Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in July 2019. This article began editorial review in November 2021 and was accepted for publication in January 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Health and Social Care Delivery Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Bayliss et al. This work was produced by Bayliss et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Bayliss et al.

Background and introduction

Informal carers or family carers (‘carers’ for short) are defined as ‘lay people in a close supportive role who share in the illness experience of the patient and who undertake vital care work and emotion management’. 1 When we refer to family in this report we use a broad definition which includes not only those related through partnerships, birth and adoption, but also others who have strong emotional and social bonds with a person, such as friends and neighbours.

An estimated 500,000 family carers provide end-of-life (EOL) care in England annually. 2 These carers have been found to provide a median of 70 hours of care per week in the final months of life,3 and are a main factor in sustaining care at home at the EOL. 4,5 This is likely to reduce acute inpatient care costs and pressures on care-home beds. Family carers therefore provide substantial benefit for patient care and the NHS.

Caregiving for patients at the EOL has substantial negative impacts on carers’ own health, especially their mental health. 6 The reported prevalence of carer anxiety and depression during palliative care is 34–72%7–12 and 39–69%,11–14 respectively. However, prevalence of clinically significant carer psychological morbidity during patients’ final three months was found to be as high as 83% in a recent national survey. 6 These high levels of psychological morbidity arguably represent a considerable public health problem with likely longer-term effects on carers themselves; carers’ pre-bereavement mental health is a main predictor of post-bereavement mental health. 15,16 Additionally, if carers become unable to cope, this is likely to impact negatively on the quality or continuation of patient care and may precipitate hospital or care-home admissions.

Research shows there is large individual variation in the level of carer psychological morbidity from EOL caregiving. Understanding what may cause this variation can help us identify those at risk and enable improved design of interventions that may help. Funk et al. 17 conducted a comprehensive review of qualitative research into family caregiving at the EOL published between 1998 and 2008 and identified a range of factors that may contribute to carer stress and challenges. These included patient diagnosis, deterioration and suffering; physical demands of caregiving and sleep disturbances; a lack of preparedness for caregiving; social isolation; carer lifestyle changes and disruption, time pressures, and impacts on finances and employment. Conversely, factors that may improve the caregiving experience included good relationships with the care recipient and other family members; good informal support including social networks and shared caregiving; and good formal support, including adequate, competent, flexible provision that is coordinated, consistent, organised and accessible, with good communication, advice and consistent information, delivered with a caring attitude. The review also noted how caregiving experiences are shaped by the broader context, including ethnicity and cultural and normative ideas of family care and death at home. Although indicating the scope of potential factors, Funk et al.’s17 review did not specifically focus on what affected carers’ mental health. We need to gain a clearer, systematic picture of the range of factors affecting carer psychological morbidity to inform a comprehensive, rather than piecemeal, strategy for improving carers’ mental health.

The review of qualitative research reported here is part of a larger project to synthesise the qualitative and quantitative literature on what may affect carers’ psychological morbidity, and to communicate these findings to the stakeholders most able to act on this information. This qualitative synthesis formed the starting point of this work, as it is important to capture potential factors contributing to psychological morbidity as perceived by those with lived experience and ensure the voice of carers themselves is heard. Others, including practitioners, may have more limited insight into the factors that carers themselves see as critical to their well-being. 18

The review is timely as our reliance on EOL carers is likely to increase in the future, given projected demographic increases in number of deaths,19 people over 85 and those with life-limiting illness20 and dependency in their final years. 21 Health and social care services will struggle to meet the increasing related future demands. We need to recognise carers as a vital resource and provide better initiatives and interventions to support carers and prevent adverse health outcomes from caregiving and subsequent negative consequences.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of the project is to help reduce psychological morbidity among carers during EOL care by conducting a mixed-methods evidence synthesis of factors that increase or decrease carer psychological morbidity during EOL caregiving by:

-

drawing on observational quantitative studies, qualitative studies and intervention studies

-

integrating our findings into a coherent framework of factors, and

-

translating findings into accessible, bespoke information for key stakeholders to help them better target efforts to reduce carer psychological morbidity.

The objective of the current review is to conduct a comprehensive synthesis of qualitative studies of carer perspectives on factors affecting their psychological morbidity during EOL care, where morbidity is mainly defined as anxiety, depression, distress and reduced quality of life, but also includes terms more commonly used by carers such as ‘mental health’ or ‘well-being’.

The observational quantitative and intervention syntheses and integration of findings into a wider framework are reported elsewhere. 22,23 Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) contributions to the project as a whole will be further detailed in a separate report.

Method

This was a thematic synthesis of factors affecting carer psychological morbidity, followed by a best-fit framework synthesis, informed by principles of meta-ethnography. PPI in the form of a carer Review Advisory Panel (RAP) helped shape the search, thematic analysis and results framework.

The reported method represents some simplification of the search, selection and extraction process from the original protocol due to the volume of literature and time pressures, including limitation to 2009–19, fewer databases, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) country and English or Scandinavian publications only, exclusion of dissertations and grey literature, and single screening and extraction once consistency was established. This was in consultation with the project’s external Study Steering Committee and with notification to NIHR HS&DR.

Search strategy

The carer RAP consisted of five carer members and a carer RAP chair. The RAP were given an introduction to review methods in order that they could review the search strategy. They were also asked to comment on the suitability of definitions and inclusion and exclusion criteria, to ensure these were most likely to capture their experiences.

Following piloting, searches were completed in December 2019, using Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms relevant to informal carers supplemented with string carer terms including variations on ‘family caregiver’ and ‘informal carer’. These were combined with MeSH terms for ‘palliative care’ supplemented by string terms ‘end-of-life’ and ‘end of life’, as well as the MeSH term ‘qualitative research’ supplemented by string term ‘qualitative’ when searching for Cochrane Qualitative Reviews. The search strategy can be viewed in full in Appendix 1.

The literature search was performed using MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, Social Science Citation Index, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Cochrane Qualitative Reviews. Only peer-reviewed empirical papers published in academic journals between 1 January 2009 and 24 November 2019 were included and the search was limited to articles from OECD countries published in English and Scandinavian languages, which would not require further translation (given team fluency).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Box 1 describes the inclusion and exclusion criteria for all studies in the project.

Studies had to fall within the following definitions of Population, Factor, Outcome and Setting:

-

Population Lay adults who were supporting and caring for a patient who was at EOL. EOL was conceptualised as a palliative, terminal, or otherwise ‘advanced’ or ‘end-stage’ phase of care where the patient was likely to die within a year. Articles not giving enough information to ascertain disease stage/palliative phase were excluded.

-

Factor Any factor which may have affected psychological morbidity in carers.

-

Outcome All studies which described psychological morbidity were reviewed. Psychological morbidity included outcomes such as anxiety, depression, distress, quality of life and outcomes that carer advisers considered to be important.

-

Setting Care had to be predominantly provided in a home-care setting. Papers which reported that most care occurred while the patient was in a facility (i.e. care home, hospital) were excluded.

Additionally, studies included for the qualitative synthesis had to have as their aim to investigate psychological morbidity in informal carers from the perspectives of EOL carers themselves. Qualitative studies were defined as those that collected data using specific qualitative techniques such as unstructured interviews, semi-structured interviews or focus groups, either as stand-alone methodology or as a discrete part of a larger mixed-method study.

Screening and selection of studies

Potentially eligible records for the qualitative, observational and intervention reviews were imported to EndNote and duplicate references identified and deleted. Ten per cent of both titles/abstracts and full texts were screened independently by two reviewers. Over 90% agreement was established in each case, indicating that no further modifications to the inclusion and exclusion criteria were required. Subsequent studies on titles/abstracts and full texts were screened by one reviewer.

