Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/104/04. The contractual start date was in April 2011. The draft report began editorial review in April 2016 and was accepted for publication in November 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Chestnutt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction, background and objectives

Introduction

Dental caries (tooth decay) is among the most common diseases to affect humankind. In 2010, it was estimated that 35% of the global population, that is, 2.4 billion people, had untreated caries in their permanent dentition. 1 The NHS in England spends around £3.4B per year on dental services, and it is estimated that the private market accounts for a further £2.3B annually. 2

Dental caries results from the metabolism of sugars by bacteria that are normally resident in the oral cavity. The acids produced cause the demineralisation (breakdown) of the tooth surface. Initially, the caries lesion is confined to the dental enamel. In its early stages, the disease process can be halted or even reversed by a process known as remineralisation. This is facilitated by the presence of fluoride at the interface between the tooth surface and the overlying biofilm of the dental plaque.

Untreated, the disease process continues to involve the underlying dentine and eventually the dental pulp becomes inflamed, resulting in pain: toothache. Once the dentine is involved, the tooth requires a restoration to halt caries progression. Ultimately, an inflamed pulp will die and a dental abscess may result. Resolution will require either root-filling or the extraction of the tooth.

The past four decades have seen great improvement in oral health in England and Wales. In 1973, the mean number of decayed, missing, filled teeth in permanent dentition (DMFT) in 15-year-olds was 8.4. 3 By 2013 this had fallen to 1.4. 4 This improvement is widely attributed to the introduction and the widespread use of fluoride-containing toothpaste in the 1970s. However, improvements in oral health have not been uniformly distributed across the population.

Children at risk of dental caries

Mean population values of dental caries prevalence mask an important fact. Similar to many chronic, lifestyle-associated diseases, caries prevalence is markedly linked to social and economic deprivation,5,6 and the prevalence is markedly skewed. At the age of 5 years, the prevalence of dental decay in children resident in the most deprived localities is more than twice that of children living in the least deprived communities. As oral health has improved, dental caries has become concentrated in children from poorer backgrounds.

Teeth at risk of dental caries

Individual teeth differ in their susceptibility to dental decay. This largely reflects the fact that dental plaque (oral biofilm) is more likely to form in specific areas. One such area is the occlusal (or biting) surface of molar teeth. This fissured surface predisposes teeth to oral bacteria multiplying in the depths of the fissures and forming an environment favourable to the fermentation of sugars into acid.

The first permanent molars (FPMs) erupt at the back of the mouth around 6 years of age. The occlusal surface of these teeth is particularly prone to dental caries, often within a short period of eruption into the mouth. Management of occlusal caries on permanent molars has proven to be a great challenge to the dental profession. 7 Occlusal caries accounts for the majority of affected tooth surfaces in adolescents and adults. 8–11

It is, therefore, apparent that preventing dental caries on the occlusal surfaces of FPMs is a key objective in preventative dental care. These surfaces represent the surfaces most susceptible to decay and are present in susceptible children. Actions to prevent and arrest dental caries, targeted at these surfaces, have the potential to significantly improve oral health and to address inequalities.

Preventative dental technologies

There are two preventative dental technologies that have the potential to be targeted specifically at occlusal surfaces of FPMs: pit and fissure sealant and fluoride varnish (FV). The terms ‘pit and fissure sealant’ and ‘fissure sealant’ (FS) refer to the same material. Unless referring to the term used specifically by a referenced source, the term FS is used throughout this report.

Pit and fissure sealant

Pit and fissure sealant contains a bisphenol A and glycidyl methacrylate (bis-GMA) resin, which hardens on exposure to light. It is applied to the tooth surface using acid-etch technology. FS prevents dental caries by physically obliterating the pit and fissure system that has great potential to harbour cariogenic organisms. Eliminating the pit and fissure system removes this ecological niche and reduces the initiation of caries in this highly susceptible site. First developed in the 1960s, FS is an established technology and is widely used in clinical practice.

Numerous studies have investigated the clinical effectiveness of FS. A 2013 Cochrane systematic review12 of sealants for preventing dental decay in the permanent teeth concluded that, in 12 trials in which resin-based sealants were compared with no sealant controls, the sealed teeth were significantly less likely to be carious at 2 years’ follow-up [odds ratio (OR) 0.12, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.07 to 0.19], although five of these trials were conducted in the 1970s, when caries prevalence was higher than it is now. The authors of the review concluded that the application of sealants was recommended to prevent and control dental caries. They found that the application of FS to occlusal surfaces of permanent molars was clinically effective when compared with unsealed control teeth up to 48 months but, beyond that time, effectiveness was uncertain. They further concluded that, although sealing was effective in high-risk children, evidence in other circumstances is scarce, and they were unable to achieve a primary objective of determining the effectiveness of sealants in relation to the baseline prevalence of dental caries in the population. 12

Fluoride varnish

The caries-preventative effect of fluoride has been recognised for > 100 years. Evidence arising from ecological studies in the early twentieth century linked the presence of fluoride in the public water supply to reduced caries prevalence in the population. 13 Subsequently, fluoride has been incorporated into a range of caries-preventative products for both professional use and self-use.

Fluoride primarily exerts cariostatic properties by a topical effect. 14 The presence of fluoride at the tooth surface prevents demineralisation of the dental enamel and encourages remineralisation.

Fluoride-containing varnishes were developed in the 1960s. They contained fluoride at a much higher concentration [22,600 parts per million (p.p.m.)] than that present in water fluoridation programmes (0.5–1 p.p.m. fluoride) or toothpaste (1000–1500 p.p.m fluoride). FVs were developed to prolong the contact of fluoride ions with the tooth surface, thereby enhancing their cariostatic effect.

The most widely used FV preparation in the UK is Duraphat® varnish [Colgate-Palmolive (UK) Ltd, Manchester, UK], marketed by Colgate®. This product contains 5% of sodium fluoride (22,600 p.p.m. of fluoride). Owing to the high fluoride content, the product is licensed as a prescription-only medicine and can be prescribed only by a medical or dental professional. FV is designed for application by a dental professional to specific at-risk tooth surfaces or early caries lesions. The recommended frequency of application is 2–4 times per year.

The clinical effectiveness of FV has been the subject of a recent Cochrane systematic review. 15 The authors identified 13 studies that compared FV with a placebo or no treatment, and concluded that the pooled decayed, missing, filled tooth surfaces in permanent dentition (DMFS)-prevented fraction was 43% (95% CI 30% to 57%; p > 0.0001). However, the reviewers reported that the quality of the evidence was moderate, as it mainly included studies that were at a high risk of bias with considerable heterogeneity. 15

Fissure sealant versus fluoride varnish

From the above reviews it is evident that both FS and FV are effective caries preventative agents. The question arises, therefore, as to which is the more effective, particularly in relation to the prevention of dental caries in FPMs.

Ahovuo-Saloranta et al. 16 have recently published a Cochrane systematic review on the relative effectiveness of FS versus FV. This updates a previous version of the review published in 2010. 17 The review identified four trials that had compared resin-based FS with FV. Two of these four studies, involving 358 children, suggested that, compared with FV, FS prevented more caries in FPMs at 2-year follow-up. The pooled OR was 0.65 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.94; p = 0.02). The authors stated that the body of evidence was assessed as low. Ahovuo-Saloranta et al. 16 concluded that the conclusion of the updated review remained the same as the last update in 2010, that is, as a result of the limited number of data available it is was not possible to draw clear conclusions about possible differences in effectiveness for preventing or controlling dental caries on occlusal surfaces of permanent molars.

The importance of establishing the relative clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and patient preferences in relation to fissure sealant or fluoride varnish

Although the relative clinical effectiveness of FS and FV is important, a number of other factors should also be considered when choosing between these technologies.

Application and equipment

The application of FS requires the use of the acid-etch technique to achieve adhesion of the sealant to the tooth surface. Adequate moisture control is known to be a critical component of achieving a satisfactory bond. 18 This means that sealants can reasonably be applied only in the confines of a ‘dental surgery’, be that fixed or mobile. The use of a ‘3-in-1’ water/air spray is required, along with adequate aspirating facilities.

In contrast, the application of FV is much less technique sensitive and does not require the degree of specialist equipment needed for sealant placement. FV can simply be painted onto teeth using a small brush. Moisture control using cotton wool rolls or pads is sufficient. As a result, FV can be applied in a school medical room or other private location and does not necessarily need to be done within a clinic or traditional health-care setting.

Personnel required for placement

Whereas FS can be applied only by a dentist, dental therapist or dental hygienist in the UK, FV can be applied by an appropriately trained dental nurse. These factors raise the question of the relative costs associated with providing either FS or FV. Although the equipment and personnel costs required to provide FS are potentially higher, these need to be offset against the requirement for FV to be applied every 6 months and the single application and subsequent periodic check-up/top-up required for FS.

Patient acceptability

A further consideration is the relative acceptability of FS and FV to patients. At the age of 6 years, children may have limited experience of dental care. The more technically involved procedure of FS application may pose a greater challenge to an anxious or nervous child than the apparently more straightforward application of FV.

Approaches to improve oral health

There are three main approaches to improving oral health: a whole-population approach, a targeted-population approach and a high-risk individual approach. 19

The Designed to Smile programme in Wales, part of the Welsh Government’s National Oral Health Improvement Programme, takes a targeted population approach. There are several elements to the Designed to Smile programme, one of which is a FS scheme. This work is delivered in schools via the Community Dental Service (CDS) using mobile dental clinics (MDCs). This setting provided the backdrop to the current study. To ascertain whether FS or FV is the more effective technology in preventing occlusal caries in FPMs is of importance to the NHS. This was recognised in the call by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Board, which commissioned the research reported here. In addition to clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness is of interest. As discussed above, FV requires less time than FS and can be applied by staff with less training. However, although FV requires twice-yearly application, FS require only periodic checking and maintenance. It is therefore possible that the technologies will differ in their costs and, thus, in their cost-effectiveness.

