Notes

Article history

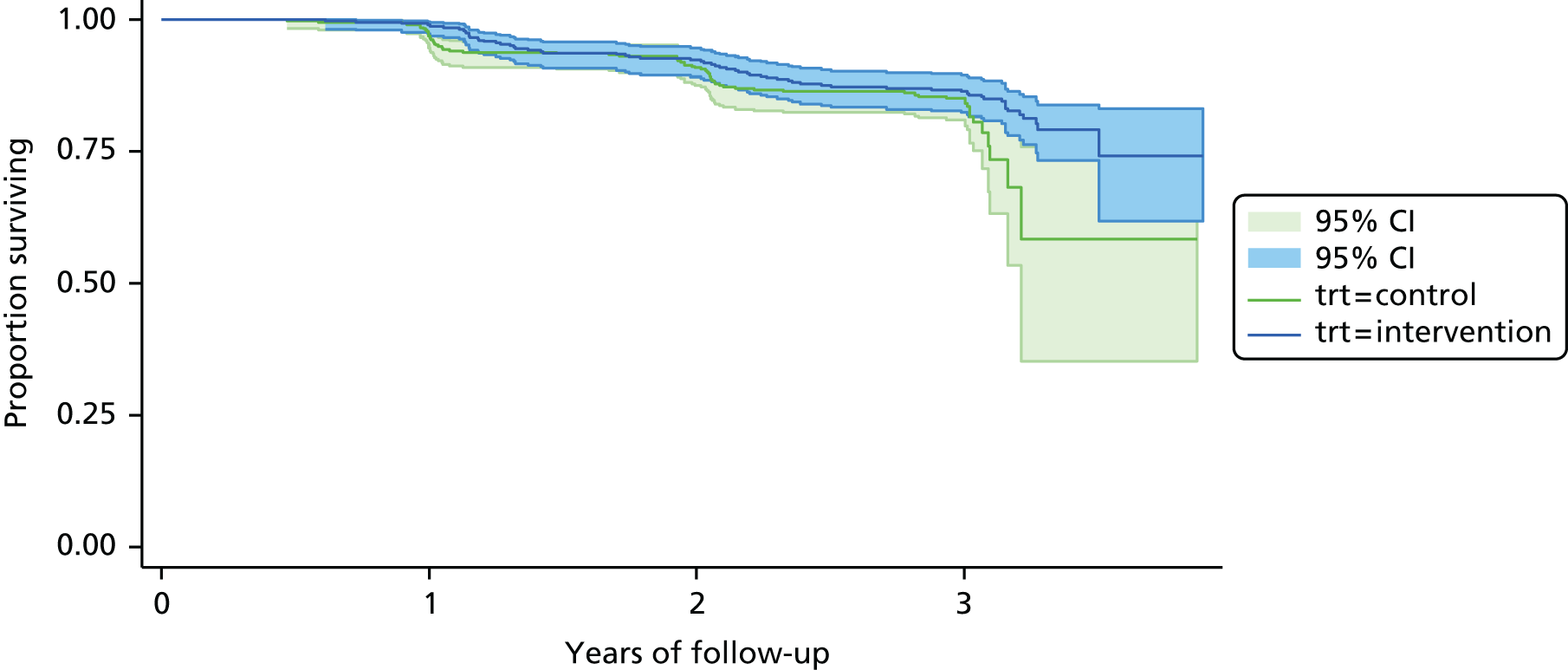

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0606-1272. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in January 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Melanie Davies has acted as consultant, advisory board member and speaker for Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca and Janssen, and as a speaker for Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation. She has received grants in support of investigator and investigator-initiated trials from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis and Eli Lilly and Company. She has received grants and support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of this study. Alastair Gray reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Kamlesh Khunti reports that he has acted as a consultant and speaker for Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company and Merck Sharp & Dohme. He has received grants in support of investigator and investigator-initiated trials from Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Kamlesh Khunti has received funds for research, honoraria for speaking at meetings and has served on advisory boards for Eli Lilly and Company, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Novo Nordisk.

Permissions

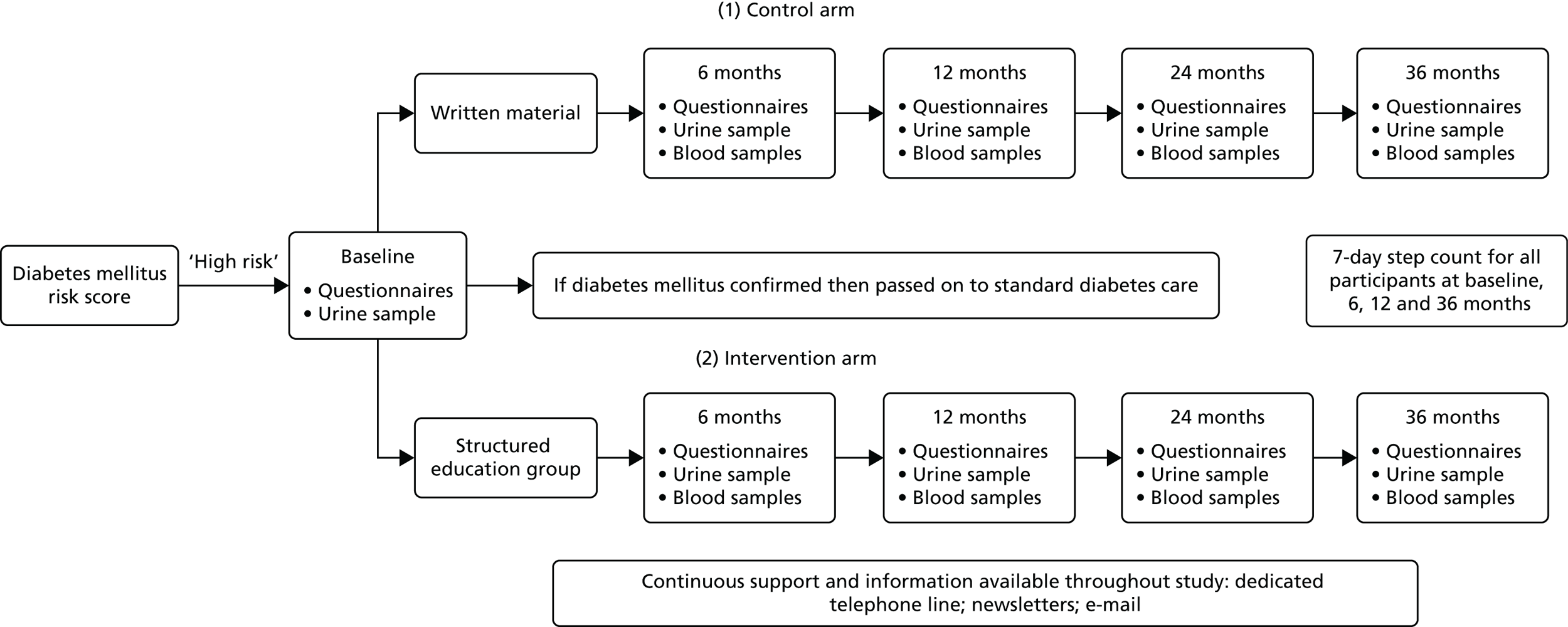

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Davies et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic and debilitating disease characterised by elevated blood glucose through insulin resistance, relative impairment of insulin secretion and increased hepatic glucose output. In the short term, the symptoms of T2DM are associated with a reduced quality of life, whereas in the longer term the disease may lead to serious complications such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), blindness, renal failure and amputation. 1 The life expectancy of individuals with T2DM may be shortened by as much as 10 years, with up to 75% of individuals dying of CVD. 2,3

The prevalence of T2DM has risen so steeply over the past few decades that it is now commonly referred to as an epidemic, and elevated blood glucose levels are currently estimated to be the third leading modifiable cause of mortality globally. 4 Currently, diabetes mellitus accounts for 5–13% of total health-care spending across low- to high-income regions of the globe;5 in the UK, diabetes mellitus currently accounts for approximately 10% of the total health-resource expenditure, which is projected to increase to around 17% in 2035/36. 6 The vast majority of the burden of diabetes mellitus is attributable to the T2DM form of the disease. 6

This devastating health-care burden has necessitated a shift in focus from traditional health-care models focused on treatment to those that incorporate pathways and systems for prevention. International and national health-care organisations now recognise the importance of developing targeted approaches to prevention through research, health-care recommendations and policy. In the UK, the NHS Health Check programme (formally vascular checks) was formed to address this need and is aimed at screening all individuals aged between 40 and 75 years for vascular and metabolic disease risk and treating high-risk individuals accordingly. 7 However, changes to policy have tended to precede programmes of research focused on developing and evaluating prevention pathways in the real world; therefore, there has been a lack of evidence-based tools and programmes that are suitable for implementation into routine primary care and that are available to commissioners. Our programme of work was designed to address this limitation and to develop robust evidence-based tools and systems for identifying and intervening in those with a high risk of T2DM.

Here, we highlight the background to our work with a specific focus on approaches used for identifying those with a high risk of T2DM and considerations of how to prevent T2DM with lifestyle intervention.

Identification

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is at one end of a continuous glucose control spectrum, with normal glucose control at the other. In between these two extremes there is a clinically important and much-researched state in which glucose levels are elevated but not over the threshold for diagnosis of T2DM. This state of glucose control has historically been termed prediabetes mellitus (PDM), impaired glucose regulation (IGR) or intermediate hyperglycaemia. Individuals with these elevated glucose levels are significantly more likely to develop T2DM than those with normal blood glucose.

The tests that can be used to identify those at high risk of T2DM include the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and, more recently, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c). There are usually two blood measurements taken for an OGTT: fasting plasma glucose (which is the glucose measured after 12 hours of fasting before glucose is taken) and the 2-hour post-challenge plasma glucose (which is measured 2 hours after the glucose is taken). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) as a 2-hour post-glucose reading of > 7.8 mmol/l but < 11.1 mmol/l, whereas impaired fasting glucose (IFG) is defined as fasting plasma glucose concentration of > 6.1 mmol/l but < 7 mmol/l. 8 IFG and IGT can occur as isolated, mutually exclusive conditions or together. Estimates of progression to T2DM within 1 year suggest that those with isolated IGT have over five times the risk, those with isolated IFG have seven times the risk and those with both IGT and IFG have over 12 times the risk than normoglycemic individuals. 9 Both the terms PDM and IGR are commonly used to describe the presence of IFG and/or IGT as defined by the WHO.

