Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0609-10106. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The final report began editorial review in March 2015 and was accepted for publication in May 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimers

this report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Raine et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Overview of the ASCEND programme

In this chapter, we describe the background to, and rationale for, our research programme – ASCEND – the first major research programme to focus specifically on tackling socioeconomic inequalities in uptake in an organised cancer screening programme.

Background

Burden of disease and NHS context

Bowel cancer constitutes a significant public health burden in the UK. It is the fourth most common cancer (approximately 41,600 cases annually) and the second leading cause of cancer death (15,700 deaths annually). 1 Its incidence rises with age2 and early diagnosis is vital to improve outcomes: 93% of patients with early-stage disease (Dukes A) survive for 5 years, compared with 6.6% of those with late-stage (Dukes D) disease. 3

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have demonstrated that bowel cancer mortality can be reduced by screening using the guaiac faecal occult blood test (gFOBt). 4 Following successful pilots (the first conducted in two English health authorities and three Scottish health boards; the second conducted in the English sites only),5,6 the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme (BCSP) began in England in 2006. 7 Reduction in mortality as a consequence of population screening is dependent on participation. Thus, the combined results of four international RCTs (including the UK’s Nottingham Trial8) showed that participation rates of > 50% in biennial population screening reduced mortality by 16%,9 saving up to 2500 lives a year. 10

The Nottingham Trial, which began in 1981, reported uptake of 57%, and a 13% reduction in bowel cancer mortality at 11-year follow-up. 11 Subsequently, the first and second NHS BCSP pilots reported initial and ongoing uptake of 58.5% and 51.9%, respectively. 5 Data from the first 2 years of the English NHS BCSP showed uptake of 54%. 12 Further decreases in mortality can be achieved through improvements in the population participation rate. 9,13

The NHS BCSP offers the gFOBt every 2 years to 60- to 74-year-olds. Five hubs covering England co-ordinated a call/recall programme and were also responsible for analysing the gFOBt kit samples. Further details of the screening programme are provided in Chapter 2.

Relevance to priorities and needs of the NHS

A commitment to improve health and reduce inequalities in health and health care forms the cornerstone of the government’s public health and health-care policies. 14,15 Organised screening programmes have been assumed to be superior to opportunistic screening in terms of socioeconomic equity, because they use population lists to ensure that all eligible individuals are invited and call/recall systems to avoid under- or overscreening. Direct financial barriers are also avoided in the UK because the screening programmes are run by the NHS and, therefore, individuals incur no costs either for the primary screening test or for follow-up investigations or treatment. In addition, bowel cancer screening with the home-based gFOBt kit avoids barriers associated with travelling to a medical facility or interacting with health professionals. Nonetheless, striking gradients in uptake across levels of deprivation were reported in the two pilot studies and the first 2 years of the national screening programme. 5,12,16 The initial pilot reported 61% participation in the most socially advantaged areas, falling to 37% in the most deprived areas,5,12 and this gradient persisted in the beginning of the national programme, when participation was 61% in the least deprived areas and 35% in the most deprived areas. 12

Identifying effective strategies to achieve equity in uptake is vital to avoid exacerbating inequalities in mortality. Our research programme focuses on reducing the socioeconomic gradient in uptake without compromising uptake in any socioeconomic circumstance (SEC) group. In contrast with most inequalities research, we address the gradient in uptake rather than the gap between the most and least socioeconomically advantaged, in order to take account of the stepwise relationship between SECs and health, whereby more socioeconomically advantaged individuals have better health and better access to health care. 17 Thus, the costs of inequalities are borne not only by those at the bottom of the SEC hierarchy but at every level. Policies that target the most disadvantaged subgroups only, or which aim to narrow the gap between the most and least disadvantaged, underestimate the pervasive effect across the SEC hierarchy and exclude those in need in the intermediate SEC groups. This research programme was therefore designed to focus on reducing the socioeconomic gradient in uptake, which entails designing interventions that increase uptake to a greater extent in lower than higher SEC groups. Our approach reflects the concept of proportionate universalism whereby actions are universal, but with a scale or intensity proportionate to the level of disadvantage. 18

This programme was developed to contribute directly to the following three additional national initiatives:

-

The Department of Health’s target for cancer mortality, which includes a target to reduce the inequalities gap. 19

-

The Cancer Reform Strategy,20 which began the National Cancer Equality Initiative to focus on improving collection of data to improve understanding about current inequalities, promoting research to fill knowledge gaps about inequalities, and spreading good practice.

-

The Marmot Review of Health Inequalities which highlighted the need for ‘bespoke initiatives’ to reduce the socioeconomic gradient in bowel cancer screening uptake and which championed proportionate universalism. 18

Need for research in this area and rationale for our research programme

We have previously examined whether or not the socioeconomic inequalities identified during the Bowel Cancer Screening Pilot persisted once the NHS BCSP was rolled out. We analysed national uptake for the smallest geographical unit that is routinely recorded by the NHS BCSP, namely postcode sector, each of which contains an average of 3000 addresses. We found that between October 2006 and January 2009, overall screening uptake was 53% but it varied from 61% in the least deprived quintile of postcode sectors to 35% in the most deprived quintile. 12

As further evidence of the need for this research, and as part of the ASCEND programme, we undertook a new study to evaluate the extent of and factors associated with socioeconomic-related inequality in bowel cancer screening uptake in England using individual-level data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). We used data from the fifth wave of data collection of ELSA for 1833 participants who were eligible for at least one NHS BCSP invitation. Our outcome measure was completion of a gFOBt home testing kit. We ranked the sample using a composite measure of socioeconomic status, predicted from net non-pension wealth and a number of individual-level socioeconomic and sociodemographic characteristics and plotted the cumulative uptake of bowel cancer screening against it using a concentration curve. We then derived the concentration index, which provided a measure of socioeconomic-related inequality in screening uptake. We then fitted univariate probit models for the association between a number of sociodemographic (age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education), socioeconomic (quintiles of net non-pension wealth, housing, vehicle ownership, economic activity, social class) and health-related (self-reported general health, long-standing illness, difficulties with daily activities and using the toilet, health literacy, partner screening status) variables and the probability of screening. Variables showing significant associations were included in a multivariate model and in a decomposition analysis of the Concentration Index. 21,22 This provided a measure of socioeconomic inequality by accounting for the probability of screening and the distribution of each variable across different levels of SEC. We found a significant pro-rich gradient in screening uptake [concentration index +0.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) +0.04 to +0.09] with 41.7% of individuals in the poorest and 65.5% in the richest quintiles of predicted non-pension wealth participating in screening. Socioeconomic-related inequalities in screening were mostly explained by differences in education (19.6%), partner screening status (17.4%), disability (14.3%) and health literacy (8.7%). The findings suggest that interventions for reducing the gradient in bowel cancer screening participation should aim to increase acceptability and comprehension of the screening test among those with lower levels of literacy and emphasise the social implications of screening and its benefit not just to the individual but also to their family and friends. 23

In other work,24 we have also demonstrated that the low uptake and striking socioeconomic gradient is not seen among people with a positive gFOBt kit result who are invited for further investigation (usually colonoscopy). Overall, colonoscopy uptake is 84% with little variation between socially advantaged and disadvantaged areas (86–80%). 12 The high uptake of colonoscopy regardless of SEC indicates that addressing the gFOBt uptake gradient should improve subsequent uptake of effective treatment and, therefore, contribute to reducing inequalities in survival.

Prior to the establishment of the NHS BCSP, there was evidence that more disadvantaged patients with bowel cancer tended to present as emergency admissions and at a later disease stage25,26 and their outcomes are poorer. Furthermore the deprivation gap in survival is widening, reaching 7% for colon cancer and 9% for rectal cancer. 27 These findings further demonstrate the need to devise strategies to achieve early diagnosis among all social groups as well as reduce inequalities, if we are to improve survival across the board.

Previous research into improving uptake of cancer screening has focused primarily on factors such as ways of establishing contact. 28 Although this approach can help reach screening targets, it is unlikely to reduce inequalities and may even increase them if more socioeconomically advantaged individuals are more responsive.

A few studies have specifically addressed socioeconomic inequalities in uptake, but often by focusing on underserved groups, for example by providing community support workers. 29 Even if they are successful, these initiatives serve only one group in the population and do not address the gradient. In addition, they are often highly intensive and therefore impractical for wide-scale implementation.

Therefore, we set out to design and evaluate effective interventions which focus specifically on the socioeconomic gradient in uptake. Multiple potential causes for lower uptake of screening in more socioeconomically deprived groups include general factors (e.g. stress caused by lack of financial resources, reduced subjective life expectancy) which limit ability to engage in future-focused health protective actions30,31 and more specific factors, such as greater concern about the negative aspects of the test itself (e.g. embarrassment, contact with faecal material). 32,33 Health literacy limitations are also implicated in comprehension of the screening information materials34 and recognition of the organisation that sends the screening invitations. All these factors may have their upstream roots in the more stressful, constrained lives of people with fewer social and economic resources. 30 In addition, life stress may directly affect screening uptake if ‘passive’ barriers in the form of competing priorities reduce translation of screening intentions into action. 35 The four interventions that we tested addressed some of these barriers to uptake. We were required to design interventions that could easily be added to (rather than replace) existing invitation and information materials (which had been through formal approval procedures).

Aim and objectives

Our aim was to reduce socioeconomic inequalities in bowel cancer screening uptake in England without compromising uptake in any socioeconomic group.

In order to achieve this, we set out the following objectives:

-

to explore psychosocial and cultural determinants of low uptake of the gFOBt

-

to develop and test four theoretically based interventions to reduce the socioeconomic gradient in screening uptake

-

to undertake RCTs to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of each intervention within the NHS BCSP.

ASCEND workstreams

Our programme was divided into three workstreams to address our objectives.

Workstream 1

In order to explore the psychosocial and cultural determinants of low uptake of gFOBt, we conducted 18 focus groups and 16 key informant interviews. These generated rich qualitative data, which are reported in Chapters 3 and 4 and which were used to inform workstream 2.

