Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10386. The contractual start date was in July 2008. The final report began editorial review in March 2015 and was accepted for publication in May 2016. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Krysia Dziedzic was appointed a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Fellow during the programme period (2013–16), received an NHS England Regional Innovation Fund award to implement aspects of the programme, and was an invited speaker by the British Health Professionals in Rheumatology to present the results. John Edwards was in receipt of a National Institute for Health Research In-Practice Fellowship (2010–12) to carry out parts of this programme and was an invited speaker by the European League Against Rheumatism to present the results. He is also a general practice contractor and benefits from payments under the Quality and Outcomes Framework of the General Medical Services Contract.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Hay et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) programme described in this report concerns people with osteoarthritis (OA) and their primary health care.

Osteoarthritis is a condition of pain and stiffness in the joints that is common among older adults (adults aged ≥ 45 years) and constitutes a major portion of the global causes of disability. 1 It is the most frequent cause of restricted physical and social activity in older people in the UK,2 the most common long-term condition managed in UK general practice3,4 and estimated to become the dominant preventable cause of chronic disability in the UK by the year 2030. 5

Osteoarthritis is a long-term condition. Relief of pain and the maintenance of active participation in daily work, domestic and social life are the goals for treatment and management of most patients, rather than complete cure. 6 However, dramatic improvements can be achieved by joint replacement surgery, which is conducted in the minority of patients who develop advanced and severe OA. 7

At the time that this programme was formulated (2008–9), there was evidence that simple interventions that were available in primary care could provide short-term relief of pain and restricted activity in persons with OA. 8–14 This evidence provided the basis and support for core guidance on care for patients with OA by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which was published in 2008. 15 It was also apparent that most people with OA have other health conditions (comorbidities)16,17 and, if effective care is provided for these other conditions, the pain and disability of OA improves. 18 We also knew that self-management programmes could improve outcomes in patients with long-term conditions (such as irritable bowel syndrome) which, like OA, are managed predominantly in primary care and the community. 19–21 However, there was also evidence that the quality of OA care ranked lower than care for other long-term conditions managed in primary care22,23 and there was much variability in the content and quality of primary care offered to patients with OA. 24 For example, most persons with OA were not receiving the full range of NICE core treatments for OA,24 including advice and information regarded by NICE as a core requirement. 15 Patients with OA told us that they wanted help and support to self-manage their condition,6,22,25–28 because short-term changes in behaviour that benefit persons with OA, such as increased physical activity, are often not maintained in the long term,29–34 and their comorbidities were often under-recognised in primary care and the community. 35–39

Our interpretation of the literature at that time highlighted an absence of evidence and information about key aspects of OA care in the community and primary care, including no clear estimate of the potential for prevention of OA in the population and health-care benefits among older people with joint pain and disability in the UK community. It is likely that small effects from simple core treatments applied to large numbers of people with OA could result in substantial population health gains at reasonable cost. 40 Although evidence about the effectiveness of certain non-pharmacological interventions was encouraging, we did not know the best way for general practitioners (GPs) and the primary care team to consult with persons with OA to deliver these interventions and support self-management, or how to measure quality of OA primary care. 23 Prior to our programme, there had been few attempts to involve OA patients in shaping what information they wanted, or needed, and what to do to manage their condition24 (see Appendix 1). Lastly, there was evidence that most OA patients and health-care professionals were pessimistic (or, at best, stoical) about the long-term course of OA and the likelihood of getting effective care until the condition was bad enough to require an operation. 22,41,42 Patients perceived doctors’ views to often be negative: ‘not much to be done’ and ‘what else can be expected at your age?’. 41–44

The conclusion was that OA care in the UK was not as good as it could be, despite evidence that primary care and community-based interventions can reduce pain and disability. The research gaps identified included the need for development and evaluation of better information for public health, patients and clinicians, and for new approaches to delivering OA care in practice. The ambition of our programme was to address these gaps.

Methodological note

The studies in this programme were developed in parallel and not in series. This had two methodological implications. First, the development of a theoretical model for estimating the cost-effectiveness of different primary care approaches to OA management (study 3, workstream 1) could not draw on the results of the other workstreams. However, it has been designed so that it can be populated with new data in the future. Second, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) was not available at the time of the development of the protocols for the studies and this explains the use of the earlier EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) in this programme.

Chapter 2 Workstream 1: modelling optimal primary care for osteoarthritis

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Wulff. 59

Abstract

Background: The cost-effectiveness of primary care approaches for patients with OA in primary care is not known.

Objectives: (1) Identify key predictors of 3-year outcomes of pain and function in a population-based sample of people aged ≥ 50 years with joint pain and OA, (2) summarise evidence regarding the effectiveness of core primary care interventions for OA and (3) design a decision model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of implementing evidence-based, core primary care management for OA.

Methods: Secondary analysis of population cohort data to identify predictors. An evidence synthesis and meta-analysis to summarise evidence of the effectiveness of four core primary care interventions [advice and information, simple analgesics, topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and exercise] for OA. The effect estimates derived from the evidence synthesis were used to populate an economic decision model.

Results: The prediction models showed that, in this population, the strongest predictors of future pain and functional limitation include baseline pain, function, physical activity, general health, obesity and socioeconomic indicators. The models showed good internal validity, but needed to be further developed to account for generalised pain in people with OA and to investigate the predictive value of modifiable prognostic factors (including physical activity and obesity) to identify groups that benefit from specific treatments. The meta-analysis showed statistically significant small to moderate improvements in pain and function from advice and information, topical NSAIDs and exercise interventions compared with controls, while simple analgesia failed to demonstrate statistically significant improvements in either pain or function. The decision model examined the cost-effectiveness of two hypothetical approaches to delivering primary care interventions for hip and knee OA (stepped care and ‘one-stop-shop’ care) compared with current primary care. The hypothetical stepped-care intervention was the most cost-effective, dominating ‘one-stop-shop’ and current care, and this result was robust to the sensitivity analyses conducted.

Conclusion: This work provides a platform for modelling the long-term cost-effectiveness of interventions for OA. The model will require further development, including use of more accurate data on the short-term course of OA pain to provide better estimates and the incorporation of evidence on hand and foot OA.

Introduction

Reliable information regarding the likely course of symptoms and factors predicting poor long-term outcomes in people with joint pain and OA is important to inform public health about the burden of these conditions in local communities and, linked with evidence about treatment efficacy and effectiveness, to estimate for policy-makers the probable costs and benefits of health interventions. Such information would provide evidence to inform the potential usefulness of identifying subgroups of persons with OA at higher risk of poor outcomes who may preferentially benefit from targeted timely interventions.

Previous studies have developed prediction models for OA, but most were developed to predict the onset of OA45,46 or the outcome of a specific treatment,47,48 or were focused on a specific joint – usually the knee. 49–52 Most people with OA have multiple joint pains53–55 and our aim was to develop prognostic models and estimate the cost-effectiveness of offering core treatments for OA regardless of the site of pain.

Modelling studies help to identify desirable resource shifts and guide public health and health-care policy. 56 In estimating potential health gains and reductions in disability in relevant subgroups of patients and estimating the costs associated with these gains, policy-makers can determine the gaps between current treatment and optimal management for OA and quantify the need to invest in services and research. 57 Few modelling studies in OA have been carried out in population-based or primary care cohorts58 and there are not many studies that have used longitudinal data on the long-term outcomes of pain and function. 57 We aimed to address and avoid these limitations by using data from a large, prospective population-based cohort with linked morbidity records from health care in order to estimate the probability and key predictors of unfavourable long-term outcome in people with OA, and the cost-effectiveness of implementing core primary care management for OA.

The objectives of this workstream were to (1) identify key predictors of long-term (3-year) pain and limitation in function in a population-based sample of people with joint pain and OA, (2) synthesise evidence regarding the effectiveness of core primary care interventions and (3) estimate the cost-effectiveness of implementing evidence-based, core primary care management for OA. The study also aimed to provide a basic model as a resource for future analyses of the cost-effectiveness of primary care interventions for joint pain and OA, including novel approaches such as those under investigation in the other workstreams of this programme. The population-based cohort (used in study 1) and the evidence synthesis (study 2) provided data to support the design of this basic health economic model (study 3).

The work described in this chapter was undertaken in the framework of a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD). 59

The cohort and modelling studies in this workstream were based on an existing population-based cohort [the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Projects (NorStOP) study], which included people aged ≥ 50 years. This age criterion contrasts with the criterion of people aged ≥ 45 years who took part in workstreams 2–4 of the programme. The high prevalence of joint pain found in NorStOP was one reason for lowering the minimum age for these other workstreams in order to include interventions early in the course of OA.

Study 1: predicting long-term outcome in people with joint pain and osteoarthritis

This section describes the methods and results of a prognostic study aiming to identify predictors of future long-term (3-year) risk of pain and functional limitation in a population-based sample of older adults with joint pain.

Methods

Design and study population

Data were used from the NorStOP study, a series of population-based prospective cohorts of adults aged ≥ 50 years who were registered with one of eight general practices in North Staffordshire, UK. 60 These cohorts were originally set up through Medical Research Council (MRC) programme funding and NIHR primary care centre funding, and continue to be a resource for researchers from inside and outside Keele University. A two-stage mailing strategy was used, comprising a health survey sent to all persons in the sampling frame and a subsequent regional pain questionnaire sent to those who had responded to the health survey, given consent to be contacted again and indicated they had experienced pain in the hip, knee, hand or foot in the previous year. Participants received similar follow-up questionnaires at 3 years. Ethics approval was obtained from the North Staffordshire Local Research Ethics Committee (NS-LREC 1351 and 1430). This analysis includes all responders who reported hand, hip, knee or foot joint pain at baseline that had lasted ≥ 3 months over the previous 12 months and who returned the 3-year follow-up survey.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures for the prognostic models were (1) moderate or more severe pain in at least one joint site and (2) limitations in physical function in accordance with the Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials (OMERACT) consensus statement on key outcome measures for OA. 61

The pain subscales of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) (range 0–20),62 Australian/Canadian Osteoarthritis Hand Index (AUSCAN) (range 0–20)63 and Foot Pain Disability Index (FPDI) scores (range –3.32 to 3.33)64,65 were used to measure pain related to the hip/knee, hand and foot, respectively. All three questionnaires have been validated in relevant populations. To define a dichotomous measure of at least moderate pain, cut-off points for increased scores on the WOMAC, AUSCAN or FPDI scores were selected using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis with a 0- to 10-point numerical rating scale (NRS) for pain with a validated cut-off point of 5 as the anchor (0–4 mild pain, 5–10 moderate to severe pain). 66 Based on maximal area under the ROC curve, the cut-off points for at least moderate pain obtained for WOMAC pain were 6 and 5 for the hip and knee, respectively, 9 for AUSCAN hand pain, and –0.479 for FPDI foot pain. Participants with scores below any of the relevant cut-off points at the 3-year follow-up were classified as having ‘no or mild pain’, while those with scores equal to or above the cut-off point were classified as having ‘moderate to severe pain’.

