Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 17/69/02. The contractual start date was in June 2018. The draft report began editorial review in December 2020 and was accepted for publication in August 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Reeve et al. This work was produced by Reeve et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Reeve et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Overview

Polypharmacy is common practice in modern health care, offering benefits to many patients. However, a report by The King’s Fund1 on polypharmacy recognised growing awareness of the potential for harm and waste associated with the long-term use of multiple medicines, especially in patients with complex health problems (e.g. multimorbidity). It recommended that all medication reviews include a consideration of whether or not medicines could be stopped. Deprescribing was thus recognised as an important component in optimising the use of medicines in a polypharmacy context, with a call for practice to be tailored to individual circumstances. The need for new evidence to support patient-centred understanding of deprescribing practice was therefore identified. This is the focus of the TAILOR synthesis.

Describing the problem: managing problematic polypharmacy

Polypharmacy, the concurrent use of multiple medicines in a single person, is on the rise, driven by an expanding population living with multiple long-term conditions (multimorbidity). It is estimated that around 1 in 5 patients takes five or more medicines per day. 1 Polypharmacy can be appropriate, extending life expectancy and improving quality of life. 1 However, 40% of people taking five or more medicines per day report feeling significantly burdened by their medication. 2 These individuals are experiencing what has been described as problematic polypharmacy: the use of multiple medicines on a long-term basis when the intended benefit of the medicines is not achieved, or the potential risks outweigh the intended benefits. 1 Problematic polypharmacy is associated with treatment burden, potential harm and waste (through non-concordance). 1 It is, therefore, a challenge for patients, professionals and health services alike.

In its 2013 review1 of the challenge of polypharmacy, The King’s Fund highlighted the potential importance of deprescribing as part of the response to problematic polypharmacy. The report recommended that consideration of stopping medicines should be an integral part of all medication reviews. The report also underlined the importance of adopting a person-centred approach when making decisions about medicines use, recognising that the perspectives and priorities of the medicines taker (patient) and indeed their family and carers may or may not match the priorities of the prescriber. 1,3 The King’s Fund report1 recognised that compromises may be needed between a prescriber’s goal to optimise medical management and a patient’s choices based on individual circumstances. This compromise was described in Denford et al. ’s3 review as a process of balancing the benefits and harms from medication use through the mutually agreed tailoring of medicines.

A strong and growing body of evidence-based guidelines recognises benefit and harms, and so describes best practice, in starting medication for various conditions. Equivalent guidance on stopping medicine (deprescribing) has been slower to appear. Notable exceptions include the Scottish polypharmacy guidelines (first published in 2012, and updated in 2015, 2018 and 2019). 4,5 Similar to the report by The King’s Fund,1 the guidelines4,5 advocate individualised reviews of the merits of each medicine prescribed to an individual, including consideration of whether or not it should be continued. However, although deprescribing (in the context of person-centred care) was increasingly seen as good practice in principle, there remained a shortage of evidence-informed guidelines on how to deprescribe in practice. This gap was recognised by a call in 2017 from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) (17/69), ‘Safely and effectively stopping medications in older people with multimorbidity and polypharmacy’. The call asked for research to ‘describe the benefits, harms and optimal strategies for the safe withdrawal of medication in older people with multimorbidity to reduce polypharmacy and treatment burden’. TAILOR was a response to that call.

Addressing the problem: what we already know about deprescribing

Dealing with problematic polypharmacy means knowing how to safely and effectively taper, withdraw or stop medications that may be offering more harm than benefit. 6 However, discontinuing long-term medicines is a process that causes anxiety and concern for clinicians and patients alike. 6,7 Deprescribing is the process of supervised withdrawal of potentially inappropriate medication,8 a planned/supervised process of dose reduction or the stopping of medicines that may be causing harm or conferring no additional benefit. However, clinicians remain concerned about the safety and impact of stopping medicines, including the potential consequences for them as decision-makers. 7,8

Part of the challenge lies in recognising what is ‘inappropriate medication’ that can or should be withdrawn. The withdrawal of medicines that are causing acute harm to patients (e.g. following an acute adverse reaction) is a common experience for patients and prescribers alike. In such situations, the risk–benefit ratio of acute discontinuation, and hence the clinical decision to be made, is usually clear. Long-term medication can be more challenging. Guidance on stopping longer-term, potentially inappropriate, medicines (defined on biomedical grounds) has been around for a number of years [e.g. Beers criteria9 and the Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to the Right Treatment (STOPP/START) tool10]. Such tools help identify potentially inappropriate drugs, considering dose and duration, but do not provide explicit support on stopping the medicines. A particular challenge comes in knowing how and when to stop medication that may be seen as ‘appropriate’ from a clinical perspective (including condition-specific guidelines) but potentially ‘not right for this individual’ as judged by the patient or their clinician (e.g. discontinuation of primary prevention medication). 6

The second challenge comes in managing the process of withdrawal, including understanding potential issues related to safety and impact. The Scottish polypharmacy guidelines4 address this issue by offering clinicians clear guidance on the potential absolute benefit of medication use (e.g. the numbers needed to treat with warfarin to prevent one stroke in people living with atrial fibrillation). This offers clinicians useful data to discuss likely benefit with patients, and so, if appropriate, support a conversation about discontinuation. However, to our knowledge, there is no comprehensive review, or data set, describing absolute effects of stopping medication.

Since NIHR published the funding call that supports this TAILOR project, we have seen publication of a range of resources to support deprescribing. These include a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline11 focused specifically on the deprescribing of hypnotics and a number of institutional resources describing best practice aimed at supporting staff managing the problem in the field,12–14 as well as expert commentaries from academics working in the field. 15,16 All seek to support professionals in the complex process of tailoring medication use to individual circumstances and in making ‘defendable decisions’ with regard to the individual tailoring of medicines. 6,17

Much of the guidance to date draws on the principles of good prescribing practice, supported by data on prescribing for specific conditions. Both the principles of good prescribing practice and data on prescribing for specific conditions offer support for deprescribing practice in highlighting the absolute (limitations to) benefit of medication in given conditions, and in offering permission in principle for person-centred care. 18

