Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-1210-12011. The contractual start date was in August 2013. The final report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in March 2022. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research, or similar, and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Byng et al. This work was produced by Byng et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Byng et al.

SYNOPSIS

In February 2020, there were over 83,000 people incarcerated in England and Wales, the majority (95%) of whom were male. The rate of mental illness in this group is very high and much higher than the general population1,2 (Table 1). Prevalence rates vary internationally due to methodological differences, but a consistent finding is that about one in seven people in prison have major depression or psychosis. 1 Comorbidity for this group is the norm, as are chaotic lifestyles with a wide range of personal and social problems, including homelessness, unemployment and broken relationships with partners and children. 9 In our earlier descriptive study,10 we found that of 200 offenders (100 offenders serving prison sentences and 100 offenders serving community sentences), 59% reported having common mental health problems, 37% reported problems with family relationships and the majority (65–70%) were unemployed or on long-term sickness benefit. For people leaving prison, the transition into the community is associated with increased rates of suicide and self-harm. For example, the risk of suicide for male offenders leaving prison is eight times the national average. 11,12 Although mental illness rates for female prisoners are consistently higher,13 the Engager project focused on male prison leavers because of the smaller numbers of females in prison estates.

| Mental health condition | Male prisoners (%) | Male general population (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Psychosis3 | 4 | 1 |

| Major depression3 | 10 | 2–4 |

| Affective disorder/anxiety4 | 6–29 | 4–10 |

| Any personality disorder3 | 65 | 5–10 |

| Antisocial personality disorder3 | 47 | 5–7 |

| Alcohol misuse/dependence5 | 18–30 | 14–16 |

| Drug misuse/dependence5 | 10–48 | 14–16 |

| PTSD6 | 4–21 | 2 |

| Intellectual disability7 | 0.5–1.5 | 1 |

| ADHD8 | 26 | 1–5 |

In 2018, 63% of custodial sentences received were for less than 12 months. 14 Short custodial sentences are known to be less effective than community sentences at reducing reoffending,15 with the 12-month proven reoffending rates for short-sentence prisoners currently close to 60%. 16 As well as reoffending, frequent transitions in and out of prison take a high toll on the individual, their family and their social tenure. 17 Comorbidity is high for this group,18 as is the financial cost of failing to address these health and social care issues. 19

In the UK, although the NHS commissions all health services, it appoints a range of providers from NHS, private, and voluntary and community sectors. On the one hand, a prison may have multiple providers and each service will provide a specific service only (e.g. primary care, general physical health care, mental health care). On the other hand, in some cases, a prison may use a number of different providers for services such as primary and secondary mental health care, or drug and alcohol services. However, using a number of different providers can make continuity of care more complex, especially for people who require input from multiple services, as often these providers do not operate in an integrated way. This issue is further complicated at the point of release, as often the health-care providers within a prison will not be the same services that operate in the community.

There has been investment in prison mental health services for those with severe and enduring mental illness. 20 There is research evidence that critical time intervention, that is, a structured, time-limited form of case management,21 can be adapted for people with severe and enduring mental illness who are in prison. In a randomised controlled trial (RCT),22 critical time intervention demonstrated increased engagement with community mental health services at 6 weeks post release from prison.

The identification of common mental health problems may occur during induction, through self-reporting or when staff raise concerns. However, we know from other studies that this will miss many people and will under-represent the level of need. 23 In addition, provision of psychological therapy for people with common mental health problems who are in contact with the criminal justice system (CJS) is limited in both prison and community settings. 10 Once released into the community, ex-prisoners with common mental health problems are, in theory, provided for by mainstream statutory services, including general practice, community mental health teams and Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services; however, few ex-prisoners access these services,10 suggesting that a lack of care on release is the norm. 24

Despite negligible uptake and high need, to the best of our knowledge, worldwide, no systems have been identified for actively engaging people with common mental health problems while in prison, providing support and working with them to engage with community services. Organisational interventions, such as collaborative care (i.e. a complex intervention based on a chronic disease management model), have been shown to be beneficial for those with depression25 and comorbid physical health problems. 26 However, such interventions are yet to be tested with prison leavers. Elements of collaborative care have the potential to ensure continuity over time and co-ordination between teams and practitioners, as well as support for self-care.

The points above provide clear theoretical grounds for the potential health gain in developing an intervention that (1) focuses on short-term prisoners with common mental health problems, (2) takes a collaborative care approach to span all the different agencies/professionals involved and (3) takes into account the wide range of social and health problems individuals may face. There is very limited research into developing and evaluating mental health interventions within prisons. 27 RCTs within the CJS can be more complex than in other settings because of a range of factors, such as organisational difficulties, maintaining trial arm allocation, poor follow-up rates and difficulties selecting appropriate outcome measures. 1,17,28–30

How to navigate the Engager research programme and report

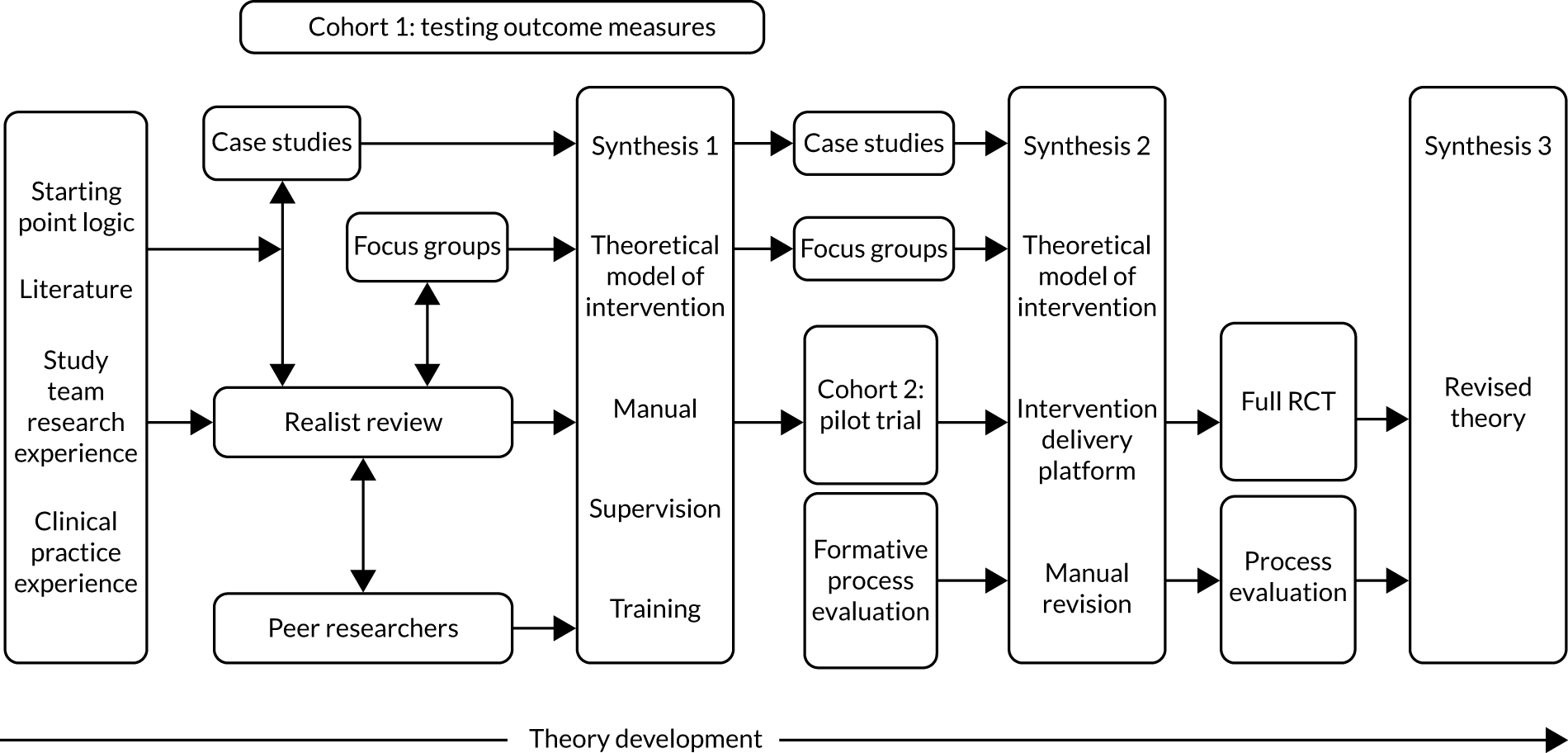

The National Institute for Health and Care Research-funded Engager research programme ran between 2013 and 2020, across two phases. Figure 1 depicts the whole Engager research programme. The Engager research programme was designed to work iteratively between questions relating to intervention development and questions relating to trial science. The Engager research programme included four interlinked workstreams delivered across two phases. Workstream 4, addressing health economics, continued across both phases.

FIGURE 1.

The Engager research programme.

