Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/184/02. The contractual start date was in April 2017. The final report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in July 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Ponsford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

This chapter includes material reproduced or adapted from Ponsford et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Description of the problem

The UK has the highest rate of teenage births in western Europe, despite significant declines over the last 20 years and the success of the England Teenage Pregnancy Strategy. 2,3 Teenagers are the age group at highest risk of unplanned pregnancy, with around half of conceptions to those aged < 18 years ending in abortion. 4 Even after controlling for prior disadvantage, teenage parenthood is associated with adverse medical, social, educational and economic outcomes for both mothers5–7 and children. 8,9 Teenage childbearing is subject to and contributes to health inequalities. 10 In 2006, teenage pregnancy cost the NHS £63M per year. 11 In 2009–10, £26M was paid in benefits to teenage mothers on income support. 12 Other adverse sexual health outcomes also cost the NHS large sums. 13,14 Reducing rates of unintended teenage pregnancy in England, therefore, remains a priority. Existing systematic reviews suggest that traditional classroom-based relationships and sex education (RSE) may not be sufficient on its own to produce consistent, sizeable and sustained changes in the behaviours underlying teenage pregnancy and, therefore, population-level reductions in this outcome. 15–17

Description of the intervention

A recent systematic review of social-marketing interventions to reduce teenage pregnancy examined studies of interventions embracing social-marketing elements,18 regardless of whether or not these were explicitly termed ‘social marketing’. 19 Heterogeneity precluded meta-analysis, but narrative synthesis concluded that this was a promising approach. 19 We developed an intervention, Positive Choices, with the National Children’s Bureau’s (NCB’s) Sex Education Forum (SEF) and other stakeholders. This intervention was informed by selected components from two effective interventions included in the above review – ‘Safer Choices’ and the ‘Children’s Aid Society (CAS) Carrera’ programme – plus selected elements from the ‘Gatehouse Project’, which, although not included in the review, also embraced social-marketing principles and was effective in increasing the age at sexual debut.

Safer Choices is a school-based social-marketing intervention involving a school health promotion council (SHPC) co-ordinating intervention activities, a classroom–based RSE curriculum, student-led social-marketing campaigns and information for parents. A US randomised controlled trial (RCT) of this intervention reported reduced unprotected last sex and reduced numbers of partners with whom unprotected sex occurred, but did not measure effects on pregnancy. 20–22 Positive Choices was informed by all of the above elements of Safer Choices. The ‘CAS Carrera’ programme is an after-school intervention providing careers, academic, arts, sports and life-skills sessions, and sexual health services. A RCT of this intervention in New York City reported fewer pregnancies and delayed sexual debut among girls. 23 An attempted replication study in other US locations reported no such reductions, reportedly owing to poor fidelity. 24 Positive Choices was informed by the emphasis on general life skills as well as sexual health-specific skills within the CAS Carrera curriculum. The Gatehouse Project is a school-based intervention that includes a student needs survey and classroom-based curriculum addressing social and emotional learning. Although primarily addressing mental health, a RCT in Australian high schools reported participants’ increased age at sexual debut, but did not measure impacts on teenage pregnancy. 25 Positive Choices was informed by all of the above elements of the Gatehouse Project.

Rationale for the current study

Our optimisation, feasibility assessment and pilot RCT of Positive Choices was, to our knowledge, the first UK study of a whole-school social-marketing intervention to prevent unintended teenage pregnancy. The intervention involved multiple components. Those in years 9 and 10 (aged 13–15 years) would be targeted because proximal risk factors are manifesting,26 prevention is not too late, and RSE is acceptable. 21,27,28 Consultation with schools, which informed the proposal, suggested that provision to year 11 students would be unfeasible because of General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) preparation. Although not aiming to replicate existing interventions, the intervention was informed by approaches and certain components used in the previous Safer Choices,20–22 CAS Carrera23 and Gatehouse interventions. 25 Optimisation refers to the elaboration of the intervention, developing it from a basic description of a new intervention, its theory of change and components, to a fully specified intervention with full materials.

Our study involved three elements: (1) optimising the intervention to elaborate its components and develop intervention materials in collaboration with SEF and one state secondary school; (2) assessing the feasibility of each component of the intervention by implementing, assessing and refining it in the secondary school involved in optimisation; and (3) undertaking a pilot RCT of the intervention across six other schools to assess the feasibility and value of conducting a future Phase III RCT of the effectiveness of the intervention.

Study aims and objectives

Aims

-

In collaboration with SEF, one secondary school and other stakeholders, to optimise Positive Choices, a school-based social-marketing intervention to promote sexual health, prevent unintended teenage pregnancies and address health inequalities in England.

-

To conduct a formative feasibility assessment and refinement of the intervention in collaboration with the secondary school involved in optimisation.

-

To conduct a pilot RCT (four intervention and two control schools) to determine the feasibility and utility of conducting a Phase III RCT of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

-

To answer the study’s research questions.

Objectives

-

To optimise Positive Choices in collaboration with SEF, the staff and students from one secondary school, and other stakeholders.

-

To assess the feasibility and acceptability of implementing each component of the intervention in the school involved in optimisation, and to make any necessary refinements in the light of this feasibility assessment.

-

To recruit six schools for the pilot RCT, undertake baseline surveys of students at the end of year 8 (age 12/13 years) and randomise schools.

-

To implement the intervention to students in year 9.

-

To conduct quantitative and qualitative elements of the process evaluation.

-

To undertake follow-up surveys at 12 months post baseline.

-

To link self-report data to routine administrative data on teenage pregnancies 18 months post baseline.

-

To conduct data analysis addressing all of the above research questions and draft a report of the pilot evaluation.

-

To disseminate findings and determine whether or not progression to a Phase III RCT is justified.

Study research questions

-

Is it possible to optimise Positive Choices in collaboration with SEF, a secondary school and other stakeholders?

-

Is it feasible and acceptable to implement each component of this intervention in the secondary school involved in optimisation, and what refinements are suggested?

-

In the light of a pilot RCT across six schools, is progression to a Phase III RCT justified in terms of prespecified criteria?

-

The intervention is implemented with fidelity in three or four out of four intervention schools.

-

Process evaluation indicates that the intervention is acceptable to a majority of students and staff involved in implementation.

-

Randomisation occurs and five or six out of six schools accept randomisation and continue within the study.

-

Student questionnaire follow-up rates are ≥ 80% in five or six out of six schools.

-

Linkage of self-report and routine administrative data on pregnancies is feasible.

-

-

Are secondary outcome and covariate measures reliable and what refinements are suggested?

-

At what rates are schools recruited to and retained in the RCT?

-

What level of student reach does the intervention achieve?

-

What do qualitative data suggest in terms of intervention mechanisms and refinements to programme theory and theory of change?

-

How do contextual factors appear to influence implementation, receipt and mechanisms of action?

-

Are any potential harms suggested and how might these be reduced?

-

What sexual health-related activities occur in and around control schools?

-

Are methods for economic evaluation in a Phase III RCT feasible?

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter includes material reproduced or adapted from Ponsford et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This chapter also includes material reproduced or adapted from the ISRCTN registry. 29 This material is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this registry, unless otherwise stated. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Design

The study involved three phases with different designs: (1) a facilitated, systematic optimisation of the Positive Choices intervention using participative methods; (2) a formative feasibility assessment of intervention components in one secondary school and refinement using a case study design; and (3) an external pilot cluster RCT across six schools with integral process evaluation and economic evaluation feasibility study.

Optimisation

Key elements of the theory of change of the intervention, as well as the basic outline of its core components, had already been determined, informed by, but not directly replicating, selected elements from the Safer Choices, CAS Carrera and Gatehouse interventions. Further work was required to elaborate and optimise the intervention for the UK context, developing in detail the intervention components and intervention materials. The optimisation of the intervention was led by the research team and staff from SEF, and involved the staff and students from one secondary school plus other youth and policy and practitioner stakeholders. Optimisation occurred in phases. Elaboration of the intervention theory of change, logic model and overall approaches of the intervention occurred between April 2017 and June 2017. Development of the student needs survey, the manual guiding the SHPC and the staff training package occurred between June 2017 and August 2017. Development of the student curriculum occurred between September 2017 and December 2017. Development of guidance for the student-led social marketing and review of school sexual health services occurred between January 2018 and March 2018.

In each case, optimisation of the above resources occurred through a systematic process as follows:

-

review by researchers and SEF staff of existing systematic reviews and the evaluations of the Safer Choices, CAS Carrera and Gatehouse interventions, and materials from Safer Choices

-

drafting of resources by SEF staff and the research team

-

consultation with staff and students from one secondary school, as well as the Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement (ALPHA) group [a group of young people based at the Centre for Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions (DECIPHer) Centre at Cardiff University who are trained to advise on public health research] and other stakeholders

-

refinement of these resources.

