Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/36/37. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The draft report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in March 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Dias et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scaphoid fracture accounts for 90% of all carpal fractures1 and 2–7% of all fractures. 2 It is an important public health problem, as it predominantly affects young active individuals (mean age 29 years)3 in their most productive working years.

The scaphoid typically fractures when the wrist is suddenly extended either when putting the hand out to break a fall or when the palm is struck forcibly by an object.

Most fractures (64%) affect the waist of the scaphoid, but 5% affect the proximal pole (the proximal 20% of the scaphoid) and around 13.3% involve the distal part of the scaphoid. The tuberosity fractures in 18.1% of cases. Figure 1 illustrates this.

FIGURE 1.

Locations of scaphoid fractures and the proportions reported (information sourced from Garala et al. 4) Non-tuberosity fractures account for 81.9% of all scaphoid fractures and 78.2% of these involve the waist.

The scaphoid, lunate and triquetrum form the proximal carpal row, attached to each other by ligaments. These bones are subject to loads when the muscles whose tendons cross the wrist bones contract. This row acts together like a helix. When the scaphoid flexes under load, the triquetrum extends so that the middle section, the lunate, remains in a neutral and stable position. 5,6

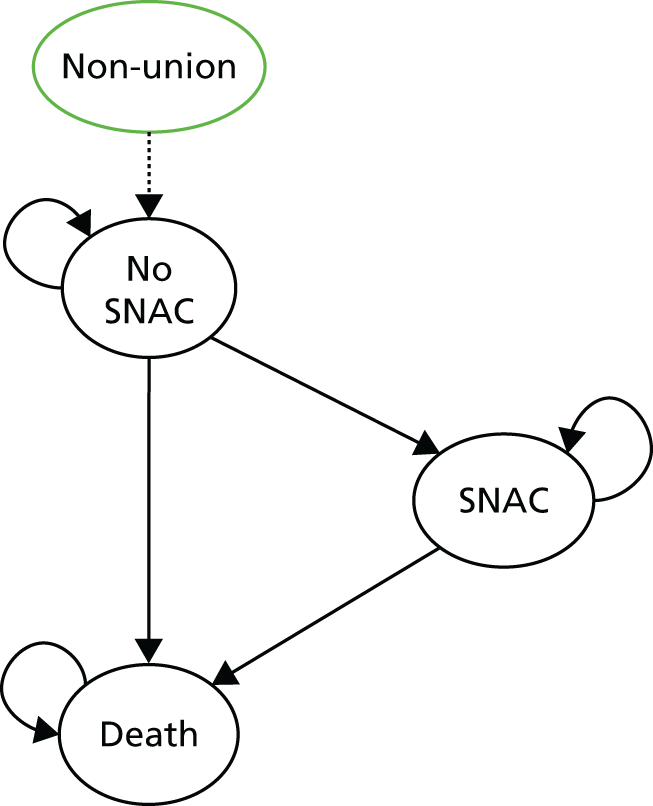

A fracture of the scaphoid breaks this helix so that the two parts then rotate; the distal scaphoid fragment flexes under load while the remainder of the proximal carpal helix extends. After a fracture, the proximal carpal row can no longer stabilise the distal carpal row and hence the wrist. The resulting abnormal loading between the distal part of the broken scaphoid and the distal radius leads to cartilage degeneration and arthritis, while the proximal part extends, causing carpal collapse. This pattern after failure of union is called a scaphoid non-union advanced collapse (SNAC) wrist. 7

Scaphoid fractures disrupt the proximal carpal row and alter the complex mechanics of this row, thereby altering how the wrist is stabilised to permit the hand and digits to function efficiently.

About 88–90% of these fractures unite when treated initially in a plaster cast. However, 10–12% of scaphoid fractures treated with plaster cast do not unite, with a higher incidence (14–50%) in displaced fractures. 8–10 Retrograde intraosseous circulation11 jeopardises the blood circulation, particularly in the proximal scaphoid, and may explain the higher failure of union in proximal fractures. Non-union, if untreated, almost inevitably leads to arthritis, especially in the radioscaphoid joint, usually within 5 years. 12,13 This disables patients at a very young age.

Diagnosis of the fracture is usually confirmed in emergency departments on radiographs of the scaphoid taken in different projections and it is usual to obtain a ‘scaphoid series of radiographs’, which include posterior–anterior, lateral and 45° supination and pronation views, as shown in Figure 2. In addition, an elongated view of the scaphoid is obtained to avoid missing any fractures that may be obscured because of the palmar and radial inclination of the scaphoid. It is possible to have an incomplete fracture of the scaphoid and these usually heal uneventfully. 14 However, clear and bicortical fractures cause clinical concern, as these are more likely to be unstable.

FIGURE 2.

Five radiographic views of the scaphoid. (a) Posterior–anterior view, in which the fracture is just visible; (b) elongated scaphoid view, in which the fracture is ‘clear’ and ‘bicortical’; the gap could be > 1 mm and the radial margin shows a small step; (c) semisupine oblique view; (d) lateral view, through which alignment can be assessed; and (e) semiprone view, which also shows the fracture and suggests displacement.

Treatments

Getting a fracture to heal restores the integrity of the proximal carpal row and thereby the stability of the wrist. This stability restores hand function, reduces the feeling of weakness and significantly reduces the risk of carpal collapse and the resulting arthritis15 (SNAC).

The aim of treatment is to immobilise the fracture while the physiological processes of healing occur. Immobilising the fracture fragments relative to one another can be done in various ways. Movement between fracture fragments can be constrained by immobilising the injured wrist in a cast or by surgically introducing a screw across the fracture.

Fixation

Immediate surgical fixation may avoid the need to immobilise the wrist in a cast and could accelerate return to function, work and sport;16 however, this method requires the person to have an operation and be exposed to surgical risks. The fracture is fixed with a standard Conformité Européenne (CE)-marked headless screw generating compression at the fracture site but avoiding the pressure effects of the screw head on articular cartilage. This can be done either percutaneously or in open surgery. 17–19 The surgical techniques for this method are well described and are now standard. 20–22 These screws did not change during the recruitment period for this study. Some surgeons use splintage for the first few weeks after surgery.

Cast treatment

The usual treatment is immobilisation in a below-elbow cast for 6–10 weeks, followed by mobilisation. The type of below elbow cast used does not affect union rate. 8 The 10–12% of patients who develop non-union [as seen on radiographs and/or computed tomography (CT) scans] usually have urgent surgical fixation. This is the current standard non-operative pathway. 3

Current evidence

Eight randomised controlled trials (RCTs)3,18,23–28 have reported on 463 participants with undisplaced or minimally displaced fractures of the scaphoid waist who had either of these two treatments. These RCTs had small sample sizes (ranging from 25 to 88 participants) and have been systematically reviewed nine times;29–37 these reviews all commented on the low quality of the evidence.

Some studies reported that fracture fixation facilitated earlier restoration of function and return to previous activity levels, especially if a cast or splint was not used after fixation, but patients had a higher rate of complications, of between 9% and 22%, although these were usually minor. 3,18,25

It is unclear if patients who had surgical fixation of undisplaced or minimally displaced scaphoid fractures had better longer-term benefits than those treated in a cast.

The rate of union was similar between the surgical and cast treatments, with early fixation of those fractures that failed to unite. 3 Another study28 reported similar outcomes at 10 years.

Displaced fractures

A scaphoid fracture is considered displaced if there is a step or gap of ≥1 mm. 38 Angulation and rotation between fragments are more difficult to assess. A systematic review reported that non-union occurs in around 18% of displaced fractures39 and that, when treated in a cast, the relative risk of non-union between undisplaced and displaced fractures is 4.4 [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.3 to 8.7]. 39 At present, the evidence of the treatment of displaced fractures is weak and recommendations are based on case series. 40 When the displacement is > 2 mm, clinicians consider the fracture so unstable that they usually recommend early reduction and fixation.

Increase in surgical activity

Despite insufficient evidence, there is an increasing trend41 to immediately fix scaphoid fracture rather than to immobilise in a cast for 6 weeks and fix only the 10–12% that fail to unite. 3 This current trend to fix fractures may be attributed to short-term benefits, but concerns remain about the lack of evidence on the long-term benefits and additional risks of surgery, such as malunion, infection, implant-related problems and avascular necrosis.

Hospital Episode Statistics for NHS hospitals in England recorded a two-third increase in acute scaphoid fracture fixations between 2007/8 and 2009/10 (1534, 1720 and 2582 in 2007/8, 2008/9 and 2009/10, respectively), before this study was commissioned. The rate of surgical fixation42 rose very slightly from 37% to 41% from 2007/8 to 2008/9 but then increased sharply to 62% in 2009/10. This trend of an increasing intervention rate emphasised the need for this study.

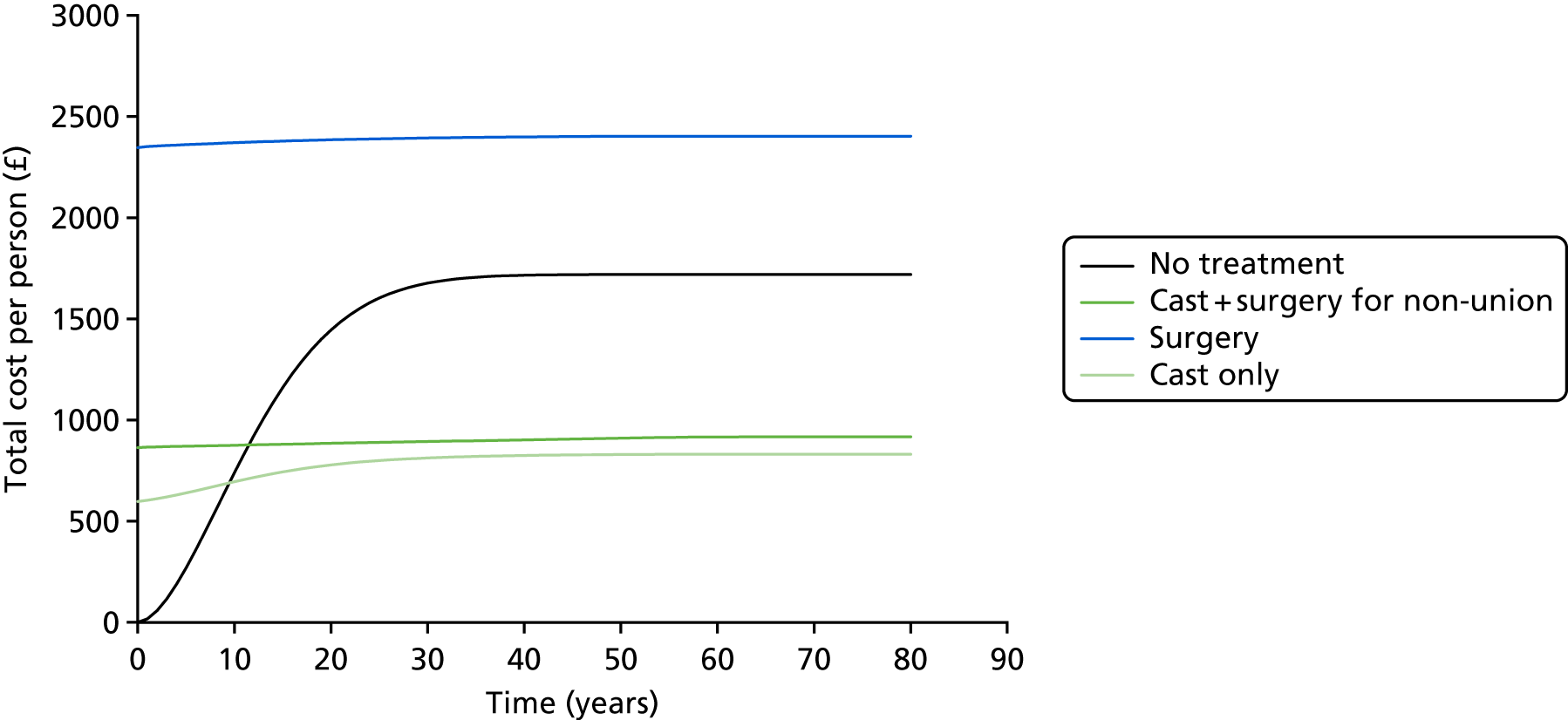

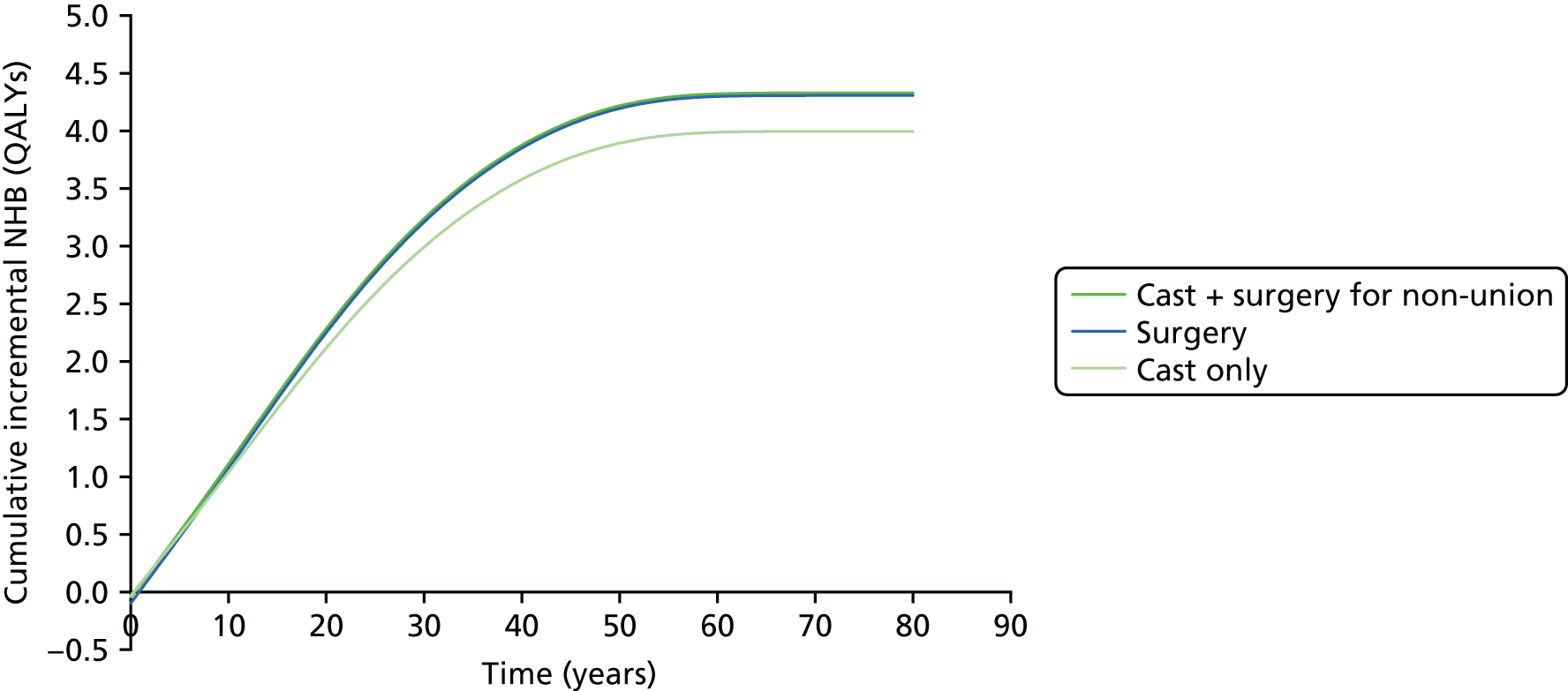

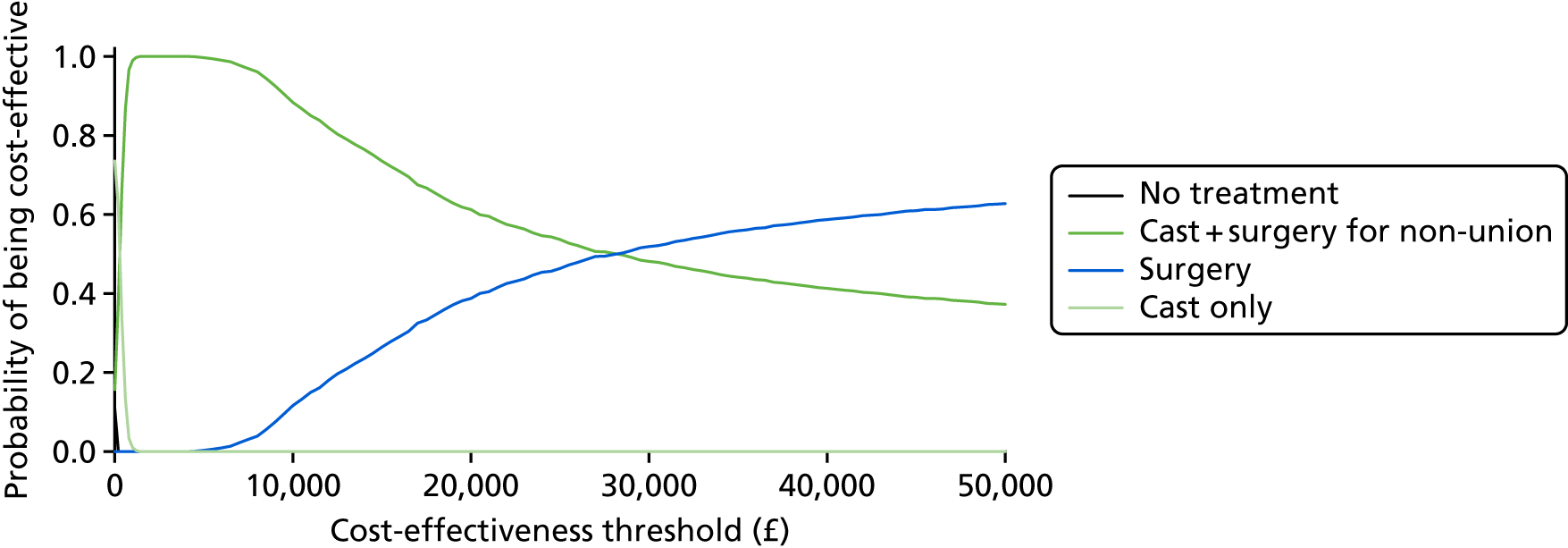

Economic aspects

There is also a lack of information on the economic aspects43 of this injury and its treatment. One study used a decision-analytic model43 and utility scores were obtained from 50 medical students. This study concluded that early fixation provided more quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and consumed fewer economic resources than cast treatment. However, a different view has also been suggested,44,45 namely that cast treatment is economically less costly. This conclusion came from studies of both non-randomised (95 patients) and randomised evidence (52 patients), based on a comparison of direct and indirect costs in patients who had their fracture treated in a cast or had it fixed.

What do patients feel and experience?

There is little published evidence on patients’ experiences and preferences after a scaphoid fracture. Understanding our patients’ priorities helps efficient patient-centred clinical decision-making. We know little about patients’ experience of their recovery and the impact that the injury and treatment have on them. We also have a poor understanding of the issues pertinent to recruiting participants in surgical clinical trials. 46,47

Five-year review

The long-term consequences of cast immobilisation and internal fixation have not been adequately determined in RCTs. The consolidation of partial union of the fracture has not been investigated, nor has the progression of carpal malalignment or the development of arthritis. Although this report focuses on outcomes at 52 weeks, the study will investigate function, impairment and arthritis at 5 years. 48

Null hypothesis

There is no difference in the Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation (PRWE)49 score at the 52-week follow-up between adults with a scaphoid waist fracture treated with screw fixation versus those treated with plaster cast immobilisation and with fixation of only those fractures that fail to unite.

Research question

Our aim was to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of surgical fixation versus plaster cast treatment (with early fixation of 10–12% of fractures that fail to unite) of scaphoid waist fractures in adults in an adequately powered multicentre pragmatic RCT [the Scaphoid Waist Internal Fixation for Fractures Trial (SWIFFT)]48 and to qualitatively investigate patients’ experiences of their treatment and participation in the trial.

