Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/04/22. The contractual start date was in December 2018. The final report began editorial review in March 2019 and was accepted for publication in April 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’™ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© King’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Brady et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health and Care Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 King’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this report have been adapted with permission from Brady et al. 1 © Wolters Kluwer Health Inc.

Aphasia

Of the estimated 10.3 million people worldwide who experience a stroke each year, 3.6 million people (35%2) are likely to have a stroke-related language impairment known as aphasia. Each year, an estimated 35,000 people in the UK experience a newly acquired aphasia, affecting not only their language abilities (ability to speak, understand, read and write words and sentences), but may also affect their ability to use gesture, tell the time, use money and perform simple mathematical calculations. Of those who experience aphasia, 61% continue to have communication problems 1 year later. 3 Approximately 350,000 people in the UK are thought to be living with aphasia. 4

Impact of aphasia

Aphasia is one of the most common and most devastating long-term consequences of stroke5 and extends beyond the communication domain. Stroke survivors with aphasia have poorer functional recovery (p = 0.007)6 {comprehension deficits, in particular, affect activities of daily living [odds ratio (OR) 5.38, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.35 to 12.34; p < 0.001]},7 continence (p = 0.003)8 and emotional well-being (r = 0.51; p = 0.001)9 after stroke than stroke survivors without aphasia. People with aphasia receive less pain medication than other stroke surviors. 10 Aphasia also negatively affects hospital discharge destination (p = 0.002),6 the likelihood of successful return to work (p = 0.009)11 and self-rated health after stroke. 12 These outcomes are despite people with aphasia having more contact with rehabilitation specialists2 and more rehabilitation interventions13 (contributing to the higher cost of care for people with aphasia) than those without. 14 In the USA alone, the presence of aphasia at the time of stroke adds US$2.16B, annually, to the cost of acute stroke care. 15 The communicative quality of those rehabilitation interactions may, thus, benefit from closer investigation.

Aphasia and psychosocial impacts

Aphasia directly influences a person’s perception of their own identity16,17 isolating the person with the communication impairment from their spouse, family and wider social networks. 18,19 Family members have also described feeling isolated. 20 Aphasia intensifies social problems more generally associated with a stroke, restricting or altering social activities. 21 This leads to fewer friendships and smaller social networks than before the stroke, and than both healthy peers and stroke survivors with preserved language abilities. 18,21 With restricted opportunities for social participation, people with aphasia become socially isolated, which severely affects their emotional well-being. 19 Spontaneous recovery of language and communication abilities has been thought to be limited beyond the first year after aphasia onset. 22 Emerging research has questioned this premise,23 and further evidence indicates that focused therapeutic interventions may provide benefit in later stages after stroke. 24–26

Aphasia recovery

Aphasia recovery and participant demographics

Clinical guidelines recommend that people with aphasia are provided with ‘realistic recovery prospects’ following aphasia,27 but, based on current evidence, accurate prognosis is difficult. Although age has been associated with language recovery, the nature of that interaction remains unclear. 3,13,28,29 Patient sex has been reported by some to be linked to the incidence of aphasia13 and initial aphasia profile (but not recovery3,28), although several large, well-controlled studies found no evidence of this effect. 2,3,30 Conducting a large-scale investigation of aphasia after stroke has often required compromise, with language data based on a single item in a global stroke severity scale,2,3,29 and, in some cases, restricted to one aspect of language use. 3 Details on the ability to speak, understand, read, write and participate in everyday communication activities are often unavailable in these tools, thereby limiting our clinical interpretation of aphasia impact and recovery.

The contribution that socioeconomic status and educational background make to recovery may also be relevant, but the interconnectedness of these factors with cognition and performance on measures of language ability makes this a difficult concept to untangle. 3,31–33 The incidence of aphasia is similar among monolingual and bilingual stroke survivors, although it has been suggested that bilinguals experience a milder aphasia. 34 However, studies using imaging data found that bilinguals’ performances on a detailed language assessment protocol were worse than monolinguals’ performances. 35 Social support prior to and following a stroke may also positively influence outcome36,37 and, although opportunities to practise functional language use have been shown to decrease as a consequence of aphasia,18 they are also an important factor in aphasia recovery38,39 and research. 38

Aphasia recovery and stroke profile

Initial stroke severity13,28 and time since stroke may be important factors in language recovery, the latter specifically in relation to the acceptability of high-intensity therapy. 40,41 There is growing evidence that the site and size of stroke lesion (although perhaps not structural connectivity) are indicators of language recovery. 31,42 Stroke-related problems, including depression and cognition, vision and hearing impairments, are also thought to be important to language recovery and rehabilitation. 43–45 Others suggest that the initial aphasia profile (i.e. severity, domains involved, abilities retained) may predict the pattern of language recovery. 3,28,31 Concomitant stroke-related speech disorders, such as dysarthria (a motor speech disorder) and apraxia (disordered planning of movement to produce speech), may also affect initial functional outcomes and recovery. 46

Speech and language therapy for people with aphasia after stroke

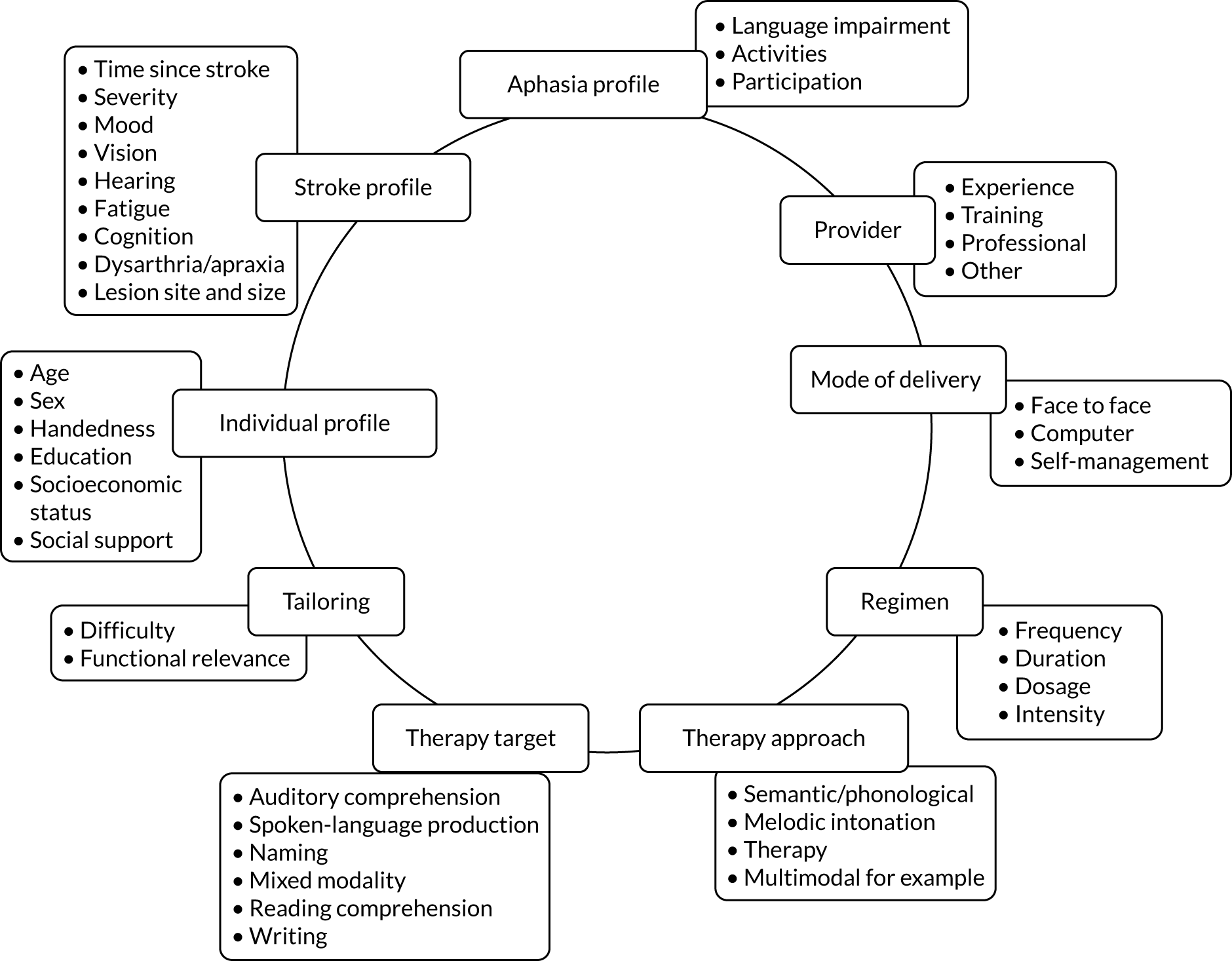

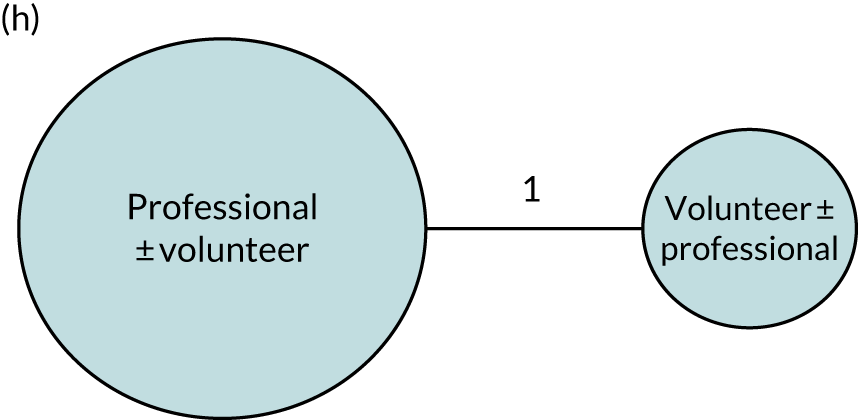

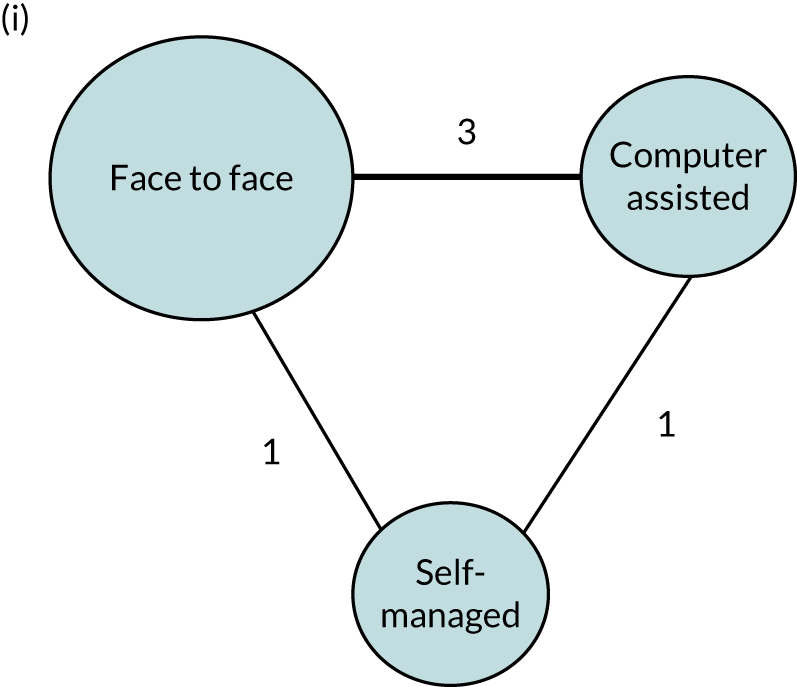

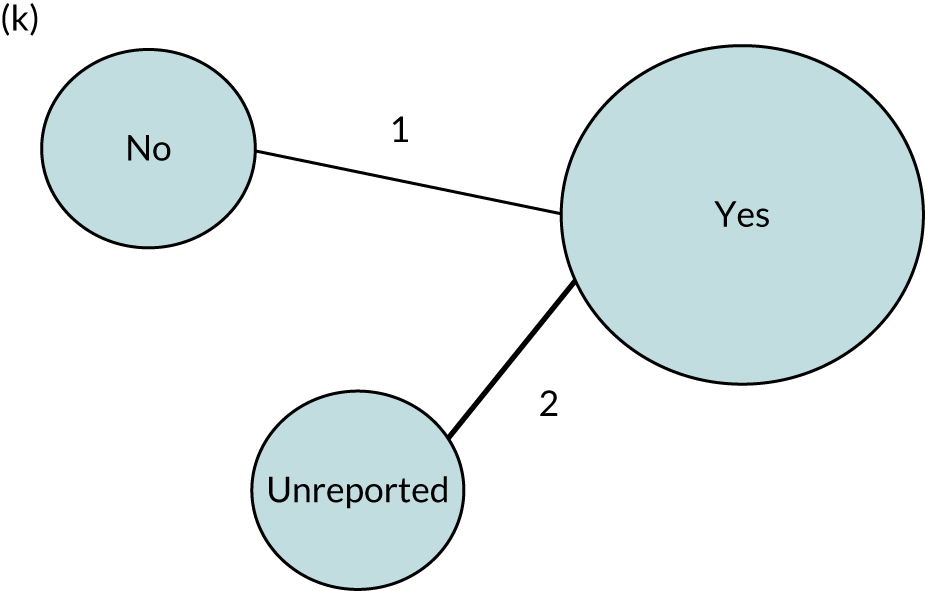

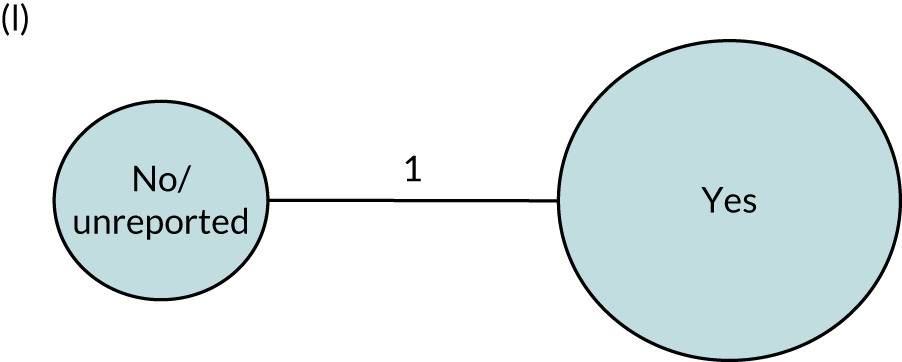

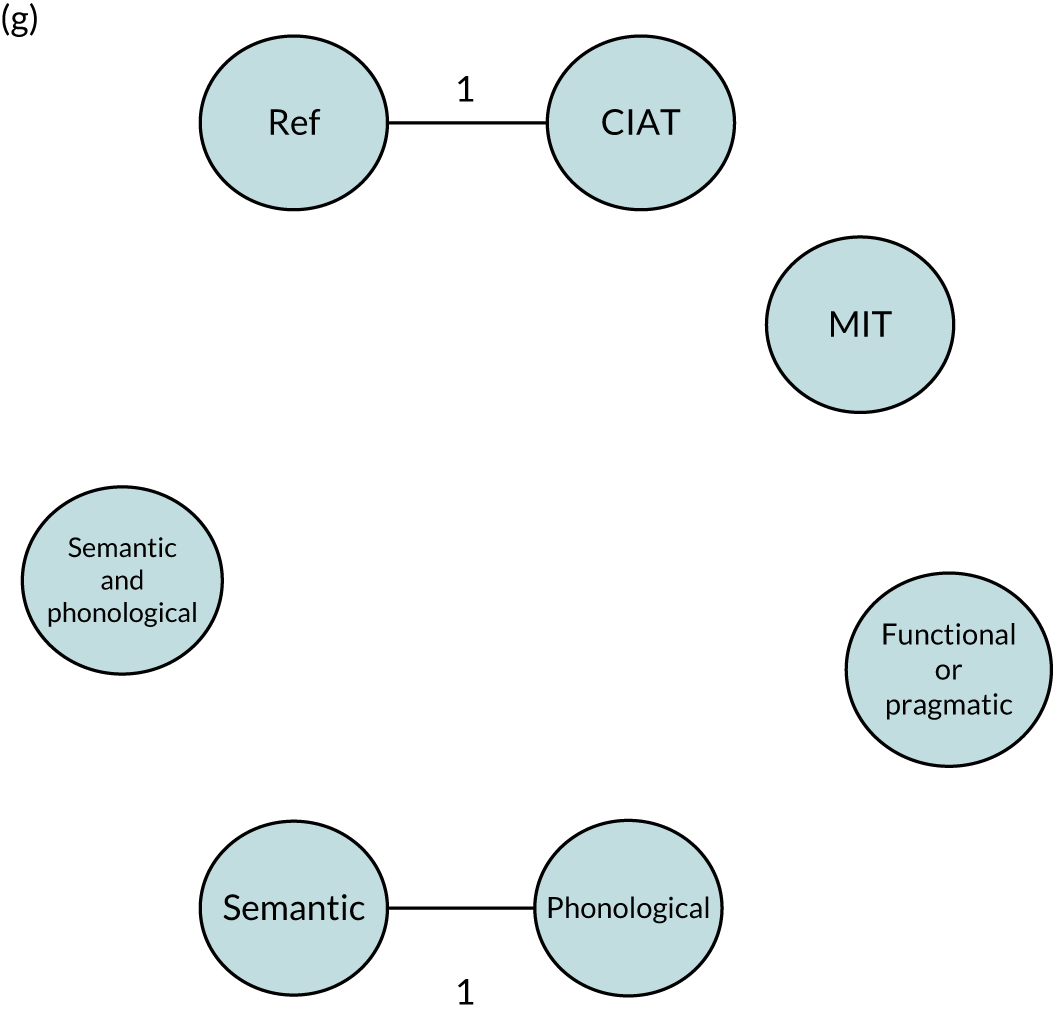

Effective management and rehabilitation of aphasia is vital. 41 People with aphasia experience significant benefits on measures of functional communication, understanding and spoken language after stroke following speech and language therapy (SLT) than those who do not receive therapy. 41 SLT for people with aphasia is highly complex47 and typically tailored to a heterogeneous group (Figure 1).

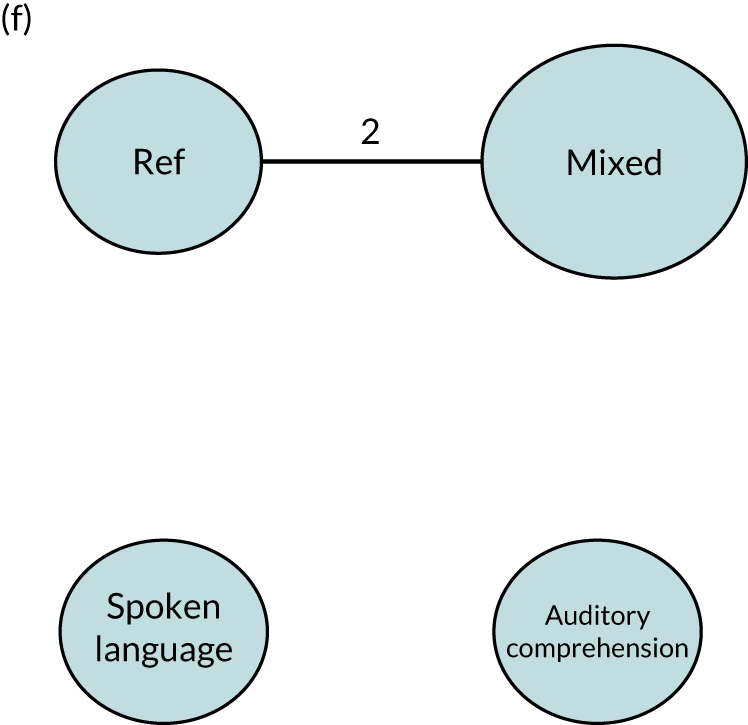

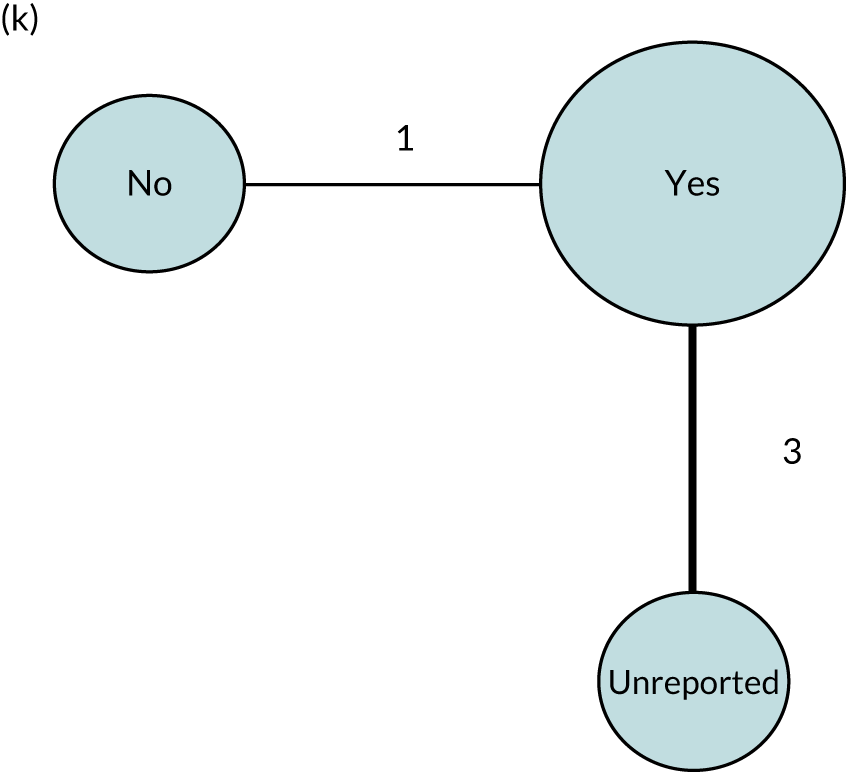

FIGURE 1.

Speech and language therapy for aphasia.

Therapy activities may be delivered by a range of therapist-trained providers (therapists, volunteers or family members). 41 There is no indication that individual, group or self-managed therapy delivery approaches using personalised computer software, for example, affect SLT benefits for people with aphasia. 41 Therapy interventions may target a range of language domains (e.g. spoken language, auditory comprehension, writing) or aim to educate carers and staff to maximise communicative effectiveness through conversational support for the person with aphasia. Interventions may adopt any one or more of several theoretical approaches (e.g. melodic intonation or functional, semantic, phonological or multimodal therapy), while the optimum intervention regimen (timing, intensity, frequency, duration and dosage) remains uncertain. 22,41,48,49

Regimen

Early stroke rehabilitation has been advocated50 to maximise the period of neuronal reorganisation in the brain subsequent to the stroke lesion,51 in a context of enhanced rehabilitation environments and stimulation. 52,53 Recent randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of SLT interventions have recruited within clinically relevant timelines (days to weeks after stroke)54–56 with mixed results, whereas others have demonstrated benefits among more chronic participants. 57 The optimal timing of language rehabilitation for people with aphasia after stroke continues to be uncertain, and evidence of the most effective SLT intervention regimen, based on therapy frequency (number of therapy sessions weekly), duration (start to end of therapy intervention), intensity (number of hours weekly) or dosage (total hours) provided, is also unclear.

Intensive SLT intervention has been found to benefit functional communication, written language and severity of aphasia, but significantly more people withdrew from (dropouts for any reason p = 0.005), or declined to continue with (non-adherence p < 0.00001), intensive therapy than less intensive therapy. 41 Interestingly, differential withdrawal and non-adherence rates and the language recovery benefits were observed only among people within 3 months of their stroke. Thus, therapy regimen and participant factors may be important independent and interdependent factors in the effectiveness of and tolerance to SLT for aphasia after stroke.

Clinical guideline recommendations

UK and international clinical guidelines on aphasia after stroke highlight the paucity of guidance to support therapists’ provision of aphasia rehabilitation interventions. 58 Evidence-based stroke clinical guidelines rarely offer specific therapy approach, regimen or mode of delivery recommendations, in contrast to movement rehabilitation recommendations for strength and fitness training, orthoses, electric stimulation and more. 59–61

Early62,63 and high-intensity SLT64 may be effective, but these historic reviews of SLT for aphasia were limited in their design (time-bound, English language only, small number of studies included, summary data analysis only). The Cochrane review (57 RCTs, n = 3002 participants) found that the potential benefit of high-intensity SLT was confounded by a significantly higher dropout rate from intensive SLT groups. 41 Tailoring to the individual is considered essential,65 but is based on best practice recommendation. High-quality information from large-scale research projects does not currently exist to guide therapists’ choice of an effective therapeutic approach best suited to a specific patient with aphasia (and their families).

Data sets capturing a large number of people with aphasia after stroke are typically based on single-centre data with relatively small numbers of individual participant data (IPD). In studies for which larger numbers of IPD are available (n > 200), the quality of information on language outcomes is often restricted, informed by a language data item on a generic stroke scale or screening tool gathered by non-language specialists2,3,29 and lacking a full description across a range of language skills.

Availability of speech and language therapy for people with aphasia

Information on clinical services for people with aphasia after stroke is difficult to gather. A 2003 UK survey found that therapists providing adult services reported that only one-quarter of their time was spent on aphasia. Of available SLT time for aphasia, just 5% was spent on interventions with an intensity of > 3 hours weekly. 66 Half of SLT time was invested in interventions at an intensity of < 3 hours weekly. 66 An earlier survey reported in 2000 indicated that the average total duration of SLT interventions for people with aphasia ranged from one to five sessions in the UK and Australia. 67 North American SLT interventions ranged from 16 to 20 sessions. 67 Since then, hospital-based SLT in Australia may have increased, with a 2009 survey describing typical intervention intensity of 4 hours weekly (2 hours weekly in acute settings). 68 Information about the SLT received by 278 people with aphasia from across the UK prior to their involvement in the Big Clinical and cost-effectiveness of aphasia computer treatment versus usual stimulation or attention control long term post-stroke (Big CACTUS) trial69 showed that, in the first 3 months from the index stroke and pre recruitment, participants had received a total dosage of 11 hours of SLT, delivered at an intensity of approximately 1 hour weekly. People who were ≥ 5 years after the index stroke received a total dosage of 2.75 hours over the preceding 3-month period, delivered at an intensity of 45 minutes monthly,69 even lower than the 1 hour weekly reported for people with aphasia in the Australian community. 68

National audits, although capturing information on access to clinical services, rarely distinguish between time spent with a speech and language therapist for dysphagia (swallowing problems) and aphasia. 2 The Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP) does, however, highlight the lack of resources for SLT services, a sentiment echoed by therapists. 70 The 2016–17 SSNAP data71 highlighted stroke specialist services with no speech and language therapist, whereas others had a very limited service (one or less full-time equivalent therapist), leaving service provision for aphasia vulnerable should a therapist be on leave, move post or retire.

There is some suggestion, however, that standard SLT services may be changing in some centres. Usual care provided to participants with aphasia in a recent Australian Phase III trial72 found that the usual care arm provided early SLT intervention to 81% of participants, compared with just 12% in the Phase II trial. 56 Similarly, the Phase III trial72 usual care participants received more frequent SLT, and a SLT dosage of 9.5 hours over the first 7 weeks (approximate intensity of 1.5 hours of SLT weekly), compared with an average intensity of 14 minutes of SLT weekly in the Phase II trial. 56 Although the triallists acknowledge that this could be related to the sites simply being part of a trial (the observer effect), it may also suggest a shift in usual SLT interventions over time in those centres. 56,72

Aphasia: a research priority

Aphasia intervention research was identified twice in the shared top 10 research priorities by stroke survivors, family members and health-care professionals in the 2011 James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership. 73 Effective aphasia rehabilitation and support interventions for people with aphasia and their families were agreed to be urgent unmet research needs. 73 More recently, the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists (in the UK) identified aphasia research as a top five research priority topic among their membership. 74 Two further priority-setting initiatives for aphasia research also identified the need for clinically relevant information regarding aphasia therapy intervention approaches, timing, intensity, duration, dose of therapy and therapy provider among the research priorities. 48,49

Rehabilitation of aphasia after stroke: a research challenge

The recent priority-setting initiatives have highlighted the gaps in evidence informing the delivery of SLT to people with aphasia. Growing recognition of the importance of focused, early rehabilitation after stroke (for example by Bernhardt et al. 75) has occurred in parallel with increasingly constrained NHS therapy budgets. Prognostic indicators may inform the development of predictive models that acknowledge the existence of parallel spontaneous recovery alongside the benefits of early intervention and brain plasticity. 51 The diversity among people with aphasia and the range of therapeutic interventions have led some to question whether or not large RCTs of SLT for aphasia is the optimal approach to gaining insights into what works best and for whom. 76

Complex SLT interventions (see Figure 1) may be optimised, and specific patient subgroups may benefit from particular SLT interventions. Large-scale investigations of SLT for aphasia are possible and worthwhile. 25,26,55–57,72 International collaboration in this field may be further challenged by the difference in languages across centres and the lack of non-English-language aphasia assessment measures. However, examining the impact of the many permutations of a complex intervention such as SLT on a complex population, which varies by participant, aphasia and stroke profile, would need decades of large, logistically challenging and costly RCTs. Much insight may be gained to inform the design of clinical services and future aphasia research by exploring existing aphasia research data sets.

Synthesising pre-existing aphasia research data

Data synthesis and secondary analysis of large, aphasia-specific data sets has informed our understanding of SLT for aphasia after stroke. Pooling of group-level summary (aggregated) data demonstrated the effectiveness of SLT for aphasia across language domains. It also identified a possible interaction between the SLT regimen and timing of therapy after stroke, and also methodologically in relation to the choice of attention control interventions. 38,41 Meta-analysis has provided a cost-effective way to inform our understanding of aphasia recovery and rehabilitation before moving forward with costlier RCTs. Such an approach, however, also has limitations.

Traditional meta-analysis makes paired comparisons (therapy A vs. therapy B), but does not easily permit a comparison of therapy A versus B versus C versus D. Clinically, SLT interventions are tailored to individual patients’ degrees of language impairment across modalities, attention or levels of fatigue. Group-level summary statistics prevent examination of the influence of participant-level covariates (e.g. age, time since stroke, aphasia severity or sex) on treatment effects.

Secondary analysis of IPD ensures that individuals (their aphasia and stroke profile, recovery and, when relevant, tailored therapy approach) would be analysed in the context of their individual data set, and not aggregated and averaged across a highly heterogeneous group. A collaborative, international approach to data-sharing and retrieval of published and unpublished data sets would support the development of a substantive database to explore key clinical and research questions, such as the patterns and predictors of language recovery, optimum SLT approaches for aphasia rehabilitation and treatment effect modifiers, benefiting researchers, therapists and people with aphasia.

Aims

The aims were to explore the contribution that individual characteristics (including stroke and aphasia profiles) and intervention components make to the natural history of recovery and rehabilitation of people with aphasia following stroke, and to inform future research design by utilising pre-existing aphasia data to explore the following:

-

the natural history of language recovery

-

the patient, aphasia, stroke and environmental characteristics that are linked to good language recovery

-

the components of effective therapy interventions.

Research questions

The research questions are in Box 1.

-

What is the pattern of language recovery following stroke-related aphasia?

-

What is the natural history of language recovery?

-

When is language recovery most likely to occur?

-

Which components of language are most/least likely to recover (overall language ability, spoken language, auditory comprehension, reading comprehension and writing)?

-

Does this vary by language?

-

-

What are the predictors of language recovery outcomes following aphasia in relation to:

-

Aphasia profile (the degree to which overall language ability, auditory comprehension, spoken language, reading comprehension and writing have each been affected in one or more languages)?

-

Individual characteristics (age, education, cognition, mono- or multilingual)?

-

Rehabilitation environment (social support, socioeconomic demographics, ethnicity)?

-

Stroke profile (severity, lesion type, size, location)?

-

-

What are the components of effective aphasia rehabilitation interventions in relation to:

-

Timing of intervention?

-

Frequency, duration, intensity and dose of intervention?

-

Repetition and adherence to home-based therapy tasks?

-

Functional relevance and theoretical approach?

-

-

Are some interventions (or intervention components) more beneficial for some patient subgroups (individual, stroke or aphasia characteristics) than others?

Chapter 2 Methods

Overview

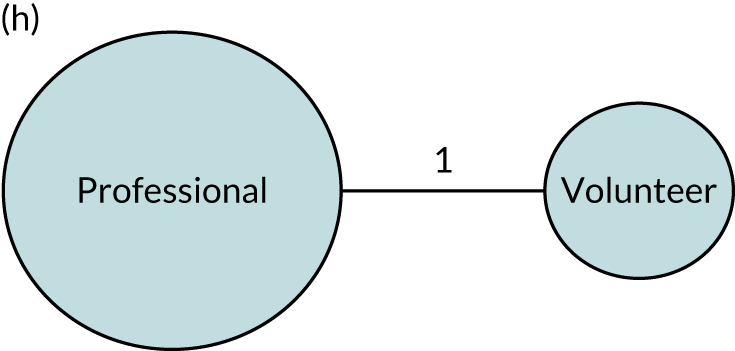

We created an international, multilingual database that included IPD on demographics, language impairment, stroke and SLT interventions. The purpose of our database was to support exploration of a range of key clinical questions relating to SLT for aphasia after stroke. The REhabilitation and recovery of peopLE with Aphasia after StrokE (RELEASE) IPD meta-analysis and network meta-analysis study followed a prespecified protocol and identified suitable data sets following a systematic review of the literature (PROSPERO CRD42018110947). We did not employ a strict experimental approach and hypothesis-testing. Instead, we sought to use statistical inferencing to identify promising lines of enquiry for specific investigation in future large-scale definitive experimental investigations in which participant populations and data items could be well defined.

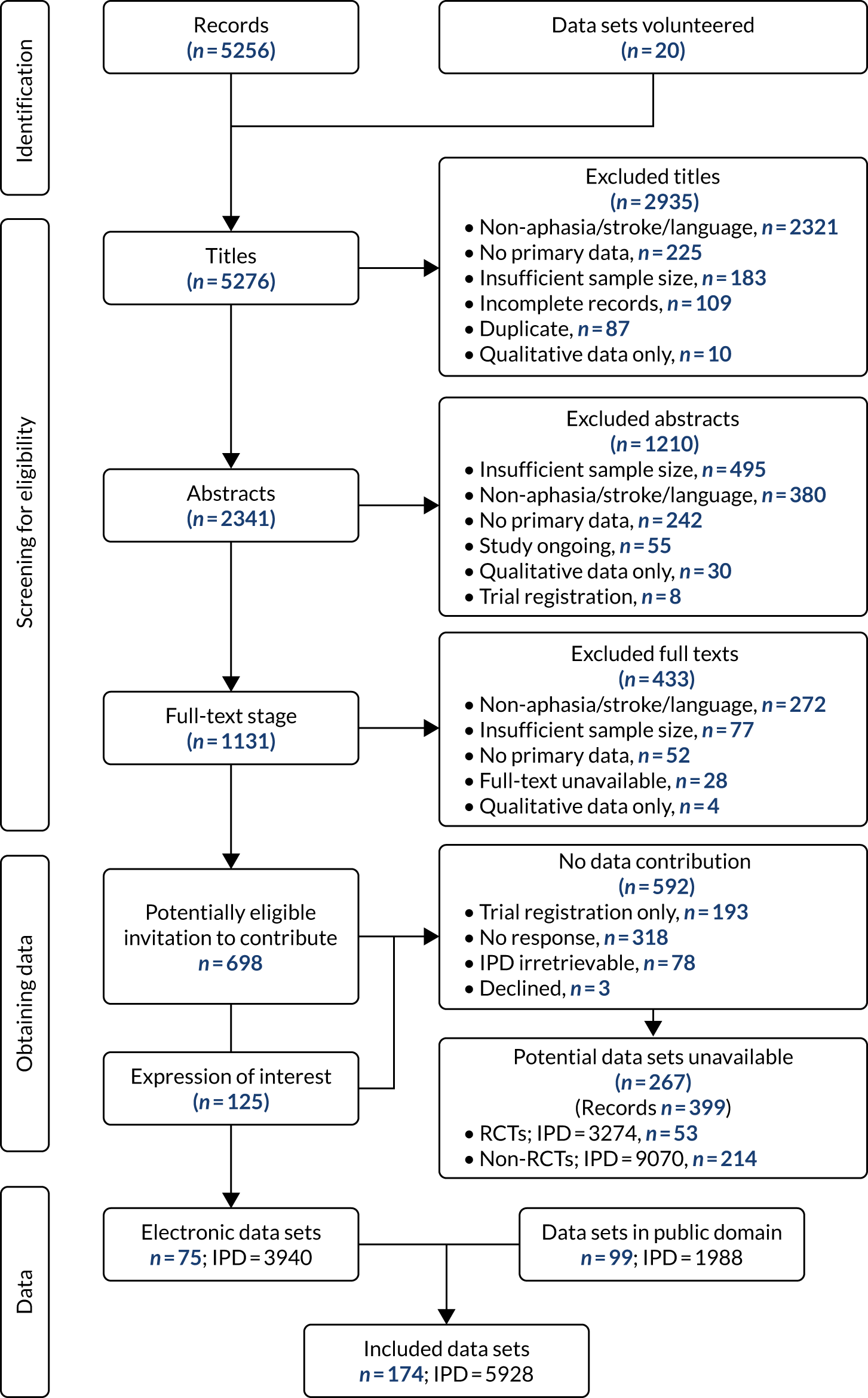

The RELEASE study database (Integrated Research Application System number 179505) (Figure 2) met existing data-sharing guidelines78 and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ proposal,79 and the reporting observes the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and relevant extensions. 80–85 We employed the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) to support data extraction of the complex SLT interventions,86 the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2)87 and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system to support judgements of the impact of the quality of the evidence on our findings. 88

FIGURE 2.

Creation of the RELEASE study database. ID, identification.

Studies included in the review

Types of studies

Data sets with IPD on people with aphasia after stroke were sought. We particularly looked for IPD data sets from RCTs, recognising their rigour and robustness for our planned analyses, by using a RCT-optimised search strategy. However, other study designs that met our eligibility criteria were also included, for example non-RCT, cohort and case series studies,89,90 as well as clinical and research registries (Box 2). Non-RCT designs (including cohort and case series) were included in covariate-adjusted analyses of recovery profiles and predictors of prognosis after stroke. 89,91 We applied no restrictions to study design, data set age, country, minimum number of time points, duration of follow-up, language of data collection or publication.

We accepted data sets that contained anonymised IPD:

-

collected as part of an ethically approved primary research study or clinical or research register

-

on a minimum of 10 individual participants with aphasia because of stroke

-

on aphasia severity

-

on time since stroke (or time since aphasia onset) at the time of initial assessment

-

relating to formal measures of functional language use, language expression, auditory comprehension, reading or writing.

Data sets were excluded if they were:

-

qualitative data only

-

non-language data only (e.g. response times)

-

presenting group summary level data only.

Types of study designs included

The primary research studies included in the RELEASE study were categorised according to study design:

-

RCTs – participants were randomly allocated to study groups that typically differed in the intervention received [or received a control (or no) intervention].

-

Non-RCT studies – participants were recruited but random allocation was not applied to group selection by the primary research team.

-

Cohort/case series – data sets from a single participant group that did not compare different SLT interventions.

-

Registries – clinical or research databases holding information (e.g. demographic, stroke, aphasia and SLT intervention details) on people with aphasia after stroke, which was not directly gathered to address a single research question.

Interventional or non-interventional

Studies were also classified according to whether they were (1) interventional, whereby SLT was provided in the context of the study, or (2) non-interventional, whereby no SLT was provided in the context of the study.

Crossover data sets

We identified crossover data sets (crossover RCTs or non-RCTs) and carefully extracted all data up to the point of crossing over.

Types of participants

We screened all participants for inclusion in the RELEASE study database and subsequent analyses. We had no exclusion criteria relating to participants’ time since stroke, age, language impairment or access to SLT. If aphasia was not the result of a stroke, those participants’ data were excluded and the remaining IPD from that data set (when all other eligibility criteria were met) were included. We defined three participant subgroups relevant to our analysis:

-

Natural history subgroup – participants recruited within 15 days of first stroke and allocated to receive no SLT intervention for a defined period of time in the primary research study. These participants were unlikely to have received significant historical language rehabilitation or SLT.

-

Historical SLT subgroup – participants allocated to receive no SLT intervention in a primary research study, but recruited beyond 15 days of stroke onset. Given the context of aphasia research activity, we assumed that these participants had some clinical access to SLT for their aphasia prior to their study entry.

-

SLT subgroup – participants allocated to receive SLT in the context of a primary research study (research SLT) or permitted continued access to standard SLT during the study period and recruited any time after onset of aphasia.

Speech and language therapy interventions

Speech and language therapy was defined as ‘any targeted practice or rehabilitation tasks that aimed to improve language or communication abilities, activities, or participation.’41 When relevant, we sought primary research studies that included a description of a SLT intervention (Table 1) to inform our research questions. Although therapy was typically delivered by a speech and language therapist (a protected professional title in the UK), we also included other therapy providers, as this was one aspect of our planned analysis.

| Type of SLT | Description |

|---|---|

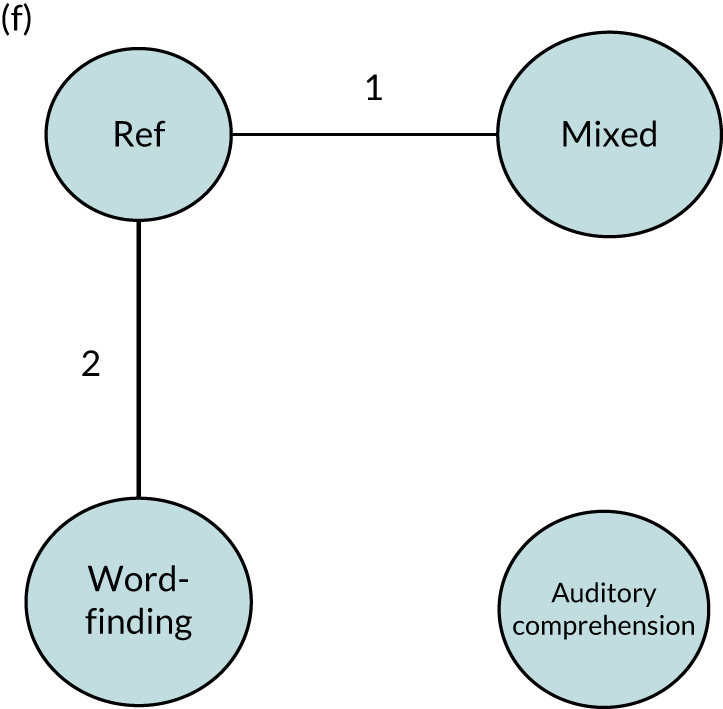

| Therapy approach defined by treatment target | |

| 1. Mixed SLT | Targets both auditory comprehension and spoken-language impairments |

| 2. Spoken-language SLT | Targets rehabilitation of spoken language |

| 3. Auditory comprehension SLT | Targets rehabilitation of auditory comprehension |

| 4. Word-finding SLT | Targets rehabilitation of word retrieval or naming |

| 5. Reading comprehension SLT | Targets rehabilitation of reading comprehension |

| 6. Writing SLT | Targets rehabilitation of written language |

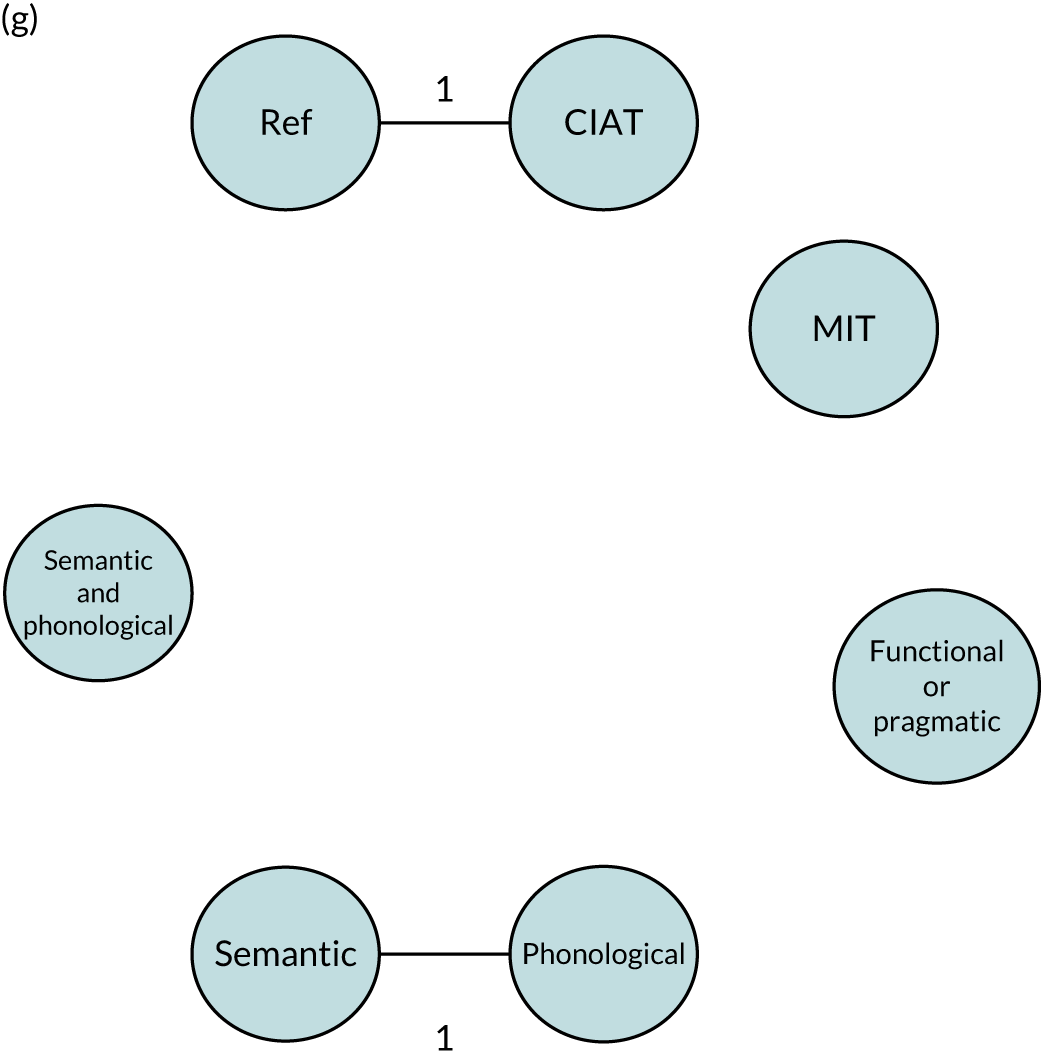

| Therapy approach defined by theoretical approach | |

| 7. Functional or pragmatic SLT | Targets improvement in communication activities and tasks considered useful in day-to-day functioning and often involves targeted practice in real-world communication situations |

| 8. Phonological SLT | Uses phonological approaches and seeks to improve the sound structure of language by targeting improvements in phonological input and output routes |

| 9. Semantic SLT | Uses semantic approaches that focus on interpretation of language, with the aim of improving semantic processing |

| 10. Semantic and phonological SLT | Employs a treatment programme that uses both semantic and phonological approaches |

| 11. Constraint-induced aphasia therapy | Participants are required to use spoken communication alone. Other communicative methods such as gesture may be discouraged |

| 12. Melodic intonation therapy | Employs rhythm and formulaic language to support recovery of language and exaggerated melodic sentence patterns to elicit spontaneous speech |

| 13. Conversational partner-training SLT | Targets communication interaction between the person with aphasia and their conversation partner(s). Conversational partners may be spouse, family member, friends or health-care professionals |

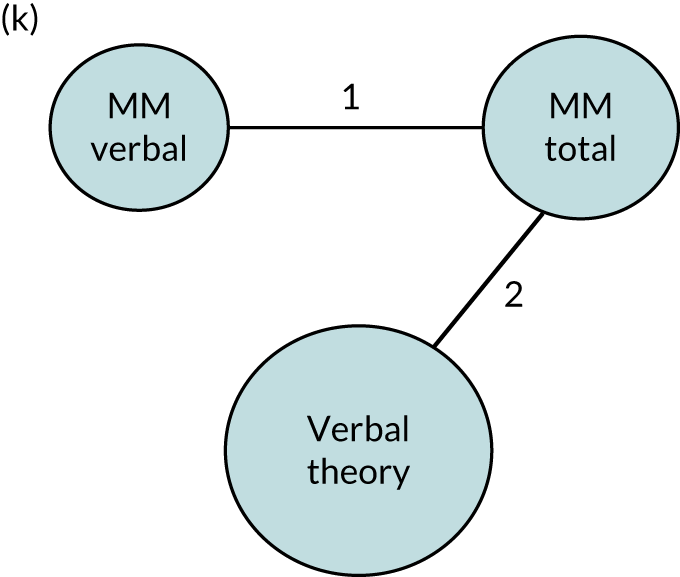

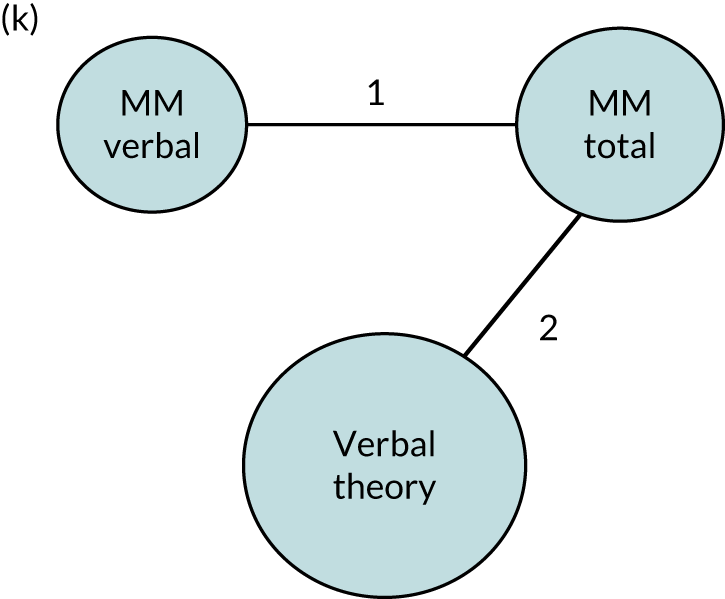

| 14. Verbal therapy | Seeks to improve verbal communication through tasks that include auditory comprehension, spoken language, repetition, naming, sentence construction, semantic or phonological judgements, reading or writing, but do not include music, singing, drawing or gesture-cueing tasks |

| 15. Multimodal therapy | Therapy tasks as listed for verbal therapy (auditory comprehension, spoken language, repetition, naming, sentence construction, semantic or phonological judgements, reading or writing), but that include music, singing, drawing or gesture, with the aim of improving (1) verbal communication (multimodal verbal), whereby non-verbal modalities are employed to facilitate or augment language rehabilitation or (2) total communication (multimodal total), whereby non-verbal modalities are a method of communication |

Speech and language therapy interventions were summarised to support clinically meaningful data synthesis and meta-analyses. Narrative descriptions of the SLT approaches, materials and procedures employed were initially extracted as direct quotations (when possible) from published reports. Descriptions were then tabulated and similar approaches were grouped by an experienced speech and language therapist. These narrative descriptions and preliminary groupings were shared among the collaborators for review and discussion. Following discussion and consensus, we identified 15 possible SLT approaches categorised from two perspectives:

-

the impairment target, for example rehabilitation of spoken language

-

the theoretical approach, for example semantic therapy.

