Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/57/46. The contractual start date was in June 2012. The draft report began editorial review in March 2016 and was accepted for publication in July 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Pasquale Giordano reports personal fees, from THD UK, outside the submitted work, and Paul Skaife is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Elective and Emergency Specialist Care (EESC) panel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Brown et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Haemorrhoidal tissue, which forms the ‘anal cushions’, is a normal component of the anal canal and is composed predominantly of vascular tissue, supported by smooth muscle and connective tissue. Haemorrhoids result from enlargement of the haemorrhoidal plexus and pathological changes in the anal cushions. They are common, affecting as many as 1 in 3 of the population. 1

Approximately 23,000 haemorrhoidal operations were carried out in England in 2004–5,2 and the prevalence may be even higher in professionally active people. Repeated visits to hospital for therapy represent a significant disruption to the personal and working lives for this population in particular.

Treatment is dictated by the degree of symptoms and the degree of prolapse, and ranges from dietary advice – to rubber band ligation (RBL) in the outpatient department – to an operation under general or regional anaesthetic. Although RBL is cheap, it has a high recurrence rate, and patients often require further visits to the outpatient department for repeat banding before exploring surgical options. 3 Although there are some variations [such as LigaSure® (Covidien – Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) haemorrhoidectomy], surgery is commonly traditional ‘open’ haemorrhoidectomy (OH) or a stapled haemorrhoidopexy (SH); both require an anaesthetic. OH is associated with considerable postoperative discomfort, sometimes necessitating an overnight hospital stay and a delay in return to normal activity, but has a low recurrence rate; SH has a slightly higher recurrence rate, but is carried out as a day case and patients return to normal activity more quickly. 4 An alternative treatment is haemorrhoidal artery ligation (HAL), which also requires an anaesthetic, but is thought to enable even quicker return to normal activity. Recurrence rates are reportedly similar to SH, but complication rates are lower. 5

There are substantial data in the literature concerning the efficacy and safety of RBL, including multiple comparisons with other interventions. 6–12 Recurrence varies from 11% to > 50%. This broad range probably reflects the definition of recurrence (patient symptoms or clinical appearance), the grade of haemorrhoids treated (grade I, no prolapse; grade II, spontaneously reducible prolapse; grade III, prolapse requiring manual reduction; and grade IV, unreducible prolapse), the number of treatments and/or the intensity and length of follow-up. In most studies, the incidence of recurrence is > 30% and appears greatest for grade III haemorrhoids. Pain is common for a few hours following RBL and occasionally patients experience pain so severe as to require admission to hospital (around 1%3), bleeding (3–4%, sometimes necessitating further treatment9) and vasovagal symptoms (3%13). There have also been rare incidences of blood transfusion3,11,14–18 and severe pelvic sepsis, with a few instances leading to death. 13 Recurrences can be treated by re-banding or by surgical intervention.

Although HAL requires an anaesthetic, evidence suggests a recovery similar to RBL, but an effectiveness that approaches the more intensive surgical options. The substantial data concerning effectiveness include four systematic reviews,5,19–21 11 randomised controlled trials (RCTs),22–32 seven non-randomised trials33–39 and > 60 case series. An overview has been carried out by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), which concludes that current evidence shows it to be a safe alternative to OH or SH;40 this is summarised below.

-

In terms of efficacy, studies with > 1 year follow-up suggest bleeding, pain on defecation, and prolapse (surrogates of recurrent symptoms) in 10%, 9% and 11% of patients, respectively.

-

Regarding safety, postoperative haemorrhage requiring intervention (readmission, transfusion, reoperation or correction of coagulopathy) was reported in < 1.2%, haemorrhoidal thrombosis was seen in < 3.5% of patients and fissure formation in < 2.1%.

-

The data from the three RCTs comparing HAL with SH and OH are difficult to combine, but efficacy seems similar for all of the procedures, with OH perhaps being superior in treating prolapse, although it is unclear if a ‘pexy’ stitch was used in the HAL cases to reduce prolapse. OH appears to lead to the most postoperative pain and longest recovery. There are conflicting results as to whether or not the HAL technique results in less pain compared with SH. Complications were also more frequent in the OH group, but occurred at a similar frequency when SH and HAL were used.

Rationale

Both of the systematic reviews and the NICE overview highlight the lack of good-quality data as evidence for the advantages of the technique; most data are from case series. Even the numerous RCTs have significant methodological drawbacks that make them subject to selection, performance, attrition and detection bias. Indeed, none of the studies is powered to reach any meaningful conclusion. There are no existing RCTs that compare HAL with RBL, although there is now one non-randomised comparison with small numbers of patients. 41

Research objectives

The HubBLe study aimed to establish the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HAL compared with conventional RBL in the treatment of people with symptomatic second- or third-degree (grade II or grade III) haemorrhoids.

The primary objective was to compare patient-reported symptom recurrence at 12 months following the procedure.

The secondary objectives were to compare postoperative:

-

symptom severity score (adapted from Nyström et al. 42)

-

health-related quality of life [HRQoL; using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)43]

-

continence (using the validated Vaizey incontinence score44)

-

pain [using a 10-cm visual analogue scale (VAS)]

-

surgical complications

-

need for further treatment

-

clinical appearance of haemorrhoids at proctoscopy following recurrence

-

health-care costs

-

cost-effectiveness.

Text reproduction

The findings of this trial have been published in The Lancet and as such there is reproduced text on pp. 24–26 of The Lancet publication. 45

Chapter 2 Methods

This report is concordant with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement (2010). 46

Trial design

We undertook a multicentre, parallel-group RCT of HAL compared with conventional RBL in the treatment of people with symptomatic second- or third-degree (grade II or grade III) haemorrhoids in 17 NHS Trusts in the UK. Participants were individually randomised to HAL or RBL, in equal proportion at all centres.

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

Recruitment commenced on 12 November 2012, and, following this, in response to early observations, a number of changes were made to the protocol (see Appendix 1) and trial methods. Between the initial Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval and study commencement, there were two substantial amendments clarifying the serious adverse event (SAE) reporting and the expected adverse events. The protocol was published in BMC Gastroenterology in October 2012. 47

In October 2012 (substantial amendment 3; protocol version 4.0), a change was made to the eligibility criteria to exclude patients with hypercoagulability disorders [in addition to those on warfarin or clopidogrel bisulfate (clopidogrel)] following a request from one of the Principal Investigators during a site set-up visit.

In January 2013 (substantial amendment 6; protocol version 5.0), the baseline data collection was changed to the day of surgery, rather than at randomisation. Sites and treatment arms differed in the time between randomisation and treatment, and this change was made to standardise the data collection as much as possible. This also standardised the time between the baseline and the 12-month follow-up, as the follow-up time point was based on the date of trial treatment.

In March 2013 (substantial amendment 7; protocol version 6.0), we removed one inclusion criterion and replaced it with three exclusion criteria for clarification. The inclusion criterion ‘Either presenting for the first time or after failure of one banding’ at sites had caused some confusion at sites and it was also decided during the review of this criterion that patients with some historical treatments for haemorrhoids could be included.

The study team, the sponsor and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) discussed the windows in which treatment is clinically relevant, and agreed that there should be a difference between surgical and non-surgical treatment for haemorrhoids (and that dietary advice would not exclude patients). The amended criteria clarified that all previous surgery for haemorrhoids and more than one injection treatment or banding in the previous 3 years would lead to exclusion. For non-surgical treatments, > 3 years was considered a historical event and therefore not relevant to the current research. As one previous banding was allowed within the protocol, this was also the case for injection treatments, as they were both non-surgical; one previous course of injection treatment would not mean that patients were excluded.

In April 2013 (substantial amendment 8; protocol version 7.0), we added ‘patients will have at least 24 hours to decide whether to take part’ to the protocol, in order to provide clarification, as it was not explicitly stated previously. The 24-hour period was an appropriate time frame for the study population and intervention.

A pre-randomisation questionnaire was introduced in July 2013 (substantial amendment 9; protocol version 8.0). The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) suggested that patient-reported outcomes can be affected by the knowledge of their allocation. As baseline data collection took place on the day of surgery (following Substantial Amendment 6), the majority of patients knew their allocation by this point; the concern was that perceived pain and quality of life (QoL) may differ between the groups due to expectation bias at this time,48 even though no procedure had yet taken place. The senior trial statistician reported that the early data did indeed support this hypothesis, in particular with higher self-reported symptoms in the HAL arm. As a result of this, the protocol was amended to incorporate a questionnaire to be completed before randomisation.

To improve the questionnaire completion rates at the 12-month follow-up, we introduced a prize draw for participants who returned the questionnaires in February 2014 (substantial amendment 7; no change to protocol). We completed three draws of £50 each.

Owing to the long waiting times for the HAL procedure, the dropout rate prior to the procedure was higher than expected. To account for this attrition, in April 2014 (substantial amendment 12; no change to protocol) the recruitment target was increased to 370 in order to achieve the sample size of 350 prior to treatment.

Participants and eligibility criteria

The trial was coordinated from the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) in the Sheffield School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR). Delegated study staff located at individual centres identified and consented potential participants.

The target population was patients referred to collaborating centres for treatment of haemorrhoids.

Potential participants fell into three groups:

-

Patients presenting to the surgical outpatient clinic (SOPC) with symptomatic haemorrhoids that did not require further tests: this group was identified by the clinical team from the general practitioner (GP) referral letter and a patient information sheet was sent to them prior to their clinic appointment. If they were willing to participate then they were consented and randomised when they attended the appointment.

-

Patients presenting to the SOPC with symptomatic haemorrhoids that required further tests to exclude other diagnoses: this group were identified by the clinician at the clinic appointment and given a patient information sheet. They underwent the necessary outpatient tests (usually endoscopy) and, if negative (i.e. the symptoms are due to haemorrhoids), they were contacted by the research nurse prior to attending their follow-up clinic appointment. They were then randomised and consented when they reattended the clinic.

-

Patients who returned to SOPC following one unsuccessful RBL: they were identified by the clinician at their first clinic appointment (when they have RBL) and given a patient information sheet. They were contacted prior to a follow-up appointment (usually 6 weeks after treatment) by a research nurse. If they remained symptomatic and were willing to participate, they were consented and randomised when they reattended.

All potential participants had a minimum of 24 hours in which to decide whether or not they wished to take part. Patients with investigations excluding pathologies other than haemorrhoids, and all of those who had undergone RBL, were contacted by the research nurse before the planned follow-up clinic to ascertain whether or not they met entry criteria and were interested in entering the trial. They would then be seen by the consultant and research nurse in clinic where recruitment and randomisation took place.

Potential participants were invited to take part in the trial if they were aged ≥ 18 years and had symptomatic second- or third-degree haemorrhoids.

Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria:

-

have had previous surgery for haemorrhoids (at any time)

-

have had more than one injection treatment for haemorrhoids in the past 3 years

-

have had more than one RBL procedure in the past 3 years

-

with known perianal sepsis, inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal malignancy, pre-existing sphincter injury

-

with an immunodeficiency

-

unable to have general or spinal anaesthetic

-

currently taking warfarin, clopidogrel or have any other hypercoagulability condition

-

pregnant women

-

unable to give full informed consent (this may be due to mental capacity or language barriers)

-

previously randomised to this trial.

Settings and locations where the data were collected

The CTRU coordinated the follow-up and data collection in collaboration with centres. Participant study data were collected and recorded on study-specific case report forms (CRFs) by centre research staff, and then entered on to a remote web-based data capture system at site. To improve the rate of completion, research nurses could complete the participant questionnaires with the participants at the visit or over the telephone, or the participants could return the questionnaires by post to the centres at all time points. Patient questionnaires, at 12 months, could also be completed online and could be returned to the CTRU by participants for data entry.

Interventions

Participants were randomised to receive either RBL or HAL. Both interventions are established and well-documented procedures, which are considered standard care by NICE. 40,49

Conventional RBL uses a device that allows a rubber band to be applied to each haemorrhoid via a proctoscope. The device used across sites was a suction device (various manufacturers), but bands can be applied using a forceps ligator. This rubber band constricts the blood supply causing it to become ischaemic before being sloughed approximately 1–2 weeks later. The resultant fibrosis reduces any element of haemorrhoidal prolapse that may have been present. This is a very commonly performed procedure in all SOPCs; figures from an audit of current practice at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals (STH) highlighted that prior to the trial over 20 such procedures were carried out every week. The procedure is a basic surgical skill with which all senior staff are familiar and competent in performing. All surgeons involved in the study performed this procedure routinely.

Haemorrhoidal artery ligation uses a proctoscope that is modified to incorporate a Doppler transducer. There are two types of equipment in common use: the HALO (haemorrhoidal artery ligation operation) device [Agency for Medical Innovations (AMI) HAL Doppler system, CJ Medical, Truro, UK] and the THD (transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation) device (THD Lab, Correggio, Italy). Both devices operate on the same principle, essentially enabling accurate detection of the haemorrhoidal arteries feeding the haemorrhoidal cushions. Targeted ligation of the vessels with a suture reduces haemorrhoidal engorgement. When combined with a ‘pexy’ suture, both bleeding and haemorrhoidal prolapse are addressed. All of the surgeons participating in the trial ensured that the need for a pexy suture was routinely assessed and recorded. The procedure is simple, uses existing surgical skills and has a short learning curve, with the manufacturers recommending at least five mentored cases before independently practising. All of the surgeons involved in the study had completed this training prior to the start and, in addition, had carried out more than five procedures prior to delivering the study treatment.

Trial procedures were carried out as soon as possible after randomisation. RBL is a brief procedure, which, in many cases, can be carried out at the initial clinic visit. By contrast, HAL is an invasive procedure, usually performed under general anaesthetic, and requires a theatre admission, which may be some considerable time after assessment. The HubBle trial defined ‘baseline’ as being the date of procedure, and ‘recurrence at 1 year’ as being from this date onwards.

Outcomes

Measurement of outcomes

Following consent but prior to randomisation, a participant-completed questionnaire was administered which included questions relating to pain, symptoms, EQ-5D-5L (European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, 5-level version), continence and use of pain medications. The research nurse completed a patient assessment form, which included demographics and details of the haemorrhoids, including previous treatment(s).

The same participant questionnaire was repeated at baseline, defined as the day of the procedure; in addition, the procedure details CRF was completed by the consultant or the research nurse.

Short-term outcome assessments were completed by participants either via return of a postal questionnaire or a telephone call with the research nurse at days 1, 7 and 21 post procedure. This covered EQ-5D-5L, pain and use of pain medication.

