Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 10/3010/01. The contractual start date was in March 2012. The final report began editorial review in November 2016 and was accepted for publication in February 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stuart Logan reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health, Research and Care. He also reports a grant from the NIHR Public Health Research programme during the conduct of the study. Colin Green served as a member of the funding panel for the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme from 2009 to 2013. Colin Green (2007–13) and Siobhan Creanor (2013–present) served as members of the NIHR Research Funding Committee for the South West Region of the Research for Patient Benefit Programme. Intervention costs for this study were paid for by the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry. Stuart Logan (NF-SI-0515–10062) and Rod Taylor (NF-SI-0514–10155) are NIHR senior investigators. This study was undertaken in collaboration with the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (CTU), a UK Clinical Research Collaboration-registered CTU in receipt of NIHR CTU support funding. None of the funders had any involvement in the Trial Steering Committee, data analysis, data interpretation, data collection or writing of the report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Wyatt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Obesity is considered to be one of the greatest challenges facing public health in the 21st century. Currently, one-fifth of boys and girls in England start school overweight or obese, and one-third of children leave primary school (aged 11 years) overweight or obese. 1 Childhood obesity is strongly associated with socioeconomic status, with children from the least affluent decile being twice as likely to be obese as children from the most affluent decile. 2 Childhood obesity tracks into adulthood; a recent systematic review3 reported that obese children are five times more likely than non-obese children to be obese as adults, and that 80% of obese adolescents were still obese in adulthood.

School-based obesity preventative interventions have the potential to reach a large number of children and families across the socioeconomic spectrum, and schools provide the organisational, social and communication structures to educate children and parents about healthy lifestyles. Systematic reviews of school-based interventions to prevent obesity and/or increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviours show, at best, moderate evidence of effectiveness, with the majority of studies conducted in the USA. 4 Several methodological shortcomings have also been identified, such as differential loss to follow-up, not having sufficient statistical power to detect clinically meaningful differences between groups, particularly on adiposity outcomes, and short-term follow-up. 5,6

Evidence for the effectiveness of school-based obesity prevention programmes

In 2012, Khambalia et al. 7 examined the quality of evidence and findings from existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses of school-based programmes in the control and prevention of childhood obesity published between 1990 and 2010. Eight reviews and 112 studies were examined in total, with the most recent literature search conducted in 2008. All eight reviews acknowledged that the studies they included had heterogeneous designs, outcomes and ages of participants. The reviews were judged for their quality, and five were considered to be high quality according to their prespecified criteria.

These five reviews included three meta-analyses: Cook-Cottone et al. ,8 which examined study factors and effect sizes in obesity prevention programmes in 6- to 12-year-olds; Gonzalez-Suarez et al. ,9 which focused on the management of obesity in 11- to 18-year-olds; and Katz,10 which determined the effectiveness of school-based strategies for both obesity prevention and obesity management in 3- to 18-year-olds. The other two reviews were qualitative systematic reviews: Brown and Summerbell,11 which assessed the effectiveness of prevention programmes focusing on changing dietary intake and/or physical activity levels in 5- to 18-year-olds; and Kropski et al. ,12 which provided a focused evaluation of the quality and results of long-term obesity prevention programmes in 2- to 19-year-olds.

Despite the heterogeneity of studies included in these reviews, the authors concluded that there was evidence to recommend that school-based obesity prevention programmes include both diet and physical activity components, involve the child’s family and be of longer duration. However, they did suggest that, given no one single intervention will fit all school populations, further high-quality research needs to focus on identifying specific programme characteristics and approaches predictive of success.

Wang et al. 4 is the most recent systematic review and meta-analysis of childhood obesity prevention programmes. Of the 139 intervention studies identified, 115 (83%) were located in the primary school, of which 37 were school-based only. These studies assessed the effect of a combined diet and physical activity intervention on weight-related outcomes. The approaches included intensive classroom physical activity lessons led by trained teachers, moderate to vigorous physical activity sessions, nutrition and education materials, and promoting and providing a healthy diet. There was weak evidence that these approaches were effective at reducing body mass index (BMI), BMI standard deviation score (SDS), prevalence of obesity and overweight, percentage body fat, waist circumference and skinfold thickness. Intervention studies that reported a significant effect tended to be of long duration (between 52 and 156 weeks), with the longer-term programmes having the greatest effect. A further 28 studies were school-based with a home component (e.g. family homework lessons, training and information sheets for parents, nutrition programme for children and family). These studies provided moderate evidence of effectiveness, with half reporting statistically significant beneficial intervention effects. However, in all studies, a range of adiposity measures was used and there was high study heterogeneity in terms of setting, design, sample size, characteristics, intervention approach and length of follow-up, which makes cross-comparisons challenging. The review was unable to identify specific programme characteristics and approaches predictive of success or to explore the comparative effectiveness of specific intervention approaches (e.g. educational interventions vs. environmental intervention).

Since the publication of the above reviews, a number of additional evaluations of school-based interventions13–16 have been published involving children of a similar age to those in the Health Lifestyles Programme (HeLP) study. However, evidence of effectiveness in changing behaviours and/or weight status of children continues to be inconsistent and the content of the intervention varies greatly between studies.

In 2010, The Healthy Study Group13 published its findings from a 3-year cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a multicomponent programme addressing risk factors for diabetes among American children whose race or ethnic group and socioeconomic status placed them at high risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The intervention consisted of four integrated components: (1) nutrition, (2) physical activity, (3) behavioural knowledge and skills, and (4) communications and social marketing. No significant group differences were observed in the prevalence of overweight and obesity (primary outcome), but children in the intervention schools had a greater reduction in the secondary outcome of BMI SDS (–0.01 vs. –0.05; p = 0.04) at 3-year follow-up.

In 2011, Jansen et al. 15 published their findings from an 8-month cluster RCT of a school-based intervention to reduce overweight and improve fitness in 6- to 12-year-old primary school children in a multiethnic, low-income, inner-city neighbourhood in Rotterdam, Netherlands. This was a multicomponent programme based on behavioural and ecological models, involving physical education sessions delivered by a specialist physical education teacher, additional sport and play activities outside school hours, and an educational programme. Significant positive intervention effects were found in terms of the percentage of overweight children, waist circumference and 20-minute shuttle run among those aged 6–9 years. The prevalence of overweight in 6 to 8-year-olds increased by 4.3% in the control group and by 1.3% in the intervention group. No significant effects were found for BMI for 9- to 12-year-olds.

In 2014, the results of the Active for Life-year 5 (AFLY5)16 study, a UK primary school-based cluster RCT aimed at increasing physical activity, reducing sedentary behaviours and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in 9- to 10-year-old children, were published. No differences were observed between the intervention and control groups in the three primary outcomes outlined above. The intervention was effective for three out of nine secondary outcomes after multiple testing was taken into account: self-reported time spent in screen viewing at the weekend, self-reported servings of snacks per day and servings of high-energy drinks per day were all reduced. The intervention was an adaptation of the American school-based intervention Planet Health,17 consisting of 16 lessons (delivered by the class teacher) and 10 pieces of homework in which the children were encouraged to work with their parents.

Grydeland et al. 14 assessed the effect of a 20-month cluster RCT of a school-based intervention trial on the BMI of 11-year-old children in Norway. The intervention took a multilevel approach including collaboration with school principals and teachers, school health services and parent committees. School teachers were the key in delivering the intervention components, which included lessons, fact sheets for parents, meetings and awareness raising of leisure time activities. There was no significant effect of the intervention overall, although significant effects were found for both BMI (p = 0.024) and BMI SDS (p = 0.003) in girls. Furthermore, children of higher-educated parents seemed to benefit more from the intervention, highlighting the need to develop interventions that do not widen the health inequalities that already exist between children from different socioeconomic groups.

Rationale for HeLP

We began work to design, pilot and then fully evaluate a school-based obesity prevention programme in primary schools in 2006. Our aim was to create a novel programme of activities using an intervention mapping approach18 and to follow the UK Medical Research Council’s (MRC) framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions. 19 The intervention mapping approach combines theoretical and stakeholder perspectives, empirical evidence and new research to assess and develop a potential set of possible solutions for a particular problem, rather than defining a practice or research agenda around a specific theory. We therefore searched the literature for appropriate systematic reviews of school-based obesity prevention programmes and carried out extensive stakeholder consultation with practitioners (teachers, head teachers and drama specialists), local policy-makers (director of public health and the public health policy lead), public health commissioners and the local healthy schools team, in order to understand the school, education and public health context at that time. The overarching aim of the research was to develop a school-based intervention, assess its feasibility and complete pilot work before we sought funding to run the full-scale effectiveness trial, were that deemed appropriate. 20

Around the time of our initial research, the Brown and Summerbell review11 concluded that interventions that increase activity and reduce sedentary behaviours may help children to maintain a healthy weight, although the results were short term and inconsistent. Their conclusions were that a combined approach was likely to be more effective in preventing children becoming overweight in the long term.

We wanted to incorporate these recommendations into our programme and address the methodological limitations reported in other trials, such as insufficient statistical power; biased recruitment from, and retention of, more affluent schools, children and families; short follow-up periods; and high levels of attrition. Thus, a crucial focus in developing HeLP was to promote the engagement of schools, children and their families throughout the intervention, as we believed this to be essential for behaviour change to occur. In line with the World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools framework,21 we aimed to develop activities that were compatible with the existing school curriculum and promote messages in a manner that could have an impact on the wider school culture, as well as specific behaviours of children and their families. First and foremost, we sought to build supportive and trusting relationships with teachers, children and their families by employing people with specific skills and competencies to deliver the intervention.

We developed an initial phase of the intervention to create a receptive context for the programme and utilised engaging delivery methods to try to increase school, child and family engagement with the programme. Previous research into preventing childhood obesity has found that it can be difficult to engage parents in order to affect change within the family;22,23 thus, we believed that the delivery methods needed to be sufficiently dynamic, creative and empowering to motivate the children to talk about the activities at home with their parents and encourage parents to come into the school to attend key events. This thinking led us to explore the use of interactive drama, as it had shown promise in promoting positive attitudes towards a number of health behaviours24 and was a means of delivering a range of behaviour change techniques in manner that could engage the children.