In 2011, after the start of this work, WHO revised the criteria for the diagnosis of T2DM to include the use of HbA1c. 10 This precipitated a shift in clinical practice, with the use of OGTT in the diagnosis of T2DM being gradually phased out and HbA1c becoming the dominant method of classification. As it is potentially burdensome and confusing to define categories on a continuous glucose spectrum with different measures, this change necessitated a discussion around the definition of an HbA1c-defined PDM category analogous to that of IGT or IFG. Although the WHO found insufficient evidence for the use of HbA1c in the definition of PDM, statements from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and an international expert committee recommended that HbA1c be used to signify a high-risk state at levels of between 5.7% and 6.4%, and 6.0% and 6.4%, respectively. 11,12 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have since adopted the recommendation of 6.0% to 6.4% as an alternative to fasting or 2-hour glucose in the identification of PDM. 13 Follow-up studies have shown similar rates of progression to diabetes mellitus from the HbA1c-defined prediabetic state as seen for IFG. 14

In most countries, around 15% of adults have PDM based on WHO criteria;15 this figure rises in some minority populations and with age. For example, in elderly populations up to 50% of individuals are estimated to have PDM. 16 Of those with PDM, an estimated 4–12% develop T2DM per year, with the highest rates seen among those with both IGT and IFG. 15,17 Evidence from prospective studies suggests that approximately 25–40% of individuals with PDM go on to develop diabetes mellitus over a 3- to 8-year period, and as many as 70% will eventually develop T2DM over the course of their lifetime. 17

Along with an increased risk of T2DM, the risk of CVD and premature mortality is also elevated in individuals with PDM. 15,18 For example, those with PDM have been shown to be 50% more likely to die of CVD than people with normal blood glucose control. 19 Interestingly, as the prevalence of PDM is four times greater than T2DM, there are likely to be more premature deaths attributable to PDM than to diabetes mellitus. 19,20

Research published by Diabetes UK proposed that, although the terms IGR, IFG and IGT may be useful when talking to health-care professionals, the term ‘prediabetes’ was found by focus groups to be preferable when talking to the public. It was noted that people identified with this term and felt that it adequately portrayed the seriousness of the condition and its future risk. 21,22 Recent recommendations suggest that individuals with either IGT, IFG or elevated HbA1c be referred to as ‘persons at high risk of T2DM’; however, at the onset of this study the term PDM was commonly used and thus has been adopted throughout this report. The term PDM is used to refer interchangeably to IGT, IFG and/or elevated HbA1c, according to any recommended definition. 12,13,23 Throughout this report we shall use the term PDM to include IGT-, IFG- or HbA1c-identified high risk of T2DM.

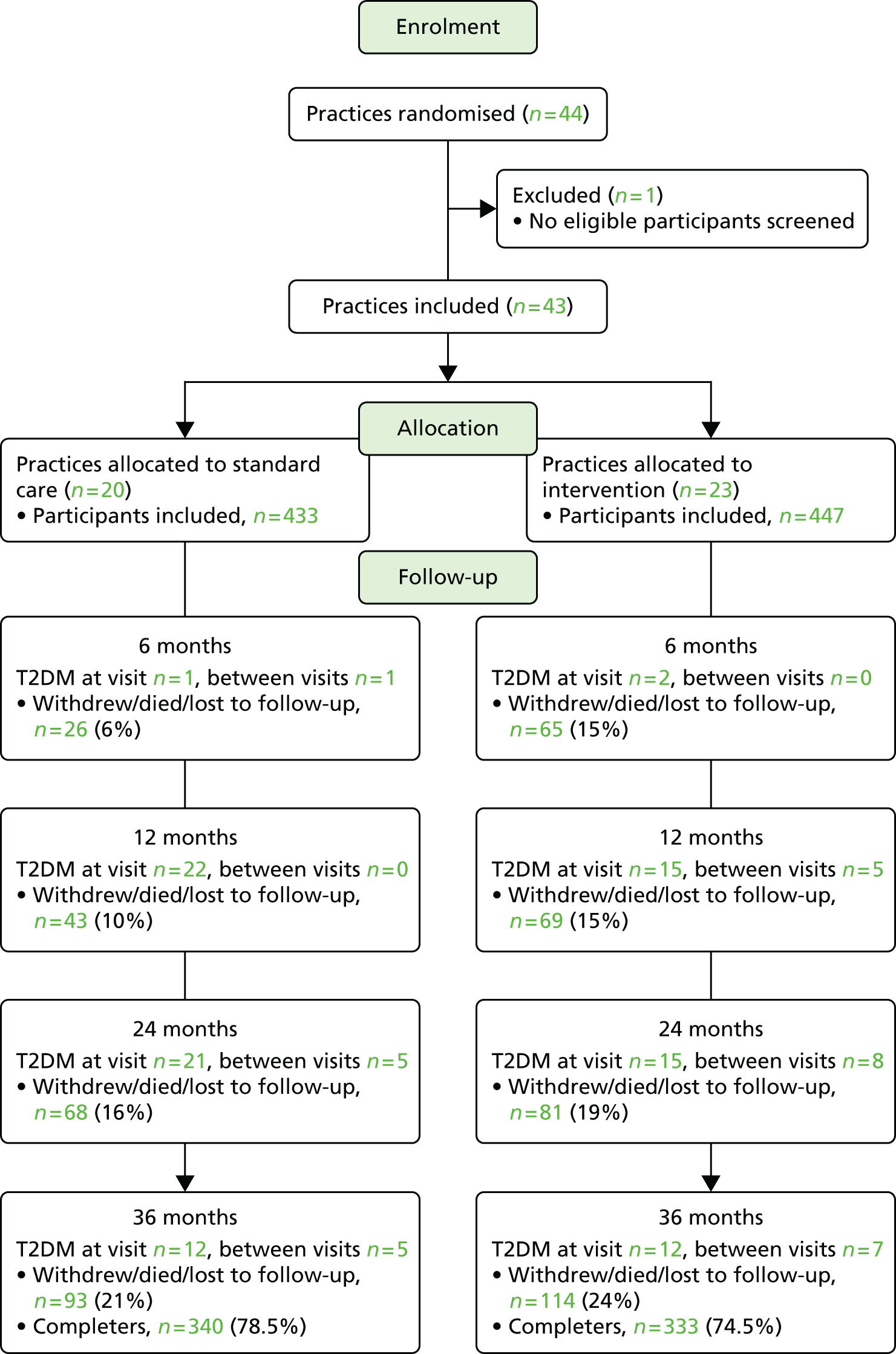

Regardless of the invasive biochemical test used to define risk status, universal screening for T2DM risk status is problematic for several important reasons. First, screening tests are relatively expensive and there is limited appetite in an era of restricted health-care budgets for screening apparently healthy individuals for disease risk. This is consistent with a review of the evidence commissioned by the Health Technology Assessment programme, which concluded that screening for T2DM meets most of the National Screening Committees’ key criteria, although it fails on several, including a lack of adequate staffing and facilities. 24 In addition to cost and resource, there is high variation in the risk of developing both T2DM and CVD across categories of PDM, regardless of the assessment method used. For instance, data from the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS) showed that the risk of T2DM in those with IGT more than doubled with the presence of other readily identifiable risk factors. 25 It is also known that the risk of CVD increases linearly with increasing levels of dysglycaemia, and there is no distinct threshold that justifies the use of distinct risk categories. 26 Given these factors, there has been much international focus on developing pragmatic systematic approaches for identifying and stratifying individuals with an elevated risk of T2DM for referral into diabetes-prevention initiatives. These have primarily focused around the use of risk-score technology.

Risk scores

Risk scores use non-invasive determinants of T2DM to estimate or rank risk. Work conducted in Finland in the 1990s led to the development of the seminal Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC), which uses weighted scores from eight risk characteristics [age, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, physical activity levels, fruit/vegetable intake, antihypertensive medication, previous history of high glucose and family history of T2DM] to calculate an overall risk profile for developing T2DM. 27 FINDRISC has been shown to have good sensitivity (≈0.8) and specificity (≈0.8) at predicting the 10-year absolute risk of T2DM in a white European population. 27 FINDRISC is now commonly used internationally within research and clinical care contexts. However, there is a recognised need to tailor and validate risk score technology according to local circumstances and population characteristics. 28 For example, in a society in which blood glucose levels are not routinely measured, asking participants about previous blood glucose levels is redundant. Furthermore, the ethnic makeup and distribution of risk factors, such as BMI, differ markedly between populations, which affects the weighting that each factor receives to maximise risk score accuracy. Furthermore, there is a need to distinguish between self-assessment risk scores, such as FINDRISC, and automated practice-based risk scores which are designed to run on routine care databases to enable health-care professionals to easily and quickly identify diabetes mellitus risk within their registered population. This grant directly funded the development and validation of a practice-based risk score designed to rank individuals for the risk of undiagnosed T2DM and PDM based on factors routinely coded within primary care (see Chapter 3). This work was further developed into a freely available piece of software available to all general practices nationally (see Chapter 9). In addition, we secured additional funding from Diabetes UK to develop and validate a self-assessment risk score specific to the UK (see Chapter 9).

Two-stepped approach

Diabetes mellitus risk scores, predominantly those based on FINDRISC, are now routinely used within many health-care contexts internationally. However, an emerging consensus has moved towards a two-stage approach whereby risk scores are used to identify moderate- to high-risk individuals and blood tests are then employed to confirm risk status and check for undiagnosed T2DM. 29 We have also shown that this approach is the most cost-effective method of identifying those at high risk of T2DM. 30 Following a comprehensive review and analysis of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different screening strategies to identify T2DM risk status, NICE supported the use of a stepped algorithm involving risk-score technology to identify individuals ranking above the 50th percentile of risk followed by a fasting or HbA1c blood test to confirm their risk status. 13 Although NICE guidance on the prevention of T2DM in high-risk populations was published after this programme grant was awarded, we nevertheless employed a two-stepped approach using the practice-based risk score developed (see Chapter 3) followed by an OGTT; those confirmed to have PDM were included in the randomised controlled trial (RCT) (see Chapter 5).

Prevention programmes

Clinical trials have unequivocally demonstrated that lifestyle interventions reduce the risk of progressing to T2DM by 40–60% in those with PDM, specifically IGT. 31 For example, the Finnish DPS found that the risk of T2DM was reduced by 58% in those with an intensive lifestyle intervention compared with usual care over a 3-year period. 32 Identical findings were reported for Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) conducted in the USA. 33 Similar and consistent results have been observed in many different and diverse countries including India,34 Japan35 and China. 36 Lifestyle interventions aimed at the prevention of T2DM have been based on promoting moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity, generally 150 minutes per week, and a healthy diet aimed at weight maintenance for normal-weight individuals or weight loss for overweight or obese individuals. For example, DPS had five intervention goals: (1) a reduction in body weight of ≥ 5%; (2) < 30% of energy intake derived from fat; (3) < 10% of energy intake derived from saturated fat; (4) at least 15 g of fibre per 1000 kcal; and (5) at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity per day. 32 Interestingly, there was not a single case of T2DM over the 3-year study period in those who achieved four of these goals. 32

Successful lifestyle-change programmes have also been shown to have so-called legacy effects whereby the effect persists well after the active intervention has ceased. DPS, DPP and the Chinese Da Qing diabetes mellitus prevention study all found sustained reductions in the incidence of T2DM relative to the control group after 7–20 years of follow-up. 37–39 These findings suggest that once individuals are enabled to successfully change and self-regulate their lifestyle behaviours, benefits can be sustained long after active lifestyle interventions have ceased.

Economic modelling studies have consistently demonstrated that lifestyle-based interventions are likely to be cost-effective and may even be cost saving in some populations. 40 When considering the whole process from screening to treatment, Gillies et al. 41 estimated that screening for T2DM and PDM followed by tailored treatment to each group was more cost-effective than screening for T2DM alone in the UK, with lifestyle interventions being more cost-effective than pharmaceutical therapy for prevention [£6242 vs. £7023 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained].

