Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1247. The contractual start date was in June 2011. The final report began editorial review in September 2012 and was accepted for publication in March 2013. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

David Gunnell, Keith Hawton and Nav Kapur are members of England's National Suicide Prevention Advisory Group. David Gunnell is also a member of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) Pharmacovigilance Expert Advisory Group. Keith Hawton and Sue Simkin acted as temporary advisers to the MHRA for its evaluation of the efficacy and safety profile of co-proxamol. Nav Kapur was chairperson of the Guideline Development Group for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2011 guidelines on the longer-term management of self-harm.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews, and similar, conducted in the course of the research and contains language which may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Gunnell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Suicide and self-harm are the most serious and devastating consequences of mental illness. More than 4000 people take their lives every year in England and there are over 200,000 hospital presentations for self-harm annually. 1 Almost one-quarter of people who self-harm repeat their act within 12 months. As suicide occurs predominantly in young people – > 50% of deaths occur in those aged < 45 years – it is a major contributor to potential years of life lost (PYLL), accounting for more PYLL than strokes or road traffic accidents. 2 Death by suicide has a profound long-term impact on the family, friends and colleagues of the deceased.

In view of the impact of suicidal behaviour on population health, suicide prevention has been a key area in the health strategies of successive UK governments, and in 2002 the Department of Health (England) launched its National Suicide Prevention Strategy. 3 However, the evidence base to inform the prevention strategy is limited. 4,5 The causes of suicidal behaviour are complex, vary at different phases of the life course and operate both at an individual level and at a societal level;6,7 thus, national prevention strategies include a range of clinical and public health approaches to reduce its incidence. 3,8 In this context and in discussion with major stakeholders, we developed a programme of research to address several key areas of relevance to suicide prevention in England. The following paragraphs outline the rationale for our choice of research questions.

Priority areas in suicide prevention

Suicide statistics

Good-quality suicide statistics are critical to inform suicide prevention priorities and to assess the impact of prevention strategies. However, whether a self-inflicted death is recorded as a suicide, an open verdict, a misadventure or an accidental death by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) depends on the outcome of a coroner's investigation, and coroners differ in their threshold for labelling deaths as suicide. 9 Such differences and changes in coroners' categorisation of possible suicides over time may compromise an assessment of the incidence of suicide and so undermine the evaluation of specific preventative activities using routine data. 10

Medicines commonly taken in fatal overdoses

Suicide may occur in the context of serious mental illness or result from an impulsive act in a moment of crisis. Whether an episode of self-harm results in death depends on the ease of availability of lethal suicide methods, and some of the best evidence concerning suicide prevention concerns restricting access to lethal methods. 5,11 Drugs associated with high case fatality when taken in overdose are therefore a common target for preventative intervention. Overdoses of paracetamol (acetaminophen), co-proxamol and dosulepin account for 10% of suicides in England, and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has implemented a number of initiatives to reduce the incidence of suicides using these and other medicines. One of the most recent initiatives has been the phased withdrawal of co-proxamol since 2005. The impact of the withdrawal of co-proxamol requires evaluation to inform both international prescribing policies and future interventions of this sort, such as restricting the use of dosulepin. Furthermore, continued deaths from paracetamol overdose since regulatory action in 199812 suggest the need to review existing sales regulations and evaluate the long-term effects of the legislation.

Assessment and management of people who self-harm

Whether someone who attempts suicide and survives later successfully repeats his or her act may depend on the NHS's response to his or her initial attempt. 13 Yet there is uncertainty concerning the most appropriate service structures to assess and manage self-harm patients. This uncertainty was demonstrated in our previous studies showing wide variations between hospitals in their management of self-harm. 14,15 It is unclear whether or not these variations have any implications for patient outcomes; although person-based studies suggest that some aspects of service provision may affect outcome,16–18 these findings may be confounded both because patient characteristics may influence the services they receive and because high-risk patients may be most likely to self-discharge without receiving care. It is crucial to assess whether or not differences in hospital management influence outcomes in this key area.

Trials of interventions to reduce self-harm in high-risk clinical populations

Half of all people who die by suicide have been in contact with health services within a month of their death. 19 The two highest-risk groups are patients who have recently been discharged from psychiatric inpatient care and those who have self-harmed. One-quarter of all people who die by suicide have been under the recent care of psychiatric services,20 and around half have been in contact with services following a previous episode of self-harm. 6 Thus, interventions to reduce suicide risk in these groups are a priority; yet, Cochrane reviews21 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance13 have highlighted the lack of good-quality evidence concerning the management of self-harm. Trials of contact by telephone or letter, or the provision of ‘crisis cards’ facilitating access to urgent care following self-harm have had mixed results. 22 Likewise, only one randomised controlled trial of an intervention to reduce the risk of suicide following psychiatric inpatient discharge has been carried out,23,24 and, although this trial showed promising results, it has not been replicated.

Aim

Our overall aim was to carry out a programme of linked research studies aimed at improving the management of self-harm, reducing the incidence of suicide and providing reliable data to evaluate the impact of the 2002 National Suicide Prevention Strategy for England. 3

Objectives and research questions

Our research programme consisted of four interlinked studies, each of which related to key aspects of the 2002 National Suicide Prevention Strategy for England. 3 Our objectives were to:

-

conduct a review of the inquest records of 12 coroners, spanning a period of 15 years, to quantify the extent to which suicide rates, secular trends in suicide, and suicides from co-proxamol, paracetamol and tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) overdose may be over- or underestimated when they are based on deaths given suicide and open verdicts by coroners

-

carry out a series of pharmacoepidemiological studies using national mortality data together with information from self-harm registers in Oxford and Manchester and coroners' records to investigate:

-

(a) associations between blood paracetamol levels and liver damage (note: because of challenges obtaining relevant data, this was subsequently modified to a comparison of the impact of differing parcetamol regulations in the UK and Ireland)

-

(b) whether or not the current sales limit for paracetamol is appropriate and being adhered to, determined by interviewing a sample of people who have taken a paracetamol overdose about their episode

-

(c) whether or not any compensatory increased use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) has led to increased rates of gastrointestinal (GI) haemorrhage

-

(d) the impact on suicide of the recent withdrawal of co-proxamol

-

(e) whether or not regulatory action is warranted concerning dosulepin (a TCA)

-

-

assess whether or not between-hospital variations in four key aspects of self-harm services (psychosocial assessment, general hospital admission, psychiatric admission and follow-up) influence patient outcome, as indexed by repeat self-harm

-

develop, pilot and evaluate contact-based interventions aimed at reducing:

-

(a) repeat self-harm

-

(b) self-harm following specialist inpatient psychiatric treatment.

-

Structure of this report

Chapters 2–8 present the findings from the component substudies relevant to each of the research objectives described in the previous section. Although these objectives are grouped thematically, they do not reflect the number of different methodologies used to achieve them. Some research objectives were investigated using a single methodology whereas others were investigated using more than one. For this reason the chapters of this report vary in whether they outline the findings related to one or to several of the research objectives:

-

Chapter 2 outlines the study relating to objective 1, examining the influence of changes in coroners' practices on the validity of national suicide rates in England.

-

Chapter 3 outlines the findings of four separate studies relating to objectives 2(a), (b) and (c). Objective 2(b) was investigated in two studies (Chapter 3, Study 2 and Study 3). All of these studies investigate the various impacts of reduced pack sizes of paracetamol for sale in England and Wales.

-

Chapter 4 outlines the research relating to objective 2(d), evaluating the effects of the withdrawal of co-proxamol from the England and Wales markets.

-

Chapter 5 outlines the research on antidepressant toxicity relating to objective 2(e).

-

Chapter 6 details the findings of a study relating to objective 3 regarding variations in self-harm service delivery across 32 centres in England.

-

Chapter 7 relates to objective 4(a) and describes the findings of a study carried out to develop and pilot a contact-based intervention to reduce self-harm.

-

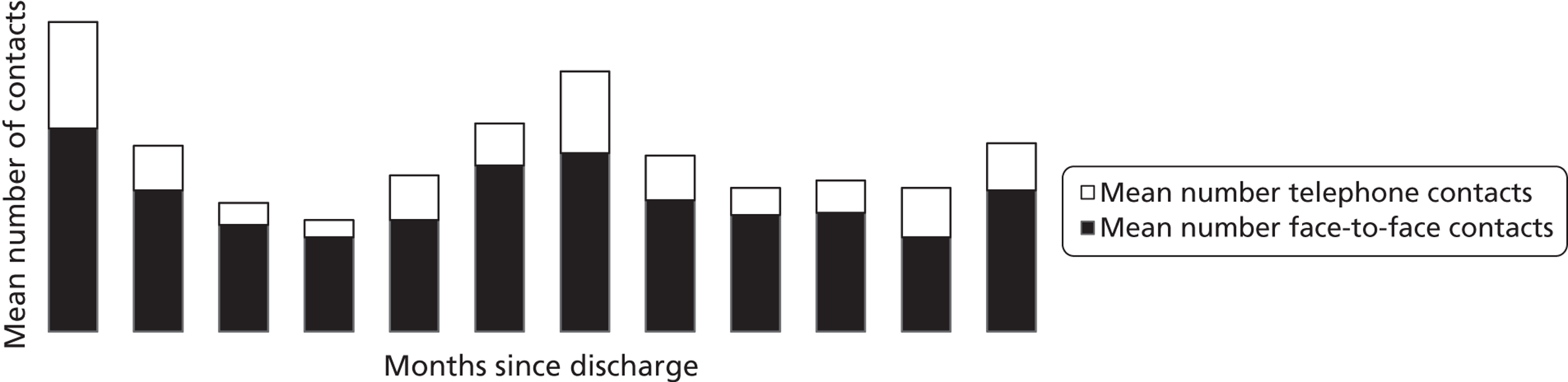

Chapter 8 relates to objective 4(b) and details the pilot testing of a letter-based intervention aimed at reducing self-harm specifically among patients discharged from psychiatric hospitals.

-

The final chapter, Chapter 9, brings together all of our findings and discusses their relevance to suicide prevention practice and policy.

Each of these chapters presents a brief introduction outlining the context of the substudy and relevant previous literature, the methods used, the main findings and a discussion of the key implications of the findings.

Definitions

Throughout the report, ‘self-harm’ is defined as intentional self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of type of motivation, including degree of suicidal intent. 25 It therefore includes acts with clear suicidal intent, those with varying lesser degrees of suicidal intent and those in which suicidal intent was absent but the behaviour would have been intended to have other outcomes (e.g. communication of distress, cessation of consciousness, relief of tension). ‘Suicide’ is defined as an act of self-harm that results in death.

Chapter 2 The influence of changes in coroners' practices on the validity of national suicide rates in England

Abstract

Reliable mortality statistics are critical for monitoring trends in suicide and identifying appropriate priorities for prevention. We used coroners' inquest records for possible suicides (n = 2086) carried out in 12 areas of England in 1990–1, 1998 and 2005 together with Ministry of Justice data for all inquests throughout England in 2001–2 and 2008–9 to investigate temporal changes in the validity of national suicide statistics. In addition to the data from these years, we also used the coroners' inquest data from 2006 and 2007 to investigate the possible underestimation of suicide from co-proxamol, paracetamol and TCA poisoning when estimates are based only on deaths given suicide and open verdicts.

Between 1990 and 2005, the proportion of researcher-defined suicides given a suicide verdict by coroners decreased by 7% [p(trend) = 0.001], largely because of an increased use of accident/misadventure verdicts for researcher-defined suicides, particularly for deaths involving poisoning. The numbers of suicides by co-proxamol, paracetamol and TCA poisoning are underestimated by between 12% (co-proxamol) and 26% (paracetamol) when estimates are based on suicide and open verdict deaths alone.

In our analysis of national Ministry of Justice data we found a marked rise in the use of narrative verdicts and wide geographical variation in their use, with up to 50% of deaths in some areas receiving a narrative verdict. Coroners who gave more narrative verdicts gave fewer suicide verdicts (r = − 0.41, p < 0.001). In the 10 coroners' areas where the highest proportions of narrative verdicts were given, the officially recorded incidence of suicide decreased by 16% between 2001–2 and 2008–9, whereas in the areas served by the 10 coroners who used narratives infrequently the officially recorded incidence of suicide increased by 1%. This indicates that the use of narrative verdicts may distort local suicide statistics. Taken together, these findings indicate (1) that the ONS should consider including ‘accidental’ deaths by poisoning with medicines in the statistics available for monitoring trends in national suicide rates and (2) that small-area suicide rates, and changes in these rates over time since 2000, should be interpreted with caution. Further increased use of narrative verdicts will compromise the quality of national suicide statistics.

Background

Reliable mortality statistics are critical for assessing the population burden of suicide, as well as for developing prevention strategies and monitoring their impact on suicide rates. Officially reported suicide rates in England are derived from figures for the underlying cause of death produced by the ONS. ONS suicide statistics are based on death certificates provided by coroners following their investigation of a possible suicide. The cause of death information provided by coroners on death certificates is assessed by ONS coders who follow internationally agreed rules [currently the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10)] to assign an underlying cause of death to all deaths.

The likelihood that a death was self-inflicted is not always clear-cut. The legal criteria used by coroners to determine whether a death was suicide mean that it must be clear beyond reasonable doubt that the deceased had intended to take his or her life. When coroners are uncertain about an individual's intent, or if it is unclear whether the death was self-inflicted or accidental, they may give either an open verdict or, in more recent years, a narrative verdict.

In contrast to the legal definition of suicide, clinicians and researchers assess the likelihood that a death was suicide on the balance of probability, and research has shown that a high proportion of deaths given an open verdict by coroners are highly likely to be suicides. 26–28 For this reason, ONS suicide statistics and monitoring of suicide trends in the National Suicide Prevention Strategy3 are based on deaths given suicide verdicts by coroners as well as a high proportion of open verdict deaths.

Narrative verdicts record in several sentences how, and in what circumstances, the death occurred, rather than giving a single short-form verdict such as suicide, open or accidental death. 10,29 Use of narrative verdicts increased exponentially between 2001 and 2009; they now account for over 10% of all verdicts given by coroners (n = 3012 in 2009). 29 This increased use has potentially important implications for the estimation of national suicide rates, as ONS's interpretation of international death coding rules mean that, when suicide intent is uncertain from such narrative accounts, as is often the case, the ONS code such deaths as accidents. The ONS gave the following example of a narrative verdict in a recent publication:29

Mr X, after being found hanging in his cell at X youth offenders institution on [date], died on [date] at X infirmary. It was a serious omission by X youth offenders institution not to have informed X’s parents on each occasion that X had self-harmed. The jury’s verdict is that X died from hanging.

Because intent was not mentioned within the narrative, the death was classified by the ONS as accidental, but suicide is strongly implied.

As well as the recent impact of narrative verdicts on suicide rates, two further issues are of more long-standing importance in relation to the interpretation of suicide statistics. First, some deaths that are considered by clinicians to be probable suicides are given accidental verdicts by coroners. 30,31 Such deaths are not considered as possible suicides by the ONS, although it recognises that a proportion of these deaths are likely to be ‘missed’ suicides. 32 If coroners' practices regarding their relative use of short-form open verdict and accidental verdict cause of death categories change over time, this may distort apparent secular trends in suicide rates. In Australia, an increasing trend in recording of possible suicides as accidental deaths is thought to have exaggerated an apparent decline in suicide rates, although the degree of impact is debated. 33,34 Second, there are > 100 coroners in England and they vary both in the criteria that they use in determining the likelihood that a death was suicide35,36 and in their use of narrative verdicts. 37 These variations may distort small-area differences in suicide rates as geographical patterning may be influenced by the local coroner's practice as well as real area differences in self-inflicted deaths.

Objectives

The original aim of this element of our research programme was to quantify the extent to which suicide rates and secular trends in suicide may be over- or underestimated when they are based on deaths given suicide and open verdicts by coroners (as was then the case). We were interested in determining whether there had been changes over time in the frequency of use of accidental/misadventure verdicts for possible suicides and their impact on suicide rates. We also used data obtained in this strand of the research programme to investigate whether suicides by co-proxamol, paracetamol and TCA poisoning are underestimated when estimates are based only on those deaths given a suicide or an open verdict by coroners.

As described earlier, an additional emerging issue concerning the accuracy of national suicide statistics – the rise in the use of narrative verdicts by coroners – became apparent over the course of the research programme. We therefore extended the brief of this element of our programme to additionally investigate the impact of the growth in use of narrative verdicts on small-area suicide rate estimates.

