Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0707-10093. The contractual start date was in January 2009. The final report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in July 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Killaspy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background to the REAL research programme

This programme of research focuses on one of the most socially excluded groups in society: people with longer-term mental health problems whose needs are such that they require inpatient rehabilitation. The majority of this group have a diagnosis of schizophrenia. 1 The National Service Framework for Mental Health2 implemented specialist community mental health teams in England (assertive outreach, early intervention and crisis resolution services) that have reduced reliance on inpatient services. 3 However, a proportion of users of these and other mental health services have such complex problems that they continue to require lengthy hospital admission. 4,5 It has been estimated that, at any time, up to 10% of people with schizophrenia are in receipt of inpatient rehabilitation with the aim of recovering adequate social function to live outside hospital. 6

Although there is good evidence for specific interventions [such as medications, cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and family psychoeducation] that can improve outcomes for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia,7 these can only be delivered in well-resourced services and to individuals able to engage with them. Most people are referred for inpatient rehabilitation after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline algorithm for the treatment of schizophrenia has been exhausted. 7 Many people with severe and enduring mental health problems, such as schizophrenia, experience ongoing active symptoms of illness and impairments in cognition and conation, social stigma and the secondary handicaps consequent on the illness. By definition, those who are referred for rehabilitation are those whose problems are of such complexity or severity that they have not been able to be discharged home following an acute admission. These problems include treatment resistance (non-response to first-line medications), which occurs in up to 30% of people affected;8 cognitive impairment (most commonly affecting executive function and verbal memory) and pervasive negative symptoms such as apathy, amotivation and blunted affect;9–11 and coexisting problems such as substance misuse, premorbid learning disability and developmental disorders, such as those on the autism spectrum. 1 These kinds of complex problems contribute to major impairments in social and everyday functioning and challenging behaviours that impede recovery and increase the risk of adverse outcomes. 6

Although the National Service Framework for Mental Health brought major investment in specialist community services across England, there appeared to be a simultaneous disinvestment in rehabilitation services. 12 At the same time, there was a rapid growth in independent sector provision for people with complex mental health problems who required longer-term care in hospital, nursing and residential care home settings. This phenomenon has also been noted elsewhere in Europe13 and has been critically referred to as a ‘virtual asylum’. 14 This rise in so-called ‘out-of-area treatments’ (OATs) has been of great concern, as these facilities are often geographically displaced from the service users’ area of origin, leading to social dislocation, and criticisms of the quality of care in some have been made with regard to the lack of implementation of statutory Care Programme Approach processes and institutional cultures that lack a rehabilitative ethos. 15 In addition, the inadequacy of systems for monitoring the quality of OATs and whether or not individuals have an ongoing need for the level of support they provide has been highlighted. 16 In addition to these concerns, OATs are around 65% more expensive than locally provided NHS rehabilitation services. 17

As well as the significant clinical challenges this service user group poses for professionals, the care of this group constitutes a major resource pressure for the NHS and social services. Depending on what is included in the estimate, the costs amount to 25–50% of the total mental health budget. 18 The identification of approaches and interventions that can reduce the need for inpatient care, even by a small reduction in length of stay, will have a very large impact on the mental health budget. Therefore, understanding which approaches are best able to promote service users’ progress towards greater independence and successful community discharge is highly clinically relevant and potentially cost-effective for the NHS. Despite the high levels of need of rehabilitation service users and the high costs of care for this complex group, there is currently very little evidence for effective interventions available to guide mental health rehabilitation practitioners.

A common focus in rehabiliation services is occupational therapy; a previous national telephone survey of rehabiliation services in England found that almost all had at least one full-time occupational therapist (OT). 19 It has long been known that facilitating service users’ activity reduces negative symptoms,20,21 and there is some evidence that this may also lead to improvements in social function through the promotion of motivation and daytime structure. 22–24 Nevertheless, there is evidence that the level of activity of users of acute inpatient services is alarmingly low: in one survey in a London trust, service users spent < 17 minutes per day in an activity other than sleeping, eating or watching television. 25 There are, however, very limited published data on the number and types of activities undertaken in inpatient rehabilitation services. Shimitras et al. 26 found that, although users of these services spent more time sleeping than did community rehabiliation service users, they also spent more time engaged in active leisure activities. Other community samples have also found that people with schizophrenia spend a large amount of time engaged in passive activities such as sleeping and watching television. 27,28 This suggests that although inpatient rehabilitation may improve activity levels, these gains are not sustained following discharge. Inpatient rehabilitation services, therefore, need to work with community services to enable service users to extend and maintain their range of community activities. The government’s Social Exclusion Unit report of 200429 highlighted the role of education, training, volunteering, arts, leisure and sports in promoting community participation for mental health service users. To date, interventions that aim to achieve this have not been evaluated. Although the importance of staff facilitation of service user activities has been highlighted,30 prior to the Rehabilitation Effectiveness for Activities for Life (REAL) programme there had been no randomised controlled trials to test the efficacy of interventions to train and engage staff in promoting service user activities in rehabilitation units.

Our programme of research aimed to increase the evidence base in mental health rehabilitation to inform how best to focus resources on this especially complex patient group, and identify improvements in care that could potentially reduce the length of inpatient rehabilitation admission required and the need for expensive longer-term OAT placements.

Aims and objectives of the REAL research programme

The area of mental health rehabilitation has previously been referred to as ‘an evidence-free zone’. 19 Little is known about the characteristics of users of these services, the components of care delivered, the costs of these services and which approaches are effective. This research programme aimed to address this paucity of evidence through four main objectives:

-

to provide a detailed understanding of the scope of current NHS mental health rehabilitation service provision in England, including the characteristics of their service users and the content and costs of care delivered

-

to develop a staff training intervention to facilitate service users’ activities and improve their social functioning

-

to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the staff training intervention through a randomised controlled trial

-

to carry out a longitudinal study to identify the components of care associated with better service user outcomes.

The research questions we specified in our original proposal were:

-

What is the current provision of NHS mental health rehabilitation services in England and does it reflect relative levels of socioeconomic deprivation and variation in clinical need?

-

What is the range of quality of these rehabilitation services in England?

-

What are the characteristics of the users of these services and do they vary between services?

-

Do areas with poorer-quality NHS rehabilitation services have higher proportions of service users placed out of area?

-

Is training front-line staff to promote service users’ activities for community living a cost-effective intervention to improve poorer-quality services?

-

Is service user activity associated with better clinical and social outcomes?

-

Is greater quality of the rehabilitation service associated with better outcomes for service users?

Objective 1 and research questions 1–4 and 7 were addressed by phase 1 of our research programme, the national scoping exercise of rehabilitation services (project months 1–24).

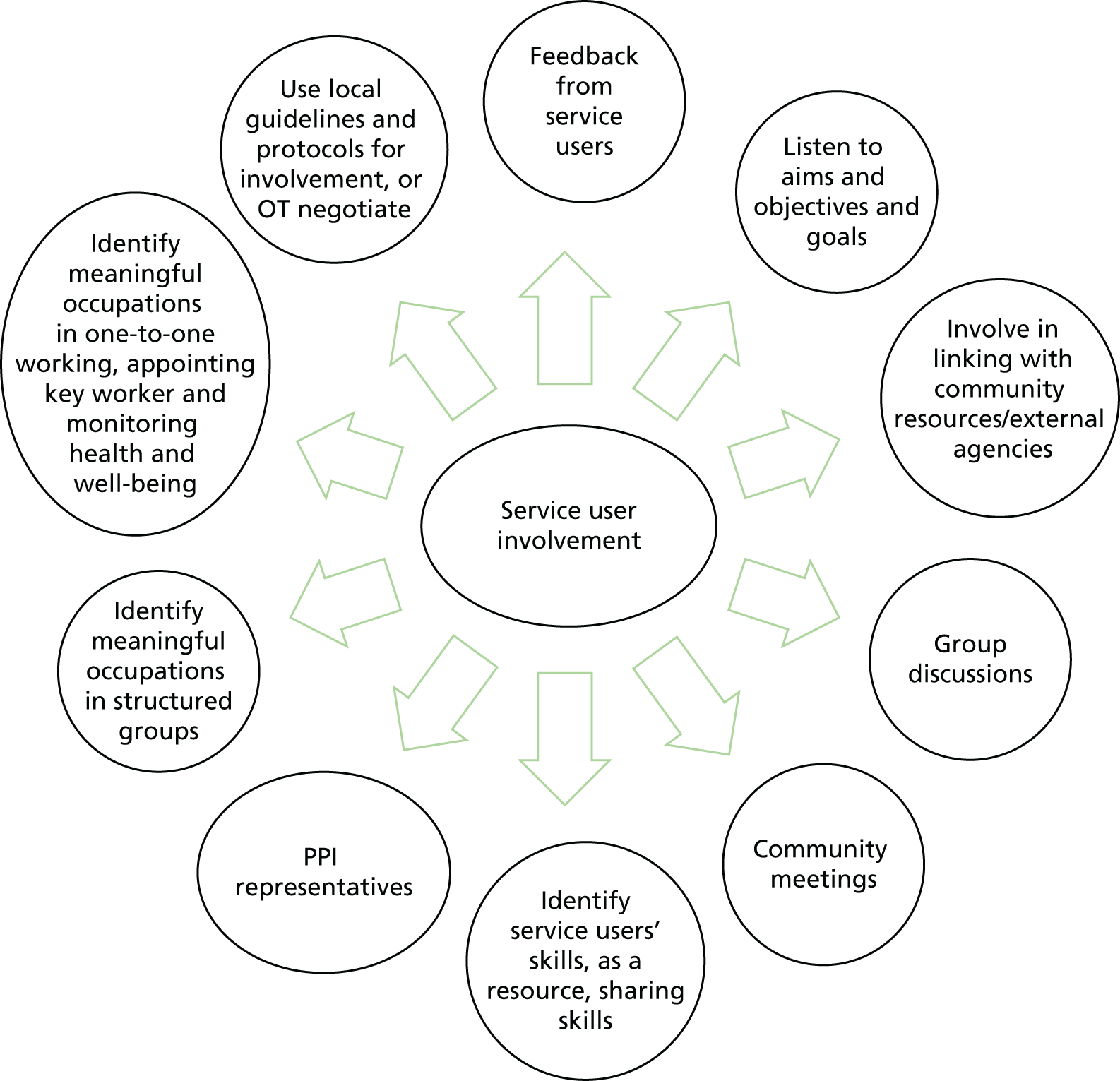

Objective 2 was addressed by phase 2 of the programme, the development of a staff training intervention to enhance service users’ activities: the ‘GetREAL’ intervention (project months 18–24).

