Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/141/01. The contractual start date was in September 2009. The draft report began editorial review in September 2015 and was accepted for publication in February 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Robert Freeman reports personal fees from speaker fees for Astellas and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. John Norrie reports non-financial support from Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board and personal fees from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) Editorial Board, outside the submitted work. He is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group. Andrew Elders reports a grant from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study; his institution (Glasgow Caledonian University) is due to receive payment for statistical analysis from the University of Aberdeen using funds from their NIHR grant.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Glazener et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The PROSPECT Study (PROlapse Surgery: Pragmatic Evaluation and randomised Controlled Trials)

In 2009, the UK government National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme funded the PROSPECT Study. This monograph describes the research.

PROSPECT was a major multicentre UK randomised controlled trial (RCT) investigating the effectiveness (including safety) and cost-effectiveness of surgical treatment, primarily in terms of improvement in prolapse symptoms, in women who were having a primary or a secondary prolapse repair.

Description of the underlying health problem

Pelvic organ prolapse is the descent from its normal anatomical position of one or more of the female genital organs. Pelvic organ prolapse is caused by herniation through deficient pelvic fascia or due to weaknesses or deficiencies in the ligaments or muscles that should support the pelvic organs. There is little epidemiological research into this condition because it has a variety of presentations and they do not all cause symptoms, particularly in the early stages. 1 Commonly reported symptoms include a feeling of dragging or heaviness in the vagina, uncomfortable bulge distending the introitus, urinary symptoms (urgency and voiding difficulty), bowel symptoms, such as incomplete emptying, and sexual dysfunction.

Prevalence and natural history

Estimates of the prevalence of prolapse vary from 41% to 50% of women aged > 40 years. 2,3

It has been estimated that women have a lifetime risk of 11% of undergoing surgery for urinary incontinence (UI) or prolapse and 7% for prolapse alone. 4 The annual incidence of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse is within the range of 15–49 cases per 10,000 women-years, and it is likely to double in the next 30 years. 1,5 Little is known about the prevalence and effectiveness of different types of operations but they are notoriously prone to failure: around 30% of women undergo further operations; the mean time interval between the first and a subsequent procedure is about 12 years, and the time interval between subsequent procedures decreases with each successive repair. 4

Gynaecologists have recognised for some time that both anatomical failure of supporting pelvic structures and recurrence of prolapse after surgery are common. More recently, it has also been recognised that surgery can be followed by a greater impairment of quality of life (QoL) than the original prolapse itself (e.g. new UI after surgery). In addition, repair of one type of prolapse may predispose the women to the development of a different type of prolapse (a new or de novo prolapse) in another compartment of the vagina due to alteration in the dynamic forces within the pelvis. 4

Significance in terms of ill health and use of NHS resources

Surgery is common. In England and Wales in 2004–5, 26,947 women were admitted to hospital with a main diagnosis of female genital prolapse, and 28,297 operations were performed (some women had more than one type of prolapse operation). 6 The majority of the operations (93%) were undertaken in women who were having anterior repair (n = 8560), posterior repair (n = 5406) or both operations (n = 5654), or with a concomitant uterine prolapse (n = 6837). Only 7% were in women with vault prolapse (n = 1840). Assuming a population of about 20 million women in the age group at risk for prolapse surgery (50–85 years), the UK operation rate is currently around 14–16 women who were having prolapse operations per 10,000 per year. 6,7

The need is likely to increase because of the rising number of elderly women. It has been projected that the number of women in the age group 50–85 years (those most likely to need prolapse surgery) will increase by 1.44 million between 2012 and 2020. 6

Description of standard management

Women with prolapse may be managed conservatively with pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and pessaries, or with surgery. In addition they require management of associated conditions, for example lower urinary tract symptoms, such as UI or overactive bladder syndrome; bowel problems, such as constipation or faecal incontinence (FI), sexual dysfunction and oestrogen deficiency if postmenopausal.

Conservative management for women with prolapse

Although there is only one RCT to inform the use of mechanical devices (pessaries or rings), these are often used for women who are unfit for surgery or who wish to avoid surgery. They can be very efficacious, but questions remain about the best type of device, the long-term adverse effects and the use of supplementary treatment such as oestrogen. Further research is required. 8

Conservative physical treatments such as PFMT are also often recommended as first-line management. A recent update of the relevant Cochrane review9 has found some evidence supporting the use of PFMT to reduce prolapse symptoms and severity, as well as benefits for urinary and bowel symptoms.

In addition, vaginal oestrogen treatment can be used to reduce symptoms for postmenopausal women, before or after surgery. The evidence supporting its use is limited and inconclusive. 10

Surgical management for women with anterior or posterior vaginal wall prolapse

The PROSPECT Study compared surgical operations for vaginal wall pelvic organ prolapse:

-

anterior vaginal wall prolapse (urethrocele, cystocele, paravaginal defect)

-

posterior vaginal wall prolapse (enterocele, rectocele, perineal deficiency).

A woman may present with prolapse of one or both of these sites, and she may be having a primary or a secondary procedure. She may also have a concomitant uterine or vault prolapse or stress UI that requires a continence procedure. For each of these sites there are several alternative traditional surgical techniques, none of which has been properly evaluated in adequately powered multicentre RCTs. Major potential adverse effects include infection, bleeding, mesh exposure and dyspareunia, as well as failure of repair and failure to cure symptoms.

The techniques for performing anterior or posterior repair or implanting mesh or graft can vary widely between gynaecologists. These include the following.

Standard anterior and/or posterior repair

In the standard approach, the vaginal skin is opened in the midline, the fascia is separated from the skin and the fascial defect is plicated (sutured or buttressed). Any redundant vaginal skin is excised and the skin is closed.

Standard repair with mesh inlay

Over the last 10 years, gynaecologists have begun to include small pieces of mesh inlays as an extra support to the fascial defects through which the pelvic organs prolapse, analogous to the use of mesh in hernia surgery. 11 If mesh is used, it can be positioned over or under the fascial defect as a ‘mesh inlay’ and sutured in place to reinforce the tissues.

The proposed advantage of using mesh is that it will optimise surgical outcome without compromising vaginal capacity or sexual function. 12 The rationale is that it may help to reduce failure rates from breakdown of weakened tissue or failure to identify all fascial defects. 13 Although the mesh materials used may be stronger than the woman’s own fascial tissue, the indications for use and choice of materials remain controversial. 13 The extent to which mesh inlays are currently used is unknown, but recent surveys suggest that many gynaecologists are already incorporating mesh into their practice both in the UK and in the USA. 14,15 The decision to use mesh is complicated by the different types available:

-

absorbable synthetic (e.g. polyglactin)

-

absorbable biological (e.g. fascia lata, porcine dermis)

-

combined or semi-absorbable (e.g. polyglactin and polypropylene) and

-

non-absorbable (e.g. polypropylene).

There are theoretical pros and cons to each, but there is not enough evidence available to allow rigorous comparison.

Mesh insertion using a trocar (introducer device): mesh kits

Some commercial manufacturers of mesh have introduced large mesh systems, analogous to the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) slings used in incontinence surgery. 16 These commercial devices (‘mesh kits’) are available for anterior or posterior compartments, or can be used together for both. The mesh is inserted using a trocar (introducer device). This involves blind penetration of pelvic spaces by trocars in order to thread mesh tails into positions from which they support a central mesh layer or hammock, which supports and corrects the prolapse defect. Currently available devices use non-absorbable synthetic mesh, but kits using other types of mesh (combined) have also been used.

These have been actively promoted and introduced to clinical practice without first being evaluated in rigorous independently managed RCTs. These meshes are inserted blindly using introducer devices or trocars that may damage surrounding organs or blood vessels. 17 Prospective studies have suggested that the mesh devices have been used worldwide, but it is not clear whether this is driven by gynaecological preference or commercial marketing pressure. However, clearly some women have been willing to undergo this new technology despite lack of evidence for safety or efficacy.

Evidence for the use of mesh or graft in prolapse surgery

The most recent update of the Cochrane review of surgery18 for lower compartment prolapse concludes:

The use of mesh or graft inlays at the time of anterior vaginal wall repair reduces the risk of recurrent anterior wall prolapse on examination.

The authors further add:

Anterior vaginal polypropylene mesh also reduces awareness of prolapse; however these benefits must be weighed against increased operating time, blood loss, rate of apical or posterior compartment prolapse, de novo stress urinary incontinence, and reoperation rate for mesh exposures associated with the use of polypropylene mesh.

For posterior wall repairs, the Cochrane review18 concludes:

The evidence is not supportive of any grafts at the time of posterior vaginal repair.

Repeat surgery for recurrent prolapse

There were no data on the differential effects in women who were having primary as opposed to repeat (secondary) surgery: all of the trials reported both groups of women together despite their potentially different prognoses. There is, therefore, no evidence to suggest whether or not the use of mesh (particularly non-absorbable synthetic mesh, which has the strongest mechanical strength and remains in situ indefinitely) should be reserved for more complex or recurrent prolapse. Although gynaecologists have stated that this is their belief and practice, evidence suggests that the majority (70%) of the current recipients of mesh are having their first prolapse operation. 14

An Interventional Procedures (IP) review of 503 women and a further recent case series of 289 women drew attention to the high incidence of serious adverse effects (e.g. 2.8% with damage to surrounding organs) in women who were having mesh inserted with blind introducer devices (‘mesh kits’). 17,19 Our opinion was that until benefits and risks have been properly evaluated, mesh kits using non-absorbable synthetic mesh should be reserved for more complex cases of prolapse. Therefore, in PROSPECT we limited this option to women being treated for a recurrence of prolapse in the site where previous surgery had occurred.

Current recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

An IP review, conducted for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2008, investigated the use of mesh for women who were having anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall prolapse repair. 19,20 The total number of women receiving mesh in this review was 4569: mesh was inserted using an introducer device, trocar or kit in 503 of these women. 19 The IP review also included additional data from non-randomised comparative studies and case series. Using these extra data, non-absorbable synthetic mesh had the lowest failure rate compared with:

-

absorbable synthetic mesh [odds ratio (OR) adjusted for bias from study design 0.23, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.12 to 0.44]19

-

absorbable biological mesh (OR adjusted for bias from study design 0.37, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.59). 19

On the other hand, the mesh erosion (now termed ‘exposure’) rates increased from 1% (95% CI 0.1% to 4.0%) with synthetic absorbable mesh to 6% with absorbable biological mesh to 10% with non-absorbable synthetic mesh. 19 The data were too sparse, however, for other reliable statistical analysis. There were insufficient data on women’s subjective prolapse symptoms or complications, such as infection, blood loss or dyspareunia, and none on long-term outcomes. Particular safety worries were related to the use of introducer devices (trocars) that were used for the blind insertion of mesh into intrapelvic spaces. 17

These and other findings were presented to the Interventional Procedures Advisory Committee (IPAC) in January 2008 and their guidance has now been published. 21 The committee recommended that mesh should be used only under special arrangements for clinical governance, consent and audit or research: hence the PROSPECT Study was funded to fill the evidence gap.

Decision to test alternative forms of surgery

There is not enough evidence from RCTs to guide management for women with prolapse. Additionally, the Cochrane and the IP reviews conclude that there is insufficient information about any of the surgical options to guide management of any type of pelvic organ prolapse in any population of women with prolapse.

We identified that the largest group of women are those with anterior and/or posterior prolapse, who constitute around 90% of those having prolapse surgery (including those having a concomitant hysterectomy). The evidence underlying surgery for these women was clearly inadequate, with very little evidence regarding subjective prolapse symptoms, effect on QoL and safety.

Both the Cochrane and the IP reviews18,19 identified a need for adequately powered RCTs of the use of mesh in prolapse surgery. PROSPECT comprises the largest, adequately powered and independent RCT comparing traditional prolapse operations with new methods incorporating mesh as an inlay or mesh inserted using an introducer system (mesh kit).

Questions addressed by this study

Principal objectives

To determine the effectiveness (including safety) and cost-effectiveness of surgical treatment, primarily in terms of improvement in prolapse symptoms, in women who were having anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall pelvic organ prolapse surgery, separately in two trials:

-

In women who were having a primary prolapse repair, the effects of:

-

a standard repair versus a standard repair using a non-absorbable or combined mesh inlay and

-

a standard repair versus a standard repair using a biological graft inlay.

-

-

In women who were having a repeat prolapse repair, the effects of:

-

a standard repair versus a standard repair using a non-absorbable or combined mesh inlay and

-

a standard repair versus a mesh kit procedure.

-

The two groups are being considered independently because different surgical options are considered to be appropriate for clinical reasons.

Secondary objectives

-

To determine the differential effects on other outcomes, such as urinary, sexual and bowel function, QoL, general health, need for secondary surgery and adverse effects.

-

To identify possible effect modifiers (e.g. different types of mesh, concomitant procedures, age, complex prolapse types).

-

To establish if the findings of the research, including implications for service delivery, training and introduction of mesh, are generalisable to the UK NHS.

This study assessed which of the most frequently employed techniques for the most common types of prolapse (anterior and posterior vaginal wall prolapse) are most clinically effective and safe. The study also assessed cost-effectiveness. This will guide gynaecologists in their surgical practice and purchasers in their choice of provision of health care. Given the number of prolapse procedures currently performed (28,000 annually in the UK) and the anticipated rise in need for such surgery with an ageing population (a twofold increase in the age group at risk in the next 30 years is predicted), the potential cost implications for the health service are considerable. 6

Chapter 2 Methods and practical arrangements

Study design

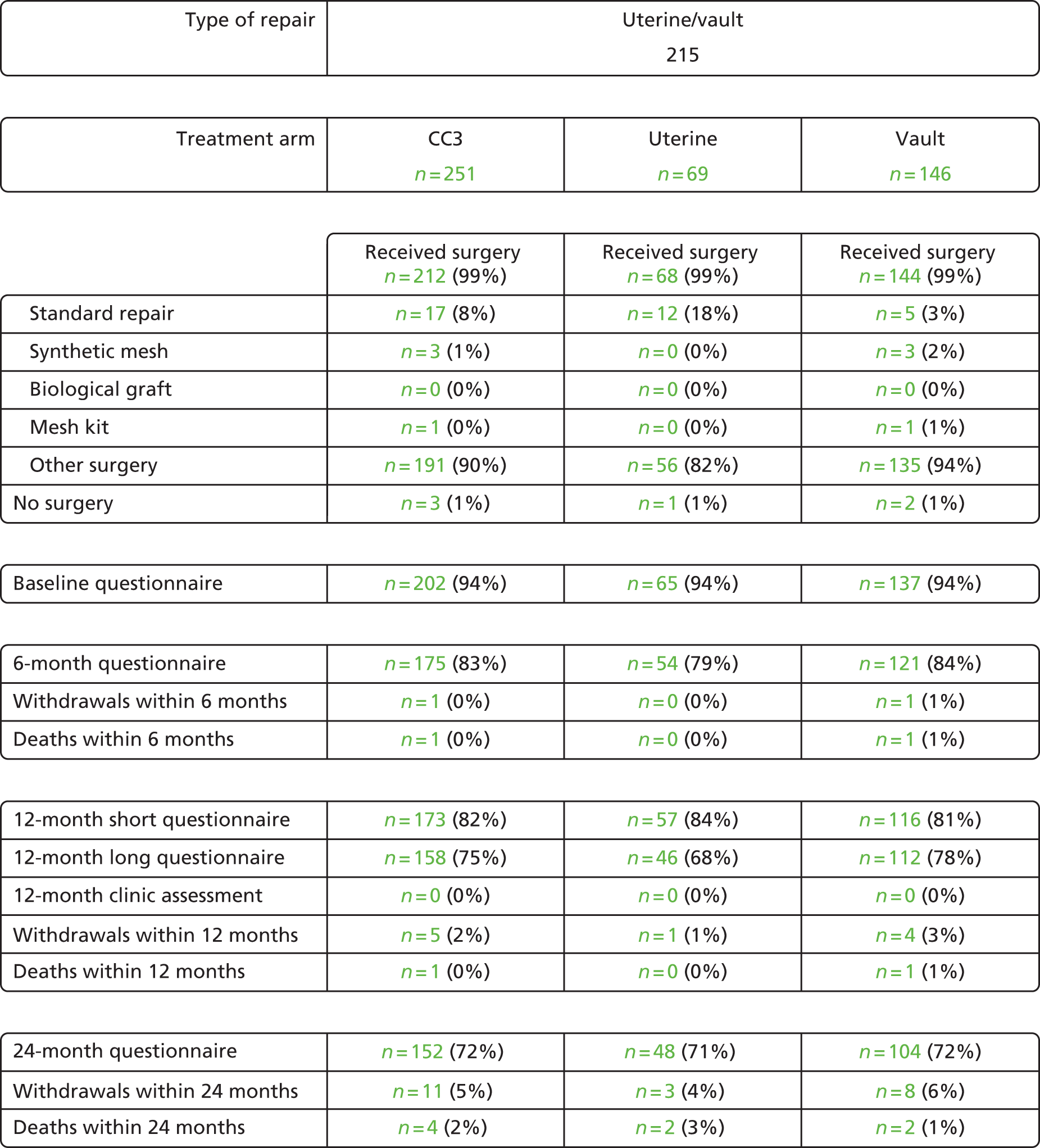

PROSPECT comprised two RCTs within a comprehensive cohort (CC) study. It was designed to determine the effectiveness (including safety) and cost-effectiveness of surgical treatment, primarily in terms of improvement in prolapse symptoms, in women who were having anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Women who were having a primary prolapse repair and those having a secondary prolapse repair were considered independently because different surgical options were deemed to be appropriate for clinical reasons. If a woman did not receive surgery then no follow-up questionnaires were issued.