Limitations in physical function were assessed with the 10-item physical functioning subscale of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) (range 0–100, higher scores indicating better physical functioning),67 which was completed by all participants regardless of the location of pain. The scale was converted into a binary variable based on its median score of 55, as its distribution was heavily skewed. Respondents with a score of less than the median value were classified as having important functional limitation.

Potential predictors

The baseline health survey included questions on physical functioning, joint pain, participation restriction, general health, sociodemographic factors, lifestyle characteristics, comorbidity, medication use and psychosocial factors (including illness perceptions, anxiety and depression). Full details of the variables and their descriptions have been reported elsewhere. 59 These variables were all considered as potential predictors in the prognostic analysis as they have been shown to be associated with symptoms of OA or are considered to be potential predictors of outcome in pain conditions more generally. All variables with prevalence of < 10% or > 90% or with fewer than 30 participants giving a positive response were excluded from the analysis to facilitate successful convergence of the models68 and optimal discrimination between people with favourable or unfavourable outcome.

Statistical analysis

Model development and internal validation

Poisson regression was used to develop prognostic models, as it estimates the true risk as incidence rate ratio (IRR) for each predictor. The number of events (i.e. those with at least moderate pain or functional limitation at follow-up) was high and consequently the odds ratios (ORs) from logistic regression would not approximate true underlying risk, which was required to estimate population attributable risk (PAR) and number needed to treat (NNT) (see Selection of the most important predictors based on population attributable risk and number needed to treat). Robust variance estimation was used to provide accurate effect estimates and their uncertainty. 69 The models were constructed using a backward stepwise variable selection procedure, retaining only those variables with a statistically significant association with outcome (p < 0.05) based on the likelihood ratio test. The c-statistic was used as a measure of the predictive performance of the models. Bootstrapping (500 samples) was subsequently used to adjust performance estimates for optimism. 70

Selection of the most important predictors based on population attributable risk and number needed to treat

Epidemiological parameters (PAR and NNT) were calculated for each predictor to allow for better understanding of the potential impact of individual prognostic factors and to support the selection of the most relevant predictors for identification of vulnerable subgroups of people with joint pain. 71

The PAR and NNT were estimated for each predictor selected in the models.

The PAR represents the proportion of the risk of poor outcome in the whole population that is explained by a particular predictor. It provides an indication of maximum achievable population health gain if exposure to that predictor was completely eliminated by successful intervention. PAR, adjusted for other predictors in the model, was calculated using the Stata® version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) command aflogit, based on a formula proposed by Greenland and Drescher. 72

The NNT represents the number of people needed to be treated to prevent one additional person from suffering from an unfavourable outcome. It was calculated as the inverse of the absolute risk difference between the exposed and unexposed groups. NNT is usually presented as an estimate of treatment effect.

In this observational study, following the procedure proposed by Smit et al. ,71 PAR and NNT were used as impact measures in order to select a limited set of predictors based on high effect size (IRR), high PAR and low NNT. The predictive performance of this key set of predictors was compared with the performance of the original Poisson models.

Non-response and missing values

A non-response analysis has previously been carried out for the NorStOP cohorts by comparing age and sex distribution of responders and non-responders to the baseline questionnaire. 73 We also compared demographic characteristics, pain, physical function, mental health and obesity between participants who completed the 3-year follow-up questionnaire and those dropping out of the study. Furthermore, multiple imputations by chained equation were used to generate data for predictor variables with > 3% missing values. Content and performance of prediction models based on the imputed data sets were similar to that of the complete case analysis; hence, only results of complete cases have been reported here. All analyses were performed using Stata version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Response

In the original NorStOP cohorts, a total of 26,705 people aged ≥ 50 years were identified from eight general practices and posted the health survey. A total of 18,474 participants responded (estimated response 71.8% after adjustment for age and sex). Among this group of responders were 10,057 persons who reported joint pain in the previous year and gave their consent for further contact. This group was sent a second questionnaire at baseline (the regional pain questionnaire) and a follow-up questionnaire 3 years later.

The cohort for the current analysis, which is described here and was supported by the NIHR programme grant, was the subgroup of 3563 responders at the 3-year follow-up (57.6% of all 3-year regional pain questionnaire responders) who responded at 3 years and had reported pain in at least one joint site at baseline for a duration of ≥ 3 months over the 12 months prior to the baseline survey.

Characteristics of participants

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of the sample, stratified according to the presence of severe pain and functional limitation at the 3-year follow-up. The mean age of participants was 64 years (range 50–93 years) and 60% were female. Non-responders at baseline and at the 3-year follow-up were slightly younger and more often male. At the 3-year follow-up, more than two-thirds (71%) of the participants reported severe pain, while 43% had poor function. The distribution of pain, physical function, obesity, anxiety and depression scores were similar for individuals responding at follow-up and those who dropped out from the study at 3 years (data not shown).

| Variables | Pain at 3 years, n (%) | Functional limitation at 3 years, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild or no pain | Moderate to severe pain | Good function | Poor function | |

| N = 1019 (29%) | N = 2544 (71%) | N = 2028 (57%) | N = 1535 (43%) | |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 50–64 | 556 (55) | 1306 (51) | 1221 (60) | 641 (42) |

| 65–74 | 322 (32) | 852 (34) | 617 (30) | 557 (36) |

| ≥ 75 | 141 (13) | 386 (15) | 190 (10) | 337 (22) |

| Median (IQR) | 63 (56–70) | 64 (57–71) | 62 (56–68) | 66 (59–74) |

| Female sex | 567 (56) | 1556 (61) | 1175 (58) | 948 (62) |

| Married | 788 (78) | 1810 (72) | 1575 (78) | 1023 (67) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 314 (32) | 584 (24) | 729 (37) | 169 (11) |

| Retired | 538 (54) | 1352 (55) | 965 (48) | 925 (63) |

| Unemployed | 145 (14) | 525 (21) | 292 (15) | 378 (26) |

| BMI | ||||

| Normal weight (20–24.9 kg/m2) | 383 (39) | 728 (29) | 736 (38) | 375 (26) |

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 452 (47) | 1052 (43) | 885 (45) | 619 (42) |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 137 (14) | 678 (28) | 341 (17) | 474 (32) |

Predictors of poor outcome at three years

Multivariable Poisson regression identified a large number of baseline predictors that were statistically significantly associated with increased risk of moderate to severe pain at 3 years, including variables related to pain severity, poor physical function, socioeconomic factors, obesity, anxiety, hypertension and little use of pain medication or other remedies. Baseline predictors associated with increased risk of functional limitation at 3 years included several measures of poor function, being unemployed or retired from work, lower levels of activity, fewer years in education, joint pain severity, obesity, hypertension and poor health perceptions. Predictive performance was good for both models with c-statistics adjusted for optimism of 0.83 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 0.85] for predicting moderate to severe pain and 0.91 (95% CI 0.90 to 0.92) for predicting limitation in function at 3 years.

Selection of important predictors

Both models included a large number of predictors, which limited their clinical utility. In this study, the most relevant predictors for severe pain and poor functional limitation at 3 years were selected using the rule employed by Smit et al. 71 to select subgroups of participants at increased risk of developing anxiety in later life. The rule selects predictors based on large effect size (IRR), high PAR and low NNT, which have the ability to select factors for which the highest possible health benefit (IRR and PAR) and the lowest possible effort and cost (NNT) can be achieved if interventions are completely successful. In addition, the predictive performance of the set of predictors had to be comparable to that of the original Poisson regression models.

Based on high effect size (IRR), high PAR and low NNT, the following prognostic factors were selected as the most relevant predictors of moderate to severe pain at 3 years: presence of knee pain in the last year (IRR 1.31, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.43), high WOMAC knee pain score (IRR 1.15, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.24), poor physical function (IRR 1.14, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.22), hand pain in the last year (IRR 1.12, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.20), not attended further full-time education after secondary school education has been completed (IRR 1.12, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.23) and obesity (95% CI 1.11, 1.05 to 1.17). The predictive performance (apparent c-statistic) of this reduced set of predictors was 0.75 (95% CI 0.73 to 0.77), indicating some reduction in performance for the reduced pain model. The adjusted PAR estimates for these factors were 17%, 9%, 11%, 7%, 9% and 2%, respectively, while their (unadjusted) NNT estimates were n = 5, n = 6, n = 4, n = 7, n = 9 and n = 6, respectively (Figure 1).