Objective 3 and research questions 5 and 6 were addressed in phase 3 of the programme, a cluster randomised controlled trial to investigate the clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the ‘GetREAL’ intervention (project months 25–60).

Objective 4 and research question 7 were addressed in phase 4 of the programme, the cohort study (project months 25–60).

Summary of progress and outputs

Please note that all project months refer to a start date of 1 April 2009.

Phase 1 was completed on time (project month 24), despite recruitment exceeding the original estimate of 90 units (133 units were recruited). The analysis of the phase 1 quantitative data is complete, and a paper presenting the findings has been published in the British Journal of Psychiatry. 31 The main analysis of qualitative data is complete, and the findings were fed into phase 2 (the development of the staff training intervention to facilitate service users’ activities). Further analysis is ongoing as part of a doctor of philosophy (PhD) project being carried out by one of the REAL programme researchers (Nicholas Green). The main findings are being prepared for publication.

Phase 2 was completed on time (project month 24). The protoype GetREAL staff training intervention manual was drafted and refined through consultations with representative groups of mental health OTs, service users and staff of mental health rehabilitation units. The GetREAL teams were recruited and started in post in February 2011. The intervention was piloted in two units and further refined in response to piloting. A paper describing the development of the GetREAL intervention has been published in the British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 32

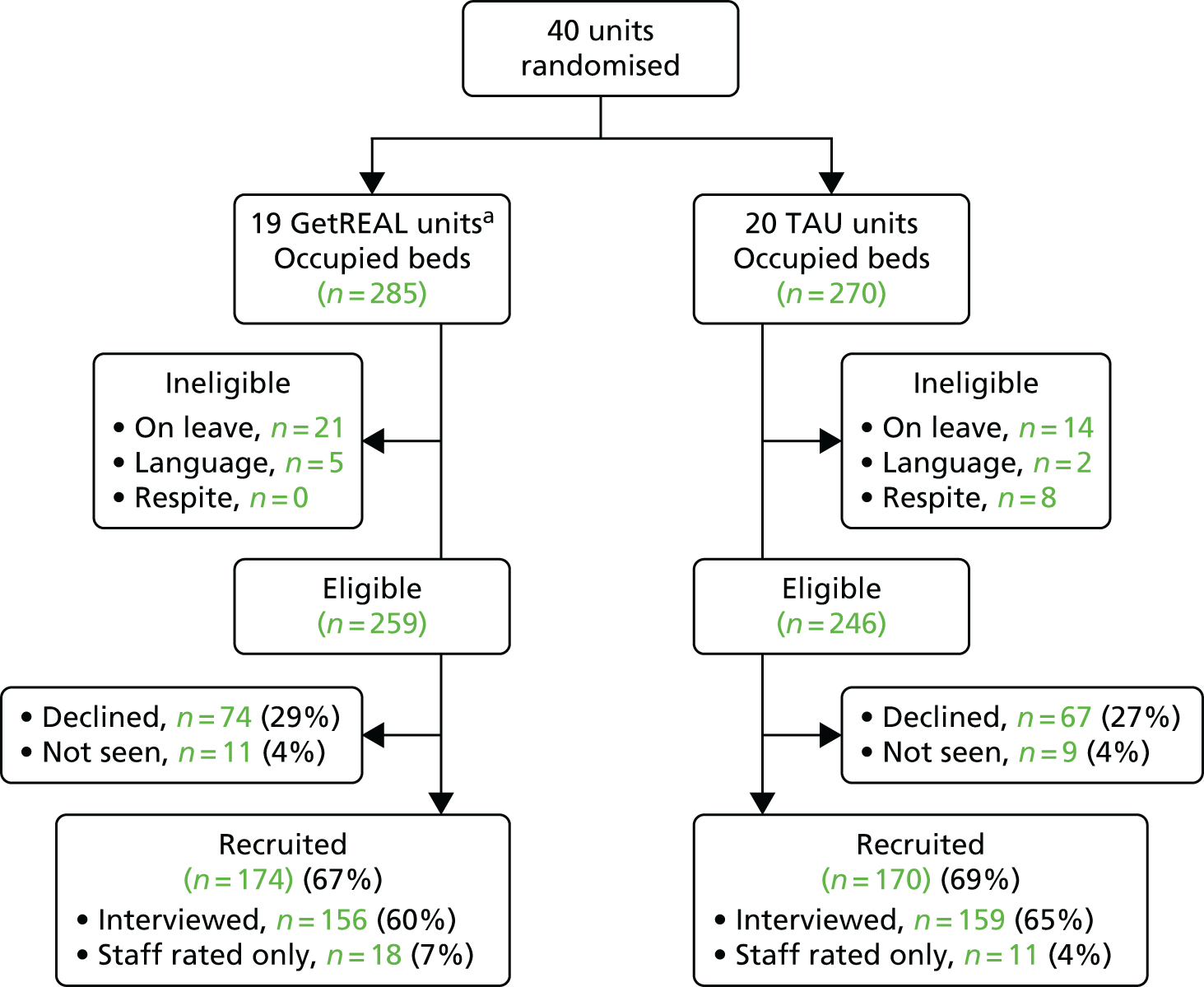

Phase 3 started in April 2011 (project month 25) and was also completed on time. The main results, including the health economic analysis, have been published in Lancet Psychiatry. 33 A total of 40 units participated (randomly selected from the sampling pool of 64 eligible units identified in phase 1: those scoring below the median on our quality assessment tool and that had at least eight beds). Randomisation was carried out by an organisation independent of the research team, and units that agreed to participate were randomised in batches of 10 on an equal basis either to receive the ‘GetREAL’ intervention or to continue to deliver usual care. Staff focus groups and individual qualitative interviews with service users at 10 intervention sites, which were purposively selected to represent a range of location and size, were carried out on average 6 months after the GetREAL team left. The results of the qualitative component have been published in BMC Psychiatry. 34 A further paper describing the role of the OTs in facilitating change in the intervention sites was published in the British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 35

Phase 4 commenced in June 2011 (project month 27). A 3-month delay to the start of phase 4 was agreed by the Programme Management Group (PMG) so that baseline data collection for the phase 3 units could be prioritised. This did not lead to any delay in the completion of phase 4. The main results from phase 4 have been published in BMC Psychiatry. 36

An additional component to the programme was also carried out, which was led by Dr Sarah Cook at Sheffield Hallam University and funded by an underspend in the programme budget that facilitated the agreement of a 12-month no-cost extension to complete this extra work. This component commenced in April 2014 and comprised a ‘realistic evaluation’ of the intervention developed in phase 2 and a cluster randomised controlled trial that assessed the intervention in phase 3. This component has been completed and the results have been published in the Journal of Advanced Nursing37 and BMC Psychiatry. 38

Programme preparation activities

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) project contract officially started on 1 January 2009. The recruitment of our research team was then undertaken; the team comprised two full-time researchers (Nicholas Green and Isobel Harrison) and a part-time project manager (Melanie Lean). Ms Lean commenced in post in March 2009, Mr Green in April 2009 and Ms Harrison in May 2009. The NIHR kindly agreed a 3-month no-cost extension to our contract to acknowledge the time-lag between the official contract start date and the date on which the research team came into post.

Application for ethics approval for the programme was made in April 2009 and full approval for the whole programme was received on 9 June 2009 from the South East Essex Research Ethics Committee (reference 09/H1102/45). The programme was adopted by the Mental Health Research Network on 29 September 2008. Clinical studies officers from the Mental Health Research Network gathered information about the rehabilitation services in areas that they covered, as well as relevant contact details for these services. These details were added to those from our previous telephone survey of mental health rehabilitation services in England, carried out in 2004, that identified 90 short-term (i.e. length of stay of up to 12 months) inpatient mental health rehabilitation units. 19 Once our research team was in post, it contacted all NHS mental health trusts in England to confirm whether they had an inpatient or a community mental health rehabilitation unit that accepted patients referred from acute admission wards. The research was conducted in keeping with usual research governance guidance, and local approvals were gained at each site that had eligible mental health rehabiliation unit(s). Along with the chief investigator, members of the research team were involved in preparing the final version of the questionnaires for each phase of the research programme, in assisting with the application for ethical approval and with submissions for local research and development approvals at each site. The researchers were trained by HK in the use of the all study materials and piloted these prior to use.

