Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/156/20. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The final report began editorial review in December 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Scott Weich was a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Mental, Psychological and Occupational Health Panel (2009–15), the HTA Prioritisation Group (2009–15) and the HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials Committee (2015–19). Sophie Staniszewska was an associate member of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Commissioning Board (researcher led) (2009–18). Carole Mockford was an associate member of the HSDR Commissioning Board (researcher led) (2009–18). Frances Griffiths reports receiving grants from the National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Weich et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction to the final EURIPIDES report

Patient experience and the link to quality improvement

All NHS providers are required to collect feedback routinely on patients’ experiences of care. This data collection takes place within an increasingly constrained wider organisational context in which the NHS is under pressure to deliver effective, timely and affordable care. The manifold pressures exerted on the wider system, and a series of high-profile incidents,1–5 have given rise to concerns about quality and the standards of care.

As a result of a national inquiry and concerns being raised, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the NHS National Quality Board and others have called for a stronger patient voice and have reiterated core principles of patient-centred care including compassion, dignity, autonomy and choice. 1–3,6,7 Despite this emphasis, there remains little evidence about what to measure, how best to collect this information and how to use the data collected to improve service quality. 8,9

We do not know if reporting patients’ experiences is associated with improved clinical or functional outcomes, improved quality of life, reduced carer burden or reduced costs of care. 10,11 In addition, we do not understand how any such effects may be mediated, for example by better treatment adherence, nor do we know which types of patient experience data are used or useful in improving quality of care and driving service change. 8,10,12–15

Despite trusts routinely collecting patient experience data,16,17 these data are often felt to be of limited value8,18 because of methodological problems (including poor or unknown psychometric properties or missing data) or because the measures used lack the granular detail necessary to produce meaningful action plans to address the concerns raised. 19 The most commonly adopted measure in inpatient settings is the Friends and Family Test (FFT), the results of which are reported to NHS England monthly. 20 Despite aspects of care being captured in satisfaction surveys, it has been recognised that these tests do not capture information that is sufficiently detailed to inform service change. 18

The Evaluating the Use of Patient Experience Data to Improve the Quality of Inpatient Mental Health Care (EURIPIDES) study was commissioned in response to a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) call to address the dearth of evidence about these issues. The call invited applications for studies examining known concerns with timely and informative data collection, on the alignment of national and/or local needs and on the level at which data should be shared to be most effective and to lead to change. The call recognised the further issue of data being collected but not used and raised concerns about organisational capacity to respond to information gleaned from data. The call expressly asked how these data should be used alongside other data to produce reliable quality indicators.

The EURIPIDES study was unique in responding to this call through a focus on mental health inpatient settings. Thus, it represents the first study of patient experience in acute adult mental health settings and offers a unique contribution to knowledge through providing an evidence base on the approach to collecting and using patient experience data to improve service outcomes.

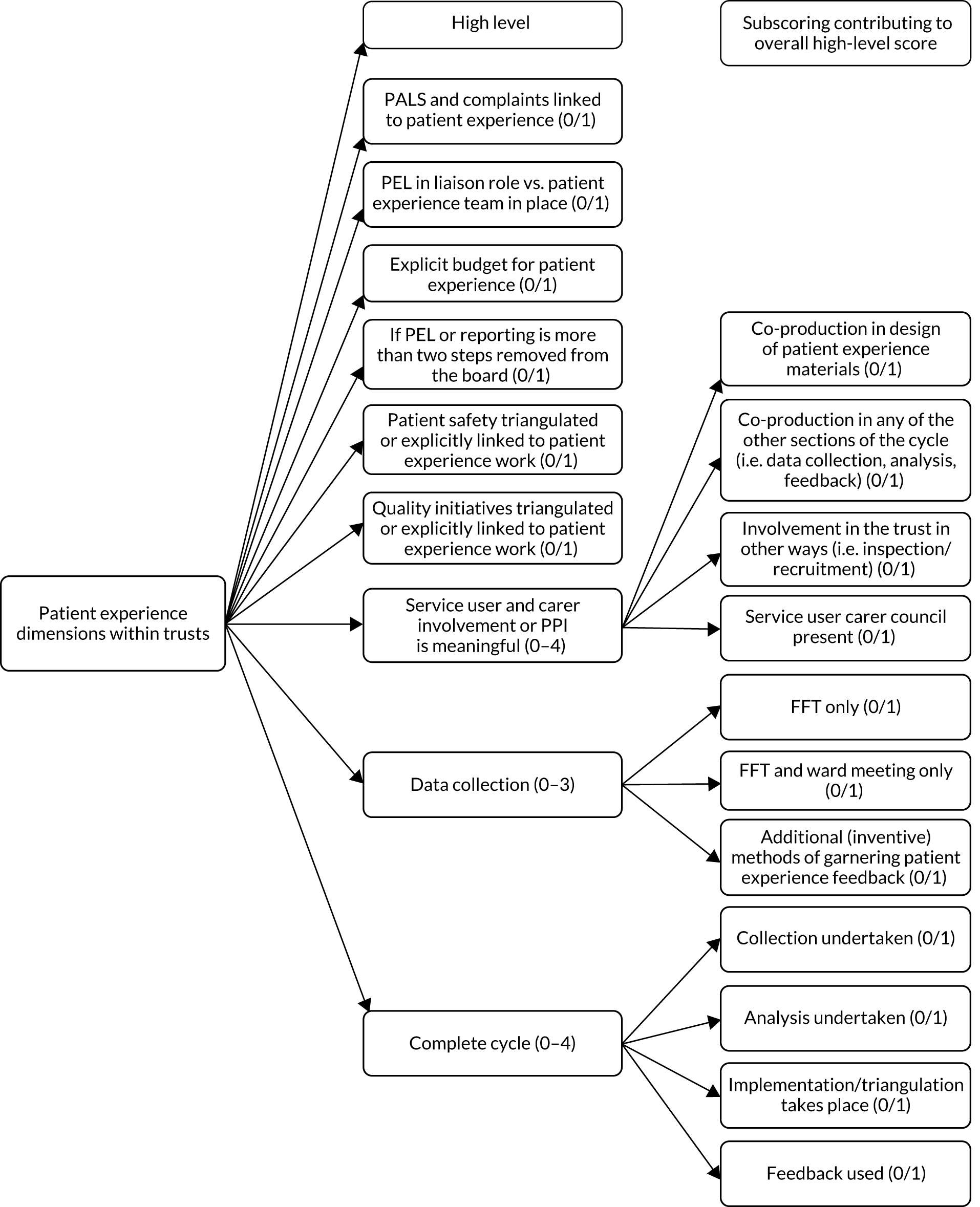

We hypothesised that we would be able to discern differences between service providers in their commitment to and capacity for using patient experience data to improve services. 2 We further hypothesised that these differences would be apparent in the ways that NHS mental health trusts went about collecting experience data from users of inpatient services, the analysis of these data, the embeddedness of patient experience work in trusts’ core business and the involvement of service users and carers in these processes. 21–23

Based on evidence from other studies, we predicted that differences between providers might include commitment to service improvement among senior leaders, decentralised decision-making, role clarity within the organisation, and support for risk-taking. 21,22 We hypothesised that organisations that use patient experience data most effectively would also have robust data collection strategies. Finally, we hypothesised that organisations that are more patient centred will demonstrate the adoption of co-produced or co-designed approaches to service improvement and will involve service users and carers. 24,25 These hypotheses were central to the programme theory-building (see Chapter 2 and Appendix 17).

The context of inpatient settings

The EURIPIDES study examined inpatient mental health services on the grounds that these are important but costly services that remain unpopular with service users23 and are the settings in which many serious incidents, such as suicide, continue to occur. We knew little about the processes required or used to collect, analyse, interpret and translate meaningful patient experience data into better outcomes for patients and more efficient and cost-effective care. 8,9 We did not know what kinds of feedback were most important or what management processes were needed to translate this into effective action plans and we did not know if this made any difference to patients themselves.

We identified three initiatives that attempt to raise the standards of inpatient mental health care, including the Productive Ward programme,26 led by the NHS Institute for Improvement and Innovation, which focuses on the adoption and spread of a model of ‘lean working’; Star Wards,27 a third-sector initiative that uses patient experience information to develop and share best practice; and the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Accreditation for Inpatient Mental Health Services scheme, which is based on evaluation against a quality standard and broadly focuses on raising general standards of care, timely and purposeful admission, safety, the environment and facilities, and therapies and activities. 28 In addition, there is a NICE quality standard that applies to inpatient care that identifies four domains of focus, namely shared decision-making, contact with staff, meaningful activity and the use of compulsion. 5,6

Reports about inpatient settings highlight adverse experiences such as fear of assault, overcrowding, noise, lack or privacy and dignity, lack of therapeutic activities, limited individual recovery-focused support and an emphasis on coercion, control and restraint. 24,29 In addition, inpatient mental health services remain the locus of the most pronounced ethnic inequalities in mental health service experience. 25 Patients of black ethnicity (including both African Caribbean and black African groups) remain over-represented in inpatient settings;30 they receive higher doses of medication and experience higher rates of seclusion, physical restraint and injury31 and they have higher rates of suicide. 32 Likewise, many patients are detained under the Mental Health Act33 and, therefore, have no choice about admission. 29 This raises questions about how and when to ascertain information about their experiences.

Inpatient settings therefore represent one of the more challenging areas within the NHS in which to obtain patient experiences, but one in which there are, hypothetically, significant gains possible if quality improvement could be driven by this feedback. The EURIPIDES study represents the first attempt both to provide an overview of the ways in which individual NHS providers of inpatient adult mental health services in England are collecting, managing and using patient experience data, and to interrogate how these processes operate in more granular detail.

Aims and objectives

We set out to understand how, and under what conditions, patient experience feedback processes could be used to support the improvement of health care in NHS adult inpatient mental health settings in England. We addressed this lacuna in knowledge by using a realist research design across five work packages (WPs) to develop a set of recommendations informed by both theory and evidence. Our results were intended to be relevant to front-line staff; service managers; those responsible for the design, implementation or management of patient experience or quality processes; and policy-makers.