Methods

Examination of coroners’ inquest records

To investigate the impact on trends in national suicide rates of possible changes in coroners' use of different verdicts for likely suicides, we examined the inquest records of a sample of 12 of the 107 coroners' jurisdictions in England in 2005. Our sample comprised the three coroners whose jurisdictions covered the three collaborating research centres (the cities of Bristol, Oxford and Manchester) and a random sample of nine further jurisdictions within 90 minutes' travel time of each of these three centres. Four of the study jurisidictions were urban, three were rural and five were mixed urban/rural. We have previously conducted collaborative studies with these 12 coroners. Ministry of Justice data38 indicate that the relative proportions of suicide, accident/misadventure, open and other (mainly narrative) verdicts given by our sample of 12 coroners in 2005 were broadly similar to those in England as a whole in that year (participating vs. non-participating jurisdictions: suicide 14.3% vs. 19.3%; accident/misadventure 62.7% vs. 53.5%; open 13.5% vs. 15.1%; other 9.6% vs. 12.1%).

Sample size

The sample size for this study was based on our experience working with the Bristol coroner in a previous study30 in which 10% of people identified as definite or probable suicides by the research team were given a misadventure or an accident verdict by the coroner (unpublished data). Based on an estimated 400 suicides per year across the areas served by the 12 coroners with whom we had previous collaborative links, we estimated that we were able to detect (80% power, 5% level of statistical significance) a change in the proportion of missed suicides (researcher-defined suicides given accident/misadventure verdicts by coroners) from 10% to 4% (if this practice was decreasing) or from 10% to 17% (if the practice was growing) between 1990 and 2005. Differences of this size are large enough to have an impact on apparent secular trends in suicide.

Data collection

The records available to us in each of the 12 coroners' districts differed somewhat, as did the approach used by coroners to index records according to verdict. We searched coroners' electronic databases and ledgers or, if neither of these was available, we manually searched all inquest files for information on all cases assigned a verdict of suicide or an open, narrative or accident/misadventure verdict when the death had occurred in 1990 (1991 for one jurisdiction where 1990 data were no longer available), 1998 or 2005. A 15-year period was selected based on our desire to examine a long enough period to detect gradual changes in practice and for the practical consideration that, if we had studied a longer time period, older inquest files might have been destroyed. To increase the sample size for our analysis of deaths from co-proxamol, paracetamol and TCA poisoning, we extended our search of coroners' records to include deaths occurring in 2006 and 2007.

Exclusions

We extracted data using a structured form (see Appendix 1) on all suicides and possible suicides assigned open, narrative or accident/misadventure verdicts. We excluded all deaths that occurred outside the UK and those where the deceased was aged < 10 years, as suicide is rare in this age group. We also excluded deaths for which the cause was clearly not suicide, for example industrial disease; post-surgery deaths; burns for which the fire report indicated an accidental cause; falls that were not from a height (e.g. slips on pavements); and other deaths for which suicide was an extremely unlikely cause or impossible to determine, such as decomposed bodies on which, because of the state of the body, blood tests could not be carried out (or were negative) and there was no other evidence of self-harm. Furthermore, we excluded people given accident/misadventure verdicts in which the cause of death was a vehicular accident or poisoning by a drug of abuse only (e.g. alcohol, heroin), as our previous experience suggested that accidental deaths from these causes are difficult to distinguish from suicides. We included cases given open verdicts in which the death had been caused by a traffic accident or drug of abuse if there was any evidence in the records of current or past emotional distress.

Classification of cause of death

After the exclusions listed above, all remaining deaths given open or accident/misadventure verdicts were defined as possible suicides. These deaths included approximately 50% of all open verdict deaths but < 10% of accident verdict deaths across the 12 coroners' districts. For all possible suicides assigned an open, a narrative or an accident/misadventure verdict, data were extracted from coroners' files on sociodemographic and economic characteristics and clinical characteristics of the death, as well as on circumstances leading up to the death and information retrieved from the death scene. In particular, we recorded details of contact with psychiatric services, whether there had been a previous episode of self-harm, whether there had been a suicide note, and the levels of medication and alcohol in post-mortem blood samples. Vignettes of up to 800 words in length, based on information recorded in coroners' inquest records and witness statements, were written for all possible suicide cases. These described in detail the relevant history and circumstances leading to the death.

Three clinical members of the research team (DG, KH, NK) with extensive experience in suicide research read the vignettes and other data recorded about the possible suicides, blind to year of death, the identity of the coroner and the verdict assigned. They then independently rated the likelihood of suicide as high, moderate, low or unclear. When there was disagreement, consensus decisions were reached on whether a case was a probable suicide or not (see Appendix 2 for a description of the protocol followed). Cases rated as being of high or moderate likelihood of suicide were included in our sample of researcher-defined suicides together with those given suicide verdicts by the coroner.

Verdicts given to probable suicides by co-proxamol, paracetamol and tricyclic antidepressant poisoning

We identified all deaths by poisoning with co-proxamol, paracetamol and TCAs that were investigated by the 12 study coroners for the years 1990–1, 1998 and 2005–7. We excluded from this analysis deaths given narrative verdicts, as we could not be sure how such deaths would be coded by the ONS. We analysed separately total deaths for which some mention of one of these particular drugs was made in combination with other drugs and deaths for which no other drugs (except alcohol) were mentioned in the coroners' reports, that is, ‘pure’ poisoning.

Use of Office for National Statistics data

To investigate the relationship between researcher-defined suicides and coding of death by the ONS for use in national statistics, data on the numbers of suicides, undetermined deaths [International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) E980–E989, ICD-10 Y10–Y34] and accidental/misadventure deaths (for which the cause of death, such as self-poisoning, jumping/falling or hanging, was similar to that for the undetermined and suicide cases) during 1998 and 2005 were provided by the ONS for 11 of the 12 coroners' jurisdictions. These data were available for only 9 of the 12 jurisdictions for deaths in 1990.

Data analysis

Analyses were carried out using Stata version 11.2 for Windows (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive and logistic regression analyses were used to assess temporal change in the use of verdicts (suicide and open vs. accidental/misadventure) that might have led to an underestimate of suicides using official data. Using a chi-squared test for trend, we investigated whether there was any statistical evidence that the proportion of researcher-defined suicides receiving an accident/misadventure verdict increased across the three time periods included in this study. We then carried out a logistic regression analysis to determine whether any trends in the proportion of deaths receiving accident/misadventure verdicts were explained by changes in the characteristics of the people who had suicided (in terms of age and sex) or the methods that they used (hanging, self-poisoning, drowning, jumping or other method). The latter characteristic was included because an individual's choice of method influences the verdict that he or she receives: some more ‘ambiguous’ methods such as overdose and drowning are more likely to receive open or accidental verdicts than methods such as hanging. 39 We fitted an unadjusted model including year of death as an ordered categorical variable. We then investigated the impact of including terms for age, sex and suicide method in the model on the association between year of death and verdict. Descriptive data were also used to identify the proportion of researcher-defined suicides with an accident/misadventure verdict, by method, as a proportion of all cases using that method and coded as accidental by the ONS.

Analysis of Ministry of Justice data on narrative verdicts

To investigate the impact on suicide rates of the growth in use of narrative verdicts, we obtained data on the number and types of coroners' verdicts for the 113 jurisdictions in England and Wales for 2008–9 from annual statistics published by the Ministry of Justice. 40 We excluded data for the Isles of Scilly and the Queen's Household because of the very small numbers of deaths in these jurisdictions.

To investigate geographical variation in the use of narrative verdicts we used a proxy measure: the number of verdicts classified as ‘other’ verdicts by the Ministry of Justice. ONS data suggest that approximately 80% of ‘other’ verdicts in 2008 and 2009 were narrative verdicts. 29 We were unable to obtain data on the specific numbers of narrative verdicts by coroner jurisdiction as the Ministry of Justice receives data on the breakdown of ‘other’ verdicts from only around three-quarters of coroners and these data are of varying quality, making the estimation of narrative verdicts at this level difficult (Mark Edwardes, Ministry of Justice, 1 July 2011, personal communication).

To investigate the possible impact of the use of narrative verdicts on apparent trends in suicide we compared changes in suicide rates between 2001–2 and 2008–9 in the English local authorities (LAs) served by the 10 coroners who gave the highest proportion of ‘other’ verdicts and the 10 LAs whose coroners gave the lowest proportion of such verdicts. We combined suicide data for these two 2-year periods to reduce the impact of small-area variations in suicide rates based on small numbers of events. We obtained the suicide data [ICD-10 codes X60–X84 (suicide – ‘Intentional self harm’) and Y10–Y34 (open verdicts – ‘Event of undetermined intent’)] for the LA served by each coroner from the National Compendium of Clinical and Health Indicators. 41 As this source includes data for England only, this part of our analysis was restricted to English LAs. Because many coroners serve more than one LA, we present rates for all LAs within relevant coroners' jurisdictions and pooled LA rates for the top and bottom 10 coroners' jurisdictions.

Data analysis

We used Spearman's rank correlation coefficients to investigate associations between use of ‘other’ verdicts and deaths certified as suicide, open, due to natural causes, accidental or due to industrial disease – the five most frequently used verdicts. Weighted mean rates of suicide for the 10 coroners making the most frequent use of narrative verdicts and the 10 using them least often were calculated by summing the total number of suicides in each LA and dividing this by the sum of the populations of these LAs.

Results

Examination of coroners’ records

Search of the coroners' records for 1990–1, 1998 and 2005 led to the retrieval of 1296 coroner-defined suicides and 790 cases of possible suicide. Amongst the 790 cases of possible suicide, 518 (65.6%) had been assigned an open verdict, 240 (30.4%) a verdict of accident or misadventure and 32 (4.1%) a narrative verdict.

The 790 possible suicides were reviewed independently by DG, KH and NK. They agreed on the inclusion/exclusion of 632 (80.0%) of the cases without the need for discussion. The remaining 158 (20.0%) cases were discussed face to face or by teleconference. Following this review, more than three-quarters of the possible suicides assigned an open (415/518, 80.1%) or narrative verdict (25/32, 78.1%) by the coroner were rated as suicide, as were about half (131/240, 54.6%) of those with an accident/misadventure verdict. Altogether, 571 (72.3%) of 790 possible suicides with a non-suicide verdict were rated as suicide (Table 1).

| Verdict | No. of cases of possible suicidea | No. (%) rated as suicide |

|---|---|---|

| Open | 518 | 415 (80.1) |

| Accident/misadventure | 240 | 131 (54.6) |

| Narrative | 32 | 25 (78.1) |

| Total | 790 | 571 (72.3) |

Characteristics of researcher-defined suicides

Subsequent analyses were based on the 1867 researcher-defined suicide cases: the 1296 (69.4%) cases assigned a verdict of suicide by the coroners and 571 (30.6%) cases with an open, accidental or narrative verdict assessed as probable suicides by the research team. Three-quarters (1405/1867, 75.3%) of the suicide cases involved males. The median age was 41 years, with males (median age 40 years) slightly younger than females (median age 46 years). The most common methods used for suicide were hanging (689/1867, 36.9%) and self-poisoning (521/1867, 27.9%).

The characteristics of the researcher-defined suicide cases in 2005, stratified by the coroner's verdict, are shown in Table 2. We restricted this analysis to data for 2005 – because of resource constraints we did not record detailed clinical information on cases given a coroner's verdict of suicide in 1990–1 or 1998. Suicide cases tended to be older (mean age 46.2 years) than those receiving open or accident/narrative verdicts (mean age 42.6 years and 40.7 years respectively). Cases given suicide verdicts were somewhat more likely to be male than those given ‘other’ verdicts: 79% of suicide verdicts involved males compared with 69% of open verdicts and 73% of accident/narrative verdicts. The proportion of cases who had previously self-harmed or who had a history of contact with specialist mental health services was similar across the three categories of verdict. Surprisingly, 11% of those given open verdicts and 15% given accidental/narrative verdicts left a suicide note but despite this did not receive a suicide verdict. Method of suicide differed markedly across verdict categories. Deaths by self-poisoning and drowning accounted for over half of open and accident/narrative verdict cases whereas they accounted for less than one-quarter of all cases given a suicide verdict. It is noteworthy that 40 open verdict deaths and 15 accident/narrative verdict deaths (9.6% of all researcher-defined suicides) were by hanging.

| Characteristic | Coroner's verdict | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide (n = 388) | Open (n = 126) | Accident/narrative (n = 79) | Total (n = 593) | |

| Mean age, years | 46.2 | 42.6 | 40.7 | 44.7 |

| Male, n (%) | 307 (79.1) | 87 (69.0) | 58 (73.4) | 452 (76.2) |

| Current or past contact with psychiatric services, n (%)a | 189 (56.3) | 72 (64.9) | 43 (65.2) | 304 (59.3) |

| Suicide note, n (%)b | 193 (50.9) | 14 (11.3) | 12 (15.2) | 219 (37.6) |

| Previous self-harm, n (%)c | 187 (54.5) | 61 (53.0) | 31 (46.3) | 279 (53.1) |

| Suicide method, n (%) | ||||

| Self-poisoning | 66 (17.0) | 55 (43.7) | 37 (46.8) | 158 (26.6) |

| Hanging | 221 (57.0) | 35 (27.8) | 20 (25.3) | 276 (46.5) |

| Car exhaust gas | 18 (4.6) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 19 (3.2) |

| Jumping/falling | 17 (4.4) | 10 (7.9) | 5 (6.3) | 32 (5.4) |

| Rail | 16 (4.1) | 4 (3.2) | 4 (5.1) | 24 (4.0) |

| Fire/burns | 7 (1.8) | 2 (1.6) | 4 (5.1) | 13 (2.2) |

| Drowning | 6 (1.5) | 11 (8.7) | 7 (8.9) | 24 (4.0) |

| Other | 37 (9.5) | 8 (6.3) | 2 (2.5) | 47 (7.9) |

Temporal change in verdicts assigned by coroners to researcher-defined suicide cases

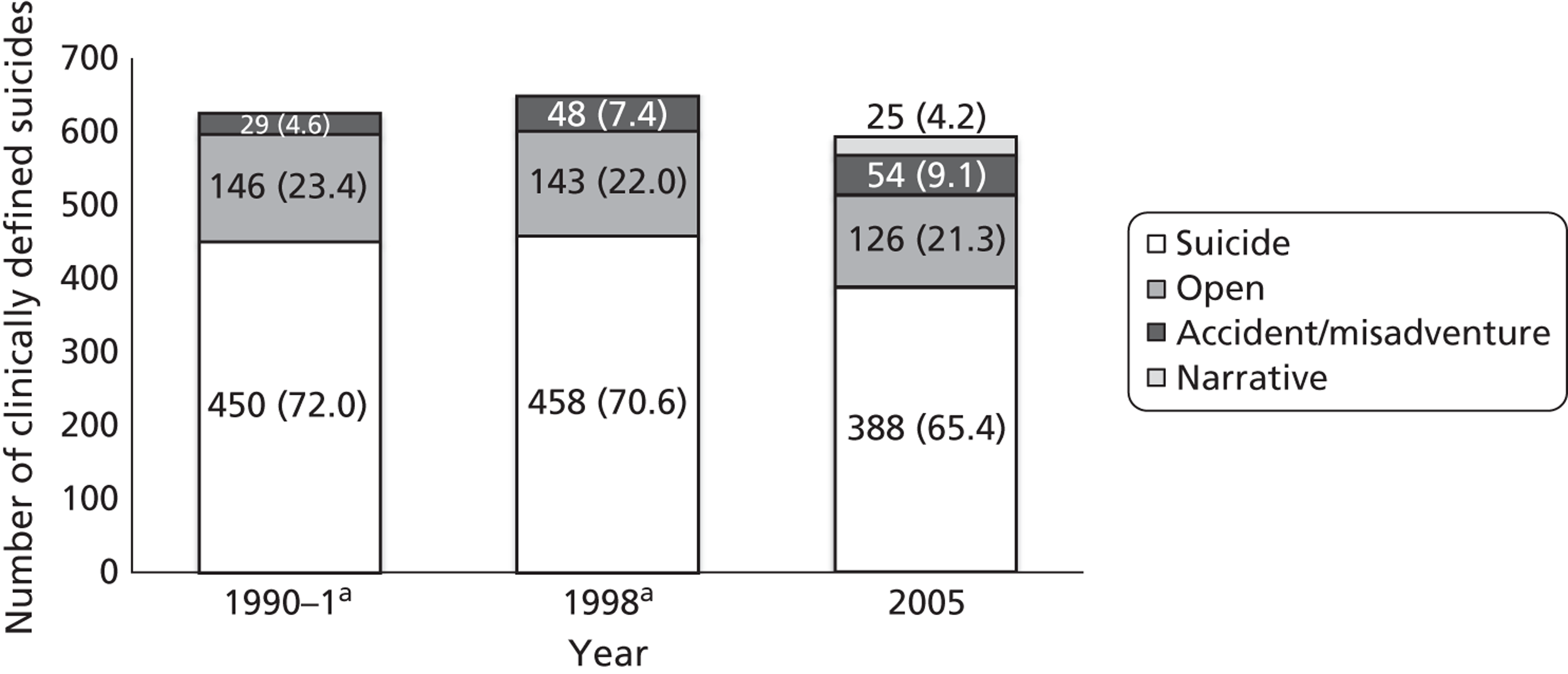

In keeping with national suicide statistics,42 the number of suicide cases that we identified from our sample of 12 coroners rose between 1990 and 1998 before falling between 1998 and 2005. In 1990–1, 72.0% [95% confidence interval (CI) 68.3% to 75.5%] of researcher-defined suicide cases in our sample had been assigned a verdict of suicide by the coroner. By 2005 this had decreased somewhat to 65.4% (95% CI 61.4% to 69.2%) (Figure 1). There was also a slight decrease in researcher-defined suicide cases assigned an open verdict between 1990–1 and 2005. In contrast, the proportion of researcher-defined suicide cases with a coroner's verdict of accident/misadventure nearly doubled between 1990 and 2005, from 4.6% (95% CI 3.1% to 6.6%) to 9.1% [95% CI 6.9% to 11.7%; p(trend) = 0.02]. Most of this rise was due to an increase in the number of cases of researcher-defined suicide by self-poisoning. In 1990–1, 12.3% (20/163) of cases of researcher-defined suicide by self-poisoning had been assigned an accidental verdict by the coroner; this increased to 22.2% (35/158) in 2005. In logistic regression models controlling for age, sex and method of suicide, statistical evidence for the trend towards increasing use of accidental verdicts for probable suicides increased [p(trend) = 0.001]. This indicates that neither changes in the age/sex distribution of suicides nor changes in the methods used account for the observed increase in use of accidental verdicts for probable suicides.

