Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as award number 16/111/91. The contractual start date was in June 2018. The draft manuscript began editorial review in June 2022 and was accepted for publication in May 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Wright et al. This work was produced by Wright et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Wright et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Materials throughout this chapter have been adapted from the trial protocol by Wright et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article unless otherwise stated.

Background

Autism spectrum condition

Around 1 in 57 (1.76%) children in England are on the autism spectrum. 2 Autism spectrum condition (ASC) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition characterised by differences in social communication and interaction and restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour and interests. 3 Autism is also associated with strengths, such as some individuals having excellent attention and memory for detail and a strong drive to detect patterns. 4 Throughout this report, we will refer to ‘autistic children’ or ‘children on the autism spectrum’ to reflect the general preference for identity-first language rather than person-first language in the autistic community5 and amongst our public involvement representatives.

Children on the autism spectrum experience a higher prevalence of mental health problems than typically developing children, including anxiety and low mood. 6 Many children on the autism spectrum experience anxiety in social settings and feelings of frustration. 7 The International Society for Autism Research (INSAR) has recently highlighted that more research evaluating early interventions for autistic children is needed to ensure practitioners and policy-makers have robust data on intervention effectiveness and implementation to secure optimal outcomes for children on the autism spectrum. 8

Supporting children on the autism spectrum in primary school

Children on the autism spectrum often struggle socially and academically in educational settings, which may be due to differences in their experiences of social situations, differences in social communication and experiences of anxiety. 9 The educational environment can present many challenges for a child on the autism spectrum,10 such as busy classroom environments, frequent changes in school routines and difficulties navigating peer relationships. Given these challenges, the school environment can be difficult for autistic children to follow and engage with. 9 Autistic children can also have difficulty understanding the point of view, thoughts or feelings of someone else and have difficulties with the social use of language which can make forming and maintaining peer relationships challenging. 11 Children on the autism spectrum may struggle to manage their compulsions, sensory sensitivities and preoccupations within the school routine if reasonable adjustments are not made to account for these differences. Educational professionals face many demands on their time and may not be able to focus enough on the child’s needs for them to achieve their full educational potential.

Little is known about the best ways to support children on the autism spectrum12 in primary school, and more information is needed about what training is required for staff to feel confident supporting these children. Current interventions designed to support children on the autism spectrum can be time-consuming, needing involvement of outside experts. For example, specialist social skills support is delivered within Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). It is important that educational professionals recognise the social challenges of children with autism,11 and there is a need for low-cost, child-friendly and evidence-based interventions that can be delivered in community settings to support children on the autism spectrum with the aim of potentially reducing the need for specialist referral elsewhere. A systematic review of school-based social skills interventions for autistic children suggested that these can be effective in improving social outcomes for students on the autism spectrum. 11 However, further randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to further understand which interventions are most clinically effective and cost-effective. 12

Social Stories™ intervention

One intervention that attempts to alleviate these social difficulties while not being intrusive, time-consuming or requiring extensive involvement of outside experts is Carol Gray’s Social Stories. 9 Social Stories are a highly personalised intervention aiming to share accurate, meaningful information about a particular goal or topic that the child needs help with in a positive and reassuring way. 9 Social Stories can be written and delivered by both parents and professionals in a range of settings and represent a less time-consuming and intrusive intervention than other more intensive interventions. They are typically better suited to primary-aged children (age 4–11 years),13 though they are also sometimes used with older children.

Social Stories are short stories which describe a social situation or skill to help children on the autism spectrum to understand a situation applicable to the child more easily. They write a child into their own personal story about themselves to help them learn new social information. They are commonly used to enable children to understand socially expected behaviours and norms. Social Stories are defined by 10 criteria which guide story development as detailed below. 14

-

The Social Story Goal. Authors follow a defined process to share accurate information using content, format and voice that is descriptive, meaningful and physically, socially and emotionally safe for the Audience.

-

Two-Step Discovery. Authors gather information to (1) improve their understanding of the Audience in relation to a situation, skill or concept and (2) identify the topic and focus of each Story/Article. At least 50% of all Social Stories applaud achievements.

-

Three Parts and a Title. A Social Story/Article has a title and introduction that clearly identifies the topic, a body that adds detail and a conclusion that reinforces and summarises the information.

-

FOURmat. The Social Story format is tailored to the individual abilities, attention span, learning style and – whenever possible – talents and/or interests of its Audience.

-

Five Factors Define Voice and Vocabulary. A Social Story/Article has a patient and supportive ‘voice’ and vocabulary that is defined by five factors. These factors are: (1) First- or Third-Person Perspective; (2) Past, Present and/or Future Tense; (3) Positive and Patient Tone; (4) Literal Accuracy and (5) Accurate Meaning.

-

Six Questions Guide Story Development. A Social Story answers relevant ‘wh’ questions that describe the context, including place (WHERE), time-related information (WHEN), relevant people (WHO), important cues (WHAT), basic activities, behaviours or statements (HOW) and the reasons or rationale behind them (WHY).

-

Seven is About Sentences. A Social Story is comprised of Descriptive Sentences, as well as optional Coaching Sentences. Descriptive Sentences accurately describe relevant aspects of context, including external and internal factors, while adhering to all applicable Social Story Criteria.

-

A GR-EIGHT Formula. One Formula ensures that every Social Story describes more than directs.

-

Nine to Refine. A story draft is always reviewed and revised if necessary to ensure that it meets all defining Social Story criteria.

-

Ten Guides to Implementation. The Ten Guides to Implementation ensure that the Goal that guides Story/Article development is also evident in its use. They are: (1) Plan for Comprehension; (2) Plan Story Support; (3) Plan Story Review; (4) Plan a Positive Introduction; (5) Monitor; (6) Organise the Stories; (7) Mix and Match to Build Concepts; (8) Story Reruns and Sequels to Tie Past, Present and Future; (9) Recycle Instruction into Applause; and (10) Stay Current on Social Story Research and Updates.

Their original designer, Carol Gray, believes these criteria are the hallmark of their success. The criteria guide story development to ensure an overall patient supportive quality and relevant content that is descriptive, meaningful and safe for the audience. These stories are written in a specific way using a variety of defined sentence types and a formula for the ratio of sentences in a social story. Using this formula and framework suggested by Carol Gray, Social Stories can be a flexible intervention that can be individualised to different social situations.

The imperative to tailor these stories is particularly important for helping a child on the autism spectrum, as every autistic child has different strengths and weaknesses. 4 When deciding on the goal for a Social Story, it is important to consider: ‘What is the challenge or problem facing the child?’, ‘What do we know about why this is happening from the child’s perspective?’, ‘What does the child and young person need help with?’ and ‘What positive outcome would we like to see for the child?’. Individuals are asked to consider the child’s individual needs, including their current known empathy/socio-emotional skills, their ability to ‘get the gist’ of social situations, their communication and imagination skills and how they engage with their sensory environment. Understanding the child’s preoccupations, routines and how stress, anxiety or frustration emerge in various situations is also important so that the child’s needs and perspectives can be considered within a Social Story. The goal that is set for a Social Story should be positive for the child and specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-limited (also known as a SMART goal). Social Stories can also be used to coach adults around the child about how to respond to an autistic child in certain situations and can help adults understand the child’s perspective so that they are better able to support the child.