The development of the intervention was guided by the information, motivation and behavioural skills (IMB) model25 and intervention activities were ordered to enable support and sustain behaviour change in accordance with the health action process model. 26

Between 2006 and 2008, we worked with 8- to 11-year-old children in one local primary school to assess a range of delivery methods for key objectives identified in the intervention mapping process. We then went on to refine the newly developed intervention based on feedback from teachers, children and parents, and carried out a feasibility study (examining before-and-after intervention changes in the same children) in a second primary school from a more economically deprived ward of Exeter, Devon. In the feasibility study we focused solely on children aged 9–10 years, as our early work demonstrated that this age group was more receptive to the messages and, crucially, engaged their families to the greatest extent. 27 Teachers also informed us that the Year 5 curriculum had the flexibility to deliver the healthy lifestyles week, whereas in Year 6 there was pressure to focus on Standard Assessment Tests (SATs). Based on qualitative data from teachers and head teachers in the piloting stages, the intervention was extended to add activities at the beginning of Year 6. Teachers felt that this would not have an impact SATs teaching and was important in further motivating the children to change behaviours. Minor refinements were also made to the education lessons and the drama scripts to enhance delivery and continuity. In 2008 we carried out an exploratory RCT [funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research for Patient Benefit programme] with 202 children aged 9–10 years in four schools to assess ‘proof of concept’ and the feasibility of running a cluster RCT of HeLP. The trial design and the intervention were feasible and acceptable to schools, children and their families. At 18 months, compared with children in the control schools, children in the intervention schools consumed fewer energy-dense snacks and more healthy snacks, had less negative food markers and more positive food markers, had lower mean television/screen time and spent more time doing moderate to vigorous physical activity every day. 28 Children in the intervention group had lower average anthropometric measures at 18 and 24 months than children in the control group, with larger differences at 24 months than at 18 months for all measures. 28

Funding for the definitive trial was awarded in March 2012 and the trial began in September 2012. None of the schools that were involved in the feasibility and pilot work were included in the definitive trial presented in this monograph.

Rationale for our study design

The HeLP study was designed to address some of the methodological weaknesses in previous school-based RCTs to prevent obesity. Schools have been highlighted as providing a captive audience with the potential to access children across the socioeconomic spectrum; however, few studies took a relational approach to both the intervention and the trial design, whereby the building of relationships with all participants to enhance engagement with the programme and the trial was a key focus in recruitment, data collection, and intervention design and delivery.

Specifically, the design of the HeLP study ensured that (1) baseline measurements were collected before schools (and children) were allocated to the intervention or the control group; (2) a standardised objective measure with a significant follow-up time was utilised to assess obesity prevention (BMI SDS at 24 months); (3) an objective measure of physical activity, with evidence of high compliance, was used29 (GeneActiv activity monitor; www.activinsights.com); (4) half of the schools had ≥ 19% of children eligible for free school meals (the national average at the time of the trial) to ensure that the results were generalisable across the socioeconomic spectrum; and (5) loss to follow-up was minimised by creating detailed standard operating procedures for the collection of all measures at each time point, with a focus on enhancing positive relationships with teachers, children and parents.

During intervention delivery we ensured that (1) delivery personnel had the necessary skills and competencies to build relationships; (2) there was one key contact person per school who co-ordinated the research hand delivery (the HeLP co-ordinator); (3) the delivery methods used were suitably engaging and dynamic for the target group, so that the children would be motivated to take the messages home and initiate discussion with their family; (4) the intervention used strategies to enhance identification with, and ownership of, the healthy lifestyle messages and enabled children to explore possible solutions and propose changes in preparation for real-life situations; (5) information and guidance on promoting healthy eating and physical activity went home to parents throughout the intervention period; and (6) parents were involved in setting goals with their child.

The intervention aimed to change behaviours both inside and outside the school environment; these measurements were concerned with behaviours across the week, including weekends. We aimed to capture physical activity data across the whole week for children at baseline and at 18-month follow-up. To support this aim, we used wrist-worn activity monitors (the GeneActiv accelerometer), as feasibility studies had demonstrated high rates of compliance with this monitor in this age group. 30 We took account of the clustered nature of the trial design in the sample size calculation and analysis, and examined the effect of the intervention 6 months (18 months post baseline) and 12 months (24 months post baseline) after its completion in order to examine whether or not any observed effects of the intervention were sustained (see the published trial protocol31).

Aim and objectives

The aim of this cluster RCT was to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HeLP in preventing overweight and obesity in children.

Our objectives were:

-

to assess the effectiveness of HeLP in children aged 9–10 years by comparing between intervention and control schools:

-

BMI SDS at 24 months (primary outcome)

-

BMI SDS at 18 months

-

waist circumference SDS at 18 and 24 months

-

percentage body fat SDS at 18 and 24 months

-

proportion of children classified as underweight, overweight and obese at 18 and 24 months

-

physical activity (average time spent per day in sedentary, light, moderate, moderate to vigorous and vigorous activity) and average weekly volume of physical activity in milligravity (mg) units at 18 months

-

food intake (number of energy-dense snacks, healthy snacks, negative and positive food markers) at 18 months.

-

-

to estimate the costs associated with the delivery of the HeLP intervention and its cost-effectiveness versus usual practice

-

to conduct a mixed-methods process evaluation and mediational analysis to explore the way the programme worked (i.e. how it was delivered, taken up and experienced, and the possible mediators of change).

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Study design

We carried out a pragmatic, superiority, cluster RCT with blinded outcome assessment, allocating schools (1 : 1) to either the HeLP intervention or usual school practice. As the intervention was designed to be delivered in schools, a cluster design was used. Individual child measurements were collected at baseline, 12 months [My Lifestyle Questionnaire (MLQ) only, which assessed potential mediating variables], 18 months and 24 months (anthropometric only) post baseline. Alongside the evaluation of effectiveness, we carried out a parallel economic and process evaluation.

Following the exploratory trial28 and after assessing delivery requirements, we decided to run the trial in two cohorts, each with the same number of intervention and control schools. All schools were recruited in spring 2012 and then allocated to cohort 1 (commencing the trial in September 2012) or cohort 2 (commencing the trial in September 2013).

Ethics approval and research governance

We obtained ethics approval for the trial from the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry Research Ethics Committee (reference number 12/03/140) in March 2012. Research governance approval was obtained in June 2012 from our sponsor, the Royal Devon & Exeter NHS Foundation Trust (study number 1304762). A Trial Steering Committee (TSC) was composed and chaired by Professor Martin White (editor-in-chief of the Public Health Research programme), with five other independent members and the research and development director for the Royal Devon & Exeter NHS Trust as the research sponsor (see Appendix 1). After discussion at the first TSC meeting (5 November 2012), it was agreed that a Data Monitoring Committee was not necessary because the risk of harm was considered low and no interim analyses were planned.

Stakeholder involvement

The development of HeLP and the conduct of the trial benefited greatly from the extensive stakeholder involvement in both intervention and trial design. We worked with a group of teachers, head teachers, parents and children from the early piloting of HeLP27 who became our Project Advisory Group (PAG). We invited teachers and parents from our PAG to be partners on our research bids for both the exploratory28 and the definitive trial. 31

Membership of the PAG increased as we progressed though the piloting phases. Meetings were held when required and at times convenient to the group (usually 4–6 p.m.), and all expenses were paid, including cover for teaching staff when necessary. Our PAG members advised us on what was feasible and acceptable when taking behavioural and anthropometric measures from 9- to 10-year-old children, and how to communicate with parents about the research process so that they would (1) receive the information, (2) understand it and (3) feel that they were able to engage with the researchers if they had any concerns or queries. In addition, it was important for us to understand how best to recruit schools and engage teachers with both the programme and the trial. The head teacher in our PAG suggested that we recruit schools via a regional network of primary school heads (the Devon Association of Primary Headteachers) during one of their quarterly briefing sessions, and a teacher involved in the exploratory trial28 offered to talk to head teachers about her experiences of being involved in the programme during the session.

Our PAG also supported the intervention development and delivery, providing invaluable feedback on possible intervention activities and delivery methods and ensuring that they were acceptable to and feasible for schools, children and their families. It was important that any intervention we developed did not widen existing health inequalities and had the potential to engage children and their families from across the socioeconomic spectrum. Our PAG highlighted the importance of quality delivery by personnel who were able to engage school staff, children and their families. Two parent members helped us to recruit the HeLP co-ordinators for the definitive trial, in addition to providing critical feedback during practise delivery of the parent engagement events.

Eligibility and recruitment of schools and children

Schools from across Devon were eligible for inclusion, and they were recruited via the Devon Association of Primary Headteachers and local primary school learning community meetings between March and July 2012. The inclusion criteria were state primary and junior schools with children in at least one single Year 5 group of ≥ 20 children. At the start of the trial we estimated that approximately 125 schools were eligible. All children in all Year 5 classes in the school were invited to participate. We aimed to have half of the schools in the trial with at least the national average percentage of pupils eligible for free schools meals (19% at the time of recruitment of schools). Special schools (for children whose additional needs cannot be met in a mainstream setting) were excluded because they were unlikely to be teaching the standard national curriculum around which the intervention had been designed.

Schools that were willing to participate and fulfilled all of the inclusion criteria were then purposely sampled to represent a range of number of Year 5 classes (1–3 classes), locations (urban and rural) and deprivation (< 19% and ≥ 19% of children eligible for free school meals). Schools that were eligible but not sampled for the study were asked if they were prepared to go on a ‘waiting list’ in case any of the schools allocated to participate in cohort 2 dropped out during the interim 1-year period before commencing participation in the trial.

Children were recruited using an ‘opt-out’ system, in which detailed written information about the trial was sent directly home to parents/carers via the school, with parents returning an ‘opt-out’ form if they did not want their child to participate in the measures only or in either the intervention or the measures. Parents were given 3 weeks to return the opt-out form and class teachers regularly reminded the children during this period to encourage their parent(s) to read the pack. Parents were able to speak to the class teacher or the school’s allocated HeLP co-ordinator at any time if they required further information, which was also made clear in the written information provided.