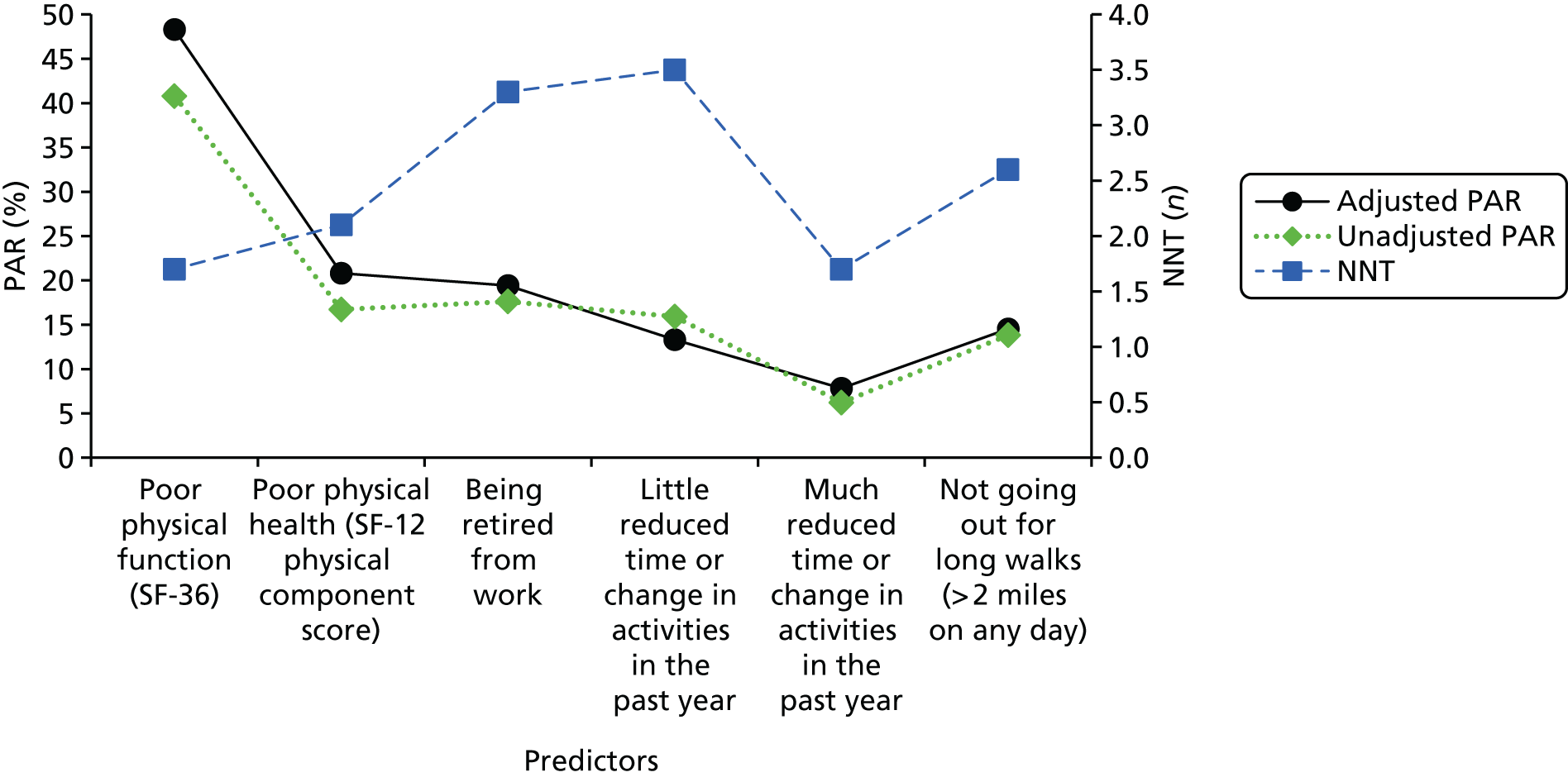

FIGURE 1.

The PAR and NNT for the most important predictors of moderate to severe pain at 3 years.

Using the same procedure for selecting predictors, poor physical function (subscale SF-36, IRR 2.48, 95% CI 2.02 to 3.05), poor physical health [SF-12 physical component score (PCS), IRR 1.44, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.67], being retired from work (IRR 1.39, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.64), reporting reduction in time of or change in activities in the past year (IRR 1.31, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.70), with IRR estimates shown separately for ‘much’ and ‘little’ reduction in Figure 2 and not going out for long walks (> 2 miles on any day) (IRR 1.28, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.48) were identified as the most important predictors for functional limitation (see Figure 2). Their adjusted PAR estimates were 48%, 21%, 19%, 8%, 13% and 15%, respectively, with unadjusted NNT estimates of n = 2, n = 2, n = 3, n = 3, n = 2 and n = 3, respectively (see Figure 2). The predictive performance (apparent statistic) of this reduced model was 0.71 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.73), indicating a considerable reduction in predictive performance when compared with the full Poisson model.

FIGURE 2.

The PAR and NNT for the most important predictors of limitation in function at 3 years.

Discussion

This study identified key baseline predictors of moderate to severe pain and functional limitation at 3 years in a community sample of older people with joint pain or OA. The predictive performance was good for the full prediction models but lower (as expected) for the reduced models, especially for the model predicting functional limitation. Key predictors of poor outcome included high baseline levels of pain and poor function, poor general physical health, low levels of physical activity, indicators of lower socioeconomic status and obesity.

Our data set provided the opportunity to derive prognostic models for long-term outcomes of joint pain in a community sample. The study identified a mix of potentially modifiable and non-modifiable predictors, taking into account a wide range of factors. Selection of predictors for the reduced, more feasible models was not only based on the strength of association of predictors with outcome (IRR), but also on the PAR and NNT associated with these predictors. These indicators take the prevalence of the predictor in the sample into account, providing a measure of impact and facilitating interpretation of findings (Box 1).

For example: the adjusted PAR of 17% for presence of knee pain at baseline (IRR = 1.33) indicates that 17% of the risk of severe pain 3 years later in the population of all people who start off with pain in at least one joint (adjusted for known confounders) is explained by having pain located specifically in the knee.

The NNT of n = 5 indicates that were baseline knee pain to be successfully treated or prevented in five individuals in this population, this would prevent one additional person having long-term severe pain 3 years later.

Although these indicators are useful for presenting findings, and can serve as useful indicators for planning health-care resources and identifying vulnerable subgroups, they have to be interpreted with caution. The PAR assumes there are no other competing risks and, when the PAR is interpreted as an indicator of maximum achievable health gain, the assumption is that predictors are causally associated with outcome and can be optimally addressed by an effective intervention. 74

This study uniquely derived outcome prediction models for OA regardless of the joints involved. We felt this to be important as most people with OA have multiple pains and may consult with pain and problems at different joints. The onset of multiple joint pain has been shown to be associated with more frequent or severe pain at follow-up and larger increases in locomotor disability. 75,76 The presence of generalised pain is likely to influence the outcome of treatment and should be taken into account when managing musculoskeletal conditions such as OA. 77

Our analysis started with a large number of potential predictors. The shortcomings of using many variables in a stepwise model include a lack of stability of the selected set of predictors and potential bias in the estimation of regression coefficients due to multiple testing. 78 However, testing of our performance estimates using bootstrapping showed limited optimism, indicating adequate internal validity of our models.

Approximately 29% of the total sample did not respond to the baseline health survey. A comparison of non-responders with responders at baseline showed non-responders to be slightly younger and more often male. Therefore, they may also differ with respect to levels of pain, functional limitation or other characteristics. However, this is not likely to greatly influence associations between baseline predictors and 3-year outcomes of pain and function in our subsample of participants with joint pain at baseline. More importantly, approximately one-third of participants did not respond to the follow-up questionnaires at 3 years, mainly because they did not provide consent for further contact or declined to continue with the study. The non-response analysis showed a slightly different age and sex distribution in responders, but very similar baseline scores for other sociodemographic variables and for pain, function, and physical and mental health, limiting the risk of bias when identifying key predictors of long-term pain and functional limitation in this study. A recent study of the potential effects of attrition in the NorStOP cohorts confirmed that there was little evidence that responders at follow-up points represented any further selection bias to that present at baseline. 79

Conclusion

In a population sample of older people with symptoms of joint pain that is probably attributable to OA, the strongest predictors of moderate to severe pain and functional limitation 3 years later are baseline measures of:

-

location and severity of pain

-

physical function

-

physical activity

-

general health

-

obesity

-

socioeconomic indicators.

Outputs

-

These findings were used as the basis for the modelling of primary care strategies for population health gain in OA (see Study 3: estimating cost-effectiveness of delivering core primary care management for osteoarthritis).

-

One potential implication of the findings for the primary care of OA is that improving the most severely affected patients will be needed in order to shift population levels of pain and disability in the long term. However, the analysis presented here was based on a general population sample, which may over-represent prevalent cases when compared with a sample of primary care consulters, and included some characteristics that may not be modifiable, at least in the short term. Future work will need to take better account of the presence of generalised pain in people with joint pain or OA and investigate the specific predictive value of modifiable prognostic factors (including physical activity and obesity) to identify risk groups and individuals for targeting treatment, such as the interventions investigated in the Managing OSteoArthritis In ConsultationS (MOSAICS) studies and Benefits of Effective Exercise for knee Pain (BEEP) trials (see Chapters 3 and 4). The second output of this programme is, therefore, a development of the analysis based on a more selective category (‘joint pain that interferes with daily life’) as the primary outcome, designed to reflect a more severely affected population. Predictors will focus on modifiable prognostic factors for poor outcome.

Study 2: summarising evidence regarding the effectiveness of core primary care interventions

An evidence synthesis and meta-analysis was conducted to summarise available evidence regarding the effectiveness of primary care interventions recommended by NICE for patients with OA (i.e. advice and information, paracetamol, topical NSAIDs and exercise). The aim of the evidence synthesis was to obtain effect estimates that can be used to populate the health economic decision model presented in study 3 (see Study 3: estimating cost-effectiveness of delivering core primary care management for osteoarthritis). Interventions to lose weight were not included in this analysis as the decision model did not solely concern overweight or obese patients.

Methods

There are numerous published systematic reviews of the effectiveness of conservative treatments for OA, which made it possible to design an efficient search strategy, identifying relevant randomised trials first from existing systematic reviews and then by an updated search of trials not yet included in the reviews. As this work was conducted at the start of the funding period for this Programme Grants for Applied Research report, this evidence synthesis included trials published until August 2010.

Search strategy

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses were searched in MEDLINE and The Cochrane Library from January 1990 to August 2010. Subsequently, an additional search in MEDLINE, covering the period from the year 2000 to August 2010, was conducted to identify individual trials that were not yet included in reviews. The search terms were developed in consultation with an information specialist and were based on the following (exploded) medical subject heading terms: OA, family practice, general practice, primary health care, community health services, ambulatory care, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, exercise therapy. Reference lists from all retrieved systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were checked to identify additional potentially eligible RCTs.

Selection of trials

Included in the evidence synthesis were full reports of RCTs, published in English, that evaluated the effectiveness of advice or information regarding self-management approaches and of paracetamol, topical NSAIDs and exercise in patients diagnosed (radiographically or symptomatically) with OA at one or more joint sites (hand, hip, knee or foot). Given the focus of this study on primary care, RCTs were only selected if they had been conducted in a primary care or direct access setting. One reviewer (JW) scored eligibility of all identified publications, with an additional reviewer (DvdW, MB or SJ) judging eligibility of all potentially relevant studies.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from RCTs included in this review to enable description of setting, study design, trial population, interventions and outcome measures. Estimates of absolute mean or changes in mean scores after treatment and their respective standard deviations (SD) were extracted and used to calculate standardised mean differences (SMDs) for outcomes of pain and functional limitation. 80 When relevant reports were available, effect estimates were calculated based on intention to treat analysis. Effect estimates of 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 were described as small, moderate and large, respectively. 81

Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias of RCTs was assessed using The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. 82

The risk of bias domains considered most important in this analysis were adequacy of randomisation, concealment allocation, blinding of outcome assessors and loss to follow-up. These were scored by JW as high risk, low risk or unclear risk of bias. Sensitivity analyses were performed, omitting trials with high risk of bias in at least one of the domains considered.

