Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/60/01. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The draft report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in August 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Judith Watson reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme during the conduct of the study. Ed Day reports grants from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme, personal fees from PCM Scientific and personal fees from Public Health England outside the submitted work and he is the author of the treatment manuals Routes to Recovery via Criminal Justice and Routes to Recovery via the Community. Materials from these manuals influenced the final treatment manual in this study. He produced these manuals with the aid of a small grant from Public Health England and they are now freely available in the public domain [see www.nta.nhs.uk/routes-to-recovery.aspx (accessed 29 November 2016)]. Louca-Mai Brady reports that public involvement of young people in this study has also formed a case study for her PhD thesis, for which she received a bursary from the University of the West of England. This does not constitute a conflict of interest and any claims to intellectual property have been waived. Caroline Fairhurst reports grants from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme during the conduct of the study. Kim Cocks reports grants from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme during the conduct of the study. Eilish Gilvarry reports grants from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme during the conduct of the study. Alex Copello reports having a patent relating to Social Behaviour and Network Therapy for Alcohol Problems (Adult), broadly relevant to this work, with royalties paid.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Watson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

This report presents the findings from a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme-funded programme of work to develop and explore the feasibility of a new family and social network intervention for young people who misuse drugs and alcohol. This study had three main aims: first, to adapt a British, evidence-based, adult-focused family and social network intervention (social behaviour and network therapy or SBNT) to the under 18 years age group; second, to assess the feasibility and acceptability of this intervention; and, third, to explore the potential for evaluating its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness through a future, definitive trial. The new intervention has been named youth SBNT (hereafter Y-SBNT).

This chapter provides the background context in terms of the extent of substance use problems among young people, the effectiveness of current family interventions and barriers to implementation of interventions in the UK. The remainder of the report is divided into the following chapters:

-

Chapter 2 – intervention adaptation

-

Chapter 3 – feasibility trial methods

-

Chapter 4 – protocol changes

-

Chapter 5 – results

-

Chapter 6 – qualitative results

-

Chapter 7 – treatment fidelity rating

-

Chapter 8 – involving young people in the study

-

Chapter 9 – discussion.

Background

Substance use among children and young people

The two most commonly consumed substances by young people, accounting for 90% of treatment admissions, are cannabis and alcohol. 1 Statistics on drinking and drug use among young people are divided between those drawn from surveys of school-age children and those drawn from surveys of adult populations, including young adults. Among children of school age, although the proportion of those drinking at all has dropped slightly since 1988, the average number of units consumed increased markedly between 1990 and 2006 and has since stabilised at this level. 2,3 On the other hand, contrary to media reporting, average alcohol consumption among young adults (aged 16–24 years) has fallen since a peak in 2000–2. Nonetheless, 15- to 16-year-olds in the UK still come third highest out of 36 European countries in the proportion self-reporting drunkenness in the past 30 days (26%). 4 Cannabis use has also shown a decline among school-age children since reaching a peak in 2000–33 and a longer decline among young adults since 1998. 5 However, the UK is among the 10 European countries with the highest proportion of 15- to 16-year-old students reporting smoking cannabis within the past 30 days. 4

Since the commissioning of the current study, there has been increasing public concern about the use of novel psychoactive substances (NPSs) or ‘legal highs’ among young people. Accordingly, new questions were introduced to the smoking, drinking and drug use school survey conducted in 2014 in participating secondary schools across England, with 2% of pupils in Years 7–11 reporting using a NPS/legal high in the past year. 3 In addition, employing a generic definition of NPS use for the first time, data from the most recent Crime Survey for England and Wales show only slightly higher NPS use among 16- to 24-year-olds (2.8%) in 2014. 5

Early onset of drug use, including alcohol, has been associated with later problematic use. 6,7 Early onset of use and early hazardous use have also been associated with a range of other problems including risky sexual behaviour, injury, antisocial behaviour, violence and changes in brain development. 8,9 Moreover, in considering the impact of substance use on the family, research has shown that substance use among young people can adversely affect relationships with parents, carers and other family members,10 but also that family involvement in interventions can influence the course of the problem in a positive way. 11

Family-based interventions

Research has highlighted the pivotal role that families play as both a risk for, but also a protection against, substance-related problems. 11 As a consequence, a range of preventative and treatment approaches has focused on the family. In the UK there has been a strong focus on preventative programmes. A systematic review by Foxcroft et al. 12 identified the Strengthening Families Programme (SFP),13 developed in the USA, as the most promising, with positive outcomes in both the short and the long term. Emerging findings from the application of this model to the UK context have also been promising. 14

Turning to the treatment field, reviews of evaluations of family-based interventions with young substance users have tended to show that the most empirically supported family interventions are multidimensional family therapy (MDFT), multisystemic therapy (MST), brief strategic family therapy (BSFT) and functional family therapy (FFT) (Carmel Bennett, School of Psychology, University of Birmingham, 2013, unpublished review). Eleven literature reviews were included in a two-part review undertaken as part of the current feasibility study of Y-SBNT (Carmel Bennett, unpublished review). Although there is growing evidence for the effectiveness of these interventions (particularly MDFT and MST), problems exist concerning initiation, engagement and retention, treatment decay and translating research into practice.

Initiation, engagement and retention

The initiation, engagement and retention of young people and their families in substance use treatment has long been recognised in the literature as a significant issue. 15–17 Initiation, engagement and retention therefore formed a key focus of the review undertaken for this project (Carmel Bennett, unpublished review) and has also formed the main focus of a subsequent article from the USA. 18 Despite the widespread recognition of the saliency of the issue, there is notable inconsistency and lack of analysis among studies in this field with regard to the definition of initiation, retention and, particularly, engagement18 (Carmel Bennett, unpublished review). Nevertheless, there is clearly variation in the degree to which programmes have been able to involve young people and their families and maintain treatment through to completion. Dembo et al. 19 report completion rates of 40% for adolescents and their families attending brief intervention services. Similarly, Dakof et al. 16 found engagement rates as low as 53%. However, structured family interventions studied as part of well-resourced evaluations show much higher completion rates of between 70% and 90% (e.g. Pullmann et al. ,18 Rigter et al. 20 and Henggeler et al. 21). In addition, comparative studies have shown that a family component can reduce dropout. In a study by Hendriks et al. ,22 of the 54 participants allocated to cognitive–behavioural therapy only 16 completed treatment, whereas 44 of the 55 participants allocated to MDFT completed treatment.

A key issue affecting the initiation and retention of young people and families in treatment is the extent to which perceived ‘coercion’ is involved. In the UK context, criminal justice referrals constitute the largest referral source for young people in specialist substance misuse services (29%) followed by education (26%). 1 As Pullmann et al. 18 point out, initiation and attendance are ‘usually driven through compliance with family, court, school or employer demands, rather than intrinsic motivation’ (p. 348). In this context, defining engagement in behavioural terms as turning up for treatment sessions is likely to be primarily measuring the degree and nature of coercion and the penalties for not ‘engaging’. Researchers have therefore sought to explore other definitions of engagement that are rooted in active participation,23 with one such commonly used measure being therapeutic alliance. 24

Recognising the importance of retention and engagement, one of the aims of the review undertaken for the current study (Carmel Bennett, unpublished review) was to identify the characteristics of interventions that appear to be associated with successful retention. To achieve this, the four family programmes associated with the best outcomes (MDFT, MST, FFT and BSFT) were selected for detailed study, including research papers, literature reviews, clinical papers and direct communication with authors and programme developers. As a result, a number of key components were identified.

An overview of intervention components associated with retention and engagement can be seen in Table 1. They have been subdivided into components related to therapist style and orientation, structural factors, therapy orientation and additional factors.

| Therapist style and orientation | Structural factors | Therapy orientation | Additional factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflective listening (MDFT, MST, BSFT, FFT) | Flexibility (MDFT, MST, FFT) | Goal setting (MST) | Contingency management |

| Realistic hope and reinforcement (MDFT, MST, BSFT, FFT) | More frequent client contact based on need (MST, FFT) | Therapeutic alliance (parent–therapist) (MDFT) | Waiting time |

| Authenticity (MDFT, MST, BSFT, FFT) | Individualised service (MDFT, MST, FFT) | Strength focused (MST) | Use of social and mobile media |

| Productive communication (MDFT, MST, BSFT, FFT) | Tracking family members by telephone or in person (BSFT) | Reduction of parent burden (MDFT) | |

| Empathy (MDFT, MST, BSFT, FFT) | Preparing families for their own disengagement (MST) | Intrapersonal restructuring by telephone and strategic structural systems (BSFT) |

Therapist style and orientation

Therapist style and orientation factors that have been related to retention and engagement focus on the individual therapist’s interpersonal communication and interaction skills. Being able to listen to and reflect on a family’s thoughts, feelings and concerns, especially during the early stages of the intervention when participants and therapists need to build a good therapeutic alliance, have been outlined by all four selected intervention approaches. 25,26 In addition, instilling realistic hopes and providing pragmatic and proportionate reinforcement when progress is made and presenting oneself as an authentic individual by being honest and consistent are crucial aspects that develop family engagement and subsequently retention in the intervention. 27 Two further factors that have been highlighted by all four therapeutic approaches are a therapist’s ability to maintain and improve productive communication between family members and between the therapist and the family, and the universally named ability to show empathy. 27

Structural factors

A range of structural factors have been highlighted as fostering family engagement and retention. Being flexible with regard to the time of therapy sessions and places in which these sessions are held is embraced by approaches such as MDFT, MST and FFT. 21 It is suggested that sessions may be held in the family home, temporary accommodation and public places such as restaurants. MST and FFT manuals also indicate that flexibility with regard to the frequency of client contact is a crucial element of these interventions, which improves engagement and retention. 26 MST therapists are available 24/7, allowing for crisis management and greater assistance during times of heightened need within the family. 21 Being able to individualise services for families also plays a role in maintaining a family’s engagement as multiple and changing needs can be addressed in a timely manner, ensuring that families feel that an intervention addresses pressing issues relevant to them rather than following a strict plan that does not address their current concerns and problems. 21 Actively working towards a family’s engagement has also been cited as a means by which engagement and retention can be improved.

Similarly, Tuerk et al. 27 suggest that families need to consider their own potential disengagement from an early stage, allowing effective structures to be put in place to avoid the dropout of families from interventions. A therapist may be able to access some of the family’s supports, getting to know some other people in their social circle such as neighbours and friends, who the therapist could contact and ask for information should the family become less involved in the therapy at any point. Other approaches include ‘the foot in the door technique’ for initially resistant families, whereby the therapist seeks to engage such families through persistence in arranging meetings and offering short drop-in sessions to check up on families rather than longer more intense sessions. The idea here is that, once families have agreed to such a drop-in session, the likelihood of extending the visit and engaging with the family more intensely is increased. Tuerk et al. 27 also describe ‘going above and beyond’ by bringing food to meetings, for example, or by leaving food on the family’s doorstep. Bringing food may reduce the burden of purchasing and cooking meals for some families in which parents are very busy or economically unstable. In addition, this and other techniques and tools emphasise and reflect the therapist’s commitment and enthusiasm to work with a family. 27

Therapy orientation

Therapy orientation factors related to engagement and retention include focusing on strengths rather than weaknesses and setting goals, both of which aid the development of a successful therapeutic alliance. 28 A strong therapeutic alliance in turn has also been highlighted as a crucial factor for engagement and retention. By preparing families for, and guiding them through, criminal and educational proceedings (e.g. court hearings, meetings with schools), therapists are able to significantly reduce the parental burden, which is also thought to improve engagement and retention. 29 Specific therapeutic interventions directly aimed at increasing engagement by families have been put in place in BSFT. Here, strategic structural systems engagement procedures (joining, family pattern diagnosis and restructuring) are used to change those types of interactions that maintain a family’s resistance to engage with the intervention. 15,30 Joining involves keeping track of individual family members’ personal needs and goals, as well as of their specific agendas. It may also involve a discussion of the therapy’s focus on addressing these issues, thereby increasing the probability of attendance at the first meeting. Family pattern diagnosis involves the identification of maladaptive family interactions, which are linked to problems with engagement (and which may also perpetuate the substance use problems). Finally, restructuring involves the modification of the maladaptive family interactions through clinical tools such as reframing and shifting of alliances. 30

Additional factors

Additional factors including rewarding families for engagement and the use of social and mobile media have also shown promising results for engagement and retention in substance abuse programmes. In contrast, other factors such as long waiting times have been identified as possible barriers to treatment entry and engagement.

