Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 17/130/05. The contractual start date was in May 2019. The draft report began editorial review in May 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research, or similar, and contains language which may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Channon et al. This work was produced by Channon et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Channon et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

The context of obesity in pregnancy

Prevalence and risk

More than 50% of women who gave birth in the NHS between 1 April 2016 and 31 March 2017 had a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 25 kg/m2 (which would be classified as being in the overweight range),1 including 26.7% who had a BMI in the obese category (BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2). Obesity levels are expected to continue to rise, with the majority of the UK population expected to be obese by 2050. 2 Obesity places women at a greater risk of experiencing complications during the antenatal, intrapartum and post-partum periods. Maternal risks associated with obesity in pregnancy include backaches, leg pain, increased fatigue, gestational diabetes, miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, thromboembolism, slow labour progress, high caesarean section rates, post-partum haemorrhage, hypertension and maternal death. 3,4

There is also a generational dimension, as described in the Foresight report,2 with an increased risk of adverse effects on the child due to biological, social and environmental factors, including child obesity,4 developing insulin resistance5 and, for girls, having polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). 6 With the increasing evidence of the influence of the periconceptional period on fetal growth and long-term effects on risk factors for non-communicable diseases, it is essential that services incorporate interventions not only to reduce obesity levels of women in the preconception period and maintain weight loss during pregnancy and post partum, but also to prevent this passage of risk to the next generation. 7

The Southampton Women’s Survey reported that, in their community sample, almost half of the women recruited gained excessive weight in pregnancy according to the 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines,8 and there are health risks associated with gestational weight gain (GWG), irrespective of pre-pregnancy weight status. 9 However, women with overweight or obesity are at greater risk of excessive GWG in early pregnancy. The development of interventions targeting women in the preconception period, with the aim of reducing GWG, may potentially reduce the risks associated with early GWG. 10

There are clear health gains from a reduction in BMI pre pregnancy. In a population-based study in Canada11 comprising 226,958 women (64% with normal weight, 20% with overweight and 12% with obesity) with singleton pregnancies, a 10% lower preconception BMI was associated with a clinically meaningful risk reduction in pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, preterm delivery, macrosomia and stillbirth.

Excessive GWG is associated with weight retention in the longer term,12 and women in the post-partum period describe barriers to losing post-partum weight, including depression and a lack of weight management support. 13 The cumulative effects of excessive GWG without post-partum weight loss in multiple pregnancies may, therefore, contribute to obesity. Systematic reviews of weight loss interventions (WLIs) in the post-partum period suggest that WLIs with diet and physical activity components combined or that use diet alone, but not physical activity alone, can contribute to post-partum weight loss. 14 Furthermore, post-partum interventions that have an information or communication technology component may also be effective in increasing weight loss post partum. 15 However, further research and larger, high-quality trials with longer follow-up are required.

Guidelines for health-care practitioners providing care for women before conception and during pregnancy

The risks associated with obesity in pregnancy are reflected in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for health-care practitioner consultations with all women before and during a pregnancy. 16 These guidelines make lifestyle recommendations, such as stopping smoking, taking folic acid and avoiding alcohol, and they include weight management. Specific recommendations are made for consultations with women with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2. Women in this group planning a pregnancy should receive information regarding the risks of obesity during pregnancy and childbirth, and advice and support to help them achieve a healthy weight prior to pregnancy, with the suggestion that losing 5–10% of their body weight would make a significant difference. Once pregnant, women with a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 should be offered tailored information about their diet and exercise. Women should be told about the risks that a raised BMI poses to the pregnancy but also should be told not to diet in pregnancy and that the risks will be managed by the health-care practitioners caring for them. The monitoring of GWG during pregnancy is not advised unless there is a clinical need. These recommendations are supported by the Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries/Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)17 and the RCOG’s Care of Women with Obesity in Pregnancy guidelines. 18

NICE guidance also recommends that health-care practitioners be equipped with behaviour change knowledge, skills and competencies and receive communication skills training to be able to discuss weight sensitively with women. However, unlike the IOM guidance in the USA,19 there are no UK-specific guidelines for recommended optimal weight gain in pregnancy. The FIGO (International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics) guidelines stress that ‘management of obesity in pregnancy should be considered in the context of a life course approach, linking with preconception and post-partum and interconception services to prevent excess weight gain before and during pregnancy’. 20

Interventions in pregnancy

There has been a considerable focus, particularly in the last decade, on weight management interventions in pregnancy. A meta-analysis21 of individual participant data from 36 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including 12,000 participants, demonstrated that weight management interventions targeting diet and/or weight management in women across all BMI categories have not been associated with beneficial maternal or child outcomes, with the exception of caesarean section rates. However, weight management interventions in pregnancy were associated with a small but significant reduction in GWG (–0.7 kg),21 A review of reviews by Farpour-Lambert et al. 22 demonstrated moderate- to high-quality evidence of significant reduction in several outcomes in women across all BMI categories receiving a weight management intervention targeting diet and/or physical activity. These included reductions in GWG (–1.8 to 0.7 kg), excessive GWG, caesarean section rates [relative risk (RR) 0.91–0.95] and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome rates in the child (RR 0.56). However, in women with overweight/obesity, the evidence demonstrating beneficial outcomes of weight management interventions was of low to moderate quality. There was also heterogeneity among studies; study methods, intervention settings, target population and main intervention components varied between studies and interventions.

A systematic review by Agha et al. 3 across 14 studies in pregnancy and one in the preconception period demonstrated that the techniques most commonly used in interventions effective at reducing GWG included diet and physical activity counselling, motivational counselling, weight monitoring and feedback at appointments with health-care practitioners. In a meta-analysis of 89 RCTs, the authors concluded that although there was no optimal intensity, frequency, duration and delivery method that predicted success, interventions containing a group component or a healthy eating component, no matter the intensity, were more likely to be effective. 23

The timing of the initiation of a weight management intervention is important. Excessive weight gain in the first trimester is predictive of excessive weight gain throughout pregnancy24 and gestational diabetes mellitus. 25 This means that starting an intervention in pregnancy may well be too late, as the first point of contact with a health-care practitioner in pregnancy is usually towards the end of the first trimester. Interventions most effective at reducing GWG are those initiated in early pregnancy rather than those delivered later in pregnancy,3 and in Farpour-Lambert et al. ’s22 meta-analyses investigating the effects of lifestyle interventions on GWG or post-partum weight retention, the authors concluded that weight loss prior to pregnancy is probably required to achieve both GWG goals and optimal pregnancy outcomes.

Given the limited success of interventions for obesity in pregnancy, the issue of timing and the key impact of health behaviours in the very early days of conception, attention has turned to the preconception phase as critical to improving maternal and child health. However, owing to the paucity of WLIs in the preconception stage, evidence of their overall effectiveness or of what intervention components may be beneficial is limited.

Preconception health and care

The preconception period

The World Health Organization defines preconception care (PCC) as:

. . . the provision of biomedical, behavioural and social health interventions to women and couples before conception occurs. Its ultimate aim is to improve maternal and child health, in both the short and long term.

As highlighted in the 2018 series on preconception health in The Lancet27–29 and by Stephenson et al. ,30 preconception is an ‘underappreciated period in the life course when health, behavioural, and environmental exposures can have far-reaching consequences, not only for pregnancy outcomes but also for health across generations’. 30 One of the complexities, critical to the clarity of focus of any programme or intervention, is defining the meaning of preconception. Stephenson et al. ,27 suggested that there were three perspectives to consider in a discussion of preconception: (1) biological perspective (the days or weeks before the embryo develops), (2) individual perspective (the weeks or months before conception for individuals who have a conscious intent to conceive) and (3) public health perspective, which includes the months or years before conception. Hill et al. 31 recognised the value of this classification but felt that it lacked enough specificity to identify the population to be defined and targeted in interventions. They proposed four perspectives, each based on a particular combination of defining attributes: reproductive age, man/woman, not pregnant, sexually active, intent to conceive. Some differences from Stephenson’s classification are that the ‘public health’ group is subdivided into those of reproductive age (public health) or younger (life course) and that the individual perspective is subdivided into those with intent and those without intent (potential preconception). Many preconception interventions target the ‘intentional preconception’ group, but this excludes those who are sexually active, who may or may not be using contraception, but have not made a conscious decision to conceive.

Healthy diet/nutrition and weight management have been identified as the top two priorities in international preconception research. 32 There are significant gaps in preconception nutritional intake internationally. 33 In the UK it is estimated that 77% of women aged 18–25 years have dietary intakes below Reference Nutrient Intake daily recommendations for iodine and that 96% of women of reproductive age have intakes of iron and folate below the daily recommendations for pregnancy. 27 The situation is not greatly improved in women who are planning a pregnancy: the results of the Southampton Women’s Survey showed that only a very small proportion of women planning a pregnancy followed the recommendations for nutrition and lifestyle in the preconception period. For example, only 2.9% of women who became pregnant [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.2% to 6.0%] complied with recommended levels of folic acid supplementation and drank four or fewer units of alcohol a week, compared with 0.66% (95% CI 0.52% to 0.82%; p < 0.001) of those women who did not become pregnant. 34

The lack of engagement with the recommendations may well be due to a lack of knowledge relating to preconception health or, potentially, beliefs relating to the behaviour, as there are indications that smoking, a more commonly known risk behaviour, does reduce before pregnancy. 35 Preconception education and counselling can improve maternal knowledge, self-efficacy and risk behaviour, but the impacts on anthropometric measures and pregnancy outcomes are less clear. 36,37 There may also be demographic differences underlying differential behavioural response to information; for example, younger preconceptional women and women with children were less likely to engage in preconception health behaviours,38 and women with higher levels of education were more likely to engage. 39,40

In England, the Preconception Partnership of key stakeholders is working to operationalise policy to ensure that PCC becomes a more integrated part of routine practice. It has proposed an annual report identifying progress on a set of core metrics for agencies, reflecting planning and preparation for pregnancy at an individual and public health level. 30 This would include improving the health environment, putting the importance of preconception health on the school curriculum and embedding it in policy initiatives. On an individual level, the goals include normalising conversations about pregnancy intentions in health care, increasing support for behaviour change to improve preconception health and training health-care providers to have conversations about preconception health.

One of the issues that is often cited as the reason for the lack of preconception health care is the number of pregnancies that are planned, often assumed to be small. In a cross-sectional survey35 of 1288 women conducted in a London maternity centre, 73% had clearly planned their pregnancy and 24% were ambivalent, with only 3% of pregnancies unplanned. These figures would suggest that planning is more common than is often assumed. There are also different types of ‘planning’, for example women with high levels of pregnancy planning who take up interventions but also those who plan but describe themselves as having poor awareness of preconception actions. 41 However, if the interventions suggested by the Preconception Partnership were put in place and preconception health conversations were more integrated into routine care, the level of positive intention and planning could become less of a barrier.

Preconception and obesity

Until very recently, few studies have targeted obesity in the preconception period; interventions in the preconception period have reported programmes for very specific populations, such as gastric bypass patients,42 those with diabetes43 or couples seeking in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment,44 or have been small scale. 45 Two Cochrane reviews46,47 investigating the effectiveness of preconception and antenatal health programmes and interventions in improving pregnancy outcomes or reducing weight in obese women identified no eligible studies in the preconception phase. In a systematic review48 of the impact of preconception lifestyle interventions on live birth, birthweight and pregnancy rate, six of the included studies reported participants’ weight and BMI, five of which were in the context of assisted reproduction. The Strong Healthy Women (SHW) intervention49 (a six-session preconception health course with a social cognitive approach50 to behaviour change in preconceptional and interconceptional women living in low-income rural communities) was excluded from the reviews as it was not possible to identify outcomes by BMI category (see Studies in progress).

A more recent scoping review51 of RCTs of behavioural interventions supporting women of childbearing age in the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity identified only one intervention in the preconception period, the Prepare study protocol. 52 The Prepare trial is a pre-pregnancy intervention in the USA for women with a BMI of ≥ 27 kg/m2 identified through routine data. The intervention is based on social cognitive theory, and the intervention group received 6 months of weekly weight management calls from a health coach followed by monthly calls for 1 year. The primary outcome was GWG but with prenatal weight loss as a secondary outcome. In the results, now published,53 the women receiving the intervention lost an average of 3.5% of their weight before becoming pregnant (control arm 0.5%; p < 0.001). However, by the end of the third trimester, the GWG was the same for both groups, leading the authors to suggest that an intensive weight management approach is needed beyond preconception, and throughout pregnancy, to manage GWG.