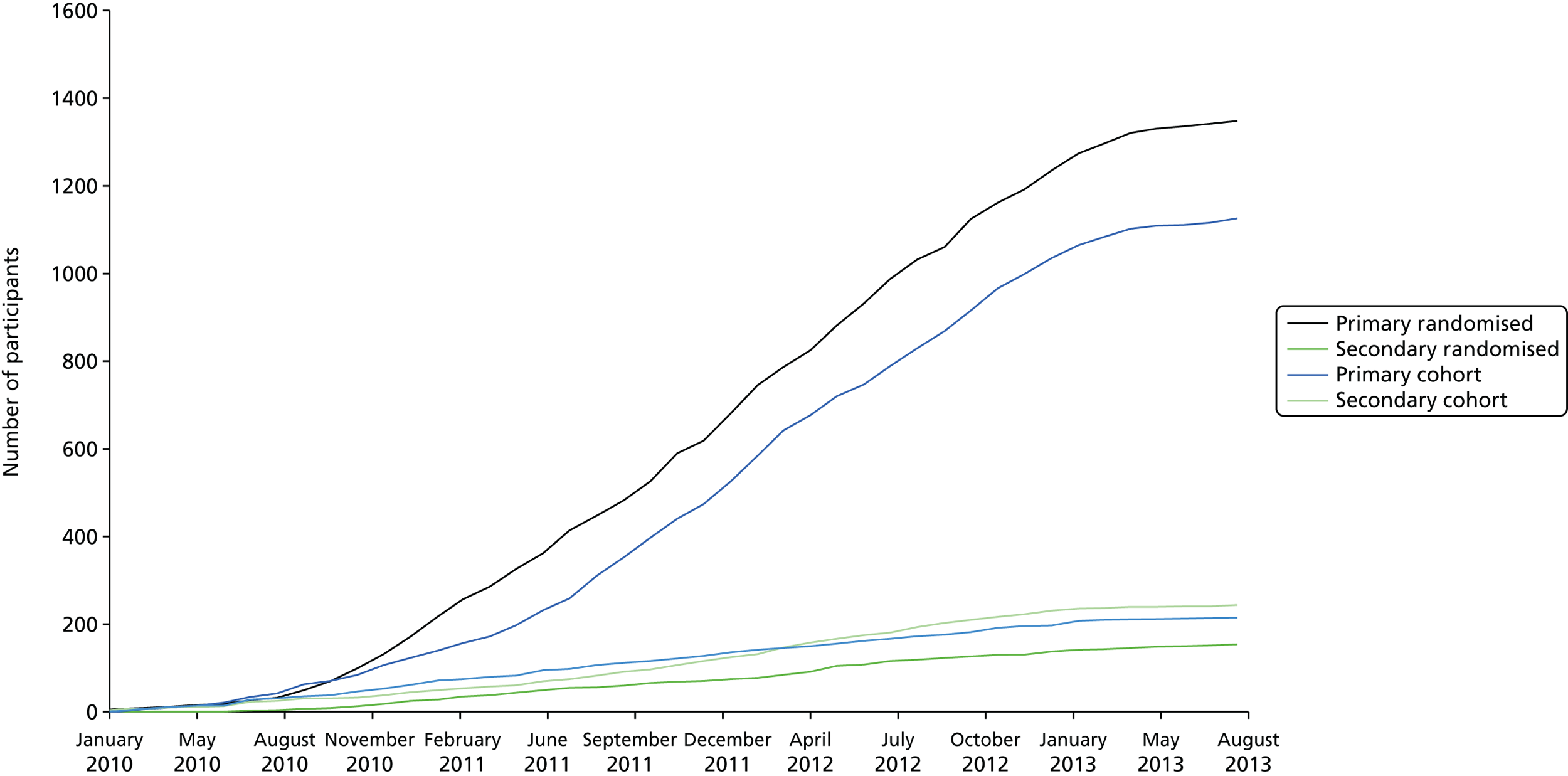

Important changes to the design after trial commencement

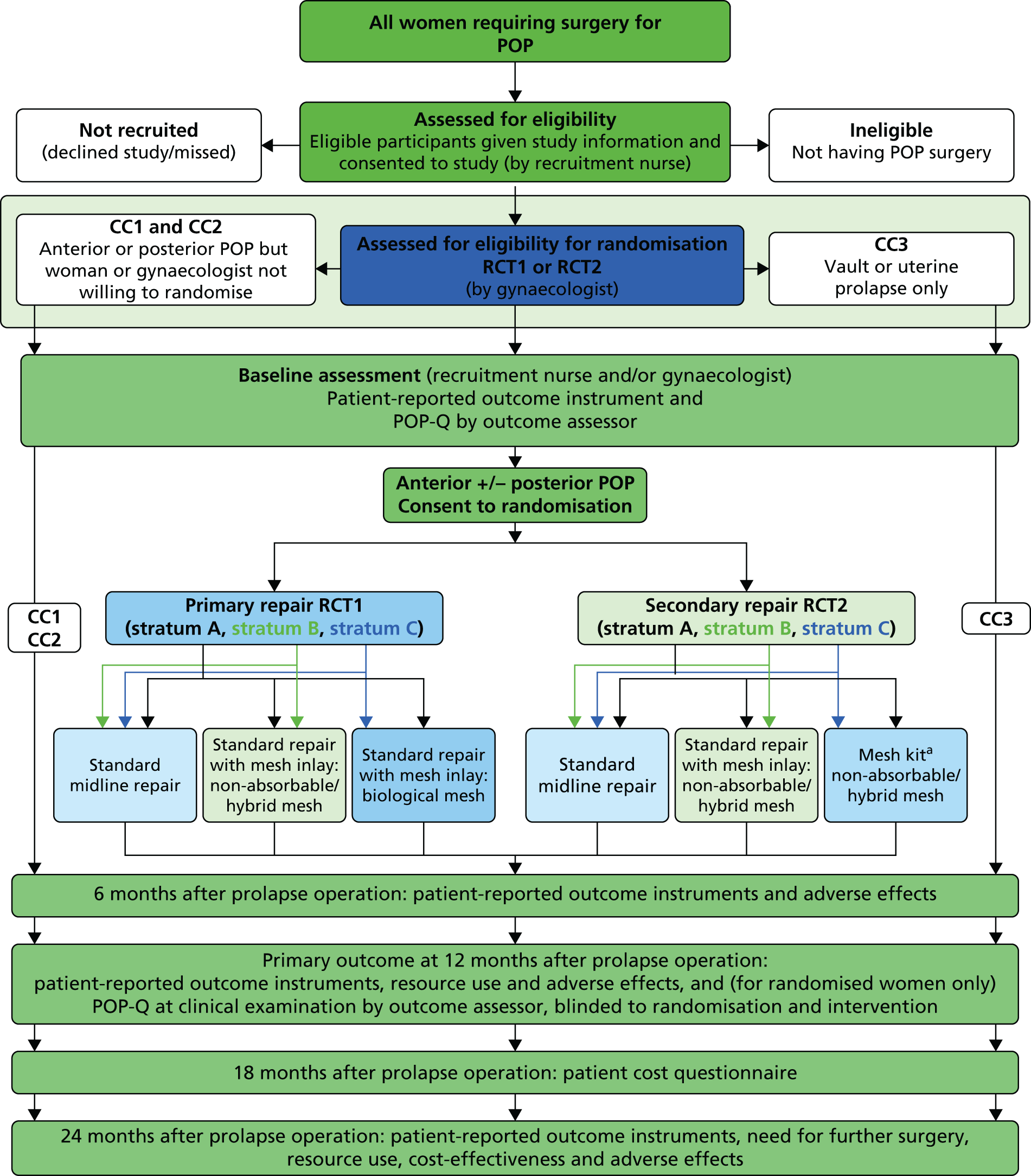

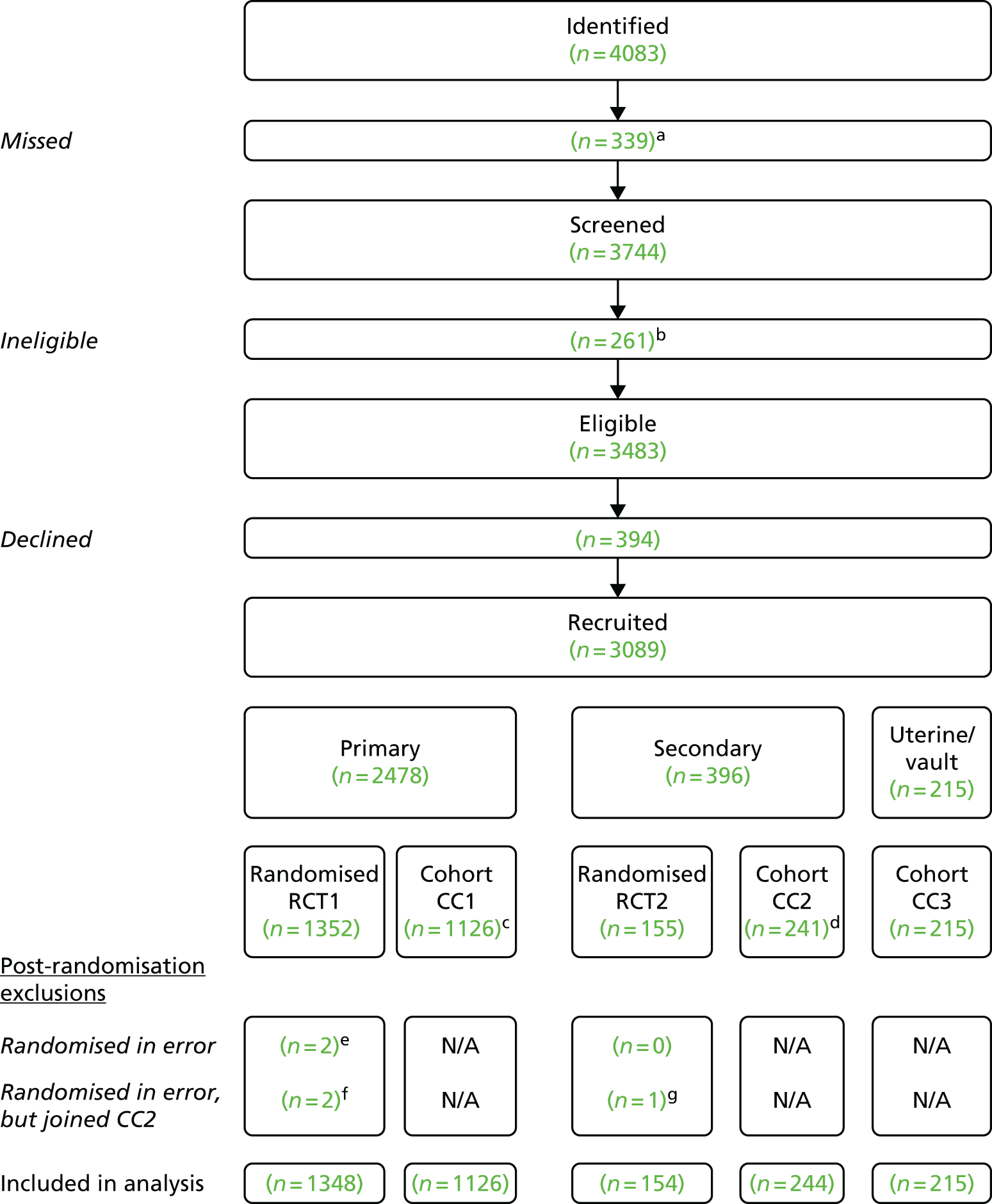

The recruitment rate to both the Primary and Secondary trials proved to be slow initially, partly because of the cost of sourcing all of the mesh types required for the study and lack of availability of certain mesh types, and partly because of some clinicians’ preference for one of the mesh types. Therefore, with the agreement of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), a decision was made in 2010 to allow surgeons to randomise between no mesh and only one of the mesh options, creating three randomisation strata in both trials. The study design showing the comparisons options available to surgeons is shown in the flow diagram in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study design. a, Only gynaecologists trained in the use of mesh kits will randomise women to this option. POP, Pelvic Organ Prolapse.

Clinical centres

Both specialist urogynaecologists and general gynaecologists were eligible to take part if they had extensive experience and training in urogynaecological reconstructive surgery. To participate they had to be prepared to allow treatment allocation to be decided at random for at least a proportion of their patients: the remainder could be entered into the CC study if the patient agreed. Before participating in the trial, the surgeons had to formally choose to which comparisons they were willing to contribute.

Study population

All women under the care of a collaborating surgeon were potentially eligible for inclusion if a decision had been made to have primary or secondary pelvic organ prolapse surgery for anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Women undergoing concurrent hysterectomy/cervical amputation, vault surgery or continence procedures were also eligible. Only women who were unable or unwilling to give competent informed consent, or who were unable to complete study questionnaires, were deemed ineligible.

Two parallel but separate trials were conducted: one among women who were having a primary prolapse repair and the other in women who were having a secondary prolapse repair. For the purposes of PROSPECT, a secondary prolapse was defined as a recurrence of prolapse after a primary procedure, when the recurrence was in the same compartment. If the prolapse was in a different compartment and the original site did not require revision surgery, the woman was classed as having a primary repair of a de novo prolapse.

In addition, women who were unwilling or unsuitable for randomisation were eligible to be followed up using the same protocol as part of the CC study. This included women who were having uterine or vault surgery only.

Consent to participate

All women who required pelvic organ prolapse surgery were identified by a dedicated recruitment officer (RO) in each centre. A log was maintained of all of the women meeting the eligibility criterion (admission for prolapse surgery), describing reasons if they did not agree to enter the study or be randomised (see Appendix 1). Every woman was allocated a unique study number.

Every eligible woman was given a flyer containing a brief summary of the study when attending the initial clinic appointment (the fliers are reproduced in Appendix 1). The women were then given the patient information leaflet (PIL; see Appendix 1) with their admission documents (which could be during the initial clinic appointment or by separate mail, if the woman agreed). Women were given the opportunity to discuss all aspects of the study with their general practitioner (GP) and/or family members before admission, their gynaecologist, the RO, staff at preadmission clinics and/or when admitted to hospital. In addition, all documentation contained the PROSPECT Study office contact details to enable women to obtain information from the study organisers. Signed consent was obtained from each woman to participate (and, if suitable, to be randomised) and followed up after her prolapse surgery by questionnaires and an examination in Gynaecology Outpatients (the latter in randomised women only). The PIL and the consent form (see Appendix 1) both refer to the possibility of long-term follow-up, being contacted about other prolapse research and access to their NHS records for these purposes. A letter and GP information sheet were also sent to the woman’s GP (see Appendix 2). A copy of the consent form, together with a summary of the study, was filed in the woman’s hospital notes.

Women who did not wish to be randomised, or who were not suitable for randomisation, were still eligible to be followed up using the same study protocol as part of the CC study. They completed all of the study procedures and documents including follow-up, except for the clinical examination at 12 months.

Women who initially agreed to enter the study but later decided to withdraw or became unable to continue were asked for verbal consent to enable us to retain their existing data and access relevant NHS data. Women who did not agree to participate in the study (randomised or cohort) were logged anonymously along with a minimum data set of age and type of prolapse (anterior, posterior, uterine, vault; primary or secondary procedure) (see Appendix 1).

Health technologies being compared

Women were randomised to an intervention according to their surgical history (previous prolapse repair or not), the availability of the mesh (non-absorbable, biological and/or mesh kits) and the skill capacity of their operating gynaecologist (trained in mesh kit use or not). The study design is shown in the flow diagram in Figure 1.

If one of the mesh types was temporarily or permanently unavailable (owing to financial constraints) then the women could be randomised to one of the other two arms.

In addition, the expectation was that mesh kits would normally be used only for women who had been randomised to this option. If the operating gynaecologist was not trained in the use of mesh kits then the women under their care could be randomised to one of the other two arms only. Furthermore, in view of the scarcity of data about their safety and efficacy, mesh kits were used only for women who were having a secondary procedure, who have a more complex prolapse problem.

Therefore, women who were having a primary repair were randomised to:

-

standard anterior and/or posterior repair (with native tissue only) (reference technique)

-

standard anterior and/or posterior repair with a synthetic non-absorbable or hybrid mesh inlay or

-

standard anterior and/or posterior repair with biological graft inlay.

Women who were having a secondary repair were randomised to:

-

standard anterior and/or posterior repair (with native tissue only) (reference technique)

-

standard anterior and/or posterior repair with a synthetic non-absorbable or hybrid mesh inlay or

-

a mesh kit (using an introducer device/trochar) with a non-absorbable or hybrid mesh.

Treatment allocation

After entering contact details, essential baseline information and confirmation of signed consent into the internet-based PROSPECT database, the local researcher was able to randomise the woman (if appropriate) to one of the arms for which she was eligible. Randomisation was carried out as close to the time of surgery as was practical, taking into account the hospital routines and time needed for setting up the operating theatre.

Randomisation utilised the existing proven remote automated computer randomisation application at the study administrative centre in the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials [CHaRT, a fully registered UK Clinical Research Network clinical trials unit] in the Health Services Research Unit (HSRU), University of Aberdeen. This randomisation application was available only as an internet-based service.

Randomisation was computer allocated and stratified depending on whether a woman was having a primary or secondary repair. If not eligible for randomisation, the woman was allocated to the CC.

Primary prolapse (de novo) was defined as a prolapse in a compartment that had not been previously repaired. If the woman was having two primary procedures (i.e. both anterior and posterior vaginal wall prolapses required repair) then the randomised allocation applied to both prolapse repairs.