FIGURE 1.

Number (%) of researcher-defined suicide cases (all methods) assigned each verdict for deaths in 1990–1, 1998 and 2005. a, No narrative verdicts were recorded in 1990–1 or 1998. Source: Gunnell D, Bennewith O, Simkin S, Cooper J, Klineberg E, Rodway C, et al. Time trends in coroners' use of different verdicts for possible suicides and their impact on officially reported incidence of suicide in England: 1990–2005 [published online ahead of print 1 November 2012]. Psychol Med 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712002401. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press.

Temporal change in the use of accident verdicts for researcher-defined suicide across coroners' jurisdictions

An examination of verdicts stratified by coroner jurisdiction showed an increase in the use of the accident/misadventure verdict for researcher-defined suicide between 1990 and subsequent years for most of the 12 coroners' jurisdictions (Table 3). The jurisdiction with the highest number of researcher-defined suicides with a verdict of accident/misadventure in 2005 (n = 24, coroner A) also had the highest increase in the use of that verdict, from 3.4% (4/117) of all researcher-defined suicides in 1990 to 22.6% (24/106) in 2005. When a sensitivity analysis was carried out, excluding data for this coroner, the magnitude of the temporal increase in the use of the accident/misadventure verdict was diminished [1990–1: 25/508, 4.9%, 95% CI 3.2% to 7.2% use of the accident/misadventure verdict; 2005: 30/487, 6.2%, 95% CI 4.2% to 8.7%; p(trend) = 0.3].

| Year | Researcher-defined suicide cases given an accident/misadventure verdict, n (%) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | Total | |

| 1990 | 4 (3.4) | 7 (10.3) | 1 (4.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | 6 (12.0) | 2 (3.1) | 4 (9.1) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.8) | 29 (4.6) |

| 1998 | 19 (19.2) | 6 (8.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (19.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (1.9) | 4 (5.3) | 3 (6.5) | 4 (7.4) | 2 (3.3) | 3 (3.9) | 48 (7.4) |

| 2005 | 24 (22.6) | 2 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (8.0) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (4.6) | 1 (2.2) | 4 (9.1) | 3 (5.4) | 2 (3.7) | 8 (11.1) | 54 (9.1) |

Method of death for cases assigned a verdict of accident/misadventure

Using ONS data on the total number of accidental deaths by each method, around half of all poisoning, rail, hanging and car exhaust gas deaths in 1998 and 2005 assigned an accident/misadventure verdict across 11 coroners' jurisdictions were judged to be suicides in our study (Table 4). These proportions are probably somewhat overestimated as information in the coroners' files available to the research team enabled us to clearly identify the suicide method used, but such information was not available to the ONS when it coded the death certificates. For example, the death certificates of some rail suicide cases state cause of death as ‘multiple injuries’ without mentioning that these occurred on the railway; similarly, a few deaths by hanging were recorded on death certificates as due to asphyxiation.

| Suicide method | No. of accident/misadventure deaths recorded by the ONS for the 11 coroners | Researcher-defined suicide cases coded as accident/misadventure, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-poisoninga | 102 | 51 (50.0) |

| Hanging | 27 | 12 (44.4) |

| Car exhaust gas | 4 | 2 (50.0) |

| Jumping/falling | 645 | 6 (0.9) |

| Rail | 10 | 6 (60.0) |

| Fire/burnsb | 81 | 4 (4.9) |

| Drowning | 42 | 9 (21.4) |

Verdicts given to probable cases of suicide by co-proxamol, paracetamol and tricyclic antidepressant poisoning

In 1990–1, 1998 and 2005–7, the 12 coroners investigated 91 deaths from co-proxamol poisoning, 107 from paracetamol poisoning and 161 from TCA poisoning. Most of these deaths were assigned a researcher-defined verdict of probable suicide (Table 5).

Most deaths from pure co-proxamol poisoning (74/76, 97.4%) were thought by the research team to be likely suicides. Nine (12.2%) of the 74 probable cases of suicide would have been excluded from analyses focusing only on coroner-defined suicide and open verdict deaths because they were given accidental death verdicts. In fact, the research team classified as probable cases of suicide most of the pure co-proxamol poisoning deaths (9/11, 81.8%) receiving accidental verdicts from the coroners.

The research team also classified the majority of deaths from pure paracetamol poisoning (65/81, 80.2%) as probable cases of suicide. Seventeen (26.2%) of the 65 probable suicides from paracetamol would have been excluded from analyses focusing only on coroner-defined suicide and open verdict deaths because they were given accidental death verdicts. In fact, almost two-thirds (17/28, 60.7%) of the pure paracetamol poisoning deaths receiving accidental verdicts were also thought to be probable cases of suicide.

Most deaths from pure TCA poisoning (108/115, 93.9%) were assigned a researcher-defined verdict of suicide. Eighteen (16.7%) of the 108 probable suicides would have been excluded from analyses focusing only on coroner-defined suicide and open verdict deaths because they were given accidental death verdicts. The researcher team also thought that almost three-quarters (18/25, 72.0%) of pure tricyclic poisoning deaths receiving accidental verdicts were probable cases of suicide.

For all three substances, analyses based on mixed overdoses yielded similar conclusions.

| Cause of death | Suicide | Open | Accident/misadventure | Total deaths, n | Total RD suicides, n (% of total deaths) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD suicide, n (% of total deaths) | RD suicide, n (% of total RD suicides) | CD open, n (% of total deaths) | RD suicide, n (% of total RD suicides) | CD accident/misadventure, n (% of total deaths) | RD suicide, n (% of total RD suicides) | |||

| Co-proxamol | ||||||||

| ‘Pure’ poisoning deaths | 38 (50.0) | 38 (51.4) | 27 (35.5) | 27 (36.5) | 11 (14.5) | 9 (12.2) | 76 | 74 (97.4) |

| Total poisoning deaths | 47 (51.6) | 47 (52.8) | 31 (34.1) | 31 (34.8) | 13 (14.3) | 11 (12.4) | 91 | 89 (97.8) |

| Paracetamol | ||||||||

| ‘Pure’ poisoning deaths | 32 (39.5) | 32 (49.2) | 21 (25.9) | 16 (24.6) | 28 (34.6) | 17 (26.2) | 81 | 65 (80.2) |

| Total poisoning deaths | 46 (43.0) | 46 (51.1) | 26 (24.3) | 21 (23.3) | 35 (32.7) | 23 (25.6) | 107 | 90 (84.1) |

| TCAs | ||||||||

| ‘Pure’ poisoning deaths | 53 (46.1) | 53 (49.1) | 37 (32.2) | 36 (33.3) | 25 (21.7) | 18 (16.7) | 115 | 107 (93.0) |

| Total poisoning deaths | 76 (47.2) | 76 (51.4) | 47 (29.2) | 45 (30.4) | 38 (23.6) | 27 (18.2) | 161 | 148 (91.9) |

Analysis of Ministry of Justice data on verdicts given by coroners and local authority suicide data

In 2008 and 2009, coroners delivered 58,777 inquest verdicts: 28,996 in 2008 and 29,781 in 2009. The mean annual number of verdicts given per coroner was 262 (range 17–979). Of these, the most common verdict (figures for 2009) was accident or misadventure (n = 8673, 29%), closely followed by natural causes (n = 8281, 28%); there were 3797 (13%) ‘other’ (mainly narrative) verdicts, 3330 (11%) suicide verdicts and 2240 (8%) open verdicts.

There is considerable variation between jurisdictions in the proportion of inquest outcomes recorded as ‘other’ (mainly narrative) verdicts: these ranged from 0% to 50% (median 9%) of all inquests. Table 6 shows the number (%) of verdicts given by the coroners in the 10 jurisdictions with the highest proportionate use of ‘other’ verdicts in 2008 and 2009 and by the coroners in the 10 jurisdictions with the lowest proportionate use of ‘other’ verdicts in 2008 and 2009. Jurisdictions ranked in the top 10 gave ‘other’ verdicts in > 20% of inquests whereas jurisdictions in the bottom 10 gave ‘other’ verdicts in < 2% of cases. In Birmingham and Solihull an ‘other’ verdict was recorded in 985 (50.3%) of the 1958 inquests. The proportions of suicide verdicts were higher in the bottom 10 jurisdictions, with a mean proportion of 15.2% compared with 9.3% in the top 10 jurisdictions. Of note, the jurisdictions with the greatest proportion of ‘other’ verdicts seem to also deal with a higher number of inquests overall, with an average of 669 inquests in 2008 and 2009 compared with an average of 450 across England and Wales. Conversely, jurisdictions with a lower proportion of ‘other’ verdicts dealt with a lower average number of inquests over the same period (mean 218 per year).

Analysis based on all 113 jurisdictions confirmed that the use of ‘other’ (mainly narrative) verdicts was inversely related to the recording of suicide verdicts (r = − 0.41, p < 0.001), although there was only a weak association with the proportion of open verdicts (r = − 0.16, p = 0.09) (Table 7). There was no association between the proportion of natural death verdicts given by coroners and their use of ‘other’ verdict categories (r = 0.01), although the proportion of accidental death verdicts was also inversely associated with ‘other’ verdicts (r = − 0.50, p < 0.001). Surprisingly, there was no association between the proportions of suicide verdicts and open verdicts given by coroners (r = 0.02, p = 0.8).

| Position of Coroner's jurisdiction based on their use of ‘other’ verdicts | Coroner jurisdiction | Populationa | Total no. of inquests | No. (%) of ‘other’ verdicts | No. (%) of suicide verdicts | No. (%) of open verdicts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 10 coroners' jurisdictions ranked according to percentage of ‘other’ verdicts | Birmingham and Solihull | 1,233,900 | 1958 | 985 (50.3) | 36 (1.8) | 60 (3.1) |

| Cardiff and Vale of Glamorgan | 460,800 | 830 | 258 (31.1) | 34 (4.1) | 69 (8.3) | |

| Stoke-on-Trent and North Staffordshire | 458,900 | 820 | 237 (28.9) | 50 (6.1) | 36 (4.4) | |

| North Lincolnshire and Grimsby | 318,100 | 290 | 82 (28.3) | 42 (14.5) | 13 (4.5) | |

| Telford and Wrekin | 162,300 | 147 | 38 (25.9) | 20 (13.6) | 10 (6.8) | |

| South and East Cumbria | 226,500 | 329 | 85 (25.8) | 23 (7.0) | 22 (6.7) | |

| Blackburn, Hyndburn and Ribble Valley | 278,700 | 641 | 145 (22.6) | 51 (8.0) | 14 (2.2) | |

| Wolverhampton | 238,500 | 232 | 50 (21.6) | 17 (7.3) | 29 (12.5) | |

| Suffolk | 714,100 | 555 | 116 (20.9) | 94 (16.9) | 78 (14.1) | |

| Preston and West Lancashire | 708,700 | 883 | 184 (20.8) | 117 (13.3) | 39 (4.4) | |

| Bottom 10 coroners' jurisdictions ranked according to percentage of ‘other’ verdicts | Central Hampshire | 347,500 | 388 | 5 (1.3) | 59 (15.2) | 36 (9.3) |

| York City | 198,800 | 197 | 3 (1.5) | 34 (17.3) | 12 (6.1) | |

| North and West Cumbria | 268,700 | 222 | 3 (1.4) | 38 (17.1) | 25 (11.3) | |

| Blackpool/Fylde | 216,300 | 235 | 3 (1.3) | 43 (18.3) | 15 (6.4) | |

| North West Kent | 338,200 | 416 | 3 (0.7) | 59 (14.2) | 39 (9.4) | |

| Isle of Wight | 140,200 | 156 | 2 (1.3) | 15 (9.6) | 27 (17.3) | |

| Ceredigion | 76,400 | 76 | 1 (1.3) | 8 (10.5) | 4 (5.3) | |

| Western Dorset | 160,800 | 156 | 1 (0.6) | 21 (13.5) | 39 (25.0) | |

| Carmarthenshire | 180,800 | 175 | 0 (0.0) | 33 (18.9) | 15 (8.6) | |

| Pembrokeshire | 117,400 | 158 | 0 (0.0) | 27 (17.1) | 4 (2.5) |

| Verdict | r | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Other and suicide | − 0.41 | < 0.001 |

| Other and open | − 0.16 | 0.090 |

| Other and natural death | 0.01 | 0.904 |

| Other and accidental death | − 0.50 | < 0.001 |

| Other and industrial disease | − 0.03 | 0.715 |

The weighted average change in the rate of suicide between 2001–2 and 2008–9 was − 16% (95% CI − 27% to 5%) in the 30 LA areas served by the 10 English coroners' jurisdictions giving the highest proportions of ‘other’ (mainly narrative) verdicts (Table 8); in the 30 LA areas served by the 10 English coroners' jurisdictions giving the lowest proportions of ‘other’ verdicts the rate did not change (0%, 95% CI − 15% to 6%) (Table 9). There was weak statistical evidence that these two changes in rates differed: difference in rates 1.51 (95% CI − 0.14 to 3.36) per 100,000 (p = 0.09). These findings were based on suicide data for England and so we were unable to include the four Welsh LAs listed in Table 6 in this analysis.