Categories were not mutually exclusive, that is one SLT intervention could include more than one component, and thus be profiled across several categories.

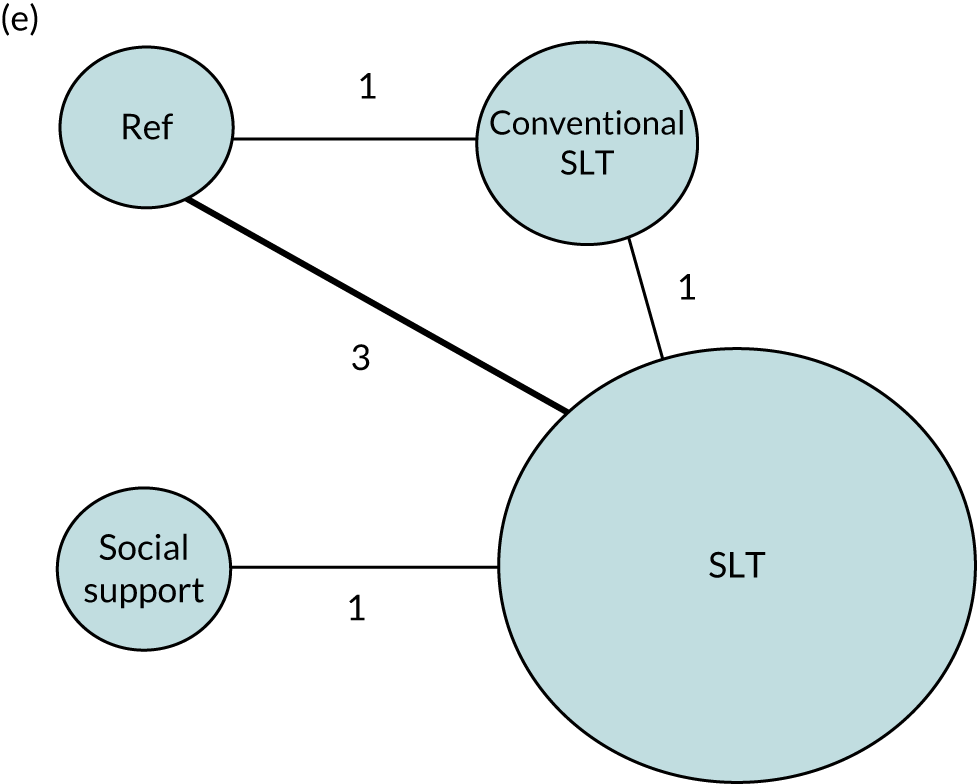

Social support and stimulation of communication

Social support and stimulation interventions provided informal support and functional language stimulation to the person with aphasia, but did not include targeted therapeutic interventions that aimed to resolve participants’ speech and language impairments. Historically they have been used as an attention control in trials of SLT for aphasia or as an adjunct to SLT providing an opportunity to apply new learning in functionally relevant communicative situations.

Conventional speech and language therapy

Interventions described as ‘conventional’, ‘traditional’, ‘standard’, ‘typical’, ‘as directed by the therapist’ or ‘usual’ SLT (and for which absence of detail prevented more specific categorisation) were referred to as ‘conventional SLT’. Such interventions were often delivered in a comparative group or clinical registry. We recognise that conventional therapy in one context may not be comparable with another.

Speech and language therapy co-interventions

We did not explore the impact of pharmacological or neurostimulation (e.g. magnetic or electrical stimulation such as transcranial direct-current stimulation) co-interventions, which are not typically within the remit of therapists in the UK. Examining the contribution of these co-interventions to language recovery among people with aphasia was beyond the scope and remit of the RELEASE study. We extracted information about the presence of such co-interventions and the timing of delivery and noted this in the data analysis.

Types of outcome measures

Improved ability to use language in real-world situations is the primary goal for aphasia rehabilitation and research. People with aphasia and their family members prioritise functional language use [linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) components of activity and participation], alongside improvements in language ability (body function). 93 Meta-analysis of functional communication measures is methodologically challenging, as they may be self-reports or proxy reports using rating scales, profiles or questionnaires. Discourse analysis, which observes the use of communication features within a sample of functional language, offers yet another approach, and debate continues about its usefulness and rigour. 94,95 In trials of aphasia rehabilitation, measurement of ‘real-world’ language use and functional communication is uncommon,41 and inconsistently captured across studies. 93 Measures of language impairment are considerably more common,41,96 and reflect overall language abilities (or aphasia severity) across several subtests, which typically include auditory comprehension, spoken language, reading, writing and functional language use.

Main outcome

The main outcome was change from baseline to follow-up in language performance (language recovery) on formal measures of language ability across six prespecified domains (overall language ability, auditory comprehension, spoken-language production, reading comprehension, writing and functional communication) (Box 3).

-

Demographic information (age, sex, handedness, education, cognition, dysarthria, apraxia, languages spoken, depression, other neurological diagnosis, vision and hearing abilities, ethnicity).

-

Environmental descriptors (living environment, social support, socioeconomic status).

-

Stroke characteristics (hemisphere, type, time since stroke, severity, first or subsequent stroke).

-

Overall language ability.

-

Auditory comprehension.

-

Spoken-language production.

-

Reading.

-

Writing.

-

Functional communication.

-

Design.

-

Inclusion/exclusion criteria (e.g. dementia, prior stroke).

-

Recruitment dates (or publication).

-

Number of participants.

-

Country and language of data collection.

-

Data collection time point(s).

-

Blinding.

-

Dropouts.

-

Randomisation (RCTs only).

-

Concealment of allocation (RCTs only).

-

Who: provider.

-

How: delivery mechanism(s).

-

Where: context of intervention.

-

How much: duration (total number of weeks over which therapy was delivered).

-

How much: intensity (hours of therapy provided on a weekly basis).

-

How much: frequency (how many days therapy was provided on a weekly basis).

-

How much: dosage (total number of hours of therapy provided, home-based practice tasks).

-

Tailoring: by difficulty, by functional relevance.

-

How well: adherence (data capture and actual adherence rates).

-

What: theoretical approach.

-

What: treatment target.

Adapted with permission from Brady et al. 92 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The box includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original box.

Given the multinational and multidisciplinary nature of this study, we did not predefine a list of all relevant language assessments and language versions of those measures. Instead, we established eligibility criteria that included any language assessment that (1) captured an outcome of relevance to this study, (2) was published and (3) met with the approval of the RELEASE study collaborators. Agreement was achieved on all measures included and their alignment with specific language domains. We excluded screening tools owing to their variable psychometric properties and lack of sensitivity (due to ceiling effects), and the subsequent impact that this would have on our analysis. 97

Data collection time points

We extracted data on participants at recruitment or entry to the primary research study and at all available time points following this. When follow-up data were available, the time of follow-up was recorded in a continuous fashion in days since primary study baseline. When time to follow-up was given in a category (e.g. 3–6 months), the mean of this time span was taken (i.e. 4.5 months in this example) and converted to days.

Identification of data sets for inclusion

Electronic search methods

We searched the following databases from inception to September 2015 using a RCT-optimised search strategy: Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and other Cochrane Library databases (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and Health Technology Assessment Database), MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, Linguistic and Language Behavior Abstracts and SpeechBITE (see Appendix 1). We also reviewed all studies included in and excluded from a 2016 systematic review. 41 We imposed no language restrictions.

Study records

All study records identified in the searches were screened for eligibility for inclusion. When references described potentially eligible data sets, we invited the primary research teams to confirm eligibility and (where appropriate) to contribute their IPD data sets to our RELEASE study database. We also extended an invitation to contribute through our pre-existing networks, including the Collaboration of Aphasia Trialists [www.aphasiatrials.org (accessed 5 June 2020)].

Selection of studies

One researcher (LRW or KVB) screened titles and abstracts of the records identified using the methods described above and applied the inclusion criteria. Obviously irrelevant titles or reports were excluded. Full-text copies of all the remaining data set reports were reviewed by an independent researcher (KVB, LRW or MCB). Eligibility criteria were ascertained through review of published reports for each study. When published reports were unavailable (for recently completed studies, clinical registries or similar), we clarified eligibility through discussion with the primary research team. Any disagreements about eligibility were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

Data collection

For all potentially eligible records identified, we used a systematic approach, starting with an e-mail to the corresponding author describing the aims and objectives of the RELEASE study, enquiring about the potential eligibility of their data set, inviting them to confirm the data set’s eligibility and to contribute the anonymised electronic data set. If there was no response, a second approach was attempted 1 month later. When e-mail addresses were invalid, or when there was no response to the second approach, we attempted contact with other members of the authorship team. If these attempts went unanswered, we recorded this as ‘no response’. All unavailable data sets and associated IPD were recorded.

We recorded all communications with primary research teams, including queries around eligibility, invitations to contribute and other correspondence. If the primary research team expressed an interest in contributing, we invited them to submit a copy of their anonymised electronic data set in an encrypted format through the Collaboration of Aphasia Trialists’ website [www.aphasiatrials.org (accessed 5 June 2020)]. We requested that all electronic data set contributions were accompanied by a data dictionary, a funder report or other reporting of that data set and findings if available. Evidence of gatekeeper (data controller) approval to share the data set with the RELEASE study collaborators and ethics approval for primary research studies were required. When the primary research team required additional permissions to share the data set for the purposes of secondary data analysis, we requested a copy. We also identified eligible IPD data sets in the public domain and extracted the relevant data for inclusion.

Data extraction

We developed and piloted a data extraction table to support systematic retrieval of data. The data items were identified with reference to our research questions and best practice in reporting of complex interventions and meta-analyses. 82,84–86 (see Box 3). Information sources included published reports and communication with the primary research team to gather data that were otherwise unavailable. When possible, we confirmed data extraction with the primary research team for accuracy and completeness. Following the query resolution process, data items unreported or unavailable from other data sources were recorded as unreported. Items not relevant to that data set were marked as not applicable. For all data sets, a second researcher (MCB) double-checked the data extraction. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or the involvement of a third data extractor.

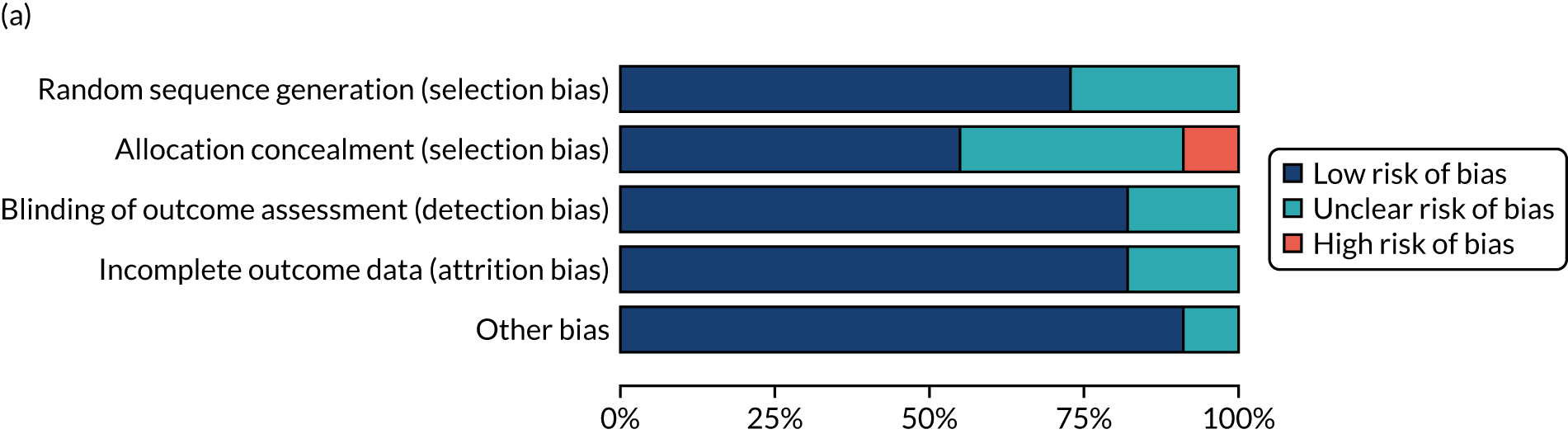

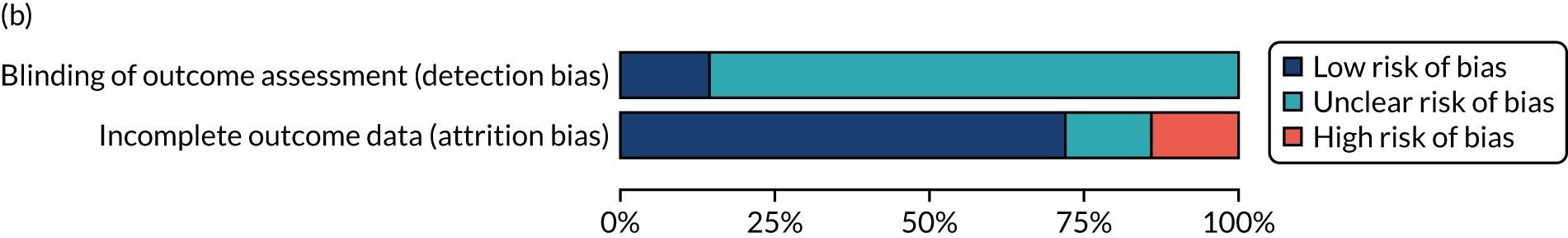

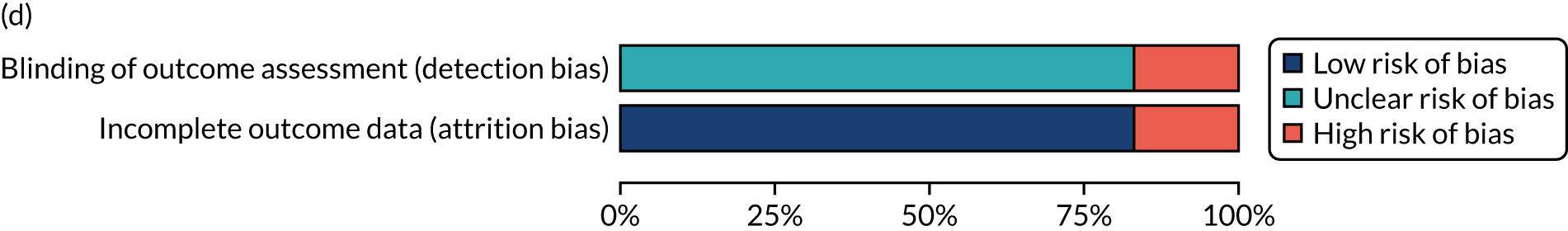

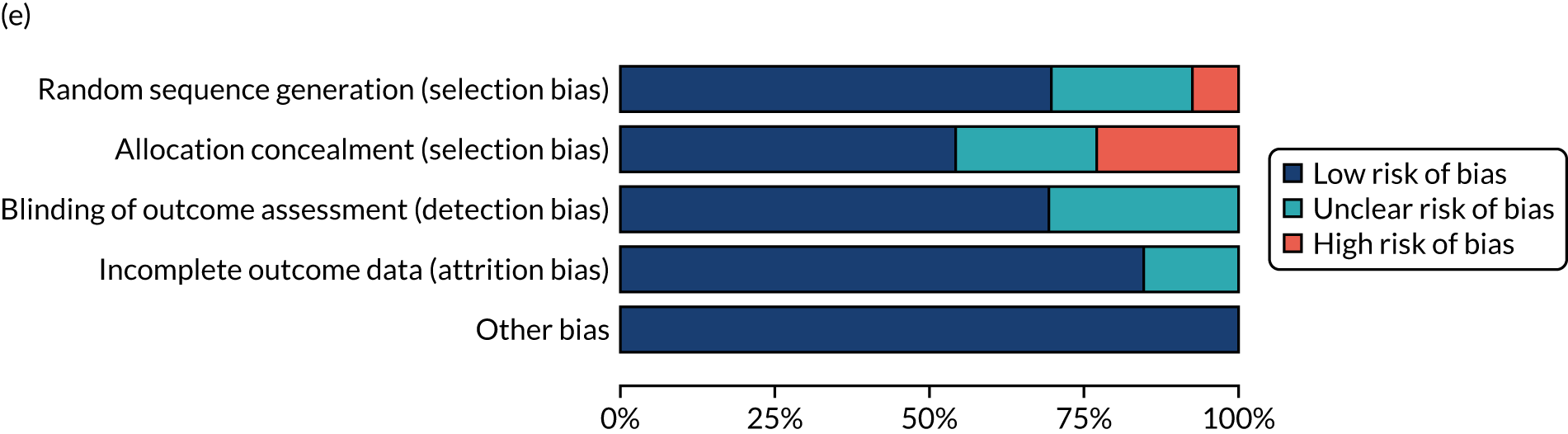

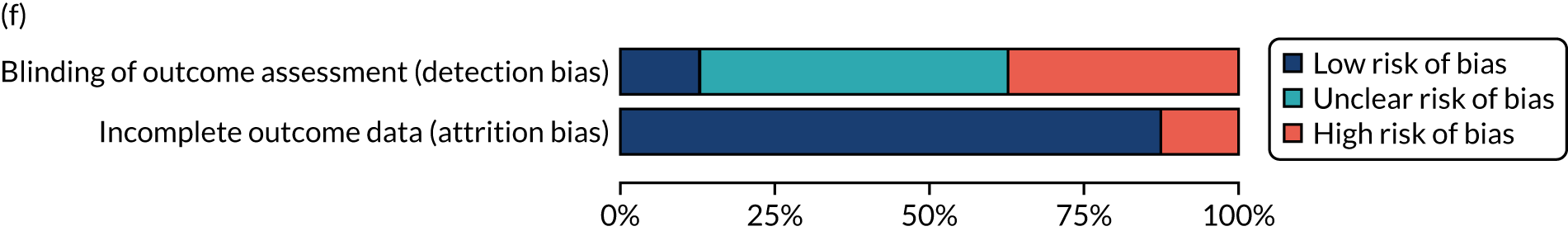

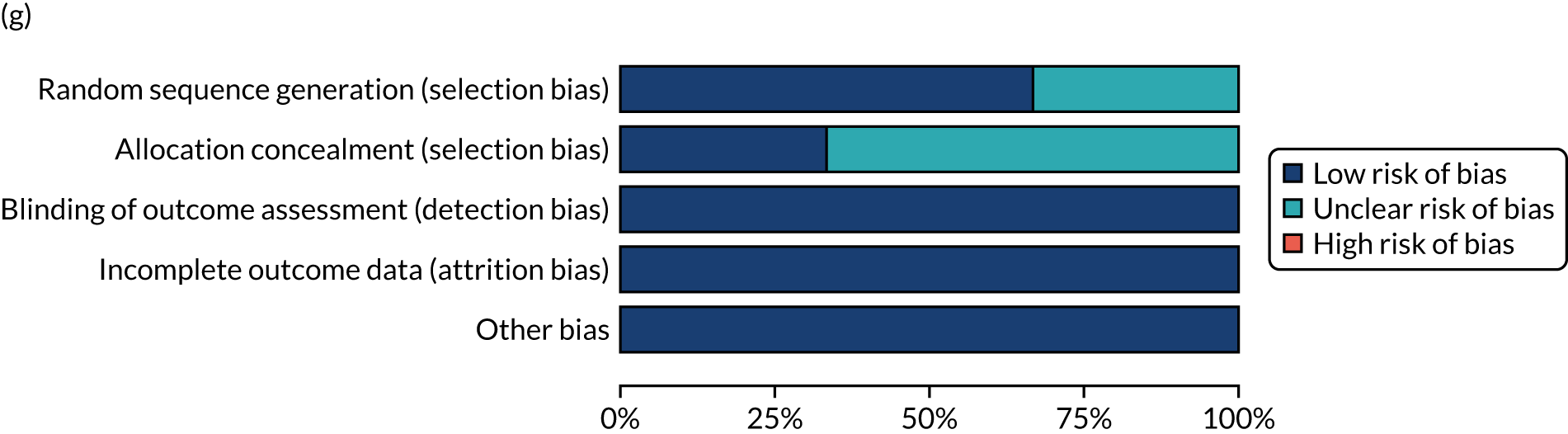

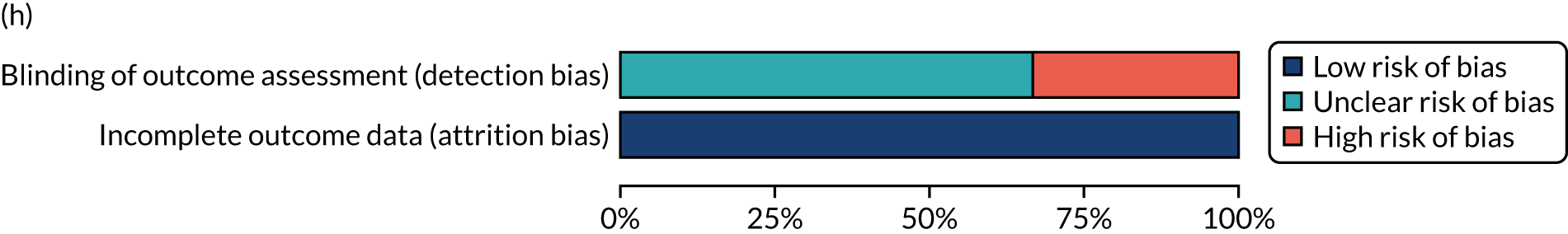

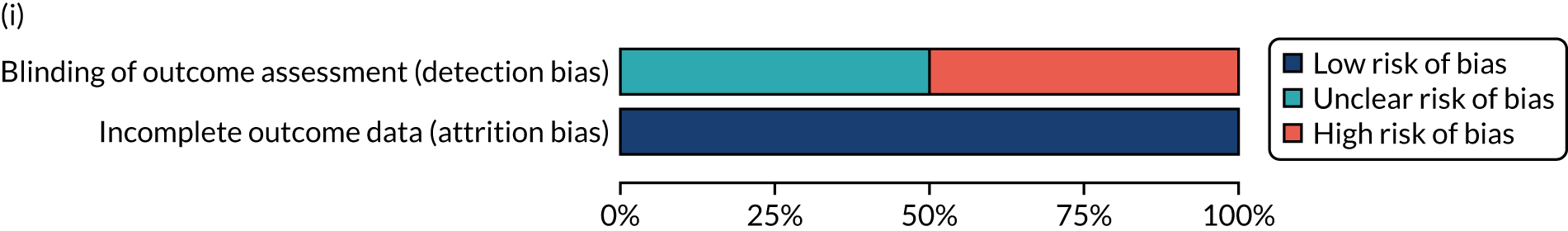

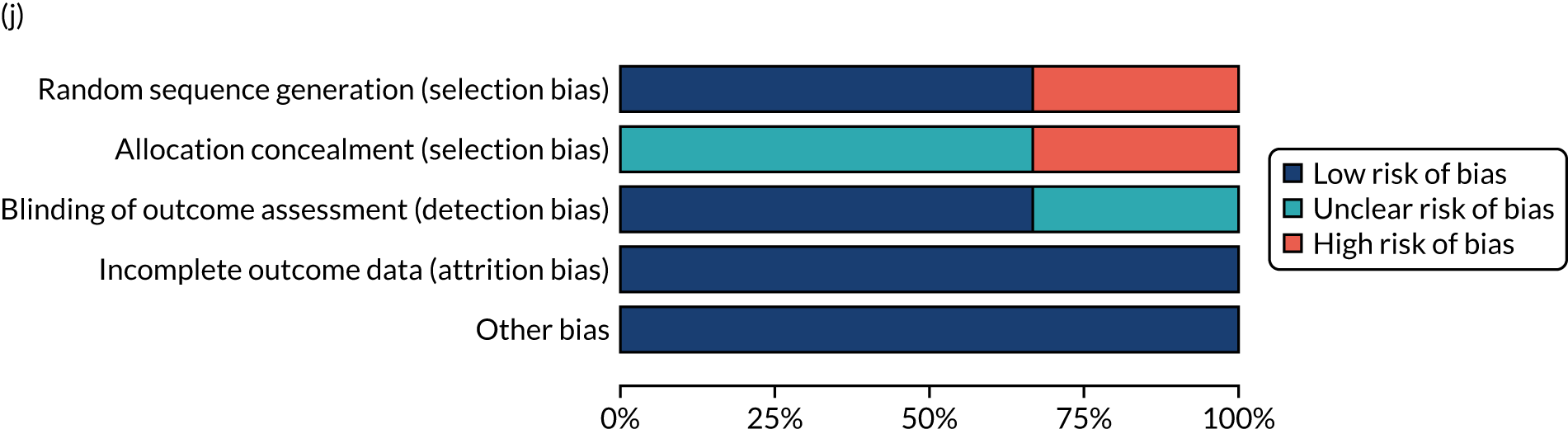

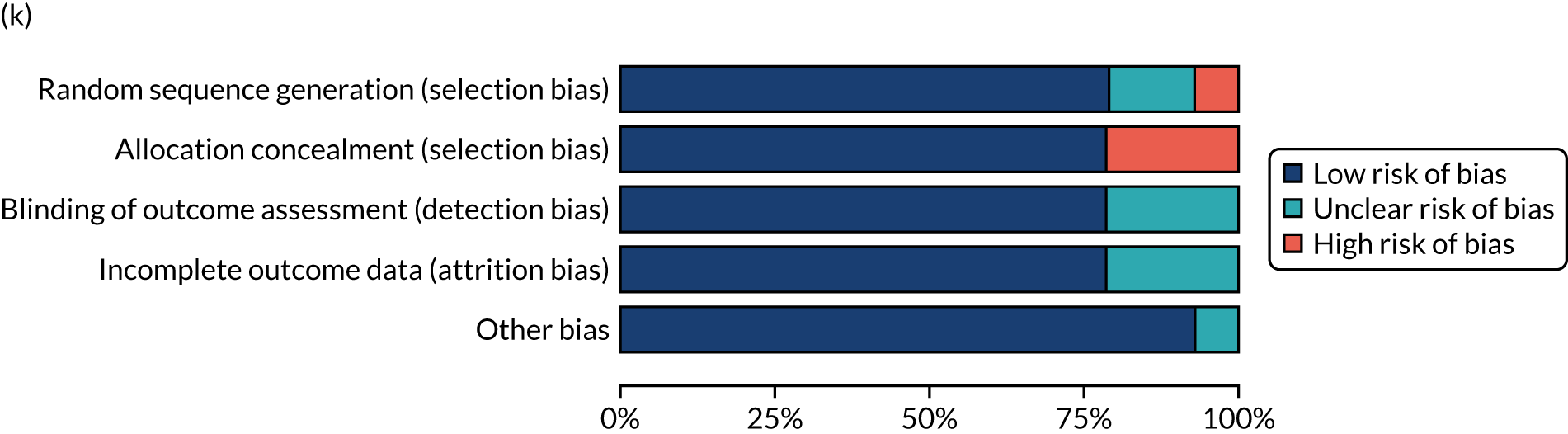

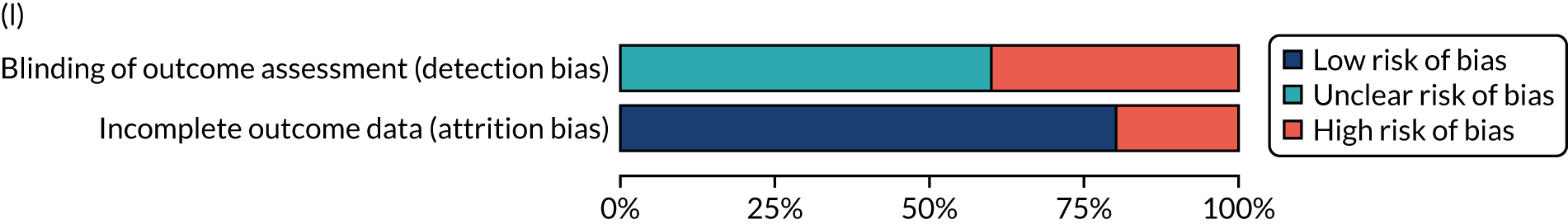

Risk of bias in included studies

We extracted information on the quality of each data set using both Cochrane quality items relating to RCTs98 and the data items from the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklists for case–control studies, case series, cohort studies, non-RCTs (quasi-experimental studies) and analytical cross-sectional studies. 99 Aspects irrelevant to our analysis were not extracted; details of the statistical analysis processes applied in the primary research were not relevant to the RELEASE study as we were working with the IPD and not summary statistics; information about exposure to the cause was irrelevant, as aphasia following stroke was a RELEASE study entry criterion; and criteria for the outcome measures used were prespecified for the RELEASE study. Similarly, items relating to data interpretation (e.g. strategies to deal with confounders) were not extracted and synthesised, as these activities reflected on the reporting of the primary research data set and not on the IPD contributed to the RELEASE study database or the planned analysis.

We considered the methodological quality of each included data set in terms of the following potential sources of bias:

-

Selection bias – using reported data, we checked whether or not there was any risk of bias in the allocation of individual participants to a specific group in an included trial. In the context of RCTs, for example, we considered whether or not the randomisation sequence generated was truly random and whether or not the sequence allocation was concealed up to the time the individual was allocated to a group. In non-RCT group comparison data sets, we considered whether or not it may have been possible to randomly allocate participants across the groups.

-

Performance bias – we documented any co-interventions delivered and whether or not there was any difference between RCT or non-RCT studies. Blinding participants to the delivery of SLT (or not) is almost impossible, although we did seek any examples of when it may have occurred (e.g. computer-based language stimulation vs. a non-verbal cognitive task).

-

Detection bias – for all data sets with data collection at baseline and at a post-SLT intervention (or comparison group) follow-up time point, we extracted data on whether or not outcome assessors were blinded to the group, time since onset or other key information.

-

Attrition bias – we examined whether or not there was evidence of a systematic difference between comparison groups in the number of dropouts (withdrawals for any reason) or number of non-adherents (those who decline to continue participation during the intervention) after study entry.

-

Other biases – we considered other possible sources of bias, such as the similarity of comparison group at baseline, the primary study’s relevance to our research questions and outcome reporting bias, when outcomes collected were unavailable and did not contribute to the data synthesis.

For all possible risks of bias, we coded the studies as being at a low, unclear or high risk of bias. We also considered the impact of any potential biases on the findings using sensitivity analyses or narratively.

Data management

Data encryption and storage

All data contributed to the RELEASE study database were stored at the Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professions (NMAHP) Research Unit at Glasgow Caledonian University (GCU), UK, according to the university’s information systems policy. Original primary research data sets and any additional study data were stored on a secure hard drive [a 1 terabyte IronKey™ Enterprise H300 password-protected and encrypted external hard drive (Kingston Technology Corporation, Fountain Valley, CA, USA)] with centralised management. The hard drive was kept in locked storage in a password-protected room. These data were available as data descriptors on the GCU hard drive, which restricted access to the GCU-based project management team only. The primary research data sets were preserved unmodified. Anonymised, password-protected working copies of these primary research data sets were created and stored on the NMAHP Research Unit’s designated portion of the university server. Adjustments to these working data sets did not affect the original primary research data.

Security and access

Primary research IPD data sets, data sets created for this project and analyses data sets were accessed only by the RELEASE study project management team at GCU. 100 Data were not accessible to those outside the project collaboration. The project management team and collaborators governed use of the research data, and participated in data analysis plans, interpretation of the findings and preparation and review of the manuscripts based on the planned analyses. All collaborators had an opportunity to contribute to the planned secondary analyses [which were conducted in SAS® version 2.8 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA)].

Data preparation for analysis

We undertook a rigorous process of preparing the IPD data sets for analysis to ensure that the data were valid, as complete as possible, consistent and uniform.

Quality assurance and verification

Each data set was cross-checked against the primary source, such as published papers, protocols and other outputs. We checked within data sets for duplicate participant data sets. We also identified duplication of participant demographics whereby participants taking part in one study went on to participate in a subsequent study led by the same research team, or were reported across dual publications (e.g. as a study group in one study but a comparison group in another). Duplicate participants were identified through (1) careful review of the supporting literature and study materials across primary research teams, (2) checking demographic data across IPD data sets contributed by the same primary research teams and (3) when possible, correspondence with the primary research team. Duplicate entries and any risk of double-counting participant data were excluded from the analysis. This was achieved by removing duplicate participant data sets from one of the data sets, and removing duplicate demographic data prior to any overview in which the participant descriptors would be double-counted. Other data were considered on a variable-by-variable and analysis-by-analysis basis.

Variable labels for data sets collected in non-English languages were translated by the contributing primary research teams. We confirmed the accuracy and completeness of translations with contributors. Following data extraction, the representative from each primary research team was sent an overview of the data items and details relating to their contributed data set. They were asked to confirm that the information was accurate and complete.

Data cleaning and mapping to unit of analysis

Data were contributed in a range of different formats such as Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), SAS and Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) (formerly Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) [IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA (IBM SPSS Statistics from version 19 onwards) or SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA (version 18 and below)]. In the first instance, we cleaned all data sets to reclassify duplicated variable names, removed blank lines and transposed data into a one row per participant format (short form). We converted all data sets into SAS. Prior to analysis, data relating to prespecified variables needed for the RELEASE study analyses (see Box 3) were cleaned. These variables were decided a priori by the research and analysis team and presented to the wider RELEASE study collaboration for review and comment. We ensured that the variable entry matched an agreed uniform format to inform our planned analyses. For example, time since stroke was recorded in days, months and years across RELEASE data sets; the RELEASE collaboration agreed to record ‘time since stroke’ in the format of ‘days since stroke’. When necessary, entries as years or months after stroke were converted to days. In some cases, the record format was a date entry from which days since stroke could be calculated when date of study entry was considered. For each variable of relevance, the primary research data sets and other data sources (publications, protocols, data dictionary) were searched for that variable or indicative surrogate measures. Decisions on how to synthesise these data into a common nomenclature were based on agreement of the wider collaboration. A decision tree was used to ensure standardisation of variable names and ranges when converting data from the original data sets to the RELEASE study analysis data sets.

For some variables, the relevant data were common to all participants across a data set and not included in the contributed electronic IPD data set. For example, if the primary research entry criteria specified right-handed participants, then all participants in that data set were right-handed, whether or not this was recorded in the submitted electronic data set. Similarly, when a specific intervention was delivered to one randomised group, then (unless otherwise specified) the intervention description was common to all participants in that group. In such cases, we imputed and translated those data using one-to-many merging and in keeping with the agreed format for the RELEASE study analyses.

The collaboration then agreed on standard definitions to describe therapeutic interventions in terms of the theoretical and target approach (see Box 3). These definitions were applied to all intervention studies. In some instances, those participants who were allocated to no SLT were permitted to receive usual care SLT after the study’s active intervention period had finished. In these cases, we identified the follow-up times that corresponded to the duration of no SLT and took those observations forward for analysis in the no-SLT group. We also identified cases of usual SLT care, study SLT intervention and the corresponding follow-up time points associated with each. We identified the presence of crossover in treatment and took all measurements up to the point of crossover. These data were identified, cleaned to a standardised format and entered into the analysis data set.

According to the needs of the analysis, data-cleaning processes included examining the data set for validity of contents, such as receipt of all relevant participants’ data; matching numbers of IPD transferred with those reported in publications; matching variable names to known published assessments and ascertaining any missing domains of assessment from the original data set; examining the content of fields to ensure that they matched prescribed minimums and maximums for known assessments; ascertaining any transformations of data that had occurred prior to transfer and resolving such queries [e.g. use of a mix of t-scores and raw scores in the Aachen Aphasia Test (AAT) across studies]; examining odd values in a given range (e.g. data sets containing a zero value for assessments when this indicated that no assessment had been conducted); and converted data into a numeric format.

Data integrity and validation

Ensuring data integrity was essential to the project. We audited the data sets using statistical and database methods to detect anomalies and contradictions. For example, we checked the validity and plausibility of contributed data, specifically ensuring that data entries were within the acceptable ranges of variables and outcome measures used in the primary research. When this was not the case, we cross-checked the data with all study records or publications, and communicated with the primary research teams to confirm extreme outliers or other questionable values. 98 We examined distributions and descriptive statistics to audit contributed data and identified irregularities or inconsistencies that required further clarification. These were manually checked with the source data, the data report (if available) and the SAS file.

We checked for any imbalance at baseline between individuals included in RCT or non-randomised groups. Working with IPD at the study level, we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to look for significant between-group differences in baseline characteristics, including age, sex, years in education, handedness, time since stroke onset (days) and aphasia severity. For comparisons of sex and handedness between groups, we used the chi-squared test.

Measures of treatment effect

We identified language outcome measures and worked with outcome data, transformed to the anchor measure, for each domain (see Anchor and minority measures and Data transformation). We defined measure of treatment effect as the mean of the absolute change from baseline on transformed measures for each of the domains of interest. Effect sizes were estimated and reported with 95% CIs and significance was set at the 5% threshold throughout.

Sample size

We prespecified that each analysis would be based on a minimum of two data sets. As our eligibility criteria dictated that each data set would have a minimum of 10 IPD, our minimum sample size was 20 people with aphasia after stroke.

Data conversion and reformatting data files

Data were converted and stored in SAS version 9.4 format for ease of management.

Data synthesis

Most SLT interventions were described at the primary research study or group level, and only rarely were aspects of that intervention (e.g. the duration or dosage) reported at IPD level in an electronic data set. SLT intervention data were therefore extracted from narrative descriptions in the primary research protocol, electronic data set, published report or through discussion with the primary research team.

A separate data set was generated for each of the following:

-

study description and participant demography

-

outcomes describing the domains of interest

-

SLT intervention and language rehabilitation (and co-interventions when present).

Each data set contained the unique identifier (ID) for constituent participants. This meant that multiple data sets could be linked using this ID to generate a complete picture of the participant’s profile across multiple data sets, and all unique participants could be brought together for each of the planned analyses.

Anchor and minority measures

We prespecified several language domains or outcomes for analysis in the RELEASE study:

-

overall language ability

-

auditory comprehension

-

spoken-language production (including naming)

-

reading comprehension

-

writing

-

functional communication.

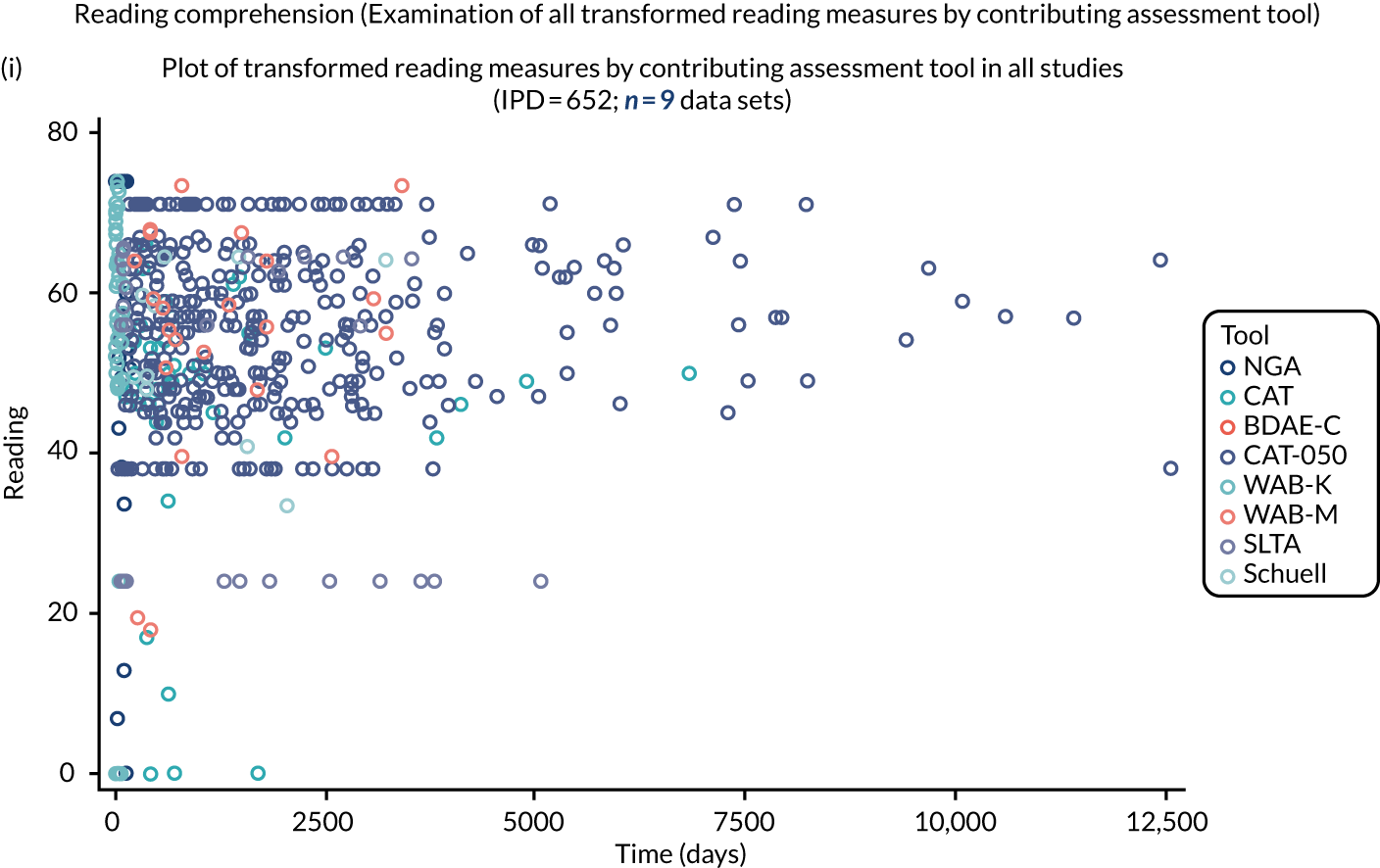

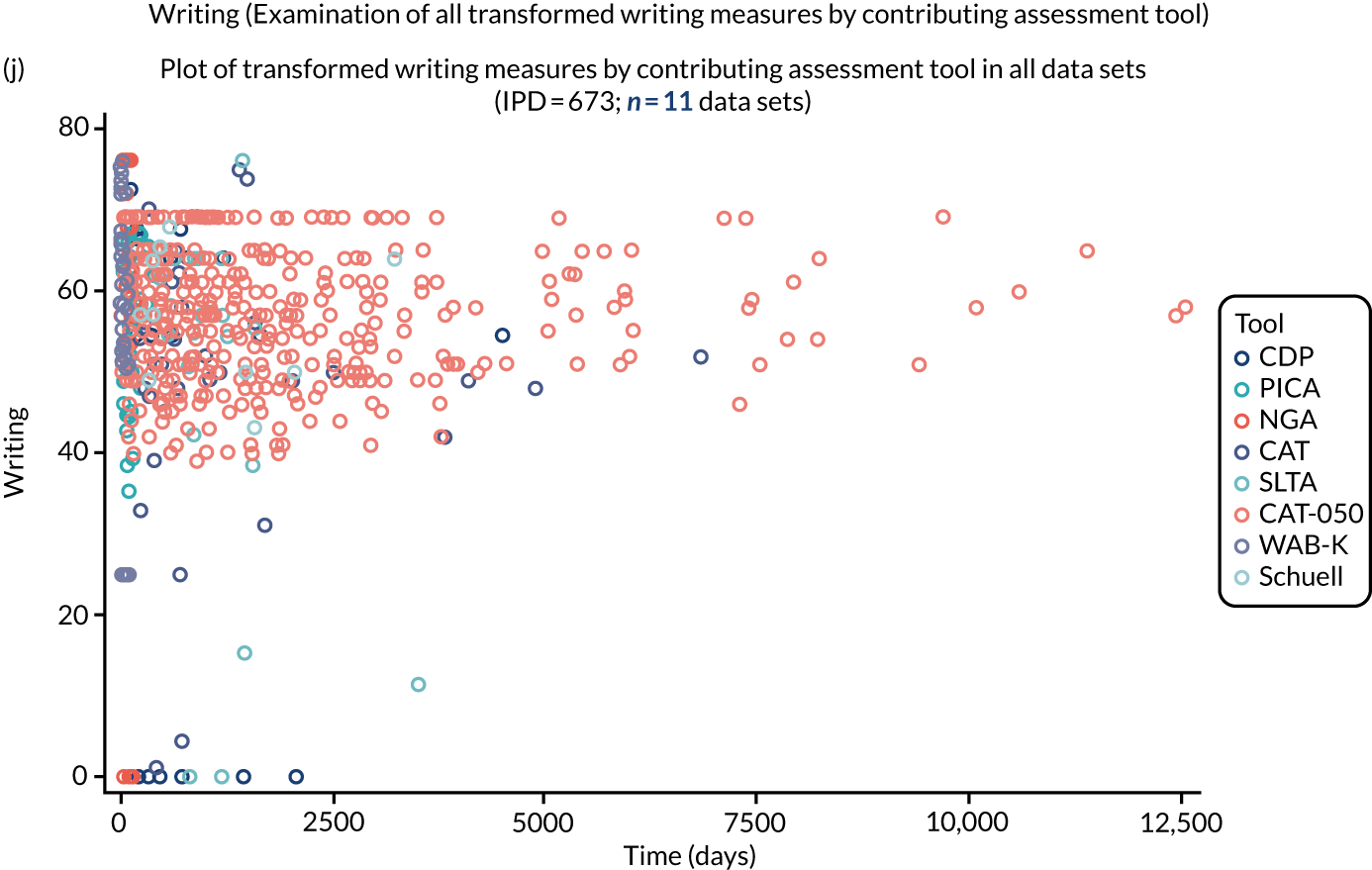

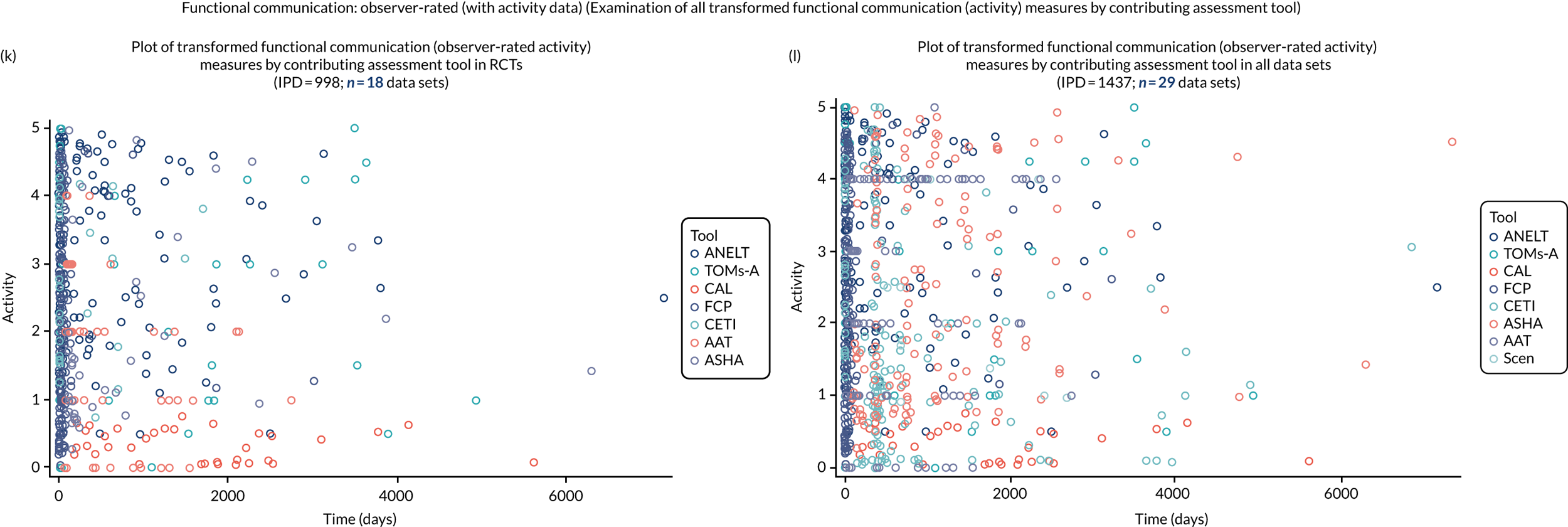

For each of these outcomes, a range of assessments (sometimes in various language adaptations) was used. To synthesise the IPD from across these multiple measures, we first identified the most commonly used measurement for each outcome. We profiled all measures used to capture data on that outcome, the number of studies using that measure and the number of IPD available, and calculated the median score, interquartile range (IQR), minimum and maximum for each measurement tool. Language or version variations were treated as separate tools.