Finally, the preference of children and their parents for FS or FV merits investigation. The less invasive nature of FV placement compared with FS placement means that examination of the relative acceptability of these treatments is required.

The aims and objectives of the trial were, therefore, as follows. 20

Trial aims and objectives

Trial aim

The overall aim of the study was to identify and compare the relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of two established technologies, FS and FV, for the prevention of dental caries in FPM teeth in children aged 6 or 7 years.

Trial objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective of this trial was to compare the clinical effectiveness of FS and FV in preventing dental caries in FPMs in 6- and 7-year-olds, as determined by the:

-

proportion of children developing new caries on any one of up to four treated FPMs

-

number of treated FPM teeth that are caries free at 36 months.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives of this trial were to:

-

establish the costs and budget impact of FS and FV delivered in a community/school setting and the relative cost-effectiveness of these technologies

-

examine the impact of FS and FV on children and their parents/carers in terms of quality of life (QoL) and treatment acceptability measures

-

examine the implementation of treatment in a community setting with respect to the experience of children, parents, schools and clinicians.

Chapter 2 Methods

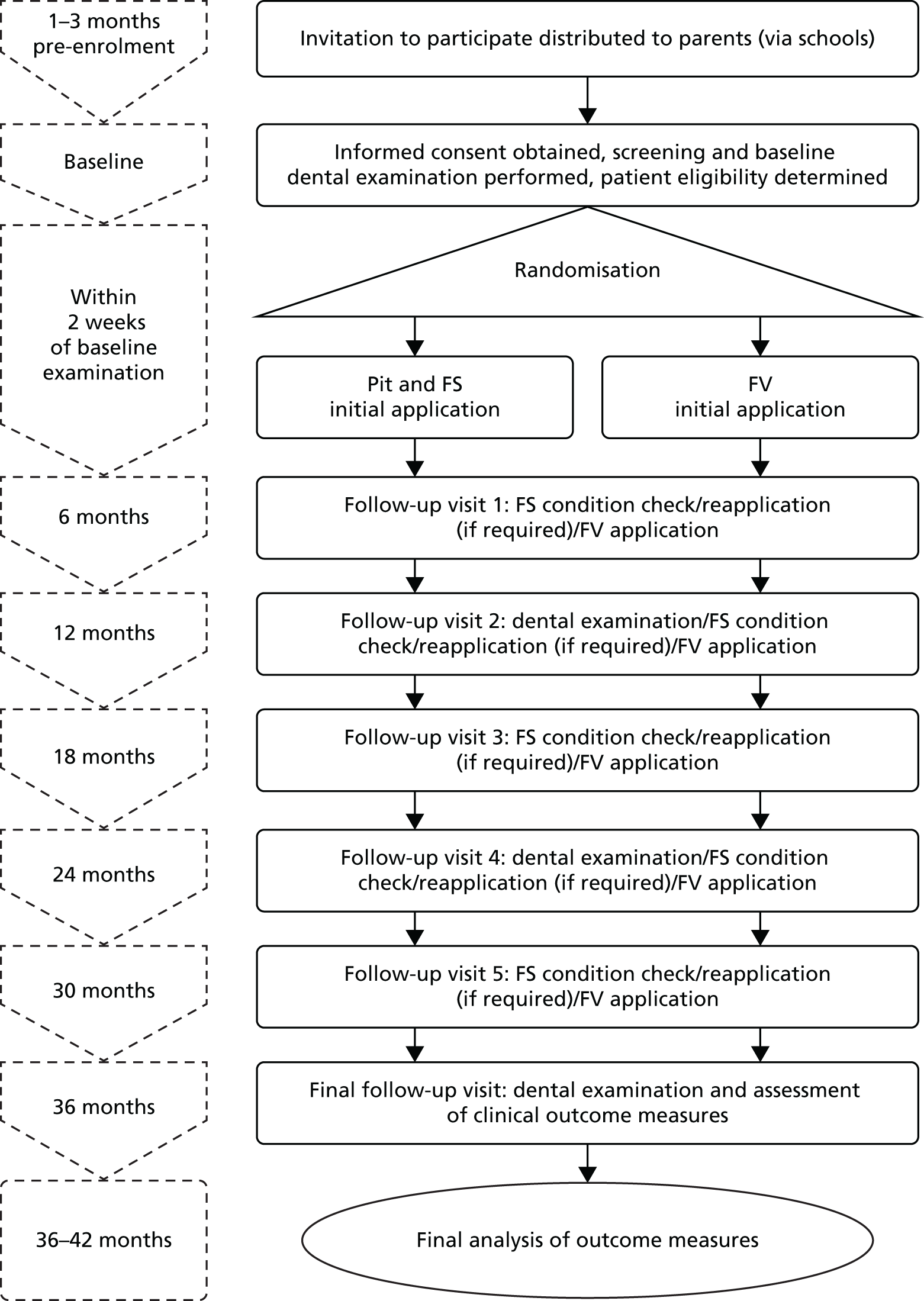

Trial design

The study was a Phase IV randomised, allocation-blinded, two-arm, parallel-group trial. The participants were randomised on a 1 : 1 allocation ratio to receive one of:

-

resin-based FS

-

FV.

There were no significant changes to the trial methodology after trial commencement. With the exception of some minor changes to improve the return rate of follow-up questionnaires, the trial was conducted as per the original protocol. 20

Approvals obtained

The Research Ethics Committee (REC) for Wales 3 (formerly known as the REC for Wales) approved the study on 15 February 2011 (reference 11/MRE09/6). The details of the REC and the NHS Research and Development department approvals and clinical trials authorisation from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) are provided in Appendices 1–3.

Participants

The target population were children aged 6 or 7 years attending primary schools in designated Communities First areas; the Welsh Government has identified these localities as areas of social and economic deprivation. All children in such schools are deemed to be at high risk of caries, according to Public Health England and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, and qualify for FS/FV application. 21,22

Participant selection and eligibility criteria

Children were considered eligible to join the trial if they met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria. 20 It was possible to assess whether or not children met some of these criteria prior to a clinical dental examination; however, for other eligibility criteria, examination by a dentist was required.

Inclusion criteria

Children were eligible for inclusion if:

-

they were aged 6 or 7 years and attended the schools participating in the current Cardiff and Vale University Health Board Designed to Smile programme

-

the person with parental responsibility has provided written informed consent

-

they had at least one fully erupted FPM free of caries into dentine.

Exclusion criteria

Children were ineligible for inclusion if:

-

their medical history precluded inclusion [i.e. those with a history of hospitalisation for asthma, severe allergies or allergy to Elastoplast (Beiersdorf AG, Hamburg, Germany), which was determined from a medical history form (MHF) that was completed by parents]

-

they had a known sensitivity to colophony, or any of the product ingredients (e.g. methylacrylate in FS, determined from a MHF that was completed by parents)

-

they had any abnormality of the lips, face or soft tissues of the mouth that would cause discomfort in the provision of FS/FV

-

they were currently participating in another clinical trial involving an investigational medicinal product (determined from a MHF that was completed by parents)

-

they showed obvious signs of systemic illness (e.g. colds, influenza, chickenpox; determined at baseline examination).

Recruitment into the trial

Number of participants

It was planned to recruit 920 participants, who would be randomised equally (n = 460 per arm) to the two technologies (FS and FV) investigated in this trial. The statistical justification for this number is discussed below.

Recruitment of schools

Eligible schools involved in the Cardiff and Vale University Health Board (UHB) CDS Designed to Smile programme were invited to participate in the trial. The trial management team visited those schools that expressed an interest in participating to discuss the practical and logistical aspects of the trial. When applicable, agreement to participate in the trial was documented.

Recruitment of participants

In line with the procedures for informing parents of children of the existing Designed to Smile programme, teachers distributed invitation packs to children for them to take home to their parents.

The following documents were included in the invitation packs:

-

participant information sheet (PIS) for parents (see Appendix 4)

-

MHF (see Appendix 5)

-

informed consent form (ICF) (see Appendix 6).

Participant information sheet for parents

The PIS was developed in conjunction with a parents’ group and approved by the REC (detailed in Design of study materials and strategy for maximising questionnaire follow-up rates). The PIS contained all of the necessary information for a parent or legal guardian to make an informed choice about their child’s participation in the trial, as detailed in section 4.8 of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. 23

Medical history

The medical history of potential participating children was ascertained by asking their parents or legal guardian to complete a MHF. Data were collected that specifically related to allergies, asthma (including whether or not this had resulted in hospitalisation) and sensitivity to constituents of either FS or FV, and if the child was currently participating in a clinical trial involving an investigational medicinal product. Whether or not the child was registered with a general dental practitioner was also ascertained.

Following a child’s enrolment into the trial, any changes to their relevant medical history (as described above) was established via a brief MHF (see Appendix 7), which was sent to parents in advance of the annual clinical dental examination at 12 and 24 months. Parents were instructed to complete and return the MHF to the dental team only if there had been a change in their child’s relevant medical history.

Informed consent

So that the trial could be conducted as pragmatically as possible, the consent process from the existing CDS FS programme was utilised, in that consent was provided remotely by parents completing consent forms at home and returning them to the school via their children. The consent rates for the existing FS programme are usually > 70% (depending on the school); therefore, effectively communicating the concept of the trial to parents without negatively affecting recruitment was key to the success of the trial. Given the setting and the low-risk nature of the trial, obtaining consent remotely was successfully justified to the REC.