Research objectives

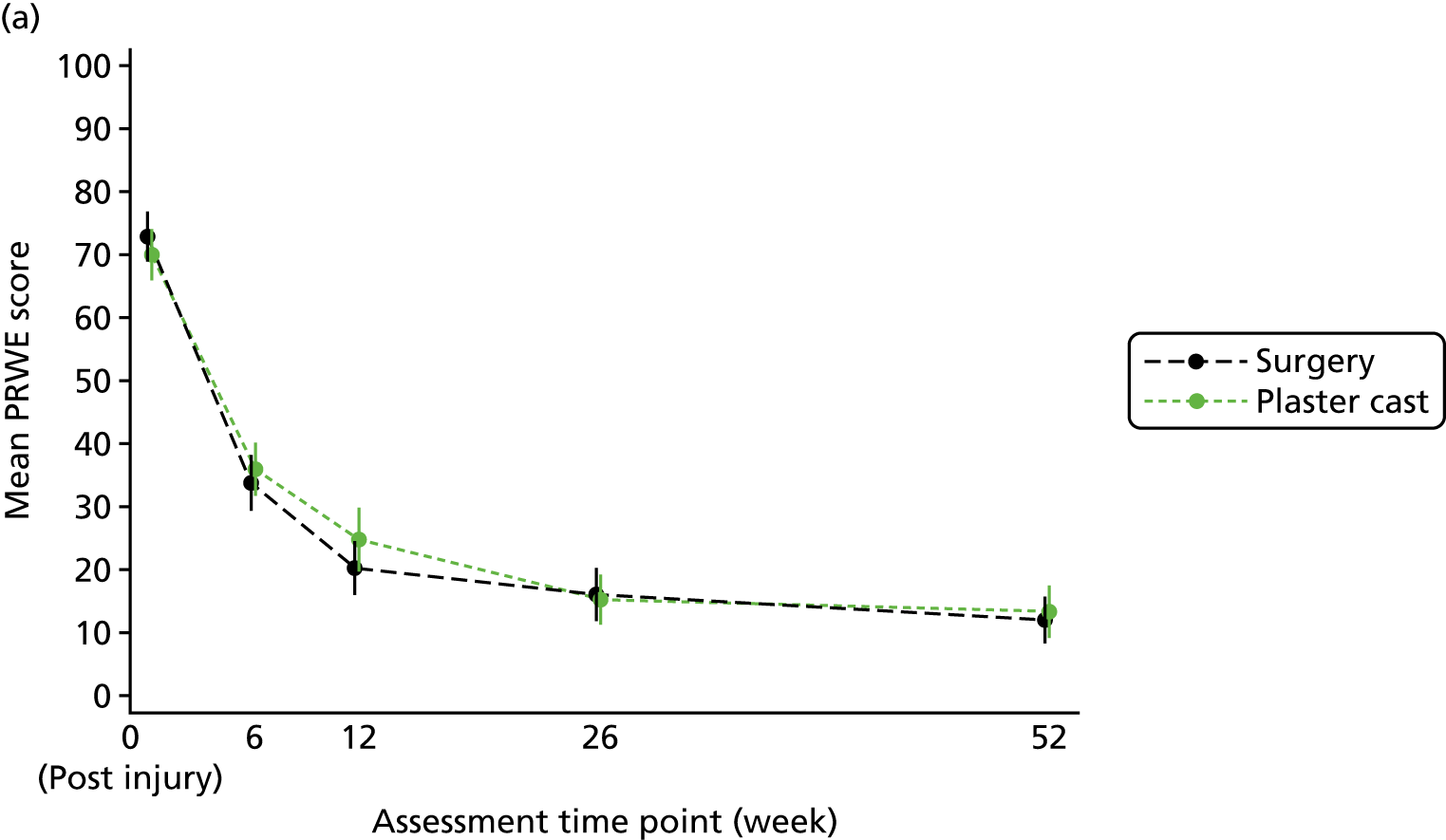

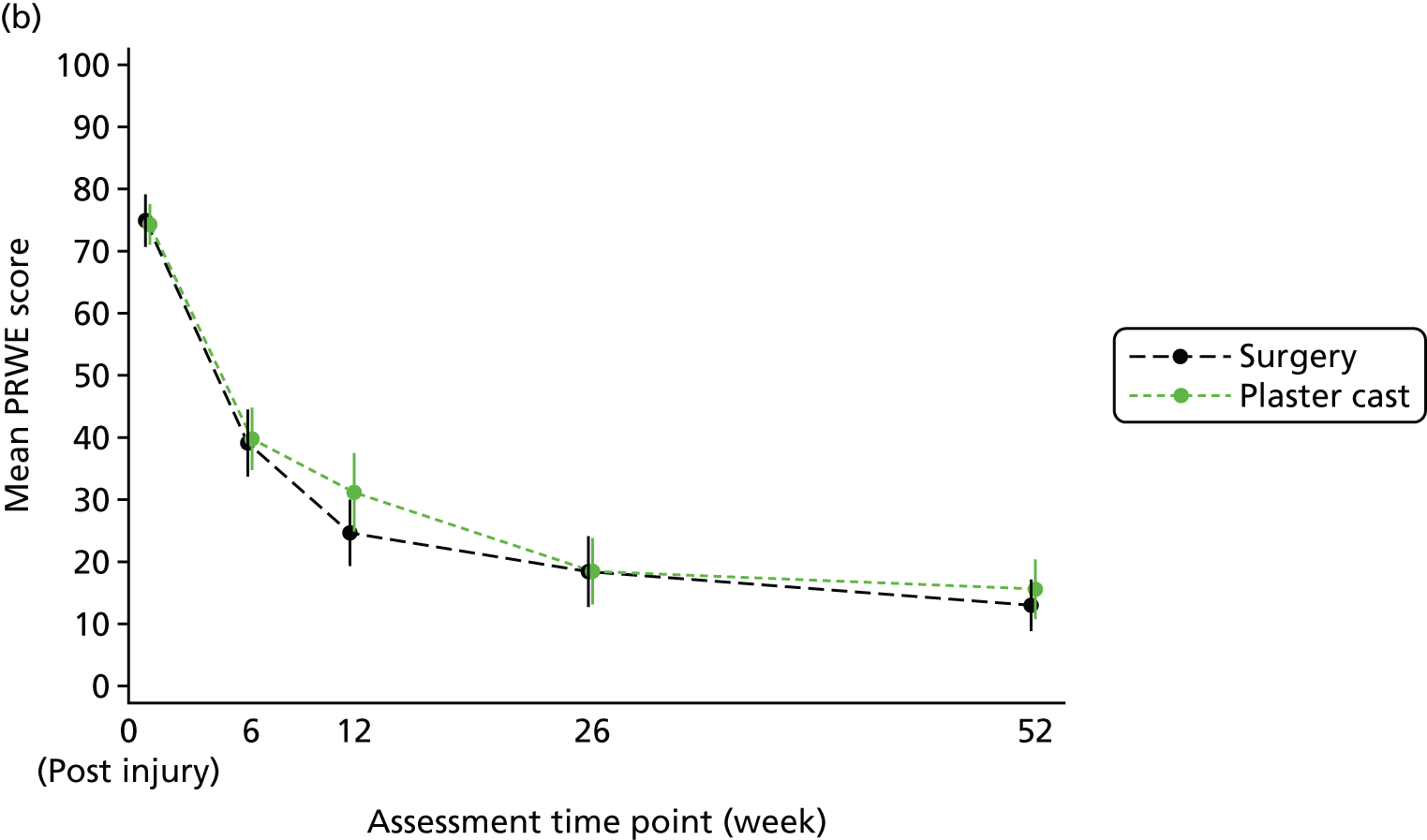

Our primary objective was to determine the effectiveness of surgical fixation versus non-operative plaster cast treatment (with fixation of those that fail to unite, estimated to be 10–12% of the total) of scaphoid waist fractures in adults. The outcome was assessed using the PRWE50 (a patient self-reported assessment of wrist pain and function) at 52 weeks, which was the primary end point. The PRWE was also completed at 6, 12 and 26 weeks and will be completed at 5 years. The power of the study permitted identification of a clinically meaningful difference of 6 points in the PRWE.

Our secondary objectives were to:

-

assess radiological union of the fracture at 52 weeks using radiographs and CT scans; recovery of wrist range and strength; return to work and unpaid recreational activities; and complications

-

conduct an economic analysis to investigate the cost-effectiveness of surgical fixation versus initial immobilisation in a plaster cast

-

qualitatively explore patients’ experiences of fracture and its treatment and to investigate attitudes towards, and experiences of, participating in a surgical clinical research trial

-

undertake a 5-year clinical review of all trial participants to determine the long-term consequences of cast immobilisation and internal fixation.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

This chapter describes the trial design and methods used to address the objectives regarding the clinical effectiveness of the health-care interventions being compared. The methods of the health economic evaluation and the nested qualitative study are described in their dedicated chapters.

Trial design

This was a multicentre, stratified [displacement present or not, with equal allocation (1 : 1)], parallel-group design conducted in England and Wales among patients aged ≥ 16 years with a clear bicortical fracture of the scaphoid waist as seen on plain radiographs. Patients were randomly assigned to either immediate surgical fixation or initial non-operative wrist immobilisation in a below-elbow cast with later surgical fixation of only those fractures that failed to unite.

Participants

The diagnosis of fracture was on standard radiographic views available at each hospital (i.e. posterior–anterior, lateral, 45° semiprone, 45° semisupine) and an elongated scaphoid view (e.g. Ziter51). If these radiographic views were not taken routinely at a participating site, we sought to obtain them after the patient had consented in the trial to confirm eligibility before randomisation.

A CT scan was also taken at baseline to compare with the CT scan at 52 weeks for the bone union assessment. The baseline CT scan was taken within 2 weeks of the patient’s injury (i.e. before randomisation) or, if that was not feasible, before surgery if the patient was allocated to surgery. It was decided that, although eligibility assessments should be based on the radiographic views, because a baseline CT scan was available, it was necessary for a member of the radiology team to confirm whether a fracture was visible or not. If the baseline CT scan was viewed before randomisation, and a member of the radiology team could not confirm to the participating site staff that there was a clear bicortical fracture of the scaphoid waist, the surgeon would decide whether or not to continue to recruit the patient. This was to prevent the potential for an immediate crossover to plaster cast if the surgeon thought there was a not a sufficiently visible fracture to operate on. If this happened after randomisation, the patient remained in the trial because there was a fracture on the series of radiographic views. This could, however, influence the surgeon’s decision to continue to operate on the patient when allocated to surgery (i.e. could lead to a crossover).

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible for the trial if they:

-

were skeletally mature and aged ≥ 16 years

-

presented at a participating site within 2 weeks of their injury and within which time it was feasible to have surgery

-

had a clear, unequivocal bicortical fracture of the scaphoid waist seen on a series of plain radiographs of the scaphoid that:

-

– did not involve the proximal pole (the proximal 20% of the scaphoid) and

-

– included minimally displaced fractures with a step or gap of ≤ 2 mm on any radiographic view.

-

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the trial if:

-

their fracture had > 2-mm displacement, as these fractures are likely to be unstable and require surgical intervention

-

they had a concurrent wrist fracture in the opposite limb

-

they had a trans-scaphoid perilunate dislocation

-

they had multiple injuries in the same limb

-

they lacked the mental capacity to comply with treatment or data collection

-

they were pregnant, because radiation exposure would be contraindicated

-

they were not resident in the trauma catchment area of a participating site to allow follow-up.

Setting

The trial recruited from the orthopaedic departments of 30 NHS hospitals in England and one hospital in Wales. There were three additional hospitals in England that screened for patients but did not recruit to the trial. Recruitment started in July 2013 and the final follow-up was in September 2017. All 34 participating trusts are listed in Appendix 1.

Interventions

Cast treatment followed by surgical fixation if there is confirmed non-union

The control treatment was non-operative, with wrist immobilisation in a below-elbow cast for 6–10 weeks, followed by mobilisation. The below-elbow cast could include the thumb or not, as this does not affect union rate. 8 Early CT was obtained if plain radiographs at 6–12 weeks raised any suspicion of non-union. If non-union was confirmed on radiographs and/or CT scans, urgent surgical fixation was expected to be performed and was encouraged by the trial team, which monitored this with the completion of the 6- and 12-week treatment confirmation forms (see Report Supplementary Materials 1 and 2). The surgical procedure to treat a non-union and postoperative care were similar to the surgical arm of this trial. Cast immobilisation, identification and confirmation of non-union at 6–12 weeks, and immediate surgical fixation of confirmed non-union is the current standard non-operative pathway. 3 We anticipated that most, if not all, fixation of confirmed non-union would occur by around 12 weeks.

Surgical fixation

Surgical treatment was by percutaneous or open surgical fixation depending on the surgeon’s preferred technique. Standard CE-marked headless compression screws18,52 were used to avoid the pressure effects of the screw head on articular cartilage. These are standard surgical techniques. 20–22 The type of implant used was not restricted, but the screw used was recorded (see Report Supplementary Material 3). The surgical approach or the postoperative care was not specified and was instead left to clinical discretion, as it was expected that most surgeons would use some splintage for the first few weeks after surgery. The application of a plaster cast or splint following surgery, and its duration, was recorded. At each recruiting site, it was agreed which surgeons would fix the scaphoid fractures and that surgeons would use techniques with which they were familiar to avoid learning-curve problems.

Rehabilitation

All participants randomised into the two groups received standardised, written physiotherapy advice detailing the exercises they needed to perform for rehabilitation following their injury (see Report Supplementary Material 4). All participants were advised to move their shoulder, elbow and finger joints fully within the limits of their comfort. Those participants treated in a cast performed range-of-movement exercises at the wrist as soon as their plaster cast was removed at the 6-week follow-up appointment as long as there were no concerns regarding bone union. Those participants who had the fracture fixed began their wrist exercises as soon as comfort permitted, if they did not have a plaster cast, or as soon as the cast was removed. Any other rehabilitation input beyond the written information sheet (including a formal referral to physiotherapy) was the decision of the treating clinicians. A record of any additional rehabilitation input (including the reason for referral and number of appointments) was recorded at the 52-week hospital visit.

Outcomes

The outcomes and the time points when various outcomes were assessed are described below.

