Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/65/01. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The draft report began editorial review in June 2016 and was accepted for publication in October 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sandra Lawton reports receiving an honorarium from Thornton & Ross and Bayer for educational activities outside the submitted work. Hywel C Williams is Director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. Andrew Gribbin reports salary support from Clinical Research Network and non-financial support from Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit, outside the submitted work. Sara J Brown reports grants from the Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship in Clinical Research (106865/Z/15/Z) during the conduct of the study and personal fees from the American Academy of Asthma Allergy and Immunology outside the submitted work, and has patent GB 1602011.7 pending (outside the submitted work). Sara J Brown holds a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship in Clinical Research (106865/Z/15/Z). Tracey Sach reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme and grants from the NIHR Career Development Fellowship during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Thomas et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Atopic eczema (AE) (also known as atopic dermatitis or eczema) is a chronic, itchy, inflammatory skin condition that is common throughout the world. 1 Childhood AE has a substantial impact on the quality of life of both children and their families. 2–4 Standard treatment options for AE focus on topical medications: emollients, with the addition of topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors, tailored according to the severity of the AE. 5 Although most cases of AE can be successfully treated with topical medications, many parents express inconvenience and/or concern in using these preparations and are keen to identify new ways of managing the symptoms of AE using non-pharmacological approaches. 6

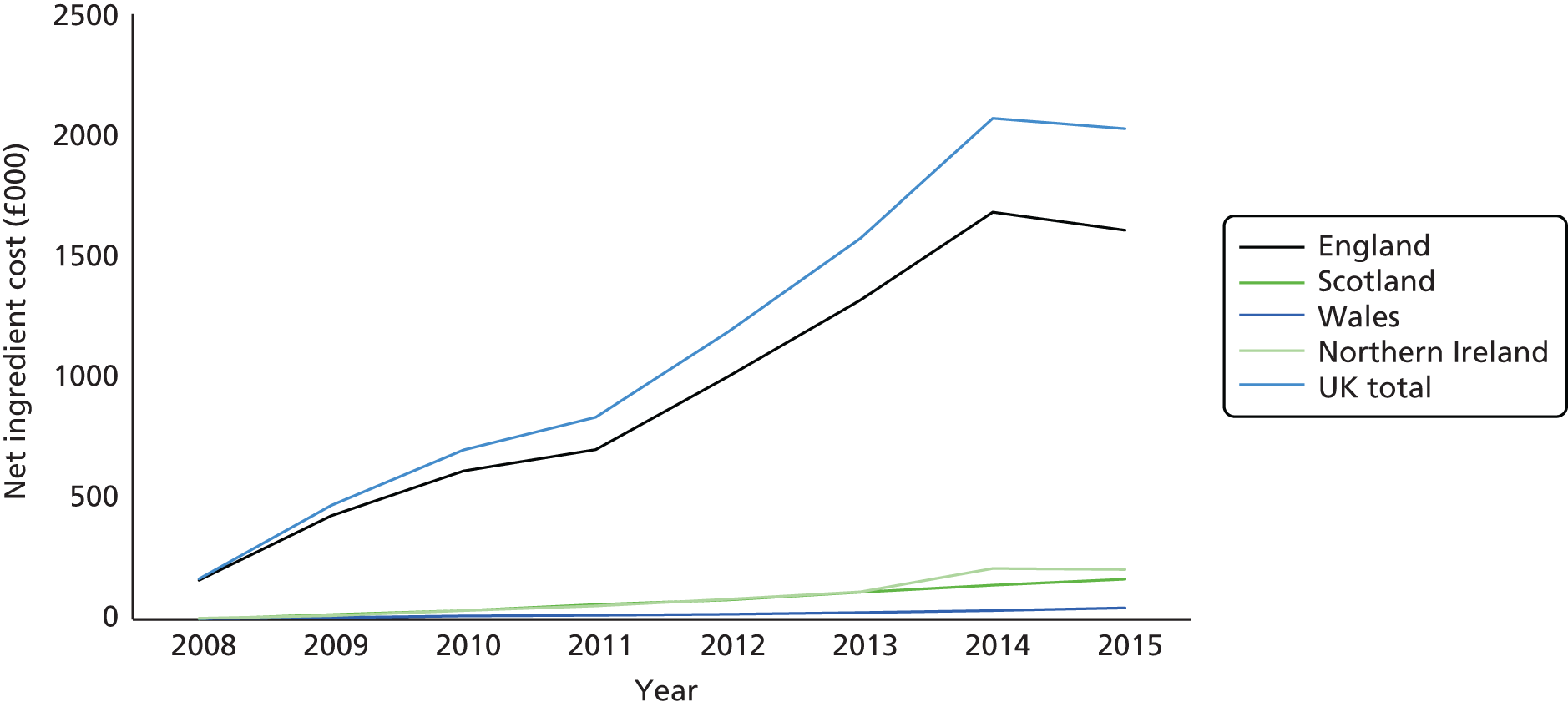

Clothing may play a role in either soothing or exacerbating AE symptoms and patients are commonly advised to avoid wool because of its tendency to worsen itch and to use cotton or fine-weave materials next to the skin. 7 Specialist clothing is now available on prescription in the UK in a variety of forms, including sericin-free silk, viscose and silver-impregnated fabrics. 8 The therapeutic silk garments included in this study are available on prescription in the UK, at a cost ranging from £66 to £155 per set of top and leggings (2014/15 prices). 8 These garments are claimed to be beneficial for the management of AE, as they can help to regulate the humidity and temperature of the surface of the skin, are smooth in texture and may reduce skin damage from scratching. Some products have antimicrobial properties that may help to reduce the bacterial load on the skin, which may be important in AE. 9 However, the evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) supporting the use of silk garments is limited. 10,11

To identify RCTs published prior to the CLOTHES trial, we searched the Global Resource of Eczema Trials database. 12 At the time of starting the CLOTHES trial, 14 small RCTs assessing the effects of therapeutic clothing had been published: three RCTs investigated silk clothing [DermaSilkTM (AlPreTec Srl, San Donà di Piave, Italy)];13–15 two investigated silver-coated textiles;16,17 three investigated cellulose seaweed fibres with silver;18–20 one investigated cellulose;21 one investigated an anion textile;22 two investigated types of ethylene vinyl alcohol fibre;23,24 one investigated borage oil-coated garments;25 and one investigated cotton and synthetic fibres. 26 Since the start of the trial, an additional study on chitosan-coated textiles has been published. 27

The three previously published silk clothing RCTs are summarised in Table 1 (for further details of all trials of therapeutic clothing for AE, see Appendix 1).

| Reference | Duration (months) | Participants | Interventions | Main results | Comments on study design and interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koller et al. (2007)13 | 3 | 22 children with mild to moderate AE (unclear how many included in analysis) Within-person trial |

Intervention A: DermaSilk arm tubes (with antimicrobial coating). Worn all day on one arm for 3 months Intervention B: silk (without antimicrobial coating) arm tubes worn all day for 2 weeks, followed by cotton arm tubes for the remaining time in the trial Concurrent medication: emollients and antihistamines were permitted, but not topical corticosteroids |

No difference in local SCORAD of DermaSilk group compared with cotton group at week 2 [median (quartile 1–quartile 3)] [7.5 (6–9) vs. 8 (6.25–9.75); p = 0.274] Significant reduction of local SCORAD index in the DermaSilk-covered arm observed after 4, 8 and 12 weeks in comparison with cotton-covered arm [4 weeks: 6.5 (5–8) vs. 8 (7–9; p < 0.002; 8 weeks: 6 (5.25–7.75) vs. 8 (7–9); p < 0.0001; and 12 weeks: 6 (5–6) vs. 8 (7.25–10); p < 0.0001] |

|

| Stinco et al. (2008)14 | 1 | 30 children and adults with AE (26 analysed) Within-person trial |

Intervention A: DermaSilk (knitted fabric sleeves with bonded antimicrobial AEGIS AEM 5772/5) Intervention B: knitted silk fabric sleeves without antimicrobial finish Both interventions were worn all night and all day. One change per day, for 28 days |

No difference between groups in mean local SCORAD at 7 and 14 days. At 21 days and 28 days, mean local SCORAD of the DermaSilk group was better than the unmodified silk group (p = 0.02 and p ≤ 0.0001, respectively; confidence interval for difference in means not given). Difference of mean local SCORAD between groups over whole study was significant [mean 10.05 (SD ±9.22); p < 0.0001] No difference in mean pruritus values at day 7. At 14, 21 and 28 days, mean value of pruritus in DermaSilk group was better than unmodified silk group (p = 0.03, p = 0.01 and p ≤ 0.0001, respectively) |

|

| Fontanini et al. (2013)15 | 24 | 22 infants aged 4–18 months (20 analysed) Parallel-group trial |

Group A (n = 9): DermaSilk long-sleeved top and trousers Group B (n = 11): cotton clothing Both interventions were to be worn every day for 24 months, except during the summer and on very hot days in other seasons Both groups also received antimite mattresses, pillows and mometasone furoate for management of flares |

Topical corticosteroid use was significantly lower in the DermaSilk group [median 0.07 (interquartile range 0.05–0.09) tubes/month] than in the cotton group [0.17 (0.09–0.33) tubes/month] (p = 0.006) All parents in the DermaSilk group were satisfied with outcome (regarding itching reduction), compared with five (45%) in the cotton group |

|

In view of the limited evidence for silk garments in AE, the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme issued a funding call in 2011 and, subsequently, commissioned the CLOTHing for the relief of Eczema Symptoms (CLOTHES) Trial.

Objectives

Primary objective

-

To assess whether or not the addition of silk therapeutic garments to standard AE care reduces AE severity in children with moderate to severe disease over a period of 6 months.

Secondary objectives

-

To estimate the within-trial cost-effectiveness of silk therapeutic garments from a NHS and wider (family and employer) perspective.

-

To explore parent/guardian and child views on and experiences of using silk garments and factors that might influence the use of these garments in everyday life.

-

To examine prescribers’ and commissioners’ views on the use of silk garments for the management of AE.

Role of the funder

The study was funded by the NIHR HTA programme. Espère Healthcare Ltd (UK and Ireland distributor for DermaSilk) and DreamSkinTM Health Ltd (Hatfield, UK) donated the garments. The NIHR had input into trial design through peer review of the funding proposal and the garment companies provided advice in defining how the intervention should be used. Neither of the clothing companies had a role in data collection, analysis or interpretation or writing of the report. However, both had sight of the report prior to publication and had the opportunity to comment. The corresponding author had full access to all the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit.

Chapter 2 Methods

Extracts of text, figures and tables throughout this report have been published in Thomas KS, Bradshaw LE, Sach TH, Batchelor JM, Lawton S, Harrison EF, et al. Silk garments plus standard care for treating eczema in children: a randomised controlled observer-blind pragmatic trial (CLOTHES TRIAL). PLOS Med 2017; in press. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002280. 28 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Trial design

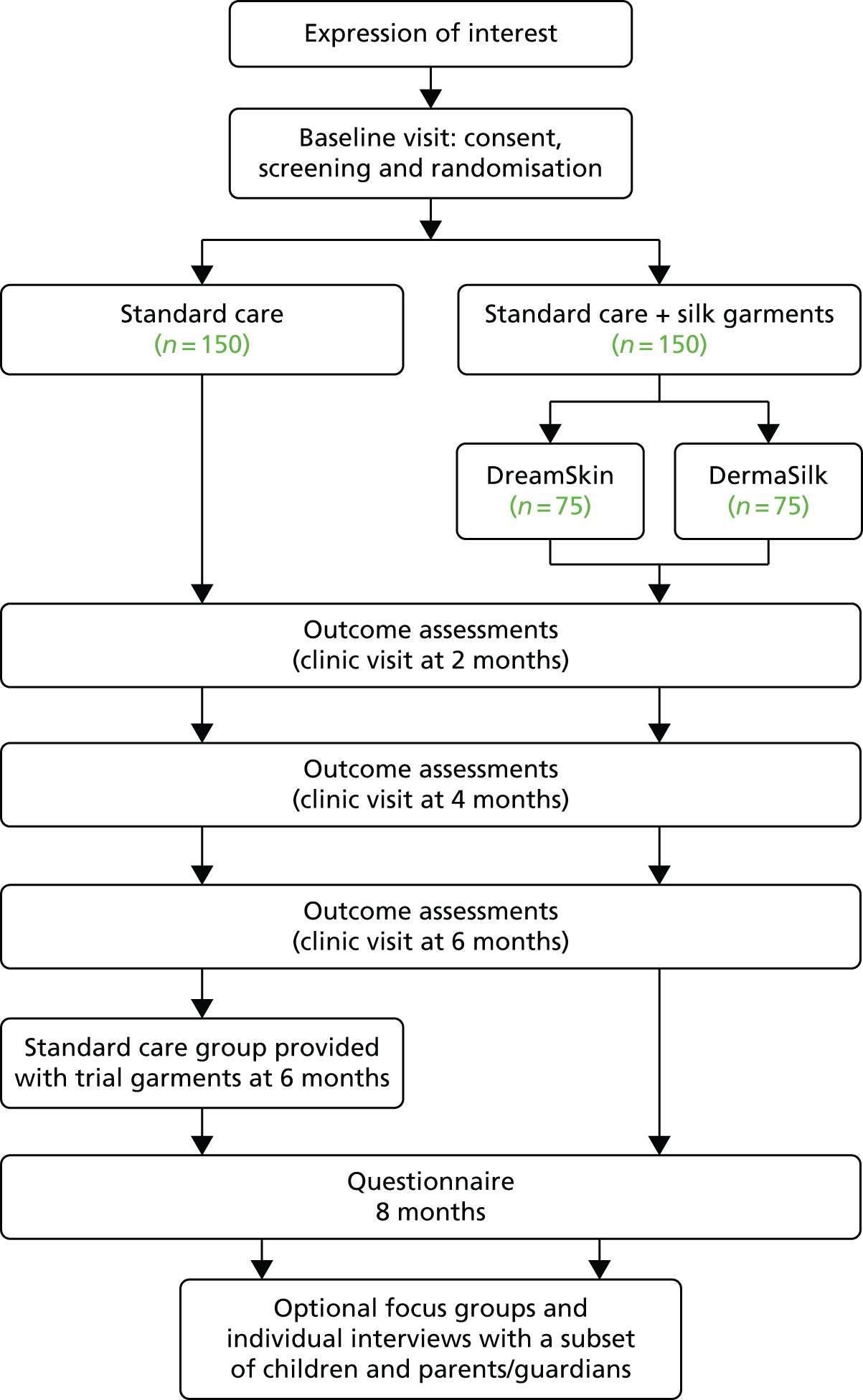

The CLOTHES trial was a multicentre, parallel-group, observer-blind, pragmatic RCT of 6 months’ duration, followed by a 2-month observational period (Figure 1). Children aged 1–15 years with moderate to severe AE were randomised (1 : 1) to receive either silk garments plus standard AE care or standard AE care alone. The primary outcome was assessed by research nurses blinded to the treatment allocation at baseline, 2, 4 and 6 months.