Context and quality appraisal

KB collated data on the details of each qualitative study and entered this into an Excel spreadsheet. A quality appraisal of each study was completed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Studies checklist. 24 Ten per cent of papers were reviewed by both KB and GG for extraction of study details and quality appraisal. More than 90% agreement was achieved and differences were discussed. KB then appraised the remaining papers independently. Studies were given a score of 1 for each criterion met and 0 if not met or not possible to tell, with a maximum total score of 10. No papers were removed as a result of the quality assessment. See Table 1 for an overview of study characteristics and CASP score.

| Reference and country | Study aims | Participants (number; demographics; carer–patient relationship) | Patient condition | Methods (data collection and analysis) | Quality appraisal (CASP score, possible range 2–10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil et al. (2010)31 Canada |

Examine how the comprehensive nature of the Stress Process Model could elucidate on the stressors associated with caring for a palliative cancer patient | N = 12 Mean age = 64 years (range 46–84 years) 8 females, 4 males; 10 spouse, 2 daughter |

Cancer | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Chi et al. (2018)32 USA |

Explore the challenges and needs of family caregivers of adults with advanced heart failure receiving hospice care in the home | N = 28 Mean age = 59.65 years 22 females, 6 males, 25 white; 17 child, 3 spouse/partner |

Heart failure | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Duggleby et al. (2010)33 Canada |

- Describe the experience of significant transitions experienced by older rural persons who were receiving palliative home care and their families - Develop a substantive theory of transitions in this population |

N = 10 Mean age = 62.0 years 8 females, 2 males All family members |

Cancer | Open-ended interviews Constructivist grounded theory |

10 |

| Duggleby et al. (2013)34 Canada |

Examine the effects of the Living with Hope Program in rural women caring for persons with advanced cancer and to model potential mechanisms through which changes occurred | N = 36 (all female) Mean age = 59 years 33 white; 33 spouse/partners, 3 daughters |

Cancer | Journaling as part of time-series embedded mixed method design Narrative analysis |

10 |

| Epiphaniou et al. (2012)35 UK |

Identify existing coping and support mechanisms among informal cancer caregivers in order to inform intervention development | N = 20 Mean age = 55.5 years (range 25–79 years) 11 females, 9 males 16 white; 12 spouse/partner, 3 child, 3 friend, 1 parent, 1 other |

Cancer | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Farquhar et al. (2017)36 UK |

Identify carers’ educational needs (including what they wanted to learn about) and explore differences by diagnostic group in order to inform an educational intervention for carers of patients with breathlessness in advanced disease | N = 25; Mean age = 68 years (range 42–84 years) 21 females, 4 males; 20 spouses, 4 children, 1 friend |

COPD & Cancer | In-depth interviews; Framework analysis |

10 |

| Ferrell et al. (2018)37 USA |

To better understand the quality-of-life needs of the family caregiver population, particularly those who encounter financial strain related to patients’ cancer and treatment | N = 20; Age range = 28–80 years 14 females, 6 males 11 white, 6 Hispanic, 2 black, 1 other; carer-patient relationship not reported |

Cancer | Semi-structured interviews; Thematic content analysis |

9 |

| Fitzsimons et al. (2019)38 UK & Ireland |

Explore caregivers experience when caring for a loved one with advanced heart failure at the end of life and to identify any unmet psychosocial needs | N = 30 Age > 18 years 25 females, 5 males; 15 spouse/partners, 8 son/daughters, 5 parents, 1 sister, 1 niece/nephew |

Advanced heart failure | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Galvin et al. (2016)39 UK |

Describe an informal caregiver cohort, their subjective assessment of burden and difficulties experienced as a result of providing care to people with ALS | N = 81 Mean age = 54.9 years (range 25–76 years) 57 females, 24 males 58 spouse/partners, 18 son/daughters, 2 parents, 2 siblings, 1 friend |

ALS | Semi structured interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Heidenreich et al. (2014)40 Australia |

- Explore the influence of Chinese cultural norms and immigration on the experience of immigrant women of Chinese ancestry caring for a terminally ill family member at home in Sydney - Identify factors that may present access barriers to palliative care support |

N = 5 (all female and of Chinese ancestry) Age range = 50–65 years 3 spouses, 1 daughter, 1 daughter in law |

Terminal illness, specific condition not reported | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Hynes et al. (2012)41 UK |

Explore the experiences of informal caregivers providing care in the home to a family member with COPD | N = 11 Age range = 20–79 years 9 females, 2 males; 4 spouses, 7 daughters |

COPD | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Kitko et al. (2015)42 USA |

Determine the prevalence of incongruence between heart failure patient–caregiver dyads, areas of incongruence, and the impact on individuals in the dyadic relationship | N = 47 Mean age = 68.1 years (range 28–88 years) 39 females, 8 males; carer–patient relationship not reported |

Advanced heart failure | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

9 |

| Kutner et al. (2009)43 USA |

Understand caregivers’ needs to inform the feasibility, structure, and content of a telephone-based counselling intervention | N = 36 Mean age = 63 years (range 33–83 years) 31 females, 5 males 35 white 19 spouse/partners, 15 children |

Not reported | Interviews and focus groups Constant comparative approach |

8 |

| McCurry et al. (2013)44 USA |

Explore the decisions made by informal caregivers of multiple sclerosis care recipients and the resources they use to inform those decisions | N = 6 (all white) Age range = 48–76 years 3 females, 3 males 5 spouse/partners, 1 friend |

Multiple sclerosis | In-depth interviews Thematic content analysis |

10 |

| McDonald et al. (2018)45 Canada |

Conceptualise quality of life of caregivers from their own perspective and to explore differences in themes between those who did or did not receive an early palliative care intervention | N = 23 Mean age = 60.5 years (range 38–71 years) 16 females, 7 males 19 spouse/partners, 3 son/daughters, 1 other family |

Cancer | Semi-structured interviews Grounded theory |

9 |

| McIlfatrick et al. (2018)46 UK & Ireland |

Identify psychosocial factors associated with caregiver burden and evaluate the support needs of caregivers in advanced heart failure | N = 30 (qualitative interview stage) Aged > 18 years 15 females majority were spouses (n not reported) |

Advanced heart failure | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| McLaughlin et al. (2011)47 UK |

Explore the caring experience of relatives with Parkinson’s disease | N = 26 (all spouses) 21 aged > 55 years 17 females, 9 males |

Parkinson’s disease | Semi-structured interviews Content analysis |

10 |

| McPherson et al. (2013)48 Canada |

Explore and describe the cancer pain perceptions and experiences of older adults with advanced cancer and their family caregivers | N = 15 Mean age = 70 years (range 34–86 years) 11 females, 4 males 11 partners, 3 parents/adult children, 1 sibling |

Advanced cancer (stage III or IV) | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

9 |

| Moore et al. (2017)49 UK |

Understand the experiences of carers during advanced dementia exploring the links between mental health and experiences of EOL care | N = 35 Mean age = 62 years (range 54–69 years) 24 females, 9 males; 24 children, 7 spouses, 4 other relatives |

Dementia | Semi structured interviews Thematic analysis |

9 |

| Murray et al. (2010)50 UK |

Assess if family caregivers of patients with lung cancer experience the patterns of social, psychological and spiritual well-being and distress typical of the patient, from diagnosis to death | N = 19 11 females, 8 males 17 spouses, 2 daughters |

Lung cancer | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Parker Oliver et al. (2017)51 USA |

Understand the challenges and coping strategies used by hospice caregivers as they care for their family members | N = 52 Mean age = 62.1 years 40 females, 12 males 47 white, 4 Asian, 1 multiracial |

Mixed (including cancer, dementia, cardiovascular disease) | Telephone interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Penman (2018)52 Australia |

Explore the experience of depression among palliative care clients and caregivers, describe the strategies they use in coping with depression, and clarify the role of spirituality in preventing and/or overcoming depression | N = 14 Mean age = 59 years (range 34–77 years) 10 females, 4 males 7 white, 7 Asian carer–patient relationship not reported |

Cancer (primary diagnosis) | In-depth non-structured interviews Phenomenology |

10 |

| Phongtankuel et al. (2019)53 USA |

Ascertain the prevalence and nature of, as well as factors associated with crises in the home hospice setting as reported by family caregivers | N = 183 Aged > 18 years 144 females, 39 males 90 white, 29 black, 35 Hispanic, 17 Asian, 12 other/mixed/undisclosed |

Cancer | Semi-structured interviews Content analysis |

9 |

| Pusa et al. (2012)54 Sweden |

Illuminate the meanings of significant others’ lived experiences of their situation from diagnosis through and after the death of a family member as a consequence of inoperable lung cancer | N = 11 Mean age = 57.9 years (range 35–79 years) 9 females, 2 males; 7 partners, 3 children, 1 other family |