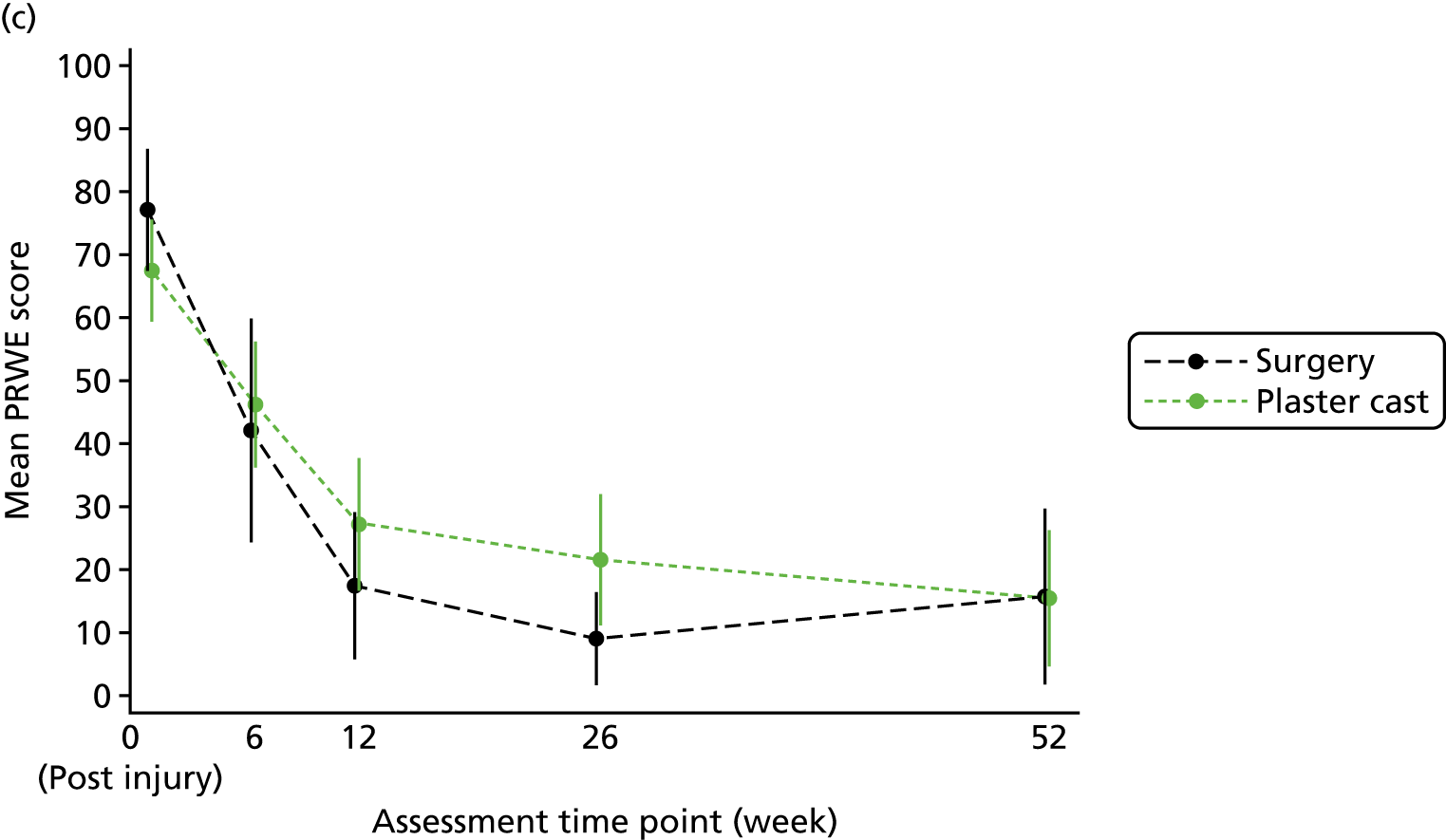

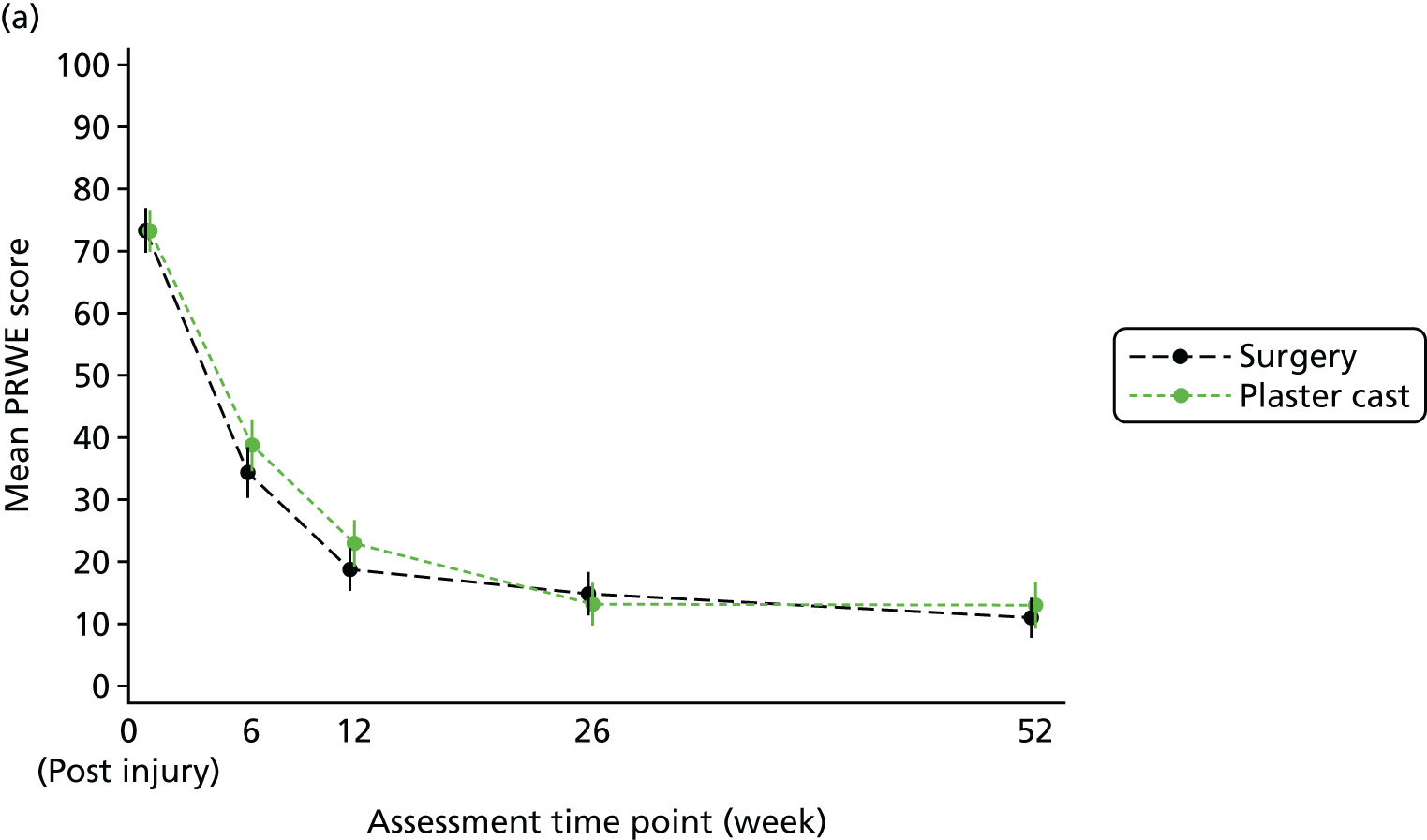

Primary outcome

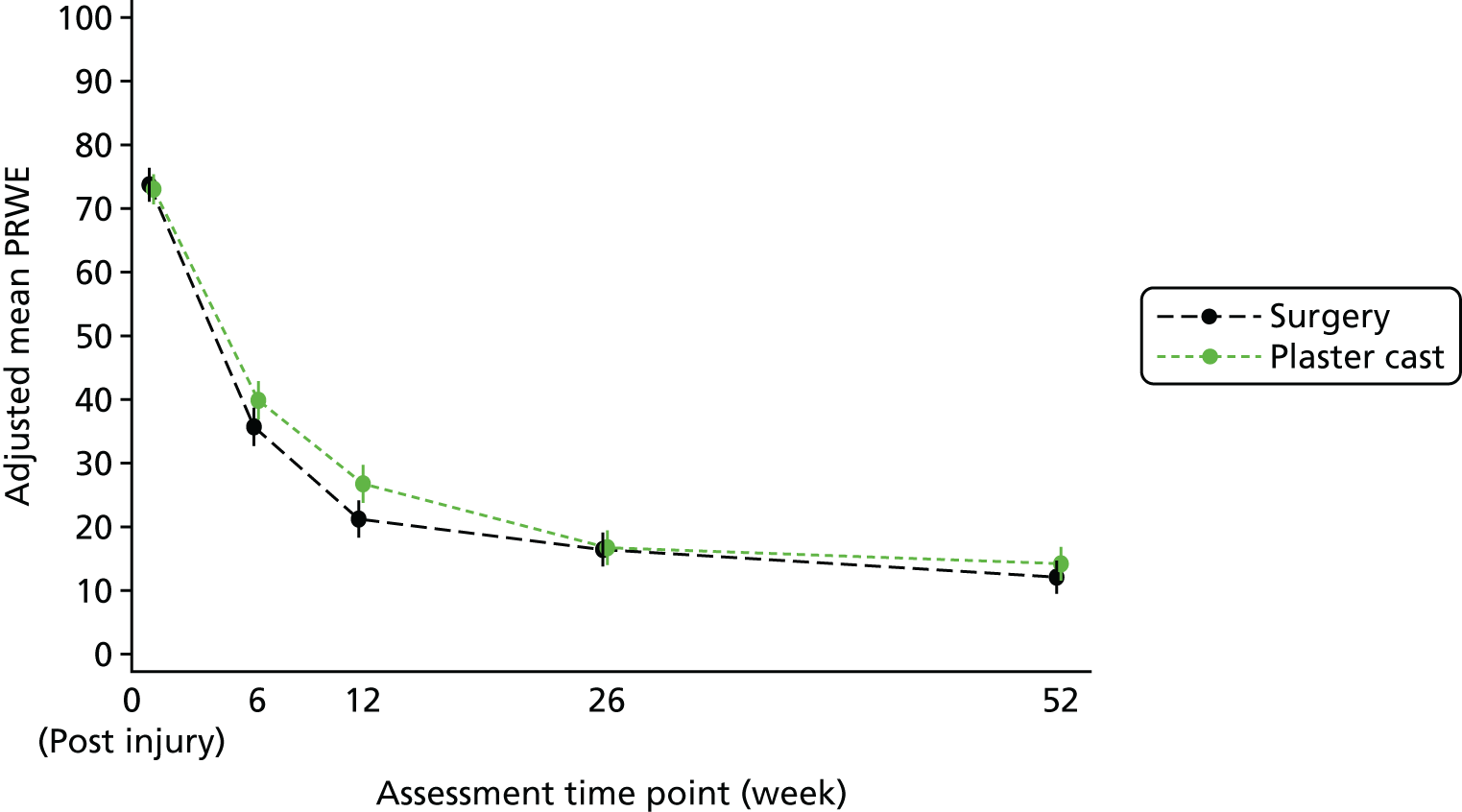

The primary outcome and end point for the trial was the PRWE total score at 52 weeks from randomisation. The PRWE was completed at baseline for the time before and after injury, and at 6, 12, 26 and 52 weeks, and will be completed 5 years after randomisation. The PRWE is a 15-item questionnaire that is completed by the participant. It is a brief, reliable and valid instrument for assessing wrist pain and disability. 50,53 Scoring for all the questions is on a 10-point ordered scale, ranging from ‘no pain’ or ‘no difficultly’ (0) to ‘worst ever pain’ or ‘unable to do’ (10). A total score can be computed on a scale of 0–100 (0 = no disability), as well as two non-overlapping subscales (pain and function), which are weighted equally. The PRWE score was chosen as the primary outcome because patient-reported functional outcomes are favoured for decision-making and it allows the assessment of both wrist pain and function.

Two small RCTs3,18 of patients with scaphoid fractures have demonstrated that there is little change in objective and subjective outcomes between 26 and 52 weeks. In the case of the 10–12% of patients who are treated initially in cast but do not heal, surgery should be performed between 6 and 12 weeks after randomisation. Therefore, if assessed at 26 weeks, this would leave only 14–20 weeks for healing and recovery to take place. To allow all patients the time to heal from surgery and to stabilise after any complications, 52 weeks was chosen as the primary end point.

Secondary outcomes

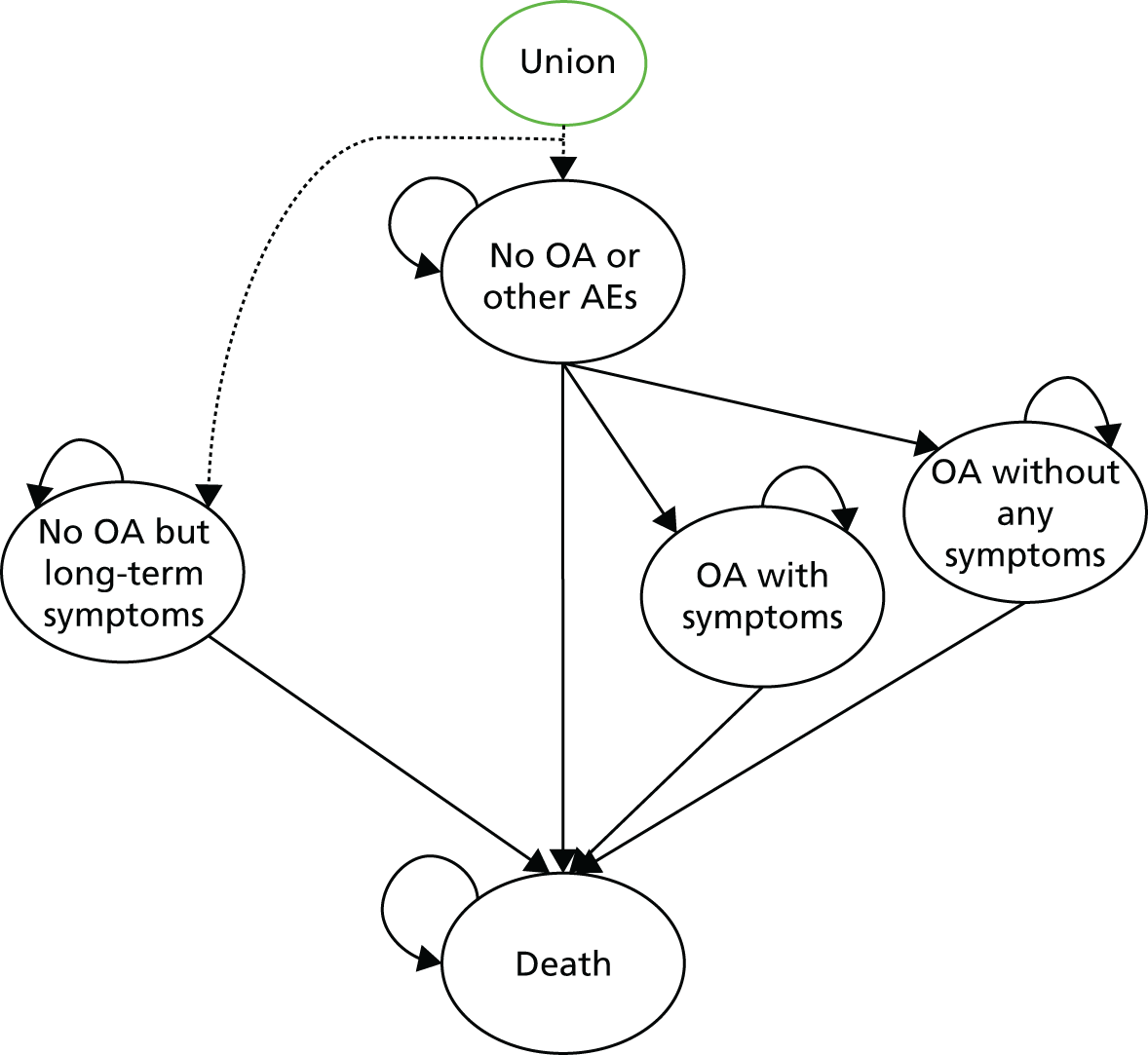

The secondary outcomes were health-related quality of life (HRQoL), bone union, range of movement and grip strength, return to work and unpaid recreational activities, and complications.

Health-related quality of life

Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation

The total PRWE scores at the other time points (6, 12, and 26 weeks) and the PRWE subscale scores of pain and function were secondary outcomes.

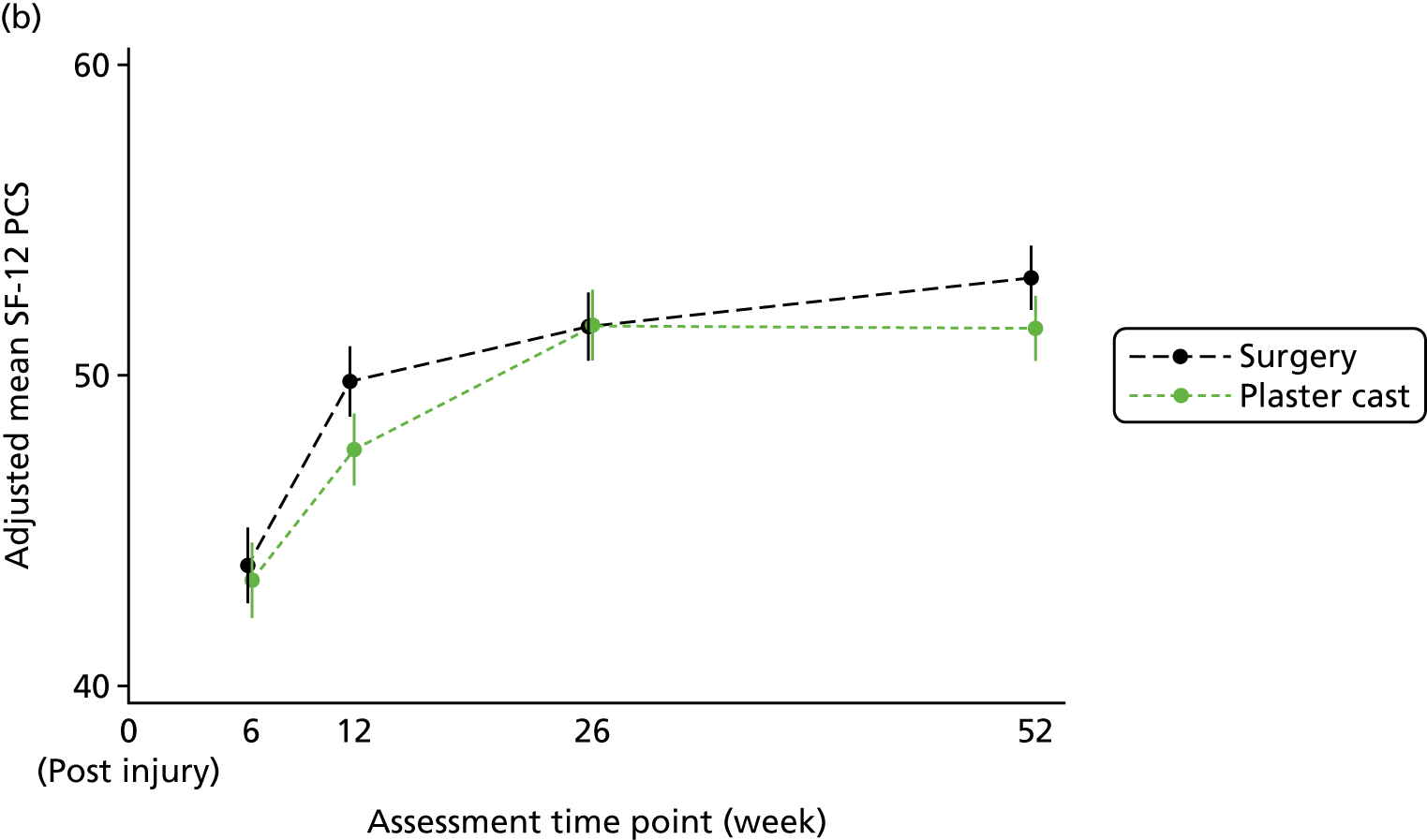

Short Form questionnaire 12-items

The Short Form questionnaire 12-items (SF-12) is a generic patient-reported outcome measure of physical and mental health, the population norms of which have a mean of 50 points and a standard deviation of 10 points; higher scores indicate better health. 54 The SF-12 was completed at 6, 12, 26 and 52 weeks to measure the potential broader consequences of a scaphoid fracture on participants’ physical and mental health.

EuroQol

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), is a validated, generic patient-reported outcome measure covering five health domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) with three response options to each domain. 55,56 The use of this non-fracture-specific instrument allows the assessment of HRQoL outcomes in the health economic analysis. The EQ-5D-3L has high validity and reliability in proximal humerus fractures57 and hip fractures. 58 It was completed at baseline and at 6, 12, 26 and 52 weeks.

Bone union

The secondary outcome of bone union59 was determined at 52 weeks (in line with the primary end point). A CT scan and a series of plain radiographs were obtained comprising posterior–anterior, lateral, 45° semiprone and 45° semisupine views and an elongated scaphoid view (e.g. Ziter-type view). Routine radiographs were also collected for bone union assessment at 6- and 12-week hospital clinics.

Union was defined as complete disappearance of the fracture line8 on radiographs and complete bridging on CT scans60,61 in comparison with those taken at baseline. Partial union was based on the proportion of the fracture plane traversed by bridging trabeculae on true sagittal and coronal multiplanar reconstructions (MPRs) of the scaphoid on CT. CT was used to determine non-union, as there is only poor to moderate inter-observer agreement (range of kappa from 0.11 to 0.53) when determining the union of a scaphoid fracture on plain radiographs. 62

Scaphoid fracture displacement was assessed on radiographs and on a CT scan. 63

Malunion was assessed on the 52-week CT scan. 64 Malunion was defined as a ratio of scaphoid height to length ≥ 0.6 in the true sagittal axis of the scaphoid, to assess any humpback deformity. 65

A limitation of this assessment of bone union, however, was that the presence of the screw to fix the fracture would unblind the observer regarding whether the participant had had an operation or not. To minimise the potential for this to introduce bias, two consultant radiologists with a special interest in musculoskeletal radiology and a consultant orthopaedic surgeon (chief investigator) interpreted the plain radiographs and CT scans independently of each other. All three met to discuss cases in which there was discordance in line with the rules defined in the standard operating procedure (see Report Supplementary Material 5). The two radiologists were both employed at participating hospital sites (Leicester and Birmingham). During the trial, they did not report on plain radiographs or CT scans of the scaphoid during clinical practice, in an attempt to maintain independence when reporting on the imaging of trial participants.

Range of movement and grip strength

The range of movement of both wrists was measured using a goniometer66 and the grip strength of both hands was measured using a calibrated Jamar dynamometer. 67–70 Both were recorded at baseline and at 6, 12 and 52 weeks (see Report Supplementary Material 6). The measurements were performed with the subject seated and their arm by their side, their elbow bent at 90° and their wrist in a neutral position for rotation. 71 Staff were advised to use the second setting on the Jamar dynamometer, except for when testing participants with large hands, when the third setting was used. 72 The Beighton joint laxity score (excluding the thumb count for the injured wrist) was recorded at baseline to measure the hypermobility of joints. 73 These assessments were standardised across participating sites using an instruction sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 7).

Return to work and unpaid recreational activities

This was established through participant self-reporting on the number of days off work and their ability to perform usual activities when at work and when performing unpaid recreational activities. This was recorded at the 6-, 12-, 26- and 52-week follow-ups.

Complications

Expected and unexpected complications were recorded at the 6-, 12- and 52-week hospital visits (see Report Supplementary Material 8). The expected complications included:

-

infection, defined as ‘surgical site infection’74

-

delayed wound healing, defined as any wound that had not healed by 2 weeks

-

complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), defined as a puffy, painful swelling of the whole hand restricting full tuck of the fingers at 2 weeks

-

nerve events (hypoaesthesia or numbness in the territory of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve, superficial division of the radial nerve or the median nerve)

-

vessel events [large (> 2 cm) haematoma in the line of the radial artery]

-

screw-related complications (protrusion of either end into the adjacent joint, fracture or bending of the screw, a radiolucent halo around any part of the screw > 1 mm, screw backing out or moving)

-

degenerative changes in the adjacent joints75

-

avascular necrosis76 of the proximal pole of the scaphoid.

In addition, the three raters reviewed the imaging at each time point for complications. This included assessing the presence (or not) of OA, the presence (or not) of screw penetration, screw lucency (none, < 1 mm or 1–2 mm) and avascular necrosis (no radiodensity, just radiodense, marked radiodensity on one view or one MPR, or marked radiodensity on more than one view or MPR).

Sample size

For surgery to justify its increased costs and the exposure to risk, it must result in greater or quicker improvement in patients’ wrist symptoms and function than non-operative management. A 6-point improvement in the PRWE score in the surgery group (compared with the controls) was chosen to be the minimally clinical important difference. The standard deviation of the PRWE score at 52 weeks was taken to be 20 points based on the PRWE user manual. 49 This figure was reported for distal radius fracture rather than scaphoid fracture at 6 months. The only published evidence for scaphoid fracture implies a standard deviation in the range of 8–10 points;28 however, this estimate was at a median of 10 years after the patient’s injury. To be conservative, a standard deviation of 20 was chosen. This gives a standard effect size of 0.3 for the 6-point PRWE difference. A superiority design was used to observe an effect size of 0.3 at 80% power using a two-sided 5% significance level requiring 350 participants in total. After allowing for 20% attrition, the recruitment target was 438 participants (219 surgery and 219 plaster cast). The estimate of attrition was expected to be realistic, given that four previous RCTs (three studies had a single centre and one study had two centres) of the treatment of scaphoid fractures had reported response rates for completion of patient-reported functional outcomes to be between 77% and 100%. 31

There were no planned interim analyses for the trial or stopping guidelines. There was, however, an internal pilot study from which the data contributed to the final analyses. The primary reason for the pilot study was to check the assumptions about the site set-up, patient recruitment and the feasibility of the trial. The independent oversight committees reviewed the progress that was made during the internal pilot and recommended that the trial continue with the planned increase in the number of sites. In the absence of a standard deviation for the primary outcome at 52 weeks, this was estimated from the participants who were recruited into the internal pilot study. This estimate corroborated the standard deviation chosen for the sample size calculation.