Workstream 2

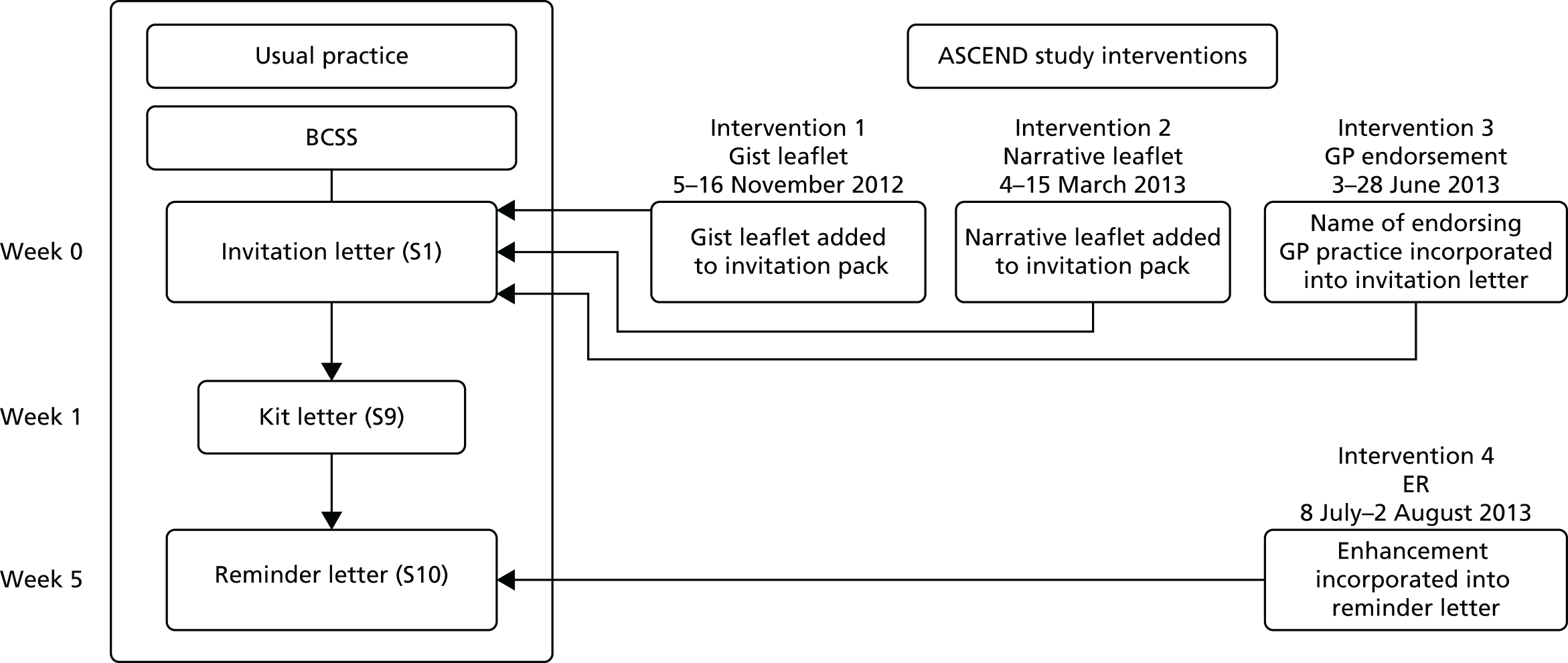

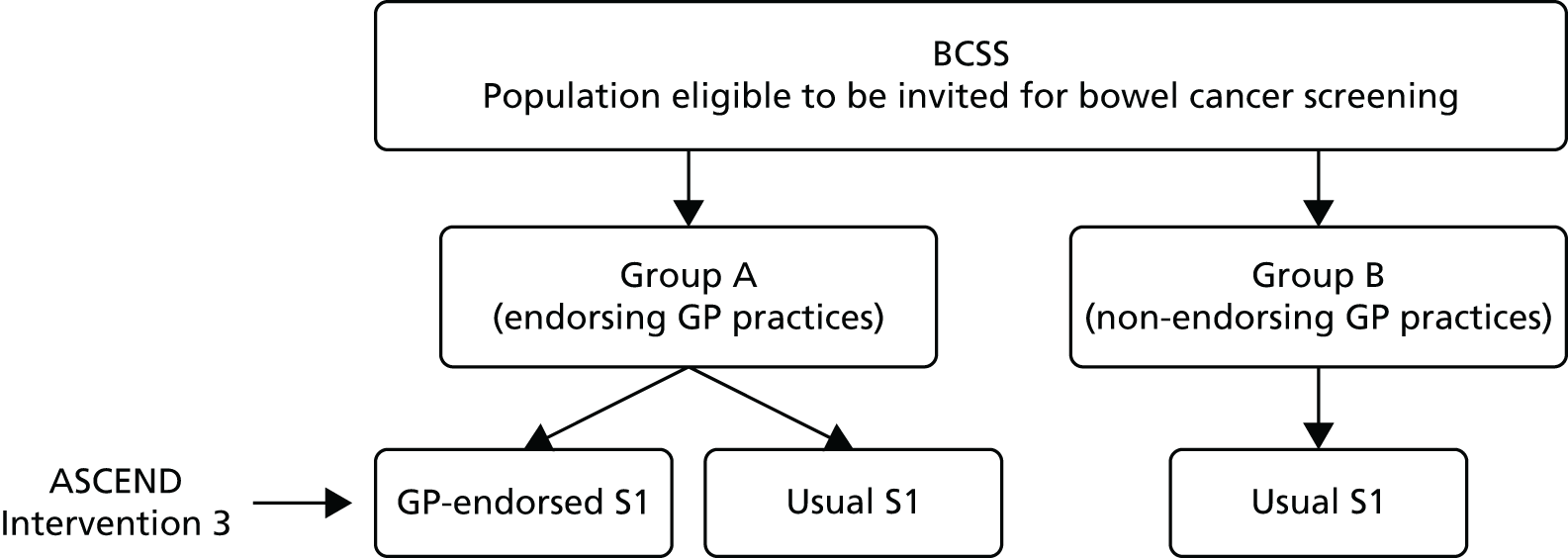

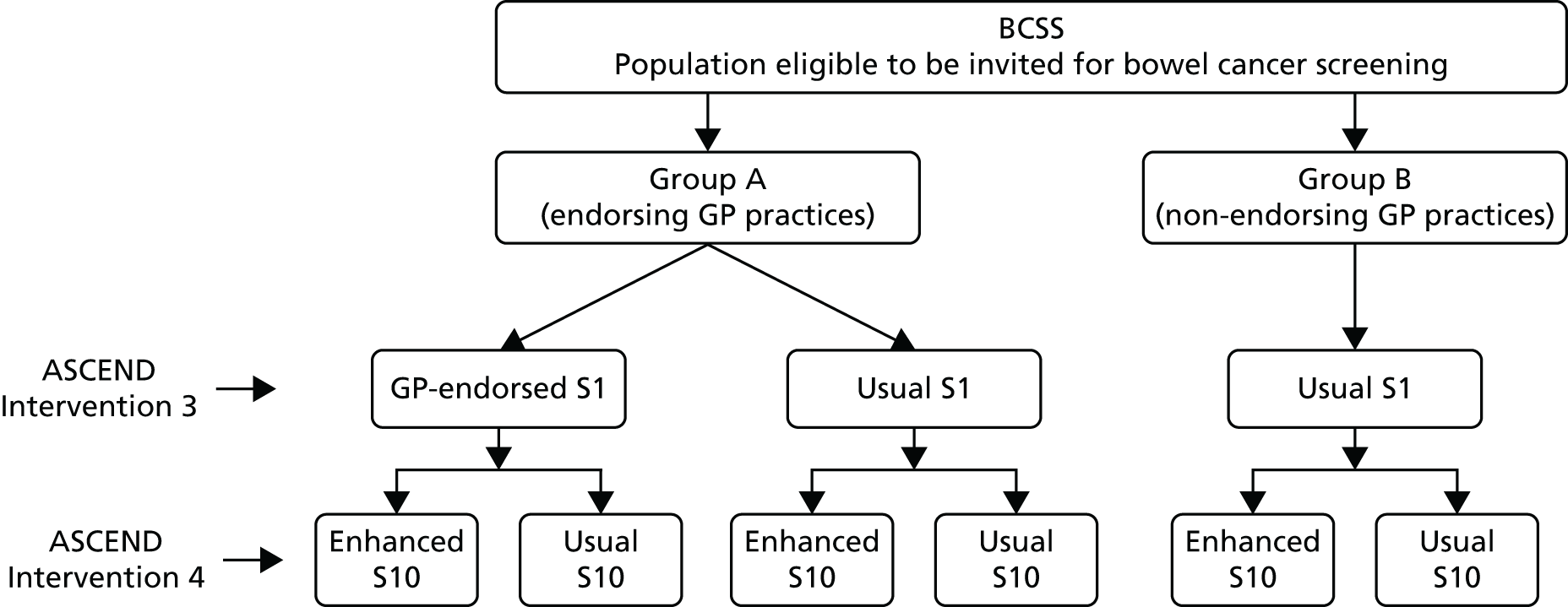

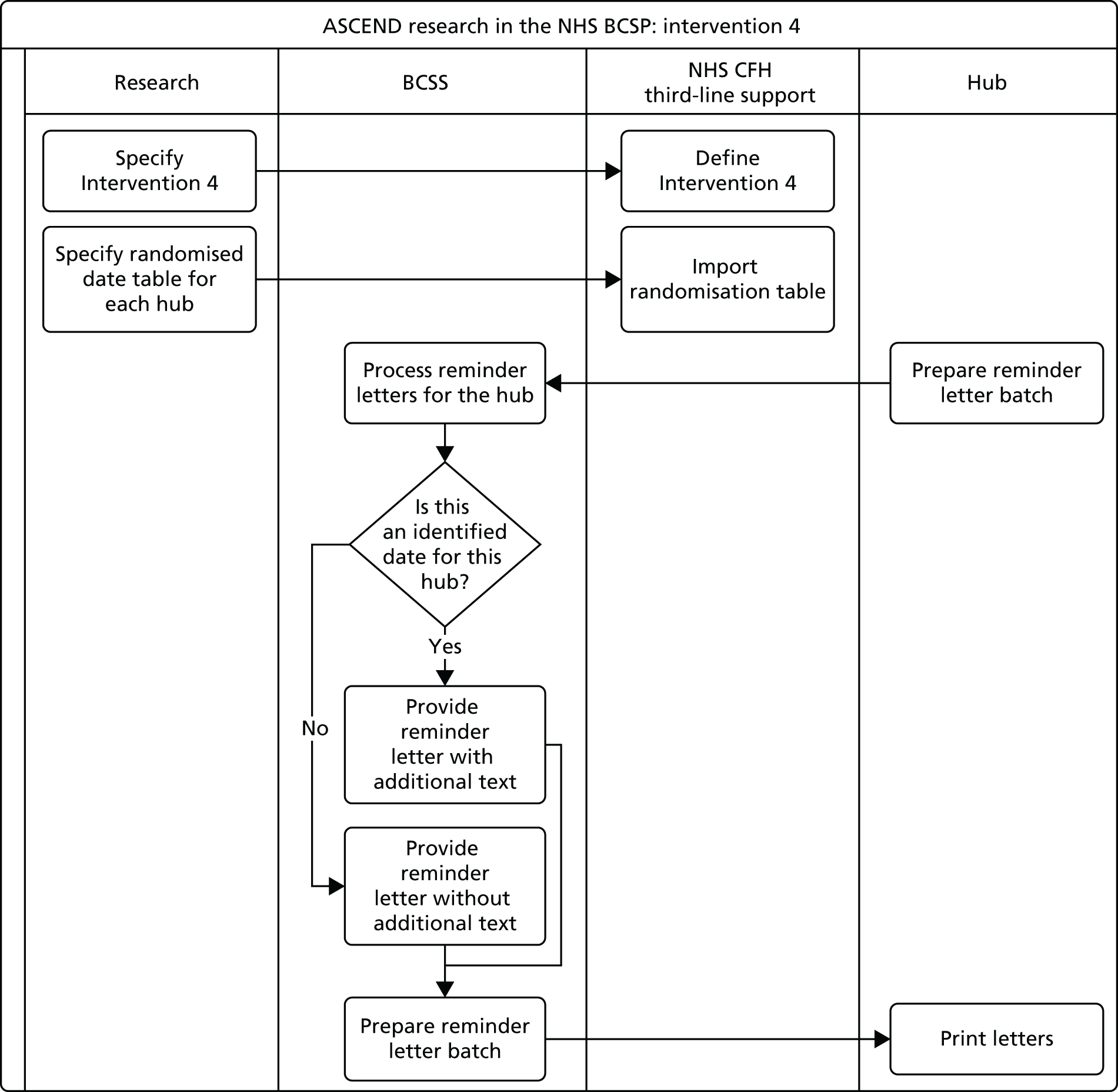

We developed and piloted four interventions designed to reduce inequalities in uptake of bowel cancer screening. Two of the interventions consisted of provision of additional information leaflets designed to meet the information preferences of individuals with lower SECs; one provided a simplified version of the screening information focusing on the ‘gist’ of the message and one provided personal narratives describing the screening experience. The third intervention added an endorsement of the programme from a familiar health professional [the individual’s general practitioner (GP)] to circumvent lack of recognition of the NHS BCSP – a strategy that has been shown to improve screening uptake in those with lower SECs. 36,37 The fourth intervention provided an enhanced ‘cue to action’, designed to help bridge the ‘intention–behaviour’ gap by briefly restating the screening offer and adding a ‘reminder’ label to the reminder letter sent to individuals who had not responded within 35 days of their initial invitation. The interventions are described individually in Chapters 5–8.