Lung cancer | Narrative interviews Phenomenological hermeneutic approach |

10 |

| Shanmugasundaram (2015)55 Australia |

Explore the needs of the family caregivers of Indians receiving palliative care services in Australia | N = 6 (all Indian) Age range = 47–68 years 4 females, 2 males 4 spouses, 2 daughters in law |

Advanced cancer and cerebral vascular accidents | Semi-structured interviews Constructivist grounded theory |

10 |

| Ugalde et al. (2012)56 Australia |

Explore how caregivers view their role and the impact of their caregiving | N = 17 Aged 18–70 years 9 females, 8 males 13 spouse/partners, 3 daughters, 1 sister |

Advanced cancer | Semi-structured interviews Grounded theory |

9 |

| Villalobos et al. (2018)57 Germany |

Explore the patients’ and family-caregivers’ needs and preferences regarding communication, quality of life and care over the trajectory of disease | N = 9 Mean age = 54 years (range 51–66 years) 6 females, 3 males 6 spouses, 1 brother, 2 son/daughters |

Advanced lung cancer | Semi-structured interviews Qualitative content analysis |

9 |

| Waldrop and Meeker (2011)58 USA |

Explore caregivers’ perceptions of the crises that preceded and were resolved by relocation during EOL care | N = 37 Mean age = 56.5 years (range 26–83 years) 30 females, 7 males 8 spouse/partners, 18 daughters, 10 others |

Mixed (including cancer, COPD, CHF, ALS, Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes) | Semi-structured interviews Constant comparative analysis and cross-case analysis |

10 |

| Walshe et al. (2017)59 UK |

- Understand successful strategies used by people to cope well when living with advanced cancer - Explore how professionals can support effective coping strategies; to understand how to support development of effective coping strategies for patients and family carers |

N = 24 Mean age = 52.5 years (range 28–74 years) 18 females, 6 males 17 spouses, 4 children, 2 parents, 1 sibling |

Advanced cancer | Serial qualitative interviews and focus groups Constant comparison analysis |

10 |

| Ward-Griffin et al. (2012)60 Canada |

Describe the provision of EOL care to older adults with advanced cancer from the perspective of family caregivers | N = 4 Mean age = 57 years (range 50–65 years) 3 females, 1 male 2 white, 2 black 3 spouses, 1 daughter |

Advanced cancer | Semi-structured interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Wasner et al. (2013)61 Germany |

Explore and document the burden of care and to identify the needs of primary malignant brain tumour patients’ caregivers in order to provide a basis for the development of a psychosocial care concept | N = 27 Mean age = 51 years (range 34–80 years) 22 female, 5 male 19 spouses, 4 parents, 4 children |

Primary malignant brain tumour | Semi-structured interviews Thematic content analysis |

10 |

| Whitehead et al. (2012)62 UK |

Explore the experiences of people with MND, current and bereaved carers in the final stages of the disease and bereavement period | N = 28 14 females, 14 males; carer–patient relationship not reported |

MND | Narrative interviews Thematic analysis |

10 |

| Williams et al. (2017)63 USA |

Explore experiences associated with burden, depressive symptoms, and perceived health in six male caregivers of persons with end-stage renal disease | N = 6 (all male) Age range = 30–61 years 1 white, 5 black 3 sons, 2 spouse, 1 father |

End-stage renal disease | Focus group Thematic content analysis |

9 |

Analysis

Thematic synthesis methods with principles of meta-ethnography, creating first-, second- and third-order constructs,25 were used to identify interrelated themes from the published qualitative studies. The meta-synthesis focused on two substantive areas. The first was the major themes and findings related to the factors that impact on the mental health of EOL carers. The second focus was on strategies for improving carer mental health as reported in the papers.

The initial plan was for data extraction and analysis to be conducted by KB and a carer co-analyst. After discussions with the carer RAP, the carers decided that instead they would all like to contribute to data extraction and analysis as a carer advisory group. This meant that five members of the group, excluding the carer chair of the group, had the opportunity to extract data from the papers and then work as a group to discuss the themes that emerged from the data.

First-order constructs

KB delivered training in research methodology and thematic synthesis techniques to the carers. Carers analysed three papers, selected on the basis of maximum variation and clarity. Carers were asked to consider the results of papers, identify sections that described things that affected carers’ mental health and write notes on the themes and subthemes within these (see Appendix 2 for RAP instructions). Carers were given questions to help them think about themes (e.g. ‘What is going on?’, ‘What is the person trying to communicate?’) and a template to record thoughts on themes, subthemes and the associated paper and section. Three of the carer RAP agreed to complete the data extraction, highlighting relevant text in the papers, adding notes and completing the template. Themes derived from these primary data are termed first-order constructs.

KB also independently completed the data extraction on the same three papers and presented these data to the RAP group. The whole group then discussed similarities and differences between the themes identified by the carers and researcher, how the findings related to the carers’ experiences and what they believed were missing. The group discussion highlighted that the carers had picked out the same themes as KB. They had also highlighted some additional subthemes and discussed potential limitations within the data. This comparison was used to validate the themes identified by the researcher and the discussion informed a preliminary framework for the thematic analysis.

The thematic framework was also validated by GG, who identified first-order constructs in 10% of the review papers (the three papers analysed by RAP members and one additional, randomly selected paper). These constructs were compared with those of KB and the carers and no discrepancies were found. KB then extracted relevant data from the remaining papers.

Second-order constructs

A further thematic synthesis was undertaken, grouping first-order constructs from each paper into core themes. These themes are termed second-order constructs as they are interpreted from the analysis of first-order constructs of the primary data. These were presented in a table where themes and subthemes were tabulated and linked with supporting quotes. KB recorded which papers contributed to each theme, in terms of relevant data or contradictory or contrasting results. KB and GG then discussed emergent themes, and their relevance to the review’s primary aims.

Once the draft second-order constructs were identified, a 2-hour discussion meeting was held with all six carer RAP members to refine and prioritise the themes. During this session, the draft themes and corresponding data were reviewed and the following questions guided the discussion:

-

Do these themes and subthemes look logical?

-

Based on your experience as a carer, do these themes reflect reality?

-

Do you think there are any important concepts described within these subthemes?

-

Do you think that the overall themes or subthemes can be changed in any way?

-

What could be the implications of these findings for carers supporting those at the EOL?

(Reproduced with permission from Bayliss et al. 26 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text above includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.)

The set of themes and questions were sent to the RAP members a week beforehand to enable them to consider them in advance. Discussion of RAP group responses to the questions supported the themes presented by the researchers and highlighted the need to report clear strategies to improve carer health, based on data extraction from the papers. KB used the feedback from the RAP to finalise the second-order constructs.

Third-order constructs: conceptual framework

To develop a third-order conceptual framework, a best-fit framework synthesis approach was adopted which represented a matrix approach to mixed-methods data synthesis. KB, GG, AW and TS developed third-order constructs by interpreting and extending the second-order constructs from the qualitative analysis to integrate the findings from the observational review within the wider project. This involved mapping agreement, conflict and evidence gaps between the data sources (further details on the combination of reviews are reported elsewhere23). Findings from the observational review mapped well onto the qualitative review findings, thus further validating the thematic framework. However, only the qualitative review was able to go beyond mere identification of potential factors that affected carer mental health, to directly inform strategies for improving carer mental health.

KB, GG, AW and TS further sought to develop a preliminary framework model based on a main model used to explain carer mental health outcomes, Pearlin et al.’s Stress Process Model. 27,28 This model in turn draws on the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping. 29 We used Yates et al.’s28 more recent version as the main model framework. This includes primary stressors (e.g. patient functional disability), primary appraisals (e.g. hours of informal care) and mediators (e.g. mastery). We included further factors from Pearlin et al. 27 (e.g. economic problems) within this model, and then sought to map our themes onto it.