All children who were on the registration list at one of the recruited schools at the start of the autumn term of 2012/13, and whose parent/carer did not complete an opt-out form, were classed as participants.

Randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding

Randomisation was by school. All schools were initially randomly allocated to intervention or control by a computer-generated sequence that was stratified by (1) the proportion of children eligible for free school meals (< 19% or ≥ 19%) and (2) school size (one Year 5 class or ≥ 2 Year 5 classes). For practical reasons, half of the schools commenced the study in 2012 (cohort 1) and the other half commenced it in 2013 (cohort 2). Randomisation was performed by a statistician in the UK Clinical Research Collaboration-registered Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit immediately after all schools had been recruited (i.e. in 2012) but each school’s allocated group (intervention or control) was not communicated to the schools, parents or researchers until after the baseline measures had been taken in each cohort (2012 for cohort 1 and 2013 for cohort 2). The Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit ensured that there were equal numbers of control and intervention schools in both cohorts in order to facilitate trial delivery.

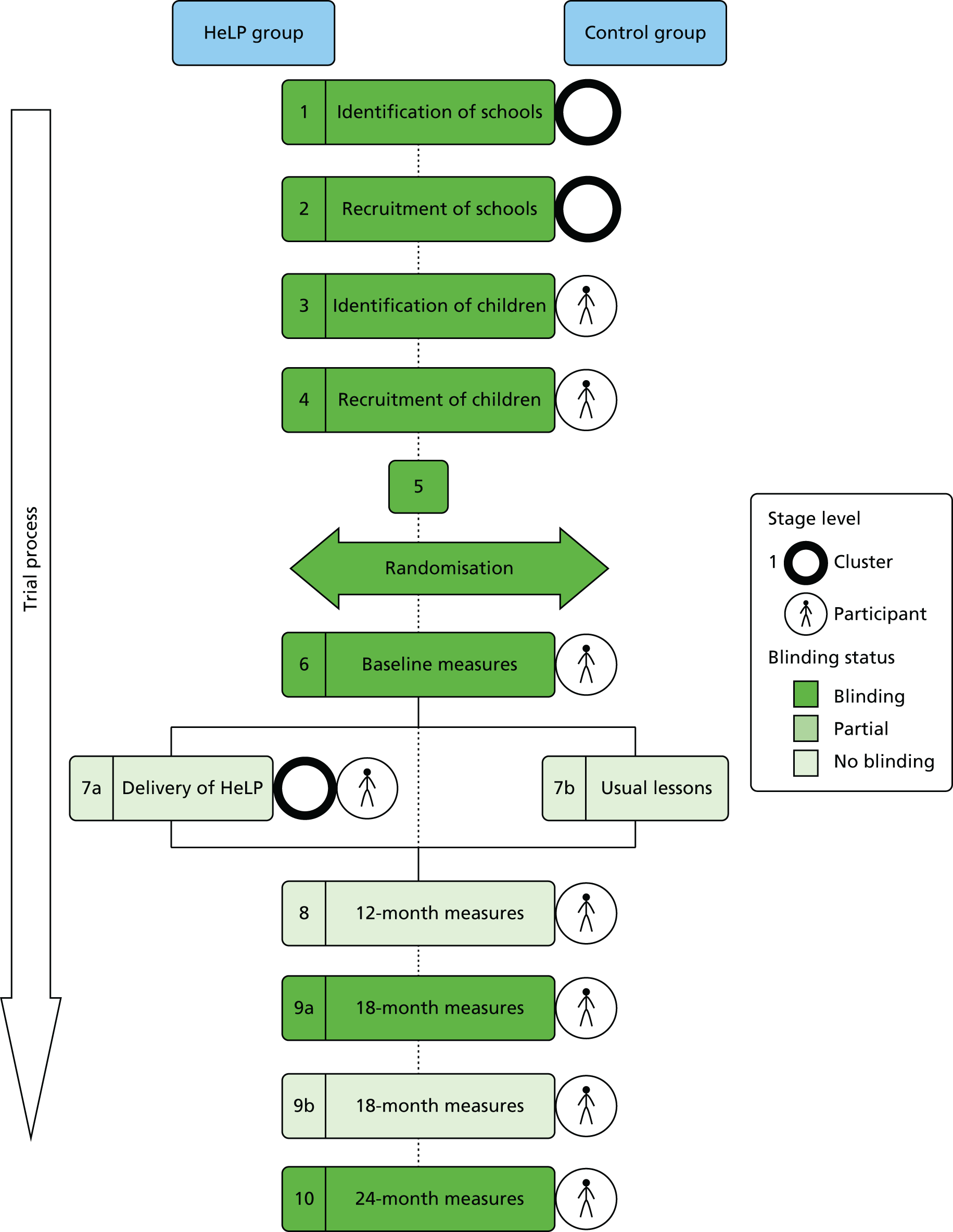

Figure 1 shows the timeline cluster33 for the HeLP study and Table 1 provides the key to the figure.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline cluster diagram for HeLP. Reproduced from Lloyd et al. 32 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 |

Identification of schools Trial team attended Devon primary head teachers’ meetings and network events |

| 2 |

Recruitment of schools All Devon state primary and junior schools with children in at least one single Year 5 group of ≥ 20 children eligible to participate. Schools that expressed interest in participating were purposely sampled to represent a range of number of Year 5 classes (1–3 Year 5 classes), locations (urban and rural) and deprivation (< 19% and ≥ 19% of children eligible for free school meals). The remaining schools were placed on a waiting list for cohort 2 (two schools allocated to cohort 2 dropped out before commencing the trial and were replaced by a school from the waiting list) |

| 3 |

Identification of children All children in Year 5 in each recruited school were eligible to participate |

| 4 |

Recruitment of children Information sent to Year 5 child’s parent/carer, who had the opportunity to opt out child from trial |

| 5 |

Randomisation Allocation of schools to intervention or control group was done using a computer-generated sequence, stratified on school size (one Year 5 class vs. ≥ 2 Year 5 classes), and percentage of pupils eligible for free school meals (< 19% vs. ≥ 19%) as an indicator of school-level socioeconomic status. After randomisation to intervention or control, schools were allocated to cohort 1 or cohort 2 by a statistician from the Clinical Trials Unit, with equal numbers of intervention and control schools in both cohorts. Allocation remained concealed from all delivery personnel, schools and children until after baseline measures were captured in each cohort |

| 6 |

Baseline measures Performed by trained assessors, who were blinded to schools’ allocated groups |

| 7a |

Intervention delivery HeLP intervention was delivered to schools and children who were allocated to the intervention group, with no blinding for schools, HeLP co-ordinators, children or parents/carers |

| 7b |

Usual care Children in schools allocated to control group received usual care, with no blinding for schools, HeLP co-ordinators, children or parents/carers |

| 8 |

12-month measure Self-completed MLQ |

| 9a |

18-month measures Anthropometric measures collected by trained independent assessors blinded to group allocation |

| 9b |

18-month measures Self-completed FIQ while children were still at primary school, 18 months post baseline. Physical activity data from a subset of children while they were still at primary school, 18 months post baseline, were objectively assessed |

| 10 |

24-month measures Anthropometric measures were collected by trained independent assessors, blinded to group allocation, after children had moved to secondary school (secondary schools had a mix of children from intervention and control schools), 24 months post baseline (12 months post intervention) |

Intervention

Full details of the intervention have been published in the trial protocol and a paper describing the intervention mapping procedures. 34 In summary, following the literature review and stakeholder consultation (step 1 of the intervention mapping process), we mapped out programme objectives and their associated behavioural and environmental determinants (step 2), selected behaviour change techniques and delivery methods (step 3) and then produced intervention components and their associated materials for delivery (step 4). Steps 5 and 6 of the intervention mapping process involved feasibility and piloting. A summary of the intervention is given below.

HeLP was a theory-based, multicomponent, school-based obesity prevention intervention delivered to all Year 5 children (aged 9–10 years) in a school. It consists of four phases delivered during three school terms, which have been ordered to enable and support behaviour change. HeLP delivers a general healthy lifestyle message, encouraging a healthy energy balance with a focus on behaviours relating to the consumption of sweetened fizzy drinks, healthy and unhealthy snacks, the amount of physical activity and the amount of screen time. An overarching message promoted throughout the programme is the ‘80/20’ rule, which recommends that we should eat healthily and be active at least 80% of the time. Brief details of each phase are as follows.

-

Four HeLP co-ordinators each organised the collection of measurements and delivery of HeLP in eight schools (four intervention and four control). The co-ordinators were also responsible for delivering components of the programme (Tables 2 and 3) and for building relationships with schools, children and families. It was believed that having one key contact person for each school would be crucial in building and strengthening relationships with teachers, children and parents during the 1-year intervention period and would increase engagement with the programme, which was believed to be necessary for behaviour change to occur.

-

The HeLP co-ordinators were provided with a written delivery manual, and practised delivery of school assemblies, parent assemblies and goal setting, with critical feedback from the trial manager and the parent representatives on the PAG, before delivering the components to the children. The HeLP co-ordinator liaised with the school administrators, head teachers and teachers to discuss the programme and arrange timings for delivery at each intervention school. The teachers were provided with easy-to-read information leaflets at appropriate points throughout the intervention delivery period to ensure that they were aware of upcoming activities. A picture of the HeLP co-ordinator and their contact details were put up at the reception desk.

-

Phase 1 (spring term of Year 5) of the intervention aimed to create a supportive context by establishing relationships, raising awareness of the programme and setting the foundation for the successful delivery of subsequent components. Professional sports people and dancers came to the schools to run practical workshops and introduce the importance of healthy lifestyles. The aim was to create a ‘buzz’ in the school and help to set a positive atmosphere for future activities. At the end of this phase, children showcased the skills they had learnt in a parent assembly, during which the HeLP co-ordinator gave parents further information about the programme.