One potential reason for the lack of evidence in relation to preconception and obesity is that weight and weight management often do not feature in preconception health programmes that have been evaluated. In a systematic review of studies identifying factors related to preconception health behaviours,38 weight status was measured in only 3 of the 24 included studies and, therefore, was not identified in the review as one of the six categories of factors. Similarly, in a scoping review of preconception health interventions, only 4 of the 29 included programmes identified weight/obesity as a risk factor to be addressed. 37 More recently, in a published trial protocol concerning the uptake of PCC in the Netherlands,54 the primary outcome was change in lifestyle behaviours (e.g. folic acid use, smoking and alcohol use) and secondary outcomes were pregnancy outcomes (e.g. miscarriage, preterm birth, gestational diabetes) and the uptake of PCC, but weight management was not included. Overall, the quantity and quality of the evidence in this field is very limited. 36

Barriers to engaging women in preconception weight loss interventions

With the rising rates of women of childbearing age who are obese,55 the development of effective preconception WLIs for women with overweight/obesity may provide an important step in reducing the health risks to mother and child. As with pregnancy,56 the preconception period may be considered a ‘teachable moment’, during which efforts may be made to positively influence women’s diet and health behaviours. However, there are barriers to overcome. As already highlighted, preconception is a difficult time to identify. ‘Planning’ a pregnancy is often declared only once the pregnancy has been confirmed; prior to this, it is something regarded by many as deeply personal and essentially private. 57 Furthermore, women may not be aware of the importance of preconception health, and they may not perceive there to be risks or that the risks are relevant to them. 45,57 Specific issues for women with overweight/obesity and who are planning a pregnancy include poor uptake of health activities, inaccurate self-categorisation of weight, unsuccessful weight loss attempts and inadequate advice regarding pre-pregnancy weight loss. 58 Often, the complex lifestyle changes required for weight loss before pregnancy are challenging to achieve, but women who recognise that they have knowledge gaps about the impact of obesity in pregnancy are keen to receive information about antenatal, intrapartum and post-partum risks. 43

The Health Survey for England (HSE)59 reports that obesity rates for women are higher in areas of highest Index of Multiple Deprivation (39%) than in the least deprived areas (22%). Evidence of obesity rates in ethnic minority groups is scarce, with the exception of the 2004 HSE. 60 These data suggest that obesity rates vary among ethnic groups, with higher rates in black and Pakistani groups and lower rates in Chinese groups than in the general population. 61 Health risks such as diabetes are observed in ethnic groups at lower rates of overweight/obesity than the white European population,62 and, therefore, reducing obesity levels in ethnic minority groups could be of increased relevance. Uptake and retention of programmes may vary in women of different ethnic backgrounds. In a process evaluation of a postnatal WLI in an ethnically diverse population, non-white British/Irish women were less likely to attend a commercial weight loss management group than white British/Irish women. The women were more likely to describe barriers to attending the sessions, such as time, access and child-care needs, than white British/Irish women. 63 Furthermore, women from ethnically diverse communities reported that they had modest or poor awareness of preconception health issues and that there was little culture of preconception preparation. 64 Therefore, cultural differences would need to be considered and addressed when targeting women from ethnic minority groups and when designing an effective intervention for ethnically diverse populations.

Health-care practitioners also experience barriers to raising weight management during preconception and pregnancy-related consultations, including lack of skills, time, financial reimbursement, sensitivity of topic and confidence in the available interventions. 65–67 Interviews with UK health-care practitioners showed that there was a low awareness of preconception health issues and confusion about responsibility for delivery of PCC. 35 Taking a broader view of health-care provision, these barriers resonate with those found in a systematic review of the barriers to and enablers of health-care practitioners in delivering behaviour change interventions (diet, physical activity, alcohol reduction, smoking cessation and weight management). 68 Four themes emerged as both barriers and enablers: (1) perceptions of the knowledge or skills needed to support patients’ behaviour change, (2) perceptions of their professional role, (3) beliefs about resources needed and (4) practitioners’ own health behaviour. Cross-disciplinary barriers included a perceived lack of time, negative attitudes towards patients and perceptions of patients’ motivation, including a lack of prioritisation of health behaviour change. 68 Training, context and attitudes towards the intervention were the enablers identified, and any programme of preconception health will need to use these to address individual and systemic barriers if provision is going to change.

Studies in progress

Several trials are in development or pre-reporting that are taking a range of approaches to weight management in the preconception period in different cultural contexts.

Strong Healthy Women was originally a six-session intervention delivered to 692 preconceptional and interconceptional women across 12 weeks in low-income and rural communities. They focused on managing stress, physical activity, nutrition (including folic acid supplementation), preventing gynaecologic infection, tobacco exposure and alcohol use (weight was not included as a focus). Their intervention adopted a social cognitive approach to behaviour change,50,69 identifying self-efficacy, motivation and intention to change as important determinants of behaviour change. Participants receiving the intervention had improved pre–post intervention outcomes relating to nutrition, physical activity and stress management compared to the control group. 70,71 At the 12-month follow-up, the intervention group had reduced weight (mean group difference of 4.33 lb), reduced BMI (mean difference of 0.75 kg/m2) and lower GWG in those who became pregnant (mean difference of 17.95 lb). 49 Despite a small sample size, these were promising results. However, the face-to-face nature of intervention delivery was considered resource-intensive and expensive by the research team, and the time investment required for participation was burdensome for some women. The study team have therefore explored a ‘smart’ version, using qualitative methods to determine which components women would be happy to receive digitally and which to retain face to face. 72

The INTER-ACT study in Belgium73 is an interpregnancy study designed to reduce pregnancy complications in women whose pregnancy weight gain exceeds the IOM-recommended levels. The lifestyle intervention incorporates an e-health application (app) and coaching delivered partially post partum and then during the following pregnancy. The women’s experience of using the app suggests that combining a personalised app with coaching is a positively received intervention.

The Jom Mama trial in Malaysia74 is a population-based pre-pregnancy intervention that recruits as couples get married. It is designed to enhance healthy dietary choices, increase exercise and manage stress. It is grounded in the theory of triadic influence and uses behaviour change counselling combined with WhatsApp chat support and an e-health habit formation app.

TOP Mums75 is a preconception intervention designed to reduce perinatal morbidity for women with a BMI of > 25 kg/m2 planning to conceive in the next year and is due to report imminently. It is a 26-week programme incorporating motivational interviewing, personalised goals and a health intervention, ‘Smarter Pregnancy’. BMI is the primary outcome from baseline to 6 weeks post partum, with GWG one of the secondary outcomes.

Other studies that will involve measurement of pre-pregnancy weight, but do not evaluate population based pre-pregnancy interventions, evaluate the quality of the preconception diet (Healthy for my Baby);76 the relationship between maternal weight and baby weight;77 reducing pre-pregnancy and pregnancy weight gain in the context of depression;78 and reducing the reoccurrence of gestational diabetes. 79

Users of long-acting reversible contraceptives

The complexities of identifying the preconception population mean that it is difficult to engage with people at the right time to have them consider taking part in a weight reduction programme to improve their preconception health. Women who use long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs) and who require removal of the device to become pregnant represent a unique group in which there is an opportunity for intervention. However, at this point in their reproductive decision-making, it may be difficult to ask women to delay conception through continued use of LARC and engage in weight loss programmes, raising pragmatic and ethical issues for both an intervention and any research study designed to establish effectiveness. A small feasibility study of an intensive WLI offered to women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more attending for LARC removal80 demonstrated that some women were willing to consider delaying LARC removal for 6 months to participate. This small evidence base suggests that there may be an interest in weight loss and a willingness to delay LARC removal in relevant populations. However, with high rates of non-participation and attrition from the programme, it has not yet been established what, if anything, the nature of an acceptable intervention would be.

To answer this question, a mixed-methods approach is required, incorporating the use of routine data, qualitative data collection and analysis, and giving a central role to stakeholders. This will lead to a better understanding of the LARC pathway from an individual and population perspective and its interface with weight management. LARC users’ and health-care practitioners’ experiences of LARC services, decision-making and management of weight around pregnancy will be explored alongside their views of the ethical and methodological issues associated with the timing of informed consent and a potential preconception WLI. Health-care practitioners’ LARC practice and consultation patterns regarding LARC use and removal will be identified utilising data sets, collected routinely across the four UK nations, to compare the population across the different health-care settings as well as over time, taking into account factors such as the impact of different general practice incentives on activity and recording. 81 All of this information will be critical to consider when developing a future intervention.

Preconception weight loss as a complex intervention

A preconception weight loss programme would be described as a complex intervention in the terms of the Medical Research Council framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions,82,83 which involve multiple interacting components in a complex context and require behaviour change on the part of practitioners and participants. The Medical Research Council framework identifies four phases in the development and evaluation of complex interventions: development, feasibility, evaluation and implementation. The Plan-it study falls into the development phase, exploring an idea for a potential intervention that could be delivered in the NHS. There are, clearly, many generic weight loss programmes that women could access in the preconception phase. The question here is whether or not it is acceptable and feasible to develop a specific preconception weight loss programme that includes a delay to a LARC removal as the entry point to the programme.

As described by O’Cathain et al. ,83 the development phase is a dynamic, iterative process that includes seeking feedback from key stakeholders on intervention ideas, reviewing evidence, drawing on theories, exploring context and undertaking some primary data collection. Through this process, the strengths of the idea and the problems can be identified and used to further refine possible intervention designs. Once an idea for an intervention has been developed that is acceptable and feasible in its formulation, it moves to the feasibility phase, when it is tested in practice, followed by an evaluation, potentially by a RCT, to establish its efficacy.

Research objectives

The aim of the Plan-it study is to establish if it is acceptable and feasible to conduct a study that asks women with overweight/obesity (BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2) to delay removal of LARC to participate in a targeted pre-pregnancy WLI.

The study objectives are to identify:

-

the annual number of women of reproductive age (16–48 years) in the UK who request LARC removal and subsequently have a pregnancy

-

the means of identifying women with overweight/obesity at study sites who plan to have LARC removal for the purpose of planning a pregnancy and opportunities to intervene

-

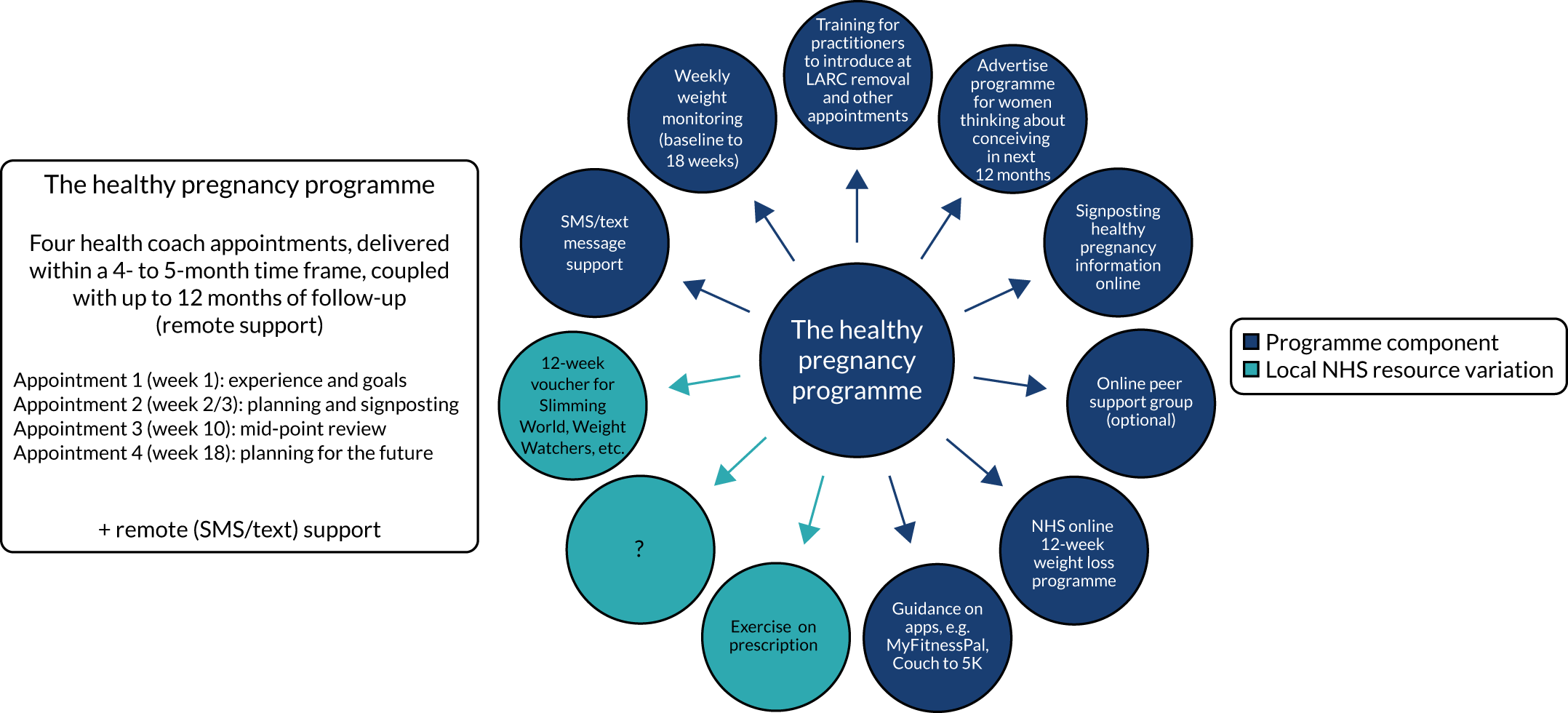

suitable and acceptable interventions that can be incorporated into a preconception WLI

-

the willingness of clinicians to raise weight loss in consultations and recruit eligible women to the intervention

-

women’s views about the acceptability and feasibility of the proposed intervention

-

future potential intervention based on feasibility and acceptability to stakeholders.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter provides a detailed description of the study design and a general overview of the study processes. Specific methods relevant to individual study work packages (WPs) are detailed in corresponding chapters.