Previous case studies have suggested that following exposure to tailored Social Stories, children on the autism spectrum have shown improvements in mealtime skills,15 making independent choices and playing appropriately,16 reducing anxiety,17 supporting improved communication,18 managing and reducing frustrations18 and reducing behaviours that challenge. 19–21 Three systematic reviews have examined the effectiveness of Social Stories for supporting children on the autism spectrum. 22–24 As reported in Marshall et al.,13 these reviews indicate an overall positive effect of Social Stories on a number of social and behavioural outcomes in individual case studies. Wright et al.’s24 systematic review included any study that used a standardised, numerical measure of outcomes but also included non-standardised, numerical measures. For single-case designs, studies had to report repeated measurements of the target behaviour to be eligible for inclusion. Outcomes explored in the reviewed literature included social abilities and awareness, communication, restricted behaviours, life skills, emotional development and sustained attention. In addition to case studies, Wright et al.’s24 systematic review included seven between-group studies, four of which were RCTs. 25–28 The interventions included in these randomised studies were often delivered over a much shorter time frame than was typically used in single-case designs, and the interventions were standard ones, rather than individually tailored to each child, meaning they did not fulfil Carol Gray’s criteria. 24 The authors highlighted that the included literature was vulnerable to selection and reporting bias and was largely US-based. 24

Based on the recommendation from the systematic reviews22–24 that further well-designed large-scale RCTs were needed in this area, Wright et al. 13 conducted a feasibility RCT to assess the feasibility of recruiting children, parents and educational professionals to a trial of Social Stories and assess retention, the appropriateness of outcome measures and any barriers to delivering training and the intervention in mainstream primary and secondary schools. This trial focused on writing and delivering individualised Social Stories that followed the Carol Gray criteria within the school setting. 13 The results suggested that a future trial would be feasible to conduct and could inform the policy and practice of using Social Stories in primary schools. It was not recommended to include secondary schools in the full trial, as qualitative work revealed that the intervention was not viewed as appropriate for secondary-aged children due to being too simplistic and more difficult to implement. The feasibility results were in line with previous research that suggested that it is possible to train tier-one professionals, for example, teachers and teaching assistants (TAs), to develop and use Social Stories tailored to a child. 29 As previously described, studies examining the use of Social Stories have yielded mostly positive results but have largely been single-case studies. Despite the lack of rigorous evidence, numerous schools and families are already accessing Social Stories training and delivering the intervention with children, and therefore a fully powered RCT is timely. Schools have limited resources and limited access to specialist practitioner interventions, and therefore it is important that interventions such as Social Stories undergo robust evaluation. If they are found to be clinically effective and cost-effective, they can be delivered within schools on a day-to-day basis.

Rationale for research, aims and objectives

Rationale

Individuals on the autism spectrum require varying levels of support from different services (such as the NHS and charitable organisations), as the condition can have a widespread and persistent impact on quality of life (QoL), relationships, employment and standards of living. 30 An evaluation of the economic cost of autism in the UK30 revealed that the annual costs of supporting children on the autism spectrum were estimated to be £2.7 billion each year, and for adults, these costs were £25 billion each year. Given this significant cost and limited funding available for specialist support in schools31 and for other services, there is a need for low-cost, child-friendly and evidence-based interventions that can be delivered in community settings such as schools to support children on the autism spectrum, with the aim of potentially reducing the need for specialist referral elsewhere.

The current work aims to address this gap by exploring whether one promising intervention (Social Stories) could be effective in supporting children on the autism spectrum in primary school. This RCT follows a feasibility study,13 which explored the acceptability of running a trial examining Social Story use with 50 children across 37 primary and secondary mainstream schools. This demonstrated a high degree of acceptability with young people, families and schools. This main trial now seeks to assess the clinical and cost effectiveness of Social Stories, addressing the lack of fully powered RCTs in this area.

Study aims

As outlined in the study protocol,1 the aim of this trial was to assess whether Social Stories alongside care as usual is clinically effective and cost-effective in improving child social impairment, reducing behaviours that challenge and improving social and emotional health in children on the autism spectrum in primary schools when compared with care as usual alone.

Primary objective

The primary objective of the study was to establish whether Social Stories can improve social responsiveness in children on the autism spectrum in primary schools across Yorkshire and the Humber when compared to children who have received care as usual only.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives of this trial were:

-

to investigate whether Social Stories can reduce behaviours that challenge children on the autism spectrum in primary schools

-

to investigate whether Social Stories can improve social and emotional health in children on the autism spectrum in primary schools

-

to assess the cost-effectiveness of Social Stories

-

to examine the effects of Social Stories delivered in the classroom on general measures of health-related QoL

-

to examine whether Social Stories improve classroom attendance

-

to assess the sustainability of Social Stories in an educational setting across a 6-month period

-

to examine any changes in parental stress

-

to examine any associations between treatment preference and outcomes

-

to examine how elements of session delivery [e.g. session frequency, length and any associated problems/adverse events (AEs)] are associated with outcomes.

Chapter 2 Methods

Materials throughout this chapter have been adapted from the trial protocol by Wright et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article unless otherwise stated.

Main trial methods

Trial design

This trial was a multisite pragmatic cluster RCT comparing Social Stories and care as usual with a control group receiving care as usual alone. Care as usual being defined as the existing support routinely provided for a child on the autism spectrum from educational and health services such as specialist autism teacher teams, mental health teams or other associated professionals. The trial included an internal pilot, an economic evaluation and a nested process evaluation. The full trial protocol is published online via the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Journals Library (https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/111/91).

Patient and public involvement

The development of the Autism Spectrum Social Stories In Schools Trial 2 (ASSSIST-2) trial was supported by three core patient and public involvement (PPI) members, a parent of an autistic child, a specialist teacher and a member of the National Autistic Society. Two of these representatives were named co-applicants for the funding awarded from the NIHR to deliver the trial, and all were involved in the trial from its conception. In addition to these core members, a local youth council, which also worked with members of the trial team on a previous feasibility study of Social Stories,24 reviewed and contributed to the design of the present trial. This included shaping information leaflets and giving advice on young people’s preferences regarding the research study.

Furthermore, the study team utilised findings from the qualitative interviews completed during the previous feasibility study which included young people with autism, teachers and parents/carers. 24 The findings from these interviews informed the use of questionnaires, the presentation and content of materials such as information sheets and consent forms, the logicising of intervention delivery and the best means of contacting participants. These interviews, in conjunction with our PPI representatives, also informed the training manual used during this study. 9 Advice was also provided from parents, teachers and educational psychologists regarding more general aspects of trial delivery within education settings. Both the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Trial Management Group (TMG) included PPI representatives who were able to contribute to discussions around the trial throughout its implementation.

A PPI event was held at the end of the trial to disseminate the key findings to representatives from key sectors, specifically educational settings, parents, charities, mental health services and the local authority. Advice and guidance were sought with regard to dissemination activities, including the appropriateness of language and terminology around autism as well as key considerations for any roll-out and future research avenues.

Regulatory approvals and research governance

Initially, the trial opened as a non-NHS trial, recruiting schools and families directly with no NHS involvement. Ethics approval for the trial was obtained from the Health Sciences Research Governance Committee embedded within the Department of Health Sciences at the University of York on 2 July 2018. At a later stage of the research, ethical approval was sought and awarded from the Health Research Authority (HRA) on 24 July 2019 and the North East – York Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 23 July 2019 (REC reference number 19/NE/0237) to allow opening of an additional recruitment stream via the NHS. Substantial and non-substantial amendments to approve changes to the protocol and study documentation were submitted to the REC, HRA, the Department of Health Sciences Research Governance Committee and each NHS site’s research and development office as required during this trial. The trial sponsor was Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust.

Trial registration

The trial was assigned the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) ISRCTN11634810 on 23 April 2019.

Setting

The Social Stories intervention was delivered within educational settings by educational professionals. Educational settings included both mainstream primary schools and Special Educational Needs (SEN) schools. Parents/caregivers were invited to receive Social Stories training and were encouraged to utilise Social Stories within the home environment, though this was not considered part of the intervention. Parents were specifically advised not to deliver the story written for the purposes of the trial at home as the trial sought to evaluate the intervention through a school-based delivery model. No data were collected on the use of Social Stories at home.

Recruitment

Recruitment was on a rolling basis through the recruitment period, with schools being randomised as and when all pre-randomisation criteria had been fulfilled, that is, all relevant parties had provided consent and all baseline data had been collected. No additional children could be recruited from a school once it had been randomised. Participants were recruited via the following recruitment pathways.

Recruitment from schools

Primary schools across Yorkshire and the Humber were contacted with information about the trial via e-mail or post. Meetings were then set up with school head teachers to establish willingness at the school level to support the trial and undertake the necessary trial activities. Where schools agreed to participate, they were asked to distribute information sheets (see Report Supplementary Material 1) and Expression of Interest (EOI) forms to parents/guardians of eligible children. Parents/guardians who returned an EOI form or consented for school staff to pass on their details were contacted by a member of the research team to discuss the trial, answer any questions and arrange collection of informed consent from parents/guardians and, where possible, assent from the child. Consent was also obtained from education professionals taking part in the trial (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

Recruitment via the National Health Service

In total, seven CAHMS teams from five NHS Trusts within the Yorkshire and Humber area were opened to act as a participant identification centre (PIC). PICs were required to screen their patient case lists to identify potential children who were likely to meet the inclusion criteria for the trial. They then distributed recruitment packs prepared by the York Trials Unit (YTU) containing information sheets about the trial and EOI forms to be returned to the trial team. A member of the trial team then contacted families via their preferred method to confirm eligibility and request contact details for the child’s education setting. Recruitment then followed the procedure set out for schools, as it was necessary for the child’s school to agree to take part before the family could be formally consented.