FIGURE 1.

CLOTHES trial flow chart.

Participants randomised to silk garments were further randomised to receive one of the two brands of garments used in the trial (DermaSilk or DreamSkin). Two products were used in the trial in order to improve the generalisability of the trial findings and to avoid commercial advantage to one particular company.

Participants allocated to the standard care group were given the silk garments after the primary outcome had been recorded at 6 months and used the garments for the remaining 2-month observational period. This was done in order to minimise loss to follow-up and potential contamination in the standard care group.

The trial included a nested qualitative evaluation, health economic analysis and subgroup analysis based on presence or absence of loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin (FLG). This was performed because loss-of-function mutations in FLG are known to increase the risk of eczema and it is possible that they affect response to silk clothing.

During the first 6 months of trial recruitment, an internal pilot was conducted to assess ability to recruit, adherence to the intervention and retention in the trial.

The study was approved by Health Research Authority East Midlands – Nottingham 1 Research Ethics Committee (reference number 13/EM/0255) and the local research and development department for each participating centre prior to recruitment commencing at that site. The trial was registered on Current Controlled Trials prior to start of recruitment (ISRCTN77261365 11 October 2013).

Recruiting centres

Recruitment took place in five UK centres: Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust and Isle of Wight NHS Trust.

Participants were identified through secondary and primary care, or by self-referral in response to adverts placed in local media, in the community and online. Potential participants were identified when they attended a secondary care clinic or by responding to invitation letters and patient information sheets that were sent to parents of children identified from secondary care clinic lists. A parent information sheet and three separate age-appropriate child information sheets (for children aged 0–5, 6–10 and 11–15 years) were used in the study (see Appendices 2–5).

A number of press releases were issued at the start of the trial. Posters and flyers were displayed in recruiting centres and research nurses also took an active role in advertising the trial in the community by placing posters and flyers in local schools, shops and community centres. The trial was promoted online by the National Eczema Society and the Nottingham Support Group for Carers of Children with Eczema and adverts were also posted in relevant web forums using ethics-approved text. If parents were interested, either they contacted the recruiting centres directly or they enquired at the trial co-ordinating centre and their details were passed on to the relevant recruiting centre.

General practice surgeries and other hospitals local to the recruiting centres were used as patient identification centres by displaying trial posters and flyers.

Participants

Children were considered for entry into the trial if the following inclusion criteria were met:

-

they were aged 1–15 years at baseline

-

they had a diagnosis of AE according to the UK Working Party’s diagnostic criteria29 and a score of ≥ 9 on the Nottingham Eczema Severity Score,30 denoting moderate or severe AE over the preceding 12 months

-

they had at least one area of active AE on a part of the body that would be covered by the silk garments

-

they were resident within travelling distance of a recruiting centre.

In addition, children were not entered into the trial if any of the following exclusions applied:

-

they had taken systemic medication (e.g. ciclosporin, oral corticosteroids) or received light therapy for AE in the preceding 3 months

-

they had used wet/dry wraps at least five times in the last month

-

they had started a new medication or treatment regimen that may affect AE in the last month

-

they were currently using silk garments for their AE and were unwilling to stop during the trial

-

they were currently taking part in another clinical trial

-

they had expressed a wish not to take part in the trial.

Only one child was enrolled per family; if more than one child in a family was eligible, the decision as to which child would be involved was made by the parents and children concerned.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the parent/guardian of each participant at the baseline visit, prior to any trial procedures being carried out. In addition, assent was provided by the children if they wanted to. Consent to take part in the genetic study (FLG genotyping), and for samples to be stored and used for potential future research, was included as optional.

Interventions

Silk garments

The silk garments used in the study are licensed as a medical device with a Conformité Européenne (CE) mark for use in AE, denoting that they comply with European Union legislation and safety requirements. They are 100% silk garments made from antimicrobially protected, knitted, sericin-free silk. Sericin is removed from the silk fibres during manufacturing because it is a protein that coats the outside of the fibres and has the potential to cause allergic reactions.

Two products were chosen for inclusion in the trial (DermaSilk and DreamSkin), as these were the two brands available on prescription in the UK at the time of trial design. Distribution of the intervention to participants was handled from the co-ordinating centre, where a stock of garments across a range of sizes in both brands was maintained. Participants received three sets of garments (long-sleeved vest and leggings or long-sleeved body suits and leggings, depending on the age of the child) and were instructed to wear the garments as often as possible during the day and at night, either as underwear or as pyjamas (Figure 2). Three sets were provided to allow for the washing and rotation of garments. The child’s height at randomisation was used to determine the correct size of garments, which were posted out to participants as soon as possible after randomisation. On receipt of the garments, participants were instructed to try on one set to check that they fitted correctly and then confirm this with the co-ordinating centre. Standardised care instructions were provided on a paper insert included in the garment package (Box 1) and instructions were also replicated in the participant diary.

FIGURE 2.

Garments being worn.

Please wear the garments as often as possible, both during the day and at night (either as underwear or as pyjamas).

Moisturising creams should be applied thinly to the skin (just enough for the skin to glisten) and should be applied a few minutes before putting on the clothing to allow the creams to be absorbed into the skin.

How do I care for the garments?You will be given three sets of garments during the trial. This will allow one set to be in use, one in the wash and one spare. We recommend that you use all three sets within 1 week, rotating frequently.

To machine wash: wash at up to 40 °C using your usual mild non-biological detergent. The fibres of the garment are quite delicate and washing the garment inside a pillowcase on a delicate cycle will protect it during the wash. If possible, lay the garment flat to dry.

To hand wash: place in hand-hot water containing your usual mild non-biological detergent and agitate by hand for a few minutes. Rinse well with plenty of warm, clean water and squeeze dry. Do not wring. If possible, lay the garment flat to dry.

Other important pointsPlease do not use bleach. Make sure there are no bleaching agents in your detergent [such as Vanish (Reckitt Benckiser, Slough, UK)].

Please do not use fabric softeners.

Please do not tumble dry.

Any reduction in garment length is likely to be a result of a tightening of the knit. A cool steam iron can be used to restore the shape of a garment that appears to have shrunk.

Garments were replaced as required during the 6-month RCT (if they were worn out, were lost or no longer fitted the child). If replacement garments were required, the participants returned the worn garments to the co-ordinating centre with a completed garment request form and new garments were sent out. After the 6-month RCT period was over, garments were not replaced.

Standard care

All participants continued with their standard AE care in line with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance,5 including regular emollient use, avoidance of irritants and topical corticosteroids (or calcineurin inhibitors) for controlling inflammation. Participants were asked not to change their standard AE treatment for the duration of the trial unless medically warranted.

Participants who frequently used wet- or dry-wrap dressings for their AE were excluded, but occasional use of wet or dry wraps was monitored but not prohibited.

If a research nurse suspected that the AE had become infected, participants were advised to contact their normal medical team for confirmation of diagnosis and subsequent treatment.

Outcomes

Details of derivations for outcomes can be found in the statistical analysis plan (see Appendix 6).

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of AE severity measured using the objective Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI)31 was assessed at baseline and at 2, 4 and 6 months. Baseline EASI score was used as a covariate in the analysis model. EASI score was assessed by trained research nurses who were blinded to treatment allocation. EASI score was chosen as the primary outcome as it is a validated scale recommended as the core outcome instrument for AE signs. 32 EASI involves an evaluation of four AE signs [erythema (redness), excoriation (scratching), oedema/papulation (swelling and fluid in the skin) and lichenification (thickening of the skin)] and an assessment of percentage area affected by eczema in four body regions (head and neck, upper limbs, trunk and lower limbs). EASI score ranges from 0 to 72, with higher scores representing more severe disease.

All research nurses received training in the use of EASI (using standardised training photographs and assessment of patients with AE by two independent assessors until concordance was reached). Resources were provided to assist in assessing the signs and body surface area (see Appendix 7).

Participants were assessed by the same research nurse at all time points in order to minimise interobserver variability.

Secondary outcomes

-

Global assessment of AE by research nurses [Investigator Global Assessment (IGA)] and by participants [Patient Global Assessment (PGA)] at baseline and at 2, 4 and 6 months, using a six-point scale (clear, almost clear, mild, moderate, severe and very severe).

-

Self-reported AE symptoms using the recommended core outcome instrument,33 the Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), which captures frequency of itch, sleep loss, bleeding, weeping/oozing, cracking, flaking and dryness. 34 It has a range from 0 to 28, with higher scores representing more severe disease. POEM scores were collected weekly using an online questionnaire for the first 6 months and once again at 8 months. Obtaining self-reported eczema severity every week for 6 months was used to capture long-term control of flares as well as self-reported eczema symptoms.

-

Three-Item Severity (TIS) scale35 at baseline and at 2, 4 and 6 months, assessed by research nurses at a single representative body site (defined as the most bothersome patch of AE that was covered by the garments). The selected representative body site did not have to be the same at each visit. The TIS measures three clinical signs (erythema, oedema/papulation and excoriation) and the total score ranges from 0 to 9, with higher scores representing more severe disease. Given the importance of an objective measure to capture eczema severity in this observer-blind trial, it was felt that a second validated eczema severity scale was warranted.

-

Use of AE treatments: number of days of use of topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, emollients and wet/dry wrapping, assessed weekly throughout the trial. At each visit, research nurses assessed change in AE treatment regimen and categorised as no change, neutral change, reduction or escalation.

-

Health-related quality of life at baseline and at 6 months from the perspectives of the family [Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI)],36 the main carer [EuroQoL-5 Dimensions-3 Levels (EQ-5D-3L)]37 and the child [Atopic Dermatitis Quality of Life (ADQoL) preference-based index38 and Child Health Utility-9 Dimensions (CHU-9D)39 in those aged ≥ 5 years].

-

Durability of the garments, adherence and acceptability of use (as assessed by children and parents/carers). Adherence was collected weekly, and information on durability and acceptability was captured at 6 and 8 months in the participant questionnaires. Sticker charts were provided for children to record how many days/nights the garments had been worn for the intervention group and how many days/nights they had been in the study for the standard care group (see Appendix 8). These were intended to help keep children engaged in the study and to assist in completing the adherence data in the weekly questionnaires.

-

Health resource use for treatment of AE throughout the trial: health-care visits, inpatient stays, medications, tests, personal items for AE and time off work or school.

Safety outcomes

Skin infections requiring antibiotic or antiviral treatment self-reported by parents and serious adverse events related to AE (hospitalisation as a result of AE) were recorded.

Tertiary outcomes

Although it was assumed that the different brands of garments were similar, the effects of receiving different brands of garments were also explored. Another additional exploratory analysis was conducted based on AE severity scores in areas covered by the garments (body and limbs) compared with areas uncovered by the garments (head and neck). All tertiary analyses were considered exploratory.

Data collection

Trial data generated by all centres were entered by research nurses directly into a web-based MACRO database (MACRO 4 version 3800, Elsevier, London, UK), maintained by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). Access to the trial database was controlled by user logins and research nurses could enter/edit data for their site only. Paper worksheets were provided for research nurses to record data during the clinic visit (see Appendix 9) and were transcribed after the visit. Participant questionnaires completed at clinic visits were transcribed by the research nurses into the trial database. Data entry was checked against the paper record for 100% of the primary outcome and for a 10% sample of all data.

Participants were provided with a diary booklet in which they were encouraged to record all health-care visits for eczema, eczema prescriptions, purchases for AE and time off work/school because of AE (see Appendix 10). The diary was reviewed by the research nurse at each clinic appointment and used as an aide memoir to complete the relevant sections of the trial database.

Missing and/or ambiguous data were queried with research nurses and resolved whenever possible.

Weekly questionnaires were completed by the participant online or in paper format (see Appendix 11) and sent to the Nottingham CTU for data entry on the bespoke in-house system. The preference for paper or online questionnaires was recorded at baseline. Participants completing online questionnaires were emailed a unique web link to the questionnaire each week on the day completion was due. A further reminder e-mail was sent at the beginning of day 3 if the questionnaire had not been completed. Links remained active until the end of day 3, after which time the week’s entry was classed as missing. Participants who failed to complete the weekly questionnaire for ≥ 3 weeks in a row were contacted by the Nottingham CTU and encouraged to complete the questionnaires.

For the week 24 (6-month) (see Appendix 12) and week 32 (8-month) (see Appendix 13) questionnaires, online submission remained open for 14 and 7 days, respectively, in order to ensure maximum data completion at the primary end point and end of trial. For these time points, non-responders were contacted by telephone and a paper copy of the questionnaire was sent by post if required.

Sample size

Three hundred participants provided 90% power, at the 5% significance level (two-tailed), to detect a difference of around 3 points between the groups in mean EASI scores. Although this between-group difference is approximately half the published minimum clinically important difference for EASI that was suggested from one study in adults,40 we wanted to be sure that a clinically important difference to patients was not missed as a result of our focus on an objective outcome for the primary outcome. Sample size was based on repeated measures analysis of covariance, assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 13, a correlation between EASI scores at different time points of 0.6 and loss to follow-up of 10%.