-

Phase 2 (summer term of Year 5) was the intensive healthy lifestyles week, which involved education lessons (delivered by the class teacher) every morning and interactive drama activities (delivered by a local drama group) every afternoon during the week. Table 4 lists the learning objectives for each education and drama session. Teachers were provided with a teaching manual containing all five lesson plans and associated resources, including a compact disc. No training was required for the teachers to deliver the lessons and each lesson plan was set out clearly with objectives linking to the national curriculum at Key Stage 2. Short and simple homework tasks were given at the end of each session for the children to complete in time for the next session. The drama framework was built around four characters (Disorganised Duncan, Fooball Freddie, Snacky Sam and Active Amy), each represented by an actor whose attributes related to the three key programme behaviours. Children were asked to choose the character they felt they most resembled and, during the week, they worked closely with that actor to help the character change their behaviour. These sessions were dynamic and interactive and involved role play, games, dance, problem-solving, food tasting and forum theatre. Forum theatre35 is a technique in which actors act out a family scene and children must focus on the behaviours of one character. If they notice that the character is not adhering to the healthy lifestyle messages, they can shout ‘stop’ and suggest a change the character could make to improve the outcomes. The child then enters the scene, taking on the role of the character, and the scene is rerun with the suggested change. This method brings the children into the performance, enabling them to have a direct input into the dramatic action they are watching. A drama facilitator led the drama sessions and co-ordinated the delivery of the activities within this component. All actors and the drama facilitator completed a 4-day training programme and were given a detailed manual of the drama scripts and an overview (verbal presentation and written document) of the HeLP intervention. Members of the drama team were expected to liaise with each other to practise the scripts before delivering the sessions in each school. The themes for each lesson and drama session were:

-

the energy balance (energy in)

-

the energy balance (energy out)

-

overcoming temptation

-

decision-making and responsibility

-

food marketing and goal-setting.

-

| Phase | Function | BCTs | Component (frequency and duration) | Delivery personnel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Phase 1 Creating a supportive context Spring term (Year 5) January–March |

|

|

Whole school assembly (1 × 20 minutes) Newsletter article Literacy lesson (to create HeLP rap) (1 × 1 hour) Activity workshops (2 × 1.5 hours) Parent assembly (1 × 1 hour) involving child performances |

HeLP co-ordinators HeLP co-ordinators Class teacher Professional sportsmen/dancers Class teachers/HeLP co-ordinator/drama group |

|

Phase 2 Intensive Healthy Lifestyles Week – 1 week Summer term (Year 5) April–June |

|

|

Education lessons (5 × 1 hour) (morning) Drama (5 × 2 hours) (afternoon) (forum theatre; role play; food tasting, discussions, games, etc.) |

Class teacher Drama group |

| Phase | Function | BCTs | Component (frequency and duration) | Delivery personnel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Phase 3 Personal goal setting with parental support Summer term (Year 5), June–July |

|

|

Self-reflection questionnaire (1 × 40 minutes) Goal-setting sheet to go home to parents to complete with child (1 × 10 minutes) One-to-one goal-setting interview (1 × 10 minutes) (goals sent home to parents) Forum theatre assembly (1 × 1 hour) |

HeLP co-ordinator HeLP co-ordinator/parents HeLP co-ordinator HeLP co-ordinator/drama group |

|

Phase 4 Reinforcement activities Autumn term (Year 6), September–December |

|

|

Education lesson (1 × 1 hour) Drama workshop (1 × 1 hour), followed by a class-delivered assembly about the project to rest of school (1 × 20 minutes) One-to-one goal-supporting interview to discuss facilitators/barriers and to plan new coping strategies (1 × 10 minutes) (renewed goals sent home to parents) |

Class teacher Drama group HeLP co-ordinator HeLP co-ordinator |

| Session | Education lesson learning objectives | Drama session learning objectives |

|---|---|---|

| 1: The energy balance (energy in) |

|

|

| 2: The energy balance (energy out) |

|

|

| 3: Temptation and strategies |

|

|

| 4: Decision-making and responsibility |

|

|

| 5: Food marketing and goal-setting |

|

|

An information sheet for each topic above was sent home to parents in their child’s book bag.

-

Phase 3 (summer term of Year 5) was personal goal setting with parental support. Children were encouraged to reflect on their own behaviours and set goals (based on the HeLP messages) with their parents and this was followed up with each child having a 10-minute one-to-one goal-setting discussion with their school’s HeLP co-ordinator. A sheet with each child’s goals and the character they worked with was sent directly home to parents and a copy was also kept at school in the children’s healthy lifestyles folder.

-

Phase 4 (autumn term of Year 6) focused on reinforcing all of the messages covered during Year 5 and involved a range of components to refocus the children and their parents on the HeLP messages and behaviour change strategies. This phase included a further lesson (led by the class teacher), a drama workshop (delivered by the actors), a class-delivered assembly to the whole school about the programme and a second one-to-one goal discussion with the HeLP co-ordinator.

-

Each phase of HeLP was designed to involve parents as much as possible. In phase 1, a newsletter was sent to parents and there was a parent assembly. In phase 2, an information leaflet was sent home to parents each day based on the theme covered in the drama session and parents were invited in to the school to watch work in progress during the last two drama sessions of the week. In phase 3, children set goals at home with their parent/carer on a ‘goal-setting’ sheet and returned to school with this sheet to discuss with the HeLP co-ordinator. Finalised goals were then typed up and sent directly home to parents along with the HeLP ‘80/20’ fridge magnet as a further reminder of the programme. Another parent assembly took place after the completed goals sheet had been sent home. In phase 4, following the one-to-one goal-supporting session, a further sheet with the child’s goals was, once again, sent home in the post.

-

Some components of each phase were directed to the whole school rather than to only the Year 5 children. For example, there was a whole school assembly in phase 1 and a class-delivered assembly to the whole school in phase 4.

-

HeLP was designed to allow for some flexibility, so that each activity could fit the context of the school. For example, schools were able to select the timings of parent assemblies and, throughout the year-long intervention delivery period, the HeLP co-ordinator worked closely with the teachers to understand how best to engage and involve the parents, which varied from school to school.

Phases 1–3 of the intervention took place when the children were in school Year 5 (aged 9–10 years) and phase 4 took place at the beginning of school Year 6 (aged 10–11 years). The intervention was designed to fit in with the national curriculum at Key Stage 2 and all lessons and drama sessions included learning objectives relating to personal, social and health education, science, numeracy and literacy. All learning objectives were clearly stated in the HeLP manuals and referenced against the objectives specified in the national curriculum at Key Stage 2.

Usual practice

Schools randomised to the control group continued standard education provision throughout the intervention delivery period, including any involvement in additional health promoting activities, but had no access to the HeLP resources and scripts, which have not been published and were not made available by the research team anywhere except to the intervention schools.

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was informed by the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for BMI SDS collected during the pilot/feasibility work27 and by data from another large study involving the National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP). 36 For our primary outcome measure of BMI SDS, we determined the number of schools required (assuming an average of 35 Year 5 children per school, with coefficient of variation of 0.5, and an ICC of 0.02) to detect a between-group difference in BMI SDS of 0.25 units at 24 months with 90% power, a two-sided 5% significance level, a standard deviation (SD) of 1.3 and adjusting for baseline BMI SDS (assuming within-child correlation of 0.8). We allowed for a conservative 20% loss to follow-up or missing data at 24 months. 31 These calculations showed that we needed to recruit 28 schools with a total of at least 952 children to ensure that we had 24 outcome data from 762 children for the analysis. We decided to recruit 32 schools to ensure that we had a minimum of 28 schools completing the trial, each with an estimated average of 35 children.

Outcome measures

Measurements with children were taken at baseline (before schools’ allocated groups were revealed) and at 12 (MLQ only), 18 and 24 months post baseline. The primary outcome measure of effectiveness was change in BMI SDS at 24 months. The secondary outcome measures included BMI SDS at 18 months, waist circumference SDS, percentage body fat SDS and the percentage of children classified as underweight/healthy weight, overweight and obese at 18 and 24 months with raw anthropometric measures being presented for completeness and comparison with other studies. Physical activity was measured using accelerometry and self-reported food intake scores using the validated Food Intake Questionnaire (FIQ) at 18 months, weekday and weekend. (Although this was not explicitly stated in the trial registration or published protocol, the FIQ assesses both weekday and weekend dietary behaviours and it was always our intention to analyse these data separately as well as scores averaged across the week.) Independent blinded assessors were used for the collection of the 18- and 24-month anthropometric measures.

Outcome assessments

Detailed standard operating procedures were created for the collection of each measure at each time point. Letters were sent home to parents at each assessment time point to remind them that measurements were going to take place. Within each cohort, all child-level measures were collected over an 8-week time period.

Baseline assessments (before revealing schools’ allocated groups) were undertaken in the autumn term of school Year 5, between October and November in 2012 (cohort 1) and in 2013 (cohort 2). Outcome assessments were completed: immediately post intervention in October/November 2013/14 (12 months post baseline) for the MLQ only, at 6 months post intervention in June/July 2014/15 (18 months post baseline), which included all behavioural and anthropometric measures; and at 12 months post intervention in October/November (24 months post baseline), which included only anthropometric measures. Anthropometric measurements (height, weight, percentage body fat and waist circumference) were undertaken by trained assessors, co-ordinated by the HeLP co-ordinator (all had completed enhanced Criminal Records Bureau/Disclosure and Barring Service checks). Outcome assessors completed refresher training before each data collection time point. The coefficients of variation to assess inter-rater reliability for height and waist circumference were 0.2% and 1.3% at baseline, 0.1% and 1.2% at 18 months and 0.1% and 0.4% at 24 months, indicating high inter-rater reliability. The independent outcome assessors were blinded to the allocation of schools. At 24 months post baseline, children were measured in their secondary school, and thus secondary school classes contained a mix of intervention and control children. The outcome assessors did not know the child’s group allocation. If a child said something to reveal their group allocation, the assessor was asked to record, on the pro forma, that the measurement had been taken unblinded.