Recruitment from local community groups

Local community groups within the catchment area, for example, AWARE, a parent-run family support group, were contacted with information about the trial, and researchers distributed study information to interested parents/guardians. On receipt of an EOI, recruitment followed the procedure outlined for schools.

Liaising with local authority professionals

The trial protocol outlined that relevant local authority professionals, for example, educational specialists in autism, could be contacted and asked to disseminate study information and EOI forms to the parents/guardians of potentially eligible children. On receipt of an EOI, recruitment could then follow the procedure outlined for schools. However, this recruitment pathway was not implemented due to the success of the other channels; hence, the additional burden this would place on local authorities was deemed unnecessary.

Recruitment from local publicity

Some families heard about the trial from a range of sources, for example, publicity on Twitter (@COMICResearchUK), and contacted the research team directly. In this instance, the team confirmed the child’s eligibility and sent out study information. It was made clear that participation was dependent on the child’s school taking part, and recruitment continued in line with the procedure outlined for schools.

Consenting participants

Participation in the ASSSIST-2 trial was entirely voluntary. There were three types of participants involved in the trial, namely, educational professionals, parents/caregivers and the children themselves. The consent process varied slightly depending on whether participants joined the trial prior to or during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, consent was typically obtained in person during face-to-face visits to the child’s school by a trained research assistant (RA). Information sheets were always distributed to the relevant parties at least 24 hours prior to consent being taken. During the COVID-19 pandemic, consent forms were posted to participants and an appointment was scheduled for a RA to go through the form with the participants either over the telephone or via videoconferencing.

Educational professionals and parents/caregivers provided their own consent. Due to the age of the children, parents/caregivers provided consent on behalf of the children, though verbal assent was gained if possible. During the consent process, participants could opt in to being contacted to participate in the qualitative interviews for the process evaluation. They could also opt in to be sent details about future relevant research.

Participant eligibility

All children and schools were screened based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. After an EOI to participate was received, screening took place via two telephone calls led by a RA, one with a parent/carer and one with the child’s teacher. Screening questionnaires were completed during screening calls.

Inclusion criteria

-

The child was aged 4–11 years at the time of recruitment.

-

The child attended a participating primary or SEN school within Yorkshire and the Humber.

-

The child has a clinical diagnosis of ASC as confirmed by the parent/carer during a screening call and has daily challenging behaviour as confirmed during a screening call with the child’s teacher.

-

Parents/guardians of the child were able to self-complete the English language outcome measures (with assistance if necessary).

Exclusion criteria

-

The school had used Social Stories for any pupil in the current or preceding school term.

-

The child or interventionist teacher had taken part in the previous Social Stories feasibility study (ASSSIST). Schools that have taken part were not excluded.

Where families were identified to be eligible to participate but the child’s school was unwilling or unable to participate, families were notified by telephone or e-mail.

Where children were confirmed eligible and consent had been taken from all relevant parties, baseline questionnaires were distributed to parents/carers and educational professionals. A school was considered ‘ready to randomise’ once all consent forms and baseline questionnaires had been received by the trial team.

Sample size

The primary end point was that the teacher completed the Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2) T-score at 6 months. Within the pilot data, outcomes were measured at 6 and 16 weeks. The correlation between baseline and 6 weeks [r = 0.67, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.44 to 0.80] was lower than that at 16 weeks (r = 0.83, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.91) for the pilot data. To be conservative, the lower 95% confidence limit was chosen for the lowest correlation between baseline and follow-up that we observed within our pilot data (r = 0.44). Assuming a difference of 3 points, standard deviation (SD) = 7, 5% alpha, 90% power, average cluster size 1.35, ICC = 0.34, correlation = 0.44 and 25% attrition, a total sample size of 278 was required.

Given the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent closure of schools during this period, recruitment fell behind target. Recruitment began in mid-November 2018, and at the time of the first UK lockdown on 23 March 2020, 194 children (across 67 schools) had been screened, of which 134 (51 schools) had been randomised (53.8% of the final sample). The trial status was appraised by the TMG in October 2020, and it was decided that recruitment should end on 31 May 2021 with a total of 249 participants recruited. This was informed by the data collected to date and the impact on power was modelled. Keeping all sample size assumptions the same as the original outlined above, 249 participants would reduce the power from 90% to 86%. We also knew that the original assumption of the average cluster size of 1.35 was too low and this should be increased to 2.86 (the average school size), which would lead to a further reduction in power. As we had recent data to provide more accurate estimates of correlation between baseline and 6-month SRS-2 T-scores and attrition, we updated the sample size scenarios as outlined in Table 1. The estimate for correlation increased from 0.44 to 0.54, and attrition decreased from 25% to 23%. Unfortunately, we did not have enough data to get reliable estimates of the ICC; however, we had some information which may inform our choice of ICC further than that observed in the pilot trial. The ICC of the teacher SRS-2 T-scores at baseline was 0.09 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.24). Scenario 1 in Table 1 shows that 249 participants would provide 89% power, assuming the reduced estimate of the ICC (0.09) and other updated estimates of correlation (0.54), attrition (23%) and average cluster size (2.87). As the updated estimate of the ICC was not based on 6-month follow-up data, it is possible that our true ICC may be greater than this. For further assurance, we looked at the highest value of ICC we could have while still providing 80% power, and this would still be achieved with an ICC of 0.3, which is over three times > 0.09 and is greater than the upper confidence limit of the baseline ICC of 0.24. Evidence suggests that an ICC of 0.2 would be plausible in an educational setting,32 which gives us some confidence that a value of 0.3 would be conservative. Both updated scenarios provide at least 80% power, which gave us some assurance that ending recruitment with 249 participants would mean we had an adequate level of power even if the ICC were greater than expected. This change to the sample size was agreed by the trial oversight committees and funder.

| Scenario | Cluster sizea | ICC | Correlation | Attrition | Delta | Power (%) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 1.35 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 25% | 0.43 | 90 | 278 |

| Updated recruitment | 1.35 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 25% | 0.43 | 86 | 249 |

| Updated based on trial estimates on 27 May 2021 | |||||||

| Scenario 1 | 2.86 | 0.09 | 0.54 | 23% | 0.43 | 89 | 249 |

| Scenario 2 | 2.86 | 0.30 | 0.54 | 23% | 0.43 | 80 | 249 |

Randomisation

Participants were entered on to a bespoke trial management system developed at YTU if they fulfilled the eligibility criteria, and their parent/caregiver and school staff provided written consent to take part. This system was used to record key identifiable data required to facilitate trial participation and data collection, as well as the various dates (e.g. baseline completion, randomisation, etc.) used to schedule and manage follow-up data collection. Randomisation was clustered at the school level; hence, all pupils within a school were allocated the same trial arm, Social Stories or usual care. Randomisation occurred after consent/assent and valid baseline data had been obtained from all participating families and educational professionals within a school. The randomisation process was completed by unblinded members of the trial team via the trial management system. Stratified blocked randomisation was used to allocate school clusters, with randomly varying block sizes (4, 6 and 8), and stratification by school type (SEN school or mainstream school) and the number of participating children within a school (≤ 5 or > 5 participating children). There were no stipulations regarding the minimum number of participants per school cluster (i.e. any school with ≥ 1 eligible/consented child with available baseline data was eligible for randomisation). Prior to COVID-19, schools were notified of their study allocation via telephone, e-mail and postal letter with parents/guardians receiving only a letter. Post COVID-19, all correspondence regarding allocation was via e-mail or telephone.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the intervention, all participant types were unblinded to allocation. Research assistants collecting outcome data and the main trial statistician were blinded to study allocation until final data analysis. The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) had access to unblinded data throughout the study. Any instances of unblinding were recorded using a bespoke form. In such instances, a substitute blinded RA collected participant data wherever possible.

