Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0108-10023. The contractual start date was in April 2010. The final report began editorial review in October 2015 and was accepted for publication in August 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Priebe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Approximately 1% of the population is affected by schizophrenia and related disorders, with particularly high rates in urban areas. 1 These disorders are associated with a range of disruptive symptoms such as disordered thoughts, delusions, apathy and hallucinations. Such disorders result in significant distress for patients and carers and account for a substantial societal burden. They also generate high costs to the NHS, through the need for ongoing intensive care and frequent hospitalisation, and to the society at large caused by loss of employment of patients and frequently also carers. 2,3 Currently, established pharmacological and psychological treatments only have limited effect sizes in the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and are associated with substantial rates of non-adherence. 4–6

Patients with severe forms of schizophrenia are now regularly cared for in the community. As a result of major reforms of and substantial additional investment in mental health care since the 1970s, multidisciplinary community mental health teams (CMHTs) have been set up throughout the UK and provide ongoing care. 7 More than 100,000 patients with these diagnoses are in the care of CMHTs (or other secondary care teams with similar functions) in England at any time. 8 Every patient has a designated clinician or care co-ordinator (usually a nurse or social worker by background) who has regular meetings (at least once per month) with the patient to assess their needs, engage them in treatment, discuss different treatment options and co-ordinate their care. Currently, the interaction in these meetings is based more on common sense than on evidence-based methods.

Although evidence suggests that a more positive patient–clinician relationship is associated with more favourable outcomes, there is no evidence-based intervention to achieve a better therapeutic relationship in community mental health care. 9–13 In addition, until relatively recently, there was no evidence-based method to structure the communication between patient and clinician in a way that would eventually lead to more favourable clinical outcomes. 14 A trial in the Netherlands15 found that asking patients what they wanted to discuss with their psychiatrists improved clinical decisions; however, this intervention did not impact on clinical outcomes. The FOCUS (Function and Overall Cognition in Ultra-high-risk States) trial16 in London involved patient- and clinician-rated outcomes being collected monthly and fed back to both staff and patients every 3 months. The intervention led to a reduction of treatment costs through reduced bed use, but did not improve subjective and other clinical outcomes. It is possible that these interventions did not have an effect on patient outcomes because they failed to influence clinician behaviour within routine clinical meetings. Any attempt to improve patient–clinician interactions in community care should structure action and behaviour change, instead of merely providing information.

The DIALOG intervention

To address this issue, DIALOG was developed as the first intervention to directly structure the patient–clinician interaction in community mental health care. In this technology-supported intervention, clinicians regularly presented patients with 11 fixed questions regarding their satisfaction with their (1) mental health, (2) physical health, (3) job situation, (4) accommodation, (5) leisure activities, (6) friendships, (7) relationship with their partner/family, (8) personal safety, (9) medication, (10) practical help received and (11) meetings with mental health professionals. Patients gave their answers by using a rating scale (1 = couldn’t be worse, 2 = displeased, 3 = mostly dissatisfied, 4 = mixed, 5 = mostly satisfied, 6 = pleased and 7 = couldn’t be better) and also indicated their needs for additional help in each area. Subsequently, their ratings were displayed graphically and could be compared with ratings from previous meetings.

This assessment provided a structure to the meetings and aimed to make them patient-centred and focused on change. In a cluster randomised controlled trial in six European countries, DIALOG was tested in the community treatment of patients with psychosis compared with treatment as usual. At the end of the 1-year study period, the intervention was associated with significantly better subjective quality of life, fewer unmet treatment needs and higher treatment satisfaction. 17

The effectiveness of the intervention may have been caused by three mechanisms. First, patients and clinicians were required to talk about eight life domains and three treatment aspects, which automatically provided a structured and comprehensive assessment of the patient’s situation and needs. There is widespread evidence in medicine that more comprehensive assessments can lead to more effective treatments. 18–20 Second, clinicians asked patients to indicate their satisfaction and wishes. Thus, it focuses the communication on the patient’s views and makes it patient-centred. Patient-centeredness is widely seen as an indicator of positive clinical communication. 21 Third, patients were asked about their wishes for different treatment. This could facilitate a negotiation of those wishes and lead to shared decision-making, which has been shown to be associated with more positive outcomes across medicine. 22

The DIALOG intervention is not a specialist programme for a small number of patients, but a generic method that can be utilised in routine care throughout the NHS. It does not require the setting up of new services or restructuring of organisations. It can be implemented at relatively low cost, particularly as it does not require extensive training of clinical staff and can benefit tens of thousands of patients at the same time. Thus, even small health and social gains for individual patients could add up to substantial public health effects. This also applies to potential cost savings. The FOCUS study16 mentioned previously suggested that annual cost savings of regular outcome data feedback (which is also provided in DIALOG) was equivalent to £5172 per patient through reduced bed use. If replicated for only 20% of patients with schizophrenia and related disorders in community care in the NHS, the savings would exceed £100M every year.

The regular outcome data generated through DIALOG (i.e. patients’ ratings of satisfaction with life and treatment and requests for further care) can be used to evaluate services on a local, regional and national level. So far, attempts to establish outcome assessment in routine community mental health care have largely failed, partly because it is difficult to motivate clinicians and patients to rate and enter outcome data on a regular basis. 23–25 The DIALOG intervention provided a method to generate such data in a way that is meaningful to clinicians and patients, and was likely to facilitate routine outcome assessment in mental health care.

Next steps: the DIALOG+ intervention

Although the DIALOG intervention implemented a structured patient assessment within routine meetings, it did not provide any guide for clinicians on how to respond to patients’ ratings and requests for additional help. The psychotherapy literature shows that it is important for clinicians to have a clear model for their interventions. 13 We proposed that the DIALOG intervention could be extended to ‘DIALOG+’ by equipping clinicians with a manual to respond to patients’ statements. Elements of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and solution-focused therapy (SFT) could be used to develop such a guide, including defined responses to help patients explore their beliefs, feelings and behaviours, and facilitate self-management skills. The CBT model has a strong evidence base supporting its effectiveness,26–28 is a widely accepted model among health professionals, includes patient-based outcome monitoring and can be generically applied. SFT has some overlap with CBT, appears particularly suited to a very brief intervention as it would be required to expand DIALOG to DIALOG+, is forward looking, which is in line with the DIALOG approach and, like CBT, can also be generically applied.

Before DIALOG and/or DIALOG+ could be rolled out, it was also necessary to ensure that the practical procedure of implementing the technology-supported intervention was as user-friendly as possible. DIALOG was designed using common sense, but with very limited systematic research on patients’ and clinicians’ experiences. We noted that certain features of the DIALOG intervention could be improved, for example how the questions are posed to patients, the labelling of the response options, how results are displayed and compared with previous ratings, and the usability of the software and hardware. Mobile technologies, such as tablet computers, have developed significantly since the original DIALOG trial, representing an opportunity to produce a more user-friendly application (app) that can be widely rolled out at low cost.

Objectives

Against this background, the overall aim of this programme was to make community mental health care of patients with schizophrenia more beneficial by structuring part of routine meetings with a manualised, technology-supported intervention. The specific objectives of the programme were:

-

to optimise the practical procedure and technology of DIALOG/DIALOG+ to make it more user-friendly, so that it is widely acceptable and sustainable in routine care in the NHS

-

to manualise elements of CBT and SFT that equip clinicians to respond effectively to the information provided by patients in the DIALOG intervention, to develop a corresponding training programme for this new ‘DIALOG+’ intervention, and to test the effectiveness of DIALOG+ in an exploratory randomised controlled trial

-

to test the cost-effectiveness of the DIALOG+ intervention and develop a protocol for a definitive trial.

To achieve these objectives, a mixed-method approach throughout the wider programme was taken. To inform the updated procedure and technology of DIALOG, video data from DIALOG sessions in the original trial were qualitatively analysed. Findings from this analysis informed a topic guide for focus groups with patients from the target population, to ensure that the views of the end users of the technology were taken into consideration in further developing the software. Recommendations based on the video analysis, together with feedback from the focus groups, informed the final specification for the new DIALOG software.

Concurrently, consultations were held with a network of three groups of expert consultants: three experts conducting research on the use of CBT with patients with psychosis; four experts in delivering training in SFT with private clients with mental health issues; and six leading community-based practitioners in the UK, who informed the development of an extended, manualised intervention – ‘DIALOG+’ – to accompany the new software. The manual and a corresponding training programme were tested and refined in a small internal pilot involving two clinicians, who would later train others in use of the new approach.

Having developed the new software and extended the intervention to DIALOG+, an exploratory cluster randomised controlled trial was selected as the method through which to gain evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the DIALOG+ intervention in improving outcomes for patients with schizophrenia or a related disorder. In order to gain a broader understanding that was not purely quantitative, focus groups with clinicians and patients were also conducted, to learn about the unique experiences of the participants with DIALOG+. Video data of DIALOG+ sessions were also analysed to provide a further qualitative perspective.

This mixed-methods approach ensured a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the DIALOG+, which would inform a protocol for a definite trial on the new intervention.

Chapter 2 Developing the DIALOG software

Study A1: analysis of video-recorded DIALOG sessions

Introduction

The use of software on hand-held computers during meetings between patients and clinicians is a new approach to communication in the community mental health setting, on which little research has been conducted. Therefore, it is important to consider what effect, if any, the use of these devices may have on patient–clinician interaction, particularly with respect to their therapeutic relationship. Although difficult to define, the therapeutic relationship has been conceptualised as consisting of three components in a psychometrically validated assessment scale. 29 The first is ‘positive collaboration’, referring to how well the patient and the clinician get on together. The second is ‘positive clinician input’, referring to the extent to which the patient perceives the clinician to be encouraging, understanding and supportive. The third is ‘non-positive clinician input’ or ‘emotional difficulties’, referring to the presence of problems in the relationship, for example a perceived lack of empathy.

The importance of the therapeutic relationship is well established. It has been documented that the quality of the relationship between therapist and patient is a consistent and strong predictor of outcome in many different forms of psychotherapy;29 furthermore, the quality of the relationship has been found to predict treatment adherence and outcomes for patients with a range of diagnoses and in different treatment settings. 30–33 Qualitative interviews and surveys have found that patients recognise and value the importance of the therapeutic relationship,34,35 and some research suggests that the relationship itself has the potential to be curative. 36 Findings on the moderators of the effect seen in the DIALOG intervention further emphasise the importance of the therapeutic relationship. 37 In their study, Hansson et al. 37 found that the effect of receiving DIALOG versus treatment as usual was greatest for dyads with a better baseline therapeutic relationship.