Stopping rules and discontinuation

An internal pilot RCT was conducted over the first 6 months of trial recruitment to ensure delivery of the trial to time and target. Pre-defined stop/go criteria were assessed by the Trial Steering Group at 6 months as outlined in Table 2. Target recruitment for the RCT phase was ≥ 75 participants.

| Criteria to be assessed at 6 months of recruitment | Proposed action |

|---|---|

| ≥ 90% of target recruitment and retention | Continue with main trial as planned |

| 70–89% of target recruitment and retention | Continue with main trial, implement strategies for improvement |

| 50–69% of target recruitment and retention | Urgent measures required, discuss plans with Trial Steering Committee and NIHR HTA |

| < 50% of target recruitment and retention | Stop trial unless good reason for delay and rectifiable solution can be readily implemented |

Adherence to wearing the clothing was defined as a trigger for concern if participants reported using the clothing < 50% of the time.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation was stratified by recruiting hospital and by participant’s age: < 2, 2–5 or > 5 years. A computer-generated pseudo-random code with random permuted blocks of randomly varying size (2, 4 or 6) was created by the Nottingham CTU, in accordance with their standard operating procedure, and held on a secure University of Nottingham server. Research staff at sites were not aware of the block sizes. Participants were further randomised to one of the two silk garment brands (DermaSilk or DreamSkin) using a computer-generated pseudo-random code with random permuted blocks of randomly varying size, stratified by allocated group.

Research nurses accessed the randomisation website by means of a remote, internet-based randomisation system developed and maintained by the Nottingham CTU. Access was controlled by unique user logins. The sequence of treatment allocations was concealed until interventions had all been assigned and recruitment and data collection were complete. Study statisticians were blinded to treatment allocations until the database was locked.

After each allocation, the randomisation system notified staff at the Nottingham CTU, who then sent a letter confirming the treatment allocation to the participant (along with the silk garments as necessary). Staff at the Nottingham CTU removed branding labels from the garments and repackaged them in plain trial packaging before sending so that participants were not aware of which brand of garments they had received.

Although it was not possible to blind participants to their treatment allocation, efforts were made to minimise expectation bias by emphasising in the trial documents that the evidence supporting the use of silk garments for AE was limited and that it was not yet known if such garments offered any benefit over standard care. Participant-facing study documents also avoided the use of value-laden terms such as ‘specialist’ or ‘therapeutic’ garments.

In order to preserve blinding of the research nurses, participants were reminded in the study literature and in their clinic appointment letters/texts not to wear the garments when they attended the clinic nor to mention the garments when talking to the research nurses. Additionally, children were sent cards, both to thank them for their participation and remind them not to disclose to the research nurse whether or not they had been given the garments. All questions relating to the acceptability and use of the garments were completed by either postal or online questionnaires, and telephone and e-mail contact with participants was made by staff from the Nottingham CTU whenever possible. If the research nurses became unblinded, this was recorded. Full details of blinding arrangements are summarised in Table 3.

| Role in trial | Blinding status | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Not blinded | Not possible to blind participants, efforts made to minimise expectation bias |

| Research nurses and principal investigators | Blinded | Participants were reminded in their clinic appointment letters not to wear the clothing when attending the clinic or to mention the clothing in any way when talking to the research nurses |

| Trial staff at the Nottingham CTU | Not blinded | Acted as the main point of contact for participants wishing to contact the research team, packaged and posted the clothing to the participants according to the randomisation schedule, and provided general advice |

| Statistician | Blinded | Statistician finalised the statistical analysis plan prior to revealing the treatment codes |

FLG genotype analysis

If participants gave written informed consent to collect a saliva sample, these samples were collected using SalivaGeneTM Collection Module II (Stratec Biomedical Systems, Birkenfeld, Germany), or SalivaGeneTM Buccal Swab (Stratec Biomedical Systems, Birkenfeld, Germany) if children were unable to spit into the container. After collection, samples were packaged by research nurses and posted to the University of Dundee, UK, where deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extraction was performed.

Samples were tested for the six most prevalent FLG loss-of-function mutations in the white European population as previously reported: R501X, 2282del4, R2447X, S3247X, 3702delG and 3673delC. 41 Only participants of white European ethnicity were included in the FLG genotype subgroup analysis because FLG mutations are known to be ethnically specific. Individuals in whom the four most prevalent mutations (R501X, 2282del4, R2447X and S3247X) were successfully genotyped were categorised as FLG wild type (none of the prevalent mutations was identified; these individuals constituted the control cohort), FLG heterozygotes (carrying one FLG null mutation) or FLG homozygotes or compound heterozygotes (individuals carrying two FLG null mutations).

Statistical methods

Analyses are detailed in the statistical analysis plan (see Appendix 6), which was finalised prior to database lock and release of treatment allocation codes for analysis. All analyses were carried out using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The main approach to analysis was modified intention to treat, that is, analysis according to randomised group regardless of adherence to allocation and including only participants who provided outcome data at follow-up. Estimates of the intervention effect are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values.

All outcomes collected at the 2-monthly clinic visits were summarised by time point and treatment group. All outcomes collected from the weekly questionnaires were summarised by week and treatment group. Correlation matrices between outcomes at the 2-monthly clinic visits are given in Appendix 14 (see Table 53) and between POEM scores at 8, 16 and 24 weeks are given in Appendix 15 (see Table 55). All regression models included the randomisation stratification variables of recruiting site and age as covariates and also included baseline scores (if measured). Adjusted differences in means for the intervention group compared with the standard care group are presented for continuous outcomes, and adjusted risk differences and relative risks for binary outcomes.

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics of demographic and clinical measures were used to examine balance between the randomised arms at baseline.

Primary outcome

The primary analysis used a multilevel model with observations at 2, 4 and 6 months, nested within participants, and included participants in whom EASI was assessed at least once at follow-up. The model assumed that missing EASI scores were missing at random given the observed data. The model used a random intercept and slope at the participant level, with an unstructured covariance matrix for these random effects. Diagnostic plots to check the normality of the residuals from the fixed part of the model, homogeneity of the variance of the residuals and the normality of the random effects when the model was initially fitted indicated that the assumptions for the multilevel model were not met. The score was therefore log-transformed for analysis and the effect of the trial garments is presented as a ratio of geometric means. 42,43 This ratio was back-transformed to the original EASI scale to facilitate interpretation of findings.

The effect of trial garments on AE severity changing over the study period was explored by including an interaction term between group and time point in the model. There was no evidence of a differential effect over time, so a single treatment effect has been reported that averages the treatment effect over all time points.

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome were performed:

-

To adjust for variables that had an observed imbalance between the groups at baseline.

-

Using multiple imputation (by chained equations) for missing outcome data.

-

To explore the impact of adherence in wearing the garments on the primary outcome by estimating the complier average causal effect (CACE) at 6 months using instrumental variable regression methods. This analysis aims to provide an unbiased estimate of the treatment effect among compliers, defined as participants who would comply with their allocation regardless of the treatment arm to which they were randomised. Estimates are presented for two measures of compliance:

-

binary compliance, defined as participants who wore the trial garments for at least 50% of the days or 50% of the nights

-

continuous compliance, defined as each additional 10% of time that the garments were worn. This was calculated by summing the number of days and nights that the trial garments were reported to be worn, then dividing by the total number of days and nights in questionnaires completed about garment wear.

-

A planned subgroup analysis based on the presence or absence of loss-of-function mutations in FLG was conducted by adding an interaction term between allocated treatment and FLG genotype (none, one or two FLG null mutations) to the primary analysis model.

Secondary outcomes

The global assessment scores (IGA and PGA) were dichotomised into ‘clear, almost clear or mild AE’ versus ‘moderate, severe or very severe AE’, and analysed using generalised estimating equations to allow estimation of risk difference and risk ratio. The TIS score was analysed using the multilevel model framework as outlined above for the primary outcome (not transformed). For the global assessment scores and the TIS score, the effect of the trial garments changing over the study period (2-, 4- and 6-month visits) was explored by including an interaction term between group and time point in the models. There was no evidence of a differential effect over time for any outcomes, so a single treatment effect per outcome has been reported that averages the treatment effect over all time points.

For each participant from the weekly questionnaire data, the mean of their weekly POEM scores between week 1 and week 24 and the percentage of days that topical treatments were used were calculated. The participant mean POEM scores and percentage of days that topical steroids were used were analysed using a linear model weighted according to the number of weekly questionnaires completed.

Quality-of-life outcomes at 6 months were analysed using linear models. Changes to treatment regimen were based on whether or not a participant had reported any treatment escalation over the 6-month RCT period and analysed using a generalised linear model. Skin infections were analysed using negative binomial regression.

Adherence to wearing the trial garments was summarised using the percentage of days and nights that the study garments were worn. Participants were classified as adherent if they wore the trial garments for at least 50% of the days or 50% of the nights. This was done for participants who completed at least half (12/24) of the weekly questionnaires. Sensitivity analyses explored adherence for all participants by making different assumptions about garment wear during periods in which the questionnaire was not completed. Adherence to wearing the trial garments was explored descriptively according to age group and baseline eczema severity.

Serious adverse events, durability and acceptability of use of the garments and information from the follow-up questionnaire at 8 months were summarised descriptively.

Tertiary outcomes

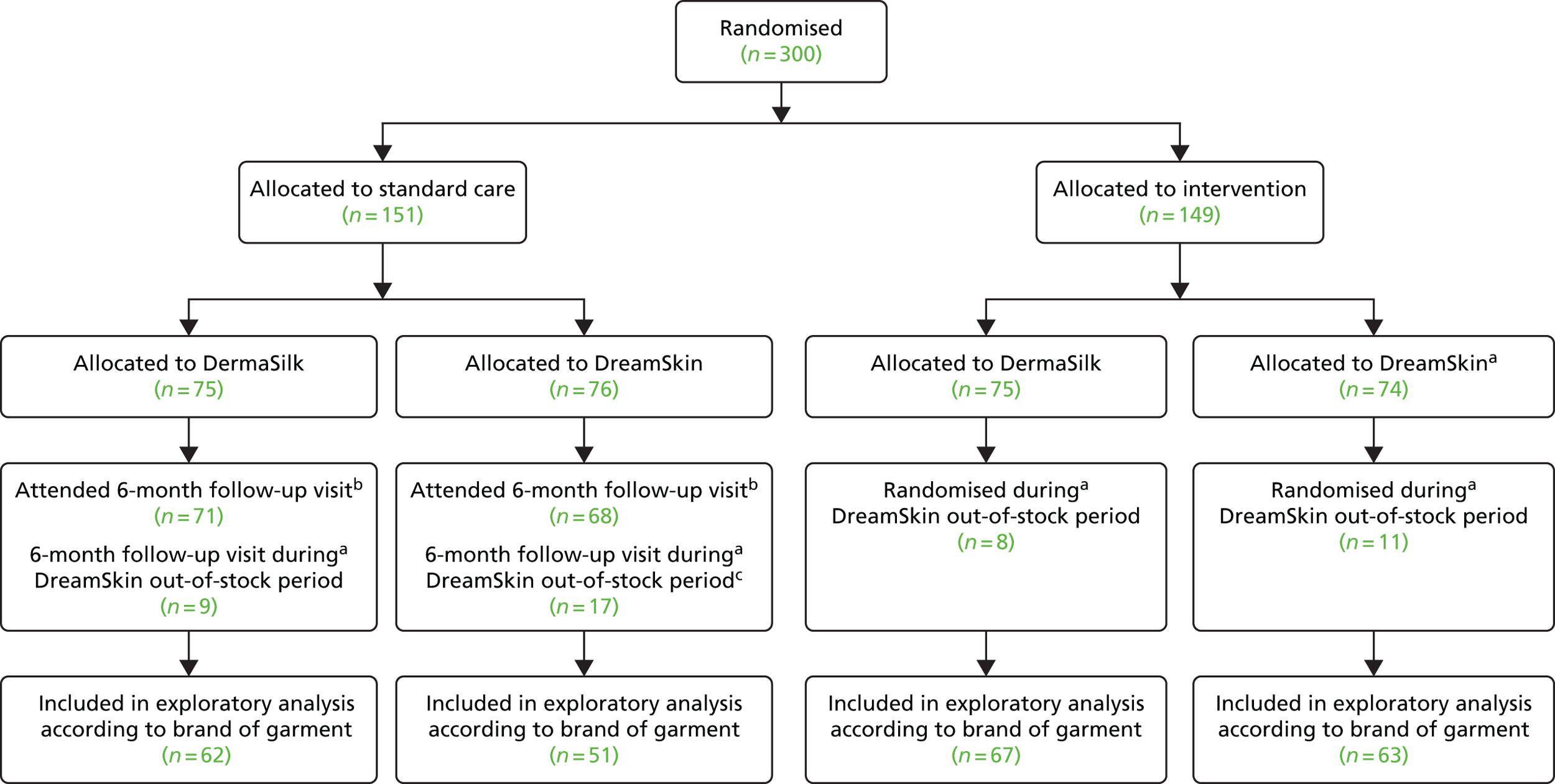

The primary analysis assumed that the effect of the different brands of garments was similar, but the impact of garment brand on AE severity was explored in a tertiary analysis. AE severity according to brand was explored by adding a term for garment brand to the primary analysis model for the EASI described above. AE symptoms according to brand were explored by comparing POEM scores after 2 months of garment wear (baseline and 2 months for the intervention group and 6 and 8 months for the standard care group).

During the study there was a supply problem with one of the garment suppliers (DreamSkin), which meant that the randomised schedule was not followed during this time and participants received the alternative brand (DermaSilk). Any participants randomised to the intervention group during a time period that DreamSkin garments of the required size were out of stock were not included in the tertiary analysis by brand of garments. Similarly, any participants in the standard care group who completed their 6-month visit during a period when DreamSkin garments of the required size were out of stock were not included.