Branson et al. 31 investigated the efficacy of low-cost contingency management in a sample of substance abusing adolescents aged 12–17 years. Adolescents who attended on time were able to select a slip from a ‘fishbowl’ and to immediately exchange this slip for a prize. The prizes ranged from verbally delivered social reinforcements to large prizes worth £20, with the probability of drawing low-cost prizes being proportionally higher than the probability of drawing high-value prizes. Additionally, perfect attendance (attending all three sessions in 1 week) was associated with a bonus draw. Branson et al. 31 found that those adolescents who were in the contingency management condition showed higher levels of engagement with the intervention (indicated by the percentage of attended sessions) than their peers in the treatment as usual (TAU) control condition.

Waiting time is a potential barrier to treatment engagement in evidence-based treatments. Westin et al. 32 found that families who had to wait longer before starting an intervention were more likely to prematurely exit treatment. The same authors carried out post hoc analyses on their data, revealing that, although longer waiting times were related to a higher likelihood of treatment dropout in FFT, this was not true for MST. These findings indicate that individual treatment modalities are associated with different engagement strategies, which differentially moderate the relationship between waiting time and treatment engagement.

Finally, factors such as the use of social and mobile media may be useful when trying to engage and retain families. Therapists commonly contact individuals through Short Message Service (SMS or ‘texting’) to confirm appointments and to send reminders about upcoming sessions. Although other forms of communication through social media websites such as Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) or Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) may be possible, it remains unclear how data protection and confidentiality issues could be dealt with. Nevertheless, these areas will prove interesting for future research into successful engagement and retention techniques.

Barriers to implementation in the UK

In terms of translating research into practice, specialist training is needed for family interventions, which can be an obstacle to their implementation. 33 Public Health England statistics suggest that < 1% of interventions with the under-18s consisted of ‘family work’. 1 The large majority of young people with substance misuse problems receive psychosocial or harm reduction interventions that focus on the individual user and do not engage family members. Likewise, a survey conducted in the UK with services for adult family members showed that even those family interventions recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),34 such as behavioural couples therapy,35 are rarely implemented in services. 36 It should also be noted that some of the components and techniques described above and in Table 1 assume a level of resources – and a level of assertiveness – that may not be achievable or acceptable in a UK context. Finally, there are problems with defining ‘the family’, a contested concept that carries implications for the delivery of family interventions. 37 Young people with substance use problems frequently come from disrupted families and may be looked after by single parents, grandparents, other relations or the state (e.g. Lloyd7 and Boys et al. 38). Traditional, systemic family approaches may be difficult to deliver in such situations.

In summary, the research evidence shows that there is a high prevalence of substance use among young people in the UK. Early onset and high levels of use are associated with a range of negative outcomes, including increased risk of later problematic use and dependence. A growing body of research has identified family interventions to be effective at treating young people’s substance use problems and a range of techniques has been identified to encourage engagement and retention. However, despite this evidence, take-up of family-based approaches, at least in the UK, has been low. A key factor appears to be the resource-intensive nature of many family interventions, making them difficult to implement and deliver in many service settings, especially in the context of funding cuts to drug and alcohol services for young people. 39 Another potential barrier may be the cultural adaptation of approaches developed in the USA to a UK setting. There is a growing awareness of the need to adapt evidence-based treatments to different cultural groups and settings to ensure successful implementation. 40–42 Finally, it should be noted that a key distinguishing feature of drug treatment with young people is the coercive context in which it frequently takes place. This may encourage physical attendance but does not necessarily encourage therapeutic engagement.

Social behaviour and network therapy

Social behaviour and network therapy is an intervention developed in the UK that has been shown to be effective with harmful drinkers43 and is recommended in recent NICE guidance. 44 The original SBNT intervention was developed and tested as part of the UK Alcohol Treatment Trial (UKATT) conducted in UK alcohol treatment services. 43 It was later developed further for use with people with other drug problems. The conceptual underpinning of the approach is the positive influence of social as well as more addiction-specific (or abstinence-related) support on the improvement and eventual resolution of addictive behaviour. General social support, alcohol-specific social support and the drinking behaviour of the social network of alcohol users, for example, have all been shown to be unique predictors of positive alcohol treatment outcomes (for examples see Beattie et al. ,45 Havassy et al. ,46 Longabaugh et al. ,47 McCrady,48 Wasserman et al. 49 and Mohr et al. 50). SBNT brings together elements of network therapy,51 social aspects of the community reinforcement approach (e.g. Meyers et al. 52), relapse prevention (e.g. Chaney et al. 53) and approaches with family and concerned others (e.g. Copello et al. 10).

Utilising cognitive and behavioural strategies, SBNT helps clients to develop family and social networks that are supportive of change. A key strength of the approach is the primary focus on addressing drug and alcohol problems by engaging with a network of positive support for lifestyle change. SBNT has additional advantages to help sustain engagement with vulnerable young people, who may be disconnected from their families, by broadening the reach of the intervention beyond the traditional family to include supportive peers. Core strategies such as motivational techniques, improving communication and coping mechanisms are used, as well as (given the nature of substance misuse) developing a network-based relapse management plan. Using such a therapeutic approach also provides scope to address client-focused elective areas such as educational requirements. 54

Involving young people in research

Involving those who are the focus of research can have a positive impact on what is researched, how research is conducted and the impact of research findings (e.g. Brett et al. 55 and Staley56). In recent years there has been increasing interest in children and young people’s involvement in research,57–60 both as sources of data and through their active involvement in the planning and process of research. Although there is less of an evidence base in relation to children and young people’s involvement in research compared with the involvement of adults, the case for this involvement has been explored in a number of publications. 57,61,62 Research that actively involves children and young people should lead to research, and ultimately services, that better reflect their priorities and concerns63,64 and enhance the opportunity for optimal health outcomes. 65 However, the voices of children and young people who are less frequently heard, for example users of mental health services66,67 and looked-after children,59 are often absent from the literature on children and young people’s involvement in health and social care research.

As well as being located within the wider traditions of public involvement in research, young people’s involvement in this study was also developed with reference to children and young people’s involvement in the development and delivery of health and social care services. 64,68,69 Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child70 states that all children have the right to express their views in all matters that affect them, and this applies to children’s involvement in both decisions about their own experience as patients and service users and the development of health services and research. 68 In addition to drawing on previous work by the research team and other published studies, the Y-SBNT study sought from the outset to actively involve young people with experience of substance misuse services throughout the study. Young people’s involvement in the study was key to ensuring that the research addressed the concerns and issues faced by young people with substance misuse problems and we hope that this will also be an important addition to the wider evidence bases on public involvement and young people’s involvement in research.

Believing that SBNT could be successfully adapted to the youth context and would have great potential as a clinically effective and cost-effective intervention that could be readily and widely implemented in services for young people, the research team adapted the current SBNT approach to produce a purpose-designed therapy manual and resource kit. The feasibility of recruiting young people to receive this specifically developed family- and network-based intervention was then investigated in a feasibility study to establish the acceptability of the intervention to young people, their therapists and network members.

Research objectives

Intervention development phase

-

To adapt an evidence-based family and social network intervention developed and tested with adult substance misusers to the youth context.

-

To undertake a review of the evaluation and implementation literature to inform this adaptation.

-

To involve young people, parents and therapists in the adaptation process to improve acceptability to these groups and ensure ready implementation in routine services.

-

To develop a manual, resource kit and training programme for the delivery of the adapted intervention in a feasibility trial.

Feasibility randomised controlled trial phase

-

To demonstrate the feasibility of recruiting young people to a family- and network-based intervention (Y-SBNT) across two service sites.

-

To test the feasibility of training staff from existing young people’s addiction services to deliver the family and social network intervention.

-

To evaluate the level of treatment retention among participants randomised to the family and social network intervention.

-

To explore through qualitative interviews the participants’ views, acceptability and experiences of the intervention and the study process.

-

To explore through qualitative interviews the views and experiences of those attending treatment sessions as members of the young person’s network and whether the intervention was acceptable.

-

To establish treatment effectiveness through 3- and 12-month quantitative outcome data.

-

To explore cost-effectiveness in preparation for a large definitive randomised controlled trial.

-

To explore and develop models of public involvement that support the involvement of young people in a study of this nature.

Chapter 2 Intervention adaptation

The overall aim of the intervention adaptation phase was to adapt the original evidence-based family and social network intervention (SBNT) developed and tested with adult substance misusers to the youth context. The related tasks were to:

-

undertake a review of the evaluation and implementation research literature on family interventions for young people with substance misuse problems

-

involve young people, parents and therapists in the adaptation process to improve acceptability to these groups and ensure ready implementation in routine services

-

adapt the manual and develop any necessary additional materials to support a training programme for the delivery and ongoing monitoring of the adapted intervention in a feasibility trial.

To achieve the aim and tasks, the published manual for SBNT in adults,54 which was tested in the UKATT and subsequent studies with drug users (e.g. Copello et al. 71 and Day et al. 72), provided a platform for the adaptation work. The output of this phase was the development of an intervention that could be delivered to young people (aged 12–18 years) with substance use problems within the context of existing UK services. The work undertaken is described in the following sections, followed by a description of the adaptations made to the final intervention used in the pilot.

Review of the family-based substance misuse intervention evaluation and implementation literature

The first step in the adaptation process involved undertaking a systematic review of reviews of family interventions in young people with drug and alcohol problems (Carmel Bennett, unpublished review), described in the previous chapter. The search strategy used is provided in Appendix 1. This review highlighted that a number of family-focused interventions have been shown to be effective in young people with substance misuse problems and a number of intervention components are conducive to increased engagement and retention. These factors were illustrated previously in Table 1 and included therapist style and orientation, structural factors, therapy orientation and additional factors. Each of the components identified was considered with respect to the adaptation process. Some were already part of the social and family approach, for example flexibility, goal setting and productive communication. Others were considered carefully and discussed but, for pragmatic and resource reasons, were not incorporated, for example contingency management strategies. All of these components were explored as part of therapist training and a brief description of each was included in the revised set of materials to supplement the training manual.

Involvement of/consultation with young people, family members and therapists in the adaptation process

The study sought to actively involve young people with experience of substance misuse services from the outset, to ensure that the intervention was relevant to, and addressed the issues faced by, young people in treatment. Public involvement activity during the development of the intervention therefore focused on ensuring that the treatment was acceptable and relevant to the study’s target group and reflected the views of service users and their families. In addition, the views of therapists were sought within this early phase and process.

Young people with experience of services

Involvement of young people was based on a series of young advisor and consultation meetings (see Chapter 8 and Appendix 2). During these meetings, the two public involvement leads and other members of the study team worked with young people to explore the principles behind the intervention (i.e. social networks, social support, engaging with services) as well as to obtain young people’s input/comments on the content and components of the intervention itself. The core principles and aspects of the Y-SBNT approach were retained, as the young advisors considered these to be relevant to their experience, but they also suggested adaptations to aspects of the approach and associated materials to make them more relevant to young people.

Activities undertaken with young people in relation to the content of the intervention included considering the nature of social networks and how these may differ between young people and adults using substance misuse services, such as thinking about the important people in young people’s lives and why they might be helpful/supportive or unhelpful/unsupportive (examples in Box 1).

-

Supportive GPs willing to suggest helpful ideas.

-

Supportive family members who understand, willing to help.

-

Getting involved in work, college, voluntary work, etc., with new friends, activities, etc.

-

Different types of help from different therapists regarding different issues.

-

Supportive partner.

-

Friends with the same problems and willingness to seek help.

-

A really helpful key worker who has looked at me as an individual and helped me to change my life.

-

Friends who do not use.

-

Supportive and educated hostel staff.

-

Family members who know about the issue but who do not take an active part in your use.

-

Other users in group sessions or work, etc. They can suggest going outside to use.

-

Fellow family users – because they might not want to stop and you do.

-

Friends who are going through the same problems as you but who are not willing to stop.

-

Therapists who are disinterested or not helping, just there!

-

A friend who is staying with me and smoking cannabis in my house when I am trying to quit.

Examples of young people’s input into the development of the youth social behaviour and network therapy intervention

Structured discussions with young advisors generated materials used in the adapted intervention training resources, including examples from the young people in terms of processes perceived as important to obtain social network support; good and unhelpful aspects of services; and examples of social network diagrams from young people (later used to develop examples in the revised training materials). Some examples are included below and in Appendix 3.

-

Exploring the components of the original adult SBNT intervention and asking the young people to reflect on how these may or may not be relevant to young people (examples in Table 2).

-

Exploring what young people find helpful or what the barriers are to engaging with substance misuse services.