Phase 1: intervention development and trial methodology

A mixed-methods approach was used for the development of a theoretically informed person-centred co-ordinated intervention (workstream 1) and this involved:

-

a realist review

-

organisational case studies

-

focus groups

-

a rapid realist review of implementation

-

a formative process evaluation.

The data were brought together at two time points (i.e. synthesis 1 and synthesis 2) to iteratively develop the theory and practice of the intervention. The Engager intervention is summarised in this synopsis, with more detail provided in Report Supplementary Material 6.

In parallel, we developed the trial science methodology to evaluate the intervention (workstream 2) and this involved:

-

selection of outcome measures

-

development of tools to measure ‘the process of care’

-

a pilot trial to test the trial procedures

-

initial health economics modelling (workstream 3).

Phase 2: trial, process evaluation and cost-effectiveness (workstreams 3 and 4)

In phase 2 we conducted:

-

an RCT

-

a cost-effectiveness analysis and a cost–consequence analysis

-

a mixed-methods process evaluation, which took a realist-informed approach to examining fidelity, problems with implementation and potential improvements to theory.

Our patient and public involvement work was extensive and interwoven through all workstreams and both phases. For ease of reading, workstream 4 has been split into two sections, that is, phase 1 (economic modelling) and phase 2 (cost-effectiveness and cost–consequence analyses).

Alterations to the programme

The initial contract was to develop the intervention and to carry out an exploratory trial. A proposal to switch to a definitive trial was agreed at the mid-programme checkpoint report. An extension to collect data at 12 months was agreed once recruitment viability had been established in the main trial. Owing to the decision to have a definitive trial, along with issues of data availability, it was agreed that the initial plan for decision modelling of economic benefits of a full trial would be replaced by carrying out a trial-based cost–consequence analysis.

Developing a theoretical model of the intervention (phase 1, workstream 1)

Developing solutions to complex problems within complex systems is challenging, as it requires an in-depth understanding of the nature of the intervention and the implementation context. 31 Relatively little attention is paid to the developmental phase of the complex intervention cycle and it has been argued that realist-informed methods may become routine once sufficient empirical examples are available to guide practice. 32,33

The aim of workstream 1 was to develop an empirical example of a theoretical model of the Engager intervention. We used realist methods34 as an overall framework with which to establish the mechanisms involved and the causal pathways and contextual conditions that might lead to positive outcomes. Behaviour change theory35 influenced our understanding of the mechanisms needed to bring about change. Throughout the development, the intervention was seen as a two-step behaviour change model, that is, how the system and research team supported practitioners and then how practitioners supported offenders. The former became the intervention delivery platform (IDP) and the latter was developed into a detailed set of practitioner behaviours that were designed to support a heterogeneous group of offenders towards better well-being and rehabilitation, and is expressed as the programme theory. Through testing this programme theory, we offer empirical examples to guide future practice for other researchers considering realist-informed approaches to developing and evaluating interventions with complex groups.

There were three stages to the theory development. An initial starting point model, articulated in the original funding bid, was based on the team’s clinical and research knowledge and previous patient and public involvement work. The first stage involved a realist review, focus groups and organisational case studies, which were synthesised (i.e. synthesis 1) into a prototype intervention that was then delivered in the pilot trial. The second stage involved a realist formative process evaluation within the pilot trial, a further organisational case study and focus group, and a realist review of implementation literature. The results of these were brought together (i.e. synthesis 2) to inform the intervention theory and IDP (e.g. training, manual, supervision), which were then operationalised in the main trial. Throughout this workstream, the peer researchers commented on the academic researchers’ findings and the intervention development, helping the academic researchers to identify gaps in understanding. The sections below detail the components of workstream 1 and illustrate how each component contributed to the development of the programme theory of the Engager intervention.

Realist review

The realist review has been published36 and, in accordance with RAMESES II (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards II) reporting standards,31 the realist review aimed to specify how an integrated person-centred system to improve the mental health of offenders with common mental health problems might work. Therefore, the focus was on in-depth theory-building as a key contribution to the development of the intervention. The review is methodologically novel in the way that it operationalises a realist approach [e.g. use of ‘if–then’ statements, structured questions for synthesis of context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations] in parallel with the timelines and methods of a large research project. The following three-stage process was used:

-

We identified sources providing rich descriptions of interventions (and/or their delivery) providing care for offenders with common mental health problems through hand-searching a core set of 16 journals, citation-chasing, elicitation from experts (including men with lived experience of prison and release) and database searches. Searches were extended beyond offender health where insufficient sources were located. Screening of sources, therefore, included those relating to mental health care, and health and social inclusion service delivery in vulnerable groups.

-

We identified explanatory accounts (i.e. ideas about how a problem can best be addressed) (n = 347). ‘Working backwards’ from outcomes (including those from meetings with the Peer Researcher Group of men with lived experience), explanatory accounts were extracted and tabulated, and then expressed as ‘if–then’ statements, specifying (as far as the source allowed) CMO configurations.

-

We consolidated explanatory accounts (n = 75) and produced a conceptual platform (i.e. a core set of processes about how intended effects could be achieved). To enable feedback about expression and scope, consolidated explanatory accounts were shared throughout the process with our expert group of practitioners and academics.

An overview of the conceptual platform developed for the Engager intervention depicts the key agents and their relationships (Figure 2). The three columns in Figure 2 describe different key interactions relating to participating in a mental health improvement intervention both before and after release from prison. The contextualised interactions can be between practitioners and offenders, between the practitioner/offender and other practitioners, or between the offender and family members, peers or mentors. At the centre of the intervention are the core interactions between practitioners and offenders. It is within these interactions that the intervention had the potential to activate mechanisms that affect offenders’ thinking, emotions and behaviours. In between these core interactions, the interactions of both the practitioner and offender with other people (i.e. the central three circles in Figure 2) can further affect changes in thinking, emotions and behaviours, and how these interact with their contexts. These changes influence the subsequent interaction between the practitioner and offender and generate other potentially beneficial effects.

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual platform developed for Engager. Reproduced with permission from Pearson et al. 36 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the figure.

This realist review contributed substantively to our understanding of how an integrated person-centred system might work. Findings suggested that supporting positive mechanisms for change involved optimising the local support available and minimising the potential for complex relationships with services to destabilise an individual. Box 1 outlines the core set of processes proposed in the conceptual platform.

-

Different systems, in particular health and criminal justice, and having goals that are consistent with one another.

-

Attaining consistency between strategic goals and the goals of practitioners.

-

Making referral pathways and links between organisations comprehensible to practitioners and providing opportunity for the development of constructive working relationships.

-

Practitioners being facilitated and enabled to balance factors that can be in tension, for example ‘knowing how’, as well as ‘knowing that’, analysing one’s own behaviour while remaining attentive to emotions, and working towards an individual’s goals.

-

Practitioners being facilitated and enabled to apply scientific and experiential knowledge judiciously in working with individual offenders and colleagues, and the systems in which services are delivered.

-

Practitioners having sufficient knowledge about mental health and how to develop supportive relationships with people with mental health issues.

-

Recognising the individuality of offenders throughout all interactions in the criminal justice, health and social care systems.

-

Aligning resources to enable offenders to achieve their collaboratively agreed goals.

-

Practitioners supporting reconnection with, and/or development of, networks of support outside prison.

-

Offenders having reasons to trust practitioners, services and systems.

For pragmatic resource reasons, we did not take on the task of reviewing psychological therapies, having made an early decision to use mentalisation-based approaches (MBAs)37 to support existing competencies because of high co-occurrence of traits, such as emotional reactivity linked to the diagnosis of a personality disorder. The realist review also provided a detailed methodological example of theory-driven intervention development. In particular, the conceptual platform was used to help us understand where we had gaps in our understanding and how the organisational case studies, focus groups and peer researchers could help fill these gaps. For example, the conceptual platform highlighted a gap in our understanding of how families and peer mentors may inform the intervention and, therefore, one of the focus groups was developed to look at the role of families and another organisational case study site involved analysis of the use of peer mentors.

Organisational case studies

The organisational case studies article is published. 38

The organisational case studies aimed to augment our emerging core intervention theory by gaining learning from a range of promising services that provided support and/or treatment for people experiencing common mental health problems within the CJS. The organisational case studies also aimed to identify key elements of practice, for example what was and was not effective in engaging people and maintaining contact with the service. Organisational case studies were particularly useful in eliciting grounded knowledge that was unpublished and, therefore, unavailable for the realist review.

Four cases were selected. Organisational case studies 1 and 2 were undertaken prior to the formative evaluation and organisational case studies 3 and 4 were undertaken after the formative evaluation. Data included documents (e.g. service standard operating procedures), field notes and semistructured interviews. Realist-informed interview schedules (see Report Supplementary Material 1) were constructed using the CMO configurations in our developing theory. All documents were analysed using deductive content analysis. Interview data were interrogated through a qualitative framework approach. 39

Seven main themes were identified: (1) collaboration, (2) client engagement, (3) client motivation, (4) supervision, (5) therapeutic approach, (6) peers and (7) preparations for ending. The case studies highlighted that engaging and motivating clients was dependent on the relationship built with the professional. Consistent, respectful, open and honest communication over time was needed to activate mechanisms that produced a sense of trust and rapport. Professionals were often unable to provide this level of support if they did not work in multiagency collaborations, supported by supervision.

