study37 and one investigation considering number of carers’ unmet needs by health professionals in another study15 found that they were related to worse carer mental health.

Features of communication with practitioners during care planning sessions made little difference. An investigation in one study found that a faster dialogue pace was related to worse carer mental health,89 whereas another investigation found no relationship. 89 No associations were found for language complexity, length of interaction or the team taking turns to speak. 89

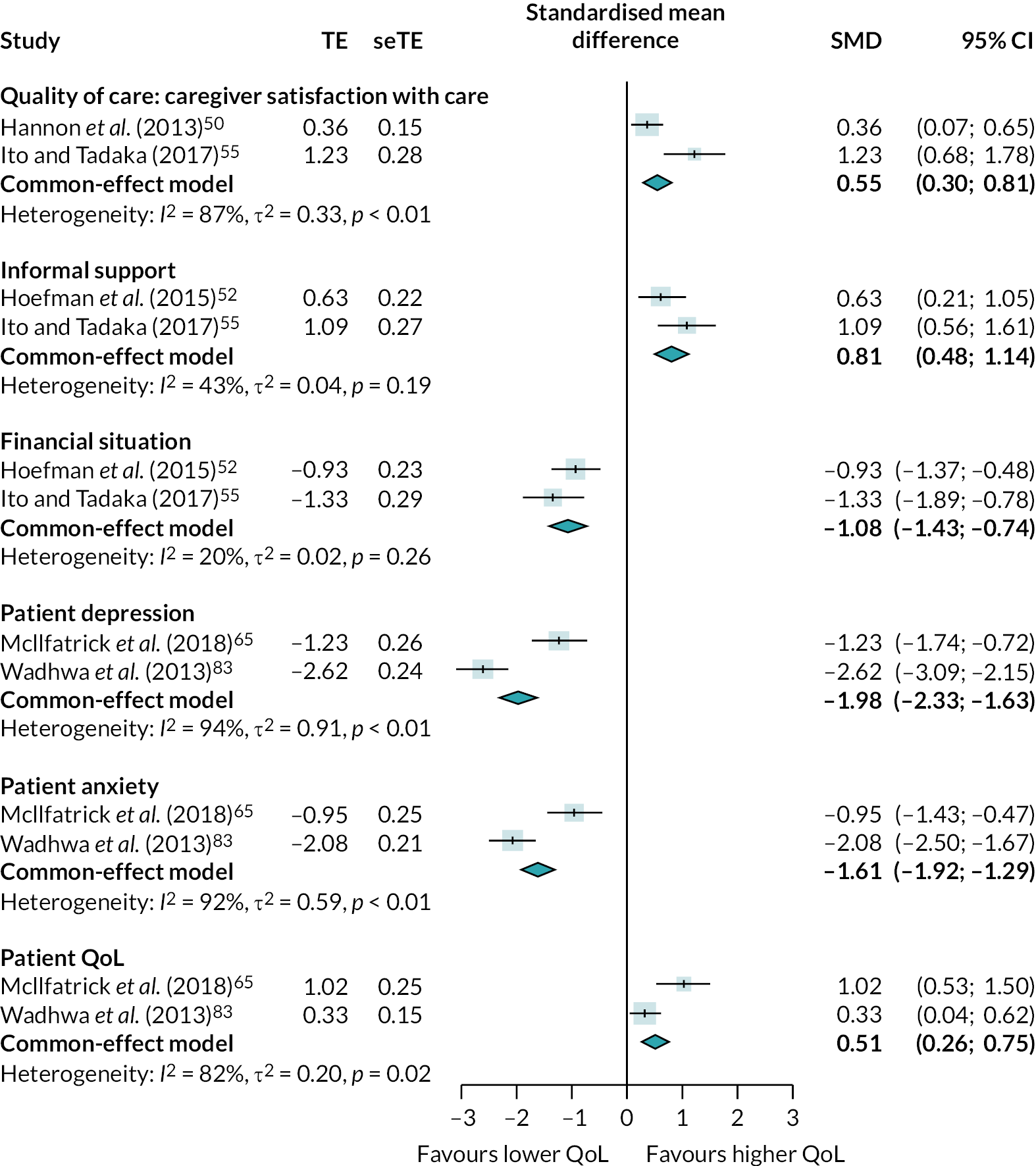

Carer satisfaction with patient care (two studies)50,55 and patient satisfaction with care (one study)50 were associated with better carer mental health, while carer perception of problems with patient unmet needs was related to worse mental health (one study). 70 Perhaps counterintuitively, carers in the same study, who perceived more problems with the patient’s emotional and spiritual support, had better mental health. 70 No associations were found for practitioners’ lack of understanding of patient symptom severity62 or whether services received were considered necessary by the carer55 (one study each).

One study reporting only multivariate analysis found that carers with good healthcare providers had better mental health. 46

Contextual factors