Workstream 3

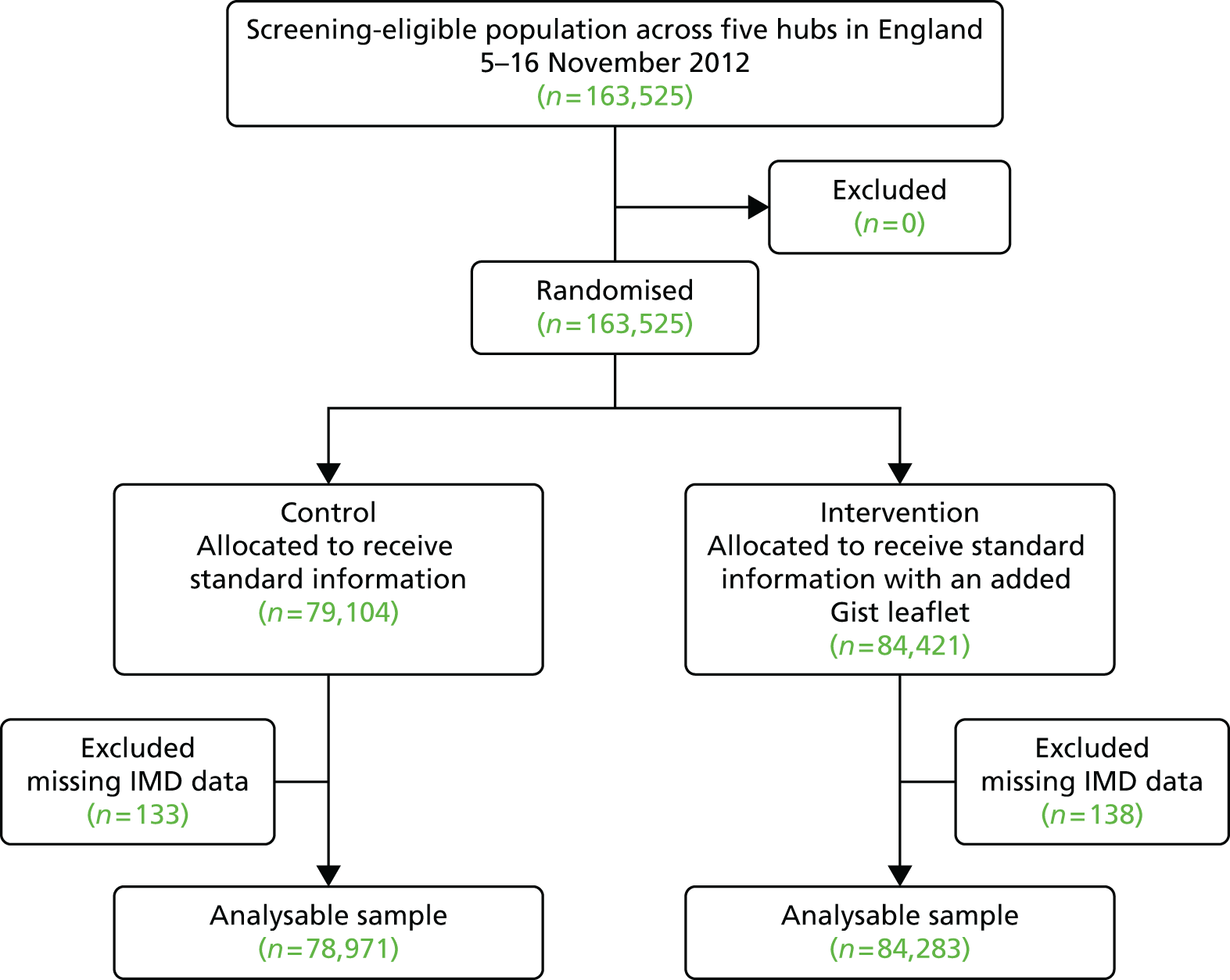

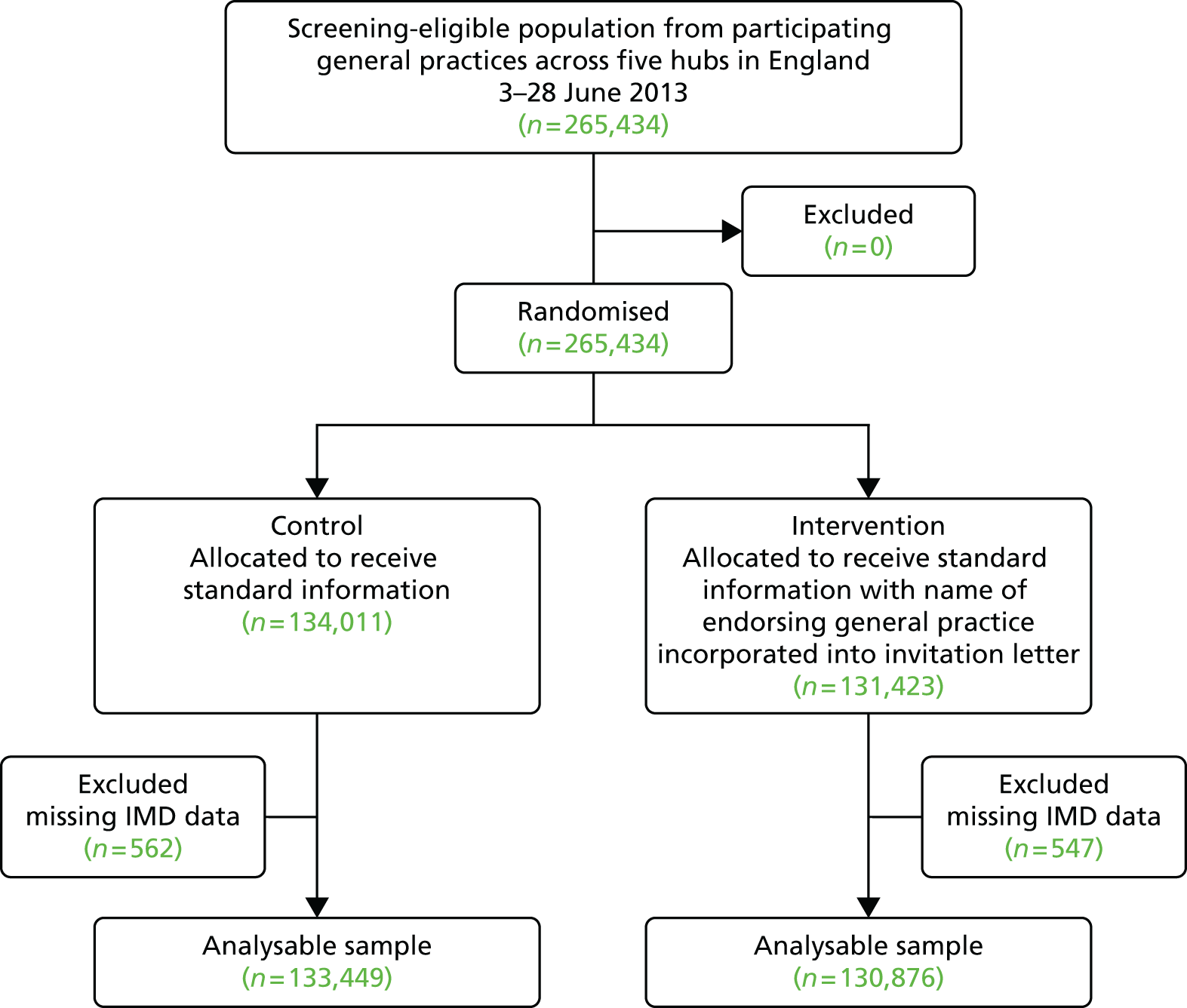

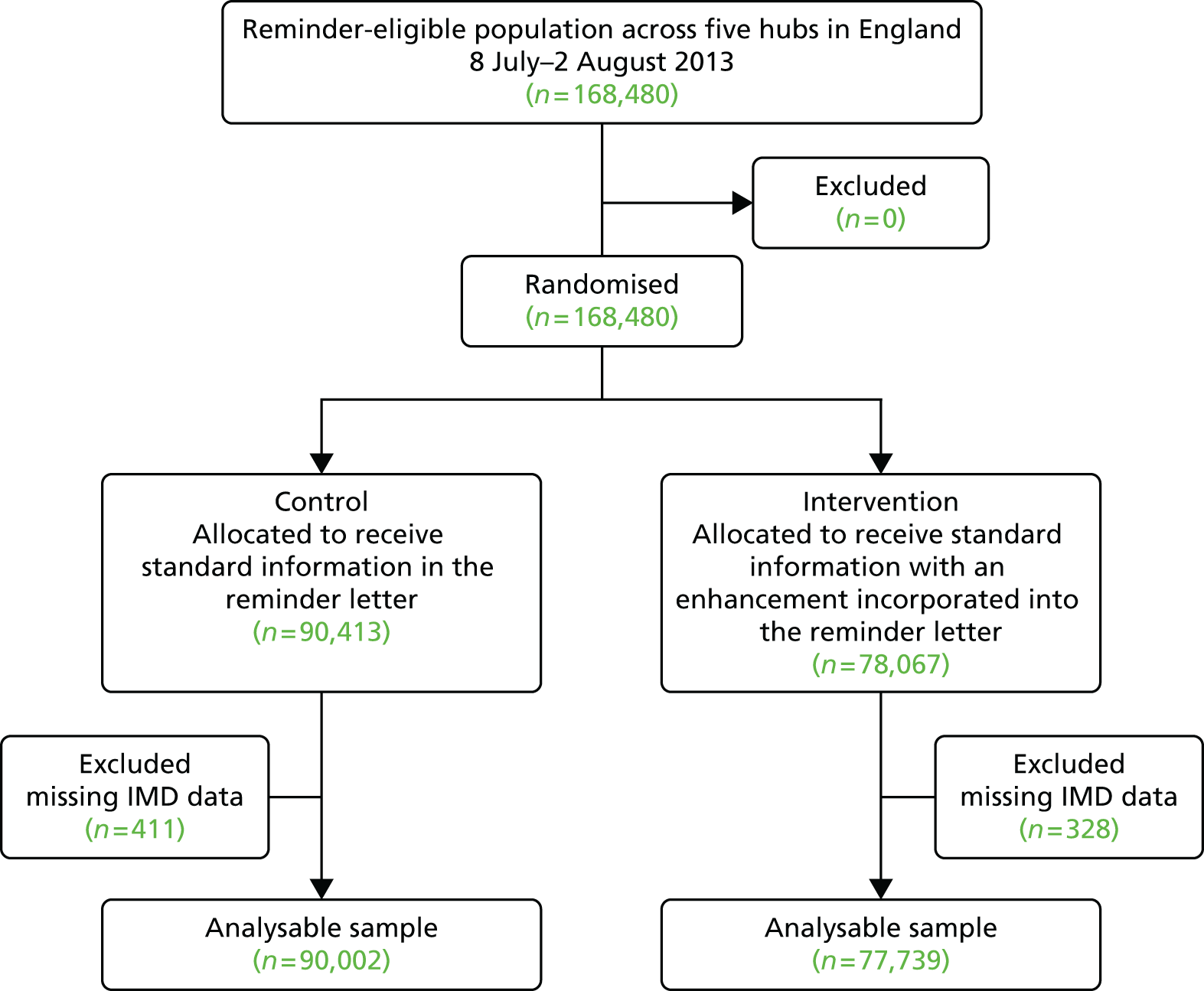

Each of the four interventions developed in workstream 2 were tested in separate two-arm, cluster randomised trials targeting all individuals who were routinely invited for bowel cancer screening in the NHS BCSP in England over each study period. The RCTs took place between November 2012 and August 2013. We hypothesised that each intervention [the ‘gist’ leaflet, the ‘narrative’ leaflet, the general practice endorsement (GPE) and the enhanced reminder (ER)] would be low cost and progressively more effective at improving screening rates across increasing levels of deprivation. We also undertook a national survey of research activities and health promotion activities to ascertain usual practice during the trial period. This workstream is described in Chapters 9–11.

Workstream 4

We planned to combine the successful components from workstream 3 into a complex intervention for experimental evaluation; however, the results of the trials of the individual interventions did not justify this.

Conclusions

We draw conclusions from the study and make recommendations for future research and practice in Chapter 12.

Patient and public involvement and engagement

Our first ASCEND patient representative, Mr Fuller, contributed expertise from a patient perspective during the drafting of the original application, particularly regarding workstream 2 and the planning of the development of the interventions. Unfortunately, Mr Fuller was unable to offer further support following the grant being awarded owing to ill health. We recruited another patient representative (Mr Band), who reviewed some of the ASCEND development work (namely the narrative leaflet) and attended our Advisory Group meeting prior to the start of the national trials. In addition, we worked with individuals from a number of charity and community groups and organisations, Primary Care Research Networks and faith settings who helped us to identify specific groups of people to take part in the development stages of the study (see Chapters 3–6 for further details).

The research team also undertook engagement activities, presenting information about the study at conferences and to other groups, as well as publishing peer-reviewed papers of the study findings.

Chapter 2 Overview of Bowel Cancer Screening Programme usual practice

Introduction

The NHS BCSP, established in England in 2006, offers bowel cancer screening every 3 years to adults aged 60–69 years (inclusive) using a gFOBt kit that is completed at home. Between 2008 and 2014, the programme was gradually extended to include subjects aged 70–74 years. Primary endoscopy screening is now being added to the programme following the UK Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Screening Trial,38 with a single flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) offered at 55 years. FS screening started after the completion of the ASCEND programme.

Bowel Cancer Screening Programme hubs

Five NHS BCSP hubs provide the ‘call and recall’ service for the screening programme in England: London, Southern England, Eastern England, Midlands and North West England and North East England (Figure 1). This involves the use of the Bowel Cancer Screening System (BCSS) database to invite the eligible population as their screening becomes due. To support this process, all hubs offer a helpline service to provide advice and a laboratory service to test all returned kits.

FIGURE 1.

Map of England showing the five Bowel Cancer Screening hubs.

Screening pathway

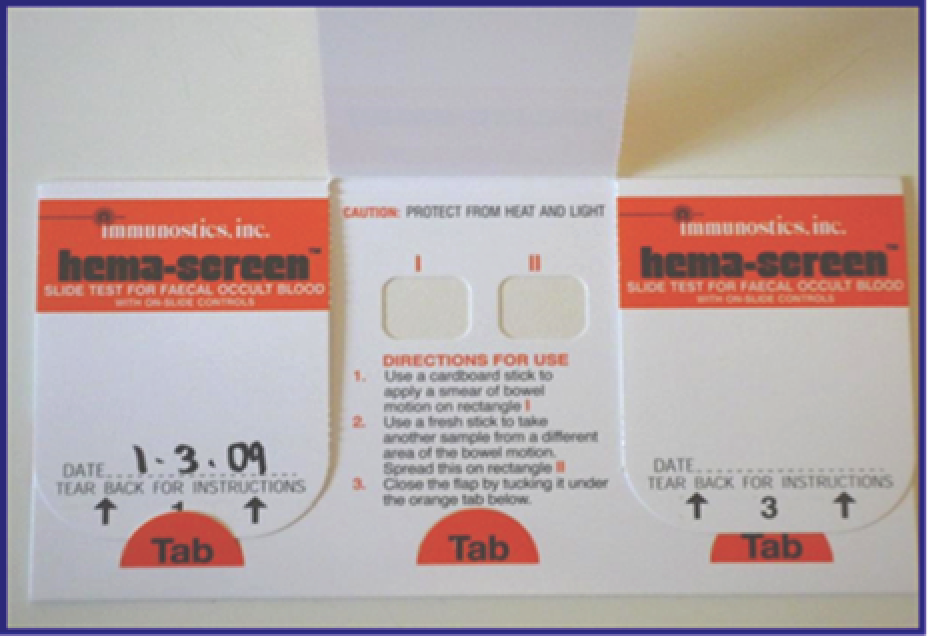

A detailed diagram of the NHS BCSP screening pathway is included in Appendix 1. In brief, each hub sends an initial invitation (‘pre-invitation’) pack to all eligible people in their area describing the programme and its objectives. The pre-invitation pack contains a letter (see the S1 letter, Appendix 2) and ‘The Facts’ booklet (see Appendix 3). A week later, the hub sends out the gFOBt kit (Figure 2) with a formal invitation letter (referred to as the S9 letter; see Appendix 4) and a leaflet explaining how to do the test (the screening instruction test kit leaflet; see Appendix 5). The test kit includes the gFOBt card, cardboard spatulas for sample collection