Engager organisational case studies highlighted the clear need for an intervention to have in its toolbox a range of psychological therapies. In addition, the case studies suggested that the addition of a MBA would be beneficial to support the relationship between the practitioner and client, as well as to help deal with mood lability. Supporting individual offenders to mentalise effectively about their situations also aligned with the realist notion of activating generative reasoning mechanisms that enable change in thinking, emotions and behaviours.

The organisational case studies were also critical to our understanding of the importance of a ‘strong’ IDP (i.e. manual, training and supervision) that would support the practitioners in operationalising the Engager theory. The findings focused specifically on the role of supervision in ensuring ongoing support for practitioners as part of a team and on the additional need for external supervisors.

Furthermore, the organisational case studies highlighted the importance of preparatory work in prison to build trust, rapport and engagement. The case studies also prioritised the need to prepare clients for the end of the intervention as a positive step in a longer journey, including providing clients with a summary of their progress.

Finally, the initial prototype and the realist review highlighted the use of peers to support engagement and improve outcomes. The organisational case studies evidenced benefits for peers delivering support, but there was less evidence of benefit for the recipient. The Peer Researcher Group strongly asserted the importance of peer support. However, the research team reluctantly decided, following protracted discussions with the Peer Researcher Group, that this potential component was not logistically deliverable within the resources of this project. Instead, Engager practitioners would encourage and facilitate access to peer/mentoring services.

Focus groups

This work has been published. 40

The published work focuses on the methodological development of the focus groups. The aim of the focus groups was to explore the views of subgroups of the target population whose experiences were not represented by previous published data, the realist review and organisational case studies.

The following four focus groups were convened: (1) homelessness on release from prison, (2) young men who had served prison sentences, (3) people with a ‘loved one’ in prison and (4) men recently released from prison. Each group was recruited through a community-based service that already knew the participants and continued to support them afterwards.

Data were coded and analysed deductively using our theorical framework. This analysis consisted of four columns representing time points (i.e. initial meeting with the participant, actions in prison, actions in the community and preparations for endings) and six rows representing the main functions of the intervention (i.e. shared understanding of individual goals, shared action plan to achieve individual goals, therapeutic approach, family and community capabilities, peer or other volunteer mentor support, and liaison by practitioner and participant with other professionals/teams).

Conversations within the focus group predominantly related to the following areas within our framework.

Developing the shared understanding by making links between a person’s emotions, thinking, behaviour and social outcome

Members of the focus groups talked about a reluctance to discuss emotions for fear of appearing weak. Often, emotions were being masked by other behaviour (e.g. using substances or ‘putting on a front’) and this highlighted the need to build trust and engagement before moving too quickly into talking deeply about emotions; however, periods of abstinence may be windows of opportunity for this work.

Developing the shared action plan: matching goals to resources

Men in the focus groups talked about a range of resources within prison that they could use to pass the time and/or could help if they were feeling low, including education, workshops, gym and chaplain. These resources would be key resources that the Engager practitioners could link with in the prison.

Developing the shared action plan: other professionals

The men talked about how, in their experience, a diagnosis of mental illness was often not helpful, as it could limit access to other services or professionals and it may cause professionals to treat them more negatively. This supported our initial thoughts that, although the focus of the Engager intervention is for those with common mental health problems, it would be a person- rather than diagnostic-centred intervention.

Developing the shared action plan: other people as a resource

The roles of other people, especially family members, were talked about at length in the focus groups. The men highlighted that often families receive little information. Family members are often reluctant to ask for information, help or support because of the perceived stigma of having a family member in prison. The men also talked about preparing both the soon-to-be released prisoner and family about expectations. Prisoners cannot always expect to return to situations as they left them. Proactive expectation management can facilitate communication, including creating awareness of how a family member or friend has had to do things differently to manage on their own and has had to make other changes over time. A partner may have grown in confidence and independence; this can be difficult for released prisoners to adjust to and also the family member may feel guilty about this. These discussions highlighted a gap within the developing intervention, that is, the Engager practitioner may also have to work closely with family members to provide information, to support contact with services and, importantly, to prepare both sides for what release would be like.

What to do in prison to prepare for community contact

The focus groups gave us many practical actions that the Engager practitioners could do to prepare released prisoners for contact in the community. The men talked about accommodation and money as key concerns during the initial release period and, therefore, the Engager practitioners could work alongside other services to try to secure accommodation and money on release. We recognised that this would not always be possible and that some people would be homeless upon release. The men suggested making sure that prisoners knew all of the locations a person may present at if they were homeless (e.g. drop-in centres, homeless shelters or soup kitchens).

Community (first meetings)

The men suggested that it can be hard to establish a routine in the first few weeks and this was a key factor in the likelihood of retuning to prison, alongside insecure accommodation and financial issues. This indicated to us that another role the Engager practitioner could have is working with the person to develop a new routine.

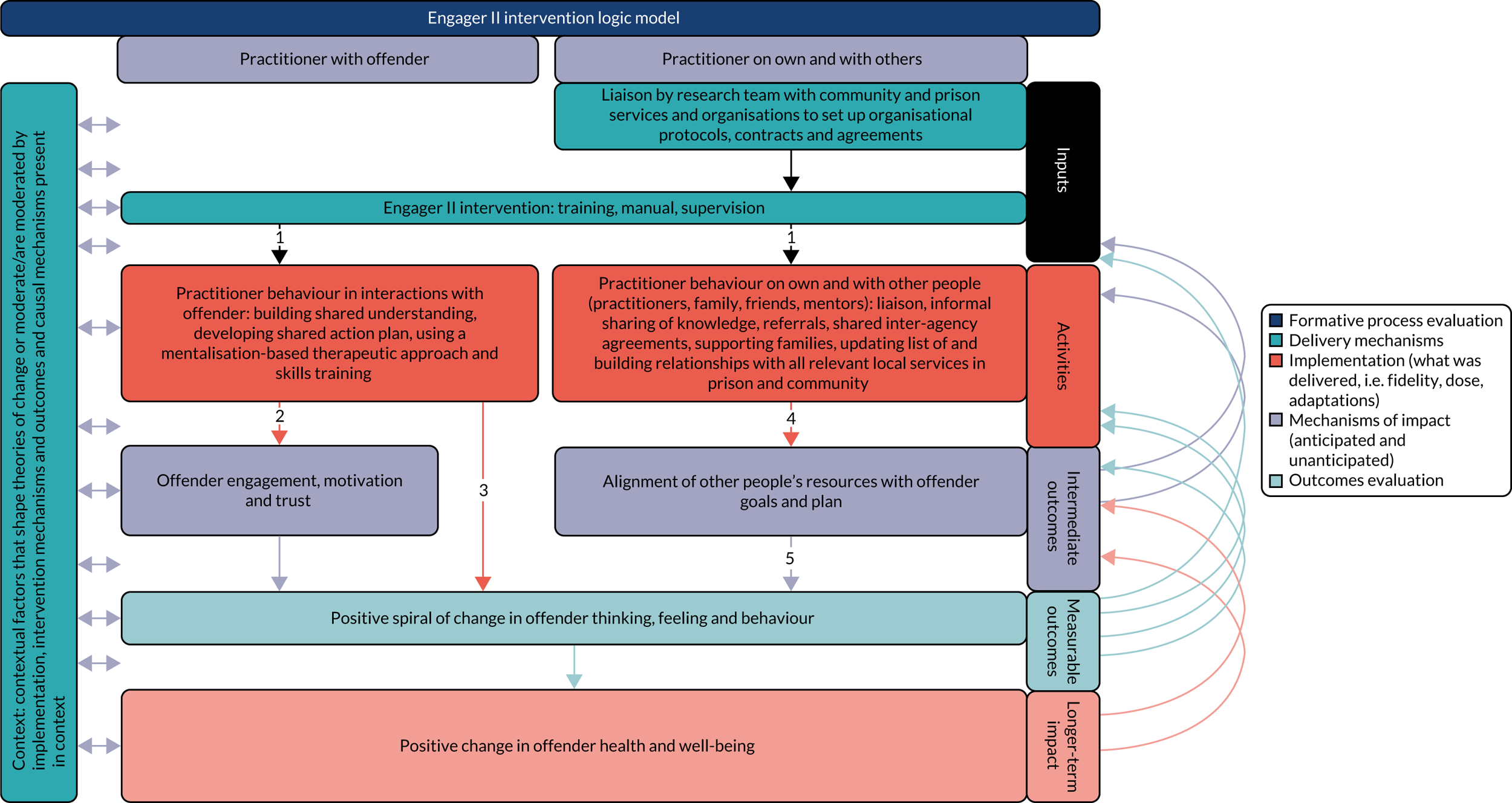

The data from the realist review, focus groups, organisational case studies and peer researcher meetings were synthesised into a prototype intervention (i.e. synthesis 1), which was then delivered and evaluated in the pilot trial and formative process evaluation. Figure 3 depicts the overarching structure of the Engager logic model theory. More detail of that synthesis process is detailed in Report Supplementary Material 2. During the synthesis, narratives were produced of the core components (see Report Supplementary Material 3 for details of the theory for shared understanding, a shared action plan, action in prison and action in the community).