The PIS included in the Seal or Varnish? (SoV) invitation pack introduced the trial to the parents and asked them to take the time to read the PIS before deciding whether or not they wanted their child to participate. Parents were also informed of the option for their child to enter the existing Designed to Smile programme instead of the trial. Explicit in the PIS was the opportunity to discuss any aspect of the trial with a member of the trial team over the telephone. A dedicated telephone number was provided for this purpose, with the provision for parents to leave a telephone number and e-mail address to be contacted by a member of the trial team at the next available opportunity. Parents were also asked to discuss the trial with their child.

After considering the information provided in the SoV invitation pack, and discussing the trial with a member of the trial team (if required), parents who wanted their child to participate were asked to sign and date the ICF (see Appendix 6). They were also asked to confirm on the ICF that they had been given the opportunity to discuss the trial with a member of the trial team or, alternatively, if they did not require any further information, to make a decision regarding their child’s participation.

Children returned the completed ICF and MHF forms to their class teacher. On receipt of the ICF and MHF, a designated member of the SoV MDC team liaised with an appropriate member of school staff to verify that the name and signature on the ICF were in agreement with the school’s records for the person with parental responsibility for that child.

Interventions

Study setting

The study interventions took place in the MDC, which visited schools in areas of high social and economic deprivation in the Cardiff and Cwm Taf Health Board areas in South Wales, UK. The MDCs were operated by the CDS, Cardiff and Vale UHB, under the Designed to Smile programme,24 which was a national oral health improvement programme.

Technologies evaluated

The two technologies evaluated in this trial (FS and FV) are well established and have been used routinely for several decades to prevent dental caries, as discussed in Chapter 1. Eligible participants were randomised to receive either FS or FV and remained on the intervention to which they were randomised for the duration of the study.

Pit and fissure sealant

The FS used was Delton® Light Curing Opaque Pit and Fissure Sealant (Dentsply Ltd, Stonehouse, UK; CE0086). This is one of the most commonly used FS brands in the UK. FS was supplied as 2.7-ml bottles for multiple applications and applied topically as a thin layer to the occlusal surface of eligible FPMs. The standard clinical protocol, as described by the product manufacturers, was used to apply the FS (Box 1). The full details of the clinical protocol for FS application are given in Appendix 8.

-

Prior to sealing, if necessary, teeth are cleaned with a toothbrush.

-

The tooth is isolated using dry guards/cotton wool rolls and saliva ejectors to aid moisture control.

-

The tooth surface is dried.

-

The etchant is applied to all the pits and fissures and a few millimetres beyond the final margin of the sealant for 30–60 seconds in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

-

The etchant material is washed from the tooth for at least 30 seconds and the tooth dried until it has a chalky, frosted appearance. Teeth that fail to etch properly are re-etched for a further 20 seconds. Great care is taken to avoid salivary contamination, as there is agreement that moisture contamination at this stage of the process is the most common cause of sealant failure.

-

The sealant material is applied to the occlusal surface and cured by shining a polymerisation light on the tooth surface for at least 20 seconds.

-

The sealant is evaluated visually and tactically and an attempt is made to dislodge it with a probe. Any deficiencies in the material are repaired to ensure an intact sealant surface.

The initial application of FS took place within 2 weeks of the baseline dental examination and was performed by a suitably qualified and trained dental hygienist. In the case of partially erupted molars, sealant was applied if sufficient tooth surface was available. This situation was most common in the case of upper molars. The same two dental hygienists provided treatments throughout the trial using two MDCs.

The condition of the FS was re-examined at 6, 12, 18, 24 and 30 months. FS was reapplied if the existing sealant had become detached or if occlusal coverage was considered insufficient as a result of either further eruption of the tooth or part of the sealant becoming lost.

All applications of FS were documented on treatment record forms, which captured the date, batch number, participant identification (ID) number and number of teeth (one to four) treated.

Fluoride varnish

The FV used for evaluation in the study was Duraphat 50 mg/ml dental suspension (PL 00049/0042), equivalent to 22,600 p.p.m. fluoride. This is the most commonly used FV brand in the UK. FV was supplied in 10-ml tubes for multiple applications and applied topically as a thin layer to the pits, fissures and smooth surfaces of eligible FPMs. As per the Duraphat summary of product characteristics (see Appendix 9), the dosage per single application did not exceed 0.4 ml. The standard clinical protocol was used to apply the FV, as described in Box 2.

-

Prior to FV application, teeth are cleaned with a toothbrush if necessary.

-

The tooth is isolated using a cotton roll in the buccal sulcus.

-

The tooth is dried using a cotton roll.

-

A thin layer of FV is applied to the pits, fissures and smooth surfaces of FPMs using a disposable microbrush.

-

The cotton roll is removed from the buccal sulcus.

-

This procedure is repeated for all FPMs included in the trial.

-

The child is advised not to eat or drink for 30 minutes and not to brush their teeth for 4 hours after application.

The initial application of FV occurred within 2 weeks of the baseline dental examination and was performed by a qualified and trained dental hygienist in accordance with the conventional clinical protocol established by the CDS (see Box 2). FV was reapplied at 6, 12, 18, 24 and 30 months, that is, on six occasions at 6-monthly intervals in the course of the trial. The full details of the clinical protocol for FV application are given in Appendix 10.

All applications of FV were documented on treatment record forms, which captured the date, batch number, participant ID number and number of teeth (one to four) treated.

Clinical assessments

Participant eligibility

The demographic and medical history information collected from the parents was reviewed to determine if the child met the inclusion/exclusion criteria prior to a clinical examination. Children considered eligible underwent a baseline clinical examination to determine their eligibility, based on the clinical inclusion/exclusion criteria detailed in Inclusion criteria and Exclusion criteria.

Clinical dental examination

Study participants were examined in the MDC while supine under a standard overhead dental clinical light, using a plane dental mirror and a ball-ended probe. The probe was used only to remove debris and to determine surface texture. It was not used to probe for cavitation. Teeth were not dried prior to clinical dental examination. Gross debris was removed using a toothbrush.

Caries assessment using International Caries Detection and Assessment System

Caries status was assessed and recorded at baseline, for all children considered eligible, by trained and calibrated dentists using conventional diagnostic caries criteria at the d1/D1–d6/D6 level in accordance with nationally recognised diagnostic criteria. 25 Data were recorded using charts specifically designed for the collection of International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) dental codes26 (see Appendix 11). An assessment of molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH) was also carried out.

Further clinical examination, including ICDAS caries assessment, was performed at 12-month intervals for 36 months. Experienced community dental officers undertook the clinical dental examinations. A total of six officers were used during the study, with one examiner involved in all years of the project.

Training and calibration

An intensive training and calibration exercise was undertaken in advance of each round of annual clinical examinations. Prior to each calibration exercise, the examiners were asked to complete the online e-learning package developed by the ICDAS team. 26 At each calibration event, the examiner team received an interactive lecture to review the ICDAS caries criteria. The calibration exercise was based on projected images of 74 extracted primary teeth. The gold standard was determined by Professor Chris Deery (a trained and calibrated ICDAS examiner), who provided the images. At each calibration exercise, the images were projected under standardised conditions and compared with the gold standard examiner. The caries code (the second digit of the ICDAS code) was recoded as 0, ‘free of caries into dentine’ (caries code 0–3), and 4, ‘caries at ICDAS level 4 or higher‘, that is, ‘caries into dentine’ (caries code 4–6). Calibration was based on these categorisations at the ‘caries into dentine’ level.

As part of the annual caries assessment, approximately 5% of study participants were re-examined to determine intra-examiner reproducibility. The details of the analysis of ICDAS caries data are provided in Statistical methods.

Nomenclature for recording dental caries in the Seal or Varnish? trial

In the SoV trial dental caries was recorded using ICDAS. 26 As there is potential for confusion between the different codes and thresholds used to describe dental caries when using ICDAS and previous caries indices/scoring systems, Table 1 describes the terms used to define thresholds and levels of dental caries experience.

| Terms used in this study (designation) | ICDAS caries codes | Traditional caries scores, (e.g. BASCD, WHO) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caries free | 00 | Sound | Describes the condition as free of either enamel or dentine caries |

| Free of caries into dentine | 00, 01, 02 and 03 | Sound, D1 and D2 | This is the status traditionally regarded as ‘caries-free’. This is the principal diagnostic level used for both primary and secondary outcomes in the study |

| Enamel caries (d1–3/D1–3) | 01, 02 and 03 | D1 and D2 | Caries lesions limited to enamel |

| Dentine caries (d4–6/D4–6) | 04, 05 and 06 | D3, both cavitated and non-cavitated | Caries lesions involving dentine, also referred to as obvious dental decay |

In this study, dental caries status is described using the following principal terms: caries free, free of caries into dentine, enamel caries and dentine caries.

Treatment acceptability assessment

Treatment acceptability was assessed in three ways. A modified version of the Delighted–Terrible Faces (DTF) scale27,28 was used with children to determine participant acceptability (see Appendix 12). During the clinical placement of the technologies under investigation, the treating dental hygienist and dental nurse recorded the following indicators of participant acceptability and adverse outcomes: vomiting, crying, gagging, excessive arm/leg movements and other signs of distress. 29 As part of the process evaluation, children and their parents from each trial arm were interviewed in order to compare their experiences of FS and FV treatment (see Chapter 5).

Caries risk-related habits

For children deemed eligible to participate in the trial, information relating to the caries risk-related habits was obtained via a dental health questionnaire (DHQ) (see Appendix 13) sent to parents at baseline and at 12, 24 and 36 months post treatment.

The questionnaire asked about tooth brushing frequency, if the child brushed on their own or with parental assistance, the type of toothpaste used and the quantity of toothpaste dispensed to the toothbrush. An enquiry was also made as to the age at which tooth brushing started. The use of mouthwash, fluoride drops and fluoride tablets was determined, as was any previous application of FV by the child’s own dentist. Attendance at a dentist outside the Designed to Smile programme was ascertained, as was the frequency of dental attendance. Parents were asked about lifetime residency in South Wales. The annual questionnaire also collected data on dietary habits, with an emphasis on the frequency of the consumption of sugar-rich food and drinks. The remaining questions enquired about the use of dental services, which informed the economic analysis of the trial.