An ‘anchor measure’ was identified for each language domain (e.g. reading) as the measurement instrument used by the most data sets in the RELEASE study database. When this approach resulted in two possible anchor measures, the assessment that had the greater number of IPD in that language domain was identified as the anchor measure. All other assessment tools measuring the same domain, but which were informed by smaller numbers of data sets, were considered ‘minority measures’. Minority measures were then transformed to match the format and range of each anchor measure (one for each language domain) through an adapted version of the method previously used in large-scale data synthesis (see Appendix 2, Box 4).

Data transformation

Our transformation process was based on the underlying assumption that the anchor and minority measures for a described outcome were similar. 101 The transformations were based on an investigation of the medians, IQRs, minima and maxima of both the anchor and minority measures according to an algorithm (see Appendix 2, Box 4). A linear transformation from each minority measure to the anchor measure was applied to each quartile and repeated for each language outcome. Each threshold in the minority instrument was mapped to the corresponding threshold in the anchor measure. Values in the minority measure that fell within a quadrant were mapped to the anchor measure relative to the distance from the quadrant edges. The formula was repeated for each quadrant. In this way, the clinical relevance of changes in scores on the anchor measure was retained.

Three alternative approaches to transformation (normalising, internal normalising and direct linear) were considered but rejected. Normalising transformations (e.g. van der Waerden102) requiring pooled ranks across the measures would not be feasible owing to the differences in the width of the various scales. For both normalising and internal normalising approaches, the clinical meaning of any scores or change of scores would be lost. Direct linear transformation would retain the anchor measure values and, thus, clinical relevance. However, it would require mapping the distribution of the minority measures to the anchor measures without retaining the distribution of the anchor measure itself and, as the measures are often naturally skewed in different directions, this would affect the interpretability.

For each of our analyses, values were generated first for the anchor measure and then for the minority measures. Checks were performed to assess whether or not the ranges, values and directions of changes observed for each anchor measure were consistently reflected when transforming each minority measure into the anchor measure.

Meta-synthesis methods

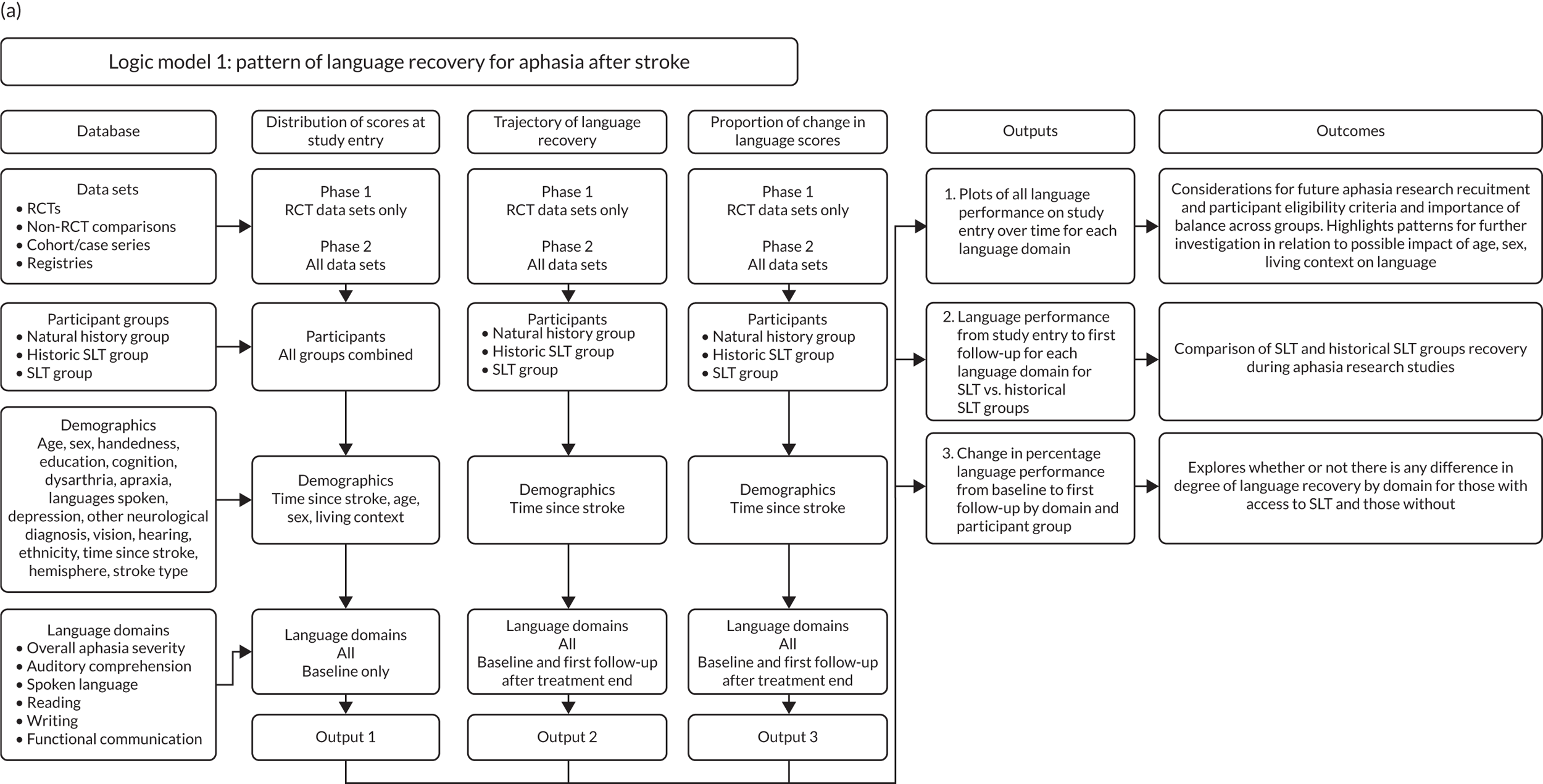

Four research questions were addressed in the context of the RELEASE study, in line with the study objectives (see Box 1). The RELEASE study database supported investigation of (1) the progression of language recovery over time following aphasia after stroke, (2) the individual factors, such as demographic and aphasia profile, that potentially play a role in language recovery over time following aphasia after stroke, (3) the components of effective rehabilitation interventions that best facilitate recovery over time following aphasia after stroke and (4) whether or not certain interventions (or intervention components) are more beneficial for some participant subgroups than others.

Meta-analysis and network meta-analysis

Meta-analyses of aphasia intervention research already exist and have provided evidence-based review and data synthesis of the clinical effectiveness of SLT for aphasia after stroke (e.g. Brady et al. ,41 Robey63 and Bhogal et al. 64). Methodologically, these meta-analyses are usually based on the data synthesis of aggregate group-level summary data. Large group summary approaches taken by RCTs and meta-analysis of RCTs have limitations, particularly in relation to the risk of ecologic bias; aggregate data generated across a complex participant population, such as people with aphasia, risk concealing the possibility of varying individual response to a complex rehabilitation intervention. 76

Traditional meta-analysis is limited to direct between-treatment (or control) comparisons and group-level descriptors of interventions and aggregated group data on the treatment effects. 103 A more detailed examination of the effectiveness of a specific therapy component is not possible owing to the variability of complex SLT across data sets. Similarly, such approaches cannot accommodate or control for participant demographics or other factors relevant to recovery. 41 Network meta-analysis approaches, however, allow for an estimate of the difference between two (or more) treatments that are not directly compared. For example, studies comparing A versus B or A versus C (direct comparisons) can be combined to give an estimate of B versus C (indirect comparison). 104

Individual participant data network analysis approach

Network meta-analysis can be applied to aphasia intervention research using group-level summary statistics,38 but this approach does not address the limitations of ecological bias, highlighted in the previous section. Confounding is also a risk. We conducted a network meta-analysis based on a large IPD database, which allowed us to explore the subtleties of a highly heterogeneous group of people with aphasia after stroke, control for individual predictors and support the detailed exploration of the influence of participant-level covariates on SLT treatment effects across a range of language-specific measures. 104 Meta-analyses based on aggregated data are typically unable to examine such interactions. In addition, we were aware of some studies that had recorded valuable information on SLT intervention at IPD level.

One-stage versus two-stage approach

There are two main approaches to an IPD network meta-analysis: a one- or two-stage approach. 104 Two-stage approaches are very similar to the standard meta-analysis approach, working first with IPD to centrally generate aggregate data for each contributed data set (rather than using the primary research team’s reported summary statistics). These aggregate data could then be meta-analysed with summary statistics from other trials for which only aggregate data were available. This approach can, however, lead to bias in effects, greater heterogeneity and lower power to detect associations between language outcomes and continuous variables. 104 It is also very similar in methodology to existing reviews and meta-analyses of summary data.

In contrast, a one-stage approach would allow all available IPD from across the contributed data sets and IPD retrieved from the public domain, filtered for relevance to each analysis, to be combined into a single model (which considered the clustering of IPD within a study). One benefit of this methodological approach is that it can address confounding by enabling the examination of the impact of several participant and language variables on an intervention effect at the same time.

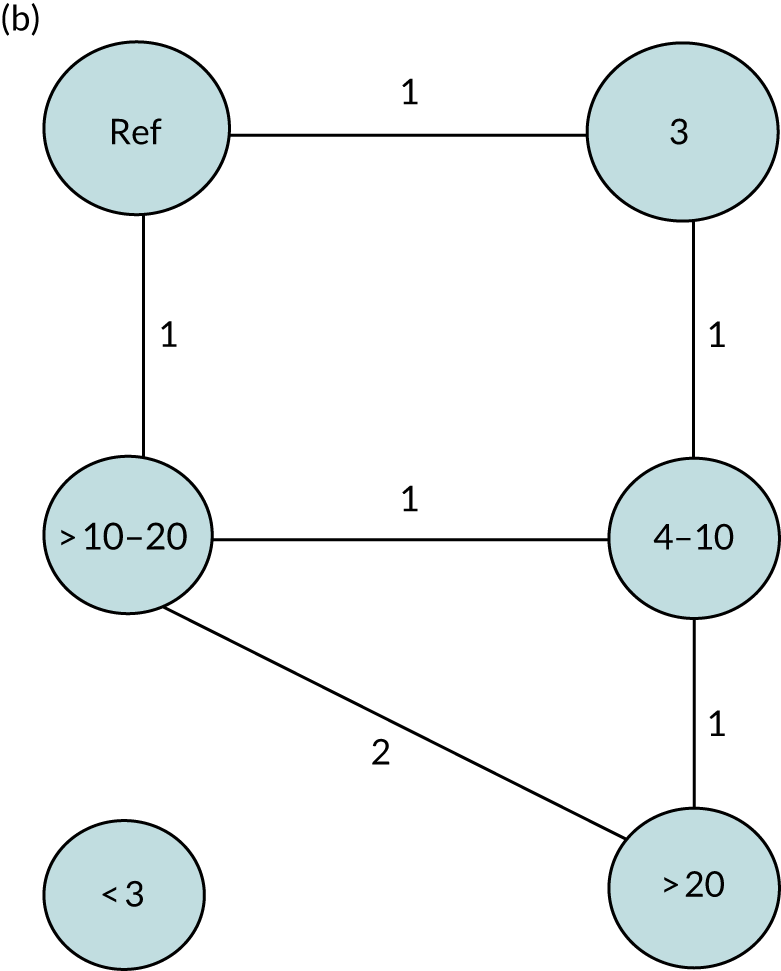

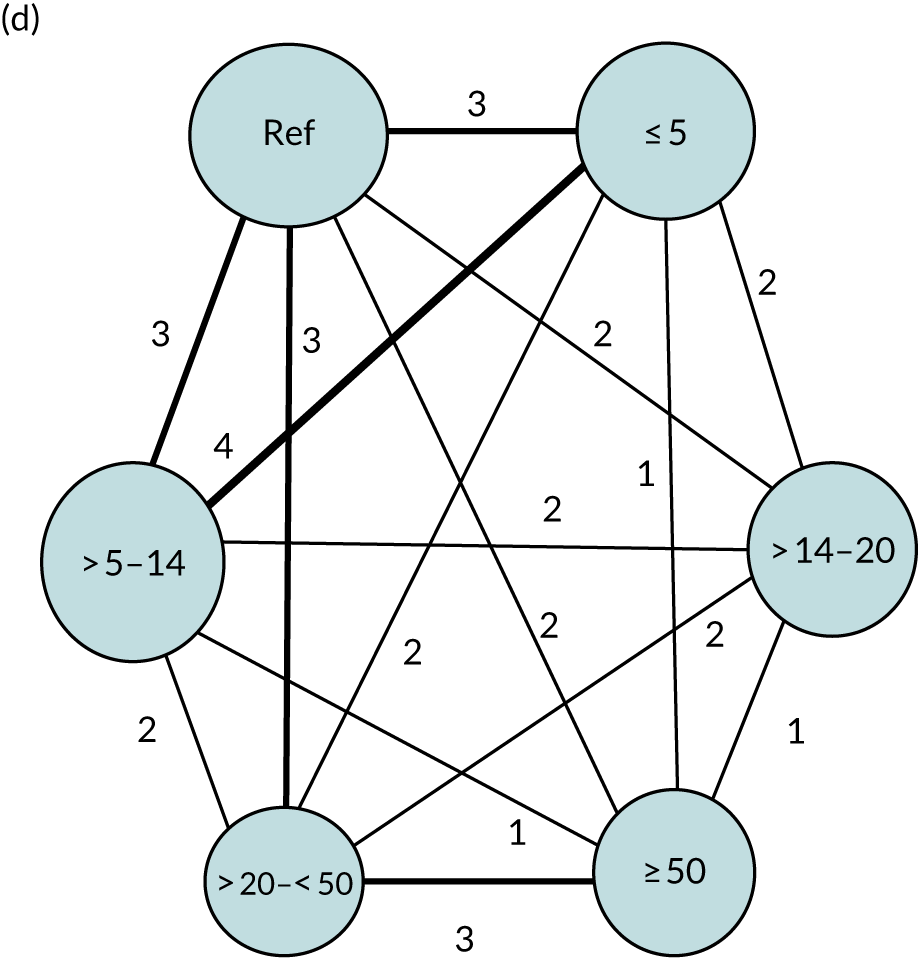

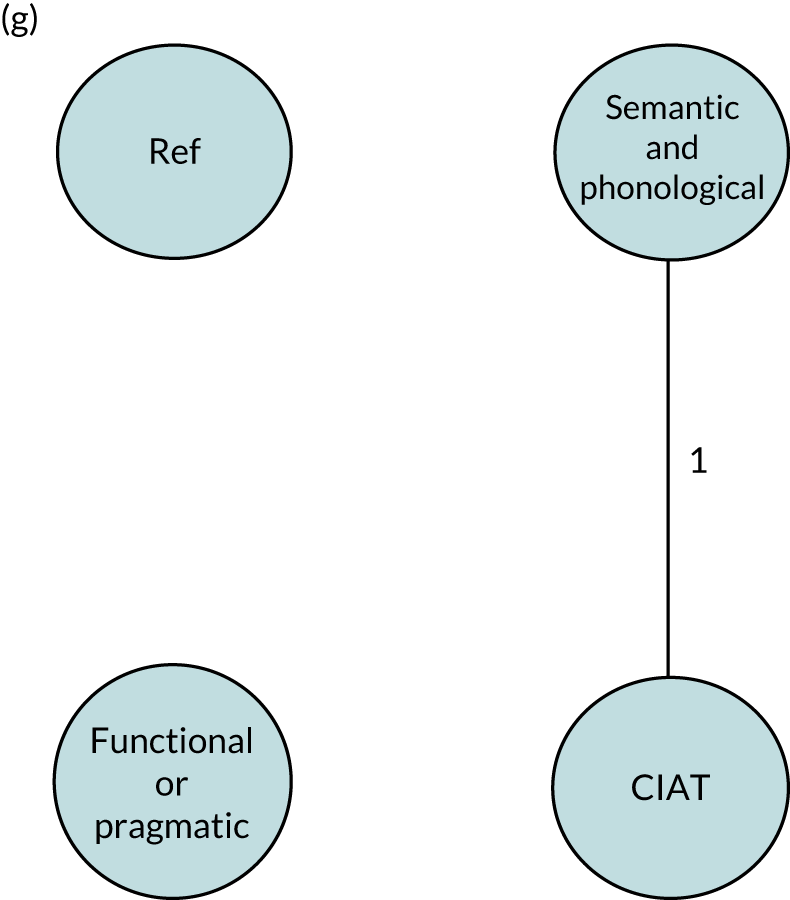

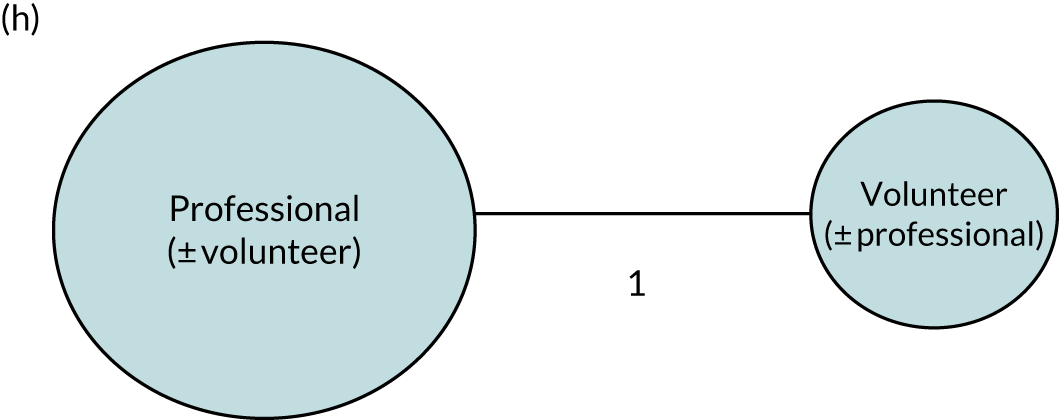

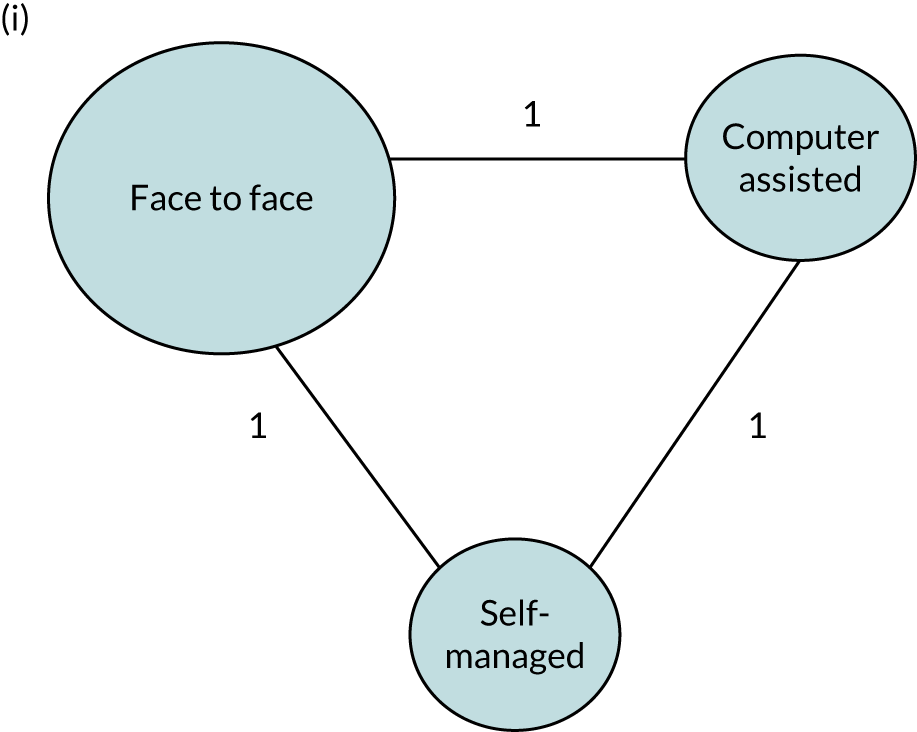

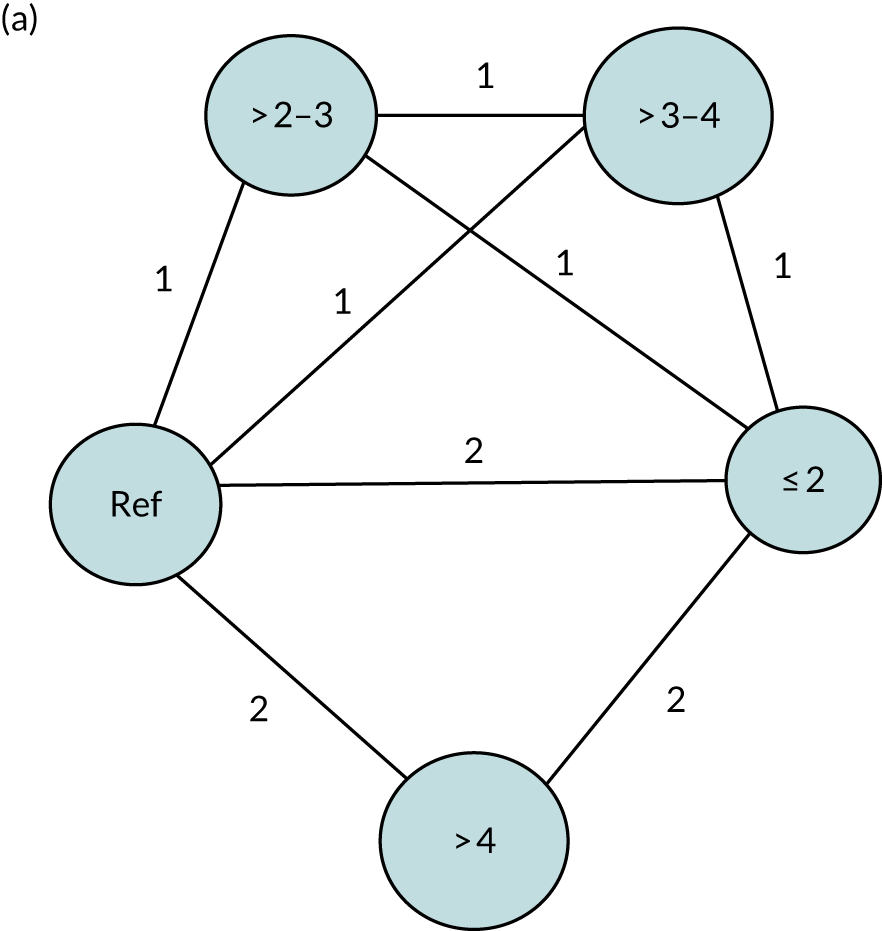

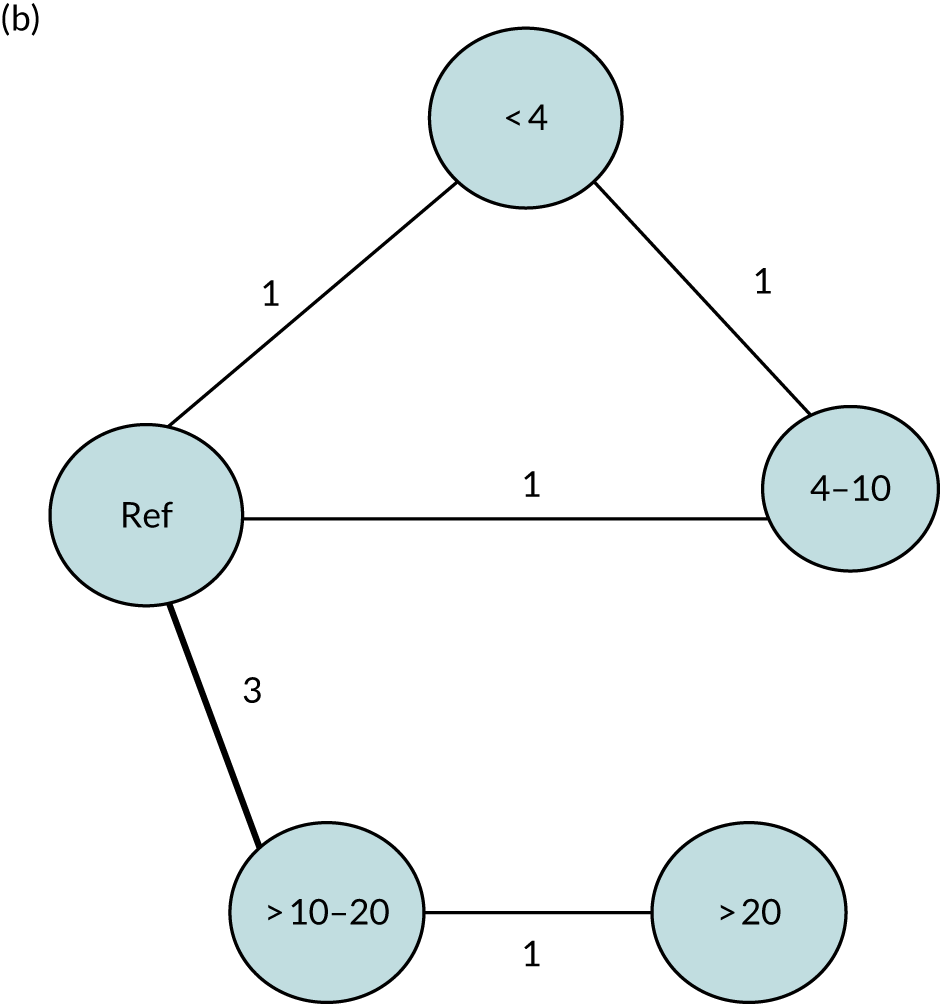

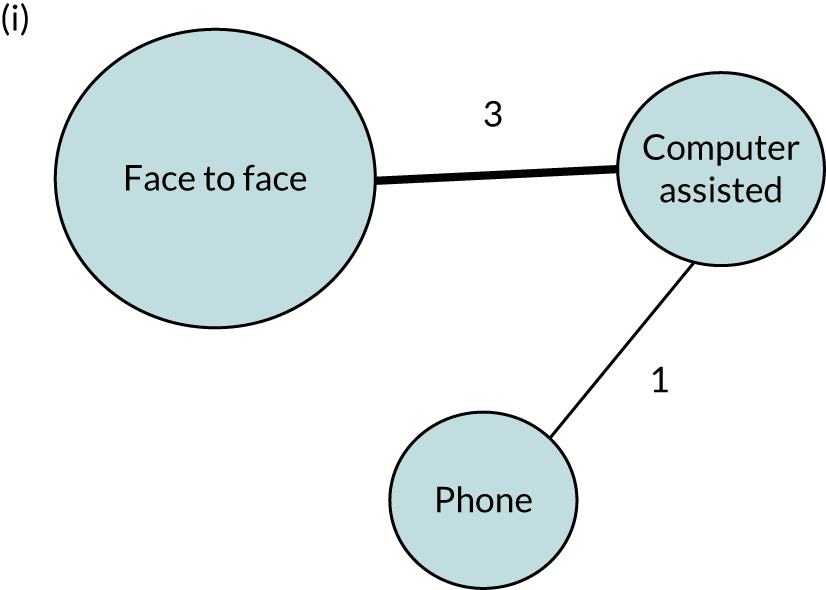

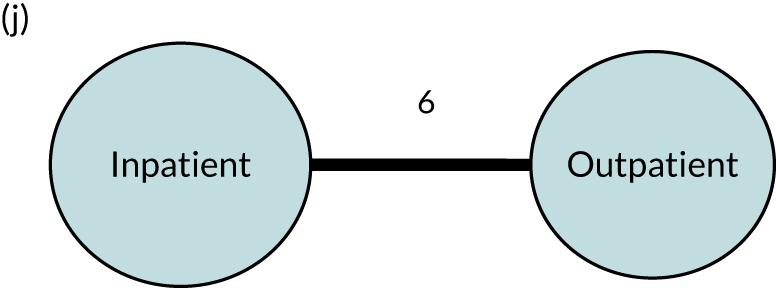

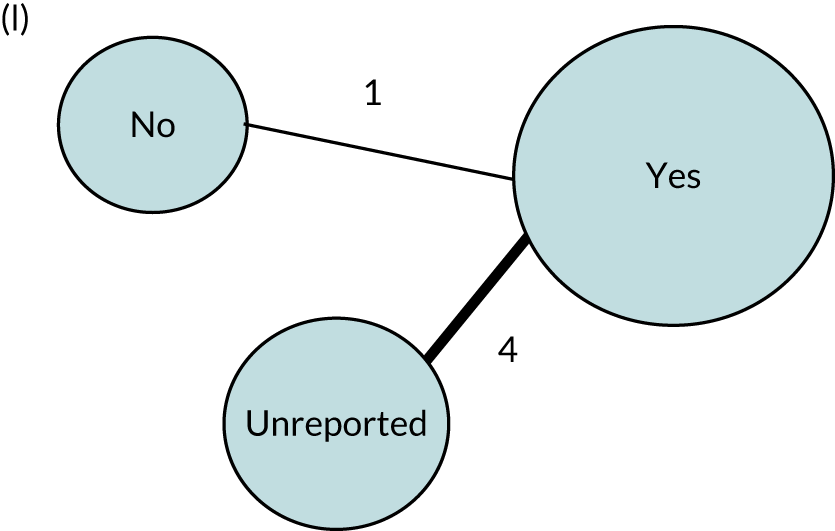

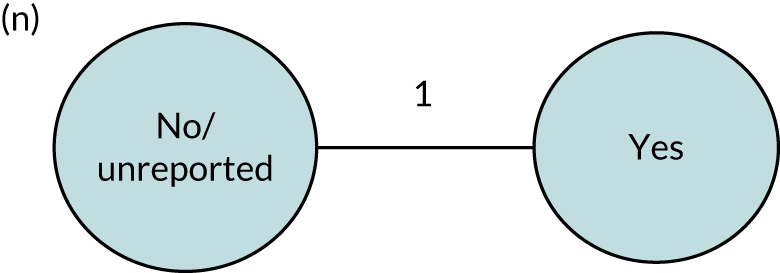

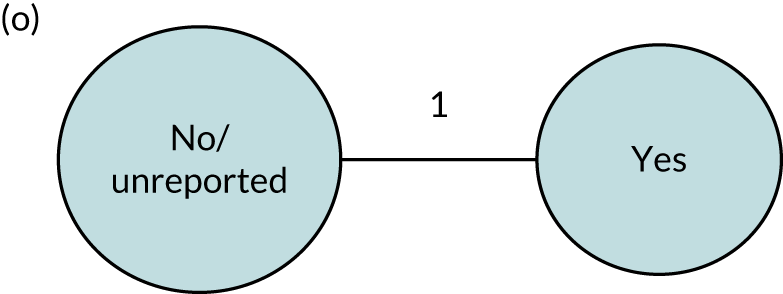

Network meta-analysis

We performed our one-stage network meta-analysis in SAS, using PROC MIXED, with fixed demographic and treatment effects, and study as a random effect. The variance structure was allowed to be unstructured. Study homogeneity was assessed by examining the variance parameters. Network diagrams for each treatment factor were drawn up. Each comparison within each domain was illustrated by a network graph, and supplemented by a table of the number of available IPD in each RCT and treatment node. We used the graphs to explore the balance of the networks and whether or not all levels in a treatment were compared across and within studies. Each comparison in each domain was illustrated by a network graph, and supplemented by a table of the number of available IPD in each RCT and treatment level. Feasibility was contingent on the number of trials and IPD available.

The populations in each data set were expected to differ, and so a base model of age, sex, time since stroke and baseline score was created for each language domain. We also planned to examine interactions between demographic characteristics and treatments, should sample sizes be sufficient. Given the number of tests likely to be undertaken, we were aware of the high risk of false positives. However, the aim of the RELEASE study exploratory analysis was not to generate definitive answers, but to use inference to suggest priority avenues for future research; therefore, we were more concerned with estimated effect sizes than statistical significance.

Primary analysis

We used RCT data as the gold standard for each planned analysis, with only participants from RCTs included in the primary analyses. Analyses that included data from non-RCTs, cohort/case series studies, observational studies, registries and other study design types (as relevant) followed the primary analysis, to judge whether or not they supported the RCT findings (see Appendix 3, Figure 26). When they did not agree, the data were further explored to quantify this difference.

To maintain the independence of subjects, we ensured that IPD did not appear in more than one data set for intervention type comparisons, although they could appear in more than one data set when grouped by language domains (e.g. overall language ability, auditory comprehension, reading) (see Appendix 3, Figure 26).