FIGURE 3.

Engager logic model. Reproduced with permission from Brand et al. 41 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

The peer researchers contributed to the discussions and challenged the academic researchers throughout the group meetings. The peer researchers required the academic researchers to prioritise the importance of ‘self-care’ and ‘family support’, even when the published data and financial capabilities suggested that these might not be achievable. Consequently, focus groups addressing these issues were held and a decision was made that Engager practitioners should work with participants’ families when appropriate.

Formative process evaluation

The formative process evaluation is published. 41

The formative process evaluation continued the realist approach. Realist approaches addressed the need to build theory prior to outcome evaluation33 and the need for greater attention to be paid to context during delivery and to effective scale-up during later implementation. 42

Face-to-face semistructured realist interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews were conducted with Engager practitioners, Engager supervisors, prison leavers and CJS, health and/or social care professionals. In addition, Engager practitioners used a pro forma to record notes about what practitioners had carried out in each session with, or on behalf of, participants, and any significant issues that had been discussed. Scanned copies of practitioner notes were examined using a structured pro forma to describe which components of the intervention were delivered, where they were delivered and over what time.

The findings presented in the published paper are both methodological and substantive. The paper provides a consolidated version of the core programme theory, with illustrative examples. A full overview of all the core programme theories examined and not included in the published paper are provided in Report Supplementary Material 4.

Key learning from the formative process evaluation led to direct modifications to the intervention and adjustments to IDP resources to support practitioner teams. The direct modifications included the following:

-

Emphasising the importance of engagement and building a trusting relationship.

-

Activating trust mechanisms (e.g. feeling cared for) as an important mechanism for undertaking meaningful goal-setting.

-

A reinforcement of the importance of ‘quick wins’ for activating trust mechanisms (i.e. the practitioner delivering something for them that may seem small but is of significance to the participant and gives a concrete demonstration of help).

-

The need for a more protocolised sharing of the written plan with the participant and other services at release to help galvanise resources to support personalised goals.

-

Highlighting the difficulties of balancing the competing demands of immediate (often social, but sometimes emotional) crises and working towards longer-term goals.

-

Practitioners needing to anticipate barriers and also respond flexibly when crises emerged.

Adjustments to IDP included the following:

-

The addition of a ‘content of the manual’ session to the training to ensure consistent practice delivery.

-

The need for clearer and more consistent risk assessment processes and support for practitioners in making risk assessments from team supervisors.

-

The need to specify the expected content of the supervision process more clearly. The theory of supervision needed to focus on mechanisms that would develop practitioner competencies to deliver the intervention as intended.

-

The need for a more robust team structure and management at each site, including re-emphasising the importance of joint decision-making and meeting together regularly to reflect on cases.

-

The need to add a section to the manual about practitioners taking care of their own emotional well-being.

Intervention delivery platform: rapid realist review

In recognition of the importance of effective implementation and delivery of complex interventions in challenging contexts, an IDP was developed as a means of supporting practitioners to deliver the intervention as intended. The IDP incorporated training, a manual, supervision and organisational support. Having previously conducted the realist formative process evaluation41 with evidence from the organisational case studies, the research team acknowledged that they lacked adequate, relevant knowledge about intervention implementation. Rather than conducting a second realist review, we decided to use our existing realist review resource to deepen our understanding of relevant implementation issues and supportive strategies.

Studies were identified from the search conducted for the realist review. The flow of sources through the IDP review and information about the 29 included sources are shown in Report Supplementary Material 5. We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research36 as a framework for structuring our identification and synthesis of evidence, and these findings are also shown in Report Supplementary Material 5.

This rapid realist review synthesised knowledge from a wider literature about complex implementation issues. This enabled us to go beyond simple descriptions of ‘practitioners’ experiences’ to provide a sounder, contextually refined foundation on which to base implementation activities. Although the review was not decisive on any one aspect of the implementation strategy, across the board it played a significant role in supporting emerging findings from other parts of the research programme. For example, working iteratively with the formative process evaluation, the review identified the importance of the manual catering for different learning styles and describing the intervention in ways that aligned with existing service design. The review also informed our understanding of how supervision should be delivered in a way that is theoretically consistent with the intervention. Some parts of the review simply played a supportive role, for example by alerting us to areas where there was scant existing research evidence or insufficient detail in the published evidence, and this was particularly the case for organisational agreements. The requirement for these organisational agreements became evident in discussions with practitioners and managers during set-up and delivery, and the agreements were necessary in order to put in place the formal clinical governance requirements that would enable teams to operate under research conditions but within NHS and voluntary sector services.

After the formative evaluation, the IDP was strengthened through acknowledging the need for top-up training and additional supervision for mentalisation. A decision was made to combine the role of Engager team leader and supervisor to create coherence and promote decisions in the local setting, taking into consideration the whole caseload and workload, as well as fidelity to the model for each individual (see Report Supplementary Material 3 for our developing theory of supervision).

The Engager model going into the trial

At this point, the results of the realist formative process evaluation and of the realist review of implementation literature, plus synthesis 1, were brought together in a second round of synthesis (i.e. synthesis 2). This synthesis was to inform the intervention theory (i.e. what practitioners do and why) and the IDP (i.e. training, manual and supervision), which would be then operationalised in the main trial.

Details of synthesis 2 are detailed in Report Supplementary Material 2.

There are several ways of gaining a description of the Engager intervention in addition to what is already presented:

-

Box 2 describes the key elements and rationale behind the intervention theory going into the main trial.

-

Report Supplementary Material 6 describes the details of the practitioners, training and supervision arrangements in place going into the trial.

-

The Engager programme provides a link for requesting a copy of the trial version of the Engager manual (URL: www.plymouth.ac.uk/research/primarycare/criminal-justice/engager; accessed 9 June 2022).

The intervention was originally conceived to be an adaptation of collaborative care intervention proven to be effective for individuals with depression. The principles of collaborative care – a psychological intervention, joint working between professionals and case-based supervision – were extended on the basis of the findings of the realist review and case studies to incorporate flexibility of delivery and practitioner behaviours to overcome distrust; co-ordination across all services involved in an individual’s care and continuity with a single practitioner, if possible; engagement in prison; meeting on the day of release; and continued care for 3–5 months following release.

Specific evidence-informed mental health and psychological therapy components were included. Early on, a MBA was selected as the supportive psychological method most likely able to assist practitioners in dealing with emotional lability (an aspect of personality disorder) and to help them to understand different perspectives and support psychological thinking. A generic approach to psychological formulation was taken, and simplified, as a shared understanding and action plan to be comprehensible for support workers with limited training and offenders with limited capacities. The shared understanding aims to understand the links for the individual between emotions, thinking, behaviour and current situation. The aim was to identify the means to enhance positive behaviours and to reduce negative ones, such as substance use, self-harm and aggressive behaviour.

The concept of the plan was also extended beyond what services could deliver to bring together all the relevant available resources to address those goals individuals had selected as the most important. Resources included not just the therapeutic support of practitioners, but the potential support of other teams, friends and family and the individual’s own personal resources for self-care. Finally, the concept of ‘discharge’ was transformed into the possibility of next steps, either alone or supported by other services.

Development of trial methodology (phase 1, workstreams 2 and 4)

Conducting RCTs in prisons presents numerous practical and methodological challenges. Simply gaining access to prisons to conduct research and to deliver an intervention can be a difficult and lengthy process. There are uncertainties about the number of people who might be eligible to participate, the level of acceptability and the level of compliance with the intervention and research procedures. There are additional challenges when trying to follow up recently released prisoners in the community. Low retention rates are a common problem for studies that involve following up recently released prisoners. 28 Our preparatory work for the programme demonstrated our ability to follow up 65% of released prisoners at 3 months after release. 29 Some people experience homelessness when released from prison, and for people who do have accommodation this is often temporary, which makes contacting them post release difficult. Even when researchers are able to contact people after release, people need to be willing to meet up with a researcher, answer questions and complete outcome measures. There are also fundamental uncertainties about how to measure the effectiveness of a complex intervention, as this population frequently has a complex array of inter-related problems. Therefore, it is not clear which problems are the most important, which should be the target of an intervention and, once these are decided, how to measure them as outcomes in the context of a RCT.

When the Engager team began this programme of work, there were, to the best of our knowledge, no published studies of evaluations of through-the-gate mental health interventions for incarcerated men with common mental health problems. Therefore, alongside the intervention development work in workstream 1, we conducted a separate workstream to develop the trial science methodology to evaluate the intervention.

This work programme aimed to address the following methodological questions:

-

What outcome measures should be used to evaluate a through-the-gate intervention for incarcerated men with common mental health problems?

-

What trial procedures are required to deliver a RCT of a through-the-gate intervention for incarcerated men with common mental health problems?