Study design

The Plan-it study used a concurrent mixed-methods approach, incorporating the use of routine NHS data and qualitative data collection, analysis and synthesis across WPs to address study objectives (see Chapter 1).

Work package 1 established the feasibility of defining and understanding the study population through routine data and addressed study objectives 1 and 2 (see Chapter 3):

-

to identify the annual number of women of reproductive age (16–48 years old) in the UK who request LARC removal and subsequently have a pregnancy

-

to ascertain opportunities to identify women with overweight/obesity at study sites who plan to have LARC removal for the purpose of planning a pregnancy and opportunities to intervene with a potential preconception WLI.

Work package 2 identified potentially suitable preconception/pregnancy-related WLIs and the theories underpinning them, using realist methods,84 in addition to assessing the feasibility and acceptability of a preconception WLI to stakeholders (LARC users and health-care practitioners). Study objectives 3–5 were addressed:

-

to identify suitable and acceptable programme components to be incorporated into a preconception WLI

-

to assess the willingness of health-care practitioners to raise weight loss in consultations and recruit eligible women to the intervention

-

to assess LARC users’ views on the acceptability and feasibility of the proposed intervention and of future research.

The findings from the two WPs were collated, and the barriers to and facilitators of a potential future intervention were assessed by stakeholders (see Chapter 7), to address objective 6:

-

future potential intervention based on feasibility and acceptability to stakeholders.

Work package 1: defining and understanding the population through routine data

To address study objectives 1 and 2, WP1 used routine data from Welsh sexual health clinics (SHCs) and UK general practices relating to women attending for LARC removal to:

-

understand the pattern of LARC use to identify opportunities to intervene

-

report the annual number of women in the UK requesting removal of LARC without replacing it with an alternative prescribed contraception

-

identify women, who request LARC removal and subsequently become pregnant, who would be eligible for recruitment to a WLI study

-

identify events in general practitioner (GP) and hospital records to explore time from LARC removal to conception or appointments relating to difficulties conceiving (if possible).

Comprehensive WP1 methodologies are described in Chapter 3.

Work package 2: understanding context and stakeholder views

Work package 2 was conducted in two phases. Phase 1 comprised scoping work to develop an understanding of the typical preconception pathways related to LARC use/LARC removal and weight from the perspectives of LARC users and service providers and to identify suitable weight loss and weight-related health behaviour interventions and the theories that underpin them using realist synthesis. Phase 2 focused on establishing the acceptability and feasibility of a proposed intervention.

Work package 2 phase 1: realist review – scoping suitable interventions and underlying theories

Programme theories regarding how and when health behaviour interventions in the preconception phase may function were developed, guided by the principles of scientific realism. 84 Studies of WLIs prior to and during pregnancy and relevant behaviour change interventions were identified through literature searches, including searches of systematic reviews, companion papers (e.g. qualitative studies and process evaluations) and grey literature (the search strategy is detailed in Appendix 6). These provided an understanding of how and when preconception WLIs might be delivered successfully. Barriers to and facilitators of engagement in preconception health behaviour change interventions and identified health gains or risks to health associated with the intervention were incorporated into the review. The outcome of this review was a set of context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations and key components of the intervention. These were explored in stakeholder advisory groups (SAGs) as the basis of an early overall programme theory, and further developed in phase 2.

Work package 2 phase 1: understanding the preconception pathways relating to LARC

A range of qualitative methods were used to generate a detailed understanding of typical preconception pathways related to LARC use/LARC removal and weight from the perspectives of both service users (LARC users) and service providers (health-care practitioners and weight loss practitioners). LARC removal service contexts, LARC management (in the context of LARC users and health-care practitioners), the inter-relationship between discussions about overweight/obesity and family planning, feasible opportunities to intervene and potential intervention components including additional preconception health-related content were assessed. The phase comprised three components: (1) an analysis of policy documents, (2) engagement with LARC users and (3) service provider engagement (health-care and weight loss practitioners).

Analysis of policy documents

A review of policies, best practice guidelines and other clinical/advisory documents pertaining to the use (and particularly the removal) of LARCs in the UK was conducted to understand how services are expected to approach discussions of weight loss with women with overweight/obesity, how LARC treatment pathways currently operate, guidance on health behaviours prior to conception and the practical/ethical challenges to successful service delivery in current service structures, including equity of access to interventions (for detailed methodologies, see Chapter 4).

Engagement with LARC users

Qualitative surveys using closed and open-text questions were utilised to understand women’s experiences of discussing weight with health-care practitioners; how, where and when women access preconception WLIs; women’s knowledge of the risks of overweight/obesity in pregnancy; the barriers to and facilitators of the introduction of a WLI at LARC removal appointments; and the preferred components of a potential intervention. Detailed methodologies are described in Chapter 4.

Engagement with service providers (health-care and weight loss practitioners)

Qualitative surveys with health-care practitioners using closed and open-text questions focused on: PCC provision; the discussion of weight and preconception health both generally and in the specific context of LARC removal; challenges to service delivery; equity of access to interventions; and views on the potential for an intervention postponing LARC removal as part of preconception weight loss plan. Weight loss practitioners (i.e. people who support women to lose weight as part of their role) were recruited via existing contacts and a range of social media platforms. Qualitative surveys with weight loss practitioners addressed the feasibility and experiences/views on the provision of weight loss programmes in the preconception phase. Detailed methodologies are described in Chapter 4.

Summary of phase 1 findings

Information gathered in phase 1 was synthesised to describe the core components of a potential intervention, together with the contextual factors likely to be important influences on outcomes and engagement. This was refined through work with two SAGs, a LARC user SAG and a health-care practitioner SAG, recruited through the exploratory work in phase 1. The health-care practitioner SAG was run as part of a Continuing Professional Development event to incentivise health-care practitioners to attend but without disruption to clinical activity. The LARC user SAG took the form of a focus group, held remotely via Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA). The objectives of both SAGs were to generate the stakeholders’ views of the potential intervention components and to consider the key questions to ask participants in phase 2. Detailed methodologies are described in Chapter 6.

Phase 2: acceptability and feasibility of proposed intervention

The outputs from phase 1 were explored in phase 2, with targeted qualitative work addressing acceptability and feasibility of a potential WLI to women in the target population and to health-care practitioners. Phase 2 qualitative interview schedules were informed by the feedback from the SAGs, and the interviews further tested and refined the theories developed in phase 1. Interviews with 20 LARC users and 10 health-care practitioners were conducted over the telephone or remotely via Zoom or Microsoft Teams. Health-care practitioners were asked to explore their views regarding the type of intervention and their willingness to recruit women to a potential study. LARC users were asked to explore their views regarding the acceptability and feasibility of the potential WLI. Findings from the targeted qualitative phase 2 work were discussed at LARC user and health-care practitioner SAGs. The SAGs were conducted as a focus group remotely via Zoom or an online group discussion. The findings from phase 2 were collated, and the key design elements of a potential intervention were described.

Literature review methods

For each of the search strategies (detailed in Appendix 6), relevant papers were identified through purposive and snowball searching. A broad search strategy was developed and run in the following search engines: MEDLINE, PubMed and ScienceDirect® (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Papers were restricted to English language only between set dates. Search strategies were agreed between two members of the team for each search, inclusion criteria were set and the relevance of each paper was assessed. Data to be extracted were agreed prior to analysis and a sample of data extraction was double checked by a second member of the study team. Quality was assessed and integrated into the analysis and synthesis to ensure that the findings were not overinterpreted.

Study setting and participant selection/recruitment

The study setting and participant population is described in Table 1.

| Study stage | Participant population | Setting |

|---|---|---|

| WP1 | Participants will be included in routine data sets if they met eligibility criteria | N/A |

| WP2 phase 1 | LARC users of reproductive age who self-identify as having/previously having overweight/obesity | Identified via social media/online platforms. Recruited online via Cardiff Online Surveys (formerly Bristol Online Surveys) |

| Health-care practitioners who insert or remove coils as part of their role | Identified at up to eight professional meetings. Recruited online via Cardiff Online Surveys or face to face | |

| Weight loss practitioners who support women to lose weight as part of their role | Identified via existing contacts or social media/online platforms. Recruited online via Cardiff Online Surveys | |

| WP2 end of phase 1 SAGs | LARC users of reproductive age who self-identify as having/previously having overweight/obesity | Purposively sampled from the WP2 phase 1 participant population, who had agreed to be contacted by the study team |

| Health-care practitioners who insert and/or remove coils as part of their role | Identified and recruited at a BASHH audit-focused professional meeting | |

| WP2 phase 2 interviews | LARC users of reproductive age who self-identify as having/previously having overweight/obesity | Purposively sampled from the WP2 phase 1 participant population, who had agreed to be contacted by the study team, excluding members of the phase 1 SAG |

| Health-care practitioners who insert and/or remove coils as part of their role | Purposively sampled from the WP2 phase 1 participant population, who had agreed to be contacted by the study team | |

| WP2 end of phase 2 SAGs | LARC users of reproductive age who self-identify as having/previously having overweight/obesity | Purposively sampled from the WP2 phase 1 participant population, who had agreed to be contacted by the study team |

| Health-care practitioners who insert and/or remove coils as part of their role | WP2 phase 1 participant population, who had agreed to be contacted by the study team |

Eligibility criteria

Participants were included in routine data sets if they met the eligibility criteria and in the online surveys if they self-identified as meeting the eligibility criteria. See Chapter 4 for a detailed description of LARC user and health-care practitioner eligibility criteria and Chapters 6 and 7 for relevant LARC user and health-care practitioner sampling criteria.

Informed consent

For the surveys, all inclusion and exclusion criteria were specified in publicity materials, and for the surveys, interviews and SAGs all participants were provided with a participant information sheet (PIS) and followed a consent procedure (see Chapters 4, 6 and 7).

Data management and confidentiality

All procedures for data storage, processing and management complied with the Centre for Trials Research (CTR) Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and Public Health Wales (PHW) data-sharing agreements and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR),85 as appropriate. A full Data Management Plan was developed, and all data will be kept for 15 years on a Cardiff University secure server, in line with Cardiff University’s Research Governance Framework Regulations for clinical research.

The online survey was hosted by Cardiff Online Surveys (previously Bristol Online Surveys) on a Cardiff University secure server, and access was password protected. A member of the research team acted as administrator.

Hard-copy consent forms were stored in a locked filing cabinet. All electronic data, including consent/contact details, were stored in password-protected servers maintained on Cardiff University networks. All electronic identifiable data (consent, contacts forms) were stored separately from interview data. Interviews and SAGs were recorded on encrypted password-protected audio recorders, and voice files remained password protected and were accessible only to relevant members of the research team once transferred to secure Cardiff University servers. Recordings were transcribed and pseudonymised in line with the CTR SOPs. All essential documents generated by the study were kept in the study master file and/or on the electronic study master file.

Analysis

Findings from iterative literature searches were synthesised using a realist approach to evaluation. 84,86 The extracted information was summarised descriptively in explanatory accounts and then consolidated to generate potential CMO configurations to be explored in phase 2 stakeholder interviews.

Survey responses were downloaded. Responses to closed or multiple-choice questions were described. For each qualitative data collection method (open-text questions in survey responses, interviews or SAGs), responses were thematically analysed in each group of participants (LARC users, health-care practitioners and weight loss practitioners) separately. Qualitative synthesis across all interviews provided an overarching synthesis of LARC users’ and service providers’ perceptions related to the study objectives. A full qualitative analysis plan was written by the qualitative researcher and approved by the Study Management Group (SMG) and Study Steering Committee (SSC) prior to analysis taking place.

Withdrawal

For WP1, data were aggregated and anonymised, and, therefore, it was not possible to remove records once an extract had been produced. Participants in the WP2 surveys and qualitative interviews were able to withdraw at any time prior to analysis by contacting the study team. Participants in SAGs were able to withdraw at any time by leaving the SAG meeting. However, the nature of a focus group meant that any contribution thus far was unable to be withdrawn.