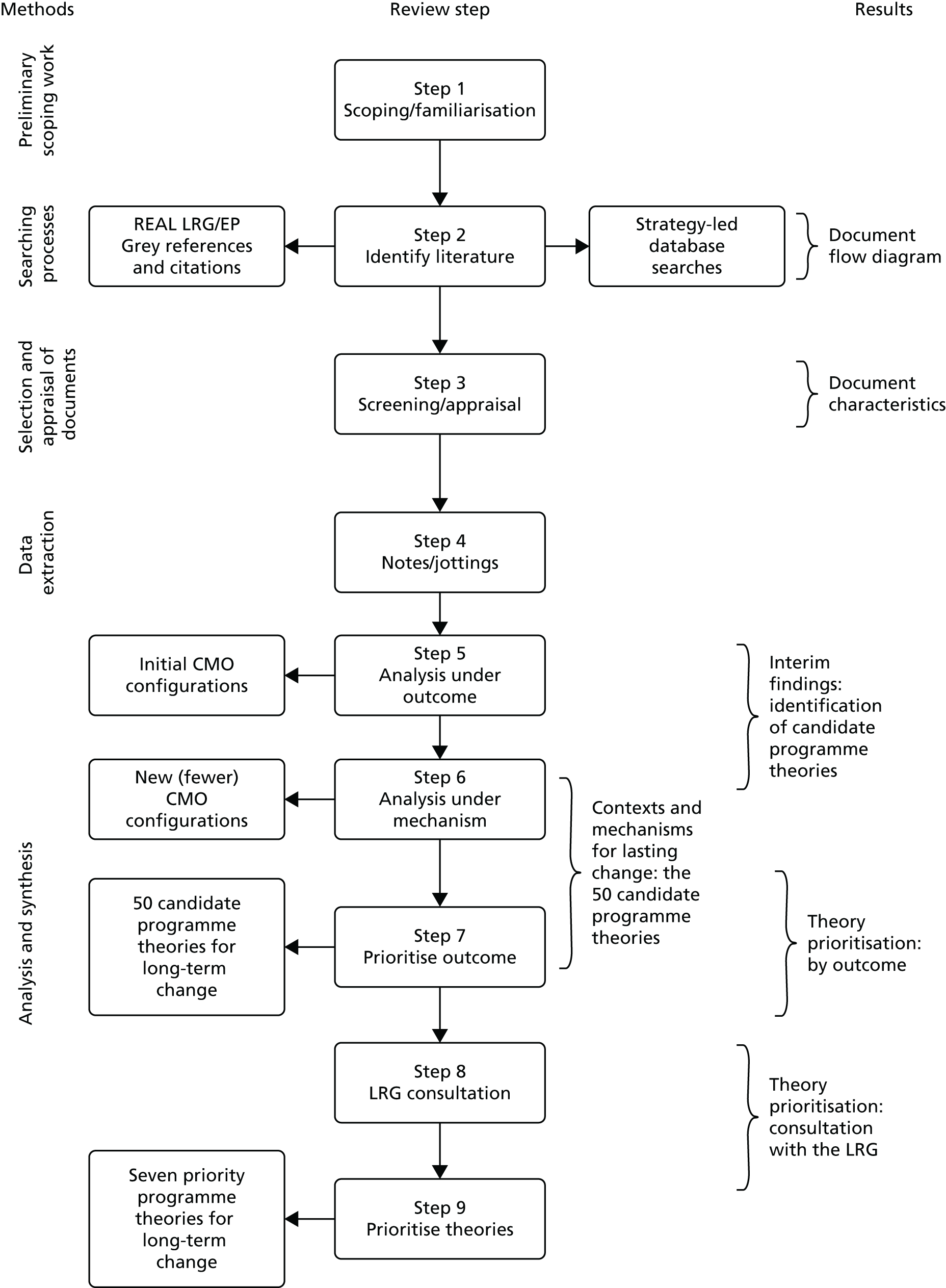

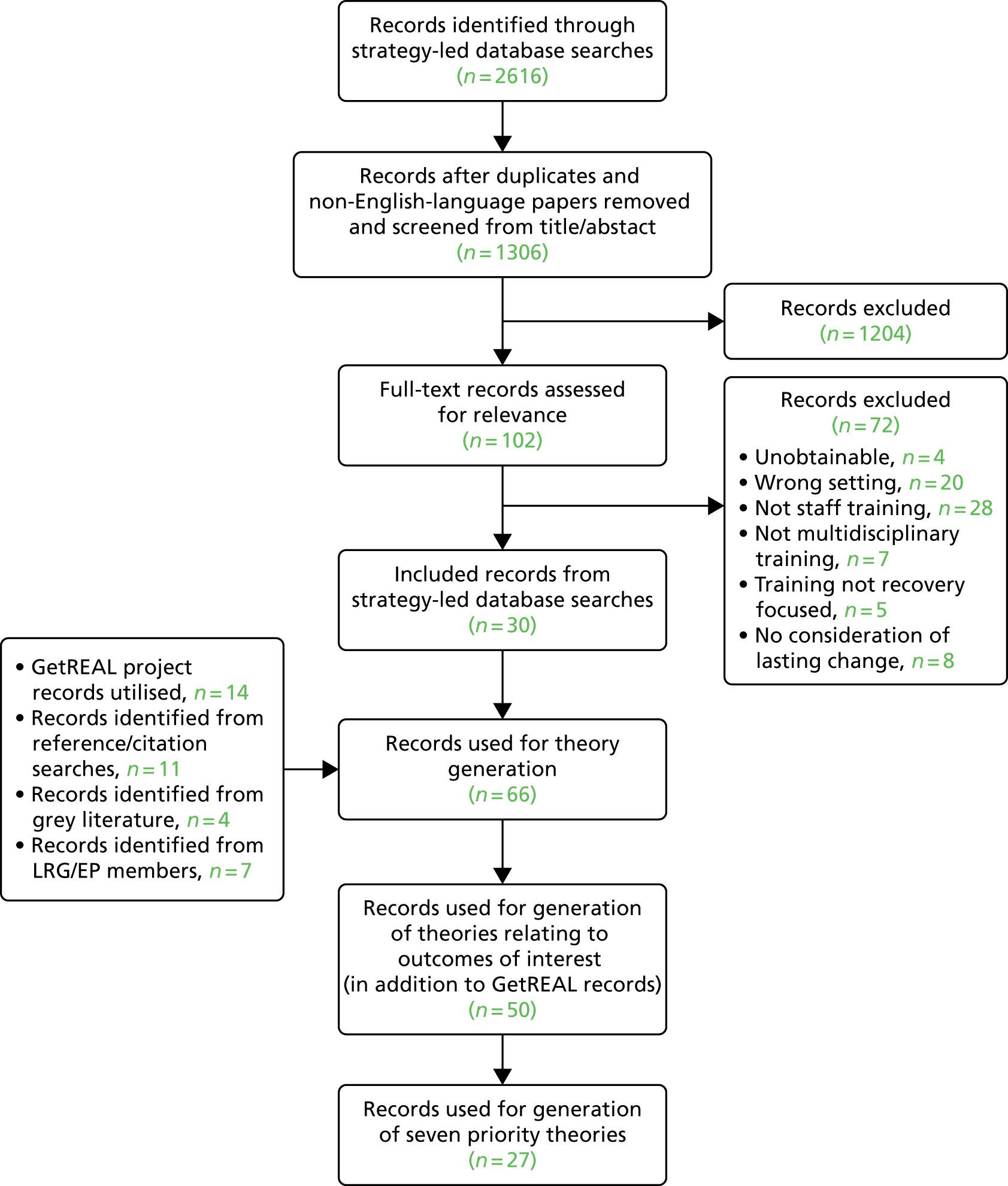

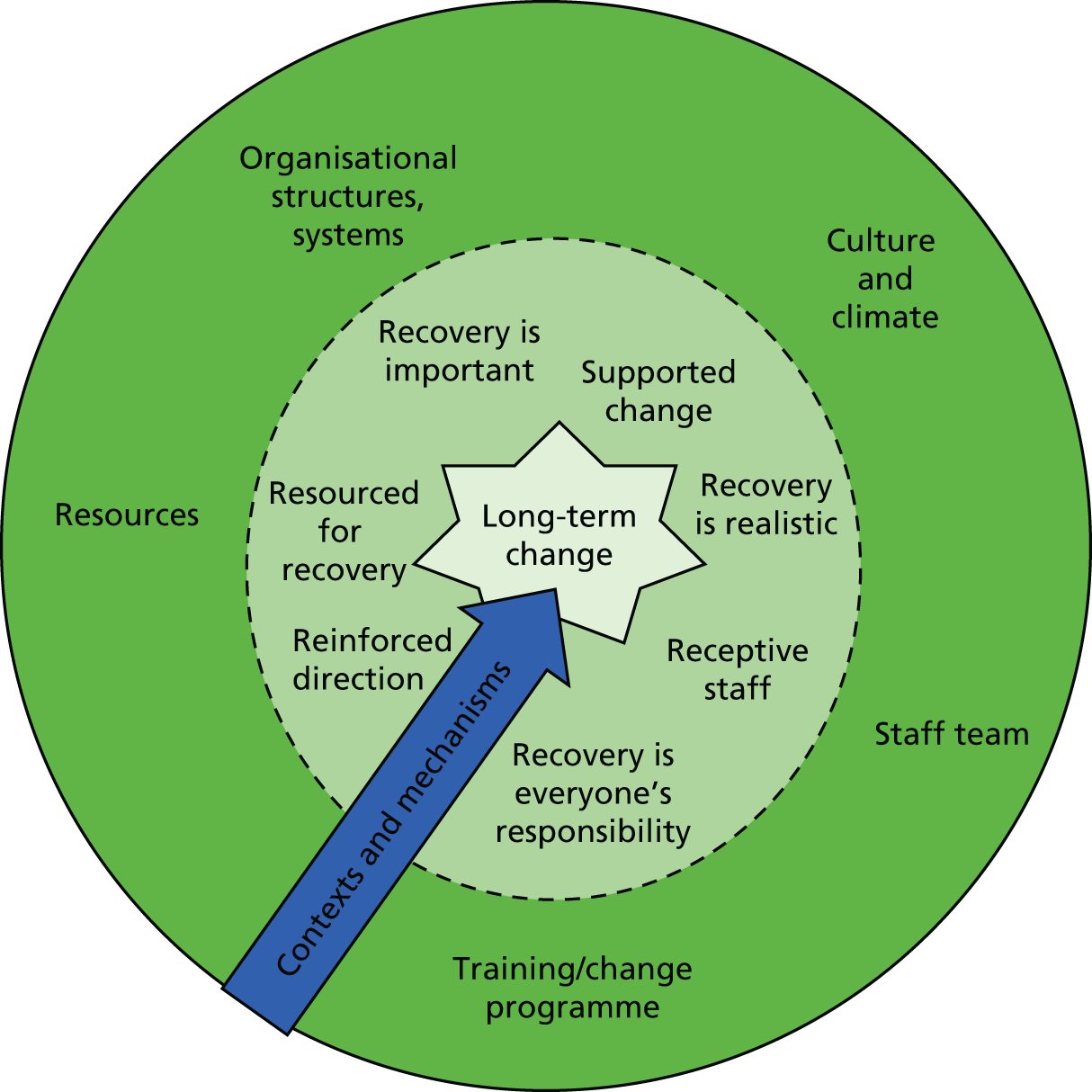

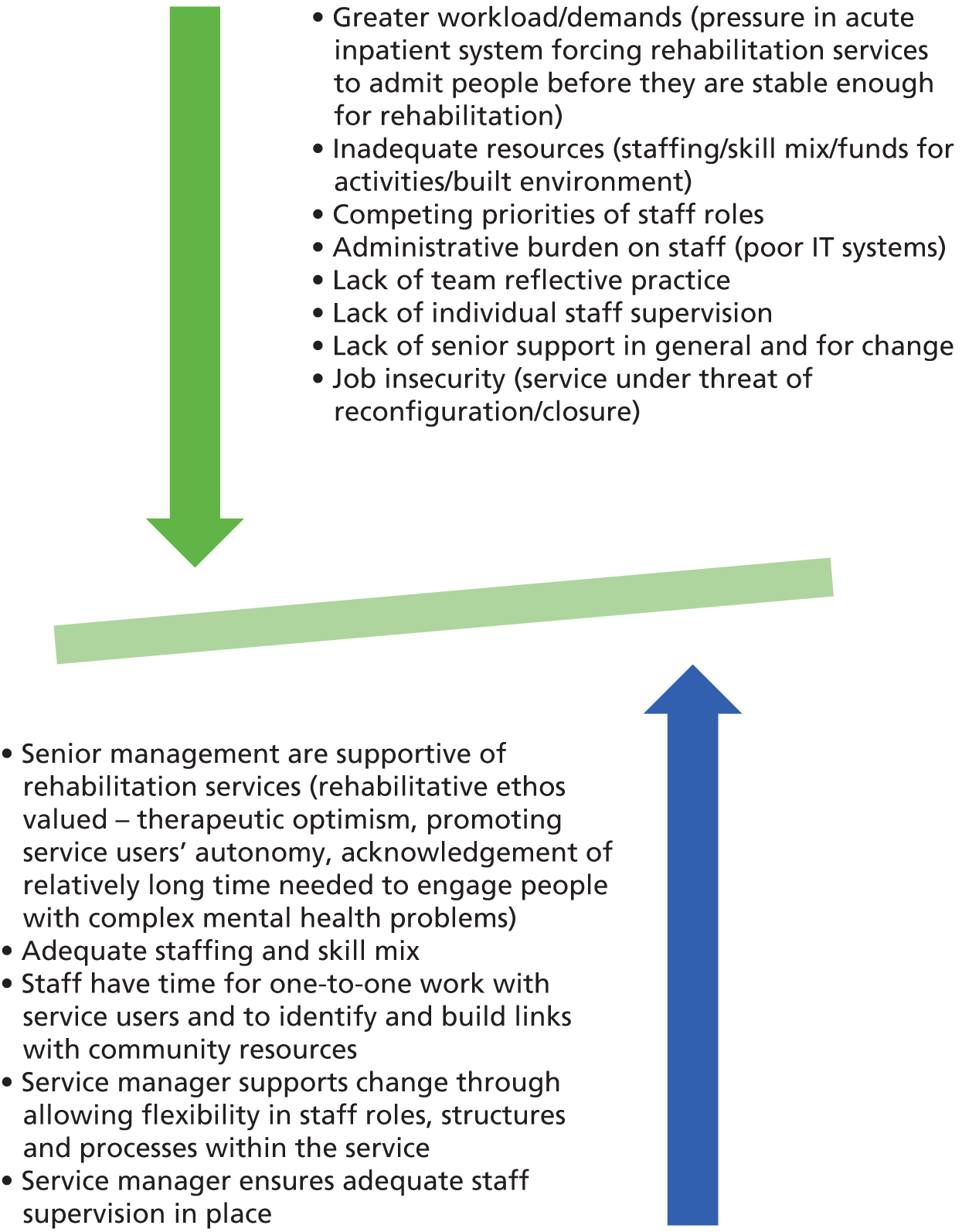

The ‘realistic evaluation’ was an additional component to the programme that was undertaken to increase our understanding of the resuts of phase 3 of the programme, the cluster randomised controlled trial.

There were three aims:

-

to investigate factors associated with variation in units sustaining the skills and changes in practice during the reinforcing stage of the GetREAL intervention

-

to investigate whether or not uptake of the intervention, particularly during the reinforcing stage, was associated with outcome

-

to recommend modifications to the GetREAL intervention for testing in a future trial.

Application for ethics approval for the realistic evaluation was made in March 2014 and appproval was received on 15 July 2014 from the Faculty Research Ethics Committee at Sheffield Hallam University (reference 2013–4/HWB/HSC/STAFF/19/SHUREC1). Three part-time researchers were employed to carry out this component: Sadiq Bhanbhro (0.8 full-time equivalent), a senior researcher, and Melanie Gee (0.4 full-time equivalent), an information scientist, were both employed from 2 June 2014 to 31 March 2015, and Helen Brian (0.3 full-time equivalent), a research assistant, was employed from 14 July 2014 to 31 March 2015.

Chapter 2 Phase 1: national scoping exercise of rehabilitation services

Method

Phase 1 commenced in July 2009. The researchers contacted each service identified during the preparatory phase to gain consent from the service manager for the unit’s potential participation in phase 1. Services that agreed were then visited by one of the two researchers for up to 1 week in order to gain informed consent from the unit manager, from whom detailed descriptive data about the unit were gathered, and an assessment of its quality was made using the Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care (QuIRC).

The QuIRC was developed through an international study conducted between 2007 and 2010, led by HK and funded by the European Commission: the Development of a European Measure of Best Practice in Institutional Care (the DEMoBinc project). 39 It is a standardised, reliable and comprehensive toolkit for the assessment of the quality of inpatient and community-based units for people with longer-term mental health problems. During the project, a systematic review of the international literature and care standards pertaining to longer-term mental health units was carried out,40 along with a three-stage international Delphi exercise involving service users, carers, mental health professionals and advocates in 10 European countries41 to ascertain the ‘critical ingredients’ for recovery for this service user group. The QuIRC was designed to assess these aspects of care. It is completed by the unit manager through a face-to-face interview and takes 45–60 minutes to complete. It comprises 145 questions that are collated to give percentage ratings of seven domains of care (living environment, therapeutic environment, treatments and interventions, self management and autonomy, social inclusion, human rights and recovery-based practice). These ratings include data on the setting (hospital or community) and size (number of beds) of the unit; the average length of stay; the proportion of male and female service users; the proportion of service users detained under the Mental Health Act;42 the degree of disability of service users; the staffing of the unit (staff numbers of different disciplines); staff training in rehabilitative skills (e.g. CBT, family interventions, recovery-based practice and motivational interviewing); the provision of staff supervision; staff turnover, vacancies and disciplinaries; the unit’s provision of evidence-based pharmacological and psychosocial interventions, occupational therapy and the facilitation of community activities (education, employment and leisure); interventions for physical health care and promotion (such as smoking cessation programmes, dietary advice, and access to and support for exercise); the therapeutic milieu; collaborative and individualised care planning; service users’ involvement in their own care and the running of the unit; the protection of service users’ human rights, including their privacy and dignity, access to advocacy; the response to challenging behaviours including the use of de-escalation, control and restraint, and seclusion; and the quality of the built environment. The QuIRC has excellent inter-rater reliability,43 and the ratings gained from the unit manager have been shown to reflect service users’ experiences of care and the degree to which the unit promotes their autonomy. 44

Each service received a detailed report on the quality of its service. These reports were generated by the web-based QuIRC application (www.quirc.eu): data were entered by the project manager and a 12-page PDF report was produced for each unit, which first described the unit and then reported its performance on the seven domains of care as percentages, displayed on a ‘spider web’-style diagram. The mean percentage scores are shown for the unit alongside those of all similar (hospital or community based) mental health rehabilitation units in England. Further details were then given on the aspects of care assessed in each domain so that the staff could reflect on how they could potentially improve their unit’s rating.