Review of existing literature and materials

The research team reviewed existing systematic reviews, Safer Choices, CAS Carrera and Gatehouse Project evaluation reports, and literature on school-based interventions to identify best practices and inform the intervention design and materials. SEF reviewed Safer Choices materials, as well as materials from other interventions and resource packages, to inform drafting of intervention materials with research team input. Staff from ETR Associates and CAS (originators of the Safer Choices and Carrera interventions, respectively) also contributed to intervention optimisation, advising on learning from their interventions.

Production of draft materials

The National Children’s Bureau led the drafting of intervention materials. These were reviewed by the research team, including to ensure these aligned with the intervention’s theory of change, and then redrafted.

Consultation

We consulted with students and staff from one London secondary school in June 2017. This school was purposively selected based on its location in south-east England, and it having a higher than median local Index of Multiple Deprivation and value-added GCSE attainment, suggesting a high level of need for the intervention, but with high organisational capacity to participate in optimisation and refinement. 26 The school was recruited via our existing contacts to ensure that the school had the capacity to participate.

The consultation session involved teachers and students from different year groups, focused on acceptability of the proposed intervention aims, components and delivery models (particularly the tasks of the SHPC); teacher preference for the format and content of the manual guiding the intervention and presentation of the needs data; students views on the curriculum content; and implementation of the SHPC. The data collection tools used for the session are in Report Supplementary Material 1. Further planned consultation on intervention materials was not possible because of school capacity. The consultation was facilitated by one researcher and one member of SEF staff. Following introductions, teachers and students worked separately in small groups. The session was audio-recorded. Field notes were also taken during and directly after the session. Because these optimisation activities were framed as co-design and not in-depth qualitative research, a summary was then prepared based on audio-recordings and field notes, but formal qualitative analysis was not carried out. Students and staff participating in focus groups were treated as research participants and provided with written information about the research 1 week beforehand, as well as orally just prior to the research. All students completed written opt-in consent/assent forms. Parents of participating students were also provided with information 1 week in advance and could opt out their children.

As part of the optimisation phase, we also consulted with the ALPHA group in July 2017 and in April 2018, to explore these young people’s perspectives on parent engagement in the Positive Choices intervention, and the acceptability and potential challenges of implementing student-led social-marketing campaigns in schools. These sessions were audio-recorded and summaries drafted by the group’s professional facilitator. ALPHA participants gave written, informed consent for their participation in the group.

In March 2018, we also convened a meeting of practitioners and policy-makers from governmental and non-governmental organisations working in education and health to inform optimisation. Following presentations by research staff on the intervention, participants provided feedback via small-group discussion on questions set by researchers, focusing on intervention design and practical challenges to implementation. Drawing on facilitator notes, researchers drafted an anonymised summary of the event, again with no formal qualitative analysis. Consultation with practitioners and policy-makers was treated as public engagement rather than research, so no ethics review was undertaken and no consent was sought. Participants were made aware of how their contributions would be used and received a summary of discussion to which they could suggest amendments.

Refinement of resources

The researchers and SEF staff discussed the summaries above, agreeing how these should inform elaboration of the interventions, models of delivery and materials.

The outcome for the optimisation phase was meeting the criterion for progression to feasibility testing: for the materials for the training, SHPC, social-marketing meetings, student curriculum and sexual health services review to be optimised in line with the theory of change and to the satisfaction, expressed in writing, of the research team, SEF, the participating secondary school and the Study Steering Committee (SSC).

Feasibility testing

Intervention components were implemented and assessed for feasibility and acceptability in the same secondary school that was involved in optimisation. This occurred over 1 school year, in phases, overlapping with optimisation:

-

term 1 (September–December 2017) – implementation of the student needs survey with year 9 students, staff training and SHPC

-

term 2 (January–March 2018) – implementation of the student curriculum

-

term 3 (April–July 2018) – implementation of the student-led social marketing and review of school sexual health services.

The feasibility-assessment involved a case study design with no comparator. Intervention components were assessed by the research team as they were implemented to inform phased refinements led by SEF staff as follows:

-

January–March 2018 – refinements of the survey, materials for SHPC and staff training

-

April–July 2018 – refinement of the student curriculum

-

June–August 2018 – refinement of the student-led social marketing and review of school sexual health services.

Data collection

In the feasibility-testing phase, our process evaluation aimed to collect data via audio-recording of SEF training for school staff; surveys of school staff trained by SEF; logbooks completed by school staff implementing the SHPC, curriculum and social-marketing meetings; structured observations of the SHPC, curriculum lessons and social-marketing meetings; and interviews with four SEF and four schools’ staff (purposive by role/seniority), and group interviews with eight year 9 students [purposive by sex and socioeconomic status (SES)].

Progression criteria and data analysis

Outcomes for the feasibility-testing phase were to meet the criteria for progression to the pilot RCT: according to audio recordings, diaries and researcher observations, the training, SHPC, social-marketing meetings, student curriculum and sexual health services review components were implemented with > 70% fidelity in the participating school; and interviews with students and staff conducted as part of the process evaluation indicated that the intervention was acceptable to at least 70% of students and staff involved in implementation.

Fidelity was assessed using data derived from audio-recordings, diaries and observations; the specific sources are reported for each aspect of fidelity in our results. Quantitative tick-box quality metrics were developed for each intervention component. Each training session was assessed against session-specific quality metrics relating to the number of participants, the topics covered, the exercises used and opportunities for discussion. Meetings of the SHPC were assessed against meeting-specific quality metrics relating to the agenda items covered, actions agreed and opportunities for discussion. The curriculum was assessed against lesson-specific metrics concerning the essential topics covered, exercises used and opportunities for discussion. The student-led social marketing was assessed against metrics concerning the items discussed, actions agreed and opportunities for discussion. The review of sexual health services was assessed against quality metrics concerning the review of existing services and actions taken to enhance these. The specific metrics used to assess each element are provided in Report Supplementary Material 2.

Acceptability of the optimised Positive Choices intervention was quantitatively assessed via two specific questions included in the interview and focus group schedule as a measure of intervention acceptability. These were:

-

Do you think your school should deliver the Positive Choices Programme again?

-

Do you think other schools should?

Our data analyses determined whether the study should proceed to the pilot RCT phase against the criteria described above. Findings were fed back to SEF staff, who were then responsible for refining the intervention ready for implementation in the pilot RCT.

Pilot randomised controlled trial

We then conducted a pilot RCT (four intervention and two control schools; different from those involved in the intervention optimisation), with an integral process evaluation and economic evaluation feasibility study. In this phase, the research and intervention teams were managed separately to ensure that the evaluation was independent and did not distort intervention delivery.

Pilot study population and inclusion/exclusion criteria

State secondary schools (including free schools and academies) in south-east England (maximum 1-hour rail journey from London) were eligible to participate. Private schools, pupil referral units or special schools for those with learning disabilities were excluded. Boys’ but not girls’ schools were also excluded from the pilot RCT as our primary outcome focused on unintended pregnancies among girls. In a Phase III RCT, the intervention would target students in years 9 and 10. In the pilot RCT, the intervention targeted year 9 students, reflecting the truncated timescales of the pilot compared with a Phase III RCT; therefore, students nearing the end of year 8 at the baseline survey (conducted in the term before the intervention was to begin) were eligible to participate. No student deemed competent by their teacher to consent was excluded from our study. Those with mild learning difficulties or poor English were supported to complete the questionnaire by fieldworkers.

Sample size

The pilot RCT focused on various aspects of feasibility and no power calculation was performed. Having four schools implementing the intervention in the pilot RCT combined with two schools acting as controls balanced the need to assess implementation in a diverse range of schools with ensuring that the pilot was small enough to be appropriate as a preliminary to a larger Phase III RCT. The planned analytic sample for outcome assessment in the pilot RCT was 1159 students at the end of year 8 (aged 12/13 years) at baseline, with follow-up at 12 and 18 months. Our pilot aimed to provide estimates for recruitment and retention rates that would allow us to estimate more accurately the sample size required for a Phase III RCT.