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis focused on comparisons that were of interest to the design of the decision model (see Study 3: estimating cost-effectiveness of delivering core primary care management for osteoarthritis): (1) advice and information versus no treatment, (2) simple analgesics versus advice/placebo/no treatment, (3) topical NSAIDs versus advice/placebo/no treatment and (4) exercise versus advice/simple analgesics/no treatment. Pooled effect estimates for each comparison were calculated using a fixed- or random-effects model depending on the extent of heterogeneity present. Fixed-effects models were used when the I2 estimate was ≤ 50%, otherwise random-effects models were used. Depending on the data presented in the original trial reports, SMDs for pain and functional limitation were derived using either mean change or the final outcome score at the end of treatment. This does not pose a problem in meta-analysis as both scores are considered to be addressing the same underlying intervention effect in RCTs. 83 Differences in mean final scores will be the same as differences in mean change scores if randomisation has been successful and baseline values of outcome measures are similar.

Funnel plots and Egger’s test84 were used to assess the risk of small-study bias for comparisons including an adequate number of studies.

Results

Search results

A total of 41 RCTs (27 from Cochrane reviews, 11 from other reviews and three additional trials from MEDLINE) met the selection criteria and were included in the evidence synthesis. Four RCTs investigated the clinical effectiveness of advice and information, two investigated simple analgesics, four investigated topical NSAIDs and 31 examined exercise interventions. A full list of references and summary of the main characteristics of the included RCTs are available from the authors of this report.

The knee was the most commonly affected joint among the RCTs considered in this review, with 24 RCTs investigating the knee only and 17 enrolling participants with either knee or hip OA. No trials investigating hand or foot OA met the inclusion criteria for this evidence synthesis and none assessed treatment effects independently of the joint affected.

Risk of bias

In general, the RCTs included in this review appeared to have good methodological quality and none of the medication trials (analgesics or NSAIDs) showed a high risk of bias on any of the domains. All 41 trials were judged to be at low risk of bias in terms of random allocation of interventions. Among four trials investigating advice and information interventions, one was at a high risk of bias in terms of loss to follow-up. For exercise interventions, the proportion of RCTs at a high risk of bias was 7 out of 31 (23%) for blinding of outcome assessment and 5 out of 31 (16%) for loss to follow-up.

Clinical effectiveness of primary care interventions for osteoarthritis

The 41 RCTs included in this review provided data on 6715 subjects assessed for pain and 5322 subjects assessed for functional limitation. Table 2 summarises the results of the meta-analysis for each of the four comparisons.

| Comparison | Pain outcomes | Functional limitation outcomes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of trials | Number of participants | I2 (Cochran’s Q-test for heterogeneity p-value) | Pain SMD (95% CI) | Number of trials | Number of participants | I2 (Cochran’s Q-test for heterogeneity p-value) | Functional limitation SMD (95% CI) | |

| Advice and information vs. no treatment | 4 | 771 | 0.0%, p = 0.961 | –0.17 (–0.31 to –0.03) | 4 | 771 | 1.7%, p = 0.384 | –0.20 (0.34 to –0.06) |

| Analgesics (paracetamol) vs. advice/placebo/no treatment | 2 | 400 | – | –0.11 (–0.31 to 0.08) | 1 | 57 | – | –0.01 (–0.53 to 0.51) |

| Topical NSAIDs vs. advice/placebo/no treatment | 4 | 790 | 0.0%, p = 0.985 | –0.35 (–0.49 to –0.21) | 4 | 789 | 0.0%, p = 0.900 | –0.31 (–0.45 to –0.17) |

| Exercise vs. analgesics/advice/no treatment | 31 | 1389 | 0.0%, p = 0.990 | –0.32 (–0.43 to –0.21) | 27 | 1240 | 0.0%, p = 0.726 | –0.27 (–0.39 to –0.16) |

Only one of the four RCTs investigating advice and information showed statistically significant improvement when compared with control. There was no evidence of heterogeneity across the studies for either pain (I2 = 0.0%) or functional limitation (I2 = 1.7%) outcomes. The pooled analysis showed a small, statistically significant, reduction in pain (SMD = –0.17, 95% CI –0.31 to –0.03, n = 771) as well as a small, statistically significant, improvement in function (SMD = –0.20, 95% CI –0.34 to –0.06, n = 771) in favour of advice and information (mean duration of treatment was 19 weeks) when compared with control.

The two RCTs investigating the effectiveness of analgesia (paracetamol, mean duration of treatment was 9 weeks) failed to demonstrate a significant difference compared with control interventions. The pooled effect estimates were small and not statistically significant: SMD = –0.11(95% CI –0.31 to 0.08, n = 400) for pain and –0.01 (95% CI –0.53 to 0.51, n = 57) for function. Given the small number of studies, these estimates have to be interpreted with caution.

Four RCTs compared the efficacy of topical diclofenac with placebo, with three RCTs showing beneficial effects. There was no evidence of heterogeneity of effects among the studies for either pain (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.985) or functional limitation (I2 = 0.0%; p = 0.900). Pooled estimates of SMD showed moderate reduction in pain (–0.35, 95% CI –0.49 to –0.21, n = 790) and moderate improvement in function (–0.31, 95% CI –0.45 to –0.17, n = 789) of topical diclofenac compared with placebo after a mean duration of treatment of 5.5 weeks.

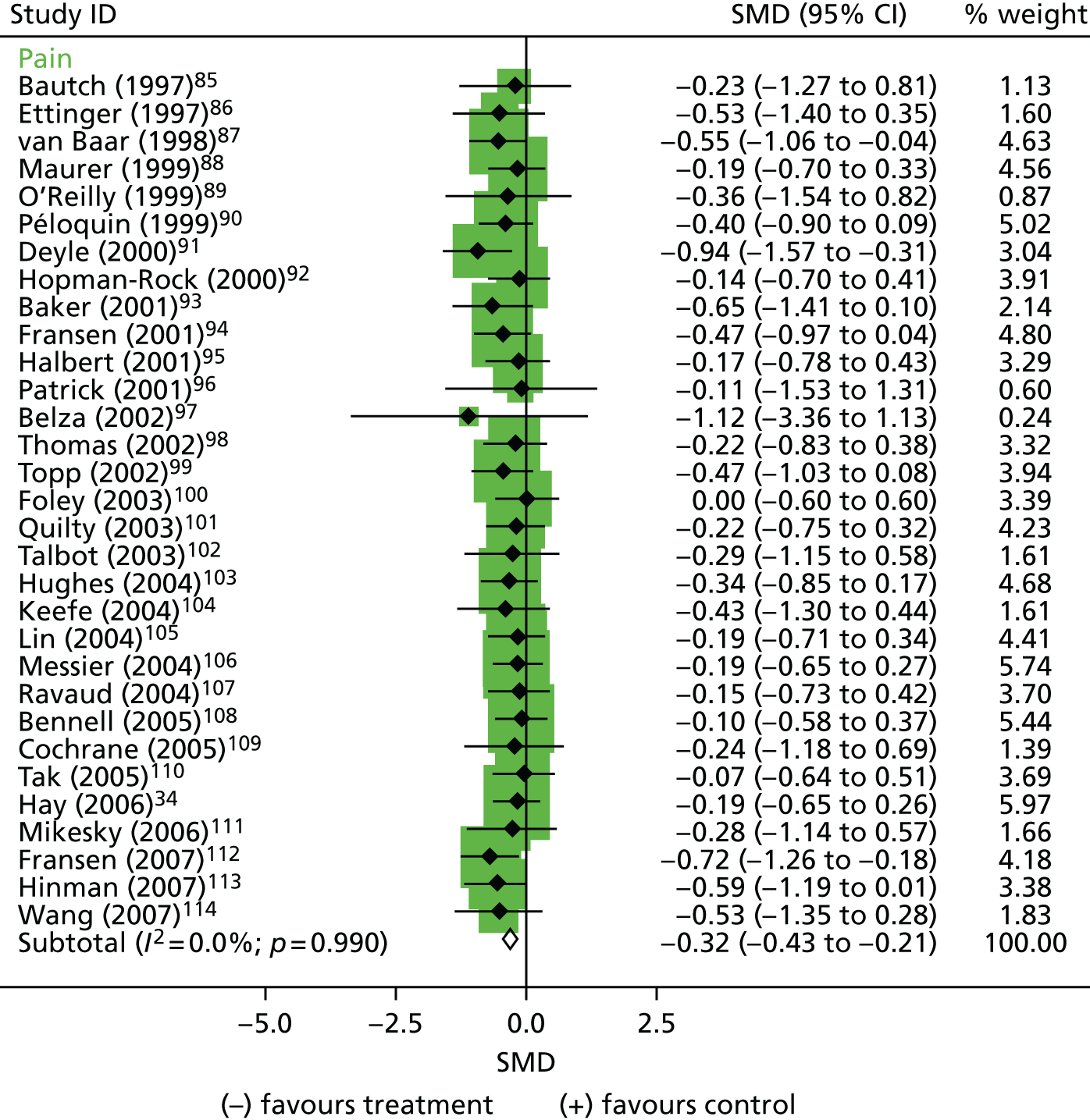

A wide range of exercise interventions was assessed among the 31 exercise trials, comprising both individual and group programmes, and with variable content focusing on strength, flexibility, balance and/or aerobic exercises. These references are included in Figure 3. Three RCTs showed a statistically significant reduction in pain (see Figure 3) and a statistically significant improvement in functional limitation. There was minimal statistical heterogeneity among the studies for both outcome measures (see Table 2). The pooled analyses showed a moderate reduction in pain (SMD –0.32, 95% CI –0.43 to –0.21, n = 1389) and moderate improvement in function (SMD –0.27, 95% CI –0.39 to –0.16, n = 1240) for exercise (mean duration of 19 weeks) compared with control interventions.

FIGURE 3.