-

How can we measure the process of care of a collaborative care intervention designed to support incarcerated men with common mental health problems near to, and following, release from prison?

Addressing these questions in the first phase of the programme was a prerequisite for continuing to a full trial. Specifically, to proceed to a full trial we needed to demonstrate that we could achieve a follow-up of at least 50% and also demonstrate intervention acceptability in a pilot trial.

Development of a set of outcomes for a randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the Engager intervention

Our aim was to select a set of outcome measures that captured the most important areas of outcome using measures that were acceptable to the target population and, as far as possible, met scientific validity criteria.

We adopted a four-stage approach, involving:

-

a single-round Delphi survey to identify the most important outcome domains

-

a focused review to identify potentially suitable measures within the three most highly rated outcome domains

-

testing of these measures in the target population to assess acceptability and the psychometric viability of the measures43

-

a consensus panel meeting to select the primary outcome measure for the RCT and key secondary outcome measures.

More detailed description of these stages can be found in Report Supplementary Material 7.

We actively sought the input of our Peer Research Group, with 10 members of the group completing the Delphi survey and four members of the group attending the consensus meeting.

In the single-round Delphi exercise, although the most important areas that people thought we should be capturing outcome data for were mental health symptoms, substance misuse and social inclusion, many of the other outcome domains were rated as important. Although the outcomes of this exercise were clear and, we believed, unlikely to change much in a second round, we recognised that not all outcome domains would be relevant to all participants or amenable to change through an intervention.

To address this, we tested using a measure that captured outcomes across multiple domains and two measures that captured personalised goals. Specifically, we included the Camberwell Assessment of Need – Forensic Version (CAN-FOR),44 which captured outcomes across multiple domains and has been used as a composite measure for offenders with mental health problems. We also included the PSYCHLOPS measure45 and the Goal Attainment Scale (GAS),46 both of which allow the participants to specify personalised goals and, therefore, enabled the capturing of idiographic outcomes that were not specific to one domain.

When we tested potential measures on men in prison who were close to release, we found that we were unable to identify a measure of social inclusion that had the psychometric properties necessary to be included as an outcome measure in the RCT. The use of PSYCHLOPS was problematic in that participants tended to identify problems that were primarily due to their situation of being in prison, and these problems no longer existed once they had been released. Similarly, the GAS was also problematic in that goals were often poorly specified and, therefore, measuring change in a systematic and standardised way at follow-up was difficult. Consequently, PSYCHLOPS and the GAS were not included in our considerations for the primary or secondary outcome measures.

At the consensus meeting, we first discussed measures by domain before focusing on the primary outcome. Of the measures tested within the mental health symptom domain, the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM)47 was selected as the preferred measure over the General Health Questionnaire-1248 because of its wider range of constructs. The Patient Health Questionnaire-949 and General Anxiety Disorder-750 were not selected as many individuals were subthreshold on one or the other measure. The data we collected using the CAN-FOR also indicated that it would be a psychometrically viable option to be included as an outcome measure. No other composite measures were considered.

Two-thirds of participants reported having a substance misuse problem and, although it was decided that a substance misuse measure should not be the primary outcome, two short measures were included as secondary outcomes, with one capturing information on which substances were being used and the other capturing level of dependence.

After discussion about outcome measure criteria for trials and close reading of the measures, and with peer researchers supported to ask questions, the CORE-OM and CAN-FOR received the same number of votes to be the primary outcome measure. We opted for the CORE-OM as the primary outcome measure, as it had marginally superior psychometric properties and could be administered in a highly scripted fashion that would reduce researcher bias.

The four-stage process we conducted, incorporating the opinions of our Peer Research Group, enabled us to be confident that the outcome measures we selected focused on important areas of outcome and were acceptable to our target population. The outcome measures also demonstrated psychometric properties that indicated that they would be suitable for evaluating the effectiveness of the Engager intervention. However, some questions arise on this latter point. None of the selected instruments was specifically designed for, or validated on, prison populations and, therefore, may not accurately reflect the acutely stressful effects of custodial environments. Moreover, the transition from custody to community may itself have a significant impact on mental health, perhaps ‘swamping’ effects brought about by the intervention. As most of our data testing was undertaken when the participants were still in prison, we did not establish the efficacy of the measures in community settings. Although the above are clearly limitations of this study, it should be added that trials are usually expected to use validated and established instruments, which greatly restricts choice, and that any trial measuring change ‘through the gate’ is likely to be complicated by recovery among both arms simply as a consequence of leaving prison.

Finally, we considered using outcomes based on practitioner records, such as those from the Offender Assessment System (OASys) and other assessments entered by offender managers on nDelius, the Probation Service case management system (URL: https://data.gov.uk/dataset/8dae5fb2-82a2-4232-ae79-87e9c9fcfe46/ndelius; accessed 1 August 2022). However, it quickly became clear that these records were not recorded in a sufficiently consistent way to merit inclusion: they were not undertaken at set time points, were often subjective in terms of focus and they suffered from missing data. Above all, mental health was an issue that received relatively little attention.

Development and piloting procedures for a randomised controlled trial

This work is published. 43

Alongside the work undertaken in selecting a set of outcomes, we piloted RCT procedures to test the feasibility of a larger RCT. A key objective was to demonstrate that we could achieve a retention rate of > 50% when following up participants at 3 months post release from prison. Additional aims of the pilot RCT were to test out trial procedures, such as recruitment, consent and randomisation, to assess the levels of participation with the intervention, to test our ability to maintain research blinding and to model workforce requirements for the research team for a larger trial.

We reviewed the records of 864 individuals and identified 182 records of individuals who met the initial eligibility criteria. Of these individuals, we screened 110 potential participants to identify 60 eligible participants who were randomised at a ratio of 2 : 1 to receive either the Engager intervention plus usual care (i.e. the intervention group) or usual care alone (i.e. the control group). We achieved follow-up rates of 73% at 1 month and 47% at 3 months post release from prison.

No participants withdrew from the trial between consent and up to, and including, the point of randomisation, indicating that the trial procedures relating to recruitment, screening and randomisation were acceptable. However, maintaining researcher blinding was problematic and by the time of the 1-month follow-up the researchers were aware of the allocation of practically every participant. This was usually a consequence of participants sharing their allocation with the researchers who they frequently came across in the closed prison environment.

There were very high levels of data collection and completion across all the measures used at baseline and at follow-up, with few missing data. However, during the pilot trial we were still testing a range of potential outcome measures to use in the full trial and, therefore, not all participants completed the same set of outcome measures. Given the relatively small number of participants that completed each set of outcomes, we were unable to establish whether the intervention was able to bring about change on the measures, and whether or not such a change would be discernible over and above any change in scores that may have been due to whether the participants were in prison or the community. This issue was a key limitation of the pilot trial.

With regard to intervention acceptability, 90% of participants allocated to the intervention group received some of the intervention. Of the four participants who did not receive any intervention, three were either released or transferred to another prison before being seen by a practitioner and one decided the intervention was not for him prior to having contact with the practitioners. Of the 36 participants who did receive the intervention, 28 met with their practitioners in the community following their release from prison. There was strong indication that receiving support on the day of release led to ongoing contact in the community.

Overall, we found the trial procedures and intervention to be feasible to deliver, as well as acceptable to participants. With regard to contamination between the intervention and usual care, we found no evidence of this and, as the Engager practitioners were a stand-alone team, with many not working within the prison prior to the Engager intervention, there was little risk of contamination. The one major exception was in maintaining researcher blinding, which was a problem that was almost universal at both sites. We considered possible solutions to this problem, but it was felt that any solution created potentially more challenging problems. For example, we considered using a different researcher to collect data at follow-up, but felt that this might have a negative impact on follow-up rates, as participants may not be willing to meet a researcher they had not built up trust and rapport with. Ultimately, we opted to accept that unblinding would occur in the trial and to focus attention on reducing biases by training researchers to apply measures consistently, while continuing to allow flexibility for the whole schedule.

The retention rate for the 3-month follow-up was 46%, which was lower than hoped. To address this for the full trial, we broadened the window of time during which follow-ups could be completed. Participants often led chaotic lives and were very difficult to contact for periods of time and so it was felt that giving researchers longer to make contact with and meet participants in the community would increase the follow-up rate. In addition, we also decided to offer ‘thank you’ vouchers to compensate participants for their time when we interviewed them in the community, and we received approval from the Ministry of Justice to do this. Last, many of the participants worked with a range of services on their release from prison, and the introduction of the community rehabilitation companies (around the time of the pilot trial) meant that all people leaving prison were to be provided with support from probation for 12 months following their release. We developed closer working practices with services in the community, including establishing information-sharing agreements, to help researchers contact participants in the community.

The whole of the feasibility study also allowed us to test and develop the intervention and to model researcher workforce requirements and recruitment rates for small or more extensive geographical follow-up areas and different participant eligibility criteria, and this was critical for both assessing viability of and planning for the full trial.