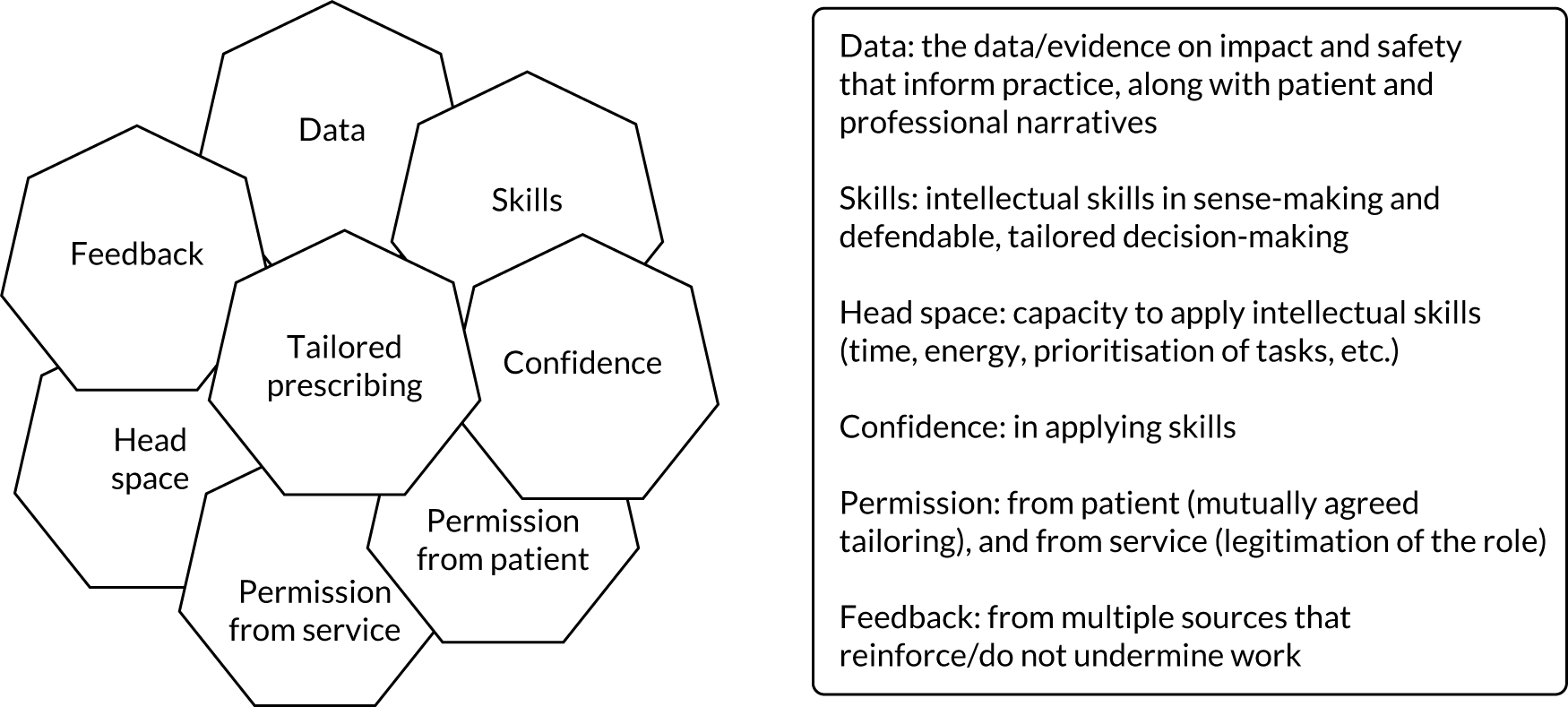

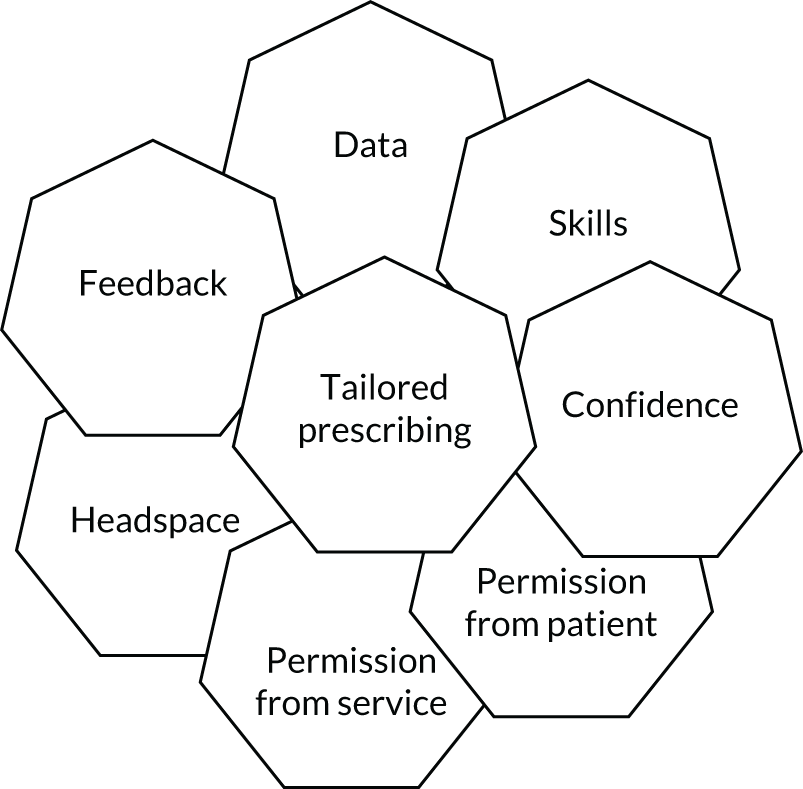

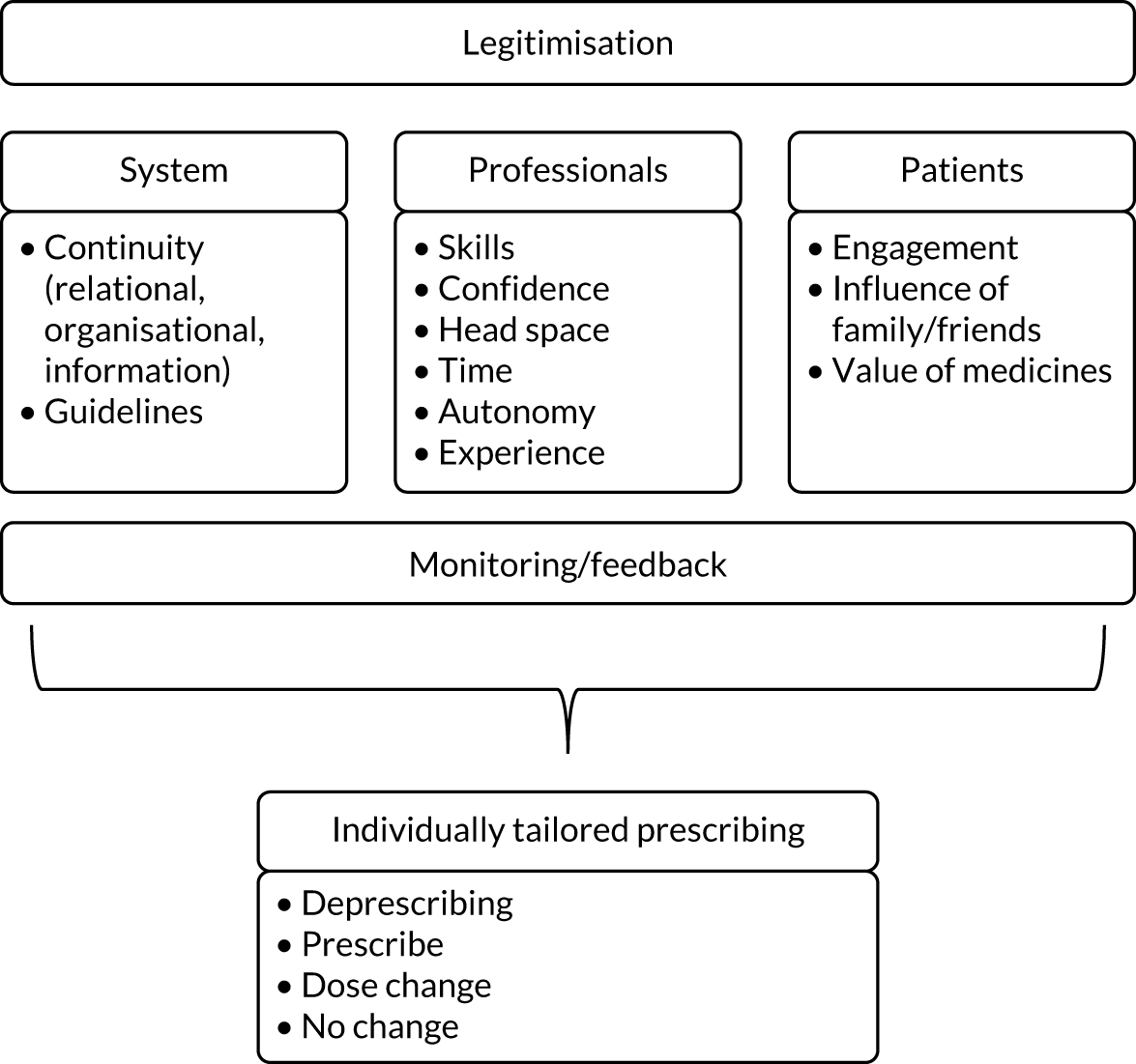

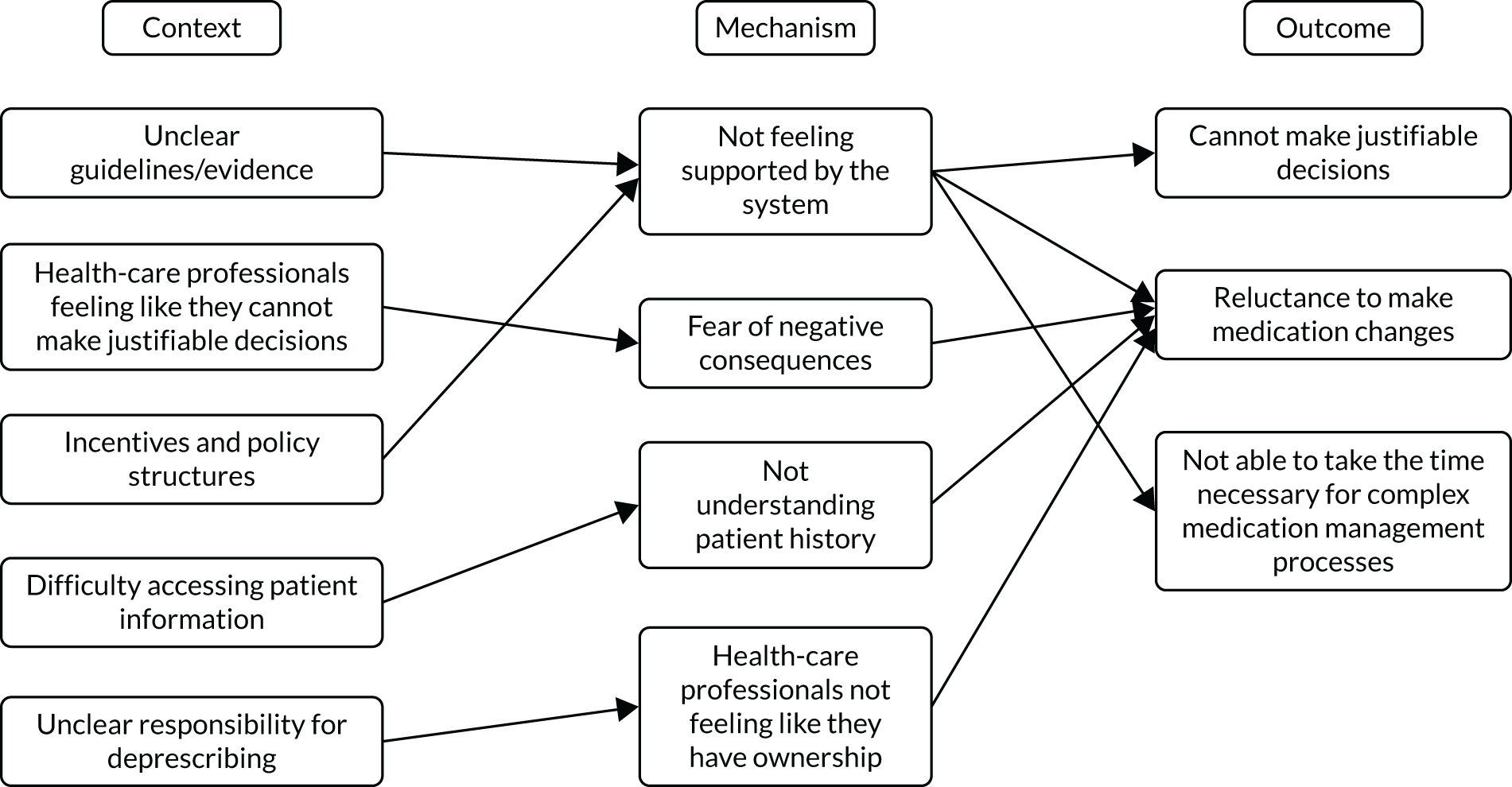

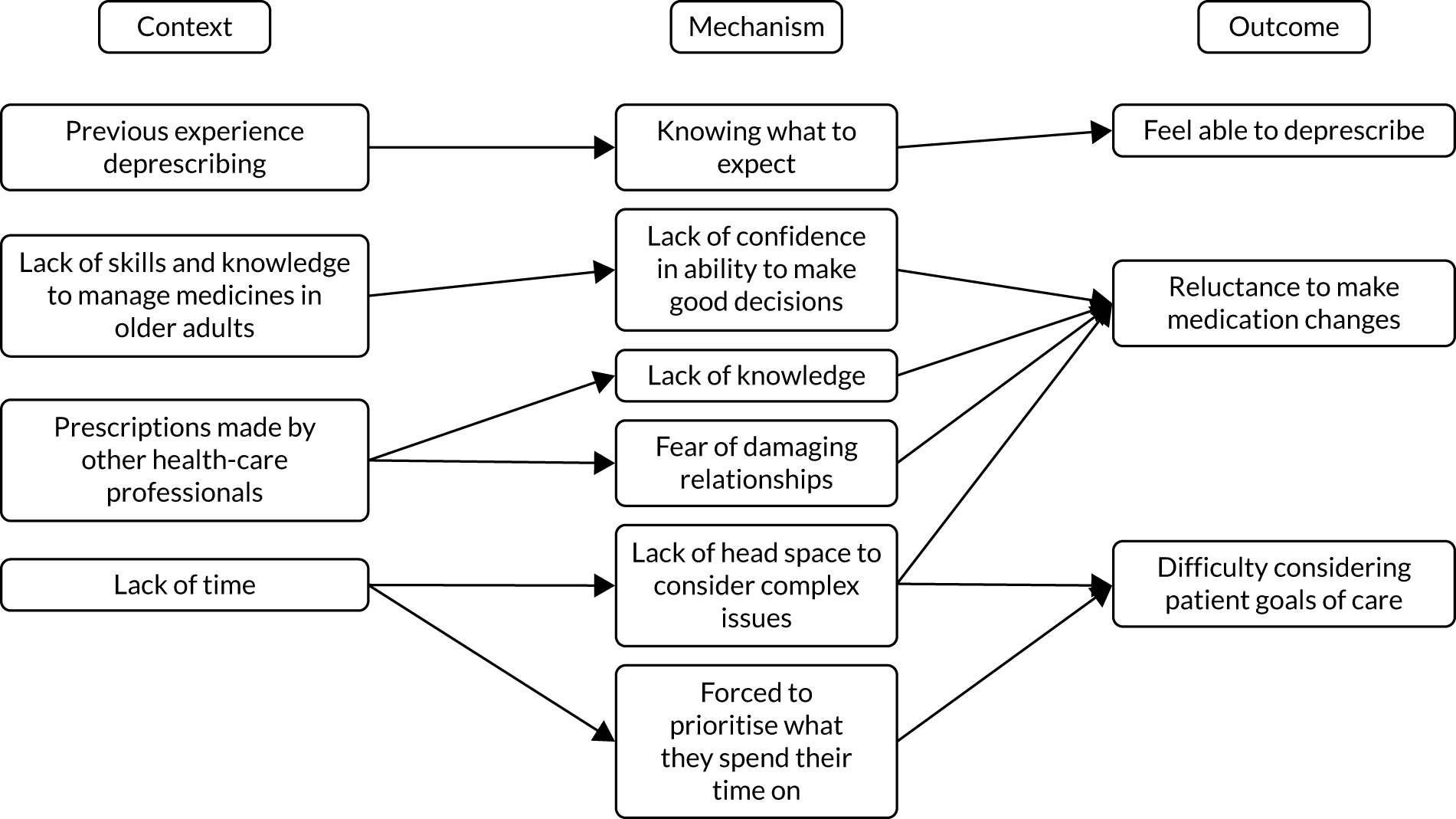

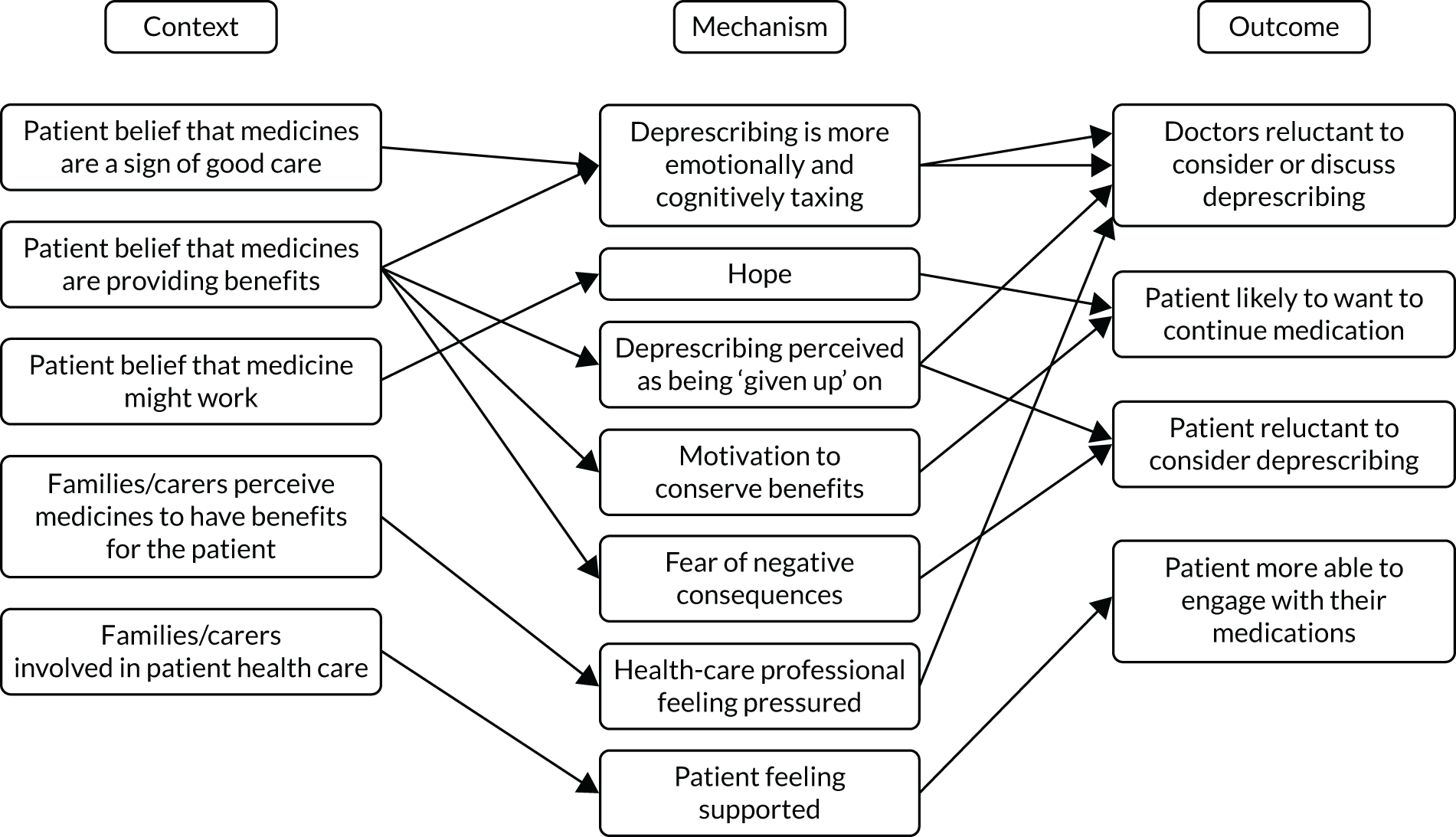

However, our previous research has revealed four barriers to tailored care, and specifically tailored prescribing, which would suggest that the guidance to date could have a limited impact. 6,17 Professionals involved in the complex decision-making (knowledge work)19 of providing beyond-guideline (tailored) care report a lack of confidence in undertaking this work because of a lack of perceived support in four areas (Table 1).

| Barrier | Description |

|---|---|

| Permission to work beyond guidelines and outside specialist frameworks | Guideline care is perceived as ‘best’ practice; beyond guideline care is ‘exceptional’ practice and needs to be justified. Lines of responsibility are unclear for generalists (e.g. GPs) reviewing medication started in specialist practice20 |

| Prioritisation of the greater workload involved | Practice workflow is designed to support delivery of usual care, with insufficient time17 and headspace6 built into the day to support the extended conversations and considerations (including justifications) for beyond-protocol care |

| Professional skills in complex decision-making and the confidence to use them | The extended skills of expert generalist (tailored) decision-making are not consistently taught (often learnt through experience and apprenticeship), with professionals describing lack of confidence in using the skills they have |

| Performance management supportive of the task | Complex decision-making is often not adequately recognised and rewarded by performance management processes (e.g. the Quality and Outcomes Framework), and may even be criticised (e.g. excessive exception reporting) |

Research therefore describes whole-system barriers to tailored (de)prescribing practice at consultation, organisation of practices and policy levels. 21 Structural changes, such as the design of health-care systems (including workflow) and performance management tools, may require evidence that different models of care provision offer efficient, effective and equitable care. But this research also points to work6,17 that may support individual clinicians and patients (consultation-level changes) in tackling problematic polypharmacy through tailored care. It does this specifically by providing them with evidence-based support that addresses ‘permission’ (why you could tailor care) and professional skills and confidence (how you could tailor care).

Addressing the gaps in our knowledge: describing the TAILOR evidence synthesis

Based on our overview of the current literature on problematic polypharmacy, stakeholder discussions and our own research in this field, we identified two specific additional areas of knowledge needed to support clinicians in the decision-making (knowledge work) of tailored deprescribing. These form the basis for the work of the TAILOR evidence synthesis.