Ethics

Ethics approval for this study was given by the Cardiff University School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee on 30 April 2019, reference number 19/42 (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Participant and public involvement

Participant and public involvement (PPI) representatives contributed to both the SMG and the SSC (one PPI member in each committee) and took an advisory role in study design, study progress and results dissemination.

At the end of each phase of WP2, PPI input took the form of SAGs whose role was to:

-

refine findings from WP2 phase 1 to generate potential intervention components, collaboratively with the research team, and to consider key questions to take forward in phase 2 (phase 1)

-

discuss findings from the targeted qualitative phase 2 work to describe the key design elements of a potential intervention or the reasons why a trial is currently not feasible to deliver (phase 2).

Changes to the protocol

Three changes were made to the original study protocol. (1) Phase 1 engagement with health-care practitioners via qualitative individual interviews and a qualitative survey was changed to solely the qualitative survey. This was for two reasons. First, conducting qualitative interviews during professional events proved to be impractical and, second, the study team felt that the in-depth nature of individual qualitative interviews was not required in addition to the survey at stage 1. (2) In-depth interviews with weight loss practitioners who support women to lose weight were not conducted in WP2, phase 1, as planned. This was due to a poor response rate to the phase 1 online survey and resulting limited number of participants to sample. (3) COVID-19-related restrictions led to the phase 1 LARC user SAG and the phase 2 SAGs being conducted remotely (via Zoom or Padlet) rather than face to face.

Chapter 3 Routine data work package

Introduction

Aims of the chapter

The Plan-it routine data WP used anonymised routinely collected data from SHCs in England, Wales and Scotland and the CPRD linked to the Pregnancy Register to determine the most appropriate LARC removal settings, the annual numbers of potential participants available to be recruited and an indicative time frame for recruitment.

The objectives were to set up access to anonymised data from multiple health settings to:

-

understand the pattern of LARC use (removal/insertion/in situ) to identify opportunities to intervene

-

identify women, who request LARC removal and subsequently become pregnant, who would be eligible for recruitment to a WLI study

-

report the annual number of women in the UK requesting removal of LARC without replacing it with an alternative prescribed contraception

-

identify events in GP and hospital records to explore time from LARC removal to conception or appointments relating to difficulties conceiving (if possible).

The outcomes identified were:

-

rates of women in the UK who request LARC removal and subsequently have a pregnancy from routine data

-

identification of opportunities to intervene in the preconception pathway.

Methods

Study design/setting

Routine data providers and data sets

Clinical Practice Research Datalink

The CPRD provides UK-wide individual anonymised patient GP data. Data cover > 20% of general practices in the UK and are representative of practices by country, rurality and deprivation quintiles. 87 Anonymised primary care patient data requested from CPRD include data linked to secondary care and other health-based data sets, including the Pregnancy Register. The Pregnancy Register is created by an algorithm that lists all pregnancies identified in the CPRD database. 88 For pregnancies resulting in live births, deidentified information of the linked babies in the CPRD Mother Baby Link were also provided (baby ID, baby month and year of birth, pregnancy start and end dates, gestational age of baby, and mother’s age at pregnancy). LARC-related Read codes were identified using the Read code dictionary and from the literature and reviewed by the clinical co-investigators for accuracy and inclusivity of all possible codes. Cardiff University held an Academic Risk Sharing Licence with CPRD and following Independent Scientific Advisory Committee approval, and data were made available via a Cardiff University-employed data analyst.

Sexual health clinic data

Sexual health clinic data are collected and held separately in Wales, England and Scotland. Public Health Wales holds individual-level patient data from all SHCs in Wales (from 2012), and these were made available to the study team in an aggregate format based on data requirements. Aggregated data from PHW were transferred to Cardiff University servers on agreement of data release. The required tabulations of outputs were agreed with PHW to ensure that the eligibility applied to CPRD patients was applied to the SHC data. In Scotland and England, SHC data are collated and reported by NHS National Services Scotland and NHS Digital, respectively. National statistics annual reports on sexual health service use provide open data tables that were used as a national comparison with Wales (with no formal data access requests required for these open data tables). 89,90

Study population

Clinical Practice Research Datalink

The Plan-it Study was interested in identifying women with overweight or obesity who had their LARC removed for the purpose of conception and were, therefore, eligible for a targeted pre-pregnancy WLI. The predefined study population was women of reproductive age (16–48 years inclusive) with at least one LARC event between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2018.

Defining a LARC event

A list of LARC events was prespecified from the Clinical (medical history data entered on the GP system), Referral (referral details recorded on the GP system) and Therapy (all prescriptions issued by the GP on the GP system) data sets in the CPRD and agreed by the SMG (see Appendix 1). These were categorised as followed: LARC insertion, in situ (checks), removal. LARC event codes that belonged to males or to women who were under 16 or over 48 years old at the date of consultation, those for events before 2009 or after 2018, those with no consultation date, duplicate codes (same code recorded on the same day) or those that belonged to women who were not in the predefined study population were excluded.

Identifying women who were planning a pregnancy following LARC removal

The study population were grouped as follows:

-

Group 1 – planning a pregnancy

-

Group 2 – possibly planning a pregnancy

-

Group 3 – probably not planning a pregnancy.

Table 2 shows the algorithm used to define these groups based on the initial LARC event, a consultation code following the LARC event that either confirmed or refuted planning a pregnancy, and a confirmation of a pregnancy. Codes to refute or confirm that a pregnancy was planned are in Appendix 3.

| Group | Group description | LARC event | Consultation following LARC event (and prior to pregnancy if applicable) | Pregnancy event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Planning a pregnancy | LARC removal/inserted/in situ | Read code indicating a pregnancy was being planned | Yes |

| 1 | Planning a pregnancy | LARC removal/inserted/in situ | Read code indicating a pregnancy was being planned | No |

| 2 | Possibly planning a pregnancy | LARC removal/inserted/in situ | No code present to indicate that the woman was planning a pregnancy or not. No code present to indicate an unplanned pregnancy | Yes |

| 3 | Probably not planning a pregnancy | LARC removal/inserted/in situ | Code to indicate a pregnancy was not being planned (e.g. alternative contraception), menopause indication (e.g. blood tests) | Yes |

| 3 | Probably not planning a pregnancy | LARC inserted/in situ | No code present to indicate that the woman had a LARC removed or was planning/not planning a pregnancy | No |

| 3 | Probably not planning a pregnancy | LARC removal/inserted/in situ | Code to indicate a pregnancy was not being planned (e.g. alternative contraception), menopause indication (e.g. blood tests) | No |

| Not enough information | LARC removal | No code present to indicate that the woman was planning/not planning a pregnancy | No | |

Identifying a pregnancy

We requested Pregnancy Register data on the predefined population and used the estimated pregnancy start date provided as the index date at which to examine prior LARC use. The estimated pregnancy start date was estimated using the timing of the start of pregnancy (first day of their last menstrual period) and additional data from ‘Additional Clinical Details’ files. In the absence of such data, pregnancy start dates were imputed according to the type of pregnancy outcome. We excluded pregnancies that had a defined start date occurring before 2009 or after 2018, duplicate events (repeated events, overlapping events, and events that had a start date within 31 days of the previous start date).

Identifying clinical events after the LARC removal

The clinical events between the two events (LARC removal and pregnancy start date) or following the LARC event were examined to either confirm or refute that a pregnancy had been planned. These events were identified from the Clinical file in CPRD (see Appendix 2 for the list of Read codes that were prespecified and agreed by the SMG):

-

refuting a planned pregnancy – an alternative prescribed contraception (see Appendix 2, Table 23), indication of the menopause (see Appendix 3, Table 24), and an unplanned pregnancy (see Appendix 3, Table 26)

-

confirmation of a planned pregnancy – indicating trying to get pregnant, a planned pregnancy (see Appendix 3, Tables 25 and 26).

The following assumptions were agreed by the Plan-it study team in advance:

-

For those with a pregnancy, only codes that were within the 456 days (1 year and 3 months) prior to the pregnancy start date were investigated. For those with no pregnancy, only codes that were within 456 days of the LARC event were investigated.

-

If the gap between a LARC removal and LARC situ events was < 28 days, it was assumed that the woman was having a LARC check-up. These two events were combined as one rather than included twice.

-

For a woman who had the LARC in situ/insertion and LARC removal event on the same date, LARC replacement was assumed and the LARC removal event was excluded.

-

For clinical codes that appeared between a pregnancy start and end, only the planned pregnancy and unplanned pregnancy code were included.

-

LARC in situ or insertion within a week of a pregnancy start was coded as unplanned pregnancy.

-

For a woman with their first LARC code between a pregnancy start and end and after a week of a pregnancy start, the whole event was excluded.

-

For a woman who has both unplanned and planned pregnancy code between LARC removal and pregnancy start, the code that was closest to the pregnancy start was used as an indicator for grouping the woman.

-

For a woman who had both the alternative contraception and the trying/difficult to get pregnant code on the same day, the trying/difficult to get pregnant code was used as an indicator and the contraception code excluded.

-

Women with too many planned/unplanned codes were coded as Unable to code.

Body mass index

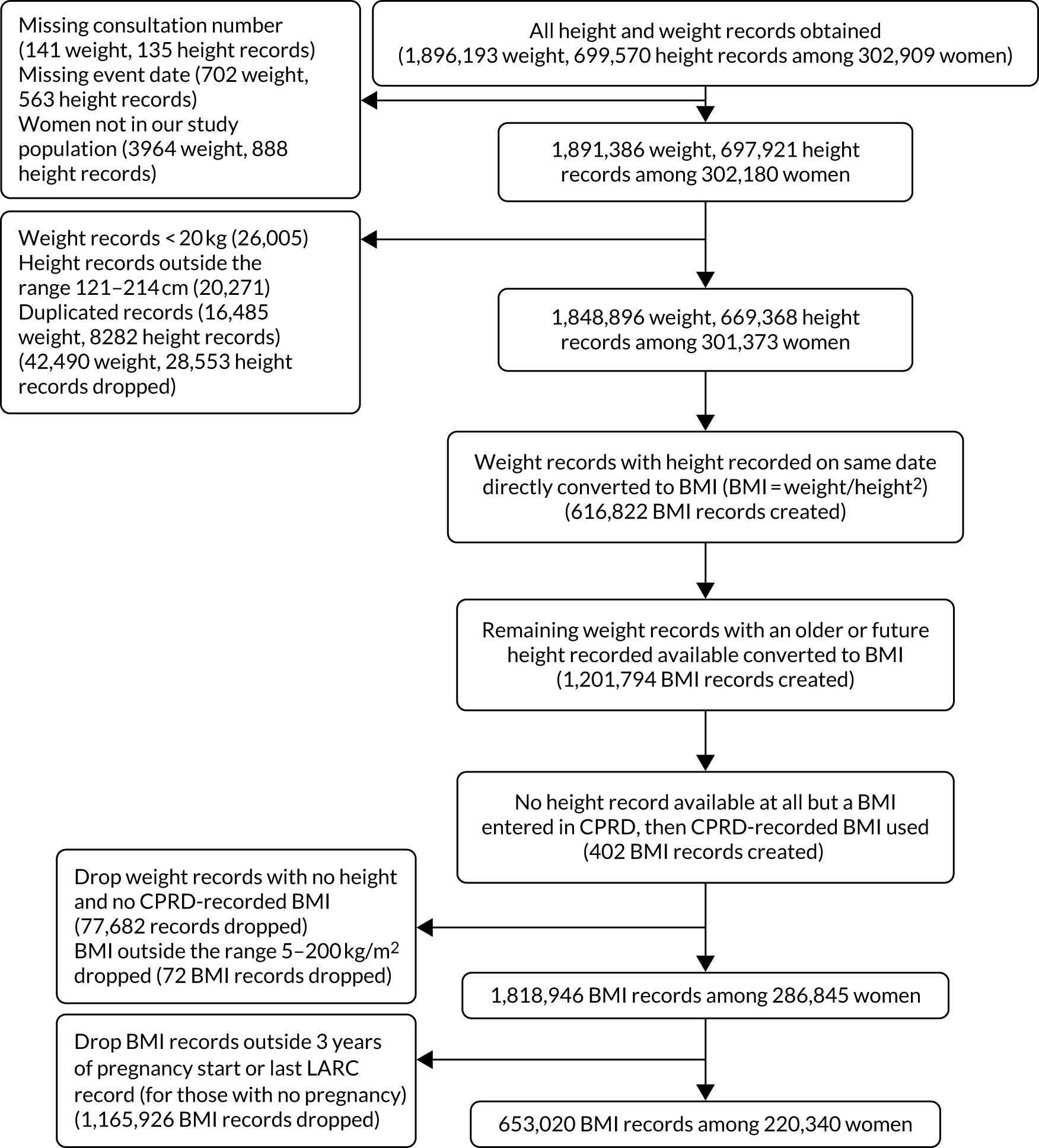

Weight and height data were selected from the ‘Additional Clinical Details’ file in CPRD (Entity Type 13 and 14). The BMI was generated following the method described in Bhaskaran et al. 92 (representativeness). Only BMIs that were recorded within 3 years of either the pregnancy start date or the last LARC event for those with no associated pregnancy were included. Appendix 5 depicts the data flow for BMI.