-

Using an exercise that involved writing an open letter to an important person about what it is like to have a problem with alcohol or drugs and how the young person would like that important person to help and support them. Excerpts from these letters were subsequently used (with permission) in the intervention training materials given to staff in the pilot services. Extracts from an open letter can be seen in Box 2 and Appendix 3.

| Component | What young people wrote |

|---|---|

| That I spend less time with those who are not helpful or encourage drug and alcohol use | Although it’s hard to cut off your friends completely, it was important to try and stay away from friends who use. Most of my friends used drugs so it can also isolate people. Solution: going to groups with YP who want to change their drug use. Time away from drug users/stressful situations |

| That we communicate well and openly and we solved problems together | Everyone involved needs to remain involved, and in contact with everyone else, and needs to be on the same page as everyone else to ensure the correct support is given. Consistency is importantTrust is important, if you can trust people you can be honest about the problems you are facing. All services working with the person need to stay in contact and also keep the person they’re working with included in decisions/stuff that affects them |

| We all have positive views of the value of supporting each other | It’s nice to help people and be able to make a change to someone’s life. I think it’s important people can see the value of supporting each other and the benefits the person they are supporting will get – there needs to be advice/support for the person helping the YP with an issue |

| We all have the same understanding of the problem | We all have our own thoughts on drugs/alcohol but we all need the understanding what’s best for the young person |

| That we all know specifically what we are doing to support each other | All people involved need to be clear on what is going to help the personAll understand and know their role and involvement in the support of a young person, and how to communicate with each other |

| That I manage to get over barriers that get in the way of getting support from others – young people identified trust as a barrier | It is important you can trust them, you need to be reassured as many YPs may have been through many services, been let down by family/friends and have trust issuesSome young people aren’t close to parents or other support that may be very beneficial to them and maybe the first stage is to build relationships |

| That I know how to ask and to give emotional, practical and social support | It’s important to know where to get support/ask for advice and after sorting your own stuff out, be able to support and help others through their issuesSupport also needs to be offered as much as possible as some people will just not ask for support or just support on some topics/problems |

| That those who support me have support themselves | Some people that are supporting young people may need support themselves. Example: a parent may want to support their child but may be a user themselves and may need/have an adult service to support them |

| That I spend time doing fun things with positive friends and family members | It is important to have fun, have a hobby that you can enjoy with friends/family. Mediation may be needed to get to this pointIt is good to have fun with friends and family away from all the ‘crap’Everything costs money! Have a list of open days and free activities for families to do for fun |

You’ve supported me through many dark times and I can see that you care deeply for me (as I, you). However, your lack of experience with drugs completely dominates your treatment of me and I want you to know that it’s not helping me. You’re a caring, strong and loyal person, but you seem to think I am oblivious to the dangers surrounding drugs and that’s simply not true.

. . . Maybe instead of judging me, you could have come with me to my drug counselling. Instead of making a formal complaint about my social worker because she knew and didn’t tell you, you could have recognised that she could see I was responsible and mature . . . .

There are a number of ways you could have handled the situation in a much more helpful and supportive way. Don’t ban me from smoking weed entirely, straight away. Talk to me about the feelings that make me want to be stoned all day and work with me to identify replacement activities, or distractions . . . perhaps an incentive would have helped. Something small but worth it, to keep me going when all I want is a joint, and to show me that you recognise how hard I’ve worked when I cut down.

The identification of potential network support that was wider than the biological family and included peers and support workers was seen as very important. This was particularly relevant for the target group of young people, who in some instances experienced fragmented family networks and family breakdown and who had contacts with a range of services that were experienced as significant and important sources of support to them. A range of ways of drawing social network diagrams was also suggested including more use of colours and drawings if the young person preferred this way of representing networks. Some of these methods of generating social networks were also later explored with therapists during the initial pilot casework with young people.

The challenges in developing an intervention based on the idea of bringing others into the therapy sessions led to important discussions, as many young advisors were unsure about this aspect. We therefore explored with them how best to develop and deliver a network-centred intervention with young people who do not want others in their sessions. In addition, the clear and sensitive way in which the notion of developing social support from others was introduced to young people at the beginning of the intervention was seen as highly important.

Finally, the notion of treatment goals was discussed and young people felt that it was important to identify goals in a wide number of areas, not only substance use. Young people recognised that it was not always the case that those entering services perceived their substance use problem as something that they wanted to change straight away, despite possibly being aware of the difficulties and problems that it was creating in their lives. The broadening of goals to include other aspects that may have contributed to their problem was seen as important during public involvement. This was seen as a vehicle to maximise early engagement with some young people. A goal-setting diagram to be used within sessions was therefore adapted with active advice from the young people, who suggested the domains that were later included in the identification of the goals resource handout. The following domains were used: drug or alcohol use, family relationships, friends and other important people, living arrangements, problems with the law and ‘other’ areas identified by the young person.

Family/network members

The involvement of family members as part of this adaptation phase consisted of a focus group discussion with two adults (woman with foster daughter and mother with adopted son). The discussions highlighted the challenges faced by these two women that would influence both their engagement and that of the young people in something like Y-SBNT. The participants felt that, to some extent, social network support was already in existence for young people, although it was not always positive as some contacts promoted continued substance use behaviour. They identified communication between themselves and the young person to be ‘poor’ and that the intervention may help with this aspect. However, they felt that the work would depend on the extent to which the young person was ready to engage, for example ‘I just feel that mine would only engage as much as she wanted to engage . . . she would only share what she wanted to share’, and being able to be open and honest about their substance use was perceived to be central, for example ‘I don’t think she’s ready or in the frame of mind where she could open up to a different network’. The theme of ‘honesty’ from the young person was prominent in the discussions. Both participants felt that they would ‘definitely’ get involved in an intervention such as Y-SBNT if invited and would find the ‘opportunity to talk to the young person helpful and useful . . . if you are hearing it from a user’s point of view I can understand it a bit more’. One of the participants stated that involvement in sessions may help her as a mother to have more ‘tolerance and understanding’ as it was not something she had been brought up with or understood. Also, the idea of working together and supporting the young person was discussed; for example, ‘it would be the unison of it, both of us working towards a common goal which we’ve both got an understanding of’. Therefore, in summary, the two participants felt that the intervention was feasible and acceptable. There were some perceived potential benefits of the intervention including the potential for better and more open communication, increased understanding and supporting agreed goals. Potential challenges were identified in terms of the young person being ready to be ‘open and honest’ about their difficulties and being able to discuss them with potentially supportive people.

Therapists

Consultation was conducted with seven therapists as an early part of the training workshops. In addition, therapists were interviewed at the end of the study (see Chapter 6) when their experiences of intervention delivery were explored in more detail using one small group interview (two therapists) and individual interviews.

As part of the adaptation work, an early session with therapists involved providing them with a detailed description of the intervention including some of the additional materials developed following the work with young people described earlier in this chapter. This was followed by a discussion about the feasibility of delivering the intervention in their services as well as their views on its acceptability to young people. The components (core and elective sessions) of the intervention presented in Box 3 were discussed one at a time. These were perceived as appropriate by therapists and contrasted to routine practice. Some of the strategies, for example talking to teachers, hostel workers or other important people as part as the development of network support, were said by the therapists to be performed occasionally in routine work with young people. But the perception was that the structure of the Y-SBNT intervention and the coherent focus on positive help and support made it easier to deliver it in a more planned, consistent and coherent way.

-

Communication.

-

Coping.

-

Enhancing social support networks.

-

Developing a network-based relapse management plan.

-

Basic education on drugs/alcohol.

-

Increasing pleasant activities.

-

Employment.

-

Minimising support for drug/alcohol use.

-

Active development of positive support.

The overall feedback stressed that more emphasis was needed on the different experiences and social contexts of young people but that there was no need to change the structure or content of the psychological components and strategies of the original SBNT intervention. An additional map/framework of the intervention journey (illustrated in Figure 1) was produced and included with the revised materials.

FIGURE 1.

The treatment map.

The adapted youth social behaviour and network therapy intervention

The final intervention, termed Y-SBNT, retained the original structure, timings and components of the adult version. The revised treatment map guided therapists through the clinical delivery and decision-making process. As in the original approach, there was a blend of structure yet an element of flexibility that allowed clinician decision-making in terms of what topics to deliver for each particular case. As far as it was possible at this stage, additional case materials were produced based on cases involving young people, although more materials and examples became available as the feasibility pilot progressed and could potentially inform further adaptation work.

Following adaptation work, a decision was made, which was discussed with the project Trial Steering Committee (TSC), to retain the original SBNT manual as part of the set of training materials rather than rewriting large sections that needed minimal change but to supplement this with an additional shorter manual that made reference to relevant sections of the original manual when appropriate. Additional resources in the form of treatment maps for young people were also produced. The final revised sections included (1) new examples of social network diagrams based on young people, (2) a revised treatment journey map outlining the various stages of the intervention and (3) broadening of goal setting to include a range of areas and production of a new resource handout. In addition, further resources were produced as handouts to support the therapists’ work for some of the core topics including communication and coping.

The final set of resources given to all therapists as part of training and ongoing supervision for the pilot study were:

-

the original published SBNT manual54

-

the Y-SBNT brief companion manual, including a summary of the evidence on family interventions with young people with substance misuse problems, the intervention aims and philosophy and the revised/adapted materials.

Summary

In summary, the stages of adaptation undertaken led to the conclusion that the intervention was adaptable to use with younger people. This was reported by all three stakeholder groups including young people with experience of substance misuse treatment, family members and therapists. There were areas where the materials needed to be changed to reflect the realities of the younger population, in particular the potential different composition of social networks and the identification of broader goals beyond substance use. In addition, the introduction of the intervention to young people in terms of developing support from others (family and wider networks) had to be tackled sensitively and explained clearly, with the value of support emphasised as well as the fact that young people were always in control of who to engage when/if seeking support. There were some strengths and limitations of this work phase. The stakeholder consultation element was a strength but some of the challenges in involving young people and family members were evident and are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8 as part of the proposed development of models of public involvement of young people in a study of this nature.

Chapter 3 Feasibility trial methods

This chapter is based on the study protocol, which has been previously published (© Watson et al. ; licensee BioMed Central. 2015). 73 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Trial design

The adapted Y-SBNT intervention trial was a pragmatic, two-armed, randomised controlled open feasibility trial with equal randomisation delivered in two young people’s services. Young people aged 12–18 years, newly referred and accepted for structured interventions for drug and/or alcohol problems and who consented to participate, were randomised (1 : 1) to receive either:

-

Y-SBNT – an adaptation of SBNT developed during the early phases of the project, consisting of social network identification, goal setting, improving communication and coping mechanisms and, when relevant, developing a network-based relapse management plan, with an initial appointment followed by five further sessions over a maximum of 12 weeks (aiming for one per week when possible) or

-

TAU – usual care delivered by the two services with appointments offered as required.

Sample size

Treatment service outcome data collected in the 6 months prior to the commencement of the trial showed that one of the participating services received approximately 45 new referrals per month, with a caseload of > 200 clients. The second service was accessed by approximately 280 young people in the previous year.

As a feasibility study, the main purpose here was to assess the acceptability and feasibility of, and to obtain information that would inform the design of, a larger full-scale trial. A sample size calculation was used so that the feasibility study could rule out the likelihood of an effect smaller than that desired being observed in the main trial. 74

For the main trial we would want to detect an effect size of magnitude 0.3 of a standard deviation (SD) between the two groups in the primary outcome, which would require a sample size of approximately 350 patients. Cocks and Torgerson74 estimate that feasibility trials should have at least 9% of the sample size of the main future trial. They suggest that a sample size for a pilot trial should be a sufficient size such that, if the observed difference between the two groups in the pilot trial is zero, then the upper confidence limit of an 80% one-sided confidence interval (CI) will exclude the estimate that is considered ‘clinically significant’ in the planned definitive trial. A sample size of 32 patients was required to exclude an effect size of 0.3 in the event of a zero or negative intervention effect (using a one-sided 80% CI). Unless there was a clear explanation, we considered that there was poor justification for moving towards a fully powered trial if the upper 80% confidence limit of the effect size for the main clinical outcome was < 0.3 as it would be unlikely that an effect size of ≥ 0.3 would be found in a main trial. If there was a positive intervention effect in the pilot study, we would conclude that the main trial was worthwhile, as long as adequate recruitment and an adequate follow-up rate were observed.

Allowing for the reasonably high level of attrition that was expected in this patient population, it was felt that 60 participants needed to be recruited to the trial to achieve the required 32 patients with outcome data.

Approvals obtained

West Midlands – Coventry and Warwickshire Research Ethics Committee approved the study on 24 February 2014 (reference number 14/WM/0021). Local research and development (R&D) approval was obtained as well as agreement to participate from the relevant services. The trial was assigned the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial number ISRCTN93446265 and the UK Clinical Research Network ID 16111.

Trial sites

The study was conducted in two young people’s services in England based on existing professional relationships and for pragmatic reasons:

-

West Midlands A tier 3 service providing information, advice and treatment for issues related to the use of drugs, alcohol and other substances for people aged ≤ 18 years. The service consisted of a multidisciplinary team including therapists from various backgrounds supported by psychiatry and nursing staff, offering individual and group services to young people with substance misuse problems and complex needs.