| Coroner jurisdiction | LA | Population | Average rate 2001–2b | Average rate 2008–9b | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birmingham and Solihull | Birmingham MCD | 1,028,700 | 10.11 | 7.08 | − 3.03 (− 30) |

| Solihull MCD | 205,200 | 6.14 | 4.48 | − 1.66 (− 27) | |

| Stoke-on-Trent and North Staffordshire | Stoke-on-Trent UA | 239,300 | 13.26 | 6.83 | − 6.44 (− 49) |

| Staffordshire Moorlands CD | 95,400 | 9.53 | 8.61 | − 0.93 (− 10) | |

| Newcastle-under-Lyme CD | 124,200 | 10.01 | 5.59 | − 4.42 (− 44) | |

| North Lincolnshire and Grimsby | North East Lincolnshire UA | 157,100 | 10.64 | 8.48 | − 2.16 (− 20) |

| North Lincolnshire UA | 161,000 | 8.33 | 8.73 | 0.40 (5) | |

| Telford and Wrekin | Telford and Wrekin UA | 162,300 | 10.38 | 7.82 | − 2.57 (− 25) |

| South and East Cumbria | Barrow-in-Furness CD | 70,900 | 11.97 | 7.25 | − 4.73 (− 39) |

| Eden CD | 51,800 | 2.26 | 6.31 | 4.05 (180) | |

| South Lakeland CD | 103,800 | 7.56 | 7.64 | 0.08 (1) | |

| Blackburn, Hyndburn and Ribble Valley | Blackburn with Darwen | 139,900 | 14.98 | 9.96 | − 5.02 (− 33) |

| Hyndburn | 81,100 | 10.76 | 8.74 | − 2.02 (− 19) | |

| Ribble Valley | 57,700 | 7.27 | 11.87 | 4.60 (63) | |

| Wolverhampton | Wolverhampton MCD | 238,500 | 10.30 | 9.85 | − 0.45 (− 4) |

| Suffolk | Waveney CD | 117,700 | 12.04 | 10.50 | − 1.54 (− 13) |

| Suffolk Coastal CD | 124,100 | 6.58 | 7.45 | 0.87 (13) | |

| Ipswich CD | 126,600 | 9.71 | 10.06 | 0.35 (4) | |

| Babergh CD | 85,800 | 9.75 | 7.68 | − 2.07 (− 21) | |

| Mid Suffolk CD | 94,200 | 8.33 | 10.23 | 1.90 (23) | |

| St Edmundsbury CD | 103,500 | 7.60 | 9.18 | 1.58 (21) | |

| Forest Heath CD | 62,200 | 8.56 | 13.41 | 4.85 (57) | |

| Preston and West Lancashire | Chorley | 104,800 | 8.57 | 14.24 | 5.67 (66) |

| Lancaster | 139,800 | 11.33 | 6.18 | − 5.15 (− 45) | |

| Preston | 134,600 | 11.85 | 13.52 | 1.67 (14) | |

| South Ribble | 108,200 | 8.38 | 6.65 | − 1.73 (− 21) | |

| West Lancashire | 110,200 | 3.25 | 9.15 | 5.90 (182) | |

| Wyre | 111,100 | 9.20 | 11.43 | 2.23 (24) | |

| East Riding and Hull | Kingston upon Hull, City of UA | 261,100 | 11.19 | 10.82 | − 0.38 (− 3) |

| East Riding of Yorkshire UA | 336,100 | 10.48 | 5.62 | − 4.86 (− 46) | |

| Weighted means and % mean difference (all 10 jurisdictions) | 9.82 | 8.27 | − 1.55 (− 16) |

| Coroner jurisdiction | LA | Population | Average rate 2001–2b | Average rate 2008–9b | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Dorset | West Dorset CD | 96,500 | 9.18 | 11.77 | 2.60 (28) |

| North Dorset CD | 64,300 | 4.97 | 11.96 | 7.00 (141) | |

| North West Kent | Sevenoaks CD | 113,200 | 5.53 | 4.30 | − 1.24 (− 22) |

| Tunbridge Wells CD | 107,600 | 9.69 | 10.04 | 0.35 (4) | |

| Tonbridge and Malling CD | 117,400 | 4.44 | 8.52 | 4.08 (92) | |

| Blackpool/Fylde | Blackpool UA | 140,000 | 20.99 | 12.34 | − 8.65 (− 41) |

| Fylde CD | 76,300 | 6.67 | 6.25 | − 0.42 (− 6) | |

| Isle of Wight | Isle of Wight UA | 140,200 | 13.16 | 14.68 | 1.52 (12) |

| Central Hampshire | Winchester CD | 113,300 | 7.78 | 11.29 | 3.51 (45) |

| Test Valley CD | 113,400 | 8.28 | 9.36 | 1.09 (13) | |

| Eastleigh CD | 120,800 | 9.41 | 7.20 | − 2.21 (− 23) | |

| North and West Cumbria | Allerdale CD | 94,300 | 8.90 | 13.40 | 4.50 (51) |

| Carlisle CD | 104,700 | 12.38 | 8.79 | − 3.59 (− 29) | |

| Copeland CD | 69,700 | 12.81 | 9.01 | − 3.80 (− 30) | |

| York City | York UA | 198,800 | 5.82 | 8.55 | 2.73 (47) |

| Teesside | Redcar and Cleveland UA | 137,800 | 10.65 | 10.00 | − 0.65 (− 6) |

| Middlesbrough UA | 140,100 | 12.51 | 7.96 | − 4.55 (− 36) | |

| Stockton-on-Tees UA | 189,800 | 7.98 | 8.76 | 0.78 (10) | |

| Spilsby and Louthc | East Lindsey CD | 140,800 | 7.54 | 15.16 | 7.62 (101) |

| Essex and Thurrock | Thurrock UA | 157,200 | 7.96 | 4.11 | − 3.85 (− 48) |

| Brentwood CD | 73,800 | 5.55 | 5.96 | 0.41 (7) | |

| Basildon CD | 174,100 | 7.38 | 7.29 | − 0.09 (− 1) | |

| Epping Forest CD | 124,000 | 9.53 | 4.75 | − 4.78 (− 50) | |

| Chelmsford CD | 167,800 | 4.20 | 7.75 | 3.55 (84) | |

| Maldon CD | 62,900 | 5.74 | 6.85 | 1.11 (19) | |

| Uttlesford CD | 75,600 | 6.11 | 8.56 | 2.45 (40) | |

| Braintree CD | 142,700 | 7.32 | 5.49 | − 1.84 (− 25) | |

| Colchester CD | 177,100 | 6.39 | 7.84 | 1.45 (23) | |

| Tendring CD | 148,000 | 8.31 | 4.49 | − 3.82 (− 46) | |

| Harlow CD | 80,600 | 8.36 | 3.90 | − 4.46 (− 53) | |

| Weighted mean and % mean difference (all 10 jurisdictions) | 8.56 | 8.52 | − 0.04 (0) |

Discussion

Our results support four main conclusions. First, national suicide rates may have been underestimated in recent years both because of the growth in the use of narrative verdicts29 and because of a trend for coroners to give accidental death verdicts to cases that in the past they may have given open or suicide verdicts to. If these trends continue, so too will the underestimation of suicide rates. Second, there is substantial variation between coroners in the extent to which their practices have changed. Such variation means that differences in suicide trends in different areas of England must be treated with extreme caution. Third, the main cause of accidental death where a high proportion of deaths are considered on clinical grounds to be probable suicides is death by medicine poisoning. Approximately half of accidental deaths due to poisoning by medicines are probably suicides. Fourth, estimates of total numbers of suicides by ‘pure’ poisoning with co-proxamol, paracetamol and TCAs may be underestimated by 12.2%, 26.2% and 16.8%, respectively, when these are based only on deaths receiving suicide or open verdicts.

Concerns about the accuracy of national suicide statistics are neither new27,32,35,43 nor unique to English suicide data. 44,45 Nevertheless, the issues that we have investigated suggest that, in the last 20 years, suicide rates are likely to have been underestimated to a greater extent than in previous years, and local trends in suicide may be particularly misleading. For example, health strategists in the areas served by the Birmingham and Solihull coroners, who give narrative verdicts at more than half of their inquests,37 may be falsely reassured that suicide rates in their areas are declining. Any such favourable trends may, in fact, reflect coding difficulties experienced by the ONS when it attempts to classify deaths given narrative verdicts. Similarly, recent downwards trends in English suicide rates may have been overestimated. The ONS has recently assessed the extent of possible underestimation of suicide rates: it reported that, if all deaths from hanging and poisoning given narrative verdicts by coroners and coded as accidents by the ONS were, in fact, suicides, the 2009 suicide rate would have been underestimated by 6% – a difference equivalent to almost one-third of the 2002 National Suicide Prevention Strategy's3 20% reduction target. This may be a conservative assessment because the ONS's analysis did not include other common methods of suicide, such as drowning and jumping; furthermore, Ministry of Justice data for 2010 and 2011 indicate a continuing rise in the use of narrative verdicts.

A possible contributor to changes in the pattern of coroners' verdicts over time may be an increase in the popularity of methods of suicide such as drowning and self-poisoning, in which intent can be more ambiguous. However, between 1990 and 2005, the main changes in the methods used for suicide in England and Wales were a > 50% increase in the use of hanging42 (this method accounted for over half of suicides over the study period) and a reduction in the use of all other methods. In keeping with this, our multivariable analysis controlling for differences in age and sex and methods used by people dying by suicide strengthened the statistical evidence for an increasing trend in the use of accidental verdicts for probable (researcher-defined) suicides.

The ONS suggestion that suicide rates may be underestimated by up to 6% because of the increased use of narrative verdicts, combined with our analysis indicating that 9% of researcher-defined suicides are given accidental death verdicts by coroners, suggest that suicide rates may have been underestimated by approximately 15% in England in recent years. The extent of the problem is likely to be somewhat less than this as some deaths of undetermined intent (around 20%; see Table 1) currently included in national statistics are not suicides. Evidence for the growth in use of accident verdicts for researcher-defined suicides and narrative verdicts when suicide or open verdicts might previously have been given means that decreases in suicide rates since 1990 are likely to have been overestimated. A practical impact of these trends is that they may lead to health policy-makers in England underestimating the impact of the current economic crisis on suicide or providing false reassurance concerning the magnitude of the public health problem caused by suicide in England. 10 Furthermore, the number of suicides from paracetamol poisoning and, to a lesser extent, co-proxamol and TCA poisoning will be underestimated when these are based on deaths receiving suicide and open verdicts alone.

Limitations

In our assessment of the likelihood of suicide among individuals given open, narrative or accidental verdicts by the 12 coroners in our study, there was an initial lack of consensus across the three coders for about one-fifth of the cases examined, illustrating the difficulties involved in deciding whether some cases were suicide or not. Although the coroners' jurisdictions studied comprised 10% of all jurisdictions in England and Wales, the number of jurisdictions and the variability in their size meant that a difference in practice (verdicts assigned) by a single coroner with a large jurisdiction could bias the assessment of a temporal increase in the use of the accident/misadventure verdict. Furthermore, because of resource limitations, we studied only three time periods. An analysis of data for additional years would have increased confidence in our assessment of time trends.

The main limitation of our analysis of Ministry of Justice data is that we used ‘other’ verdicts as a proxy for narrative verdicts. Nevertheless, recent ONS analysis29 indicates that this is a reasonable assumption, with over three-quarters of ‘other’ verdicts in 2008–9 being narratives. It remains possible that there are regional variations in the proportion of narratives amongst ‘other’ verdicts. The Ministry of Justice does not receive consistent nor reliable data from individual coroners on their ‘other’ verdicts, which prevents the accurate reporting of narrative verdict use in each jurisdiction.

Conclusions

National suicide statistics are crucial to public health surveillance and this research has a number of policy and public health implications. First, small area (primary care trust/LA)-specific suicide rates and trends in suicide rates should be treated with caution in those areas where local coroners make high use of narrative verdicts. Second, approaches to ensure the future reliability of national suicide statistics should be taken – these might include asking coroners to both record the short-form verdict and, when appropriate, accompany this with a longer narrative account of the death. LA medical examiners and the post of Chief Coroner may lead to improvements in reporting practices; what is clear is that approaches are needed to ensure consistency in reporting cause of death between coroners. Third, the ONS might consider including in its suicide statistics deaths from medicine poisoning given verdicts of accident/misadventure by coroners. In particular, the assessment of the overall burden of suicide from co-proxamol, paracetamol and TCA poisoning is best achieved by combining deaths from these medicines receiving suicide, open and accidental verdicts.

Chapter 3 Studies to evaluate the impact of the 1998 UK legislation restricting pack sizes of paracetamol