Data were collected 6 weeks following the procedure and again at 12 months following the procedure in order to establish which patients required further treatment for recurrent symptoms or complications. Participants attended a 6-week clinic visit following the intervention at which they were asked details regarding GP visits, hospital attendance or further treatment since the procedure; the baseline questionnaire was also repeated at this time. A clinical assessment was recorded wherein complications, SAEs and further treatment (planned or completed) were reported; the haemorrhoidal grade was recorded when it was clinically assessed. The clinician was also asked whether or not, in his/her opinion, the patient’s symptoms were improved.

Twelve-month data were collected from three sources. Details of further procedures were obtained from hospitals (by reviewing hospital records and asking the patients’ consultants), by contacting the patients’ GPs and, finally, by questioning the patient via telephone interview or postal questionnaire at 12 months.

Primary outcome measure

The main research question of the study was to ascertain the 1-year incidence of recurrence following HAL or RBL. The primary outcome was defined as the proportion of patients with recurrent haemorrhoids at 12 months post procedure, as derived from the patient’s self-reported assessment in combination with GP and hospital records.

The trial was a pragmatic design with a dichotomous outcome. As no validated patient-reported symptom score exists, we based our definition of recurrence on Shanmugam et al. ’s systematic review12 definition:

1. Cured or improved: Symptom free or mild residual symptoms but not requiring further treatment at the end of study period; or, 2. Unchanged or worse: No symptom improvement and requiring further intervention or suffered complication or deterioration of symptoms.

This study simplified Shanmugam’s criteria12 into the following question, asked at 12 months by a research nurse: ‘At the moment, do you feel your symptoms from your haemorrhoids are (1) cured or improved compared with before starting treatment or (2) unchanged or worse compared with before starting treatment?’

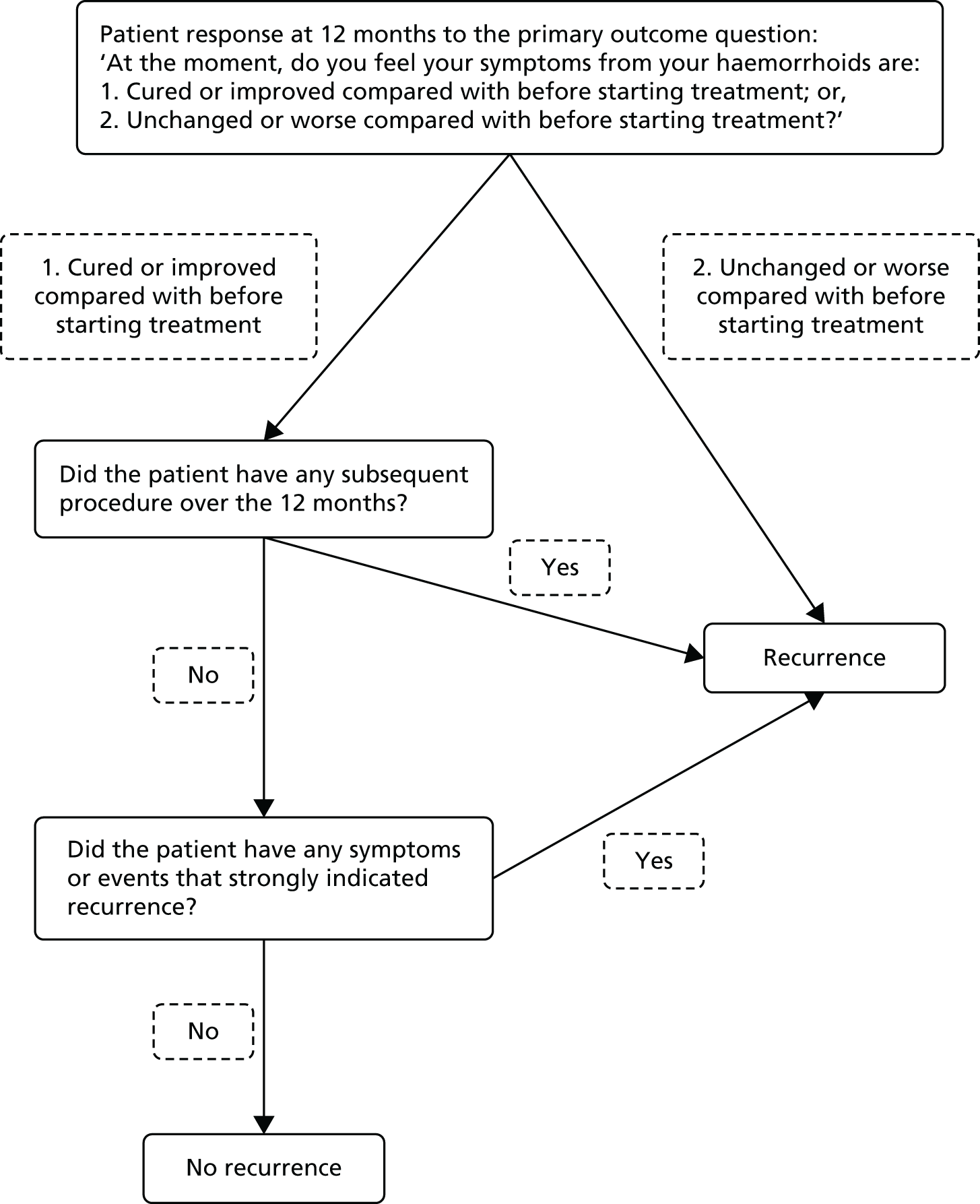

Patients were considered to have recurrent haemorrhoids when any of the following were recorded (as shown in Figure 1):

-

‘Unchanged or worse compared with before starting treatment’ at 12 months, as reported by the patient, or

-

Any subsequent procedure (RBL, HAL, THD, haemorrhoidectomy, haemorrhoidopexy, haemorrhoidal injection or other relevant procedure) over the 12 months, or

-

Presence of any symptoms or events that strongly indicated recurrent haemorrhoids [among patients not meeting (i) or (ii), as adjudicated by two trial investigators (JT, SB) who were blinded to allocated treatment].

FIGURE 1.

Decision tree for recurrence at 1 year.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary end points seek to identify which treatment – HAL or RBL – is the most cost-effective, which is the least painful procedure with the fewest complications, and which has the greatest effect on the patient’s QoL. Secondary end points are therefore:

-

Persistence of significant symptoms defined analogously to the 12-month outcome.

-

Symptom severity score (adapted from Nyström et al. 42). This score is the sum of the scores from all five questions and is therefore a number on a nominal scale in the range of 0 to 15; where an increase in number is an increase in symptoms.

-

HRQoL using the EQ-5D-5L. 43 A summary index with a maximum score of 1 can be derived from the five dimensions by conversion using a table of scores. The maximum score of 1 indicates the best health state, by contrast with the scores of the individual questions, where higher scores indicate more severe or frequent problems.

-

Continence using the validated Vaizey incontinence score. 44 The Vaizey incontinence score is simply the sum of the scores from all of the seven questions, and is also a number on a nominal scale in the range of 0–24, for which an increase in number indicates more severe incontinence.

-

Pain using a 10-cm VAS, for which ‘0’ is ‘no pain’ and ‘10’ is ‘worst imaginable pain’.

-

Surgical complications.

-

Need for further treatment.

-

Clinical appearance of haemorrhoids at proctoscopy following persistent symptoms at 6 weeks.

-

Health-care costs/cost-effectiveness/quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

The schedule for collecting these end points is shown in Table 1.

| Assessment instrument | Time of assessment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomisation | Pre-surgery (baseline) | 1 day | 7 days | 21 days | 6 weeks | 1 year | |

| EQ-5D–5L | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ● |

| Visual analogue pain score | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ | |

| Vaizey incontinence score | ○ | ○ | ● | ||||

| Haemorrhoids symptom score | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | |||

| Complications review interview | ○ | ●a | |||||

| Health and social care resource-use data | ○ | ●a | |||||

| Further treatment questionnaire | ○ | ●a | |||||

| Recurrence (primary outcome) | ●a | ||||||

| Clinical appearance at proctoscopy (when applicable) | ○ | ||||||

Sample size

Assuming that the proportion of patients who experience recurrence following RBL is 30% and following HAL is 15%, the sample size calculated to detect a difference in recurrence rates with an odds ratio (OR) of 2 with 80% power and 5% significance was 121 individuals per group. In order to account for any between-surgeon variation and loss to follow-up, this was increased to 175 per group.

This increase was based on the conservative assumption that there would be 14 surgeons in the trial (one per centre, although the number of sites was increased) and intraclass correlation (ICC) of 2.5% in keeping with typical ICCs observed by Ukoumunne et al. 50 However, it was considered likely that each site would have a minimum of two surgeons, in which case the power to detect this difference was 85% (90% power if there was no between-surgeon variation). Because the surgical procedure was well developed and standardised, ICC was expected to be virtually zero and the proposed sample size was hoped to have closer to 90% power.

The impact of loss to follow-up was minimal for the primary end point (haemorrhoidal recurrence at 12 months). Patients who did not complete their 12-month follow-up still had their hospital notes reviewed, and their GP was contacted to ascertain whether or not any complications or operative procedures were recorded. The only dropout expected was if the patient should die, move out of the area or have no traceable patient notes; we anticipated this would be less than the 5% that we allowed for in this patient population (a previous study of RBL that used only clinical follow-up reported a 1-year loss to follow-up of 10%51).

Explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines

No formal interim analyses for efficacy were carried out. However, the safety of the treatments was assessed by an independent DMEC, the members of which convened annually to review SAEs experienced by study participants.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation was undertaken using the CTRU’s web-based randomisation system. After consent, participants were individually randomised, in a 1 : 1 ratio, to either HAL or RBL by a member of the research team at site. To ensure equal allocation across centres, randomisation was stratified by centre using permuted blocks of random sizes 2, 4 and 6. Allocation concealment was achieved by ensuring that the participant identifier was entered, following which the allocation was revealed; no member of the study team had access to the randomisation schedule during recruitment. The study was open label, with no blinding of participants, clinicians or research staff attempted.

Statistical methods

Analysis populations

The primary analyses were intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses in which individuals were analysed according to the treatment to which they were randomised, regardless of whether or not they underwent their allocated surgery. Secondary analyses were undertaken on a per protocol (PP) basis, which was restricted to those individuals who complied with the protocol. The categories of non-compliance were eligibility, missed windows, consent and treatment issues, which included patients who did not receive their allocated treatment. Safety summaries were reported, based both on randomised and actual treatment where these differed.

Analysis of 1-year recurrence (primary outcome)

The primary outcome was the recurrence of haemorrhoids at 1 year, as defined above (see Primary outcome measure). Analyses were undertaken using a random intercept logistic regression model in which the covariates were treatment allocation, gender, age at surgery and history of previous intervention as fixed effects; the surgeon was included as a random effect. Further sensitivity analyses assessed whether or not other baseline characteristics [including symptom score, EQ-5D-5L and body mass index (BMI)] altered the strength of the treatment effect and/or appeared to modify the treatment effect. ‘Goodness of fit’ of the logistic regression model was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. 52 ICC coefficients were calculated to summarise the clustering that may exist around surgeons.

Secondary outcomes

Persistent significant symptoms at 6 weeks

Recurrence at 6 weeks was analysed in the same manner as the primary outcome. Unlike the 12-month recurrence, no blind review was incorporated, as common symptoms (e.g. severe pain or bleeding) may be due to the procedure rather than the haemorrhoids.

Haemorrhoid symptom severity score

The severity of haemorrhoidal symptoms was compared using a generalised least squares regression mixed model using the same covariates as the primary outcome. The prespecified analysis did not include baseline symptoms as a covariate because of the concerns noted below (see Important Changes to Methods after Trial Commencement), but sensitivity analyses were also undertaken, which adjusted for severity at randomisation (when available) and at baseline, and the average of the two. The difference in symptom severity was compared separately for the 6-week and 12-month time points.

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (5-level version) status

Health utility was assessed by the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire using the Value Set for England normative data. 53 EQ-5D-5L was assessed at days 1, 7 and 21. Longitudinal analyses of EQ-5D-5L were conducted as part of the economic evaluation described below (see Health-economic methods).

Vaizey faecal incontinence score

Incontinence was assessed using the Vaizey inventory and analysed in the same manner as haemorrhoidal symptoms.

Pain

Pain was measured using a 10-cm VAS. The VAS scores for HAL and RBL were compared at each time point using the same methods as the haemorrhoid symptom severity. The VAS was collected at randomisation, baseline, days 1, 7 and 21, and, finally, at 6 weeks.

Safety outcomes

Complications

The secondary outcome of procedural complications (adverse events such as pain from thromboses, bleeding requiring consultation, fissuring of the anal canal) elicited during the complications review interview, or from the patient notes at 6 weeks and 1 year post surgery, was compared between the two groups at each time point using Poisson regression.

Serious adverse events

An adverse event is recorded as ‘serious’ if it is an untoward occurrence that:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

consists of a congenital anomaly or birth defect, or

-

is otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

Serious adverse events were reported as the number of events, and the number and percentage of participants experiencing each event. Each SAE was classified as systemic complication; urinary retention; pelvic sepsis; or other.

Further treatment

The incidence of the need for further treatment, either surgical or medical, was recorded.

Clinical appearance at proctoscopy (if persistent significant symptoms)

Data were recorded for patients who underwent examination at 6 weeks. This included the clinical assessment of grade and the change from baseline.

Additional/post hoc analyses

Additional, unplanned analyses were undertaken to address questions that arose during the trial progression. These were undertaken in a similar manner to the analyses described above, with adjusted analyses using the same covariates unless otherwise stated.

General considerations

All analyses were undertaken on an ITT basis unless otherwise stated. All confidence intervals (CIs) were two-sided 95% intervals, and all statistical hypotheses were two-sided tests. Continuous measures were summarised as mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) as appropriate to the distribution of the data. Categorical data were summarised as numbers and percentages.