We have no reason to assume that introducing technology to patient–clinician meetings impacts negatively on the patient’s care, given the higher treatment satisfaction seen in patients who used DIALOG in the original trial. 17 Indeed, some authors propose that the use of both visual and auditory techniques may facilitate communication by improving patient attention and information assimilation and by reducing interference from psychiatric symptoms such as delusions in patients with psychosis. 38

The aim of the current study was to consider the impact of the original DIALOG procedure on the therapeutic relationship, using exploratory methods. Specifically, we aimed to investigate any problems with the version of DIALOG implemented in the original trial and to consider how a new version of DIALOG might be designed to safeguard this relationship.

Methods

Data

Video-recorded sessions of patient–clinician dyads using DIALOG were analysed for the purpose of this study. These were recorded as part of the original DIALOG study,17 which received a favourable ethical opinion from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES). A total of 13 video clips were analysed, involving 10 patients with schizophrenia or a related disorder and four clinicians in CMHTs in the East London NHS Foundation Trust (ELFT). The participants were diverse with respect to age, gender and ethnicity.

Analysis

Two researchers independently viewed the video clips and noted instances where they considered that the DIALOG procedure was potentially problematic in its impact on the therapeutic relationship, based on concepts in the literature. 39,40 The researchers compared their findings, noted discrepancies in their interpretations and, subsequently, reviewed their findings and discussed the discrepancies until consensus was reached. This was in accordance with the principle of intersubjectivity,41 in order to lend greater reliability to the study. In addition, the researchers presented their findings at regular intervals in an iterative process to senior members of the DIALOG research team, which included two experts in the therapeutic relationship [Stefan Priebe (SP) and Rosemarie McCabe (RMC)], who provided feedback and guidance.

Results

The findings of this exploratory analysis are presented in three categories. These categories are (1) technology issues, (2) content and procedure issues and (3) training issues.

Technology issues

These were issues surrounding the technology through which DIALOG was implemented, as distinct from the content of the DIALOG intervention.

Use of styluses

As part of the original DIALOG procedure, the users viewed the DIALOG software on a palmtop computer and input data by means of a stylus. The person holding the stylus was generally seen to dictate how the DIALOG procedure was conducted, in that they determined the pace of the meeting, deciding when to proceed from one domain to the next. In the majority of cases, one member of the dyad was seen to hold the stylus for the duration of the meeting, effectively maintaining control of the meeting, with little opportunity for working collaboratively.

When it was the patient who held the stylus, this could lead to them proceeding very quickly from one domain to the next, with little opportunity for the clinician to discuss the patient’s reports and raise issues that they felt were important and relevant. In one video clip, the clinician was seen to ask the patient holding the stylus to slow down. In another, the patient was seen to use DIALOG in silence, with the role of the clinician in the procedure rendered redundant.

When it was the clinician who held the stylus, this could lead to them proceeding from one domain to the next without allowing the patient to elaborate on their situation when they felt inclined. There were instances of the clinician proceeding while the patient was still discussing the previous domain, effectively shutting down the patient’s communication, impacting negatively on the therapeutic relationship.

The DIALOG intervention was designed to be a collaborative process between the patient and the clinician. The use of a stylus created an undesirable situation of a leader and a follower, and appeared to be a barrier to the therapeutic relationship.

Restrictive palmtop keyboard

Patients were asked if they would like additional or different help a total of 11 times per session as part of the original DIALOG procedure. When patients selected ‘yes’, the patient or the clinician (usually the latter) typed a description of the help requested into a text box in the DIALOG software. This was seen to be problematic, as it required the clinician to put down the stylus and start typing, using a keyboard that was considerably smaller than most laptop keyboards widely used today. As a result, the clinician often typed into the keyboard using their two index fingers, causing delays. In addition, they tended to hunch over and stare at this small keyboard in order to type in the request, with the result that the clinician’s attention was focused fully on the device. This was seen to impact negatively on the therapeutic relationship.

Procedure issues

These were issues surrounding elements of the DIALOG intervention itself, rather than the technology through which it was administered.

Problems with Likert scale labels

In the original software, the labels of the Likert scale were 1 = couldn’t be worse, 2 = displeased, 3 = mostly dissatisfied, 4 = mixed, 5 = mostly satisfied, 6 = pleased and 7 = couldn’t be better. It appeared that these labels were not sufficiently distinct from one another or sensitive in capturing information as, in most cases, patients were seen to choose one positive-oriented rating and one negative-oriented rating and then use these two ratings alone to indicate whether they were satisfied or unsatisfied, more generally. In particular, the differences between ‘mostly satisfied’ and ‘pleased’, and between ‘mostly dissatisfied’ and ‘displeased’, may have been too subtle for patients to distinguish. As the language used to label the scale was not consistent (‘satisfied’ vs. ‘pleased’ vs. ‘couldn’t be better’), patients did not memorise the labels easily and appeared to forget which label corresponded with which numerical rating. The grammatical structure of the labels ‘couldn’t be better’ and ‘couldn’t be worse’ were notably complex and appeared to confuse patients. Thus, on the whole, the scale was not very meaningful or accessible to them. This rendered the provision of ratings somewhat redundant and patient inertia in completing these ratings may have the potential to impact negatively on the therapeutic relationship.

Documentation of requests for additional help

Linked to the technology problem of the restrictive palmtop keyboard described previously was the procedural expectation for clinicians to constantly document patients’ needs for additional help throughout the meeting. Clinicians were seen to type extensive descriptions of patients’ requests for help, causing them to be distracted with documentation for lengthy periods. In many cases, clinicians appeared to be more focused on getting the documentation right than paying attention to the patient. Eye contact was frequently lost, as was the pace and general momentum of the meeting. Long pauses were common, and, in some cases, there was complete silence for extended periods of time.

In one clip, the patient was seen to yawn repeatedly as the clinician typed into the computer. However, the patient had not made any explicit request for help ahead of this, so this clinician must have been involved in some other form of note-taking that was not prescribed by the intended DIALOG intervention, which was distracting him from engaging with the patient. In another clip, the patient displayed bored and restless body language (fidgeting, looking around, shuffling in his seat) as the care co-ordinator typed into the device, again to an extent that was deemed to be excessive.

Lengthy documentation by the clinician of needs for additional help should not be part of the updated DIALOG procedure. Rather, any such documentation should take place at the end, after the administration of the assessment. Otherwise, the potentially negative impact on the therapeutic relationship of typing at length during meetings is significant. Clinicians should not use available text boxes in software for other routine documentation.

Review of ratings

Although the DIALOG software featured a function whereby clinicians could review the ratings submitted by the patient and compare these ratings with previous sessions – including an overall picture across domains as well as the option to examine domains individually – this function was not automatic in the software. As a result, it was rarely used. Clinicians failed to initiate a review of the domains, despite instructions from the original research team to conduct such reviews routinely as part of the procedure, in the company of the patient, for the patient’s benefit. In the few cases in which such reviews were conducted, clinicians appeared to be at a loss as to how to comment on ratings, particularly when ratings had not changed much. As a result, such reviews were not particularly informative for patients, which may have undermined the exercise of undertaking the DIALOG intervention. If patients believe that such activities are not worthwhile, they could potentially be damaging to the therapeutic relationship.

Training issues

These were matters that were not related to the technology or procedure of the intervention, but related to the specific instructions and training provided to clinicians regarding how they should use DIALOG.

Perception of DIALOG as a task for completion

In many of the video clips, the clinician was seen to place undue emphasis on acquiring a rating of satisfaction, rather than facilitating discussion. That is, the clinician was focused on identifying where the patient lay on the seven-point Likert scale rather than considering the information arising from such a rating. Often, the interaction seemed as though the clinician was administering a questionnaire, rather than conducting a structured conversation.

In some cases, the patient appeared to have more to say beyond simply providing a rating but did not get the opportunity, or found difficulty in expressing themselves in terms of a rating without elaborating on their situation first to provide context. However, clinicians repeated questions when the original question did not result in the patient providing a rating. In most cases, the clinicians restricted themselves to the two core questions (i.e. satisfaction and help needed) for each of the 11 domains, without probing or encouraging elaboration. The consequence of this was that some of the domains were simply assessed, but not addressed in any meaningful way. In a few cases, the patient was seen to describe problematic situations, warranting further discussion between the two of them, only for the clinician to proceed directly to the next question. It appeared as though clinicians were uncomfortable deviating from the framework of the DIALOG tool.

Positioning of the device

In some of the video clips, the patient was seen holding the device on their lap. In others, the clinician was seen to have placed the device on a desk that was outside the line of vision of the patient. Neither of these scenarios was desirable. Patients holding the device on their lap were often seen to stare down at the device, without directing their gaze and attention to the clinician. The clinician frequently showed difficulty in engaging the patient and pacing the meeting, without having control of the device. This is likely to impact negatively on the therapeutic relationship. In the case of the clinician having the device on a desk, they were often seen to turn away from the patient while tending to the device. In a few instances, the position of the device on the desk enabled the clinician to avoid certain topics raised by the patient, by maintaining their gaze on the device and not engaging with the patient’s concerns.

Clinicians should be trained to keep the device in a shared space in order to facilitate a collaborative process in which both clinician and patient can be active partners.

Reading of response options aloud by the clinician

In some cases, particularly when the device was in the clinician’s possession and outside the gaze of the patient, the clinician was seen to read out the various response options on the seven-point Likert scale to the patient. This caused long delays and, generally, appeared to be monotonous for both the patient and the clinician, seemingly impacting negatively on their therapeutic relationship.

Clinicians omitting elements of the intervention

In some cases, the clinician was seen to omit important aspects of the intervention. This ranged from neglecting to ask patients whether or not they needed additional help and what help they would like, to not indicating that the satisfaction questions were to be answered with a prescribed set of response options, to omitting the review of ratings, as previously discussed. Any future redesign must consider how omission of key processes in the DIALOG procedure can be prevented.

Discussion

In the original DIALOG study, the DIALOG intervention was found to lead to an improvement on subjective quality of life, treatment satisfaction and level of unmet needs in patients with psychosis. 17 This was irrespective of any problems identified by the current study with respect to the therapeutic relationship. In this respect, we may wish to be conservative as regards any potential redesign of the DIALOG procedure. Yet, the data suggested that the practical procedure of DIALOG can be further optimised.