Additional data on the diagnostic and risk profile of service users were gathered from unit managers in an anonymised, aggregated form. The managers also gave details of the unit’s annual budget; the unit’s assessment process for new referrals; the number of serious incidents in the preceding 12 months; the provision of local community rehabilitation services; the provision of local supported accommodation; the number of service users discharged to different types of unsupported/supported accommodation in the last 12 months locally and elsewhere; and the involvement of the consultant rehabilitation psychiatrist in funding/placement panels for service users requiring supported accommodation and in reviews of service users placed outside the local area.

A rating of the psychiatric morbidity of the area served by the unit was also made using the Mental Illness Needs Index (MINI)45 relevant to the postcode for each unit. This index provides a rating of psychiatric morbidity based on socioeconomic demographic data from the 2001 census, with a standardised mean of 1.0. A MINI rating of 1.2 represents an area with mental health needs 20% higher than the national average.

Service users who gave informed consent participated in a research interview that took approximately 30 minutes. After collecting sociodemographic data, confirming diagnosis and length of history from the case notes, the researchers interviewed service users to rate their autonomy, quality of life and experiences of care and the therapeutic milieu of the unit. Autonomy was assessed using the Resident Choice Scale (RCS);46 the service user rates the degree to which they have choice over 22 aspects of daily activities and the running of the unit on a four-point scale (‘I have no choice at all about this’, ‘I have very little choice about this’, ‘I can express a choice about this but I do not have the final say’ and ‘I have complete choice about this’). The RCS has a maximum possible score of 88. Quality of life was assessed using the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA);47 the service user rates 12 aspects of their life on a scale from 1 (couldn’t be worse) to 7 (couldn’t be better), and a total mean score of between 1 and 7 is generated. Their experiences of care were assessed using the Your Treatment and Care (YTC)48 questionnaire, which has been used in the UK in service user-led assessments of mental health services. The service user rates 25 items related to their care (e.g. ‘I know who my doctor is’) as ‘yes, ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’. The total number of ‘yes’ answers is summed, giving a maximum possible score of 25. Service users’ views on the unit’s therapeutic milieu were assessed using the General Milieu Index (GMI);49 the service user rates their general satisfaction with the unit, with staff and with other residents, and the degree to which they feel the unit facilitates their confidence and abilities, on a scale of 1 to 5 (from ‘not at all’ to ‘very much’), and a total mean score between 5 and 25 is generated. An assessment of service user function was also made by the researcher using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale50 to take this into account as a potential mediator between service quality and clinical outcomes. All service user interviews were completed within 1 month of the unit manager interview.

Data analysis

The specific research questions we detailed in our original proposal that would be addressed in phase 1 were:

-

What is the current provision of rehabilitation services in England?

-

Does it reflect relative levels of socioeconomic deprivation and variation in clinical need?

-

What is the range of quality of rehabilitation services in England?

-

What are the characteristics of the users of these services, and do they vary between services?

-

Do areas with poorer-quality rehabilitation services have higher proportions of service users placed out of area?

To address these questions, a subgroup of the PMG (the chief investigator, the study statisticians and Professor King) agreed on the data analysis plan for phase 1 (see Appendix 1) with the following four objectives:

-

to determine the current provision and quality of inpatient mental health rehabiliation units in England

-

to describe the characteristics of users of these services

-

to investigate whether or not unit quality is related to service user characteristics and the psychiatric morbidity of the local area

-

to investigate whether or not service user outcomes are related to the quality of the unit.

The study statisticians, RO and LM, carried out the data analyses using Stata version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive data reporting on our first two objectives are presented as frequencies and percentages or means and standard deviations (SDs), as appropriate.

With regard to our third objective, multiple linear regression was used to investigate which covariates were associated with unit quality (QuIRC domain scores). Our sample size (133 units) allowed us to estimate up to eight coefficients in each model, using the rule of 15 observations per coefficient estimated to achieve adequate precision. The covariates selected a priori were location of unit (hospital or community; units within hospital grounds were recategorised as community, as previously they were found to be more similar in profile to community-based units than to hospital wards);43 psychiatric morbidity of the area local to the unit; percentage of male service users; mean age of service users; service users’ mean GAF score; and percentage of service users detained involuntarily.