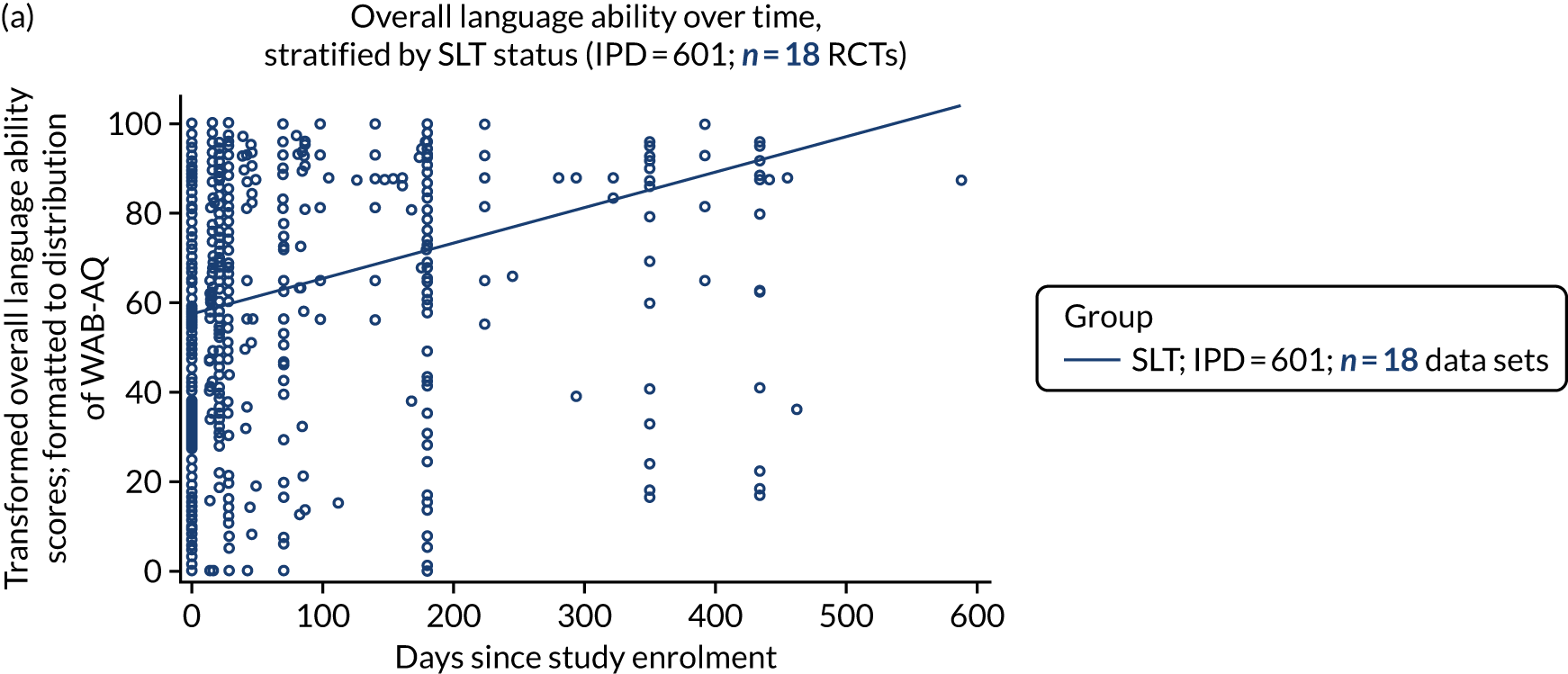

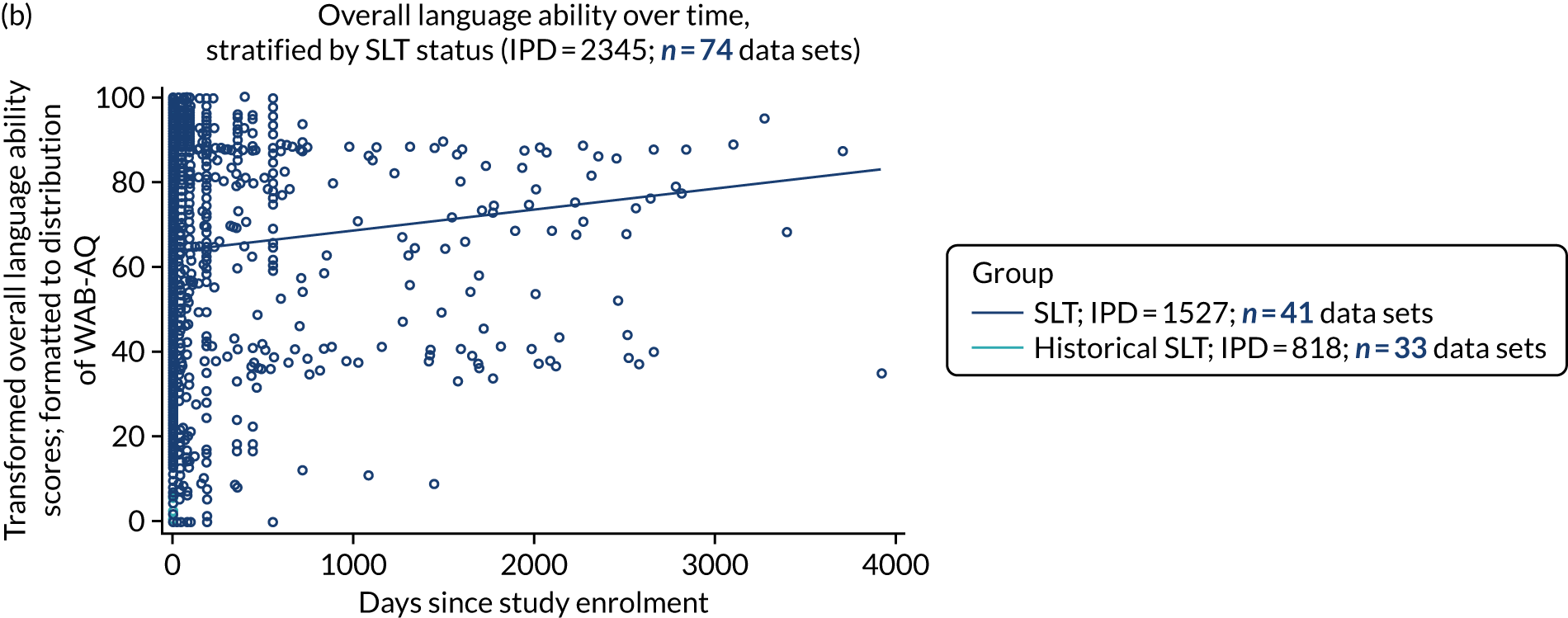

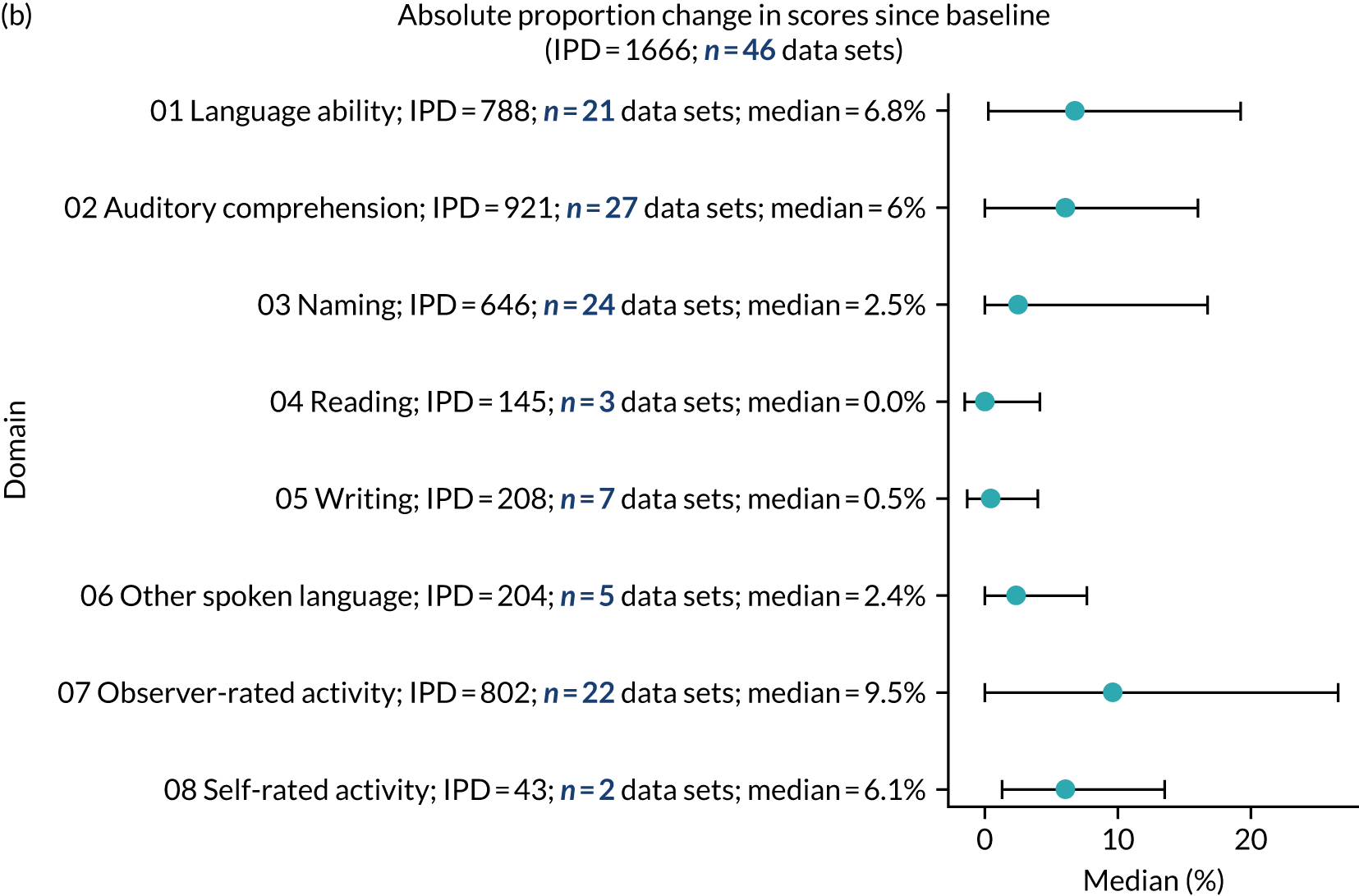

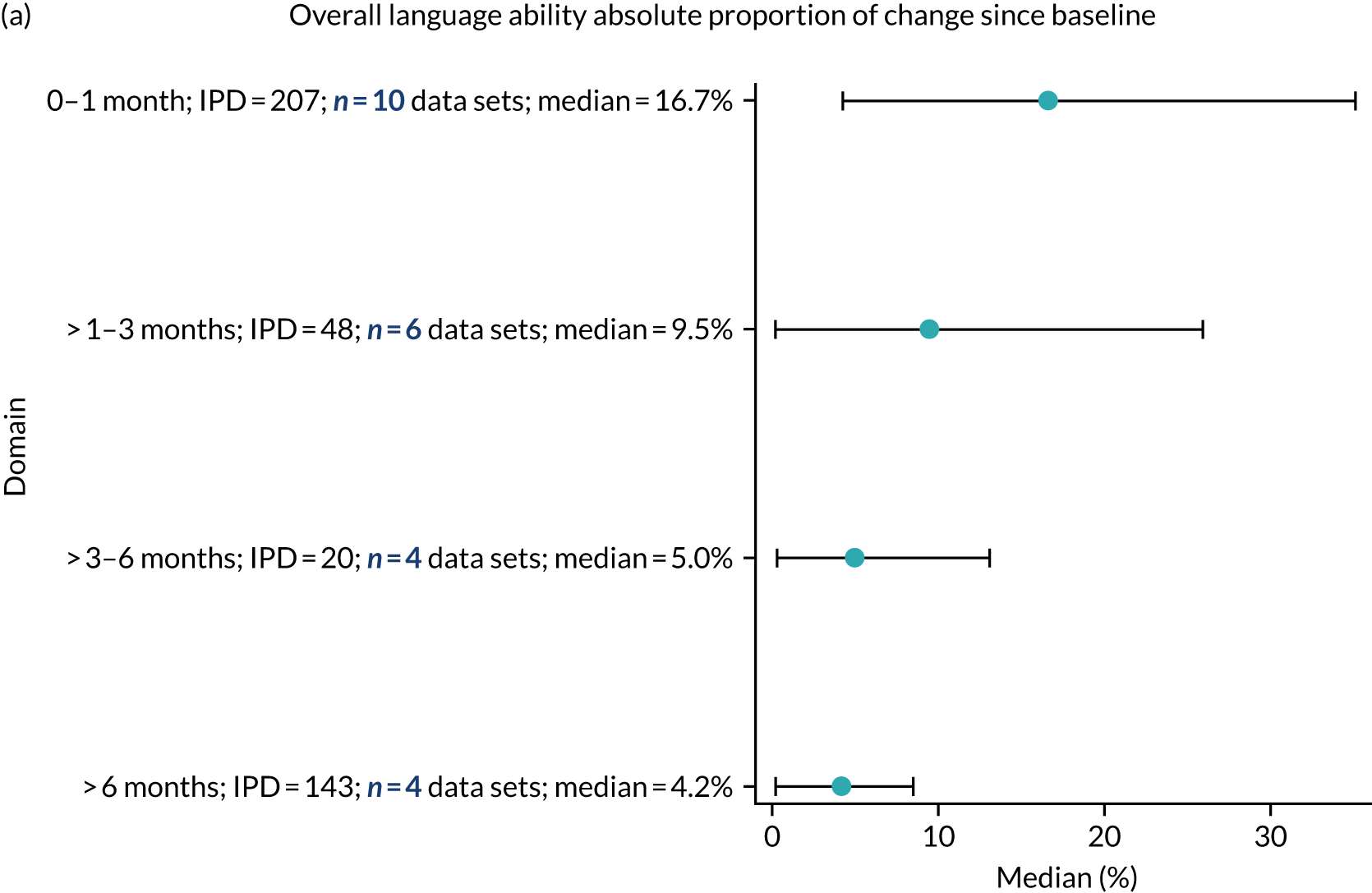

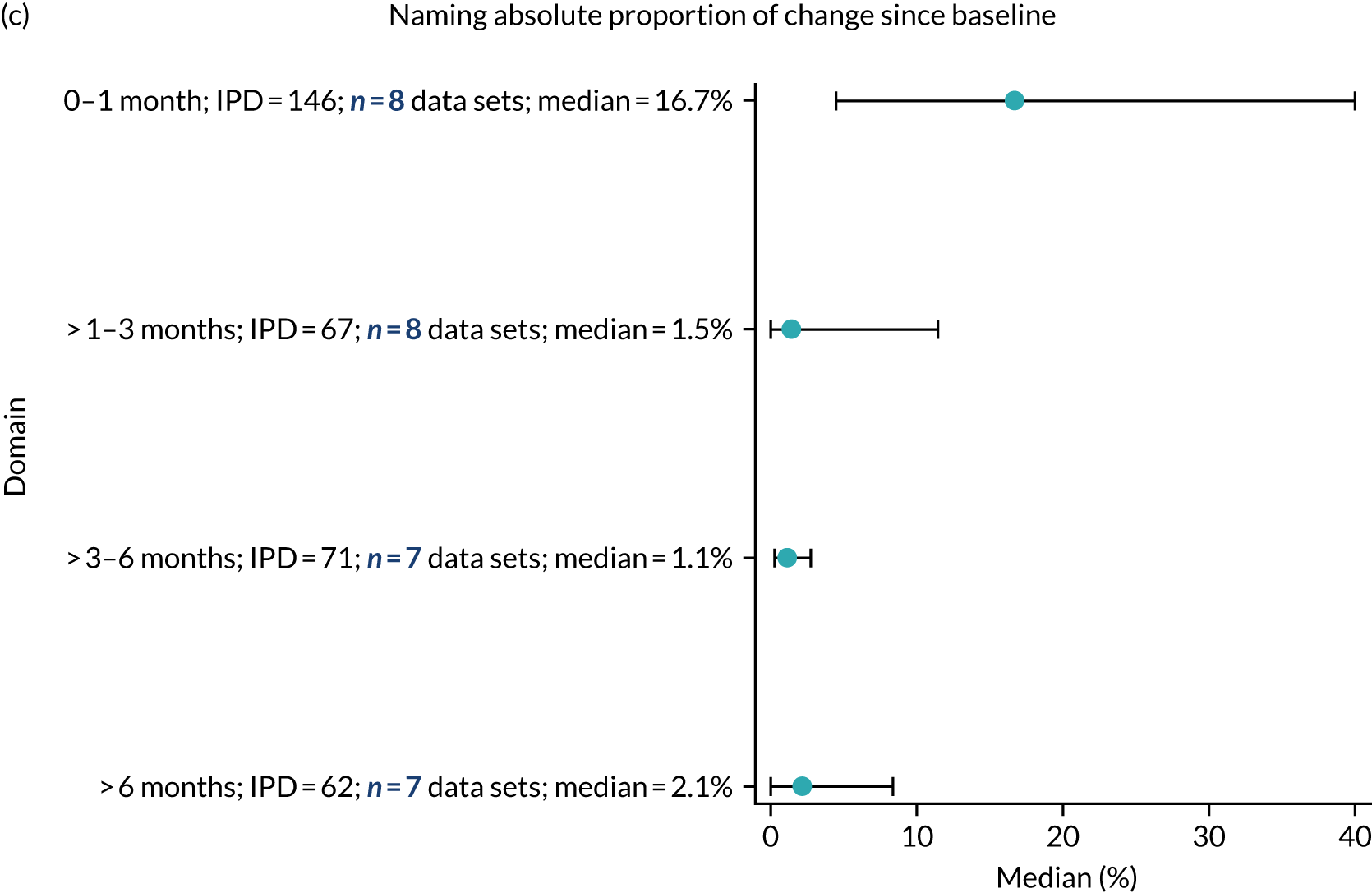

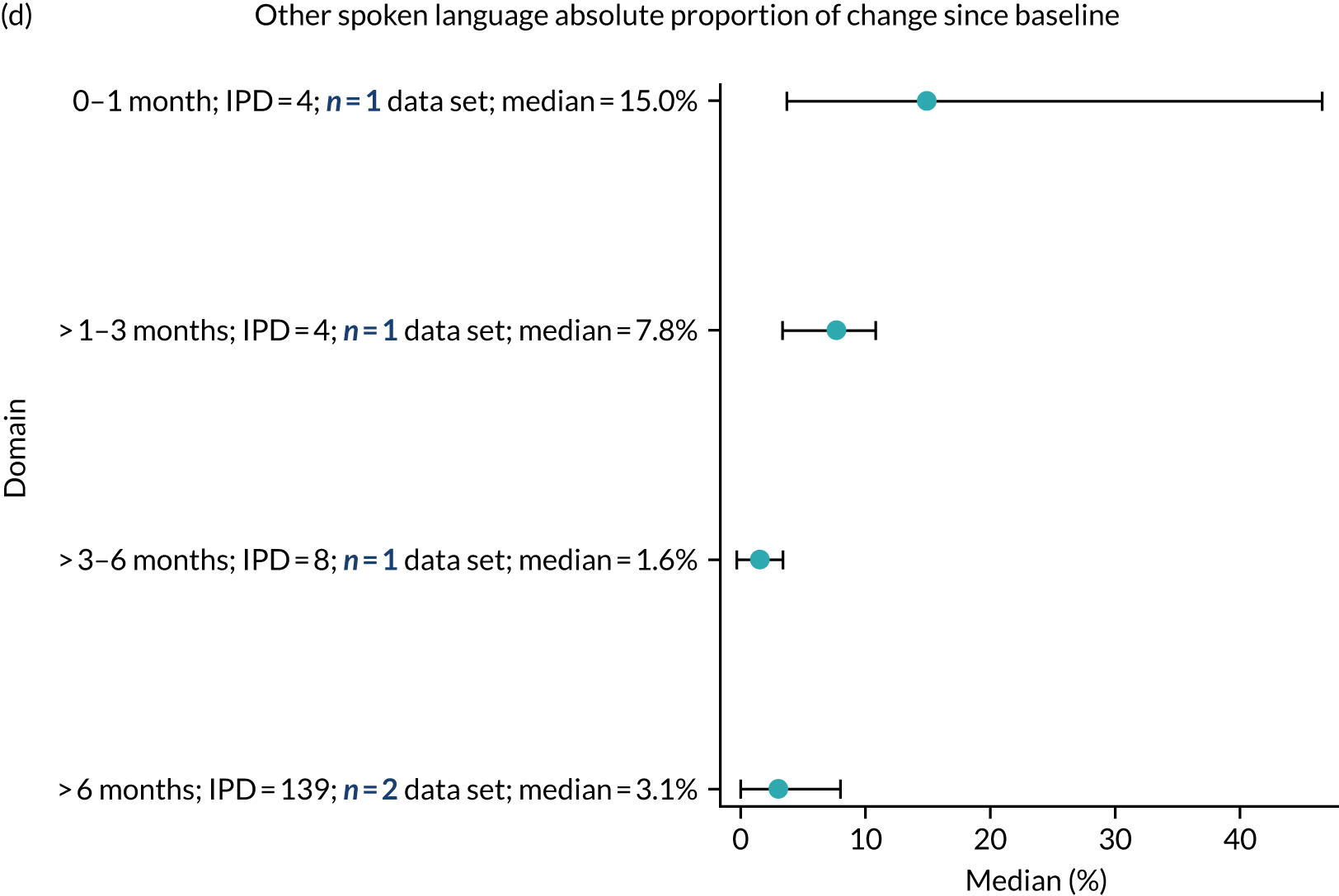

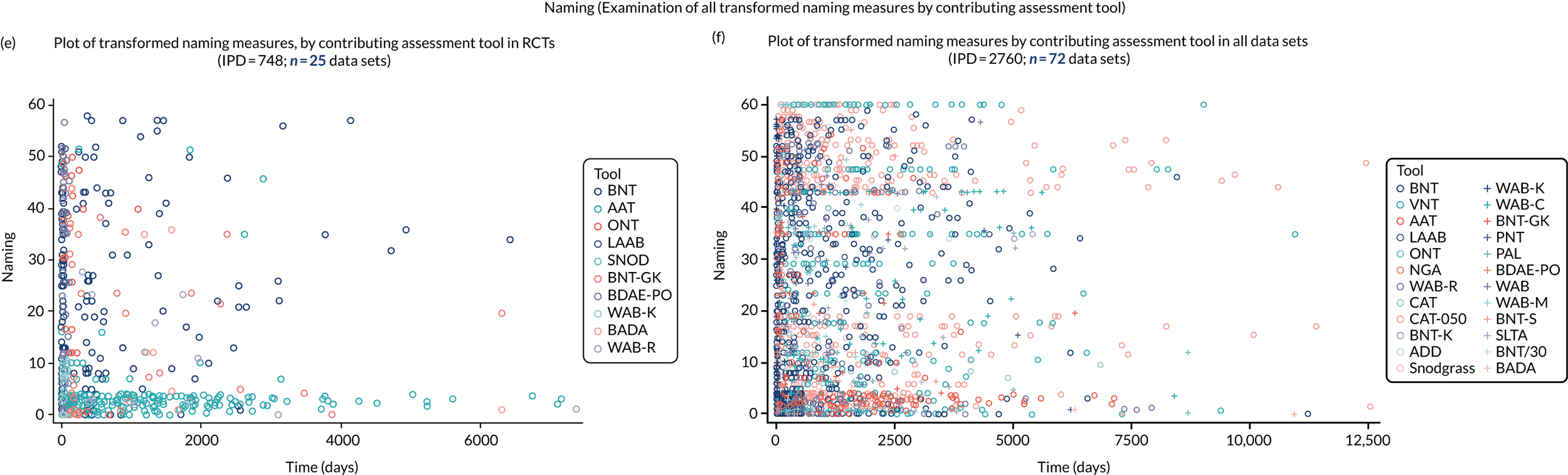

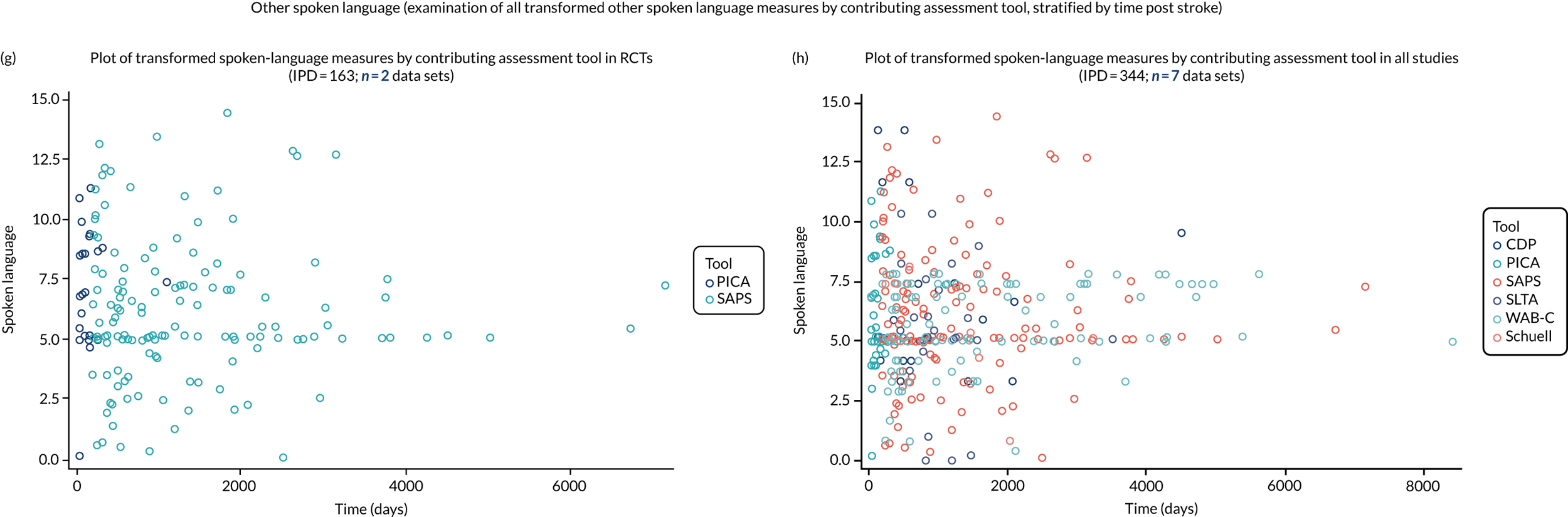

Patterns of language recovery

We examined language recovery among people with aphasia across the prespecified language domains: overall language ability, auditory comprehension, naming, other spoken-language production, reading comprehension, writing and functional communication. Analyses were based initially on RCT data, and then expanded to include all study design types (non-RCT group comparisons, cohort, case series and registry data sets).

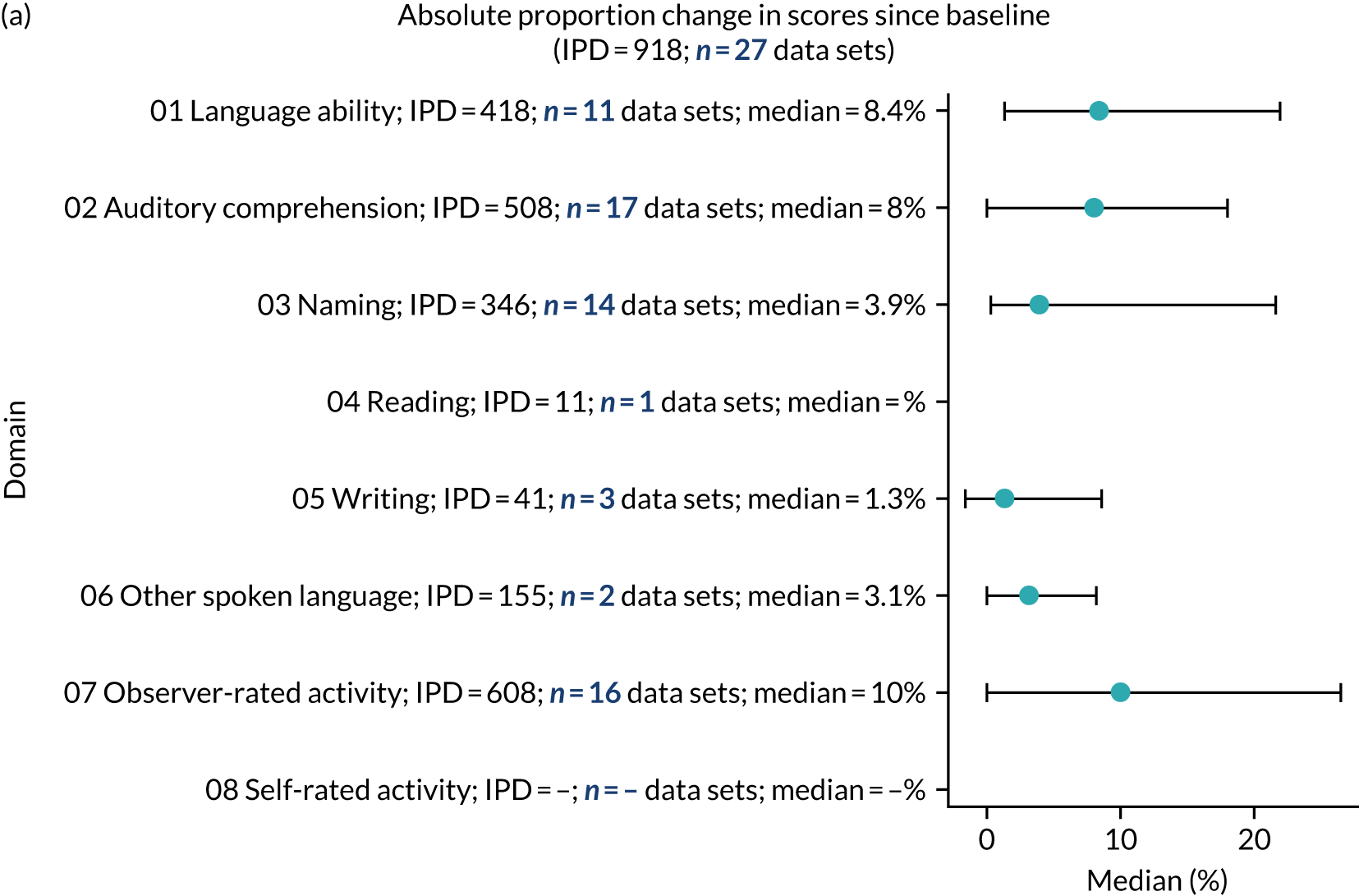

Descriptions of the patterns of aphasia recovery were generated using four methods across each language domain. As data availability permitted, we described the:

-

natural history of recovery among participants that had no access to SLT

-

trajectory of language recovery over time among participants by assessing their baseline and follow-up scores

-

distribution of language domain scores for participants at study entry

-

absolute proportion of change in language scores from study entry to first follow-up across all domains.

Natural history of language recovery

We defined the natural history population as a population for whom no active SLT intervention was present, and for whom there was no history of previous SLT. People who were allocated to the no-SLT group in a study were typically permitted to receive usual care SLT after the intervention period of the study had been completed. Any SLT intervention could have an impact on the post-intervention follow-up measures. Depending on the time since the onset of their aphasia, they may also have had historical SLT prior to entering the study as part of usual care. We therefore implemented the following restrictions when extracting eligible IPD to support the examination of the natural history of aphasia recovery:

-

Allocation to the no SLT group in an intervention study.

-

Enrolment to the study with baseline assessment commencing within 15 days of index stroke, to reduce the possibility of unreported initiation of SLT as part of usual care.

-

No history of prior stroke.

-

When longer-term follow-up measurements were available, we reported on the first post-intervention follow-up only, when applicable, to eliminate all instances of access to SLT as part of usual care SLT after the study intervention period, as identified in our data extraction.

We plotted baseline language domain scores along with corresponding language domain values that were available at first follow-up, to examine the trajectory of the natural history of language recovery over time in those participants who were allocated to no-SLT groups.

Language recovery in the context of speech and language therapy

We also examined the trajectory of language recovery among participants who had access to SLT; we identified those who had access to SLT either as a study participant (SLT group) or reported (or reasonable grounds to assume) historical access to SLT as part of standard health care prior to study enrolment (historical SLT group). We also identified those who were allocated to the historical SLT group (with enrolment beyond 15 days post stroke to exclude those who were part of the natural history analysis) and assessed whether or not there were sufficient data available at the first follow-up period. We sought to eliminate the impact of any SLT intervention (even usual care) in any follow-up data collection time points.