Secondary prolapse was defined as a recurrence of prolapse after a previous procedure, when the recurrence was in the same compartment. If the woman also required a concomitant primary repair of a de novo prolapse in a different compartment, this procedure was chosen on clinical grounds/surgeon choice (i.e. not dictated by the randomisation allocation for the secondary procedure).

If the new prolapse was in a different compartment (de novo) and the original site did not require revision surgery, the woman was classed as having a primary repair of the de novo prolapse and randomised in the Primary trial.

The allocation was computer-generated in ratios of 1 : 1 : 1 for the Primary trial and 1 : 1 : 2 for the Secondary trial. Randomisation was unbalanced in the Secondary trial in favour of mesh kits to account for the skill set of the available surgeons (not all surgeons would be trained in their use). Allocation was further minimised according to:

-

the woman’s age (< 60 years or ≥ 60 years)

-

type of prolapse being randomised (anterior, posterior or both)

-

need for a concomitant continence procedure (e.g. TVT) or not

-

need for a concomitant upper vaginal prolapse procedure (e.g. hysterectomy, cervical amputation, vault repair) or not and

-

surgeon.

Clinical management

Within the randomised comparisons, surgeons could use any mesh, graft or mesh kit, providing that any synthetic mesh was monofilament macroporous polypropylene and mesh inlays were secured with peripheral sutures. Surgeons used their mesh material of choice and followed their standard practice so that the technique that they normally used was not modified for the purposes of the trial. All of the other aspects of care were left to the discretion of the responsible surgeon. Each surgeon was asked to complete a surgical standardisation form (see Appendix 3) so that their preferred method of surgical repair could be recorded.

We did suggest, however, that the mesh or graft should be inserted under the fascial layer and secured at five points around the periphery of the inlay. If they did so, or wished to secure the inlay in another way (e.g. attach the inlay to the white line), we asked them to record the method used in the surgical standardisation form, but did not obtain information on whether or not this was actually done for individual participants.

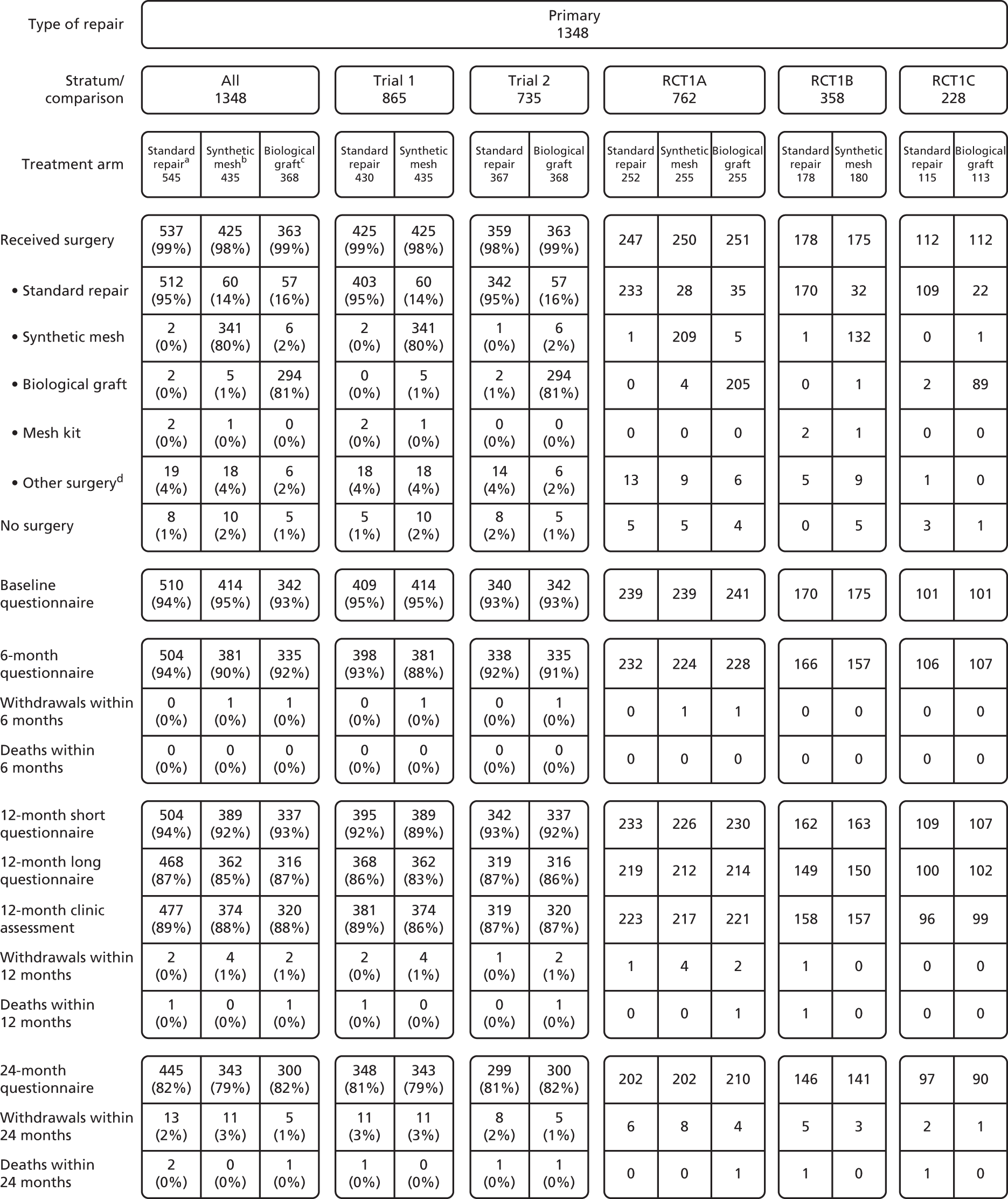

Data collection and processing

Participant-reported outcomes were assessed by self-completed questionnaires at baseline (before surgery; see Appendix 4) and self-completed postal questionnaires at 6, 12, 18 (Participant Cost Questionnaire only) and 24 months following surgery (see Appendix 4). Where participants ticked more than one box for each question, we recorded this using the worst-case scenario. For randomised women, following one postal reminder, participants who had not returned the questionnaire were telephoned and offered the option of completing the questionnaire over the telephone. For cohort women, only a second postal reminder was issued. A number of other measures were taken to promote ongoing interest in, and commitment to, the trial, including participant newsletters and annual Christmas cards (both randomised and CC women, and collaborators at the clinical centres).

The study-specific questionnaires also included questions about care in general practice, physiotherapy and outpatient consultations related to their prolapse, as well as any complications, readmissions, reoperations and costs. Reported hospital readmissions and complications were confirmed with the clinical centre when required.

Intraoperative and postoperative data were collected by the gynaecologists, supported by ROs. This involved completing a questionnaire (see Appendix 3) at the time of surgery, providing details of the operative procedures, complications and resource use, and a short clinical questionnaire (see Appendix 3) at the 12-month outpatient review appointment, including a Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) measurement (only randomised women).

Study outcome measures

We identified three primary outcome measures.

-

Women’s symptoms of prolapse were measured using the patient-reported Pelvic Organ Prolapse Symptom Score (POP-SS)22 at 12 months after surgery. This scale was derived from the seven questions that were judged to be most directly related to prolapse symptoms (see Appendix 4) and has been shown to reflect the range and intensity of symptoms experienced by women, as well as being responsive to change over time. 23,24 Scores were determined for each of the seven items (ranging from 0 for ‘never’ to 4 for ‘all of the time’) with an overall POP-SS out of 28. Participants who only partially completed the seven-item response schedule were assumed to have no symptoms, when no response had been given to any individual items. Women were considered to be symptomatic if their overall score was > 0.

-

QoL (condition-specific) was measured as the woman’s rating of the overall effect of prolapse symptoms on everyday life on a 0–10 visual analogue scale (VAS), for which 10 is worst.

-

The primary economic outcome measure of cost-effectiveness was the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), based on the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, 3-level version (EQ-5D-3L). 25

Other outcome measures included objective prolapse measurement; urinary, bowel and sexual symptoms [using the International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI) suite of validated questionnaires];26 intraoperative and postoperative complications, including the need for additional surgery (repeat surgery for prolapse recurrence or incontinence, and surgery required for adverse effects); cost; and cost-effectiveness.

Objective prolapse measurement

We intended that, at baseline and (for randomised women) at 12 months after surgery, women would have objective measurements of their prolapse compartments. Objective prolapse staging was carried out using the POP-Q system. 27 This measures the maximum descent of each of the three prolapse compartments (anterior, posterior and upper) relative to the hymen (at 0 cm): measurements inside the vagina are negative, whereas those outside are positive. A measure of prolapse (classified from stage 0 to 4) was determined for anterior, posterior and uterine/vault, with the leading edge of the most descended compartment used to define overall stage. An algorithm was used to ensure that POP-Q staging was correctly calculated from the component measurements of the POP-Q [Aa, Ba, C, D, Bp, Ap and total vaginal length (TVL)] in which common recording errors (e.g. Ba measurement less than Aa) were corrected or queried. If data were discrepant, they were corrected by consultation with the local hospital records to obtain additional data. If POP-Q data were missing, we accepted the surgeon’s qualitative record of stage, both overall and in individual compartments (i.e. surgeons could specify the stage without giving the POP-Q measurements).

Usually, using the classic Bump et al. 27 criteria for the POP-Q system, any measurement from –1 cm (inside the hymen) to 1 cm outside counts as stage 2. However, we further subdivided stage 2 into prolapse at the hymen or within (–1 cm to 0 cm; stage 2a or less) compared with prolapse at > 0 cm (stage 2b). 28,29 Thus, women were classified as having objective prolapse if the leading edge was at any point outside the hymen (measured at > 0 cm, stage 2b, 3 or 4).

Urinary, bowel and sexual symptoms

Symptoms related to other aspects of pelvic floor dysfunction were measured using the ICI suite of validated questionnaires. 26

Urinary incontinence was assessed using the International Consultation on Incontinence-Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI-SF). Other urinary symptoms were recorded by the ICIQ-Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-FLUTS). The latter provides subscales for filling, voiding and incontinence symptoms.

The International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ)-Bowel Symptom was not finalised when we began PROSPECT. We therefore adapted draft questions to produce a short summary of relevant bowel symptoms. We used similar questions to map on to the ROME criteria to define constipation (Table 1). 30

| ROME criteria – any two of: | Equivalent PROSPECT questions |

|---|---|

| Fewer than three bowel movements per week | Stool passing once a week or less |

| Straining | Straining most or all of the time |

| Lumpy or hard stools | Hard stools |

| Sensation of incomplete defecation | Feeling that bowel has not completely emptied most or all of the time |

| Manual manoeuvring required to defecate | Manual manoeuvre to empty bowel most or all of the time (splinting of perineum or vagina, or digital evacuation of the bowel) |

| Sensation of anorectal obstruction | No equivalent PROSPECT question |

We assessed vaginal and sexual symptoms using the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Vaginal Symptoms (ICIQ-VS). The ICIQ-VS provides a brief and robust measure to assess the impact of vaginal symptoms and associated sexual matters on QoL and outcome of treatment. It provides subscales for vaginal symptoms, sexual matters and the overall impact of vaginal symptoms on QoL. Women were asked if they were sexually active and, if not, whether or not this was because of their vaginal or prolapse symptoms, or for another reason, including no partner. Women’s responses to this question were post-coded to ensure reliability and consistency. Data were included in the analysis of sexual outcomes for women who were sexually active or for women who were sexually inactive because of prolapse symptoms.

Safety reporting

Adverse effects were notified to the study office in a variety of ways. They could be recorded by the centre staff using the recruitment officer case report form (RO CRF; see Appendix 3) or at the time of the 12-month clinic review. Women also reported effects and readmissions in the follow-up questionnaires. If an adverse effect was suspected, it was verified if possible.

All related serious adverse effects [serious adverse events (SAEs)] and adverse effects [adverse events (AEs)] were recorded on the serious adverse event report form (see Appendix 3). Unrelated SAEs or AEs were not recorded.

Within PROSPECT, a SAE or an AE was defined as ‘related’ if it occurred as a result of a procedure required by the protocol (i.e. prolapse surgery), whether or not this procedure was the specific intervention under investigation, and whether or not it would have been administered outside the study as normal care. Signs or symptoms of the disease being studied were not considered an adverse effect.

An AE was defined as a SAE if it resulted in death, was life-threatening, required hospitalisation or prolongation of an existing admission, resulted in significant disability/incapacity or was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

Adverse effects that were expected after prolapse surgery are listed below. Any AEs that were deemed to be related and serious but unexpected (i.e. not on the list below) required expedited onward reporting to the sponsor. During the conduct of PROSPECT no unexpected SAEs were reported.

Within PROSPECT the following occurrences were potentially expected:

-

Possible (expected) intraoperative occurrences associated with surgery were injury to organs or blood vessels, excess blood loss, blood transfusion, anaesthetic complications, death.

-

Possible (expected) occurrences following surgery were thrombosis, infection [urinary tract infection (UTI), sepsis, abscess], pain, urinary retention, bowel obstruction, constipation, mesh erosion, excess blood loss, haematoma, vaginal adhesions, skin tags, granulation tissue, new or persistent urinary tract symptoms, death.

Reported SAEs and AEs were further classified using the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of complications that are related directly to the insertion of prostheses (meshes, implants, tapes) and graft in female pelvic floor surgery,31 and complications related to native tissue female pelvic floor surgery. 32

Sample size calculation

Primary trial

Pilot data showed a conservative estimate of the standard deviation (SD) of the primary participant-reported outcome POP-SS at 1 year to be eight units, and we considered a difference in means of two units to be a clinically important difference. The sample size calculation for the Primary trial was, therefore, based on a standardised effect size of 0.25. To detect a difference of 0.25 SDs with 90% power and alpha equal to 0.025 (to maintain the nominal p-value at 0.05 with tests for two comparisons), we planned to follow-up 400 women in each arm of the primary repair RCT (a total of 1200 participants). The sample size was inflated to 1450 participants, which allowed for a dropout rate of 17.5%. A trial of this size is also adequately powered to detect important differences in the economic and secondary outcomes.

Secondary trial

It was estimated that 30% of women requiring anterior and/or posterior repair would receive a secondary or subsequent repair. Therefore, during the proposed time period required for recruiting 1450 women to the primary repair RCT above, it was anticipated that approximately 620 women who were having secondary surgery would be randomised to the secondary repair RCT (assuming the same rate of eligibility and willingness to participate as in the primary repair RCT. The total expected recruitment across both trials was therefore 2070 randomised women.

Pilot data indicated that women who were having secondary repairs have a higher level of symptoms at baseline. Therefore, we considered it to be biologically plausible that these women might show a larger benefit from surgical treatment than women who were having their first repair. We therefore calculated that it would be possible to detect, with 90% power and alpha equal to 0.025, a standardised effect size of 0.38, which equates to three points on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Symptom scale.

Avoidance of bias, including blinding

Group allocation was concealed from the woman and the ward staff, although blinding in theatre was not possible, given that this was a surgical trial. Women were not informed after their surgery of the procedure actually carried out unless they specially requested this information. Outcome assessment was largely by participant self-completed questionnaires, so avoiding interviewer bias.

Where possible, the clinical review at 12 months in outpatients was conducted by research staff who were blinded to allocation, rather than the clinical staff caring for the woman. Although women and research staff were not explicitly informed of which operation was randomly selected, examination may have revealed which operation was actually carried out.

A researcher who was blinded to allocation conducted the data collection, data entry and analysis, using study numbers only to identify women and questionnaires. In the RCTs, an intention-to-treat approach was used in all primary analyses. In addition, all analyses were clearly predefined to avoid bias (see Appendix 5).

Statistical analysis

The trial analysis was by intention to treat (all participants remained in their allocated group for analysis), giving the least biased estimate of effectiveness between interventions. Two comparisons were analysed in the primary repair RCT – standard repair compared with synthetic mesh (trial 1, combining the strata 1A and 1B; see Figure 1) and standard repair compared with biological mesh (trial 2, combining strata 1A and 1C) and three comparisons were analysed in the secondary repair RCT – standard repair compared with synthetic mesh (trial 3, combining strata 2A and 2B) and standard repair compared with mesh kit (trial 4, combining strata 2A and 2D). Study analyses were conducted according to a statistical analysis plan (SAP), using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) (see Appendix 5).

For each time point (baseline, 6, 12 and 24 months), all outcome measures are presented as summaries of descriptive statistics (mean and SD for continuous measures, and proportion for ordinal and dichotomous measures). Comparisons between randomised groups were analysed at 12 months and 24 months using general linear regression models (GLMs). POP-SS, prolapse-related QoL, EQ-5D-3L and readmissions data at 6 months were also analysed. Models were adjusted using minimisation covariates (age group, type of prolapse, concomitant continence procedure and concomitant upper compartment prolapse surgery), the equivalent baseline measure, where appropriate, and (in the primary repair trial) for randomisation stratum.

Continuous outcomes were analysed using linear mixed models, with surgeon fitted as a random effect. POP-Q stage, bowel frequency and satisfaction scales were analysed using ordinal logistic regression, and dichotomous outcomes were analysed using binary logistic regression (proportional odds models with cumulative logits). Estimates of treatment effect size were expressed as the fixed-effect solution for the mean difference (MD) in the mixed models, ORs in the ordinal models and risk ratios (RRs) in the binary models. For all estimates, 95% CIs were calculated and reported.

Subgroup analyses were carried out on the primary outcome in the primary repair RCTs (POP-SS at 1 year) to test subgroup by treatment interaction effects. Subgroups were determined a priori to be age group (< 60 years or ≥ 60 years), type of planned prolapse repair (anterior, posterior or both), planned concomitant continence procedure (yes or no), planned concomitant upper prolapse procedure (yes or no) and parity (0–2 or 3+).