Health-economic methods

Background

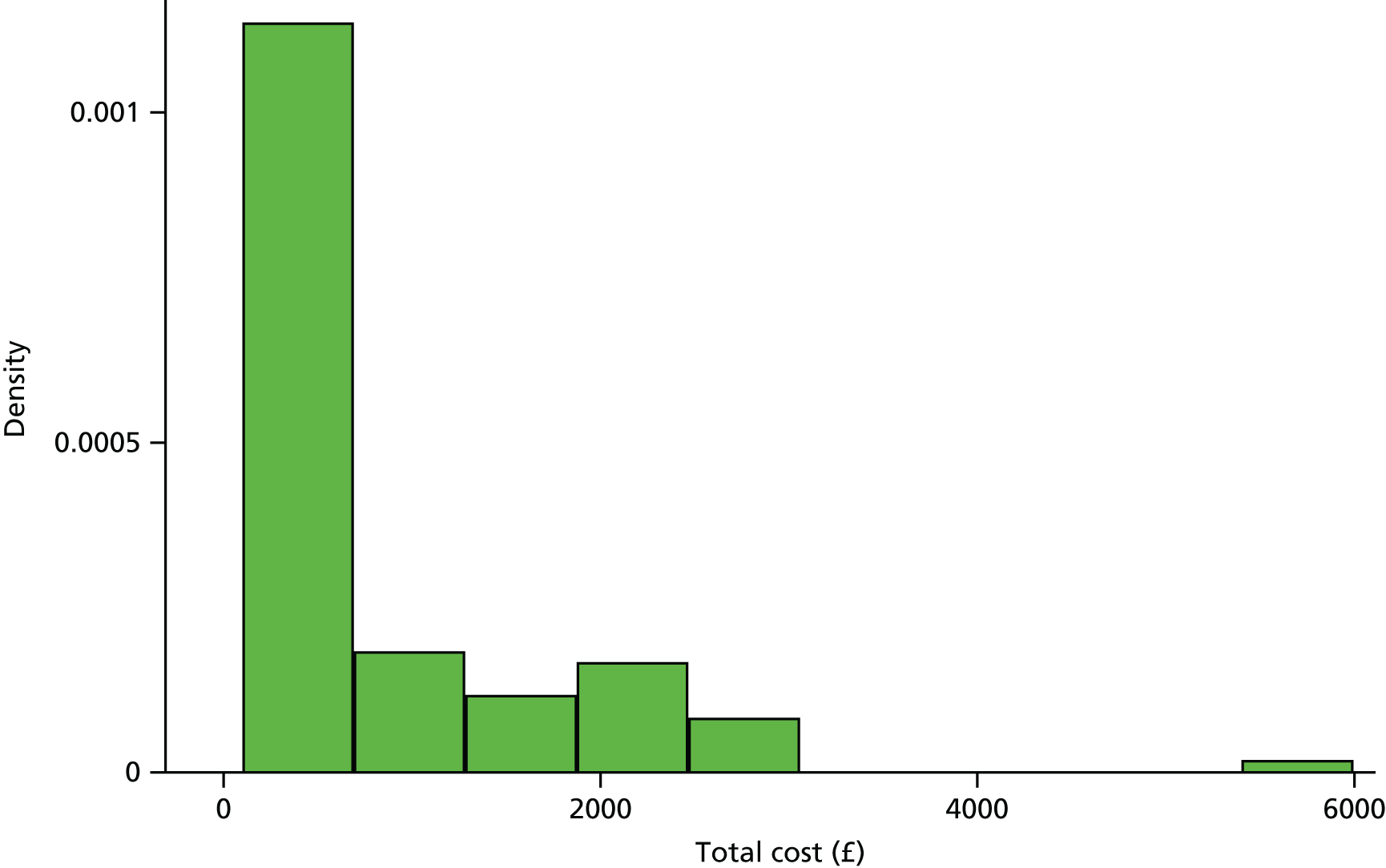

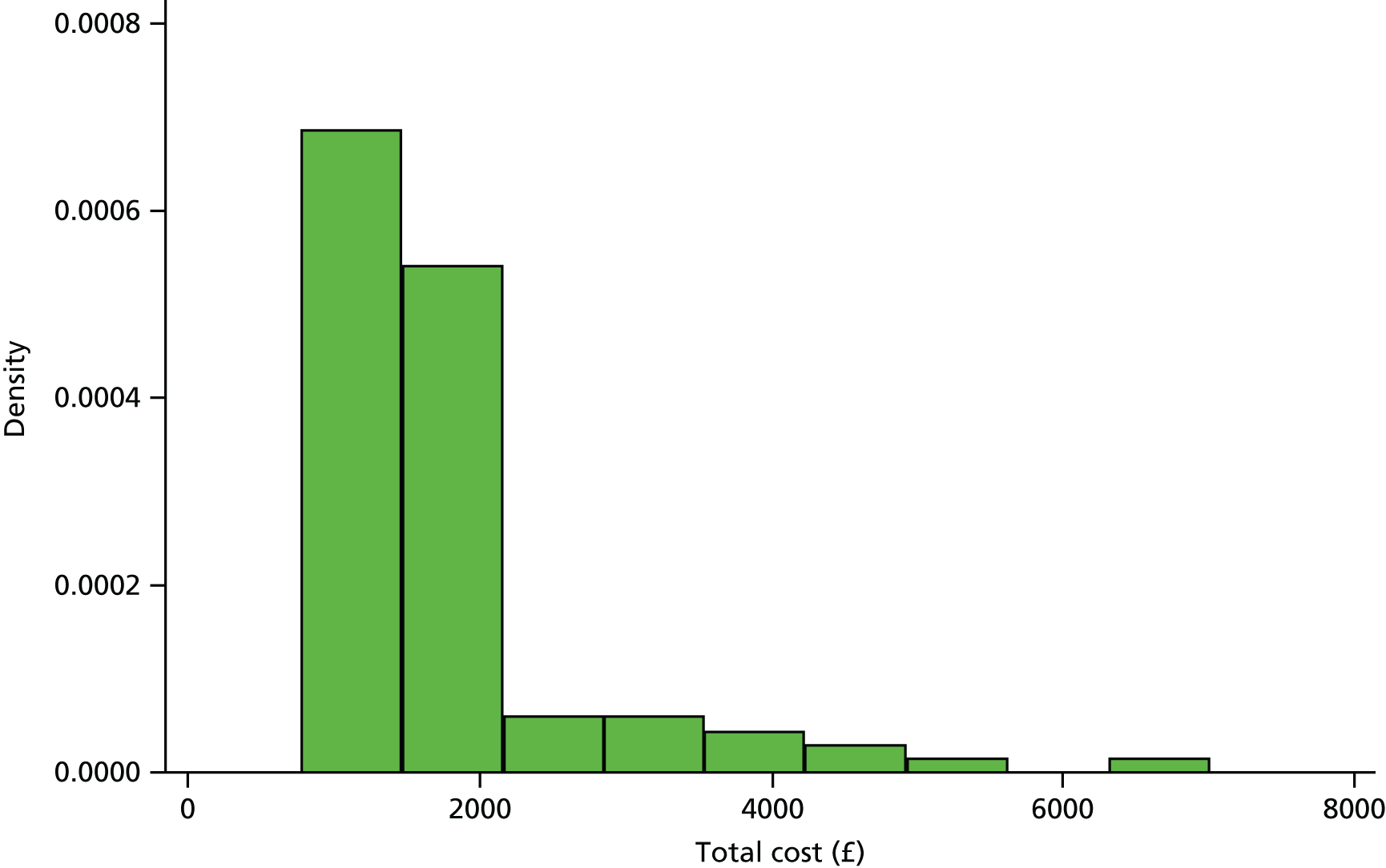

We collected data as part of the trial that allowed us to conduct a full economic evaluation. The main economic analysis focused on estimating the incremental cost per QALY of HAL compared with RBL over the 12-month follow-up period of the trial. We have also presented results in terms of the incremental cost per recurrence avoided.

Patients were asked to complete the EQ-5D-5L instrument at pre-randomisation, pre-surgery (baseline) and subsequent time points following the treatment. The UK population tariffs were then used to calculate QALYs for each patient. 54 EQ-5D has been applied in previous studies in this area55 and appears to be sensitive to changes in patient outcomes. Pain was likely to be one of the main symptoms in which we might expect the treatments to differ and this is well reflected in the EQ-5D-5L instrument.

Overview

Aim

The aim of the economic evaluation was to assess the cost-effectiveness of HAL compared with RBL in terms of incremental cost per QALYs over 12 months’ follow-up.

Methods

Perspective

The economic evaluation took a NHS and Personal Social Services perspective as per NICE recommendations. 49 The estimated resource use covers the period in which a patient is in hospital, post discharge and primary care services, including costs related to recurrence of haemorrhoids.

Method of economic evaluation

We conducted a cost–utility analysis (CUA) as the main method of economic evaluation, for which the outcome was expressed in QALYs. We then carried out a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) for which the outcome was expressed in terms of incremental cost per recurrence avoided with HAL compared with RBL. All health-economic analyses were conducted on an ITT basis, including all of the patients randomised to each group. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

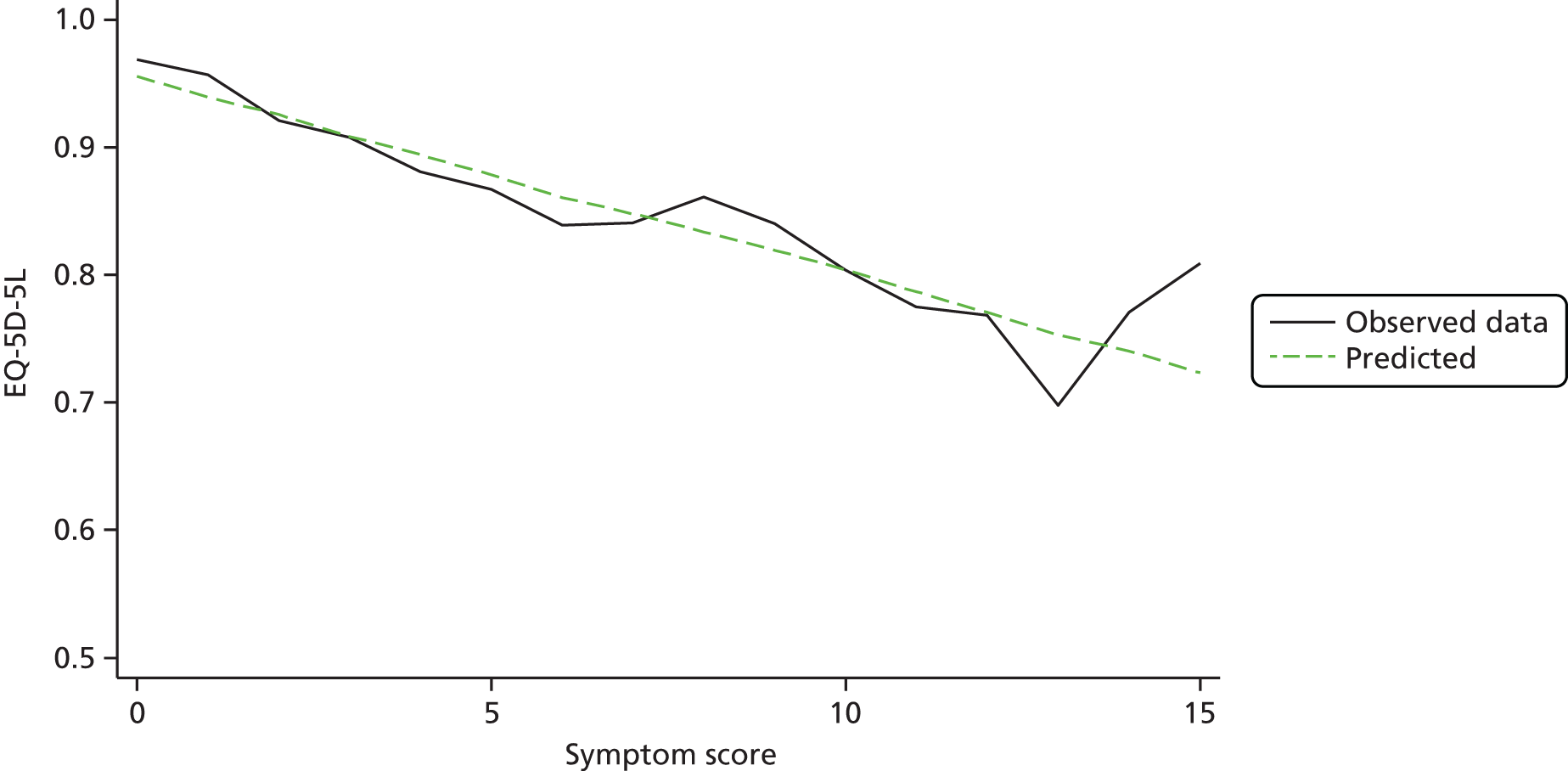

Outcomes

The EQ-5D-5L was used for collecting QoL data at seven time points: pre-randomisation, baseline, 1 day, 7 days, 21 days, 6 weeks and 12 months. The EQ-5D is a generic standardised instrument for measuring HRQoL. The EQ-5D-5L is a five-level version of the EQ-5D, which was recently launched to improve sensitivity of the descriptive system while keeping the same structure of the original instrument [European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions, 3-level version (EQ-5D-3L)]. 53 The EQ-5D-5L utility scores we applied were obtained using recently published tariffs based on the UK general public. 54 The individual patient-level QALYs were calculated from EQ-5D-5L scores at baseline and subsequent follow-up time points for 1 year using the area under the curve method. Discounting was not used for the calculated QALYs in the main analyses, as it was carried out for a 1-year time horizon. We examined the relationship between EQ-5D-5L and symptom scores to check the appropriateness of using this instrument in this setting.

Costs

The costing approach followed the standard stages used in economic evaluation and involves identification of resource use, measurement and valuation. 56

Resource use

Identification of resource use

We identified a range of resource use based on different CRFs and questionnaires used for collecting relevant data at different time points of the trial follow-up. These include the procedure details, clinical assessment at 6 weeks, consultant questionnaire at year, GP questionnaire at 1 year, and participant questionnaire at 1-year time points. The resource use identified is categorised in the following three domains:

Resource use during rubber band ligation procedure

-

Procedure event.

-

Procedural complications.

-

Postprocedural complications.

-

Hospital admissions.

-

Medication on discharge.

Resource use during haemorrhoidal artery ligation procedure

-

Anaesthetic.

-

Procedure event.

-

Intraoperative complications.

-

Hospital admissions.

-

Postoperative complications.

-

Medication on discharge.

Post discharge

-

Outpatient treatments.

-

Surgical treatments.

-

Emergency admissions.

-

Contact with health professionals.

-

Further treatments and medications.

-

Recurrence treatments.

Measurement of resources

All events relating to resource use identified were recorded throughout the trial using different data collection forms at different time points. These were the procedure details form at day 0, clinical assessment form at 6 weeks, consultant questionnaire at 1 year, and GP questionnaire at 1 year. The instruments used for measuring resource use within the trial are provided in Appendix 2. For the HAL procedure event, resource use included the type of anaesthetic used, grade of operating surgeon, whether or not the procedure was supervised by a consultant, timing for surgery, and overall time spent in the operating theatre. Detailed medications prescribed on discharge or as further treatment were also recorded.