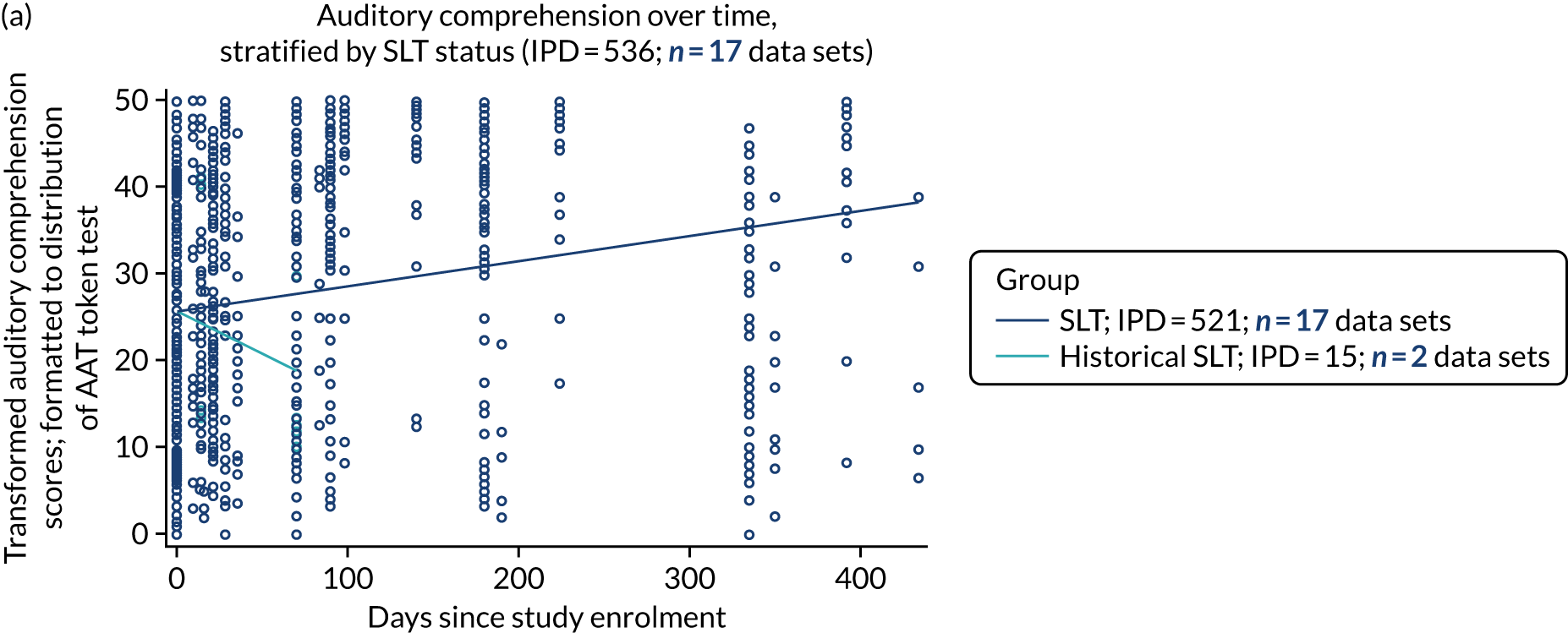

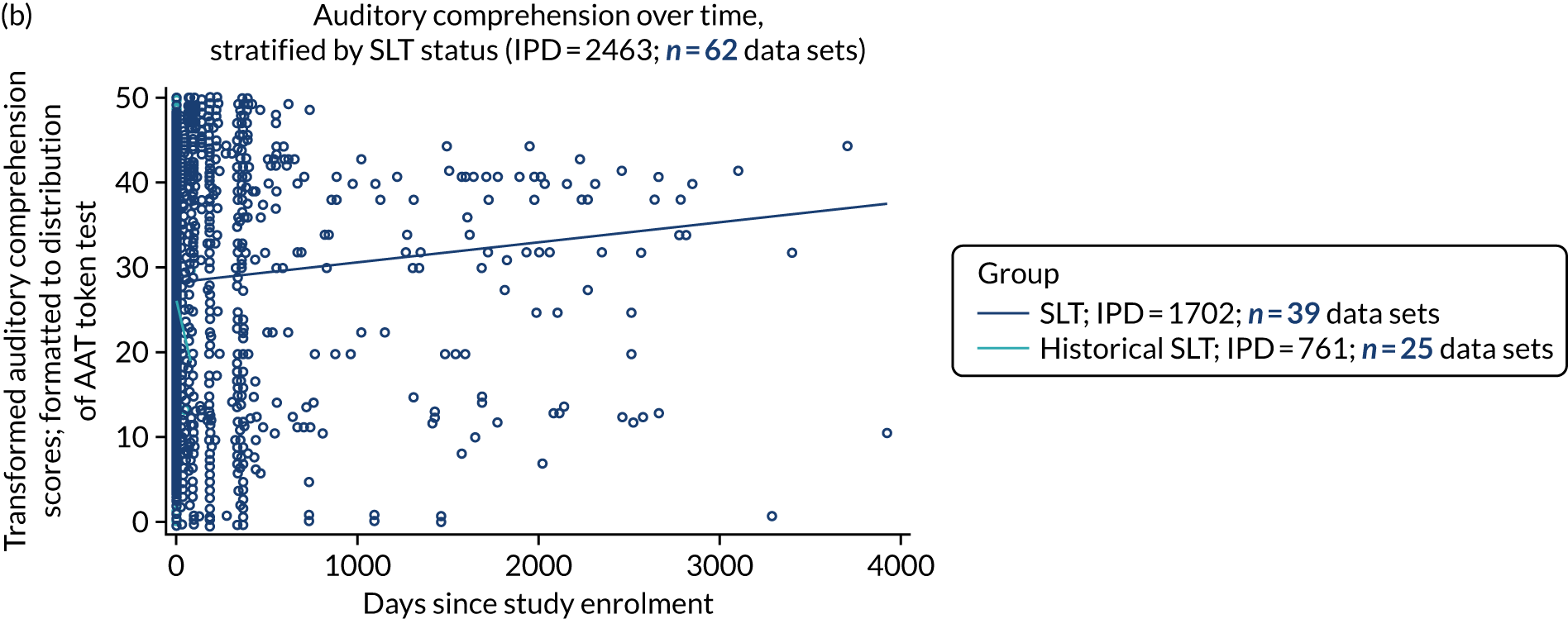

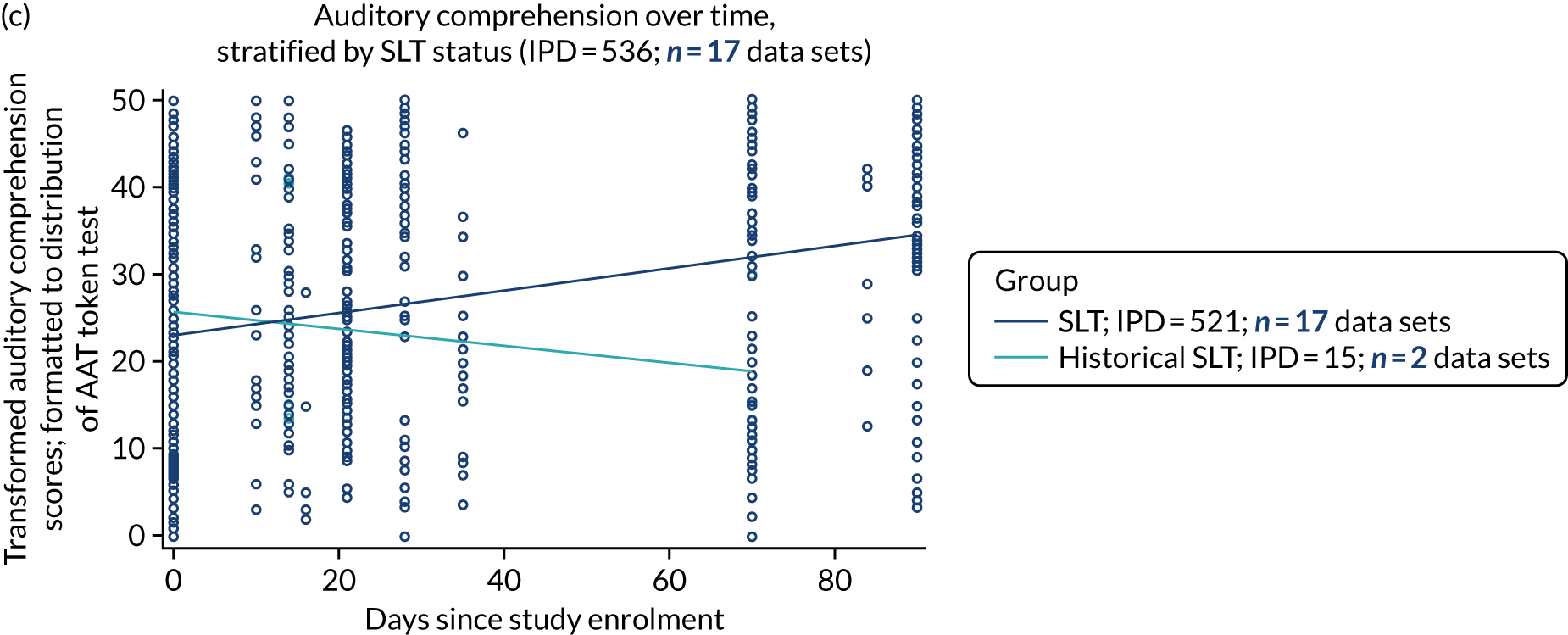

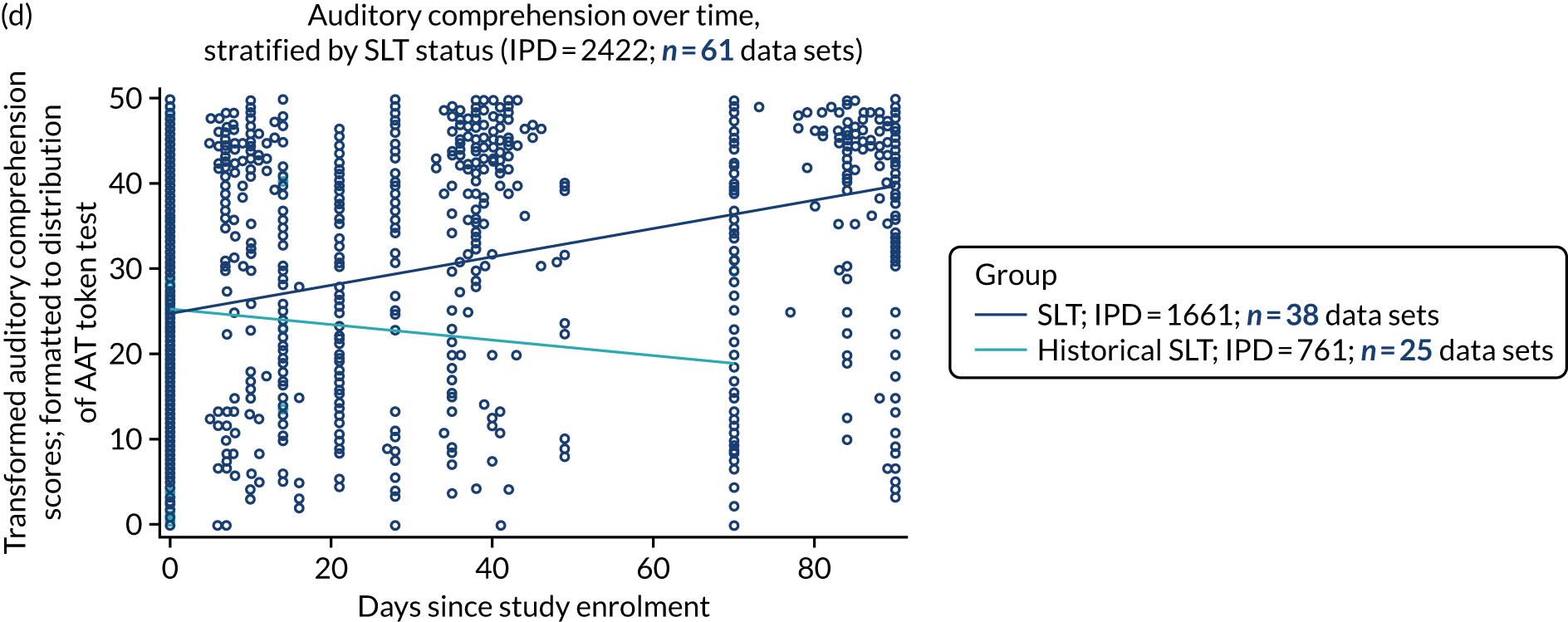

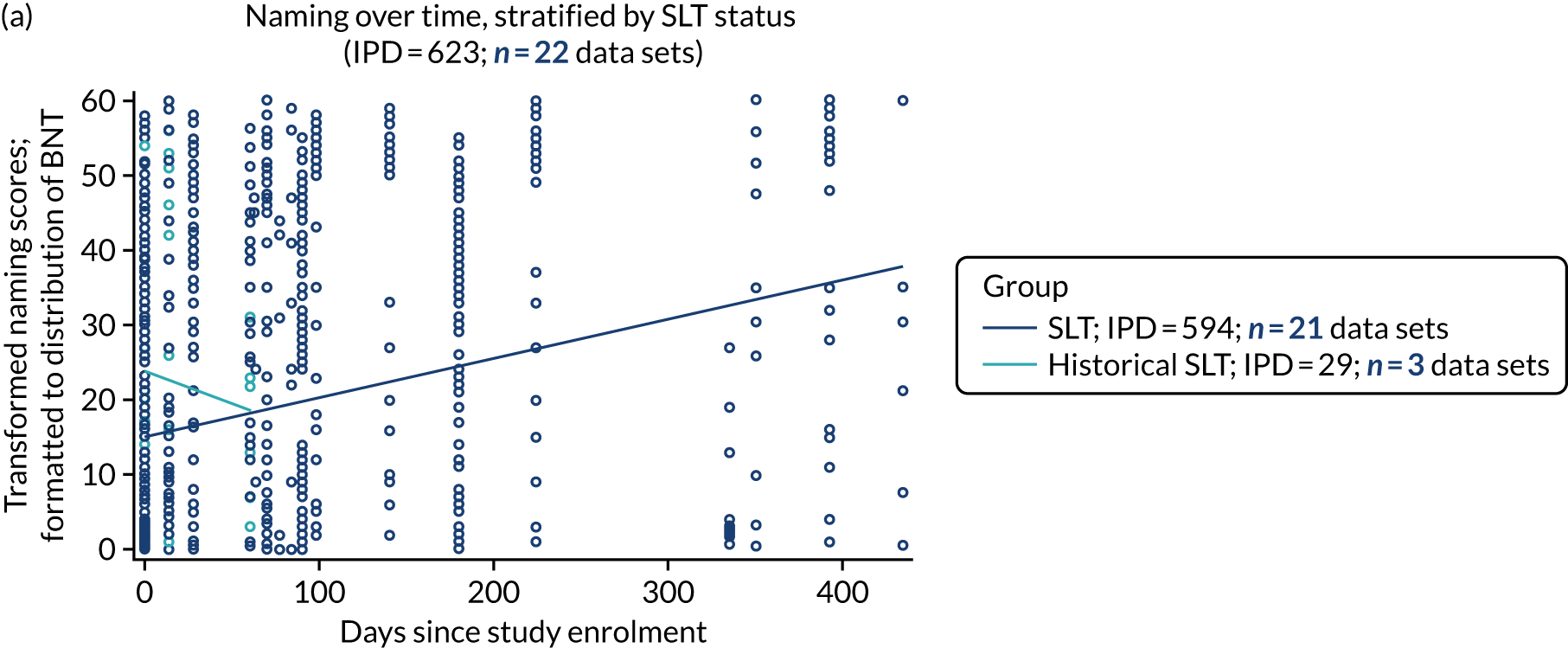

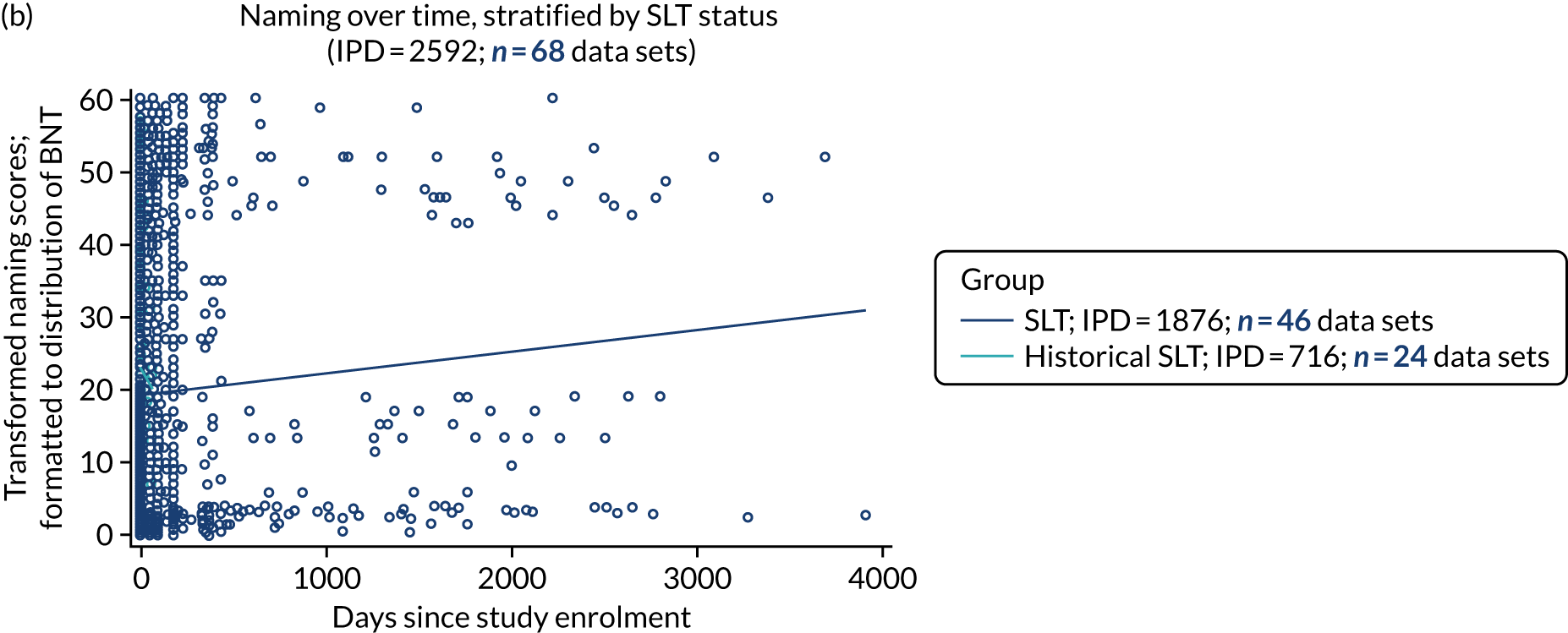

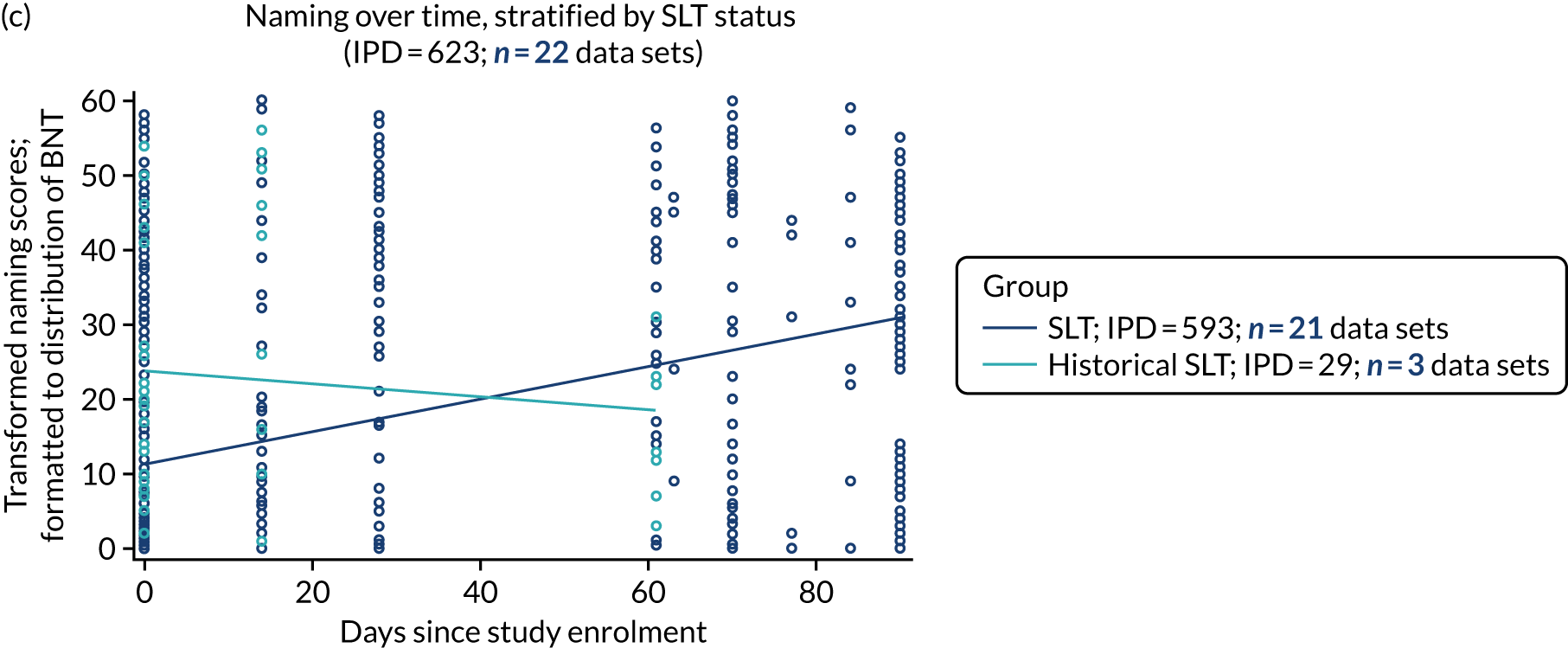

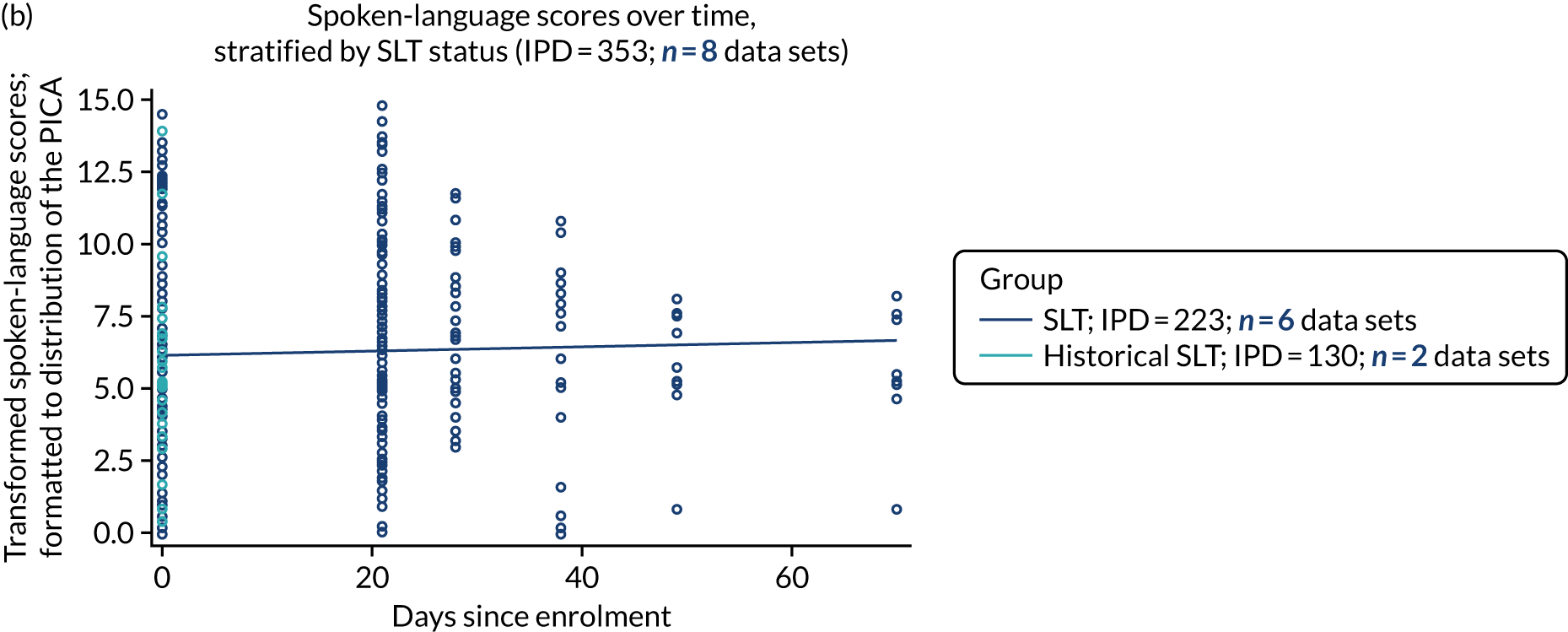

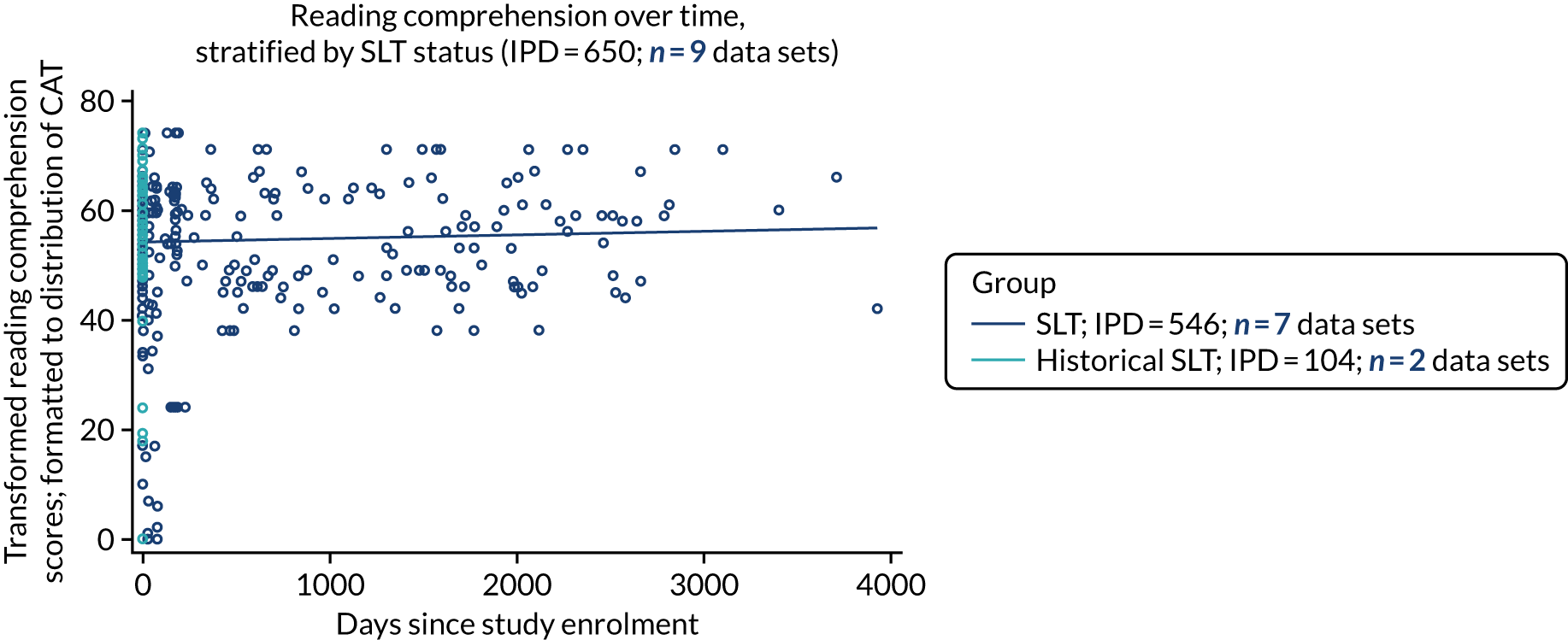

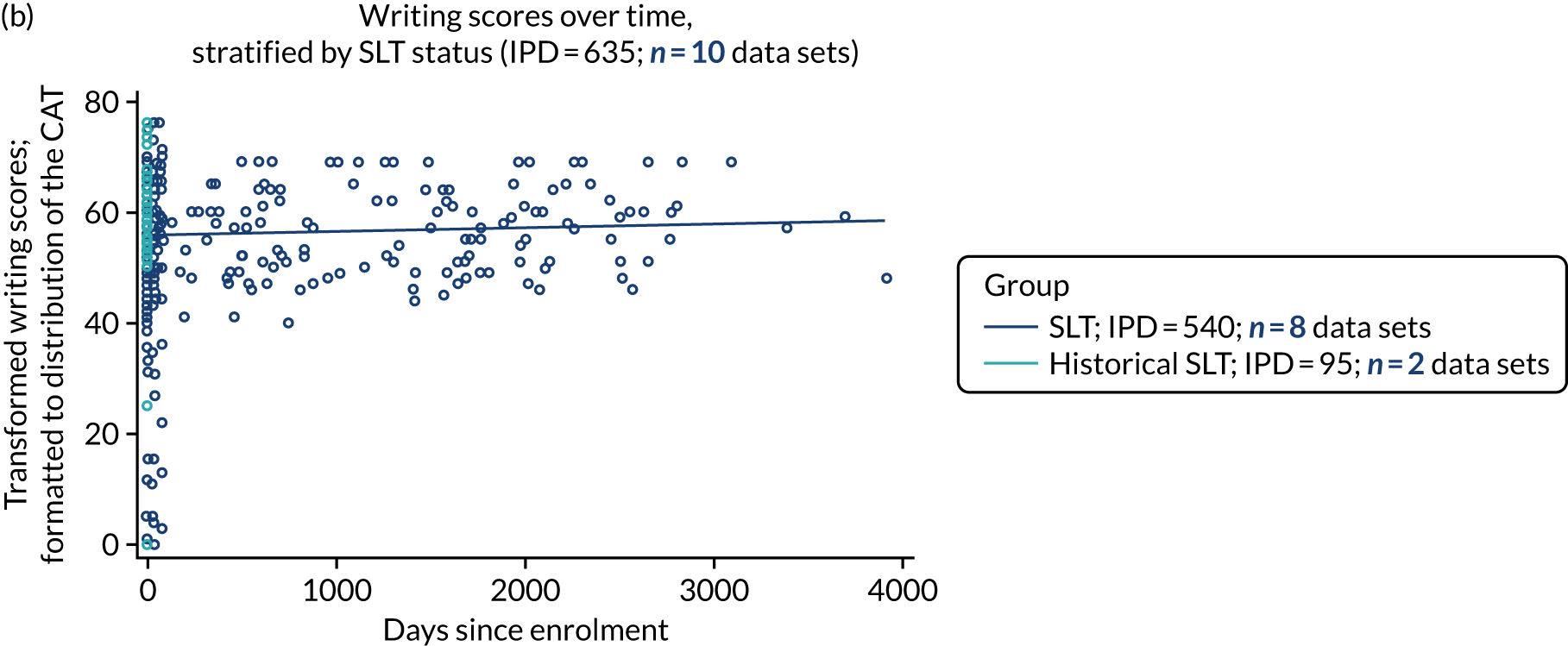

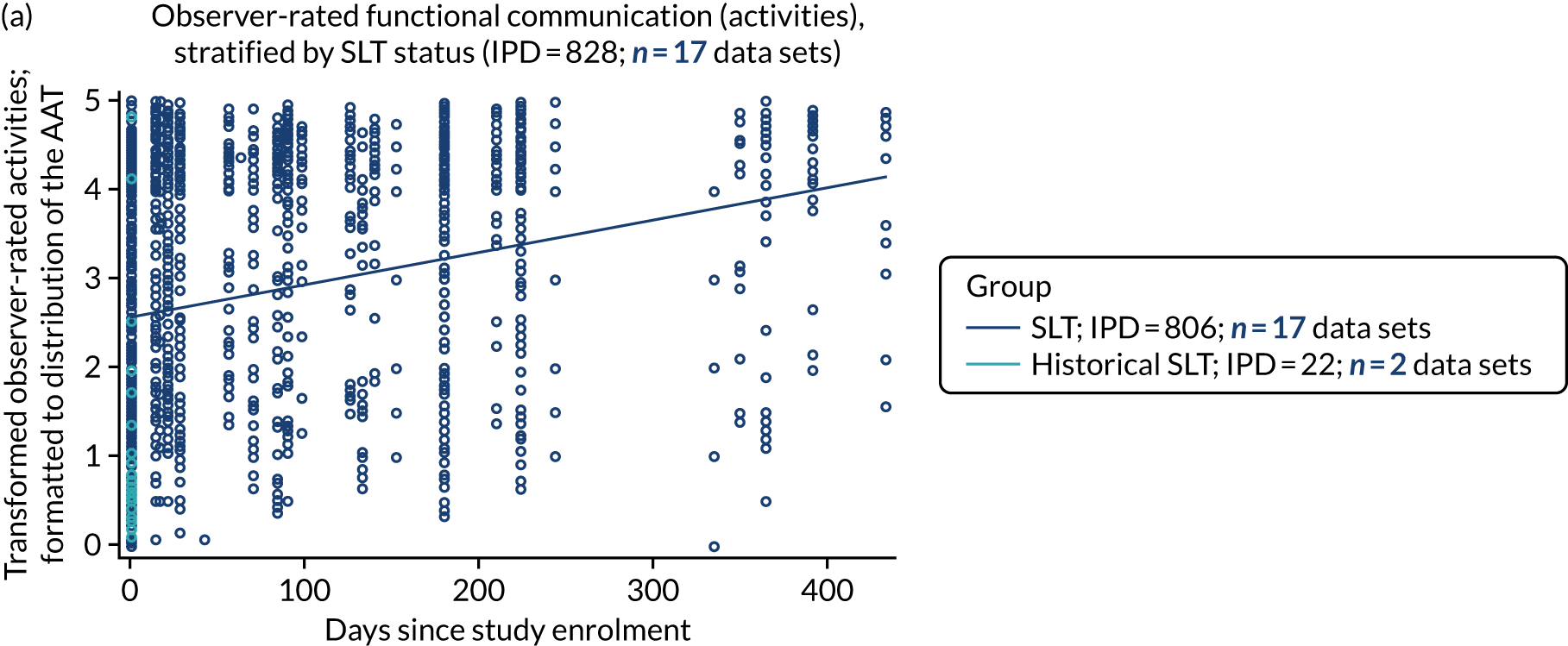

We described baseline and follow-up scores in all available groups for each language domain, when sufficient data were available. Data were presented as plots of language domain scores over time (relative to study entry) and, when applicable, stratified by SLT, no SLT or historical SLT intervention.

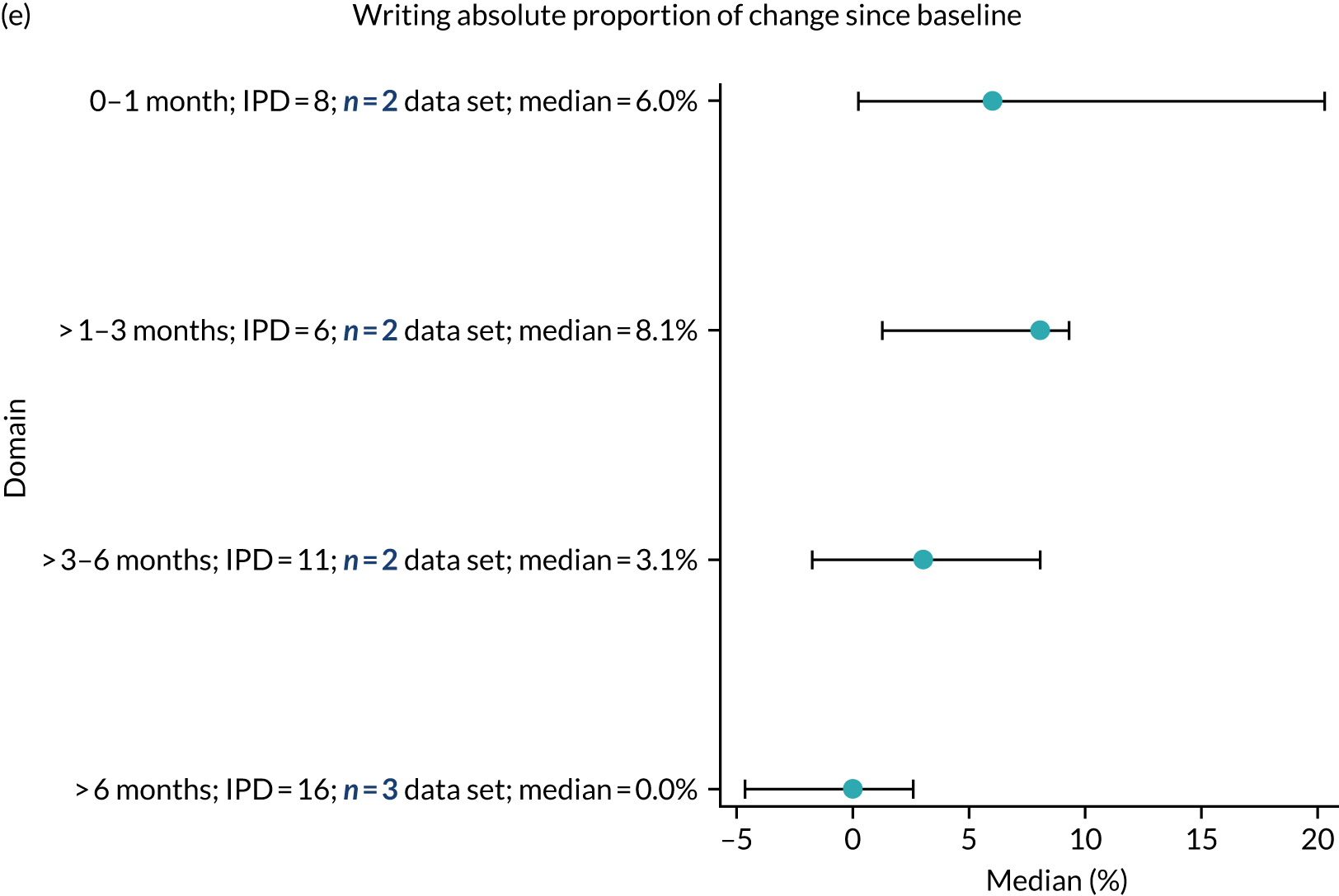

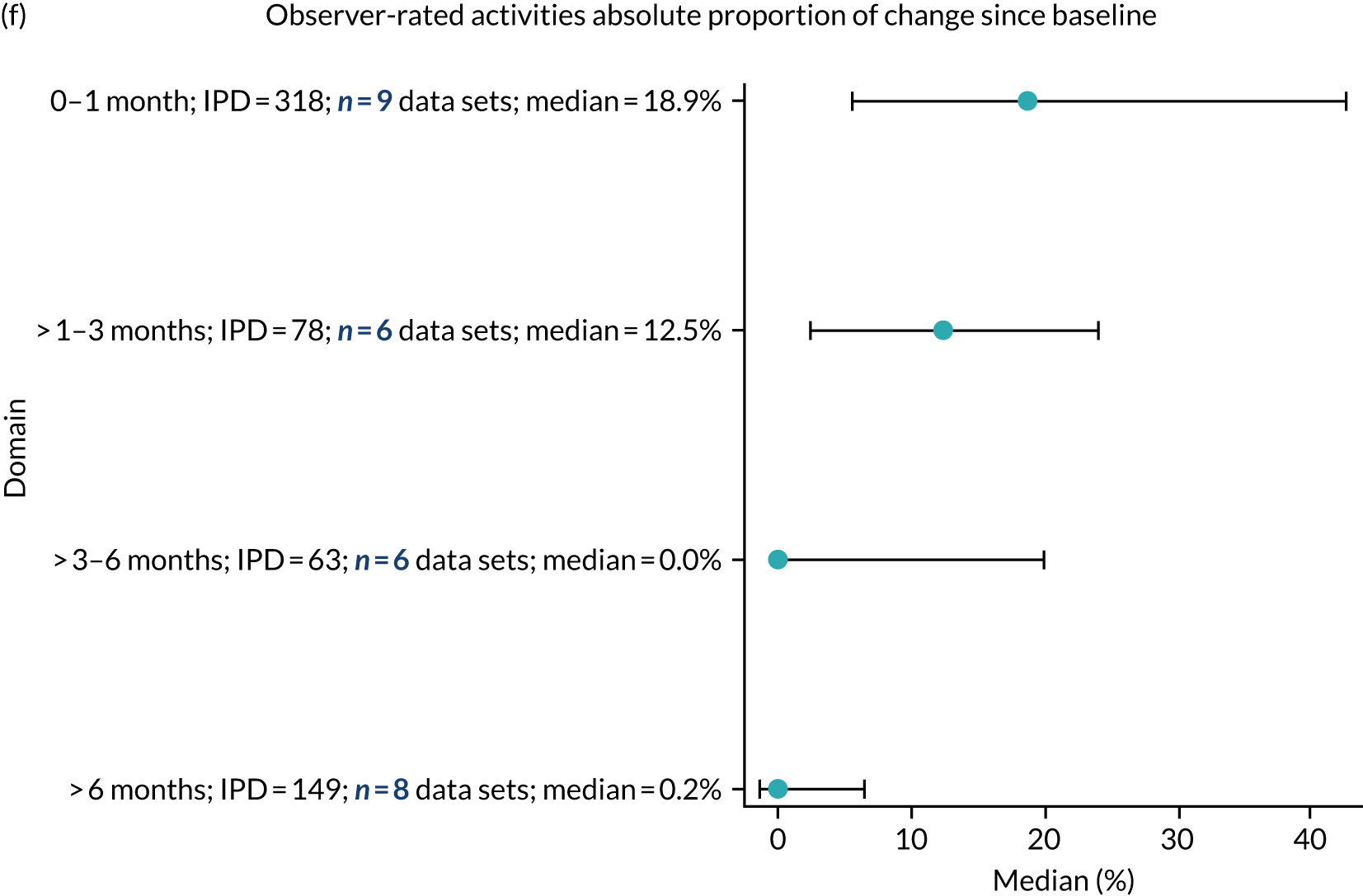

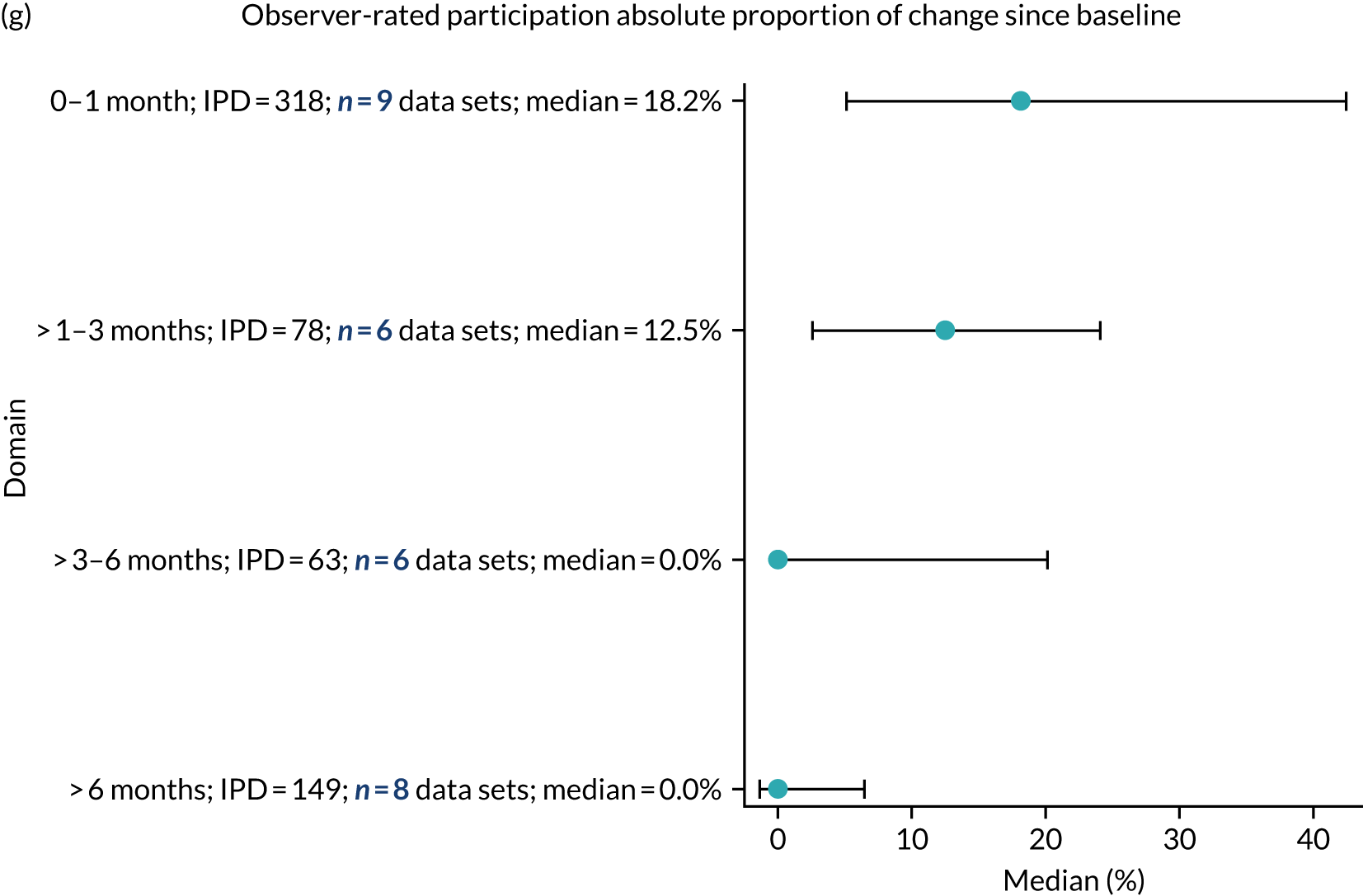

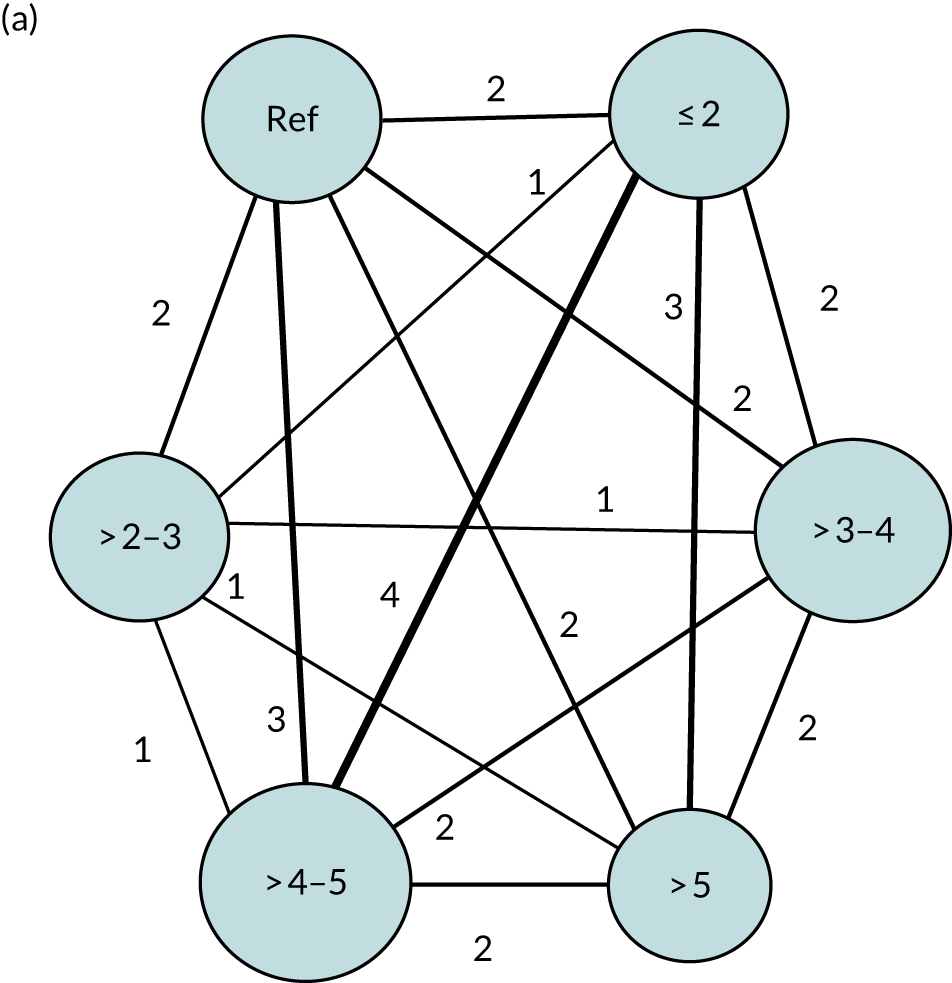

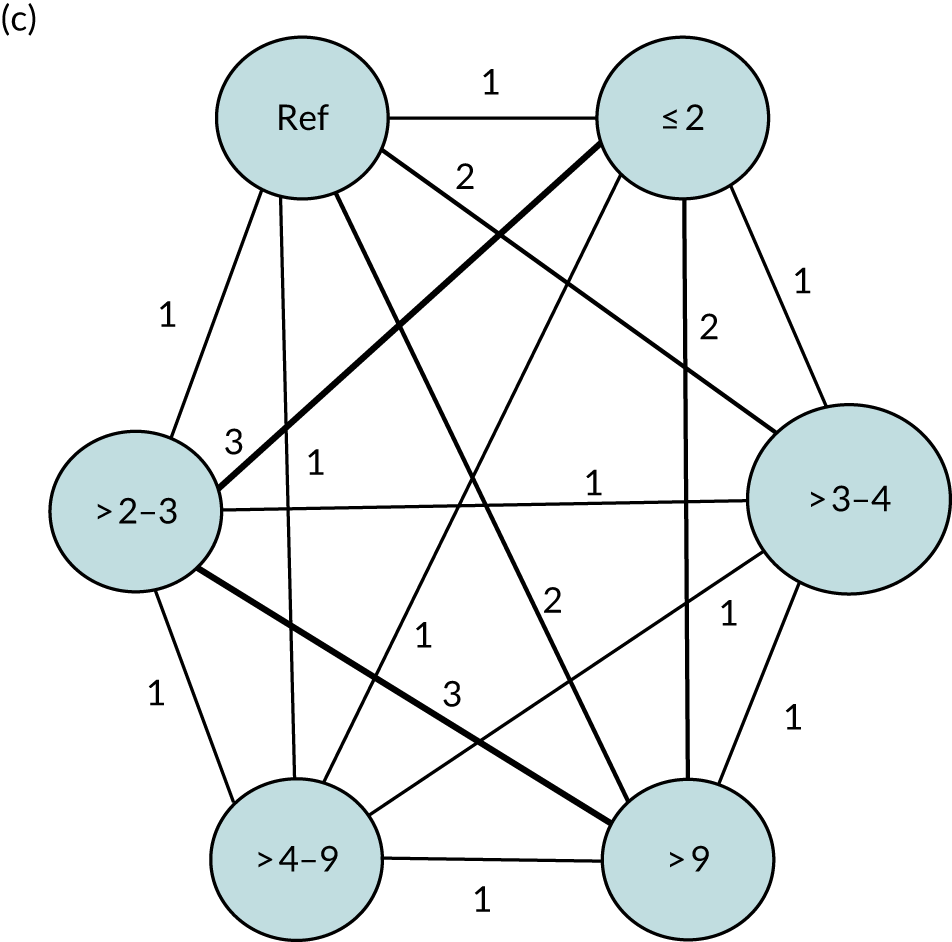

Language recovery: change in language scores from baseline by time since stroke

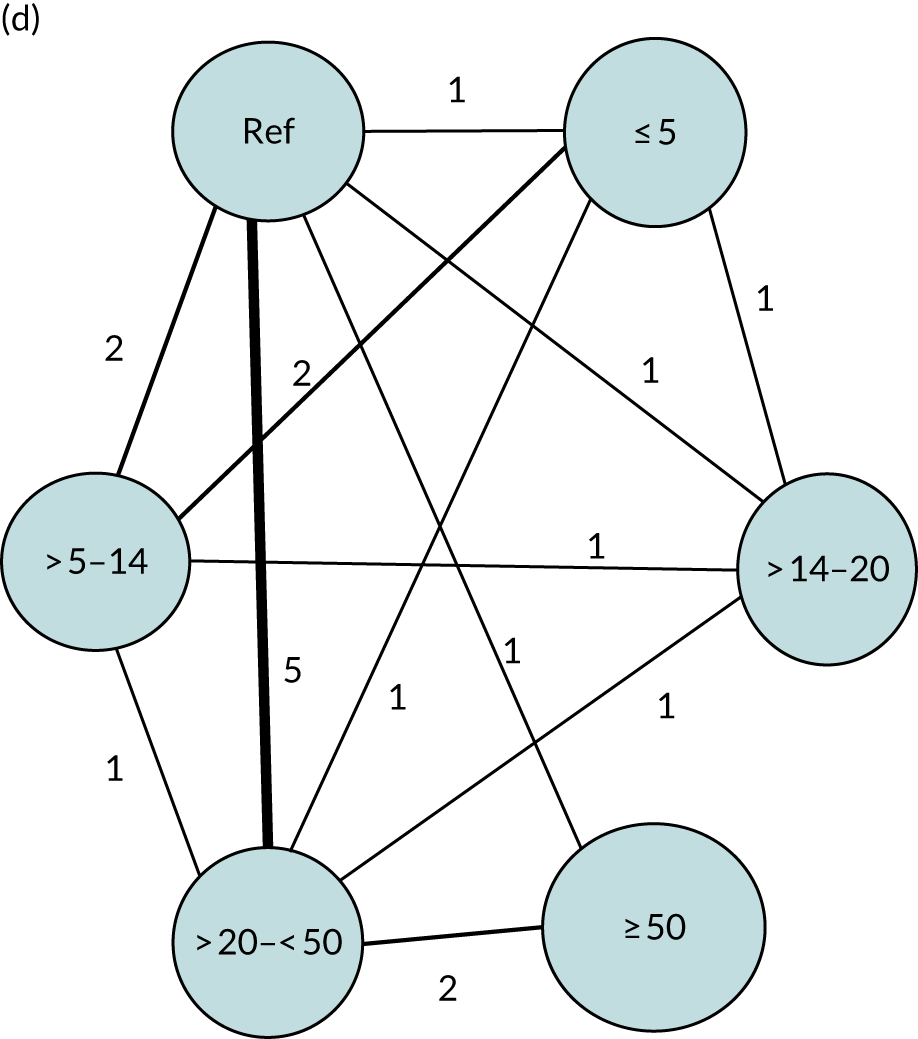

We examined the role that time since index stroke and study enrolment played on the proportion of recovery observed for each domain score. The study enrolment period in the primary data set was stratified into the following groupings:

-

0–1 month

-

> 1–3 months

-

> 3–6 months

-

> 6 months following index stroke.

We ascertained whether or not participants were allocated to receive a SLT intervention; when possible, we described the absolute proportion of change observed for SLT versus historical SLT (excluding those who were assessed as part of the natural history analysis). We calculated the proportion of change (%) in each language domain score from baseline to first follow-up and plotted these proportion changes by study enrolment period (as categorised earlier). This was described for the RCT population, and then for all study types. We plotted each language domain separately to visualise the proportion of change observed in each domain at different study entry time points. We opted not to stratify data according to baseline severity stratum in combination with aphasia chronicity, as this would have resulted in very small strata and much wider confidence limits, thus precluding informative analyses. We also accounted for the skewness of data measuring language impairment by opting to present medians and IQRs, rather than means and standard errors of the means.