Dental care during the trial

Parents were asked for details of their child’s dentist. The principal investigator wrote to the dentist and informed them that the child was participating in the SoV trial. Dentists were asked to refrain from providing FS or FV treatment for the duration of the study. For children who were patients of the CDS, a flag was placed on their dental record to indicate that they were participants in the SoV study and therefore should not receive FS or FV treatments.

Children and their parents continued with their usual oral hygiene regime, details of which were gathered via the annual questionnaire detailed in Caries risk-related habits.

Data collection regime

The data collection regime is shown in Table 2.

| Data type | Prior to baseline evaluation | Baseline evaluation | Randomisation and initial FS/FV application | Follow-up period (months) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 | 36 | ||||

| Clinical data | |||||||||

| Medical/dental history/demographics | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Eligibility (inclusion/exclusion criteria) | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Caries risk-related habits | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| ICDAS caries assessment | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Pre-treatment assessmenta | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Adverse event assessment | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Health economics data | |||||||||

| NHS resource usage interviews | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Parental Resource Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| School Resource Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Health-related quality of life (CHU-9D) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Treatment acceptability and process evaluation data | |||||||||

| Observational scaleb | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| DTF scale | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Interviews with children | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Interviews with parents | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Questionnaires/interviews with schools | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Interviews with dental teamc | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Interviews with non-consenting parents | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Interviews with non-responding parent | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Interviews with withdrawing parents | d | d | d | d | d | d | d | ||

Trial outcomes

Outcome measures for dental caries

The primary outcome measure was the development of dental caries on FPMs at 36 months. This was recorded as:

-

the proportion of children developing new caries in dentine on any one of up to four treated FPMs at 36 months

-

the number of treated FPM teeth that were free of caries into dentine at 36 months.

Outcome measures for health economic analysis

Indicators of clinical effectiveness were used alongside costs to estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of FS and FV.

Two additional outcome measures were used for the cost-effectiveness analysis. These were used to estimate incremental costs per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) estimates.

Health-related quality of life: Child Health Utility Index 9D

A generic preference-based measure of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), the Child Health Utility Index 9D (CHU-9D),30 was used to determine HRQoL. Designed specifically for use with children, the CHU-9D consists of a set of nine questions (dimensions), with five levels of responses available per question. It has a recall period of today/last night and is intended to be self-completed by the child (see Appendix 14).

Quality-adjusted tooth-years

Utility values were measured as quality-adjusted tooth-years (QATYs),31,32 which is the production of additional years of life (tooth-year) of each tooth adjusted for the quality of the tooth. An unrestored tooth has a QATY equal to 1 in the year it was restoration free, and a restored, crowned or root canal-treated tooth has a QATY of less than perfect (i.e. < 1) in the year that it was restored and in subsequent years. The QATY for an extracted tooth is equal to 0 in that year and in subsequent years. Data to inform the calculation of QATYs were derived from the clinical data collected.

Sample size

Data from a previous cohort study among primary school children under the care of the Cardiff and Vale UHB CDS were used to derive the caries incidence in children (mean age 6.5 years) with at least one erupted FPM. 33 Overall, 40% of children had caries in one or more of their FPMs by the age of 10 years. Based on recent Cochrane reviews, it is estimated that FV would reduce the 3-year incidence from 40% to 30% in this population,15 whereas FS would reduce it further to 20%. 12 For an individually randomised trial at a power of 80% with a significance level of 5%, at least 313 children per group were required for a comparison of caries incidence of 20% versus 30% at 36-month follow-up.

Randomisation

The randomisation of participants was stratified by school and balanced for sex and primary dentition baseline caries levels using minimisation in a 1 : 1 ratio for treatments. A random component was added to the minimisation algorithm,34 such that it was not completely deterministic. The algorithm that allocated children to the study arm minimised imbalance with respect to sex and baseline caries levels, with a probability of 0.8 reducing the predictability of allocation. 35

Sequence generation

Randomisation was carried out in the South East Wales Trials Unit (SEWTU) using lists of pupil sex and caries chart data collected by the CDS from each school they visited for the screening examination. Eligible children were randomised using the minimisation algorithm. Allocation lists were produced and provided to the CDS, with a 2-week window before the CDS returned to the school for the baseline treatments.

Allocation concealment mechanism

All randomisation and allocation lists were produced by SEWTU independently of the recruiting and examining personnel in the CDS.

Implementation

The CDS carried out an initial screening examination at all schools. Data from these visits were provided to SEWTU and used to produce the allocation lists for the CDS. Allocations were provided to the CDS prior to each return school visit, ready for the children’s baseline treatment.

Blinding

The physical nature of the technologies under test limited the scope for blinding. Both the participant and the dental hygienist were aware of the treatment provided. The dentist undertaking the clinical dental examinations at baseline and at 12, 24 and 36 months was not informed of the arm to which the participant had been randomised. However, the presence or absence of FS at assessment would obviously indicate the likely treatment received.

Statistical methods

All comparative analyses were carried out on an intention-to-treat basis (without imputation). The primary outcome (D4–6MFT) was analysed using a logistic regression model to compare arms. The results for binary outcomes are presented as unadjusted and adjusted ORs for the FV arm compared with the FS arm (the reference arm). All models were adjusted for the randomisation balancing variables, sex and baseline caries, in the primary dentition. Baseline caries (decayed, missing, filled teeth in primary dentition, i.e. D4–6MFT) was categorised as none, one or two, or three or more. The number of FPMs per child in the trial was also added to the models as a covariate but removed if non-significant. As the intervention was carried out within schools, a two-level logistic model was used to determine if there was any significant clustering by school. If clustering was found to be negligible, the primary analysis outcome was taken to be the single-level model. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) are given in tables or text for all two- and three-level models. For subgroup analyses, the appropriate addition of main effects and interaction terms was made to the primary model, as was the addition of any covariate effects.

For categorical outcomes with multiple categories, ordinal regression was fitted. The test of parallel lines was conducted to check that the assumption of proportional odds was satisfied. Count data were analysed using Poisson and negative binomial regression models. When the data were found to be overdispersed (greater variance than might be expected in a Poisson distribution), the negative binomial regression model was taken as the better-fitting model. When an inflation of zeros in the data was found, zero-inflated Poisson regression and zero-inflated negative binomial regression models were employed. The Akaike information criterion was used to determine the best-fitting model. The results were presented as adjusted incidence rate ratios in the FV arm compared with the FS arm.

For continuous outcomes, a linear regression model was fitted after transformation to normality, if required. When a natural log transformation was employed, the results were interpreted as percentage difference between the arms. When baseline measurements were taken into consideration, an analysis of covariance was used, with baseline measurement as a covariate. This model extends the usual logistic regression model to include correlated interim outcome data. It allows the main treatment effects to be adjusted for changes over time and for differences between time points to be examined. Differential changes over time in caries outcome between trial arms can be examined through the inclusion of a treatment × time interaction term.

When data were collected over several time points, a repeated measures model (using a generalised logistic mixed model) was used with time points (12, 24 and 36 months). For tooth- and surface-level binary outcomes, two- and three-level logistic models were used when appropriate. An interaction term was used in the three-level models to investigate any differential effect of treatment on occlusal versus non-occlusal surfaces. For all primary and secondary outcomes, 95% CIs and p-values are presented.

Primary outcome calculation

The primary outcome was the proportion of children experiencing caries into dentine at ICDAS level 4–6 on any one of up to four FPMs in the trial at 36 months. The D4–6MFT variable was calculated (and converted to a binary outcome) from the full caries charts of those children attending the 36-month examination and included only those FPMs in the trial. FPMs that were already sealed, carious into dentine, filled or affected by post-eruptive breakdown (PEB) at baseline were excluded from the trial.

Secondary outcomes calculation

Secondary caries models at child, tooth and surface levels were as follows:

-

the number of FPMs remaining free of caries into dentine per child for those FPMs included in the trial (child-level ordinal analysis)

-

the caries status of the FPMs (treated or untreated caries code 4, 5 or 6) included in the trial (tooth-level binary analysis)

-

the number of surfaces on each FPM remaining dentine caries free per tooth within child for those FPMs included in the trial (tooth-level ordinal analysis)

-

the caries status of treated or untreated caries on each surface of each FPM, caries code 4, 5 or 6 (surface-level binary analysis)

-

the binary outcome of caries occurrence on occlusal versus non-occlusal surfaces of each FPM (surface-level binary analysis with an interaction term for surface type × arm).

The primary analysis was undertaken using 12- and 24-month follow-up time points (child-level binary analyses). In addition, an investigation of the treatment differences on the earlier stages of caries development (enamel caries) was carried out using level 1, 2 and 3 of the ICDAS classification of caries at 36 months (child-level binary analysis). One additional post hoc analysis was carried out as a surface-level analysis of the binary outcome of all caries (ICDAS 1–6) with an interaction term for surface type to investigate occlusal versus non-occlusal surface interaction with treatment.

Treatment time

The treatment times at each time point were examined and found to be non-normally distributed. A natural log-transformation of the treatment time data was performed and a linear regression analysis was used to compare arms. Treatment effects are, therefore, interpreted as percentage difference between arms. The regression model was adjusted for the randomisation balancing variables sex and baseline caries.

Sealant retention

The sealant status at each treatment visit and the retention at each clinical examination were tabulated.

Molar incisor hypomineralisation

The presence and severity of MIH in the FPMs was tabulated at each dental examination, and the prevalence was reported by treatment arm. Severe MIH presenting with PEB at baseline excluded a FPM from the study.