Data on hospital admissions and type of admissions were recorded, and data on the durations of admissions were measured based on the NHS average estimates for some events, such as non-elective emergency admissions. Visits for health-care professionals including consultants, GPs and general practice nurses were recorded. However, the duration of each visit was not recorded and therefore average estimates were used based on the NHS or the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU), University of Kent approaches, where relevant. 57

Valuation of resources

Costs were estimated in UK pound sterling based on the financial year 2014–15. Unit costs were applied for each resource-use event at the individual patient level to calculate the total cost of resource use over a 12 months’ time horizon.

Unit costs

Procedure event unit cost

The unit cost for a RBL procedure event was estimated as an outpatient procedure, and was obtained from the National schedule of NHS reference costs for 2014–15. 58 Admissions unit costs were also obtained from the NHS reference costs. 58 For a HAL procedure, a microcosting approach was applied, based on cost per minute in procedure, recovery time and theatre overhead per minute. The cost per minute in procedure was based on the actual time spent by clinical staff operating and supervising the procedure and the PSSRU staff unit cost. The unit costs for the surgical kits used in the HAL procedure were obtained from the NHS supply system. Blood transfusion unit cost was obtained from the blood transfusion costing statement issued by NICE. 59 Unit costs for medications prescribed on discharge were calculated using the cost of generic drugs from the British National Formulary (BNF) 2015. 60

Post discharge unit cost

The unit costs for surgical treatments following recurrence of haemorrhoids were obtained from different sources. The cost for SH procedure was taken from McKenzie et al. 55 and adjusted for inflation. Unit costs for excisional haemorrhoidectomy (EH) and RBL in the theatre procedures were estimated using the NHS reference costs 2014–15. 58 The unit costs for repeated RBL and HAL procedures were calculated using the average cost for participants within the HubBLe trial. For contacts with health-care professionals, the PSSRU unit costs were applied.

All unit costs used in the economic analyses are summarised in Tables 2–4.

| Event | Description | Unit cost (£) | Source | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure cost | RBL procedure | 109.00 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | Outpatient procedure |

| Blood transfusion | 170.14 | NICE 201559 | Blood transfusion costing statement | |

| Hospital admission | Inpatient bed-day | 303.00 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | – |

| Medication prescribed post procedure | Paracetamol | 1.27 | BNF 201560 | 500 mg, 32-tablet pack |

| Co-codamol | 6.73 | BNF 201560 | 30/500 mg, 100-tablet pack | |

| Codeine | 1.23 | BNF 201560 | 15 mg, 28-tablet pack | |

| NSAID | 3.50 | BNF 201560 | Ibuprofen 200 mg, 84-tablet pack | |

| Tramadol | 14.10 | BNF 201560 | 100 mg, 30-tablet pack | |

| Laxative | 3.82 | BNF 201560 | Bisacodyl 5 mg, 100-tablet pack | |

| Antibiotic | 5.03 | BNF 201560 | Augmentina 375 mg, 21-tablet pack |

| Event | Description | Unit cost (£) | Source | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaesthetic | General and local anaesthetic | 100.08 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | |

| Spinal anaesthetic | 200.00 | |||

| HAL procedure | Consultant cost per minute | 2.30 | PSSRU 201557 | Includes costs of qualifications |

| Associate specialist cost per minute | 2.13 | PSSRU 201557 | Includes costs of qualifications | |

| Surgical trainee cost per minute | 2.13 | PSSRU 201557 | Includes costs of qualifications | |

| Fellow cost per minute | 2.13 | PSSRU 201557 | Includes costs of qualifications | |

| Specialist nurse cost per minute | 1.52 | PSSRU 201557 | Includes costs of qualifications | |

| Research nurse cost per minute | 1.52 | PSSRU 201557 | Includes costs of qualifications | |

| Registrar cost per minute | 1.20 | PSSRU 201557 | Includes costs of qualifications | |

| Scrub nurse cost per minute | 1.52 | PSSRU 201557 | Includes costs of qualifications | |

| Cost per minute in recovery | 0.41 | McKenzie 200955 | Adjusted for inflation | |

| Cost per minute for theatre overheads | 13.74 | McKenzie 200955 | Adjusted for inflation | |

| Operating event | Outpatient procedure | 109.00 | PSSRU 201557 | |

| Surgical kit for HAL procedure | 432.00 | NHS Supply system | ||

| Excision of skin tags | 109.00 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | Outpatient procedure | |

| Procedure cost | Cost of HAL surgery (used in sensitivity analysis) | 1128.00 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | Intermediate anal procedure (FZ22B-E) |

| Hospital admission | Inpatient bed-day | 303.00 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | |

| Need for blood transfusion | 170.14 | NICE 201559 | Blood transfusion costing statement | |

| Medication on discharge | Paracetamol | 1.27 | BNF 201560 | 500 mg, 32-tablet pack |

| Co-codamol | 6.73 | BNF 201560 | 30/500 mg, 100-tablet pack | |

| Codeine | 1.23 | BNF 201560 | 15 mg, 28-tablet pack | |

| NSAID | 3.50 | BNF 201560 | Ibuprofen 200 mg, 84-tablet pack | |

| Tramadol | 14.10 | BNF 201560 | 100 mg, 30-tablet pack | |

| Laxative | 3.82 | BNF 201560 | Bisacodyl 5 mg, 100-tablet pack | |

| Antibiotic | 5.03 | BNF 201560 | Augmentin 375 mg, 21-tablet pack | |

| GTN paste | 39.30 | BNF 201560 | GTN ointment 0.4%, 30 g | |

| Diltiazem paste | 73.83 | BNF 201560 | 2% diltiazem cream |

| Event | Description | Unit cost (£) | Source | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient treatment | Outpatient visit | 114.00 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | |

| Injection sclerotherapy | 4.79 | BNF 201560 | Phenol 5% injection, 5-ml ampoule | |

| EH | 1508.72 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | FZ22E (elective) | |

| SH | 2478.42 | McKenzie 200955 | Adjusted for inflation | |

| RBL (in theatre) | 1338.45 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | FZ22E (elective) | |

| Other elective procedure | 1338.45 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | FZ23A | |

| Emergency admissions | Emergency admission for symptoms related to RBL/HAL | 1565.00 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | Non-elective |

| Blood transfusion | 170.14 | NICE 201559 | Blood transfusion costing statement | |

| Emergency operation | 2761.00 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | FZ23A | |

| Contact with health professionals | GP visit | 46.00 | PSSRU 201557 | |

| Nurse visit (GP practice) | 13.70 | PSSRU 201557 | Based on 15.5 minutes per visit | |

| Consultant visit | 114.00 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | ||

| Further treatments | GTN paste | 39.30 | BNF 201560 | GTN ointment 0.4%, 30 g |

| Diltiazem paste | 73.83 | BNF 201560 | 2% Diltiazem cream | |

| Recurrence treatment costs | Proctoscopy at 6 weeks’ assessments | 10.99 | ||

| RBL after recurrence | 523.16 | Mean RBL cost within HubBLe trial | ||

| Admissions with complications | 1565.00 | UK NHS reference costs 2014–15 58 | Non-elective |

Outcomes

Recurrence is the primary outcome for this study (please refer to Primary Outcome Measure, above, for details). For the economic evaluation, the difference in the number of recurrence between the intervention group (HAL) and the control group (RBL) was used as an outcome for assessing the cost-effectiveness in terms of cost per recurrence avoided.

Analysis

The base-case analysis was based on imputed data, whereas complete-case analysis was conducted as a sensitivity analysis. The economic analysis involves CUA as a primary analysis, and a CEA was performed as a secondary analysis. Both analyses involve the estimation of differential costs and differential outcomes.

A subgroup analysis was performed for patients with new haemorrhoids and patients with recurrence following RBL before randomisation. Different sensitivity analyses were performed to address uncertainty associated with the estimates from our base-case analysis.

Resource use

Resource-use data were used for costing the different clinical events and service use at individual patient level. Where RBL or HAL procedures are repeated following recurrence after the initial procedure within this trial, the mean level of resource use within the HubBLe trial was applied.

Difference in costs

The mean total costs and the differences in mean total costs between HAL and RBL groups were analysed using complete-case analysis and descriptively reported alongside the numbers of complete cases, their percentage from the total participants per group, SDs and CIs. The mean costs for each group of resource-use items were similarly reported in tabular format.

Missing data

Missing data may lead to misleading estimates of within-trial CEA, and in this context complete-case analysis is undesirable, as it would reduce the sample size and may affect the power of the study. 61 To check the patterns of missing data, we performed two types of descriptive analyses of missing data: (1) number of missing data by treatment group to assess whether or not missing data differ by group; and (2) missing data patterns to determine whether or not data are missing for all items or individual items of utility scores and resource-use items over the trial follow-up. 61 The multiple imputation chained equation (MICE) method with predictive mean matching was utilised for imputing missing values of costs, QALYs and baseline utility. 61 Age, gender, grade of haemorrhoids, site code and randomisation group were used as imputation variables in this model. The number of imputations specified in this model was 53, based on the highest percentage of missing data for the variables of interest (baseline utility, QALYs and total cost). 61 The imputation was performed per randomisation arm, for all imputed variables, except baseline utility, for which imputation was performed across all observations. This model allowed the prediction of missing values from the posterior distribution of missing observations, given the values of observed data from the imputation variables.