The consistent clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lifestyle interventions aimed at decreasing the risk of T2DM is unsurprising given that unhealthy lifestyle practices associated with modern ‘obesogenic’ environments are the primary causal factor for T2DM. The prevalence of T2DM has been estimated to have increased by a factor of six over the past couple of centuries, ruling out genetic change as a direct causal factor. 42 Although there are some genetic factors that increase the risk of T2DM, they can be expressed only in combination with unhealthy modern environments. Given the centrality of lifestyle factors in the pathophysiology of T2DM, and considering the strong evidence of efficacy for lifestyle intervention, the promotion of lifestyle change is central to the prevention of T2DM. This has been recognised by NICE, which recommends that those identified as being at high risk of T2DM should be referred to a lifestyle intervention before pharmaceutical agents, such as metformin (e.g. Glucophage, Merck), are considered. 13

Translating lifestyle research into practice

Despite strong evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lifestyle intervention in the prevention of T2DM, there has been a large translational gap between clinical trial evidence and implementation into routine clinical care. This is predominantly attributable to the resource-intensive nature of the lifestyle interventions tested within clinical trials. For example, the lifestyle intervention within the DPP involved 16 lengthy one-to-one counselling sessions, followed by in-person one-to-one contact at least once every 2 months and additional group-based sessions four times annually. 33 If this level of intervention was directly translated into routine care within the UK to those with PDM, it would require an estimated additional 150 million consultations per year, clearly a level that would be unachievable in even the most highly funded and resourced health-care system. Therefore, the emphasis needs to be shifted from maximising behaviour change and resources within the context of a clinical trial to examining the minimum level of intensity and resource allocation needed to produce meaningful clinical effects in routine care. In addition, there are important considerations relating to how new interventions become embedded within routine care and gain universal access. Professor Ann Albright, Director of the Division of Diabetes Translation within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, identified six distinct steps from basic science to national distribution, termed the continuum of translation, which are needed achieve the universal implementation of diabetes mellitus prevention. 43 More recently, Schwarz et al. 29 identified six key areas of focus when implementing diabetes mellitus prevention programmes: (1) intervention cost; (2) training and expertise of intervention providers; (3) uptake to both screening and intervention; (4) ensuring the sustainability of funding and support within health-care and political arenas; (5) developing quality management across intervention providers; and (6) using and improving technology to support the behaviour change of both patients and health-care professionals.

Finland and the USA have been at the forefront of integrating diabetes mellitus prevention programmes into health-care and community settings. In Finland, tailored lifestyle interventions offered to those classified as being at a high risk of T2DM were based on the goals of DPS but delivered in a less-intensive format of four to eight group-based education sessions. 44 In the USA, lifestyle intervention has focused on a community-based programme run through Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) facilities, which consists of 16 1-hour group-based sessions delivered by trained quality-assured lifestyle coaches. 45 Numerous smaller-scale diabetes mellitus prevention programmes, largely based on group education and intervention approaches, have also been developed and evaluated in the USA. 46 Internationally, European-wide diabetes mellitus prevention guidance and tools for health-care professionals have also been developed and published. 47 As discussed later (see Chapter 2), those diabetes mellitus prevention programmes that have been tailored to, and implemented in, routine care or community settings internationally have continued to demonstrate meaningful changes to some markers of health status, such as BMI.

In the UK, group-based approaches to promoting self-management and behaviour change, in the form of structured education, are already an integral and established part of many disease-management pathways, particularly T2DM. For example, the Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND) structured education programme developed by our group has been shown through a multicentre trial to improve CVD risk profiles, reduce depression, enhance smoking cessation and promote health behaviour change, including weight loss, in those with T2DM, while being highly cost-effective, with a cost per QALY gained of £2092. 48,49 DESMOND is now the most widely implemented self-management programme for T2DM and is currently part of routine diabetes mellitus pathways within half of all clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) nationally (www.desmond-project.org.uk/). Given that the infrastructure for delivering structured education as part of routine diabetes mellitus pathways within primary care is already established in the UK, there was a recognised opportunity to harness this approach for prevention. This is important because it does not require primary care organisation to develop and implement new programmes or systems of care; rather, existing pathways and programmes could be rolled backwards to incorporate the prevention as well as the management of T2DM. Early work undertaken by our group demonstrated the potential efficacy of structured education combined with pedometer use at promoting physical activity in those with PDM50,51 (see Chapter 9), and NICE subsequently went on to provide detailed recommendations for the content and format of lifestyle interventions aimed at the prevention of T2DM that were consistent with group-based structured education. 13

One of the central aims of our programme was to incorporate the lifestyle goals from clinical trials, including diet, weight management and physical activity, into a structured education programme that was suitable for implementation within routine care and, once developed, to evaluate its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Summary

In conclusion, the prevention of T2DM is a recognised national and international health-care priority. However, in order to make prevention a reality rather than an aspiration within primary care, there is an urgent need to develop methods and pathways that can facilitate the identification of those with PDM and provide methods of delivering lifestyle intervention that are both evidence-based and suitable for mass implementation within the existing health-care infrastructure. Our programme grant was aimed at addressing this unmet need within the context of primary care in the UK.

The main objectives of the programme grant were:

-

to develop and validate a risk score to identify those who require diagnostic testing to identify undiagnosed T2DM and those at high risk of future T2DM and CVD in a multiethnic population

-

to use this risk score to identify and engage those at highest risk of T2DM and offer them a lifestyle self-management programme with the aim of reducing the risk of progression to T2DM and reducing cardiovascular risk

-

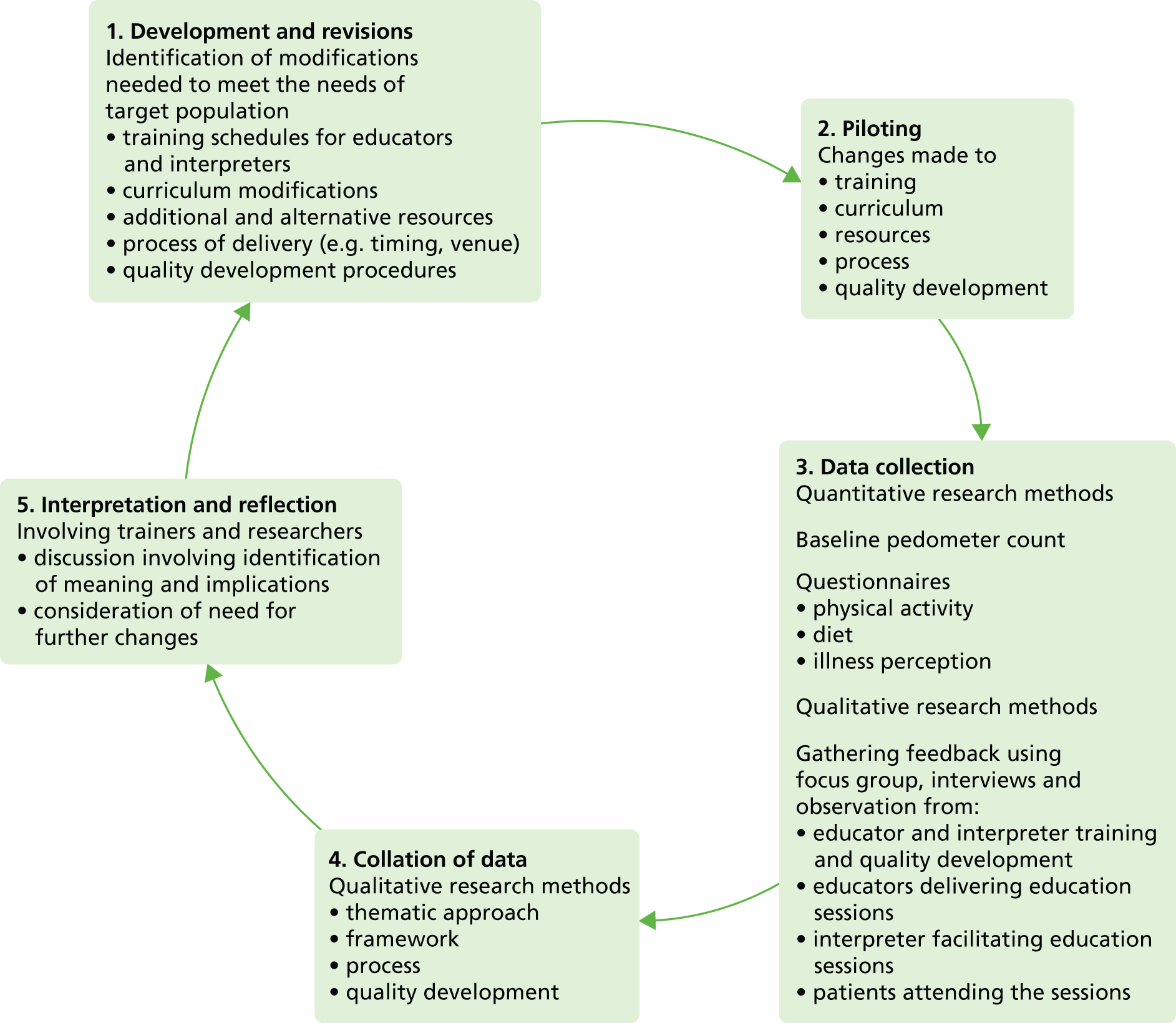

to pilot and test a lifestyle self-management programme based on group care, targeting the five key areas, using information currently collated from the European Union-funded Diabetes in Europe Prevention using Lifestyle, physical Activity and Nutritional intervention (DEPLAN) project

-

to develop a training and quality-assurance programme for community-based health trainers, who may include health-care professionals, to deliver the initial programme and provide ongoing support to those at highest risk of T2DM

-

to evaluate the lifestyle self-management programme and its cost-effectiveness

-

to explore how a two-stage screening programme and prevention intervention can be implemented in primary care.

Chapter 2 Systematic review

This chapter presents a systematic review and meta-analysis of the current evidence on the effectiveness of pragmatic lifestyle interventions for the prevention of T2DM. The content is based on a previously published review conducted by our research group52 which identified studies up to July 2012 [reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-NoDerivative Works 3.0 Unported License (CC BY-NC-ND) and courtesy of the ADA]. For this report, the review has been updated and includes published evidence up to August 2014.

Introduction

A major opportunity exists to drastically reduce the incidence of T2DM, a disease that has a huge impact on patients and health-care systems worldwide. Large, high-quality clinical trials31,33,39 show that relatively modest changes in diet and physical activity reduce the incidence of T2DM by > 50% for people with PDM. Indeed, within-trial data show that the rate of progression to T2DM after 7 years of follow-up was reduced to almost zero for people who had succeeded in making five modest lifestyle changes. 39 The main drivers of diabetes mellitus prevention appear to be weight loss and physical activity. 53,54 However, a substantial challenge remains in translating these findings into routine clinical practice. The intensive and prohibitively expensive interventions used in clinical trials to ensure lifestyle change need to be translated into practical, affordable interventions that are deliverable in real-world health-care systems and that, nevertheless, retain a reasonable degree of effectiveness. 29

Since the publication of the original diabetes mellitus prevention clinical trials between 1996 and 2001, a number of translational or ‘real-world’ diabetes mellitus prevention programmes55,56 have aimed to translate the evidence. 32–34,36 A meta-analysis of the evidence on translational interventions was published in 2010,55 although this review excluded 15 studies that were conducted in non-health-care settings. A more recent meta-analysis was published in 2012. 46 However, the authors focused only on translation of evidence from the US DPP and also included studies where up to half of the population already had diabetes mellitus. Other systematic reviews of diabetes mellitus prevention interventions have either not included a meta-analysis54,56–60 or not focused on translational studies. 31,54,57,58,61–65 Overall, the systematic reviews conducted to date indicate that real-world diabetes mellitus prevention programmes vary widely in their effectiveness, although most produce lower levels of weight loss than the more intensive interventions used in the clinical efficacy trials. 55

To consolidate the evidence we undertook a systematic review of studies, considering the effectiveness of translational interventions for prevention of T2DM in high-risk populations. The primary aim was to conduct a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of pragmatic interventions on weight loss. If sufficient data were available, a secondary aim was to consider other diabetes mellitus risk factors using similar methods.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

We included experimental and observational studies that considered the effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention (diet and/or exercise) alone or compared with control, for which the stated aim of the intervention was diabetes mellitus risk reduction or prevention of T2DM and the focus of the study was to translate evidence from previous diabetes mellitus efficacy trials into routine health care or a community setting. For studies to be eligible for inclusion, we required them to include adults (aged ≥ 18 years) identified as being at high risk of developing T2DM (e.g. obese, sedentary lifestyle, family history of diabetes, older age, metabolic syndrome, PDM or elevated diabetes mellitus risk score);13 have a minimum follow-up of 52 weeks; and have an outcome relating to diabetes mellitus risk, as measured by a change in body composition or a change in glycaemic control, or report progression to diabetes mellitus (incidence or prevalence). The focus of the review was primary prevention; therefore, we excluded trials where > 10% of the population had established diabetes. We included only studies published in the English language and as full-length articles.