Adherence and acceptability of the garments at 6 and 8 months were summarised descriptively by allocated group and allocated garment brand.

Additional analyses

On completion of the pre-planned analyses, and following concerns that the baseline EASI scores appeared lower than might be expected for children with moderate to severe eczema, an additional post hoc analysis was conducted to explore the interaction between baseline severity and treatment group. This was conducted by adding an interaction term between allocated group and baseline EASI score (log-transformed and continuous) to the primary analysis model.

Summary of changes to the protocol

The full protocol and statistical analysis plan are available on the CLOTHES website (www.nottingham.ac.uk/CLOTHES). Changes to the protocol initiated after the start of recruitment included an increase in the number of FLG genotype mutations to be included in the genetic analysis (two additional mutations were added: 3702delG and 3673delC) and addition of details of the nested qualitative evaluation.

Chapter 3 Results: clinical findings

Recruitment and follow-up

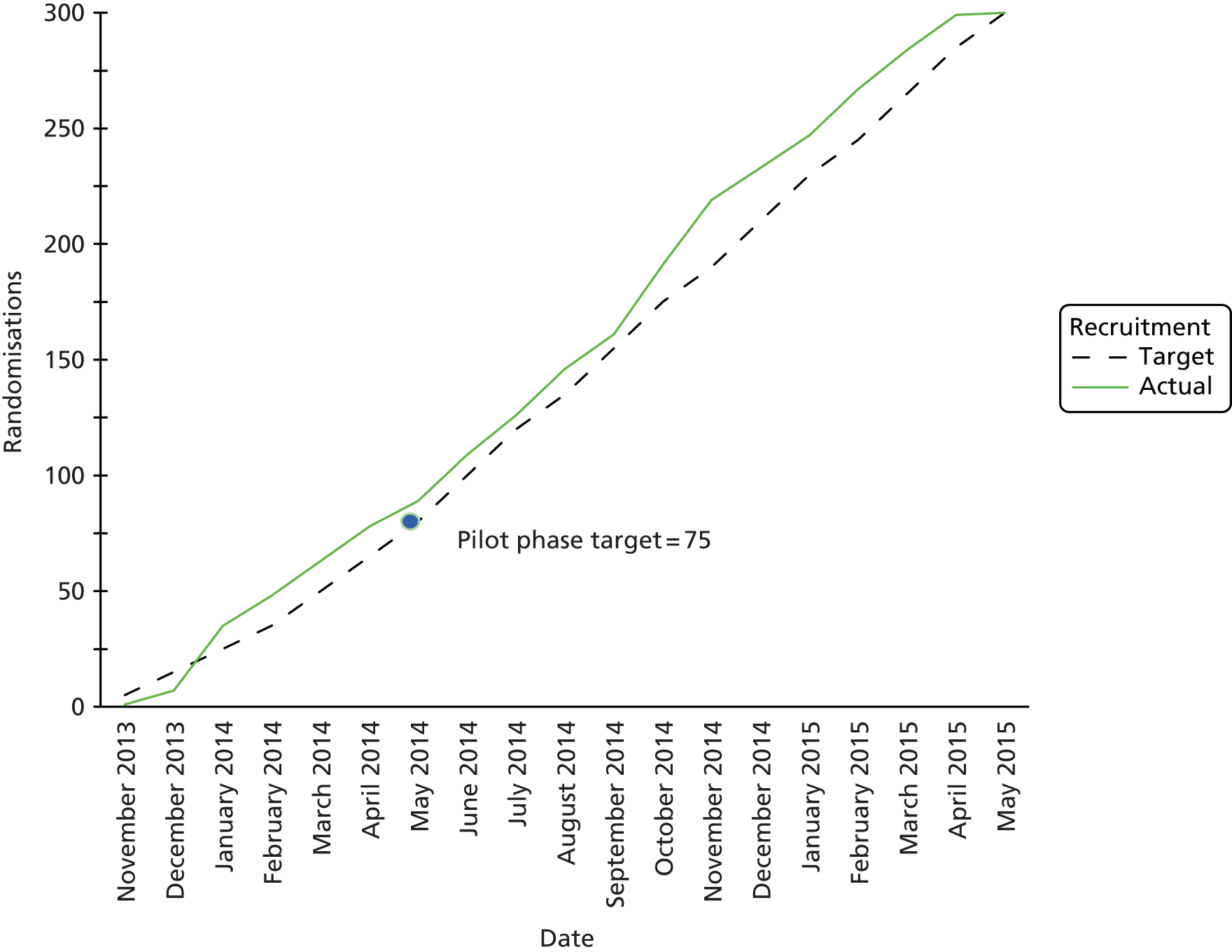

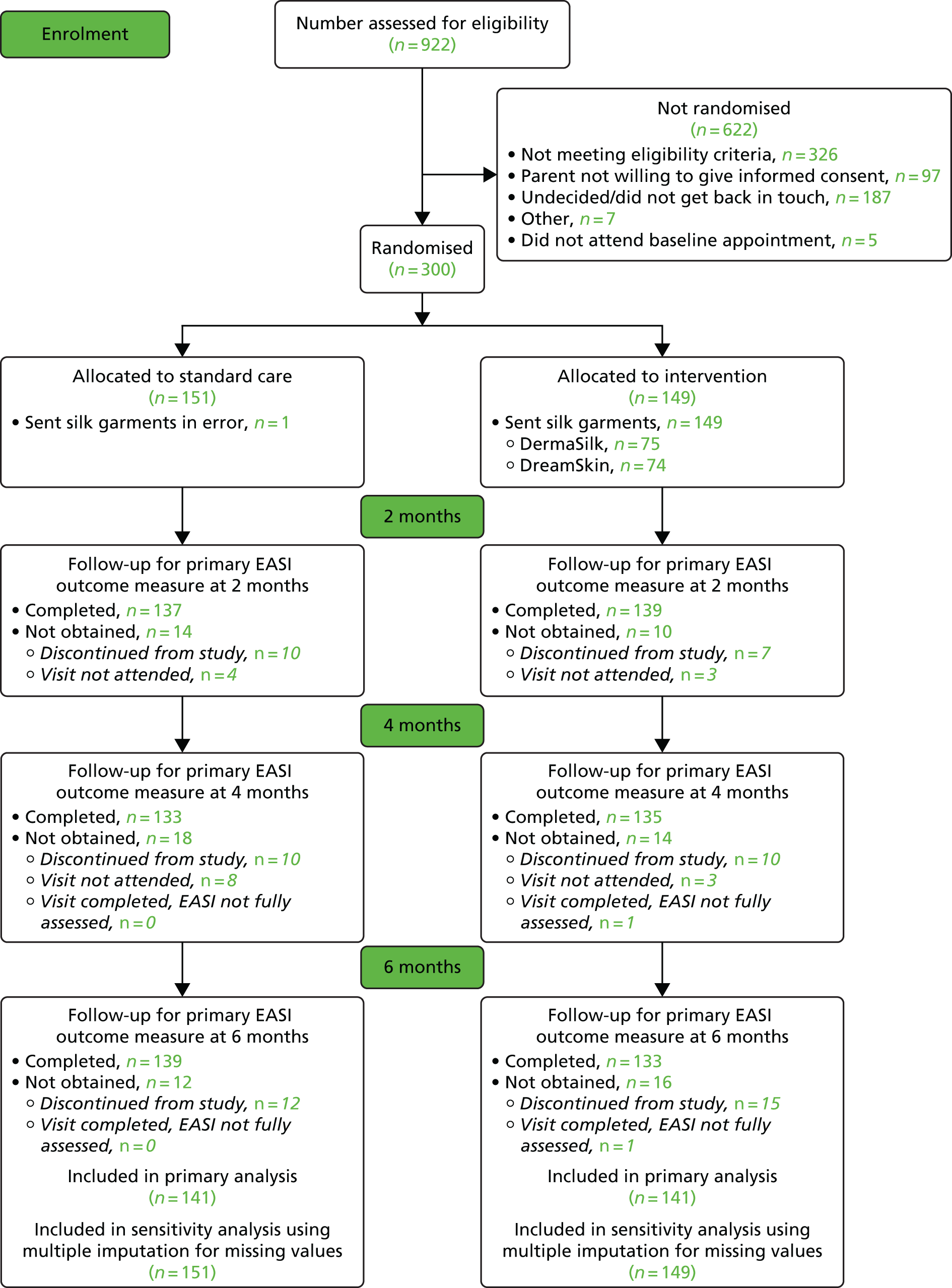

Recruitment to the study took place between 26 November 2013 and 5 May 2015 (Figure 3). During this time, 922 children were assessed for eligibility and 300 were subsequently randomised (Figure 4). Eighty-nine children were randomised within the first 6 months of recruitment, meeting the target of 75 participants as specified for the internal pilot phase.

FIGURE 3.

Cumulative recruitment.

FIGURE 4.

Participant flow through the study.

Attendance at follow-up visits was ≥ 90% for all clinic visits. In both groups, 129 (85%) attended all three follow-up visits. The same nurse performed the outcome assessments for all study visits for all but four participants.

The primary analysis included 141 participants in each group (participants were included if the primary outcome was assessed at least once after baseline) (see Figure 4).

In the case of the weekly online questionnaires (24 questionnaires over 6 months), 127 out of 151 (84%) participants in the standard care group and 126 out of 149 (85%) participants in the intervention group completed 12 or more. The median number completed was 22 (25th to 75th centile, 17 to 24) in both groups. The number of participants completing the questionnaire each week was very similar in the standard care and intervention groups (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Percentage questionnaire completion by week and group.

Baseline data

Participants

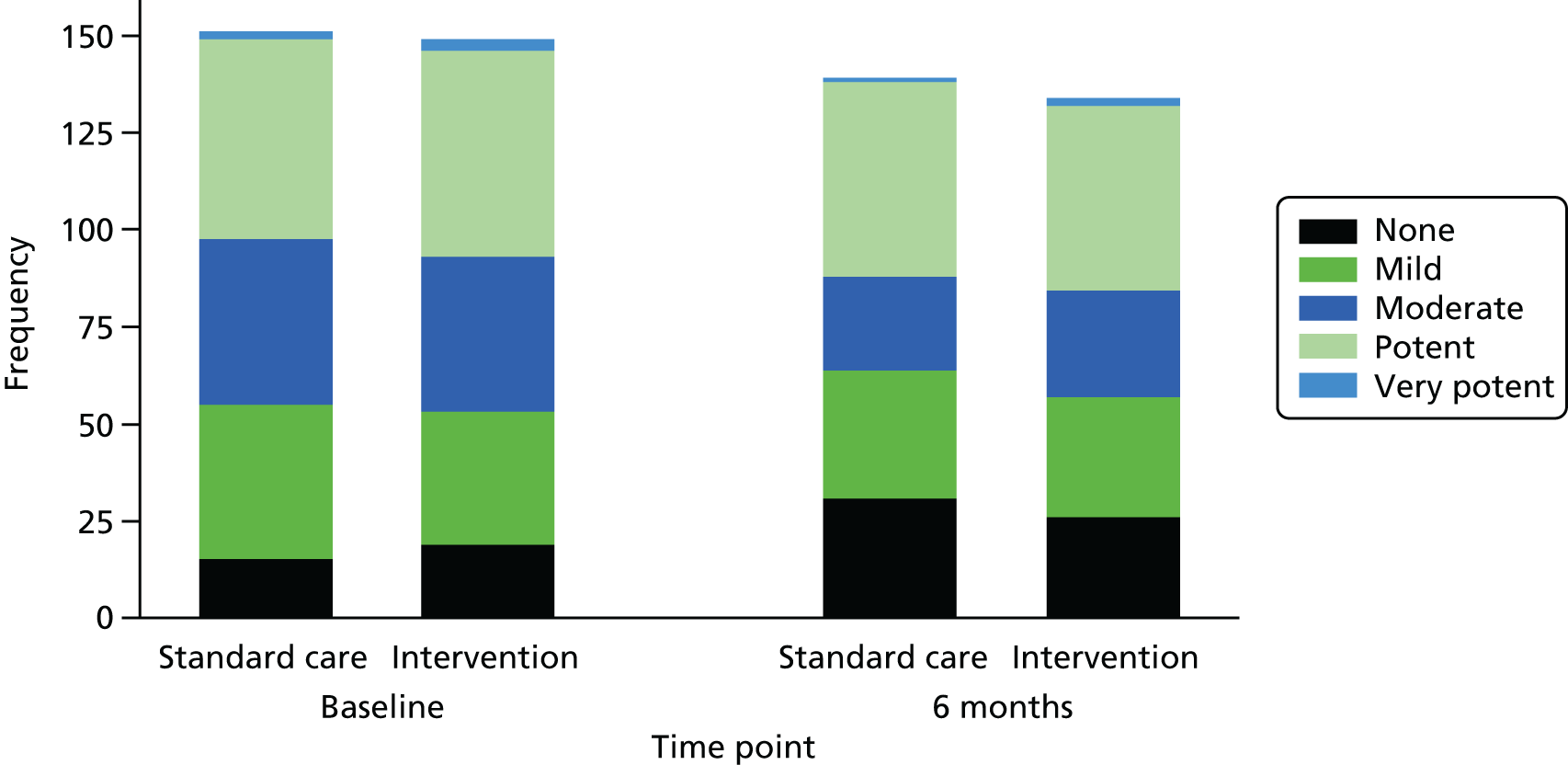

The mean age of participants was 5 years (SD 3.6); 58% were male and 79% were of white ethnicity (Table 4). The majority (72%) had previously been treated in secondary care for their AE, 72% had moderate or severe AE (based on IGA scores at baseline) (Table 5) and 37% were reported to use a potent or very potent steroid as their main steroid (Table 6).