The central research question asked was as follows: which approaches to collecting and using patient experience data are the most useful for supporting improvements in inpatient mental health care?

The specific objectives of the EURIPIDES study were to:

-

complete a systematic review to identify evidence-based patient experience themes relevant to mental health care (aim 1)

-

identify, describe and classify approaches to collecting and using patient experience data to improve inpatient mental health services across England by conducting a national survey of patient experience leads (PELs) (aim 2)

-

use the information from the national survey to populate a sampling frame to select diverse sites for six in-depth case studies, in which we would interview those who deliver and receive these services to conduct a realist evaluation of what works, for whom, in what circumstances and why (aim 3)

-

identify which types of patient experience measures and organisational processes facilitate effective translation of these data into service improvement actions, and present these findings to a consensus conference of experts (including service users and carers) at which recommendations about implementing best practice would be agreed (aim 4)

-

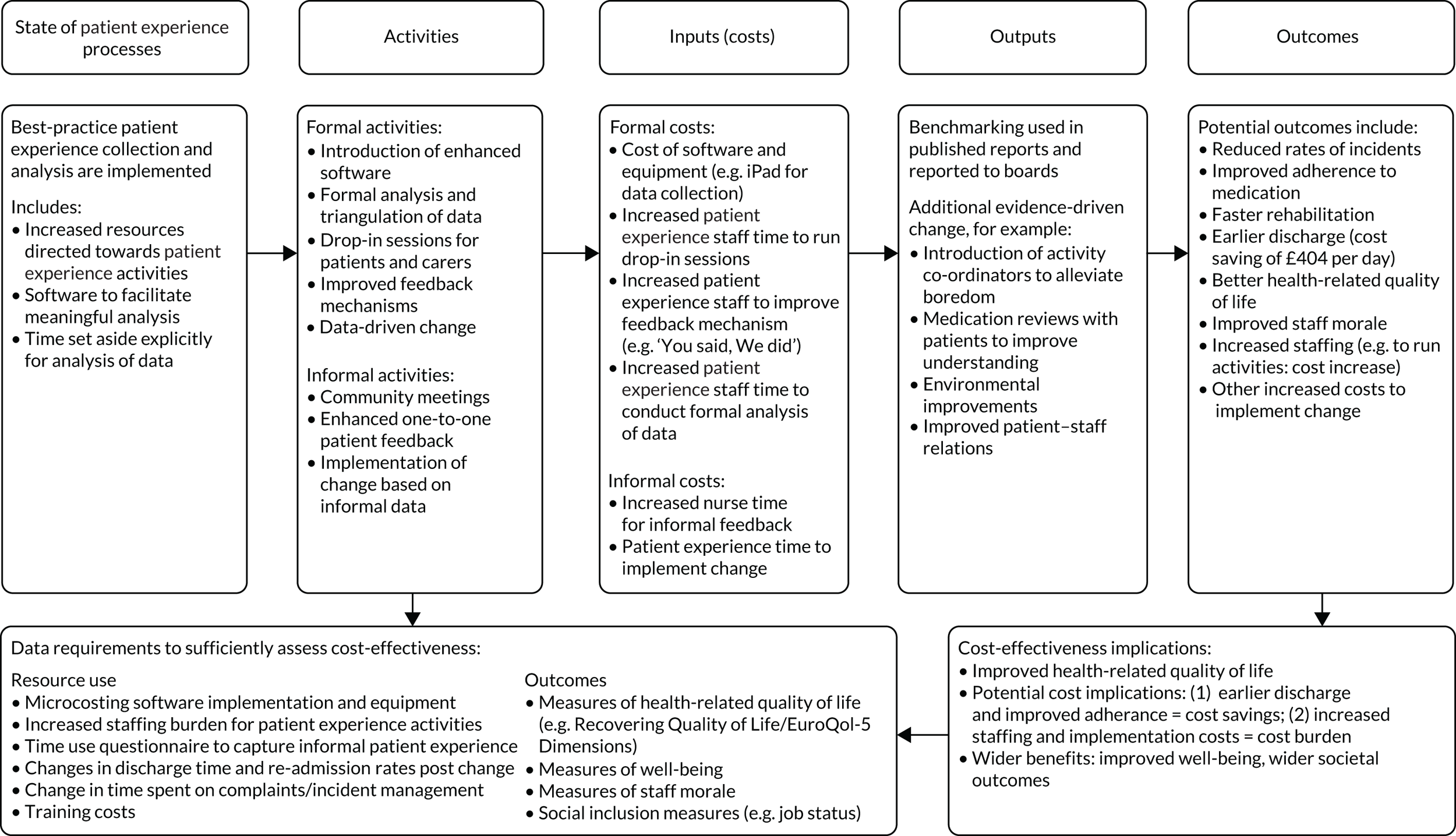

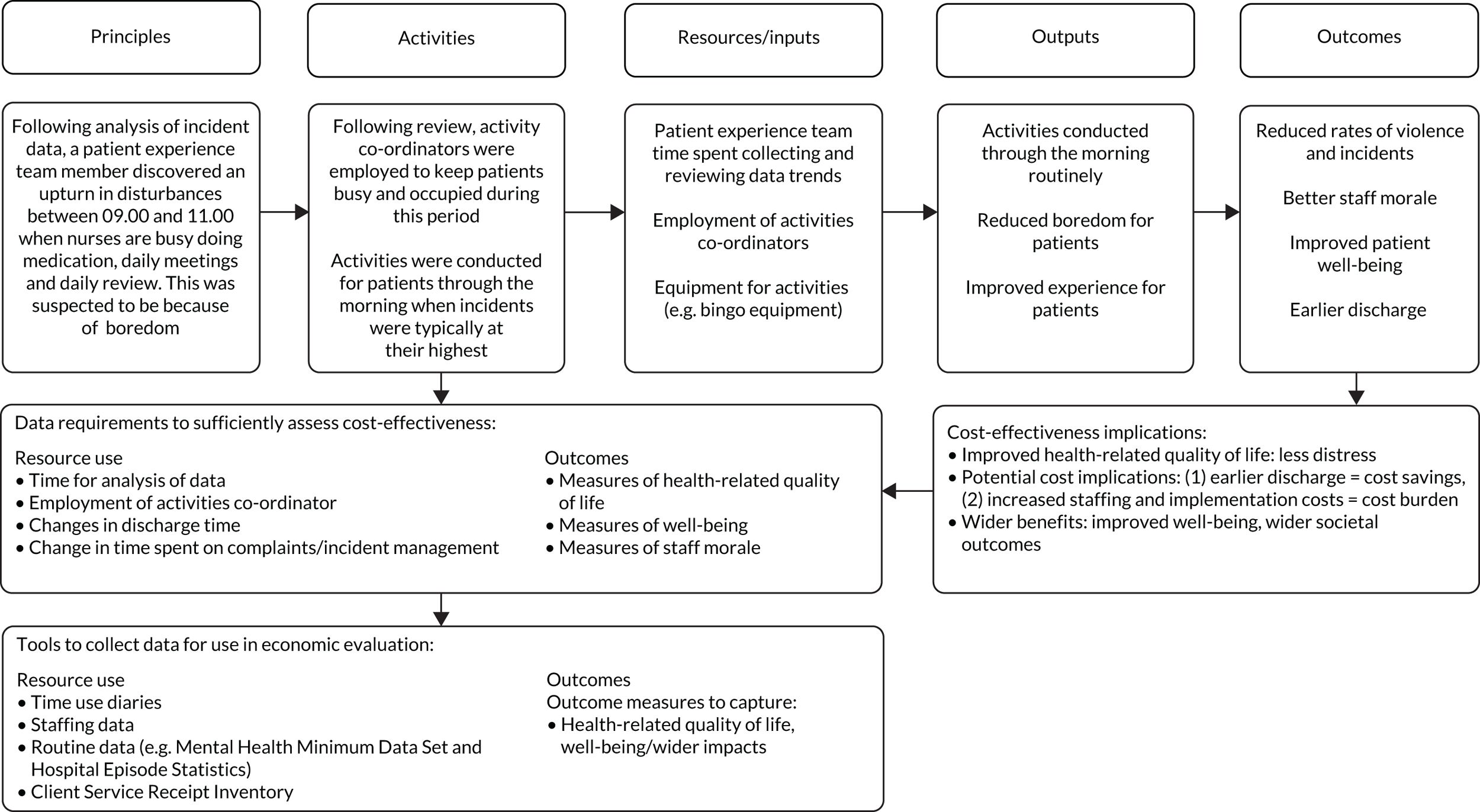

model variation in resources (costs) associated with adopting new ways of collecting and using patient experience data and associated service improvements, the obstacles to this and the value (i.e. cost) of evidence required to convince NHS commissioners and providers to substantially alter the way in which they deliver inpatient mental health care (aim 5).

Outputs from the EURIPIDES study include evidence-based recommendations on the most effective existing ways to collect and use patient experience data to improve the quality of inpatient mental health services. Our recommendations cover data collection methods, optimal organisational processes for translating data into action plans, and evidence of (potential) impact. Results are grounded in robust consensus about what is happening presently in an NHS context and on the feasibility, acceptability and sustainability of proposed changes.

Project overview and reporting structure

The overarching research design is set out in Chapter 2 and full details of the methods used at each stage of the study are reported in the corresponding chapters that relate to the five study aims set out above. In essence, the study comprised five interlinked WPs:

-

a systematic review (WP1, aim 1)

-

a survey of NHS providers of inpatient mental health care in England to populate a sampling frame for WP3 (WP2, aim 2)

-

a realist evaluation of six in-depth case studies selected using the WP2 findings (WP3, aim 3)

-

a consensus conference to agree recommendations about best practice and understand challenges to and opportunities for implementation in real-world NHS settings (WP4, aim 4)

-

health economic modelling to estimate the resource required for and barriers to the adoption of best practice (WP5, aim 5).