Group allocation

Intervention

Children in the intervention arm of the trial received Social Stories in addition to their care and education as usual. The Social Stories intervention was delivered by a trained educational professional (the interventionist) who was employed within each school allocated to the intervention arm. The interventionist varied between the schools [e.g. a teacher, TA or Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCO)] but was most typically a TA. A core aspect of the intervention was to first agree a behavioural goal around which the story would be set. The goal was typically a behavioural challenge the child was struggling with, for example, sharing with their teacher how they were feeling. This goal was agreed during a collaborative ‘goal-setting meeting’ attended by the child’s teacher, a parent/caregiver, a member of the research team and sometimes the child’s TA. Occasionally, the children themselves were able to feed into the goal-setting process if deemed appropriate. The goal-setting meeting lasted around 15 minutes. Parents/carers were asked if they had a preference for the goal beforehand via e-mail or during baseline. The parents’ preferred goal was discussed during the meeting. If teachers and parents/carers disagreed on the goal, ultimately the teachers’ preferred goal was used given that the intervention is school-based and intended to support school-based challenges. Parents/carers were invited to attend training so that they could write their own stories at their discretion.

The intervention is designed to provide social information to the child, and so the goal sought to reflect this. In this way, many goals sought to reduce the child’s anxiety or frustration by equipping them with information or providing reassurance around appropriate behaviours within a given circumstance. We assessed goal attainment in terms of how frequently a child was able to implement the desired behaviours, for example, if a goal for a particular child was to use calming strategies when they were upset, we asked teachers to rate how often a child was able to do this.

In this trial, stories were developed collaboratively during a training session attended by the child’s interventionist (often a TA) and facilitated by a member of the trial team. Sometimes the child’s class teacher was also able to attend this session. Parents/carers were invited to attend the session with the view of providing contextual information around the child’s behaviour so that they could write their own stories at home if they so wished, though any such stories did not form part of the trial and no data were collected with regard to home use. Schools were provided with a resource pack containing worksheets designed to help them develop the stories. Included in this resource pack was a copy of a handbook9 designed during the feasibility trial. 24

Initially, all training was delivered in person; however, due to restrictions imposed as a consequence of COVID-19, schools randomised after 23 March 2020 were trained online. In-person training typically consisted of a 3-hour training session comprising psychoeducational training around the differences associated with autism, training around the trial procedures (e.g. completion of questionnaires and session logs) and the collaborative writing of the story.

Those who were trained online were required to complete more directed independent learning by watching an online version of the training presentation and spending some time thinking about the child/children who were participating in the trial. They then received a training session online via videoconferencing, which reiterated key components of the training presentation, provided information about trial procedures and the collaborative writing of the story. These online sessions typically took around 1 hour per story.

Stories were around eight pages in length and were required to adhere to the 10 Carol Gray criteria as outlined in Background. A fidelity checklist was used to assess conformity to the criteria and was completed by one of the trainers on the research team. This checklist was developed during the feasibility trial and is documented within the Social Stories manual given to schools.

One of the Carol Gray criteria centres on making refinements to the story if needed. The intervention affords some level of flexibility, and schools were free to make changes to the story if circumstances changed, which meant content within the story was no longer accurate or relevant or if content was found to be upsetting to the child. Schools were also free to adapt the way the story was delivered, for example, if a child needed to move around, they could place pages of the book around a room so the child could move between them.

Schools were asked to read the story at least six times over a 4-week period with the child and to record each reading within a session log.

Usual care

Participants allocated to the control arm of the trial received care and education as usual. Schools in the control arm were asked to continue delivering any other support but to refrain from delivering any Social Stories for the duration of their trial involvement. Given that there is considerable variation in the level of support needed by children on the autism spectrum, we sought to define what comprises ‘usual care’ through the process evaluation. Teachers were asked at both baseline and 6-month follow-up what interventions, including Social Stories, children had received in the previous 6 months. They were also asked to describe any classroom-based support. This is described in Chapter 5.

Participant follow-up

All educational professionals (teachers and interventionists) and parents were followed up approximately 6 weeks and 6 months post randomisation. Interventionists were also asked to return session logs documenting their intervention (story-reading) sessions with the children. Follow-up data were collected in several ways.

Educational professionals

Educational professionals were primarily followed up using postal questionnaires. This approach offered the most flexibility, with educational professionals being able to complete questionnaires at their convenience. However, some completed questionnaires over the telephone or via videoconferencing with a RA, depending on their preference. Interventionists were provided with a stamped address envelope to return session logs to the trial team at the end of their 6-week intervention period.

Parents/carers

Prior to the COVID-19-related lockdown in March 2020, all parent/carer follow-ups were completed in person, either at home or within school, by a RA. After March 2020, parent/carer data were collected through a combination of postal questionnaires and telephone/videoconferencing by RAs, depending on parent/carer preference.

In all cases where data were not received within 2 weeks of the due date, RAs made four attempts to contact parents/carers to request data. This approach included a combination of telephone and e-mail contacts. At the 6-week follow-up point, if data could not be collected after four contacts, no further attempts were made, but the parents/carers remained in the trial and were sent their 6-month questionnaires at the usual time interval. Where data could not be collected after four contacts at the 6-month time point, participants were considered lost to follow-up.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of the trial was the teacher-reported SRS-2, with the primary end point being the measurement of this outcome obtained at 6 months post randomisation. This teacher was not the interventionist. This outcome was also collected at 6 weeks post randomisation. The SRS-2 identifies the presence and severity of social difficulty within the autism spectrum33 and consists of 65 questions. For each question, the person completing the form selects a score from 1 to 4 (1 = not true, 2 = sometimes true, 3 = often true, 4 = almost always true) that best describes the child’s behaviour. The responses to these 65 items are transformed by subtracting 1 from the available item scores, and 17 of the items are reverse scored so that all non-missing items have an integer score between 0 and 3, where higher scores indicate greater social difficulties. If there are strictly fewer than eight missing responses (across all 65 items), then the transformed and reversed item scores are used to generate five raw subscale scores by summing various mutually exclusive subsets of items: Social Awareness (0, 24), Social Cognition (0, 36), Social Communication (0, 66), Social Motivation (0, 33) and Restricted Interests/Repetitive Behaviour (0, 36). If there are eight or more missing items, then these scores are not calculated. These five raw subscale scores are then summed to generate the SRS-2 total raw scores (0, 195), with higher scores indicating greater social difficulties.

The available SRS-2 total raw scores are used to generate a T-score based on the sex of the child and the person completing the form (teacher). These T-scores are integers in the range (38, 90) (higher scores indicate greater difficulties) and are based on scores obtained for a nationally representative standardisation sample by the developers of the instrument. The total raw scores are mapped to T-scores so that the mean T-score in the standardisation sample is 50, with a SD of 10. The developers of the SRS-2 provide the following guidance regarding the interpretation of the total T-scores.

| SRS-2 total T-score (T) range | Guideline interpretation |

|---|---|

| T ≤ 59 | Within normal limits |

| 60 ≤ T ≤ 65 | Mild range |

| 66 ≤ T ≤ 75 | Moderate range |

| T ≥ 76 | Severe range |

Secondary outcomes

All secondary outcomes are listed below (grouped by respondent) and were collected at baseline, 6 weeks and 6 months post randomisation unless otherwise specified.

Parent questionnaires:

-

SRS-2. 33

-

Scoring and interpretation essentially identical to the primary outcome (Teacher-reported SRS-2).

-

-

Demographic information pertaining to the child and the parent – baseline only.

-

Parenting Stress Index short form. 34

-

Thirty-six Likert items with five levels of response (5 = Strongly agree, 4 = Agree, 3 = Not sure, 4 = Disagree, 5 = Strongly disagree).

-

Used to derive three subscale scores [Parental Distress (12, 60), Parent–Child Dysfunctional Interaction score (12, 60) and Difficult Child score (12, 60)], no missing items permitted, higher scores indicate greater distress, dysfunctionality or difficulties.

-

Subscale scores summed to obtain the Total Stress Score (36, 180) (higher scores indicating greater stress) which is mapped to a Total Stress percentile (0, 100) (higher scores indicating greater stress).

-

Guidelines for interpretation of Total Stress percentile (p); p ≤ 80 = Typical stress, 81 ≤ p ≤ 89 = High stress, p ≥ 90 = Clinically significant stress.

-

-

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions-Youth Questionnaire (EQ-5D-Y) (3L proxy version). 35

-

Five items (Mobility, Self-care, Usual activities, Pain/discomfort, Anxiety/depression), with three levels of response.

-

Used to derive health state and utilities for economic analyses.