Recruitment

A research nurse identified patients who were potentially eligible for fracture clinics, referred from accident and emergency (A&E) departments or other sources (e.g. walk-in centres, cottage hospitals). The orthopaedic surgeon confirmed eligibility (see Report Supplementary Material 9) and invited the patient to consider joining the study. The research nurse or clinician provided the patient with an information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 10) and answered any questions. The patient was asked to consent at that time or was offered up to 48 hours to discuss the study with family or friends before deciding whether to take part or not. When patients gave consent (see Report Supplementary Material 11), they were asked to complete a baseline form (see Report Supplementary Material 12). The site staff then contacted York Trials Unit (YTU), either by telephone or via the internet, to access the secure randomisation service. For patients who did not consent, a form was completed to record the following aspects: reasons for non-consent, patient and surgeon treatment preferences, and the agreed treatment plan (see Report Supplementary Material 13). Both patients who consented to take part in the trial [using the main trial information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 10)] and those who did not consent to take part in the trial [using a separate information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 14)] were invited to take part in an interview. This is explained further in Chapter 5.

Strategies for achieving adequate participant enrolment to reach the target sample size included seeking advice from a patient focus group, sharing best practice with the research nurses at participating sites, and biannual discussions with our principal investigators (PIs) at the scientific meetings of the British Society for Surgery of the Hand (BSSH). Hospital staff were provided with training about study procedures at the site initiation visits and with a trial site manual. During the trial, training sessions and reminders were communicated using e-mail bulletins, face-to-face meetings with the PIs at BSSH conferences and a training day with research nurses. In addition, the trial co-ordinators provided support and guidance to staff at participating sites (e.g. when new staff joined or replaced existing site staff) and also sought guidance from the chief investigator.

Randomisation

The randomisation sequence was based on a computer-generated randomisation algorithm provided by a remote randomisation service (telephone or online access) at YTU. The unit of randomisation was the individual patient on a 1 : 1 basis. As the non-union rate for displaced scaphoid fractures is 14%, compared with 10% for transverse undisplaced fractures,8,10,39 randomisation was stratified by the presence or not of displacement as assessed by the staff at the recruiting site. Random block sizes of 6 and 12 were used. Displacement was defined as a step or gap of 1–2 mm inclusive as seen on any radiographic view. The research nurse used the remote randomisation service to register eligible and consenting participants before computer generation of the allocation. The research nurse then informed the treating surgeon of the allocation. This ensured treatment concealment and immediate unbiased allocation.

Blinding

As the trial was pragmatic and compared surgery with initial cast treatment, blinding of participants and clinicians to treatment allocation was not possible. When possible, the treating surgeon took no part in the postoperative assessment of participants. The statistician was blind to group allocation until after data were hard locked and no further changes could be made. To minimise bias in the assessment of bone union, all radiographs and CT scans were assessed independently by two consultant musculoskeletal radiologists and a consultant orthopaedic surgeon (chief investigator). Any disagreement was resolved through discussion.

Statistical methods

Analyses were conducted using the principles of intention to treat (ITT), including all randomised participants in the groups to which they were allocated, where data were available. Analyses were conducted in Stata® v15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) using two-sided statistical tests assessed at the 5% significance level.

Recruitment

Site and patient recruitment was presented. The characteristics of the population of patients who were screened, ineligible and eligible, stratified by consent, were summarised. The flow of participants through the trial was presented in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

Baseline characteristics of randomised participants

Baseline participant characteristics and fracture details were summarised descriptively overall and by randomised group, both ‘as randomised’ and ‘as analysed’, comparing the groups as included in the primary outcome analysis model (i.e. with full data for the baseline covariates and valid PRWE data for at least one post-randomisation time point). No formal statistical comparisons were undertaken on baseline data.

Follow-up

For each time point, the number of participant questionnaires sent and returned, with median [interquartile range (IQR)] days to completion and return, was presented by treatment group and overall. The number of questionnaires completed at home, over the telephone or in the hospital was reported. Return rates for hospital forms were tabulated by randomised group and time point.

Hospital visits

Participants were asked to attend a hospital follow-up visit at 6, 12 and 52 weeks post randomisation. Baseline participant characteristics and fracture details were summarised descriptively overall and by randomised group according to whether or not participants attended the hospital visit at each time point.

Compliance with random allocation and treatment received

The treatment received by participants in the two groups was summarised, with reasons given for any treatment crossover.

Primary outcome (Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation) analysis

The PRWE was assessed at baseline (pre and post injury, prior to randomisation) and at 6, 12, 26 and 52 weeks post randomisation. The PRWE total score is a value between 0 and 100, where a higher score indicates worse pain and functioning. The score is computed by scoring the two subscales out of 50 (pain = sum of items 1–5; function = sum of items 6–15 divided by two) and summing them, so that pain and function problems are weighted equally. If there was up to one missing item in each subscale, then the missing item was replaced by the mean of the completed items within that subscale. 49 If two consecutive responses (between 0 and 10) to a particular item were selected, then the higher of the two (the worse response) was taken for analysis. Other ambiguous responses were treated as missing. If more than one item was missing in either subscale, then a score for that subscale, or for the total, could not be calculated.

The number and percentage of participants with valid and partial PRWE data were reported by randomised group and time point. Baseline participant characteristics and fracture details were summarised descriptively overall and by randomised group according to whether or not participants had valid PRWE outcome data at each post-randomisation time point. Total PRWE scores were summarised by time point according to whether or not participants had valid data for (1) all post-randomisation time points, (2) at least one, but not all, post-randomisation time points or (3) no post-randomisation time points. PRWE scores (subscales and total) were summarised descriptively by treatment group and overall.

Total PRWE scores were compared between the two groups using a covariance pattern, mixed-effect linear regression model incorporating all post-randomisation time points. Treatment group, time point, a treatment-by-time interaction, participant age at randomisation, baseline fracture displacement and dominance of injured hand were included as fixed effects, and participant was included as a random effect (repeated observations per participant). Fracture displacement was used as a stratification factor in the randomisation; however, there were several instances in which the wrong displacement category was used in the randomisation. Such stratification errors were identified when there was a discrepancy between the data provided at randomisation and the data recorded on the study eligibility form. If the randomisation data were incorrect, a file note was raised and the trial statistician was notified; if the data on the study eligibility form were incorrect, the form was amended. The displacement used in the randomisation was the variable included in the primary analysis, but the errors were discussed. The primary model was not adjusted for baseline total PRWE, as, in this young population, we expected pre-injury PRWE score to be low and have little variability and post-injury PRWE score to be confounded, as patients would most likely be in a plaster cast.

An unstructured covariance pattern for the correlation between the observations for a participant over time was specified in the final model based on Akaike information criterion (AIC)77 (smaller value preferred).

An estimate of the difference between treatment groups in total PRWE score was extracted from the repeated measures model for each time point, and overall, with a 95% CI and p-value. The primary end point was the treatment effect estimate at 52 weeks. Estimates for the treatment effect at other time points (6, 12 and 26 weeks) and overall served as secondary outcomes. This repeated-measures approach is more efficient and parsimonious than conducting separate linear regressions for each time point, and also allows for the ‘overall’ (across the whole 52 weeks) effect to be investigated using the same model. The analysis takes advantage of the extra information provided at, and the correlation between, all post-randomisation time points. The standard errors for treatment effects at individual time points were calculated using information from all time points and were hence more robust and accurate than standard errors calculated from separate analyses at each time point. An additional advantage of the mixed model approach is that the presence of missing data across time points does not cause a problem under the assumption that they are missing at random. For the estimates at a single time point, say at 52 weeks, it is primarily the observations at that time point that determine the treatment effect and power; however, owing to the covariance between the post-randomisation time points, greater power and precision is obtained than that from a comparison using only the 52-week data. 78

Model assumptions were checked as follows: the normality of the standardised residuals was checked using a quantile–quantile plot and homoscedasticity was assessed by means of a scatterplot of the standardised residuals against fitted values.

Sensitivity analyses

Missing data

Any response bias was partially minimised by using a mixed-effect, repeated measures model, which allows the inclusion of intermittent responders in the primary analysis. Multiple imputation by chained equations was also used to handle missing PRWE outcome data. Missing outcome and covariate data were predicted by age, fracture displacement, hand dominance and available PRWE data at other follow-up time points. A ‘burn-in’ of 10 was used and 20 imputed data sets were created. Separate linear regressions were then run on the multiply imputed data set to compare the PRWE between the two groups at 6, 12, 26 and 52 weeks, adjusting for age, displacement and dominance of injured wrist. Estimates were combined using Rubin’s rules via the ‘mi estimate’ command in Stata. 79

Handling multisite data

Participants were recruited from multiple sites. To investigate whether or not site affects the outcome, a sensitivity analysis was conducted including site as a random effect (within which participants were nested) in the model as described for the primary analysis. 80

Timing of data collection

The primary analysis model was repeated including only data collected 1 week either side of the 6-week time point, 2 weeks either side of the 12-week time point, 6 weeks either side of the 26-week time point and 8 weeks either side of the 52-week time point.

Post hoc sensitivity analysis including smoking status

Current smoking status (yes/no) was included as a covariate in the primary analysis model in a post hoc sensitivity check, as this factor was found to be imbalanced by chance at baseline between the randomised groups and thought to be associated with healing and complications. The decision to conduct this sensitivity analysis was taken after the primary analysis results were known; this decision was not prespecified in the statistical analysis plan.

Displacement and lack of fracture as assessed by independent review of baseline imaging data

Discrepancies were reported between the displacement of the fracture (< 1 mm or 1–2 mm inclusive) as judged by the treating clinician on plain radiographs and as used for the randomisation and the judgement agreed on by three independent reviewers using the baseline CT scans and radiographs. The primary analysis model was rerun including a variable indicating the level of displacement judged by the three raters instead of that on which randomisation was based.

We report the numbers of cases in which a consensus was reached between the three raters that (1) there was no fracture or (2) displacement of the fracture was > 2 mm, based on their assessment of the baseline radiographs/CT scans, as these were exclusion criteria. Separate sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome model were conducted excluding these patients.

Complier-average causal effect analysis

To account for non-compliance (surgery to plaster cast) and contamination (plaster cast to surgery), a complier-average causal effect (CACE) analysis was conducted. A two-stage least squares instrumental variable approach81,82 was used with randomised treatment as the instrumental variable (implemented using the ‘ivregress’ command in Stata) to compare PRWE scores at 52 weeks, adjusting for age, fracture displacement and hand dominance. For this analysis, it was assumed that, had they been offered surgery, participants allocated to the plaster cast group would have the same probability of non-compliance as those allocated to the surgery group; likewise, it was assumed that, had they been offered non-surgical management, participants allocated to the surgery group would have the same probability of contamination as those allocated to the plaster cast group. Finally, it was assumed that simply being offered the allocated treatment has no effect on the outcome. These assumptions were plausible under randomisation, which should balance covariates across the two groups.

Subgroup analysis

In total, three subgroup analyses were undertaken: one exploring patient treatment preferences as expressed at baseline and two exploring fracture displacement. Owing to the errors in classification of fracture displacement at randomisation, two approaches for the displacement subgroup analysis were taken: one using displacement as defined at randomisation and one using the classification given on the study eligibility forms. Total PRWE scores are summarised by randomised group and time point, stratified by the levels of the baseline factor of interest. To investigate whether the treatment effect varied across the levels of these baseline factors, the factor was included in the primary analysis model alongside an interaction between randomised treatment allocation and baseline factor, using a two-sided p-value of 0.05. Interpretation of these models was made cautiously, as the trial was not powered for interactions. 83,84

Descriptive summaries of baseline participant and fracture data and PRWE scores are presented for:

-

participants in the plaster cast arm stratified by whether or not they needed surgery owing to non-union

-

participants in the surgery arm stratified by whether or not the surgical screw used was too long and caused cartilage damage, as determined on the CT scans by the three independent raters.

There were two feasibility requirements for this trial: (1) that a CT scan was performed within 2 weeks of a patient’s injury (or before surgery if this occurred earlier) and (2) that, for patients in the surgery arm, surgery was performed within 2 weeks after presentation to A&E or another clinic. It was considered a protocol deviation if these tasks were performed outside these parameters. A linear regression for the surgery arm only investigated whether the time from injury to surgery in days was predictive of total PRWE score at 52 weeks, adjusted for age, fracture displacement and hand dominance. Descriptive summaries of baseline participant and fracture data and PRWE scores are presented for:

-

participants stratified by whether or not their CT scan was performed within 2 weeks of the injury (or before surgery if this occurred earlier)

-

participants in the surgery arm stratified by whether or not their surgery was performed outside the target 2-week period from first presenting at A&E or another clinic.

Secondary analysis

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes, namely the pain and function subscales of the PRWE, the physical and mental health component summaries of the SF-12 and grip strength, were summarised descriptively for each time point by treatment group and overall, and were analysed using the same method as for the primary outcome, adjusting for the same covariates. The most appropriate choice of covariance structure was identified separately for use with each outcome, which was always an unstructured pattern.

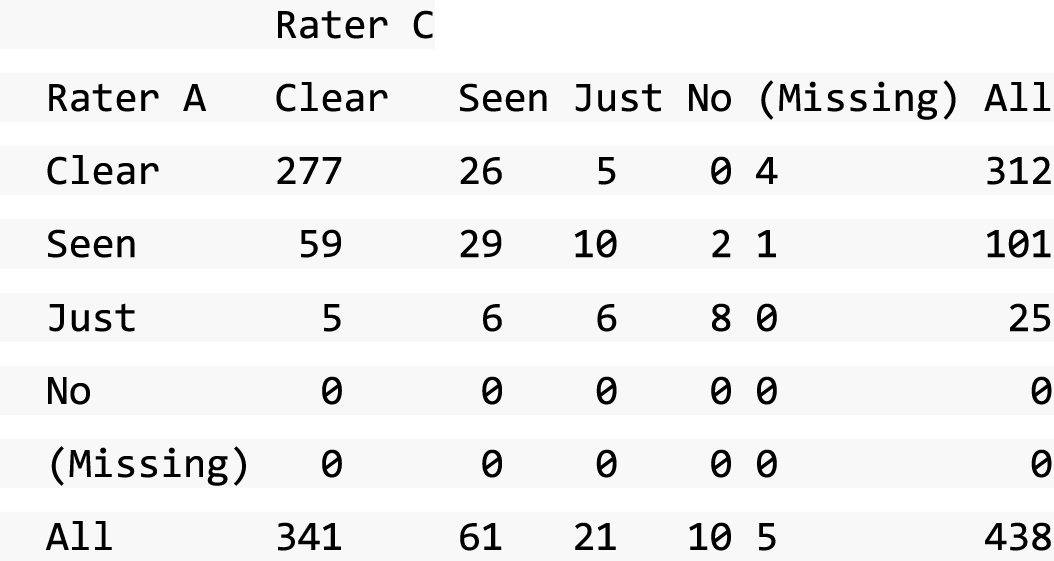

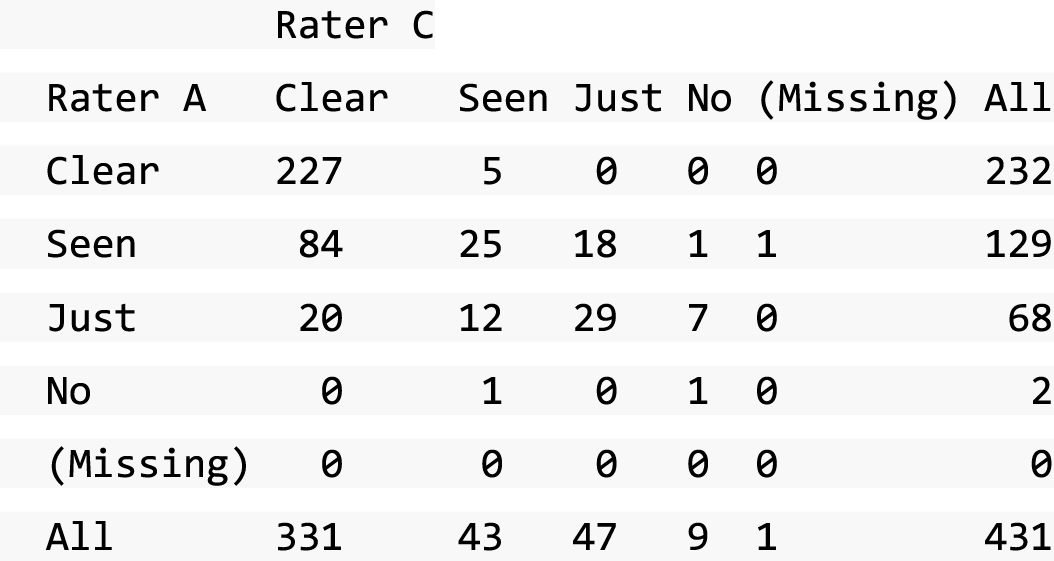

Union

Plain radiographs at 6, 12 and 52 weeks and CT images at 52 weeks were reviewed by three independent raters at the end of the trial for union of the fracture. Union, as reviewed on CT images at 52 weeks, was measured as a percentage (0–100%) and categorised as 0% (non-union), > 0–20% (slight union), > 20–70% (partial union), > 70–100% (but not including 100%; mostly united) and 100% (complete union). The same categories of union were used for radiograph images at 6, 12 and 52 weeks. The extent of union was presented for each time point by randomised group. Participants were dichotomised at each time point as ‘probably need surgery’ (non-union and slight union) and ‘probably do not need surgery’ (partial to complete union) and analysed using a logistic regression model (52-week data only). It was originally planned that a mixed-effect logistic regression model would also be conducted to compare the treatment groups at 52 weeks, with participant as a random effect to account for the repeated measures of union at 6, 12 and 52 weeks, adjusting for age, displacement and dominance of injured wrist as fixed effects. However, this model did not converge. As an alternative sensitivity check, multiple imputation was used to impute the dichotomised union variables at 6, 12 and 52 weeks (imputation included union variables, age, displacement, dominance of injured wrist and allocation). A ‘burn-in’ of 10 was used and 20 imputed data sets were created. A logistic regression was run on the multiply imputed data set to compare union between the two groups at 52 weeks, adjusting for age, displacement and dominance of injured wrist.

The 52-week PRWE scores for patients overall and for patients who did and did not attend imaging at 52 weeks were summarised by treatment group.

Malunion

Scaphoid height and length were measured by the three independent raters of the CT images and plain radiographs. Malunion was defined using a ratio of scaphoid height to length of > 0.6. During the study, literature was published that suggested that a threshold ratio of 0.7 might be more appropriate85 than 0.6. 64 Rates of malunion at the 0.6 and 0.7 thresholds are presented overall and for each treatment group at 6, 12 and 52 weeks.

Complications

Complications were defined as medical, surgical and plaster cast related, and were assessed by clinical examination at 6, 12 and 52 weeks. The number of patients who experienced a complication of a certain type was summarised by randomised group. The presence of any medical, surgical or cast complication recorded on the complications form up to 52 weeks was analysed by logistic regression, adjusting for age, hand dominance and fracture displacement.

Cases in which two out of the three raters agreed, based on the imaging, that there was a complication were reported.

Adverse events

All serious and non-serious adverse events (AEs) were summarised by treatment group.