The use of a touch screen that eliminates the need for a stylus may be helpful in maintaining the therapeutic relationship. This technology would allow multiple parties to interact and engage with the DIALOG software, thereby reducing the issue of the balance of control between the patient and the clinician. The technology should be sufficiently large for both the patient and the clinician to view the screen. Ideally, it should be portable and easily shared, so that it is not strictly in the possession of one or the other.

Revisions to the Likert scale are warranted in DIALOG. The seven-point scale might be retained, but with simpler labels that are clearly hierarchical and quantitatively distinct from one another, in logical increments. Potential labels can be generated and explored in focus groups with patients. The Likert scale should use consistent language throughout (i.e. subtle distinctions between markers such as ‘mostly satisfied’, ‘pleased’ and ‘couldn’t be better’ should be avoided). This will be more intuitive for patients with psychosis and may help them to complete ratings with less difficulty, thereby removing the barrier to communication between patient and clinician that sometimes accompanies defined Likert scales.

Training issues are less straightforward. Although it is possible to train clinicians in the use of the DIALOG approach, this creates a considerable expense for an otherwise inexpensive intervention. Although a manual is clearly needed to accompany the DIALOG software, describing explicitly where the clinician should position the device, how they should address each domain, etc., it can never be guaranteed that this manual will be read or adhered to. It may be necessary to design the software in such a way that the behaviour of the clinician is prescribed by the software. For example, a review of the ratings, which was often omitted by clinicians, should be presented automatically. The software should also prescribe that each question on need for additional help (another element that was frequently omitted by clinicians) is answered before proceeding to the next question. Importantly, the software should remove the expectation (and the opportunity) for clinicians to record lengthy descriptions of patients’ reports and requests.

In summary, the DIALOG tool facilitates structured interaction between clinicians and patients with psychosis in the community mental health setting. However, adjustments to the procedure are warranted to safeguard a positive interaction, and maintain the therapeutic relationship. Further research involving focus groups with patients treated in CMHTs will assist in taking key decisions, as described in the subsequent study A2.

Study A2: focus groups exploring preferences for updated DIALOG software

Introduction

The previous substudy involved analysis of video data collected in the original DIALOG trial, leading to a preliminary brief for the updated DIALOG software (see Study A1: analysis of video-recorded DIALOG sessions). Following this analysis, a software developer joined the research team and produced options for an updated version of the DIALOG software based on the findings. The present study sought to gain feedback from the end users (i.e. patients in CMHTs) on mock-ups of the DIALOG software, to inform the final specification. Specifically, we explored how user-friendly patients found the software, which version of the software interface they thought was best and what changes to the software – particularly in terms of content – they felt were necessary. A full description of the development of the finalised technology is available in the subsequent study A3 (see Study A3: technology development).

Method

Study design

This study was a qualitative study involving focus groups. This methodology was selected in order to facilitate a permissive, non-threatening environment among peers;41 synergy and spontaneity between interacting participants42 and greater elaboration as a consequence, relative to individual interviews. 43 The study received a favourable ethical opinion from the NRES (Chelsea, London; reference number 11/LO/1779).

Participants

Participants were patients who were care co-ordinated in CMHTs in ELFT. Consultation with patients in these focus groups ensured that there was patient and public involvement in the development of the software, a tool with the potential to be used widely across the UK. Participants learned of the study through an information sheet provided by their care team. This information sheet had been reviewed for user-friendly language by a service user reference group comprising three service users with experience of psychosis and treatment in a CMHT. Interested participants subsequently met a researcher to learn more about the study. The inclusion criteria were (1) experience with a designated care co-ordinator as part of routine care in the community, (2) having a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or a related disorder [International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Edition (ICD-10): category F20–29],44 (3) aged between 18 and 65 years, (4) having a sufficient command of English to understand the instructions and questions and (5) having the capacity to provide written informed consent. A total of 17 participants were recruited to six focus groups, comprising three participants in five of the groups and two participants in the sixth group. Participants were diverse with respect to age, gender and ethnicity across groups. Five patients had verbally consented to each group prior to the event; however, not all of them arrived on the day of the focus group. The 17 participants provided written informed consent on the day of the group, with no participants withdrawing their consent during the group.

Procedure and data collection

A semistructured interview schedule (see Appendix 1) was developed by the research team, referring directly to the content of the DIALOG intervention (i.e. the questions on satisfaction, the response options, the additional help question, etc.), along with three mock-ups of the DIALOG software, demonstrated on iOS iPads. The schedule was then piloted with the service user reference group and subsequently refined. Groups were conducted between May and August 2011. All groups were conducted by an experienced facilitator and co-facilitator, audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim. The three software interface options were presented in a different order than in the previous focus group, to mitigate order effects. Participants were observed in using the software in addition to being interviewed in a group. Once transcripts were produced, they were anonymised and recordings were destroyed. Participants received £15 for participation and their travel expenses were reimbursed. Following the sixth focus group, the research team agreed that data saturation had been reached, given that an initial review of the transcripts demonstrated that similar data had arisen across the six sessions.

Analysis

The transcripts were independently reviewed by the facilitator and a co-facilitator. For each aspect of the DIALOG intervention discussed throughout the groups (e.g. the seven response options, the preferred layout of the software), the researchers summarised the opinions of the participants using verbatim quotes, representing consistency across groups, as well as differences of opinions. These summaries were presented to the wider research team and the service user reference group and implications for the software were discussed. A final decision on the content, features and preferred interface for the updated DIALOG software was then reached. The software was then developed for the iOS iPad (see Study A3: technology development) in preparation for using the software in the implementation of the new, extended DIALOG+ intervention (see Chapter 3), to be tested in a randomised controlled trial (see Chapter 4).

Results

Participants offered their opinions from a patient’s perspective on how best to deliver the DIALOG and DIALOG+ interventions using the new DIALOG software. Their views in regards to specific features of the software are presented below, accompanied by verbatim quotes, where helpful, in illustrating the design issue under consideration.