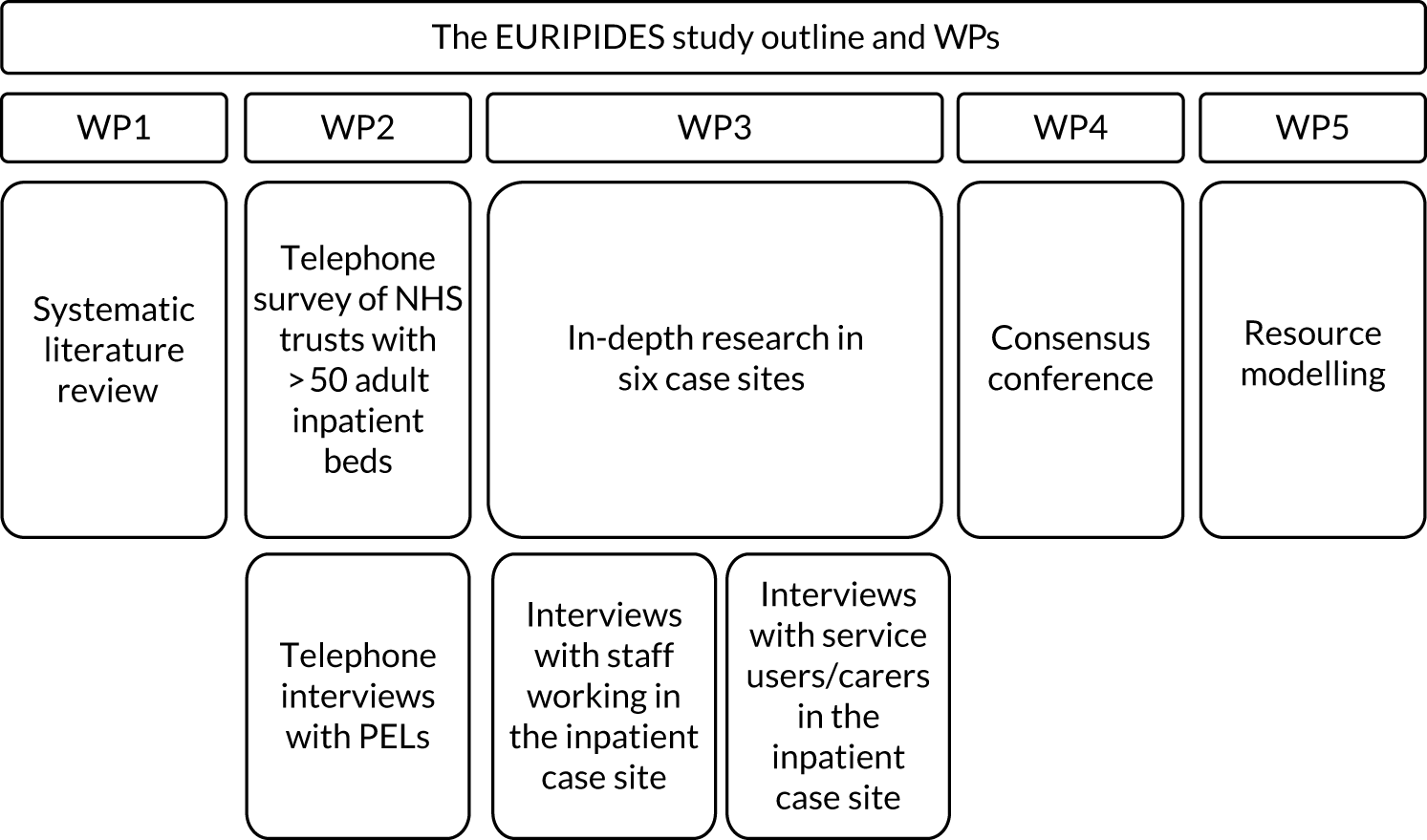

These WPs are represented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study outline indicating the content of the different WPs.

Throughout the 3-year study, the multidisciplinary project team met frequently to discuss emerging findings to ensure that each WP informed and complemented the others. The project team benefited from the expertise of those with lived experience who worked alongside academic colleagues drawn from the fields of psychiatry, nursing, psychology, clinical psychology, general practice, health economics and social policy. The work reported under the separate chapter headings, although distinct in focus, is therefore interlinked and the study outcomes are knitted together in a summative integrated findings chapter.

The research was underpinned by a robust two-strand approach to patient and public involvement (PPI). A lay service user and carer reference group is referred to throughout the report as the patient and public involvement team (PPIT). The PPIT comprised people with lived experience of adult inpatient settings and two survivor researchers who supported the study from its design, through data collection, to analysis and writing.

In compiling this report, we have sought to produce a synthesis that embraces the complexity of integrating a realist approach across different research activities to understand the processes of collecting and using patient experience data in adult inpatient mental health settings. We aimed, in particular, to understand how these are currently linked to improvements in service, and under what conditions this might be optimised.

Chapter 2 Realist framework and research design for the study

Introduction

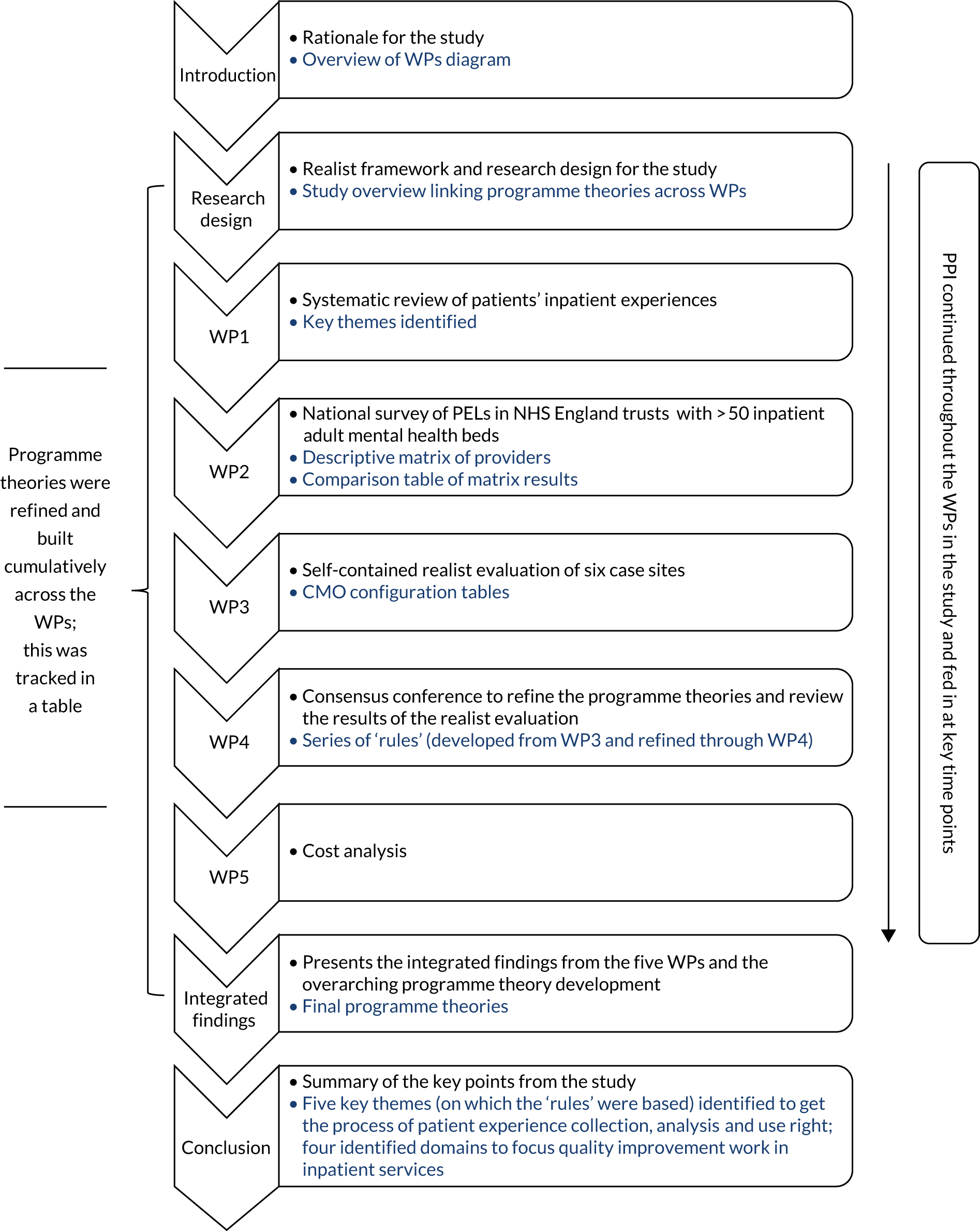

The EURIPIDES study was underpinned throughout the five WPs by a realist research design. Although the five WPs were discrete and self-contained, each was designed to feed successively into the understanding of the others. Nested within the research design was a self-contained realist evaluation (WP3). In this way, there is an underpinning realist philosophy and thread running through all of the WPs contained in this study (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Overview of the chapters contained in this report to show how programme theories are linked across the WPs (in blue are the data that were used to develop and refine the programme theories). CMO, context–mechanism–outcome.

How does the realist research design underpin the work packages?

The ambition of realist research is to understand and analyse the ‘mechanisms and structures behind phenomena’. 34 It builds on the work of critical realists such as Bhaskar and Danermark. 35 In the field of health and social policy, Pawson and Tilley36 developed the realist evaluation approach to move from successionist models of causation in evaluation (which ask does this intervention or programme work?) to consider generative causation in evaluation, instead asking what works, for whom, in what circumstances and why?

Realist evaluation is a way of evaluating a particular programme in context, which, in our case, was the use of patient experience data in adult inpatient mental health settings in NHS England. The purpose of the method is to refine the understanding of how a programme or intervention works in a particular setting. Realist evaluation is theory driven, starting and ending with programme theory.

What do we mean by programme theory?

Programme theories explain how a programme or intervention works. They embody what the problem is, what the solution might be and how this is hypothesised to bring about change, and so encapsulate ideas about causation. Programme theory should not be so specific that it explains things only at the individual level and should not be so abstract that it is generally applicable.