| Characteristic | Standard care (N = 151) | Intervention (N = 149) | Total (N = 300) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5 (3.6) | 5.1 (3.7) | 5.1 (3.6) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 4 (2, 8) | 4 (2, 7) | 4 (2, 7.5) |

| Minimum, maximum | 1, 14 | 1, 15 | 1, 15 |

| 1–4, n (%) | 86 (57) | 77 (52) | 163 (54) |

| 5–11, n (%) | 57 (38) | 62 (42) | 119 (40) |

| 12–15, n (%) | 8 (5) | 10 (7) | 18 (6) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 82 (54) | 92 (62) | 174 (58) |

| Female | 69 (46) | 57 (38) | 126 (42) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 123 (81) | 114 (77) | 237 (79) |

| Indian | 5 (3) | 2 (1) | 7 (2) |

| Pakistani | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Bangladeshi | 0 | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Black Caribbean | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Black African | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 7 (2) |

| Black (other) | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Chinese | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Other Asian (non-Chinese) | 0 | 4 (3) | 4 (1) |

| Mixed race | 12 (8) | 13 (9) | 25 (8) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| History of atopy, n (%) | |||

| Asthma | 57 (38) | 46 (31) | 103 (34) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 60 (40) | 56 (38) | 116 (39) |

| Food allergy | 80 (53) | 68 (46) | 148 (49) |

| Anaphylaxis | 23 (15) | 23 (15) | 46 (15) |

| Type of AE, n (%) | |||

| Discoid | 19 (13) | 17 (11) | 36 (12) |

| Flexural | 144 (95) | 147 (99) | 291 (97) |

| Location of AE, n (%) | |||

| Head and neck | 115 (76) | 120 (81) | 235 (78) |

| Hands and wrists | 116 (77) | 108 (72) | 224 (75) |

| Feet and ankles | 100 (66) | 96 (64) | 196 (65) |

| Limbs | 151 (100) | 149 (100) | 300 (100) |

| Trunk | 128 (85) | 122 (82) | 250 (83) |

| Previous medical care, n (%) | |||

| No previous treatment | – | – | – |

| GP only | 41 (27) | 40 (27) | 81 (27) |

| GP and in secondary care | 110 (73) | 109 (73) | 219 (73) |

| Severity assessment | Standard care (N = 151) | Intervention (N = 149) | Total (N = 300) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EASIa | |||

| Mean (SD) | 9.6 (7.8) | 11.4 (10.6) | 10.5 (9.3) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 7.3 (4.2, 12) | 7 (4.1, 15.4) | 7.2 (4.1, 13.7) |

| Min., max. | 1.1, 41.1 | 1, 47 | 1, 47 |

| TISb | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 (1.8) | 4.9 (1.8) | 4.9 (1.8) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 5 (4, 6) | 5 (3, 6) | 5 (4, 6) |

| Min., max. | 1, 9 | 1, 9 | 1, 9 |

| Nottingham Eczema Severity Scorec | |||

| Mean (SD) | 13.1 (1.6) | 13.2 (1.7) | 13.1 (1.6) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 13 (12, 14) | 13 (12, 15) | 13 (12, 14) |

| Min., max. | 9, 15 | 9, 15 | 9, 15 |

| Moderate AE (9–11), n (%) | 28 (19) | 30 (20) | 58 (19) |

| Severe AE (12–15), n (%) | 123 (81) | 119 (80) | 242 (81) |

| IGA, n (%) | |||

| Almost clear | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Mild | 39 (26) | 39 (26) | 78 (26) |

| Moderate | 77 (51) | 67 (45) | 144 (48) |

| Severe | 30 (20) | 36 (24) | 66 (22) |

| Very severe | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 6 (2) |

| PGA, n (%) | |||

| Almost clear | 5 (3) | 6 (4) | 11 (4) |

| Mild | 33 (22) | 45 (30) | 78 (26) |

| Moderate | 83 (55) | 67 (45) | 150 (50) |

| Severe | 27 (18) | 25 (17) | 52 (17) |

| Very severe | 3 (2) | 6 (4) | 9 (3) |

| PGA completed by, n (%) | |||

| Parent/guardian | 129 (85) | 125 (84) | 254 (85) |

| Child | 22 (15) | 24 (16) | 46 (15) |

| POEMd | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.6 (4.8) | 17.3 (5.8) | 17 (5.4) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 16 (13, 20) | 17 (13, 21) | 17 (13, 20) |

| Min., max. | 4, 28 | 4, 28 | 4, 28 |

| POEM completed by, n (%) | |||

| Parent/guardian | 128 (85) | 122 (82) | 250 (83) |

| Child | 23 (15) | 27 (18) | 50 (17) |

| Medication usage | Standard care (N = 151), n (%) | Intervention (N = 149), n (%) | Total (N = 300), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Used emollient within the last month | 150 (99) | 146 (98) | 296 (99) |

| Consistency of main emollient | |||

| Light | 13 (9) | 6 (4) | 19 (6) |

| Creamy | 53 (35) | 57 (38) | 110 (37) |

| Greasy | 20 (13) | 21 (14) | 41 (14) |

| Very greasy | 64 (42) | 62 (42) | 126 (42) |

| Topical steroid used within the last month | 136 (90) | 130 (87) | 266 (89) |

| Potency of main steroid | |||

| Mild | 40 (26) | 34 (23) | 74 (25) |

| Moderate | 43 (28) | 40 (27) | 83 (28) |

| Potent | 51 (34) | 53 (36) | 104 (35) |

| Very potent | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Calcineurin inhibitors used within the last month | 14 (9) | 15 (10) | 29 (10) |

| Strength of main calcineurin inhibitor | |||

| Mild | 9 (6) | 8 (5) | 17 (6) |

| Moderate | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 8 (3) |

| Strong | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Use of wet/dry wraps in the past month | |||

| No | 138 (91) | 135 (91) | 273 (91) |

| Yes | 13 (9) | 14 (9) | 27 (9) |

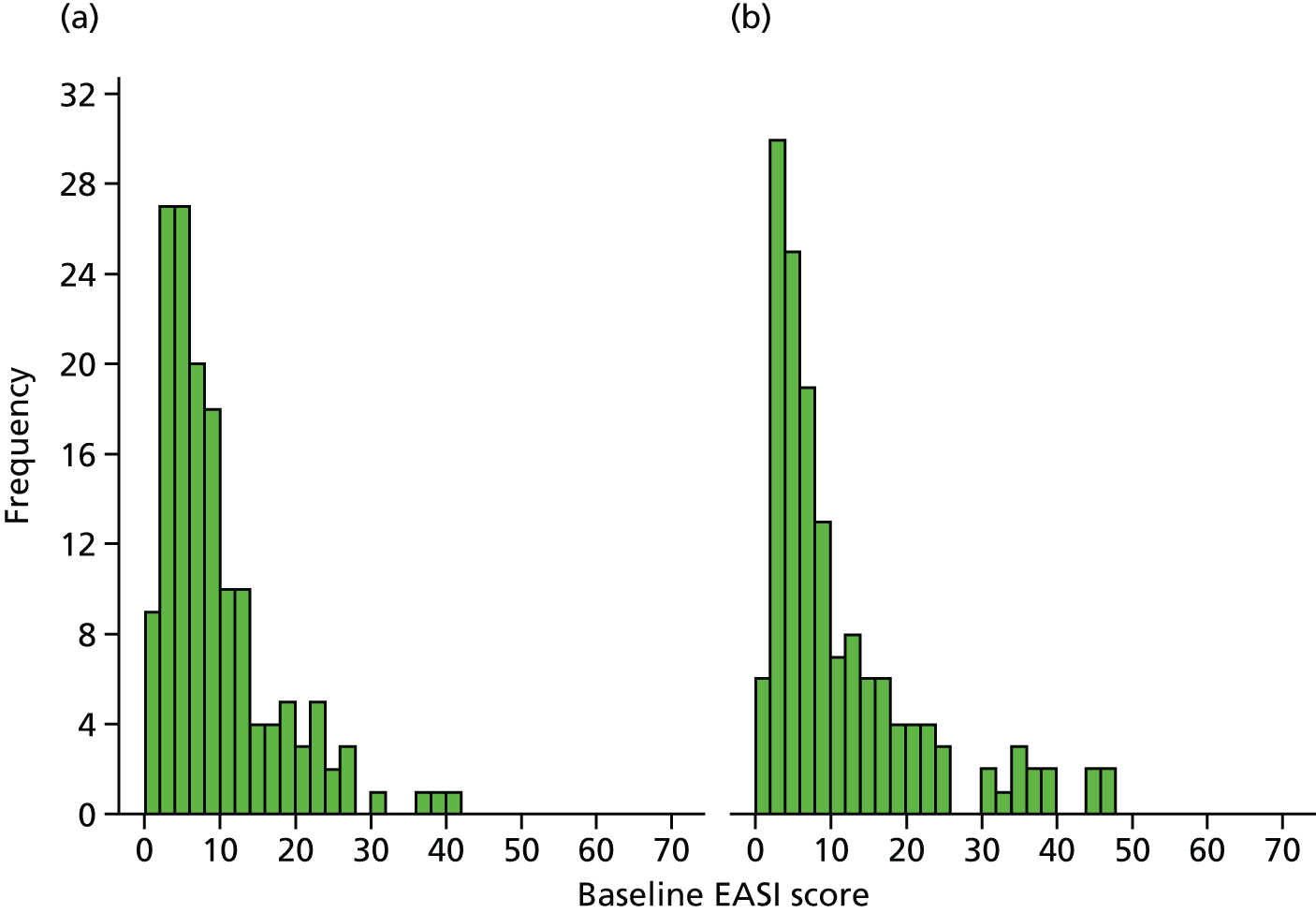

The demographic and AE characteristics were well balanced at baseline, although there were slightly more boys in the intervention group than in the standard care group, and parent-reported history of asthma and food allergy was higher in the standard care group than in the intervention group (see Table 4). The mean EASI score was slightly higher in the intervention group than in the standard care group, as more children had a baseline EASI score of > 30 (intervention, 14 participants; standard care, 4 participants; Figure 6); however, the median and interquartile ranges were similar between the groups (see Table 5). Other AE severity measures were similar between the two groups apart from the PGA scores [a greater proportion of participants in the standard care group rated their AE as moderate, severe or very severe than the intervention group (75% vs. 66%) (see Table 5)]. Health-related quality of life in the two groups was similar at baseline (Table 7).

FIGURE 6.

Histogram of baseline EASI scores by group. (a) Standard care; and (b) intervention group.

| Quality-of-life measure | Standard care (N = 151) | Intervention (N = 149) | Total (N = 300) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFIa | |||

| Mean (SD) | 12.0 (6.3) | 12.4 (6.6) | 12.2 (6.4) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 11 (7, 15) | 12 (7, 16) | 11 (7, 16) |

| Min., max. | 0, 29 | 0, 30 | 0, 30 |

| Health state from EQ-5D-3L for parentb,c | |||

| Mean (SD) | 79.5 (17.5) | 77.3 (18.2) | 78.4 (17.9) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 80 (72, 90) | 80 (70, 90) | 80 (70, 90) |

| Min., max. | 8, 100 | 8, 100 | 8, 100 |

| Utility from EQ-5D-3L for parentb,d | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.8983 (0.1612) | 0.9018 (0.1710) | 0.9 (0.1658) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 1 (0.812, 1) | 1 (0.812, 1) | 1 (0.812, 1) |

| Min., max. | –0.016, 1 | 0.101, 1 | –0.016, 1 |

| n | 151 | 147 | 298 |

| CHU-9Db,e | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.8292 (0.1263) | 0.8386 (0.1115) | 0.8341 (0.1184) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 0.849 (0.7853, 0.9058) | 0.8561 (0.7524, 0.92) | 0.8503 (0.7637, 0.9189) |

| Min., max. | 0.4661, 1 | 0.5584, 1 | 0.4661, 1 |

| n | 64 | 70 | 134 |

| Completed by (n) | |||

| Parent/guardian | 17 | 23 | 40 |

| Child | 47 | 47 | 94 |

| ADQoLf | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.6952 (0.13) | 0.6883 (0.1409) | 0.6918 (0.1354) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 0.744 (0.648, 0.768) | 0.744 (0.634, 0.768) | 0.744 (0.648, 0.768) |

| Min., max. | 0.356, 0.841 | 0.356, 0.841 | 0.356, 0.841 |

| n | 151 | 149 | 300 |

| Completed by [n (%)] | |||

| Parent/guardian | 104 (69) | 102 (68) | 206 (69) |

| Child | 47 (31) | 47 (32) | 94 (31) |

FLG genotype

Table 8 shows the FLG genotyping results for participants of white ethnicity. Samples from 219 participants were tested for the six most prevalent FLG loss-of-function mutations in the white European population: R501X, 2282del4, R2447X, S3247X, 3702delG and 3673delC. Genotyping methods for the four most prevalent genotypes (R501X, 2282del4, R2447X and S3247X) were largely successful (n = 217 were included in the analysis), but the genotyping methods used for 3703delG and 3673delC were unsuccessful for 24 participants (11% of samples tested) owing to the suboptimal quality and quantity of DNA obtained from paediatric saliva samples.

| Genotype status | Standard care (N = 123), n (%) | Intervention (N = 114), n (%) | Total (N = 237), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informed consent provided for genetic study | |||

| No | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | 11 (5) |

| Yes | 117 (95) | 109 (96) | 226 (95) |

| If yes, saliva sample collected | |||

| Noa | 1 (1) | 5 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Yes | 116 (94) | 104 (91) | 220 (93) |

| Result obtainable on FLG mutation from sampleb | |||

| No | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Yes | 115 (93) | 102 (89) | 217 (92) |

| Sample not received by Dundee | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Result not obtainable for each mutation tested | |||

| R501X | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2282del4 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| R2447X | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| S3247X | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 3702delG | 9 | 15 | 24 |

| 3673delC | 9 | 15 | 24 |

| FLG genotype (using mutations R501X, 2282del4, R2447X and S3247X) | |||

| No mutations | 72 (59) | 71 (62) | 143 (60) |

| One FLG null mutation | 31 (25) | 20 (18) | 51 (22) |

| Two FLG null mutations | 12 (10) | 11 (10) | 23 (10) |

| Not known | 8 (7) | 12 (11) | 20 (8) |

In total, 217 participants of white European ethnicity were categorised as FLG wild type (individuals in whom none of the prevalent mutations was identified), FLG heterozygotes (carrying one FLG null mutation) and FLG homozygotes or compound heterozygotes (individuals carrying two FLG null mutations) for the four most prevalent mutations (R501X, 2282del4, R2447X and S3247X). Of these, 74 participants had at least one mutation.