Data on safety and impact of discontinuing medication

Advice for clinicians published by NICE,22 which it recognises as ‘guidelines not tramlines’ provides non-mandatory advice to inform, but not dictate, best practice. The limitations of guidelines for clinical practice are well recognised, for example in being ‘condition specific’ and ‘context blind’. 23 Guideline development has been criticised for using evidence that often excludes patients with multimorbidity,20 or for overlooking, or placing less weight on, evidence related to patients’ lived experiences of illness or treatment (e.g. theoretical or qualitative work). 24 Clinical practice for person-centred care inevitably involves working beyond guidelines, especially for people with multimorbidity, to reduce the risk of burden and iatrogenic harm. 25

In practice, guidelines are one source of data used by clinicians in the complex task of interpreting individual patient need,26–28 with their limitations well recognised. 29 Clinicians delivering tailored, whole-person care engage in a complex task of data collection, described by Donner-Banzhoff and Hertwig30 as inductive foraging, which draws on data from patient consultation, external data sources (including guidelines and evidence) and professional experience and expertise. 28

Access to data that helps clinicians in this process (to discuss the safety and impact of discontinuing medication with their patients and/or carers) is therefore key to tailored prescribing. 6 TAILOR addresses that gap through a scoping review to summarise the current available evidence on deprescribing in a form that makes a useful reference source for clinicians.

Framework for judging ‘best’ practice for tailored prescribing decisions

Tailored decisions require professional interpretation of multiple data sets, often in varied and varying circumstances, to generate individualised assessments of potential for risk and benefit. 14,28 Tailored prescribing may require the use of ‘clinically appropriate overrides’ of evidence-based guidance. 31 Outcomes of patient-centred care focus on clinical decisions that optimise health-related capacity for daily living, not simply condition- or medication-specific outcomes. 32–37

Defining and delivering best practice in tailored (de)prescribing can therefore be understood as a ‘wicked problem’: a complex (and often messy) problem that cannot be fixed because of incomplete, competing and changing requirements, but can be managed through iterative, adaptive and ongoing responses,38,39 resulting in solutions and outcomes that are better described as ‘better or worse’ rather than ‘right or wrong’. 40–42 Clinicians, patients and wider stakeholders, therefore, need a framework using which they can judge ‘better or worse’.

Medicines optimisation is the framework currently used to guide best practice, emphasising outcomes focused on clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and minimising both harmful effects and waste. 43 However, it is known that patients define benefit from medicines differently from clinicians. What a medical perspective may describe as effective or optimal care may be experienced as burdensome by patients. 1,32,44 Evidence highlights that patients prioritise the impact of care (including medicines use) on their continued daily living33,44–47 over the management of disease. 48,49 Assessing best, or better, practice by adherence to guidelines will be insufficient.

Tailored care actively incorporating patients’ priorities and perspectives into clinical decision-making may produce varied outcomes depending on individual patient circumstances and priorities. Outcomes of tailored prescribing decisions may also not be immediately apparent. For example, a tailored decision to stop primary prevention medication may not produce any recordable effect for some time, if at all. Assessing best, or better, practice using simple outcome measures may not be sufficient.

The research demonstrates that if we are to address the identified barriers to tailored (de)prescribing of permission and supporting professional confidence in the knowledge work of complex decision-making, clinicians need additional tools to support judgement of better practice. 6 Clinicians describe needing ‘permission’ to work ‘beyond guidelines’6,28 and so seek a validated framework against which they can judge and defend these interpretations. 28 TAILOR addresses that gap through developing a realist programme theory that describes best practice for tailored deprescribing, and so provides critical framework for practitioners, patients and managers to judge the quality of tailored care. The TAILOR framework will also provide the additional evidence needed to address the identified organisational barriers to delivery and so describe practice redesign.

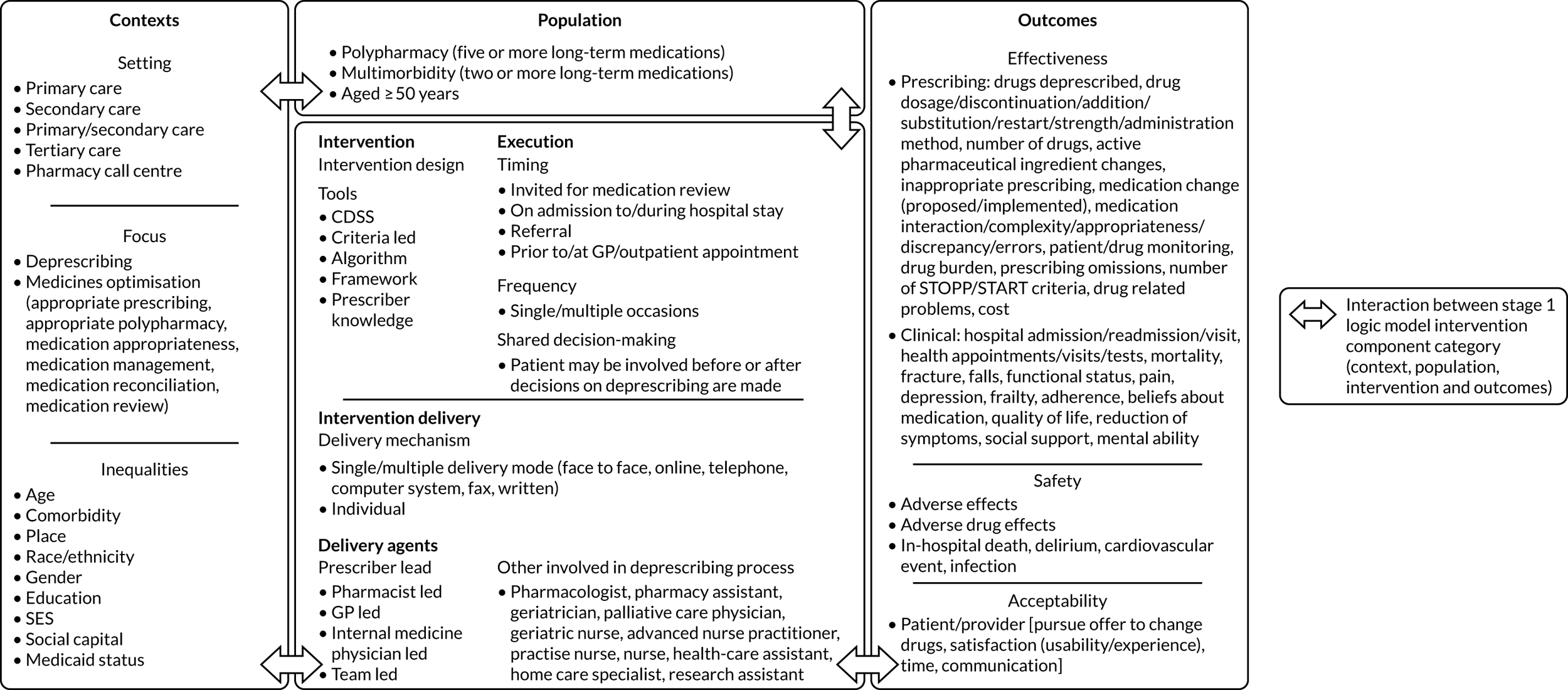

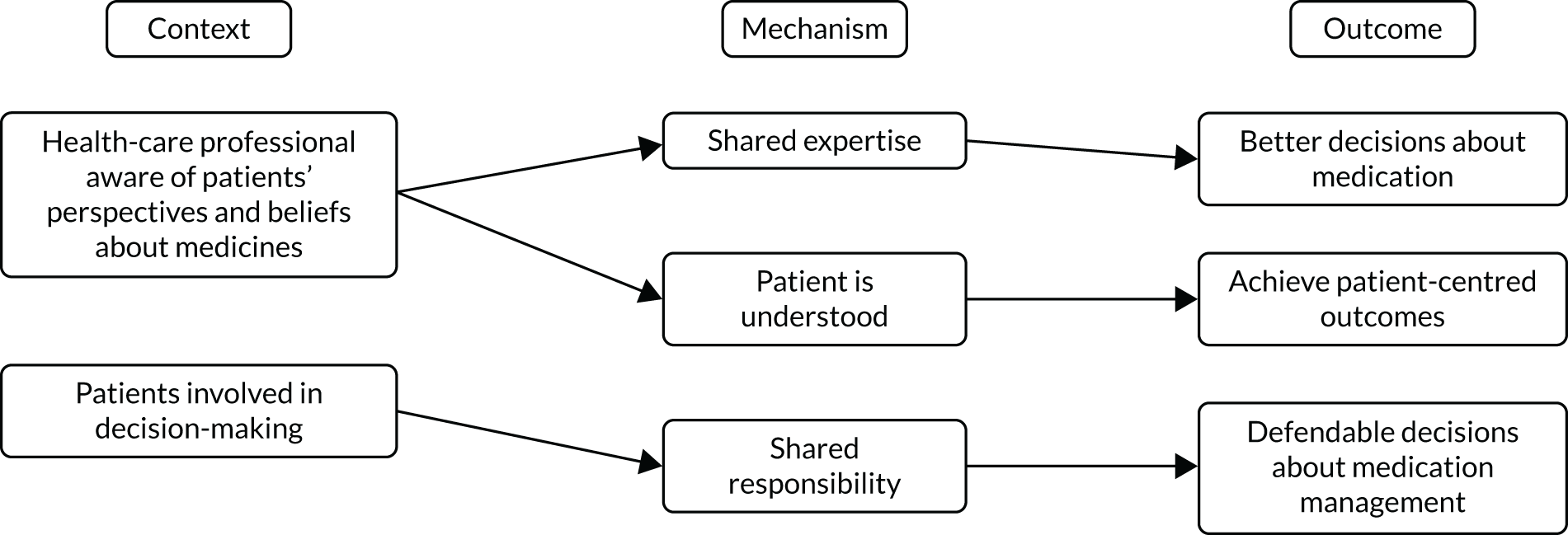

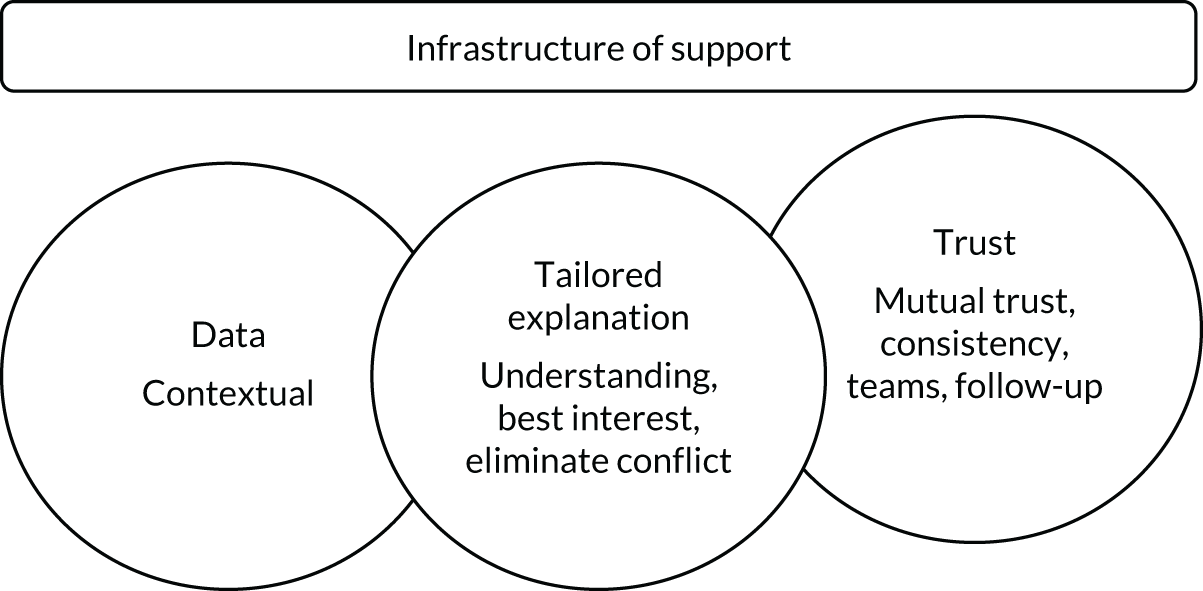

Our review of the literature, previous research and stakeholder engagement described a number of elements that may be important in developing this framework. These were incorporated into a draft programme theory used to inform the TAILOR realist review (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Draft programme theory describing elements needed for individual tailoring of medicines.

In Chapter 2, we describe how these findings and observations shaped the design of the TAILOR evidence synthesis.

Chapter 2 Research questions and design

Overview

In outlining the problem in supporting tailored deprescribing in the person-centred management of problematic polypharmacy, we have identified two key gaps in the existing body of knowledge available to clinicians to support robust and safe tailored decision-making around deprescribing. First, we recognise the need for a structured overview of the data on safety and effectiveness of deprescribing to provide clinicians with a key resource for interpretive practice. 28 Second, we need a robust, evidence-informed framework describing the key components of good clinical practice for tailored prescribing. In this chapter, we outline the decision to address these needs using two distinct review methodologies, interlinked through a shared initial search strategy and ongoing combined critical reflection.

Research questions

Our literature review in Chapter 1 led us to formulate two research questions for TAILOR to address:

-

What quantitative and qualitative evidence exists to support the safe, effective and acceptable stopping of medication in older people with multimorbidity and polypharmacy?

-

How, for whom and in what contexts can safe and effective individual tailoring of clinical decisions related to medication use work to produce desired outcomes?

Aims and objectives

Our aim was to deliver to clinicians, patients and policy-makers the resources that they need to support safe and effective compromise when tailoring medicines to individual needs and circumstances. Our two research questions prompted the use of different methodological approaches to answer them and so generated our first two objectives. The third objective recognised our commitment to delivering outputs that can have an impact on clinical care.

We therefore describe three objectives:

-

to complete a robust scoping review of the literature on stopping medicines in this group to describe what is being done, where and for what effect

-

to undertake a realist synthesis review to construct a programme theory that describes ‘best practice’ and helps explain the heterogeneity of deprescribing approaches

-

to translate findings into resources to support tailored prescribing in clinical practice.

Our intended outputs were to deliver (1) a reference data set for clinicians describing the approaches to deprescribing being used and what is known on effectiveness, safety and acceptability; and (2) a framework describing best (‘better’)41 practice in the individual tailoring of medicines, generating a set of recommendations for practice.

Justification for design

The research questions identified by our review of the literature (see Chapter 1) led us to recognise the need for different methodological approaches to answer each question.

Justification for a scoping review

Preliminary searches undertaken in preparing our bid demonstrated that the current body of evidence on deprescribing is disparate with significant heterogeneity. Studies cover many topic areas (e.g. clinical problems and research methods used), although the volume of scholarship in each area appears to be relatively small. We concluded that standard systematic review methods (including meta-analysis) would not allow us to adequately describe and integrate the diverse literature in a way that met our goals to offer clinicians, patients and policy-makers resources to support safe and effective tailored deprescribing.