The draft conceptual framework and model were then discussed at a meeting with the RAP. Materials were sent to the group a week in advance to enable them to consider materials. The group explored whether they felt the framework or model were missing any important elements of the carer experience. Carers were also asked if they could ‘relate’ to the findings (resonance), whether they felt that they ‘made sense’ for them, that they had utility in informing carer support, and if the presentation of the findings was meaningful to carers. The carers felt the conceptual framework and its themes were valid. However, they did not feel the model reflected the dynamic nature of caregiving and how themes may interact and influence each other. It was felt that we could not say anything definitive about the relationship between themes in the model on the basis of the review findings. The discussion rather emphasised the importance of the themes themselves and the evidence that they were likely to affect carer mental health, and that this was what should be taken forward in further presentation of findings and stakeholder consultation (this process will be further described in a separate report.)

Using carer interview quotes when presenting the results of the analysis

Carer interview quotes in this paper have been reproduced under the principle of ‘fair dealing’ within the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (legislation.gov.uk) Section 30,30 which permits use of quotations provided the purpose is for criticism or review, the quoted material is available to the public, its use is fair, and is accompanied by sufficient acknowledgement. Accordingly, we use interview quotes from published literature in this review to show that its themes and conclusions are a fair representation of findings of reviewed studies. Further, quotes are accompanied by the publication reference with page number, enabling readers readily to check the source and context. It is core to qualitative research to present participant interview quotes to satisfy readers that reported findings give a trustworthy account of the evidence. Correspondingly, qualitative reviews utilise interview quotes from reviewed papers to demonstrate the evidence on which their findings are based. Finally, the use of interview quotes is essential in a review of carers’ perspectives to allow carers’ own voices to be heard. Conversely, basing the presentation of findings solely on researchers’ second-hand interpretation of carers’ views would undermine the review’s credibility.

Results

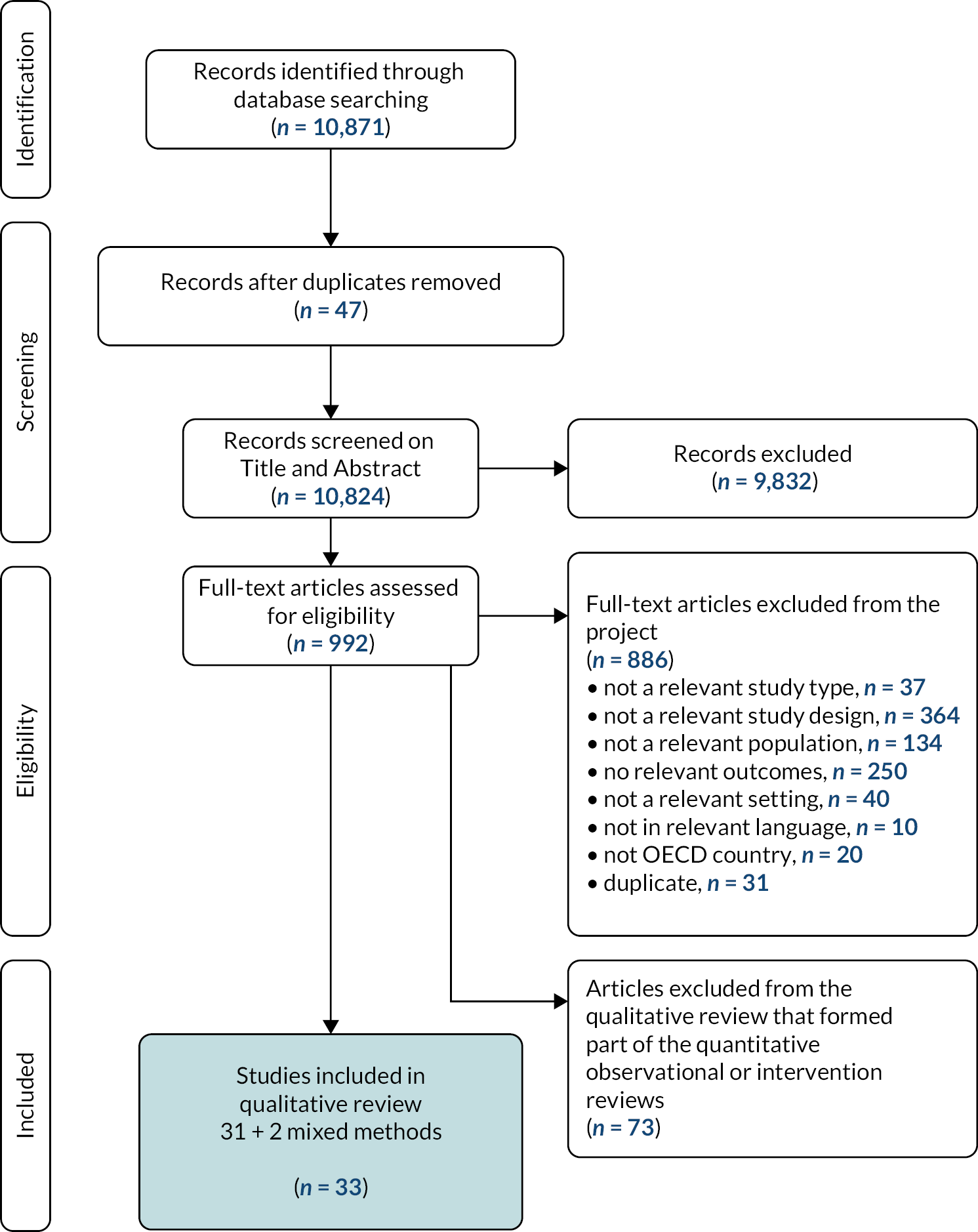

In total 10,871 potentially eligible records for the qualitative, observational and intervention reviews were imported to EndNote and 47 duplicate references were identified and deleted. After screening and exclusions, 33 qualitative papers were included. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart (see Figure 1) provides further details of the study selection process. Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of each study included in the meta-synthesis and their quality appraisal score.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study identification and selection.

The six themes that reveal the factors that affect the mental health of carers caring for those at the EOL include: the patient condition, impact of caring responsibilities, relationships, finances, carer internal processes, and support. The strategies to improve mental health are linked to the final two themes, with suggestions on how to manage carer internal processes and build appropriate support.

The synthesis of the data is presented in two sections. The first section describes the six themes and 22 subthemes that represent the factors that affect carers’ mental health when caring for someone at the EOL. The second section describes the two themes and eight subthemes that explore strategies to sustain or improve mental health. Relevant quotes supporting each theme and subtheme are included with the source paper and page number. An overall summary of the themes and subthemes is shown in Box 2. Further details on the data underpinning analysis can be found on the project website https://arc-gm.nihr.ac.uk/carer-project-.

-

1. Factors that negatively affect the mental health of carers caring for those at the EOL

-

1.1 The patient condition

-

1.1.1 Patient physical decline

-

1.1.2 Patient cognitive decline

-

1.1.3 Fear of future decline

-

-

1.2 Impact of caring responsibilities

-

1.2.1 Exhaustion

-

1.2.2 No time for respite and self-care

-

1.2.3 Loneliness and isolation

-

1.2.4 Conflicting responsibilities

-

-

1.3 Relationship with the patient

-

1.3.1 Change in roles

-

1.3.2 Quality of the carer–patient relationship

-

1.3.3 Patient ‘non-compliance’

-

-

1.4 Finances

-

1.4.1 Current finances

-

1.4.2 Work and benefits

-

1.4.3 Distress over future financial situation

-

-

1.5 Carer internal processes

-

1.5.1 Loss of self-determination and autonomy

-

1.5.2 Lack of confidence in the caring role

-

1.5.3 Transitions, crisis and pre-loss grief

-

-

1.6 Support

-

1.6.1 Inadequate information

-

1.6.2 Lack of collaboration between health professionals and carers

-

1.6.3 Inadequate professional support

-

1.6.4 Disjointed care

-

1.6.5 Lack of informal support

-

-

-

2. Strategies to improve mental health

-

2.1 Carer internal processes

-

2.1.1 Time for respite and treats

-

2.1.2 Positive self-talk

-

2.1.3 Spirituality

-

2.1.4 Ignoring own emotions and needs

-

-

2.2 Support

-

2.2.1 Professional support

-

2.2.2 Accessing information

-

2.2.3 Informal support

-

2.2.4 Religious community

-

-

1 Factors that negatively affect the mental health of carers caring for those at the EOL

1.1 The patient’s condition

1.1.1 Patient physical decline

Witnessing a decline in the patient’s condition appeared to contribute to poor mental health in carers. Carers reported that seeing the patient suffer was distressing and caused a feeling of powerlessness and ‘a level of anxiety that never really goes away’ (McDonald et al., 2018,45 p. 73):

It’s exhausting ….. It’s heartbreaking to know, you’re, like sitting on your hands. There’s nothing I can do for my mom … . Watching her suffer I suppose is the hardest part … .