Abstract

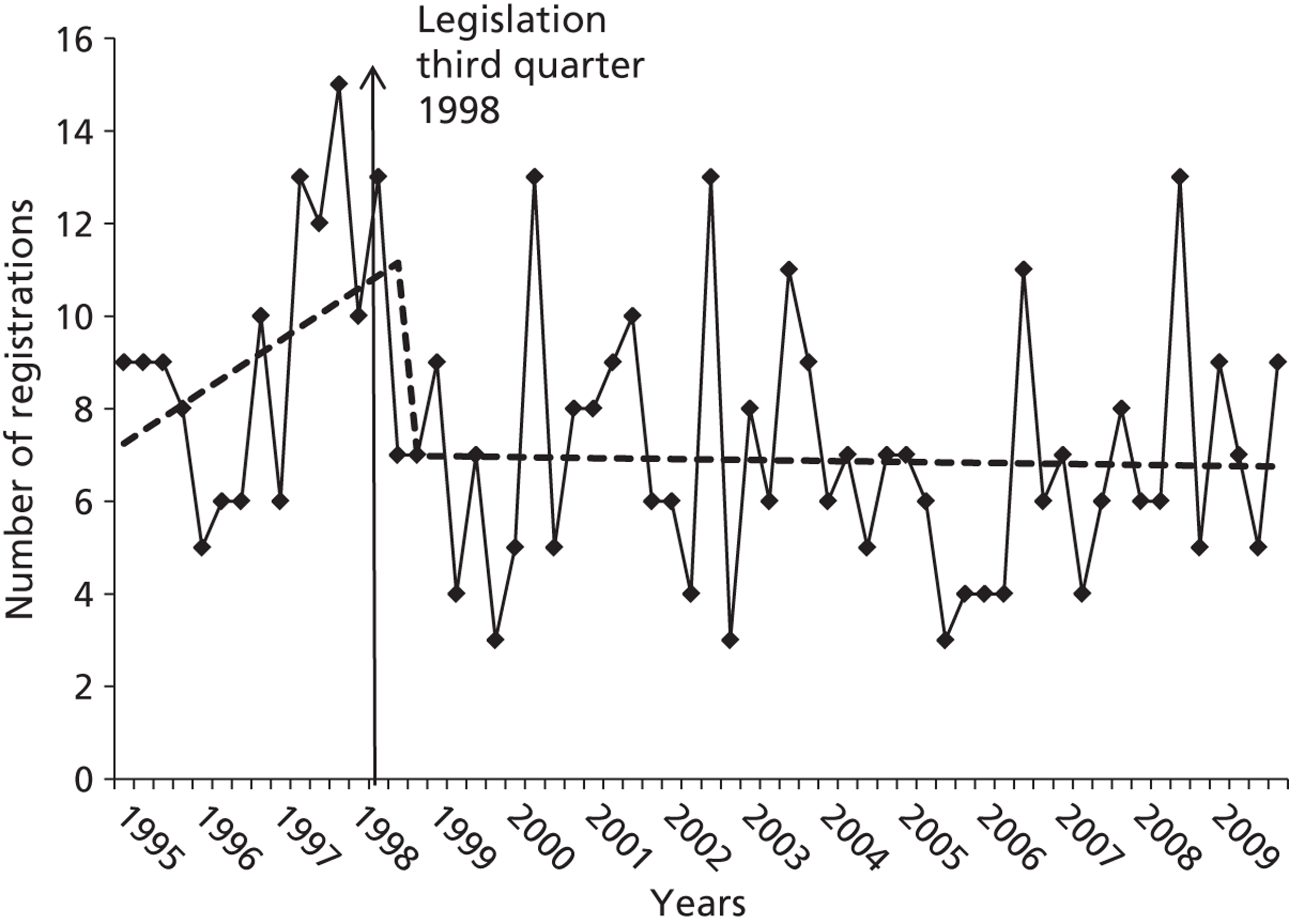

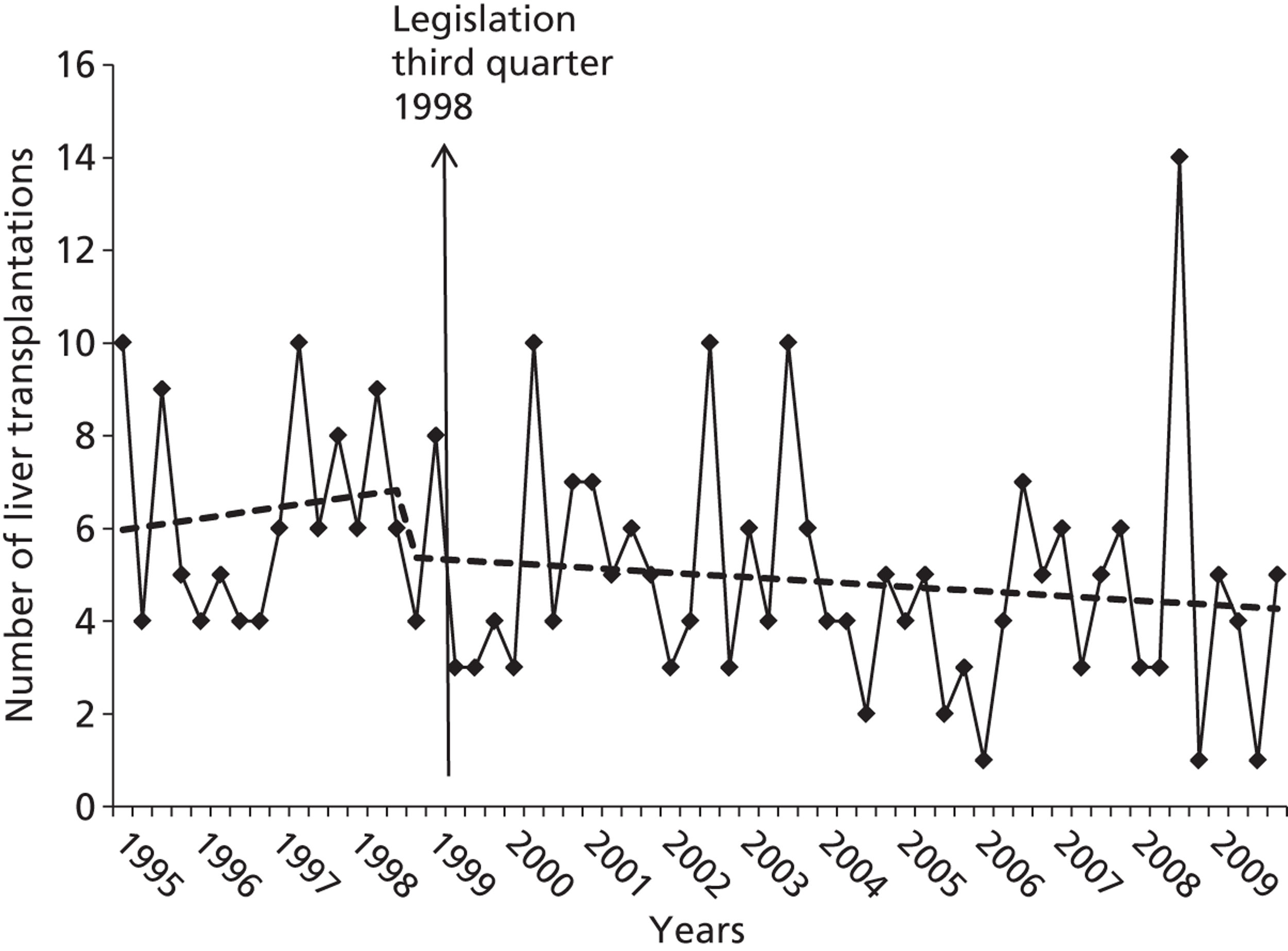

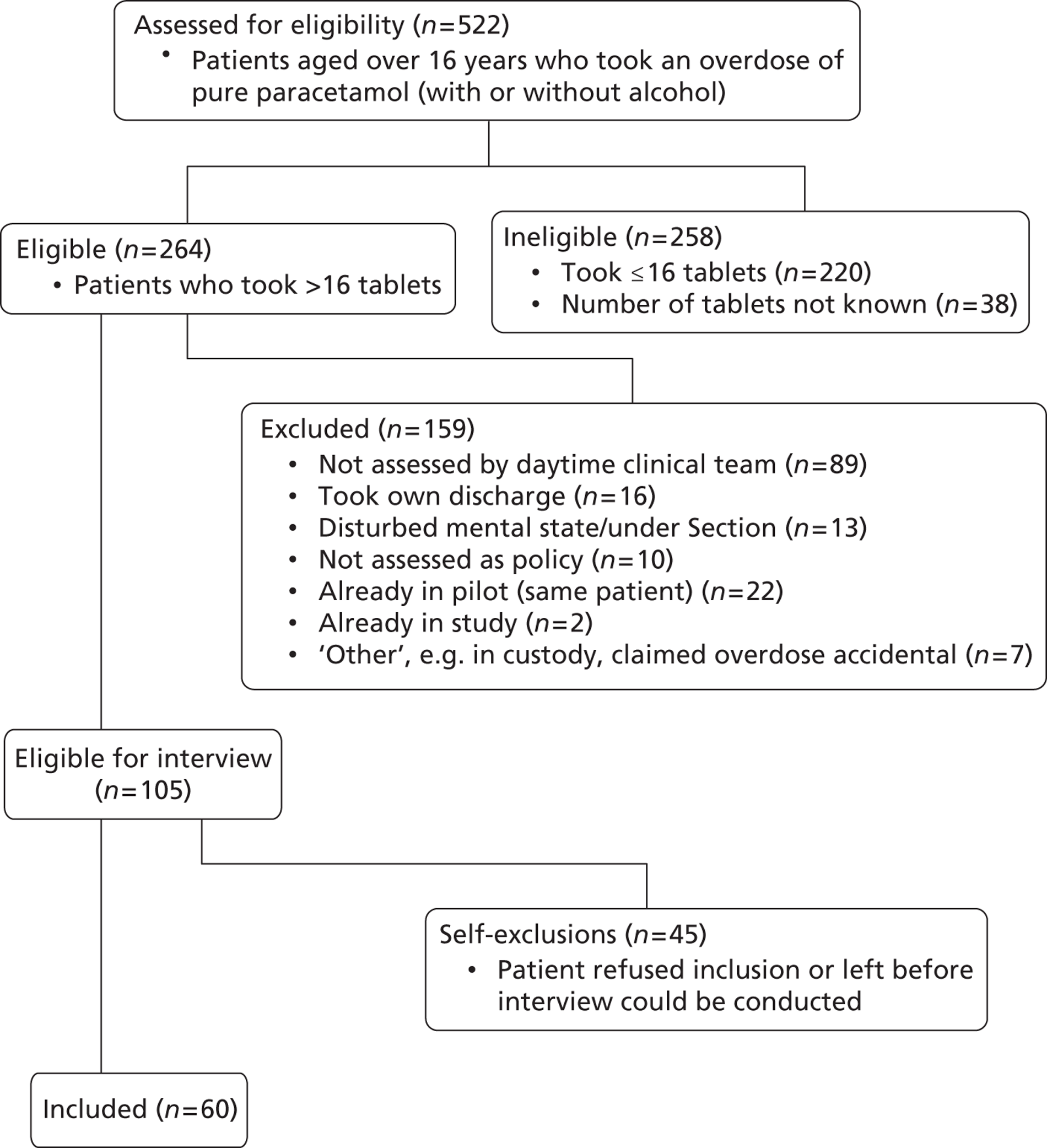

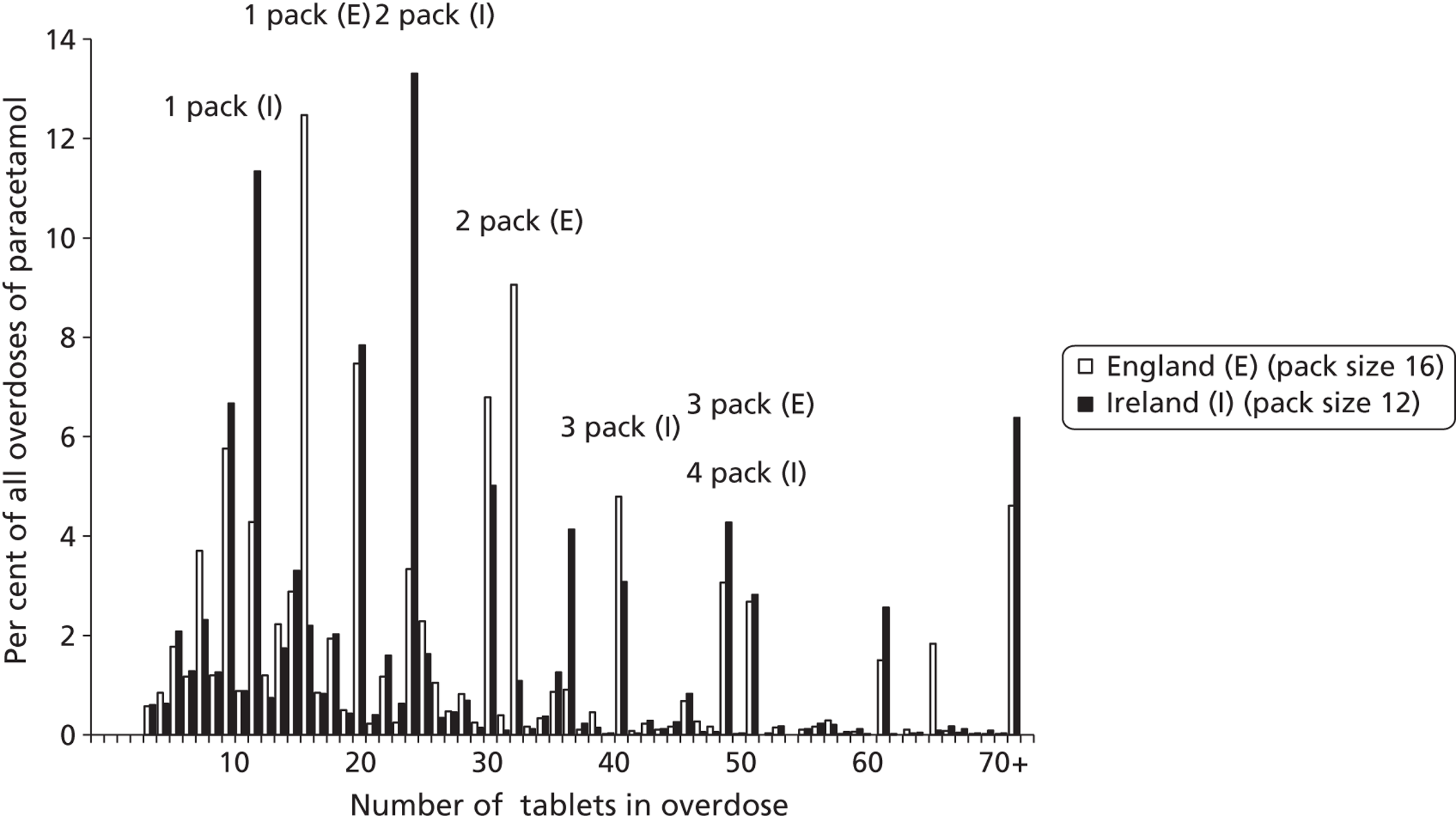

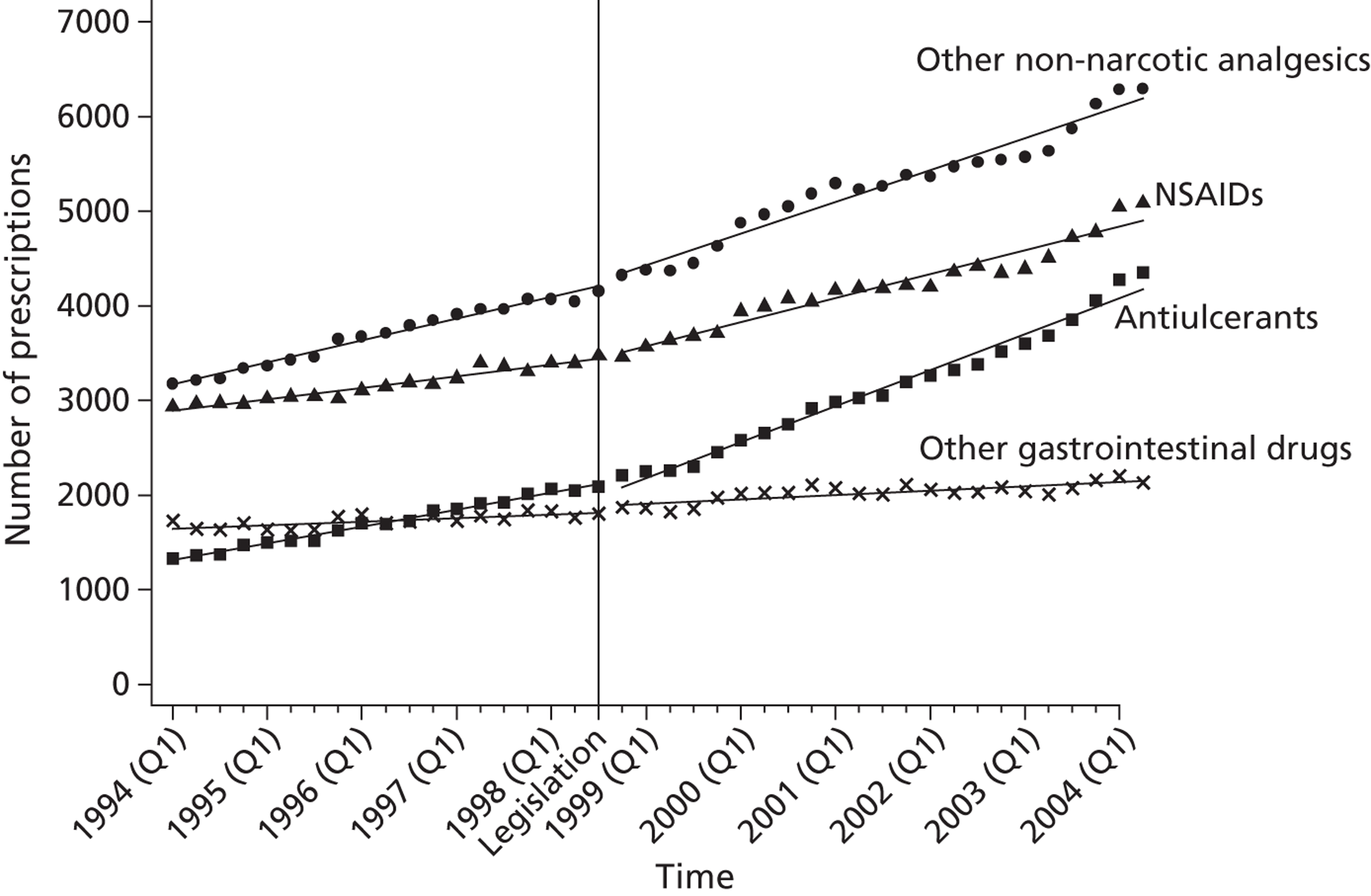

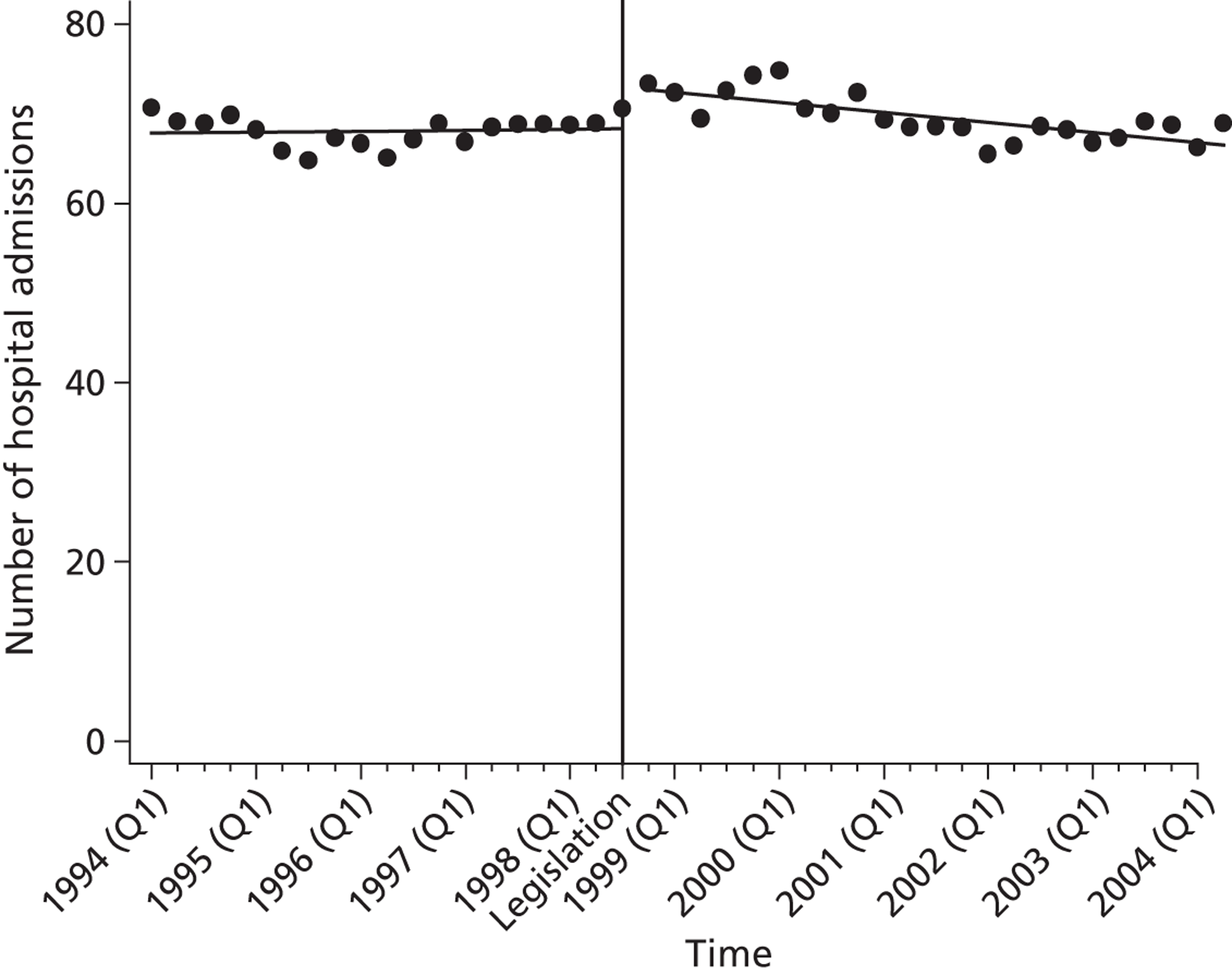

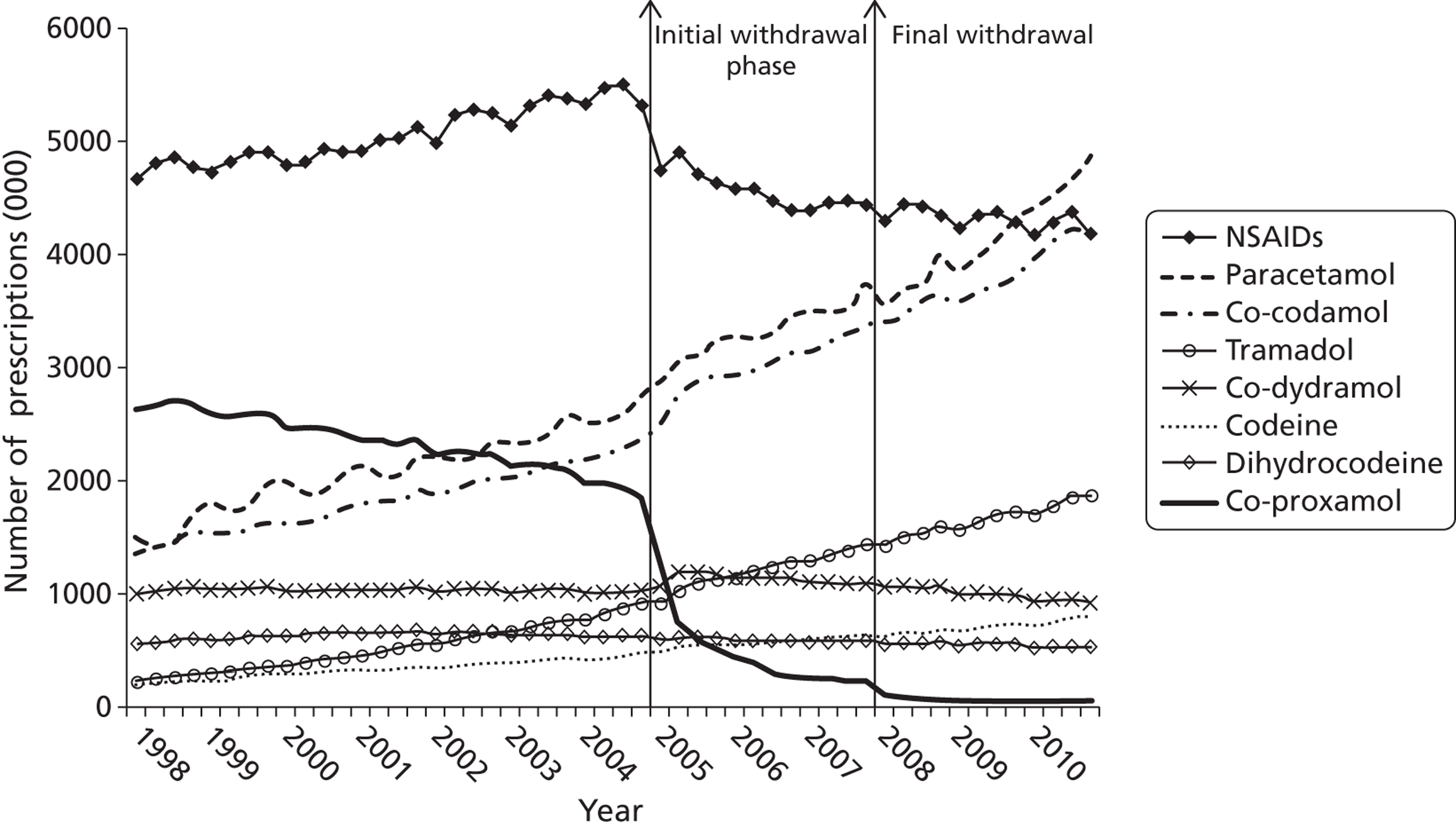

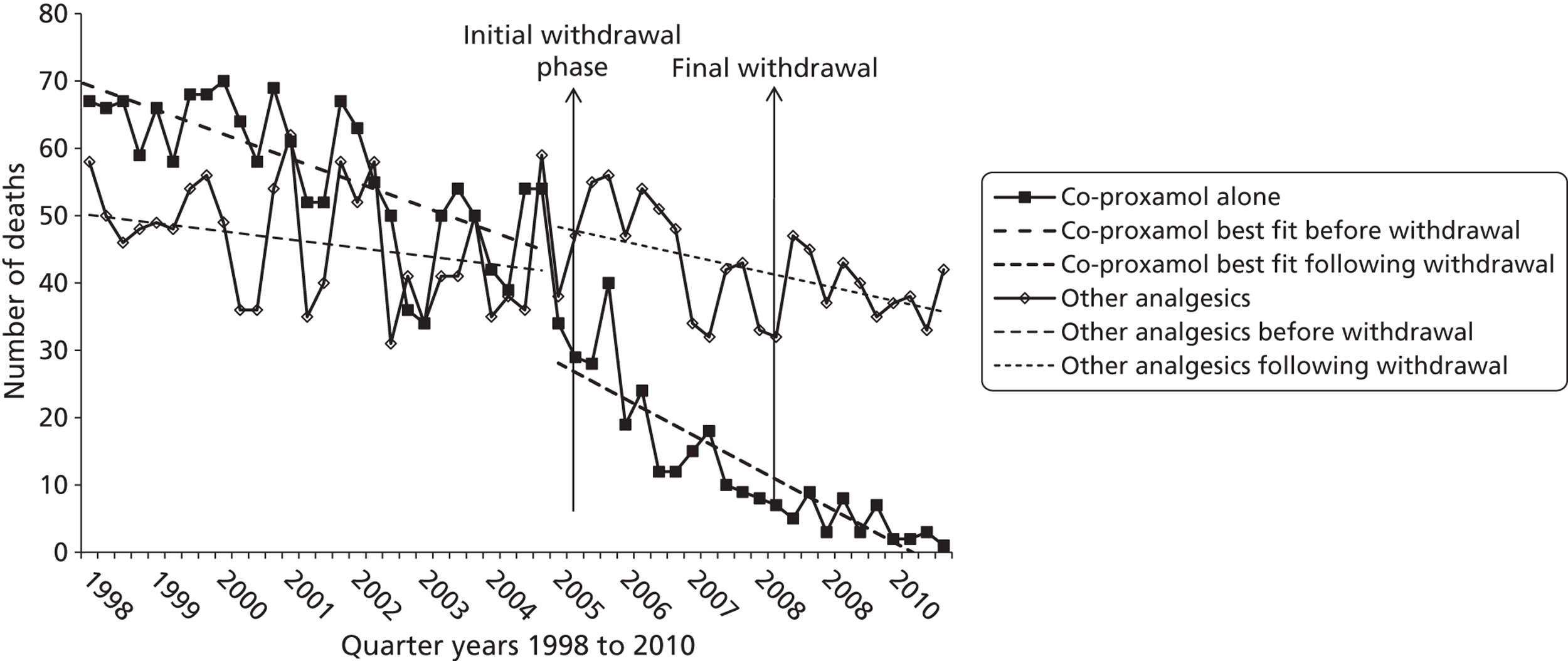

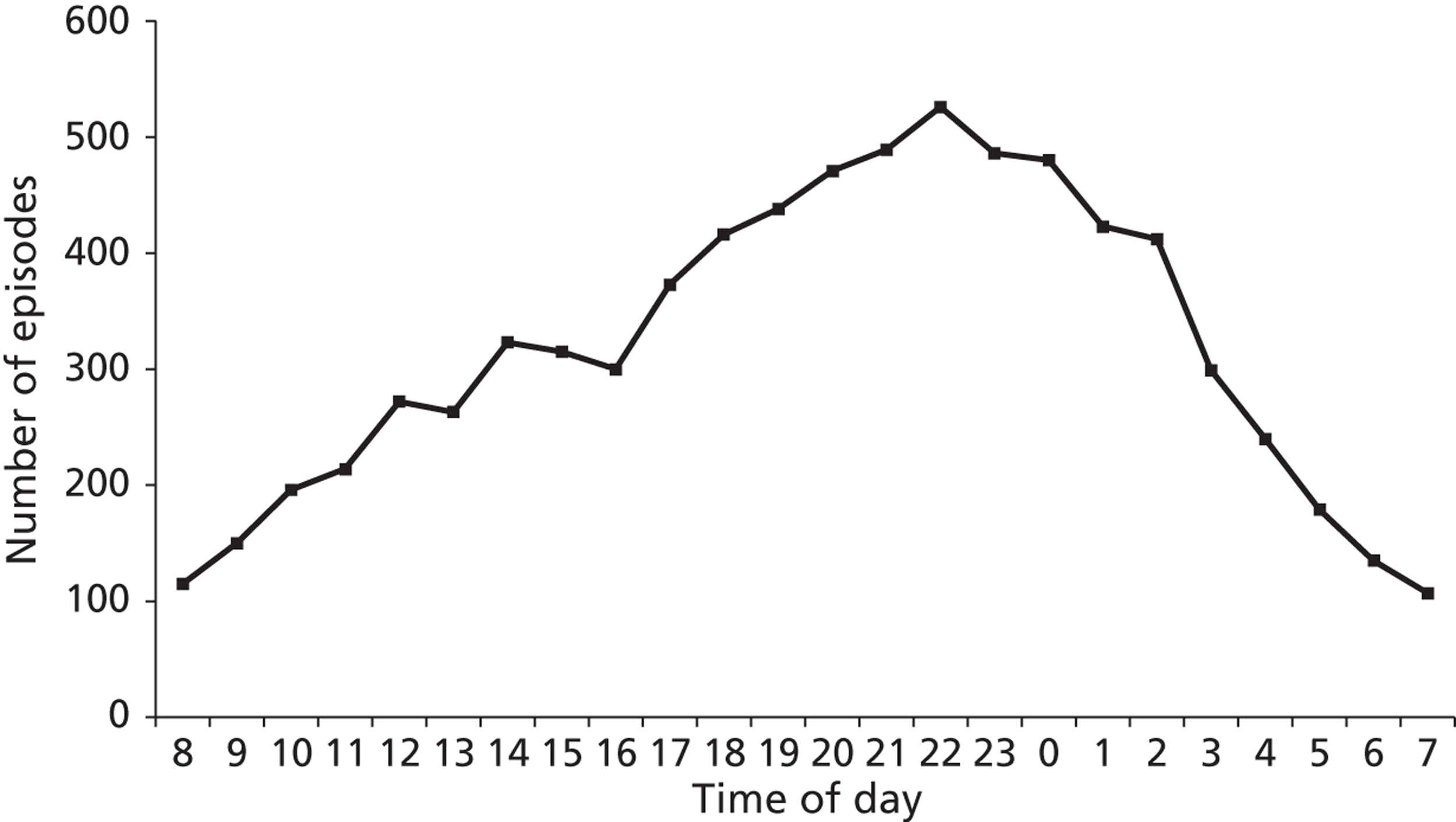

In 1998, legislation was introduced restricting pack sizes of paracetamol sold over the counter in an attempt to reduce self-poisonings and paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity. We conducted four studies related to this legislation. Analysis of mortality data for England and Wales and UK liver unit data showed that the legislation was followed by significant reductions in deaths over an 11-year period (43% or 765 fewer deaths; 990 when accidental deaths were included) and in liver transplantation for paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity (61% fewer transplantations). Interviews with 60 general hospital patients who had been admitted after taking overdoses of ≥ 16 paracetamol tablets showed that most used paracetamol because it was readily available, although few breaches of sales guidance were reported. Evidence of media (including internet) influence on the choice of paracetamol for self-poisoning was found. Examination of data from the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England and the National Registry of Deliberate Self Harm in Ireland indicated that, despite smaller pack sizes in Ireland, there was no major difference in overdose size between the two settings. More ‘pack equivalents’ were generally consumed in Ireland, raising questions about whether sales guidance is followed as strictly as in the UK. Finally, GP prescribing data for the UK (from IMS Health) showed that prescribing of NSAIDs following the 1998 legislation increased in line with prescribing of other analgesics, with no evidence of an increase in admissions for GI bleeds in Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data. However, a gradual increase in use of antiulcerants may have offset any increase in incidence of GI symptoms.

Although the 1998 legislation appears to have been beneficial, the continuing toll of deaths from paracetamol overdose suggests that further initiatives may be necessary. Media (including internet) influences should be addressed.

Background

Paracetamol, an analgesic available over the counter, is the most common drug used for self-poisoning in the UK. 22,46 It is also a frequent cause of poisoning in many other countries. 47–53 If untreated, an overdose of 10–15 g (20–30 tablets) of paracetamol can result in fatal hepatotoxicity. 54,55