-

-

Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) short form. 36

-

Forty-seven Likert items with four levels of response (0 = Never, 1 = Sometimes, 2 = Often, 3 = Always) used to derive six subscale scores [Social Phobia (0, 27), Panic Disorder (0, 27), Major depression (0, 30), Separation Anxiety (0, 21), Generalised Anxiety (0, 18), Obsessive – Compulsive (0, 18)], up to two missing items per subscale permitted (missing items pro-rated using non-missing subscale scores), higher scores indicate presence of more severe symptoms.

-

Subscale scores summed to obtain the RCADS total score (0, 141), where higher scores indicate greater symptoms of anxiety and depression.

-

-

Bespoke resource use questionnaire, capturing healthcare and non-health resource use of participants and parents/carers – baseline and 6 months only.

-

Bespoke treatment preference questionnaire – baseline only.

-

Single visual analogue scale (VAS) (0, 100), where 0 indicates strong preference for usual care/support, 100 indicates strong preference for Social Stories and 50 indicates indifference/no preference.

-

Associated teacher/TA questionnaires:

-

SRS-2. 33

-

A goal-based outcome measure (adapted from the Child Outcomes Research Consortium). 37

-

Single integer rating (0, 10) of the frequency that the child is meeting the goal set for them (0 = None of the time, 5 = Half of the time, 10 = All of the time).

-

-

Bespoke resource use questionnaire – baseline and 6 months only.

-

Bespoke treatment preference questionnaire – baseline only.

-

Bespoke resource use questionnaire determining current school care/education plan interventions – baseline and 6 months only.

-

Teacher demographics.

-

Age (years), Current professional role(s), Time spent working with children/young people (years), Self-reported knowledge and experience of working with children with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) (Limited, Moderate, Sound, In-depth).

-

Interventionist Teacher/TA Questionnaires:

-

Bespoke Social Story session log – used after each Social Story session.

-

A bespoke sustainability questionnaire – 6 weeks and 6 months only.

-

Interventionist demographics.

Adverse event data

Although unlikely due to the nature of the intervention, possible harm as a result of the study was monitored according to YTU standard operation procedures (SOPs). Adverse events reported by individuals participating in the study were recorded using a bespoke Adverse Events Recording Form and assessed for seriousness. It was outlined in the trial protocol1 that any AE will be recorded as a serious adverse event (SAE) if it results in death, is life-threatening, prolongs or requires hospitalisation or results in disability or incapacity. All AEs were reported to the Chief Investigator, Professor Barry Wright, a child psychiatrist. The protocol specified that any SAEs related to the study should be reported to the study Sponsor, DMEC and TSC. The TSC and DMEC committees reviewed AE data at approximately 6-monthly intervals throughout the trial.

Participant withdrawal

Parents/carers and/or educational professionals could withdraw from the trial at any point during the course of the study. Parents/carers also had the option of fully withdrawing their child from the trial. Unless the parent/carer opted to fully withdraw the child from the trial, follow-up of the other participants associated with the child continued as usual where possible. If a participant indicated that they wanted to withdraw from the study, a member of the research team completed a change of circumstance form, and the new participant status was recorded on the trial management system.

Trial completion and exit

Participants completed the trial once they had completed the 6-month follow-up period post randomisation. At this stage, the educational professionals and parents/caregivers allocated to the usual care arm were offered Social Stories training. No further follow-up was required post training; however, support in story writing was available on demand. Participants (of any level) were considered to have exited the trial if they had withdrawn or lost to follow-up at the 6-month follow-up point. Parents/carers were offered a Love2Shop voucher to the value of £20 upon completion of the trial. These were delivered via post. Schools were offered £50 per participating child, paid in cash.

Data management

All information collected during the study was kept strictly confidential and stored on a secure password-protected server located at the University of York for the purposes of assisting in follow-ups during the study. All paper documents were stored securely, initially at the sponsor’s office (Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (LYPFT), throughout data collection prior to transferring the documents to the University of York, which occurred on a monthly basis.

Case Report Forms (CRFs) were initially checked for errors by the research team, and any queries were raised immediately with participants. CRFs were then logged on the YTU’s bespoke data management system and scanned using Cardiff Teleform. Original data sheets were securely stored at YTU. All data were collected and retained in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation 2018 and YTU SOPs. All data will be archived for 10 years following the end of the study and then securely destroyed.

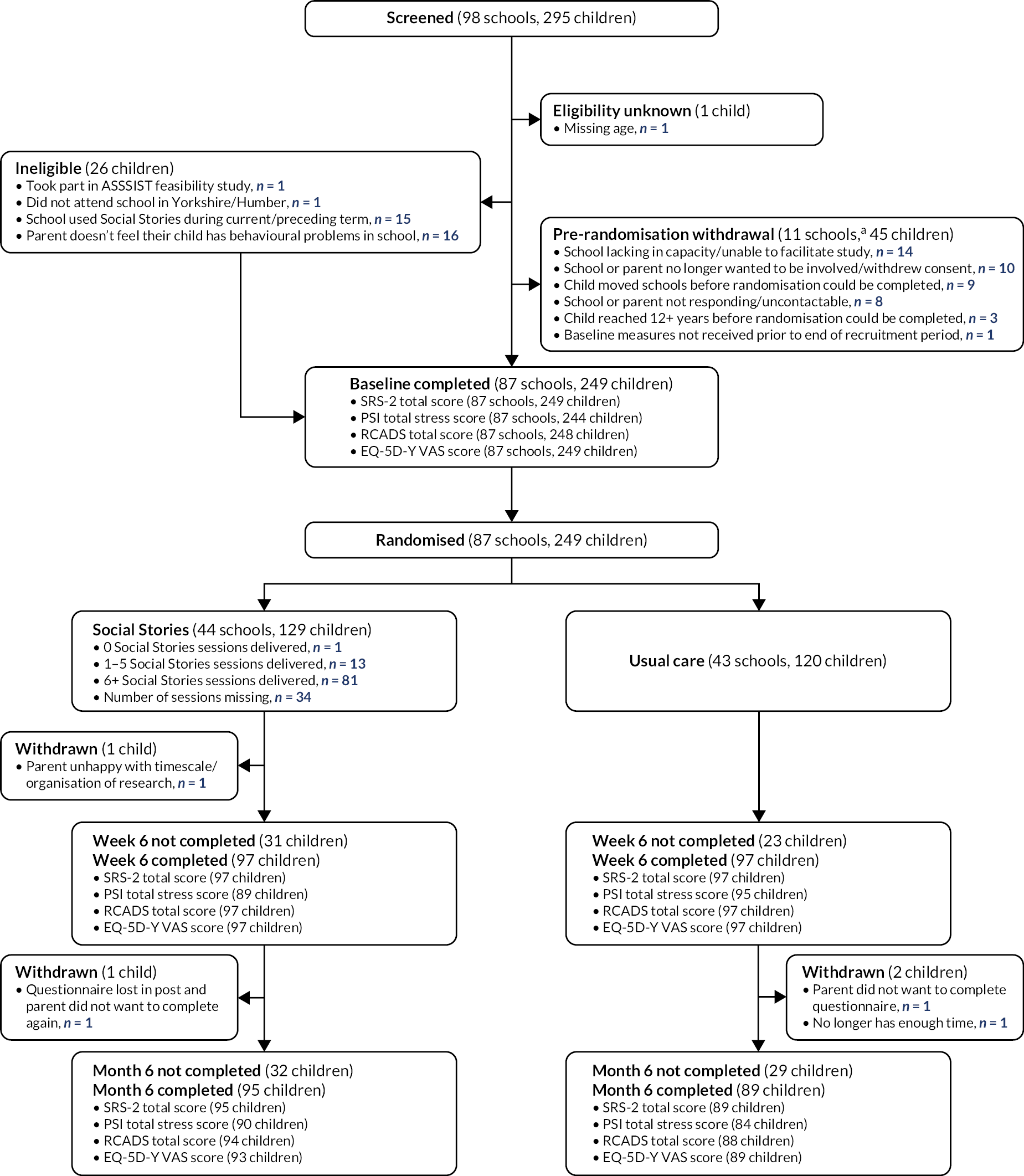

Data analysis

All outcomes were analysed after the trial had ended according to a pre-specified statistical analysis plan (SAP). Analyses were conducted using Stata version 17,38 following the principles of intention to treat (ITT), with available outcome data analysed according to the participants’ allocated group regardless of protocol deviations or non-compliance (unless otherwise stated). All statistical tests are two-sided tests of a point null hypothesis, and reported interval estimates are based on two-sided 95% CIs. The trial was designed and reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 39 Participant withdrawals (number, type and timing) and follow-up response rates are presented overall and by allocation. Compliance data, as measured through session logs, are also summarised. All participant baseline data are summarised by trial arm and overall, with no formal statistical comparisons being undertaken. All continuous/quantitative data are reported in terms of their mean, SD, median, interquartile range, minimum and maximum, with categorical data reported in terms of frequencies and percentages.