Effect estimates (SMD) for pain outcomes of exercise interventions for OA. Reproduced with permission from Jerome Wulff. 59

The number of trials of exercise interventions was sufficient to reliably assess the risk of small-study bias. The funnel plots for both outcome measures appear to be symmetrically shaped (Figure 4) and Egger’s bias estimates confirm the lack of evidence for small-study bias for pain (bias estimate –0.49, 95% CI –1.41 to 0.44; p = 0.292) and function (bias estimate –1.14, 95% CI –2.47 to 0.18; p = 0.087).

FIGURE 4.

Funnel plot for trials investigating exercise interventions for OA (pain outcomes). Reproduced with permission from Jerome Wulff. 59

Sensitivity analyses were performed for advice and information, and exercise intervention studies, with results showing minimal differences in the pooled effect estimates after exclusion of studies with a high risk of bias.

Discussion

This evidence synthesis and meta-analysis involved summarising the results of RCTs that had evaluated the effectiveness of advice and information, simple analgesics, topical NSAIDs and exercise interventions for primary care patients with OA. All trials investigated knee and/or hip OA. The meta-analyses demonstrated statistically significantly more reduction in pain and functional limitation for information and advice, topical NSAIDs and exercise interventions than control treatments. This was not the case for simple analgesics, namely paracetamol. The effect sizes varied (0.17 and 0.49) and may be rated as small to moderate.

Although our evidence synthesis only included trials carried out in primary care or open access settings, the results of the meta-analyses are in agreement with findings of previous or subsequent reviews on advice and information,115 medication,116–119 and exercise120–122 in people with hip or knee OA, which show effect sizes for pain and function of similar magnitude.

This evidence synthesis showed that a minority of RCTs have been carried out in primary care settings, in particular those on advice and medication. Furthermore, this synthesis was mainly based on a search of available systematic reviews and only included full-trial reports published in English. This is a weakness of this review but it is reassuring that the magnitude of effect sizes were comparable with those reported in other systematic reviews based on broader search strategies, that is, including studies from health-care settings other than primary care and, therefore, not the focus of this review and evidence synthesis.

The quality of the RCTs included in the evidence synthesis appeared to be good, although information was often lacking regarding the methods used for concealing treatment allocation, blinding of outcome assessment and loss to follow-up. We accept that single reviewer assessment of quality was a weakness in the methods of this evidence synthesis, but sensitivity analyses excluding RCTs with a high risk of bias for at least one domain resulted in very similar effect estimates, which justifies use of estimates based on all available evidence.

Conclusion

This work provided effect estimates for the four primary care interventions included in the decision-modelling study (see Study 3: estimating cost-effectiveness of delivering core primary care management for osteoarthritis), which aimed to estimate the cost-effectiveness of different strategies to deliver core primary care management for OA. The main shortcomings of the available evidence for this particular purpose concerned the relatively small number of trials carried out in primary care, the lack of trials focusing on hand or foot OA and the lack of long-term follow-up in available primary care trials.

Outputs

-

As stated above, estimates were provided for the modelling in the section Study 3: estimating cost-effectiveness of delivering core primary care management for osteoarthritis

-

The specific aim and content of the review presented here was extended into a full review and network meta-analysis of randomised trials of exercise interventions for OA as a linked output of workstreams and workstream 3. 122

Study 3: estimating cost-effectiveness of delivering core primary care management for osteoarthritis

This section presents work undertaken to develop a decision model for optimal OA primary care and provides a basic template that can be developed and further refined using new or accumulating evidence on the cost-effectiveness of interventions.

The model aimed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of two hypothetical interventions for delivering core primary care compared with current care for adults with OA, from a health-care perspective.

The two modes of delivery chosen to illustrate the template were (1) stepped care and (2) a ‘one-stop shop’, with both interventions containing four of the core primary care interventions for OA: advice and information, paracetamol, topical NSAIDs and exercise. The individual interventions were selected because they are recommended by NICE,15 European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI)10–14,32 as core interventions for managing OA. Therefore, the evidence synthesis described in study 2 (see Study 2: summarising evidence regarding the effectiveness of core primary care interventions) did not influence selection of interventions for the modelling study (paracetamol was found to be no more effective than placebo or alternatives, as judged by statistical significance, in the synthesis), but the synthesis did provide the standardised effect estimates for all four interventions included in the modelling study. The two hypothetical strategies were proposed by a consensus meeting consisting of clinicians and OA researchers.

Methods

Study population

The patient population was adults aged ≥ 50 years with symptomatic knee and/or hip pain or OA in a primary care setting in the UK, using data from the NorStOP cohort. 60 The original idea was to use a similar target population to that used for the prediction modelling study described above in study 1 (see Study 1: predicting long-term outcome in people with joint pain and osteoarthritis), in which participants had pain at baseline at one or more joint site (hand, hip, knee or foot). However, the proportion of participants with only hand or foot OA was low (< 5% each) and the evidence synthesis (described in study 2, see Study 2: summarising evidence regarding the effectiveness of core primary care interventions) provided effect estimates only for hip and/or knee OA. Therefore, it was decided to define this sample more narrowly than in study 1 of the workstream and the pain scores provided by the WOMAC questionnaire from study 1 were used to represent hip or knee pain status. If an individual had pain scores for both joints, the highest score was used to reflect the joint with greater pain.

Model structure

A Markov cohort model was built to reflect the clinical history of OA. The model considered four health states (no pain, mild, moderate and severe pain), defined using baseline WOMAC scores (range from 0 to 20). A score of zero was defined as no pain, 1–5 as mild pain, 6–10 as moderate pain and 11–20 as severe pain. 62 Everyone started in the model with some pain (mild, moderate or severe) and moved health state when their condition improved or worsened; alternatively, they could remain in the same health state. Therefore, the model includes no pain as a state through which people could pass during follow-up, even though persons in that state were not included as one of the start points. Movement could only be to the next better or worse health state. A time horizon of 3 years was used in the base-case analysis, reflecting the follow-up period of the NorStOP cohorts used in this model. Death was not included in the model as the time horizon was short and the condition does not directly lead to death. A 3-month time cycle was used, as it was considered to be a clinically meaningful time period for OA in terms of expected changes in the symptoms of OA, duration of treatment and timing of decision-making by a GP. The structure is presented in Figure 5.

Interventions

Three packages of primary care were considered by the model: stepped care, ‘one-stop shop’ and current care. These hypothetical scenarios were discussed with clinicians to ensure assumptions were realistic.

Stepped care

This intervention included all four core interventions and assumed that interventions were prescribed by GPs in a stepped fashion. The first line of treatment was advice and paracetamol, and all patients were modelled as being offered this regardless of their baseline level of pain. If pain worsened or did not improve from a moderate or severe pain state, then the next (second) line of treatment prescribed was topical NSAIDs. The same principle applied for movement from the second to the third line of treatment (exercise, assumed to be supervised by a physiotherapist). If there was no improvement after the third line of treatment, patients returned to current care. Those who were originally in a severe pain health state and whose condition improved to moderate pain were moved to a ‘moderate-from-severe’ health state. If they remained in this ‘moderate-from-severe’ health state, the same line of stepped-care treatment was received, as maintaining any improvement from the most severe state was assumed to be a positive situation. Each step-up of treatment was assumed to involve a practice nurse appointment to introduce the new treatment.

‘One-stop shop’

In the ‘one-stop-shop’ package of care, participants were offered all four core interventions simultaneously. It was assumed that the package was prescribed by a GP, with a physiotherapist offering the initial exercise package. The rationale behind this intervention was that it allowed patients to receive all optimal interventions at the same time, irrespective of pain severity. If a patient moved to a worse health state or did not improve from a moderate or severe pain state, they returned to current care. The rationale behind this assumption was that some participants will not respond or adhere to treatment and will then return to their GP to be placed under current care. The assumption regarding the continuation of an intervention once a moderate health state has been achieved after improvement from the more severe state also applied here.

Current care

Current care for OA was informed by the observational cohort study (NorStOP) and a primary care-based RCT from the UK, which included a usual-care arm. 123,124 Data from the cohort study indicated that many patients only consult their GP about their condition once within a period of 3 years. Patients consulting their GP were likely to be initially offered advice and pain medication(s) according to the severity of their symptoms and, thereafter, stronger pain medications, referral for physiotherapy and eventually surgery as the last treatment option if the pain persisted. Surgery was not considered in this study given the 3-year time horizon, during which arthroplasty was not very likely. Owing to the lack of detailed data on health-care resource use in the cohort, the costs of current care were considered to be as reported in the control arm (current GP-led care) in a trial of exercise in knee OA patients. 123,124 Treatments included advice, exercise and pain medication(s) including simple analgesia (paracetamol and aspirin), topical and oral NSAIDs, and opioids.

Data inputs

Table 3 contains information on the baseline proportion of patients in each health state at baseline and provides estimates for the clinical effectiveness of individual treatments. The initial distributions in each health state at the start point of the model were estimated from NorStOP baseline data. Participants with no knee or hip pain at baseline were excluded because the model assumed only participants with pain would consult primary care and receive treatment. The numbers excluded from the sample used in study 1 above (i.e. those with only foot or hand pain) were small. Estimates of the SMD for each of the primary care interventions compared with their controls were obtained from the review in study 2.

| Parameter | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Start point health state (pain) | Baseline proportion | |

| No pain | 0 | NorStOP data |

| Mild | 0.3245 | |

| Moderate | 0.4177 | |

| Severe | 0.2578 | |

| Treatment effect estimates | SMD (95% CI) | |

| Advice and information vs. no treatment | –0.17 (–0.31 to –0.03) | Systematic review (see Table 2) |

| Simple analgesia (paracetamol) vs. advice/placebo/no treatment | –0.11 (–0.31 to 0.08) | Assumption |

| Topical NSAIDs [diclofenac gel (Voltarol® gel, GlaxoSmithKline)] vs. advice/placebo/no treatment | –0.35 (–0.49 to –0.21) | |

| Exercise vs. analgesics/advice/no treatment | –0.32 (–0.43 to –0.21) | |

| ‘One-stop shop’ | –0.50 |

Table 4 presents the transition probabilities for current care and all interventions. Current-care data on pain severity at baseline and 3 years from the NorStOP cohort was used to provide transition probabilities for the model. Matrix multiplication was utilised to transform actual transitions over 3 years into 3-monthly transitions. The treatment effect estimates were then applied to the current-care transition probabilities to obtain new transition probabilities. In the stepped-care intervention, only the effectiveness of the specific intervention at that step was applied, even though the patient was likely to be continuing to receive previous interventions. The estimate of effect (SMD) for the ‘one-stop shop’ was set at 0.5. This estimate was agreed during the consensus meeting of clinicians and OA researchers as it is larger than the strongest effect estimate of the individual primary care interventions. The clinicians in particular were clear that they often used the interventions as a package and agreed that a large additive effect between these concurrent interventions was unlikely.