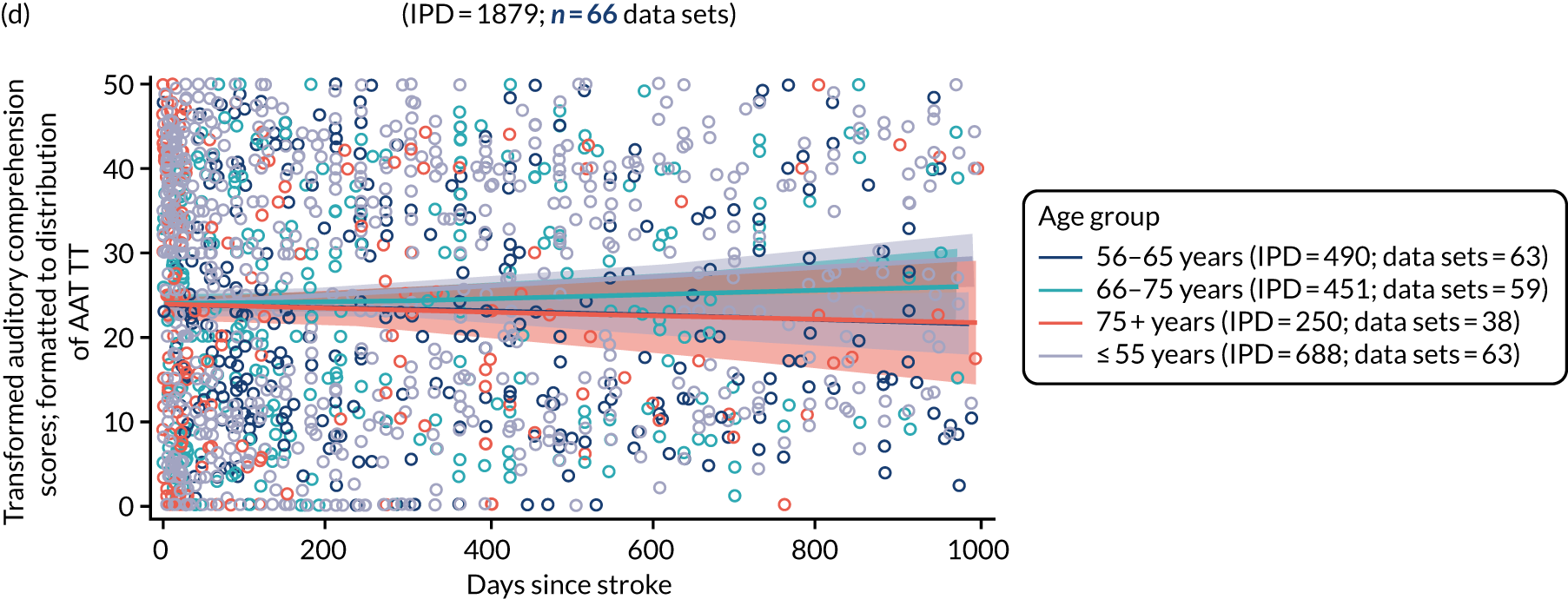

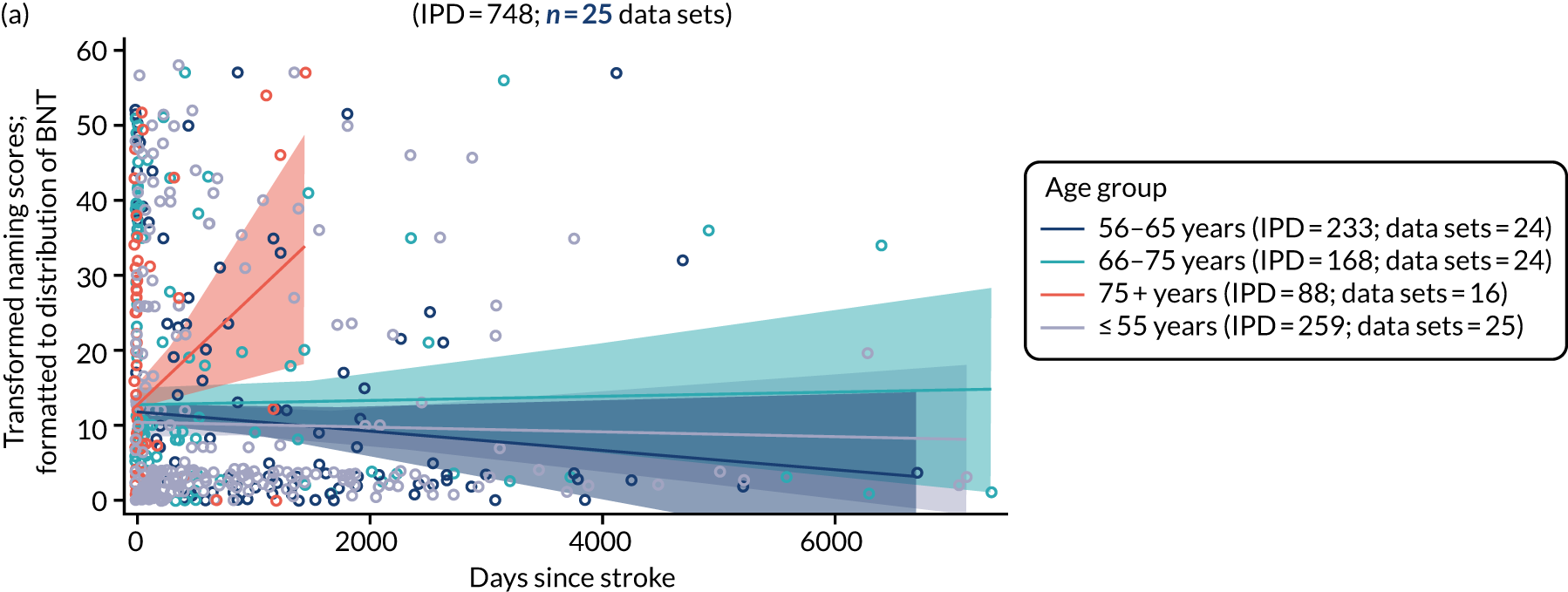

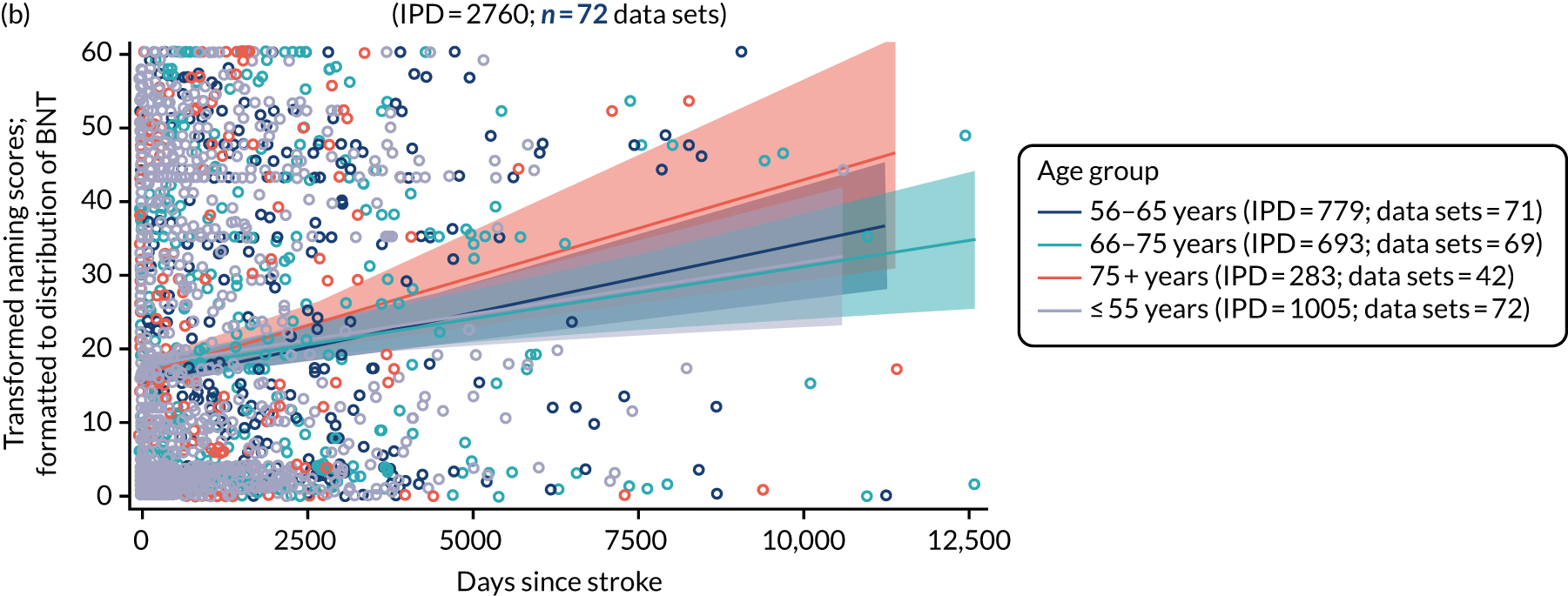

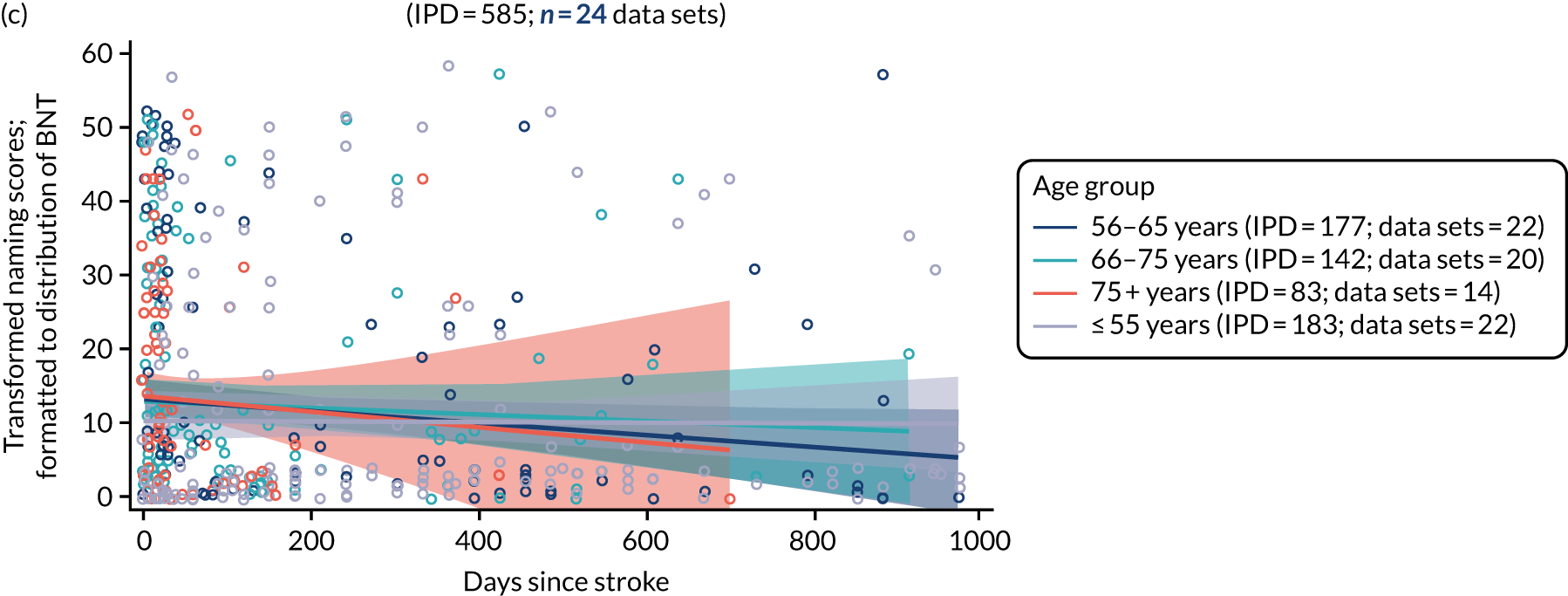

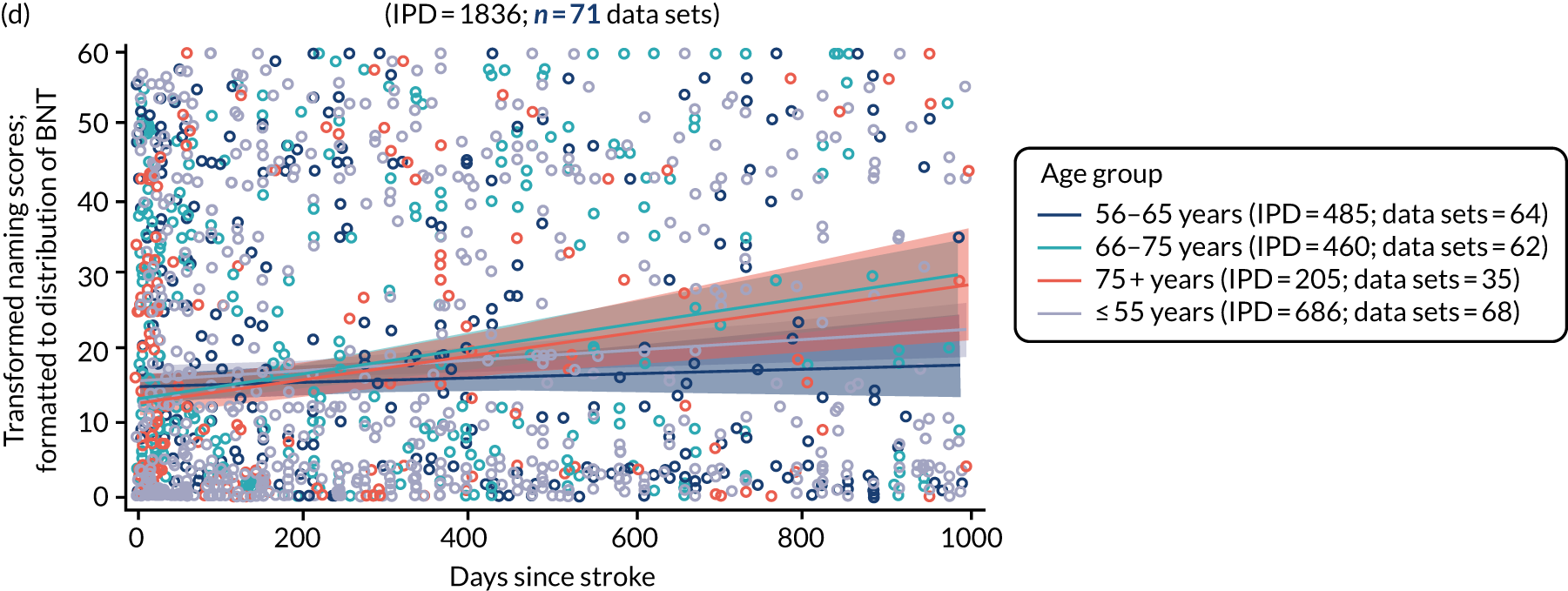

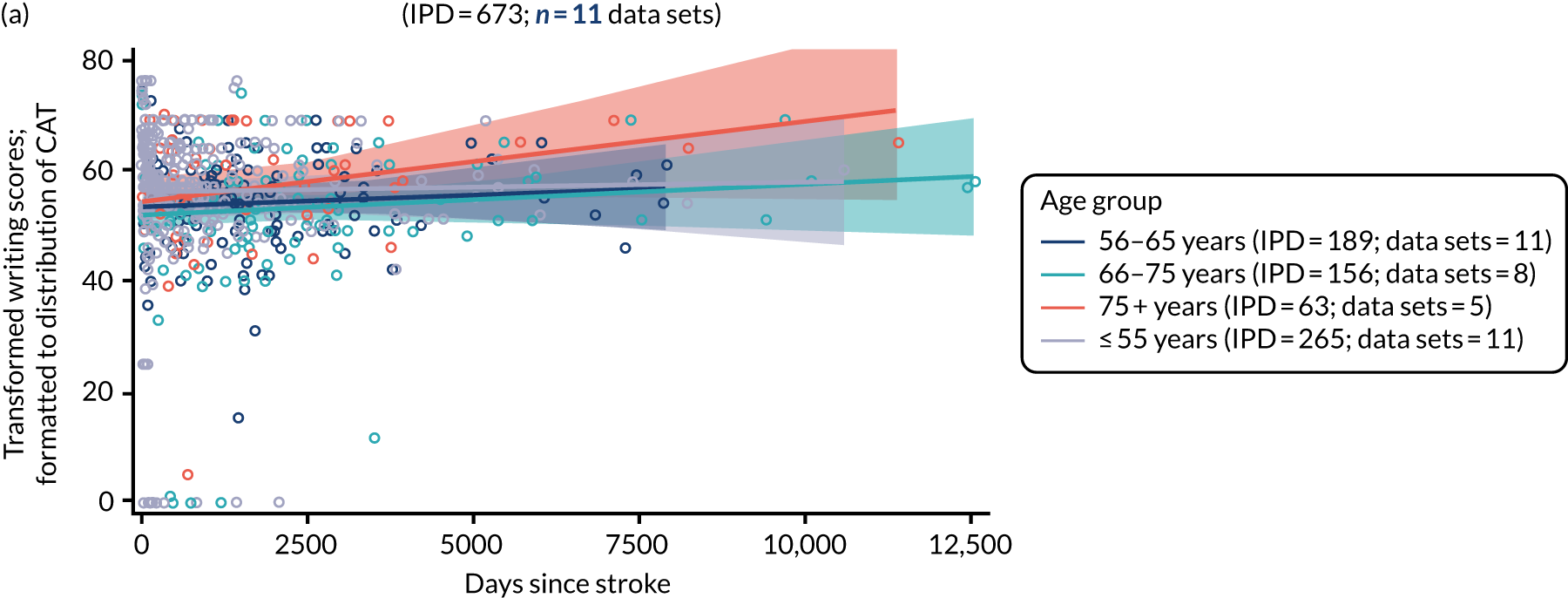

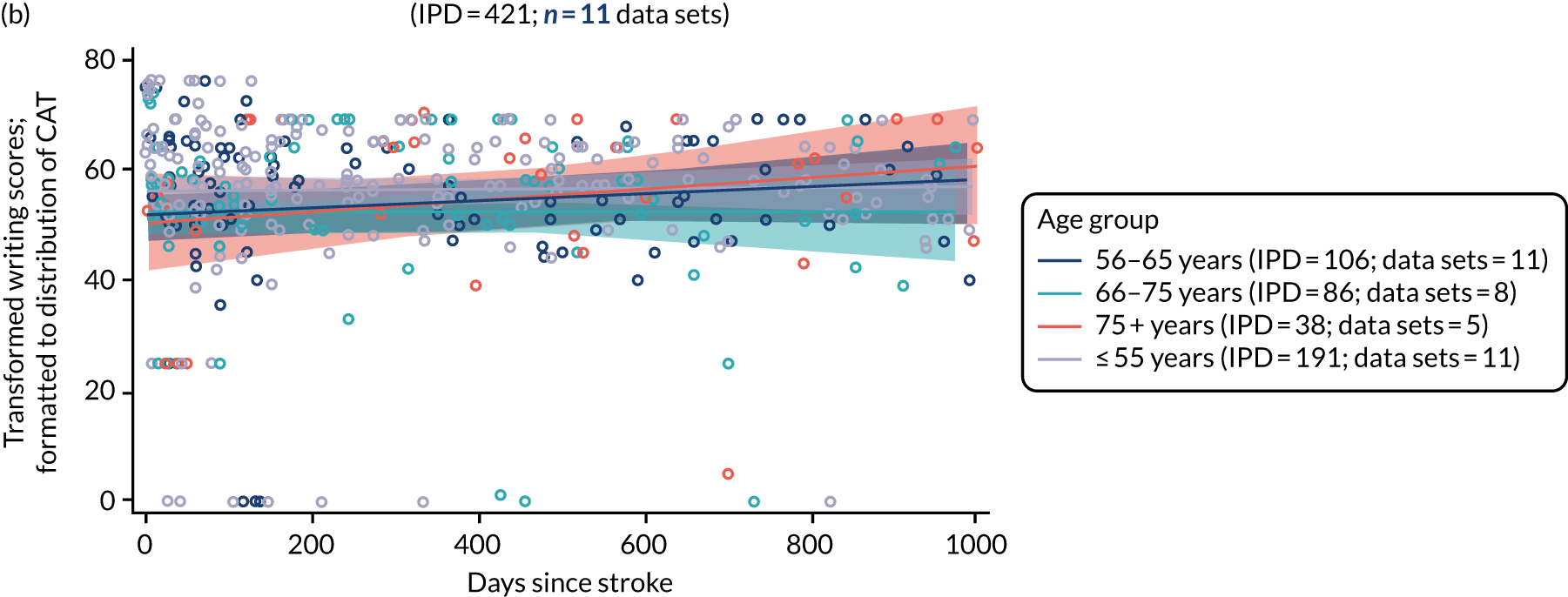

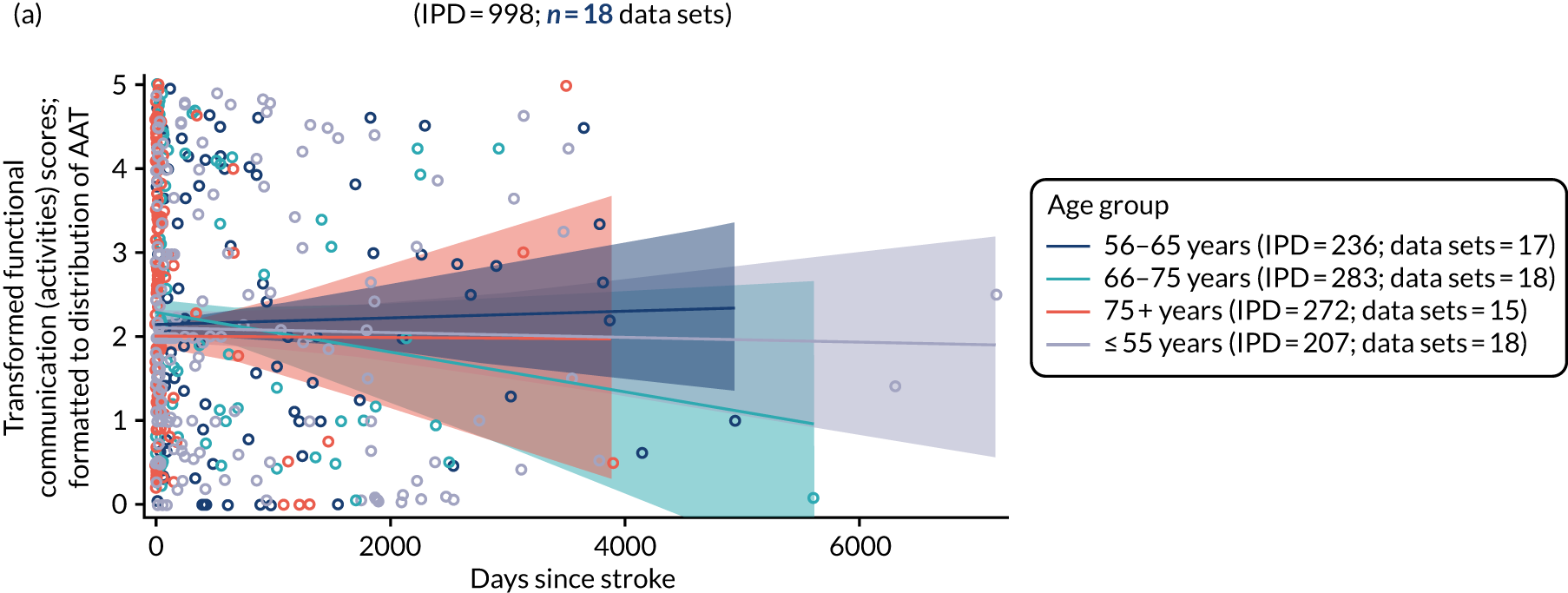

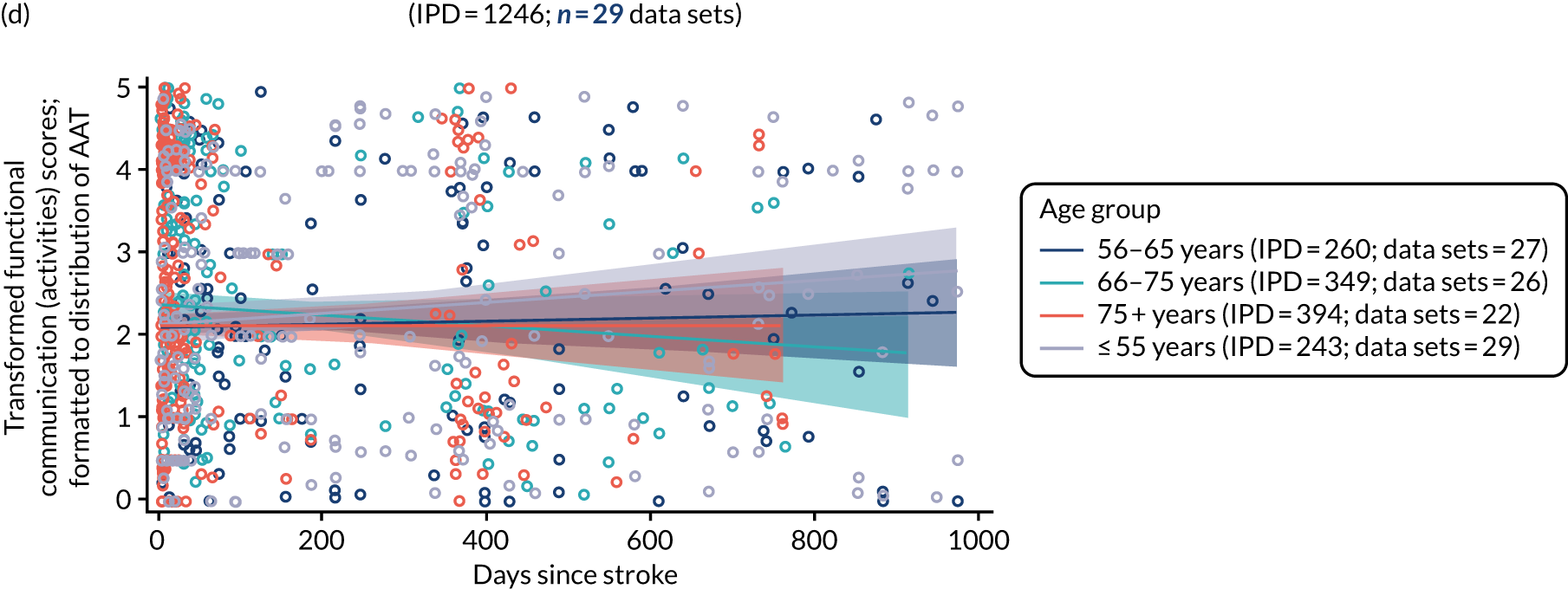

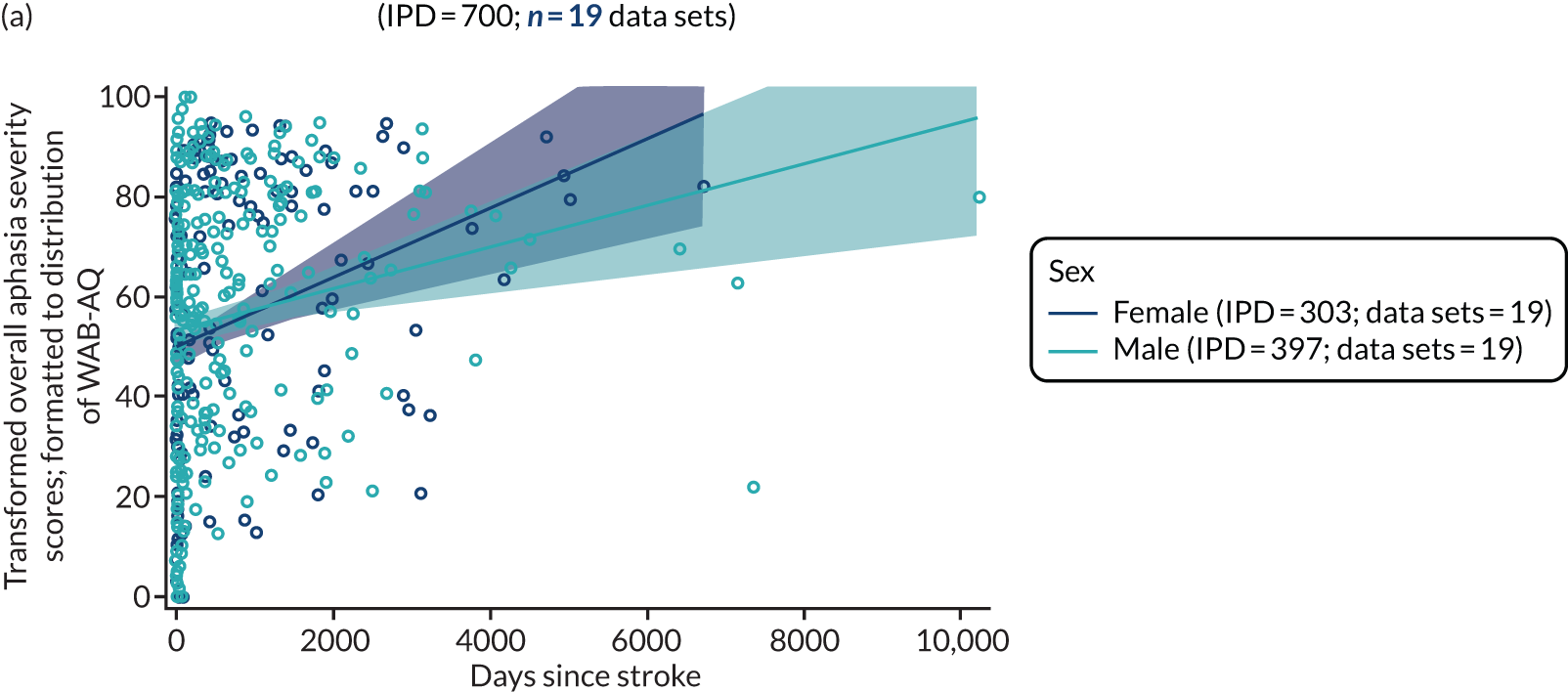

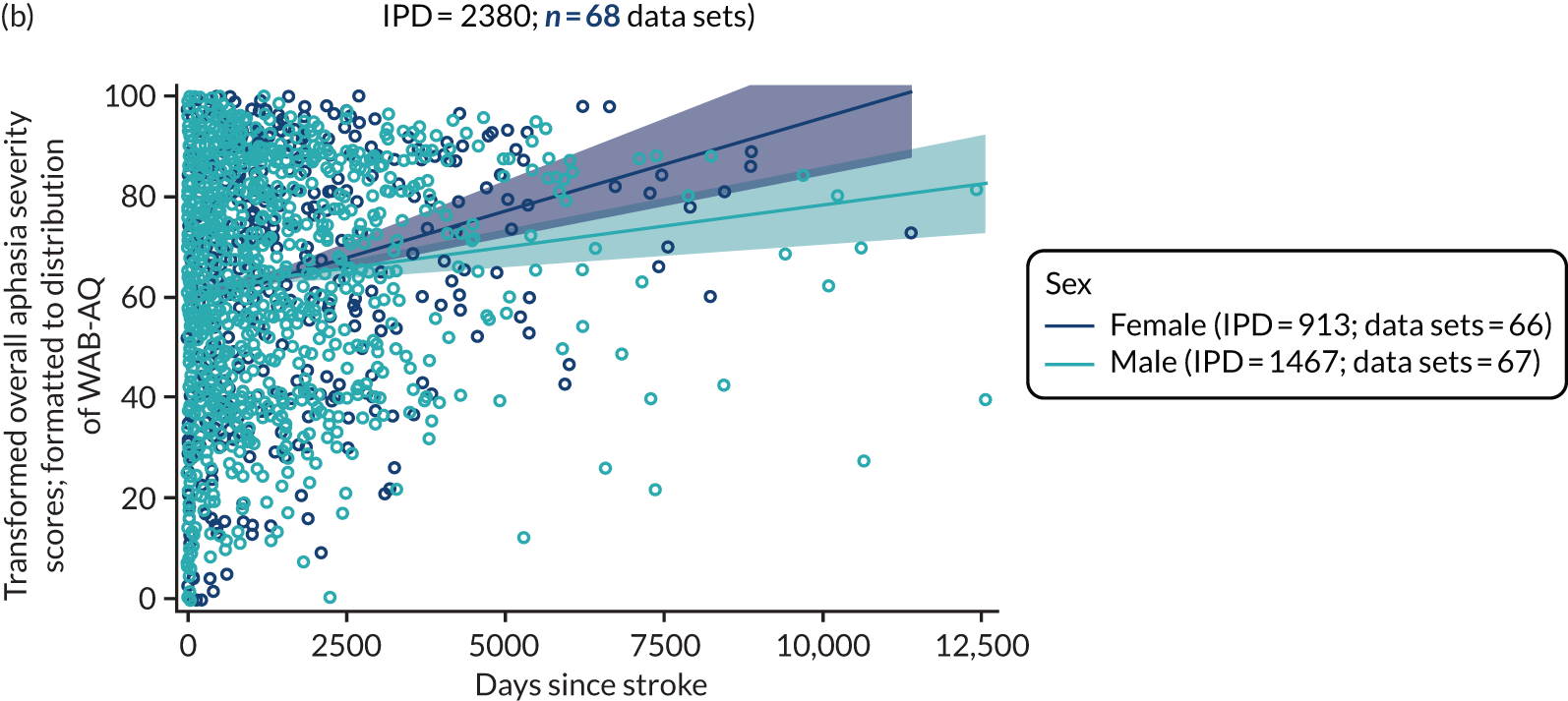

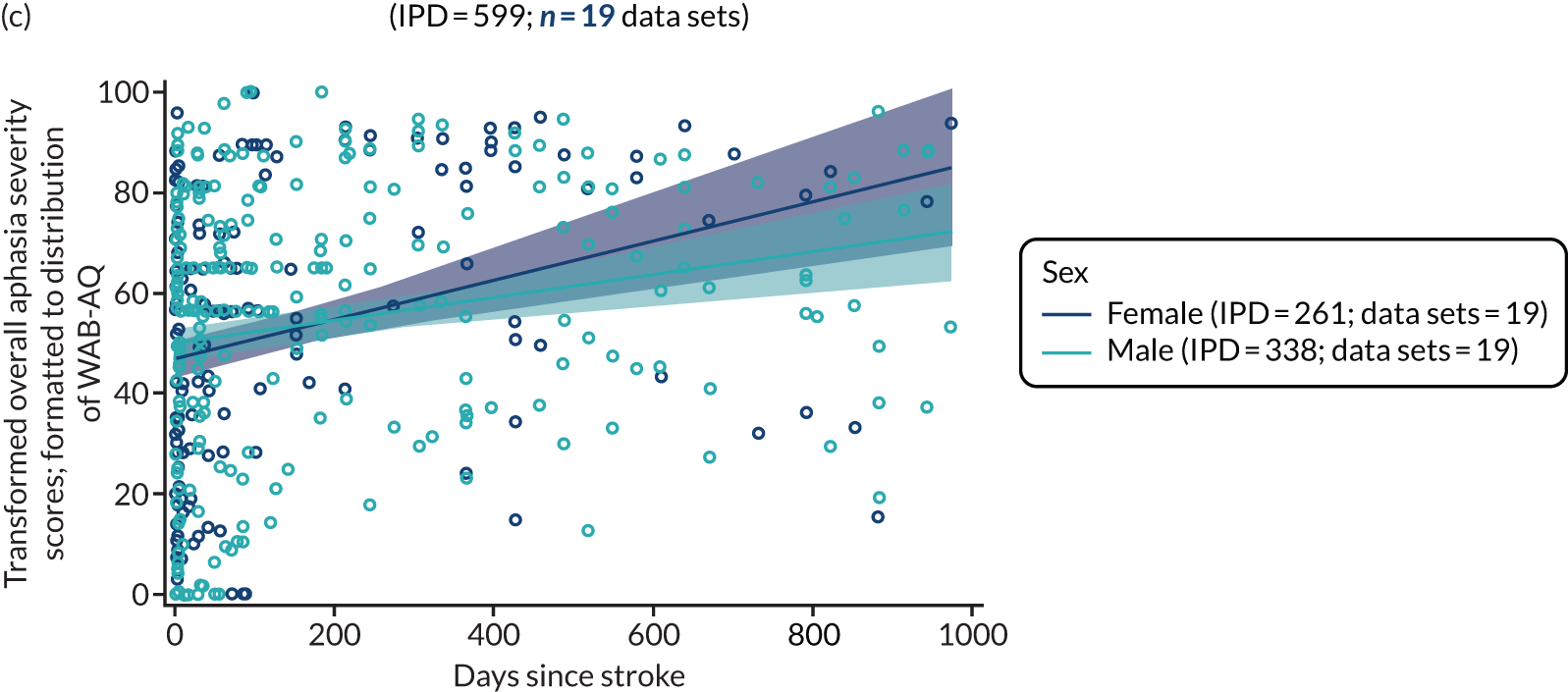

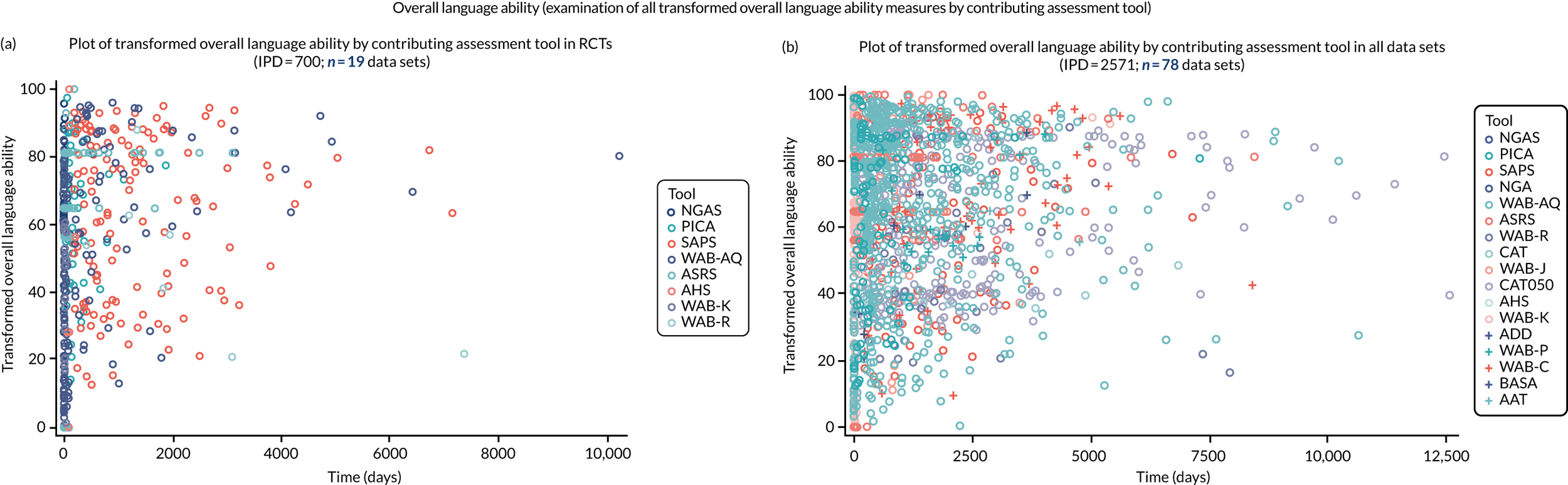

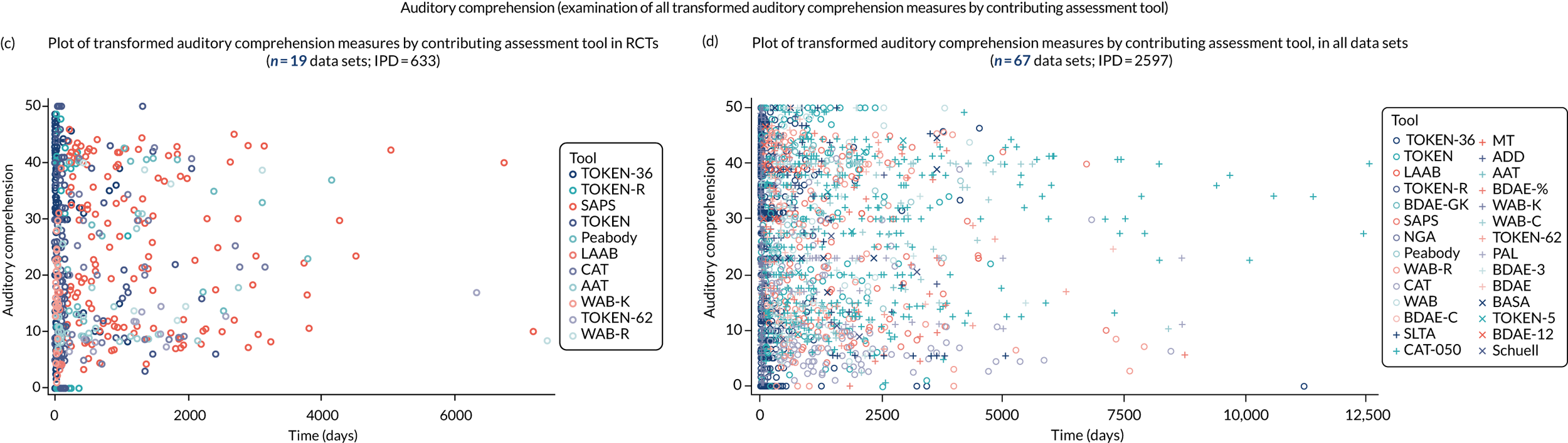

Distribution of language scores at study entry by time since stroke

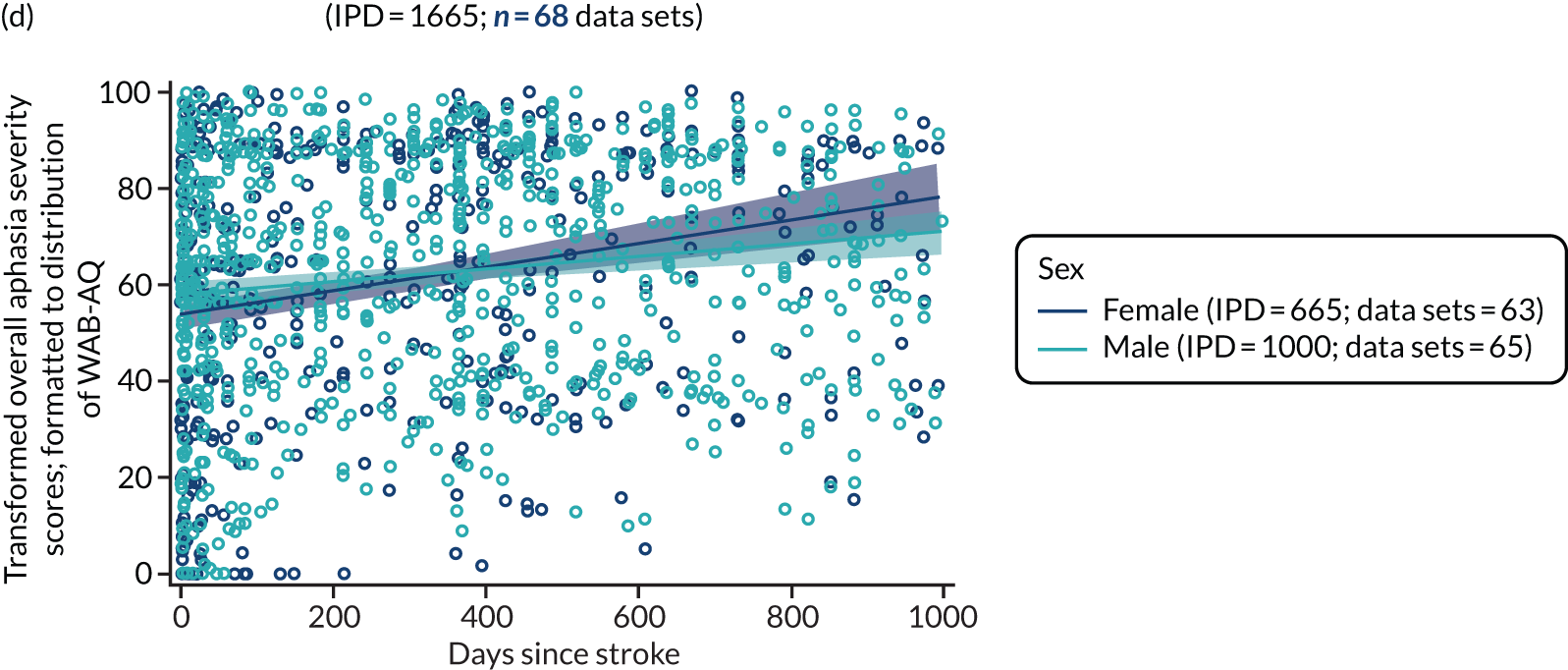

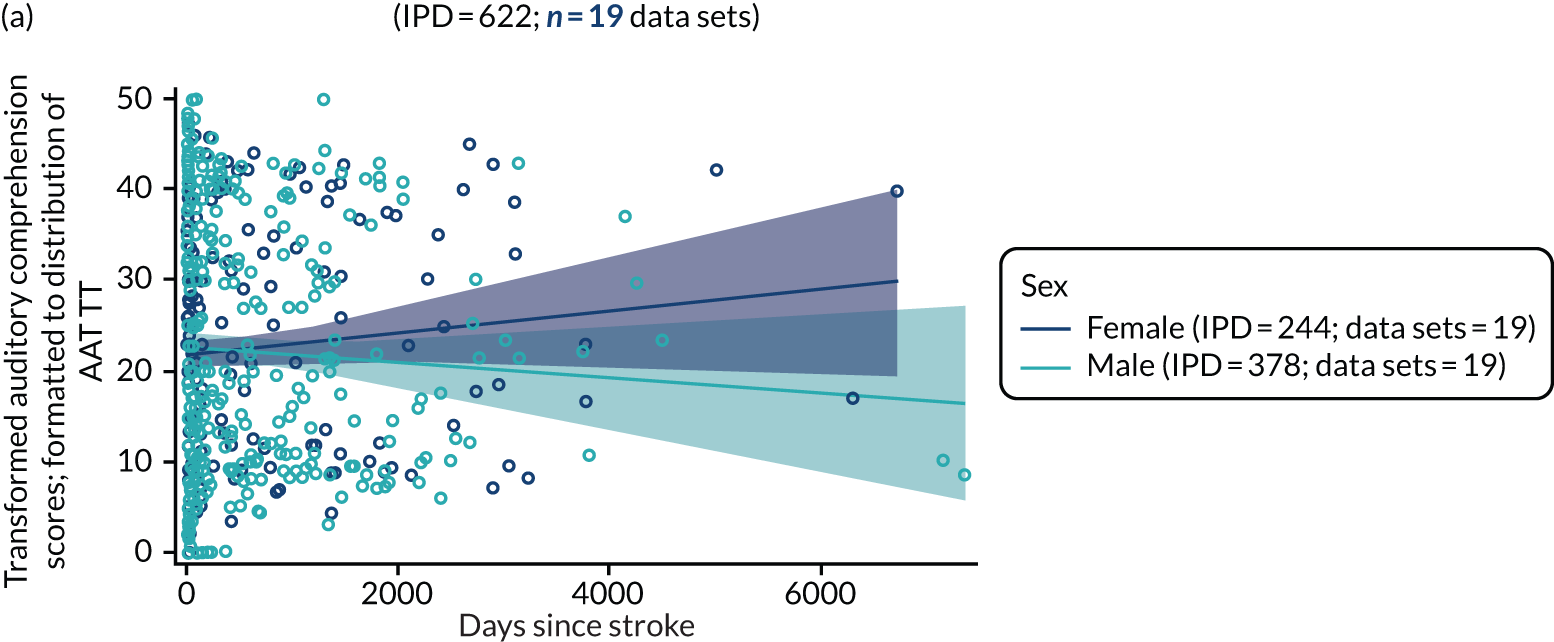

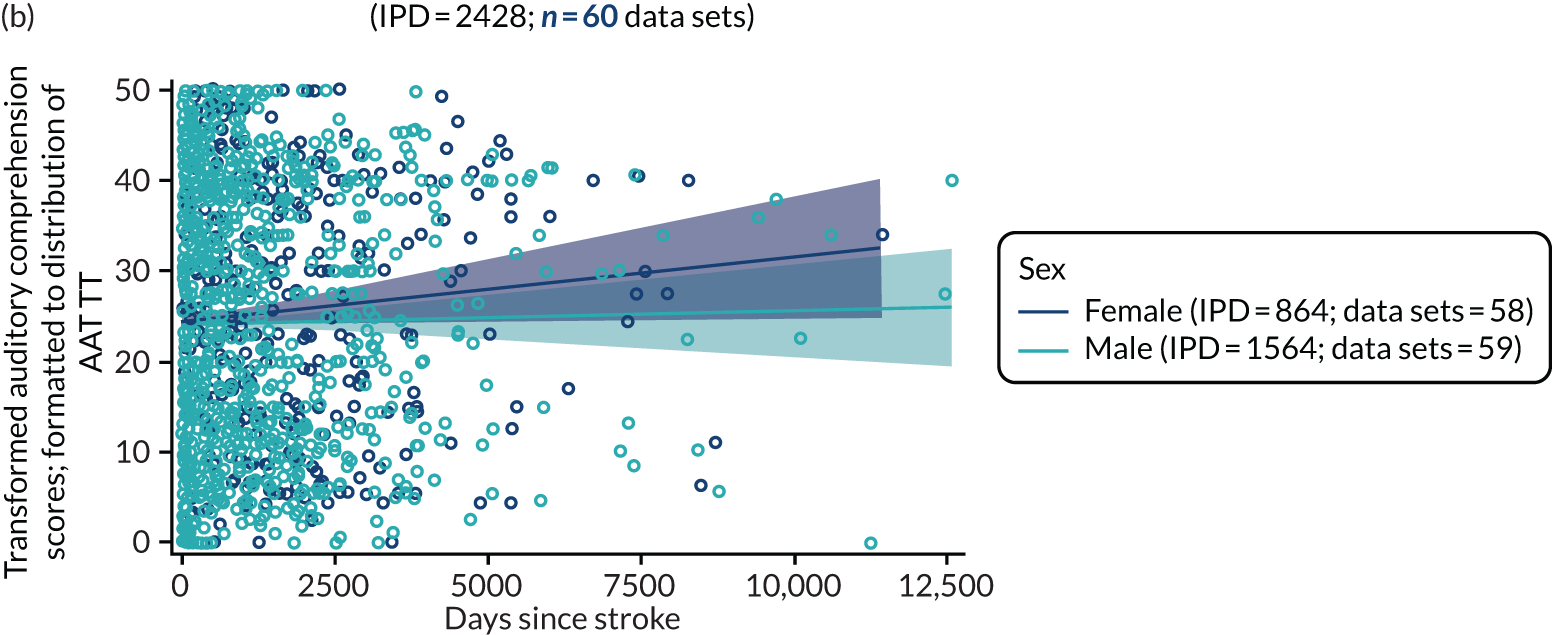

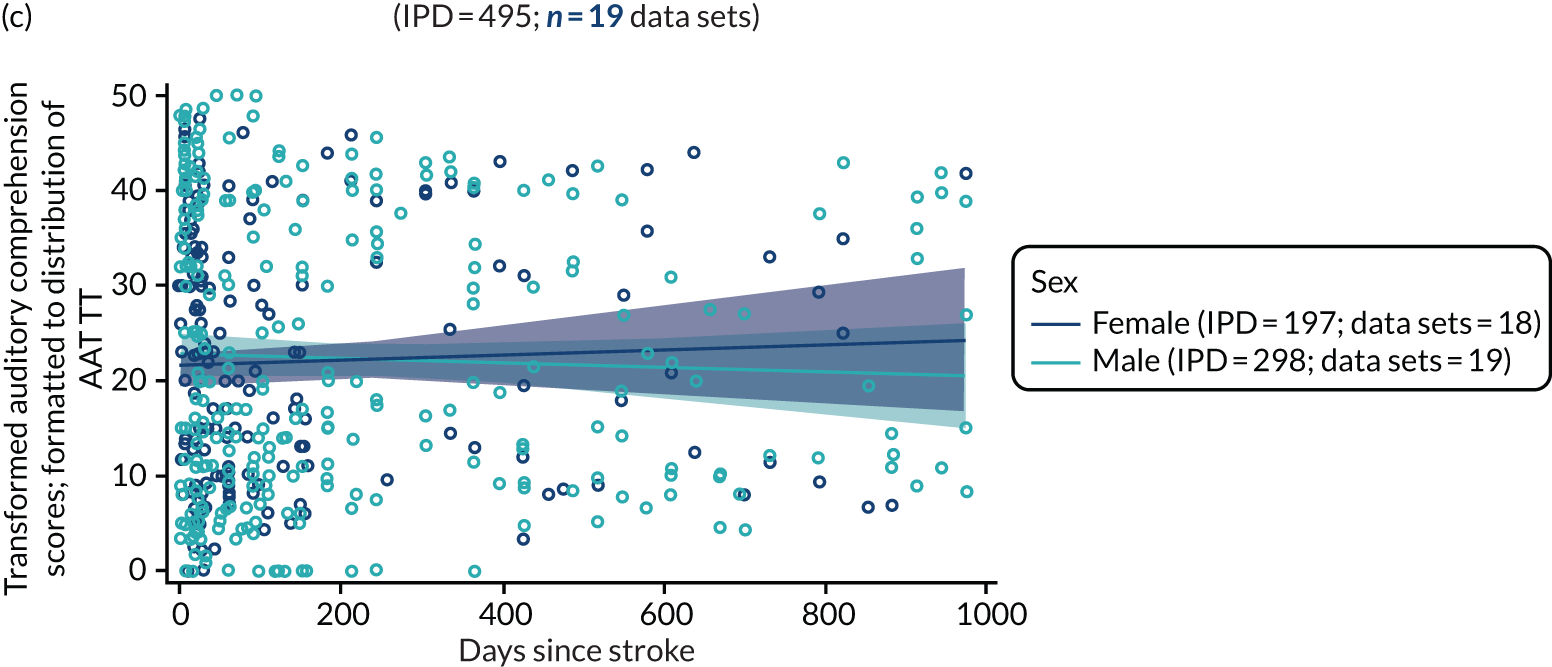

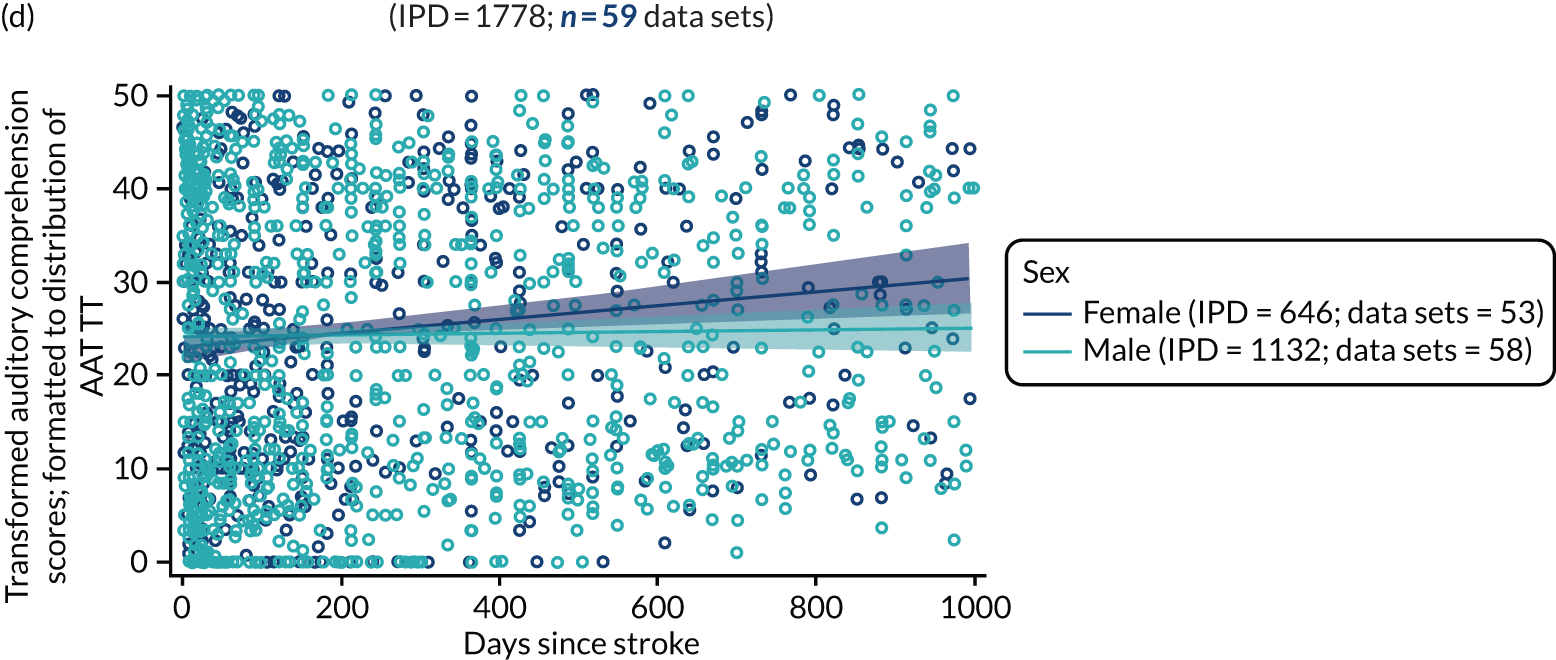

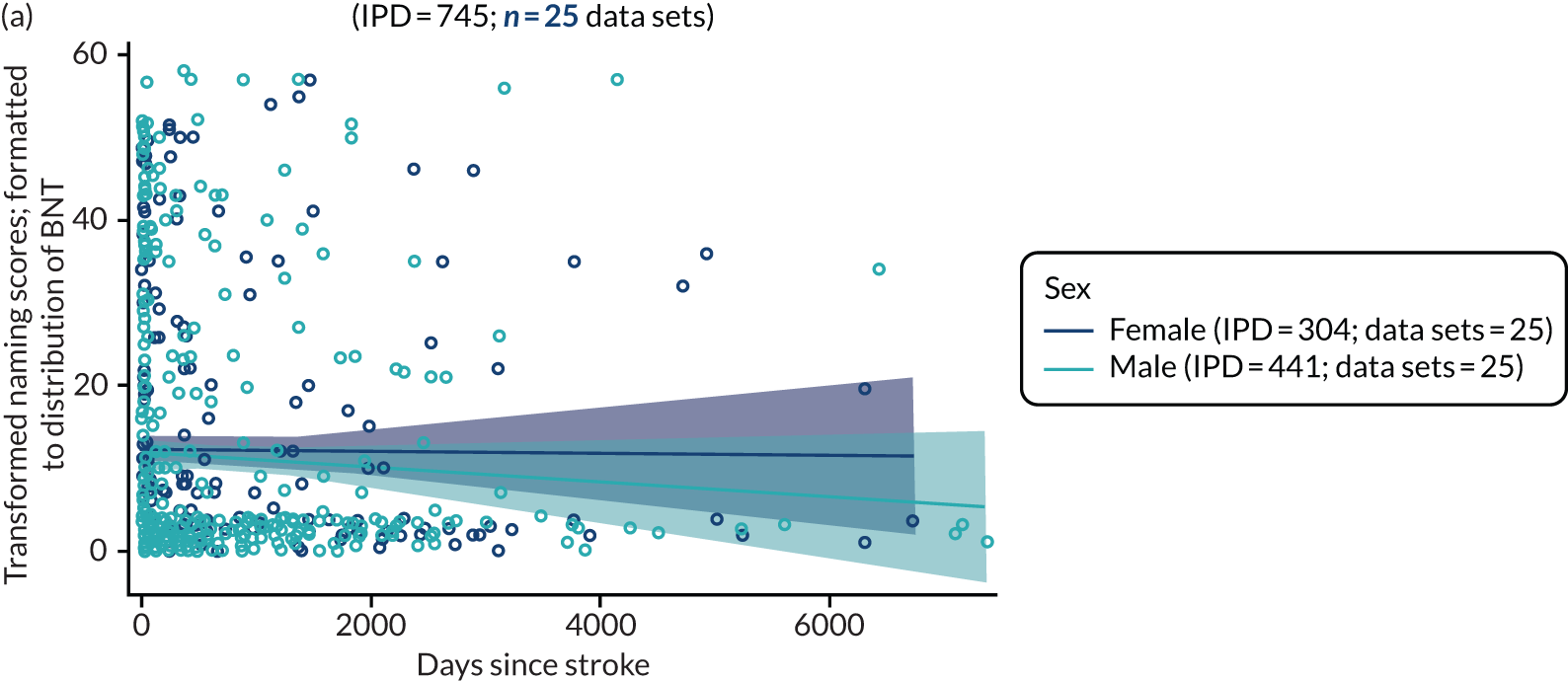

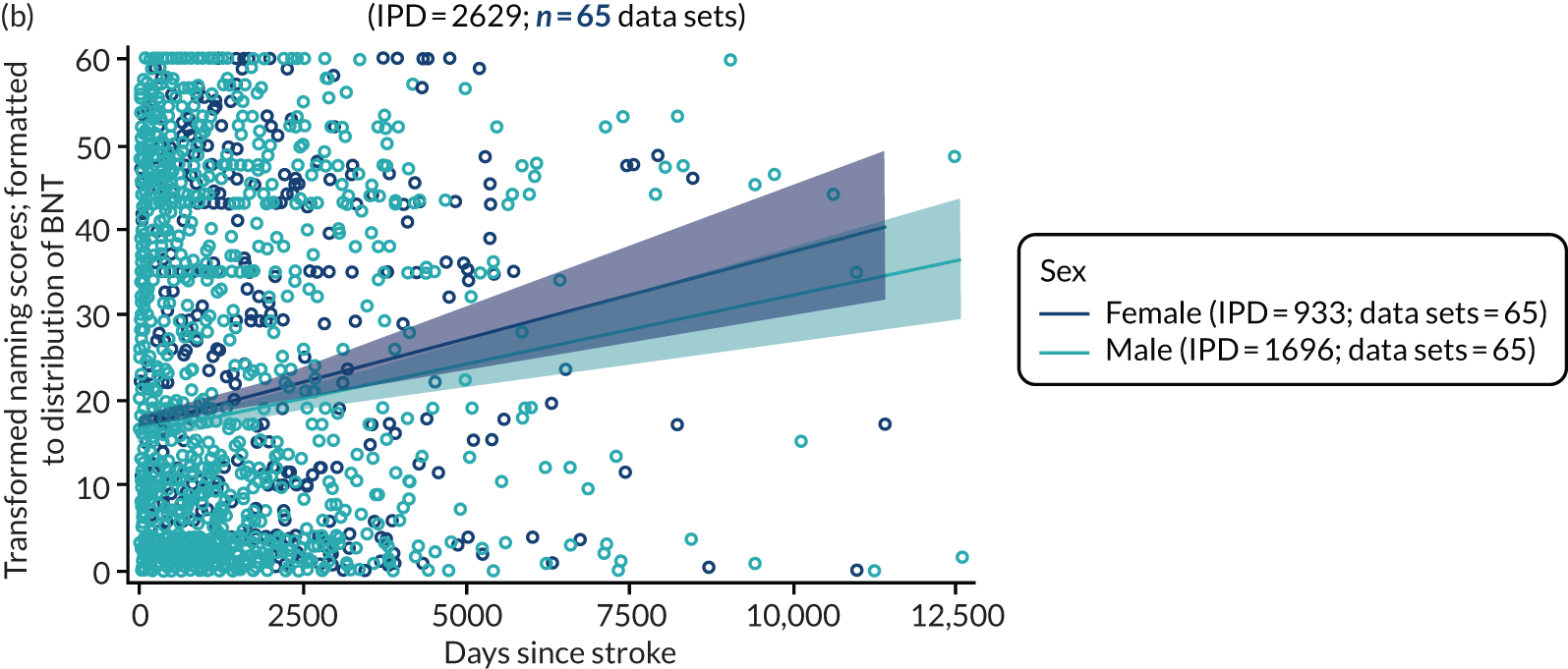

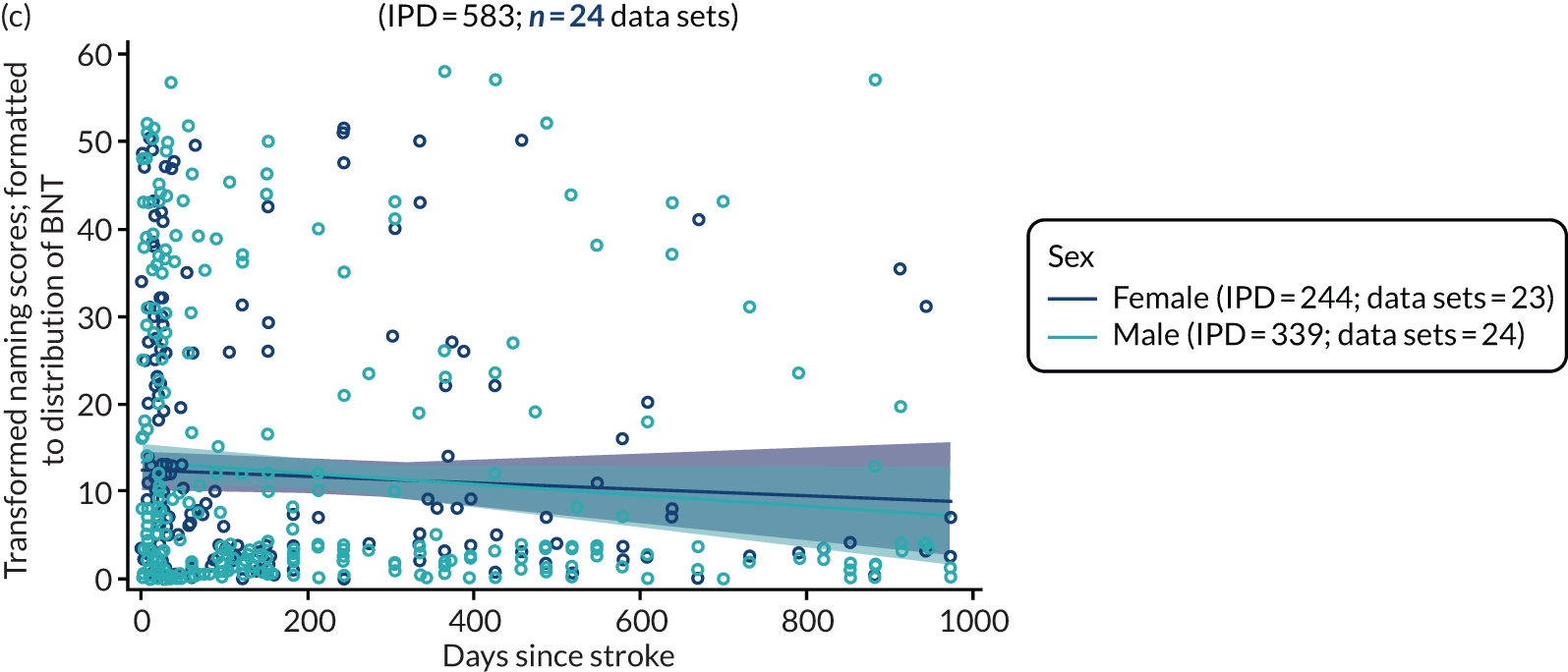

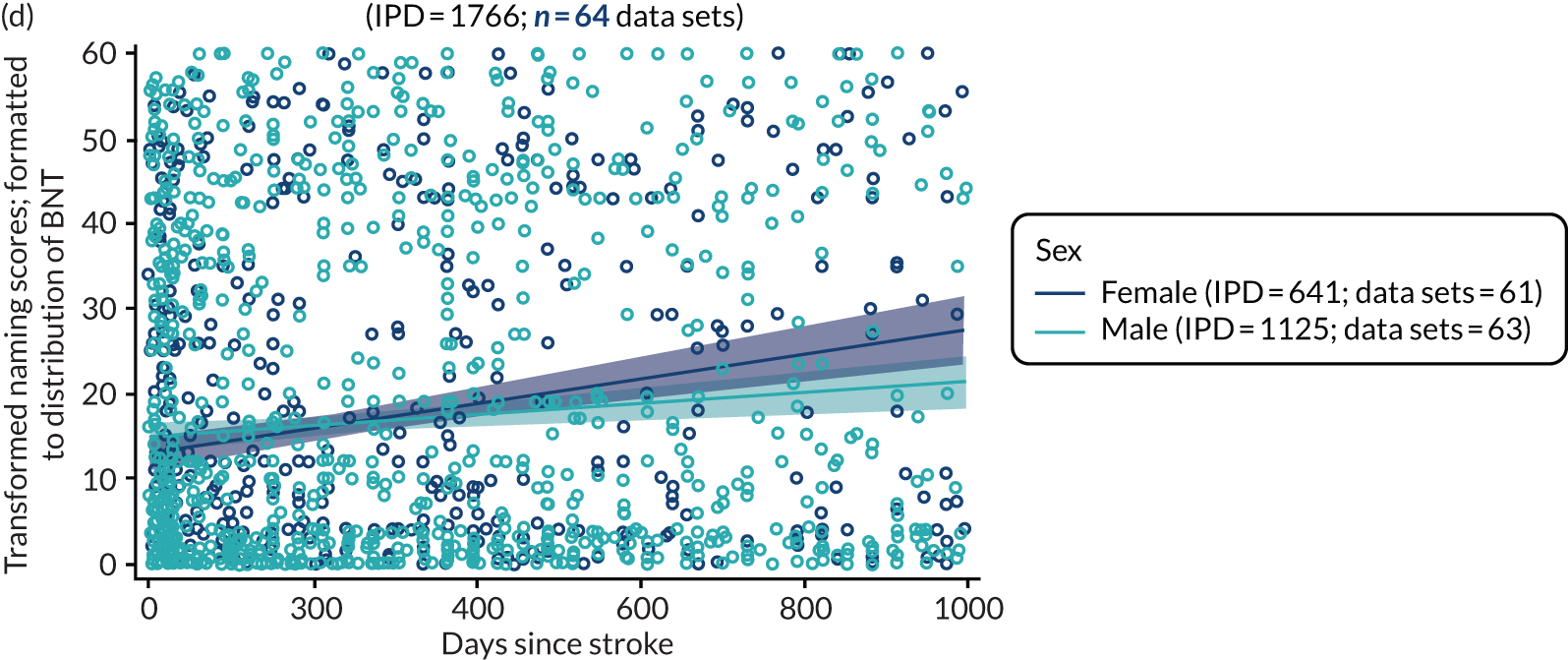

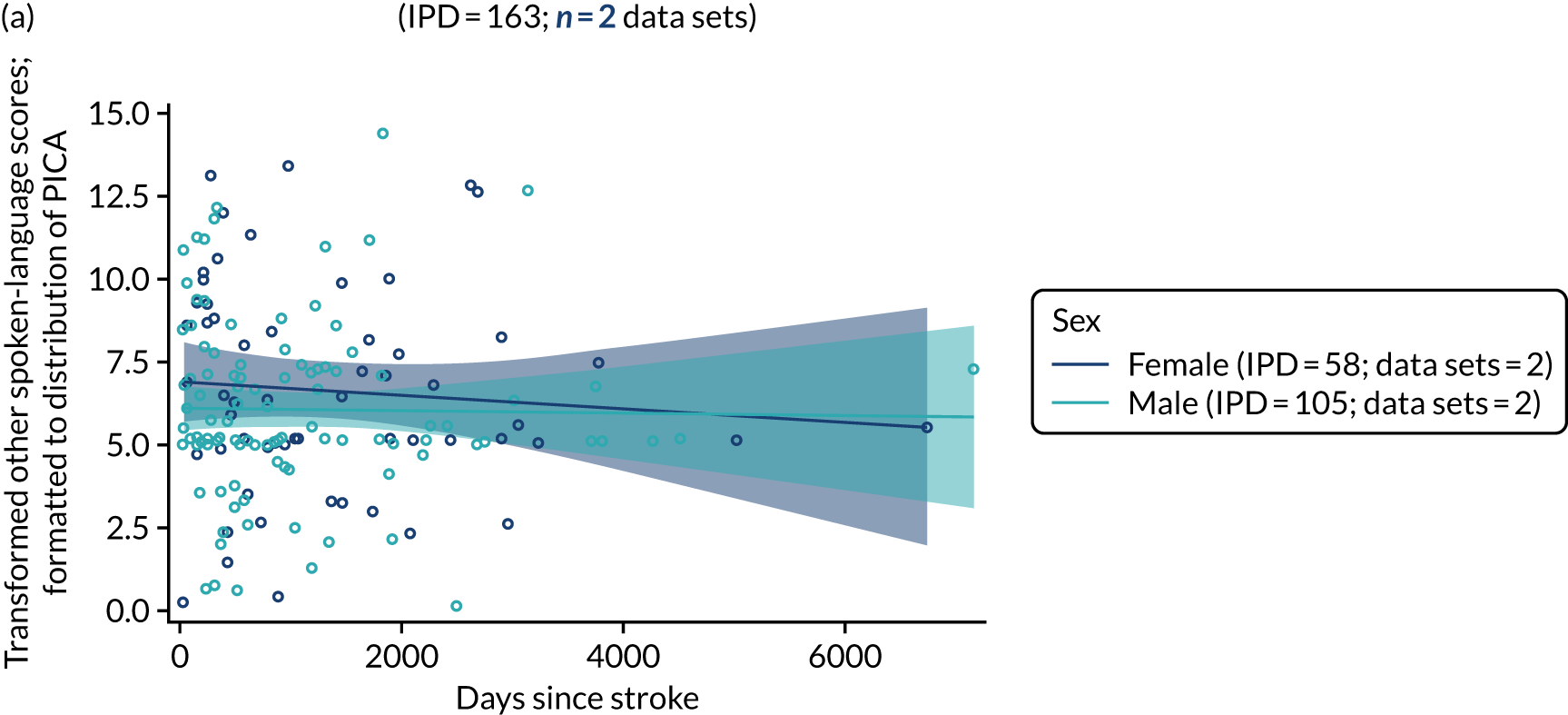

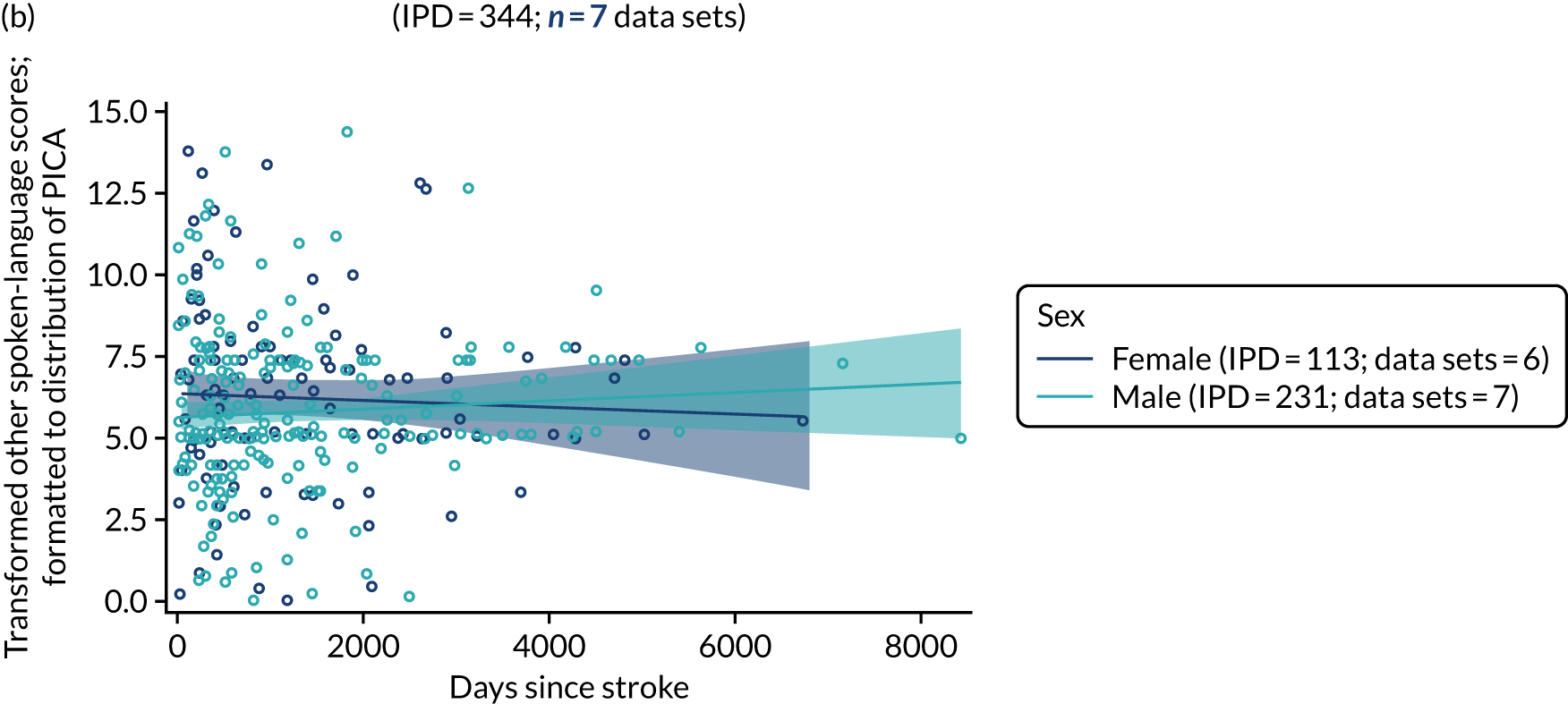

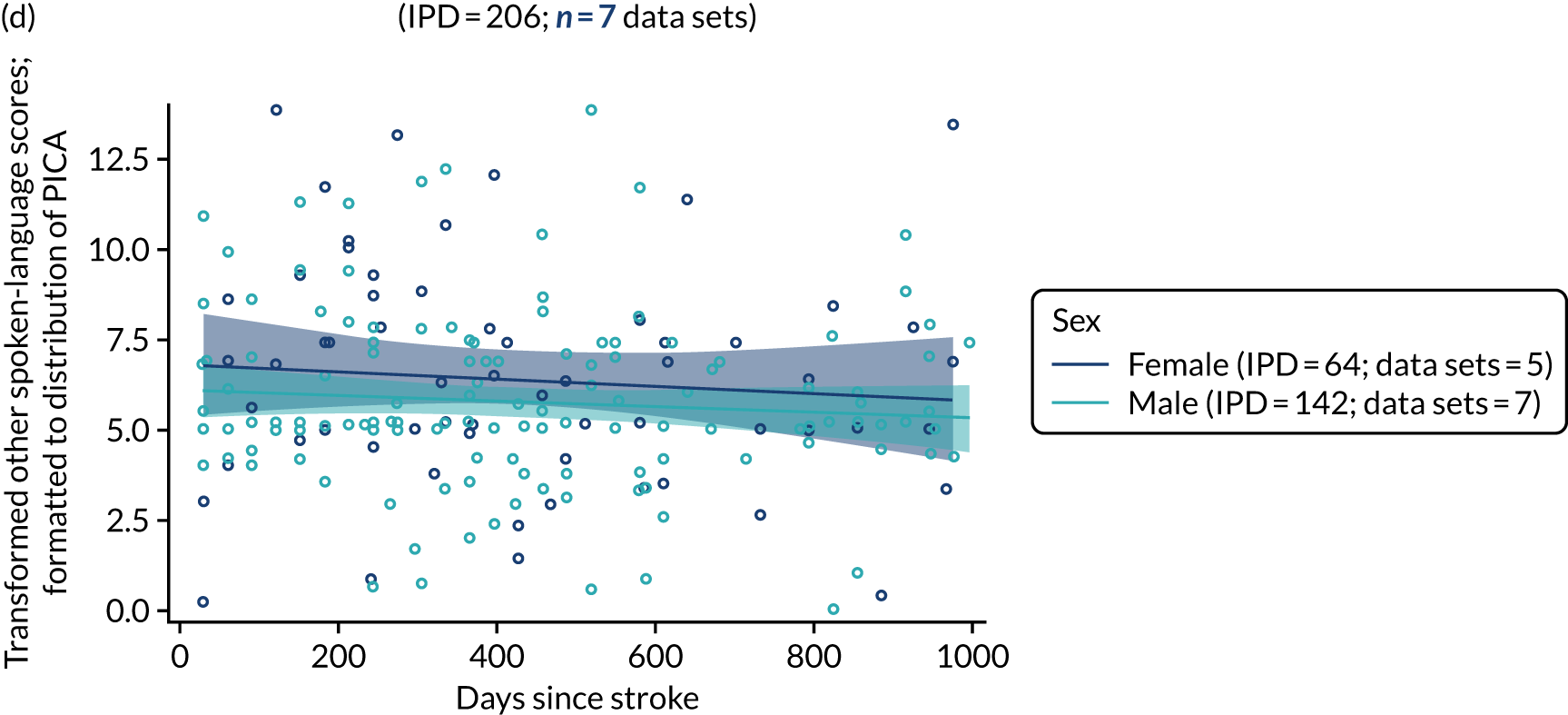

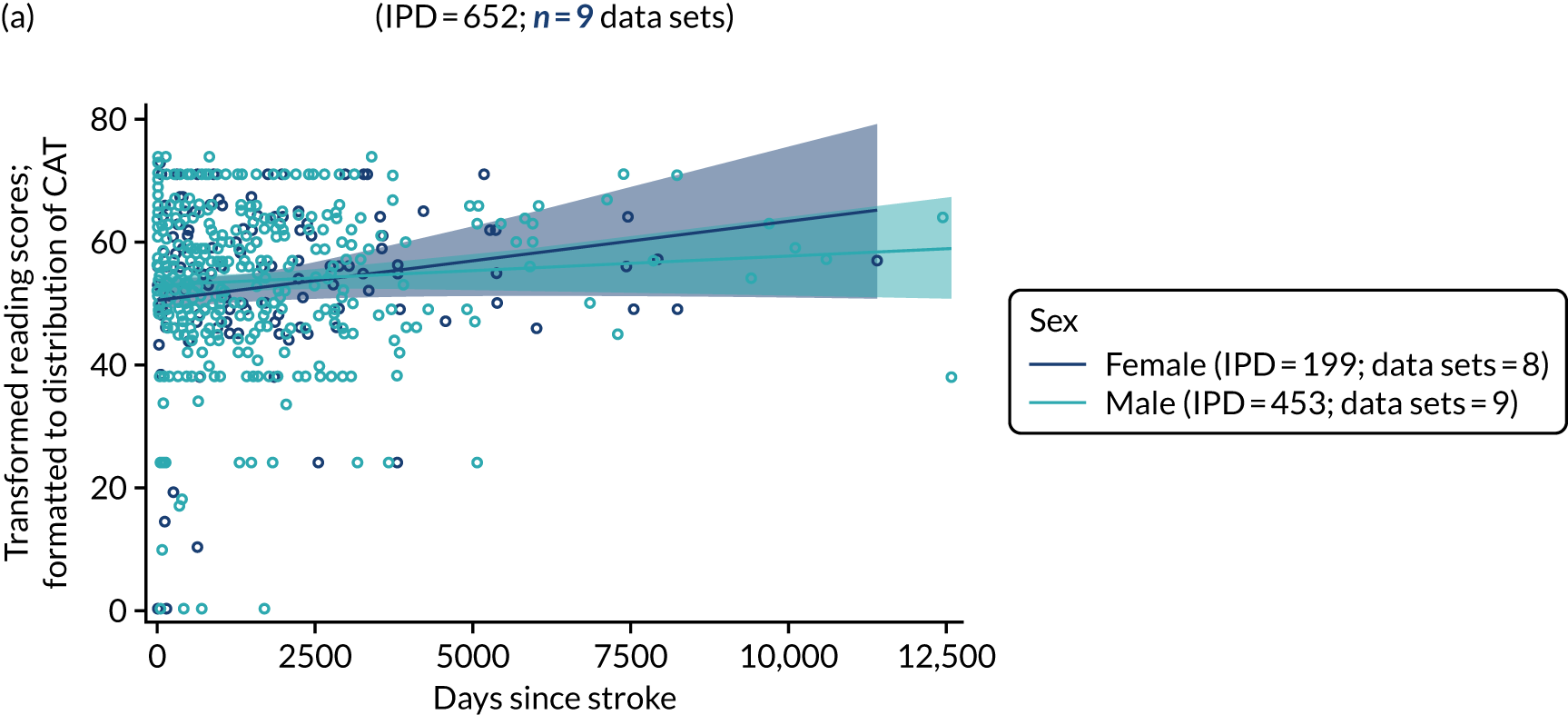

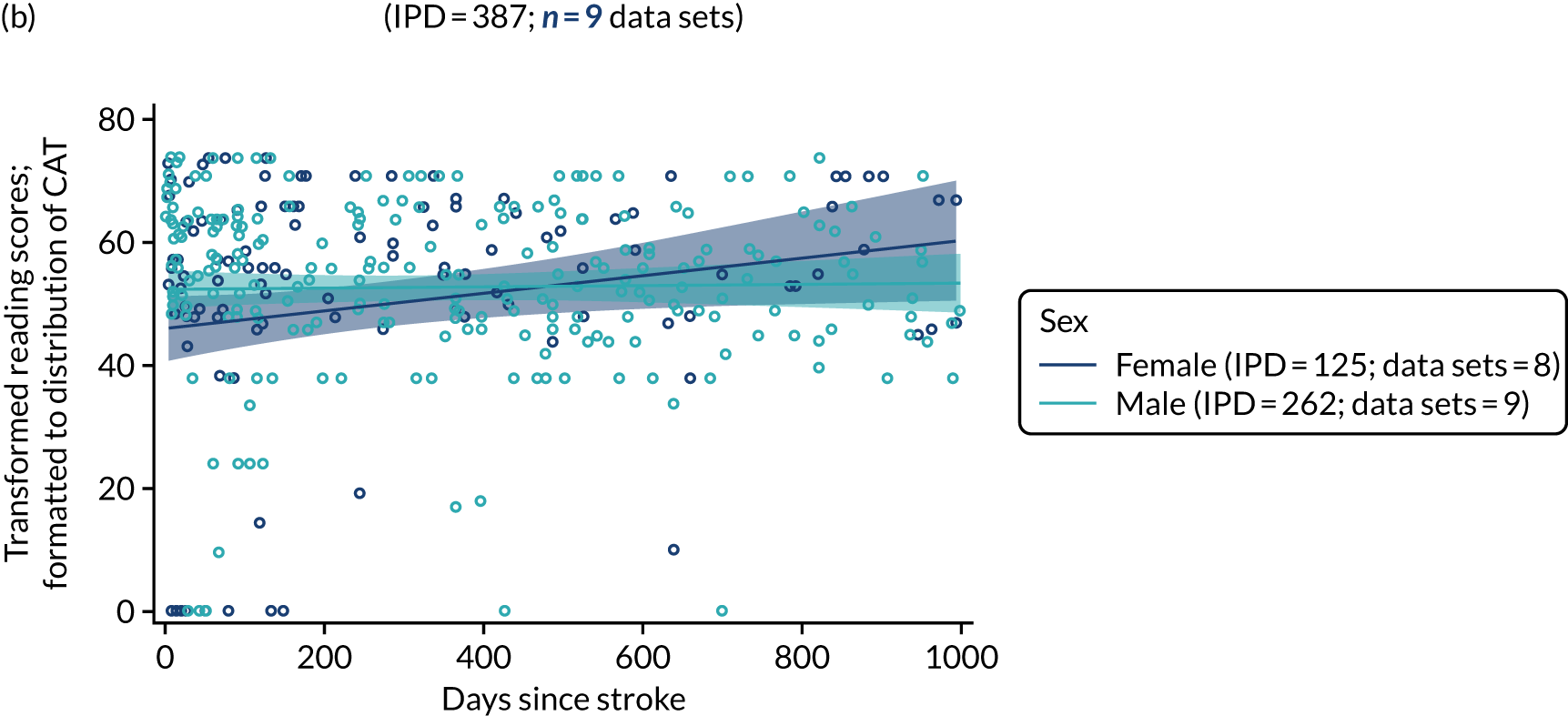

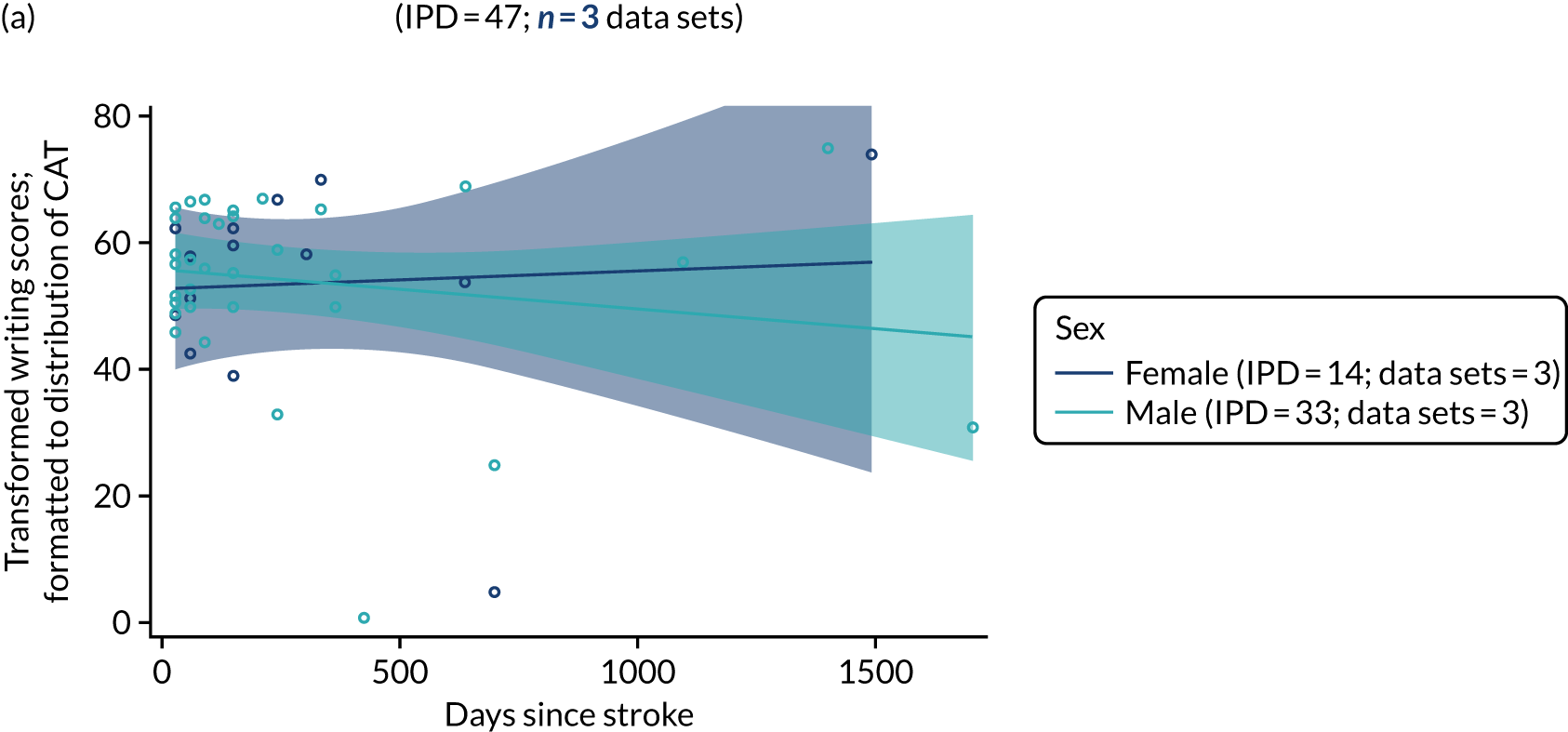

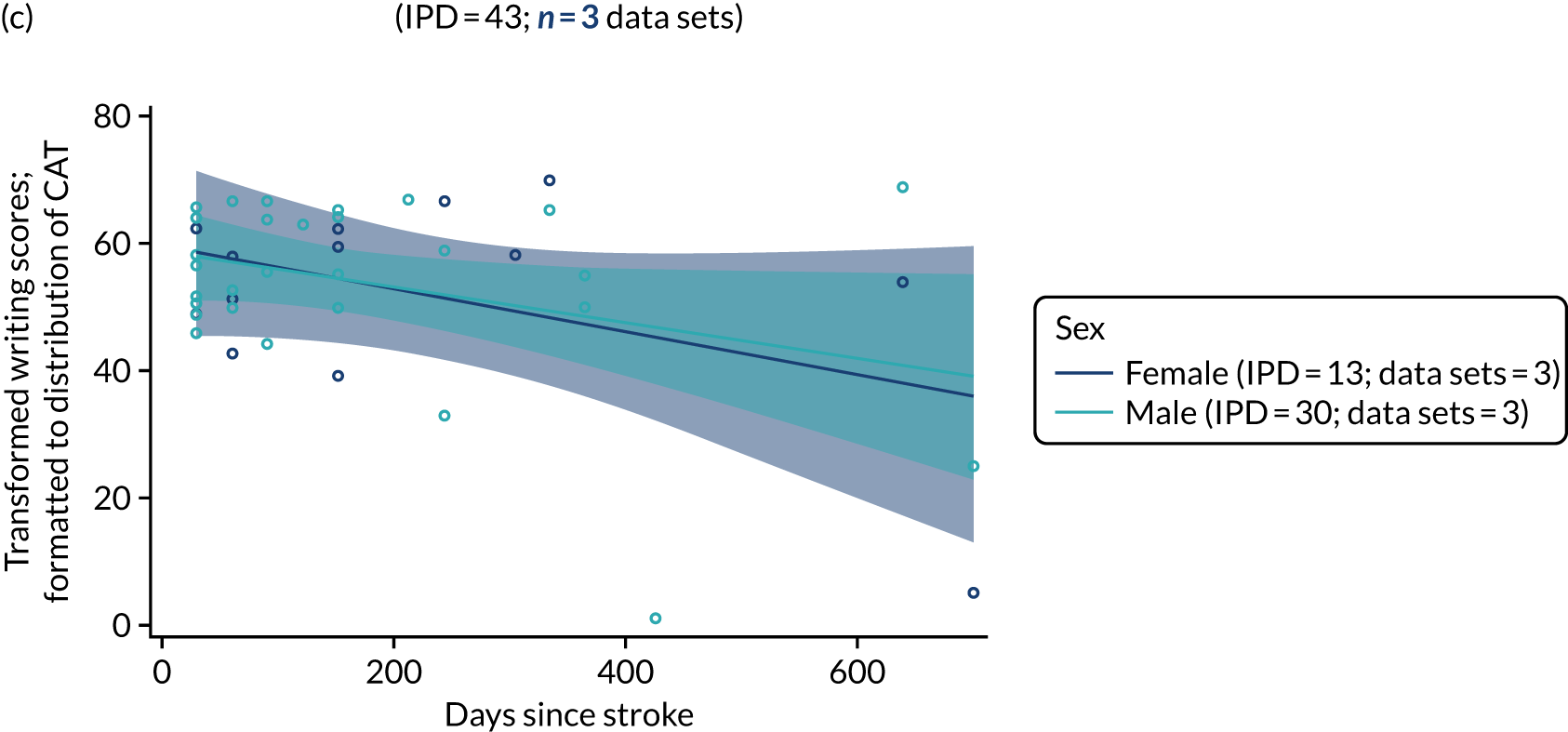

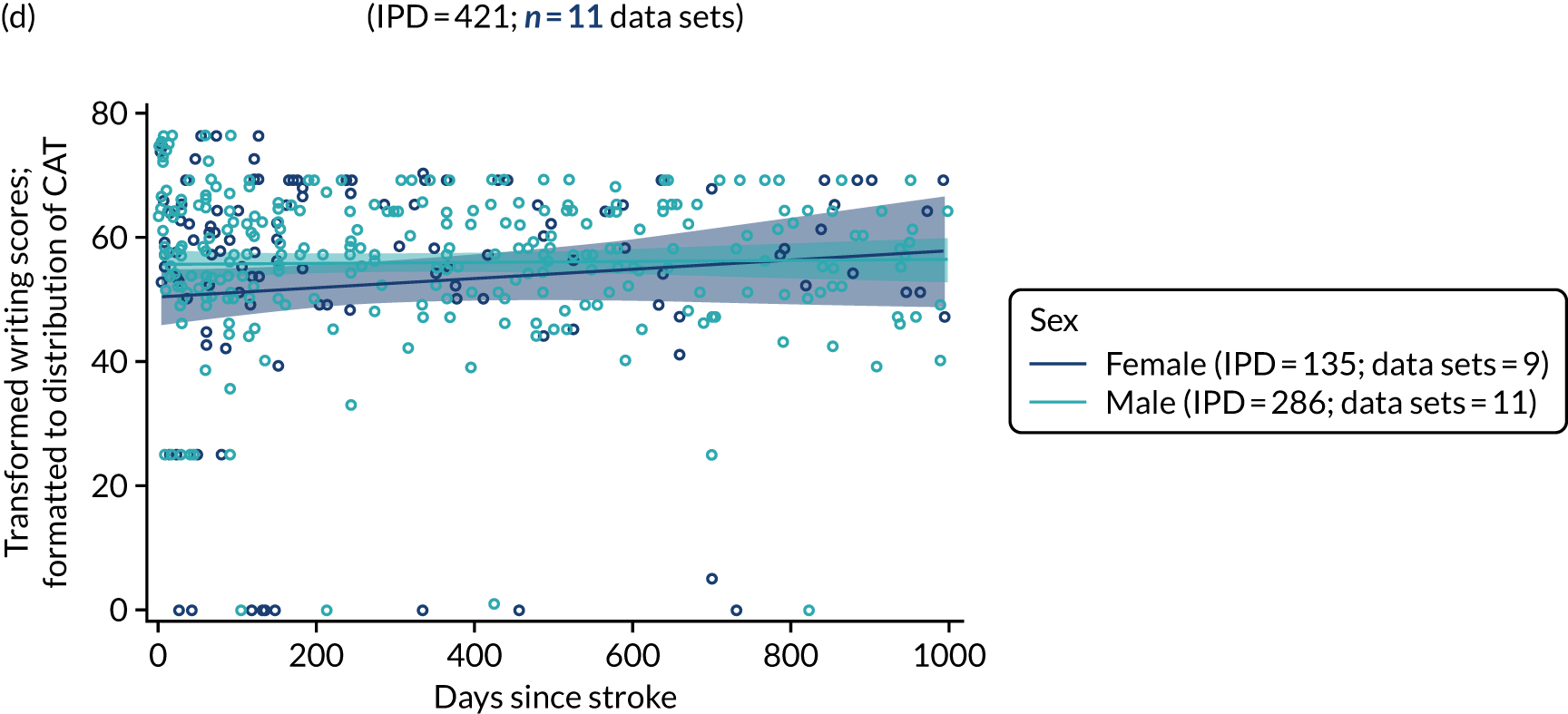

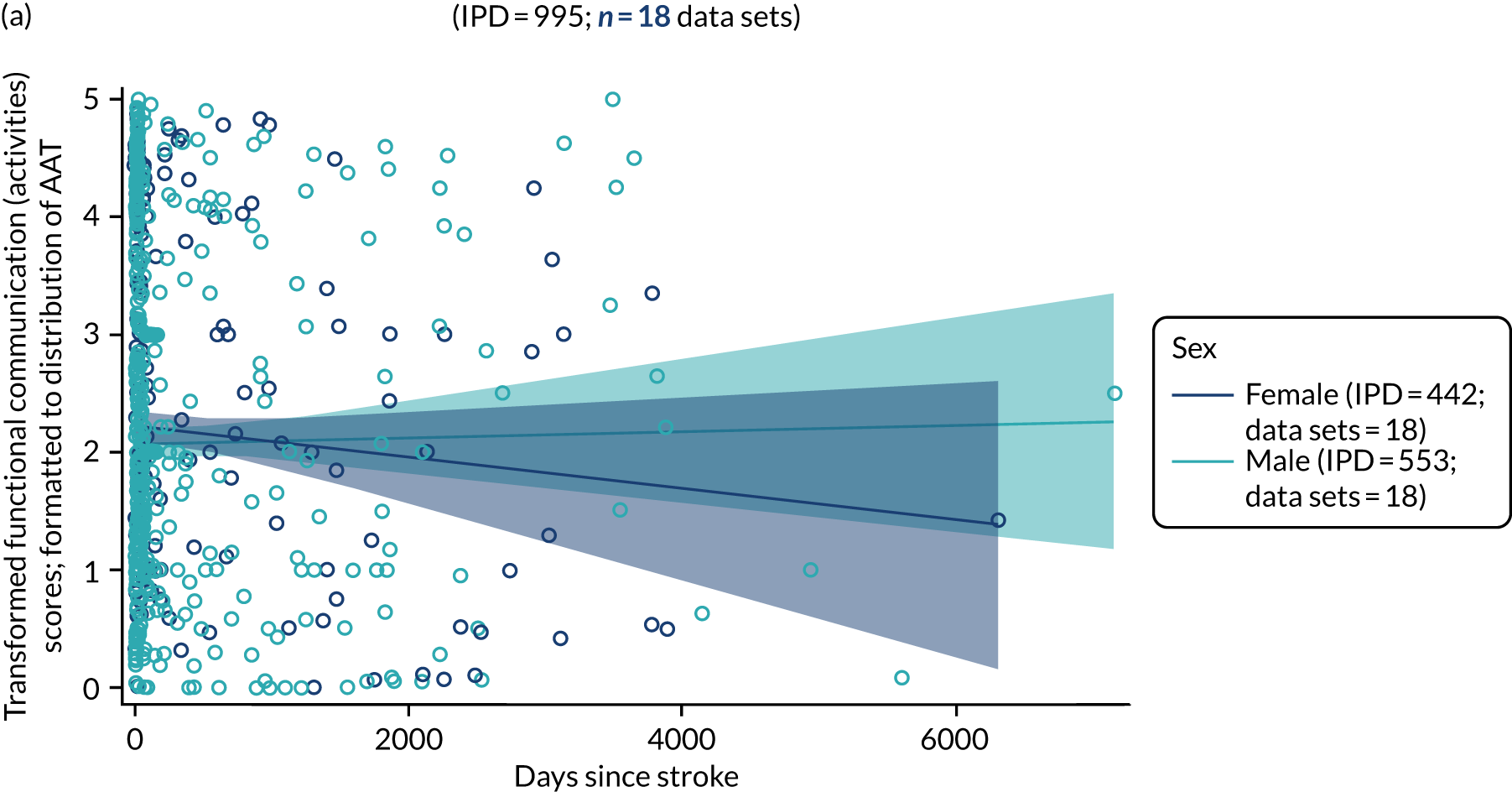

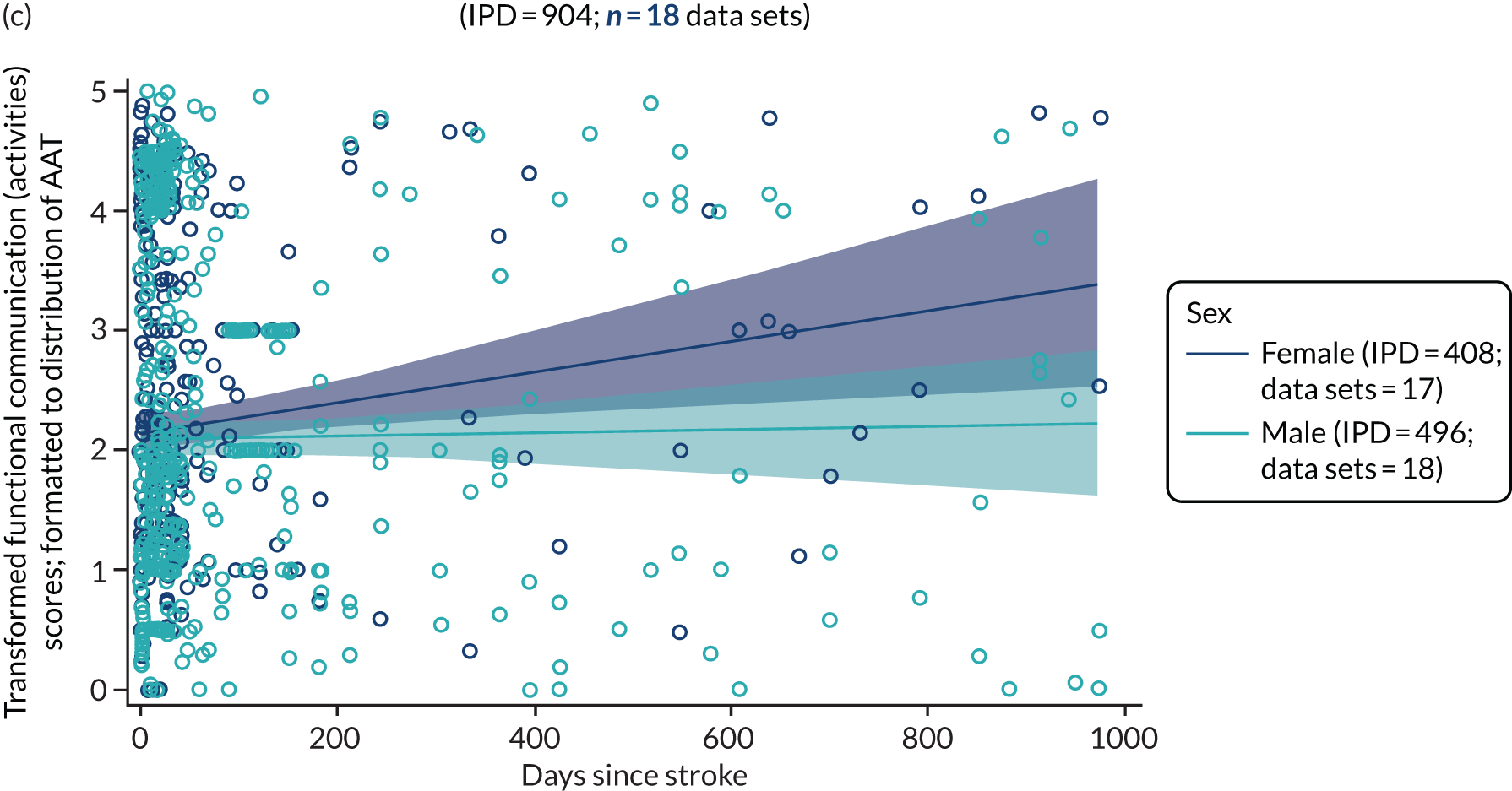

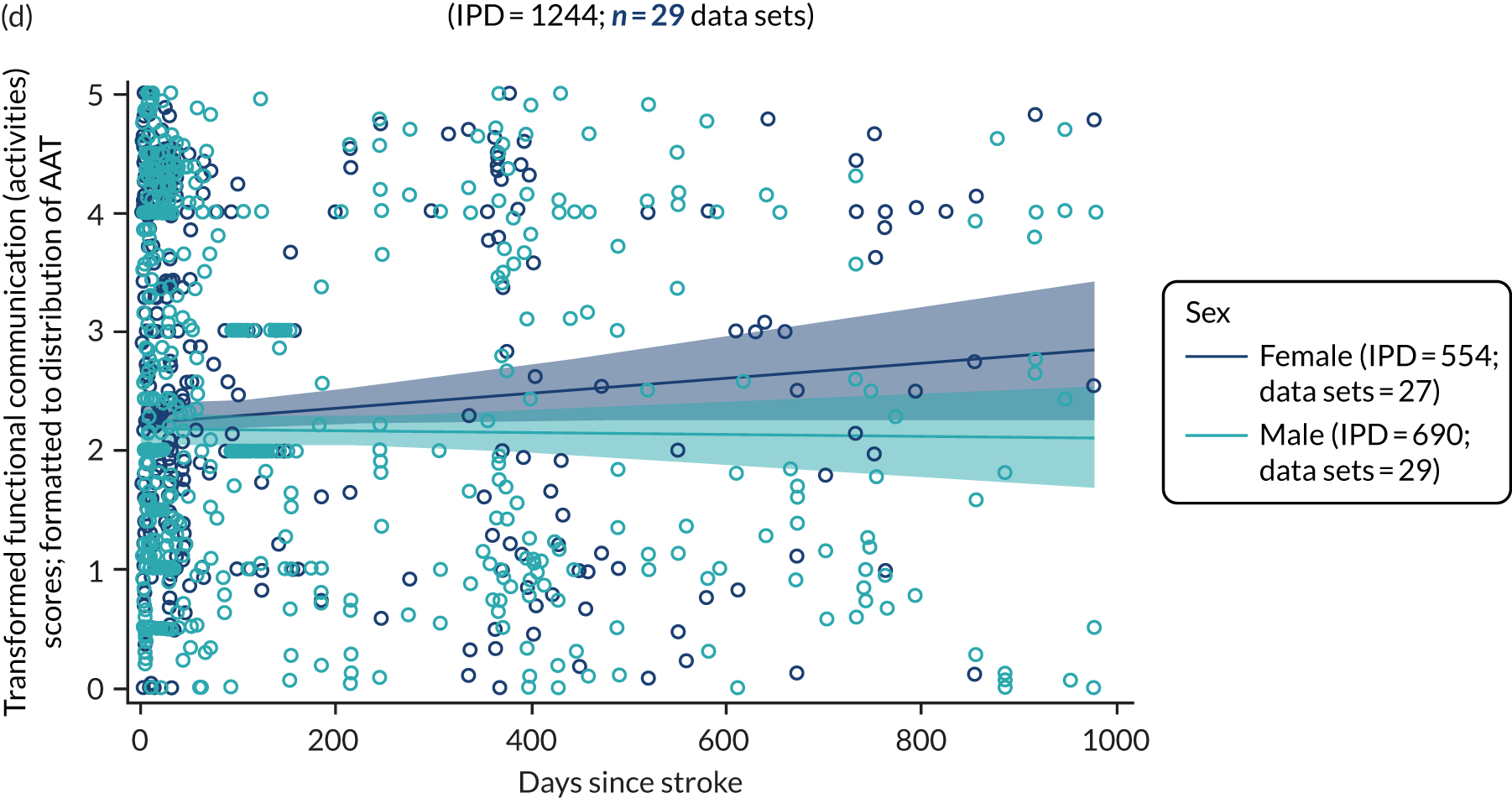