Secondary analysis of primary outcomes

Additional important covariates were collected via the DHQ. The variables relating to tooth brushing frequency, toothpaste, mouthwash, fluoride tablets and fluoride drops were utilised in the primary model if there were ≥ 10 percentage points of difference between the binary categories. The variables relating to tooth brushing, amount of toothpaste and FV/gel applied were utilised in the primary model if there were ≥ 20 percentage points of difference between the binary categories. The following categorisations were used for covariates added to the primary analysis:

-

frequency of tooth brushing – ‘twice or more a day’ versus ‘once or less a day’

-

toothpaste type – ‘family toothpaste’ versus ‘children’s toothpaste or other’

-

amount of toothpaste – ‘smear, pea or never’ versus ‘cover bristles’

-

additional fluoride intake – ‘any mouthwash, drops or tablets or gel’ versus ‘none’.

Global oral hygiene regimen

A combined global rating scale of fluoride use and tooth brushing regimen was created as a summed score of the binary categories for tooth brushing frequency (twice a day); who carries out tooth brushing (adult or observed); toothpaste type (family toothpaste); amount of toothpaste (cover bristles); and additional fluoride (any yes response). This resulted in a score of 0–6, which was collapsed into four categories (0–1.49, 1.5–2.49, 2.5–3.49 and 3.5–6).

Length of time tooth brushing

The age of a child in months at baseline minus the age at which they started tooth brushing (in months) was converted to years (divided by 12). The distribution for length of time spent tooth brushing had slight negative skew but was entered into a linear regression untransformed.

Cariogenic score

The cariogenic score was calculated by summating the seven cariogenic items (scored 0–5) asked as part of the diet question in the DHQ (these items were c, d, e, g, h, k and m). At least four of these items had to be completed for a score to be calculated; if three or fewer of these items were ticked, the sugar intake score was set to missing. Following summation, the score was divided by (five times the number of completed items) and then multiplied by 100.

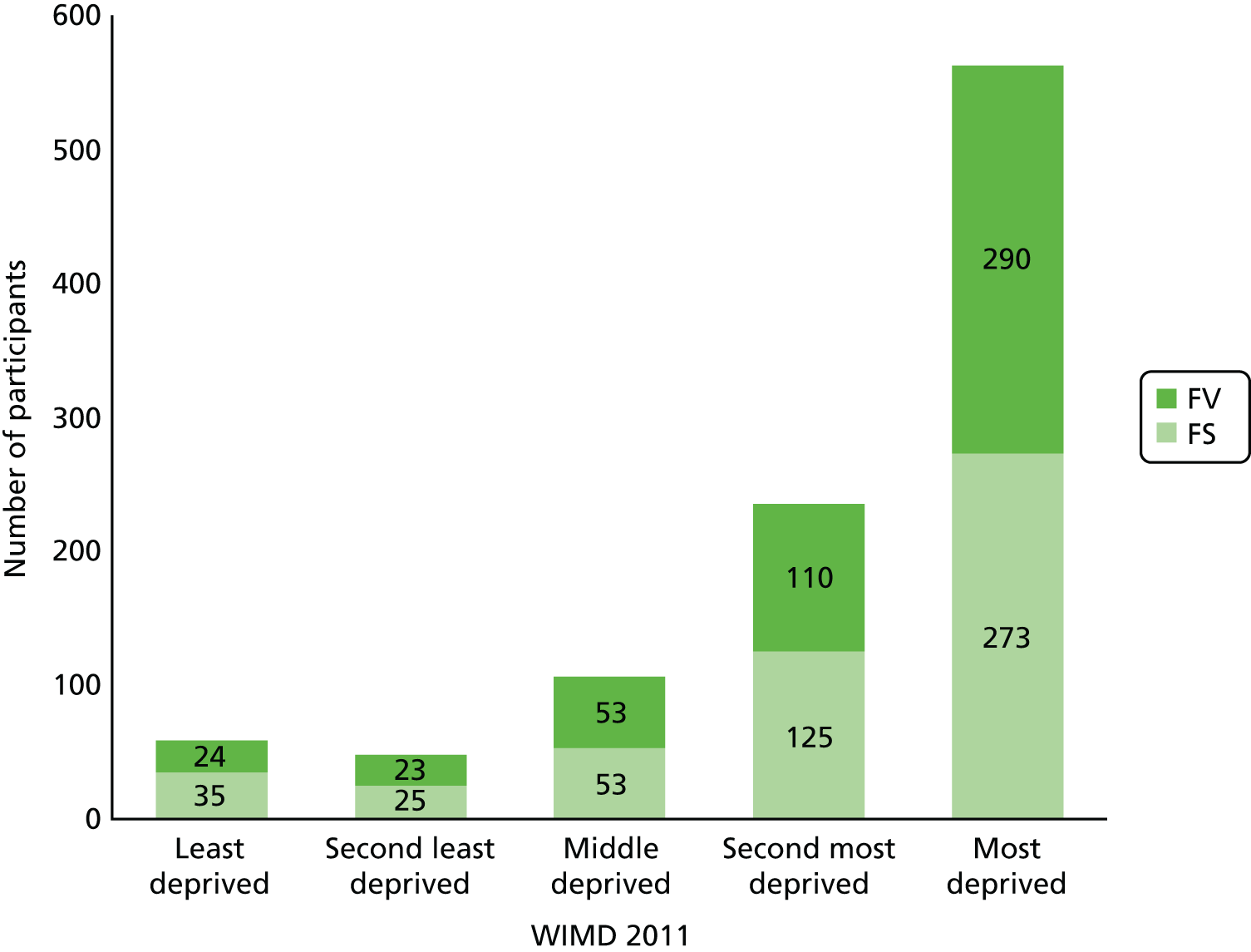

School and child deprivation

From the parental questionnaire, the child’s postcode was used to calculate the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) 2011. 36 The WIMD is categorised as quintiles and these were compared with the population of Wales as a whole. For analyses, the WIMD was trichotomised into categories 1–3, 4 or 5. The school postcode was coded in the same way and categorised as quintile for school-level analyses. School size was also tested in these two-level regression models.

Socioeconomic group

Parental occupation had five categories: ‘higher managerial, administrative and professional occupations’, ‘intermediate occupations’, ‘routine and manual occupations’, ‘unemployed’ and ‘homemaker, carer, student or grandparent’. These categories were based on those described by the Office for National Statistics. 37

Sensitivity analyses specific to primary outcomes

-

Adjustment of the primary analysis for all treatments within the specified time window, 4 weeks either side of the scheduled treatment due date.

-

The efficacy of the number of FV treatments on the primary outcome was estimated in a way that preserves randomisation using complier average causal effect (CACE) modelling. As-treated or per-protocol analyses have been widely used as secondary analyses if the effect of treatments when actually received is of interest. However, these secondary analysis methods may yield seriously biased estimates of treatment effects. Given the questionable validity of these analyses, statistical methods such as CACE estimation have been developed to better estimate treatment efficacy, taking into account non-compliance. The efficacy of the number of treatments on the primary outcome is estimated in a way that preserves randomisation. The structural mean model (SMM) approach for CACE was implemented here by fitting an instrumental variables regression. Applications of SMMs were developed to adjust for adherence in trials with active treatments and an untreated control arm. Although SoV has two active treatments, we have assumed, for the purposes of the CACE analysis, that the sealant is a one-off standard treatment comparable with a control arm, and so treatment visits were set to a constant zero. SoV also has a binary outcome, whereas CACE is more usually applied to linear outcomes. Hence, the standard instrumental variables regression in Stata® (version 13, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was applied with the addition of robust standard errors. Adherence in the FV arm was defined as the number of FV treatment visits that a child attended (the instrumental variable) and the outputted estimate is interpreted as the efficacy per visit. A small, non-significant efficacy estimate indicates little effect of additional treatment visits and negligible adherence effects in the trial. Future work beyond the scope of this report will take these methods further and adjust for compliance, as well as for predictors of compliance in both arms.

-

The SMM approach was implemented by fitting an instrumental variables regression. 38 Adherence was defined as the number of FV treatment visits that a child attended.

Subgroup analyses specific to primary outcome

Appropriate interaction terms were entered into the primary regression analysis in order to conduct prespecified subgroup analyses: cohort, baseline caries group. The trial was not powered to detect significant interactions and, as such, these analyses are exploratory only. ORs and 95% CIs were reported.

Imputation

Imputation was to be considered after an examination of the number of missing primary outcome data and the likely mechanism for missing data. If the primary outcome was deemed to be missing completely at random and the proportion of data missing for reasons other than moving out of the SoV area was less than 10%, then imputation would not be performed and a compete case analysis would be carried out to estimate an unbiased treatment effect. If differential dropout was observed between arms, this would indicate a missing at random or missing not at random mechanism. Mixed modelling is appropriate if the data are missing at random, whereas multiple imputation and associated sensitivity analyses may be more appropriate if the missing data were determined to be missing not at random.

Reliability

Calibration of the dental examiners was carried out each year of the study, and kappa scores were calculated for reliability. At each clinical examination, a 5% sample was re-examined and caries charts were completed a second time.

Statistical software employed

All analyses were carried out in IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), except the zero-inflated Poisson regression, zero-inflated negative binomial regression and ivregress (CACE) models, which were carried out in Stata.

Assessment of adverse effects

During the course of the study, the occurrence of any serious adverse events or serious adverse reactions was ascertained and recorded using the study serious adverse events form (see Appendix 15).

As per the Design to Smile programme, the clinical staff involved in the delivery of the intervention monitored participants during and immediately following the administration of FS or FV, and were available to manage any adverse events or serious adverse reactions in accordance with current clinical practice.

Parents were asked to tell the CDS team if their child experienced any dental or medical problems during the 48 hours after each treatment.