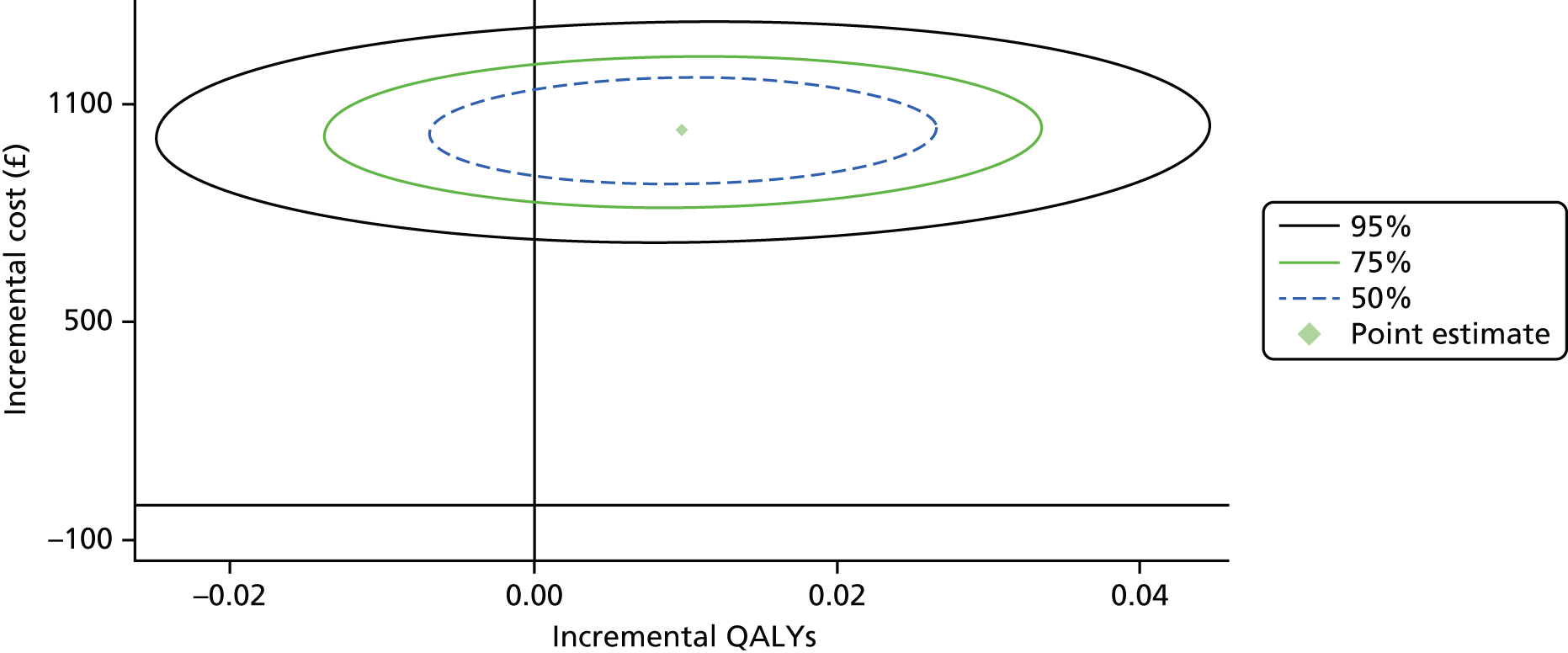

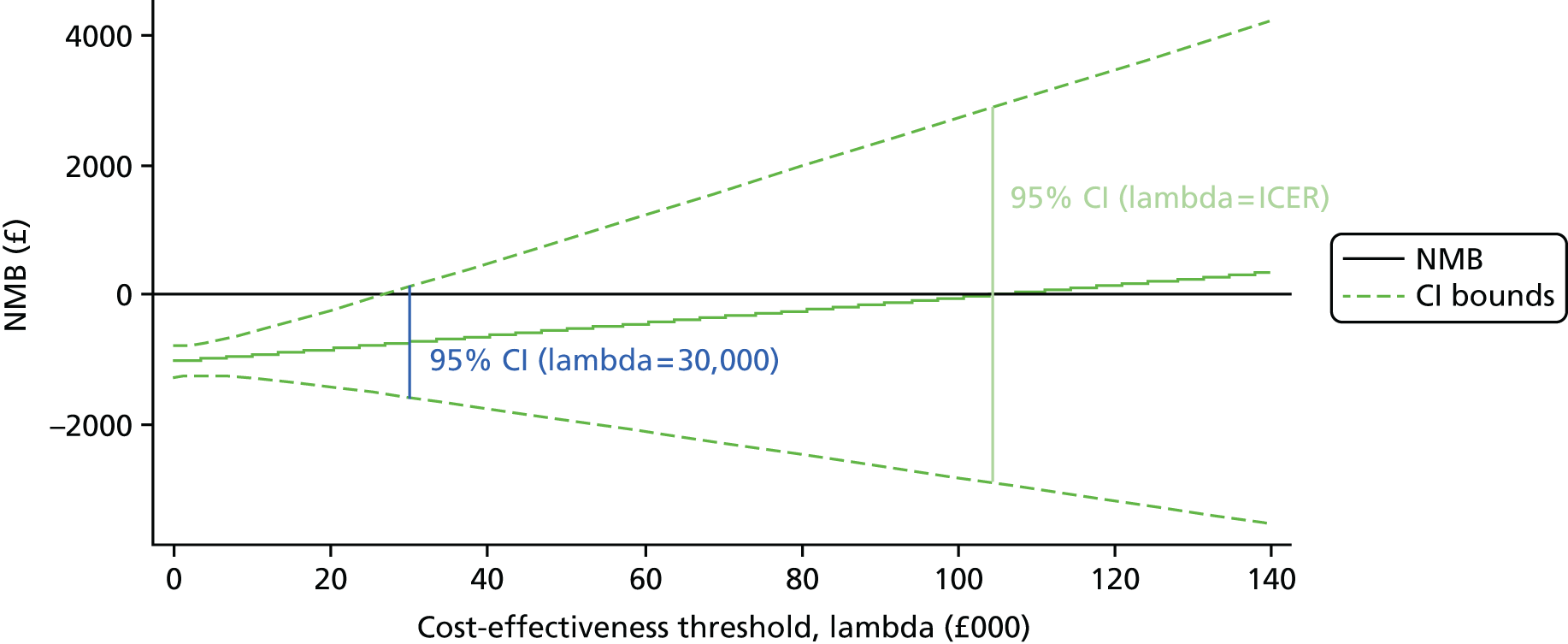

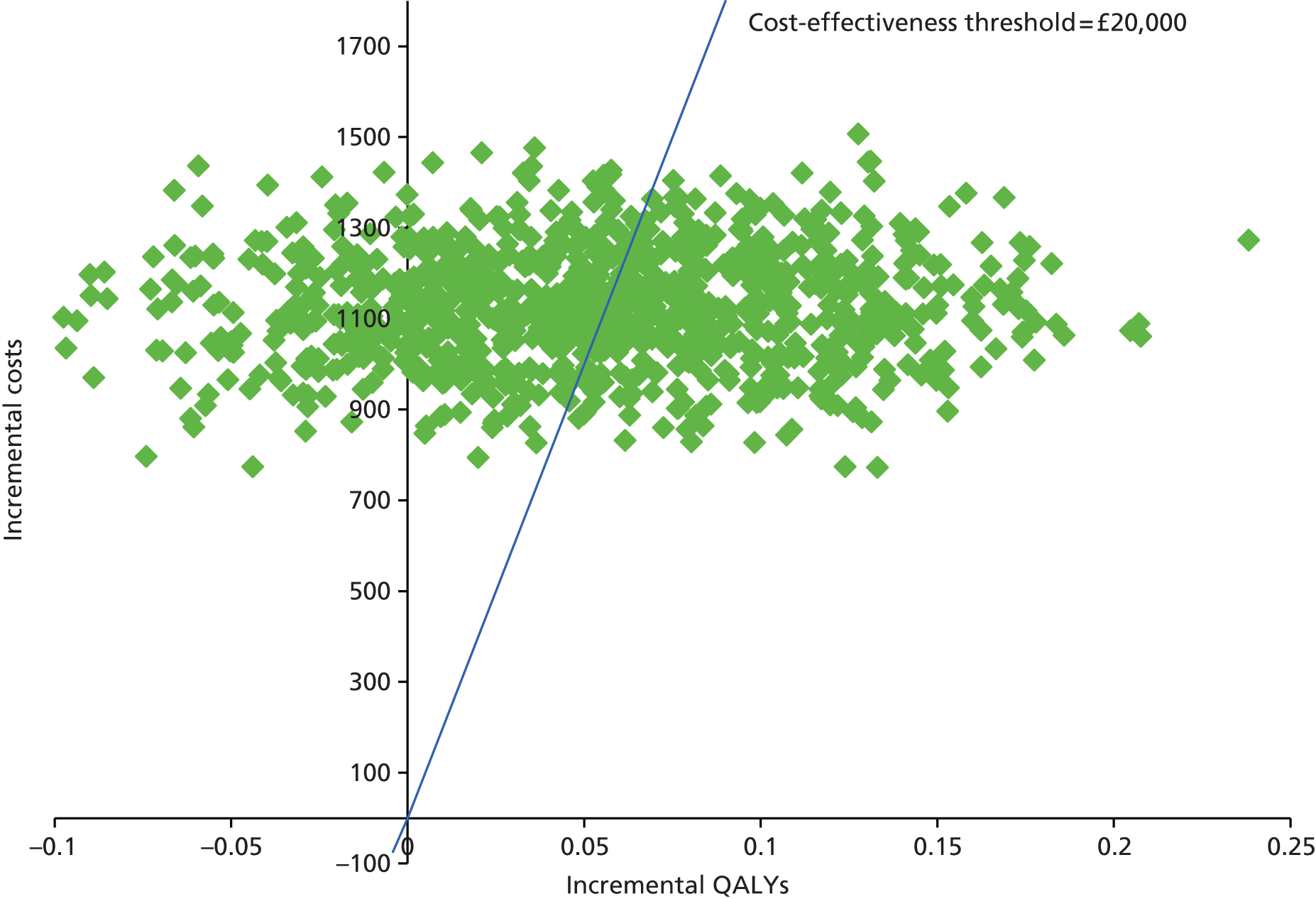

Cost–utility analysis

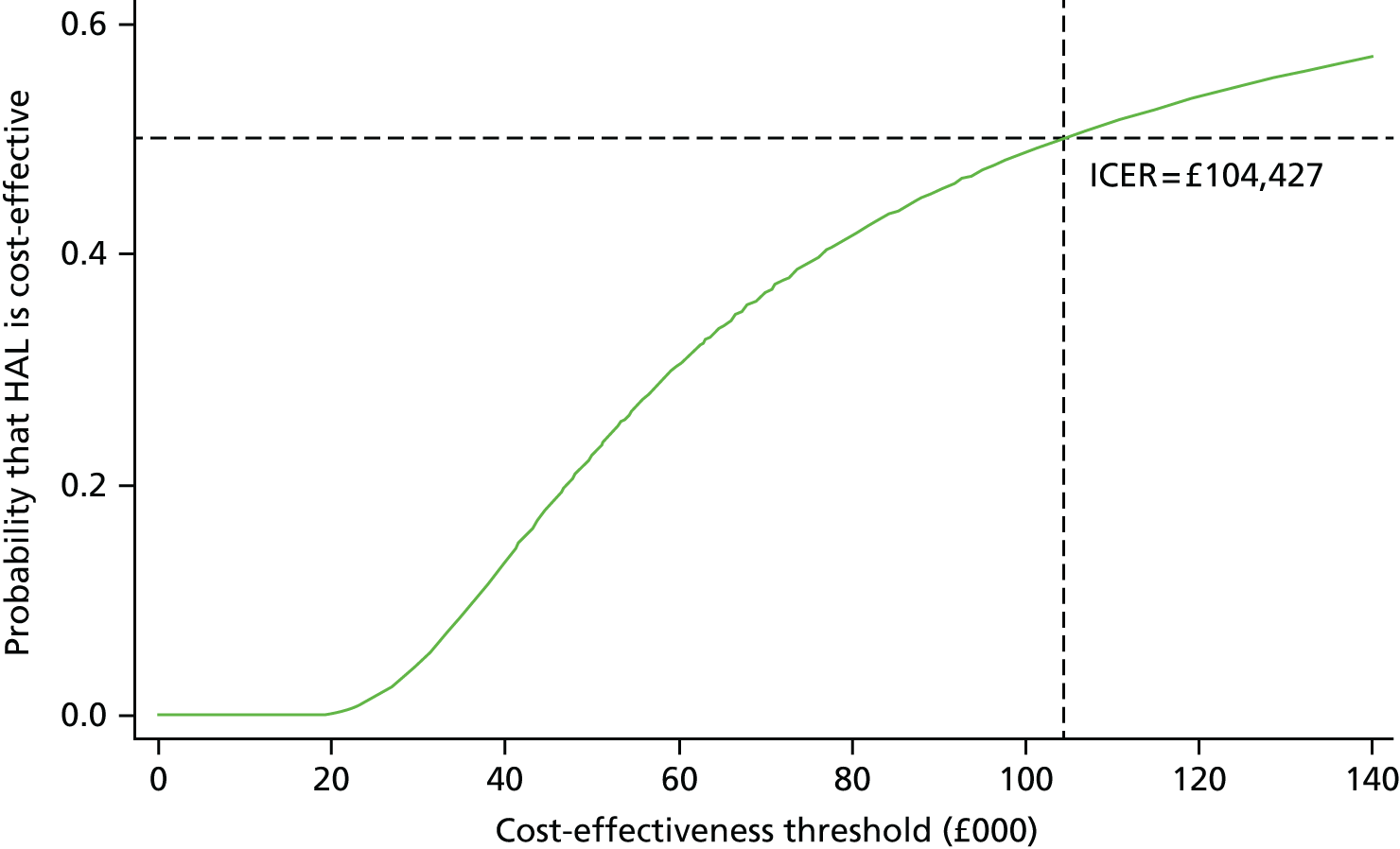

Cost–utility analysis was performed as the primary economic analysis for estimating the cost-effectiveness of HAL compared with RBL. A seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) model was fitted for estimating differential costs and differential QALYs, while controlling for imbalance in baseline utility and taking into account the correlation between cost and QALYs. Controlling for imbalance in baseline utility is recommended as good practice for within-trial CEA. 62 The fitted SUR model also provided the estimation of full variance–covariance matrix which was further used for addressing uncertainty using the parametric method. 63 In addition to the advantage of controlling for heterogeneity between patients (such as an imbalance in baseline utility) offered by traditional ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, SUR offers two additional advantages: it allows (1) the use of different sets of covariates for cost and effectiveness (QALYs) to assess their joint impact on cost-effectiveness simultaneously; and (2) the testing of joint hypothesis regarding the important coefficients (difference in costs and QALYs) across the two regression equations. 63

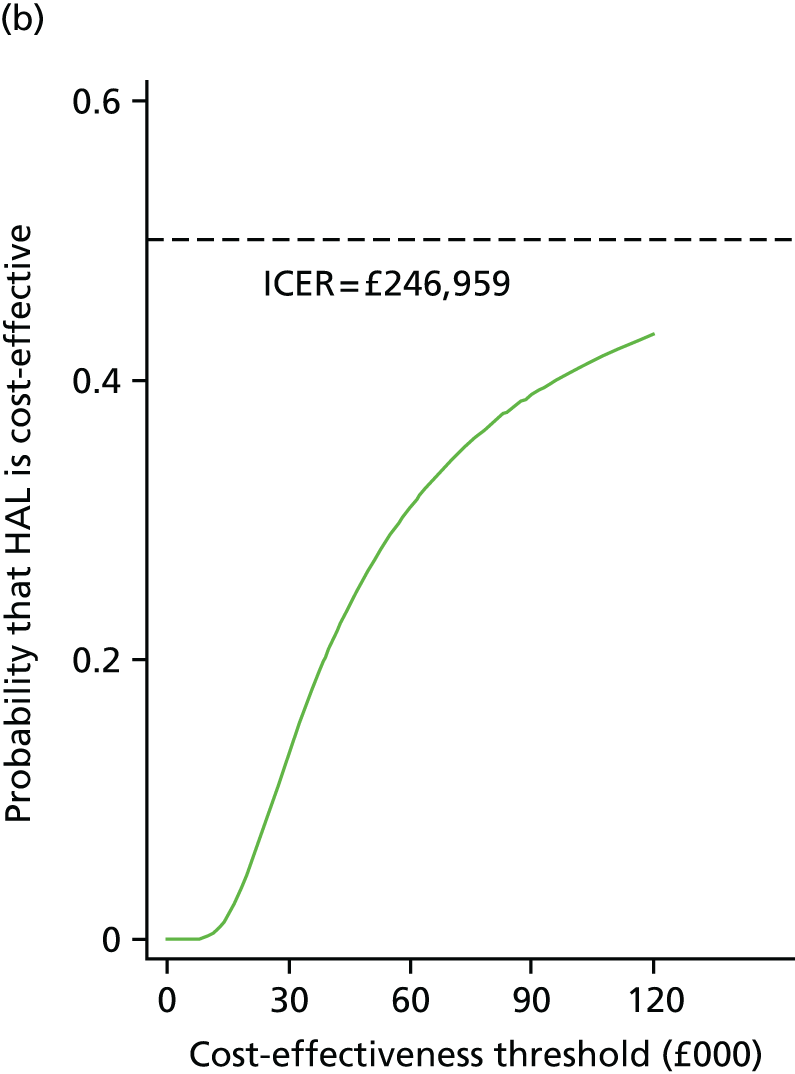

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was estimated from the SUR regression output, based on analysis of imputed data for the base case. The ICER is then compared with NICE cost-effectiveness threshold range of £20,000–30,000 per QALY gained.

To address uncertainty around our CUA estimates, a number of approaches were used based on the parametric method. We used five key parameters from the SUR regression output and conducted a fully parametric CUA. These parameters were difference in mean QALYs, standard error (SE) of the mean differential QALYs, difference in mean costs, SE of mean differential costs, and covariance between costs and QALYs. From these parameters, we produced three different graphs: the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC), the cost-effectiveness confidence ellipses and the net benefit line with CIs. The higher bound of NICE cost-effectiveness threshold of £30,000 per QALY was used as a standard decision rule in this analysis for illustrative purposes. The cost-effectiveness threshold was varied from £0 to £140,000 for addressing uncertainty associated with the cost–utility estimates across different levels of willingness to pay.

Combined CEAC curves were generated from the subgroup analysis for patients with new haemorrhoids and patients with recurrence following RBL to allow for easy comparisons. We also conducted an additional analysis by controlling for the grade of haemorrhoids in addition to baseline utility within the SUR model. This allowed us to assess the effect of the grade of haemorrhoids on our CUA in terms of differential cost, differential QALYs and the ICER.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The CEA followed the standard approach for which the total difference in costs was divided by the difference in recurrence to generate the incremental cost per recurrence avoided. However, it should be noted that treatments differed following recurrence, and these were also captured by our costing approach and constitute a key part within the primary CUA.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed a number of sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our estimates and address some issues, which might be associated with our costing approach and unit costs applied in the base-case analysis. The main sensitivity analysis was based on using the NHS reference costs for HAL procedure rather than the microcosting approach. In this scenario, HAL was considered as a day case intermediate anal procedure and the cost associated with this Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) was applied. This was assumed to include all of the other procedure-related costs, including the anaesthetic cost, the surgical kits, staff time and theatre overhead cost as per the HRG costing approach. A similar imputation model and SUR were used for estimating differential cost, differential QALYs and the ICER for this scenario of sensitivity analysis. We also produced a CEAC curve using the same methods applied in our base-case analysis.