Sexual health clinic data

Women of reproductive age (i.e. 16–48 years old) with at least one LARC event (inserted, removed or in situ) between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2018 were included. Data were sourced from the Sexual Health in Wales surveillance system. Data on patients who attended a SHC in Wales were recorded and coded by front-line SHC staff and then collated by PHW. Data fields of relevance to this project included date of birth (for age to be calculated), date of attendance (for year to be derived), main contraception method [CM2: implant; CM3: intrauterine device (IUD); CM4: intrauterine (IU) system], health board and deprivation quintile.

Statistical methods

For the individual anonymised data from CPRD, rates of fitting and removal of LARC in general practice were calculated and reported over time (either quarterly or annually, depending on numbers). Rates were calculated as the number of LARCs fitted and removed as a proportion of all women of reproductive age.

Trends in rates were examined by country, LARC type and, where available, attendance type (pre-booked vs. walk-in consultations). Similarly, we examined trends using the Welsh SHC data. This enabled a comparison of the case mix of women recorded for a LARC removal in general practice and those who visit a SHC by age, ethnicity, BMI and deprivation. The data from SHCs in Scotland and England were in aggregate format at NHS Sexual and Reproductive Service provider level and reported rates of fitting and removal annually. Trends in rates by age group at time of fitting or removal, change of contraception method from/to a LARC and, if recorded, BMI category and deprivation quintile were explored. These rates were compared with those arising from the SHC data in Wales. The quality of recording of BMI in all data sets was explored. Previous work in the CPRD shows that completeness of BMI has increased over time (to around 77%) and was higher in female individuals, especially those of reproductive age. 92

Analysing these data sets identified variation in the numbers, pattern and duration of use of LARCs in the different health settings, geographical areas (rural/urban) and demographic groups. It was possible to consider what opportunities (e.g. consultation types, frequency of consultations) are available to intervene in the different service delivery designs across the UK. The routine data analysis determined the most appropriate LARC removal settings, the annual numbers of potential participants available to recruit and an indicative time frame for recruitment.

For patients attending their GP for the fitting or removal of their LARC, the data allowed exploration of the duration of LARC use prior to removal and the changes to contraception use over time; through linking to the Pregnancy Register algorithm, a pregnancy episode related to the women in the cohort (estimated start of pregnancy) was flagged. Accessing these data will enable a broader understanding of the population for whom this intervention will be targeted and, potentially, identify those who had a LARC removed for the purpose of planning a pregnancy. An examination of how time to conception may differ between BMI and age categories was also possible. For women whose pregnancy was identified following a LARC removal, the natural distribution of the time between the two events (LARC end and pregnancy start) was examined to assess whether or not a rule could be applied to indicate that the pregnancy and LARC removal were associated.

Although the data between GP surgeries and SHC data could not be linked, the recording of a LARC removal in a SHC setting was explored in the GP notes. Previous work using an alternative primary care data source (The Health Improvement Network) identified that 24% of LARC-related records in primary care came from SHC letters. 93 The reporting of routine data was in accordance with RECORD (REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected Data). 94

Data access, linkage and cleaning methods

At the time of the project, Cardiff University held a licence with CPRD that allowed approved university staff members to access the CPRD GOLD database. The population relevant to this study was identified using the agreed code list (see Defining a LARC event). This list of patients was then linked to the Pregnancy Register (this linkage is completed by CPRD and not by Cardiff University staff). Once linked, these data sets were made available to the project staff.

Ethics

Data access requests to CPRD were reviewed by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (Protocol: 19_188). The CPRD has broad National Research Ethics Service Committee ethics approval for purely observational research using the primary care data and established data linkages. No further ethical review was required for this element of the project.

Results

Defining the study population in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink

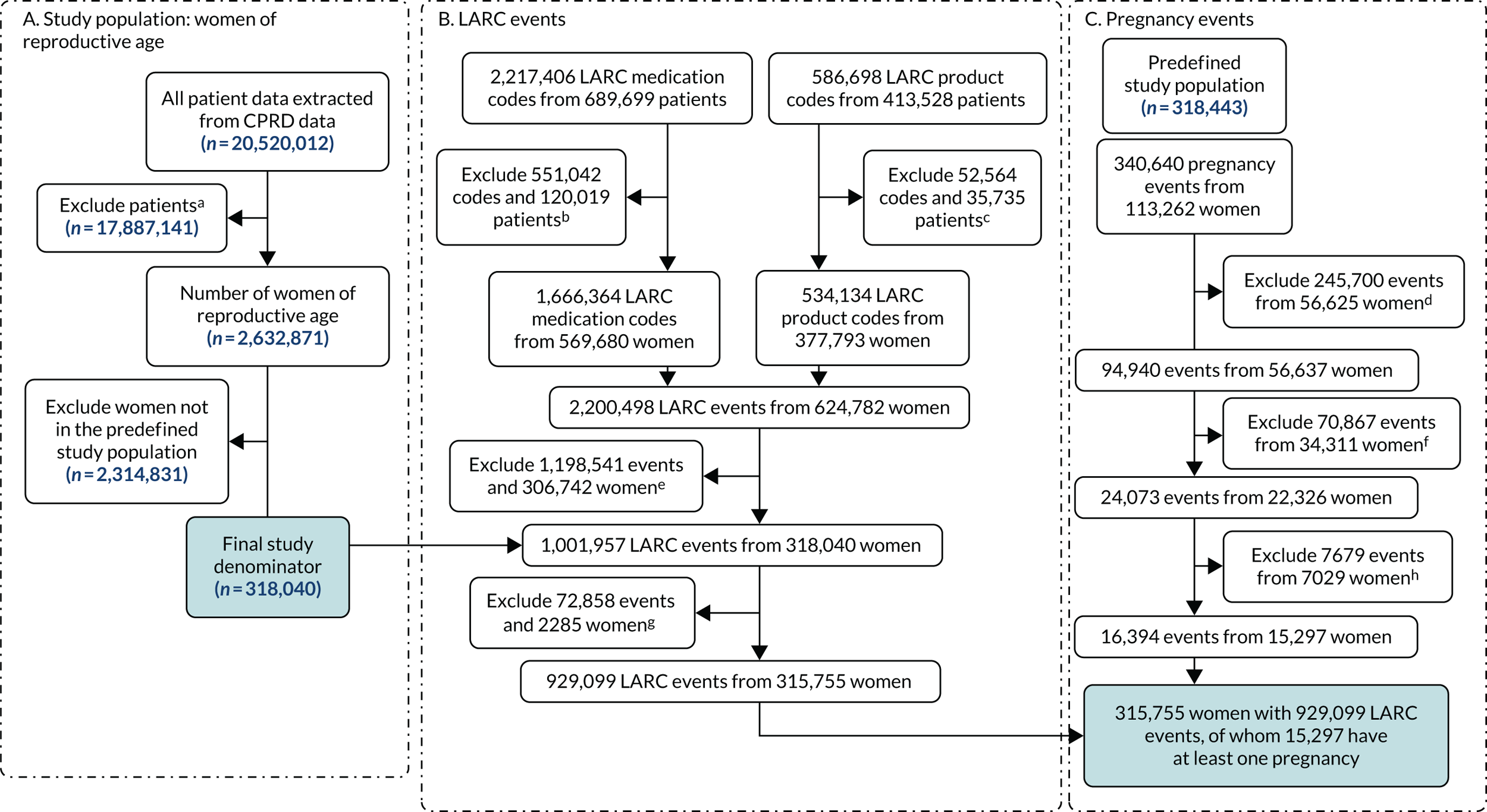

The study population generation is reported in Figure 2. The study population was identified using the CPRD Patient file, which included just over 20 million patient records. Practices were excluded from the study population if the practice’s last contribution date was before 2009 or their up-to-standard date was after 2018. Practices with < 1 year between their last contribution date and their up-to-standard date (< 1 year of data available) and those not meeting the criteria in the specified years were also excluded. The following patient groups were excluded: male patients; patients of unknown or indeterminate gender; patients whose data were outside the up-to-standard date; patients whose year of birth was outside 1961–2002; patients who had died before 2009; patients registered with the practice after 2018; and patients whose current period of registration with the practice was after 2018.

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow diagram. Reproduced with permission from Channon et al. 91 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

This left 2,632,871 women at reproductive age in the study denominator. However, 2,314,831 were excluded as they were not in the predefined study population (i.e. with one LARC event), leaving 318,040 eligible women of reproductive age in the study population. The rate of women at reproductive age in the study denominator was constant over the time period 2009–18 (Table 3).

| Year | Number of women aged 16–48 years (study denominator) | Number of general practices with data available | Rate of women per practice per 10,000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 1,413,791 | 738 | 5.22 |

| 2010 | 1,408,118 | 728 | 5.17 |

| 2011 | 1,380,332 | 713 | 5.17 |

| 2012 | 1,355,832 | 699 | 5.16 |

| 2013 | 1,330,823 | 680 | 5.11 |

| 2014 | 1,244,434 | 645 | 5.18 |

| 2015 | 1,108,991 | 580 | 5.23 |

| 2016 | 914,755 | 491 | 5.37 |

| 2017 | 812,739 | 437 | 5.38 |

| 2018 | 741,453 | 397 | 5.35 |

Objective 1: understand the pattern of LARC use (removal/insertion/in situ) to identify opportunities to intervene

Women attending general practice for a LARC-related consultation

To identify women who attended a GP surgery for a LARC event, a combination of Read and prescription codes were used. The flow chart (see Figure 2) shows that, from using these codes for LARC, 929,099 codes were present in the study population of 315,755 women. Table 4 shows these data broken down by LARC consultation type and type of LARC. Women in our study population could experience more than one code over the study period. For example, among the 127,909 women who had at least one LARC in situ code, 49,285 (39%) had more than one code recorded over the study period. Of those 269,999 women who had a LARC insertion, 182,090 (67%) had more than one LARC insertion code recorded over the study period. Of those 108,987 women who had a LARC removal, 12,615 (12%) had more than one LARC removal code recorded during the study period.