Programme theory is a ‘middle-range theory’ that helps to explain in what ways and how a programme or intervention may or may not be operating successfully in particular circumstances for particular types of actors. Initial programme theory can be developed in a range of ways. In our study, the initial programme theories were based on previously published research, practice knowledge and lived experience. These explanations about how the programme or intervention works were drawn from published literature, practitioners, people with lived experience of mental illness and distress, and the NIHR funding call. We used these initial programme theories to develop the research proposal. These were then refined throughout the study, based on the outcomes of each WP.

What do we mean by generative mechanisms?

Programmes or interventions work or do not work as a result of different individuals responding (or not responding) to that programme or intervention. These responses result in different patterns of outcomes. The biological, psychological or social drivers underpinning each individual’s response are referred to as generative mechanisms. 37,38

Mechanisms are likely to operate at different levels of a system, over different time scales, and to involve interactions that may not be observable. If we define mechanisms in relation to the response of individuals to a programme or intervention, there are only a finite number of ways in which they can respond (e.g. in respect of the experience of inpatient mental health care, trusting staff or feeling disempowered). These responses are commonly recognised as (observable) aspects of human behaviour; however, what is not clear is how these responses are triggered by particular aspects of programmes or interventions in specific contexts. It is not just high-level mechanisms such as trust that we need to understand, but we also need to understand how the programme/intervention works in triggering individual responses that are characterised as the experience of trust.

Realist evaluation and context–mechanism–outcome configurations

Realist evaluation is operationalised through developing context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations. In realist evaluation, outcomes are understood as the product of the context and mechanism. For example, trust may be an obvious mechanism in relation to patient experience; however, how that trust becomes activated (or not) in the inpatient setting is less clear. Understanding this is the work of realist evaluation. 39,40

The ‘context’ of realist evaluation is significant, as it can influence reasoning and behaviour, and it is the context that ‘activates’ (through the circumstances being right) mechanisms and that influences if, and if so which, mechanisms operate. 36,37 Outcomes are contingent, therefore, on both context (which may provide alternative explanations of different observed patterns of outcomes) and mechanism (based on the reasoning and resources38 of actors).

The development of CMO configurations helps to understand both proximal outcomes (which are more immediate and the result of generative mechanisms being activated in relation to the reasoning and resources of actors) and distal outcomes (which are more slowly developing patterns that are observed and built, often from the accumulation of proximal outcomes).

In this study, the outcome being examined was the collection, analysis and use of patient experience data in order to change services, and linked to quality improvement strategies in adult inpatient mental health settings in NHS England.

Evolution of the method: our approach to realist evaluation – laminations and the inverted case study

Realist evaluation has developed since its inception over 20 years ago and is increasingly being adopted to study complex health-care systems. As a result of the diverse approaches to realist research, reporting standards for realist evaluation were developed. 41 This study has paid close attention to those standards.

However, to conduct a study with multiple WPs and an overarching realist research design (including a nested realist evaluation), the programme theory was developed and refined iteratively across the WPs as the study progressed. Two key additions also were made to evolve the realist evaluation approach:

-

taking a laminated (multilayered) approach to understanding cases

-

undertaking analysis using temporal sequencing.

What do we mean by laminations in case study design?

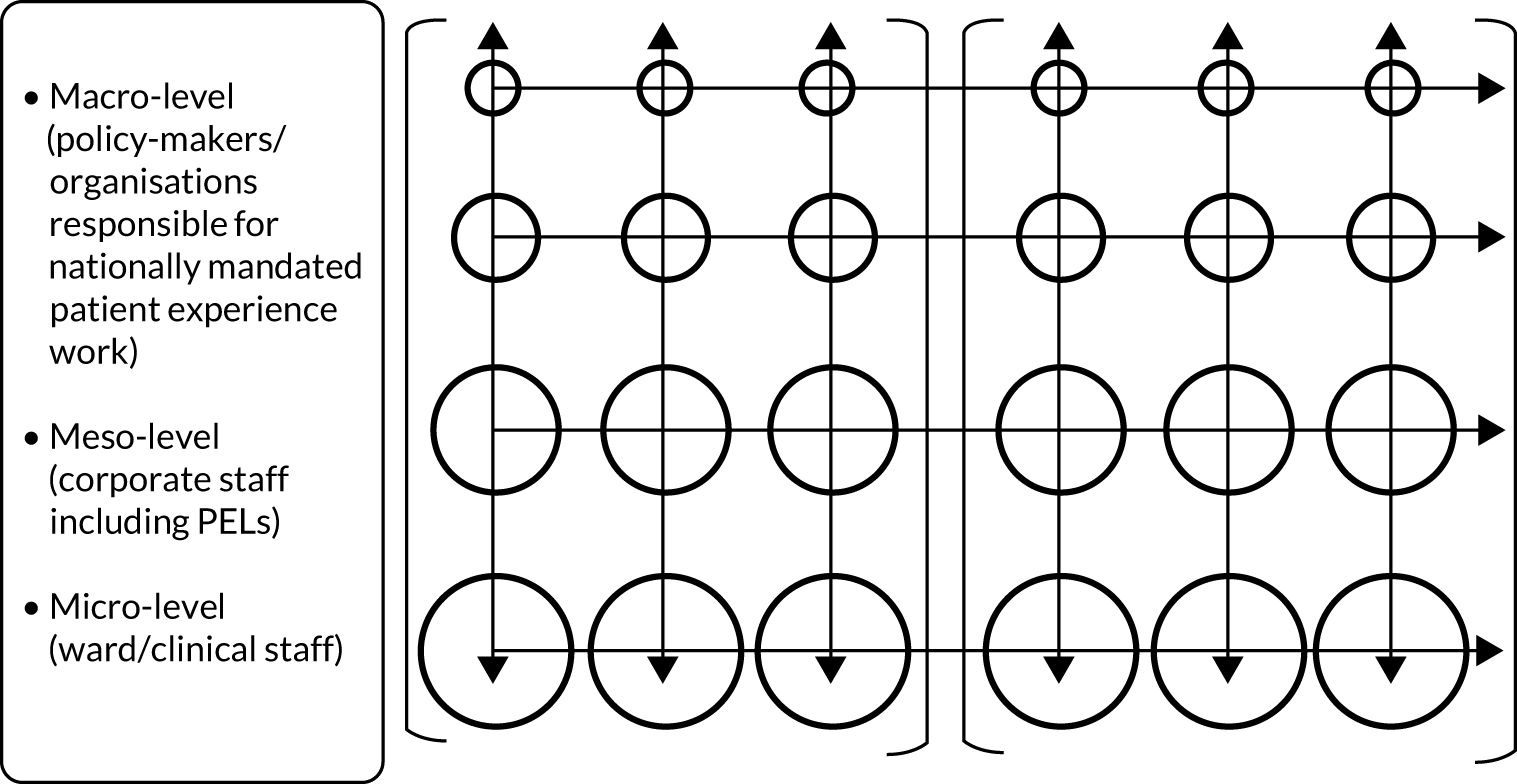

In a classic case study design, a case would be clearly bounded as a unit of analysis and viewed as embedded within a wider system,42 and extraneous factors are viewed in relation to their impact on that case. If utilising a classic multiple case study research design, one would compare distinct and bounded cases. 43 Each case would be discrete and the comparison would take place between cases (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Classic case study research design comparing between cases (adapted with permission from Fenton44).

We adopted a different type of case study research design using the idea of a laminated system43,44 with defined, distinct levels of agency. We operationalised the idea of laminations in our research with the individual- or biographical-level experience understood as patients or carers, the micro- and small-group-level understood as staff working on the wards, the meso-level understood as corporate staff including PELs and senior managers in trusts, and the macro-level understood as policy-makers and organisations responsible for collecting nationally mandated patient experience feedback (Figure 4). Research interviews were conducted across these laminated levels (WP2 and WP3).

FIGURE 4.

Inverted case study research design comparing across and within the laminated structure (adapted with permission from Fenton44).

To utilise the concept of laminations within a realist evaluation framework, we undertook research in these sites (WP3) to explore and understand the generative mechanisms operating within and between laminations in each of the case sites. 44 This approach enabled us to read down and through those laminations to understand the generative mechanisms being activated (or not) at different levels in case sites, and facilitated reading across the case sites at the level of each lamination to understand the reach and impact of extraneous factors.

The rationale for using this particular research design was twofold:

-

Rather than use a lamina (or level; interviews with inpatients, for example) as a window into those patients as the object of study, we used those interviews as windows out onto the wider system. While we used context to inform our understanding of generative mechanisms, we privileged narratives at the different levels identified. This makes it is easier to determine what contributes to middle-range theory and to determine those generative mechanisms that are particularly context driven and so relevant to specific case contexts.

-

Case studies traditionally have strong internal validity but suffer from weak external validity and generalisability from the case to the wider population. 42 In our approach, although cases were identified and bounded, we were able to read within levels across case sites to explore what features of a programme or intervention are common to everyone at that laminate level and what features are contextually driven and unique to the case. 44 This strengthened our external validity, without compromising or weakening our internal validity.

How was temporal sequencing introduced to realist evaluation?

Using inpatient experience feedback to improve the quality of care has an embedded temporal sequence, which forms part of the context for our realist evaluation. We brought this into our realist analysis through using a temporal coding framework: collecting, receiving, analysing, implementation and change (see Report Supplementary Material 10).

We adapted and developed these laminated and temporal additions to our realist analysis to ensure generative mechanisms were not identified at too superficial a level to be useful and to understand how combinations of different actors’ reasoning and different contexts interacted to produce different patterns of outcomes.

Ethics approvals for the study

Ethics approval was obtained for this study from the West Midlands (South Birmingham) NHS Research Ethics Committee [reference number 16/WM/0223, Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) project identifier 181897]. The systematic review (WP1) was registered as PROSPERO CRD42016033556.

The research posed ethics issues primarily through the research activity of WP2 (the national survey) and WP3 (the realist evaluation of case study sites). There were ethics issues identified in relation to ensuring anonymity and that adequate consent has been obtained, working with participants who may be identified as being a vulnerable group owing to their mental health issues and minimising possible distress of participants when interviewing.

To address these issues, participants’ details were anonymised and interviews were anonymised prior to transcription and given a unique identifier. Participants were initially approached by a member of clinical staff for permission to share contact details with the study team. Written consent was obtained from all individuals participating in the study and we did not interview individuals who lacked capacity. Taking part had no impact on clinical care and there were no repercussions for not taking part; participation was entirely voluntary. If it had been required, the use of qualified and trained interpreters would have been offered and provided during the interview. A procedure was put in place for managing whistleblowing and disclosure.