The main analysis was a complete case analysis with no imputation of missing values. Sensitivity analyses, however, were carried out on the primary outcome in the primary repair RCTs (POP-SS at 1 year) to investigate the impact of missing data under various assumptions. The first sensitivity analysis used multiple imputation (MI) using fully conditional specification, which assumed the data to be missing at random. Imputed values were obtained from the generation of 10 data sets and based purely on observed values (minimisation covariates and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Symptom scale scores at baseline). Subsequent sensitivity analyses assumed data to be missing not at random, with scenarios for systematic differences between missing and observed values being examined, and whether or not this might have differed between randomised groups. These analyses adjusted the imputed values in the initial sensitivity analysis by either adding two points to the imputed Pelvic Organ Prolapse Symptom scale scores or subtracting two points. These adjustments were then repeated in one arm only, and repeated again by applying the adjustments in the other arm only. We consider two points on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Symptom scale to be the minimum clinically important difference and hence a meaningful systematic difference to test in the sensitivity analyses. An additional sensitivity analysis was performed whereby individual unanswered Pelvic Organ Prolapse Symptom scale items were assumed to be missing (rather than assumed to be asymptomatic).

Health-economic evaluation

This section outlines the methods for the trial-based economic evaluation. The methods are applicable to both the analysis of the Primary and Secondary trial data at 1-year and 2-year follow-up. Further detailed methods regarding how the trial data are used to inform the development of a decision-analytic model for the choice of primary prolapse surgical repair, as well as detailed model methods, will be reported in the decision modelling chapter (see Chapter 9). Data were analysed at 1-year follow-up, thus following the timeline for the Primary trial outcome analysis. A further analysis was undertaken using 2-year follow-up data, which improve the information relating to recurrence/failure and the associated resource implications in terms of NHS resources consumed as well as QoL. All health-economic analyses within the RCT were based on the intention-to-treat principle. Results from the within-trial economic evaluation are presented as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). The primary framework of analysis for the health-economic evaluation is a cost–utility analysis, reporting results as incremental cost per QALY gained of adopting one treatment approach over another.

For all comparisons of costs and QALYs undertaken in the primary repair trial, results are based on complete case data and are presented for the following comparisons:

-

synthetic mesh repair versus standard repair

-

biological graft repair versus standard repair.

For assessments of the probability of cost-effectiveness, data are considered within a net benefit framework for complete cost and QALY pairs, and for a three-way comparison as per RCT1A (women randomised across all treatment options). For the secondary repair trial, tables of results are presented in a similar manner; however, data from all randomised women are used, not just those randomised to the three-way comparison as above. The justification of the alternative approach is to ensure best use of limited data available. For both the Primary and Secondary trial analyses, we have conducted sensitivity analysis around the choice of data used in the comparisons to explore the impact of these decisions on cost-effectiveness results.

Quality of life (quality-adjusted life-years)

The primary health-economic analysis is based on a cost–utility framework, with results reported as incremental cost per QALY gained. The purpose of a cost–utility analysis is to provide information to health-care decision-makers regarding the scarce allocation of health resources at a health-care level. It allows for a determination of value for money of one treatment approach over another and is used to guide recommendations to UK policy-makers, such as NICE.

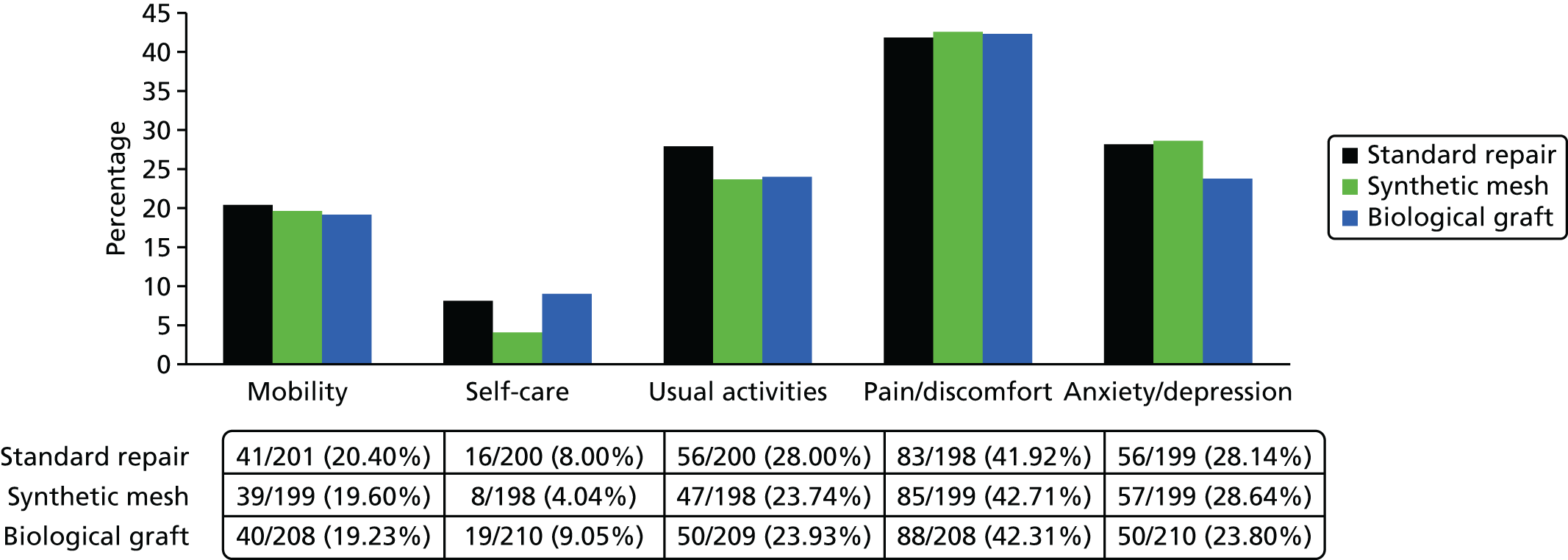

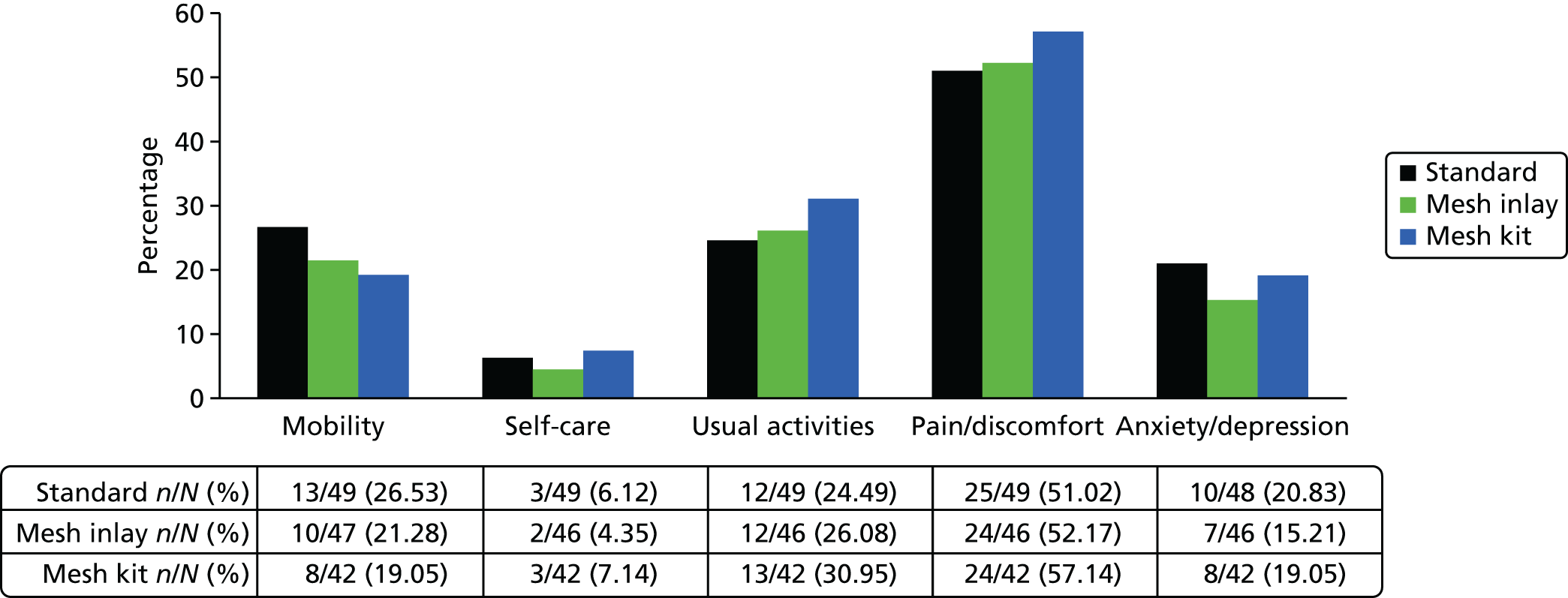

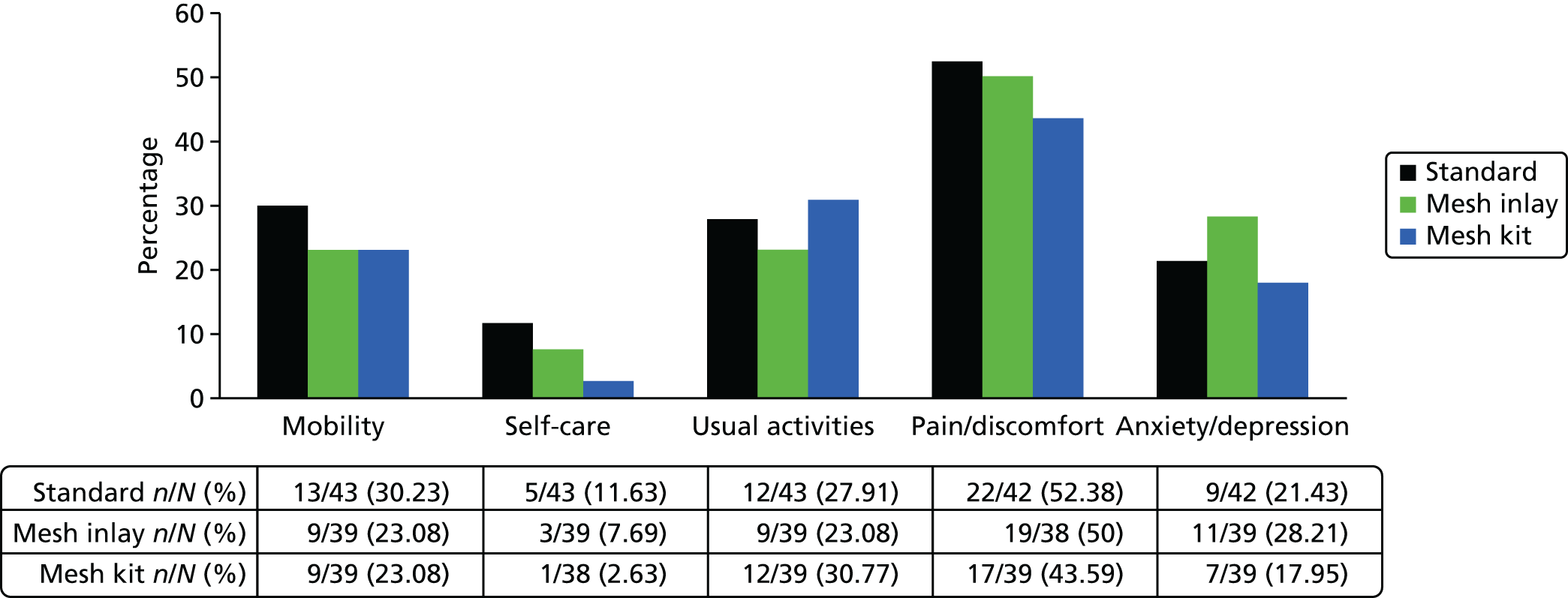

The EQ-5D-3L25 generic QoL instrument was administered to all trial participants at baseline and at 6-month, 1-year and 2-year follow-up. The EQ-5D-3L measure divides health status into five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depressions). Each of these dimensions have three levels, so 243 possible health states exist. EQ-5D-3L responses are presented in graphical format, illustrating the percentage of respondents with any or severe problems on each health domain, split by randomised arms of the trial. The results are presented in accordance with EuroQoL guidelines. 25

The responses to the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire were valued using UK general population tariffs, based on the time trade-off technique to generate a utility score for every participant within the trial. 25 QoL data derived from the EQ-5D-3L were combined with mortality data from the trial, using the standard assumption that all participants who have died in the trial will have a utility value of 0 from the date of death to the end of follow-up. QALYs were then calculated on the basis of these assumptions, using an area beneath the curve approach, assuming linear extrapolation of utility between time points.

Resource use and costs

The perspective of the primary economic analysis is that of the NHS. A supplementary analysis presents costs from a wider patient/societal perspective. In all cases, resource use and costs relate to consultations in primary and secondary care which are related to women’s prolapse or prolapse-related symptoms.

Health services costs

The resource-use data were sourced from participant-completed questionnaires and supplemented with data that were post-coded to patient records for secondary care resource use. Post-coding was conducted by checking all reported cases of secondary care resource use against patient notes to verify reported length of stay, category of care use (so, outpatient or inpatient) and to verify that the reported use of care was for issues related to prolapse and not for some other unrelated reason. Data were obtained from the clinical centres for the price of mesh and clinical expert opinion was sought to bridge any data gaps relating to staff requirements for surgery. National average unit costs were applied to resource-use data to generate total costs to the health services. The sources of unit costs were the British National Formulary (BNF) and the NHS Business Services Authority electronic drug tariff online catalogue33 for medications resource use;34 Information Services Division (ISD) Scotland35 and NHS reference costs36 for secondary care resource-use data; and Personal and Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) unit costs of health and social care for primary care resource-use data. 37 The costs were reported in 2013–14 UK pound sterling (£). The costs incurred in the second year of follow-up were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per annum. The sensitivity analysis explored the impact of varying the discount rate in accordance with NICE recommendations. 38

The resource-use data and costs for the health-economic analysis were broken into the following categories of NHS resource use:

-

intervention costs (including costs of completing the surgery, preparation costs and hospital resource-use costs in theatre, based on operation time, staff time and other additional treatments)

-

postoperative costs (from surgery to discharge) including time on ward, return to theatre and cost of treating any infections or complications

-

inpatient costs (cost of any follow-up operations and length of stay in hospital related to prolapse symptoms, including overnight and day-case admissions)

-

outpatient costs (including all outpatient contacts over the trial follow-up)

-

primary care costs (including GP contacts, occupational therapist, physiotherapist and nurse contacts)

-

medications and other treatments related to treating prolapse and UI symptoms.

Unit costs

Costs to the health services are estimated by combining resource-use data with unit costs of resource use. Table 2 includes a list of all unit costs used in the within-trial economic analysis, together with their source and any assumptions used to develop the unit cost used for analysis. Further details regarding calculations underpinning the unit costs presented in Table 2 are outlined in more detail in Appendix 6. Unit costs applied to the Primary and Secondary trial analyses were similar with the exception of the unit cost of mesh materials to complete the operative procedure.

| Resource-use item | Unit | Cost per unit (£) | Comments | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic mesh material | Per mesh unit | 111.09 | Average per unit cost of meshes used at all participating sites. Mean cost imputed for centres not returning data | Direct contact with sites/manufacturer price lists |

| Biological graft materials | Per mesh unit | 305.41 | Average per unit cost of meshes used at all participating sites using biological graft. Mean cost imputed for centres not returning data | Direct contact with sites/manufacturer price lists |

| Anterior mesh kits (Secondary trial only) | Per mesh kit | 645.45 | Average per unit cost of meshes used at all participating sites using anterior mesh kits. Mean cost imputed for centres not returning data | Direct contact with sites/manufacturer price lists |

| Posterior mesh kits (Secondary trial only) | Per mesh kit | 583.00 | Average per unit cost of meshes used at all participating sites using posterior mesh kits. Mean cost imputed for centres not returning data | Direct contact with sites/manufacturer price lists |

| Gynaecologist/anaesthetist time (consultant) | Per hour | 142 | If surgery was supervised, assume supervision provided by a consultant grade. Includes qualification costs | PSSRU 201437 |

| Gynaecologist/anaesthetist time (registrar) | Per hour | 124 | Includes qualification costs | PSSRU 201437 |

| Gynaecologist/anaesthetist time (associate) | Per hour | 71 | Includes qualification costs | PSSRU 201437 |

| Band 5 theatre nurse | Per hour | 100 | Including qualification costs, cost per 1 hour of patient contact. Assume three band 5 nurses present for all procedures (Dr Karen Cranfield, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, 2015, personal communication) | PSSRU 201437 |

| Band 4 theatre nurse | Per hour | 91.59 | Per hour of client contact, including qualification costs. Assume one band 4 nurse present for duration of all procedures (Dr Karen Cranfield, personal communication) | |

| General anaesthesia | Per case | 20.60 | Based on calculation (see Appendix 6) | BNF;34 personal communication |

| Spinal anaesthesia | Per case | 1.85 | Based on calculation (see Appendix 6) | BNF;34 personal communication |

| Local anaesthesia | Per case | 0.40 | Based on calculation (see Appendix 6) | BNF;34 personal communication |

| Surgical antibiotics | Per case | 1.06 | Assume co-amoxiclav (Augmentin®; GSK, Middlesex, UK); Dr Karen Cranfield, personal communication | BNF;34 personal communication |

| Other surgical drugs | Per case | 6.45 | For general and spinal anaesthesia only; resource use provided by Dr Karen Cranfield (see Appendix 6 for detailed calculation) | BNF;34 personal communication |

| Theatre overheads | Per hour | 352.69 | Currently excludes consumables | ISD35 Scotland R140X |

| Cost of catheterisation | Per catheter | 6.25 | Assume Folysil® all-silicone catheters, female (Coloplast Ltd, Peterborough, UK); NHS EDT, April 2015 – assume no additional procedure time required if catheterised during surgery | NHS EDT33 |

| Vaginal pack | Cost per vaginal pack | 4.67 | Sorbsan packing (Aspen Medical Europe Ltd, Ashby-de-la Zouch, UK) 30 cm/2 g: £3.47 plus Hibitane obstetric cream (Derma UK, Bedfordshire, UK): £1.20 |