The HeLP co-ordinators led the collection of the behavioural measures (FIQ and physical activity using accelerometry), as well of as the MLQ.

Anthropometric measurements

All anthropometric measures were collected over the course of 1 day in each school. If a child was absent on the day of measurement, up to three further attempts to collect their data were made for up to a further 2 weeks from the day of absence. Height was measured using a SECA stadiometer (Hamburg, Germany), recorded to an accuracy of 1 mm. Weight was measured using the Tanita Body Composition Analyser SC-330 (Tanita, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Weight was recorded to within 0.1 kg and children were asked to take off their shoes and socks or tights. Percentage body fat was estimated from leg-to-leg bioelectric impedance analysis (using the Tanita Body Composition Analyser SC-330). Waist circumference was measured using a non-elastic flexible tape measure placed 4 cm above the umbilicus.

We were mindful that, at baseline, the HeLP co-ordinator had yet to develop a working relationship with the children, so, to put the children at ease and minimise any possible stigmatisation of overweight or sensitive children, the collection of these measurements formed part of a specially designed lesson that was based around measuring in general and ways in which information can be presented. The HeLP co-ordinator led the lesson, which provided them with a good opportunity to learn the children’s names and allowed the children to become familiar with the HeLP co-ordinator. Each child, one at a time, left the classroom during the lesson to go to a private room and have their height, weight, waist circumference and percentage body fat by bioelectrical impedance measured by two other trained researchers. For the 18- and 24-month measurements, no special lesson took place, as the children were familiar with the measurement process and felt at ease with the HeLP co-ordinator, who co-ordinated the smooth running of the measurements in each school.

At each data collection time point, the children had the option to decline one or more measurements. For the anthropometric measures using the Tanita scales, a printout was produced that provided information on the child’s weight, BMI and percentage body fat. While the measurements were taken, the electronic reading was covered so that the child was unable to read their results. This process had been developed during the pilot phases to reduce any stigmatisation of overweight/obese and underweight children and to minimise any discussion about weight.

Accelerometer measurements

We used a wrist-worn triaxial accelerometer, called the GeneActiv,37 to objectively measure physical activity and sedentary time for a subset of the recruited children (one randomly selected class per participating school). These accelerometers are waterproof so they do not need to be removed for swimming or showering. We asked children to wear the accelerometer continuously (including at night) for 8 consecutive days on the wrist of their non-dominant arm. To assist with adherence, information packs were sent to parents 1 week before their child was fitted with the GeneActivs, providing information on wearing the accelerometer as well as guidance to be distributed to sports coaches to prevent the accelerometer being removed during sport. On the day the accelerometers were issued, the HeLP co-ordinator spoke to groups of 10 children about how to comply with the procedures, and answered any questions. Following recommended guidance, children were included in the analysis if they had at least 4 days (including a weekend day) of 10 hours of wear time on each of those days. 38 In these analyses, non-wear was determined if at least two accelerometer axes had a SD of < 13 mg and a range of < 50 mg over 60-minute windows, using moving increments of 15 minutes. 39

Food Intake Questionnaire

Food intake was assessed using the adapted version of the validated FIQ. 40 The FIQ asks children about the food and beverages they consumed the previous day and allows an estimation of the number of different types of healthy and unhealthy food and drink items consumed per day. This questionnaire was developed for children of the same age as those in this study, and it can be adapted to capture information on the consumption of a number of food groups, depending on the focus of an intervention (Dr Allan Hackett, Liverpool John Moores University, 21 September 2006, personal communication). We adapted the questionnaire so that we could focus specifically on healthy (10 items) and unhealthy (13 items) snacks and drinks, and negative (25 items) and positive (22 items) food markers. Children had to answer yes or no as to whether or not they had consumed each food item the previous day. A number of items make up each category to provide a total score from which an average number consumed per day is calculated. Questionnaire items, the scoring system and the tolerances for missing data can be seen in Appendix 2.

Children completed the FIQ twice, at baseline and at 18 months, to allow the assessment of weekday (completed Tuesday to Friday) and weekend (completed on a Monday) food intake. The HeLP co-ordinator led the two lessons required for the children to complete the questionnaires at each time point. Children were arranged in literacy tables to ensure that assistance could be given as efficiently as possible. Support was also provided by an additional researcher, the class teacher and the teaching assistant.

My Lifestyle Questionnaire

The MLQ was designed to assess knowledge and a series of potential cognitive and behavioural mediators of any observed differences in outcome between the control and the intervention groups. The questionnaire included items designed to assess knowledge, self-efficacy, intentions, peer norms, family approval, attitudes towards restrictions on behaviour, parental provision and rules, goal-setting, self-monitoring and a range of relevant behavioural skills, including suggestions to and discussion with parents, shopping, cooking and trying new snacks. These items were derived from previous research applying the IMB and health action process models but tailored to the logic model underpinning the development of HeLP (see Appendix 3).

School assessment

Information on the school-level characteristics and policies on physical activity and nutrition adopted in each school was collected at baseline (October/November 2012/13) and at 18 months (June/July 2014/15) (see Appendix 4) using a questionnaire that was completed by a member of staff and/or an administrator.

Index of Multiple Deprivation

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score was assigned to the lower super output area of each school and pupil as determined by their postcode. 41 The school’s IMD score was included as a continuous measure within the mediational analysis; the child-level IMD score was also used as a continuous measure in the secondary analysis of the primary outcome to assess whether or not there was a differential effect on BMI SDS, and the child IMD score was used as quartiles when assessing whether or not there was any differential effect of engagement by socioeconomic status in the process evaluation.

Changes to trial protocol

There were two substantial amendments to the protocol during the course of the trial. The first amendment was to clarify the inclusion criteria to include schools who had one single Year 5 class but who may have had a second class that mixed Year 5 and Year 6 children. The second amendment related to schools allocated to cohort 2 of the study, which were due to start the study in September 2013 (cohort 1 schools started in September 2012). These schools were re-contacted in July 2013, at which time two indicated that their circumstances had changed and that they were no longer able (or eligible) to participate in the trial. Schools that had been placed on the waiting list were then contacted to establish if they were still willing and eligible to participate, of which two were. Given the possibility of selection bias in the two withdrawn schools and in terms of potential imbalance between intervention and control groups in school-level confounders (known and unknown), the 16 schools in cohort 2 (i.e. after replacing the two withdrawn schools with the two schools from the waiting list) were all reallocated to the intervention or the control group. This was completed using a minimisation approach to ensure reasonable balance in the stratification factors between the allocated groups across the combined two cohorts.

Statistical analysis

A detailed analysis plan was developed by the Trial Management Group and approved by the TSC in November 2015. 42 Three minor amendments were made following the TSC meeting in July 2016 (see Appendix 5). These amendments were approved by the TSC chairperson in September 2016. The analysis plan and a summary of the amendments are published on the NIHR Public Health Research programme website, along with the study protocol. 43

General methods

The reporting and presentation of data from this trial are in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for cluster randomised trials. 44 The primary comparative analyses were conducted on a complete-case intention-to-treat basis, with children analysed according to the group (intervention or control) to which their school was randomised. All comparative analyses allowed for the clustered nature of the data (i.e. children within schools). Unless otherwise specified, all adjusted comparative analyses were adjusted for the two stratification variables (the proportion of children eligible for free school meals and the number of Year 5 classes) and baseline values for the outcome under consideration, when available. The analyses were also adjusted for gender and cohort. Between-group differences with only adjustment for clustering are presented for completeness. 45 The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for between-group comparisons were calculated and these are presented in Chapter 3. When given, p-values for statistical significance are two-sided and the significance level was set at ≤ 0.05.

Adjustments were not made for multiple testing as the primary outcome of interest was clearly defined a priori. As this is a trial of a complex intervention, the secondary outcomes are all potentially of interest and relevance to participants, parents and other stakeholders. Interpretation of the clinical significance of any differences between the two groups acknowledges the range of variables being measured.

Summaries of continuous/measurement variables comprise the number of schools or participants and either

-

the mean and SD or

-

the median and interquartile range

as appropriate for the distributional form of the data under consideration.

Summaries of categorical variables comprise the number of schools or participants and the number and percentage of observations in each category.

Participating schools were compared with state primary schools in Devon and England at the time of school recruitment into the trial (2012) in terms of the following characteristics:

-

percentage of children eligible for free school meals

-

average number of pupils per school

-

percentage of children achieving level 4 at Key Stage 2

-

proportion of pupils with English as an additional language.