In addition, we recognised that, when discussing the experience of being asked about inpatient mental health services, this could have triggered an emotional response from participants during WP3. Although these interviews were not intended to elicit detailed accounts of individual service user inpatient experience, it was likely that sensitive issues such as perceived coercion, a lack of privacy and difficult discharge procedures would be touched on. We therefore provided participants with information about sources of support. A senior member of the project team supervised the research fellow (RF) and research associates (RAs). The survivor researchers had an identified supervisor to access for support through the Mental Health Foundation (MHF) and were supported in the case sites by the RF.

To train, manage and support the research staff, a comprehensive lone-working, disclosure and whistleblowing policy was devised. The RF trained both the RAs and the survivor researchers in these protocols and offered supervision and support to them while they were interviewing. Any disclosures were immediately reported to the RF, the chief investigator and, if appropriate, the NHS trust. Staff were given time out after difficult interviews if they needed it, and a daily debriefing or check-in with the RF took place to provide emotional support and to keep a log of any lone working. To ensure that the RF and whole research team were supported, weekly supervision meetings were held with the WP3 lead, the chief investigator and the RF when undertaking the case site research. In addition, group meetings to review case site data and to discuss issues and emergent themes took place between the WP3 lead, the RF and the RAs.

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement in the EURIPIDES study

Introduction

The aim of the EURIPIDES study was to understand which of the many different approaches to collecting and using patient experience data are the most useful for supporting improvements in inpatient mental health-care settings. To ensure that the patient voice is heard, NHS trusts are required to collect feedback from patients and, in some cases, they have spent years setting up local systems for this. The project aimed to identify the kinds of feedback that are most important, the management processes needed to translate feedback into effective action plans and if this makes any difference to patients themselves. The study was developed in partnership with the MHF, which led the PPI aspect of the work. Our PPI strategy aimed to ensure that mental health service users (and carers) were genuinely and meaningfully involved at all stages and levels of the research process using for the ‘4Pi’ national standards service user involvement in research45 (Box 1).

In this chapter, we describe and report on the effectiveness of PPI in the EURIPIDES study. We followed the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 (GRIPP2) long- and short-form guidance checklists for reporting on involvement46 (Box 2 and see Appendices 19–22) to structure this report.

This chapter was written by David Crepaz-Keay (MHF) who co-ordinated PPI in the study, Michael Larkin (EURIPIDES Project Oversight Group) and Emma Ormerod and Stephen Jeffreys (survivor researchers). We are grateful to Sarah-Jane Fenton (RF), Lizz Kimber and Nicole De Valliere (Master of Research students, University of Birmingham) for their contributions.

-

Principles: how do we relate to each other? Meaningful and inclusive involvement starts with a commitment to shared principles and values.

-

Purpose: why are we involving people? Why are we becoming involved?

-

Presence: who is involved? Are the right people involved in the right places?

-

Process: how are people involved? How do people feel about the involvement process?

-

Impact: what difference does involvement make? How can we tell that we have made a difference?

-

Aim: report the aim of PPI in the study.

-

Methods: provide a clear description of the methods used for PPI in the study.

-

Study results: outcomes – report the results of PPI in the study, including both positive and negative outcomes.

-

Discussion and conclusions: outcomes – comment on the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall. Describe positive and negative effects.

-

Reflections/critical perspective: comment critically on the study, reflecting on the things that went well and those that did not, so others can learn from this experience.

Involving service users and carers

The EURIPIDES study was designed with two forms of PPI at its core: first, by employing survivor researchers as co-researchers alongside the RF and RAs during the data collection phases of the project and, second, through the recruitment of a PPIT. The group was referred to as the Service User and Carer Reference Group for the duration of the project. However, the group told us that they felt uncomfortable with the term ‘service user’, as they felt that it implied ‘drug user’. They asked to be referred to as the PPIT in publications and this is how we refer to them in this document.

During the development of the original grant application, the MHF hosted a development meeting of three survivor researchers, the proposed PPI lead and the principal investigator. This group set out the initial approach to PPI across the study. The original plan proposed three layers of PPI: a co-investigator as a member of the project leadership team who was a survivor researcher with overall responsibility for PPI across the study; a team of four survivor researchers who would contribute to data collection and analysis; and a PPIT, comprising people with personal experience of inpatient care or of informal caring.

Patient and public involvement team

The PPIT comprised people who were unlikely to have prior experience of, or involvement with, research, but were experts by experience, having had historical or recent experience of adult mental health inpatient admission or of informal care for someone who had been an inpatient.

We aimed to recruit 8–10 PPIT members through the MHF’s extensive network, ensuring that the group included a degree of diversity with respect to age, gender, ethnicity and geographical location.

Our initial meeting was poorly attended, for a variety of reasons. Only two of the eight people recruited attended, with four sending apologies in advance and two failing to arrive owing to transport issues. After consultation with a number of the project team members and discussions with a service user and carer group, which met regularly close to the MHF’s London office (at a club known as the Dragon Café), we agreed to strengthen the PPIT with members from the Dragon Café. We also increased the payment offered to PPIT members and provided additional support to ensure that people were able to attend.

This led to a much stronger attendance at subsequent meetings and, because the new members knew each other, the PPIT immediately gelled as an entire group. There were a number of consequences of this approach. We sacrificed some geographical diversity (the vast majority of the PPIT were from London, with one regular attendee from the West Midlands and one from the south coast), but we increased ethnic and age diversity. We also increased the number of people involved who had current or very recent experience of inpatient care. Only a small proportion of the group had any experience of PPI in academic research.

We therefore increased support to ensure that the PPIT meetings were accessible for the participants. Initially, we proposed that there would be four PPIT meetings during the lifespan of the study. It became apparent after the first meeting that there were ways in which we might be able to do things differently and more meaningfully. PPIT members gave feedback after the first meeting and it was clear that, to make the most of their expertise, we would need to take more time to get know each other and we would need to plan our meetings more creatively (and with much less paper). As a consequence, we held seven PPIT meetings over 2 years. The format of these meetings was innovative and the benefits were significant. Adaptation enabled more equitable and honest engagement that allowed the PPIT to challenge the research team about the data and ways of working.

Some members of the PPIT found it difficult to maintain concentration, some were less confident with literacy and technical language, and some were voice hearing. There were periods over the 2 years of the study in which people were re-admitted to inpatient units or suffered significant life events. We worked to ensure that nobody felt left out or left behind. We adapted our approach to ensure that everyone was able to participate at the level they felt was appropriate. We used role play and small group discussions and we built in time for plenty of breaks and sandwiches. We visited the group in locations familiar to them outside the formal meetings to ensure that they had space for reflection and to ask for changes or updates ahead of the next meetings. This enabled us to engage people with no prior research experience.

A link worker at MHF (Jo Ackerman) supported the group outside the meeting times to ensure that there were opportunities for everyone to articulate their own opinions, both during and outside meetings. We ensured that travel arrangements were as simple as possible and that no one was left out of pocket on the days of the meeting. Together, we thought carefully about how to support the group in the context of their EURIPIDES study meetings. Working in this way has allowed us to be sensitive to disclosures and helped us to manage risk when it presented.

We began each meeting by demonstrating how the research had been shaped by the PPIT’s involvement (i.e. from changing the ways we interviewed and the tools we used, to implementing a coding structure that they helped us co-design). We also adapted our techniques of working with the PPIT to meaningfully include everybody and let them lead on the approach taken (i.e. through the workshop-style activities that included dramatisation and role play as opposed to reviewing textual materials). It was particularly important to be responsive to fluctuations in the group dynamics if people were unwell and to keep striving to engage people in a supportive way that was accepting of their individual situations. We co-designed (by asking how, in what ways and when they felt the next meetings should take place) the approach, not just the study, and we recognised their role as integral to steering the project.

The members of the PPIT played a critical role in the design of the research tools, in designing coding frameworks and in reflecting on the data throughout analysis. For example, they commented on the systematic review and they refined programme theories (the hypotheses we were testing), and their comments relating to the systematic review findings about what patients said about their experience were built into the interview tools for patients through a process of co-designing flash cards to support realist interviewing (WP3).

In addition, the PPIT chose the priorities for the ongoing research questions in their meeting forum and this shaped the entire data collection process. The PPIT also developed and refined our programme theories (the core work of realist analysis). This work refined our research questions and shaped the conduct of the fieldwork. The PPIT analysis workshop provided us with categories crucial to our data-coding. The impact of this involvement has been significant and it has led each planning and development phase of the primary data collection. Members of the PPIT attended the consensus conference and, to mark the end of the study, we hosted a celebration event to thank participants and recognise the enormous contribution they made to the EURIPIDES study.

Survivor researchers

The survivor researchers (who were people with lived experience of mental illness and its treatment who also held professional roles and had experience conducting research) were people who either had previously worked with the MHF or were recommended by the MHF. We adopted the term ‘survivor’ (rather than ‘patient’ or ‘service user’), as this was preferred by the individuals concerned.

The intention was for survivor researchers to be involved in the study by (1) advising on the questionnaire, topic guide and recruitment materials and on selection of case study sites, (2) advising on all aspects of the conduct of WP3, including planning and undertaking interviews with service users and (3) recruiting service user and carer participants and acting as facilitators at the consensus conference (WP4).

Four survivor researchers were initially recruited to the EURIPIDES study team through the National Survivor User Network and MHF networks and were actively involved in the early stages of the research: advising on recruitment materials, topic guides and approaches to realist interviewing. However, we had a difficult start to the fieldwork, as gaining access to case study sites was complex and time-consuming, as was the bureaucracy around research passports. This contributed to communication issues with the survivor researchers and impeded involvement. In addition, two of the survivor researchers made the decision to withdraw from the study prior to the fieldwork. Once research passport administration issues had been resolved, the two remaining survivor researchers were involved in data collection at only two of the six case study sites.