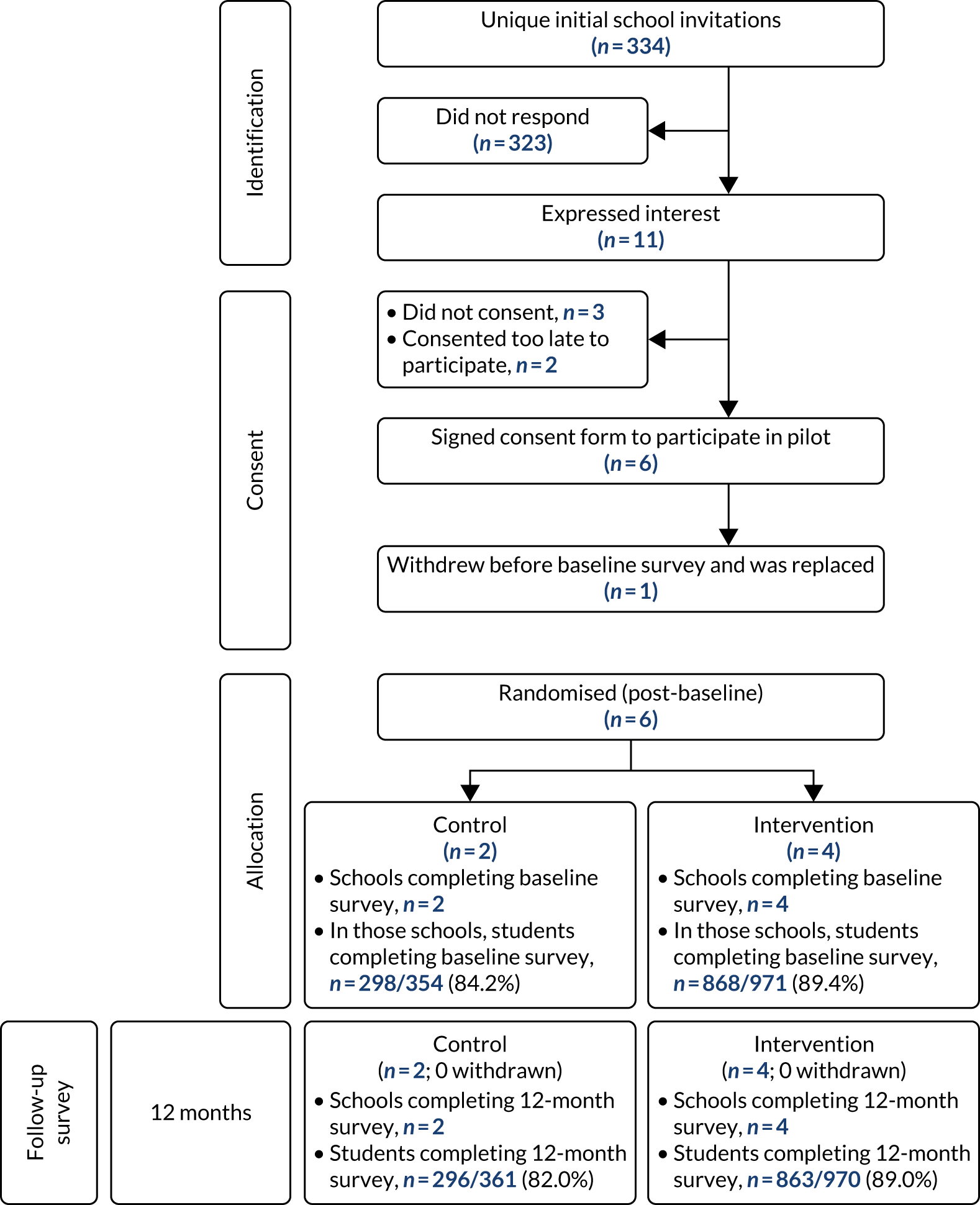

Recruitment

Six schools across south-east England were recruited (purposively varying by local deprivation and school-level GCSE attainment). Schools were recruited to the pilot RCT via e-mail mailouts. For the pilot RCT phase, we aimed to recruit only six schools spread across different parts of south-east England and did not want to focus recruitment on schools already known to us; therefore, our strategy aimed to be broad in geographical scope (to recruit a diverse range of schools) but not intense in how we communicated with schools (because we only needed to recruit six). We sent a single e-mail to schools’ general administrative e-mail addresses with no follow-on emails, no telephone calls and no targeting of head teachers or other named members of staff. Response rates were recorded, as were any stated reasons for non-participation.

Randomisation

After baseline surveys with students at the end of year 8, schools were randomly allocated to intervention/control remotely by London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) clinical trials unit (CTU) on 9 July 2018, stratified by GCSE attainment, a key predictor of pregnancy. 26 Allocation was 2:1 favouring the intervention (compared with 1 : 1 in any future Phase III RCT).

Planned interventions

Below, we describe the Positive Choices intervention using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework. 30

Theory of change

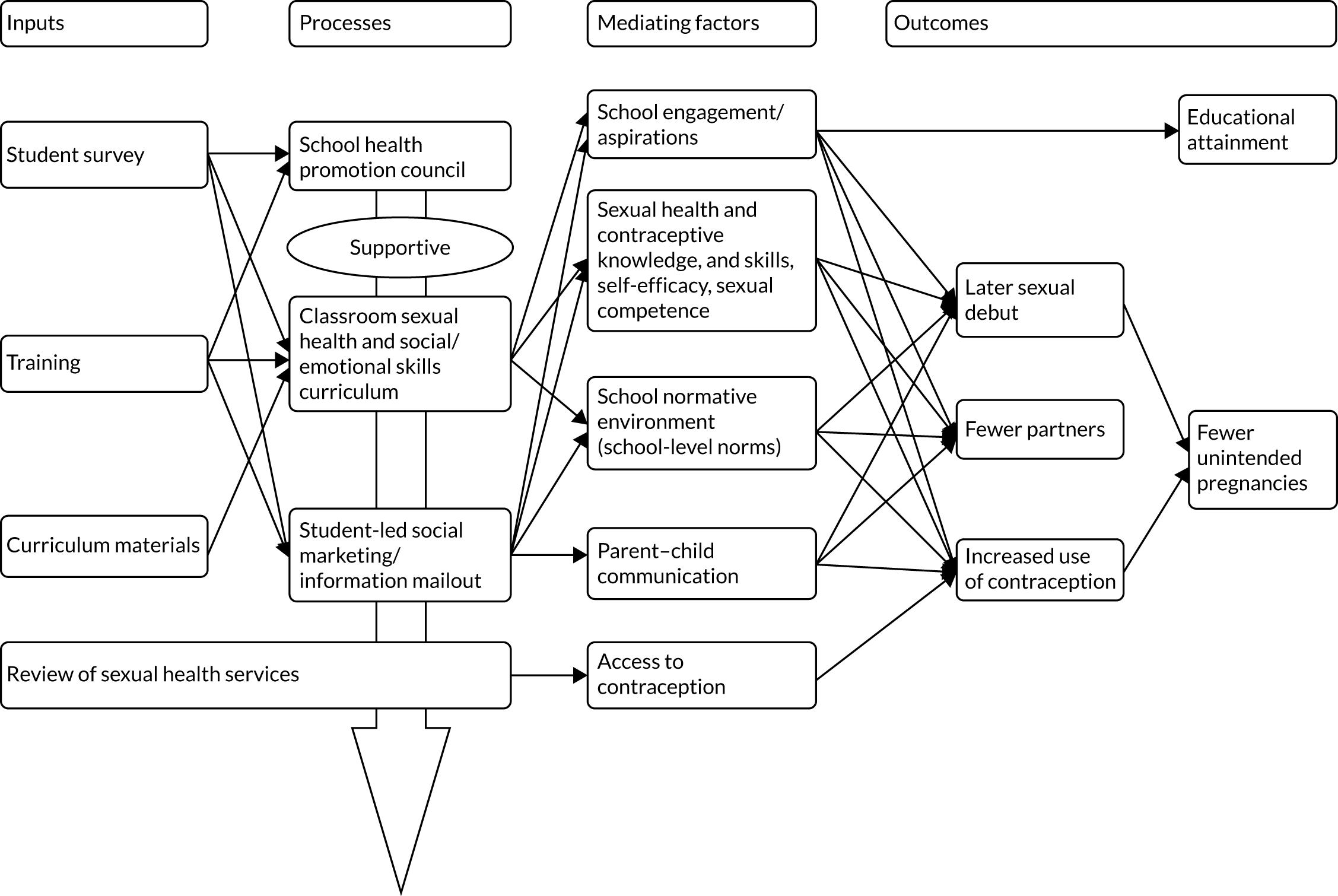

Positive Choice’s programme theory is informed by social-marketing principles and has been developed with experts in this field, addressing the ‘4Ps’: product, place, price and promotion. 31,32 The intervention aims to ‘sell’ consumers a product they want (education on emotions, relationships and sexual health) in an accessible place (school) at a low price (free to students), with promotion to peers and parents (campaigns, parent information),19,31 and to address competing influences from their peers, the media, etc. 33 The needs survey component enables SHPCs (with student involvement) to tailor provision in each school to local consumer priorities. The intervention’s theory of change has been informed by the Safer Choices20–22 intervention theory and models of school change,34 social influence35 and social cognitive theory36 to address the following determinants of unintended teenage pregnancy: sexual health and contraceptive knowledge; self-efficacy to communicate about sex; sexual health skills and competence; communication with parents; and school-wide social norms supporting positive relationships/sexual health. The curriculum was informed by the CAS Carrera intervention theory,23 in terms of the social development model,37 and by addressing additional protective factors: positive aspirations and school engagement. 38 Refined school sexual health services aim to provide advice and contraception in line with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance. 39 The intervention is a universal intervention that has the potential for greater population-level impacts than targeted interventions while minimising the risk of ‘positive deviancy training’, which can be a problem in targeted interventions,10,26 as they bring together at-risk individuals to increase harm. 40 The logic model for the intervention is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Positive Choices Logic Model.