| Pain health states by health-care category or intervention | No pain | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline probabilities | 0 | 0.3245 | 0.4177 | 0.2578 |

| Current care | ||||

| No pain | 0.6022 | 0.3978 | 0 | 0 |

| Mild | 0.0613 | 0.8836 | 0.0551 | 0 |

| Moderate | 0 | 0.0456 | 0.9194 | 0.0350 |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | 0.0462 | 0.9538 |

| Advice and paracetamol | ||||

| No pain | 0.6022 | 0.3978 | 0 | 0 |

| Mild | 0.1301 | 0.8148 | 0.0551 | 0 |

| Moderate | 0 | 0.0969 | 0.8681 | 0.0350 |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | 0.0980 | 0.9020 |

| Topical NSAIDs | ||||

| No pain | 0.6022 | 0.3978 | 0 | 0 |

| Mild | 0.2940 | 0.6509 | 0.0551 | 0 |

| Moderate | 0 | 0.2189 | 0.7461 | 0.0350 |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | 0.2215 | 0.7785 |

| Exercise | ||||

| No pain | 0.6022 | 0.3978 | 0 | 0 |

| Mild | 0.2729 | 0.6720 | 0.0551 | 0 |

| Moderate | 0 | 0.2032 | 0.7618 | 0.0350 |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | 0.2056 | 0.7944 |

| ‘One-stop shop’ | ||||

| No pain | 0.6022 | 0.3978 | 0 | 0 |

| Mild | 0.4010 | 0.5439 | 0.0551 | 0 |

| Moderate | 0 | 0.2986 | 0.6664 | 0.0350 |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | 0.3021 | 0.6979 |

Costs

Table 5 shows the unit cost data applied in this study. The cost of current care for each pain severity health state was estimated using patient-level data from the current-care arm of the exercise trial by Hurley et al. 124 The unit cost of drugs was updated from a price year of 2003/4 to 2010 using British National Formulary (BNF) costs126 and an average cost per 3 months of treatment calculated.

| Parameter | Cost/person/3 months (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Current care | ||

| No pain | 9.60 | Hurley et al.124 |

| Mild pain | 24.00 | Hurley et al.124 |

| Moderate pain | 39.70 | Hurley et al.124 |

| Severe pain | 65.70 | Hurley et al.124 |

| Intervention | ||

| Advice in GP consultation | 28.00 | PSSRU125 |

| Paracetamol | 7.78 | BNF126 |

| Topical NSAIDs | 16.17 | BNF126 |

| Exercise | 34.75 | Whitehurst et al.127 |

| Staff costs | ||

| GP consultation | 28 | PSSRU125 |

| Nurse-led consultation | 14 | PSSRU125 |

| Physiotherapist | 34 | PSSRU125 |

In stepped care, there was an initial cost for consultation with a GP, a nurse appointment for each new line of treatment and the cost of the intervention. The exercise intervention was six sessions of exercise at 30 minutes per session over a period of 6 weeks with an experienced physiotherapist. 128 It was assumed that when participants moved to the next line of treatment, they all continued to use the preceding interventions. The ‘one-stop-shop’ intervention cost included the cost of an initial GP consultation, ongoing costs for paracetamol and topical NSAIDs, a consultation with an experienced physiotherapist to introduce the exercise intervention at an initial consultation and the cost of exercise. Costs were accumulated over the 3-year time horizon to give total costs for each of the three modelled treatment strategies.

Outcomes

Baseline Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) component scores of the NorStOP participants with hip and/or knee pain were used to derive utility values for each health state, using the algorithms developed by Brazier and Roberts. 128 Table 6 shows the mean utility scores for the four health states used in this study. Utilities were accumulated over the 3-year time horizon to give total quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for each strategy in the model.

| Variable | Mean (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| No pain (n = 131) | 0.7925 (0.7706 to 0.8144) |

| Mild pain (n = 964) | 0.7604 (0.7518 to 0.7690) |

| Moderate pain (n = 1193) | 0.6886 (0.6803 to 0.6969) |

| Severe pain (n = 718) | 0.5593 (0.5499 to 0.5687) |

Analysis

Base case

An incremental cost–utility analysis was undertaken to compare the cost-effectiveness of the two proposed primary care strategies with current care, from a health-care perspective. The interventions were ordered in descending order according to cost. Costs and QALYs were discounted at an annual rate of 3.5% in accordance with the current UK treasury guidelines. 129 Costs were expressed in Great British pounds using 2010/11 as the price year. A threshold of cost-effectiveness of £20,000 per QALY gained was adopted for this study. 15

Deterministic sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were carried out to test the robustness of the primary results by changing some of the most important assumptions used in the model construction.

The following sensitivity analyses were performed:

-

Extension of the time horizon of the model from 3 years to 5, 10 and 20 years.

-

Application of GP costs instead of nurse costs for subsequent consultations in stepped care.

-

Selection of only those subgroups with moderate or severe pain categories (excluding mild pain patients) to reflect a health-care seeking population.

-

Varying the effect size (SMD) of exercise using 95% CIs.

-

Varying the effect size (SMD) for ‘one-stop shop’ between –0.4 and –0.6.

Results

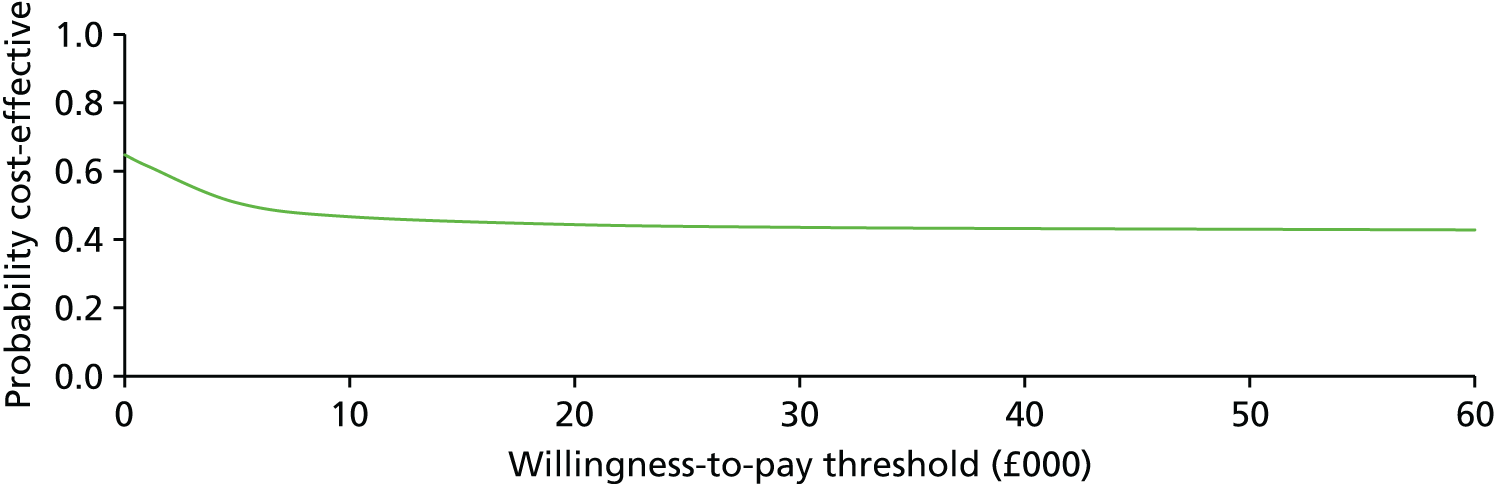

The results of the base-case analysis are presented in Table 7. Current care and the ‘one-stop shop’ intervention are both dominated by stepped care, which is cheaper and more effective. However the difference in QALYs is marginal. The ‘one-stop-shop’ intervention was cost-effective when compared with current care, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £1341 per additional QALY gained.

| Treatment | Cost (£) | QALYs | Cost difference | QALY difference | ICER (£/QALY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison of all three options | |||||

| Stepped care | 393.00 | 2.01 | – | – | – |

| Current care | 427.15 | 1.94 | 34.16 | –0.06 | (Dominated) |

| One-stop shop | 507.62 | 2.00 | 114.62 | –0.01 | (Dominated) |

| One-stop shop vs. current care | |||||

| Current care | 427.15 | 1.94 | – | – | – |

| One-stop shop | 507.62 | 2.00 | 80.47 | 0.06 | 1341.17 |

Stepped care continued to dominate in all but one of the sensitivity analyses and the one-stop shop was always more cost-effective than current care. If a patient were assumed to visit a GP rather than a nurse at every change of treatment in stepped care, mean costs were only marginally increased (£24). Running the model for an equal proportion of patients with moderate or severe pain increased the costs of all the three interventions and decreased total QALYs. The lower effectiveness estimate for exercise slightly decreased the QALYs for stepped care. If the SMD for ‘one-stop shop’ is changed to –0.4 then stepped care still dominates, but if it is changed to –0.6 then total QALYs become greater than for stepped care, giving an ICER of £29,281 per QALY gained. This value is above the suggested lower threshold for NICE of £20,000/QALY and so ‘one-stop shop’ is still unlikely to be interpreted as cost-effective.

Discussion

This is the first model-based economic analysis of primary care interventions for knee and hip OA. The results of this study have demonstrated that the hypothetical stepped-care intervention was the most cost-effective, dominating ‘one-stop-shop’ and current care. This result was robust to the sensitivity analyses conducted.

Inevitably, building a model of this type with hypothetical strategies has required a large number of assumptions to be made. First, the data used to provide transition probabilities for current care were available only for baseline and 3 years, and were converted to 3-month probabilities. It is highly unlikely that the long-term trajectory of 3 years can represent the short-term fluctuations in pain every 3 months. In addition, one-third of the cohort participants were lost to follow-up. As explained in Characteristics of participants, these participants had a slightly different age and sex distribution from responders. However, their other baseline measures (sociodemographic, pain, function, physical and mental health) were similar, limiting the likelihood of selection bias. The model was run for only 3 years in the base case, a short time horizon for a Markov model, although sensitivity analyses were conducted for long time periods. A longer time horizon would require the model structure to incorporate both joint replacement and all-cause death, both omitted from this model.