As the project progressed, we were able to integrate the survivor researchers into the project. Survivor researchers were able to exchange ideas and perspectives during the last two site visits with other members of the research team and were also involved in two meetings to design and refine coding frameworks at the analysis stage. One of the survivor researchers (Emma Ormerod) also participated in role plays of some sections of the interviews for discussion at the PPIT meetings. Both survivor researchers were involved in the final stages of the research process and co-authored this chapter.

What was different about patient and public involvement in the EURIPIDES study?

Often, PPI is poorly understood and conceptualised. 47,48 At best, effective PPI can reduce the chances of health research being ‘wasted’ or disregarded,49 it can improve the outcomes and increase the success of a study,50 and it can also be an empowering experience for the people involved. 51 However, very little is known about the power dynamics, impact and influence of PPI48 and we were also aware that there can often be a significant difference between the rhetoric of involvement and the tokenistic reality. 52

The plans for PPI have to be acceptable to many audiences, including funders, researchers, user groups and NHS trusts. Throughout this study, we have tried to engage all levels and to follow principles of ‘co-production’ with regard to our PPI, whereby power and responsibility are shared at all stages of a project53 (Box 3).

-

Sharing of power: the research is jointly owned and people work together to achieve a joint understanding.

-

Including all perspectives and skills: make sure the research team includes all those who can make a contribution.

-

Respecting and valuing the knowledge of all those working together on the research: everyone is of equal importance.

-

Reciprocity: everybody benefits from working together.

-

Building and maintaining relationships: an emphasis on relationships is key to sharing power. There needs to be joint understanding and consensus and clarity over roles and responsibilities. It is also important to value people and unlock their potential.

Reproduced with permission from INVOLVE. 53

We believe that we have succeeded in some areas and that, as the study progressed, all members of the team began to communicate more effectively with each other and integrate the perspectives and skills of everyone involved. But we are also aware that there are areas for improvement that require further reflection and there are areas of learning that we can take forward for future studies.

We offer the following first-hand reflections from a survivor researcher and from the EURIPIDES study RF (on behalf of the study team):

Survivor researcher reflections (Emma Ormerod):

As a ‘survivor researcher’ it is often easy to feel that you have a curious hybrid identity that reflects the ongoing epistemological tensions between the place of ‘expert/professional’ knowledge and that of the experiential knowledge that is gained through lived experience of mental and emotional distress. At a personal level, it can lead to feelings of uncertainty and confusion about one’s role within and possible contribution to a research study. Other survivor researchers have also written about their ‘double identity’54 and the feeling that they sometimes ‘fall between the two stools: being too professional to be a ‘real’ service user and insufficiently academic to be a ‘real’ researcher’. 55

It is now widely recognised that the involvement of patients/service users, carers and other members of the public in research is vital. By including a diverse range of perspectives and experiences the intention is to shape and positively influence the research process and subsequent outcomes. However, as survivor researchers we know that sometimes this involvement continues to be tokenistic, that our contributions can often be limited to advisory roles, and that many people continue to be marginalised within processes of involvement in research.

As survivor researchers in the EURIPIDES project team, we brought our skills and experiences as researchers, our lived experiences of mental distress and secondary mental health community services (including day services), together with our own experiences of user involvement and feedback-gathering initiatives as both service users and researchers. We were increasingly involved in the research process as the project progressed. But rather than attempting to define our role as survivor researchers in isolation, it might be more helpful to reflect on this as one of the perspectives within a collaborative knowledge-making process, so that understanding the contribution of researchers with lived experience of mental distress becomes ‘not just a question of “what difference do they make?” but an interrogation of how who we all are, as academics, clinicians and service users, shapes the knowledge we produce’. 56 During the course of the research process we began as a team, however informally, to reflect on our own identities, to recognise their multiple and complex nature, and move towards a more equal place of collaborative knowledge-making. It is our hope that future studies will foreground this approach.

The research passport process took longer than anticipated and we spent some time waiting to hear when the data collection would commence. On enquiring, we discovered that because of the administration issues, fieldwork had already commenced without the involvement of the survivor researchers. It was disappointing and concerning to feel ‘out of the loop’. Once research passports had been approved, there was very little time to work with the team (who were already working at case study sites) in order to prepare for interviews or explore issues regarding how the service user/survivor experience could be brought to the interviewer role (e.g. how and when to foreground this in interviews and what the anticipated effect might be).

Due to the knock-on effect of the administration and communication issues, one of us considered withdrawing from the project, but decided to attend the next meeting at the case study site to see how things progressed. Once we met with the other members of the research team and started building relationships with them, these fears around communication were allayed. Despite the initial difficulties, we appreciated the close working relationship with the other members of the research team once on site and their commitment and willingness to share their experiences from earlier sites. We were able to talk informally with them which allayed concerns and enabled us to ‘hit the ground running’.

The two of us only worked on one case study site each (both ‘green’ sites scoring most highly in the survey of mental health inpatient providers). This meant that it was not possible to make effective comparisons at the analysis stage. Both of us conducted interviews with members of the research team, but only one of us moved on to solo interviewing due to a practice of mentoring researchers on their initial interviews and a shortage of recorders.

We noted that there were contrasting areas of worry/concern between the research team and survivor researchers as we began the fieldwork. The research team were extremely careful not to impose themselves on or get in the way of ward staff, but as survivor researchers we noted that this approach was sometimes at odds with how we wanted to position ourselves on the wards (i.e. less deferentially) which may have arisen from our own service user experiences. The research team were also keen to provide us with as much support as we needed and were understandably concerned that we might be affected by the emotionally demanding nature of the fieldwork including possible disclosures from interviewees. However, we were more concerned about practical matters such as travel arrangements, getting up early, etc. As we began to build relationships with the team it felt easier to explain that, for example, for one of us, travelling to and from the case study site was a much greater cause of anxiety than the interviews themselves. Once this had been explained, other members of the research team were very supportive and practical arrangements were put in place to assist with this.

Reflections on behalf of the EURIPIDES study team (Sarah-Jane Fenton):

There were two core components to the PPI work undertaken within the EURIPIDES study, both of which strengthened the overall quality of the study. There was a reference group of people with lived experience of adult inpatient environments who did not have research backgrounds and most of whom had no prior experience of research, which was complemented by survivor researchers who had specific expertise in relation to research activity. It would not have been possible to conduct or complete the study in the way that we did, nor to such a high standard, without this dual strand involvement.

As the RF on the study, I was responsible for being the link person between the two groups alongside colleagues from the MHF. For the PPIT reference group, having a link contact person (Jo Ackerman) to manage the relationships outside the formal meetings based in the MHF really helped to offer an easily accessible point of contact for individuals in between meetings.

Reflecting on what else worked well within the reference group, I felt it was the establishment of clear boundaries at the start and end of each meeting, particularly around signposting people safely to supports and both recognising and not diminishing distress (for example, addressing suicidality when it was presented in meetings), which created a supportive and safe space enabling everyone to contribute. In addition, it was extremely important to be responsive to the different literacy levels and sensitive to both an individual’s reported physical and mental health needs and the wider group dynamics.

It would be easy to create a long list of things that seem obvious in relation to facilitating group work: good communication, clear boundaries, establishing a clear purpose for each meeting, listening, responding to the needs of the group, etc. However, really what has stuck with me over the course of working with the group was the need to allow them to lead and manage as much of the process as possible. Whilst I was clear what the tasks were we needed to achieve in relation to the research at each time point that we met, letting the group determine how we would work on those tasks, letting the group dictate the pace and flow of the meetings, and letting the group challenge and hold us accountable for how their hard work was shaping the study was the real strength in the work.

It was this power-sharing (for a group who had experienced a great deal of disempowering practice), underpinned by all the other good group work practice, that generated or activated underlying mechanisms of trust that led to outcomes of authentic engagement and enjoyment of the co-research process. Being a genuine member of the wider research team, and everyone recognising that each person has a different role to play, was integral to the success of the PPI work.

This underpinning philosophy of mutual respect and shared goal-setting was equally important with the survivor researchers. We did not start off the piece of work together here so well, and there is learning to be drawn out of those earlier less helpful interactions. Despite that, the contribution made by both the research team and the survivor researchers when we did get up and running was unique and powerful. Survivor researcher involvement should not be limited to ‘interviewing the patients’ – but actually their expertise should be woven throughout the study meaningfully as researchers in their own right. The survivor researchers in the field were treated no differently to the research associates – we debriefed together, ate together, travelled together, talked and discussed ideas together. Whilst each of us knew our role and there were clear lines of accountability, it was a team effort and we knew we could trust and rely on the other. This reflexive way of working meant that if people needed to step back or had a particularly difficult experience on the wards, another of us would step in. It was just a more humane way of working with what at times can be a difficult and distressing subject matter.

We adopted this inclusive, supportive approach across the PPI work – departing from the model set or agreed with the funder, and trying out new ways of working. I am grateful to the chief investigator and the wider Project Oversight Group for agreeing this new flexible, innovative way of working, because it genuinely opened up the space for real collaboration and appreciation for everyone’s involvement. It resulted in there being no involvement that was tokenistic or wasted – everything discussed or done together was built consciously back into the study, changing and shaping the way it developed.

Limitations

There were also limitations to the PPI work undertaken in the course of this research. During the early stages of the project, it may have helped with communication and mutual trust to have spent additional time getting to know each other by sharing different perspectives and experiences. It may also have helped for the whole team to have met together (PPIT, survivor researchers and other members of the research team), as this did not happen until the later stages of the research process. For example, when some members of the PPIT met one of the survivor researchers at a later stage in the project, they expressed surprise at realising that service users can also work as researchers (i.e. that some use their own experiences as part of their work as ‘survivor researchers’ and others work as researchers but choose not to integrate their experiences into their research work). Discussions of this nature may have been encouraging for some members of the PPIT, in addition to acknowledging that research skills can be obtained through various means – not just postgraduate and doctoral routes.

Time constraints and limited involvement in fieldwork prevented the survivor researchers from developing their approaches to realist interviewing informed by their own lived experiences of mental distress. The two WP3 case study sites where the survivor researchers were involved were ‘green-rated’ sites that had scored most highly in the WP2 survey of inpatient providers. As some interviews were conducted jointly (with other study researchers) as well as independently, we were unable to fully assess the extent to which specific interview dynamics between interviewee and researcher with lived experience might have shaped the study findings. This is something that could be reflected on as part of a collaborative research process in future projects.