Our fourth objective was to investigate whether or not unit quality (QuIRC domain scores) was associated with service user outcomes, namely autonomy (RCS), quality of life (MANSA), experiences of care (YTC) and therapeutic milieu (GMI). Our sample included 739 service users, with 616 service users having complete data on all variables. Using an intracluster correlation of 0.04, an average cluster size of 14 and the rule of 15, this allowed us to estimate up to 27 coeffcients with adequate precision in each model. As YTC data were left skewed, they were categorised into tertiles and analysed using the proportional odds regression with robust standard errors to account for clustering within unit. The assumption of proportional odds required by the model [that the odds ratio (OR) comparing one level of a particular covariate with another level was constant across all categories of the YTC] was satisfied by the data. Other outcomes were analysed using linear marginal models based on generalised estimating equations. 51 All variables (covariates and outcomes) apart from the MANSA had only a small proportion of missing values.

As part of the secondary analyses, we also used multiple imputation based on chained equations52 to estimate the missing MANSA values. To determine which variables were included in the imputation model, all unit and service user variables were first tested univariably using logistic regression models with robust standard errors, allowing for clustering within centres, to examine whether or not they were significantly associated with missing MANSA data (a binary variable was created by allocating 1 to any service user with a missing MANSA value and 0 otherwise). Three unit-level and two service user variables associated with missing MANSA data were identified. The unit-level variables were all from the QuIRC: access to a psychiatrist, other interventions provided and percentage of patients detained involuntarily. The service user variables were ‘would like more leisure time’ and tertiles of the experiences of care measure (YTC). A number of additional variables were included in the model for consistency, as they had been agreed as variables of interest in the models for the other outcomes and for the analysis of MANSA without imputation. For service user level these were age, sex and GAF score, and for unit level these were MINI score for the area local to the unit, all QuIRC domain scores, a dichotomous variable to indicate whether or not the unit had ≥ 4 domains scoring less than the national median, and location of the unit (hospital or community). To control for clustering of the data within centres in the imputation model, an estimate of the random effects (obtained by fitting a multilevel model) was also added. As with the complete case analysis, the age, sex, GAF score and location of the unit and each QuIRC domain separately (seven models) were included in the marginal model based on generalised estimating equations after multiple imputation.

The results of these analyses are expressed per 10 percentage point change in QuIRC domain score.

Results

Response

All of the 60 NHS mental health trusts in operation in England in 2009 had at least one inpatient (or community-based equivalent) mental health rehabilitation unit. Three trusts declined to participate in the study, two failed to complete local research governance approval within the phase 1 study period and, therefore, could not be included, and three trusts closed their rehabiliation units prior to participation. The response rate was, therefore, 87% (52/60). A total of 133 units were identified, with a median of two units per trust [interquartile range (IQR) 1–2]. These units had a total of 1809 beds, of which 1641 (91%) were occupied. A total of 442 service users occupied beds that were designated respite or continuing care. Of the remaining 1199 service users, 129 (11%) lacked the capacity to be able to give informed consent to participate in a research interview, 20 (2%) lacked adequate English for participation, 108 (9%) were unavailable as they were on planned leave from the unit, 12 (1%) were unavailable as they were absent from the unit without leave, 191 (16%) declined to participate and 739 (62%) were interviewed. The response rates of service users across units ranged from 40% to 100% but were not found to have any association with unit quality (QuIRC domain scores).

Unit characteristics

The unit characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority of units were based in suburban areas in the community, and they had a mean of 14 beds and a mean of 16 admissions in the previous year. Overall, 124 (93%) units provided single bedrooms only and 85% provided separate women-only and mixed-sex communal areas. Most service users were admitted from acute admission wards or directly from the community, with a small number coming from secure settings. Overall, 42% of units used standardised measures in their assessment process and 89% used them routinely after admission. All units had input from a psychiatrist and all units were staffed by nurses and support workers, but 21 (17%) had no access to a clinical psychologist and 13 (10%) had no access to an OT. The total mean staff per unit was 21 (SD 6), and a mean of 20% (SD 15%) had left in the previous 2 years. The mean staff-to-service user ratio was 1.58 (SD 0.47).

| Characteristic (N = 133) | n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit location | |||

| Inner city | 26 (20) | ||

| Suburbs | 96 (72) | ||

| Rural area | 11 (8) | ||

| Unit type | |||

| Hospital ward | 15 (11) | ||

| Community based | 79 (59) | ||

| Within hospital grounds | 39 (29) | ||

| Unit has max. length of stay | 27 (20) | ||

| Max. length of stay (years), mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.5) | ||

| Staffing (N = 127) | No access | Access outside unit | Works in unit |

| Psychiatrist | 0 | 38 (30) | 89 (70) |

| Clinical psychologist | 21 (17) | 65 (51) | 41 (32) |

| OT | 13 (10) | 21 (17) | 93 (73) |

| Nurse | 0 | 0 | 127 (100) |

| Support worker | 0 | 0 | 127 (100) |

| Social worker | 27 (21) | 93 (73) | 7 (6) |

| Volunteer | 67 (53) | 41 (32) | 19 (15) |

| Arts therapist | 66 (52) | 53 (42) | 8 (6) |

| Ex-service user(s) work in unit | 40 (31) | ||

| Ex-service user(s) on payroll (n = 37) | 24 (65) | ||

| Years unit open, mean (SD) | 10 (6) | ||

| Beds | Mean (SD) | ||

| Beds available in the unit | 14 (5) | ||

| Beds occupied | 13 (5) | ||

| Percentage of beds occupied | 91 (12) | ||

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ||

| New admissions last 12 months | 16 (17) | 10 (6–19) | |

| From acute wards | 9 (8) | 6 (3–11) | |

| From community | 5 (13) | 1 (0–3) | |

| From low secure units | 1 (2) | 1 (0–1) | |

| From another rehabilitation unit | 1 (2) | 0 (0–2) | |

| Unit manager views on service user functioning (N = 132) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| % service users able to do most things without assistance | 48 (31) | 41 (25–74) | |

| % service users able to do some things without assistance | 38 (29) | 33 (19–50) | |

| % service users able to do very little without assistance | 14 (17) | 9 (0–25) | |

| % service users who are difficult to engage with | 34 (23) | 29 (19–47) | |

| Unit manager estimates of service user interventions | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| % families receiving psychoeducation (N = 128) | 10 (21) | 0 (0–12) | |

| % service users receiving CBT (N = 124) | 14 (27) | 0 (0–18) | |

| Hours per day service users spend doing planned activity | 4 (1.6) | 4 (3–5) | |

| % service user who regularly participate in activities on unit | 76 (24) | 80 (63–100) | |

| % service users who regularly participate in activities in community | 70 (31) | 75 (47–100) | |

| Local supported accommodation beds | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| Nursing homes | 18 (19) | 14 (2–30) | |

| Residential care homes | 44 (58) | 22 (1–75) | |

| 24-hour supported tenancies | 30 (77) | 13 (1–30) | |

| < 24-hour supported tenancies | 38 (30) | 40 (10–66) | |

| Floating outreach | 37 (83) | 20 (2–36) | |

| Discharges in last 12 months | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | |

| Nursing homes | < 1 (1) | 0 (0–1) | |

| Residential care homes | 1 (1) | 1 (0–2) | |

| 24-hour supported tenancies | 2 (3) | 1 (0–3) | |

| < 24-hour supported tenancies | 1 (3) | 0 (0–2) | |

| Floating outreach | 1 (2) | 0 (0–1) | |

| Other | 4 (8) | 1 (0–3) | |

| Out-of-area placement | 1 (1) | 0 (0–1) | |

| Service users ready for discharge, awaiting suitable accommodation | 2 (2) | 2 (1–3) | |

| QuIRC domain scores (possible range 1–100%; N = 133) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Living environment | 73 (10) | ||

| Therapeutic environment | 68 (6) | ||

| Treatments and interventions | 62 (6) | ||

| Self-management and autonomy | 73 (9) | ||

| Recovery-based practice | 71 (9) | ||

| Social inclusion | 63 (12) | ||

| Human rights | 75 (8) | ||

A mean of 1 (SD 2) member of staff was trained in family psychoeducation and a mean of 1 (SD 2) service user was receiving this intervention in each unit. A mean of 1 (SD 2) member of staff was trained in CBT and 2 (SD 3) service users were receiving it per unit. Most (85%) unit managers reported that their service users usually received < 10 CBT sessions. All units used individualised care plans and 126 (95%) provided individualised programmes of activities. Most (95%) unit managers reported that their service had links with local community sports facilities. A wide range of other community links was also reported: 74% of units had links with local churches or other religious organisations, 61% had links with local entertainment venues such as cinemas, 53% had links with local cafés and 20% had links with other community organisations. In 18% of units, at least one service user was reported to be attending a mainstream employment scheme and a mean of 1 (SD 1) service user was attending a local college. Overall, a mean of 70% (SD 22%) of service users in each unit were prescribed atypical antipsychotic medication. Very few were prescribed more than two antipsychotic medications (25 service users across all units) and a mean of 33% (SD 20%) were prescribed clozapine.

There were few serious incidents (n = 35) or staff disciplinaries (n = 21) in the preceding 12 months across all units. Of those unit managers who answered the question, 30 out of 96 (31%) reported that the consultant psychiatrist was involved in agreeing funding of out-of-area placements, and 58 out of 98 (59%) reported that they were involved in reviewing people placed outside the local area. Half of the unit managers who answered the question reported that the service had a local community rehabilitation team (53/104, 51%).