and a reply-paid envelope in which to return the test for analysis at the NHS BCSP hub laboratory. There are three flaps on the test kit, each of which covers two sample application ‘windows’. Two tiny samples are taken from a bowel motion and spread onto each of the two windows using the cardboard spatulas provided. The flap is then sealed and dated and the process is repeated for the second and third bowel motions (using the windows under the second and third flaps, respectively). Once all six windows have been used, the test kit is returned to the laboratory for analysis. The test kit must be received by the hubs within 21 days (subjects are told 14 days, to allow time for return postage) of the first sample being taken to ensure that a valid test result can be obtained. The hubs process the completed gFOBt kits in their laboratories and send out result letters to participants within 2 weeks of receiving a completed test kit. If a test kit has not been returned within 4 weeks of the date it was sent, the hub sends out a reminder letter (referred to as the S10 letter; see Appendix 6).

FIGURE 2.

The gFOBt kit.

The possible test results for kit 1 are described in Table 1. Up to three test kits may be needed to reach a ‘definitive’ test result of ‘normal’ or ‘abnormal’. If none of the six windows is positive for blood in the faecal sample on the first test kit, the test result is normal and the participant will be invited to be screened again in 2 years’ time (if they remain within the eligible age group). If five or six windows test positive on their first kit, the result of the screening test is abnormal and the participant is offered an appointment with a specialist screening practitioner (SSP). If between one and four windows are positive on their first kit, the result of that test is ‘unclear’ and the participant will be asked to repeat the test. If one or more windows test positive on a second test kit the definitive test result is abnormal (‘weak positive’) and the participant is referred to a SSP. If no windows are positive on the second test kit, a third test kit is sent and any positive windows result in referral to SSP. Participants will be asked to repeat the test if a test was completed incorrectly (‘spoilt’) or there was a problem in the laboratory during processing (‘technical failure’).

| gFOBt kit result | Spoilt kit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Unclear | Abnormal | Technical failure | ||

| Explanation | 0 positive spots | 1–4 positive spots | 5 or 6 positive spots | Technical problem in the laboratory’s processing of the kit | Unreadable test kit owing to incorrect use, out-of-date sample or no readable date |

| Action | Participants are sent a discharge letter. The letter also contains a list of the symptoms of bowel cancer to promote awareness between screening episodes and after the age of 74 years. The gFOBt is offered again in 2 years if < 75 years | Participants are sent a covering letter and another kit. If the second kit gives an abnormal or unclear result, participants are offered an appointment to see a specialist nurse. If the second kit is normal, participants are sent another kit to confirm a definitive result overall | Participants are sent a covering letter containing a clinic appointment to see a specialist nurse within 2 weeks of the gFOBt kit being processed | Participants are sent a covering letter and one further kit | Participants are sent a covering letter with an explanation of why the kit could not be processed and a replacement kit |

General practitioners are not directly involved in the delivery of the NHS BCSP but the practice receives written (or electronic) notification of the screening results for their patients including a notification of a SSP appointment and colonoscopy outcome. Practices are also informed about subjects who have not taken part in screening.

Each NHS BCSP hub provides a freephone helpline service. Helpline staff are not medically trained but have received training on common diseases of the bowel and have a sound knowledge of the screening pathway. Helpline staff provide guidance on how to complete the test kit, are able to answer queries about the appropriateness of screening (complex clinical queries are passed to the hub management team) and can reschedule clinical NHS BCSP appointments etc.