Agreement analysis

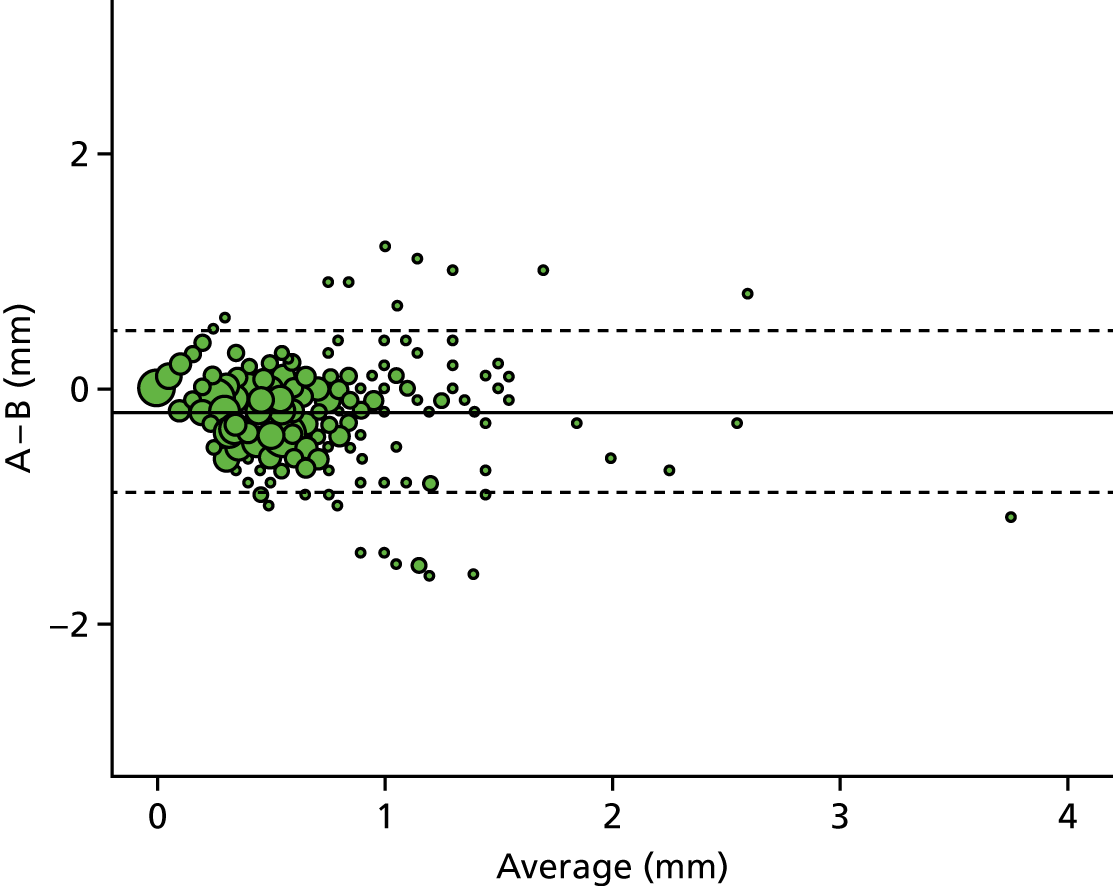

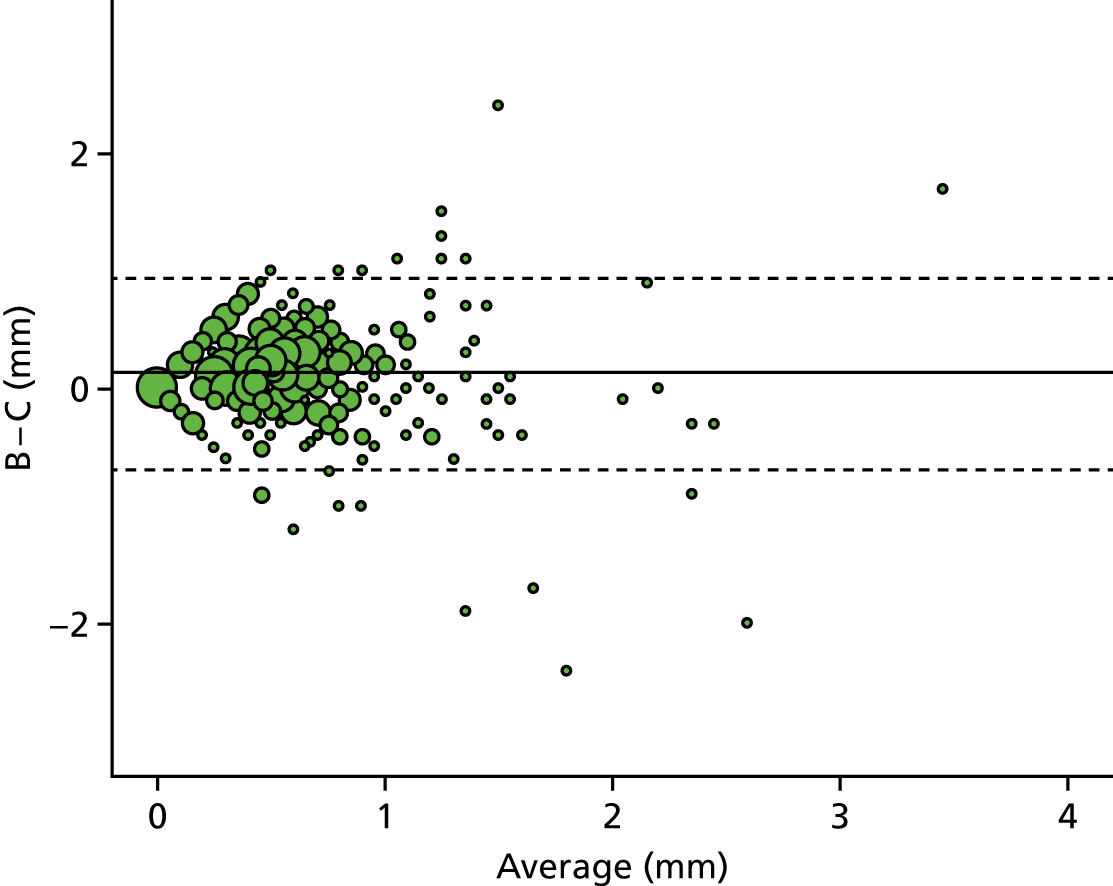

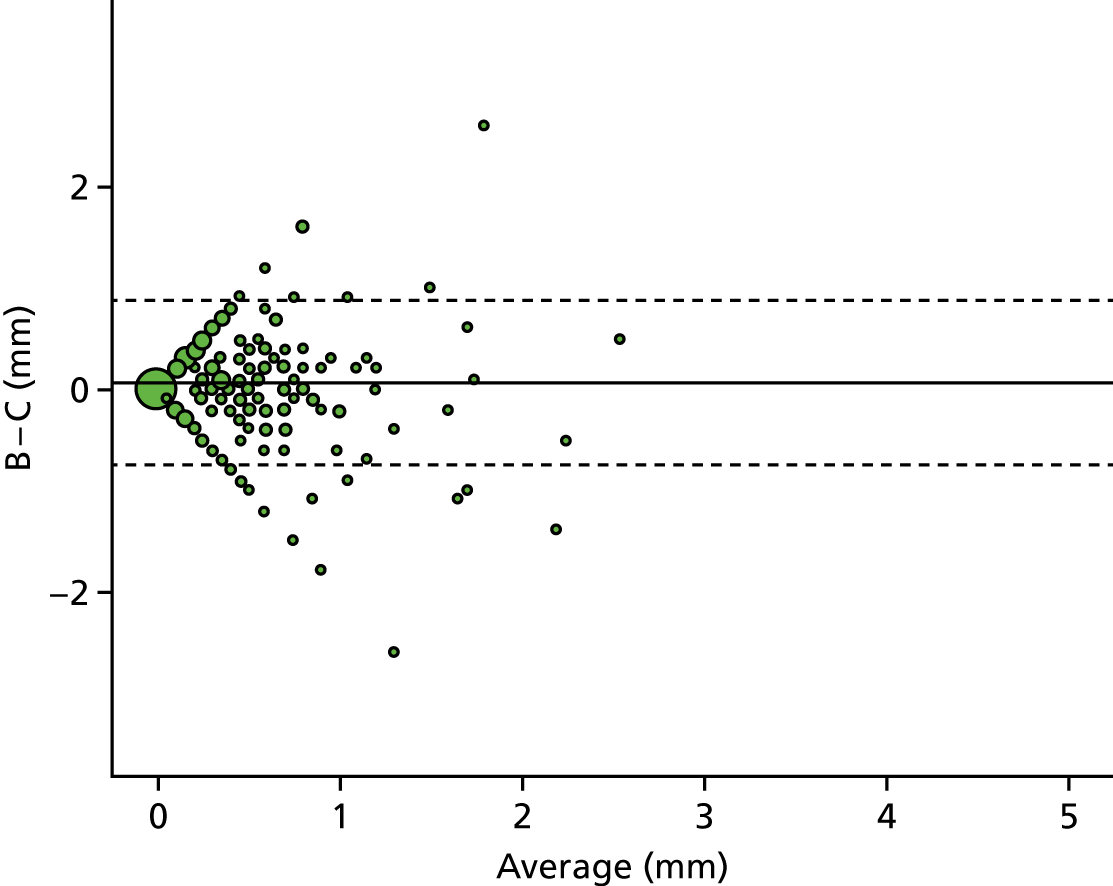

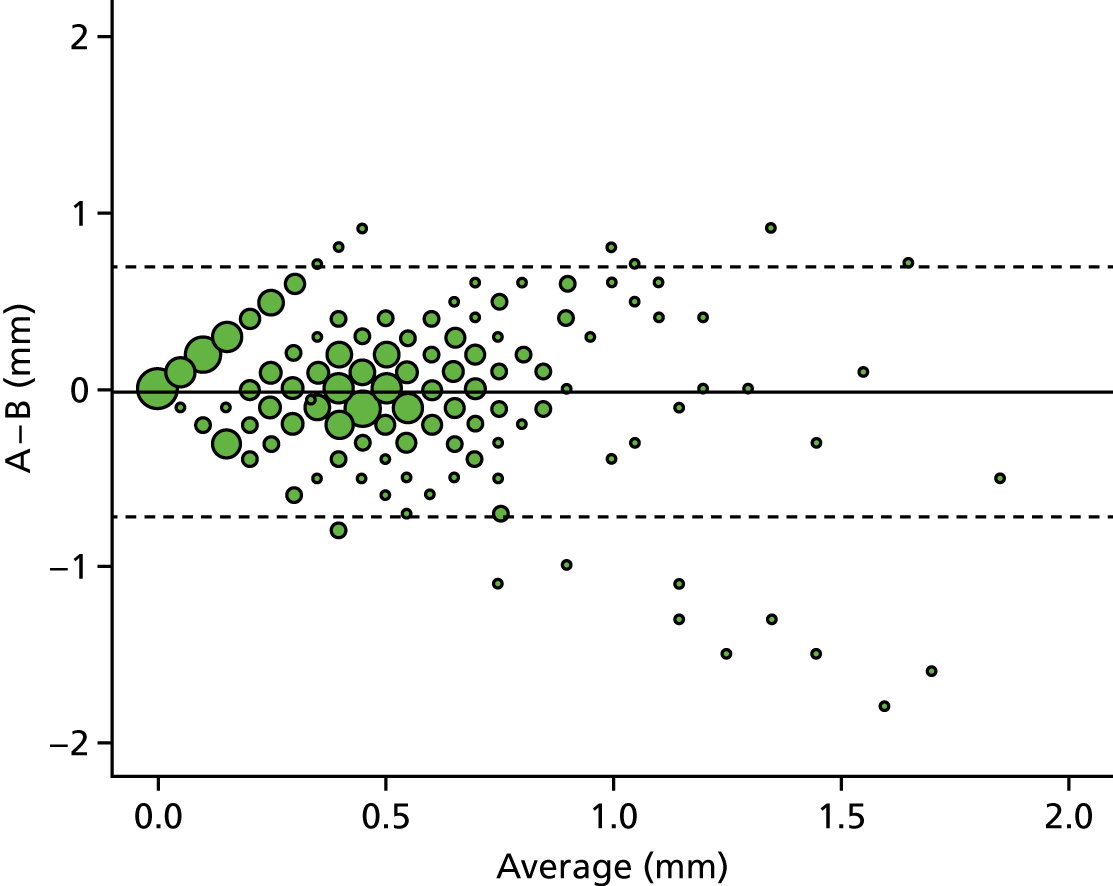

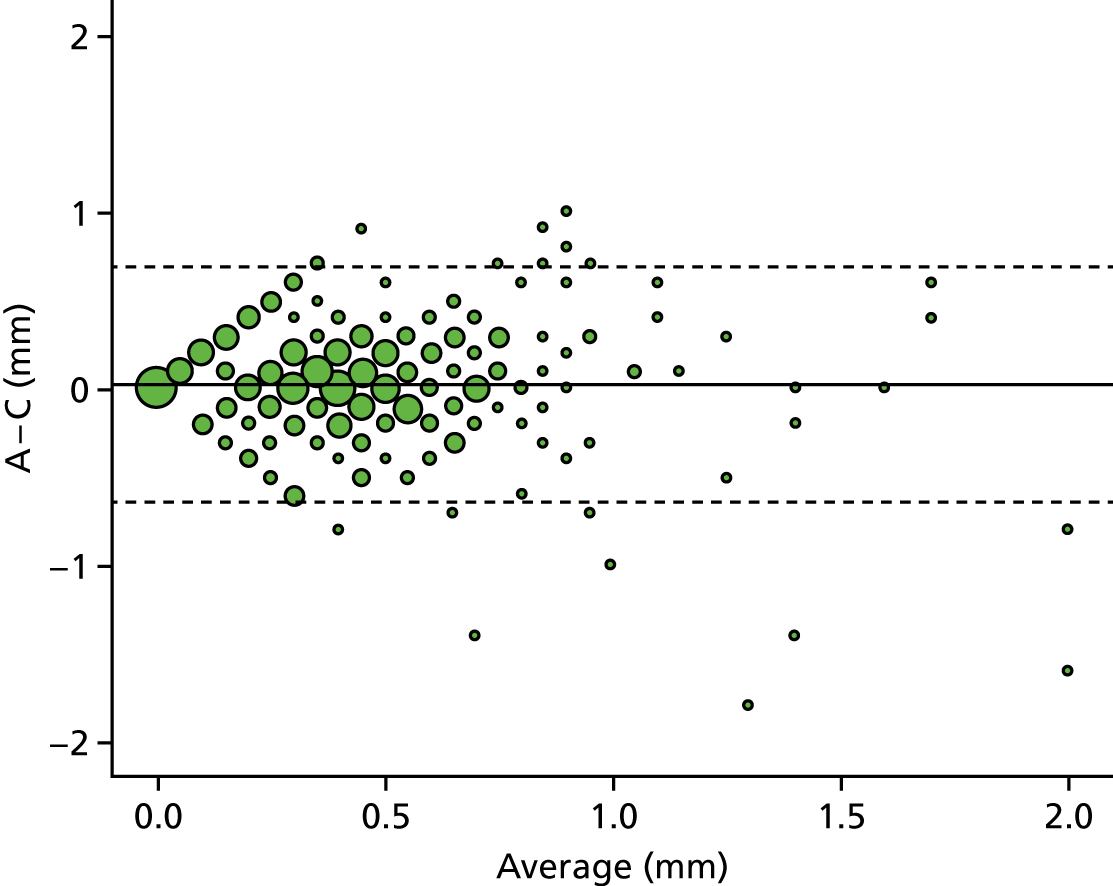

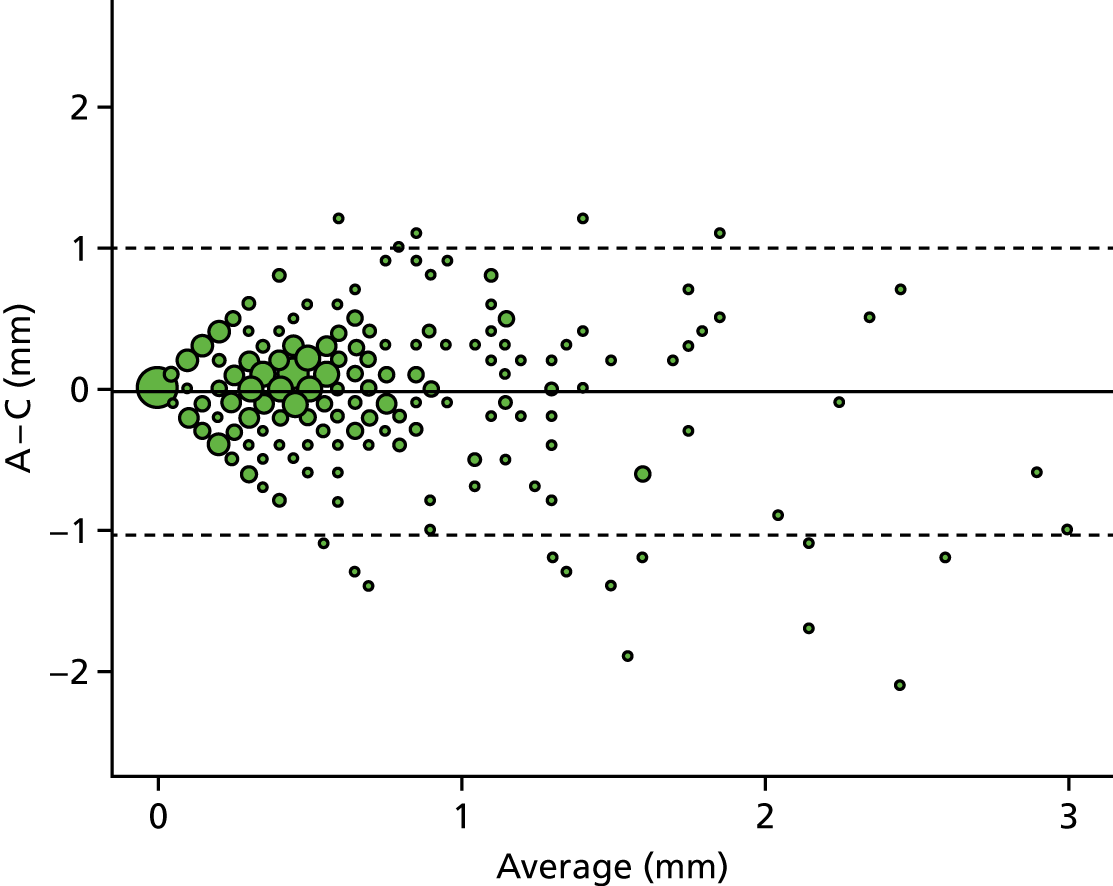

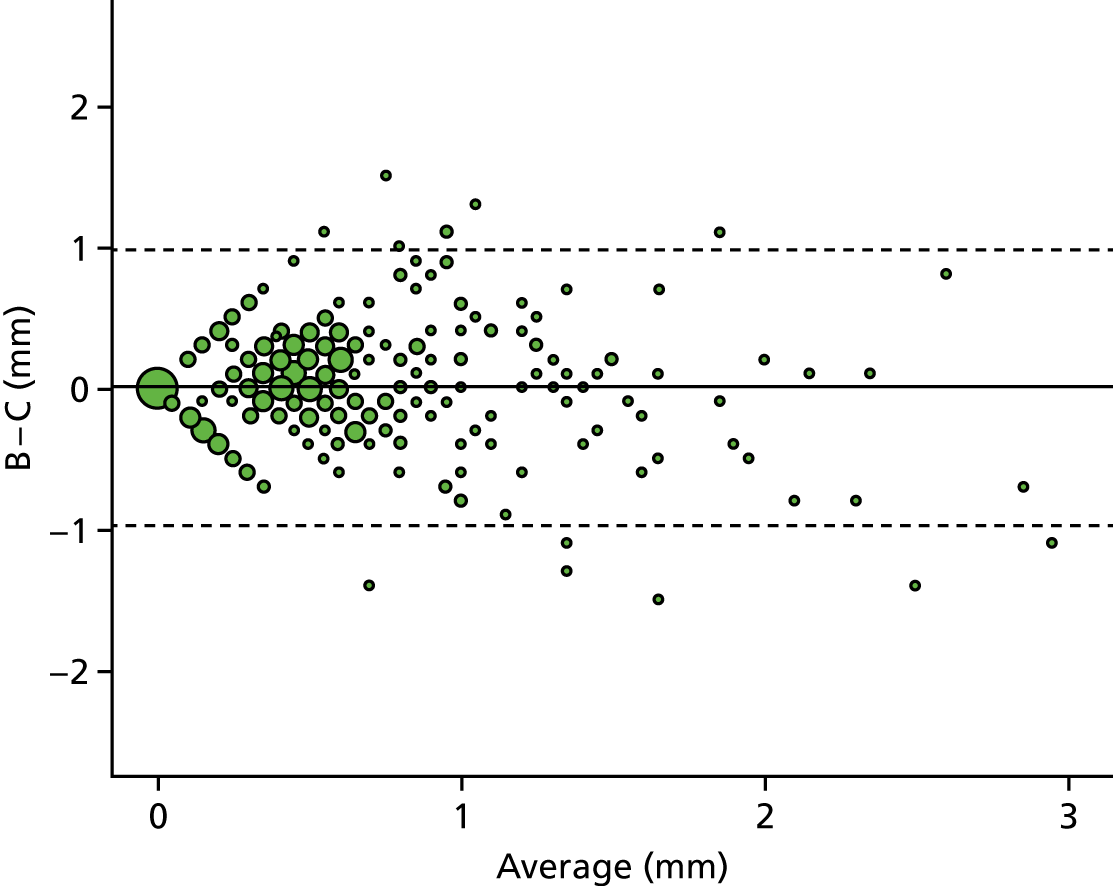

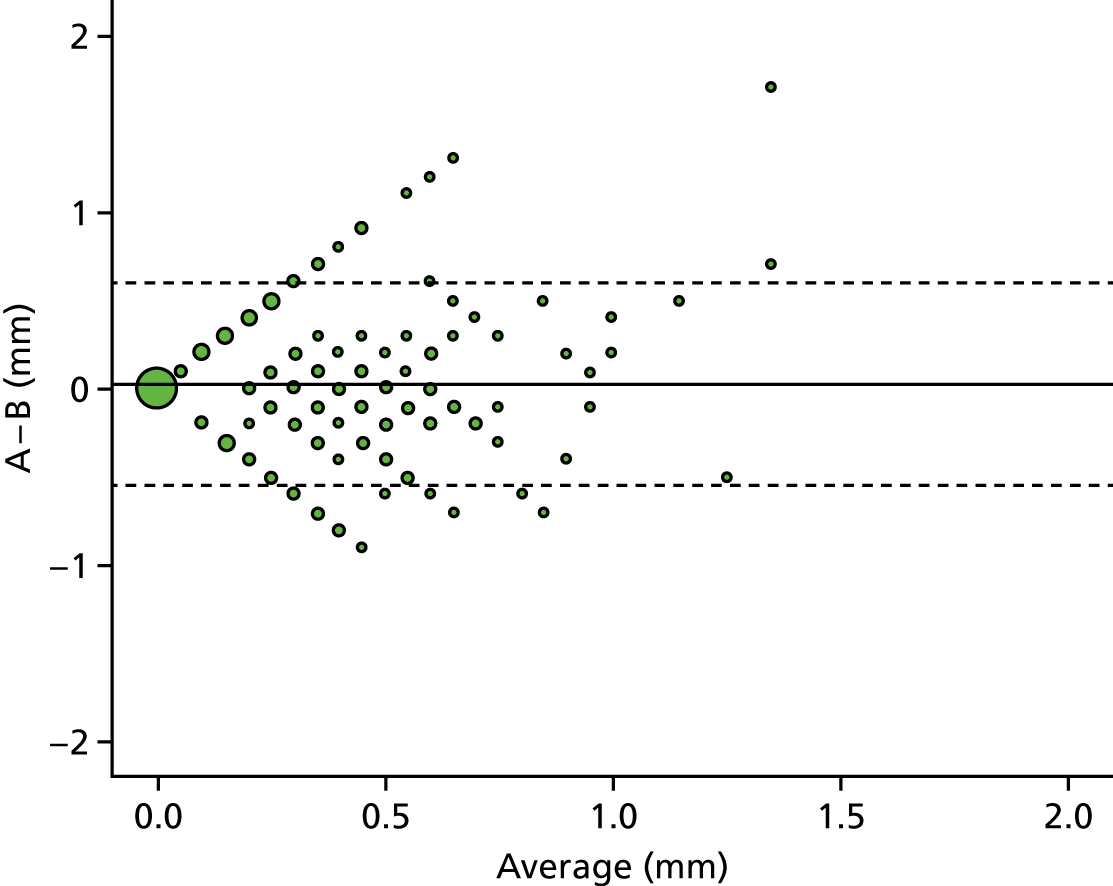

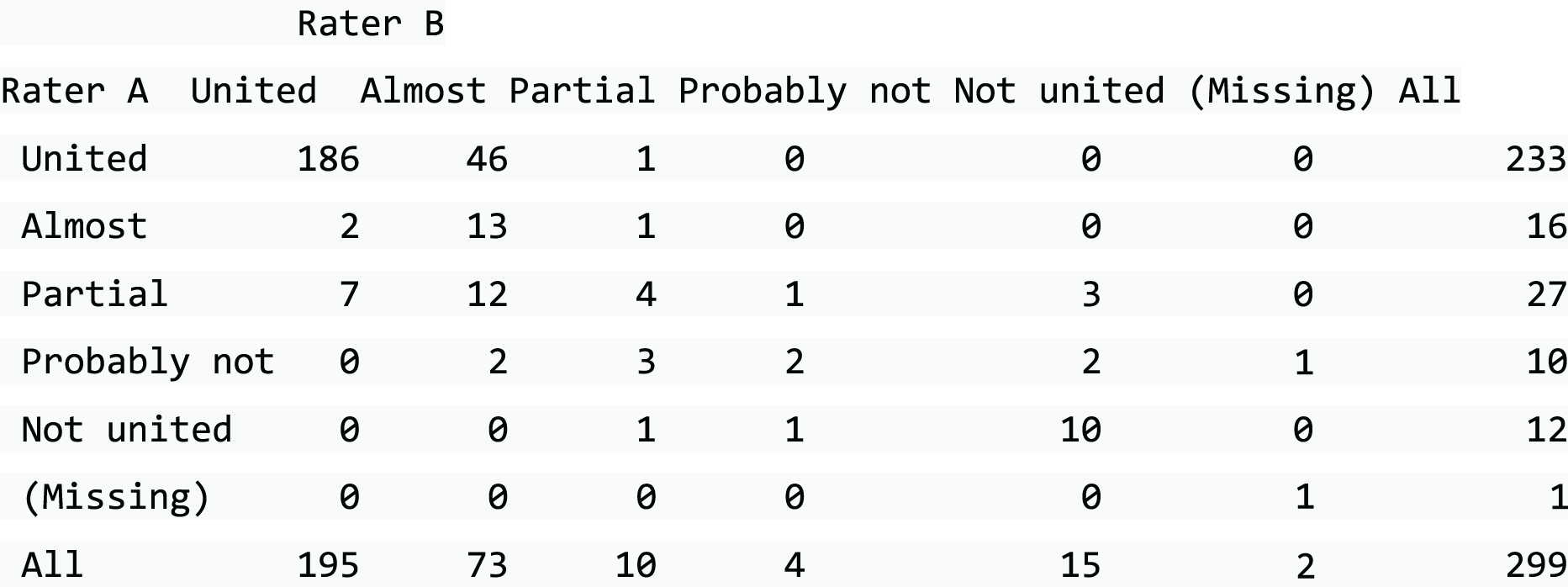

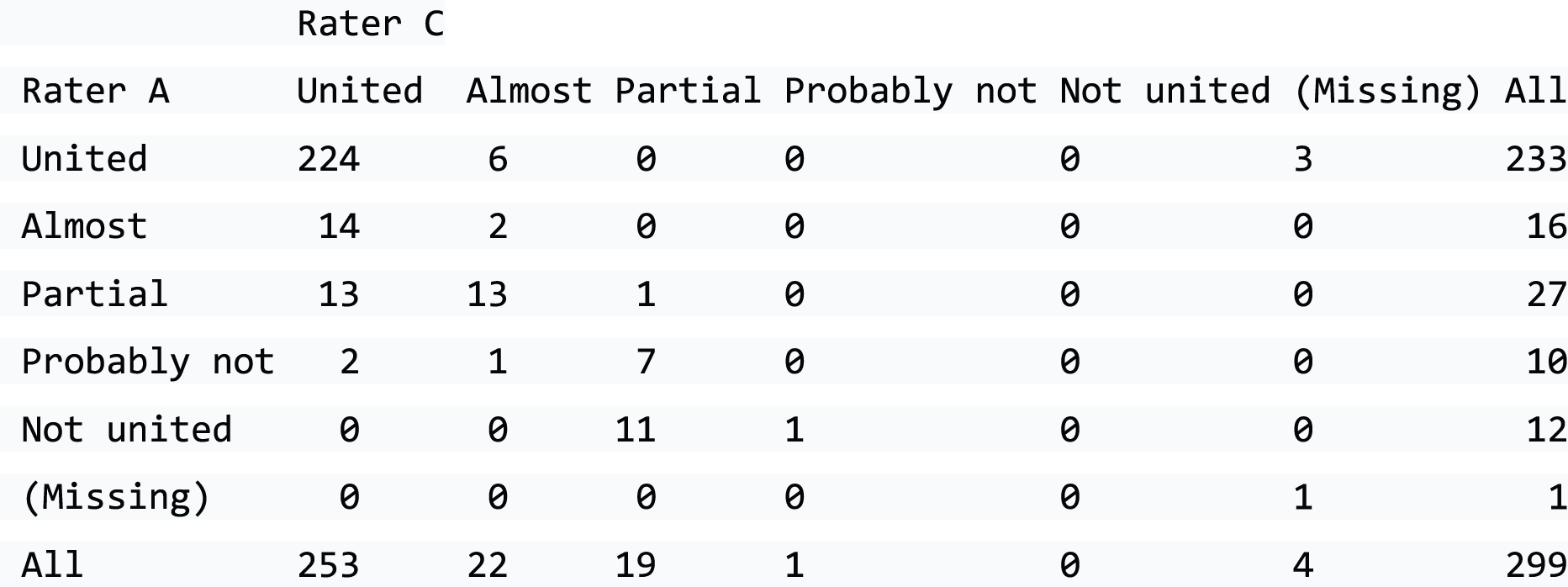

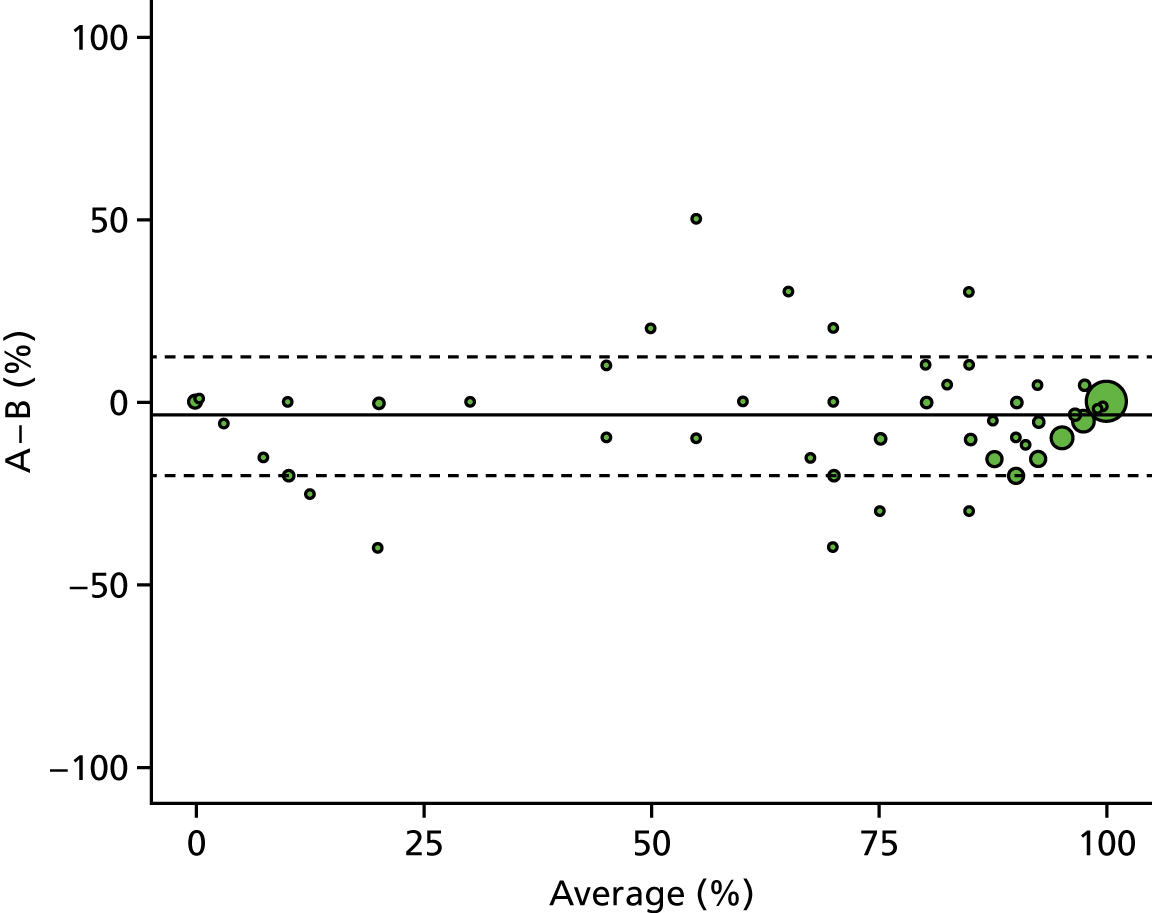

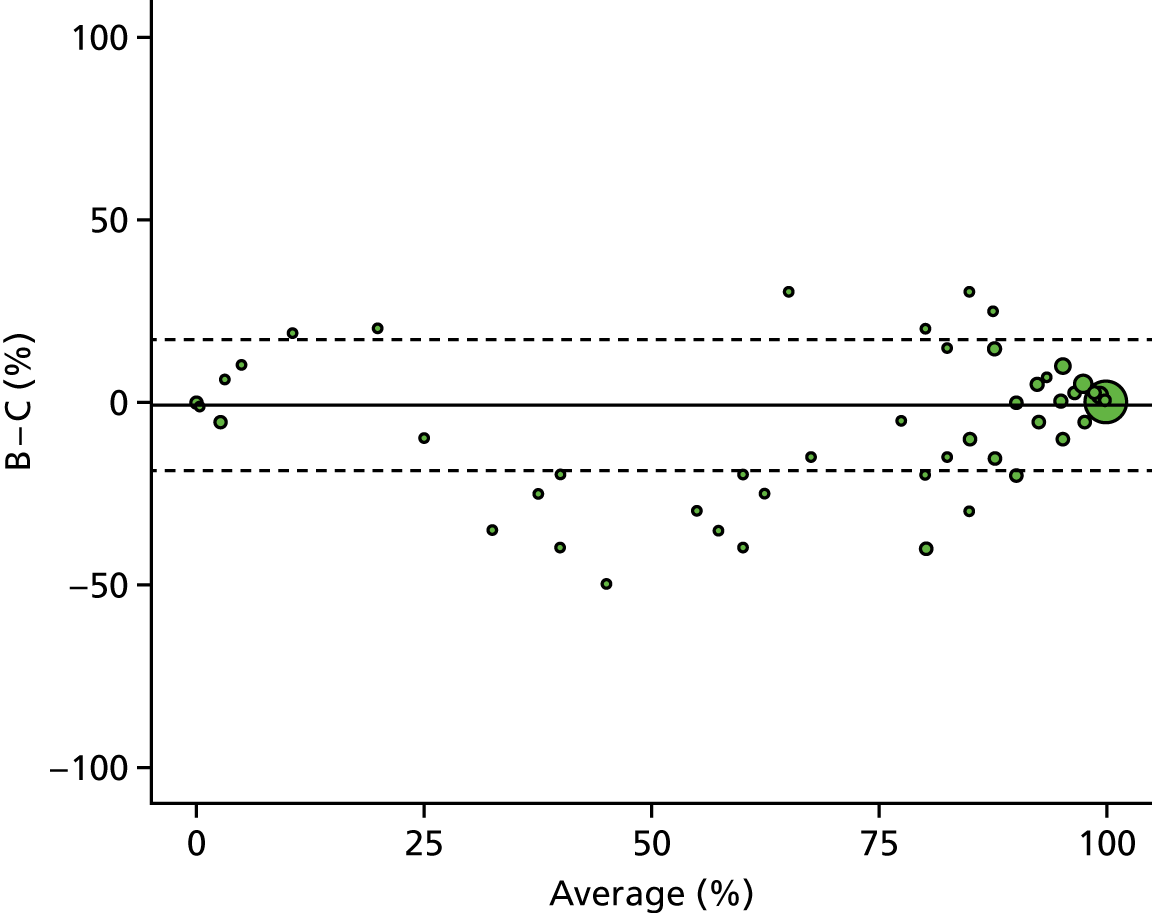

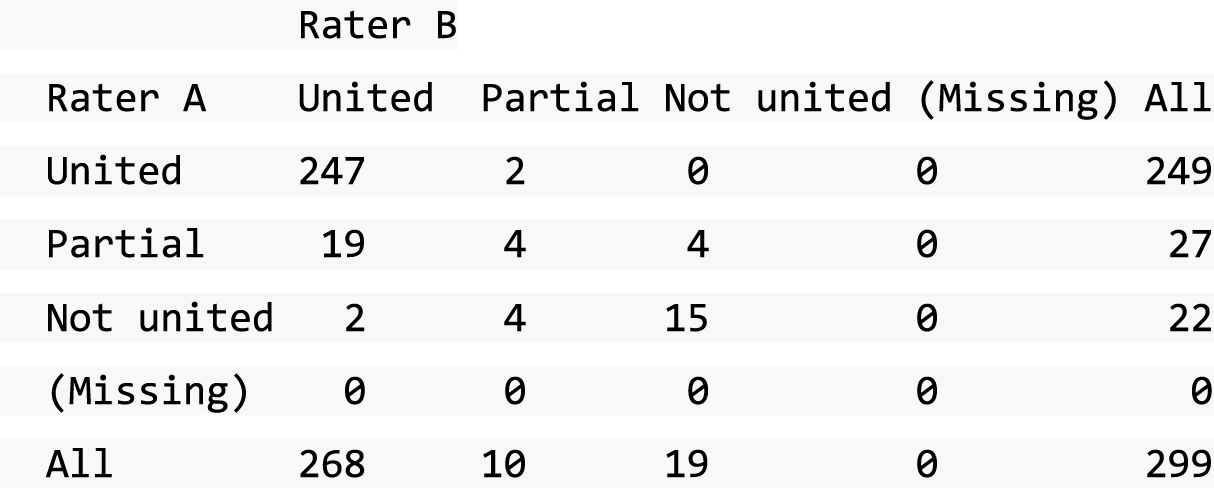

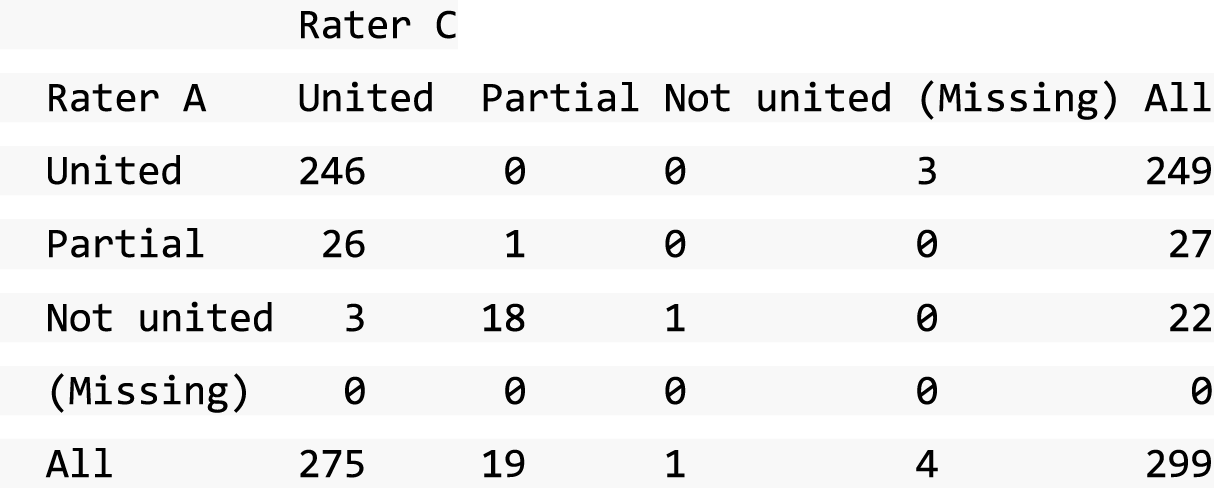

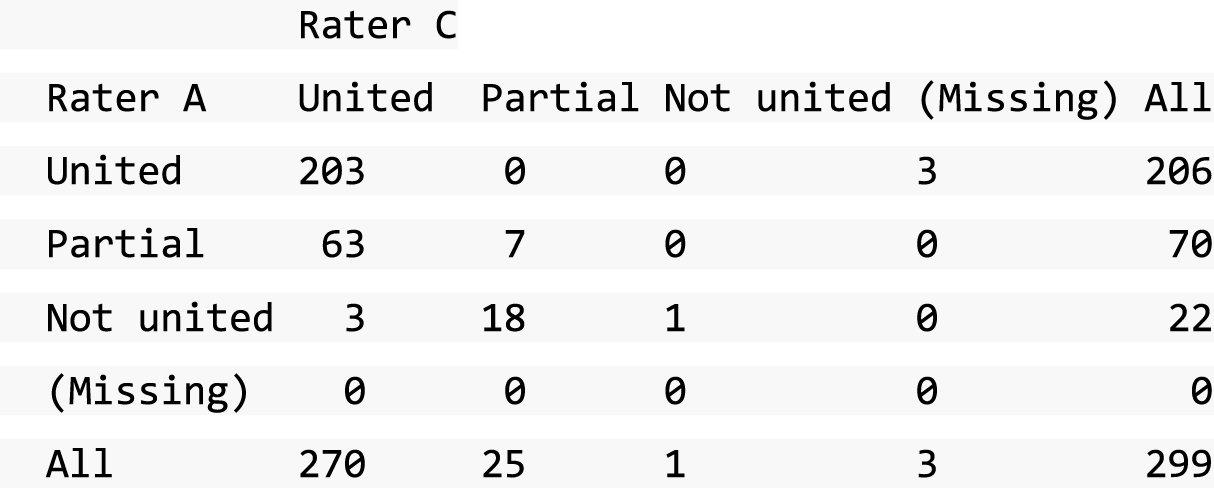

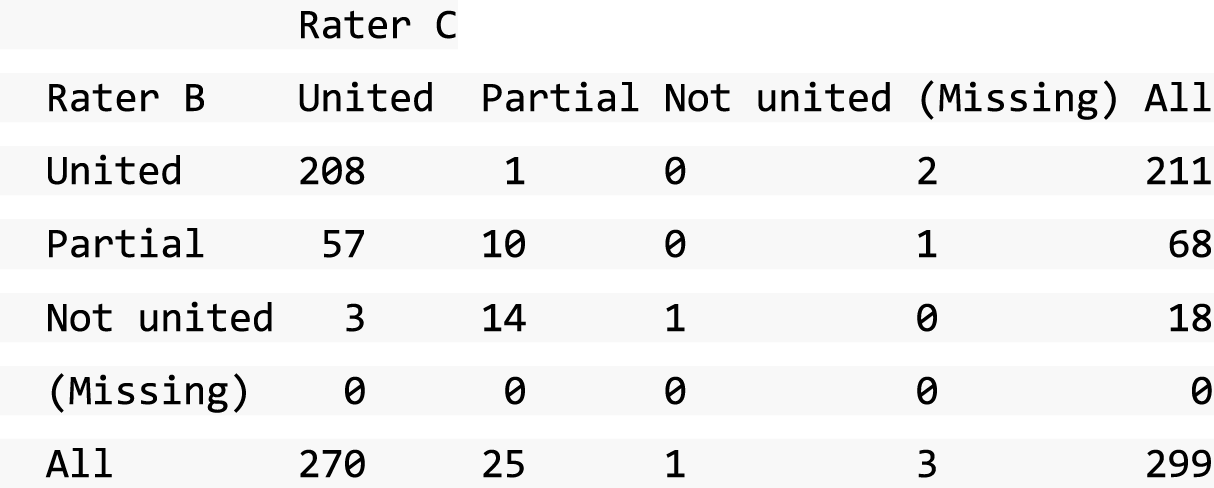

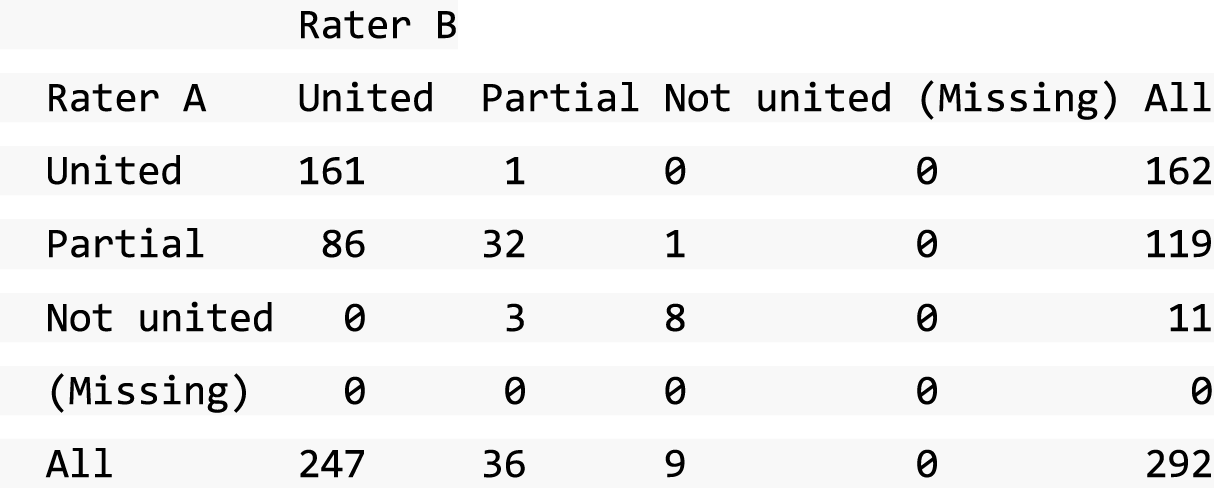

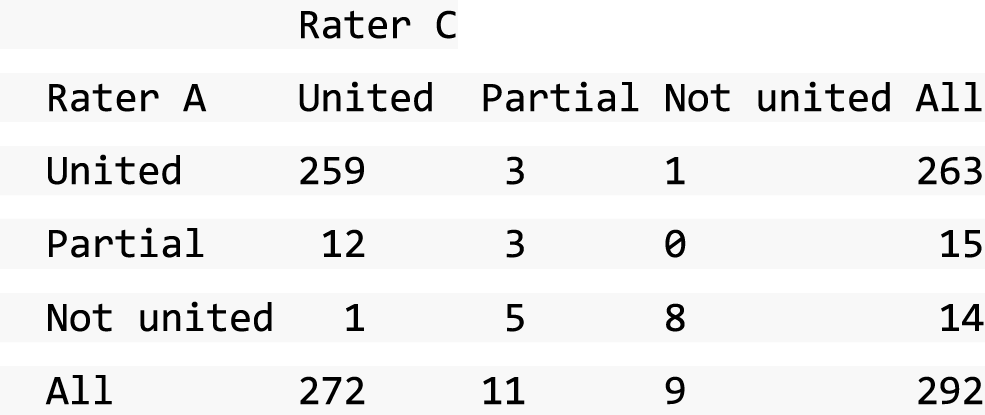

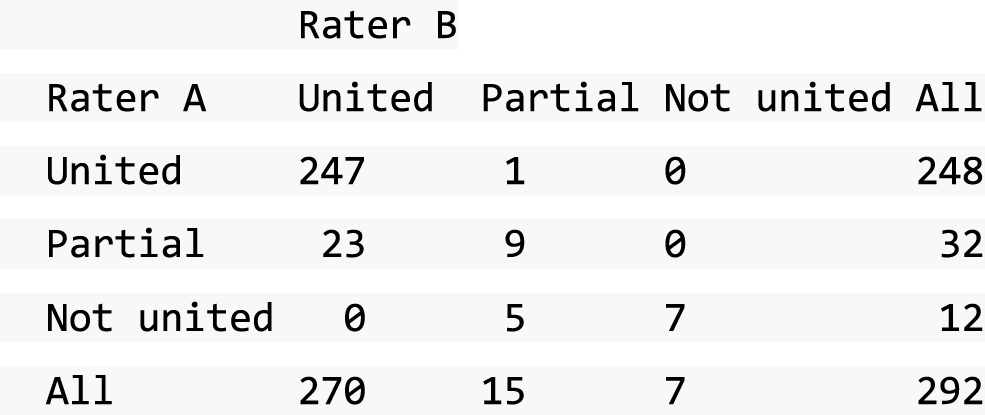

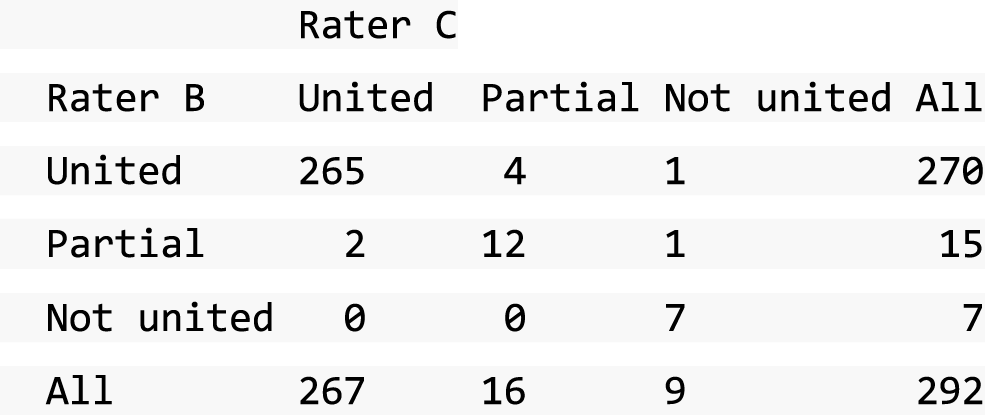

A descriptive analysis of agreement between the three raters was performed. Radiographs provide categorical grades of fracture, displacement and union and these were summarised by cross-tabulating the results from each pair of raters and calculating their percentage agreement. The CT scans provide continuous measures of displacement and of the percentage of union. Agreement between these continuous measures was summarised in Bland–Altman plots that compared each pair of raters, and the limits of agreement were calculated. For all numerical summaries, 95% CIs were provided.

Data management

All hospital forms, imaging compact discs and participant questionnaires were sent from and returned to YTU. A central database at YTU was used to prompt the sending out and return of participant questionnaires and hospital case report forms (CRFs). This included automated e-mail reminders sent to participating sites to help ensure the timely return of hospital CRFs.

Essential trial documentation, which individually and collectively permits evaluation of the conduct of a clinical trial and the quality of the data produced, was kept with the Trial Master File and Investigator Site Files. This documentation will be retained for a minimum of 5 years after the conclusion of the trial in accordance with Good Clinical Practice. The postal questionnaires and hospital CRFs will be stored for a minimum of 5 years after the conclusion of the trial as paper records and for a minimum of 20 years in electronic format. 86

Design of patient questionnaires and hospital case report forms

The patient questionnaires and hospital CRFs were designed using TeleForm software (version 10; Cardiff Software, Cambridge, UK). Specification CRFs were populated with variable names and appropriate scoring. To maximise data quality, when hospital CRFs were returned to YTU, key variables required for the statistical analysis were reviewed for completion and accuracy by a trial co-ordinator/research data administrator who resolved any queries with the research nurse at the site. The hospital sites were reimbursed according to a payment schedule for the completion of CRFs and provision of research imaging up to a total of £430.30. This was agreed between each trust and trial sponsor using a Clinical Trial Agreement. No checks regarding the data quality of the postal questionnaires were made on immediate return to YTU. A trial co-ordinator did, however, as a duty of care, check if a participant had responded with the extreme answers to the following: questions 4a, 4b, 6a and 6b of the SF-12 and the final EQ-5D-3L question. The trial co-ordinator also checked free-text responses to see if the participant could be at harm. When this occurred, the PI and research nurse at the recruiting site were notified by e-mail.

After this initial check, all postal questionnaires and hospital CRFs were prepared for scanning by a research data administrator using the TeleForm software. When a form would not scan, the data were manually entered. When a form was scanned, the data were then verified depending on what TeleForm identified as requiring correction. The verified data were then temporarily held in the download database and available for second checking. This involved each hard copy of all forms being compared against the entry stored in the download database and correcting the electronic data as necessary. All data were scanned, downloaded and second checked in the validate database. The automated data validation was undertaken by the data manager who applied predetermined rules to check for agreed variables to see if the data were recorded correctly. Data that had been validated were then held in the survey database and were available on a formal request from the trial statistician and health economist.

Strategies to follow up patients