-

North East A specialist service that links with a number of tier 2 generic youth services and with other primary care services, such as general practitioners (GPs) and school nurses. There were therapists from various backgrounds such as social work, third sector, primary care and offender management, with considerable experience in addictions and youth development. This service was for those aged ≤ 18 years, with a mean age of service users of 15/16 years.

Participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria

Young people were considered potentially eligible if they met all of the following criteria:

-

were aged 12–18 years inclusive

-

had drug and/or alcohol problems and were newly referred and accepted for treatment by one of the two agencies during the period of recruitment

-

were willing and able to provide written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Young people were excluded if they met any of the following criteria:

-

had a concurrent severe mental illness that precluded them from active participation

-

suffered from severe mental or physical illness likely to preclude active participation in treatment or follow-up

-

were unable or unwilling to provide written informed consent.

Recruitment into the trial

All young people newly referred to the two treatment services during the recruitment period were considered potential participants.

Eligibility assessment

All referred young people initially took part in an assessment session (routine part of the service referral and assessment processes) at the treatment agency, at home or at the usual place of treatment. Before conducting the assessment, a competency test based on the Gillick test was routinely administered to ensure that the young person was ‘competent’ to understand the implications of treatment as well as provide independent and valid consent. This UK assessment refers to a legal case that looked specifically at whether doctors should be able to give contraceptive advice or treatment to those aged < 16 years without parental consent. 75 Since then, it has been more widely used to help assess whether a child aged < 16 years has the capacity to consent to treatment without parental or guardian consent. Those found to be appropriately referred and meeting the inclusion criteria were deemed potentially eligible for the trial. Eligible young people who did not wish to take part (i.e. unwilling to give consent) and those found to be ineligible went on to receive usual care from the service outside of the trial. When proffered, reasons for non-participation were collected to inform future studies. Eligible young people and their parents/person with parental responsibility were given a leaflet (see Appendix 4) and patient information sheet (see Appendix 5) by the assessment staff. If the young person remained interested in taking part in the trial after reading the materials, a face-to-face meeting was conducted by a researcher allocated to the centre.

Consent procedure

During the meeting with those eligible and interested in participating, the researcher fully explained the study and provided an opportunity for the young person to ask questions.

The research process was conducted in a manner that ensured that informed decisions were made by the young person and his or her parents/person with parental responsibility. This included bearing in mind that competence is not related to age in a simple way but depends on a child’s ability to understand, weigh the options and reach an informed decision. 76

As the research in question was integral to the service that the young person was already involved in, and the parents or person with parental responsibility would have already given consent for the young person to attend that service, it was not deemed necessary to additionally obtain consent from the parents/person with parental responsibility for the child to participate in this study. This was in line with National Children’s Bureau (NCB) guidelines. 60 Conversely, there may have been situations when, given the nature of the service, seeking parental consent would have potentially breached the young person’s right to confidentiality if he or she was attending the service without his or her parent’s knowledge. NCB guidelines state that in such situations parental/person with parental responsibility consent may be waived. 60

For the purpose of this study, the following was applied.

-

If consent was not forthcoming from a parent/person with parental responsibility, but the young person (aged 12–15 years) did consent, he or she entered the trial.

-

For those aged ≥ 16 years, consent was sought only from the young person, as those aged between 16 and 18 years were presumed to be competent to give consent.

-

If consent was given by a parent/person with parental responsibility but the young person did not consent, the young person did not enter the trial.

However, the potentially complex lives of the young people were considered and consent in all cases was handled in a sensitive and pragmatic manner.

Baseline assessment

After written informed consent had been obtained (see Appendix 5), baseline data were collected by the researcher. The following data were collected in the baseline questionnaire (see Appendix 6) prior to randomisation:

Demographics

Details including age, sex, sexual identity (if aged ≥ 16 years), ethnicity, nationality, religion, education, employment and current living arrangements were collected.

Timeline Follow-Back interview

The Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB) interview77 records substance use, particularly the proportion of days on which the main problem substance was used in the preceding 90-day period. This interview is based on a retrospective calendar review of each day’s consumption and has previously been validated and widely used with adolescent populations. 78–80 It has been shown to demonstrate high comparability with the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) (r = 0.7–0.8) in a population of adolescents aged 12–18 years admitted to a residential treatment programme for substance abuse or dependence. 78 Applying the TLFB interview allowed the collection of detailed data on the full range of licit and illicit drugs used by participants. Participants were asked to recall on which days they had used their primary problem substance in the last 90 days. The number of days was summed and divided by 90 to obtain the proportion (from 0 to 1).

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

The self-report Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a brief behavioural screening questionnaire designed to be completed by adolescents. 81,82 The 25-item questionnaire has five separate subscales for different aspects of problems or behaviours: emotional problems, conduct/behaviour problems, inattention/hyperactivity, relationships with peers and prosocial behaviour. Scores for the first four scales can be added together to produce a score for total difficulties ranging from 0 to 40, with a lower score indicating greater emotional well-being and a score of ≥ 20 indicating an ‘abnormal’ score. The SDQ has been used extensively and has demonstrated high levels of reliability and validity. 83,84 In a factor analysis with 3983 11- to 15-year-olds, all 25 items loaded on the predicted factors relating to the five subscales (> |0.33|). 84 A few items also loaded on additional factors > 0.30, but the loadings on the predicted factors were higher than the loadings on the additional factors for all but one item. The total SDQ score demonstrated good reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80 and test–retest reliability of no less than 0.62.

Important People Drug and Alcohol interview

Given the emphasis on family and peer support of the intervention, social network support was measured using the Important People Drug and Alcohol (IPDA) interview85 to understand the influence of social support on treatment for substance misuse, assess the degree to which social network changes had been achieved and assess the extent to which these changes still needed to be made. This interview requires the participant to provide information on up to 12 significant people who have featured in their lives in the previous 3 months. Data collected on these people include their relationship with the young person, frequency of contact, importance, supportiveness and use of drugs and alcohol. This instrument has a three-factor structure of substance involvement (α = 0.92), general/treatment support (α = 0.84) and support for substance use (α = 0.85),85 established in an adult population.

Family Environment Scale: Family Relationships Index

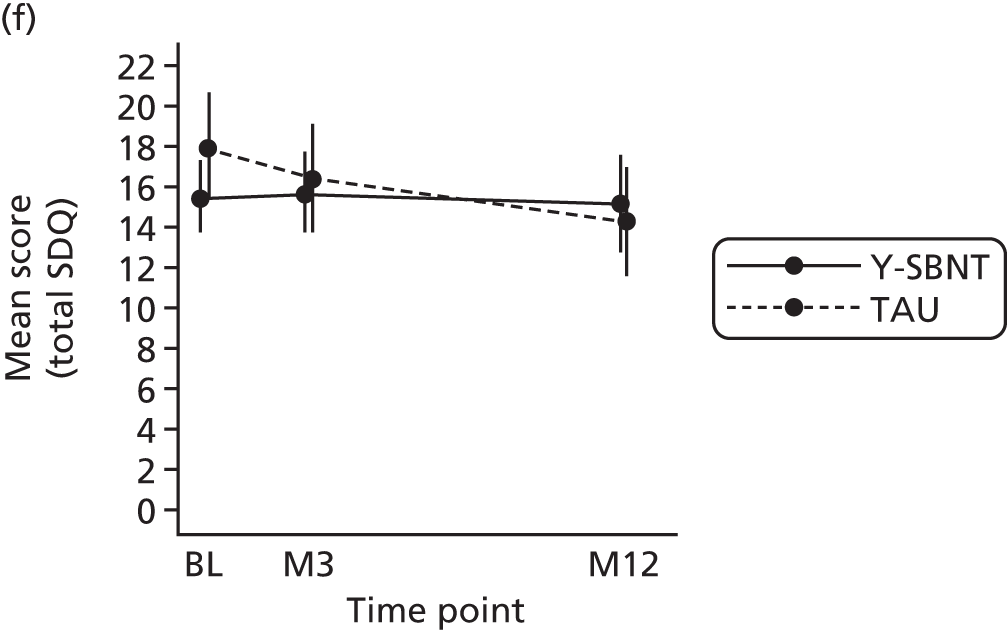

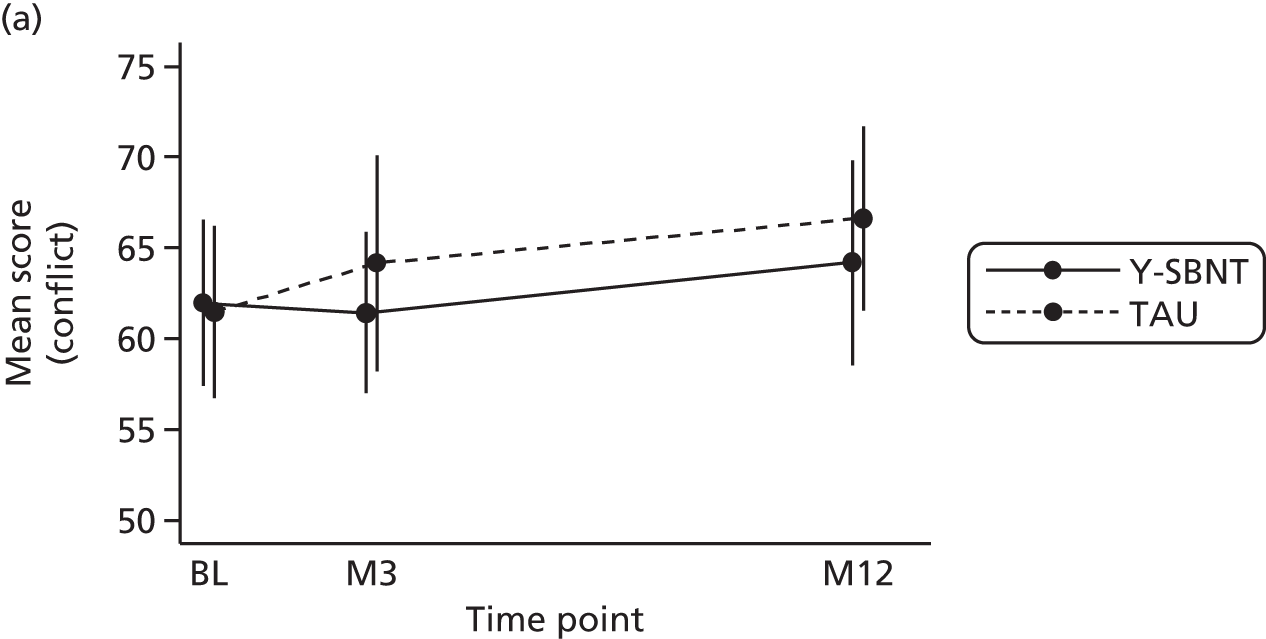

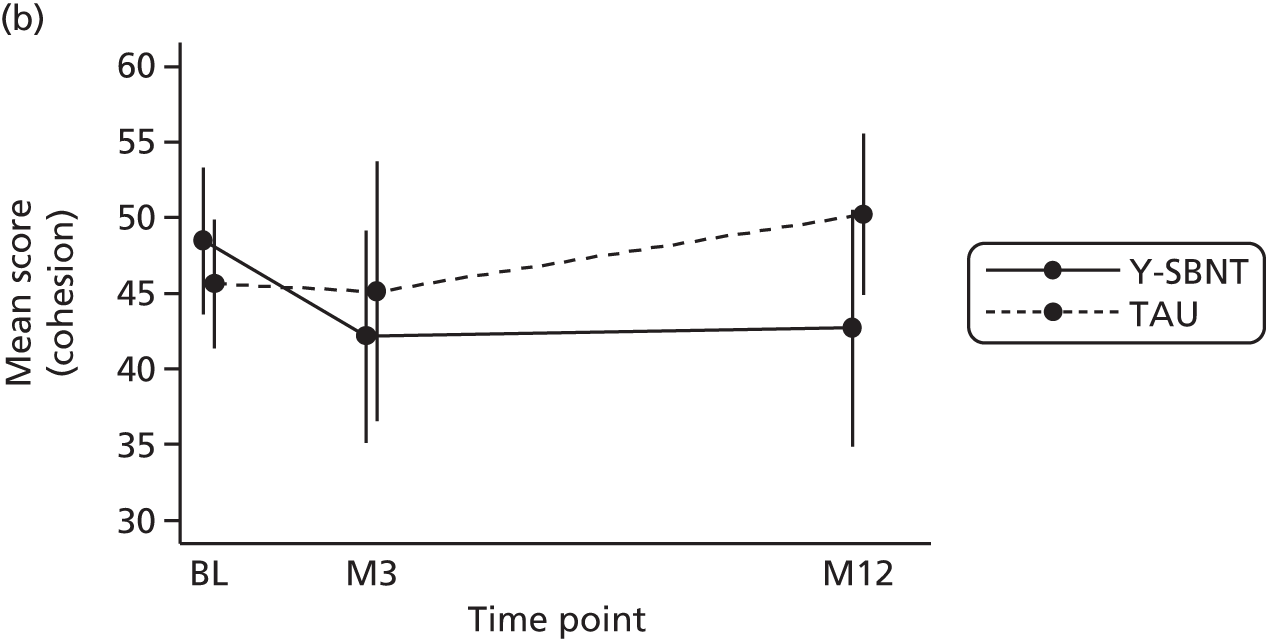

The 27-item relationship dimension of the Family Environment Scale (FES)86 consists of cohesion, expressiveness and conflict subscales (nine items each), for which a raw score from 0 to 9 can be calculated and converted to a standard score. 87 The standard scores range from 4 to 65 for the cohesion subscale, from 16 to 71 for the expressiveness subscale and from 33 to 80 for the conflict subscale; a higher standard score indicates greater cohesion and expressiveness and lower levels of conflict among family members, respectively.