Developing a process of care framework

In addition to developing a set of outcome measures for a RCT to evaluate the Engager intervention, we sought to develop a framework for capturing the care that prisoners received during their participation in the trial from the Engager intervention and standard services. A detailed description of the work we undertook in developing methods to capture the process of care is provided in Report Supplementary Material 8.

Measuring routine care

We recognised that the RCT was going to take place at a time of considerable change within the probation service, as well as at a time of ongoing changes in the NHS environment. Therefore, it was also important to capture what ‘usual care’ comprised. One of the key components of the Engager intervention was to support participants to work with services that could help them work towards achieving their goals. This might involve the Engager practitioners identifying appropriate organisations, liaising with those organisations and supporting the participant in meeting with those organisations. Therefore, it was anticipated that the Engager intervention could increase the amount of care received from other organisations and, potentially, improve the effectiveness of that care in meeting the participants’ needs.

To capture the care received from organisations, we adapted the service use elements of the Client Service Receipt Inventory. 51 Specifically, we expanded the list of organisations to include third-sector organisations and organisations providing social support (e.g. accommodation, employment and benefits). To help participants recall the services they had been in contact with, we split the services up by the type of service and asked about each type of service contact at relevant points in the interview schedule. For example, service use relating to accommodation was captured immediately after asking participants about their current accommodation situation and level of need in relation to accommodation. This also created a more coherent conversation and reduced annoyance induced by revisiting topics.

In addition, we included questions on how helpful the contact with each organisation was as a proxy measure of the effectiveness of the support received from each organisation. We asked participants about who initiated contact with each organisation (e.g. self, CJS, health service or the Engager practitioner) to provide an indication of how much service contact was initiated by the Engager practitioner.

Last, we asked participants to complete the Brief Inspire,52 which is a tool designed to assess a service user’s experience of the support they receive. We supplemented the five questions used in the Brief Inspire with a further nine items that were identified in workstream 1 as important for participants to have a good experience with a service (e.g. participants can trust the service and participants feel that the service listens to them). Although participants were likely to engage with many services, we decided to ask participants to provide ratings of their experiences of working with services in general, using the Brief Inspire to reduce participant burden.

Quantifying care from the Engager intervention

We sought to capture the amount of support participants received from the Engager practitioner and information regarding the response to this support. This was important to assess fidelity to the intervention and in understanding whether or not the intervention worked in the way we anticipated from the logic model. 41

To capture the process of care provided by the Engager practitioners, we developed a range of tools. First, to capture the amount (i.e. extent and dose) of contact between participants and the Engager practitioners, practitioners were asked to complete timesheets detailing every contact they had with the participant, providing details of the length of each contact and the location (i.e. prison or community). In addition, the Engager practitioners wrote clinical notes for each session they had with participants. The notes acted as a confirmation of the information recorded in the timesheets and provided details of the nature of the meetings between the practitioner and participant, as well as which components of the intervention were delivered (e.g. practical or psychological).

Last, to capture information regarding which components of the intervention were delivered, and whether or not they had the intended consequences, we developed a series of ‘if–then’ statements. The ‘if’ statement captured information relating to how often a component was delivered and the ‘then’ statement captured the extent to which it had its intended consequence, according to the Engager programme theory. The ‘if–then’ statements were rated by practitioners for each participant they had on their caseload, and were also rated by each participant. More expansive qualitative comments were also recorded.

The programmatic nature of the grant allowed us to focus on developing bespoke ways of capturing usual care and intervention content, which is required both for interpretation of the trial and understanding the way in which the intervention might work. However, such development work often requires iterative mixed-methods approaches and we were not able to fully test and refine the measures for the Engager intervention.

Economic modelling

This part of the economic analyses comprised conceptual model development, decision model specification and assessment of the feasibility of conducting estimated value of perfect information analysis (see Report Supplementary Material 10).

Development and testing of a simulation model to estimate the outcomes of the Engager intervention

A discrete event simulation model of the short-term outcomes and costs of the Engager intervention was developed based on (1) two previous relevant models (i.e. the revolving doors agency financial analysis model53 and the Home Office’s model for the economic and social costs of crime54) and (2) a systematic review of economic evaluations and cost-of-illness studies relating to the commonly overlapping problems that many prisoners and ex-prisoners face, such as drug or alcohol misuse. For both treatment strategies, that is, the Engager intervention and usual care, the model simulates an individual’s pathway through different events, recording the events experienced and calculating the total costs and outcomes associated with that pathway. The model assumed that prisoners had 4 months in prison before release, and then incorporated contact with health services in the community, medications, non-fatal self-harm events and deaths.

For people receiving the Engager intervention, there would be a probability of an improvement in mental health within prison once treatment with the Engager intervention started. After release from prison, there would be an increase in the probability of planned contact with health services (with probabilities differing depending on the type of health service) and a subsequent decrease in the probability of unplanned contact with services.

Modelled outcomes

This initial stage of modelling was based on a model with service use for mental health and drug misuse, as well as general practitioner (general practice) attendances in the pilot work. The challenges of obtaining and using data that could potentially be available from the full trial to enable these basic models to generate plausible cost and cost-effectiveness were expected to be considerable. The challenges would certainly prevent the possibility of the kinds of cross-sectoral estimated value of perfect information analysis that were originally planned. Along with the shift to a definitive RCT, the challenges informed the decision to make the economic evaluation of the main trial a combination of three cost-effectiveness analyses (using the three main trial outcomes) alongside a cost–consequence analysis.

Evaluation of Engager: randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis (phase 2, workstreams 3 and 4)

Randomised controlled trial

The results of the RCT have been published. 55 To date, there has been a dearth of research developing and evaluating mental health interventions for prison leavers. 27 Trials within prison settings are particularly challenging to undertake because of a range of factors, such as organisational difficulties, maintaining masking, poor follow-up rates and selecting appropriate outcomes measures. 1,17,28–30

Design

The individually randomised superiority trial of the Engager intervention was set in three prisons (south-west of England, n = 2; north-west of England, n = 1) and nearby communities between 2016 and 2019.

To detect a change of 3.5 units for the primary outcome measure (i.e. CORE-OM43) with 90% power and a significance threshold of 0.05, assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 7.556 and allowing for 30% attrition, 280 participants were recruited and randomised [1 : 1 allocation; stratified by site (i.e. Devon or Manchester)] to either the Engager intervention plus usual care (n = 140) or usual care only (n = 140).

Intervention

The Engager intervention was a manualised person-centred intervention that aimed to address mental health needs, as well as to support wider issues, such as accommodation, education, social relationships and money management. Experienced support workers and a supervisor with experience of psychological therapy delivered the Engager intervention. A mentalisation-informed approach underpinned all elements of the intervention. At the pre-release stage, the practitioner and participant developed a shared understanding of the participant’s needs and goals, recognising the links between emotion, thinking, behaviour and social outcomes. A goal attainment plan was developed and followed, including liaison with relevant agencies and the participant’s social networks.

Engagement was maintained throughout the pre-release period and, when required, all-day support was given on the release day. Following release, the practitioner provided support for the participant to re-enter the community and engage with services. The practitioner continued to work with the participant and any relevant organisations to help them achieve their goals, while encouraging the participant to take responsibility for self-care. The practitioner also prepared the participant for the end of the intervention, while liaising with relevant community organisations regarding continuity of care.

Participants

Individuals recruited into the trial needed to be released to defined geographical areas and were required to score ≥ 10 points on the Patient Health Questionnaire-949 to indicate depression, ≥ 10 points on the General Anxiety Disorder-750 to indicate anxiety or score ≥ 3 points on a bespoke questionnaire to indicate likelihood of difficulties on release. Those individuals with psychosis under the care of prison in reach teams or part of the personality disorder service were excluded. All participants were assessed at six time points, that is, at baseline (before randomisation), during the week before release from prison, and then at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months post release from prison.