Second, assumptions were included regarding the effectiveness and cost of treatments. The level of effect of an intervention was assumed to be the same irrespective of the current pain health state, and the effect was assumed to be constant over time, even though estimates were from studies with short time frames. In reality, different types of patients may have different levels of benefit from interventions and the effectiveness of interventions may decrease over time. As patients moved from one treatment to the next in stepped care, there was no additive effect of treatment, even though it was assumed that the patient would still be receiving the previous intervention. Finally, the effect estimate for ‘one-stop shop’ was obtained from expert opinion to reflect the strength of the combined effect of the interventions. The value is likely to be reasonable, given that an additive effect is improbable when several interventions are combined. The current-care cost estimate used in this study was obtained from a data set for chronic knee pain, although this model considered both knee and hip OA.

Further assumptions were made with regard to patient pathways. When all treatments in the hypothetical interventions ceased to provide any improvement, the model assumed that patients moved back to current care in the next 3-month cycle, with a worse patient trajectory. In reality, this time frame may be too short. GPs may, for example, persevere with current interventions for longer and patients may be offered stronger medications, such as opioids, or be referred for surgery. The nature of the model does not allow the pain history of a patient to be taken into account. This limitation could be resolved by creating additional Markov health states or changing the type of model to one that can be run with individual patient histories (e.g. an Individual Sampling Model). 130

Despite these many assumptions, the results concur with a common-sense view of how these alternative strategies for primary care interventions in OA would work out in practice. The basic difference between ‘one-stop shop’ and ‘stepped-care approaches’, based on the same set of possible core interventions, is that the former strategy will, by definition, mean that all consulters will receive all possible interventions, whereas the latter strategy can potentially be more parsimonious in restricting the proportion of people who will receive all four interventions.

Conclusion

Building this model and estimating the cost-effectiveness of two hypothetical primary care intervention strategies illustrates that economic modelling can be used to extrapolate beyond short-term clinical trials in OA. The results presented here are indicative of the type of output that can be produced and provide a template for future analysis. As they stand, they are not designed to provide immediate guidance for decision-makers.

However, it is likely that current care for some OA patients already follows either a stepped care or ‘one-stop-shop’ approach, although its content and delivery may differ from the assumptions made in the hypothetical models. Therefore, this work provides a platform for modelling long-term cost-effectiveness of interventions for OA, to which additional data can be added.

Outputs

-

The template developed, described and tested here is a stand-alone resource for future modelling exercises.

-

The practical application and content of the template described here was constrained by available data at this stage of the programme (population data and secondary care trials). A second application of the model will use the output of the primary care trial data, such as that which has now emerged from the later stages of the programme in workstreams 2–4 for new analyses in the future. This second application will also further develop the template through:

-

probabilistic sensitivity analysis, taking into account all parameter uncertainty simultaneously, which was not undertaken here in this first application

-

inclusion of data on the course of OA pain over time, including short-term fluctuations, to provide more appropriate transition probabilities

-

adaptation to look at a broader range of OA pain sites.

-

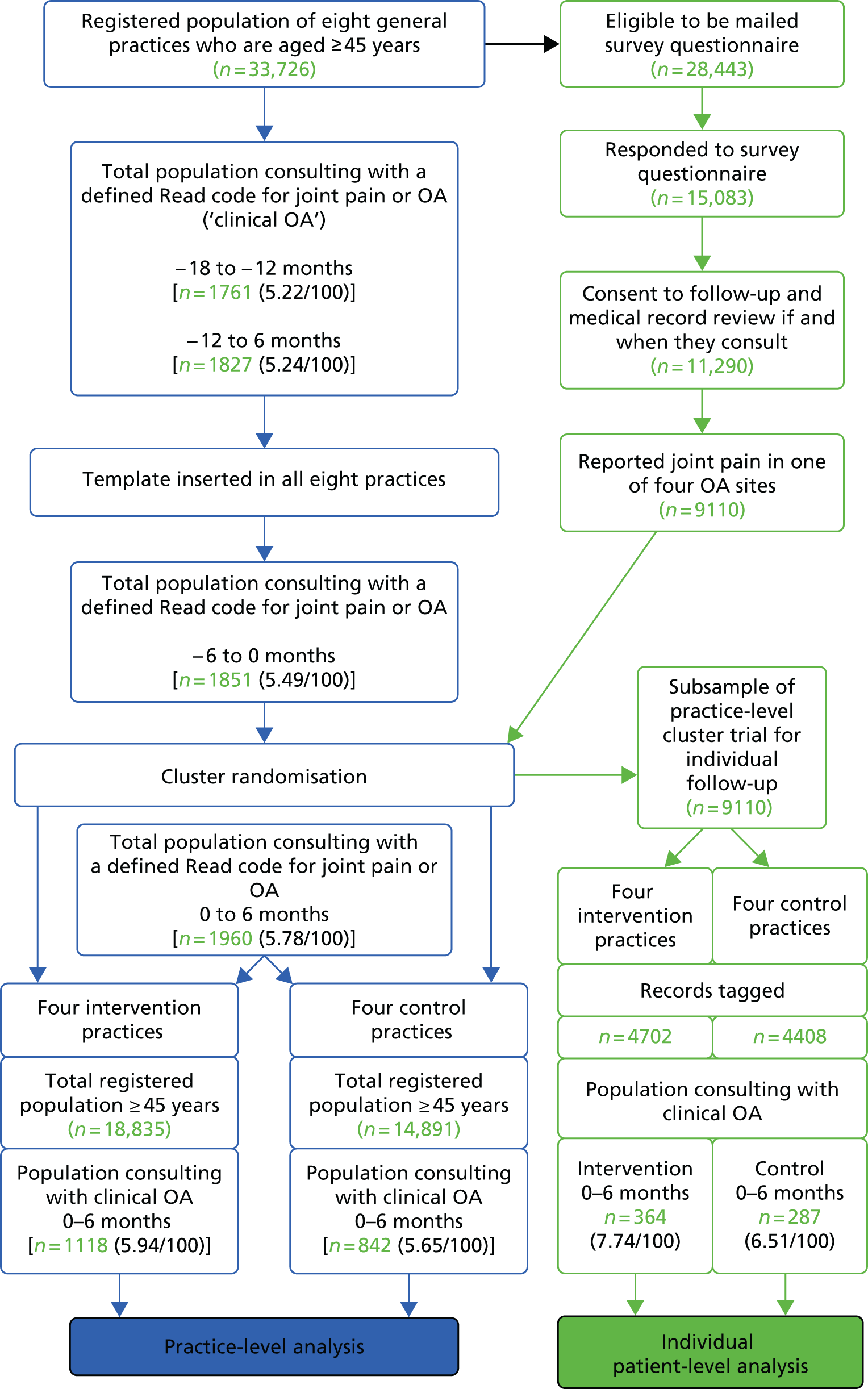

Chapter 3 Workstream 2: The MOSAICS studies

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Dziedzic et al. 131 © 2014 Dziedzic et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Abstract

Background: UK NICE guidance for primary care of OA patients is not implemented in practice. 15,24

Aim: To develop and evaluate novel ways to deliver core NICE guidance for OA in primary care, and to investigate their implementation and clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Methods: A suite of mixed-methods studies within the framework of a cluster RCT, in which four general practices implementing a new model of OA care (MOSAICS) were compared with four control practices.

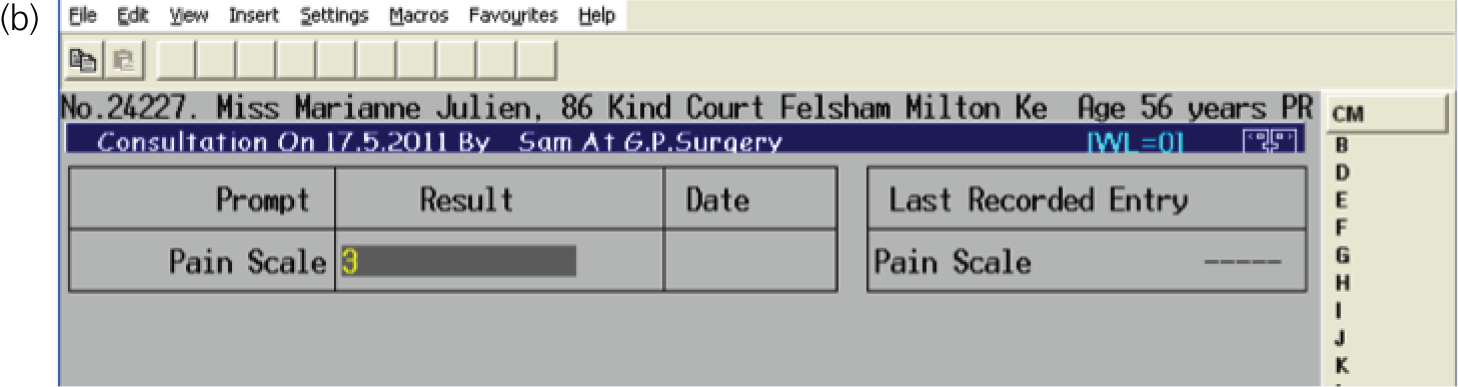

Results: Pre randomisation: practical support for delivering NICE guidelines was developed, including training in model OA consultations for GPs and practice nurses, and OA patient guidebook developed with patients and health-care professionals.

A novel pop-up computerised template (the ‘e-template’) to record quality markers of care was implemented in the eight participating practices132 and associated with improved recording of components of quality OA care and changed clinician prescribing and referral behaviour.

Post randomisation: the MOSAICS approach improved delivery of NICE core treatments, including provision of written information, simple analgesia and reduced radiography and increased physiotherapy referrals.

Only a minority of patients were referred to the practice nurse-led service. Among patients followed up post-consultation, MOSAICS innovations were regarded positively (by patients and health-care practitioners), pain and disability did not improve compared with controls, and visits to orthopaedic specialists and time off work declined.

Problems of implementation included difficulty maintaining change over time (patients and practitioners), practitioner variation in recording care and variable patient response to nurse-led clinics.

Conclusion: Improved implementation of NICE OA guidance can be achieved in primary care at no incremental cost, but does not result in better patient-reported pain and disability.

Ethics permission: This study was approved by the North West 1 Research Ethics Committee (REC), Cheshire (REC reference 10/H1017/76).