Core interface

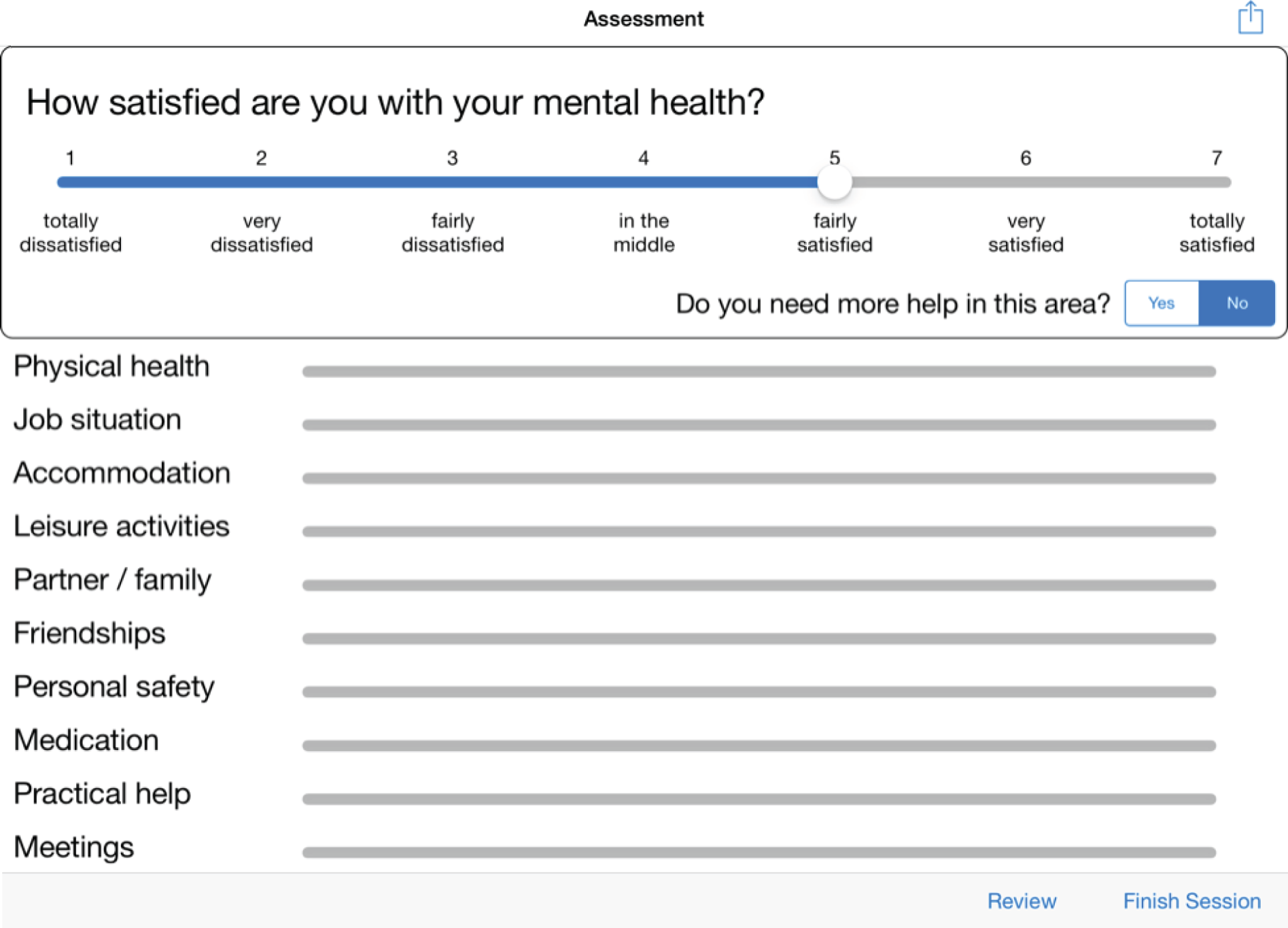

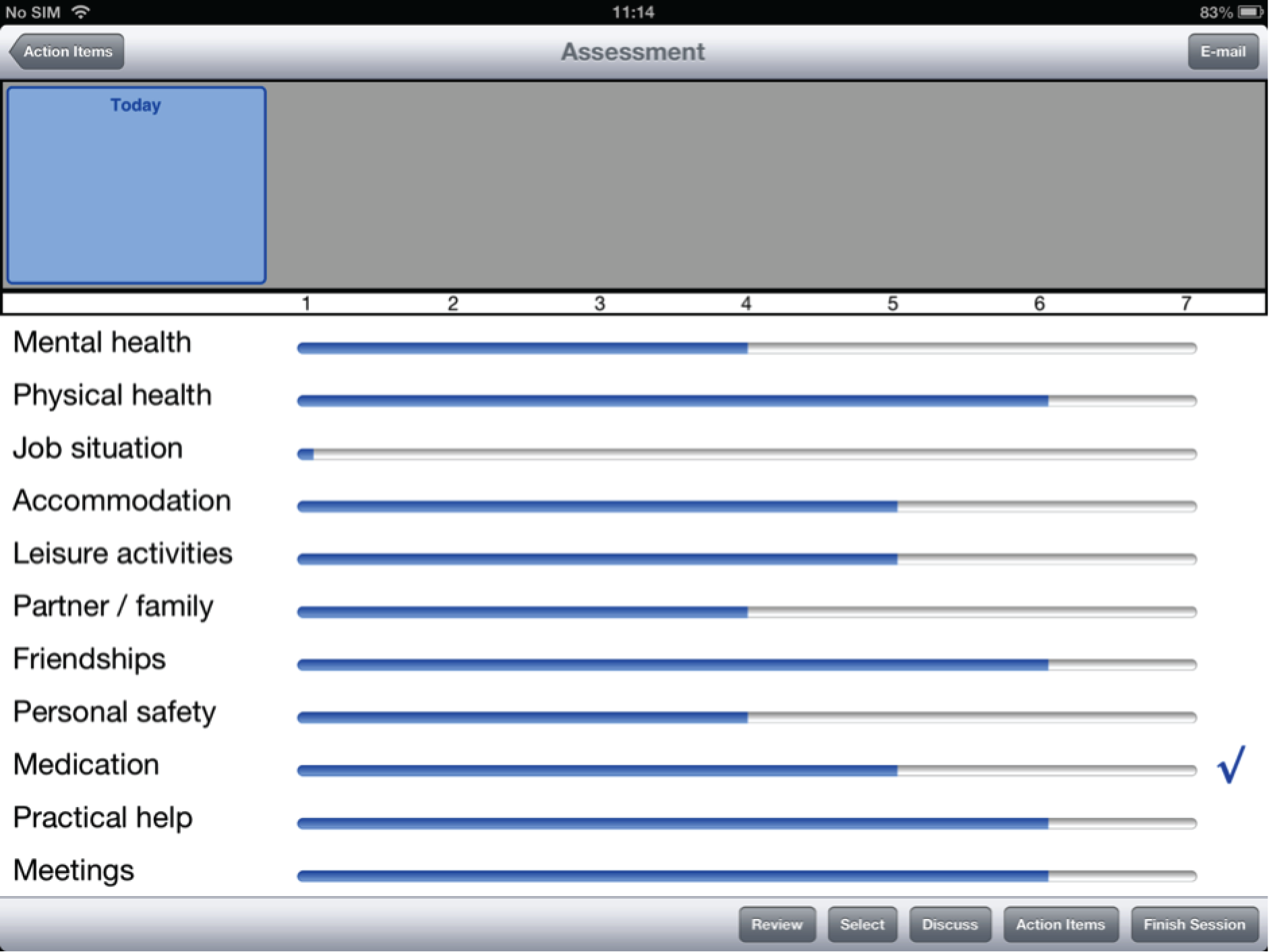

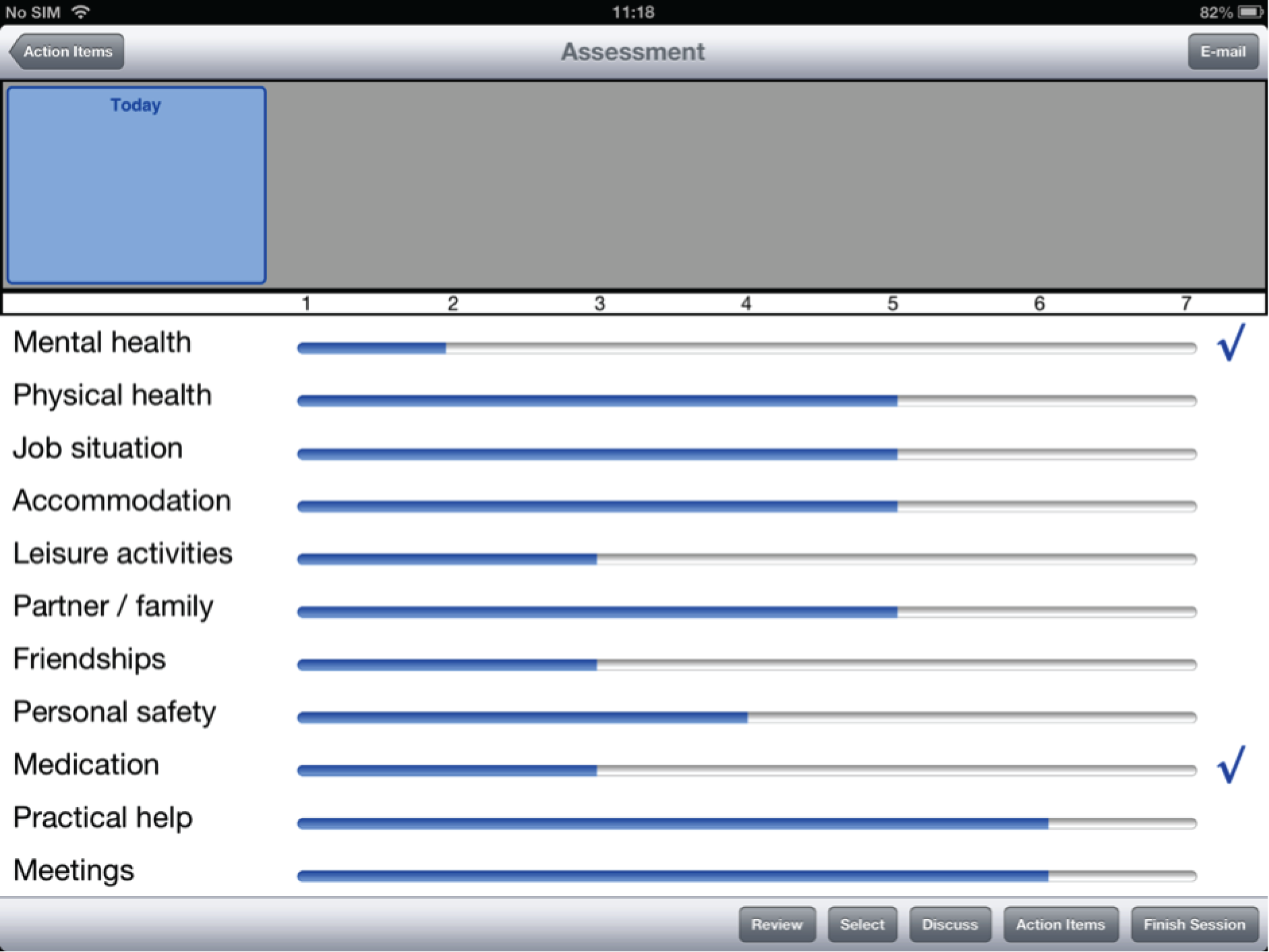

Of the three design layouts presented at the focus group meetings, a strong majority of participants favoured the design depicted in Figure 1 (interface A). This design presents one ‘active’ question pertaining to satisfaction at any one time, to which a Likert scale to be rated corresponds, as well as a question pertaining to additional help. ‘Mental health’ is the active domain in Figure 1. The other 10 domains of the questionnaire are visible on the screen, but they are in truncated form and are inactive. In order to proceed to any one of these, the user has to press on the desired domain to activate that domain, in which case it will appear in large form on the screen, along with the accompanying question on satisfaction, the Likert scale to be rated and the additional help question. Mental health will now be inactive, as will be the other nine domains. The values from any previously rated domains will still be visible in truncated form, with a checkbox indicating when there has been a request for additional help.

FIGURE 1.

Interface A, the favoured version of the DIALOG software, as it appears in the final interface (including revised response options on the Likert scale).

Participants favoured this design over two alternatives. The first of these was interface B, which was similar to interface A; however, all domains were presented in large form, with the Likert scale and additional help question also visible in large form for each, meaning that there was room for only a few domains on the screen at a time. The user made a hand gesture on the touch-screen interface to proceed further down the list of domains or back towards the top. Interface C featured each domain appearing individually, one at a time on the screen, with considerably large text presented for the satisfaction question, the domain, the Likert scale and the help question. A hand gesture allowed the user to proceed to the subsequent domain or return to the previous one.

Participants favoured interface A because it presented the opportunity to tend to only one domain at any given time. Yet it was possible to see the other domains and the expectation that they were to be rated shortly was therefore understood. This gave participants a sense of structure to the procedure:

This one [interface A] is better because I know which questions are coming up. I like to know what’s coming, it helps me concentrate.

Participant (P)3, focus group (FG)3

This one, this one is easier . . . With the last one [interface B] you were moving all over the place and all the questions were all together . . . I got a bit lost . . . This way, it’s one at a time . . . I can see what I’m doing.

P1, FG2

I like how this builds up the answers from top to bottom. I know what’s going on, it’s clear, it doesn’t disappear . . . I know what I’m looking at . . . It’s good.

P2, FG6

Participants appreciated that interface C was very user-friendly in having the largest text, but preferred to able to see the upcoming domains to be rated as well, rather than one domain at a time. They felt that interface B was ‘too busy’ in its design and found interface A far clearer.

User-friendliness

All of the participants responded positively to the iPad platform used for demonstration purposes. The majority of participants managed to operate the touch screen and enter ratings intuitively, without instruction. Participants said of using DIALOG:

It was pretty self-explanatory . . . Nothing complicated.

P3, FG5

Even though I’ve never used one . . . It’s straightforward.

P1, FG4

Participants offered feedback on two major features of the interface. The first was regarding the design of the ratings comparison feature. Current ratings were represented in dark blue, with previous ratings represented in light blue. Participants pointed out that it was difficult to distinguish between the two, and that clashing colours should be used instead. Some participants could not tell which rating was the current rating and which was the previous one.

The second was regarding a ‘reorder’ function in the software. The research team had proposed an idea whereby, with the push of a button, patients’ ratings could be reordered subsequent to submission, so that the lowest-scoring ratings appeared on top and the highest-scoring ratings appeared on the bottom. This was intended to help the patient and the clinician identify priorities for further discussion. However, when this was piloted with participants, it transpired that reordering was confusing to them. It was also noted that reordering seemed to undermine explicit requests for additional help.