Adherence to intervention

All participants in the intervention group were sent the silk garments, on average, 1 day after randomisation. One participant allocated to the standard care group was sent the silk garments in error, but was included in the analysis according to randomised allocation (see Figure 4).

Adherence in wearing the garments was high: 102 out of 124 (82%) participants wore the clothes for ≥ 50% of the time (see Table 9). The garments were worn more often at night than during the day (median 81% of nights and 34% days) (Table 9 and Figure 7). The mean number of times that the garments were worn remained fairly constant throughout the study period (see Figure 7). Adherence to wearing the garments was not associated with age or eczema severity at baseline (correlation coefficients 0.003 to 0.20; Table 10). Sensitivity analyses for adherence according to questionnaire completion are shown in Table 9.

| Adherence | Main analysis (participants with ≥ 12 questionnaires completed) (N = 124) | Sensitivity analysis 1b,c (N = 149) | Sensitivity analysis 2b,d (N = 149) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of nights that garments were worn for at least some of the night, median (25th, 75th centile) | 80.7 (56.8, 95.9) | 74.4 (52.1, 94.8) | 61.5 (32.9, 87) |

| Percentage of days that clothing was worn for at least some of the day, median (25th, 75th centile) | 34.1 (9.8, 75.9) | 28.6 (3.7, 74.3) | 19.3 (2.5, 63.4) |

| Adherence to wearing trial garments, n (%) | |||

| Adherente | 102 (82) | 117 (79) | 87 (58) |

| Worn for at least 50% of days and 50% of nights | 50 (40) | 54 (36) | 45 (30) |

| Worn for at least 50% of days only | – | 1 (1) | – |

| Worn for at least 50% of nights only | 52 (42) | 62 (42) | 42 (28) |

| Not adherent (wore clothing for < 50% of the time) | 22 (18) | 32 (21) | 62 (42) |

FIGURE 7.

Mean number of days/nights trial garments worn each week.

| Variable | Percentage of days that clothing was worn for at least some of the day (n = 124) | Percentage of nights that clothing was worn for at least some of the night (n = 124) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.003 | 0.20 |

| Baseline EASI score | –0.03 | 0.03 |

| Baseline POEM score | 0.08 | 0.13 |

Contamination

Only six participants in the standard care group reported wearing silk clothing during the 6-month study period.

Durability of the garments

Information about the number of garments and replacement garments sent out by the co-ordinating centre during the trial is presented in Chapter 4. This section presents information reported by parents on the 6-month questionnaire about the condition of the trial garments. Just over half of parents reported that at least one garment (top or leggings) could no longer be worn (Table 11). Children aged 4 years or under were more likely than older children to require replacement garments, as they outgrew the garments over the 6-month study period. Just over one-third of responders at 6 months reported that garments could no longer be worn as they had worn out or torn.

| Condition of garments at 6 months | Age (years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–4 (N = 63) | 5–11 (N = 51) | 12–15 (N = 7) | Intervention (N = 121) | |

| At least one garment no longer able to be worn at 6 months, n/N (%) | 41/61 (67) | 18/46 (39) | 1/5 (20) | 60/112 (54) |

| Reasons that garments can no longer be worn, n | ||||

| Too small | 22 | 6 | 0 | 28 |

| Worn out/torn | 26 | 14 | 1 | 41 |

| Lost | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Other | 6 | 2 | 0 | 8 |

Acceptability of use of silk clothing

At 6 months, 85 out of 121 (70%) participants reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the garments (95% CI 61% to 78%) and 89 out of 121 (74%) participants were either happy or very happy to wear the garments (95% CI 64% to 81%).

Blinding

Blinding appeared to be successful. Research nurses remained blinded to treatment allocation for 289 out of 300 (96%) participants. Unblinding occurred for three participants in the standard care group and eight participants in the intervention group. This unblinding was first reported at 2 months for one participant in the standard care group and seven participants in the intervention group and at the 4-month visit for all other participants.

Unblinding mainly occurred as a result of the child or parents saying that they had or had not received the garments. Unblinding occurred for two participants because they wore the garments to the assessment visit.

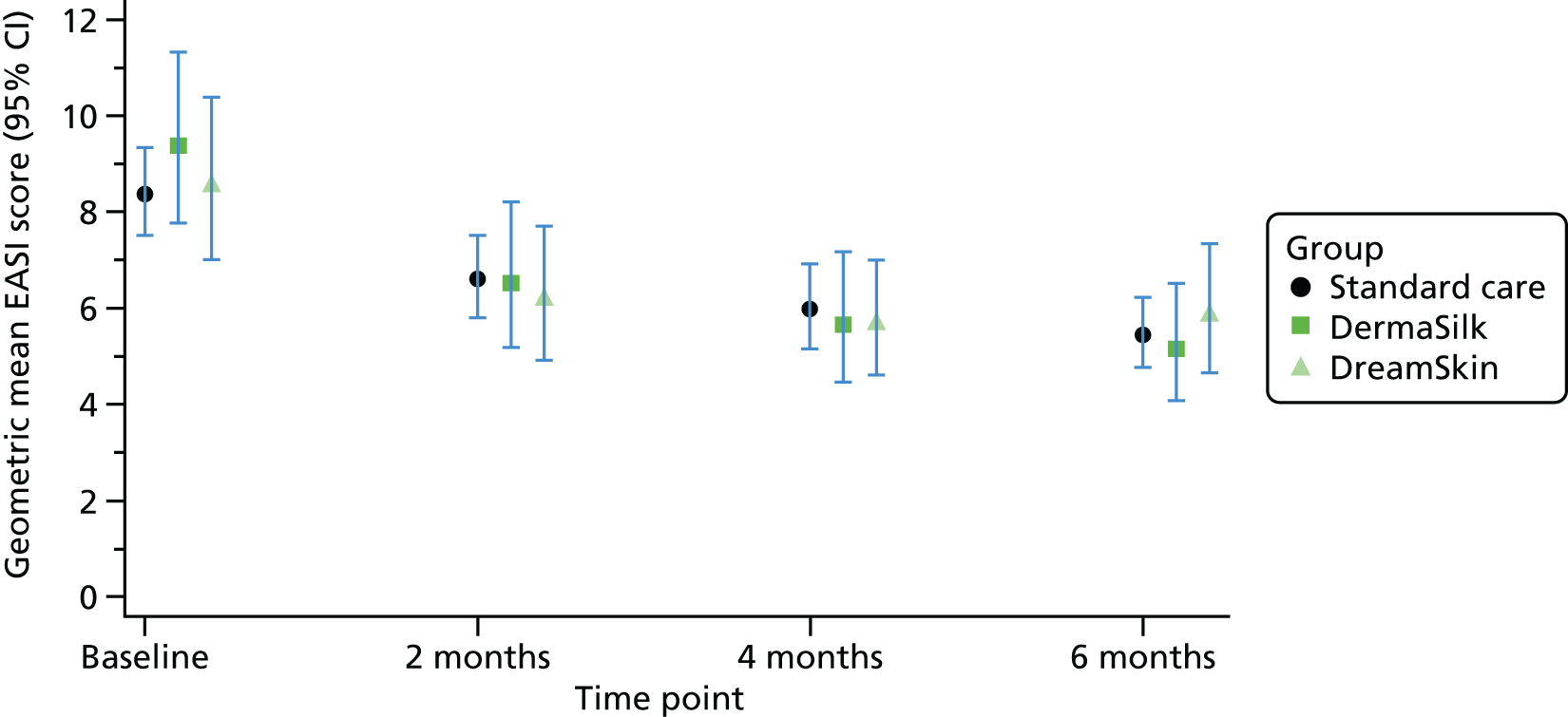

Primary outcome: Eczema Area and Severity Index

Primary analysis

Mean AE severity based on EASI scores improved in both groups during the 6-month follow-up period; however, there was no clinically important difference between the groups in the nurse-assessed EASI scores (Table 12 and Figure 8). Averaged over the 2-, 4- and 6-month follow-up visits, the ratio of geometric mean EASI scores was 0.95 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.07; p = 0.43). This CI is equivalent to a difference of approximately 1.5-point improvement to 0.5 points worse for the intervention group, compared with the standard care group in the original EASI scale units.

| Allocated group | Baseline | 2 months | 4 months | 6 months | Adjusted ratio of geometric means (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard care | |||||

| n | 151 | 137 | 133 | 139 | |

| Median | 7.3 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 4.2 | |

| 25th, 75th centile | 4.2, 12 | 2.5, 10.5 | 2.1, 10 | 2, 9.2 | |

| Geometric mean | 8.4 | 6.6 | 6.0 | 5.4 | |

| Intervention | |||||

| n | 149 | 139 | 135 | 133 | 0.95 (0.85 to 1.07); 0.43a |

| Median | 7 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 4 | |

| 25th, 75th centile | 4.1, 15.4 | 2.2, 9.9 | 2.2, 9.4 | 1.9, 7.9 | |

| Geometric mean | 9.2 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 5.4 | |

FIGURE 8.

Primary outcome: geometric mean EASI scores with 95% CIs.

Arithmetic means of the EASI scores and log-transformed EASI scores for each group and time point are given in Appendix 14 (see Table 52).

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome

Sex, history of food allergy and history of asthma were added as covariates into the analysis model because of baseline imbalance. This estimate of the ratio of the geometric mean was the same as for the primary analysis (0.95, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.07).

Multiple imputation of missing EASI data, assuming that scores were missing at random, gave a very similar result to the primary analysis (Table 13). When it was assumed that missing scores were systematically worse in the standard care group, the 95% CI for the geometric mean was equivalent to scores of 2 points lower to 0.1 points higher for the intervention group than for the standard care group.

| Sensitivity assumptions | Adjusted ratio of geometric means (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Assuming that missing EASI scores are MAR | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.05) |

| Assuming missing EASI scores are missing not at random | |

| Favouring intervention group | |

| Assuming that missing EASI scores are 3 points higher (worse) than under MAR in the standard care group and assuming MAR in intervention group | 0.89 (0.80 to 1.01) |

| Favouring standard care group | |

| Assuming that missing EASI scores are 3 points higher than under MAR in the intervention group and assuming MAR in standard care group | 0.97 (0.86 to 1.09) |

Further exploratory analysis of the EASI scores for areas covered by the garments (body and limbs) and areas uncovered by the garments (head and neck) can be found in Appendix 16.

Causal effect of adherence with wearing trial garments on primary outcome

The CACE was estimated using the EASI scores at 6 months for participants who completed 12 or more questionnaires (standard care, n = 127; intervention, n = 124). Table 14 presents the CACE estimate based on a binary definition of adherence of wearing the trial garments for at least 50% of the days or 50% of the nights and the CACE estimate for each additional 10% of the time the garments were worn. The intention-to-treat estimate for participants included in the CACE analysis is also presented using the EASI scores at 6 months for comparison (analysis according to randomised group).

| Estimate | n | Adjusted ratio of geometric means (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| ITT at 6 monthsa | 243 | 1.026 (0.87 to 1.21) |

| CACE: binary – garments worn for at least 50% of days or 50% of the nightsb | 243 | 1.031 (0.85 to 1.25) |

| CACE: each additional 10% of time garments wornb,c | 243 | 1.004 (0.977 to 1.032) |

The intention-to-treat and CACE estimate based on wearing the garments for at least 50% of the days or 50% of the nights are similar (see Table 14) as a result of 82% of intervention participants satisfying this definition (see Table 9). The ratio of geometric means for all comparisons is greater than 1, favouring the standard care group. The CACE estimate for each additional 10% of time that garments were worn suggests that eczema severity (EASI scores) did not improve with greater amounts of garment wear. A further summary table using all data at 6 months is shown in Appendix 17.

Subgroup analysis for primary outcome according to FLG status

Eczema Area and Severity Index scores according to group and FLG status (none, one or two FLG null mutations) for participants of white ethnicity are shown in Table 15 and Figure 9. Participants with FLG gene mutations were no more likely to benefit from the silk clothing than participants without a mutation (p-value for interaction effect 0.47).

| Subgroup and allocated group | Baseline | 2 months | 4 months | 6 months | Adjusted subgroup-specific ratio of geometric means (95% CI)a | Adjusted interaction effectb (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLG wild type: no mutations (+/+) | ||||||

| Standard care | ||||||

| n | 72 | 67 | 65 | 69 | ||

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 6.2 (3.9, 10.7) | 4.5 (2.4, 9.0) | 3.2 (2.1, 9.9) | 3.3 (1.8, 6.8) | ||

| Geometric mean | 7.7 | 6.1 | 5.5 | 4.8 | ||

| Intervention | ||||||

| n | 71 | 67 | 67 | 67 | ||

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 5.4 (3.3, 13.8) | 4.3 (2.1, 10.3) | 3.8 (2.2, 8.4) | 4.0 (2.3, 9.9) | ||

| Geometric mean | 8.1 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 6.1 | ||

| Analysis | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.21) | |||||

| One FLG null mutation (+/–) | ||||||

| Standard care | ||||||

| n | 31 | 28 | 27 | 29 | ||

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 8.0 (3.8, 12.0) | 5.3 (2.9, 11.4) | 4.6 (2.7, 8.6) | 4.4 (1.6, 10.7) | ||

| Geometric mean | 8.5 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 5.4 | ||

| Intervention | ||||||

| n | 20 | 19 | 19 | 19 | ||

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 8.7 (5.0, 15.7) | 6.1 (3.0, 8.4) | 4.4 (2.2, 9.5) | 4.0 (1.9, 8.0) | ||

| Geometric mean | 10.1 | 6.9 | 5.5 | 5.2 | ||

| Analysis | 0.87 (0.67 to 1.14) | 0.84 (0.61 to 1.15) | ||||

| Two FLG null mutations (–/–) | ||||||

| Standard care | ||||||

| n | 12 | 11 | 12 | 12 | ||

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 17.9 (7.7, 23.4) | 10.7 (3.8, 23.6) | 10.8 (3.6, 16.1) | 9.9 (4.1, 14.3) | ||

| Geometric mean | 13.7 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 9.9 | ||

| Intervention | ||||||

| n | 11 | 11 | 9 | 9 | ||

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 12.4 (8.6, 16.6) | 6.6 (5.4, 16.8) | 9.3 (5.3, 23.4) | 7.4 (2.6, 16.5) | ||

| Geometric mean | 13.0 | 8.9 | 10.2 | 7.8 | ||

| Analysis | 0.89 (0.60 to 1.30) | 0.85 (0.56 to 1.29) | ||||

FIGURE 9.