Service user characteristics

The majority of service users were white men, with a mean age of 40 years, a median 13-year history of contact with mental health services, and four previous admissions. The majority had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (81%). The median length of the current admission was 18 months, and one-third of service users were currently detained involuntarily. Almost half had a previous history of self-neglect or self-harm, and over half had a history of assault on others. There were very high levels of satisfaction with care (YTC) and the average GAF score suggested moderate levels of symptoms and impairment of social and occupational functioning (Table 2).

| Characteristic (N = 739) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 40 (13) |

| Male | 475 (64) |

| White | 595 (81) |

| Age at leaving full-time education (years), mean (SD) | 17 (2) |

| Employment (N = 739) | |

| Employed (paid or voluntary) | 8 (1) |

| Unemployed | 679 (92) |

| Retired | 32 (4) |

| Other | 20 (3) |

| Living situation before admission (N = 735) | |

| Alone | 134 (18) |

| With partner | 22 (3) |

| With parents | 79 (11) |

| With children aged ≤ 18 years | 5 (1) |

| With children aged > 18 years | 9 (1) |

| Other | 486 (66)a |

| Housing before admission (N = 738) | |

| Owner–occupier | 86 (12) |

| Rented flat/house | 126 (17) |

| Hostel | 33 (4) |

| Sheltered | 12 (2) |

| Residential home | 14 (2) |

| Hospital ward | 459 (62) |

| No fixed abode | 8 (1) |

| Diagnosis (N = 702) | |

| Schizophrenia | 511 (73) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 57 (8) |

| Bipolar disorder | 59 (8) |

| Other | 75 (11) |

| Psychiatric history, median (IQR) | |

| Years of contact with mental health services (n = 594) | 13 (6–22) |

| Previous admissions (n = 522) | 4 (2–9) |

| Length of current admission (months) (n = 586) | 18 (9–46) |

| Time in rehab unit (months) (n = 572) | 8 (4–19) |

| Mental Health Act status (N = 630) | |

| Detained during this admission | 427 (68) |

| Currently detained | 203 (32) |

| Previous admission to secure unit | |

| High secure unit (n = 599) | 40 (7) |

| Medium secure unit (n = 600) | 84 (14) |

| Low secure unit (n = 601) | 117 (19) |

| Prison (n = 600) | 110 (18) |

| Risk | |

| Assault on others ever (n = 599) | 349 (58) |

| Assault in last 2 years (n = 599) | 127 (21) |

| Serious assault last 2 years (n = 568) | 43 (8) |

| Self-harm ever (n = 604) | 271 (45) |

| Self-neglect (n = 604) | 295 (49) |

| Social inclusion markers | |

| Voted in last general election (n = 736) | 144 (20) |

| Has a bank/PO account (n = 735) | 623 (85) |

| Has charge of own finances (n = 736) | 534 (73) |

| Standardised outcome measures, mean (SD) | |

| Autonomy | |

| RCS (possible range 22–88) (n = 672) | 61 (7) |

| Quality of life | |

| MANSA (possible range 1–7) (n = 616) | 4.6 (0.8) |

| Experiences of care | |

| YTC (possible range 1–25) (n = 711) | 24 (4) |

| Therapeutic milieu | |

| GMI (possible range 5–25) (n = 720) | 18 (4) |

| Social functioning | |

| GAF score (possible range 1–100) (n = 739) | 54 (9) |

Factors associated with unit quality

Table 3 shows that the mean age of service users in a unit was associated with scores in five of the seven QuIRC domains, increasing age being associated with decreasing scores. The largest reduction in QuIRC domain score was in the social inclusion domain, where it decreased by 0.37 percentage points for each year of mean age [95% confidence interval (CI) –0.64 to –0.10 percentage points]. The percentage of service users detained involuntarily was also associated with a decrease in four QuIRC domain scores. The largest reduction was in the self-management and autonomy domain, which reduced by 0.12 percentage points for each percentage point increase in those detained (95% CI –0.17 to –0.06 percentage points). The percentage of men per unit was negatively associated with the social inclusion and therapeutic environment domains, having a greater influence on the former, where for each percentage point increase in male service users the social inclusion domain score reduced by 0.11 percentage points (95% CI –0.20 to –0.03 percentage points). For each point increase in MINI, the living environment domain score decreased by 6.78 percentage points (95% CI –11.09 to –2.47 percentage points). Units located in the community had a therapeutic environment score 3.58 percentage points higher (95% CI 0.11 to 7.05 percentage points) than hospital-based units after adjusting for other variables in the model.

| Variable | Coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Living environment | |

| Unit based in community (vs. hospital) | 4.47 (–1.08 to 10.03) |

| Male service users (%) | –0.02 (–0.09 to 0.05) |

| Service users’ mean age (years) | –0.12 (–0.33 to 0.09) |

| Service users’ mean GAF score (range 1–100) | 0.01 (–0.26 to 0.28) |

| Service users detained involuntarily (%) | –0.08 (–0.14 to –0.01) |

| Unit location MINI score | –6.78 (–11.09 to –2.47) |

| Therapeutic environment | |

| Unit in community | 3.58 (0.11 to 7.05) |

| Male service users (%) | –0.04 (–0.09 to 0.00) |

| Service users’ mean age (years) | –0.27 (–0.40 to –0.14) |

| Service users’ mean GAF score | 0.10 (–0.07 to 0.27) |

| Service users detained involuntarily (%) | 0.00 (–0.04 to 0.04) |

| Unit location MINI score | –0.07 (–2.77 to 2.62) |

| Treatments and interventions | |

| Unit in community | 2.97 (–1.13 to 7.07) |

| Male service users (%) | –0.03 (–0.08 to 0.02) |

| Service users’ mean age (years) | –0.19 (–0.34 to –0.03) |

| Service users’ mean GAF score | 0.04 (–0.16 to 0.24) |

| Service users detained involuntarily (%) | 0.02 (–0.03 to 0.07) |

| Unit location MINI score | –0.27 (–3.45 to 2.91) |

| Self-management and autonomy | |

| Unit in community | 2.15 (–2.45 to 6.75) |

| Male service users (%) | –0.02 (–0.08 to 0.04) |

| Service users’ mean age (years) | –0.18 (–0.35 to –0.01) |

| Service users’ mean GAF score | 0.08 (–0.14 to 0.30) |

| Service users detained involuntarily (%) | –0.12 (–0.17 to –0.06) |

| Unit location MINI score | –2.82 (–6.38 to 0.75) |

| Human rights | |

| Unit in community | –0.75 (–5.44 to 3.94) |

| Male service users (%) | –0.02 (–0.08 to 0.03) |

| Service users’ mean age (years) | –0.08 (–0.26 to 0.10) |

| Service users’ mean GAF score | 0.12 (–0.11 to 0.35) |

| Service users detained involuntarily (%) | –0.08 (–0.13 to –0.02) |

| Unit location MINI score | –1.50 (–5.14 to 2.13) |

| Recovery-based practice | |

| Unit in community | 3.84 (–1.04 to 8.72) |

| Male service users (%) | –0.05 (–0.12 to 0.01) |

| Service users’ mean age (years) | –0.25 (–0.44 to –0.07) |

| Service users’ mean GAF score | 0.13 (–0.11 to 0.36) |

| Service users detained involuntarily (%) | –0.07 (–0.13 to –0.01) |

| Unit location MINI score | –0.28 (–4.06 to 3.50) |

| Social inclusion | |

| Unit in community | 3.09 (–4.01 to 10.19) |

| Male service users (%) | –0.11 (–0.20 to –0.03) |

| Service users’ mean age (years) | –0.37 (–0.64 to –0.10) |

| Service users’ mean GAF score | 0.09 (–0.25 to 0.44) |

| Service users detained involuntarily (%) | 0.01 (–0.07 to 0.09) |

| Unit location MINI score | –4.21 (–9.72 to 1.29) |

Unit quality and clinical outcomes

Very few service users were discharged from the rehabilitation service to an out-of-area placement (see Table 1), but unit managers were unable to provide data on the number of service users placed out of area by other services in their trust. Data were, therefore, not available for the investigation of the association between unit quality and the use of out-of-area placements. With regard to other service user outcomes, clear associations were found. Most QuIRC domains were positively associated with experiences of care (YTC) (Table 4). For example, a 10 percentage point increase in the treatments and interventions domain score resulted in an odds of 1.56 (95% CI 1.17 to 2.08) for scoring in the highest tertile on the YTC compared with the lower two tertiles. All QuIRC domains were positively associated with autonomy (RCS). The largest of these associations was for the therapeutic environment domain, for which a 10 percentage point increase was associated with an increase in the RCS of 3.43 (95% CI 2.04 to 4.81) points. All QuIRC domains were significantly associated with service users’ ratings of the units’ therapeutic milieu (GMI). Here the QuIRC domain with the strongest influence was therapeutic environment, where a 10 percentage point increase was associated with an increase in GMI of 1.18 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.75 points). The quality-of-life scores (MANSA) appeared to be associated with living environment and self-management and autonomy, but here a 10 percentage point increase was associated with very small increases in MANSA scores. Repeating this analysis using imputed MANSA data gave similar results.

| Variable | ORa or coefficientb (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Experiences of care (YTC)a | |

| Living environment | 1.27 (1.05 to 1.54) |

| Therapeutic environment | 1.50 (1.09 to 2.08) |

| Treatments and interventions | 1.59 (1.19 to 2.13) |

| Self-management and autonomy | 1.43 (1.15 to 1.77) |

| Human rights | 1.34 (1.06 to 1.69) |

| Recovery-based practice | 1.20 (0.98 to 1.48) |

| Social inclusion | 1.34 (1.15 to 1.56) |

| Autonomy (RCS)b | |

| Living environment | 1.75 (0.83 to 2.67) |

| Therapeutic environment | 3.43 (2.04 to 4.82) |

| Treatments and interventions | 3.19 (1.98 to 4.41) |

| Self-management and autonomy | 2.37 (1.42 to 3.33) |

| Human rights | 2.24 (1.16 to 3.32) |

| Recovery-based practice | 2.38 (1.50 to 3.25) |

| Social inclusion | 2.06 (1.44 to 2.68) |

| Therapeutic milieu (GMI)b | |

| Living environment | 0.73 (0.33 to 1.12) |

| Therapeutic environment | 1.20 (0.62 to 1.77) |

| Treatments and interventions | 0.68 (0.10 to 1.26) |

| Self-management and autonomy | 1.10 (0.72 to 1.47) |

| Human rights | 0.92 (0.45 to 1.38) |

| Recovery-based practice | 0.85 (0.47 to 1.22) |

| Social inclusion | 0.44 (0.17 to 0.71) |

| Quality of life (MANSA)b (complete case) | |

| Living environment | 0.09 (0.02 to 0.15) |

| Therapeutic environment | 0.02 (–0.13 to 0.17) |

| Treatments and interventions | 0.00 (–0.14 to 0.16) |

| Self-management and autonomy | 0.09 (0.01 to 0.17) |

| Human rights | 0.04 (–0.06 to 0.15) |

| Recovery-based practice | 0.03 (–0.05 to 0.12) |

| Social inclusion | 0.00 (–0.06 to 0.06) |

| Quality of life (MANSA)b (imputed) | |

| Living environment | 0.09 (0.01 to 0.17) |

| Therapeutic environment | 0.03 (–0.12 to 0.18) |

| Treatments and interventions | 0.01 (–0.14 to 0.16) |

| Self-management and autonomy | 0.10 (0.02 to 0.18) |

| Human rights | 0.06 (–0.05 to 0.17) |

| Recovery-based practice | 0.05 (–0.04 to 0.13) |

| Social inclusion | 0.00 (–0.07 to 0.06) |

Discussion

The national survey component of phase 1 represents the first in-depth study of NHS mental health rehabilitation units in England. The high participation rate strengthens the generalisability of our findings. However, we acknowledge that there are many rehabilitation units in the independent sector that were not included in this study (owing to the limitations of our resources), and we were also unable to include NHS units that were designated as ‘forensic’, ‘secure’ or ‘locked’ rehabilitation. Our initial estimate of the number of NHS inpatient mental health rehabilitation units likely to be in operation was based on our previous telephone survey of practitioners in this field,19 which suggested that there would be around 90 units. However, during the scoping phase of our national survey, we identified 150 NHS mental health rehabilitation units. We decided to aim to include them all and therefore made the decision that we could not expand our study to include secure or independent sector facilities. We were also aware that the independent sector may be a less stable setting for the longer-term aspects of our programme, being perhaps subject more to ‘market forces’ than the NHS.