Materials

School staff are offered training in instituting and running a SHPC, delivering the classroom curriculum and facilitating student-led social marketing. Training materials consist of slides and handouts. Schools are provided with a manual to guide each component of the intervention. Schools are sent a report on student needs detailing the findings from a survey of year 8 students, aged 12–13 years, (drawing on baseline trial survey) about their sexual health needs, and attitudes to and experiences of school. Schools are provided with lesson plans and slides to guide delivery of the classroom curriculum. Schools send out parent information comprising three newsletters and two homework assignments per year addressing parent–child communication.

Procedures

Positive Choices is a manualised social-marketing intervention, delivered for one academic year to students in year 9 in this pilot trial, and for two academic years to years 9 and 10 in any future Phase III trial. Training comprises in-depth training for selected staff as in Materials. Guided by the manual, schools institute SHPCs comprising staff and students to review local needs data, and use this to tailor each intervention component, and then to co-ordinate delivery of the intervention. Schools deliver the curriculum in various lessons and/or tutor time to students in year 9 (13–14 years). The curriculum was designed as a set of 10 hours of learning modules to cover social and emotional skills, and relationships and sexual health. The social and emotional skills to cover were establishing respectful relationships in the classroom and the wider school; managing emotions; understanding and building trusting relationships; exploring others’ needs and avoiding conflict; and maintaining and repairing relationships. Sexual health topics to cover were healthy relationships, negotiation and communication skills, positive sexual health, sexual risk reduction, contraception and local services. The SHPCs select whether to deliver the curriculum in PSHE lessons, tutor groups or to integrate it into other lessons, and whether to use Positive Choices materials or existing materials (if these conform to the curriculum). Student-led social marketing is facilitated by trained teachers and led by teams of 12–18 students per school. Teachers actively promote recruitment among at-risk students based on the strongest evidenced risk factors for teenage pregnancy on which schools have data (i.e. free meals eligibility, persistent absenteeism and slower than expected academic progress26). This is not to target provision at those most at risk, but rather to ensure campaigns appeal to a diversity of students including those most at risk, of teenage pregnancy. When recruiting such students, teachers are open with them about this rationale. Campaigns can use social and other media, posters and events, and focus on healthy relationships, sexual and human rights, delayed sex and access to local services. Student social marketers were to use data from the student needs survey to segment the student population based on year group. The student social marketers use such information to design social-marketing campaigns that address the most important topics among the groups who needed the interventions the most. The review of school sexual health services was to involve SEF providing guidance to schools on how sexual health services in or around schools might be developed or promoted among students.

Training

Training is provided by trainers from SEF.

Delivery

All intervention components were to be delivered face to face on school premises. SEF trains school staff to implement SHPCs, implement the classroom curriculum and facilitate student-led marketing. SEF also provides guidance to schools to support refinement and promotion of existing sexual health services. In each school, a ‘product champion’ [senior leadership team (SLT) member] oversees the SHPC. SHPC members comprise at least six staff and at least six students from each school. Staff sitting on this council include those teaching the curriculum, those co-ordinating student-led social marketing and, where applicable, the school nurse. These staff attend the SHPC training and some also attend the curriculum and social-marketing training. The curriculum is delivered by trained teachers guided by lesson plans. Students sit on the SHPC and also lead social marketing to their peers guided by a teacher and a manual with clear milestones, including plans for ‘quick wins’ to build momentum and enthusiasm. 21

Dose

The SHPC and student-led social-marketing training comprises a half-day session. The curriculum training comprises a whole-day session. SHPCs meet six times per year. Students receive 10 hours’ teaching per year.

Planned adaptations

The optimisation phase led to some planned adaptations, reported in full in Chapter 3. The needs assessment was not used to determine in which lessons the Positive Choices curriculum would be taught, or whether or not to use existing or Positive Choices materials. It was used to inform the selection of add-on lessons to be taught in each school; build support for implementation of the intervention in schools; and inform the content of parent newsletters, and the focus of student-led social-marketing activities and the sexual health services review. The remit of the SHPC was refined to comprise launching the intervention in schools and promoting the intervention to parents; selecting the ‘add-on’ curriculum topics informed by the needs-assessment data; overseeing delivery of the curriculum; recruiting the social-marketing team; monitoring and voting on campaign activities; preparing and distributing parent newsletters; and carrying out the school sexual health services review. The curriculum was adapted to align with SEF-recommended comprehensive RSE, but with all of the topics included in the original protocol being addressed. Student-led social marketing was refined in line with Andreasen’s six characteristics of social marketing. 18 The student-led social marketing was also adapted so that this did not segment the student population based on cultural styles but rather only by year group, with the team comprising students from years 8 to 11. The review of school sexual health services was adapted to comprise SEF detailed guidance for the school to review and improve its own and local sexual health services, rather than SEF reviewing these services directly.

Unplanned modifications

There were no unplanned modifications.

Intervention funding

Intervention delivery in the feasibility assessment and pilot RCT phases was funded by the NCB, and by schools, which provided staffing for project oversight, the running of SHPCs, curriculum delivery and social-marketing teams.

Comparator

In the pilot RCT phase, two schools were randomised to the control group and did not receive the intervention, but continued with any existing sexual health-related provision, which was examined in our process evaluation. Retention of control schools was maximised with a £500 payment and feedback of survey data after RCT analyses.

Outcome and other measures

Outcome measures

The pilot RCT did not aim to assess intervention effects. The pilot primary outcomes were to meet the criteria for progression to Phase III, which were that the intervention was implemented with fidelity in three or four out of four intervention schools; process evaluation indicated that the intervention was acceptable to a majority of students and staff involved in implementation; randomisation occurred and five or six out of six schools accepted randomisation and continued in the study; student questionnaire follow-up rates were ≥ 80% in five or six out of six schools; and linkage of self-report and routine administrative data on pregnancies was feasible. Secondary outcomes addressed other research questions, including the feasibility of economic evaluation.

We did, however, pilot the primary outcome and other measures that we anticipated would be used in a future Phase III RCT. The primary outcome in such a RCT was anticipated to be routine data on births and abortions at 48 months (age 16/17 years) with secondary outcomes measured via self-reports at 24 months (age 14/15 years). Routine data on abortions minimise information bias and clearly indicate unintentional pregnancy; however, some unintended pregnancies will not result in abortion, and changes in abortion rates may also reflect variations in access;41 therefore, our indicative primary outcome measure piloted in this study also encompassed routine data on live births. Although it is recognised that around half of teenage pregnancies will, to some extent, be intended,42 this outcome measure was anticipated, nonetheless, to provide a better indication of the overall impact of the intervention.

We aimed to pilot indicative secondary outcome measures to examine broader intervention effects via survey self-reports:

-

pregnancy and unintended pregnancy for girls and initiation of pregnancy for boys using adapted versions of the Ripple measures41

-

diagnosed sexually transmitted infections (STIs), which focused on diagnosis with common infections, using an adapted version of the Ripple measure41

-

age at sexual debut, which focused on age at vaginal sexual debut with someone of the opposite sex using an adapted version of the Ripple measure41

-

number of sexual partners, which focused on vaginal sex partners using an adapted Ripple measure41

-

use of contraception at first and last sex, which focused on which common contraceptives, if any, were used in first and last vaginal sex, using an adapted Ripple measure41

-

non-volitional sex, which examined experience within the last 12 months of forced sex using an adapted version of the Conflicts in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI) measure43

-

educational attainment, which is a plausible intervention effect and, for scale-up, a critical outcome of our intervention,44 but which was not possible to pilot in this study because the pilot RCT involved a shorter period of follow-up than would be the case in a Phase III RCT and so did not include the time when students took public examinations.