Individuals who receive an abnormal test result are invited to attend an appointment with a SSP at a local screening centre. The SSP will discuss a follow-up investigation and arrange a colonoscopy, if appropriate. There are 60 screening centres across England (between 6 and 18 per hub area). Colonoscopy is an invasive procedure that involves passing a thin, flexible tube with a tiny camera attached through the rectum and around the bowel to look directly at the lining of the large bowel. Preparation for colonoscopy requires the subject to use a self-administered laxative for thorough bowel cleansing and a sedative is sometimes used during the procedure. If polyps are found in the bowel, most can be removed painlessly using a wire loop passed down the colonoscope tube. These tissue samples are then checked for any abnormal cells that might be cancerous. On average, for every 10 people undergoing a colonoscopy following an abnormal gFOBt kit result, five will have a normal result (or non-cancerous/non-polyp abnormality), four will have a polyp (which, if removed, may prevent cancer developing) and one will have cancer.

Screening ‘episodes’

For screening participants, a screening episode refers to the period of time from when an S1 pre-invitation letter is sent to an eligible individual to when they receive a definitive normal test result or to an outcome from colonoscopy for those referred for further investigation. If a subject has not responded by returning a test kit or contacting the hub to opt out of screening within 18 weeks of the initial pre-invitation letter being sent out, the screening episode is closed and the subject will receive another invitation to take part in screening 2 years after their previous screening due date, if they are still within the age group to be screened (60–74 years).

Subjects are first invited to take part in screening within approximately 6 weeks following their 60th birthday and may then be invited to take part in screening every 2 years, depending on test results, outcomes from any follow-up and age, and regardless of whether or not they have taken part in the past. Individuals aged ≥ 75 years can request a test kit every 2 years from the NHS BCSP if they wish to be screened.

The first time an individual is invited to be screened is referred to as the prevalent screening episode (‘prevalent previous non-responders’ refers to subjects invited to be screened at least once previously but who have not participated). ‘Incident’ screening is the term used for episodes of repeat screening (i.e. in the case of subjects who have participated in screening previously).

Initiatives to promote the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme

A number of organisations promote awareness of the NHS BCSP. Clinical Commissioning Groups [and formerly primary care trusts (PCTs)] fund a variety of local initiatives to promote uptake of screening, including promotion of screening at flu vaccination clinics, placing posters in general practices and providing information stands at health fairs, general practices, libraries, conferences and hospital open days, as well as various GPE strategies and targeted recruitment of individuals not taking part in screening. The Southern Hub is piloting a new approach to increase participation by working in partnership with general practices and sending a second reminder letter using the surgery letter head and a local GP signature. The National Awareness and Early Diagnosis Initiative also co-ordinates and provides support to activities that promote the earlier diagnosis of several cancer types in England, including breast, bowel and lung cancer.

Several charities, including Beating Bowel Cancer (Teddington, UK), Bowel Cancer UK (London, UK) and Cancer Research UK (London, UK), also fund campaigns to promote uptake of bowel cancer screening.

Chapter 3 Workstream 1: focus group study

A version of this chapter has been published as Palmer et al. 32 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/.

Introduction

In workstream 1 we explored the psychosocial and cultural determinants of low uptake of gFOBt. In this chapter, we describe how we carried out focus groups with men and women from different socioeconomic backgrounds in London and South Yorkshire in order to identify specific barriers to screening uptake.

Uptake of bowel cancer screening in South Asian communities is particularly low, at 31.9% in the Muslim community, 34.6% in the Sikh community and 43.7% in the Hindu community, compared with average uptake across the whole population (53%). 12,40–42 Low uptake of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in the UK has continued to be identified in areas with higher ethnic diversity,5,12 and within all South Asian religiolinguistic groups even when age, deprivation and gender are adjusted for. 40,43 We therefore also explored culturally specific barriers to uptake in South Asian communities to identify additional appropriate methods which could be specifically targeted at minority ethnic groups who speak English. To do this, we carried out interviews with 16 participants acting as ‘key informants’ on behalf of their communities. This interview study is described in Chapter 4.

The current research evidence in this area includes qualitative explorations of attitudes towards bowel cancer screening. Most of these studies were conducted in the USA or report insights relating to a range of screening methods including gFOBt, colonoscopy and FS. 44–47 This limits their applicability to the UK NHS BCSP. The sparse literature focusing on gFOBt33,42,48–52 has identified reasons for non-uptake including feeling healthy and having no bowel symptoms, fear of the outcome of screening and ‘not wanting to know’, which was often linked to doubts about the value of screening to detect health problems. Difficulties in understanding the kit instructions, concerns about hygiene and storage of the kit, avoiding or delaying decision-making, intention to take part but failure to do so owing to practicalities, and the preference for a doctor to do such tests have also been identified as reasons for not completing screening. 33,42,50,51,53 An association between being invited to be screened and entry into ‘old age’ has also been identified as a factor influencing the decision to be screened. 52 The need to deal with faeces to complete the test has not been reported as a major barrier to participation in screening, with previous studies42 reporting that the majority of respondents have not tended to express disgust or reluctance to handle faecal matter. However, the material realities of the gFOBt do constitute a barrier to participation for some individuals. 42,45,50

Few qualitative studies have focused on the English NHS BCSP. Two studies carried out during the NHS BCSP pilot phase explored the acceptability of gFOBt with individuals who had not yet been invited to take part in the NHS BCSP. 42,51 Findings from these studies were therefore based on participants’ hypothetical commentaries regarding the acceptability of the programme design and screening process. Recruitment of participants with actual experience of being invited to the NHS BCSP is limited to three qualitative studies. In one, the majority of the participants had completed the gFOBt kit50 and the other two report on small samples, each restricted to one geographical area in England. 33,52 The experiences of individuals who have been invited to the NHS BCSP and have not taken part, who might be expected to offer the richest insights into screening non-uptake, have been largely absent from the research literature to date. Furthermore, the beliefs of individuals who do not take part in one round of screening but subsequently take part in another round is limited to one recent study which describes how beliefs, awareness and intention change over time. 33 These participants are of particular interest because of their potential to explain why people make different uptake decisions on separate screening rounds.

Finally, research exploring the views and experiences of ethnic minority participants to an invitation to the NHS BCSP is, with the exception of Szczepura,42 extremely limited, despite ethnic diversity in the UK population and variation in screening uptake linked to ethnicity. 12,40,54

A single study on FS screening (an invasive form of bowel cancer screening not routinely used in the NHS BCSP at the time this research was conducted) identified specific cultural barriers associated with the threats to masculinity in African Caribbean men. 55 However, it is not known whether such barriers are also present in relation to gFOBt or if there are any culturally specific issues related to gFOBt screening among African Caribbean women.

The research presented here therefore adds to the literature in two important respects. First, we explored non-uptake decisions in a socially and ethnically diverse sample of individuals with experience of non-uptake within the English NHS BCSP. Second, we included participants who made different uptake decisions on separate screening rounds. This allowed us to identify ‘tipping points’, that is, the factors that changed an individual’s mind about screening.

Aims

-

To explore psychosocial determinants of bowel cancer screening uptake with an attention to the possible differences between socioeconomic and ethnic groups.

-

To explore the reasons for participating in screening following non-participation in a previous screening round.

Objective

To understand determinants of initial non-uptake and reasons for subsequent participation in gFOBt screening using focus groups, homogeneous with respect to gender, SECs and ethnicity.

Methods

Theoretical underpinnings

Our study is rooted in the interpretivist tradition of qualitative social research and thus focuses on the subjective understandings and meanings held by the participant. 56 An attention to participants’ interpretations and meanings provides a context to their actions, from which explanations for particular actions and behaviours may be derived. 57 We used a focus group design to explore the experiences of people invited to take part in the NHS BCSP and we used the rich textual data generated therein to illuminate the meanings, interpretations and influences that underlie participants’ decisions not to undertake screening. Focus groups are of particular value when exploring reasons why people choose not to do something, or what Barbour terms ‘why not?’ questions. 58 We took a nuanced view of the data we collected, accepting that while they may reveal aspects of the actual experience of receiving an invitation to screening, they also comprise ‘accounts’ that are produced within, and shaped by, the social setting of a focus group, and in which particular behaviours are likely to be framed in certain ways. 56

Recruiting participants

To explore sociocultural differences in barriers to uptake, we purposively sampled participants from two distinct geographical areas: inner-city London and two towns in South Yorkshire (Barnsley and Doncaster). In each setting we sampled individuals from a diverse range of SECs. We aimed to recruit participants who had not taken up screening on at least one occasion. We also purposively sampled participants of African Caribbean ethnic minority background owing to the dearth of research examining ethnic minority experiences of bowel cancer screening and following the finding of a study on FS that specific cultural barriers associated with threats to masculinity were experienced by African Caribbean men. 55

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our inclusion criteria were:

-

individuals who had been invited to participate in bowel cancer screening but who did not take part on at least one occasion

-

individuals who had a good understanding of, and who were able to communicate in, English.

Our exclusion criteria were:

-

individuals who did not wish to provide informed consent for the study

-

individuals who had a known previous cancer diagnosis.

Focus groups benefit from being organised around the homogeneity of the participants. 58,59 This may be especially pertinent when the research topic is of a potentially sensitive nature. Therefore, we planned to establish separate focus groups for men and women and to group participants based on their ethnic and occupational backgrounds where possible.

We planned to convene seven all-female and seven all-male English-language focus groups. Groups were to be single sex owing to the sensitive and personal nature of the topic to be covered. Two of these groups (one male and one female) would comprise African Caribbean participants to ensure ethnic diversity in our sample.

We initially planned to recruit participants through general practice lists and via community settings assisted by our charity partners Age UK (London, UK), Beating Bowel Cancer and ContinYou (London, UK). However, we encountered difficulties with these approaches, which we describe below.

Difficulties in convening focus groups

Through general practice lists

We anticipated that some focus groups would be convened through general practices serving (1) relatively affluent resident populations, (2) relatively disadvantaged populations and (3) a high prevalence of African Caribbean individuals. We planned to identify appropriate practices using routinely available data on deprivation (derived from practices’ postcode) and ethnicity from the Public Health Observatories. We established relationships with research officers at the local Primary Care Research Networks in London and the South Yorkshire and Bassetlaw Bowel Screening Health Promotion Group, which agreed to assist us in recruiting participants. However, we soon found that, although general practices held information on their patients’ bowel cancer screening uptake status, it was not held on easily searchable databases; therefore, this approach would require a great deal of effort and expense in order to identify potential participants.