(Ferrell et al., 2018,37 p. 289)

And it was very hard on her but also hard to watch. Well, you couldn’t do anything to, so to speak, take away what is hurting, you stand totally helpless and alone.

(Pusa et al., 2012,54 p. 36)

The decline that the patient experienced when they had an infection was cited as one of the most anxiety-provoking events for the carers:

My wife had it twice, the infection, and it’s a lot of pain. When you see them going through it, it bothers you extremely bad.

(Williams et al., 2017,63 p. 240)

1.1.2 Patient cognitive decline

In addition to the physical decline, carers reported the impact of the patients’ cognitive decline on their own mental health. This included the patient’s mood swings, fear about death and depression. For example:

As soon as I see him struggling or … being depressed, everything in my world, my own quality of life, comes to a screeching halt.

(McDonald et al., 2018,45 p. 72)

Other carers described how the patient’s disorientation and the loss of control was distressing. They grieved the loss of how the patient used to be:

So, and what is naturally the worst (…) there was a disorientation and absent-mindedness which now has become extremely bad. So, and now I have someone in front of me, who’s got nothing to do with the person I was with 2 months ago [crying].

(Wasner et al., 2013,61 p. 84)

Some patients also experienced personality changes as their condition progressed. Carers reported the change in a family member’s behaviour as overwhelming. They experienced a sense of loss that negatively affected their quality of life:

The worst is, that sometimes he’s so aggressive, so much changed from the feeling and sensitive person he used to be. Sometimes I think I don’t matter to him any more (…) he’s just so totally changed. Actually, I’m afraid [that] I’m going to collapse and have a breakdown.

(Wasner et al., 2013,61 pp. 81–82)

1.1.3 Fear of future decline

Carers experienced fear and anxiety around patients’ future decline. They worried about the effects on their own health and how they would cope if the patient’s condition deteriorated, especially when the carer was older. 48 The uncertainty around how much time they had left and the variability of the prognosis was anxiety-provoking, with some describing it as ‘terrifying’:45,62

I still feel a little bit like my fate is cast to the wind a bit, because we don’t know what happens next. I’m very afraid of, very afraid of the time, which will come, when [patient] is increasingly incapacitated. I’m very frightened about that.

(McDonald et al., 2018,45 p. 74)

The fact that the patient was never going to get better and that they faced a decline left some carers feeling depressed and helpless:

But the reality that this isn’t going to get better, there’s no light at the end of the tunnel on this one and those things all weigh heavy on a caregiver.

(Parker Oliver et al., 2017,50 p. 652)

1.2 Impact of caring responsibilities

1.2.1 Exhaustion

The amount of time dedicated to caring responsibilities and the nature of these tasks had a physical and mental toll on carers. This, in addition to the daily routine and unexpected stress, threatened their ability to cope:

You’re tired all the time … exhausted.

(Parker Oliver et al., 2017,51 p. 651).

Carers also described how caring is a 24/7 role where their sleep can be frequently disrupted or they are constantly watching the patient, waiting for something to happen. 47 Carers frequently reported being present to offer support when they lacked the energy to do so. 37,38 This inability to gain adequate rest could have a negative impact on the carers’ mental health:

I don’t think I slept through the night for the last year and I don’t think one realizes that you’re at a point of total exhaustion (…) you can’t even really take in what’s happening.

(Kutner et al., 2009,43 p. 1102)

Some carers reported that the stress of their situation had led to insomnia. However, they were unable to take medication to promote sleep as they needed to be available for the patient at night:

I don’t sleep a lot. And I think about going to the doctor and getting sleeping pills and then I think, no, that would not work because if I go into too deep of a sleep and he got into distress, I wouldn’t be able to hear him so it is important that I am aware …

(Ward-Griffin et al., 2012,60 p. 499)

Carers also described the impact of exhaustion on their health, with depression, hopelessness, anxiety and panic attacks being widely reported:

Tired of it! Yes, you get fed up … it’s going on a long time and … yes. I think we do feel that the pressure is getting to us really. It has been hard …

Yeah … I’d say now, a wee bit depressed, eh, wearing you down, kind of thing, you know? Oooh!

(Murray et al., 2010,50 both p. 3)

Every night I woke at 1 am or 2 am and cried and cried and can’t stop … I scared all the time and my neck’s swollen … and I couldn’t breathe (rapid huh huh huh-anxiety attacks)…. The doctor gave me Sinequan to make me slow down, make [me] not stressed too much …

(Heidenreich et al., 2014,40 p. 281)

1.2.2 No time for respite or self-care

Carers reported the relentlessness of caregiving, with restricted freedom and constraints associated with patient dependency. 39 Carers often felt unable to leave the patient alone, prioritising their caring responsibilities and restricting their normal activities. 39,41,50 Unexpected complications and the unpredictability of symptoms also meant that carers’ plans sometimes had to be cancelled:45

If you wanted to go out somewhere and she doesn’t feel well that day, then that’s it. It impacts on your life. […] It affects, the illness affects everybody.

(McDonald et al., 2018,45 p. 73)

This lack of control and respite was overwhelming and had an impact on carers’ mental health and quality of life as they suppressed their own needs and felt they were neglecting themselves:37,45,54,63

[caring is] playing a toll on me because it was to the point where I felt like I didn’t have a life.

(Participant 05)

Sometimes you get to that point of that you just want to scream.

(Participant 03) (Williams et al., 2017,63 p. 239)

Even though they felt exhausted and overwhelmed, some carers did not allow family or friends to care for the patient as they considered that only they had the experience and knowledge needed for the role. 40,41 If they did leave the patient, they felt anxious, guilty and pressured to return:38,54

You can’t give that job [caregiving] to somebody else (…) you can’t give it to a hospice nurse … You can’t give it to one of your kids … that’s a big load to carry and it’s exhausting. It wears you out because you can’t give it away … you don’t want to give it away.

(Kutner et al., 2009,43 p. 1102)

1.2.3 Loneliness and isolation

Carers described the loneliness and isolation that can occur when they are afraid to leave the patient who is at the end of their life. 41 It was reported that the carers’ social circle often became smaller, with the patient becoming the centre of their world. Without work or a social life, they grieved these previous relationships and social worlds and the variety they brought to their life:

It’s the shrinking of your world that I find the hardest (…) The social aspect of it is the hardest because most people get a lot of their social life at work or from doing other things. And with MS there’s no talking to her over dinner, ‘How did your day go honey?,’ because we both had the same day…. It’s hard, the isolation is hard …

(McCurry, 2013,44 p. 57)

As some patients neared the EOL they withdrew from family and friends. This meant that the carers’ relationships with family and friends also suffered as they became more isolated with the patient:

[H]e just didn’t want … he just kind of walled himself away. His personality really changed. His attitude and … he just wanted to be by himself. I can understand that in many ways, but it’s just difficult for the rest of us around here.

(McDonald et al., 2018,45 p. 74)

The requirements of the caring role also meant that carers may have no energy to socialise or do activities that they enjoyed, and individuals may become withdrawn, isolated and depressed:

I knew I was depressed. I didn’t want anybody around me. I didn’t want to talk to anybody or anything like that because I’m a very social person.

(Williams et al., 2017,63 p. 239)

As the patient neared the EOL, there was also a fear of losing the patient which compounded these feelings of isolation:61

What’s to happen? … Oh, no! I can’t think about being alone. I just pray every day ‘Just God help me’. Sometimes I tell the god ‘God if you like him, and you love me give him a little bit more time’.

(Heidenreich et al., 2014,40 p. 281)

Some carers also lost their faith in God during this time, which made them feel alone:

It kind of makes you a bit angry. You think, ‘is there a God?’ Sometimes you think, ‘how can He do that?’ I don’t know, I’m kind of mixed up about all that.