Primary analysis

The primary end point was the teacher-reported SRS-2 total T-score at 6 months post randomisation, with an earlier measurement of this outcome being collected at 6 weeks post randomisation. The derivation and analysis of the primary outcome (at each time point) were checked by a second statistician. Differences in expected score (Intervention – Control) were estimated using a linear mixed-effect covariance pattern model with both post-randomisation time points (6 weeks and 6 months) included as outcomes and fixed effects for treatment group, time point and their interaction. Further fixed effects were included for the following cluster and participant-level baseline covariates: school SEN status (binary, SEN/non-SEN), number of consented children attending school (binary, ≤ 5/> 5), baseline score (linear term), age at randomisation (linear term) and sex (binary, female/male). Dependence between participants within clusters was modelled using school cluster-level random intercepts (Gaussian with expected value 0 and variance estimated using the data), and dependence between repeated measurements within participants was modelled using an unstructured correlation matrix for the residual errors (distinct terms for the three residual error variance/covariance parameters). The model was fitted using restricted maximum likelihood estimation. No small sample degrees of freedom corrections were implemented when calculating the reported interval estimates or test statistics.

Missing data

We undertook analyses to assess the sensitivity of the results of the primary analysis to departures from the missing at random (MAR) assumption underpinning this analysis. 40 In particular, we used a delta-based sensitivity analysis (implemented via a pattern mixture modelling approach) to obtain point and interval estimates of the treatment effect, assuming the missing outcome data exhibit various systematic departures from MAR. 41,42

Adherence

We undertook analyses to estimate the complier-average causal effect (CACE) at 6 weeks and 6 months post randomisation. For the purposes of estimating CACE, participants allocated to the intervention group were defined as compliers if they were administered at least six Social Stories sessions. For identification, we assume there are no ‘defiers’ (i.e. participants that would receive at least six Social Stories sessions if and only if they were allocated to control) and that the usual assumptions required for causal inference apply (i.e. exchangeability, consistency, positivity and no interference). We also assume that randomisation is a valid instrument for treatment received (where receipt of treatment is defined as having/attending at least six Social Stories sessions) and that the effect of treatment received on outcome is not modified by any observed or unobserved confounders of this pathway. We use two-stage least squares estimators to estimate the CACE at 6 months and 6 weeks (with randomisation being used as the instrument in the first-stage regression). We adjusted for the same baseline covariates in the first and second stages as in the primary analysis and modelled dependence between participants within the same cluster using a school cluster random intercept.

Data collection schedule

To examine the possible impact of mistimed data collection (e.g. due to delays resulting from school holidays), analyses were conducted using only teacher-reported SRS-2 data that were collected within the data collection windows specified in the SAP, namely 2/+ 4 weeks for the 6-week follow-up and −4/+ 8 weeks for the 6-month follow-up.

Coronavirus pandemic impact analyses

Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. nationwide lockdowns and school closures), certain aspects of the trial were not delivered as intended. In particular, numerous participants had their follow-up data collection schedule disrupted (e.g. some month 6 follow-ups scheduled during summer 2020 could not be completed until September due to school closures) or received Social Stories from interventionists who were trained remotely (online) rather than in person. A number of pre-specified analyses were undertaken to investigate the possible impact of these disruptions on the effectiveness of the intervention.

To assess whether delays in the completion of the primary end point were associated with variation in treatment effect, we refitted the primary analysis model with an extra term denoting delayed outcome completion (binary – defined as the month 6 follow-up being completed more than 8 weeks after the planned follow-up date) and additional terms for all of the two- and three-way interactions between this variable, allocation and time point.

To investigate more broadly the extent to which disruption of follow-up was associated with variation in treatment effects, we refitted the primary analysis model with an additional term denoting whether or not the participant was due their month 6 follow-up during the school closures in the first UK lockdown (23 March 2020 to 3 September 2020) and additional terms for all of the two- and three-way interactions between this variable, allocation and time point.

Finally, to investigate the extent to which disruption of follow-up and online intervention delivery training were associated with variation in treatment effects, we refitted the primary analysis model, including an additional term denoting whether all available follow-up data for the primary outcome (at 6 weeks and 6 months) were provided/completed before/after the date of the start of the first UK lockdown (23 March 2020) and additional terms for all of the two- and three-way interactions between this variable, allocation and time point.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were performed to explore the potential modifying effect of the following subgroups:

-

The teacher’s preferred randomised group collected at baseline. Treatment preference was elicited using a VAS with a range (0, 100), where 0 indicates strong preference for usual care/support, 100 indicates strong preference for Social Stories and 50 indicates indifference/no preference. The participants were assigned to three preference subgroups based on the preference score indicated: (0, 50) = prefers usual care, (50) = no preference and (50, 100) = prefers Social Stories.

-

Whether the child has been diagnosed with cognitive/intellectual problems or a learning disability as collected on the comorbidities CRF at baseline (Binary – Yes/No).

-

Whether the child has been diagnosed with mental health or psychological problems as collected on the comorbidities CRF at baseline (Binary – Yes/No).

For each of the three baseline variables considered, the primary analysis model was augmented with additional terms for the main effect of the relevant subgroup, the two-way interactions between subgroup and allocation and subgroup and time point and the three-way interaction between subgroup, allocation and time point. The fitted models were used to obtain treatment effect estimates at 6 weeks and 6 months by subgroup, together with appropriate 95% CIs and p-values. As recommended by the literature, the subgroup analyses were restricted to the primary analysis, and subgroups were defined by baseline data, that is, data that are not dependent on the intervention. 43

Secondary analyses

The goal-based outcome score (6 weeks and 6 months), SRS-2 total score completed by parents (6 weeks and 6 months), RCADS total score (6 weeks and 6 months), EQ-5D-Y proxy VAS (6 weeks and 6 months) and Parental Stress Index (PSI) total stress score (6 weeks and 6 months) were analysed similarly to the primary outcome (i.e. using linear mixed-effect models with the same fixed and random effects and unstructured residual error covariance structure), but with the baseline score for the relevant secondary outcome included in the linear predictor in place of the baseline score for the primary outcome. The fitted models were used to estimate the between-group difference in expected score (for the relevant outcome) at 6 weeks and 6 months post randomisation together with appropriate 95% CIs and p-values.

Trial oversight

The conduct of the study was governed by three oversight committees:

-

a TSC

-

an independent DMEC

-

a TMG.

These committees functioned in accordance with YTU SOPs. The DMEC and TSC were both independent from the sponsor. The TSC consisted of an independent chair, an independent subject specialist, an independent clinical academic, an independent statistician and a PPI representative. The DMEC consisted of an independent chair, an independent statistician and another independent member experienced in research with children and families. The TSC and DMEC met approximately every 6 months from the start of the trial. The TMG comprised co-applicants, members of the trial team (including the data manager), PPI representatives and the trial managers. Co-applicants and trial team members were invited as required, depending on their roles.

Internal pilot

The first 10 months of the trial following the start of recruitment served as the internal pilot. Clear stop/go criteria were established at the outset of the trial with the view of reviewing progress against these criteria before proceeding to the full trial. The stop/go criteria centred on the feasibility of recruitment (target 110 children), retention (target 44 final follow-ups complete) and safety outcomes (see Appendix 1, Table 45).

At the end of the 10-month period, the trial team reported to the oversight committees, the TSC and DMEC, who then critically reviewed the feasibility of continuing recruitment. The progress against the stop/go criteria was as follows.

Recruitment

A total of 35 schools accounting for 100 children were randomised between 25 February 2019 (date of first randomisation) and 25 December 2019 falling just short of the 110-recruitment target.

Retention

In total, 49 participants had reached the 6-month follow-up point at the end of the pilot phase. Of these, 37 teacher 6-month follow-ups had been returned in addition to 36 parent follow-ups; this amounted to approximately a 75% response rate for the primary outcome.

Safety

Four AEs were reported to the trial team during the course of the pilot period, all of which were deemed unrelated or unlikely to be related to Social Stories; hence, no safety concerns were raised.