Through charity partners (Age UK, Beating Bowel Cancer and ContinYou)

Our three charity partners, Age UK, Beating Bowel Cancer and ContinYou, volunteered to help recruit participants via their networks and community groups; however, although each charity offered valuable insights and expertise to the research team, particularly during the initial planning stages of our research, it soon became clear that they would not be able to assist with identifying relevant individuals or convening appropriate focus groups. Age UK tend to have contact with people who were older than the screening age or who had already positively engaged with the NHS BCSP. Beating Bowel Cancer has a well-established, extensive network of community, health promotion and district nurses; however, it transpired that its contacts were mainly with younger people who had developed and overcome bowel cancer, but were too young for their cancer to have been identified through screening by the NHS BCSP. The charity ContinYou is a community learning organisation that focuses on engagement with socially excluded groups, including those with lower levels of educational attainment and poor health literacy, and minority ethnic groups. However, during the period between the grant proposal being submitted and the grant being awarded, ContinYou shifted its focus to deliver education services for young people and, therefore, contacts with individuals eligible for bowel cancer screening (aged 60–69 years old) had ceased.

Through community settings

Owing to the lack of research exploring the experiences of minority ethnic communities to bowel screening, we wished to maximise our opportunity to explore specific ethnic issues related to non-uptake, particularly among the British South Asian and African Caribbean communities. In order to achieve this we took account of previous studies which found that alternative recruitment strategies to those used to recruit white European origin participants may be required. 60,61 Therefore, we attempted to opportunistically sample people of African Caribbean origin through community settings. However, despite contacting 12 community groups (seven in London and five in South Yorkshire), all of which were enthusiastic to assist us, we were unable to recruit enough men who met our inclusion criteria. This was because very few men attended these groups and those who did were commonly older than the screening age range or had taken part in screening. We did, however, recruit a focus group comprising women of African Caribbean origin from a church-based exercise group in North London. This group was arranged without reference to occupational background.

The difficulties we faced recruiting non-white British participants through community groups, in combination with advice received from a bowel cancer improvement practitioner working with Muslim South Asian communities in Manchester, informed the decision to use key informant interviews in place of focus groups for the study exploring experience and access to bowel cancer screening among UK South Asian communities. This aspect of workstream 1 was redesigned and accepted by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) following peer review.

Alternative methods of recruitment

Convening focus groups through the Bowel Cancer Screening Programme

In response to the difficulties we encountered with recruitment, we approached the London NHS BCSP Hub and the North East of England NHS BCSP Hub to help with recruitment. The two hubs agreed to act as patient identification centres, enabling us to target our recruitment at participants who had not taken up screening on at least one occasion. Therefore, we identified postcodes in areas of London and South Yorkshire, within which the hubs were asked to invite people to participate in focus groups on our behalf. We did this by identifying lower-layer super output areas (LSOAs) that encompassed a range of Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) scores, including those in the least deprived and most deprived quintiles. 62 We then mapped LSOAs on to postcode maps, which enabled us to identify postcode sectors from which we wished to invite participants to participate in the study. We supplied hubs with these postcode sectors and they invited a total of 5100 eligible participants living in addresses in these areas, during two periods of recruitment to the study. In order to achieve our objectives, the hubs invited individuals with a variety of uptake experiences, including individuals who had never taken part in screening, individuals who had taken part in one round of screening but not in a subsequent round, and individuals who had not taken part in initial screening but then gone on to take part in a subsequent round.

We prepared focus group invitation packs that the hubs sent out to 2560 and 2540 potential participants from across areas in the first and second wave of recruitment, respectively. The pack contained a letter of invitation to the study signed by the hub director and the study chief investigator (see Appendix 7), an information sheet (see Appendix 8), a consent form (see Appendix 9) and a return stamped addressed envelope. Potential participants were invited to telephone or e-mail the researchers to further discuss the study if they wished. The researchers had contact only with participants who returned a consent form and expressed an interest in taking part in focus groups; all non-responders remained anonymous.

Using this method of recruitment through the NHS BCSP, we were successful in recruiting enough participants to establish 16 focus groups (four male and four female in London, and four male and four female in Yorkshire).

Convening a focus group through a market research recruitment agency

Finally, we approached an external market research recruitment agency to assist in the recruitment of a focus group with men of African Caribbean origin.

Overall we established 18 focus groups, of which eight were conducted in Yorkshire and 10 were conducted in London (Table 2).

| Focus group | Location | Gender | Occupation | Number of participants/ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG01 | London | Male | Professional | White European, n = 11 |

| FG02 | London | Male | Non-professional | White European, n = 5 |

| FG03 | London | Female | Professional | White European, n = 7; South Asian, n = 1 |

| FG04 | London | Female | Non-professional | White European, n = 5; African Caribbean, n = 1 |

| FG05 | South Yorkshire | Male | Professional | White European, n = 7 |

| FG06 | South Yorkshire | Male | Non-professional | White European, n = 8 |

| FG07 | South Yorkshire | Female | Professional | White European, n = 7 |

| FG08 | South Yorkshire | Female | Non-professional | White European, n = 6 |

| FG09 | South Yorkshire | Male | Non-professional | White European, n = 7 |

| FG10 | South Yorkshire | Male | Professional | White European, n = 8 |

| FG11 | South Yorkshire | Female | Non-professional | White European, n = 6 |

| FG12 | South Yorkshire | Female | Professional | White European, n = 6 |

| FG13 | London | Male | Non-professional | White European, n = 6 |

| FG14 | London | Male | Professional | White European, n = 7; West African, n = 1 |

| FG15 | London | Female | Non-professional | White European, n = 4; African Caribbean, n = 2 |

| FG16 | London | Female | Professional | White European, n = 6 |

| FG17 | London | Female | Not recorded | African Caribbean, n = 9; South Asian, n = 1 |

| FG18 | London | Male | Not recorded | African Caribbean, n = 6; West African, n = 1 |

Composition of each focus group

In addition to organising separate focus groups with male and female participants, we also used participants’ occupational background to group them by broadly similar SECs.

Although we invited individuals from the least deprived and most deprived areas (as defined by IMD quintile, i.e. based on postcode), we also needed to take account of the possibility of ecological fallacy (defined as ‘an error of deduction that involves deriving conclusions about individuals solely on the basis of an analysis of group data’), in this case, IMD derived by postcode rather than individualised data63 when grouping individuals of broadly similar socioeconomic backgrounds. 64

A standard measure for occupational background was not used. Instead, we used a consensus method between two researchers to group participants by ‘professional’ or ‘non-professional’ occupational background. This pragmatic approach was taken in the spirit of the qualitative research design adopted for this study in which flexibility and responsiveness to the emerging research context are required.

The two groups comprising majority African Caribbean participants were not grouped by reference to occupational background. This information was not available owing to the recruitment method used for these focus groups.

Generation of the topic guide

We developed a topic guide to ensure that key topics were covered in each focus group (see Appendix 10). We used the existing literature to inform the questions included on the guide, including questions to explore previously unreported areas of interest with our focus group participants. Iterations of the topic guide were discussed among the team to ensure that topics of importance for the study were covered and that these questions were framed to enable detailed and unstructured responses.

Running the focus groups

The first eight groups were conducted during July 2011 and a further 10 were conducted during April 2012. We elicited participants’ availability to attend a focus group on several dates and ran the groups at the times when the majority of participants were able to attend. We conducted all the London-based focus groups at university meeting rooms, apart from the female African Caribbean group, which was conducted at the church where the group met for other purposes. We identified conference centres and community spaces in South Yorkshire at locations that would be convenient for focus group participants to reach. Each group lasted approximately 1 hour and one facilitator (CP or CvW) ran the group while another member of the research team took detailed notes (MT or SS). Each group was audio-recorded with consent from each participant. We provided refreshments and at the end of the focus groups each participant was given £20 to thank them for taking part and to cover travel expenses.

Ethics

The study received ethics approval from South East London research ethics committee five (reference 11/H0805/7) and NHS trust research governance was obtained at the relevant sites. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Patient and public involvement and engagement

We collaborated with community groups to recruit potential focus group participants. In Doncaster we worked with three community centres (contact details were provided by ContinYou colleagues), an indoor bowls centre and a men’s 60+ social group, supported by AgeUK (found through our own research). ContinYou also put us in touch with three community centres in London. In addition, we approached an over-50s exercise group at a London sports centre, a ‘men’s shed’ group and an over-50s library group, inviting them to take part in our research. AgeUK worked with us in London, for example, inviting us to a black and minority ethnic elders meeting in London, where we made a contact who arranged a focus group with Caribbean women based at a church exercise group in North London. All of these groups were extremely willing to help but, unfortunately, we often found that many of the people available were outside the age bracket we were seeking and, if they were of screening age, they tended to be positive about screening.

Following the publication of our results in the British Journal of Cancer,32 we produced an information sheet summarising the findings and posted this to all participants who expressed an interest in receiving them.

Data management and analysis

After each focus group, the audio-recording was sent securely to a third-party transcription agency and transcribed verbatim. The research team members who led each focus group (CP or MT) then checked the transcripts for accuracy in comparison with the audio-recordings and written notes and removed any identifying information. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction. Audio-recordings and electronic transcripts were saved on a secure password-protected drive. Paper transcripts and written notes were kept in locked office cabinets.

An inductive analytical approach was used to generate themes from the data. During the first stage of analysis, two members of the research team (CP and MT) working with hard copies of the data descriptively coded each transcript as it was generated; this was done in a grounded way, meaning that all data were closely and repeatedly read and coded without reference to ‘a priori’ topics linked to the research questions of interest to the study. During this initial open and grounded coding stage, the researchers would meet regularly to discuss the emerging codes and areas of commonality and difference between each researcher’s codes. As further transcripts were coded, the researchers coidentified patterns of repeating or similar codes across the data, which they clustered into early themes and wrote brief descriptive summaries of each. There was little disagreement between the researchers when clustering codes into early themes; however, the labelling and descriptions of early themes were discussed and revised collaboratively to agree on wording that was acceptable to both researchers.

Following grounded coding of the first eight focus group transcripts, these data and associated codes and preliminary themes were entered in to NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to increase data manageability and retrieval. The researchers had regular meetings in which early themes and their associated data extracts were printed out and discussed with reference to the data extracts to within the theme and against other early themes. During these discussions, themes were refined and the changes saved within NVivo. The associated summaries of the early themes were also extended and refined and saved within Microsoft Office® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) documents with the associated data extracts coded within that theme. At this point, the researchers considered all thematic categories and began to jointly identify the thematic areas that were emerging to be most relevant to the research questions of interest. The researchers presented the developing themes and associated data extracts to the wider research team at frequent intervals in order to inform, when possible, the content and development of the gist, narrative, GP and ER letter interventions.

Following the identification of key themes, the researchers created a framework grid in which the data extracts illustrating each emerging key theme were inserted alongside the focus group number and participant from which they had originated. This allowed the researchers to easily identify the individual focus groups from which data extracts had been categorised and, importantly, allowed the researchers to identify the ‘spread’ of emerging key themes across the eight focus groups. This revealed that the coidentified key themes were present and repeated across the majority of the focus groups.