We searched EMBASE, MEDLINE and The Cochrane Library (issue 10, 2014) using a combination of Medical Subject Headings terms and keywords which were tailored to individual bibliographic databases. We restricted searches to articles published after January 1998; the starting point of 1998 was chosen to facilitate the identification of studies that were informed by or translating evidence from previous diabetes mellitus prevention efficacy trials. 32–34,36 In order to avoid missing papers the final search strategy included only terms related to the intervention and the study design. An example search strategy (MEDLINE) is outlined in Appendix 1. We combined the results of an initial search and an updated supplementary search that together identified papers up to the end of August 2014.

Two reviewers independently assessed abstracts and titles for eligibility and retrieved potentially relevant articles, with differences resolved by a third reviewer where necessary. Where studies appeared to meet all the inclusion criteria, but data were incomplete, we contacted authors for additional data and/or clarification. In an attempt to identify further papers not identified through electronic searching, we examined the reference lists of included papers and relevant reviews.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted by one reviewer, and a second reviewer subsequently checked for consistency. We extracted data on sample size, population demographics, intervention details and length of follow-up. Where available, we recorded outcome data for the mean change from baseline to 12 months’ follow-up for the following outcomes: weight, BMI, waist circumference, fasting glucose, 2-hour glucose, HbA1c, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, systolic blood pressure (BP) and diastolic BP. Incidence of T2DM was also recorded. We retrieved all papers relating to a particular study, including those on design and methodology (if reported separately), and any supplementary online material.

We assessed the quality of selected studies according to the UK’s NICE quality appraisal checklist for quantitative intervention studies. 66 The checklist includes criteria for assessing the internal and external validity of experimental and observational quantitative studies (RCTs, non-RCTs, single-arm before-and-after studies) and allows assignment of an overall quality grade (categories ++, + or –).

Coding of intervention content

We coded intervention content (see Appendices 2 and 3) in relation to the recommendations for lifestyle interventions for the prevention of diabetes mellitus provided by both the Development and Implementation of a European Guideline and Training Standards for Diabetes prevention (IMAGE) project47 and NICE. 13 Where a study intervention was inadequately described we requested further details from the authors. If available information was insufficient to allow coding we coded data as missing; where an intervention appeared to be well described but a particular component (e.g. engaging social support) was not mentioned or could not be inferred from other text, we assumed that the component was not used.

Data synthesis and analysis

We converted all values reported in imperial units into metric units. Capillary blood glucose values were converted to plasma equivalent values. 67 If studies did not directly report the mean and standard deviation (SD) for change from baseline to 12 months for the outcomes of interest, they were calculated. We calculated the mean change by subtracting the baseline mean value from the mean at 12 months. We calculated the SD from reported p-values or confidence intervals (CIs), as recommended by Cochrane. 68 In instances in which data were reported by subgroup, combined effect sizes and SDs were estimated using the formula advocated by Cochrane. 68 Where data were insufficient to allow calculation of the SD, we imputed values for each outcome based on the correlation estimates from those studies that reported them; for weight the correlation used in these imputations was 0.95. 69–73

Weight change was chosen as the primary outcome owing to the high number of studies reporting this outcome above others, such as those relating to glycaemic control or progression to T2DM. This is most likely to be attributable to the nature of the translational interventions, which are predominantly based on large-scale intensive diabetes mellitus prevention programmes that are founded on core goals which specifically target weight loss. In addition, studies were predominantly of ≤ 12 months’ duration, which is arguably too short a period to fully assess the effect of an intervention on progression to T2DM. For the primary outcome of interest (weight), we conducted a meta-analysis to examine the pooled effect size (change from baseline to 12 months) where data were available. Owing to the uncontrolled nature of translational interventions, the majority of included studies were single-arm before-and-after studies. In order to prevent exclusion of substantial evidence, only intervention arms were included in the meta-analysis to maximise the data available for analysis. We conducted similar analyses for the secondary outcomes of interest. We performed sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome, weight, where we restricted the analysis to RCTs only. Additional sensitivity analyses comparing intervention and control arms in RCTs only were performed for the primary outcome.

We assessed publication bias using Egger’s test and heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. Owing to high levels of heterogeneity we used random-effects models throughout to calculate effect sizes. We performed all analyses in Stata version 12.1 (StatCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Identification of studies

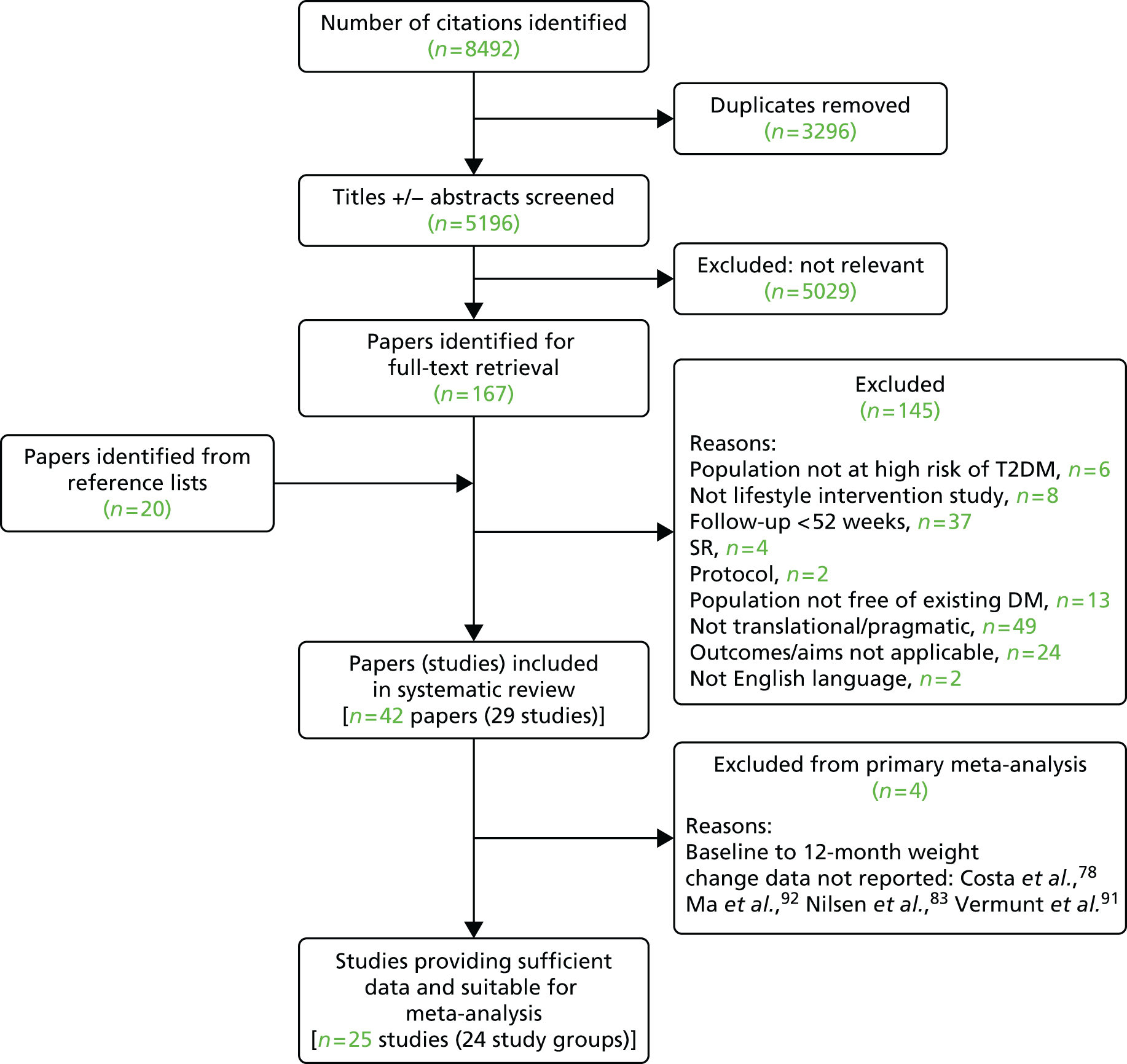

Results relating to the identification and selection of eligible trials are summarised in Figure 1. Searches yielded 8492 citations, and 5196 unique titles and/or abstracts were screened for eligibility. Following full-text retrieval of 167 potentially relevant papers, 20 additional papers were identified from reference lists, making a total of 187. Authors for 14 studies were then contacted in order to clarify eligibility criteria and/or for additional outcome data. Replies were received for 13 studies, 10 of which were subsequently included in the 29 studies50,62,69–95 (42 papers50,51,62,69–107) that met the review criteria.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of selection of studies from search to final inclusion. DM, diabetes mellitus; SR, systematic review.

Summary of included studies

The 29 studies included in the systematic review are summarised in Table 1. Study interventions included either a dietary intervention or a physical activity intervention, or both. Standard/brief advice on diet and/or exercise was considered to be comparable with usual care and not judged to be an active intervention. One study focused solely on the effectiveness of a physical activity intervention,50 three combined dietary intervention and a supervised exercise programme,82,92,95 and 25 studies considered the effectiveness of a combined dietary and physical activity intervention. Fourteen of the studies were RCTs, 12 were single-arm before-and-after studies and the remaining studies included a matched cohort, a prospective cohort and a non-RCT. All papers were published within the past 11 years.