The Family Relationships Index (FRI) is designed to look at the atmosphere in the family household with subscales that measure support, expression of opinions and angry conflict within a family. This was completed by the young person (other family members were not asked to complete this instrument). This measure has been used previously in similar populations88,89 and has undergone extensive development and validation work. It has shown acceptable levels of internal consistency in a validation study with 1298 pupils aged 11–18 years from 16 schools in Victoria, Australia (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.39 for the expressiveness scale, 0.67 for the cohesion scale and 0.72 for the conflict scale),90 test–retest reliability of each subscale of at least 0.73 and good content and construct validity. 91

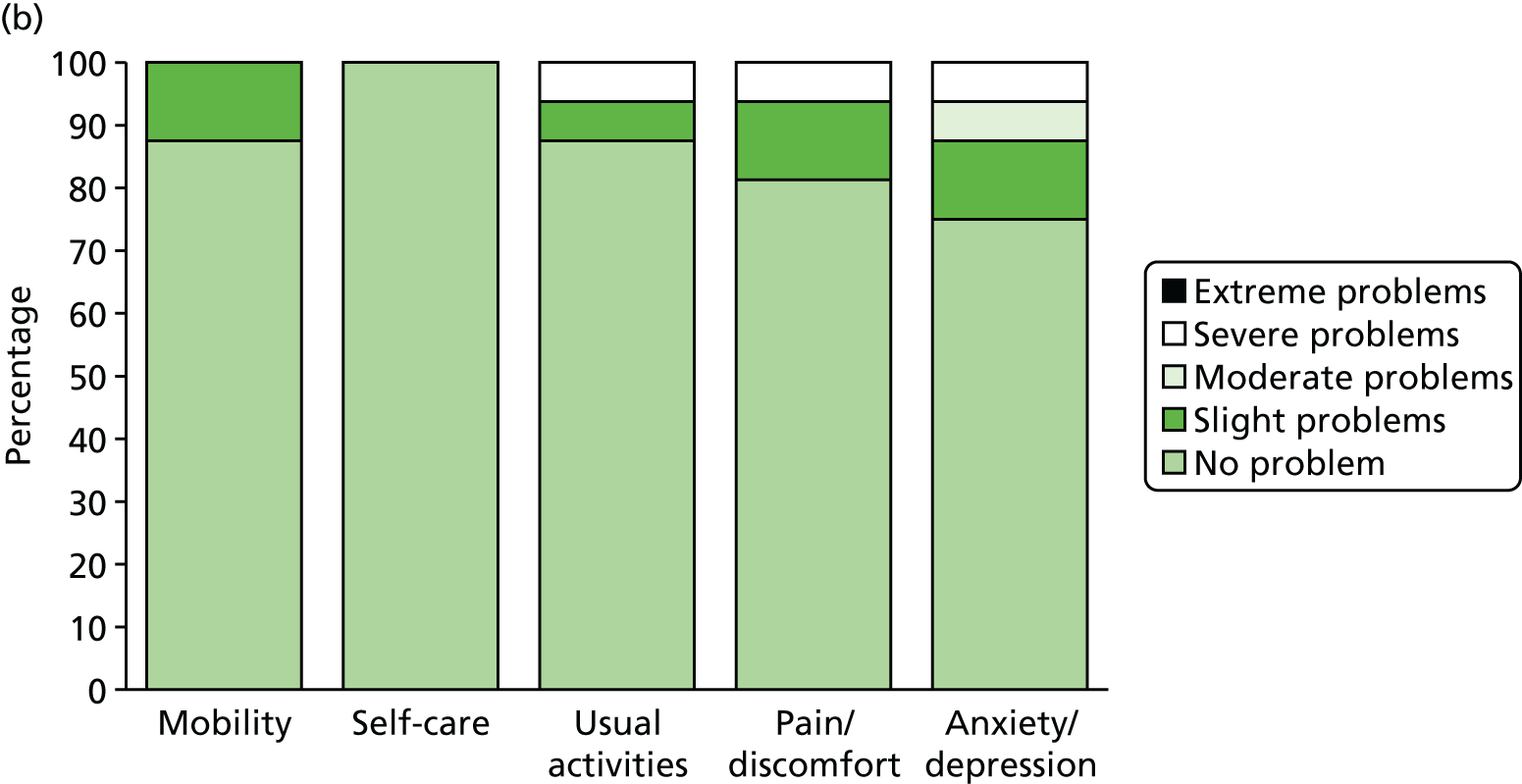

Health-related quality of life

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)92 is a standardised measure of health status developed by the EuroQol Group to provide a simple, generic measure of health for clinical and economic appraisal, with health characterised on five dimensions (mobility, self-care, ability to undertake usual activities, pain and anxiety/depression). Participants were asked to describe their level of health on each dimension using one of five levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems or extreme problems. 93 These dimensions were accompanied by a visual analogue scale (VAS), with participants asked to assign a number between 0 and 100 to measure their perceived health status.

Health and social care resource use

The feasibility of collecting details regarding hospital and primary health-care services use, contact with the police and criminal justice system and social care services use was tested in this participant group. Participants indicated how many times in the previous 12 months they had seen a GP or practice nurse or received hospital care. They were asked about any accidents that they may have had in the past 12 months and attendance and absenteeism from school or employment was recorded. In addition, contact with the police, criminal justice system and social services was documented.

This collection of self-reported resource use data was continued until participants had been in the study for 12 months or until they withdrew from follow-up or fully withdrew from the study.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised equally between the two trial arms: the Y-SBNT intervention and TAU. Randomisation was carried out using random permuted blocks, stratified by centre. To maintain allocation concealment, the generation of the randomisation sequence was undertaken by an independent statistician at the University of York and treatment allocation was performed by a secure, remote, telephone randomisation service based at the University of York. The computerised randomisation system was checked periodically during the trial following standard operating procedures. Because of the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to conceal treatment allocation from the participants or the professionals delivering the intervention.

Trial interventions

Participants were randomised to receive either Y-SBNT or TAU.

-

Y-SBNT An adaptation of SBNT consisting of social network identification, goal setting, improving communication and coping skills and, when relevant, development of a network-based relapse management plan delivered by a trained therapist as an initial appointment and followed by five further sessions over a maximum of 12 weeks (aiming for one per week where possible).

-

TAU Generally focused on engagement, description of substance use, current issues that the young person brings to sessions and that seem relevant to the substance use and practical matters such as housing or school exclusion. It generally does not involve analysis of comorbidity, discussion with family or multiagency work. Those allocated to TAU had an initial appointment with a therapist not trained in the Y-SBNT, with further appointments as required.

After allocation, participants were provided with an appointment to see the therapist appropriate to their allocation.

Training in the delivery of youth social behaviour and network therapy

Training was delivered by two professionals during two workshops in each site – West Midlands and the North East. Volunteers from the therapists’ pool in each of the two services were trained to deliver the Y-SBNT intervention (five in the West Midlands and two in the North East). Once allocated, therapists delivered Y-SBNT to participants only for the duration of the trial, with the non-trained therapists in each service delivering TAU within the other arm; hence, there was no overlap between therapists across the two trial arms.

The training took place from 0930 to 1500 on each day. After the first day, trainees conducted practice cases in their respective services before coming back to training approximately a month later for the second day when this work was reviewed.

As soon as recruitment commenced and throughout the trial period when treatment was delivered, the Y-SBNT therapists in each site received group supervision twice a month for 1 hour each time. In the West Midlands, supervision was face-to-face whereas in the North East it was delivered over the telephone. Most of the supervisions were delivered by one of the group trainers, with a couple of supervisions delivered jointly by both trainers. The group supervision sessions focused on discussion of each individual case that therapists were working with.

At one meeting during the trial all Y-SBNT therapists came together in the West Midlands for an afternoon supervision session. This was delivered by both trainers.

Supervision finished once the last client was seen within the Y-SBNT arm.

An early additional session was provided by the researchers covering protocol issues and research processes including the rationale for the study, patient eligibility, the randomisation process, study paperwork completion, digital recorder use and handling of participant withdrawal.

Intervention content

Youth social behaviour and network therapy arm

Youth social behaviour and network therapy is an adaptation of adult SBNT developed during phase 1 of the study and described in Chapter 2. The intervention was delivered by a trained therapist. The developed therapy consisted of social network identification, goal setting, improving communication and coping mechanisms and developing a network-based relapse management plan. This therapeutic approach also provided the scope to address client-focused elective areas, for example educational requirements. An initial appointment was followed by five further sessions within a maximum of 12 weeks (aiming for one session per week when possible).

Treatment as usual arm

Those participants randomised to receive TAU continued to receive the usual care delivered by the service that they were referred to. After triage, participants allocated to TAU were seen for an initial appointment with one of the therapists in the team not trained in Y-SBNT, with further appointments made as required.

Participant follow-up

Appendix 7 shows a summary of the Y-SBNT trial and the timing of follow-ups.

Trial completion

Participants were deemed to have completed the trial when their final follow-up had been completed.

Participants were deemed to have fully withdrawn from the trial when:

-

they wished to exit the trial fully

-

their therapist withdrew them fully from the trial.

Instead of withdrawing fully from the trial, participants had the option of:

-

withdrawing only from receiving trial treatment but continuing to complete follow-up data collection

-

withdrawing only from follow-up data collection but continuing to receive trial treatment.

Participants electing to withdraw from both the trial treatment and the follow-up data collection were deemed to be full withdrawals.

Measurement and verification of the primary outcome

In conjunction with the qualitative data, the primary outcome of the trial was the feasibility of recruiting young people to a family- and network-based intervention across two service sites and the potential for a future large-scale study. This feasibility was measured by:

-

recruitment rates – a quantitative assessment of the acceptability of the research was carried out using numbers referred, numbers eligible and those agreeing to participate

-

retention in treatment – evaluated by the number of sessions attended as a measure of acceptability of the intervention to participants

-

follow-up completion rates – a quantitative assessment of the number of follow-up interviews completed

-

outcome assessment – the following outcome measures were also collected at 3 and 12 months post randomisation (see Appendix 6):

-

TLFB interview

-

SDQ

-

IPDA interview

-

FES

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

-

a resource use questionnaire.

-

In addition, the following data were collected.

-

Qualitative interviews The acceptability of the Y-SBNT intervention to the young people and the wider context of the impact of the intervention were explored through semistructured qualitative interviews conducted at 3 months post randomisation. In addition, the acceptability of the intervention to those attending as network members was explored through similar semistructured interviews at 3 months post randomisation. Interviews were also conducted with the therapists and a service manager at a single time point following the completion of the interviews with young people. There were separate topic guides for each participant group (see Appendix 8), exploring their experiences and the acceptability of the active components of the new approach and study processes.