Posing of the satisfaction questions

Participants had mixed views on how the 11 satisfaction questions should be posed to the patient. They considered the options of the software presenting each domain as (1) a stand-alone topic such as ‘mental health’; (2) a statement such as ‘I am ______ with my [mental health]’; (3) the question ‘How satisfied are you with your [mental health]?’; (4) the question ‘How happy are you with your [mental health]?’ and (5) the question ‘How do you rate your [mental health]?’.

A minority favoured presenting the domains as stand-alone topics:

That way the care co-ordinator has to ask you the question . . . That means they’re talking to you. Not just reading off the screen. I think that might be better personally.

P2, FG2

It means there’s less stuff on the page. Less words . . . Might be easier.

P3, FG2

However, the majority of participants favoured presenting each domain as a question:

[Not having a question] would be an issue for me because I have problems with short-term memory. It helps me to focus on what the question actually is.

P1, FG1

I want to be sure about the question. I wouldn’t understand otherwise . . . Mental health . . . Mental health what? Do you know what I mean?

P2, FG1

None of the participants favoured presenting the domain as a statement to be completed. One participant said:

That way it doesn’t seem like a conversation. It’s not my care co-ordinator asking me a question.

P3, FG4

The majority opposed formulating the question as ‘How do you rate’, with one participant describing it as ‘too scientific’ and another noting:

That’s something completely different . . . I wouldn’t rate any of those things high . . . Accommodation and that . . . But am I satisfied? Yeah, they’ll do for now. I’m happy with them. It’s more about me. I don’t rate it as 5-star accommodation . . . Do you see!

P1, FG4

Similarly, few participants favoured formulating the question as ‘How happy are you with . . .’ The same participant noted a distinction between ‘satisfied’ and ‘happy’:

Again, it’s an issue. How happy are you, how sad are you . . . That’s different . . . I am satisfied with my physical health. I might have a funny leg and I’m not happy about it. But I’m satisfied . . . I know the situation. I know what I can do and what I can’t. I know how to manage it, it’s fine, I’m satisfied about it.

P1, FG4

The majority favoured the formulation ‘How satisfied are you with your mental health?’:

Makes sense. It’s about how satisfied am I . . . Do I need to work on it. Do I need to improve it, for myself.

P3, FG4

Additional help question

Participants were asked about how the additional help question of the DIALOG tool should be posed. A small majority said that the phrasing of this question should be amended to ‘Do you need more help in this area?’.

When invited to consider the phrasing ‘would you like’, a small minority of participants said that they preferred this option and noted that it was ‘friendlier’, which would make them more likely to ask for help if they needed it. However, the majority said that the word ‘need’ was better, in that it more accurately reflected the patient’s situation of requiring help, rather than simply desiring it. One participant said:

People are motivated by different words. I personally am more motivated by the word ‘need’. It’s very functional. I’m a very functional type of a person.

P3, FG1

Participants did not view one alternative option, ‘extra’, favourably:

Simpler . . . But, I mean, ‘extra’ help . . . It sounds like ‘all the extras’ – the stuff you don’t need. It sounds like you’re getting extra but you don’t necessarily need it. I don’t like that.

P2, FG2

I don’t like the connotation of ‘extra’ . . . sounds greedy.

P3, FG1

Order of the domains

Participants had differing views on how the domains should be ordered. One participant, when presented with the current order of the domains, remarked:

I can see what you’ve done there . . . Start off with mental health, then all the daily life, then all the stuff that happens at the team . . . I can see the logic to it. I don’t think it needs changing.

P3, FG4

Although a small majority held a similar view, there were alternative suggestions:

Maybe medication should be after mental health.

P1, FG5

I don’t think so. Mental and physical health, keep them together. Medication could be a longer discussion . . . Leave it ‘til later.

P2, FG5

Maybe not start off with mental health? It’s a big one.

P1, FG6

It is . . . But it influences everything else.

P2, FG6

With such diverse opinions, there was no strong consensus in any of the groups offering an alternative to the existing order. However, one participant noted:

If you make it (the software) so that you can answer whichever one you like [first] . . . You’ve not got a problem.

P3, FG4

Labelling of the response options

Having been asked to consider the best response options for the seven points of the DIALOG scale, participants had different individual preferences and did not reach consensus in the groups. However, all of the participants agreed that the current labels needed to be revised. These labels were 1 = couldn’t be worse, 2 = displeased, 3 = mostly dissatisfied, 4 = mixed, 5 = mostly satisfied, 6 = pleased, 7 = couldn’t be better.

‘Mixed’ is a problem. I don’t like that because of the idea of mixed diagnosis. It doesn’t belong . . . I don’t like the connotation.

P3, FG1

‘Couldn’t be better’ is just confusing. The negative in there . . . It doesn’t help. It’s complicated.

P1, FG1

I think that ‘mostly’ sounds too strong coming straight after ‘mixed’. That’s a huge jump to my mind.

P1, FG3

Mostly satisfied, then pleased, then couldn’t be better . . . You’d be better off just using the same name for all of them, but have a different amount, you know like . . . A bit satisfied. Then whatever else . . . The next strongest sounding word . . . really dissatisfied.

P2, FG6

In keeping with this, ‘satisfied’ and ‘dissatisfied’ were chosen as the consistent terms for the positive and negative sides of the scale, respectively. Of the various suggestions of the group, ‘fairly’, ‘very’ and ‘totally’ were decided on by the research team. More colloquial terms suggested by the focus groups (e.g. ‘a bit’ and ‘really’) were ruled out on the basis that they were difficult to quantify specifically.

One participant suggested ‘in the middle’ for the centre point of the scale. The research team agreed that this was the most direct way of describing the centre point, more so than the alternative suggestions – ‘neutral’, ‘good and bad’ and ‘neither’.

Discussion

The current study sought to gain the views of patients in CMHTs on mock-ups of the DIALOG software, and arrive at a user-friendly interface that would be suitable for routine use in community mental health care. The resulting specification for the software was as follows.

On initiating a session with a patient, the clinician and the patient are presented with the first of the 11 domains, mental health. The domain is presented in the context of a full question – ‘How satisfied are you with your mental health?’. A Likert scale is visible underneath, with the following labels: 1 = totally dissatisfied, 2 = very dissatisfied, 3 = fairly dissatisfied, 4 = in the middle, 5 = fairly satisfied, 6 = very satisfied and 7 = totally satisfied. There is a further question underneath the domain – ‘Do you need more help?’ – which is to be answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The remaining 10 domains are visible underneath, in truncated form. After (1) mental health, the remaining domains are presented in the following order: (2) physical health, (3) job situation, (4) accommodation, (5) leisure activities, (6) relationship with partner/family, (7) friendships, (8) personal safety, (9) medication, (10) practical help received and (11) consultations with mental health professionals.

In order to proceed to a different domain, the clinician presses on that domain from the list of domains appearing underneath the currently active domain. The newly activated domain (in this case, physical health) is now large on the screen, with an accompanying question on satisfaction, a Likert scale and an additional question on needs for more help, with all other domains truncated. Responses to all previously completed domains, including requests for additional help, are still visible and gradually build up a general overview of the assessment.