NHS EDT33 |

| Other treatments during admission for intervention | ||||

| Return to theatre | Per case | 814 | No data available on time in theatre for returns; conservatively assume duration was 1 hour | Direct cost, ISD35 R142 |

| Laxatives | Per pack of tablets | 3.43 | Bisacodyl 5 mg | BNF34 |

| Length of stay (gynaecology ward) | Per day | 179 | Payment by results tariff of £1433 spread over 8 days, so £179 per day | Payment by results, 2014 tariffs36 |

| Consultations with secondary and primary health-care professionals/procedures for subsequent treatment or consultations | ||||

| New prolapse procedure | Per procedure | 2331 | Weighted calculation of appropriate HRG codes for surgery for prolapse. See Appendix 6 for further details | NHS Reference Costs 2013–14 36 |

| New incontinence procedure | Per procedure | 1372.48 | Weighted average of elective and day-case procedures for HRG code M533 (introduction of TVT/TOT); see Appendix 6 for calculation details | NHS Reference Costs 2013–14 36 |

| Other readmission | Cost per admission | 853.64 (weighted average) | Weighted average of elective in patient/day-case procedures for HRG codes MA22/MA23 minimal/minor genital tract procedures: £803.81 (day case) £1207.85 (> 0 nights’ admission) See Appendix 6 for detailed calculations |

Payment by results, 2014 tariffs36 |

| Outpatient consultation (first attendance) | Per consultation | 133 | NHS reference costs | NHS Reference Costs 2013–14 36 |

| Outpatient consultation (repeat) | Per consultation | 81 | NHS reference costs | NHS Reference Costs 2013–14 36 |

| GP visit | Per visit | 46 | Per 11.7-minute consultation, including qualification costs | PSSRU 201437 |

| Practice nurse | Per visit | 13.69 | Per 15.5-minute consultation, including qualification costs | PSSRU 201437 |

| Community physiotherapist | Per visit | 23.94 | Per 30-minute consultation, including qualification costs | PSSRU 201437 |

| Hospital clinical nurse specialist | Per visit | 22.50 | Based on a per-hour cost of £90 per hour of client contact, assuming average appointment of 15 minutes’ duration | PSSRU 201437 |

| Community pharmacist | Per visit | 32.50 | Based on per-hour cost of £142, including qualification costs, and average appointment duration of 15 minutes | PSSRU 201437 |

| Accident and emergency | Per visit | 103 | Cost per visit (see Appendix 6 for more details on calculation) | NHS Reference Costs 2013–14 36 |

| Urodynamics | Per consultation | 186 | See Appendix 6 for calculation details. Based on HRG code LB42, assume outpatients | NHS Reference Costs 2013–14 36 |

| Ultrasound scan | Per visit to have scan | 52 | Diagnostic imaging in outpatients assumed. See Appendix 6 for further details | NHS Reference Costs 2013–14 36 |

| Other treatments | ||||

| Absorbent pads | Per pad – day | 0.61 | Based on average across a number of products and data reported in Fader 2008. Data inflated to present-day values. Unit costs multiplied by frequency of leakage to generate cost per woman (see Appendix 6 for more details) | Fader 2008;39 PSSRU 2014;37 HCIS inflation index |

| Per pad – night | 0.66 | |||

| Permanent/indwelling catheter | Per woman (yearly cost) | 390.52 | Based on a number of assumptions. See Appendix 6 for calculation details | NHS EDT 201533 |

| Reusable/intermittent catheter | Per woman (yearly cost) | 1816.50 | Based on a number of assumptions. See Appendix 6 for more details | NHS EDT;33 NHS Warrington40 Trust documentation for guidance of care |

| Oestrogen treatment | Per 24-applicator pack | 16.72 | Estradiol (Vagifem®; Novo Nordisk, West Sussex, UK) vaginal tablets, 10 µg, in disposable applicators. Multiplied by resource-use requirement over follow-up | BNF 201534 |

| Ring pessary | Per pessary | 19.98 | Average across EDT products (see Appendix 6 for calculation) | EDT 201533 |

| Shelf pessary | Per pessary | 21.51 | Average across EDT products (see Appendix 6 for calculation) | EDT 201533 |

| Drug treatment for bladder problems | Per 56-tablet pack | 2.92 | Assume tolterodine tartrate, generic version, to cover frequency and urgency symptoms, 2 mg twice daily dose assumed | BNF 201534 |

Intervention costs

The resource-use data required to deliver each intervention were collected prospectively for every participant in the study. The operative details were recorded at the time of surgery (e.g. time in theatre, grade of operating gynaecologist, grade of anaesthetist and grade of surgical supervision if present). The details of concomitant surgery and catheterisation were recorded and incorporated into the costing analysis. The details were sourced from data recorded on the CRFs (see Appendix 3). The data from the CRFs were supplemented with centre-specific data for the costs of mesh products. Each centre was asked to provide information on the mesh products used by each surgeon at their site for each trial intervention. The surgeon-specific data on mesh use were costed using NHS list prices, sourced from participating centres financial departments.

For some cases, we were not able to identify mesh costs directly from the participating surgeons. This resulted in some missing data for mesh costs. In such cases, we imputed mean costs of mesh calculated from those surgeons/centres that provided data. It is possible that there is heterogeneity across surgeons in terms of the size of mesh product used, or within individual surgeons, who may use different mesh sizes on a case-by-case basis. Where possible, we have costed the same (or similar) mesh sizes across different mesh products so as to avoid any bias against individual mesh products. It should be noted that the analysis does not seek to make statements about the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of individual mesh products, but rather seeks to develop an average cost for each arm of the trial, which is relevant and generalisable to clinical practice in the UK.

When data regarding surgical resource use (particularly regarding the number of supplementary staff present during a typical surgical procedure, such as nurses and theatre assistants) were unavailable from formal records, we have made assumptions based on the clinical opinion of experts working on the trial team. When there was uncertainty in the resource-use estimates to complete the intervention, and when any assumptions were required, sensitivity analysis explored the impact of these assumptions on the total intervention cost and on the estimates of cost-effectiveness.

The purpose of the intervention costing analysis was to find an average procedure cost, based on typically used meshes at participating centres. Data on mesh usage were available from the 35 participating centres. Unit costs of mesh usage were also sourced through a separate costing exercise directly from centres, which were asked to provide NHS list prices. When data were missing for individual mesh products at centres, the average of all mesh products within that category (e.g. synthetic mesh) was assumed and applied as the unit cost. A similar approach was taken for biological graft repair.

Inpatient costs over follow-up

As length of stay is one of the secondary outcomes of the trial, we collected detailed data on inpatient length of stay in relation to both the participant’s prolapse surgery and their UI. The hospital-based costs in the immediate aftermath of the surgery (up until date of discharge of the patient) were recorded on the RO CRF (see Appendix 3), eliciting information on whether or not the patient returned to theatre for a procedure-related event within 72 hours of having their operation and if catheterisation was required in the first 10 days postoperatively. Longer-term inpatient resource-use data were collected from the participant-completed questionnaires issued at 6-month, 1-year and 2-year follow-up. When participants reported having a hospital readmission, these were checked against patient records to determine the reason for admission. Furthermore, this post-coding exercise identified any participant reporting errors (e.g. patient confused follow-up surgery with index operation; participant double-counted single admissions on both 1-year and 2-year questionnaires; participant misidentified reason for readmission). The costs of additional surgery related to prolapse and/or urinary leakage were estimated using national tariffs, as well as any other inpatient costs. The data collected from both the 1-year and the 2-year follow-ups were used to inform the economic model extrapolating resource use over the patient’s lifetime.

Outpatient costs

The participant-completed questionnaires were used to determine outpatient contacts related to the women’s prolapse symptoms over follow-up. Again, these were post-coded against patient records to check the accuracy of the data and resolve any discrepancies.

Owing to the post-coding exercises undertaken, we have a high degree of confidence in the estimates of secondary care resource use across the trial for each individual woman returning a questionnaire. Therefore, if a woman did not report a secondary care event, it was assumed that no resource use was incurred. If a woman did not return a questionnaire then data were treated as missing.

Primary care costs

Participants were asked to provide detailed information on contacts with primary care health professionals in relation to their prolapse symptoms and UI (see Appendix 4). This included visits to the GP, practice nurse, occupational therapist and physiotherapist at each follow-up time point.

For primary care resource-use questions that are left blank on a returned participant questionnaire, resource use is assumed to be zero. The reason for this is to ensure the best possible use of the available data to generate a reasonably sized complete case data set for the economic analysis. Sensitivity analysis explored the effect of multiply imputed data. As with the secondary care data, if a participant questionnaire is not returned then data are treated as missing.

Total NHS costs

The total costs from the health services perspective were calculated by summing all intervention treatment and follow-up costs related to the respective prolapse repairs for each participant in the data set. If one of the component costs was missing because of a non-returned questionnaire then that participant was dropped from the complete case analysis. If a component cost was missing for primary care consultations then these data were treated according to the assumptions outlined above. The total NHS costs and individual component costs incurred within the second year were discounted by 3.5%.

Participant- and companion-incurred costs and indirect costs, including opportunity costs of time and travel

Participant resource utilisation comprised three main elements: self-purchased health care; travel costs for making return visit(s) to NHS health care (such as petrol, public transport and parking); and time costs of travelling and attending NHS health care (such as time involved away from usual activities or work). All self-purchased health care relate to treatment purchased for the management or treatment of prolapse-related symptoms. Likewise, time and travel costs relate to time spent travelling to and attending hospital or primary care for prolapse symptoms. Estimation of travel costs required information from participants about the number of visits to, for example, their GP or physiotherapist (estimated from the health-care utilisation questions) and the unit cost of making a return journey to each type of health-care provider (from the participant time and travel cost questionnaire; see Appendix 4).

The cost of participant time was estimated in a similar manner. The participant was asked, in the participant time and travel cost questionnaire, how long they spent travelling to, and attending, their last visit to each type of health-care provider. Participants were also asked what activity they would have been undertaking (e.g. paid work, leisure, housework) had they not attended the health-care provider. They were further asked if they were accompanied by a friend or a relative. If so, their time and travel costs were also incorporated into the analysis. These data are presented in their natural units, for example hours, and also costed using standard economic conventions, using the Department of Transport estimates for the value of work and leisure time. 41 These unit time costs were then combined with the number of health-care contacts derived from the health-care utilisation questions to elicit a total time and travel cost from a patient perspective.

The data collected through the health services resource-use questionnaire were used to estimate the costs of self-purchased health care, including pads bought by the participant, prescription costs and over-the-counter medications. The cost to the participant of any self-purchased health care was collected directly within the questionnaire.

Indirect costs were defined as the production losses resulting from treatment when the participant was unable to return to work or was required to take sick leave due to her prolapse problems. The cost of days lost was estimated using the average UK gross hourly wage in the economy. When a participant’s own reported costs associated with a specific type of health service visit were missing, the mean cost for that type of visit was imputed. Participants completing the annual health resource utilisation questionnaire were asked how many days they were off work in the last 12 months as a result of prolapse symptoms or problems. Questions were asked at both 1-year and 2-year follow-up. The data were recorded as natural units and multiplied by standard economic costings as reported below (see Table 3). The total production losses due to time away from work for non-retirees as a result of prolapse symptoms were estimated and compared across treatment groups.

The unit costs applied to the participant (and companion) time, travel and indirect economic costs data are outlined in Table 3. The unit costs were based on standard economic sources and were inflated, where appropriate, to 2014 values. For the purposes of inflation, we utilised the Cochrane economics group inflation calculator application, using International Monetary Fund-reported inflation data. 44

| Activity | Unit cost (£, 2014) | Assumptions made/notes | Source of data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit costs applied to participant and companion travela | |||

| Cost per mile travelled by car | 0.45 per mile | HMRC-approved mileage rate (most recent data: year 2013) | HMRC42 |

| Car parking charges | Various | Specified in participant questionnaire | Participant-reported data |

| Cost of public transport fares (bus, train, taxi) | Various | Specified in participant questionnaire | Participant-reported data |

| Cost of return journey by hospital car | 18.00 per return journey | Various costs across NHS Trusts (data from South Devon publicly available and applied to all) | Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust43 |

| Cost of non-emergency patient transport service (via ambulance) | 44.65 per return journey | Not included in reference costs since 2011 (therefore indicative cost only) Note: incurred directly by PCTs, so not included in total participant cost calculation |

NHS Reference Costs 2009–1036,44,45 |

| Unit costs applied to participant and companion time | |||

| Paid work | 13.21 per hour | Based on average economic wage per week of £518, assuming 39.2-hour working week | ONS; annual survey of hours and earnings 201446 |

| Housework | 10.53 per hour | Costs of housework in the NHS (assumed annual salary of £21,000 gross; 2012 values inflated to 2014) | NHS pay review body report 201247 |

| Child care | 13.21 per hour | As paid work | ONS 201448 |

| Caring for a friend/family member | 13.21 per hour | As paid work | ONS 201448 |

| Voluntary work | 13.21 per hour | As paid work | ONS 201448 |

| Leisure activities | 6.54 per hour | Value of non-working time (2010 values inflated to 2014) | TAG data book, autumn 201341 |

| Retired | 6.54 per hour | Value of non-working time (2010 values inflated to 2014) | TAG data book, autumn 201341 |

| Unemployed | 6.54 per hour | Value of non-working time (2010 values inflated to 2014) | TAG data book, autumn 201341 |

| Ill/disabled (long term, unrelated to prolapse) | 6.54 per hour | Value of non-working time (2010 values inflated to 2014) | TAG data book, autumn 201341 |

The data on time and travel costs, participant-incurred medical costs and time away from work or usual activities (to attend medical appointments and as a result of recovery from surgery) were all summed together to generate a total participant cost. The incremental cost differences between groups from a participant perspective were estimated using the same methods outlined in the statistical analysis of economic data detailed in the following section.

Statistical analysis of economic data

The economic analysis was conducted following the intention-to-treat principle. The perspective was predominantly that of the NHS, with a supplementary wider economic and patient perspective conducted. The period of follow-up was 2 years and costs and QALYs in the second year were discounted at a rate of 3.5%. All components of costs were described with the appropriate descriptive statistics where relevant: mean and SD for continuous and count outcomes; numbers and percentages for dichotomous and categorical outcomes (e.g. numbers reporting problems on EQ-5D-3L). All analyses were conducted using Stata® version 14.1 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

To investigate the potential for skewed cost data (i.e. a small proportion of participants incurring very high costs), we used GLMs, testing alternative model specifications for appropriate fit to the data. The GLM models allow for heteroscedasticity by selecting and specifying an appropriate distributional family for the data. This family offers alternative specifications to reflect the relationship between the mean and variance of the estimates under consideration. 49,50 Two diagnostic actions were performed to select the most appropriate distributional family: (1) a modified Park test, which identified two potentially viable distributional families for costs, namely Gaussian or gamma, and (2) as a check on the most appropriate model, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) was consulted, which identified a Gaussian model with an identity link as having the lowest AIC score and the most appropriate model fit. This suggests a standard ordinary least squares (OLS) model should be fitted for cost data. The next-best model fit according to the AIC criteria was a gamma regression with log link, and this was explored in sensitivity analysis. Regression models applied to cost components (such as ‘other treatments’ and ‘hospital costs’) in the analyses above are also assumed to follow the same distributional assumptions as the total cost data. A standard OLS model was also identified as the most appropriate model and applied to the analysis of incremental QALY gains. All analyses were conducted using heteroscedastic robust standard errors (SEs).