| First author and year | Study design | Study name | Definition of high risk of T2DM | Focus of intervention(s) | Number recruited overall (and by group) | Number of study groups | Follow-up (months) | Setting | Country | Ethnicity (%) | Age, years (mean) | Male (%) | BMI, kg/m2 (mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absetz et al., 200774 (and 200996) | Single-arm before and after | GOAL | Aged 50–65 years; any risk factor from obesity, ↑ BP, ↑ plasma glucose, ↑ lipids; FINDRISC score of ≥ 12 | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 352 | 1 | 12 and 36 | Primary care | Finland | NR | 58 (F); 59 (M) | 25 | 33 (F); 32 (M) |

| Ackermann et al., 200875 (and 201197) | RCT | DEPLOY | BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2; ADA diabetes mellitus risk score of ≥ 10; CBG random (110–199 mg/dl) or fasting (100–199 mg/dl) | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 92 | 2 | 12 | Community (YMCA) | USA | 82% white; 3% Hispanic; 12% African American; 5% other | 58 | 45 | 31 |

| Almeida et al., 201076 | Matched cohort | KPCO | Existing IFG (110–125 mg/dl) identified from medical records | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 1640 (1520 data available) | 2 | 12 | Integrated health-care organisation | USA | NR | 55 | 47 | 30 |

| Boltri et al., 200877 | Single-arm before and after | DPP in faith-based setting | ADA diabetes mellitus risk score of ≥ 10; CBG fasting (100–125 mg/dl) | Lifestyle (diet and supervised exercise) | 8 | 1 | 12 | Community (church) | USA | African American community | 52a | 42a | 32 |

| Costa et al., 201278 | Prospective cohort | DE-PLAN Spain | FINDRISC score of ≥ 14 or 2-hour OGTT (≥ 7.8 mmol/l and < 11.1 mmol/l) | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 552 (219 + 333) | 2 | Median 4.2 years | Primary care | Spain | White European | 62 | 32 | 31 |

| Davis-Smith et al., 200779 | Single-arm before and after | NR | ADA diabetes mellitus risk score of ≥ 10; CBG fasting (100–125mg/dl) | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 11 | 1 | 12 | Community (church) | USA | African American community | NR | 27 | 36b |

| Faridi et al., 201062 | Non-RCT | PREDICT | One or more risk factor from BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2, FH diabetes, gestational diabetes | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 146 | 2 | 12 | Community (church) | USA | African American 100% | NR | 32 | 33 |

| Gilis-Januszewska et al., 201169 | Single-arm before and after | DE-PLAN Poland | FINDRISC score of ≥ 14 | Lifestyle (diet and exercise, optional supervised sessions) | 175 | 1 | 12 | Primary care | Poland | NR | NR | 22 | 32 |

| Janus et al., 201293 | RCT | pMDPS | Aged 50–75 years; AUSDRISK score of ≥ 15 | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 92 (49 + 43) | 2 | 12 | Community/primary care | Australia | 100% non-Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander | ≈ 65 | 34 | ≈ 31 |

| Kanaya et al., 201294 | RCT | Live Well, Be Well | Moderate/high diabetes mellitus risk score and CBG fasting (106–160 mg/dl) | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 238 (119 + 119) | 2 | 12 | Community | USA | 20% African American; 20% non-Hispanic white; 32% Latino; 14% Asian; 14% other | ≈ 56 | 36 | ≈ 30 |

| Katula et al., 201180 (and 2013)107 | RCT | HELP-PD | BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 < 40 kg/m2 and CBG random; FPG (95–125 mg/dl) | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 301 (151 + 150) | 2 | 12, 18 and 24 | Community various venues | USA | 74% white; 25% African American; 1% other | 58 | 43 | 33 |

| Kramer et al., 200970 | Single-arm before and after | GLB 2005–8 | BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 and metabolic syndrome or CBG fasting (100–125 mg/dl) | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 42 | 1 | 12 | Primary care and university-based support centre | USA | White 100% | 57 | 21 | 35 |

| Kramer et al., 201281 | Single-arm before and after | GLB 2009 | Fasting glucose of 100–125mg/dl | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 60 (31 + 29) | 2 | 12 | Community (YMCA) and university | USA | 90% Caucasian | 55 | 35 | ≈ 36 |

| Kulzer et al., 200971 | RCT | PREDIAS | FINDRISC score of ≥ 10 or assessed as ↑ risk of diabetes mellitus by primary care physician | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 182 (91 + 91) | 2 | 12 | Outpatient setting | Germany | NR | 56 | 57 | 32 |

| Laatikainen et al., 200772 (and 201298) | Single-arm before and after | GGT study | FINDRISC score of ≥ 12 | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 311 | 1 | 12 | Primary care | Australia | NR | 57 | 28 | 34 |

| Ma et al., 201392 (Ma et al., 2009106 and Xiao et al., 2013105) | RCT | E-LITE | BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 and fasting plasma glucose of 100–125 mg/dl or metabolic syndrome | Lifestyle (diet and exercise; supervised exercise for one group)b | 241 (79 + 81 + 81) | 3 | 15 and 24 | Primary care | USA | 78% non-Hispanic white; 17% Asian/Pacific Islander | 53 | 53 | 32 |

| Makrilakis et al., 201073 | Single-arm before and after | DE-PLAN Greece | FINDRISC score of ≥ 15 | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 191 | 1 | 12 | Primary care, workplace | Greece | NR | 56 | 40 | 32 |

| Mensink et al., 200382,99 (Roumen et al., 2008102 and 2011103) | RCT | SLIM study | Aged > 40 years and FH diabetes mellitus or BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2; IGT (OGTT 2-hour glucose ≥ 7.8 and< 12.5) and FPG of < 7.8 | Lifestyle (diet and supervised exercise) | 114 (55 + 59) | 2 | 12, 24, 36, 48 (Roumen) | Unclear | Netherlands | White Caucasian | 57 | 56 | 30 |

| Nilsen et al., 201183 | RCT | APHRODITE study | FINDRISC score of ≥ 9 | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 213 (104 + 109) | 2 | 18 | Primary care | Norway | NR | 47 | 50 | 37 |

| Ockene et al., 201284 | RCT | Lawrence Latino DPP | BMI of ≥ 24 kg/m2; > 30% increased likelihood of diabetes mellitus over next 7.5 years from validated risk algorithm | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 312 (150 + 162) | 2 | 12 | Community, family health centre | USA | 60% Dominican; 40% Puerto Rican | 52 | 26 | 34 |

| Parikh, 201085 | RCT | Project HEED | BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 and PDM; CBG fasting of < 126 mg/dl and 2-hour CBG following 75 g glucose | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 99 (50 + 49) | 2 | 12 | Community various venues | USA | 89% Hispanic; 9% African American | 48 | 15 | 32 |

| Payne et al., 200886 | Single-arm before and after | NR | Aged ≥ 45 years (or aged ≥ 35 years Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islanders, Pacific Islanders, Indian, Chinese) and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and/or ↑ BP; existing CVD, PCOS, gestational diabetes; first-degree FH diabetes; IGT or IFG | Lifestyle (diet and exercise programme) | 122 (62 + 60) | 2 | 12 | Outpatient facility | Australia | NR | 53 | 22 | 35 |

| Penn et al., 200987 | RCT | NR | BMI of > 25 kg/m2 and aged > 40 years; IGT (OGTT 2-hour glucose of ≥ 7.8 and < 11.1) | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 102 (51 + 51) | 2 | 12 and 3.1 years mean | Outpatient setting | UK | NR | 57 | 40 | 34 |

| Penn et al., 201395 | Single-arm before and after | NR | Aged 45–65 years, and FINDRISC score of 11–20 or > 20 if GP confirms no diabetes mellitus | Lifestyle (diet and supervised exercise) | 218 | 1 | 12 | Community and leisure centres | UK | NR | 54 | 31 | 34 |

| Ruggiero et al., 201188 | Single-arm before and after | NR | BMI of ≥ 24.9 kg/m2 | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 69 | 1 | 12 | Community various venues | USA | Hispanic | 38 | 7 | 31 |

| Saaristo et al., 201089 (Rautio et al., 2011100 and 2012101) | Single-arm before and after | FIN-D2D | FINDRISC score of ≥ 15 or IFG or IGT or CVD event or gestational diabetes | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 2798 | 1 | 12 | Primary care | Finland | NR | 54 | 49 | ≈ 31 |

| Sakane et al., 201190 | RCT | NR | IGT identified as follows: IFG of ≥ 5.6 and < 7.0; random PG (≥ 7.8 < 11.1 within 2 hours of meal) or (≥ 6.1 and < 7.8, ≥ 2 hours after meal); IGT | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 296 (146 + 150) | 2 | 12 and 36 | Various: primary care, workplace, collaborative centre | Japan | NR | 51 | 51 | 25 |

| Vermunt et al., 201291 (and 2011104) | RCT | NR | FINDRISC score of ≥ 13 | Lifestyle (diet and exercise) | 925 (479 + 446) | 2 | 18, 30 | Primary care | Netherlands | NR | NR | NR | ≈ 29 |

| Yates et al., 200950 (and 201151) | RCT | PREPARE | BMI of ≥ 25 (23 for SAs); screened detected IGT | Lifestyle (exercise) | 98 (33 + 31 + 34) | 3 | 12, 24 | Outpatient setting | UK | 75%c white; 24% SA; 1% black | 65c | 66c | 29.2c |

Studies were conducted in the USA (n = 13), Australia (n = 3), Europe (n = 12) and Japan (n = 1); however, ethnicity was poorly reported. The number of people who were enrolled into the intervention arms in individual studies ranged from 8 to > 2700, with 26 studies including at least 50 participants. The criteria used, alone or in combination, to identify high risk included: elevated BMI, elevated diabetes mellitus risk score [FINDRISC,108 ADA,27 the Australian type 2 diabetes risk assessment tool (AUSRISK)109], raised random, fasting or 2-hour glucose (finger prick or venous sample); older age; ethnicity; family history of diabetes mellitus; previous medical history of CVD, polycystic ovary syndrome, gestational diabetes, metabolic syndrome, elevated BP or lipids. Length of follow-up ranged from 12 months to approximately 4 years. The mean age and BMI of participants ranged from 38 to 65 years and from 25 to 37 kg/m2, respectively, and the proportion of males ranged from 7% to 66%.

Outcome data for change in weight were available for 28/29 studies (not Costa et al. 78); 25 of 29 studies reported weight at 12 months (see Appendix 4). Additional 12-month data reported for 26 studies (Appendices 4 and 5) included change in BMI (20 studies), waist size (18), fasting glucose (17), 2-hour glucose (11), HbA1c (7), total cholesterol (14), LDL (9), HDL (14), triglycerides (12), systolic BP (15), diastolic BP (12) and the incidence of diabetes mellitus after 12 months (9). Outcome data for change in physical activity and diet were poorly reported. Overall, considerable heterogeneity was evident between studies in relation to several key characteristics including the setting, population, criteria used to identify diabetes mellitus risk, interventions and follow-up.

Study quality

Most studies achieved a ‘high quality’ grading for internal validity (28/29). However, details relating to the source/eligible population and area and the selected participants were less well reported; only 13 studies achieved a high quality score for external validity. (For a breakdown of study quality, see Appendix 6.)

Scoring of intervention content

Details of coding scores for study interventions are presented in Appendix 3. A total of 14 of the 28 intervention groups included in the main meta-analysis attained an overall score of ≥ 9 out of a possible 12, in relation to meeting NICE guideline recommendations; 21 scored ≥ 7. For IMAGE guideline recommendations, an overall score of ≥ 5 out of a possible 6 was achieved by 13 study groups.

Meta-analysis

Twenty-five studies involving 5785 participants (estimated 36% male) were included in the meta-analysis for mean weight change at 12 months. One study was excluded from the primary meta-analysis, as weight change was not recorded as a study outcome. 78 Three were excluded from all analyses as one study reported only 15-month data,92 and two were excluded as they reported only 18-month data. 83,91 Two studies included in the meta-analysis had two intervention arms,50,81 meaning that 27 study groups were analysed.

The pooled result of the meta-analysis (Figure 2) shows that lifestyle interventions resulted in a mean weight loss of 2.31 kg (95% CI –2.87 to –1.76 kg; I2 = 92.9%).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot showing mean weight change in each study and the overall pooled estimate. Adapted from Dunkley et al. 52 under Creative Commons public licence 3.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/. Additional studies (Janus et al. ,93 Kanaya et al. 94 and Penn et al. 95) have been added; therefore, the subtotal line and overall line in the plots have changed, as they now include additional data. Boxes and horizontal lines represent mean weight change and 95% CI for each study. Size of box is proportional to weight of that study result. Diamonds represent the 95% CI for pooled estimates of effect and are centred on pooled mean weight change. CPC, carbohydrate reduction and hunger focus post core; TPC, traditional post core.