-

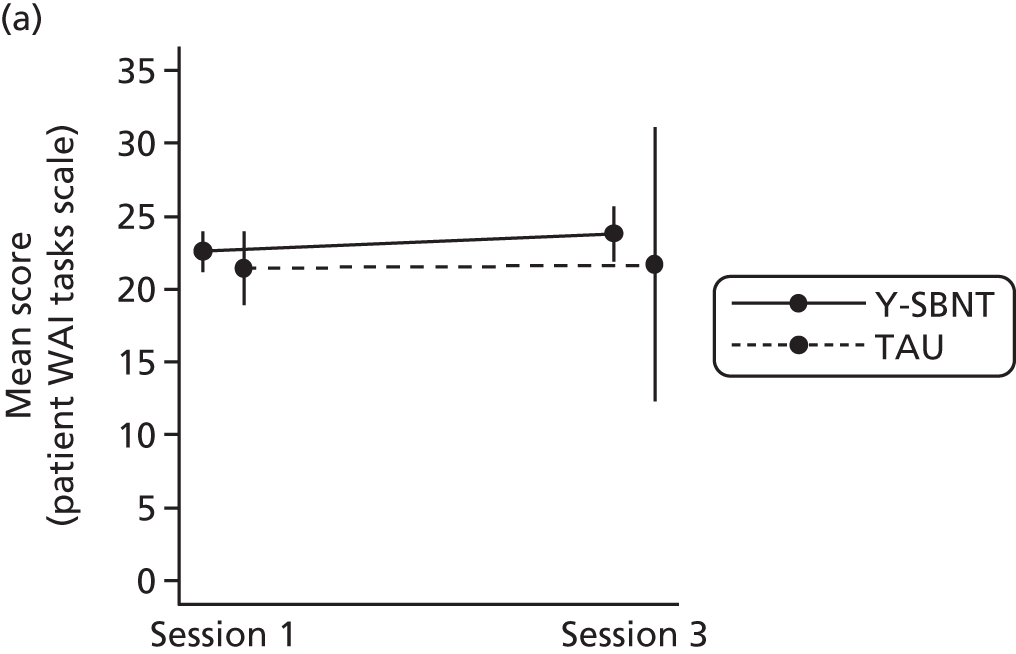

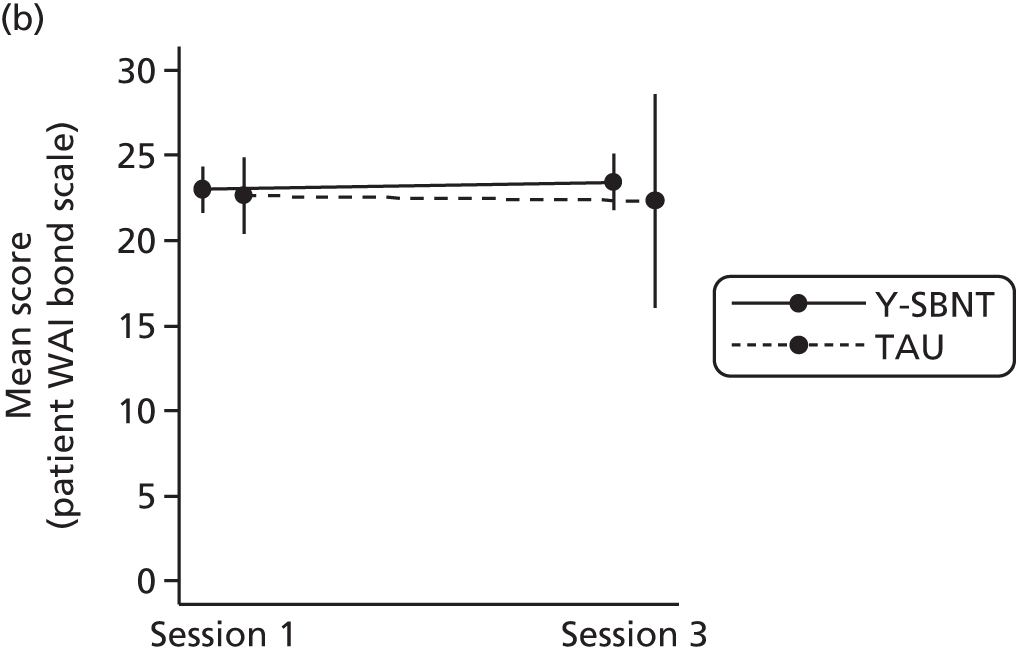

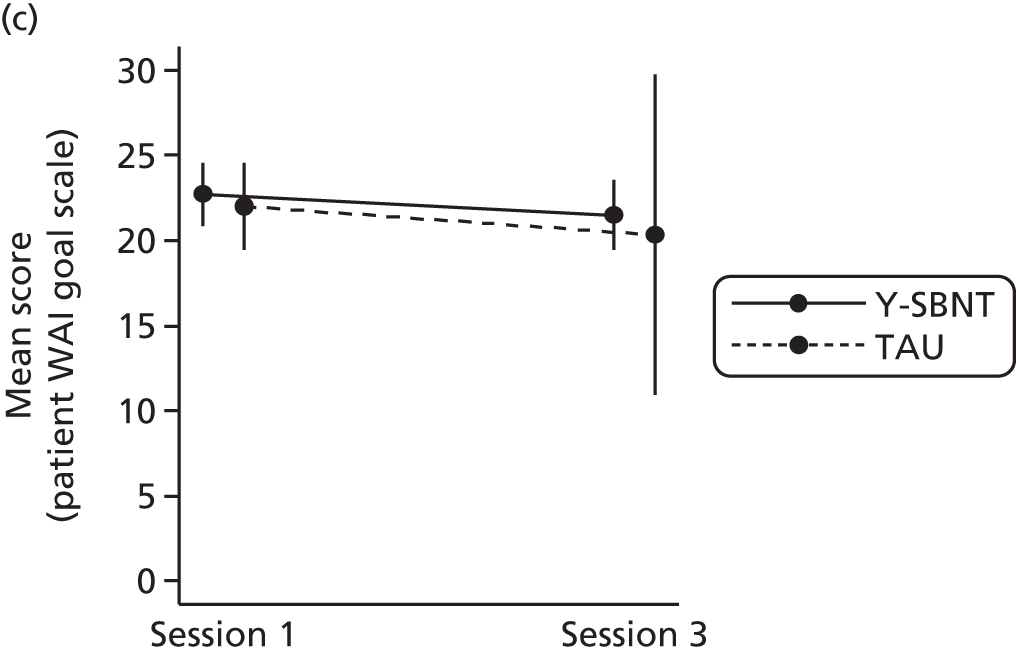

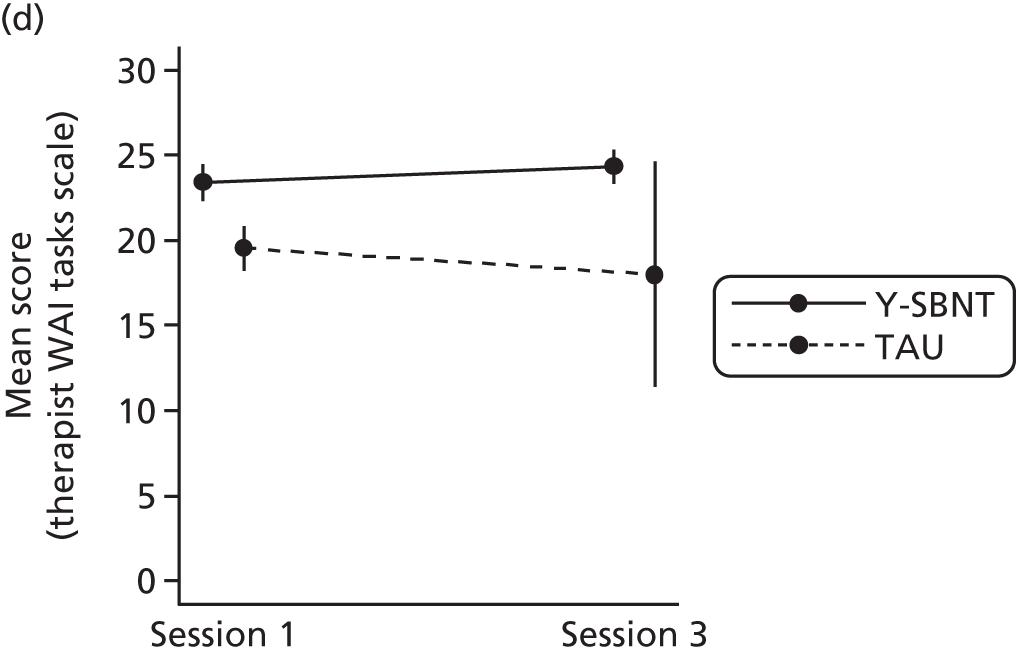

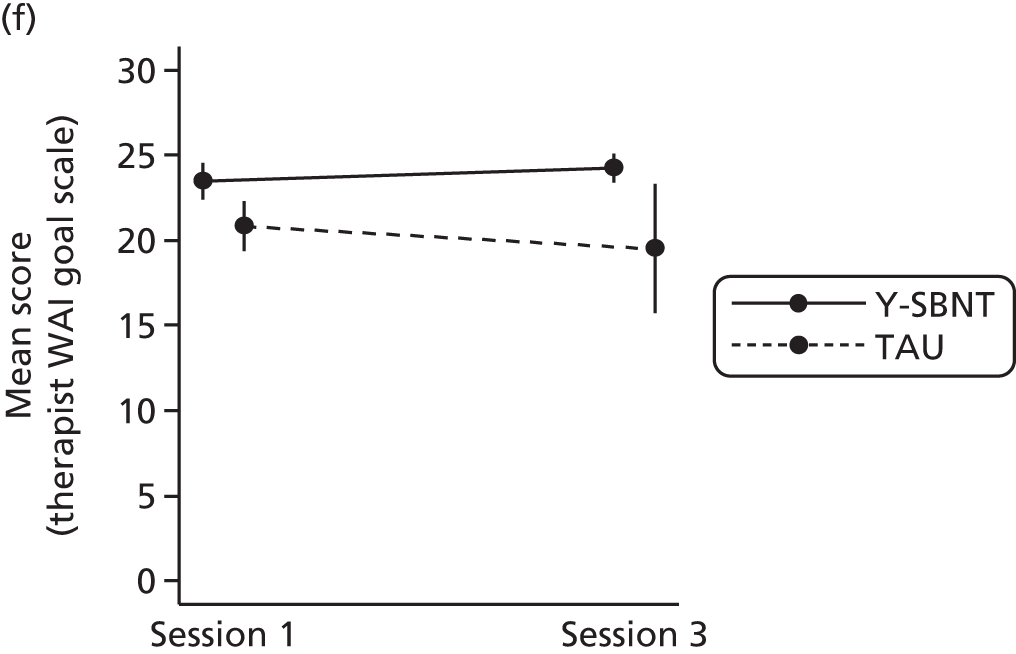

Working Alliance Inventory (WAI)94 The WAI was to be administered at the end of treatment sessions 1 and 3 to the young people and also to the therapists delivering the intervention and TAU (see Appendix 6). The questionnaire measures the perceived strength of the working alliance between therapists and their clients during therapy sessions. The young people were provided with an envelope in which to seal their completed WAI.

-

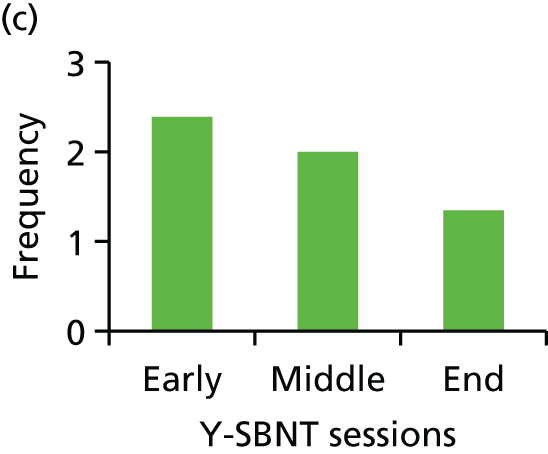

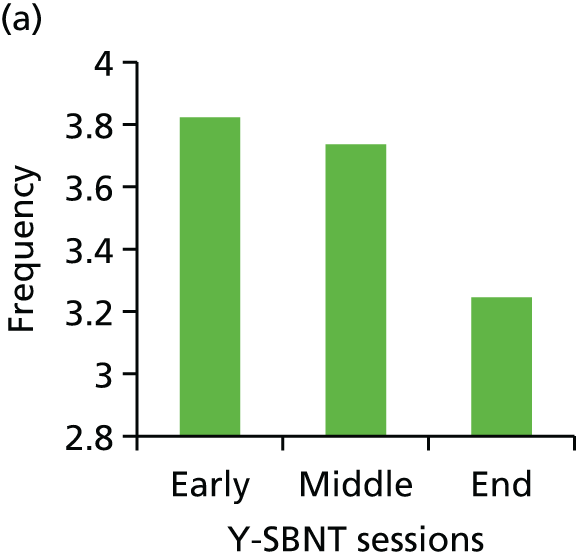

Treatment fidelity Participants were asked to provide consent to have all treatment sessions recorded for the purpose of assessing staff fidelity and adherence to the intervention protocol. Assessment of fidelity and adherence to the protocol was conducted by rating the frequency of use and quality of behaviour change techniques using an adaption of the fidelity assessment scale developed as part of the UKATT trial. 95 This was carried out on all available Y-SBNT recordings. In addition, the intention had been to assess 10–20% of the TAU sessions to identify the components of TAU. However, as only a small number of sessions was ultimately available, all TAU recordings were rated. The aim was to collect samples from across all therapists from both centres from the beginning, middle and end of the therapy.