| Unique number of events | Number of women with at least one event | |

|---|---|---|

| LARC consultation typea | n = 938,161 | |

| In situ | 222,555 | 127,909 |

| Insertion | 592,402 | 269,999 |

| Removal | 123,204 | 108,987 |

| Type of LARC | n = 934,903 | |

| IUD | 411,514 | 167,008 |

| IU system | 308,058 | 131,889 |

| Implant | 215,331 | 125,497 |

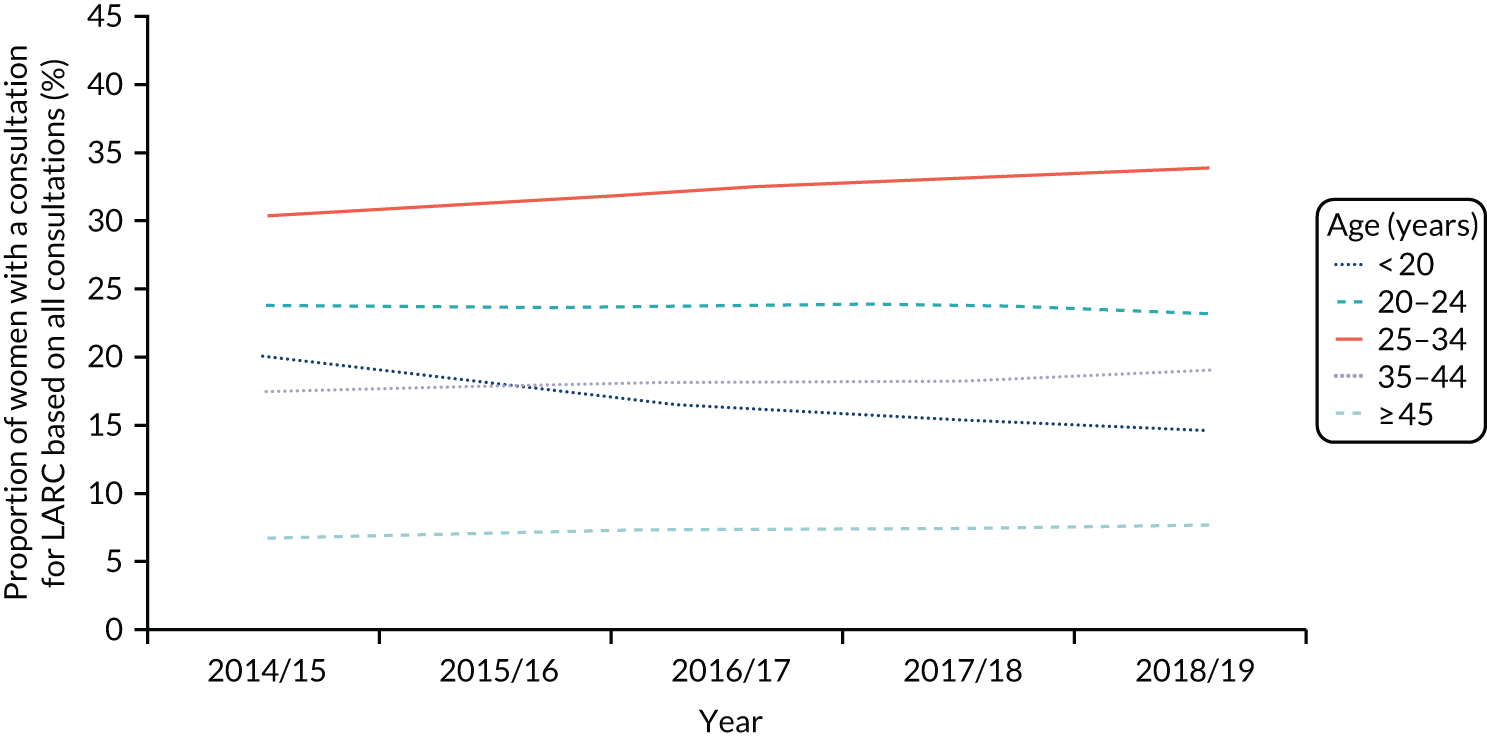

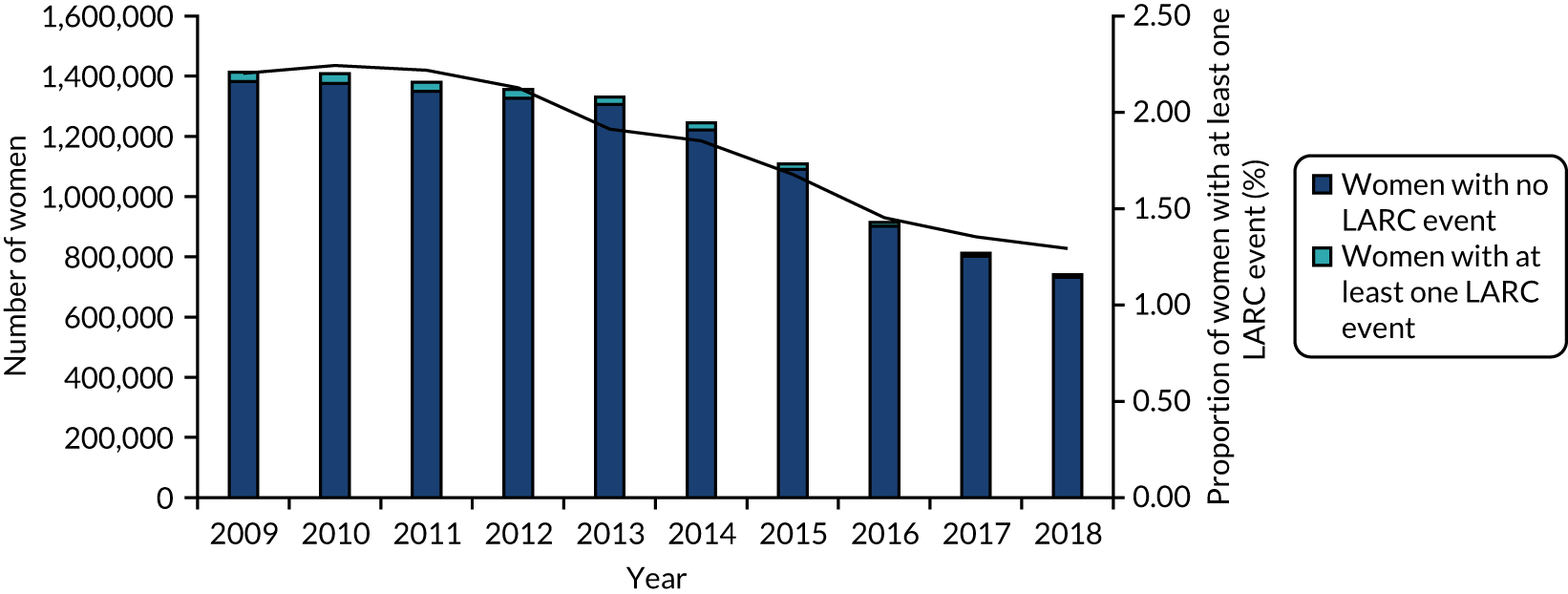

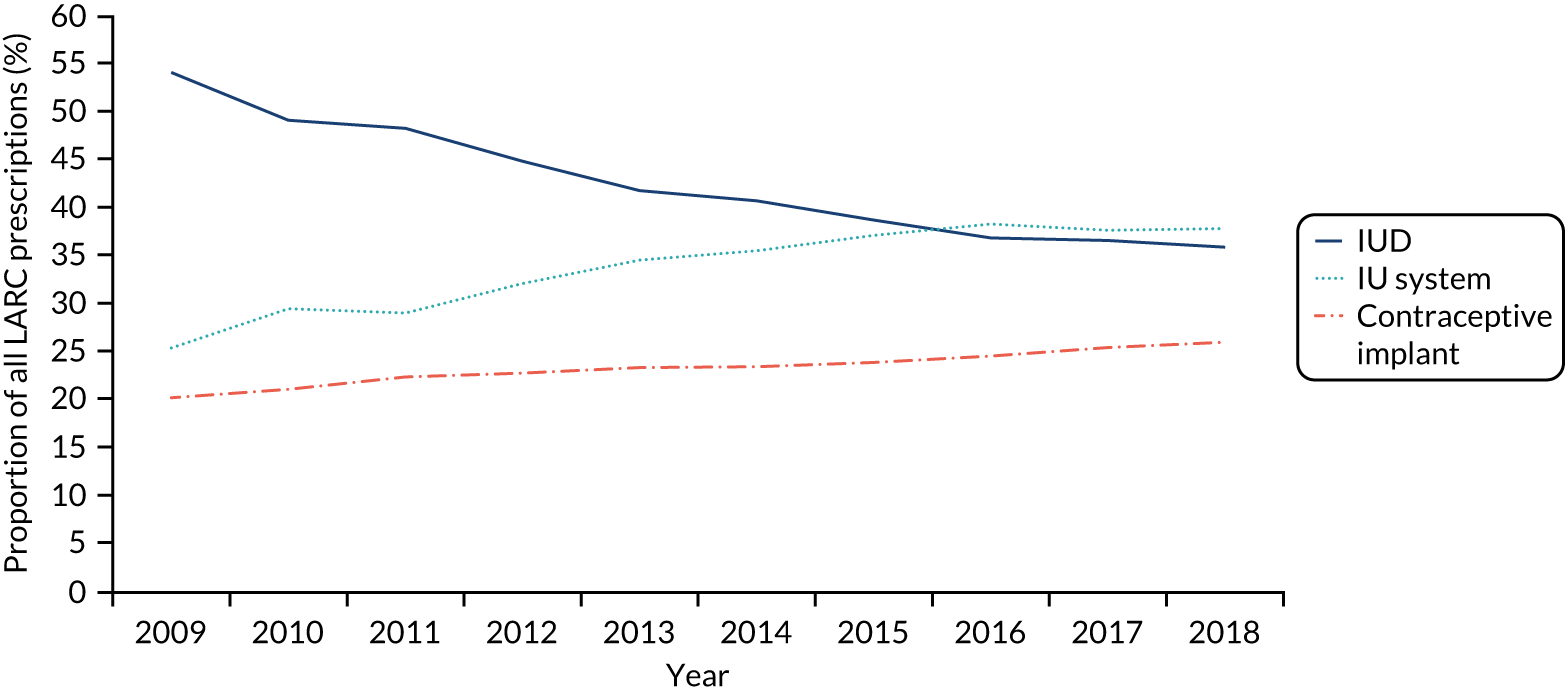

The number of women in the study population decreased over time due to the number of practices contributing to the CPRD declining; the rate of women per practice was constant (Figure 3 and Table 5). The proportion of women with one or more LARC consultations decreased over time, from 2.2% in 2009, which is approximately 42 LARC events per practice, to 1.3% in 2018, 24 LARC events per practice. By contrast, the Wales SHC data show a different picture (Figure 4); in 2018 the rate of women with SHC contact for LARC use out of contacts for any contraception was higher, at 24%.

FIGURE 3.

LARC users over time: CPRD (2009–18).

| Year | Study denominator | Study population | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women aged 16–48 years (n) | Consultations (n) | Year of first LARC consultationa | LARC consultation typeb | Type of LARC | ||||||||||||

| In situ | Insertion | Removal | IUD | IU system | Implant | |||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| 2009 | 1,413,791 | 2,253,647 | 61,440 | 4.3 | 31,074 | 1.4 | 65,523 | 2.9 | 11,293 | 0.5 | 58,232 | 2.6 | 27,390 | 1.2 | 21,814 | 1.0 |

| 2010 | 1,408,118 | 2,385,300 | 51,850 | 3.7 | 31,479 | 1.3 | 75,430 | 3.2 | 12,402 | 0.5 | 58,576 | 2.5 | 35,194 | 1.5 | 25,222 | 1.1 |

| 2011 | 1,380,332 | 2,474,914 | 43,456 | 3.1 | 30,540 | 1.2 | 72,290 | 2.9 | 13,891 | 0.6 | 56,355 | 2.3 | 33,977 | 1.4 | 26,207 | 1.1 |

| 2012 | 1,355,832 | 2,561,659 | 36,994 | 2.7 | 28,768 | 1.1 | 72,904 | 2.8 | 14,150 | 0.6 | 51,866 | 2.0 | 37,175 | 1.5 | 26,387 | 1.0 |

| 2013 | 1,330,823 | 2,485,337 | 32,975 | 2.5 | 25,384 | 1.0 | 71,152 | 2.9 | 14,735 | 0.6 | 46,513 | 1.9 | 38,469 | 1.5 | 26,058 | 1.0 |

| 2014 | 1,244,434 | 2,353,969 | 26,816 | 2.2 | 22,996 | 1.0 | 64,713 | 2.7 | 14,283 | 0.6 | 41,533 | 1.8 | 36,231 | 1.5 | 23,945 | 1.0 |

| 2015 | 1,108,991 | 2,149,417 | 21,344 | 1.9 | 18,558 | 0.9 | 55,091 | 2.6 | 13,410 | 0.6 | 33,673 | 1.6 | 32,266 | 1.5 | 20,780 | 1.0 |

| 2016 | 914,755 | 1,751,839 | 15,662 | 1.7 | 13,258 | 0.8 | 42,554 | 2.4 | 10,985 | 0.6 | 24,542 | 1.4 | 25,507 | 1.5 | 16,365 | 0.9 |

| 2017 | 812,739 | 1,479,553 | 13,268 | 1.6 | 10,972 | 0.7 | 38,001 | 2.6 | 9585 | 0.6 | 21,364 | 1.4 | 21,983 | 1.5 | 14,881 | 1.0 |

| 2018 | 741,453 | 1,304,630 | 11,950 | 1.6 | 9526 | 0.7 | 34,744 | 2.7 | 8470 | 0.6 | 18,860 | 1.4 | 19,866 | 1.5 | 13,672 | 1.0 |