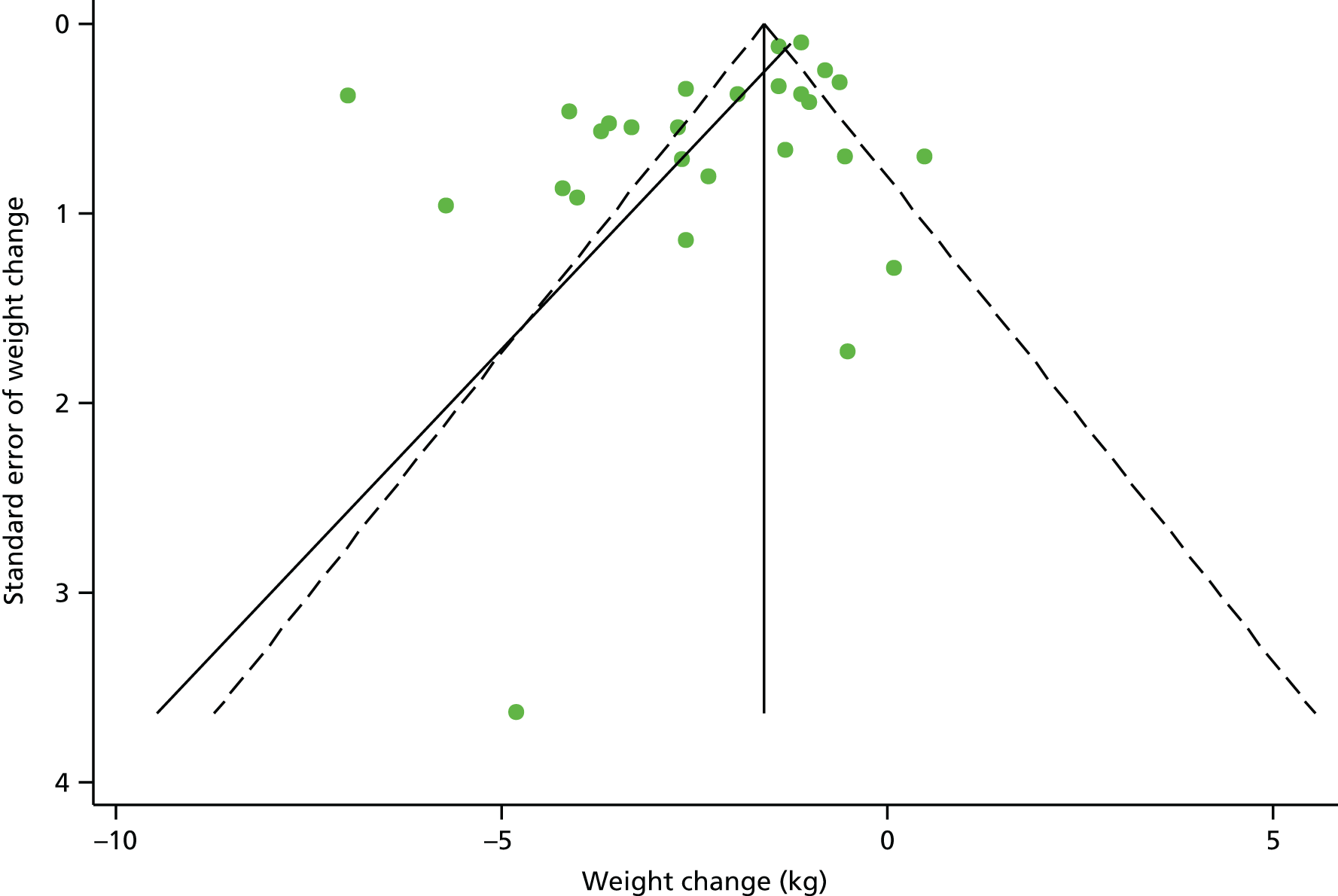

Sensitivity analysis, restricted to RCTs only, indicated a mean weight change (–2.5 kg, 95% CI –3.8 to –1.2 kg) that is similar to the overall result. Additional analysis comparing the difference in weight lost between the treatment and control arms, for RCTs only, suggests that, on average, the intervention arm lost an extra –1.79 kg (95% CI –2.78 kg to –0.80 kg; p < 0.001). Furthermore, sensitivity analyses that included studies scoring ++ for external validity demonstrated a slightly greater weight loss in higher-quality studies (–2.8 kg, 95% CI –4.1 to –1.5 kg). However, there was some evidence of publication bias (p = 0.033, Egger’s test; see Figure 3 for funnel plot).

FIGURE 3.

Funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits assessing publication bias for the primary outcome weight change.

All other outcomes showed an improvement at 12 months (Table 2), with all of these reaching statistical significance with the exception of HDL cholesterol. The pooled result for the 19 studies (20 study groups) that reported BMI demonstrates that lifestyle interventions resulted in a mean decrease in BMI of 0.98 kg/m2 (95% CI –1.28 to –0.68 kg/m2; I2 = 95.2%). A collective decrease in waist circumference of 3.36 cm (95% CI –4.33 to –2.39 cm; I2 = 97.5%) was found across the studies that reported the measure (n = 18). The pooled result for the studies that conveyed HbA1c percentages (n = 8) indicated that lifestyle intervention corresponded to a 0.11% (95% CI –0.19% to –0.03%; I2 = 97.1%) decrease in HbA1c. Significant reductions in fasting glucose of 0.10 mmol/l (95% CI –0.18 to –0.02 mmol/l; I2 = 86.0%) and 0.36 mmol/l (95% CI –0.66 to –0.06 mmol/l; I2 = 92.8%) in 2-hour glucose were suggested for lifestyle intervention. Total cholesterol was reported for 16 study groups, for which the pooled result of the direct pairwise meta-analysis indicated a 0.18 mmol/l (95% CI –0.23 to –0.13 mmol/l; I2 = 39.8%) mean decrease in total cholesterol at 12 months for those in receipt of lifestyle intervention. A slightly smaller reduction in LDL cholesterol of 0.15 mmol/l (95% CI –0.22 to –0.07 mmol/l; I2 = 66.0%) was demonstrated for the intervention groups by the pooled result for the meta-analysis including 10 study groups. The pooled result for HDL cholesterol indicated a 0.02 mmol/l (95% CI –0.002 to 0.04 mmol/l; I2 = 92.8%) increase for the intervention groups across 16 study groups; however, this was not a statistically significant finding. The overall effect of lifestyle intervention on triglycerides showed a 0.1 mmol/l (95% CI –0.18 to –0.01 mmol/l; I2 = 99.2%) decrease in triglycerides measurement spanning 14 study groups. Significant combined effects of intervention on BP were demonstrated, with a decrease in systolic BP of 4.02 mmHg (95% CI –5.66 to –2.37 mmHg; I2 = 77.1%) over 16 study groups and 3.88 mmHg (95% CI –5.24 to 2.52 mmHg; I2 = 83.7%) in diastolic BP across 12 study groups. Across the nine studies that reported incident diabetes mellitus, the pooled incidence rate was 35 cases per 1000 person-years (95% CI 24 to 53 cases per 1000 person-years), which gives the number needed to treat as 29.

| Outcome | Number of study groups | Pooled effect | 95% CI | p-value | I 2 | Publication bias p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 27 | –2.31 | –2.87 to –1.76 | < 0.001 | 92.9% | 0.033 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20 | –0.98 | –1.28 to –0.68 | < 0.001 | 95.2% | 0.067 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 20 | –3.36 | –4.33 to –2.39 | < 0.001 | 97.5% | 0.136 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8 | –0.11 | –0.19 to –0.03 | 0.009 | 86.7% | 0.961 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/l) | 19 | –0.10 | –0.18 to –0.02 | 0.014 | 86.0% | 0.344 |

| 2-hour glucose (mmol/l) | 12 | –0.36 | –0.66 to –0.06 | 0.018 | 92.8% | 0.156 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 16 | –0.18 | –0.23 to –0.13 | < 0.001 | 39.8% | 0.776 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 10 | –0.15 | –0.22 to –0.07 | < 0.001 | 66.0% | 0.278 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 16 | 0.02 | –0.002 to 0.04 | 0.082 | 92.8% | 0.931 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 14 | –0.10 | –0.18 to –0.01 | 0.022 | 99.2% | 0.585 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 16 | –4.02 | –5.66 to –2.37 | < 0.001 | 77.1% | 0.018 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 12 | –3.88 | –5.24 to –2.52 | < 0.001 | 83.7% | 0.005 |

| Incident diabetes mellitus (per 1000 person-years)a | 9 | 35.3 | 23.6 to 52.7 | < 0.001 | 79.5% | 0.117 |

High levels of heterogeneity were demonstrated for all secondary outcomes. Further significant evidence of publication bias was apparent for the reporting of systolic (p = 0.018) and diastolic (p = 0.005) BP outcomes via Egger’s test. No other significant evidence of publication bias was detected.

Discussion

The 25 translational diabetes mellitus prevention programmes included in our meta-analysis significantly reduced weight in their intervention arms by a mean 2.3 kg at 12 months’ follow up. Where data were available, we found significant reductions in other diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular risk factors, including blood glucose, BP and some cholesterol measures. The pooled diabetes mellitus incidence rate in the intervention arms was 35 per 1000 person-years (number needed to treat 29). Outcome data on changes in the key lifestyle behaviour targets (physical activity and diet) were poorly reported.

Relationship to other literature

The mean level of weight loss achieved was around a half to one-third of the levels reported at the same time point within the intervention arms of clinical efficacy trials, such as the US DPP (≈6.7 kg) and the Finnish DPS (≈4.2 kg). 32,33 This is consistent with the findings of a meta-analytic systematic review published in 2010 by Cardona-Morrell et al. 55 which identified a mean net weight loss after 12 months of 1.82 kg (95% CI –2.7 to –0.99 kg). Cardona-Morrell et al. 55 interpreted the lower level of weight loss and a lack of significant differences in fasting plasma glucose and 2-hour glucose as meaning that the interventions ‘appear to be of limited clinical benefit’. Our view is that, despite the drop-off in intervention effectiveness in translational studies, the level of weight loss found in our analysis is still likely to have a clinically meaningful effect on diabetes mellitus incidence. This is based on data from the US DPP study which show that each kilogram of mean weight loss is associated with a reduction of approximately 16% in future diabetes mellitus incidence. 53 Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis, which included studies without an intervention in order to look at natural diabetes mellitus progression rates in high-risk individuals, found that progression rates to diabetes mellitus from IFG, IGT and both were 47, 56 and 76 per 1000 person-years, respectively. 14 The rate of 35 per 1000 person-years that we found suggests that the real-world lifestyle interventions studied here did lower diabetes mellitus progression rates.

For our review, the mean proportion of weight lost (%) at 12 months’ follow-up was –2.6%. This amount was slightly lower than was demonstrated by a recent meta-analysis conducted by Ali et al. ,46 which considered translational studies aimed at populations with existing diabetes mellitus (≤ 50%) or at high future risk. They found a mean weight loss of −4.1% (95% CI −5.9% to −2.4%) after at least 9 months of follow-up. 2 This difference may in part be due to a lower mean BMI at baseline in studies included in our review than in studies in the Ali et al. 46 review (range 25–36 kg/m2 and 31–40 kg/m2, respectively), and a slightly longer follow-up period (12 months vs. ≥ 9 months). In addition, their review focused on interventions based only on the US DPP, whereas we considered a broader set of interventions.