We therefore opted for a scoping review to identify, map and draw together data in a useable form. Scoping reviews are recognised to be the most appropriate methodology when reviewing the evidence on complex interventions, allowing for the variability and complexity of the intervention and evaluation methods. 50 We chose a scoping review to enable us to systematically distil, from a diverse literature, the data that would support clinical decision-making.

Justification for a realist review

Our second goal was to provide a robust, evidence-informed framework describing the key components needed to deliver person-centred (tailored) deprescribing. Our intention was that this framework provide clinicians with a model of ‘best practice’ to support them in their daily work, and a model that could explain the heterogeneity in the literature on deprescribing.

We recognised tailored deprescribing as a complex intervention. 1 An intervention is defined as complex (rather than complicated) because it consists of numerous components interacting in non-linear ways and is sensitive to context. 51 As discussed in Chapter 1, Addressing the problem: what we already know about deprescribing, addressing problematic polypharmacy needs a tailored approach to prescribing that recognises compromise between biomedical (condition-specific factors increasingly in the context of multimorbidity) and biographical (individual context, preferences and priorities) perspectives. 1 Decisions involve weighing up multiple factors that vary in themselves and through interaction with each other. 21 Tailored deprescribing is therefore an example of a complex intervention, in which controlled and uncontrollable variation is inevitable and the active ingredient(s) may behave differently in varying contexts and for different people. 52

The realist review methodology is particularly useful for understanding and illuminating the relationships and impact of the interaction between the components of a complex intervention. 53,54 Realist reviews ask ‘what works, for whom, in what circumstances, to what extent, how and why?’ and consider the interaction between context, mechanism and outcome [how particular contexts (e.g. people, practices) trigger or interfere with mechanisms to generate the observed outcomes]. 55 Realist reviews generate explanations about the mechanisms by which stopping medication may (or may not) achieve impact in different settings and within different subgroups.

We therefore opted to use a realist review methodology to address our second research question, providing clinicians with a framework that describes and explains what is needed to support ‘better’ practice. 41 Our intention was to provide a framework against which to ‘defend’ good practice, addressing the recognised barriers to tailored care of permission, professional confidence and performance management (see Table 1). We also anticipated that that framework could help explain the heterogeneity revealed in reviews of the literature.

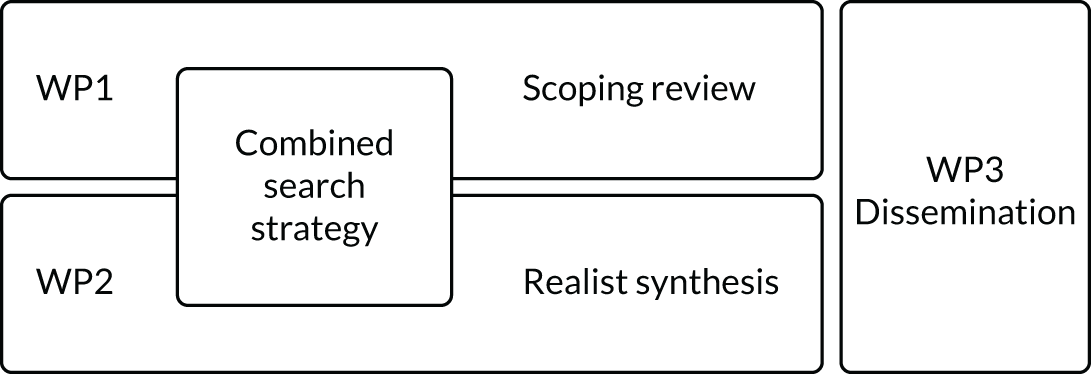

Justification for a combined literature search

Although we identified a need for two distinct analytical approaches, our common goal was to deliver outputs that supported the clinical task of tailored deprescribing to address problematic polypharmacy. Our funders had stipulated a particular focus on an older population living with multimorbidity. Our initial proposal, therefore, was to use a combined search strategy to collect the initial data for analysis using both methodological approaches (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Outlining the initial workflow for the TAILOR medication synthesis. WP, work package.

Refining the work plan

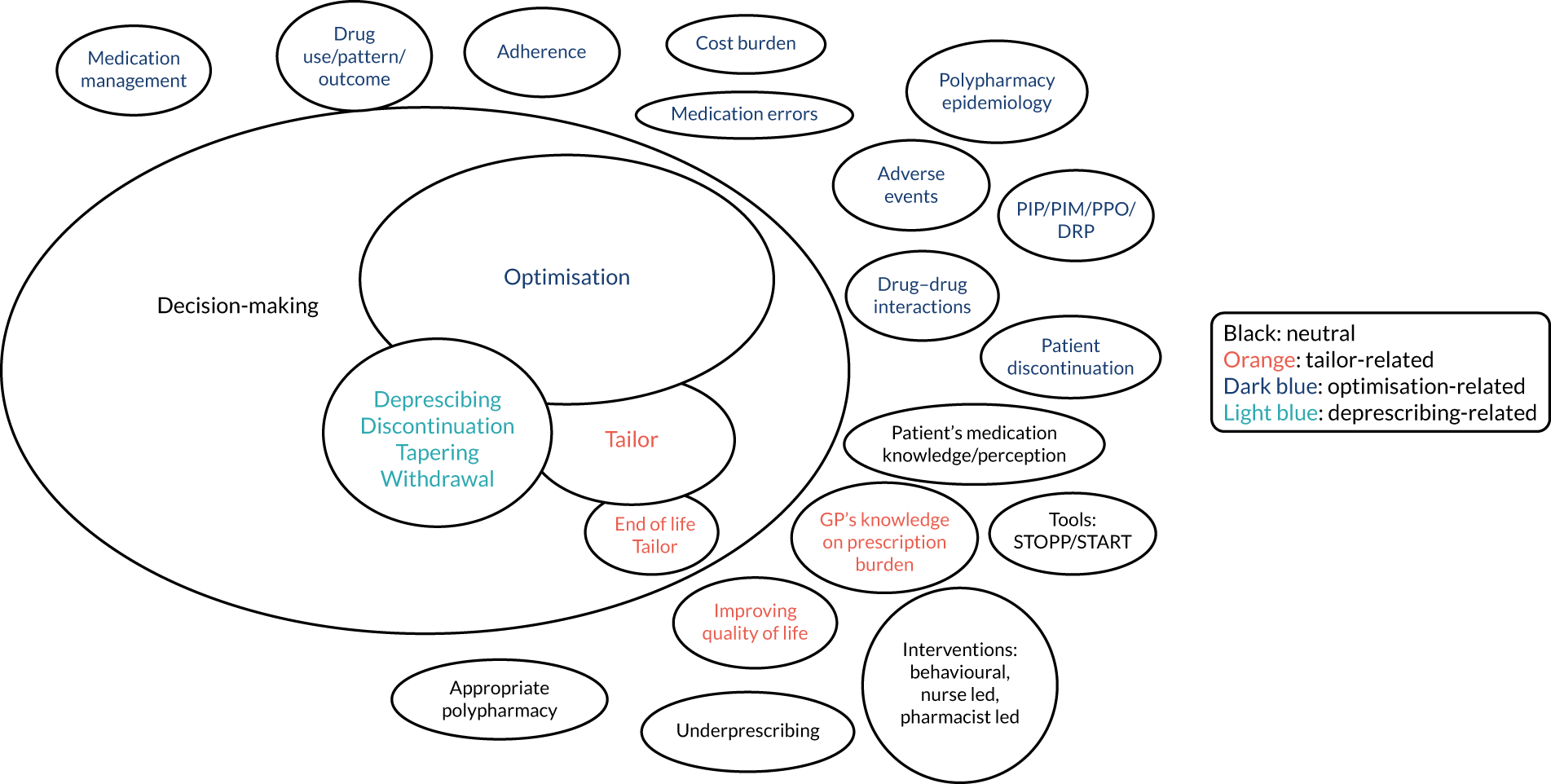

During the set-up stages of TAILOR, Nia Roberts (co-applicant) ran an initial literature search using our combined search strategy (described in Chapter 6). This generated an initial list of > 2000 studies. Kat Kavalidou (a research fellow working with us temporarily during the set-up stages) undertook initial work to categorise these studies to inform detailed discussions on developing the scoping review. Kat Kavalidou presented an initial thematic overview of the data set.

This work revealed that studies addressed a wide range of goals for practice. Three inter-related but distinct health-care goals could be identified: medicines optimisation (with a predominant focus on safety and biomedical effectiveness), deprescribing (the specific act of stopping medication) and tailored care (person-centred care around medication use). A wide range of research goals was also described, including research that aimed to define appropriate polypharmacy, improve appropriate medication use, recognise patterns of medication behaviour, improve adherence, develop and evaluate tools to recognise/address potentially inappropriate medication, and support end-of-life care.

Kavalidou’s summary of the complexity of the field is shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Mapping the themes identified from a descriptive overview of the literature on deprescribing. ‘De-prescribing’-related refers to studies looking at stopping specific medicines, ‘optimisation’-related studies focused on safety and biomedical effectiveness, ‘tailor-related’ studies were person focused and ‘neutral’ refers to studies that did not clearly state the underlying goal. DRP, drug-related problems; PIM, potentially inappropriate medication; PIP, potentially inappropriate polypharmacy; PRO, potential prescribing omissions.

Finalising work plans

Kavalidou’s findings were discussed at an extended team meeting. We recognised that this data set provided the richness needed for a realist review. However, we were concerned that it would not allow us to meet our goal to provide a useful resource to clinicians from a scoping review. We therefore opted for a revised and refocused scoping review based on a revised search strategy.

The revised final work packages for TAILOR are shown in Table 2.

| Work package | Led by | Chapters |

|---|---|---|

| 1: scoping review | Michelle Maden, Ruaraidh Hill; Liverpool University | 3–5 |

| 2: realist synthesis | Amadea Turk, Kamal Mahtani, Geoff Wong; Oxford University | 6–8 |

| 3: dissemination | Joanne Reeve; Hull University | 10 |

Joanne Reeve provided overview of, and support for, all work packages.

Detailing the research team

As described in our protocol (version 1.1, July 2019), we assembled a team of people to undertake this work including:

-

core research team (project working group) – responsible for delivery of the work as detailed in Table 2

-

academic advisory group – the additional co-authors of this report (see Chapter 10, Reviewing how we went about the work) responsible for overseeing the academic rigour of the research

-

stakeholder group – consisting of end users of our work, responsible for ensuring that the research remains relevant and for supporting the dissemination activities.

Chapter 3 Scoping review design and methods

Overview

In outlining the problem related to supporting tailored deprescribing in the person-centred management of problematic polypharmacy, we recognised the need for a structured overview of the evidence on the safety and effectiveness of deprescribing to provide clinicians with a key resource for interpretive practice. 27

Through our scoping review, we aimed to produce this reference set by outlining the approaches to the use of deprescribing and what is known about its effectiveness, safety and acceptability. Having described the heterogeneity of the literature based on an initial search (see Chapter 2, Refining the work plan), we identified the need for a refocused scoping review. This chapter details the approach used.

Aim

The aim of the scoping review was to map and characterise the available evidence on the approaches, effectiveness, safety and acceptability of interventions to taper/tailor and stop medication in older people living with multimorbidity and polypharmacy.

Methods

Scoping reviews allow for the mapping of research findings and identification of gaps in the evidence base. 56 The methodology allowed us to identify, map and draw together the current evidence base on strategies to support safe medication withdrawal in this population, including recognising the impact of health systems and context on prescribing practice. The TAILOR scoping review was specifically designed to signpost health-care professionals and policy-makers to the quantitative and qualitative data they need to support decisions about when, if and how to stop medications. We also sought to provide valuable information to researchers and funders on the gaps in the current evidence base where new research can be prioritised. We aimed, for example, to determine the feasibility of conducting further evidence syntheses, and identify the types of synthesis needed (e.g. meta-analysis of effectiveness or meta-synthesis).

This scoping review followed the methodology for conducting a scoping review as set out by the Joanna Briggs Institute. 57 This draws on the methodological framework from Arksey and O’Malley56 and is enhanced by Levac et al. ,58 which has been used to map the evidence of complex interventions. Five stages are described: (1) setting the research question, (2) identifying studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating and reporting. Consistent with the scoping review methodology, risk of bias was not assessed.

Stage 1: setting the research question

The scoping review questions were agreed by the research team in collaboration with our stakeholder and advisory groups. The overarching research question was to identify what recent quantitative and qualitative evidence exists to support the safe, effective and acceptable stopping of medication in older people with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. We wanted to offer clinicians a resource (data) set to inform their clinical judgement when making tailored prescribing decisions. Our intention was therefore to produce a map of the current evidence base for deprescribing practice outlining what is being done, where and for what effect. Our map was also to describe the ongoing gaps in our knowledge: areas where clinical judgement is particularly necessary. We therefore described a focused set of subquestions for the scoping review:

-

What research methods (study designs) have been used in the studies that focus on this topic? This offers clinicians an overview of what types of research have been done and where there are gaps (e.g. clinical trials with a biomedical outcome and/or intervention studies with a patient-centred outcome). It allows clinicians to judge the value and limitations of the reported TAILOR data set in relation to the specific clinical challenges they face.

-

What clinical strategies, contexts and outcomes have been studied on this topic? This offers clinicians an overview of what types of clinical interventions have been studied, and where there are gaps. It allows clinicians to judge the value and limitations of the reported TAILOR data set in addressing the specific clinical challenges they face.

-

What tools are available to support addressing problematic pharmacy in older people with multimorbidity and polypharmacy? This offers clinicians an overview of what tools for clinical practice exist and what the data tell us about the use and effectiveness of these tools.