Geometric mean EASI scores by group and FLG status. FLG +/+ denotes no mutations; FLG +/– denotes one FLG null mutation; and FLG –/– denotes two FLG null mutations.

Post hoc subgroup analysis for primary outcome according to baseline eczema severity

Eczema Area and Severity Index scores according to group and baseline eczema severity (almost clear or mild EASI scores and moderate or severe EASI scores)44 are shown in Table 16. There was no evidence that the clothing was more or less effective depending on the severity of eczema at baseline.

| Subgroup and allocated group | Baseline | 2 months | 4 months | 6 months | Adjusted subgroup-specific ratio of geometric means (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almost clear/mild baseline EASI scores (1 to 7) | |||||

| Standard care | |||||

| n | 73 | 66 | 65 | 68 | |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 4 (2.6, 5.5) | 2.9 (1.8, 4.8) | 2.7 (1.5, 4) | 2.3 (1.4, 4.3) | |

| Geometric mean | 4.8 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 3.5 | |

| Intervention | |||||

| n | 75 | 72 | 72 | 70 | 0.95 (0.81 to 1.12) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 4.1 (2.8, 5.5) | 2.8 (1.6, 4.3) | 2.7 (1.6, 4.3) | 2.5 (1.2, 4.2) | |

| Geometric mean | 4.9 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.7 | |

| Moderate/severe baseline EASI scores (7.1–50) | |||||

| Standard care | |||||

| n | 78 | 71 | 68 | 71 | |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 12 (8.8, 18.8) | 9.2 (5.2, 15.8) | 9.4 (4.7, 16.4) | 7.7 (4.1, 12.3) | |

| Geometric mean | 14.2 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 8.2 | |

| Intervention | |||||

| n | 74 | 67 | 63 | 63 | 0.95 (0.81 to 1.12) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 15.4 (10, 23.1) | 9.6 (5.6, 19.6) | 8 (4, 17.3) | 6.9 (3.9, 13.8) | |

| Geometric mean | 17.3 | 11.3 | 9.5 | 8.3 | |

Secondary outcomes

Global assessment of atopic eczema

The proportion of participants with a nurse-assessed IGA of AE of moderate severity or worse decreased in both groups during the follow-up period, but there was no difference between the two groups: relative risk 0.98 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.12; p = 0.63; Table 17).

| Outcome and allocated group | Baseline, n/N (%) | 2 months, n/N (%) | 4 months, n/N (%) | 6 months, n/N (%) | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI); p-value | Adjusted relative risk (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGA | ||||||

| Standard care | 108/151 (72) | 72/137 (53) | 63/133 (47) | 56/139 (40) | –0.1% (–9.3% to 6.3%); 0.70 | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.12); 0.63 |

| Intervention | 108/149 (72) | 71/139 (51) | 60/136 (44) | 58/134 (43) | ||

| PGA | ||||||

| Standard care | 113/151 (75) | 82/137 (60) | 72/133 (54) | 60/139 (43) | –10.1% (–18.3% to –2.0%); 0.01 | 0.83 (0.70 to 0.98); 0.03 |

| Intervention | 98/149 (66) | 62/139 (45) | 56/135 (41) | 51/134 (38) | ||

In contrast, for the participant-rated IGA, fewer participants rated their AE as moderately severe or worse in the intervention group than standard care: relative risk 0.83 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.98; p = 0.03; see Table 17).

Self-reported atopic eczema symptoms using the Patient Oriented Eczema Measure

Mean weekly POEM scores by group are shown in Figure 10. The mean of the participants’ mean weekly POEM scores over the 6-month study was 2.8 points lower in the intervention group than in the standard care group (95% CI –3.9 to –1.8; p < 0.001; Table 18). There was a more obvious separation of the groups in the first 3 months of the trial than in the final 3 months.

FIGURE 10.

Mean weekly patient reported symptoms (POEM scores) with 95% CI. Baseline POEM scores (16.6 standard care; 17.3 intervention): data not shown on graph as scores were collected in clinic rather than by online questionnaire.

| POEM scores | Standard care (n = 147), mean (SD) | Intervention (n = 145), mean (SD) | Adjusted difference in means (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| POEM score at baseline clinic visit | 16.6 (4.8) | 17.3 (5.8) | |

| Participant mean of weekly POEM score during the 6-month RCT | 14.2 (5.5) | 11.6 (5.6) | –2.8 (–3.9 to –1.8); < 0.001 |

Three-Item Severity scale

The mean TIS scores improved in both groups during the follow-up period. No between-group differences were observed: difference in means 0.09 (95% CI –0.22 to 0.40; p = 0.57; Table 19).

| Allocated group | Baseline | 2 months | 4 months | 6 months | Adjusted difference in means (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard care | |||||

| n | 151 | 137 | 133 | 139 | |

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 (1.8) | 4 (1.9) | 4.1 (2.2) | 3.7 (1.9) | |

| Intervention | |||||

| n | 149 | 139 | 136 | 134 | 0.09 (–0.22 to 0.40); 0.57 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 (1.8) | 4.1 (2) | 4.1 (2.1) | 3.7 (2) | |

Use of atopic eczema treatments

The percentage of days during the study that emollients, topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors and wet/dry wraps were used is shown in Table 20.

| Frequency of medication use | Standard care (n = 147), mean (SD) | Intervention (n = 145), mean (SD) | Adjusted difference in means (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of days topical steroids used | 44.1 (28.2) | 39.3 (27.8) | –3.7 (–9.6 to 2.3); 0.23 |

| Percentage of days emollients used | 88.4 (20.1) | 86.0 (22.1) | |

| Percentage of days calcineurin inhibitors used | 5.8 (15.9) | 5.7 (16.3) | |

| Percentage of days wet/dry wraps used | 5.2 (17.1) | 3.1 (12.5) |

The mean percentage of topical corticosteroid use was slightly less in the intervention group than the standard care group, equivalent to using topical corticosteroids on 6 days fewer over the 24 weeks (95% CI equivalent to using steroids for between 16 days fewer and 4 days more). The mean frequency of usage was similar in the two groups for the other topical treatments. Details of the amount of topical corticosteroid prescribed over the 6-month trial are summarised in Chapter 4, Table 30.

The potency of participants’ main topical corticosteroid was similar in the two groups at 6 months (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11.

Potency of main steroid at baseline and follow-up.

Changes in AE treatments during the trial are shown in Table 21. There were no differences between the groups in the percentage of participants who escalated their AE treatment between baseline and 6 months, although participants in the standard care group were more likely to have escalated treatment within the first 2 months of the study.

| Change in medication use | Standard care (N = 151), n (%) | Intervention (N = 149), n (%) | Adjusted risk difference (95% CI); p-value | Adjusted relative risk (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between baseline and 2 months | ||||

| Treatment escalation | 34 (25) | 15 (11) | ||

| Neutral change | 18 (13) | 13 (9) | ||

| No change | 81 (59) | 105 (76) | ||

| Treatment reduction | 4 (3) | 6 (4) | ||

| n | 137 | 139 | ||

| Between 2 and 4 months | ||||

| Treatment escalation | 16 (12) | 16 (12) | ||

| Neutral change | 17 (13) | 8 (6) | ||

| No change | 96 (72) | 107 (79) | ||

| Treatment reduction | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | ||

| n | 133 | 136 | ||

| Between 4 and 6 months | ||||

| Treatment escalation | 16 (12) | 16 (12) | ||

| Neutral change | 10 (7) | 15 (11) | ||

| No change | 105 (76) | 93 (69) | ||

| Treatment reduction | 8 (6) | 10 (7) | ||

| n | 139 | 134 | ||

| Any treatment escalation between baseline and 6 monthsa | 50 (36) | 42 (30) | –5.3% (–16.3% to 5.7%); 0.34 | 0.87 (0.62 to 1.22); 0.43 |

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality-of-life outcomes for the DFI, EQ-5D-3L, ADQoL and CHU-9D are shown in Table 22. There were no differences between any of these quality-of-life outcomes between the two groups. The difference in means were all close to 0 and favoured the intervention group for DFI, EQ-5D-3L and ADQoL, and favoured the standard care group for CHU-9D.

| Quality-of-life outcome and allocated group | Baseline | 6 months | Adjusted difference in means (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFI | |||

| Standard care | –0.8 (–2.1 to 0.4); 0.18 | ||

| n | 151 | 138 | |

| Mean (SD) | 12.0 (6.3) | 8.6 (6.8) | |

| Intervention | |||

| n | 149 | 133 | |

| Mean (SD) | 12.4 (6.6) | 7.6 (6.1) | |

| ADQoL | |||

| Standard care | 0.0260 (–0.0018 to 0.0539); 0.07 | ||

| n | 151 | 139 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.6952 (0.1300) | 0.7292 (0.1308) | |

| Intervention | |||

| n | 149 | 134 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.6883 (0.1409) | 0.7515 (0.1273) | |

| CHU-9D (aged ≥ 5 years only) | |||

| Standard care | –0.0243 (–0.0584 to 0.0098); 0.16 | ||

| n | 64 | 67 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.8292 (0.1263) | 0.8828 (0.1059) | |

| Intervention | |||

| n | 70 | 65 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.8386 (0.1115) | 0.8677 (0.1114) | |

| EQ-5D-3L index for parents health-related quality of life | |||

| Standard care | 0.0115 (–0.0185 to 0.0415); 0.45 | ||

| n | 151 | 138 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.8983 (0.1612) | 0.9107 (0.1529) | |

| Intervention | |||

| n | 147 | 134 | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.9018 (0.1710) | 0.9184 (0.1564) | |

Safety outcomes

The number of participants reporting a skin infection was similar in the two groups (Table 23).

| Safety outcomes | Standard care (n = 141) | Intervention (n = 142) | Adjusted relative risk (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any skin infection during 6-month RCT, n (%)a,b | 39 (28) | 36 (25) | 0.89 (0.54 to 1.47); 0.66 |

| Number of skin infections per participant | |||

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | |

| Min., max. | 1, 5 | 1, 8 | |

| n | 39 | 36 | |

| Number of inpatient stays per participant because of AE, n (%)a,c | |||

| 0 | 139 (99) | 138 (97) | |

| 1 | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| 2 | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| ≥ 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total number of nights in hospital because of AE | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.5 (2.1) | 2.8 (1.7) | |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 2.5 (1, 4) | 2.5 (1.5, 4) | |

| Min., max. | 1, 4 | 1, 5 | |

| n | 2 | 4 | |

Four participants in the intervention group and two in the standard care group had a hospital inpatient stay because of AE. The two hospital inpatient stays required by one participant in the intervention group were classified as potentially related to trial treatment by the medical monitor.

Open follow-up period

The questionnaire at 8 months was completed by 111 participants (74%) in the standard care group and 116 participants (78%) in the intervention group.

The frequency with which the clothing was worn during the open follow-up period (when all participants received the garments) is shown in Table 24. Just under half of the responders reported that the garments were worn for all or most of the time for the days and/or nights between 6 and 8 months.