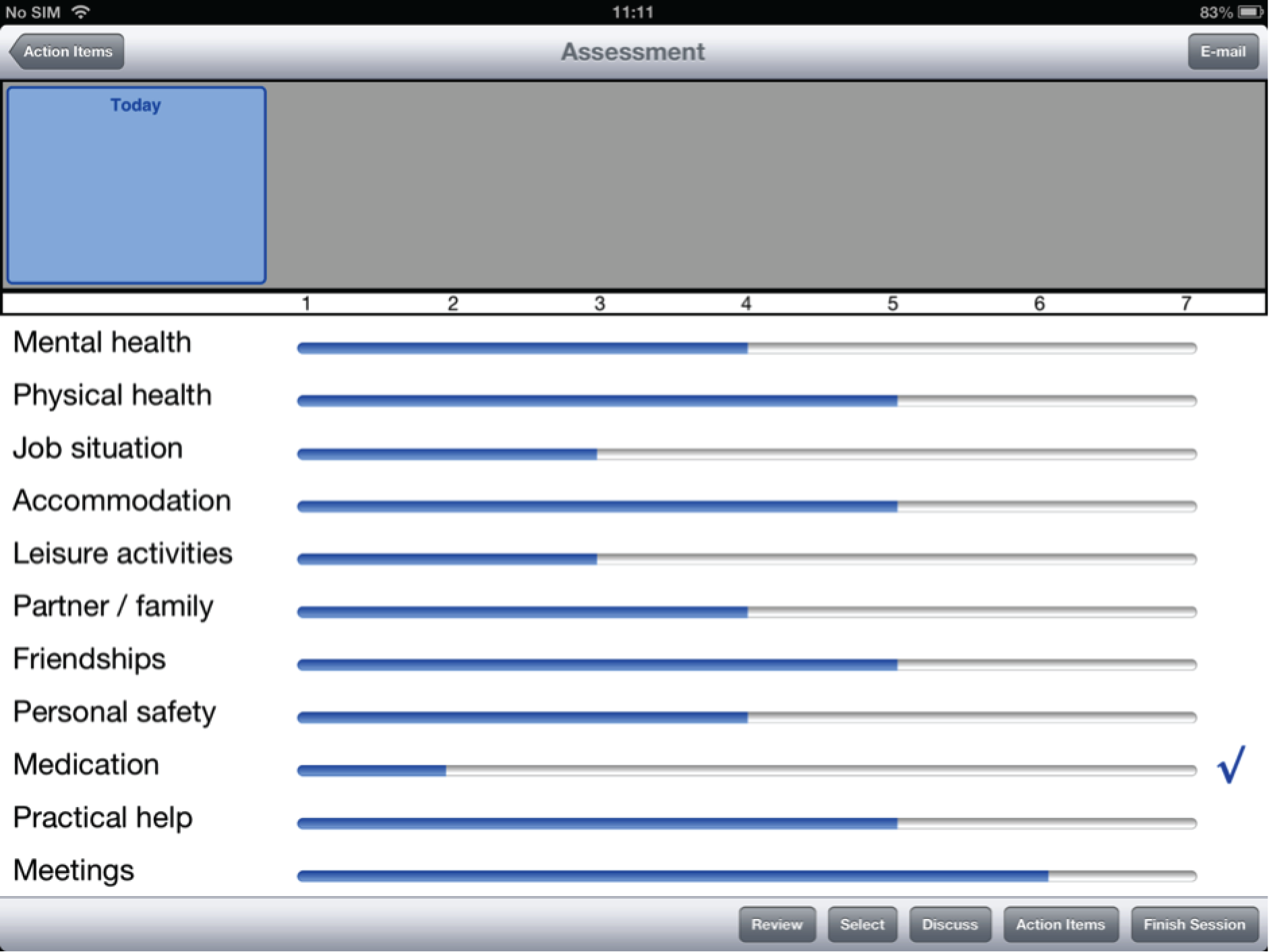

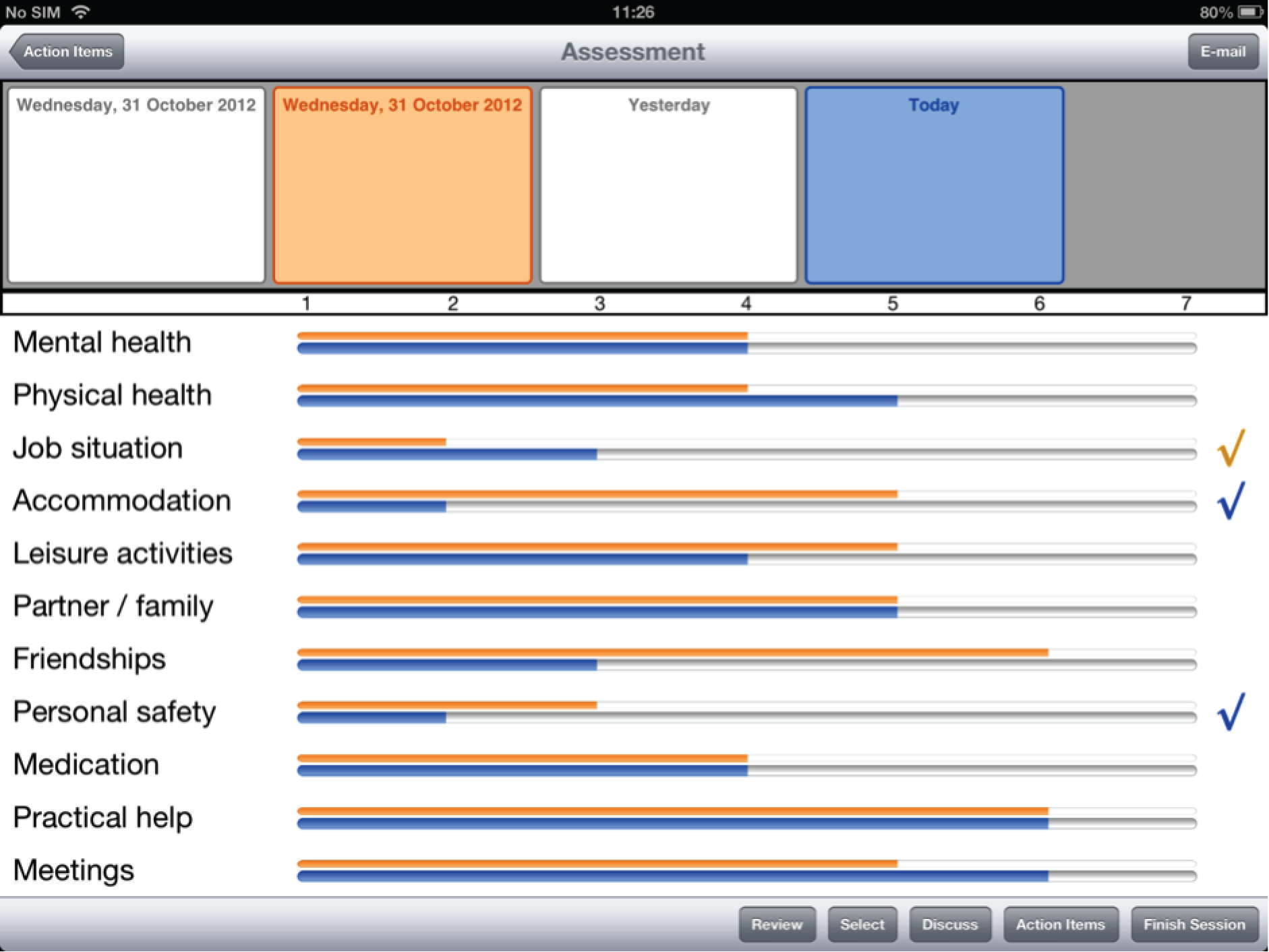

From the second use of DIALOG+ onwards, the clinician and the patient may compare the current ratings with those of any previous session. On pressing the ‘compare’ button, a timeline appears at the top of the screen, showing the dates of all the previous meetings. When the clinician presses on any one of these dates, the ratings from that date appear, in orange, next to the ratings from the current session, in blue.

Following the results of concurrent studies in this programme concerned with the development of a manualised guide for a new ‘DIALOG+’ intervention, it was agreed that the software should not only represent DIALOG, but also DIALOG+. This decision was strongly favoured by the Programme Steering Committee. As a result, the software was further developed (see Study A3: technology development).

Study A3: technology development

Introduction

Following substudy A1 (see Study A1: analysis of video-recorded DIALOG sessions), an initial brief for the specification of the new DIALOG software was developed. This brief stipulated the following requirements:

-

The software should run on a portable device, which clinicians can easily bring to home visits with patients, and can be shared and passed back and forth.

-

The software should run on a device with a large screen to facilitate the patient’s engagement with the tool.

-

The software should run on a touch-screen-operated device to facilitate the patient’s engagement with the tool.

In anticipation of a trial involving the use of this software in real-world mental health services, further requirements were added to the brief by the research team:

-

The software should be fully operational even when an internet connection in not available.

-

Data should be stored safely and encrypted inside the device.

-

When an internet connection is available, the data should be posted on a server and be erased from the device’s memory.

-

Updates and security fixes should be easily distributed.

We sought to develop the new DIALOG software and a corresponding server for storage of data in accordance with this brief. This was an iterative process that took place concurrently with substudy A2 (see Study A2: focus groups exploring preferences for updated DIALOG software). Thus, study A2 informed the development described in this substudy also.

Method

We formed a DIALOG software development team comprising the principal investigator (SP); RMC; Pat Healey (PH), Professor of Human Interaction at the School of Electronic Engineering and Computer Science, Queen Mary University of London (QMUL), London, UK; a research assistant on the programme; and a software developer. The team met weekly between October 2011 and September 2012 to discuss issues surrounding development of the new software.

Informed by the findings of studies A1 and A2 and the resulting specification, it was agreed that the most suitable platform for the new DIALOG software would be a ‘tablet’ device. Larger than a mobile phone, and more portable and less heavy than a laptop, a tablet would allow for the DIALOG software to be easily shared between the patient and the clinician and would enable clinicians to use it during home visits.

Following this decision, we researched the three most popular mobile developing platforms: iOS 6 (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) and Android version 4.1–4.3.1 (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), as well as a cross-platform solution using web development in hypertext markup language 5 (HTML5). We considered the advantages and disadvantages of each, both in terms of implementing a trial and distributing the software more widely following the conclusion of the programme.

Once the platform had been selected, the software developer commenced development of the DIALOG software and the corresponding server, overseen by PH. The implementation of the iOS app was made using the Objective-C 2.0 (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) programming language. The design was based on the model–view–controller (MVC) design pattern. This is a classic design pattern that separates the system design into three distinct entities. The model is the layer that holds and manages all the data of the app, the view is the only layer visible to the user, allowing him/her to interact with the app and the controller is the layer between model and view, which manages the data from the model and presents them to the view. MVC is important for a clean and well-defined design. 45 One of the greatest advantages of applying the MVC design pattern is that the app can easily be ported to different devices. In that case, only the view and some parts of the controller layer have to be redefined and implemented.

The implementation was made using the objective C programming language, an object-oriented implementation of the C language.

Results

Evaluation of operating systems

Apple iOS

Apple iOS is the operating system that runs inside all portable devices made by Apple Inc.: iPhones, iPod Touch and iPads (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA). It was released in June 2008 with the first iPhone device and was based on the core of Mac OS X (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA), Apple Inc.’s desktop computer operating system. Based on reports from Strategy Analytics, iOS held 66.6% of the market share for tablets at the end of 2011,46 making it the most popular mobile operating system in the world at the time.

Selecting this environment for developing DIALOG presented the following matters for consideration:

-

Deployment: apps are easily distributed using the App Store (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) – users can download apps instantaneously with the push of a button. Submission of apps to the App Store requires approval from Apple Inc., which delays the distribution by 5–10 days.

-

Cross-platform functionality: apps developed in iOS can only be operated on Apple Inc. platforms, that is, iPhones and iPads. Apps need to be specifically optimised to operate on both platforms and are often developed for either one or the other.

-

System access: native apps run securely in an isolated environment (they are ‘sandboxed’), meaning that an app cannot access data of other apps installed on the device. Furthermore, all system resources are protected from the operating system, making it more secure and stable.

-

Security: as a result of the restrictions applied by Apple Inc.’s approval process prior to distribution, no viruses affecting iOS devices have been detected to date. Thus, iOS devices offer superior security.

-

App updates: updates are automated, but require reapproval from Apple Inc., which delays the update distribution by 5–10 days.

-

Operating system updates: updates to the operating system are automated and very fast.

-

Data storage: all data are secure and encrypted inside the device.

-

Pricing: Apple Inc. hardware products are considered premium products, and tend to be more costly than alternative platforms.

Google Android

Android is the newest mobile platform, having released its first stable version on October 2008. It is based on the Linux kernel and was developed by Google as an open-source project, available for free to all smartphone manufacturers. According to Strategy Analytics, Android held 26.9% of the tablet market share at the end of 2011,46 making it the second most popular mobile operating system in the world at the time.

Selecting this environment for developing DIALOG presented the following matters for consideration:

-

Deployment: apps are easily distributed – using the Google Play Store (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), users can download apps instantaneously with the push of a button. This does not require approval from Google, meaning that an app can be made available on the Play Store within 1–2 hours.

-

Cross-platform functionality: Android offers cross-platform functionality across a range of mobile and tablet devices. This means that Android software is not restricted to one company and is compatible with different devices offered by Samsung, Sony and Nokia, among others.

-

System access: the latest Android versions also run the apps securely in an isolated environment (they are ‘sandboxed’), but some apps can acquire special permissions in order to access the device’s data storage, which makes the platform vulnerable.