Design of study materials and strategy for maximising questionnaire follow-up rates

Participant information sheet

As described in section 4.8 of the ICH Guideline for Good Clinical Practice,23 in order that research participants (or their legal guardians) are able to make an informed decision on whether or not to take part in a clinical trial, all relevant information must be provided to the participants in such a way that it is as non-technical and understandable as possible.

With this in mind, it was essential that all participant materials (including the PIS) were developed taking into consideration the diverse literacy levels of the target population (i.e. parents of children in Communities First areas).

To achieve this, the PIS was developed in consultation with a parents’ group in Newport. This group is in a Communities First area of South Wales but one that is not served by the Cardiff and Vale CDS; therefore, it was not within the catchment area of the trial.

After the initial draft by the SoV project team, the PIS and consent form were reviewed by the parents’ group, and the following points that they made were taken into account for subsequent revisions.

-

All of the parents agreed that the overall amount of information/text presented was too extensive and would be very likely to discourage them from thoroughly reading the information sheet (if they read it at all). Furthermore, they felt that the tone of the wording needed to be made more ‘positive’. Once the parents had had time to digest the information and understand the study, they agreed that it was a ‘positive’ thing and would want their children to participant if a similar study was run in their area.

-

Parents felt that having separate information sheets for parents and children was unnecessary, and that it would be easier for parents to be given one simplified information sheet, which they could use to discuss the study with their child. Parents felt that the wording used in the information sheet for children was much more accessible and that the one simplified information sheet should contain wording more similar to this.

-

Parents showed a strong aversion to the word ‘research’ being used (the image of children being used as ‘guinea pigs’ was expressed by several parents). They felt that ‘evaluation’ or ‘assessment’ conveyed the same concept in a more acceptable and understandable way.

-

The use of cartoons/graphics/photographs was encouraged.

-

Parents felt that the duplication of wording in the information sheet and the consent form was unnecessary, and that cross-referencing should be used to help the parents understand better which items on the consent form referred to which parts of the PIS.

Despite considering the recommendations of the parents’ group, we were mindful of the guidance provided in section 4.8.10 of ICH topic E 6 (Guideline for Good Clinical Practice23), and tried to convey to those in the group that a minimum level of information was required when developing an information sheet for a clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product (CTIMP). The revised PIS was therefore intended to represent a risk-based approach to the information provided to parents for a CTIMP.

In addition to ensuring that the content of the PIS was suitable, the visual appeal of the document was further developed by a graphic designer, incorporating the child-friendly logos and colour schemes of the CDS.

Follow-up questionnaires: development and return rate

Information relating to caries risk-related habits and parental resource utilisation was obtained from parents via a single combined DHQ (see Appendix 13) at baseline and at 12, 24 and 36 months. This was accompanied (at the 12-, 24- and 36-month time points only) by the CHU-9D (see Appendix 14), both of which were distributed to participants’ homes at the required time points.

The initial return rates of these questionnaires were lower than expected. The initial follow-up strategy allowed for one follow-up telephone call 2 weeks after the questionnaires were handed out. However, unanswered calls and inactive numbers made this strategy ineffective.

Initially, a £5 shopping voucher was included with the questionnaires in an effort to boost return rates, but responses remained poor, with an overall return rate of 53%. A consultation exercise followed with parents of children at a primary school in a Communities First area not involved in the trial. Between this consultation and ideas developed by the trial management group, the following changes to the strategy for follow-up of questionnaires were made.

-

The questionnaire pack was to be given to the child at treatment/examination.

-

A trial-branded giveaway (pen, eraser or fridge magnet) was included.

-

A text message reminder was sent if the questionnaire was not returned 1 week after distribution.

-

A second copy of the questionnaire was sent to participants’ homes if the original was not received 2 weeks after distribution.

-

A telephone call was made directly to parents to remind them/aid with questionnaire completion (DHQ only) and return.

-

Participants were informed that all returned questionnaires gained entry to a prize draw for an iPad® (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) at each time point.

-

The questionnaires were reformatted to increase their visual appeal, and were designed to be consistent with the PIS and ICF, using the colours and graphics of the Designed to Smile programme.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) in the SoV trial has been utilised in two main ways. The first has been described in previous sections regarding the development of the study materials with the help of members of a parents’ group in Newport. This PPI input was pivotal in producing user-friendly materials, contributing to the successful recruitment to target. Without this detailed input, we would not have been able to justify the carefully judged brevity and clarity of the PIS to the REC.

The second major use of PPI was in the redesign of participant-facing materials, as described in Design of study materials and strategy for maximising questionnaire follow-up rates. This helped to boost the return rate of follow-up questionnaires, thereby increasing our overall data collection.

Patient and public involvement was maintained throughout the trial via lay member representation on the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). Our TSC lay member is a member of the Involving People network, a Welsh Government-funded organisation that promotes PPI in research across Wales. The contribution of this member to TSC meetings was invaluable, bringing a lay perspective to deliberations.

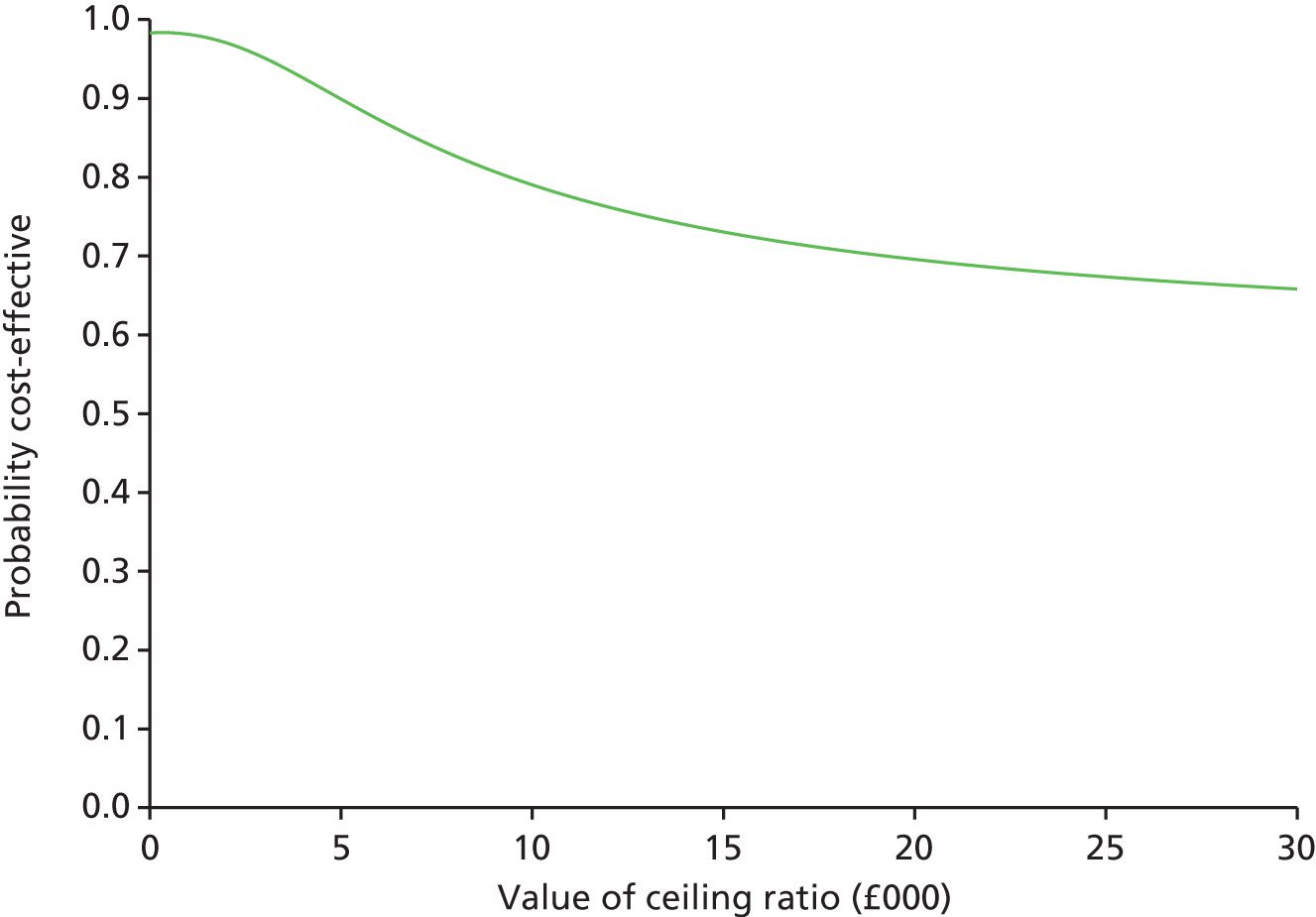

Health economic assessment

A health economic evaluation was conducted alongside the trial. The evaluation set out to:

-

estimate the costs of providing FS versus FV and the outcomes for the NHS, children and their families and education in order to consider a partial societal perspective

-

establish the relative cost-effectiveness of FS versus FV

-

calculate the budget impact on the NHS of FS and FV delivered in a community/school setting.

The costs associated with the interventions for each trial participant were collected and summarised into the following categories:

-

Implementation costs of the interventions.

-

Health-care utilisation costs associated with travel or caregiving/time of work for families.

-

Costs associated with the schools, for example as a result of child absence. Published unit costs were used or, when unavailable, local financial records were used to value resources in monetary terms using 2015 as the price year.

A series of within-trial incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated (based on a NHS perspective) to estimate the cost per:

-

caries increment avoided

-

QALY, using the CHU-9D to derive health utilities

-

QATY as an exploratory analysis.

Post-trial modelling was conducted to estimate the longer-term cost-effectiveness of the interventions. One-way sensitivity analysis was undertaken to assess the impact on changes to individual parameters on the base-case results with probabilistic sensitivity analysis undertaken to estimate the joint uncertainty around parameters. A budget impact analysis was undertaken to estimate the impact on NHS budgets in delivering the interventions. A detailed report on the health economic methods is provided in Chapter 4.