In September 1998, legislation was introduced by the UK government following a recommendation by the UK Medicines Control Agency (now the MHRA) restricting pack sizes of paracetamol (and other analgesics) sold through pharmacies to a maximum of 32 tablets and restricting non-pharmacy sales to 16 tablets56,57 (although MHRA guidance in 2009 suggests that up to two packs of 16 tablets can be bought from the latter58). This policy was introduced because of the large number of people taking paracetamol overdoses59–61 and the increasing numbers of deaths62 and liver transplants63 resulting from paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity. Another motivation for the legislation was the knowledge gained from interviewing people who had presented to hospital following paracetamol overdoses, many of whom reported that the act was often impulsive and involved the use of medication already stored in the home. 64,65

Our research group showed that the UK legislation had beneficial effects in England and Wales during the first few years following its introduction in terms of paracetamol-related deaths, liver transplants and numbers of tablets consumed in overdoses. 12,66 Although other studies supported these findings,67,68 some commentators have questioned the impact of the legislation. 69,70 Furthermore, in Scotland, no evidence of an impact on deaths has been found. 71,72 More long-term studies are therefore required to assess whether or not the legislation has been a success. 68

There is also evidence that some retail outlets have not fully complied with the intention of the legislation, and that it is possible to purchase large quantities of paracetamol over the counter. 73–76 Furthermore, the increase in internet sites from which drugs can be bought is also a potential cause for concern.

In Ireland, similar legislation was introduced in October 2001,77 but pack sizes were restricted to lower maximum amounts than in the UK, namely a maximum pack size of 24 tablets in pharmacies and 12 tablets in non-pharmacy outlets, with just a single pack to be supplied in any one transaction.

One area of concern relating to the introduction of this legislation is whether the reduced paracetamol pack size may have resulted in increased use of NSAIDs, with adverse consequences in terms of GI bleeds,78 which might also be reflected in increased prescribing of drugs for GI disorders.

To investigate some of these issues, we conducted four research studies to address the following questions:

-

What has been the long-term impact of the 1998 legislation to reduce pack sizes of paracetamol in terms of deaths and liver disease?

-

What are the circumstances associated with larger overdoses of paracetamol, and are the intentions of the legislation being complied with?