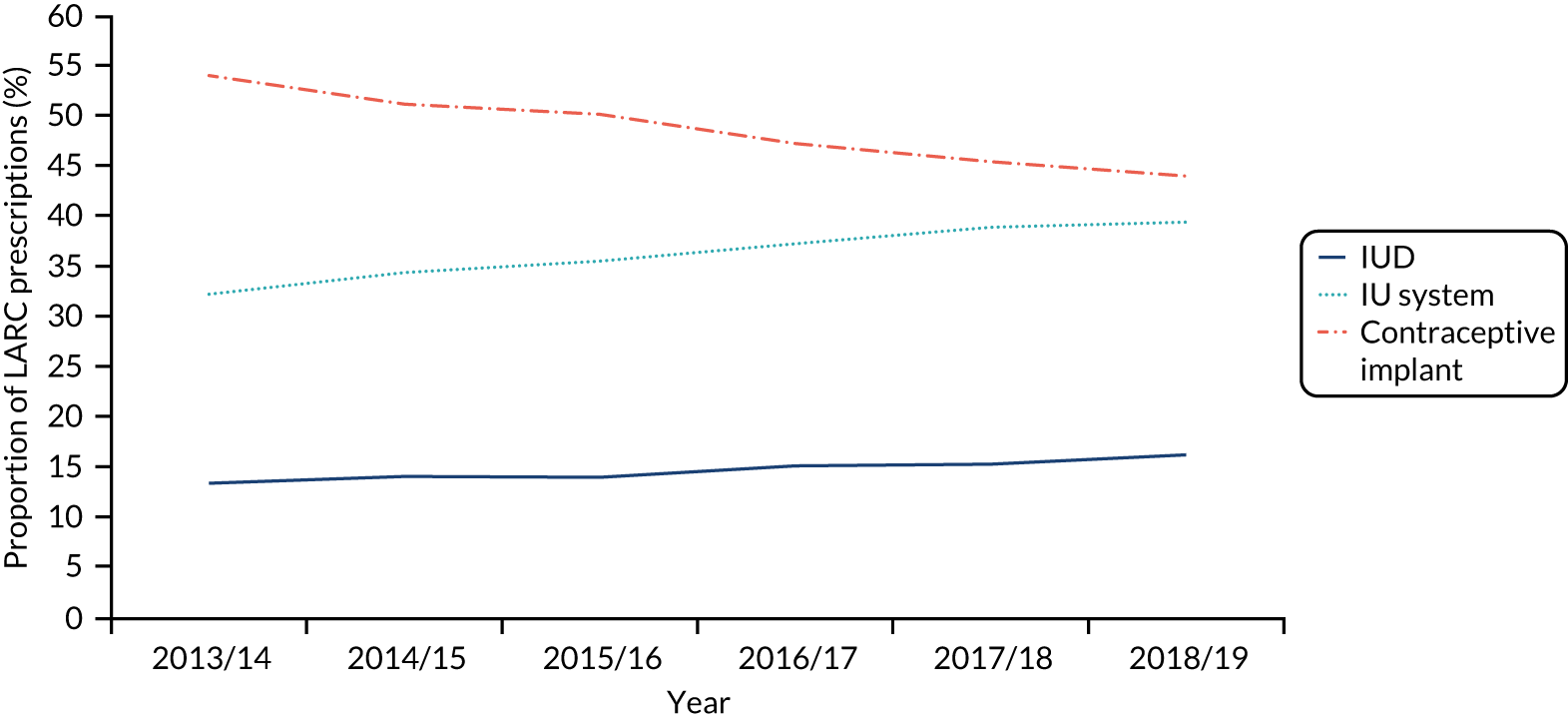

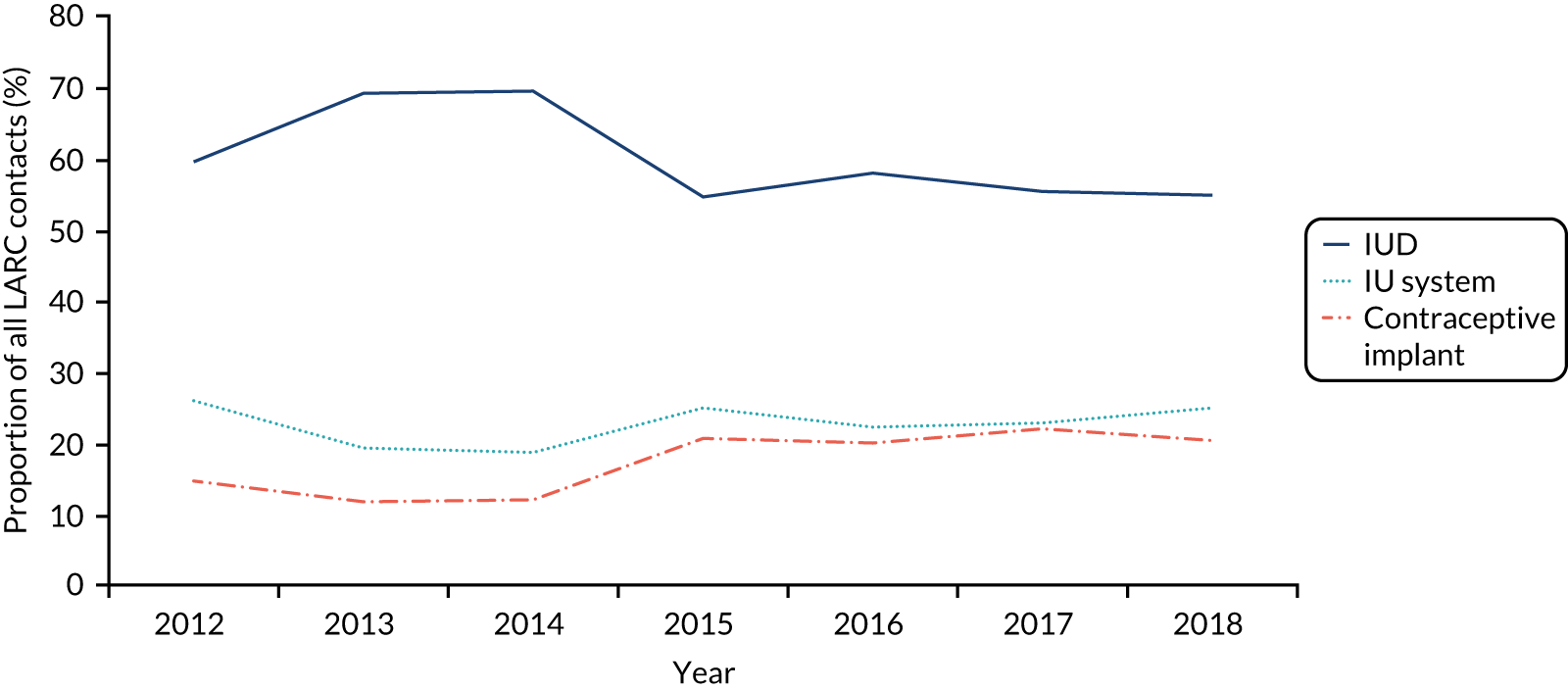

FIGURE 4.

LARC users over time: Wales SHC data (2009–18). Note: data from 2012 to 2015 are unreliable due to under-reporting by some health boards.

To further understand LARC use in general practice and SHCs, patterns were examined by LARC consultation type (insertion, in situ, removal), type of LARC used (IUD, IU system, implant) and age group type to identify opportunities to intervene. SHC data were obtained from open-access sources, and extracts are presented in Appendix 4. LARC insertions are most frequently performed in general practice (see Figure 4) (see Appendix 3 for details of type of LARC use over time).

Objective 2: identify women requesting LARC removal who subsequently become pregnant who would be eligible to recruit to a weight loss intervention study

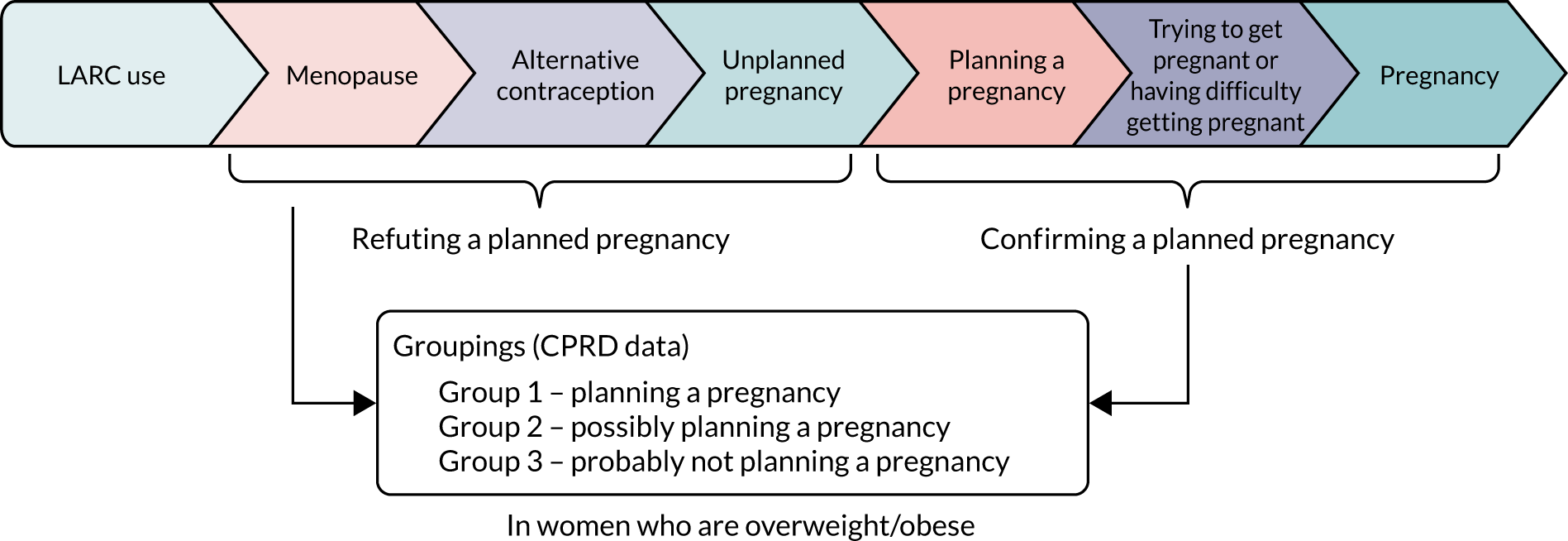

To identify eligible women to recruit to a WLI study, several stages need to be established (Figure 5):

-

LARC use (objective 1)

-

pregnancy within 1 year and 3 months

-

codes to refute or confirm that the pregnancy was planned

-

BMI status.

FIGURE 5.

Stages of identifying women for a WLI study.

Identifying a pregnancy

A total of 340,640 pregnancy events were identified from 113,262 (35.5% of predefined study population) women. After excluding 245,935 events that were outside the study period (before 2009 or after 2018) and duplicate entries, we have 94,705 pregnancy events from 56,637 women. A further 70,632 events were excluded, leaving 24,073 pregnancy events from 22,326 (7.0%) women in the study population.

LARC removal for the purposes of planning a pregnancy

In the 24,073 pregnancy events from 22,326 (7.0%) women in the study population, 11,381 (47.3%) conceptions occurred within the window of 1 year and 3 months (456 days), and 3090 (12.8%) occurred outside the window of 1 year and 3 months. With regard to the 411 (1.7%) pregnancy events with a removal code between pregnancy start and pregnancy end, we considered them as an unplanned pregnancy if the removal code was within 7 days after pregnancy start; otherwise, we would investigate other LARC code (if any) or exclude the pregnancy event and the removal code in between. For the 9191 (38.2%) pregnancy events with no removal code between start and end date, we included the event if the pregnancy start date was within the window of 1 year and 3 months after the last LARC in situ or LARC insertion date; otherwise, the pregnancy event would be excluded.