Participants at the 6-, 12-, 26- and 52-week follow-ups were notified by post to expect the questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 15) 2 weeks before it was due. Reminder letters were sent 2 and 4 weeks after the due letter was sent out. When there was no response to reminder letters, a trial co-ordinator at YTU contacted participants by telephone, who were invited to provide answers for, as a minimum, the primary outcome (PRWE) and EQ-5D-3L. At 52 weeks only (the primary time point for the study), in addition to the telephone call at 6 weeks, a letter was sent to non-responding participants requesting that they complete the PRWE only. At 26 weeks, if participants did not attend a hospital appointment, an unconditional incentive of £5 was included with the postal questionnaire. At 52 weeks, a £40 payment was made to participants who attended the clinic. For the final 11 months of the follow-up period of the study, participants were also offered up to £40 to cover their travel expenses, or more if this was agreed with the trial team. The participants could complete the follow-up questionnaires during the clinic visits.

Various techniques were used to minimise loss to follow-up. This included regular participant newsletters, which publicised the progress of the study on the trial website (www.swifft.co.uk). A trial ‘tagline’ was placed on postal envelopes sent to participants to highlight the importance of their involvement in the research (i.e. ‘SWIFFT Study: Patients helping to improve healthcare through research’). As the return of postal questionnaires can be improved when participants are included in a prize draw,87 anyone who returned their questionnaire at 26 weeks could win an iPad® (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) worth £500. Participants who attended their hospital clinic appointment at 52 weeks were also entered into a prize draw to win an iPad worth £500. If, at 52 weeks, it was difficult to arrange the hospital appointment, a letter was sent from the hospital to the participant along with a leaflet to encourage their attendance. Other strategies to collect follow-up data on participants who did not return their questionnaire or attend clinics included using a participating hospital’s Picture Archiving Communication System (PACS) for the local area/region to retrieve imaging of patients; accessing Summary Care Records to view participants’ addresses and/or the general practitioner (GP) they were registered with to help contact them; and asking a participant’s GP if they have had an operation on their scaphoid fracture.

A trial participant could withdraw from the study at any time for any reason, but any data collected up to that point was used in the analysis. A participant could withdraw from all data collection, or from postal questionnaire collection or hospital data collection only, which was recorded using a change in status form (see Report Supplementary Material 16).

Data management for the review of imaging

The forms used to capture assessments of the scaphoid fracture and conduct measurements on the imaging collected were created using the ‘Design’ module in Formic Fusion® software (5.5.1; Formic Limited, Middlesex, UK) and include the SWIFFT master radiograph form, SWIFFT baseline CT form and SWIFFT 52-week CT form.

Once completed by reviewers, variables within each form were checked visually for completeness and for whether or not measurements were within an expected range. Completed forms were then scanned using the Formic ‘Capture & Process’ module and responses were reviewed. The Formic scanning software flagged hand-written text and those checkboxes with no mark or more than one mark; these were manually corrected to reflect the entry on the form. The scanned image of the form was also held within the database to permit independent verification. Once exported to the ‘SWIFFT logging database’ (Microsoft Access®, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), the data then went through a final electronic check to ensure all measurements were within the limits assigned by the chief investigator and to check for errors in measurements (e.g. cm instead of mm). The data were then checked for these rules in Stata v15 and potential problems were flagged and checked by each reviewer.

Data from the three reviewers were assessed and any classification conflicts on fracture displacement at baseline and state of the union at 52 weeks were identified and resolved in ‘conflict resolution meetings’ using specific forms (SWIFFT conflict CT form, SWIFFT conflict radiograph form and SWIFFT 52-week inter-observer conflict forms), which were used when conflicts were resolved. Predefined agreement rules were used to generate the final data based on all three reviewers’ assessments.

All conflicts identified were reviewed by all reviewers at face-to-face/teleconference meetings. All reviewers looked at the images together and a collective decision was made and recorded. From the 439 baseline radiographs reviewed, 106 were taken back to a conflict meeting. Of the 431 CT images reviewed at baseline, 155 were taken back to a conflict meeting to agree displacement thresholds. These baseline conflicts were reviewed over 26 meetings between September 2013 and February 2018. At 52 weeks, 297 radiographs and 292 CT scans were reviewed. All radiographs and CT scans at 52 weeks that were classified as a ‘non-union’ by any one reviewer were brought back to the conflict resolution meeting for confirmation. Of both radiographs and CT scans, only 17 were taken back to three conflict meetings to agree the state of the union.