Eligibility criteria

From these questions, we identified a refocused set of eligibility criteria for the scoping review, outlined in Table 3.

| Inclusion criteria | Explanation/justification |

|---|---|

| Populations |

Eligible studies included patients and/or health-care professionals Patients: patients with polypharmacy (i.e. five or more long-term medications) and multimorbidity (two or more long-term conditions) and aged ≥ 50 yearsa Health-care professionals: health-care professionals (e.g. clinicians, pharmacists) involved in deprescribing for people (aged ≥ 50 years) with multimorbidity (two or more long-term conditions) and polypharmacy (five or more long-term medications)b |

| Interventions | Eligible studies included those assessing a strategy or strategies used to safely deprescribe (withdraw) medications in older people with multimorbidity and polypharmacy and the outcomes used to measure the success of these strategies in relation to effectiveness, safety and acceptability (may include, but were not restricted to, patient benefits and harms, acceptability to patients and prescribers, health-related quality of life/functional status, treatment burden, safety including adverse events, and service use) |

| Context |

Studies in any context were eligible for inclusion We defined context as relating to personal context (e.g. gender, ethnicity), wider environmental context (country), setting or service (e.g. general practice, pharmacy, home, acute/interface care, secondary/tertiary care, outreach from secondary care or community pharmacy), care context (e.g. end-of-life care, dementia care) and/or deprescribing intervention context (e.g. medicines optimisation, deprescribing, tailoring) |

| Study design |

All study designs using quantitative [e.g. experimental (randomised controlled trials, quasi-randomised controlled trials, non-randomised clinical trials), quasi-experimental (interrupted time series, controlled before–after studies), observational (cohort, case–control, cross-sectional, case series)] or qualitative (e.g interviews, open-ended questionnaires, focus groups) methodologies were eligible for inclusion We excluded case reports. Practice guidelines or deprescribing manuals were excluded, unless reporting outcome data or process outcomes Relevant systematic reviews were retained and their reference lists scanned for other potentially relevant studies |

| Limits |

From 2009 English language No conference abstracts Our focus was on the most recent evidence to support deprescribing in the elderly. Analysis of records in PubMed indicated that studies focusing on deprescribing were published after 2009 |

Stage 2: search strategy

We used a comprehensive, broad and iterative approach to identify relevant literature. We conducted an initial exploratory search using search terms identified by the review team and PubMed PubReminer [URL: https://hgserver2.amc.nl/cgi-bin/miner/miner2.cgi (accessed 16 June 2021)] in MEDLINE (via Ovid). We then identified a set of key relevant studies identified in a recent scoping exercise undertaken by Kat Kavalidou (see Chapter 2, Refining the work plan). Free-text and thesaurus terms of MEDLINE records of the relevant key studies were analysed and the search strategy was amended to ensure that it captured all key relevant records. We conducted a sensitivity analysis on the search by comparing the retrieval of different search techniques (e.g. proximity operators, phrase searching and field searching) to develop a scoping search strategy that ensured the retrieval of all key relevant studies.

The exploratory search was then peer-reviewed by a second reviewer (RH). The following keywords formed the main structure of the search: A – multimorbidity terms combined with OR; B – polypharmacy terms combined with OR; C – deprescribing terms combined with OR; D – aged terms combined with OR. The initial findings suggested that not all relevant studies would be captured by combining A AND B AND C AND D; therefore, a multisearch combination approach was developed: search 1 – (A OR B) AND C AND D, Search 2 – A AND B AND C, Search 3 – (A OR B) AND C AND Qualitative terms. The results of search 1, search 2 and search 3 were combined with OR to obtain a single set of search results. The final version of the exploratory search was then translated into other databases (see Appendix 1 for full details of the search strategies).

We conducted comprehensive searches in MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library [Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)], Joanna Briggs Institute Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and Google Scholar (targeted searches for both Google sources). The search was limited to studies published in English between 2009 and 30 August 2019. The search was then updated on 23 June 2020 with an addition to the search of ‘five or more’ as a free-text term in polypharmacy concept (searches with this new term were also backdated to 2009 to capture any earlier studies that may have been missed in the initial search). An additional supplementary PubMed search was also conducted to ensure that online preprints were captured. An experienced information specialist (MM) conducted the searches. All searches were peer-reviewed by at least one other member of the review team. We also scanned through the reference lists of eligible articles to identify additional relevant studies. Finally, we conducted an abbreviated version of the CLUSTER search approach,60 using key relevant studies to identify sibling studies and additional relevant studies (via citation searching, lead author searching and project/tool searching).

Stage 3: selecting studies

Search results were downloaded into EndNote [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA], deduplicated and then uploaded into Covidence software (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) for screening. A two-stage screening process was conducted. First, all titles and abstracts were screened. Records that clearly met the inclusion criteria, or records for which it was not possible to tell from the title and abstract whether or not the study was relevant, were sent through to full-text screening. Full-texts were then screened against the eligibility criteria. One reviewer screened all records (MM) and a second reviewer (Gerlinde Pilkington, Yenal Dundar and Katherine Edwards) independently screened all records. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (RH).

Stage 4: charting the data

Data were extracted on study design, population characteristics, intervention characteristics [using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework],61 health inequalities [using the PROGnosis RESearch Strategy partneship+ (PROGRESS+) framework],62 and outcomes of interest. The template was piloted and all data were extracted by two reviewers (MM, Katherine Edwards) independently and cross-checked using Microsoft Access® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Stage 5: collating and reporting

The results were synthesised to address the aims of the review (i.e. provide a map of the evidence in relation to the effects, safety and acceptability of interventions to support deprescribing in the elderly with multimorbidity and polypharmacy). A narrative descriptive approach to the synthesis was adopted to map the evidence on research methods, contexts, tools and outcomes used in deprescribing interventions for elderly people with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. Outcomes were categorised as effects, safety or acceptability. In addition, intervention outcome results were summarised as having a positive, negative or equivocal effect. A framework synthesis approach was adopted using the TIDieR framework61 to synthesise data on deprescribing intervention characteristics. TIDieR is a checklist designed to unpick complex intervention components; however, it is a generic checklist designed to be applied to all different types of complex interventions. Item 4 of the TIDieR framework (‘What procedures’; see Table 7) asks the reviewer to ‘Describe each of the procedures, activities, and/or processes used in the intervention, including any enabling or support activities’. 61 Given the complexity of the ‘procedures, activities and/or processes’ that we observed in the reported deprescribing studies, we expanded this TIDieR item using Reeve et al. ’s63 published framework detailing the expected elements of the deprescribing process. This allowed us to extract in greater detail and in a consistent manner the specific deprescribing processes from across multiple studies. Full details are described in Appendix 2, Table 23. In some studies, insufficient information was reported to rate an item as a full ‘yes’ and therefore a ‘partial yes’ was assigned. Based on the findings of the scoping review, a stage 1 logic model64 [i.e. a static (visual) model of components of the logic rather than the interactions/interdependencies] was developed to summarise the evidence in terms of population, intervention, context, outcome (PICO).

Chapter 4 Results of scoping review

Overview

The results of our review described the diversity of research approaches and the range of clinical strategies, contexts and outcomes being used, and identified a set of tools available to support tailored deprescribing in this patient group.

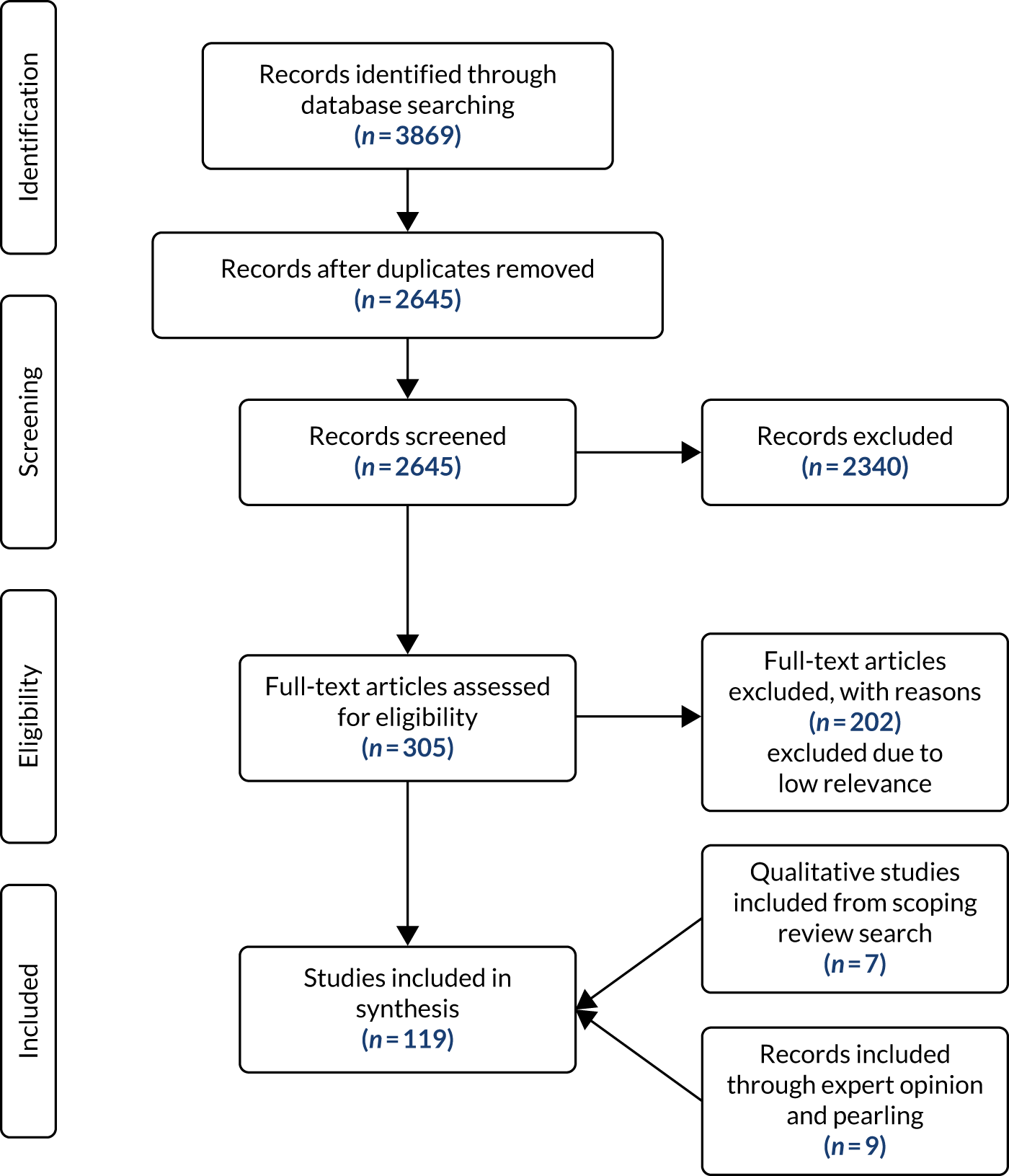

Search and screening result

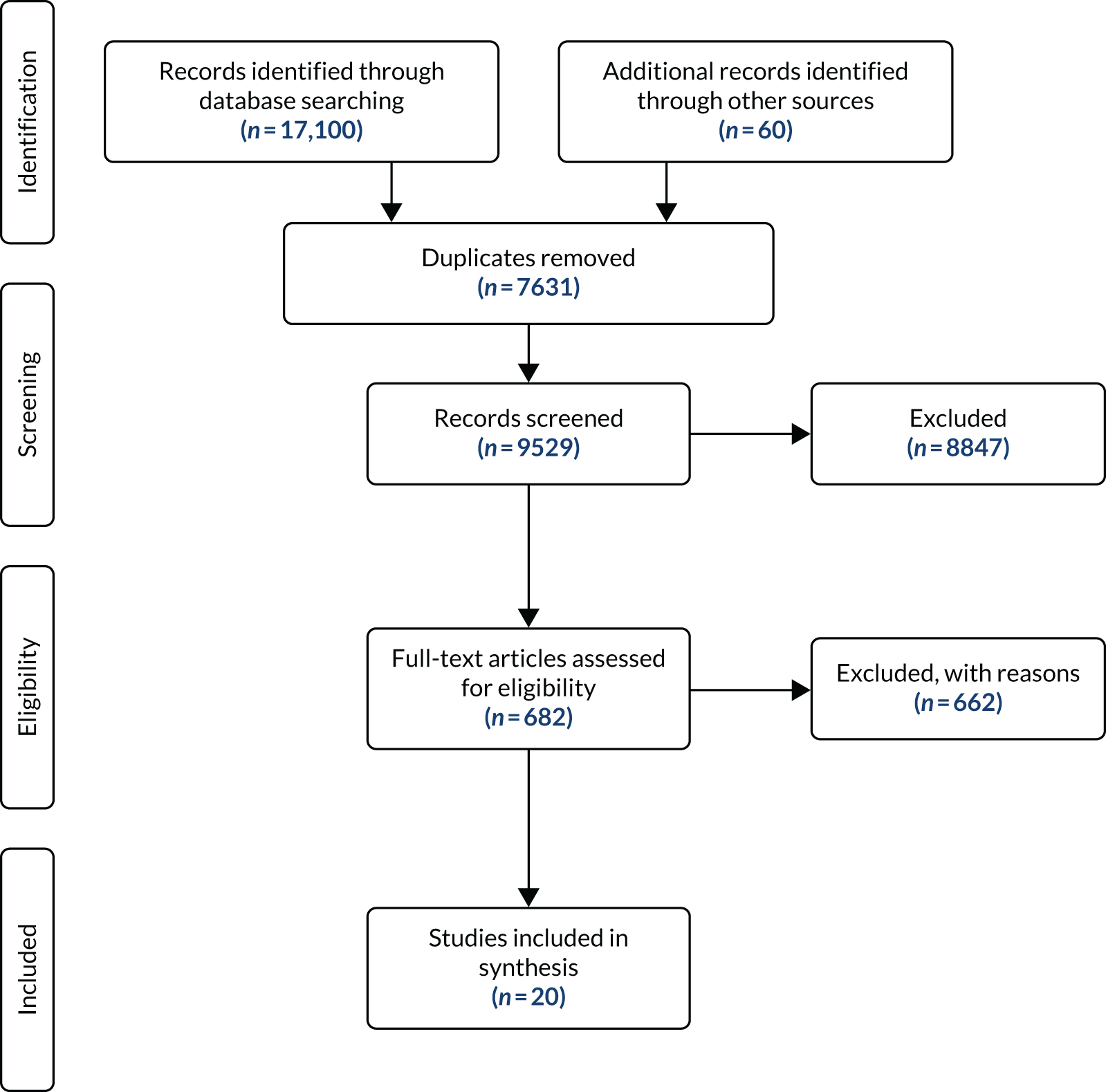

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)65 flow chart (Figure 4) outlines the search and screening results.

FIGURE 4.

The PRISMA flow chart for the scoping review.

This scoping review found that between 2009 and 2020, 20 studies (reported in 27 references) examined the effectiveness, safety and acceptability of deprescribing in older adults (aged ≥ 50 years) with polypharmacy (five or more prescribed medications) and multimorbidity (two or more long-term conditions) (see Appendix 3, Table 24, with additional detail on study characteristics in Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 27; assessed effectiveness, impacts and outcomes for included studies are detailed in Report Supplementary Material 2, Table 28). 66–85

Of the 662 studies excluded at full-text stage, 148 were not explicit in stating or did not meet the number of multimorbidities [i.e. did not define their population as multimorbid (two or more long-term conditions), or reported mean/medians] and did not define or meet polypharmacy as being five or more drugs, 99 studies met the polypharmacy criteria (five or more prescribed medications) but did not meet/state the number of multimorbidities as two or more long-term conditions and 26 met the multimorbidity criteria but did not meet or define the polypharmacy criteria (see Report Supplementary Material 3, Table 29).