Process evaluation methods

The process evaluation was cross-sectional and longitudinal, encompassing all aspects of the Social Stories intervention. The aim of the process evaluation was to assess the fidelity of the programme, consider the views of various stakeholders and identify barriers and facilitators to successful implementation. 44 We aimed to achieve this through a combination of data collection techniques, including interviews, focus groups, questionnaires, surveys (see Report Supplementary Material 6) and diaries (session logs).

Research questions

The research questions for the process evaluation were:

-

What does baseline practice in participating schools look like (in the control and intervention arms) in terms of interventions to support children on the autism spectrum in school?

-

To what extent do the schools and interventionists implementing the Social Stories intervention adhere to the intended delivery model (e.g. sessions delivered six times over 4 weeks)?

-

What variability in implementation exists? Are there any barriers or adaptations?

-

How well have the Social Stories been delivered, and how well have children on the autism spectrum and school staff engaged with it?

-

-

What are the views of specified stakeholders (interventionists, teachers and parents) about the implementation and effectiveness of the intervention during the trial period?

-

To explore the views of RAs and trainers about the goal-setting process as part of the Social Stories intervention and to describe any challenges faced.

-

To what extent do schools continue to deliver the intervention after the trial period?

-

What are the barriers and facilitators to continuing to deliver the intervention?

-

Process evaluation methods

A full overview in relation to each of the process evaluation objectives is presented in Table 2.

| Method of data collection | Who or what? | N planned | Research questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semistructured interviews conducted via videoconference or telephone at 3 or 6 months post randomisation | Parents/carers who attended Social Stories training | Approximately 20 in total | What are the views of parents about the implementation and effectiveness of the intervention during the trial period? |

| Semistructured interviews conducted via videoconference or telephone at 3 or 6 months post randomisation | Interventionists who attended Social Stories training | What are the views of interventionists about the implementation and effectiveness of the intervention during the trial period? | |

| Semistructured interviews conducted via videoconference or telephone at 3 or 6 months post randomisation | Teachers who may have attended Social Stories training and were involved in completing outcome measures about the participating children | What are the views of teachers about the implementation and effectiveness of the intervention during the trial period? | |

| Focus groups facilitated by independent researcher at the end of the data collection period | Social Stories trainers | 1 | What were the trainers' experiences of delivering Social Stories training? What did they think about the training they had received? |

| Focus groups facilitated by independent researcher at the end of the data collection period | RAs involved in setting Social Stories goals with teachers and parents/carers in person (prior to COVID-19) | 1 | What are the views of RAs about the goal-setting process as part of the Social Stories intervention? What challenges were faced? |

| Focus groups facilitated by independent researcher at the end of the data collection period | RAs involved in setting Social Stories goals with teachers and parents/carers during online meetings (post COVID-19) | 1 | What are the views of RAs about the goal-setting process as part of the Social Stories intervention? What challenges were faced? |

| Questionnaires completed by the teachers and interventionists at baseline, 6 weeks and 6 months post randomisation | Teachers and interventionists | All participating teachers and interventionists | What does baseline practice in participating schools look like (control and programme) in terms of interventions to support children on the autism spectrum in school? To what extent do schools continue to deliver the intervention after the trial period? |

| Session logs completed by interventionists during the intervention period (4 weeks) | Interventionists | All participating interventionists | To what extent do the schools and interventionists implementing the Social Stories intervention adhere to the intended delivery model? How well have the Social Stories been delivered, and how well have children on the autism spectrum and school staff engaged with it? |

| Online survey – following completion of the 6-month follow-up | Parents/carers | All participating parents who consented to additional research | What are the views of parents about the implementation and effectiveness of the intervention during the trial period? |

| Online survey – following completion of the 6-month follow-up | Interventionists | All participating interventionists who consented to additional research | All research questions addressed |

| Online survey – following completion of the 6-month follow-up | Teachers | All participating teachers who consented to additional research | All research questions addressed |

Qualitative data

The Social Stories intervention is complex, as not only does it involve several interacting components (training, goal-setting, writing and delivering Social Stories), but it also requires tailoring to meet the needs of each child, setting and behaviour. The extent to which interventions are delivered as intended is a particular challenge when designing and evaluating pragmatic RCTs of complex interventions. 45–47 There is a wealth of evidence that has aimed to define the key components of intervention fidelity. 48 The Hasson framework44 is an updated version of a conceptual framework, which was originally developed by Carroll et al. 44 as a result of a critical review that synthesised existing research on intervention fidelity. Hasson proposes nine elements, as a way of conceptualising intervention fidelity: adherence, exposure or dose, quality of delivery, participant responsiveness, programme differentiation, intervention complexity, facilitation strategies, recruitment and context (see Appendix 1, Table 46). The Hasson framework44 has since been used to explore how qualitative findings can be used to understand intervention fidelity within a NIHR-funded pragmatic RCT that evaluated a multifaceted podiatry intervention trial. 46,49 In this process evaluation, we have adopted a similar approach, and by using the Hasson framework44 to underpin our analysis, we have addressed the aims of our qualitative study and provided an in-depth exploration of the key factors that affected the fidelity of the Social Stories intervention during the ASSSIST-2 trial. This approach has also enabled us to identify the key areas to consider prior to any potential future rollouts of the intervention.

The decision to use Hasson’s components of intervention fidelity as an analytical framework was based on early familiarisation with our qualitative data set during the early stages of data collection and analysis, where it became clear that many of the initial themes we had identified and indeed our research questions related to fidelity. This decision was also a pragmatic one due to the number of researchers involved in analysis, and we needed a framework which could be used consistently, broadly and flexibly (i.e. allowing new themes and/or subthemes to be identified) by the group, while at the same time allowing for an in-depth, deductive analysis of our qualitative data based on the overarching constructs proposed by Hasson to be undertaken.

Design

The qualitative study consisted of (1) interviews with interventionists who had received Social Stories training and delivered the intervention, (2) interviews with teachers who may have attended the training and were involved in completing outcome measures about the participating children, (3) interviews with parents who attended training and (4) focus groups with trainers to explore their experiences of delivering training and with the study RAs to explore their experiences of setting goals for the Social Stories with teachers and parents.

Sampling and participants

In the protocol,1 we specified that we would undertake semistructured interviews with a minimum total of 20 participants and would purposively select individuals from the cohort of trainers, interventionists and associated teachers who have been involved in the trial, as well as parents who attended training. To achieve maximum variation, we proposed selecting participants according to age, gender, time in profession and experience with ASC. The COVID-19 pandemic meant that we had to move from an in-person to a virtual training model. We therefore adapted our sampling frame and recruitment strategy to ensure that we selected participants according to whether they had received training online or in person, at both early and late stages of the transition to the online training model. To ensure further variation in our sampling, we also selected participants that represented schools and areas that were diverse geographically and in terms of the student population (e.g. school size and type) and setting (rural, urban). Data collection continued until a varied sample of teachers, interventionists and parents had been obtained50 (see Appendix 1, Table 47). This was assessed through monthly qualitative team meetings held between the RAs, the trial coordinator and lead qualitative researcher.

In total, 30 participants took part in the qualitative study, with 21 interviews (five teachers, seven interventionists and nine parents) and three focus groups (nine research team members) conducted. The 21 participants represented 15 schools throughout Yorkshire and the Humber. Schools were diverse in size (9 schools > 200 pupils, 6 schools < 200 pupils) and rurality (seven urban, eight rural). Three focus groups were conducted: one with trainers who delivered training (n = 4), one with RAs who were involved in goal-setting with parents and teachers when they could visit participants in person (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) (n = 2) and one with RAs who were involved in goal-setting with parents and teachers during online meetings (during the COVID-19 pandemic) (n = 4). One RA participated in two focus groups as they had become unblinded to help deliver the Social Stories training.