-

Do differences in pack sizes of paracetamol in the UK and Ireland have an impact on overdoses of the drug?

-

Did the UK legislation on pack sizes of paracetamol result in an increased rate of GI disorders because of greater use of NSAIDs?

STUDY 1: LONG-TERM EVALUATION OF THE IMPACT OF REDUCED PACK SIZES OF PARACETAMOL ON POISONING DEATHS AND LIVER TRANSPLANT ACTIVITY IN ENGLAND AND WALES

Objective

The objective of the study was to investigate the long-term impact in England and Wales of the 1998 introduction of smaller paracetamol pack sizes on poisoning deaths, especially suicides, and liver unit activity for paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity, in terms of registration for liver transplantation and actual transplants.

Methods

Data sources

Deaths

To evaluate the impact of the legislation on suicides, we used data on deaths receiving a suicide verdict and deaths recorded as being of undetermined intent (open verdicts) (see Chapter 2). The ONS provided quarterly information on drug-poisoning deaths (suicides, open verdicts and accidental poisonings) involving paracetamol, the more common paracetamol compounds used for self-poisoning (paracetamol with codeine, dihydrocodeine, ibuprofen or aspirin) and all drugs, based on death registrations from 1993 to 2009 in England and Wales. We did not include deaths involving the paracetamol/dextropropoxyphene compound (co-proxamol) as dextropropoxyphene is usually the lethal agent in co-proxamol poisonings and the drug was withdrawn in 200779 (see Chapter 4). We have restricted our analyses to deaths involving single drugs (paracetamol or paracetamol compounds) with or without alcohol, for individuals aged ≥ 10 years. Similar data were supplied for all deaths receiving suicide and open verdicts.

Registrations for liver transplantation and actual transplants

We used data supplied by UK Transplant (now NHS Blood and Transplant) on registrations for liver transplantation and actual liver transplants as a result of paracetamol poisoning between 1995 and 2009 in residents of England and Wales aged ≥ 10 years.

Non-fatal self-poisoning with paracetamol

We used data collected through the Oxford Monitoring System for Attempted Suicide25 (which includes all hospital presentations for self-harm) to examine trends in non-fatal overdoses involving paracetamol (in pure or compound form) throughout the period 1993–2009.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using Stata version 10.0. We used interrupted time-series analysis80 to estimate changes in levels and trends following the 1998 legislation. We compared the mean quarterly numbers of deaths and liver unit registrations and transplantations that might have occurred in the post-intervention period without the legislation with the number that occurred with the legislation. 81 The end of the third quarter of 1998 was chosen as the point of intervention. For more details of this method see Appendix 3.

In addition to the basic regression model for the analysis of paracetamol-related deaths, we included adjustment for potentially confounding trends in ‘all drug-poisoning suicide deaths’ by inclusion of ‘all drug suicide deaths excluding paracetamol' as a covariate. We also calculated a conservative estimate of the absolute effect, which assumed no increase in the number of deaths in the absence of the legislation. The absolute effect of the legislation was determined as the difference between the outcome expected at the last point of the pre-intervention period and the outcome expected at the mid-point of the post-intervention period. For analysis of liver unit registrations and transplantations we also used the basic regression model and the conservative estimate analysis.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine whether our results changed when January 1998 was used as the intervention point – this corresponds to the date when the packaging changes began to occur (9 months before the legislation).

Results

Deaths

The numbers of deaths in England and Wales between 1993 and 2009 from poisoning with all drugs and from paracetamol specifically that received suicide, open and accidental verdicts are shown in Table 10. Paracetamol poisoning deaths constituted between approximately 9% and 10% of drug-poisoning suicide deaths before the legislation and between approximately 7% and 9% after the legislation.

| Year | All causes, n | All drugs, n (%) | Paracetamol, n (%a) | Paracetamol compounds,b n (%a) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide, open | Suicide, open | Suicide, open, accidental | Suicide, open | Suicide, open, accidental | Suicide, open | Suicide, open, accidental | |

| 1993 | 5182 | 1314 | 1897 | 132 (10.0) | 181 (9.5) | 17 (1.3) | 22 (1.2) |

| 1994 | 5090 | 1298 | 2003 | 126 (9.7) | 163 (8.1) | 15 (1.2) | 20 (1.0) |

| 1995 | 5127 | 1390 | 2140 | 122 (8.8) | 155 (7.2) | 24 (1.7) | 27 (1.3) |

| 1996 | 4910 | 1325 | 2103 | 121 (9.1) | 158 (7.5) | 24 (1.8) | 26 (1.2) |

| 1997 | 4830 | 1406 | 2252 | 149 (10.6) | 204 (9.1) | 21 (1.5) | 27 (1.2) |

| 1998 | 5347 | 1432 | 2246 | 135 (9.4) | 183 (8.1) | 16 (1.1) | 20 (0.9) |

| 1999 | 5241 | 1414 | 2294 | 113 (8.0) | 150 (6.5) | 29 (2.1) | 33 (1.4) |

| 2000 | 5081 | 1309 | 2143 | 90 (6.9) | 123 (5.7) | 29 (2.2) | 31 (1.4) |

| 2001 | 4904 | 1280 | 2176 | 108 (8.4) | 142 (6.5) | 18 (1.4) | 27 (1.2) |

| 2002 | 4762 | 1227 | 1983 | 90 (7.3) | 124 (6.3) | 22 (1.8) | 28 (1.4) |

| 2003 | 4811 | 1194 | 1843 | 91 (7.6) | 120 (6.5) | 22 (1.8) | 28 (1.5) |

| 2004 | 4883 | 1246 | 2008 | 88 (7.1) | 127 (6.3) | 31 (2.5) | 40 (2.0) |

| 2005 | 4718 | 1154 | 1926 | 92 (8.0) | 126 (6.5) | 33 (2.9) | 37 (1.9) |

| 2006 | 4513 | 979 | 1821 | 92 (9.4) | 131 (7.2) | 35 (3.6) | 46 (2.5) |

| 2007 | 4322 | 888 | 1852 | 66 (7.4) | 90 (4.9) | 23 (2.6) | 36 (1.9) |

| 2008 | 4603 | 884 | 2071 | 61 (6.9) | 106 (5.1) | 26 (2.9) | 44 (2.1) |

| 2009 | 4682 | 898 | 2185 | 69 (7.7) | 125 (5.7) | 26 (2.9) | 39 (1.8) |

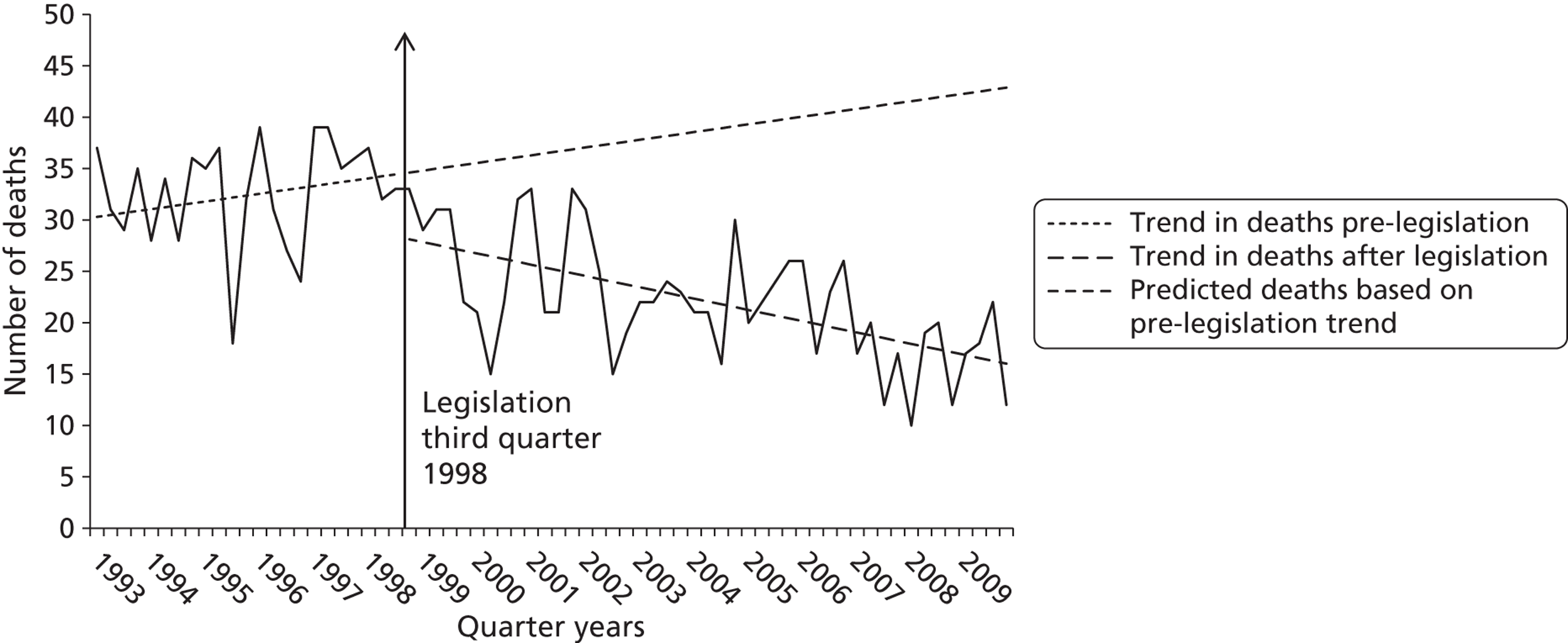

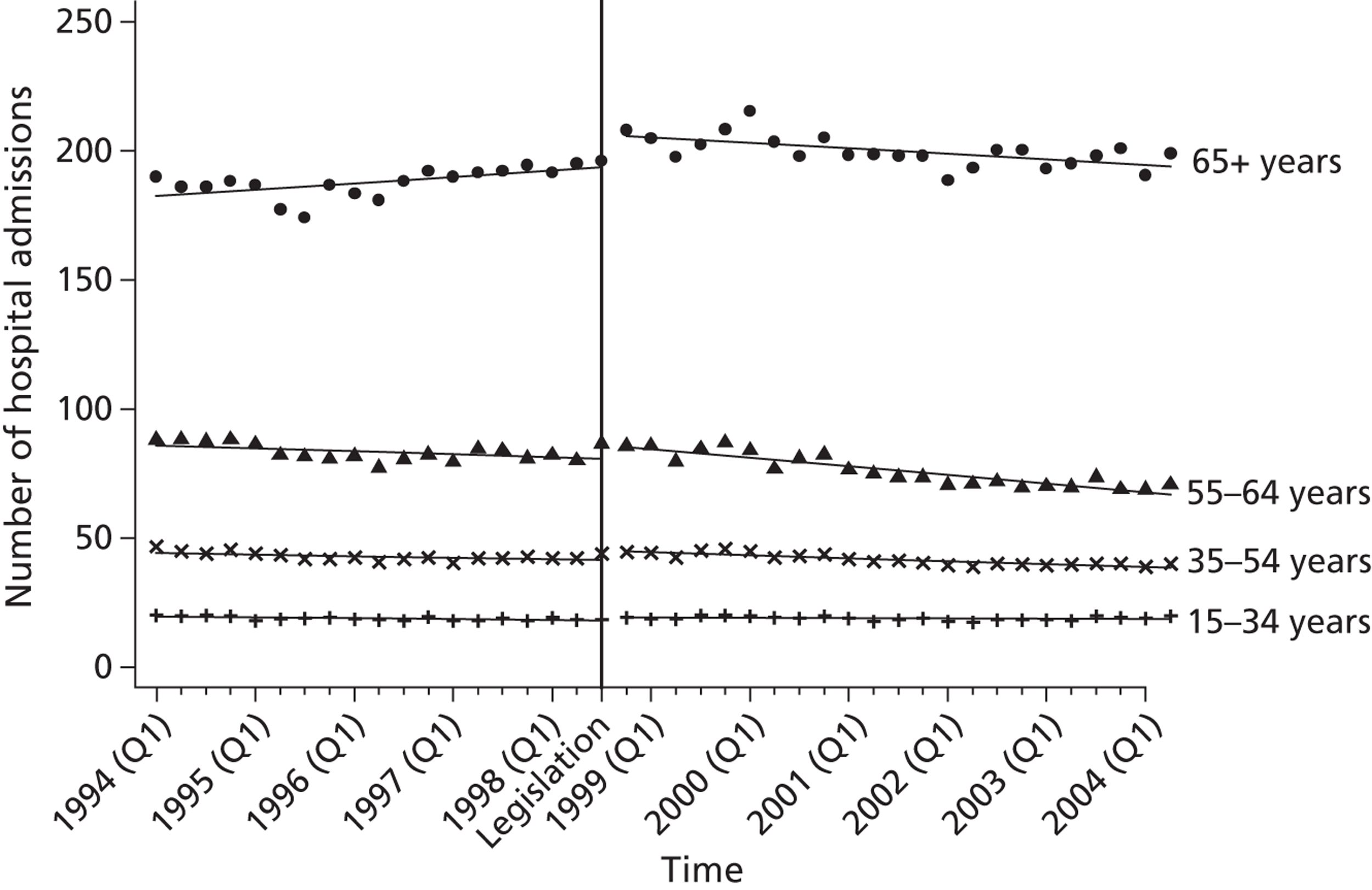

Regression analysis of quarterly data indicated a significant decrease corresponding to the September 1998 legislation in both level (i.e. step change) and trend in deaths involving paracetamol in England and Wales that received a suicide or open verdict (Figure 2 and Table 11).

FIGURE 2.

Number of suicide and open verdict deaths involving paracetamol alone in England and Wales, 1993–2009, by quarter years, and best fit regression lines related to the 1998 legislation.

| Cause of death | Segmented regression models | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base-level coefficient (β0) | Robust SE | p-value | Base-trend coefficient (β1) | Robust SE | p-value | Step-change coefficienta (β2) | Robust SE | p-value | Trend-change coefficienta (β3) | Robust SE | p-value | |

| Suicide, open | ||||||||||||

| Paracetamol | 30.103 | 1.901 | < 0.001 | 0.188 | 0.116 | 0.111 | − 6.023 | 2.430 | 0.016 | − 0.463 | 0.132 | 0.001 |

| Paracetamol (adjusted)b | 21.085 | 7.208 | 0.005 | 0.149 | 0.113 | 0.194 | − 6.473 | 2.397 | 0.009 | − 0.328 | 0.164 | 0.049 |

| Paracetamol compounds | 4.801 | 1.081 | < 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.087 | 0.933 | 1.249 | 1.534 | 0.419 | 0.013 | 0.095 | 0.892 |

| All drug poisoning except paracetamol | 291.078 | 12.757 | < 0.001 | 1.290 | 0.886 | 0.150 | 12.928 | 12.150 | 0.291 | − 4.347 | 0.925 | < 0.001 |

| All drug poisoning | 321.373 | 14.007 | < 0.001 | 1.462 | 0.966 | 0.135 | 7.142 | 13.067 | 0.587 | − 4.795 | 1.011 | < 0.001 |

| All causes | 1277.176 | 28.050 | < 0.001 | − 1.075 | 2.365 | 0.651 | 36.928 | 41.443 | 0.376 | − 2.893 | 2.574 | 0.265 |

| Suicide, open, accidental | ||||||||||||

| Paracetamol | 39.344 | 2.460 | < 0.001 | 0.309 | 0.158 | 0.055 | − 10.300 | 3.111 | 0.002 | − 0.521 | 0.0176 | 0.004 |

| Paracetamol (adjusted)b | 30.171 | 7.099 | < 0.001 | 0.236 | 0.170 | 0.170 | − 9.959 | 3.085 | 0.002 | − 0.426 | 0.191 | 0.029 |

| Paracetamol compounds | 5.777 | 1.172 | < 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.087 | 0.842 | 0.358 | 1.489 | 0.811 | 0.081 | 0.094 | 0.392 |

| All drug poisoning except paracetamol | 445.966 | 27.361 | < 0.001 | 2.919 | 1.885 | 0.126 | − 10.246 | 29.152 | 0.726 | − 3.931 | 2.042 | 0.059 |

| All drug poisoning | 468.263 | 29.352 | < 0.001 | 3.122 | 1.989 | 0.121 | − 18.461 | 31.001 | 0.554 | − 4.361 | 2.140 | 0.046 |

The estimated average decrease in number of deaths was 17 per quarter (95% CI − 25 to − 9 deaths per quarter) in the post-intervention period compared with the expected number based on trends in the pre-intervention period (Table 12). This change equated to an overall decrease in number of deaths of about 43% in the 11.25 years post legislation, or 765 fewer deaths than would have been predicted based on trends during 1993–September 1998. An overall decrease of 36% was found when a conservative method of analysis was used (see Table 12).