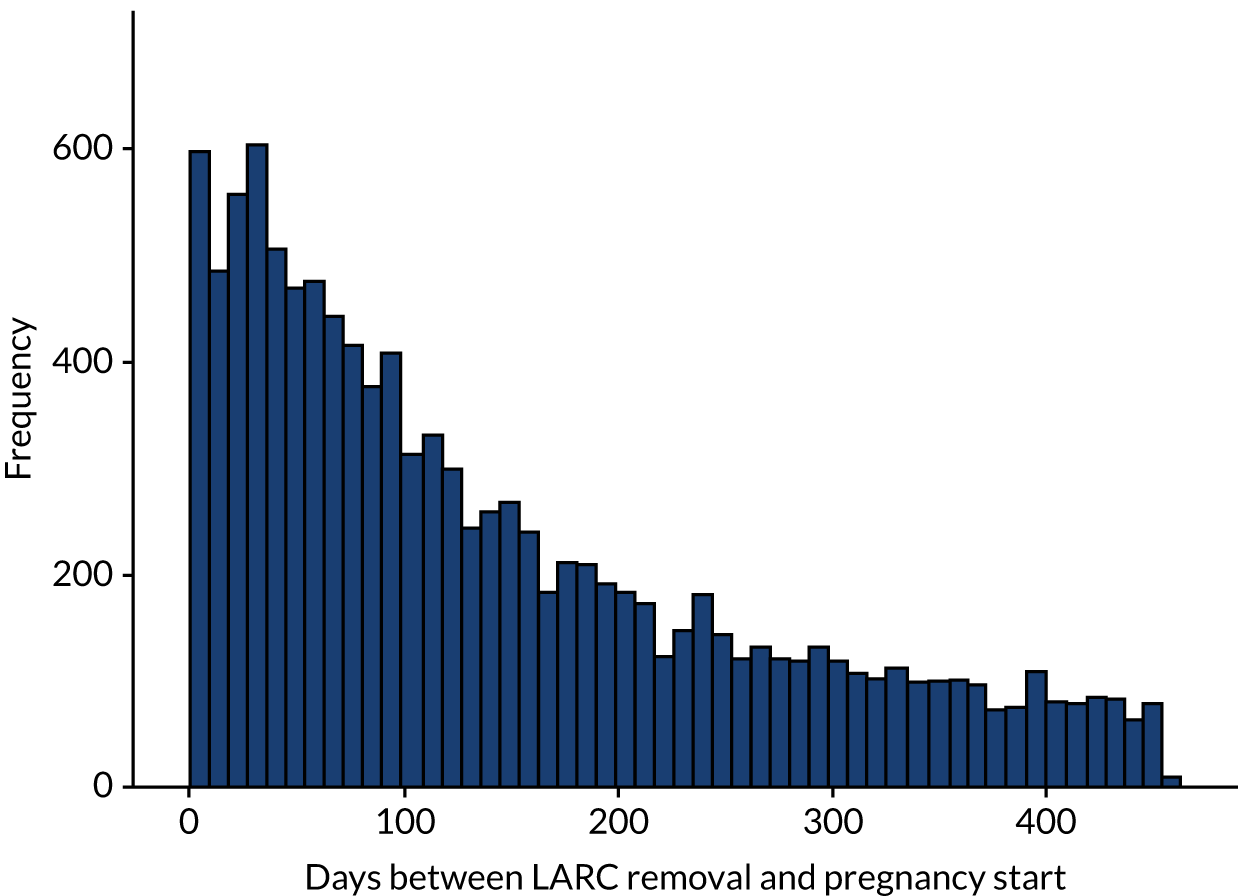

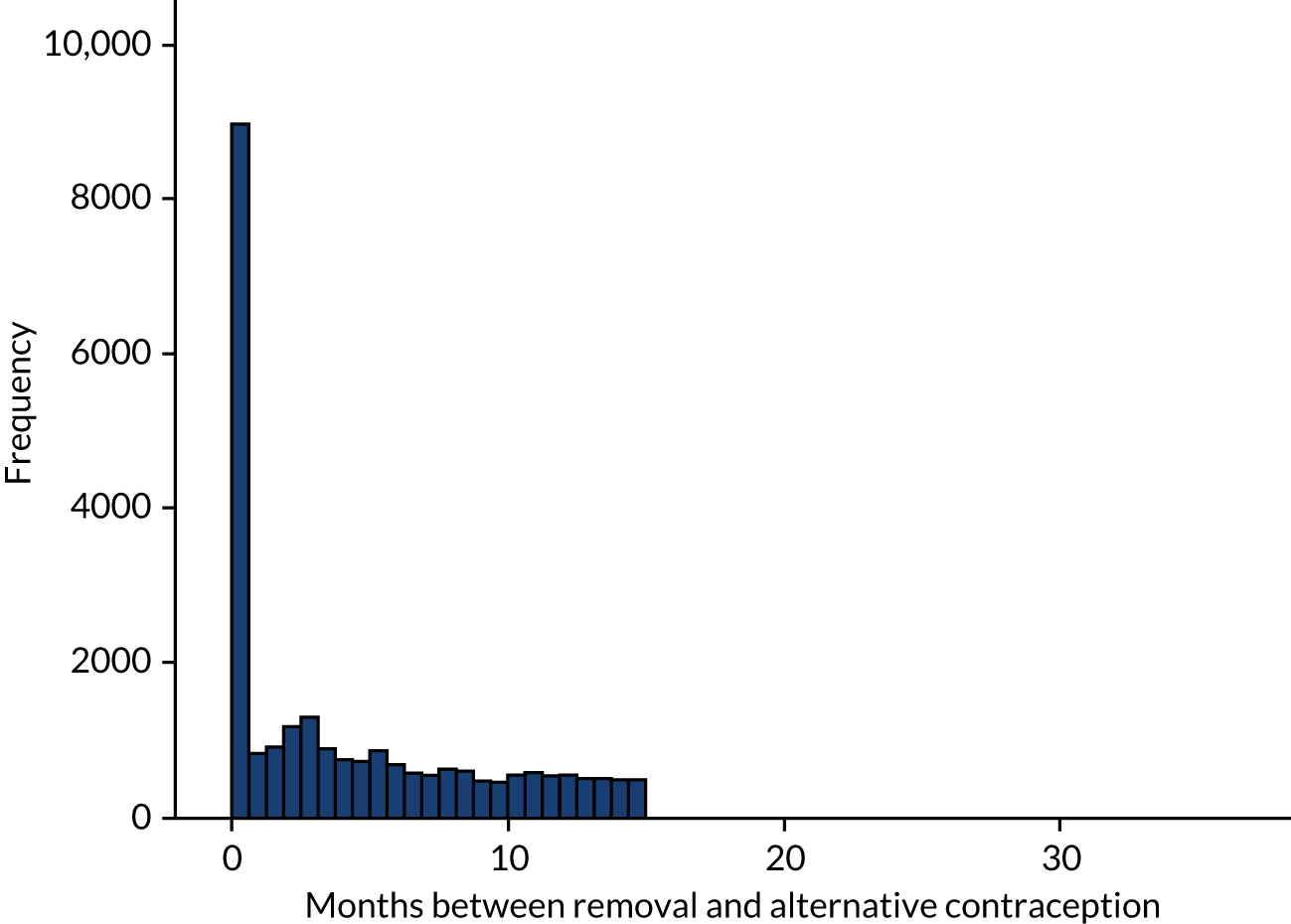

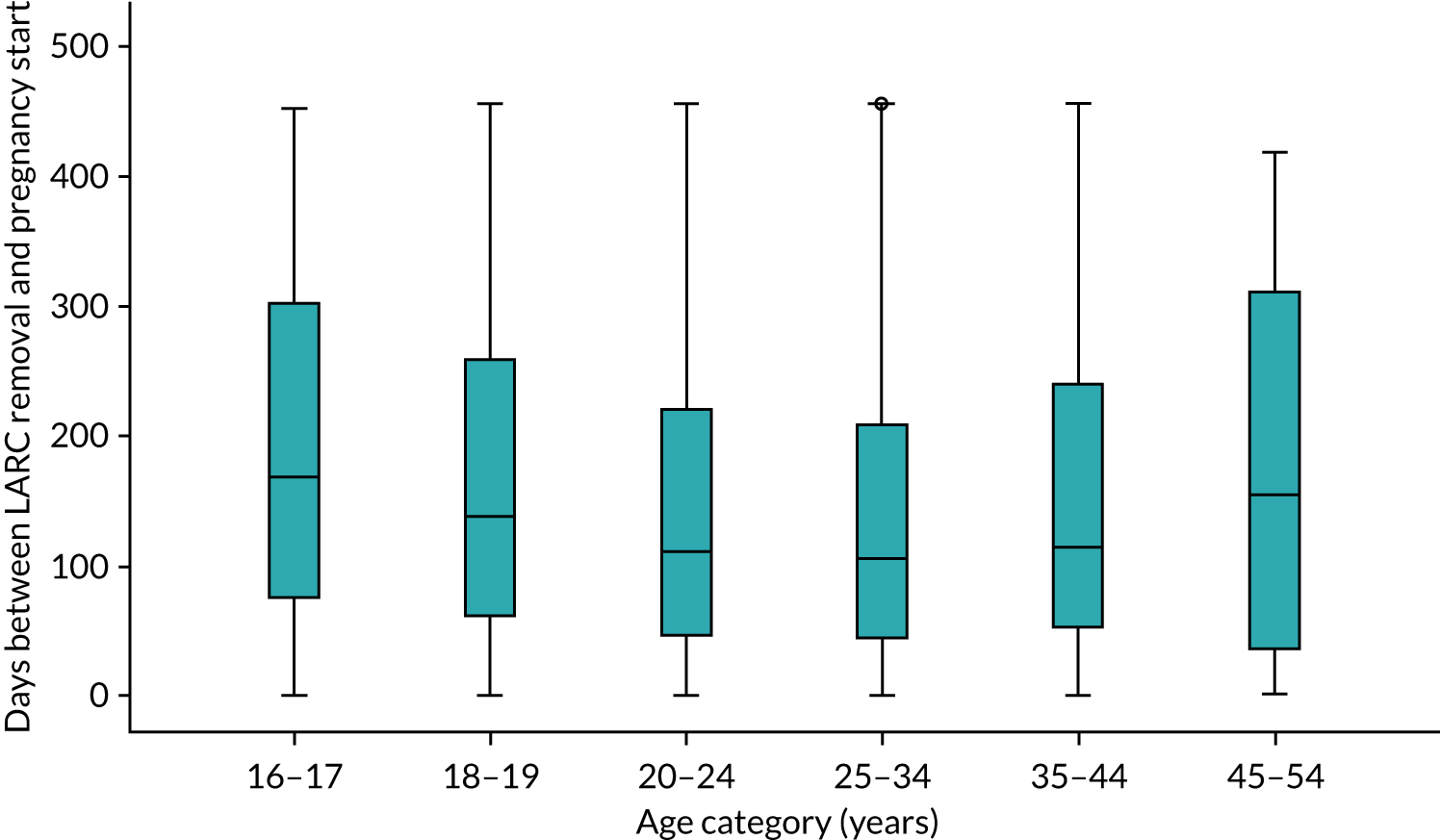

Among the 315,755 women in the study population with a LARC event, 15,297 women had at least one pregnancy, with 16,394 pregnancy events (Table 6). Of those, 4753 (29.0%) pregnancy events did not have a LARC removal code before pregnancy started and 299 (1.8%) had a removal code between pregnancy start and end. The number and percentage of the 16,394 pregnancy outcomes are described in Table 6. For the remaining 11,342 events, the median time to conception was 109 days (25th to 75th centiles = 47 to 220 days) (Figure 6).

| Pregnancy outcome | Frequency (n) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Live birth | 8910 | 54.3 |

| Stillbirth | 33 | 0.2 |

| Miscarriage | 1700 | 10.4 |

| TOP | 241 | 1.5 |

| Miscarriage or TOP or ectopic | 1231 | 7.5 |

| Ectopic | 163 | 1.0 |

| Molar | 6 | 0.0 |

| Blighted ovum | 5 | 0.0 |

| Unspecified loss | 107 | 0.7 |

| Delivery based on a third-trimester pregnancy record | 278 | 1.7 |

| Delivery based on a late-pregnancy record | 46 | 0.3 |

| Outcome unknown | 3674 | 22.4 |

| Total | 16,394 |

FIGURE 6.

Conception time for events within 456 days (n = 11,342).

We have defined 479,044 different scenarios or pathways to a pregnancy event or not among 317,684 women (note that women can have more than one scenario). The number of scenarios and number of women in each group are summarised in Table 7.

| LARC use | Read code indicating an event | Pregnancy | Group | Number of scenarios | Number of women | Age (years), mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: LARC removal/inserted/in situ | A Read code to indicate the pregnancy was being planned (planned pregnancy code or trying/difficult to get pregnant) either between a LARC (removal/inserted/in situ) and pregnancy start, or between a pregnancy start and end | Yes | 1: planning a pregnancy | 1635 | 1616 | 29.0 (5.81) |

| 2: LARC removal/inserted/in situ | No Read code to indicate that the pregnancy was planned (planned pregnancy code or trying or difficult to get pregnant) or not planning a pregnancy (alternative contraception and menopause). No Read code to indicate that this pregnancy was unplanned (unplanned pregnancy code) | Yes | 2: possibly planning a pregnancy | 10,902 | 10,387 | 28.5 (6.06) |

| 3: LARC removal/inserted/in situ | A Read code to indicate that a pregnancy was not being planned (alternative contraception and menopause) | Yes | 3: probably not planning a pregnancy | 3851 | 3761 | 26.5 (5.98) |

| 4: LARC removal/inserted/in situ | A Read code to indicate that a pregnancy was being planned (planned pregnancy code or trying/difficult to get pregnant) | No | 1: planning a pregnancy | 4871 | 4717 | 30.6 (7.26) |

| 5: LARC removal | After a LARC removal code, no Read code or a Read code present to indicate that the woman was planning/not planning a pregnancy | No | Not enough information | 73,290 | 69,455 | 32.4 (9.03) |

| 6: LARC inserted/in situ | No code present to indicate that the woman had a LARC removed or was planning/not planning a pregnancy | No | 3: probably not planning a pregnancy | 379,495 | 277,144 | 33.0 (9.22) |

| 7: LARC removal/inserted/in situ | Code to indicate a pregnancy was not being planned (e.g. alternative contraception), menopause indication (e.g. blood tests) | No | 3: probably not planning a pregnancy | |||

| 8 | Yes | Unable to code | 6 | 6 | ||

| 9 | No | Unable to code | 59 | 59 |