-

Security: as a result of Google’s automated approval of new apps and all corresponding updates, 80 infected apps were discovered as of January 2011. This number increased by 400% to 400 infected apps as of June 2011. 47

-

App updates: updates are automatically approved by Google and take only 1–2 hours to be distributed.

-

Operating system updates: updates to the operating system are usually delayed because of the inconsistencies across devices of different hardware providers, and the necessity to make updates compatible with all of them. This is an especially important consideration when a vulnerability to the system is discovered.

-

Data storage: all data are secure, but not encrypted by default inside the device.

-

Pricing: cost depends on the hardware selected to support the Android app. Prices vary, however they are generally less costly than Apple Inc. products.

HTML5

Hypertext markup language is the open standard used to create web pages. The latest version at the time of software development, HTML5, provides several useful features such as web storage for saving data locally to the device’s internal memory.

Selecting this environment for developing DIALOG presented the following matters for consideration:

-

Deployment: apps are not distributed, but run on a web server. Devices need to open a web browser and type the server’s URL to use the app.

-

Cross-platform functionality: as apps are not distributed and run inside a web server, an implementation in HTML5 allows access to virtually any user on any device via the device’s web browser.

-

System access: apps have limited access to the device’s data storage.

-

Security: the security of this method depends on the device used to access the app.

-

App updates: as the app runs inside the server, updates are automated and instant.

-

Operating system updates: updates to the operating system depend on the device used to access the app.

-

Data storage: when saved locally on the device, data are not secured and not encrypted. Otherwise, a constant internet connection is required to use the app and save data to the server.

-

Pricing: HTML5 apps can be operated in web browsers, whether the browsers are on tablets or on desktops; therefore, the cost of hardware to support the app varies hugely (e.g. if choosing a laptop over a tablet).

Platform decision

Although all of the platforms described above were deemed suitable for the implementation of DIALOG, Apple Inc.’s iOS was selected as the superior option for the following reasons:

-

iPads are widely used and have the largest market share, at 66.6%.

-

It is the most secure option, with no virus threats or critical vulnerabilities detected to date. 48

-

Although software updates can take 5–10 days to be approved from Apple Inc., this makes the system more secure than other alternatives. 48

-

Apps natively built for iOS can run fast, even when an internet connection is not available.

-

The platform provides strong hardware encryption on the device’s data.

Model design

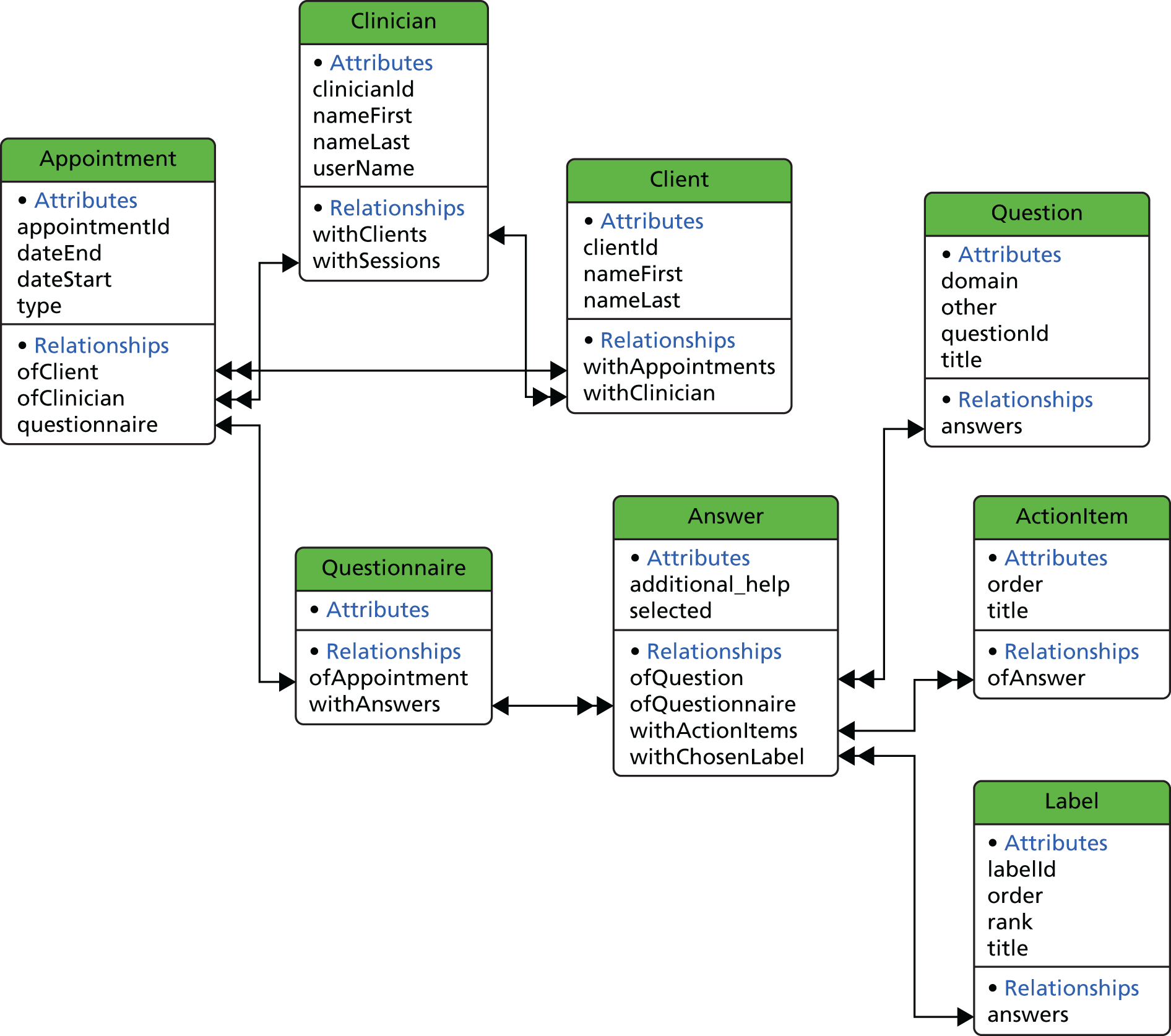

The model is the layer that holds and manages all data of the app. It usually takes the form of a database or a JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) file. In this project, we used the Apple Inc. Core Data persistent framework, which uses a database to store the data internally. 49 Figure 2 shows the model design of DIALOG, with a description of all entities existing in this model.

FIGURE 2.

Model design of DIALOG based on the Apple Inc. Core Data persistent framework.

Clinician

A clinician entity represents the current user of the software. In this implementation, only one clinician can exist. We introduced this in case multiple user support is required in the future.

Client

A client entity represents a patient registered to the existing clinician.

Appointment

An appointment entity represents an actual appointment registered by a client and connected to the related client. It has several properties related to an appointment (e.g. date, duration), as shown in Figure 2.

Questionnaire

When an appointment takes place, it needs to be associated with a new questionnaire object. This represents an actual session that takes place between a clinician and a client.

Answer

Every questionnaire has 11 entities with the type of answer. Each answer represents one answered question.

Question

This entity contains a list of all available questions. An answer object is associated with 11 questions of this type. The available questions are:

-

How satisfied are you with your mental health?

-

How satisfied are you with your physical health?

-

How satisfied are you with your job situation?

-

How satisfied are you with your accommodation?

-

How satisfied are you with your leisure activities?

-

How satisfied are you with your relationship with your partner/family?

-

How satisfied are you with your friendships?

-

How satisfied are you with your personal safety?

-

How satisfied are you with your medication?

-

How satisfied are you with the practical help you receive?

-

How satisfied are you with your meetings with mental health professionals?

Label

This entity contains a list of all available answers. An answer object is associated with seven labels of this type. The available labels are:

-

totally dissatisfied

-

very dissatisfied

-

fairly dissatisfied

-

in the middle

-

fairly satisfied

-

very satisfied

-

totally satisfied.

Action item

Every answer is also associated with a number of action items. These represent plans or action points agreed by the clinician and the client, which should be carried out before the next meeting.

Security and data protection

Security and data protection were essential to this project. We used the built-in hardware encryption that all iOS devices provide, provided the user sets a passcode to unlock the device. This was implemented by adding the data protection provision profile and set into the level of complete protection. According to Apple Inc., use of this level of protection ensures that all files are encrypted and inaccessible when the device is locked. This passcode was requested every time the user attempted to unlock the iPad.

In order to increase the strength of this encryption, all devices were configured using the Configurator tool (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA), with the following requirements for setting a password:

-

A simple passcode of four digits was not allowed.

-

A minimum passcode length of at least six alphanumeric characters was required.

-

The passcode required at least one digit and one complex character.

-

The device automatically erased its data after 10 failed passcode attempts.

Finally, we used an additional security layer to the app itself. Every time DIALOG was launched, a similar but separate passcode to the one described above was required. This mechanism protected the app data independently. We used the iOS keychain feature to securely store the Secure Hash Algorithm 1 [SHA-1; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Gaithersburg, MD, USA] hash of the passcode to the device, making it practically impossible to recover and read the original passcode in case the device got stolen.

Server communication

One of the main requirements of this project was the ability to sync the data with a server, when an internet connection is available. The server was developed in Python 2.7 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) programming language using the Django 1.4 (Django Software Foundation, Lawrence, KS, USA) web framework. Data were transmitted over a secure hypertext transfer protocol (SHTTP) connection using secure sockets layer (SSL) encryption, and stored on a MySQL database (Oracle Corporation, Redwood City, CA, USA) connected to the server and located in the Department of Electronic Engineering and Computer Science at QMUL. Every time a clinician was synchronised with the server, all new data were pushed to the server and erased from the device. If the clinician had a planned future appointment with a patient, the data of that specific patient were synchronised back to the device in order to be available for the session. All data were available to the researchers via a web interface, protected with an administrator user account.

Discussion

The technology arising from this substudy was implemented in the subsequent study on the effectiveness of DIALOG+, described in Chapter 4. The app is now available to download for free from the App Store by searching for ‘DIALOG’ or following this link: www.itunes.apple.com/us/app/dialog/id914252327?ls = 1&mt = 8 (iPad only). Any person or service can set up a server and configure the app to post the data on it. Any server with a running web service that accepts JSON files can be used. To learn about an alternative version of the DIALOG app for a different platform developed at a later stage of the programme, see Chapter 9.