We found that all NHS trusts had at least one rehabilitation unit catering for a group with particularly complex needs; the relatively high levels of clozapine prescription and extended length of admission corroborate previous descriptions of the treatment-resistant nature of illness in this service user group. 6 Around half required assistance with some or most activities, and one-third was difficult to engage in activities.

Although the recommended range of supported accommodation needed to help individuals move on to more independent living53 was usually provided, ‘delayed discharges’ affected about 14% of service users, suggesting inadequate provision of local supported accommodation and ‘silting’ of the care pathway. Service users were discharged only rarely from a rehabilitation unit to an out-of-area placement, but the local psychiatrist with responsibility for the rehabilitation service was commonly not represented on the local placement panel. Current guidance emphasises the importance of this involvement in ensuring the appropriate placement of service users in facilities that are tailored to their needs, that opportunities for local treatment and support have been fully explored prior to a placement being made out of area, and that there is ongoing review of an individual’s suitability for local repatriation at the earliest opportunity. 54 Our results suggest that this guidance is inadequately followed.

Units with a higher proportion of older patients, male patients and patients detained involuntarily were of poorer quality, although the degree of association between these service user characteristics and service quality was small. However, the psychiatric morbidity of the local area had a greater impact on service quality than the nature of the users placed there, although it influenced only one quality domain, namely the living environment. As areas with greater deprivation tend to have higher levels of psychiatric morbidity,45 there may be a greater pressure on resources in these areas, with less available for investment in the built environment. Community-based units appeared to fare better than inpatient units on only one domain of quality (therapeutic environment), corroborating previous reports of the less ‘institutional’ culture of non-hospital settings. 40 However, our findings suggest that, in all other respects, the rehabilitation delivered in hospital-based units was of a similar quality to that in community-based units.

Most unit managers reported high levels of participation in activities on and off the unit, despite around one-third of service users being difficult to engage. The high level of individualised activity programmes may have facilitated this. However, very few service users were receiving psychological interventions as recommended by NICE. 7 This is not surprising, as few staff were adequately trained to deliver these. In the current economic context, further investment in clinical psychologists seems unlikely, but a greater focus on training and supervising nurses and other staff to deliver psychological interventions has been shown to be possible in some psychosis services,55 although problems with sustainability have also been identified. 56,57 This might include so-called ‘low-intensity’ psychological interventions that, although lacking a strong evidence base, may be easier for service users with complex mental health problems to engage with and assist with addressing some of the comorbidities and other issues that impede progress towards successful community discharge (e.g. anxiety management, relapse prevention, motivational interviewing).

There were strong indications that the quality of care provided by units was associated with service users’ autonomy, experiences of care and perception of their therapeutic environment, although it was not associated with quality of life. The cross-sectional nature of our data means that we cannot be sure of the direction of these associations, but they are encouraging. Although it may be difficult to prevent the destructive impact of chronic psychotic illness on quality of life, it seems that rehabilitation services are providing a positive experience of care that facilitates individuals’ autonomy. In addition, the quality-of-life measure we used considers social and community aspects of life that may simply be outside the current experiences of this service user group, who, because of the severity of their symptoms and impairments, have been admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation unit. Our cross-sectional data could not assess the longitudinal associations between the quality of rehabilitation services and service users’ quality of life, but these were explored in later phases of the REAL research programme.

Our findings represent the first comprehensive description of NHS mental health rehabilitation services in England and provide national ‘quality benchmarking’ data for these services. We found a positive association between quality of care and clinical outcomes in these services, suggesting that interventions that improve the quality of care provided are likely to promote service users’ autonomy and experiences of care. As the promotion of autonomy is the main goal of rehabilitation,19,53 ongoing investment in these services is needed to continue to deliver high-quality care that promotes service users’ recovery and abilities so that they can leave hospital and live as independently as possible in the community. Additional investment in the local supported accommodation pathway is, therefore, also needed to ensure that service users have an appropriate place to move on to when they are ready to leave the rehabilitation unit.

Finally, this phase of the REAL study has also shown that collection of comprehensive service quality assessment data on a national scale is possible when a tailored, reliable and well-validated tool is available. The QuIRC has been incorporated into the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Accreditation for Inpatient Mental Health Services, which ensures that the ongoing standardised assessment of the quality of these services can continue.

Phase 1 health economic component

Phase 1 also included an investigation of the costs of care for inpatient mental health rehabilitation service users.

Staffing levels and staff contacts

Data on staffing levels in rehabilitation units were obtained from a senior staff member by the researchers during phase 1 data collection, as described previously. Information on whether or not service users had access to staff of different disciplines, as well as on the number of full-time equivalent staff members of each discipline employed in the unit, was also collected. Most commonly, these were psychiatrists, nurses, OTs and support workers. Therefore, the health economic component of phase 1 focused on these four ‘core’ disciplines. The costs were calculated based on data on recent salary and on cost estimates for health and social care services in England. 58 As part of the research interviews carried out with service users in phase 1, information on health and social care service use over the previous 4 weeks was collected using an adapted version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI). 59 The data gathered were corroborated through review of the case notes (when informed consent for this was provided). Based on estimates of average group sizes in the study, the unit costs for individual sessions were estimated by dividing the number of group sessions by 3.8 and added to the number of one-to-one contacts to compute the overall number of contacts for the respective professionals.

Statistical analysis

To assess the strength of the association between the quality of care as assessed by the QuIRC43 and staffing levels, product-moment correlation coefficients were calculated. Moreover, we explored the association between service user characteristics and the number of self-reported contacts with the four aforementioned ‘core’ professional disciplines in a complete case analysis. To avoid confounding between individual and unit effects, we used the percentage difference of the staff contacts relative to the unit mean as the dependent variable and the demeaned predictors as independent variables in our regression model. Owing to the highly skewed nature of the service use data, we computed bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap standard errors with 1000 replications. The choice of predictors of service use cost was informed by a review of related studies. 60

Results

As reported earlier, with a response rate of 87%, 52 NHS mental health trusts across England participated in the study. Service use information was collected on a total of 131 units and 739 service users, amounting to 59% of those able to provide consent. The mean (SD) age of service users was 40 years (13 years), and the majority were male (64%) and white European (81%), with 35% currently being detained involuntarily under the Mental Health Act. 42 Schizophrenia was the most common diagnosis (71%), and the mean (SD) GAF score was 54 (9). The units were predominantly community based (59%) and the mean (SD) sample size per unit was 5.6 (2.2).

A mean of 1.57 (SD 0.47) members of staff per bed were employed in the rehabilitation units (Table 5). As expected, most of these were either nurses or support workers; however, there was a relatively large variation in staffing levels between units. Among the ‘core’ staff these two disciplines also accounted for the largest fraction of staffing costs (56% and 27%, respectively). The quality of inpatient care was statistically significantly associated with nurse and overall staffing level, albeit with a relatively low coefficient in absolute terms. With the exception of OT contacts, there was no significant correlation between staffing levels and the mean number of self-report contacts.

| Staff type | Number of full-time equivalent staff per bed | Mean (SE) cost per bed-day | Correlation with QuIRC (p-value) | Correlation with number of mean self-report contacts with the professional (p-value) | n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Min. | Max. | |||||

| Psychiatrist | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.01 | 0.36 | 28 (3) | 0.08 (0.42) | 0.04 (0.66) | 108 |

| OT | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.01 | 0.36 | 10 (1) | 0.02 (0.82) | 0.29 (< 0.01) | 93 |

| Nurse | 0.68 (0.2) | 0.25 | 1.14 | 122 (3) | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.69) | 122 |

| Support worker | 0.63 (0.24) | 0.13 | 1.41 | 58 (2) | 0.08 (0.39) | –0.1 (0.27) | 122 |

| Total number of unit and visiting staff | 1.57 (0.47) | 0.69 | 2.8 | n/a | 0.27 (< 0.01) | n/a | 119 |

The regression results at the service user level, as shown in Table 6, suggest that female service users had 17% (95% CI 2% to 35%) fewer contacts with psychiatrists than did male service users. There was a statistically significant association between nurse contacts and service users’ GAF scores, with every unit increase relative to the unit average associated with a 1% increase in GAF score (95% CI 0.2% to 2.2%). In the regression analysis on OT contacts, if the service user was currently involuntarily detained in the rehabilitation unit they were predicted to have reported 32% fewer contacts with an OT (95% CI 9% to 57%). Finally, for each year of age, service users had 0.9% (95% CI 0.2% to 1.8%) fewer contacts with support workers than the unit average.

| Predictor/statistic | Staff type | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrist contacts (n = 628) | Nurse contacts (n = 630) | OT (n = 548) | Support worker (n = 608) | |||||

| Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Female | –17.1 (8.5) | –34.9 to –1.7 | 10.6 (9.7) | –8.2 to 31.3 | 17.7 (13.4) | –7.6 to 45.3 | 23.7 (13.1) | –1.9 to 50.6 |

| Age | –0.5 (0.3) | –1 to 0.2 | 0.1 (0.3) | –0.5 to 0.8 | –1.2 (0.6) | –2.2 to –0.1 | –0.9 (0.4) | –1.8 to –0.2 |

| GAF score | 0.3 (0.6) | –0.7 to 1.5 | 1.2 (0.5) | 0.2 to 2.3 | 0.9 (0.8) | –0.7 to 2.5 | 0.5 (0.8) | –1 to 2 |

| White European | 18 (13.8) | –9.8 to 43.5 | –1 (13.2) | –26.4 to 25.4 | 24 (18.8) | –14 to 57.1 | 2.5 (18.7) | –39.1 to 36.8 |

| Involuntary admission | 13.5 (9.8) | –4 to 34 | –5.5 (6.2) | –16.4 to 8.1 | –32.2 (12.2) | –56.2 to –8.4 | 7.5 (12) | –13.5 to 31.8 |

Discussion

The health economic component of phase 1 of the REAL study provides an account of staffing levels and service use in a representative sample of NHS mental health rehabilitation units in England. Given the lack of published evidence in this area, this may aid decision-makers in planning processes. In comparison with acute psychiatric care settings in the UK, the number of nurses per bed appeared to be lower in rehabilitation units and the variation of nurses per bed between units was higher. 61 Owing to the cross-sectional nature of the sample, it should be noted that the associations we found are not necessarily causal. We found that nurse staffing levels were positively associated with quality of care. Therefore, it may be of value to consider more carefully the reasons for and consequences of staffing variations in the context of budget allocations. In this study no information on staff seniority was collected and only ‘core’ staff members were considered, which limits the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the reported costings. However, the findings suggest that the share of nurse costs was lower than in those in the only other study on the costs of rehabilitation care that the authors are aware of, which was carried out in Scotland in the 1980s,62 suggesting reduced investment in these services over the last 30 years.