Evaluation summary

Michael Larkin and Elizabeth Newton (EURIPIDES Project Oversight Group members) and Lizz Kimber and Nicole De Valliere (postgraduate research students) conducted a subsidiary research project to evaluate the acceptability and development of the PPI component. This evaluation focused on the engagement and role of the PPIT and it aimed to identify barriers to and facilitators of involvement in the EURIPIDES study, and to provide us with a basis from which to reflect on what we had learned by working together. A full report will be published subsequently, but the following represents a brief overview.

Full ethics review was sought, and approval was received, from the Life and Health Sciences Ethics Committee at Aston University, Birmingham, where Michael Larkin is registered as principal investigator for this subproject.

Sampling

We invited members of the PPIT, members of the research team most involved in working with the PPIT, colleagues from the MHF and the survivor researchers to take part in these research interviews. Potential participants were given the option of taking part in a one-to-one interview or a group interview.

Data collection

At a pre-evaluation meeting with the PPIT, we co-designed a timeline for the project, which captured memorable milestones. We subsequently developed an interview guide around this timeline. The interview guide explored people’s experiences of being involved with the EURIPIDES study and also asked about key barriers to and facilitators of people’s involvement, drawing on a structure commonly used in critical incident technique interviewing.

Interviews with PPIT members were conducted by Michael Larkin and Elizabeth Newton. The remaining participant groups were interviewed by Lizz Kimber. Twelve interviews were conducted; two of these were group interviews. A total of 18 people took part, with representation from each of the four stakeholder groups. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed in full and then anonymised.

Data analysis

We used template analysis to code and organise the data. A template in this sense is a set of categories or headings for organising the content of the data. In template analysis, preliminary templates can be developed using an existing framework or they can be developed from exploratory coding of the data. We took the latter approach and we had the luxury of independent coders to help us with this. Nicole De Valliere began coding the interviews conducted with PPIT members (six transcripts) and Lizz Kimber began coding the remainder (six transcripts). When each coder had completed three transcripts, they shared their developing template structures with Michael Larkin, who produced a merged template structure. The remaining interviews were coded according to the structure of this preliminary template. The template was further refined and developed during this stage. The final template structure is detailed and complex, and can be used as the basis for identifying cross-cutting themes. In subsequent reporting, we will take this approach. For the purposes of this document, what follows is a more ‘concrete’ focus on barriers and facilitators.

Analysis

Getting involved gradually

Participants from the PPIT reflected on the gradient of their involvement. To begin with, it was ‘a bit hard to take in, it was a bit complicated’. They described getting to grips with their role, getting to know the study team and coming to an understanding of what the study was about. They described how the study became ‘a constant’ for them. This was positive: a reliable break from other routines and an enjoyable experience. It soon entailed a commitment: ‘[i]t’s a commitment, and it means “yes” all the time. I’ve got my (other regular group activity). I should’ve gone. We told them we couldn’t go today. This has become more important than that.’

Different kinds of contributing

The participants also described ways in which they had contributed, emphasising particularly their role in helping the researchers to understand the problem they were studying: ‘I’ve made them feel informed’. When they did this, they grounded their claims in the value of their experiential insights: ‘I think we’ve all got that experience . . . We could share what we knew about it.’

In addition, PPIT members reflected on other contributions, such as group facilitation (‘I hope that, from time to time, I’ve put forward an idea that might get people moving together to get a consensus’), problem-solving (‘[i]t’s [trying to reconcile the range of views within the group] sort of quite infuriating sometimes, but it’s also very interesting’) and data analysis (‘[w]e went through the interviews . . . we picked out themes that were important’).

One issue that merits some reflection is that some PPIT members seemed to be unclear about the connection between research and practice. There was a tendency to overestimate the speed and directness with which their input might change practices. There is a difficult balance to strike between presenting PPI as a genuine opportunity to make a difference (which it can be) and the frustratingly slow process of translating research insights into practical or political change.

Challenges to contributing

Some of the things that made contributing more difficult were simple practical issues, which research teams can easily resolve if they are prepared to adapt: confusing or complicated concepts, being presented with too much information and a lack of clarity about the PPI role or the research process. Others issues were relational. There was a lot of material about the atmosphere and environment on the first (unsuccessful) meeting, for example. One participant described a ‘quite daunting’ atmosphere, with the group spaced out around a ‘massive table’, listening to strange people talk ‘in quite lengthy terms’, and then said: ‘[a]nd I was sort of sweating and shaking. I’m like “What have I let myself in for?”.’

Some of the relational issues were about getting to know the group. Several participants reflected on the challenges of speaking in large groups. It helped that many PPIT members knew each other, either from the Dragon Café or other activities, but not everybody did, and they also had to get to know the research team and MHF workers. In addition, they were mindful of treading on toes: ‘I think carers have to be very, very careful not to speak for service users’.

Personal factors could also be a barrier at times. A generic issue was the background phenomenon of stigma and personal history. One participant reflected on having to get used to the novelty of being asked for their opinion, for example: ‘[be]cause, by and large, having lived experience of mental health that has you down, and makes you cowed’. Others talked about more specific or intermittent difficulties (such as getting worked up by a particular issue or getting side-tracked) and life events (such as getting sectioned and missing a meeting).

Facilitators of contributing

Factors that helped with involvement were often driven by the motivation to make a difference. Participants described wanting ‘to break down the taboo’, ‘to put across the real’, ‘to help people’ and ‘to improve mental health’. Many people reported very upsetting inpatient experiences (‘[y]ou had to fight to protect yourself’), so the topic was very salient for them. This went hand-in-hand with the appraisal of the research as worthwhile or important: ‘[i]t can change things’.

Practical details such as travel arrangements, appropriate payment and appropriate refreshments were still important (‘[t]hat sort of thing has helped’ but ‘[w]e don’t come here just for the money’). The research team and the MHF participants reflected on the considerable amount of planning and communication that went on to build the right team to support these activities, to get all of the practical details right and to maintain a positive experience for the PPIT.

Some of the above-mentioned relational and personal barriers were overcome because the research team created an environment that felt comfortable (‘welcoming, friendly’, ‘easy going and relaxed’, ‘they’re all calm’, ‘we’ve been treated with respect’, ‘very caring’) but sustained a clear focus and purpose (‘it’s a general discussion’, ‘it’s a structured environment’). In part, this was achieved by stepping outside the routine day-to-day world and coming to the university: ‘[i]f we was in London, and we was talking about this, I don’t think we could be so relaxed. It’s a different environment and we can speak about what we speak about.’ In part, it was achieved by academics offering a different form of professional interest (‘[w]e know that what we said can be trusted. Some places you can’t be trusted – on the wards, cause they say they’re assessing you.’). The participants from the research team described how they had tried to promote equality and offer engaging ways of working. PPIT members were positive about the range of ways to contribute (‘[w]e talked all about it, everybody, and then we changed, swapped and went round over to other people and it was a different experience. It was brilliant.’).

The sense of the group as a group of friends, with a shared purpose, began to cut through worries about group dynamics: ‘[h]aving my friends around me, who also have been going through the same things I’ve been going through, it kind of makes you feel it’s a family’. Positive feedback from the research team about how the PPIT contributions were being taken forward was appreciated (‘[t]his is what you did last time – that’s been important and useful’). Efforts by the team to make sure that everyone had a chance to contribute were also noticed and valued. Honest feedback was appreciated in all quarters and all participant groups described times when it had been provided in a helpful way.

Summary

A more detailed analysis is required, but our initial evaluation highlights the importance of research teams being flexible and for this to be understood and supported by funders and other partners. The PPI component has made an invaluable contribution to the conduct of the EURIPIDES study and it would appear that this has largely been a positive experience for the people involved. These are both excellent outcomes, but they are a consequence of effective adaptation more than a consequence of our initial plans.

Issues with the employment of the survivor researchers (outlined in the previous section) were relatively difficult to resolve, because it proved difficult for partner organisations (and particularly NHS partners) to adapt quickly. By contrast, the problems at the beginning of our PPI programme were resolved quite quickly, because we were supported in responding flexibly to the feedback we received.

What did we learn and what would we recommend?

The EURIPIDES study afforded many opportunities for us to learn what is needed for effective PPI. We would summarise our learning as follows.

Commitment to principles

To ensure that involvement is genuine and meaningful rather than tokenistic, it needs to be taken seriously, both in principle and in practice. It is important to have a clear understanding of and commitment to shared principles of involvement from the outset. We aimed to do this by using resources such as the 4Pi national involvement standards,45 which is a framework for good practice developed by service users and carers themselves. However, we could have spent further time exploring the purpose of involving people with lived experience, particularly with the survivor researchers in relation to issues such as disclosure of service use and the extent to which interview dynamics between interviewee and researcher with lived experience might be present or potentially contributing to the kinds of knowledge produced.

Appropriate resources need to be allocated to PPI work for it to be effective. We realised that, to support the work of the PPIT, we needed to hold more meetings than were originally planned. We also needed to develop ways of supporting the group outside meetings and the PPI work itself (e.g. by arranging visits by team members to the Dragon Café in London and ongoing support from the link worker at the MHF). Although there are often many competing priorities, when making resource allocation decisions it is important to prioritise these principles of involvement when negotiating funding and spending.

Diversity of experience

Although our initial aim was to ensure that PPIT members included a degree of diversity with respect to age, gender, ethnicity and geographical location, issues with recruitment meant that, ultimately, the majority of PPIT were members from the Dragon Café in London. The benefits were substantial in that there was already a degree of mutual trust and understanding between members, which meant that it may have been easier for them to be open during discussions and to disclose experiences. The Dragon Café was also a place to meet the group members where they felt comfortable. However, it may also have meant that a narrower range of perspectives were represented in the PPIT (e.g. this was a very urban/London-centric group) and collective views may already have been consolidated around some issues.