Recruitment and consent

All ASSSIST-2 trial participants (interventionists, teachers, parents/carers) who expressed an interest in participating in a qualitative interview on the consent form and who had been involved in the intervention were eligible for participation in the qualitative study. Up until April 2021, eligible participants were approached to take part in the qualitative study after they had returned all 6-month follow-up data. This was to avoid the RAs who were conducting the interviews becoming unblinded. After April 2021, one RA became unblinded and was able to invite participants to take part in the qualitative study 3 months after randomisation (between the 6-week and 6-month follow-up points). Trial participants were recruited via e-mail which contained a participant information sheet (PIS) (see Report Supplementary Material 1) and consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Recruitment e-mails also informed trial participants that a RA would contact them via telephone to find out if they would be willing to take part in the qualitative study. Once consent forms had been completed by participants and received by the research team, a date and time for the interview were arranged. If the interview took place via videoconference, the participants could choose whether or not they appeared on video and whether the video was recorded. For focus groups, RAs and trainers were contacted directly by the lead qualitative researcher via e-mail and were asked if they were willing to take part in a focus group. Prior to all interviews and focus groups, informed consent was obtained, and participants were assured anonymity and confidentiality and were given the opportunity to ask questions.

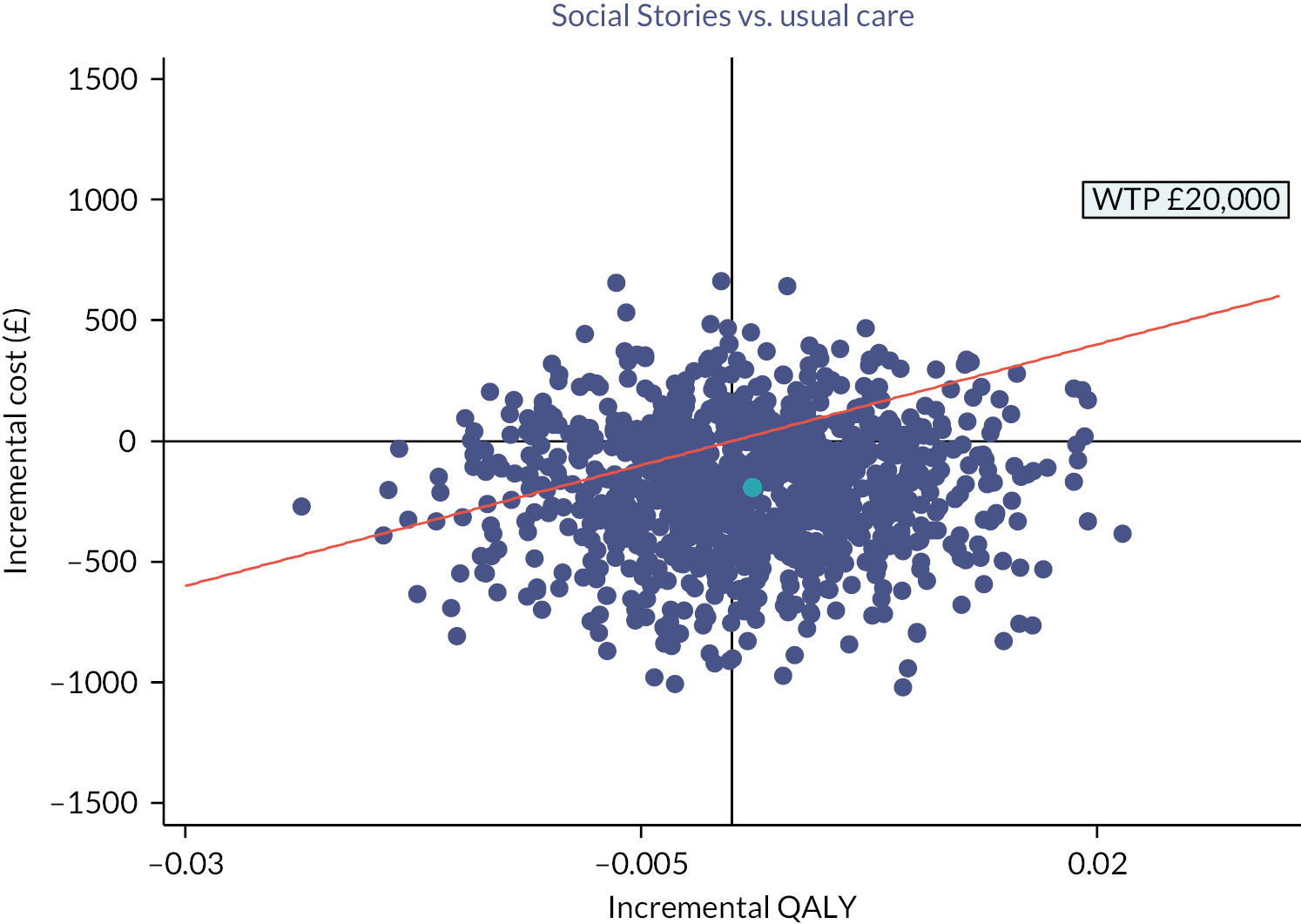

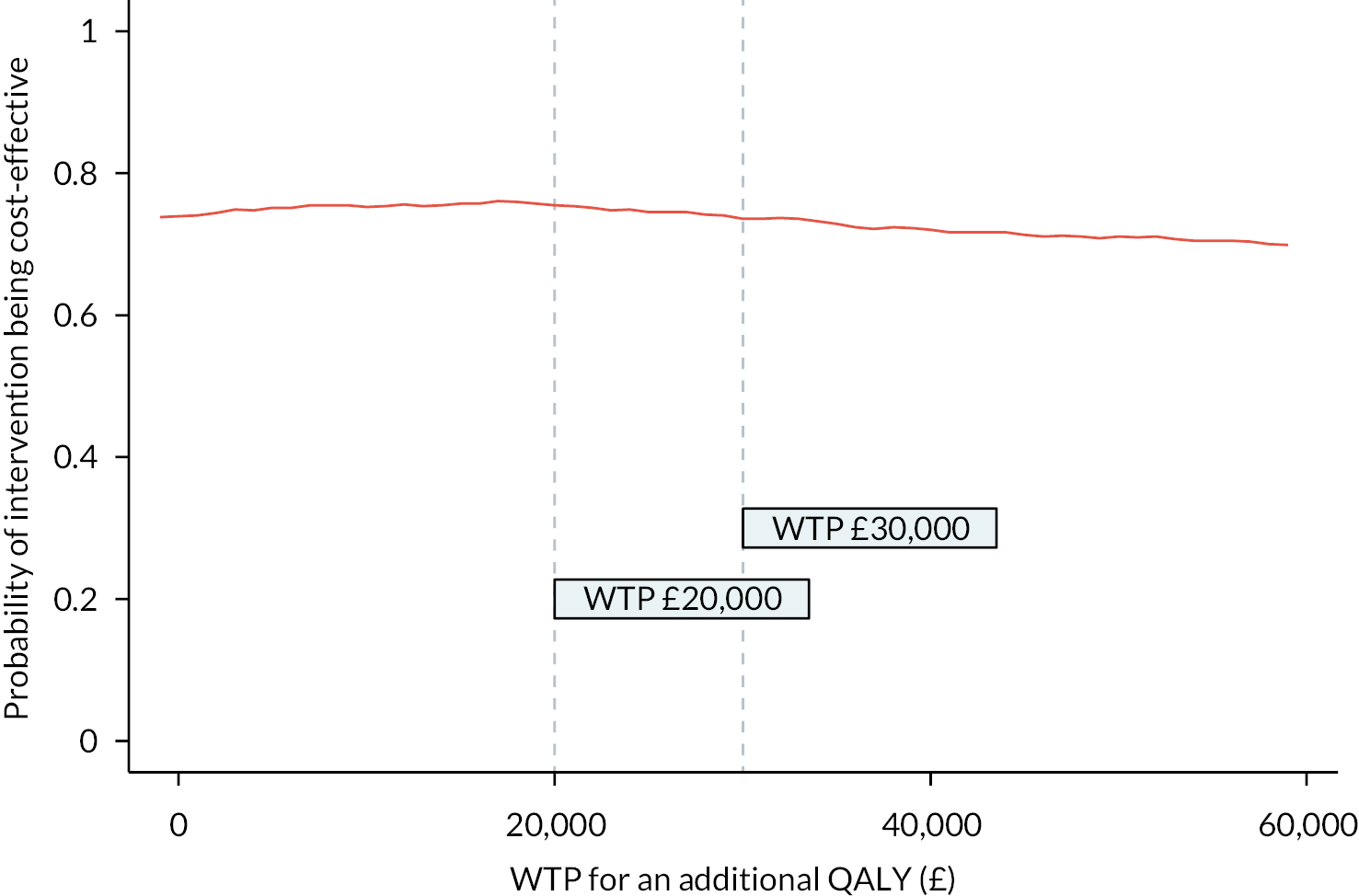

Data collection