An additional sensitivity analysis was undertaken by controlling for the grade of haemorrhoids, in addition to baseline utility, using the same regression model. This was carried out to assess the interaction effect of the grade of haemorrhoids on our CUA. The results from this form of sensitivity analysis are presented in terms of ICER.

We also carried out a sensitivity analysis by conducting another scenario of CUA using complete cases. A similar SUR model was run for estimating differential costs, differential QALYs and the ICER based on complete cases only. The results of this analysis were reported in a tabular format.

Another sensitivity analysis was conducted by estimating a utility decrement for each subsequent procedure performed during the trial follow-up. As the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire was completed at particular follow-up time points that did not coincide with any follow-up procedures, estimated QALY decrements were applied. The QALY decrements following subsequent HAL or RBL procedures were estimated using mean utility scores from the trial at baseline, day 1 and day 7. For SH and EH utility decrements were taken from a published UK study. 2 Utility scores during the recovery period of 0.756 for EH and 0.767 for SH were used for estimating QALY decrements. 2 QALY decrements were applied at the individual patient-level data and a regression analysis was run using the same model specification in our base-case analysis.

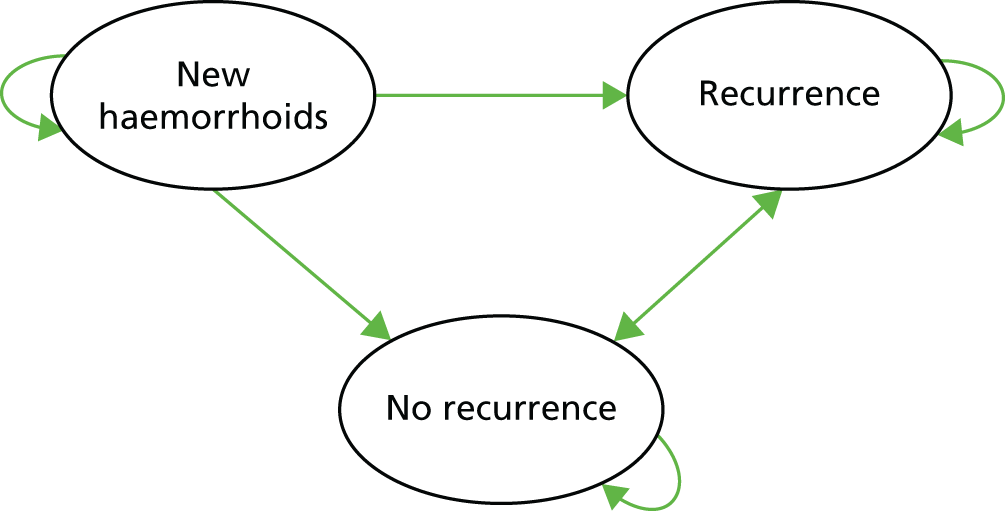

Long-term cost-effectiveness

A long-term extrapolation analysis was undertaken to assess the cost-effectiveness of HAL compared with RBL beyond the trial time horizon. The cost and utility data reported at 1-year follow-up within the trial were used in combination with external data to estimate longer-term costs and QALYs. A time horizon of 3 years beyond the trial was chosen for this analysis. This choice of time horizon was driven by data from external studies for which recurrence data were available over this follow-up time. We constructed a three-health states Markov model for extrapolating within-trial cost–utility analyses to long-term cost-effectiveness. To maintain consistency with the trial analyses, health states were chosen based on the primary outcome of the trial – recurrence. Heath states included were new haemorrhoids, recurrence and no recurrence. The extrapolation model structure is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Extrapolation model structure.

Regression analysis was used to estimate costs and utilities from the trial data using a similar SUR model described earlier, with recurrence at baseline added as a covariate. This allowed us to estimate costs and utilities by health state. We assumed that costs and outcomes follow the same pattern observed within the trial for the purpose of these extrapolation analyses. For instance, the mean costs and QALYs for patients with recurrence following RBL after 1 year and treated with further procedures were assumed to be same. Costs and health benefits (utilities) occur at different time points within the long-term time horizon of this analysis. We used the UK Treasury discount rate of 3.5% per year for discounting all future costs and QALYs as recommended by NICE. 49

The annual probability of recurrence for years 1–3 beyond the trial were estimated from two studies3,37 that have reported long-term recurrence estimates. For RBL, the annual probability of recurrence was calculated from a retrospective study3 that reported 4 years’ follow-up (n = 805). For HAL, the probability of recurrence was calculated at 5-year follow-up in a study37 that assessed the long-term success rates for treating patients with grade II and III haemorrhoids following Doppler-guided HAL (n = 100). 37 The mean total costs over four years, per patient, within each group (HAL and RBL) were calculated based on the annual probabilities of transition between health states. The mean total QALYs over the same period were similarly estimated and adjusted for recurrence. The long-term ICER was then estimated from the model and is reported below (see Long-term cost-effectiveness).

A probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was performed to address the uncertainty around parameter estimates from external sources (i.e. long-term recurrence rates). The PSA was run on 1000 Monte Carlo simulations. The distribution of costs and QALYs used in the PSA simulations were estimated from the regression analysis on the trial data.

Patient and public involvement

We were committed to involving service users at each stage of our research, from design to dissemination. From our patient and public consultation event, we identified an individual who was willing to join the grant application team. This person attended the TSC meetings in order to provide input into study oversight and have commented on the report, particularly the plain language summary, and the patient view regarding the choice of treatment. We also had input from service users with regards to the study design, including some of the patient questionnaires and the length of follow-up involved, and sought the TSC member’s opinion on study documents submitted to the REC, both initially and relating to protocol amendments.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and participant flow

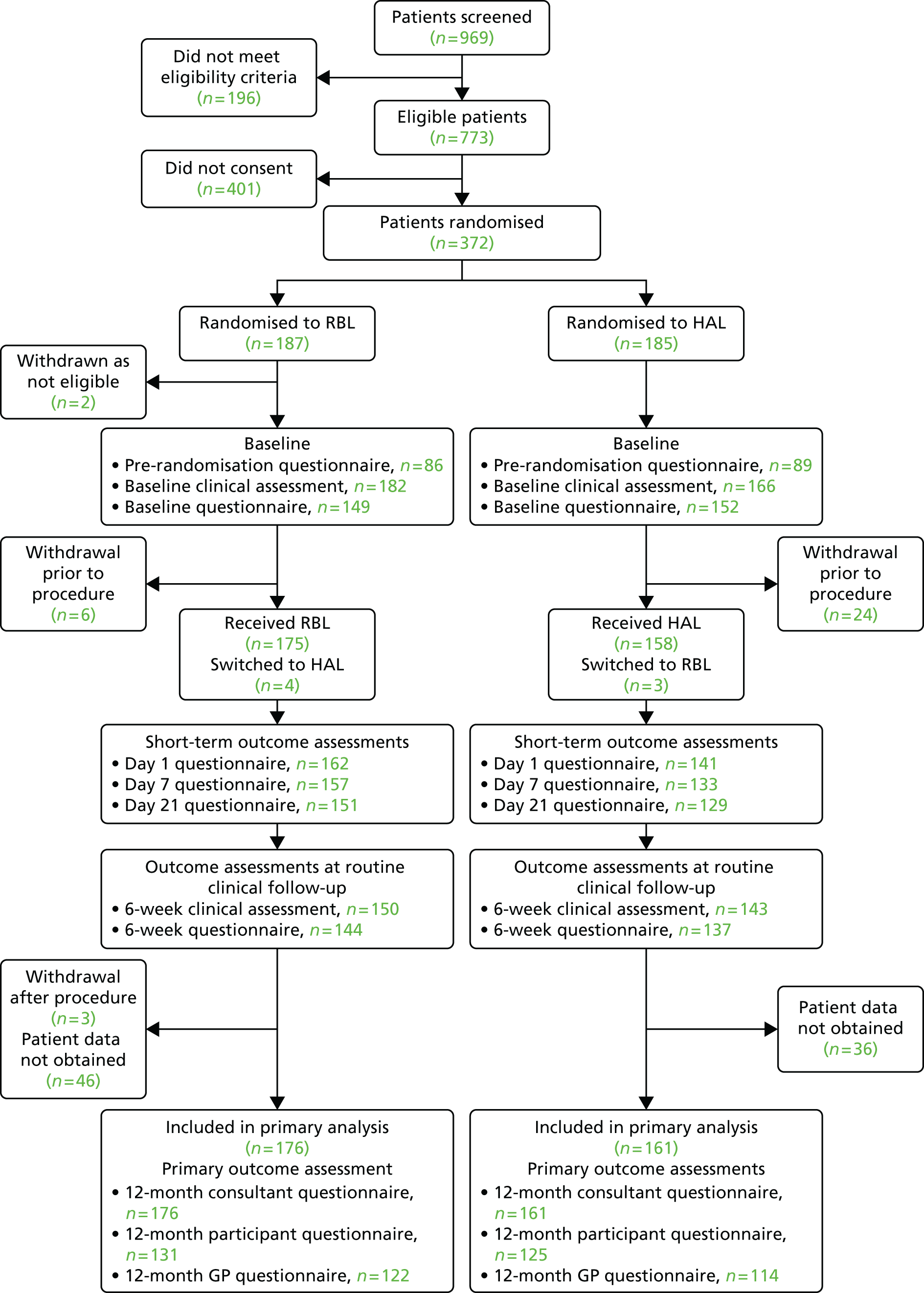

Participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment and were analysed for the primary outcome

Recruitment to the trial is represented in Figure 3. A total of 372 participants were randomly assigned to receive RBL or HAL; 187 patients were allocated to receive RBL, and 185 were allocated to receive HAL. Two of these participants (both randomised to RBL) were removed from the trial completely, as they were ineligible at the time of consent; therefore, a total of 370 participants were entered into the trial. In total, 969 patients were screened for entry into the trial and the reasons for non-recruitment are shown in Table 5.

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment graph.

| Reason | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Patient preference | 251 |

| Patient preference for RBL | 128 |

| Patient preference for HAL | 70 |

| Patient preference for other surgery | 5 |

| Patient preference for immediate treatment | 3 |

| Patient preference related to general anaesthetic | 6 |

| Patient did not want any intervention or treatment | 39 |

| Clinical decision | 41 |

| Patient did not attend appointment/uncontactable | 26 |

| Patient unsure or declined (no further reason given) | 29 |

| Other reason | 12 |

| Unknown | 42 |

| Total | 401 |

Patient preference was the main reason for non-consent by patients, with 128 patients opting for RBL and 70 patients opting for HAL.

Losses and exclusions after randomisation

A total of 340 participants received treatment as part of the trial and the participant flow is shown in Figure 4; reasons for withdrawal during the trial are provided in Table 6. Primary outcome data were collected for 337 participants (161 HAL and 176 RBL): 256 patient questionnaires were returned at 12 months; 236 GP forms were returned at 12 months, and 337 consultant forms were completed at 12 months. There were 183 participants where all 3 of the 12 months forms were completed/returned.

FIGURE 4.

Flow chart summarising the numbers of each type of questionnaire completed throughout the trial.

| Reason for withdrawal | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| HAL (n = 24) | RBL (n = 11) | |

| Prior to procedure | ||

| Found to be ineligible during baseline assessments | 0 | 2 |

| Participant withdrew consent | 15 | 3 |

| Lost to follow-up prior to procedure | 6 | 2 |

| Symptoms resolved | 2 | 1 |

| Ineligible at time of procedure | 1 | 0 |

| After procedure | ||

| Participant withdrew consent | 0 | 3 |

Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up

The first site to open to recruitment was STH NHS Foundation Trust on 9 September 2012, and recruitment finished at all sites on 6 May 2014. Follow-up was due to end 1 year after the end of recruitment but to allow for the delay in receiving the trial treatment we extended this period and the follow-up was completed at sites on 28 August 2015.

Table 7 shows the duration between randomisation and treatment (waiting time) by treatment group for the trial. These data do not include individuals who withdrew prior to treatment; 24 participants withdrew prior to the procedure in the HAL group, compared with six (eligible) participants in the RBL group. In the RBL group, 114 of 179 (63.4%) participants received treatment on the same day as they were randomised (0 days), whereas none of the HAL group participants was treated on the same day. Although the maximum waiting time is greater for RBL, the mean and median shows that waiting times are higher for HAL.

| Treatment group | Waiting time (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Median | |

| HAL | 2 | 276 | 75.9 | 62 |

| RBL | 0 | 413 | 20.3 | 0 |

Baseline data

The characteristics of the participants included in the final analysis is shown in Table 8. The groups appear balanced at baseline in regards to gender, age, BMI, the grade of haemorrhoids and previous treatment for haemorrhoids.

| Demographic | Value | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBL (n = 176) | HAL (n = 161) | ||

| Gender | Male (%) | 99 (56) | 85 (53) |

| Female (%) | 77 (44) | 76 (47) | |

| Age | Mean (SD) | 49.0 (12.9) | 48.5 (13.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 50.5 (38.5–58.0) | 49.0 (38.0–60.0) | |

| Range | 21.9–79.3 | 20.2–74.6 | |

| BMI | Mean (SD) | 28.0 (5.5) | 28.2 (7.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 27.0 (24.4–31.7) | 26.8 (24.1–30.0) | |

| Range | 17.4–44.9 | 18.8–67.4 | |

| Grade | II (%) | 115 (65) | 92 (57) |

| III (%) | 60 (34) | 68 (42) | |

| Not recorded (%) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Previous treatment | No (%) | 124 (70) | 124 (77) |

| Yes (%) | 52 (30) | 36 (22) | |

| Not recorded | 0 | 1 (0.6) | |

| Grade of surgeon undertaking procedure | Consultant or equivalent (%) | 148 (84) | 121 (75) |

| Junior trainee, supervised by consultant (%) | 6 (3) | 34 (21) | |

| Junior trainee, not supervised by consultant (%) | 22 (13) | 6 (4) | |

The majority of the procedures were conducted by consultant or equivalent (clinician accredited for independent practice, including a clinical nurse specialist), or supervised by a consultant (87% for RBL and 96% for HAL). There were a few cases that were carried out by a trainee doctor. However, these trainees met our pre-existing competencies.

Numbers analysed

The ITT population, in which patients were analysed by their original assigned groups, included all 161 participants in the HAL arm and 176 in the RBL arm for whom recurrence data were available from either the patient, clinician or GP. Of these, the patient-completed questionnaire was returned for 125 and 131 participants in the HAL and RBL groups, respectively. The number of participants included in each analysis is provided for each measure in this section.