Changes in the four key dietary and physical activity targets (≤ 30% energy from fat; ≤ 10% energy from saturated fat; fibre ≥ 15 g/1000 kcal; ≥ 30 minutes moderate physical activity daily) have also been shown to have independent effects on diabetes mellitus risk reduction, irrespective of weight loss. 53 However, few of the studies we examined provided data on dietary intake or physical activity, so we cannot be sure whether diabetes mellitus prevention in these studies is driven by increased physical activity, dietary change or both.

Strengths and limitations

This study is novel in that it provides an updated meta-analysis of a global set of lifestyle interventions for diabetes mellitus prevention. Our study used comprehensive search criteria and focused on establishing the utility of pragmatic attempts to achieve diabetes mellitus prevention in real-world service delivery settings.

The study is limited in that there were insufficient data to analyse outcomes beyond 12 months; our findings may not translate into long-term therapeutic value owing to uncertainty around sustaining outcomes, such as weight loss, in the longer term. 110 Furthermore, results in individual studies were not always reported on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis, leading to a probable overestimation of effect sizes.

Owing to the nature of pragmatic implementation studies, which include a number of uncontrolled studies, our analysis was restricted to intervention arms only; however, sensitivity analysis, restricted to RCTs only, indicated a mean weight change (–2.5 kg, 95% CI –3.8 to –1.2 kg) that is similar to the overall result. Additional sensitivity analysis restricted to RCTs showed that intervention arms lost 1.79 kg (95% CI –2.78 to –0.80 kg) more weight than control arms. This does suggest that the true intervention effect is smaller than suggested by the analysis restricted to intervention arms only.

Weight change was chosen as the primary outcome, as the majority of studies reported this outcome as opposed to other measures such as changes in glucose measures or progression to T2DM. Progression to T2DM would have been the preferable outcome to analyse diabetes mellitus risk reduction; however, as most studies were restricted to a 12-month follow-up, it is questionable whether or not this is a suitable period of time to fully evaluate the effect of intervention on the proportion of individuals who progress to T2DM. Although fasting and 2-hour glucose outcomes were reasonably well reported among studies, HbA1c was the least reported. This is most likely to be a result of the fact that the WHO began recommending the use of HbA1c as a T2DM diagnostic tool only in 2011, whereas many studies in this review predate this introduction. 50,62,69–80,82,85–87,89,96,97,99,102,106

Unpublished literature was not considered for inclusion in this review, leading to potential selection bias. Further bias may have also been introduced via the decision to limit studies to English-language studies only.

The results of Egger’s test for publication bias indicated evidence of publication bias for the primary outcome mean weight change, as well as for mean change in systolic and diastolic BP outcomes. However, the test has low power to detect publication bias for outcomes with few studies. In addition, when there are high levels of between-study heterogeneity, as is the case for all outcomes in this review, Egger’s test may not detect publication bias if present.

Implications for practice

Our review suggests that pragmatic lifestyle interventions are effective at promoting weight loss and that they could potentially lead to a reduced risk of developing diabetes mellitus and CVD in the future. However, the difficulties in translating this evidence into practice and in delivering guideline-based interventions need to be overcome. The ability to implement these findings in practice may be further hampered by a lack of resource for service provision, the design of efficient risk identification systems, and engagement of politicians and health-care organisations in funding national diabetes mellitus prevention programmes. Diabetes mellitus prevention strategies require substantial up-front investment to accrue longer-term benefits. 29

Future directions

More research is needed to examine the longer-term clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of pragmatic lifestyle interventions for diabetes mellitus prevention, including diabetes mellitus incidence as well as weight-loss outcomes. The practical value of diabetes mellitus prevention interventions would be much clearer if we had data on longer-term outcomes. Research is also needed to identify the role of different types of physical activity and dietary changes,54,111 and ways to increase effectiveness without increasing cost. Possible approaches might include the use of larger group sizes and the substitution or supplementation of intervention techniques using self-delivered formats (e.g. internet, smartphone or workbook). 112

Summary

Overall, the interventions were effective, but there was wide variation in effectiveness. More research is needed to establish optimal strategies for maximising both cost-effectiveness and longer-term maintenance of the lifestyle changes that these programmes can achieve.

Chapter 3 Developing the risk score

This chapter was based on previously published data, reproduced with kind permission from Springer Science+Business Media: Diabetologia, Detection of impaired glucose regulation and/or type 2 diabetes mellitus, using primary care electronic data, in a multi-ethnic UK community setting, vol. 55, 2012, pp. 959–66, Gray LJ, Davies MJ, Hiles S, Taub NA, Webb DR, Srinivasan BT, Khunti K, excerpts of text, tables 1, 2 and 3, and figures 1 and 2 (please note that minor edits have been made, with the permission of the authors, for consistency). 113

Introduction

Risk scores are a way of stratifying a population for targeted screening. They use data from risk factors to calculate an individual’s score; a higher score reflects higher risk. Risk scores can be applied either to an individual as a questionnaire (these scores generally require only data from non-invasive risk factors, which would be known by members of the public) or to a population. Population risk scores are usually developed for use in primary care where a piece of software is used to calculate the score for everyone listed on the electronic medical records using routinely stored data. Screening invitations can then be sent to those at the highest risk.

Over the past decade, a plethora of risk scores have been developed and validated for detecting those at risk of T2DM. One of the first risk scores developed in this field was the FINDRISC score. This risk score was developed for use in Finland; it is questionnaire based and designed to be completed by members of the public to detect those at risk of developing T2DM in the future. 27 It includes eight questions relating to age, BMI, waist circumference, BP, history of high blood glucose, family history of diabetes mellitus, physical activity and consumption of vegetables, fruits or berries. This score has been shown to have acceptable levels of discrimination and, since its development in 2003, it has been validated for use in Greece,114 Bulgaria,115 Italy,116 Spain117 and Sweden. 118 It was decided not to validate this score for use in this project for a number of reasons. First, the FINDRISC was not developed for detecting those with existing undiagnosed PDM (IFG and/or IGT) and T2DM. Second, it is well reported that risk scores that have been developed for a particular population tend to have low validity when used on another. In addition, the FINDRISC does not include ethnicity, which is an important risk factor when assessing risk in a multiethnic population such as in the UK. 28,119,120 Third, the questionnaire nature of this risk score and the inclusion of patient-specific risk factors that would not be available routinely in primary care meant that this risk score could not be implemented in primary care for population-based stratification.

The Cambridge Diabetes Risk Score (CDRS) addresses some, but not all, of these issues. 121 This score was developed to detect undiagnosed T2DM and it collects data on age, sex, BMI, steroid and antihypertensive medication, and family and smoking history. This score would be suitable for use in primary care but it does not detect current undiagnosed PDM and it does not reflect the higher incidence of T2DM in those from black and minority ethnic (BME) groups. The FINDRISC identifies people who are at risk of developing T2DM in the next 10 years, with the CDRS detecting current undiagnosed T2DM only. To date, there is no evidence base for intervening in such a group for the prevention of T2DM. The evidence from the large pivotal trials for preventing T2DM is in people with IGT. 31 The ultimate aim of this programme of work is to develop and test a pragmatic intervention, taking the learning of the previous trials, delivered in a UK primary care setting. Therefore, we wished to identify people who have PDM rather than those at risk of developing diabetes mellitus in the future. Hence, it was decided to derive and statistically validate a new risk score that detects PDM/T2DM for use in a multiethnic population using data from two existing population-based screening studies from Leicester and Leicestershire. 122,123

The development and validation of the Leicester Practice Risk Score (LPRS) had three phases. Initially, a pilot score was developed and validated, and tested in two general practices (phase one). The aim of the pilot phase was not so much to assess the performance of a risk score per se, but to test the feasibility of a risk-score approach for identifying people with PDM in primary care. Owing to the milestones required for the programme of work, this feasibility testing needed to be completed before the final data set from the large population-based screening study was ready for analysis. A very simple pragmatic score was therefore derived to enable this approach to screening to be tested. Reporting of details of how this score was derived is outside the scope of this report. Following this pilot, complete data from a large-scale population-based screening study [Anglo–Danish–Dutch study of Intensive Treatment In people with screen detected diabetes in primary care (ADDITION)] became available; therefore, the score was redeveloped based on the learning from the pilot study. This score was subsequently used to identify those at high risk for screening within Let’s Prevent (phase two). Following this, the score was updated based on subsequent improvements in data completeness in primary care and the addition of HbA1c to the diagnostic criteria for T2DM (phase three). Given that this score is published and used in clinical practice, full details of the development and validation are given for the final updated score.

Data sets

Data sets from two existing closely related screening studies were used throughout all three phases, that is, ‘Screening Those At Risk’ (STAR) and ADDITION. These are described briefly below and their shared methodology is outlined in the final section.

Screening Those At Risk

The STAR study aimed to identify the prevalence of PDM and undiagnosed T2DM in those with at least one recognised risk factor for diabetes mellitus. Between 2002 and 2004, 3225 individuals aged 40–75 years inclusive (25–75 years for those with South Asian, Afro-Caribbean and other ethnicity owing to the reported higher risk of T2DM) with at least one risk factor for T2DM were invited for screening from 17 general practices. Risk factors for inclusion into the study included a documented clinical history of coronary heart disease, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, cerebrovascular disease or peripheral vascular disease, previous history of IGT, gestational diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome in those with a BMI of > 25 kg/m2, a first-degree relative with T2DM or BMI of > 25 kg/m2, and current or ex-smokers. Full details of the methodology and results are published. 122

Anglo–Danish–Dutch study of Intensive Treatment In people with screen detected diabetes in primary care-Leicester

This study has been described in detail elsewhere. 123 In summary, ADDITION-Leicester invited a randomly selected 30,950 people aged 40–75 years (25–75 years if non-white, although those aged 25–40 years are excluded from these analyses) without diagnosed diabetes mellitus from 20 practices from Leicester and the surrounding county for screening between 2004 and 2008; 6749 individuals attended screening (response rate 22%). All 6749 participants underwent an OGTT and, therefore, people with PDM and previously undiagnosed T2DM were identified. Those found to have undiagnosed T2DM were included in a RCT of intensive treatment versus standard care;124 data from this trial are not included in this analysis. The analysis is based solely on the cross-sectional screening data and, therefore, includes people identified with normal glucose, PDM and T2DM.

Shared protocols

In both studies all screened participants received an OGTT using 75g of glucose, and had biomedical and anthropometric measurements taken by a trained member of research staff, which included data such as medical history, medication, BMI, BP, and a self-completed questionnaire. The questionnaire collected data on smoking status, alcohol consumption, occupational status, ethnicity, physical activity, the FINDRISC score and a number of scales to measure domains such as well-being and anxiety.

All participants were diagnosed with screen-detected IFG, IGT and T2DM according to WHO 1999 criteria,8 with PDM referring to the composite of IGT and/or IFG. HbA1c was collected for all participants at baseline.

Anthropometric measurements were performed by trained staff following standard operating procedures, with height being measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a rigid stadiometer (Seca, Hamburg, Germany) and weight in light indoor clothing measured to the nearest 0.1 kg with a Seca scale (Seca UK, Birmingham, UK). BMI was defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared (kg/m2). Waist circumference was measured at the mid-point between the lower costal margin and the level of the anterior superior iliac crest to the nearest 0.1 cm.