Mediators and covariates

Informed by our theory of change, we also piloted the following mediators using existing self-report measures:

-

school-level social norms supportive of positive relationships and sexual health, using an adapted measure from the Safer Choices study22

-

perceived behavioural norms about early sexual experience and use of condoms and contraception, using an adapted measure from the Safer Choices study22

-

sexual health knowledge, which used an adapted version of a measure from the Share trial27

-

sexual health and contraceptive skills and access, using a measure adapted from the Share study27

-

sexual health service access, using a measure adapted from the Share study27

-

sexual communication self-efficacy, using selected items appropriate for young people from the Sexual Communication Self-Efficacy scale45

-

sexual competence, using the Natsal measure46

-

communication with parents using a measure from the Ripple study41

-

school engagement using the Beyond Blue School Climate Questionnaire (BBSCQ) measure47

-

career/educational aspirations, using an adapted version of the measure from the Ripple study. 41

We did not pilot a measure of intentional self-regulation as originally planned because we determined that, given the intervention theory of change, it was sufficient to measure self-efficacy of sexual communication.

All of the above measures were assessed for reliability in our pilot, by reporting intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) for repeat measures over time and Cronbach’s alpha statistics at baseline and follow-up for scaled outcomes.

Potential confounders/moderators were SES, as measured using the Family Affluence Scale (FAS),48,49 sex and ethnicity, using standard Office for National Statistics (ONS) categories. 50 The FAS score was calculated by scoring item responses numerically, with the least affluent options being scored 0, and the item scores being summed to give a total scale score. We originally planned to pilot moderator analyses, but this was not done as these analyses would have been severely underpowered.

A detailed table describing key measures is provided in Report Supplementary Material 3.

Economic evaluation outcomes

Given the lack of previous economic evaluations in this area, the aim of the economic analysis was to examine whether or not it would be feasible to assess the cost-effectiveness of the Positive Choice intervention using a cost–consequences analysis within a Phase III trial. The objectives of the economic analysis were to estimate the costs of delivering this new intervention; collect data on health-related quality of life among students and examine response rates and data quality, and to undertake a pilot analysis of intervention impact; and make recommendations about the feasibility of undertaking a cost–consequences analysis alongside a Phase III RCT.

Within the pilot, study methods to measure the incremental cost of the intervention in a Phase III RCT study were developed and piloted. With use of a broad public and third-sector perspective, resources to be measured included those used by SEF, schools and the NHS. Within this, key interventional resources included SEF and school staff time, training events/workshops and consumables. Measures included standardised sessional checklists to monitor and document attendance, preparation and delivery time for key training events and SHPCs; logbooks e-mailed to school staff charged with intervention delivery, assessing time spent on tasks relating to intervention; and all intervention staff travel and other expenses relating to the intervention charged to a specific project grant code.