Finally, the reviewers also agreed the cases that did not have an identifiable fracture on baseline radiographs (one) and CT scans (five). There were also a total of 52 conflicts identified on the categorical data at baseline. For baseline radiographs, 15 conflicts were identified from the categorical classification of the orientation of the fracture line. These were reviewed by all reviewers and were resolved. For baseline CT scans, 37 conflicts were identified involving the fracture line (27) and fracture location (10). All of these were reviewed at a conflict meeting in January 2018 and all were resolved.

Adverse event management

Adverse events were defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a trial participant that did not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment. Serious AEs (SAEs) were defined as any untoward medical occurrence that:

-

resulted in death

-

were life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing inpatient hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

was a congenital anomaly or birth defect.

In addition, SAEs included any other important medical condition that, although not included in the above, may have required medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the outcomes listed. (S)AEs related to scaphoid fracture and its treatment during the 12 months after randomisation were recorded by site PIs on a CRF (see Report Supplementary Materials 17 and 18). The trial office was notified of any SAEs within 24 hours of the PI becoming aware of them, and of any AEs within 5 days. The categorisation of causality and expectedness was confirmed by the chief investigator. AEs that were expected with this injury to the wrist and related to anaesthesia and/or surgery were infection, CRPS, screw-related complications, chondrolysis, delayed wound healing, nerve or vessel events, fracture of scaphoid tuberosity, and nausea and/or disorientation. AEs specific to the plaster cast were soft cast/broken cast that led to movement of the wrist, CRPS, pressure sores, nerve compression or pain due to a tight cast. Movement in a cast was considered untoward, as it could mean that the fracture was not properly immobilised and could result in failure to unite.

All (S)AEs were routinely reported to the Trial Management Group (TMG), Trial Steering Committee (TSC), Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) and sponsor. SAEs that were related to the research and unexpected were reported to the Research Ethics Committee (REC). The chief investigator reviewed all (S)AEs that were unresolved at initial reporting a month later. This was to ensure that adequate action had been taken. Additional reviews at 1-month intervals were conducted until the chief investigator confirmed that no further monitoring was required.

The chief investigator was also informed, by the reviewers of the radiographs/CT scans collected for the study, of any abnormalities identified. The chief investigator judged whether or not the abnormality was clinically important and could affect patient safety (e.g. a protruding screw). The need to notify the PI of the site, and whether or not to record this as an AE, was also considered. No actions or treatments were discussed with the PI.

Ethics approval and monitoring

Standard NHS cover for negligent harm was available. There was no cover for non-negligent harm.

Ethics committee approval and any changes to the project protocol

SWIFFT was approved by Derby Research Ethics Committee – East Midlands on 21 May 2013 (REC reference 13/EM/0154). NHS permission was given by the research and development department of each participating site. A summary of the changes made to the protocol since the original REC approval are listed in Appendix 2. The trial protocol was published in BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 48

Trial Management Group

The day-to-day management of the trial was overseen by the TMG, which met on a quarterly basis. A representative of the sponsor attended when available. These meetings monitored the progress as regards recruitment (e.g. enrolment, consent and eligibility), allocation to study groups, adherence of the trial interventions to the protocol, retention of trial participants, monitoring of (S)AEs and reasons for participant withdrawal. The review of progress was undertaken at the level of the participating site and, as necessary, feedback was given to the PI and research nurses at each site.

Trial Steering Committee

A TSC was appointed by the funding body to provide overall supervision of the trial and to advise on its continuation. Membership is listed in the Acknowledgements.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was appointed by the funding body with access to the unblinded comparative data as provided by a statistician at YTU who was independent of the trial team. The DMC monitored the data and notified the TSC of whether or not there were any ethical or safety reasons why the trial should not continue. Membership is listed in the Acknowledgements.