There was also a downwards trend in all drug-poisoning (excluding paracetamol) deaths receiving a suicide or open verdict during the post-legislation period, although this was smaller in magnitude (25%) and was not associated with the step change seen for paracetamol following the introduction of the 1998 legislation. When the change in paracetamol deaths was adjusted to take account of the fall in poisoning deaths involving other drugs, the decline in paracetamol deaths changed very little (see Table 12). Similar results were found when accidental poisoning deaths involving paracetamol were included with suicides and open verdicts (see Table 12). The reduction in deaths in the post-legislation period when accidents were included equated to 990 fewer deaths than expected. Although suicides (including open verdicts) involving any method showed a significant downwards trend during the post-legislation period, there was no step change associated with the legislation (see Table 11).

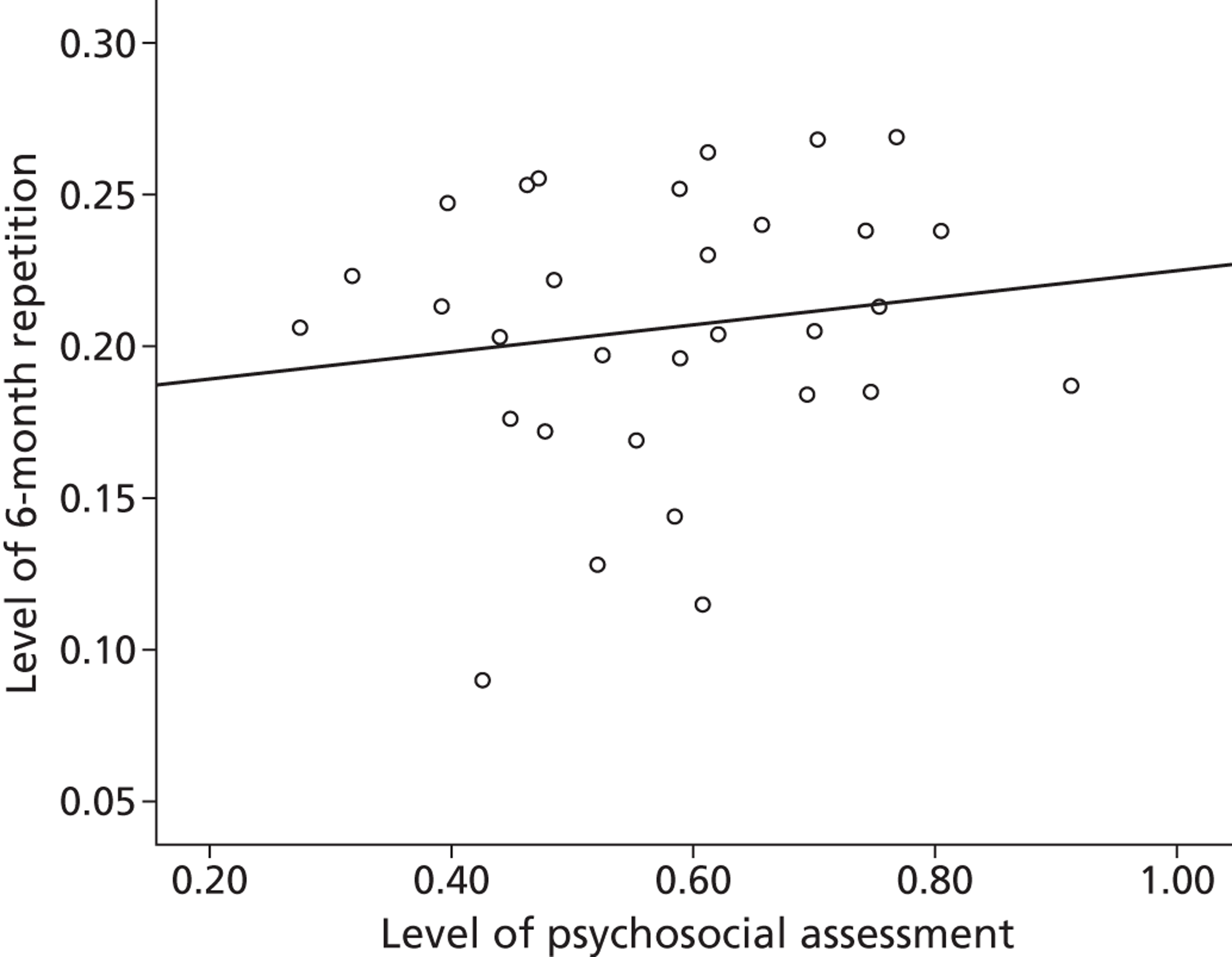

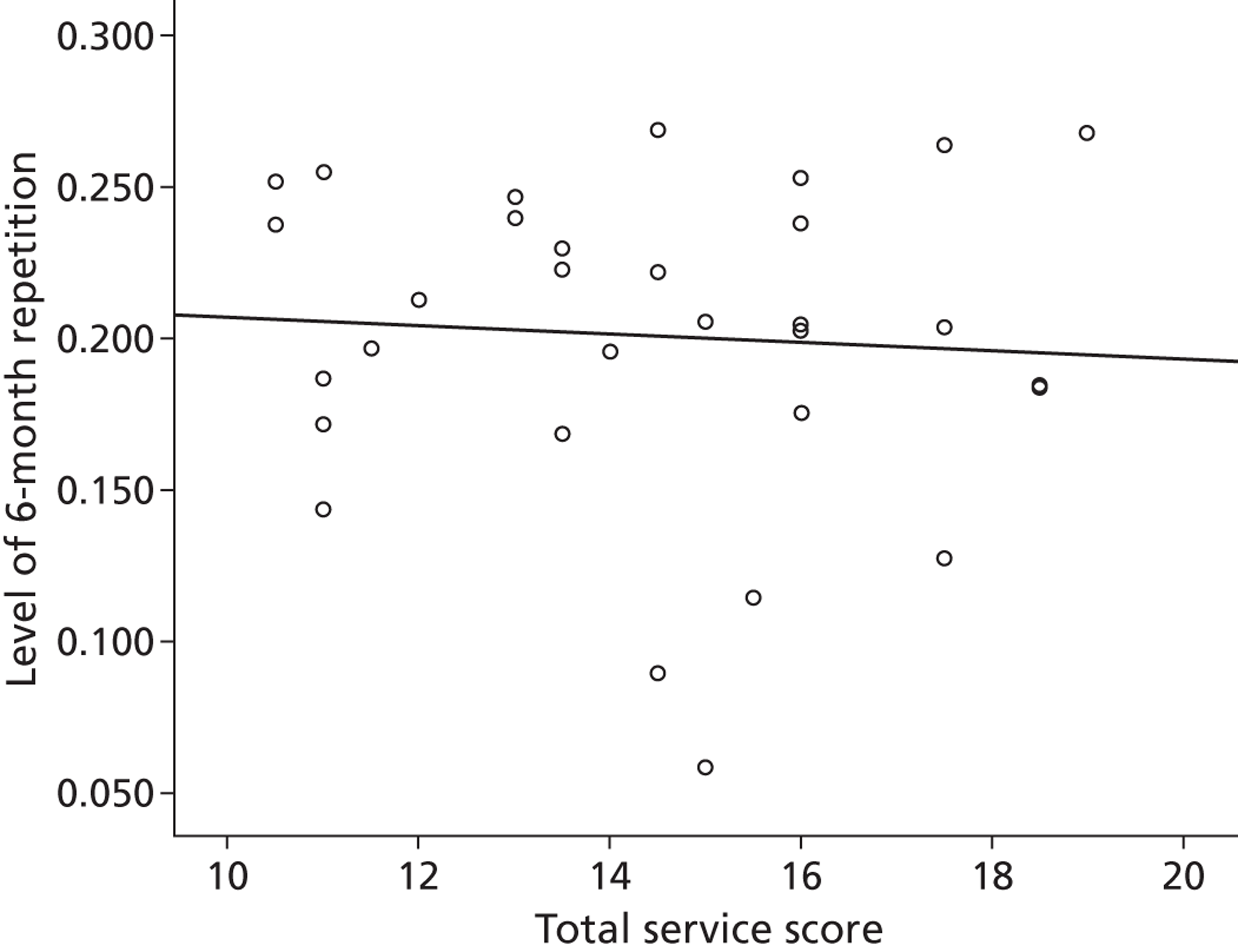

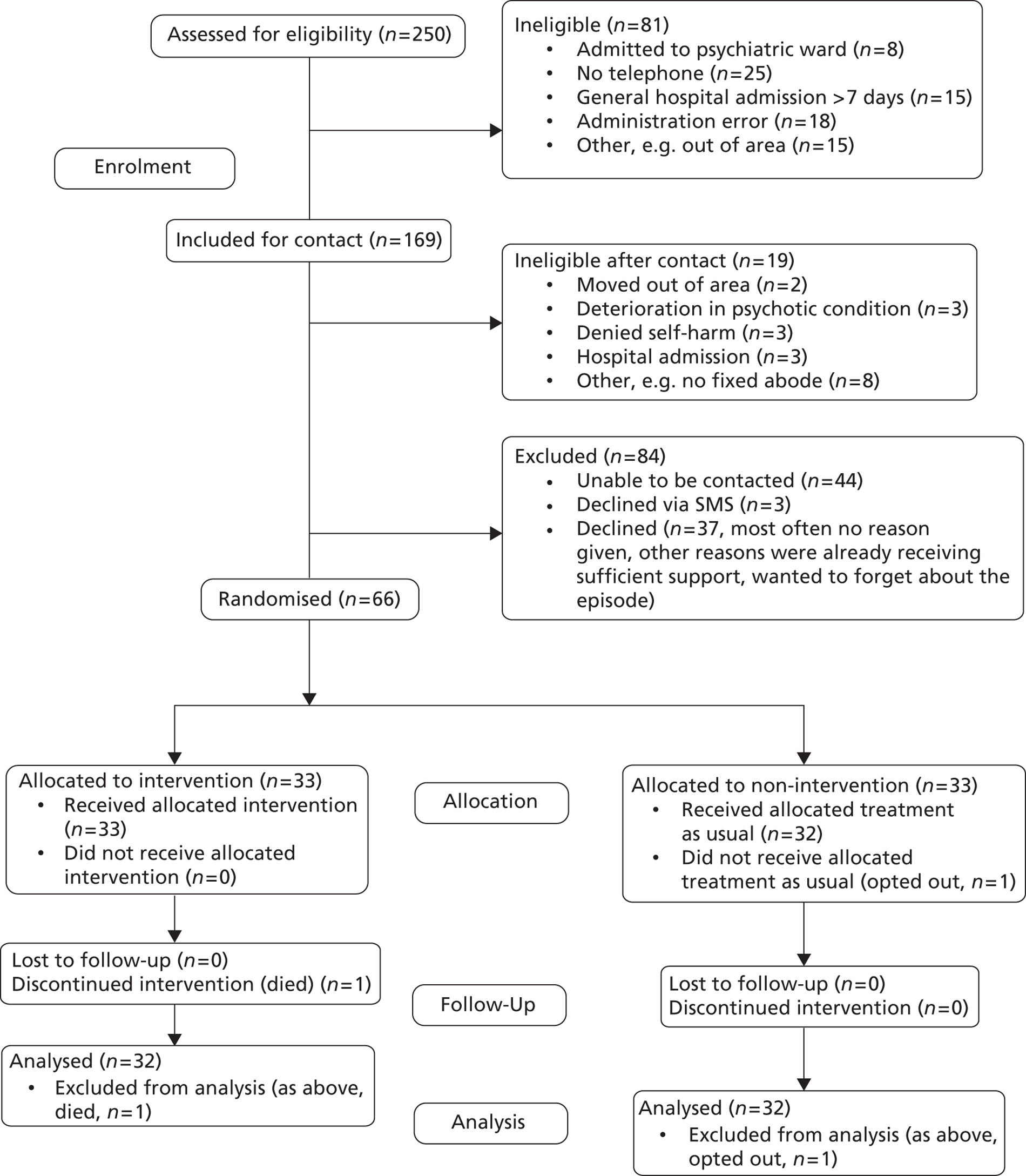

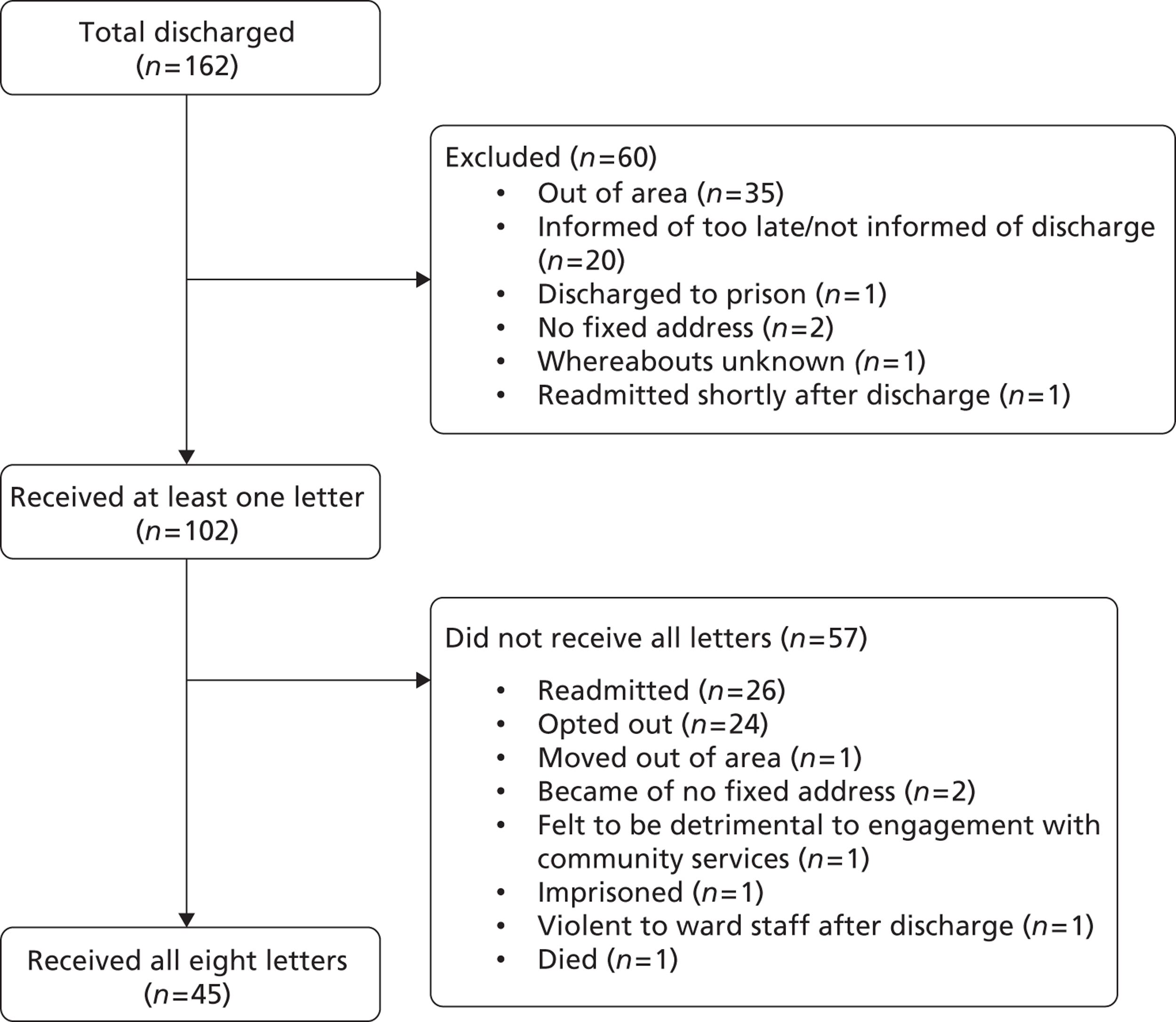

When the intervention point was moved back 9 months to the beginning of 1998 to take account of earlier introduction of packaging changes, there remained a significant downwards trend in suicide and open verdict deaths involving paracetamol during 1998–2009 but no step change (see Appendix 3, Table 45).