All participants were selected from the total population of people with aphasia after stroke. We identified all data available at study entry for each language domain. This time point was selected as all participants were assessed prior to receiving any study intervention. We then ascertained the time of assessment relative to stroke onset. We plotted all transformed language domain observations available at study entry against time of study entry, relative to stroke onset, for each language domain. We then fitted a regression line to these observations and conducted linear regression analyses to describe whether there was a significant trend towards increased or decreased language domain scores with later time to study entry. We considered whether or not the baseline data reflected the trajectory findings based on participants’ language scores over time (see Chapter 4). We considered the distribution of language scores at clinically relevant time points (e.g. study entry between 0 and 1000 days since stroke). Finally, we considered whether or not there was any suggestion of selection bias in recruitment to aphasia studies based on participants’ language scores over time since stroke.

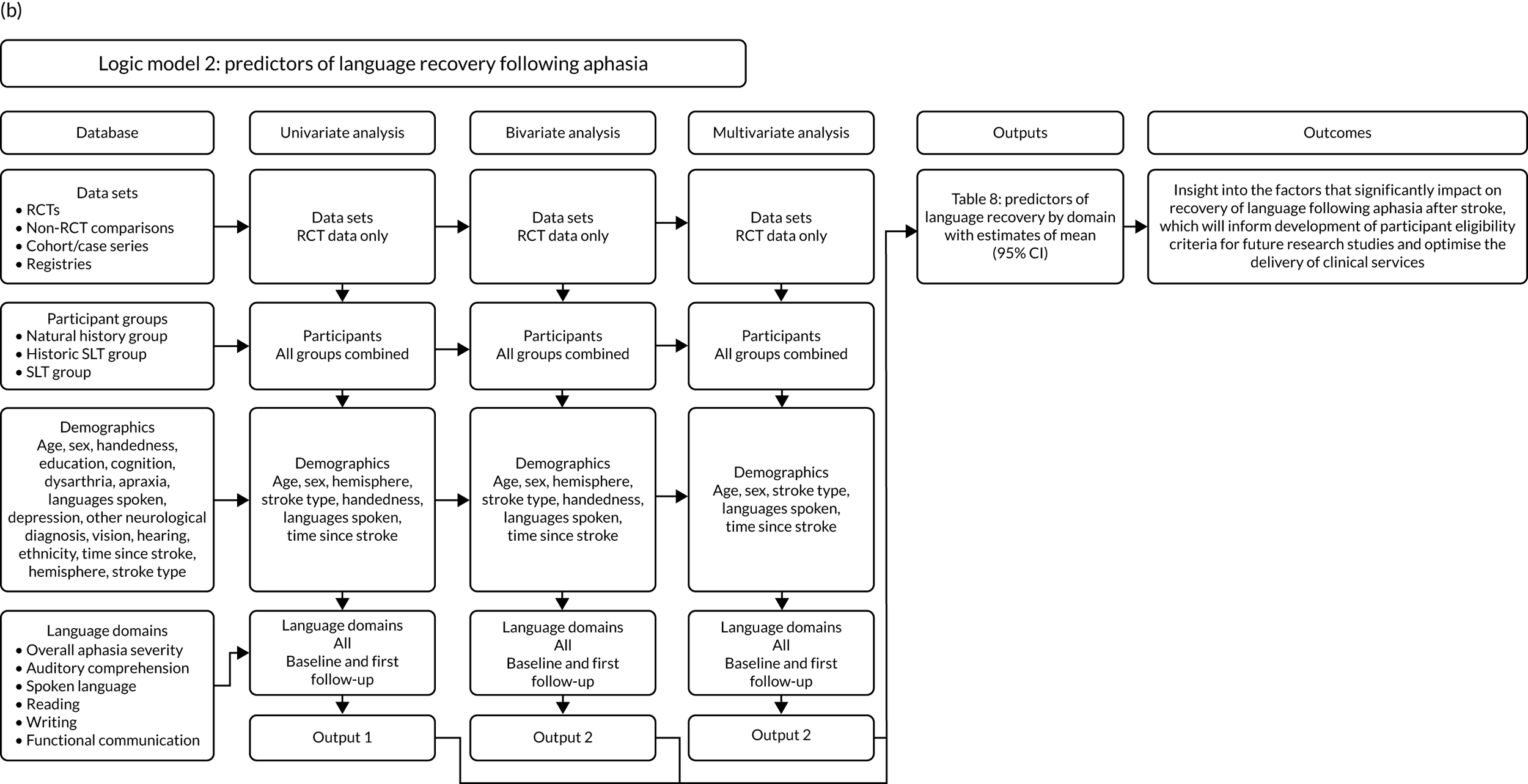

Predictors of language recovery

Demographic and stroke covariates identified as statistically significant from the patterns of language recovery analysis (see Appendix 3, Figure 26a) informed our primary statistical analysis of the predictors of language recovery over time. We considered evidence informing other areas of stroke rehabilitation and common assumptions in the context of aphasia rehabilitation.