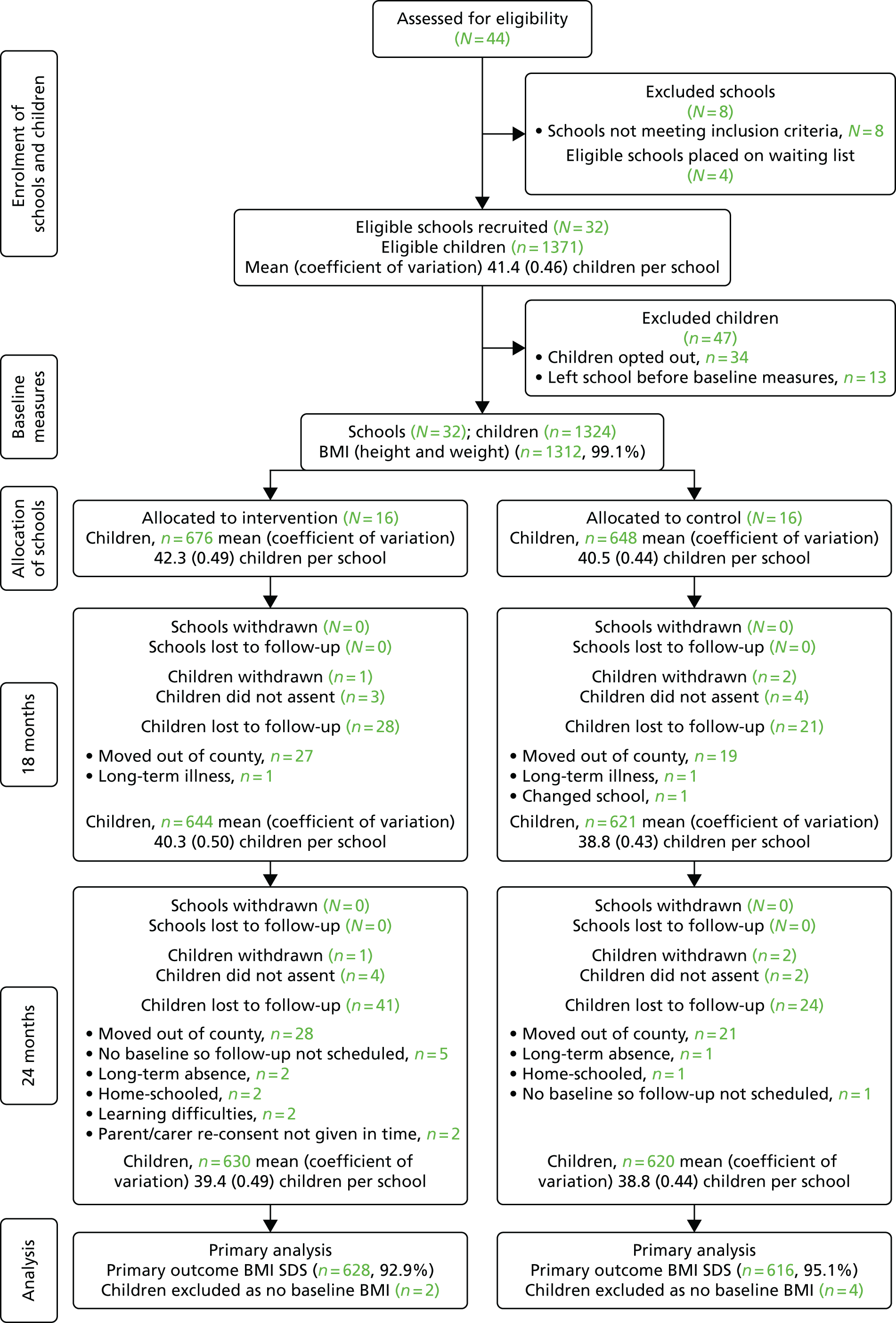

The recruitment, flow and follow-up of schools and children in the trial are summarised using the CONSORT-style flow diagram appropriate for cluster trials. The extent and distribution of missing data for each variable were assessed and dealt with as detailed in General methods, Missing outcome data.

Data sources and data entry

The data analysed came from a number of sources. Data collection for all sources followed standard operating procedures, as outlined in Study design, Outcome measures. Anthropometric measures were captured on a specifically designed data collection form.

All data were entered twice, first by the data manager and then by another member of the research team, and stored on a secure purposively designed database. Data queries were raised and resolved at data entry. Data discrepancies following second data entry were discussed and resolved with the trial manager. Electronic data were extracted from the database during the course of the study for the purpose of checking (validating) and for study progress reports, as well as for the end-of-study statistical analyses.

Comparison of baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics were collected at the beginning of each cohort of the trial and appropriate summary statistics were computed to compare allocated groups for appropriate balance and to provide an overview of the study sample, at both school and child levels. At the school level, the characteristics included the percentage of children eligible for free school meals, the IMD score derived from the school’s postcode, the number of Year 5 classes and the average educational attainment at Key Stage 2 SATs. At the child level, the characteristics included gender, age at baseline data collection, ethnicity, individual IMD value, all anthropometric measurements, physical activity and FIQ.

The formal statistical comparison at baseline of randomised groups is not good practice46 and, thus, was not undertaken: only summary statistics are presented in Chapter 3. We prespecified that should there be any substantial imbalance between randomised groups at baseline, in terms of any relevant variables not already being adjusted for in the primary analysis, further adjusted sensitivity analyses may be performed, to allow for such variable(s), in addition to the prespecified variables for adjustment, to assess the robustness of the primary analysis. 46

Primary analysis of primary outcome measure (body mass index standard deviation scores at 24 months)

The primary analysis of the primary outcome, BMI SDS at 24 months, was based on the observed data only and utilised random-effects linear regression modelling, allowing for the clustered nature of the data. Adjusted analyses included the two school-level stratification variables as covariates, as well as baseline BMI SDS, gender and cohort. The means and SDs are presented for each group, together with the mean difference (intervention minus control) between groups, the 95% CI for the mean difference and the corresponding p-value. The ICC (with 95% CI) from the random-effects regression model for BMI SDS is also reported.

Secondary analyses of the primary outcome

A small number of sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome were prespecified in the analysis plan to assess how robust the results of the primary analyses were to any biases from missing data or to children in the intervention group who were categorised as non-compliers. These sensitivity analyses were revised following the TSC meeting in July 2016. The proposed amendments were approved by the TSC (chairperson) prior to undertaking the sensitivity analyses outlined below.

Amendment 1

Given the low number of missing BMI scores and the low number of data deemed missing at random, a sensitivity analysis was undertaken to look at the effect of missing data using a best-case/worst-case scenario analysis.

The first set of these analyses was based on hypothetically driven assumptions. Given the hypothetical preventative nature of the HeLP intervention, the best-case scenario:

-

assumed no change between baseline and 24 months in BMI SDS for children allocated to the intervention group (i.e. the baseline BMI SDS value will be carried forward to replace the missing 24-month BMI SDS value)

-

imputed missing 24-month BMI SDS values for children allocated to the control group with their corresponding baseline BMI SDS value plus the (marginal) mean change between baseline and 24 months for the children allocated to the control group with complete baseline and 24-month BMI SDS data.

The worst-case scenario:

-

assumed that children allocated to the intervention group who were not obese at baseline were obese at the 24 month follow-up: the 24 month BMI SDS value will be set at the Public Health England threshold for obesity (i.e. the 95th percentile; this is 1.645). For children allocated to the intervention group who were obese at baseline, the baseline BMI SDS value will be carried forward to replace the missing BMI SDS value

-

imputed missing 24-month BMI SDS values for children allocated to the control group with their corresponding baseline BMI SDS value plus the (marginal) mean change between baseline and 24 months for the children allocated to the control group with complete baseline and 24-month BMI SDS data.

After imputing the missing 24-month BMI SDS scores for both scenarios, the primary analyses model was fitted to the full intention-to-treat data set to allow us to ascertain if the missing primary outcome data significantly influenced the results of the primary effectiveness analysis.

In addition to the primary analyses, exploratory analyses of the following possible interactions were undertaken to assess whether any effect of the HeLP intervention was modified by (1) gender, (2) baseline BMI SDS, (3) number of Year 5 classes within school and (4) child-level socioeconomic status. These subgroup analyses were performed by adding the interaction term between allocated group and the subgroup variable into the random-effects regression model. A test of the interaction was also performed to assess whether or not there was evidence that the effect of the intervention differed across the two cohorts. As the study was not powered for these exploratory interaction analyses, the results have been interpreted with caution, based on the corresponding CIs for the subgroups.

Finally, a repeated measures model was fitted to all the observed BMI SDS data at baseline, 18 months and 24 months, including effects of time and the interaction term between allocated group and time, to assess whether or not there was evidence that any effect of the intervention differed across time (see Appendix 6). In this model, adjustment was made for gender, a child-level fixed effect, and the school-level factors comprising the two stratification variables. The best fitting model was determined through a chi-squared test of the likelihood ratio of the log-likelihoods for the above model for different nested covariance patterns of each child’s block of visits in the residual matrix. Stepwise comparisons were made between covariance patterns of increasing parsimony up to an exchangeable pattern. The stopping rule for further pattern simplification was a change in the log-likelihood determined to be significant at the 5% level to the next more parsimonious covariance pattern.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were compared between groups based on the observed data only. Most of the secondary outcomes were of a continuous nature and so comparative analyses followed the approach detailed above for the primary outcome, using random-effects linear regression modelling, allowing for the clustered nature of the data and including the stratification factors, baseline value of the variable under consideration and gender and cohort. Binary outcomes (such as the proportion of children classified as obese at 24 months) were analysed using binary logistic regression, allowing for the clustered nature of the data and including the stratification factors, baseline BMI SDS and cohort. Ordinal outcomes (e.g. categorisation of weight status) were similarly analysed using ordinal logistic regression. For all models, corresponding distributional assumptions were investigated, as outlined below.

Checking distributional and modelling assumptions

Initial frequency and normal probability plots helped to inform the selection of models fitted to each outcome and whether transformation or model-based transformation under a generalised linear model might be necessary. When outcomes were discrete, sparse categories were amalgamated to create new levels with a sufficient number of participants in each for subsequent modelling as ordinal outcomes.

The tenability of assumptions for modelling outcomes as normally distributed variables was inspected through frequency and normal probability plots of the residuals from the fitted models, as well as box plots of residuals by allocated group and plots of residuals against fitted values. Model fit was judged through inspection of these plots along with plots of the observations against the fitted values. The distribution of the random school effect was checked by way of a normal probability plot of the best linear unbiased predictors from each model. Either the applied model was revised or a different model was sought if there were any marked deviations from the assumptions. Model stability and influence of the most extreme values were diagnosed through plotting the dfbetas calculated for each modelled factor and covariate, with careful attention paid to those for the allocated group. Any observations identified with sufficient influence to change the significance of the intervention effect would prompt further investigation, with results presented both with and without any such data points.

When the outcomes were deemed ordinal and fitted with an ordinal mixed-effects model, the assumption of proportional odds was tested through application of the generalised ordinal model (clustered on schools) to the data, using the gologit2 package in Stata (version 14, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Any significant changes in the coefficients across the levels of the outcome would be identified from significance testing of the Peterson–Harrell parameters. 47

Missing outcome data

The recruitment target for this trial allowed for a conservative 20% attrition rate by 24 months, with 24-month data required from 762 children to achieve 90% power in the primary analysis. Substantially more children were recruited than the target, given the higher than expected number of recruited schools with more than one Year 5 class: 1371 children were eligible for recruitment, compared with a pre-estimated target of around 950.