Data sets used for development and statistical validation of the risk scores

The use of each data set across the three phases is outlined in Table 3. Given the larger sample size and population-based approach, the ADDITION data set is preferable for the development of a risk score, with STAR then being used for temporal (i.e. evaluation on external data from the same centre) validation. Owing to the unavailability of the ADDITION study data in a format suitable for analysis in late 2007 when the pilot study was commenced, the development of the initial risk score was divided into two phases. In phase one, a pilot risk score was developed using data from the STAR study, specifically for use in the pilot screening study. Temporal validation using the ADDITION study data set was carried out retrospectively. In phase two, the risk score for use in the Let’s Prevent study was developed. Its design is based on analysis of the ADDITION study data set, which, being larger than the STAR data set, allows greater sensitivity to the possible predictive values of potential risk factors. The same approach was used when the risk score was updated in 2010.

| Risk score | Phase | STAR | ADDITION |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot risk score | Development | ✓ | |

| Validation | Temporal | ||

| Initial LPRS | Development | ✓ | |

| Validation | Temporal | ||

| Updated LPRS | Development | ✓ | |

| Validation | Temporal |

The characteristics of those included in the two data sets are given in Table 4. The mean age in the ADDITION-Leicester data was 57.3 years, with 48% being male. Three-quarters of the cohort were white European, with 23.5% of other ethnicity (of which the majority were South Asian, 91%). Of the 6390 people aged ≥ 40 years screened as part of the ADDITION study, 927 (14.5) were found to have PDM and 206 (3.2) had undiagnosed T2DM based on an OGTT, which rises to 485 (7.6%) when including HbA1c in the diagnostic criteria. The STAR data set had similar characteristics but with slightly more people reporting that they were smokers (25% vs. 14%).

| Variable | ADDITION (n = 6390) | STAR (n = 3004) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 57.3 (9.6) | 56.7 (9.8) |

| Sex male, n (%) | 3046 (47.7) | 1383 (46.1) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White European, n (%) | 4688 (75.8) | 2138 (73.7) |

| Other, n (%) | 1499 (24.3) | 763 (26.3) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 78.3 (16.0) | 77.9 (16.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.1 (5.0) | 28.2 (5.2) |

| Waist circumference (cm), mean (SD) | 94.2 (13.1) | 95.6 (13.0) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 137.9 (19.4) | 134.0 (20.5) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 85.6 (10.6) | 80.4 (10.8) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 891 (13.9) | 762 (25.4) |

| HbA1c (%), mean (SD) | 5.7 (0.6) | 5.8 (0.7) |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol), mean (SD) | 39 (17) | 40 (7) |

| Cholesterol (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 5.6 (1.1) | 5.4 (1.0) |

| LDL (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.9) |

| HDL (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) |

| PDM, n (%) | 927 (14.5) | 407 (12.6) |

| T2DM (OGTT), %, mean (SD) | 206 (3.2) | 92 (3.1) |

| T2DM (OGTT or HbA1c), %, mean (SD) | 485 (7.6) | 367 (11.4) |

Statistical methods

The purpose of the risk scores was to identify those at greatest risk of glucose intolerance, defined as those with either T2DM or PDM (which includes IFG and/or IGT) who, up until screening with an OGTT, had been undiagnosed. All of the scores developed and validated as part of this project used similar methodology. To avoid repetition this is detailed below. Where differences occurred, these are also summarised.

Development

Variables considered

The variables to be considered for inclusion in the score are limited to those that are included in the ‘typical’ general practice database with a good level of reliability and completeness. The consensus is that the following items satisfy these conditions: age, sex, BMI, ethnicity (white European or other), family history (of type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus), smoking status (current smoker or ex or non), prescribed antihypertensives, statins or steroids, history of CVD (myocardial infarction, stroke, heart valve disease, atrial fibrillation, angina, angioplasty or peripheral vascular disease) and deprivation [measured using the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) calculated from the individual’s postcode]. This pool of variables assessed covers the majority of those included in previously developed screening tools and screening guidelines. 125,126

Modelling

All modelling was carried out in Stata (version 11.1) using logistic regression with the composite of IGR [defined as IFG or IGT on OGTT (not including HbA1c 6.0–6.4 at this stage)] or T2DM [OGTT or HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol)] versus normal as the dependent variable. A staged approach to variable selection was taken. First, we assessed the association of each variable and the outcome independently (PDM/T2DM). Those that were significantly (p < 0.05) associated with the outcome were then assessed in combination and those that became non-significant when adjusted for other variables in the model were removed. This process was then repeated. Each combination of variables was compared in terms of the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, with the aim of maximising this. The effect of adding each previously excluded variable into the model was assessed to make sure that no potentially important variables were missed; again, their significance and effect on the ROC was assessed. Once a final model was established we assessed all possible two-way interactions and the addition of polynomial terms, although we acknowledged that we would have limited power to explore these. The importance of introducing functional polynomial terms was also assessed using the Akaike information criterion. 127 Throughout the analysis, missing data were not imputed and analysis was carried out on a complete-case basis.

The updated risk score (described in phase three) also included HbA1c of ≥ 6.5% in the definition of T2DM, given that HbA1c was recommend as a diagnostic tool by WHO in 2011. 10 HbA1c was not used in the definition of PDM as, although using a range of 6.0–6.4% has been recommended for identifying those at high risk of developing diabetes mellitus in the future,12 WHO concluded that there was insufficient evidence for classifying PDM using HbA1c. 10

Creating a scoring system

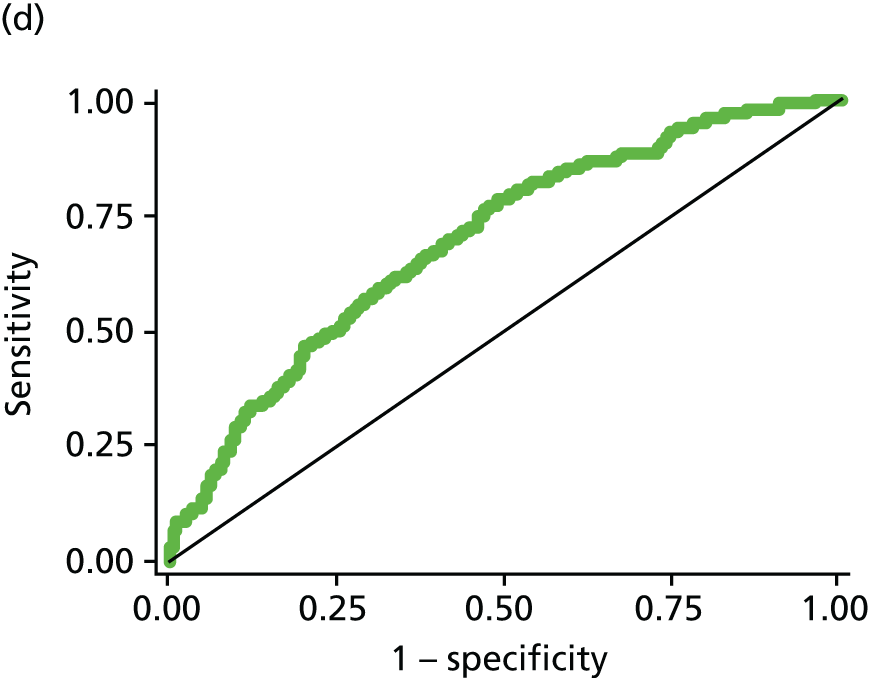

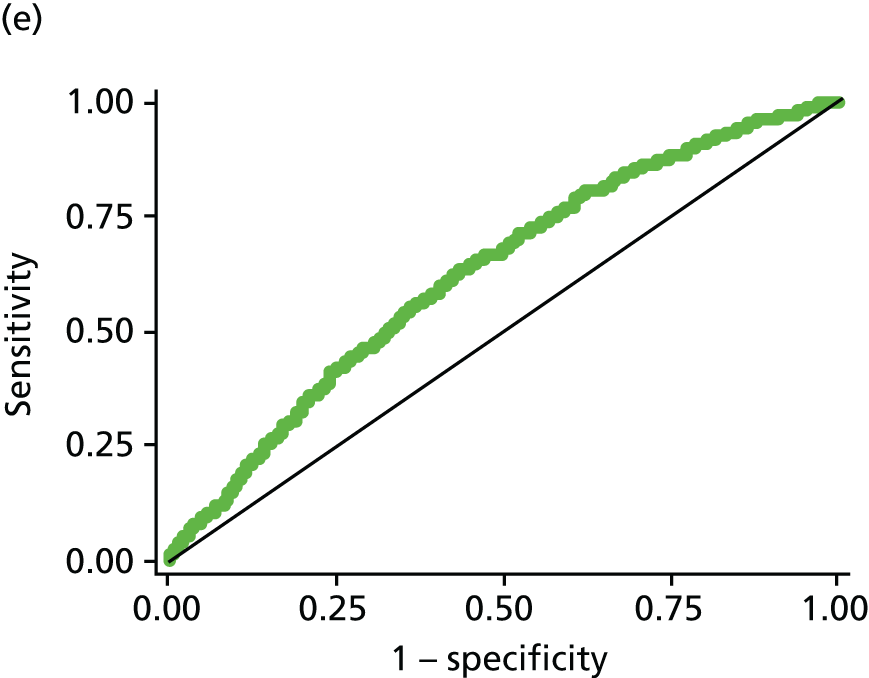

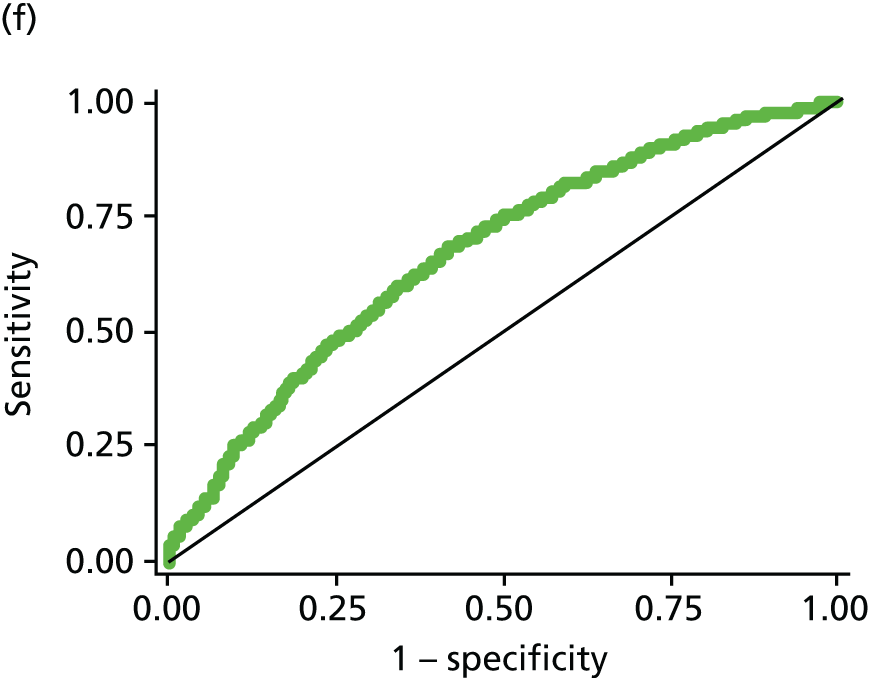

Once a final model has been developed a risk score needs to be devised from this. For the pilot score a crude, easy-to-calculate score was developed (see Phase one: pilot risk score results for details). For the initial and updated risk scores, the scores were derived by summing each of the β coefficients from the best fitting model.