Trial registration: Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN06984617.

Introduction and overview of the MOSAICS studies

In the UK, OA is the second most frequent reason for consultations with older patients in primary care. 3 Most such consultations are with a doctor (the GP or family practitioner). 133 Primary care provides the arena in which most patients with OA in the population who seek care from the UK NHS are seen and managed.

In 2008, the UK NICE identified evidence-based interventions for patients with OA consulting in primary care (Figure 6). 15 These included a core set of interventions considered potentially applicable to all patients consulting about OA in primary care (represented by the inner circle in Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

The NICE core recommendations for treatment of OA (redrawn using relevant components from NICE15).

Evidence has shown that most OA patients in primary care were not receiving or continuing with these interventions24 and that there was widespread dissatisfaction and pessimism among doctors, health professionals and patients about primary care management of OA and about the potential to alter the natural history of the minority who will progress to joint replacement surgery. 22,41,42,44

This context provided the ambition and purpose for this second workstream of the NIHR programme RP-PG-0407-10386. The workstream comprised a suite of studies (MOSAICS) designed to develop practical evidence-based ways to support the implementation of NICE guideline core interventions in primary care and, thereby, to enhance the value of the primary care consultation for patients with OA.

The focus of the NICE core guidance is on self-management. 15 The guidance characterises self-management in terms of access to information and advice, including specific advice about exercise and physical activity, optimal use of simple oral and topical analgesia and, when appropriate, weight loss. The OA research user group (RUG) at Keele (see Appendix 1) had highlighted, prior to submission of the NIHR programme proposal, that their main concern about NHS recommendations for self-management was, from the perspective of patients, the lack of information, support and help to adopt and maintain self-management approaches. This user view provided the underlying rationale for the content of the MOSAICS interventions. A model OA consultation for GPs in primary care backed up by new patient information, an electronic template for monitoring quality of care and referral for a series of practice nurse-led model OA consultations formed the ‘MOSAICS model of care’, and this was defined as the vehicle to deliver NICE guidelines into practice. The theoretical basis for developing the intervention to change GP behaviour is described in detail by Porcheret et al. 134

The components of the MOSAICS approach were based on the Whole systems Implementing Self-management Engagement (WISE) model,19 which embraces the needs of the patient, the health-care professional and the service. The key components in MOSAICS that were developed and evaluated in this workstream were as follows:

-

Model OA consultations by GPs and practice nurses.

-

Training for primary care health professionals to deliver model OA consultations.

-

A new guidebook for patients, developed by patients and health-care professionals together, as the principal source of written information. 135

-

An electronic computer-based method (the ‘e-template’) for routine recording of components of quality OA care by GPs and practice nurses.

-

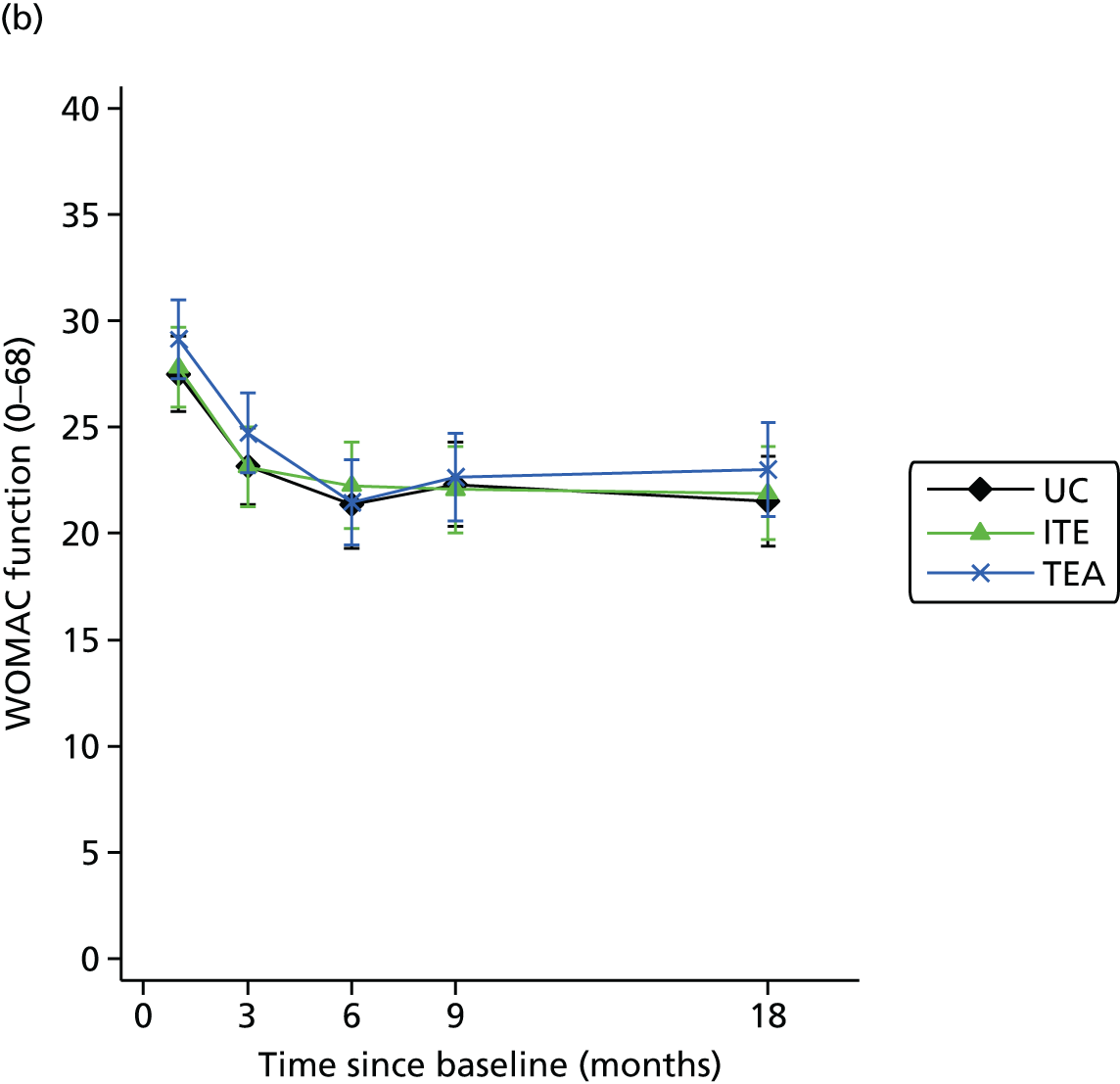

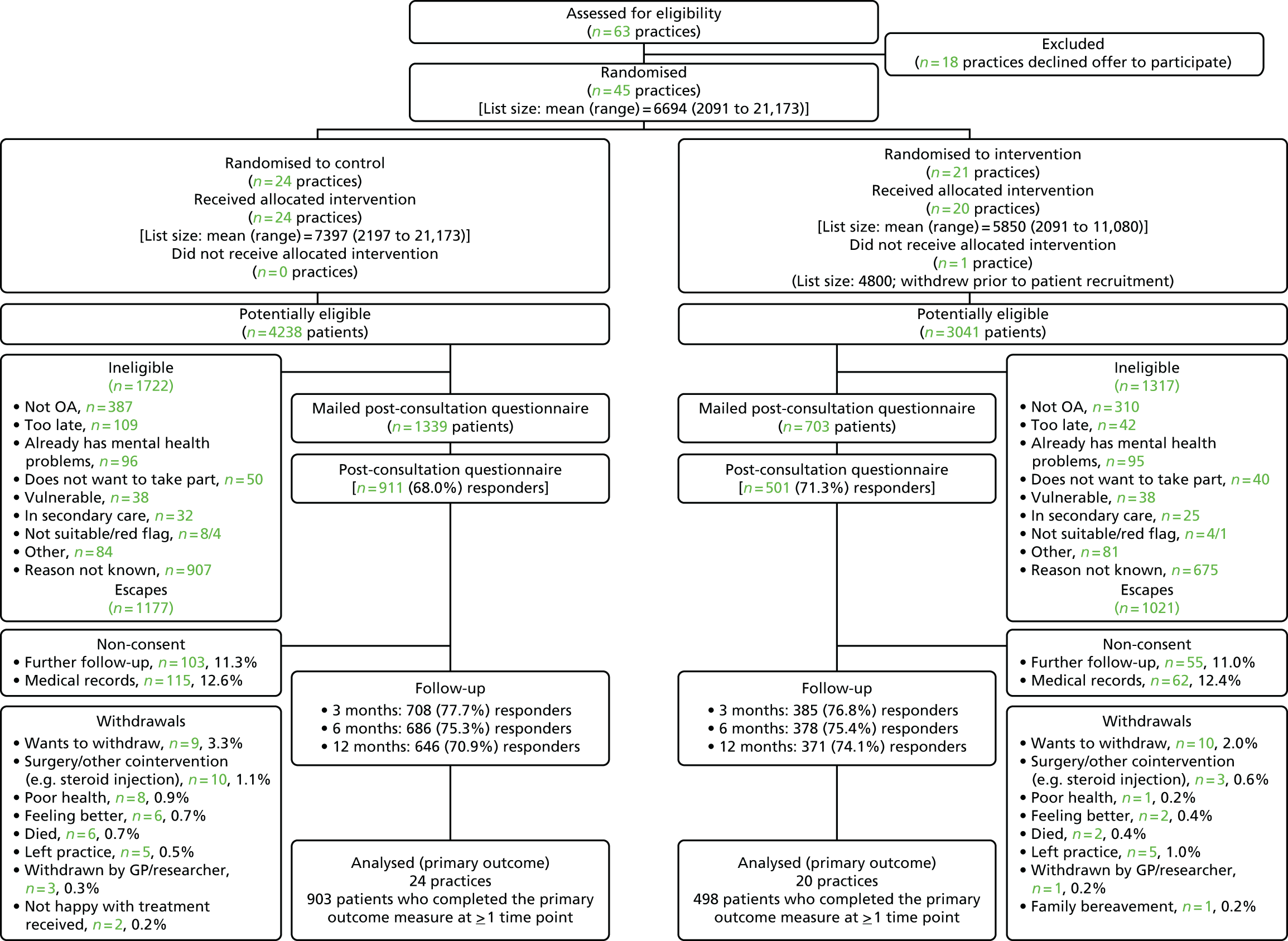

New nurse-led OA clinics in general practice.