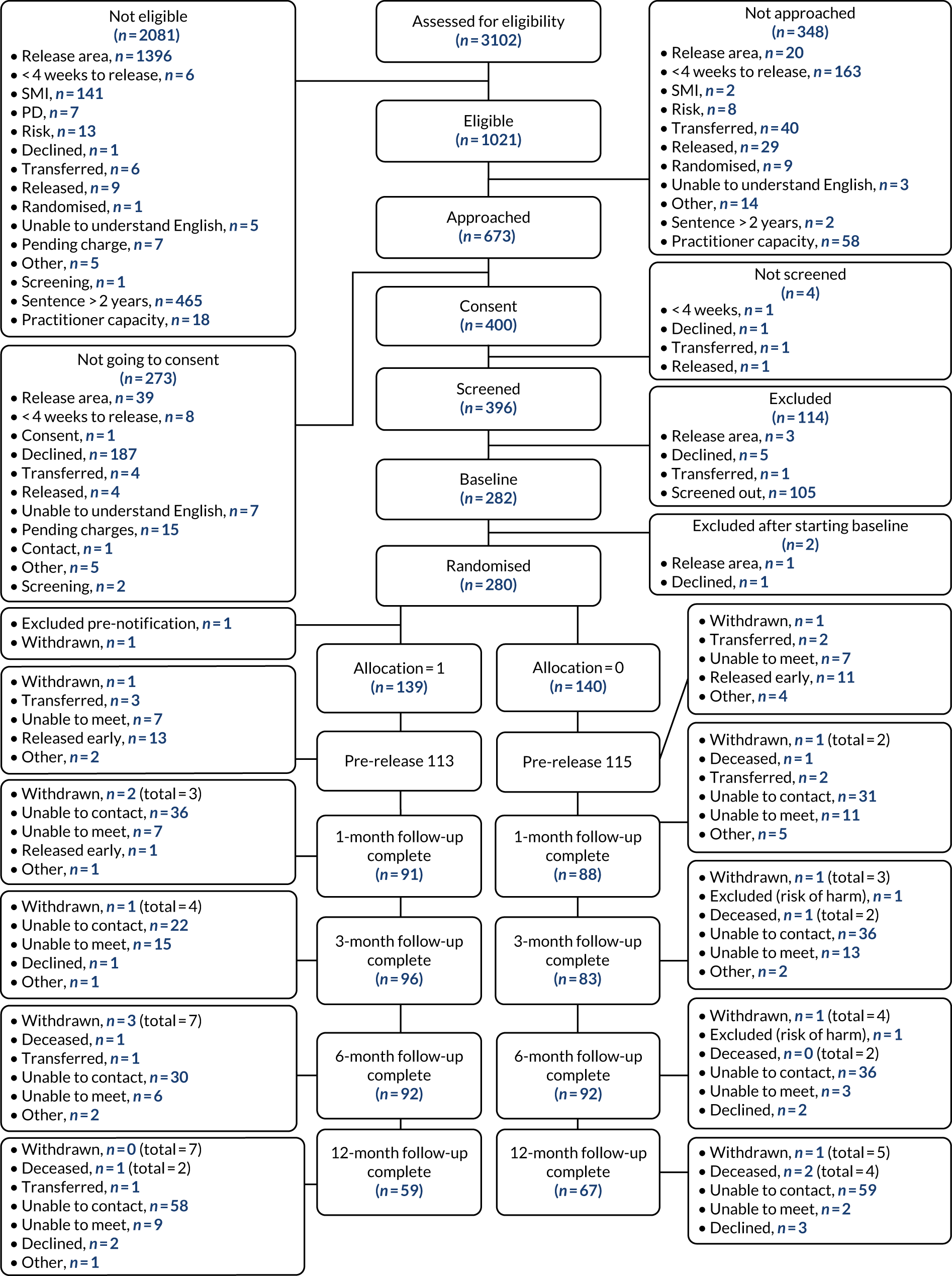

A total of 3102 prisoners received assessment for eligibility. Of these prisoners, 673 were identified as potentially eligible for the trial and approached for consent. One hundred and eighty-seven of the 673 prisoners declined involvement and a further 90 prisoners were found not to be eligible or were excluded for other reasons, leaving 396 prisoners to be screened for common mental health problems. Of these prisoners, 78% were found to be eligible and, therefore, selected to take part. After a small number of withdrawals, the 280 prisoners who remained were randomised into two groups of 140. Figure 4 depicts the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram.

FIGURE 4.

A CONSORT flow diagram. Reproduced with permission from Byng et al. 55 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Analysis

Demographic data and participant characteristics were reported descriptively at baseline, using mean and SD, with median and minimum and maximum, as appropriate, for continuous measures, and percentages for categorical measures.

For the primary analyses of the outcome variables, the intention-to-treat principle was used, with participants being analysed according to their randomised allocation irrespective of treatment actually received. Only participants with observed data were included for the primary analyses. Primary analyses used linear regression models for continuous outcomes and logistic models for binary outcomes.

Sensitivity analyses were performed for comparison with the primary analyses, that is, per-protocol analysis, complier-average causal effect analysis and inclusion of only those participants whose follow-up assessments took place within the specified ‘window’. The definition of per protocol for the Engager intervention plus usual-care group was receipt of at least two contacts prior to initial release and at least eight contacts following initial release. As a secondary analysis, mixed-effects models (random effect on participant intercept) were performed including participants with data available at any of the four follow-up time points. Results of all inferential analyses were reported as between-group differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Global p-values were also provided with regard to categorical explanatory variables. The threshold for determining significant effects was set at p < 0.05. No adjustment of p-values was made in the light of multiple testing.

All analyses were adjusted for baseline values of continuous outcomes and study site. Baseline participant characteristics were to be compared by treatment group, with any covariates found to be unbalanced included in the analyses if thought to be predictive of outcome.

For the CORE-OM at 6- and 12-month follow-up, we investigated interactions (i.e. moderation effects) between intervention and specific participant characteristics, including study site, personality disorder (based on the Standardised Assessment of Personality – Abbreviated Scale), previous trauma, pre-prison accommodation and alcohol/substance abuse. Further sensitivity analyses were performed to address missing data, based on the assumption that missing data were missing at random. The level of missingness for the CORE-OM was evaluated, with 55% of participants found to have missing data at 12 months. Sensitivity analyses were performed using combined observed and imputed data.

Results

There were some imbalances between the two groups at baseline. The Engager intervention group had a higher proportion of people with unstable accommodation [n = 76 (54%) vs. n = 58 (41%)], a higher proportion of people who were unemployed [n = 104 (75%) vs. n = 85 (61%)] and a higher proportion of people with physical health problems [n = 64 (45%) vs. n = 48 (34%)]. A higher proportion of people in the usual-care group had experienced relational trauma [n = 89 (64%) vs. n = 74 (53%)]. At 6 months, 184 (66%) participants were followed up, with 45% of participants followed up at 12 months.

There were between-group imbalances in participant characteristics at baseline for type of accommodation (people in the usual-care group had more stable accommodation before prison), employment (people in the usual-care group were more likely to be employed), previous trauma (people in the usual-care group had experienced more relational trauma) and physical health problems (people in the usual-care group had fewer problems). Therefore, these characteristics were included as covariates in all analyses.

Of 140 participants allocated to the intervention, 92% received at least one session in prison [mean 5.7 (SD 3.9)] and 108 (77%) participants received at least one post-release community session [mean 12.9 (SD 11.6)].