Curiosity and flexibility

It is important to be curious and to listen to the feedback of everyone involved. What do people need or want to make involvement work for them? We discovered that these do not necessarily need to be ‘big things’, for example ensuring that information was presented in an accessible way without the need for paperwork, finding ways to ensure that people felt less anxious about travelling and accommodating preferences in relation to food and refreshments.

As the project progressed, we learned the importance of flexibility and the need to be responsive to other members of the team, even if this meant making changes to original plans. This meant that initial problems were swiftly resolved and it helped to build trust and relationships between the research team and the PPIT.

Communication

For people to be fully involved, communication needs to be open and transparent throughout the research process. This encompasses discussion of shared principles and values at the start of the project, establishing clear lines of communication and support, discussing boundaries and issues around disclosure, negotiating and clarifying roles for different parties, encouraging feedback from team members, etc.

We have acknowledged some of the initial difficulties with regard to communication with the survivor researchers and recognise that improved communication at the research passport and administration stage of the process would have helped to build trust and relationships. However, as the project progressed, all members of the team began to communicate more effectively with each other and integrate the skills and perspectives of everyone involved in the EURIPIDES study.

Sharing of power

The NIHR INVOLVE principles53 state that research needs to be jointly owned. People with a range of prior experiences need to be involved at all levels and stages of the research process. During the course of the study, we acknowledged the importance of sharing power and letting the PPIT lead and manage as much of the process as possible (e.g. with regard to how we worked on tasks and the pace of meetings). Involving and including everyone required a degree of flexibility and creativity and the methods we used were different at each stage in the research process (e.g. role playing sections of interviews for PPIT members to discuss emerging themes, which fed into coding frameworks).

Power-sharing also involves an explicit recognition that, although members of the team occupy specific roles on account of their research experience or their experience of mental/emotional distress, the reality is, of course, that people bring a variety of different overlapping experiences. Challenging hierarchies within research teams is vital for effective PPI and our learning outcomes for future projects would include the need for us to reflect together on our own identities and experiences to create knowledge in more collaborative ways.

Chapter 4 Work package 1: systematic review of patient experiences of mental health inpatient care

Background

Patient experience evidence is increasingly used to enhance the quality of health-care services and to ensure that such services are effective and acceptable to patients. Collecting, synthesising and using experiential data can provide a key way to enhance practice over time, drawing on evidence about what needs to change, for whom, why and in what way, to provide the highest-quality patient experience. 23,25

Mental health inpatients have reported both positive and negative experiences. 6,24,29,31,57,58 A review of mental health services in England by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) in 201759 highlighted a range of concerns about inpatient care, including poor design of buildings that did not meet patient needs, unsafe staffing levels and care provided some distance from patients’ homes. Such negative experiences contrast with the strong policy focus on strengthening the patient voice through care that is compassionate, provides choice and ensures that patients have autonomy and dignity. 1–3,6,7,60 With greater understanding of the key role of patient experience data in service development, NHS trusts routinely collect and use such data, with varying degrees of success. 59,61–63

Despite the focus on data collection, the difference such information makes to the quality of care is not always clear. 8 The quality of data collection methods has varied19 and there is no agreement about which dimensions of patient experiences are most important to users of inpatient mental health care. These and other challenges represent significant barriers to the collection and use of patient experience data in these settings. 8,9 This highlighted the need to identify the most important dimensions of the mental health inpatient experience, to inform our study of current practice in the collection and use of patient experience data to improve services.

Aims and objectives

Aim

The aim was to identify and synthesise evidence-based patient experience themes relevant to mental health inpatient care.

Objectives

The objectives were to systematically:

-

review studies reporting patient experiences of mental health inpatient services

-

identify patient experience themes and subthemes that are relevant to delivering high-quality inpatient mental health care.

Methods

Work package 1 was divided into two parts: a scoping study and a main systematic review. The scoping study was designed to inform the main systematic review by ascertaining the nature and size of the evidence base.

Protocol and registration

The systematic review was registered as PROSPERO 2016 CRD42016033556.

Scoping review

A scoping review was first conducted to ascertain the extent, range and nature of studies, to map emerging key themes without describing the findings in full or performing a quality check64 and to inform the main review. Six key authors known to be experts in mental health patient experience were contacted for new or unpublished reports and studies.

Patient and public involvement team

Draft themes from the scoping review were presented to the PPIT to ensure face and content validity and to discuss gaps in the research (21 September 2016). The PPIT comprised 10 people with experience of inpatient care or caring for someone who had been an inpatient and who had been recruited by the MHF. Members of the PPIT were invited to two consultation meetings for the purpose of the review. The first meeting was to discuss the research team’s early familiarisation with the literature exploring the themes identified in the scoping review, to obtain their views on these and to add further concepts that PPIT members felt were important but that had not been identified from papers. The second meeting was to discuss the themes identified from the systematic review, to obtain PPIT members’ opinions on these and to identify perceived gaps in the literature. Both discussions were important for assuring content and face validity of the subthemes and themes. Public involvement in this WP is reported in Appendix 19 using GRIPP2.

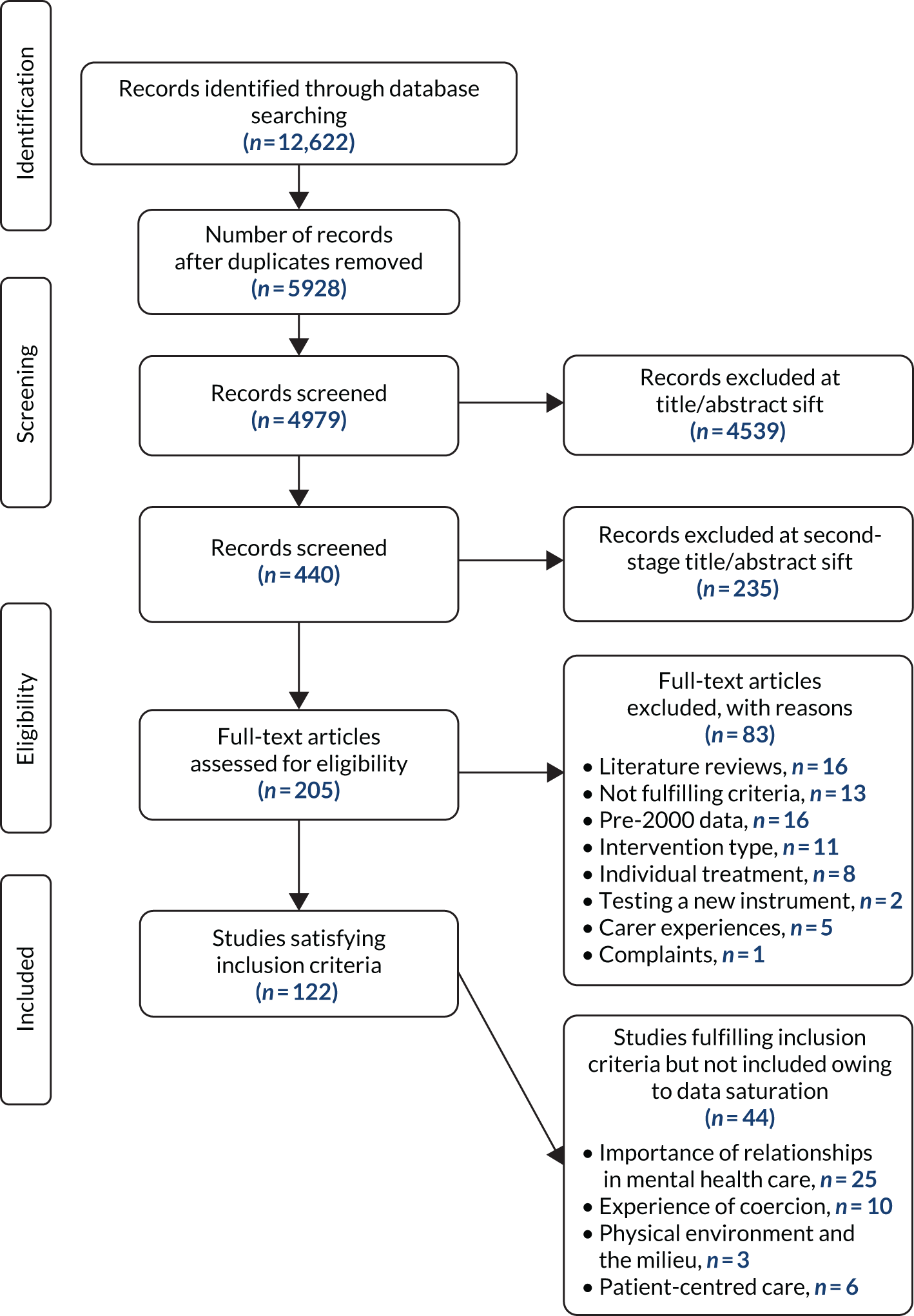

Identification of studies for the systematic review

The themes that emerged from the scoping review guided the development of search terms and the search strategy for the systematic review. These were applied to MEDLINE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and PsycINFO. An example of search terms and results are reported in Appendix 14. Reference lists of included papers were scanned. The search deviated from the protocol in that only three of five databases were searched owing to the large numbers of abstracts retrieved.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All study designs were considered if papers included experiences of current or former inpatients of mental health institutions. No restrictions were applied based on country. Articles were included if they reported primary research, were peer reviewed and were published in English between January 2000 and January 2016. Papers were excluded if they were not primary studies, were based on pre-2000 data, included children and adolescents (aged < 18 years) or were not in English. When study participants included both inpatients and outpatients, only data regarding inpatient experiences were extracted. Reviews (see Report Supplementary Material 1) were noted and reference lists were scanned, but these were excluded from the review to avoid bias.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were screened (by Carole Mockford and Greg Chadburn), of which 20% were independently cross-checked for agreement prior to obtaining full-text articles (Sophie Staniszewska and Carole Mockford). Full texts were obtained when the abstract was unclear. Any disagreements could be resolved by consensus (Carole Mockford, Greg Chadburn and Sophie Staniszewska), but no disagreements occurred.

Data extraction

The data were extracted to Microsoft Excel® (version 2013; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), and included citation details, sample recruitment and research methods and findings related to key concepts; any other emerging concepts were added (Carole Mockford).

Quality and risk of bias in individual studies