Patient and public involvement

A patient who had a fracture of their left wrist and was treated at the sponsor site commented on the study documentation and was invited to TMG meetings. Alternatively, their opinion was sought outside these meetings. This patient also contributed to a video that was posted on the trial website, which was publicised in a newsletter to participants, to encourage completion of postal questionnaires and attendance at hospital visits. In Leicester, a group of eight individuals [six of whom had experience of a scaphoid fracture and two who had not but were typical of the patient population (i.e. male and aged under 30 years)] met to advise the TMG on strategies to maximise the retention of trial participants; these individuals were also contacted by e-mail for advice. 88 This meeting was led by the chief investigator, a senior qualitative researcher and the patient representative on the TMG. This group will also advise on the summary of the findings for trial participants and other dissemination activities. In one of our newsletters to participants, a photograph and positive feedback about their involvement in the trial was included from the participant who won the prize draw of the iPad at the 26-week follow-up. Two members of the Patient Liaison Group of the British Orthopaedic Association were independent members of the TSC and advised on strategies to maximise recruitment and retention.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness results

Recruitment

Site recruitment

In our original protocol, we estimated that we would need 17 sites to recruit patients into SWIFFT. The number of sites was increased to meet the slightly lower than planned recruitment rate. Forty sites were approached to take part in SWIFFT between May 2013 and March 2015 and, in total, 34 sites were set up and opened to recruitment, the last of which commenced screening/recruitment in June 2015. Thirty-three sites screened at least one patient and 31 sites recruited at least one participant (median 10, range 1–61). Two of the three sites that did not recruit any participants screened one and two patients, respectively, one of which was eligible but non-consenting. The lead site, Leicester Royal Infirmary within the University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, recruited the highest number of patients of all sites (n = 61). Table 1 presents the number of patients recruited by each site, ordered by when each site was set up to recruit (Leicester first), with sites identified at trust level. One hospital from each trust took part in SWIFFT. All sites agreed to recruit an average of one patient per month, but only two sites achieved this.

| Site | Date opened | Months open | Number recruited | Average number ofrecruits per month |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust | 1 July 2013 | 37 | 61 | 1.6 |

| South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 17 August 2013 | 36 | 10 | 0.3 |

| University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust | 9 September 2013 | 35 | 24 | 0.7 |

| Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust | 25 September 2013 | 35 | 27 | 0.8 |

| Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 19 November 2013 | 11a | 0 | 0.0 |

| Southport and Ormskirk Hospital NHS Trust | 21 November 2013 | 13a | 0 | 0.0 |

| Bolton NHS Foundation Trust | 2 December 2013 | 32 | 17 | 0.5 |

| Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | 6 February 2014 | 30 | 5 | 0.2 |

| Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust | 7 February 2014 | 30 | 35 | 1.2 |

| University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust | 10 February 2014 | 30 | 17 | 0.6 |

| Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust | 10 February 2014 | 30 | 9 | 0.3 |

| Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust | 10 February 2014 | 30 | 4 | 0.1 |

| Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust | 26 February 2014 | 30 | 5 | 0.2 |

| Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust | 10 March 2014 | 8a | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 17 March 2014 | 29 | 6 | 0.2 |

| Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Trust | 17 March 2014 | 29 | 23 | 0.8 |

| Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 22 April 2014 | 28 | 5 | 0.2 |

| Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust | 9 May 2014 | 27 | 24 | 0.9 |

| Cardiff and Vale University Health Board | 12 May 2014 | 27 | 22 | 0.8 |

| Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust | 21 May 2014 | 27 | 5 | 0.2 |

| Taunton and Somerset NHS Foundation Trust | 1 June 2014 | 26 | 7 | 0.3 |

| University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust | 9 June 2014 | 26 | 20 | 0.8 |

| North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust | 12 June 2014 | 26 | 17 | 0.7 |

| Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 16 June 2014 | 26 | 5 | 0.2 |

| The Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust | 17 June 2014 | 26 | 5 | 0.2 |

| Barts Health NHS Trust | 20 June 2014 | 26 | 24 | 0.9 |

| Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 10 July 2014 | 25 | 15 | 0.6 |

| North Bristol NHS Trust | 1 September 2014 | 23 | 13 | 0.6 |

| University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust | 6 October 2014 | 22 | 10 | 0.5 |

| Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 10 November 2014 | 21 | 11 | 0.5 |

| Medway NHS Foundation Trust | 12 November 2014 | 21 | 2 | 0.1 |

| Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 24 November 2014 | 21 | 1 | 0.05 |

| University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust | 16 February 2015 | 18 | 6 | 0.3 |

| King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 22 June 2015 | 14 | 4 | 0.3 |

Patient recruitment

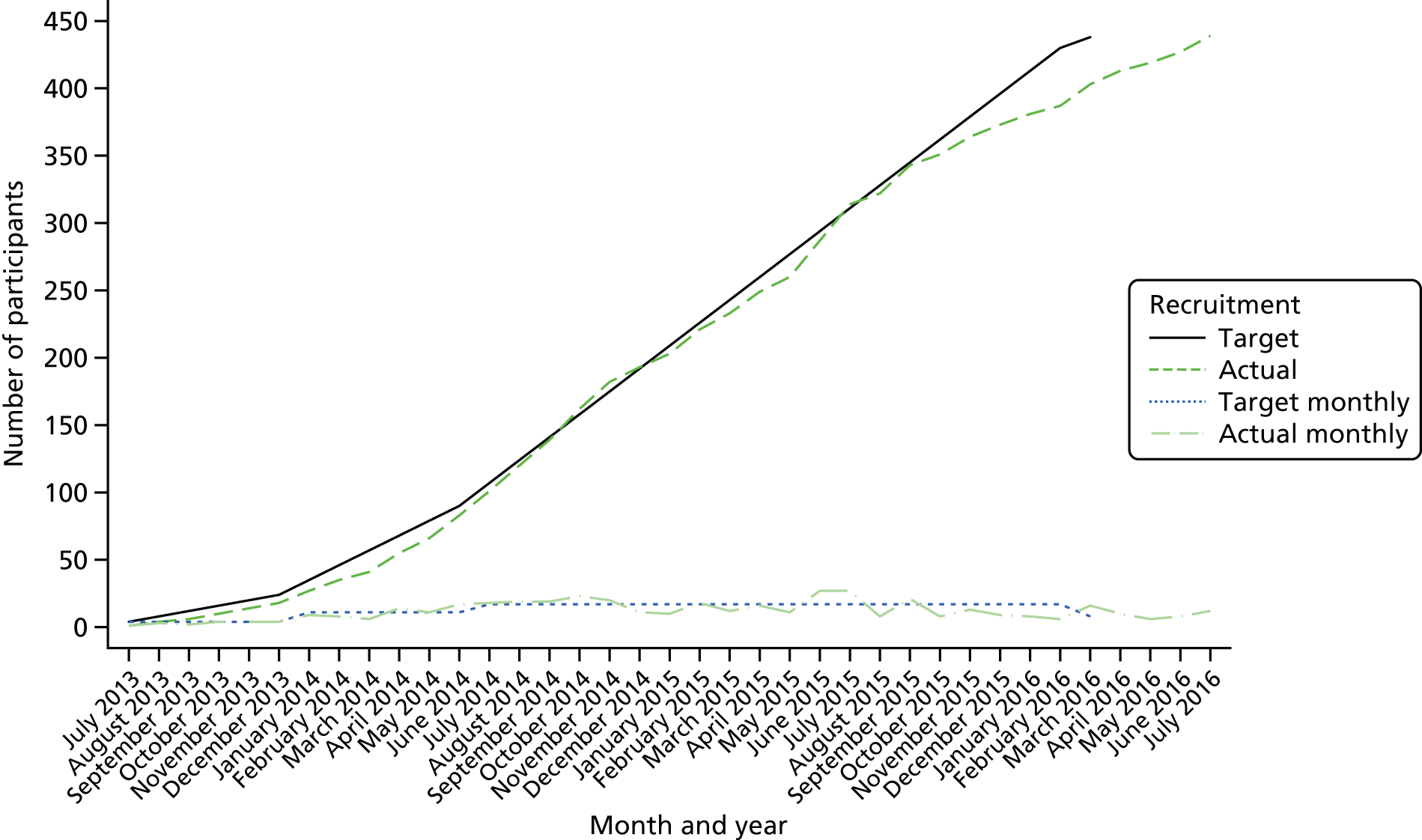

Our required sample size was 438 participants, which we aimed to achieve by the end of March 2016; however, recruitment was slightly slower than anticipated in the final few months and we agreed with the trial sponsor, the trial funder and the REC (February 2016) to extend recruitment beyond March 2016 until the 438 patients had been recruited.

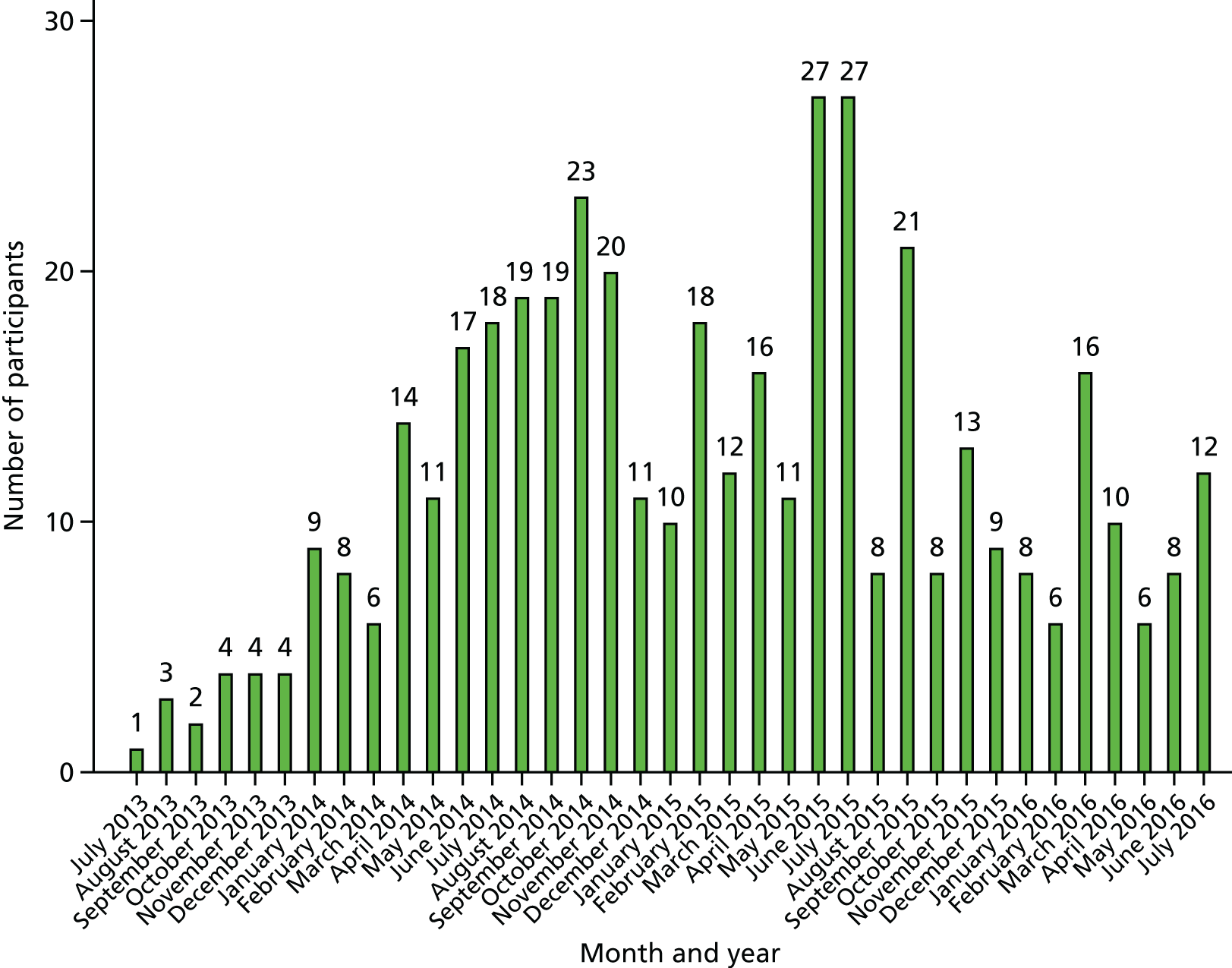

The first participant was randomised on 23 July 2013. As of 31 July 2016, 439 patients had been enrolled in the trial and sites were notified that recruitment should cease; thus, patients were recruited over 37 months. Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate our final recruitment figures.

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment into SWIFFT by month.

FIGURE 4.

Recruitment targets of participants into SWIFFT.

Characteristics of screened patients

A total of 1047 patients who met the inclusion criteria (aged 16 years or over and skeletally mature, presenting within 2 weeks of injury with a radiologically confirmed clear and bicortical fracture of the scaphoid waist that does not include the proximal pole) were assessed for participation in the trial from July 2013 to July 2016, of which 775 (74.0%) were eligible and 439 (41.9%) were eligible and consenting, the latter all being randomised. The number of participants screened per site ranged from 1 to 133 (median 23) and the percentage of screened participants who were eligible per site ranged from 0 to 100% (median 83.3%). Table 2 displays the characteristics of the different populations. Eligible patients tended to be younger and were more likely to be male and have a displaced fracture than ineligible patients. There were no marked differences between consenting and non-consenting patients in gender, age or time since injury; however, there was an indication that consenting patients were more likely to have a displaced fracture than non-consenting patients. The numbers of patients for whom each type of radiograph was used to determine eligibility, along with the percentage of those screened, are as follows: elongated scaphoid view (n = 910, 86.9%), posterior–anterior view (n = 1024, 97.8%), 45° semisupine view (n = 610, 58.3%), lateral view (n = 1017, 97.1%) and 45° semiprone view (n = 834, 79.7%). Screened patients had a median of four scaphoid radiographic views taken.

| Characteristic | Screened (N = 1047) | Ineligible (N = 272) | Eligible (N = 775) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-consenting (N = 336) | Consenting (N = 439) | |||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 834 (79.7) | 203 (74.6) | 268 (79.8) | 363 (82.7) |

| Female | 210 (20.1) | 66 (24.3) | 68 (20.2) | 76 (17.3) |

| Missing | 3 (0.3) | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| n | 1040 | 266 | 335 | 439 |

| Mean (SD) | 33.7 (14.8) | 36.6 (17.5) | 32.5 (14.6) | 32.9 (12.7) |

| Median (min., max.) | 29.2 (16.0, 94.8) | 30.0 (16.2, 94.8) | 28.2 (16.0, 79.7) | 29.3 (16.1, 80.6) |

| Time since injury (days)a | ||||

| n | 1044 | 269 | 336 | 439 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.0 (1.8) | 1.2 (2.5) | 1.0 (1.5) | 0.8 (1.4) |

| Median (min., max.) | 0 (0, 14) | 0 (0, 14) | 1 (0, 9) | 1 (0, 10) |

| Displacement involvement,b n (%) | ||||

| Displacement | 342 (32.7) | 61 (22.4) | 111 (33.0) | 170 (38.7) |

| No displacement | 651 (62.2) | 160 (58.8) | 222 (66.1) | 269 (61.3) |

| Missing | 54 (5.2) | 51 (18.8) | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

Reasons for exclusion

A total of 272 (26.0%) of the 1047 patients screened were ineligible for the trial for one or more reasons (Table 3). Twenty-nine of these should strictly never have been screened for participation in the trial, as they did not fulfil the inclusion criteria: their injury was more than 2 weeks old (n = 15), they did not have a radiologically confirmed bicortical fracture (n = 7), their fracture included the proximal pole (n = 6) or they were skeletally immature (n = 1). A further 156 patients failed at least one of the exclusion criteria, most commonly having a concurrent other injury in the same limb (n = 70). The remaining 87 were ineligible for other reasons: the site did not think it was feasible for the patient’s surgery (if allocated) to be scheduled within 2 weeks from presentation (n = 30), the patient was not approached about study (e.g. they presented at the weekend when there was no clinician available to confirm eligibility) (n = 21), the patient was deemed to be unsuitable for surgery (n = 16), the fracture was seen on radiography but not on the subsequent CT scan (n = 8) or other miscellaneous/unknown reasons (n = 12).

| Reason for ineligibility | Number of (%) ineligible patients (N = 272) |

|---|---|

| Exclusion criteria (N = 156) – reasons not mutually exclusive | |

| Fracture displaced by > 2 mm | 43 (15.8) |

| Concurrent wrist fracture in the opposite limb | 12 (4.4) |

| Trans-scaphoid perilunate dislocation | 8 (2.9) |

| Multiple injuries in the same limb | 70 (25.7) |

| Patient not a resident in the trauma centre catchment area of the participating site | 21 (7.7) |

| Previous injury or disease in the same wrist | 2 (0.7) |

| Patient lacks the mental capacity and is unable to understand the trial and instructions for treatment | 11 (4.0) |

| Patient is pregnant | 6 (2.2) |

| Other reasons (N = 116) | |

| Patient did not meet the inclusion criteria to be approached about the trial | 29 (10.7) |

| Presenting > 2 weeks after injury | 15 |

| No radiologically confirmed bicortical fracture | 7 |

| Fracture includes proximal pole | 6 |

| Aged < 16 years and/or skeletally immature | 1 |

| No fracture seen on CT scan prior to randomisation | 8 (2.9) |

| Surgery not feasible within 2 weeks of injury | 30 (11.0) |

| Patient not suitable for surgery | 16 (5.9) |

| Study not discussed with patient (e.g. patient presented at the weekend) | 21 (7.7) |

| Othera | 12 (4.4) |

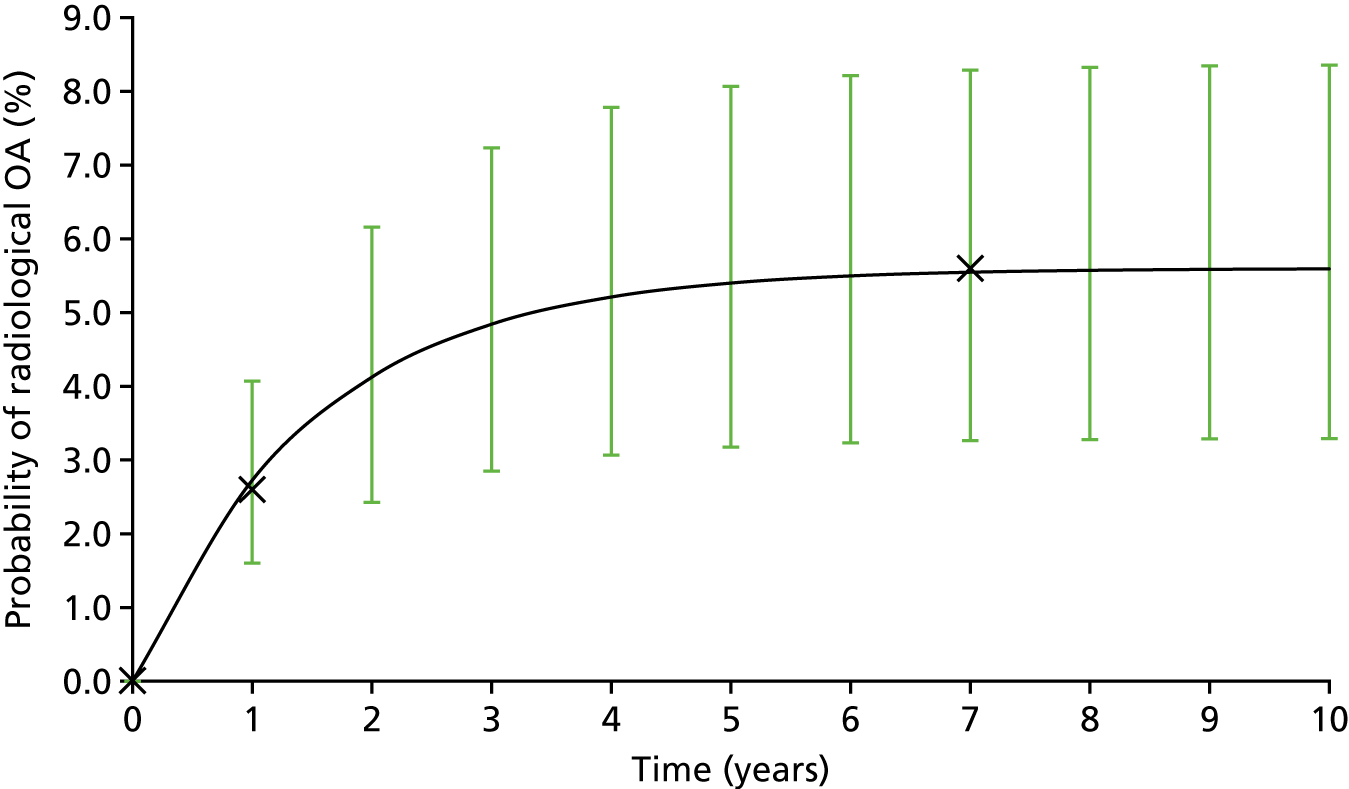

Patient consent