| Qualitative feedback | Standard care (N = 111), n (%) | Intervention (N = 116), n (%) | Total (N = 227), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency clothing worn during the follow-up period (6–8 months) | |||

| Never | 8 (7) | 17 (15) | 25 (11) |

| Rarely | 20 (18) | 18 (16) | 38 (17) |

| Some of the time | 26 (23) | 27 (23) | 53 (23) |

| All/most of the time (days only) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 5 (2) |

| All/most of the time (nights only) | 42 (38) | 25 (22) | 67 (30) |

| All/most of the time (days and nights) | 7 (6) | 24 (21) | 31 (14) |

| Not answered | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 8 (4) |

| Feel that AE improved because of trial clothing | |||

| Yesa | 25 (23) | 57 (49) | 82 (36) |

| No | 28 (25) | 27 (23) | 55 (24) |

| Not sure | 49 (44) | 28 (24) | 77 (34) |

| Not answered | 9 (8) | 4 (3) | 13 (6) |

| Would ask GP to prescribe clothing | |||

| Yesb | 48 (43) | 61 (53) | 109 (48) |

| No | 32 (29) | 31 (27) | 63 (28) |

| Not sure | 22 (20) | 20 (17) | 42 (19) |

| Not answered | 9 (8) | 4 (3) | 13 (6) |

| Have asked GP to prescribe clothing | |||

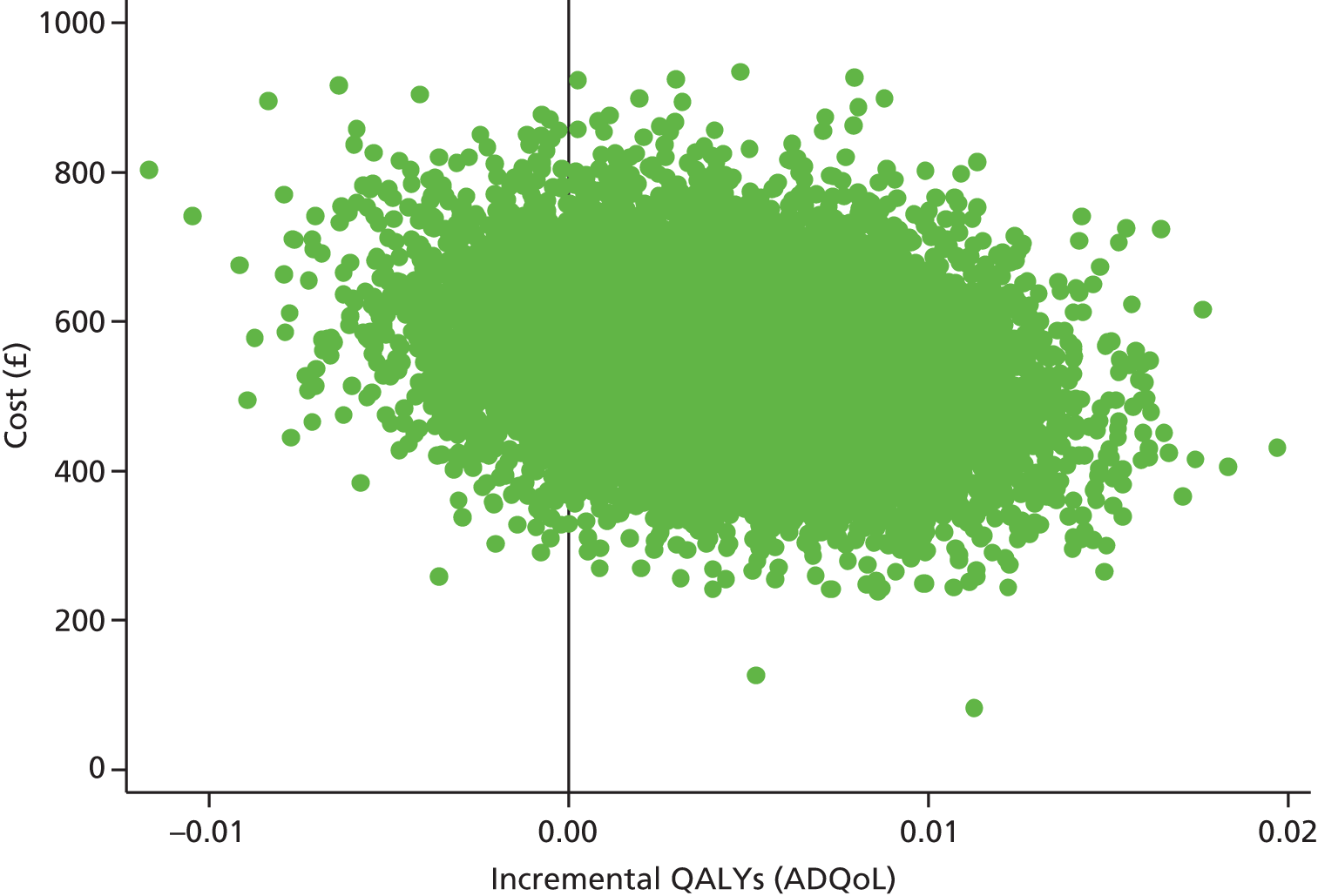

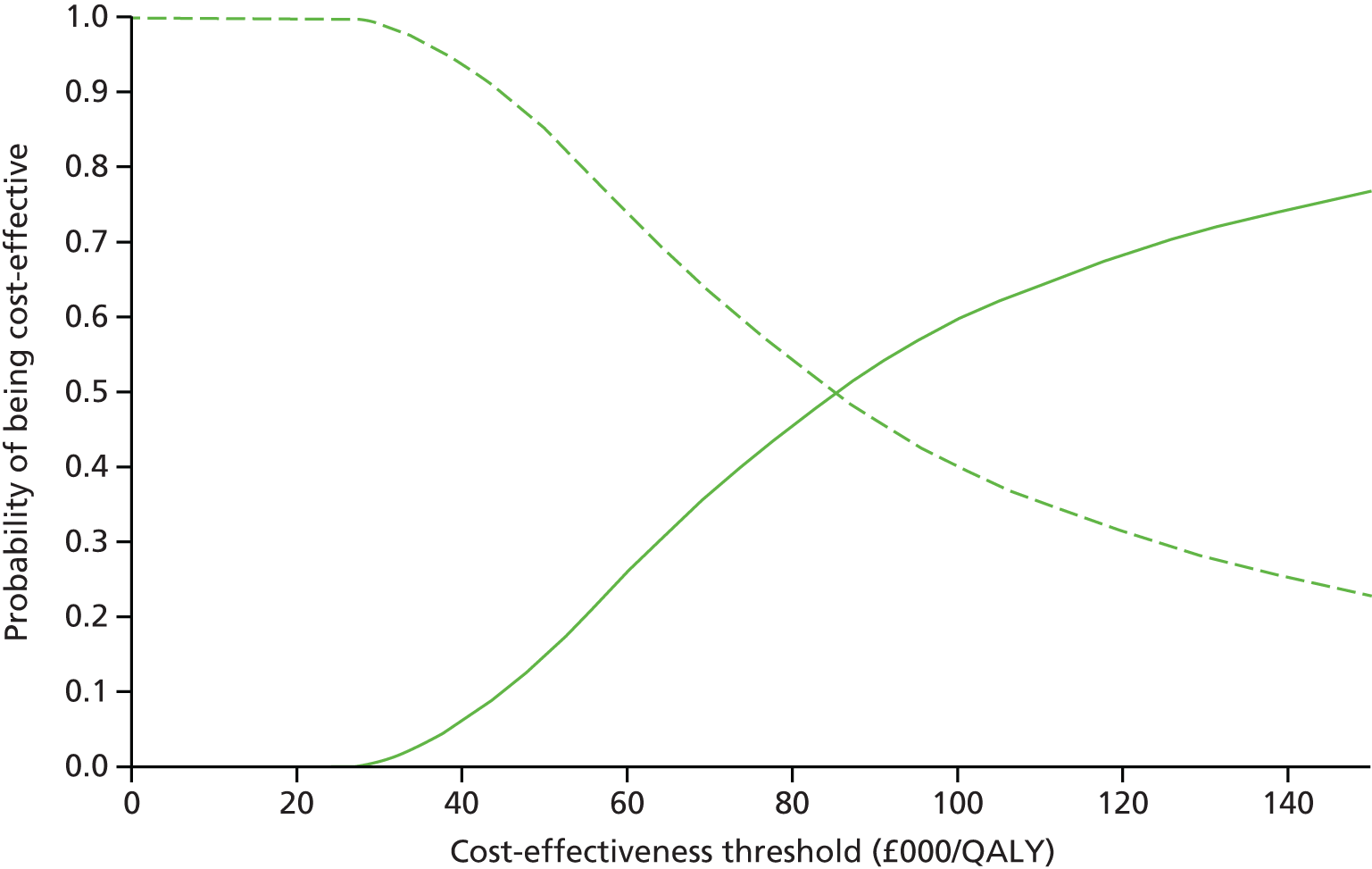

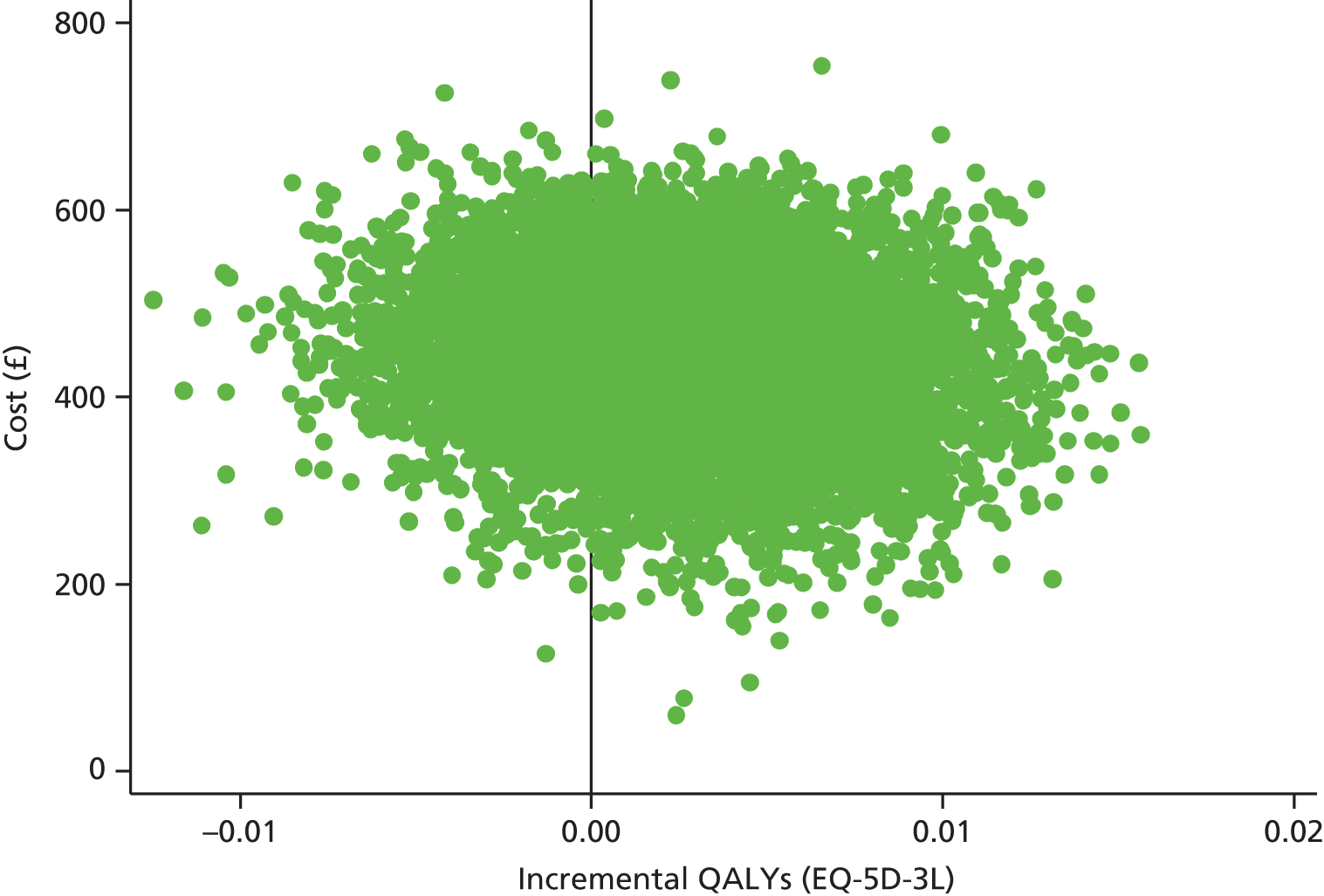

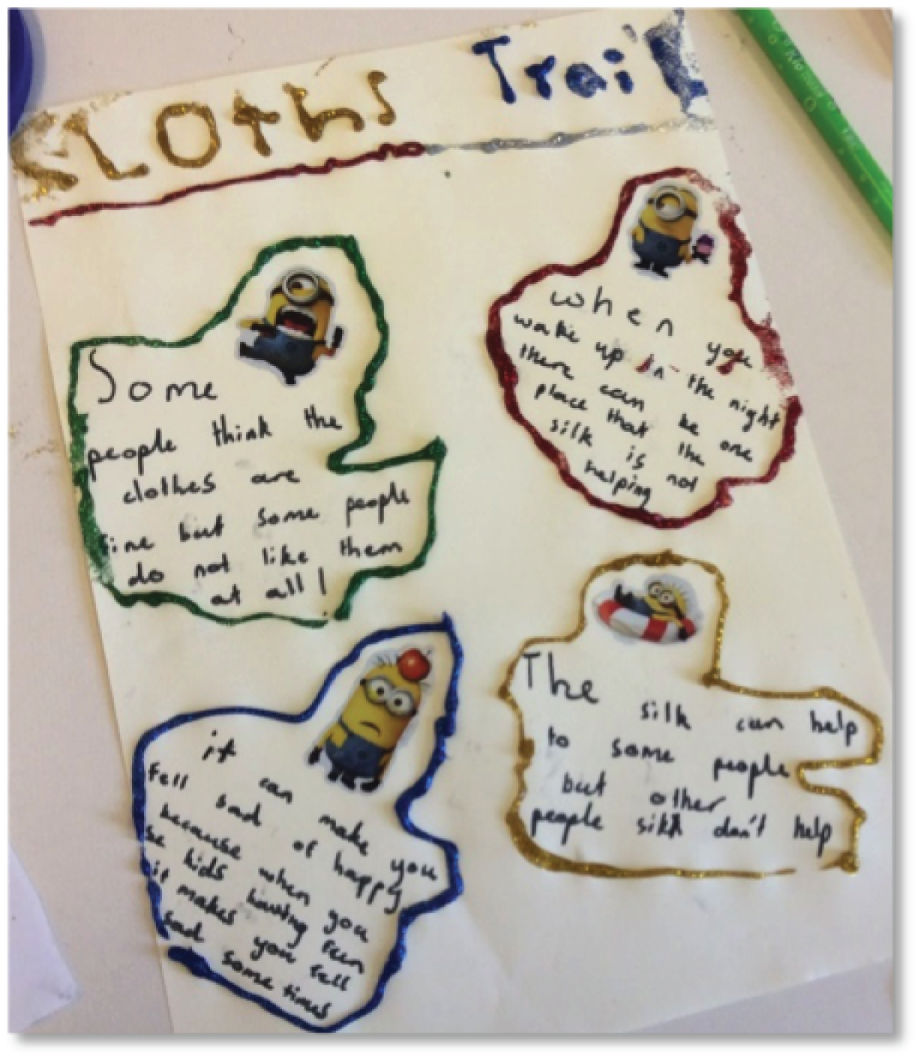

| Yes | 5 (5) | 9 (8) | 14 (6) |