Adverse events

There were no anticipated risks in relation to either treatment arm and there was no documented evidence of adverse events arising as a results of either TAU or Y-SBNT, but a mechanism for recording them was in place if any arose (see Appendix 9).

Statistical methods

Primary analysis

As this was a feasibility study, outcomes were primarily summarised only descriptively. The end point of main clinical interest, the TLFB interview, was analysed to obtain the effect size and CI. Analysis was conducted in Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Primary outcomes

Recruitment rates

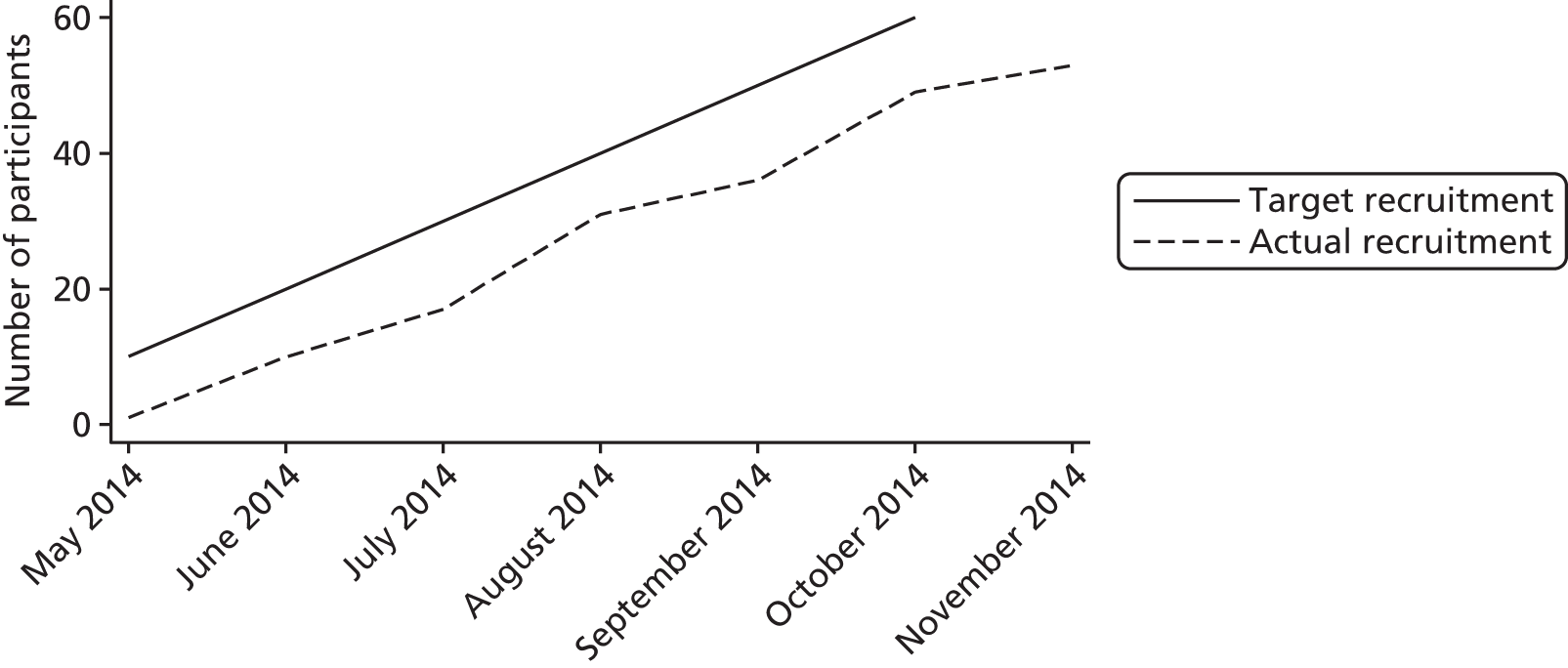

Graphs showing the number of patients entering the study each month and the cumulative monthly recruitment rate are presented. An average recruitment rate was calculated for the period between randomisation of the first participant and randomisation of the last participant.

Baseline data

Patient baseline characteristics are summarised descriptively by treatment group using mean, SD, median, minimum and maximum for continuous measures and number and percentage for categorical measures. The referral route of participants is also described.