Analysis models were run to estimate the incremental effect of treatment group on costs and QALYs. Models were adjusted using minimisation covariates (age group, type of prolapse, concomitant continence procedure and concomitant upper compartment prolapse surgery), as well as surgeon and baseline EQ-5D-3L score. 51 For the Secondary trial, using all available data, analyses were further adjusted for randomised stratum. The coefficient on treatment in the respective linear OLS models is taken as the estimate of incremental costs for use in the economic evaluation. 49,50

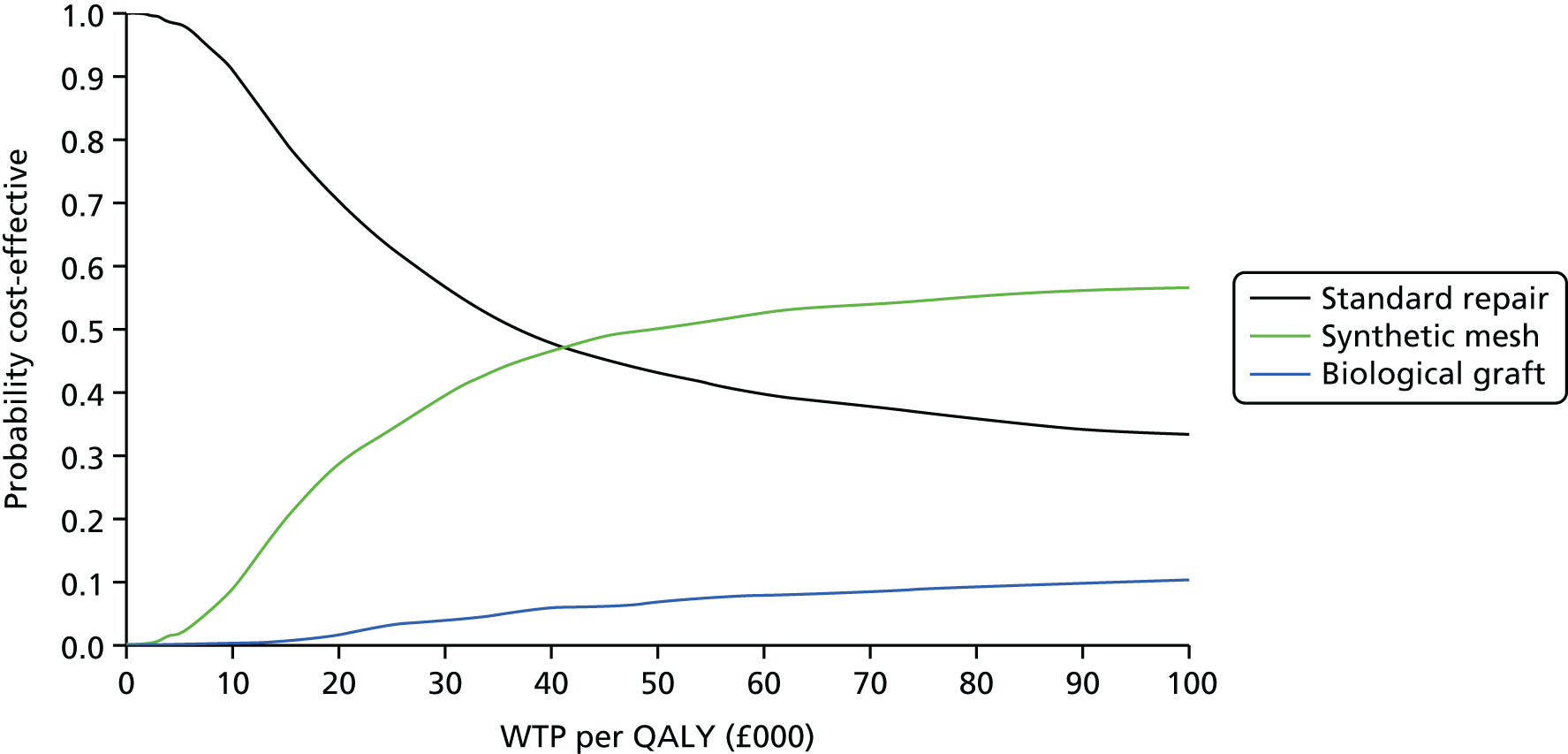

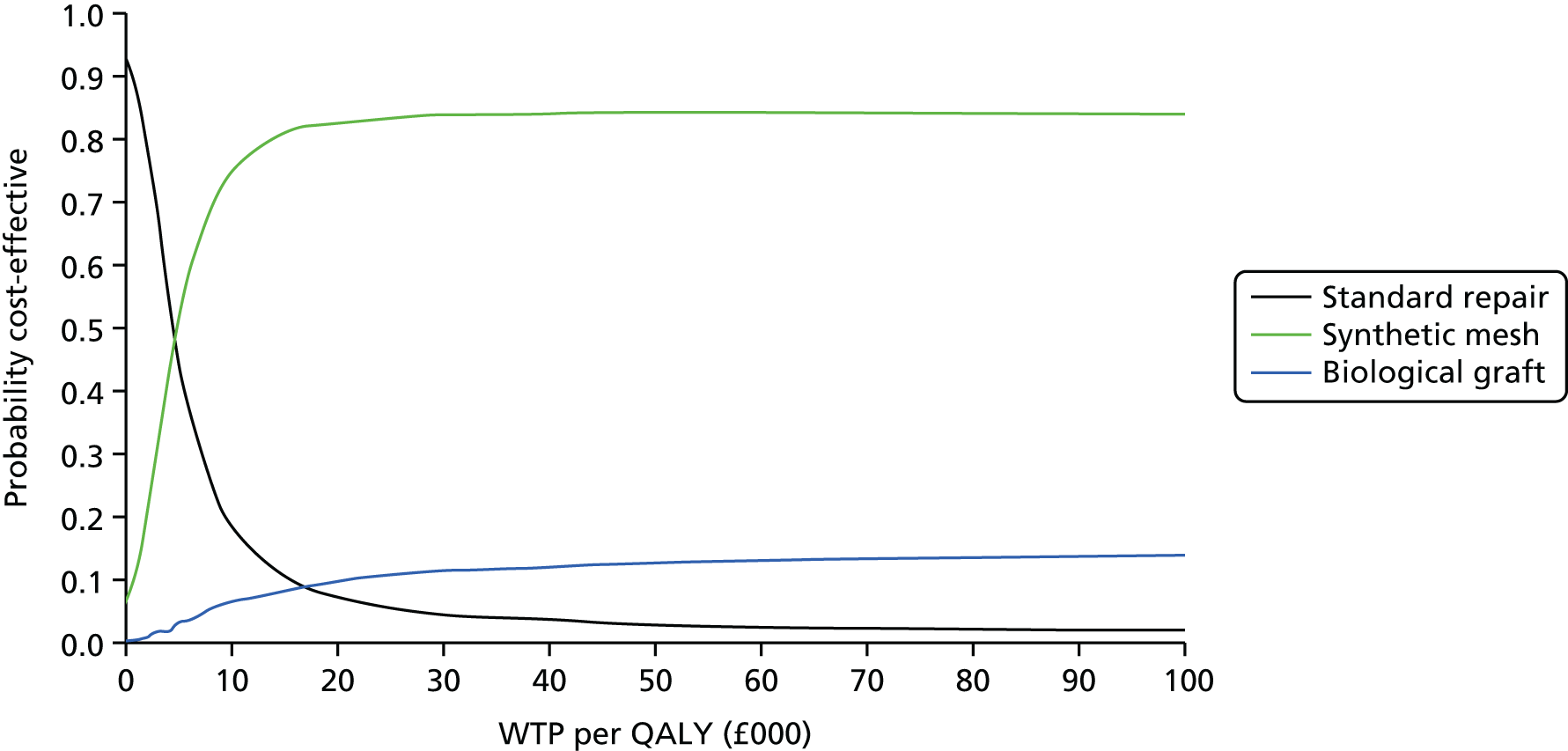

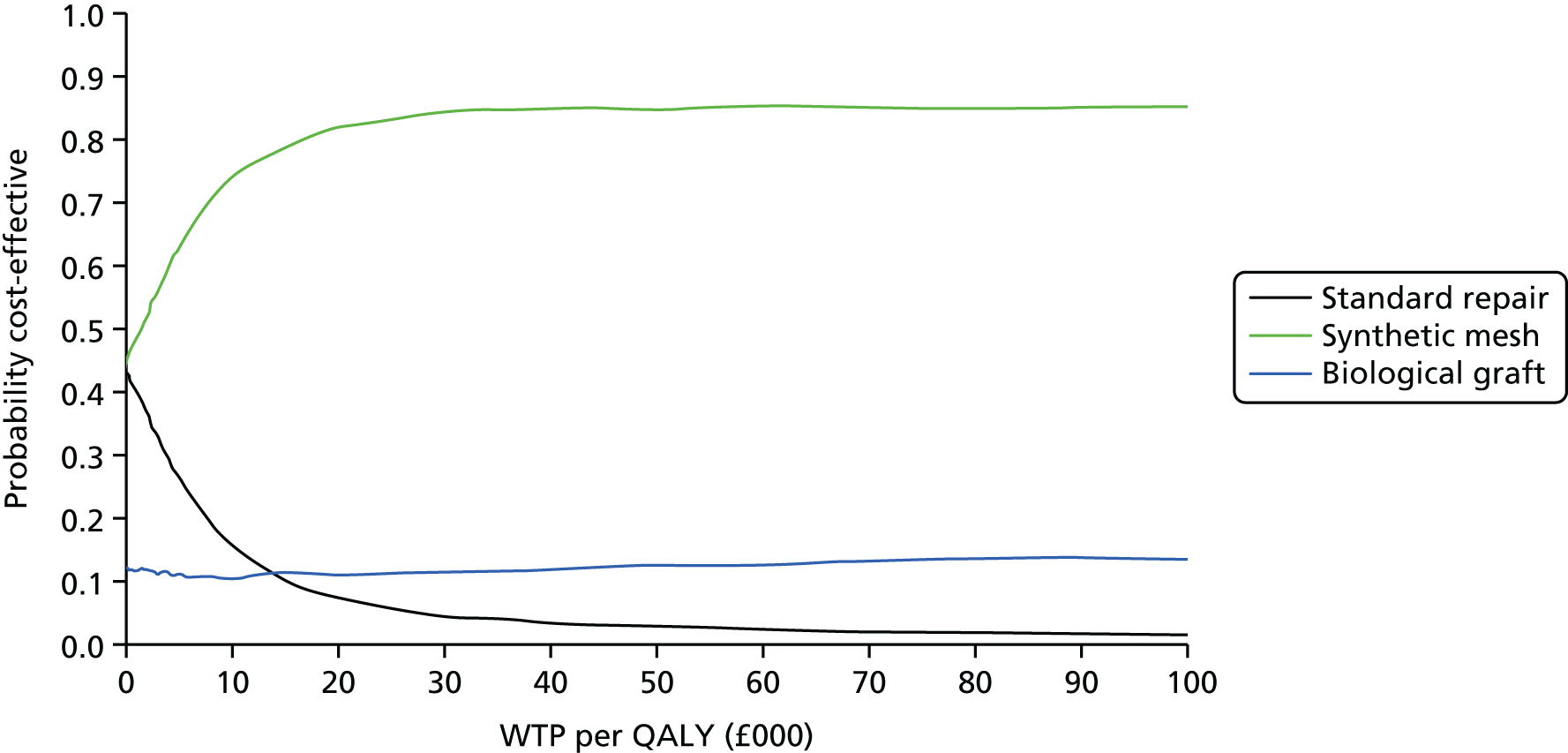

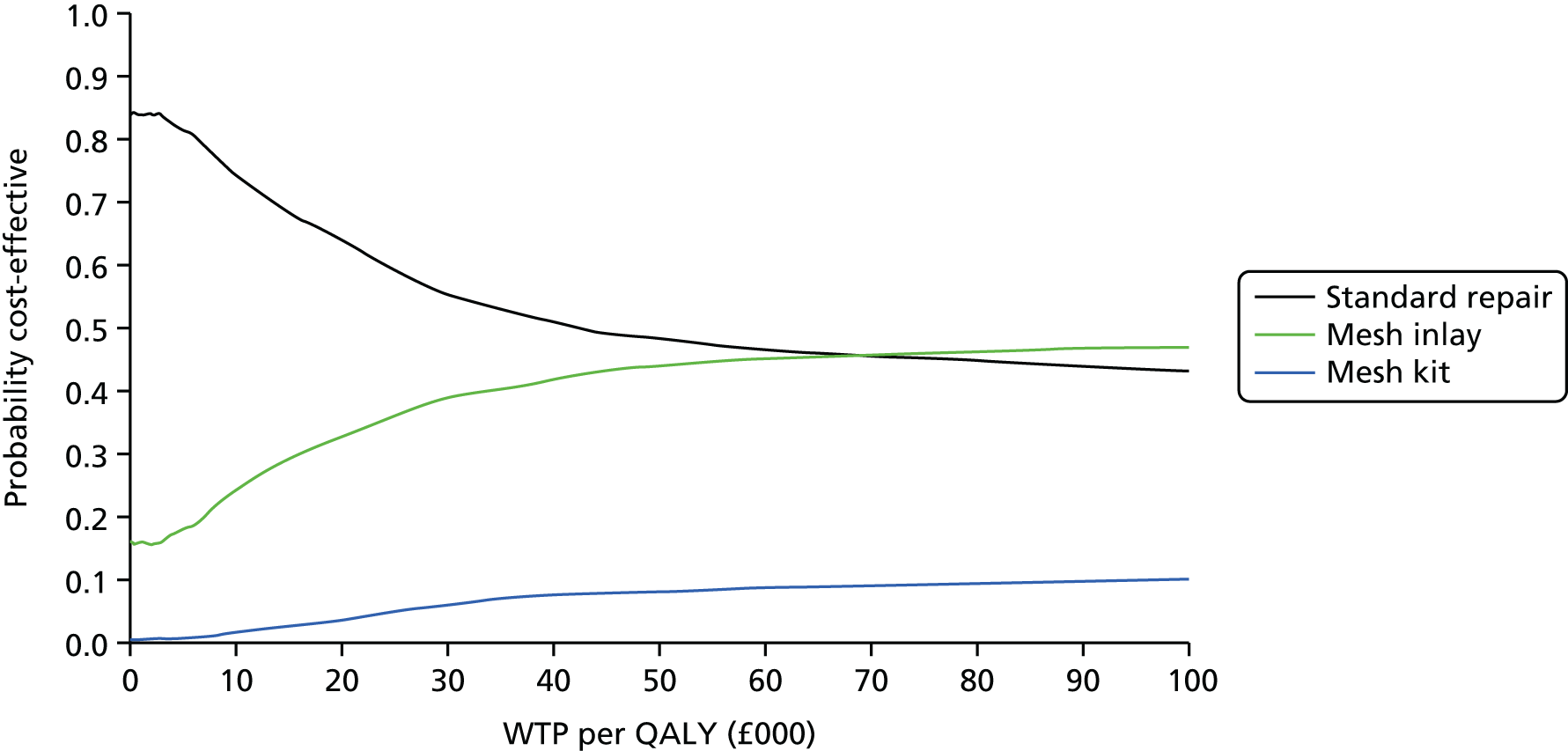

Overall results of the cost–utility analysis are reported as incremental cost per QALY gained for different treatment arms (relative to standard repair). The cost per QALY is presented using the ICER, calculated as the coefficient of treatment effect on costs divided by the coefficient of treatment effect on QALYs from the respective linear regression models. Estimates of the ICER are then compared with the recommended willingness-to-pay (WTP) decision-making threshold in the UK, currently between £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY gained. 38