(Murray et al., 2010,50 p. 4)

1.2.4 Conflicting responsibilities

The caring role can also present conflicting responsibilities when an individual needs to care for multiple people. For example, carers reported the pressures of caring while also looking after young children:

Got a new baby, trying to take care of my child. Then, I’m trying take care of her, and all of this was coming on me and trying to work at the same time. It was a lot. It had me extremely tired.

(Williams et al., 2017,63 p. 239)

When carers could not fulfil other responsibilities, such as seeing their children, this led to stress and resentment towards the patient:

For about a year I felt like I needed to visit my son who is overseas. I was trying to get help from the family to place her somewhere while I was visiting. (…) The tension was increasing to the point that I knew that I was walking a fine line between giving care and also, you know, I didn’t want abuse (…) but I knew I was reaching the edge.

(McCurry, 2013,44 p. 55)

Caring responsibilities could also extend beyond the patient to supporting other family members who may be struggling with the patient’s condition and may even require more support than the patient:

… my mother, she feels the need to still be in control, she has violent outbursts at me … There’s been a shift in the caring role and that’s changed the dynamics of the family, he [patient] is not the problem at all; I’m worried I’m going to have to look after my mother and will have no life.

(Galvin et al., 2016,39 p. 6)

Caring for multiple family members adds to the workload of their caring role and can therefore have a negative impact on levels of anxiety and depression.

1.3 Relationships with the patient

1.3.1 Change in roles

The patient’s condition could lead to changes in existing roles such as children assuming the role of carer for their parent,37 or the relationship of husband and wife being replaced with nurse and patient. 33,54 There was a feeling of grief surrounding the loss of the previous relationship which preceded the patient’s illness, resulting in anxiety, distress or uncertainty:33,36,39,61

I believe I also am doing some grieving because we’re not the same couple. He’s not the same person and our life is not the same.

(McDonald et al., 2018,45 p. 73)

Carers may also need to take on additional roles or responsibilities that would have been previously done by the patient. This adds to their workload and can feel overwhelming:

I had to assume his (responsibilities). He used to pay the bills … he used to know when to call the oil man (…) Not only my things, I have his things.

(McCurry, 2013,44 p 56)

1.3.2 Quality of the carer–patient relationship

The quality of the existing relationship between the carer and patient played a significant role in how they perceived their experience and the level of stress they reported. 63 When relationships were not strong, or a carer had taken on the role out of necessity rather than love, the losses associated with having to provide care led to anger and resentment towards the patient and a diminished sense of responsibility:

It was stressful when (…) I was taking care of her at home. We would get into it like you wouldn’t believe. We’d bicker back and forth.

(Waldrop and Meeker, 2011,58 p. 120)

As some patients neared the EOL, the increased workload for the carer meant there was less time to share memories or build new experiences. Changes in the patient’s mood and increased emotional needs also meant that carers could not share their own emotions or experiences from their day within the dyad, which may lead to the carer feeling distant from the patient and experiencing a loss of intimacy. 37

A lack of understanding or gratitude from the patient about the efforts made when caring also impacted on the quality of the relationship, as carers stated this could be frustrating, hurtful and add to the emotional impact of the role:

the pressure that my mam [patient] puts me under, her expectations …

(Galvin et al., 2016,39 p. 5)

1.3.3 Patient ‘non-compliance’

When patients did not go along with their treatment plan, carers reported being upset that their feelings had not been considered and that they were not listened to. This level of discord could be frustrating for the carer, resulting in increased stress, anxiety and distress:42

He just would not listen to me or the doctors, it was very hard on me watching him do what he did, he missed out on so much … the grandkids. I am mad at him for how poorly he cared for himself and the hard time he gave me for trying to do it.

(Kitko et al., 2015,42 p. 393)

If the patient would not take their medication, carers worried that the illness would progress and that they would not be able to cope. Carers could also feel pressure to conceal that the patient was not following their treatment at hospital appointments42 and feel unable to discuss their concerns with the patient as they did not want to cause distress when they were unwell:

I will say to (patient’s name) do you know what the outcome is going to be if you don’t take your insulin … you are going to lose your leg or something else (…) I said I’m not going to be able to care for you (…) He does not want to talk about it and I don’t want him to get upset with his heart being weak.

(Kitko et al., 2015,42 p. 394)

Carers also reported occasionally going against the patient’s wishes regarding their care, which could cause tension. Feelings of loyalty in relation to the patient’s integrity and autonomy resulted in conflicting feelings and distress. There can be a conflict between the patient’s right to decide for themselves versus questions around their capacity to know what was best for them:54

I knew he was getting short of breath and needed to be seen but he refused to let me call the office. It got to the point where I called 911 … I am worried (patient’s name) will be upset with me when he realizes what I did.

(Kitko et al., 2015,42 p. 393)

1.4 Finances

1.4.1 Current finances

Carers could experience financial challenges that could cause enormous emotional stress. 37,51 Costs of caring for someone at the end of their life can include medical expenses, equipment, home renovations and travel costs. When the patient was the main or only earner in a household, carers struggled to cope with the loss of income when they were no longer able to work:

My husband was the only earning member in the family. Now he is suffering with cancer and admitted to the hospital (…) I stress about finance.

(Shanmugasundaram, 2015,55 p. 540)

Delays in professional care or in receiving equipment also meant that some carers were forced to pay privately for trained or private carers, adding to the financial burden of caring. 47

1.4.2 Work and benefits

Balancing work and caring became increasingly difficult as the patient neared the EOL. Carers reported health-care workers or private carers not showing up, so they were required to provide last-minute care themselves. The unpredictability of the patient’s illness was also a source of distress, especially if the carer’s workplace did not offer flexible arrangements. Many employers were not able to support the carer to take frequent periods of leave:

People want you to work every day. They don’t want you to have to call in sick 2 or 3 days in a row. I was working for a little while when he first took ill but I was in constant worry about whether he had remembered to take his medication, hoping he didn’t go too far …

(Ward-Griffin et al., 2012,60 p. 504)

As a result, some carers had to reduce their hours or stop working all together to provide care. Carers expressed financial concerns due to these changes, which impacted on their mental health:32

Because my husband is sick, I have to give up my job and take care of him … lots of financial problems. Sometimes it gives me so much stress and frustration with the cost … I was very depressed, and I went to a psychiatrist for treatment.

(Shanmugasundaram, 2015,55 p. 540)

Some carers also found it difficult to access information about benefits. Most were not aware what help was available, what they were entitled to, or who to contact and were unsure how to complete the necessary forms, viewing the process as very time-consuming. This resulted in some not claiming for financial support and others only finding out by chance what was available. Some requests were also rejected, which caused further upset and frustration:

Benefits! (we) knew nothing about that at all. We lost 4 years of benefits and I just happened to find out about the way about them.

(McLaughlin et al., 2011,47 p. 180)

1.4.3 Distress over future financial situation

Without a job some carers experienced stress and anxiety around how they would support themselves financially after the patient died:

That was the worst for me, losing my job because of my husband’s illness plus the whole financial situation. When he’s gone, I’ll desperately need a job, otherwise I won’t even be able to pay the rent.

(Wasner et al., 2013,61 p. 87)

I get worried about … how I’m going to live after [patient] dies (…) I do live with some fear of not wanting to be … wanting to have enough money to take care of my needs …

(Parker Oliver et al., 2017,51 p. 651)

Even those who were currently financially stable were anxious about future costs such as nursing homes. This was especially the case in countries that required health-care insurance such as the USA:37

Umm [I am feeling the financial pressure], so then I start to think if he goes into a nursing home and I will not get the carer’s pension and I don’t go to work what are we going to do as income and finance?(…) then surviving is a problem for us.

(Heidenreich et al., 2014,39 p. 281)

1.5 Carer internal processes

1.5.1 Loss of self-determination and autonomy

The loss of self-determination and autonomy had a negative impact on mental health. The feeling of not being in control was a common theme:33

there’s something that has come into your life that is both robbing you and robbing your wife … and it’s not going to get any better.