Whether or not participants had received SLT in the primary research study (SLT/historical SLT or no SLT) was also included in the analyses (see Appendix 3, Figure 26b). Language recovery on a continuous scale was regressed onto the covariates of interest. Initially, each predictor was checked using univariable analysis; covariates significantly associated with the primary outcome at a univariable level (i.e. a p-value of < 0.1) were included in the multivariable regression analysis. Thereafter, covariates were introduced and retained in the final multivariable model only if found to be statistically significant. Each analysis included the study ID as a random covariate, to account for possible variability in the outcome measure between studies.

Participants’ stroke profiles, demographic characteristics and living contexts at baseline and follow-up (when available) were explored graphically and using summary statistics by showing means and standard deviations for continuous and count data (or median and IQR if data were skewed), and frequency and percentages for binary and categorical data. Standard statistical tests (e.g. chi-squared tests) were employed to check formally for statistical differences.

Factors associated with language score changes: age, sex and time since stroke

We performed regression, modelling a trend towards increasing proportion of change, and including age, sex and time since stroke (days) as covariates in this model, to ascertain whether or not there was a relationship between age, sex and time since index stroke on the degree of recovery observed.

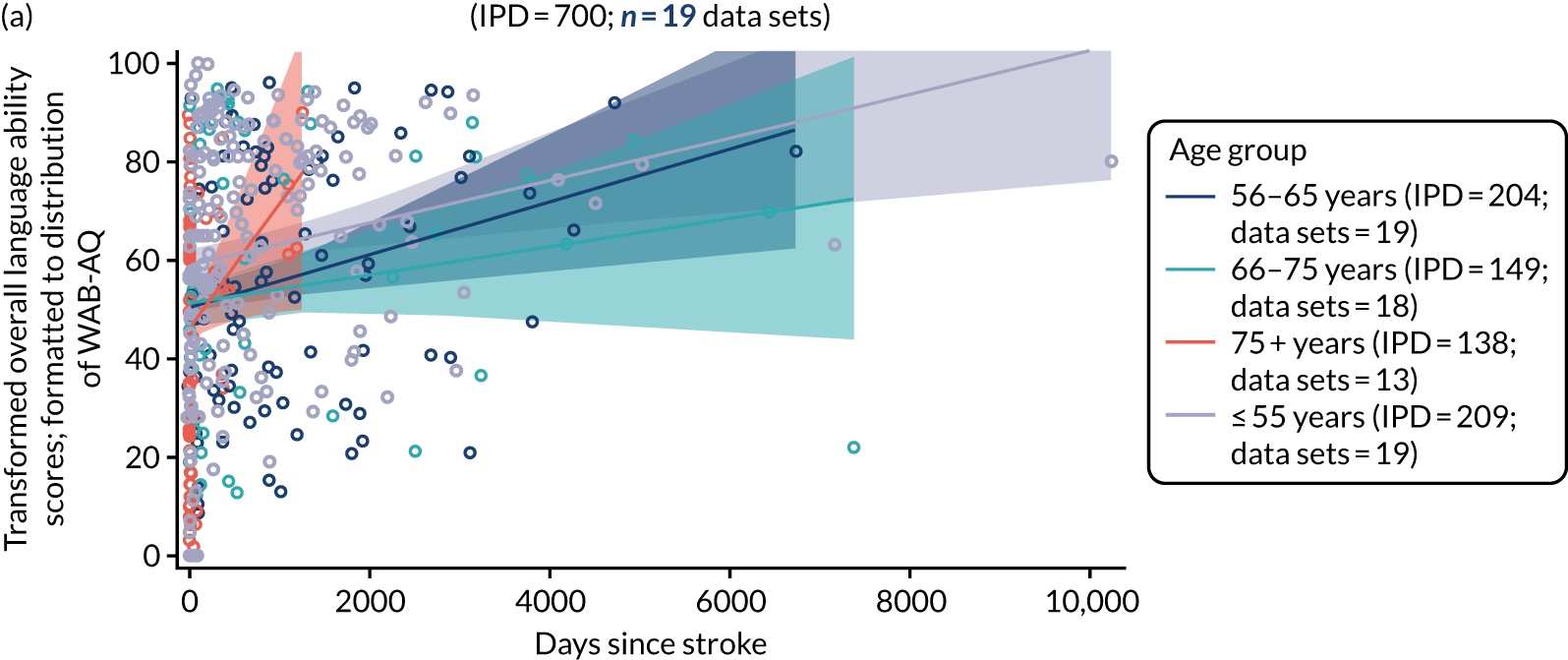

Distribution of language scores at study entry: age, sex and living context

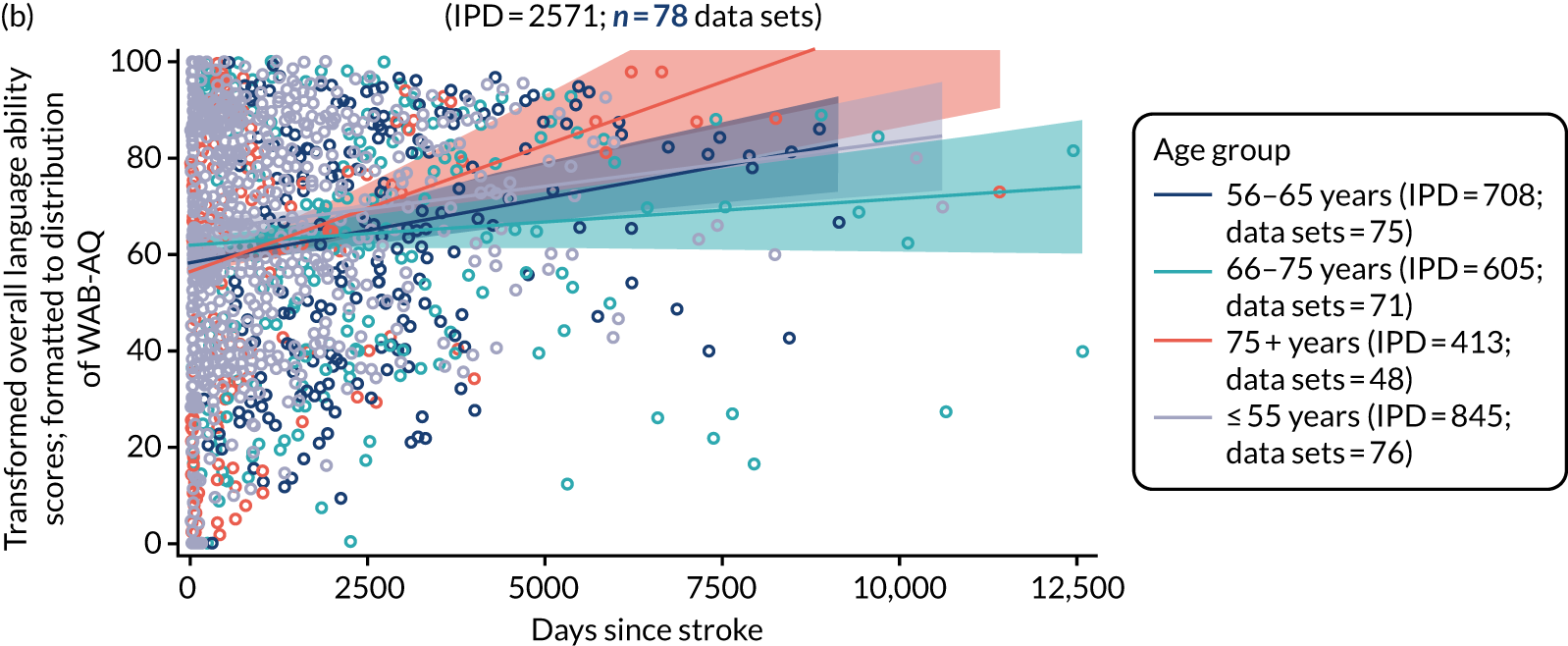

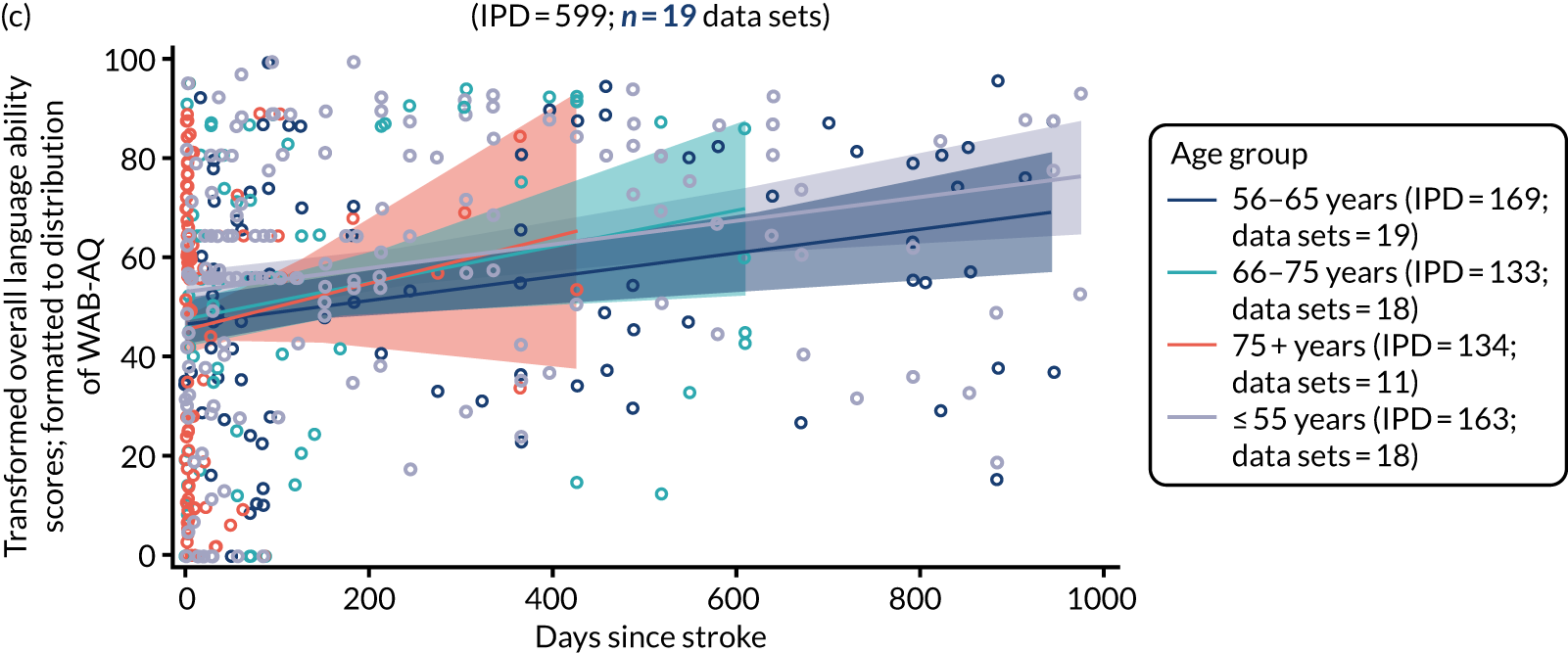

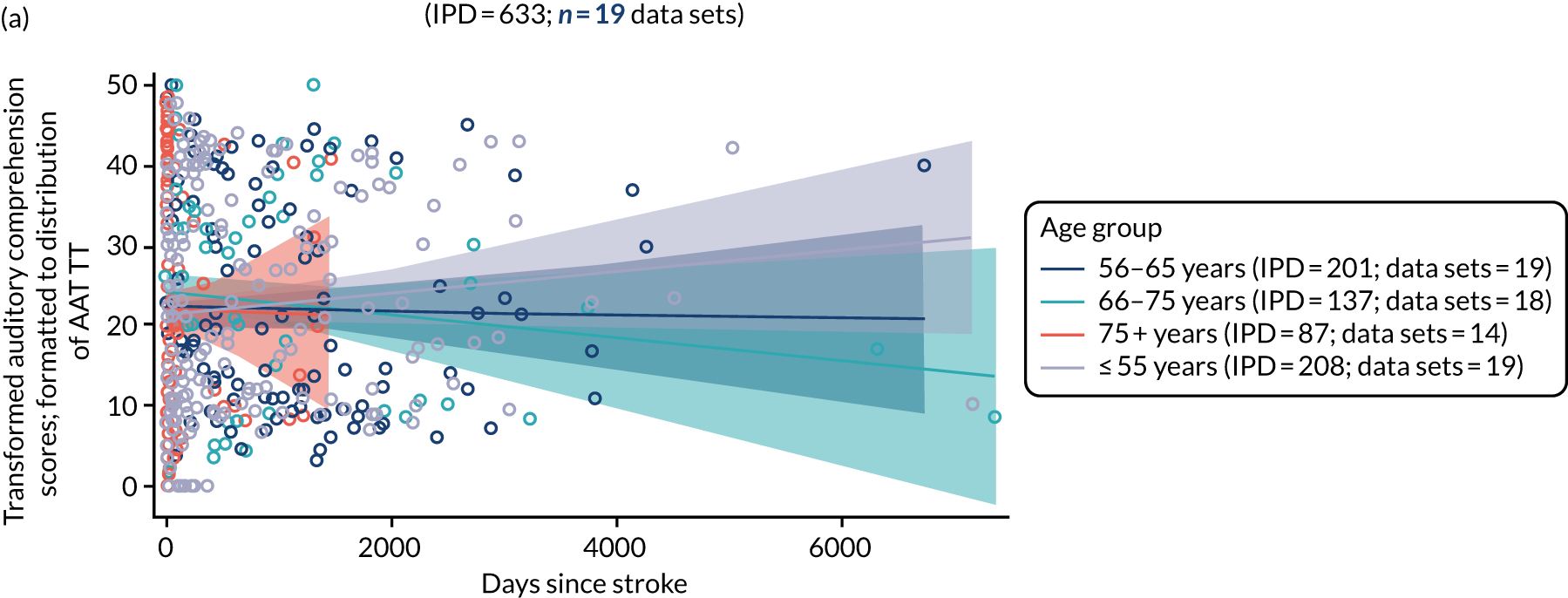

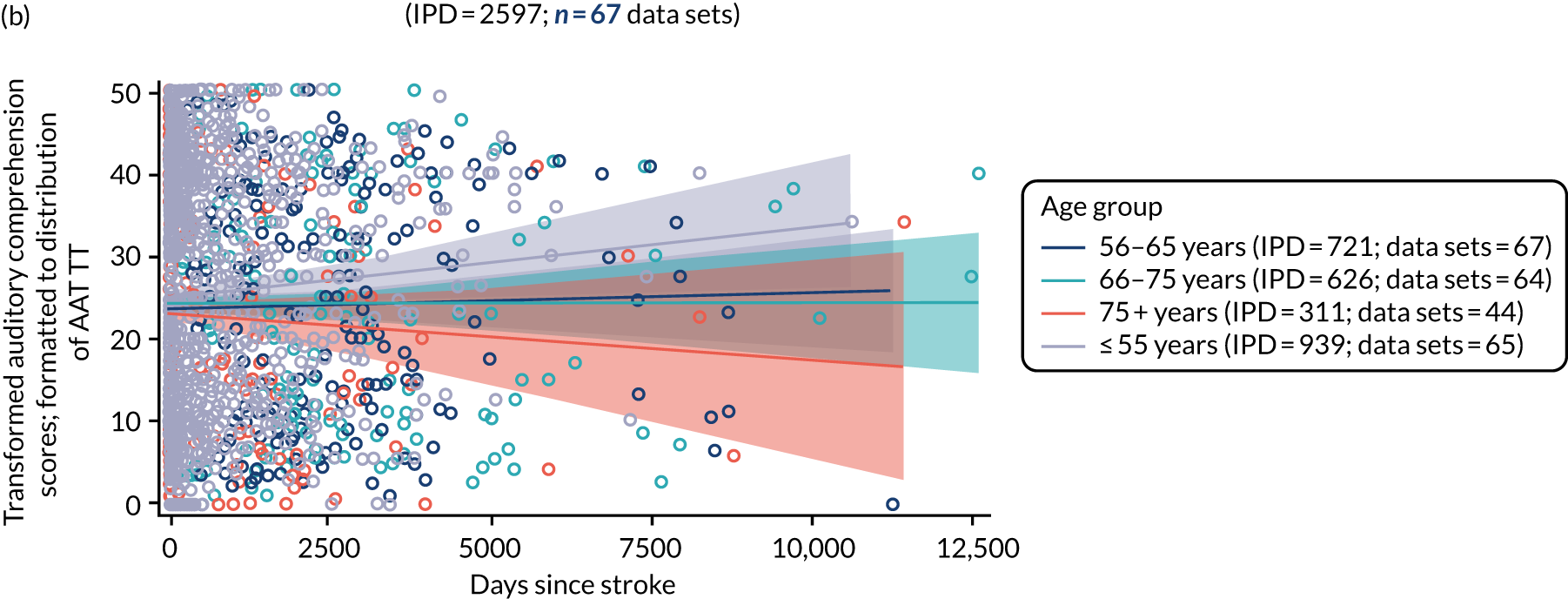

Building on the earlier analyses, we identified all participants’ data from across all data sets for the specified language domains at study entry in advance of any study-level intervention. Using the data on time since stroke, we plotted the language scores and explored their distribution across different age groups (≤ 55, 56–65, 66–75 and > 75 years), sex and living contexts.

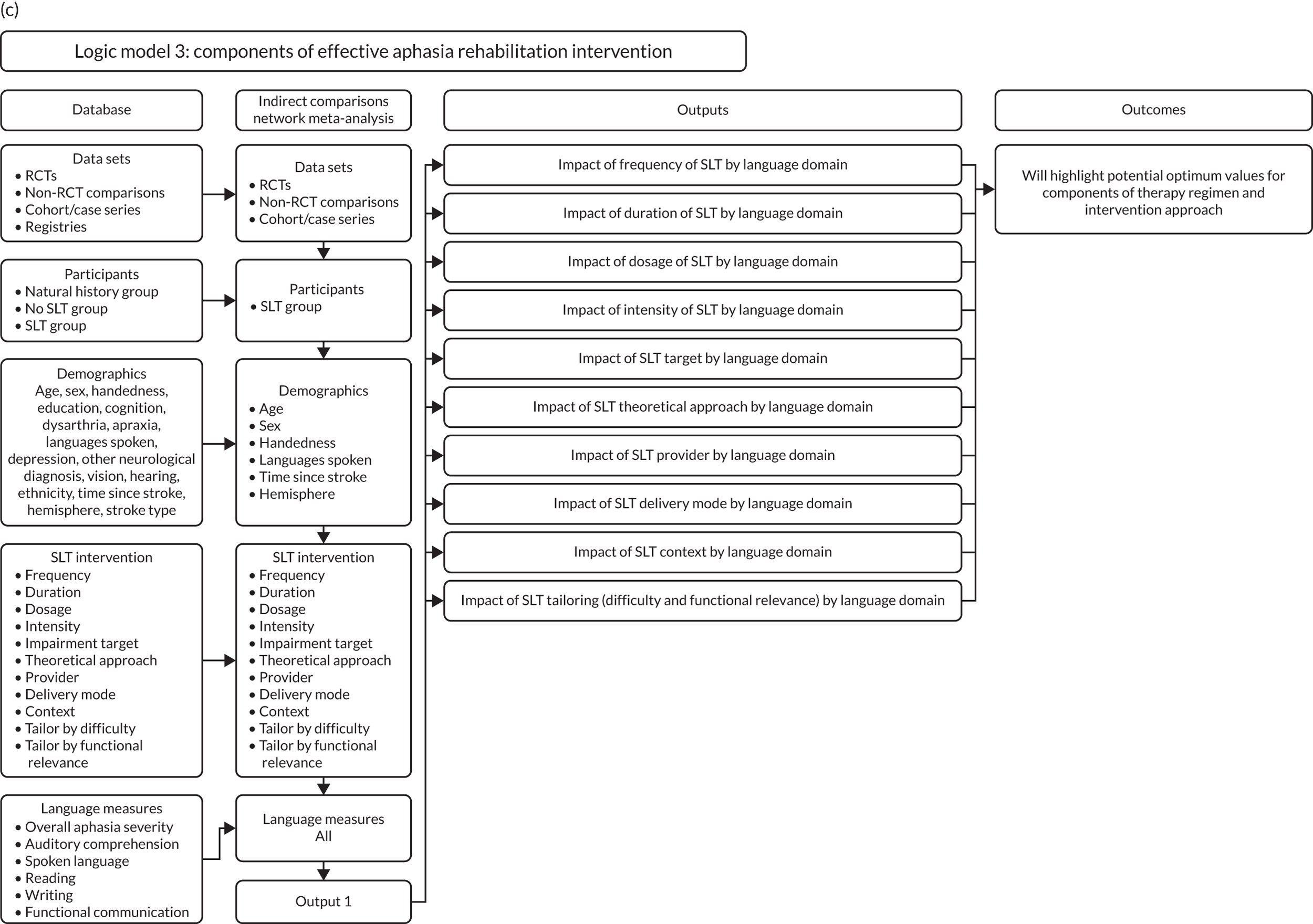

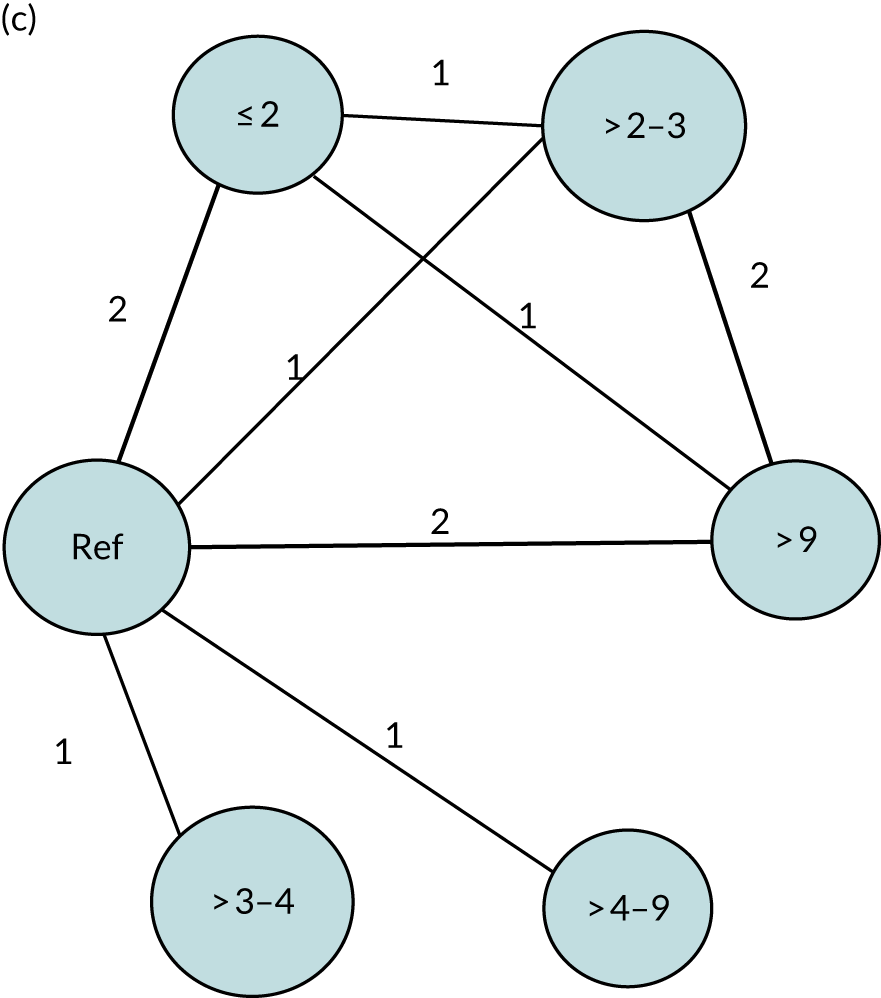

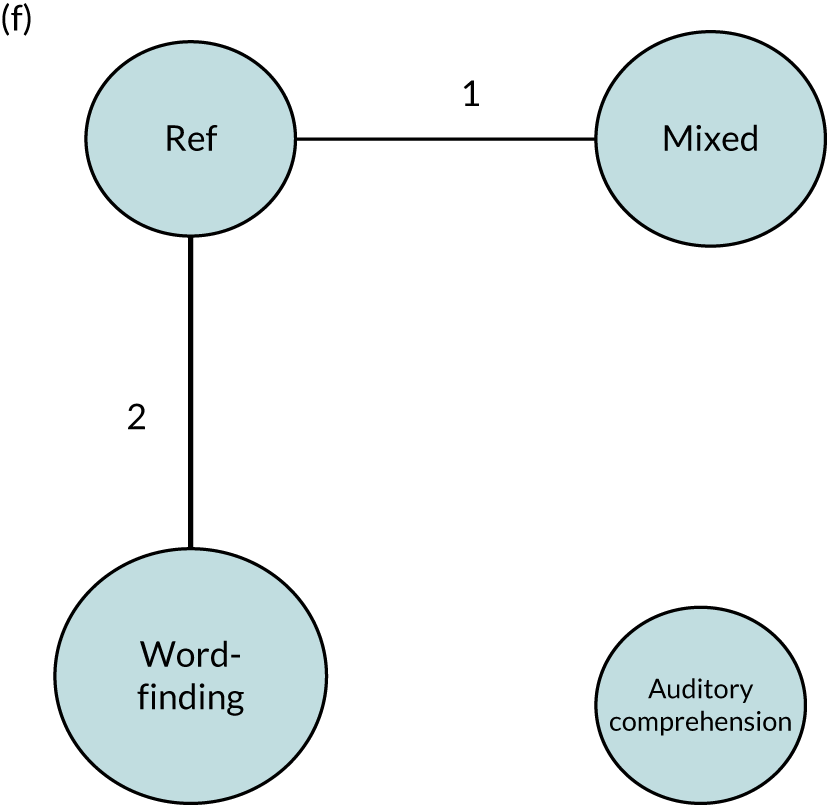

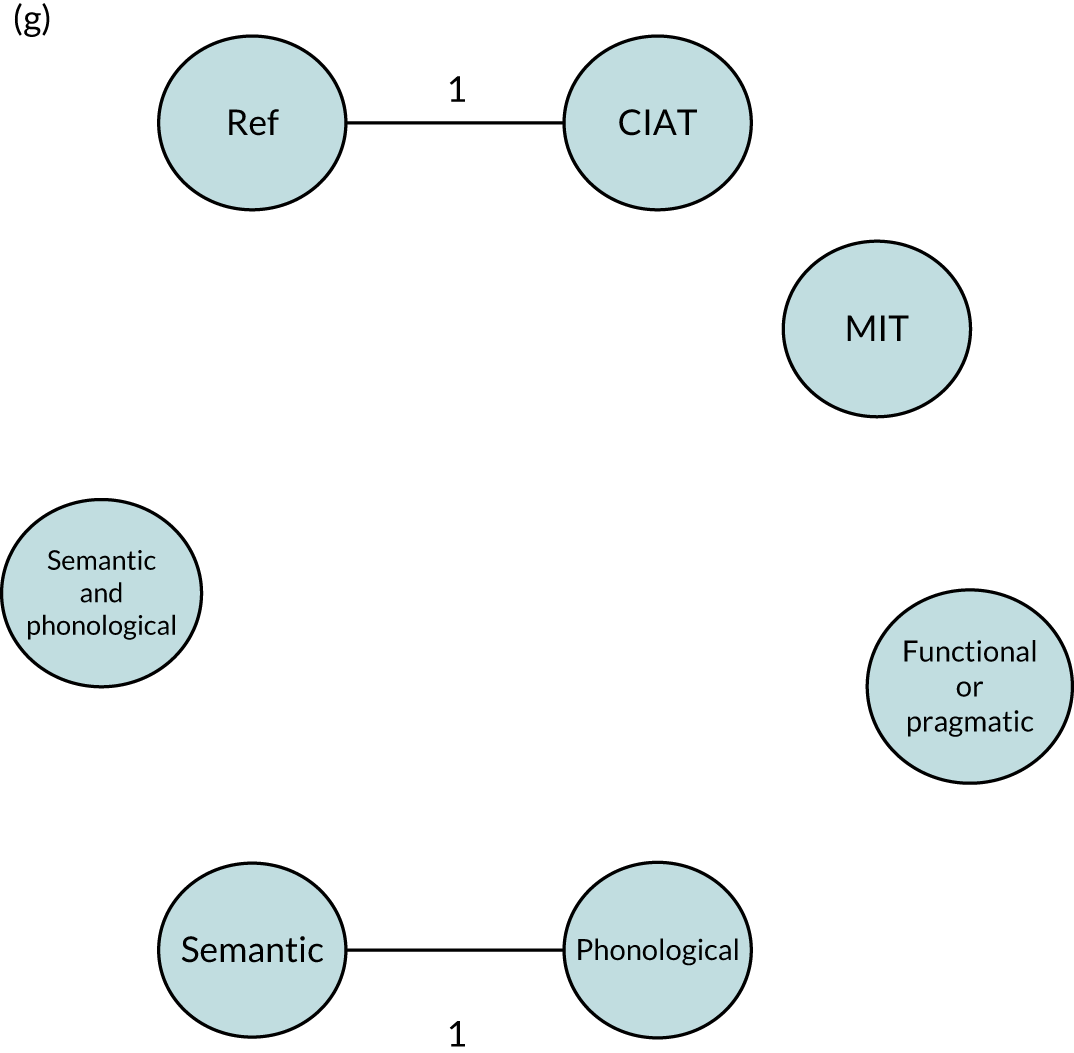

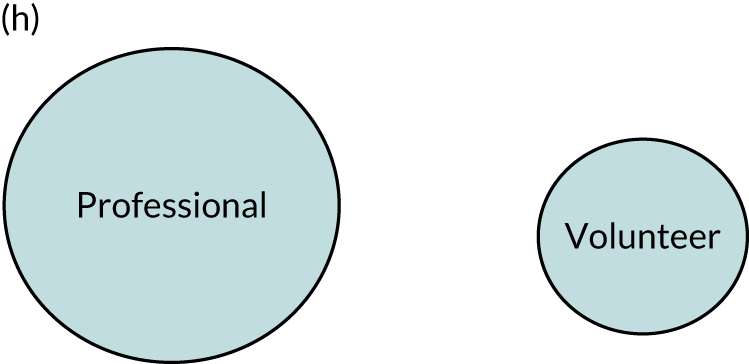

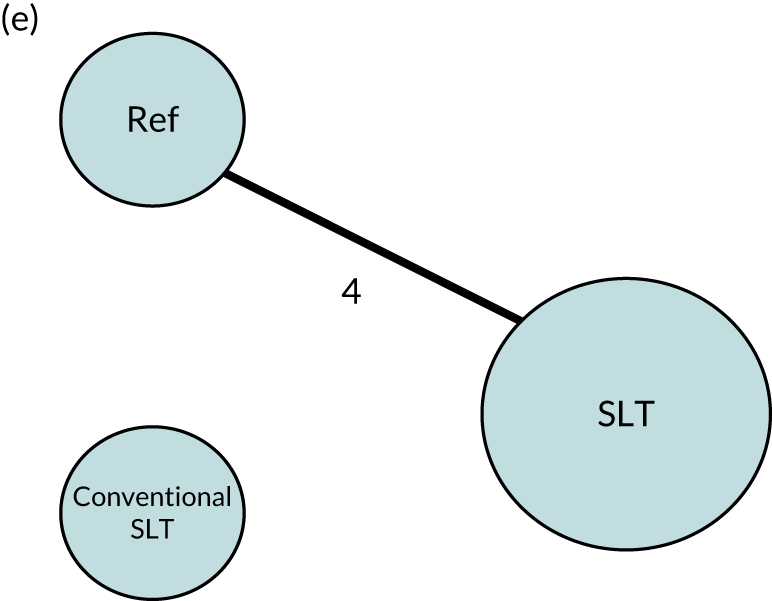

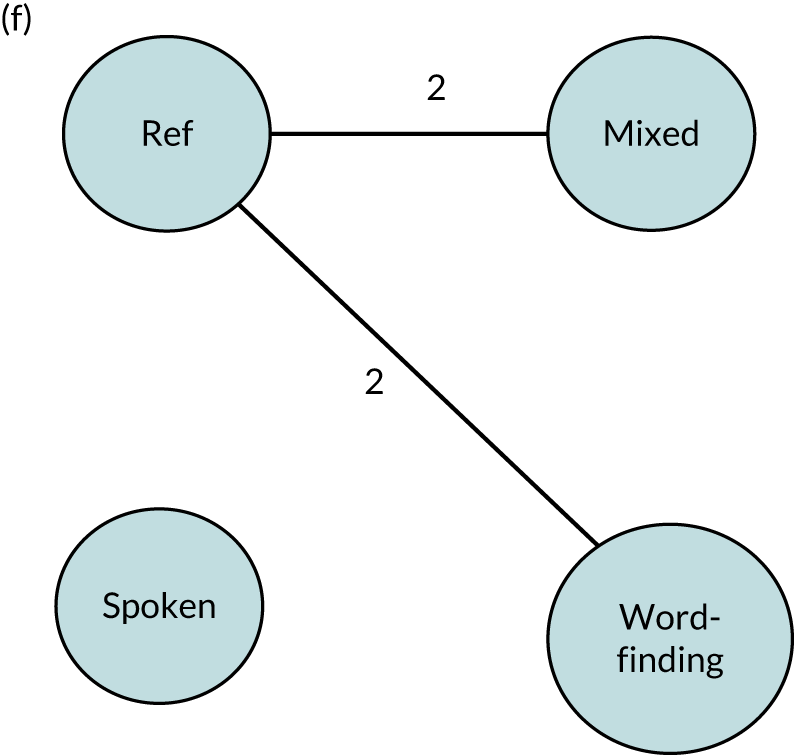

Optimum approach to speech and language therapy for aphasia

The demographic and stroke covariates identified as statistically significant in earlier analyses were used to create the baseline model to consider the components of effective rehabilitation interventions for people with aphasia after stroke. Once the model was built, additional SLT variables were examined for impact on the primary outcomes (see Appendix 3, Figure 26c). Data were analysed as mixed-effects models, with data set as the random effect. Components of therapy (see Box 3) were considered on a continuum and explored for meaningful categories.

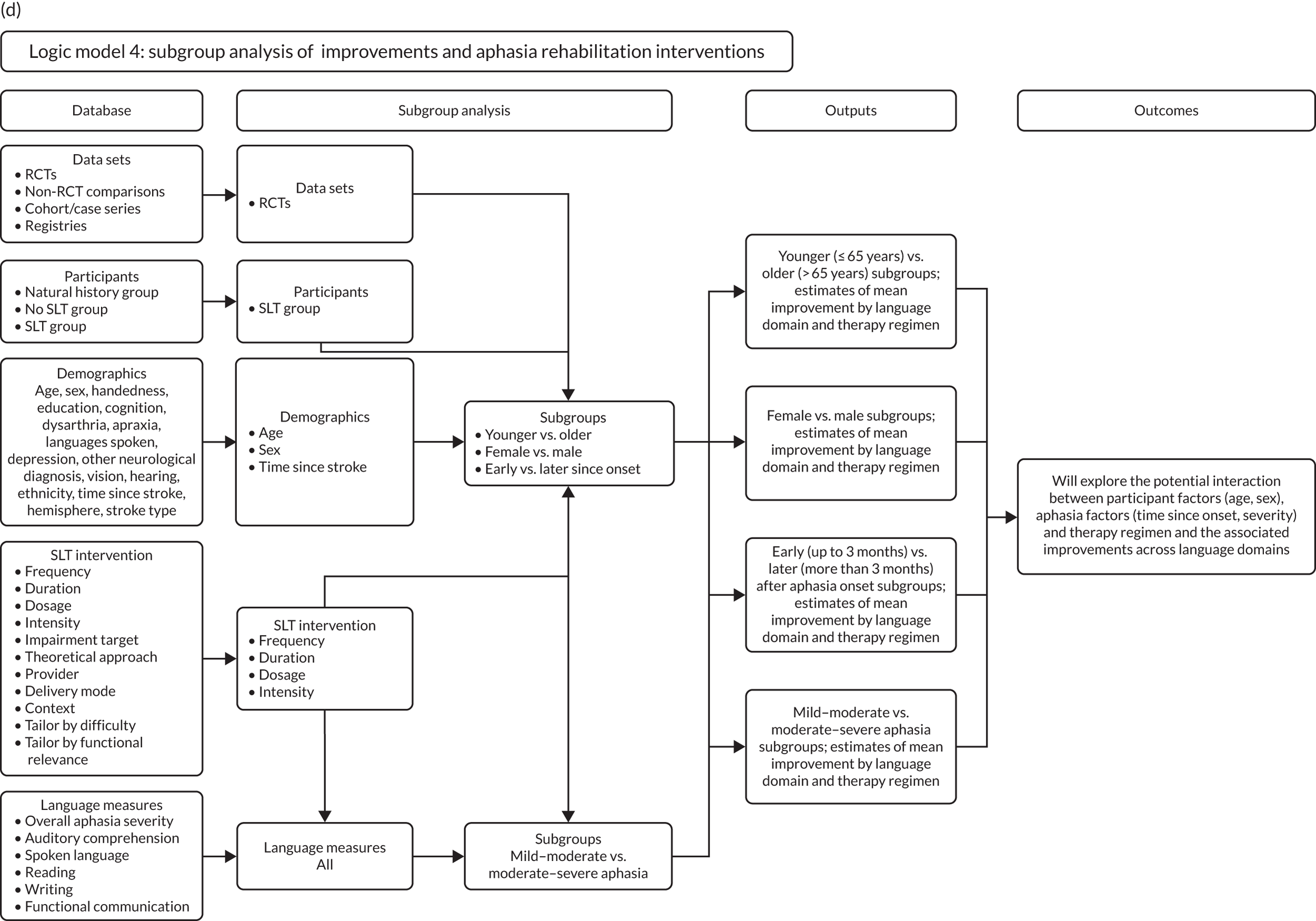

Beneficial speech and language therapy approaches to language recovery for participant subgroups

We explored whether or not some interventions (or intervention components) may be more beneficial for some participant subgroups than others. When demographic/stroke variables were significant to the model, a series of one-stage subset analyses were carried out to explore whether or not certain participant groups responded better to certain therapy interventions (see Appendix 3, Figure 26d). We also examined participant clustering within trials, which would allow us to distinguish individual participant-based interactions from any data set-based interactions. 103

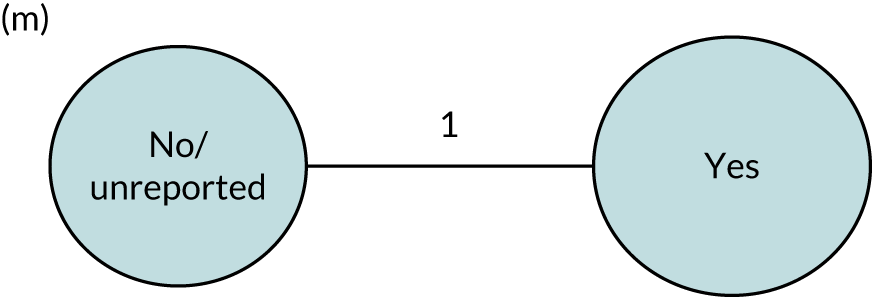

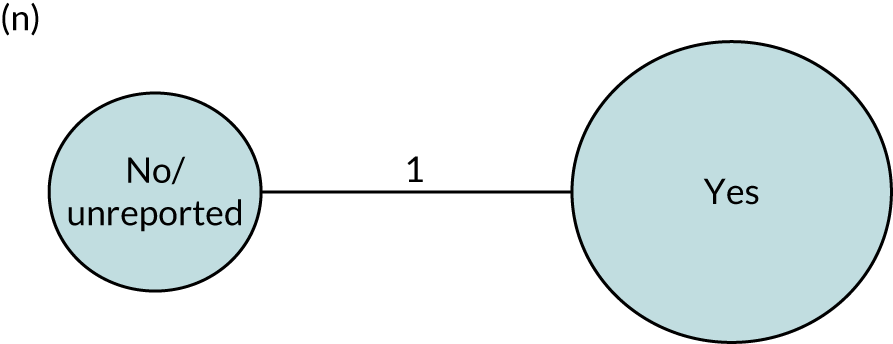

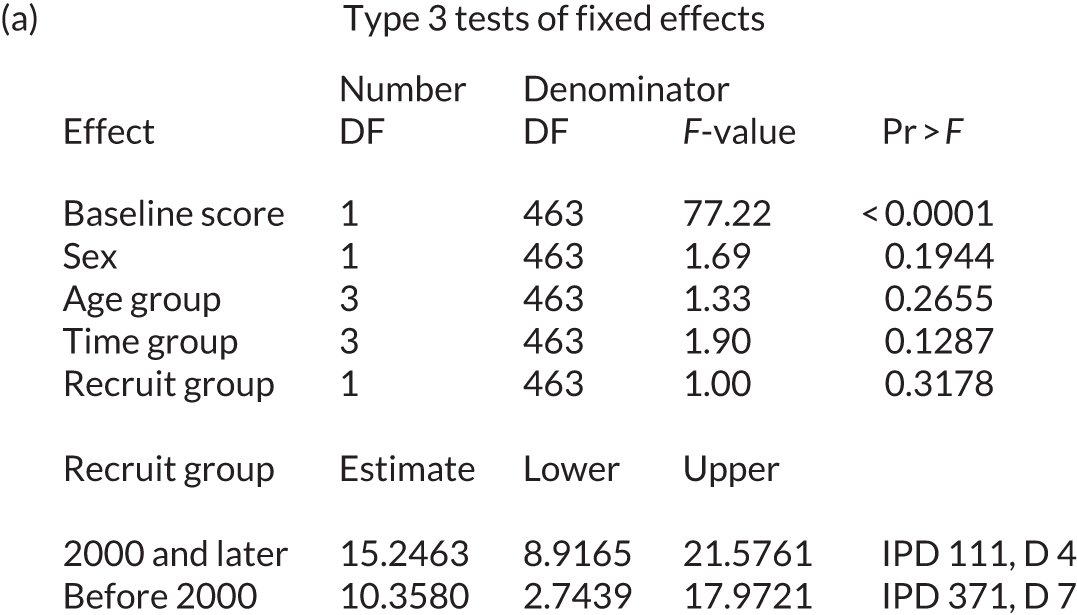

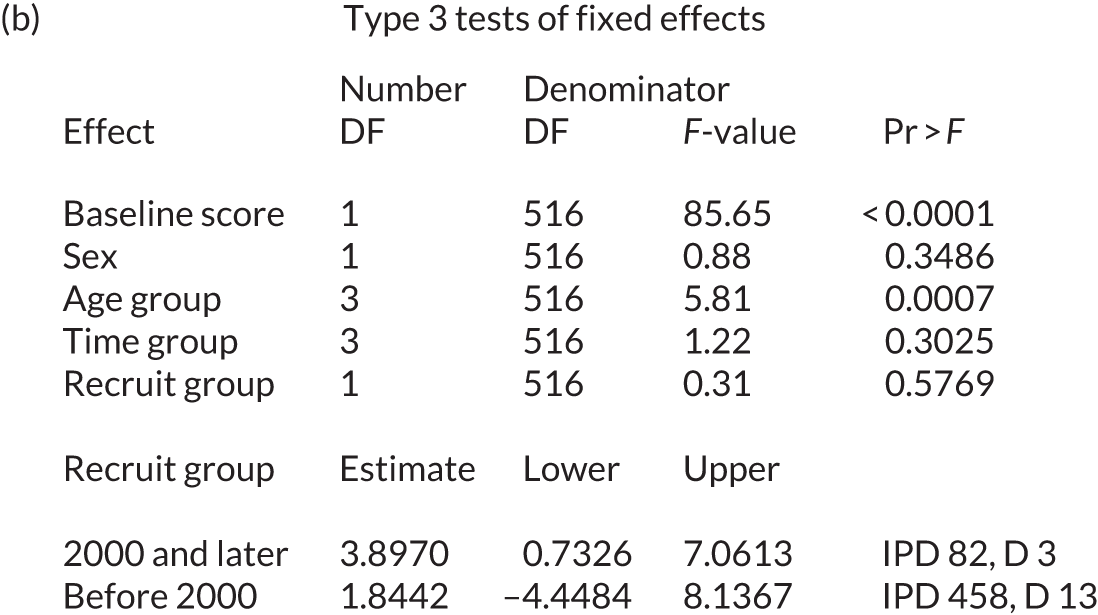

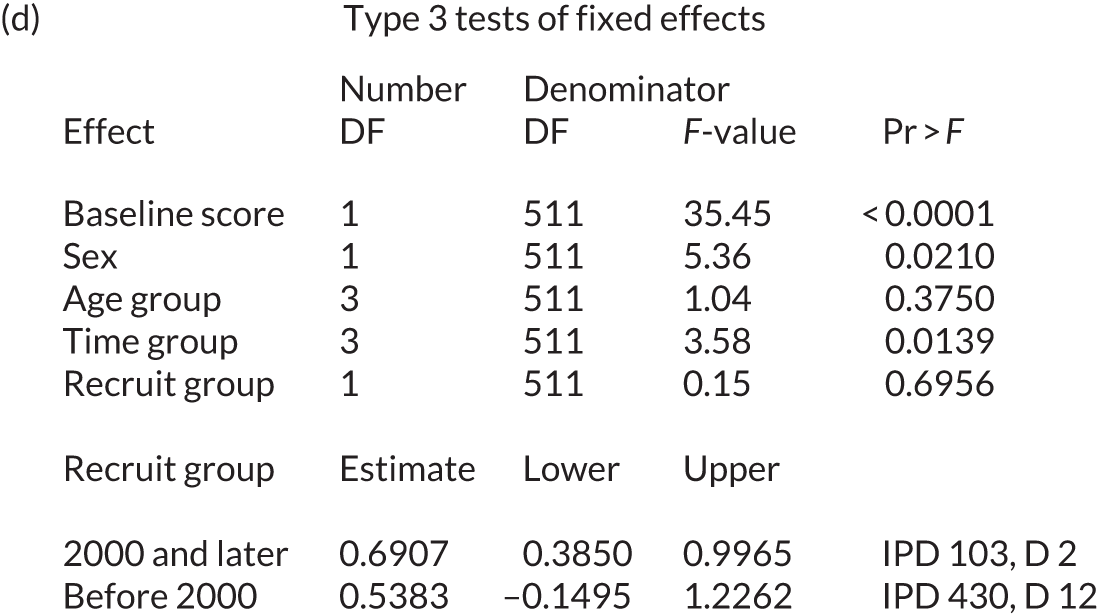

Risk of meta-biases