As the remaining 10 focus groups were completed and transcribed, the data were coded by the same two researchers using the thematic framework developed during analysis of the first eight groups. The researchers also undertook some open coding for which data did not fit into a pre-developed theme. The themes were revised and refined with reference to these data when necessary, as were the thematic summaries. The thematic framework was barely changed with the addition of the second phase of focus group data indicating that the key themes relating to gFOBt non-uptake had reached saturation. However, analysis of these data did lead to the generation of new codes relating to ‘tipping points’ to screening, which were clustered into themes following the same processes described above and saved as word documents comprising a descriptive summary below which all the relevant data extracts were saved. The identification of these new themes was due to the inclusion of participants in the second phase of focus groups who had changed from non-uptake to uptake of gFOBt on a subsequent invitation to the NHS BCSP. The framework grid of key themes and illustrative data extracts was extended with data extracts and the new ‘tipping point’ themes from focus groups 9–18. Our analysis produced detailed summaries of the key themes accompanied by extensive illustrative empirical material, which were written up for publication.

Once all focus group data had been analysed, the researchers undertook additional comparative analyses to determine if themes could be identified that were specific to focus groups clustered by gender, occupational background, ethnicity or geographical location. Only one such theme was identified, which related to the way in which participants with ‘professional occupations’ described ‘delay’ as a key component of their gFOBt non-uptake. However, in the vast majority, the key themes relating to gFOBt non-uptake were present and repeated in each focus group. The key theme relating to ‘tipping points’ to screening was present and repeated across groups 9–18 because these were the groups containing participants with experience of taking part in a subsequent screening round.

Throughout the analytical process, emerging themes and their associated illustrative quotations continued to be presented to the wider research team for discussion and to inform intervention development. The key themes were also presented to study coapplicants present at the ASCEND steering group.

Results

Participant characteristics

In the first wave of recruitment, 2560 participants were invited (1280 from areas served by each hub). We anticipated a 2.5% response rate, which would equate to approximately 32 responders in each hub area. We estimated that we should be able to convene two focus groups of between 6 and 12 participants in both areas with this level of response. Our response rate was actually nearer 5% and, therefore, we were able to convene four focus groups in each area. In the second wave of recruitment (and in order to achieve at least a further six focus groups), the hubs posted invitations to 2540 individuals (1270 from areas served by each hub).

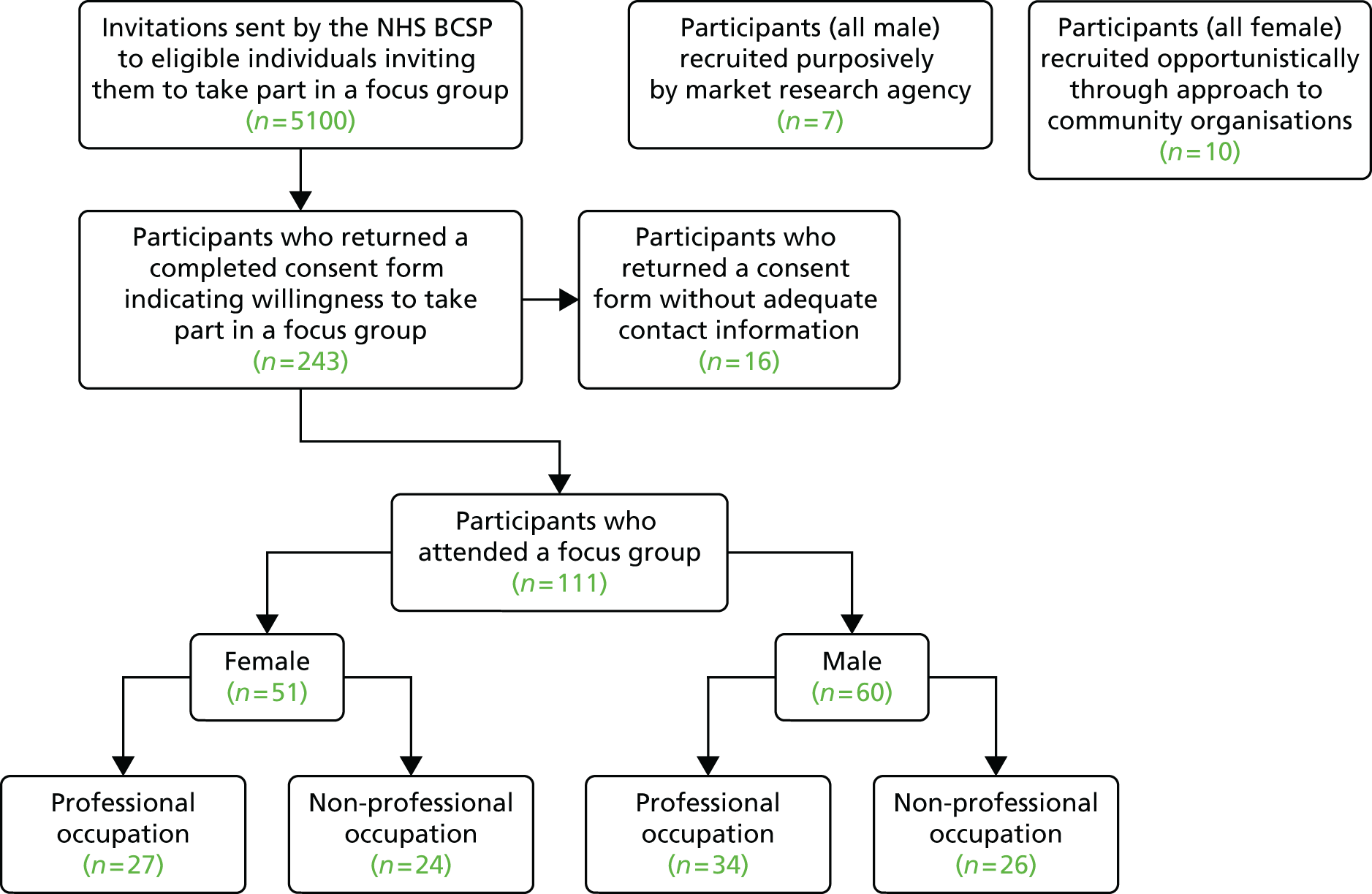

As a result of these two separate waves of recruitment via the NHS BCSP, we received 243 completed consent forms from 129 men and 114 women. A total of 111 individuals subsequently attended a focus group. We intended to run 14 focus groups but were able to hold 16 owing to higher than anticipated response rates. We paid attention to ensuring the sample included a balance of men (n = 60) and women (n = 51), and individuals with reported professional (n = 61) and non-professional (n = 50) occupational backgrounds (see Table 2). Reported professional occupations included teacher, local government officer, solicitor, civil servant, nurse, dentist, journalist, artist and social worker, and non-professional occupations included sales assistant, cook, cleaner, carer, builder, miner, driver, waitress, postman and carpenter.

Recruitment using a market research company resulted in one focus group of seven primarily African Caribbean men and the approach by the research team to the north London church exercise group resulted in one focus group of 10 primarily African Caribbean women. In common with the purposively sampled focus groups, the two opportunistically recruited focus groups comprising individuals of African Caribbean origin also included participants who had and had not taken part in bowel cancer screening; however, these two groups were not organised with reference to occupational background.

In total, 18 focus groups were held with a total of 128 participants (Figure 3). The majority of participants recalled receiving invitation(s) and gFOBt kit(s) from the NHS BCSP. One hundred participants reported gFOBt non-uptake on at least one occasion, of whom 31 went on to complete the gFOBt kit when they were invited to take part in a subsequent screening round. Nine participants had not completed the gFOBt owing to ‘alternative uptake’ of bowel cancer screening, such as colonoscopy, endoscopy or gFOBt kit completion in primary or private care. Our comparative analyses found high consistency in accounts for non-uptake regardless of gender, ethnicity, occupational background or geographical location.

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment of focus group participants.

Themes

We present our findings as a series of six themes described below. To ensure anonymity, the identity of participants who provided the selected direct quotations is limited to focus group attended (i.e. FG01) and assigned participant number within this group (e.g. P1).

Themes common across non-professional and professional occupational groups

Risks posed by faeces

Participants in all focus groups explained their aversion to completing a gFOBt kit by reference to the perceived risks that collecting, storing and posting samples of faeces posed to hygiene. These risks were heightened by the requirement to complete the kit with samples from three separate bowel movements, which meant that the kit had to be stored over several days. Participants reported that the completion of the gFOBt kit threatened to physically pollute them or their environment and that they would need to go to extreme lengths to manage these perceived threats:

People’s hands have to handle this yes? You don’t know how strong germs get . . . so I don’t fancy it going through the post.

FG17P1

It’s like sort of not flushing, only worse, it’s sort of not nice . . . I wanted to scrub the bathroom down every day, so I thought it’s not worth the hassle.

FG03P5

Completion of the gFOBt kit was considered to pose serious and fundamental threats to notions of socially acceptable and proper behaviour. Participants reported discomfort at the idea of handling faeces because this was an activity that was abnormal, broached a cultural taboo or could cause embarrassment and shame:

You wouldn’t normally leave faeces in your bathroom for 3 days.

FG07P3

It’s just not the done thing is it?

No – to mess about with it.

What will happen in the bathroom with it . . . you know the whole complication of where to put it and if someone else walks in and finds it.

FG16P4

The perceived taboo of interacting with faeces was further illustrated by participants’ concerns about being ‘found out’ to have completed the gFOBt kit. Being found to have stored or posted faecal samples was believed to be potentially socially and personally damaging, in that it could reflect badly on the individual and undermine them in the eyes of others. Some participants described the requirements of the gFOBt as ‘offensive’ and ‘degrading’. The use of the term ‘degradation’ is of particular significance, because it carries ideas of personal cost in that it compromises the individual. Thus, completing the kit raised the threat of being at best embarrassed and, at worst, disgraced and discredited:

Put your poo in the post . . . I thought oh god, y’know it’s got your name on it and what if they open it.

FG15P5

I’ve had two I’ve sent them both in the dustbin. I won’t discuss it but I were a bit offended.

FG09P6

I’ve had one and I ain’t done it, I just felt degraded to tell you the truth.

FG11P5

The aversion to dealing with faeces that emerged in participants’ accounts of non-uptake is underpinned by deeply ingrained definitions of faeces as a taboo substance65 and rigid social rules surrounding how it is appropriately dealt with.

Detachment from familiar health-care settings

Participants reported discomfort with the detachment of the gFOBt from ‘usual’ health-care settings and professionals. They expressed a preference to attend a health setting such as a general practice or hospital and for ‘someone else’ to undertake the screening on their behalf:

Why don’t they send you t’doctors or hospital to have it done there? . . . if the doctor sent for me and said I want to do so and so for you I’d go, or the hospital but doing that meself, I didn’t like it at all.

FG09P6

On one level, participants linked their desire to ‘go somewhere’ such as a general practice or hospital with the avoidance of having to collect and sample their faeces. However, participants’ references to medical settings as ‘preferred’ also revealed that the invitation to the NHS BCSP was out of context and unsettling, because it required them to undertake a health procedure outside the settings in which health care is usually practised. Further linked to this was a perception of ‘self-testing’ as unusual and unexpected, particularly in comparison with other screening experiences or medical interactions where ‘a professional’ is involved in the procedure:

I thought ‘oh my god now we are asked to be doctors’.