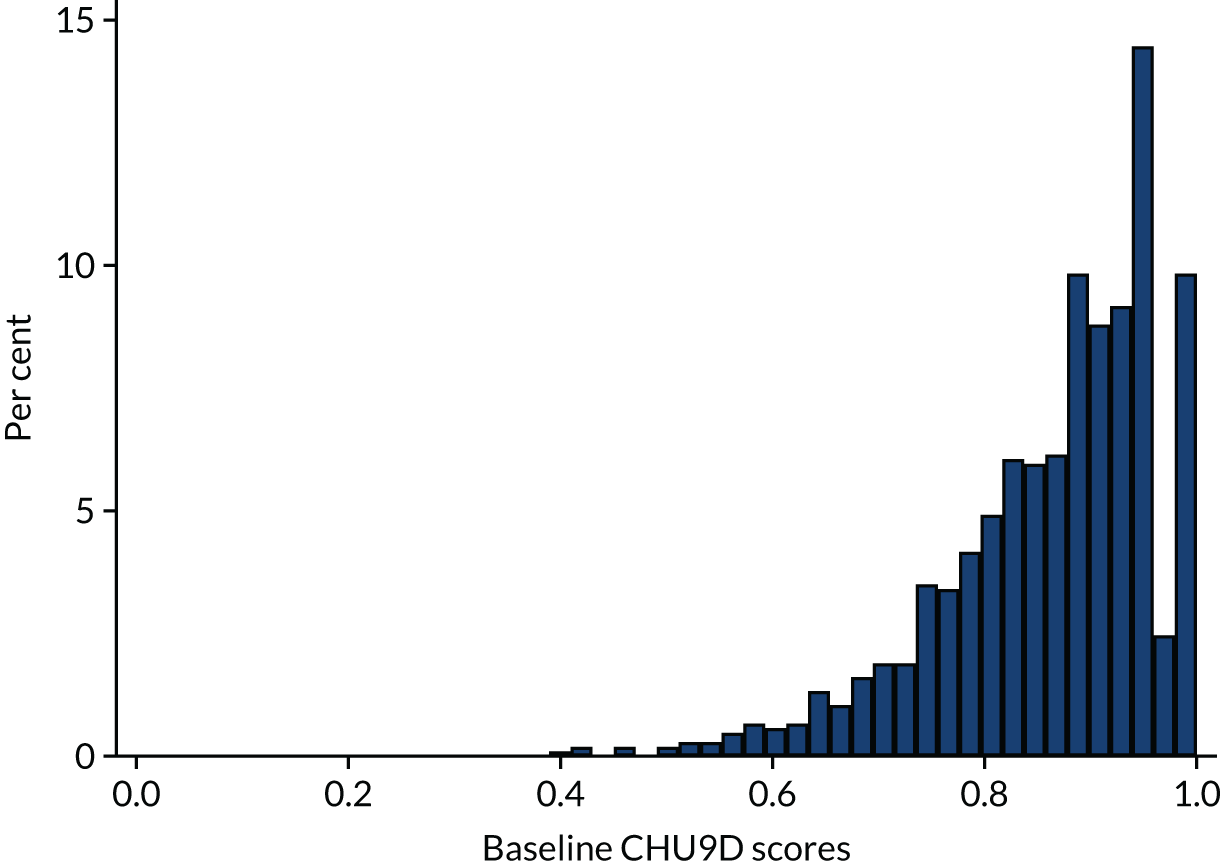

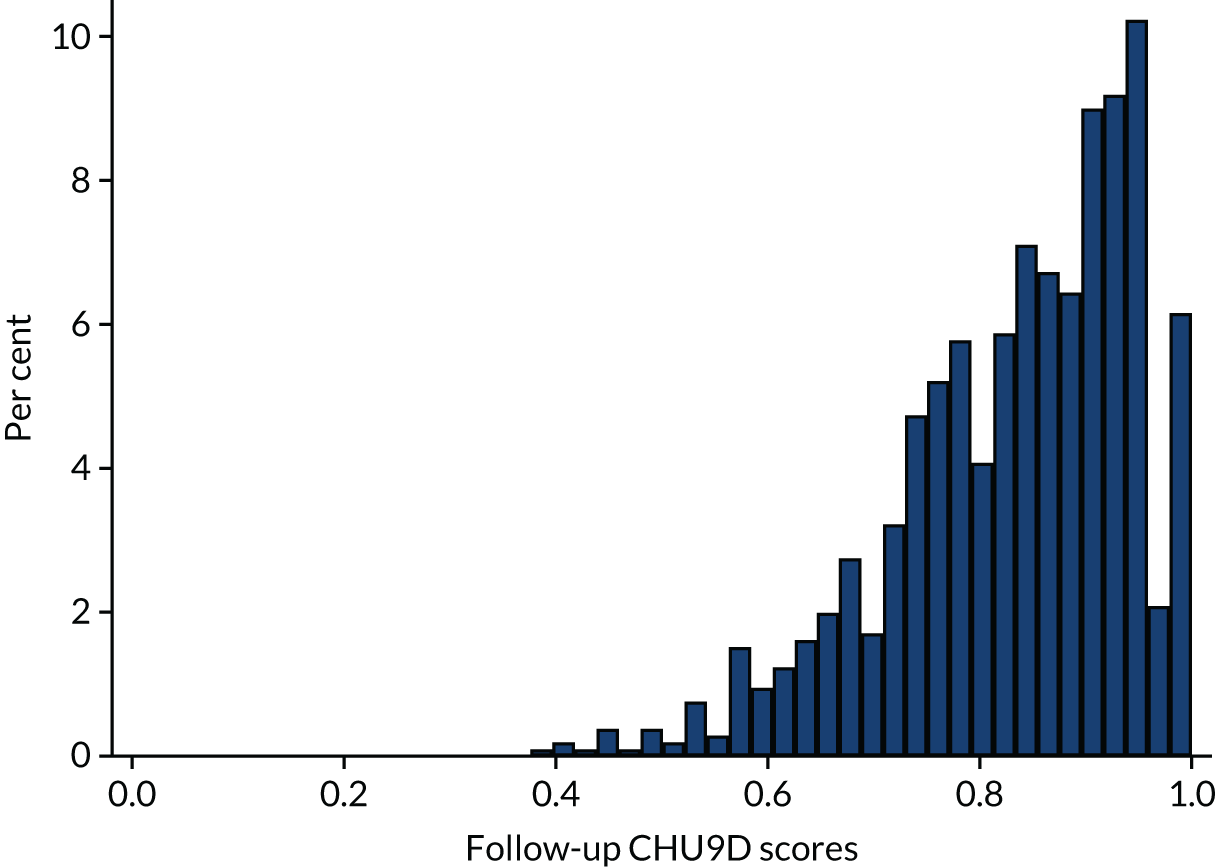

The Child Health Utility-9D (CHU9D) measure was used to assess students’ health-related quality of life. 51 The CHU9D is a validated, age-appropriate measure that was explicitly developed using children’s input and has been suggested to be more appropriate and function better than other health utility measures for children and adolescents. Student utility values were converted into utility scores using a UK valuation set. 52 CHU9D utility values are measured on a scale from 0 to 1, anchored at 1 for full health and 0 for dead. We calculated the completion rates for the CHU9D based on the number of students for whom it was possible to compute CHU9D utility scores at baseline and follow-up. We then observed the distribution of CHU9D scores at both time points, calculating summary statistics and drawing histograms showing the percentage of values at each CHU9D value. We assessed the inter-item reliability of the nine dimensions of the CHU9D using Cronbach’s alpha and the ordinal alpha.

Finally, we undertook a pilot analysis of intervention impact on CHU9D scores using unadjusted and adjusted regression analyses. We regressed (using ordinary least squares) student-level CHU9D utility scores at follow-up against whether the student was in an intervention school or not (1 = yes, 0 otherwise). We ran unadjusted and adjusted analyses. For the latter, we ran two models: the first controlled for baseline age, sex, ethnicity and SES as measured by the FAS, and the second controlled for these variables plus baseline CHU9D utility scores. Results were presented as marginal effects [mean difference (MD) in utility scores between students in intervention and those in control schools] and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Assessment of harms

It was considered unlikely that any harms would arise because of the intervention or the research. The pilot study was not powered to examine intervention effects (beneficial or harmful), but qualitative data were collected as part of the process evaluation to explore any potentially harmful mechanisms.

Data collection

Student surveys

Baseline surveys were conducted before randomisation as students neared the end of year 8 (age 12/13 years) in June 2018, collecting data on outcome measures and potential confounders and moderators. Around 1 week before completing the surveys, students were given an information sheet about the study and the survey. Immediately prior to completing the surveys, students were given an oral description of the study and had the chance to ask questions. Students were then invited to assent to participate in data collection. As is conventional with UK RCTs in secondary schools (including RCTs of sexual health interventions),41,53,54 parents/carers were sent a letter and a detailed information sheet around 1 week before data collection and asked to contact the school or research team should they wish for their child not to participate in the RCT. Paper questionnaires were completed confidentially in classrooms, supervised by fieldworkers, with teachers remaining at the front of the class to maintain quiet and order, but unable to see student responses. Absent students were surveyed by leaving questionnaires and stamped, addressed envelopes with schools for the students to complete.

Students were resurveyed 12 months later in June 2019 as they neared the end of year 9 (age 13/14 years), collecting data on outcomes and mediators using the same consent and fieldwork procedures. Fieldworkers were blind to allocation. Based on past experience, we expected 95% baseline survey participation and 90% at follow-up. 28,53

Data linkage

In the pilot, we sought to link our self-report data with administrative data on abortions and births up to 18 months after baseline surveys, in collaboration, respectively, with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and the ONS. This was to occur by linking data on female RCT participants to routine data on statutory abortion notifications and registration of births, by staff blind to allocation. Linkage of such data had been previously conducted for observational studies26 and initial discussion with ONS had established that data linkage was feasible despite the limited identifiers attached to abortion records, and was consistent with DHSC and ONS guidance and data protection law.

In the case of obtaining birth data from ONS, the research team aimed to implement the following procedures to ensure the anonymity and confidentiality of data. The fieldwork team would securely transfer a password-protected data set of female participants’ names, postcodes and dates of birth (DOBs), to which the CTU did not have access, linked to a unique identifier code for each participant (with the data set not including any self-report survey data). ONS would then prepare a data set containing unique identifier codes (but not other identifiers) linked to any births among trial participants. Having been accredited by the ONS, Elizabeth Allen would then attend the ONS secure data centre to access and carry out analysis of birth data with these having been imported into the main anonymised trial data set. A similar process was to occur to access abortion data, but, in this case, using only DOB and postcode information and not participant names (because routine records of abortion data do not contain patient names), and would involve the secure sending of each data set, rather than in-person visits. Although ONS initially committed to providing data on births up to 18 months after baseline surveys, in the course of the project it reported that it could provide such data up to only 11 months after baseline surveys (from July 2018 to June 2019) because of the time needed to undertake internal quality checks before releasing data.

Process evaluation

Approach to process evaluation

Integral process evaluation informed by existing frameworks54–56 had three purposes: first, to examine intervention feasibility, fidelity, reach and acceptability; second, to assess provision in control schools and potential contamination; and, third, to explore context and potential mechanisms of action, including potential harmful and other unintended effects, in order to refine the intervention theory of change and design.

Intervention feasibility, fidelity, reach and acceptability

Fidelity metrics were finalised once the intervention was fully optimised (August 2018) and approved by the SSC prior to their use (see Appendix 1, Tables 41–44 and Boxes 1–3). Fidelity was defined as:

-

≥ 70% delivery of defined essential elements for the SEF-delivered training

-

≥ 100% attendance of the target number of participants at all training and SHPCs

-

≥ 70% fidelity of defined essential items covered in at least one SHPC and student-led social-marketing meeting, and 70%+ fidelity of other defined essential items covered in every SHPC and every student-led social-marketing meeting

-

≥ 70% delivery of essential elements of eight core and two add-on lessons, including for two homework topics

-

≥ 70% fidelity of defined essential elements of sexual health services review processes.

Data were collected via observation and audio-recording of SEF training for school staff; logbooks of school staff implementing SHPCs, curriculum and social-marketing meetings; and structured observations of a randomly selected session per school of SHPCs, curriculum lessons and social-marketing meetings.

In addition to assessing feasibility and fidelity, we also examined reach and acceptability via qualitative research, as well as student questionnaire survey items at follow-up and surveys of trained staff. Qualitative research explored participants’ experiences to assess their engagement and satisfaction with the intervention and what factors influenced this. Our protocol indicated that we would examine how reach varied by sociodemographic, educational and neighbourhood characteristics; however, because we lacked information on students’ baseline educational attainment or postcode, we confined these analyses to an assessment by SES, ethnicity and sex.

Provision in control schools and potential contamination

We examined sexual health provision in and around control schools in order to describe our comparator. We examined the potential for contamination across arms to ensure that this would not be a threat to internal validity in a Phase III RCT. Data were collected via interviews with at least two members of staff per control school (purposive by seniority) and at least four year 9 students (purposive by sex and SES) per control school.

Context and mechanisms of action

In addition to piloting intermediate outcome variables required for mediator analyses in a subsequent Phase III RCT, we collected qualitative data and analysed these to explore potential mechanisms of action and how these might vary with context to refine and optimise the intervention’s theory of change. We also analysed qualitative data to explore any mechanisms that might give rise to unintended, potentially harmful consequences. Data were collected via individual or group interviews with SEF trainers, at least four staff per intervention school (purposive by seniority/activity involved in), and at least six year 9 students per intervention school (purposive by intervention involvement, risk status and gender).

Sources of data

We aimed to observe one randomly selected session per school of SHPCs, curriculum lessons and social-marketing meetings and to audio-record the SEF-delivered trainings in each intervention school.

After training, staff participants completed anonymous satisfaction surveys, which were an intrinsic part of the intervention.

Each school received a logbook for each school staff member leading the SHPC, or implementing the curriculum or social-marketing meetings. Logbooks contained lists of activities and staff were asked to mark those that were covered.