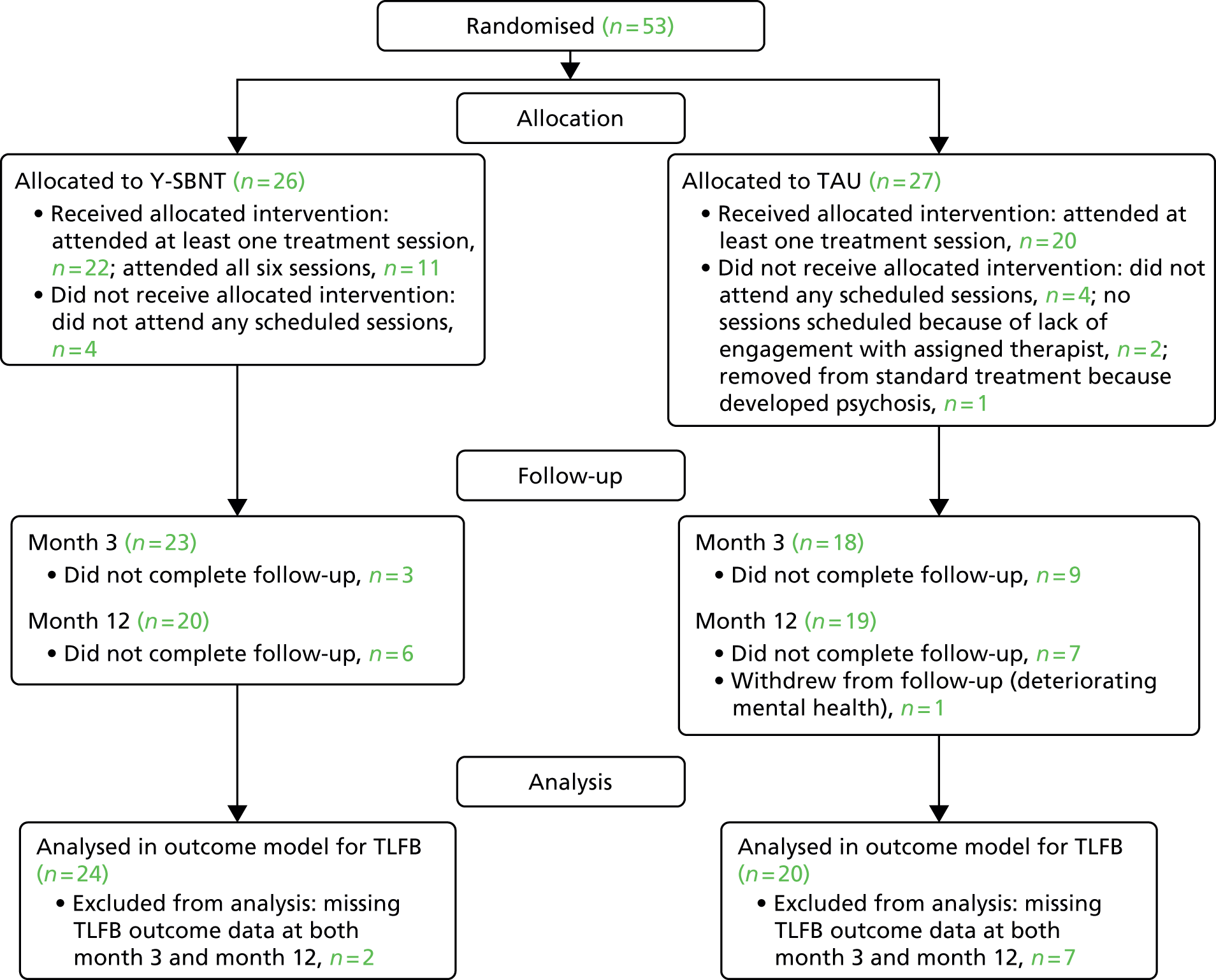

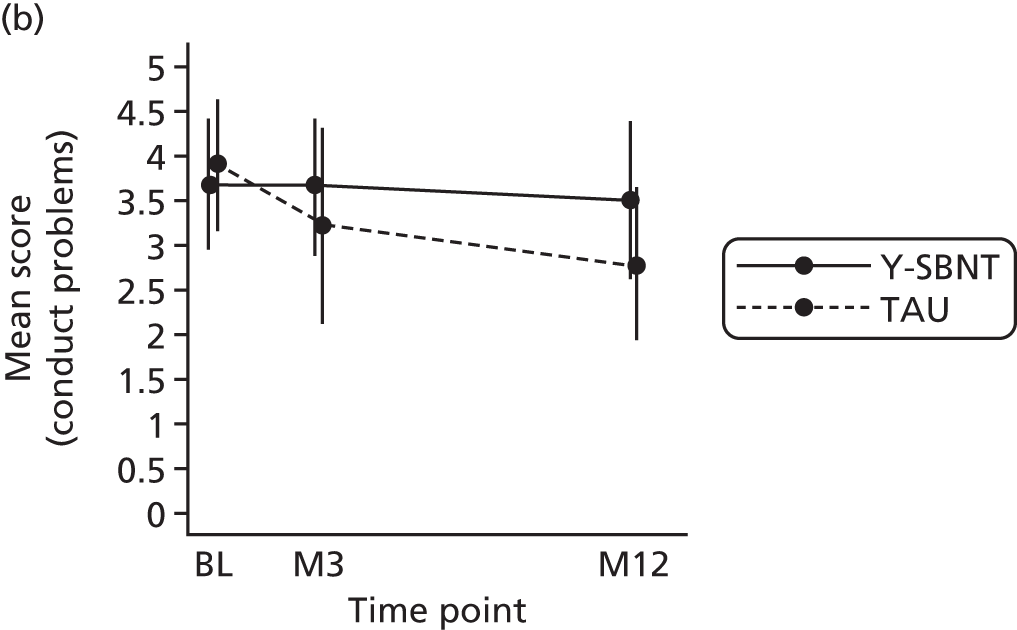

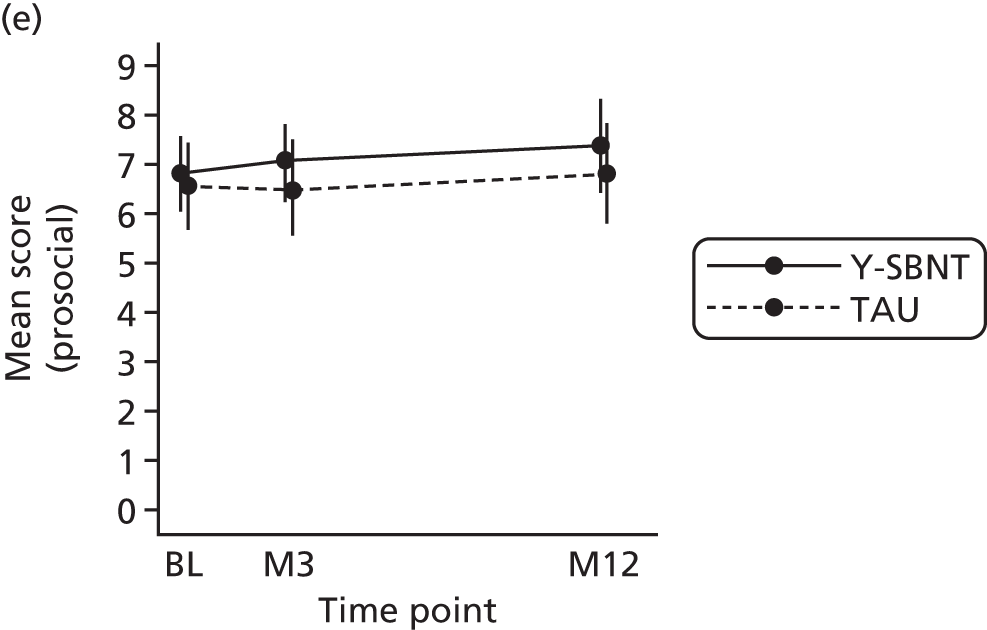

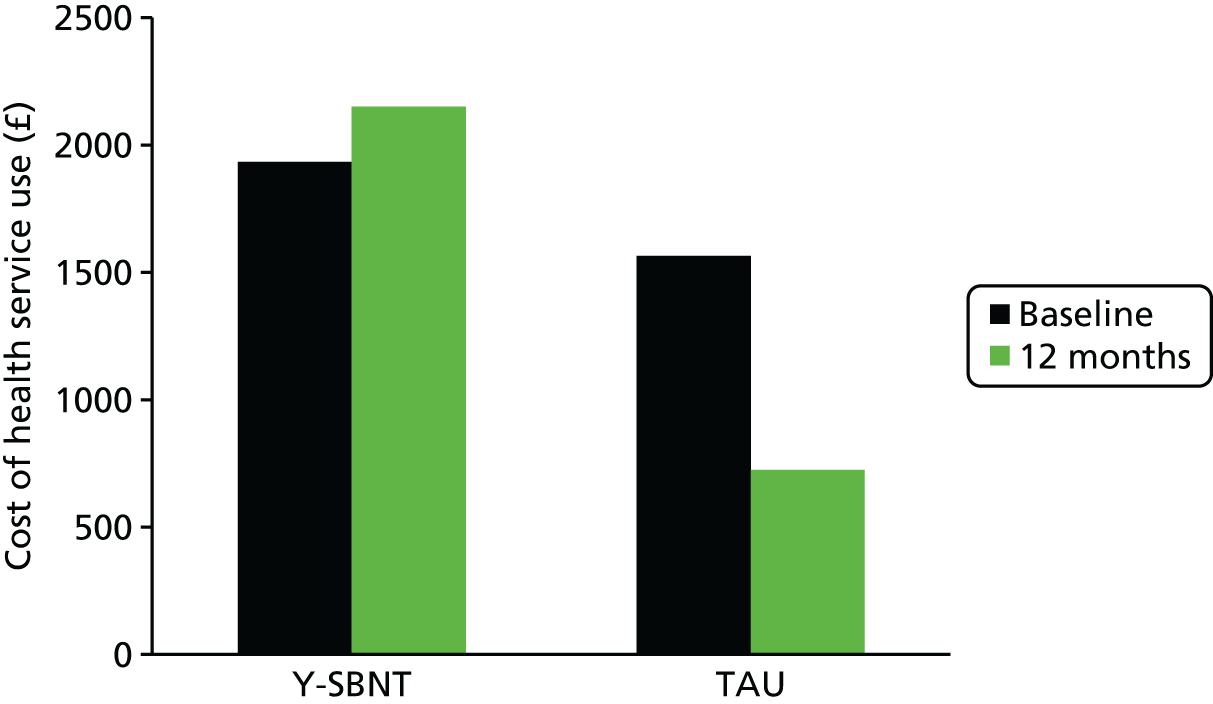

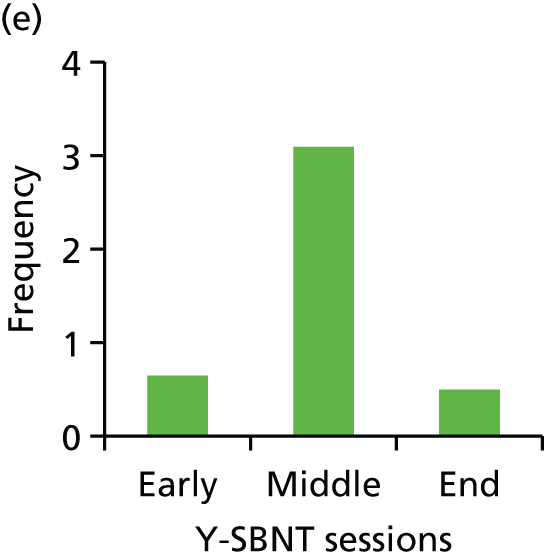

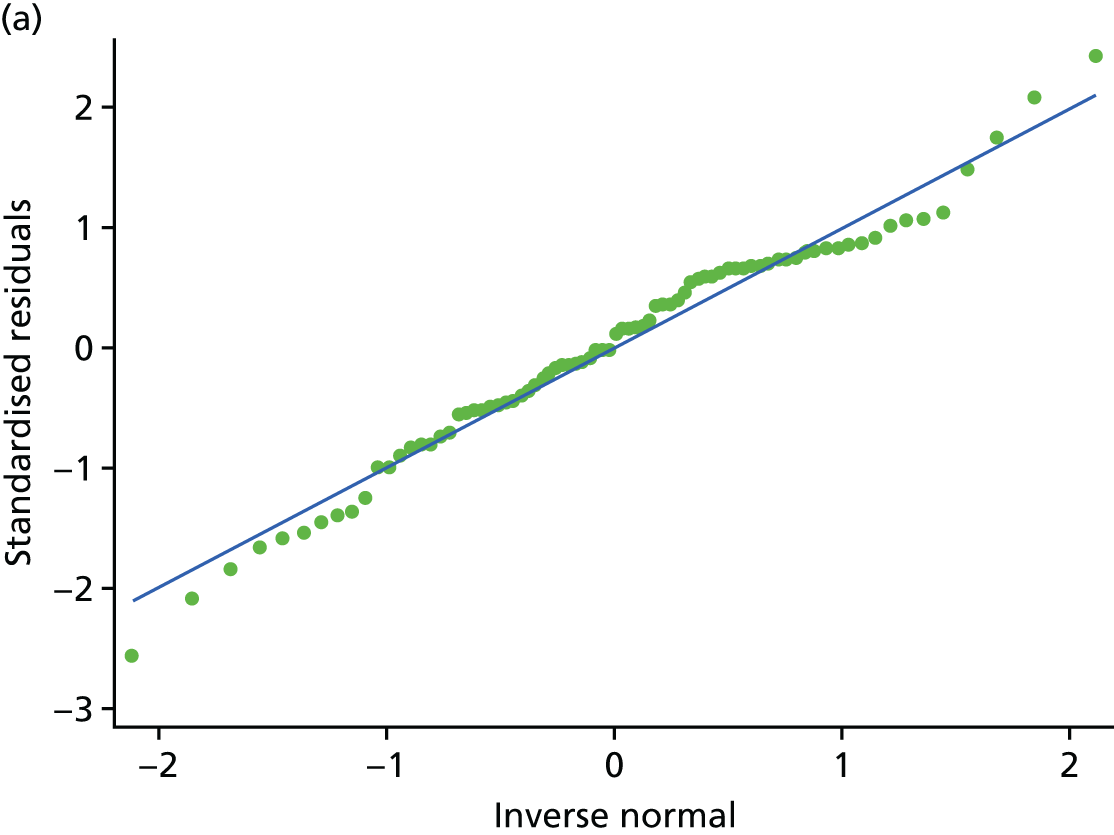

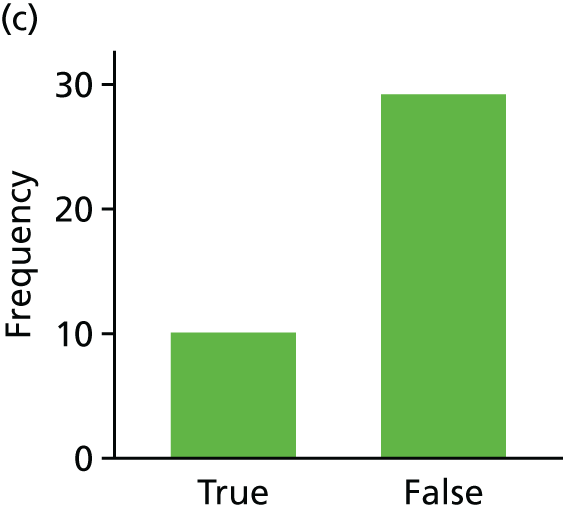

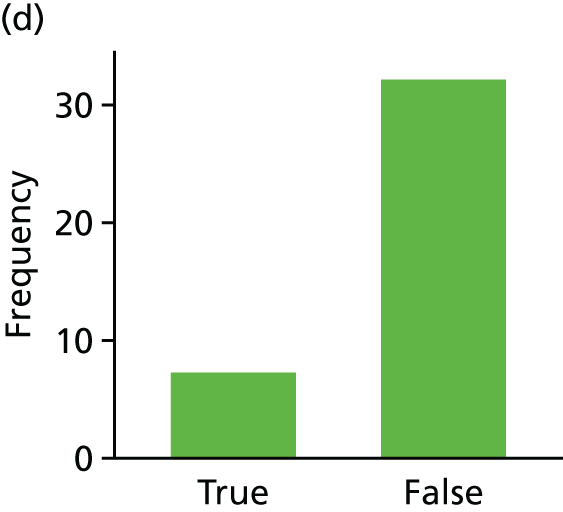

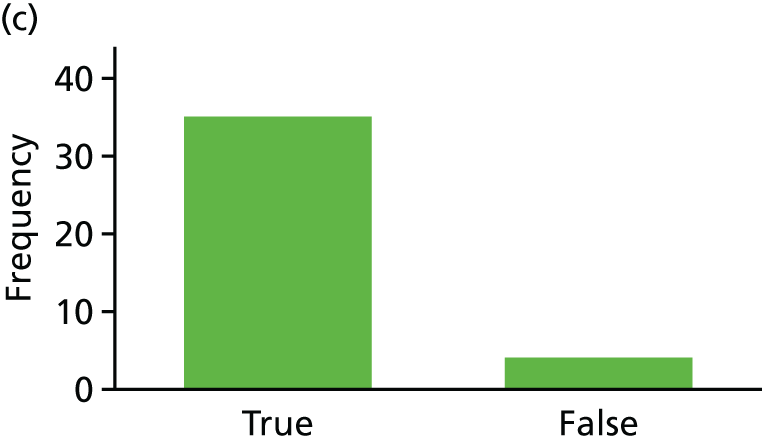

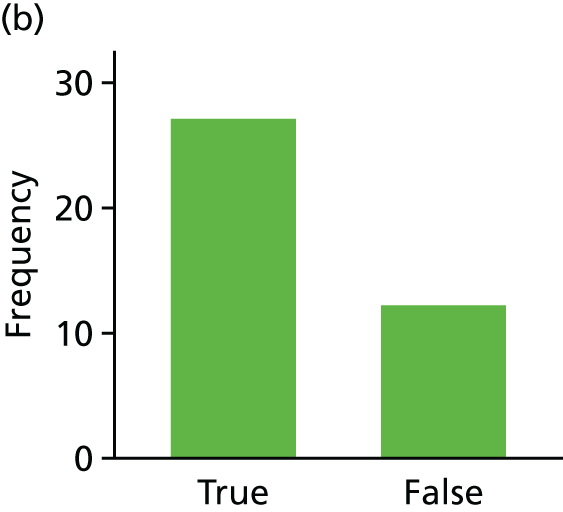

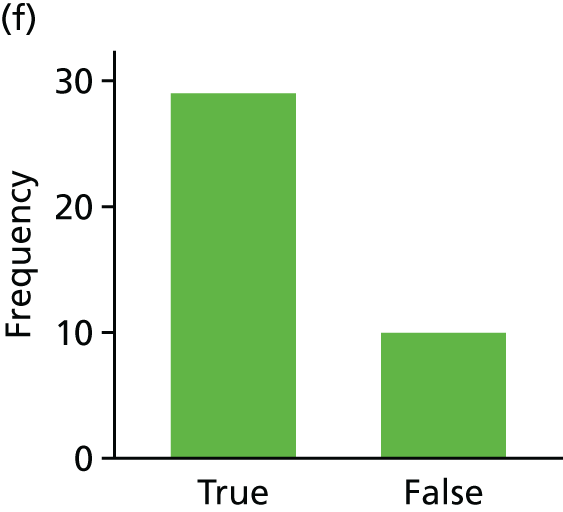

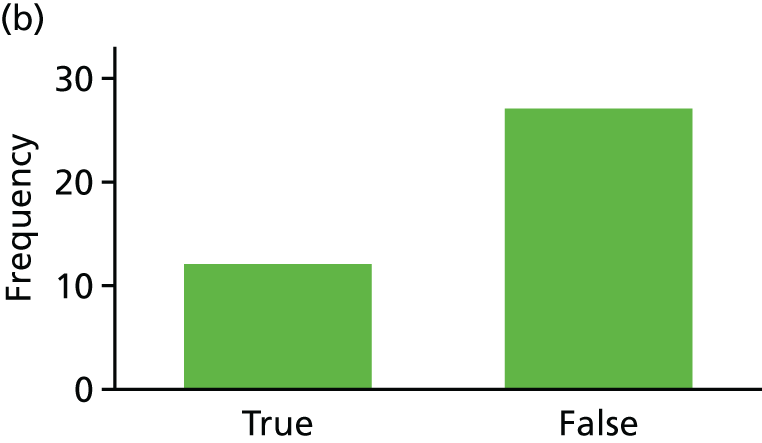

Follow-up completion rates