Chapter 3 Developing the DIALOG+ intervention

Study B1: development of the DIALOG+ manual

Introduction

The original DIALOG trial demonstrated that structuring the communication between patients and clinicians in CMHTs by routinely assessing key topics regarding patients’ satisfaction with life and treatment was sufficiently powerful to improve patient outcomes. However, the video clip study described in Chapter 2 showed that clinicians did not intuitively know how best to utilise the DIALOG tool and meetings did not always appear well structured and therapeutically helpful. There was a need for a manualised guide for clinicians on how to respond to patients who presented with low levels of satisfaction and the need for more help. The addition of this manual could potentially make the DIALOG tool considerably more effective. Evidence suggests that clinicians’ interactions are more therapeutic when they are guided by a clear model. 13

Patients treated in the community see clinicians (nurses or social workers) who act as their care co-ordinators at least once per month – more regularly than a psychiatrist (approximately every 3 months) or a psychologist (if such a referral is made; the patient must be deemed eligible, waiting times can be long, and sessions are for a finite duration). Considering the regularity with which patients meet their care co-ordinators, perhaps there is a missed opportunity for treating patients with a more psychological, evidence-based approach to problems. Two such approaches are CBT and SFT. There is a strong evidence base supporting the effectiveness of CBT,26–28 and it plays a major role in governmental plans to roll out psychological treatment in the UK. 50 It is commonly taught in teaching programmes and is widely accepted as a beneficial model among health professionals. SFT is becoming increasingly popular in the UK, because of the ‘brief’ nature of its training and generic approach that can be widely applied to different contexts, with a modest body of evidence for its effectiveness. 51–53

The aim of the current study was to develop a new and more extensive version of the DIALOG intervention – the ‘DIALOG+’ intervention – through the addition of a simple and robust manual for clinicians on how to respond to information gauged through the DIALOG assessment, informed by principles of CBT and SFT. This manual would guide clinicians in using the data arising from the DIALOG assessment to inform further discussion during the meeting, with a focus on tackling problems and identifying solutions. The approach described in the manual would be used in conjunction with the new software developed, as described in Chapter 2.

Methods

Study design

We established and worked with a network of three groups of expert consultants: three experts conducting research on the use of CBT with patients with psychosis; four experts in delivering training in SFT with private clients with mental health issues, ranging from mild anxiety to severe mental illness; and six leading community-based practitioners in the UK. These experts used the DIALOG tool with patients on their caseloads or private clients, and regularly reported to the research team on their experiences, with suggestions on guiding principles to inform the development of the DIALOG+ intervention. (They used the original software, as this study took place concurrently with studies A1 and A2, prior to the finalisation of the specification for the new software.) In an iterative process, these guidelines were fed back to the various members, discussed and refined, and specific recommendations for incorporating different components of CBT and SFT were made.

The core research team of this programme subsequently drafted the manual under the supervision of the principal investigator. The manual was repeatedly presented to a multidisciplinary research team of researchers, psychologists and psychiatrists based at the Unit for Social and Community Psychiatry, QMUL, with a wide range of experience in delivering novel, manualised interventions, including communication training for psychiatrists54 and group body psychotherapy. 55 In addition, the core questions in the manual to be asked of patients were presented to the service user reference group, and to patients in the focus groups detailed in Chapter 2, Study A2.

Following the feedback of the research team and the patient groups, the manual underwent further refinement, before being presented to the Steering Group of the programme, who provided further input. Lastly, the manual was piloted with the service user reference group. This ensured that key concepts in the manual could be understood, and that the terminology used with patients as part of the four-step approach was appropriate and easily understood. The final version of the manual was then further discussed, amended and agreed by the research team.

Results

Guiding principles informing the DIALOG+ intervention

Reviewing

All consultants placed importance on patients having the opportunity to review their ratings subsequent to submitting them. This would help the patient to take stock of their situation and ownership of their own data, developing an understanding that the ratings were for their benefit as much as for the clinician’s. This would also allow them to revise the ratings if necessary, an option that was notably absent from the original DIALOG software. Consultants noted that, according to the existing procedure, such reviews were on the initiative of the clinician, rather than being incorporated into the procedure dictated by the software. They proposed that the new software could automatically present a review immediately subsequent to the DIALOG assessment.

There were mixed opinions about the utility of the comparisons feature of DIALOG, whereby ratings from the current session could be compared with ratings from a previous session, and how this should be incorporated into the intervention. CBT experts valued being able to review progress from session to session, whereas SFT experts preferred that all sessions be future focused. Ultimately, it was agreed that the feature was useful and should be available as an option, but should not form an essential component of the DIALOG+ intervention (i.e. such comparisons would be on the initiative of the clinician or patient).

Agenda-setting

Consultants, in particular CBT experts, emphasised the importance of ‘agenda-setting’ in therapeutic meetings. They proposed that, following the initial assessment of a range of topics as part of the DIALOG assessment, it would be useful to choose priorities for further discussion. These could then be discussed individually in a more extensive and thorough manner, using a structured approach to problematic situations informed by CBT and SFT.

Which topics were to be chosen as priorities would be informed by the ratings and expressions of need for more help captured through the DIALOG assessment. Consultants proposed that it would be feasible to choose three or four topics to discuss at length during routine meetings.

Setting the agenda in this manner was intended to guide the patient in adhering to a new, structured approach to meetings from the outset, to help the patient to identify which topics were most important to them and to ensure that the time available was used productively.

Shared decision-making

All consultants emphasised the importance of shared decision-making in agenda-setting. They maintained that the patient should have the final say on which topics to discuss at length and that the clinician should explicitly invite the patient to take the lead with selecting priorities. However, they acknowledged that negotiation between clinician and patient was important and proposed that clinicians make suggestions on topics for discussion when appropriate.

Algorithm

While emphasising the importance of shared decision-making, the consultants also asserted that there needed to be a defined algorithm governing agenda-setting. The clinician delivering DIALOG+ would be responsible for explaining the algorithm to the patient and identifying topics that met the criteria for selection where necessary and appropriate, while ensuring that the final decision remained with the patient.

Some felt that any explicit request from the patient for additional help in a given area warranted that topic being put on the agenda. Others maintained that any topics that were explicitly low rated (i.e. 5, 6 or 7) should be put on the agenda. It was suggested that both of these aspects could inform decisions on which topics to be discussed during agenda-setting.

Positive commentary

Solution-focused therapy experts warned against the intervention being overly problem focused and noted that a wholly solution-focused intervention rarely involves extensive discussion of problems. They emphasised the importance of tending to domains where ratings had improved as well as problematic areas. They recommended that, subsequent to the initial DIALOG assessment, clinicians be instructed to comment on areas in which patients had improved on a previously negatively rated domain or maintained a positively rated domain and explore with the patient how they had achieved this.

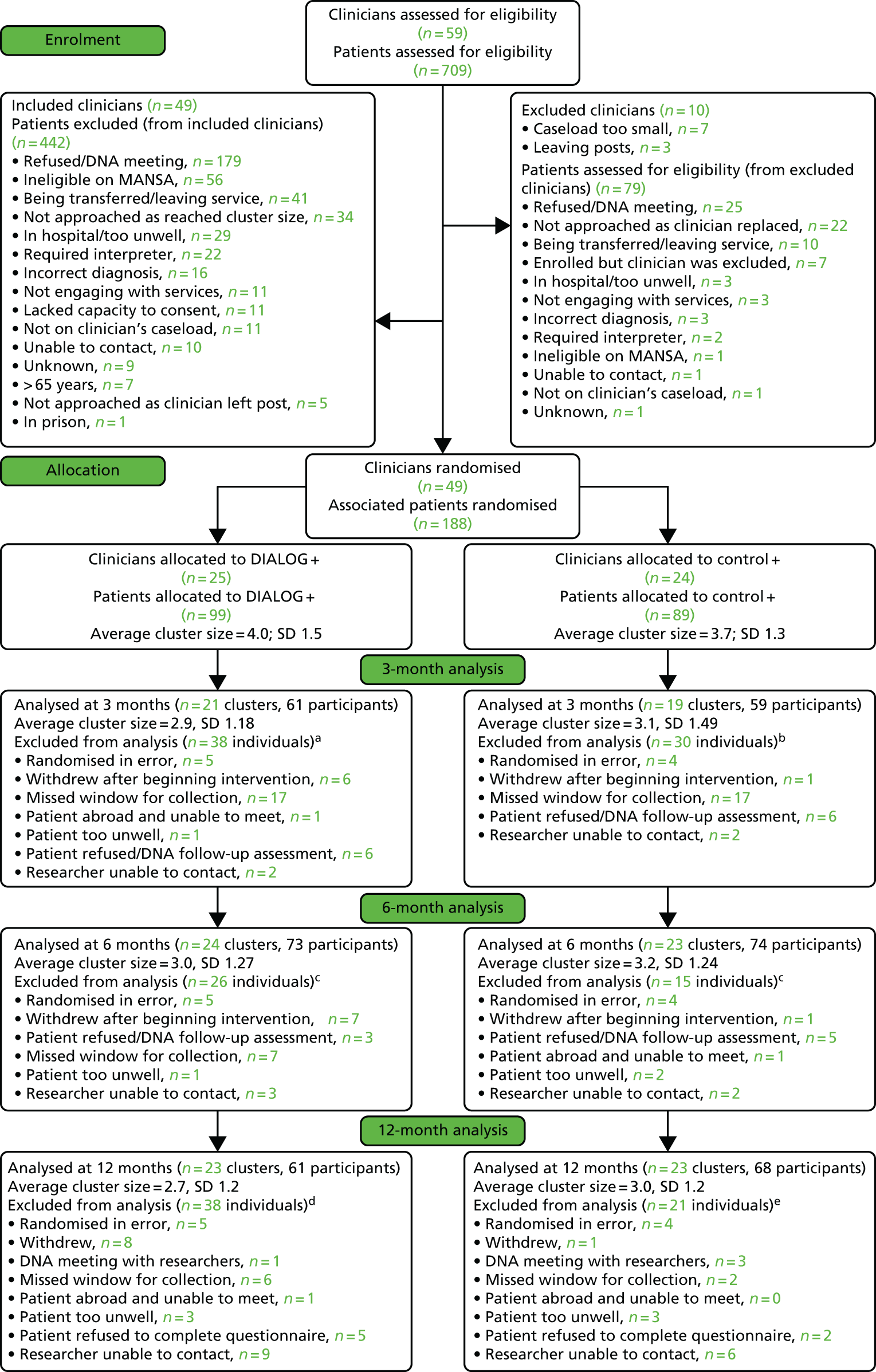

Special attention to mental health