Interviews with school staff and students were conducted at schools by trained researchers using semistructured interview guides (see Report Supplementary Material 4). No staff were present at student interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed in full. We note the student’s gender where it is identifiable in interview transcripts. We also conducted two interviews with SEF staff which explored their experiences and views of the different phases of the research.

Data analysis

Our main analyses aimed to determine whether or not the criteria for progression to a Phase III RCT were met. Descriptive statistics on fidelity drew on audio-recordings of training, diaries of providers and structured observations of intervention activities. Statistics on acceptability drew on surveys of students and trained staff, and interviews with staff and students. School randomisation and retention, and student response rates at baseline and follow-up were described using a CONSORT flow diagram. 57 We aimed to assess the precision of data linkage in association with DHSC and ONS researchers.

Other analyses addressed our additional research questions. Descriptive summaries of baseline and follow-up data by arm were tabulated. Item completion rates were calculated with the denominator being all students or, where appropriate, students who were routed to these items on the basis of earlier responses. We assessed the reliability of secondary outcome measures by reporting ICCs for repeat measures over time and Cronbach’s alpha statistics at baseline and follow-up for scaled outcomes.

We piloted intention-to-treat analyses of outcomes57 to ensure that these were feasible but, because such analyses were highly underpowered, did not aim to determine intervention effectiveness. In a deviation from protocol, we did not attempt to pilot moderator analyses (how effects vary by SES, sex, ethnicity and baseline risk) because our experience in an earlier study indicated that such analyses would be so severely underpowered as to be completely meaningless. 58 The analysis of the indicative primary outcome included data on pregnancies and abortions at follow-up only. All other outcomes included student-level covariates. For the secondary outcomes, no contraception at first and last sex, students were categorised as reporting this outcome if they reported vaginal sex and a lack of a reliable method of contraception at the sexual event in question. Students who reported no vaginal sex or use of a reliable method of contraception were categorised as not reporting this outcome. For the secondary outcome, non-volitional sex, students were categorised as reporting this outcome if they reported sex with a same- or opposite-sex partner and had experience of forced sex. Students who reported no sex or no forced sex were categorised as not reporting this outcome. Students not providing data to be able to categorise in this way were treated as missing.

As per our protocol, analyses of outcomes adjusted for baseline age, sex, ethnicity and SES as measured by the FAS, with these being imputed from follow-up data when missing at baseline. The protocol originally described the intended analysis as repeat cross-sectional; however, because of low rates of attrition in this pilot and to be able to adjust for baseline student-level covariates, we instead used a longitudinal approach to analysis. For binary outcomes, the fitted model was a mixed-effect logistic regression with random effect for school, reporting odds ratios (ORs). For continuous outcomes (i.e. age at sexual debut and number of partners), a linear mixed model was used, reporting MDs. Standard, rather than bootstrap, CIs were estimated because with these very small numbers more robust inference would represent misleading precision.

Qualitative data were subject to thematic content analysis using techniques drawn from grounded theory such as in vivo and axial codes, and constant comparison. 59 Although deriving themes inductively from the data, analyses were sensitised by realist approaches to evaluation60 and May’s implementation theory55 to examine potential mechanisms of action and of harm, and how contextual factors influence implementation and mechanisms; describe relevant activities in and around intervention and control schools; and refine our programme theory and theory of change.

Our economic feasibility study piloted collection of quality of life data and assessed the feasibility of methods to be used within a Phase III RCT, which, in line with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance,39 would involve a wider cost–consequences analysis, comparing intervention costs with the full range of study outcomes.

Protecting against bias

Although the aim of this study was to optimise the intervention, assess feasibility and then pilot outcome measures and analyses, rather than estimate intervention effects, we piloted methods aimed at minimising bias. The investigator team and the intervention delivery team were separately managed. In the pilot RCT, outcome data were collected and analysed blind to allocation, and we examined effects adjusting for potential baseline confounders. We aimed to maximise response rates at each pilot RCT site at baseline and at follow-up to minimise non-response and attrition bias, for example following up those individuals not present during survey sessions. Response rates and qualitative data were analysed to refine data collection methods prior to a Phase III RCT examining effectiveness. Blinding of participants to allocation was not possible.

Consultation with public, policy and practice stakeholders

Positive Choices was optimised by the research team, SEF staff, and staff and students from one secondary school. Young people from the ALPHA group were consulted three times during the project: in July 2017, April 2018 and January 2019. Policy and practice stakeholders were consulted twice: in March 2018 and June 2019. The first two consultations with the ALPHA group and the first policy and practitioner stakeholder group focused on intervention optimisation and their methods are described in Optimisation, with the results presented in Chapter 3. The third meeting of the ALPHA group focused on refining sexual behaviour questions and consent materials for the pilot follow-up. Findings from this meeting, as well as findings from earlier consultations that focused on the research rather than the intervention, are reported in Chapter 4. The second meeting of the policy and practitioner stakeholder group provided a progress update to participants and shared some early findings from the ongoing process evaluation. A further meeting scheduled with the ALPHA group and one with the policy and practice stakeholder group will focus on interpreting the results and implications of the study, mechanisms for knowledge exchange and future research.

Registration

The study protocol was published online (https://pilotfeasibilitystudies.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s40814-018-0279-3) and registered Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN12524938.

Revisions to the protocol

The protocol was revised a number of times between 23 May 2017 to 22 February 2018 (see Appendix 2, Table 45).

Deviations from the protocol

There were also a number of deviations from the protocol, which are listed in Chapter 6 and summarised in Table 40.

Socioeconomic position and inequalities

In the pilot RCT, six schools in south-east England were recruited (varying by local deprivation and school-level GCSE attainment) to ensure diversity and balance on key predictors of teenage pregnancy. 26 Our process evaluation aimed to assess how implementation and intervention mechanisms appeared to vary by student SES and gender.

Research governance

The principal investigator (PI), Chris Bonell, had overall responsibility for the conduct of the study. The day-to-day management of the study was co-ordinated by the trial manager, Ruth Ponsford, based in LSHTM. The PI (CB) chaired weekly Trial Executive Group meetings with the trial manager, statistician (EA) and, where appropriate, SEF, CTU and fieldwork staff. Chris Bonell also chaired a Trial Investigators’ Group, which included all co-investigators and members of the Trial Executive Group; the Trial Investigators’ Group met monthly during the early stages of the research (months 1–6), and every 3 months thereafter. An independent SSC was established and met three times throughout the life of the project to advise on the conduct and progress of the RCT, and on relevant practice and policy issues. Professor Angela Harden of the University of East London chaired the SSC. Because this was a pilot and not a Phase III RCT, the SSC undertook data monitoring and ethics duties and was informed of any serious adverse events (SAEs) as described in Ethics arrangements. The project employed standardised research protocols and prespecified progression criteria, which were agreed and monitored by the Trial Investigators’ Group and SSC.

Ethics arrangements

Ethics review

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the LSHTM Ethics Committee on 21 March 2017.

Policies and checks

Any member of the research/fieldwork team visiting a school was required to have a full Disclosure and Barring Services check. All work was carried out in accordance with guidelines laid down by the Economic and Social Research Council, the Data Protection Act 1998, the latest Directive on Good Clinical Practice (2005/28/EC) and the General Data Protection Regulation 2018.

Informed consent/assent

Informed, written consent was sought from head teachers for random allocation and intervention. Informed written consent (for adults) and assent (for young people) was sought for participation in research activities from all research participants judged competent to provide this. We sought advice from Professor Richard Ashcroft, Professor of Medical Ethics at Queen Mary University of London, who is an expert on informed consent. He advised that in the case of secondary-school students, unless individuals were deemed not competent by teachers to provide it, assent for participation should be sought from the young people themselves.

For surveys, interviews and focus groups, observations and audio-recordings, participants were given an information sheet around 1 week before data collection. Just before data collection, participants also received an oral description of the study and had the chance to ask questions. Participants were advised that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any point. All participants were advised that they were free to withhold consent and this matter would not be communicated to teachers or, in the case of staff participants, their managers. Students opting not to participate in surveys were offered alternative activities in the classroom. Those opting out of other data collection were free to continue with their normal activities.

The research also involved the piloting of the linkage of student survey data to administrative data on births and abortions with, respectively, the ONS and DHSC. Female survey participants were informed of this process as part of consent procedures for follow-up surveys, and their specific assent for this was sought.

In addition, students’ parents were contacted by letter 1 week prior to research activities, informing them about informed consent and providing them with the option of withdrawing their child by contacting the school or the research team. Parental consent for intervention was not required because this was a universal intervention delivered in schools as part of broader educational activities.