FG16P6

I threw mine away, I’d rather have it done for me.

FG04P5

I’d rather go somewhere and have it done to be quite honest.

FG04P6

Participants emphasised that it was unusual to play an active role in a health procedure, when the norm in medical encounters was for them to be the passive ‘receiver’ of care. They also disliked the impersonal nature of home testing:

I would prefer my doctor to have some obvious interaction with me in the actual process rather than it being done with an anonymous third party.

FG01P8

By extension, it was noteworthy how many participants claimed that, had they been given an appointment to attend, or been told by their GP to complete a gFOBt kit, they would have done so. Therefore, it appeared that the detachment from clinical settings and professional roles may have reduced the perceived importance of the offer of screening:

The message that was communicated to me was that this was hardly urgent or serious because if it was they would send me off to have a clinician do it.

FG01P1

If the letter had come from my GP . . . I would have taken it more seriously.

FG18P6

The prospect of self-sampling at home inhibited rather than facilitated uptake.

The implications of knowing the screening results

The most complex theme to emerge related to the implications of knowing the screening results. Participants preferred not to be in possession of this information for several reasons. First, they commonly referred to the undesirable implications of a positive result. Thus, they expressed unwillingness to undergo the recommended procedures that may follow a positive gFOBt kit result, such as colonoscopy or bowel surgery. These participants often referred to previous experiences (their own or those of family members) of bowel investigations or treatment for gastroenterological problems and described their negative consequences:

It’s the after effects, if they do find something, that would put me off taking the test in the first place . . . it’s the colonoscopy, the treatment of the colonoscopy.

FG10P3

Non-uptake was therefore a means to protect oneself from the possible unpleasant consequences of a positive test.

Second, participants distinguished between ‘being unwell’ and ‘knowing about being unwell’. A positive screening result meant that they would need to ‘redefine’ themselves as being unwell, which they did not wish to do because they believed it was unnecessary:

If there’s something the matter with me now, and I don’t know about it, I’m fine. If somebody says I’ve got a problem, I’m going to worry about it, and I don’t want that, you know you live life as it is now and I don’t want people finding things.

FG10P6

Thus, there emerged from participants’ accounts an alternative reading of screening as an activity that, rather than maintaining good health, may actually be complicit in generating ill health. By presenting screening as a process that could undermine health and questioning the value of the knowledge offered by screening to the maintenance of good health, participants pointed out that the benefit of declining to complete the gFOBt kit allowed one to ‘get on with life’:

This is just like sticking your head down the loo and thinking you’ve got cancer all day, you know there’s a balance of how much ‘into’ things you should get.

FG03P3

To me it’s like mollycoddling yourself so everything working right, don’t mess about with yourself.

FG05P1

Finally, the possibility that screening might identify cancer and result in subsequent interventions was described by some participants as too frightening to contemplate. The knowledge offered by screening was, for some, a stressful and frightening prospect, to the extent that actively choosing not to be in possession of this information was preferable:

I’m scared, simple as that . . . it’s the test coming back positive that worries me, so I tend to ignore it and hope it goes away.

FG02P2

What’s frightening?

What actually might be discovered, what I don’t know is not there like, if you know what I mean.

Thus, some participants demonstrated an ambivalence towards, or overt rejection of, the knowledge offered by screening. Analysis of the accounts of participants who ‘didn’t want to know’ found that it was also common for such participants to describe cancer as a particularly serious and frightening diagnosis for which treatment was unpleasant and often futile. Participants’ attitude towards cancer treatment further underpinned their rejection of the knowledge offered by screening because, if there was perceived to be little benefit associated with treatment, there was little point in taking part in screening:

[A friend] went through all that chemotherapy and all that suffering it didn’t make a . . . difference.

FG08P6

Judgements of good health and low relevance of screening

Many participants believed that the gFOBt was irrelevant because they were certain that they did not have, and were unlikely to get, bowel cancer. The evidence they cited included a lack of symptoms, being physically active and having no family history of bowel cancer:

I’ve got no symptoms so I’m all right, y’know, I go to the toilet regular and y’know, I exercise and I’m fit.

FG09P1

Descriptions of being in good health were often interwoven with other themes of non-uptake.

Themes present among professional occupational groups only

Delaying uptake, leading to non-uptake

No themes emerged solely from participants with non-professional backgrounds; however, we identified one theme associated with non-uptake which was discussed only by participants with professional backgrounds. These respondents commonly described their non-uptake in terms of delay, rather than outright rejection. Participants reported that the gFOBt kit was ‘put to one side’, or ‘put in the in-tray’ implying some degree of intention to participate, but ultimately kits were not completed. Delay was often linked to descriptions of the complexity of the instructions for completing the gFOBt kit and also the time-consuming nature of kit completion:

You’ve got to really sit down and read it, you can’t, it’s not just something you can pick up and say ‘oh I’ll go and do that now’, you’ve got to study it.

FG12P4

It’s quite a long-winded, drawn out thing I just kept putting off doing it.

FG03P8

There was a common misconception among participants in all focus groups that samples had to be taken on three consecutive days. Respondents from professional backgrounds cited this rigid, 3-day ‘window’ for test completion as a cause of delay and subsequent non-completion because it was not possible to fit the test requirements in with their bowel movements or routine and lifestyle:

If I start it on one day I’ve got to remember then to do it for the next 2 days and that was a big block for me because I’m very rarely in the same place for 3 days in a row.

FG14P8

Non-uptake followed by uptake in a subsequent screening round: the power of talk – a key ‘tipping point’

Participants from all occupational backgrounds who reported that they had not initially participated in screening and had then completed the gFOBt kit in a subsequent screening round described being influenced by discussions with family members, friends and health professionals. They reported being questioned about their initial refusal to complete the test or being told outright to take part in bowel cancer screening. They also recalled supportive discussions in which their concerns about or aversions to the gFOBt kit were discussed and challenged. Participants reported that becoming aware that their partner or friends had already completed the gFOBt kit was influential. In addition, they reported that becoming aware that a family member or friend had developed bowel cancer influenced them to take part in screening:

My brother-in-law was diagnosed with bowel cancer after I’d had the first request which I totally ignored . . . my wife did [her gFOBt kit] and she got her results back which were clear, peace of mind, I thought well you silly bugger, you know, why didn’t I do [it].

FG09P4

A friend also had it and she was telling me about how she did it and I thought gosh it’s not as complex as I think.

FG16P2

Discussions in which other individuals championed participation in screening or revealed their own gFOBt kit uptake were repeatedly implicated by participants as the key tipping point to a decision to undertake screening on a subsequent occasion. Through talking with others, participants described themselves as ‘nagged’, encouraged and reassured to undertake the gFOBt. Furthermore, through talking with others and becoming aware of others’ completion of the gFOBt kit, uptake was repositioned as a normal activity. The particular power of talk appeared to normalise the unusual, unexpected and potentially taboo aspects of the gFOBt kit:

I think as well it’s a critical mass isn’t it, so you discover your friends are all doing it or whatever so then it does become a slightly normal thing to do.

FG16P1

Discussion

Our analysis of participants’ accounts has identified key themes that inform understanding of why non-uptake of bowel cancer screening occurs. Furthermore, our comparative analysis of focus group data by area (inner-city London, Doncaster and Barnsley), gender, occupational background and ethnicity found few differences in the ways in which participants accounted for non-uptake. In common with previous studies,45,50,51 we have identified the threats to hygiene posed by completion of a gFOBt kit. However, our analysis extends the understanding of the problems posed by faeces with the concept of ‘social pollution’. Taboos surrounding interactions with faeces65,66 mean that completion of a gFOBt kit may be considered ‘improper’ in addition to unpleasant. The troubling nature of faeces is therefore a key element in participants’ non-uptake of the gFOBt. In addition, we found that the requirement to undertake the gFOBt kit oneself and in one’s own home represented a detachment from familiar medical settings and roles, which, in turn, impersonalised or devalued screening as a valid health endeavour. The prospect of self-testing at home was for some unsettling rather than facilitating of uptake. This finding is unreported elsewhere in the literature.

Ambivalence about the value and benefit of the knowledge offered by screening, and of medical intervention more generally, has been identified previously. 47,50,51 Participants confidently articulated the negative implications of participation in screening and emphasised the benefits of not being in possession of such knowledge. Non-uptake was therefore presented as having protective and beneficial effects. In addition, we found that participants described delay and non-uptake of the gFOBt kit owing to its prolonged and complex nature, and identified misconceptions about correct test completion that may contribute to perceptions of complexity. We further identified the well-documented misconception that having no symptoms meant that screening was not needed. 44,47,49,50 Finally, we have identified the influence of talking with others as a tipping point to uptake of screening. We suggest that it is through talk that completion of a gFOBt kit may be ‘reformed’ as a normal and culturally appropriate activity, and that concerns about its unexpected and potentially inappropriate aspects may be alleviated.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study adds significantly to the qualitative literature exploring gFOBt non-uptake and offers unique insights relating to the NHS BCSP in England. The strength of the study lies in our grounded and inductive analysis of an extensive qualitative data set generated through focus groups with participants who had actual experience of screening non-uptake within the NHS BCSP. Moreover, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to have explored changes of uptake decision at a subsequent screening round to generate insights into the ‘tipping points’ for uptake of gFOBt. Importantly, our analysis has identified the ‘faecal factor’ to be a key element in non-uptake of screening, differing somewhat from previous studies that have found such concerns to be downplayed. 45,50,51 However, in these studies, the majority of participants had undertaken screening and, therefore, such concerns were likely to have been minimised.

Our data comprise the accounts of participants who recalled an invitation to screening, who knew they had not taken part and were, as such, able to report on the experience in a focus group. However, there were a small number of participants who exhibited little knowledge or recollection of being invited to screening. These participants illustrated that it is possible to be unaware of one’s non-uptake, possibly because the invitation to screening or purpose of the gFOBt has made little or no impression (or may never have been received). Low literacy on the part of a participant may render the entire experience of being invited to screening inaccessible and unknown67 and, thus, ‘unreportable’ in the context of a focus group. We therefore acknowledge the limitations, as well as the utility, of insights based on participants’ accounts. Finally, we acknowledge that our sample excluded participants who required care owing to dementia, stroke or learning difficulties because of challenges for such participants to take part in a focus group.

A further strength of the study is the unique method of recruitment, which was largely achieved through direct invitation from the NHS BCSP. This enabled us to ensure that our sample included a majority of individuals who had not taken part in screening. It further enabled composition of the focus groups which maximised the potential for comparative analyses of the data by reference to gender, area (inner-city London and two towns in South Yorkshire) and SECs of participants. However, we were not able to specifically recruit low-literacy adults (one of the groups we had intended to recruit via ContinYou) using this method, as we might have been able to had we been able to recruit participants through our charity partners and community settings. Indeed, inviting people by a written letter may have positively excluded low-literacy individuals.