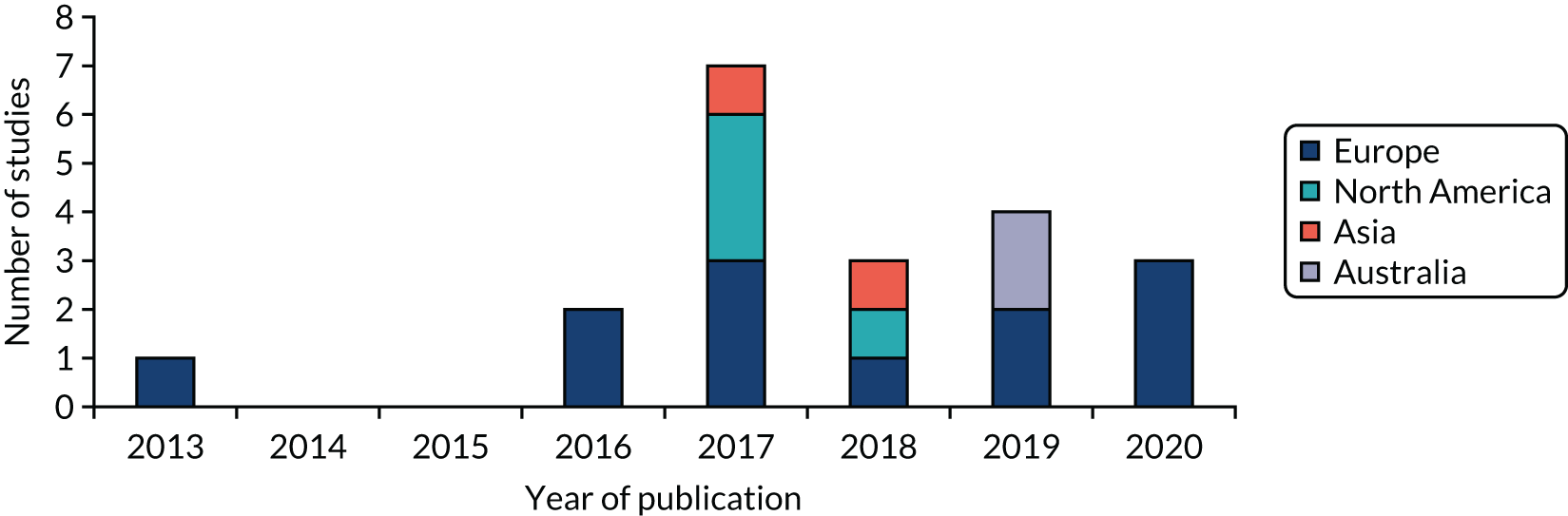

Figure 5 displays the region and year of publication of the included studies. Studies were published from 2013 onwards (our earliest publication date searched for was 2009) and were carried out across Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. Table 27 in Report Supplementary Material 1 provides more detailed study characteristics.

FIGURE 5.

Region and year of publication of included studies: scoping review.

Findings

What research methods are being used in the studies on this topic?

Our first review question asked, ‘what type of research methods are used to explore deprescribing in this patient group?’. Our findings revealed variability in the study designs used, study populations and durations, and the definitions of multimorbidity applied.

Study designs

Table 4 outlines the study designs of the included studies. Just under half were interventional studies and just over half were observational studies. Specifically, 13 (65%) used an intervention design, six (30%) used observational designs and one (5%) used an exploratory design. Nineteen (95%) were quantitative studies and one (5%) was a qualitative study. Seven randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (35%) were included, featuring three cluster RCTs (one was also a stepped-wedge design), two pragmatic RCTs and one open-label, multicentre RCT. Five (25%) were pilot studies.

| Study design | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| RCT | 7 (35) |

| Non-RCT | 2 (10) |

| Pre/post study | 4 (20) |

| Prospective cohort | 2 (10) |

| Retrospective cohort | 2 (10) |

| Cross-sectional | 2 (10) |

| Exploratory | 1 (5) |

Seven papers provided additional information on the studies above, four related to protocols and one was a validation study that provided further details on the intervention. One publication that covered multiple studies reported on additional outcomes and one study was a retrospective analysis of a RCT.

Inclusion criteria, sample size and length of follow-up

Table 5 outlines the inclusion criteria, sample size and length of follow-up in the included studies. Most studies focused on populations of people who were aged ≥ 65 years and taking five or more medicines per day. Around half the studies were classed as small (sample size < 100 participants); 35% were moderate (sample size 100–500 participants). Follow-up times were short, with only one study being > 12 months, and 30% of studies did not report the duration. All studies included multimorbid populations, but only 6 out of the 20 studies were explicit in recruiting multimorbid patients. In the remaining 14 studies, all patients included were multimorbid (according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index),59 but the researchers did not specify multimorbidity in their inclusion criteria. None of the studies focused specifically on the deprescribing of a single drug or category of drug.

| Inclusion criteria | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Population age (years) | |

| ≥ 60 | 2 (10) |

| ≥ 65 | 13 (65) |

| ≥ 70 | 2 (10) |

| ≥ 75 | 3 (15) |

| Polypharmacy (number of drugs) | |

| ≥ 4a | 1 (5) |

| ≥ 5 | 16 (80) |

| ≥ 7 | 1 (5) |

| ≥ 8 | 1 (5) |

| ≥ 15 | 1 (5) |

| Multimorbidity (number of diseases) | |

| ≥ 2 | 2 (10) |

| ≥ 3 | 4 (20) |

| Not explicit (CCI) | 14 (70) |

| Sample size (number of participants) | |

| 1–100 | 9 (45) |

| 101–500 | 7 (35) |

| 501–1000 | 2 (10) |

| 1001–5000 | 1 (5) |

| > 5000 | 1 (5) |

| Length of follow-up (months) | |

| Up to 3 | 6 (30) |

| Up to 6 | 2 (10) |

| Up to 8 | 1 (5) |

| Up to 12 | 4 (20) |

| > 12 | 1 (5) |

| Not applicable | 6 (30) |

Multimorbidities

Fourteen studies report on the type of multimorbidities included in the study samples (Table 6). In Van Summeren et al. ’s study,84 cardiovascular disease was the focus of the study population. In Muth et al. ’s study,78 patients had to have diseases affecting at least two different organ systems (not including diseases of the eyes and ears and diseases of the thyroid gland without hyperthyroidism). The remaining 12 studies reported various multimorbidities in their populations. Six (30%) studies did not specify any type of multimorbidity.

| Multimorbidity | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Addictions | 2 |

| Asthma | 4 |

| Cancer | 5 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 12 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 |

| COPD | 6 |

| Dementia | 7 |

| Diabetes | 10 |

| Endocrine | 2 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 4 |

| Gout | 1 |

| Haematological disorders | 2 |

| Hypertension | 5 |

| Liver disorders | 4 |

| Mental health disorders | 4 |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 5 |

| Neurological diseases | 2 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 2 |

| Vision disorders | 1 |

| Others (not stated) | 9 |

In summary, the review identified studies that were mainly interventional or observational in design, small to moderate in size, undertaken on older populations (aged > 65 years) and with clinically short follow-up times.

What clinical strategies, contexts and outcomes have been studied on this topic?

Clinical strategies

We used the TIDieR framework61 supplemented by the Reeve et al. 63 framework for deprescribing to describe the clinical strategies used as interventions in these studies.

Owing to the complex nature of the deprescribing interventions employed, the TIDieR framework was found to be insufficient on its own to allow for a rich description of the deprescribing strategies. Specifically, this related to the lack of a detailed description of the deprescribing intervention components. Therefore, we used a novel approach in supplementing the TIDieR framework with Reeve et al. ’s63 deprescribing process framework (see Appendix 2, Table 23). Reeve et al. 63 described seven steps needed to support robust deprescribing practice: (1) a comprehensive medical history, (2) an assessment of risk/harm, (3) an identification of potentially inappropriate medicines, (4) a shared decision on whether or not to stop, (5) communication of a plan, (6) implementation and monitoring and (7) documenting the process.

The purpose of using both these frameworks to describe and assess included studies was twofold: first, to assess the quality of the reporting in deprescribing studies and, second, to identify specific intervention components and delivery modes of the deprescribing strategies to allow for an assessment of the replicability of the deprescribing strategies in practice. In using the two frameworks together, therefore, we can provide clinicians with a more detailed map of what deprescribing strategies are used and how they are used.

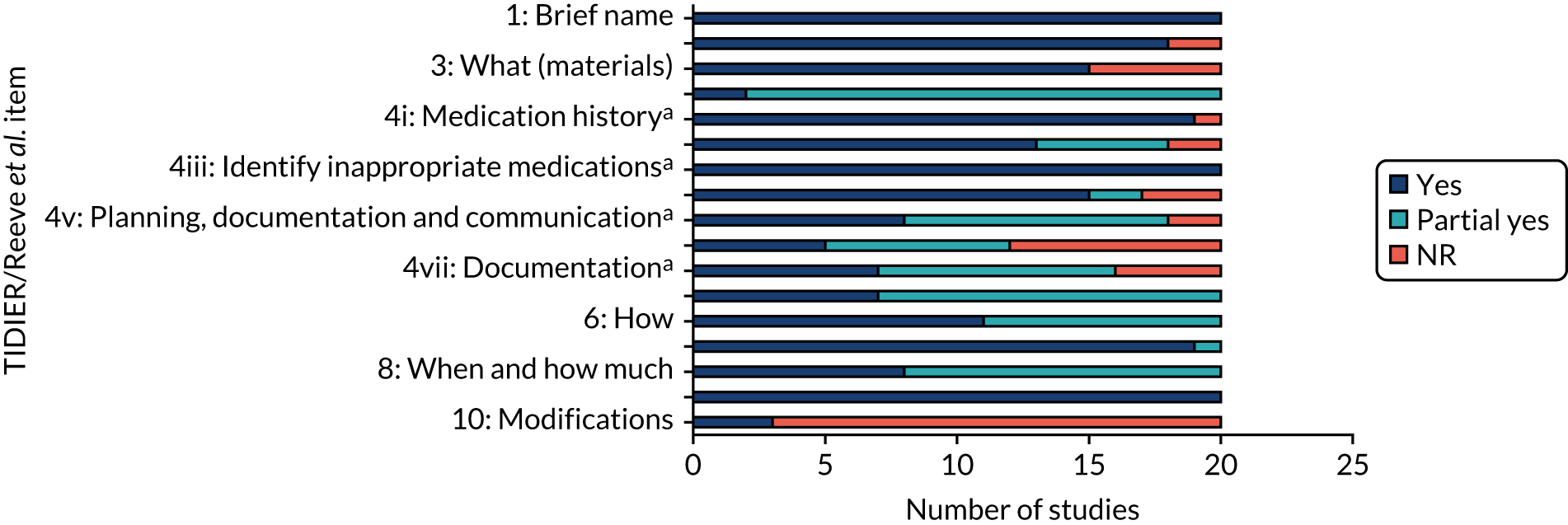

The extent to which individual studies (Table 7) and the studies collectively (Figure 6) reported on each of the TIDieR items is shown on the following pages (see also Appendix 2, Table 23, for further details of the frameworks).

| Study (first author and year) | 1: brief name | 2: why | 3: what (materials) | 4: what (procedures code) | 4a: medication historya | 4b: assess risk and patient factorsa | 4c: identify inappropriate medicationsa | 4d: shared decision-makinga | 4e: planning, documentation and communicationa | 4f: monitoring and supporta | 4g: documentationa | 5: who provided | 6: how | 7: where | 8: when and how much | 9: tailoring | 10: modifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boersma 201966 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | P | Y | P | P | NR | NR | P | Y | Y | P | Y | Y |

| Caffiero 201767 | Y | Y | NR | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR |

| Campins 201768 | Y | Y | Y | P | NR | NR | Y | Y | P | P | P | P | P | Y | P | Y | NR |

| Chiarelli 202069 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | P | Y | NR | P | NR | Y | P | P | Y | Y | Y | NR |

| Curtin 202070 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR |

| Fried 201771 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | NR | P | Y | Y | P | Y | NR |

| Köberlein-Neu 201672 | Y | Y | NR | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR |

| Komagamine 201773 | Y | NR | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR | P | P | P | P | Y | P | Y | NR |

| Komagamine 201874 | Y | Y | NR | P | Y | P | Y | NR | NR | P | NR | P | P | Y | P | Y | NR |

| Martín Lesende 201380 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | P | Y | P | P | NR | NR | P | P | Y | P | Y | NR |

| McCarthy 201775 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | P | P | P | P | Y | P | Y | Y |

| McDonald 201976 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR |

| Muth 201677 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | NR | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Muth 201878 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | NR | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR |

| Petersen 201879 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | P | Y | P | Y | NR |

| Potter 201981 | Y | Y | NR | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | P | Y | Y | P | Y | NR |

| Russell 201982 | Y | Y | NR | P | Y | NR | Y | Y | P | NR | P | P | P | Y | P | Y | NR |

| San-José 202083 | Y | NR | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | NR | P | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | NR |

| van Summeren 201784 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NR |

| Zechmann 201985 | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | NR | P | P | P | P | P | Y | NR |

A more detailed description of each criterion from the TIDieR framework is offered below, including items 11 and 12.

Item 1: brief name

All included studies (100%) reported the name of or a phrase that described the intervention. Eleven studies provided precise names for the intervention. The remaining studies provided a brief phrase or description.

Item 2: why (rationale, theoretical framework, goal)

Eighteen (90%) of the included studies provided the rationale for the intervention. None of the studies was explicit in reporting a named theory (e.g. theory of planned behaviour) to underpin their intervention. The rationale or underlying theories provided were largely based on the findings of previous research with reference to intervention components [e.g. academic detailing, medication review and specific tools (e.g. STOPP/START criteria) known to be effective], barriers to and facilitators of deprescribing (e.g. availability of health-care specialists with familiarity in managing polypharmacy in multimorbid populations and patient priorities) or setting (e.g. patients in hospital are seen as a captive audience and therefore more likely to be motivated to stop medications, which provides time for patients to discuss their options and the opportunity to observe patient outcomes closely).

Item 3: what (materials)

Fourteen (70%) studies reported using 20 different tools to guide the deprescribing process. Seven types of tools were identified: six studies (30%) used a clinical decision support system (CDSS), five (25%) studies used a criteria-led tool, one (5%) study used an algorithm, one (5%) used a CDSS plus criteria-led tool and one (5%) used an algorithm plus criteria-led tool (see What tools are available to support addressing problematic pharmacy in older people with multimorbidity and polypharmacy? and Table 27 in Report Supplementary Material 1 for details on the specific tools used). Twelve (60%) studies report using a single tool. Two (10%) studies used more than one tool to guide deprescribing. Six (30%) studies did not use a specific tool to guide the deprescribing process. Instead, pharmacists and clinicians were free to use any tool they wished or rely on their own expertise to propose and implement medication changes.