Confidentiality, safeguarding and serious adverse events

All participants, including students, were informed in the consent materials of the confidentiality with which the information they provided would be treated, as well as the circumstances in which we would need to breach confidentiality to ensure student safeguarding. In collaboration with a qualified social worker specialising in child protection, we developed a priori categories of abuse that, if reported through the research, would necessitate our breaching confidentiality to ensure that individuals were offered care and protection: if they reported sex at age ≤ 12 years or if they wrote anything on the questionnaire that would lead us to believe that they were at risk of ongoing serious harm. These criteria were established so that we could balance our ethical duty of promoting participant autonomy by respecting confidentiality and our ethical duty of safeguarding participant well-being when we determined that we needed to breach confidentiality to address abuse that appeared to be serious and ongoing. It was planned that where such abuse was reported through a questionnaire, we would contact the safeguarding lead at the school. Where such abuse was reported directly to research staff, we planned to first discuss the need for a response with the research participant prior to contacting the school safeguarding lead (see Appendix 3).

Qualitative research (i.e. interviews, focus groups and observations) did not ask staff or students about their experience of sex; however, if participants nonetheless described any sexual abuse, or otherwise became upset in any way, our researchers were trained in how to respond. In the case of focus groups, our researchers were trained to ensure that discussions did not move in the direction of personal disclosures of sexual behaviour since this was not the purpose of the groups and it would have been very difficult to ensure that all focus group participants did not talk about such disclosures outside the group. Our staff were trained to identify the potential for such disclosures, working to avoid them but then approaching participants immediately after the focus group to offer support and to assess whether or not any other response was needed, using the same procedures as described above.

In addition, we requested information on SAEs from participating schools and assessed the plausibility that any of the SAEs were related to intervention or research activities in collaboration with school safeguarding leads.

It was planned that the SSC and LSHTM Ethics Committee would be provided with anonymised reports of all disclosures of serious abuse and SAEs, categorised by type, circumstances and the extent of any possible connection with intervention or research activities.

In each school and within NCB, a senior member of staff was identified who was not directly involved with the intervention and whom staff or students could go to if they had complaints about any elements of the research study. This was communicated to students outside the research process to increase trust that this was truly independent.

Data anonymity and security

Quantitative and qualitative data were managed by project staff using secure data management systems and stored anonymously using participant identification numbers. Quantitative data were managed by LSHTM’s accredited CTU. Files containing participant identification numbers and corresponding participant names were held in password-protected files separate to files containing self-report survey data, which were attached only to student identification numbers. No single researcher had access to both sets of data. The names used in qualitative data were replaced with pseudonyms in interview/focus group transcripts. In reporting the results of the process evaluation, care was taken to use quotations that did not reveal the identity of respondents. The methods by which anonymity was maintained in relation to the linkage of survey data and routine data on births and abortions are described in Data linkage.

In line with Medical Research Council guidance on personal information in medical research, we will retain all research data for 20 years after the end of the study. This is to allow secondary analyses and further research to take place, and to allow any queries or concerns about the conduct of the study to be addressed. In order to maintain the accessibility of the data, the files will be refreshed annually and upgraded, if required.

Chapter 3 Results: optimisation and feasibility testing

This chapter includes material reproduced or adapted from Ponsford et al. 1 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Overview

The first phase of the Positive Choices study involved intervention optimisation in collaboration with SEF, one London secondary school and other youth, practitioner and policy stakeholders. As explained earlier, optimisation refers to the elaboration of the intervention, developing it from a basic description to a fully specified intervention with materials. Optimisation overlapped with feasibility assessment in the participating London secondary school, with the student needs survey, the manual guiding the SHPC and the staff training package being optimised June–August 2017 and tested September–December 2017; the student curriculum being optimised September–December 2017 and tested January–March 2018; and the student-led social marketing and sexual health services review being optimised January–March 2018 and tested April–July 2018. Feasibility testing was followed by further intervention refinement in preparation for the pilot. This part of the report presents the results from the optimisation and feasibility-testing phases.

Optimisation

Initial elaboration of Positive Choices

Initial elaboration of Positive Choices was carried out following a review by researchers of existing systematic reviews, Safer Choices, CAS Carrera and Gatehouse Project evaluations, and a review by SEF of materials from Safer Choices and other interventions and resource packages, as well as a telephone conversation with Karin Coyle of ETR Associates who led the Safer Choices RCT. Initial points of elaboration agreed between researchers and SEF prior to consultation with schools, other youth and practitioner and policy stakeholders are outlined below. Where these deviated from the specification in the original protocol, this is highlighted.

Needs survey to tailor intervention components

The original protocol had specified that a student needs survey of year 8 students (drawing on the baseline RCT survey) would be used to tailor Positive Choices to local priorities in each school. There was, however, a need for some elaboration of the content of the needs survey and how it would be used to inform the intervention. Regarding the curriculum, the protocol originally specified that, informed by the needs assessment data, SHPCs would select the order in which to deliver modules; whether to deliver them within personal, social, health and economic education (PSHE), tutor groups or by integrating them into other lessons; and whether to use materials from Positive Choices or existing materials, if these conformed to our curriculum. However, SEF advised that, in practice, not all of these things would be likely to be open to influence by the needs data or the SHPC. In which lessons the curriculum would be taught, for example, would probably already be determined by school leaders. Whether to use existing or Positive Choices materials would be determined through an assessment by SEF of the resources to which the school already had access. SEF also felt that there should be a logical order to lessons (e.g. understanding reproduction before contraception), which precluded SHPCs determining this.

It was agreed that the most useful way to use the student needs assessment was to inform the selection of curriculum lessons for each school. Students would be asked in the needs survey what RSE topics they had covered previously in school, how well they had been covered and what they wanted to cover in year 9. To ensure alignment with the intervention theory of change and that all basic SEF-recommended material was covered in a logical order, the curriculum was initially designed to include a set of five ‘essential’ lessons to be covered by all schools and a bank of 10 ‘add-on’ lessons, five of which could be selected by the SHPC based on the student needs data. This was a deviation from the protocol.

Questions on how well RSE topics had been covered in school, knowledge of conception, contraception and STIs, knowledge of services, parental communication, experiences of sending/receiving sexual imagery and sexual harassment at school were included in the needs survey (see Report Supplementary Material 5) to lend more general support for implementation of Positive Choices in schools and to inform the content of parent newsletters, the focus of student-led social-marketing activities and the review of sexual health services.

School health promotion council activities

Although the original protocol stated that the role of the SHPC would be to review local needs data and to use these to tailor each intervention component, and co-ordinate intervention delivery, the exact tasks of the SHPC (other than those set in relation to the student curriculum) were not specified. Based on a review of the Safer Choices materials and discussion between researchers and SEF, it was agreed that the main activities of the SHPC would involve reviewing the student needs data and identifying how the data could inform decisions about the implementation of each intervention component of Positive Choices; launching the intervention in schools and to parents; selecting the ‘add-on’ curriculum topics informed by the needs data; taking a role in recruiting the social-marketing team and monitoring campaign activities; preparing and distributing parent newsletters; and carrying out the school sexual health services review. These elaborations did not constitute a deviation from the protocol.

Topics covered by curriculum

Although the curriculum areas identified in the protocol reflected those recommended by SEF for inclusion in a comprehensive year 9 curriculum, they did not map exactly onto the SEF’s suggested curriculum structure and there were some additional topics such as ‘pornography and the law’, ‘female genital mutilation’ (FGM) and ‘body image’ that SEF wanted to ensure were covered for year 9. Inclusion of topics such as ‘the male/female body and reproduction’ were also considered to be essential, as these provided the building blocks for later learning, which many students may not have received in primary school or in years 7 or 8. It was agreed that the curriculum format and lesson titles suggested by SEF would be adopted, but that all topics referred to in the protocol would be embedded within the lessons to ensure alignment between the lessons and intervention theory of change. This did not constitute a deviation from the protocol.

The curriculum was initially designed within the optimisation and feasibility-testing phase to include the following five essential lessons: (1) the female/male body and reproductive organs; (2) reproduction, pregnancy and contraception; (3) STIs and safer sexual practices; (4) sexual response and pleasure; and (5) building blocks to good relationships to cover the core topics specified in the protocol. Five of the following 10 ‘add-on’ lessons were also to be selected, informed by the student needs data: (6) readiness for intimacy; (7) unsafe relationships; (8) love; (9) sexual identity, gender and orientation; (10) understanding consent; (11) pregnancy options; (12) FGM; (13) pornography and the law; (14) body image and the digital world; and (15) values in our community. However, the number of lessons and titles, and the balance between ‘essential’ and ‘add-on’ lessons were modified again when moving from the feasibility-testing to the pilot RCT phase of the study.

Student-led social marketing