Treatment acceptability assessment and process evaluation

Treatment acceptability was assessed in three ways:

-

acceptability scales were completed by clinical staff

-

acceptability scales were also completed by the children participating in the trial

-

qualitative interviews were conducted with a subsample of children.

The treatment acceptability scales and the qualitative interviews are described in Chapter 5.

Chapter 3 Clinical results

This chapter describes the clinical findings of the trial.

Introduction

The chapter begins with a description of the number of children randomised to the trial, and a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram39 describes participant flow through the trial. The baseline characteristics of the participants are described in relation to trial arm and to those starting, completing and failing to complete the trial. Next, potential confounding factors such as fluoride exposure, diet and dental attendance are reported. Participation and retention data are also described.

The main clinical results of the study in relation to the primary outcome measure, the proportion of children developing caries into dentine on any treated FPM, are reported. The impact of baseline caries experience, school attended, deprivation status and trial cohort is examined, before the impact of oral hygiene habits, diet and dental attendance is analysed.

The second main trial outcome, the number of teeth developing dentine caries (D4–6MFT) at 36 months, is reported next at both tooth and tooth-surface level. Fidelity is then described using CACE analysis. Compliance with treatment windows is also reported.

The effect of including enamel caries (D1–6MFT) in the analysis is then described. This is followed by examining the impact of the FS and FV treatments on all permanent teeth, not only FPMs. Trial outcomes at 12 and 24 months are reported to illustrate the shorter-term impact of the trial interventions. Finally, the following data are presented: sealant retention, examiner reproducibility, adverse effects and treatment time.

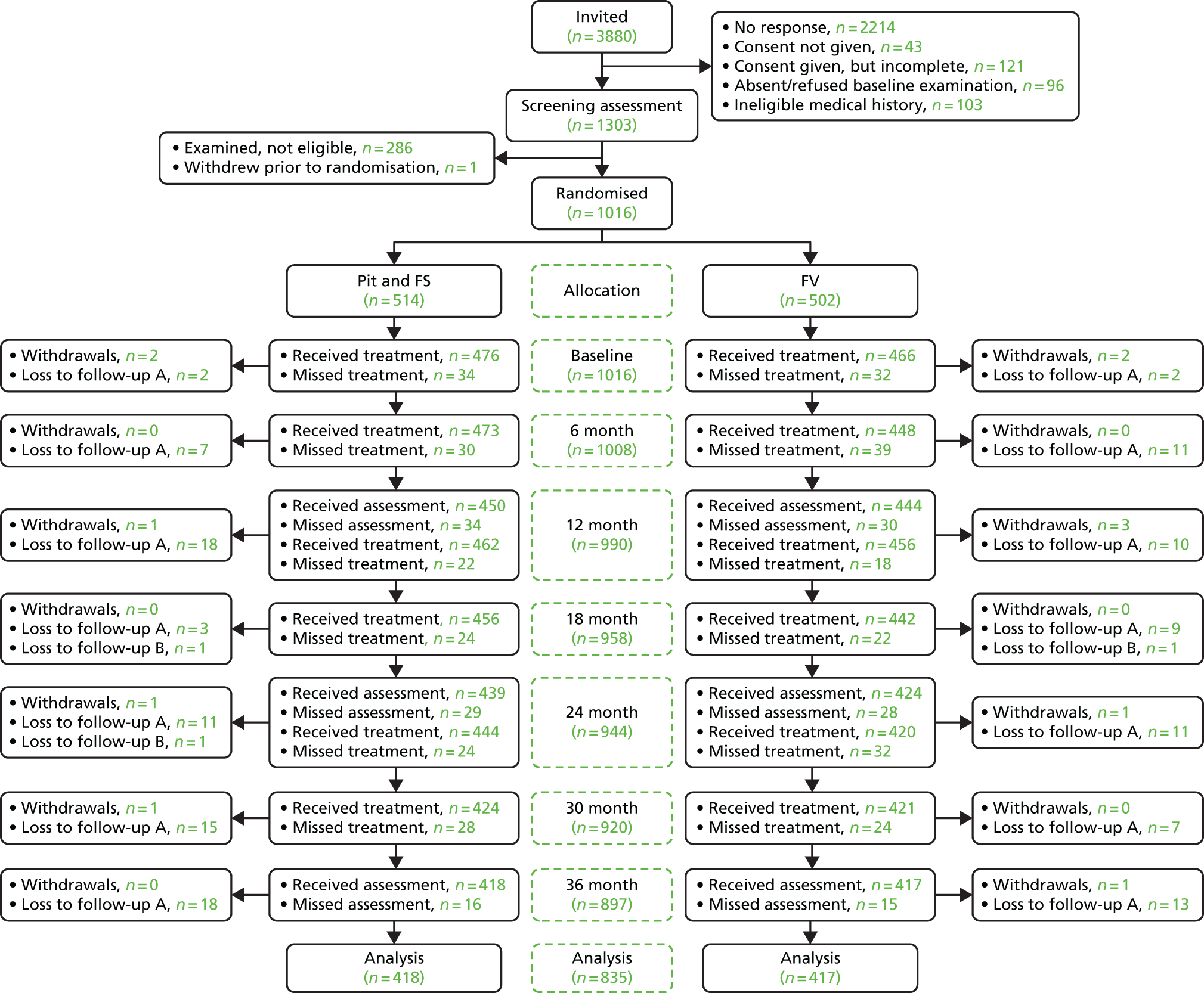

Participant screening for participation in the trial

In total, 1303 children for whom parental consent had been obtained were screened for participation in the trial (Figure 2). Of these, 1016 were deemed eligible for inclusion, but one participant subsequently withdrew consent for participation and for the use of any of their data. At screening, 287 children were excluded. The participants were recruited in two cohorts between October and January in the school years 2011/12 and 2012/13.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT diagram of participant flow through the trial. One participant from the FV arm subsequently withdrew consent to use all data. Loss to follow-up A, moved to a non-participating school; loss to follow-up B, change in medical circumstances prevented further participation in the trial.

Participant randomisation

Participants were randomised to receive FS (514 children) or FV (501 children), as described in Chapter 2.

Characteristics of included participants at baseline

The characteristics of the study participants who were randomised at baseline are shown in Table 3. There were no apparent differences between trial arms in sex or in the proportion of children with caries experience in their primary dentition. The high prevalence of dental caries experienced in the primary dentition at baseline (54.1%) reflects the fact that the programme was specifically targeted at schools in areas of high social and economic deprivation. As shown in Figure 3, 78.6% of children randomised lived in the bottom two quintiles of deprivation in Wales. Within quintiles of deprivation, the distribution of children across trial arms was broadly similar.

| Characteristic | Intervention arm | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FS, n (%) | FV, n (%) | ||

| Children randomised | 514 (50.6) | 501 (49.4) | 1015 (100) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 237 (46.1) | 235 (46.9) | 472 (46.5) |

| Female | 277 (53.9) | 266 (53.1) | 543 (53.5) |

| Children with dentine caries in the primary dentition (d4–6) | 286 (55.6) | 266 (53.1) | 552 (54.1) |

| Children with dentine caries in the primary dentition (d4–6mft) | 342 (66.5) | 339 (67.7) | 681 (67.1) |

| Children with untreated dentine caries in any FPM (D4–6) | 22 (4.3) | 23 (4.6) | 45 (4.4) |

| Children with dentine caries in any FPM (D4–6MFT) | 27 (5.3) | 31 (6.2) | 58 (5.7) |

| d4–6mft, mean (SD) | 3.2 (3.4) | 3.2 (3.3) | 3.2 (3.3) |

| d1–6mft, mean (SD) | 4.6 (3.8) | 4.6 (3.7) | 4.6 (3.7) |

| d4–6mfs, mean (SD) | 8.9 (12.3) | 9.6 (12.4) | 9.3 (12.3) |

| d1–6mfs, mean (SD) | 11.0 (12.9) | 11.6 (12.9) | 11.3 (12.9) |

FIGURE 3.

Social and economic profile of trial participants at baseline by trial arm and by quintile of WIMD (2011).

The characteristics at baseline of the 835 children who completed the trial and of the 180 children who either were lost to follow-up or withdrew are shown in Tables 4 and 5. There were no marked differences in the baseline characteristics of either of these groups in relation to dental caries experience at baseline.