(McLaughlin et al., 2011,47 p. 180)

Carers’ lives were often determined by the patient’s illness and they described the difficulty of living in the patient’s world rather than their own. 45 Some carers felt so consumed by their role that they struggled to separate their sense of self from the patient.

I as a person do not exist any more.

(Wasner et al., 2013,61 p. 85)

I need to separate myself, but I also need to feel like we’re one. How do I detach, knowing I have a life too? That was hard, working out what to do with myself.

(Ugalde et al., 2012,56 p. 1178)

you become insignificant as a person yourself, you lose your sense of identity, you’re defined as patient’s wife and MND. You nearly don’t know how to behave any more.

(Galvin et al., 2016,39 p. 5)

Others felt angry about their role and there was also a feeling that the suffering that the disease had inflicted on the family was unfair:54

you’re putting your life on hold for someone and its ok to be mad about that … your brain is going through something horrific … the stress of it will do horrible, irrational things to you.

(Parker Oliver et al., 2017,51 p. 652)

1.5.2 Lack of confidence in the caring role

A combination of huge responsibility as a carer and limited experience in their role led to a lack of confidence that was distressing for many. Carers report being uncertain about their own capabilities, with anxiety around whether the care provided is adequate or sufficient:39

It’s actually quite frightening, that you’re in charge of somebody so sick and you don’t know what to do for them and yet you know they need serious medical help.

(Fitzsimons et al., 2019,38 p. 16)

Carers found it difficult to carry out a variety of medical and nursing tasks for patients, especially responding to side effects of medications and changes in symptoms. For example, carers reported how they often made decisions about administering medications alone and felt uncomfortable administering narcotic medication where the patient becomes ‘too incoherent to talk’ (Chi et al., 2018,32 p. 6). The anxiety and uncertainty associated with this increased when the decision was made for the convenience or quality of life of the caregiver. 44 The responsibility of deciding when to start emergency medication could be a major concern for carers:

we never quite know […] … it’s like a balancing act whether to start the steroids or … I know they say leave it 24 hours, but you’re still a bit unsure … you know?

(Farquhar et al., 2017,36 p. 10)

So, I was second-guessing how bad he was. It was a very, very stressful time. It was stressful because I felt completely, completely, alone. I felt completely responsible.

(Fitzsimons et al., 2019,38 p. 15)

1.5.3 Transitions, crisis and pre-loss grief

Transitions often triggered additional stress and anxiety for carers. This included the diagnosis, grieving a previous life, becoming a carer and pre-loss grief. When faced with the diagnosis, carers described how the news was sudden and overwhelming, and it made them feel suffocated, confused and depressed:

You know this suffocating feeling when the air is sucked out of the room, that’s how it felt when the doctor said, ‘We cannot do anything any more’.… We just sank into depression.

(Penman, 2018,52 p. 247)

In the final weeks of life, carers described a pre-loss grief where they feel unprepared for the loss:

… you think right I’m ready, you know, I’m gonna cope and all but then like X does get really, really sick and I think God I’m not ready at all, do you know.

(Hynes et al., 2012,41 p. 1072)

In addition to transitions, carers could also experience a caregiving crisis at any point in their journey. This is when the needs of the dying person and caregiver outweigh available resources. It often combines a rapid decline, more frequent and difficult care, and patient resistance. 58 The crisis period is characterised by heightened anxiety and exhaustion.

1.6 Support

1.6.1 Inadequate information

Carers stated that the quality and quantity of information they received were not adequate and failed to facilitate their understanding of the patients’ diagnosis, symptoms, treatment options and support needs. The uncertainty around how the illness will progress was described as ‘exhausting’ and ‘heartbreaking’ (Ferrell et al., 2018,37 p. 289). As a result, carers felt ignored and ill-equipped to deal with the demands of the situation in which they were placed:36

You’re just sent home to deal with it on your own, find your own solutions.

(Farquhar et al., 2017,36 p. 6)

If I’d have had a session with me and someone at the beginning, face to face, to say ‘right your mum has been diagnosed; this is what you need to expect’. But in a very gentle kind of (…) That would’ve been brilliant … being ignorant isn’t going to save you in the long term …

(Moore et al., 2017,49 p. 8)

Parker Oliver et al. 51 found carers were not always told about treatment consequences or details of care options, negating the possibility of shared decision-making for patients and their carers. 38 Carers felt that they had to be demanding in order to receive appropriate care, which they found stressful and frustrating:

The surgeon never warned her of the consequences of doing radiation in the surgical area. As a result she has a hole in her shoulder … that will never heal. So that’s part of my job is to replace the dressings on that everyday.

(Parker Oliver et al., 2017,51 p. 652)

You did not know what was going to happen the next day, what examination he would have or anything.

(Pusa et al., 2012,54 p. 37)

Other carers did not understand the acronyms used by health-care professionals with implications for disease labelling/recognition, trajectory and management. Carers noted that educational interventions are focused on the patient, with limited information for themselves. 36 This made them feel vulnerable and unprepared, causing unnecessary stress as they worried about the significance of new symptoms:

I looked it up and then to be honest just lately I am just wondering how much of it actually is emphysema and because again, it wasn’t really explained.

(Hynes et al., 2012,41 p. 1071)

Information on mental health services could also be lacking, with some carers reporting that they needed support but did not know how to access this:

So, I don’t really know whether I really need to talk to psychiatrist […] I don’t know what they … would it be psychologist or whoever they provide just to help people get through it. I don’t know what I’d say to them (…) Sometimes you’re just sort of reaching for something, but you don’t know what.

(McDonald, 2018 et al.,45 p. 75)

In cases where information was provided about the patient’s condition, it could be given in a condescending manner or directly to the patient who may not be able to understand or retain the information. 61 Time pressure and lack of resources meant that health-care providers were short of time and could also lack sensitivity when delivering information which could be distressing for the carer:

The neurologist here said to me, ‘Be happy, (if) you don’t know what’s going on, then you won’t have to get upset’. I raged when I heard this; then I already knew through the Internet that it could be a Glio IV and it was pretty clear to me what the consequences would be. It was totally idiotic to say to me, ‘Don’t worry’. That was the worst, this information block.

(Wasner et al., 2013,61 p. 85)

Suddenly, during a 5-minute talk with my mother in the corridor, she was told that a new tumor had been discovered and that she has to be prepared that dad has 4 months to live. I just can’t understand that.

(Wasner et al., 2013,61 p. 87)

Carers wanted honesty from health-care professionals to enable them to face the reality of the prognosis, know what to expect, support the patient and allow them to prepare both practically and emotionally for their patient’s death:

Nobody said, ‘Your mother has progressive heart failure and is going to die’. I think consultants need to be honest, stop being afraid, if your loved one is dying, then say it.

(McIlfatrick et al., 2018,46 p. 886)

Cultural barriers, such as when the carer did not speak the same language as the health-care provider, can also be problematic. Participants’ resistance to using an interpreter may further hinder support. 40

1.6.2 Lack of collaboration between health professionals and carers

Whitehead et al. 62 describe how health-care professionals may not collaborate with patients and carers when planning patients’ care. For example, one bereaved carer described her distress around the complete disregard of her husband’s wishes by health professionals when he was admitted to the local hospital in an emergency:

… I showed him the part where it says in the event of serious collapse, the patient does not want to resuscitated, but the A and E doctor said ‘well it’s not worth the paper it’s written on, what are you talking about?’

(Whitehead et al., 2012,62 p. 372)

Other carers spoke of the knowledge they had built up over time in providing care at home but which was not acknowledged by health-care professionals. Carers felt they were not seen as an essential component of the EOL care team. 60 This made them feel disempowered and frustrated that they were not being listened to:

It’s so frustrating when she goes into the hospital and the nurses and the doctors say it’s her condition, you know. I’m like I’m with her twenty-four hours a day, I know how breathless she is without infection and I know how breathless she is with an infection and there’s a major difference.