Various trial processes were put in place to minimise missing data. For example, missing data items, such as age and sex, were queried at the time of data entry and up to three visits were made to the school to take measurements for children who were absent on the first measurement day. For the FIQ, when participants were missing a subset of the items, the total score was extrapolated based on the average scores across the four categories (energy-dense snacks, healthy snack foods, negative food markers and positive food markers). To be included in the physical activity analysis, children needed to comply with the required minimum wear time of ≥ 10 hours per day for at least 3 weekdays and 1 weekend day. Non-wear was determined as outlined previously in Study design, Outcome measures, Accelerometer measurements. 39 To minimise missing data due to non-wear, each 15-minute period of device non-wear time was replaced by the children’s own data from the same time of day, averaged across all other recorded days. 48 This approach provided a person-specific method for imputing missing data. Any time window with > 50% non-wear was treated as missing. 39

With the measures to minimise missing data put in place, the likely reasons for a child having missing outcome data at the 18- or 24-month follow-up were as follows.

-

The parent/carer opted the child out of the trial before follow-up data collection at either 18 or 24 months.

-

The child refused to participate in the collection of anthropometric measures at 18 months but remained in the trial.

-

The child refused to participate in the collection of anthropometric measures at 24 months.

-

The child had moved out of the county before follow-up data collection at either 18 or 24 months.

-

The anthropometric data were missing because the child was withdrawn (but had not left the school) before that time point.

-

The child was absent on the day of measurement and on subsequent follow-up visits.

Missing some but not all of the anthropometric measures could occur if a child did not give their assent/consent for a particular measure (e.g. the child did not want to remove their tights, meaning that it was not possible to collect the percentage body fat measurement). Therefore, the numbers of children with valid data for each of the baseline measurements varied. We explored whether or not the missing data for a particular measure were similar in the two allocated groups.

Analysis populations and missing data

Full intention-to-treat analysis (i.e. including all participants in the main analyses) requires that all participants have complete follow-up data/no missing data. It was expected from the outset that a small proportion of children would be lost to follow-up by 24 months. As has been previously noted,49 all statistical methods for handling missing data, including complete-case analysis (i.e. analysis of observed data), have assumptions on the nature or reasons for missingness, which are generally not testable, and so it is necessary to consider the assumptions within the particular context. During the development of the analysis plan, the Trial Management Group considered that the missing at random assumption, necessary for many of the common statistical methods for handling missing data, would be plausible: randomisation was at the school level, opt-out consent was used before baseline measures were collected and it was felt highly unlikely that the delivery of the intervention, or lack of the intervention programme in the control schools, would affect the likelihood of children being absent on days when study data were being collected. Within Devon, it is also known that movement between schools is relatively low.

There was, therefore, no strong a priori reason to assume that children who were lost to follow-up would be missing not at random. For the primary analysis, no imputation of missing anthropometric data was undertaken and the primary outcome analysis was based on the complete-case/observed outcomes data set49 (i.e. a modified intention-to-treat approach). Given the assumption that any missing primary outcome measures at 24 months would be missing at random, a sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome measure was planned, with missing BMI SDS at 24 months to be imputed using multiple imputation and the analysis re-run on the imputed data set. However, as outlined above in Statistical analysis, Secondary analyses of the primary outcome, this sensitivity analysis was subsequently replaced by best-case/worst-case sensitivity analyses.

Derived outcome variables

-

Body mass index for each child was calculated from height and weight (i.e. weight/height2). The BMI was then standardised by age and gender to obtain the BMI SDS (sometimes known as BMI z-scores); we used the British 1990 (UK90) growth reference charts, and we implemented the calculations using the package LMSgrowth, developed by Cole. 50

-

Categorisations of weight status into underweight, normal, obese or overweight was made based on the definitions from Cole et al. ;51 these are the categories used by Public Health England when measuring population of children (e.g. when reporting NCMP results). The weight status categories are defined using the following UK 1990 population cut-off points: underweight, ≤ 2nd centile; healthy weight, > 2nd to < 85th centile; overweight, ≥ 85th centile; and obese, ≥ 95th centile.

-

Waist circumference was similarly standardised by age and gender, based on the British 1990 growth reference charts, and implemented using the LMSgrowth package. 52

-

Percentage body fat was estimated from leg-to-leg bioelectric impedance analysis (Tanita Body Composition Analyser SC-330) and standardised by age and gender, based on the British 1990 growth reference charts, and implemented using the LMSgrowth software. 53

-

Average time per day in sedentary, light, moderate, vigorous and moderate to vigorous physical activity intensities was calculated using published cut-off points for children at baseline and at 18 months. 30 In addition, the average volume of physical activity (mg) for all valid days was derived. This outcome was added following the first HeLP TSC meeting (November 2012).