The reasons for the low levels of correlation between staffing levels and mean number of contacts in this study were unclear. Non-response bias, lack of information on contact duration, variations in the number of contacts over time or misclassification of staff types may be part of the explanation. However, it may also suggest that, in a setting in which a certain number of health-care staff is designated to care for service users for a certain proportion of their time, to estimate average resource it may be more effective to measure staffing levels rather than rely on self-report data. This would also suggest that it is of value to go beyond staff ratios or direct measurement of time staff spent with service users, as in previous studies, and consider the perception of the amount of care received from the service user’s perspective. 63

Phase 1 qualitative component

Background

In phase 1 we aimed to examine the current provision of NHS mental health rehabilitation services in England using a cross-sectional, quantitative method. The data gathered would allow an identification of the characteristics of service users and services and an exploration of factors related to service quality. However, such services are inherently complex and influenced by a range of factors, including contextual and cultural factors, that may not be easily explained by quantitative methods alone. The NIHR reviewers of our proposal suggested that we add a qualitative component to section 1 of the research programme to address these issues and that we include a social scientist in our research team. In response to the reviewers’ suggestions, we invited Professor Gerard Leavey to join the team as a coinvestigator. He has extensive expertise in qualitative health services research and has previously collaborated with other members of the research team. One of the researchers, NG, registered for a PhD with the Division of Psychiatry at University College London (supervisors MK and HK) in 2010 and has led the data analysis and write-up of the phase 1 qualitative component as part of his PhD project.

The principal aim of the qualitative component in phase 1 was to identify aspects of policy and practice in mental health rehabilitation that could potentially be included in the GetREAL intervention developed in phase 2. However, we were also interested in the more detailed elements of service provision, structural and cultural, that facilitate excellence in rehabilitation services or, conversely, act as barriers. The objectives of this component were, therefore, to explore staff and service users’ views of the purpose of rehabilitation, their experiences of these services and the facilitators of and barriers to successful rehabilitation.

Method

Recruitment and data collection

We aimed to recruit two or three ‘front-line’ staff and two or three service users from 10–15 units for participation. Ideally, we would have selected units purposively to represent a range of sizes, locations (hospital or community based), geographic spread and quality representative of all units included in phase 1. Similarly, we would, ideally, have selected service users and staff on the basis of characteristics that were representative of our national survey data. However, as the qualitative component was carried out concurrently with the collection of the section 1 national survey data, these characteristics were not available. Nevertheless, we sought to include units of different sizes, locations and geographic locations. Service users were approached for participation with the aim of ensuring maximum variation, with a range of sexes, ages and lengths of stay, and, similarly, staff were approached for recruitment to try to ensure a range of disciplines, seniority, sex and experience. Informed consent was gained from all participants before they were interviewed.

Separate topic guides for staff and service users were developed in consultation with members of the PMG and the North London Service User Research Forum (SURF). These incorporated the ethos of the unit, aspirations and expectations of rehabilitation, the activities available on the unit, links with the community, service users’ access to community resources and activities, and the facilitators of and barriers to successful rehabilitation (see Appendices 2 and 3).

The interview was piloted in two units. A total of four staff and four service users were interviewed, and the data were transcribed. These recordings and transcriptions were reviewed by GL and HK to ensure that the interviews were being carried out consistently and consideration was given to possible amendments to the topic guides. In fact, no amendments were felt to be needed, as, although the interviews were structured to accommodate the core thematic interests set out in the topic guide, they were intended to be flexible, allowing interviewees to introduce new issues for exploration.

Each staff interview lasted around 30 minutes. Service user interviews tended to be shorter. The interviews were recorded, and the project manager and another administrator subsequently transcribed them. In addition, following each visit, the researchers recorded their observations about each unit, taking detailed field notes on the environmental context of the services such as the unit’s location, decor and furnishings, and on staff interaction with patients, the range and type of activities provided and the general ambience of the unit.

Data analysis

The data analaysis was carried out by NG under the supervision of GL and HK. The transcripts were imported into specialist software (Atlas.ti 6; Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) for analysis. As we were not pursuing any particular hypothesis or seeking to develop theory in this component but, rather, to add rich contextual information about the activities, functioning and quality of rehabilitation units, we adopted a straightforward approach to the analysis, using a standard coding and thematic procedure. However, although this assumes a more ‘realist’ approach to the phenomena in question, an interpretive engagement with the data is still possible. A grounded theory approach was not possible because the data for the qualitative component could be collected from units only during visits carried out for section 1 quantitative data collection. As such, interviews were usually undertaken with consideration of the time and availability of staff and service users. In addition, the data had to be collected within the time frame available for section 1 of the REAL study that did not allow time for concurrent qualitative data analysis. It was also recognised that the interviews required a relatively tight structure, constrained by the need to provide information for the development of the intervention in section 2 of the REAL study. Additionally, this type of interview schedule was appropriate, given the staff time limitations and service users’ difficulty with verbal performance due to the negative symptoms of psychosis. For these reasons, a thematic approach was deemed both pragmatic and useful.

Nicholas Green read and coded the transcripts. We began by using the topic guide as the initial coding frame covering the main ares of interest and then added codes and other key themes that were detected in the texts. We then developed an analytical framework to organise the data into themes. Members of the team (NG, HK, GL, IH and ML) discussed the coding and the emergent themes in depth during regular seminars, which also incorporated the exploration of relationships between thematic areas. Thus, we used conceptual maps to explore relationships and connections in the data, and also identified a series of detailed themes that were employed for further analysis.

The themes used to further consider the data were:

-

What ‘helps and hinders’ service users of mental health rehabilitation services in their recovery?

-

What is the nature and quality of the relationships between staff and service users?

-

What are the roles and responsibilities of front-line staff working within mental health rehabilitation units?

-

What are the potential benefits of multidisciplinary working?

-

What are the barriers within and between disciplines with regard to the effective delivery of rehabilitation services?

Results

Characteristics of units, staff and service users interviewed

A total of 26 service user interviews and 22 staff interviews were carried out by the two researchers (NG and IH) between September 2009 and July 2010. Of the service users, 24 of the 26 who completed qualitative interviews had also participated in the quantitative research interviews, the results of which are reported in Chapter 1. The participants were recruited from 12 units across eight trusts. The unit characteristics are shown in Table 7.

| Characteristic | Phase 1 qualitative study units (N = 12), n (%) | All phase 1 units (N = 133), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Unit location | ||

| Inner city | 3 (25) | 26 (20) |

| Suburbs | 7 (58) | 96 (72) |

| Rural area | 2 (17) | 11 (8) |

| Unit type | ||

| Hospital ward | 2 (17) | 15 (11) |

| Community based | 9 (75) | 79 (59) |

| Within hospital grounds | 1 (8) | 39 (29) |

The units ranged in size from 8 to 20 beds, with a mean of 15 beds. Nine units provided facilities for both men and women, and three were male only. Bed occupancy was 92%. All units were staffed by nurses and support workers, and all had a consultant psychiatrist. All but one had at least one OT working on the unit part-time (ranging from 0.2 full-time equivalent to 0.3 full-time equivalent). Only three units had a clinical psychologist working in the unit, but eight of the remaining nine had access to psychology from elsewhere in the trust. Staffing was therefore similar to that in all inpatient rehabilitation units across England.

Of the 22 staff interviewed, 15 were nurses (three of these were unit managers), three were OTs, three were support workers and one was an activity worker. Twelve of the staff interviewed were female and all but one were white European. Their mean age was 40 years (range 22–56 years).

The service user participant characteristics are shown in Table 8. Two-thirds of the 26 service users interviewed were male, with a mean age of 35 years. The majority had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The mean length of stay on the unit was 15 months (range 4 months to 4 years). Overall, those who participated in qualitative interviews were generally similar to service users of all inpatient rehabilitation units across England, except that fewer were currently detained under the Mental Health Act42 (4% vs. 32%).

| Characteristic | Phase 1 qualitative study participants (N = 26), n (%) | All phase 1 service users (N = 739), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 35 (11) | 40 (13) |

| Male | 19 (64) | 475 (64) |

| White | 22 (85) | 595 (81) |

| Age at leaving full-time education (years), mean (SD) | 16 (2) | 17 (2) |

| Diagnosis | N = 23 | N = 702 |

| Schizophrenia | 19 (73) | 511 (73) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 1 (4) | 57 (8) |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 (4) | 59 (8) |

| Other | 2 (8) | 75 (11) |

| Psychiatric history, mean (SD) | N = 23 | N = 594 |

| Years’ contact with mental health services | 12 (11) (n = 22) | 16 (12) (n = 522) |

| Previous admissions | 4 (4) (n = 20) | 6 (6) (n = 586) |

| Length of current admission (months) | 33 (46) (n = 19) | 19 (59) (n = 572) |

| Length of current admission to rehabilitation unit (months) | 15 (32) | 19 (33) |

| Mental Health Act status | N = 24 | N = 630 |

| Detained during this admission | 11 (42) | 427 (68) |

| Currently detained | 1 (4) | 203 (32) |

| Social functioning | N = 24 | N = 739 |

| GAF score (range 1–100), mean (SD) | 57 (5) | 54 (9) |

Main themes

The results of the five main themes are described sequentially. Within each of the main themes, a number of subthemes emerged, and these are also reported.

Theme 1: what ‘helps and hinders’ service users of mental health rehabilitation services in their recovery?

With regard to this theme, four subthemes were identified: (1) the suitability of the service user for rehabilitation and the importance of the pre-admission assessment; (2) the unit ethos and approach provided; (3) the quality and suitability of the built environment; and (4) the facilitation of activities.

Generally, staff felt that, for them to be able to assist people in their recovery, it was essential that the service user was prepared or ‘suitable’ for rehabilitation.

One of the things that was established before I started, was that was quite a clear referral pathway into us, so people have to meet criteria to be deemed suitable for the placement.

Unit 0503, female, unit manager, 49