(Hynes et al., 2012,41 pp. 1072–3)

1.6.3 Inadequate professional support

Carers reported that they did not receive adequate nursing care for patients at the EOL, which left them exhausted and overwhelmed:

It just got very difficult as far as the amount of help that we could get (…) The restrictions on the hours that we would get a month when you’re dealing with somebody that has cancer of the brain and you know you’re dealing with behavioural and mobility problems …

(Brazil et al., 2010,31 p. 113)

Inadequate pain management was also an issue, with carers feeling dissatisfied and angry with how the patient was treated and distressed by their unnecessary suffering:

My wife was in pain for a long time. No one turned up.

(Shanmugasundaram, 2015,55 p. 540)

Carers also experienced anxiety when patients came home from hospital with no support or instruction on how to care for them:38

When he comes home ‘No’, there’s nothing in place. Now I lost it when he came home, I just exploded. Burst out into tears and really got very upset.

(Fitzsimons et al., 2019,38 p 16)

When carers did receive support from health-care professionals, this was often described as poor quality, with carers reporting feelings of disappointment and anxiety, sometimes sensing that professionals saw patients as a burden and that their compassion was not genuine. 54 For example, carers reported that professionals lacked empathy or were rude, while private carers were often unskilled in palliative care. 62 Some carers also felt that more education and training were needed for health and social care professionals:47

one of these ladies would come and stop through the night so I could get a night’s sleep … but it didn’t work really, … she got me up anyway […], I don’t know if it was more than she expected …, but it didn’t go according to plan.

(Whitehead et al., 2012,62 p. 373)

Practical support was also described as being too late. Nursing care is often offered in the very final stages of the illness, which can mean that staff struggle to become accustomed to the patient’s needs and the carer can find it difficult to adjust:

he got it but he didn’t live long enough to get anything from it, really it should have been brought out six months before, probably more care at an earlier stage and for longer than that, … the continuing care came in too late.

(Whitehead et al., 2012,62 p. 373)

When carers were experiencing poor mental health, the health-care service did not provide adequate psychological support. This meant that the carers were more distressed and less likely to cope with their role:

I was left alone. There was no one to be concerned about me. I did not receive any mental support as a husband. I was really very upset about this.

(Shanmugasundaram, 2015,55 p. 541)

Negative experiences with the health-care system also meant that carers sometimes refused support from health-care providers when it was offered:

at the end, and the doctor said ‘shall we get him into hospital? And I said ‘no’ (…) I couldn’t let him go into hospital, knowing how much he hated it and how he was poorly cared for.

(Whitehead et al., 2012,62 p. 373)

1.6.4 Disjointed care

Carers reported confusion about the number of different health-care professionals they interact with and the lack of coordination. Most patients had comorbidities and were receiving specialist care from multiple disciplines, making caring for them at home more complex. Carers felt passed around different health-care providers who often gave conflicting advice. Delayed or irregular medial reviews with specialists were also reported, resulting in poor symptom management which caused further stress for the carer. 47 Villalobos et al. 57 also describe how lung-cancer patients and carers were sent to numerous physicians, without receiving clear answers or open communication, leaving them feeling left alone, often with a sense of ‘shock’ and ‘disbelief’ (Villalobos et al., 2018,57 p. 3).

In addition, appropriate communication with and access to other professionals, e.g. social workers or occupational therapists, may be missing or delivered ad hoc, which meant carers may be unaware of accessible services until there is a crisis. 47 Carers felt frustrated and wanted a more coordinated approach to their interactions:

I think sometimes one hand doesn’t know what the other hand is doing … because I mean I have phoned up about things and its pass-the-buck sort of thing.

(McLaughlin et al., 2011,47 p. 179)

1.6.5 Lack of informal support

Poor mental health can arise when a carer lacks family who can provide practical and emotional support. This lack of support can cause conflict and feelings of resentment towards those who did not help:39,40,43

Sometimes I tell my husband’s brothers and sisters, but they don’t help me. Sometimes they get cranky to me … So I keep it inside my heart you know. I can’t talk with someone.

(Heidenreich et al., 2014,40 p. 281)

Other carers reported that family are too busy to offer support or live too far away. 55 For example, Chinese carers living in Australia expressed how isolated they felt as they missed their family care-related culture where children often remained in the family home and were therefore able to provide support:

She [my mother-in-law] got two other daughters, but they all working and they’ve got kids at school so they can’t come to care for mother and help me

I am having a big depression and loss, because you have to care single-handedly (…) having to shoulder all these responsibilities the pressure is becoming heavier and heavier …

(Heidenreich et al., 2014,40 p. 279)

Some carers described how friends started to visit less as they were unsure what to say, felt uncomfortable or wanted to remember the patient as they were. 31 Conflict and stress could arise when friends did not ask about the carers’ well-being, offer assistance, or invite them to join activities outside of caregiving. 60 The carers’ sense of loss increased as their social network became smaller:50

I don’t find my friends calling me (…) I would be dishonest if I didn’t say I’m starting to get a little pissed off. Yeah, I know that I am not supposed to feel that way (…) I am just feeling down and depressed … I have never ever expected anything from anybody, but a telephone call would be nice.

(Ward-Griffin et al. , 2012,60 p. 503)

2 Strategies to improve mental health

The next section considers what carers said about strategies used to sustain or improve their mental health.

2.1 Carer internal processes

2.1.1 Time for respite and treats

Carers reported techniques for managing negative emotions that were often self-directed or a result of their own internal processes. For example, taking time for respite played an important role in reducing anxiety, depression and exhaustion. It was important that this time was spent building adaptive coping strategies, finding activities that the carer found rewarding or reviving, including work, meditation, reading, exercise or the ‘opportunity for solitude’ (McDonald et al., 2018,45 p. 75).

Meditating a lot helped me to take apart the negatives and see the positives in it (…) First thing, I was like I want to go get a salad, and I wanted to go running.

(Williams et al., 2017,63 p. 240)

In addition to respite, some carers recognised the need to take care of themselves, so they could continue to take care of their patients, for instance, making sure they exercised, attended doctors’ appointments and had checkups. 37

Treats played a role in maintaining good mental health and ‘lifting spirits’ (Walshe et al., 2017,59 p. 12). For some, this took the form of increasing the frequency of activities that would usually be regarded as luxuries such as a ‘going out for a nice lunch’ (Walshe et al., 2017,59 p. 11). For others it was behaviours that demonstrated thoughtfulness, or giving gifts to the patient, which they reported increased their own feelings of well-being. Carers developed strategies to include low and non-cost ‘treats’ even where material resources were very limited:59

I think I’ve tried to be a bit more attentive, caring … but you know, yes attentive I think is the word, just holding hands and just yes.

(Walshe et al., 2017,59 p. 11)

Another action to reduce stress included understanding personal limits and choosing to reduce the quality of care provided. Carers reported that when they were giving 100%, all other areas of their life suffered. Also, when having a bad day, carers stated the importance of being gentle with yourself:

Because it’s there, I must remind myself that, it’s like you might not manage as much …one day … but you have to tell yourself to try to take it easy, and that this day is like an upside-down day; that it doesn’t feels so good. So it is.

(Pusa et al., 2012,54 p. 38)

2.1.2 Positive self-talk

Positive self-talk, motivational audio recordings37 and thinking about what you still have33 were found to reduce anxiety and depression:

Do we, you know, wallow in our pity and have what time we’ve got together, you know, we are not going to enjoy him, we don’t want to remember it because it’s that down? Or do we make the best of everything and carry on as much as you possibly can, deal with it, being normal as normal as it is to get us through it?

(Walshe et al., 2017,59 p. 9)

2.1.3 Spirituality

Negative emotions associated with the lack of control that EOL care can involve were also mediated by spirituality. This belief in something greater than themselves helped carers to accept the lack of control:

‘I just want peace of mind, nothing else. The rest is whatever God decides.’ I said, ‘So be it. No problem. We’ll do it.’

(McDonald et al., 2018,45 pp. 74–75)

2.1.4 Ignoring own emotions and needs

Carers described ignoring their own needs or denying the situation existed as a strategy to manage their emotions. 63 For example, carers reported being so focused on helping the patient that they had not spent time thinking or processing their own feelings about the diagnosis. 56 Others had to deny their own feelings in order to support the patient and endure the circumstances:

I’m not focused on myself, I haven’t had a think about everything. I don’t allow myself the luxury of doing that.

(Ugalde et al., 2012,56 p. 1179)