Item 4: what (procedures)

The seven elements of the deprescribing process as reported in Reeve et al. 63 were used to further define the procedures involved in the intervention. Only two (10%) studies reported on all seven items.

Nearly all studies (19/20, 95%) were explicit in detailing the taking of a patient medication history. One study, by Boersma et al. ,66 reported using a tool [Structured History taking of Medication use (SHiM)]66 to inform the medication review process.

Eighteen (90%) studies recorded an assessment of risk of harm and benefit and/or patient factors. Two studies did not report an assessment of these factors in the deprescribing process. Two studies used a checklist-based pre-consultation interview tool, Medication-Monitoring-List (MediMoL), to assess risk and patient factors. 77,78

All 20 (100%) studies recorded details of how potentially inappropriate medications were identified (see Chapter 3, Methods, for details on the tools used).

Seventeen (85%) studies reported incorporating patient preferences into the deprescribing process. Seven studies (35%) incorporated patient preferences into the process before providers decided on the medications to deprescribe. 72,75,77–79,84,85 Of these, six were conducted in the primary care setting and one was conducted in a tertiary setting. Seven studies (35%) involved patient discussion at the end of the process, only after medications for deprescribing had been identified. 67,68,70,71,73,76,79 Three studies utilised tools to elicit patient preferences prior to the identification of medicines to be deprescribed; Muth et al. 77,78 used MediMoL, whereas van Summeren et al. 84 used the outcome prioritisation tool. 84 Patient preference was the focus of the deprescribing process in van Summeren et al. 84 In three studies it was unclear at what point in the deprescribing process the patient was involved.

Eight (40%) studies described planning the tapering or withdrawal process with documentation and communication among health-care professionals. Ten (50%) studies lacked information on the tapering and withdrawal process. Two (10%) studies did not state a plan for the tapering or withdrawal of medications.

Twelve (60%) studies detailed monitoring and/or support for patients following deprescribing. This involved the symptom and safety monitoring of patients (e.g. for adverse drug withdrawal events or disease relapse). Support offered included additional consultations and telephone follow-ups.

Sixteen (80%) studies described the process for documenting the outcome of deprescribing (e.g. dose reduced or medication ceased). Of these, seven (35%) describe sharing the documentation with all relevant health-care professionals.

Item 5: who provided

In more than half (n = 11, 55%) of the studies a physician led the deprescribing process (i.e. identified the medications to deprescribe). Of these, seven studies were general practitioner (GP)/primary care physician led and one was led by a specialist registrar in geriatric medicine. Five studies (25%) were pharmacist led and in four studies (20%) the deprescribing recommendations were made by the team involved in patient care. Three studies involved a single intervention provider (two GP led, one clinician led). The majority (n = 17, 85%) involved more than one provider in the deprescribing process. Pharmacists and specialist geriatric physicians were more likely to be involved in the deprescribing process in secondary care settings than in primary care settings. Table 27 (see Report Supplementary Material 1) provides more information on the personnel involved in the provision of the intervention.

Item 6: how

All studies (n = 20, 100%) detailed to some extent the mode of delivery of the deprescribing intervention. Multiple methods of delivery were reported involving face-to-face, online, telephone, electronic health record, fax and written modes of delivery. All studies (n = 20, 100%) employed an individual delivery format.

Item 7: where

Ten studies (50%) carried out the intervention in primary care settings, seven (35%) studies were set in secondary care settings, two (10%) studies were set in tertiary care settings and one (5%) study was set in a pharmacy call centre (Table 8).

| Setting | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary care | 10 (50) |

| Secondary care | 7 (35) |

| Tertiary care | 2 (10) |

| Other (pharmacy call centre) | 1 (5) |

Item 8: when and how much

All studies (100%) described when the deprescribing intervention took place. Seven (35%) studies invited patients for a medication review. In seven (35%) studies patients were invited to participate upon or during hospital admission. Four (20%) studies invited patients who were attending another GP or outpatient appointment or were awaiting a primary care appointment. Two (10%) studies referred patients from primary care or hospital. Four (20%) studies reported the intervention as being delivered on a single occasion and one (5%) study offered an optional second consultation. In two studies a medication review was offered twice (once at hospital admission and again at discharge, and once after invitation for medication review and again at 6 months) and one study offered an annual medication review with quarterly targeted reviews. In 12 studies (60%) it was unclear how many times the intervention was delivered.

Item 9: tailoring

All 20 (100%) studies reported tailoring their interventions with decisions to deprescribe based on individual patient requirements as described under item 4d. Additional tailoring approaches described included protected time for individual consultations to discuss prescribing decisions and incorporation of individual patient medication-related problems. These were in addition to medications that physicians judged to be inappropriate or unnecessary but were sometimes continued owing to patients’ preference, and recommendations made regarding the need to simplify the regimen of patients with problems with adherence, compliance and poor social support.

Item 10: modifications

Three (15%) studies reported modifying the intervention. Boersma et al. 66 modified the intervention during the study by introducing consensus-based instructions to standardise the prescribing recommendations. Two pilot studies reported on making changes to the intervention after completion of the study to inform larger studies. Muth et al. 77 intensified the provider training and written CDSS manual. McCarthy et al. 75 made minor modifications to the training videos and medication review template to improve clarity of instruction and reduce repetition.

Item 11: adherence to the study recommendations

One (5%) study reported training pharmacists and home care specialists with a planned assessment of the training on 10 patients. Eleven studies (55%) reported that training of intervention providers was undertaken but planned assessment was not reported. Six studies planned assessment of patient adherence.

Item 12: outcome of training

None of the 11 studies that reported training intervention providers reported on the outcome of the training. Five of the six studies that planned to assess patient adherence reported on adherence outcomes.

Overall, in summary, our analysis revealed that studies offered clear accounts of the goals of the deprescribing interventions used and to whom they were offered (i.e. which patients were included). However, there was often less detail reported on who delivered the intervention and how (what specifically was done).

Using Reeve et al. ’s63 framework to further analyse details of the interventions revealed that most studies offered clear accounts of the assessment of patients leading to a decision to potentially deprescribe. Details on subsequent actions, including communication, documentation and planning, follow-up monitoring and support, and documentation of the clinical plan were all less clearly described.

Contexts

We sought to understand the context in which deprescribing interventions were being delivered by considering the clinical focus of the study (whether on stopping medication, or improving prescribing–medicines optimisation). We also examined the extent to which researchers considered the population context in which studies took place, through an examination of assessment of markers of inequalities.

Focus of the intervention

Deprescribing was the focus of the intervention in eight studies. The remaining 12 studies involved deprescribing as part of a wider medicines optimisation context (Table 9).

| Focus of the intervention | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Deprescribing | 8 (40) |

| Medicines optimisation | 12 (60) |

Inequalities

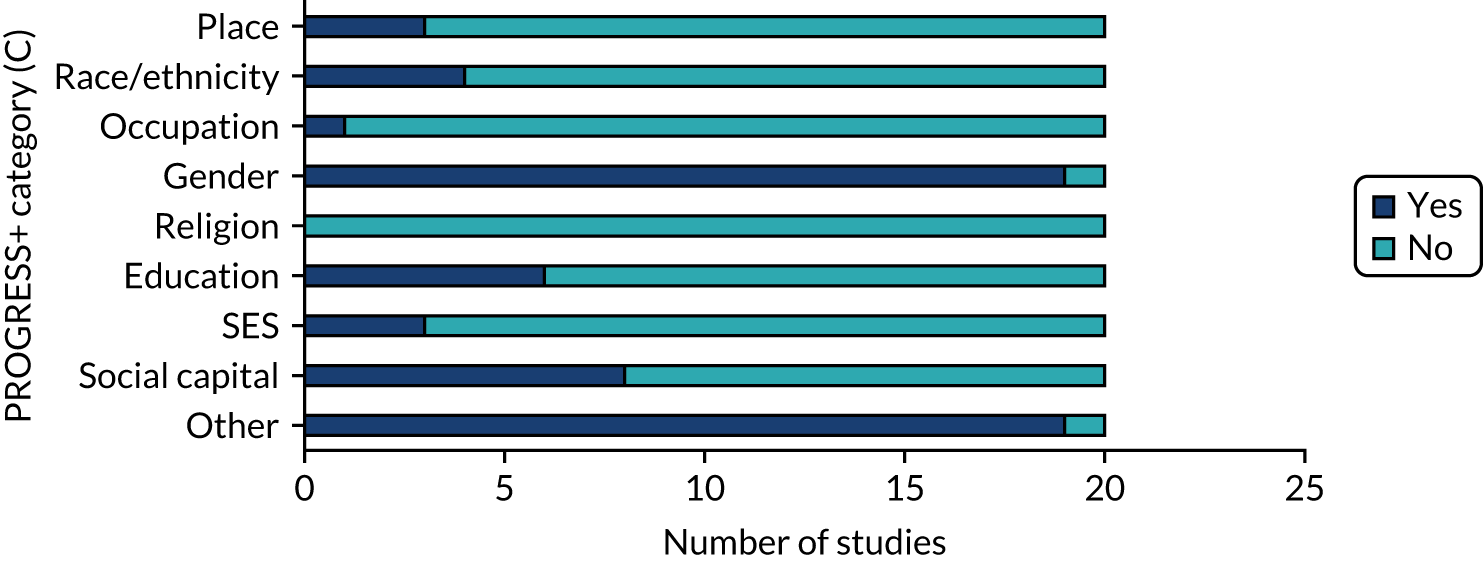

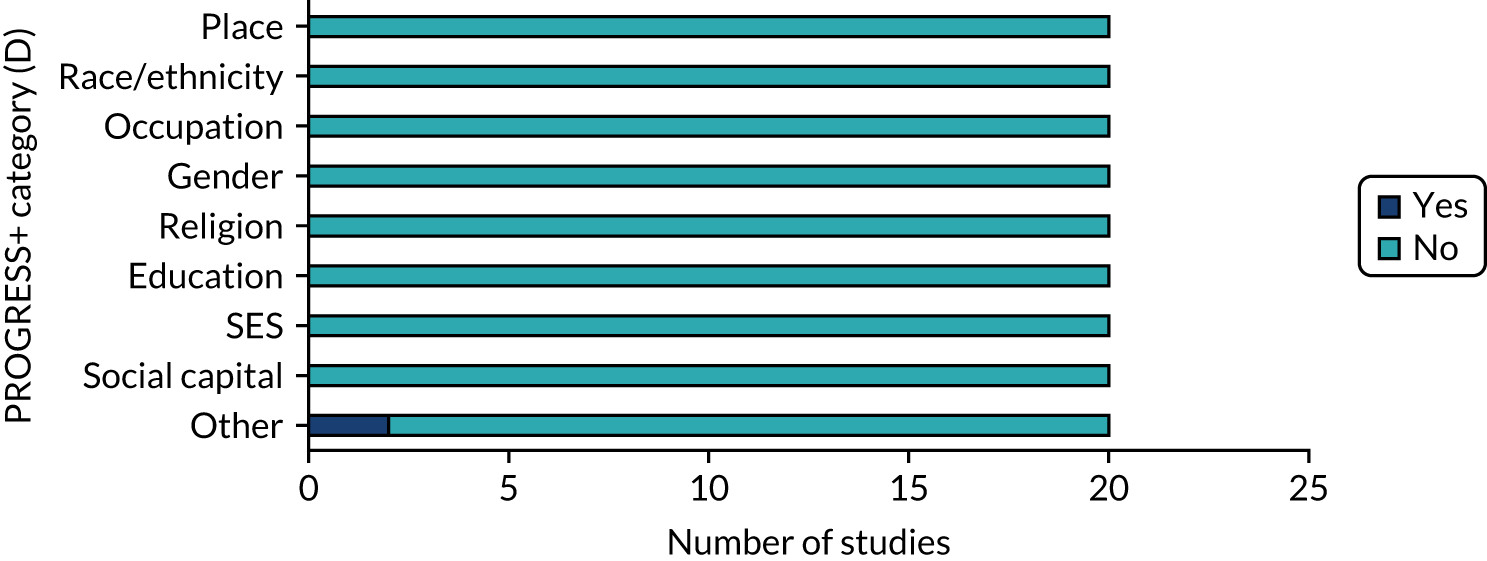

By assessing population characteristics using the PROGRESS+ framework,62 we sought to offer end users of our review an analysis of which populations the findings could be generalised to. Given the focus of our research question, all studies considered age and comorbidity inequalities. We assessed the extent to which other population contextual factors were also considered through an assessment of inequalities using the PROGRESS+ framework. This describes nine characteristics that stratify health opportunities and outcomes within populations, namely place, race/ethnicity, occupation, gender, religion, education, socioeconomic status, social capital and other.

Only two studies (10%) explicitly report a PROGRESS+ inequality, namely Medicare status, as being the focus of their study population.

PROGRESS+ inequalities collected

Nineteen studies (95%) collected baseline data from participants on characteristics described by the PROGRESS+ inequalities (Figure 7). All 19 studies collected data on gender. The one study that did not report baseline inequality characteristics reported pilot data within a study protocol. Other inequalities collected were age and comorbidity status (which reflected the target population) and Medicare status (i.e. health insurance).

FIGURE 7.

PROGRESS+ inequalities collected. SES, socioeconomic status.