Outcomes and estimation

Recurrence (primary outcome)

The overall proportion of participants with a recurrence at 12 months was 49% in the RBL arm compared with 30% in the HAL arm (absolute difference 19.6%; adjusted OR 2.23, 95% CI 1.42 to 3.51; p = 0.0005). The breakdown of recurrences, overall and by criterion, is presented in Table 9. Self-reported recurrence rates were almost identical, with 29% of respondents in both arms stating that they believed that their haemorrhoids had either improved or been cured (adjusted OR for self-reported recurrence = 1.06, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.85; p = 0.85). The increased recurrence associated with RBL is mainly attributable to the high rate of additional procedures undertaken following the initial procedure [33%, compared with 14% in the HAL group (adjusted OR for further procedure = 2.86, 95% CI 1.65 to 4.93; p < 0.001)]. A further three (2%) participants in the RBL arm were considered to have symptoms that were consistent with recurrent haemorrhoids following blind review. In two cases the participants were recorded as possibly requiring further treatment at their 6-week visit but were subsequently lost to follow-up; a third patient had been hospitalised twice for excessive bleeding, but had not undergone treatment.

| Recurrence | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| RBL (n = 176) | HAL (n = 161) | |

| Overall recurrence (%) | 87 (49) | 48 (30) |

| Criteria for recurrencea (%) | ||

| Self-reported recurrence (%) | 37 (29b) | 34 (29b) |

| Subsequent procedure for haemorrhoids (%) | 57 (33) | 23 (14) |

| RBL | 31 (18) | 14 (9) |

| HAL | 23 (13) | 7 (4) |

| EH | 4 (2) | 7 (4) |

| SH | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| From blinded review (%) | 3 (2) | 0 |

Sensitivity analyses were undertaken in which alternative covariates (EQ-5D-5L at randomisation or preoperative, BMI at randomisation, and grade of haemorrhoids at randomisation) were adjusted for; doing so yielded reasonable consistency in the ORs (range 2.05–2.81), all of which remained statistically significant. The PP analysis again provided a similar OR (2.21, 95% CI 1.38 to 3.54; p = 0.001).

Of the baseline covariates assessed, none had a statistically significant association with recurrence. Recurrences were more common, however, among participants who were male, had grade III haemorrhoids, had undergone previous treatment and had higher symptom scores.

Among the 80 participants who required a further intervention, the majority of participants underwent a single procedure. In most cases this was RBL, as described in Table 9, although some variation was noted across centres as described in Table 10: as the primary interest is to document second-line treatment, the treatment groups here refer to treatment, as received, as opposed to ‘as randomised’, which was reported previously. As RBL is a brief procedure with (relatively) minimal inconvenience to the patient, it could be argued that a second-line RBL is not itself indicative of a recurrence because the initial haemorrhoids remain incompletely treated. Consequently, an additional (and unplanned) analysis investigated the extent to which recurrence differed if follow-up RBL were not considered a recurrence. In total, 45 participants (31 in the RBL arm, 11 in HAL) underwent RBL as follow-up procedure. Of the 31 patients who underwent repeat RBL, six considered their haemorrhoids to be unchanged or worse at 1 year; three underwent further procedures; and one was considered a recurrence based on blind review. In the HAL arm, 8 of the 11 participants who were undergoing subsequent RBL considered their haemorrhoids to be unchanged or worse at 1 year and two participants underwent further procedures. Thus, if subsequent RBL were not considered a recurrence, the number with recurrent haemorrhoids is 66 (37.5%) in the RBL arm and 44 (27.3%) in the HAL arm (adjusted OR 1.53, 95% CI 0.96 to 2.44; p = 0.071). If a single HAL is compared with multiple RBLs the number with recurrent haemorrhoids is 66 (37.5%) in the RBL arm and 48 (30%) in the HAL arm (adjusted OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.85–2.15; p = 0.20).

| Site | Treatment group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBL (N = 175) | HAL (N = 162) | |||||||

| n | RBL | HAL | Haemorrhoidectomy | n | RBL | HAL | Haemorrhoidectomy | |

| Sheffield | 39 | 8 | 12 | 0 | 34 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Birmingham | 34 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 31 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Oxford | 28 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 29 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Liverpool | 21 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 23 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| North Tees | 13 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Other centres | 40 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 35 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

Persistent significant symptoms at 6 weeks

At 6 weeks, data were available for 150 participants in the RBL arm and 143 in the HAL arm: 43 (24%) participants in the RBL arm reported their haemorrhoids as being unchanged or worse compared with 12 (7%) in the HAL arm; additionally, one participant in each arm had subsequently undergone RBL, thus resulting in the overall number of patients with persistent symptoms being 44 (29%) compared with 13 (9%) (adjusted OR 4.35, 95% CI 2.19 to 8.65; p < 0.001).

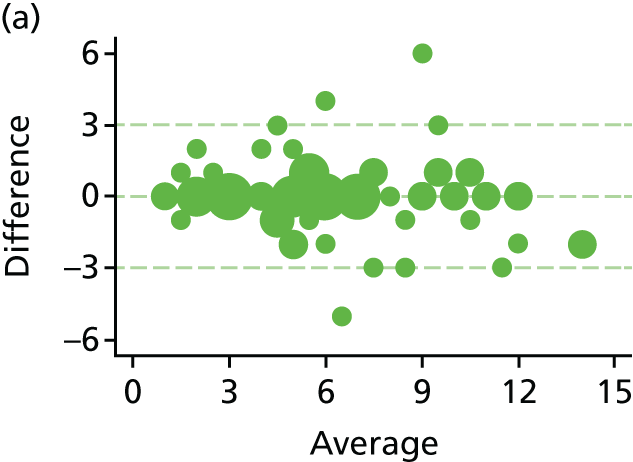

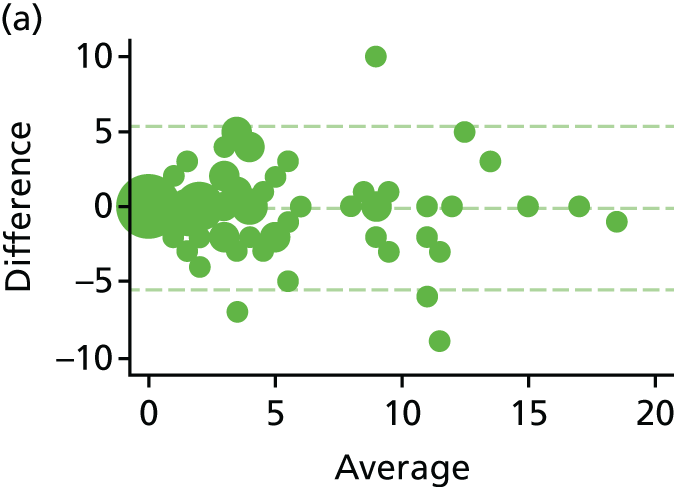

Haemorrhoid symptom severity score

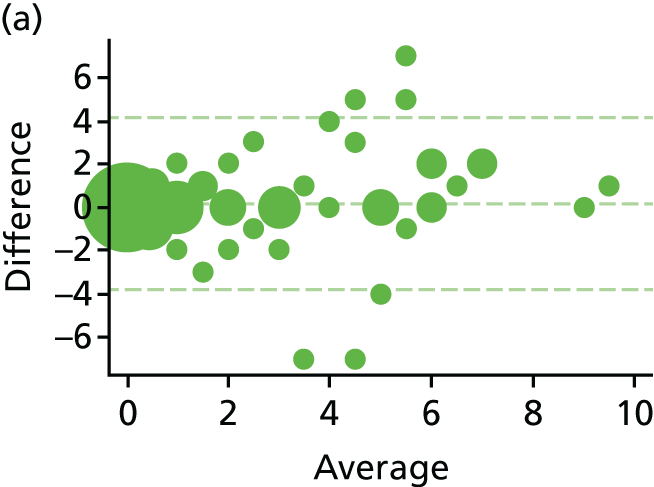

The haemorrhoid symptom severity scores are summarised in Table 11 and displayed graphically in Figure 5: higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. At 6 weeks, haemorrhoids symptom severity scores were higher in the RBL group, indicating that short-term symptoms were less pronounced following HAL. The mean (SD) scores were 4.0 (3.5) in the RBL group and 3.0 (3.1) in the HAL group, with an adjusted mean difference of 1.0 (95% CI 0.3 to 1.8; p = 0.010). No difference was apparent at 1 year, with the mean (SD) being 3.6 (3.2) for RBL and 3.6 (3.3) for HAL (adjusted difference = 0.0, 95% CI –0.8 to 0.8; p = 0.98).

FIGURE 5.

Haemorrhoid symptom severity scores. Note that the area of data points is proportional to the number of participants with that value. Vertical lines represent median and IQR.

| Time point | Treatment group | Difference (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBL | HAL | ||

| Randomisation | |||

| n | 83 | 80 | |

| Mean (SD) | 6.5 (3.2) | 6.4 (3.4) | |

| Median (IQR) | 6.0 (4.0–8.5) | 6.0 (4.0–9.0) | |

| Baseline | |||

| n | 146 | 150 | |

| Mean (SD) | 6.5 (3.3) | 6.4 (3.0) | |

| Median (IQR) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 6.0 (4.0–8.5) | |

| 6 weeks | |||

| n | 142 | 137 | 1.0 (0.3 to 1.8); 0.01 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.0 (3.5) | 3.0 (3.1) | |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) | 2.0 (1.0–5.0) | |

| 12 months | |||

| n | 131 | 123 | 0.0 (–0.8 to 0.8); 0.98 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.6 (3.2) | 3.6 (3.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 3.0 (1.0–5.2) | |

A further (post hoc) analysis looked at the proportion of participants whose symptom score was either ‘0’ or ‘1’, as this corresponds to the definition used by Nyström et al. 42 These numbers are shown in Table 12. The proportions are consistent with the previous analysis, with a greater proportion of participants in the HAL arm reporting either a score of 0 or 1 at 6 weeks.

| Time point | Treatment group | OR (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBL | HAL | ||