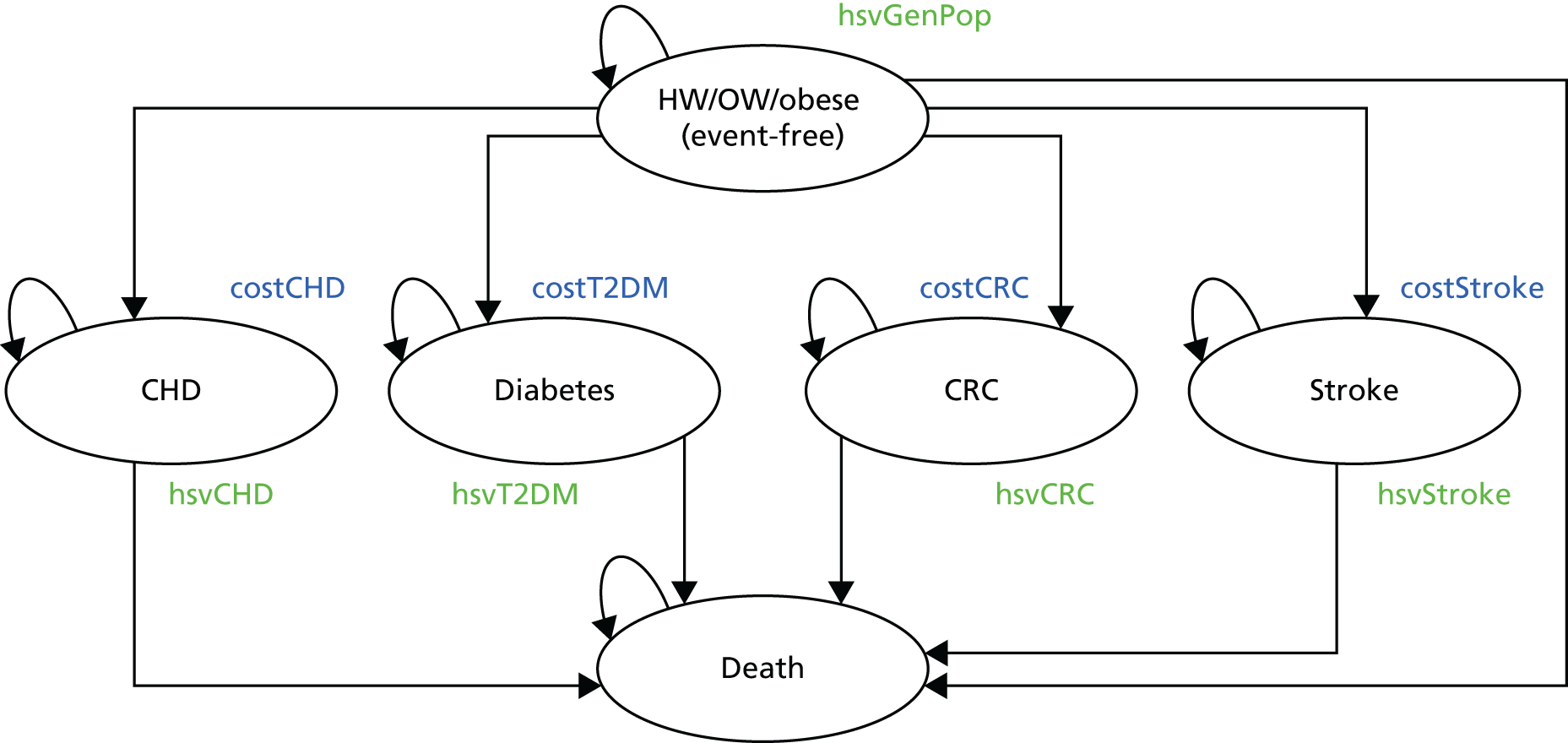

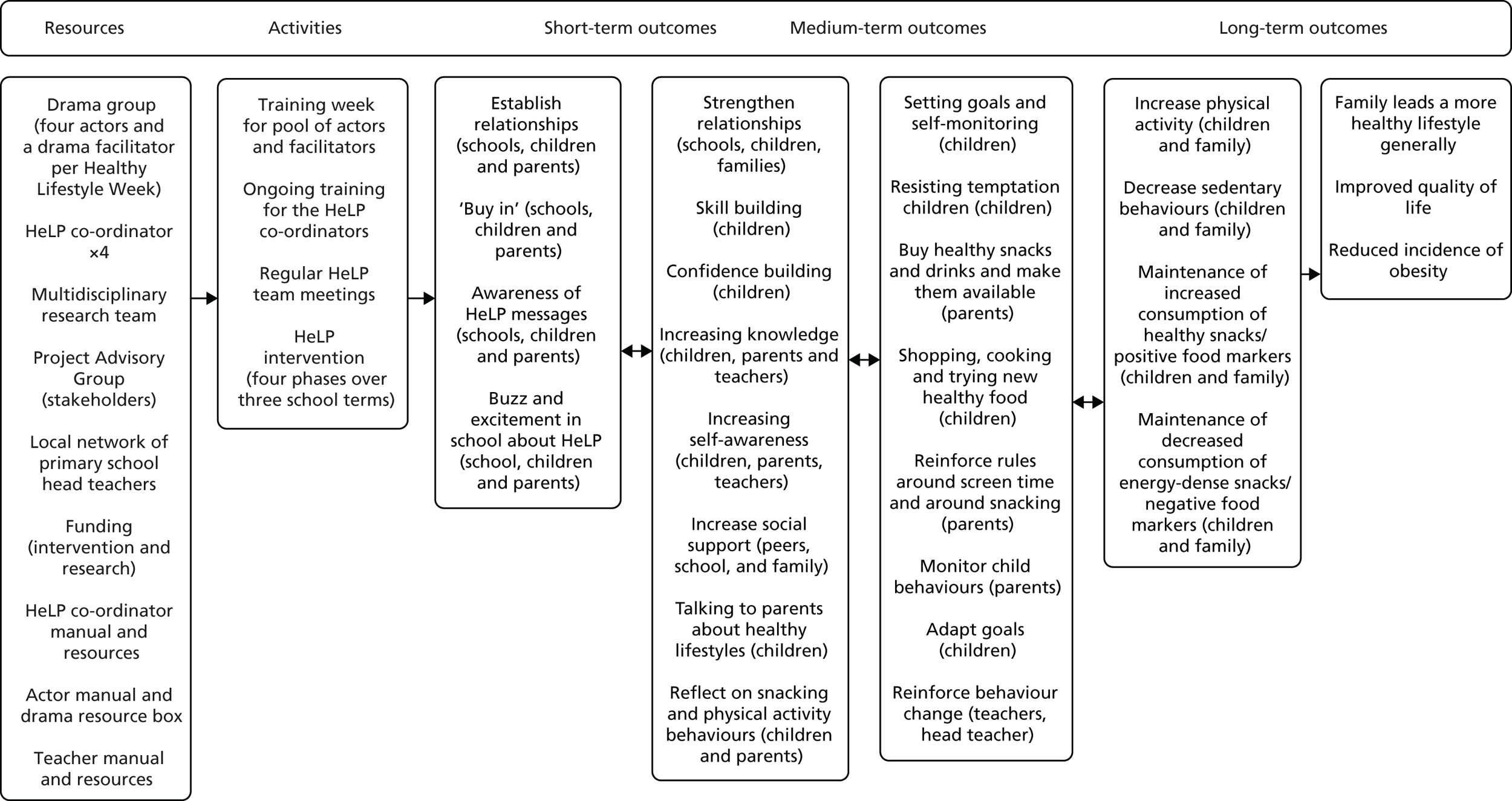

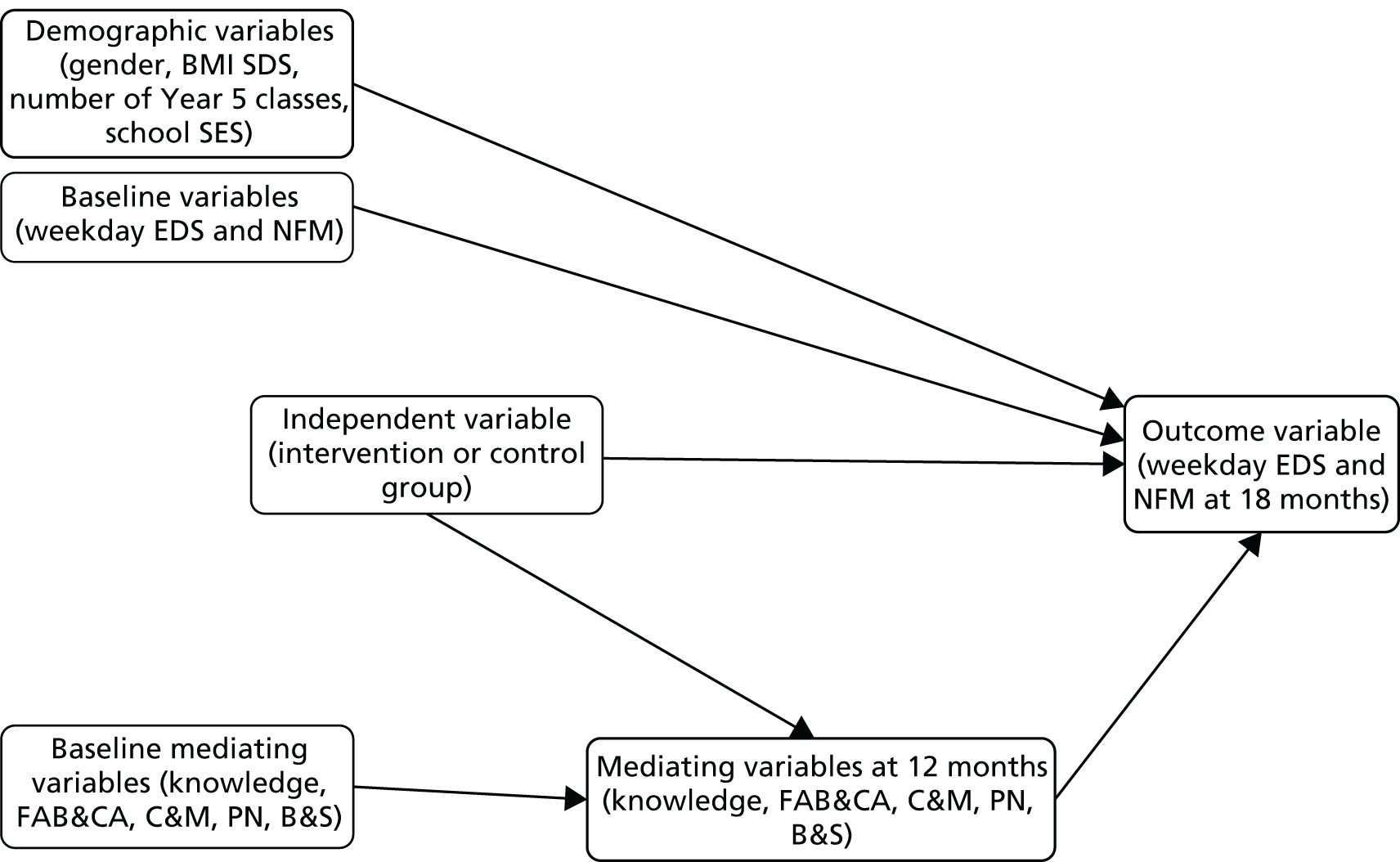

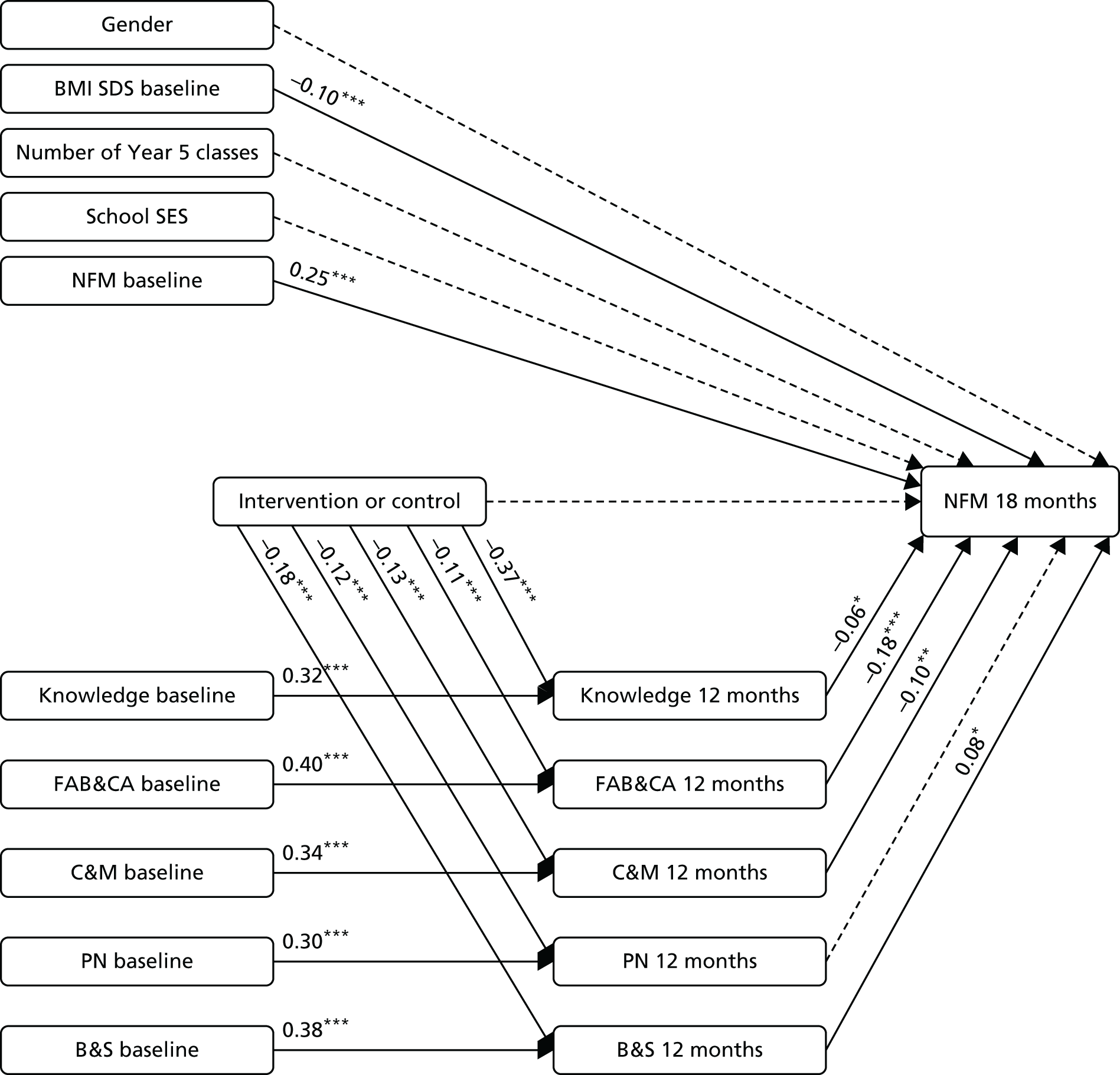

-