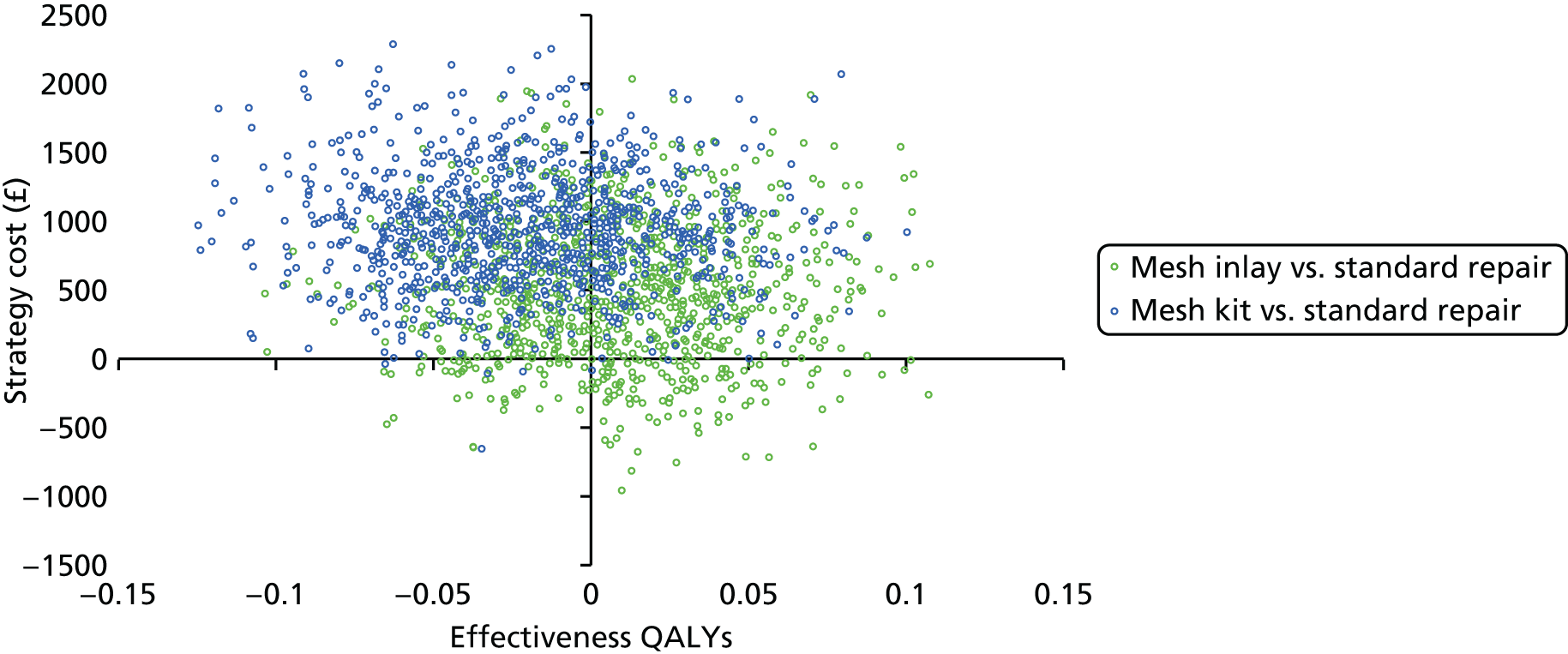

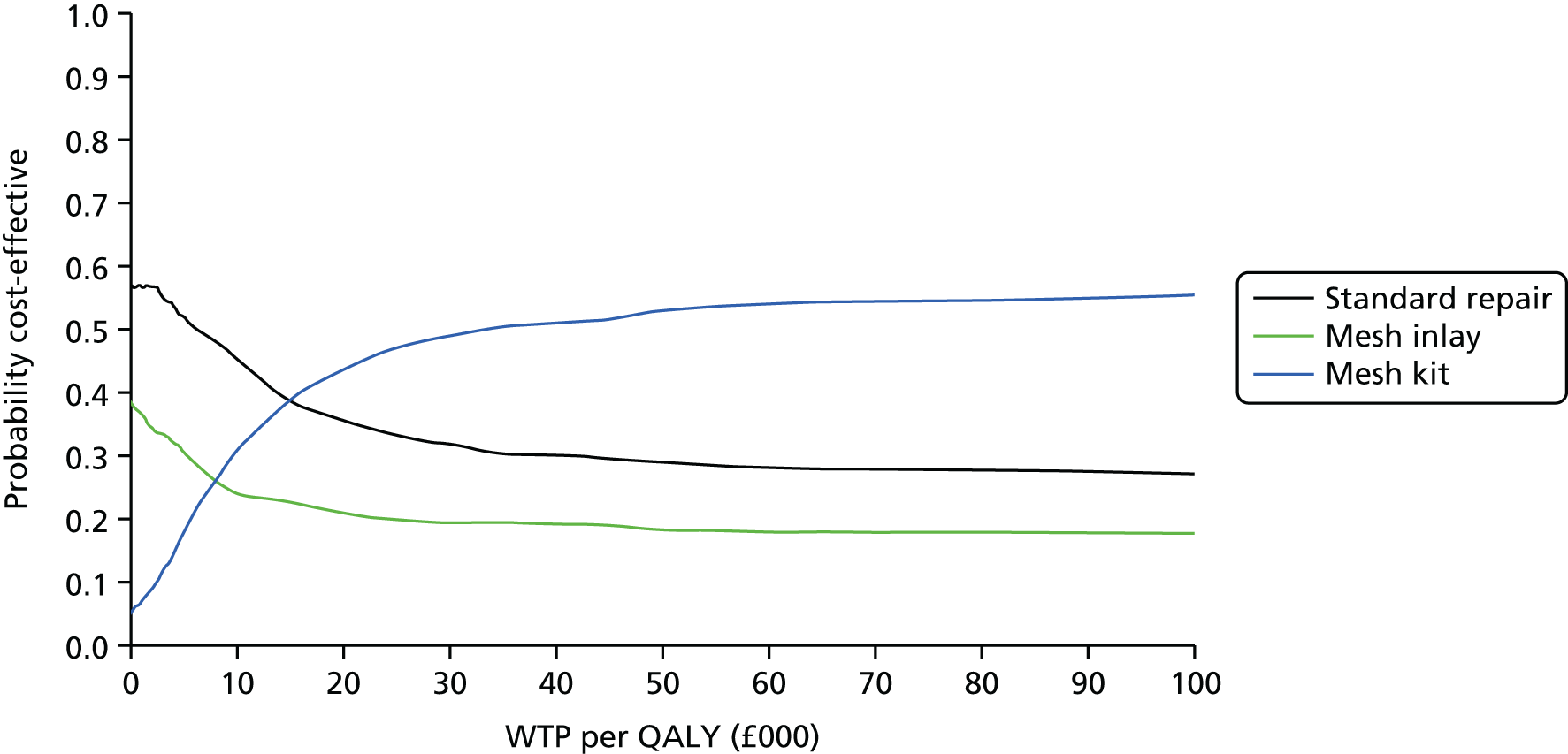

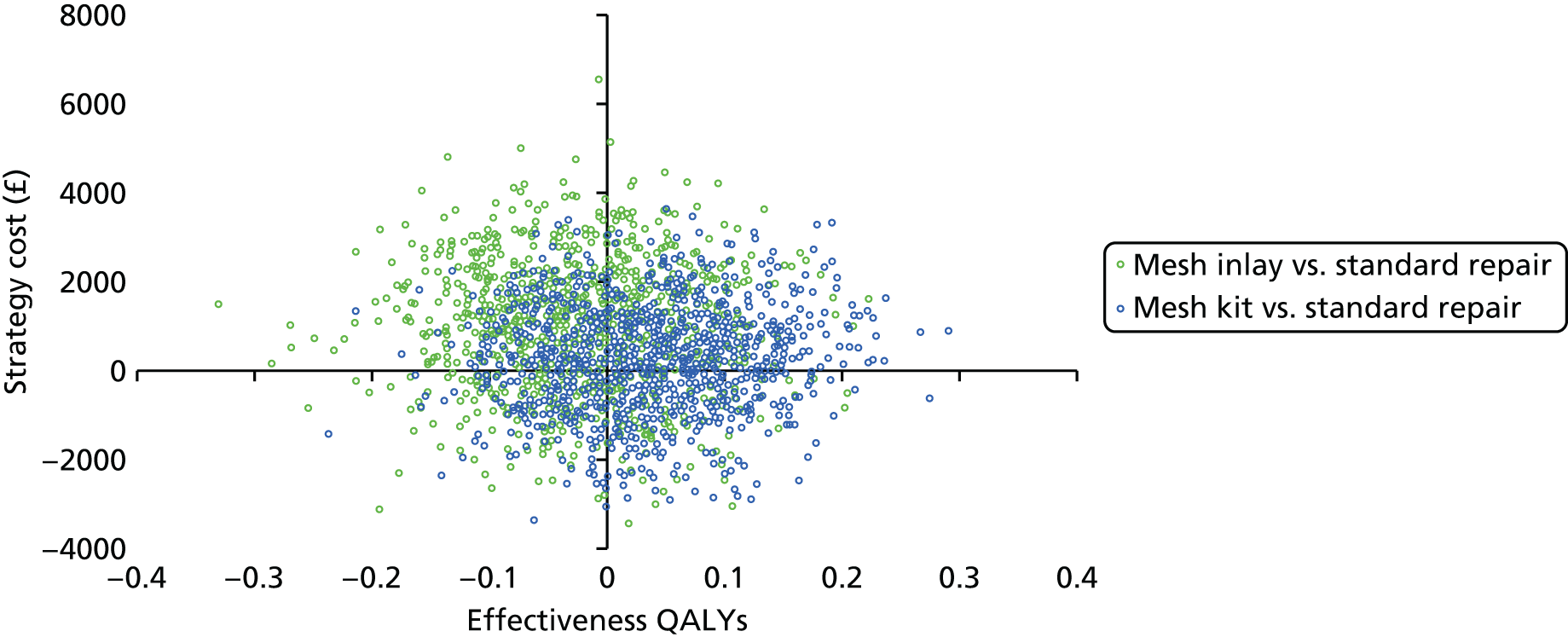

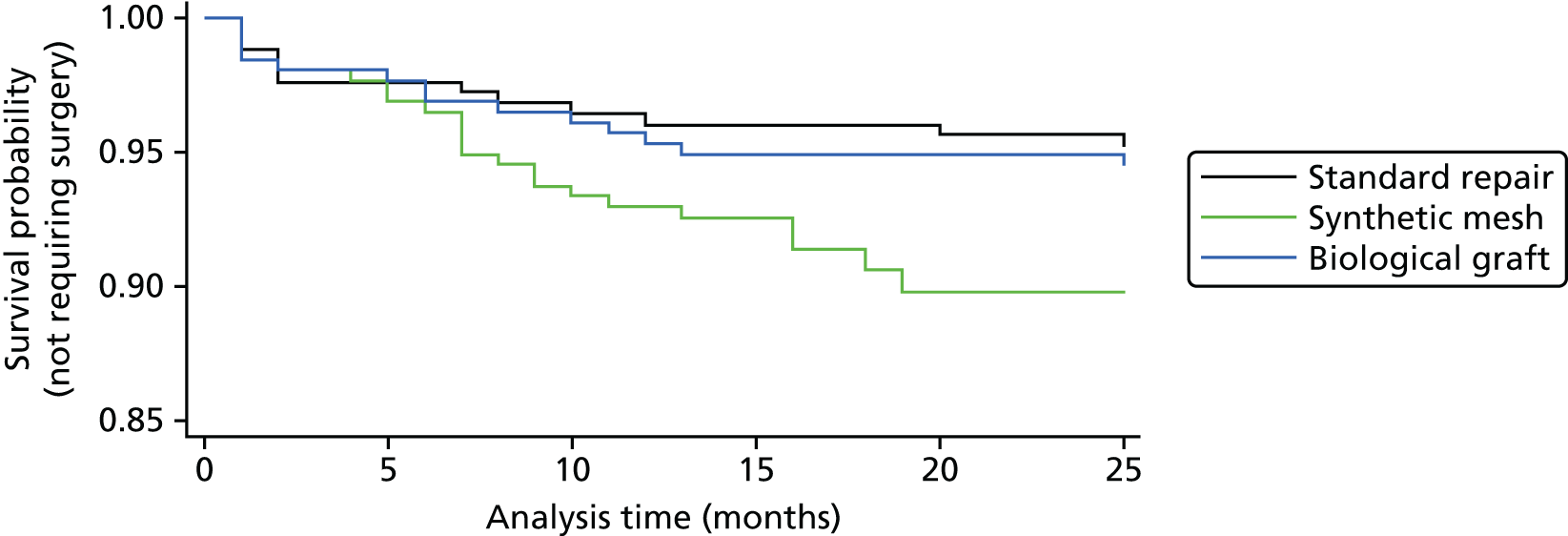

We used non-parametric bootstrapping methods to estimate 95% CIs for treatment effects on costs and QALYs, using 1000 repetitions. 52 These were further used to summarise the uncertainty surrounding the estimated ICERs, which was illustrated using:

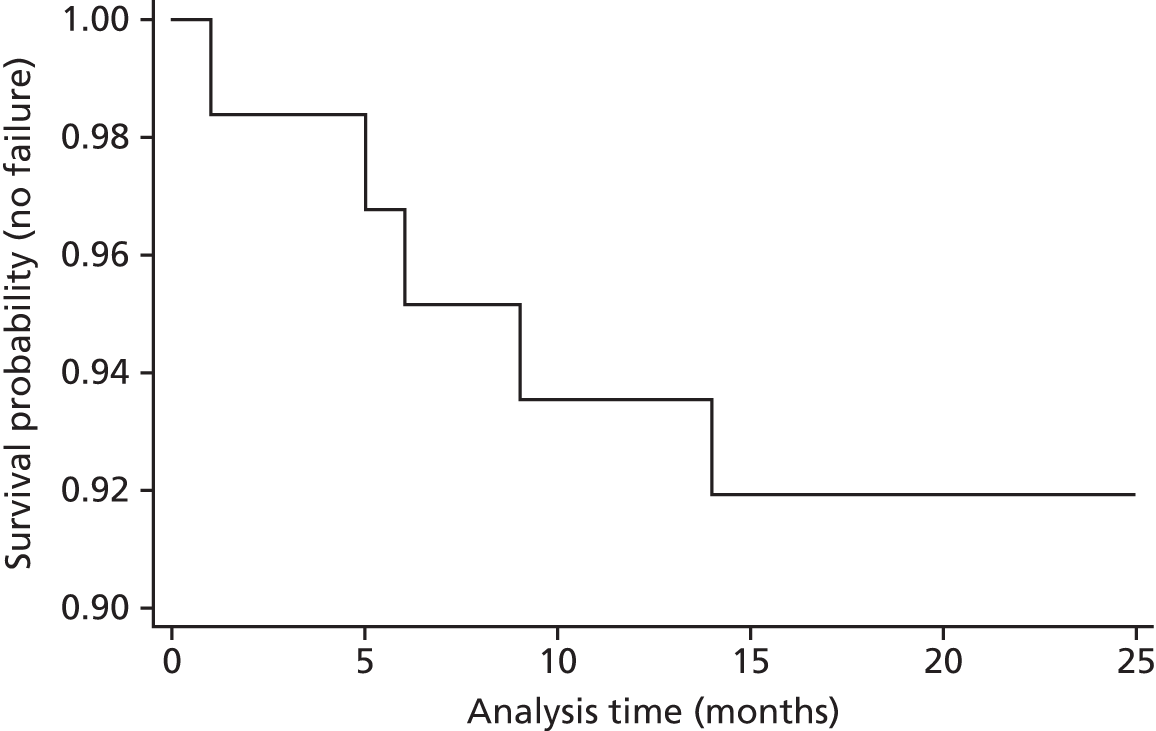

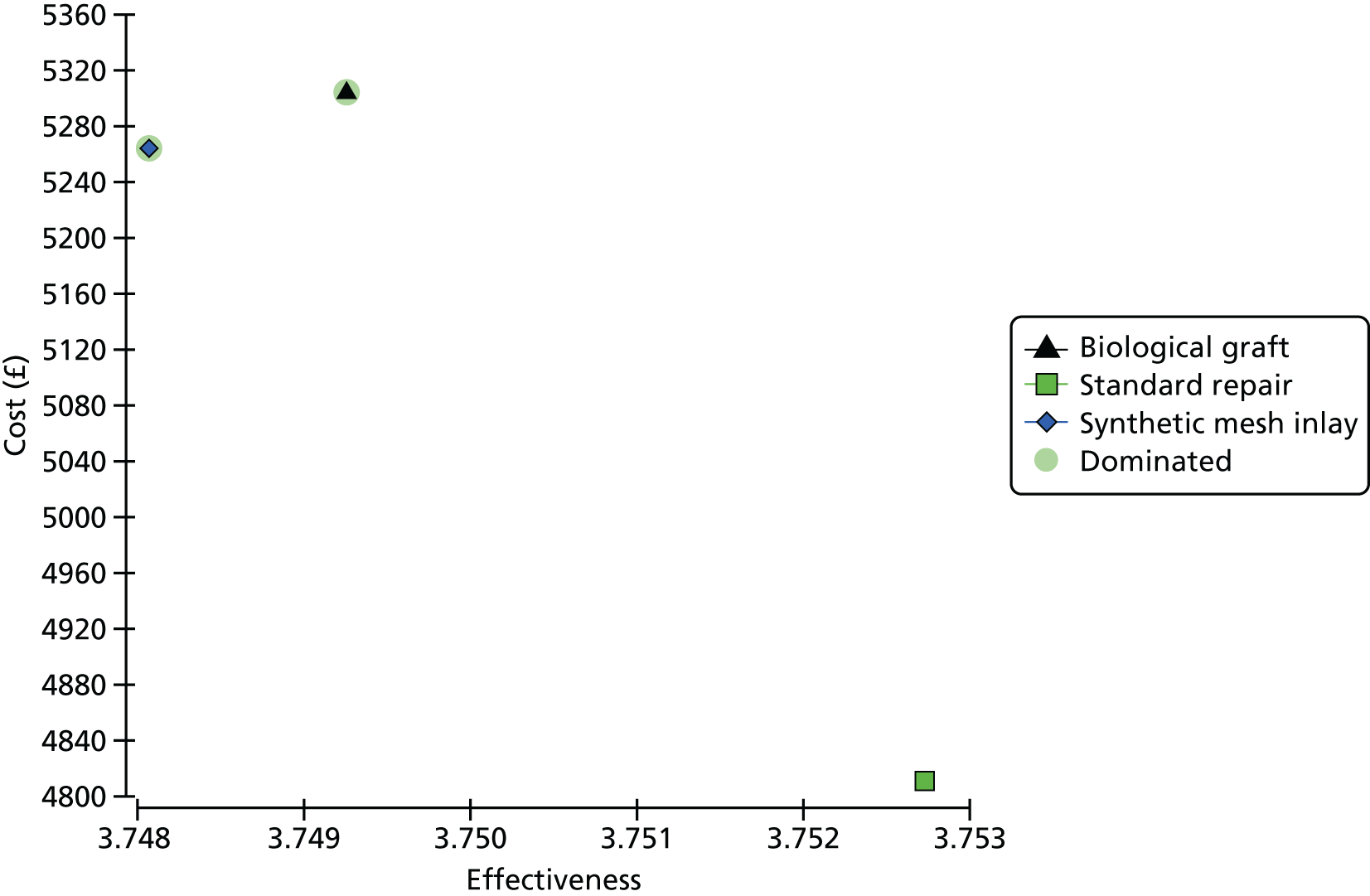

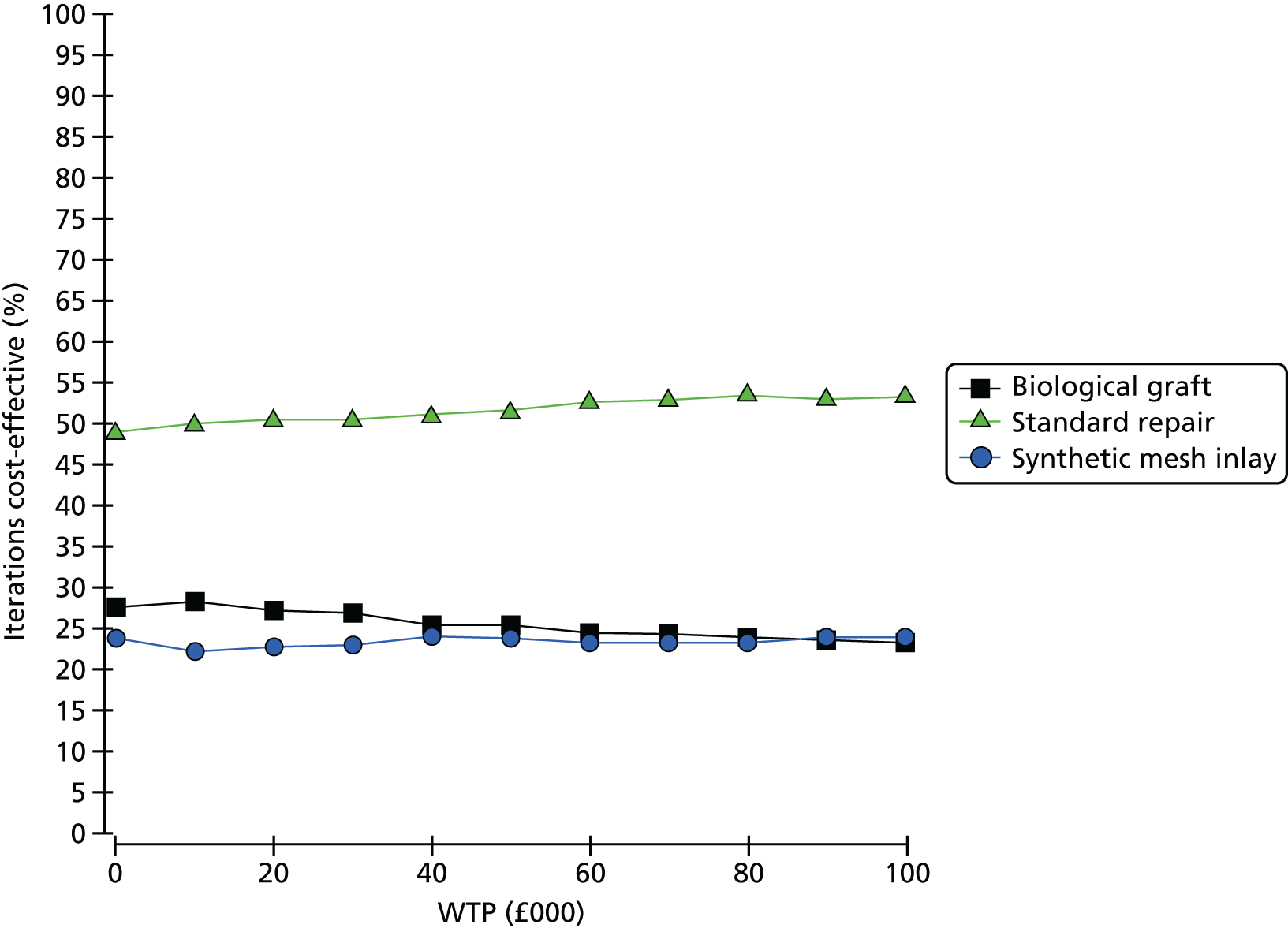

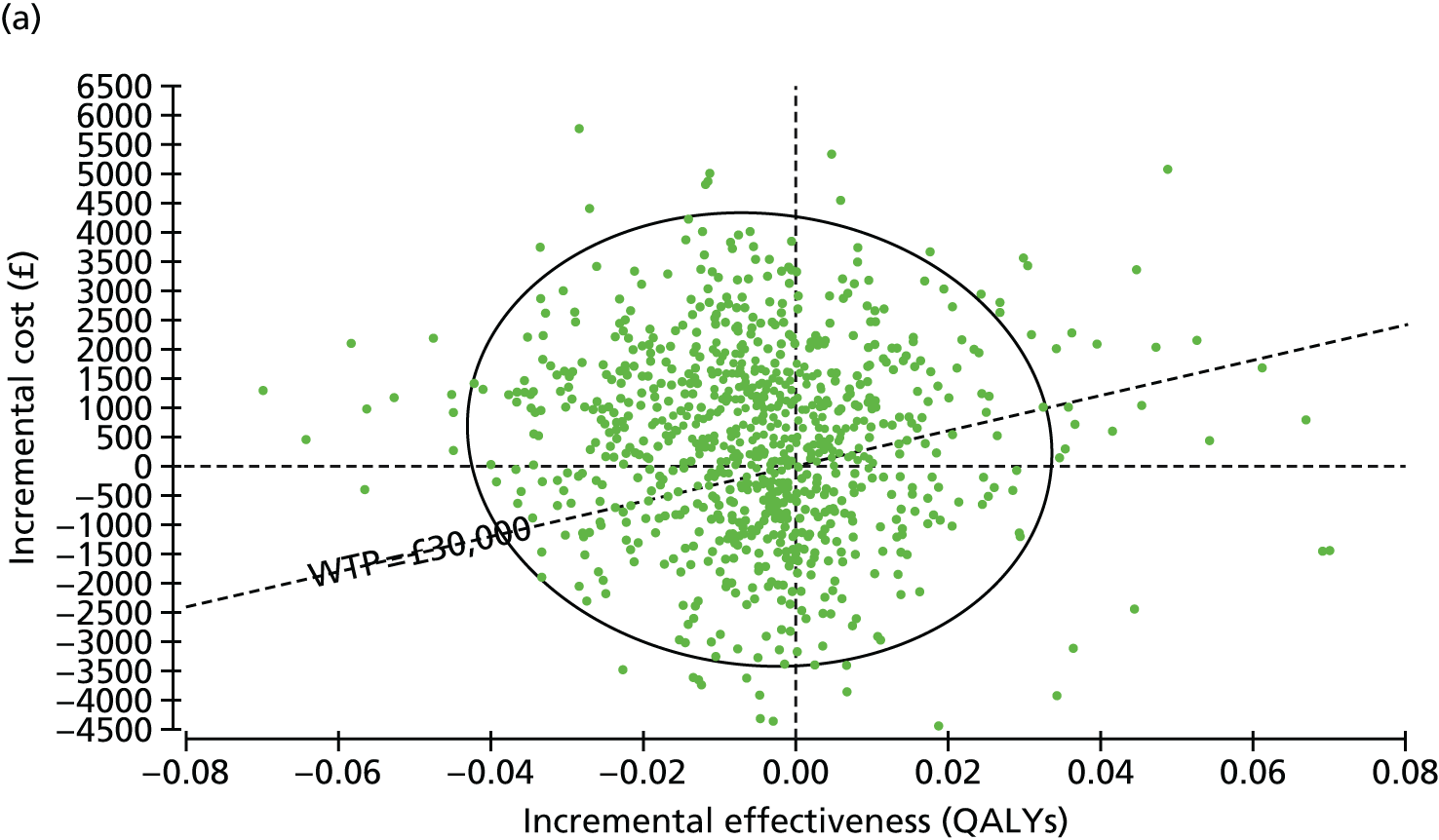

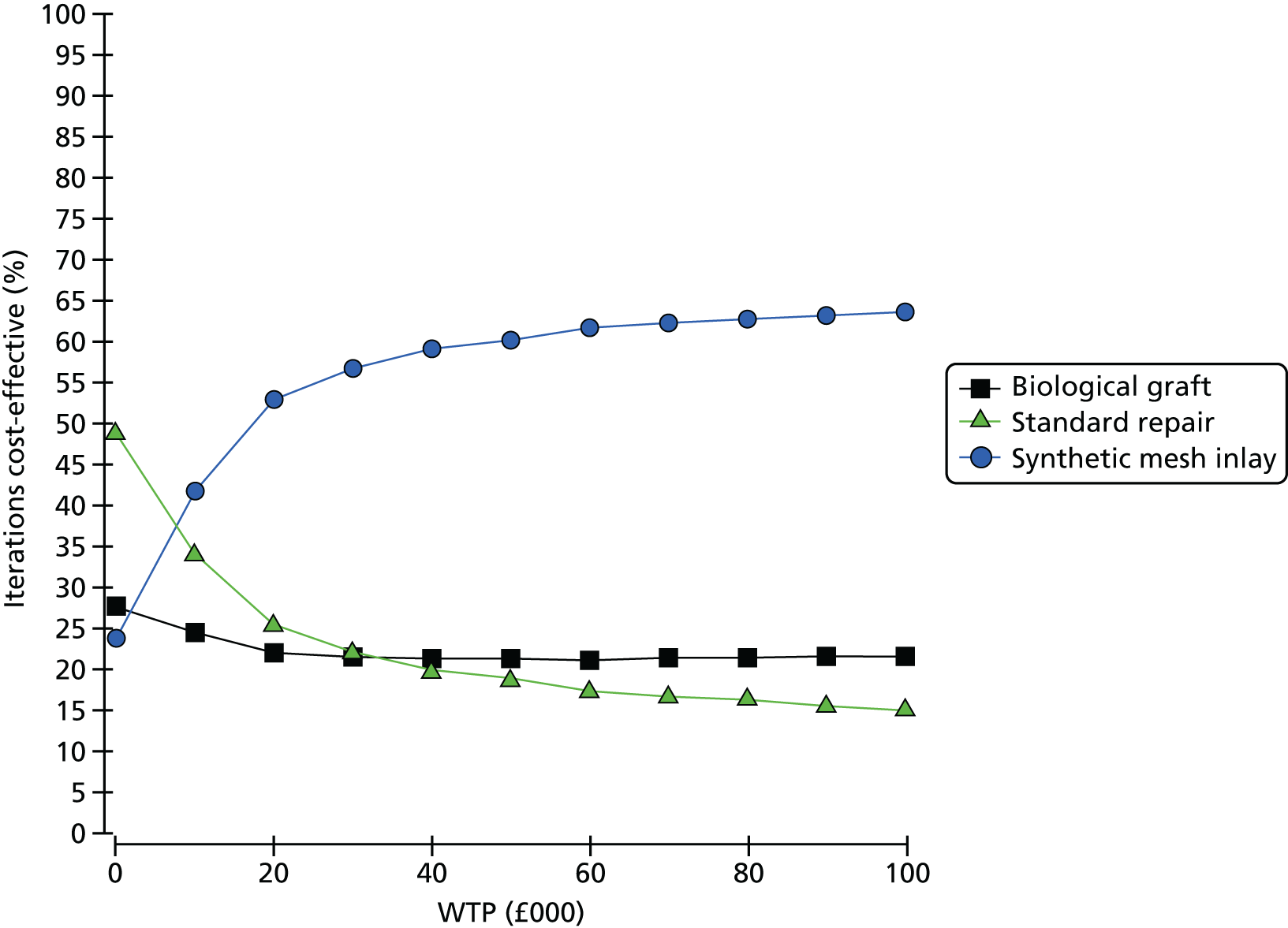

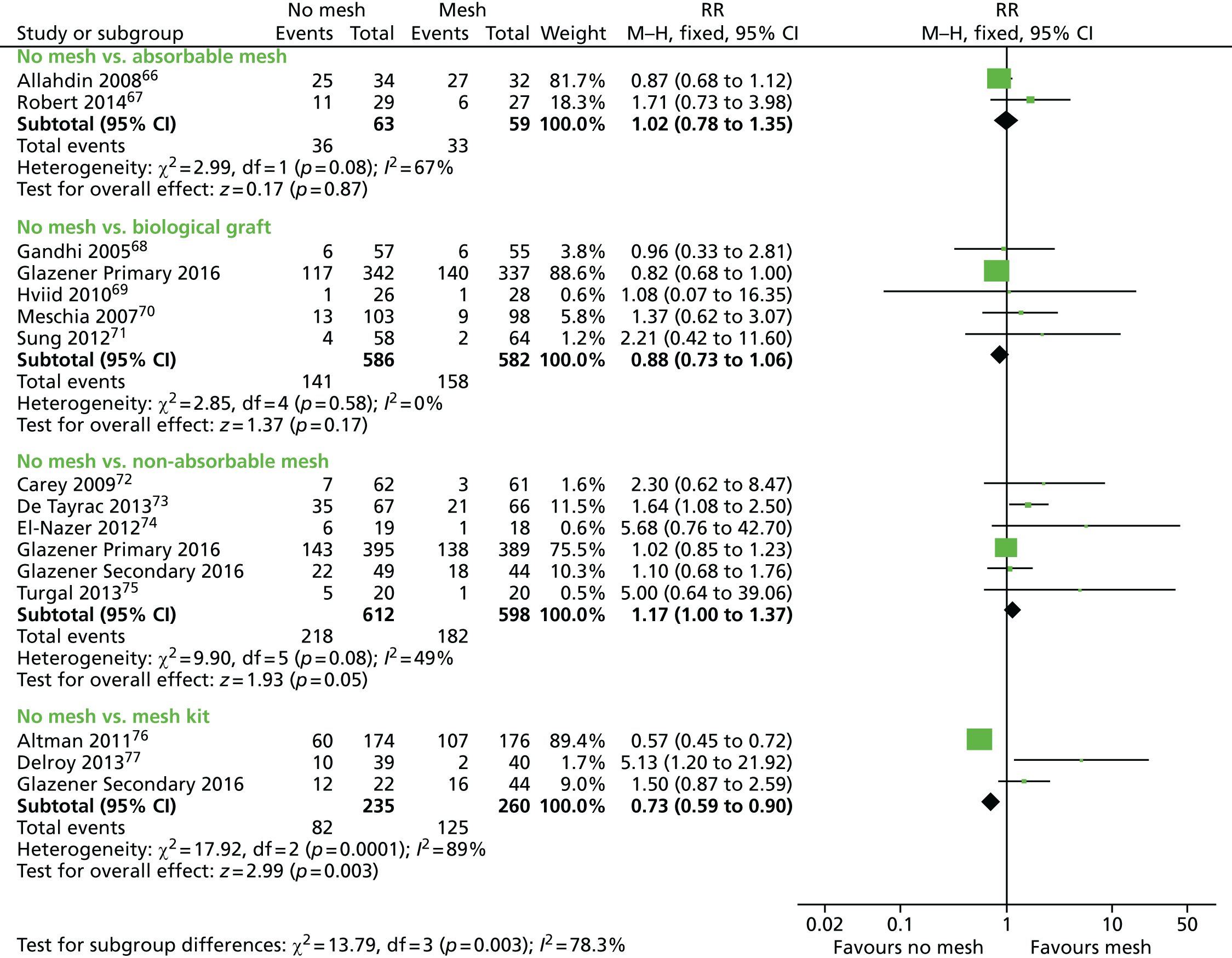

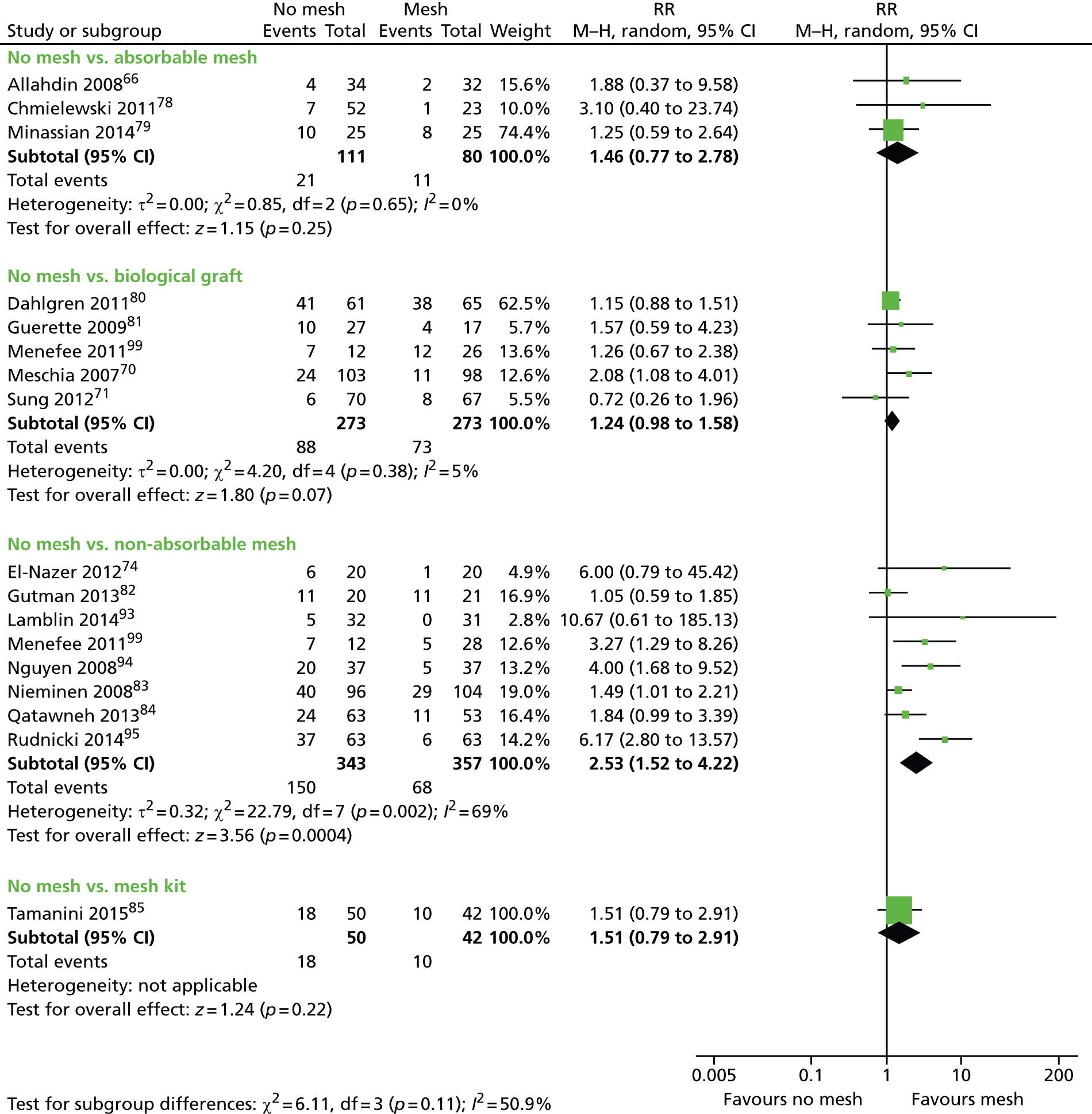

-