| Randomisation | 2/83 (2%) | 4/80 (5%) | |

| Baseline | 2/146 (1%) | 5/150 (3%) | |

| 6 weeks | 44/142 (31%) | 52/137 (38%) | 0.73 (0.44 to 1.22); 0.23 |

| 1 year | 35/131 (27%) | 38/123 (31%) | 0.79 (0.46 to 1.38); 0.42 |

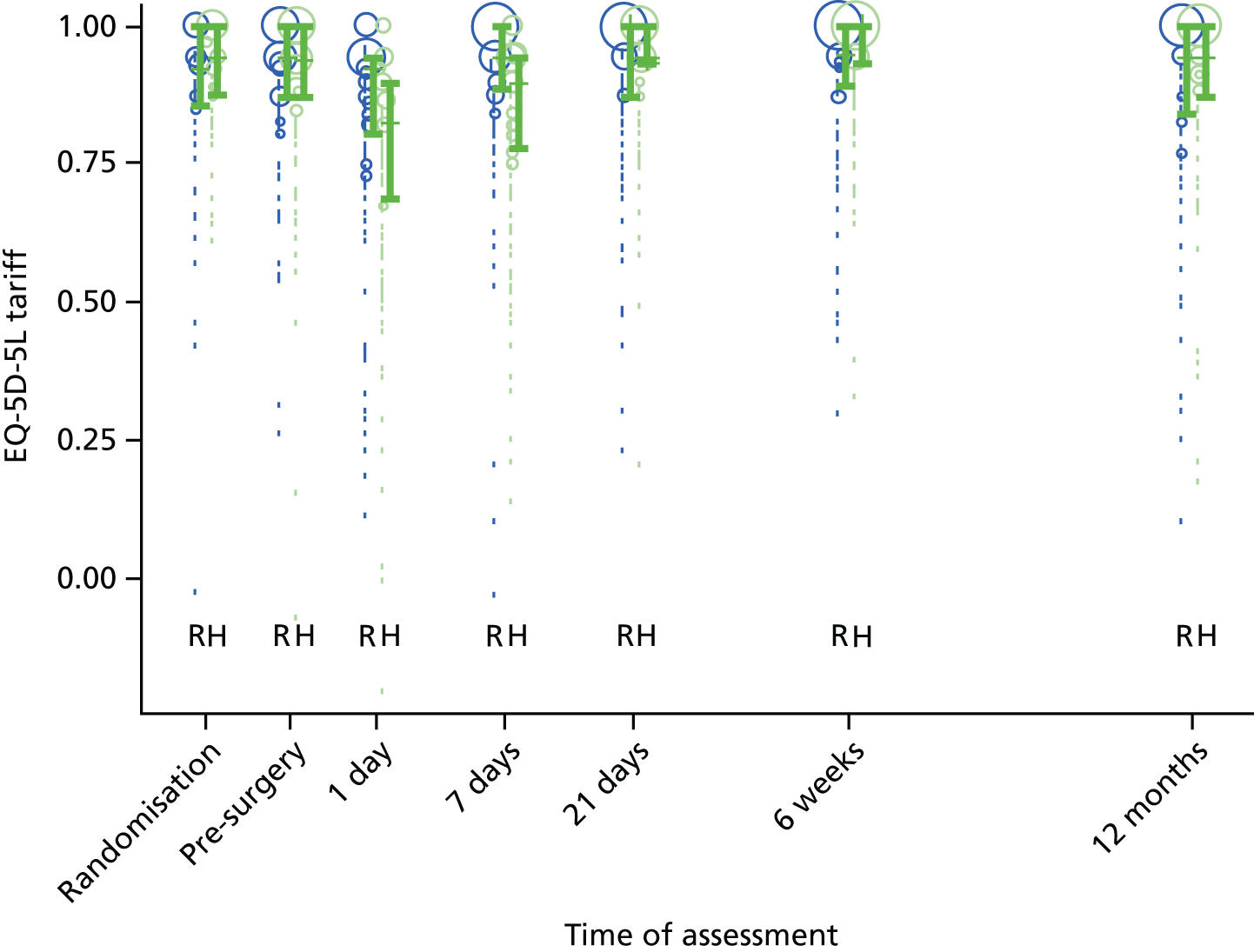

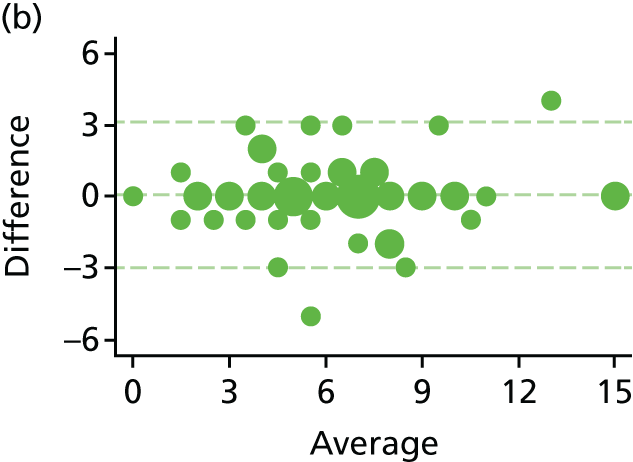

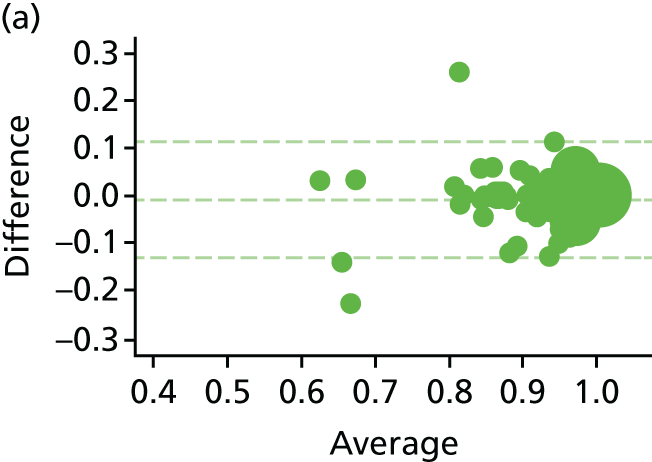

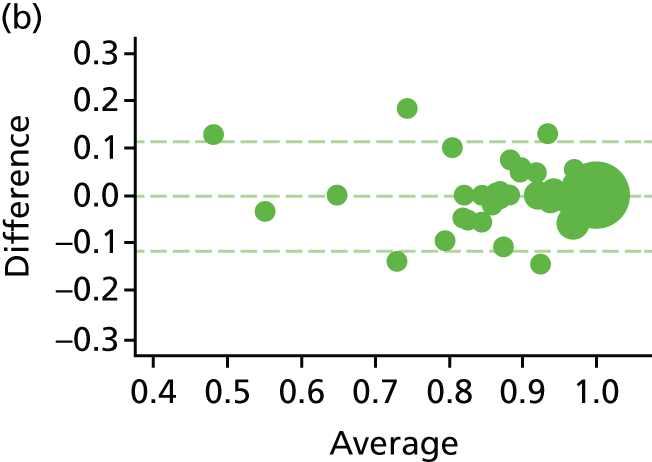

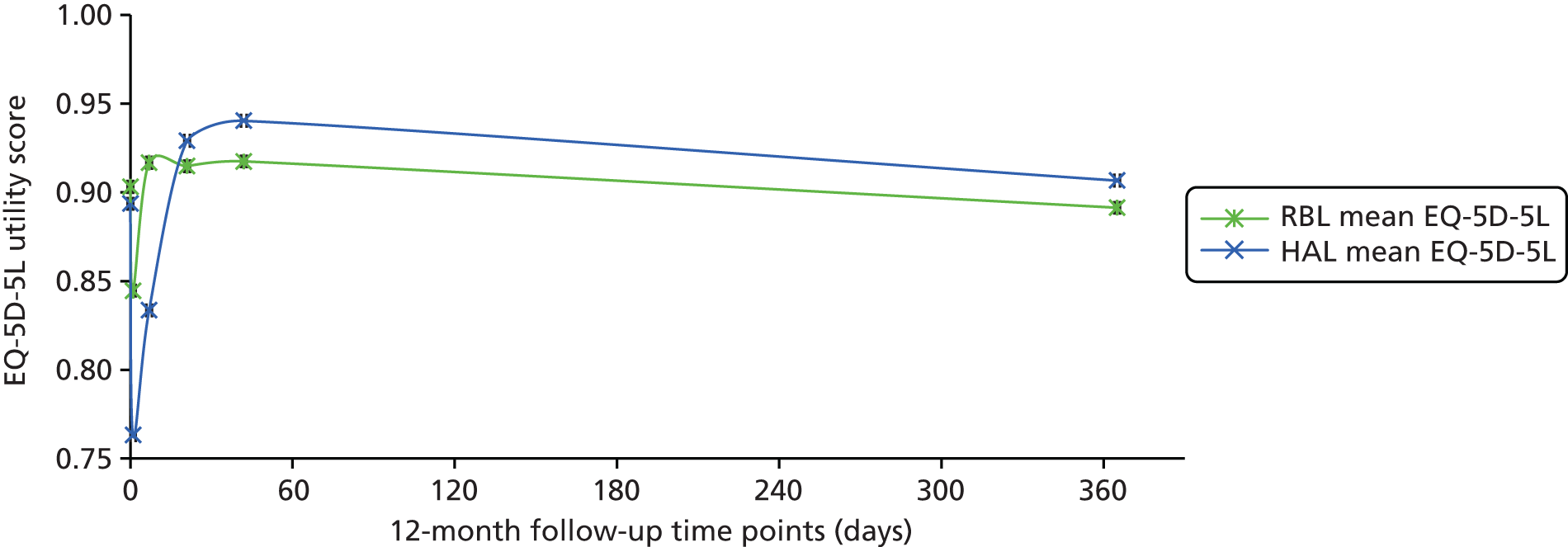

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (5-level version)

The EQ-5D-5L health tariff is summarised in Table 13 and Figure 6: higher figures indicate a better health state. Prior to procedure, the mean health utility was around 0.9 in both groups but declined at days 1 and 7 in the HAL group. For RBL the mean (SD) at 1 day was 0.84 (0.19) and at 7 days 0.92 (0.15); in other words, health state was reduced for the first day but had reverted back at 1 week. By contrast, the mean health state for HAL had not returned to baseline values by 7 days, with the mean (SD) being 0.76 (0.22) and 0.83 (0.18) at 1 and 7 days, respectively. The adjusted mean differences were 0.08 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.13; p < 0.001) at 1 day and 0.08 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.12; p < 0.001) at 7 days. The two arms were nearly similar with no statistical differences (and above baseline values) at all time points from day 21 onwards.

The EQ-5D-5L inventory was also used to derive the health state used in QALYs that are reported within the health-economic analysis in the following section.

FIGURE 6.

The EQ-5D-5L. Note that the area of data points is proportional to the number of participants with that value. Vertical lines represent median and IQR.

| Time point | Treatment group | Difference (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBL | HAL | ||

| Randomisation | |||

| n | 86 | 89 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.89 (0.16) | 0.92 (0.09) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.92 (0.86–1.00) | 0.94 (0.88–1.00) | |

| Baseline | |||

| n | 149 | 152 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.90 (0.12) | 0.89 (0.15) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.94 (0.87–1.00) | 0.94 (0.87–1.00) | |

| 1 day | |||

| n | 162 | 141 | 0.08 (0.04 to 0.13); < 0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.84 (0.19) | 0.76 (0.22) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.94 (0.87–0.94) | 0.82 (0.69–0.90) | |

| 7 days | |||

| n | 157 | 133 | 0.08 (0.05 to 0.12); < 0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.92 (0.15) | 0.83 (0.18) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.94 (0.89–1.00) | 0.90 (0.78–0.94) | |

| 21 days | |||

| n | 151 | 129 | –0.01 (–0.04 to 0.02): 0.35 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.92 (0.14) | 0.93 (0.11) | |

| Median (IQR) | 1.00 (0.87–1.00) | 0.94 (0.93–1.00) | |

| 6 weeks | |||

| n | 144 | 137 | –0.02 (–0.05 to 0.01): 0.12 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.92 (0.13) | 0.94 (0.11) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.00) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.00) | |

| 1 year | |||

| N | 128 | 123 | –0.02 (–0.06 to 0.03): 0.46 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.89 (0.17) | 0.91 (0.16) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.94 (0.84 to 1.00) | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.00) | |

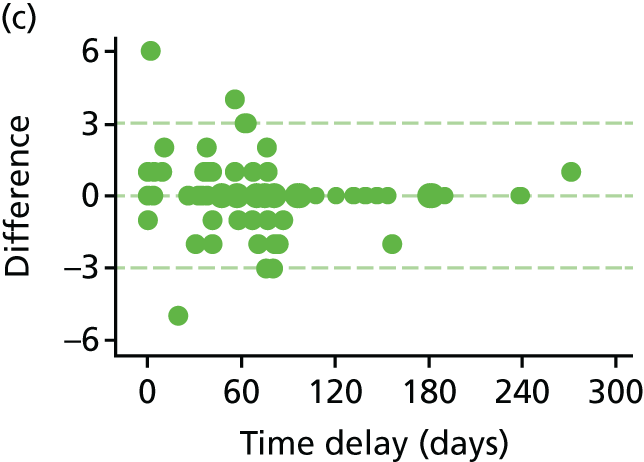

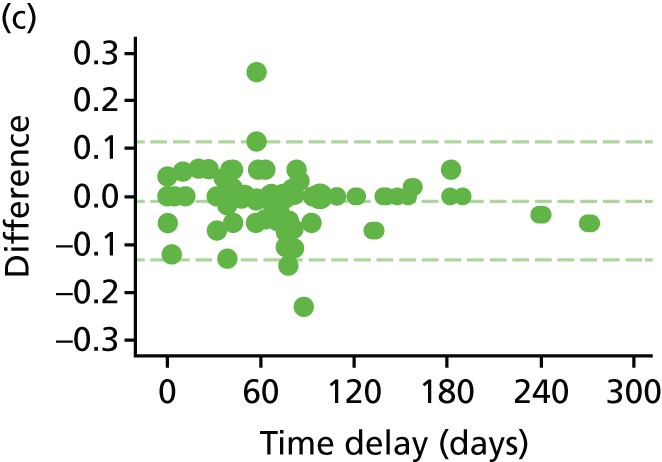

Vaizey faecal incontinence score

Vaizey faecal incontinence scores are provided in Table 14 and Figure 7; higher scores indicate more severe incontinence. No between–group differences were noted in the Vaizey faecal incontinence scores. An improvement of around 1 unit was noted in both arms at 6 weeks, with a difference between arms of –0.1 (95% CI –1.3 to 1.0; p = 0.86). The improvement was maintained at 1 year, with a difference of –0.5 (95% CI –1.8 to 0.7; p = 0.38). A summary of these findings is presented in Table 14 and Figure 7.

| Time point | Treatment group | Difference (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBL | HAL | ||

| Randomisation | |||

| n | 84 | 88 | |

| Mean (SD) | 6.0 (5.3) | 4.9 (4.6) | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (1.0–10.0) | 4.0 (2.0–7.5) | |

| Baseline | |||

| n | 142 | 147 | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.9 (5.2) | 5.3 (4.8) | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (1.0–9.0) | 4.0 (2.0–8.0) | |

| 6 weeks | |||

| n | 137 | 132 | –0.1 (–1.3 to 1.0); 0.86 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.0 (4.5) | 4.1 (4.9) | |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (0.0–6.0) | 3.0 (0.0–6.0) | |

| 1 year | |||

| n | 118 | 107 | –0.5 (–1.8 to 0.7); 0.38 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.0 (4.7) | 4.5 (4.5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0–6.0) | 3.0 (1.0 –7.0) | |

FIGURE 7.

Vaizey faecal incontinence score. Note that the area of data points is proportional to the number of participants with that value. Vertical lines represent median and IQR.

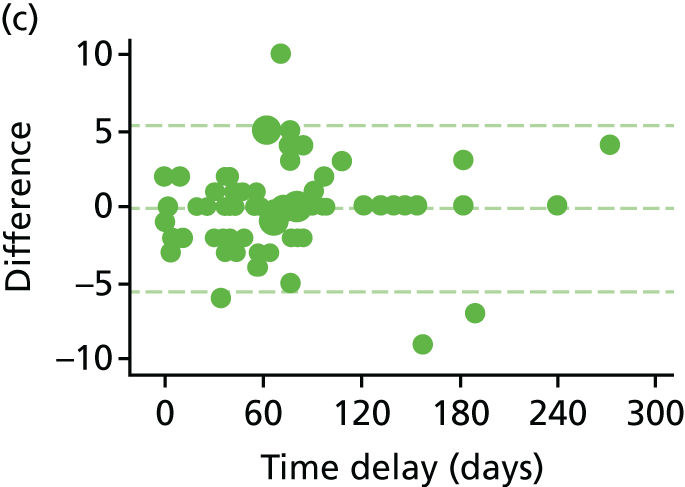

Pain

Haemorrhoidal pain was assessed by asking the patient to rate his/her pain related to haemorrhoids as of today and over the last week. Pain today was asked at baseline and again at days 1, 7 and 21, and, finally, at 6 weeks. Pain over the last week was asked at days 7 and 21, and, finally, at 6 weeks. Both of these are summarised in Tables 15 and 16 and Figures 8 and 9; a score of ‘0’ = ’no pain’, whereas a score of ‘10’ = ’worst imaginable pain’. The change in pain as recorded by VAS is shown in Table 17. Pain was increased in the HAL group at one and seven days after the procedure, but the groups were similar at day 21 and at 6 weeks.

| Time point | Treatment group | Difference (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBL | HAL | ||

| Randomisation | |||

| n | 84 | 89 | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.4 (2.6) | 2.3 (2.5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 1.0 (0.0–3.3) | |

| Baseline | |||

| n | 148 | 150 | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.2 (2.5) | 2.5 (2.7) | |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 1.0 (0.0–5.0) | |

| 1 day | |||

| n | 162 | 140 | –1.2 (–1.8 to –0.5); < 0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (2.8) | 4.6 (2.8) | |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–5.2) | 5.0 (2.0–7.0) | |

| 7 days | |||

| n | 157 | 133 | –1.5 (–2.0 to –1.0); < 0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (2.3) | 3.1 (2.4) | |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | |

| 21 days | |||

| n | 151 | 129 | –0.1 (–0.6 to 0.3); 0.44 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.3 (2.0) | 1.4 (1.9) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | |

| 6 weeks | |||

| n | 144 | 137 | 0.2 (–0.2 to 0.7); 0.32 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.2 (2.1) | 1.0 (1.8) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | |

| Time point | Treatment group | Difference (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBL | HAL | ||

| 7 days | |||

| n | 157 | 133 | –2.3 (–3.0 to –1.6); < 0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.9 (3.2) | 6.3 (2.9) | |

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (1.0–7.0) | 7.0 (4.0–9.0) | |

| 21 days | |||

| n | 151 | 129 | –0.3 (–0.9 to 0.4); 0.38 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.1 (2.7) | 2.4 (2.5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | |

| 6 weeks | |||

| n | 144 | 137 | 0.2 (–0.4 to 0.7); 0.56 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.7 (2.6) | 1.6 (2.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | |

FIGURE 8.