| Characteristic | Intervention arm | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FS, n (%) | FV, n (%) | ||

| Children completing the trial | 418 (50.1) | 417 (49.9) | 835 (100) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 193 (46.2) | 196 (47.0) | 389 (46.6) |

| Female | 225 (53.8) | 221 (53.0) | 446 (53.4) |

| Children with dentine caries in the primary dentition (d4–6) | 228 (54.5) | 219 (52.5) | 447 (53.5) |

| Children with dentine caries in the primary dentition (d4–6mft) | 271 (64.8) | 280 (67.1) | 551 (66.0) |

| Children with untreated dentine caries in any FPM (D4–6) | 16 (3.8) | 17 (4.1) | 33 (4.0) |

| Children with dentine caries in any FPM (D4–6MFT) | 18 (4.3) | 24 (5.8) | 42 (5.0) |

| d4–6mft, mean (SD) | 3.1 (3.4) | 3.2 (3.3) | 3.2 (3.4) |

| d1–6mft, mean (SD) | 4.5 (3.7) | 4.6 (3.7) | 4.5 (3.7) |

| d4–6mfs, mean (SD) | 8.8 (12.4) | 9.7 (12.7) | 9.3 (12.5) |

| d1–6mfs, mean (SD) | 10.9 (12.9) | 11.7 (13.2) | 11.3 (13.1) |

| Characteristic | Intervention arm | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FS, n (%) | FV, n (%) | ||

| Children randomised | 96 (53.3) | 84 (46.7) | 180 (100) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 44 (45.8) | 39 (46.4) | 83 (46.1) |

| Female | 52 (54.2) | 45 (53.6) | 97 (53.9) |

| Children with dentine caries in the primary dentition (d4–6) | 58 (60.4) | 47 (56.0) | 105 (58.3) |

| Children with dentine caries in the primary dentition (d4–6mft) | 71 (74.0) | 59 (70.2) | 130 (72.2) |

| Children with untreated dentine caries in any FPM (D4–6) | 6 (6.2) | 6 (7.1) | 12 (6.7) |

| Children with dentine caries in any FPM (D4–6MFT) | 9 (9.4) | 7 (8.3) | 16 (8.9) |

| d4–6mft, mean (SD) | 3.4 (3.3) | 3.3 (3.1) | 3.4 (3.2) |

| d1–6mft, mean (SD) | 4.8 (3.9) | 4.7 (3.4) | 4.8 (3.6) |

| d4–6mfs, mean (SD) | 9.5 (11.8) | 9.2 (11.2) | 9.4 (11.5) |

| d1–6mfs, mean (SD) | 11.7 (12.9) | 11.3 (11.5) | 11.5 (12.3) |

Characteristics of first permanent molars in children randomised to the trial

The status of the FPMs by quadrant is shown in Table 6. From this, it is apparent that the prevalence of decay into dentine was very low at baseline, the D4–6MFT ranging from 1.2% of upper-right permanent first molars to 2.9% of lower-right FPMs. A greater proportion of upper FPMs (9.2–9.4%) were unerupted than lower FPMs (4.7–5.9%). The percentage of erupted (or partially erupted) FPMs that were free of caries into dentine was recorded as 89.7% in the upper-right quadrant and 93.5% in the lower-right quadrant.

| Status | FPM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UR (N = 1015), n (%) | UL (N = 1015), n (%) | LR (N = 1015), n (%) | LL (N = 1015), n (%) | |

| Unerupted | 93 (9.2) | 95 (9.4) | 60 (5.9) | 48 (4.7) |

| D1–3T | 114 (11.2) | 120 (11.8) | 109 (10.7) | 107 (10.5) |

| D4–6T | 11 (1.1) | 10 (1.0) | 24 (2.4) | 12 (1.2) |

| MT | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| FT | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) |

| D1–3MFT | 115 (11.3) | 125 (12.4) | 114 (11.2) | 112 (11.0) |

| D4–6MFT | 12 (1.2) | 15 (1.5) | 29 (2.9) | 17 (1.7) |

| D1–3S | 115 (11.3) | 123 (12.1) | 114 (11.2) | 111 (10.9) |

| D4–6S | 11 (1.1) | 10 (1.0) | 24 (2.4) | 12 (1.2) |

| MS | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| FS | 1 (0.1) | 6 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) |

| D1–3MFS | 116 (11.4) | 128 (12.6) | 118 (11.6) | 116 (11.4) |

| D4–6MFS | 12 (1.2) | 15 (1.5) | 29 (2.9) | 17 (1.7) |

| Free of caries (D1–6MFT = 0) | 796 (78.4) | 785 (77.3) | 817 (80.5) | 843 (83.1) |

| Free of caries into dentine (D4–6MFT = 0) | 910 (89.7) | 905 (89.2) | 926 (91.3) | 950 (93.5) |

With 1015 children randomised to participate in the trial and assessed at baseline, the overall number of FPMs was 4060. In total, 161 (4%) of these were excluded at baseline because of the presence of FS (71 teeth), caries into dentine (56 teeth), filled teeth (17 teeth) and teeth with PEB (17 teeth) (Table 7).

| FPM | Total (N = 4060) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UR (N = 1015) | UL (N = 1015) | LR (N = 1015) | LL (N = 1015) | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Teeth included | 978 | 96.4 | 983 | 96.8 | 962 | 94.8 | 976 | 96.2 | 3899 | 96.0 |

| Teeth excluded | 37 | 3.6 | 32 | 32.2 | 53 | 5.2 | 39 | 3.8 | 161 | 4.0 |

| Reason for exclusion (n, % excluded) | ||||||||||

| Sealed | 20 | 54.1 | 14 | 43.8 | 20 | 37.7 | 17 | 43.6 | 71 | 44.1 |

| Filled | 1 | 2.7 | 6 | 18.8 | 5 | 9.4 | 5 | 12.8 | 17 | 10.5 |

| Caries at into dentine (D4–6) | 11 | 29.7 | 9 | 28.1 | 24 | 45.3 | 12 | 30.8 | 56 | 34.9 |

| PEBa | 5 | 13.5 | 3 | 9.4 | 4 | 7.5 | 5 | 12.8 | 17 | 10.5 |

Baseline characteristics: fluoride exposure, diet and dental attendance

A questionnaire distributed to the participants’ parents was used to collect information on exposure to fluoride, dietary intake and dental attendance. At the baseline examination, 597 questionnaires were returned, representing 58.8% of the study participants.

Fluoride exposure

From Table 8, it is apparent that the arms were reasonably well matched in terms of reported exposure to fluoride outside the trial interventions. Reported tooth brushing frequency was higher in the FV group, with 74.6% claiming twice-daily brushing, compared with 68.5% in the sealant group.

| Variable | Scoring | FS (N = 314), n (%) | FV (N = 283), n (%) | Total (N = 597), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of tooth brushing | Never | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Less than once a day | 4 (1.3) | 4 (1.4) | 8 (1.4) | |

| Once a day | 77 (25.0) | 48 (17.4) | 125 (21.4) | |

| Twice a day | 221 (68.5) | 206 (74.6) | 417 (71.4) | |

| More than twice a day | 16 (5.2) | 18 (6.5) | 34 (5.8) | |

| Toothpaste type | Family toothpaste | 168 (55.3) | 134 (48.9) | 302 (52.2) |

| Children’s toothpaste | 131 (43.1) | 133 (48.5) | 264 (45.7) | |

| Other | 5 (1.6) | 7 (2.6) | 12 (2.1) | |

| Amount of toothpaste | A smear | 24 (7.8) | 23 (8.3) | 47 (8.0) |

| A pea-sized amount | 250 (81.4) | 222 (80.1) | 472 (80.8) | |

| Cover the bristles | 33 (10.7) | 32 (11.6) | 65 (11.1) | |

| Use of mouthwash | 97 (32.1) | 82 (30.3) | 179 (31.2) | |

| Use of fluoride tablets | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Use of fluoride drops | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Use of FV | 51 (16.6) | 35 (12.6) | 86 (14.7) | |

| Lifetime resident in South Wales | 238 (90.8) | 215 (91.9) | 453 (91.3) | |

A greater proportion (55.3%) of parents in the FS arm than in the FV arm (48.9%) reported that their child used family toothpaste to clean their teeth. The amount of toothpaste used on toothbrushes was broadly similar between the trial arms. In both trial arms, 91% of the participants were lifetime residents of non-fluoridated South Wales.

Global oral hygiene regimen

The combined global rating scale of fluoride use and tooth brushing regimen, calculated as described in Chapter 2, is shown in Table 9. This shows that the global oral hygiene score increased in both trial arms from baseline to 12 months and was marginally higher in the FV arm than in the FS arm at 12, 24 and 36 months.

| Intervention | Overall | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS | FV | |||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| Global oral hygiene regimen | ||||||

| Baseline | 309 | 2.50 (1.083) | 280 | 2.47 (1.018) | 589 | 2.49 (1.052) |

| 12 months | 296 | 2.72 (1.136) | 270 | 2.81 (1.183) | 566 | 2.76 (1.159) |

| 24 months | 312 | 2.71 (1.204) | 292 | 2.78 (1.130) | 604 | 2.74 (1.169) |

| 36 months | 269 | 2.70 (1.035) | 254 | 2.83 (1.090) | 523 | 2.76 (1.063) |

Diet

Reported dietary intake at baseline is shown in Table 10 and summarised in Table 11.

| Variable | Scoring | Intervention arm | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS, n (%) | FV, n (%) | |||

| Milk | Never and up to 4–6 times per week | 102 (33.6) | 93 (34.1) | 195 (33.8) |

| 1 per day to 2–3 times per day | 202 (66.4) | 180 (65.9) | 382 (66.2) | |

| Water | Never and up to 4–6 times per week | 88 (29.4) | 69 (25.3) | 157 (27.4) |

| 1 per day to 2–3 times per day | 211 (70.6) | 204 (74.7) | 415 (72.6) | |

| Fizzy drinks | Never and up to 4–6 times per week | 264 (88.6) | 233 (87.3) | 497 (88.0) |

| 1 per day to 2–3 times per day | 34 (11.4) | 34 (12.7) | 68 (12.0) | |

| Squash | Never and up to 4–6 times per week | 174 (60.0) | 135 (51.5) | 309 (56.0) |

| 1 per day to 2–3 times per day | 116 (40.0) | 127 (48.5) | 243 (44.0) | |

| Fruit juice | Never and up to 4–6 times per week | 210 (72.2) | 186 (70.3) | 395 (71.3) |

| 1 per day to 2–3 times per day | 81 (27.8) | 78 (29.7) | 159 (28.7) | |

| Diet/light drinks | Never and up to 4–6 times per week | 202 (69.9) | 167 (63.5) | 369 (66.8) |

| 1 per day to 2–3 times per day | 87 (30.1) | 96 (36.5) | 183 (33.2) | |

| Sweets/confectionery | Never and up to 4–6 times per week | 236 (77.4) | 214 (79.6) | 450 (78.4) |

| 1 per day to 2–3 times per day | 69 (22.6) | 55 (20.4) | 124 (21.6) | |