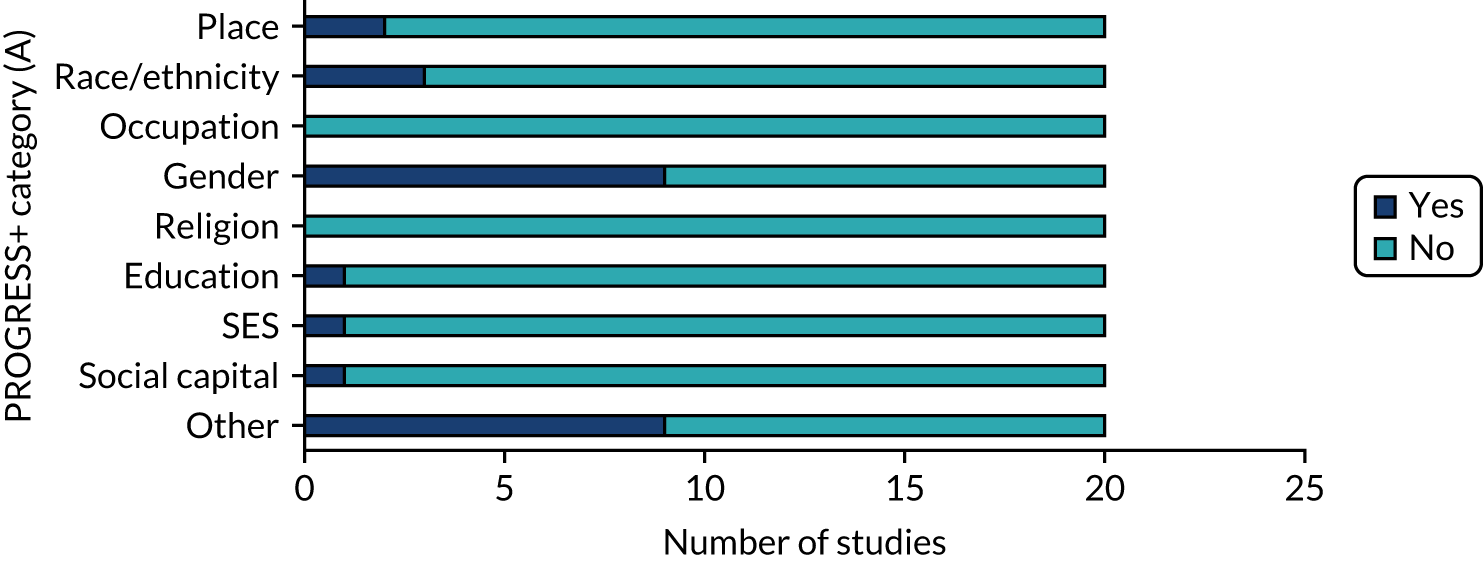

PROGRESS+ inequalities analysed

Nine studies (45%) analysed data on PROGRESS+ inequalities (Figure 8). The most common inequality analysed was gender (nine studies). Other inequalities analysed were age and comorbidity status (which reflected the target population) and Medicare status (i.e health insurance). Inequality variables were mostly adjusted for in statistical analyses (e.g. through logistic regression models). However, only one study discussed the effect of population characteristics and inequalities on outcomes (Figure 9).

FIGURE 8.

PROGRESS+ inequalities data analysed. SES, socioeconomic status.

FIGURE 9.

PROGRESS+ inequalities data discussed. SES, socioeconomic status.

In summary, population-level contextual information in the form of key characteristics known to have an impact on inequalities was poorly reported and discussed across the studies. Reporting of clinical contextual information (deprescribing vs. medicines optimisation) was present in most studies, with approximately half looking at deprescribing.

Outcomes

Our review demonstrated that studies used multiple outcomes relating to the effectiveness, safety and acceptability of interventions. These are summarised in Table 10. Altogether, 461 outcomes were reported relating to effectiveness (n = 382), acceptability (n = 49), safety (n = 23) and other (n = 7) (see also Report Supplementary Material 2, Table 28).

| Effects/safety/acceptability | Type of outcome | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Effects (prescribing) | Drugs deprescribed (stopped/withdrawn/tapered/dose reduced, etc.) | 9 |

| Drug dosage (increased, decreased, application interval shortened/prolonged, pill splitting started/stopped) | 36 | |

| Drug discontinuation | 24 | |

| Drug addition | 6 | |

| Drug substitution | 10 | |

| Drug restart | 6 | |

| Drug strength | 8 | |

| Drug administration method | 3 | |

| Number of drugs | 32 | |

| Active pharmaceutical ingredient changes | 3 | |

| Inappropriate prescribing | 25 | |

| Medication change | 9 | |

| Proposed change in medication | 22 | |

| Implemented change in medication | 25 | |

| Medication interaction | 3 | |

| Medication complexity | 4 | |

| Medication appropriateness | 13 | |

| Patient/drug monitoring | 2 | |

| Drug burden | 2 | |

| Medication discrepancy | 4 | |

| Medication errors | 1 | |

| Number of START criteria | 10 | |

| Number of STOPP criteria | 10 | |

| Prescribing omission | 4 | |

| Drug-related problems | 2 | |

| Cost | 2 | |

| Effects (clinical) | Hospital admission/readmission/visits | 23 |

| Health appointments/visits/tests | 11 | |

| Mortality | 10 | |

| Fracture | 2 | |

| Falls | 3 | |

| Functional status | 8 | |

| Pain | 4 | |

| Depression | 2 | |

| Frailty | 1 | |

| Adherence | 20 | |

| Beliefs about medication | 16 | |

| Prioritised health outcome | 8 | |

| Quality of life | 15 | |

| Social support | 1 | |

| Mental ability | 1 | |

| Safety | Adverse event (unspecified) | 2 |

| Adverse drug event (unspecified) | 4 | |

| Delirium | 1 | |

| Cardiovascular event | 2 | |

| In-hospital death | 3 | |

| Infection | 1 | |

| Acceptability (patient) | Pursue offer to change drugs | 23 |

| Acceptability (provider) | Satisfaction (usability/experience) | 16 |

| Acceptability( patient/provider) | Time | 3 |

| Communication | 5 | |

| Participation | 1 |

We summarise the outcomes reported across the 20 studies included in this review in Table 11.

| Studies | Outcomes reported | Effects | Safety | Acceptability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative data on prescribing behaviour | Comparative data on clinical outcomes | Single data point on prescribing behaviour | AE reported | ADE reported | AE clinical outcome reported | Adverse effect single data point | Patient | Provider | Patient and Provider | ||

| Setting | |||||||||||

| Primary care, n = 9 | 310 | ↑41 | ↑25 | • 84 | ↑1 | ↑2 | • 1 | ↑4 | ↑2 | • 2 | |

| ↓35 | ↓36 | ||||||||||

| • 18 | • 5 | ↓1 | • 3 | • 31 | |||||||

| ↔8 | ↔11 | ||||||||||

| Secondary care, n = 7 | 114 | ↑21 | ↑6 | • 49 | ↑6 | ↑2 | ↑2 | • 3 | • 1 | • 2 | |

| • 3 | ↓9 | ||||||||||

| ↔2 | ↓4 | ||||||||||

| • 4 | |||||||||||

| Tertiary care, n = 2 | 28 | ↑17 | • 4 | • 1 | • 4 | ||||||

| ↓2 | |||||||||||

| Other, n = 2 | 2 | ↑1 | |||||||||

| ↓1 | |||||||||||

| Intervention tool | |||||||||||

| Algorithm, n = 1 | 2 | • 1 | • 1 | ||||||||

| Algorithm and criteria led, n = 1 | 55 | ↑11 | ↑6 | • 13 | • 5 | ||||||

| ↓4 | ↓12 | ||||||||||

| • 1 | • 3 | ||||||||||

| CDSS, n = 6 | 210 | ↑30 | ↑17 | • 40 | ↑1 | ↑2 | ↑2 | • 4 | ↑4 | ↑2 | • 1 |

| ↓29 | ↓19 | ||||||||||

| ↔8 | ↔8 | ↓1 | • 2 | • 15 | |||||||

| • 20 | • 5 | ||||||||||

| CDSS and criteria led, n = 1 | 22 | • 21 | • 1 | ||||||||

| Criteria led, n = 5 | 99 | ↑36 | ↑8 | • 24 | ↑5 | ↑1 | ↑2 | • 8 | • 4 | ||

| ↓2 | ↓8 | ||||||||||

| ↔1 | |||||||||||

| No tool, n = 6 | 66 | ↑3 | ↓6 | • 39 | ↓4 | • 1 | • 1 | • 4 | |||

| ↓3 | ↔4 | ||||||||||

| • 1 | |||||||||||

| Lead prescriber | |||||||||||

| GP/primary care physician led, n = 7 | 211 | ↑16 | ↑17 | • 59 | ↑1 | ↑2 | • 1 | ↑4 | ↑2 | • 2 | |

| ↓29 | ↓18 | ||||||||||

| ↔8 | ↔8 | ↓1 | • 3 | • 22 | |||||||

| • 17 | • 1 | ||||||||||

| Pharmacist led, n = 5 | 99 | ↑14 | ↑6 | • 39 | • 1 | • 10 | |||||

| ↓7 | ↓14 | ||||||||||

| • 1 | ↔3 | ||||||||||

| • 4 | |||||||||||

| Secondary care physician led, n = 4 | 55 | ↑20 | ↑6 | • 6 | ↑5 | ↑1 | ↑2 | • 1 | • 1 | ||

| ↓5 | |||||||||||

| • 3 | ↔1 | ||||||||||

| • 4 | |||||||||||

| Team, n = 4 | 89 | ↑30 | ↑2 | • 33 | ↑1 | ↑1 | ↓4 | • 3 | • 4 | ||

| ↓2 | ↓8 | ||||||||||

| ↔1 | |||||||||||

| Context | |||||||||||

| Deprescribing focus, n = 8 | 88 | ↑22 | ↑5 | • 31 | ↑2 | ↑1 | ↓4 | • 4 | • 2 | • 1 | • 5 |

| ↓3 | ↓7 | ||||||||||

| ↔1 | |||||||||||

| Medicines optimisation, n = 12 | 366 | ↑58 | ↑26 | • 106 | ↑4 | ↑2 | ↑4 | • 1 | ↑4 | ↑2 | • 1 |

| ↓35 | ↓38 | ||||||||||

| ↔8 | ↔12 | ↓1 | • 2 | • 32 | |||||||

| • 21 | • 9 | ||||||||||

| Total: 454 per category | |||||||||||

Outcomes from the included studies have been grouped by setting, intervention modality, profession of lead prescriber(s) implementing the intervention and context. Outcomes are reported under the three headings of effects, safety and acceptability.

Table 11 reports the total number of outcomes reported for each category of study setting, intervention, prescriber and context. It also details the number of outcomes reported under each heading with the direction of effect (positive, negative or neutral) when comparative data were reported and able to be interpreted.

For example, nine primary care studies (row 1) reported a total of 310 outcome measures (column 2). Of these, 102 related to prescribing behaviour [such as number of medications (de)prescribed], with 41 showing a positive effect, 35 showing a negative effect and 18 being unclear (column 3). When outcome data either showed mixed effects or were uncertain, the number of outcomes is indicated with the ‘dot’ symbol. Outcomes were classified as uncertain if the effect was not reported or was unclear, or if the data were observational in nature.

The outcomes are reported under three headings of effects, safety and acceptability. These included ‘clinical outcomes’ experienced by the patient or service impacts, such as mortality or hospital admission; safety-related adverse effects classed as ‘AE’ (adverse effect) or ‘ADE’ (adverse drug effect); or ‘AE clinical outcome reported’ [framed in the source paper as relating to the patient experiencing an adverse outcome related to (de)prescribing]. Acceptability outcomes were taken from stated acceptability measures but also derived form study ‘process outcomes’, such as number of patients accepting or number of professionals applying the deprescribing intervention. Acceptability outcomes are mapped as patient, provider and a combination of patient and provider.

In summary, Table 11 reveals considerable variation in the reported effects of deprescribing work with both improvement and decline in reported outcomes. Safety outcomes were reported only for clinician-led (rather than pharmacist-led) interventions. The majority of safety outcomes reported were positive, but safety concerns were noted for general clinical outcomes in secondary care-based studies where no clinical tool was used. Acceptability was variably reported and was usually based on observation. When reported, studies indicated acceptability of interventions to professionals, with patient acceptability less clearly reported.

What tools are available to support addressing problematic pharmacy in older people with multimorbidity and polypharmacy?

Studies reported a range of tools used to support deprescribing. A CDSS is a computer application designed to aid clinicians in making deprescribing decisions. It may incorporate algorithm- or criteria-led tools in its design. Algorithms are a set of rules or steps that guide deprescribing and are followed in a pre-determined way to lead to an outcome. Criteria-led decision-making involves the use of a list of criteria to consider when making decisions to deprescribe medications. Five studies69,72,77–79 reported the use of tools within a wider structured framework involving a process-driven approach to deprescribing, which details a set of rules or steps to be followed from patient identification through to discharge and follow-up.

Table 12 details the tools used in the deprescribing interventions. The seven studies employing a CDSS reported using seven different CDSSs. Many were created by the clinical team or study team for the purposes of the study, commonly drawing on previously published criteria or algorithms (see Table 12). In addition, five studies report using other tools to inform medication reviews. One used a tool to identify patient priorities and one study used a protocol for the withdrawal and reinstatement of drugs associated with potential for adverse drug withdrawal events. The most reported tool was the criteria-led STOPP/START tool.

| Tool type (number of studies) | Tool name | Tool references provided in included studies |

|---|---|---|

| CDSS (7) | AiDKinik®77 | Not reported |

| AiD®78 | Not reported | |

| INTERcheck69 | Ghibelli et al.86 | |

| MedSafer76 | Available online at URL: www.medsafer.org (accessed 16 June 2021) | |

| SPPiRE online medication review 75 | SPPiRE medication review process template reported in McCarthy et al.75 | |

| STRIP Assistant66 | References studies evaluating STRIP Assistant: Meulendijk et al.87 and Willeboordse et al.88 | |

| TRIM71 | Components of the TRIM clinical decision support system described in related study (Niehoff et al.89) | |

| Criteria led (6) | STOPP/START (version 2)68,69,80,83 |

O’Mahony et al. 10 Delgado et al. 90 |

|

STOPP79 STOPPFrail70 |

Gallagher and O’Mahony91 Lavan et al. 92 |

|

| Beers69,79 |

American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel93 (in Chiarelli et al. 69) American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel94 (in Petersen et al. 79) |

|

| SPC69 | SPC provided by the Italian Medicine Agency [URL: www.aifa.gov.it/note-aifa (accessed 16 June 2021)] | |

| Author reported criteria in Komagamine et al.73 | As reported in Komagamine et al.73 | |

| Algorithm (2) | Adapted GPGP algorithm85 | As reported in Zechmann et al.85 |

| GPGP algorithm68 | Garfinkel and Mangin95 | |

| Other (5) | MediMoL to identify medication-related problems and patient preferences77,78 | Not reported |

| SHiM to inform medication review66 | Drenth van Maanen et al.96 | |

| Outcome Prioritisation Tool to elicit patients’ prioritisation84 | Available online at URL: www.optool.nl (accessed 16 June 2021) | |

| Author-reported protocol for withdrawal and reinstatement of drugs associated with potential for adverse drug withdrawal events70 | As reported in Curtin et al.70 |

Seven of the CDSS tools report incorporating criteria-led or algorithm tools or other frameworks (Table 13).

| CDSS | Incorporated criteria-led or algorithm tools |

|---|---|

| Adapted GPGP algorithm85 |

|

| INTERcheck69 |

|

| MedSafer76 |

|

| ShedMEDS79 | |

| SPPiRE (online medication review)75 |

|

| STRIP Assistant66 |

|

| TRIM71 |

|

As described in Table 11, acceptability for all tools was poorly reported. Clinicians reported acceptability across all tools, but patient perceptions of acceptability were not generally recorded. Clinical safety concerns were described for secondary care studies not using any tool but inconsistently reported (positive or negative) in other contexts. Effectiveness reports were varied for all tools.

Integrating our findings