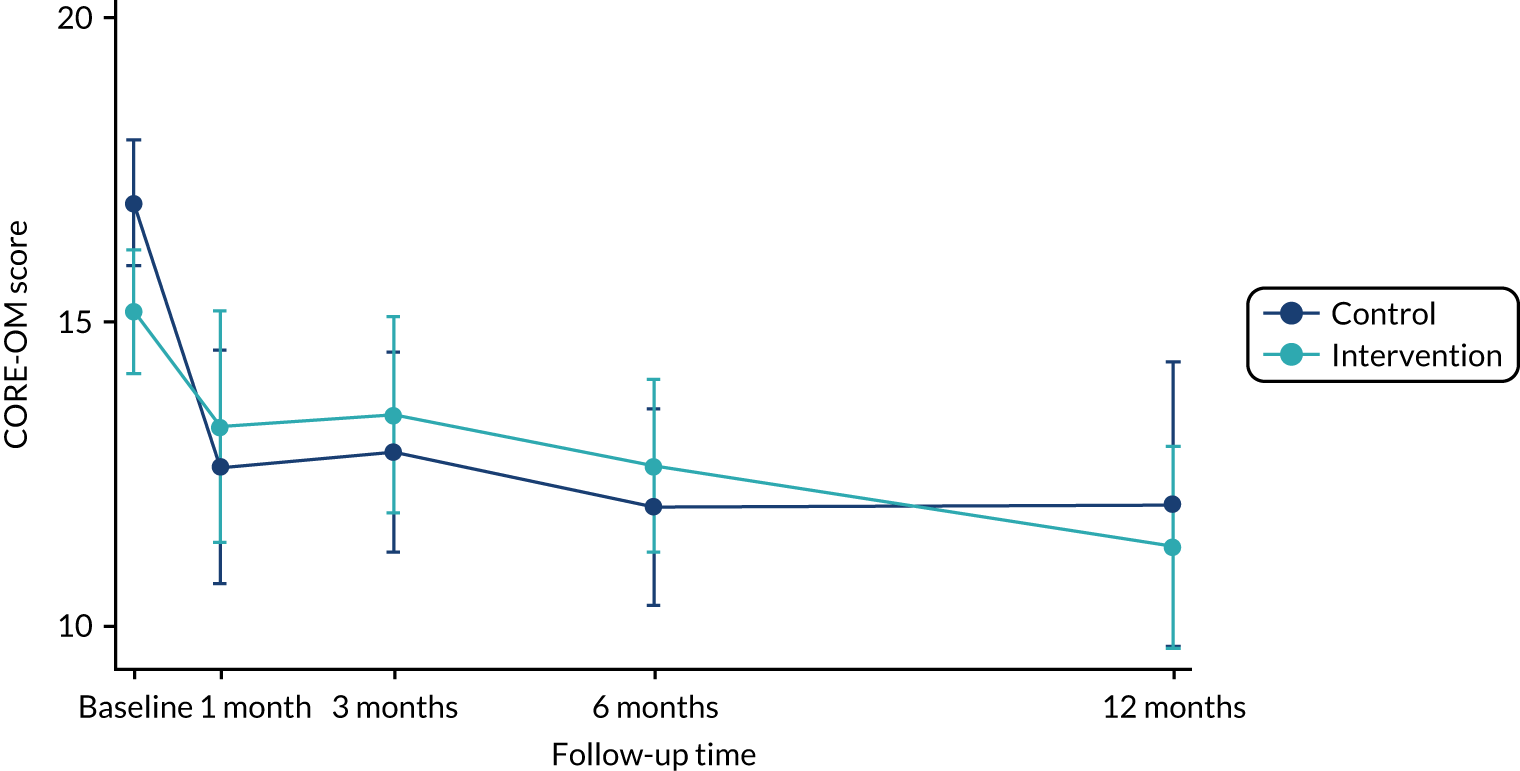

There were no significant differences in mean CORE-OM (primary outcome) scores between the groups at 6 months [Engager intervention group mean 12.6 (SD 6.9), n = 92; usual-care group mean 11.9 (SD = 7.7), n = 90; between-group difference 1.1 (95% CI –1.1 to 3.2); p-value 0.325]. Figure 5 depicts the change in CORE-OM score over the four time points.

FIGURE 5.

Graph of CORE-OM score over time. Reproduced with permission from Byng et al. 55 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

There were a small number of statistically significant differences between the two groups on the secondary outcomes [including CAN-FOR, Intermediate Outcomes Measurement Instrument, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) and ICEpop CAPability measure for Adults (ICECAP-A)] for a variety of sensitivity analyses (i.e. complier-average causal effect and per protocol), but this is most likely due to the effects of multiple testing. At the time of writing, it had still not been possible to obtain Police National Computer data on reoffending.

Further exploratory analysis

After our neutral finding was revealed and the baseline imbalances were identified, we carried out some further exploratory analyses to rule out or put forward any contributing factors or possible explanations for the neutral finding. The details of this exploratory analysis are found in Report Supplementary Material 9. We found imbalances in CORE-OM scores at baseline, with the Engager intervention group scoring as less mentally unwell (mean 15.2 vs. 16.9). It is possible that the people in the usual-care group were more willing to acknowledge their common mental health problems or may have struggled with being in prison but may have had less social disadvantage on release into the community. Conversely, people in the Engager intervention group may be less likely to report their difficulties in the prison environment, as they may not wish to show their vulnerabilities.

We identified that the mean scores for the CORE-OM dropped differentially over time, depending on which trial arm participants were in and whether or not the participants were serving a new prison sentence at time of follow-up.

Health economic analyses

We conducted a trial-based economic evaluation to identify the mean incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained with the Engager intervention compared with current practice. Report Supplementary Material 10 describes in detail the health economics modelling, and the results of the health economic analyses are published. 57

The cost of the Engager intervention included the cost of training and supervision based on practitioner-reported activities. As a conservative estimate, the cost per participant of training and supervision was calculated as the total cost of training and supervision for the Engager trial divided by the number of participants in the intervention arm of the trial.

Unit costs for accommodation-, education-, training-, employment-, money-, relationship- and criminal justice-related service use are reported in Hunter et al. 57 table 1. All costs are reported in 2017/18 GBP (i.e. the most recent year costing data were available), with costs for earlier years adjusted to 2017/18 values.

The trial primary outcome CORE-OM was converted to the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – 6D (CORE-6D) utility to calculate QALYs. QALYs were calculated as the area under the curve using the CORE-6D responses at baseline and at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months post release. QALYs were also calculated and reported in a similar manner using responses to the EQ-5D-5L at baseline and at 3, 6 and 12 months post release and (1) the mapping algorithm and (2) the EQ-5D-5L value set. Years of full capability (YFCs) (equivalent) were calculated for the Engager intervention compared with usual care using patient-level responses to the ICECAP-A at baseline and at 3, 6 and 12 months post release.

We assumed that data missing at follow-up were missing at random. No predictors of ‘missingness’ were found. Costs, utility scores and the ICECAP-A tariff were imputed for the number of 30 data sets using chained equations [i.e. multiple imputation using chained equations (MICE)] and predictive mean matching.

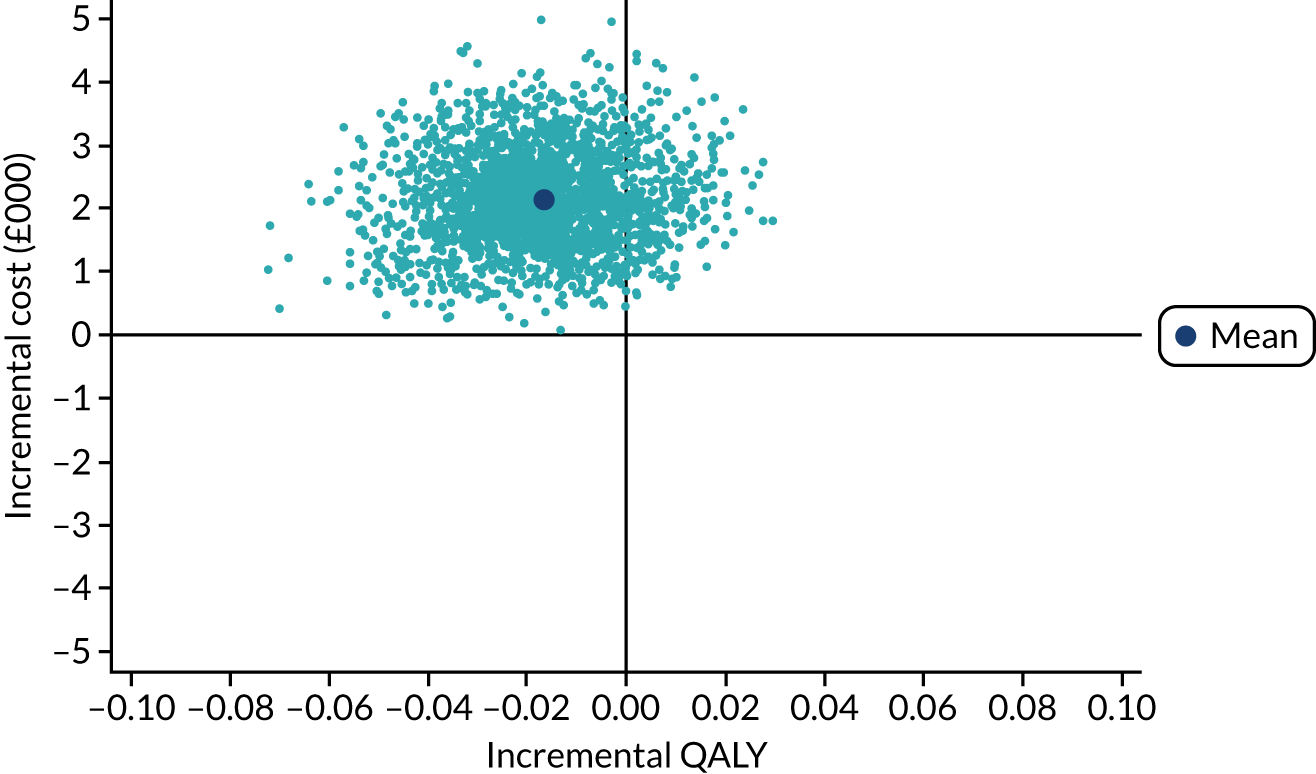

For the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, we used regression to account for the correlation between costs and outcomes to calculate the incremental mean cost per QALY or per YFC gained of the Engager intervention compared with usual care. The primary analysis was calculated using the multiple imputation data set and was bootstrapped. The incremental mean cost per QALY and per YFC were used to calculate cost-effectiveness acceptability curves and cost-effectiveness planes. A range of sensitivity analyses and a cost–consequences analysis were also conducted.

The total cost of training and supervision for the duration of the Engager trial was £59,303. If the total cost of the training and supervision is divided by the 140 participants randomised to the intervention, then the training and supervision cost was £424 per participant. The total average cost per participant of delivering all intervention sessions (i.e. prison, meeting at the gate and community) was £467 (SD £475). When the cost of training and supervision is added, then this results in an average cost per participant in the Engager arm of £891.

Descriptive statistics for CORE-6D, EQ-5D-5L (cross-walk and time trade-off tariff) and ICECAP-A tariff are reported. 57 There were no significant differences between trial arms.

The bias-corrected bootstrapped difference in health-care costs, adjusting for baseline, of the Engager intervention compared with usual care is £751 (95% CI –£1593 to £3096). When the cost of the Engager intervention is added (including the cost of training and supervision), the difference in costs is £1795 (95% CI –£575 to £4164). The cost difference for CJS costs including the cost of the intervention is £8166 (95% CI £1692 to £14,640). If productivity gains/losses are included, then the cost difference is £5344 (95% CI –£1228 to £11,916).